Decoding Tumor Heterogeneity through Single-Cell Ubiquitination Analysis: Mechanisms, Methods, and Therapeutic Translation

This article explores the critical intersection of single-cell analysis and ubiquitination states in dissecting tumor heterogeneity, a central challenge in oncology.

Decoding Tumor Heterogeneity through Single-Cell Ubiquitination Analysis: Mechanisms, Methods, and Therapeutic Translation

Abstract

This article explores the critical intersection of single-cell analysis and ubiquitination states in dissecting tumor heterogeneity, a central challenge in oncology. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive synthesis of how single-cell multi-omics technologies are revolutionizing our understanding of the ubiquitin-proteasome system's role in cancer. The content spans from foundational concepts of intra-tumoral diversity and ubiquitination networks to advanced methodological applications for identifying drug targets and predictive biomarkers. It further addresses key technical and analytical challenges in the field and outlines robust validation frameworks essential for clinical translation. By integrating the latest research, this review serves as a strategic resource for leveraging single-cell ubiquitination profiling to overcome therapy resistance and advance precision oncology.

The Ubiquitin Code and Cellular Diversity: Unraveling the Bedrock of Tumor Heterogeneity

Tumor heterogeneity represents a fundamental challenge in clinical oncology, underlying therapeutic resistance, metastatic progression, and variable treatment responses among patients. This heterogeneity manifests at multiple levels, encompassing both inter-tumoral heterogeneity (variations between tumors from different patients or even different lesions within the same patient) and intra-tumoral heterogeneity (diversity within individual tumors) [1] [2]. These variations arise from the complex integration of both genetic and non-genetic influences that shape clinically important phenotypic traits, including metastatic potential and survival under therapeutic pressure [2].

The somatic evolution of tumors was historically viewed primarily through a genetic lens, with successive clonal expansions driven by accumulating mutations. However, emerging research highlights that non-genetic heterogeneity serves as a mutation-independent driving force for tumor progression [3] [4]. This non-genetic variability results from gene expression noise, epigenetic modifications, and the multi-stable states of gene regulatory networks, creating heritable phenotypic variants that can serve as a temporary substrate for natural selection even in the absence of mutations [3]. Within this framework, single-cell multi-omics technologies have revolutionized our ability to dissect this complexity at unprecedented resolution, enabling the identification of rare cellular subsets and the delineation of tumor evolutionary trajectories that were previously obscured by bulk analysis approaches [5].

Table 1: Fundamental Sources of Tumor Heterogeneity

| Heterogeneity Type | Genetic Sources | Non-genetic Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Inter-tumoral | Different mutation profiles between patients; Subgroup-specific driver mutations [1] | Differential epigenetic states; Variable tumor microenvironment composition [2] [5] |

| Intra-tumoral | Clonal genetic diversity; Branched evolutionary patterns [2] | Stochastic gene expression; Phenotypic plasticity; Cancer stem cell dynamics [3] [2] |

Characterizing Heterogeneity Through Single-Cell Multi-Omics Technologies

Technological Platforms for Single-Cell Analysis

Advanced single-cell isolation and sequencing methods form the cornerstone of modern heterogeneity research. Current platforms enable high-resolution dissection of tumors across multiple molecular layers:

Cell Isolation Strategies: Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) allow antibody-based selection of specific cell populations, while microfluidic technologies provide high-throughput, low-noise isolation with minimal cellular stress [5]. Laser capture microdissection (LCM) offers precise spatial context preservation, enabling correlation of molecular profiles with histological features [5].

Multi-omics Profiling: Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) characterizes transcriptional heterogeneity and identifies distinct cell states through unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) and cell-specific barcodes [6] [5]. Single-cell DNA sequencing (scDNA-seq) directly profiles genomic alterations, including copy number variations and single nucleotide variants, with broader genomic coverage than inferred approaches [5]. Single-cell assay for transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing (scATAC-seq) maps chromatin accessibility landscapes, while single-cell CUT&Tag profiles histone modifications [5].

Computational Tools for Deciphering Splicing Heterogeneity

Alternative splicing represents a crucial layer of post-transcriptional regulation that substantially contributes to transcriptional diversity. The SCSES (Single-Cell Splicing EStimation) computational framework addresses the technical challenges of characterizing splicing changes at single-cell resolution, including high dropout rates and limited coverage [7]. This network diffusion-based imputation method utilizes both cell and event similarities to accurately recover percent spliced-in (PSI) values across main types of splicing events, outperforming existing algorithms in recovering splicing diversity across cell populations [7].

SCSES Computational Workflow for Splicing Analysis: This framework processes scRNA-seq data to reconstruct splicing heterogeneity through iterative data diffusion across cell and event similarity networks.

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System in Tumor Heterogeneity

Ubiquitination Landscapes in Cancer Development

Ubiquitination, a pivotal post-translational modification, orchestrates diverse cellular processes including proteolysis, metabolism, signaling, and cell cycle regulation through the reversible addition of ubiquitin molecules to substrate proteins [8]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system comprises a enzymatic cascade including ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1s), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2s), ubiquitin ligases (E3s), and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that collectively regulate approximately 80-90% of cellular proteolysis [8]. Recent studies utilizing single-cell multiomics analysis have revealed that malignant cells exhibit elevated scores for ubiquitination-related enzymes and ubiquitin-binding domains compared to normal epithelial cells, with 53 ubiquitination-related molecules showing prognostic significance in lung adenocarcinoma [6].

Integration of genomic and transcriptomic data from single-cell and bulk sequencing datasets has enabled comprehensive exploration of the ubiquitination modification landscape across cancer types. For instance, PSMD14, a critical deubiquitination enzyme, has been identified as a promising therapeutic target that stabilizes AGR2 protein by reducing its ubiquitination, thereby promoting lung adenocarcinoma progression [6]. Furthermore, pancancer analyses have revealed that ubiquitination regulatory networks influence histological fate decisions, with ubiquitination scores positively correlating with squamous or neuroendocrine transdifferentiation in adenocarcinoma [8].

Experimental Protocol: Ubiquitination Profiling in Single Cells

Objective: To characterize ubiquitination heterogeneity at single-cell resolution and identify key enzymes associated with malignant progression.

Sample Preparation:

- Obtain fresh tumor tissues and matched normal adjacent tissues (1:1 ratio)

- Process tissues within 1 hour of resection to maintain viability

- Prepare single-cell suspensions using gentleMACS Dissociator with appropriate enzyme cocktails

- Filter through 40μm strainers and assess viability (>90% required)

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing:

- Load 10,000 cells per sample onto 10x Genomics Chromium Chip

- Generate barcoded cDNA libraries using 10x Genomics Single Cell 3' Reagent Kits

- Sequence libraries on Illumina NovaSeq platform (target: 50,000 reads/cell)

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Process raw sequencing data with Cell Ranger pipeline

- Normalize, cluster, and annotate cell types with Seurat package in R

- Distinguish malignant from epithelial cells using InferCNV

- Evaluate AUC scores of ubiquitination-related enzymes using AUCell

- Perform survival and differential analyses to identify significant molecular markers

Functional Validation:

- Confirm target expression (e.g., PSMD14) using RT-qPCR and Western blot

- Establish knockdown cell lines using lentiviral shRNAs

- Assess effects on cellular processes (proliferation, apoptosis, migration)

- Evaluate tumor formation in mouse xenograft models

- Predict interacting proteins and assess impact on substrate half-life

Table 2: Key Ubiquitination-Related Research Reagents

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Partitioning individual cells for barcoding | Single-cell RNA sequencing of tumor tissues [6] |

| AUCell Algorithm | Evaluation of ubiquitination-related enzyme activity | Scoring enzyme and ubiquitin-binding domain activity in malignant vs. normal cells [6] |

| InferCNV | Copy number variation analysis | Distinguishing malignant from epithelial cells in tumor samples [6] |

| LASSO Cox Regression | Prognostic model construction | Developing ubiquitination-related prognostic signatures [8] |

| OTUB1-TRIM28 Assay | Ubiquitination regulation analysis | Modulating MYC pathway and influencing patient prognosis [8] |

Signaling Pathways Linking Ubiquitination to Heterogeneity

The OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination regulatory axis represents a crucial mechanism influencing tumor heterogeneity through modulation of the MYC pathway. This regulatory module demonstrates how ubiquitination enzymes can shape histological fate decisions in cancer cells, particularly in squamous cell carcinoma (SQC), adenocarcinoma (ADC), and neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) transdifferentiation [8]. The ubiquitination score derived from this and related pathways effectively stratifies patients into high-risk and low-risk groups with distinct survival outcomes across multiple cancer types, including lung cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, urothelial cancer, and melanoma [8].

Ubiquitination Regulation of Histological Fate: The OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination axis modulates MYC signaling and oxidative phosphorylation to drive histological transdifferentiation and therapy resistance.

Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Opportunities

Diagnostic and Prognostic Applications

The comprehensive characterization of tumor heterogeneity has profound implications for cancer diagnostics and patient stratification. Spatial genetic heterogeneity within tumors means that single biopsies may not adequately represent the complete molecular landscape, as different regions of the same tumor can exhibit distinct diagnostic signatures and synonymous driving mutations independently arising in distinct clones [2]. This topological heterogeneity in the distribution of diagnostically important phenotypes necessitates multi-region sampling or liquid biopsy approaches for accurate assessment.

Ubiquitination-related prognostic signatures (URPS) have emerged as powerful tools for risk stratification across multiple cancer types. These signatures effectively categorize patients into high-risk and low-risk groups with distinct survival outcomes and differential responses to immunotherapy [8]. The integration of URPS with single-cell RNA sequencing data has further enhanced their utility, enabling more precise classification of distinct cell types and revealing associations with immune cell infiltration patterns within the tumor microenvironment, particularly macrophage subsets [8].

Therapeutic Development and Resistance Mechanisms

Tumor heterogeneity constitutes a major source of therapeutic resistance through multiple mechanisms. Initial phenotypic heterogeneity within tumor cell populations creates a diverse substrate for selection pressures, while adaptation to therapy and selection for resistant phenotypes further shapes the evolutionary trajectory [2]. Both genetic and non-genetic determinants contribute to this resistance, necessitating therapeutic approaches that account for this dynamic complexity.

Targeting ubiquitination regulators represents a promising strategy for addressing traditionally "undruggable" targets like MYC. By screening ubiquitination regulatory modifiers through pancancer ubiquitination regulatory networks, researchers can identify new therapeutic alternatives for improving immunotherapy efficacy and patient prognosis [8]. Additionally, the development of prognostic models based on ubiquitination patterns shows significant potential for predicting immunotherapy response, with the capacity to identify patients who are more likely to benefit from these interventions in clinical settings [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Core Research Solutions for Heterogeneity Studies

| Category | Essential Resources | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Single-cell Platforms | 10x Genomics Chromium; BD Rhapsody | High-throughput single-cell partitioning and barcoding [6] [5] |

| Computational Tools | Seurat; InferCNV; AUCell; SCSES | Data normalization, clustering, CNV analysis, pathway scoring [6] [7] |

| Ubiquitination Databases | Integrated Ubiquitin and Ubiquitin-like Conjugation Database (iUUCD) | Comprehensive repository of ubiquitination enzymes and domains [6] |

| Functional Validation | Lentiviral shRNAs; Mouse xenograft models | Target validation through knockdown and in vivo assessment [6] |

| Spatial Context | Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM) | Precise isolation of specific cell populations with spatial preservation [5] |

The deconstruction of intra-tumoral and inter-tumoral heterogeneity through genetic and non-genetic lenses has revealed astonishing complexity in cancer biology. Single-cell multi-omics technologies have been instrumental in illuminating these dynamics, providing unprecedented resolution to dissect the intricate regulatory networks governing tumor evolution. The integration of ubiquitination profiling with these approaches has further enriched our understanding of post-translational mechanisms contributing to phenotypic diversity and therapeutic resistance. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they promise to transform precision oncology through truly personalized therapeutic interventions that account for the multifaceted nature of tumor heterogeneity. The ongoing development of computational tools, experimental protocols, and targeted agents against heterogeneity drivers will be essential for overcoming the clinical challenges posed by this fundamental aspect of cancer biology.

Ubiquitination is a critical and reversible post-translational modification that orchestrates a vast array of cellular processes, ranging from targeted protein degradation to intricate immune signaling pathways. This sophisticated enzymatic process involves the sequential action of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligase) enzymes that covalently attach ubiquitin molecules to target proteins, while deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) mediate ubiquitin removal [9] [10]. The human genome encodes approximately 2 E1 enzymes, 38 E2 enzymes, and over 600 E3 ligases, which confer substrate specificity and enable precise regulation of protein fate and function [11]. Different ubiquitin linkage types—including K48-linked chains for proteasomal degradation, K63-linked chains for signal transduction, and K27/K29-linked chains for other regulatory functions—determine the ultimate functional consequences for substrate proteins [12] [9].

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) constitutes the primary pathway for intracellular protein degradation, responsible for 80-90% of cellular proteolysis and governing essential processes including cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and inflammatory responses [8] [11]. Beyond its fundamental role in protein turnover, ubiquitination has emerged as a central regulatory mechanism in immunity, modulating both innate and adaptive immune responses through precise control of signaling pathway components, immune receptor activation, and immune cell differentiation [12] [9] [11]. This application note explores the multifaceted roles of ubiquitination in cellular regulation, with particular emphasis on its implications for tumor heterogeneity and the emerging technologies enabling single-cell analysis of ubiquitination states.

Ubiquitination in Innate Immune Signaling: The cGAS-STING Pathway

The cGAS-STING pathway represents a quintessential example of ubiquitination-mediated immune regulation, serving as a crucial defense mechanism against cytoplasmic DNA derived from pathogens or cellular damage. Recent research has elucidated how ubiquitination precisely controls both DNA sensor cGAS and adaptor protein STING through multifaceted mechanisms [12].

cGAS Regulation: Multiple E3 ubiquitin ligases target cGAS with distinct ubiquitin linkages that dictate its activity and stability. TRIM56 catalyzes cGAS monoubiquitination at Lys335, enhancing dimerization, DNA-binding affinity, and cGAMP production essential for antiviral immunity [12]. RNF185 mediates K27-linked polyubiquitination to augment cGAS enzymatic activity, while K48-linked ubiquitination targets cGAS for p62-dependent autophagic degradation [12]. The deubiquitinating enzyme USP14 counteracts degradative ubiquitination by cleaving K48-linked chains at Lys414, thereby stabilizing cGAS, whereas USP27X removes K48-linked polyubiquitin chains to enhance cGAS stability [12]. Nuclear cGAS undergoes SPSB3-mediated recognition and CRL5 complex-dependent ubiquitination and degradation, providing a compartment-specific regulatory mechanism [12].

STING Trafficking and Degradation: STING ubiquitination regulates its intracellular trafficking, activation, and termination. TRIM56 and TRIM32 promote K63-linked ubiquitination that facilitates STING dimerization, Golgi accumulation, and TBK1 recruitment for interferon production [12]. The AMFR-GP78/INSIG1 complex mediates K27 polyubiquitination to enable TBK1 recruitment, while RNF144A ubiquitinates STING at K236 to control its translocation [12]. Negative regulation occurs through RNF5-mediated K48-linked ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, and K63-linked ubiquitination at Lys288 targets STING for ESCRT-mediated microautophagy to prevent excessive immune activation [12]. The deubiquitinase USP21 negatively regulates STING by hydrolyzing K27/K63-linked chains, whereas UFL1 competitively binds STING to reduce K48-linked ubiquitination and enhance antiviral responses [12].

Table 1: Key Ubiquitin Enzymes Regulating the cGAS-STING Pathway

| Enzyme | Target | Ubiquitin Linkage | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRIM56 | cGAS | Monoubiquitination (Lys335) | Enhances dimerization, DNA binding, and cGAMP production |

| RNF185 | cGAS | K27-linked polyubiquitination | Increases enzymatic activity |

| TRIM56 | STING | K63-linked polyubiquitination | Promotes dimerization and Golgi accumulation |

| TRIM32 | STING | K63-linked polyubiquitination | Enhances downstream signaling |

| RNF5 | STING | K48-linked polyubiquitination | Promotes proteasomal degradation |

| USP14 | cGAS | K48-chain removal | Stabilizes cGAS protein |

| USP21 | STING | K27/K63-chain hydrolysis | Negatively regulates interferon production |

The following diagram illustrates the complex ubiquitination-mediated regulation of the cGAS-STING pathway:

Ubiquitination in Cancer Biology and Tumor Heterogeneity

Ubiquitination modifications play a transformative role in cancer biology, influencing tumor development, progression, and response to therapy through the regulation of oncoproteins, tumor suppressors, and immune microenvironment components. Recent pan-cancer analyses have revealed that ubiquitination regulatory networks effectively stratify patients across multiple cancer types based on prognostic outcomes and therapeutic vulnerabilities [8].

Pan-Cancer Ubiquitination Signatures: Integration of transcriptomic data from 4,709 patients across 26 cohorts encompassing five solid tumor types (lung cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, urothelial carcinoma, and melanoma) has identified conserved ubiquitination-related prognostic signatures (URPS) that effectively categorize patients into distinct risk groups with differential survival outcomes [8]. These ubiquitination signatures correlate with specific histological differentiation patterns—notably squamous (SQC) or neuroendocrine (NEC) transdifferentiation in adenocarcinomas (ADC)—and exhibit associations with therapeutic resistance mechanisms [8]. The OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination axis has been identified as a key regulator modulating MYC pathway activity and oxidative stress response, ultimately influencing immunotherapy efficacy and patient prognosis [8].

