Advances in Specificity for Ubiquitination Site Identification: From Computational Predictions to Experimental Validation

The precise identification of ubiquitination sites is crucial for understanding cellular regulation, disease mechanisms, and developing targeted therapies.

Advances in Specificity for Ubiquitination Site Identification: From Computational Predictions to Experimental Validation

Abstract

The precise identification of ubiquitination sites is crucial for understanding cellular regulation, disease mechanisms, and developing targeted therapies. This article synthesizes current methodologies and emerging technologies aimed at improving the specificity of ubiquitination site mapping. We explore foundational concepts of the ubiquitin code and site-specific consequences, evaluate advanced computational tools like Ubigo-X that integrate deep learning with image-based features, and examine cutting-edge experimental techniques such as the BioE3 system for E3 ligase-specific substrate profiling. The content addresses critical challenges including low stoichiometry, linkage complexity, and PTM cross-talk, while providing a comparative analysis of prediction algorithms and validation strategies. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to implement high-specificity approaches in their ubiquitination studies.

Decoding the Ubiquitin Landscape: Fundamental Principles and Specificity Challenges

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This section addresses common experimental challenges in ubiquitination research, focusing on improving the specificity of ubiquitination site identification.

FAQ 1: How can I improve the specificity and coverage for mapping ubiquitination sites via mass spectrometry?

Answer: A major challenge in MS-based ubiquitinomics is the low abundance of ubiquitinated peptides and the need for highly specific enrichment. The UbiSite Approach directly addresses this.

- Core Technology: Utilize an antibody (UbiSite) that is highly specific for the C-terminal 13 amino acids of ubiquitin, which remain attached to modified lysine or protein N-terminal after LysC digestion [1].

- Key Advantage: This method avoids the need for tryptic digestion that leaves a bulky Gly-Gly remnant on lysines, instead leveraging the specificity of LysC. It allows for the comprehensive identification of both lysine and N-terminal ubiquitination sites with high confidence [1].

- Protocol Summary:

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells in a denaturing buffer to preserve modifications and inactivate deubiquitinases (DUBs).

- Protein Digestion: Digest the proteome with the endoproteinase LysC.

- Peptide Enrichment: Enrich for ubiquitinated peptides using the UbiSite antibody.

- Secondary Digestion: Digest the enriched peptides with trypsin to prepare them for MS.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Analyze the peptides using high-accuracy mass spectrometry [1].

FAQ 2: My western blot signals for polyubiquitinated proteins are weak. What high-affinity tools can I use for detection?

Answer: Weak signals often result from low-affinity detection reagents or the transient nature of ubiquitination. Tandem Hybrid Ubiquitin Binding Domain (ThUBD)-based technologies offer a significant improvement.

- Recommended Solution: Use reagents based on Tandem Hybrid Ubiquitin Binding Domain (ThUBD). This engineered domain exhibits unbiased, high-affinity binding to all types of ubiquitin chains [2].

- Performance Data: In a 96-well plate format, ThUBD-coated plates demonstrated a 16-fold wider linear range for capturing polyubiquitinated proteins compared to older TUBE (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entity) technology [2]. The following table quantifies this performance:

Table 1: Comparison of Ubiquitin Capture Technologies

| Technology | Affinity for Ubiquitin Chains | Linkage Bias | Detection Sensitivity | Best Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ThUBD-coated plates | High (nanomolar range) | Unbiased | 0.625 μg (16x more sensitive than TUBE) | High-throughput, global ubiquitination profiling [2] |

| TUBE-coated plates | Low-micromolar range | Biased towards specific chain types | 10 μg | General ubiquitination detection [2] |

| Standard Antibodies | Variable, often low | High (often linkage-specific) | Variable | Target-specific assays with confirmed specificity [2] |

- Troubleshooting Protocol for TUF-WB (ThUBD-based Ubiquitin Fractionation - Western Blot):

- Capture: Incubate your cell lysate with ThUBD-coated plates or ThUBD-conjugated beads.

- Wash: Use a stringent wash buffer (e.g., containing 0.1% SDS) to reduce non-specific binding.

- Elution: Elute the captured ubiquitinated proteins with a standard Laemmli buffer for western blotting.

- Detection: Proceed with standard western blot protocol using your target protein antibody [2].

FAQ 3: How can I specifically monitor K48- vs. K63-linked ubiquitination of my protein of interest in a high-throughput format?

Answer: Discriminating between ubiquitin chain linkages is crucial for understanding a protein's fate. Chain-specific TUBEs enable this in assay plates.

- Technology: Use linkage-specific TUBEs (e.g., K48-TUBE or K63-TUBE) coated on high-density 96-well plates [3].

- Application Example: This method has been successfully used to differentiate the ubiquitination of RIPK2:

- Experimental Workflow:

- Treatment & Lysis: Treat cells (e.g., THP-1) with your stimulus or inhibitor. Lyse cells with a buffer that preserves polyubiquitination.

- Incubation: Add lysate to the chain-specific TUBE-coated plate.

- Capture & Wash: Allow endogenous ubiquitinated proteins to bind, then wash away unbound material.

- Detection: Detect your specific target protein using a tagged or enzyme-linked antibody in the plate, enabling quantitative, high-throughput readout [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Advanced Ubiquitination Research

| Research Reagent | Core Function | Key Application in Ubiquitination Research |

|---|---|---|

| UbiSite Antibody [1] | Highly specific immuno-enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides post-LysC digestion. | Comprehensive, site-specific mapping of lysine and N-terminal ubiquitination for mass spectrometry. |

| ThUBD (Tandem Hybrid Ubiquitin Binding Domain) [2] | Unbiased, high-affinity capture of all ubiquitin chain linkages. | Sensitive detection and quantification of global ubiquitination signals in western blot (TUF-WB) or plate-based assays. |

| Chain-Specific TUBEs (K48, K63) [3] | Selective enrichment of proteins modified with a specific ubiquitin chain topology. | Investigating the functional outcome of ubiquitination (e.g., degradation vs. signaling) in high-throughput screening formats. |

| Reconstituted Ubiquitination System (E1, E2, E3, Ub) [4] | Provides the core enzymatic machinery for in vitro ubiquitination assays. | Mechanistic studies of E3 ligase function, inhibitor screening, and validation of direct substrate ubiquitination. |

| PROTACs [5] [3] | Heterobifunctional molecules that recruit E3 ligases to target specific proteins for degradation. | A key therapeutic modality that exploits the ubiquitin-proteasome system for targeted protein degradation. |

Experimental Pathways & Workflows

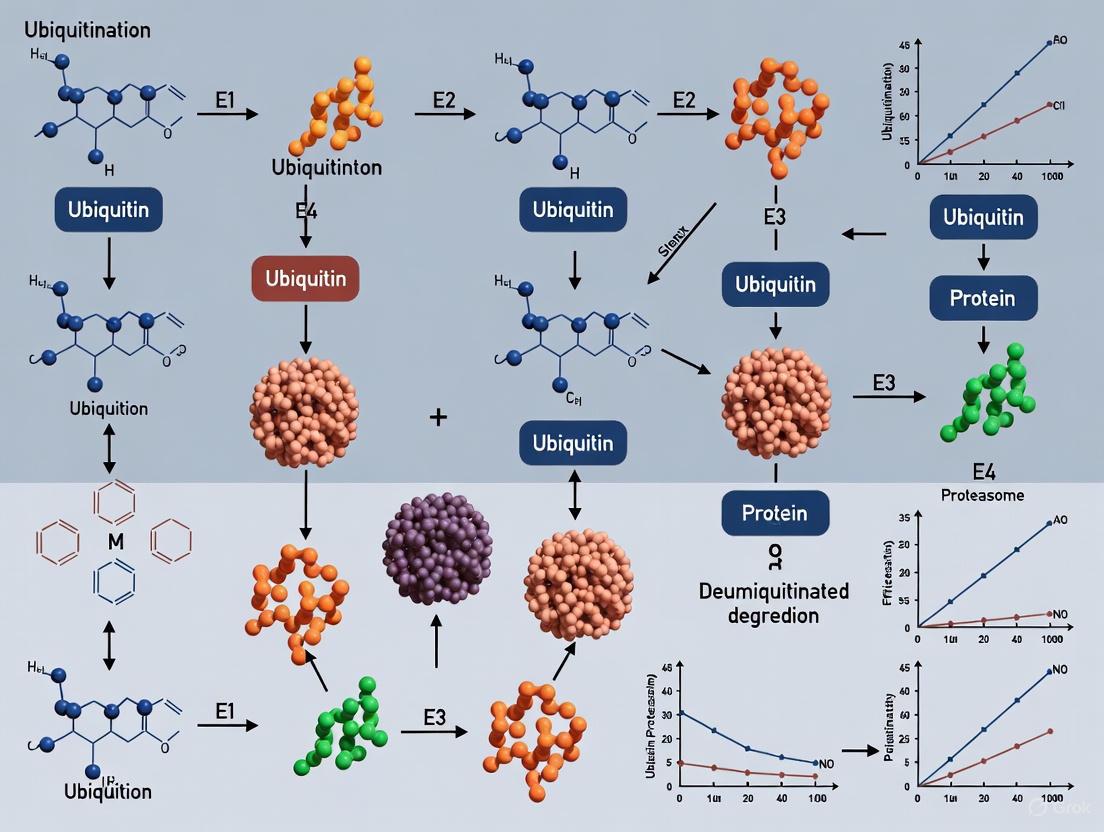

The following diagrams illustrate key signaling pathways and experimental workflows in ubiquitination research.

