Decoding the Ubiquitin Code in Cancer: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targeting, and Clinical Frontiers

The ubiquitin code, a complex system of post-translational modifications, is fundamentally altered in cancer, driving tumorigenesis through dysregulated protein stability, signaling, and cellular homeostasis.

Decoding the Ubiquitin Code in Cancer: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targeting, and Clinical Frontiers

Abstract

The ubiquitin code, a complex system of post-translational modifications, is fundamentally altered in cancer, driving tumorigenesis through dysregulated protein stability, signaling, and cellular homeostasis. This article synthesizes current research for a scientific audience, exploring how specific alterations in ubiquitin ligases, deubiquitinases, and chain topology contribute to hallmarks of cancer such as metabolic reprogramming, immune evasion, and therapy resistance. We examine foundational concepts of the ubiquitin code, methodological advances in its study, challenges in therapeutic targeting, and emerging preclinical and clinical strategies, including PROTACs and molecular glues, that aim to exploit ubiquitin system vulnerabilities for precision oncology.

The Ubiquitin Code: Foundational Principles and Its Dysregulation in Oncogenesis

The Core Enzymatic Cascade of the UPS

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) is a crucial selective proteolytic system that maintains cellular protein homeostasis by degrading short-lived, misfolded, damaged, and regulatory proteins [1] [2]. This degradation is essential for controlling countless cellular processes, including immune response, apoptosis, cell cycle, differentiation, and signaling [1]. The process involves a hierarchical enzymatic cascade that conjugates the small, highly conserved protein ubiquitin onto substrate proteins, marking them for degradation by the proteasome [1] [3].

The Ubiquitin-Conjugation Cascade The conjugation of ubiquitin to substrate proteins is a three-step enzymatic process [4] [2] [5]:

- Activation (E1): A ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner. The E1 forms a high-energy thioester bond between the C-terminal glycine (Gly76) of ubiquitin and a cysteine residue in its active site [4] [3].

- Conjugation (E2): The activated ubiquitin is transferred from the E1 to the active site cysteine of a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2), forming an E2-ubiquitin thioester intermediate [4] [3].

- Ligation (E3): A ubiquitin ligase (E3) binds both the E2-ubiquitin complex and the protein substrate, facilitating the final transfer of ubiquitin to a lysine residue on the substrate, forming an isopeptide bond [4]. The E3 ligase provides specificity to the system by recognizing and recruiting target substrates [1].

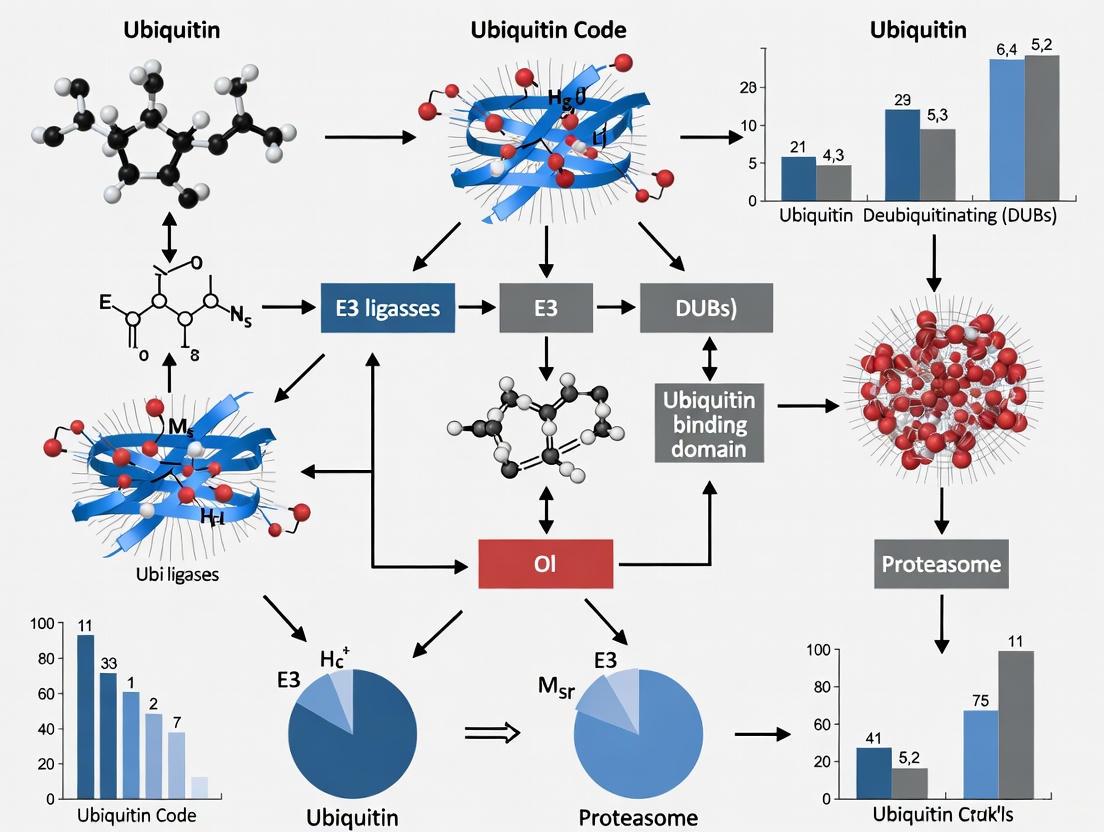

This cascade is visually summarized in the diagram below.

The Complexity of the Ubiquitin Code

Ubiquitination is not a single signal but a diverse post-translational modification that forms a complex "ubiquitin code" [2]. The functional consequences of ubiquitination depend on the type of ubiquitin modification attached to the substrate [4].

Types of Ubiquitin Modifications

- Monoubiquitination: Attachment of a single ubiquitin molecule to a substrate lysine. This modification is typically non-degradative and can regulate protein-protein interactions, protein activity, and subcellular localization [4] [6].

- Multi-Monoubiquitination: Attachment of single ubiquitin molecules to multiple different lysine residues on the same substrate protein [6].

- Polyubiquitination: Formation of a chain of ubiquitin molecules by conjugating additional ubiquitins to one of the seven internal lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or the N-terminal methionine (M1) of the previously attached ubiquitin [1] [4] [2]. Polyubiquitin chains can be homogenous (composed of a single linkage type), heterogeneous (mixed linkages), or branched (multiple chains on a single ubiquitin) [4] [6]. The topology of the chain determines the fate of the modified protein.

Table 1: Major Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Primary Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Known Function(s) | Proteasomal Degradation |

|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Major signal for proteasomal degradation [1] | Yes [1] |

| K11-linked | Proteasomal degradation, particularly in ERAD and cell cycle regulation [1] [4] | Yes [1] |

| K29/K48-branched | Potent signal for proteasomal degradation, can overcome DUB protection [7] | Yes [7] |

| K63-linked | DNA damage response, endocytosis, inflammatory signaling; generally non-degradative [1] [4] | No [1] |

| M1-linked (Linear) | NF-κB activation, inflammatory signaling [2] [6] | No |

| K27-linked & K33-linked | Context-dependent roles in immune signaling, autophagy [1] | Context-dependent |

Deubiquitinases (DUBs): Editors of the Ubiquitin Code

The ubiquitin system is dynamic and reversible. Deubiquitinases (DUBs) are proteases that cleave ubiquitin from substrates or disassemble ubiquitin chains, providing an essential editing and regulatory layer to the ubiquitin code [2] [6]. DUBs can counteract E3 ligase activity, rescue proteins from degradation, refine the ubiquitin signal by trimming chains, and recycle ubiquitin to maintain the cellular pool [1]. They are classified into seven families based on their catalytic domains: USP, OTU, MJD, UCH, JAMM, MINDY, and ZUFSP [7] [6]. Some DUBs, like OTULIN, show high specificity for particular linkage types such as M1-linear chains, while others have broader activity [2].

Experimental Analysis of the UPS

Studying the UPS requires specific methodologies to identify substrates, elucidate enzymatic functions, and characterize ubiquitin chain topology.

Key Experimental Workflows

A powerful approach for discovering novel E3 ligase substrates involves combining genetic perturbation (e.g., siRNA knockdown) with quantitative proteomics, as demonstrated in a 2025 study identifying the DUB OTUD5 as a substrate of the E3 ligase TRIP12 [7]. The general workflow for such a discovery pipeline is illustrated below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for UPS Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Lysine Ubiquitin Mutants (e.g., Ub-K48Only, Ub-K63Only) | Determine the linkage specificity of E3 ligases and DUBs in in vitro assays [7]. | Allows for the formation of homogenous ubiquitin chains of a defined topology. |

| TUBE (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entity) | Affinity purification of polyubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates; protects chains from DUBs [7]. | High-affinity, pan-specific ubiquitin chain binder composed of multiple UBA domains. |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Binders (e.g., GST-TRABID-NZF1 for K29/K33) | Enrich and detect specific ubiquitin chain types from cell lysates or in vitro reactions [7]. | Uses naturally occurring ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) with defined linkage preferences. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132, Bortezomib) | Block degradation of ubiquitinated proteins, allowing for their accumulation and detection. | Essential for studying endogenous protein ubiquitination levels in cells. |

| PROTACs (PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras) | Bifunctional molecules that recruit E3 ligases to neosubstrates, inducing their ubiquitination and degradation [1] [4]. | Tool for targeted protein degradation and a promising therapeutic modality. |

UPS Alterations in Cancer and Therapeutic Targeting

Dysregulation of the UPS is a hallmark of cancer, contributing to uncontrolled proliferation, evasion of growth suppressors, and resistance to therapy [4] [6]. E3 ligases and DUBs can function as oncogenes or tumor suppressors, and their mutations or aberrant expression are common in tumors [4].

