Decoding the Ubiquitin Chain Architecture: Detection Challenges and Advanced Methodologies

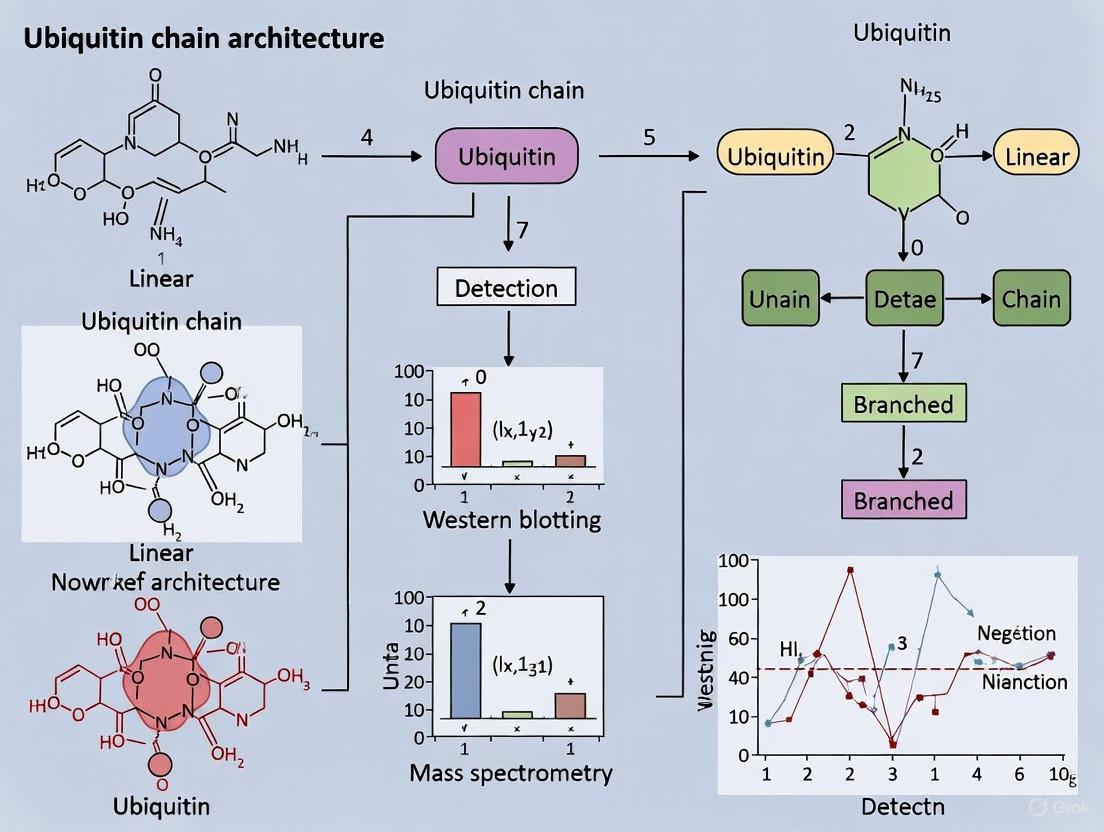

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how the complex architecture of ubiquitin chains—including homotypic, mixed, and branched topologies—presents significant challenges for detection and characterization.

Decoding the Ubiquitin Chain Architecture: Detection Challenges and Advanced Methodologies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how the complex architecture of ubiquitin chains—including homotypic, mixed, and branched topologies—presents significant challenges for detection and characterization. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of ubiquitin signaling, details cutting-edge methodological approaches like UbiCRest and UbiChEM-MS, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and validates findings through comparative analysis. By synthesizing the latest research, this review serves as an essential guide for navigating the technical landscape of ubiquitin chain analysis and highlights its critical implications for understanding disease mechanisms and developing targeted therapies.

The Complex Language of Ubiquitin: From Homotypic Chains to Branched Architectures

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates virtually all cellular processes in eukaryotes, from protein degradation and immune signaling to DNA repair and cell cycle control [1]. This versatility stems from the ability of the 76-amino acid protein ubiquitin to form diverse polymeric chains through a process called polyubiquitination [2] [3]. The resulting array of chain structures and functions is often referred to as the "ubiquitin code" [1] [4].

The complexity of this code arises from several factors: the number of ubiquitin moieties attached to a substrate, the specific inter-ubiquitin linkage type, and the formation of heterotypic or branched ubiquitin chains [2] [5]. Furthermore, ubiquitin itself can be modified by phosphorylation or acetylation, adding another layer of regulation [4]. Decrypting this complex language is fundamental to understanding cellular physiology and developing new therapies for diseases like cancer and neurodegenerative disorders [1].

The Ubiquitin Machinery: Writers, Erasers, and Readers

The Enzymatic Cascade

Ubiquitination requires a sequential enzymatic cascade involving three distinct classes of enzymes [3]:

- E1 (ubiquitin-activating enzymes): ATP-dependent enzymes that initiate the process by activating ubiquitin. Humans possess two E1 enzymes (Uba1 and Uba6) [3].

- E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes): Carry the activated ubiquitin and work in concert with E3 enzymes. The human genome encodes approximately 40 E2s [3].

- E3 (ubiquitin ligases): Confer substrate specificity and catalyze the final transfer of ubiquitin to the target protein. With over 600 members in humans, E3s are the most diverse component of the system [3].

E3 ligases fall into three main mechanistic categories. RING/U-box ligases facilitate direct ubiquitin transfer from the E2 to the substrate. HECT ligases and RBR ligases form a transient thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate [2] [3].

Specific E3 Complexes and Linkage Determination

Different E3 complexes generate specific linkage types. A prime example is the Linear Ubiquitin Chain Assembly Complex (LUBAC), the only known E3 capable of forming Met1-linked linear ubiquitin chains [2]. LUBAC comprises three core subunits: the catalytic subunit HOIP, and the regulatory subunits HOIL-1 and SHARPIN. The unique C-terminal Linear ubiquitin chain Determining Domain (LDD) of HOIP is essential for positioning the N-terminus of the acceptor ubiquitin for peptide bond formation [2].

Reversibility and Signal Interpretation

Ubiquitination is a reversible modification. Deubiquitinases (DUBs) hydrolyze the bonds between ubiquitin molecules or between ubiquitin and substrate proteins, providing dynamic control over ubiquitin signals [2] [1]. The signal is interpreted by proteins harboring Ubiquitin-Binding Domains (UBDs). More than 150 UBDs have been identified, belonging to diverse structural families such as alpha-helical motifs, zinc fingers, and pleckstrin-homology domains [3]. These domains recognize ubiquitin chains with high selectivity, translating the ubiquitin code into specific cellular outcomes [2].

The Architecture of Ubiquitin Chains

Linkage Types and Their Functions

Ubiquitin chains are classified based on the connectivity between monomers. A ubiquitin molecule can be modified on its N-terminal methionine (Met1) or any of its seven internal lysine residues (Lys6, Lys11, Lys27, Lys29, Lys33, Lys48, Lys63), leading to eight possible homotypic linkage types [2] [3]. Each linkage type adopts a distinct three-dimensional structure, enabling specific interactions with effector proteins and resulting in defined biological outcomes [2].

Table 1: Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Primary Functions

| Linkage Type | Major Cellular Functions |

|---|---|

| Met1 (Linear) | Immune signaling, NF-κB activation, cell death regulation [2] [1] |

| Lys48 | Target protein degradation by the 26S proteasome [3] [1] |

| Lys63 | DNA repair, NF-κB signaling, endocytosis, inflammation [3] [1] |

| Lys11 | Cell cycle control, ER-associated degradation (ERAD) [3] [5] |

| Lys29 | Proteasomal degradation, lysosomal targeting [3] |

| Lys33 | AMPK-related kinase regulation [3] |

| Lys6 | DNA repair, mitochondrial homeostasis [3] |

| Lys27 | Stress response, mitophagy [3] |

Quantitative Linkage Abundance

The relative abundance of different ubiquitin linkages varies between organisms and cell types, as revealed by mass spectrometry. The table below shows a comparison between mammalian cells and yeast.

