APF-1 to Ubiquitin: A Comprehensive Guide to the Covalent Conjugation Assay and Its Modern Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the APF-1 ubiquitin covalent conjugation assay, from its foundational discovery to its contemporary methodological applications.

APF-1 to Ubiquitin: A Comprehensive Guide to the Covalent Conjugation Assay and Its Modern Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the APF-1 ubiquitin covalent conjugation assay, from its foundational discovery to its contemporary methodological applications. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content details the historical context of APF-1's identification as ubiquitin and the elucidation of the enzymatic cascade. It covers modern, quantitative assay techniques, including spectrophotometric and mass spectrometry-based methods, alongside practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. The article also discusses rigorous validation protocols and comparative analyses with other ubiquitin-like protein assays, offering a complete resource for leveraging this critical tool in proteostasis research and therapeutic development.

The Discovery of APF-1: From a Vague Idea to the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

The Historical Enigma of ATP-Dependent Intracellular Proteolysis

For decades, the fundamental question of why intracellular protein degradation requires adenosine triphosphate (ATP) presented a major paradox in biochemistry. While hydrolysis of peptide bonds is thermodynamically favorable and occurs spontaneously in standard protease reactions, cellular systems demonstrated an absolute dependence on metabolic energy for protein breakdown [1]. This enigma persisted despite the discovery of the lysosome by Christian de Duve, as bacteria—which lack lysosomes—still exhibited the same ATP requirement for proteolysis, indicating a more fundamental mechanism [1] [2]. The resolution to this mystery began to emerge through the discovery of ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1 (APF-1), later identified as ubiquitin, and the elaborate enzyme system that coordinates the targeted degradation of cellular proteins [2] [3].

This application note situates these historical discoveries within contemporary research methodologies, providing detailed protocols and analytical frameworks for investigating ATP-dependent proteolytic systems, with particular emphasis on ubiquitin covalent conjugation assays relevant to current drug discovery efforts.

Historical Background: Key Discoveries

The Initial Paradigm and Its Limitations

Early biochemical investigations into protein degradation consistently revealed that intracellular proteolysis required metabolic energy. Initial speculation suggested that ATP might be necessary for lysosomal function, but this hypothesis failed to explain energy-dependent proteolysis in bacterial cells that lack these organelles [1]. This fundamental contradiction suggested that the ATP requirement represented a more universal property of the degradative process itself, independent of compartmentalization [1].

Throughout the 1970s, several research groups contributed key observations that challenged the lysosomal paradigm. Studies on reticulocytes and hepatoma cells demonstrated ATP-dependent degradation of abnormal proteins, while investigations in Escherichia coli revealed similar energy requirements in prokaryotic systems [2]. These parallel findings across biological kingdoms pointed toward a conserved mechanism distinct from lysosomal degradation.

The Discovery of APF-1/Ubiquitin

The breakthrough began with the identification of ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1 (APF-1) in reticulocyte lysates, a heat-stable polypeptide that conjugated to other proteins in an ATP-dependent manner [2]. Simultaneously, Goldstein isolated a universally represented polypeptide with lymphocyte-differentiating properties, initially termed ubiquitous immunopoietic polypeptide (UBIP) [3]. The convergence of these separate research pathways occurred when Wilkinson et al. identified APF-1 as ubiquitin, linking the ATP-dependent proteolytic system with the previously characterized protein [2] [3].

The subsequent isolation of the ubiquitin-ligase system components from reticulocytes in 1982 by Hershko and Ciechanover established the biochemical framework for the stepwise mechanism of ubiquitination involving E1, E2, and E3 enzymes [3]. This provided the foundation for understanding how the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to target proteins marks them for degradation.

Table 1: Key Historical Discoveries in ATP-Dependent Proteolysis

| Year Range | Key Discovery | Experimental System | Major Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950s-1960s | Lysosome Identification [2] | Rat liver fractions | Intracellular organelles containing hydrolytic enzymes |

| 1970s | ATP Dependence [1] | Bacterial and animal cells | Energy requirement conserved across evolution |

| 1978-1980 | APF-1 Identification [2] | Rabbit reticulocytes | Heat-stable protein factor required for ATP-dependent proteolysis |

| 1980 | APF-1 as Ubiquitin [2] [3] | Reticulocyte lysates | Connection between ubiquitin and proteolytic targeting |

| 1982 | E1-E2-E3 Enzyme System [3] | Reticulocyte fractionation | Stepwise mechanism of ubiquitin conjugation |

| 1980s-1990s | Proteasome Structure [4] [5] | Multiple systems | Self-compartmentalized protease with sequestered active sites |

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: Core Components

The resolution to the historical enigma emerged through the complete characterization of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, which couples the energy-dependent process of substrate recognition and preparation with the actual peptide bond hydrolysis.

ATP-Dependent Protease Families

Multiple families of ATP-dependent proteases share common mechanistic principles while differing in their architectural organization:

- Lon Protease: Contains both ATPase and proteolytic domains within a single polypeptide, with a Ser-Lys catalytic dyad in the active site [6]. Functions as oligomeric assemblies, typically forming six- or seven-membered rings.

- HslVU Protease: Consists of separate HslU ATPase and HslV protease components, with HslV representing a prokaryotic proteasome homolog containing N-terminal threonine active sites [4].

- 26S Proteasome: The eukaryotic proteasome complex comprises a 20S core particle (CP) with proteolytic activity and 19S regulatory particles (RP) that recognize ubiquitinated substrates and unfold them in an ATP-dependent manner [2] [5].

These proteases all exhibit self-compartmentalized structures with proteolytic active sites sequestered within internal chambers, requiring substrate unfolding and translocation for degradation [5].

The Energy Requirement Explained

ATP hydrolysis drives multiple essential steps in the proteolytic cycle:

- Ubiquitin Activation: E1 enzyme activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction, forming a thioester bond [3].

- Substrate Unfolding: AAA+ ATPase components unfold protein substrates using mechanical force generated through ATP binding and hydrolysis [5] [6].

- Translocation: Unfolded polypeptides are translocated through narrow channels into the proteolytic chamber against entropy and potential interactions with channel walls [4] [6].

- Gating and Regulation: ATP hydrolysis cycles control the association between regulatory and proteolytic particles, gating access to the internal proteolytic sites [4].

Table 2: ATP Utilization in Proteolytic Systems

| ATP-Dependent Step | Energy Function | Protease Examples | Structural Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Activation | Formation of E1-ubiquitin thioester | 26S Proteasome | E1 enzyme active site |

| Substrate Recognition | Conformational changes in recognition components | 26S Proteasome, HslVU | AAA+ ATPase domains |

| Protein Unfolding | Mechanical force generation | Lon, FtsH, HslVU, Proteasome | AAA+ module conformational changes |

| Translocation | Polypeptide translocation into proteolytic chamber | All ATP-dependent proteases | Axial channels through rings |

| Complex Assembly | Stabilization of protease-regulator interaction | HslVU, ClpAP, Proteasome | Nucleotide-dependent binding interfaces |

Experimental Protocols & Applications

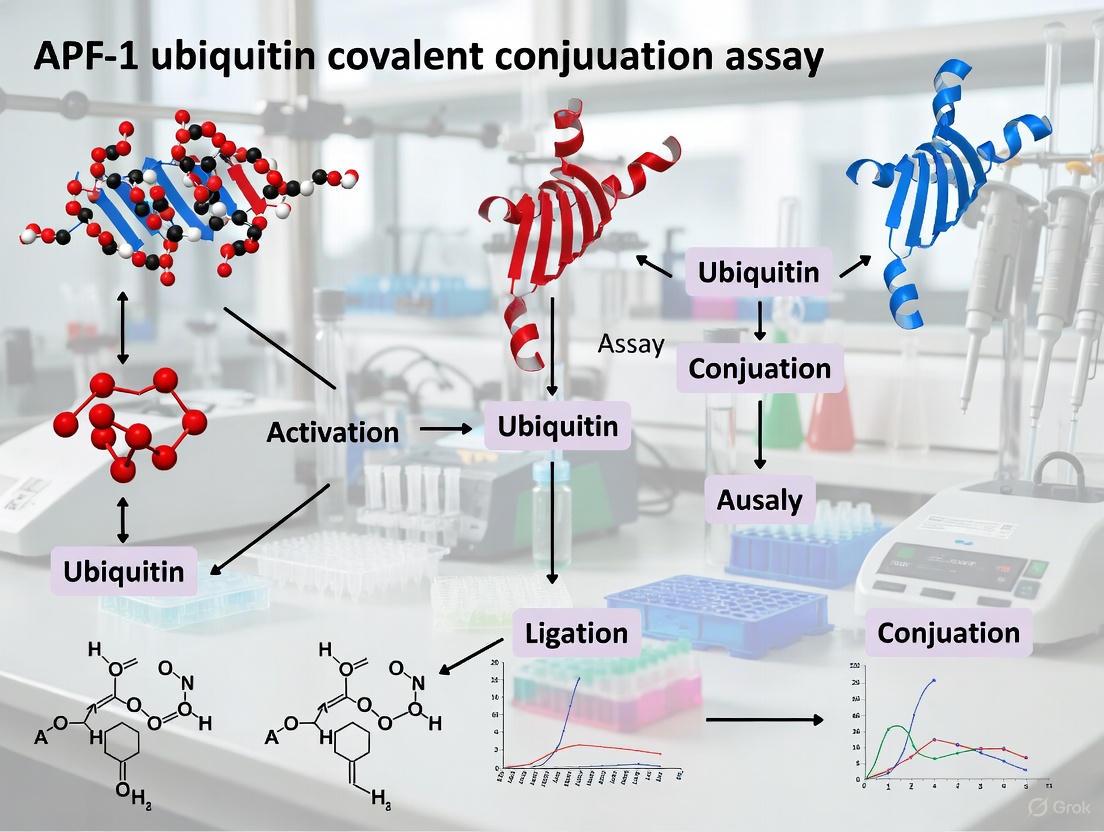

Ubiquitin Covalent Conjugation Assay

This protocol adapts historical discovery methodologies for contemporary analysis of ubiquitin conjugation, particularly relevant for screening small molecule inhibitors of E1-E2-E3 enzyme cascades.

