Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitination Pathways in Cancer: From Molecular Mechanisms to Precision Therapeutics

Ubiquitination, a crucial post-translational modification, is profoundly dysregulated across cancer types, influencing tumorigenesis, progression, and therapeutic response.

Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitination Pathways in Cancer: From Molecular Mechanisms to Precision Therapeutics

Abstract

Ubiquitination, a crucial post-translational modification, is profoundly dysregulated across cancer types, influencing tumorigenesis, progression, and therapeutic response. This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of ubiquitination pathway alterations in diverse cancers. We explore the foundational biology of the ubiquitin-proteasome system and examine advanced methodological approaches for profiling the cancer ubiquitinome. The article addresses key challenges in the field and discusses innovative strategies for targeting ubiquitination pathways therapeutically. Through a cross-cancer lens, we validate prognostic ubiquitination signatures and synthesize insights that bridge fundamental research with emerging clinical applications, including proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) and immunotherapy combination strategies. This synthesis aims to equip researchers and drug developers with a holistic understanding of ubiquitination as a central regulatory node in cancer biology.

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: Core Machinery and Cancer-Specific Alterations

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) stands as one of the most crucial regulatory mechanisms in eukaryotic cells, governing the precise degradation of intracellular proteins to maintain cellular homeostasis [1]. At the heart of this system operates a finely tuned enzymatic cascade comprising three core enzyme classes: E1 (ubiquitin-activating), E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating), and E3 (ubiquitin-ligating) enzymes [2] [3]. This sequential pathway conjugates the small protein modifier ubiquitin to specific substrate proteins, thereby dictating their stability, activity, or localization [4]. The specificity of this system, particularly conferred by the extensive E3 ligase family, allows for the selective regulation of virtually every cellular process, from cell cycle progression and DNA repair to signal transduction and immune responses [3] [5]. In cancer biology, this pathway becomes critically dysregulated, with aberrant ubiquitination patterns contributing directly to sustained proliferation, evasion of apoptosis, and other hallmark capabilities of cancer cells [3] [5]. A comparative analysis across malignancies reveals both common themes and cancer-specific adaptations in how the ubiquitination cascade is co-opted during oncogenesis, presenting compelling opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

The Core Enzymatic Machinery: E1, E2, and E3

The ubiquitination cascade is a three-step enzymatic process that culminates in the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to substrate proteins.

The Sequential Catalytic Steps

The process initiates with the E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme, which activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction to form an E1~ubiquitin thioester intermediate [6]. In humans, only two E1 enzymes, UBA1 and UBA6, initiate the majority of ubiquitination cascades, highlighting a key regulatory bottleneck [7]. The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to the catalytic cysteine residue of an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (UBC) via a transthioesterification reaction [6]. Structural analyses reveal that this transfer is facilitated by specific residues in the E1 enzyme, such as Thr601 and Arg603, which help stabilize the reactive transition state and modify the pKa of the incoming E2 nucleophile [6]. The human genome encodes approximately 40 E2s, which begin to impart some specificity to the pathway [8].

The final and most specific step involves the E3 ubiquitin ligase, which mediates the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine residue on the target protein. With over 600 members identified, E3 ligases are responsible for substrate recognition and confer the remarkable specificity of the ubiquitin system [3]. They accomplish this through specialized domains that recognize specific peptide motifs, or degrons, within their target substrates [3]. These degrons include phospho-degrons, proline-rich motifs, and other structural features that ensure precise substrate selection.

Table 1: Core Components of the Ubiquitination Enzymatic Cascade

| Component | Number in Humans | Core Function | Catalytic Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Activating) | 2 (UBA1, UBA6) | Ubiquitin activation via ATP hydrolysis | Forms E1~Ub thioester via adenylation |

| E2 (Conjugating) | ~40 | Ubiquitin carrier and E3 cooperation | E2~Ub thioester intermediate |

| E3 (Ligating) | >600 | Substrate recognition and specificity | Direct or indirect ubiquitin transfer to substrate |

Structural and Mechanistic Diversity of E3 Ligases

E3 ubiquitin ligases are categorized into three major families based on their structural features and catalytic mechanisms [3]. The RING (Really Interesting New Gene) finger family represents the largest group and functions by directly catalyzing the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2~Ub complex to the substrate without forming a covalent intermediate [3]. Notable subtypes include the multisubunit Cullin-RING ligases (CRLs) and the Anaphase Promoting Complex/Cyclosome (APC/C) [3]. In contrast, HECT (Homologous to the E6AP C Terminus) family E3s form a catalytic thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate [3]. The RING-between-RING (RBR) family employs a hybrid mechanism, utilizing RING domains for E2 binding and a catalytic cysteine similar to HECT ligases for ubiquitin transfer [3]. This mechanistic diversity enables precise temporal and spatial control over protein ubiquitination, allowing the system to regulate a vast array of cellular processes.

Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitination Pathways Across Cancers

Dysregulation of the ubiquitination cascade is a hallmark of numerous malignancies, though the specific components affected and functional consequences vary significantly across cancer types.

Glioblastoma: E3 Ligases in Pro-Survival Signaling and Therapeutic Resistance

In glioblastoma (GB), E3 ubiquitin ligases play multifaceted roles in promoting tumor survival and resistance to standard therapies. Receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling, particularly through EGFR, is aberrantly regulated by several E3 ligases in GB [5]. Casitas B-lineage lymphoma (Cbl), a well-characterized E3, normally targets activated EGFR for degradation via ubiquitination; however, in GB, the constitutively active EGFRvIII mutant displays hypophosphorylation at the Cbl docking site (Y1045), attenuating Cbl-dependent internalization and degradation and leading to sustained oncogenic signaling [5]. Furthermore, the E3 ligase PARK2, frequently lost or mutated in GB, normally suppresses EGFR expression through direct ubiquitination and degradation, with its loss contributing to enhanced EGFR signaling [5]. The β-TrCP E3 ligase complex regulates Akt signaling by targeting the phosphatase PHLPP1 for degradation, thereby enhancing pro-survival signaling pathways in GB cells [5]. These alterations collectively promote tumor progression and represent potential therapeutic vulnerabilities.

Cervical Cancer: HPV Oncoprotein Subversion of the Ubiquitin Cascade

HPV-driven cervical cancer provides a striking example of viral subversion of the host ubiquitination machinery. The viral oncoproteins E6 and E7 directly interact with and manipulate cellular E3 ligases to promote viral persistence and cellular transformation [8]. Specifically, HPV E6 recruits the cellular E3 ligase E6AP to form a complex that targets the tumor suppressor p53 for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, effectively disabling a critical checkpoint against uncontrolled proliferation [8]. Meanwhile, HPV E7 promotes the degradation of the retinoblastoma protein (pRb) through another E3 ligase complex, driving aberrant cell cycle progression [8]. Recent bioinformatic studies have identified specific ubiquitination-related genes, including MMP1, RNF2, TFRC, SPP1, and CXCL8, that are significantly associated with cervical cancer outcomes and can stratify patient risk [1]. The risk score model developed from these biomarkers demonstrates strong predictive value for patient survival (AUC >0.6 for 1/3/5 years), highlighting the clinical relevance of ubiquitination pathways in this malignancy [1].

Pan-Cancer Commonalities and Distinctions

Across cancer types, several common themes emerge in the dysregulation of the ubiquitination cascade. First, E3 ligases frequently function as tumor suppressors when their normal role is to degrade oncoproteins, with their loss or inactivation leading to stabilization of drivers such as c-Myc, β-catenin, and cyclins [3]. Second, certain E3 ligases can act as oncoproteins when overexpressed or hyperactive, leading to excessive degradation of tumor suppressors like p53, p27, and PTEN [3]. Third, the specificity of E3 ligases makes them attractive therapeutic targets, with both small-molecule inhibitors and proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) being actively explored across multiple cancer types [5]. However, tissue-specific expression patterns of E2 and E3 enzymes, differential substrate availability, and distinct mutational backgrounds create cancer-type specific vulnerabilities that necessitate comparative analyses for effective therapeutic development.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitination Cascade Alterations Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Key Altered Components | Functional Consequences | Clinical/Prognostic Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glioblastoma | Cbl, PARK2, β-TrCP, CHIP | Dysregulated RTK signaling, enhanced PI3K/Akt pathway, resistance to therapy | Associated with stemness and therapeutic resistance; potential for PROTAC-based therapies |

| Cervical Cancer | E6AP, UBE2 enzymes, MMP1, RNF2, TFRC | p53 and pRb degradation, sustained proliferation, immune evasion | 5-gene signature predicts survival (AUC>0.6); associated with immune cell infiltration |

| Multiple Cancers | CRL complexes, APC/C, MDM2 | Cell cycle dysregulation, genomic instability, evasion of growth suppression | Common therapeutic target across malignancies; small-molecule inhibitors in development |

Experimental Approaches for Profiling Ubiquitination Cascades

Proximity Labeling for Mapping Localized Ubiquitination Networks

Recent advances in proximity labeling technologies have revolutionized our ability to profile ubiquitination cascades in specific cellular compartments. The iAPEX (in situ APEX activation) system represents a significant innovation that combines APEX2 with a D-amino acid oxidase (DAAO) to locally generate hydrogen peroxide, thereby minimizing toxicity and reducing non-specific background labeling associated with traditional APEX approaches [9]. This enzyme cascade enables sensitive and specific proteomic mapping in challenging biological systems, including primary cilia, mitochondria, and lipid droplets [9]. The experimental workflow involves: (1) fusing DAAO to a specific organelle or protein complex of interest; (2) co-expressing or fusing APEX2 to the same location; (3) providing D-amino acids (e.g., D-Ala) to drive local H2O2 production; (4) adding biotin-tyramide to enable APEX2-mediated biotinylation of proximal proteins; and (5) streptavidin-based purification and mass spectrometric identification of labeled proteins [9]. This approach has been successfully applied to profile the proteomes of primary cilia in cell lines previously inaccessible to conventional APEX labeling, identifying novel ciliary proteins and revealing heterogeneity in primary cilia composition across cell types [9].

