Beyond K48 and K63: The Emerging Functions of Atypical Ubiquitin Chains K6, K27, and K29 in Cell Signaling and Disease

This review synthesizes current knowledge on the structures, biological functions, and regulatory mechanisms of the atypical ubiquitin chain linkages K6, K27, and K29.

Beyond K48 and K63: The Emerging Functions of Atypical Ubiquitin Chains K6, K27, and K29 in Cell Signaling and Disease

Abstract

This review synthesizes current knowledge on the structures, biological functions, and regulatory mechanisms of the atypical ubiquitin chain linkages K6, K27, and K29. Once considered rare and enigmatic, these non-canonical chains are now recognized as critical regulators of diverse cellular processes, including innate immunity, mitochondrial quality control, cell cycle progression, and mRNA stability. We explore the specialized tools and methodologies required for their study, address common experimental challenges, and compare their distinct signaling outcomes. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this article highlights the therapeutic potential of targeting these unique ubiquitin codes in human diseases such as cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and inflammatory conditions.

Decoding the Atypical Trio: Structural and Functional Foundations of K6, K27, and K29 Ubiquitin Chains

Ubiquitination represents one of the most sophisticated post-translational modifications in eukaryotic cells, functioning as a complex molecular code that governs protein fate and function. While the canonical K48 and K63-linked ubiquitin chains have been extensively characterized, recent research has unveiled the critical roles played by atypical linkages—K6, K27, and K29—in regulating specialized cellular processes. These non-canonical chains exhibit unique structural properties and mediate diverse functions beyond protein degradation, including innate immune signaling, transcription regulation, and cell cycle control. This technical review comprehensively examines the assembly mechanisms, structural characteristics, and functional significance of these atypical ubiquitin linkages, with particular emphasis on their implications for therapeutic development. We integrate current methodologies for studying these complex modifications and provide visual schematics of key signaling pathways to elucidate this rapidly evolving field.

The Ubiquitin Code: Fundamental Concepts

Ubiquitin is a small 76-amino acid regulatory protein that is covalently attached to substrate proteins through a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 activating, E2 conjugating, and E3 ligase enzymes [1]. The process initiates with E1-mediated ATP-dependent ubiquitin activation, followed by transfer to an E2 enzyme, and culminates in E3-facilitated substrate recognition and ubiquitin transfer [2] [3]. Ubiquitin itself contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1) that serve as potential linkage sites for polyubiquitin chain formation [1] [4].

The "ubiquitin code" hypothesis posits that distinct chain topologies—including homotypic, mixed, and branched chains—encode specific functional outcomes that are decoded by ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) present in effector proteins [3] [5]. This molecular code exhibits remarkable complexity due to several factors: the diversity of possible linkage combinations, variations in chain length, and the potential for further post-translational modifications on ubiquitin itself [6]. While K48-linked chains predominantly target substrates for proteasomal degradation and K63-linked chains regulate signaling pathways, the functional roles of atypical linkages are more specialized and context-dependent [7].

Table 1: Fundamental Components of the Ubiquitination System

| Component | Number in Humans | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|

| E1 Enzymes | 2 [4] | Ubiquitin activation via ATP hydrolysis |

| E2 Enzymes | ~40 [2] | Ubiquitin conjugation; influences chain topology |

| E3 Ligases | >600 [2] | Substrate recognition; specific ubiquitin transfer |

| Deubiquitinases (DUBs) | ~100 [4] | Ubiquitin chain removal; signal termination |

Atypical Ubiquitin Linkages: Structural and Functional Diversity

K6-Linked Ubiquitination

K6-linked ubiquitin chains have emerged as crucial regulators in quality control pathways, particularly in mitochondrial homeostasis and the DNA damage response. During mitophagy, the E3 ligase Parkin decorates damaged outer mitochondrial membrane proteins with K6, K11, K48, and K63-linked chains, with K6 and K63 linkages primarily designating mitochondria for autophagic clearance [3]. This process is tightly regulated by deubiquitinating enzymes USP8 and USP30, with the latter showing preference for removing K6-linked chains and thereby antagonizing Parkin-mediated ubiquitination [3].

In the DNA damage response, K6-linked auto-ubiquitination occurs in the BRCA1-BARD1 complex, and K6-linked chains accumulate during replication stress and double-strand break repair [3]. The E3 ligase HUWE1 generates the majority of cellular K6-linked species upon inhibition of valosin-containing protein (VCP/p97/Cdc48), suggesting a role in protein disposal [3]. Beyond degradation-related functions, K6-linked chains also play non-proteolytic roles in innate immunity, where they enhance the DNA-binding capacity of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) during antiviral responses [3].

K27-Linked Ubiquitination

K27-linked ubiquitination serves as a versatile signaling mechanism in innate immune regulation, with context-dependent outcomes determined by specific E3 ligase-substrate pairs. Multiple TRIM family E3 ligases utilize K27 linkages to modulate antiviral signaling pathways: TRIM23 mediates NEMO ubiquitination leading to NF-κB and IRF3 activation [8], while TRIM26 promotes type I interferon production through interaction with NEMO [8]. Conversely, TRIM40 attenuates antiviral responses by targeting RIG-I and MDA5 for proteasomal degradation [8].

The functional diversity of K27 linkages extends beyond simple activation/inhibition paradigms. For instance, K27-linked ubiquitination of Rhbdd3 recruits the deubiquitinase A20 to remove K63-linked chains from NEMO, thereby preventing excessive NF-κB activation and maintaining signaling homeostasis [8]. Similarly, MARCH8 induces K27-linked ubiquitination of MAVS, leading to its autophagy-mediated degradation and subsequent attenuation of type I interferon production [8]. These examples illustrate how K27 chains can function as scaffolds for protein complex assembly or as degradation signals depending on cellular context.

K29-Linked Ubiquitination

K29-linked ubiquitin chains have traditionally been associated with proteasomal degradation but recent evidence reveals additional roles in transcriptional regulation and cellular stress responses. During the unfolded protein response (UPR), K29-linked ubiquitination of SMC1A and SMC3 proteins within the cohesin complex increases significantly, leading to disrupted formation of transcription initiation complexes and subsequent downregulation of cell proliferation-related genes such as SERTAD1 and NUDT16L1 [9].

Structurally, K29-linked diubiquitin adopts an extended conformation with exposed hydrophobic patches on both ubiquitin moieties, enabling diverse protein interactions [10]. K29 linkages frequently exist within mixed or branched chains containing other linkage types, increasing the combinatorial complexity of the ubiquitin code [10]. The HECT E3 ligase UBE3C collaborates with the deubiquitinase vOTU to assemble and edit K29-linked chains, demonstrating sophisticated regulation of this modification [10].

Table 2: Atypical Ubiquitin Linkages: Functions and Regulatory Enzymes

| Linkage | Key E3 Ligases | Biological Functions | Regulatory DUBs |

|---|---|---|---|

| K6 | Parkin, HUWE1, RNF144A/B | Mitophagy, DNA damage response, antiviral immunity [3] | USP30, USP8 [3] |

| K27 | TRIM23, TRIM26, TRIM40, TRIM21, MARCH8, RNF185, AMFR | Innate immune regulation, NF-κB and IRF3 activation, MAVS and STING regulation [8] | USP13, USP21, USP19 [8] |

| K29 | UBE3C, SKP1-Cullin-Fbx21 | Transcriptional regulation in UPR, proteasomal degradation [9] [8] | vOTU [10] |

| K11 | RNF26, APC/C (with UBE2S) | Cell cycle regulation, STING regulation, innate immunity [8] [3] | USP19 [8] |

| K33 | RNF2 | Suppression of ISG transcription [8] | USP38 [8] |

Branched Ubiquitin Chains: Complexity Multiplied

Branched ubiquitin chains represent a higher level of complexity in the ubiquitin code, where individual ubiquitin monomers are simultaneously modified at multiple sites to create branched architectures. These specialized structures include K11/K48, K29/K48, and K48/K63 branched chains with distinct physiological functions [5]. The synthesis of branched chains frequently involves collaborative efforts between E3 ligases with different linkage specificities. For instance, during NF-κB signaling, TRAF6 and HUWE1 cooperate to produce branched K48/K63 chains, while in yeast, Ufd4 and Ufd2 collaborate to synthesize branched K29/K48 chains on substrates of the ubiquitin fusion degradation pathway [5].

The functional significance of chain branching is particularly evident in processes requiring precise temporal control. During apoptosis, the regulatory protein TXNIP is first modified with non-proteolytic K63-linked chains by ITCH before UBR5 attaches K48 linkages to form branched K48/K63 chains, resulting in proteasomal degradation of TXNIP [5]. This sequential modification represents an efficient mechanism for converting non-degradative signals to degradative marks. Similarly, the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) collaborates with UBE2C and UBE2S to form branched K11/K48 chains on mitotic substrates, enhancing their recognition by the proteasome [5].