Ubiquitin Cascade and Functional Outcomes

UbiSite MS Workflow for Ubiquitination Site Mapping

TUBE-based Assay for Linkage-specific Ubiquitination

Core Concepts: The Ubiquitin Code

Ubiquitination is a post-translational modification where a small protein, ubiquitin, is covalently attached to substrate proteins. This process is mediated by a cascade of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes [6] [7]. The E3 ligases are particularly crucial for conferring substrate specificity [6].

The functional outcome of ubiquitination is determined by the site of modification on the substrate and the type of ubiquitin chain formed. Ubiquitin itself contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1), all of which can serve as linkage points for polyubiquitin chains. This creates a "ubiquitin code" that is interpreted by cellular machinery [6] [7].

Table: Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Primary Functions

| Linkage Type | Chain Length | Primary Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| K48 | Polymeric | Canonical signal for proteasomal degradation [8] [9]. |

| K63 | Polymeric | Innate immunity, inflammation, DNA repair, endocytic trafficking [8] [7] [9]. |

| M1 (Linear) | Polymeric | Cell death, immune signaling (NF-κB activation), protein quality control [7] [9]. |

| K6 | Polymeric | Mitophagy, antiviral responses, DNA repair [7] [9]. |

| K11 | Polymeric | Cell cycle regulation, proteasomal degradation [7] [9]. |

| K27 | Polymeric | DNA damage response, innate immunity [7] [9]. |

| K29 | Polymeric | Neurodegenerative disorders, Wnt signaling regulation [7] [9]. |

| Monoubiquitination | Monomer | Endocytosis, histone regulation, DNA damage responses [6] [9]. |

A key concept is site-specificity—the exact residue on a substrate that is ubiquitinated can dictate the molecule's fate. For example, ubiquitination at specific lysines can induce conformational changes or alter the protein's energy landscape, making it more susceptible to proteasomal degradation. In contrast, ubiquitination at other sites on the same protein may trigger non-degradative signaling roles [6].

Figure 1: The Ubiquitin Code Decision Tree. Different ubiquitin chain linkages direct substrate proteins toward proteasomal degradation or various non-degradative signaling functions. Some linkages, like K11, can signal for both fates [7] [9].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Common Ubiquitination Research Challenges

Q1: My western blot for ubiquitinated proteins shows a high background smear. How can I improve the signal-to-noise ratio? A: A common cause is non-specific binding of ubiquitin antibodies. To address this:

- Use a high-affinity, specific enrichment tool like the Ubiquitin-Trap (ChromoTek) for immunoprecipitation prior to western blotting. This pulldown is designed for low-background isolation [9].

- Ensure your antibodies are specific and have been validated for the application. Many commercial ubiquitin antibodies are non-specific and bind artifacts [9].

- Treat cells with a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG-132, typically 5-25 µM for 1-2 hours) before harvesting. This prevents the rapid degradation of polyubiquitinated proteins, thereby enriching for them. Avoid overexposure to prevent cytotoxicity [9].

Q2: I have identified a potential ubiquitination site via mass spectrometry. How can I validate that it is functionally important for degradation? A: Functional validation requires a combination of biochemical and cellular assays.

- Mutation Analysis: Mutate the specific lysine residue(s) to arginine (K→R). If the mutant protein shows increased stability (longer half-life) compared to the wild-type, it suggests the site is critical for degradation-targeting ubiquitination [10].

- Biophysical Assays: Consider that ubiquitination can cause site-specific thermodynamic destabilization. Techniques like NMR or differential scanning calorimetry can probe whether ubiquitination at your site of interest induces partial unfolding, a signal recognized by the proteasome [6].

- Pulse-Chase Analysis: Perform a pulse-chase experiment to directly measure the half-life of your wild-type and K→R mutant proteins.

Q3: How can I determine which E3 ligase is responsible for ubiquitinating my protein of interest at a specific site? A: Identifying the responsible E3 ligase is complex due to the large number of E3s and potential redundancy.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Start by analyzing the sequence around the ubiquitination site. Some E3s recognize specific motifs or "degrons," and intrinsic disorder in the region can be a facilitating factor [11].

- Functional Screening: Use siRNA or CRISPR-based screens to knock down/out candidate E3 ligases and observe the effect on your substrate's ubiquitination status or stability.

- Biochemical Interaction Studies: Perform co-immunoprecipitation to identify E3 ligases that physically interact with your substrate. Follow up with in vitro ubiquitination assays using purified components to confirm activity [6].

Q4: I suspect non-degradative ubiquitination is regulating my protein's activity. How can I investigate this? A: Focus on linkages and readouts unrelated to protein half-life.

- Linkage-Specific Tools: Use linkage-specific ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., anti-K63, anti-M1) in pulldown or western blot experiments to detect chains associated with non-degradative functions [8] [9].

- Functional Assays: Look for ubiquitination-dependent changes in your protein's activity, such as altered kinase activity, changed interaction partners in co-IP experiments, or subcellular relocalization [6] [7].

- Non-Hydrolyzable Mutants: Express ubiquitin mutants that can only form specific chain types (e.g., K63-only) in your cells and assess the impact on your protein's signaling function [7].

Systematic Troubleshooting for Failed Ubiquitination Experiments

When an experiment fails, a systematic approach is critical [12].

- Repeat the Experiment: Rule out simple human error or a single equipment malfunction by repeating the procedure [12].

- Verify the Result: Revisit the scientific literature. Is your negative result biologically plausible, or does it strongly indicate a technical failure? [12]

- Check Controls: Ensure you have included the proper controls.

- Positive Control: A known ubiquitinated substrate to confirm your detection method is working.

- Negative Control: A sample without the E3 ligase or with a catalytically dead E3 mutant [12].

- Inspect Reagents and Equipment:

- Confirm reagents (enzymes, antibodies, cell lines) have been stored correctly and have not expired [12].

- Check that equipment (mass spectrometers, centrifuges) is properly calibrated and functioning.

- Change One Variable at a Time: If the problem persists, methodically test one potential variable at a time [12]. Common variables include:

- Ubiquitination Assay: E1/E2/E3 enzyme concentrations, reaction time/temperature, ATP concentration.

- Cell-Based Assay: Proteasome inhibitor concentration and treatment duration, transfection efficiency, cell lysis conditions (including deubiquitinase inhibitors).

- Document Everything: Meticulously record all steps, conditions, and observations in a lab notebook. This is essential for identifying patterns and solving complex problems [12].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Identifying Ubiquitination Sites by Mass Spectrometry

This is a robust method for the direct, site-specific identification of ubiquitination.

Workflow Overview:

- Enrich Ubiquitinated Proteins: To overcome the low stoichiometry of ubiquitination, enrich modified proteins from cell or tissue lysates. This can be done using:

- Ubiquitin-Trap Immunoprecipitation: Use agarose or magnetic beads coupled with a high-affinity anti-ubiquitin nanobody (e.g., ChromoTek Ubiquitin-Trap) [9].

- Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs): Use other high-affinity ubiquitin-binding modules.

- Cell Treatment: Pre-treat cells with a proteasome inhibitor (MG-132) to stabilize polyubiquitinated proteins [9].

- Digest Proteins: Digest the enriched proteins into peptides using a specific protease like trypsin or Glu-C [11]. A signature di-glycine remnant (Gly-Gly, +114.1 Da) remains on the modified lysine after tryptic digestion, which serves as a mass tag.

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): Separate the peptides by liquid chromatography and analyze them by tandem mass spectrometry. The mass spectrometer will detect the +114.1 Da mass shift on lysine residues and fragment the peptides to determine their sequence and the exact site of modification [11].

- Data Analysis: Use bioinformatic tools (e.g., SEQUEST, PeptideProphet) to process the spectral data and identify peptides with high confidence [11].

Figure 2: Ubiquitination Site Identification by MS. Workflow for the enrichment and mass spectrometry-based identification of ubiquitination sites, highlighting key steps like enrichment and bioinformatic analysis [11] [9].

Protocol 2: Validating Ubiquitination Site Functionality

After identifying a potential site, follow this protocol to confirm its functional role.