Table 2: Relative Abundance of Ubiquitin Linkages in Different Cell Types

| Linkage Type | HEK293 Mammalian Cells [3] | S. cerevisiae (Yeast) [3] |

|---|---|---|

| Lys6 | ≤ 0.5% | 10.9% ± 1.9% |

| Lys11 | 2% | 28.0% ± 1.4% |

| Lys27 | ≤ 0.5% | 9.0% ± 0.1% |

| Lys29 | 8% | 3.2% ± 0.1% |

| Lys33 | ≤ 0.5% | 3.5% ± 0.1% |

| Lys48 | 52% | 29.1% ± 1.9% |

| Lys63 | 38% | 16.3% ± 0.2% |

Beyond Homotypic Chains: Heterotypic and Branched Architectures

Beyond homotypic chains, ubiquitin can form more complex heterotypic chains, which include mixed-linkage chains and branched ubiquitin chains [5]. In branched chains, at least one ubiquitin monomer is simultaneously modified on two different acceptor sites, creating a forked structure [5]. Branched chains account for a significant 10–20% of all ubiquitin polymers in cells [6] [7]. Notable examples include K11/K48-branched chains, which act as a priority signal for proteasomal degradation during cell cycle progression and proteotoxic stress [6] [5]. Other branched chains with physiological functions include K29/K48 and K48/K63 linkages [5].

How Chain Architecture Influences Detection and Research

The structural complexity of the ubiquitin code presents significant challenges for its detection and quantification. The transient nature of ubiquitination, the sub-stoichiometric modification of targets, and the vast diversity of chain architectures require highly specific and sensitive tools [2]. A key challenge is that many detection methods have inherent linkage bias, meaning they preferentially recognize or capture some ubiquitin chain types over others, potentially leading to a distorted view of the cellular ubiquitinome [8].

The Impact of Chain Length

Beyond linkage type, the length of a ubiquitin chain is a major determinant of how it is recognized by ubiquitin-binding proteins (UBPs). Research using length-defined ubiquitin chains has demonstrated that many UBPs show a clear preference for longer polymers (e.g., Ub6+), while others interact preferentially with shorter chains (Ub2, Ub4) [9]. For example, a proteome-wide screen found that 64-70% of significant interactions with K27, K29, and K33-linked chains occurred exclusively with long polymers (Ub6+) [9]. This length selectivity adds another layer of complexity to deciphering ubiquitin signals and must be considered when designing detection assays.

Advanced Detection Methodologies

Ub-clipping for Architectural Insights

Ub-clipping is an innovative methodology that uses an engineered viral protease (Lbpro*) to incompletely cleave polyubiquitin chains, leaving the signature C-terminal Gly-Gly dipeptide attached to the modified lysine residue [7]. This technique "collapses" complex polyubiquitin into manageable GlyGly-modified monoubiquitin units, enabling detailed analysis.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Ubiquitin Detection

| Research Tool | Function and Utility |

|---|---|

| Tandem Hybrid UBD (ThUBD) | An engineered, high-affinity ubiquitin-binding domain that captures all ubiquitin chain types without linkage bias, used in assays like TUF-WB and high-throughput plates [8]. |

| Lbpro* (Engineered Viral Protease) | The core enzyme in Ub-clipping. It cleaves polyubiquitin chains after Arg74, generating truncated ubiquitin and GlyGly-modified ubiquitin for mass spectrometry analysis [7]. |

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Tandem repeats of UBDs used to purify polyubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates, protecting them from deubiquitinases (DUBs) and enabling enrichment [7]. |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Antibodies developed to recognize a specific ubiquitin linkage type (e.g., K48-only, K63-only). Useful for immunoblotting but can have cross-reactivity or limited coverage [8]. |

| GlyGly-Antibody | An antibody that recognizes the di-glycine remnant left on lysine after tryptic digestion of ubiquitinated proteins. Used for proteome-wide ubiquitination site mapping [7]. |

Experimental Workflow for Ub-clipping [7]:

- Isolate Polyubiquitin: Use TUBE pulldowns to enrich polyubiquitinated proteins from a cell lysate or in vitro reaction.

- Lbpro* Digestion: Treat the sample with the Lbpro* protease. This cleaves the polyubiquitin chains into a mixture of:

- Truncated ubiquitin (residues 1-74) from distal subunits.

- GlyGly-modified ubiquitin (1-74) from internal and branched subunits.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze the products by intact mass spectrometry and AQUA (Absolute QUAntitation) MS.

- Intact Mass: Reveals the number of GlyGly modifications on a single ubiquitin molecule, directly indicating chain branching (e.g., di-GlyGly ubiquitin indicates a branch point).

- AQUA MS: Quantifies the relative abundance of different linkage types (K6, K11, K48, etc.) in the original sample.

This workflow provided the key insight that 10-20% of ubiquitin in cellular polymers exists in the context of branched chains [7].

High-Throughput Detection with ThUBD Plates

To address the need for unbiased, high-throughput ubiquitination assays, researchers have developed 96-well plates coated with the Tandem Hybrid Ubiquitin Binding Domain (ThUBD). This platform allows for the sensitive and specific capture, identification, and quantification of proteins modified with any type of ubiquitin chain directly from complex proteome samples [8] [10].

A study demonstrated that ThUBD-coated plates exhibit a 16-fold wider linear range for capturing polyubiquitinated proteins compared to previous technologies that used Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) [8]. This high sensitivity and lack of linkage bias make it particularly useful for applications in drug development, such as monitoring the efficiency of PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras), which function by inducing target protein ubiquitination [8].

Understanding the basic building blocks of ubiquitin—from the single moiety to the diverse array of homotypic, mixed, and branched chains—is fundamental to cell biology. The architecture of these chains, defined by their linkage, length, and branching, forms a complex code that dictates precise cellular outcomes. However, this very complexity directly shapes detection research, demanding tools that are not only sensitive but also unbiased. Methodologies like Ub-clipping and ThUBD-based platforms represent significant advances in this regard, providing researchers with the means to accurately decipher the ubiquitin code. As these tools continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly accelerate both our basic understanding of ubiquitin signaling and the development of novel therapeutics that target the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

Protein ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates virtually all cellular processes, from protein degradation to signal transduction and DNA repair [11]. The versatility of ubiquitin signaling stems from the capacity of ubiquitin itself to form diverse polymeric chains. While early research focused on homotypic chains (linked through a single ubiquitin residue type), recent advances have revealed an astonishing complexity in heterotypic chains that contain multiple linkage types [5]. These heterotypic structures can be further classified as mixed chains (containing different linkages but each ubiquitin modified at only one site) or branched chains (containing at least one ubiquitin molecule modified concurrently at two or more sites) [12]. This architectural diversity expands the ubiquitin code's informational capacity, enabling precise control over cellular responses. Understanding these complex topologies is essential for deciphering their specialized functions in health and disease, particularly in the context of targeted protein degradation therapies.

Architectural Diversity: Defining Heterotypic Ubiquitin Chains

Structural Classification of Ubiquitin Polymers

Ubiquitin chains are categorized based on their linkage patterns and overall topology. Homotypic chains represent the simplest architecture, consisting of ubiquitin monomers linked uniformly through the same acceptor site (e.g., K48-linked chains that primarily target substrates for proteasomal degradation) [5]. In contrast, heterotypic chains exhibit greater complexity and can be divided into two distinct categories:

- Mixed linkage chains: These polymers contain more than one type of ubiquitin linkage, but each ubiquitin monomer within the chain is modified on only a single acceptor site. While topologically linear like homotypic chains, they encode different information through their alternating linkage pattern [12].

- Branched chains: These architectures contain at least one ubiquitin subunit that is simultaneously modified on two or more different acceptor sites, creating a branch point within the polymer [12]. This branching can occur at proximal, internal, or distal positions within the chain, generating structural diversity that exceeds that of mixed chains.

Branched chains account for an estimated 10-20% of all ubiquitin polymers in cells, with K11/K48-branched chains being among the best characterized [6]. The structural organization of these different chain types has profound implications for their recognition by ubiquitin-binding effectors and their subsequent biological functions.

Experimentally Characterized Branched Ubiquitin Chains

Advanced biochemical and mass spectrometry approaches have identified several biologically relevant branched ubiquitin chains with distinct functions:

Table 1: Experimentally Confirmed Branched Ubiquitin Chains and Their Functions

| Linkage Type | Biological Context | Cellular Function | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| K11/K48 | Cell cycle progression, protein quality control | Enhanced proteasomal degradation | [13] [6] |

| K48/K63 | NF-κB signaling, apoptosis | Regulation of signaling complexes, proteasomal degradation | [12] [5] |

| K29/K48 | Ubiquitin fusion degradation pathway | Proteasomal degradation | [12] [5] |

| K6/K48 | Parkin-mediated mitophagy | Unknown (in vitro) | [12] |

The K11/K48-branched chains have emerged as particularly important signals that promote rapid proteasomal clearance of specific substrates, including mitotic regulators, misfolded nascent polypeptides, and pathological Huntingtin variants associated with neurodegenerative disease [13]. Recent structural studies have revealed that the 26S proteasome recognizes K11/K48-branched chains through a multivalent mechanism involving RPN2, RPN10, and RPT4/5 subunits, explaining their priority degradation signal [6].

