E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Mutations in Human Cancers: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targeting, and Clinical Implications

This review synthesizes current knowledge on the critical role of E3 ubiquitin ligase mutations in human carcinogenesis.

E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Mutations in Human Cancers: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targeting, and Clinical Implications

Abstract

This review synthesizes current knowledge on the critical role of E3 ubiquitin ligase mutations in human carcinogenesis. It explores how genetic alterations in these ligases, including members of the RING, HECT, and RBR families, disrupt vital cellular processes by misregulating oncoproteins and tumor suppressors. The article details advanced methodologies for studying these mutations, analyzes the challenges of drug resistance and optimizing targeted therapies like PROTACs, and evaluates emerging clinical strategies, including small-molecule inhibitors and degraders in development. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this work provides a comprehensive roadmap for translating the understanding of E3 ligase biology into novel cancer therapeutics.

The Ubiquitin System and E3 Ligase Families: A Primer on Structure, Function, and Oncogenic Dysregulation

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) is a highly selective, ATP-dependent mechanism that serves as the primary pathway for targeted protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, playing an indispensable role in maintaining cellular homeostasis [1]. This sophisticated system regulates the precise turnover of short-lived, misfolded, and damaged proteins, thereby influencing virtually every cellular process, including cell cycle progression, signal transduction, apoptosis, and DNA repair [2] [1]. The process begins with ubiquitination, a canonical post-translational modification where ubiquitin—a small, 76-amino acid protein that is highly conserved across eukaryotes—is covalently attached to a target protein substrate [2] [3]. This ubiquitin "tag" serves as a recognition signal for the 26S proteasome, which degrades the marked protein into small peptides, allowing for the recycling of amino acids [1].

The clinical and therapeutic relevance of the UPS is profoundly evident in cancer biology. Cancer cells frequently exhibit a heightened dependence on the UPS to rapidly degrade tumor suppressor proteins and cell-cycle regulators, facilitating their uncontrolled proliferation and survival [4] [1] [5]. Consequently, the UPS, and particularly the E3 ubiquitin ligases which confer substrate specificity, has emerged as a compelling target for anticancer drug development. The clinical success of proteasome inhibitors like bortezomib in treating hematological malignancies such as multiple myeloma has validated the UPS as a therapeutic target and spurred extensive research into more precise interventions, including small molecule inhibitors of specific E3 ligases and novel modalities like PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) [1] [5]. This review will delineate the core enzymatic cascade of the UPS, with a particular focus on the structure and function of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes, framing this molecular machinery within the context of E3 ligase mutations in human cancers.

The Ubiquitination Enzymatic Cascade

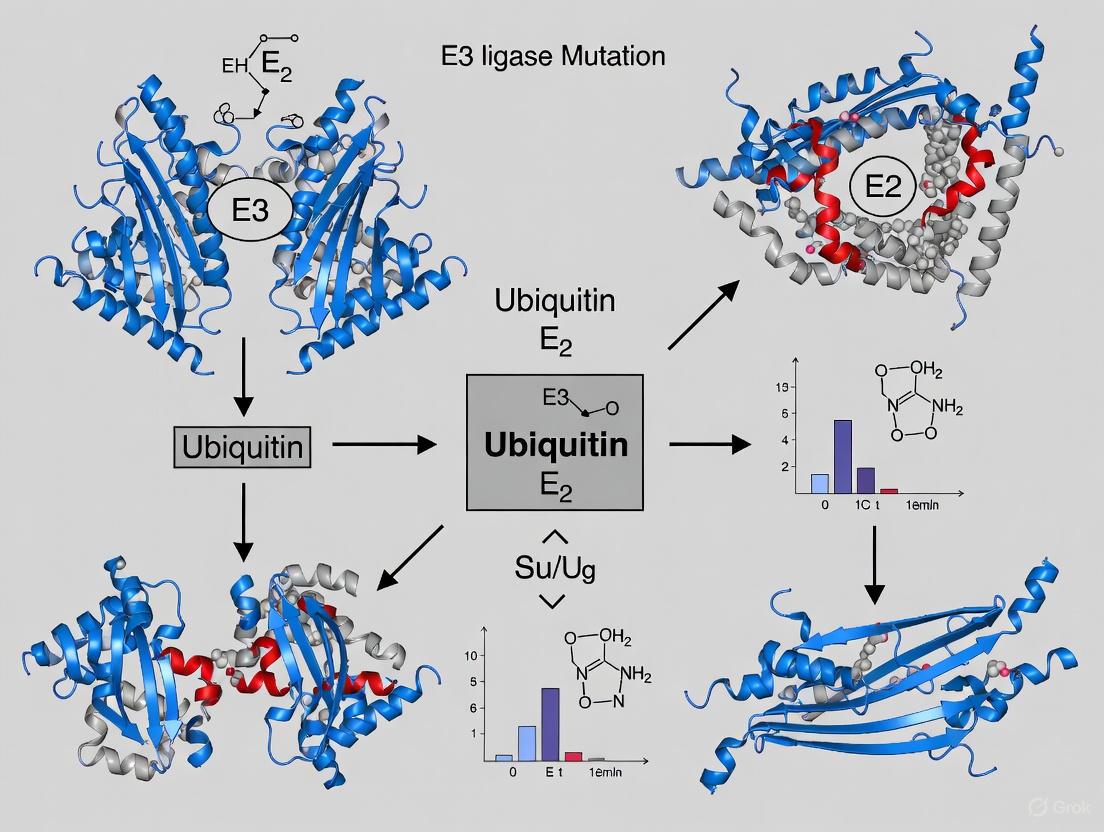

The conjugation of ubiquitin to a substrate protein is a three-step enzymatic cascade involving E1 (ubiquitin-activating), E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating), and E3 (ubiquitin-ligase) enzymes. The following diagram illustrates this sequence and the subsequent degradation of the tagged protein by the proteasome.

E1: Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme

The initial and committed step in the ubiquitination cascade is mediated by a single major E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme [6]. This step involves ATP-dependent activation of ubiquitin. The E1 enzyme hydrolyzes ATP to AMP and inorganic pyrophosphate, generating a high-energy thioester bond between its own active-site cysteine residue and the C-terminal glycine (Gly76) of ubiquitin [2] [7]. This E1~Ub intermediate represents an activated ubiquitin ready for transfer. The E1 enzyme then recruits an E2 conjugating enzyme and catalyzes the trans-thiolation of ubiquitin from its own active site to the active-site cysteine of the E2 [7]. Given its role as the apex of the entire UPS, inhibition of E1 activity leads to an almost immediate shutdown of global protein ubiquitination, highlighting its critical function in cellular homeostasis [7].

E2: Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme

The E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (also known as UBC) accepts the activated ubiquitin from E1 via a transthiolation reaction, forming a similar E2~Ub thioester intermediate [2] [3]. The human genome encodes approximately 40-50 E2 enzymes, which exhibit greater diversity than E1s but less than E3s [3]. E2s are characterized by a conserved catalytic core domain of about 150 amino acids that contains the active-site cysteine. While the E2~Ub complex is relatively stable, the transfer of ubiquitin to the final substrate is facilitated by an E3 ligase. The specific E2 involved in a reaction can influence the type of ubiquitin chain linkage formed on the substrate, thereby determining the fate of the modified protein [7]. E2s work in concert with specific E3 partners, and their interaction is crucial for efficient ubiquitination [8].

E3: Ubiquitin Ligase - The Specificity Factor

E3 ubiquitin ligases are the most diverse and pivotal components of the UPS, responsible for recognizing specific protein substrates and mediating the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine residue on the substrate [2] [4]. The human genome encodes over 600 E3 ligases, which allows for exquisite substrate specificity and precise regulation of a vast array of cellular processes [2] [4] [6]. E3s function as scaffolds that simultaneously bind to the E2~Ub complex and the target protein, bringing them into close proximity. Based on their structure and mechanism of ubiquitin transfer, E3 ligases are classified into three main families, as detailed in the table below.

Table 1: Classification and Features of Major E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Families

| E3 Family | Mechanism of Ubiquitin Transfer | Key Structural Domains | Representative Examples | Role in Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RING (Really Interesting New Gene) [4] [3] | Direct transfer from E2 to substrate; acts as a scaffold/catalyst. | RING finger domain (binds E2). | MDM2, BRCA1/BARD1, SCF complexes (e.g., SKP2), CRL complexes, APC/C [4] [3] [6]. | Largest family; frequent mutations (e.g., MDM2 amplification, FBXW7 loss) linked to tumorigenesis [4] [9]. |

| HECT (Homologous to E6AP C-terminus) [4] [3] | Two-step transfer: Ub is first transferred to a catalytic cysteine on HECT domain, then to substrate. | HECT domain at C-terminus. | NEDD4, E6AP, HERC family, SMURFs [4] [3]. | Regulates growth factor signaling & cell proliferation; implicated in various cancers [4] [10]. |

| RBR (RING-Between-RING) [3] [8] | Hybrid mechanism: RING1 binds E2~Ub, Ub transferred to cysteine in RING2, then to substrate (like HECT). | Two RING domains with a catalytic cysteine in the second. | Parkin, HOIP, HOIL-1 [3]. | Involved in neurodegen. and immune signaling; Parkin is a tumor suppressor [3]. |

The specificity of E3 ligases is achieved through the recognition of short, specific amino acid sequences or chemical motifs on the substrate known as degrons [6]. These include:

- Phosphodegrons: A degron that becomes active upon phosphorylation, a common mechanism for regulating cell cycle proteins [6].