- Oncoprotein Stabilization & Tumor Suppressor Degradation: Aberrant UPS activity can lead to the hyper-stabilization of oncoproteins (e.g., RAS isoforms via altered ubiquitination [8]) or the accelerated degradation of tumor suppressors like p53 [4].

- Immune Evasion: The UPS regulates immune checkpoint proteins like PD-1/PD-L1. For instance, the DUB USP2 stabilizes PD-1, promoting tumor immune escape, while the E3 ligase AIP4 promotes PD-L1 internalization and degradation, inhibiting immune escape [6].

- Therapeutic Strategies:

- Proteasome Inhibitors: Drugs like Bortezomib inhibit the proteasome broadly, used in hematologic malignancies but with broad effects [1].

- Targeted Protein Degradation (PROTACs): Bifunctional molecules like ARV-110 and ARV-471 re-purpose E3 ligases to selectively degrade disease-driving proteins, offering a more precise therapeutic approach [1] [4] [6].

- E1/E2/E3/DUB Inhibitors: Developing specific inhibitors for individual components of the UPS cascade is an active area of cancer drug discovery [4] [9] [6].

The ubiquitin code represents a sophisticated post-translational signaling system that regulates virtually all aspects of cellular physiology in eukaryotes. This complex language, composed of monoubiquitination and diverse polyubiquitin chain topologies, dictates fundamental processes including protein degradation, DNA repair, immune signaling, and cell cycle progression. When dysregulated, alterations in ubiquitin signaling contribute significantly to oncogenesis, making the ubiquitin system an attractive therapeutic target. This technical review comprehensively examines the mechanisms of ubiquitin chain formation, the structural characteristics of distinct chain topologies, and their functional consequences, with particular emphasis on cancer development. We integrate current experimental methodologies and research tools essential for investigating ubiquitin signaling, providing a foundation for developing novel cancer therapeutics that exploit the ubiquitin code.

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification involving the covalent attachment of the 76-amino acid protein ubiquitin to substrate proteins. This process regulates nearly all aspects of eukaryotic cell biology, from protein degradation to signal transduction and DNA repair [10]. The modification occurs through a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes, with E3 ligases providing substrate specificity [11] [12].

The term "ubiquitin code" describes the complex language generated through diverse ubiquitin modifications. This coding capacity arises from several variables: (1) the number of ubiquitin molecules attached (mono- versus polyubiquitination); (2) the specific lysine residues used to connect ubiquitin molecules in chains; (3) chain architecture (homotypic, heterotypic, or branched); and (4) additional modifications to ubiquitin itself, such as phosphorylation or acetylation [10]. This sophisticated system generates an extensive repertoire of biological signals that determine cellular outcomes, with particular relevance to cancer development where ubiquitin signaling pathways are frequently dysregulated [11] [13].

Monoubiquitination: Mechanisms and Functional Outcomes

Definition and Molecular Mechanisms

Monoubiquitination refers to the attachment of a single ubiquitin molecule to a substrate protein, typically occurring on lysine residues but also possible on serine, threonine, or cysteine residues [11] [14]. This modification differs fundamentally from polyubiquitination in both structure and function. While historically overshadowed by the more extensively studied degradative polyubiquitination, monoubiquitination has emerged as a critical regulator of non-proteolytic cellular processes.

The mechanism of monoubiquitination involves the same E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade but is often determined by specific E2/E3 combinations that favor single ubiquitin transfer. Research on the SCF(^{Cdc4})/Cdc34 complex in yeast demonstrated that point mutations in the catalytic core of the Cdc34 E2 enzyme can convert it from a polyubiquitinating enzyme into a monoubiquitinating enzyme, highlighting how subtle structural determinants direct the mode of ubiquitination [15]. This specificity arises from amino acid determinants in the E2 catalytic region and their compatibility with residues surrounding acceptor lysines in substrates [15].

Biological Functions and Cancer Relevance

Monoubiquitination regulates diverse cellular processes through non-proteolytic mechanisms:

Membrane Trafficking and Endocytosis: Monoubiquitination of cell surface receptors targets them for internalization and subsequent lysosomal degradation, providing a mechanism for signal termination [14]. This process is hijacked in cancer to downregulate tumor suppressor receptors or enhance oncogenic signaling.

DNA Damage Repair: Histone monoubiquitination, particularly of H2A and H2B, alters chromatin structure to facilitate access of DNA repair machinery [14] [16]. This function is crucial for maintaining genomic integrity, and its disruption promotes cancer progression.

Transcriptional Regulation: Monoubiquitination of transcription factors can either activate or inhibit their function, representing a rapid mechanism for adjusting gene expression programs in response to cellular signals [13]. In cancer, oncogenic transcription factors may be stabilized through altered monoubiquitination patterns.

Protein Activation and Localization: Monoubiquitination can serve as a switch that modulates protein activity or subcellular localization, influencing signaling pathway output [14].

The functional significance of monoubiquitination is amplified through multi-monoubiquitination, where multiple lysine residues on a single substrate are modified with individual ubiquitin molecules, creating a robust signal for processes such as endocytosis [14].

Polyubiquitin Chain Topologies: Structural and Functional Diversity

Classification of Ubiquitin Linkages

Polyubiquitin chains are classified based on the specific lysine residue used to connect ubiquitin molecules, with eight distinct linkage types identified: Met1 (linear), Lys6, Lys11, Lys27, Lys29, Lys33, Lys48, and Lys63. Each linkage type generates structurally distinct chains with unique functional properties [11] [10]. The table below summarizes the key characteristics and functions of major ubiquitin linkage types.

Table 1: Ubiquitin Chain Linkage Types and Their Functional Roles

| Linkage Type | Structural Features | Primary Functions | Key E2/E3 Enzymes | Cancer Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lys48 | Compact conformations | Proteasomal degradation [11] | CDC34/SCF complexes [15] | Tumor suppressor degradation [11] |

| Lys63 | Extended "open" conformations [17] | DNA repair, signaling, endocytosis [15] | Ubc13-MMS2 complex [15] | NF-κB activation, survival signaling |

| Met1 (Linear) | Extended and compact conformations [17] | NF-κB activation, inflammation [11] | LUBAC complex (HOIP, HOIL-1) [11] | Inflammatory signaling in tumor microenvironment |

| Lys11 | Mixed compact/extended | Cell cycle regulation, ERAD [11] | UBE2S/APC/C [12] | Cell cycle dysregulation |

| Lys27 | Not well characterized | Mitochondrial quality control, innate immunity [11] | Parkin, RNF185, AMFR [11] | Mitophagy dysregulation |

| Lys29 | Not well characterized | Proteasomal degradation, innate immunity [11] | HECT-type E3s [11] | Unfolded protein response |

| Lys6 | Not well characterized | DNA damage response [11] | Unknown | Genomic instability |

| Lys33 | Not well characterized | Intracellular trafficking [11] | Unknown | Metabolic reprogramming |

Chain Conformations and Functional Implications

The three-dimensional architecture of polyubiquitin chains plays a crucial role in determining their functional specificity. Single-molecule FRET studies have revealed that differently linked diubiquitin (diUb) chains exist in multiple conformational states in solution, and these dynamics provide an additional layer of regulation in the ubiquitin system [17].

Lys48-linked diUb: Adopts predominantly compact conformations (~90% high-FRET, ~10% low-FRET) with limited exposure of hydrophobic patches, facilitating proteasomal recognition [17].

Lys63-linked diUb: Exists in an equilibrium between extended (~25-30% non-FRET) and compact conformations (~70-75% low-FRET), enabling diverse interactions with signaling proteins [17].

Met1-linked diUb: Displays both extended and compact conformations, with the UBAN domain of NEMO selecting pre-existing compact conformations to activate NF-κB signaling [17].

These conformational equilibria enable ubiquitin chains to be recognized by different ubiquitin-binding proteins, with domains such as UBDs and DUBs selecting pre-existing conformations rather than inducing structural changes [17]. This conformational selection mechanism has profound implications for how ubiquitin signals are decoded in cellular pathways relevant to cancer.

Diagram 1: Ubiquitin Code Decoding Pathway. This diagram illustrates how different ubiquitin chain types adopt specific conformations that determine cellular outcomes.

