Cross-Species Ubiquitination Conservation in Cancer: From Evolutionary Pathways to Therapeutic Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the remarkable evolutionary conservation of the ubiquitin system and its critical implications for cancer biology and therapy.

Cross-Species Ubiquitination Conservation in Cancer: From Evolutionary Pathways to Therapeutic Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the remarkable evolutionary conservation of the ubiquitin system and its critical implications for cancer biology and therapy. We explore foundational concepts of ubiquitin pathway conservation from archaea to humans, examine cutting-edge computational and experimental methods for cross-species ubiquitination analysis, address key challenges in translating findings across species boundaries, and validate conserved ubiquitination mechanisms through pan-cancer genomic studies. By synthesizing insights from model organisms and human cancers, this review establishes a framework for leveraging evolutionary conservation to identify novel therapeutic targets and advance drug development strategies for cancer treatment.

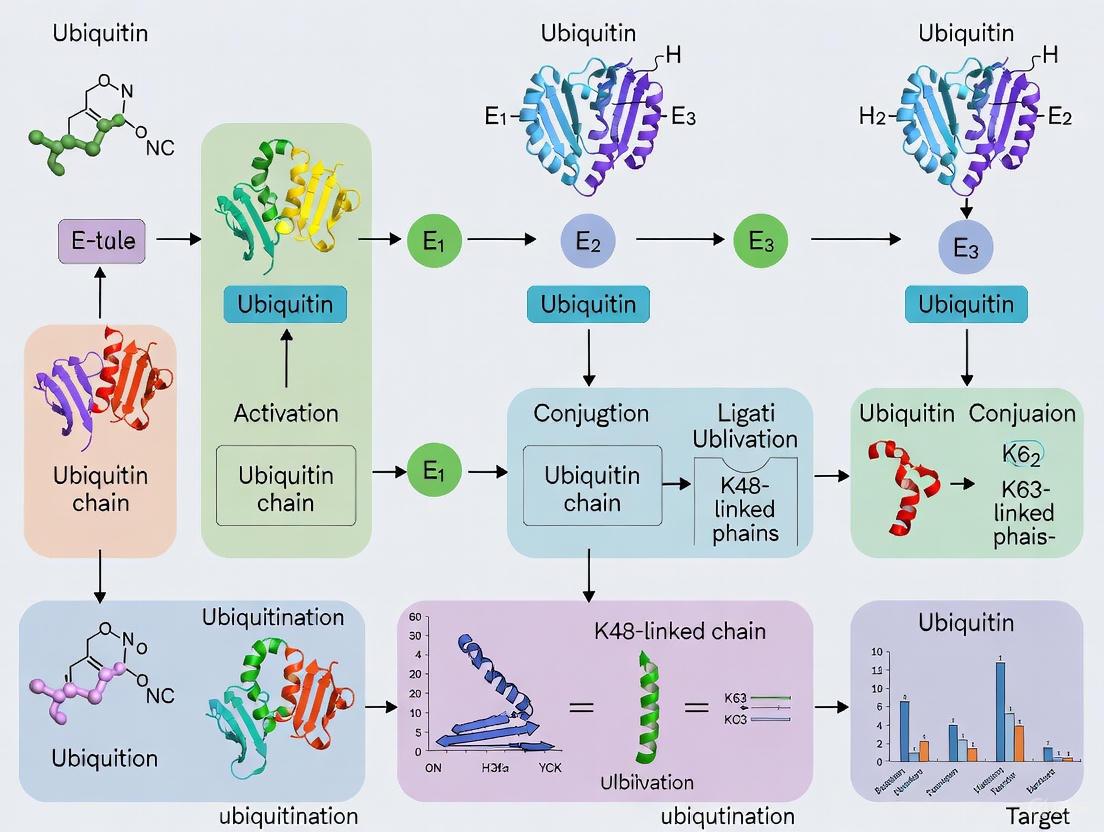

The Deep Evolutionary Roots of Ubiquitin Signaling in Cancer

Ubiquitin is a small, 76-amino-acid protein that is highly conserved across all eukaryotic species, playing a fundamental role in regulating cellular processes by tagging proteins for degradation or functional modification. This post-translational modification, known as ubiquitination, affects nearly every aspect of cell biology, from cell cycle progression and DNA repair to immune responses. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) functions through a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes that covalently attach ubiquitin to target proteins. The specificity and outcomes of ubiquitination are determined by the number of ubiquitin molecules attached (mono- versus polyubiquitination) and the type of linkage between them, with different chain topologies triggering distinct cellular responses. What makes ubiquitin particularly remarkable from an evolutionary perspective is its extraordinary sequence conservation; the amino acid sequence of ubiquitin is virtually identical across the entire eukaryotic domain, from yeast to humans. This extreme conservation suggests that nearly every residue in ubiquitin is critical for its function, with minimal tolerance for sequence variation. This guide explores the experimental evidence validating this conservation and examines its critical implications for cancer research and therapeutic development.

Quantitative Evidence of Ubiquitin Sequence Conservation

Ubiquitin's sequence has remained essentially unchanged throughout eukaryotic evolution due to strong functional constraints. The structural and functional features that underpin this conservation are quantified below.

Table 1: Key Structural and Functional Features of Ubiquitin Under Evolutionary Constraint

| Feature | Description | Functional Implication | Conservation Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-grasp Fold | A five-stranded mixed β-sheet surrounding a central α-helix [1]. | Essential for structural integrity and interaction with partner proteins. | Extremely High (Maintained across all eukaryotes) |

| Lysine Residues | Seven conserved lysines (K6, K11, K27, K33, K48, K63) and N-terminal methionine [1]. | Serve as linkage points for forming polyubiquitin chains with distinct biological signals. | Extremely High |

| C-terminal Glycine | Terminal glycine-glycine motif (G75-G76) [2]. | Critical for activation by E1 enzymes and conjugation to substrate lysines. | Absolute |

| Hydrophobic Patch | A surface patch centered around I44 [3]. | Primary recognition site for many ubiquitin-binding domains. | Extremely High |

Experimental analyses confirm that ubiquitin's sequence and structure are so optimized that even non-native linkages created through chemical methods recapitulate the structural and functional properties of native isopeptide bonds. Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) has demonstrated that scattering profiles for native and non-native ubiquitin dimers are strikingly similar and can be matched to analogous structures, indicating profound structural robustness [3].

Furthermore, deubiquitinases (DUBs), the enzymes that cleave ubiquitin chains, show comparable efficiency and selectivity in hydrolyzing both native and non-native isopeptide linkages. This functional conservation highlights that the ubiquitin code is read based on structure and connectivity rather than the precise chemical path used to assemble the chain [3].

Experimental Methodologies for Analyzing Ubiquitin Conservation

Several key experimental approaches are used to quantify and validate ubiquitin's sequence and structural conservation, each providing complementary insights.

Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) for Structural Comparison

Purpose: To analyze and compare the solution structures of native and synthetic ubiquitin chains in a non-crystalline, near-native state [3]. Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Purify native ubiquitin dimers (linked via natural isopeptide bonds) and synthetic dimers connected by non-native linkages.

- Data Collection: Expose the samples to a high-intensity X-ray beam and record the elastic scattering pattern at low angles.

- Profile Analysis: Compare the resulting scattering profiles (intensity vs. scattering angle) between native and non-native dimers.

- Model Fitting: Use an experimental structural library and atomistic simulations to generate molecular models that best fit the experimental SAXS data. Key Outcome: The demonstration that non-native ubiquitin dimers can be matched to structures analogous to those of native dimers, confirming structural conservation despite synthetic linkage [3].

Proteome-Wide Structural Analysis

Purpose: To quantify structural conservation at a genomic scale, moving beyond sequence-based comparisons [4]. Workflow:

- Data Compilation: Gather experimental structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and computationally modeled structures from the AlphaFold2 database for multiple species.

- Domain Parsing: Use a graph-based clustering algorithm (e.g., Leiden) on AlphaFold2's Predicted Aligned Error (PAE) matrix to identify and trim unstructured regions and separate folded, distinct protein domains.

- Structural Alignment: Perform pairwise, sequence-independent structural comparisons across proteomes.

- Twilight Zone Characterization: Identify and analyze homologous protein pairs with low sequence identity (<20-25%) but significant structural similarity. Key Outcome: This approach confirms that protein structure is more conserved than sequence and allows for the identification of evolutionary relationships that are undetectable by sequence alignment alone [4].

Steady-State Kinetic Analysis of Deubiquitinases (DUBs)

Purpose: To measure the efficiency and selectivity of DUBs against different types of ubiquitin linkages [3]. Workflow:

- Substrate Incubation: Prepare reaction mixtures containing the DUB enzyme and ubiquitin substrate (native or non-native chains).

- Reaction Monitoring: Measure the initial rate of product formation (e.g., free ubiquitin) under conditions where substrate concentration is not limiting.