Workflow Overview:

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Generate a mutant construct of your protein where the target lysine (K) is replaced by arginine (R). Arginine is a conservative substitution that maintains a positive charge but cannot be ubiquitinated [10].

- Express Wild-Type and Mutant Proteins: Transfect cells with constructs for the wild-type (WT) and K→R mutant protein.

- Assess Ubiquitination Status:

- Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot: Immunoprecipitate your protein and probe for ubiquitin. A significant reduction in ubiquitination signal in the K→R mutant compared to the WT indicates the specific site is a major target for modification [10].

- Determine Functional Consequence:

- For Degradative Ubiquitination: Perform a cycloheximide chase or pulse-chase experiment to measure protein half-life. Stabilization of the K→R mutant suggests the site is used for degradation [6].

- For Non-Degradative Ubiquitination: Assess the functional output of the pathway (e.g., kinase activity, reporter gene assay, protein-protein interactions). Loss of function in the K→R mutant implicates ubiquitination at that site in the signaling process [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitination Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| MG-132 (Proteasome Inhibitor) | Stabilizes polyubiquitinated proteins by blocking their degradation by the proteasome, allowing for enrichment and detection [9]. | Use at optimized concentrations (e.g., 5-25 µM); overexposure is cytotoxic [9]. |

| Ubiquitin-Trap (Agarose/Magnetic) | High-affinity nanobody-based resin for immunoprecipitating monomeric ubiquitin, ubiquitin chains, and ubiquitinylated proteins from cell lysates with low background [9]. | Not linkage-specific. Binding capacity can vary due to heterogeneous chain lengths [9]. |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies | Western blot detection or validation of specific polyubiquitin chain topologies (e.g., K48, K63) [9]. | Essential for differentiating between degradative and non-degradative ubiquitin signals. Quality and specificity vary by vendor. |

| UbPred Software | Bioinformatics tool for in silico prediction of ubiquitination sites from protein sequence [11]. | A random forest-based predictor; useful for prioritizing lysines for experimental validation [11]. |

| E1, E2, and E3 Enzymes | For in vitro ubiquitination assays to reconstitute the ubiquitination cascade and study specific enzyme-substrate relationships [6]. | Requires purification of active enzyme components. E3 ligases determine substrate specificity [6]. |

| K→R Mutant Constructs | Validating the functional importance of a specific ubiquitination site by preventing modification at that residue [10]. | A conservative mutation; multiple sites may need to be mutated if there is redundancy [10]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Low Stoichiometry and Detection Sensitivity

Q: Why is it so difficult to detect ubiquitination sites in my experiments, even when I know my protein of interest is ubiquitinated?

A: The primary reason is the characteristically low stoichiometry of ubiquitination. This means that at any given moment, only a very small fraction of a specific protein substrate is ubiquitinated. This low abundance is further compounded by the dynamic and rapid turnover of the modification, as ubiquitinated proteins are often quickly degraded by the proteasome or deubiquitinated [13]. The median ubiquitination site occupancy is three orders of magnitude lower than that of phosphorylation, making it a challenge for detection methods without prior enrichment [14].

- Recommended Solution: Implement a robust enrichment strategy prior to mass spectrometry analysis. The following table compares the most common methods.

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Remnant Immunoaffinity Enrichment [15] | Uses antibodies (e.g., K-ε-GG antibody) to enrich for tryptic peptides containing the di-glycine remnant. | - Excellent for site identification- Compatible with quantitative MS (SILAC, TMT) [16] | - Cannot distinguish linkage types- May miss peptides due to incomplete digestion |

| Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) [15] | Uses engineered high-affinity ubiquitin-binding domains to purify ubiquitinated proteins. | - Protects ubiquitin chains from DUBs- Captures proteins with diverse chain linkages | - Does not provide direct site information without downstream MS |

| Affinity-Tagged Ubiquitin (e.g., His, Strep) [15] | Cells are engineered to express tagged ubiquitin; ubiquitinated proteins are purified via the tag. | - Powerful for proteome-wide profiling | - Potential for artifacts from tag overexpression- Not suitable for clinical or tissue samples |

FAQ 2: Dynamic Regulation and Quantitative Measurement

Q: How can I accurately measure the changes in ubiquitination of my substrate under different conditions (e.g., drug treatment, pathway activation)?

A: The dynamic nature of ubiquitination, controlled by the opposing actions of E3 ligases and deubiquitinases (DUBs), means that steady-state levels provide an incomplete picture [17]. To understand flux through a ubiquitin-driven pathway, you need quantitative methods that can capture kinetics and stoichiometry [16].

- Recommended Solution: Combine ubiquitin enrichment with quantitative mass spectrometry techniques.

- Stable Isotope Labeling with Amino acids in Cell Culture (SILAC): Allows for precise relative quantification between different cellular states (e.g., control vs. E3 ligase inhibited) [16] [15].

- Tandem Mass Tagging (TMT): Enables multiplexing of up to 10-18 samples simultaneously, ideal for time-course experiments or dose-response studies [16].

- Critical Consideration: When using TMT, an LC-MS3 method is highly recommended to overcome the issue of "signal compression" and ensure accurate quantification [16].

FAQ 3: Structural Diversity and Linkage Specification

Q: My target protein appears to be polyubiquitinated. How can I determine the linkage type of the chain and its functional consequence?

A: Ubiquitin chains can be formed through different lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or the N-terminus (M1), each encoding distinct functional outcomes [18] [19]. K48-linked chains typically target proteins for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains are often involved in non-proteolytic signaling [18] [17]. This structural diversity requires specialized tools for characterization.

- Recommended Solution:

- Linkage-Specific Antibodies: Use well-validated antibodies for immunoblotting to identify common chain types (e.g., K48 or K63)[ccitation:6].

- Advanced Mass Spectrometry: Employ specialized MS workflows that preserve the intact ubiquitin chain during analysis. Techniques like "top-down" or "middle-down" MS can help identify polyubiquitin chains and their linkage types directly [18] [15].

- Ubiquitin Mutants: Express ubiquitin mutants where all lysines except one are mutated to arginine (e.g., Ub-K48-only). If this mutant rescues the ubiquitination signal, it suggests the chain is primarily K48-linked.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent or No Detection of Ubiquitination

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High background in western blot; non-specific bands | Antibody cross-reactivity or poor sample quality. | - Pre-clear lysate with protein A/G beads.- Include DUB inhibitors (e.g., N-ethylmaleimide) in lysis buffer to prevent chain disassembly [15]. |

| Signal is lost upon lysine mutation | The mutated lysine is a key ubiquitination site. | - Confirm by identifying the site via MS/diGlycine remnant enrichment.- Be aware that mutation may disrupt E3 binding rather than the site itself [13]. |

| Ubiquitination is detected in vitro but not in cells | The E3 ligase is not present or active in the cellular context; or the site is masked by other PTMs. | - Validate E3-substrate interaction in cells (e.g., co-IP).- Check for phosphorylation or acetylation that may regulate E3 recognition [16]. |

Problem: Different Ubiquitin Linkages

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitination does not lead to protein degradation | The chain may be a non-degradative type (e.g., K63, monoUb). | - Use linkage-specific antibodies to characterize the chain topology.- Inhibit the proteasome (e.g., with MG132); if the protein does not stabilize, the ubiquitination is likely non-degradative [17]. |

| A single protein has multiple functional outcomes from ubiquitination | The protein is modified by different chain types under different conditions. | - Perform immunofluorescence to see if different ubiquitin signals localize to different cellular compartments.- Use TUBEs to enrich all ubiquitinated forms, then probe for specific linkages [15]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents used in modern ubiquitination research to address the core challenges.

| Research Reagent | Function and Utility |

|---|---|

| K-ε-GG Antibody [15] [13] | The cornerstone of ubiquitin remnant profiling; enables immunoenrichment of tryptic peptides containing the di-glycine signature for mass spectrometry. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (MG132, Bortezomib) [14] | Block the degradation of ubiquitinated proteins, thereby increasing their intracellular abundance and facilitating detection. |

| DUB Inhibitors (NEM, PR-619) [15] | Added to lysis buffers to prevent the removal of ubiquitin chains by deubiquitinating enzymes during sample preparation, preserving the native ubiquitination state. |

| Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) [15] | High-affinity tools for purifying ubiquitinated proteins from complex lysates while offering protection from DUBs. |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies [15] | Allow for the detection and immunoprecipitation of specific polyubiquitin chain types (e.g., K48, K63) via western blot or immunofluorescence. |

| Affinity-Tagged Ubiquitin (His, HA, Strep) [15] | Enables purification of ubiquitinated proteins from cellular overexpression systems for downstream analysis. |

| Activity-Based Probes for DUBs/E1s [15] | Chemical tools that covalently label active deubiquitinases or E1 enzymes, useful for profiling their activity in cell lysates. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ: What are the main types of E3 ubiquitin ligases and their mechanisms? E3 ubiquitin ligases are primarily classified into four types based on their structure and mechanism. The major types are RING, HECT, RBR, and U-box. RING and U-box types facilitate the direct transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 enzyme to the substrate. In contrast, HECT and RBR types form a reactive thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to the target protein [20].