Atypical Ubiquitin Linkages and Their Functions

Beyond the well-characterized Lys48 and Lys63 linkages, "atypical" ubiquitin chains (Lys6, Lys11, Lys27, Lys29, Lys33, and Met1) have emerged as important regulators of specialized cellular processes:

Lys11-linked chains: Play crucial roles in cell cycle regulation and ER-associated degradation (ERAD), with the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) and E2 enzyme UBE2S specifically generating Lys11-linked chains to control mitotic progression [11] [12].

Lys27-linked chains: Regulate mitochondrial quality control through Parkin-mediated mitophagy and modulate innate immune response via RNF185-targeting of cGAS and AMFR-targeting of STING [11].

Lys29-linked chains: Involved in proteasomal degradation, innate immune response, and regulation of AMPK-related protein kinases [11].

Lys6 and Lys33 linkages: Participate in DNA damage response and intracellular trafficking, respectively, though their mechanisms remain less characterized [11].

The expanding understanding of atypical ubiquitin linkages reveals an unexpected sophistication in ubiquitin signaling, with chain topology serving as a critical determinant of functional specificity in pathways frequently altered in cancer.

E3 Ubiquitin Ligases: Writers of the Ubiquitin Code

Classification and Mechanisms of E3 Ligases

E3 ubiquitin ligases constitute a diverse family of enzymes that determine substrate specificity in the ubiquitination cascade. Humans possess over 600 E3 ligases, classified into four major types based on their structural and mechanistic features [11]:

Table 2: Major Classes of E3 Ubiquitin Ligases

| E3 Class | Representative Members | Catalytic Mechanism | Structural Features | Cancer Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RING-finger | MDM2, CBL, COP1 | Direct ubiquitin transfer from E2 to substrate [11] | Zinc-binding RING domain [11] | MDM2-p53 axis dysregulation |

| HECT | NEDD4, HERC, HUWE1 | E3-Ub intermediate via catalytic cysteine [11] | HECT C-terminal domain [11] | HERC6 overexpression in cancers |

| RBR | Parkin, HOIP | RING-HECT hybrid mechanism [11] | RING1-IBR-RING2 domains [11] | Parkin mutations in Parkinson's |

| U-box | CHIP, UFD2 | Similar to RING but without zinc [11] | U-box domain stabilized by hydrogen bonds [11] | CHIP in protein quality control |

Regulatory Mechanisms of E3 Ligases

E3 ligase activity is tightly controlled through multiple regulatory mechanisms that ensure precise spatiotemporal control of ubiquitination:

Non-covalent ubiquitin interactions: Many E2 and E3 enzymes contain secondary ubiquitin-binding sites that regulate their activity. For example, the Arkadia RING E3 ligase binds regulatory ubiquitin molecules that enhance processive ubiquitin chain formation [12].

Post-translational modifications: Phosphorylation, acetylation, and other modifications directly regulate E3 ligase activity, localization, and substrate specificity.

Multi-subunit complexes: Many RING E3 ligases, particularly cullin-RING ligases (CRLs), assemble into multi-protein complexes that integrate regulatory inputs and enhance catalytic versatility [11].

Allosteric activation: Some E3 ligases, such as Parkin, are maintained in autoinhibited states until activated by specific signals, preventing spurious ubiquitination [10].

The dysregulation of E3 ligase activity represents a common mechanism in oncogenesis, with both tumor-suppressive and oncogenic E3s being frequently altered in human cancers through mutations, amplifications, or deletions [11] [13].

Experimental Methods for Studying Ubiquitin Signaling

Biochemical and Biophysical Approaches

Several sophisticated methodologies have been developed to investigate the structure and function of ubiquitin modifications:

Single-molecule FRET (smFRET): Enables real-time observation of ubiquitin chain conformational dynamics by measuring energy transfer between fluorophores attached to different ubiquitin molecules [17]. This approach revealed the conformational equilibria of Lys48-, Lys63-, and Met1-linked diUb.

Linkage-specific antibodies: Monoclonal antibodies that recognize specific ubiquitin linkages (Met1, Lys11, Lys48, Lys63) allow immunological detection and quantification of chain types in cells and tissues [10].

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics: Advanced MS techniques, including AQUA and TMT labeling, enable comprehensive identification and quantification of ubiquitination sites and chain topologies [10].

X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy: Provide high-resolution structural information about ubiquitin chains and their complexes with binding proteins [17].

In Vitro Ubiquitination Assays

Reconstituted biochemical systems allow detailed mechanistic studies of ubiquitination:

Protocol: SCF/Cdc34 Ubiquitination Assay [15]

Reagent Preparation:

- Purify SCF E3 complex (Skp1, Cul1, Rbx1, and F-box protein Cdc4)

- Prepare E1 (Uba1) and E2 (Cdc34) enzymes

- Obtain substrate (Sic1) and ubiquitin

Reaction Setup:

- Assemble 50 μL reaction containing: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM ATP, 0.2 mM DTT, 2 mM creatine phosphate, 0.1 U creatine phosphokinase

- Add 100 nM E1, 1-5 μM E2, 100-500 nM SCF complex, 5-20 μM ubiquitin, and 1-5 μM substrate

Reaction Conditions:

- Incubate at 30°C for 0-120 minutes

- Terminate by adding SDS-PAGE sample buffer

Analysis:

- Resolve products by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot with substrate-specific antibodies

- Assess mono- versus polyubiquitination patterns

This assay enabled the discovery that amino acids surrounding acceptor lysines and key residues in the Cdc34 catalytic core determine the efficiency of ubiquitination and choice between mono- versus polyubiquitination [15].

Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitin Code Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linkage-specific Antibodies | Anti-K48, Anti-K63, Anti-M1 [10] | Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence | Selective recognition of specific ubiquitin linkages |

| Activity-based Probes | Ubiquitin vinyl sulfones, HA-Ub-VS [10] | DUB profiling, mechanism studies | Covalent trapping of active DUBs |

| E2/E3 Expression Systems | Baculovirus (E1/E2/E3), Bacterial (Ub) [15] | In vitro ubiquitination assays | Recombinant enzyme production |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | AQUA ubiquitin peptides, SILAC labeling [10] | Ubiquitin proteomics | Absolute quantification of ubiquitin modifications |

| Chain-specific DUBs | OTUB1 (K48-specific), AMSH-LP (K63-specific) [17] | Chain linkage validation, cleavage | Enzymatic confirmation of chain topology |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | K48R, K63R, K0 (all lysines mutated) [15] | Mechanism studies | Block specific chain formation |

Ubiquitin Code Alterations in Cancer Development

Dysregulation of the ubiquitin system contributes fundamentally to oncogenesis through multiple mechanisms:

Tumor suppressor degradation: Oncogenic E3 ligases, such as MDM2, inappropriately target tumor suppressors like p53 for proteasomal degradation, enabling uncontrolled cell proliferation [13].

Oncoprotein stabilization: Loss of tumor-suppressive E3 ligases or gain of deubiquitinases (DUBs) can stabilize oncoproteins, enhancing their half-life and signaling output [13].

DNA repair defects: Alterations in ubiquitin-mediated DNA damage response, particularly involving Lys63-linked and Lys6-linked chains, promote genomic instability [11] [16].

Signaling pathway dysregulation: Ubiquitination regulates key cancer-relevant pathways including NF-κB, Wnt, and TGF-β, with chain-type specific alterations driving pathway hyperactivation or suppression [11].

Transcription factor modulation: Ubiquitination directly regulates transcription factors such as NF-κB, c-Myc, and p53, with cancer-associated mutations frequently affecting their ubiquitin-mediated control [13].

Therapeutic targeting of ubiquitin code alterations represents a promising anticancer strategy, with approaches including PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) that hijack the ubiquitin system to degrade specific oncoproteins, and small molecule inhibitors targeting specific E3 ligases or DUBs [11] [16] [13].

The ubiquitin code represents a sophisticated language that governs cellular physiology through diverse modifications including monoubiquitination and polyubiquitin chains of distinct topologies. The structural characteristics of different ubiquitin linkages, their conformational dynamics, and specific recognition by effector proteins create a complex signaling network that determines protein fate and function. In cancer development, alterations in writing, reading, and erasing the ubiquitin code contribute fundamentally to hallmark capabilities including sustained proliferation, evasion of growth suppression, and genomic instability. Continued elucidation of ubiquitin code mechanisms, coupled with advanced experimental approaches to decipher this complexity, will accelerate the development of novel cancer therapeutics that target specific aspects of ubiquitin signaling.

