APF-1: From Apoptotic Protease Activating Factor to DNA Sensor – Function, Inhibition, and Therapeutic Targeting

This article provides a comprehensive overview of APF-1, a critical regulator of cell fate more commonly known as Apaf-1 (Apoptotic protease-activating factor 1).

APF-1: From Apoptotic Protease Activating Factor to DNA Sensor – Function, Inhibition, and Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of APF-1, a critical regulator of cell fate more commonly known as Apaf-1 (Apoptotic protease-activating factor 1). Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, we explore its foundational role in the intrinsic apoptosis pathway as the core component of the apoptosome, detailing its structure, regulation, and classical activation by cytochrome c. The scope extends to cutting-edge research redefining APF-1 as an evolutionarily conserved DNA sensor that influences the switch between apoptosis and inflammation. We further cover methodological approaches for studying APF-1, challenges in targeting it therapeutically, and the validation of novel small-molecule inhibitors like ZYZ-488 for conditions such as ischemic heart disease, synthesizing key insights for future biomedical innovation.

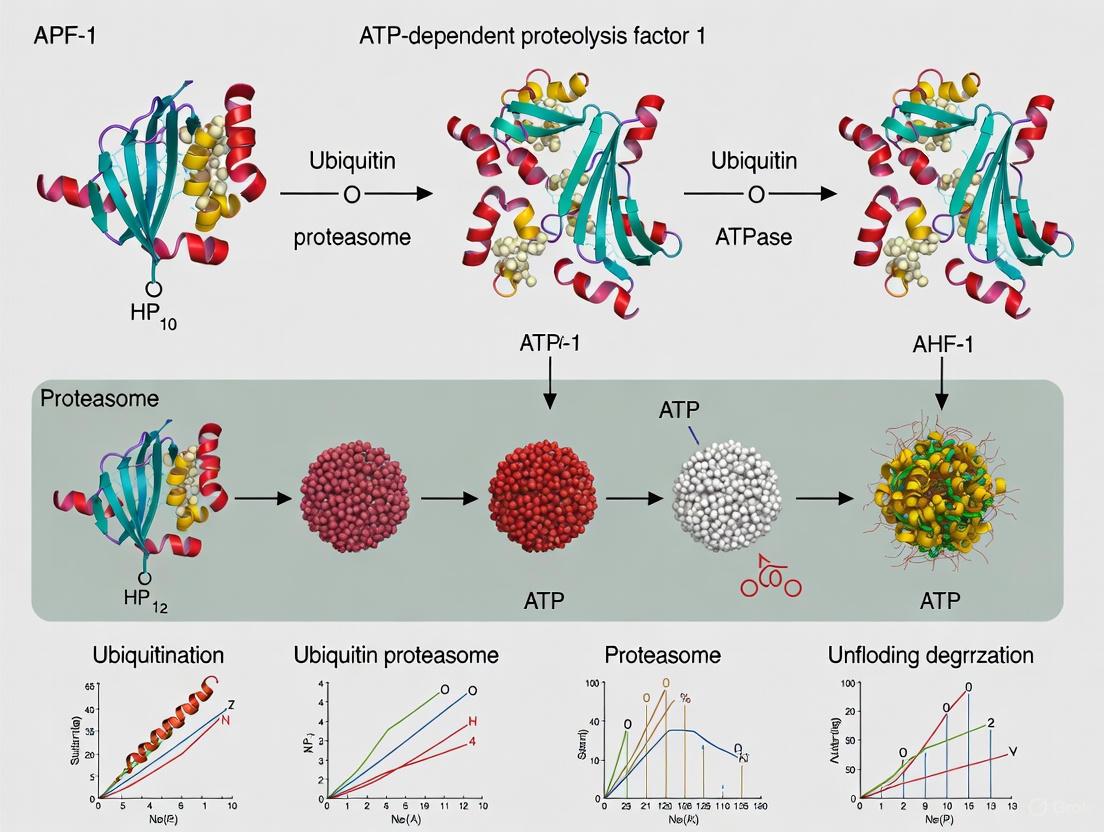

APF-1 Uncovered: The Architect of the Apoptosome and its Canonical Role in Programmed Cell Death

This whitepaper traces the extraordinary scientific journey of APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1), from its initial characterization in the ubiquitin-proteasome system to its identity as Apaf-1 (Apoptotic Protease Activating Factor 1), a central regulator of mitochondrial apoptosis. Framed within a broader thesis on APF-1 function research, we examine how seminal biochemical discoveries in protein degradation pathways illuminated fundamental mechanisms in cell death regulation. We present comprehensive experimental protocols that defined these pathways, analyze emerging research that expands Apaf-1's function to include innate immune DNA sensing, and explore therapeutic targeting of Apaf-1 for ischemic heart disease. This synthesis of historical and contemporary research provides a unified framework for understanding Apaf-1's multifunctional roles in cellular homeostasis and disease pathogenesis, offering new avenues for targeted therapeutic interventions across multiple disease states.

The story of APF-1 represents a remarkable case study in scientific discovery, where investigations into a fundamental cellular process—protein degradation—unexpectedly illuminated entirely different biological pathways. Initially identified as an essential component of ATP-dependent proteolysis in reticulocytes, APF-1 was later recognized as the previously characterized protein ubiquitin, establishing the foundation for the ubiquitin-proteasome system [1] [2]. Simultaneously, the acronym Apaf-1 emerged in the late 1990s to describe a biochemically distinct factor that assembled the "apoptosome" complex to initiate programmed cell death [3]. This nomenclature convergence on "APF-1/Apaf-1" represents neither coincidence nor simple linear progression, but rather demonstrates how focused investigation of core cellular machinery frequently reveals unexpected molecular connections with profound biological implications.

Historical Foundation: APF-1 and the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

Discovery of ATP-Dependent Intracellular Proteolysis

The initial discovery of APF-1 emerged from investigating a fundamental biochemical paradox: why did intracellular proteolysis in mammalian cells require ATP when peptide bond hydrolysis is energetically favorable? This question originated with Simpson's 1953 observation of energy-dependent protein turnover [1], but remained unresolved for decades. By the late 1970s, Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose established a reconstituted system from reticulocyte lysates that reproduced ATP-dependent degradation of abnormal proteins, enabling biochemical fractionation of the required components [1] [4].

Identification and Characterization of APF-1

Through systematic fractionation, researchers identified two essential components: Fraction I contained a single heat-stable polypeptide designated APF-1, while Fraction II contained a higher molecular weight complex [1]. Critical experiments demonstrated that:

- 125I-labeled APF-1 formed high molecular weight conjugates with cellular proteins in an ATP-dependent manner

- This association was covalent and surprisingly stable to alkaline treatment

- The modification occurred on multiple acceptor proteins in Fraction II [1]

The convergence of multiple lines of evidence established that APF-1 was identical to ubiquitin, a previously known protein of uncertain function [5] [2]. This critical identification connected ATP-dependent proteolysis to a specific post-translational modification system.

Table 1: Key Experimental Evidence Establishing APF-1 as Ubiquitin

| Experimental Approach | Key Findings | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis | APF-1 and ubiquitin co-migrated in five different systems | Identical physical properties |

| Amino Acid Analysis | Excellent agreement between APF-1 and ubiquitin compositions | Identical primary structure |

| Functional Reconstitution | Both proteins activated ATP-dependent proteolysis system | Identical biological activity |

| Covalent Conjugation | 125I-APF-1 and 125I-ubiquitin formed identical conjugates | Identical biochemical behavior |

Evolution of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Model

The initial APF-1 research established the fundamental paradigm of ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis:

- ATP-dependent activation of ubiquitin

- Covalent conjugation to substrate proteins

- Targeting of modified substrates for degradation [4]

Subsequent research revealed that APF-2 (later identified as the 26S proteasome) contained the proteolytic activity that degraded ubiquitin-tagged proteins [6]. This foundation ultimately expanded to recognize the diversity of ubiquitin signals beyond proteolytic targeting, including roles in signaling, localization, and complex assembly.

The Emergence of Apaf-1 in Apoptotic Signaling

Discovery of the Apoptosome Complex

While ubiquitin research progressed, investigations into programmed cell death revealed a critical regulator of mitochondrial apoptosis. In 1997, researchers purified a cytochrome c- and dATP-dependent complex that initiated caspase activation [3]. This complex consisted of:

- Apaf-1 (Apoptotic Protease Activating Factor-1)

- Cytochrome c (released from mitochondria)

- Caspase-9 (initiator caspase, initially termed Apaf-3) [3]

The core mechanism involved Apaf-1 and caspase-9 binding via their respective NH2-terminal CED-3 homologous domains in the presence of cytochrome c and dATP, leading to caspase-9 activation and subsequent initiation of a protease cascade [3].

Structural Organization and Domain Architecture of Apaf-1

Apaf-1 is a multidomain adapter protein characterized by distinct functional regions:

- CARD (Caspase Recruitment Domain): N-terminal domain that recruits procaspase-9

- NB-ARC (Nucleotide-Binding Domain): Central nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain shared with plant R proteins and animal NLRs

- WD40 Repeats: C-terminal domain involved in ligand binding and autoinhibition [7] [8]

In the absence of apoptotic signals, Apaf-1 exists in an autoinhibited state. Cytochrome c binding to the WD40 repeats, coupled with dATP/ATP binding, induces conformational changes that promote oligomerization into the heptameric apoptosome complex [8] [9].

