Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs) in Cancer: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targeting, and Future Directions

This comprehensive review elucidates the critical functions of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) in oncogenesis and cancer progression.

Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs) in Cancer: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targeting, and Future Directions

Abstract

This comprehensive review elucidates the critical functions of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) in oncogenesis and cancer progression. Covering foundational biology to clinical applications, it details how DUBs regulate key cancer hallmarks—including cell proliferation, metabolic reprogramming, and immune evasion—by controlling protein stability and signaling pathways. The article systematically analyzes recent advances in DUB inhibitor development, current challenges in therapeutic targeting, and emerging strategies like PROTACs and DUBTACs. Through validation of specific DUBs as biomarkers and therapeutic targets across cancer types, this resource provides researchers and drug development professionals with an integrated perspective on targeting the ubiquitin system for novel cancer therapeutics.

The Biology of DUBs: Unraveling Their Roles in Cancer Pathogenesis

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) is a highly selective, ATP-dependent mechanism that serves as the primary pathway for intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, playing a critical role in maintaining cellular protein homeostasis [1] [2]. This system regulates a vast array of cellular processes, including cell cycle progression, apoptosis, signal transduction, DNA repair, and immune responses [1] [2]. Dysregulation of the UPS is implicated in numerous human diseases, most notably cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and autoimmune conditions, making it a focal point for therapeutic development [3] [4] [5].

The core function of the UPS is to target specific proteins for degradation by covalently tagging them with ubiquitin polymers. Ubiquitin is a small, 76-amino acid polypeptide that is highly conserved across species [2] [6]. The process of ubiquitin conjugation, known as ubiquitination, involves a sequential enzymatic cascade [1] [6]:

- E1 (Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme): Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction

- E2 (Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme): Accepts the activated ubiquitin from E1

- E3 (Ubiquitin Ligase): Recognizes specific protein substrates and facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to the target protein

The fate of the ubiquitinated protein is determined by the topology of the ubiquitin chain. Proteins tagged with K48-linked or K11-linked polyubiquitin chains are typically directed to the 26S proteasome for degradation [1]. In contrast, monoubiquitination or K63-linked polyubiquitination often serves non-proteolytic functions, regulating processes such as endocytosis, DNA repair, and kinase activation [1] [2].

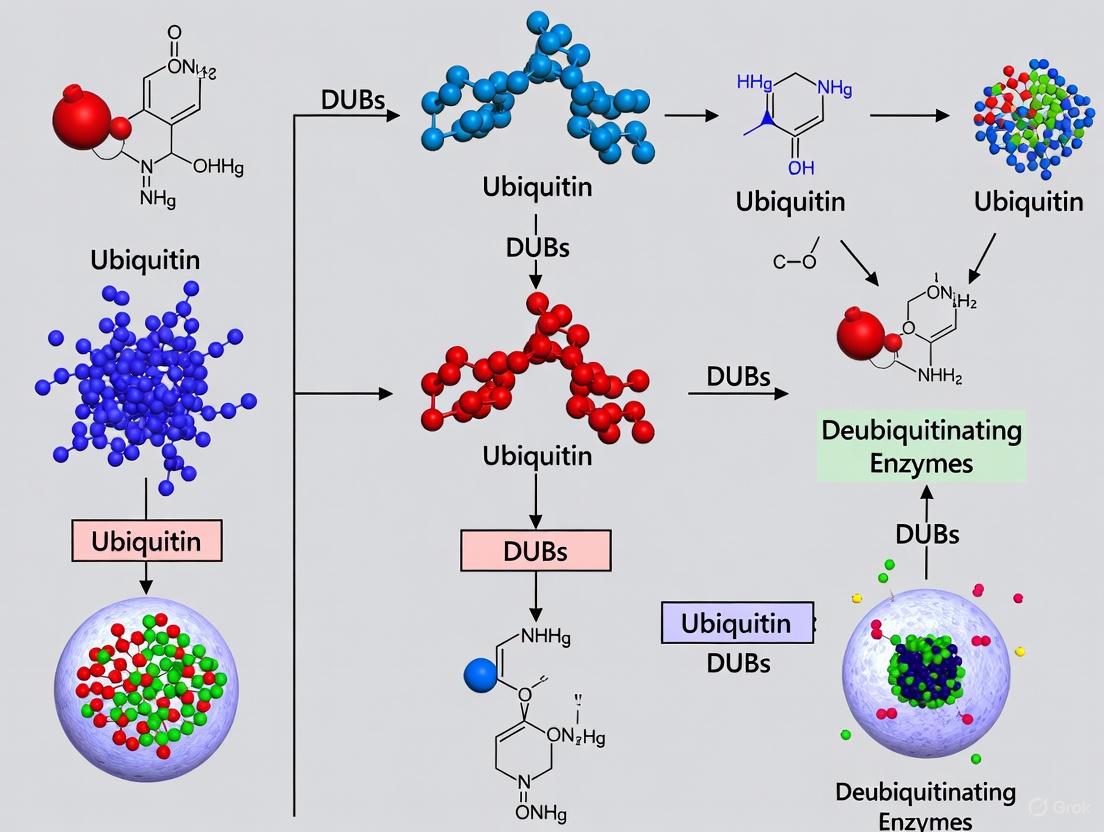

Figure 1: The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Pathway. This diagram illustrates the sequential enzymatic cascade of ubiquitination, culminating in proteasomal degradation of the target protein.

Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs): Classification and Functions

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) constitute a diverse family of proteases that catalyze the reverse reaction of ubiquitination, removing ubiquitin moieties from modified proteins [3] [4]. This activity allows DUBs to exert precise control over ubiquitin-dependent signaling pathways by: rescuing proteins from degradation, editing ubiquitin chain topology, recycling ubiquitin, and processing ubiquitin precursors [3]. The human genome encodes approximately 100 DUBs, which are categorized into seven families based on their catalytic domain structure and mechanism of action [3] [4].

Table 1: Major Deubiquitinating Enzyme (DUB) Families

| Family | Representative Members | Catalytic Mechanism | Key Functions in Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| USP (Ubiquitin-Specific Proteases) | USP1, USP7, USP9X, USP14, USP22, USP28, USP33, USP34 | Cysteine Protease | DNA damage repair, oncoprotein stabilization, stemness regulation, chemoresistance [3] [4] [7] |

| OTU (Ovarian Tumor Proteases) | OTUB1, OTUD1, OTUD3, A20 | Cysteine Protease | Immune signaling regulation, suppression of metastasis [3] [4] |

| UCH (Ubiquitin C-Terminal Hydrolases) | UCH-L1, UCH-L3, UCH-L5, BAP1 | Cysteine Protease | Neurodegeneration, tumor suppression, histone modification [3] [4] [5] |

| MJD (Machado-Josephin Domain Proteases) | Ataxin-3, MJD1, MJD2 | Cysteine Protease | Protein aggregation diseases, transcriptional regulation |

| JAMM/MPN (Zinc Metalloproteases) | PSMD14, BRCC36, AMSH | Zinc Metalloprotease | Proteasomal subunit, DNA damage response, endosomal sorting [3] |

| MINDY | MINDY-1, MINDY-2 | Cysteine Protease | Preferential cleavage of K48-linked ubiquitin chains |

| ZUP1 | ZUP1 | Cysteine Protease | RNA regulation, ribosome-associated quality control |

Except for the JAMM/MPN family, which are zinc metalloproteases, all DUB families utilize a cysteine protease mechanism [3]. The catalytic triad for cysteine protease DUBs typically consists of three conserved amino acids: histidine, cysteine, and asparagine/aspartate [3]. Metalloprotease DUBs rely on the coordination of histidine, aspartic acid, and serine residues with zinc ions for their catalytic activity [3].

DUBs demonstrate remarkable specificity for different ubiquitin chain linkages. For instance, certain DUBs preferentially cleave K48-linked chains (typically associated with proteasomal degradation), while others target K63-linked chains (often involved in signaling) or other atypical linkages [1] [3]. This specificity allows for precise regulation of diverse ubiquitin-dependent processes.

DUBs in Cancer Biology and Therapeutic Resistance

Dysregulation of DUB activity is a hallmark of numerous cancers, with specific DUBs functioning as either oncogenes or tumor suppressors depending on cellular context [4] [7]. DUBs contribute to tumorigenesis through multiple mechanisms, including stabilization of oncoproteins, inactivation of tumor suppressors, regulation of DNA damage response, and modulation of cancer stemness [4] [7].

In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), several DUBs have been identified as key drivers of disease progression. USP28 promotes cell cycle progression and inhibits apoptosis by stabilizing the transcription factor FOXM1, thereby activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [4]. USP21 maintains cancer stemness by stabilizing TCF7 and promotes tumor growth through mTOR signaling activation and micropinocytosis induction, supporting amino acid sustainability [4]. Interestingly, USP9X demonstrates context-dependent functions, acting as a tumor suppressor in some PDAC models while promoting tumor cell survival in others [4].