Cancer-Type Specific Ubiquitination Alterations: In lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), ubiquitination-related gene signatures demonstrate prognostic value and association with immune infiltration patterns. A nine-gene risk model (B4GALT4, DNAJB4, GORAB, HEATR1, LPGAT1, FAT1, GAB2, MTMR4, TCP11L2) effectively stratifies LUAD patients, with high-risk patients showing significantly worse overall survival and distinct immune cell infiltration profiles [10]. Functional validation has confirmed that HEATR1 knockdown markedly reduces LUAD cell viability, migration, and invasion, establishing its role as a potential therapeutic target [10]. Similarly, in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC), ubiquitination-related biomarkers (WDR54, KAT2B, NBEAL2, LNX1) show diagnostic and prognostic significance, with expression validation in clinical samples confirming their potential utility [13].

Table 2: Ubiquitination-Based Biomarkers Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Biomarkers/Regulators | Clinical/Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Pan-Cancer | OTUB1-TRIM28 axis | Modulates MYC pathway, oxidative stress, immunotherapy response |

| Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD) | HEATR1, B4GALT4, DNAJB4, GORAB, LPGAT1, FAT1, GAB2, MTMR4, TCP11L2 | Prognostic stratification, immune infiltration patterns, cell proliferation and invasion |

| Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (LSCC) | WDR54, KAT2B, NBEAL2, LNX1 | Diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers, therapeutic targets |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) | Multiple E3 ligases (e.g., RNF family) | Regulate PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, innate immune signaling, therapy resistance |

Hepatocellular Carcinoma Mechanisms: In HCC, ubiquitination regulates critical signaling pathways including PI3K/AKT/mTOR, which influences innate immunity through multiple mechanisms: suppression of immune cell activity, inhibition of immune cell development and differentiation, modulation of inflammatory cytokine production, and alteration of immune cell metabolic states [11]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system represents a promising therapeutic target in HCC, particularly in combination with immunotherapy, where strategic manipulation of ubiquitination pathways can potentiate PD-1/PD-L1 blockade efficacy while mitigating therapeutic resistance through modulation of tumor-associated macrophages and exhausted T cell populations [11].

Single-Cell Analysis of Ubiquitination States: Methodological Approaches

The emergence of single-cell multi-omics technologies has revolutionized our ability to dissect tumor heterogeneity and characterize ubiquitination-related processes at unprecedented resolution. These approaches enable comprehensive profiling of cellular diversity, rare cell populations, and dynamic molecular changes underlying treatment resistance and immune modulation [5].

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) Workflow: Modern scRNA-seq platforms (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium X, BD Rhapsody HT-Xpress) enable profiling of over one million cells per run through optimized workflows incorporating efficient mRNA reverse transcription, cDNA amplification, and utilization of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) with cell-specific barcodes to minimize technical noise [5]. Cell isolation strategies include fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS), and microfluidic technologies, each offering distinct advantages in throughput, cellular stress, and cost considerations [5]. For ubiquitination studies, scRNA-seq enables inference of ubiquitination pathway activity through expression profiling of E1/E2/E3 enzymes, DUBs, and ubiquitination-related genes, allowing correlation with cell states and phenotypic outcomes [8] [5].

Splicing Analysis at Single-Cell Resolution: The SCSES (Single-Cell Splicing EStimation) computational framework addresses the challenge of characterizing splicing heterogeneity from scRNA-seq data, which conventionally suffers from high dropout rates, technical noise, and limited coverage [7]. SCSES employs data diffusion techniques to impute missing splicing information by sharing information across similar cells and events, utilizing cell similarity networks based on RNA-binding protein expression or splicing patterns, and event similarities derived from sequence features and regulatory correlations [7]. The platform implements distinct imputation strategies for different biological scenarios: direct PSI value imputation for non-dropout (ND) cases, junction matrix imputation for biological dropout (BD) and technical dropout with information (TD+Info) cases, and additional event-based diffusion for technical dropout without information (TD-Info) cases [7].

Multi-Omics Integration: Single-cell DNA sequencing (scDNA-seq) provides complementary genomic information through methods including multiple displacement amplification, offering broader genomic coverage for mutation detection [5]. Single-cell epigenomic technologies—including scATAC-seq for chromatin accessibility, bisulfite sequencing for DNA methylation, scCUT&Tag for histone modifications, and scMNase-seq for nucleosome positioning—enable comprehensive characterization of the regulatory landscape governing ubiquitination enzyme expression and activity [5]. Spatial transcriptomics further contextualizes ubiquitination processes within tissue architecture, revealing spatial patterns of ubiquitination pathway activity in tumor microenvironments [5].

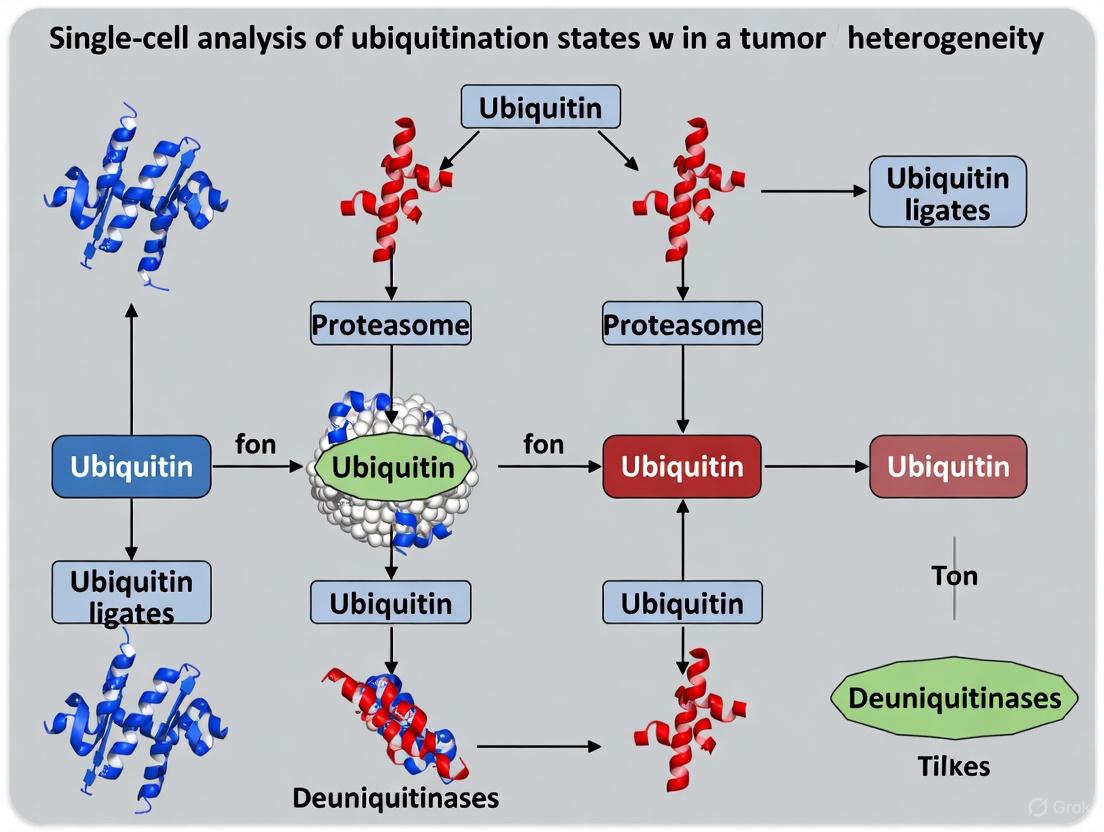

The following diagram illustrates an integrated workflow for single-cell analysis of ubiquitination states:

Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitination Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Ubiquitination and Single-Cell Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq Platforms | 10x Genomics Chromium X, BD Rhapsody HT-Xpress | High-throughput single-cell transcriptomics of ubiquitination pathways |

| Cell Isolation Technologies | FACS, MACS, Microfluidic devices | Isolation of specific cell populations for ubiquitination analysis |

| Ubiquitination Pathway Antibodies | Anti-K48 ubiquitin, Anti-K63 ubiquitin, E3 ligase-specific antibodies | Detection of specific ubiquitin linkages and enzyme expression |

| Computational Tools | SCSES, MAGIC, PHATE, BRIE2 | Analysis of splicing heterogeneity and ubiquitination-related gene expression |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Experimental manipulation of ubiquitin-proteasome system function |

| E3 Ligase Modulators | Small molecule inhibitors/activators of specific E3 ligases | Functional interrogation of specific ubiquitination pathways |

| Validation Reagents | siRNA/shRNA libraries, CRISPR-Cas9 systems | Functional validation of ubiquitination-related gene targets |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Single-Cell RNA Sequencing for Ubiquitination Pathway Analysis

Sample Preparation and Cell Isolation:

- Obtain fresh tumor tissues and process immediately to single-cell suspensions using appropriate dissociation protocols (e.g., enzymatic digestion with collagenase/hyaluronidase mixtures).