Figure 1: The Apaf-1-Mediated Apoptotic Pathway. This cascade illustrates the central role of Apaf-1 in mitochondrial apoptosis.

Experimental Approaches: Methodologies Defining APF-1/Apaf-1 Functions

Key Historical Protocols: APF-1 Identification

Reticulocyte Lysate Fractionation Protocol

The original experimental approach that identified APF-1 involved:

- System Preparation: Rabbit reticulocyte lysates were prepared and fractionated by DEAE-cellulose chromatography into Fraction I (unbound) and Fraction II (bound) [1]

- ATP-Dependent Proteolysis Assay: Fractions were reconstituted with ATP-regenerating system and 125I-labeled bovine serum albumin as substrate

- APF-1 Purification: Fraction I was further purified by heat treatment (90°C, 10 minutes) and gel filtration

- Conjugation Assays: 125I-APF-1 was incubated with Fraction II and ATP to detect covalent complex formation [1] [2]

This methodology established the requirement for both fractions and enabled the identification of APF-1 as the essential heat-stable component.

Ubiquitin Identification Experiments

Critical experiments confirming APF-1's identity as ubiquitin included:

- Electrophoretic Comparison: Side-by-side analysis of APF-1 and authentic ubiquitin in five different polyacrylamide gel systems and isoelectric focusing [2]

- Amino Acid Analysis: Quantitative comparison of amino acid composition [5]

- Functional Replacement: Demonstration that ubiquitin could substitute for APF-1 in supporting ATP-dependent proteolysis [2]

- Conjugate Formation: Comparison of 125I-APF-1 and 125I-ubiquitin conjugate patterns by SDS-PAGE [5]

Contemporary Protocols: Apaf-1 Functional Characterization

Apoptosome Reconstitution Assay

The fundamental protocol for studying Apaf-1 function involves in vitro apoptosome reconstitution:

- Component Purification: Recombinant Apaf-1, caspase-9, and cytochrome c are purified individually

- Complex Assembly: Proteins are mixed in equimolar ratios (20-100 nM) in buffer containing dATP/ATP and Mg2+

- Incubation: Reaction mixture is incubated at 30°C for 30-60 minutes

- Activity Assessment: Caspase-3 processing or DEVDase activity is measured fluorometrically [3] [9]

This approach enabled the identification of cytochrome c and dATP as essential cofactors and established the minimal components required for caspase activation.

DNA Binding Assays for Apaf-1

Recent research revealing Apaf-1's DNA-sensing capability employs:

- DNA Affinity Purification: Cytosolic extracts incubated with biotinylated dsDNA (e.g., interferon stimulatory DNA) conjugated to streptavidin beads

- Competition Experiments: Specificity determined by adding excess unlabeled DNA, RNA, or other potential ligands

- Elution and Analysis: Bound proteins eluted and identified by SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry [7]

This methodology demonstrated Apaf-1's direct binding to cytoplasmic DNA and its competition with cytochrome c for Apaf-1 binding.

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Apaf-1 DNA Binding Specificity

| Competitor | Concentration | Binding Inhibition | Specificity Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSV60 dsDNA | 0.1-1.0 μg/μL | Complete inhibition | Specific competition |

| Poly(dG:dC) | 0.1-1.0 μg/μL | Complete inhibition | Specific competition |

| E. coli genomic DNA | 0.1-1.0 μg/μL | Complete inhibition | Specific competition |

| Poly(I:C) (dsRNA) | 0.1-1.0 μg/μL | No inhibition | No cross-reactivity |

| MDP (peptidoglycan) | 10-100 μM | No inhibition | No cross-reactivity |

| Cyclic dinucleotides | 10-100 μM | No inhibition | No cross-reactivity |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for APF-1/Apaf-1 Investigations

| Reagent/Catalog | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | Source of APF-1/ubiquitin system components | ATP-dependent proteolysis reconstitution [1] |

| Biotinylated ISD DNA | DNA affinity purification ligand | Identification of DNA-binding capability [7] |

| Cytochrome c | Apoptosome activation ligand | Caspase activation assays [3] |

| dATP/ATP | Essential nucleotide cofactors | Apoptosome assembly and ubiquitin activation [3] |

| ZYZ-488 Compound | Small molecule Apaf-1 inhibitor | Therapeutic targeting in ischemia models [9] |

| Caspase-3 Fluorogenic Substrates | e.g., DEVD-AMC; protease activity detection | Apoptosome functional output measurement [3] [9] |

| H9c2 Cardiomyocyte Cell Line | Hypoxia/ischemia model system | Apaf-1 inhibition therapeutic assessment [9] |

Expanding Horizons: Non-Apoptotic Functions of Apaf-1

Apaf-1 as an Evolutionarily Conserved DNA Sensor

Recent research has revealed that Apaf-1 functions as a DNA sensor in innate immunity, demonstrating striking evolutionary conservation:

- Evolutionary Conservation: Apaf-1-like molecules from lancelets, fruit flies, mice, and humans maintain DNA sensing functionality [7]

- Mechanistic Insight: Mammalian Apaf-1 recruits RIP2 via its WD40 domain, promoting RIP2 oligomerization to initiate NF-κB-driven inflammation upon cytoplasmic DNA recognition [7]

- Structural Basis: Protein-DNA docking analyses reveal a conserved positively charged surface between NB-ARC and WD1 domains that facilitates DNA binding across species [7]

Cell Fate Determination: Apoptosis vs. Inflammation

The competition between cytochrome c and DNA for Apaf-1 binding establishes Apaf-1 as a critical cell fate checkpoint:

- Ligand Competition: DNA and cytochrome c compete for Apaf-1 binding

- Functional Switching: Cytochrome c binding promotes apoptosome formation and apoptosis, while DNA binding promotes RIP2-mediated inflammation [7]

- Biological Significance: This mechanism enables cells to appropriately respond to different stress signals by activating distinct pathways

Figure 2: Apaf-1 as a Cell Fate Checkpoint. Competitive binding determines pathway selection between apoptosis and inflammation.

Therapeutic Applications: Targeting Apaf-1 in Human Disease

Apaf-1 Inhibition for Ischemic Heart Disease

Excessive Apaf-1 activity induced by myocardial ischemia causes cardiomyocyte death, making it an attractive therapeutic target:

- Compound Development: ZYZ-488, a metabolite of the natural alkaloid leonurine, was identified as a novel small molecule competitive inhibitor of Apaf-1 [9]

- Mechanism of Action: ZYZ-488 disturbs the interaction between Apaf-1 and procaspase-9, suppressing caspase activation cascades [9]

- Efficacy Assessment: In hypoxia-induced H9c2 cardiomyocytes, ZYZ-488 (10 μM) significantly increased cell viability (55.19 ± 1.28% vs 41.76 ± 1.90% in vehicle) and reduced apoptotic cells (13.1 ± 0.26% vs 16.38 ± 0.13% in vehicle) [9]

Molecular Docking and Target Identification

Target fishing and molecular docking studies provide structural insights into Apaf-1 inhibition:

- Binding Site: ZYZ-488 likely binds to the Apaf-1 CARD domain at the procaspase-9 binding interface [9]

- Key Interactions: The compound may mimic three critical arginine residues (Arg 13, Arg 52, and Arg 56) from procaspase-9 that form hydrogen bonds with Asp 27/Glu 40 from Apaf-1 CARD [9]

- Therapeutic Potential: As one of the few known Apaf-1 inhibitors, ZYZ-488 represents a promising candidate for treating cardiac ischemia and other apoptosis-related diseases [9]

The scientific journey from APF-1 to Apaf-1 exemplifies how fundamental biochemical research into basic cellular processes frequently reveals unexpected connections with profound physiological implications. Initially characterized as a component of the ATP-dependent proteolytic system, APF-1/ubiquitin established the paradigm for post-translational regulation of protein stability and function. The independent emergence of Apaf-1 as a central regulator of mitochondrial apoptosis created a nomenclature coincidence that belies deeper biological connections.

Contemporary research continues to expand Apaf-1's functional repertoire, particularly its evolutionarily conserved role in DNA sensing and inflammation, establishing it as a critical determinant of cellular fate decisions between apoptosis and inflammatory responses. The structural similarities between Apaf-1, plant R proteins, and animal NLRs suggest deep evolutionary conservation in threat detection systems across kingdoms.

Therapeutic targeting of Apaf-1 represents a promising approach for diseases characterized by excessive apoptosis, particularly ischemic conditions. However, the complexity of Apaf-1's functions—spanning apoptosis regulation, DNA sensing, and inflammatory signaling—demands careful consideration of potential unintended consequences when developing targeted interventions.