- Parameter Calculation: Determine kinetic parameters such as kcat (catalytic turnover number) and KM (Michaelis constant).

- Specificity Calculation: Compare the catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) across different substrates to assess selectivity. Key Outcome: The finding that different DUB families hydrolyze native and non-native isopeptide linkages with comparable efficiency, demonstrating functional conservation [3].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the experimental observation of ubiquitin's conservation and the methodologies used to confirm it.

The Cancer Research Context: Ubiquitin Conservation in Pathogenesis and Therapy

The extreme conservation of ubiquitin has profound implications for cancer research, as viruses and cancer cells often hijack this essential, conserved system.

HPV-Driven Carcinogenesis

High-risk Human Papillomaviruses (HR-HPVs) are a primary case study in how pathogens co-opt the UPS. The viral oncoproteins E6 and E7 manipulate ubiquitination to drive cellular transformation [1].

- E6 and p53: The HPV E6 protein recruits a host E3 ubiquitin ligase to the tumor suppressor p53, leading to its ubiquitin-mediated degradation. This abrogates a critical cellular defense mechanism, allowing infected cells to evade apoptosis and accumulate genetic damage [1].

- E7 and pRb: Similarly, the E7 oncoprotein targets the retinoblastoma protein (pRb) for proteasomal degradation, causing uncontrolled cell cycle progression from G1 to S phase [1].

This viral strategy relies on the conserved nature of the ubiquitin machinery to effectively disable universally critical tumor suppressors.

Targeting the UPS in Immunotherapy

The conservation of ubiquitin components also presents unique therapeutic opportunities. Ubiquitin-Specific Proteases (USPs), the largest family of deubiquitinating enzymes, are increasingly recognized as viable drug targets in cancer [5].

- USP7: This DUB stabilizes the Foxp3 protein in regulatory T cells (Tregs), enhancing their immunosuppressive function within the tumor microenvironment. Inhibiting USP7 can therefore enhance antitumor immunity [5].

- USP16 and USP36: These DUBs exhibit cross-reactivity between ubiquitin and the ubiquitin-like protein Fubi, which is essential for ribosomal maturation. This highlights how the conserved ubiquitin fold can be exploited for dual-specificity enzyme functions [6].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin and Cancer Research

| Reagent / Tool | Core Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Activity-Based Probes (e.g., Ub-VS, Fubi-VS) | Covalently trap active-site cysteines of DUBs/deFubiylases [6]. | Chemoproteomic identification of enzyme subsets with specific hydrolytic activities. |

| Non-Native Ubiquitin Oligomers | Synthetic chains with non-isopeptide linkages that mimic native structure/function [3]. | Serve as surrogate substrates to study chain recognition and hydrolysis by DUBs. |

| Species-Specific Prediction Models (e.g., SSUbi) | Deep learning models integrating sequence and structural data [7]. | Accurate prediction of ubiquitination sites, accounting for species-specific sequence patterns. |

| AlphaFold2 Predicted Structures | Computationally modeled protein structures with high accuracy [4]. | Enables proteome-wide structural comparisons and analysis of evolutionary relationships. |

The diagram below illustrates how the conserved ubiquitin system is central to both viral oncogenesis and modern cancer therapeutic strategies.

The extreme sequence and structural conservation of ubiquitin across eukaryotes is not merely a biological curiosity but a fundamental feature with direct consequences for human disease and treatment. Experimental data from SAXS, kinetic studies, and proteome-wide structural analyses consistently demonstrate that ubiquitin's structure-function relationship is under intense evolutionary constraint. This conservation is exploited by pathogens like HPV to disrupt cellular homeostasis and drive carcinogenesis. Conversely, this very same conservation makes the ubiquitin system a fertile ground for therapeutic intervention, as evidenced by the development of small-molecule inhibitors targeting specific USPs for cancer immunotherapy. Understanding the depth of ubiquitin conservation provides a critical framework for ongoing research aimed at manipulating this system to combat cancer and other diseases.

Once considered a hallmark of eukaryotic cells, the ubiquitin signaling system has deep evolutionary roots in archaea. The discovery of simplified, operon-like genetic clusters encoding ubiquitin-system components in archaea such as Caldiarchaeum subterraneum provides a crucial missing link in understanding the origin of eukaryotic protein regulation. This guide compares these ancestral systems with their eukaryotic counterparts and bacterial relatives, highlighting conserved mechanisms, structural similarities, and functional divergences. We present comprehensive experimental data and methodologies that reveal how archaeal ubiquitin-like proteins (SAMPs) and associated enzymes represent a functional and evolutionary intermediate between bacterial sulfur-carrier systems and the complex eukaryotic ubiquitin-proteasome system, with significant implications for understanding the evolutionary trajectory of protein regulatory mechanisms relevant to cancer research.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents one of the most sophisticated mechanisms for post-translational protein regulation in eukaryotic cells, controlling approximately 80-90% of cellular proteolysis and governing virtually all aspects of cell physiology [8]. For decades, this system was considered a eukaryotic innovation; however, comparative genomic and biochemical analyses have revealed functional antecedents in prokaryotic organisms, particularly archaea [9] [2].

Archaeal ubiquitin-like (Ubl) systems represent a fascinating evolutionary intermediate, sharing mechanistic features with both bacterial sulfur-transfer systems and eukaryotic protein-modification pathways. The recent identification of operon-like ubiquitin system clusters in certain archaeal species provides compelling evidence for the prokaryotic origin of ubiquitin signaling [10]. These simplified genetic arrangements contain all core components necessary for a functional ubiquitination cascade, offering a unique window into the ancestral state of this crucial regulatory system.

Understanding these ancient ubiquitin mechanisms provides valuable insights for cancer research, as the ubiquitin system regulates core cancer hallmarks including cell cycle progression, DNA repair, metabolic reprogramming, and immune evasion [8] [11]. The evolutionary conservation of these pathways underscores their fundamental importance in cellular regulation and highlights potential ancient mechanisms that may be co-opted in oncogenesis.

Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitin System Architecture

Component Conservation Across Domains

Table 1: Comparison of ubiquitin system components across domains of life

| Component | Bacteria | Archaea | Eukaryotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin-like proteins | ThiS, MoaD (sulfur carriers) | SAMPs (protein modifiers & sulfur carriers) | Ubiquitin, UBLs (protein modifiers) |

| E1-like enzymes | ThiF, MoeB | UbaA | UBA1, UBA6 |

| E2-like enzymes | Rare (e.g., in Caldiarchaeum) | Identified in operon systems | ~38 E2 enzymes |

| E3 ligases | Not found | RING-type in operon systems | >600 E3 ligases |

| Deubiquitinases | JAB domains | JAB domains | ~100 DUBs |

| Primary function | Sulfur transfer for cofactor biosynthesis | Protein modification & sulfur transfer | Protein degradation & signaling |

The comparison reveals a clear evolutionary trajectory from specialized bacterial sulfur-transfer systems to the multifunctional regulatory systems of eukaryotes, with archaeal systems occupying an intermediate position. Archaeal ubiquitin-like systems demonstrate dual functionality, participating in both sulfur transfer for biomolecule biosynthesis and protein modification, suggesting these functions diverged from a common ancestral system [9] [12].

Genetic Organization: Operon-like Clusters vs Dispersed Systems

Table 2: Genetic organization of ubiquitin system components

| Organism Type | Genetic Organization | Key Features | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Sporadic operons | Limited distribution | Actinobacteria, Planctomycetes |

| Archaea | Operon-like clusters | Minimal complete systems | Caldiarchaeum subterraneum |

| Eukaryotes | Dispersed genes with redundancy | Tandem repeats, fused genes | All eukaryotes |

The operon-like cluster found in Caldiarchaeum subterraneum represents the most simplified known genetic arrangement encoding a eukaryote-like ubiquitin signaling system, containing five genes organized in a single cluster: one ubiquitin gene, one E1 activating enzyme, one E2 conjugating enzyme, one RING-type E3 ligase, and one deubiquitinating enzyme related to the proteasome subunit Rpn11 [10]. This compact organization contrasts sharply with the dispersed, redundant genetic architecture of eukaryotic ubiquitin systems, which include multiple ubiquitin genes (often arranged in tandem repeats) and hundreds of enzymes distributed throughout the genome [10].

Experimental Analysis of Archaeal Ubiquitin-like Systems

Key Methodologies for Characterizing Archaeal Ubl Systems

1. Comparative Genomic Analysis

- Protocol: PSI-BLAST searches with iterative profile refinement (e-value threshold 0.01) against archaeal genomic databases, followed by identification of conserved C-terminal motifs (GG or CC) characteristic of Ubl proteins [9].

- Application: Identification of eight distinct arCOGs (archaeal clusters of orthologous groups) meeting Ubl criteria, including six with β-grasp fold and C-terminal GG motifs [9].