- Remove debris and dead cells using density gradient centrifugation or dead cell removal kits.

- For immune cell-rich populations, consider enrichment strategies (e.g., CD45+ selection for tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes).

- Assess cell viability and concentration using automated cell counters or flow cytometry, ensuring >85% viability for optimal sequencing results.

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Process cells through single-cell partitioning systems (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium) according to manufacturer protocols, targeting 5,000-10,000 cells per sample for adequate representation.

- Generate cDNA libraries incorporating cell barcodes and UMIs during reverse transcription.

- Amplify libraries with appropriate cycle optimization to maintain representation while minimizing amplification bias.

- Perform quality control using capillary electrophoresis (e.g., Bioanalyzer) and quantitative PCR before sequencing.

- Sequence on appropriate platforms (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq) with sufficient depth (≥50,000 reads per cell) for confident detection of ubiquitination-related transcripts.

Data Analysis Pipeline:

- Process raw sequencing data through standard alignment (e.g., Cell Ranger) and quality control metrics (mitochondrial content, unique genes per cell).

- Normalize data using appropriate methods (e.g., SCTransform) and remove batch effects when integrating multiple samples.

- Perform dimensionality reduction (PCA, UMAP) and clustering to identify cell populations.

- Analyze ubiquitination pathway activity through gene set enrichment analysis of E1/E2/E3 enzymes and DUBs across cell clusters.

- Correlate ubiquitination signatures with functional states (proliferation, immune activation, stress response) using established gene signatures.

Protocol 2: Functional Validation of Ubiquitination-Related Targets

Gene Manipulation in Cancer Models:

- Design and validate siRNA/shRNA constructs or CRISPR guide RNAs targeting candidate ubiquitination genes identified from single-cell analyses.

- Transfect/transduce target cancer cell lines (e.g., LUAD lines for HEATR1 validation) using appropriate delivery systems (lipofection, lentiviral transduction).

- Include non-targeting controls and rescue experiments with cDNA constructs to confirm specificity.

Phenotypic Assays:

- Assess proliferation using CCK-8 assays according to manufacturer protocols, with measurements at 0, 24, 48, and 72 hours post-transfection.

- Evaluate migration capacity using wound healing assays: create uniform scratches in confluent monolayers, capture images at 0, 12, and 24 hours, and quantify closure rates using image analysis software.

- Measure invasion potential through Transwell assays with Matrigel-coated chambers: seed transfected cells in serum-free medium upper chambers, place complete medium in lower chambers as chemoattractant, fix and stain migrated cells after 24-48 hours, and count in multiple microscope fields.

- Analyze cell cycle distribution and apoptosis through flow cytometry with propidium iodide and Annexin V staining according to standard protocols.

Mechanistic Studies:

- Examine protein stability and degradation rates through cycloheximide chase experiments: treat cells with protein synthesis inhibitor and collect samples at timepoints (0, 2, 4, 8 hours) for western blot analysis of target proteins.

- Investigate ubiquitination status through immunoprecipitation: lyse cells in RIPA buffer with protease and deubiquitinase inhibitors, incubate with target protein antibodies, pull down complexes with protein A/G beads, and detect ubiquitin modifications by western blot with linkage-specific antibodies.

- Analyze pathway alterations through western blotting or phospho-antibody arrays to identify downstream signaling consequences of ubiquitination target manipulation.

Ubiquitination represents a master regulatory mechanism that integrates protein degradation with immune modulation through sophisticated enzymatic networks and substrate-specific modifications. The emergence of single-cell multi-omics technologies has enabled unprecedented resolution in mapping ubiquitination-related processes across heterogeneous cell populations, revealing novel insights into tumor biology, immune regulation, and therapeutic resistance mechanisms. The integration of ubiquitination signatures with histological and molecular classification schemes provides powerful frameworks for patient stratification and treatment selection, particularly in the context of immunotherapy where ubiquitination pathways significantly influence response outcomes. Future research directions should focus on developing more comprehensive single-cell ubiquitination profiling methods, including spatial context and proteomic dimensions, to further elucidate the complex role of ubiquitination in cellular regulation and disease pathogenesis.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a critical post-translational regulatory mechanism that governs nearly all aspects of cellular physiology through targeted protein degradation and signaling modulation [14]. Ubiquitination involves a sequential enzymatic cascade mediated by E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes that conjugate ubiquitin molecules to substrate proteins, while deubiquitinases (DUBs) reverse this process [15] [14]. Dysregulation of this precise equilibrium drives oncogenesis by directly influencing cancer hallmarks including sustained proliferation, evasion of apoptosis, and metastasis [16] [17]. Within the tumor microenvironment, single-cell analyses have revealed remarkable heterogeneity in ubiquitination states across different cell populations, contributing to therapeutic resistance and disease progression [5] [18]. This application note provides a structured experimental framework for investigating ubiquitination dysregulation in cancer, with specific protocols and resources tailored for research on tumor heterogeneity.

Quantitative Landscape of Ubiquitination in Cancer Processes

Table 1: Ubiquitination Regulation of Proliferation, Apoptosis, and Metastasis

| Cancer Hallmark | Regulatory Enzyme | Substrate/Target | Ubiquitin Linkage | Functional Outcome | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustained Proliferation | E3 Ligase TRIM30α | SOX17 | K48 [17] | Degradation, activates β-catenin signaling | Papillary Thyroid Cancer [17] |

| E3 Ligase FBXO22 | LKB1 | K63 [17] | Inhibits activity, promotes growth | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer [17] | |

| USP7, USP1 | p53, Cell Cycle proteins | N/A [17] | Stabilizes oncoproteins, defective DNA repair | Multiple Cancers [17] | |

| Evasion of Apoptosis | USP8 | Bcl-2 | N/A [17] | Stabilizes anti-apoptotic protein | Gastric Cancer [17] |

| Aumdubicin (Inhibitor) | Bax | N/A [17] | Induces Bax-dependent apoptosis | Lung Cancer Cell Lines [17] | |

| E3 Ligase SCFFBXO22 | Bim | K48 [17] | Degradation, confers chemoresistance | Epithelial Cancers [17] | |

| Activation of Metastasis | OTUB1, USP37 | SNAIL | N/A [15] | Stabilizes EMT transcription factor | Multiple Cancers [15] |

| USP9X | SMAD4 | N/A [15] | Promotes TGF-β signaling | Multiple Cancers [15] | |

| FBOX33 | p53 | K29 [17] | Enhances EMT | Gallbladder Cancer [17] |

Table 2: Ubiquitination Enzymes in Lipid Metabolism Reprogramming

| Metabolic Enzyme | Regulatory Ubiquitin Enzyme | Cancer Type | Effect on Lipid Metabolism | Impact on Tumor Growth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACLY | E3 Ligase NEDD4 | Lung Cancer | Decreases stability, reduces lipogenesis [14] | Inhibits proliferation [14] |

| E3 Ligase UBR4 | Lung Cancer | Reduces acetylation-mediated stability [14] | Inhibits proliferation [14] | |

| CUL3/KLHL25 Complex | Lung Cancer | Ubiquitination and degradation [14] | Inhibits xenograft growth [14] | |

| FASN | E3 Ligase COP1 | Liver Cancer | Ubiquitin-mediated degradation [14] | Tumor suppression [14] |

| E3 Ligase TRIM21 | Multiple Cancers | Deacetylation-enhanced ubiquitination [14] | Reduces lipogenesis and cell growth [14] | |

| E3 Ligase SPOP | Prostate Cancer | Reduces expression and fatty acid synthesis [14] | Tumor suppression [14] |

Experimental Protocols for Ubiquitination Analysis

Protocol: Single-Cell RNA-Sequencing for Ubiquitination States

Purpose: To identify cell subpopulations with distinct ubiquitination-related gene expression profiles within heterogeneous tumors [5] [18].

Workflow Steps:

- Sample Preparation & Single-Cell Isolation:

- Obtain fresh tumor tissue and process into single-cell suspensions using mechanical dissociation and enzymatic digestion (e.g., collagenase IV).

- Isolate viable single cells using Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) or microfluidic technologies (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium). Assess cell viability (>80%) and integrity [5].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing:

- Use a platform such as 10x Genomics Chromium for single-cell barcoding, cDNA synthesis, and library construction.

- Incorporate Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to correct for amplification bias [5].

- Sequence libraries on an Illumina platform to a minimum depth of 50,000 reads per cell.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Process raw data using Seurat (v4.4.0) or similar packages. Apply quality control: exclude cells with <200 genes, >7000 genes, or >15% mitochondrial gene expression [18].

