Endogenous Ubiquitination Detection: Overcoming Key Challenges in Basic Research and Drug Development

Accurately detecting endogenous protein ubiquitination is a cornerstone for understanding cellular regulation and developing targeted therapies like PROTACs.

Endogenous Ubiquitination Detection: Overcoming Key Challenges in Basic Research and Drug Development

Abstract

Accurately detecting endogenous protein ubiquitination is a cornerstone for understanding cellular regulation and developing targeted therapies like PROTACs. However, researchers face significant challenges including low endogenous stoichiometry, the complex architecture of ubiquitin chains, and the limitations of traditional, low-throughput methods. This article explores the foundational complexities of the ubiquitin system, evaluates current and emerging methodological solutions—from advanced mass spectrometry to chain-specific TUBEs and live-cell assays—and provides a framework for troubleshooting and validation. By comparing the applications and limitations of these technologies, we provide a comprehensive guide for scientists to navigate the technical hurdles and reliably characterize ubiquitination in physiological and drug discovery contexts.

The Ubiquitin Code: Unraveling the Fundamental Challenges in Native System Analysis

The detection of endogenous protein ubiquitination—the process of identifying a protein's ubiquitin modification without artificial overexpression of system components—remains a formidable challenge in molecular and cellular biology. Despite its critical importance for understanding disease mechanisms and developing targeted therapies, researchers face significant technical hurdles including low endogenous stoichiometry, the dynamic nature of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, and interference from abundant polyubiquitin chains. This technical guide examines the fundamental obstacles in endogenous ubiquitination detection, evaluates current methodologies and their limitations, and provides detailed experimental protocols for overcoming these challenges. By framing these issues within the broader context of ubiquitination research, we aim to equip scientists with the strategic approaches necessary to generate reliable, physiologically relevant data on endogenous protein ubiquitination.

Ubiquitination represents one of the most versatile and complex post-translational modifications in eukaryotic cells, regulating diverse cellular functions including protein degradation, signal transduction, DNA repair, and immune responses [1] [2]. The term "endogenous ubiquitination" refers to the naturally occurring modification of substrate proteins by ubiquitin under physiological conditions without experimental manipulation such as overexpression of ubiquitin or target proteins. Investigating endogenous ubiquitination is crucial because it reflects the authentic regulatory state of proteins without the artifacts introduced by overexpression systems, which can overwhelm natural enzymatic pathways and produce non-physiological ubiquitination patterns.

The fundamental challenge in detecting endogenous ubiquitination stems from the biological nature of the process itself. Unlike phosphorylation or acetylation, ubiquitination involves the covalent attachment of an entire 8.6 kDa protein to substrate proteins, creating structural complexities that complicate analysis [2]. Additionally, the ubiquitin system generates an extraordinary diversity of modification types—including monoubiquitination, multiple monoubiquitination, and various polyubiquitin chain linkages—each with distinct functional consequences that require precise characterization to draw meaningful biological conclusions [1] [3].

Table: Key Characteristics of Endogenous Ubiquitination That Complicate Detection

| Characteristic | Biological Significance | Detection Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Low Stoichiometry | Prevents unnecessary protein turnover | Below detection limits of most conventional methods |

| Multiple Linkages | K48 (degradation), K63 (signaling), etc. [3] | Requires linkage-specific detection methods |

| Dynamic Regulation | Rapid conjugation and deconjugation by DUBs [4] | Transient signal difficult to capture |

| Structural Diversity | Monoubiquitination vs. polyubiquitin chains | Single antibodies rarely detect all forms |

| Endogenous Interference | High abundance of free ubiquitin and polyubiquitin | Masks substrate-specific ubiquitination signals |

Fundamental Technical Obstacles

Low Stoichiometry of Endogenous Modification

The most significant barrier in endogenous ubiquitination detection is the exceptionally low proportion of any given protein that is ubiquitinated at steady state. Unlike overexpression systems where a substantial fraction of a target protein may be artificially modified, endogenous ubiquitination typically affects only a minute fraction—often less than 1%—of a specific substrate pool at any given time [4]. This low stoichiometry places enormous demands on detection sensitivity, as the signal from the ubiquitinated species must be distinguished from the overwhelming background of the unmodified protein. This challenge is further compounded when studying dynamically regulated processes where ubiquitination states may change rapidly in response to cellular signals.

The problem of low stoichiometry is biologically intentional—if a larger proportion of essential proteins were ubiquitinated at any given moment, uncontrolled degradation would disrupt cellular homeostasis. However, this protective feature creates a substantial detection dilemma for researchers. As one study noted, "only a small percentage of a given protein is ubiquitinated in the steady state" [4], making enrichment steps absolutely necessary before detection can be attempted. Without such enrichment, the ubiquitinated forms remain undetectable against the high background of unmodified protein.

Ubiquitin System Dynamics and Lability

The ubiquitination process is inherently dynamic, with continuous conjugation by E1-E2-E3 enzyme cascades and rapid deconjugation by deubiquitinase enzymes (DUBs). This dynamic equilibrium presents a second major challenge for detection, as ubiquitination events on endogenous proteins are often transient in nature [2]. The lability of ubiquitin modifications is particularly problematic during cell lysis and sample preparation, when the disruption of cellular compartments releases DUBs that can rapidly remove ubiquitin from substrates before analysis.