- Significance: Revealed near-universal distribution of Ubl proteins in archaea, absent only in few methanogens (Methanococcus jannaschii, Methanopyrus kandleri, Methanococcus aeolicus) [9].

2. Functional Characterization in Haloferax volcanii

- Protocol: Genetic manipulation of SAMP (small archaeal modifier protein) genes and UbaA (E1-like enzyme) in H. volcanii, followed by analysis of protein conjugates via SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry [9] [12].

- Application: Demonstration that SAMPylation requires UbaA and accumulates in proteasome-deficient mutants, linking archaeal protein modification to degradation pathways [9].

- Significance: Established SAMPs as dual-function proteins involved in both protein modification and sulfur transfer for tRNA thiolation and molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis [12].

3. Structural Analysis via X-ray Crystallography

- Protocol: Protein purification, crystallization, and structure determination of Ubl proteins and associated enzymes [2].

- Application: Confirmation of β-grasp fold conservation in archaeal Ubl proteins and identification of structural similarities with eukaryotic ubiquitin and bacterial MoaD/ThiS [2].

- Significance: Revealed that despite low sequence similarity, archaeal Ubl proteins share the characteristic β-grasp fold with eukaryotic ubiquitin, explaining functional conservation [2].

Quantitative Experimental Data

Table 3: Experimental data from archaeal ubiquitin system studies

| Experimental Parameter | SAMP1 (Hvo_2619) | SAMP2 (Hvo_0202) | Operon System (C. subterraneum) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein modification targets | 100s of proteins (SDS-PAGE); sites mapped to 2 lysines of MoaE | 100s of proteins (SDS-PAGE); sites mapped to 11 lysines of 9 proteins | Predicted protein modification |

| Sulfur transfer function | Molybdopterin precursor | Pre-thiolated tRNA | Unidentified |

| E1 dependence | UbaA | UbaA | E1l (CSUB_C1476) |

| Additional components required | None for conjugation | None for conjugation | E2l (CSUBC1475) & Zn finger (CSUBC1477) |

| Proteasomal connection | Accumulates in proteasome mutants | Accumulates in proteasome mutants | Rpn11-like deubiquitinase |

The experimental data demonstrate that archaeal Ubl systems exhibit both simplicity and complexity—they function with minimal components compared to eukaryotic systems yet still achieve substantial target diversity through limited machinery. The accumulation of SAMP conjugates in proteasome-deficient mutants strongly suggests a functional connection between archaeal protein modification and regulated proteolysis, representing a primordial form of the eukaryotic ubiquitin-proteasome pathway [9] [12].

Evolutionary Pathways and Conserved Mechanisms

From Sulfur Carriers to Protein Modifiers

The evolutionary relationship between bacterial sulfur-carrier systems and eukaryotic ubiquitin signaling becomes evident when examining the structural and mechanistic conservation:

Figure 1: Evolutionary trajectory of ubiquitin-like systems from bacteria to eukaryotes, showing functional specialization from sulfur transfer to protein modification.

The mechanistic conservation centers on the β-grasp fold and activation mechanism. All ubiquitin-like proteins across domains share:

- β-grasp fold: Characterized by four or five beta strands forming an anti-parallel sheet and one alpha helix region, providing compact, stable architecture resistant to proteolysis and environmental stresses [10].

- C-terminal glycine motif: Essential for activation, where the terminal carboxylate is adenylated by E1-like enzymes using ATP, then transferred to a conserved cysteine residue in the E1 via a thioester linkage [12] [2].

- Sulfur transfer mechanism: In bacterial systems and some archaeal functions, the ubiquitin-like proteins form thiocarboxylates for sulfur incorporation into cofactors, while in eukaryotic protein modification, the thioester linkage is used for protein conjugation [2].

Operon to Distributed Genomic Organization

The transition from operon-like organization in prokaryotes to dispersed genetic arrangement in eukaryotes represents a fundamental genomic reorganization:

Figure 2: Transition from operon organization in prokaryotes to dispersed genomic arrangement in eukaryotes, enabling system complexity.

This organizational shift enabled the massive expansion of the ubiquitin system in eukaryotes, permitting:

- Specialization: Multiple E2 and E3 enzymes with distinct substrate specificities

- Regulatory complexity: Independent transcriptional control of system components

- Functional diversity: Evolution of distinct ubiquitin chain types signaling different outcomes

- Redundancy: Multiple ubiquitin genes ensuring system robustness

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential research reagents for studying archaeal ubiquitin-like systems

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Organisms | Haloferax volcanii | Genetic manipulation of SAMP/UbaA systems | Functional studies [9] [12] |

| Caldiarchaeum subterraneum | Study of minimal operon system | Evolutionary studies [10] | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | PSI-BLAST | Identification of distant Ubl homologs | Comparative genomics [9] [2] |

| HHPred | Protein fold prediction | Structural annotation [9] | |

| Promals3D | Multiple sequence alignment | Phylogenetic analysis [9] | |

| Enzymatic Assays | ATP-PPi exchange | E1 enzyme activity measurement | Functional characterization [12] |

| Thioester formation assays | E1~Ub/E2~Ub intermediate detection | Mechanistic studies [12] | |

| Structural Methods | X-ray crystallography | High-resolution structure determination | β-grasp fold confirmation [2] |

Implications for Cancer Research and Therapeutic Development

The evolutionary perspective on ubiquitin systems provides valuable insights for cancer research and drug development. The conservation of core mechanisms highlights the fundamental importance of these pathways in cellular regulation, while the evolutionary innovations explain the system complexity that can be co-opted in cancer.

Cancer cells frequently exploit ubiquitin system components to:

- Accelerate degradation of tumor suppressors: Enhanced ubiquitination of p53, PTEN, and other tumor suppressors

- Stabilize oncoproteins: Reduced ubiquitination of oncogenic drivers like c-Myc

- Evade immune surveillance: Ubiquitin-mediated regulation of PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoints

- Rewire metabolism: Ubiquitination control of metabolic enzymes like PKM2 [8] [11]

The evolutionary simplicity of archaeal systems provides a conceptual framework for developing targeted cancer therapies against specific ubiquitin system components. The successful development of proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib, carfilzomib) and ongoing clinical trials targeting E1 enzymes (MLN4924), E2 enzymes (CC0651, NSC697923), and E3 ligases demonstrate the therapeutic potential of modulating ubiquitin pathways [13] [11].

Archaeal operon-like ubiquitin systems represent a crucial evolutionary missing link, providing simplified yet functional models of the complex eukaryotic ubiquitin-proteasome system. The comparative analysis presented here demonstrates a clear evolutionary trajectory from bacterial sulfur-carrier systems through dual-function archaeal SAMPs to specialized eukaryotic ubiquitin signaling. The conservation of core mechanisms—including the β-grasp fold, E1-mediated activation, and covalent target modification—highlights the ancient origin and fundamental importance of this regulatory paradigm.

For cancer researchers, understanding these evolutionary relationships provides valuable context for the frequent dysregulation of ubiquitin pathways in oncogenesis and highlights potential therapeutic targets. The operational simplicity of archaeal systems offers conceptual insights for developing targeted interventions against specific ubiquitin system components, potentially with greater precision than broad proteasome inhibition. As research continues to unravel the complexities of ubiquitin signaling across domains of life, the evolutionary perspective will undoubtedly yield further insights into both basic biology and disease mechanisms.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a cornerstone of eukaryotic cellular regulation, controlling pivotal processes such as protein degradation, cell cycle progression, DNA repair, and signal transduction [10]. At the heart of this system operates a conserved enzymatic cascade consisting of ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), and ubiquitin-ligating (E3) enzymes, which work in sequence to tag substrate proteins with ubiquitin molecules [10]. While traditionally considered a eukaryotic innovation, recent discoveries have revealed the existence of surprisingly complex ubiquitination machinery in archaeal organisms, providing unprecedented insights into the evolutionary origins of this sophisticated regulatory system [14]. This conservation from simple archaea to complex eukaryotes underscores the fundamental importance of this enzymatic architecture in cellular homeostasis. Moreover, dysregulation of ubiquitination pathways features prominently in human diseases, particularly cancer, where it influences oncoprotein stability, metabolic reprogramming, and therapeutic responses [15] [16] [17]. Understanding the deep evolutionary conservation of the E1-E2-E3 cascade provides a valuable framework for investigating its roles in tumor biology and for developing targeted therapeutic interventions.