The ubiquitin code, a complex system of post-translational modifications, fundamentally governs cellular homeostasis by precisely regulating protein stability, localization, and interaction networks. In oncogenesis, this code undergoes profound alterations, directly enabling the hyperactivation of oncogenic pathways and the inactivation of tumor suppressive networks. This whitepaper provides a technical analysis of ubiquitin code alterations within five core cancer pathways—RAS, mTOR, PTEN, p53, and c-Myc. We synthesize the molecular mechanisms of pathogenic ubiquitination and deubiquitination, summarize key experimental methodologies for their investigation, and visualize the disrupted signaling networks. Furthermore, we catalog essential research tools and emerging therapeutic strategies, including proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs), that aim to correct the dysregulated ubiquitin signaling in human malignancies. The insights presented herein frame ubiquitin code alterations as a central thesis in cancer biology, offering a roadmap for future research and drug discovery.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a critical enzymatic cascade responsible for the controlled degradation of intracellular proteins, thereby regulating fundamental processes such as the cell cycle, DNA repair, and signal transduction [18] [19]. Ubiquitination involves a sequential reaction catalyzed by ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), and ubiquitin-ligating (E3) enzymes, which conjugate the 76-amino-acid ubiquitin protein to specific substrate lysine residues [20]. The specificity of this process is largely determined by the E3 ligases, of which there are over 600 in the human genome [19]. Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) counteract this process by removing ubiquitin chains, adding a dynamic layer of regulation [6] [21]. The functional consequence of ubiquitination is dictated by the topology of the ubiquitin chain. Whereas K48-linked polyubiquitination primarily targets substrates for proteasomal degradation, K63-linked chains often serve non-proteolytic roles in signaling activation, and monoubiquitination can regulate protein activity and trafficking [22] [18]. Cancer cells hijack this sophisticated system to destabilize tumor suppressors, stabilize oncoproteins, and rewire core signaling pathways, making the UPS a compelling area for therapeutic intervention [23] [18].

Ubiquitin Code Alterations in Core Signaling Pathways

The following sections detail the specific alterations to the ubiquitin code within five critical cancer pathways.

RAS Ubiquitination

RAS proteins are the most frequently mutated oncoproteins in human cancers, driving tumor proliferation, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance [8] [24]. Recent research has revealed that ubiquitination is a key mechanism for the dynamic post-translational regulation of RAS stability, membrane localization, and signal transduction.

- Regulatory Enzymes and Sites: A series of E3 ligases, DUBs, and regulatory proteins orchestrate the ubiquitination of RAS. Studies have identified specific ubiquitination sites and demonstrated heterogeneity in ubiquitination patterns across different RAS isoforms (KRAS4A, KRAS4B, NRAS, and HRAS), which contribute to their functional disparities in cancer [8] [24].

- Therapeutic Targeting: Targeting the RAS ubiquitination pathway presents novel therapeutic opportunities. Future research directions include integrating protein structure analysis with high-throughput screening to develop specific ubiquitination modulators. Combination strategies that pair RAS ubiquitination-targeting agents with direct RAS inhibitors or immunotherapy hold promise for overcoming RAS-driven malignancies [8].

mTOR Ubiquitination

The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a central kinase that integrates environmental and intracellular signals to control cell growth and metabolism, and its ubiquitination represents a critical regulatory node.

- K63-Linked Ubiquitination for Activation: The E3 ligase TRAF6 mediates K63-linked polyubiquitination of mTOR in an amino acid-dependent manner. This modification, facilitated by the adapter protein p62, promotes the translocation of the mTORC1 complex to the lysosomal surface, a prerequisite for its full activation [21]. This mechanism is frequently upregulated in cancer cells.

- Regulation of Stability: Conversely, the E3 ligases FBX8 and FBXW7 have been implicated in the K48-linked ubiquitination of mTOR, which can lead to its proteasomal degradation. The decreased activity of these ligases in some cancers results in mTOR stabilization and pathway hyperactivation [21].

PTEN Ubiquitination

The tumor suppressor PTEN (Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog) antagonizes the oncogenic PI3K-AKT pathway, and its activity is tightly controlled by ubiquitination.

- Regulation of Stability and Localization: PTEN can undergo both monoubiquitination and polyubiquitination. Monoubiquitination has been shown to regulate PTEN's nuclear-cytoplasmic trafficking, which is important for its tumor-suppressive functions in different cellular compartments [18].

- Oncogenic Degradation: Several E3 ligases promote the polyubiquitination and degradation of PTEN, effectively inactivating its phosphatase activity and leading to constitutive AKT signaling. The identity of specific E3 ligases involved and their counteracting DUBs that stabilize PTEN are active areas of investigation with significant therapeutic implications [18].

p53 Ubiquitination

The p53 tumor suppressor is a master regulator of the cellular stress response, and its stability is predominantly controlled by ubiquitination.

- Major Regulator MDM2: The primary E3 ligase for p53 is MDM2 (Mouse Double Minute 2). MDM2 mediates the K48-linked polyubiquitination of p53, targeting it for proteasomal degradation and maintaining low basal levels in normal cells [18]. In many cancers, MDM2 is overamplified, leading to excessive degradation of p53.

- Non-Proteolytic Ubiquitination: In addition to degradation, p53 can be modified by K63-linked and monoubiquitination. For instance, TRAF6 can modify p53 with K63 linkages, which can convert it into a mitochondrial pro-survival factor under certain conditions, illustrating the context-dependent nature of the ubiquitin code [22].

- Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs): Several DUBs, including USP7 (HAUSP), USP10, and USP29, can deubiquitinate and stabilize p53, forming a complex regulatory network that determines p53's fate in response to genotoxic stress [6] [18].

c-Myc Ubiquitination

The c-Myc oncoprotein is a transcription factor that drives cell proliferation and metabolism, and its rapid turnover is essential to prevent tumorigenesis.

- Degradation by SCF Complexes: The stability of c-Myc is primarily regulated by the SCF (SKP1-CUL1-F-box protein) family of E3 ubiquitin ligases. Specifically, the F-box protein FBXW7 (also known as CDC4) recognizes phosphorylated degrons on c-Myc and mediates its K48-linked polyubiquitination and degradation [18].

- Stabilization in Cancer: Mutations in FBXW7 or the phosphorylation sites on c-Myc are common in cancers, leading to c-Myc stabilization and enhanced oncogenic activity. Additionally, the DUB USP28 has been shown to antagonize FBXW7, deubiquitinating and stabilizing c-Myc in certain contexts [6] [18].

Table 1: Summary of Ubiquitin Code Alterations in Core Cancer Pathways

| Pathway | Key E3 Ligases | Key DUBs | Ubiquitin Linkage | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAS | Various, isoform-specific | Various, isoform-specific | Not Specified | Alters stability, membrane localization, signaling [8] [24] |

| mTOR | TRAF6, FBXW7, FBX8 | Not Well Characterized | K63, K48 | K63: Activates via lysosomal recruitment; K48: Targets for degradation [21] |

| PTEN | Multiple | Not Well Characterized | Mono, K48 | Mono: Regulates localization; K48: Targets for degradation [18] |

| p53 | MDM2, TRAF6 | USP7, USP10, USP29 | K48, K63, Mono | K48: Degradation; K63/Mono: Alters activity/localization [22] [18] |

| c-Myc | FBXW7 | USP28 | K48 | FBXW7 mediates degradation; USP28 stabilizes [6] [18] |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating the Ubiquitin Code

A robust methodological framework is essential for dissecting the complexities of ubiquitination. Below are detailed protocols for key experimental approaches.

Ubiquitination Assays

Objective: To confirm a specific protein is ubiquitinated and identify the type of ubiquitin linkage formed. Workflow:

- Cell Lysis and Immunoprecipitation (IP): Lyse cells under denaturing conditions (e.g., using RIPA buffer with 1% SDS followed by dilution) to preserve transient ubiquitination and disrupt non-covalent interactions. Immunoprecipitate the protein of interest using a specific antibody.

- Immunoblotting (Western Blot): Resolve the immunoprecipitated proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a membrane.

- Detection: Probe the membrane with anti-ubiquitin antibodies. To determine chain topology, use linkage-specific ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., anti-K48-Ub, anti-K63-Ub). A characteristic upward smear on the blot indicates polyubiquitination. Critical Notes: Always include controls with proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG132) to enhance the detection of K48-linked ubiquitinated species, and co-transfect epitope-tagged ubiquitin (e.g., HA-Ub, MYC-Ub) to facilitate detection [22] [18].

Identification of E3 Ligases and DUBs

Objective: To discover the specific E3 ligase or DUB that regulates a target protein. Workflow:

- Functional Screening: Perform siRNA or CRISPR-based screens targeting libraries of E3 ligases or DUBs. Monitor changes in the abundance or ubiquitination status of the target protein via immunoblotting.

- Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP): To validate physical interaction, lyse cells under non-denaturing conditions and immunoprecipitate the target protein. Probe for co-precipitating E3s or DUBs by western blot.

- In Vitro Ubiquitination/Deubiquitination Assay: Purify the candidate E3 ligase (or DUB), the target protein, and the necessary E1/E2 enzymes (and ubiquitin). Incubate the components with ATP. Analyze the reaction products by western blot to detect ubiquitination (smear) or deubiquitination (loss of smear) of the target protein [6] [20].

Proteomics for Ubiquitin Signatures

Objective: To profile global ubiquitination changes in response to a stimulus (e.g., drug treatment, pathway activation) or in a disease state. Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Lyse cells or tissues.

- Enrichment of Ubiquitinated Peptides: Digest the protein lysate with trypsin and use antibodies specific for di-glycine (diGly) remnants—a signature left on ubiquitinated lysines after trypsin digestion—to enrich for ubiquitinated peptides.