DUBs also play critical roles in developing chemoresistance across various cancer types [7]. They can confer resistance by stabilizing drug targets, enhancing DNA repair capacity, inhibiting apoptosis, and promoting survival pathways. For instance, USP1 regulates DNA damage repair and is associated with resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy [3] [7]. USP7 stabilizes MDM2, leading to p53 degradation and reduced apoptosis in response to genotoxic stress [3] [7]. USP9X inhibits apoptosis by stabilizing anti-apoptotic proteins like MCL1, contributing to resistance in various blood cancers and solid tumors [7].

Table 2: DUBs in Cancer Chemoresistance and Their Mechanisms

| DUB | Cancer Type | Resistance Mechanism | Therapeutic Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| USP1 | Non-small cell lung cancer, ovarian cancer | DNA damage repair regulation, replication stress response | USP1 inhibitors reverse cisplatin resistance [3] [7] |

| USP7 (HAUSP) | Multiple cancers | Stabilizes MDM2, promotes p53 degradation, enhances DNA repair | USP7 inhibition restores p53 function and chemosensitivity [3] [7] |

| USP9X | Blood cancers, pancreatic cancer | Stabilizes MCL1, BCL2 family proteins, inhibits apoptosis | USP9X inhibition promotes apoptosis in combination with chemotherapy [7] |

| USP22 | Triple-negative breast cancer | Regulates Warburg effect via c-Myc deubiquitination | Promotes stemness, EMT, and chemoresistance [7] |

| USP14 | Multiple cancers | Proteasome-associated, regulates protein turnover | Inhibition enhances sensitivity to proteasome inhibitors [3] |

| UCH-L1 | Breast cancer, lymphoma | Regulates oxidative stress response, stabilizes oncoproteins | Elevated in chemoresistant cancers, potential biomarker [7] [5] |

| USP8 | Pancreatic cancer | Stabilizes Nrf2, enhances antioxidant response | Promotes gemcitabine resistance [7] |

Experimental Approaches for DUB Research

Screening and Profiling DUB Inhibitors

The development of selective DUB inhibitors requires robust screening methods and careful assessment of compound properties. Key approaches include:

High-Throughput Screening (HTS): Utilizes fluorogenic substrates such as Ubiquitin-Rhodamine (Ub-Rho) to identify initial hit compounds [8]. This assay measures DUB activity by the increase in fluorescence upon cleavage of ubiquitin from the rhodamine tag.

Competitive Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP): Employs electrophilic probe compounds that covalently modify the active site cysteine of DUBs, enabling assessment of target engagement and selectivity across the DUB family [8]. This approach helps characterize inhibitor selectivity and identify potential off-target effects.

On-Chip Preconcentration Microchip Capillary Electrophoresis: An advanced method for high-throughput selectivity profiling of DUB inhibitors, providing improved sensitivity and resolution for assessing compound binding [8].

Open-Source Electrophilic Fragment Screening: Identifies chemical starting points for covalent inhibitor development, particularly useful for challenging targets like UCHL1 [8].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Tools for DUB Studies

| Research Tool | Composition/Type | Application in DUB Research |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin-Rhodamine (Ub-Rho) | Fluorogenic ubiquitin substrate | High-throughput screening of DUB inhibitors [8] |

| Activity-Based Probes (ABPs) | Covalent probes with reporter tags | Profiling DUB activity and inhibitor selectivity [8] |

| Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Engineered ubiquitin-binding domains | Protection of polyubiquitin chains from DUBs, isolation of ubiquitinated proteins [6] |

| PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) | Bifunctional molecules (E3 ligase binder + target binder) | Targeted protein degradation by recruiting E3 ubiquitin ligases [1] [6] |

| DUBTACs (Deubiquitinase-Targeting Chimeras) | Bifunctional molecules (DUB binder + target binder) | Selective stabilization of target proteins by recruiting DUBs [3] |

Target Validation and Functional Assessment

Once potential DUB inhibitors are identified, comprehensive validation is essential:

Cellular Target Engagement: Confirm compound interaction with the intended DUB in live cells using cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) or competitive ABPP [8].

Pathway Modulation: Assess effects on known DUB substrates and downstream signaling pathways through immunoblotting, quantitative PCR, or proteomic analyses [4] [7].

Phenotypic Screening: Evaluate impact on cancer cell viability, apoptosis, cell cycle progression, migration, and invasion [4] [7].

Combination Studies: Test synergy with standard chemotherapy agents to assess potential for overcoming chemoresistance [7].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for DUB Inhibitor Discovery. This diagram outlines the key stages in identifying and validating potential therapeutic DUB inhibitors.

Therapeutic Targeting of DUBs in Cancer

The strategic inhibition of specific DUBs represents a promising approach for cancer therapy, particularly for overcoming chemoresistance [3] [7]. Several DUB inhibitors have shown promising results in preclinical studies and are advancing through clinical development.

USP1 inhibitors have demonstrated potential for treating cancers with DNA repair deficiencies, particularly in combination with DNA-damaging agents [3]. In non-small cell lung cancer models, USP1 inhibition has been shown to reverse cisplatin resistance [3] [7]. USP7 inhibitors can reactivate p53 signaling by disrupting the USP7-MDM2 interaction, leading to p53 stabilization and restoration of apoptosis in response to chemotherapy [3] [7]. USP9X inhibitors have shown efficacy in blood cancers and solid tumors by promoting the degradation of anti-apoptotic proteins like MCL1 [7].

Beyond monotherapies, DUB inhibitors show significant promise in combination regimens with conventional chemotherapy or targeted agents [7]. For example, USP9X inhibition enhances the efficacy of gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer by inhibiting autophagy and promoting apoptosis [7]. Similarly, USP8 inhibition sensitizes gastric cancer cells to chemotherapy by suppressing RhoA and Ras-mediated signaling pathways [7].

Emerging technologies are expanding the therapeutic potential of DUB targeting. PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) repurpose E3 ligases for targeted degradation of disease-causing proteins [1] [6]. Conversely, DUBTACs (Deubiquitinase-Targeting Chimeras) represent a novel approach to stabilize beneficial proteins by recruiting DUBs to prevent their degradation [3]. These bifunctional molecules offer new avenues for precisely manipulating the ubiquitin-proteasome system for therapeutic benefit.

The continued development of selective DUB inhibitors, combined with a deeper understanding of DUB biology in specific cancer contexts, holds significant promise for advancing cancer therapy, particularly for overcoming the persistent challenge of chemoresistance.

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) represent a critical regulatory node in the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), functioning as proteases that cleave ubiquitin from protein substrates to reverse ubiquitin signaling [9] [10]. The human genome encodes approximately 100 DUBs that regulate diverse cellular processes including protein degradation, localization, activity, and protein-protein interactions [11] [9]. By antagonizing the function of E3 ubiquitin ligases, DUBs create a dynamic, reversible signaling system that responds to environmental cues and maintains cellular homeostasis [11] [10]. Dysregulation of DUB activity disrupts this delicate balance, leading to aberrant stabilization of oncoproteins or destabilization of tumor suppressors, which contributes fundamentally to cancer pathogenesis across multiple malignancies [11] [4] [12]. The classification of DUBs into distinct families based on sequence and structural similarity provides a critical framework for understanding their mechanistic roles in cancer biology and developing targeted therapeutic interventions.

Comprehensive DUB Family Classification

Deubiquitinating enzymes are classified into two fundamental classes based on their catalytic mechanisms: cysteine proteases and metalloproteases [9]. The cysteine protease class encompasses five major families (USP, UCH, OTU, MJD, MINDY), while the metalloprotease class contains only the JAMM family [9] [13]. This classification reflects evolutionary relationships and provides insights into structural characteristics and catalytic mechanisms that inform drug discovery efforts.

Table 1: Major Deubiquitinating Enzyme Families in Humans

| Family | Class | Catalytic Mechanism | Human Members | Representative DUBs | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USP | Cysteine protease | Catalytic triad (Cys, His, Asp/Asn) | ~58 [9] | USP28, USP9X, USP22, USP7 | Large, diverse domains; insertions in catalytic domain [9] |

| UCH | Cysteine protease | Catalytic triad (Cys, His, Asp/Asn) | 4 [9] | UCH-L1, UCH-L5, BAP1 | Compact structure; restricted substrate access [11] |

| OTU | Cysteine protease | Catalytic triad (Cys, His, Asp/Asn) | 16 [9] [4] | OTUD5, A20, OTUB1 | Variant of USP-like fold; linkage specificity [4] |

| MJD | Cysteine protease | Catalytic triad (Cys, His, Asn) | 4 [9] | Ataxin-3, MJD1, MJD2 | Josephin domain; ubiquitin-interacting motifs [12] |

| MINDY | Cysteine protease | Catalytic triad (Cys, His, Asn) | 5 [4] | MINDY1-3 | Prefers K48-linked polyubiquitin chains [4] |

| JAMM | Metalloprotease | Zinc-dependent metalloprotease | 12 [13] | Rpn11, BRCC36, CSN5, AMSH | JAMM motif (ExnHxHx7Sx2D); MPN domain [13] |