Methodologies for Analyzing Branched Ubiquitin Chains

UbiCRest: Deubiquitinase-Based Linkage Analysis

The UbiCRest (Ubiquitin Chain Restriction) method employs linkage-specific deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) to decipher ubiquitin chain composition and architecture [11]. This approach takes advantage of the intrinsic linkage preferences of various DUBs to selectively cleave specific ubiquitin linkages in parallel reactions, followed by gel-based analysis to interpret the results.

Table 2: Linkage-Specific DUBs Used in UbiCRest Analysis

| Linkage Specificity | DUB Enzyme | Working Concentration | Notes on Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| All linkages (positive control) | USP21 or USP2 | 1-5 µM | Cleaves all linkages including proximal ubiquitin |

| Lys48 | OTUB1 | 1-20 µM | Highly Lys48-specific, not very active |

| Lys63 | OTUD1 | 0.1-2 µM | Very active, non-specific at high concentrations |

| Lys11 | Cezanne | 0.1-2 µM | Very active, non-specific at very high concentrations |

| Lys6 | OTUD3 | 1-20 µM | Also cleaves Lys11 chains equally well |

| Lys27 | OTUD2 | 1-20 µM | Also cleaves Lys11, Lys29, Lys33 |

| Lys29/Lys33 | TRABID | 0.5-10 µM | Cleaves Lys29 and Lys33 equally well |

Experimental Protocol for UbiCRest:

- Sample Preparation: Immunopurify the ubiquitinated protein of interest or isolate polyubiquitin chains. Even western blotting quantities of endogenously ubiquitinated proteins can be sufficient for analysis.

- DUB Panel Setup: Set up parallel reactions containing the substrate and individual DUBs at their specified working concentrations in appropriate buffer conditions.

- Incubation: Conduct reactions at 37°C for 1-2 hours. Optimization of incubation time may be necessary for different substrates.

- Termination and Analysis: Stop reactions with SDS sample buffer, separate proteins by SDS-PAGE, and analyze by immunoblotting with ubiquitin-specific antibodies.

- Data Interpretation: Compare the cleavage patterns across different DUB treatments. Complete cleavage by a linkage-specific DUB indicates the presence of that linkage type. Partial cleavage patterns can suggest the presence of branched chains where only specific linkages are accessible.

The UbiCRest method is particularly valuable for identifying branched chains because different DUBs may show partial or sequential cleavage patterns depending on the chain architecture and the positioning of branch points [11].

Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) for Linkage-Specific Enrichment

TUBEs are engineered tandem-repeated ubiquitin-binding entities that exhibit high-affinity interactions with polyubiquitin chains. Recent advances have developed chain-specific TUBEs with selectivity for particular linkage types, enabling the capture and analysis of endogenous ubiquitination events in a linkage-specific manner [14].

Protocol for TUBE-Based Analysis:

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells in a buffer optimized to preserve polyubiquitination (e.g., containing N-ethylmaleimide to inhibit DUBs).

- Enrichment: Incubate cell lysates with chain-specific TUBEs (e.g., K48-TUBEs or K63-TUBEs) immobilized on magnetic beads or plate surfaces.

- Washing: Remove non-specifically bound proteins through rigorous washing.

- Detection: Elute and detect bound proteins by immunoblotting for the protein of interest, or perform in-situ detection in plate-based formats.

This approach has been successfully applied to differentiate context-dependent ubiquitination events, such as distinguishing between K63-linked ubiquitination of RIPK2 induced by inflammatory stimuli versus K48-linked ubiquitination induced by PROTAC molecules [14]. The method offers advantages for high-throughput applications and can detect ubiquitination of endogenous proteins without genetic manipulation.

Bispecific Antibodies for Direct Detection

Bispecific antibodies that simultaneously recognize two different ubiquitin linkages provide a powerful tool for specifically detecting branched chains. For example, a K11/K48-bispecific antibody created using knobs-into-holes heterodimerization technology functions as a coincidence detector that gains avidity from simultaneous binding to K11 and K48 linkages [13].

Key validation data for K11/K48-bispecific antibody:

- Shows ~500-1000-fold higher affinity for K11/K48-branched ubiquitin trimers compared to control antibodies

- Efficiently recognizes K11/K48-branched trimers but fails to detect monomeric or dimeric ubiquitin species

- Displays high selectivity for K11/K48-branched chains over other branched types (K11/K63, K48/K63, or M1/K63)

- Recognizes both branched trimers and mixed trimers with proximal K11 and K48 linkages

This antibody enabled the identification of physiological substrates of K11/K48-branched chains, including mitotic regulators and aggregation-prone proteins, establishing their importance in cell cycle control and protein quality control [13].

Mass Spectrometry-Based Approaches

Advanced mass spectrometry techniques have become indispensable for comprehensive ubiquitin chain analysis:

- Ubiquitin Absolute Quantitation (Ub-AQUA): Uses stable isotope-labeled internal standards to quantify the relative abundance of different ubiquitin linkages in a sample [6].

- Middle-down MS: Characterizes chain length and linkage by partial trypsin digestion under optimized native conditions, resulting in a single cleavage event at Arg74 of ubiquitin [11].

- Ubiquitin Clipping: Employs the viral Lbpro* protease to quantitatively cleave ubiquitin chains for subsequent LC-MS/MS analysis, enabling mapping of chain architecture [6].

These MS-based approaches can identify branched chains through the detection of ubiquitin molecules modified at multiple sites and provide quantitative information on linkage composition.

Synthesis and Disassembly of Branched Ubiquitin Chains

Mechanisms of Branched Chain Assembly

Branched ubiquitin chains are synthesized through multiple distinct mechanisms, often requiring collaboration between ubiquitylation enzymes:

Single E3 with Multiple E2s: The anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C), a multisubunit RING E3, cooperates sequentially with UBE2C (which builds initial chains with mixed linkages) and UBE2S (which extends K11 linkages) to form branched K11/K48 chains on mitotic regulators [12] [5].

Collaborating E3 Pairs: Pairs of E3 ligases with distinct linkage specificities work together to assemble branched chains. Examples include:

- ITCH and UBR5 collaborating to form branched K48/K63 chains on TXNIP during apoptotic responses [12]

- TRAF6 and HUWE1 cooperating during NF-κB signaling to produce branched K48/K63 chains [12] [5]

- Ufd4 and Ufd2 working together in yeast to form branched K29/K48 chains on substrates of the ubiquitin fusion degradation pathway [5]

Single E3 with Innate Branching Activity: Some E3 ligases can synthesize branched chains with a single E2, including:

Single E2 with Branching Activity: Rare E2s such as UBE2K have an innate ability to promote the assembly of branched K48/K63 chains [12].

The mechanisms underlying branch point selection are complex and may involve specific recognition of the growing chain by ubiquitin-binding domains within the E3 ligases [5].

Disassembly by Deubiquitinating Enzymes

Branched ubiquitin chains are dynamically edited and disassembled by specialized deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs):

UCH37: This proteasome-associated DUB is activated by binding to RPN13 and preferentially cleaves K48 linkages from branched ubiquitin molecules while leaving the variable secondary linkages intact [12]. This editing activity can convert a branched degradative signal into a non-degradative signal, potentially rescuing substrates from proteasomal degradation.

Other DUBs: Several DUBs show preference for specific linkage types and can edit branched chains by selectively removing one linkage type while preserving others [15].

The balance between branching E3 ligases and debranching DUBs creates a dynamic regulatory system that can rapidly modulate ubiquitin-dependent signaling outcomes.

Functional Consequences of Branched Ubiquitination

Enhanced Proteasomal Degradation

Branched ubiquitin chains, particularly those containing K48 linkages in combination with K11, K29, or K63 linkages, often function as potent degradation signals that enhance the efficiency of substrate delivery to the proteasome [13] [6]. Several mechanisms underlie this enhanced degradation:

Multivalent Proteasome Engagement: Branched chains enable simultaneous engagement of multiple ubiquitin receptors on the proteasome. Recent cryo-EM structures revealed that K11/K48-branched chains form a tripartite binding interface with RPN2, RPN10, and RPT4/5 subunits of the 26S proteasome, creating stronger avidity interactions than homotypic chains [6].

Protection from Deubiquitination: The complex architecture of branched chains may provide partial protection from complete disassembly by DUBs, prolonging the degradation signal [15].

Priority Degradation Signals: K11/K48-branched chains are specifically recognized as priority signals during cell cycle progression and proteotoxic stress, ensuring rapid clearance of key regulatory proteins [6].

Regulation of Signaling Complexes

Certain branched chains function in non-proteolytic roles to regulate the assembly and activity of signaling complexes:

- Branched K48/K63 chains formed by TRAF6 and HUWE1 during NF-κB signaling inhibit CYLD cleavage and modulate signal duration [12].

