APF-1 to Ubiquitin: Decoding the Seminal Discovery that Launched the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

This article traces the pivotal discovery that ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1) is identical to the protein ubiquitin, a breakthrough that unified disparate lines of biological research and laid the...

APF-1 to Ubiquitin: Decoding the Seminal Discovery that Launched the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

Abstract

This article traces the pivotal discovery that ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1) is identical to the protein ubiquitin, a breakthrough that unified disparate lines of biological research and laid the foundation for the modern understanding of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational history, the critical methodological insights that resolved initial experimental discrepancies, and the profound biochemical implications of the APF-1/ubiquitin sequence. Finally, we examine how this key finding validates ubiquitin's roles beyond proteolysis and its direct relevance to contemporary therapeutic development for cancers and neurodegenerative diseases.

The Historical Discovery: From APF-1 to Ubiquitin

The Puzzling Requirement for ATP in Intracellular Proteolysis

Intracellular protein degradation is an essential process for maintaining cellular health, regulating protein levels, and disposing of damaged or misfolded proteins. For decades, the fundamental requirement for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in this process presented a significant biochemical puzzle: why would a catabolic process, which breaks down molecules to release energy, require energy input? This question persisted until the discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), the primary pathway for targeted protein degradation in eukaryotic cells. The solution to this puzzle reveals a sophisticated, multi-step mechanism where ATP consumption enables exquisite specificity and controlled degradation of cellular proteins. Within the broader context of APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1) versus ubiquitin sequence comparison research, it is now established that APF-1 and ubiquitin are identical molecules [1], and the ATP requirement spans both the ubiquitination process and the function of the 26S proteasome itself [2] [3] [4]. This energy investment allows the cell to execute a destructive process with precision, preventing uncontrolled proteolysis and maintaining cellular homeostasis.

Historical and Conceptual Framework

The initial assumption that protein degradation occurred primarily within the lysosome was challenged by several lines of evidence suggesting the existence of a non-lysosomal, ATP-dependent pathway [1]. A series of groundbreaking experiments in the late 1970s and early 1980s, particularly in reticulocyte systems, led to the identification of a heat-stable polypeptide that was essential for this energy-dependent proteolysis. This factor was initially termed APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1) [1]. Subsequent research revealed that APF-1 was identical to ubiquitin, a previously known protein of 76 amino acids [5] [1]. The critical function of ubiquitin is dependent on its C-terminal sequence; the active form terminates in -Arg-Gly-Gly, and cleavage by trypsin-like proteases to a form ending in -Arg74 renders it inactive for stimulating proteolysis [5]. This discovery unified two separate lines of research and laid the foundation for our modern understanding of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. The requirement for ATP thus became understandable not as a paradox, but as a necessity for driving the complex machinery that marks, unfolds, and translocates protein substrates for degradation.

The Multifaceted Roles of ATP in the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

The degradation of a protein via the UPS can be divided into two major phases, both requiring ATP: the tagging of the substrate with a ubiquitin chain, and its degradation by the 26S proteasome. The 26S proteasome itself is a massive complex composed of a 20S core particle (CP), where proteolysis occurs, and one or two 19S regulatory particles (RP) that recognize substrates and prepare them for degradation [3] [4]. The following diagram illustrates the central role of ATP in this process.

Diagram: ATP-Driven Processes in the UPS. ATP fuels both ubiquitin conjugation and multiple functions of the 19S regulatory particle, including substrate unfolding, gated entry into the proteolytic core, and translocation.

ATP in Ubiquitin Activation and Conjugation

The first ATP-dependent step is the activation of ubiquitin itself. This process involves a cascade of enzymes (E1, E2, E3) where ATP is hydrolyzed to form a thioester bond between ubiquitin and the E1 activating enzyme, a crucial energy investment that drives the entire tagging process [1]. Without ATP, ubiquitin cannot be activated and thus cannot be conjugated to target proteins.

ATP-Dependent Mechanisms of the 26S Proteasome

The 19S regulatory particle contains six distinct AAA-ATPase subunits (Rpt1-Rpt6) that form a hexameric ring [3] [4]. These ATPases are the workhorses of the proteasome, and ATP binding and hydrolysis by these subunits power several critical and energy-intensive steps:

- Substrate Binding and Deubiquitination: The initial recognition of ubiquitinated substrates and the coupled process of deubiquitination require the activity of the ATPase subunits [4].

- Unfolding of Globular Proteins: The proteolytic chamber of the 20S core can only accommodate unfolded, linear polypeptides. The unfolding of tightly folded, globular protein domains is the only step that absolutely requires ATP hydrolysis [3]. This process consumes a significant portion of the ATP used in degradation.

- Gate Opening: The entry channel to the 20S core is gated by the N-terminal tails of the α-ring subunits. The C-terminal tails of the 19S ATPases, containing a conserved HbYX (Hydrophobic-Tyr-X) motif, bind to pockets in the α-ring in an ATP-dependent manner, triggering the opening of this gate [3] [4].

- Translocation: Once unfolded, the polypeptide substrate must be translocated into the 20S core. Surprisingly, this step requires ATP-binding but not necessarily hydrolysis, and may occur by facilitated diffusion through the ATPase ring in its ATP-bound form [3].

Quantitative Analysis of ATP Consumption in Proteolysis

The energy cost of degrading a single protein molecule is not trivial. Research has quantified this cost, revealing that the ATPases function in a highly cooperative, cyclical manner rather than independently [4].

Cooperative ATP Hydrolysis

Mutational studies preventing ATP binding to individual Rpt subunits (Rpt3, Rpt5, or Rpt6) showed that each single mutation reduced basal ATP hydrolysis by approximately 66% and completely blocked the stimulation of ATPase activity induced by ubiquitinated substrates [4]. This demonstrates a high degree of cooperativity among the six ATPase subunits, where the function of each is dependent on the others in an ordered cycle.

Energy Cost per Protein Molecule

The ATP consumption for degrading a single protein molecule has been directly measured. The degradation of a model substrate, ubiquitinated dihydrofolate reductase (Ub~5~-DHFR), consumes approximately 50-80 ATP molecules per substrate molecule under normal conditions [4]. This cost is not fixed; it is influenced by the properties of the substrate itself. When Ub~5~-DHFR was stabilized in a more tightly folded state by its ligand (folate), the time required for degradation and the associated energy cost both increased approximately two-fold [4]. This establishes that the ATP cost of degradation is directly proportional to the stability and folding state of the target protein.

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of ATP Consumption in Proteasome Function

| Experimental Parameter | Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal ATP for 26S activity in vitro | ~50-100 µM [2] | Physiological ATP levels (0.5-5 mM) may exert negative regulation. |

| ATP Cost for Ub~5~-DHFR degradation | 50-80 ATPs/substrate [4] | Degradation is an energy-intensive process. |

| Effect of substrate stability | 2-fold increase in ATP cost with tighter folding [4] | Protein structure directly determines energy expenditure. |

| Mode of ATPase action | Ordered, cooperative cycle [4] | Single subunit dysfunction severely impairs overall function. |

Bidirectional Regulation of Proteasome Function by ATP

A fascinating and counterintuitive regulatory mechanism has emerged, showing that ATP exerts bidirectional regulation over proteasome function. While ATP is essential for the proteasome's activity, its concentration has a paradoxical effect.

In vitro studies with purified 26S proteasomes demonstrate that ATP at concentrations lower than 50-100 µM stimulates the proteasome's chymotrypsin-like activity. However, at higher concentrations within the physiological range (0.5-5 mM), ATP exerts a dose-dependent suppression of these peptidase activities [2]. This phenomenon is also observed in living cells. Manipulating intracellular ATP levels in cultured cells (e.g., using oligomycin to inhibit oxidative phosphorylation or 2-deoxyglucose to inhibit glycolysis) leads to bidirectional changes in the levels of proteasome substrates like poly-ubiquitinated proteins, p27, and I-κBα [2]. For instance, a moderate reduction of ATP can enhance proteasome activity and reduce substrate levels, while a severe depletion of ATP inhibits proteasome function and causes substrate accumulation [2].

This bidirectional relationship suggests a novel regulatory model: under normal, energy-replete conditions, physiological ATP levels keep proteasome activity in a partially suppressed state. Upon moderate energy stress, the consequent reduction in ATP releases this inhibition, rapidly up-regulating proteasome capacity to clear damaged proteins. This mechanism allows the cell to dynamically reserve and mobilize its proteolytic power in response to metabolic status [2].

Experimental Approaches and Research Tools

Studying ATP-dependent proteolysis requires specialized experimental protocols and reagents. Key methodologies include assays for proteasome activity and techniques for manipulating and monitoring intracellular ATP.