Table 2: Key Characteristics of DUB Families

| Family | Ubiquitin Linkage Preference | Cellular Functions | Regulatory Mechanisms | Cancer Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USP | Broad specificity | DNA repair, cell cycle, signaling pathways, chromatin remodeling [11] | Protein-protein interactions, post-translational modifications, subcellular localization [10] | USP28 (overexpressed in colon/lung cancer) [9]; USP9X (context-dependent in PDAC) [4] |

| UCH | Monoubiquitin, small adducts | Ubiquitin recycling, processing precursors [9] | Dimerization, substrate access control [11] | UCH-L1 (elevated in malignancies) [9]; BAP1 (tumor suppressor mutated in multiple cancers) [11] [4] |

| OTU | Linkage-specific | NF-κB signaling, immune regulation, DNA damage response [11] [14] | Oxidation sensitivity, interaction partners [10] | OTUD5 (stabilizes YAP1 in TNBC) [14] |

| MJD | K48, K63-linked chains [10] | Protein homeostasis, endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation, transcription regulation, DNA repair [10] [12] | Ubiquitin-interacting motifs, polyglutamine expansions [12] | Ataxin-3 (overexpressed in gastric, lung, breast cancers) [12] |

| MINDY | Prefers K48-linked chains [4] | Proteasomal degradation regulation | Unknown | Under investigation in cancer |

| JAMM | Linkage-specific (varies by member) | Proteasome function (Rpn11), DNA repair (BRCC36), endocytosis (AMSH) [13] | Complex assembly, subcellular localization, Ins-1 loop conformation [13] | BRCC36 (DNA damage control); CSN5 (PD-L1 stabilization) [13] [14] |

DUB Family Classification

Structural Features and Catalytic Mechanisms

Cysteine Protease DUBs

The cysteine protease DUBs constitute approximately 90% of all deubiquitinating enzymes and share a common catalytic mechanism centered on a nucleophilic cysteine residue [9] [10]. These enzymes employ catalytic dyads or triads (typically cysteine, histidine, and aspartate or asparagine) to facilitate hydrolysis of the isopeptide bond between ubiquitin and substrate proteins [9]. The histidine residue acts as a base to polarize the cysteine residue, lowering its pKa and enhancing its nucleophilicity for attack on the carbonyl carbon of the scissile bond [9]. This mechanism renders cysteine protease DUBs particularly sensitive to oxidative inactivation, as reactive oxygen species can directly modify the catalytic cysteine, providing a regulatory link between cellular redox state and ubiquitin signaling [10].

JAMM Metalloprotease DUBs

The JAMM family represents the only metalloprotease DUBs, characterized by a catalytic JAMM motif (ExnHxHx7Sx2D) that coordinates a Zn²⁺ ion to activate a water molecule for nucleophilic attack on the isopeptide bond [9] [13]. Unlike cysteine proteases, JAMM metalloproteases are not susceptible to oxidative inactivation of their catalytic site, making them attractive therapeutic targets with distinct pharmacological properties [13]. Structural studies reveal that most JAMM proteins contain two unique insertions (Ins-1 and Ins-2) that facilitate substrate recognition and binding [13]. The Ins-1 segment undergoes conformational transitions between inactive and active states, functioning as a regulatory gate that controls access to the catalytic site [13].

DUB Catalytic Mechanisms

DUB Functions in Cancer Biology and Signaling Pathways

Dysregulation of DUB activity contributes to oncogenesis through multiple mechanisms, including stabilization of oncoproteins, inactivation of tumor suppressors, and modulation of cancer-relevant signaling pathways. The tables below highlight specific DUBs with established roles in cancer progression.

Table 3: Oncogenic DUBs and Their Mechanisms in Cancer

| DUB | Family | Cancer Type | Substrate/Mechanism | Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USP28 | USP | Colon, lung, PDAC | Stabilizes c-Myc, Notch1, ΔNp63, FOXM1 [9] [4] | Promotes proliferation, chemoresistance, cell cycle progression |

| USP9X | USP | Pancreatic cancer | Context-dependent: regulates Hippo pathway, LATS kinase, YAP/TAZ [4] | Tumor promoter or suppressor depending on context |

| USP22 | USP | Pancreatic cancer | Modulates PTEN-MDM2-p53 axis; stabilizes DYRK1A [4] | Cancer stem cell marker; promotes proliferation |

| USP10 | USP | PDAC | Deubiquitinates YAP1; upregulates PD-L1 and galectin-9 [14] | Immune evasion; desensitizes to NK cell killing |

| Ataxin-3 | MJD | Gastric, lung, breast | Regulates PI3K/Akt, Hippo/YAP pathways; modulates p53 [12] | Promotes proliferation, metastasis, poor prognosis |

| BAP1 | UCH | Mesothelioma, melanoma, renal carcinoma | Deubiquitinates H2A; frequently mutated in cancers [4] | Tumor suppressor; "BAP1 cancer syndrome" |

| OTUD5 | OTU | Triple-negative breast cancer | Stabilizes YAP1; upregulates M2-related cytokines [14] | Promotes M2 macrophage polarization and metastasis |

| CSN5 | JAMM | Multiple | Deubiquitinates PD-L1 [14] | Immune evasion; inhibits NK cell function |

Table 4: Tumor Suppressor DUBs and Their Mechanisms

| DUB | Family | Cancer Type | Substrate/Mechanism | Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYLD | USP | Cylindromatosis, hepatocellular carcinoma | Deubiquitinates TRAF2/6, NEMO; inhibits NF-κB pathway [11] | Familial tumor suppressor; NF-κB pathway negative regulation |

| BAP1 | UCH | Renal tumorigenesis, various cancers | Deubiquitinates H2A; chromatin remodeling [11] | Tumor suppressor; frequently mutated in cancers |

| USP9X | USP | Pancreatic cancer | Regulates Hippo pathway; cooperates with LATS kinase [4] | Suppresses tumor growth in specific contexts |

DUB Dysregulation in Cancer Pathways

Experimental Approaches for DUB Research

Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP)

Activity-based protein profiling represents a powerful chemoproteomic approach for identifying active DUBs in complex biological systems and assessing inhibitor engagement [15]. This methodology utilizes reactive covalent probes that target the catalytic cysteine of cysteine protease DUBs, enabling quantitative assessment of DUB activity states and inhibition profiles in cell lysates and live cells [15].

Protocol Summary:

- Design and synthesis of a bespoke covalent library targeting the catalytic cysteine

- Primary screening in cell lysates using activity-based protein profiling with mass spectrometry readout

- Hit validation through biochemistry assays, intact protein mass spectrometry, and cysteine profiling

- Target engagement assessment in live cells to confirm cellular activity [15]

DUB Inhibitor Development Strategies

The development of selective DUB inhibitors has evolved significantly, moving from non-selective compounds to highly specific chemical probes. Current approaches emphasize structure-guided diversification combined with high-content chemoproteomic screening to simultaneously identify hits and drive structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis against challenging DUB targets [15].

Key Methodological Considerations:

- Covalent vs. non-covalent strategies: Covalent libraries target the catalytic cysteine, while non-covalent approaches may offer alternative selectivity profiles

- Selectivity profiling: Comprehensive assessment against multiple DUB families to minimize off-target effects

- Cellular target engagement: Validation of inhibitor binding and functional effects in physiologically relevant systems

Research Reagent Solutions for DUB Studies

Table 5: Essential Research Tools for DUB Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity-Based Probes | Ubiquitin-based covalent probes; HA-Ub-VS | DUB activity profiling; identification of active DUBs [15] | Target catalytic cysteine; require mass spectrometry detection |

| Selective Inhibitors | b-AP15 (USP14/UCHL5); HBX41108 (USP7); WP1130 (USP9X) [12] | Functional validation; therapeutic potential assessment | Varying selectivity profiles; require careful control experiments |

| Genetic Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 knockout libraries; siRNA/shRNA collections | Target identification; functional screening | Context-dependent effects; potential compensation mechanisms |

| Ubiquitin Linkage-Specific Reagents | K48- vs K63-linked ubiquitin chains; linkage-specific antibodies | DUB specificity profiling; substrate characterization | Define linkage preference; inform biological function |

| Mass Spectrometry Platforms | Quantitative proteomics; ubiquitin remnant profiling | Global ubiquitome analysis; substrate identification | Complex data analysis; specialized computational tools |

| Cellular Assay Systems | Reporter cell lines; patient-derived organoids | Physiological relevance; translational potential | Model system limitations; microenvironment considerations |

Therapeutic Targeting of DUBs in Cancer

The strategic targeting of dysregulated DUBs represents an emerging frontier in cancer therapeutics, with several approaches showing promising preclinical results. The development of DUB inhibitors has gained significant momentum, with compounds targeting specific DUB families advancing toward clinical evaluation.

JAMM Family Targeting

The JAMM metalloproteases present particularly attractive drug targets due to their distinct catalytic mechanism and smaller family size compared to cysteine protease DUBs [13]. Several JAMM inhibitors have demonstrated promising therapeutic efficacy in preclinical models:

- BRCC36 inhibitors: Target DNA damage repair pathways in cancer cells

- CSN5 inhibitors: Modulate PD-L1 stability and immune checkpoint regulation

- Rpn11 inhibitors: Disrupt proteasome function and protein homeostasis [13]

Cysteine Protease DUB Inhibitors

The cysteine protease DUBs represent the majority of therapeutic targets, with several advanced compounds:

- USP7 inhibitors (HBX41108, P22077): Under investigation for neuroblastoma, acute leukemia

- USP14/UCHL5 inhibitors (b-AP15, VLX1570): Evaluated in multiple myeloma models

- USP9X inhibitors (WP1130): Tested in colorectal, lung, and prostate cancers [12]

The future clinical application of DUB inhibitors will likely involve combination strategies with existing modalities, particularly immune checkpoint blockade, where DUB inhibition can modulate the tumor microenvironment and enhance antitumor immunity [14].