Future research directions should focus on:

- Structural characterization of full-length Apaf-1 in complex with different ligands

- Detailed mechanistic understanding of how ligand binding determines functional outcomes

- Development of context-specific modulators for therapeutic applications

- Exploration of Apaf-1's role in integrating mitochondrial stress with immune responses

This synthesis of historical discovery and contemporary research provides a comprehensive framework for understanding APF-1/Apaf-1's multifunctional roles in cellular homeostasis and disease pathogenesis, offering exciting avenues for future investigation and therapeutic development.

The intricate regulation of cellular processes relies heavily on the modular architecture of proteins, where specific domains confer unique functions and mediate critical interactions. This whitepaper decodes the structural and functional characteristics of three essential domains—CARD, NB-ARC, and WD40—within the context of APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1) research. APF-1, now universally known as ubiquitin, serves as the foundational component of a sophisticated protein tagging system that directs cellular proteins for degradation [1]. The discovery of APF-1/ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis, awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004, revealed that the covalent attachment of this small protein to target substrates is a primary mechanism for energy-dependent intracellular proteolysis in eukaryotic cells [1]. Understanding the domain architecture of proteins involved in the ubiquitin-proteasome system is therefore crucial for comprehending cellular homeostasis, protein quality control, and the targeted destruction of regulatory molecules.

Domain Architectures: Structural Blueprints and Functional Roles

Caspase Recruitment Domain (CARD)

- Structural Fold and Function: The CARD domain is a member of the death domain-fold superfamily, characterized by a compact bundle of six anti-parallel amphipathic α-helices. This arrangement facilitates homotypic protein-protein interactions, meaning CARD domains interact exclusively with other CARD domains [10].

- Biological Context: CARD domains function as adaptor modules in pathways that regulate inflammation and cell death. They are found in a diverse array of proteins, including caspases, kinases, and cytosolic pattern-recognition receptors.

- Specific Example - NLRC5: The NOD-like receptor family CARD domain-containing 5 (NLRC5) possesses an untypical CARD (uCARD) domain. NLRC5 is the largest member of the NLR family and functions as a major transcriptional coactivator of MHC class I genes. Its activity is regulated through domain-specific interactions with various ligands in different cellular microenvironments [10].

Nucleotide-Binding Domain, APF-1, and Cell Death (NB-ARC)

- Name Origin and Function: The NB-ARC domain's acronym reveals its functional connections. It is a central Nucleotide-Binding domain, and its name explicitly links it to APF-1 (ubiquitin) and programmed cell death, or apoptosis. This domain belongs to the AAA+ (ATPases Associated with diverse cellular Activities) superfamily of molecular machines [1] [11].

- Mechanistic Role: NB-ARC domains function as molecular switches. They bind and hydrolyze nucleotides (ATP), with the energy from this hydrolysis driving conformational changes that regulate the activity of associated functional domains, such as protease domains in ATP-dependent proteases [11].

- Structural Composition: The core AAA+ module consists of a larger nucleotide-binding domain (α/β-domain) containing Walker A and B motifs, and a smaller helical domain (α-domain) containing sensor motifs. These work in concert to bind ATP, hydrolyze it, and transduce the resulting energy into mechanical work, such as protein unfolding or complex disassembly [11].

WD40 Repeat Domain

- Structural Architecture: The WD40 domain adopts a highly stable β-propeller architecture, typically composed of seven blades that form a circular, doughnut-like structure. Each blade itself is formed by a four-stranded anti-parallel β-sheet [12].

- Primary Function: WD40 domains primarily serve as versatile, non-enzymatic scaffolds for protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions. Their interaction surfaces include the top, bottom, and sides of the propeller, allowing them to nucleate the formation of large multi-protein complexes. No WD40 domain has been found to possess intrinsic enzymatic activity [12].

- Ubiquitin System Connection: WD40 domains are critical components within multi-subunit ubiquitin ligase complexes, such as the Cullin-RING ligases (CRLs). In these complexes, substrate-recognition receptors often contain WD40 domains that help bring the ubiquitin-conjugating machinery and the specific protein substrate into close proximity, facilitating the polyubiquitination of the substrate and its subsequent degradation by the proteasome [12].

Table 1: Comparative Summary of CARD, NB-ARC, and WD40 Domains

| Feature | CARD Domain | NB-ARC Domain | WD40 Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Structure | Bundle of 6 α-helices | AAA+ module (α/β & α domains) | 7-bladed β-propeller |

| Key Motifs | N/A | Walker A & B, Sensor-1, Sensor-2 | WD repeat sequences |

| Catalytic Activity | No | ATP binding and hydrolysis | No |

| Primary Function | Homotypic adaptor | Molecular switch, energy transduction | Protein-protein interaction scaffold |

| Role in Ubiquitination | Inflammatory signaling | Powers proteolytic machines (e.g., Lon) | Substrate recognition in E3 ligases |

Experimental Protocols in APF-1/Ubiquitin Research

The foundational discoveries of the ubiquitin system were made possible through meticulous biochemical experimentation. The following protocols are derived from the seminal work of Ciechanover, Hershko, and Rose.

Protocol 1: Reconstitution of ATP-Dependent Proteolysis using Reticulocyte Lysate Fractions

This methodology established the core requirements for ubiquitin-mediated degradation [1].

- Objective: To fractionate the ATP-dependent proteolytic system from reticulocyte lysate and reconstitute its activity in vitro.

- Materials:

- Reticulocyte Lysate: A cell-free extract derived from rabbit reticulocytes, chosen for its high proteolytic activity and lack of lysosomes [1].

- ATP-Regenerating System: Typically includes ATP, creatine phosphate, and creatine phosphokinase to maintain a constant supply of ATP.

- Radiolabeled Protein Substrate: A denatured or abnormal protein (e.g., (^{125})I-labeled lysozyme) whose degradation can be tracked.

- Chromatography Resins: For fractionating the lysate (e.g., DEAE-cellulose, hydroxyapatite).

- Methodology:

- Lysate Preparation and Fractionation: Prepare a lysate from fresh reticulocytes and separate it into two biochemical fractions (I and II) via ion-exchange chromatography [1].

- APF-1 (Ubiquitin) Isolation: Fraction I is further purified to isolate the heat-stable protein component, APF-1.

- Proteolysis Assay: Incubate the radiolabeled substrate with a reaction buffer, an ATP-regenerating system, and the reconstituted fractions (Fraction I + Fraction II).

- Analysis: Measure the release of acid-soluble radioactivity (degradation products) over time to quantify proteolytic activity.

- Key Finding: Proteolysis occurred only when Fraction I (containing APF-1), Fraction II, and ATP were all present, demonstrating the multi-component, energy-dependent nature of the system [1].

Protocol 2: Detection of Covalent APF-1-Protein Conjugates

This critical experiment revealed the novel mechanism of covalent protein tagging [1].

- Objective: To demonstrate the ATP-dependent formation of covalent complexes between APF-1 and target proteins.

- Materials:

- (^{125})I-labeled APF-1: Radioactively tagged APF-1 for sensitive detection.

- Fraction II: The lysate fraction containing the enzymatic machinery for conjugation.

- ATP and ATP-depletion reagents.

- SDS-PAGE and Autoradiography Equipment.

- Methodology:

- Conjugation Reaction: Incubate (^{125})I-labeled APF-1 with Fraction II in the presence or absence of ATP.

- Stability Assay: Treat a portion of the reaction mixture with strong denaturants like sodium hydroxide (NaOH) or SDS to test if the APF-1-protein association is covalent.

- Separation and Detection: Resolve the reaction products using SDS-PAGE. Transfer the gel to autoradiography film to visualize the high molecular weight complexes containing (^{125})I-APF-1.

- Key Finding: (^{125})I-APF-1 was promoted to high molecular weight forms in an ATP-dependent manner. These complexes were stable to NaOH treatment, proving the linkage was covalent and not a non-covalent association [1].

Visualization of Domain Functions and Experimental Workflows

Ubiquitin Ligase Complex Featuring WD40, NB-ARC, and CARD Domains

The following diagram illustrates how different domains can contribute to the function of a multi-protein ubiquitin ligase complex, facilitating substrate recognition, ubiquitin charging, and ligation.

Foundational APF-1 Conjugation and Degradation Assay

This diagram outlines the key experimental workflow that led to the discovery of ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Studying Ubiquitin and Protein Domains

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | A cell-free system amenable to biochemical fractionation; was crucial for discovering the components of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway [1]. |

| ATP-Regenerating System | Maintains a constant supply of ATP in vitro, which is essential for the energy-demanding processes of ubiquitin conjugation and proteasome-mediated degradation [1]. |

| Radiolabeled Substrates | Enable sensitive tracking of protein conjugation and degradation through techniques like SDS-PAGE/autoradiography and acid-solubility assays [1]. |

| Specific Domain Antibodies | Allow for the immunoprecipitation, localization, and quantification of proteins containing CARD, NB-ARC, or WD40 domains. |

| Recombinant Ubiquitin & Mutants | Used to dissect the ubiquitination cascade, study chain topology (e.g., K48-linked vs K63-linked), and understand the role of specific lysine residues [1]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132, Bortezomib) | Block the proteasome's proteolytic activity, allowing for the accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins and facilitating their study. |

| Crystallography & Cryo-EM | High-resolution structural techniques essential for determining the 3D architecture of domains and multi-protein complexes like ubiquitin ligases [12] [11]. |

The study of ATP-dependent intracellular proteolysis represents a cornerstone of modern cell biology, framing our understanding of how cellular protein levels are regulated. Within this context, the initial discovery of ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1 (APF-1) emerged from investigations into a fundamental biochemical curiosity: why did the degradation of intracellular proteins require energy when the hydrolysis of peptide bonds is itself an exergonic process? [1] This enigma persisted for decades after Simpson's initial observation in 1953 until the collaborative work of Rose, Hershko, and Ciechanover identified APF-1 as a central component of an ATP-dependent proteolytic system in reticulocytes [1]. Their seminal work, published in 1980, demonstrated that APF-1 was not merely a cofactor but was covalently attached to protein substrates in an ATP-dependent manner, marking them for degradation [1]. This discovery ultimately revealed that APF-1 was the previously characterized protein ubiquitin, establishing the conceptual foundation for the ubiquitin-proteasome system [5].