- Mass Spectrometry (MS) Analysis: Analyze the enriched peptides by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

- Data Analysis: Use bioinformatic tools to identify the sites of ubiquitination and quantify changes in ubiquitination levels across different conditions [22].

Diagram 1: Experimetal workflow for ubiquitination analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific Ub Antibodies | Antibody | Detect specific ubiquitin chain topologies (K48, K63, etc.) by Western Blot/IF | Determining if a protein is degraded (K48) or signal-activated (K63) [22] |

| Epitope-Tagged Ubiquitin (HA-, MYC-, FLAG-Ub) | DNA Construct | Express ubiquitin in cells; tag allows specific pulldown and detection | Overexpression to enhance detection of ubiquitinated proteins in IP assays [18] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (MG132, Bortezomib) | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Block proteasomal degradation, causing accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins | Essential for visualizing K48-polyubiquitinated substrates in assays [18] |

| E1 Inhibitor (MLN7243) | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Blocks the ubiquitination cascade at its initiation step | Positive control to confirm ubiquitin-dependent processes [18] |

| siRNA/shRNA E3/DUB Libraries | Functional Genomics Tool | For high-throughput screens to identify regulators of a target protein | Identifying novel E3 ligases or DUBs for a protein of interest [6] |

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Affinity Reagent | Bind polyubiquitin chains with high affinity, enriching ubiquitinated proteins from lysates | Proteomics studies; stabilizing labile ubiquitination events [22] |

| PROTACs (e.g., ARV-110, ARV-471) | Bifunctional Degrader | Recruit E3 ligases to neo-substrates, inducing their ubiquitination and degradation | Targeted protein degradation as a therapeutic strategy and research tool [23] [6] |

Visualization of Pathway Alterations and Crosstalk

The following diagram synthesizes the ubiquitin-mediated regulatory network connecting the five core cancer pathways, highlighting key ubiquitination events and their functional consequences.

Diagram 2: Ubiquitin-mediated regulation in core cancer pathways.

Concluding Remarks and Therapeutic Perspectives

The intricate alteration of the ubiquitin code is a non-genetic hallmark of cancer that empowers the rewiring of core pathways like RAS, mTOR, PTEN, p53, and c-Myc. A deep mechanistic understanding of these processes, facilitated by the experimental and reagent tools outlined herein, is paving the way for a new class of therapeutics. The clinical success of proteasome inhibitors has already validated the UPS as a target. The future lies in developing more precise agents, such as specific E3 ligase inhibitors, DUB inhibitors, and most notably, PROTACs, which leverage the cell's own ubiquitination machinery to degrade previously "undruggable" oncoproteins [23] [6] [18]. As research continues to decode the complexities of ubiquitin chain diversity and crosstalk with other post-translational modifications, the development of biomarker-guided combination therapies that target the ubiquitin code will be crucial for achieving durable responses in cancer patients.

The RAS family of GTPases (KRAS4A, KRAS4B, HRAS, and NRAS) represents one of the most frequently mutated oncoprotein families in human cancers, with mutations occurring in approximately 19% of all malignancies [25]. These mutations drive constitutive activation of downstream signaling pathways such as MAPK and PI3K-AKT, leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance [25]. While oncogenic mutations have long been the focus of RAS biology, recent research has illuminated that post-translational modifications (PTMs), particularly ubiquitination, play a pivotal role in regulating RAS protein stability, membrane localization, and signaling transduction [8] [25].

Ubiquitination exerts bidirectional control over RAS activity: it can promote degradation to suppress oncogenic signaling or activate RAS via non-degradative mechanisms that alter GTP binding, effector interaction, and subcellular localization [25]. This review synthesizes current understanding of the heterogeneous ubiquitination patterns across RAS isoforms, their functional consequences in cancer progression, and the experimental approaches driving these discoveries. Understanding these isoform-specific regulatory mechanisms provides crucial insights for developing novel therapeutic strategies against RAS-driven cancers [8].

Molecular Mechanisms of RAS Ubiquitination

The Ubiquitination Machinery

Ubiquitination involves a sequential enzymatic cascade comprising E1 ubiquitin-activating enzymes, E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, and E3 ubiquitin ligases [26]. The E3 ligase, as the most heterogeneous component, provides substrate specificity by recognizing specific "degron" motifs on target proteins [25] [26]. The process concludes with the covalent attachment of one or more ubiquitin molecules to lysine residues on the target protein [26]. This modification is reversible through the action of deubiquitinases (DUBs), which remove ubiquitin chains, thereby stabilizing substrates [25] [26].

The fate of ubiquitinated RAS proteins is predominantly determined by the topology of ubiquitin chains. Canonical K48-linked polyubiquitination predominantly marks substrates for proteasomal degradation, whereas K63-linked chains often act as signals for alternative degradation routes, including the autophagy-lysosomal pathway, or for non-degradative signaling functions [25]. The dynamic balance between ubiquitinating and deubiquitinating enzymes precisely controls RAS protein homeostasis and function [25].

Structural Determinants of RAS Ubiquitination

Mammalian RAS comprises four isoforms—KRAS4A, KRAS4B, HRAS, and NRAS—encoded by three genes, all sharing a conserved G domain but diverging in their hypervariable regions (HVRs) [25]. The G domain contains conserved motifs critical for RAS function: GTP binding sites, the phosphate binding loop (P loop), and two switch regions (Switch I/II). The C-terminal HVR, through PTMs including prenylation and palmitoylation, directs RAS trafficking between the plasma membrane and endomembranes [25].

Both the G-domain and the HVR contain sites of ubiquitination, directly linking structural features to proteostatic regulation. The table below summarizes key ubiquitination sites identified in RAS proteins and their functional consequences:

Table 1: Key Ubiquitination Sites in RAS Proteins and Their Functional Impacts

| Ubiquitination Site | RAS Isoform | Functional Consequence | Molecular Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lys117 | Pan-RAS | Enhanced activation | Facilitates nucleotide exchange [25] |

| Lys147 | Pan-RAS | Enhanced activation | Hinders GAP-mediated GTP hydrolysis [25] |

| Lys104 | KRAS | Enhanced activation | Promotes binding with GEF [25] |

| Lys128 | Pan-RAS | Attenuated activation | Facilitates RAS binding to GAP [25] |

| Lys170 | HRAS | Altered localization | Impairs membrane association [25] |

Isoform-Specific Ubiquitination Landscapes

Regulatory Enzymes with Isoform Specificity

The ubiquitination landscape of RAS isoforms is shaped by distinct profiles of E3 ligases and DUBs that confer isoform-specific regulation. This intricate regulatory network enables precise control over individual RAS family members despite their structural similarities.

Table 2: E3 Ubiquitin Ligases in RAS Regulation

| E3 Ligase | Type | Substrate | RAS Regulation | Role in Cancer | Cancer Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEDD4-1 | HECT E3 | Pan-RAS | Degradation | Bifunctional | Cervical cancer, colorectal cancer, glioblastoma [25] |

| Rabex5 | RING E3 | HRAS, NRAS | Location, GTP-binding | Bifunctional | Colorectal, breast, prostate cancer [25] |

| β-TrCP | RING E3 | Pan-RAS | Degradation | Bifunctional | Colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, melanoma [25] |

| SMURF2 | HECT E3 | KRAS | Degradation | Bifunctional | Lung cancer, colorectal cancer [25] |

| LZTR1 | RING E3 | Pan-RAS | Location, degradation | Tumor suppressor | Lung adenocarcinoma, liver cancer, glioblastoma [25] |

| WDR76 | RING E3 | Pan-RAS | Degradation | Tumor suppressor | Colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma [25] |

| FBXL6 | RING E3 | KRAS | Effector binding | Tumor promoter | Hepatocellular carcinoma, lung cancer [25] |

The HECT-family E3 ligase NEDD4-1 exemplifies this regulatory complexity, targeting multiple RAS isoforms for degradation while exhibiting context-dependent functions in various cancer types [25]. In contrast, RABEX5 demonstrates more restricted substrate specificity, primarily regulating HRAS and NRAS through mechanisms that influence subcellular localization and GTP-binding capacity rather than degradation [25]. The CRL family adapter LZTR1 represents another critical regulator, assembling with CUL3 to facilitate the degradation of RAS proteins through ubiquitination, with particular significance in Noonan syndrome and cancer contexts [25].

Mutation-Specific Effects on Ubiquitination

Oncogenic mutations in RAS genes not only confer constitutive activation but also potentially alter the ubiquitination landscape. Most RAS oncogenic mutations drive constitutive activation through three distinct mechanistic categories: (1) impairing GTP hydrolysis (e.g., G12D, Q61L) by inducing steric hindrance or disrupting catalytic networks; (2) accelerating nucleotide exchange (e.g., G13D, A59G) via enhanced GEF interaction or destabilized GDP binding; and (3) rewiring conformational states (e.g., A146T) to modulate effector selectivity [25].