The systematic classification of deubiquitinating enzymes into distinct families provides an essential framework for understanding their diverse functions in cellular homeostasis and cancer pathogenesis. The structural and mechanistic differences between cysteine protease and metalloprotease DUB families present unique opportunities for targeted therapeutic intervention. As research continues to elucidate the complex roles of specific DUBs in oncogenic signaling, immune evasion, and therapeutic resistance, the strategic targeting of these enzymes holds significant promise for advancing cancer treatment. The ongoing development of selective chemical probes and inhibitors, coupled with sophisticated screening methodologies, continues to accelerate this rapidly evolving field, positioning DUBs as compelling targets for next-generation cancer therapeutics.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) serves as a critical regulatory mechanism for protein homeostasis in eukaryotic cells, governing the degradation of proteins and influencing virtually every cellular process [16] [17]. Ubiquitination involves the covalent attachment of a small 76-amino acid protein, ubiquitin, to target proteins via a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes [18] [19]. This process can mark proteins for degradation by the 26S proteasome or alter their function, activity, and localization through non-proteolytic mechanisms [19]. The reversibility of this modification is equally crucial, achieved through a specialized group of proteases known as deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) [18] [16].

DUBs counterbalance the action of E3 ubiquitin ligases by cleaving the isopeptide bond between ubiquitin and substrate proteins or between ubiquitin molecules within a polyubiquitin chain [17]. In humans, approximately 100 DUBs have been identified, categorized into seven subfamilies based on sequence and domain conservation [14] [16]. These enzymes are pivotal regulators in numerous biological processes, and their dysregulation is frequently associated with pathological conditions, most notably cancer [16] [20]. This review provides an in-depth technical analysis of the biochemical mechanisms by which DUBs reverse ubiquitination and dictate protein fate, with a specific focus on their implications in oncogenesis and cancer therapy.

DUB Classification and Biochemical Mechanisms

Major DUB Families and Their Characteristics

Deubiquitinating enzymes are classified into two major classes based on their catalytic mechanism: cysteine proteases and metalloproteases. The vast majority of DUBs are cysteine proteases, which include six subfamilies. The JAMM/MPN domain-associated metallopeptidases (JAMMs) constitute the only metalloprotease family [14].

Table 1: Major Deubiquitinating Enzyme (DUB) Families and Characteristics

| DUB Family | Catalytic Type | Number of Members | Representative Members | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USPs (Ubiquitin-Specific Proteases) | Cysteine Protease | ~54 | USP28, USP21, USP34, USP9X, USP22 | Largest DUB family; diverse substrate recognition; involved in multiple cancer-associated processes [18] [16] |

| OTUs (Ovarian Tumor Proteases) | Cysteine Protease | ~16 | OTUD5, OTUB2 | Often exhibit linkage specificity for particular ubiquitin chain types [21] [16] |

| UCHs (Ubiquitin C-Terminal Hydrolases) | Cysteine Protease | ~4 | BAP1, UCHL1 | Primarily involved in processing ubiquitin precursors and cleaving small adducts [16] |

| MJDs (Machado-Josephin Domain-containing Proteases) | Cysteine Protease | ~4 | ATXN3, MJD | Josephin domain-containing proteases [18] [16] |

| MINDYs (Motif-Interacting with Ubiquitin-containing Novel DUB Family) | Cysteine Protease | ~4 | MINDY1, MINDY2 | Preferentially cleave K48-linked polyubiquitin chains [18] [16] |

| JAMMs (JAB1/MPN/MOV34 Metalloenzymes) | Metalloprotease | ~5 | POH1, BRCC36 | Zinc-dependent metalloproteases; often part of multi-protein complexes [18] [14] [16] |

Core Biochemical Functions of DUBs

DUBs execute four primary biochemical functions that maintain ubiquitin homeostasis and regulate protein fate [17]:

- Processing of Ubiquitin Precursors: Ubiquitin is transcribed as linear fusion polymers (e.g., polyubiquitin or fused to ribosomal proteins). DUBs hydrolyze these precursors to generate mature, biologically active free ubiquitin monomers, which are essential for initiating the ubiquitination cascade [21] [17].

- Reversal of Protein Ubiquitination: This is the most recognized function, wherein DUBs completely remove ubiquitin chains from modified protein substrates. This activity can rescue proteins from proteasomal degradation, thereby stabilizing them and altering their abundance within the cell [16] [17]. For instance, USP28 stabilizes the transcription factor FOXM1 by deubiquitinating it, promoting cell cycle progression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) [18].

- Chain Editing and Trimming: DUBs can selectively cleave polyubiquitin chains at specific positions or linkages, thereby editing the topology of the ubiquitin signal. This can alter the fate of the substrate—for example, converting a K48-linked chain (typically degradative) into a K63-linked chain (typically signaling) [21] [16].

- Ubiquitin Recycling: During proteasomal degradation, DUBs associated with the 19S regulatory particle (e.g., USP14, UCHL5, and POH1) disassemble polyubiquitin chains from substrates being degraded, ensuring the recycling of ubiquitin to maintain a sufficient cellular pool of free ubiquitin [21] [17].

The following diagram illustrates the central role of DUBs in maintaining the ubiquitin cycle and regulating protein fate.

Diagram Title: The Ubiquitin Cycle and DUB Intervention Points.

Regulation of Protein Fate by DUBs in Cancer

DUBs govern critical aspects of cellular function by determining the stability, activity, and localization of key regulatory proteins. In cancer, the dysregulation of these processes drives tumorigenesis and disease progression.

Stabilization of Oncoproteins and Transcription Factors

A primary oncogenic mechanism of DUBs is the stabilization of proteins that promote cell growth and survival. This is achieved by removing degradative ubiquitin chains, thereby increasing the half-life of these oncogenic factors.

- Proliferation and Cell Cycle Regulation: In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), USP28 stabilizes the transcription factor FOXM1, which activates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway to drive cell cycle progression and inhibit apoptosis [18]. Similarly, USP5 stabilizes FOXM1 to accelerate PDAC tumor growth and also regulates DNA damage response and apoptosis [18].

- Transcription Factor Stability: The regulation of transcription factors (TFs) by DUBs is a key mechanism in drug resistance. As directly targeting TFs with small molecules is challenging, inhibiting their stabilizing DUBs presents an attractive therapeutic strategy [20]. For example, USP15 negatively regulates the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response by deubiquitinating its inhibitor, Keap1 [20].

Table 2: Selected DUBs and Their Key Substrates in Cancer

| DUB | Cancer Type | Key Substrate(s) | Biological Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USP28 | Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma | FOXM1 | Promotes cell cycle progression, inhibits apoptosis | [18] |

| USP21 | Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma | TCF7, MAPK3 | Maintains stemness, activates mTOR signaling | [18] |

| USP10 | Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma | YAP1 | Upregulates PD-L1 and Gal-9, desensitizes to NK cells | [14] |

| OTUB2 | Colorectal Cancer | PKM2 | Enhances glycolysis, accelerates cancer progression | [19] |

| USP7 | Glioblastoma | p53, PLK1 | Regulates cell cycle, DNA damage response, and apoptosis | [20] |

| USP22 | Various Cancers | PTEN, DYRK1A, Histones | Promotes proliferation, regulates epigenetics | [18] [21] |

| BAP1 | Mesothelioma, Melanoma | Histones (H2A) | Tumor suppressor; frequently mutated | [18] |

Modulation of the Tumor Microenvironment and Immune Evasion

Emerging research highlights the critical role of DUBs in shaping the tumor microenvironment (TME) to foster immune evasion, a key hallmark of cancer. DUBs expressed in either tumor cells or infiltrating immune cells can suppress anti-tumor immunity [14].

- Regulation of Immune Checkpoints: DUBs directly regulate the stability of immune checkpoint proteins. USP10 in PDAC cells deubiquitinates and stabilizes YAP1, which transcriptionally upregulates PD-L1 and Galectin-9, leading to impaired Natural Killer (NK) cell function and immune tolerance [14]. Furthermore, USP2 can stabilize PD-1 on T cells, promoting T-cell exhaustion and tumor immune escape [19].

- Control of Immune Cell Infiltration and Polarization: DUBs influence the recruitment and function of immune cells within the TME. For instance, macrophage-intrinsic OTUD5 deubiquitinates and stabilizes YAP1, driving M2 polarization (an immunosuppressive phenotype) of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and promoting metastasis in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [14]. Similarly, USP22 has been shown to suppress NK cell infiltration in pancreatic cancer by altering the tumor cell transcriptome [14].

The diagram below summarizes how DUBs in different cellular compartments of the tumor microenvironment contribute to immune evasion.