Researchers have documented that "DUBs have sizable enzymatic activity and further decrease levels of ubiquitinated proteins upon cell lysis" [4], making preservation of the endogenous ubiquitination state a technical race against time. This problem necessitates the inclusion of DUB inhibitors in lysis buffers and rapid processing of samples to minimize artificial deubiquitination. However, even with these precautions, the inherently transient nature of many endogenous ubiquitination events means that capture represents a snapshot of a dynamically changing process that may not fully reflect the physiological state.

Polyubiquitin Chain Interference

In endogenous settings, free ubiquitin and polyubiquitin chains represent some of the most abundant proteins in the cell, creating substantial interference in detection assays. As noted in proteomic studies, "ubiquitin is the most abundant ubiquitinated protein in the cell due to the prevalence of poly-Ub chains, masking the identification of other substrates" [4]. This high background noise effectively obscures the detection of specific ubiquitinated substrates, particularly when studying low-abundance proteins that may be critical regulatory targets.

The interference from polyubiquitin chains affects multiple detection methodologies. In western blotting, the smear of polyubiquitin chains can obscure specific signals, while in mass spectrometry-based approaches, peptides derived from ubiquitin itself can dominate the analysis, reducing the capacity to detect peptides from ubiquitinated substrates. This problem necessitates specialized enrichment strategies that can distinguish between free ubiquitin, polyubiquitin chains, and specifically ubiquitinated substrates—a challenging proposition given the structural similarities between these different states.

Diversity of Ubiquitin Linkages and Architectures

The structural complexity of ubiquitin modifications presents a fourth major obstacle to comprehensive endogenous detection. Ubiquitin contains eight potential linkage sites—M1, K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, and K63—each capable of forming functionally distinct polyubiquitin chains [3] [2]. Additionally, mixed or branched chains containing multiple linkage types further complicate the analytical landscape. This diversity means that detecting "ubiquitination" as a monolithic modification provides insufficient biological information; instead, researchers must determine the specific linkage types involved to understand functional consequences.

The linkage diversity problem is particularly relevant for endogenous studies because different linkages frequently occur in distinct physiological contexts. For example, "K48-linked polyubiquitin was found to be involved in DNA repair while K48-linked polyubiquitin was crucial for protein degradation and cell cycle progression" [3]. This linkage-function relationship means that simply detecting ubiquitination provides limited insight; the specific linkage pattern must be deciphered to understand biological significance. Most conventional detection methods lack the specificity to distinguish between these different linkage types, requiring specialized reagents and approaches for comprehensive analysis.

Methodological Limitations and Solutions

Conventional Immunodetection Approaches

The most straightforward approach for detecting endogenous ubiquitination involves immunoprecipitation of the target protein followed by western blot analysis with anti-ubiquitin antibodies. This method requires "a good antibody against the target working in IP; alternatively, one could express a tagged version of the protein, possibly at the endogenous level" [5]. While conceptually simple, this approach faces significant sensitivity challenges due to the low stoichiometry of endogenous ubiquitination and the limited specificity of many ubiquitin antibodies.

A reverse approach involves "IP ubiquitinated proteins from total cell lysate followed by detection with the antibody against the protein of interest" [5], but this method relies on "the availability of specific and very efficient antibodies against Ub" [5]. Both variations of the immunodetection approach struggle with the fundamental signal-to-noise ratio problem presented by endogenous ubiquitination levels. Additionally, western blotting provides primarily semi-quantitative data, making it difficult to precisely measure dynamic changes in ubiquitination levels across different experimental conditions.

Advanced Enrichment Methodologies

To address the sensitivity limitations of conventional approaches, researchers have developed specialized enrichment techniques that improve the capture of ubiquitinated proteins from complex mixtures. These methodologies typically exploit ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) or specialized antibodies to selectively isolate ubiquitinated species before detection.

Table: Comparison of Endogenous Ubiquitin Enrichment Methodologies

| Methodology | Principle | Sensitivity | Linkage Specificity | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoaffinity with Pan-Ub Antibodies [2] | Antibodies recognizing all ubiquitin linkages | Moderate | None | High background from abundant Ub proteins |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies [2] | Antibodies specific to particular chain linkages | Variable | High | Limited availability; uncertain coverage |

| Single UBD Domains [4] | Single ubiquitin-binding domains | Low | Variable | Low affinity limits utility |

| Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) [3] [2] | Multiple UBDs in tandem for avidity | High | Can be engineered for specificity | Potential loss of architectural information |

| Ubiquitin Remnant Antibodies | Antibodies recognizing diglycine remnant on lysine | High for site identification | None | Requires mass spectrometry analysis |

Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) represent a particularly promising approach for endogenous ubiquitination studies. TUBEs consist of "multiple UBA domains displayed avidity in poly-Ub binding" [4], significantly improving affinity compared to single domains. These reagents can be engineered for linkage specificity, enabling researchers to discriminate between different functional ubiquitin signals. For example, "chain-specific TUBEs with nanomolar affinities for polyubiquitin chains" [3] have been successfully employed to differentiate between K48-linked ubiquitination associated with proteasomal degradation and K63-linked ubiquitination involved in signal transduction.

