Deubiquitinating Enzymes: Gatekeepers of Ubiquitin Homeostasis in Health and Disease

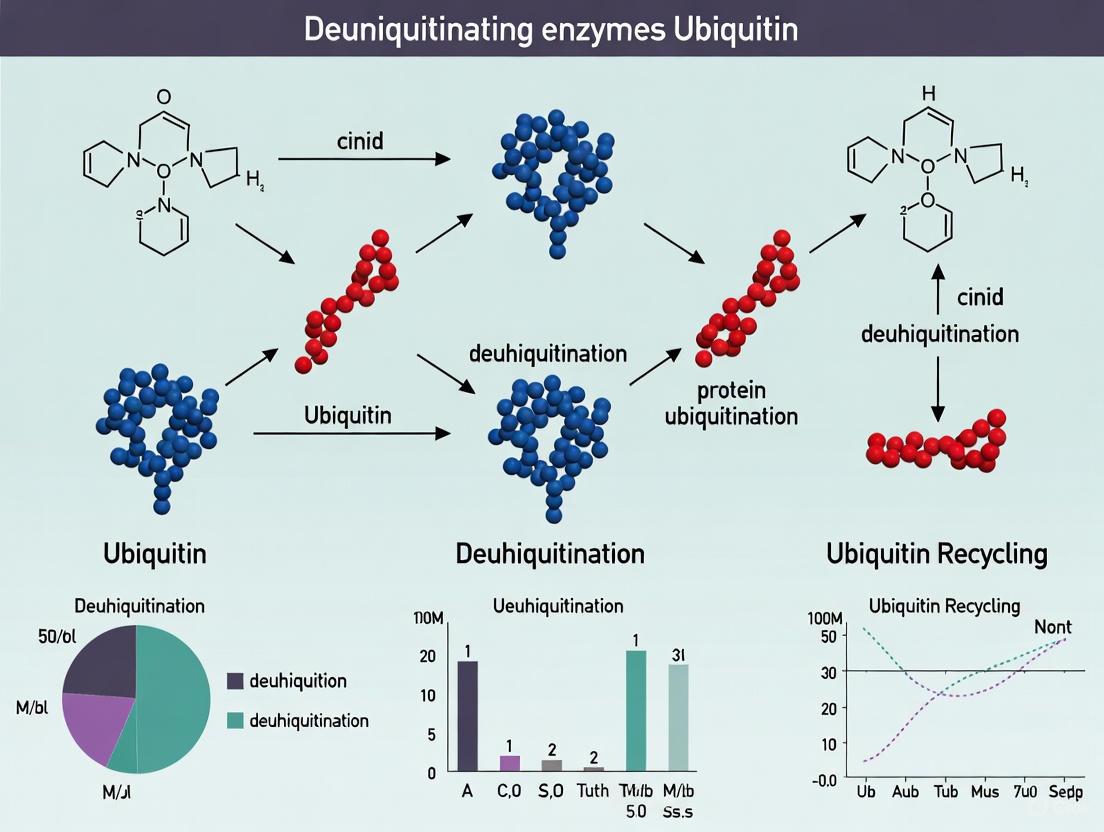

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical role Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs) play in maintaining ubiquitin homeostasis, a process fundamental to cellular health.

Deubiquitinating Enzymes: Gatekeepers of Ubiquitin Homeostasis in Health and Disease

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical role Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs) play in maintaining ubiquitin homeostasis, a process fundamental to cellular health. We explore the foundational biology of DUB families and their regulatory mechanisms, then delve into advanced methodologies for profiling DUB activity and the discovery of selective inhibitors. The content addresses key challenges in DUB research and drug development, including issues of enzyme specificity and inhibitor selectivity. Finally, we examine the validation of DUBs as therapeutic targets across various pathologies, notably in cancer and neurodegeneration, by comparing biological models and clinical evidence. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to understand and target the DUB family for therapeutic intervention.

The Ubiquitin Code and DUBs: Defining Fundamental Roles in Cellular Homeostasis

Core Components of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) is the primary pathway for selective protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, playing a crucial role in maintaining cellular protein homeostasis and regulating numerous cellular processes including cell cycle progression, apoptosis, DNA repair, and immune responses [1] [2]. This sophisticated system operates through a coordinated series of enzymatic reactions that tag target proteins for degradation with ubiquitin chains, which are then recognized and processed by the proteasome.

Table 1: Core Enzymatic Components of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

| Component Type | Number in Humans | Key Function | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Ubiquitin-activating enzyme) | ~2 | Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner | UBA1, UBA6 |

| E2 (Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme) | ~60 | Accepts activated ubiquitin from E1 and collaborates with E3 for substrate transfer | UBE2D, UBE2K |

| E3 (Ubiquitin ligase) | >600 | Confers substrate specificity by recognizing target proteins and facilitating ubiquitin transfer | Cbl, MDM2, VHL |

| Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs) | >100 | Reverses ubiquitination by removing ubiquitin from substrates | USP7, A20 |

The process of ubiquitination involves a three-step enzymatic cascade [2]. Initially, the E1 enzyme activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent process, establishing a thioester bond between the C-terminal carboxyl group of ubiquitin and the cysteine group of the E1 enzyme. The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to the active site of an E2 conjugating enzyme. Finally, an E3 ligase facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to a lysine residue on the target protein, forming an isopeptide bond.

The 26S proteasome is a massive 2.5 MDa multi-subunit complex that serves as the proteolytic machine of the UPS [2]. It comprises two main subcomplexes: the 20S core particle, which contains the proteolytic active sites, and the 19S regulatory particle, which recognizes ubiquitinated proteins, removes ubiquitin chains, and unfolds substrates for translocation into the proteolytic core.

The Ubiquitin Code and Its Functional Diversity

Ubiquitination is a remarkably versatile post-translational modification that can signal different cellular fates depending on the topology of ubiquitin conjugation. The "ubiquitin code" refers to this complex language where different ubiquitin chain linkages confer distinct functional consequences for the modified protein [2] [3].

Table 2: Diversity of Ubiquitin Modifications and Their Functional Consequences

| Ubiquitin Modification Type | Structural Features | Primary Functions | Key Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monoubiquitination | Single ubiquitin on one lysine | Endocytosis, histone regulation, DNA repair, virus budding | Membrane receptor internalization |

| Lys48-linked Polyubiquitination | Chains via ubiquitin Lys48 residues | Targets proteins for degradation by the 26S proteasome | Degradation of cell cycle regulators |

| Lys63-linked Polyubiquitination | Chains via ubiquitin Lys63 residues | DNA repair, signal transduction, endocytosis, kinase activation | NF-κB signaling via IκB kinase activation |

| Mixed/Lys11/Lys29 Chains | Various chain linkages | Diverse functions including ER-associated degradation | Cell cycle regulation |

This ubiquitin code is dynamically written by ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and erased by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), which cleave ubiquitin from modified substrates [4] [5]. DUBs are responsible for processing inactive ubiquitin precursors, proofreading ubiquitin-protein conjugates, removing ubiquitin from cellular adducts, and maintaining the 26S proteasome free of inhibitory ubiquitin chains. The balance between ubiquitination and deubiquitination constitutes a critical regulatory mechanism for controlling protein stability and function.

Experimental Methodologies for Studying the UPS

Identifying E3 Ligase Substrates

Understanding E3 ligase-substrate relationships is fundamental to deciphering UPS function. Several sophisticated approaches have been developed for substrate identification:

shRNA or CRISPR-Cas9-mediated screening: These loss-of-function genetic approaches allow researchers to identify potential substrates by observing protein accumulation when specific E3 ligases are inhibited [2].

In vitro ubiquitination assays: These biochemical reconstitution experiments involve incubating putative substrates with purified E1, E2, E3 enzymes, ubiquitin, and ATP, followed by detection of ubiquitination via immunoblotting.

Global Protein Stability (GPS) profiling: This genome-wide screening strategy utilizes reporter proteins fused with hundreds of potential substrates independently [2]. By inhibiting ligase activity and monitoring reporter accumulation, researchers can identify previously unknown E3-substrate relationships on a global scale.

USP7-UBA52-BECN1/ULK1 Regulatory Axis Analysis

Recent research has revealed specific experimental approaches for studying DUB function in autophagy regulation. The investigation of the USP7-UBA52-BECN1/ULK1 axis provides an excellent example [6]:

Protein-protein interaction studies: Co-immunoprecipitation and proteomic analyses identified UBA52 as a physiological binding partner of MLKL in brain tissue.

Biochemical assessment of ubiquitin homeostasis: Researchers measured ubiquitin levels following genetic manipulation of MLKL or USP7, demonstrating that MLKL deletion impaired UBA52 cleavage and led to cellular ubiquitin deficiency.

K63-linked ubiquitination assays: Specific immunoprecipitation of BECN1 and ULK1 followed by ubiquitin linkage analysis revealed that reduced K63-linked ubiquitination decreased protein stability of these key autophagy initiators.