Principle: The assay monitors the ATP-dependent formation of covalent ubiquitin-protein conjugates, recreating the essential steps of the ubiquitination cascade.

Reagents and Solutions:

- ATP Regeneration System: 2mM ATP, 10mM phosphocreatine, 0.1mg/mL creatine phosphokinase in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.6)

- Ubiquitin Source: Recombinant ubiquitin (5mg/mL in PBS)

- E1-E2-E3 Enzymes: Fraction II from rabbit reticulocyte lysate or recombinant enzymes

- Detection Reagents: Anti-ubiquitin antibodies, SDS-PAGE reagents

Procedure:

- Prepare reaction mixture (50μL final volume) containing:

- 40mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6)

- 2mM DTT

- 5mM MgCl₂

- ATP regeneration system

- 0.2-0.5mg/mL ubiquitin

- Enzyme source (Fraction II or recombinant E1/E2/E3 combination)

- Test compounds (for inhibitor screening)

Incubate at 37°C for 30-60 minutes.

Terminate reactions by adding SDS-PAGE sample buffer with 5% β-mercaptoethanol.

Analyze by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using anti-ubiquitin antibodies.

Quantify high molecular weight ubiquitin conjugates using densitometry.

Technical Notes:

- For kinetic analyses, sample at multiple time points (5, 15, 30, 60 minutes)

- Include controls without ATP, without ubiquitin, and without enzyme source

- For E3 ligase specificity studies, include relevant substrate proteins

Ubiquitin Conjugation Cascade

Protease La (Lon) Allosteric Activation Assay

Based on the landmark study demonstrating that protein substrates allosterically activate protease La [7], this protocol measures stimulation of peptidase activity by protein substrates.

Principle: Protein substrates bind both the active site and an allosteric site on protease La, enhancing its ability to degrade fluorogenic peptide substrates.

Reagents:

- Protease La: Purified Lon protease (0.1-0.5mg/mL)

- Protein Substrates: Casein, ovalbumin, or specific regulatory proteins (2-5mg/mL)

- Peptide Substrate: Z-GGL-AMC or similar fluorogenic peptide (100μM stock)

- Nucleotide Solutions: 5mM ATP, ADP, or ATPγS in Mg²⁺-containing buffer

Procedure:

- Prepare assay buffer (50mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10mM MgCl₂, 1mM DTT)

- Add Lon protease (10-50nM final) to buffer

- Pre-incubate with protein substrates (0.1-1mg/mL) for 5 minutes at 37°C

- Initiate reaction with fluorogenic peptide substrate (50μM final) and ATP (2mM final)

- Monitor fluorescence (excitation 380nm, emission 460nm) continuously for 30 minutes

- Calculate initial rates and fold activation compared to no protein substrate control

Applications:

- Characterizing substrate-induced activation mechanisms

- Screening for allosteric modulators of ATP-dependent proteases

- Investigating specificity of substrate recognition

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for ATP-Dependent Proteolysis Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATP System Components | ATP, ATPγS, ADP, AMP-PNP | Nucleotide substrates and analogs | ATPγS supports stable complex formation [4] |

| Protease Inhibitors | Lactacystin, NLVS, PMSF, N-ethylmaleimide | Mechanism-based protease inhibitors | Lactacystin targets proteasome β-subunits [4] |

| Ubiquitin System Reagents | Recombinant ubiquitin, E1/E2/E3 enzymes, Methylated ubiquitin | Ubiquitination cascade components | Methylated ubiquitin blocks chain formation [3] |

| Detection Systems | Fluorogenic peptides (Z-GGL-AMC), Anti-ubiquitin antibodies | Activity assays and conjugate detection | Z-GGL-AMC used for HslVU and proteasome assays [4] |

| Cellular Fractions | Rabbit reticulocyte lysate, Tissue homogenates | Source of native enzyme systems | Maintain ATP-regenerating systems [2] |

Analytical Framework and Data Interpretation

Quantitative Analysis of Active Site Utilization

Studies on HslVU protease revealed that only approximately six of the twelve potential active sites in the HslV dodecamer are utilized simultaneously, demonstrating that maximal catalytic efficiency does not require all potential active sites [4]. This finding has implications for inhibitor design and mechanistic understanding of processive degradation.

Key Experimental Findings:

- Mixed dodecamers with increasing inactive (T1A) subunits showed little activity reduction until ~6 active sites remained

- Further reduction in active sites resulted in proportional activity decreases

- Proteasome inhibitor binding to active sites stabilized HslV-HslU interactions

Interpretation Framework:

- Each ATP-bound HslU subunit activates one HslV subunit

- Substrate engagement at active sites stabilizes the protease-ATPase complex

- This mechanism supports processive degradation while minimizing wasteful ATP hydrolysis

Pathway Visualization: ATP-Dependent Proteolytic Cycle

ATP-Dependent Proteolytic Cycle

Contemporary Research Applications

The historical principles of ATP-dependent proteolysis now underpin multiple modern research and therapeutic areas:

Drug Discovery Applications:

- Protective Protein Degradation: Development of proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) that redirect E3 ubiquitin ligases to target specific pathogenic proteins for degradation [3]

- Inhibitor Screening: Assays for identifying specific inhibitors of ubiquitin-activating (E1), conjugating (E2), or ligase (E3) enzymes

- Oncology Therapeutics: Targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in cancer treatment, exemplified by bortezomib and other proteasome inhibitors

Research Tools Development:

- Activity-based probes for profiling ATP-dependent protease activities

- Engineered ubiquitin variants with altered linkage specificity

- High-throughput screening platforms for ubiquitination modulators

The resolution of the historical enigma of ATP-dependent intracellular proteolysis has thus not only answered a fundamental biochemical question but has also created entirely new avenues for therapeutic intervention in human disease.

Prior to 1980, the requirement of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) for intracellular protein degradation presented a fundamental biochemical paradox, as peptide bond hydrolysis is an exergonic process [8]. The pivotal 1980 PNAS papers from the laboratories of Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose transformed this conceptual barrier by unveiling APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1) and its covalent conjugation to substrate proteins as the missing link [9]. This discovery laid the experimental foundation for understanding the ubiquitin-proteasome system, a pillar of cellular regulation. This application note reconstructs the core methodologies from these seminal studies, providing a framework for researchers investigating targeted protein degradation.

Key Experimental Findings and Quantitative Data

The 1980 investigations established the biochemical characteristics of APF-1 conjugation. The following table summarizes the quantitative data and critical observations reported in these foundational studies.

Table 1: Key Experimental Findings on APF-1 Conjugation from Pivotal 1980 Studies

| Experimental Parameter | Observation/Measurement | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Requirement | Absolute dependence on ATP (Km ∼ 0.2 mM MgATP2-); UTP/GTP inactive [9] [10] | Explained the ATP paradox in proteolysis; indicated a multi-step enzymatic process |

| APF-1 Identity | Heat-stable polypeptide (8.6 kDa); later identified as ubiquitin [8] [11] | United disparate research paths (proteolysis and chromatin biology) |

| Conjugate Stability | Resistant to SDS, heat denaturation, mild acid/alkali, and reducing agents [9] | Demonstrated a covalent, isopeptide-type bond formation |

| Inhibitor Sensitivity | Inhibited by N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) [9] | Suggested the involvement of a critical cysteine residue in the enzymatic cascade |

| Stoichiometry | Multiple molecules of APF-1 conjugated to a single substrate protein [8] | Established the concept of polyubiquitin chains as a degradation signal |

The experimental workflow for the foundational APF-1 conjugation assay is outlined below.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: APF-1 Covalent Conjugation Assay

This protocol is adapted from the original methods described in "ATP-dependent conjugation of reticulocyte proteins with the polypeptide required for protein degradation" [9].

Reagents and Biological Materials

- Reticulocyte Lysate: Prepared from rabbit reticulocytes as a source of intracellular proteolytic machinery [8] [12].