The influence of distinct site-specific ubiquitination on these various RAS mutants remains an active area of investigation. Certain mutations may potentially create or obscure degron motifs recognized by specific E3 ligases, thereby altering the ubiquitination efficiency and subsequent degradation of mutant RAS proteins. This mutation-specific regulation may contribute to the varying degradation rates observed among different RAS mutants and their corresponding sensitivities to ubiquitination-targeting therapies [25].

Experimental Approaches for Studying RAS Ubiquitination

Methodological Framework

Deciphering the ubiquitination landscape of RAS proteins requires a multidisciplinary approach combining biochemical, cellular, and computational methods. The following workflow outlines key experimental strategies for identifying and validating RAS ubiquitination events:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying RAS Ubiquitination

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Expression Plasmids | HA-Ub, FLAG-Ub, Myc-Ub | Detection of ubiquitinated proteins via immunoprecipitation and Western blot [25] |

| E3 Ligase Expression Constructs | NEDD4-1, RABEX5, SMURF2, LZTR1 | Functional studies of specific E3 ligases in RAS regulation [25] |

| RAS Isoform Constructs | Wild-type and mutant KRAS4A/B, HRAS, NRAS | Isoform-specific ubiquitination studies and functional assays [25] |

| Site-Directed Mutants | K117R, K147R, K104R, K128R | Identification of specific ubiquitination sites and functional consequences [25] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib | Assessment of proteasomal degradation dependence of ubiquitinated RAS [25] |

| Deubiquitinase Inhibitors | PR-619 (broad-spectrum DUB inhibitor) | Investigation of DUB function in RAS stability and signaling [25] |

| Computational Prediction Tools | Ubibrowser 2.0 | Prediction of E3 ligase-substrate interactions for RAS proteins [25] |

Functional Consequences and Therapeutic Implications

Biological Outcomes of RAS Ubiquitination

The functional consequences of RAS ubiquitination extend across multiple cellular compartments and signaling pathways, as illustrated in the following pathway map:

The spatiotemporal control of RAS signaling through ubiquitination directly impacts critical cancer hallmarks. By regulating RAS protein abundance through degradative ubiquitination, the ubiquitin system can suppress oncogenic signaling [25]. Conversely, non-degradative ubiquitination events at specific lysine residues can enhance RAS activation by facilitating nucleotide exchange or impeding GTP hydrolysis, thereby amplifying downstream effector pathways that drive proliferation, metastasis, and therapy resistance [25]. The balance between these opposing functions depends on the specific E3 ligases and DUBs engaged, the cellular context, and the genetic background of the tumor.

Therapeutic Exploitation of RAS Ubiquitination

Targeting the ubiquitination pathway offers novel strategies to overcome RAS-driven cancers. Several therapeutic approaches are emerging:

- E3 ligase enhancers: Small molecules that promote the interaction between specific E3 ligases and mutant RAS proteins could selectively degrade oncogenic RAS [25].

- DUB inhibitors: Compounds targeting RAS-stabilizing DUBs could reactivate endogenous degradation mechanisms against oncogenic RAS [25].

- Combination therapies: Ubiquitination-targeting agents combined with RAS inhibitors or immunotherapy may help overcome resistance mechanisms [25].

- PROTAC technology: Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) that recruit E3 ligases to RAS proteins represent a promising avenue for targeted degradation [6].

Future research should integrate protein structure analysis and high-throughput screening to develop specific ubiquitination modulators and explore combination strategies with direct RAS inhibitors or immunotherapy, aiming to overcome RAS-driven malignant phenotypes [8] [25].

The heterogeneous ubiquitination of RAS isoforms represents a critical layer of regulation in cancer development and progression. The distinct ubiquitination patterns, E3 ligase associations, and functional outcomes across KRAS, NRAS, and HRAS underscore the complexity of the ubiquitin code in RAS biology. Understanding these isoform-specific mechanisms provides not only fundamental insights into RAS pathophysiology but also exciting opportunities for therapeutic intervention. As our knowledge of the RAS ubiquitin code expands, so does the potential for developing innovative strategies to target this once "undruggable" oncoprotein family in precision oncology.

The ubiquitin code—a complex system of post-translational modifications (PTMs) that controls protein stability, localization, and function—is frequently dysregulated in cancer development. Ubiquitination does not function in isolation; rather, it engages in extensive crosstalk with other PTMs, including phosphorylation, acetylation, and SUMOylation, to orchestrate sophisticated signaling networks that drive tumorigenesis. This dynamic interplay creates regulatory circuits that allow cancer cells to adapt to therapeutic pressures, evade immune surveillance, and maintain proliferative advantages. The integration of these modification systems generates a complex signaling language that researchers are only beginning to decipher. Understanding this crosstalk is critical for developing novel cancer therapeutics that target the ubiquitin-proteasome system and its interconnected networks, particularly in the context of overcoming treatment resistance [16] [22].

The following diagram illustrates the core conceptual framework of PTM crosstalk with ubiquitination in cancer biology:

Ubiquitin-Phosphorylation Crosstalk: Reciprocal Regulation in Signaling Networks

The interplay between ubiquitination and phosphorylation represents one of the most prevalent and biologically significant forms of PTM crosstalk in cancer. These modifications engage in reciprocal regulation, where phosphorylation often creates recognition motifs for E3 ubiquitin ligases, while ubiquitination can conversely modulate kinase activity and stability. This bidirectional relationship forms sophisticated regulatory circuits that control key oncogenic and tumor suppressive pathways.

Phosphorylation-Dependent Ubiquitination

The phosphodegron motif—a specific phosphorylated sequence recognized by E3 ubiquitin ligases—serves as a critical interface in ubiquitin-phosphorylation crosstalk. The F-box protein FBXW7 exemplifies this mechanism by specifically recognizing phosphorylated degrons on substrates such as p53. When p53 is phosphorylated at residues S33 and S37, it creates a phosphodegron that facilitates FBXW7-mediated ubiquitination and subsequent degradation, promoting radioresistance in colorectal cancer [22]. This phosphorylation-dependent recognition system enables precise temporal control over protein stability, directly linking kinase activity to proteasomal degradation.

The contextual nature of this crosstalk is demonstrated by FBXW7's opposing roles in different cancer types. While it promotes radioresistance in p53-wildtype colorectal tumors, FBXW7 enhances radiosensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with SOX9 overexpression by destabilizing SOX9 and alleviating p21 repression. This functional switch highlights how tumor-specific genetic backgrounds influence the outcome of ubiquitin-phosphorylation crosstalk [22].

Ubiquitination-Mediated Kinase Regulation

Ubiquitination reciprocally regulates kinase activity through both proteolytic and non-proteolytic mechanisms. K63-linked ubiquitin chains play particularly important roles in organizing kinase signaling complexes. For instance, TRAF4 utilizes K63 modifications to activate the JNK/c-Jun pathway, driving overexpression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL in colorectal cancer and MCL-1 in oral cancers [22]. This non-degradative ubiquitination creates signaling platforms that enhance kinase activity and promote survival pathways in cancer cells.

The functional consequences of ubiquitin-phosphorylation crosstalk are illustrated in the following experimental findings from cancer research:

Table 1: Experimental Evidence of Ubiquitin-Phosphorylation Crosstalk in Cancer

| E3 Ligase/ Enzyme | Kinase/ Phosphorylation Site | Substrate | Functional Outcome | Cancer Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBXW7 | p53-S33/S37 phosphorylation | p53 | Degradation → Radioresistance | Colorectal Cancer |

| FBXW7 | SOX9 phosphorylation | SOX9 | Degradation → Radiosensitivity | NSCLC |

| TRAF4 | JNK/c-Jun pathway activation | Bcl-xL, MCL-1 | Stabilization → Anti-apoptotic signaling | Colorectal & Oral Cancers |

| ATM | RNF168 phosphorylation | H2A/H2AX | Altered conformation enhances ubiquitination | Multiple Cancers |

| RNF126 | MRE11 phosphorylation | MRE11 | Activates ATM-CHK1 axis → Error-prone repair | Triple-Negative Breast Cancer |

Experimental Approaches for Studying Ubiquitin-Phosphorylation Crosstalk

Deciphering the complex relationship between ubiquitination and phosphorylation requires integrated methodological approaches:

Phosphomimetic and Phosphodeficient Mutagenesis: Replace phosphorylatable serine/threonine residues with glutamic acid (phosphomimetic) or alanine (phosphodeficient) to assess the impact on ubiquitination efficiency and substrate stability. For example, mutating S33/S37 of p53 to alanine prevents FBXW7 recognition and degradation [22].

Co-immunoprecipitation with Phosphospecific Antibodies: Validate phosphorylation-dependent protein interactions by immunoprecipitating with antibodies specific to phosphorylated epitopes, followed by detection of associated E3 ligases.

Kinase Inhibitor Screens Combined with Ubiquitination Assays: Treat cancer cells with targeted kinase inhibitors while monitoring changes in substrate ubiquitination status to identify regulatory kinases.

Mass Spectrometry with Phospho- and Ubiquitin-Enrichment: Combine phosphopeptide enrichment (using TiO2 or IMAC) with diGly remnant enrichment (K-ε-GG antibody) to comprehensively map phosphorylation and ubiquitination sites on the same protein.