Functional autophagy assays: Autophagic flux was monitored using LC3 turnover assays and electron microscopy, while cognitive function was assessed through behavioral tests in MLKL knockout mice.

Research Reagent Solutions for UPS Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Investigations

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, MG132 | Cancer research, protein turnover studies | Blocks proteasomal degradation, causing accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins |

| TBK1 Inhibitors | GSK8612, MRT67307 | Pexophagy, selective autophagy studies | Inhibits TBK1 kinase activity to investigate downstream signaling |

| ROS Scavengers | N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) | Oxidative stress studies | Neutralizes reactive oxygen species to elucidate upstream signaling events |

| Autophagy-Lysosome Inhibitors | Bafilomycin A1, Chloroquine | Autophagic flux measurement | Blocks autophagosome-lysosome fusion to assess autophagy activity |

| Genetic Manipulation Tools | siRNA libraries, CRISPR-Cas9 | High-throughput screening | Targeted gene knockdown/knockout to identify pathway components |

| Ubiquitin System Components | E1, E2, E3 enzymes, ubiquitin mutants | In vitro ubiquitination assays | Reconstitution of ubiquitination cascades for mechanistic studies |

DUBs in Cellular Homeostasis and Disease Relevance

Deubiquitinating enzymes serve as crucial regulators of the UPS by providing reversibility to ubiquitin modifications. DUBs are involved in maintaining the free ubiquitin pool, proofreading ubiquitin conjugates, and rescuing proteins from degradation [4] [5]. The dynamic balance between ubiquitination and deubiquitination allows for precise control of protein stability and function in response to cellular signals.

Dysregulation of DUB activity has been implicated in various human diseases. For instance, USP7 regulates ubiquitin homeostasis by controlling the processing of UBA52, one of four ubiquitin precursors in mammalian cells [6]. Disruption of this pathway in neural cells reduces K63-linked ubiquitination of autophagy proteins BECN1 and ULK1, impairing autophagy and leading to cognitive dysfunction in animal models. This demonstrates how DUB-mediated control of ubiquitin availability directly impacts protein quality control mechanisms in the brain.

The clinical significance of the UPS is further highlighted by the development of therapeutic interventions targeting this pathway. Bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor, has been successfully deployed in the treatment of multiple myeloma, validating the UPS as a druggable target [2]. Ongoing research focuses on developing more specific inhibitors targeting individual E3 ligases or DUBs to minimize off-target effects while maintaining therapeutic efficacy.

Concluding Perspectives

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System represents one of the most sophisticated regulatory mechanisms in cell biology, with reversible ubiquitination serving as a dynamic control point for numerous cellular processes. The expanding repertoire of DUB functions highlights their importance as key regulators of ubiquitin homeostasis, with implications for understanding disease mechanisms and developing novel therapeutic strategies. Continued investigation of the intricate balance between ubiquitination and deubiquitination will undoubtedly yield new insights into cellular regulation and provide opportunities for therapeutic intervention in cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and other human diseases.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a crucial regulatory mechanism for intracellular protein turnover, governing both the degradation and the non-degradative signaling of a vast array of proteins [7]. Ubiquitination, the process of covalently attaching a ubiquitin molecule to target proteins, is a dynamic and reversible post-translational modification. Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) are the proteases that catalyze the reverse reaction, cleaving ubiquitin from its substrates and thereby providing a critical counterbalance to the activity of E3 ubiquitin ligases [8] [9]. This equilibrium between ubiquitination and deubiquitination is fundamental to cellular homeostasis, regulating essential processes such as the cell cycle, DNA repair, transcriptional regulation, and immune signaling [7]. Dysregulation of DUB activity disrupts this delicate balance and is implicated in numerous human diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and inflammatory conditions [10] [11] [8]. The human genome encodes approximately 100 DUBs, which can be classified into six major families based on the structure and mechanism of their catalytic domains: Ubiquitin-Specific Proteases (USPs), Ovarian Tumor Proteases (OTUs), Ubiquitin C-Terminal Hydrolases (UCHs), Machado-Josephin Domain-containing proteases (MJDs), Motif Interacting with Ubiquitin-containing Novel DUB family (MINDYs), and JAB1/MPN/Mov34 Metalloenzymes (JAMMs) [12] [10] [11]. This review provides an in-depth examination of these families, their roles in maintaining ubiquitin homeostasis, and their emerging potential as therapeutic targets.

Classification and Characteristics of DUB Families

DUBs are primarily categorized by their catalytic mechanisms and structural folds. The USPs, OTUs, UCHs, MJDs, and MINDYs are all cysteine proteases, utilizing an active-site cysteine nucleophile for catalysis. In contrast, the JAMM family members are zinc-dependent metalloproteases that coordinate a zinc ion to activate a water molecule for nucleophilic attack [11] [8]. The table below summarizes the key quantitative characteristics of these families.

Table 1: Classification and Key Characteristics of Human Deubiquitinating Enzyme Families

| Family | Catalytic Type | Approx. Human Members | Catalytic Motif/Feature | Representative Members |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USP | Cysteine Protease | 56-58 | Cysteine, Histidine, Asparagine/Aspartate (Catalytic Triad) | USP7, USP15, USP22, USP33, USP34 |

| OTU | Cysteine Protease | 14-17 | Linkage-specific selectivity for ubiquitin chains | OTUB1, A20, OTULIN |

| UCH | Cysteine Protease | 4 | Cysteine and Histidine (Catalytic Dyad); specialized for small adducts | UCH-L1, UCH-L3, BAP1 |

| MJD | Cysteine Protease | 4-5 | Josephin Domain; polyglutamine disease association | Ataxin-3 |

| MINDY | Cysteine Protease | 5 | Preferential cleavage of K48-linked ubiquitin chains | Not Specified in Sources |

| JAMM | Zinc Metalloprotease | 7 (Active) | ExnHxHx7Sx2D (JAMM motif coordinating Zn²⁺) | Rpn11/PSMD14, BRCC36, AMSH, CSN5 |

Cysteine Protease DUB Families

Ubiquitin-Specific Proteases (USPs)

The USP family is the largest among DUBs, characterized by high diversity in their sequence length and domain architecture outside the conserved catalytic core [12] [13]. The catalytic domain contains a classic catalytic triad (Cys, His, Asp/Asn) [12]. USPs are known for their diverse roles and are often regulated by accessory domains and protein-protein interactions. For instance, many USPs contain Ubiquitin-Like (UBL) domains and Domain present in Ubiquitin-Specific Proteases (DUSP) domains, which can regulate catalytic activity, influence substrate recognition, or mediate localization [12]. USP7 (HAUSP) is a prominent example, stabilizing the p53 tumor suppressor and its regulator Mdm2, thereby creating a complex feedback loop [9]. USP15 has been shown to deubiquitinate and stabilize ALK3/BMPR1A to enhance bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling, and ERK2 and SMAD2 to enhance TGF-β signaling [14] [15].

Ovarian Tumor Proteases (OTUs)

The OTU family is distinguished by its linkage specificity toward different types of polyubiquitin chains [9]. Structural studies reveal that embedded ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) and specific subsites (S1' sites) within the catalytic domain work together to position the proximal ubiquitin moiety and orient the isopeptide bond for cleavage, conferring selectivity for one or two specific ubiquitin linkages [9]. Notable members include A20 (TNFAIP3) and CYLD, which are critical negative regulators of the NF-κB pathway, and OTULIN, which specifically hydrolyzes linear (M1-linked) ubiquitin chains and works with LUBAC in the TNF receptor signaling pathway [13] [15].

Ubiquitin C-Terminal Hydrolases (UCHs)

The UCH family is relatively small, with members featuring a compact catalytic domain that utilizes a catalytic dyad [12]. UCHs are particularly efficient at cleaving small adducts from the C-terminus of ubiquitin, such as peptides or small cellular nucleophiles, which may be generated during the ubiquitination process or from the cleavage of ubiquitin precursor genes (UBA52, RPS27A, UBB, UBC) [12]. UCH-L1 is highly expressed in the brain and in various malignancies, while BAP1 is a well-characterued tumor suppressor whose mutation leads to a "BAP1 cancer syndrome" [10] [9].

Machado-Josephin Domain-containing proteases (MJDs) and MINDYs

The MJD family, including the founding member Ataxin-3, is characterized by the Josephin domain [12]. Ataxin-3 is known to bind and edit K63-linked ubiquitin chains and has been implicated in protein quality control and neurodegenerative diseases [12]. The more recently identified MINDY family exhibits a strong preference for cleaving K48-linked polyubiquitin chains, the principal signal for proteasomal degradation, suggesting a specialized role in regulating protein stability [10] [11].