- N-degrons: The N-terminal amino acid of a protein, according to the "N-end rule," can determine its stability [6].

- Oxygen-dependent degrons: As seen with VHL recognition of hydroxylated HIF-α under normoxic conditions [6].

- Misfolded and sugar degrons: Recognized by E3s involved in quality control, such as those in the ERAD pathway [6].

E3 Ligase Mutations in Human Cancers: Pathophysiology and Clinical Significance

The critical role of E3 ligases in maintaining cellular homeostasis is underscored by the fact that their dysregulation is a hallmark of many human cancers. Mutations in E3 ligases can lead to the aberrant stabilization of oncoproteins or the premature degradation of tumor suppressor proteins, thereby driving tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis [2] [4]. The following table summarizes prominent examples of E3 ligases implicated in cancer pathogenesis.

Table 2: E3 Ubiquitin Ligases Mutated in Human Cancers and Their Mechanisms

| E3 Ligase | Genetic Alteration | Affected Substrate(s) | Consequence & Associated Cancers |

|---|---|---|---|

| VHL (Von Hippel-Lindau) [2] | Loss-of-function mutation (Tumor Suppressor) | HIF-1α (Hypoxia-inducible factor) | HIF-1α stabilization → Uncontrolled expression of VEGF, EPO → Renal cell carcinoma, Hemangioblastoma [2]. |

| MDM2 [2] [6] | Amplification/Overexpression (Oncogenic) | p53 Tumor Suppressor | p53 degradation → Evasion of apoptosis & uncontrolled proliferation → Sarcoma, Glioblastoma [2] [6]. |

| FBXW7 (F-box/WD repeat) [4] [10] | Loss-of-function mutation (Tumor Suppressor) | c-Myc, Cyclin E, Notch, c-Jun | Oncoprotein stabilization → Sustained proliferation & genomic instability → Colorectal, breast, and gynecological cancers [4] [10]. |

| SKP2 [4] | Overexpression (Oncogenic) | p27Kip1 (CDK inhibitor) | p27 degradation → Unchecked cell cycle progression from G1 to S phase → Lymphoma, Prostate Cancer [4]. |

| BRCA1 [9] [6] | Loss-of-function mutation (Tumor Suppressor) | Multiple DNA repair proteins | Defective Homologous Recombination (HR) DNA repair → Genomic instability → Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer [9] [6]. |

The pathophysiology of these mutations is exemplified by VHL disease. The VHL protein is part of a CRL E3 complex that targets HIF-1α for degradation under normal oxygen conditions. When VHL is mutated, HIF-1α accumulates, leading to the transcriptional activation of genes promoting angiogenesis (e.g., VEGF) and cell growth, even in the presence of oxygen, thereby fostering a tumorigenic environment [2]. Similarly, in colorectal cancer, mutations in the APC (Adenomatous Polyposis Coli) tumor suppressor, a component of the β-catenin destruction complex, prevent the ubiquitination and degradation of β-catenin. This results in constitutive activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, driving uncontrolled cell proliferation [2] [10].

Beyond somatic mutations, the dysregulation of E3 ligases can also occur through altered expression, mislocalization, or changes in the activity of their regulatory partners. For instance, the E3 ligase TRIM6 promotes CRC proliferation by degrading the anti-proliferative protein TIS21, while ITCH suppresses proliferation by targeting CDK4 for degradation [10]. This dual role—where some E3s act as oncogenes and others as tumor suppressors—highlights their complex, context-dependent nature and underscores their potential as therapeutic targets.

Experimental Methodologies for Studying the UPS

Research into the UPS and E3 ligase function relies on a suite of sophisticated biochemical, genetic, and proteomic techniques. Below is a diagram and explanation of a key experimental workflow for identifying E3 substrates.

Key Experimental Protocols

In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

This biochemical assay reconstitutes the ubiquitination cascade using purified components to directly demonstrate that an E3 ligase can ubiquitinate a specific substrate [2]. The standard reaction mixture includes:

- Purified E1 activating enzyme.

- Purified E2 conjugating enzyme.

- Purified E3 ligase (the enzyme being studied).

- Purified substrate protein.

- Ubiquitin.

- ATP in an appropriate reaction buffer.

The reaction is incubated at 30°C, terminated by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer, and then analyzed by western blotting. A shift in the molecular weight of the substrate protein or the appearance of higher molecular weight smears indicates polyubiquitination. Using different ubiquitin mutants (e.g., lysine-less ubiquitin) can help determine the type of polyubiquitin chain formed [2].

Global Protein Stability (GPS) Profiling

This is a genome-wide screening strategy designed to identify novel substrates of E3 ligases [2]. The GPS system uses reporter proteins (e.g., fluorescent proteins) fused to hundreds of potential substrate proteins independently. When the E3 ligase of interest is inhibited (genetically or chemically), its true substrates accumulate, leading to increased reporter signal (e.g., fluorescence). By monitoring changes in reporter activity upon E3 perturbation, researchers can identify which proteins are potential substrates of that E3 ligase on a global scale [2].

shRNA or CRISPR-Cas9 Screening

Genetic screens using shRNA (short hairpin RNA) or CRISPR-Cas9 technology are powerful tools for identifying E3 ligase substrates and understanding their functional roles in a physiological context [2]. By knocking down or knocking out a specific E3 ligase in cells, researchers can monitor the resulting changes in the proteome (e.g., via mass spectrometry) or in specific phenotypic readouts (e.g., cell viability, DNA damage response). The stabilization of a protein upon E3 depletion strongly suggests it is a direct substrate. This approach has been instrumental in linking E3 ligases to specific cancer pathways [2] [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitination and UPS Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., Bortezomib, MG132) [1] [5] | Block degradation of ubiquitinated proteins by the proteasome, causing accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins. Used to demonstrate UPS-dependent degradation. |

| E1 Inhibitor (e.g., PYR-41, TAK-243) [7] | Inhibits the ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1, globally shutting down the UPS cascade. A tool for validating UPS-dependence. |

| Specific E3 Ligase Inhibitors (e.g., Nutlin-3 for MDM2) [4] | Small molecules that block the activity of specific E3 ligases, used to stabilize their substrates and as potential therapeutic agents. |

| Ubiquitin Mutants (K48R, K63R, K0) [3] | Used in in vitro assays to determine the type of ubiquitin linkage (e.g., K48 vs. K63) being formed on a substrate. |

| Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) [6] | Affinity reagents that bind polyubiquitin chains with high affinity, used to enrich and purify ubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates for proteomic analysis. |

| Deubiquitinating Enzyme (DUB) Inhibitors | Inhibit enzymes that remove ubiquitin, helping to stabilize ubiquitination events for easier detection. |

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System, with its sequential E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade, represents a master regulatory mechanism for controlling protein fate within the cell. The specificity afforded by the vast family of E3 ligases allows for precise temporal and spatial regulation of a myriad of substrates governing cell proliferation, DNA repair, and apoptosis. It is this very precision that, when corrupted by mutation or dysregulation, becomes a powerful driver of oncogenesis. The delineation of E3 ligase functions and substrates in cancers has not only deepened our understanding of tumor biology but has also opened up a rich landscape for therapeutic intervention. Moving beyond broad proteasome inhibitors, the future of UPS-targeting therapy lies in the development of highly specific small molecule inhibitors, activators, and molecular degraders (e.g., PROTACs) that target individual pathogenic E3 ligases or their substrates. As our experimental methodologies and molecular understanding continue to advance, so too will our ability to harness the UPS for innovative cancer treatments.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a crucial regulatory mechanism for intracellular protein levels, degrading misfolded, damaged, or short-lived proteins [11]. Ubiquitination involves a sequential enzymatic cascade: an E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme, an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, and an E3 ubiquitin ligase [11] [12]. E3 ligases confer substrate specificity and are pivotal in determining the fate of modified proteins, with misregulation linked to numerous human cancers [13] [12]. This review provides a mechanistic classification of the three primary E3 ligase families—RING, HECT, and RBR—framed within their relevance to oncogenesis. Understanding their distinct mechanisms and mutations provides a foundation for developing targeted cancer therapies, such as proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) [13].

The RING Family: Largest Class of E3 Ligases

Canonical Mechanism and Structural Features

The Really Interesting New Gene (RING) family is the largest class of E3 ligases, characterized by a cross-brace structure coordinating two zinc ions [11]. Unlike other families, canonical RING E3s function as scaffolds that facilitate the direct transfer of ubiquitin from an E2~Ub thioester intermediate to a substrate lysine residue. They do not form a covalent intermediate with ubiquitin [14] [15]. A key feature of their mechanism is the promotion of a "closed" conformation of the E2~Ub complex, which primes the thioester bond for nucleophilic attack [16]. This is often stabilized by a conserved cationic "linchpin" (LP) residue (typically an arginine) in the RING domain that forms hydrogen bonds with both the E2 and ubiquitin [16]. RING E3s can function as monomers, homodimers, or heterodimers, and their activity is often regulated by multimerization [16].