Key Experimental Protocols

1. Measuring Proteasome Peptidase Activity:

- Principle: Use of fluorogenic peptides (e.g., Suc-LLVY-AMC) where proteasome cleavage releases the fluorescent AMC molecule, allowing continuous measurement [6] [4].

- Protocol: Incubate proteasomes (10 nM) in assay buffer (e.g., 25 mM HEPES/KOH pH 8, 2.5 mM MgCl~2~, 125 mM potassium acetate, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM DTT) with the fluorogenic substrate. Monitor the increase in fluorescence (excitation ~365 nm, emission ~444 nm) over time [4].

2. Monitoring Degradation of Full-Length Protein Substrates:

- Principle: Use of engineered protein substrates like GFPu (GFP fused to a degron) or radiolabeled ubiquitinated proteins (e.g., Ub~5~-DHFR) [2] [4].

- Protocol: For radiolabeled substrates, incubate with 26S proteasomes and ATP. At intervals, precipitate the reaction with trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and measure the release of acid-soluble radiolabeled peptides, which indicates degradation [4]. For GFPu, monitor fluorescence or protein levels via western blotting [2].

3. Manipulating Intracellular ATP:

- Principle: Use of metabolic inhibitors to modulate ATP production.

- Protocol: To decrease ATP, treat cells with oligomycin (inhibits oxidative phosphorylation) in glucose-free medium, or with 2-deoxyglucose (inhibits glycolysis). To increase ATP, provide ample D-glucose [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Studying ATP-Dependent Proteolysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Key Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorogenic Peptides (e.g., Suc-LLVY-AMC) | Peptide substrates that release fluorescent AMC upon proteolytic cleavage. | High-throughput measurement of proteasome chymotrypsin-like activity [6] [4]. |

| AMC-Labeled Proteins | Full-length proteins labeled with 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin via reductive methylation. | Non-radioactive method to study proteolysis of full-length, modifiable protein substrates [6]. |

| Oligomycin | Specific inhibitor of mitochondrial ATP synthase (Complex V). | Experimental reduction of intracellular ATP levels from oxidative phosphorylation [2]. |

| 2-Deoxyglucose (2DG) | Glycolytic inhibitor; competitive antagonist of glucose. | Experimental reduction of intracellular ATP levels from glycolysis [2]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132, Bortezomib) | Small molecules that directly inhibit the proteolytic activity of the 20S core particle. | Validating UPS-dependent degradation and inducing proteotoxic stress [2]. |

| Engineered Cell Lines (e.g., GFPu/RFP) | Cells stably expressing UPS reporters (GFPu/dgn) and normalization controls (RFP). | Accurate monitoring of UPS function in live cells, controlling for general protein synthesis effects [2]. |

The puzzling requirement for ATP in intracellular proteolysis is now understood as a cornerstone of cellular regulation. ATP hydrolysis is indispensable for the specificity, control, and efficiency of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, powering everything from the initial tagging of a substrate to its final translocation and degradation within the proteasome. The discovery of bidirectional regulation by ATP adds a layer of metabolic sensing to this system, linking proteolytic capacity directly to the energetic state of the cell.

These fundamental insights have profound implications for drug development, particularly in oncology. The efficacy of proteasome inhibitors like bortezomib, used to treat multiple myeloma, is influenced by cellular ATP levels; higher intracellular ATP can make cancer cells more susceptible to proteasome inhibitor-induced cell death [2]. Understanding the intricate relationship between ATP and the UPS opens avenues for novel therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating proteasome function by targeting cellular energy metabolism, potentially offering new hope for treating life-threatening diseases.

Avram Hershko and Aaron Ciechanover's Identification of a Heat-Stable Factor

In the late 1970s, Avram Hershko and Aaron Ciechanover embarked on a series of groundbreaking experiments that would ultimately redefine our understanding of cellular regulation. Their investigation into the energy-dependent proteolytic pathways in mammalian cells led to the identification and characterization of a crucial heat-stable factor, known initially as ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1 (APF-1). This discovery, later confirmed to be the protein ubiquitin, unveiled a sophisticated system for targeted protein degradation. This guide provides a detailed comparison of the key experimental findings, methodologies, and reagents that underpinned this seminal work, offering researchers a comprehensive resource on the foundational experiments that revealed the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

Historical Context and the Proteolysis Paradox

In the decades preceding this discovery, the fundamental question of how cells regulate the breakdown of intracellular proteins remained largely unanswered. While the genetic code and protein synthesis were under intense study, protein degradation was a neglected area, often simplistically attributed to the lysosome [1]. A critical biochemical paradox puzzled scientists: the hydrolysis of peptide bonds is an exergonic (energy-releasing) process, yet experimental evidence consistently showed that intracellular proteolysis required ATP, an energy source [7] [1]. This apparent contradiction suggested the existence of a complex, energy-requiring mechanism preceding the actual breakdown of proteins. Furthermore, it was observed that abnormal or damaged proteins were rapidly cleared from cells, and that key metabolic enzymes had vastly different half-lives, implying a selective and regulated process far beyond the presumed indiscriminate activity of lysosomes [7]. It was within this context that Hershko and Ciechanover began their systematic biochemical investigation.

Experimental Systems and Key Methodologies

The following section details the core experimental approaches and workflows used to identify and characterize APF-1.

Foundational Experimental Model

Hershko and Ciechanover employed a well-defined cell-free system derived from rabbit reticulocytes (immature red blood cells) [7] [8] [1]. This system was strategically chosen for several reasons:

- Lack of Lysosomes: Reticulocytes are devoid of lysosomes, allowing the researchers to isolate and study the non-lysosomal, ATP-dependent proteolytic pathway directly [8].

- High Proteolytic Activity: These cells naturally undergo extensive remodeling, destroying many internal proteins as they mature into hemoglobin-specialized cells, providing a rich source of the relevant enzymatic machinery [8].

- Biochemical Tractability: A cell-free extract allowed for fractionation, reconstitution, and precise manipulation of components under controlled conditions [7].

Key Experimental Workflow

The overall experimental strategy progressed from a functional fractionation of the reticulocyte lysate to the precise biochemical identification of its essential components. The diagram below outlines this logical progression.

Critical Experimental Protocols

Two pivotal experimental protocols were crucial for the discovery.

Fractionation and Heat-Stability Assay

This protocol established the existence and basic nature of APF-1 [7] [8] [1].

- Lysate Preparation: Rabbit reticulocyte lysate was prepared and fractionated using chromatography into two complementary fractions (I and II).

- Functional Reconstitution: Individually, neither fraction could support ATP-dependent degradation of a radiolabeled protein substrate (e.g., denatured albumin). Activity was restored only upon recombining both fractions.

- Boiling Fraction I: Fraction I was subjected to heat treatment (95°C for 5-10 minutes).

- Centrifugation: The boiled sample was centrifuged, denaturing and precipitating the vast majority of proteins (like hemoglobin), while a small, heat-stable component remained soluble and active in the supernatant.

- Assay: The heat-stable supernatant, when added to Fraction II and ATP, successfully restored ATP-dependent proteolytic activity. This active component was termed APF-1.

Covalent Conjugation Assay

This protocol revealed the novel mechanism of action of APF-1 [7] [8].

- Radiolabeling: The purified APF-1 factor was labeled with radioactive iodine (¹²⁵I).

- Incubation with ATP: The ¹²⁵I-APF-1 was incubated with Fraction II in the presence of ATP.

- SDS-PAGE Analysis: The reaction mixture was analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, a technique that separates proteins by molecular weight.

- Autoradiography: The gel was exposed to X-ray film to visualize the location of the radioactive label.

- Observation: Instead of a single band at the low molecular weight of free APF-1, a "ladder" of multiple, higher molecular weight radioactive bands appeared. This indicated that ¹²⁵I-APF-1 had become covalently attached to a wide array of proteins in Fraction II. The bond was found to be stable to harsh treatments like high pH, confirming its covalent, isopeptide nature.