Metalloprotease DUB Family: JAMMs

The JAMM family is unique as the only known group of zinc metalloprotease DUBs in the human genome [11]. Unlike the cysteine proteases, JAMMs feature a characteristic JAMM motif (ExnHxHx7Sx2D) that coordinates a zinc ion (Zn²⁺) to activate a water molecule for hydrolyzing the isopeptide bond [11]. Most active JAMM DUBs, such as AMSH, BRCC36, and Rpn11, function within multi-protein complexes. Their activity is often regulated by accessory subunits and conformational changes. For example, the Ins-1 segment in JAMMs like Rpn11 and CSN5 can undergo a conformational transition from a closed, inactive state to an open, active β-hairpin that facilitates substrate binding and cleavage [11]. Rpn11 is an integral subunit of the proteasome's lid and is essential for proteosomal degradation, while BRCC36 functions in the BRCA1-RAP80 complex to regulate DNA repair [13] [11].

Experimental Approaches for DUB Research

Systematic investigation of DUB function has been accelerated by global proteomic and bioinformatic approaches. A landmark study utilized a retroviral library of 75 Flag-HA tagged DUBs expressed in HEK293 cells, followed by affinity purification and mass spectrometry (AP-MS) to identify protein interactors [13]. To manage the high rate of nonspecific interactions typical of proteomic datasets, the researchers developed a software platform called CompPASS (Comparative Proteomic Analysis Software Suite).

Key Methodology: CompPASS-Based Interactome Mapping

This methodology provides a robust framework for defining the DUB interaction landscape.

- Step 1: Generation of a Tagged DUB Library. A library of 75 DUBs (out of ~95 in the human genome) was constructed with N-terminal Flag-HA tandem affinity tags.

- Step 2: Cell Culture and Protein Expression. The DUBs were expressed in a human embryonic kidney cell line (HEK293), which endogenously expresses 69 of the 75 DUBs analyzed, ensuring a physiologically relevant context.

- Step 3: Affinity Purification. Each Flag-HA-DUB was purified using anti-HA antibody-coupled resin under native conditions to preserve protein complexes.

- Step 4: Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Purified protein complexes were trypsinized, and the resulting peptides were analyzed by LC-MS/MS in duplicate to create a database of DUB-associated proteins. Total spectral counts (TSCs) were used to approximate protein abundance.

- Step 5: Data Analysis with CompPASS. The CompPASS platform was used to assign confidence measurements to identified interactions from the parallel, non-reciprocal proteomic datasets. It employs two scoring metrics:

- Z-score: Identifies proteins that are present in multiple purifications but are highly enriched in a specific subset.

- Normalized Weighted D-score (NWD): A novel metric designed to address the limitation of the Z-score by weighting unique interactors according to their spectral abundance.

- Step 6: Validation and Functional Studies. High-confidence candidate interacting proteins (HCIPs) were validated (achieving a 68% experimental validation rate) and linked to biological pathways using Gene Ontology, interactome topology, and sub-cellular localization. For example, functional validation for USP13's role in ER-associated degradation (ERAD) was conducted using RNA interference (RNAi) depletion and monitoring of model ERAD substrate accumulation [13].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of the CompPASS-based DUB interactome analysis:

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for systematic DUB interactome mapping.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and tools used in the featured CompPASS study and broader DUB research, as identified in the search results.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DUB Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function in Research | Example from Search Results |

|---|---|---|

| Tagged DUB Library | Enables standardized purification of multiple DUBs and their complexes from a cellular environment. | Flag-HA tandem tag retroviral library of 75 DUBs [13]. |

| Affinity Resins | Immobilized beads for isolating tagged protein complexes from cell lysates. | Anti-HA antibody coupled resin [13]. |

| LC-MS/MS Platform | High-sensitivity instrumentation for identifying and quantifying proteins in purified complexes. | Used for proteomic analysis of DUB immunocomplexes [13]. |

| Bioinformatic Software (CompPASS) | Analyzes parallel AP-MS datasets to distinguish specific, high-confidence interactions from nonspecific background. | CompPASS software using Z-score and NWD metrics [13]. |

| Small-Molecule Inhibitors | Pharmacological tools to probe DUB function and validate therapeutic potential. | P22077 (USP7 inhibitor), IU1 (USP14 inhibitor), OAT-4828, MTX325 [16] [15]. |

| RNAi Tools | Gene silencing (e.g., siRNA, shRNA) to study loss-of-function phenotypes of specific DUBs. | RNAi depletion of USP13 to study ERAD [13]. |

DUBs in Disease and Therapeutic Targeting

Dysregulation of DUB activity is a hallmark of numerous diseases, particularly cancer, where they can function as either oncogenes or tumor suppressors. The role of DUBs in maintaining ubiquitin homeostasis positions them as critical nodes in cellular signaling networks whose disruption leads to pathology.

DUB Dysregulation in Human Disease

- Cancer: Many DUBs are aberrantly expressed in cancers and drive tumorigenesis by stabilizing oncoproteins or destabilizing tumor suppressors. USP28 is overexpressed in colon and lung cancers, where it stabilizes oncogenes like c-Myc and Notch1 [12]. USP22 is a marker of cancer stem cells, promotes stemness in hepatocellular carcinoma, and stabilizes PD-L1 to facilitate tumor immune evasion [7] [10]. Conversely, USP9X exhibits context-dependent roles, acting as a tumor suppressor in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) by regulating the Hippo pathway, but as an oncogene in other malignancies by stabilizing anti-apoptotic proteins like MCL-1 [10] [9].

- Neurological Disorders: Mutations in DUBs are linked to neurodegeneration. For example, Ataxin-3, an MJD family member, is the protein mutated in Machado-Joseph disease, and UCH-L1 is associated with Parkinson's disease [12] [9].

- Inflammatory and Bone Diseases: CYLD and A20 are critical negative regulators of inflammatory NF-κB signaling, and mutations in CYLD cause cylindromatosis [13]. In bone homeostasis, DUBs like USP15 and E3 ligases like Smurf1/2 tightly regulate BMP/TGF-β signaling, and their dysregulation contributes to osteoporosis and fracture non-union [14] [15].

Emerging DUB-Targeted Therapeutics

The high specificity and central regulatory roles of DUBs make them attractive therapeutic targets. The development of DUB inhibitors has become a rapidly advancing frontier in drug discovery. The following table lists selected DUB inhibitors currently in development, highlighting the focus on specific families, particularly USPs and JAMMs.

Table 3: Selected DUB Inhibitors in the Therapeutic Pipeline

| DUB Inhibitor | Target DUB | Development Stage | Indication / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| P22077 | USP7 | Preclinical | Osteoarthritis, Cancer [15] |

| IU1 | USP14 | Preclinical | Osteoarthritis, Neurodegenerative Diseases [15] [9] |

| MTX325 | USP30 | Phase I (as of 2025) | Parkinson's Disease [16] |

| OAT-4828 | USP7 | Preclinical/Phase I (as of 2025) | Cancer [16] |

| TNG348 | USP? | Phase I (as of 2025) | Cancer (BRCA-mutant) [16] |

| KSQ-4279 | USP1 | Phase I (as of 2025) | Cancer [16] |

| VLX1570 | USP14 / UCHL5 | Clinical Trials | Multiple Myeloma [16] |

The pipeline for DUB inhibitors is diverse, with candidates like MTX325 (a USP30 inhibitor) receiving significant funding for Parkinson's disease research, reflecting the therapeutic potential of DUB modulation beyond oncology [16]. The following diagram illustrates the strategic workflow from DUB identification to therapeutic application, integrating the concepts of homeostasis, dysregulation, and intervention.

Figure 2: Therapeutic strategy for targeting DUBs in disease.

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) constitute a critical regulatory family within the ubiquitin system, performing essential functions that maintain cellular protein homeostasis. As key antagonists to the ubiquitination machinery, DUBs process ubiquitin precursors, edit ubiquitin chain architecture, and recycle ubiquitin from protein conjugates, thereby preserving the cellular pool of free ubiquitin necessary for myriad signaling events [17] [4]. The precise regulation of these core functions enables DUBs to control fundamental biological processes including protein degradation, DNA repair, transcription, and cell signaling [18] [17]. This technical guide examines the molecular mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and functional significance of these core DUB activities within the broader context of ubiquitin homeostasis research.

Core Functional Mechanisms of DUBs

Processing of Ubiquitin Precursors

DUBs generate mature, biologically active ubiquitin by cleaving ubiquitin gene products. Eukaryotic cells synthesize ubiquitin as precursor proteins, either as linear fusions (polyubiquitin genes) or as N-terminal fusions to ribosomal proteins [17] [4]. These precursors require precise proteolytic processing to liberate functional ubiquitin monomers with exposed C-terminal glycine residues necessary for conjugation.

- Ubiquitin C-terminal Hydrolases (UCHs): Specialized in cleaving small adducts from the C-terminus of ubiquitin, including peptide remnants from ubiquitin precursor proteins [19].

- Ubiquitin-Specific Processing Proteases (USPs): Process both ubiquitin precursors and polyubiquitin chains through hydrolysis of peptide bonds at the ubiquitin C-terminus [19] [4].

This processing function is fundamental to maintaining adequate free ubiquitin levels, as demonstrated by studies showing that DUB impairment leads to severe ubiquitin depletion and loss of cell viability [19].