- Normalize data and identify highly variable genes.

- Perform dimensionality reduction (PCA, UMAP) and cluster analysis (KNN, resolution=0.6) [18].

- Calculate a "ubiquitination score" for each cell using gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) with a curated ubiquitination gene set (e.g., 405 genes from GeneCards, relevance score >10) [18].

- Annotate cell types using known marker genes and analyze cell-cell communication using tools like CellChat [18].

Protocol: Functional Validation of Ubiquitination using Co-Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

Purpose: To confirm physical interaction and ubiquitination status between a specific E3 ligase/DUB and its substrate.

Workflow Steps:

- Cell Lysis and Pre-Clearance:

- Culture relevant cancer cell lines (e.g., pancreatic cancer lines for TRIM9 studies). Transfect with plasmids encoding your protein of interest (e.g., TRIM9), vector control, or specific siRNAs.

- Lyse cells in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors, 10mM N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM), and 20mM iodoacetamide to inhibit endogenous DUBs.

- Pre-clear lysates with Protein A/G beads for 1 hour at 4°C.

- Immunoprecipitation:

- Incubate pre-cleared lysates with antibody against the target protein (e.g., anti-HNRNPU) or control IgG overnight at 4°C.

- Add Protein A/G beads and incubate for 2-4 hours.

- Wash beads stringently 3-5 times with lysis buffer.

- Western Blot Analysis:

- Elute immunoprecipitated proteins by boiling in SDS-PAGE loading buffer.

- Resolve proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to PVDF membrane.

- Probe the membrane with specific antibodies:

- Treat cells with proteasome inhibitor MG132 (10µM, 4-6 hours) prior to lysis to enrich for ubiquitinated species.

Protocol: In Vivo Tumor Xenograft Models for Ubiquitination Studies

Purpose: To assess the functional role of ubiquitination enzymes in tumor growth and metastasis in a physiological context.

Workflow Steps:

- Animal Model and Cell Implantation:

- Use immunodeficient mice (e.g., NOD/SCID or NSG).

- Generate stable cancer cell lines with knockdown (shRNA) or overexpression (lentiviral transduction) of your ubiquitination gene of interest (e.g., TRIM9) [18].

- Implant 1-5x10^6 cells subcutaneously into the flanks or orthotopically into the relevant organ (e.g., pancreas).

- Tumor Monitoring and Analysis:

- Monitor tumor growth weekly via caliper measurements or in vivo imaging.

- At endpoint (e.g., 4-8 weeks), harvest tumors and weigh them.

- Process tumor tissue for downstream analyses: flash-freeze for protein/RNA extraction, or fix in formalin for immunohistochemistry (IHC) and spatial transcriptomics [18].

- Spatial Transcriptomics Validation:

- For fixed tumor tissue, perform spatial transcriptomics (e.g., using 10x Genomics Visium platform) [18].

- Map the expression of your target ubiquitination genes and correlate with tumor regions, proliferation markers (Ki67), and stromal interactions.

- Use deconvolution algorithms (e.g., "spacexr" RCTD method) to annotate cell types within the spatial data based on your single-cell RNA-seq reference [18].

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: Ubiquitination Network Regulating Cancer Hallmarks. This diagram illustrates the enzymatic cascade of ubiquitination and its regulation of key substrates, culminating in the activation of core cancer hallmarks. E3 ligases and DUBs serve as critical nodes determining substrate fate.

Diagram 2: TRIM9-Mediated Ubiquitination in Pancreatic Cancer. Based on multi-omics analysis, TRIM9 acts as a tumor suppressor by promoting K11-linked ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of the oncogenic protein HNRNPU, thereby inhibiting pancreatic cancer progression [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitination and Single-Cell Cancer Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | High-throughput single-cell RNA-seq library preparation | Enables profiling of >1 million cells per run; compatible with multi-omics [5]. |

| Seurat R Package | Comprehensive single-cell data analysis | Version 4.4.0+; used for QC, normalization, clustering, and differential expression [18]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Stabilize ubiquitinated proteins for detection | MG132 (10µM), Bortezomib; add 4-6 hours prior to cell lysis. |

| DUB Inhibitors | Investigate DUB function in cells | Aumdubicin, PR-619; use with controls to assess apoptosis induction [17]. |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies | Detect specific ubiquitin chain types | Critical for distinguishing degradative (K48) from signaling (K63) ubiquitination [17]. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms | Map gene expression in tissue context | 10x Genomics Visium; use with RCTD deconvolution for cell-type annotation [18]. |

| PROTACs | Induce targeted protein degradation | Bispecific molecules recruiting E3 ligase to target; overcome drug resistance [16] [17]. |

The tumor microenvironment (TME) represents a complex ecosystem comprising malignant cells, immune populations, stromal components, and vascular elements, all engaged in dynamic crosstalk that dictates disease progression and therapeutic response. Traditional bulk sequencing approaches average signals across this heterogeneous cellular milieu, obscuring critical cell-to-cell variations and rare but functionally important subpopulations. Single-cell multi-omics technologies have emerged as transformative tools that dissect this complexity at unprecedented resolution, enabling simultaneous measurement of multiple molecular layers—genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, and spatial context—within individual cells [5]. This technological revolution provides a powerful lens through which to examine tumor heterogeneity, immune evasion mechanisms, and cellular plasticity within the TME, ultimately advancing precision oncology strategies [5] [19].

The integration of single-cell methodologies with ubiquitination state analysis offers particular promise for elucidating post-translational regulatory mechanisms that govern protein stability, signaling transduction, and metabolic reprogramming within the TME. As up to 30% of proteins are regulated by ubiquitination, connecting this layer of regulation to transcriptional and epigenetic states at single-cell resolution can reveal novel therapeutic vulnerabilities [20]. This Application Note outlines comprehensive protocols and analytical frameworks for leveraging single-cell multi-omics to resolve TME heterogeneity, with emphasis on technical considerations, computational integration, and clinical translation.

Key Single-Cell Multi-Omics Technologies and Platforms

Table 1: Comparison of Major Single-Cell Multi-Omics Platforms

| Platform | Technology Type | Molecular Modalities | Throughput (Cells) | Key Applications in TME |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Microfluidics | GEX, ATAC, PROT, CRISPR | 10,000-100,000 | Immune cell mapping, clonal evolution |

| Tapestri (Mission Bio) | Droplet-based | DNA, Protein | 10,000+ | Genotype-phenotype linking, MRD monitoring |

| BD Rhapsody | Microwell | GEX, ATAC, PROT | 10,000-1,000,000 | Rare cell detection, comprehensive immune profiling |

| CITE-seq | Droplet-based | GEX, Surface Proteins | 5,000-100,000 | Surface proteogenomics, immune phenotyping |

| SEQ-Well | Nanowell | GEX, ATAC | 1,000-10,000 | Fixed/archived samples, clinical specimens |

Core Methodological Principles

Single-cell multi-omics approaches rely on sophisticated barcoding strategies to label molecules from individual cells before pooling and sequencing. The fundamental workflow involves: (1) single-cell isolation and compartmentalization, (2) molecular barcoding with cell-specific identifiers, (3) library preparation for multiple modalities, and (4) sequencing and bioinformatic demultiplexing [5] [19]. Cell isolation strategies include fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS), and microfluidic technologies, each with distinct advantages in throughput, viability, and recovery [5].

Unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) and cell barcodes are critical for distinguishing technical noise from biological signal and for accurately assigning sequenced fragments to their cell of origin [5]. Recent platforms such as 10x Genomics Chromium X and BD Rhapsody HT-Xpress enable profiling of over one million cells per run with improved sensitivity and multimodal compatibility, dramatically enhancing our ability to characterize rare cellular states within the TME [5].

Experimental Protocols for TME Characterization

Integrated Protocol: Dissecting Metabolic Heterogeneity in Breast Cancer TME

This protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for analyzing metabolic heterogeneity and its relationship to immune suppression in breast cancer, integrating scRNA-seq with bulk transcriptomic data to construct prognostic signatures [20].

Sample Preparation and Single-Cell Sequencing

- Tissue Dissociation: Process fresh tumor specimens using gentleMACS Dissociator with enzymatic cocktail (Collagenase IV [1.5 mg/mL], Dispase [1 mg/mL], DNase I [0.2 mg/mL]) at 37°C for 30-45 minutes with continuous agitation. Filter through 40μm strainer and resuspend in PBS with 0.04% BSA.

- Viability and Concentration Assessment: Use AO/PI staining on automated cell counter; require >90% viability for sequencing.

- Cell Surface Protein Staining (for CITE-seq): Incubate with hashtag antibodies (TotalSeq-B, BioLegend) for 30 minutes on ice, wash twice with PBS+0.04% BSA.

- Single-Cell Partitioning and Library Preparation: Load cells onto 10x Genomics Chromium Chip (Targeting 10,000 cells/sample). Generate GEX, ADT, and cell multiplexing libraries per manufacturer's protocol.