- Fraction II: DEAE-cellulose-retained fraction from reticulocyte lysate, pre-treated with hexokinase and glucose to deplete endogenous ATP where specified [8] [9].

- 125I-labeled APF-1: APF-1 (ubiquitin) purified and radioiodinated to high specific activity.

- ATP-Regenerating System: 2 mM ATP, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM phosphocreatine, and creatine phosphokinase.

- Control Nucleotides: 2 mM UTP or GTP for specificity assessment.

- Inhibitor: 5 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM).

- Stop Solution: SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing 2% SDS and 2% 2-mercaptoethanol.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Reaction Setup: In a series of 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes, assemble the following reaction mixture on ice:

- 50 μL Fraction II (∼5 mg/mL protein)

- 2 μL 125I-APF-1 (∼50,000 cpm)

- 5 μL ATP-regenerating system (or equimolar control nucleotides for control reactions)

- Nuclease-free water to a final volume of 100 μL.

Incubation:

- Vortex mixtures gently and centrifuge briefly.

- Incubate reactions at 37°C for 30 minutes in a water bath.

Reaction Termination:

- Stop the reactions by adding 100 μL of 2X SDS-PAGE stop solution.

- Boil samples for 5 minutes.

Analysis:

- Resolve proteins by SDS-PAGE on a 10% polyacrylamide gel.

- Dry the gel and perform autoradiography using X-ray film to visualize 125I-APF-1 and its conjugates.

Critical Control Reactions

- Minus ATP: Replace the ATP-regenerating system with an equal volume of water.

- Nucleotide Specificity: Use UTP or GTP instead of ATP.

- Enzyme Inhibition: Pre-incubate Fraction II with 5 mM NEM for 10 minutes on ice before setting up the reaction.

- Zero-Time Point: Add stop solution to the reaction mixture before incubation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for APF-1/Ubiquitin Conjugation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Workflow | Key Characteristics & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate (ATP-depleted) | Source of E1, E2, E3 enzymes and proteasome; provides the native enzymatic environment [8] [12] | Must be fractionated (DEAE-cellulose) to separate APF-1/Ubiquitin (Fraction I) from conjugating enzymes (Fraction II) [8] |

| Purified APF-1/Ubiquitin | The central tagging molecule for covalent modification of substrate proteins [11] | Heat-stable 8.6 kDa protein; can be radioiodinated (125I) for detection [9] |

| ATP-Regenerating System | Provides sustained chemical energy for the multi-enzyme activation and conjugation cascade [11] [10] | Critical for E1-mediated ubiquitin activation; UTP/GTP serve as negative controls [9] |

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | Sulfhydryl alkylating agent used to inhibit E1 and certain E2 enzymes [9] | Validates the enzyme-mediated nature of the reaction by blocking the active-site cysteine |

| Denaturing SDS-PAGE | Analytical method to separate and visualize protein conjugates by molecular weight [9] | Confirms covalent bonding due to conjugate stability under denaturing conditions |

Pathway and Mechanistic Interpretation

The covalent conjugation of APF-1 revealed the outline of a multi-enzyme pathway. The subsequent identification of the E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade provided the mechanistic logic for this process.

The model derived from the 1980 papers established that APF-1/ubiquitin conjugation is not the proteolytic step itself, but a critical tagging signal that precedes and targets substrates for degradation [8] [10]. The formation of a poly-APF-1 chain (polyubiquitin chain) on the substrate creates a recognition marker for the 26S proteasome, which then degrades the tagged protein while releasing ubiquitin for reuse [8] [11]. This explained the cell's ability to selectively degrade specific proteins with high precision at the cost of metabolic energy.

The seminal discovery that ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1) was the previously known protein ubiquitin unified two seemingly distinct fields of biology: energy-dependent protein degradation and chromatin regulation. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, researchers led by Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose identified APF-1 as a heat-stable polypeptide essential for ATP-dependent proteolysis in reticulocyte lysates [2] [8]. Their critical finding that APF-1 formed covalent conjugates with substrate proteins represented a radical departure from conventional understanding of intracellular proteolysis [8]. Subsequent work by Wilkinson, Urban, and Haas demonstrated that APF-1 was identical to ubiquitin, a small protein previously known to be conjugated to histones in chromatin [11] [13]. This convergence revealed that the same protein modification system mediated both regulatory protein degradation and chromatin organization, establishing a fundamental paradigm in cell biology and earning the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004 [11].

Biochemical Characterization of the APF-1/Ubiquitin Conjugation System

The Ubiquitin Conjugation Cascade

The ubiquitination process involves a three-enzyme cascade that conjugates ubiquitin to target proteins [11]. Table 1 summarizes the key components and functions of this system.

Table 1: Enzymatic Components of the Ubiquitin Conjugation System

| Component | Number in Humans | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Ubiquitin-activating enzyme) | 2 [11] | Activates ubiquitin in ATP-dependent manner | Forms thioester bond with ubiquitin via cysteine residue [11] |

| E2 (Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme) | 35 [11] | Accepts ubiquitin from E1 and mediates transfer to E3 | Contains conserved UBC fold [11] |

| E3 (Ubiquitin ligase) | ~600-1000 [14] [11] | Recognizes specific substrates and facilitates ubiquitin transfer | Determines substrate specificity; contains RING, HECT, or RBR domains [14] |

The conjugation mechanism proceeds through three well-defined steps:

- Activation: E1 catalyzes adenylation of ubiquitin's C-terminus, forming a thioester bond between its active-site cysteine and ubiquitin [11]

- Conjugation: Activated ubiquitin is transferred to E2's active-site cysteine [11]

- Ligation: E3 facilitates transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to substrate lysine residues, forming an isopeptide bond [11]

Structural Requirements for Functional Ubiquitin

The C-terminal sequence of ubiquitin is critical for its function in proteolysis. As demonstrated in Table 2, the intact C-terminal sequence Arg-Gly-Gly is essential for activation and conjugation.

Table 2: Structural Requirements for Functional Ubiquitin

| Parameter | Active Form | Inactive Form | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length | 76 amino acids [13] | 74 amino acids (ubiquitin-t) [13] | Intact C-terminus required for activation |

| C-terminal Sequence | -Arg-Gly-Gly [13] | -Arg [13] | Gly76 forms thioester with E1 and isopeptide with substrates |

| Molecular Mass | 8.6 kDa [11] | ~8.4 kDa | Mass shift detectable by SDS-PAGE |

| Conjugation Site | C-terminal glycine (Gly76) [11] | N/A | Forms isopeptide bond with substrate lysines |

The discovery that ubiquitin's C-terminal glycine (Gly76) forms an isopeptide bond with substrate lysine residues explained why early preparations containing ubiquitin-t (lacking the terminal Gly-Gly) showed reduced activity in proteolysis assays [13]. This structural insight was crucial for developing functional assays to study the ubiquitin system.

Experimental Protocols for APF-1/Ubiquitin Conjugation Assays

Preparation of Reticulocyte Lysate System for ATP-Dependent Proteolysis

Principle: This protocol recreates the original experimental system used to identify APF-1/ubiquitin, utilizing ATP-dependent proteolysis in reticulocyte lysates [8].

Reagents and Solutions:

- Rabbit reticulocyte lysate (fresh or commercially available)

- ATP-regenerating system: 2mM ATP, 10mM phosphocreatine, 50μg/mL creatine phosphokinase

- Ubiquitin-depletion reagents: Fraction I and II columns [8]

- Radiolabeled substrate protein (e.g., (^{125})I-lysozyme or denatured (^{14})C-globin)

- Buffer: 50mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 5mM MgCl₂, 1mM DTT

- Protease inhibitor cocktail (without ATPase inhibitors)

Procedure:

- Prepare reticulocyte lysate by standard methods or obtain commercially available lysate

- Deplete endogenous ubiquitin by fractionation into Fraction I (contains ubiquitin) and Fraction II (ubiquitin-depleted) [8]

- Set up reaction mixtures containing:

- 50μL Fraction II (ubiquitin-depleted lysate)

- ATP-regenerating system

- 2μg radiolabeled substrate protein

- Buffer to final volume of 100μL

- Add back purified ubiquitin/APF-1 (0.5-5μg) to test samples

- Incubate at 37°C for 60 minutes

- Terminate reactions by adding 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA)

- Measure acid-soluble radioactivity by scintillation counting to quantify proteolysis

- Analyze ubiquitin-protein conjugates by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography

Critical Notes:

- Maintain strict temperature control during incubations

- Include controls without ATP and without ubiquitin to demonstrate specificity

- Use freshly prepared ATP-regenerating system for optimal results

- For conjugate analysis, use non-reducing SDS-PAGE to preserve thioester bonds

Covalent Conjugation Assay for APF-1/Ubiquitin

Principle: This method directly demonstrates the covalent attachment of APF-1/ubiquitin to protein substrates, a key finding in the original discovery [8].