Editing of Ubiquitin Chains

DUBs exert precise editorial control over ubiquitin chain architecture, dynamically modulating the signals conveyed by different ubiquitin linkages. Through linkage-specific cleavage, DUBs can reverse or reshape ubiquitin signals to fine-tune cellular responses [17] [20].

Table 1: DUB Specificity for Ubiquitin Linkage Types

| Ubiquitin Linkage Type | Primary Signaling Function | Representative DUBs | Cleavage Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48-linked chains | Targets substrates to 26S proteasome for degradation [18] | USP14, UCH37 | Preferentially cleaves K48 linkages [17] |

| K63-linked chains | Regulates signal transduction, DNA repair, endocytosis [18] | AMSH, CYLD | Highly specific for K63 linkages [17] [20] |

| K11-linked chains | Cell cycle regulation, ER-associated degradation [20] | Cezanne | Preferentially cleaves K11 linkages [20] |

| M1-linked (linear) chains | NF-κB signaling pathway activation [20] | OTULIN | Specific for linear ubiquitin chains [20] |

| Mixed/K6-linked chains | DNA damage response, mitochondrial regulation [18] | USP30 | Mitochondrial outer membrane enzyme [20] |

The editorial function of DUBs occurs through distinct cleavage modes:

- Distal cleavage: Removal of single ubiquitin monomers from the chain end

- Endo-cleavage: Cleavage within the ubiquitin chain, typically performed by OTU family DUBs [20]

- Base cleavage: Removal of entire chains from substrate proteins, commonly executed by USPs [20]

This editorial capacity allows DUBs to terminate ubiquitin signals, remodel chain architectures, or rescue substrates from degradation, providing a dynamic regulatory layer to the ubiquitin system [17] [20].

Recycling of Ubiquitin

Perhaps the most critical housekeeping function of DUBs is ubiquitin recycling from proteasome-bound and endocytosed substrates. As ubiquitin is a stable protein with limited cellular abundance, its efficient recovery is essential for maintaining ubiquitin homeostasis [19].

The Doa4 enzyme in Saccharomyces cerevisiae represents a paradigm for DUB-mediated ubiquitin recycling. Doa4 acts at both the proteasome and the vacuole (lysosome) to reclaim ubiquitin before substrate degradation [19]. In doa4Δ mutants, ubiquitin is rapidly depleted as cells approach stationary phase, leading to marked loss of cell viability due to insufficient ubiquitin for essential cellular functions [19]. This ubiquitin depletion can be rescued by provision of additional ubiquitin, confirming the recycling defect as the primary deficiency [19].

Mechanisms of ubiquitin recycling:

- Proteasomal recycling: DUBs associated with the 19S regulatory particle (e.g., Rpn11) remove ubiquitin chains from substrates immediately before proteasomal degradation [4]

- Endolysosomal recycling: DUBs such as Doa4 and UBPY/USP8 reclaim ubiquitin from membrane proteins destined for vacuolar/lysosomal degradation [19]

- Ubiquitin pool maintenance: By preventing ubiquitin degradation alongside substrates, DUBs maintain the free ubiquitin pool necessary for continuous ubiquitination cycles [17]

Figure 1: The Ubiquitin Maintenance Cycle. DUBs process ubiquitin precursors to maintain the free ubiquitin pool and recycle ubiquitin from substrates targeted for degradation, ensuring ubiquitin homeostasis.

Experimental Assessment of DUB Functions

Quantitative DiGly Proteomics for Ubiquitinome Analysis

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics has revolutionized the systematic analysis of ubiquitin modifications. The diGly proteomics approach exploits the tryptic digestion signature of ubiquitin conjugates—a diglycine remnant on modified lysines—enabling global identification and quantification of ubiquitination sites [21].

Protocol: DiGly Proteome Enrichment and Quantification

Cell Lysis and Protein Extraction: Harvest cells using urea-based lysis buffer (6M urea, 2M thiourea, 50mM Tris pH 8.0) with protease inhibitors and 10mM N-ethylmaleimide to preserve ubiquitin conjugates [21].

Trypsin Digestion: Reduce, alkylate, and digest proteins with sequencing-grade trypsin (1:50 w/w) at 37°C for 16 hours [21].

diGly Peptide Immunoaffinity Enrichment: Incubate digested peptides with anti-diGly lysine monoclonal antibody-conjugated beads for 2 hours at 4°C [21].

Peptide Cleanup: Wash beads extensively with ice-cold PBS and elute diGly-modified peptides with 0.2% trifluoroacetic acid [21].

LC-MS/MS Analysis: Separate peptides using reverse-phase C18 chromatography coupled to a high-resolution mass spectrometer operating in data-dependent acquisition mode [21].

Data Processing: Identify diGly sites using database search algorithms (e.g., MaxQuant, Spectrum Mill) with the following parameters:

- Variable modification: GlyGly (K) (+114.04293 Da)

- Fixed modification: Carbamidomethyl (C)

- Mass tolerance: 20 ppm for MS1, 0.6 Da for MS2 [21]

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for DiGly Proteomics

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-K-ε-GG Monoclonal Antibody | Immunoaffinity enrichment of diGly-modified peptides | Clone: N/A; Isotype: Rabbit IgG [21] |

| Sequencing-grade Trypsin | Protein digestion to generate diGly-containing peptides | Specificity: C-terminal to Lys/Arg; Activity: >90% [21] |

| C18 Reverse-phase Columns | Peptide separation prior to MS analysis | Particle size: 1.9μm; Pore size: 120Å [21] |

| High-resolution Mass Spectrometer | Identification and quantification of diGly peptides | Configuration: LC-MS/MS with Orbitrap detection [21] |

This approach enabled identification of approximately 19,000 diGly-modified lysine residues within ~5,000 human proteins, providing the first comprehensive view of the human ubiquitinome [21]. Quantitative diGly proteomics further revealed distinct kinetic classes of ubiquitinated substrates and established that ubiquitinome formation largely depends on ongoing protein synthesis [21].

Functional Analysis of Ubiquitin Recycling

The classic Doa4 study established a robust experimental framework for assessing DUB function in ubiquitin recycling [19]. This methodology combines genetic, biochemical, and cell biological approaches to quantify ubiquitin stability and turnover.

Protocol: Assessing Ubiquitin Recycling Function

Strain Construction: Generate DUB deletion mutants in appropriate genetic backgrounds (e.g., doa4Δ in S. cerevisiae) [19].

Growth Condition Optimization: Culture wild-type and mutant strains in rich (YPD) or defined minimal media to appropriate densities, noting particular sensitivity in stationary phase [19].

Ubiquitin Immunoblot Analysis:

- Prepare protein extracts using trichloroacetic acid precipitation

- Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE (15% gels optimal for ubiquitin separation)

- Transfer to PVDF membranes and probe with anti-ubiquitin antibodies

- Quantify free ubiquitin levels by densitometry [19]

Pulse-Chase Analysis of Ubiquitin Turnover:

- Metabolically label cells with 35S-methionine/cysteine for 10 minutes

- Chase with excess unlabeled methionine/cysteine

- Collect samples at timepoints (0, 30, 60, 120, 240 minutes)

- Immunoprecipitate ubiquitin and quantify radioactivity by scintillation counting [19]

Genetic Suppression Analysis: Introduce ubiquitin overexpression constructs or mutations in proteasome/vacuolar degradation components to test for functional rescue [19].

Key experimental observations from Doa4 studies:

- doa4Δ mutants show accelerated ubiquitin degradation compared to wild-type cells

- Ubiquitin half-life decreases from >10 hours in wild-type to ~2 hours in doa4Δ mutants

- Ubiquitin depletion precedes cell viability loss in stationary phase

- Synthetic lethality with proteasome impairment demonstrates functional interaction [19]

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Assessing Ubiquitin Recycling. Pulse-chase analysis combined with immunoprecipitation enables quantification of ubiquitin stability in DUB-deficient cells.

Research Reagent Solutions for DUB Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for DUB Functional Analysis

| Category | Specific Reagents | Research Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| DUB Activity Probes | HA-Ub-VS, HA-Ub-PA | Activity-based protein profiling | Covalently label active site cysteine of multiple DUB families [22] |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Reagents | K48-, K63-linked ubiquitin chains | In vitro DUB specificity assays | Defined chain topology to determine linkage preference [20] |

| DUB Inhibitors | IU1 (USP14 inhibitor), Vialinin A (USP4/5 inhibitor) [18] | Functional perturbation studies | Selective inhibition to probe physiological functions [18] [22] |

| Genetic Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 knockout constructs, DUB-specific shRNAs | Loss-of-function studies | Enable targeted genetic disruption in cells and model organisms [18] |

| Expression Systems | Ubiquitin overexpression plasmids, Inducible DUB constructs | Rescue experiments and mechanistic studies | Permit controlled expression in various cellular contexts [19] |

Implications for Therapeutic Development

The core functions of DUBs represent attractive therapeutic targets for various human diseases. DUBs implicated in cancer, including USP1, USP7, USP14, and USP30, have prompted development of small-molecule inhibitors now in preclinical and clinical evaluation [22]. Understanding DUB functions in ubiquitin precursor processing, chain editing, and recycling provides foundational knowledge for rational drug design targeting the ubiquitin system.