Mass Spectrometry-Based Strategies

Mass spectrometry offers a powerful alternative for detecting endogenous ubiquitination, particularly through the identification of the characteristic diglycine remnant left on tryptic peptides from ubiquitinated proteins. This "signature" mass shift of 114.043 Da on modified lysine residues enables precise mapping of ubiquitination sites [4] [2]. However, this approach requires substantial enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides to overcome sensitivity limitations, as unmodified peptides dominate typical proteomic digests.

The most successful mass spectrometry workflows combine multiple enrichment strategies—such as TUBE-based protein-level enrichment followed by diglycine-remnant peptide-level enrichment—to achieve the sensitivity needed for endogenous ubiquitination site mapping. These sophisticated workflows have enabled studies such as the identification of "294 endogenous ubiquitination sites on 223 proteins from human 293T cells without proteasome inhibitors or overexpression of ubiquitin" [4]. Despite these advances, mass spectrometry approaches remain technically demanding, requiring specialized instrumentation and expertise that may not be accessible to all researchers.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

TUBE-Based Endogenous Ubiquitination Detection

The following protocol details the use of Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) for detecting endogenous ubiquitination of a target protein, based on methodologies described in recent literature [3] [2]. This approach offers significantly improved sensitivity compared to conventional immunoprecipitation methods.

Reagents and Solutions:

- GST-qUBA beads: Recombinant GST fusion of four tandem ubiquilin-1 UBA domains immobilized on glutathione-sepharose beads

- Lysis Buffer: NETN buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40) supplemented with protease inhibitor mixture and DUB inhibitors (1 mM iodoacetamide and 8 mM 1,10-o-phenanthroline)

- Wash Buffer: NETN buffer with DUB inhibitors

- Elution Buffer: 50% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid or 2× SDS-PAGE loading buffer

- Primary antibodies: Target-specific antibody and ubiquitin detection antibody

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Treatment: Grow twenty 150-mm dishes of cells to confluence under appropriate conditions. Apply experimental treatments to modulate ubiquitination states.

- Cell Lysis: Harvest cells and lyse using brief sonication in ice-cold Lysis Buffer. Maintain samples on ice throughout to minimize deubiquitination.

- Clarification: Centrifuge lysates twice at 100,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble material.

- Affinity Enrichment: Incubate clarified lysates with 200 μL of immobilized GST-qUBA beads at 4°C for 40 minutes with gentle agitation.

- Washing: Wash beads four times with 1 mL of ice-cold Wash Buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elution: Elute bound proteins using either 50% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid for mass spectrometry analysis or by boiling in SDS-PAGE loading buffer for western blot analysis.

- Detection: Separate eluted proteins by SDS-PAGE, transfer to membranes, and probe with target-specific antibodies to detect ubiquitinated species.

Critical Considerations:

- Include DUB inhibitors throughout the process to prevent loss of ubiquitin signals

- Process controls in parallel without TUBE enrichment to assess specificity

- Optimize lysis conditions for your specific target protein to maintain solubility while preserving ubiquitination

- For linkage-specific detection, use engineered TUBEs selective for particular ubiquitin chain types

Immunoprecipitation-Based Detection of Endogenous Ubiquitination

This protocol describes the conventional approach for detecting endogenous ubiquitination of a specific target protein through immunoprecipitation and western blotting [5].

Reagents and Solutions:

- IP Lysis Buffer: RIPA buffer or NP-40-based buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors and DUB inhibitors (10 mM N-ethylmaleimide or 1 μM PR-619)

- IP Wash Buffer: Similar composition to lysis buffer but with reduced detergent concentration

- Antibodies: High-quality antibody against target protein for immunoprecipitation, anti-ubiquitin antibody for detection (P4D1, FK1, or FK2)

- Protein A/G Beads: Agarose or magnetic beads coupled to Protein A or G

Procedure:

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells in IP Lysis Buffer (500 μL to 1 mL per 10⁷ cells) by gentle vortexing or pipetting. Incubate on ice for 10-30 minutes.

- Clarification: Centrifuge lysates at 10,000-20,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Transfer supernatant to a new tube.

- Pre-clearing: Incubate lysate with control IgG and Protein A/G beads for 30 minutes at 4°C. Pellet beads and transfer supernatant to a new tube.

- Immunoprecipitation: Add target-specific antibody (1-5 μg) to lysate and incubate for 2-4 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation.

- Bead Capture: Add Protein A/G beads and incubate for an additional 1-2 hours to capture antibody-target complexes.

- Washing: Wash beads 3-4 times with IP Wash Buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elution: Elute proteins by boiling in 2× SDS-PAGE loading buffer for 5-10 minutes.