Reagents:

- (^{125})I-ubiquitin (prepared by iodination)

- Unlabeled ubiquitin (as competitor)

- Reticulocyte Fraction II

- ATP-regenerating system

- Crosslinking reagents (optional)

- SDS-PAGE sample buffer (with and without β-mercaptoethanol)

Procedure:

- Prepare reaction mixtures containing:

- 50μL Fraction II

- ATP-regenerating system

- 1μL (^{125})I-ubiquitin (100,000 cpm)

- With or without 5μg unlabeled ubiquitin (competition control)

- Incubate at 37°C for 15-30 minutes

- Stop reactions by adding SDS-PAGE sample buffer

- Analyze by SDS-PAGE (6-15% gradient gel)

- Visualize by autoradiography or phosphorimaging

- Identify high molecular weight conjugates as evidence of covalent attachment

Expected Results: The original experiments showed multiple high molecular weight bands representing ubiquitin-protein conjugates [8]. These conjugates required ATP and were stable under alkaline conditions, confirming their covalent nature.

Functional Ubiquitin Preparation and Characterization

Principle: Isolate and characterize active ubiquitin with intact C-terminal sequence, essential for functional studies [13].

Reagents:

- Bovine erythrocytes or other ubiquitin source

- CM-Sephadex column

- Reverse-phase HPLC column (C18)

- Trypsin-agarose (for limited proteolysis)

- Acid-urea PAGE system

Procedure:

- Prepare ubiquitin from bovine erythrocytes by acid extraction and CM-Sephadex chromatography [13]

- Separate ubiquitin isoforms by reverse-phase HPLC using acetonitrile gradient

- Identify active (76-amino acid) and inactive (74-amino acid) forms by retention time

- Confirm identity by acid-urea PAGE and N-terminal sequencing

- Generate ubiquitin-t (inactive form) by limited trypsin digestion of active ubiquitin

- Test biological activity in reticulocyte proteolysis assay

Quality Control:

- Verify intact C-terminus by mass spectrometry

- Confirm stimulation of ATP-dependent proteolysis

- Ensure absence of contaminating proteases

Visualization of the Ubiquitin Conjugation Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the complete ubiquitin conjugation cascade, from activation to substrate targeting, integrating the key discoveries from the APF-1 research.

Ubiquitin Conjugation Cascade and Proteosomal Targeting

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for APF-1/Ubiquitin Conjugation Studies

| Reagent | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate (Fraction II) | Ubiquitin-depleted system for reconstitution assays | Prepare fresh or use commercial sources; verify ubiquitin depletion [8] |

| Intact Ubiquitin (76-aa) | Active form for conjugation assays | Verify C-terminal sequence by HPLC and mass spectrometry [13] |

| ATP-Regenerating System | Maintains ATP levels during prolonged incubations | Essential for demonstrating ATP dependence [8] |

| (^{125})I-Ubiquitin | Radioactive tracer for conjugate visualization | Use specific activity 1000-5000 cpm/ng; monitor decomposition |

| E1, E2, E3 Enzymes | Reconstitute minimal ubiquitination system | Commercial sources available; validate activity with control substrates |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (MG132) | Distinguish conjugation from degradation | Use 10-50μM in cell culture; confirm inhibition of proteolysis |

| Ubiquitin-Aldehyde | Inhibit deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) | 1-5μM in assays; stabilizes ubiquitin conjugates |

| Chain-Linkage Specific Antibodies | Detect specific polyubiquitin linkages | K48-specific for proteasomal degradation; K63-specific for signaling |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Development

The discovery that APF-1 was ubiquitin has spawned multiple therapeutic approaches, particularly in oncology and neurodegenerative diseases. The recognition that E3 ubiquitin ligases determine substrate specificity (with ~600-1000 in humans) has made them attractive drug targets [14] [11]. Recent advances include:

- PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras): Bifunctional molecules that recruit E3 ligases to target specific proteins for degradation [15]

- Molecular Glues: Compounds that enhance interaction between E3 ligases and specific substrates [15]

- Ubiquitin System Profiling: Mass spectrometry-based methods to identify ubiquitinated proteins and modification sites [16]

The original observation that abnormal proteins are preferentially degraded by the ubiquitin system [8] has informed therapeutic strategies for diseases of protein misfolding, including the development of agents that enhance clearance of toxic protein aggregates in neurodegenerative disorders.

Elucidating the E1, E2, E3 Enzymatic Cascade for Ubiquitin Transfer

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a fundamental regulatory mechanism governing intracellular protein degradation and homeostasis. The discovery of this system originated with the identification of a heat-stable polypeptide in the 1970s, initially termed ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1), which was found to covalently attach to substrate proteins in an ATP-dependent manner [2] [17]. This factor was later identified as ubiquitin, an 8.6 kDa protein consisting of 76 amino acids that is expressed in all eukaryotic tissues [11] [18]. The covalent attachment of ubiquitin to substrate proteins marks them for proteolytic degradation via the 26S proteasome, a process often referred to as the "molecular kiss of death" [11]. This discovery, which earned the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004, unveiled a complex enzymatic cascade involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes that work in concert to transfer ubiquitin onto specific protein substrates [2] [19]. This application note details the experimental approaches for investigating this crucial biochemical pathway within the context of APF-1/ubiquitin covalent conjugation assay research.

The Ubiquitin Transfer Mechanism

The Enzymatic Cascade

Protein ubiquitination occurs through a sequential three-step enzymatic mechanism:

Step 1: Activation (E1) - Ubiquitin is activated in an ATP-dependent reaction where the E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme forms a thioester bond between its active-site cysteine and the C-terminal glycine (Gly76) of ubiquitin [11] [19]. This process involves the initial formation of a ubiquitin-adenylate intermediate [20]. The human genome encodes two E1 enzymes: UBA1 and UBA6 [11].

Step 2: Conjugation (E2) - The activated ubiquitin is transferred from E1 to the active-site cysteine of an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, forming a E2-ubiquitin thioester intermediate [11] [19]. Humans possess approximately 35-40 E2 enzymes, each characterized by a highly conserved ubiquitin-conjugating catalytic (UBC) fold [11] [17].

Step 3: Ligation (E3) - The E2-ubiquitin complex interacts with an E3 ubiquitin ligase, which facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin to a lysine residue on the target substrate protein [21] [11]. With over 600 E3 enzymes encoded in the human genome, this final step provides the specificity that determines which proteins are targeted for ubiquitination [18].

Table 1: Enzyme Classes in the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

| Enzyme Class | Representative Examples | Number in Humans | Core Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Activating) | UBA1, UBA6 | 2 [11] | ATP-dependent ubiquitin activation |

| E2 (Conjugating) | UbcH7, UbcH5a, UBE2C, UBE2S | ~35-40 [11] [17] | Ubiquitin transfer from E1 to E3-substrate complex |

| E3 (Ligating) | HECT-type, RING-type, RBR-type | >600 [18] | Substrate recognition and ubiquitin transfer |

E3 Ligase Mechanisms

E3 ubiquitin ligases fall into two major mechanistic categories based on their mode of action:

HECT E3 Ligases: These enzymes form a transient thioester intermediate with ubiquitin on their active-site cysteine before transferring it to the substrate [21] [11]. The E6-AP protein, which participates in human papillomavirus E6-induced ubiquitination of p53, represents a well-characterized example of this mechanism [21].

RING E3 Ligases: These function as scaffolds that simultaneously bind both the E2-ubiquitin complex and the substrate protein, facilitating the direct transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to the substrate without forming a covalent E3-ubiquitin intermediate [11] [20].

The following diagram illustrates the complete ubiquitin transfer cascade:

Quantitative Analysis of Ubiquitin Cascade Components

Enzyme Specificity and Kinetics

Research has revealed significant differences in specificity and kinetics throughout the ubiquitination cascade. E1 enzymes demonstrate considerable promiscuity toward E2 partners, while E2 enzymes show more selective interactions with specific E3s [17]. This hierarchical organization allows for both broad regulation and precise substrate targeting within the ubiquitin system.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Parameters in Ubiquitin Transfer

| Parameter | Experimental Value | Method of Analysis | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| UB C-terminal recognition | Arg72 mutation increases Kd with E1 by 58-fold [20] | Phage display & kinetic assays | Critical for E1 binding and activation |

| Polyubiquitin chain linkages | K48 > K63 > K11 >>> K33/K29/K6 preference in A. thaliana [19] | Mass spectrometry | Chain topology determines functional outcome |

| E2-E3 binding affinity | High affinity with fast kinetics [17] | Interaction studies | Enables rapid ubiquitin transfer |

| Ubiquitin pool genes | 4 genes in humans (UBA52, RPS27A, UBB, UBC) [11] | Genomic analysis | Ensures adequate ubiquitin supply |

Experimental Protocols

E1-E2-E3 Thioester Cascade Assay

This protocol outlines the methodology for demonstrating the formation of thioester intermediates during ubiquitin transfer, based on foundational research by Scheffner et al. (1995) [21].