Evolutionary Conservation of the Ubiquitination Machinery

From Archaeal Operons to Eukaryotic Networks

The evolutionary trajectory of the ubiquitination system reveals a remarkable journey from compact archaeal operons to expansive eukaryotic networks. Genomic analysis of the archaeon Candidatus 'Caldiarchaeum subterraneum' uncovered a minimal, yet complete, ubiquitination system encoded within an operon-like cluster, containing single genes for a ubiquitin homolog, E1, E2, a RING-type E3, and a deubiquitinating enzyme related to Rpn11 [10] [14]. This organization represents the most simplified genetic arrangement encoding a eukaryote-like ubiquitin signaling system known to date [10]. Biochemical reconstitution studies have demonstrated that these archaeal enzymes function together as a bona fide ubiquitylation cascade, mediating sequential activation and transfer reactions reminiscent of the eukaryotic process [14]. The C. subterraneum E1 enzyme activates the ubiquitin homolog, which is then transferred to the E2 conjugating enzyme, culminating in E3-dependent substrate modification [14].

In stark contrast to this compact archaeal system, eukaryotic genomes exhibit substantial expansion and diversification of ubiquitination components. Even early-diverging eukaryotes like Naegleria gruberi, which emerged over one billion years ago, possess more than 100 ubiquitin signaling system genes, including multiple E2s and E3s [10]. This expansion follows a consistent E1 < E2 < E3 pyramidal network across eukaryotes, with humans possessing 2 E1s, approximately 30 E2s, and roughly 600 E3s [18]. This diversification enables the sophisticated regulatory capacity of the eukaryotic ubiquitin system, allowing precise control over a staggering breadth of cellular processes [18].

Table 1: Evolutionary Comparison of Ubiquitination System Components

| Component | Archaeal System | Eukaryotic System | Key Conservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin | Single-copy gene, requires C-terminal processing by Rpn11 [14] | Multiple loci (polyubiquitin genes, fusions with ribosomal proteins) [10] | Beta-grasp fold, C-terminal di-glycine motif [10] |

| E1 Enzyme | Single E1-like enzyme [10] | 2 E1 enzymes in humans [18] | Ubiquitin adenylation and thioester formation capabilities [14] |

| E2 Enzyme | Single E2-like enzyme [10] | ~30 E2 enzymes in humans [18] | Conserved catalytic cysteine, structural fold for E1/E3 interaction [14] |

| E3 Ligase | Single RING-type srfp protein [10] [14] | ~600 E3s in humans (RING, HECT, RBR families) [18] | RING domain with cross-brace zinc coordination in some archaea [14] |

Extreme Sequence and Structural Conservation

The ubiquitin molecule itself exhibits extraordinary sequence conservation across eukaryotic evolution, with virtually no variation observed between highly distant species [10]. This extreme conservation is maintained through concerted evolution mechanisms that prevent mutation accumulation in redundant ubiquitin genes [10]. Structurally, ubiquitin belongs to the beta-grasp fold superfamily, characterized by four or five beta strands forming an anti-parallel sheet and one alpha helix region [10]. This compact architecture provides remarkable stability, rendering ubiquitin highly resistant to proteolytic processing, temperature changes, and pH fluctuations [10].

Structural modeling of the C. subterraneum E1 and E2 enzymes reveals significant conservation of key catalytic features with their eukaryotic counterparts [14]. The archaeal E2 enzyme maintains the characteristic first N-terminal alpha-helix containing motifs essential for E1 and E3 interactions, as well as conserved loop structures (loops 4 and 7) that facilitate specific binding with cognate E3 ligases [14]. Similarly, the archaeal RING-type E3 exhibits the cross-brace zinc coordination motif characteristic of eukaryotic RING domains [14]. These structural conservations underpin the functional compatibility between archaeal and eukaryotic ubiquitination components.

Table 2: Functional Capabilities of Minimal vs. Expanded Ubiquitination Systems

| Functional Aspect | Archaeal Minimal System | Eukaryotic Expanded System |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Organization | Operon-like cluster [10] | Dispersed genes with redundancy [10] |

| System Complexity | Single E1, E2, E3 [14] | Pyramidal network (2 E1s, ~30 E2s, ~600 E3s in humans) [18] |

| Ubiquitin Topology | Mono-ubiquitination demonstrated [14] | Diverse chains (mono, multi, polyubiquitination) [10] |

| Biological Scope | Likely limited substrate range | Vast regulatory scope (degradation, signaling, trafficking) [10] |

| Proteasome Linkage | SAMPs implicated in proteasome-dependent degradation [10] | Well-established proteasomal targeting [10] |

Experimental Approaches for Studying Ubiquitination Conservation

Biochemical Reconstitution of Archaeal Ubiquitination

The functional characterization of the archaeal ubiquitination cascade provides a paradigm for minimal system operation and has been achieved through careful biochemical reconstitution approaches.

Experimental Protocol: Archaeal Cascade Reconstitution [14]

- Gene Synthesis and Protein Purification: Synthetic genes encoding C. subterraneum ubiquitin, E1, E2, and srfp (E3) components are cloned into expression vectors, expressed in E. coli, and purified using standard chromatographic techniques.

- Pro-ubiquitin Processing: The C. subterraneum pro-ubiquitin (with C-terminal extension) is incubated with the Rpn11 metalloprotease homologue to generate mature ubiquitin exposing the di-glycine motif. Reaction products are analyzed by SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry to confirm cleavage.

- E1 Activation Assay: Mature ubiquitin is incubated with E1 enzyme and ATP. Ubiquitin activation is assessed through formation of E1-ubiquitin thioester intermediates (detectable by non-reducing SDS-PAGE) and E1 auto-ubiquitylation (detectable by reducing SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry).

- E2 Charging Assay: E2 enzyme is added to the E1 activation reaction. Transfer of ubiquitin to E2 is evaluated through E2-ubiquitin thioester formation (non-reducing SDS-PAGE) and E2 auto-mono-ubiquitylation (reducing SDS-PAGE, mass spectrometry).

- E3 Ligase Activity: Full cascade reactions including E1, E2, E3, ubiquitin, and ATP are performed to demonstrate sequential ubiquitylation. Substrate ubiquitylation can be assessed using known eukaryotic substrates or through auto-ubiquitylation events.

This experimental approach confirmed that the archaeal system operates through a sequential mechanism analogous to eukaryotic ubiquitylation, with ATP-dependent E1 activation, transthioesterification to E2, and E3-dependent target modification [14].

Advanced Probe Technologies for Monitoring Cascade Activity

Modern chemical biology approaches have developed sophisticated tools for monitoring ubiquitination cascade activities. The UbDha (UbGly76Dha) cascading activity-based probe represents a particularly innovative technology that enables tracking of ubiquitin transfer through the entire E1-E2-E3 pathway [18].

Experimental Protocol: Cascading Activity-Based Probe [18]

- Probe Design and Synthesis: UbDha is synthesized by replacing the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin with a dehydroalanine (Dha) moiety, creating a latent electrophile that can covalently trap active site cysteine residues of ubiquitination enzymes.

- Enzyme Trapping Assays: UbDha is incubated with E1, E2, or E3 enzymes in the presence of ATP. The probe undergoes normal adenylation and thioester formation but can also irreversibly trap catalytic cysteine residues at each step of the cascade.

- Reaction Monitoring: Trapped enzyme-probe adducts are detected by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. ATP dependence confirms the mechanism-based nature of the labeling.

- Proteome-wide Profiling: Cell lysates are treated with UbDha to identify active ubiquitination enzymes under various physiological conditions or in response to inhibitors.

This methodology enables direct monitoring of sequential E1, E2, and E3 activities in diverse experimental settings, including live cells, and provides structural insights through stable trapping of catalytic intermediates [18].

Diagram Title: UbDha Cascading Probe Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Ubiquitination Cascade Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Cascading ABP (UbDha) [18] | Mechanism-based monitoring of E1-E2-E3 activities | Irreversibly traps catalytic cysteines; follows native cascade trajectory |

| Reconstituted Archaeal Systems [14] | Minimal system for mechanistic studies | Defined components; ancestral-like architecture |

| Cross-species Integration Algorithms (scANVI, scVI, SeuratV4) [19] | Computational comparison of ubiquitination components across species | Corrects species-effect in transcriptomic data; identifies conserved expression patterns |

| Homology Mapping Methods [19] | Gene ortholog identification for evolutionary studies | Includes one-to-one, one-to-many, and many-to-many ortholog mapping |

| Rpn11-like Protease [14] | Processing of pro-ubiquitin precursors | Essential for generating mature ubiquitin with exposed diglycine motif |

| Structural Modeling (I-TASSER) [14] | Prediction of enzyme structures from sequence data | Identifies conserved catalytic residues and interaction surfaces |

Implications for Cancer Research and Therapeutic Development

The deep evolutionary conservation of the E1-E2-E3 cascade underscores its fundamental importance in cellular regulation, with particular relevance for understanding and treating cancer. Dysregulation of ubiquitination pathways contributes significantly to oncogenesis through multiple mechanisms, including altered stability of oncoproteins and tumor suppressors, metabolic reprogramming, and modulation of immune responses [15] [16] [17].