- Western Blot: Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE, transfer to membrane, and probe with anti-ubiquitin antibody to detect ubiquitinated target protein.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Include positive and negative controls to validate antibody specificity and ubiquitination detection

- Optimize antibody concentrations to maximize signal while minimizing background

- Use high-sensitivity chemiluminescent substrates to detect low-abundance ubiquitinated species

- Consider using target protein knockdown/knockout cells as a negative control for antibody specificity

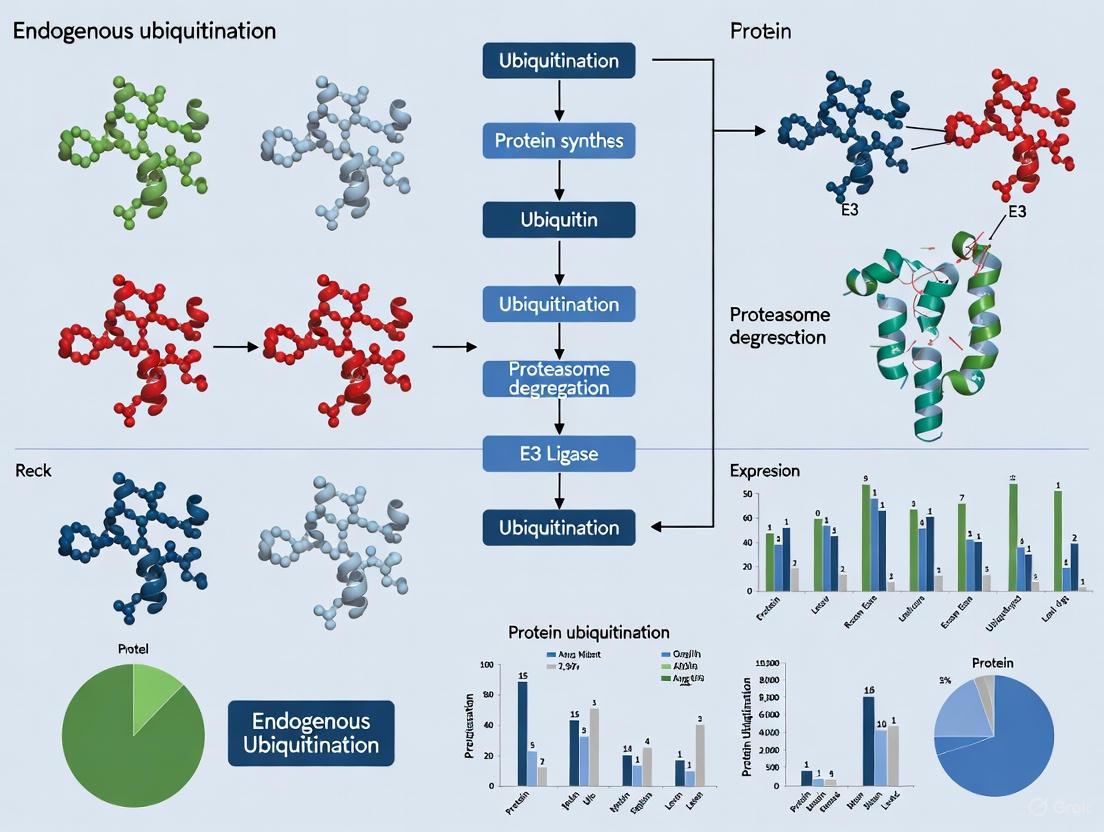

Visualization of Experimental Approaches

Endogenous Ubiquitination Detection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for detecting endogenous protein ubiquitination, highlighting critical decision points and methodological options:

Ubiquitin Chain Linkage Diversity

This diagram illustrates the complexity of ubiquitin chain linkages that complicate endogenous detection efforts:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful detection of endogenous ubiquitination requires specialized reagents designed to address the unique challenges of low abundance and lability. The following table details key solutions used in the field:

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Endogenous Ubiquitination Detection

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Utility | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DUB Inhibitors | N-ethylmaleimide, PR-619, Iodoacetamide | Prevent deubiquitination during sample processing | Critical for preserving endogenous ubiquitination signals during lysis |

| TUBE Reagents | GST-qUBA, K48-TUBE, K63-TUBE [3] | High-affinity capture of polyubiquitinated proteins | Engineered tandem UBDs with avidity effect; linkage-specific versions available |

| Ubiquitin Antibodies | P4D1, FK1, FK2, Linkage-specific antibodies [2] | Detection of ubiquitinated proteins in western blot | Varying specificity; some recognize all linkages, others are linkage-specific |

| Linkage-Specific Reagents | K48-specific TUBEs, K63-specific TUBEs [3] | Discrimination between functional ubiquitin signals | Essential for understanding biological consequences of ubiquitination |

| Affinity Matrices | Ni-NTA agarose, Strep-Tactin resin | Purification of tagged ubiquitin conjugates | Used in tagged-ubiquitin approaches; potential for non-specific binding |

| Mass Spec Standards | Heavy-labeled ubiquitin, DiGly remnant peptides | Quantification of ubiquitination sites | Enable absolute quantification in mass spectrometry approaches |

The detection of endogenous protein ubiquitination remains non-trivial due to fundamental biological and technical constraints, including low stoichiometry, dynamic regulation, and structural diversity of ubiquitin modifications. While significant methodological advances—particularly in enrichment technologies like TUBEs and sensitive mass spectrometry approaches—have improved our capacity to study endogenous ubiquitination, these techniques remain demanding and require careful optimization. The field continues to evolve with emerging technologies such as activity-based probes for DUBs, improved linkage-specific reagents, and single-cell ubiquitination analysis methods that promise to further enhance our capabilities.