- Sequencing Parameters: Sequence on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 with 28bp Read1 (cell barcode+UMI), 90bp Read2 (transcript), and 10bp i7 index (sample index). Target: ≥20,000 reads/cell for GEX, ≥5,000 reads/cell for ADT.

Computational Analysis Pipeline

- Data Preprocessing: Use Cell Ranger (10x Genomics) for demultiplexing, barcode processing, and UMIs counting. Perform quality control: remove cells with <500 genes, >10% mitochondrial reads, or >20,000 genes (potential doublets).

- Integration and Clustering: Normalize data using SCTransform, integrate samples with Harmony, and cluster cells using Leiden algorithm at resolution 0.8 in Scanpy.

- Cell Type Annotation: Use SingleR with reference datasets (Blueprint, ENCODE, Monaco Immune) combined with manual annotation based on canonical markers.

- Metabolic Pathway Analysis: Calculate metabolic scores (glycolysis, OXPHOS) using AUCell with gene sets from KEGG and Reactome. Identify metabolic subpopulations within epithelial compartment.

Single-Cell Analysis of TME Metabolic Heterogeneity

Protocol: Epigenetic-Transcriptomic Coupling Analysis with HALO

This protocol utilizes the HALO (Hierarchical causal modeling) framework to characterize coupled and decoupled relationships between chromatin accessibility and gene expression within the TME, revealing regulatory mechanisms underlying cellular plasticity and therapeutic resistance [21].

Multiome (GEX+ATAC) Sample Preparation

- Nuclei Isolation: Prepare nuclei isolation buffer (10mM Tris-HCl pH7.4, 10mM NaCl, 3mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween-20, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 1% BSA, 1U/μL RNase inhibitor). Dounce homogenize tissue (15 strokes loose pestle, 15 strokes tight pestle) on ice. Filter through 40μm strainer, pellet nuclei at 500rcf for 5min at 4°C.

- Transposition Reaction: Resuspend nuclei in Diluted Nuclei Buffer (10x Genomics), count, and adjust to 5,000-10,000 nuclei/μL. Perform tagmentation with Tn5 transposase (37°C, 60min).

- Partitioning and Library Prep: Load onto 10x Genomics Chromium Chip for Multiome (GEX+ATAC). Generate paired libraries following manufacturer's protocol.

- Sequencing: Sequence on Illumina platform: GEX (28bp Read1, 90bp Read2), ATAC (50bp+50bp paired-end). Target: ≥25,000 reads/cell for GEX, ≥30,000 fragments/cell for ATAC.

HALO Causal Analysis Implementation

- Software Installation: Install HALO from GitHub (https://github.com/namharmalo/halo) in Python 3.8+ environment with dependencies: torch, scikit-learn, scanpy, episcanpy.

- Data Preprocessing: Create AnnData objects for RNA and ATAC. Filter features: RNA (mincells=10), ATAC (mincells=5). Normalize RNA counts by library size (log(CP10K+1)), binarize ATAC data.

- Peak-Gene Linkage: Identify cis-regulatory links using Signac (distance<500kb), create paired dataset.

- Model Training: Configure HALO parameters: latent dimensions (coupled=15, decoupled=15), batch size=64, learning rate=0.001. Train for 1000 epochs with early stopping (patience=50).

- Interpretation: Extract coupled/decoupled scores for gene-peak pairs. Perform Granger causality testing for distal cis-regulation. Identify super-enhancer interactions using H3K27ac ChIP-seq data if available.

HALO Causal Analysis of Epigenetic-Transcriptomic Dynamics

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell TME Analysis

| Category | Product/Resource | Vendor/Provider | Key Functionality | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissociation Kits | Human Tumor Dissociation Kit | Miltenyi Biotec | Gentle tissue dissociation | Maintains viability of rare immune populations |

| Cell Viability Stains | AO/PI Solution | Nexcelom | Live/dead discrimination | Critical for data quality; use automated counters |

| Hashtag Antibodies | TotalSeq-B/C | BioLegend | Sample multiplexing | Enables cost reduction through sample pooling |

| Feature Barcoding | CITE-seq Antibodies | BioLegend | Surface protein measurement | Validated panels for immune/TME characterization |

| Nuclei Isolation | Nuclei EZ Lysis Buffer | Sigma-Aldrich | Nuclear extraction for ATAC | Maintains nuclear integrity for epigenomics |

| Library Prep | Chromium Next GEM | 10x Genomics | Single-cell partitioning | Optimized for multiome (GEX+ATAC) applications |

| Analysis Pipelines | Cell Ranger ARC | 10x Genomics | Multiome data processing | Handles paired GEX+ATAC data alignment |

| Reference Data | Human Cell Atlas | CZ CELLxGENE | Annotation references | 100M+ cells for cross-validation [22] |

Advanced Computational Frameworks and Foundation Models

The analysis of single-cell multi-omics data requires sophisticated computational approaches that can handle high dimensionality, technical noise, and multimodal integration. Foundation models pretrained on massive single-cell datasets have emerged as powerful tools for cross-species cell annotation, in silico perturbation modeling, and gene regulatory network inference [22].

Table 3: Computational Foundation Models for Single-Cell Multi-Omics

| Model | Architecture | Training Scale | Key Capabilities | TME Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scGPT | Transformer | 33 million cells | Zero-shot annotation, perturbation prediction | Predicting therapy response across TME states |

| scPlantFormer | Phylogenetic transformer | 1 million cells | Cross-species integration, lightweight | Evolutionary conservation in TME pathways |

| Nicheformer | Graph transformer | 53 million spatial cells | Spatial context modeling | Cell-cell communication in TME niches |

| HALO | Interpretable neural network | Dataset-dependent | Causal epigenetic-transcriptomic links | Regulatory mechanisms in drug resistance [21] |

| PathOmCLIP | Contrastive learning | 5 tumor types | Histology-transcriptomics alignment | Spatial heterogeneity mapping in biopsies |

Implementation Protocol: scGPT for TME Cell State Prediction

- Model Loading: Install scGPT from PyPI (

pip install scgpt). Load pre-trained model weights (33M cells) usingscGPT.from_pretrained(). - Data Preprocessing: Normalize counts using scGPT's built-in functions. Harmonize batch effects using

scGPT.batch_integration(). - Zero-Shot Annotation: Project query TME data onto reference embedding. Generate predictions using

scGPT.annotate()with Human Cell Atlas as reference. - In Silico Perturbation: Simulate therapeutic interventions (e.g., immune checkpoint blockade) using

scGPT.perturb(). Predict expression changes in response to targeted perturbations. - Interpretation: Identify key driver genes using attention weights and gradient-based importance scoring.

Integration with Ubiquitination State Analysis in Tumor Heterogeneity Research

Connecting single-cell multi-omics with ubiquitination states provides unprecedented insights into post-translational regulation within the TME. Technical advances now enable the mapping of ubiquitination pathways through integration of scRNA-seq with proteomic and ubiquitin remnant signatures.

Experimental Design Considerations:

- Sample Processing: Preserve ubiquitination states through rapid processing and protease/deubiquitinase inhibition.

- Antibody Panels: Include ubiquitination-related proteins (E1/E2/E3 enzymes, deubiquitinases) in CITE-seq panels.

- Computational Inference: Infer ubiquitination activity from transcriptional signatures of ubiquitin ligases and substrate expression.

- Validation: Correlate with ubiquitin remnant proteomics where feasible.

The convergence of single-cell multi-omics with ubiquitination analysis reveals how post-translational modifications shape cellular identities within the TME, influence protein turnover rates, and create therapeutic vulnerabilities that can be exploited through targeted protein degradation approaches.

Troubleshooting and Quality Control Guidelines

Common Challenges and Solutions:

- Low Cell Viability: Optimize dissociation protocols; include viability dyes in sorting; use nuclear sequencing for compromised samples.

- Batch Effects: Implement multiplexing with hashtag antibodies; use computational integration tools (Harmony, Scanorama).

- Doublet Detection: Employ doublet detection algorithms (DoubletFinder, scDblFinder); adjust loading concentrations.

- Sparse Data: Optimize sequencing depth; use imputation methods (MAGIC, DeepImpute) judiciously.

- Integration Difficulties: Leverage foundation models (scGPT) for cross-dataset alignment; use reference-based mapping.

Quality control metrics should be rigorously applied at each step, with particular attention to cell number recovery, genes/cell, mitochondrial percentage, and library complexity. For multiome data, assess transcription start site (TSS) enrichment in ATAC data and ensure correlation between matched modalities.

Single-cell multi-omics technologies have fundamentally transformed our ability to resolve the complex cellular architecture and dynamic interactions within the tumor microenvironment. The protocols and frameworks outlined in this Application Note provide a roadmap for comprehensive TME characterization, connecting genetic, transcriptional, epigenetic, and proteomic layers to reveal mechanisms underlying therapeutic response and resistance.