- The conversion of K63-linked chains to K48/K63-branched chains on TXNIP by sequential action of ITCH and UBR5 represents a mechanism to convert a non-degradative signal to a degradative signal, thereby inactivating a signaling protein [5].

Implications for Targeted Protein Degradation Therapeutics

The understanding of branched ubiquitin chains has significant implications for targeted protein degradation therapeutics, including PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) and molecular glues:

- Efficient target degradation often requires the formation of branched ubiquitin chains [15].

- The collaboration between E3 ligases recruited by PROTACs and endogenous E3s may promote branching and enhance degradation efficiency.

- Chain-specific TUBEs enable monitoring of PROTAC-induced K48-linked ubiquitination in high-throughput screening formats, facilitating drug development [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Branched Chain Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Analyzing Branched Ubiquitin Chains

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linkage-specific DUBs | OTUB1 (K48), OTUD1 (K63), Cezanne (K11) | UbiCRest analysis to decipher linkage composition and chain architecture | Must profile specificity at working concentrations; commercial sources available |

| Chain-specific TUBEs | K48-TUBEs, K63-TUBEs, Pan-TUBEs | High-affinity enrichment of linkage-specific ubiquitination from native cell lysates | Enable study of endogenous proteins; applicable to HTS formats |

| Bispecific antibodies | K11/K48-bispecific antibody | Direct detection of specific branched chain types | Functions as coincidence detector; requires rigorous validation |

| Linkage-specific antibodies | K11-, K48-, K63-linkage antibodies | Western blot detection and immunoprecipitation of specific linkages | Commercial availability varies by linkage type |

| Ubiquitin mutants | K-to-R mutants, linear ubiquitin mutants | Dissecting chain requirements in cellular assays | May not fully recapitulate wild-type ubiquitin function |

| Mass spectrometry standards | Ub-AQUA quantification standards | Absolute quantification of linkage composition in samples | Requires specialized instrumentation and expertise |

Branched and heterotypic ubiquitin chains represent a sophisticated layer of regulation in the ubiquitin system, expanding the coding capacity of ubiquitin signaling beyond what is possible with homotypic chains alone. These complex architectures enable specialized functions ranging from enhanced proteasomal degradation to precise regulation of signaling complexes. The study of branched chains has been accelerated by developing specialized methodologies, including UbiCRest, chain-specific TUBEs, bispecific antibodies, and advanced mass spectrometry techniques. As our understanding of branched chain synthesis, recognition, and disassembly grows, so does our appreciation of their importance in fundamental biological processes and therapeutic applications, particularly in the rapidly advancing field of targeted protein degradation. Future research will undoubtedly uncover additional branched chain types, assembly mechanisms, and functional specializations, further illuminating the complexity of the ubiquitin code.

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates a vast array of cellular processes in eukaryotes, including protein degradation, DNA repair, signal transduction, and immune responses [5] [16]. The versatility of ubiquitin signaling stems from its ability to form diverse polymeric structures—ubiquitin chains—where the C-terminus of one ubiquitin moiety is linked to a specific lysine residue or the N-terminal methionine of another ubiquitin molecule [5]. While early research focused predominantly on homotypic chains (uniform linkages through the same ubiquitin site), recent technological advances have revealed an astonishing complexity in ubiquitin chain architecture, particularly through the discovery and characterization of branched ubiquitin chains [17] [5].

In branched ubiquitin chains, individual ubiquitin monomers are simultaneously modified on at least two different acceptor sites, creating bifurcated structures that significantly expand the signaling capacity of the ubiquitin system [17]. Similar to how branched oligosaccharides on cell surfaces enable complex cell-cell recognition, branched ubiquitin architectures create sophisticated interaction platforms that can be specifically recognized by distinct effector proteins within the cell [5]. This article explores how the three-dimensional architecture of ubiquitin chains, particularly branched configurations, determines their biological functions and presents the cutting-edge methodologies enabling these discoveries in ubiquitin research.

Ubiquitin Chain Architecture: Beyond Simple Linear Polymers

Classification of Ubiquitin Chains

Ubiquitin chains can be classified into three major categories based on their linkage patterns:

- Homotypic chains: Uniform linkages through the same acceptor site (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63, or M1)

- Heterotypic mixed chains: Contain more than one linkage type, but each ubiquitin is modified on only one site

- Heterotypic branched chains: Comprise ubiquitin subunits simultaneously modified on at least two different acceptor sites [5]

Table 1: Major Types of Homotypic Ubiquitin Chains and Their Primary Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Known Functions |

|---|---|

| K48-linked | Targets substrates for proteasomal degradation [16] |

| K63-linked | Regulates protein-protein interactions, DNA repair, NF-κB signaling [16] |

| K11-linked | Cell cycle regulation, proteasomal degradation [16] |

| M1-linked (Linear) | NF-κB inflammatory signaling [16] [18] |

| K6-linked | DNA damage repair [16] |

| K27-linked | Controls mitochondrial autophagy [16] |

| K29-linked | Cell cycle regulation, stress response [16] |

| K33-linked | T-cell receptor-mediated signaling [16] |

Branched Ubiquitin Chains: Architectures and Synthesis

Branched ubiquitin chains represent a significant fraction of cellular polyubiquitin, with recent estimates suggesting they constitute 10-20% of all ubiquitin polymers in cells [7] [6]. These complex structures can vary in their linkage combinations, branch point locations, and overall architecture, creating a nearly limitless repertoire of possible signaling molecules [5].

Several physiologically relevant branched ubiquitin chains have been identified:

- K11/K48-branched chains: The best-characterized branched topology, functions as a potent proteasomal targeting signal [6]

- K29/K48-branched chains: Involved in the ubiquitin fusion degradation (UFD) pathway in yeast [5]

- K48/K63-branched chains: Function in NF-κB signaling and apoptotic responses [5]

The synthesis of branched chains often involves collaboration between pairs of E3 ligases with distinct linkage specificities. For example, during mitotic progression, the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) cooperates with two different E2 enzymes (UBE2C and UBE2S) to assemble branched K11/K48 chains on substrates [5]. Similarly, in apoptosis, the HECT E3 ITCH first modifies the pro-apoptotic regulator TXNIP with K63-linked chains, which are subsequently converted to degradative K48/K63-branched chains through UBR5-mediated K48 linkage attachment [5].

Functional Consequences of Chain Architecture

Enhanced Proteasomal Targeting

Branched ubiquitin chains, particularly K11/K48-branched topologies, function as priority signals for proteasomal degradation [6]. Recent cryo-EM structures of the human 26S proteasome in complex with K11/K48-branched ubiquitin chains have revealed a multivalent recognition mechanism wherein:

- The canonical K48-linkage binding site (formed by RPN10 and RPT4/5) engages one branch

- A previously unidentified K11-linkage binding groove (formed by RPN2 and RPN10) engages the other branch

- RPN2 recognizes an alternating K11-K48-linkage through a conserved motif [6]

This tripartite binding interface creates enhanced avidity, explaining why K11/K48-branched ubiquitin chains facilitate more efficient substrate degradation compared to homotypic K48-linked chains, particularly during cell cycle progression and proteotoxic stress [6].

Signal Conversion and Amplification

The sequential action of E3 ligases with different linkage specificities enables temporal control of signaling outcomes. The conversion of non-proteolytic signals (e.g., K63-linked chains) to degradative signals (e.g., K48/K63-branched chains) provides an efficient mechanism for regulating the activation and inactivation of signaling proteins [5]. This "signal conversion" mechanism ensures that specific cellular events are terminated in a timely manner through controlled protein degradation.

Methodological Advances in Studying Ubiquitin Chain Architecture

Ub-Clipping: A Breakthrough Technology

Traditional tryptic digestion-based mass spectrometry approaches for studying ubiquitination lose architectural information about polyubiquitin chains [7]. The recently developed Ub-clipping methodology addresses this limitation by utilizing an engineered viral protease, Lbpro*, that cleaves ubiquitin after Arg74, leaving the signature C-terminal GlyGly dipeptide attached to the modified lysine residues [7].

Key advantages of Ub-clipping include:

- Collapses complex polyubiquitin samples to GlyGly-modified monoubiquitin species

- Enables quantification of multiply GlyGly-modified branch-point ubiquitin

- Reveals coexisting ubiquitin modifications (e.g., phosphorylation)

- Allows assessment of chain length and branching frequency [7]

Application of Ub-clipping to global ubiquitin analysis revealed that approximately 10-20% of ubiquitin in cellular polymers exists as branched chains, with about 0.5% of all ubiquitin representing branch points in whole cell lysates, increasing to 4-7% in TUBE-enriched polyubiquitin fractions [7].