As research progresses, the integration of multiple complementary approaches will likely provide the most comprehensive insights into endogenous ubiquitination dynamics. Cross-validation between immunodetection methods, TUBE-based enrichment, and mass spectrometry analysis offers the most robust strategy for confirming endogenous ubiquitination events [5]. Furthermore, the development of standardized protocols and reference materials would significantly improve reproducibility across laboratories. Despite the challenges, mastering these complex detection methods is essential for advancing our understanding of ubiquitin biology and developing novel therapeutic strategies that target the ubiquitin-proteasome system in human disease.

Ubiquitination, the covalent attachment of the 76-amino acid protein ubiquitin to target substrates, represents one of the most versatile post-translational modifications in eukaryotic cells [1]. Originally characterized as a signal for proteasomal degradation via K48-linked polyubiquitin chains, our understanding of ubiquitin signaling has expanded dramatically to encompass at least eight distinct linkage types (M1, K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, and K63) that regulate diverse non-proteolytic processes [6] [3] [7]. The specific cellular outcomes of ubiquitination are determined by the ubiquitin code—a complex language comprising chain linkage type, length, and architecture that enables precise control over protein fate, activity, and localization [8] [1] [9].

This functional diversity originates from ubiquitin's structure, which contains seven lysine residues and an N-terminal methionine, each capable of forming distinct polyubiquitin chains with unique three-dimensional structures recognized by specific effector proteins [1] [7]. While K48-linked chains remain the canonical degradation signal and K63-linked chains are well-established regulators of signal transduction, recent research has revealed sophisticated signaling roles for the less-studied "atypical" ubiquitin linkages (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33) and complex chain architectures including branched ubiquitin chains [10] [7] [11]. This whitepaper examines the expanding functional repertoire of ubiquitin chain linkages, with particular emphasis on the technical challenges inherent in deciphering this complex post-translational modification system.

The Ubiquitin Code: Linkage Types and Functional Significance

Canonical Linkages: K48 and K63

The K48 and K63 ubiquitin linkages represent the best-characterized components of the ubiquitin code, with clearly defined functional specializations established through decades of research.

Table 1: Canonical Ubiquitin Chain Linkages and Their Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Functions | Key Enzymes | Cellular Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48 | Proteasomal degradation [6] [3] | UBR5, APC/C [10] [11] | Protein turnover, cell cycle regulation [3] [7] |

| K63 | Signal transduction, protein trafficking, DNA repair [8] [6] | Ubc13/Mms2 complex [8], TRAF6 [11] | NF-κB signaling, endocytosis, inflammation [6] [3] |

K48-linked ubiquitin chains serve as the principal signal for proteasome-mediated degradation, with their discovery representing a foundational moment in ubiquitin biology [8] [3]. In contrast, K63-linked chains function predominantly in non-proteolytic signaling, including roles in inflammatory response pathways where they serve as scaffolding elements for the assembly of signaling complexes such as the IKK complex in NF-κB activation [6] [3]. The structural basis for K63-chain assembly was elucidated through crystallographic studies of the Ubc13/Mms2 heterodimer, which revealed how Mms2 positions K63 of the acceptor ubiquitin toward Ubc13's active site to ensure linkage specificity [8].

Atypical Ubiquitin Linkages

Beyond the canonical K48 and K63 linkages, five additional linkage types (M1, K6, K11, K27, K29, K33) contribute to the complexity of ubiquitin signaling, though their functions remain less comprehensively characterized.

Table 2: Atypical Ubiquitin Chain Linkages and Their Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Functions | Key Enzymes | Cellular Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| K6 | Mitophagy, DNA damage response [7] | Parkin, HUWE1 [7] | Mitochondrial quality control, genome maintenance |

| K11 | Cell cycle regulation, proteasomal degradation [7] [11] | APC/C, UBE2S [7] [11] | Mitotic progression, ER-associated degradation |

| K27 | Immune signaling [2] | LUBAC complex [8] | Innate immunity, inflammatory response |

| K29 | Proteasomal degradation (in branched chains) [10] | TRIP12, Ufd2/Ufd4 [10] [11] | ER-associated degradation, UFD pathway |

| K33 | Protein trafficking, kinase regulation [7] | Unknown | Endosomal sorting, metabolic regulation |

| M1 (Linear) | NF-κB signaling [8] [7] | LUBAC complex [8] | Innate immunity, inflammation |

The K6-linked chains have emerged as important regulators of mitochondrial quality control through the PINK1-Parkin pathway, where they promote mitophagy in response to mitochondrial damage [7]. Additionally, K6 linkages participate in the DNA damage response, with BRCA1-BARD1 complexes capable of K6-linked auto-ubiquitination [7]. K11-linked chains, often found in conjunction with K48 linkages, play specialized roles in cell cycle regulation through the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) and function in endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) [7] [11]. The K29 and K27 linkages have been implicated in specialized degradation pathways and immune signaling, respectively, while K33 linkages appear to regulate intracellular trafficking and kinase activity [7]. M1-linked linear chains, generated by the LUBAC complex, create recruitment platforms for NF-κB signaling components [8].