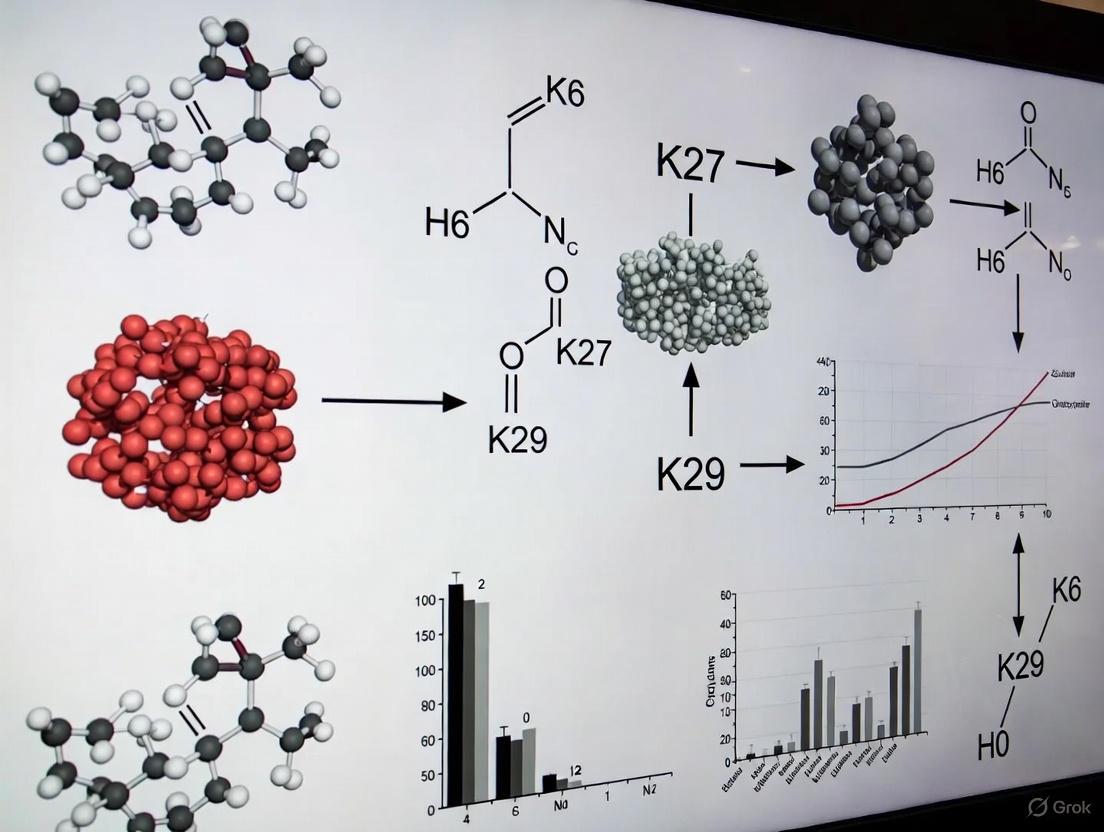

Diagram 1: Collaborative synthesis of branched ubiquitin chains by E3 ligases with distinct specificities. The sequential addition of different linkage types creates complex architectures with specialized functions, such as enhanced proteasomal recognition.

Methodological Approaches for Studying Atypical Ubiquitination

Affinity Enrichment Strategies

Advanced affinity separation techniques form the cornerstone of modern ubiquitin research, enabling the selective isolation and characterization of ubiquitinated proteins and specific chain types. Immunoaffinity methods utilizing ubiquitin-specific antibodies or linkage-selective antibodies (e.g., for K48, K63, or M1 chains) provide high specificity for targeted applications [6]. The development of K-ε-GG antibodies that recognize the characteristic diglycine remnant left after tryptic digestion of ubiquitinated proteins has revolutionized ubiquitin site identification by mass spectrometry, enabling large-scale mapping of ubiquitination sites [6].

Ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) and engineered tandem ubiquitin-binding entities (TUBEs) offer complementary approaches for ubiquitin enrichment. Naturally occurring UBDs, such as the UBA domain of hHR23A (preferring K48 chains) or UIMs of RAP80 (specific for K63 chains), provide inherent linkage selectivity [6]. TUBEs represent significant methodological advances, created by fusing multiple UBDs to generate reagents with avidity effects and enhanced affinity for polyubiquitin chains [6] [7]. Chain-specific TUBEs with nanomolar affinities enable differentiation between ubiquitin linkage types in high-throughput formats, as demonstrated in studies investigating RIPK2 ubiquitination in inflammatory signaling [7].

Mass Spectrometry and Proteomic Approaches

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics has dramatically expanded our understanding of the ubiquitin code. Advanced techniques now allow for system-wide identification of ubiquitination sites, quantification of chain linkage abundance, and even characterization of branched chain architectures. The integration of affinity enrichment with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) has enabled the identification of thousands of ubiquitination sites from complex biological samples [6]. Specialized workflows, such as the Ub-ProT method, combine TUBE-based enrichment with protection from trypsinization to analyze native ubiquitin chain length and composition [6].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Atypical Ubiquitin Linkages

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Specific Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| K-ε-GG Antibody [6] | Immunoaffinity reagent | Ubiquitination site mapping | Recognizes diglycine remnant after trypsinization |

| UbiSite Antibody [6] | Immunoaffinity reagent | Ubiquitination site mapping | Recognizes ubiquitin C-terminal 13-amino acid peptide |

| Chain-specific TUBEs [7] | Engineered UBD fusion | Linkage-specific ubiquitin enrichment | Nanomolar affinity; selective for K48, K63, etc. |

| Linkage-specific Antibodies [6] | Immunoaffinity reagent | Detection of specific chain types | Antibodies specific for K48, K63, M1 linkages |

| UBE3C-vOTU Complex [10] | Enzymatic system | K29 chain assembly and editing | Enables controlled synthesis of K29-linked chains |

| Dominant-negative Ubiquitin Mutants [7] | Genetic tool | Linkage function analysis | Lysine-to-arginine mutations to block specific linkages |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol: Analysis of Linkage-Specific Ubiquitination Using TUBEs

This protocol enables the capture and assessment of endogenous protein ubiquitination with linkage specificity, particularly useful for evaluating PROTAC efficacy or inflammatory signaling.

Cell Lysis and Sample Preparation

- Culture THP-1 cells under appropriate conditions and treat with stimuli (e.g., 200-500 ng/ml L18-MDP for K63 ubiquitination or PROTAC for K48 ubiquitination) for 30-60 minutes [7].

- Lyse cells using a specialized lysis buffer optimized to preserve polyubiquitination (e.g., containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, plus protease and deubiquitinase inhibitors) [7].

- Clarify lysates by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

TUBE-Based Affinity Capture

- Coat 96-well plates with chain-selective TUBEs (K48-TUBE, K63-TUBE, or pan-TUBE) according to manufacturer's specifications [7].

- Incubate 100-500 μg of cell lysate with TUBE-coated plates for 2 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation.

- Wash plates 3-5 times with wash buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40) to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

Detection and Analysis

- Elute bound proteins using 2× Laemmli buffer containing DTT or directly proceed to in-well detection.

- Analyze captured ubiquitinated proteins by immunoblotting with target-specific antibodies (e.g., anti-RIPK2 for inflammatory signaling studies) [7].

- Quantify band intensity using densitometry software to compare linkage-specific ubiquitination across conditions.

Protocol: Assessment of Branched Ubiquitin Chains

This methodology enables the detection and characterization of branched ubiquitin chains, which often contain atypical linkages.

Enrichment of Ubiquitinated Proteins

- Express epitope-tagged ubiquitin (e.g., His-FLAG-ubiquitin) in cells of interest and treat with relevant stimuli or inhibitors.

- Lyse cells under denaturing conditions (e.g., 6 M guanidine-HCl) to preserve ubiquitination states and prevent deubiquitination.

- Perform immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) under denaturing conditions to purify ubiquitinated proteins.

Chain Topology Analysis

- Digest enriched ubiquitinated proteins with specific proteases (e.g., trypsin, Lys-C) that generate characteristic ubiquitin fragments.

- Analyze digestion products by LC-MS/MS with methods optimized for ubiquitin branch point detection.

- Use specialized software tools to identify diagnostic ions indicative of branched ubiquitin chains.

Validation Experiments

- Express ubiquitin mutants (e.g., K48R, K63R) to perturb specific branching patterns and confirm findings.

- Utilize E3 ligase knockout/knockdown approaches to identify enzymes responsible for branched chain synthesis.

- Implement in vitro reconstitution assays with purified E2 and E3 enzymes to validate branching mechanisms.

Diagram 2: Workflow for linkage-specific ubiquitination analysis. TUBE-based affinity enrichment followed by mass spectrometry or immunoblotting enables precise characterization of ubiquitin chain types in response to cellular stimuli.