Bioinformatics Approaches for Ubiquitination Signature Identification

Computational methods have been developed to identify ubiquitination-related gene signatures with prognostic significance in cancer. As demonstrated in cervical cancer research, the typical workflow involves: (1) identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between tumor and normal samples across multiple datasets; (2) intersecting these DEGs with known ubiquitination-related genes (UbLGs) to identify key crossover genes; (3) applying univariate Cox regression and LASSO algorithms to identify prognostic biomarkers; (4) constructing a risk score model based on biomarker expression; and (5) validating the model using independent datasets and functional assays such as RT-qPCR [1]. This approach successfully identified a five-gene ubiquitination-related signature (MMP1, RNF2, TFRC, SPP1, and CXCL8) that effectively stratifies cervical cancer patients into high- and low-risk groups with significant differences in survival outcomes [1]. Furthermore, immune infiltration analyses revealed that this ubiquitination-related signature correlates with distinct immune microenvironments, including differences in memory B cells, M0 macrophages, and immune checkpoint expression [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying the Ubiquitination Cascade

| Reagent/Method | Primary Function | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| iAPEX Proximity Labeling | Spatial proteomic mapping of ubiquitination microenvironments | Identification of ubiquitination complexes in specific organelles | Superior to traditional APEX with reduced background; requires DAAO expression and D-amino acid substrates |

| Ubiquitin Remodeling Assays | Profiling ubiquitin chain linkage and topology | Determining K48 vs K63 linkages in specific pathways | Requires linkage-specific antibodies or UBD probes; mass spectrometry for detailed characterization |

| PROTAC Molecules | Targeted protein degradation via E3 ligase recruitment | Therapeutic validation of E3 ligase functionality | Blood-brain barrier permeability crucial for CNS malignancies like glioblastoma |

| Bioinformatic Ubiquitin Signatures | Prognostic stratification based on ubiquitination-related genes | Patient risk assessment and therapeutic targeting | Multigene models (e.g., 5-gene cervical cancer signature) show clinical relevance |

The enzymatic cascade of ubiquitination represents a master regulatory system whose dysregulation features prominently across cancer types. While common principles govern its operation, comparative analyses reveal cancer-specific alterations that inform both biological understanding and therapeutic development. The E1-E2-E3 axis offers multiple nodes for therapeutic intervention, with E3 ligases presenting particularly attractive targets due to their substrate specificity. Emerging technologies such as iAPEX proximity labeling and sophisticated bioinformatic approaches are deepening our understanding of ubiquitination networks in spatial and disease contexts. Future research directions will likely focus on developing tissue-specific E3 ligase modulators, understanding the functional significance of atypical ubiquitin chain topologies in cancer, and exploiting synthetic lethal interactions based on ubiquitination pathway alterations. As our toolkit for studying and manipulating this system expands, so too does our potential to develop innovative therapies that restore normal ubiquitination homeostasis in cancer cells.

Ubiquitination is a fundamental post-translational modification that involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin, a 76-amino acid protein, to substrate proteins. This process regulates virtually all aspects of eukaryotic cell biology, including protein degradation, DNA repair, cell signaling, and immune response [10]. The ubiquitination cascade involves three key enzymes: E1 (ubiquitin-activating enzyme), E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme), and E3 (ubiquitin ligase), which work in concert to attach ubiquitin to specific substrate proteins [11] [12]. The human genome encodes approximately 8 E1 enzymes, 41 E2 enzymes, and over 600 E3 ligases, providing tremendous specificity in substrate selection and regulatory control [13].

The versatility of ubiquitin signaling stems from the ability of ubiquitin itself to be modified in different ways. Monoubiquitination involves attachment of a single ubiquitin molecule to a substrate lysine, while polyubiquitination forms chains through linkage between ubiquitin molecules. Ubiquitin contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1) that can form polyubiquitin chains, each creating structurally distinct signals with different functional consequences [10]. This diversity of ubiquitin modifications constitutes a complex "ubiquitin code" that determines specific functional outcomes for modified substrates, ranging from proteasomal degradation to non-proteolytic signaling functions [14] [10].

Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitination Types

Structural and Functional Diversity

The type of ubiquitin modification determines the functional outcome for the modified substrate protein. Monoubiquitination typically serves regulatory roles in membrane trafficking, endocytosis, histone function, and DNA repair [11] [15]. In contrast, polyubiquitin chains generate diverse three-dimensional structures that are recognized by specific ubiquitin-binding domains, leading to different cellular outcomes depending on the chain linkage type [10].

Table 1: Comparative Functions of Ubiquitin Chain Linkages

| Chain Type | Primary Functions | Cellular Processes | Outcome for Substrate |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Proteasomal targeting [11] | Cell cycle control, protein turnover [14] | Degradation [12] |

| K63-linked | Signaling scaffold assembly [14] | DNA repair, kinase activation, inflammation [11] [14] | Altered activity/localization [12] |

| K11-linked | Proteasomal degradation [12] | Cell cycle regulation [10] | Degradation [10] |

| K27-linked | DNA damage response [10] | Kinase activation [11] | Signaling adaptation [14] |

| K29-linked | Proteasomal targeting (minor) [16] | Stress response [10] | Degradation or signaling [10] |

| K33-linked | Kinase regulation [10] | Signal transduction [10] | Altered activity [10] |

| M1-linked | NF-κB signaling [10] | Immune and inflammatory responses [10] | Signaling complex assembly [10] |

The mechanisms controlling lysine selection during ubiquitin chain formation involve both structural features of E2/E3 complexes and sequence determinants surrounding acceptor lysines. For the E2 enzyme Cdc34, specific residues in its catalytic core (such as S139 and Y89) can determine whether substrates undergo monoubiquitination or polyubiquitination [11]. Single point mutations in these residues can convert Cdc34 from a polyubiquitinating enzyme into a monoubiquitinating enzyme, demonstrating the precise control mechanisms governing ubiquitin signaling outcomes [11].

Cancer-Specific Ubiquitin Signaling Pathways

In cancer biology, ubiquitination pathways demonstrate remarkable context-dependent functionality across different tumor types. The following table summarizes key ubiquitin system components with dual roles in cancer radioresistance, illustrating how the same enzyme can exert opposite effects depending on cellular context.

Table 2: Context-Dependent Roles of Ubiquitin System Components in Cancer Radioresistance

| Enzyme | Tumor Type | Pro-tumor Role | Anti-tumor Role | Therapeutic Vulnerability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBXW7 | Colorectal cancer | Degrades p53 to promote radioresistance [14] | - | MDM2/FBXW7 co-inhibition [14] |

| NSCLC | - | Degrades SOX9 to enhance radiosensitivity [14] | SOX9 targeting [14] | |

| USP14 | Glioma | Stabilizes ALKBH5 to maintain stemness [14] | - | USP14 inhibitors [14] |

| HNSCC | Degrades IκBα to activate NF-κB [14] | - | Catalytic inhibition [14] | |

| TRIM21 | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | Degrades VDAC2 to suppress cGAS-STING immunity [14] | - | Combined immunotherapy [14] |

| β-TrCP | Lung cancer | K48-linked degradation of radioprotective LZTS3 [14] | - | EGFR-directed PROTACs [14] |

The functional duality of ubiquitin enzymes in cancer is exemplified by FBXW7, which promotes radioresistance in p53-wildtype colorectal tumors by degrading p53, yet enhances radiosensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with SOX9 overexpression by destabilizing SOX9 and alleviating p21 repression [14]. This contextual duality extends to metabolic adaptation, where SMURF2-mediated HIF1α degradation compromises hypoxic survival, while SOCS2/Elongin B/C-driven SLC7A11 destruction increases ferroptosis sensitivity in liver cancer [14].