Branched Ubiquitin Chains: Complexity in Signaling

Architectures and Synthesis Mechanisms

Branched ubiquitin chains represent a sophisticated layer of regulation in the ubiquitin code, wherein individual ubiquitin monomers are modified at multiple sites to create complex topological structures [11]. These branched architectures can significantly alter signaling outcomes compared to their homotypic counterparts.

Table 3: Branched Ubiquitin Chain Types and Their Functions

| Branched Chain Type | Synthesis Mechanism | Biological Functions | Participating Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|

| K29/K48 | Sequential action of TRIP12 (K29) and UBR5 (K48) [10] | Targets DUB-protected substrates for degradation [10] | TRIP12, UBR5 [10] |

| K11/K48 | APC/C with UBE2C and UBE2S E2 enzymes [11] | Cell cycle regulation, enhanced degradation [11] | APC/C, UBE2C, UBE2S [11] |

| K48/K63 | Sequential ubiquitination by ITCH (K63) then UBR5 (K48) [11] | Converts non-proteolytic to degradative signal [11] | TRAF6/HUWE1 or ITCH/UBR5 pairs [11] |

| K6/K48 | Single E3 ligases (e.g., Parkin, bacterial NleL) [11] | Proteasomal degradation during mitophagy [11] | Parkin, NleL [11] |

The synthesis of branched ubiquitin chains frequently involves collaboration between E3 ligases with distinct linkage specificities. For example, in the formation of K29/K48-branched chains on OTUD5, TRIP12 first installs K29-linked chains that are subsequently branched with K48-linked chains by UBR5 [10]. This cooperative mechanism enables the conversion of non-proteolytic ubiquitin signals into degradation signals, as demonstrated during the regulation of TNF-α-induced NF-κB signaling [10]. Alternatively, single E3 ligases can generate branched chains through recruitment of multiple E2 enzymes with different linkage specificities, as observed with the APC/C complex during cell cycle regulation [11].

Figure 1: Synthesis of K29/K48-Branched Ubiquitin Chains via Collaborative E3 Activity

Functional Consequences of Chain Branching

Branched ubiquitin chains serve as priority signals for proteasomal degradation, particularly effective against substrates protected by deubiquitinases (DUBs) [10]. The combination of DUB-resistant linkages (e.g., K29) with proteasome-targeting linkages (e.g., K48) creates a robust degradation signal that can overcome cellular deubiquitination activities [10]. This mechanism is exemplified by OTUD5 degradation, where K29 linkages resist OTUD5's DUB activity (which preferentially cleaves K48 linkages), thereby facilitating UBR5-dependent K48 branching and subsequent proteasomal targeting [10].

Branched chains also enhance proteasome recruitment through increased ubiquitin density and provide binding platforms for specialized ubiquitin receptors. For instance, K11/K48-branched chains demonstrate preferential association with both the proteasome and p97 segregase, accelerating substrate degradation [11]. The strategic incorporation of branched chains enables cells to convert non-degradative signals into degradative ones, as observed during the regulation of apoptosis where K63-linked chains on TXNIP are subsequently branched with K48 linkages to initiate destruction of the pro-apoptotic regulator [11].

Methodological Challenges in Ubiquitination Research

Technical Limitations in Detection and Characterization

The study of ubiquitin chain diversity faces significant technical hurdles, primarily stemming from the low stoichiometry of ubiquitination events, the transient nature of many ubiquitination signals, and the remarkable structural complexity of ubiquitin chains [2]. Traditional methodologies like immunoblotting provide limited information about linkage specificity and are inadequate for capturing dynamic ubiquitination events [6] [2]. Mass spectrometry-based approaches, while powerful, require sophisticated instrumentation and struggle with linkage-specific analysis of endogenous proteins without prior enrichment [6] [2].

A fundamental challenge lies in distinguishing between different chain architectures (homotypic, mixed, branched) and accurately quantifying their relative abundances under physiological conditions [2] [11]. The use of ubiquitin mutants (e.g., lysine-to-arginine substitutions) to study specific linkages may introduce artifacts, as these mutants cannot replicate the full complexity of wild-type ubiquitin interactions [6] [3]. Additionally, the limited availability of high-quality linkage-specific antibodies further constrains comprehensive ubiquitin profiling [2].

Advanced Methodologies for Ubiquitin Analysis

Recent technological advances have begun to address these challenges through the development of specialized tools for ubiquitin research.