Ubiquitin-SUMOylation Crosstalk: Balancing Act in Genome Integrity and Immune Signaling

The interplay between ubiquitination and SUMOylation represents a sophisticated regulatory axis in cancer biology, with these ubiquitin-like modifiers engaging in both antagonistic and cooperative relationships. SUMOylation—the covalent attachment of small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) proteins to target lysines—shares structural and mechanistic similarities with ubiquitination but typically serves distinct cellular functions, primarily modulating protein-protein interactions, subcellular localization, and activity rather than promoting degradation.

SUMO-Directed Ubiquitination

A key mechanism of ubiquitin-SUMOylation crosstalk involves SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases (STUbLs) that recognize SUMO-modified proteins and catalyze their ubiquitination. RNF4, a prominent STUbL, binds to poly-SUMO chains through its SUMO-interaction motifs (SIMs) and mediates ubiquitination of the SUMOylated substrate, targeting it for proteasomal degradation. This sequential modification creates a SUMO-to-ubiquitin switch that regulates protein stability in response to specific cellular cues [27].

This crosstalk plays a particularly important role in maintaining genome integrity. Radiation-induced RNF168 activation is amplified by ZNF451-dependent SUMOylation, which subsequently promotes ubiquitination of H2A/H2AX to open chromatin and recruit BRCA1-A complexes, enhancing DNA repair fidelity but potentially promoting radioresistance in cancer cells [22]. This coordinated modification system ensures precise control over DNA damage response pathways.

Competitive Modification and Functional Interplay

SUMOylation and ubiquitination often compete for modification of the same lysine residues on substrate proteins, creating a modification switch that toggles protein function between different states. This competitive relationship is evident in the regulation of transcription factors and chromatin modifiers, where the balance between SUMOylation and ubiquitination determines transcriptional output and chromatin dynamics.

The functional integration between these pathways is further facilitated by shared enzymes. Certain deubiquitinases (DUBs), including USP7 and USP11, also function as SUMO-targeted ubiquitin-specific proteases (STUbPs), cleaving ubiquitin chains from SUMOylated substrates and adding another layer of regulatory complexity [27]. This enzymatic promiscuity enables fine-tuned control of the SUMO-ubiquitin equilibrium in cancer cells.

Table 2: Experimental Evidence of Ubiquitin-SUMOylation Crosstalk in Cancer

| Modification Type | Key Enzymes | Substrate | Functional Outcome | Cancer Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUMO-directed Ubiquitination | RNF4 (STUbL) | Poly-SUMOylated proteins | Ubiquitination → Degradation | Multiple Cancers |

| SUMO-enhanced Ubiquitination | ZNF451 (E4), RNF168 | H2A/H2AX | Chromatin opening → Enhanced DNA repair | Radioresistant Cancers |

| Competitive Modification | Shared lysine residues | Transcription factors | Functional switching | Altered transcriptional programs |

| SUMOylation-induced Stability | UBC9, PIAS | NSUN2, MDM2 | Prevents ubiquitination → Oncogene stabilization | Colon, Prostate Cancer |

| DeSUMOylation-induced Degradation | SENPs | β-catenin | Enables ubiquitination → Tumor suppressor | Myeloma |

SUMOylation in Tumor Immunity and Therapeutic Targeting

Recent research has illuminated the significance of ubiquitin-SUMOylation crosstalk in regulating anti-tumor immunity. SUMO hyperexpression drives covalent SUMO conjugation to STAT1 at K703, impairing IFN-I/II-triggered STAT1 activation dynamics in several cancers, including human glioblastoma astrocytoma, cervical cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma [27]. This SUMOylation creates an immune-evasive environment by dampening interferon signaling.

Therapeutic targeting of this crosstalk shows promising preclinical results. Combination of SUMOylation inhibitors such as TAK-981 or 2-D08 with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) significantly improves tumor prognosis by reactivating anti-tumor immunity [27]. These approaches leverage the ubiquitin-SUMO interplay to overcome resistance to cancer immunotherapy.

Experimental Strategies for Analyzing Ubiquitin-SUMOylation Crosstalk

SIM/UIM Mapping: Identify SUMO-interaction motifs (SIMs) in ubiquitin system components and ubiquitin-interaction motifs (UIMs) in SUMO pathway enzymes through peptide array screens and co-immunoprecipitation.

Tandem Affinity Purification with SUMO/Ubiquitin Traps: Utilize sequential purification with SUMO-binding entities (SUBEs) followed by ubiquitin-binding domains to isolate proteins dually modified or engaged in cross-regulatory complexes.

SUMO Protease Sensitivity Assays: Treat cell lysates with SENP proteases to remove SUMO conjugates while monitoring changes in ubiquitination patterns to identify SUMO-dependent ubiquitination events.

STUbL Activity Assays: Measure ubiquitin ligase activity of candidate STUbLs toward SUMOylated substrates in vitro using recombinant proteins.

The relationship between SUMOylation and ubiquitination pathways can be visualized as follows:

Ubiquitin-Acetylation Crosstalk: Metabolic Regulation and Transcriptional Control

The intersection between ubiquitination and acetylation represents a crucial regulatory nexus in cancer, particularly in the contexts of metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic regulation. These modifications engage in both competitive and cooperative relationships on shared lysine residues, creating a dynamic interplay that influences protein stability, activity, and complex formation.

Competitive Lysine Modifications

Acetylation and ubiquitination directly compete for modification of the same lysine residues, creating a modification switch that determines protein fate. Acetylation neutralizes the positive charge on lysine residues, which can sterically hinder ubiquitination and thereby stabilize proteins by blocking degradation signals. This competition is particularly relevant for metabolic enzymes and transcription factors that require rapid regulation in response to cellular signals.

The reciprocal regulation also occurs, where ubiquitination can influence acetylation dynamics. For instance, acetylation of ubiquitin itself at K6 and K48 inhibits the formation and elongation of ubiquitin chains, adding another layer of complexity to this crosstalk [18]. This chemical modification of ubiquitin represents an emerging area of investigation in cancer biology.

Metabolic Regulation Through Dual Modification

The ubiquitin-acetylation crosstalk plays a significant role in cancer metabolic reprogramming, a hallmark of tumorigenesis. The E3 ligase Parkin facilitates the ubiquitination of pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), a key glycolytic enzyme, while the deubiquitinase OTUB2 interacts with PKM2 to inhibit its Parkin-mediated ubiquitination, thereby enhancing glycolysis and accelerating colorectal cancer progression [6]. This balance between ubiquitination and deubiquitination directly controls metabolic flux in cancer cells.

Similarly, ubiquitination critically regulates cancer metabolism by reprogramming processes such as ferroptosis susceptibility, hypoxia adaptation, and nutrient flux. SMURF2-mediated HIF1α degradation compromises hypoxic survival [22], while SOCS2/Elongin B/C-driven SLC7A11 destruction increases ferroptosis sensitivity in liver cancer [22]. These ubiquitination events are potentially modulated by acetylation status, though the precise mechanisms remain under investigation.

Experimental Approaches for Ubiquitin-Acetylation Crosstalk

Acetyl-lysine Mimetic Mutagenesis: Replace target lysines with glutamine (acetyl-mimetic) or arginine (acetylation-deficient) to assess impact on ubiquitination efficiency and protein half-life.

HDAC and HAT Inhibitor Treatments: Modulate cellular acetylation status using pharmacological inhibitors while monitoring changes in ubiquitination patterns via ubiquitin remnant profiling.

Combined Immunoprecipitation with Acetyl- and Ubiquitin-Specific Antibodies: Sequential IP with acetyl-lysine antibodies followed by ubiquitin detection to identify dually modified proteins.

Structural Biology Approaches: Utilize X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM to visualize competitive binding of ubiquitination and acetylation machinery to shared lysine residues.

Research Toolkit: Experimental Methods and Reagent Solutions

Investigating PTM crosstalk requires specialized methodological approaches and research tools. The following table summarizes key experimental methods and reagents essential for deciphering the complex relationships between ubiquitination and other PTMs:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying PTM Crosstalk

| Research Tool Category | Specific Reagents/Assays | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitination Detection | K-ε-GG antibody; TUBE (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities); Ubiquitin remnant profiling | Enrichment and detection of ubiquitinated proteins; DiGly remnant mass spectrometry | Lysis conditions critical to preserve modifications; Proteasome inhibition often required |

| SUMOylation Tools | SUMO-traps (SUBEs); SENP proteases; SUMOylation consensus mutagenesis | Isolation of SUMOylated proteins; Validation of SUMO-dependent functions | Rapid denaturation needed to preserve SUMO conjugates; Multiple paralogs add complexity |

| Phosphorylation Resources | Phosphospecific antibodies; Phos-tag gels; Kinase inhibitor libraries | Mapping phosphodegrons; Assessing phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination | Phosphatase inhibition essential; Context-dependent effects |

| Acetylation Reagents | Acetyl-lysine antibodies; HDAC/HAT inhibitors; Acetyl-mimetic mutants | Competitive modification studies; Metabolic regulation analysis | Short inhibitor treatments preferred to avoid compensatory mechanisms |

| Genetic Manipulation | CRISPR/Cas9 knockout; siRNA/shRNA knockdown; Dominant-negative constructs | Functional validation of specific enzymes; Pathway manipulation | Redundancy challenges; Off-target effects monitoring |

| Proteomic Approaches | Sequential IP; Tandem affinity purification; Cross-linking mass spectrometry | Identification of modification networks; Complex mapping | Bioinformatics expertise required; Validation essential |

| Structural Biology | X-ray crystallography; Cryo-EM; NMR spectroscopy | Molecular mechanism elucidation; Interface mapping | Technical complexity; May require truncated constructs |

Integrated Workflow for PTM Crosstalk Analysis

A comprehensive approach to studying PTM crosstalk involves multiple complementary techniques:

Initial Discovery Phase: Utilize quantitative proteomics (SILAC, TMT) with PTM-specific enrichment to identify coordinated changes in ubiquitination, phosphorylation, SUMOylation, and acetylation in response to specific cancer-relevant stimuli.