Therapeutic Targeting and Future Perspectives

The intricate regulation of cellular processes by atypical ubiquitin linkages presents compelling opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Several strategies are emerging to target these pathways, particularly in oncology and inflammatory diseases. PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) represent a groundbreaking approach that hijacks E3 ubiquitin ligases to induce targeted protein degradation [7]. These heterobifunctional molecules simultaneously bind to a target protein and an E3 ligase, facilitating ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation [2]. While current PROTACs primarily exploit a limited set of E3 ligases (e.g., CRBN, VHL), the expanding knowledge of atypical linkage-specific E3s may enable next-generation degraders with improved selectivity [7].

In inflammatory diseases, targeting K63-linked ubiquitination components (TRAF6, Ubc13, Mms2) has shown promise in preclinical models of rheumatoid arthritis and colitis [7]. Similarly, modulation of linear ubiquitination via LUBAC components or the deubiquitinases OTULIN and CYLD offers therapeutic potential for autoinflammatory conditions [4]. The development of small-molecule inhibitors targeting specific E1, E2, and E3 enzymes continues to advance, with several candidates in clinical development for hematological malignancies and solid tumors [2].

Future research directions will likely focus on deciphering the complex crosstalk between different ubiquitin linkage types, understanding the spatial and temporal regulation of chain assembly and disassembly, and developing more sophisticated tools to manipulate specific aspects of the ubiquitin code. The clinical translation of ubiquitin-based therapeutics will require enhanced selectivity to minimize off-target effects and comprehensive biomarker strategies to identify responsive patient populations.

The expanding universe of atypical ubiquitin linkages—K6, K27, K29, and beyond—has fundamentally transformed our understanding of cellular signaling networks. These non-canonical modifications mediate sophisticated regulatory functions beyond protein degradation, including immune response coordination, transcriptional control, and stress adaptation. The structural diversity of ubiquitin chains is further multiplied through branching and mixed linkage formation, creating an exceptionally complex coding system that integrates multiple signals to determine functional outcomes.

Methodological advances in affinity enrichment, mass spectrometry, and chemical biology continue to unravel the intricacies of the ubiquitin code, revealing new biological insights and therapeutic opportunities. As our toolbox for studying and manipulating these modifications expands, so too does our potential to develop novel therapeutic strategies for cancer, inflammatory diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, and infectious diseases. The continued exploration of atypical ubiquitin linkages promises to yield fundamental discoveries about cellular regulation and unlock new avenues for precision medicine.

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates a vast array of cellular processes, with the specificity of signaling outcomes largely determined by the topology of ubiquitin chain linkages. Among the eight possible linkage types, K6-linked ubiquitin chains belong to the category of "atypical" chains that are less abundant but increasingly recognized for their specialized functions. These chains are formed when the C-terminus of one ubiquitin molecule creates an isopeptide bond with the lysine at position 6 (K6) of another ubiquitin. Once considered poorly characterized, K6-linked ubiquitination has emerged as a critical regulator in essential quality control pathways, particularly in DNA damage response and mitochondrial homeostasis. The significance of K6 linkages is further highlighted by their implication in neurodegenerative diseases and cancer, positioning them as potential therapeutic targets in the broader landscape of ubiquitin research.

The study of K6-linked chains has historically been constrained by technical challenges, including the scarcity of linkage-specific detection reagents and enzymatic tools for their manipulation. However, recent advances in chemical biology and protein engineering have begun to illuminate the unique properties and functions of these chains. This technical guide synthesizes current understanding of K6-linked ubiquitin chains, with particular emphasis on their mechanistic roles in cellular stress response pathways, detailed experimental approaches for their investigation, and emerging opportunities for therapeutic intervention targeting the ubiquitin system.

Molecular Mechanisms and Functional Roles

K6-Linked Ubiquitination in DNA Damage Response

The involvement of K6-linked ubiquitin chains in maintaining genomic integrity represents a significant aspect of their functional repertoire, with emerging evidence connecting them to DNA repair processes:

BRCA1-BARD1 Association: Early investigations identified K6-linked ubiquitination in the context of the BRCA1-BARD1 complex, a heterodimeric E3 ubiquitin ligase with established tumor suppressor functions in breast and ovarian cancers. This complex has been shown to assemble K6-linked chains both on itself and on associated substrates, suggesting a potential role in DNA repair pathways that is distinct from the canonical functions of BRCA1 in homologous recombination [11] [12]. The precise mechanistic contribution of K6 linkages to DNA damage signaling remains an active area of investigation, but their presence on this critical tumor suppressor complex underscores their potential significance in maintaining genomic stability.

Cellular Stress Response: Beyond specific repair complexes, K6-linked chains demonstrate a broader involvement in cellular stress adaptation. Research has documented that levels of K6- and K33-linked chains increase following DNA damage induced by genotoxic agents, indicating a potential role in the cellular response to genomic insult [11]. This elevation suggests that K6 linkages may participate in signaling networks that detect, process, or resolve DNA lesions, possibly through the regulation of protein recruitment, activity, or stability at damage sites.

Central Role in Mitophagy and Mitochondrial Quality Control

The most extensively characterized function of K6-linked ubiquitin chains lies in the regulation of mitochondrial quality control, particularly in the PINK1-Parkin mediated mitophagy pathway that ensures the selective removal of damaged mitochondria:

Parkin-Mediated Mitophagy: Parkin, an RBR (RING-Between-RING) E3 ubiquitin ligase mutated in familial forms of Parkinson's disease, plays a central role in marking damaged mitochondria for autophagic clearance. Upon mitochondrial depolarization, Parkin translocates to mitochondria and ubiquitinates numerous outer mitochondrial membrane proteins. Research has demonstrated that Parkin assembles K6-linked ubiquitin chains as part of this process, which are important for the efficient recruitment of Parkin to depolarized mitochondria and subsequent mitophagy [13] [11]. The deposition of K6 linkages represents one of several ubiquitin chain types generated by Parkin, creating a complex ubiquitin code that orchestrates the mitophagy cascade.

USP8 Regulation: The deubiquitinating enzyme USP8 (ubiquitin-specific protease 8) has been identified as a key regulator of Parkin-mediated mitophagy through its specific action on K6-linked ubiquitin chains. USP8 preferentially removes K6-linked ubiquitin conjugates from Parkin itself, a process required for the efficient recruitment of Parkin to depolarized mitochondria and their subsequent elimination [13]. This regulatory mechanism represents a critical control point in mitophagy, wherein USP8-mediated deubiquitination of K6-linked chains from Parkin facilitates Parkin activation and translocation. The antagonistic relationship between Parkin (K6 chain assembly) and USP8 (K6 chain disassembly) fine-tunes the mitophagy response, ensuring that mitochondrial clearance occurs only when appropriate.

HUWE1 and Mitofusin-2 Regulation: Beyond the PINK1-Parkin axis, the HECT E3 ligase HUWE1 has been identified as another significant source of K6-linked ubiquitin chains in cells. Pull-down experiments using K6-specific affimers, combined with mass spectrometry analysis, revealed HUWE1 as a major E3 ligase responsible for cellular K6 chains [11]. Specifically, HUWE1 decorates the mitochondrial protein mitofusin-2 (Mfn2) with K6-linked polyubiquitin, positioning it as a regulator of mitochondrial dynamics. Cells lacking HUWE1 or subjected to HUWE1 knockdown show significantly reduced levels of K6 chains, underscoring the importance of this ligase in the K6-linked ubiquitin landscape [11].

Table 1: Key E3 Ligases and DUBs Regulating K6-Linked Ubiquitination in Mitochondrial Quality Control

| Enzyme | Type | Function on K6 Chains | Biological Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parkin | RBR E3 Ligase | Assembles K6-linked chains on mitochondrial substrates | Promotes mitophagy; mutations cause Parkinson's disease |

| HUWE1 | HECT E3 Ligase | Major cellular source of K6 chains; modifies Mfn2 | Regulates mitochondrial dynamics; potential tumor suppressor |

| RNF144A/B | RBR E3 Ligase | Assembles K6-, K11-, and K48-linked chains in vitro | DNA damage response; p53 regulation |

| USP8 | Deubiquitinase | Preferentially removes K6-linked chains from Parkin | Facilitates Parkin recruitment to mitochondria; regulates mitophagy efficiency |

| USP30 | Deubiquitinase | Antagonizes Parkin-mediated mitophagy; K6-selective | Mitochondrial DUB; counteracts mitophagy on mitochondrial surface |

Branched Ubiquitin Chains Involving K6 Linkages

Beyond homogeneous K6-linked chains, recent research has revealed that K6 linkages can form part of more complex branched ubiquitin architectures, significantly expanding their signaling potential:

K6/K48-Branched Chains: Parkin has been demonstrated to synthesize branched ubiquitin chains containing both K6 and K48 linkages, creating a hybrid degradation signal that may combine features of both linkage types [12]. These branched architectures potentially enable more sophisticated regulation of substrate fate than homogeneous chains, possibly integrating degradative signals with specialized regulatory functions.