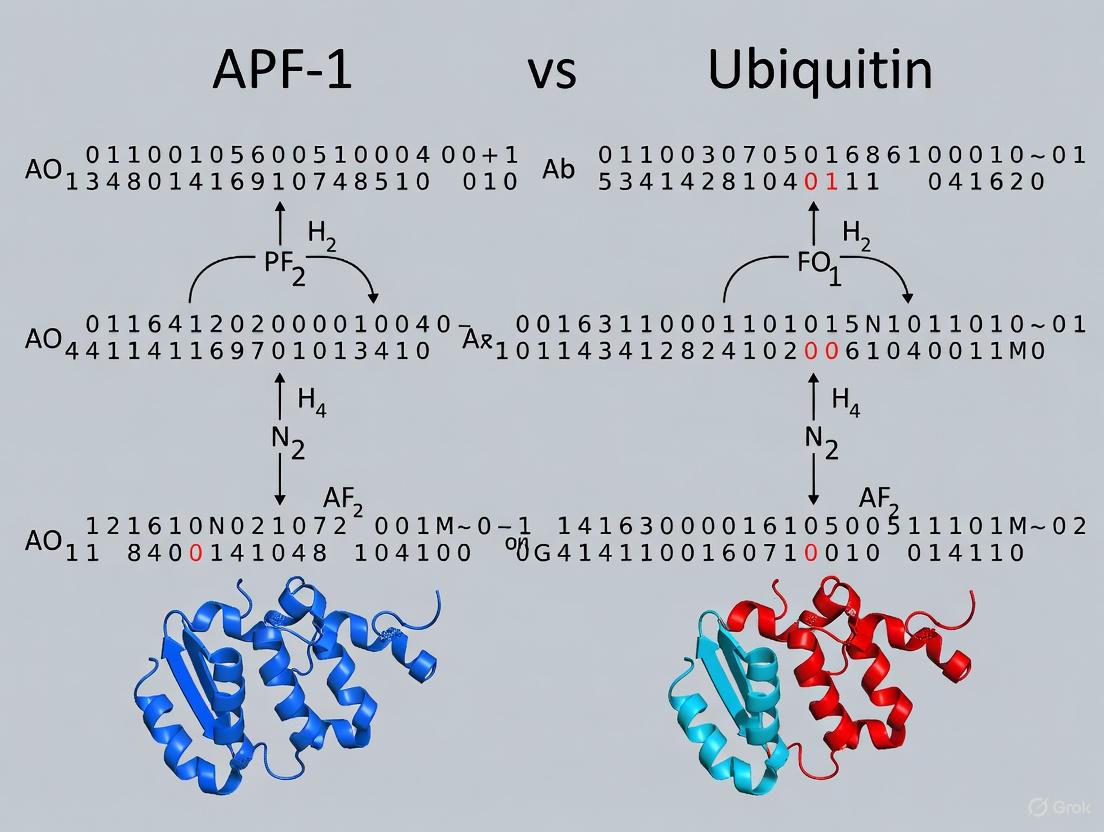

APF-1 vs. Ubiquitin: A Comparative Analysis

The subsequent identification of APF-1 as the previously known protein ubiquitin was a key moment of scientific convergence. The table below compares the profiles of this protein from both research contexts.

Table 1: Characteristic Comparison of APF-1 and Ubiquitin

| Characteristic | APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1) | Ubiquitin (Ubiquitous Immunopoietic Polypeptide) |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Known Function | Essential factor for ATP-dependent protein degradation in reticulocyte lysates [7]. | Previously known protein of unknown function; found conjugated to histone H2A in chromatin [7] [8]. |

| Size & Structure | Small, ~8-9 kDa polypeptide [7] [1]. | Small, 76-amino acid, highly conserved protein [9]. |

| Key Property | Remarkably heat-stable; remained active after boiling [7] [8]. | Known to be an extremely stable protein [7]. |

| Covalent Conjugation | Found to form covalent, isopeptide bonds with a wide range of target proteins in an ATP-dependent manner [7] [8]. | Known to be covalently linked via an isopeptide bond to histone H2A (in protein A24) [7]. |

| Functional Implication | Conjugation was proposed as a marking mechanism for targeting proteins for degradation by a then-unknown protease [7]. | Physiological role of its conjugation was unknown prior to 1980. |

| Identification | Identified through biochemical fractionation and functional proteolysis assays [7]. | Isolated by Gideon Goldstein in search for thymopoietin [7]. |

The critical link was made when researchers noticed the parallel between the covalent conjugation of APF-1 and the known conjugation of ubiquitin to histones. Subsequent experiments, involving antibody cross-reactivity and direct sequence comparison, conclusively demonstrated that APF-1 and ubiquitin were the same molecule [7].

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway

The discovery of APF-1/ubiquitin as a degradation tag was the first step in elucidating an entire pathway. The subsequent work of Hershko, Ciechanover, Rose, and Varshavsky defined the enzymatic cascade and the final degrading machine, the proteasome. The following diagram illustrates the complete pathway as understood today.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and materials that were fundamental to these discoveries, providing a resource for understanding the experimental requirements of this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | A cell-free system derived from rabbit reticulocytes, serving as the source of the ubiquitin-proteasome system machinery, free of lysosomal activity [7] [1]. |

| ATP (Adenosine Triphosphate) | The essential energy source required for the activation of ubiquitin and the subsequent proteolytic process [7] [8]. |

| Radiolabeled Protein Substrates (e.g., ¹²⁵I-labeled albumin) | Denatured or abnormal proteins used to track and quantify the process of ATP-dependent degradation [8] [1]. |

| Chromatography Resins (e.g., DEAE-cellulose) | Used for the fractionation of the reticulocyte lysate into distinct biochemical fractions (I and II) to isolate and identify essential components [7]. |

| ¹²⁵I for Iodination | Radioactive isotope used to label APF-1/Ubiquitin, enabling the visual tracking of its covalent conjugation to target proteins via SDS-PAGE and autoradiography [7] [8]. |

| SDS-PAGE Apparatus | A core technology for separating proteins by molecular weight, which was critical for observing the shift of APF-1 into higher molecular weight conjugates [7]. |

| Heat-Stable Protein Fraction | The boiled and centrifuged supernatant of Fraction I, which contained the active, heat-stable APF-1/Ubiquitin [7] [1]. |

The meticulous biochemical work of Hershko and Ciechanover to identify the heat-stable APF-1 factor represents a paradigm of discovery-driven science. Their systematic fractionation and functional reconstitution assays uncovered not just a new protein, but a fundamental physiological principle: that cells employ a covalent protein-tagging system to direct and regulate the destruction of specific proteins. The subsequent identification of APF-1 as ubiquitin unified previously disparate fields and opened up an entirely new area of research. The recognition that this system controls central cellular processes—including the cell cycle, DNA repair, and transcription—has had profound implications for understanding human disease, particularly cancer and neurodegenerative disorders. This work, honored with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004, directly led to the development of novel therapeutics, such as the proteasome inhibitor Bortezomib (Velcade) for multiple myeloma, validating the immense translational potential of basic biochemical research [10].

In the late 1970s, a fundamental puzzle captivated researchers studying cellular physiology: why did the breakdown of intracellular proteins require adenosine triphosphate (ATP)? The hydrolysis of peptide bonds is an exergonic process that releases energy, making an ATP requirement seem thermodynamically paradoxical [7]. This question led Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and their colleagues to embark on a series of experiments that would uncover a previously unknown proteolytic system. Their investigation revealed ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1), a small, heat-stable protein that would later be recognized as the central mediator of what we now know as the ubiquitin-proteasome system [7] [1]. This discovery, which would eventually earn the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004, revolutionized our understanding of how cells selectively target proteins for destruction and opened new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Experimental Foundation: Isolating and Characterizing APF-1

Development of the Reticulocyte Lysate System

The initial breakthrough came with the establishment of a cell-free experimental system that reproduced ATP-dependent proteolysis. Earlier work by Etlinger and Goldberg had demonstrated that reticulocyte lysates (which naturally lack lysosomes) could degrade abnormal proteins in an ATP-dependent manner [7] [11]. Hershko and Ciechanover exploited this system, fractionating reticulocyte extracts to isolate the essential components required for proteolysis [7] [8]. Through sequential chromatography, they separated the lysate into two complementary fractions: Fraction I and Fraction II [7]. Neither fraction alone could support ATP-dependent proteolysis, but when recombined, protein degradation was restored.