This whitepaper focuses on a distinct but mechanistically analogous system where the abbreviation APF-1 refers to Apoptotic Protease-Activating Factor 1, a key regulator of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway. Although functionally different from the original APF-1 (ubiquitin), Apaf-1 operates within a similar paradigm of ATP-dependent protease activation, representing another crucial example of energy-dependent regulation of proteolytic processes in eukaryotic cells [13]. The Apaf-1 apoptosome complex exemplifies how the broader principle of ATP-dependent proteolytic control—first identified in the ubiquitin system—manifests in programmed cell death pathways essential for development and tissue homeostasis [14].

Structural Composition of the Apaf-1 Monomer

Apaf-1 is a multidomain adapter protein that exists in an autoinhibited, monomeric state in the cytoplasm of healthy cells. Its domain architecture is intricately organized to maintain this latent conformation until an apoptotic signal is received.

Domain Organization and Function

Table: Functional Domains of Apaf-1

| Domain | Abbreviation | Location | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caspase Recruitment Domain | CARD | N-terminus | Mediates homophilic interaction with procaspase-9 CARD domain |

| Nucleotide-Binding Domain | NBD/NB-ARC | Central region | Binds (d)ATP; undergoes conformational changes during activation |

| Helical Domain 1 | HD1 | Central region | Contributes to nucleotide binding and oligomerization interface |

| Winged Helix Domain | WHD | Central region | Stabilizes autoinhibited state; participates in nucleotide binding |

| Helical Domain 2 | HD2 | C-terminal region | Connects regulatory region to the central hub |

| WD40 Repeats | WDR | C-terminus | Forms β-propeller structures that bind cytochrome c and maintain autoinhibition |

The CARD domain serves as the recruitment module for procaspase-9, utilizing homotypic interactions to bring the initiator caspase into the complex [13]. The central NBD domain, also referred to as NB-ARC (Nucleotide-Binding and Apaf-1, R gene, and CED-4), is homologous to CED-4 in C. elegans and contains characteristic Walker A and B motifs that coordinate (d)ATP and Mg²⁺ binding [13]. This region functions as the molecular switch that controls the transition from monomer to oligomer. The C-terminal WD40 repeats are organized into two distinct β-propellers—a 7-bladed WD-7 propeller and an 8-bladed WD-8 propeller—that encase the rest of the protein in the autoinhibited state [15] [16].

Conformational State in the Absence of Apoptotic Signals

In healthy cells, Apaf-1 exists predominantly in an ADP-bound or dATP-bound autoinhibited state [15]. The structure is maintained through extensive intramolecular interactions that prevent spontaneous oligomerization. The WD40 domains fold over the central hub, creating a compact conformation that sterically hinders the oligomerization interfaces [15]. Specifically, the WHD stacks against the NBD/HD1 module through a combination of hydrogen bonds and van der Waals contacts, including charged interactions between residues such as Asp365-Lys351 and Asp439-Lys318 [15]. This intricate domain stacking maintains Apaf-1 in a "locked" conformation that is energetically stable but primed for activation upon cytochrome c binding.

The Molecular Trigger: Cytochrome c Release and Binding

The intrinsic apoptosis pathway is initiated by diverse cellular stressors, including DNA damage, growth factor withdrawal, and endoplasmic reticulum stress. These signals converge on mitochondria, leading to mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) and the release of cytochrome c from the intermembrane space into the cytoplasm [17].

Mechanism of Cytochrome c Release

Cytochrome c release occurs through a carefully regulated process involving Bcl-2 family proteins. Pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins either directly activate the effector proteins BAX and BAK or neutralize anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members [13]. Activated BAX and BAK form oligomeric pores in the outer mitochondrial membrane, allowing cytochrome c and other pro-apoptotic factors (e.g., Smac/DIABLO) to escape into the cytosol [13]. This release process is facilitated by the displacement of cytochrome c from its association with the inner membrane phospholipid cardiolipin, which normally tethers it to the mitochondrial electron transport chain [17].

Structural Basis of Cytochrome c Recognition by Apaf-1

Upon entering the cytoplasm, cytochrome c binds specifically to the WD40 repeat domain of Apaf-1. Structural studies using cryo-electron microscopy have revealed that cytochrome c docks between the two β-propellers (WD-7 and WD-8) of the WD40 domain [15]. This binding interface is characterized by electrostatic interactions between positively charged lysine residues on cytochrome c and acidic residues on Apaf-1.

Table: Critical Cytochrome c Residues for Apaf-1 Binding

| Cytochrome c Residue | Functional Significance | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Lys72 | Most critical residue; replacement abolishes activity | Mutation to Arg, Trp, Gly, Leu, or Ala diminishes caspase activation [16] |

| Lys7 | Important for binding affinity | Glu mutation in combination with Lys8Glu reduces activity 10-fold [16] |

| Lys8 | Contributes to binding interface | Double mutant with Lys7 shows additive effect [16] |

| Lys25 | Significant for interaction | Pro mutation in combination with Lys39His reduces activity 10-fold [16] |

| Lys39 | Involved in salt bridge formation | His mutation in combination with Lys25Pro reduces activity 10-fold [16] |

| Lys86 | Participates in electrostatic interactions | Mutation decreases apoptosome formation [16] |

| Lys87 | Contributes to binding energy | Substitution impairs caspase activation [16] |

The binding mode involves distinctive bifurcated salt bridges, where a single lysine residue from cytochrome c interacts with two adjacent acidic residues on Apaf-1 [16]. This configuration creates a high-affinity interaction that likely promotes the conformational change necessary for Apaf-1 activation. The evolutionary conservation of these acidic residue pairs in vertebrate Apaf-1 sequences correlates with the cytochrome c-mediated mechanism of apoptosome formation that is characteristic of higher organisms [16].

The Activation Sequence: From Nucleotide Exchange to Oligomerization

The binding of cytochrome c to Apaf-1 initiates a precisely coordinated activation sequence that proceeds through several distinct steps, culminating in the formation of the active apoptosome complex.

Conformational Changes Induced by Cytochrome c Binding

The initial docking of cytochrome c between the WD-7 and WD-8 β-propellers triggers a rotational movement of the WD-7 domain [16]. This displacement disrupts the intramolecular interactions that maintain the autoinhibited state, particularly those involving the WHD and HD2 domains [15]. The conformational change is transmitted through the HD2 domain to the central nucleotide-binding region, creating a more open conformation that exposes the nucleotide-binding pocket and facilitates nucleotide exchange [15].

Nucleotide Hydrolysis and Exchange

In the autoinhibited state, Apaf-1 is bound to ADP or dATP. Cytochrome c binding stimulates the hydrolysis of bound (d)ATP, transitioning the protein through a semi-open conformation that is susceptible to unproductive aggregation [13]. This intermediate state is resolved through nucleotide exchange, where ADP is replaced by ATP or dATP [15]. The exchange process is accelerated in vitro by a protein complex consisting of Hsp70, the tumor suppressor PHAPI, and cellular apoptosis susceptibility (CAS) protein [13]. The replacement of ADP with ATP/dATP provides the energy required for the extensive conformational changes that enable oligomerization.

Oligomerization into the Heptameric Apoptosome

Upon binding of cytochrome c and ATP/dATP, Apaf-1 undergoes dramatic structural rearrangements that expose its oligomerization interfaces. The NBD, HD1, and WHD domains form a central hub, while the HD2 domains extend outward as spokes connecting to the WD40 repeats and bound cytochrome c molecules [15]. Seven activated Apaf-1 monomers assemble into a wheel-like heptameric complex approximately 145 Å in height and with a central hub diameter of 80 Å [15]. This oligomerization brings multiple CARD domains into proximity, creating a recruitment platform for procaspase-9.

Diagram Title: Apaf-1 Activation and Apoptosome Assembly Pathway

The Active Apoptosome: Architecture and Caspase Activation

The fully assembled apoptosome represents a sophisticated proteolytic activation machine whose structure has been elucidated through cryo-electron microscopy at near-atomic resolution.