Materials and Reagents

- Recombinant ubiquitin (wild-type and mutant forms)

- E1, E2, and E3 enzymes (purified recombinant forms)

- ATP regeneration system (ATP, creatine phosphate, creatine kinase)

- Reaction buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl₂, 0.2 mM DTT

- SDS-PAGE sample buffer (without reducing agents)

- Antibodies specific to ubiquitin and relevant enzymes

Procedure

- Prepare master mix containing 2 μg E1 enzyme, 2 mM ATP, and ATP regeneration system in reaction buffer

- Add 5 μg recombinant ubiquitin and incubate at 30°C for 5 minutes

- Introduce 2 μg E2 enzyme and continue incubation for 10 minutes

- Add 2 μg E3 enzyme and substrate protein (if applicable), incubate for additional 30 minutes

- Split reaction mixture into two aliquots:

- Aliquot A: Add non-reducing SDS-PAGE buffer

- Aliquot B: Add SDS-PAGE buffer with 100 mM DTT

- Analyze samples by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using ubiquitin-specific antibodies

Expected Results

- Non-reducing conditions (Aliquot A): Higher molecular weight bands corresponding to E1-UB, E2-UB, and E3-UB thioester complexes

- Reducing conditions (Aliquot B): Disappearance of thioester-linked complexes with concomitant increase in free ubiquitin

- E3-dependent substrate ubiquitination: Appearance of high molecular weight smears indicating polyubiquitinated substrates

The experimental workflow for this assay is illustrated below:

Activity-Based Protein Profiling of Ubiquitination Enzymes

This protocol utilizes ubiquitin-derived probes to capture active components of the ubiquitination machinery, based on methodologies described in recent research [22].

Materials and Reagents

- Ub-Dha probe (biotinylated ubiquitin with dehydroalanine at C-terminus)

- Cell lysate (asexual blood-stage P. falciparum or other relevant source)

- NeutrAvidin resin

- ATP and apyrase (for negative control)

- Lysis buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, protease inhibitors

- Wash buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 0.2% NP-40

- Elution buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1% SDS

Procedure

Prepare experimental and control lysates:

- Experimental: Supplement with 2 mM ATP

- Negative control: Deplete ATP with apyrase treatment

Incubate lysates with 1 μM Ub-Dha probe for 1 hour at 30°C

Capture probe-conjugated proteins using NeutrAvidin resin with gentle rotation for 2 hours

Wash resin extensively with wash buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins

Elute bound proteins with elution buffer

Analyze eluates by SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry for protein identification

Expected Results

- ATP-dependent enrichment of E1, E2, and HECT E3 enzymes in experimental sample

- Minimal recovery of ubiquitination enzymes in apyrase-treated control

- Identification of novel ubiquitination enzymes through mass spectrometric analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent | Function | Example Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ub-Dha Probe | Activity-based probe that covalently traps active ubiquitination enzymes [22] | Identification of active E1/E2/E3 enzymes in complex lysates | Requires ATP for activation; use apyrase-treated controls |

| Epitope-tagged Ubiquitin (e.g., His₆-, HA-, FLAG-UB) | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins [16] | Large-scale identification of ubiquitination substrates | Enables purification under denaturing conditions |

| E1/E2/E3 Recombinant Enzymes | Catalytic components for in vitro ubiquitination assays [21] [20] | Reconstruction of ubiquitination cascade | Quality control via autoubiquitination assays recommended |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132, Bortezomib) | Block degradation of ubiquitinated proteins [18] | Stabilization of polyubiquitinated substrates | Can induce cellular stress responses with prolonged treatment |

| DUB Inhibitors | Prevent deubiquitination [20] | Stabilization of ubiquitination events for analysis | Varying specificity toward different DUB classes |

| ATP-Regeneration System | Maintains constant ATP levels during extended reactions [21] | In vitro ubiquitination assays | Critical for multi-step enzymatic reactions |

The E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade for ubiquitin transfer represents a sophisticated biochemical system that enables precise control over protein fate and function within eukaryotic cells. The experimental approaches outlined in this application note, rooted in the foundational discovery of APF-1/ubiquitin, provide researchers with robust methodologies for investigating this crucial regulatory pathway. As research continues to elucidate the complexities of ubiquitination, particularly in disease contexts such as cancer and neurodegenerative disorders, these protocols will remain essential tools for advancing our understanding of cellular regulation and developing novel therapeutic strategies targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

From Reticulocyte Lysates to a Universal Regulatory Mechanism

The ubiquitin system represents a fundamental regulatory mechanism governing intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotic cells. This sophisticated pathway involves the covalent attachment of a small, conserved protein—ubiquitin—to substrate proteins, thereby signaling for their processing, alteration in activity, or degradation by the proteasome [23] [11]. The discovery of this system, which earned the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004 for Aaron Ciechanover, Avram Hershko, and Irwin Rose, emerged from pioneering investigations utilizing an ATP-dependent proteolytic system derived from rabbit reticulocyte lysates [10] [12].

Initial research into protein degradation faced a significant paradox: the process of breaking down proteins liberates energy, yet this degradation demonstrated a dependency on ATP (adenosine triphosphate), the cellular energy currency [12]. This observation suggested a complex, energy-requiring regulatory mechanism rather than a simple digestive process. The key to unraveling this mystery was the development of a cell-free system based on reticulocyte lysates, which allowed for the biochemical fractionation and characterization of the components involved [12]. Within these lysates, researchers identified a heat-stable polypeptide initially termed ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1), later recognized as ubiquitin [10] [12]. This document details the key experiments and methodologies that led from the initial observations in reticulocyte lysates to our current understanding of the universal regulatory mechanism of ubiquitination.

Experimental Foundation: Key Assays and Discoveries

The elucidation of the ubiquitin pathway was driven by a series of critical experiments, primarily utilizing the reticulocyte lysate system. The following section summarizes the core quantitative findings and provides detailed protocols for key assays.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings from Early Ubiquitin Research

| Experimental Observation | System Used | Key Quantitative Result | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| APF-1/Ubiquitin Conjugation | Rabbit reticulocyte lysate [12] | Multiple molecules of APF-1 conjugated to a single substrate protein (e.g., lysozyme) [12] [11] | Suggested a multi-step tagging mechanism for targeting proteins, rather than single modification. |

| ATP Dependence | Reticulocyte lysate fraction II [12] | Proteolysis and conjugation were absolutely dependent on the presence of ATP [12]. | Confirmed an energy-dependent, enzymatic process distinct from lysosomal degradation. |

| Polyubiquitin Chain Formation | Biochemical assays [12] | Proteins with polyubiquitin chains (e.g., via Lys48) were more efficiently degraded than mono-ubiquitinated ones [11]. | Identified the specific signal (Lys48-linked chains) for proteasomal recognition and degradation. |

| Enzyme Cascade Identification | Affinity purification & biochemical resolution [10] | Identification of three enzyme classes: E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) [10] [23] [11]. | Established the sequential enzymatic mechanism underlying the ubiquitination pathway. |

Detailed Protocol: ATP-Dependent Ubiquitin Conjugation Assay

This protocol is adapted from the foundational work that identified APF-1/Ubiquitin conjugation in reticulocyte lysates [12].

Principle: To demonstrate the ATP-dependent, covalent conjugation of ubiquitin to a target substrate protein in a cell-free system.

Materials:

- Nuclease-Treated Rabbit Reticulocyte Lysate: Serves as the source of E1, E2, E3 enzymes, ubiquitin, and proteasomes. Commercially available (e.g., Promega L4960) [24].

- Radioiodinated APF-1/Ubiquitin: Prepared by iodination of purified ubiquitin.

- Test Substrate: A known short-lived protein (e.g., lysozyme) or an abnormal protein (e.g., one containing canavanine).

- Energy-Regenerating System: ATP (1-5 mM), MgCl₂ (5 mM), Phosphocreatine, Creatine Phosphokinase.

- Control: ATP depletion system (e.g., Apyrase or Hexokinase/Glucose).

- Stop Solution: SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing DTT or β-mercaptoethanol.

- Equipment: Water bath, Microcentrifuge, SDS-PAGE apparatus, Gel dryer, Autoradiography supplies.

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a 50 µL reaction mixture containing:

- 25 µL rabbit reticulocyte lysate.

- 1 mM ATP.

- 5 mM MgCl₂.

- An energy-regenerating system.

- ~1 µg of test substrate.

- Radioiodinated APF-1/Ubiquitin (100,000-500,000 cpm).

- For the negative control, replace ATP and the regenerating system with an ATP-depletion system.

- Incubate reactions at 37°C for 30-60 minutes.

- Prepare a 50 µL reaction mixture containing:

- Termination and Analysis:

- Stop the reactions by adding 50 µL of 2X SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiling for 5-10 minutes.

- Resolve the proteins by SDS-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

- Dry the gel and perform autoradiography to visualize radioactively labeled bands.

Expected Results: In the complete reaction containing ATP, a ladder of high-molecular-weight radioactive bands will be visible on the autoradiograph. These bands represent the target substrate with multiple molecules of APF-1/Ubiquitin covalently attached. This ladder will be absent or significantly diminished in the ATP-depleted control reaction, demonstrating the energy dependence of the conjugation process.

Detailed Protocol: Fractionation of Reticulocyte Lysate to Identify E1, E2, and E3 Activities

Principle: To separate and reconstitute the individual enzymatic components of the ubiquitination cascade through biochemical fractionation of the reticulocyte lysate.