Table 4: Methodologies for Ubiquitin Chain Characterization

| Methodology | Principle | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities) | Engineered high-affinity ubiquitin-binding domains [6] [2] | Enrichment of endogenous ubiquitinated proteins; linkage-specific analysis [6] [3] | Potential bias in chain recognition; requires validation |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Antibodies recognizing specific ubiquitin linkages [2] | Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence, immunoprecipitation of specific chain types [2] | Limited availability for atypical linkages; potential cross-reactivity |

| Ubiquitin AQUA/PRM | Absolute quantification using heavy isotope-labeled ubiquitin peptides [10] | Precise quantification of linkage abundance in samples [10] | Requires mass spectrometry expertise; expensive |

| DiGly Antibody Enrichment | Antibodies recognizing diglycine remnant on lysine after trypsin digestion [2] | Proteome-wide ubiquitination site mapping [2] | Does not provide linkage information; bias toward abundant sites |

Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) represent a particularly promising technology, offering nanomolar affinities for polyubiquitin chains and compatibility with high-throughput applications [6] [3]. Chain-specific TUBEs enable researchers to discriminate between different ubiquitin linkages in cellular contexts, as demonstrated by the differential capture of K63-linked RIPK2 ubiquitination induced by inflammatory stimuli versus K48-linked ubiquitination induced by PROTAC treatment [6] [3]. This technology provides a significant advantage over traditional methods by preserving labile ubiquitination signals during cell lysis and allowing more accurate assessment of endogenous ubiquitination dynamics.

Figure 2: TUBE-Based Workflow for Linkage-Specific Ubiquitination Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific TUBEs | K63-TUBE, K48-TUBE, Pan-TUBE [6] [3] | Selective enrichment of specific ubiquitin linkages | High affinity (nM range), linkage specificity, preserves ubiquitination during lysis |

| Tagged Ubiquitin Constructs | His-tagged Ub, Strep-tagged Ub, HA-Ub [2] | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins | Enables substrate identification; may alter ubiquitin structure |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K48-linkage specific, K63-linkage specific [2] | Detection and enrichment of specific chain types | Limited to characterized linkages; quality varies between lots |

| DUB Inhibitors | PR-619, N-ethylmaleimide [2] | Preservation of ubiquitination during sample preparation | Broad-specificity or linkage-selective options available |

| Activity-Based Probes | Ub-VS, Ub-PA [2] | Profiling DUB activity and specificity | Identifies active DUBs; can be linkage-specific |

| E3 Ligase Modulators | PROTACs, Molecular Glues [6] [12] | Targeted protein degradation; E3 functional studies | Enables precise manipulation of ubiquitination pathways |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Perspectives

The expanding understanding of ubiquitin linkage diversity has profound implications for therapeutic development, particularly in the field of targeted protein degradation [6] [12]. PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) and molecular glues represent groundbreaking therapeutic modalities that hijack the ubiquitin-proteasome system to eliminate disease-causing proteins [6] [12]. These approaches predominantly utilize K48-linked ubiquitination to target proteins for degradation, but emerging research suggests that incorporating alternative linkages or branched chains could enhance degradation efficiency, particularly for challenging substrates [10] [12].

The ability to specifically modulate inflammatory signaling through interference with K63 ubiquitination presents another promising therapeutic avenue [6] [3]. Small molecule inhibitors targeting enzymes involved in K63 chain assembly (e.g., TRAF6, Ubc13) have shown efficacy in preclinical models of inflammatory diseases, highlighting the potential of linkage-specific ubiquitin modulation as a treatment strategy [6] [3]. Additionally, DUBs that specifically cleave K63-linked chains offer alternative targets for modulating inflammatory pathways [6] [3].

Future progress in ubiquitin research will depend on overcoming persistent methodological challenges, particularly the development of more comprehensive tools for analyzing the full complexity of the ubiquitin code under physiological conditions. Advances in mass spectrometry sensitivity, the generation of additional high-affinity linkage-specific reagents, and the integration of computational approaches will be essential for deciphering the nuanced language of ubiquitin signaling in health and disease [2] [9]. As these technical barriers are addressed, our understanding of ubiquitin chain linkages will continue to evolve, revealing new biological insights and therapeutic opportunities far beyond the original degradation-centric paradigm.

Within the broader challenge of endogenous ubiquitination detection, a central and persistent hurdle is the specific discrimination between productive and non-productive ubiquitination events. Ubiquitination, the covalent attachment of the small protein modifier ubiquitin to substrate proteins, regulates a vast array of cellular processes, ranging from targeted proteasomal degradation to non-proteolytic signaling in DNA repair, endocytosis, and immune response [1] [13]. The term "productive" herein refers to ubiquitination events that trigger a specific, functional biological outcome, such as degradation via the 26S proteasome or the activation of a signaling pathway. In contrast, "non-productive" interactions are those that are functionally silent, transient, or lead to abortive outcomes, and they represent a significant source of background noise in detection assays.