RING Subfamilies and Pseudoligases in Cancer

The TRIpartite Motif (TRIM) subfamily of RING E3s exemplifies the structural and functional diversity within this class. TRIM proteins typically contain a RING domain, one or two B-box domains, and a coiled-coil region [17]. Recent research has identified the existence of "pseudoligases" within the TRIM family. These are proteins that contain a RING domain but have structurally diverged at either the homodimerisation interface or the E2~Ub binding interface, rendering them catalytically inactive in standard assays [17]. For instance, TRIMs 3, 24, 28, and 33 lack the N- and C-terminal helices required for RING dimerization, a key aspect of the catalytic mechanism for many RING E3s [17]. The discovery of pseudoligases raises intriguing questions about their non-canonical functions in physiology and disease, including potential dominant-negative regulation of active homologs [17].

Another notable subfamily is the RING-UIM E3 ligases, including RNF114, RNF125, RNF138, and RNF166. These proteins are characterized by an N-terminal RING domain, zinc finger domains, and a C-terminal Ubiquitin-Interacting Motif (UIM) [12]. The UIM domain binds ubiquitin, facilitating its transfer to the substrate. These ligases are implicated in various cancers by regulating the stability of oncogenes and tumor suppressors [12].

Table 1: Key RING E3 Subfamilies and Their Cancer Links

| Subfamily | Representative Members | Key Structural Features | Documented Roles in Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRIM | TRIM2, TRIM21, TRIM24, TRIM32 | RING, B-box(es), Coiled-coil | Oncogenesis, axonogenesis, viral restriction, autophagy [17] |

| RING-UIM | RNF114, RNF125, RNF138, RNF166 | RING, Zinc Fingers, UIM domain | Regulates proliferation, apoptosis, migration in colorectal, gastric, and other cancers [12] |

| CBL Family | Cbl-b (mentioned) | Internal RING domain | T-cell activation, autoimmune response [11] |

Diagram 1: RING E3 catalytic mechanism. The RING E3 simultaneously binds the E2~Ub complex and the substrate, facilitating direct ubiquitin transfer without a covalent E3-Ub intermediate.

The HECT Family: A Two-Step Catalytic Mechanism

Unique Catalytic Mechanism and Domain Organization

Homologous to the E6-AP C-Terminus (HECT) E3 ligases are distinguished by their two-step catalytic mechanism. They form a transient thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate [11] [14]. The C-terminal HECT domain (~350 amino acids) is conserved and consists of two lobes: a larger N-lobe that binds the E2~Ub complex and a smaller C-lobe that contains the active-site cysteine [11] [18]. The two lobes are connected by a flexible hinge region essential for catalysis [11]. The N-terminal regions of HECT ligases are variable in length and are responsible for specific substrate recognition [11].

Major HECT Subfamilies and Branching Ubiquitination

The human HECT family comprises 28 members, divided into three groups based on their N-terminal domains [11]:

- NEDD4 Superfamily: Characterized by an N-terminal C2 domain and 2-4 WW domains (e.g., NEDD4, NEDD4-2, ITCH, Smurf1, Smurf2). The WW domains typically bind to proline-rich motifs (PPxY) in substrates [11].

- HERC Superfamily: Features one or more RCC1-like domains (RLDs) in addition to the HECT domain [11].

- Other HECT E3s: Lack the WW or RLD domains and have diverse N-terminal domains [11].

A key functional insight is the role of HECT E3s in assembling complex ubiquitin chains. For example, the HECT ligase Ufd4 preferentially catalyzes K29-linked ubiquitination onto pre-existing K48-linked ubiquitin chains, forming K29/K48-branched polyubiquitin chains [18]. These branched chains act as enhanced degradation signals, accelerating the proteasomal removal of substrate proteins, a process relevant to cancer cell proliferation and survival pathways [18].

Table 2: Major HECT E3 Subfamilies and Functional Roles

| Subfamily | Representative Members | N-terminal Domain(s) | Functional Roles & Cancer Links |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEDD4 | NEDD4, ITCH, Smurf1, Smurf2, WWP1 | C2 domain, WW domains | Regulation of BMP/TGF-β signaling, cell growth, morphogenesis, transcription; linked to cancer and immune diseases [11] |

| HERC | HERC1-HERC6 | RCC1-like domains (RLDs) | Less characterized; implicated in cell cycle and signaling [11] |

| Other | Ufd4, TRIP12 | Various | Assembly of K29/K48-branched ubiquitin chains for enhanced degradation [18] |

Diagram 2: HECT E3 catalytic mechanism. This two-step process involves the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to the active-site cysteine in the HECT C-lobe, forming a transient E3~Ub thioester, before final transfer to the substrate.

The RBR Family: A RING-HECT Hybrid Mechanism

Hybrid Mechanism and Auto-inhibition

RING-Between-RING (RBR) E3 ligases constitute a third class that employs a hybrid mechanism, combining features of both RING and HECT E3s [14] [15]. The RBR catalytic unit consists of three tandem zinc-binding domains: RING1, IBR (In-Between-RING), and RING2 [14]. Similar to RING E3s, the RING1 domain initially recruits the E2~Ub complex. However, instead of direct transfer to the substrate, ubiquitin is first transferred via transthiolation to a conserved catalytic cysteine residue located in the RING2 domain, forming a transient thioester intermediate—a hallmark of HECT-like activity. The ubiquitin is then finally conjugated to the substrate lysine [14] [15]. Most RBR E3s are tightly regulated by auto-inhibition, where the enzyme maintains an inactive conformation until activated by specific protein interactions or post-translational modifications [14].

Key RBR Members in Disease and Signaling

There are 14 human RBR proteins, with several playing critical roles in disease [14]:

- Parkin (PARK2): Mutations in Parkin cause familial forms of Parkinson's disease. It is recruited to damaged mitochondria to promote their degradation (mitophagy) and has putative tumor suppressor functions [14].

- HOIP: The catalytic core of the Linear Ubiquitin Assembly Complex (LUBAC), which uniquely generates Met1-linked linear ubiquitin chains essential for NF-κB signaling in inflammation and immunity [19] [14].

- HOIL-1: Another LUBAC component, HOIL-1 exhibits unique substrate specificity. It can ubiquitinate hydroxyl groups on serine and threonine residues (O-linked ubiquitination) and even non-proteinaceous molecules like saccharides (e.g., glycogen and maltose) [19]. A critical histidine residue (His510) in its active site enables this O-linked ubiquitination while prohibiting transfer to lysine residues [19].

- HHARI (ARIH1): An Ariadne subfamily member that is specifically activated by neddylated Cullin-RING ligases (CRLs). Structural studies show it recruits its cognate E2, UbcH7~Ub, in an "open" conformation that prevents spurious ubiquitin discharge and ensures transfer to its RING2 cysteine [15].

Table 3: Prominent RBR E3 Ligases and Their Pathological Associations

| RBR Member | Subfamily | Key Functions | Associated Diseases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parkin (PARK2) | Parkin | Mitophagy, mitochondrial integrity | Parkinson's Disease, Cancer [14] |

| HHARI (ARIH1) | Ariadne | Cellular proliferation, translation regulation | Head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma [14] [15] |

| HOIP | Paul | LUBAC component, Linear ubiquitination | Inflammation, Immunity, Cancer [19] [14] |

| HOIL-1 | XAP3 | LUBAC component, Ser/Thr/Saccharide ubiquitination | Inflammation, Infection [19] [14] |

| TRIAD1 (ARIH2) | Ariadne | Myeloid cell proliferation, NF-κB regulation | Embryonic Lethality (in mice) [14] |

Diagram 3: RBR E3 hybrid catalytic mechanism. This hybrid mechanism begins with RING-like E2~Ub recruitment by RING1, followed by HECT-like transthiolation to form an E3~Ub intermediate on the RING2 domain, before final substrate modification.

Experimental Approaches for Studying E3 Ligases

Assessing E3 Ligase Activity: Key Protocols

Understanding E3 mechanism and function relies on robust biochemical and cellular assays. Below are detailed protocols for key experiments cited in this review.

Protocol 1: In cellulo Auto-ubiquitination Assay This assay assesses E3 ligase activity in a cellular context, preserving potential regulatory factors and native subcellular localization [17].

- Transfection: Co-transfect mammalian cells (e.g., HEK293T) with plasmids encoding a tagged TRIM/E3 ligase (e.g., GFP-TRIM) and HA-tagged ubiquitin.

- Inhibition: Treat cells with proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG132) and pan-deubiquitinase inhibitor (e.g., PR619) for several hours before harvesting to block degradation and deubiquitination, thereby accumulating ubiquitinated species.

- Immunoprecipitation (IP): Lyse cells and perform IP using an antibody against the E3 tag (e.g., anti-GFP nanobody beads).

- Analysis: Resolve immunoprecipitates by SDS-PAGE and analyze HA-auto-ubiquitination status by western blotting with anti-HA antibodies [17].

Protocol 2: In vitro Ubiquitination Assay This reconstituted system provides defined components to study E3 activity directly, excluding confounding cellular factors [17].

- E3 Purification: Immunopurify the tagged E3 ligase (e.g., GFP-TRIM) from transfected HEK293T cells.

- Reaction Setup: Incubate the purified E3 with a reaction mix containing:

- ATP (energy source)

- Recombinant ubiquitin

- Recombinant E1 activating enzyme

- A cocktail of recombinant E2 conjugating enzymes (e.g., UBE2D1, E1, G2, K, N/V2, W) to cover common E2 partners.