A detailed workflow of the initial fractionation experiments is provided below:

Identification of a Heat-Stable Factor

A critical observation emerged when the researchers subjected Fraction I to boiling temperatures. While most proteins denatured and precipitated under these conditions (including the abundant hemoglobin), a small, heat-stable component remained soluble and functionally active [8]. This thermostable polypeptide, designated APF-1, was purified and found to be essential for reconstituting ATP-dependent proteolysis when added to Fraction II [7]. The remarkable stability of APF-1 to heat treatment became a defining characteristic that facilitated its purification and further study.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: ATP-Dependent Proteolysis Assay [7] [11]

- Cell System: Rabbit reticulocyte lysates prepared from phenylhydrazine-treated rabbits

- Radioactive Labeling: Substrate proteins (e.g., lysozyme) labeled with 125I or 14C-amino acids

- Reaction Conditions: Incubation at 37°C in presence of ATP and Mg2+

- Proteolysis Measurement: Trichloroacetic acid-soluble radioactivity counted after incubation

- Fractionation: Lysates separated by DEAE-cellulose chromatography into Fraction I (lacking APF-1) and Fraction II (containing APF-1)

Protocol 2: Covalent Conjugation Assay [7]

- APF-1 Labeling: 125I-APF-1 prepared using iodination techniques

- Incubation Conditions: 125I-APF-1 incubated with Fraction II and ATP

- Detection Method: SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography to identify high molecular weight conjugates

- Specificity Controls: Reactions performed without ATP or with non-hydrolyzable ATP analogs

The Discovery of Covalent Conjugation: APF-1 as a Protein Tag

Unexpected Covalent Linkages

The pivotal insight into APF-1's mechanism came when researchers radioactively labeled APF-1 with 125I and incubated it with Fraction II in the presence of ATP [7]. Instead of detecting only free APF-1, they observed that the labeled protein was promoted to multiple high molecular weight forms on SDS-PAGE. This association was unexpected because:

- It required ATP hydrolysis for formation

- The linkage was stable to SDS, urea, and high pH treatments

- The bond was reversible upon ATP depletion

Further analysis revealed that these high molecular weight complexes represented covalent conjugates between APF-1 and numerous endogenous proteins in Fraction II [7]. This marked the first demonstration of what we now recognize as protein ubiquitination.

Multiplicity of Conjugation and Relationship to Degradation

Hershko et al. made another crucial observation when they examined the conjugation of APF-1 to known proteolytic substrates [7]. They discovered that:

- Multiple molecules of APF-1 attached to each molecule of substrate protein

- The conjugation appeared to be processive, with preference for adding additional APF-1 molecules to existing conjugates

- The number of APF-1 molecules per substrate increased over time before degradation commenced

- The ATP and metal ion requirements for conjugation paralleled those for proteolysis

These findings suggested that multiple APF-1 molecules formed a chain that served as a recognition signal for proteolysis, presaging the discovery of polyubiquitin chains.

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of APF-1 conjugation:

| Characteristic | Experimental Evidence | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| ATP Dependence | Conjugation required ATP hydrolysis; reversed upon ATP depletion | Energy required for bond formation between APF-1 and target proteins |

| Covalent Linkage | Stable to SDS, urea, and high pH (NaOH) treatment | Unusual isopeptide bond rather than non-covalent association |

| Multiplicity | Multiple APF-1 molecules conjugated per substrate molecule | Early indication of polyubiquitin chain formation |

| Target Diversity | APF-1 conjugated to many different proteins in Fraction II | Broad specificity of the conjugation system |

| Functional Correlation | Similar nucleotide/metal ion requirements for conjugation and proteolysis | Conjugation is prerequisite for degradation |

The Critical Identification: APF-1 is Ubiquitin

Converging Lines of Evidence

The identity of APF-1 remained unknown until researchers noticed striking similarities with a previously characterized protein called ubiquitin [7] [11]. The connection was made through collaborative discussions between Keith Wilkinson, Arthur Haas, and Michael Urban at Fox Chase Cancer Center [11]. Urban, who worked on chromatin structure, recognized that histone H2A was known to be modified by covalent attachment of a small protein called ubiquitin [7]. This prompted a direct comparison between APF-1 and ubiquitin, which revealed:

- Identical migration patterns on five different polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis systems and isoelectric focusing [12] [13]

- Excellent agreement in amino acid composition [12]

- Similar specific activity in activating the ATP-dependent proteolytic system [13]

- Electrophoretically identical covalent conjugates formed with endogenous reticulocyte proteins when using 125I-APF-1 versus 125I-ubiquitin [12]

Sequence and Functional Implications

The identification of APF-1 as ubiquitin connected two previously separate fields of research. Ubiquitin had been discovered in 1975 by Gideon Goldstein as a universally expressed polypeptide [14], but its physiological function remained unknown. The covalent attachment of ubiquitin to histone H2A had been described by Goldknopf and Busch [7], but the purpose of this modification was unclear. The work of Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose revealed that ubiquitin's function extended far beyond chromatin modification to include targeting proteins for degradation.

The relationship between the initial APF-1 characterization and its identification as ubiquitin is summarized below:

Quantitative Comparison: APF-1 Versus Ubiquitin

The experimental evidence establishing the identity of APF-1 and ubiquitin was comprehensive and multi-faceted. The following table summarizes the key comparative data that confirmed they were the same molecule:

| Parameter | APF-1 | Ubiquitin | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | ~8.6 kDa | ~8.6 kDa | SDS-PAGE migration [12] |

| Isoelectric Point | Identical | Identical | Isoelectric focusing [12] |

| Thermal Stability | Stable at 100°C | Stable at 100°C | Boiling and centrifugation [8] |

| Amino Acid Composition | Matched ubiquitin | Reference standard | Amino acid analysis [12] |

| Biological Activity | Activated ATP-dependent proteolysis | Activated ATP-dependent proteolysis | Proteolysis assay with Fraction II [13] |

| Conjugation Pattern | Identical covalent conjugates | Identical covalent conjugates | SDS-PAGE of 125I-labeled proteins [12] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The discovery of APF-1/ubiquitin depended on several critical research reagents and methodologies that enabled the key observations. The following table outlines these essential tools:

| Reagent/Method | Function in APF-1 Research | Experimental Role |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | Source of ATP-dependent proteolytic system | Provided cell-free system for fractionation and reconstitution [7] |

| DEAE-Cellulose Chromatography | Separation of Fraction I and Fraction II | Enabled identification of essential components [7] |

| 125I-Labeled APF-1 | Tracing APF-1 fate in conjugation | Allowed visualization of covalent protein conjugates [7] |

| Heat Treatment (100°C) | Purification of heat-stable factors | Separated APF-1 from thermolabile proteins like hemoglobin [8] |

| ATP-Regenerating System | Maintenance of ATP levels | Sustained conjugation and proteolysis activities in assays [7] |

| SDS-PAGE + Autoradiography | Detection of protein conjugates | Visualized high molecular weight complexes of 125I-APF-1 [7] |

Legacy and Implications: From APF-1 to the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

The initial characterization of APF-1 laid the foundation for understanding one of the most sophisticated regulatory systems in eukaryotic cells. What began as a factor in ATP-dependent proteolysis soon expanded into the elaborate ubiquitin-proteasome system that controls countless cellular processes [1] [15]. The key discoveries that emerged from this initial work include:

- The E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade responsible for ubiquitin conjugation [15]

- The 26S proteasome as the protease that recognizes and degrades ubiquitinated proteins [16]

- The code of ubiquitin linkages (K48, K63, etc.) that determine different functional outcomes [14]

- The involvement of ubiquitination in cell cycle regulation, transcription, DNA repair, and signaling [1] [15]

The trajectory from APF-1 characterization to modern ubiquitin research exemplifies how pursuing a basic biochemical paradox can unveil fundamental biological mechanisms with profound implications for understanding disease and developing therapeutics. The ubiquitin-proteasome system has since become a prime target for drug development, particularly in cancer therapy, demonstrating the far-reaching impact of these initial discoveries.

For much of the 20th century, intracellular protein degradation was considered a nonspecific, unregulated process confined to the lysosome. This perception began to shift in 1953 when Melvin Simpson demonstrated that intracellular proteolysis in mammalian cells requires metabolic energy (ATP)—a thermodynamic paradox given that peptide bond hydrolysis is an exergonic process [7]. This ATP requirement suggested the existence of a previously unrecognized, energy-dependent proteolytic pathway. By the late 1970s, researchers led by Avram Hershko and Aaron Ciechanover at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology were systematically investigating this paradox using reticulocyte (immature red blood cell) extracts, which lack lysosomes yet exhibit robust ATP-dependent proteolysis [7] [8]. Their work would ultimately lead to the discovery of a novel proteolytic system centered on a small, heat-stable protein they termed APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1), later identified as the previously known but functionally enigmatic protein ubiquitin [7] [14] [8]. This guide compares the foundational experimental approaches that deciphered the APF-1/ubiquitin system, providing researchers with a detailed analysis of the methodologies that uncovered this fundamental biological pathway.

Experimental Breakdown: Reconstitution and Covalent Conjugation

The key experiments that defined the APF-1 system can be divided into two complementary phases: the initial fractionation and reconstitution of the proteolytic activity, and the subsequent discovery of covalent protein conjugation.

Phase 1: Fractionation and Reconstitution of ATP-Dependent Proteolysis

The initial experimental goal was to identify the essential components in reticulocyte extracts responsible for ATP-dependent degradation of abnormal proteins.