Other K6-Containing Branches: Evidence also exists for the formation of K6/K11-branched chains, although the physiological functions of these specific architectures remain less defined compared to K6/K48-branched chains [12]. The formation of such diverse branched structures highlights the complexity of the ubiquitin code and suggests that K6 linkages may serve specialized functions when positioned at branch points within polyubiquitin chains.

Quantitative Profiling of K6-Linked Ubiquitination

The investigation of K6-linked ubiquitination relies on quantitative assessments of its abundance, dynamics, and enzymatic regulation under various physiological conditions. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research:

Table 2: Quantitative Data on K6-Linked Ubiquitin Chain Properties and Functions

| Parameter | Value/Measurement | Experimental Context | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Abundance | Increased after DNA damage | Cellular response to genotoxic stress | Suggests role in DNA damage response [11] |

| DUB Resistance | Resists cleavage by most deubiquitinases | Compared to K27-Ub2 which resists USP2, USP5, Ubp6 | K6-specific DUBs required for regulation [14] |

| HUWE1 Dependency | Significantly reduced K6 levels in HUWE1-/- cells | Pull-downs with K6-specific affimers | HUWE1 is major source of cellular K6 chains [11] |

| Affimer Binding | n = 0.46 (2:1 affimer:diUb complex) | ITC measurements with K6 diUb | Dimerized affimer recognizes K6 linkage specifically [11] |

| USP8 Effect | Delayed but not abolished Parkin recruitment | siRNA knockdown of USP8 | USP8 critical for timely mitophagy initiation [13] |

| Branched Chain Formation | Parkin synthesizes K6/K48-branched chains | In vitro ubiquitination assays | Expands signaling capacity beyond homotypic chains [12] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

siRNA Screening for DUBs Regulating Mitophagy

The identification of USP8 as a regulator of Parkin-mediated mitophagy through its action on K6-linked chains was achieved through a comprehensive siRNA screening approach:

Library Design: The screen targeted 87 putative deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) encoded by the human genome using a pre-designed siRNA library [13]. This comprehensive coverage ensured that both known and potentially novel regulators of mitophagy could be identified.

Cell System: Screening was performed in U2OS cells stably expressing GFP-Parkin, providing a consistent expression system for monitoring Parkin translocation. The use of GFP-tagged Parkin enabled quantitative tracking of its movement from cytosol to mitochondria following induction of mitochondrial damage [13].

Induction and Assessment: Mitochondrial depolarization was induced using carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP), a protonophore that dissipates mitochondrial membrane potential. Parkin recruitment was assessed after 1 hour of CCCP treatment by fluorescence microscopy, with USP8 knockdown identified as the only condition that significantly impaired Parkin translocation at this time point [13].

Validation Experiments: Secondary validation included time-lapse microscopy to precisely quantify the kinetics of Parkin recruitment, immunoblotting to confirm USP8 protein reduction, and rescue experiments with FLAG-USP8 expression plasmids to establish specificity [13]. Mitophagy efficiency was further assessed after 24 hours of CCCP treatment by monitoring the loss of mitochondrial markers like TOM20.

Development and Application of K6-Linkage Specific Affimers

The generation of high-affinity, linkage-specific binding reagents has been instrumental in advancing the study of K6-linked ubiquitination:

Affimer Technology: Affimers are small (12-kDa) non-antibody scaffolds based on the cystatin fold, featuring randomized surface loops that enable selection of high-affinity binders from large libraries (~10^10 variants) [11]. Selections were performed against K6-linked diUb to isolate specific binders.

Specificity Characterization: The resulting K6 affimer was characterized using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), showing tight binding to K6-diUb (n = 0.46, indicating 2:1 affimer:diUb complex formation) with no detectable binding to K33-diUb [11]. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) further confirmed linkage specificity through very slow off-rates specifically for K6-linked chains.

Application in Western Blotting: Site-specifically biotinylated K6 affimers enabled detection of K6-diUb with high linkage specificity in western blotting applications, showing only minimal cross-reactivity with other chain types [11]. This represented a significant advancement as linkage-specific antibodies for K6 chains were previously unavailable.

Structural Basis of Specificity: X-ray crystal structures of K6 affimer bound to K6-diUb revealed the mechanistic basis for linkage specificity, showing that the affimer dimerizes to create two binding sites that engage the I44 patches of both ubiquitin moieties in a K6-diUb molecule with defined spacing and orientation [11]. This mode of recognition mimics naturally occurring ubiquitin-binding domains that achieve specificity through avidity effects.

Biochemical Reconstitution of K6-Linked Ubiquitination

In vitro reconstitution of K6-linked ubiquitination provides a controlled system for mechanistic studies:

Enzyme Selection: Parkin and HUWE1 serve as the primary E3 ligases for generating K6 linkages. Parkin requires activation through phosphorylation by PINK1 and interaction with phospho-ubiquitin, while HUWE1 functions independently of these modifications [11] [12].

Reaction Conditions: Standard ubiquitination reactions include E1 activating enzyme (UBA1), specific E2 conjugating enzymes, the E3 ligase of interest, ubiquitin, and ATP in appropriate buffer. For Parkin, pre-activation with PINK1 or inclusion of phospho-ubiquitin is essential [13] [12].

Chain Analysis: Reaction products are typically analyzed by western blotting with linkage-specific reagents (affimers or antibodies), mass spectrometry for linkage identification, and deubiquitinase treatment with linkage-specific DUBs to confirm chain topology [11].

Pathway Visualization and Signaling Networks

The integration of K6-linked ubiquitination into cellular signaling pathways, particularly in mitochondrial quality control, involves complex regulatory networks that can be visualized through the following diagram:

Diagram 1: K6-Linked Ubiquitination in the PINK1-Parkin Mitophagy Pathway. This diagram illustrates the sequence of events from mitochondrial damage to mitophagy initiation, highlighting the role of K6-linked ubiquitination and its regulation by USP8.

The experimental workflow for investigating K6-linked ubiquitination combines biochemical, cellular, and analytical approaches, as visualized in the following methodology diagram:

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Investigating K6-Linked Ubiquitination. This diagram outlines the key methodological approaches used to identify and characterize the functions of K6-linked ubiquitin chains.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

The investigation of K6-linked ubiquitin chains requires specialized reagents and tools designed to address the unique challenges of studying this atypical ubiquitin linkage. The following table compiles essential research reagents for experimental work in this field:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying K6-Linked Ubiquitination

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Specific Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| K6-Linkage Specific Affimers | Engineered binding proteins | Recognize K6-linked diUb with high specificity | Western blotting, immunofluorescence, pull-down assays [11] |

| Recombinant Parkin | RBR E3 ligase | Assembles K6-linked and K6/K48-branched chains in vitro | Biochemical reconstitution of ubiquitination [13] [12] |

| Recombinant HUWE1 | HECT E3 ligase | Major cellular source of K6 linkages | In vitro ubiquitination, identification of K6 substrates [11] |

| USP8 Reagents | Deubiquitinating enzyme | Preferentially removes K6-linked chains from Parkin | Regulation studies, mitophagy modulation [13] |

| K6-Ub2 Chemical Standards | Chemically synthesized diUb | Defined K6-linked ubiquitin dimers | Method calibration, binding studies, DUB characterization [14] |

| Linkage-Specific DUBs | Deubiquitinating enzymes | Cleave specific ubiquitin linkages | Chain topology verification, substrate validation [14] |

| siRNA Libraries | Gene silencing reagents | Targeted knockdown of ubiquitin system components | Functional screens for pathway regulators [13] |

The study of K6-linked ubiquitin chains has evolved from initial observations to mechanistic understanding of their specialized functions in critical cellular quality control pathways. As detailed in this technical guide, K6 linkages play non-redundant roles in Parkin-mediated mitophagy and DNA damage response, operating through specific E3 ligases and regulated by dedicated deubiquitinating enzymes like USP8. The ongoing development of sophisticated research tools, particularly linkage-specific affimers and chemical biology approaches for branched chain synthesis, continues to accelerate discovery in this field.

Looking forward, several key challenges and opportunities merit attention. First, the physiological contexts that specifically trigger K6-linked ubiquitination, as opposed to other linkage types, require further elucidation. Second, the structural basis for recognition of K6-linked chains by downstream effectors remains largely unexplored, representing a significant knowledge gap. Third, the therapeutic potential of modulating K6-linked signaling in diseases such as Parkinson's and cancer warrants systematic investigation, particularly through the development of small molecule inhibitors or activators of relevant E3 ligases and DUBs. As these research directions advance, K6-linked ubiquitin chains will undoubtedly continue to reveal new insights into the complexity of ubiquitin signaling and its manipulation for therapeutic benefit.