Diagram Title: DUB-Mediated Mechanisms of Immune Evasion in the TME.

Experimental Approaches for Studying DUB Function

Investigating the specific functions and substrates of DUBs requires a combination of molecular, cellular, and biochemical techniques. Below is a detailed protocol for a foundational experiment to identify and validate DUB-substrate relationships.

Detailed Protocol: Identifying and Validating a DUB-Substrate Interaction

Objective: To determine whether a candidate DUB (e.g., USP10) directly binds to and deubiquitinates a protein of interest (POI, e.g., YAP1), thereby regulating its stability.

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Plasmids: Expression vectors for wild-type (WT) and catalytically inactive (C/S) mutant of the DUB, the POI, and epitope-tagged ubiquitin (e.g., HA-Ub, Myc-Ub).

- Cell Lines: Relevant cancer cell lines (e.g., PANC-1 or AsPC-1 for PDAC studies).

- Transfection Reagent: Lipofectamine 3000 or polyethylenimine (PEI).

- Lysis Buffer: RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (e.g., PMSF, aprotinin) and deubiquitinase inhibitors (e.g., N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) or PR-619) to preserve ubiquitination states.

- Antibodies: Antibodies against the DUB, the POI, the ubiquitin tag (e.g., anti-HA), and relevant control antibodies for immunoprecipitation (IP) and western blotting (WB).

- Proteasome Inhibitor: MG-132 to block protein degradation and accumulate ubiquitinated species.

Methodology:

Step 1: Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) to Assess Binding

- Transfection: Co-transfect cells with plasmids expressing the DUB (WT or C/S) and the POI.

- Cell Lysis: Harvest cells after 24-48 hours using a mild lysis buffer (without SDS) to preserve protein-protein interactions.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate the cell lysate with an antibody against the POI (or the DUB) and Protein A/G beads. Use a non-specific IgG as a negative control.

- Washing and Elution: Wash beads extensively with lysis buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins. Elute bound proteins with SDS sample buffer.

- Western Blot Analysis: Resolve eluted proteins by SDS-PAGE and perform western blotting. Probe the membrane with an antibody against the DUB to confirm interaction. Expected Outcome: The DUB should be detected in the POI immunoprecipitate, indicating a physical interaction.

Step 2: Deubiquitination Assay to Assess Functional Outcome

- Induce Ubiquitination: Co-transfect cells with plasmids for the POI, HA-tagged ubiquitin, and either the DUB (WT or C/S) or an empty vector control.

- Inhibit Degradation: Treat cells with MG-132 (e.g., 10 µM) for 4-6 hours before harvesting to enrich for ubiquitinated forms of the POI.

- Immunoprecipitation: Lyse cells in RIPA buffer with NEM. Immunoprecipitate the POI.

- Detection of Ubiquitination: Analyze the immunoprecipitates by western blotting using an anti-HA antibody to detect ubiquitinated POI species, which appear as high-molecular-weight smears or ladders. Expected Outcome: Co-expression of the wild-type DUB, but not the catalytically inactive mutant, should reduce the intensity of the ubiquitin smear, indicating deubiquitination of the POI.

Step 3: Validation of Protein Stabilization

- DUB Modulation: Generate stable cell lines with DUB knockdown (shRNA) or overexpression.

- Cycloheximide Chase Assay: Treat cells with cycloheximide (CHX, e.g., 100 µg/mL) to inhibit new protein synthesis. Harvest cells at different time points (e.g., 0, 2, 4, 8 hours).

- Western Blotting: Analyze the levels of the POI and the DUB at each time point. Expected Outcome: DUB overexpression should slow the degradation of the POI (longer half-life), while DUB knockdown should accelerate it (shorter half-life).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for DUB Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating DUB Function

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Inhibitors | PR-619 (pan-DUB inhibitor), P5091 (USP7 inhibitor), ML323 (USP1-UAF1 inhibitor), VLX1570 (USP14/UCHL5 inhibitor) | Tool compounds to acutely inhibit DUB activity in cells; used for target validation and functional studies [20] [17]. |

| Activated Ubiquitin Probes | HA-Ub-VS, TAMRA-Ub-PA | Cell-active, mechanism-based probes that covalently label the active site of a subset of DUBs; used for profiling DUB activity and engagement by inhibitors [17]. |

| Expression Plasmids | Plasmids for WT and Catalytic Mutant (C>S) DUBs, Epitope-tagged Ubiquitin (HA-Ub, Myc-Ub, FLAG-Ub) | Essential for overexpression, interaction, and deubiquitination assays. Catalytic mutants serve as critical negative controls. |

| siRNA/shRNA | ON-TARGETplus siRNA SMARTpools, Lentiviral shRNA constructs | For targeted knockdown of DUB gene expression to study loss-of-function phenotypes and substrate stabilization. |

| DUB Inhibitor Cocktails | N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM), Iodoacetamide | Added to cell lysis buffers to inhibit endogenous DUB activity during protein extraction, thereby preserving the native ubiquitination state of proteins. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG-132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Used in deubiquitination assays to block the degradation of ubiquitinated proteins, allowing for their accumulation and detection. |

Therapeutic Targeting of DUBs in Cancer

The critical roles of DUBs in oncogenesis and drug resistance make them attractive targets for cancer therapy. The development of DUB inhibitors (DUBi) is a rapidly advancing field with several compounds in preclinical and clinical development [20] [17].

Strategies for DUB Inhibition

- Small Molecule Inhibitors: These compounds are designed to bind the catalytic pocket of DUBs, competitively inhibiting their activity. For example, VLX1570, an inhibitor of USP14 and UCHL5, advanced to clinical trials for multiple myeloma but was halted due to toxicity concerns [17]. KSQ-4279 is a USP1 inhibitor currently in clinical trials [20].

- Combination Therapies: A promising approach is combining DUBi with existing therapies to overcome drug resistance. For instance, inhibiting USP9X can enhance the efficacy of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) by preventing the stabilization of anti-apoptotic proteins like MCL-1 [20].

Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite the promise, developing specific DUB inhibitors faces challenges. The catalytic sites of many DUBs, particularly USPs, are shallow and highly conserved, making it difficult to design highly selective inhibitors. Future efforts will focus on developing allosteric inhibitors or proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) that degrade DUBs rather than just inhibit their enzymatic activity. Furthermore, understanding the complex biology and context-dependent roles of DUBs, such as the dual function of USP9X as both an oncogene and tumor suppressor in different cancers, is crucial for designing effective and safe therapeutic strategies [18] [20].

Deubiquitinating enzymes are master regulators of cellular signaling, exerting precise control over protein fate by reversing ubiquitination. Through their ability to stabilize oncoproteins, modulate transcription factors, and reshape the tumor immune microenvironment, DUBs play indispensable roles in cancer initiation, progression, and therapeutic resistance. A deep and mechanistic understanding of how DUBs recognize their specific substrates and execute their deubiquitinating functions provides the foundational knowledge required to translate these insights into novel cancer therapeutics. The continued development of sophisticated experimental tools and highly specific inhibitors will be paramount in targeting the DUB family for next-generation anti-cancer strategies.

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) represent a critical component of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, comprising approximately 100 proteases that specifically cleave ubiquitin from modified substrate proteins [22] [23]. This deubiquitination process functions as a dynamic reversal mechanism that regulates protein stability, localization, and activity, thereby influencing virtually all cellular processes [24] [25]. The dysregulation of DUB activity emerges as a fundamental characteristic in numerous cancers, where these enzymes modulate core hallmarks of tumorigenesis through stabilization of oncoproteins, disruption of tumor suppressor pathways, and alteration of DNA repair fidelity [22] [19]. DUBs are classified into seven distinct families based on their ubiquitin-protease domains: ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), ovarian tumor proteases (OTUs), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), Machado-Joseph disease proteases (MJDs), JAB1/MPN/MOV34 metalloenzymes (JAMMs), motif interacting with ubiquitin-containing novel DUB family (MINDY), and zinc-finger and UFSP domain protein (ZUFSP) [22] [24]. Understanding the mechanistic roles of specific DUBs in proliferation, apoptosis evasion, and DNA damage response provides not only crucial insights into cancer biology but also reveals promising therapeutic targets for innovative cancer treatment strategies.

DUBs and Uncontrolled Proliferation

Regulation of Cell Cycle and Growth Signaling

DUBs control tumor cell proliferation primarily through direct regulation of cell cycle components and central growth signaling pathways. They ensure the precise stability of cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), and transcription factors that drive cell division, often overriding checkpoint controls [22] [24].

USP17 demonstrates high expression in colon, esophageal, and cervical cancers, where it facilitates the G1-S transition by deubiquitinating and destabilizing the CDK inhibitor p21, thereby removing a critical barrier to cell cycle progression [22]. Simultaneously, USP17 stabilizes the transcription factor ELK-1, further promoting proliferation [22]. OTUD6B-2, operating downstream of mTORC1 signaling in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), stabilizes both cyclin D1 and c-Myc, two fundamental drivers of G1 phase progression [22]. USP22, identified as a cancer stem cell marker, enhances breast cancer growth by stabilizing c-Myc and cyclin D1, thereby accelerating the G1-S transition [26]. USP14, frequently elevated in breast cancer tissues, controls cell cycle progression by deubiquitinating CyclinB1, regulating G2-M phase transition, with its knockdown inducing G2/M arrest [26].