Experimental Methodologies for Ubiquitin Research

Advanced Techniques for Ubiquitinome Analysis

The comprehensive analysis of ubiquitin modifications requires specialized methodologies that can capture the diversity and dynamics of the ubiquitin code. Several advanced platforms have been developed to address the challenges in studying ubiquitin-like protein modifications:

BioUbL System: This comprehensive platform utilizes in vivo biotinylation with the E. coli biotin protein ligase BirA to study ubiquitin-like modifications. The system employs multicistronic expression vectors that enable rapid validation of UbL conjugation for both exogenous and endogenous proteins. A key advantage is the ability to purify under denaturing conditions, which inactivates deconjugating enzymes and preserves ubiquitination states, while stringent washes remove UbL interactors and non-specific background [17].

Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs): These molecular traps consisting of tandem ubiquitin-binding domains enable enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins from complex mixtures. TUBEs protect ubiquitin chains from deubiquitinating enzymes and allow purification under native conditions, making them particularly valuable for studying endogenous ubiquitination dynamics [17].

Di-Gly Residual Peptide Antibodies: Monoclonal antibodies specifically recognizing the di-glycine remnant left on trypsinized peptides after ubiquitination enable proteome-wide identification of ubiquitination sites by mass spectrometry. This approach has identified tens of thousands of ubiquitination sites, revealing that most cellular proteins undergo ubiquitination at some point [17] [10].

Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Tools: The development of linkage-specific antibodies and ubiquitin-binding domains has enabled researchers to specifically detect and purify particular polyubiquitin chain types. These tools are essential for deciphering the functional consequences of specific ubiquitin linkages in cellular pathways [10].

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Ubiquitin Modification Analysis. This diagram outlines key methodological approaches for studying ubiquitin modifications, highlighting both denaturing and native purification strategies.

Targeted Protein Degradation Technologies

The understanding of ubiquitin signaling mechanisms has enabled the development of revolutionary therapeutic platforms, particularly in targeted protein degradation:

PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras): These heterobifunctional molecules consist of two ligands connected by a linker - one that binds to an E3 ubiquitin ligase and another that binds to a target protein of interest. This proximity-induced ubiquitination leads to target degradation by the proteasome. PROTACs have matured from a chemical biology concept to a promising drug discovery paradigm, currently exploiting E3 ligases including VHL, CRBN, MDM2, IAPs, and DCAF15 [13] [14].

Molecular Glues: These small molecules induce or stabilize interactions between E3 ubiquitin ligases and target proteins, leading to ubiquitination and degradation. Unlike PROTACs, molecular glues are not necessarily bifunctional but work by altering the surface topography of protein complexes to enable new interactions [14].

Radiotherapy-Activated PROTACs: Innovative platforms such as radiotherapy-triggered PROTAC (RT-PROTAC) prodrugs are activated by tumor-localized X-rays to degrade specific targets like BRD4/2, synergizing with radiotherapy in cancer models. Similarly, X-ray-responsive nanomicelles selectively release PROTACs within irradiated tumors, enabling spatially-controlled protein degradation [14].

Ubiquitin Signaling Networks in Cancer Biology

DNA Damage Response and Repair Pathways

Ubiquitin signaling plays critical roles in the cellular response to DNA damage, with distinct chain types orchestrating specific repair pathways. K63-linked ubiquitin chains serve as platforms to assemble DNA repair complexes at damage sites, while K48-linked chains target inhibitory proteins for degradation to facilitate repair progression [14]. The E3 ligase RNF126 promotes ATR-CHK1 activation through K63-linked ubiquitination in triple-negative breast cancer, creating synthetic lethality with ATM inhibition [14]. Meanwhile, the deubiquitinase OTUB1 stabilizes CHK1 to enhance repair fidelity in lung cancer, making OTUB1 inhibition a promising strategy for radiosensitization [14].

Diagram 2: Ubiquitin Signaling in DNA Damage Response and Repair. This diagram illustrates how different ubiquitin chain types coordinate DNA repair processes through distinct mechanisms, with K63-linked chains facilitating signaling complex assembly and K48-linked chains mediating proteolytic events.

Epigenetic Regulation Through Ubiquitin Signaling

Recent research has revealed sophisticated mechanisms by which ubiquitin signaling regulates chromatin dynamics and epigenetic states. The ASB7 E3 ligase serves as a key negative regulator of heterochromatin maintenance by targeting the H3K9me3 methyltransferase SUV39H1 for degradation [18]. ASB7 localizes to heterochromatin through interaction with HP1 proteins via a conserved PxVxL motif, restricting the spread of repressive H3K9me3 marks beyond heterochromatin boundaries [18].

This ubiquitin-mediated epigenetic regulation is dynamically controlled through the cell cycle. During mitosis, CDK1-Cyclin B1 phosphorylates ASB7 at multiple residues, disrupting its ability to bind and degrade SUV39H1. This mitotic inactivation permits transient SUV39H1 accumulation and H3K9me3 re-establishment post-replication, while ASB7 reactivation in G1 phase restricts further heterochromatin propagation [18]. The identification of truncating ASB7 mutations in cancers, particularly in its SOCS domain, highlights the therapeutic relevance of this ubiquitin-epigenetics crosstalk [18].

Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Ubiquitin Signaling Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Activation Inhibitors | PYR-41, TAK-243 | E1 enzyme inhibition | Blocks ubiquitination initiation [12] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Proteasome function studies | Stabilizes ubiquitinated proteins [12] |

| DUB Inhibitors | PR-619 (pan-DUB inhibitor), USP14 inhibitors, OTUB1 inhibitors | Deubiquitinase functional analysis | Linkage-specific or general DUB blockade [14] |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K48-linkage specific, K63-linkage specific, M1-linkage specific | Ubiquitin chain typing | Selective detection of chain architectures [10] |

| Activity-Based Probes | Ubiquitin-based fluorogenic substrates, HA-Ub-VS | DUB activity profiling | Mechanism-based DUB capture and identification [17] |

| Recombinant E2/E3 Enzymes | Cdc34 mutants (S139D, Y89N), SCF complexes | In vitro ubiquitination assays | Study of enzyme mechanisms and specificity [11] |

| Biotinylated Ubiquitin Tools | BioUbL system, AviTag-ubiquitin conjugates | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins | High-affinity streptavidin-based capture [17] |

The UbiHub database represents a valuable online resource that integrates biological, structural, and chemical data on phylogenetic trees of human protein families involved in ubiquitination signaling, including E3 ligases and deubiquitinases. This platform enables researchers to visualize diverse data types and informs target prioritization and drug design efforts [13].

The complexity of ubiquitin signaling pathways presents both challenges and opportunities for therapeutic intervention, particularly in oncology. The development of PROTACs has demonstrated the feasibility of harnessing the ubiquitin-proteasome system for targeted protein degradation, with several candidates advancing through clinical development [13] [14]. The functional redundancy within the ubiquitin system and the contextual duality of many E3 ligases and DUBs necessitate careful patient stratification and biomarker-guided approaches for successful clinical translation [14].

Emerging strategies focus on exploiting tumor-specific vulnerabilities created by ubiquitin pathway alterations, such as synthetic lethality between E3 ligases and DNA repair pathways, or targeting the ubiquitin-mediated control of epigenetic states [14] [18]. The integration of advanced ubiquitin profiling technologies with functional genomics approaches will continue to uncover novel therapeutic opportunities within this complex regulatory system, ultimately enabling more precise manipulation of ubiquitin signaling for cancer therapy.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a critical regulator of cellular homeostasis, governing approximately 80-90% of intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotic cells. This comprehensive pan-cancer analysis examines the genetic and expression alterations of ubiquitination enzymes across multiple cancer types, revealing consistent dysregulation patterns that correlate with prognosis, immune infiltration, and therapeutic response. By integrating multi-omics data from large-scale cancer cohorts, we demonstrate that ubiquitination enzymes including E1 activators, E2 conjugators, E3 ligases, and deubiquitinases exhibit cancer-specific mutation signatures and expression profiles that significantly influence tumor progression and patient outcomes. Our findings establish the UPS as a rich source of prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets across the cancer spectrum.

Ubiquitination represents the second most prevalent post-translational modification following phosphorylation, enacting a sophisticated enzymatic cascade mediated by ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3). This system facilitates the covalent attachment of ubiquitin molecules to substrate proteins, regulating diverse cellular processes including proteolysis, signal transduction, cell cycle progression, and DNA repair. The reverse reaction, deubiquitination, is catalyzed by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs). Mounting evidence indicates that dysregulation of ubiquitination enzymes constitutes a hallmark across multiple cancer types, driving oncogenic transformation, metabolic reprogramming, and therapeutic resistance.