Structural Organization of the Mature Complex

The apoptosome exhibits a striking seven-spoked wheel architecture with CARD domains forming a flexibly tethered disk above a central hub composed of oligomerized NBD, HD1, and WHD domains [15]. Each spoke consists of an Apaf-1 molecule with its WD40 domains extending radially outward, each bound to a cytochrome c molecule sandwiched between the two β-propellers [15]. The central hub features a ring of positively charged residues on its top surface, while the bottom surface is enriched with negatively charged amino acids [15]. This charge distribution may facilitate the recruitment of additional factors or promote the proper orientation of the complex within the cytoplasm.

Mechanisms of Caspase-9 Activation

The apoptosome activates caspase-9 through two complementary mechanisms that integrate proximity-induced dimerization with allosteric regulation:

Proximity-Induced Homodimerization: The clustering of multiple procaspase-9 molecules on the CARD platform significantly increases their local concentration, facilitating the formation of active homodimers [18]. The homodimerization interface involves a conserved GCFNF motif in the small subunit of caspase-9, and mutations in this motif (e.g., F404D) abolish catalytic activity [18]. Unprocessed procaspase-9 has a higher affinity for itself than the cleaved form, promoting stable dimer formation on the apoptosome.

Heterodimerization with Apaf-1: Procaspase-9 can also form heterodimers with Apaf-1 through interactions between its small subunit and the NOD domain of Apaf-1 [18]. These heterodimers more efficiently activate procaspase-3 than homodimers, suggesting a complementary activation mechanism.

Following recruitment to the apoptosome, procaspase-9 undergoes autoprocessing at Asp-315, separating the large (p35) and small (p12) subunits [18]. This cleavage event initiates a "molecular timer" mechanism by reducing the affinity of caspase-9 for the apoptosome, leading to its eventual displacement and allowing new procaspase-9 molecules to be recruited and activated [18]. Further processing by caspase-3 at Asp-330 removes the linker between subunits, generating a p35/p10 heterodimer with partially restored activity [18].

Diagram Title: Caspase-9 Activation Mechanisms on the Apoptosome

Experimental Approaches for Studying Apoptosome Assembly

Research into apoptosome formation and function employs diverse biochemical, structural, and cell biological methods that provide complementary insights into the mechanism of this complex machinery.

Key Methodologies and Assay Systems

Table: Experimental Systems for Apoptosome Research

| Methodology | Key Features | Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate System | ATP-dependent; fractionation into I and II; identifies essential factors | Original APF-1 characterization; conjugation assays | [1] |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy | Near-atomic resolution (3.8 Å); single-particle analysis | Atomic structure of apoptosome; cytochrome c binding interface | [15] |

| Split-Luciferase Assay | Quantifies protein-protein interactions in cell-free and cell-based systems | Monitoring apoptosome formation; comparing truncated vs. full-length Apaf-1 | [19] |

| SEC-MALS | Size-exclusion chromatography with multi-angle light scattering | Determining oligomeric state; caspase-9 homo-dimerization | [18] |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulations | Models dynamic interactions; predicts salt bridge formation | Cytochrome c/Apaf-1 binding mode; bifurcated salt bridges | [16] |

| Site-Specific Crosslinking | Direct detection of protein interactions in complexes | Demonstrating caspase-9 homodimerization in apoptosome | [18] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagents for Apoptosome Research

| Reagent | Composition/Features | Research Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full-length Apaf-1 | Human, baculovirus-expressed; purified to homogeneity | Structural studies; in vitro reconstitution | Platform for apoptosome assembly [15] |

| Cytochrome c | Horse or human; oxidized form | Triggering apoptosome assembly | Apaf-1 ligand; relieves autoinhibition [15] |

| dATP/ATP | Deoxynucleoside triphosphates | Nucleotide exchange in activation | Energy source; promotes oligomerization [13] [15] |

| Procaspase-9 Constructs | Wild-type, non-cleavable (TM), dimerization-deficient (F404D) | Mechanism of caspase activation | Apoptosome effector protease [18] |

| WD40-truncated Apaf-1 (ΔApaf-1) | Deletion of WD40 repeat domain | Dominant-negative studies; mapping interactions | Constitutively active; different oligomerization [19] |

| Cytochrome c Mutants | Lysine substitutions (K72A, K7/8E, etc.) | Mapping binding interface | Identifying critical interaction residues [16] |

Detailed Protocol: In Vitro Reconstitution of the Apoptosome

The following methodology, adapted from Zhou et al. (2015), allows for the assembly and analysis of functional apoptosome complexes [15]:

Protein Preparation: Express and purify full-length human Apaf-1 using a baculovirus-insect cell expression system. Confirm homogeneity through SDS-PAGE and size-exclusion chromatography.

Complex Assembly: Incubate purified Apaf-1 (0.5-1.0 mg/mL) with a 2-5 molar excess of horse cytochrome c and 1 mM dATP in assembly buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl₂) for 30-60 minutes at 25°C.

Complex Purification: Separate assembled apoptosomes from unincorporated components using size-exclusion chromatography (Superose 6 Increase 10/300 GL column). Monitor elution profile at 280 nm; the apoptosome elutes as a high molecular weight complex in the void volume.

Activity Validation: Assess functional integrity of the assembled complex by measuring its ability to activate caspase-9 using fluorogenic substrates (e.g., LEHD-amc) or through processing of procaspase-3 in a coupled activation assay.

Structural Analysis: For cryo-EM studies, apply the apoptosome sample to freshly glow-discharged quantifoil grids, blot, and plunge-freeze in liquid ethane. Collect images using a Titan Krios microscope operating at 300 kV. Process data through reference-free 2D classification and 3D reconstruction to obtain high-resolution structures.

This protocol typically yields a heptameric complex of approximately 1.0-1.3 MDa that activates caspase-9 with high efficiency and is suitable for both functional assays and structural studies [15].

Research Implications and Therapeutic Perspectives

The elucidated mechanism of APF-1/Apaf-1 oligomerization represents more than a fundamental biological discovery; it provides a strategic framework for therapeutic intervention in human diseases characterized by apoptotic dysregulation.

The intricate process of cytochrome c-mediated Apaf-1 activation offers multiple targetable nodes for pharmacological manipulation. Small molecules that stabilize the autoinhibited state of Apaf-1 could potentially attenuate excessive apoptosis in neurodegenerative conditions, while compounds that promote apoptosome formation might overcome the apoptotic resistance characteristic of many malignancies [19]. The observed differential oligomerization behavior between full-length and truncated Apaf-1 suggests that strategic disruption of specific interfaces could achieve selective pathway modulation [19].

From a broader perspective, the Apaf-1 apoptosome exemplifies how the fundamental principle of ATP-dependent proteolytic control—first established through the original APF-1 (ubiquitin) research—manifests in the regulated activation of protease cascades beyond the proteasome [1] [14]. This mechanistic conservation across distinct proteolytic systems highlights the evolutionary optimization of energy-dependent switches for controlling irreversible cellular processes, from targeted protein degradation to programmed cell death. Continued structural and functional dissection of the apoptosome will undoubtedly reveal further insights into the exquisite precision of cell death regulation and provide novel avenues for therapeutic development in apoptosis-related diseases.

Caspase-9 serves as the initiator caspase in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, converting various cellular stress signals into the first proteolytic event that leads to programmed cell death [20]. This pathway represents one of the most conserved and fundamental processes in mammalian biology, with its proper function being essential for normal development and tissue homeostasis. The activation of caspase-9 occurs through its incorporation into a multiprotein activation platform known as the apoptosome, whose formation is triggered by the critical factor APF-1 (Apoptotic Protease-Activating Factor 1, now known as Apaf-1) [13] [3]. The seminal discovery that cytochrome c and dATP-dependent formation of the Apaf-1/caspase-9 complex initiates an apoptotic protease cascade established the molecular framework for understanding intrinsic apoptosis [3]. Within this complex, caspase-9 becomes activated and proceeds to cleave and activate downstream effector caspases, including caspase-3, -6, and -7, which then execute the orderly dismantling of cellular structures [21]. The regulation of this initiating step is therefore a critical control point in determining cellular fate, with profound implications for both degenerative and proliferative diseases.

Table 1: Core Components of the Intrinsic Apoptotic Pathway

| Component | Full Name | Function in Apoptosis |

|---|---|---|

| Caspase-9 | Cysteine-aspartic protease 9 | Initiator caspase; activates executioner caspases |

| APF-1/Apaf-1 | Apoptotic protease-activating factor 1 | Forms the apoptosome platform upon cytochrome c binding |

| Cytochrome c | Cytochrome c | Mitochondrial protein; triggers apoptosome formation when released |

| Caspase-3, -6, -7 | Executioner caspases | Mediate proteolytic cleavage of cellular substrates during apoptosis |

Molecular Structure and Activation Mechanisms

Structural Domains of Caspase-9

Caspase-9 shares the fundamental structural organization of initiator caspases, consisting of three primary domains: an N-terminal pro-domain, a large subunit, and a small subunit [21]. The N-terminal pro-domain, also referred to as the long pro-domain, contains a CARD (Caspase Activation and Recruitment Domain) motif, which mediates critical protein-protein interactions essential for its activation [20]. This CARD domain selectively binds to the complementary CARD domain in Apaf-1 through homotypic interactions, facilitating the recruitment of caspase-9 to the apoptosome complex [20] [13]. A flexible linker loop connects the pro-domain to the catalytic domain, which is composed of the large and small subunits that together form the active protease [20]. Unlike effector caspases that possess the conserved active site motif QACRG, caspase-9 contains the distinctive motif QACGG, which contributes to its unique regulatory properties and broader substrate specificity [21].