In RAS-driven cancers, ubiquitination dynamically regulates the stability, membrane localization, and signaling transduction of RAS proteins, profoundly impacting their oncogenic functions [16]. Distinct ubiquitination patterns across RAS isoforms (KRAS4A, KRAS4B, NRAS, and HRAS) contribute to their functional disparities in cancers, presenting novel targeting opportunities [16]. Similarly, in tumor lipid metabolism—a crucial aspect of cancer progression—ubiquitination regulates key enzymes including adenosine triphosphate citrate lyase (ACLY) and fatty acid synthase (FASN) [17]. The E3 ligases NEDD4, UBR4, CUL3-KLHL25 complex, and TRIM21 have all been implicated in controlling metabolic enzyme stability, creating dependencies that might be therapeutically exploited [17].

The construction of pancancer ubiquitination regulatory networks has enabled stratification of patients into distinct risk groups with divergent survival outcomes and immunotherapy responses [15]. For instance, the OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination axis modulates MYC pathway activity and influences patient prognosis, revealing potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets [15]. As our understanding of ubiquitination conservation deepens, targeting these ancient regulatory pathways continues to offer innovative approaches for cancer therapy, including strategies to overcome resistance to conventional treatments.

The E1-E2-E3 ubiquitination cascade represents a remarkably conserved enzymatic architecture maintained from simple archaeal organisms to complex eukaryotes. This evolutionary preservation highlights the fundamental efficiency and versatility of this sequential activation and transfer mechanism for protein modification. The experimental approaches outlined—from biochemical reconstitution of minimal archaeal systems to advanced activity-based probes and cross-species computational analyses—provide powerful methodologies for investigating both conserved principles and lineage-specific adaptations of ubiquitination signaling. In cancer research, understanding this deep evolutionary conservation illuminates why ubiquitination pathways are so frequently co-opted in oncogenesis and offers valuable insights for developing targeted therapeutic strategies. As research continues to unravel the complexities of ubiquitination regulation across the tree of life, the conserved E1-E2-E3 architecture stands as a testament to the elegant economy of nature's molecular solutions.

Ubiquitination, the covalent attachment of a small protein called ubiquitin to target substrates, represents a universal post-translational modification system that transcends species boundaries and cellular contexts. Often described as a sophisticated "code," this system enables eukaryotic cells to precisely regulate protein stability, activity, localization, and interactions through diverse ubiquitin chain topologies [8] [20]. The ubiquitin code operates through a conserved enzymatic cascade involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes that work in concert to attach ubiquitin to specific substrate proteins, with this process being reversible through the action of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) [20] [21]. This fundamental regulatory mechanism governs virtually all cellular processes, including cell cycle progression, DNA damage repair, signal transduction, and immune responses, with its dysregulation being implicated in numerous human diseases, particularly cancer [22] [8] [23].

The conservation of the ubiquitin code across species underscores its fundamental biological importance while providing unique opportunities for comparative research. From yeast to humans, the core components of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) maintain remarkable structural and functional similarity, enabling researchers to utilize model organisms to unravel complex ubiquitin-related processes relevant to human disease [23]. This evolutionary conservation extends beyond mere protein degradation, encompassing sophisticated signaling networks that control cellular decision-making processes. As we explore the molecular architecture, functional diversity, and experimental approaches to studying the ubiquitin code, its position as a universal language of cellular regulation becomes increasingly evident, highlighting its profound implications for understanding disease mechanisms and developing targeted therapies.

Molecular Architecture of the Ubiquitin System

The Ubiquitination Cascade Enzymatic Machinery

The ubiquitination process initiates with a single E1 activating enzyme that utilizes ATP to form a high-energy thioester bond with the C-terminal glycine (Gly76) of ubiquitin in a two-step adenylation process [20]. This activated ubiquitin is subsequently transferred to the catalytic cysteine residue of an E2 conjugating enzyme, again via a thioester linkage. The final step involves one of approximately 600 E3 ubiquitin ligases, which recognize specific substrate proteins and facilitate the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine residue on the substrate, forming an isopeptide bond [24]. This hierarchical E1-E2-E3 network provides both specificity and diversity, with different combinations of E2-E3 enzymes generating distinct ubiquitination patterns on specific substrates. The reversibility of this process is ensured by approximately 100 deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that cleave ubiquitin from modified substrates, thereby antagonizing ubiquitination and maintaining cellular ubiquitin homeostasis [8] [21].

The E3 ubiquitin ligases represent the most diverse and specialized components of this system, falling into several structural categories defined by their catalytic domains and mechanisms. Really Interesting New Gene (RING) E3s function as scaffolds that simultaneously bind E2~Ub and substrate, facilitating direct ubiquitin transfer. Homologous to the E6AP C-Terminus (HECT) E3s form a catalytic thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to substrates. RING-In-Between-RING (RBR) E3s employ a hybrid mechanism, combining aspects of both RING and HECT-type catalysis [8] [20]. This structural and mechanistic diversity enables the precise spatiotemporal control of substrate ubiquitination, allowing the ubiquitin system to regulate virtually every aspect of cell physiology.

Diversity of the Ubiquitin Code

The ubiquitin code's complexity arises from the ability to form different types of ubiquitin modifications, each encoding distinct functional outcomes for the modified protein. Monoubiquitination involves attachment of a single ubiquitin molecule and typically regulates protein activity, interactions, and subcellular localization, as observed in histone modification and receptor endocytosis [8] [20]. Multi-monoubiquitination occurs when single ubiquitin molecules attach to multiple lysine residues on the same substrate, often serving as a signal for endocytic trafficking.

Polyubiquitination involves the formation of ubiquitin chains through covalent linkage between the C-terminus of one ubiquitin and one of the seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or the N-terminal methionine (M1) of another ubiquitin molecule [8] [20]. These chain types confer specific functional consequences: K48-linked chains primarily target proteins for proteasomal degradation; K63-linked chains facilitate non-proteolytic signaling in DNA repair, inflammation, and trafficking; while M1-linear chains regulate NF-κB signaling and immune responses [8] [20] [25]. More recently, the discovery of mixed or branched chains, where a single ubiquitin molecule is modified at multiple lysine residues, has added another layer of complexity to the ubiquitin code, enabling sophisticated regulatory fine-tuning [8] [20].

Figure 1: The Ubiquitination Enzymatic Cascade. The process initiates with ATP-dependent ubiquitin activation by E1, followed by transfer to E2, and culminates in E3-mediated substrate modification. Each step confers increasing specificity, with E3 ligases determining substrate selection.

Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitin Code Conservation

Evolutionary Conservation of Core Machinery

The fundamental components of the ubiquitin system demonstrate remarkable evolutionary conservation from yeast to humans, underscoring their essential cellular functions. Core elements including E1 activating enzymes, the ubiquitin protein itself, and many E2 conjugating enzymes maintain high sequence similarity across eukaryotic species [23]. This conservation extends to several E3 ligase families and deubiquitinating enzymes, particularly those governing critical processes such as cell cycle regulation and DNA damage response. The structural conservation of ubiquitin-fold domains and ubiquitin-binding domains across evolution enables recognition and decoding of ubiquitin signals through similar mechanistic principles regardless of species origin [23] [24]. This evolutionary preservation facilitates cross-species research, where findings in model organisms frequently provide insights applicable to human biology and disease mechanisms.

Despite this strong conservation, species-specific adaptations have emerged in the ubiquitin system, particularly in pathways related to immune regulation, developmental programs, and specialized metabolic functions. For instance, certain immune-related ubiquitin-like proteins such as ISG15 demonstrate more recent evolutionary origins and greater divergence between species [23]. Similarly, the number and diversity of E3 ligases have expanded in higher eukaryotes, correlating with increased cellular complexity and specialized regulatory requirements. These evolutionary patterns reflect both the constrained core machinery essential for basic eukaryotic cell function and the adaptable components that enable species-specific physiological specialization.

Functional Conservation in Signaling Pathways

The ubiquitin code demonstrates profound functional conservation in regulating essential cellular signaling pathways across diverse species. The p53 tumor suppressor pathway provides a compelling example, where ubiquitination by MDM2 and other E3 ligases controls p53 stability and activity in organisms ranging from invertebrates to mammals [23]. Similarly, the NF-κB signaling pathway employs conserved ubiquitin-dependent mechanisms for IκB degradation and pathway activation, with key regulators like the A20 deubiquitinase maintaining functional conservation despite sequence divergence [8] [23]. DNA damage response pathways also showcase striking conservation of ubiquitin signaling, with RNF8-RNF168-mediated histone ubiquitination facilitating repair factor recruitment in both mammalian and simpler eukaryotic systems [25].

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway further illustrates this functional conservation, with β-catenin stability being regulated by a conserved destruction complex whose activity is modulated by ubiquitin-dependent mechanisms [26]. Recent research has revealed additional conservation in the PARylation-dependent ubiquitination (PARdU) pathway, where tankyrase and RNF146 collaborate to regulate Axin degradation and Wnt signaling across multiple species [26]. These examples highlight how the ubiquitin code preserves core functional relationships in critical signaling networks throughout evolution, enabling coordinated control of cell fate decisions, stress responses, and developmental programs across the eukaryotic lineage.