Despite the established role of individual ubiquitination enzymes in specific cancer contexts, a systematic pan-cancer analysis of the entire ubiquitination apparatus has been lacking. This study fills this critical knowledge gap by providing a comprehensive characterization of genetic alterations and expression dysregulation across the complete ubiquitination enzyme spectrum. By employing integrated bioinformatics approaches on multi-omics data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and complementary datasets, we reveal consistent patterns of ubiquitination enzyme dysregulation that transcend individual cancer types, offering novel insights for prognostic stratification and therapeutic development.

Results

Expression Dysregulation of Ubiquitination Enzymes Across Cancers

Ubiquitination enzymes demonstrate consistent overexpression patterns across diverse cancer types compared to normal tissues. Pan-cancer analyses reveal significant elevation of key enzymes including UBE2T, UBA1, UBA6, and USP37 in multiple malignancies, with distinct patterns according to cancer and histological subtypes.

Table 1: Ubiquitination Enzyme Dysregulation Across Cancer Types

| Enzyme | Enzyme Class | Cancer Types with Overexpression | Associated Clinical Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| UBE2T | E2 conjugating enzyme | Pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, renal cell carcinoma, ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, retinoblastoma | Reduced overall and progression-free survival [19] [20] |

| UBA1 | E1 activating enzyme | Lung cancer, liver cancer, colorectal cancer | Poor prognosis, associated with advanced tumor stage [21] |

| UBA6 | E1 activating enzyme | Multiple cancer types | Correlation with tumor grade and stage [21] |

| USP37 | Deubiquitinating enzyme | Colorectal cancer, renal cancer, breast cancer, gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer | Poor prognosis, associated with immune infiltration [22] |

| CDC20 | E3 ligase | Lung adenocarcinoma | Poor patient prognosis, associated with immune cell infiltration [23] |

The ubiquitination-related prognostic signature (URPS), derived from ubiquitination enzyme expression patterns, effectively stratifies patients into distinct risk categories across multiple cancers including lung cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, urothelial cancer, and melanoma. High-risk URPS patients demonstrate significantly worse overall survival (HR = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.39–0.73, p < 0.001) in lung adenocarcinoma, with validation across six external cohorts confirming its prognostic value (HR = 0.58, 95% CI: 0.36–0.93, p<0.023) [24] [25].

Genetic Alterations in Ubiquitination Enzymes

Genomic analyses reveal distinctive mutation patterns across different classes of ubiquitination enzymes. The UBE2T gene displays "amplification" as its predominant genetic alteration, followed by mutations, with copy number variations occurring more frequently than single nucleotide variants across pan-cancer cohorts [19]. In lung adenocarcinoma, comprehensive analysis of E3 ubiquitin ligases identified 19 key genes with significant dysregulation, including CDC20, AURKA, CCNF, POC1A, and UHRF1, which are specifically overexpressed in tumor tissues and associated with poor prognosis [23].

ActiveDriver analysis of acetylation and ubiquitination sites demonstrates significant enrichment of cancer mutations in these functionally important regions, with stronger evolutionary conservation and accumulation in protein domains. Mutations in post-translational modification sites occur in known oncoproteins including TP53, AKT1, and IDH1, and accumulate in cancer-related processes such as cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, chromatin organization, and metabolism [26].

Table 2: Genetic Alteration Patterns in Ubiquitination Enzymes

| Genetic Alteration Type | Affected Enzymes | Functional Consequences | Analysis Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copy number variations | UBE2T, UBA1, UBA6 | Increased enzyme expression, enhanced oncogenic activity | GSCALite database analysis [19] [21] |

| Single nucleotide variants | Multiple E3 ligases, DUBs | Altered substrate specificity, enzyme activity modulation | ActiveDriver, cBioPortal analysis [22] [26] |

| Mutation hotspots in PTM sites | TP53, AKT1, IDH1, histone proteins | Disrupted regulatory switches, pathway dysregulation | ActiveDriver method [26] |

| Amplifications | CDC20, AURKA, UHRF1 | Enhanced proliferation, cell cycle disruption | TCGA pan-cancer analysis [23] |

Ubiquitination Enzymes in Cancer Signaling and Immune Regulation

Ubiquitination enzymes regulate crucial cancer-associated signaling pathways across different cancer types. The OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination axis modulates MYC pathway activity and influences oxidative stress responses, contributing to immunotherapy resistance and poor patient prognosis [24]. USP37 regulates lung cancer cell proliferation and the Warburg effect by deubiquitinating and stabilizing c-Myc expression [22]. In lung adenocarcinoma, CDC20 enrichment correlates with activation of G2/M checkpoint, mTORC1 signaling, oxidative phosphorylation, and glycolysis pathways [23].

The tumor immune microenvironment is significantly influenced by ubiquitination enzyme activity. Ubiquitination scores positively correlate with squamous or neuroendocrine transdifferentiation in adenocarcinoma and associate with macrophage infiltration patterns [24]. UBE2T expression shows significant associations with tumor immune markers, checkpoint genes, and immune cell infiltration, while USP37 expression correlates strongly with immune regulators, tumor mutational burden (TMB), and microsatellite instability (MSI) [19] [22]. E3 ubiquitin ligases in lung adenocarcinoma demonstrate negative correlations with B cells and dendritic cells, but positive associations with neutrophil infiltration [23].

Diagram 1: Ubiquitination Enzyme Regulation of Cancer Signaling and Immune Pathways. Ubiquitination enzymes modulate critical cancer-associated pathways including MYC signaling, mTORC1 activity, immune checkpoint expression, and tumor microenvironment (TME) infiltration, contributing to therapy resistance and metabolic reprogramming.

Prognostic and Predictive Value of Ubiquitination Signatures

Ubiquitination-based biomarkers demonstrate significant prognostic value across multiple cancer types. The ubiquitination-related risk score (URRS) developed for lung adenocarcinoma, incorporating DTL, UBE2S, CISH, and STC1 expression, effectively stratifies patients into high-risk and low-risk categories with distinct clinical outcomes [25]. High URRS patients exhibit worse prognosis, elevated PD-1/PD-L1 expression, increased tumor mutation burden (TMB), higher tumor neoantigen load (TNB), and distinctive tumor microenvironment scores (p < 0.001) [25].

The URPS signature shows predictive value for immunotherapy response, potentially identifying patients more likely to benefit from immune checkpoint inhibition across multiple solid tumors including lung cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, urothelial cancer, and melanoma [24]. Ubiquitination scores also associate with histological fate decisions in cancer cells, particularly squamous or neuroendocrine transdifferentiation in adenocarcinoma contexts [24].

Discussion

This pan-cancer analysis establishes ubiquitination enzymes as central players in cancer pathogenesis, with consistent patterns of genetic and expression dysregulation across diverse malignancies. The frequent overexpression of E1, E2, E3, and deubiquitinating enzymes, coupled with specific mutation signatures in functional domains, underscores the fundamental role of ubiquitination deregulation in oncogenic processes.

The prognostic significance of ubiquitination-related signatures across multiple independent cohorts highlights their potential clinical utility for risk stratification. Notably, the consistency of these signatures across cancer types suggests common mechanisms of ubiquitination-mediated oncogenesis that transcend tissue-of-origin specificities. The association between ubiquitination signatures and immune microenvironment composition further reinforces the interconnected nature of protein homeostasis and anti-tumor immunity.

From a therapeutic perspective, the ubiquitin-proteasome system presents attractive targeting opportunities. The success of proteasome inhibitors in hematological malignancies has established proof-of-concept for targeting protein degradation pathways in cancer. Our findings suggest that specific ubiquitination enzymes, particularly those with recurrent genetic alterations or consistent overexpression patterns, may represent promising targets for drug development. The predictive value of ubiquitination signatures for immunotherapy response merits particular attention, as this may enable better patient selection for immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the substrate specificities of dysregulated ubiquitination enzymes, developing isoform-selective inhibitors, and exploring combination therapies targeting ubiquitination pathways alongside conventional treatments. The integration of ubiquitination signatures into clinical trial designs may facilitate personalized treatment approaches based on individual tumor ubiquitination profiles.

Methods

Data Collection and Processing

We extracted RNA sequencing data and clinical information from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) pan-cancer cohort, encompassing 33 cancer types and normal tissue data from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) database [22]. A total of 966 ubiquitination-related genes (URGs), including ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1s), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2s), and ubiquitin-protein ligases (E3s), were collected from the iUUCD 2.0 database [25]. Additional validation datasets were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), including GSE30219, GSE135222, GSE126044, GSE183924, GSE53625, GSE44001, and GSE56303 [24].

Ubiquitination Enzyme Expression Analysis

Differential expression analysis of ubiquitination enzymes between tumor and normal tissues was performed using the TIMER 2.0 database, with statistical significance assessed via Wilcoxon test [19]. Protein expression patterns were validated using the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) database [21] [22]. Consensus clustering analysis employing the "KM" method with Euclidean distance was applied to identify distinct molecular subtypes based on URG expression patterns, implemented through the "ConsensusClusterPlus" R package with maxK=5, reps=1000, pItem=0.8, pFeature=1 [25].