- Incubation: Allow the reaction to proceed at 30°C for a defined time.

- Detection: Terminate the reaction and analyze conjugated ubiquitin by:

- ELISA: Using the FK2 antibody specific for conjugated ubiquitin for quantification [17].

- SDS-PAGE/Western Blot: For visual confirmation of ubiquitin ladder formation.

Protocol 3: Analyzing Branched Ubiquitination (e.g., for HECT E3 Ufd4) This specialized protocol identifies the formation of branched ubiquitin chains [18].

- Reconstitution: Set up ubiquitination reactions with purified E1, E2 (Ubc4), HECT E3 (Ufd4), WT Ub, and a defined ubiquitin chain substrate (e.g., K48-linked diUb).

- Mutation Analysis: Repeat assays using ubiquitin mutants (e.g., Ub-K29R) or chain substrate mutants (e.g., K48-linked diUb with proximal K29R) to test linkage specificity.

- Product Analysis:

- Biochemical Assays: Compare ubiquitination efficiency via gel electrophoresis.

- Middle-down Mass Spectrometry (Ub-clipping): Digest the polyubiquitination product with a specific protease (e.g., Usp2cc) to generate ubiquitin remnants with di-glycine signatures. Analyze by LC-MS/MS to identify branched linkages (e.g., detection of di-glycine remnants on both K29 and K48 of a single ubiquitin molecule) [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for E3 Ligase Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| HA-Ubiquitin Plasmid | Enables detection of ubiquitinated proteins in cells. | Co-transfection for in cellulo auto-ubiquitination assays [17]. |

| MG132 & PR619 | Proteasome and deubiquitinase inhibitors, respectively. | Stabilize polyubiquitinated conjugates in cellular assays [17]. |

| Recombinant E1, E2, Ubiquitin | Defined components for in vitro reconstitution. | Essential for in vitro ubiquitination assays to study direct E3 activity [17]. |

| Linkage-Specific Ub Mutants (e.g., K29R, K48O) | To determine the specificity of ubiquitin chain linkage formation. | Identifying Ufd4's preference for K29-linked branching on K48 chains [18]. |

| E2~Ub Thioester Mimetics (e.g., UbcH7-Ub) | Stable isopeptide-linked E2-Ub complex for structural studies. | Solving crystal structures of E2~Ub in complex with RBR E3s like HHARI [15]. |

| FK2 Antibody | Antibody recognizing conjugated ubiquitin (not free ubiquitin). | Detection of ubiquitination in ELISA-based in vitro activity assays [17]. |

| Branched Ubiquitin Probes (triUb~probe~) | Chemically synthesized probes mimicking branched ubiquitin transition state. | Trapping enzymatic intermediates for Cryo-EM studies of HECT E3s like Ufd4 [18]. |

The precise mechanistic classification of E3 ubiquitin ligases—RING, HECT, and RBR—is fundamental to understanding their roles in cellular homeostasis and disease. Mutations or dysregulation in these enzymes are implicated in numerous cancers, affecting processes like cell cycle progression, DNA repair, and signal transduction [13] [12]. The discovery of pseudoligases and the expanding knowledge of non-canonical ubiquitination (e.g., on serine/saccharides by HOIL-1) reveal an additional layer of complexity in ubiquitin signaling [17] [19]. This mechanistic insight is directly driving innovative therapeutic strategies. The advent of targeted protein degradation technologies, such as PROTACs and molecular glues, which harness the cell's native E3 machinery to eliminate disease-causing proteins, underscores the translational potential of basic research in E3 ligase biology [13]. Future efforts to map cancer-specific E3 mutations and substrate networks will be crucial for developing the next generation of targeted cancer therapies.

E3 ubiquitin ligases represent a critical nexus in cellular homeostasis, governing the precise regulation of protein stability, localization, and function across fundamental biological processes. This technical review examines the sophisticated mechanisms by which E3 ligases control cell cycle progression, apoptotic signaling, and DNA damage repair pathways, with particular emphasis on how their dysregulation contributes to oncogenesis. We integrate current structural and functional classifications with emerging data on somatic mutations in cancer genomes, providing a framework for understanding these enzymes as both guardians of genomic integrity and potential therapeutic targets. The development of targeted protein degradation strategies, including PROTACs, further highlights the growing clinical relevance of harnessing E3 ligase biology for cancer intervention, offering novel approaches to drug previously undruggable oncogenic drivers.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system serves as the primary mechanism for regulated protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, with E3 ubiquitin ligases standing as its most specialized components. The ubiquitination process involves a sequential enzymatic cascade: a ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner, a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) accepts the activated ubiquitin, and an E3 ubiquitin ligase finally facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin to specific target substrates [20] [21]. This three-enzyme system enables precise spatiotemporal control over protein fate, with E3 ligases conferring substrate specificity through their diverse substrate recognition domains.

With over 600 E3 ligases encoded in the human genome, these enzymes are classified into three major structural families based on their mechanism of ubiquitin transfer: Really Interesting New Gene (RING), Homologous to E6AP C-Terminus (HECT), and RING-In-Between-RING (RBR) ligases [20] [22]. RING E3 ligases function primarily as scaffolds that facilitate direct ubiquitin transfer from E2 enzymes to substrates, while HECT ligases form an obligate thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before substrate modification. RBR ligases employ a hybrid mechanism, utilizing RING1 domains for E2 binding and RING2 domains for catalytic activity with an intermediate cysteine residue [22]. The complexity of E3 ligase function is further enhanced by their ability to generate diverse ubiquitin chain topologies through different lysine linkages (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63), with K48-linked chains typically targeting substrates for proteasomal degradation and K63-linked chains mediating non-proteolytic signaling functions [20] [23].

E3 Ligase Classification and Molecular Mechanisms

Structural Families and Functional Characteristics

Table 1: Classification of E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Families

| Family | Representative Members | Catalytic Mechanism | Structural Features | Cellular Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RING | BRCA1/BARD1, RNF168, MDM2 | Scaffold-mediated direct transfer from E2 to substrate | RING domain for E2 binding, varied substrate recognition domains | DNA repair, cell cycle control, apoptosis |

| HECT | NEDD4, HERC2, HUWE1 | Covalent intermediate via catalytic cysteine | C-terminal HECT domain, N-terminal substrate recognition domains | Endocytosis, signal transduction, transcription |

| RBR | PARKIN, HOIP, ARIH1 | RING1 for E2 binding, RING2 for catalysis with cysteine | RING1-IBR-RING2 architecture | Mitophagy, inflammation, oxidative stress response |

| Multimeric RING (CRL) | SCF complexes, CRL3, CRL4A/B | Modular scaffold with substrate-specific adaptors | Cullin scaffold, RING protein, adaptor, substrate receptor | Cell cycle progression, DNA replication, transcription |

The Cullin-RING ligase (CRL) family represents a particularly important subclass of multimeric RING E3s, comprising approximately 20% of all ubiquitination events in cells [22]. CRLs utilize cullin proteins (CUL1-7, CUL9) as central scaffolds that simultaneously bind RING proteins (RBX1/2) at their C-termini and substrate recognition receptors at their N-termini via specific adaptor proteins. For instance, CRL1 (SCF complexes) employs Skp1 as an adaptor that bridges CUL1 to F-box proteins, which serve as substrate receptors determining target specificity [22]. The combinatorial assembly possibilities within CRL complexes enables remarkable substrate diversity and regulatory precision across cellular processes.

Regulatory Mechanisms and Adaptor Proteins

E3 ligase activity and specificity are tightly controlled through multiple regulatory mechanisms, including autoinhibition, post-translational modifications, subcellular localization, and interactions with adaptor proteins. Adaptor proteins play particularly crucial roles in modulating E3 ligase function by influencing substrate recognition, catalytic activity, and cellular localization [22]. For example, the COP9 signalosome (CSN) regulates CRL activity through deneddylation, while DCAF (DDB1- and CUL4-associated factor) proteins serve as substrate receptors for CRL4 complexes [24] [22]. The dynamic interplay between E3 ligases and their regulatory partners ensures precise contextual control over substrate ubiquitination, allowing appropriate cellular responses to changing environmental conditions and stress signals.

E3 Ligases in Cell Cycle Regulation

E3 ubiquitin ligases serve as master regulators of cell cycle progression, controlling the timed degradation of key cell cycle regulators to ensure orderly phase transitions and faithful genome duplication. The anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) and SCF (Skp1-Cul1-F-box protein) complexes represent the two primary families of E3 ligases governing cell cycle progression, with distinct but complementary functions.

The APC/C functions primarily during mitosis and G1 phase, targeting key substrates including cyclins and securin to initiate anaphase and exit mitosis. In contrast, SCF complexes regulate G1/S transition and S phase progression through the action of specific F-box proteins that recognize phosphorylated substrates. For example, SCFᴺᴿᴼᴾ² mediates the degradation of the CDK inhibitor p27ᴷᴵᴾ¹, thereby promoting G1/S transition, while SCFᶠᴮᵂ⁷ controls the abundance of multiple oncoproteins including cyclin E, c-Myc, and c-Jun [21]. The precise regulation of these ligases ensures unidirectional cell cycle progression and prevents re-replication of DNA.