Linkage-Specific Tools and Methodologies

Researchers now have multiple tools for dissecting ubiquitin chain architecture:

Table 2: Key Methodologies for Ubiquitin Chain Architecture Analysis

| Methodology | Principle | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ub-clipping [7] | Engineered Lbpro* protease cleaves ubiquitin after Arg74, preserving GlyGly modifications | Branch identification, chain architecture analysis, quantification of branching frequency | Requires specialized expertise, may not detect all branch types |

| Linkage-specific Antibodies [16] [19] | Antibodies recognizing specific ubiquitin linkages | Enrichment and detection of chains with particular linkages | Limited to known linkages, potential cross-reactivity |

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) [7] [19] | Tandem-repeated ubiquitin-binding domains with high affinity for polyubiquitin | Enrichment of polyubiquitinated proteins, protection from deubiquitinases | May preferentially bind certain chain types |

| Absolute Quantification (AQUA) MS [7] | Mass spectrometry with heavy isotope-labeled ubiquitin peptides | Precise quantification of different linkage types | Requires specialized standards, loses architectural context |

| Ubiquitin Tagging [19] | Expression of epitope-tagged ubiquitin (e.g., His, Strep, HA) | Purification of ubiquitinated proteins, identification of ubiquitination sites | May not fully mimic endogenous ubiquitin, potential artifacts |

Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Architecture Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Branched Ubiquitin Chains

| Research Tool | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered Proteases | Lbpro* (L102W mutant) [7] | Ub-clipping methodology for branch point identification |

| Linkage-specific E3 Ligases | APC/C (K11/K48 branches) [5], UBR5 (K48/K63 branches) [5], TRAF6/HUWE1 (K48/K63 branches) [5] | Synthesis of specific branched ubiquitin chains for functional studies |

| Deubiquitinases (DUBs) | UCHL5 (K11/K48 debranching) [6], OTULIN (M1-specific) [18], CYLD (K63/M1-specific) [18] | Branch-specific disassembly, pathway modulation |

| Ubiquitin Binding Reagents | TUBEs (tandem ubiquitin-binding entities) [7] [19], Linkage-specific antibodies [16] [19] | Enrichment and detection of specific chain architectures |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | AQUA (Absolute Quantification) peptides [7] | Quantitative analysis of linkage composition |

| Proteasomal Receptors | Recombinant RPN1, RPN10, RPN13 [6] | Studies of branched chain recognition and degradation |

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutic Interventions

The expanding understanding of ubiquitin chain architecture opens new avenues for therapeutic intervention. Several aspects of the ubiquitin system are already being targeted in clinical development:

- Proteasome inhibitors (e.g., bortezomib) have demonstrated efficacy in multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma [16]

- E1 enzyme inhibitors (e.g., MLN4924) have entered clinical trials for cancer treatment [16]

- E3 ligase inhibitors (e.g., Nutlin targeting Mdm2-p53 interaction) show promise in preclinical models [16]

The specificity inherent in branched ubiquitin chain recognition suggests that targeting the enzymes that create or interpret these signals could yield highly specific therapeutics with reduced off-target effects. For instance, inhibitors targeting the collaboration between specific E3 ligase pairs that generate pathogenic branched chains, or compounds that modulate branch-specific DUBs like UCHL5, represent promising therapeutic strategies [6].

The architecture of ubiquitin chains, particularly branched configurations, represents a critical regulatory layer in cellular signaling that determines biological function. The shape and connectivity of ubiquitin polymers directly influence their recognition by effector proteins, ultimately dictating whether a modified protein will be degraded, activated, or relocalized within the cell. Advanced methodologies like Ub-clipping, linkage-specific proteomics, and structural biology approaches are rapidly illuminating this complex landscape, revealing how branched ubiquitin chains function as sophisticated priority signals in processes ranging from cell cycle control to stress response pathways. As our understanding of the "ubiquitin shape code" deepens, so too will opportunities for therapeutic intervention in the many diseases characterized by ubiquitin system dysregulation.

Ubiquitination represents one of the most complex post-translational modifications in eukaryotic cells, governing virtually all aspects of cell biology through a sophisticated signaling system known as the "ubiquitin code." This code derives its complexity from the ability of ubiquitin to form diverse polymeric chains through its seven internal lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or N-terminal methionine (M1). These chains can be homotypic (uniform linkage), mixed (multiple linkages in linear sequence), or branched (multiple linkages at a single ubiquitin molecule), creating an almost infinite array of possible signals [5] [1]. While homotypic K48-linked chains were first identified as the primary signal for proteasomal degradation, and K63-linked chains for signaling processes, recent research has revealed that branched ubiquitin chains constitute 10-20% of all ubiquitin polymers and function as specialized signals, with K11/K48-branched chains acting as priority degradation signals during cell cycle progression and proteotoxic stress [6] [5].

The structural complexity of ubiquitin chains creates fundamental challenges for detection and interpretation. Unlike simpler post-translational modifications, ubiquitin architectures display remarkable structural plasticity, adopting different conformations in various molecular contexts [20]. This review examines the core challenges posed by complex ubiquitin structures in detection research, detailing current methodological approaches and emerging solutions that enable researchers to decipher this sophisticated signaling system.

Structural Diversity and Detection Challenges

The Architecture of Ubiquitin Signals

Ubiquitin chains are classified based on their linkage patterns and overall architecture. The functional diversity of these structures stems from their ability to adopt distinct conformations that are recognized by specific receptors:

- Homotypic chains: Uniform linkages throughout the chain (e.g., all K48 linkages)

- Mixed chains: Multiple linkage types along a linear sequence

- Branched chains: Multiple linkage types originating from a single ubiquitin molecule [5]

The structural dynamics of these chains further complicate detection. For instance, K48-linked di- and tetra-ubiquitin chains exist in equilibrium between "closed" conformations (where hydrophobic patches are sequestered) and "open" conformations, while K63-linked chains predominantly adopt extended structures that expose these patches [21]. Recent cryo-EM studies of the human 26S proteasome revealed that K11/K48-branched ubiquitin chains are recognized through a multivalent mechanism involving a novel K11-linked Ub binding site at the RPN2-RPN10 groove alongside the canonical K48-linkage binding site [6]. This structural insight explains the molecular basis for preferential recognition of branched chains but also highlights the challenge of detecting conformations that may be transient in solution.

Fundamental Detection Challenges

The complex architecture of ubiquitin chains creates several interconnected detection dilemmas:

Table 1: Fundamental Challenges in Detecting Complex Ubiquitin Structures

| Challenge Category | Specific Limitations | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage Complexity | Discrimination between linkage types in mixed/branched chains; overlapping structural features | Inability to assign specific biological functions to distinct chain architectures |

| Chain Length Variability | Differential binding affinities based on polymer length; technical limitations in separating chains by size | Underestimation of length-dependent effects in ubiquitin signaling |

| Structural Dynamics | Conformational flexibility and transient states; equilibrium between open/closed conformations | Difficulty capturing physiologically relevant states in experimental conditions |

| Spatiotemporal Resolution | Limitations in detecting ubiquitin chain modifications in real-time within cellular environments | Incomplete understanding of ubiquitin chain dynamics during cellular processes |

The chain length of ubiquitin polymers adds another dimension of complexity. Research has demonstrated that ubiquitin-binding proteins (UBPs) exhibit clear length-dependent binding preferences, with 64-70% of significant interactions for K27-, K29-, and K33-linked chains occurring exclusively with longer polymers (Ub~6~+) [9]. This length specificity creates a significant detection challenge, as traditional methods often fail to resolve chain length distributions in complex biological samples.

Current Detection Methodologies and Limitations

Conventional Techniques and Their Constraints

Traditional approaches for ubiquitin detection include western blotting with linkage-specific antibodies, mass spectrometry-based methods, and fluorescence-based assays [16]. While these methods have advanced our understanding of ubiquitination, they face significant limitations when applied to complex ubiquitin architectures:

- Linkage-specific antibodies may fail to distinguish between homotypic and branched chains sharing the same linkage type

- Mass spectrometry struggles with capturing labile branched chain structures and requires sophisticated instrumentation

- Mutant ubiquitin approaches (where specific lysines are mutated to arginine) may not accurately represent modifications involving wild-type ubiquitin [22]

The development of Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) has improved our ability to capture polyubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates while protecting them from deubiquitinase activity. Recent advances include chain-selective TUBEs with nanomolar affinities for specific polyubiquitin chain types, enabling discrimination between K48- and K63-linked ubiquitination in PROTAC-induced degradation studies [22]. However, even these advanced tools face challenges in resolving complex branched architectures where multiple linkage types coexist.