Genetic Alteration Analysis

Genomic alterations in ubiquitination enzymes were analyzed using cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics, examining mutation frequencies, copy number variations, and structural rearrangements across cancer types [22]. The GSCA database facilitated analysis of single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and copy number variations (CNVs) [19] [21]. Site-specific mutation enrichment in post-translational modification sites was assessed using ActiveDriver, which employs a Poisson regression model accounting for protein disorder, direct and flanking PTM residues, and site density [26].

Survival and Prognostic Analysis

Survival analysis was conducted using univariate Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier methods, with patients stratified into high and low expression groups based on median expression values of target ubiquitination enzymes [24] [22]. The ubiquitination-related risk score (URRS) was developed through integration of univariate Cox regression, Random Survival Forest algorithm (variable importance >0.25), and LASSO Cox regression analysis [25]. Time-dependent ROC curves evaluated the predictive accuracy of URRS for one-, three-, and five-year survival endpoints.

Immune Infiltration Analysis

Correlations between ubiquitination enzyme expression and immune cell infiltration were assessed using the CIBERSORT algorithm to estimate the relative proportions of 22 immune cell types [21]. The TISIDB database facilitated analysis of associations with immune subtypes and checkpoint expression [21]. ESTIMATE algorithm was employed to calculate immune scores, stromal scores, and estimate scores in the tumor microenvironment [25].

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was performed using the "clusterProfiler" R package with the hallmark gene set file (h.all.v7.4.symbols.gmt) from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) [22]. Significance thresholds were set at nominal p-value <0.05 and false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05 [23]. Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes analyses identified biological processes and pathways enriched in ubiquitination enzyme-high tumors.

Diagram 2: Computational Analysis Workflow. The integrated bioinformatics pipeline encompasses data acquisition from TCGA and GEO databases, ubiquitination enzyme annotation, multi-dimensional analysis of molecular features, and validation in independent cohorts.

Experimental Validation

For key ubiquitination enzymes, experimental validation was performed using pancreatic cancer cell lines (PANC1, ASPC, BXPC3, MIA2, SW1990, CAPAN1) and normal pancreatic epithelial cells (HPDE) [19]. Western blotting was conducted using established protocols with primary antibodies specific to target proteins (e.g., UBE2T at 1:2,000 dilution) and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5,000) [19]. Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq kits with β-actin as internal control, calculating relative expression via the 2−ΔΔCq method [19] [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Enzyme Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Application | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| iUUCD 2.0 Database | Comprehensive repository of ubiquitination enzymes | Identification of E1, E2, E3 enzymes and DUBs for analysis | http://iuucd.biocuckoo.org/ [25] |

| TCGA Pan-Cancer Data | Multi-omics data across 33 cancer types | Differential expression, survival analysis, genomic alteration studies | https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga [22] |

| UALCAN Database | TCGA data analysis portal | Protein and mRNA expression analysis in cancer vs. normal tissues | http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/ [19] [21] |

| cBioPortal | Visualization and analysis of cancer genomics data | Genetic alteration frequency and patterns across cancer types | http://cbioportal.org [22] |

| Human Protein Atlas | Tissue immunohistochemistry database | Protein expression validation in normal and cancer tissues | https://www.proteinatlas.org/ [21] [22] |

| TISIDB Database | Tumor-immune system interaction database | Analysis of associations with immune subtypes and infiltration | http://cis.hku.hk/TISIDB/ [21] |

| ConsensusClusterPlus | Unsupervised clustering package | Identification of molecular subtypes based on expression patterns | R Bioconductor package [25] |

| CIBERSORT Algorithm | Deconvolution of immune cell fractions | Estimation of immune cell infiltration from expression data | https://cibersort.stanford.edu/ [21] |

Ubiquitination, a fundamental post-translational modification, regulates protein stability, localization, and function through a coordinated enzymatic cascade involving E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes, E3 ligases, and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) [27]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) degrades approximately 80-90% of intracellular proteins, maintaining cellular homeostasis and genomic integrity [1] [20]. Dysregulation of ubiquitination pathways represents a hallmark of cancer pathogenesis, influencing critical processes including cell cycle progression, DNA damage repair, immune evasion, and therapeutic resistance [27] [28].

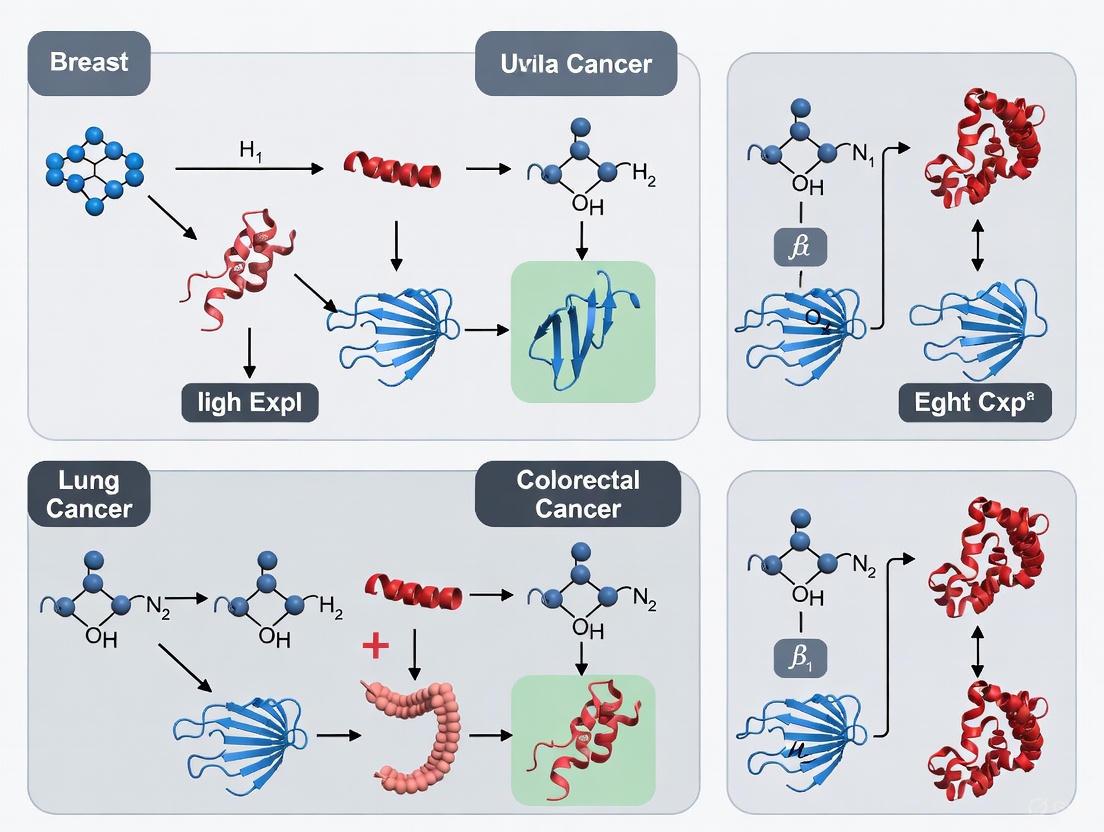

While core ubiquitination machinery is conserved across tissues, emerging evidence reveals remarkable tissue-specificity in how ubiquitination pathways are altered in different cancers. This comparative analysis examines ubiquitination pathway alterations across major cancer types—including cervical, lung, breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers—to identify both shared and tissue-specific molecular patterns. By integrating recent transcriptomic studies, risk model analyses, and mechanistic investigations, this review aims to elucidate the tissue-specific ubiquitination signatures that drive cancer progression and influence therapeutic outcomes, providing a foundation for developing targeted interventions that exploit these pathway-specific vulnerabilities.

Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitination-Related Gene Signatures Across Cancers

Table 1: Ubiquitination-Related Biomarkers and Their Prognostic Value Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Key Ubiquitination-Related Biomarkers | Risk Model Performance (AUC) | Biological Functions Affected | Clinical Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical Cancer | MMP1, RNF2, TFRC, SPP1, CXCL8 [1] | 1/3/5-year AUC >0.6 [1] | Immune infiltration, Angiogenesis, Extracellular matrix organization [1] | Survival prediction, Immune checkpoint expression [1] |

| Lung Adenocarcinoma | DTL, UBE2S, CISH, STC1 [29] | Validated in 6 external cohorts (HR=0.58) [29] | Cell proliferation, Epithelial-mesenchymal transition, Immune evasion [29] | Tumor mutation burden, PD-1/L1 expression, Chemotherapy response [29] |

| Breast Cancer | FBXL6, PDZRN3, RNF126 [30] [27] | Multiple validation cohorts [30] | DNA damage repair, ATR-CHK1 pathway, Cell cycle regulation [30] | Therapeutic resistance, Immune microenvironment, Patient survival [30] |

| Colorectal Cancer | HSPA1A, USP21, USP44, USP51 [31] [28] | Strong prognostic value [31] | Wnt/β-catenin signaling, HIF1A stabilization, Chemoresistance [31] [28] | Lymph node metastasis, Recurrence, Post-chemotherapy survival [31] |

| Prostate Cancer | USP21, UBE2T, EZH2, FOXD1 [32] [20] | Independent validation [32] | Androgen receptor signaling, HIF1-α transcription, DNA repair [32] [20] | Castration resistance, Metastatic progression, Therapeutic vulnerability [32] |

The development of ubiquitination-related gene signatures has revealed both common and cancer-specific prognostic biomarkers across malignancies. In cervical cancer, a 5-gene signature (MMP1, RNF2, TFRC, SPP1, and CXCL8) demonstrates significant predictive value for patient survival, with particular strength in forecasting 1-, 3-, and 5-year outcomes [1]. These biomarkers predominantly influence immune modulation and extracellular matrix remodeling, with upregulated expression of MMP1, TFRC, and CXCL8 confirmed in tumor tissues [1].

Lung adenocarcinoma exhibits a distinct 4-gene ubiquitination signature (DTL, UBE2S, CISH, STC1) that effectively stratifies patients into high- and low-risk groups [29]. Notably, this signature shows robust performance across six independent validation cohorts, with high-risk patients demonstrating elevated tumor mutation burden, increased PD-1/L1 expression, and differential sensitivity to conventional chemotherapeutics [29].

Breast cancer ubiquitination patterns reveal substantial heterogeneity, with research focusing particularly on triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and its associated immunological and metabolic aspects [27]. An 8-gene prognostic signature has been developed, with FBXL6 and PDZRN3 experimentally validated as critical regulators of breast cancer development through in vitro and in vivo models [30].

Colorectal cancer investigations have identified HSPA1A as a central regulator among ubiquitination-related genes, with knockdown experiments demonstrating significant inhibition of cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion both in vitro and in vivo [31]. Multiple ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), including USP21, USP44, and USP51, contribute to colorectal cancer progression through regulation of key signaling pathways including Wnt/β-catenin and HIF1A [28].

Prostate cancer studies highlight USP21 as a key oncogenic driver that correlates with poor prognosis [32]. USP21 mediates deubiquitination and stabilization of YBX1, which in turn transactivates HIF1A expression, creating a pro-tumorigenic signaling axis that promotes disease progression [32].

Tissue-Specific Ubiquitination Pathway Alterations

Cervical and Breast Cancer: Immune and Angiogenic Regulation

In cervical cancer, ubiquitination pathways predominantly influence tumor immunity and angiogenesis. The identified ubiquitination-related biomarkers (MMP1, RNF2, TFRC, SPP1, and CXCL8) significantly impact immune cell infiltration patterns, with notable differences observed in memory B cells, M0 macrophages, and multiple T-cell populations between high- and low-risk patient groups [1]. Additionally, immune checkpoint expression varies significantly according to ubiquitination risk profiles, suggesting potential implications for immunotherapy responsiveness [1].

Breast cancer ubiquitination pathways demonstrate strong associations with hormone receptor status and therapeutic resistance mechanisms. The ubiquitin-related gene signature effectively stratifies patients based on estrogen receptor status, AJCC stages, and nodal involvement [30]. Furthermore, risk groups show differential sensitivity to endocrine therapies (tamoxifen, fulvestrant), chemotherapeutic agents (cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, paclitaxel, epirubicin), and targeted therapies (gefitinib, lapatinib), highlighting the clinical utility of ubiquitination-based classification [30].

Lung Cancer: KCTD10/β-catenin/PD-L1 Axis

In lung cancer, the KCTD10 protein exemplifies tissue-specific ubiquitination regulation by functioning as a novel E3 ligase adaptor that promotes β-catenin degradation through K48-linked ubiquitin chains [33]. This mechanism has profound implications for both tumor progression and immunotherapy response. Reduced KCTD10 expression in lung cancer tissues leads to β-catenin accumulation, resulting in enhanced PD-L1 transcription and immune evasion [33]. This establishes a direct molecular connection between ubiquitination pathways and immune checkpoint regulation.

The therapeutic potential of targeting this axis was demonstrated through combination experiments where KCTD10 overexpression synergized with anti-PD-1 antibodies to suppress lung cancer progression and brain metastatic colonization in murine models [33]. Additionally, vascular endothelial cell-specific knockout of Kctd10 promoted lung cancer metastasis and tumor angiogenesis through β-catenin signaling, highlighting the importance of ubiquitination regulation within the tumor microenvironment [33].

Gastrointestinal Cancers: Wnt/β-catenin and HIF1A Signaling

Colorectal and prostate cancers share common ubiquitination-mediated regulation of central signaling pathways, albeit through distinct molecular mechanisms. In colorectal cancer, multiple ubiquitin-specific proteases including USP44 and USP38 regulate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway through deubiquitination and stabilization of Axin1 and HMX3, respectively [28]. Additionally, USP51 stabilizes HIF1A through deubiquitination, creating a positive feed-forward loop that maintains cancer stemness and chemoresistance [28].

Prostate cancer employs a different mechanism wherein USP21 deubiquitinates and stabilizes YBX1, which subsequently enhances HIF1A transcription [32]. This USP21/YBX1/HIF1-α axis promotes prostate cancer malignancy and represents a promising therapeutic target, with pharmacological inhibition of USP21 using Bay-805 demonstrating significant antitumor efficacy in experimental models [32].

Table 2: Tissue-Specific Ubiquitination Pathway Alterations and Functional Consequences

| Cancer Type | Key Ubiquitination Pathways | Primary Molecular Mechanisms | Downstream Effects | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical Cancer | Immune checkpoint regulation [1] | Ubiquitination-related biomarker expression (MMP1, RNF2, TFRC, SPP1, CXCL8) [1] | Altered immune cell infiltration, Angiogenesis promotion [1] | Immunotherapy response prediction [1] |

| Lung Cancer | KCTD10/β-catenin/PD-L1 axis [33] | KCTD10-mediated β-catenin ubiquitination and degradation [33] | PD-L1 downregulation, Enhanced immune surveillance [33] | Synergy with anti-PD-1 therapy [33] |

| Breast Cancer | DNA damage response, Cell cycle regulation [30] | RNF126-mediated ATR-CHK1 pathway regulation [30] | Radiation sensitivity, Proliferation control [30] | Radiation sensitization, Targeted therapy [30] |

| Colorectal Cancer | Wnt/β-catenin, HIF1A stabilization [31] [28] | USP-mediated deubiquitination of pathway components [28] | Cancer stemness maintenance, Chemoresistance [28] | USP inhibitor development [28] |

| Prostate Cancer | USP21/YBX1/HIF1-α axis [32] | USP21-mediated YBX1 deubiquitination and stabilization [32] | HIF1-α transactivation, Metabolic reprogramming [32] | Bay-805 (USP21 inhibitor) application [32] |

Methodologies for Ubiquitination Pathway Analysis

Bioinformatics Approaches for Ubiquitination Signature Development

The identification of ubiquitination-related gene signatures across cancer types employs standardized bioinformatics workflows. Typically, ubiquitination-related genes are compiled from specialized databases such as iUUCD 2.0 or Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB), yielding approximately 763-1,006 genes encompassing E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes, E3 ligases, and deubiquitinating enzymes [29] [30].

Differentially expressed ubiquitination-related genes between tumor and normal tissues are identified using packages such as DESeq2 or limma, with standard thresholds of |log2FoldChange| > 0.5-0.585 and p-value < 0.05 [1] [31]. Prognostic gene selection typically employs univariate Cox regression analysis followed by feature refinement using Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) Cox regression and Random Survival Forests algorithms [29] [31]. Risk scores are calculated using the formula: Risk score = Σ(coefficient of genei × expression of genei), with patients stratified into high- and low-risk groups based on median risk score thresholds [29].

Validation procedures include internal validation through cross-validation approaches and external validation using independent cohorts from databases such as GEO and TCGA [29] [30]. Model performance is assessed through Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, and calculation of concordance indices (C-index) [1] [29].

Experimental Validation Techniques

Functional validation of ubiquitination-related biomarkers employs standardized experimental approaches both in vitro and in vivo. Gene expression validation typically utilizes Reverse Transcription-Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) and western blotting on paired tumor and normal tissues [1] [20]. For functional characterization, gene manipulation through small interfering RNA (siRNA) or short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated knockdown and cDNA overexpression are performed in relevant cancer cell lines [30] [32].