During DNA replication, the CRL4ᶜᴰᵀ² E3 ligase plays a critical role in maintaining genome stability by targeting the replication licensing factor CDT1 for degradation during S phase, ensuring that replication origins fire only once per cell cycle [25]. Additionally, the E3 ligase RAD18 monoubiquitinates PCNA in response to replication stress, facilitating the switch from replicative to translesion synthesis polymerases to bypass DNA lesions [25]. The coordinated actions of these E3 ligases establish robust control mechanisms that preserve genomic integrity during cell division.

Diagram Title: E3 Ligase Regulation of Cell Cycle Progression

E3 Ligases in Apoptosis Regulation

E3 ubiquitin ligases function as critical decision-makers in the regulation of programmed cell death, controlling the balance between pro-survival and pro-apoptotic signals. They exert precise control over apoptosis through the ubiquitination of key components in both the intrinsic (mitochondrial) and extrinsic (death receptor) pathways.

The inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) family of E3 ligases, including XIAP, cIAP1, and cIAP2, directly regulates caspase activity through ubiquitin-mediated degradation and inhibition [23]. IAP proteins can ubiquitinate active caspases, targeting them for proteasomal degradation and thereby suppressing apoptosis. Conversely, the ARF-BP1/MULE E3 ligase promotes apoptosis by targeting the anti-apoptotic protein MCL-1 for degradation, while SCFᶠᴮᵂ⁷ controls the stability of both pro-apoptotic (MCL-1) and anti-apoptotic (c-MYC) factors [23].

The p53 tumor suppressor pathway represents a particularly important node in apoptosis regulation, with the MDM2 E3 ligase serving as its primary negative regulator. MDM2 targets p53 for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, maintaining low p53 levels under normal conditions. During cellular stress, MDM2 activity is suppressed, allowing p53 accumulation and induction of pro-apoptotic target genes [21]. This regulatory circuit ensures that apoptosis occurs only when appropriate, preventing excessive or insufficient cell death. Dysregulation of these E3 ligases contributes significantly to cancer development and treatment resistance.

Diagram Title: E3 Ligase Control of Apoptotic Pathways

E3 Ligases in DNA Damage Response and Repair

The DNA damage response (DDR) represents a complex signaling network that detects DNA lesions, coordinates repair, and determines cell fate. E3 ubiquitin ligases play indispensable roles in virtually every aspect of the DDR, from initial damage recognition to repair pathway choice and termination of the response.

Double-Strand Break Repair and Histone Ubiquitination

Following DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), the RNF8-RNF168 ubiquitination cascade establishes a critical chromatin platform that coordinates the recruitment of downstream repair factors [25] [9]. RNF8 initiates the cascade by ubiquitinating histone H1 and other substrates, followed by RNF168 which catalyzes K63-linked ubiquitination of histones H2A and H2AX at lysine 13-15 [9]. These ubiquitin marks serve as binding sites for the repair proteins 53BP1 and BRCA1, which promote non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR), respectively.

The BRCA1-BARD1 complex represents another crucial E3 ligase in DSB repair, functioning in multiple steps of the HR pathway. BRCA1-BARD1 facilitates DNA end resection, promotes RAD51 loading onto single-stranded DNA, and regulates cell cycle checkpoint activation [25]. Additionally, BRCA1-BARD1 catalyzes ubiquitination of histone H2A at lysine 127-129, which promotes DNA end resection and HR repair [9]. The precise coordination between these E3 ligases ensures appropriate repair pathway selection based on cellular context and cell cycle phase.

Replication Stress and Interstrand Crosslink Repair

Beyond DSB repair, specialized E3 ligases address various forms of replication stress and complex DNA lesions. The FAAP20-FANCL complex, part of the Fanconi anemia pathway, monoubiquitinates the FANCD2-FANCI heterodimer in response to DNA interstrand crosslinks, activating the repair of these toxic lesions [25]. Similarly, TRAIP E3 ligase promotes replication fork restart and repairs DNA-protein crosslinks through mechanisms involving ubiquitination of replisome components [25].

The RING-UIM subfamily of E3 ligases, including RNF138, plays particularly important roles in regulating DSB repair pathway choice. RNF138 promotes HR by facilitating the recruitment of MRE11 nuclease to DSB sites and ubiquitinating Ku80 to dislodge it from DNA ends, thereby limiting NHEJ and favoring HR [12] [9]. This functional specialization highlights how distinct E3 ligases coordinate to balance competing repair pathways and maintain genome stability.

Table 2: E3 Ligases in DNA Damage Response and Their Cancer Associations

| E3 Ligase | DNA Repair Pathway | Key Substrates | Cancer-Associated Alterations | Functional Consequences in Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNF168 | DSB signaling, NHEJ/HR choice | H2A/H2AX, 53BP1 | Mutated in immunodeficiency disorders | Genomic instability, radiation sensitivity |

| BRCA1 | Homologous recombination | H2A, CtIP, RAD51 | Germline mutations in hereditary breast/ovarian cancer | HR deficiency, PARP inhibitor sensitivity |

| RNF8 | DSB signaling, NHEJ | H1, γH2AX | Overexpression in various cancers | Altered DNA repair, therapeutic resistance |

| FBXW7 | Multiple pathways | Cyclin E, c-MYC, MCL1 | Mutated in cholangiocarcinoma, T-ALL | Genomic instability, chemoresistance |

| RNF138 | HR, DSB resection | Ku80, MRE11 | Amplification in breast cancer | Enhanced HR, radiation resistance |

| HERC2 | DSB signaling, NHEJ | RNF8, XPA | Mutated in melanoma, glioblastoma | Defective DDR, genomic instability |

| TRAIP | Replication fork restart, DPC repair | CMG helicase, PCNA | Mutated in primordial dwarfism | Replication stress, chromosomal breaks |

E3 Ligase Mutations in Human Cancers

The critical gatekeeping functions of E3 ubiquitin ligases in maintaining genomic integrity render them frequent targets of mutational inactivation or amplification in human cancers. Comprehensive genomic analyses have revealed that E3 ligase genes exhibit distinctive mutation patterns across cancer types, with important implications for tumor behavior and therapeutic response.

Spectrum of Somatic Mutations and Amplifications

DNA damage response-related E3 ligases demonstrate cancer-type-specific mutation patterns. For instance, RNF168 displays a high mutation frequency in certain cancers and is associated with increased mutation burden, consistent with its role in maintaining genome stability [9]. Similarly, FBXW7 is among the most frequently mutated E3 ligases in human cancers, with loss-of-function mutations observed in cholangiocarcinoma, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), and other malignancies [9]. These mutations typically disrupt the substrate-binding domain of FBXW7, leading to stabilization of oncoproteins like cyclin E, c-MYC, and NOTCH, thereby driving tumor progression.

In contrast to tumor-suppressive E3 ligases that are frequently inactivated, certain oncogenic E3 ligases undergo amplification or overexpression in cancers. SKP2, which targets the cell cycle inhibitor p27 for degradation, is amplified in various tumors including breast cancer [21]. Similarly, MDM2 is frequently amplified in sarcomas, glioblastomas, and other cancers, leading to excessive inactivation of the p53 tumor suppressor [21]. The DCAF2 E3 ligase component is overexpressed in various cancer types, making it an attractive target for tumor-selective protein degradation approaches [26].

Implications for Cancer Therapy and Synthetic Lethality

The altered expression and mutation of specific E3 ligases in cancers creates unique therapeutic vulnerabilities. Tumors with deficiencies in HR repair due to BRCA1 mutations exhibit synthetic lethality with PARP inhibitors, a therapeutic approach now approved for BRCA-mutant ovarian, breast, and prostate cancers [25]. Similarly, tumors with FBXW7 mutations demonstrate enhanced sensitivity to mTOR inhibitors and mitotic inhibitors, reflecting their dependence on compensatory signaling pathways.

The development of PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) represents a particularly promising approach to target oncoproteins through recruitment of specific E3 ligases. These bifunctional molecules simultaneously bind to an E3 ligase and a target protein of interest, facilitating ubiquitination and degradation of the target [20] [26]. Current PROTACs primarily utilize E3 ligases such as VHL and cereblon, but ongoing research aims to expand the repertoire of ligatable E3s, including DCAF2 and others with cancer-selective expression patterns [26]. This expanding therapeutic modality highlights the clinical potential of harnessing E3 ligase biology for cancer treatment.

Experimental Approaches for E3 Ligase Research

Methodologies for Studying E3 Ligase Function

Ubiquitination assays represent fundamental tools for characterizing E3 ligase activity and substrate specificity. In vitro ubiquitination assays typically involve incubating purified E1, E2, E3, ubiquitin, and ATP with potential substrate proteins, followed by immunoblotting to detect ubiquitin conjugation [21]. For cellular validation, researchers often employ co-immunoprecipitation experiments to assess E3-substrate interactions under physiological conditions, coupled with cycloheximide chase assays to measure substrate half-life changes upon E3 manipulation.

CRISPR-Cas9 screening has emerged as a powerful approach for identifying novel E3 ligase substrates and synthetic lethal interactions. Genome-wide knockout screens in isogenic cell lines can reveal context-specific dependencies, while focused screens with custom E3 ligase libraries enable systematic functional characterization [24]. For example, such approaches have identified RNF138 as a critical factor for HR repair in BRCA1-deficient cells, revealing potential therapeutic targets [9].