Emerging therapeutic strategies include:

- PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras): Leverage ubiquitin system for targeted protein degradation

- DUBTACs (Deubiquitinase-Targeting Chimeras): Recruit DUBs to stabilize target proteins [22]

- Allosteric DUB inhibitors: Exploit regulatory mechanisms to achieve specificity

The quantitative methodologies and functional insights described in this guide provide the necessary framework for advancing both basic research and therapeutic development targeting DUB functions in ubiquitin homeostasis.

Ubiquitin signaling is a dynamic, reversible process central to eukaryotic cell regulation, controlling protein stability, localization, and activity. The free ubiquitin pool—unconjugated ubiquitin available for covalent attachment to substrates—must be tightly maintained to ensure cellular homeostasis. Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) are pivotal in this process, counterbalancing ubiquitin conjugation by removing ubiquitin from substrates, recycling ubiquitin from proteasomal degradation, and processing ubiquitin precursors [17] [4]. This review examines the mechanisms by which DUBs regulate ubiquitin homeostasis, their roles in stress responses and disease, and experimental approaches to study these processes.

The Ubiquitin Cycle: Conjugation and Deconjugation

Ubiquitination involves a cascade of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes that attach ubiquitin to substrates via isopeptide bonds. Polyubiquitin chains formed through lysine linkages (e.g., K48 for proteasomal degradation, K63 for signaling) encode diverse functional outcomes [17] [18]. DUBs reverse this process by cleaving ubiquitin from substrates or disassembling chains, thereby recycling ubiquitin and shaping ubiquitin signals. The balance between ubiquitination and deubiquitination allows cells to adapt to environmental changes, such as oxidative stress or proteotoxic challenge [17] [18].

Key Functions of DUBs in Ubiquitin Homeostasis:

- Ubiquitin Recycling: DUBs like USP14 and UCH37 prevent ubiquitin degradation by cleaving it from proteasome-bound substrates, replenishing the free ubiquitin pool [23] [4].

- Precursor Processing: Ubiquitin is synthesized as fusion proteins (e.g., UBB, UBA80); DUBs cleave these into active monomers [17].

- Signal Proofreading: DUBs edit ubiquitin chains to correct erroneous ubiquitination and regulate pathway specificity [4].

DUBs are classified into cysteine proteases (e.g., USP, UCH, OTU, MJD families) and metalloproteases (JAMM/MPN+ family). Humans encode ∼100 DUBs, each with distinct substrate and linkage preferences [17] [18]. The table below summarizes key DUBs involved in ubiquitin homeostasis.

Table 1: DUB Families and Their Roles in Ubiquitin Homeostasis

| DUB Family | Representative Members | Ubiquitin Linkage Specificity | Homeostatic Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| USP | USP14, USP8 | Broad (K48, K63) | Proteasomal recycling; receptor endocytosis [17] [23] |

| UCH | UCHL1, UCHL5 | Small ubiquitin adducts | Ubiquitin precursor processing [4] |

| OTU | A20, OTUD1 | K63, K48 | NF-κB regulation; oxidative stress response [17] [18] |

| MJD | ATXN3, ATXN3L | K48, K63 | Protein quality control; ER-associated degradation [17] |

| JAMM/MPN+ | RPN11, AMSH | K63 | Proteasomal degradation; endosomal sorting [17] |

Mechanisms of DUB Regulation

DUB activity is finely tuned to maintain ubiquitin homeostasis under varying conditions. Key regulatory mechanisms include:

- Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs): Phosphorylation or oxidation can activate or inhibit DUBs. For example, reactive oxygen species (ROS) oxidize the catalytic cysteine of cysteine proteases, transiently inhibiting them during stress [17] [18].

- Protein-Protein Interactions: Binding partners localize DUBs to specific substrates. USP8 interacts with endosomal proteins to deubiquitinate receptors like EGFR, enabling receptor recycling [17] [18].

- Subcellular Localization: DUBs such as USP30 are mitochondrial; their mislocalization disrupts ubiquitin-dependent quality control [18].

Diagram: DUB Regulation by Oxidative Stress

Title: ROS-Induced DUB Inhibition Disrupts Ubiquitin Homeostasis

Experimental Models for Studying Ubiquitin Homeostasis

In Vitro and Cellular Assays

- CRISPR-Cas9 Screens: Identify DUBs and E3 ligases involved in ubiquitin dynamics. For example, knockout of RNF19A or UBE2L3 reveals roles in small-molecule ubiquitination [24].

- Immunoblotting and Mass Spectrometry: Detect ubiquitin conjugates and free ubiquitin levels. Use antibodies specific to linkage types (e.g., K48 vs. K63) [23] [25].

- Ubiquitin-Proteasome Function Assays: Monitor proteasome activity and ubiquitin turnover using fluorescent substrates (e.g., GFP-u).

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitin Homeostasis Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 KO | Gene knockout | Validating RNF19A role in BRD1732 cytotoxicity [24] |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Detect chain types | Quantifying K48/K63 chains in synaptic fractions [23] |

| LC-MS/MS | Identify ubiquitin adducts | Confirming BRD1732-ubiquitin conjugation [24] |

| Transgenic Complementation | Restore ubiquitin expression | Rescuing axJ mice with neuronal ubiquitin [23] |

| Small-Molecule Inhibitors | Target specific DUBs | IU1 (USP14 inhibitor) to study proteasome function [18] |

In Vivo Models

- Usp14-Deficient (axJ) Mice: Exhibit ubiquitin depletion, synaptic dysfunction, and lethality. Neuronal expression of ubiquitin transgenes rescues these defects, demonstrating the link between DUBs and ubiquitin pool maintenance [23].

- ALS Models: Neuronal cells expressing mutant TDP-43 or FUS show disrupted ubiquitin homeostasis, with ubiquitin sequestered in inclusions and free pools depleted [25].

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Analyzing Ubiquitin Pools

Title: Workflow for Ubiquitin Pool Analysis

Pathological Implications and Therapeutic Targeting

Dysregulation of DUBs and ubiquitin homeostasis contributes to diseases:

- Neurodegeneration: In axJ mice, loss of USP14 reduces free ubiquitin, impairing synaptic development. Ubiquitin supplementation reverses this [23]. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) models show ubiquitin sequestration in aggregates, depleting free pools [25].

- Cancer: Altered DUB activity (e.g., A20 in NF-κB signaling) promotes tumorigenesis by disrupting ubiquitin-dependent degradation of oncoproteins [17].

- Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury: DUBs like OTUD1 and USP16 modulate oxidative stress and cell death pathways, making them therapeutic targets [18].

Therapeutic Strategies:

- Small-Molecule Inhibitors: Vialinin A (targeting USP) and IU1 (USP14-specific) modulate ubiquitin dynamics [18].

- Gene Therapy: Overexpression of A20 or silencing of BRCC3 in stroke models improves outcomes [18].

DUBs are master regulators of ubiquitin homeostasis, integrating environmental cues to maintain free ubiquitin pools. Advanced tools—including linkage-specific probes, CRISPR screens, and multi-omics—will unravel DUB functions in spatiotemporal contexts. Targeting DUBs offers promise for treating neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and metabolic disorders, but requires overcoming challenges in specificity and drug delivery.

Ubiquitin homeostasis is a critical cellular process maintained by the balanced actions of ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs). The human genome encodes over 90 DUBs that fall into five primary structural classes: ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), ovarian tumor proteases (OTUs), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), Josephin (MJD) cysteine proteases, and the Jab1/Mov34/Mpr1 (JAMM) metalloproteases [26]. These enzymes hydrolyze isopeptide or peptide linkages joining ubiquitin to substrate lysines or N-termini, thereby playing a fundamental role in ubiquitin signaling pathways [26]. DUBs regulate virtually all cellular processes by controlling the stability, activity, localization, and interactions of target proteins, making their regulatory mechanisms essential for understanding ubiquitin homeostasis in health and disease [10] [26].

The regulation of DUB activity is multifaceted, ensuring precise control over biological responses. Cells employ multiple mechanisms to regulate DUB activity and specificity, including partner interactions, post-translational modifications, and substrate-induced activation [26]. These regulatory modes enable DUBs to integrate diverse cellular signals and respond appropriately to maintain proteostatic balance. Dysregulation of these mechanisms contributes to various pathologies, including cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and metabolic disorders, highlighting the therapeutic potential of targeting DUB regulatory mechanisms [27] [10] [28]. This review examines the core regulatory principles governing DUB function within the context of ubiquitin homeostasis, with emphasis on the interplay between different regulatory modes.