FAQ: My experiments are failing to identify all ubiquitination sites on my protein of interest. How can I improve the coverage? A common challenge is the low abundance of ubiquitinated peptides. Traditional protein-level immunoprecipitation (IP) followed by mass spectrometry (AP-MS) may miss many sites. A more sensitive method is peptide-level immunoaffinity enrichment using antibodies specific for the di-glycine (K-ε-GG) remnant left on ubiquitinated lysines after tryptic digestion. This method has been shown to consistently yield a greater than fourfold increase in the abundance of identified ubiquitinated peptides compared to AP-MS approaches [21].

FAQ: Are there high-throughput methods to match E3 ligases with their target substrates? Yes, recent advances have led to scalable methods. One such framework is COMET (Combinatorial Mapping of E3 Targets), which enables testing of the role of many E3s in degrading many candidate substrates within a single experiment. This approach has been successfully applied to screen thousands of E3-substrate combinations, revealing complex interaction networks that are often not one-to-one relationships [22].

FAQ: What experimental options exist for targeting a protein of interest (POI) for degradation using E3 ligases? You can utilize biodegraders (also known as bioPROTACs). These are fusion proteins consisting of an intracellular protein binder (like a single-domain antibody) specific to your POI, linked to a functional E3 ligase. A detailed protocol exists for screening libraries of E3 ligases to identify those that function effectively in this biodegrader configuration, directly monitoring POI degradation via flow cytometry if the POI is fluorescently tagged [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Yield in Ubiquitination Site Mapping

Problem: When mapping ubiquitination sites on a specific protein, you identify only a few sites despite biochemical evidence of heavy ubiquitination.

Solution:

- Switch to Peptide-Level Enrichment: Move from protein-level immunoprecipitation (IP) to K-ε-GG peptide-level immunoaffinity enrichment [21].

- Stabilize Ubiquitinated Proteins: Treat cells with proteasomal inhibitors (e.g., 10 μM MG132) for several hours before lysis to prevent the degradation of ubiquitinated proteins [21].

- Optimize Input Material: Use sufficient starting material (e.g., 1-10 mg of total protein) to ensure detection of low-abundance ubiquitinated peptides [21].

Experimental Workflow: K-ε-GG Peptide Immunoaffinity Enrichment

Issue: Identifying Which E3 Ligase Targets Your Substrate

Problem: You have a substrate protein but do not know which E3 ligase is responsible for its ubiquitination.

Solution:

- Employ a COMET-like Screening Approach: If resources allow, implement a high-throughput screen where your substrate is tested against a library of hundreds of E3 ligases to find functional pairs [22].

- Utilize a Biodegrader Screening Protocol: Use a established cell-based screening assay. This involves creating a stable cell line expressing your POI fused to a fluorescent tag (e.g., GFP) and then co-transfecting with a library of potential E3 ligases fused to a POI-binding protein. Degradation is quantitatively measured by a reduction in fluorescence via flow cytometry [23].

Experimental Workflow: E3 Ligase Biodegrader Screen

Issue: Poor Predictive Models for Ubiquitination Sites

Problem: Computational predictions of ubiquitination sites on your protein are unreliable, leading to inefficient experimental design.

Solution:

- Incorporate Machine Learning with Optimized Hyperparameters: Use prediction tools that leverage machine learning methods (like SVM or KNN) where grid search has been employed to optimize hyperparameters. This can significantly improve prediction accuracy [24].

- Utilize Physicochemical Properties (PCP): Ensure the predictive model is trained on datasets that include relevant physicochemical properties of amino acids, which can enhance model performance [24].

Quantitative Data on Ubiquitination Site Mapping

Table 1: Comparison of Ubiquitination Site Mapping Methods

| Method | Key Feature | Relative Abundance of Identified K-ε-GG Peptides (vs. AP-MS) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Level AP-MS | Immunoprecipitation of protein of interest, then MS | 1x (Baseline) | Context of intact protein complex |

| K-ε-GG Peptide Immunoaffinity Enrichment | Antibody enrichment of modified peptides after digestion | >4x higher [21] | Greater sensitivity and more comprehensive site coverage |

Table 2: Machine Learning Performance for Ubiquitination Site Prediction

| Machine Learning Method | Key Tuning Strategy | Outcome & Relative Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Grid Search with hyperparameter optimization | Top overall performer based on average AUC across datasets [24] |

| k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | Grid Search with hyperparameter optimization | Ranked as number two performer [24] |

| LASSO | Grid Search with hyperparameter optimization | Showed maximum AUC improvement of 47% on one dataset [24] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for E3 and Ubiquitination Research

| Reagent | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-K-ε-GG Antibody | Immunoaffinity enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides | Peptide-level ubiquitination site mapping by MS [21] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132, Epoxomicin) | Stabilizes ubiquitinated proteins by blocking degradation | Enriching for ubiquitinated species in pull-downs and MS experiments [21] [23] |

| E3 Ligase Biodegrader Plasmids | Vectors for fusing E3 ligases to protein binders | Screening for E3s that degrade a specific POI [23] |

| FLAG-tag Antibodies | Detection and immunoprecipitation of tagged proteins | Validating expression and pull-down of transfected E3 biodegrader constructs [23] |

| Intracellular Protein Binders (e.g., sdAbs, DARPins) | High-affinity binding to a POI for recruitment to E3 ligases | Constructing targeted biodegraders/PROTACs [23] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): The Polyubiquitin Code

1. What is the "ubiquitin code"? The "ubiquitin code" refers to the complex biological language created by the diverse ways a protein can be modified by ubiquitin. A target protein can be modified by a single ubiquitin (monoubiquitination) or by polyubiquitin chains. These chains can be formed through different linkage sites on ubiquitin itself, creating distinct structures that are recognized differently by cellular machinery, leading to different functional outcomes for the modified protein [25] [26] [27].

2. How many polyubiquitin linkage types are there, and what are their primary functions? There are at least eight known types of homotypic polyubiquitin chains, formed via one of the seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or the N-terminal methionine (M1) of a ubiquitin molecule [28] [26]. The function is largely determined by the chain linkage, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Primary Functions of Homotypic Polyubiquitin Chain Linkages

| Linkage Type | Known Primary Functions |

|---|---|

| K48-linked | The canonical signal for targeting proteins to the 26S proteasome for degradation [3] [29]. |

| K63-linked | Regulates non-proteolytic processes such as signal transduction, endocytosis, protein trafficking, DNA repair, and inflammation [30] [3] [29]. |

| K11-linked | Involved in cell cycle regulation and has been implicated in endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation [25]. |

| K29 & K33-linked | Implicated in promoting ER retention and degradation of proteins [25]. |

| K6, K27-linked | Less characterized, but associated with mitophagy (K6) and immune signaling [26]. |

| M1-linked (Linear) | Important in NF-κB inflammatory signaling pathways [27]. |

3. What analytical challenges are associated with studying specific ubiquitin linkages? The high complexity and dynamic nature of ubiquitination make its study difficult. Key challenges include [28] [3]:

- Low Abundance: Ubiquitinated proteins are often present in low stoichiometry within the cell.

- Chain Diversity: The presence of eight linkage types, which can also be mixed or branched (forked), creates a complex mixture that is hard to decipher.

- Rapid Turnover: Ubiquitination is a reversible and highly dynamic modification.

- Lack of Specific Tools: Many antibodies lack the sensitivity and linkage-specificity required to detect endogenous ubiquitination events reliably.

4. What are TUBEs and how do they improve ubiquitination analysis? TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) are engineered, high-affinity reagents composed of multiple ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domains linked together. They are designed to bind polyubiquitin chains with nanomolar affinity, protecting them from deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) during cell lysis. Chain-selective TUBEs are further engineered to preferentially bind specific linkage types (e.g., K48 or K63), enabling the selective enrichment and study of specific chain topologies from complex biological samples [28] [3] [29].

5. What is the functional consequence of "forked" or branched ubiquitin chains? Forked chains, where a single ubiquitin molecule is modified at two different lysine residues, add another layer of complexity to the ubiquitin code. For example, chains simultaneously linked through K29 and K33 have been detected. It is proposed that these forked chains can be poor substrates for proteasome-associated deubiquitinating enzymes, potentially delaying protein degradation and adding a regulatory checkpoint [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inability to Detect Specific Endogenous Polyubiquitin Linkages

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Degradation of chains during sample preparation.

- Solution: Use TUBE-based reagents in your lysis buffer. Their high affinity for polyubiquitin chains sterically hinders and protects them from the activity of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), preserving the native ubiquitination state [3].

Cause 2: Lack of specificity or sensitivity in detection methods.