Advanced structural biology techniques including cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and X-ray crystallography provide atomic-level insights into E3 ligase mechanisms. Recent cryo-EM structures of the DCAF2 E3 complex in both apo and ligand-bound states have revealed novel binding sites for targeted protein degradation, enabling structure-based drug design [26]. Similarly, structural studies of RING-UIM E3 ligases have elucidated how their distinctive domain architecture facilitates simultaneous engagement with E2~Ub conjugates and ubiquitinated substrates [12].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for E3 Ligase Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Proteins | Purified E1, E2s, E3 complexes, ubiquitin | In vitro ubiquitination assays | Requires proper folding and post-translational modifications for full activity |

| Activity Assays | Ubiquitination kits, ATP consumption assays | Functional characterization of E3 ligase activity | Should include appropriate controls (catalytic mutants, substrate-only) |

| Cell Line Models | Isogenic E3 knockout lines, cancer cell panels | Functional studies in cellular context | Important to validate genetic modifications with multiple methods |

| Proteomics Approaches | Ubiquitin remnant profiling, interactome studies | Global substrate identification | Requires specialized enrichment strategies for ubiquitinated peptides |

| Chemical Probes | PROTAC molecules, molecular glues, E3 inhibitors | Pharmacological manipulation of E3 function | Specificity and off-target effects must be carefully evaluated |

| Animal Models | Genetically engineered mouse models, xenografts | In vivo validation of E3 function | Tissue-specific knockout often necessary for lethal mutations |

E3 ubiquitin ligases stand as master regulators of cellular homeostasis, integrating signals from diverse pathways to coordinate cell cycle progression, apoptotic commitment, and DNA repair. Their exquisite substrate specificity, coupled with the reversibility of ubiquitination, makes them ideal nodes for therapeutic intervention in cancer and other diseases. The growing appreciation of E3 ligase mutations in human cancers, from the loss of tumor-suppressive ligases like FBXW7 to the amplification of oncogenic ligases like MDM2, highlights their fundamental roles in tumorigenesis.

Future research directions will likely focus on expanding the therapeutic targeting of E3 ligases through several complementary approaches. First, the continued development of PROTAC technology will benefit from expanding the repertoire of E3 ligases that can be harnessed for targeted protein degradation, particularly those with tissue-restricted or cancer-selective expression patterns like DCAF2 [26]. Second, combination therapies that exploit synthetic lethal interactions with specific E3 ligase mutations offer promising avenues for precision medicine approaches. Finally, advancing our understanding of the structural biology of E3 ligase complexes will enable rational design of small molecule inhibitors and activators with improved specificity and efficacy.

As our knowledge of E3 ligase biology continues to expand, these sophisticated molecular machines will undoubtedly yield new therapeutic opportunities for cancer treatment, particularly for malignancies driven by currently undruggable oncoproteins. The integration of basic mechanistic studies with advanced proteomic and genomic approaches will further elucidate the complex regulatory networks governed by E3 ligases, solidifying their status as critical gatekeepers of genomic integrity and attractive targets for therapeutic intervention.

E3 ubiquitin ligases, comprising over 600 members in humans, constitute a critical regulatory layer in cellular homeostasis by determining the specificity of protein ubiquitination. In physiological conditions, these enzymes function as guardians of genomic integrity, cell cycle progression, and programmed cell death. However, somatic mutations and epigenetic alterations can subvert their functions, transforming them into saboteurs that drive oncogenesis. This technical review examines the molecular mechanisms through which mutations—including point mutations, amplifications, and deletions—reprogram E3 ligase function across multiple cancer types. We synthesize current understanding of how these alterations affect key substrates in critical pathways such as p53 signaling, Wnt/β-catenin activation, and DNA damage response, with quantitative analysis of mutation frequencies from TCGA and COSMIC databases. The review further explores emerging therapeutic strategies that leverage our growing understanding of mutant E3 ligase networks, including PROTACs and molecular glues, providing a research framework for targeting these enzymes in precision oncology.

E3 ubiquitin ligases represent the pivotal specificity determinants in the ubiquitin-proteasome system, catalyzing the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 conjugating enzymes to target protein substrates [4]. With approximately 600 E3 ligases encoded in the human genome, these enzymes regulate virtually all cellular processes through both proteolytic (K48-linked ubiquitination) and non-proteolytic (K63-linked and other ubiquitination) mechanisms [27]. The RING-type E3 ligases, the largest class, facilitate direct transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to substrate, while HECT-type and RBR-type E3s form catalytic intermediates during ubiquitin transfer [4].

In their physiological "guardian" roles, E3 ligases maintain cellular homeostasis by controlling the stability of oncoproteins and tumor suppressors. For instance, MDM2 regulates p53 tumor suppressor levels, while β-TrCP controls NF-κB signaling through IκB degradation [27]. FBXW7 targets multiple oncoproteins including c-MYC, NOTCH, and cyclin E for proteasomal degradation [27]. Tissue-specific E3 ligases like VHL regulate hypoxia-inducible factors in renal cells, while PARK2 modulates mitochondrial integrity and Wnt signaling in neuronal tissues [24] [27].

The transformation of E3 ligases from guardians to saboteurs occurs through diverse genetic and epigenetic mechanisms. Somatic mutations can alter substrate recognition, protein-protein interactions, or catalytic activity, while copy number alterations and promoter methylation changes can drive aberrant expression [28] [29]. This comprehensive review examines the molecular consequences of these alterations, their roles in cancer pathogenesis, and emerging strategies for therapeutic targeting.

Molecular Mechanisms of E3 Ligase Dysregulation in Cancer

Structural Consequences of Somatic Mutations

Somatic mutations can disrupt E3 ligase function through multiple mechanisms, with distinct consequences for substrate recognition and catalytic activity. The structural domains of E3 ligases—including RING domains for E2 binding, substrate recognition modules, and protein-protein interaction domains—represent mutational hotspots across cancer types.

RING Domain Mutations: The RING domain coordinates zinc ions and facilitates E2-ubiquitin binding. Mutations in critical cysteine and histidine residues (e.g., Cys-X2-Cys-X(9-39)-Cys-X(1-3)-His-X(2-3)-Cys-X2-Cys pattern) disrupt zinc binding and E2 recruitment, abrogating catalytic activity [4]. For example, RNF168 mutations in its RING domain impair histone H2A ubiquitination, compromising DNA damage repair and promoting genomic instability [28].

Substrate Recognition Domain Mutations: In multi-subunit E3 ligases like SCF complexes, mutations in substrate recognition components (e.g., F-box proteins in SCF complexes) alter substrate specificity without affecting catalytic machinery. FBXW7 mutations in its WD40 domain prevent recognition of phosphorylated degrons in oncoproteins like c-MYC and cyclin E, leading to their stabilization [27]. Similarly, SPOP mutations in its MATH domain disrupt substrate binding in prostate and endometrial cancers [27].

Regulatory Element Mutations: Mutations outside core functional domains can affect protein stability, subcellular localization, or post-translational modifications. For instance, NEDD4 family E3 ligases show mutations in their C2 domains that alter membrane localization, affecting substrate access [30].

Table 1: Mutation Frequencies of Selected E3 Ligases Across Cancers

| E3 Ligase | Cancer Type | Mutation Frequency | Common Mutation Type | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNF168 | Various | ~10% | Missense (RING domain) | Impaired DNA damage repair |

| FBXW7 | Endometrial, cervical, blood | 4-10% | Frameshift, missense | Stabilization of c-MYC, cyclin E |

| HECW1 | Various | Up to 32.1% | Missense, truncating | Altered substrate recognition |

| HECW2 | Various | Up to 32.1% | Missense, truncating | Altered substrate recognition |

| RNF8 | Ovarian, uterine | ~4% | Amplification, missense | Dysregulated HR repair |

| SPOP | Prostate, endometrial | 5-15% | Missense (MATH domain) | Altered substrate binding |

Aberrant Expression and Copy Number Alterations

Beyond somatic mutations, E3 ligases undergo dysregulation through copy number variations (CNVs) and epigenetic modifications that alter their expression patterns. Genome-wide analyses reveal distinctive CNV profiles across cancer types, with significant implications for pathway regulation.

Amplification-Driven Oncogenesis: Several E3 ligases function as oncogenes when amplified. SKP2 amplification increases degradation of cell cycle inhibitors p21 and p27, promoting G1-S transition [4]. RNF8 amplification occurs in approximately 4.97% of ovarian cancers, potentially dysregulating homologous recombination repair [28]. Breast cancers harbor significant copy number amplifications in NEDD4 family genes, driving proliferation through enhanced growth factor signaling [30].

Deletion-Mediated Tumor Suppressor Loss: Tumor suppressor E3 ligases are frequently deleted in cancers. PARK2 (Parkin) deletions occur in breast, pancreatic, colorectal, and ovarian cancers, leading to accumulation of its substrates including cyclin D, cyclin E, and Cdc20/Cdh1 [27]. FBXW7 deletions stabilize multiple oncoproteins, contributing to tumor progression across diverse lineages [27].