Phenotypic assays assess proliferation (Cell Counting Kit-8), migration (wound healing), and invasion (Transwell chambers with Matrigel coating) [31] [30]. In vivo validation employs subcutaneous xenograft models for tumor growth assessment and tail vein injection models for metastatic potential evaluation [32] [30]. Zebrafish xenograft models provide additional platforms for assessing tumor growth and metastatic behavior [31].

Mechanistic studies utilize co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) combined with mass spectrometry to identify protein-protein interactions, while ubiquitination assays determine specific ubiquitin linkage types (K48, K63, etc.) [33] [32]. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and dual-luciferase reporter assays elucidate transcriptional regulation mechanisms [32].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Pathway Studies

| Reagent/Resource Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Tools | DESeq2, limma, ConsensusClusterPlus, CIBERSORT, ESTIMATE [1] [29] [30] | Differential expression analysis, Clustering, Immune infiltration estimation | Parameter optimization, Multiple testing correction, Batch effect adjustment |

| Databases | TCGA, GEO, iUUCD 2.0, MSigDB, UALCAN, GEPIA2 [1] [29] [30] | Data retrieval, Ubiquitination gene compilation, Pan-cancer analysis | Data normalization, Platform compatibility, Clinical annotation quality |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | Lipofectamine 3000, Specific antibodies (KCTD10, β-catenin, PD-L1, USP21), HA-tagged ubiquitin plasmids [33] [32] | Gene manipulation, Protein detection, Ubiquitination assays | Transfection efficiency, Antibody specificity, Ubiquitin chain linkage types |

| Cell Culture Models | Cancer cell lines (A549, HCT-116, DU145, MCF7), Patient-derived organoids [33] [31] [32] | In vitro validation, Drug screening, Mechanistic studies | Authentication, Mycoplasma testing, Physiological relevance |

| In Vivo Models | Mouse xenograft models, Zebrafish xenografts, Conditional knockout mice (Kctd10flox/floxCDH5CreERT2/+) [33] [31] [30] | Tumor growth assessment, Metastasis studies, Microenvironment analysis | Immunocompetent vs. deficient models, Orthotopic vs. subcutaneous implantation |

| Specialized Assays | Co-immunoprecipitation, Ubiquitination assays, Chromatin immunoprecipitation, Dual-luciferase reporter [33] [32] | Protein interaction mapping, Ubiquitination detection, Transcriptional regulation | Appropriate controls, Quantitative normalization, Specificity validation |

Ubiquitination Pathway Visualization and Signaling Networks

The ubiquitination signaling network illustrates the coordinated enzymatic cascade that regulates protein fate in cancer cells. The core machinery comprises E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes (including UBE2T and UBE2S), E3 ligases (such as RNF2, KCTD10, and FBXL6), and deubiquitinating enzymes (including USP21, USP44, and USP51) [20] [29] [33]. These enzymes collectively determine the ubiquitination status of key cancer-relevant substrates including β-catenin, YBX1, HIF1-α, and p53 [33] [32] [29].

Tissue-specific ubiquitination patterns emerge through selective expression and regulation of specific enzyme-substrate pairs. In lung cancer, KCTD10 acts as an E3 ligase adaptor that promotes β-catenin degradation, subsequently reducing PD-L1 transcription and enhancing immune surveillance [33]. Conversely, in prostate cancer, USP21 stabilizes YBX1 through deubiquitination, leading to transactivation of HIF1-α and promotion of malignant progression [32]. These tissue-specific mechanisms highlight how the core ubiquitination machinery is co-opted in distinct ways across cancer types to drive pathogenesis.

This comparative analysis reveals that while the core ubiquitination machinery is universally present across tissues, its deregulation in cancer follows distinct tissue-specific patterns. Cervical cancer ubiquitination signatures predominantly influence immune modulation, while lung cancer exhibits prominent KCTD10/β-catenin/PD-L1 regulatory axis alterations. Breast cancer ubiquitination pathways demonstrate strong associations with hormone responsiveness and DNA damage repair, whereas gastrointestinal and prostate cancers share common themes in Wnt/β-catenin and HIF1A pathway regulation through distinct molecular mechanisms.

The development of ubiquitination-related gene signatures provides robust prognostic tools across cancer types, with consistent demonstration of predictive value for patient survival, therapeutic response, and tumor microenvironment characteristics. These signatures offer clinical utility in risk stratification, treatment selection, and patient prognosis.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the precise molecular mechanisms through which identified ubiquitination-related biomarkers influence cancer progression, particularly in the context of therapy resistance. The development of targeted therapies exploiting specific ubiquitination pathway vulnerabilities, such as USP21 inhibition in prostate cancer or KCTD10 modulation in lung cancer, represents a promising frontier. Additionally, integrating ubiquitination signatures with other molecular profiling data may enable more comprehensive classification systems that reflect the complex interplay between ubiquitination pathways and other cancer hallmarks.

As our understanding of tissue-specific ubiquitination patterns deepens, the translation of these insights into clinical practice promises to enhance personalized cancer therapy through improved patient stratification and targeted intervention strategies.

Ubiquitination represents a crucial post-translational modification process that governs virtually all cellular functions through its ability to regulate protein stability, localization, and activity. This sophisticated enzymatic cascade involves the coordinated action of ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3), which collectively tag target proteins with ubiquitin molecules [34] [35]. The reverse process, deubiquitination, is mediated by deubiquitinases (DUBs) that remove ubiquitin chains, providing dynamic control over protein fate [34]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is responsible for degrading 80-90% of intracellular proteins, establishing it as a master regulator of cellular homeostasis [24] [1].

In cancer biology, ubiquitination has emerged as a pivotal mechanism governing hallmark capabilities including uncontrolled proliferation, evasion of apoptosis, and metabolic reprogramming. Dysregulation of ubiquitination pathways drives tumorigenesis through multiple mechanisms: stabilization of oncoproteins, degradation of tumor suppressors, and rewiring of signaling networks [35] [36]. The development of therapies targeting ubiquitination components, particularly proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs), has created unprecedented opportunities for cancer intervention [37] [35]. This comparative analysis examines how ubiquitination machinery orchestrates key cancer hallmarks across different tumor types, providing a foundation for developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Molecular Machinery of Ubiquitination: Components and Mechanisms

The ubiquitination cascade initiates with E1 activation using ATP, followed by ubiquitin transfer to E2 enzymes, and culminates in substrate-specific modification by E3 ligases [34]. The human genome encodes approximately 8 E1 enzymes, 39 E2 enzymes, and over 600 E3 ligases, creating tremendous specificity in substrate recognition [37]. Deubiquitinases (approximately 100 in humans) provide counter-regulation by removing ubiquitin chains [34]. This sophisticated system generates diverse ubiquitin chain topologies through different linkage types (K48, K63, K11, K27, K29, M1), each encoding distinct functional outcomes [35].

Table 1: Major Ubiquitination Linkage Types and Their Functional Consequences in Cancer

| Linkage Type | Primary Function | Cancer-Relevant Examples |

|---|---|---|

| K48-linked chains | Proteasomal degradation | Degradation of tumor suppressors like p53 [35] |

| K63-linked chains | Signal transduction, DNA repair | NF-κB pathway activation; FBXO22 inhibits LKB1 via K63 ubiquitination in NSCLC [35] |

| K11-linked chains | Cell cycle regulation | UBE2S stabilizes β-catenin via K11 ubiquitination in colorectal cancer [35] |

| K27-linked chains | Immune regulation, mitophagy | MARCH5 degrades γC through K27 ubiquitination to inhibit immune function [35] |

| K29-linked chains | Tumor progression | HECTD3 mediates K29 ubiquitination of c-Myc in gastric cancer [35] |

| M1-linear chains | Innate immune signaling | STAT3 self-regulation in glioblastoma [35] |

The following diagram illustrates the core ubiquitination machinery and its regulatory complexity in cancer cells:

Ubiquitination in Apoptosis Regulation: Balancing Cell Survival and Death

Ubiquitination exerts precise control over apoptotic pathways by regulating the stability and function of key pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic factors. The Bcl-2 family proteins, central regulators of mitochondrial apoptosis, are prominent ubiquitination substrates. Pro-apoptotic Bax undergoes ubiquitination at K21, which modulates its activity and sensitivity to TRAIL-induced apoptosis in human colon cancer HCT116 cells [35]. The deubiquitinase inhibitor Aumdubicin induces Bax-dependent apoptosis in lung cancer cells A549 and H1299 by stabilizing Bax protein levels [35].

Anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 members are similarly regulated by ubiquitination. The E3 ligase SCF^FBXO10 promotes Bcl-2 degradation, while USP9X stabilizes Mcl-1 through deubiquitination [35]. The interplay between ubiquitinating and deubiquitinating enzymes creates a dynamic equilibrium that determines cellular fate. Dysregulation of this balance enables cancer cells to evade programmed cell death, contributing to tumor progression and therapy resistance. USP7 and USP1 overexpression, frequently observed in cancers, stabilizes anti-apoptotic proteins and promotes defective DNA repair, respectively, fostering tumorigenesis [35].