When caspase-9 dimerizes within the apoptosome, it exhibits an unusual asymmetry in its active sites. The dimer contains two different active site conformations: one that closely resembles the canonical catalytic site of other caspases, and a second that lacks a complete 'activation loop', thereby disrupting the catalytic machinery in that particular active site [21]. This structural peculiarity, combined with shorter surface loops around the active site that create a more open substrate-binding cleft, provides caspase-9 with relatively broad substrate specificity compared to executioner caspases [21]. The catalytic activity of caspase-9 requires an aspartic acid residue at the P1 position of its substrates, with a preference for histidine at the P2 position [21].

Mechanisms of Activation

The activation of caspase-9 represents a fundamental departure from the proteolytic activation mechanisms of effector caspases. Extensive research has revealed that caspase-9 is activated primarily through dimerization rather than proteolytic cleavage, although cleavage events can modulate its activity [20] [22]. Two principal models have been proposed to explain the activation mechanism:

The "Induced Proximity/Dimerization" Model: This hypothesis posits that the apoptosome primarily serves as a platform to concentrate procaspase-9 molecules, promoting their dimer-driven activation [20] [22]. The increased local concentration facilitates dimerization, which is sufficient to generate catalytic activity. Strong experimental support for this model comes from studies demonstrating that both Hofmeister salts and a reconstituted mini-apoptosome activate caspase-9 through a second-order process consistent with dimerization [22]. Furthermore, when the recruitment domain of caspase-8 (an initiator caspase of the extrinsic pathway) is replaced with that of caspase-9, this chimeric caspase can be activated by the apoptosome, indicating that simple recruitment to the platform is sufficient for activation without allosteric effects [22].

The "Induced Conformation" Model: This alternative hypothesis suggests that binding to the Apaf-1 apoptosome induces conformational changes in caspase-9 that are required for its activation [20]. Structural studies of the CARD domains between Apaf-1 and caspase-9 have revealed an indispensable complementary interface for caspase-9 activation, with recent evidence suggesting that multimeric interactions involving three different types of interfaces, rather than simple 1:1 interaction, underlie caspase-9 activation [20].

The current consensus integrates elements from both models, suggesting that the apoptosome serves both to concentrate caspase-9 molecules and to induce conformational changes that stabilize the active dimeric form [20]. Once activated, caspase-9 can undergo autoprocessing at specific aspartic acid residues, producing cleaved forms (p35/p12) [20]. However, this cleavage is not strictly required for activation but rather functions as a molecular timer that regulates the duration of apoptosome activity [20] [23]. The uncleaved form of caspase-9 maintains substantial activity when bound to the apoptosome, though cleavage does affect its affinity for the complex and its susceptibility to regulatory factors like XIAP (X-linked Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein) [23].

Figure 1: Caspase-9 Activation Pathway and Regulation. The intrinsic apoptosis pathway is triggered by cellular stress, leading to cytochrome c release and apoptosome formation. The apoptosome recruits and activates caspase-9 through dimerization, which then activates executioner caspases to mediate apoptotic cell death. Regulatory mechanisms include XIAP-mediated inhibition and phosphorylation by various kinases.

Experimental Analysis of Caspase-9 Activation

Reconstitution of the Apoptosome and Caspase-9 Activation

The biochemical reconstitution of caspase-9 activation provides a controlled system for investigating the molecular requirements and mechanisms of intrinsic apoptosis. The following protocol outlines the essential methodology derived from seminal studies in the field [3] [22]:

Objective: To reconstitute the functional apoptosome complex in vitro and assess its ability to activate caspase-9.

Principle: The apoptosome is assembled by combining purified Apaf-1 with cytochrome c and dATP/ATP. This complex is then incubated with procaspase-9 to monitor its activation through dimerization and subsequent acquisition of proteolytic activity toward downstream substrates.

Materials and Reagents:

- Purified recombinant Apaf-1 (full-length)

- Purified recombinant procaspase-9

- Cytochrome c (equine heart)

- dATP or ATP solution

- Caspase assay buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT)

- Caspase-3 substrate (e.g., Ac-DEVD-pNA)

- SDS-PAGE and Western blotting equipment

- Antibodies specific for caspase-9 and cleaved caspase-3

Procedure:

- Apoptosome Assembly:

- Prepare the assembly reaction in caspase assay buffer containing:

- 50 nM Apaf-1

- 10 µM cytochrome c

- 1 mM dATP/ATP

- 1-2 mM MgCl₂

- Incubate the mixture at 30°C for 30-60 minutes to allow for oligomerization of Apaf-1 into the heptameric apoptosome complex.

- Prepare the assembly reaction in caspase assay buffer containing:

Caspase-9 Activation:

- Add purified procaspase-9 (10-50 nM) to the pre-assembled apoptosome.

- Incubate at 30°C for 30-120 minutes to allow for recruitment and activation of caspase-9.

Activity Assessment:

- Proteolytic Cleavage Assay: Remove aliquots at various time points and analyze by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using caspase-9-specific antibodies to detect processing fragments (p35/p12).

- Enzymatic Activity Measurement: Add caspase-3 (or its substrate Ac-DEVD-pNA) to the reaction and monitor cleavage spectrophotometrically at 405 nm or fluorometrically using appropriate substrates.

Key Considerations:

- The ratio of Apaf-1 to caspase-9 is critical, with evidence suggesting a 7:2 stoichiometry within the functional apoptosome [23].

- Nucleotide status significantly influences complex formation; dATP is typically more effective than ATP in supporting apoptosome assembly [13] [3].

- The presence of cytochrome c is absolutely required for proper conformational changes in Apaf-1 that enable apoptosome formation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Caspase-9/Apoptosome Studies

| Reagent | Function/Application | Experimental Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Apaf-1 | Core scaffold protein of apoptosome | In vitro reconstitution of apoptosome complex |

| Cytochrome c | Apoptosome triggering factor | Essential component for inducing Apaf-1 conformational change |

| dATP/ATP | Energy source and cofactor | Required for nucleotide exchange and apoptosome oligomerization |

| Caspase-9 Antibodies | Detection of caspase-9 forms | Western blot analysis of processing and activation |

| Caspase-3 Substrates (DEVD-pNA) | Reporter of enzymatic activity | Measurement of downstream caspase activation |

| XIAP Bir3 Domain | Selective caspase-9 inhibitor | Mechanistic studies of regulation and inhibition |

Cellular Models for Investigating Caspase-9 Function

Genetic manipulation of cell lines provides a powerful approach for dissecting the specific contribution of caspase-9 to apoptotic pathways. The following experimental approach utilizes Jurkat T-lymphocytes, a well-established model system for apoptosis research [24]:

Objective: To determine the requirement for caspase-9 in heat-induced apoptosis using genetically modified Jurkat cell lines.

Cell Lines and Genetic Modifications:

- Wild-type Jurkat T-lymphocytes (clone E6.1)

- Caspase-9-deficient Jurkat cells (generated by CRISPR/Cas9 or RNAi)

- Apaf-1-deficient Jurkat cells

- Bcl-2/Bcl-xL overexpressing Jurkat cells

Experimental Protocol:

- Apoptosis Induction:

- Expose cells to hyperthermia (44°C) for 60 minutes in a controlled water bath.

- Return cells to 37°C for 2-6 hours to allow apoptosis progression.

- Assessment of Apoptotic Parameters:

- Phosphatidylserine Externalization: Detect using Annexin V-FITC staining and flow cytometry.

- Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (ΔΨm): Measure using DiIC1(5) or JC-1 dyes and flow cytometry.

- Caspase Activation: Analyze by Western blotting for caspase-9 and caspase-3 processing, or using fluorogenic caspase substrates.

- Cytochrome c Release: Assess by subcellular fractionation followed by Western blotting.

Expected Outcomes:

- Wild-type cells should exhibit significant apoptosis following heat stress, characterized by caspase-9 and caspase-3 activation, cytochrome c release, and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential.

- Caspase-9-deficient and Apaf-1-deficient cells should demonstrate markedly reduced apoptosis, confirming the essential role of the apoptosome in this pathway.

- Bcl-2/Bcl-xL overexpressing cells should show inhibition of cytochrome c release and subsequent caspase activation, placing these regulators upstream of apoptosome formation.

This experimental approach effectively demonstrates the central position of caspase-9 in the intrinsic apoptosis pathway and provides a system for evaluating pharmacological modulators of this pathway.

Regulation of Caspase-9 Activity

The activity of caspase-9 is subject to multiple layers of regulation that ensure apoptotic cell death occurs only under appropriate circumstances. These regulatory mechanisms include post-translational modifications, protein-protein interactions, and alternative splicing.