- Core Protocol: Reticulocyte lysates were fractionated using conventional chromatography. The proteolytic activity was monitored by adding a radioactively tagged model protein substrate (e.g., denatured lysozyme) and measuring the release of acid-soluble radioactivity, indicating protein breakdown [7] [8] [17].

- Key Workflow Step: A critical and unconventional step involved boiling one of the necessary fractions (Fraction I). While most proteins, including hemoglobin, denatured and precipitated, the essential activity remained in the soluble fraction, indicating it was mediated by a remarkably heat-stable component [8] [17]. This component was purified and named APF-1.

- Central Finding: The proteolytic system was resolved into at least two essential fractions [17]:

- Fraction I: Contained the single, heat-stable component APF-1.

- Fraction II: A crude fraction containing multiple proteins, which would later be found to include the enzymatic machinery for conjugation and the proteasome.

The requirement for two complementing fractions was a radical departure from the prevailing paradigm where proteolysis was catalyzed by a single protease. This suggested a multi-step, enzymatic cascade was responsible for targeted protein degradation [17].

Phase 2: Discovery of Covalent Conjugation

The function of APF-1 was illuminated through a series of experiments tracking its fate in the presence of ATP and Fraction II.

- Core Protocol: Researchers labeled APF-1 with a radioactive iodine isotope (¹²⁵I) and incubated it with Fraction II and ATP. The reaction mixtures were then analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) to separate proteins by size [7].

- Key Observation: In the absence of ATP, radioactive labeling appeared only at the position of free APF-1 (~8.6 kDa). Upon ATP addition, the radioactivity shifted to a "smear" of high-molecular-weight species, suggesting APF-1 was forming adducts with many different proteins in Fraction II [7] [8].

- Critical Validation: The linkage between APF-1 and the target proteins was found to be covalent. It was stable to treatment with harsh denaturants like SDS, high salt, and even extreme pH (NaOH), but was reversible upon ATP removal [7] [8]. Art Haas, a postdoctoral fellow in Irwin Rose's lab, played a key role in characterizing this stable bond [7]. This indicated a novel, enzyme-catalyzed covalent modification rather than a non-covalent association.

The diagram below illustrates the logical flow and key outcomes of this pivotal experimental phase.

The following tables consolidate the key quantitative findings and experimental parameters from the seminal studies on APF-1.

Table 1: Characteristics of APF-1 and its Conjugates

| Parameter | Experimental Finding | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| APF-1 Molecular Weight | ~8.6 kDa [14] | Identified as a small, heat-stable protein. |

| Thermal Stability | Active after boiling for 10 minutes [8] [17] | Key property that enabled its purification and distinction from other proteins. |

| Conjugate Stability | Stable to SDS, high salt, and NaOH treatment [7] | Provided strong evidence for a covalent, isopeptide bond. |

| ATP Requirement for Conjugation | Half-maximal conjugation at ~20 μM ATP [7] | Correlated ATP dependence of conjugation with that of proteolysis. |

| Stoichiometry of Conjugation | Multiple molecules of APF-1 attached to a single substrate molecule [7] [8] | Suggested a "marking" mechanism; precursor to the polyubiquitin chain concept. |

Table 2: Comparison of APF-1/Ubiquitin Identity

| Feature | APF-1 | Ubiquitin |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | ~8.6 kDa [8] | 8.6 kDa [14] |

| Amino Acid Composition | Heat-stable polypeptide [17] | 76 amino acids; highly conserved [14] |

| Tissue Distribution | Component of a proteolytic system in reticulocytes [7] | Ubiquitous in eukaryotic tissues [14] |

| Known Covalent Linkage | C-terminal Glycine to substrate Lysine (isopeptide bond) [7] | C-terminal Gly76 to Lysine of target protein (isopeptide bond) [14] |

| Key Experimental Evidence for Identity | Co-migration, identical peptide maps, and antibody cross-reactivity with purified ubiquitin [7] | Direct sequence analysis confirmed APF-1 was ubiquitin [7] |

The Ubiquitination Mechanism and Pathway

The discovery of covalent APF-1 conjugation paved the way for elucidating the modern ubiquitination pathway. The "puzzle" was solved by identifying a three-enzyme cascade that activates and conjugates ubiquitin to protein targets.

The following diagram outlines this conserved enzymatic cascade, from activation to ligation.

- Activation (E1): Ubiquitin is activated in an ATP-dependent reaction. The E1 enzyme forms a high-energy thioester bond between its active-site cysteine and the C-terminal glycine (Gly76) of ubiquitin [14] [8].

- Conjugation (E2): The activated ubiquitin is transferred to a cysteine residue of an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, forming another thioester intermediate [14].

- Ligation (E3): An E3 ubiquitin ligase recruits both the E2~Ub complex and the protein substrate, facilitating the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to a lysine residue on the substrate, forming a stable isopeptide bond [14]. E3s provide substrate specificity, with hundreds existing in humans to recognize distinct targets.

The initial observation of APF-1 (ubiquitin) forming high-molecular-weight adducts was the first evidence of this entire pathway. The "polyubiquitin chain" is formed when additional ubiquitin molecules are conjugated to a lysine residue (e.g., Lys48) on the previously attached ubiquitin moiety [7] [14]. This polyubiquitin chain is the definitive signal for recognition and degradation by the 26S proteasome [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

For researchers aiming to study the ubiquitin-proteasome system, the following reagents are fundamental, many of which were critical in the original discovery.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent | Function in Research | Role in Original APF-1 Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | A cell-free system rich in ubiquitination and proteasomal machinery; used for in vitro degradation assays. | The primary source for fractionating the ATP-dependent proteolytic system [7] [17]. |

| ATP (and ATPγS) | The nucleotide fuel required for E1-mediated ubiquitin activation. Used to demonstrate energy dependence. | Essential cofactor; its omission blocked both conjugation and proteolysis [7]. |

| Heat-Stable Protein Fraction | A source of free ubiquitin, often prepared by boiling a cell extract and collecting the supernatant. | This method was used to identify and initially purify APF-1 from other proteins [8] [17]. |

| Radioiodinated APF-1/Ubiquitin | (¹²⁵I-labeled) Allows for sensitive tracking of ubiquitin conjugation and turnover in biochemical assays. | Critical for visualizing the formation of high-molecular-weight conjugates via SDS-PAGE/autoradiography [7]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132) | Block the degradation of ubiquitinated proteins, causing their accumulation. Useful for studying conjugation independently of degradation. | Not available initially; fractionation was used to separate conjugation (Fraction II) from the proteasome (APF-2) [7]. |

| E1, E2, E3 Enzymes | Purified recombinant enzymes used to reconstitute the ubiquitination cascade for mechanistic studies. | The three-enzyme cascade was later defined through further fractionation of the crude Fraction II [14] [8]. |

The observation that APF-1 forms covalent, high-molecular-weight adducts was the pivotal piece that solved the long-standing puzzle of energy-dependent intracellular proteolysis. This discovery shifted the paradigm from a model of nonspecific degradation to one of highly specific, post-translational regulation via covalent modification. The identification of APF-1 as ubiquitin unified previously disparate fields—connecting a known protein modifier to a specific proteolytic function [7]. The elegant three-enzyme cascade provides the specificity and regulation that underpin its vast physiological importance, governing processes from cell cycle progression to immune response. For drug development professionals, this system offers rich therapeutic potential, with the proteasome inhibitor Bortezomib being a direct clinical application. The foundational experiments comparing APF-1 functionality, which hinged on robust fractionation and covalent conjugation assays, remain essential methodologies for ongoing research into targeted protein degradation.

In the late 1970s, the biochemical mechanisms governing intracellular protein degradation remained largely enigmatic. While researchers understood that cellular protein breakdown required energy—an apparent thermodynamic paradox since peptide bond hydrolysis is exergonic—the underlying processes were obscure [7] [18]. The prevailing assumption attributed most intracellular proteolysis to lysosomal activity, but several experimental observations contradicted this model [1].

Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and their colleagues embarked on a systematic biochemical investigation using reticulocyte (immature red blood cell) lysates, which lack lysosomes, thereby eliminating confounding protease activity [19]. Their experiments revealed an ATP-dependent proteolytic system that required multiple factors [7]. During fractionation, they isolated a heat-stable, small polypeptide absolutely essential for this ATP-dependent degradation, which they named APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1) [19] [15]. This discovery set the stage for a unexpected connection across scientific disciplines.

Parallel Research Tracks: The APF-1 and Ubiquitin Stories

Characterizing APF-1 in the Proteolysis Pathway

The Hershko and Ciechanover team made a series of critical observations about APF-1:

- Covalent Conjugation: They discovered that APF-1 formed covalent conjugates with target proteins in an ATP-dependent manner [7] [1]. These conjugates appeared as high-molecular-weight adducts on SDS-PAGE gels [19].