Structural Biology Approaches

Structural techniques like cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and X-ray crystallography have provided unprecedented insights into ubiquitin chain recognition. Recent cryo-EM structures of the human 26S proteasome in complex with K11/K48-branched ubiquitin chains revealed a multivalent recognition mechanism involving:

- A novel K11-linked Ub binding site at the groove formed by RPN2 and RPN10

- The canonical K48-linkage binding site formed by RPN10 and RPT4/5

- RPN2 recognition of an alternating K11-K48-linkage through a conserved motif [6]

These structural insights explain the molecular mechanism underlying preferential recognition of K11/K48-branched Ub as a priority degradation signal. However, capturing such complexes requires sophisticated sample preparation and may not represent the full dynamic range of ubiquitin chain conformations in solution.

Diagram 1: Ubiquitin Detection Challenge Pathway. This diagram illustrates the relationship between ubiquitin structural features and the specific detection barriers they create.

Specialized Reagents and Experimental Solutions

The Researcher's Toolkit for Ubiquitin Detection

Addressing the detection dilemma requires specialized reagents and methodologies designed to overcome the unique challenges posed by complex ubiquitin structures:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Complex Ubiquitin Chain Detection

| Research Tool | Composition/Mechanism | Application in Detection | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chain-Selective TUBEs | Tandem ubiquitin-binding entities with linkage specificity | Selective capture of K48- or K63-linked chains from cell lysates | Nanomolar affinity; protection from DUB activity; applicable in HTS formats |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Monoclonal antibodies recognizing specific ubiquitin linkages | Western blotting, immunofluorescence, immunoprecipitation | Linkage specificity; well-established protocols |

| Triazole-Linked Ub Chains | Non-hydrolyzable ubiquitin chains with triazole linkages | Affinity purification mass spectrometry (AP-MS) studies | Resistance to DUB cleavage; defined linkage and length |

| Ubiquitin Variants (K63R, etc.) | Site-directed mutants of ubiquitin | Dissecting specific chain formation in cellular contexts | Elimination of specific linkage types; identification of essential lysines |

| Activity-Based DUB Probes | Mechanism-based inhibitors capturing active DUBs | Profiling deubiquitinase specificity and activity | Identification of DUBs with selectivity for specific chain types |

The application of chain-selective TUBEs has enabled researchers to differentiate context-dependent ubiquitination events. For example, in studying RIPK2 ubiquitination, K63-TUBEs specifically captured L18-MDP-induced ubiquitination, while K48-TUBEs captured PROTAC-induced ubiquitination, demonstrating the utility of these tools in deciphering complex signaling events [22].

Advanced Methodological Approaches

Recent methodological innovations have significantly advanced our ability to detect and characterize complex ubiquitin structures:

1. GELFrEE Fractionation with Triazole-Linked Ubiquitin Chains This approach combines non-hydrolyzable triazole-linked ubiquitin chains of defined linkage with gel-eluted liquid fraction entrapment electrophoresis to generate length-defined ubiquitin polymers. These defined polymers enable proteome-wide identification of length- and linkage-selective interaction partners, revealing that chain length significantly impacts recognition by ubiquitin-binding proteins [9].

2. Cryo-EM of Ubiquitination Complexes Advanced cryo-EM methodologies now allow visualization of full-length ubiquitin ligases during active ubiquitination. For example, cryo-EM snapshots of Tom1 ligase during ubiquitination identified a "structural" ubiquitin that contributes to K48 linkage specificity, revealing how extended domain architectures beyond the catalytic module contribute to linkage specificity [23].

3. Quantitative Ubiquitin Proteomics Absolute ubiquitin quantification (Ub-AQUA) using mass spectrometry enables precise measurement of different ubiquitin chain types in biological samples. When combined with linkage-specific antibodies, this approach can identify the presence of branched chains, as demonstrated in the detection of K11/K48-branched ubiquitin chains in proteasomal substrates [6].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Complex Ubiquitin Detection. This diagram outlines the integrated approaches required for comprehensive analysis of complex ubiquitin structures.

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The detection of complex ubiquitin structures remains challenging due to the dynamic nature of these modifications, the diversity of possible architectures, and limitations in current methodologies. However, several promising directions are emerging:

Integration of Structural and Proteomic Approaches Combining cryo-EM structures of ubiquitin-protein complexes with quantitative proteomics data will provide more comprehensive understanding of how specific ubiquitin architectures are recognized by cellular machinery. The recent structural insights into K11/K48-branched chain recognition by the proteasome [6] exemplify how such integrated approaches can reveal molecular mechanisms underlying the biological functions of complex ubiquitin signals.

Single-Molecule and Real-Time Detection Methods Developing methods to observe ubiquitin chain assembly and disassembly in real-time would transform our understanding of ubiquitin dynamics. Single-molecule techniques coupled with improved biosensors may eventually enable researchers to monitor ubiquitination events in living cells with temporal resolution.

Chemical Biology Tools for Specific Ubiquitin Architectures The design of synthetic ubiquitin chains with defined branching patterns, combined with novel crosslinking strategies, will help overcome current limitations in detecting transient interactions and rare ubiquitin architectures.

The continued development of detection methodologies for complex ubiquitin structures is not merely a technical challenge but a fundamental requirement for advancing our understanding of ubiquitin signaling in health and disease. As research progresses, decoding the sophisticated language of ubiquitin architectures will undoubtedly reveal new therapeutic opportunities for conditions ranging from cancer to neurodegenerative disorders, fulfilling the promise of the ubiquitin system as a rich source of drug targets [1].

Branched ubiquitin chains, characterized by at least one ubiquitin monomer modified at multiple sites, constitute a significant and complex layer of regulation in cellular signaling. Once enigmatic due to technical challenges, these heterotypic polymers are now recognized as abundant components of the ubiquitin code, comprising 10–20% of the total ubiquitin chain population in cells [24] [6]. Their synthesis is often a coordinated effort involving multiple E3 ligases, and they are increasingly implicated in critical processes such as cell cycle progression, NF-κB signaling, and proteasomal degradation [5] [25] [6]. The architectural complexity of branched chains poses unique challenges for detection and interpretation, directly shaping the development of new research methodologies. This whitepaper details the prevalence, biological functions, and the evolving toolkit required to study these sophisticated signaling molecules.

Protein ubiquitination is a fundamental post-translational modification that regulates virtually all cellular processes in eukaryotes. The versatility of ubiquitin signaling stems from the ability of ubiquitin itself to be modified, forming polymers known as ubiquitin chains. These chains can be classified into three major topological categories:

- Homotypic chains: All ubiquitin monomers are linked through the same residue (e.g., K48, K63).

- Heterotypic mixed chains: The chain contains more than one linkage type, but each ubiquitin is modified at only one site.

- Heterotypic branched chains: At least one ubiquitin monomer within the chain is simultaneously modified at two or more distinct sites, creating a branch point [5] [25] [26].

While homotypic chains like the canonical K48-linked chain for proteasomal degradation have been well-characterized, branched chains represent a more recent and complex frontier. They significantly expand the informational capacity of the ubiquitin system, creating unique surfaces that can be recognized, assembled, and disassembled by specific cellular machinery [5] [15]. This review focuses on the cellular abundance of these chains, their biological significance, and the critical interplay between their architecture and the methods used to detect them.

Prevalence and Quantitative Significance

Recent advances in mass spectrometry and biochemical tools have revealed that branched ubiquitin chains are not rare curiosities but are rather abundant and constitutive elements of the ubiquitin system.

Table 1: Measured Abundance of Specific Branched Ubiquitin Chains

| Branched Chain Type | Approximate Abundance | Detection Method | Cellular Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Branched Ubiquitin | 10–20% of total ubiquitin pool [24] [6] | Proteomic analysis | Mammalian cells |

| K11/K48-branched | ~3–4% of total ubiquitin population [25] [26] | UbiChEM-MS | Mitotically arrested cells |

| K48/K63-branched | High abundance [25] [26] | R54A ubiquitin mutant / MS | Mammalian cells |

The synthesis of branched chains is a highly regulated process, often requiring collaboration between pairs of E3 ligases with distinct linkage specificities. For instance, during NF-κB signaling, the E3 ligase TRAF6 first assembles K63-linked chains, which are then recognized by HUWE1, which attaches K48 linkages to form K48/K63-branched chains [5] [25]. Similarly, the E3 ligases ITCH and UBR5 collaborate to form K48/K63-branched chains on the pro-apoptotic regulator TXNIP, targeting it for degradation [5]. This collaborative mechanism allows for the temporal separation of ubiquitination events, enabling the conversion of a non-degradative signal into a degradative one [5].

Biological Functions in Signaling

Branched ubiquitin chains are not redundant with their homotypic counterparts; they encode unique and specialized biological functions.