Materials:

- Starting Material: Rabbit reticulocyte lysate.

- Chromatography Resins: DEAE-Cellulose, Hydroxylapatite, Gel Filtration columns.

- Buffers: Lysis buffer, column equilibration, and elution buffers (typically with varying salt concentrations).

- Assay Components: Purified ubiquitin, ATP, Mg²⁺, and a model substrate (e.g., radiolabeled lysozyme).

Procedure:

- Preparation of Fraction II:

- Centrifuge the reticulocyte lysate at high speed (100,000 x g) to remove ribosomes and other particulate matter.

- The resulting supernatant is designated "Fraction II," which contains the soluble ubiquitin-system enzymes [12].

Column Chromatography:

- Apply Fraction II to a DEAE-cellulose column.

- Elute bound proteins with a linear salt gradient (e.g., 0 to 0.5 M KCl).

- Assay individual fractions for E1, E2, and E3 activity using a reconstituted conjugation assay.

Activity Assay for Fractions:

- A complete reaction contains ATP, Mg²⁺, purified ubiquitin, the model substrate, and a combination of column fractions.

- E1 activity is identified by its early elution from DEAE and its ability to form a thioester with ubiquitin in the presence of ATP, detectable by non-reducing SDS-PAGE [10].

- E2 enzymes form thioester intermediates with ubiquitin only after E1 is present.

- E3 activity is identified in fractions that, when combined with purified E1 and E2, facilitate the ligation of ubiquitin to the substrate protein, observable as higher molecular weight conjugates on SDS-PAGE [10].

Expected Results: Successful fractionation will yield distinct pools enriched for E1, E2 (multiple types), and E3 activities. Full reconstitution of substrate ubiquitination requires the combination of all three enzyme classes, plus ATP and ubiquitin, demonstrating their sequential and essential roles in the pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Ubiquitin Conjugation Research

| Reagent / Material | Critical Function in the Assay | Example & Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | Source of the entire ubiquitin-proteasome machinery: E1/E2/E3 enzymes, ubiquitin, and the 26S proteasome. | Nuclease-Treated Rabbit Reticulocyte Lysate (e.g., Promega L4960) [24]. |

| Energy System | Provides the fuel (ATP) required for the activation of ubiquitin by E1. | ATP, Mg²⁺, and an energy-regenerating system (e.g., phosphocreatine/creatine phosphokinase). |

| Ubiquitin | The central signaling molecule that is conjugated to substrate proteins. | Purified ubiquitin, often radioiodinated (¹²⁵I) for detection in early studies. Now available as recombinant, epitope-tagged, or mutant forms. |

| Substrate Protein | The target protein to be ubiquitinated; often a short-lived or abnormal protein. | Lysozyme, or other well-characterized substrates like cyclins [10]. |

| Chromatography Media | For the purification and separation of individual enzymatic components from the lysate. | DEAE-Cellulose, Hydroxylapatite, Gel Filtration resins (e.g., Sephacryl S-200). |

Visualizing the Pathway and Workflow

The following diagrams illustrate the core ubiquitination cascade and the experimental workflow for its discovery.

The Ubiquitin Conjugation Cascade

Experimental Workflow from Lysate to Discovery

The pioneering work utilizing rabbit reticulocyte lysates as a model system unveiled the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, a discovery that fundamentally transformed our understanding of cellular regulation [12]. The detailed protocols for the APF-1 ubiquitin covalent conjugation assay and the biochemical fractionation of the lysate provided the foundational toolkit that enabled this breakthrough. This research demonstrated that regulated protein degradation is not a passive process but a highly specific, energy-dependent mechanism as sophisticated as protein synthesis [25] [12].

The implications of this discovery are vast, influencing nearly every field of biology. The ubiquitin system is now known to be essential for critical processes such as cell cycle progression (e.g., cyclin degradation), DNA repair, transcriptional regulation, immune responses, and apoptosis [10] [25] [23]. Furthermore, dysregulation of the ubiquitin system is implicated in numerous human diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and infectious diseases, making its components prime targets for therapeutic drug development [23] [16]. The journey from a simple cell-free lysate system to the elucidation of a universal regulatory mechanism stands as a testament to the power of classic biochemistry in revealing profound biological truths.

Modern Assay Techniques: From Traditional Methods to High-Throughput Screening

Classic Electrophoretic Mobility Shift and Radiolabeling Assays

Within the study of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, the classic Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) has been a cornerstone technique for decades. Its application was pivotal in the early research on ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1), now known as ubiquitin, where it helped demonstrate the covalent conjugation of ubiquitin to protein substrates [10]. This assay remains fundamental for investigating DNA-protein and protein-protein interactions, including those within the ubiquitin conjugation cascade. EMSA operates on the principle that a nucleic acid or protein probe, when bound by a protein, will migrate more slowly through a native polyacrylamide gel than the unbound probe, resulting in a detectable "shift" [26] [27]. This Application Note details the protocols for classic radiolabeling and contemporary fluorescent EMSA methods, contextualized within modern ubiquitination research.

Methodology

Core Principle of EMSA in Ubiquitin Research

The EMSA is a robust method for detecting the formation of complexes between proteins and their binding partners. In the context of ubiquitination, this can be adapted to study the conjugation of ubiquitin to substrates or the interactions between ubiquitin pathway enzymes. The assay directly visualizes the formation of higher molecular weight complexes through their reduced electrophoretic mobility.

Probe Labeling Strategies

Traditional Radiolabeling with ³²P

Radiolabeling with ³²P has been the historical standard for EMSA due to its high sensitivity.

- Procedure: DNA oligonucleotides are labeled using T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (PNK) and [γ-³²P]ATP. The reaction is purified to remove unincorporated nucleotides, typically using spin columns or gel filtration.

- Considerations: While sensitive, this method requires dedicated facilities for radioactivity handling, poses health risks, and involves regulatory compliance for disposal [26].

Modern Fluorescent Labeling

Fluorescent EMSA offers a safe and efficient alternative, with sensitivity comparable to radiolabeling [26] [27].

- Common Dyes: Cyanine 3 (Cy3), Cyanine 5 (Cy5), and IRDye infrared dyes are widely used [26] [27].

- Probe Preparation: Commercially synthesized oligonucleotides are end-labeled with a fluorophore. Both forward and reverse strands must be labeled and annealed to form double-stranded probes. Using a single labeled strand results in a significant (~70%) signal loss [27].

- Advantages: This method eliminates radiation hazards, is less time-consuming as it requires no membrane transfer, and allows for real-time visualization during electrophoresis [26].

Table 1: Comparison of EMSA Probe Labeling Methods

| Feature | Radiolabeling (³²P) | Fluorescent Labeling |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Very High | High |

| Safety | Requires special handling and disposal | No significant hazards |

| Time to Result | Longer (includes transfer and exposure) | Shorter (direct gel imaging) |

| Cost | Low reagent cost, high disposal cost | Higher reagent cost |

| Multiplexing | Difficult | Possible with multiple dyes [27] |

Detailed Fluorescent EMSA Protocol for DNA-Protein Interaction

This protocol uses a Cy3-labeled DNA probe and proteins isolated from host plants to ensure natural folding and post-translational modifications [26].

I. Gel Preparation

- Prepare a non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel (typically 4-6%). A sample recipe for a 4% gel (40 mL) is:

- 5.0 mL 40% Polyacrylamide (29:1 acrylamide:bis)

- 2.0 mL 1 M Tris, pH 7.5

- 7.6 mL 1 M Glycine

- 160 µL 0.5 M EDTA

- 26.04 mL H₂O

- 200 µL 10% Ammonium Persulfate (APS)

- 30 µL TEMED

- Pour the gel and allow it to polymerize for 1-2 hours [27].

II. Binding Reaction

- Set up a 20 µL binding reaction on ice:

- 2 µL 10X Binding Buffer (100 mM Tris, 500 mM KCl, 10 mM DTT; pH 7.5)

- 1 µL Poly(dI•dC) (1 µg/µL, a non-specific competitor DNA)

- 2 µL 25 mM DTT / 2.5% Tween 20 (stabilizes the fluorescent dye)

- 13 µL Nuclease-free Water

- 1 µL Cy3-labeled DNA Probe (e.g., 20 fmol)

- 1 µL Protein Extract (e.g., Raji nuclear extract or immunoprecipitated protein)

- Incubate the reaction at room temperature for 20-30 minutes in the dark [27].

III. Electrophoresis and Imaging

- Add 1 µL of 10X native loading dye (e.g., LI-COR Orange loading dye) to the reaction. Avoid dyes like bromophenol blue as they will be visible in the fluorescence image.

- Load the samples onto the pre-run native gel.

- Run the gel in 0.5X TBE or TGE buffer at 10 V/cm for approximately 30-60 minutes. Perform electrophoresis in the dark by covering the apparatus.