- Multiple Attachment: Their seminal 1980 PNAS paper demonstrated that multiple molecules of APF-1 could be attached to a single substrate protein molecule, and this multi-conjugation was associated with targeting the protein for degradation [7] [15].

- Functional Association: The energy requirement for proteolysis was linked not to the proteolytic step itself, but to the conjugation of APF-1 to substrate proteins [15].

Table 1: Key Properties of APF-1 Identified Before Its Recognition as Ubiquitin

| Property | Experimental Evidence | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat stability | Retained function after heat treatment | Distinguished from most cellular proteins | [19] |

| ATP dependence | Conjugation required ATP hydrolysis | Explained energy requirement in proteolysis | [7] [15] |

| Covalent attachment | Formed stable conjugates with diverse proteins | Suggested tagging mechanism for degradation | [7] [1] |

| Multi-point attachment | Multiple APF-1 molecules per substrate | Proposed signal amplification mechanism | [7] [15] |

The Pre-Existing Ubiquitin Identity

Unbeknownst to the proteolysis researchers, a protein named ubiquitin had already been discovered and characterized in other contexts:

- Initial Discovery: Gideon Goldstein and colleagues first identified ubiquitin in 1975 as a universal polypeptide present in all eukaryotic cells [14] [7].

- Chromatin Role: Ubiquitin was identified as a component of chromosomal proteins, specifically in a conjugate with histone H2A (protein A24) [7] [19].

- Immune Function: It was initially characterized for its lymphocyte-differentiating properties and was called "ubiquitous immunopoietic polypeptide" [7].

Table 2: Known Properties of Ubiquitin Before the APF-1 Discovery

| Property | Description | Biological Context | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size | 76 amino acids, ~8.6 kDa | Highly conserved across eukaryotes | [14] |

| Sequence | Highly conserved (96% identity between human and yeast) | Suggested fundamental cellular function | [14] |

| Gene structure | Encoded by multigene family: UBB, UBC, UBA52, RPS27A | Multiple expression strategies | [14] |

| Cellular abundance | Ubiquitously expressed in all tissues | Consistent with housekeeping function | [14] |

The Eureka Moment: Connecting APF-1 to Ubiquitin

The critical connection emerged through interdisciplinary collaboration and intellectual cross-fertilization. Irwin Rose hosted Hershko for a sabbatical at the Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, fostering an environment where this discovery could occur [7].

The key insight came when researchers in Rose's laboratory, including postdoctoral fellow Arthur Haas and others, noted the striking similarities between APF-1 and the previously characterized ubiquitin protein [7]. The experimental evidence that cemented this connection included:

- Biochemical Comparison: Direct comparison of the biochemical properties of APF-1 with ubiquitin isolated from other sources showed identical characteristics [7].

- Functional Replacement: Ubiquitin could functionally replace APF-1 in the ATP-dependent proteolysis system [7] [15].

- Structural Identity: Wilkinson, Urban, and Haas definitively demonstrated that APF-1 was indeed ubiquitin, publishing their findings in 1980 [7].

This cross-disciplinary recognition transformed the understanding of both fields, connecting a specific proteolytic pathway with a previously known but functionally enigmatic protein.

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies in the Discovery

Reticulocyte Lysate System Preparation

The foundational experimental system used for these discoveries was carefully prepared to eliminate confounding factors:

Diagram: Experimental workflow for establishing the ATP-dependent proteolysis system that led to APF-1 discovery

Detailed Protocol [7] [19] [1]:

- Reticulocyte Isolation: Rabbits were made anemic through phenylhydrazine treatment, resulting in high concentrations of immature red blood cells (reticulocytes) in circulation.

- Lysate Preparation: Reticulocytes were lysed in hypotonic buffer, and the lysate was centrifuged to remove membranes and organelles.

- Biochemical Fractionation: The lysate was separated into two essential fractions (I and II) using chromatography techniques.

- ATP-Dependence Testing: Fractions were recombined with and without ATP to identify components required for energy-dependent proteolysis.

- Heat Stability Assessment: Fractions were heated to 60°C to identify heat-stable components that retained activity.

APF-1-Ubiquitin Identification Assay

The critical experiments that confirmed APF-1's identity with ubiquitin involved several sophisticated techniques:

Radiolabeling and Conjugation Assay [7]:

- Iodination: APF-1 was labeled with ¹²⁵I using standard iodination techniques.

- Conjugation Reaction: Labeled APF-1 was incubated with fraction II in the presence of ATP and Mg²⁺.

- Covalent Linkage Confirmation: The stability of APF-1-protein conjugates was tested under alkaline conditions (NaOH treatment) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

- Comparative Analysis: The behavior of authentic ubiquitin in parallel assays directly compared with APF-1.

Functional Replacement Protocol [7] [15]:

- System Reconstitution: The ATP-dependent proteolytic system was reconstituted from purified fractions.

- Component Omission: APF-1 was omitted from the system, resulting in loss of proteolytic activity.

- Ubiquitin Addition: Purified ubiquitin from other sources was added to the system.

- Activity Measurement: Proteolytic activity was quantitatively measured using labeled substrate proteins.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions in the APF-1/Ubiquitin Discovery

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Research | Experimental Role | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte lysate | ATP-dependent proteolysis system | Provided all necessary components for the degradation pathway | [7] [19] |

| Fraction II (APF-2) | High molecular weight fraction | Contained E2/E3 enzymes and proteasome activity | [7] |

| ¹²⁵I-radiolabeled APF-1 | Tracer for conjugation studies | Enabled detection and characterization of conjugates | [7] |

| ATP regeneration system | Maintained ATP levels | Sustained enzymatic activity in cell-free system | [7] [15] |

| Denatured protein substrates | Model degradation targets | Provided measurable readout for proteolytic activity | [7] [1] |

| Chromatography resins | Fractionation of lysate components | Enabled separation and purification of essential factors | [7] [19] |

Impact and Legacy: From APF-1 to the Ubiquitin System

The identification of APF-1 as ubiquitin fundamentally transformed cell biology and opened an entirely new field of research. This cross-disciplinary connection revealed that:

- Ubiquitin is a Central Regulatory Signal: The ubiquitin system emerged as a major post-translational regulatory mechanism comparable to phosphorylation [9] [18].

- Diverse Cellular Functions: Beyond proteolysis, ubiquitination regulates transcription, DNA repair, endocytosis, and kinase activation [14] [18].

- Enzymatic Cascade: The E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzyme framework was established as the mechanistic basis for ubiquitination [19] [18].

- Medical Relevance: Dysregulation of ubiquitination is implicated in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and developmental disorders [18] [1].

Diagram: Conceptual flow showing how separate research trajectories converged to establish the ubiquitin-proteasome system

The recognition in 2004 with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose validated the profound significance of this discovery [14] [1]. Their work demonstrated how systematic biochemical approaches combined with cross-disciplinary insights can unravel complex biological mechanisms, ultimately revolutionizing our understanding of cellular regulation.

Resolving Experimental Discrepancies: The Critical C-Terminal Sequence

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a well-characterized pathway essential for regulating nearly every cellular process in eukaryotes, primarily through the ATP-dependent modification of protein substrates by ubiquitin, which can target them for degradation [9]. The hallmark of this system is the post-translational modification of substrates by ubiquitin, a highly conserved 76-amino acid polypeptide, via a covalent isopeptide bond between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin and lysine residues within substrate proteins [9].

Originally identified as ATP-dependent proteolysis factor-1 (APF-1) in pioneering experiments, ubiquitin's role was substantiated when researchers demonstrated its critical function in intracellular protein turnover [9]. This discovery laid the foundation for understanding the UPS, a complex enzymatic cascade involving E1 activating, E2 conjugating, and E3 ligase enzymes that work in concert to tag proteins for proteasomal degradation. However, a significant challenge in ubiquitin research concerns the functional consistency of ubiquitin reagents across different experimental setups, which can profoundly impact the reproducibility and interpretation of proteolysis assays.

Experimental Approaches for Profiling Ubiquitin Pathway Activity

Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) with Ub-Dha Probes

Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) has emerged as a powerful biochemical tool for delineating component interactions within the UPS, providing insights into the spatiotemporal organization and dynamics of the ubiquitin network [20]. ABPP utilizes probes containing three key elements: a reactive group enabling covalent bond formation with target active sites, a recognition element for specificity, and a reporter tag for identification [20].

Smith et al. (2025) successfully employed a ubiquitin activity-based probe (Ub-Dha) featuring a dehydroalanine (Dha) reactive group to capture active components of the ubiquitin-conjugating machinery in Plasmodium falciparum during asexual blood-stage development [20]. The bipartite reaction mechanism involves adenylation activating the latent alkene moiety of dehydroalanine, enabling nucleophilic attack by ubiquitin-binding enzymes via thioether bond formation, effectively trapping them for analysis [20].