Table 1: DUBs Regulating Cell Cycle Progression

| DUB | Phase Regulated | Key Substrate(s) | Cancer Context | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USP17 | G1-S transition | p21, ELK-1 | Colon, esophageal, cervical cancers | Depletes p21, stabilizes ELK-1 |

| OTUD6B-2 | G1 phase | Cyclin D1, c-Myc | Non-small cell lung cancer | Promotes G1 progression |

| USP22 | G1-S transition | c-Myc, Cyclin D1 | Breast cancer | Enhances cyclin stability |

| USP14 | G2-M transition | CyclinB1 | Breast cancer | Regulates mitotic entry |

| DUB3 | S/G2 transition | Cyclin A | Various cancers | Controls S/G2 progression |

| USP7 | Mitotic phase | PHF8 | Various cancers | Regulates mitotic progression |

Stabilization of Oncogenic Signaling Pathways

Beyond direct cell cycle regulation, DUBs stabilize core oncogenic signaling pathways. The p53 tumor suppressor pathway represents a frequent target, with multiple DUBs acting either directly on p53 or through its primary negative regulator MDM2 [22] [24]. USP7 exemplifies this strategy across multiple cancers, where it deubiquitinates and stabilizes both MDM2 (the E3 ligase responsible for p53 degradation) and p53 itself, creating a complex regulatory circuit [22] [26]. In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), USP10 stabilizes p53, while USP28 promotes cell cycle progression and inhibits apoptosis by stabilizing FOXM1, subsequently activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [4]. USP21 further supports PDAC growth by interacting with and stabilizing TCF7 to maintain cancer stemness and activating mTOR signaling through binding to MAPK3 [4]. USP34 facilitates PANC-1 cell survival through AKT and PKC pathways, with its suppression markedly inhibiting tumor growth in mouse xenograft models [4].

The diagram below illustrates how DUBs coordinate proliferation signaling through multiple interconnected pathways:

DUBs in Apoptosis Evasion

Direct Regulation of Apoptotic Machinery

Cancer cells evade programmed cell death through multiple mechanisms orchestrated by DUBs, which directly target both core apoptotic components and regulatory pathways. The balance between pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic factors is frequently disrupted by DUB activity, providing survival advantages to tumor cells [22] [24].

JOSD1 promotes apoptosis resistance by specifically deubiquitinating and stabilizing the anti-apoptotic protein MCL1, a critical member of the BCL-2 family that prevents mitochondrial apoptosis [22]. USP9X enhances breast cancer cell survival through stabilization of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL2, while in pancreatic cancer contexts, it demonstrates both pro-survival and tumor-suppressive functions depending on specific cellular environments [4]. USP15 supports breast tumor-initiating cells by deubiquitinating and stabilizing BMI1, a cell cycle regulator and tumor growth promoter, downstream of IL1R2 signaling [26]. Conversely, OTUD3 exhibits tumor-suppressing activity in breast cancer by rescuing p53 from MDM2-mediated degradation, thereby activating cancer cell apoptosis, and also stabilizes PTEN by removing ubiquitin chains [26].

Table 2: DUBs in Apoptosis Evasion

| DUB | Apoptotic Role | Key Substrate(s) | Molecular Mechanism | Cancer Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JOSD1 | Anti-apoptotic | MCL1 | Stabilizes anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family member | Various cancers |

| USP9X | Anti-apoptotic | BCL2 | Prevents mitochondrial apoptosis | Breast cancer, PDAC |

| USP15 | Anti-apoptotic | BMI1 | Stabilizes cell cycle regulator | Breast cancer |

| OTUD3 | Pro-apoptotic | p53, PTEN | Stabilizes tumor suppressors | Breast cancer |

| ATXN3 | Anti-apoptotic | p53 | Attenuates p53-mediated apoptosis | Various cancers |

| USP5 | Context-dependent | p53, MAF bZIP | Regulates apoptosis via p53 pathway | Various cancers |

Indirect Apoptosis Regulation Through Signaling Pathways

DUBs additionally modulate apoptotic thresholds through indirect mechanisms involving key cellular signaling pathways. CYLD, typically functioning as a tumor suppressor, is downregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tissues and cell lines [24]. Mouse models with liver-specific CYLD deletion demonstrate increased biliary injury, liver fibrosis, and susceptibility to diethylnitrosamine phenobarbital (DEN/PB)-induced liver tumor development [24]. The anti-apoptotic effects of CYLD loss involve increased infiltration of T cells and macrophages, along with elevated mRNA expression of inflammation-related genes via nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling [24]. USP7 further contributes to apoptosis evasion in breast cancer through deubiquitination and stabilization of ERα, subsequently inhibiting cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in ERα+ breast cancer [26].

The coordinated regulation of apoptotic pathways by DUBs creates a formidable barrier to cell death, enabling cancer cell survival under diverse stress conditions. This mechanistic understanding reveals potential therapeutic vulnerabilities that could be exploited to re-sensitize tumor cells to apoptotic stimuli.

DUBs in DNA Damage Response

DUBs in DNA Repair Pathway Choice and Execution

The DNA damage response (DDR) represents a complex network of pathways that detect and repair DNA lesions, with DUBs emerging as critical regulators at multiple levels of this process [23] [27]. DUB activity ensures appropriate pathway choice, regulates repair protein stability and localization, and contributes to pathway termination once repair is complete.

In the Fanconi anemia (FA) pathway, which repairs DNA interstrand crosslinks, USP1 forms a complex with UAF1 to deubiquitinate the FANCD2-FANCI heterodimer [23]. This deubiquitination is required for proper FA pathway function, as USP1 depletion results in complete monoubiquitination of the cellular FANCD2 pool and deregulated recruitment to damage sites [23]. USP7 prevents degradation of RAD18 and Pol η, thereby supporting UV-induced PCNA monoubiquitination and subsequent recruitment of TLS polymerases to stalled replication forks [23]. For double-strand break repair, USP3 modulates histone H2A and γH2AX to influence DNA end resection, while USP11 regulates BRCA2 stability in homologous recombination [22] [23]. USP1 also regulates translesion synthesis by deubiquitinating monoubiquitinated PCNA, preventing excessive recruitment of TLS polymerases that could reduce replication fidelity [23].

Table 3: DUB Roles in DNA Damage Response Pathways

| DNA Repair Pathway | Key DUBs | DUB Substrates | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fanconi Anemia (ICL Repair) | USP1 | FANCD2-FANCI complex | Maintains FANCD2 ubiquitination equilibrium |

| Translesion Synthesis | USP1, USP7 | PCNA, RAD18, Pol η | Regulates TLS polymerase recruitment |

| Homologous Recombination | USP11, USP3, USP7 | BRCA2, H2A/γH2AX, BRCA1 | Promotes error-free DSB repair |

| Non-Homologous End Joining | USP14, USP3 | H2A/γH2AX | Influences DSB repair pathway choice |

| Nucleotide Excision Repair | USP7, USP3 | RNA Polymerase II, H2A/γH2AX | Facilitates bulky lesion repair |

| Base Excision Repair | USP47, USP3 | DNA Polymerase β, H2A/γH2AX | Supports oxidative damage repair |

Methodologies for Studying DUB Roles in DNA Repair

Investigating DUB functions in DNA damage response requires specialized experimental approaches that capture the dynamic nature of repair processes. Standard methodologies include:

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and Ubiquitination Assays: Cells are transfected with plasmids expressing the DUB of interest, along with ubiquitin. After treatment with DNA damaging agents (e.g., UV radiation, cisplatin, or ionizing radiation), proteins are immunoprecipitated with specific antibodies against potential substrates. Western blotting with anti-ubiquitin antibodies reveals changes in substrate ubiquitination status upon DUB expression or knockdown [23] [26].

Immunofluorescence and Foci Formation Analysis: Cells are treated with DNA damaging agents, fixed at various timepoints, and stained with antibodies against DNA repair proteins (e.g., γH2AX, RAD51, FANCD2) and the DUB of interest. High-resolution microscopy quantifies recruitment kinetics and co-localization at DNA damage sites, with USP1-UAF1 complex regulation of FANCD2 foci serving as a well-established example [23].

DNA Fiber Assay and Replication Dynamics: Cells are sequentially labeled with nucleotide analogs (e.g., CldU and IdU), followed by DNA damage induction. Spreading of DNA fibers on glass slides and immunostaining allows visualization of replication fork progression, stalling, and restart. This approach effectively demonstrates how USP1-mediated PCNA deubiquitination influences replication fork dynamics and translesion synthesis [23].

Clonogenic Survival Assays Post-DNA Damage: Cells with DUB knockdown or overexpression are treated with increasing doses of DNA damaging agents, then allowed to form colonies for 10-14 days. Survival curves quantify cellular sensitivity, establishing functional significance of DUB activity in DNA repair proficiency, as demonstrated in studies of USP11-deficient cells showing hypersensitivity to PARP inhibitors [23].