- Solution 1: Employ chain-selective TUBEs in an affinity pulldown assay. These can be used in a microtiter plate format for higher throughput. After capturing the chains, the target protein (e.g., RIPK2) can be detected by immunoblotting, confirming both the identity of the modified protein and the linkage type captured [3].

- Solution 2: Utilize a middle-down mass spectrometry approach. This involves partial tryptic digestion of polyubiquitin chains under native conditions, which cleaves exclusively at arginine 74 (R74). This generates large ubiquitin fragments (1-74 residues) that retain the linkage information, which can then be analyzed by high-resolution MS/MS to determine both chain length and the specific lysine residue involved in the linkage [31].

Cause 3: The linkages of interest are not present on your target protein under the experimental conditions.

- Solution: Apply appropriate physiological or pharmacological stimuli. For instance, to study K63-linked ubiquitination, induce an inflammatory signal (e.g., with L18-MDP for RIPK2). To study K48-linked ubiquitination, use a PROTAC molecule designed to target your protein of interest for proteasomal degradation [3].

Problem: Determining the Functional Outcome of a Specific Linkage on Your Protein

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Traditional genetic or pharmacological inhibition of E3 ligases or DUBs affects global ubiquitination and is too broad.

- Solution: Use engineered Deubiquitinases (enDUBs). This technique involves fusing a catalytic domain from a linkage-selective DUB (e.g., OTUD1 for K63, OTUD4 for K48) to a nanobody that targets a specific protein (e.g., GFP-nanobody for GFP/YFP-tagged substrates). When expressed in live cells, these enDUBs will selectively remove only the specific polyubiquitin chain type from your target protein, allowing you to study the functional consequence (e.g., on trafficking, stability, or function) without disrupting the global ubiquitin landscape [25].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Middle-Down Mass Spectrometry for Linkage and Length Analysis

This protocol is adapted from the strategy described by Kim et al. for characterizing polyubiquitin chain structure [31].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Isolate polyubiquitin chains or ubiquitinated proteins from cells or tissues. This can be done under native conditions using affinity chromatography (e.g., His-tag pull-down) followed by glycerol gradient centrifugation for further purification [31].

2. Limited Proteolytic Digestion:

- Resuspend the purified polyubiquitin sample in a 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 7.8).

- Use a low trypsin-to-substrate ratio (e.g., 1:1 w/w) and digest at 37°C for a limited time. Under these optimized conditions, native folded ubiquitin is cleaved almost exclusively at the C-terminal side of arginine 74 (R74), leaving the globular domain and its modifications intact [31].

3. LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Separate the digested products using reverse-phase liquid chromatography (e.g., C8 column).

- Analyze the eluents with a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., LTQ-Orbitrap).

- The cleavage generates two key products for each ubiquitin in the chain: a large fragment (Ub^1-74^) and its ubiquitinated form with a diglycine tag (Ub^1-74^-GG). The molar ratio of Ub^1-74^ to Ub^1-74^-GG indicates the chain length (e.g., 1:1 for dimer, 1:2 for trimer).

- The lysine residue used for chain linkage within the Ub^1-74^-GG fragment is identified through MS/MS and MS/MS/MS sequencing [31].

Protocol 2: Using Chain-Selective TUBEs to Probe Linkage-Specific Ubiquitination

This protocol is based on the high-throughput screening assay used to study RIPK2 ubiquitination [3].

1. Cell Stimulation and Lysis:

- Treat cells (e.g., THP-1 monocytic cells) with the desired stimulus. To study K63-linkages, use an inflammatory inducer like L18-MDP (200-500 ng/ml for 30 min). To study K48-linkages, use a PROTAC targeting your protein of interest.

- Lyse cells in a buffer optimized to preserve polyubiquitination, supplemented with protease and deubiquitinase inhibitors.

2. Linkage-Specific Capture:

- Use a microtiter plate coated with chain-selective TUBEs (e.g., K48-TUBE, K63-TUBE, or Pan-TUBE).

- Incubate the clarified cell lysate with the TUBE-coated plate to allow specific binding of polyubiquitin chains.

- Wash thoroughly to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

3. Detection and Quantification:

- Detect the captured target protein by immunoblotting with an antibody against the protein of interest (e.g., anti-RIPK2).

- For higher throughput quantification, use an electrochemiluminescence-based immunoassay. Detect the captured protein with a biotinylated antibody against your target, followed by a streptavidin-based readout [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Analyzing the Polyubiquitin Code

| Research Tool | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| Chain-Selective TUBEs | Engineered affinity reagents for the enrichment and protection of specific polyubiquitin linkages (K48, K63, etc.) from complex cell lysates. Essential for pull-down and HTS assays [28] [3]. |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Traditional immunodetection tools for specific ubiquitin linkages via Western blot or immunofluorescence. Variability in specificity and affinity can be a limitation [28]. |

| Engineered DUBs (enDUBs) | Live-cell tool for substrate-specific, linkage-selective removal of polyubiquitin chains. Used to decipher the functional role of a specific chain type on a single protein target [25]. |

| Mutant Ubiquitin Plasmids | Ubiquitin genes where specific lysine codons are mutated to arginine (e.g., K48R). Used to block the formation of a particular chain type and study the resulting phenotypic effects [3]. |

| PROTACs/Molecular Glues | Heterobifunctional small molecules that recruit an E3 ligase to a target protein, inducing its polyubiquitination and degradation. Useful for studying K48-linked ubiquitination and targeted protein degradation [3] [29]. |

| Activity-Based Probes | Chemical tools that covalently bind to active-site residues of enzymes like E1, E2, or DUBs, allowing for the profiling of their activity in complex proteomes [32]. |

Visualizing the Polyubiquitin Code and Cellular Outcomes

The following diagram summarizes how different polyubiquitin chain linkages are interpreted by the cell to drive distinct functional outcomes, forming the basis of the "ubiquitin code."

Cutting-Edge Technologies for High-Specificity Ubiquitination Mapping

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Ubigo-X Experimental Challenges

Problem 1: Model Performance is Inconsistent or Poor on New Datasets

- Issue: Your independent test results show significantly lower metrics (e.g., MCC, Accuracy) than those reported in the Ubigo-X study.

- Solution:

- Verify Data Preprocessing: Ensure your new dataset undergoes the same rigorous filtering steps as the Ubigo-X training data. The original study used CD-HIT and CD-HIT-2d with a 40% sequence identity threshold to reduce redundancy and homology bias [33] [34]. Inconsistent preprocessing is a primary cause of performance drop.

- Check Data Balance: Ubigo-X demonstrated robust performance on imbalanced data (1:8 ratio), but extreme imbalance can affect outcomes. Analyze your dataset's positive-to-negative site ratio. The model achieved an AUC of 0.94 on imbalanced data, indicating a strong tolerance, but monitoring this is crucial [33].

- Confirm Feature Compatibility: Ensure that the feature extraction methods (e.g., AAC, AAindex, k-mer) are applied consistently to your new sequences. Mismatches in feature generation will lead to erroneous predictions.

Problem 2: Installation or Web Service Access Difficulties

- Issue: You cannot access the Ubigo-X web tool or encounter errors when running local scripts.

- Solution:

- Web Tool: The Ubigo-X web server is accessible at http://merlin.nchu.edu.tw/ubigox/ [33] [34]. If the page is unresponsive, first check your internet connection and try a different browser. The service status is typically operational, as it is an open-access research tool.

- Local Implementation: If you are working with the model architecture locally, confirm that all Python library dependencies are installed at their correct versions (e.g., PyTorch for ResNet34, XGBoost). Incompatible library versions are a common source of runtime errors.

Problem 3: Interpreting Model Outputs and Scores

- Issue: Uncertainty about how to interpret the prediction scores or reliability metrics provided by Ubigo-X.

- Solution:

- Understand the Voting System: Ubigo-X uses a weighted voting strategy to combine its three sub-models [33] [34]. A final score close to 1 indicates high confidence in ubiquitination site prediction. Familiarize yourself with the contribution weights of each sub-model as described in the original publication.

- Contextualize with Benchmarks: Compare your results' performance metrics against the benchmarks from the Ubigo-X paper (see Table 1). This will help you determine if the model is performing as expected on your data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for the Ubigo-X Researcher

Q1: What is the core innovation of the Ubigo-X model compared to previous tools? A1: Ubigo-X's primary innovation is the integration of image-based feature representation with an ensemble learning framework using weighted voting [33] [34]. It transforms sequence-based features into a format processable by a deep Resnet34 model and combines this with structure-based features analyzed by XGBoost, achieving superior specificity and balance as measured by the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC).

Q2: On what specific data was Ubigo-X trained and validated? A2: The model was developed using a comprehensive training strategy:

- Training Data: Sourced from the Protein Lysine Modification Database (PLMD 3.0), comprising 53,338 ubiquitination and 71,399 non-ubiquitination sites after sequence filtering [33] [34].