Experimental Protocol: Ub-Dha Probe Assay

- Prepare parasite lysate from asexual blood-stage P. falciparum

- Incubate lysate with biotin-Ub-Dha probe

- Capture probe-bound proteins using streptavidin beads

- Wash extensively to remove non-specifically bound proteins

- Elute and identify captured proteins via liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

- Validate identified enzymes through in vitro ubiquitination assays

This approach identified several E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, the E1 activating enzyme, the HECT E3 ligase PfHEUL, and an uncharacterized protein subsequently validated as a novel E2 enzyme [20]. The study further demonstrated selective functional interactions between PfHEUL and specific human and P. falciparum E2s, highlighting the utility of ABPP for mapping enzymatic relationships within the UPS [20].

Quantitative Proteomic Analysis of DUB Specificity

Rossio et al. (2024) developed a complementary quantitative proteomic approach to compare deubiquitylating enzyme (DUB) activity across hundreds of ubiquitylated proteins [21]. Their method addresses the challenge of DUB-substrate specificity profiling by systematically comparing multiple DUBs against a diverse array of physiological substrates.

Experimental Protocol: DUB Specificity Profiling

- Treat Xenopus egg extract with ubiquitin vinyl-sulfone (UbVS) to inhibit endogenous cysteine protease DUBs

- Add back single recombinant DUBs along with HA-tagged ubiquitin

- Immunopurify HA-tagged conjugates

- Analyze abundance changes using TMT-based quantitative proteomics

- Define candidate substrates as proteins reduced in abundance (log₂ fold change < -0.5, p-value < 0.05)

This systematic comparison of 30 DUBs revealed substantial variation in their impact, defined as the percentage of proteins whose abundance decreased following DUB addition [21]. Unsupervised clustering identified distinct DUB categories, with USP family DUBs generally showing higher impact than non-USP DUBs [21].

Comparative Performance of Ubiquitin Activity Assays

Table 1: Comparison of Key Methodologies for Profiling Ubiquitin Pathway Activity

| Method | Key Reagents | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ub-Dha ABPP [20] | Biotin-Ub-Dha probe, streptavidin beads, LC-MS/MS | Identification of active ubiquitin-conjugating machinery | Captures enzyme activity rather than abundance; reveals novel enzymes | Requires specific probe design; may not capture all enzyme classes |

| DUB Specificity Profiling [21] | UbVS inhibitor, recombinant DUBs, HA-ubiquitin, TMT reagents | Comparative analysis of DUB substrate preferences | Direct comparison of multiple enzymes; identifies redundant functions | Limited to cysteine protease DUBs; complex experimental workflow |

| Charge-Changing Peptide (CCP) Assay [22] | Fluorescently labeled CCPs, gel electrophoresis | Detection of specific protease activities in biological samples | Simple readout; suitable for clinical samples | Limited to preselected protease activities; lower throughput |

| Shotgun Proteomics of Ubiquitinated Proteins [9] | Epitope-tagged ubiquitin, multi-dimensional chromatography, MS/MS | Large-scale identification of ubiquitinated substrates | Comprehensive substrate identification; no prior knowledge required | Complex data analysis; bias toward abundant substrates |

Table 2: Impact and Effect of Selected DUBs from Quantitative Profiling [21]

| DUB | Impact (% of proteins reduced) | Effect (Average reduction) | Reported Substrates in Literature | Functional Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USP7 | High | Strong | 112 | Broad specificity; numerous known substrates |

| USP9X | High | Strong | 65 | High impact; substantial substrate overlap |

| USP15 | High | Strong | 18 | Previously underrecognized broad activity |

| USP24 | High | Strong | 3 | Newly identified as high impact DUB |

| USP14 | Low | Moderate | 79 | Well-studied but lower impact in profiling |

| OTU Family DUBs | Variable | Variable | Varies | Often show linkage specificity |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Studies

| Reagent | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Ub-Dha Probes [20] | Activity-based profiling of ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes | Traps active E1, E2, and E3 enzymes for identification |

| Ubiquitin Vinyl Sulfone (UbVS) [21] | Irreversible inhibitor of cysteine protease DUBs | Pan-DUB inhibition to generate ubiquitylated protein pools |

| Epitope-Tagged Ubiquitin [9] | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins | Large-scale identification of ubiquitinated substrates |

| Charge-Changing Peptides (CCPs) [22] | Protease activity sensors via net charge shift | Detection of specific protease activities in plasma samples |

| TMT Isobaric Labels [21] | Multiplexed quantitative proteomics | Simultaneous comparison of multiple DUB activities |

| HA-Tagged Ubiquitin [21] | Immunopurification of ubiquitin conjugates | Isolation of ubiquitinated proteins for downstream analysis |

Visualization of Ubiquitin Pathway and Experimental Workflows

Ubiquitination Cascade and Regulation

Ubiquitin Activity Profiling Workflows

Factors Contributing to Ubiquitin Preparation Variability

The inconsistent performance of ubiquitin preparations across proteolysis assays stems from several technical and biological factors:

Source and Purity of Ubiquitin Reagents Commercial ubiquitin preparations vary in their source (recombinant vs. synthetic), purification methods, and presence of modifiers or contaminants that can influence activity. These differences affect experimental outcomes in subtle but significant ways.

Enzyme Batch Effects Studies have revealed that recombinant DUBs expressed and purified in different batches demonstrate variable impact and effect on substrate pools [21]. This batch-to-batch variability complicates direct comparison of results across laboratories and experimental sessions.

Assay Conditions and Detection Methods The choice of detection method significantly influences the observed activity profiles. Mass spectrometry-based approaches offer comprehensive coverage but may favor abundant substrates, while targeted assays like CCPs provide cleaner readouts for specific activities but offer limited scope [9] [22].

Cross-Species Functional Compatibility Research in Plasmodium falciparum has demonstrated that ubiquitin pathway enzymes show selective functional interactions across species boundaries [20]. This incompatibility can manifest when using heterologous systems combining human and parasite enzymes, potentially contributing to inconsistent results.

The variable activity of ubiquitin preparations in proteolysis assays represents a significant methodological challenge with implications for research reproducibility and drug development. The inconsistency stems from multiple factors including reagent source, enzyme batch effects, assay conditions, and cross-species functional compatibility.

Based on comparative analysis of current methodologies, we recommend:

Standardized Characterization: Implement orthogonal validation methods (e.g., ABPP combined with functional assays) to comprehensively characterize ubiquitin reagent activity before use in critical experiments.

Systematic Profiling: Employ quantitative proteomic approaches like those used in DUB specificity profiling to establish baseline activities and identify potential redundant functions that might compensate in knockout systems.

Cross-Platform Validation: Verify key findings using multiple complementary techniques to control for method-specific biases and limitations.

Reagent Documentation: Maintain detailed records of reagent sources, batch numbers, and quality control metrics to facilitate troubleshooting and reproducibility.

As the ubiquitin field advances toward more targeted therapeutic interventions, acknowledging and addressing these sources of variability will be essential for developing robust assays and reliable drug screening platforms. The methodologies and comparative data presented here provide a framework for assessing and controlling these factors in future research.

The ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) represents one of the most sophisticated regulatory mechanisms in eukaryotic cell biology, controlling virtually all cellular processes through targeted protein degradation and signaling. The foundational discovery of this system emerged from investigations into ATP-dependent intracellular proteolysis in the late 1970s and early 1980s, which led to the identification of a critical heat-stable polypeptide initially termed ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1) [7] [15]. Through a series of elegant biochemical experiments, researchers including Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose demonstrated that this factor was covalently conjugated to target proteins in an ATP-dependent manner, marking them for degradation [7]. The critical breakthrough came when APF-1 was subsequently identified as the previously known but functionally enigmatic protein ubiquitin [7] [23], a highly conserved 76-amino acid polypeptide initially isolated from bovine thymus and found to be conjugated to histone 2A [23]. This discovery unified two separate lines of investigation and established the molecular identity of the central mediator of energy-dependent protein degradation.

The transition from APF-1 to ubiquitin terminology reflected more than merely a nomenclature change—it signified the recognition of a fundamental cellular pathway with both degradative and non-degradative functions. While early work established ubiquitin's primary role in targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation via polyubiquitin chains [7], subsequent research has revealed its involvement in diverse cellular processes including DNA repair, transcription, cell signaling, and membrane trafficking [9] [23]. The versatility of ubiquitin signaling stems from its ability to form different types of conjugates—monoubiquitination, multiubiquitination, and polyubiquitin chains connected through any of its seven lysine residues or N-terminus—each capable of transmitting distinct cellular signals [9] [24]. This comparison guide examines the historical and functional relationship between the initially identified APF-1 and its contemporary understanding as ubiquitin, with particular focus on separation methodologies that revealed active and inactive forms of this central cellular regulator.