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates nearly all aspects of cellular function through the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to target proteins. While the roles of K48- and K63-linked polyubiquitin chains in proteasomal degradation and signal transduction, respectively, are well-established, the functions of atypical ubiquitin chains (K6, K11, K27, K29, and K33) represent a frontier in ubiquitin research [8] [15]. Among these, K27-linked ubiquitin chains have emerged as critical regulators of antiviral innate immune signaling and inflammatory pathways, distinguished by their unique structural and biochemical properties [14]. K27-linked chains exhibit remarkable resistance to deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) and adopt distinct conformational states that enable specific interactions with downstream signaling components [14] [16]. This comprehensive review examines the multifaceted roles of K27-linked ubiquitination in innate immunity, detailing the molecular mechanisms, regulatory networks, and experimental approaches that define this rapidly advancing field within the broader context of atypical ubiquitin chain biology.

Structural and Functional Uniqueness of K27-Linked Ubiquitin Chains

Distinct Biochemical and Structural Properties

K27-linked ubiquitin chains possess unique characteristics that differentiate them from other ubiquitin linkage types. Structural analyses using NMR spectroscopy and small-angle neutron scattering reveal that K27-linked di-ubiquitin (K27-Ub2) adopts predominantly open conformations in solution, with minimal non-covalent interdomain contacts between ubiquitin units [14]. This structural arrangement stands in contrast to the more compact conformations observed in K48-linked chains. The proximal ubiquitin unit in K27-Ub2 exhibits the largest chemical shift perturbations among all ubiquitin linkage types, indicating significant structural reorganization upon chain formation [14].

A defining feature of K27-linked ubiquitin is its resistance to deubiquitination by most deubiquitinating enzymes. Screening against multiple DUB families including USP2, USP5 (IsoT), and Ubp6 demonstrated that K27-Ub2 resists cleavage, whereas other linkages are efficiently processed [14] [16]. This exceptional stability likely contributes to the sustained signaling functions of K27-linked ubiquitination in immune pathways and suggests specialized regulatory mechanisms for its reversal in cellular contexts.

Recognition by Ubiquitin-Binding Domains

Despite its unique structure, K27-linked ubiquitin demonstrates unexpected versatility in receptor recognition. Structural data indicate that K27-Ub2 can be specifically recognized by the UBA2 domain of the proteasomal shuttle protein hHR23a through bidentate interactions similar to those observed with K48-Ub2 [16]. This binding specificity suggests that K27-linked chains may interface with protein quality control systems while maintaining distinct signaling functions in immune regulation.

Table 1: Key Structural and Biochemical Properties of K27-Linked Ubiquitin Chains

| Property | Characteristic | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Solution Conformation | Open conformations with minimal non-covalent interdomain contacts | Enables bidentate binding to specific receptors |

| DUB Resistance | Resistant to cleavage by most deubiquitinases (USP2, USP5, Ubp6) | Provides signaling stability and persistence |

| Structural Perturbation | Largest CSPs in proximal Ub among all linkages | Significant structural reorganization upon chain formation |

| Receptor Binding | Binds UBA2 domain of hHR23a similarly to K48-Ub2 | Potential interface with protein quality control systems |

| Chain Architecture | Homogeneous chains, potential for branched formations | Creates diverse recognition platforms |

Molecular Mechanisms of K27-Linked Ubiquitination in Antiviral Signaling

Regulation of Nucleic Acid Sensing Pathways

K27-linked ubiquitination serves as a pivotal regulatory mechanism in multiple innate immune signaling cascades triggered by viral nucleic acid detection. The RIG-I/MAVS pathway, which senses cytoplasmic viral RNA, is extensively modulated by K27-linked ubiquitination through various E3 ligases [8] [17]. TRIM21 catalyzes K27-linked ubiquitination of MAVS, enhancing type I interferon production, while MARCH8 mediates K27-linked ubiquitination of MAVS that induces its autophagy-mediated degradation, thereby restricting the type I interferon response [8]. This opposing regulation illustrates how different E3 ligases utilizing the same linkage type can produce divergent functional outcomes in antiviral signaling.

In the cGAS-STING pathway responsible for cytoplasmic DNA sensing, multiple E3 ligases employ K27-linked ubiquitination to regulate signaling activity. RNF185 mediates K27-linked ubiquitination of cGAS, promoting IRF3 activation and subsequent type I interferon production [8]. Similarly, the endoplasmic reticulum-resident E3 ligase AMFR (gp78) catalyzes K27-linked ubiquitination of STING, facilitating TBK1 recruitment and IRF3 activation [8] [18]. These modifications highlight the critical positioning of K27-linked ubiquitination at key signaling hubs to coordinate appropriate immune responses to diverse viral pathogens.

Modulation of Transcriptional Activation and Inflammatory Responses

K27-linked ubiquitination directly regulates key transcriptional factors and signaling complexes that control interferon and inflammatory cytokine production. TRIM23 catalyzes K27-linked ubiquitination of NEMO (IKKγ), leading to activation of both NF-κB and IRF3 pathways [8]. Additionally, K27-linked ubiquitination of NEMO by other E3 ligases recruits the deubiquitinase A20 to remove K63-linked chains from NEMO, preventing excessive NF-κB activation and illustrating the cross-regulatory potential between different ubiquitin linkage types [8].

Table 2: E3 Ligases and DUBs Regulating K27-Linked Ubiquitination in Innate Immunity

| Enzyme | Substrate | Functional Outcome | Regulatory Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRIM23 | NEMO | Leads to NF-κB and IRF3 activation | Positive regulation |

| TRIM26 | NEMO | Increases type I IFN and cytokine production | Positive regulation |

| TRIM21 | MAVS | Enhances type I IFN production | Positive regulation |

| MARCH8 | MAVS | Induces autophagy-mediated degradation | Negative regulation |

| TRIM40 | RIG-I, MDA5 | Induces proteasome-mediated degradation | Negative regulation |

| RNF185 | cGAS | Induces IRF3 activation and cytokine production | Positive regulation |

| AMFR | STING | Recruits TBK1 and induces IRF3 activation | Positive regulation |

| USP13 | STING | Inhibits IRF3 activation and cytokine production | Negative regulation |

| USP21 | STING | Inhibits IRF3 activation and cytokine production | Negative regulation |

| USP19 | TAK1 | Inhibits proinflammatory cytokine production | Negative regulation |

Experimental Approaches for Studying K27-Linked Ubiquitination

Methodologies for Chain Synthesis and Characterization

The study of K27-linked ubiquitin chains requires specialized methodologies due to their unique biochemical properties and the absence of dedicated enzymatic synthesis pathways. Non-enzymatic chemical assembly strategies utilizing mutually orthogonal removable amine-protecting groups (Alloc and Boc) enable production of fully natural K27-Ub2 with native isopeptide linkages free of mutations [14]. This approach bypasses the limitations of linkage-specific Ub-conjugating enzymes and ensures structural authenticity.

For structural characterization, solution NMR spectroscopy provides atom-specific information about each ubiquitin unit within the chain [14]. By separately analyzing 15N-enriched distal and proximal ubiquitin units, researchers can quantify amide chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) to identify noncovalent interdomain contacts and conformational changes. Small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) coupled with in silico ensemble modeling further elucidates the dynamic conformational landscapes of K27-linked chains in solution [14] [16].

Functional Assays and Detection Methods

Deubiquitination assays employing multiple DUB families (Cezanne, OTUB1, AMSH, USP2, USP5, Ubp6) provide functional fingerprints for K27-linked chains based on their characteristic resistance to cleavage [14]. This resistance property enables K27-Ub2 to serve as a competitive inhibitor of DUB activity toward other linkages, providing an experimental tool for dissecting DUB specificity and function.

Linkage-specific binding studies using techniques such as pulldown assays with UBA domains and surface plasmon resonance have revealed the unexpected recognition of K27-Ub2 by K48-selective receptors including the UBA2 domain of hHR23a [16]. Mutagenesis studies confirm the structural basis of these interactions, highlighting the versatile recognition capabilities of K27-linked chains.

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for K27-Linked Ubiquitin Chain Analysis. This flowchart outlines the integrated approach for synthesizing, characterizing, and functionally validating K27-linked ubiquitin chains, highlighting the multi-technique methodology required to overcome the unique challenges posed by this linkage type.