Table 1: Conservation of Key Ubiquitin System Components Across Species

| Component | Conservation Level | Functional Role | Example Conserved Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin protein | Very high (>95% identity mammals-yeast) | Signal molecule for degradation & signaling | All ubiquitin-dependent processes |

| E1 activating enzymes | High | Ubiquitin activation | Entire ubiquitination cascade |

| Cullin-RING ligases (CRLs) | High | Multi-subunit E3 complexes | Cell cycle, transcription, signaling |

| MDM2/p53 axis | Moderate to high | Regulation of p53 stability | DNA damage response, apoptosis |

| RNF8/RNF168 | Moderate | Histone ubiquitination | DNA damage response, repair |

| Tankyrase/RNF146 | Moderate | PAR-dependent ubiquitination | Wnt signaling, telomere maintenance |

| A20 (TNFAIP3) | Moderate | NF-κB regulation | Immune and inflammatory signaling |

Ubiquitin Chain-Type Specificity and Conservation

The specificity of ubiquitin chain linkages and their functional consequences demonstrates significant conservation across species, though with some contextual variations. K48-linked polyubiquitin chains serve as the primary proteasomal degradation signal throughout eukaryotes, with the proteasome recognition machinery conserving its ability to interpret this signal from yeast to humans [8] [20]. Similarly, K63-linked chains consistently function in non-proteolytic signaling pathways related to DNA repair, inflammation, and protein trafficking across diverse species [20] [25]. This functional conservation of major chain types underscores their fundamental importance in eukaryotic cell biology.

More specialized chain linkages (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33) show greater evolutionary plasticity in their functions and prevalence, though they maintain conserved roles in certain contexts. K11-linked chains, for instance, have conserved functions in cell cycle regulation and ER-associated degradation (ERAD) across metazoans [8] [20]. The conservation of chain-type specificity extends to the enzymatic machinery responsible for writing, reading, and erasing these signals, with many ubiquitin-binding domains and DUBs maintaining specificity for particular chain types throughout evolution [23] [21]. This preservation of linkage-specific recognition mechanisms enables consistent interpretation of the ubiquitin code across species boundaries.

Table 2: Functional Conservation of Major Ubiquitin Linkage Types

| Linkage Type | Primary Function | Conservation Status | Key Conserved E2/E3 Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48 | Proteasomal degradation | Very high | UBE2R1/2, hundreds of E3s |

| K63 | Non-proteolytic signaling | Very high | UBE2N/UEV1A, RNF8, TRAF6 |

| K11 | Cell cycle regulation, ERAD | High | UBE2S, APC/C, HUWE1 |

| M1 (linear) | NF-κB activation, immunity | High | LUBAC complex (HOIP) |

| K27 | DNA damage response, immunity | Moderate | RNF168, HOIP |

| K29 | Proteasomal degradation, signaling | Moderate | UBE2A/B, UBR5 |

| K33 | Kinase regulation, trafficking | Moderate | Unknown |

| K6 | DNA damage response, mitophagy | Moderate | PARKIN, BRCA1-BARD1 |

Ubiquitin Code Crosstalk with Related Modification Systems

PARylation-Dependent Ubiquitination (PARdU) Pathway

The PARylation-dependent ubiquitination pathway represents a sophisticated example of ubiquitin code crosstalk with other post-translational modification systems. This pathway centers on the E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF146, which contains an N-terminal WWE domain that specifically recognizes iso-ADP-ribose (iso-ADPr) units within poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) chains [26]. When tankyrases (TNKS1/2) PARylate their substrates, RNF146 binds to these PAR modifications through its WWE domain, leading to conformational activation of its C-terminal RING domain and subsequent ubiquitination of the PARylated substrate [26]. This molecular mechanism creates a precise regulatory circuit where PARylation serves as a direct molecular trigger for ubiquitination, enabling spatiotemporal control of substrate stability.

The PARdU pathway regulates multiple biological processes with implications for cancer pathogenesis and treatment. It controls Wnt/β-catenin signaling through tankyrase-mediated PARylation and RNF146-driven degradation of Axin1/2, a key negative regulator of the pathway [26]. Additionally, the pathway regulates DNA damage response, telomere maintenance, and glucose metabolism through targeted ubiquitination of PARylated substrates [26]. From a therapeutic perspective, inhibiting tankyrase or RNF146 stabilizes Axin and suppresses Wnt signaling, presenting a potential strategy for treating Wnt-driven cancers. The discovery and characterization of this pathway highlights how ubiquitination integrates with other modification systems to create sophisticated regulatory networks that maintain cellular homeostasis.

Figure 2: PARylation-Dependent Ubiquitination (PARdU) Pathway. Tankyrase-mediated PARylation of substrates creates a recognition signal for RNF146, which subsequently ubiquitinates the PARylated protein, targeting it for proteasomal degradation. This pathway represents a key interface between ubiquitin and ADP-ribosylation modification systems.

Ubiquitin-Like Proteins and Their Modifications

The ubiquitin system exhibits extensive crosstalk with ubiquitin-like proteins (Ubls), which share structural homology with ubiquitin but perform distinct cellular functions. Key Ubls include SUMO (Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier), NEDD8 (Neural precursor cell-Expressed Developmentally Down-regulated 8), ISG15 (Interferon-Stimulated Gene 15), and FAT10, each with their own specific E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascades for conjugation to targets [23] [24]. These Ubl systems often functionally intersect with ubiquitination, creating complex regulatory networks that fine-tune cellular processes. For instance, neddylation of cullin proteins activates cullin-RING ligase complexes, enhancing their ubiquitin ligase activity and thereby linking NEDD8 and ubiquitin pathways [23].

SUMO modification frequently collaborates with ubiquitination in regulating transcription factors, DNA repair proteins, and signal transducers. SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases (STUbLs) recognize SUMO-modified proteins and promote their ubiquitination and degradation, demonstrating direct molecular crosstalk between these modification systems [23]. In the DNA damage response, RNF168-mediated ubiquitination is amplified by ZNF451-dependent SUMOylation, creating a positive feedback loop that enhances histone ubiquitination and repair factor recruitment [25]. Similarly, ISG15 modification often occurs in response to interferon signaling and viral infection, sometimes competing with ubiquitination for the same lysine residues on target proteins [23]. These examples illustrate how ubiquitin and Ubl systems form interconnected networks that expand the regulatory capacity of protein modification beyond what any single system could accomplish independently.

Experimental Methods for Studying Ubiquitin Code Conservation

Proteomic and Genomic Approaches

Advanced proteomic methodologies have revolutionized the large-scale identification and quantification of ubiquitination events across species and cellular contexts. Mass spectrometry-based ubiquitinomics employs anti-ubiquitin antibodies or ubiquitin-binding domains to enrich ubiquitinated peptides, followed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis to identify modification sites and quantify changes under different conditions [27]. For novel peptide discovery, researchers have constructed comprehensive reference libraries containing millions of open reading frames, enabling the identification of thousands of previously unannotated peptides from biological samples [27]. These approaches have revealed the astonishing complexity of the ubiquitin-modified proteome and enabled comparative analyses across species.

Functional genomic screening methods, particularly CRISPR-based approaches, allow systematic identification of ubiquitin system components essential for specific biological processes or cellular contexts. Pooled CRISPR screens enable high-throughput assessment of how loss of individual E3 ligases, DUBs, or other ubiquitin pathway components affects cellular phenotypes, drug sensitivity, or pathway activity [27]. For instance, CRISPR screening in gastric cancer cells identified 1,161 novel peptides involved in tumor cell proliferation, highlighting the functional significance of previously uncharacterized components of the ubiquitin system [27]. Integration of proteomic and genomic datasets through multiomics strategies provides a comprehensive view of ubiquitin network organization, conservation, and functional architecture, facilitating the identification of key regulatory nodes with potential therapeutic significance.

Biochemical and Structural Methods

Biochemical approaches remain fundamental for characterizing ubiquitin enzyme mechanisms and substrate relationships. In vitro ubiquitination assays reconstitute the ubiquitination cascade using purified E1, E2, E3 enzymes, ubiquitin, and ATP to demonstrate direct substrate modification and identify specific E2-E3 partnerships [26] [20]. These assays often employ ubiquitin mutants (such as ΔGG ubiquitin that cannot form chains) or linkage-specific ubiquitin mutants to dissect chain formation requirements [20]. For the PARdU pathway, researchers have characterized the molecular details of RNF146-tankyrase interactions through identification of tankyrase-binding motifs (TBMs) within RNF146 and demonstrated that PAR binding induces conformational changes that activate RNF146's E3 ligase activity [26].