Partner Interactions in DUB Regulation

Mechanisms of Partner-Mediated Regulation

Protein-protein interactions play a fundamental role in modulating DUB activity, specificity, and subcellular localization. A defining characteristic of DUBs is that many are found in complex with other proteins, forming regulatory modules that precisely control ubiquitin signaling [26]. These interactions can activate intrinsic enzymatic activity, suppress DUB function, or target DUBs to specific substrates and cellular compartments. Many DUBs exhibit weak basal isopeptidase activity that is significantly enhanced upon binding to regulatory subunits [26]. For instance, the yeast USP class enzyme Ubp8 requires incorporation into the SAGA transcriptional coactivator complex for full enzymatic competence, demonstrating how complex formation can activate dormant DUB potential [26].

Conversely, binding to partner proteins can also downregulate DUB activity, providing a mechanism for signal-dependent inhibition. This regulatory principle is observed in multiple DUB families and often involves autoinhibitory conformations that are stabilized by interacting proteins. The functional outcome of partner interactions is frequently determined by cellular context, with the same DUB sometimes exhibiting opposite regulatory patterns in different tissues or disease states [10]. USP9X exemplifies this context-dependent regulation, acting as a tumor suppressor in some pancreatic cancer models while promoting tumor cell survival in others [10].

Table 1: Representative DUBs Regulated by Protein Partner Interactions

| DUB | Regulatory Partner | Effect on Activity | Biological Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubp8 | SAGA complex | Activation | Transcriptional regulation |

| USP7 | GMP synthase | Activation | Stress response, DNA damage |

| USP33 | Unknown partners | Context-dependent | Pancreatic cancer progression |

| USP9X | LATS kinase/Hippo pathway | Suppression | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| OTULIN | LUBAC complex | Modulation | TNF signaling, inflammation |

E2-E3-DUB Complexes in Ubiquitin Homeostasis

An intriguing observation from proteomic studies is that many DUBs form stable complexes with E3 ligases, while some also associate with E2 enzymes [26]. These associations suggest coregulation of ubiquitin conjugation and removal, representing a fundamental principle in ubiquitin homeostasis. The spatial and functional coupling of opposing enzymatic activities enables rapid, localized tuning of ubiquitination states in response to cellular signals. For example, USP15 forms complexes with ALK3/BMPR1A to enhance bone morphogenetic protein signaling by counteracting ligand-induced ubiquitination [14]. Similarly, USP7 forms regulatory networks with multiple E3 ligases including MDM2 to control p53 stability and function [26] [29].

The molecular mechanisms through which partner interactions regulate DUB activity include allosteric activation, substrate targeting, and subcellular compartmentalization. Structural studies have revealed that binding partners can induce conformational changes that realign catalytic residues into productive orientations or remove autoinhibitory constraints. Additionally, interacting proteins can direct DUBs to specific subcellular locales or substrate pools, effectively concentrating DUB activity where needed. This targeting function is particularly important for DUBs with broad substrate specificity, as it enables context-dependent regulation of specific pathways without globally affecting ubiquitination states.

Post-Translational Modifications of DUBs

Phosphorylation and Oxidation Mechanisms

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) represent a versatile mechanism for rapid regulation of DUB activity, stability, and interactions. More than 650 types of protein modifications have been described, including phosphorylation, ubiquitination, glycosylation, methylation, SUMOylation, and redox modifications [27]. These PTMs can occur on specific amino acids within regulatory domains of DUBs, controlling their function by inducing conformational changes, creating docking sites for interacting proteins, or targeting DUBs for degradation [29].

Phosphorylation is among the most prevalent PTMs regulating DUB function, occurring most commonly on serine residues (86.4%), followed by threonine (11.8%) and tyrosine (1.8%) [27]. Phosphorylation can either activate or inhibit DUB activity depending on the cellular context and modification site. For instance, phosphorylation of USP7 within its C-terminal ubiquitin-like domain (HUBL) enhances its affinity for ubiquitin and promotes catalytic activity by stabilizing an active conformation of the enzyme [26]. Conversely, phosphorylation of other DUBs can create degrons that target them for proteasomal degradation, effectively reducing cellular DUB capacity.

Oxidative regulation represents another important layer of DUB control, particularly under stress conditions. Most DUBs are cysteine proteases with active site cysteines that are potentially susceptible to oxidation by reactive oxygen species. Several DUBs, including the OTU protein A20 and USP class enzymes like USP1, undergo reversible oxidation of the cysteine sulfhydryl to sulphenic acid, leading to enzyme inactivation [26]. This oxidative regulation may function as a protective mechanism, reducing DUB activity under high oxidative stress to prevent inappropriate protein stabilization. The susceptibility to oxidation varies among DUBs, with some enzymes exhibiting protective mechanisms such as active site misalignment that reduces cysteine reactivity in the absence of substrate [26].

Table 2: Post-Translational Modifications Regulating DUB Activity

| PTM Type | Target DUBs | Functional Consequences | Regulatory Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorylation | USP7, USP1, A20 | Altered activity, stability, localization | Kinases, Phosphatases |

| Oxidation | USP1, A20, OTU DUBs | Reversible inactivation | ROS, Redox enzymes |

| Ubiquitination | Multiple DUBs | Altered stability, activity | E3 ligases, Other DUBs |

| Acetylation | Undefined DUBs | Potential activity modulation | Acetyltransferases, Deacetylases |

PTM Crosstalk in DUB Regulation

Multiple PTMs often coordinate to determine functional outcomes through a phenomenon known as PTM crosstalk [30]. This crosstalk can involve identical or different modification types and occurs preferentially in intrinsically disordered protein regions where most PTM sites are located [30]. The functional consequences of PTM crosstalk depend on a complex combination of the number, positioning, and type of modifications. Multiple PTMs can mediate the same, complementary, or opposing effects, with the ratio of different modifications determining the biological outcome at a given time [30].

PTM crosstalk can affect DUB function through several mechanisms. Multiple modifications can synergize to shift the conformational equilibrium of the modified protein, modulating its interaction with partners or formation of higher-order assemblies [30]. For instance, phosphorylation and acetylation often work in concert to regulate protein stability and activity. Additionally, PTMs can act antagonistically, where one modification blocks the addition or function of another. This competitive regulation is observed in the histone code but applies equally to non-histone proteins including DUBs. The interplay between phosphorylation and ubiquitination is particularly relevant, with proteome-wide studies revealing that approximately 20% of detected phosphoproteins are simultaneously ubiquitinated, with phosphorylation sites likely to regulate ubiquitination being closer to ubiquitination sites and more evolutionarily conserved [29].

Substrate-Induced Activation Mechanisms

Structural Rearrangements in Catalytic Sites

Substrate-induced activation represents a sophisticated regulatory mechanism that ensures DUB activity only in the presence of appropriate substrates. Structural studies have revealed that many DUBs possess misaligned or occluded active sites in their apo states that must undergo rearrangements to accommodate substrates [26]. This requirement for substrate-induced alignment of active site residues was first demonstrated for USP7 (HAUSP), where the catalytic cysteine and histidine residues adopt a nonproductive conformation in the apoenzyme [26]. Ubiquitin binding triggers a significant conformational rearrangement that properly orients these residues for catalysis, effectively coupling substrate recognition with enzyme activation [26].

The molecular details of substrate-induced activation vary among DUB families. For OTULIN, an OTU class DUB that specifically cleaves linear ubiquitin chains, the catalytic histidine is misaligned in the apoenzyme but is coaxed into position by specific interactions with the N-terminal methionine of the proximal ubiquitin [26]. This mechanism ensures exquisite specificity for linear ubiquitin chains, as the required interactions are unique to this linkage type. Similarly, OTUB1 and OTUD2 employ substrate-induced conformational changes to achieve their distinct linkage specificities for K48- and K11-linked polyubiquitin chains, respectively [26]. Beyond ensuring specificity, the requirement for substrate-induced activation may protect DUBs from oxidative damage and inappropriate activity by reducing the reactivity of the catalytic cysteine in the absence of cognate substrates [26].

Allosteric Regulation and Linkage Specificity

Allosteric regulation plays a crucial role in substrate-induced DUB activation. Many DUBs contain allosteric sites distinct from their catalytic centers that, when occupied, induce conformational changes that enhance catalytic efficiency. The C-terminal ubiquitin-like (HUBL) domain of USP7 represents a classic example of allosteric regulation, where domain-domain interactions between the HUBL and catalytic domains increase affinity for ubiquitin and stimulate catalysis [26]. This stimulatory effect is mediated by a "switching loop" adjacent to the active site that governs the configuration of catalytic residues [26]. Small molecules and protein partners can further modulate these allosteric networks, adding layers of regulatory complexity.

Linkage specificity is a hallmark of many DUBs, particularly those in the OTU family, which exhibit remarkable selectivity for cleaving polyubiquitin chains with particular linkage types [26]. This specificity is achieved through a combination of substrate-induced active site rearrangements and specialized recognition domains that distinguish between different ubiquitin linkage architectures. OTULIN's specificity for linear ubiquitin chains, for instance, depends on recognition of Glu16 in the proximal ubiquitin, which orients catalytic residues and promotes the active conformation [26]. The structural basis for linkage specificity continues to be an active area of investigation, with implications for understanding how DUBs decode the complex language of ubiquitin signals in cells.