Validation Stage: Employ targeted methods such as Western blotting with modification-specific antibodies, co-immunoprecipitation, and proximity ligation assays (PLA) to confirm interactions and modifications.

Functional Characterization: Implement genetic approaches (CRISPR, RNAi) to modulate specific enzymes combined with phenotypic assays relevant to cancer biology (proliferation, invasion, therapy resistance).

Mechanistic Elucidation: Apply structural biology and biophysical techniques to understand molecular details of modification interfaces and enzymatic regulation.

The following diagram illustrates a recommended experimental workflow for investigating PTM crosstalk:

Therapeutic Implications and Future Perspectives

The intricate crosstalk between ubiquitination and other PTMs presents both challenges and opportunities for cancer therapy. Understanding these networks enables the development of innovative therapeutic strategies that exploit nodal points in PTM cross-regulation.

Targeting PTM Crosstalk in Precision Oncology

The contextual duality of many ubiquitin system components—exemplified by FBXW7's opposing roles in different cancer types—underscores the importance of biomarker-guided therapeutic approaches [22]. Successful targeting of PTM crosstalk requires careful patient stratification based on genetic background, PTM enzyme expression patterns, and metabolic dependencies.

PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) represent a groundbreaking application of ubiquitin biology that leverages the cell's natural degradation machinery. These bifunctional molecules recruit E3 ubiquitin ligases to target proteins of interest, inducing their ubiquitination and degradation. EGFR-directed PROTACs selectively degrade β-TrCP substrates in EGFR-dependent tumors (e.g., lung and head/neck squamous cell carcinomas), suppressing DNA repair while minimizing impact on normal tissues [22]. The efficacy of PROTACs can be modulated by the phosphorylation status of their targets, creating opportunities to integrate PTM crosstalk understanding into drug design.

Combination Therapies and Resistance Management

Targeting single components of PTM networks often leads to adaptive resistance mechanisms, necessitating rational combination approaches. For instance, combining SUMOylation inhibitors with immune checkpoint blockers addresses multiple vulnerabilities simultaneously: TAK-981 or 2-D08 (SUMOylation inhibitors) combined with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies significantly improve tumor prognosis in preclinical models [27].

Radiation-responsive therapeutic platforms represent another innovative approach that leverages PTM crosstalk. Radiotherapy-triggered PROTAC (RT-PROTAC) prodrugs activated by tumor-localized X-rays degrade BRD4/2, synergizing with radiotherapy in breast cancer models [22]. Similarly, X-ray-responsive nanomicelles selectively release PROTACs within irradiated tumors, creating spatial control over ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation [22].

Future Research Directions

Several emerging areas warrant further investigation in the field of PTM crosstalk:

Branched Ubiquitin Chains: The functional significance of heterotypic ubiquitin chains and their intersection with other PTMs remains largely unexplored territory with potential therapeutic implications.

Single-Cell PTM Analysis: Developing methods to map PTM crosstalk at single-cell resolution will reveal tumor heterogeneity and microenvironment-specific regulation.

Chemical Biology Tools: Creating more selective inhibitors and activators for PTM-writing, -reading, and -erasing enzymes will enable precise manipulation of these networks.

Computational Modeling: Integrating multi-omics PTM data into predictive models will help identify key regulatory nodes and optimize combination therapy schedules.

The dynamic and reversible nature of ubiquitination and its crosstalk with other PTMs offers unique clinical advantages for therapeutic intervention. As our understanding of these complex networks deepens, so too will our ability to develop precisely targeted interventions that disrupt cancer-specific pathways while sparing normal tissue, ultimately advancing toward more effective and personalized cancer treatments.

Advanced Methodologies for Mapping and Targeting the Ubiquitin Code in Malignancies

Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics and Linkage-Specific Antibodies for Ubiquitin Code Analysis

The post-translational modification of proteins by ubiquitin is a master regulator of cellular function, controlling processes as critical as protein degradation, DNA damage repair, and signal transduction. The remarkable diversity of ubiquitin signaling—termed the "ubiquitin code"—arises from the ability of ubiquitin to form polymers (polyubiquitin chains) through eight distinct linkage sites (seven lysine residues and the N-terminal methionine). These chains vary in their topology, length, and function, creating a complex regulatory language that cells use to coordinate physiological processes [28] [6]. In cancer biology, deciphering this code is of paramount importance, as malignant cells often hijack or dysregulate ubiquitin signaling to drive tumor proliferation, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance [8] [29].

The functional consequences of ubiquitination are profoundly linkage-dependent. K48-linked ubiquitin chains primarily target substrate proteins for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains typically serve as scaffolds for non-proteolytic signaling complexes, such as those activating the NF-κB pathway [29] [28]. The roles of less abundant "atypical" chains (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33) are increasingly being elucidated in cancer contexts. For instance, K29-linked chains have been implicated in proteotoxic stress response and the regulation of key chromatin modifiers like the histone methyltransferase SUV39H1, thereby influencing the cancer epigenome [30] [31]. Similarly, K27-linked chains have been shown to be critical for cell fitness and are associated with p97 activity in the nucleus [31].

For researchers investigating ubiquitin code alterations in cancer, two technological pillars have proven indispensable: mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics and linkage-specific antibodies. These methodologies enable the direct detection, quantification, and characterization of ubiquitin chain architectures on cellular substrate proteins, moving the field beyond indirect genetic approaches [32]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these core methodologies, detailing experimental protocols, analytical workflows, and their application in cancer research.

Methodological Pillars: Principles and Technologies

Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics for Ubiquitin Analysis

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics has become the cornerstone for system-wide investigations of protein ubiquitination. The primary strategy for identifying ubiquitination sites involves enriching ubiquitinated peptides from complex protein digests and analyzing them via high-resolution liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [33].

A critical innovation in this field is ubiquitin remnant profiling (also known as di-glycine proteomics). When ubiquitylated proteins are digested with the protease trypsin, a signature di-glycine (Gly-Gly) remnant (~114.04 Da mass shift) remains attached to the modified lysine residue [33]. This di-glycine modification serves as a mass tag that can be pinpointed by MS, allowing for the precise localization of the ubiquitination site within the protein sequence. To overcome the challenge of low stoichiometry, specific monoclonal antibodies (e.g., GX41) have been developed that selectively recognize the di-glycine adduct on lysine, enabling the highly specific enrichment of these modified peptides prior to LC-MS/MS analysis [33].

For quantitative analyses, ubiquitin remnant profiling is typically combined with isotopic or isobaric labeling techniques, such as:

- SILAC (Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino Acids in Cell Culture): Metabolic labeling that incorporates stable isotopes into cellular proteins.

- TMT (Tandem Mass Tagging): Chemical labeling of peptides with isobaric tags for multiplexed relative quantification.

These approaches allow researchers to compare the abundance of thousands of ubiquitination sites across different conditions—for example, between normal and cancerous tissues, or in response to therapeutic interventions [33].

Beyond site identification, advanced MS methods are being developed to characterize ubiquitin chain topology. These include techniques like Ub-clipping and the use of linkage-specific ubiquitin-binding entities (TUBEs) to enrich for proteins modified with specific chain types before MS analysis [30] [28]. A significant challenge, however, is that tryptic digestion also produces a di-glycine remnant from the ubiquitin-like modifiers NEDD8 and ISG15. Careful experimental design and data interpretation are required to distinguish these modifications from canonical ubiquitination [33].

Linkage-Specific Antibodies and Affinity Reagents

Linkage-specific antibodies represent a powerful complementary approach to MS, allowing for the direct detection and visualization of specific ubiquitin chain types in cells and tissues. These reagents are generated by immunizing animals with synthetically produced diubiquitin of defined linkage, resulting in antibodies that can distinguish, for instance, K48-linked from K63-linked chains with high specificity [32] [30].

The utility of these antibodies extends across multiple platforms:

- Western Blotting: For detecting the presence and relative abundance of specific chain linkages in whole-cell lysates.