Advancing research on K27-linked ubiquitination requires specialized reagents and tools designed to address its unique properties and overcome technical challenges.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying K27-Linked Ubiquitination

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Chemically Synthesized K29-Ub2 | Reference standard for structural studies | Native isopeptide linkage without mutations; enables biotinylation for detection |

| Linkage-Specific E3 Ligases (TRIM21, TRIM23, RNF185, AMFR) | In vitro and cellular ubiquitination assays | Catalyze formation of K27-linked chains on specific substrates |

| K27-Linkage Resistant DUBs | Negative controls in deubiquitination assays | USP2, USP5, Ubp6 show minimal activity toward K27 linkages |

| NMR with 15N-Labeled Ubiquitin | Structural and dynamic characterization | Reveals chemical shift perturbations and interdomain contacts |

| UBA2 Domain of hHR23a | Binding partner analysis | Recognizes K27-Ub2 through bidentate interactions similar to K48-Ub2 |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Detection and localization in cellular contexts | Enables visualization and quantification of endogenous K27 chains |

| Cryo-EM Sample Preparation | Structural analysis of E3-K27-Ub complexes | Captures transient ubiquitylation transition states with chemical warheads |

K27 Linkages in Context: Comparison with Other Atypical Chains

The functional significance of K27-linked ubiquitination is further illuminated when examined within the broader landscape of atypical ubiquitin chains. While K6-linked chains participate in DNA damage repair and mitophagy, and K11-linked chains regulate the cell cycle and endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD), K27 linkages have carved a specialized niche in immune regulation [15] [19]. K29-linked chains, recently shown to be among the most abundant atypical linkages in eukaryotic cells, function in proteotoxic stress response and cell cycle regulation, particularly enriched in the midbody during mitosis [20]. K33-linked chains mediate protein trafficking and signal transduction of cell surface receptors [15].

What distinguishes K27-linked chains is their particular importance in pathogen defense systems and their unique biochemical properties that include exceptional stability against deubiquitinating enzymes [14]. This specialization highlights the evolutionary adaptation of ubiquitin signaling to meet specific cellular needs, with K27 linkages serving as stable signaling platforms in the context of host-pathogen interactions.

Diagram 2: K27-Linked Ubiquitin Signaling in Antiviral Innate Immunity. This pathway map illustrates how K27-linked ubiquitination regulates multiple nodes in antiviral signaling cascades, from pathogen sensing through transcriptional activation of immune response genes.

K27-linked ubiquitin chains represent a specialized regulatory mechanism within the expanding landscape of atypical ubiquitination, serving as critical modulators of antiviral innate immune signaling and inflammatory pathways. Their unique structural properties, including open conformations and exceptional resistance to deubiquitinating enzymes, enable sustained signaling responses essential for effective pathogen defense. The multifaceted roles of K27 linkages—from regulating nucleic acid sensor pathways to controlling transcriptional activation—highlight their importance as integrative hubs in immune signaling networks.

Future research directions include developing more sensitive and specific tools for detecting endogenous K27-linked chains, elucidating the structural basis for linkage specificity among E3 ligases, and exploring the therapeutic potential of modulating K27-linked ubiquitination in inflammatory diseases and cancer. As part of the broader family of atypical ubiquitin chains, K27 linkages exemplify the sophisticated adaptation of ubiquitin signaling to meet specific cellular needs, offering rich opportunities for scientific discovery and therapeutic innovation.

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates diverse cellular processes by covalently attaching ubiquitin to target proteins. While K48- and K63-linked ubiquitin chains are well-characterized, the functions of atypical ubiquitin linkages, particularly K29-linked chains, remain less explored. K29-linked ubiquitination represents a non-canonical chain type that has recently emerged as a significant regulator in various cellular pathways beyond protein degradation. This technical review examines the multifaceted roles of K29-linked ubiquitin chains in mRNA stability, kinase regulation, and Wnt/β-catenin signaling, providing researchers with current methodologies and conceptual frameworks for investigating these complex regulatory mechanisms. Understanding K29-linked ubiquitination is essential for deciphering the ubiquitin code and its implications in cellular physiology and disease pathogenesis.

K29-linked ubiquitin chains possess unique structural characteristics that distinguish them from other ubiquitin linkages. Structural analyses reveal that K29-linked diubiquitin adopts an extended conformation with both ubiquitin hydrophobic patches exposed and available for binding interactions [10]. This structural arrangement differs significantly from the compact conformations of K48-linked chains and contrasts with the extended but differently oriented K63-linked chains. The exposed hydrophobic patches enable specific interactions with ubiquitin-binding domains that recognize K29 linkage specificity.

The TRABID zinc finger (NZF) domain exemplifies this specificity, utilizing a binding mode that exploits the inherent flexibility of K29 chains while engaging the hydrophobic patch on only one ubiquitin moiety [10]. This selective recognition mechanism allows K29-linked chains to function as distinct signaling entities in cellular pathways. Furthermore, K29 linkages frequently exist within heterotypic branched chains containing other linkage types, adding complexity to the ubiquitin code and expanding the regulatory potential of ubiquitination [10].

Cellular quantification studies demonstrate that K29-linked chains, while less abundant than K48 or K11 linkages, show tissue-specific enrichment patterns. Notably, contractile tissues such as heart and muscle exhibit relative enrichment of K29 and other atypical chains, suggesting specialized functions in these tissues [21]. This distribution pattern highlights the functional specialization of K29 linkages in specific physiological contexts.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of K29-Linked Ubiquitin Chains

| Characteristic | Description | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Chain Structure | Extended conformation with exposed hydrophobic patches | Creates unique binding surfaces for specific recognition domains |

| Cellular Abundance | Lower abundance than K48/K11, but tissue-specific enrichment | Specialized rather than universal functions |

| Chain Architecture | Often found in heterotypic/branched chains with other linkages | Increases combinatorial complexity of ubiquitin signaling |

| Recognition Domains | Specific NZF domains (e.g., TRABID) with unique binding modes | Enables specific downstream signaling outcomes |

K29-Linked Ubiquitination in Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway represents a well-characterized system where K29-linked ubiquitination exerts specific regulatory functions. Research has identified that the E3 ligase Smurf1 mediates K29-linked ubiquitination of axin, a critical scaffold component of the β-catenin destruction complex [22]. This modification occurs specifically at lysine residues K789 and K821 of axin and surprisingly does not target axin for proteasomal degradation but instead modulates protein-protein interactions within the Wnt signaling complex.

The functional consequence of Smurf1-mediated K29-linked ubiquitination of axin is the disruption of axin-LRP5/6 interaction, which subsequently attenuates Wnt-stimulated LRP6 phosphorylation and represses Wnt/β-catenin signaling [22]. This non-proteolytic function represents a paradigm shift in understanding how ubiquitination regulates Wnt signaling, moving beyond the traditional degradation-centric view. The identification of specific lysine residues on axin that undergo K29-linked ubiquitination provides mechanistic insight into how this modification interfaces with other post-translational modifications to fine-tune Wnt signaling output.

Table 2: Experimental Evidence for K29-Linked Ubiquitination in Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling

| Experimental Approach | Key Findings | References |

|---|---|---|

| In vitro ubiquitination assay | Smurf1 ubiquitinates axin primarily through K29-linked chains | [22] |

| Site-directed mutagenesis | K789 and K821 identified as critical ubiquitination sites on axin | [22] |

| Co-immunoprecipitation | K29-ubiquitinated axin shows reduced interaction with LRP5/6 | [22] |

| Luciferase reporter assays | Smurf1 overexpression inhibits Wnt/β-catenin signaling | [22] |

| Knockout MEF analysis | Enhanced Wnt signaling in Smurf1-/- murine embryonic fibroblasts | [22] |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing K29-Linked Ubiquitination of Axin

In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

- Express and purify recombinant human Smurf1 and axin proteins from E. coli using appropriate expression vectors (e.g., pET-28c for Smurf1, pGEX-4T2 for axin)

- Set up ubiquitination reaction in 30 μL mixture containing: 125 ng human E1 enzyme, 500 ng UbcH5c E2 enzyme, 10 μg ubiquitin, 2 μg axin, and 1 μg Smurf1 in reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 2 mM ATP, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT)

- Incubate at 30°C for 2 hours

- Terminate reaction by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer and analyze by Western blotting

- Detect K29-linked ubiquitination using linkage-specific antibodies (e.g., sAB-K29)

In Vivo Validation

- Co-transfect HEK293T cells with plasmids encoding Smurf1, axin, and wild-type or mutant ubiquitin (K29R)

- Treat cells with MG132 (10 μM, 6 hours) to inhibit proteasomal degradation

- Lyse cells in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors and 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide to inhibit deubiquitinases

- Immunoprecipitate axin using specific antibodies

- Analyze ubiquitination by Western blotting with K29-linkage specific antibodies

K29-Linked Ubiquitination in Kinase Regulation and Transcriptional Control

Beyond Wnt signaling, K29-linked ubiquitination plays significant roles in kinase regulation and transcriptional control, particularly during cellular stress responses. Recent research has revealed that the unfolded protein response (UPR) triggers increased K29-linked ubiquitination of the cohesin complex components SMC1A and SMC3 [23]. This specific modification occurs at potentially conserved sites (K1222 on SMC1A) and regulates transcription of cell proliferation-related genes including SERTAD1 and NUDT16L1.