Structural biology techniques including X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy have provided atomic-level insights into ubiquitin enzyme mechanisms and ubiquitin recognition. Structural studies of RNF146 revealed how its WWE domain recognizes iso-ADP-ribose units in PAR chains and how PAR binding repositions the RING domain to activate ubiquitin transfer [26]. Similarly, structural analyses of various E3 ligases in complex with their E2 enzymes and substrates have illuminated the molecular determinants of substrate specificity and catalytic mechanism [26] [20]. These structural insights facilitate understanding of evolutionary conservation by revealing how key catalytic residues and structural motifs are preserved across species, enabling comparative analyses of ubiquitin system architecture throughout evolution.

Table 3: Key Experimental Protocols for Studying Ubiquitin Code Conservation

| Method | Key Steps | Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro ubiquitination assay | 1. Purify E1, E2, E3 enzymes2. Incubate with ubiquitin, ATP, substrate3. Detect ubiquitination via immunoblot | Validate direct substrate ubiquitination, identify E2-E3 partnerships | Use ubiquitin mutants (ΔGG) as negative controls; include ATP regeneration system |

| Tandem ubiquitin binding entities (TUBEs) | 1. Express TUBE fusion proteins2. Capture polyubiquitinated proteins from lysates3. Analyze by immunoblot or MS | Enrich and protect polyubiquitinated proteins from DUBs, detect endogenous ubiquitination | Linkage-specific TUBEs available for different chain types |

| Ubiquitin remnant motif (K-ε-GG) profiling | 1. Digest proteins with trypsin2. Enrich K-ε-GG peptides with antibodies3. Analyze by LC-MS/MS | Global identification of ubiquitination sites, quantitative comparison across conditions | Distinguish from other lysine modifications; requires specific diGly antibodies |

| CRISPR screening of ubiquitin pathway | 1. Create sgRNA library targeting ubiquitin genes2. Transduce cells, select with puromycin3. Sequence sgRNAs pre/post selection | Identify functional ubiquitin components in specific pathways or disease contexts | Include non-targeting sgRNA controls; validate hits individually |

| Cross-species complementation | 1. Delete endogenous gene in model organism2. Express ortholog from other species3. Assess phenotypic rescue | Test functional conservation of ubiquitin pathway components | Consider expression level matching; potential dominant-negative effects |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitin Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin mutants | Ubiquitin-ΔGG, K48-only, K63-only, K0 (no lysines) | Determine chain type requirements, distinguish chain topology functions | Prevent chain formation (ΔGG) or restrict to specific linkages (K-only) |

| E1 inhibitors | TAK-243, PYR-41 | Block global ubiquitination, assess pathway dependence | TAK-243 blocks UA-E1 interaction; useful for acute ubiquitination shutdown |

| Proteasome inhibitors | Bortezomib, MG132, Carfilzomib | Block protein degradation, stabilize ubiquitinated proteins | Bortezomib clinically approved; MG132 for research use only |

| DUB inhibitors | PR-619 (broad-spectrum), USP14 inhibitors | Block deubiquitination, stabilize ubiquitination events | Varying specificity; some target specific DUB families |

| Linkage-specific antibodies | K48-linkage specific, K63-linkage specific, monoUb antibodies | Detect specific ubiquitin chain types by immunoblot, immunofluorescence | Variable specificity; require validation with linkage-defined standards |

| Ubiquitin binding domains | TUBEs, UIM, UBA, UBAN domains | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins, protection from DUBs | TUBEs offer high affinity and protection from DUB-mediated cleavage |

| Activity-based probes | Ubiquitin-based probes with warhead groups | Label active DUBs and E1/E2 enzymes in complex mixtures | Enable profiling of enzymatic activity rather than mere expression |

| E3 ligase modifiers | MLN4924 (neddylation inhibitor), PROTACs targeting E3s | Modulate specific E3 ligase activities | MLN4924 inhibits CRL activation; PROTACs enable targeted protein degradation |

The conserved nature of the ubiquitin code across species provides a powerful framework for understanding its fundamental role in cellular regulation and its implications for human diseases, particularly cancer. The evolutionary preservation of core ubiquitin pathway components and their functional relationships enables knowledge transfer from model organisms to human biology, accelerating the identification of disease-relevant mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets [23] [24]. The frequent dysregulation of ubiquitin signaling in cancer—through mutations in ubiquitin pathway genes, altered expression of E3 ligases or DUBs, or hijacking of ubiquitin-dependent regulatory mechanisms—highlights the therapeutic potential of targeting this system [16] [22] [8].

Emerging therapeutic strategies that exploit the ubiquitin code include proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) that redirect E3 ligases to degrade specific disease-causing proteins, molecular glues that enhance natural interactions between E3 ligases and target proteins, and small-molecule inhibitors of specific E3 ligases or DUBs [8] [20] [24]. The clinical success of bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor, validated the ubiquitin-proteasome system as a therapeutic target, while newer approaches offer the potential for greater specificity and reduced off-target effects [8] [23]. As our understanding of ubiquitin code conservation deepens, so too does our ability to develop innovative therapeutic strategies that manipulate this fundamental regulatory system to treat cancer and other diseases, ultimately fulfilling the promise of targeted protein degradation as a next-generation therapeutic modality.

Muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) in humans is an aggressive malignancy with limited treatment options and poor prognosis, exhibiting a five-year survival rate of only 38% when the tumor has spread to surrounding tissues, and a mere 6% with distant metastases [28]. The genomic landscape of human MIBC is characterized by a high mutation load and numerous altered genes, complicating the identification of true driver events among passenger mutations [28] [29]. Cross-species oncogenomics has emerged as a powerful filtering strategy to address this challenge, leveraging the evolutionary conservation of cancer pathways across species that share environmental exposures and genetic backgrounds with humans.

Spontaneously occurring urothelial carcinoma (UC) in companion animals and livestock provides unique model systems for comparative analysis. Pet dogs and cats develop UC with histological and clinical similarities to human MIBC, while cattle grazing on bracken fern develop UC associated with exposure to the carcinogen ptaquiloside (PT) [28]. These species represent relevant models of spontaneous and carcinogen-induced UC that can provide crucial insight into human MIBC pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets. The "One Medicine, One Health" concept underpins this approach, where information gained from one species can benefit others, bridging the gap between human and animal research to improve outcomes for all [30].

Cross-Species Genomic Landscape of Bladder Cancer

Mutation Profiles Across Species

Recent whole-exome sequencing studies of domestic canine (n = 87), feline (n = 23), and bovine UC (n = 8), with comparative analysis against human MIBC (n = 412), have revealed both striking similarities and important differences in mutational landscapes [28] [29]. The mutation rates vary significantly across species, with human MIBC exhibiting a median of 5.5 mutations/Mb, while canine and feline UC show substantially lower mutation rates (median 1.0 and 1.1 mutations/Mb, respectively). In contrast, bovine UC demonstrates a dramatically elevated mutation rate (median 65 mutations/Mb), reflecting exposure to the potent environmental mutagen ptaquiloside found in bracken fern [28].

Table 1: Comparative Mutation Rates in Bladder Cancer Across Species

| Species | Sample Size | Median Mutation Rate (mutations/Mb) | Primary Environmental Exposure | Most Frequently Mutated Gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 412 | 5.5 | Smoking, occupational chemicals | TP53 |

| Canine | 87 | 1.0 | Shared human environment | BRAF (61%) |

| Feline | 23 | 1.1 | Shared human environment | TP53 (61%) |

| Bovine | 8 | 65.0 | Bracken fern ptaquiloside | CSMD3, LRP1B, ROS1 (100% each) |

The most frequently mutated genes exhibit both conservation and divergence across species. In canine UC, BRAF is the predominant driver mutation (61% of cases), specifically the p.V588E (also known as p.V595E) equivalent to the human BRAF p.V600E hotspot mutation [28]. This mutation occurs significantly more frequently in terrier breeds (19/24) compared to non-terriers (34/63), suggesting breed-associated predispositions. In contrast, feline UC more closely resembles human MIBC, with TP53 being the most frequently mutated gene (61% of cases), the majority being loss-of-function mutations [28]. Bovine UC demonstrates a distinct pattern, with all cases harboring mutations in CSMD3, LRP1B, and ROS1, likely reflecting the specific carcinogenic mechanism of ptaquiloside [28].

Conserved Driver Genes and Pathways

Cross-species analysis has identified a convergence of driver genes that appear evolutionarily conserved across species boundaries. Key conserved driver genes include ARID1A, KDM6A, TP53, FAT1, and NRAS [28] [30]. Specifically, three key genes were identified in both human and feline samples (TP53, FAT1, and NRAS), while two were found in both human and canine samples (ARID1A and KDM6A) [30]. These genes primarily participate in critical cellular processes including regulation of the cell cycle and chromatin remodelling [28].