Table 2: Ubiquitination Regulation of Apoptotic Factors in Cancer

| Apoptotic Regulator | Ubiquitination Enzyme | Effect | Cancer Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bax | Unknown E3 ligase | K21 ubiquitination modulates activity | Colon cancer HCT116 cells [35] |

| Bcl-2 | SCF^FBXO10 E3 ligase | Promotes degradation | Hematological malignancies [35] |

| Mcl-1 | USP9X deubiquitinase | Stabilizes protein | Multiple cancers [35] |

| FLIP | Cullin-3 E3 ligase | Promotes degradation | Influences TRAIL sensitivity [35] |

| Caspase-8 | Cullin-3 E3 ligase | Regulates activity | Modulates apoptosis initiation [35] |

The complexity of apoptotic regulation through ubiquitination is visualized in the following pathway:

Metabolic Reprogramming Through Ubiquitination: The Lipid Metabolism Nexus

Cancer cells extensively rewire their metabolic pathways to support rapid proliferation, and ubiquitination serves as a key regulatory mechanism in this reprogramming. Lipid metabolism represents a particularly crucial target, with ubiquitination governing the stability and activity of multiple enzymes involved in lipid synthesis, storage, and utilization [34]. Adenosine triphosphate citrate lyase (ACLY), which links glycolysis to lipid metabolism by converting citrate to acetyl-CoA, undergoes sophisticated ubiquitination regulation in lung cancer. ARHGEF3 enhances ACLY stability by reducing acetylation at Lys17 and Lys86, leading to dissociation from the E3 ligase NEDD4 [34]. Conversely, Cullin 3 interacts with ACLY through adaptor protein KLHL25, promoting ubiquitination and degradation to inhibit lipid synthesis and tumor growth [34].

Fatty acid synthase (FASN), a pivotal enzyme in de novo lipogenesis, is similarly regulated by ubiquitination. In mouse livers, phosphorylated COP1 accumulates in the cytoplasm and binds FASN through Shp2, forming a FASN-Shp2-COP1 complex that mediates FASN ubiquitination and degradation [34]. Additionally, deacetylation by HDAC3 enhances FASN binding to E3 ligase TRIM21, reducing lipogenesis and inhibiting cancer cell growth [34]. The tumor suppressor SPOP, an E3 ubiquitin ligase mutated in several cancers, regulates lipid metabolism by reducing FASN expression and fatty acid synthesis in prostate cancer [34] [35].

The regulation of lipid metabolism enzymes through ubiquitination is summarized in the following table:

Table 3: Ubiquitination Regulation of Lipid Metabolism Enzymes in Cancer

| Metabolic Enzyme | Regulatory Mechanism | Biological Outcome | Cancer Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACLY | ARHGEF3 reduces acetylation, dissociating from E3 ligase NEDD4 | Enhanced stability, increased lipogenesis | Lung cancer [34] |

| ACLY | Cullin3-KLHL25 complex mediates ubiquitination | Degradation, inhibited lipid synthesis | Lung cancer [34] |

| ACLY | PCAF acetylates K540/K546/K554, reducing UBR4 binding | Enhanced stability, increased acetyl-CoA production | Lung cancer [34] |

| FASN | COP1-Shp2 complex mediates ubiquitination | Degradation, reduced lipogenesis | Liver cancer models [34] |

| FASN | HDAC3 deacetylation enhances TRIM21 binding | Degradation, reduced cancer growth | Multiple cancers [34] |

| FASN | SPOP E3 ligase mediates ubiquitination | Degradation, tumor suppression | Prostate cancer [34] |

The interconnected regulation of metabolic enzymes through ubiquitination is depicted below:

Proliferation and Cell Cycle Control: Ubiquitination as the Conductor

The ubiquitin-proteasome system exerts masterful control over cell cycle progression through targeted degradation of cyclins, CDK inhibitors, and other regulatory proteins. The anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) and SCF (Skp1-Cullin-F-box) complexes represent two major E3 ligase families that coordinate the precise timing of phase transitions [35]. Dysregulation of these systems drives uncontrolled proliferation, a fundamental cancer hallmark.

Ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes have emerged as critical players in oncogenic proliferation across cancer types. UBE2T demonstrates elevated expression in multiple tumors including breast cancer, renal cell carcinoma, ovarian cancer, and retinoblastoma, where it correlates with reduced overall and progression-free survival [38]. Functional studies connect UBE2T to key cellular processes including proliferation, invasion, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition through pathways such as cell cycle regulation, ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, p53 signaling, and mismatch repair [38].

Similarly, UBE2S promotes tumor progression in skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM) and other malignancies. Single-cell analysis reveals UBE2S involvement in 14 functional states including tumor cell stemness, invasion, metastasis, proliferation, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition [39]. The correlation between UBE2S expression and immune cell infiltration further highlights its multifaceted role in shaping the tumor microenvironment to favor cancer growth [39].

Comprehensive pan-cancer analyses have identified conserved ubiquitination-related prognostic signatures (URPS) that effectively stratify patients into distinct risk categories across multiple cancer types [24]. These signatures reveal that ubiquitination score positively correlates with squamous or neuroendocrine transdifferentiation in adenocarcinoma, influencing both tumor histology and therapeutic response [24]. The OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination axis specifically modulates MYC pathway activity and oxidative stress response, ultimately driving immunotherapy resistance and poor patient prognosis [24].

Experimental Approaches and Research Reagent Solutions

The investigation of ubiquitination in cancer relies on sophisticated methodological approaches and specialized research tools. The following section details key experimental protocols and reagent solutions essential for advancing this field.

Key Experimental Protocols

Ubiquitination-Regulated Pathway Analysis: The identification of OTUB1-TRIM28 regulation of MYC pathway exemplifies rigorous ubiquitination research [24]. This discovery involved integrated analysis of 23 datasets across six cancer types from TCGA and GEO databases, followed by experimental validation. The methodological workflow included:

- Construction of ubiquitination regulatory networks using correlation coefficient matrices with significance screening (p<0.05)

- Prognostic analysis via Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier survival methods

- Functional enrichment analysis using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

- Protein-protein interaction analysis using Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins database

- Validation through in vivo and in vitro models confirming the functional role of identified ubiquitination pairs

Prognostic Signature Development: The creation of ubiquitination-related prognostic signatures (URPS) employs standardized bioinformatics pipelines [24] [37] [1]:

- Differential expression analysis of ubiquitination-related genes between tumor and normal tissues using DESeq2 with thresholds (p<0.05 and |log2Fold Change|>0.5)

- Univariate Cox regression to identify survival-associated ubiquitination genes

- LASSO Cox regression for feature selection and overfitting prevention

- Risk score calculation using the formula: Risk score = Σ(Coefi × Expressioni)

- Stratification of patients into high-risk and low-risk groups based on optimal risk score threshold

- Validation using independent cohorts (e.g., GSE165808 and GSE26712 for ovarian cancer) [37]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies in Cancer

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Block degradation of ubiquitinated proteins; induce apoptosis through protein accumulation | Clinical use in multiple myeloma; research tool for UPS inhibition [35] |

| E3 Ligase Inhibitors | MDM2 inhibitors, SCF complex inhibitors | Interfere with specific substrate ubiquitination; modulate signaling pathways | Research tools for validating E3-substrate relationships [35] |

| Deubiquitinase Inhibitors | Aumdubicin, USP7 inhibitors | Promote substrate degradation or alter regulatory functions; induce Bax-dependent apoptosis | Aumdubicin induces apoptosis in lung cancer cells [35] |

| PROTACs | Various targeted degraders | Facilitate degradation of traditionally "undruggable" targets; overcome drug resistance | Target 50+ ubiquitination-related genes; clinical development [37] [35] |

| Ubiquitination-Related Antibodies | Anti-UBE2T, Anti-UBE2S, Anti-K48/K63 ubiquitin | Detect expression, localization, and ubiquitination status of targets | Validation of UBE2T protein expression in pancreatic cancer lines [38] |

| Cell Line Models | A549, HCT116, H1299, cancer-specific panels | Functional validation of ubiquitination mechanisms | Bax ubiquitination studies in HCT116; apoptosis assays in A549/H1299 [35] |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Perspectives

The targeting of ubiquitination pathways has yielded clinically effective cancer therapies, most notably proteasome inhibitors for hematological malignancies. However, the emerging repertoire of ubiquitination-targeted therapeutics continues to expand with several promising approaches:

PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras): These bifunctional molecules represent a breakthrough therapeutic modality, simultaneously engaging E3 ubiquitin ligases and target proteins of interest to induce selective degradation [37] [35]. Their advantages include reduced drug dosage requirements, prolonged therapeutic effects, minimized toxicity, and ability to overcome drug resistance [37]. Currently, PROTACs target more than 50 ubiquitination-related genes, with several candidates in clinical development [37].