- Independent Testing: Validated on filtered data from PhosphoSitePlus (balanced and imbalanced sets) and GPS-Uber data, demonstrating its generalizability across different databases [33].

Q3: What performance metrics should I prioritize when evaluating Ubigo-X on my own data? A3: While Area Under the Curve (AUC) and Accuracy (ACC) are important, the Ubigo-X study highlights the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) as a key metric, especially for imbalanced datasets [33]. MCC provides a more reliable measure of the quality of binary classifications when class sizes are very different.

Q4: Is Ubigo-X a species-specific predictor? A4: No, Ubigo-X is designed as a species-neutral prediction tool [33] [34]. Its training and validation incorporated data from various sources without a species-specific focus, making it broadly applicable for ubiquitination site prediction across different organisms.

Data Interpretation Support: Ubigo-X Performance Metrics

The following tables summarize the key quantitative performance data of Ubigo-X from independent tests, providing a benchmark for your own experimental results.

Table 1: Ubigo-X Performance on Balanced Independent Test Data

| Dataset Source | Ubiquitination Sites | Non-ubiquitination Sites | AUC | Accuracy (ACC) | Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PhosphoSitePlus (Filtered) | 65,421 | 61,222 | 0.85 | 0.79 | 0.58 |

| GPS-Uber Data | Information Not Explicitly Stated | Information Not Explicitly Stated | 0.81 | 0.59 | 0.27 |

Table 2: Ubigo-X Performance on Imbalanced Independent Test Data

| Dataset Source | Positive-to-Negative Ratio | AUC | Accuracy (ACC) | Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PhosphoSitePlus (Imbalanced) | 1:8 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.55 |

Experimental Protocol & Workflow

For researchers seeking to reproduce the Ubigo-X methodology or adapt it for their own workflows, the core experimental pipeline is as follows:

- Data Collection & Curation: Acquire protein sequences and known ubiquitination sites from databases like PLMD or PhosphoSitePlus.

- Sequence Filtering: Apply CD-HIT and CD-HIT-2d to filter the dataset with a 40% sequence identity cutoff to remove redundant sequences and reduce homology bias [33] [34].

- Multi-Feature Representation:

- Single-Type SBF: Extract Amino Acid Composition (AAC), physicochemical properties via AAindex, and use one-hot encoding.

- Co-Type SBF: Apply k-mer encoding (e.g., 3-mer) to the Single-Type SBF features.

- S-FBF: Predict secondary structure, calculate Relative Solvent Accessibility (RSA) / Absolute Solvent-Accessible Area (ASA), and identify signal peptide cleavage sites.

- Model Training:

- Transform the Single-Type SBF and Co-Type SBF features into image-based representations.

- Train these image-based features using a Resnet34 deep learning model.

- Train the S-FBF features using the XGBoost algorithm.

- Ensemble Prediction: Combine the predictions from the three sub-models (Single-Type SBF, Co-Type SBF, S-FBF) using a pre-defined weighted voting strategy to generate the final ubiquitination site prediction [33] [34].

Table 3: Essential Computational Resources for Ubiquitination Site Prediction

| Resource Name | Type / Function | Relevance in Ubigo-X |

|---|---|---|

| PLMD 3.0 | Database | Primary source of training data (ubiquitination and non-ubiquitination sites) [33] [34]. |

| PhosphoSitePlus | Database | Used for independent testing and validation of the model's performance [33]. |

| CD-HIT Suite | Bioinformatics Tool | Used for sequence clustering and filtering to create non-redundant training and test sets [33] [34]. |

| Amino Acid Index (AAindex) | Database | Provides numerical indices of physicochemical properties for feature extraction in the Single-Type SBF sub-model [33]. |

| ResNet34 | Deep Learning Architecture | Used to train the image-based representations of sequence-based features [33] [34]. |

| XGBoost | Machine Learning Algorithm | Used to train the structure-based and function-based features (S-FBF sub-model) [33] [34]. |

Troubleshooting FAQs: Ubiquitination Site Analysis

This section addresses common challenges in mass spectrometry workflows for ubiquitination site identification, providing targeted solutions for researchers.

1. How can I improve the coverage of low-abundance ubiquitination sites in my analysis?

- Challenge: The low stoichiometry of endogenous ubiquitination makes many sites difficult to detect without specific enrichment strategies [35] [36].

- Solution: Implement a multi-faceted approach combining sample pre-fractionation and highly specific enrichment. Fractionate peptides using basic pH reversed-phase (bRP) chromatography prior to immunoenrichment to reduce sample complexity [37] [35]. For proteasome-inhibited samples, separate fractions containing the highly abundant K48-linked ubiquitin-chain derived diGly peptide to prevent competition during antibody enrichment [35]. Optimize antibody and peptide input ratios; typically, enrichment from 1 mg of peptide material using 31.25 µg of anti-diGly antibody provides optimal results [35].

2. Why am I getting high quantitative variability in my ubiquitination site quantification?

- Challenge: Inconsistent quantification across replicates, particularly with Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) methods [35].

- Solution: Transition to Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) methods. DIA significantly improves reproducibility - in comparative studies, DIA identified approximately 36,000 distinct diGly peptides across replicates with 45% showing coefficients of variation (CVs) below 20%, compared to only 15% with CVs below 20% in DDA methods [35]. Ensure sufficient MS2 scan quality by using a fragment scan resolution of 30,000 and optimize DIA window placement based on empirical precursor distributions [35].

3. How can I reduce non-specific binding during enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides?

- Challenge: Contamination with non-ubiquitinated peptides reduces detection sensitivity for true ubiquitination sites [37] [36].

- Solution: Chemically cross-link the anti-K-ε-GG antibody to solid support beads. This substantially reduces contamination from antibody fragments and non-specific peptides in final enriched samples [37]. For protein-level enrichments using tagged ubiquitin systems, be aware that histidine-rich or endogenously biotinylated proteins can co-purify with Ni-NTA or Strep-Tactin resins respectively; include appropriate controls and consider alternative enrichment strategies [36].

Performance Comparison: DDA vs. DIA for Ubiquitinome Analysis

The table below summarizes quantitative performance data between Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) and Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) methods for ubiquitination site analysis, based on studies with MG132-treated HEK293 cells [35].

| Parameter | Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) | Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) |

|---|---|---|

| Distinct diGly Peptides Identified (single run) | ~20,000 | ~35,000 |

| Percentage with CV < 20% | 15% | 45% |

| Total Distinct Peptides Across 6 Replicates | ~24,000 | ~48,000 |

| Quantitative Accuracy | Lower | Higher |

| Data Completeness Across Samples | More missing values | Fewer missing values |

Experimental Protocol: K-ε-GG Ubiquitin Remnant Enrichment

This protocol enables large-scale identification of endogenous ubiquitination sites from cell lines or tissue samples, with detailed methodology adapted from established techniques [37].

Sample Preparation and Lysis

- Prepare fresh urea lysis buffer (8 M urea, 50 mM Tris HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with protease inhibitors (2 μg/mL Aprotinin, 10 μg/mL Leupeptin, 50 μM PR-619, 1 mM chloroacetamide or iodoacetamide, 1 mM PMSF). Add PMSF immediately before use due to its short half-life in aqueous buffers [37].

- Lyse cells or tissue samples in the prepared buffer. For tissue samples, mechanical disruption may be required.

- Determine protein concentration using a BCA Protein Assay Kit [37].

Protein Digestion and Peptide Cleanup

- Reduce proteins with 1-5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) at room temperature for 30 minutes.

- Alkylate with 10-15 mM iodoacetamide (IAM) at room temperature for 30 minutes in the dark.

- Dilute the urea concentration to 2 M and digest first with LysC (1:100 enzyme-to-substrate ratio) for 2-3 hours at room temperature.

- Further digest with trypsin (1:100 enzyme-to-substrate ratio) overnight at room temperature.

- Acidify peptides with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to pH < 3 and desalt using C18 solid-phase extraction (SPE) columns. Wash with 0.1% TFA and elute with 50% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid [37].

Basic pH Reversed-Phase Fractionation

- Fractionate peptides using basic pH reversed-phase chromatography to reduce complexity.

- Use solvent A (5 mM ammonium formate pH 10/2% MeCN) and solvent B (5 mM ammonium formate pH 10/90% MeCN) with a C18 column [37].

- For proteasome inhibitor-treated samples, identify and separately pool fractions containing the abundant K48-linked ubiquitin-chain derived diGly peptide to prevent interference [35].

- Concatenate fractions (typically from 96 to 8-9 pools) to reduce the number of samples for downstream processing [37] [35].

Anti-K-ε-GG Antibody Enrichment

- Chemically cross-link the anti-K-ε-GG antibody to protein A or G beads using dimethyl pimelimidate dihydrochloride (DMP) to prevent antibody leakage [37].