- Image the gel directly in the glass plates or carefully remove it for imaging using a fluorescence scanner or imager with the appropriate excitation/emission settings for your fluorophore [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for EMSA

| Reagent/Category | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Labeled Probes | DNA/RNA for binding studies; ubiquitin/SUMO for conjugation assays [16] [17]. |

| Non-specific Competitor DNA (e.g., Poly(dI•dC)) | Blocks non-specific protein binding to the probe, reducing background signal. |

| DTT/Tween 20 | Stabilizes fluorescent dyes, improving quantification accuracy [27]. |

| Native Gel Matrix | Separates protein-bound and free probes without denaturing complexes. |

| Fluorescent Imager | Enables sensitive, non-radioactive detection of shifted bands. |

| Linkage-specific Ub Antibodies | For "super-shift" EMSA to confirm identity of ubiquitin conjugates [28]. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in a fluorescent EMSA procedure.

Fluorescent EMSA Key Steps

Advanced Applications in Ubiquitin Research

Supershift Assay

To confirm the identity of a protein in a shifted complex, include a specific antibody in the binding reaction. If the antibody binds to the protein, it will create an even larger "supershifted" complex, providing confirmation of the protein's presence in the original complex [26].

Competition Assay

To demonstrate binding specificity, include an excess of unlabeled competitor DNA in the binding reaction.

- Self-competition: An identical unlabeled sequence should abolish the shifted band.

- Mutant competition: A DNA sequence with a mutated binding site should not compete effectively for binding, and the shifted band will remain [27]. This can be elegantly demonstrated using two different fluorophores to label wild-type and mutant probes in the same reaction [27].

Troubleshooting and Data Interpretation

- No Shift Observed: This indicates no binding occurred. Optimize binding conditions (buffer, pH, ions), verify protein activity and probe integrity. For ubiquitination assays, confirm E1, E2, and E3 enzyme activity [29].

- High Background or Smearing: This often results from non-specific binding. Increase the concentration of non-specific competitor DNA (e.g., Poly(dI•dC)) or titrate the protein amount.

- Weak Fluorescent Signal: Ensure the fluorophore is not quenched by light exposure during incubation or electrophoresis. Include DTT and Tween 20 in reactions to stabilize the dye signal [27].

- Quantification: For quantitative analysis, note that the signal intensity of unbound DNA in control lanes may not equal the sum of free and bound DNA in sample lanes due to signal stabilization upon protein binding [27].

Within the context of APF-1 (ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1, now known as ubiquitin) research, the quantification of ubiquitin conjugation is foundational [2] [30]. The E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme initiates the entire ubiquitination cascade through an ATP-dependent reaction that results in the release of inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) [31] [32]. This application note details a robust, non-radioactive spectrophotometric assay that leverages this initial chemical event to measure E1 activity and, by extension, the entire ubiquitin conjugation process. Traditional methods, such as electrophoretic mobility shift assays or techniques relying on epitope-tagged or radiolabeled ubiquitin, are often difficult to quantitate accurately and are not amenable to high-throughput screening [31]. The assay described herein overcomes these limitations by providing a colorimetric method that is rapid, requires only a spectrophotometer, and is readily adaptable for screening small molecule inhibitors targeting the ubiquitin pathway [31].

Principle of the Assay and Ubiquitination Cascade

The spectrophotometric assay is a coupled enzymatic system that quantifies ubiquitin conjugation indirectly by measuring the pyrophosphate (PPi) produced when E1 activates ubiquitin.

The Ubiquitin Conjugation Cascade

The enzymatic pathway for ubiquitin conjugation involves three key steps, with the assay monitoring a product from the first step [31] [30]:

Spectrophotometric Detection Principle

The released PPi is converted into a measurable colorimetric signal through a series of coupled reactions [31] [33]. Inorganic pyrophosphatase cleaves PPi into two molecules of inorganic phosphate (Pi). The Pi then reacts with molybdate in the presence of malachite green dye, forming a reduced molybdenum blue complex that absorbs visible light between 600 nm and 850 nm [31] [34]. The intensity of the absorbance is directly proportional to the amount of phosphate, and thus to the initial E1 activity. This principle is not exclusive to ubiquitination and has been successfully applied to study other enzymes like aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases [34].

Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table catalogues the essential reagents required to establish this assay in a research setting.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for the Pyrophosphate Release Assay

| Reagent/Material | Function/Role in Assay | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| E1 Activating Enzyme | Catalyzes the initial ATP-dependent ubiquitin activation and PPi release. | Recombinant, purified enzyme (e.g., hexahistidine-tagged human E1) is essential for specific activity [31]. |

| Ubiquitin | Substrate for the E1 enzyme. | Wild-type or mutant ubiquitin can be used to study specific mechanisms [31]. |

| Inorganic Pyrophosphatase | Coupling enzyme; hydrolyzes PPi into 2 molecules of Pi for signal amplification. | Bacterial pyrophosphatase is recommended over yeast enzyme due to lower ATPase activity and background [31]. |

| Malachite Green Reagent | Colorimetric dye that forms a complex with phosphomolybdate, absorbing visible light. | Allows for quantitative detection of Pi; commercially available kits can be used [31] [34]. |

| ATP | Cofactor for the E1-mediated ubiquitin activation step. | Essential reaction component; concentration should be optimized [31]. |

Quantitative Data and Assay Performance

The developed assay demonstrates robust performance suitable for quantitative enzymology and screening applications. The kinetics of polyubiquitin chain formation measured by this method are comparable to those determined by traditional gel-based assays, validating its accuracy [31].

Table 2: Quantitative Assay Performance and Kinetic Data

| Parameter | Value or Outcome | Context & Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Product | Inorganic Phosphate (Pi) | Indirect measure of PPi release; detected via molybdenum blue complex [31]. |

| Detection Range | ~1 to 75 nmol PPi (1 mL volume) | Linear range for accurate quantification, as established in foundational methods [33]. |

| Sensitivity | Picomoles of product | Demonstrated in analogous assays for aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases [34]. |

| High-Throughput Capability | Amenable (Z´-factor: 0.56) | Z´-factor from a similar PPi detection assay shows robustness for HTS [34]. |

| Application to Ubc13-Mms2 | Kinetics similar to gel assays | Confirms the method's reliability for measuring E2 activity and polyubiquitination [31]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Reagent Setup and Buffer Preparation

- Assay Buffer: A typical reaction buffer is 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, and 7.5 mM β-mercaptoethanol [31].

- Malachite Green Reagent: Prepare according to established protocols or use a commercial kit. The reagent is a mixture of malachite green oxalate, ammonium molybdate, and stabilizers.

- Pyrophosphatase Solution: Resuspend inorganic pyrophosphatase from E. coli in assay buffer, aliquot, and store at -20 °C [31].

Step-by-Step Assay Procedure

Reaction Mixture Assembly: In a microcentrifuge tube or a well of a multi-well plate, combine the following components on ice:

Initiation and Incubation:

- Initiate the enzymatic reaction by adding the E1 enzyme or ATP last.

- Mix the contents thoroughly but gently.

- Incubate the reaction mixture at a defined temperature (e.g., 30°C or 37°C) for a predetermined time (e.g., 30-60 minutes).

Color Development and Detection:

- Stop the reaction by adding the malachite green reagent (the volume depends on the protocol, often an equal volume to the reaction).

- Incubate at room temperature for 15-30 minutes for full color development.

- Measure the absorbance at 600–650 nm using a spectrophotometer or a plate reader.

Data Analysis:

- Generate a standard curve using known concentrations of inorganic phosphate (Pi) under identical conditions.

- Calculate the amount of Pi generated in experimental samples from the standard curve.

- Determine the amount of PPi released, accounting for the 1:2 stoichiometry (1 PPi yields 2 Pi).

The workflow is summarized below.

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is a validated target for cancer therapy, as demonstrated by the success of proteasome inhibitors like Bortezomib [31] [2]. This creates a pressing need for efficient screening tools. This spectrophotometric PPi release assay is uniquely suited for high-throughput screening (HTS) of compound libraries to identify small-molecule inhibitors of E1, E2, or E3 enzymes [31]. Its simplicity, quantifiability, and avoidance of radioactive materials make it ideal for this purpose. The assay can directly measure the inhibition of the E1 enzyme or, by incorporating specific E2 and E3 enzymes, be tailored to screen for inhibitors of specific E2-E3 partnerships, opening avenues for highly targeted therapeutic development [31]. The relevance of this approach is underscored by the fact that inhibitors for other E1-like enzymes, such as the NEDD8 E1, have already entered clinical trials [31].

Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics for Substrate and Site Identification

The ubiquitin-proteasome system is a well-characterized pathway involved in regulating nearly every cellular process in eukaryotes [16]. The hallmark of this system is the post-translational modification of protein substrates by ubiquitin, a highly conserved 76-amino acid polypeptide [16]. In pioneering research, Hershko, Ciechanover, Rose, and colleagues discovered that ATP-dependent modification of protein substrates by ubiquitin (initially termed APF-1 for ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1) targeted them for degradation [16] [2]. This discovery, which earned the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004, revealed a fundamental cellular mechanism for controlled protein turnover [11] [2].