Enhancing Proteasomal Degradation

Certain branched chains function as potent degradation signals. K11/K48-branched chains are particularly recognized for their role in "fast-tracking" the degradation of key substrates during cell cycle progression and in response to proteotoxic stress [6]. Structural studies of the human 26S proteasome in complex with a K11/K48-branched chain reveal a multivalent recognition mechanism. The proteasome engages the branched chain through multiple receptors simultaneously, including a newly identified binding site for the K11 linkage on RPN2, which explains the preferential degradation of substrates marked with this topology [6].

Regulating Signal Transduction

Branched chains are integral components of major signaling pathways. As mentioned, K48/K63-branched chains are essential for the activation of NF-κB signaling [5] [25]. Furthermore, a 2025 study using a novel technology called UbiREAD demonstrated that in K48/K63-branched chains, the identity of the chain directly attached to the substrate (the substrate-anchored chain) dictates the functional outcome, establishing a degradation hierarchy within branched ubiquitin chains [27] [24]. This finding indicates that branched chains are not simply the sum of their parts but possess emergent properties based on their overall architecture.

Stress Adaptation

The formation of specific branched ubiquitin chains is induced by various cellular stresses, implicating them in cellular adaptation to proteostasis defects. For example, the ubiquitin chain-elongating enzyme Ufd2 conjugates a unique C-terminally extended ubiquitin (CxUb) to substrates under stress, promoting their degradation and being essential for mitophagy and longevity in model organisms [28].

Methodologies for Detection and Analysis

The complex architecture of branched ubiquitin chains directly influences and challenges detection methodologies. No single method provides a complete picture; instead, a combination of techniques is required.

UbiCRest (Ubiquitin Chain Restriction)

UbiCRest is a qualitative gel-based method that uses a panel of linkage-specific deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) to probe chain architecture [11] [25].

- Experimental Protocol: Substrates (ubiquitinated proteins or purified chains) are treated in parallel reactions with a toolkit of purified DUBs, each with defined linkage preferences (e.g., OTUB1 for K48, AMSH for K63). The reactions are then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using ubiquitin-specific antibodies [11].

- Workflow: The differential digestion patterns across the DUB panel provide insights into the linkage types present and, to some extent, the chain architecture.

- Limitations: A significant challenge is that UbiCRest cannot easily distinguish between mixed and branched chains. Furthermore, some branched chains exhibit resistance to cleavage by certain linkage-specific DUBs, which can lead to misinterpretation [25] [26].

Mass Spectrometry-Based Approaches

Middle-down or ubiquitin-clipping mass spectrometry methods, such as UbiChEM-MS, are powerful tools for directly identifying branch points [25] [26].

- Experimental Protocol: Ubiquitin chains are subjected to limited proteolysis with trypsin under native conditions. This cleaves ubiquitin at Arg74, generating ubiquitin remnants (Ub~1~-74). These remnants are then analyzed by LC-MS/MS [25].

- Data Interpretation:

- Advantage: This method can provide direct evidence of branching and can be applied at a proteomic scale to quantify branched chain abundance.

Ubiquitin Variant Strategy

This genetic approach involves engineering ubiquitin with specific mutations or insertions to facilitate detection.

- Experimental Protocol: One strategy involves introducing a Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease site and a FLAG tag into the ubiquitin sequence (e.g., at Gly53 or Glu64). After TEV cleavage, branched chains produce a distinct fragment pattern on an anti-FLAG Western blot that differs from unbranched chains [25] [26]. Another strategy uses a ubiquitin R54A mutant, which upon tryptic digestion, preserves a peptide containing two Gly-Gly modifications from a single K48/K63 branch point for MS detection [25] [26].

- Limitation: This strategy requires careful design to ensure the ubiquitin variant functions normally in conjugation and may not be universally applicable to all branch types.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Studying Branched Ubiquitin Chains

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Specificity | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| DUB Toolkit (for UbiCRest) [11] [25] | Enzymes with linkage preference (e.g., OTUB1 for K48, OTUD1 for K63). | Probing linkage composition and architecture of unknown chains. |

| K11/K48 Bispecific Antibody [25] [26] | Binds specifically to K11/K48-branched ubiquitin chains. | Immunoprecipitation and imaging of specific branched chains. |

| R54A Ubiquitin Mutant [25] [26] | Allows MS identification of K48/K63 branch points. | Detection and proteomic quantification of K48/K63 chains in cells. |

| Flag-TEV Ubiquitin [25] [26] | Enables TEV protease-based detection of branched chains. | Gel-based assessment of chain branching for specific linkages. |

| UbiChEM-MS [25] [26] | Middle-down MS for direct branch point identification. | Discovery and system-wide quantification of branched chains. |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The study of branched ubiquitin chains sits at the intersection of basic cell biology and technological innovation. A major outstanding challenge is the inability to "sequence" ubiquitin chains, leaving the precise number, order, and sequence of branches within a polymer largely unknown [15]. Future advancements will likely depend on:

- Next-Generation Mass Spectrometry: Further refinement of MS techniques to provide more comprehensive and high-throughput sequencing of complex ubiquitin architectures.

- Advanced Structural Biology: Cryo-EM and other structural methods will continue to elucidate how readers and erasers of the ubiquitin code, such as the proteasome and DUBs, specifically interact with branched chains.

- Chemical Biology Tools: The chemical synthesis of defined branched ubiquitin chains of high purity will remain crucial for in vitro biochemical and structural studies [25] [26].

- Single-Cell Analysis: Developing methods to detect branched chain dynamics at the single-cell level could reveal their roles in cellular heterogeneity.

The expansion of the branched ubiquitin toolkit is also directly relevant to drug discovery. The efficacy of small-molecule proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) and other targeted protein degradation therapies often depends on the formation of specific ubiquitin chains, including branched topologies, on the target protein [15]. A deeper understanding of how to manipulate branched chain formation could lead to more effective and specific therapeutic strategies.

Branched ubiquitin chains are now firmly established as abundant, functionally significant polymers that add a rich layer of complexity to cellular signaling. Their unique architectures, which range from K11/K48 chains that accelerate proteasomal degradation to K48/K63 chains that regulate NF-κB signaling, underpin their specialized biological roles. Critically, the very complexity of these chains has been a driving force behind methodological innovation, spurring the development of techniques like UbiCRest and UbiChEM-MS. As these tools continue to evolve, they will further decode the functions of branched ubiquitin chains, enhancing our fundamental understanding of cell signaling and opening new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Advanced Tools and Techniques for Ubiquitin Chain Analysis

Protein ubiquitination is a versatile post-translational modification that regulates virtually all cellular processes, from protein degradation to immune signaling and DNA repair [19] [29]. This functional diversity originates from the structural complexity of ubiquitin chains, which can form eight distinct linkage types via one of seven internal lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or the N-terminal methionine (M1) [30] [31]. Furthermore, these chains can be homotypic (single linkage type), heterotypic (mixed linkages), or branched, creating a sophisticated "ubiquitin code" that determines specific biological outcomes [19] [31]. Deciphering this code is fundamental to understanding cellular regulation and disease mechanisms, but presents significant analytical challenges due to the low stoichiometry of modification, the transient nature of the signals, and the combinatorial complexity of possible chain architectures.

Antibody-based technologies have emerged as indispensable tools for characterizing ubiquitination, enabling researchers to map modification sites, identify substrate proteins, and determine chain linkage types. This technical guide examines two powerful immunological approaches: linkage-specific antibodies that directly decipher ubiquitin chain architecture, and bispecific antibody reagents that enable novel detection strategies. Within the context of ubiquitin research, these methods provide complementary insights into how chain architecture influences cellular signaling pathways and disease processes, offering researchers a diverse toolkit for probing the ubiquitin code.

Ubiquitin Chain Architecture: Implications for Detection

The structural diversity of ubiquitin chains directly impacts their detection and characterization. Different linkage types adopt distinct three-dimensional conformations—from open, extended chains to compact, closed structures—which influence their recognition by antibodies, ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs), and deubiquitinases (DUBs) [30] [31]. For instance, K48-linked chains typically form compact structures that target substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked and M1-linked chains often adopt more open conformations involved in signaling pathways [19]. These structural differences create both challenges and opportunities for detection methodologies.

The combinatorial complexity of ubiquitin chains necessitates sophisticated analytical approaches. As illustrated in Table 1, different chain architectures produce diverse biological consequences that require specific detection strategies.