Expression Pattern Alterations: Comprehensive pan-cancer analyses reveal tissue-specific expression changes. NEDD4 family members show elevated expression in pancreatic, esophageal, gastric, and colon cancers, but reduced expression in kidney, thyroid, and testis cancers [30]. RNF114 demonstrates tissue-specific expression patterns, with highest levels in testis, heart, liver, and kidney, but altered distribution in cancer cells [12]. ABLIM1 shows dichotomous expression—functioning as a tumor suppressor in melanoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and glioblastoma, but as an oncogene in colorectal cancer [31].

Table 2: Copy Number and Expression Alterations of E3 Ligases in Cancer

| E3 Ligase | Alteration Type | Cancer Type | Frequency | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SKP2 | Amplification | Various | Variable | Enhanced cell cycle progression |

| NEDD4 Family | Amplification | Breast cancer | High frequency | Increased proliferation |

| PARK2 | Deletion | Breast, pancreatic, colorectal, ovarian | Variable | Accumulation of cell cycle regulators |

| FBXW7 | Deletion | Various | Variable | Stabilization of oncoproteins |

| RNF4 | Overexpression | Colon adenocarcinoma | ~30% | Enhanced Wnt/β-catenin signaling |

| ABLIM1 | Overexpression | Colorectal cancer | Correlates with poor prognosis | NF-κB-CCL20 axis activation |

Critical Signaling Pathways Disrupted by Mutant E3 Ligases

p53 Pathway Dysregulation

The p53 tumor suppressor pathway represents one of the most frequently disrupted networks in cancer, with E3 ligases playing central roles in its regulation. MDM2, the primary negative regulator of p53, is amplified in multiple cancer types, particularly liposarcomas [27]. MDM2 overexpression drives excessive p53 ubiquitination and degradation, disabling the apoptosis and cell cycle arrest programs essential for tumor suppression. The E6AP/E6 complex in HPV-associated cancers represents an alternative mechanism of p53 destruction, where the viral E6 protein recruits E6AP to p53, targeting it for degradation independent of cellular regulation [27]. Additionally, the E6/E6AP complex activates hTERT promoter activity through interactions with c-Myc and NFX1-91, contributing to telomerase activation and cellular immortalization [27].

Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Activation

Aberrant Wnt/β-catenin signaling occurs in over 90% of colorectal cancers, with E3 ligases playing crucial roles in both physiological regulation and pathological activation. RNF4 stabilizes β-catenin and c-Myc through ubiquitination that does not lead to degradation but rather enhances their transcriptional activities [29]. RNF14 facilitates the interaction between β-catenin and LEF/TCF transcription factors, stabilizing the complex and ensuring high transcriptional activity even at low nuclear β-catenin concentrations [29]. In contrast, RNF43 and its homolog ZNRF3 function as tumor suppressors by promoting Wnt receptor degradation; their loss through mutation or promoter methylation leads to pathway hyperactivation [29].

DNA Damage Response Dysfunction

E3 ligases coordinate the DNA damage response (DDR) through complex regulatory networks that become disrupted in cancer. The RING-UIM subfamily (RNF114, RNF125, RNF138, RNF166) plays critical roles in homologous recombination through substrate-specific ubiquitination [12]. RNF138 facilitates HR by recruiting MRE11 to single-stranded DNA overhangs and promoting RPA loading, CtIP recruitment, and EXO1 activity [28]. RNF168-mediated histone ubiquitination at DNA double-strand breaks creates recruitment platforms for repair factors including 53BP1 and BRCA1 [28] [9]. Mutations in these E3 ligases (e.g., RNF168 with >10% mutation frequency in several cancers) cause genomic instability, a hallmark of cancer [28]. The HERC2/MDC1/RNF8 complex formation promotes RNF8 oligomerization and RNF168 recruitment, creating an amplification loop for ubiquitin signaling at damage sites [9].

Figure 1: E3 Ligase Coordination of DNA Damage Response. Mutations in RNF8, RNF168, and related E3 ligases disrupt the carefully orchestrated recruitment cascade at DNA double-strand breaks, leading to improper repair pathway choice and genomic instability.

RTK/PI3K/Akt Signaling Hyperactivation

In glioblastoma and other cancers, E3 ligases regulating receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling undergo frequent alteration. Casitas B-lineage lymphoma (Cbl) mutations impair EGFR ubiquitination and degradation, leading to sustained proliferative signaling [24]. The EGFRvIII mutant receptor in glioblastoma shows hypophosphorylation at Y1045, the major Cbl docking site, resulting in reduced internalization and degradation [24]. PARK2 loss through chromosomal deletion at 6q prevents its normal suppression of EGFR expression at both protein and mRNA levels, while TRIM11 overexpression stabilizes EGFR in glioma models [24]. In the PI3K/Akt pathway downstream of RTKs, β-TrCP targets PHLPP1 for degradation, removing an important negative regulator of Akt and enhancing survival signaling [24].

NF-κB Pathway Activation

The NF-κB pathway represents another critical signaling axis frequently dysregulated by E3 ligase mutations. ABLIM1, recently identified as a novel LIM-type E3 ligase, promotes IκBα ubiquitination and degradation in colorectal cancer, leading to NF-κB nuclear translocation and transcriptional activation of oncogenes including CCL20 [31]. This contrasts with other LIM E3 ligases like PDLIM2 and PDLIM7 that promote p65 degradation and suppress NF-κB signaling, highlighting the context-dependent functions of different E3 ligase families [31]. The CARD11-BCL10-MALT1 (CBM) complex in lymphocytes recruits E3 ligases that activate NF-κB through IκB degradation, with mutations in this system driving lymphoid malignancies.

Experimental Approaches for E3 Ligase Research

Genomic Alteration Analysis

Comprehensive genomic analysis provides the foundation for understanding E3 ligase dysregulation in cancer. Data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Catalog of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) databases reveal mutation frequencies, copy number alterations, and expression changes across cancer types [28] [30]. The cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics offers visualization tools for analyzing E3 ligase alterations in patient cohorts [28]. For example, analysis of 584 ovarian cancers in cBioPortal revealed RNF8 alteration frequencies of 4.97%, primarily through gene amplification [28]. Similarly, analysis of NEDD4 family genes across 33 cancer types identified mutation frequencies ranging from 0-32.1%, with HECW1 and HECW2 showing particularly high mutation rates [30].

Protocol: Pan-Cancer Mutation Frequency Analysis

- Access TCGA genomic data through UCSC Xena browser (https://xenabrowser.net/)

- Identify E3 ligase genes of interest from HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee database

- Query cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org/) for mutational landscapes

- Analyze copy number variations using GISTIC 2.0

- Correlate genetic alterations with clinical outcomes using survival analysis

Functional Validation of E3 Ligase Mutations

Determining the functional consequences of E3 ligase mutations requires rigorous experimental validation. Key approaches include ubiquitination assays, protein interaction studies, and functional rescue experiments.

Protocol: In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

- Express and purify wild-type and mutant E3 ligases from E. coli or insect cells

- Incubate with E1 enzyme, E2 enzyme, ubiquitin, and ATP in reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ATP, 0.5 mM DTT)

- Add potential substrate proteins and incubate at 30°C for 60-90 minutes

- Terminate reaction with SDS-PAGE loading buffer

- Analyze by Western blotting with ubiquitin-specific and substrate-specific antibodies

- Compare ubiquitination efficiency between wild-type and mutant E3 ligases

Protocol: Substrate Interaction Validation

- Co-immunoprecipitation of E3 ligase with candidate substrates from cell lysates

- Proximity ligation assays (PLA) to visualize intracellular interactions

- Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to determine binding kinetics of wild-type vs. mutant E3 ligases

- Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to quantify binding affinities

- X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM to determine structural consequences of mutations

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for E3 Ligase Mutation Characterization. A multi-modal approach combining biochemical, biophysical, and cell-based assays provides comprehensive functional validation of E3 ligase mutations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for E3 Ligase Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Plasmids | pCMV-E3 ligase constructs, pGEX-E3 ligase | Recombinant protein production | Include N-terminal tags for purification, confirm catalytic activity |

| Antibodies | Anti-ubiquitin (P4D1), anti-E3 ligase specific | Western blot, immunoprecipitation | Validate specificity using knockout controls |

| Cell Lines | HEK293T, H1299, A549, cancer cell panels | Functional studies, substrate validation | Select lines with relevant genetic backgrounds |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, bortezomib, carfilzomib | Stabilize ubiquitinated substrates | Use appropriate controls for off-target effects |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Tools | sgRNAs targeting E3 ligases | Knockout generation, functional validation | Verify complete knockout with multiple methods |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | K48-only, K63-only, K0 ubiquitin | Chain linkage specificity determination | Express in ubiquitin-deficient cells |

| Activity Probes | Ubiquitin vinyl sulfones, HA-Ub-VS | Active site labeling, mechanism studies | Confirm specificity with inactive mutants |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Targeting Mutant E3 Ligases in Precision Oncology

The mechanistic understanding of how mutations transform E3 ligase function enables novel therapeutic approaches. Small molecule inhibitors targeting oncogenic E3 ligases like MDM2 (idasanutlin, RG7388) disrupt the p53-MDM2 interaction, activating p53 in tumors with wild-type TP53 [27]. PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) harness E3 ligases to target oncoproteins for degradation; for example, ARV-110 recruits CRBN to degrade androgen receptor in prostate cancer [26]. Molecular glues like lenalidomide and thalidomide modulate CRL4CRBN E3 ligase activity, leading to degradation of specific transcription factors [27].