The diagram below illustrates the experimental workflow for characterizing DUB functions in DNA damage response:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for DUB Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DUB Modulators | siRNAs, shRNAs, CRISPR-Cas9 constructs, DUB inhibitors (e.g., P5091 for USP7) | Functional studies of DUB knockdown/knockout or pharmacological inhibition | Select validated targeting sequences; verify specificity of inhibitors |

| Ubiquitin Probes | HA-Ub, FLAG-Ub, Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Detection of protein ubiquitination status; pull-down of ubiquitinated proteins | TUBEs protect labile ubiquitin chains during purification |

| DNA Damage Inducers | Ionizing radiation, UV-C, Cisplatin, Mitomycin C, PARP inhibitors | Induce specific DNA lesions to study DUB roles in DDR | Optimize dose and timing for specific damage pathways |

| Repair Protein Antibodies | γH2AX (Ser139), RAD51, FANCD2, BRCA1, p53, PCNA | Immunofluorescence, Western blot, IP to monitor repair progression | Validate antibodies for specific applications (IF vs WB vs IP) |

| Live-Cell Imaging Reporters | GFP-tagged repair factors (e.g., 53BP1-GFP, RPA-GFP), FUCCI cell cycle indicators | Real-time tracking of repair protein recruitment and cell cycle progression | Optimize expression levels to avoid artifacts |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Stabilize ubiquitinated proteins for detection | Use appropriate controls to distinguish proteasomal effects |

DUBs occupy strategic positions in the regulation of core cancer hallmarks, functioning as crucial determinants of proliferation, apoptosis evasion, and DNA repair fidelity. Their ability to selectively stabilize key regulatory proteins places them as master regulators of tumorigenic processes, with different DUB families demonstrating both overlapping and unique substrate specificities. The mechanistic insights into DUB functions, as detailed in this review, highlight their potential as therapeutic targets, particularly through the development of selective small-molecule inhibitors. Future research directions should focus on elucidating the context-dependent functions of paradoxical DUBs like USP9X, understanding DUB cooperation in regulatory networks, and developing isoform-specific inhibitors to minimize therapeutic toxicity. As our knowledge of DUB biology expands, so too does the promise of targeting these enzymes for innovative cancer therapeutics that potentially overcome conventional resistance mechanisms.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a crucial regulatory mechanism for protein homeostasis, controlling the stability, localization, and activity of numerous cellular proteins [19]. As a reversible post-translational modification, ubiquitination is counterbalanced by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), which remove ubiquitin chains from substrate proteins [11] [16]. The human genome encodes approximately 100 DUBs, categorized into six major families based on their catalytic domains: ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), ovarian tumor proteases (OTUs), Machado-Josephin domain-containing proteases (MJDs), motif-interacting with ubiquitin-containing novel DUB family (MINDYs), and JAB1/MPN/MOV34 metalloenzymes (JAMMs) [4] [11]. DUBs regulate diverse cellular processes including cell cycle progression, DNA damage repair, signal transduction, and metabolic reprogramming through four primary mechanisms: processing ubiquitin precursors, rescuing substrate proteins from degradation, cleaving polyubiquitin chains for ubiquitin recycling, and editing ubiquitin chains to alter signaling outcomes [16].

In cancer biology, DUBs demonstrate remarkable functional diversity, acting as either oncogenes or tumor suppressors in a context-dependent manner [28] [16]. This duality presents both challenges and opportunities for therapeutic targeting. The opposing functions of DUBs stem from their regulation of key cancer-associated pathways, with their impact varying based on cellular context, cancer type, genetic background, and tumor microenvironment [4] [28]. This review comprehensively examines the molecular mechanisms underlying the context-dependent functions of DUBs in cancer, providing experimental frameworks for their investigation, and discussing emerging therapeutic strategies targeting DUB activities.

Molecular Mechanisms of Context-Dependent DUB Functions

Tissue and Cellular Context Determinants

The specific function of a DUB—whether oncogenic or tumor-suppressive—is heavily influenced by tissue type, cellular compartmentalization, and expression patterns. For instance, USP9X demonstrates contrasting roles in different cancers. In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), USP9X can function as a tumor suppressor, as demonstrated by Sleeping Beauty transposon-mediated insertional mutagenesis screens that revealed high mutation frequencies in PDAC tumors [4]. This tumor-suppressive function involves regulation of the Hippo pathway through cooperation with LATS kinase and YAP/TAZ to impede PDAC growth [4]. Conversely, in other malignancies, USP9X promotes tumor cell survival and malignant phenotypes, highlighting its context-dependent functionality [4] [28].

The subcellular localization of DUBs, controlled by post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination, significantly influences their substrate specificity and functional outcomes [16]. For example, phosphorylation of OTUB1 by casein kinase 2 facilitates its nuclear import, potentially altering its access to nuclear substrates, while AKT-mediated phosphorylation promotes nuclear export of USP4 [16]. Similarly, ubiquitination of BAP1 by UBE2O inhibits its nuclear translocation, a process reversible through auto-deubiquitination activity [16].

Genetic and Signaling Background

The genetic landscape of tumor cells profoundly influences DUB function, particularly in cancers driven by specific oncogenic mutations. In KRAS-driven pancreatic cancer (present in ~90% of PDAC cases), several DUBs interact with downstream signaling pathways to modulate tumor progression [4]. USP28 promotes cell cycle progression and inhibits apoptosis in PDAC cells by stabilizing FOXM1 to activate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [4]. Similarly, USP21 interacts with and stabilizes TCF7 to maintain PDAC cell stemness, with orthotopic pancreatic transplantation models showing that USP21-expressing cells undergo pathological progression from PanIN to PDAC [4].

The regulation of RAS proteins by ubiquitination provides another compelling example of how DUB functions are integrated with oncogenic signaling. Recent research has revealed that ubiquitination dynamically regulates RAS protein stability, membrane localization, and signaling transduction, with distinct patterns across different RAS isoforms (KRAS4A, KRAS4B, NRAS, and HRAS) [29]. This heterogeneity suggests that DUBs targeting specific RAS isoforms may demonstrate context-dependent functions based on the predominant RAS mutation profile in different cancers.

Table 1: Context-Dependent Functions of Selected DUBs in Cancer

| DUB | Cancer Type | Oncogenic Function | Tumor-Suppressive Function | Molecular Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USP9X | Pancreatic Cancer | Promotes tumor cell survival in human pancreatic tumor cells [4] | Suppresses tumor growth in KPC mouse models [4] | Regulates Hippo pathway via LATS kinase and YAP/TAZ [4] |

| BAP1 | Multiple Cancers | - | Frequently mutated in mesothelioma, melanoma, breast cancer [4] | Deubiquitinates H2A; mutations lead to "BAP1 cancer syndrome" [4] [11] |

| USP28 | Pancreatic Cancer | Promotes cell cycle progression, inhibits apoptosis [4] | - | Stabilizes FOXM1 to activate Wnt/β-catenin pathway [4] |

| CYLD | Various Cancers | - | Suppresses NF-κB and JNK pathways [11] | Deubiquitinates TRAF2/6, NEMO; familial tumor suppressor in cylindromatosis [11] |

| USP22 | Multiple Cancers | Promotes proliferation in PDAC; cancer stem cell marker [4] | - | Upregulates p21 via PTEN-MDM2-p53; increases DYRK1A levels [4] |

Substrate Specificity and Signaling Pathway Integration

The dual functions of DUBs frequently stem from their interactions with multiple substrates within competing signaling pathways. A single DUB may regulate both proliferative and suppressive pathways, with the net outcome determined by the relative dominance of these pathways in specific cellular contexts. USP7 exemplifies this principle through its regulation of both the oncogenic MDM2 and tumor-suppressive p53 [28]. By deubiquitinating and affecting the stability of both proteins, USP7 can either promote or suppress tumorigenesis depending on cellular context and interacting partners [28].

DUBs also demonstrate remarkable plasticity in response to therapeutic interventions. For example, USP1 undergoes self-processing and degradation upon UV radiation, representing an adaptive mechanism to DNA damage [16]. Similarly, the DUB OTUD5 exhibits phosphorylation-dependent catalytic activity enhancement through structural stabilization of its catalytic domain [16]. These regulatory mechanisms enable dynamic cellular responses to environmental stresses and contribute to the context-dependent functionality of DUBs in cancer progression and therapeutic resistance.

Experimental Approaches for DUB Functional Characterization

Genetic Screening and Validation Methods

Comprehensive genetic screening approaches have been instrumental in identifying context-dependent DUB functions. The Sleeping Beauty (SB) transposon-mediated insertional mutagenesis system has proven particularly valuable for uncovering DUBs that cooperate with specific oncogenic drivers. In one notable screen investigating KRASG12D-driven pancreatic cancer, USP9X emerged with the highest mutation frequency, observed in at least 50% of PDAC tumors, leading to its identification as a major tumor suppressor with high prognostic value in this context [4].

Protocol 1: Sleeping Beauty Transposon-Mediated Mutagenesis Screen for DUB Identification

- Transposon Construction: Generate a bidirectional transposon construct containing gene trap and polyA termination elements flanked by SB transposon inverted repeats.