Table 1: Ubiquitin Chain Linkage Types and Their Detection Considerations

| Linkage Type | Primary Functions | Structural Features | Detection Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Proteasomal degradation [19] | Compact conformation [19] | Most abundant; requires distinction from other types |

| K63-linked | NF-κB signaling, DNA repair [19] | Open, extended conformation [19] | Differentiate from K48 chains in signaling contexts |

| M1-linked (Linear) | NF-κB activation, cell death [31] | Linear, extended structure [31] | Transient formation, spatially regulated [31] |

| K6-linked | DNA repair, mitochondrial regulation [30] | Compact with asymmetric interfaces [30] | Low abundance, limited specific reagents |

| K11-linked | ER-associated degradation, cell cycle [19] | Compact conformation [19] | Often in heterotypic chains with K48 |

| K27-linked | Kinase activation, immune signaling [19] | Not well characterized | Frequently found in branched chains |

| K29-linked | Proteasomal degradation, Wnt signaling [19] | Not well characterized | Less studied, limited characterization tools |

| K33-linked | Kinase regulation, trafficking [19] | Not well characterized | Rare, functional roles not fully established |

The emergence of atypical ubiquitin chains (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33) and heterotypic/branched architectures further complicates their detection and interpretation [30] [19]. For example, the bacterial effector NleL can assemble heterotypic Ub chains containing both K6 and K48 linkages, creating unique challenges for biochemical analysis [30]. This complexity has driven the development of increasingly sophisticated antibody-based reagents capable of distinguishing between closely related ubiquitin architectures.

Linkage-Specific Antibodies in Ubiquitin Research

Linkage-specific antibodies represent a cornerstone of ubiquitin detection, providing direct interrogation of chain architecture. These reagents enable researchers to determine the presence and relative abundance of specific linkage types in complex biological samples, offering insights into the ubiquitin code's functional status under different physiological and disease conditions.

Generation and Validation of Linkage-Specific Antibodies

The development of linkage-specific antibodies typically involves immunization with well-characterized diubiquitin molecules of defined linkage, followed by extensive screening to ensure specificity. Early approaches relied on mutation of acceptor lysines (e.g., lysine-to-arginine mutations) to indirectly infer ubiquitination sites, but these methods provided only circumstantial evidence [32]. Contemporary approaches directly map ubiquitin attachment sites using mass spectrometry, providing more convincing evidence for modification locations [32].

Several validated linkage-specific antibodies are now commercially available, targeting K11, K27, K48, K63, and M1 linkages [19] [29]. These antibodies show minimal cross-reactivity with other linkage types when properly validated. For example, Nakayama et al. generated a novel antibody specifically recognizing K48-linked polyUb chains and demonstrated its utility in detecting abnormal accumulation of K48-ubiquitinated tau proteins in Alzheimer's disease [19]. Similarly, Matsumoto et al. engineered structural antibodies with specificity for K11-linked and linear polyubiquitin chains [29].

Experimental Workflow for Ubiquitin Chain Restriction Analysis

The UbiCRest (Ubiquitin Chain Restriction) method represents a powerful application of linkage-specific reagents for analyzing ubiquitin chain architecture [29]. This protocol uses a panel of linkage-specific deubiquitinases (DUBs) as "ubiquitin chain restriction enzymes" to characterize ubiquitin modifications on substrates of interest.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitin Chain Analysis

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific DUBs | OTUB1 (K48-specific), OTUD3 (K6-preference), vOTU (broad specificity) [30] | Enzymatic dissection of ubiquitin chain type in UbiCRest analysis |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Anti-K48, Anti-K63, Anti-K11, Anti-M1 linear [19] [29] | Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence, and enrichment of specific chain types |

| Ubiquitin-Binding Domains | Tandem-repeated Ub-binding entities (TUBEs) [19] | Affinity enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins from complex mixtures |

| Tagged Ubiquitin | His-tagged Ub, Strep-tagged Ub [19] | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins for proteomic analysis |

| Mass Spectrometry | Middle-down MS, diGly remnant mapping [32] [19] | Identification of ubiquitination sites and chain topology |

The following diagram illustrates the UbiCRest experimental workflow:

Diagram 1: UbiCRest workflow for ubiquitin chain architecture analysis

Detailed UbiCRest Protocol

Materials Required:

- Purified ubiquitinated substrate or polyubiquitin chains

- Linkage-specific DUBs (e.g., OTUB1, OTUD3, vOTU, Cezanne)

- Appropriate reaction buffers

- SDS-PAGE and Western blot equipment

- Ubiquitin antibodies (linkage-specific or pan-specific)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the ubiquitinated substrate to appropriate concentration in reaction buffer. For endogenous proteins, immunoprecipitate the target protein from cell lysates.

- DUB Treatment Setup: Aliquot samples into separate tubes and add specific DUBs to each reaction. Include a no-DUB control.

- Incubation: Incubate reactions at 37°C for 1-3 hours. Time optimization may be required for different substrates.

- Termination and Analysis: Stop reactions by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer and boiling. Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to membranes.

- Detection: Probe membranes with linkage-specific ubiquitin antibodies or pan-ubiquitin antibodies to visualize cleavage patterns.

- Interpretation: Compare cleavage patterns across different DUB treatments to determine linkage composition.

Data Interpretation: Complete digestion by a linkage-specific DUB indicates the predominant presence of that linkage type. Partial digestion suggests heterotypic chains containing multiple linkage types. For example, OTUB1 treatment of NleL-assembled heterotypic penta/hexaUb chains yielded mono-, di-, tri-, and tetraUb fragments, while OTUD3 treatment produced mainly mono- and diUb with faint triUb signals, indicating different accessibility to linkages within the chains [30].

Bispecific Antibody Reagents: Novel Detection Paradigms

Bispecific antibodies (BsAbs) represent an engineered class of immunoreagents that recognize two different epitopes, either on the same antigen or different antigens. In ubiquitin research, their application is primarily analytical, enabling innovative detection strategies that overcome limitations of conventional antibodies.

Design and Engineering of Bispecific Antibodies

BsAbs are engineered immunoglobulins produced through biochemical, biological, or genetic processes that combine two distinct antigen-binding specificities in a single molecule [33]. Common formats include tandem scFv (single-chain variable fragment) constructs, diabodies, and full-length IgGs with engineered heavy chains. Key design considerations include:

- Epitope Selection: The two target epitopes must be accessible simultaneously.

- Affinity Optimization: Balanced affinity for both targets prevents preferential binding.

- Structural Orientation: Proper spatial arrangement ensures both binding sites can engage targets simultaneously.

- Linker Design: Connection between binding domains affects flexibility and functionality.

High-throughput discovery platforms have dramatically improved BsAb development. One recently described pipeline can screen up to 1.5 million variant library cells per run, identifying rare functional clones with abundances as low as 0.001% [34]. This throughput enables comprehensive exploration of design variables including scFv binders, linker lengths and flexibilities, and VL/VH orientations [34].

DNA-Based Platforms for Bispecific Antibody Detection

Innovative DNA-based sensing platforms leverage BsAbs for highly specific detection. These systems utilize antigen-conjugated nucleic acid strands that colocalize upon BsAb binding, triggering detectable signals.

The following diagram illustrates two principal DNA-based detection strategies:

Diagram 2: DNA-based platforms for bispecific antibody detection

Experimental Protocol for DNA-Based BsAb Detection

Materials Required:

- Antigen-conjugated DNA strands (e.g., EGFR-conjugated DNA)

- Antigen-conjugated PNA strands (e.g., MUC1 peptide-conjugated PNA)

- Reporter modules (fluorophore/quencher-modified hairpin DNA)

- Target bispecific antibody

- Appropriate buffer systems

- Fluorescence detection instrumentation

Procedure for Colocalization Approach:

- Conjugate Preparation: Synthesize antigen-conjugated nucleic acid strands using EDC-NHS coupling chemistry for proteins or solid-phase synthesis for peptides [33].

- Reporter Module Assembly: Hybridize fluorophore/quencher-modified hairpin DNA with EGFR-conjugated DNA strand to form the reporter module.

- Input Module Preparation: Hybridize DNA strand with MUC1 peptide-conjugated PNA to form the input module.

- Assay Assembly: Mix reporter module (10 nM) and input module (30 nM) in appropriate buffer [33].

- Antibody Addition: Introduce the target BsAb at varying concentrations.

- Signal Detection: Incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature and measure fluorescence enhancement.

Performance Characteristics: This approach demonstrates high sensitivity (K1/2 = 1.7 ± 0.4 nM) with a detection limit of 0.6 nM in buffer, and maintains functionality in complex media like 50% plasma (K1/2 = 1.5 ± 0.2 nM; LOD = 0.4 nM) [33]. The method shows excellent specificity, with minimal signal from related monospecific antibodies (2.7-3.3% of BsAb signal) [33].

Integrated Approaches and Future Perspectives

The convergence of linkage-specific antibodies, bispecific reagents, and advanced detection platforms creates powerful synergies for ubiquitin research. Future developments will likely focus on increasing multiplexing capability, improving spatial resolution for subcellular localization, and enhancing quantitative accuracy for dynamic monitoring of ubiquitination events.