The mechanism involves K29-linked ubiquitination promoting the recruitment of the cohesin release factor WAPL, resulting in cohesin release from chromatin and subsequent transcriptional downregulation [23]. This process effectively inhibits cell proliferation during endoplasmic reticulum stress, allowing cells to conserve resources for stress recovery. The discovery was enabled by CUT&Tag profiling of K29-linked ubiquitin chains in HEK293FT cells, which demonstrated significant overlap with transcriptionally active histone modifications (H3K4me3 and H3K27ac) and accessibility regions identified by ATAC-seq [23].

In kinase regulation, K29-linked ubiquitination exhibits non-proteolytic functions that modulate enzymatic activity and signaling output. The ubiquitin chain-editing complex comprising the HECT E3 ligase UBE3C and the deubiquitinase vOTU has been implicated in the generation and regulation of K29-linked chains that influence kinase activity in various signaling pathways [10].

Figure 1: K29-linked ubiquitination in the unfolded protein response. During ER stress, the UPR triggers K29-linked ubiquitination of cohesin complex components, leading to WAPL-mediated cohesin release and transcriptional repression of proliferation genes.

Methodologies for Studying K29-Linked Ubiquitination

Linkage-Specific Reagents and Detection Methods

Advancements in linkage-specific reagents have been crucial for elucidating K29-linked ubiquitination functions. The development of sAB-K29, a highly specific antibody against K29-linked chains, has enabled precise detection and localization studies [23]. This antibody shows minimal cross-reactivity with other ubiquitin linkage types, making it suitable for various applications including immunofluorescence, Western blotting, and CUT&Tag assays for chromatin-associated ubiquitination.

For structural studies, the K29-selective ubiquitin binding domain from TRABID (NZF1) provides a valuable tool for affinity purification and structural characterization of K29-linked chains [10]. Crystallographic analyses of this domain in complex with K29-diubiquitin have revealed the molecular basis of linkage specificity, informing the design of more specific detection reagents.

Mass spectrometry-based approaches, particularly the Ub-AQUA-PRM (Ubiquitin Absolute Quantification by Parallel Reaction Monitoring) method, enable comprehensive quantification of all ubiquitin chain types in biological samples [21]. This refined assay allows quantification of ubiquitin chain linkages in 10-minute LC-MS/MS runs, facilitating high-throughput screening of ubiquitin chain composition across different tissues and conditions.

Genetic and Cellular Approaches

Genetic studies in model organisms have proven invaluable for understanding K29-linked ubiquitination functions. In S. cerevisiae, genetic interaction screens between gene deletion libraries and lysine-to-arginine ubiquitin mutants have revealed synthetic phenotypes that illuminate the functional relationships between K29 linkages and specific cellular pathways [24].

Cellular studies utilizing DUB-E3 ligase interplay have demonstrated how enzymes like Ubp2, Ubp14, Ufd4, and Hul5 regulate cellular levels of K29-linked unanchored polyubiquitin chains that influence ribosome biogenesis and direct ribosomal proteins to the intranuclear quality control compartment [25]. The accumulation of K29-linked unanchored chains disrupts ribosome assembly and activates the ribosome assembly stress response, connecting K29 ubiquitination to proteostasis maintenance.

Figure 2: Comprehensive workflow for studying K29-linked ubiquitination, encompassing detection methods, functional analysis, and therapeutic exploration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying K29-Linked Ubiquitination

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Applications and Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | sAB-K29 [23] | Immunofluorescence, Western blotting, CUT&Tag for chromatin-associated K29 chains |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | Ub-K29R [22] [24] | Genetic studies to specifically abrogate K29-linked chain formation |

| E3 Ligase Tools | Smurf1 expression constructs [22], UBE3C/vOTU complex [10] | Enzymatic generation of K29-linked chains for in vitro and in vivo studies |

| Binding Domains | TRABID NZF1 domain [10] | Affinity purification and structural studies of K29-linked chains |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | AQUA peptides for K29 linkages [21] | Absolute quantification of K29 chain abundance in complex samples |

| Cell Line Models | HEK293FT [23], Smurf1-/- MEFs [22] | Cellular validation of K29-linked ubiquitination functions |

| Deubiquitinase Tools | Ubp2, Ubp14 [25] | Regulation of K29-linked unanchored polyubiquitin chains |

K29-linked ubiquitin chains represent a functionally diverse category of ubiquitin signaling that extends beyond protein degradation to include regulation of Wnt signaling, transcriptional control during stress responses, kinase modulation, and maintenance of proteostasis. The non-proteolytic functions of K29 linkages, particularly in modulating protein-protein interactions and cellular localization, highlight the expanding complexity of the ubiquitin code.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the full spectrum of E3 ligases and deubiquitinases that specifically regulate K29-linked chains, developing more sophisticated tools for detecting endogenous K29 ubiquitination, and understanding the interplay between K29 linkages and other ubiquitin chain types in heterotypic and branched structures. Furthermore, the therapeutic potential of targeting K29-specific enzymes in disease contexts, particularly cancer and neurodegenerative disorders, warrants increased attention as our understanding of these pathways matures.

The integration of structural biology, quantitative proteomics, and genetic approaches will continue to drive discoveries in this field, potentially revealing novel regulatory mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities for manipulating K29-linked ubiquitination in human disease.

Within the intricate language of cellular signaling, ubiquitination stands out for its extraordinary complexity. While the functions of K48- and K63-linked ubiquitin chains in proteasomal degradation and signal transduction are well-established, the biological roles of atypical ubiquitin linkages (K6, K27, K29) remain a frontier in molecular biology. This whitepaper examines how the distinct structural architectures of these atypical chains directly determine their specialized cellular functions. Through integration of recent biochemical, structural, and proteomic findings, we elucidate the unique properties of K6-, K27-, and K29-linked ubiquitin chains and their implications for cellular regulation and therapeutic development. The emerging paradigm reveals that chain architecture—including linkage type, length, and branching—encodes precise biological information that is decoded by specialized cellular machinery.

Ubiquitin is a 76-amino acid protein that is covalently attached to substrate proteins through a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 activating, E2 conjugating, and E3 ligase enzymes [26]. The complexity of ubiquitin signaling arises from the ability of ubiquitin itself to form polymers through its seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or N-terminal methionine (M1) [12]. While K48-linked chains predominantly target substrates for proteasomal degradation and K63-linked chains regulate nonproteolytic processes, the so-called "atypical" chains (K6, K27, K29) exhibit unique structural properties that enable specialized cellular functions [19] [27].

The architectural diversity of ubiquitin chains extends beyond simple linkage type to include chain length and branching patterns [12]. Mixed or branched ubiquitin chains contain more than one type of linkage within the same polymeric structure, dramatically expanding the signaling potential of the ubiquitin code [28]. This review focuses specifically on the structural foundations of K6-, K27-, and K29-linked ubiquitin chains and how their unique architectures dictate biological function in health and disease.

Structural Properties of Atypical Ubiquitin Chains

K27-Linked Ubiquitin Chains

K27-linked ubiquitin chains exhibit exceptional structural and functional properties that distinguish them from all other ubiquitin chain types. Biochemically, K27-linked di-ubiquitin (K27-Ub2) demonstrates remarkable resistance to deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), resisting cleavage by linkage-nonspecific DUBs including USP2, USP5, and Ubp6 [14]. This property is unique among all lysine linkages and suggests specialized regulatory functions for K27 chains in contexts requiring stable ubiquitin signals.

Structurally, K27-Ub2 exhibits distinctive characteristics revealed through NMR spectroscopy and small-angle neutron scattering. The proximal ubiquitin unit in K27-Ub2 shows widespread chemical shift perturbations, while the distal ubiquitin exhibits minimal perturbations, indicating an absence of stable noncovalent interdomain contacts [14]. This structural feature likely contributes to the DUB resistance observed in K27 chains and enables unique binding preferences. Surprisingly, despite their structural differences, K27-Ub2 chains are specifically recognized by the UBA2 domain of hHR23a, a receptor typically associated with K48-linked chain recognition [14]. This structural versatility highlights the functional complexity of K27 linkages.

K29-Linked Ubiquitin Chains

K29-linked ubiquitin chains adopt conformations that facilitate specific biological roles in transcriptional regulation and cellular stress response. Chromatin profiling reveals that K29-linked ubiquitin chains are significantly enriched at promoter regions and overlap with transcriptionally active histone modifications including H3K4me3 and H3K27ac [23]. This chromatin association underscores the role of K29 linkages in gene regulation.

During the unfolded protein response (UPR), K29-linked ubiquitination of the cohesin complex increases substantially, with potential modification at the K1222 site on SMC1A [23]. This modification recruits the cohesin release factor WAPL, leading to cohesin release from chromatin and subsequent transcriptional downregulation of cell proliferation-related genes such as SERTAD1 and NUDT16L1 [23]. The structural properties of K29 chains thus enable specific gene regulatory functions during cellular stress.