Phosphorylation-Based Regulation

Phosphorylation represents a major mechanism for fine-tuning caspase-9 activity in response to extracellular signals and cellular conditions. Multiple protein kinases have been identified that directly phosphorylate caspase-9 and modulate its function:

AKT (PKB): This serine-threonine kinase phosphorylates caspase-9 on serine-196, acting as an allosteric inhibitor that suppresses both caspase-9 activation and protease activity [21]. The phosphorylation site is distant from the catalytic site, yet it inhibits dimerization and induces conformational changes that affect the substrate-binding cleft [21]. AKT can phosphorylate both processed and unprocessed forms of caspase-9, with phosphorylation of the processed form occurring on the large subunit [21].

ERK1/2: Phosphorylates caspase-9 at Thr125, a site located in the hinge region near the N-terminus of the large subunit [20]. This phosphorylation inhibits caspase-9 processing without preventing its recruitment to the apoptosome [20]. The phosphorylated caspase-9 may serve as a dominant-negative regulator that modulates the recruitment of non-phosphorylated caspase-9 to the apoptosome platform [20].

Other Kinases: Additional kinases including DYRK1A, CDK1-cyclinB1, and p38α have also been reported to phosphorylate caspase-9 at Thr125, providing multiple signaling inputs that converge on this critical regulatory site [20].

Table 3: Regulatory Phosphorylation Sites on Caspase-9

| Kinase | Phosphorylation Site | Functional Consequence | Cellular Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| AKT | Serine-196 | Allosteric inhibition; suppresses dimerization and activity | Survival signaling; growth factor pathways |

| ERK1/2 | Threonine-125 | Inhibits caspase-9 processing | Mitogenic signaling; stress responses |

| DYRK1A | Threonine-125 | Inhibits caspase-9 activation | Development; cell differentiation |

| CDK1-CyclinB1 | Threonine-125 | Regulates apoptosis during cell cycle | Mitosis; cell cycle progression |

| p38α | Threonine-125 | Modulates stress-induced apoptosis | Cellular stress responses |

Endogenous Protein Regulators

Beyond phosphorylation, caspase-9 activity is modulated through interactions with various endogenous proteins:

XIAP (X-linked Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein): The Bir3 domain of XIAP serves as an endogenous highly selective caspase-9 inhibitor [25]. XIAP preferentially inhibits the D315 cleaved form of caspase-9, with differential susceptibility based on the specific cleavage site [25]. This regulatory interaction provides an important checkpoint that prevents excessive caspase activation.

Caspase-9b: An endogenous alternatively spliced short isoform of caspase-9 that lacks the large catalytic subunit [25]. This isoform functions as a natural dominant-negative inhibitor by competing with full-length caspase-9 for binding to the apoptosome, thereby fine-tuning the apoptotic threshold [25].

Heat Shock Proteins: The Hsp70 complex, in conjunction with the tumor suppressor PHAPI and cellular apoptosis susceptibility (CAS) protein, accelerates nucleotide exchange on Apaf-1, thereby modulating the kinetics of apoptosome formation and consequently caspase-9 activation [13].

These multiple regulatory mechanisms collectively ensure that caspase-9 activation occurs only when the balance of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic signals tips decisively toward cell death, preventing inadvertent activation that could lead to pathological tissue loss.

Pathophysiological Implications and Therapeutic Applications

Caspase-9 in Disease Pathogenesis

Dysregulation of caspase-9 function has been implicated in numerous human diseases, highlighting its critical role in maintaining tissue homeostasis:

Cancer: Reduced caspase-9 activity represents a common mechanism by which tumor cells evade apoptosis [20]. Caspase-9 suppression has been observed in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma resistant to cisplatin, and testicular cancer cells with failed caspase-9 activation show increased apoptotic thresholds [20]. Functional polymorphisms in the CASP9 gene have been associated with susceptibility to lung, bladder, pancreatic, colorectal, and gastric cancers [20]. Additionally, certain polymorphisms in the caspase-9 promoter that enhance its expression have been linked to increased lung cancer risk [21].

Neurodevelopmental and Neurodegenerative Disorders: Caspase-9 deficiency has profound effects on brain development, with knockout mice exhibiting perinatal lethality accompanied by severe brain abnormalities due to suppressed apoptosis during development [20] [21]. In humans, caspase-9 mutations have been associated with neural tube defects [21]. Conversely, excessive caspase-9 activation contributes to neurodegenerative conditions, with activated caspase-9 and caspase-3 present at the endstage of Huntington's disease, suggesting apoptosis contributes to neuronal death [20]. Increased caspase-9 activity has also been implicated in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis progression [21].

Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases: CASP9 gene polymorphisms have been linked to multiple sclerosis, with the CASP9 (Ex5 + 32G/A) GG genotype associated with higher disease risk [20]. Altered caspase-9 expression or function has also been reported in various other autoimmune pathologies [25].

Other Conditions: Elevated caspase-9 expression and specific polymorphisms have been associated with discogenic low back pain [20]. Increased caspase-9 activity is also implicated in retinal detachment, slow-channel syndrome, and various cardiovascular disorders [21].

Therapeutic Targeting of Caspase-9

The strategic position of caspase-9 as the initiator of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway makes it an attractive therapeutic target for multiple disease conditions:

iCasp9 Safety Switch: A innovative therapeutic application involves engineered caspase-9 as an inducible safety switch for cell therapies [21]. The inducible caspase-9 (iCasp9) system has been implemented in chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapies to address potential toxicities [21]. In this approach, caspase-9 is modified by fusion with the FK506 binding protein, creating a dimerization-dependent form that can be activated by administration of a small-molecule drug such as rapamycin [21]. If CAR-T cell therapy causes severe side effects, administering the dimerizing drug triggers caspase-9 activation and selective elimination of the engineered T cells, providing a crucial safety mechanism [21].

Pharmacological Inhibition: For conditions involving excessive caspase-9 activation, selective inhibitors represent a promising therapeutic strategy. Approaches include dominant-negative caspase-9 mutants and pharmacological inhibitors derived from the XIAP protein, whose Bir3 domain serves as an endogenous highly selective caspase-9 inhibitor [25]. Such inhibitors could potentially protect neurons in neurodegenerative diseases or reduce tissue damage in ischemic injuries.

Chemosensitization: In cancer therapy, strategies to overcome caspase-9 inhibition could restore apoptotic sensitivity in treatment-resistant tumors. Understanding the molecular mechanisms that suppress caspase-9 activation in various cancers may lead to combination therapies that lower the apoptotic threshold and enhance the efficacy of conventional chemotherapeutic agents.

The dual role of caspase-9 in both physiological cell death and pathological tissue degeneration, combined with its emerging non-apoptotic functions, underscores the importance of developing precisely targeted therapeutic interventions that can modulate its activity in a context-dependent manner.

The apoptosome, a central signaling platform in intrinsic apoptosis, functions as a sophisticated molecular machine whose assembly and activity are precisely regulated by nucleotide triphosphates. This complex forms when apoptotic protease-activating factor 1 (Apaf-1) undergoes nucleotide-dependent oligomerization into a heptameric wheel-like structure, creating a platform for caspase-9 activation. While Apaf-1 has been recognized as a key component in ATP-dependent proteolysis pathways, recent structural and biochemical advances have revealed unexpected nuances in nucleotide regulation. This technical review integrates quantitative biochemical data, structural insights, and emerging models of allosteric regulation to provide a comprehensive framework for understanding how dATP/ATP binding controls apoptosome formation, function, and inactivation. The mechanistic insights summarized herein have profound implications for targeting apoptotic pathways in cancer and degenerative diseases.

Apoptotic protease-activating factor 1 (Apaf-1), initially investigated in the context of ATP-dependent proteolysis pathways, serves as the structural and regulatory core of the apoptosome complex. This large multimeric assembly platform is strictly dependent on nucleotide triphosphates for its activation cycle, from initial monomer conformational changes through caspase activation and eventual complex disassembly. The apoptosome exemplifies a sophisticated biological switch where nucleotide binding and exchange control the transition between inactive and active states, ultimately determining cellular fate. Understanding the precise molecular mechanisms of nucleotide dependence provides critical insights for therapeutic intervention in diseases characterized by apoptotic dysregulation.

Structural Organization of the Apoptosome

Domain Architecture of Apaf-1

Apaf-1 contains three major structural domains that coordinate nucleotide-dependent apoptosome assembly:

- Caspase Recruitment Domain (CARD): Mediates protein-protein interactions with procaspase-9 through CARD-CARD interactions [26] [27].

- Nucleotide-Binding and Oligomerization Domain (NOD): Comprises the central hub responsible for dATP/ATP binding and contains characteristic Walker A and Walker B motifs of the AAA+ ATPase family [26] [27]. This domain includes the nucleotide-binding domain (NBD), helical domain 1 (HD1), and winged-helix domain (WHD) [27].

- WD40 Repeat Region: Forms a V-shaped regulatory domain composed of 7-blade and 8-blade β-propellers that bind cytochrome c and maintain Apaf-1 in an autoinhibited state [26] [28].