- Mouse Model Generation: Cross SB transposon transgenic mice with appropriate Cre-driver lines (e.g., Pdx1-Cre for pancreatic cancer) and oncogene-bearing mice (e.g., KrasLSL-G12D).

- Tumor Monitoring: Monitor mice for tumor development over time, with typical PDAC formation requiring 6-12 months.

- DNA Extraction and Sequencing: Isolate genomic DNA from tumors and perform linker-mediated PCR amplification of transposon-genome junctions.

- Insertion Site Mapping: Map insertion sites to the reference genome and identify common insertion sites (CIS) using statistical algorithms (e.g., Gaussian Kernel Convolution).

- Validation: Validate candidate DUBs through immunohistochemistry of tumor tissues and functional assays in cell lines.

Mechanistic Investigation Techniques

Elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying context-dependent DUB functions requires integrated experimental approaches encompassing biochemical, cellular, and in vivo methods. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive strategy for mechanistic DUB characterization:

Protocol 2: Comprehensive DUB Functional Characterization

- Substrate Identification:

- Perform co-immunoprecipitation followed by mass spectrometry (CoIP-MS) to identify DUB-interacting proteins.

- Conduct ubiquitin remnant profiling (UbiSite) to map specific deubiquitination sites on substrates.

- Implement phage display or protein microarrays for high-throughput substrate screening.

Functional Validation:

- Establish isogenic cell lines with DUB knockout (CRISPR-Cas9) or overexpression (lentiviral transduction).

- Assess phenotypic impacts using proliferation assays (MTT, CellTiter-Glo), colony formation, and invasion assays (Boyden chamber).

- Evaluate pathway modulation through Western blotting of key signaling components and qRT-PCR of target genes.

In Vivo Validation:

- Utilize xenograft models with DUB-modified cancer cells in immunocompromised mice.

- Employ genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) with tissue-specific DUB deletion or mutation.

- Monitor tumor growth, metastasis, and therapeutic responses using bioluminescent imaging and histopathological analysis.

Research Reagent Solutions for DUB Investigation

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for DUB Functional Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Applications and Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Tools | Sleeping Beauty Transposon System [4] | Genome-wide mutagenesis screening for DUB identification |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout Libraries | High-throughput functional screening of DUB families | |

| Tetracycline-inducible Expression Systems | Controlled DUB overexpression for functional studies | |

| Chemical Inhibitors | Auranofin (UCHL5/USP14 inhibitor) [11] | Proteasome-associated DUB inhibition; induces cytotoxicity |

| SIM0501 (USP1 inhibitor) [30] | FDA-approved for clinical trials in advanced solid tumors | |

| P5091 (USP7 inhibitor) | Targets MDM2-p53 pathway; induces apoptosis in cancer cells | |

| Analytical Tools | Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Isolation of polyubiquitinated proteins for proteomics |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies (K48, K63, etc.) | Discrimination of ubiquitin chain topology in substrates | |

| Activity-Based Probes (HA-Ub-VS, HA-Ub-AMC) | Direct monitoring of DUB catalytic activity in cell lysates | |

| Model Systems | Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs) | Physiological 3D culture models for DUB function studies |

| Genetically Engineered Mouse Models (GEMMs) [4] | In vivo validation of DUB roles in specific cancer contexts | |

| Orthotopic Transplantation Models [4] | Site-specific tumor growth and metastasis analysis |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Targeting Context-Dependent DUB Functions

The dual nature of DUBs as both oncogenes and tumor suppressors presents unique challenges for therapeutic development. Successful targeting strategies must consider the cellular context, including tissue type, genetic background, and tumor microenvironment. Several DUB-targeted agents have shown promise in preclinical models and early clinical trials. Auranofin, initially developed for rheumatoid arthritis, inhibits proteasome-associated DUBs UCHL5 and USP14, demonstrating selective tumor growth inhibition in vivo and inducing cytotoxicity in cancer cells from patients with acute myeloid leukemia [11]. Similarly, the small molecule inhibitor SIM0501, which targets USP1, has received FDA approval for clinical trials in advanced solid tumors [30].

Emerging research focuses on developing isoform-selective DUB inhibitors that minimize off-target effects. The structural characterization of DUB catalytic domains has enabled structure-based drug design approaches, yielding compounds with improved specificity and potency. Additionally, PROTAC (Proteolysis Targeting Chimera) technology offers an alternative strategy for targeting DUB functions by directing their ubiquitination and degradation, rather than merely inhibiting catalytic activity [19]. ARV-110 and ARV-471 represent pioneering PROTAC candidates that have progressed to phase II clinical trials for prostate and breast cancers, respectively [19].

Biomarker-Driven Patient Stratification

Given the context-dependent functions of DUBs, identifying robust biomarkers for patient stratification represents a critical component of therapeutic development. Comprehensive molecular profiling—including genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses—can help identify cancers most likely to respond to specific DUB-targeted therapies. For instance, tumors with specific KRAS mutations might exhibit heightened sensitivity to DUBs regulating RAS ubiquitination and membrane localization [29]. Similarly, cancers with dysregulated Wnt/β-catenin signaling may demonstrate increased dependence on DUBs such as USP28 and USP21 [4].

Functional imaging approaches, including positron emission tomography (PET) with novel DUB-targeted radiotracers, offer potential for non-invasive assessment of DUB expression and activity in tumors. Such techniques could enable real-time monitoring of therapeutic responses and guide treatment adaptation in clinical settings.

Future Research Directions

Several key questions remain unresolved in the field of context-dependent DUB functions. First, the precise molecular determinants that dictate whether a DUB acts as an oncogene or tumor suppressor in specific contexts require further elucidation. Second, the regulation of DUB activity by post-translational modifications and interacting partners needs comprehensive characterization across different cancer types. Third, the potential compensatory mechanisms among DUB family members upon targeted inhibition warrants systematic investigation.

Future research should prioritize the development of more sophisticated experimental models, including patient-derived organoids and humanized mouse models, that better recapitulate the tumor microenvironment and immune context. Additionally, advanced technologies such as single-cell sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, and live-cell imaging of DUB activities will provide unprecedented insights into the dynamic regulation of DUB functions in cancer progression and treatment response.

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches for analyzing multi-omics datasets holds particular promise for predicting context-dependent DUB functions and identifying optimal therapeutic combinations. As these technologies mature, they will accelerate the development of personalized cancer therapies targeting the ubiquitin system.

Deubiquitinating enzymes represent master regulators of cellular signaling pathways with profound implications for cancer development and treatment. Their context-dependent functions as either oncogenes or tumor suppressors are dictated by a complex interplay of tissue specificity, genetic background, substrate availability, and microenvironmental influences. Understanding these nuanced relationships requires sophisticated experimental approaches that integrate genetic screening, mechanistic biochemistry, and validated disease models.

The continued elucidation of context-dependent DUB functions will undoubtedly yield novel therapeutic opportunities and biomarker strategies for precision oncology. As DUB-targeted agents progress through clinical development, careful attention to patient selection and combination therapies will be essential for maximizing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing unintended consequences. With rapid advances in structural biology, chemical proteomics, and functional genomics, the field is poised to translate fundamental discoveries about DUB biology into meaningful clinical benefits for cancer patients.

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) are critical regulators of cellular signaling pathways through their ability to cleave ubiquitin chains from substrate proteins. This technical review examines the mechanistic roles of DUBs in regulating three pivotal signaling pathways—p53, NF-κB, and Wnt/β-catenin—within the context of cancer research. We synthesize current understanding of how specific DUBs control the stability, localization, and activity of key components in these pathways, thereby influencing tumorigenesis, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance. The review also presents experimental frameworks for investigating DUB functions and discusses emerging therapeutic strategies targeting DUBs in cancer, providing researchers with both theoretical foundations and practical methodologies for advancing drug discovery in this field.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a crucial regulatory mechanism for protein degradation and functionality in eukaryotic cells. Within this system, deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) perform the reverse reaction of ubiquitination by specifically cleaving ubiquitin chains from substrate proteins, thereby modulating protein stability, activity, and interaction networks [31]. Approximately 100 DUBs have been identified in humans, classified into seven major families based on their catalytic domains: ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), ovarian tumor proteases (OTUs), Machado-Joseph disease proteases (MJDs), motif interacting with ubiquitin-containing novel DUB family (MINDY), JAMM/MPN domain-associated metallopeptidases (JAMMs), and zinc-finger containing ubiquitin peptidase 1 (ZUP1) [3].

Dysregulation of DUB activity is increasingly recognized as a contributing factor in cancer pathogenesis. DUBs govern fundamental cellular processes including cell cycle progression, apoptosis, DNA damage repair, and metabolic reprogramming by controlling the turnover of key regulatory proteins [4]. Through their substrate specificity, DUBs can function as either oncoproteins or tumor suppressors in a context-dependent manner. The balanced regulation of ubiquitination and deubiquitination is essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis, and disruption of this equilibrium can drive malignant transformation and tumor progression [30]. Consequently, DUBs have emerged as attractive therapeutic targets in cancer drug development, with several small-molecule inhibitors currently in preclinical and clinical evaluation [3].

The Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway

Pathway Mechanism and Biological Significance