Emerging strategies focus on exploiting synthetic lethal interactions with E3 ligase mutations. Tumors with specific DNA repair E3 ligase deficiencies (e.g., RNF168 mutations) show heightened sensitivity to PARP inhibitors [28]. Similarly, identifying context-specific vulnerabilities created by E3 ligase mutations represents a promising frontier. The discovery of DCAF2 as a novel E3 ligase for targeted protein degradation expands the toolkit available for PROTAC development, particularly given its frequent overexpression in various cancers [26].

Diagnostic and Prognostic Applications

E3 ligase mutation patterns offer diagnostic and prognostic value across cancer types. ABLIM1 overexpression in colorectal cancer correlates with shorter disease-free survival, suggesting utility as a prognostic biomarker [31]. Mutation signatures in DNA damage response E3 ligases (RNF8, RNF168, RNF138) may predict response to genotoxic therapies and PARP inhibitors [28]. FBXW7 mutation status informs therapeutic strategies, as mutants stabilize oncoproteins that may create specific vulnerabilities [27]. NEDD4 family gene expression patterns correlate with patient survival across multiple cancer types, suggesting broad utility as prognostic indicators [30].

The transformation of E3 ubiquitin ligases from guardians of cellular homeostasis to saboteurs driving oncogenesis represents a fundamental paradigm in cancer biology. Somatic mutations, copy number alterations, and epigenetic changes collectively reprogram E3 ligase function, altering substrate specificity, catalytic activity, and pathway regulation. The quantitative analysis of E3 ligase mutations across cancer types reveals both shared and tissue-specific patterns of dysregulation, with significant implications for DNA damage response, cell cycle control, and signaling pathway fidelity.

Future research directions should focus on comprehensive functional characterization of lesser-studied E3 ligase families, including the NEDD4 family and LIM-domain containing E3 ligases like ABLIM1. The development of more sophisticated animal models expressing cancer-associated E3 ligase mutants will enable in vivo validation of their pathological roles. From a therapeutic perspective, expanding the repertoire of E3 ligases available for PROTAC technology represents a promising approach for targeting previously "undruggable" oncoproteins. As our understanding of E3 ligase biology deepens, these critical cellular regulators offer unprecedented opportunities for diagnostic development and therapeutic innovation in precision oncology.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a critical regulatory mechanism for cellular homeostasis, governing the degradation of proteins to control processes such as the cell cycle, DNA repair, and apoptosis [32]. Central to this system are E3 ubiquitin ligases, which provide substrate specificity by recognizing target proteins and facilitating their ubiquitination [20]. Dysregulation of E3 ligases is frequently associated with oncogenesis, as mutations, amplifications, or altered expression can lead to the destabilization of tumor suppressors or stabilization of oncoproteins [33] [9]. Among the diverse families of E3 ligases, the RING-UIM family and SCF (SKP1-CUL1-F-box) complexes have emerged as significant players in specific cancer pathways, presenting compelling targets for therapeutic intervention [34] [35]. This review delineates the molecular architecture, cancer-specific mechanisms, and therapeutic targeting of these two key E3 ligase families within the broader context of E3 ligase mutations in human cancers.

The RING-UIM E3 Ligase Family: Structure and Members

The RING-UIM family represents a specialized subfamily of RING-type E3 ligases, comprising only four members: RNF114, RNF125, RNF138, and RNF166 [34] [12] [33]. These proteins are characterized by five highly conserved structural domains: an amino-terminal C3HC4-RING domain, a central C2HC and two C2H2-type zinc fingers, and a carboxyl-terminal UIM (Ubiquitin-Interacting Motif) [34] [12]. The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics of each RING-UIM family member.

Table 1: The RING-UIM E3 Ligase Family Members

| Member | Alternative Names | Molecular Weight | Cellular Localization | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNF114 | ZNF313, ZNF228 | 25.7 kDa | Nucleus & Cytoplasm (Cytoplasmic in cancer) | RING, three zinc fingers, UIM [34] |

| RNF125 | TRAC-1 | ~25 kDa | Intracellular membrane (via myristoylation) | RING, zinc fingers, UIM, N-terminal myristoylation site [34] [12] |

| RNF138 | HSD-4, NARF | ~28 kDa (245 aa) | Nucleus & Cytoplasm | RING, three zinc fingers, UIM [34] |

| RNF166 | - | ~26 kDa (237 aa) | Nucleus & Cytoplasm | RING, three zinc fingers, UIM, two putative tankyrase-binding motifs (TBMs) [34] |

The distinct domains enable the specialized function of RING-UIM ligases in the ubiquitination process. The C3HC4-RING domain recognizes and binds the E2~Ub conjugate, while the C-terminal UIM domain binds ubiquitin, facilitating its transfer to the substrate protein. The C2HC-ZnF domain stabilizes the RING domain and contributes to substrate recognition [34] [12]. Despite shared domains, variations in amino acid sequences and spatial configurations among the four members underpin their distinct physiological functions and substrate specificities [34].

Diagram 1: Functional domains of RING-UIM E3 ligases and their role in ubiquitination. The RING domain binds E2~Ub, the UIM binds ubiquitin, and zinc fingers aid substrate recognition.

SCF Complexes: Modular Assemblies for Targeted Ubiquitination

The SCF (SKP1-CUL1-F-box) complex is a multi-subunit E3 ubiquitin ligase belonging to the Cullin-RING ligase (CRL) family [35]. Its modular architecture consists of four core components:

- CUL1: A scaffold protein that binds other components.

- SKP1: An adaptor protein that links CUL1 to the F-box protein.

- F-box Protein: A variable substrate recognition subunit.

- RING Protein (RBX1/ROC1): Recruits the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme [35].

The human genome encodes numerous F-box proteins, which are classified into three subfamilies based on their substrate-binding domains: Fbxl (leucine-rich repeats), Fbxw (WD-40 repeats), and Fbxo (other domains) [35]. This diversity enables SCF complexes to target a vast array of substrates for ubiquitination. The assembly and activity of SCF complexes are regulated by factors such as the COP9 signalosome and CAND1, which influence the exchange of F-box proteins and complex stability [35].

Table 2: Core Components of the SCF Complex

| Component | Role in Complex | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| CUL1 | Scaffold Protein | Binds SKP1 at N-terminus, RBX1 at C-terminus [35] |

| SKP1 | Adaptor Protein | Links CUL1 to the F-box protein [35] |

| F-box Protein | Substrate Recruiter | Determines substrate specificity; ~69 members in humans (Fbxl, Fbxw, Fbxo) [35] |

| RBX1/ROC1 | RING Protein | Recruits E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme [35] |

Molecular Mechanisms and Roles in Specific Cancers

RING-UIM E3 Ligases in Carcinogenesis

Members of the RING-UIM family exhibit context-dependent roles as either oncogenes or tumor suppressors across different cancer types, primarily through ubiquitinating key regulatory proteins.

RNF114 is markedly overexpressed in colorectal cancer (CRC) and gastric cancer (GC), where its expression correlates with cancer invasion, TNM stage, and overall survival [34]. In GC, RNF114 facilitates the degradation of the tumor suppressor EGR1 via ubiquitination, thereby promoting cancer cell proliferation, metastasis, and tumor growth in vivo [34]. Similarly, in CRC, silencing RNF114 decreases proliferation and invasion while enhancing apoptosis of cancer cells [34].

RNF125 has been implicated as a tumor suppressor in certain contexts. It is highly expressed in lymphoid tissues and can target oncogenic proteins for degradation, though its specific roles in cancer are less defined compared to other family members [34] [12].

RNF138, a protein involved in maintaining chromosomal integrity and genome stability, plays a crucial role in DNA damage response, particularly in Homologous Recombination (HR) repair [34] [9]. It promotes HR by facilitating the recruitment of MRE11 to DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) and mediating Ku80 ubiquitylation, which influences the choice of DNA repair pathway [9]. This function positions RNF138 as a potential target in cancers with DNA repair deficiencies.

RNF166 exhibits dual functionality, mediating both ubiquitination and SUMOylation of cellular targets, suggesting context-dependent roles in protein stability and degradation [34].

SCF Complexes in Cell Cycle and Tumorigenesis

SCF complexes are master regulators of the cell cycle, controlling the degradation of key cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, and transcription factors. Their dysregulation is a hallmark of numerous cancers.

- G1/S Phase Transition: SCF complexes involving Fbxo4 and Fbxw7 regulate the degradation of cyclin D1 and other G1/S transition proteins [35]. The SCF(Fbxw7) complex, in particular, is a critical tumor suppressor that targets oncoproteins like c-Myc, cyclin E, and Notch for degradation [35].

- S Phase Progression: SCF(Skp2) drives the transition into S phase by targeting cell cycle inhibitors p21 and p27 for degradation [35]. Overexpression of Skp2 is observed in many cancers and correlates with poor prognosis.

- G2/M Phase Transition: Multiple SCF complexes, including SCF(β-TrCP), regulate the degradation of proteins like Cdc25A and Wee1, ensuring proper mitotic entry [35]. Dysregulation of these complexes can lead to genomic instability.

The table below summarizes key cancer-related mechanisms for both E3 ligase families.

Table 3: Cancer Mechanisms of RING-UIM and SCF E3 Ligases