Nucleotide-Induced Oligomerization

In healthy cells, Apaf-1 exists as an inactive monomer with ADP bound to its NBD domain. Cytochrome c binding to the WD40 region triggers nucleotide exchange, with dATP/ATP replacing bound ADP [28] [27]. This exchange induces extensive conformational changes that expose interaction surfaces, enabling heptameric oligomerization into the characteristic wheel-shaped apoptosome with 7-fold symmetry [27]. The fully assembled complex has a molecular mass of approximately 1 MDa and dimensions of 270 × 270 × 75 Å [28].

Table 1: Key Structural Features of the Human Apoptosome

| Feature | Description | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Symmetry | Heptameric (7-fold) | Creates symmetric binding platform for caspase activation |

| Central Hub | Formed by NOD domains | Stabilizes oligomerized structure; contains nucleotide-binding pockets |

| CARD Disk | Spiral of 3-4 CARD pairs | Platform for procaspase-9 recruitment and activation |

| β-Propeller Arms | WD40 repeats forming V-shaped domains | Cytochrome c binding; regulatory function |

Molecular Mechanisms of Nucleotide Regulation

Nucleotide Exchange and Conformational Activation

The transition from autoinhibited Apaf-1 monomer to assembly-competent conformer represents the critical nucleotide-dependent step in apoptosome formation. Structural studies reveal that cytochrome c binding to the WD40 domain triggers nucleotide exchange, with dATP/ATP replacing bound ADP [28]. This exchange induces large-scale conformational changes that extend the Apaf-1 molecule, exposing oligomerization interfaces in the NOD domain. The assembled apoptosome structure shows dATP molecules bound at interfaces between Apaf-1 subunits, where they help stabilize the active complex [28].

Dual Regulatory Roles of Nucleotides

Interestingly, nucleotides play dual regulatory roles in apoptosome function, acting as both positive and negative regulators depending on concentration and context. At physiological concentrations (typically <1 mM), dATP/ATP binding to Apaf-1 promotes apoptosome assembly and caspase-9 activation. However, at higher concentrations (>1 mM), ATP also binds to and directly inhibits caspase-9, providing a potential feedback mechanism [29]. This inhibition exhibits specificity for nucleotide triphosphates, as ADP and AMP do not bind to processed caspase-9 [29].

Diagram 1: Nucleotide-Dependent Apoptosome Assembly Pathway

Stoichiometry and Assembly Kinetics

Quantitative studies of apoptosome assembly reveal complex kinetics influenced by nucleotide availability. Systems biology modeling demonstrates that rapid cytochrome c release (t½ ≈ 1.5 minutes) is followed by Apaf-1 activation, which reaches completion within minutes under optimal nucleotide conditions [30]. The nucleotide-dependent assembly follows cooperative kinetics, with an apparent Kd for dATP/ATP in the low micromolar range [30]. This rapid activation kinetics ensures prompt cellular response to apoptotic stimuli.

Quantitative Analysis of Nucleotide Binding

Binding Affinities and Specificity

The nucleotide dependence of apoptosome formation exhibits remarkable specificity for purine nucleotide triphosphates. Affinity labeling studies using FDNP-ATP demonstrate potent inhibition of procaspase-9 activation with an IC50 of approximately 5-11 nM [29]. This high-affinity interaction is specific for the full-length procaspase-9, as the prodomain-truncated enzyme (ΔproCsp9) and the processed p18/p10 forms do not exhibit significant nucleotide binding [29]. The stoichiometry of FDNP-ATP labeling to procaspase-9 is 1:1, resulting in a covalently modified complex incapable of productive apoptosome formation [29].

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters of Nucleotide Binding in Apoptosome Components

| Parameter | Value | Experimental Context | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| FDNP-ATP IC50 | 5-11 nM | Inhibition of procaspase-9 binding to apoptosome | [29] |

| dATP/ATP Kd | ~0.7 μM | Procaspase-9 binding to apoptosome (calculated from IC50) | [30] |

| Inhibitory [ATP] | >1 mM | Direct caspase-9 inhibition | [29] |

| CARD-CARD Kd | ~0.7 μM | Procaspase-9 to Apaf-1 CARD domain | [30] |

Caspase-9 Regulation Through Nucleotide Binding

The identification of a nucleotide binding site in caspase-9 reveals an additional layer of regulation beyond the initial Apaf-1 activation. This site specifically binds ATP and dATP, but not ADP or AMP, and is located in a region that becomes inaccessible upon proteolytic processing or prodomain removal [29]. The functional significance of this regulatory site may involve modulation of caspase-9 activity in response to cellular energy status, potentially linking apoptotic commitment to metabolic conditions.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Core Reconstitution Protocols

Apoptosome Assembly and Purification

Objective: Reconstitute functional apoptosome complex from purified components for biochemical and structural studies.

Method Details:

- Incubate recombinant Apaf-1 (0.5-1.0 μM) with cytochrome c (1-2 μM) and dATP/ATP (1-2 mM) in buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, and 10 mM KCl for 30-60 minutes at 25-30°C [28].

- Separate assembled apoptosomes from unassembled components using glycerol gradient centrifugation (10-30% linear gradient) at 100,000 × g for 8-12 hours [28].

- Analyze gradient fractions by SDS-PAGE and coomassie staining to confirm presence of Apaf-1, cytochrome c, and bound nucleotides.

- Verify assembly quality and homogeneity by negative stain electron microscopy.

Key Considerations: Nucleotide purity is critical, as ADP contamination inhibits proper assembly. Cytochrome c freshness and proper reduction state significantly impact assembly efficiency.

Caspase Activation Assays

Objective: Quantify functional output of nucleotide-dependent apoptosome assembly through caspase-9 enzymatic activity.

Method Details:

- Incubate purified apoptosomes with procaspase-9 (100-200 nM) in activity buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA) for 15-30 minutes at 30°C [30] [28].

- Measure caspase-9 activity using fluorogenic substrates (LEHD-afc at 100 μM) by monitoring afc release (excitation 400 nm, emission 505 nm) over 30-60 minutes [30] [28].

- Determine kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax) under varying nucleotide conditions to assess nucleotide effects on catalytic efficiency.

- For inhibitor studies, pre-incubate procaspase-9 with ATP/dATP (0.1-10 mM) before apoptosome addition.

Key Considerations: Substrate concentration should approximate Km (686 μM for LEHD-afc) for accurate velocity measurements. Include kosmotropic salts (100-200 mM potassium acetate) to enhance dimerization-based activation when testing this mechanism [30].

Advanced Structural Techniques

Cryo-Electron Microscopy Analysis

Objective: Determine high-resolution structure of nucleotide-bound apoptosome complexes.

Method Details:

- Prepare apoptosome samples at 2-4 mg/mL concentration in assembly buffer supplemented with 1 mM dATP/ATP.

- Apply 3-4 μL samples to freshly glow-discharged holey carbon grids (Quantifoil R1.2/1.3 or C-flat).

- Vitrify using manual plunging or automated vitrification devices (Vitrobot) at >95% humidity, 4°C.

- Collect super-resolution movies on cryo-TEM instruments (Titan Krios) equipped with energy filters, at nominal magnifications corresponding to ~1.0-1.5 Å/pixel [28].

- Process images using single-particle analysis pipelines (RELION, cryoSPARC) with 7-fold symmetry imposition to achieve 3.5-4.5 Å resolution [28].

Key Considerations: Sample homogeneity critically impacts resolution. Include cytochrome c and fresh nucleotides throughout purification to maintain complex stability.

Diagram 2: Structural Analysis Workflow for Apoptosome Studies

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Apoptosome Studies

| Reagent | Specifications | Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Apaf-1 | Full-length human, ≥90% pure, ADP-free | Structural and functional studies | Maintain nucleotide-free state for controlled assembly |

| Cytochrome c | Equine heart, reduced form, ≥95% pure | Apoptosome activation | Fresh preparation essential; check reduction state |

| Nucleotides | dATP/ATP, high-purity (>99%), HPLC-verified | Assembly and activation studies | Avoid ADP contamination; use fresh solutions |

| Procaspase-9 | Catalytically active, full-length with CARD domain | Functional activation assays | Express in insect cells for proper folding |

| FDNP-ATP | Affinity labeling reagent, >95% pure | Nucleotide binding site mapping | Light-sensitive; prepare fresh in DMSO |

| Fluorogenic Substrates | LEHD-afc (Km = 686 μM), ≥98% pure | Caspase-9 activity assays | Use at Km concentration for kinetic studies |

Emerging Models and Controversies

Allosteric Activation vs. Proximity-Induced Dimerization

The mechanism of caspase-9 activation on the apoptosome remains actively debated, with two predominant models emerging from biochemical and structural studies:

The allosteric activation model proposes that procaspase-9 undergoes conformational activation upon binding to the apoptosome backbone, independent of homodimerization. Support for this model comes from observations that caspase-9 bound to the apoptosome processes procaspase-3 significantly more efficiently than forced-dimerized free caspase-9 [30]. Mathematical simulations further demonstrate that only allosteric activation models can accurately reproduce experimental kinetics of apoptosis execution and account for the molecular timer function of the apoptosome [30].