As these technologies continue to evolve—with improvements in spatial resolution, throughput, and multimodal capacity—they will increasingly illuminate the role of ubiquitination and other post-translational modifications in shaping tumor heterogeneity. The integration of causal modeling approaches like HALO with foundation models represents the next frontier in computational analysis, moving beyond correlation to establish causal regulatory mechanisms [21]. These advances promise to accelerate the development of personalized immunotherapeutic strategies and targeted interventions based on a mechanistic understanding of TME biology at single-cell resolution.

Within the field of cancer biology, the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) has emerged as a critical post-translational regulatory mechanism governing cellular homeostasis, protein degradation, and oncogenic pathways [23] [8]. The process of ubiquitination, involving a cascade of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligase) enzymes, regulates diverse cellular functions including signal transduction, cell cycle progression, and immune response [24] [23]. Dysregulation of ubiquitination pathways contributes significantly to tumor development, progression, and therapeutic resistance across cancer types [8] [25].

The emergence of single-cell technologies has revolutionized our understanding of tumor heterogeneity, revealing complex ubiquitination states within the tumor microenvironment (TME) that were previously obscured in bulk analyses [26] [27]. This case study examines recent advances in pancancer ubiquitination signatures, their prognostic value, and the experimental frameworks enabling their discovery, with particular emphasis on single-cell resolution approaches that capture the dynamic nature of ubiquitination in malignant progression.

Key Findings: Ubiquitination Signatures as Prognostic Indicators

Pancancer Ubiquitination Signatures

Recent multi-omics studies have identified conserved ubiquitination-related signatures that stratify patient survival across multiple cancer types. A 2025 study integrated data from 4,709 patients across 26 cohorts spanning five solid tumors (lung, esophageal, cervical, urothelial cancers, and melanoma), constructing a ubiquitination-related prognostic signature (URPS) that effectively stratified patients into distinct risk categories [8]. This signature demonstrated significant prognostic value for patients receiving both surgery and immunotherapy.

Table 1: Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Signatures Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Key Ubiquitination Genes | Prognostic Value | Biological Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD) | DTL, UBE2S, CISH, STC1 [23] | HR = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.39–0.73, p < 0.001 [23] | Associated with TME scores, TMB, TNB, and PD1/L1 expression [23] |

| Multiple Cancers (Pancancer) | OTUB1, TRIM28 [8] | Conserved risk stratification across 5 cancer types [8] | Modulates MYC pathway, influences oxidative stress, and immunotherapy resistance [8] |

| Ovarian Cancer | TOP2A, MYLIP [28] | Significant survival difference between risk groups (p<0.05) [28] | Involved in neurohumoral regulation via ion channels and neuroactive ligand-receptor interactions [28] |

| Pan-Cancer | TRIM56 [29] | Favorable prognosis in BLCA, KIRC, MESO, SKCM; Poor prognosis in COAD, GBM, LGG [29] | Affects tumor development through transcriptional regulatory complexes and immune-related pathways [30] [29] |

Single-Cell Heterogeneity in Ubiquitination States

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revealed substantial heterogeneity in ubiquitination states across tumor types. Analysis of protein autoubiquitination genes (including CNOT4, MTA1, NFX1, RNF10, RNF112, RNF115, RNF13, RNF141, RNF4, RNF8, TAF1, TRIM13, and UHRF1) demonstrated cancer-type-specific functional states that correlated with diverse cancer-related processes [24]. A novel framework for modeling response expression quantitative trait loci (reQTLs) accounting for single-cell perturbation heterogeneity identified 36.9% more reQTLs compared to standard discrete models, significantly enhancing the detection of context-dependent gene regulation in cancer [26].

Table 2: Single-Cell Profiling of Ubiquitination-Related Genes

| Analysis Type | Technical Approach | Key Findings | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-cell functional state analysis | CancerSEA platform [24] | Cancer-type-specific functional states for autoubiquitination genes | Potential for diagnostic and prognostic strategy development [24] |

| Response eQTL mapping | Poisson mixed effects model (PME) with continuous perturbation score [26] | 36.9% more reQTLs detected compared to binary perturbation models | Improved identification of genetic effects in disease-relevant contexts [26] |

| Tumor microenvironment mapping | scRNA-seq of 299,879 PBMCs from 89 donors [26] | Heterogeneous responses to perturbations (IAV, CA, PA, MTB) | Cell-type-specific reQTL effects (e.g., MX1 in CD4+ T cells; SAR1A in CD8+ T cells) [26] |

| Immune infiltration analysis | GSVA score and Immune infiltration evaluation [24] | Correlation between autoubiquitination gene set and immune cell infiltration | Associations with immunotherapy response [24] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing Pancancer Ubiquitination Regulatory Networks

Data Collection and Integration

- Data Sources: Collect RNA-seq data from public repositories (TCGA, GEO) encompassing multiple cancer types with distinct histologies (adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma) [8].

- Inclusion Criteria: Select datasets with at least five patients per histological subtype and available clinical annotation including survival data, treatment history, and pathological characteristics [8].

- Ubiquitination Network Construction: Calculate correlation coefficient matrices between ubiquitination-related genes with significance screening (p<0.05). Standardize expression data across platforms using combat or similar batch correction methods [8].

Prognostic Model Development

- Feature Selection: Apply Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) Cox regression to identify ubiquitination genes most strongly associated with overall survival [23] [8].

- Risk Score Calculation: Compute ubiquitination-related risk scores using the formula:

Risk score = Σ(βRNA * ExpRNA)where βRNA represents coefficients from multivariate Cox regression and ExpRNA represents gene expression values [23]. - Validation: Validate prognostic models in independent patient cohorts, cell line models, and through in vivo experiments to confirm biological significance [8].

Protocol 2: Single-Cell Analysis of Ubiquitination States

Sample Preparation and Sequencing

- Cell Isolation: Utilize fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or microfluidic technologies to isolate single cells from fresh tumor tissues or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) [26] [27].

- Library Preparation: Employ 10x Genomics Chromium platform for single-cell RNA sequencing with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) and cell barcodes to minimize technical noise [27].

- Perturbation Modeling: For stimulation experiments (e.g., with influenza A virus, Candida albicans), use penalized logistic regression with corrected expression principal components to predict log odds of perturbation response [26].

reQTL Mapping Framework

- Model Specification: Implement Poisson mixed effects model (PME) of gene expression in single cells as a function of genotype and its interactions with discrete perturbation state and continuous perturbation score [26].

- Statistical Testing: Apply two degree-of-freedom likelihood ratio test to assess significance of genotype interactions with both discrete and continuous perturbation terms [26].

- Quality Control: Perform exhaustive quality control to minimize false positives, including evaluation of replication in previous studies and cell-type-specific effect assessment [26].

Diagram 1: Single-Cell Analysis Workflow for Ubiquitination States. This diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational pipeline for profiling ubiquitination states at single-cell resolution, from sample collection through validation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item | Specification/Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Databases | TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) | Provides multi-omics data across 33 cancer types [24] [8] | Pancancer ubiquitination signature discovery [24] [8] |

| GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus) | Repository of functional genomics datasets [23] [8] | Validation of prognostic models in independent cohorts [23] [8] | |

| iUUCD 2.0 Database | Comprehensive ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like conjugation database [23] | Identification of ubiquitination-related genes (E1, E2, E3 enzymes) [23] | |

| Computational Tools | GSCA (Gene Set Cancer Analysis) | Integrated platform for genomic, pharmacogenomic, and immunogenomic analysis [24] | Differential expression, mutation, and survival analysis of ubiquitination genes [24] |

| CancerSEA | Web-based platform for single-cell RNA-seq data analysis [24] | Correlation between gene expression and cancer-related functional states [24] | |

| GSVA (Gene Set Variation Analysis) | R package for pathway activity scoring [24] [8] | Evaluation of cancer pathway activity based on ubiquitination gene expression [24] [8] | |

| Experimental Platforms | 10x Genomics Chromium | High-throughput single-cell RNA sequencing platform [27] | Profiling ubiquitination states across heterogeneous cell populations [27] |

| Reverse Phase Protein Array (RPPA) | Antibody-based protein expression profiling [24] | Validation of ubiquitination-related protein expression [24] |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Ubiquitination regulates cancer progression through several key signaling pathways. The OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination axis modulates MYC pathway activity and oxidative stress response, influencing squamous or neuroendocrine transdifferentiation in adenocarcinoma [8]. TRIM56 affects tumor development through transcriptional regulatory complexes and immune-related pathways, demonstrating context-dependent roles as either oncogene or tumor suppressor [30] [29]. Autoubiquitination of transcription factors controls their abundance and function, impacting cellular processes like proliferation, survival, and metastasis [24].