Experimental Approaches for Studying DUB Regulation

Methodologies for Analyzing Partner Interactions

Identifying and characterizing DUB-interacting proteins is essential for understanding regulatory mechanisms. Affinity purification coupled with mass spectrometry (AP-MS) has proven invaluable for mapping DUB interaction networks under various physiological conditions [26]. This approach involves expressing tagged DUBs in cells, purifying associated complexes under native conditions, and identifying co-purifying proteins by mass spectrometry. Quantitative AP-MS using stable isotope labeling can further reveal dynamic changes in DUB complexes in response to cellular signals. For validation, co-immunoprecipitation and Western blotting provide orthogonal confirmation of specific interactions, while crosslinking strategies can capture transient or weak associations.

Structural biology approaches are crucial for elucidating the molecular mechanisms of partner-mediated regulation. X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy have revealed how partner binding induces conformational changes in DUBs, realigns active site residues, or modulates substrate access [26]. For example, structural studies of USP7 in complex with its HUBL domain revealed how interdomain contacts allosterically activate the enzyme [26]. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is particularly powerful for studying dynamic aspects of DUB regulation, capturing conformational fluctuations and mapping interaction surfaces with residue-level resolution. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) provide quantitative information on binding affinities and thermodynamics, helping to dissect the energetic contributions of specific interactions.

Assessing PTM-Mediated Regulation

Comprehensive analysis of PTMs on DUBs requires specialized methodologies. Phosphoproteomics using titanium dioxide enrichment or phosphotyrosine-specific antibodies enables system-wide identification and quantification of phosphorylation sites [30] [29]. For redox-sensitive DUBs, differential alkylation-based methods coupled with mass spectrometry can map specific cysteine oxidation events and quantify their stoichiometry under different oxidative conditions [26]. To study PTM crosstalk, sequential enrichment strategies can be employed to capture multiple modification types from the same sample, revealing coordinated regulation [30].

Functional characterization of PTMs requires complementary approaches. Site-directed mutagenesis to create phosphorylation-defective (e.g., serine-to-alanine) or phosphomimetic (serine-to-aspartate/glutamate) mutants allows assessment of how specific modifications affect DUB activity, stability, and interactions [30]. Pharmacological or genetic manipulation of modifying enzymes (kinases, phosphatases, oxidoreductases) can establish causal relationships between PTMs and functional outcomes. Activity-based probes (ABPs) that form covalent bonds with active DUBs are particularly valuable for monitoring changes in catalytic activity in response to PTMs or cellular stimuli [28]. These probes can be used in cellular lysates or live cells to provide a direct readout of functional DUB pools.

Diagram Title: Substrate-Induced Activation Mechanism of DUBs

Research Reagent Solutions for DUB Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying DUB Regulation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity-Based Probes | HA-Ub-VS, Ub-AMC | Profiling active DUBs, inhibitor screening | Covalently labels active site cysteine, fluorescence-based activity measurement |

| DUB Inhibitors | P22077 (USP7 inhibitor), IU1 (USP14 inhibitor) | Functional validation, therapeutic exploration | Selective inhibition of specific DUB family members |

| Ubiquitin Variants | K48-, K63-linked diUb, linear diUb | Linkage specificity assays, kinetic studies | Substrates for determining DUB specificity and catalytic efficiency |

| Tagged Ubiquitin | His-Ub, HA-Ub, GFP-Ub | Pull-down assays, cellular localization | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins, visualization of ubiquitin dynamics |

| PTM Detection Reagents | Phospho-specific antibodies, ROS sensors | PTM mapping, oxidative regulation studies | Detection and quantification of specific PTMs on DUBs |

| Structural Biology Tools | Crystallization screens, NMR isotopes | Mechanistic studies, structure determination | Elucidation of DUB structures and conformational changes |

The research reagents listed in Table 3 represent essential tools for investigating DUB regulatory mechanisms. Activity-based probes (ABPs) like HA-Ub-VS contain a C-terminal vinyl sulfone group that covalently traps active DUBs, enabling profiling of functional enzymes across different cellular conditions [28]. These probes can be used for competitive screening of DUB inhibitors and for assessing how regulatory mechanisms affect catalytic competence. Linkage-specific ubiquitin variants are crucial for determining DUB specificity and understanding how regulatory inputs might alter preference for certain ubiquitin chain types. For cellular studies, inducible expression systems for wild-type and mutant DUBs allow functional characterization without confounding effects of endogenous enzymes.

Advanced reagent development continues to enhance our ability to study DUB regulation. Photo-crosslinkable ubiquitin variants can capture transient DUB-substrate interactions, while FRET-based ubiquitin sensors enable real-time monitoring of DUB activity in live cells. For structural studies, segmental isotopic labeling of DUBs facilitates NMR analysis of large, multi-domain enzymes and their complexes. The ongoing development of more selective DUB inhibitors, including allosteric compounds that target regulatory sites rather than catalytic centers, provides both research tools and potential therapeutic leads [10] [28] [15].

Concluding Perspectives

The regulatory mechanisms governing DUB function—partner interactions, post-translational modifications, and substrate-induced activation—represent interconnected layers of control that ensure precise regulation of ubiquitin homeostasis. These mechanisms enable cells to dynamically adjust DUB activity in response to physiological needs and stress conditions, maintaining appropriate balance in ubiquitin signaling networks. Understanding these regulatory principles provides fundamental insights into cellular proteostasis and reveals potential therapeutic opportunities for diseases characterized by ubiquitin pathway dysregulation.

Future research directions include elucidating the complete regulatory networks controlling major DUB families, developing chemical tools to selectively modulate regulatory sites rather than catalytic centers, and understanding how different regulatory modes integrate to control DUB function in specific cellular contexts. The therapeutic targeting of DUB regulatory mechanisms holds particular promise, as evidenced by preclinical studies showing efficacy of DUB inhibitors in cancer, osteoarthritis, and diabetic nephropathy models [10] [28] [15]. As our understanding of DUB regulation deepens, so too will our ability to therapeutically manipulate these important enzymes for human health benefit.

Profiling DUB Activity and Accelerating Therapeutic Discovery

Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) and covalent library screening represent complementary technological paradigms for interrogating enzyme function and discovering chemical probes. These approaches are particularly valuable for investigating deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), a class of approximately 100 proteases that hydrolytically remove ubiquitin from substrate proteins to maintain ubiquitin homeostasis. DUBs constitute promising therapeutic targets in multiple pathological conditions, including pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), where they regulate proliferation, metastasis, metabolic reprogramming, and chemoresistance [10]. This technical guide examines the core principles, methodological frameworks, and practical implementation of ABPP and covalent screening platforms, with emphasis on their application to DUB research and drug discovery.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a crucial regulatory mechanism in cellular physiology, controlling protein degradation, signal transduction, DNA repair, and immune responses. Ubiquitination involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to target proteins via a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes [10] [31]. Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) perform the reverse reaction, specifically cleaving ubiquitin moieties from modified substrates to precisely control protein stability, localization, and activity [10].

DUBs are classified into six major families based on sequence and structural homology: ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), ovarian tumor proteases (OTUs), ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), Machado–Josephin domain-containing proteases (MJDs), motif-interacting with ubiquitin-containing novel DUB family (MINDYs), and JAB1/MPN/MOV34 family metalloenzymes (JAMMs) [10] [31]. These enzymes maintain ubiquitin homeostasis by recycling ubiquitin, editing ubiquitin chains, and rescuing proteins from proteasomal degradation.

Dysregulation of DUB activity contributes significantly to disease pathogenesis, particularly in cancer. For instance, in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), multiple DUBs including USP28, USP21, USP34, and USP9X drive tumor progression through distinct mechanisms [10]. This established pathological significance has intensified interest in DUBs as therapeutic targets, necessitating advanced screening platforms for functional characterization and inhibitor discovery.

Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP): Fundamental Principles

Conceptual Framework and Historical Development

Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) is a chemical proteomic methodology that utilizes active site-directed covalent probes to directly monitor enzyme function in complex biological systems [32] [33]. Unlike conventional genomic or proteomic approaches that measure abundance, ABPP reports directly on enzyme activity state, providing functional insights that transcend transcription or translation levels.

The foundational ABPP workflow involves three key components:

- Activity-based probes (ABPs): Chemical reagents containing a reactive warhead that covalently targets enzyme active sites, a linker region, and a reporter tag for detection and enrichment [33].

- Bioorthogonal conjugation: Incorporation of small, minimally perturbing tags (e.g., alkynes, azides) that enable subsequent chemoselective ligation to reporters after the labeling reaction [33].

- Multiplexed analysis: Detection, quantification, and identification of labeled enzymes using analytical platforms such as fluorescent gel electrophoresis or mass spectrometry-based proteomics [32].

Originally developed to profile enzyme activities in a family-specific manner, ABPP has evolved into a versatile platform for global proteome-wide mapping of small molecule-protein interactions, including those involving non-enzymatic targets [32].