Methodologies: Separation and Identification of Ubiquitin Enzymes

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Separation

The resolution of active ubiquitin and its pathway enzymes relied heavily on advanced chromatographic techniques, particularly high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The foundational methodology for separating ubiquitin-related enzymes combined ubiquitin affinity chromatography with subsequent anion-exchange HPLC [25]. This two-step purification approach enabled researchers to isolate multiple distinct enzymatic activities from wheat germ (Triticum vulgare), which served as an inexpensive and abundant source material [25].

The experimental protocol typically involved several key stages. First, crude cellular extracts were prepared under conditions that preserved enzymatic activity, often using reticulocyte lysates or plant germ extracts. These extracts were then applied to a ubiquitin-affinity column where enzymes involved in the ubiquitin pathway specifically interacted with immobilized ubiquitin. After extensive washing to remove non-specifically bound proteins, the bound ubiquitin-enzymes were eluted using specific buffers. The eluted fractions were then subjected to anion-exchange HPLC using resins such as Mono Q or DEAE, which separated proteins based on their surface charge characteristics [25]. This high-resolution separation revealed distinct peaks corresponding to different enzymatic activities, including ubiquitin activating enzyme (E1), multiple ubiquitin carrier proteins (E2s) with molecular masses ranging from 16-25 kilodaltons, and ubiquitin-protein hydrolases (isopeptidases) [25]. The separation of these distinct forms was critical for understanding the complexity of the ubiquitin system and identifying both active ubiquitin conjugating enzymes and inactive derivatives that might regulate the pathway.

Functional Characterization of Separated Fractions

Following HPLC separation, each fraction underwent rigorous functional characterization to identify specific enzymatic activities. The ubiquitin activating enzyme (E1) was identified through its ability to form a thiol ester linkage with radioiodinated ubiquitin (125I-ubiquitin) in a strictly ATP-dependent manner [25]. This activity represented the first step in the ubiquitination cascade, wherein E1 activates ubiquitin through adenylation and then transfers it to E2 enzymes.

The separated ubiquitin carrier proteins (E2s) were characterized by their ability to accept activated ubiquitin from E1 and form E2-ubiquitin thiol esters [25]. Researchers identified multiple distinct E2s with different molecular masses (16, 20, 23, 23.5, and 25 kilodaltons), suggesting early evidence for the diversity and functional specialization within the ubiquitin pathway. Additionally, ubiquitin-protein hydrolase activity was detected through its sensitivity to hemin inhibition and its capacity to remove ubiquitin moieties from both ubiquitin-lysozyme conjugates (isopeptide linkages) and ubiquitin-extension protein fusions (peptide linkages) in an ATP-independent reaction [25].

Table 1: Key Enzymatic Activities Separated by HPLC in the Ubiquitin Pathway

| Enzyme | Molecular Mass (kDa) | Function | Identification Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Activating Enzyme (E1) | ~105 | Activates ubiquitin via ATP-dependent adenylation | ATP-dependent 125I-ubiquitin thiol ester formation |

| Ubiquitin Carrier Proteins (E2s) | 16, 20, 23, 23.5, 25 | Accepts ubiquitin from E1, transfers to substrates | Thiol ester formation with 125I-ubiquitin after E1 charging |

| Ubiquitin-Protein Hydrolase (Isopeptidase) | ~30 | Removes ubiquitin from conjugates | ATP-independent cleavage of ubiquitin-conjugates, hemin-sensitive |

Comparative Analysis: APF-1 versus Ubiquitin

The evolution from APF-1 to ubiquitin represents a paradigm shift in understanding cellular regulation. While initially identified as a single factor promoting ATP-dependent proteolysis, subsequent research has revealed ubiquitin as a member of an extensive family of related proteins and modifiers with diverse functions.

Historical and Functional Context

APF-1 was originally characterized in reticulocyte lysates as an essential component of an ATP-dependent proteolytic system [7] [15]. The critical observation was that 125I-labeled APF-1 was promoted to high molecular weight forms upon incubation with fraction II and ATP, and this association was unexpectedly found to be covalent [7]. This covalent attachment to multiple cellular proteins represented a novel regulatory mechanism distinct from previously understood proteolytic pathways.

The identification of APF-1 as ubiquitin connected this ATP-dependent proteolytic system with a previously known protein. Ubiquitin had been initially discovered as UBIP (ubiquitous immunopoietic polypeptide) and was later found to be conjugated to histone 2A, though the functional significance of this modification remained mysterious [23]. The recognition that APF-1 and ubiquitin were identical unified these disparate observations and established the molecular basis for a previously unknown regulatory system.

Structural and Functional Relationships

Ubiquitin is a highly conserved 76-amino acid polypeptide that functions as a post-translational modifier through its covalent attachment to target proteins. The C-terminal glycine (G76) of ubiquitin forms an isopeptide bond with the ε-amino group of lysine residues in target proteins, though non-lysine modifications also occur [23] [24]. This modification is reversible through the action of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), creating a dynamic regulatory system.

The terminology difference between APF-1 and ubiquitin reflects their distinct historical contexts rather than structural differences. APF-1 emphasized the functional role in proteolysis, while ubiquitin reflected its ubiquitous distribution across tissues and species. Contemporary research has expanded our understanding of ubiquitin beyond its initial degradative function to include diverse regulatory roles in signaling, trafficking, and activation, mediated through different ubiquitin chain architectures and modification types [9] [24].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of APF-1 and Ubiquitin Terminology

| Characteristic | APF-1 (Historical Context) | Ubiquitin (Contemporary Understanding) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | ATP-dependent proteolysis factor | Multi-functional post-translational modifier |

| Cellular Role | Target designation for degradation | Regulation of stability, activity, localization, interactions |

| Modification Types | Not fully characterized | MonoUb, multiUb, homotypic/chains, heterotypic/branched chains |

| Structural Features | Heat-stable polypeptide | 76-amino acids, 7 lysine residues for chain formation |

| Enzymatic System | E1, E2, E3 activities partially resolved | 2 E1s, ~40 E2s, >600 E3s, ~100 DUBs in humans |

Experimental Data and Protocols

Key Experimental Workflows

The elucidation of the ubiquitin pathway relied on carefully designed experimental protocols that enabled the separation and characterization of its components. The following workflow diagrams illustrate key methodologies that revealed the distinction between active ubiquitin and its derivatives.

Diagram 1: HPLC Workflow for Ubiquitin Enzyme Separation

Functional Assay Methods

The characterization of separated fractions employed specific biochemical assays to distinguish active ubiquitin-related enzymes from inactive derivatives:

Thiol Ester Assay for E1 and E2 Activity:

- Incubate fractions with 125I-ubiquitin, ATP, and Mg2+

- Stop reaction with SDS-containing buffer without reducing agents

- Analyze by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography

- E1- and E2-ubiquitin thiol esters appear as radioactive bands that disappear with β-mercaptoethanol treatment [25]

Ubiquitin-Protein Conjugate Formation Assay:

- Incubate E1, E2, 125I-ubiquitin, ATP, and potential substrate proteins

- Resolve reactions by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions

- Detect high molecular weight conjugates by autoradiography [25]

Isopeptidase Activity Assay:

- Pre-form ubiquitin-protein conjugates using E1 and E2 enzymes

- Incubate with HPLC fractions in appropriate buffer

- Monitor decrease in high molecular weight conjugates and increase in free ubiquitin

- Include hemin to assess sensitivity [25]

Contemporary Research Applications

Advanced Methodologies for Ubiquitin Research

Modern research on ubiquitin signaling has dramatically expanded beyond the initial HPLC separation techniques. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics has emerged as an indispensable tool for comprehensive analysis of the ubiquitin system [9] [23]. Current approaches allow for identification of ubiquitinated substrates, precise mapping of modification sites, determination of polyubiquitin chain linkages, and quantification of dynamic changes in the ubiquitinated proteome [9].

Shotgun proteomics methodologies enable large-scale identification of ubiquitination sites by combining affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins with high-resolution mass spectrometry [9]. These approaches typically involve expression of epitope-tagged ubiquitin (e.g., His, FLAG, or Strep tags) in cells, purification of ubiquitinated proteins under denaturing conditions, tryptic digestion, and LC-MS/MS analysis [9] [24]. The identification of ubiquitination sites relies on detection of the characteristic diglycine remnant (mass shift of 114.04292 Da) on modified lysine residues after tryptic digestion [24].