Diagram 2: Ubiquitination Cascade and Functional Consequences. This diagram illustrates the sequential enzymatic cascade of ubiquitination and its dual functional outcomes in protein degradation and altered signaling pathways relevant to cancer progression.

Pancancer ubiquitination signatures represent powerful tools for prognostic stratification, therapeutic targeting, and understanding the molecular basis of tumor heterogeneity. The integration of single-cell technologies has been particularly transformative, revealing previously unappreciated complexity in ubiquitination states across cellular subpopulations within tumors. Future research directions should focus on expanding single-cell ubiquitination profiling across additional cancer types, developing targeted therapies against specific E3 ligases or deubiquitinating enzymes, and integrating multi-omics approaches to fully elucidate the spatial dynamics of ubiquitination within the tumor microenvironment. The continued refinement of ubiquitination-related prognostic signatures promises to enhance personalized treatment approaches and identify novel therapeutic vulnerabilities across cancer types.

From Data to Discovery: Single-Cell Methodologies for Mapping the Ubiquitinome in Tumors

The analysis of tumor heterogeneity represents a significant challenge in cancer research, particularly when investigating post-translational modifications like ubiquitination that vary between individual cells. Bulk sequencing methods average cellular signals, obscuring rare subpopulations and subtle molecular variations that drive cancer progression and therapeutic resistance [31]. Single-cell multi-omics technologies have emerged as powerful tools to dissect this complexity by enabling simultaneous measurement of genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic information from individual cells within heterogeneous tumor samples [31] [32]. This approach is particularly valuable for ubiquitination research because it allows researchers to directly observe how ubiquitination-related genes and proteins correlate with other molecular features at single-cell resolution, revealing mechanistic insights into protein regulation and degradation in specific cellular contexts [33] [34].

The integration of single-cell isolation techniques with multi-omic sequencing creates a complete workflow that bridges cellular phenotyping with deep molecular characterization. These workflows typically begin with viable single-cell isolation using methods like FACS or microfluidics, followed by preparation of sequencing libraries that capture multiple molecular layers from the same cells, and conclude with sophisticated bioinformatic integration of the resulting data [35] [32]. When applied to ubiquitination states in cancer research, this approach can identify how specific ubiquitin-related enzymes contribute to tumor heterogeneity, disease progression, and treatment response [33] [36]. This application note provides detailed protocols and frameworks for implementing these experimental workflows, with particular emphasis on studying ubiquitination dynamics in tumor heterogeneity research.

Single-Cell Isolation Methods

The initial isolation of viable single cells is a critical first step in single-cell multi-omics workflows, directly impacting data quality and experimental success. Selection of the appropriate isolation method depends on factors including target cell type, required throughput, viability needs, and downstream analytical applications.

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS)

FACS remains a widely utilized method for single-cell isolation, particularly when specific cellular subpopulations must be purified based on surface markers or fluorescent reporters.

Protocol: FACS Isolation for Single-Cell Multi-omics

Principle: Cells in suspension are hydrodynamically focused into a single-file stream and passed through a laser beam. Fluorescence and light-scattering signals are detected, and droplets containing single cells of interest are electrically charged and deflected into collection plates [32].

Materials:

- FACS instrument (e.g., BD FACS Aria, Beckman Coulter MoFlo)

- Fluorescently conjugated antibodies against target surface markers

- Cell strainer (35-70µm)

- Collection plates (96-well or 384-well) containing lysis buffer

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with proteinase inhibitors

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dissociate tumor tissue to single-cell suspension using appropriate enzymatic digestion. Treat gently to preserve surface epitopes and cell viability.

- Staining: Incubate cells with fluorescently conjugated antibodies for 30 minutes on ice. Include viability dye (e.g., DAPI or propidium iodide) to exclude dead cells.

- Filtering: Pass cell suspension through cell strainer to remove aggregates that could clog the fluidics system.

- Instrument Setup: Calibrate FACS instrument using appropriate fluorescence standards. Set nozzle size to 85-100µm to maximize viability.

- Gating Strategy:

- Create forward scatter (FSC) vs. side scatter (SSC) plot to identify main cell population

- Apply FSC-A vs. FSC-H to exclude doublets

- Apply viability dye gate to exclude dead cells

- Apply fluorescence gates for target population based on positive controls

- Sorting: Sort single cells into collection plates containing appropriate lysis buffer for downstream multi-omic library preparation. Use "single-cell" sort mode with purity mask setting.

- Quality Control: Assess sort efficiency by re-analyzing a small fraction of sorted cells. Target should be >90% purity and >95% viability.

Applications in Ubiquitination Research: FACS enables isolation of rare tumor subpopulations with distinct ubiquitination patterns, such as cells exhibiting high ubiquitination scores identified through ubiquitination-related gene signatures [33]. It also allows sorting of cells transfected with ubiquitination-related fluorescent reporters (e.g., TRIM9-GFP) for functional studies.

Microfluidic-Based Isolation

Microfluidic technologies provide advanced alternatives to FACS, offering higher throughput, reduced reagent consumption, and improved integration with downstream processing.

Protocol: Droplet-Based Microfluidic Isolation

Principle: Cells are encapsulated into nanoliter-sized water-in-oil droplets together with barcoded beads, creating isolated reaction chambers for individual cells [35] [37].

Materials:

- Microfluidic controller (e.g., 10X Genomics Chromium Controller)

- Single-cell reagent kit (e.g., 10X Genomics 3' Gene Expression)

- Barcoded gel beads and partitioning oil

- Recovery agent

- Cell counter (e.g., Countess II)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare single-cell suspension at optimal concentration (500-1,000 cells/µl). Assess viability using trypan blue exclusion (>80% viability required).

- System Setup: Prime microfluidic chip with partitioning oil according to manufacturer instructions.

- Loading: Mix cells, barcoded beads, and master mix in appropriate ratios. Load into chip reservoirs.

- Partitioning: Run controller to generate gel bead-in-emulsions (GEMs) where each droplet contains a single cell and a single barcoded bead.

- Collection: Collect GEMs into strip tubes. Add recovery agent to break excess emulsion.

- Cleanup: Purify barcoded cDNA using silane magnetic beads.

- Quality Control: Assess cDNA yield and quality using Bioanalyzer or TapeStation.

Applications in Ubiquitination Research: Droplet microfluidics enables high-throughput profiling of ubiquitination-related gene expression across thousands of individual tumor cells, identifying rare subpopulations with dysregulated ubiquitination pathways [35] [33].

Advanced Protocol: In-Air Microfluidic Sorting with Dielectrophoresis

Principle: Recent advances enable droplet ejection in air with tunable directions, sorted by a cylindrical dielectrophoresis (DEP) electrode that deflects droplets containing cells of interest [37].

Materials:

- Custom microfluidic device with co-flow geometry

- Electropneumatic transducers for air pressure control

- Cylindrical DEP electrode

- High-speed camera for monitoring

- SYTOX Green viability dye

Procedure:

- Device Priming: Prime microfluidic channels with cell suspension medium.

- Droplet Generation: Utilize co-flow of two air flows and cell suspension phase to generate monodispersed droplets (20-30µm diameter).

- Ejection Direction Tuning: Regulate asymmetry of air pressures (2-8 psi range) to control droplet ejection direction across ~32.8° range.

- Fluorescence Detection: Implement laser-induced fluorescence detection system to identify target cells based on fluorescent markers.

- DEP Sorting: Apply AC electric field (5-10 kHz) to cylindrical electrode to generate DEP force deflecting droplets containing target cells.

- Collection: Direct sorted droplets into collection reservoirs containing culture medium or lysis buffer.

- Validation: Assess sorting accuracy (>99% achievable) and cell viability (>95%) using fluorescence microscopy and viability stains.

Applications in Ubiquitination Research: This technology enables multipath sorting of heterogeneous tumor samples into different ubiquitination states simultaneously, with minimal cellular stress that preserves native ubiquitination patterns [37].

Table 1: Comparison of Single-Cell Isolation Methods

| Method | Throughput | Viability | Multiplexing Capacity | Cost | Best Applications in Ubiquitination Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FACS | 10,000 cells/sec | >90% | 10-20 parameters | High | Isolation of rare subpopulations defined by ubiquitination-related surface markers |

| Droplet Microfluidics | 10,000 cells/sample | >80% | High (10,000 cells) | Medium | High-throughput transcriptomic profiling of ubiquitination states |

| In-Air DEP Sorting | 30 kHz | >95% | Multiple simultaneous paths | Medium-high | Gentle sorting for functional assays of ubiquitination dynamics |

Multi-omic Sequencing Technologies

After single-cell isolation, the next critical step involves preparing sequencing libraries that capture multiple molecular layers from the same individual cells. Several platforms now enable truly parallel multi-omic measurements.

Single-Cell Multi-omics Platform Protocols

CITE-seq (Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by Sequencing)