Chain Length as a Structural Determinant

Beyond linkage type, ubiquitin chain length serves as a critical structural parameter that significantly impacts recognition by ubiquitin-binding proteins. Affinity-based proteomic profiling using length-defined ubiquitin chains has demonstrated that 64-70% of significant interactions with K27-, K29-, and K33-linked chains occur exclusively with long polymers (Ub6+) rather than shorter chains [29]. This pronounced length selectivity adds another layer of specificity to ubiquitin signaling.

Table 1: Structural Properties of Atypical Ubiquitin Chains

| Linkage Type | Structural Features | DUB Sensitivity | Preferred Chain Length | Structural Methods Applied |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K27 | No stable interdomain contacts; widespread CSPs in proximal Ub | Resistant to most DUBs (USP2, USP5, Ubp6) | Long chains (Ub6+) preferred for most interactions | NMR, SANS, computational modeling |

| K29 | Chromatin-associated; enriched at promoters | Not well characterized | Length-dependent interactions observed | CUT&Tag, ATAC-seq, RNA-seq |

| K6 | Not fully characterized | Variable sensitivity | Not determined | NMR, biochemical assays |

Table 2: Functional Roles of Atypical Ubiquitin Chains

| Linkage Type | Biological Functions | Cellular Processes | Key Enzymes | Specific Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K27 | Mitochondrial quality control; proteasome regulation; innate immunity | Mitophagy; protein stabilization | Not well characterized | Miro1 |

| K29 | Transcriptional regulation; ER stress response; cell proliferation control | UPR; gene expression; Wnt signaling | Not well characterized | SMC1A, SMC3 (cohesin complex) |

| K6 | DNA damage repair; mitochondrial regulation | DNA repair pathways; quality control | BRCA1-BARD1 | Unknown substrates |

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Atypical Ubiquitin Chains

Linkage- and Length-Defined Ubiquitin Chain Synthesis

The chemical synthesis of defined ubiquitin chains represents a cornerstone methodology for structural and functional studies. Recent approaches combine click chemistry with gel-eluted liquid fraction entrapment electrophoresis (GELFrEE) to generate ubiquitin chains of defined linkage and length [29]. The methodology involves:

Ubiquitin Monomer Preparation: Generation of bifunctional ubiquitin monomers (Aha75CxPA) containing site-specific modifications at positions x=27, 29, or 33.

Copper-Catalyzed Cycloaddition: Copper(I)-catalyzed alkyne-azide cycloaddition (CuAAC)-mediated protein polymerization with simultaneous desthiobiotin modification.

Chain Length Fractionation: GELFrEE fractionation under denaturing conditions to separate ubiquitin polymers up to the tetramer level in high purity.

Refolding: Dialysis under appropriate conditions to restore native ubiquitin conformation after fractionation.

This methodology enables production of milligram quantities of linkage- and length-defined ubiquitin chains essential for biochemical and structural studies [29].

Chromatin Profiling of Ubiquitin Chains

Cleavage Under Targets and Tagmentation (CUT&Tag) methodology has been adapted to profile the chromatin landscape of atypical ubiquitin chains. The experimental workflow includes:

Cell Permeabilization: Permeabilization of HEK293FT cells to allow antibody access.

Primary Antibody Incubation: Incubation with linkage-specific antibodies (e.g., sAB-K29 for K29-linked chains).

Secondary Antibody Binding: Binding of secondary antibodies conjugated to protein A-Tn5 transposase.

Tagmentation Activation: Magnesium-dependent activation of tagmentation for targeted DNA fragmentation.

Library Preparation and Sequencing: DNA extraction, library preparation, and high-throughput sequencing.

This approach has demonstrated significant enrichment of K29-linked ubiquitin chains at promoter regions, overlapping with transcriptionally active histone marks [23].

Structural Characterization Techniques

Multiple biophysical approaches are employed to characterize the structural properties of atypical ubiquitin chains:

NMR Spectroscopy: Sequential assignment of chemical shifts for both proximal and distal ubiquitin units in di-ubiquitin; quantification of chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) to identify interdomain interactions and conformational changes [14].

Small-Angle Neutron Scattering (SANS): Collection of scattering data under contrast-matched conditions; ensemble modeling to determine conformational distributions and chain compactness [14].

Affinity Enrichment Proteomics: Immobilization of length- and linkage-defined ubiquitin chains on streptavidin agarose; incubation with HEK293T whole cell lysates; LC-MS/MS analysis of enriched proteins; label-free quantification to identify length-selective interaction partners [29].

Functional Implications of Atypical Ubiquitin Chain Architecture

K29-Linked Ubiquitination in Transcriptional Regulation

The architectural properties of K29-linked ubiquitin chains enable specific functions in transcriptional regulation during cellular stress. Under endoplasmic reticulum stress, cells activate the unfolded protein response (UPR), leading to increased K29-linked ubiquitination of the cohesin complex [23]. This modification occurs specifically at promoters of cell proliferation-related genes and recruits the cohesin release factor WAPL, ultimately leading to transcriptional downregulation and inhibition of cell growth [23]. This mechanism demonstrates how K29 chain architecture facilitates gene expression control in response to proteostatic stress.

Branched Ubiquitin Chains in Signal Integration

Branched ubiquitin chains containing atypical linkages represent an emerging dimension of ubiquitin signaling. These complex structures are synthesized through collaborative efforts between E3 ligases with distinct linkage specificities [12]. For example, Ufd4 and Ufd2 collaborate to synthesize branched K29/K48 chains on substrates of the ubiquitin fusion degradation pathway in yeast [12]. Similarly, the APC/C cooperates with UBE2C and UBE2S to form branched K11/K48 chains during mitosis [12].

The functional significance of chain branching lies in its ability to integrate multiple regulatory signals. Branched K48/K63 chains are produced by TRAF6 and HUWE1 during NF-κB signaling, potentially enabling simultaneous engagement of degradative and non-degradative signaling pathways [12]. This architectural complexity allows for sophisticated regulation of protein fate that exceeds the capabilities of homotypic chains.

Research Tools and Reagent Solutions

The study of atypical ubiquitin chains requires specialized reagents and methodologies designed to address their unique structural properties and relative low abundance in cellular contexts.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Atypical Ubiquitin Chains

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | sAB-K29 (K29-specific) | CUT&Tag; immunofluorescence; immunoblotting | High specificity over seven other linkage types |

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | K63-TUBEs; K48-TUBEs; Pan-TUBEs | Affinity enrichment; HTS assays; ubiquitination detection | Nanomolar affinities; protection from DUBs |

| Engineered Ubiquitin Variants | His-tagged Ub; Strep-tagged Ub | Ubiquitinated protein enrichment; proteomic identification | Affinity tag incorporation; mutant ubiquitins |

| Defined Ubiquitin Chains | Triazole-linked K29-Ub2; K27-Ub4 | Structural studies; in vitro assays; interaction profiling | Linkage- and length-defined; DUB-resistant |

| DUB Inhibitors | K27-Ub2 as competitive inhibitor | DUB activity modulation; pathway analysis | Natural DUB resistance of K27 chains |

TUBE-Based Technologies for High-Throughput Applications

Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) have emerged as powerful tools for studying atypical ubiquitination in physiological contexts. These engineered binding proteins consist of multiple ubiquitin-binding domains arranged in tandem, conferring high-affinity interactions with specific ubiquitin chain types [30]. Recent applications include:

High-Throughput PROTAC Screening: K48-specific TUBEs enable rapid assessment of PROTAC-mediated target ubiquitination in 96-well plate formats, facilitating drug discovery efforts [30].

Pathway-Specific Ubiquitination Analysis: K63-specific TUBEs successfully capture inflammatory signaling-induced ubiquitination of RIPK2 following L18-MDP stimulation, demonstrating linkage-specific pathway analysis [30].

Endogenous Protein Ubiquitination Monitoring: TUBE-based platforms overcome limitations of traditional Western blotting by providing quantitative, sensitive detection of endogenous protein ubiquitination without genetic manipulation [30].

The architectural diversity of atypical ubiquitin chains represents a sophisticated mechanism for expanding the functional repertoire of ubiquitin signaling. The unique structural properties of K6-, K27-, and K29-linked chains—including their distinct conformations, chain length preferences, and resistance to deubiquitination—enable precise regulation of cellular processes ranging from transcriptional control to stress adaptation. The emerging understanding of branched ubiquitin chains further demonstrates how linkage mixing creates signaling platforms capable of integrating multiple regulatory inputs.

Future research directions will likely focus on developing more sophisticated tools for probing atypical ubiquitin chain functions in physiological contexts, including improved linkage-specific antibodies, chemical biology approaches for tracing chain dynamics in live cells, and therapeutic strategies targeting disease-relevant ubiquitin signaling nodes. The integration of structural biology with proteomic methodologies will continue to reveal how chain architecture determines biological function in this complex signaling system.

Comparative Abundance and Conservation Across Eukaryotic Species