Ubiquitination involves the covalent attachment of the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin to lysine residues within substrate proteins via an isopeptide bond [16] [11]. Substrates can be modified by a single ubiquitin (monoubiquitination), multiple single ubiquitins (multiubiquitination), or polyubiquitin chains (polyubiquitination) [16]. The type of ubiquitin modification determines the functional consequence, with Lys48-linked polyubiquitin chains typically targeting substrates for degradation by the 26S proteasome, while other chain types (e.g., Lys63, Lys11, Lys6) and monoubiquitination regulate processes such as endocytic trafficking, inflammation, translation, and DNA repair [11].

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics has become an essential tool for qualitative and quantitative analysis of cellular systems, with the biochemical complexity and functional diversity of the ubiquitin system being particularly well-suited to proteomic studies [16]. This application note details established protocols and methodologies for identifying ubiquitinated substrates and mapping precise modification sites, framed within the historical context of APF-1/ubiquitin research.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Large-Scale Identification of Ubiquitinated Substrates Using Epitope-Tagged Ubiquitin

This protocol enables system-wide identification of ubiquitinated proteins from cultured cells or tissues through affinity purification of epitope-tagged ubiquitin conjugates followed by LC-MS/MS analysis.

Materials and Reagents

- Cells or tissue expressing epitope-tagged ubiquitin (e.g., His₆-, FLAG-, or HA-tagged)

- Lysis buffer: 25 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, pH 7.4, supplemented with fresh protease inhibitors and 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to preserve ubiquitin conjugates

- Affinity resin appropriate for tag (e.g., FLAG M2-agarose, Ni-NTA agarose for His-tagged ubiquitin)

- Wash buffer: 25 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4

- Elution buffer: 0.2 mg/mL FLAG peptide in 25 mM Tris, pH 7.4 (for FLAG-tagged) or 250 mM imidazole (for His-tagged ubiquitin)

- Reduction and alkylation reagents: 45 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 100 mM iodoacetamide

- Proteases: Sequencing-grade trypsin, chymotrypsin, or Glu-C

- Solid-phase extraction cartridges for sample cleanup

Procedure

Cell Lysis and Preclearing: Lyse cells or tissue in ice-cold lysis buffer. Centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble material. Preclear lysate with control IgG-agarose for 1 hour at 4°C [35].

Affinity Purification: Incubate precleared lysate with appropriate affinity resin for 2 hours at 4°C. For His₆-ubiquitin purifications, use Ni-NTA agarose; for FLAG-tagged ubiquitin, use FLAG M2-agarose [16] [35].

Washing: Wash resin three times with wash buffer to remove nonspecifically bound proteins.

Elution: Elute bound proteins with appropriate elution buffer. For FLAG-tagged ubiquitin, incubate beads with 0.2 mg/mL FLAG peptide in 25 mM Tris, pH 7.4, for 1 hour at 4°C [35].

Protein Precipitation and Digestion: Concentrate eluate by trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation or using centrifugal filters. Resuspend protein pellet in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Reduce cysteine residues with 45 mM DTT for 30 minutes at 55°C, then alkylate with 100 mM iodoacetamide for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark [35].

Proteolytic Digestion: Digest proteins with sequencing-grade trypsin (1:40 enzyme:substrate ratio) at 37°C for 16 hours. For enhanced sequence coverage, parallel digests with chymotrypsin (4 hours) or Glu-C (6 hours) are recommended [35].

Sample Cleanup: Desalt peptides using C18 solid-phase extraction cartridges. Lyophilize and reconstitute in 0.1% formic acid for MS analysis.

Protocol 2: Site-Specific Identification of Ubiquitination Sites Using DiGly Remnant Enrichment

This protocol leverages the characteristic tryptic cleavage pattern of ubiquitin that leaves a di-glycine remnant on modified lysine residues, enabling specific enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides.

Materials and Reagents

- Anti-K-ε-GG antibody resin

- IP buffer: 50 mM MOPS-NaOH, pH 7.2, 10 mM sodium phosphate, 50 mM NaCl

- Wash buffer 1: IP buffer

- Wash buffer 2: 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, 10% glycerol

- Elution buffer: 0.15% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)

- StageTips for sample cleanup

Procedure

Protein Digestion: Prepare tryptic digests as described in Protocol 1, steps 5-7.

DiGly Peptide Enrichment: Incubate tryptic peptides with anti-K-ε-GG antibody resin in IP buffer for 1.5 hours at 4°C.

Washing: Wash resin sequentially with IP buffer and wash buffer 2.

Elution: Elute bound peptides with 0.15% TFA.

Sample Cleanup: Desalt peptides using C18 StageTips.

LC-MS/MS Analysis: Analyze enriched peptides by LC-MS/MS using a 2-hour gradient.

Mass Spectrometry Data Acquisition Parameters

Table 1: Instrument Parameters for Ubiquitin Proteomics

| Parameter | Linear Ion Trap MS | LTQ-Orbitrap-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Range | 400-2000 m/z | 400-2000 m/z |

| Full MS Resolution | Unit mass | 30,000-60,000 |

| MS/MS Scans | Up to 5 data-dependent MS/MS scans | Up to 10 data-dependent MS/MS scans |

| Dynamic Exclusion | Enabled (30-60 s) | Enabled (30-60 s) |

| Neutral Loss Triggering | MS³ for m/z -98, -80 | MS³ for m/z -98, -80 |

| Autosampler | MicroAS | EASY-nLC |

| HPLC System | Surveyor | EASY-nLC 1200 |

Data Analysis and Bioinformatics

Database Search: Process raw MS/MS data using search engines (SEQUEST, MaxQuant, or FragPipe) against appropriate protein sequence databases [16] [35].

False Discovery Rate (FDR) Control: Apply target-decoy approach to control FDR at ≤1% for both peptide-spectrum matches and protein identifications [36].

Ubiquitination Site Localization: Use software tools (e.g, MaxQuant) to calculate site localization probabilities for ubiquitinated peptides.

Quantitative Analysis: For comparative studies, employ stable isotope labeling (SILAC, TMT) or label-free quantification (MaxLFQ) to quantify changes in ubiquitination [16] [36].

Data Representation: Use the QFeatures infrastructure in R for feature aggregation from PSMs to peptides to proteins, maintaining traceability between quantitative levels [37].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitin Proteomics

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Epitope-Tagged Ubiquitin | His₆-ubiquitin, FLAG-ubiquitin, HA-ubiquitin | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins [16] |

| Activity-Based Probes | Ub-Dha (Ubiquitin-dehydroalanine) | Capture active ubiquitin-conjugating machinery [38] |

| Enrichment Reagents | Anti-K-ε-GG antibody, TUBE (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entity) resins | Selective enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins/peptides [16] |

| Proteases | Trypsin, Chymotrypsin, Glu-C | Generate complementary peptides for maximal sequence coverage [35] |

| Ubiquitin Pathway Enzymes | E1 activating, E2 conjugating, E3 ligating enzymes | In vitro ubiquitination assays [38] |

| Deubiquitinase Inhibitors | N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), PR-619 | Preserve ubiquitin conjugates during sample preparation [35] |

Visualization of Workflows

APF-1/Ubiquitin Historical Discovery Pathway

Substrate Identification Workflow

Ubiquitin Site Mapping Pipeline

Applications and Case Studies

Plasmodium falciparum Ubiquitin Pathway Characterization

Recent research on Plasmodium falciparum demonstrates the power of activity-based protein profiling (ABP) combined with MS-based proteomics. Using a ubiquitin-dehydroalanine (Ub-Dha) probe, researchers captured active components of the ubiquitin-conjugating machinery during asexual blood-stage development [38]. This approach identified the P. falciparum E1 activating enzyme, several E2 conjugating enzymes, the HECT E3 ligase PfHEUL, and a novel E2 enzyme (PF3D7_0811400) with no known homology to ubiquitin-pathway enzymes in other organisms [38]. The study highlights how ABPs enable functional interrogation of ubiquitin pathway enzymes in non-model organisms, revealing both conserved and pathogen-specific components that represent potential drug targets.

Phosphorylation Site Mapping of APPL1 Adaptor Protein

While focusing on phosphorylation rather than ubiquitination, a comprehensive study on the adaptor protein APPL1 demonstrates optimal practices for achieving near-complete sequence coverage and confident PTM site identification [35]. Using multiple proteases (trypsin, chymotrypsin, and Glu-C) in parallel experiments, researchers achieved 99.6% combined sequence coverage of the 709-amino acid protein [35]. This approach identified 13 phosphorylated residues, four located within important functional domains (BAR, PH, and PTB domains), suggesting potential regulatory roles [35]. The methodology exemplifies how complementary proteolytic digestion strategies overcome limitations of individual enzymes, enabling comprehensive PTM mapping of complex proteins.

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics has revolutionized our ability to identify ubiquitinated substrates and map modification sites at a systems level. The protocols detailed in this application note provide robust methodologies for conducting these analyses, from initial sample preparation through data interpretation. When properly executed, these approaches can identify thousands of ubiquitination sites in a single experiment, providing unprecedented insights into the scope and regulation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system.