Table 2: Evolutionarily Conserved Driver Genes in Bladder Cancer Pathogenesis

| Gene | Function | Conservation Pattern | Role in Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| TP53 | Tumor suppressor, cell cycle regulation | Human Feline | Most frequently mutated gene in human and feline UC; loss-of-function mutations |

| FAT1 | Atypical cadherin, Wnt signaling regulation | Human Feline | Putative tumor suppressor; mutations potentially disrupt cell adhesion |

| NRAS | GTPase, RAS/MAPK signaling pathway | Human Feline | Oncogenic signaling; promotes cell proliferation and survival |

| ARID1A | Chromatin remodeling, SWI/SNF complex | Human Canine | Tumor suppressor; regulates gene expression through chromatin modification |

| KDM6A | Histone demethylase, epigenetic regulation | Human Canine | Tumor suppressor; removes repressive histone marks |

| BRAF | Serine/threonine kinase, MAPK signaling | Canine-specific predominance | Oncogenic driver; 61% of canine UC cases versus only 2.7% in human MIBC |

Beyond single-gene conservation, cross-species analysis reveals common focally amplified and deleted genomic regions containing genes involved in cell cycle regulation and chromatin remodeling [28]. Additionally, specific genetic events such as mismatch repair deficiency were identified in subsets of both canine and feline UCs with biallelic inactivation of MSH2, mirroring similar defects in human cancers [28]. Structural chromosomal alterations including chromothripsis, which leads to major changes in DNA architecture, were also found to be similar across all three species, potentially highlighting a common genetic basis for these diseases [30].

Ubiquitination Pathway Conservation in Cancer Biology

Fundamentals of Ubiquitination Machinery

Ubiquitination represents the second most common post-translational modification of proteins following phosphorylation, involving the covalent attachment of ubiquitin (a 76-amino acid protein) to substrate proteins [8]. This process is mediated by a sequential enzymatic cascade comprising ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3) [8] [31]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is responsible for 80-90% of cellular proteolysis, playing fundamental roles in regulating protein stability, localization, and activity [8].

Ubiquitination can manifest in diverse forms, each encoding distinct functional consequences:

- Monoubiquitination: Attachment of a single ubiquitin molecule, affecting protein activity, interactions, and subcellular localization [8] [31].

- Multi-monoubiquitination: Multiple single ubiquitin attachments to different lysine residues on the same substrate [8].

- Polyubiquitination: Chains of ubiquitin molecules linked through specific lysine residues, with linkage type determining function [8] [31].

- Branched ubiquitination: A single ubiquitin molecule modified with multiple ubiquitin molecules, creating complex signaling outcomes [31].

The specificity of ubiquitination is largely determined by E3 ubiquitin ligases, which recognize target proteins, and deubiquitinases (DUBs), which reverse the process by removing ubiquitin chains [8]. The UPS regulates virtually all cancer hallmarks, including "evading growth suppressors," "reprogramming energy metabolism," "unlocking phenotypic plasticity," "polymorphic microbiomes," and "senescent cells" [8].

Ubiquitination in Bladder Cancer Pathogenesis

Emerging research has illuminated the critical role of ubiquitination in bladder cancer development and progression. Several key ubiquitination regulators have been identified as significantly altered in bladder cancer:

STUB1-GOT2 Axis Regulation: STUB1, a functional E3 ubiquitin ligase, is frequently downregulated in bladder cancer tissues, with low expression associated with advanced progression and poor prognosis [32]. Mechanistically, STUB1 induces K6- and K48-linked polyubiquitination of GOT2 (mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase) at K73 lysine residue, decreasing its stability and attenuating mitochondrial aspartate synthesis [32]. This STUB1-GOT2 axis represents a critical metabolic regulatory mechanism in bladder cancer, particularly under high glucose conditions that promote tumor growth through disruption of this pathway [32].

ZNF24 Ubiquitination-SUMOylation Crosstalk: Zinc finger protein 24 (ZNF24) is a conserved transcription factor that exhibits anti-proliferative and anti-metastatic activity in bladder cancer [33]. ZNF24 undergoes SUMOylation at Lys-27 by UBC9, which prevents CUL3-mediated ubiquitination and degradation [33]. In bladder cancer cells and tissues, both ZNF24 expression and SUMOylation levels are decreased, promoting its ubiquitin-mediated degradation and accelerating tumor progression [33].

RAS Pathway Ubiquitination: RAS proteins, frequently mutated oncoproteins in human cancers, are dynamically regulated by ubiquitination, which controls their stability, membrane localization, and signaling transduction [16]. As NRAS has been identified as a conserved driver gene across human and feline bladder cancers [28] [30], the ubiquitination regulation of RAS proteins may represent an evolutionarily conserved mechanism in bladder cancer pathogenesis.

Experimental Approaches in Cross-Species Cancer Genomics

Whole Exome Sequencing Methodology

The identification of conserved cancer genes across species relies on robust genomic methodologies. The following experimental protocol outlines the key steps for cross-species whole exome sequencing, as employed in the referenced studies [28]:

Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Collect tumor and matched normal tissue samples from multiple institutions to minimize ascertainment bias

- For canine UC: 87 cases (29 males, 58 females) representing 36 different pure and mixed breeds

- For feline UC: 23 cases (14 males, 9 females) representing 6 different breeds

- For bovine UC: 8 cases from 7 females with bracken fern grazing history

- Preserve samples according to standard pathological procedures

Library Preparation and Exome Capture:

- Extract high-quality DNA from tumor and normal tissues

- Fragment DNA and perform library preparation with appropriate adapters

- Enrich exonic regions using species-specific exome capture kits

- Validate library quality and quantity before sequencing

Sequencing and Data Analysis:

- Perform high-throughput sequencing on appropriate platforms (e.g., Illumina)

- Align sequence reads to respective reference genomes (CanFam3.1, FelCat9.0, UMD3.1, GRCh38)

- Call somatic single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), multi-nucleotide variants (MNVs), and small insertions/deletions (indels)

- Identify somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs) using matched normal controls

- Perform mutational signature analysis using computational tools (e.g., SigProfiler)

- Conduct cross-species synteny analysis to identify conserved genomic regions

Validation and Functional Studies:

- Validate key mutations using orthogonal methods (e.g., ddPCR, Sanger sequencing)

- Perform in vitro functional studies in human urinary bladder UC cells treated with bracken fern extracts or purified ptaquiloside for carcinogen models

- Analyze pathway conservation through gene set enrichment analysis

In Vivo Functional Validation Approaches

Functional validation of conserved cancer genes employs both in vitro and in vivo models:

Mouse Xenograft Models:

- Utilize BALB/c nude male mice (4-6 weeks of age)

- Subcutaneously inject control and genetically modified bladder cancer cells (e.g., T24 line) mixed with Matrigel (1:1 ratio)

- Monitor tumor growth over 21 days, measuring tumor volume using calipers (calculation: length × width × width × 0.5)

- For metabolic studies: randomize mice into groups with different treatments (e.g., normal water vs. high glucose water)

- Analyze tumor tissues through western blotting, immunohistochemistry (e.g., Ki67 staining), and metabolic profiling [32]

Metabolomic Analysis:

- Process cells after genetic manipulation (e.g., 48 hours post plasmid transfection)

- Digest with trypsin, wash with PBS, and count cells

- Harvest 1×10^7 cells per sample for analysis

- Perform rapid freezing in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C

- Conduct GC-MS analysis (e.g., TAQ9000 system) for amino acid metabolite profiling

- Analyze data using appropriate bioinformatic tools [32]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Cross-Species Bladder Cancer Research

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use in Bladder Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|

| Species-specific Exome Capture Kits | Enrichment of protein-coding regions for sequencing | Targeted sequencing of conserved genomic regions across human, canine, feline, and bovine specimens [28] |

| Bracken Fern Extracts/Ptaquiloside | Carcinogen exposure modeling | Recapitulation of bovine UC mutational signatures in human bladder cancer cells [28] |

| STUB1 Plasmid Constructs | E3 ubiquitin ligase overexpression | Functional studies of STUB1-GOT2 axis in bladder cancer metabolism [32] |

| GOT2 Antibodies | Protein detection and quantification | Assessment of GOT2 expression and stability in bladder cancer tissues and cell lines [32] |

| ZNF24 Expression Vectors | Transcription factor functional analysis | Investigation of ZNF24 anti-tumor activity and degradation mechanisms [33] |

| CUL3 siRNA/Knockout Constructs | E3 ubiquitin ligase inhibition | Study of ZNF24 ubiquitination and SUMOylation crosstalk [33] |

| Matrigel Matrix | In vivo tumor xenograft studies | Subcutaneous implantation of bladder cancer cells in mouse models [32] |

| GC-MS Metabolomics Platform | Metabolic profiling | Analysis of amino acid metabolites, particularly aspartate metabolism [32] |