ABPP Methodology and Experimental Workflow

The standard ABPP protocol involves sequential steps performed in intact biological systems or in cell lysates:

Step 1: In vivo or in vitro labeling Living cells, tissues, or whole organisms are treated with ABPs, which penetrate compartments and covalently modify active enzymes. Alternatively, cell or tissue lysates can be incubated with ABPs under controlled conditions [33].

Step 2: Cell lysis and protein extraction Following labeling, cells are lysed, and proteins are extracted to create a representative mixture of the cellular proteome.

Step 3: Bioorthogonal conjugation If "clickable" ABPs containing alkynes or azides are used, reporter tags (e.g., fluorophores, biotin) are attached via copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) or strain-promoted variants [33].

Step 4: Analysis and target identification Labeled proteins are separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized in-gel for fluorescent tags, or enriched via streptavidin capture (for biotinylated probes) and identified by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [32] [33].

For competitive ABPP applications, test compounds are incubated with the biological system prior to ABP treatment. Compounds that engage enzyme active sites will reduce subsequent ABP labeling, enabling quantification of target engagement and inhibition potency directly in native systems [32].

The following diagram illustrates the core ABPP workflow for competitive screening:

Covalent Library Screening: Targeted Ligand Discovery

Rationale for Covalent Compound Collections

Covalent library screening employs collections of small molecules designed to form reversible or irreversible covalent bonds with nucleophilic residues in protein binding pockets, most commonly cysteine, but also serine, lysine, tyrosine, and other residues [32]. These libraries feature diverse electrophilic "warheads" that exhibit preferential reactivity toward specific amino acids, enabling targeted interrogation of distinct enzyme families.

The strategic advantages of covalent screening include:

- Enhanced screening efficiency: Increased effective potency through prolonged target engagement

- Access to unique pockets: Targeting of non-conserved nucleophilic residues outside canonical active sites

- Interrogation of challenging targets: Disruption of protein-protein interactions and allosteric modulation

- Simplified assessment of target engagement: Direct measurement of covalent adduct formation

Modern covalent libraries incorporate carefully optimized warheads that balance reactivity with selectivity, minimizing non-specific protein modification while enabling efficient target labeling [34].

Covalent Library Composition and Design

The Enamine Covalent Screening Library exemplifies contemporary library design principles, featuring 11,760 compounds with diverse, well-validated warhead types [34]. The table below summarizes the composition of a representative commercial covalent screening library:

Table 1: Composition of the Enamine Covalent Screening Library

| Library Component | Compound Count | Primary Warhead | Target Residues | Format Options |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete Covalent Library | 11,760 | Multiple types | Various | 384-well, 10 mM in DMSO |

| Acrylamides | 4,160 | Acrylamide | Cysteine | 384-well plates |

| Cyanacrylamides | 1,920 | Cyanacrylamide | Cysteine | 384-well LDV plates |

| Chloroacetamides | 1,200 | Chloroacetamide | Cysteine | 384-well plates |

| Vinyl Sulfones | 640 | Vinyl sulfone | Cysteine | 96-well plates |

| Formyl Boronates | 480 | Formyl boronate | Serine, Threonine | 384-well echo plates |

| Sulfonyl Fluorides | 640 | Sulfonyl fluoride | Tyrosine, Lysine, Serine | Various |

| Chloropropionamides | 560 | Chloropropionamide | Cysteine | Various |

Key design features of modern covalent libraries include:

- Validated warhead chemistry: Selection of electrophiles with demonstrated utility and characterized reactivity profiles

- Recognition elements: Incorporation of diverse "head groups" that provide binding affinity and selectivity

- Balanced reactivity: Exclusion of overly reactive warheads that promote non-specific labeling

- Structured organization: Plating by warhead class to facilitate structure-activity relationship analysis and mechanism deconvolution [34]

Integrated Screening Approaches for DUB Research

ABPP and Covalent Screening Synergy

The combination of ABPP and covalent library screening creates a powerful integrated platform for DUB ligand discovery and characterization. ABPP provides a uniform functional assay for diverse DUBs in native biological systems, while covalent libraries supply optimized starting points for inhibitor development [32].

This synergistic relationship operates through several mechanisms:

- Target validation: ABPP confirms DUB activity and engagement in physiological contexts

- Mechanistic deconvolution: Warhead-class specific screening facilitates understanding of inhibition mechanisms

- Selectivity profiling: Proteome-wide ABPP enables comprehensive assessment of inhibitor specificity

- Functional annotation: Discovery of ligands for uncharacterized DUBs facilitates biological investigation

For DUBs specifically, cysteine-directed ABPs and covalent libraries are particularly valuable, as most DUB families (USPs, OTUs, UCHs, MJDs, MINDYs) utilize catalytic cysteine residues in their hydrolytic mechanisms [10] [32].

Experimental Protocols for DUB Screening

Protocol 1: Competitive ABPP Screening with Covalent Libraries

This protocol describes a functional screen for DUB inhibitors using competitive ABPP:

Sample preparation:

- Prepare PDAC cell lysates or isolated DUB complexes in physiological buffer

- Distribute lysates into screening plates (5-10 µg protein per well)

Compound addition:

- Transfer covalent library compounds (typically 1-10 µM final concentration) using acoustic dispensing or pin tools

- Include DMSO-only controls for normalization and reference inhibitors for validation

- Incubate for 30-60 minutes at 37°C to allow target engagement

ABP labeling:

- Add cysteine-directed ABP (e.g., HA-Ub-VS, HA-Ub-amide) at predetermined concentration

- Incubate for 1-2 hours under native conditions

Detection and analysis:

- Resolve proteins by SDS-PAGE, transfer to membranes, and detect with anti-HA antibodies

- Alternatively, use fluorescent ABPs for direct in-gel visualization

- Quantify band intensity to determine inhibition efficiency

Hit validation:

Protocol 2: ABPP-Mediated Target Engagement in Live Cells

This protocol evaluates target engagement of covalent DUB inhibitors in cellular contexts:

Cell treatment:

- Culture PDAC cells under standard conditions

- Treat with test compounds (0.1-10 µM) for predetermined timepoints

In vivo labeling:

- Add cell-permeable ABP directly to culture medium

- Incubate for 1-4 hours under normal growth conditions

Sample processing:

- Harvest cells, wash with PBS, and lyse with mild detergent

- Centrifuge to remove insoluble material

Click chemistry conjugation (if required):

- Add fluorescent azide reporter, copper catalyst, and reducing agent

- Incubate with rotation for 1 hour at room temperature

Analysis:

The following diagram illustrates the integrated approach for DUB ligand discovery using ABPP and covalent libraries:

Research Reagent Solutions for DUB Screening

Successful implementation of ABPP and covalent screening platforms requires specialized reagents and materials. The following table catalogs essential research tools for DUB-focused screening campaigns:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for DUB Screening

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity-Based Probes | HA-Ub-VS, HA-Ub-amide, TAMRA-Ub-PA | DUB activity profiling, inhibitor screening | Pan-DUB labeling, fluorescent or epitope tags |

| Covalent Screening Libraries | Enamine Covalent Library (11,760 cmpds) | Initial hit discovery, SAR exploration | Diverse warheads, pre-plated formats |

| Warhead-Specific Sublibraries | Acrylamides (4,160 cmpds), Cyanacrylamides (1,920 cmpds) | Targeted screening, mechanism studies | Focused chemotypes, optimized reactivity |

| Detection Reagents | Anti-HA antibodies, Streptavidin-IRdye, Copper catalyst kits | ABP detection, chemoselective conjugation | High sensitivity, minimal background |

| Specialized Labware | 384-well Echo Qualified LDV plates, Greiner 765021 plates | Compound management, screening workflows | Acoustic compatibility, DMSO stability |

| Positive Control Inhibitors | PR-619, WP1130, G5, Capzimin | Assay validation, technology benchmarking | Broad-spectrum and selective DUB inhibitors |

These reagents collectively enable the design and execution of comprehensive DUB screening campaigns, from initial target validation through lead compound characterization.

Applications in PDAC and Therapeutic Development

The integration of ABPP and covalent screening has yielded significant insights into DUB biology and therapeutic potential, particularly in challenging malignancies like pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Key applications include:

Functional Characterization of PDAC-Associated DUBs

ABPP has enabled functional annotation of DUB activities in PDAC pathogenesis:

- USP28 promotes cell cycle progression and inhibits apoptosis by stabilizing FOXM1 to activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling [10]

- USP21 maintains PDAC stemness through TCF7 stabilization and promotes growth via MAPK3 binding and mTOR activation [10]

- USP34 facilitates PDAC cell survival through AKT and PKC pathways [10]

- USP9X demonstrates context-dependent roles, acting as both tumor promoter and suppressor in different PDAC models [10]

Therapeutic Targeting of DUBs in PDAC

Covalent screening has identified promising starting points for DUB-directed therapeutics:

- Selective USP7 inhibitors demonstrate antitumor activity in preclinical PDAC models