- Incubate fractionated peptides with cross-linked antibody beads for 2 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation.

- Wash beads extensively with ice-cold PBS to remove non-specifically bound peptides.

- Elute ubiquitinated peptides with 0.2% TFA [37].

Mass Spectrometric Analysis

- Analyze enriched peptides by LC-MS/MS using either DDA or optimized DIA methods.

- For DIA, use optimized parameters: 46 precursor isolation windows with MS2 resolution of 30,000 [35].

- For identification of ubiquitination sites, search for the characteristic 114.04293 Da mass shift on modified lysine residues, corresponding to the diGly remnant [38] [36].

Ubiquitination Site Identification Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential reagents and materials for implementing advanced ubiquitination site analysis workflows.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Product/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-K-ε-GG Antibody | Specific enrichment of tryptic peptides with ubiquitin remnant motif | PTMScan Ubiquitin Remnant Motif (K-ε-GG) Kit [37] |

| SILAC Amino Acids | Metabolic labeling for quantitative comparisons between samples [37] [35] | Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino acids in Cell culture kits |

| Cross-linking Reagent | Immobilize antibody to beads to reduce contamination | Dimethyl pimelimidate dihydrochloride (DMP) [37] |

| Protease Inhibitors | Maintain ubiquitination state during lysis (Aprotinin, Leupeptin, PMSF) [37] | Various commercial protease inhibitor cocktails |

| HeLa Protein Digest Standard | System performance testing and troubleshooting [39] | Pierce HeLa Protein Digest Standard (Cat. No. 88328) |

| Peptide Retention Time Calibration Mix | LC system diagnostics and troubleshooting [39] | Pierce Peptide Retention Time Calibration Mixture |

Methodology Comparison: Enrichment Strategies for Ubiquitinated Proteins

Each enrichment method offers distinct advantages and limitations for ubiquitination site analysis, as summarized in the table below.

| Enrichment Method | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| K-ε-GG Antibody [37] [35] | Immunoaffinity enrichment of diGly remnant after trypsin digestion | High specificity for ubiquitination sites; works with endogenous proteins; enables site-specific identification | Cannot distinguish ubiquitination from NEDD8ylation/ISG15ylation (<6% of sites) [35]; antibody cost |

| Tagged Ubiquitin Systems [40] [36] | Affinity purification using His/Strep-tagged ubiquitin | Efficient for low-abundance sites; genetic targeting to specific cells | Potential artifacts from tagged ubiquitin expression; not suitable for clinical/tissue samples [36] |

| Ubiquitin-Binding Domains (UBDs) [36] | Tandem UBDs bind ubiquitin chains with higher affinity | Enriches endogenous ubiquitinated proteins; can be linkage-specific | Lower specificity compared to antibody methods; potential for non-specific binding |

DIA vs. DDA Performance Comparison

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core principle of the BioE3 system? BioE3 is a biotin-based proximity labeling method designed to identify the direct substrates of a specific E3 ubiquitin ligase. It works by fusing the E3 ligase of interest to the biotin ligase BirA and using a ubiquitin molecule fused to a modified, low-affinity biotin acceptor peptide (AviTag variant called bioGEF). When the BirA-E3 ligase fusion ubiquitinates a substrate using the bioGEF-tagged ubiquitin (bioGEFUb), it biotinylates the ubiquitin molecule in close proximity. This allows for the streptavidin-based capture and identification of the ubiquitinated substrates under denaturing conditions, distinguishing true substrates from mere interactors [41] [42].

Q2: Which types of E3 ligases is BioE3 compatible with? The BioE3 system is highly versatile and has been successfully validated with multiple types of E3 ligases, including:

- RING-type E3s: Such as RNF4 and MIB1 [41].

- HECT-type E3s: Such as NEDD4 [41].

- Multi-subunit Cullin-RING Ligases (CRLs): Such as the CRL4CRBN complex [42]. This makes it a broadly applicable tool for the ubiquitin research community.

Q3: Why is a low-affinity AviTag (bioGEF) crucial for the experiment? The widely used wild-type AviTag (bioWHE) has a high affinity for BirA, which leads to widespread, non-specific biotinylation of bioWHE-tagged ubiquitin, regardless of the BirA-E3's location [41]. The bioGEF variant contains mutations that lower its affinity for BirA. This ensures that biotinylation only occurs when the bioGEFUb is in very close proximity to the BirA-E3 fusion—that is, during the act of substrate ubiquitination. This spatial control dramatically reduces background signal and increases the specificity for genuine substrates [41].

Q4: My negative control shows high background biotinylation. What could be wrong? High background is often traced to incomplete biotin depletion. Ensure you are using biotin-depleted serum and pre-culture cells in biotin-free media for at least 24 hours before the biotin pulse [41] [42]. Furthermore, always include a catalytically inactive mutant of your E3 ligase (e.g., a RING domain mutant) as a negative control to identify and subtract any non-specific interactions [41].

Q5: The streptavidin signal is weak after pull-down. How can I optimize this? Weak signal can be improved by:

- Optimizing biotin pulse time: Test different durations (e.g., 0.5 to 2 hours) to find the optimal window for your specific E3 ligase [41].

- Proteasome inhibition: Treating cells with a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG132 or Bortezomib) can prevent the rapid degradation of ubiquitinated substrates, allowing for better accumulation and detection [42] [43].

- Confirming expression: Verify the robust expression of both the BirA-E3 fusion and the inducible bioGEFUb construct in your cell lines [41].

Troubleshooting Guide

The following table outlines common experimental problems, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High background biotinylation | Use of wild-type AviTag (bioWHE); Incomplete biotin depletion | Switch to the low-affinity bioGEF tag [41]; Use dialyzed FBS and biotin-free media; Extend pre-culture in biotin-free conditions [42]. |

| Weak or no specific signal | Short biotin pulse; Substrate degradation; Low transfection/induction efficiency | Increase biotin pulse time (e.g., up to 2 hours) [41]; Use proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG132) [43]; Check and optimize DOX induction and transfection protocols [41]. |

| Failure to identify known substrates | Incorrect subcellular localization of BirA-E3 fusion; Catalytically impaired fusion protein | Fuse BirA to the N-terminus of the E3 to avoid steric hindrance with the C-terminal catalytic domain [41]; Verify catalytic activity of the E3 ligase in the fusion context. |

| Non-specific protein identification in MS | Inadequate washing during pull-down; Contamination from non-covalent interactors | Perform streptavidin pull-down under denaturing conditions [43]; Include a catalytic mutant control and use quantitative MS to filter out background binders [41] [42]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Core Protocol: BioE3 Substrate Identification Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the step-by-step workflow for a typical BioE3 experiment.

Protocol Modifications for Different E3 Types

For Cullin-RING Ligases (CRLs):

- When studying CRLs like CRL4CRBN, the BirA tag is fused to the substrate receptor (e.g., CRBN) [42].

- To study endogenous activity, the neddylation of the cullin scaffold can be inhibited using MLN4924 as a control [42].

- This system is highly effective for identifying drug-induced neosubstrates. For example, when CRBN BioE3 is treated with pomalidomide, it can identify novel neosubstrates like CSDE1 alongside endogenous substrates [42].

For HECT-type E3 Ligases:

- The BioE3 protocol works with HECT ligases like NEDD4 without major modifications. The catalytic mechanism of HECT E3s, which involves a covalent E3~Ub intermediate, is still compatible with the proximity-dependent labeling by the BirA fusion [41].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential reagents and their functions for implementing the BioE3 system.

| Reagent | Function in BioE3 System | Key Details / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Affinity AviTag Ub (bioGEFUb) | Biotin acceptor peptide fused to Ub; incorporated into substrates. | TRIPZ-bioGEFUbwt (Addgene #208045) or non-cleavable mutant TRIPZ-bioGEFUbnc (Addgene #208044) for reduced DUB recycling [41] [44]. |

| BirA-E3 Fusion Construct | Engineered E3 ligase that catalyzes both ubiquitination and proximity biotinylation. | BirA fused to N-terminus of E3 (e.g., Lenti-BirAopt-RNF4wt, Addgene #208046) [41] [44]. |

| BirA Control Vector | Critical negative control for non-specific biotinylation. | Empty BirA vector (e.g., Addgene #208048) or BirA fused to a catalytically dead E3 mutant [41] [44]. |

| Cell Culture Media | Controls biotin availability for specific labeling. | Biotin-free DMEM supplemented with 10% dialyzed FBS [41] [42]. |

| Streptavidin Beads | Capture biotinylated substrates. | Used for pull-down under denaturing conditions to disrupt non-covalent interactions [43]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitor | Stabilizes ubiquitinated substrates for detection. | MG132 or Bortezomib; added prior to cell lysis [42] [43]. |

Mechanism and Specificity Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the molecular mechanism of the BioE3 system and how it achieves specificity compared to a non-specific wild-type AviTag system.

Ubiquitination is a critical post-translational modification where a 76-amino acid protein, ubiquitin, is covalently attached to substrate proteins, regulating diverse cellular functions from protein degradation to DNA repair and immune signaling [36] [45]. The complexity of ubiquitin signaling arises from its ability to form chains through different lysine linkages (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and N-terminal methionine (M1), each generating distinct cellular signals [36] [45]. Antibody-based approaches have become indispensable tools for deciphering this complex ubiquitin code, offering specificity and versatility for researchers investigating ubiquitination in health and disease.

Despite their widespread use, researchers face significant challenges when employing antibody-based detection methods. The transient nature of ubiquitination, coupled with the low stoichiometry of modified proteins in normal physiological conditions, makes detection difficult [36]. Additionally, the high conservation of ubiquitin limits its immunogenicity, resulting in many ubiquitin antibodies being non-specific and binding large amounts of artifacts [46]. The selection of appropriate antibodies is further complicated by differences in epitope recognition characteristics, where antibodies recognizing "open" epitopes can bind to free ubiquitin and polyubiquitin chains, while those targeting "cryptic" epitopes only recognize free ubiquitin and monoubiquitination modifications [47]. Understanding these challenges is fundamental to improving specificity in ubiquitination site identification research.

Antibody Selection Guide

Types of Ubiquitin Antibodies and Their Applications

Selecting the appropriate ubiquitin antibody requires careful consideration of your research goals and experimental design. Antibodies for ubiquitin detection generally fall into three main categories, each with distinct advantages and applications:

Pan-ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., P4D1, FK1/FK2): These antibodies recognize all ubiquitinated proteins regardless of linkage type and are ideal for assessing global changes in protein ubiquitination [36]. They typically produce characteristic smeared bands in Western blot analysis, comprehensively reflecting the overall ubiquitination state of the sample [47]. These antibodies are particularly suitable for initial screening experiments or when assessing the effects of proteasome inhibitor treatments.

Linkage-specific antibodies: These reagents precisely recognize particular ubiquitin chain topologies, enabling researchers to investigate linkage-specific biological functions. For example, K48-linkage specific antibodies (e.g., ab140601) are essential for studying proteasomal degradation pathways, while K63-linkage specific antibodies help elucidate roles in DNA damage repair and inflammatory signaling [48] [46]. The anti-ubiquitin (linkage-specific K48) antibody [EP8589] exemplifies this category, demonstrating specificity for K48-linked ubiquitin chains without cross-reactivity with K6-, K11-, K27-, K29-, K33-, or K63-linked chains [48].

Ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs): While not antibodies in the traditional sense, UBD-based tools like tandem hybrid ubiquitin-binding domains (ThUBD) and Ubiquitin-Traps offer high-affinity alternatives for capturing ubiquitinated proteins [2] [46]. ThUBD-coated plates demonstrate a 16-fold wider linear range for capturing polyubiquitinated proteins compared to traditional TUBE-coated plates, enabling unbiased enrichment of all ubiquitin chain types with significantly improved sensitivity [2] [49].

Table 1: Guide to Selecting Ubiquitin Antibodies Based on Research Objectives

| Research Goal | Recommended Antibody Type | Expected Results | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global ubiquitination profiling | Pan-ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., FK1, FK2) | Smeared pattern across high molecular weights | Ideal for monitoring effects of proteasome inhibitors; indicates overall ubiquitination status |

| Proteasomal degradation studies | K48-linkage specific antibodies | Discrete bands or smears at specific molecular weights | Correlates with protein turnover; use with proteasome inhibitors for optimal results |

| DNA repair & inflammatory signaling | K63-linkage specific antibodies | Distinct banding patterns | Useful for studying NF-κB pathway activation and kinase regulation |

| Free ubiquitin pool dynamics | Antibodies recognizing "cryptic" epitopes | Discrete bands at low molecular weights | Suitable for immunoprecipitation; does not recognize polyubiquitin chains |

| Unbiased ubiquitome profiling | UBD-based tools (ThUBD, Ubiquitin-Trap) | Comprehensive capture of all ubiquitin linkages | Higher affinity and broader specificity than most antibodies; ideal for discovery studies |

Technical Considerations for Antibody Validation

When incorporating ubiquitin antibodies into your research workflow, rigorous validation is essential to ensure reliable and reproducible results. Consider the following technical aspects:

Epitope characterization: Understand whether your antibody recognizes "open" or "cryptic" epitopes, as this determines its ability to detect polyubiquitin chains versus free ubiquitin and monoubiquitination [47]. Antibodies against "open" epitopes produce continuous smeared bands in Western blots, while those targeting "cryptic" epitopes yield discrete single or multiple specific bands.

Specificity verification: For linkage-specific antibodies, confirm minimal cross-reactivity with non-target ubiquitin linkages. The manufacturer should provide validation data similar to that shown for anti-Ubiquitin (K48) antibody [EP8589], which demonstrates specificity for K48-linked ubiquitin chains without recognizing other linkage types [48].

Application compatibility: Verify that your chosen antibody has been validated for your specific experimental application (e.g., Western blot, immunohistochemistry, immunoprecipitation, flow cytometry). Performance can vary significantly across different platforms [48] [47].

Sample compatibility: Consider your sample type when selecting antibodies. Whole cell lysates, especially those treated with proteasome inhibitors, contain abundant polyubiquitinated proteins and are most suitable for detection using smear-type antibodies. In contrast, cell models overexpressing free ubiquitin or purified ubiquitin protein samples are more suitable for analysis using band-type antibodies [47].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Even with carefully selected antibodies, researchers frequently encounter technical challenges when detecting ubiquitination. The following troubleshooting guide addresses the most common issues and provides practical solutions:

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Ubiquitination Detection

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| No bands visible | Insufficient ubiquitinated protein | • Enrich using UBD-based tools (ThUBD, Ubiquitin-Trap) [2] [46]• Treat cells with proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) [46]• Immunoprecipitate prior to Western blot [50] | • Confirm protein concentration using Bradford assay [50]• Include positive control |

| High background | Non-specific antibody binding | • Optimize blocking conditions (5% normal serum, 5% non-fat milk, or 3% BSA) [50]• Increase wash stringency (0.05% Tween-20) [50]• Titrate antibody concentration [50] | • Avoid milk/BSA when using primary antibodies derived from goat or sheep [50]• Include detergent in dilution buffers |

| Unexpected bands | Protein degradation or non-specific binding | • Add fresh protease inhibitors during sample preparation [50]• Run negative control (non-transfected cell lysate) [50]• Use reducing agents (fresh BME or DTT) [50] | • Minimize freeze-thaw cycles [50]• Prepare fresh working dilutions |

| Smiling or uneven bands | Electrophoresis issues | • Reduce voltage during SDS-PAGE [50]• Ensure proper gel polymerization [50]• Use shaker during incubation steps [50] | • Load smaller protein amounts• Use pre-cast gels for reproducibility |

| Weak or no signal | Low antibody affinity or epitope masking | • Use antibodies with "open" epitopes for polyubiquitin chains [47]• Try different retrieval methods for IHC [48]• Increase antigen-antibody incubation time [50] | • Select antibodies validated for your specific application• Verify antibody recognition characteristics |

Special Considerations for Linkage-Specific Detection

When working with linkage-specific antibodies, additional technical considerations apply:

Validation of linkage specificity: Always confirm that your linkage-specific antibody does not cross-react with other ubiquitin chain types. For example, the anti-Ubiquitin (K48) antibody [EP8589] has been validated against K6-, K11-, K27-, K29-, K33-, and K63-linked ubiquitin chains, showing specificity only for K48 linkages [48].

Signal interpretation: Understand that different linkage types may produce distinct banding patterns. While K48-linked chains often appear as high-molecular-weight smears due to their heterogeneous nature, other linkages might produce more discrete bands depending on their cellular functions and typical chain lengths.

Experimental controls: Include appropriate controls for linkage-specific experiments, such as samples with known linkage types (when available) and samples where specific linkages have been enzymatically eliminated or reduced using linkage-specific deubiquitinases.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

High-Throughput Ubiquitination Detection Using ThUBD-Coated Plates

For researchers requiring high-throughput analysis of ubiquitination signals, the ThUBD-coated plate method offers significant advantages over traditional antibody-based approaches. This protocol enables sensitive, specific, and efficient detection of global ubiquitination profiles:

Workflow Overview: High-Throughput Ubiquitination Detection

Materials Required:

- ThUBD-coated 96-well plates (Corning 3603 type recommended) [2]

- Complex proteome samples (minimum 0.625 μg) [2]

- Appropriate washing buffers

- Detection reagents (ThUBD-HRP recommended) [2]

- Plate reader for signal quantification

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Plate Preparation: Use commercially available ThUBD-coated plates or prepare your own by coating Corning 3603-type 96-well plates with 1.03 μg ± 0.002 of ThUBD [2].