This specificity problem arises from the immense complexity of the ubiquitin code. A typical protein contains numerous surface-accessible lysine residues, all of which are theoretically competent for ubiquitination [13]. The combinatorial space is further expanded by the ability of ubiquitin itself to form polymer chains through any of its seven internal lysine residues or its N-terminal methionine, with each linkage type—be it K48-linked, K63-linked, or the less common K6-, K11-, K27-, K29-, and K33-linked chains—potentially conferring a distinct fate to the modified substrate [1] [2]. Furthermore, the system is dynamically regulated by deubiquitinases (DUBs) which act as 'erasers' of the ubiquitin code [14]. Consequently, simply detecting a ubiquitinated species is insufficient; researchers must decipher the functional meaning of that modification within a specific physiological context. This guide details the modern methodologies and strategic considerations required to overcome this specificity hurdle in endogenous ubiquitination research.

Methodological Approaches for Specific Ubiquitination Analysis

A multifaceted approach is required to confidently assign function to a ubiquitination event. The table below summarizes the core methodologies, their applications, and their specific utility in distinguishing productive from non-productive interactions.

Table 1: Core Methodologies for Specific Ubiquitination Analysis

| Methodology | Primary Application | Utility in Specificity | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoblotting with Linkage-Specific Antibodies [2] | Detection of specific ubiquitin chain topologies (e.g., K48, K63). | Distinguishes degradation-signaling (K48) from signaling-specific (K63) chains. | Limited to known, well-characterized linkages; antibody cross-reactivity is a concern. |

| MS-Based Ubiquitylomics with Proteasome Inhibition [15] | Global profiling of ubiquitination sites. | Reveals ubiquitination events that directly lead to substrate degradation when compared to non-inhibited conditions. | Proteasome inhibition can artificially alter the ubiquitin landscape and deplete Ub pools. |

| Tandem-Repeated Ub-Binding Entities (TUBEs) [2] | Affinity enrichment of endogenous ubiquitinated proteins. | Protects ubiquitinated proteins from DUBs during extraction, preserving the native "productive" state. | May not differentiate between functional and non-functional polyubiquitin chains. |

| Site-Specific Mutagenesis (Lysine to Arginine) [2] | Functional validation of specific ubiquitination sites. | Establishes a causal link between modification at a specific lysine and a functional outcome (e.g., protein stabilization). | Mutagenesis may disrupt protein folding or other lysine-dependent functions, leading to indirect effects. |

| Biochemical Reconstitution with Homogeneous Ubiquitination [13] | In vitro study of the biophysical consequences of ubiquitination. | Directly tests how ubiquitination at a single, defined site alters substrate stability, conformation, or interactome. | Technically challenging to produce homogenously modified proteins; may not fully recapitulate the cellular environment. |

Strategic Application of Proteasome Inhibition

A critical strategy for identifying productive degradative ubiquitination involves the deliberate use of proteasome inhibitors, such as MG132. In a landmark quantitative proteomic study, researchers demonstrated that profiling ubiquitination both in the presence and absence of MG132 was essential for a complete picture [15]. For substrates like CDC25A and EXO1, whose ubiquitination leads to rapid degradation, the ubiquitination signal decreased upon DNA damage in the absence of MG132, not because of deubiquitination, but because the modified protein was swiftly destroyed. Only upon proteasome inhibition was the induced ubiquitination event clearly detectable [15]. Conversely, for non-proteolytic ubiquitination events, such as on PCNA, inhibition could sometimes diminish the signal, likely due to depletion of free ubiquitin pools [15]. This differential response to proteasome inhibition provides a powerful filter for classifying the functional outcome of ubiquitination.

Quantitative Insights from Proteomic Studies

Large-scale ubiquitylomic studies have begun to map the landscape of ubiquitination, providing quantitative data on regulated sites. The following table compiles key quantitative findings from targeted studies, illustrating the scale and context-dependence of ubiquitination.

Table 2: Quantitative Ubiquitination Profiles from Selected Studies

| Study Context | Total Ubiquitination Sites Identified | Regulated Sites (>2-fold change) | Key Functional Pathways Implicated | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Damage Response (UV & IR) [15] | 33,503 sites | 2,197 sites (UV), 741 sites (IR) | Nucleotide Excision Repair (NER), Fanconi Anemia (FA) pathway, mitotic spindle/centromere function. | [15] |

| Human Pituitary Adenomas [16] | 158 sites on 108 proteins | Not specified (Comparative analysis performed) | PI3K-AKT signaling, Hippo signaling, ribosome biogenesis, nucleotide excision repair. | [16] |

| Global Profiling (HeLa cells) [2] | 277 - 753 sites (varying methods) | Varies by cellular perturbation | Diverse, dependent on the specific E3 ligase or stressor studied. | [2] |

These datasets underscore that ubiquitination is a widespread modification and that a significant fraction of sites are dynamically regulated. The identification of regulated sites on proteins like CENPs (centromere proteins) in the DNA damage response also highlights that the functional consequences of ubiquitination extend far beyond the proteasome, implicating it in processes like chromosome segregation [15].

Experimental Workflow for Endogenous Ubiquitination Detection

The following diagram illustrates a integrated workflow for the specific detection and validation of endogenous protein ubiquitination, incorporating key steps to minimize artifacts and maximize functional insight.

Workflow Description

- Cell/Tissue Lysis with Stabilization: The process begins with the rapid lysis of cells or tissue under denaturing conditions to preserve the native ubiquitination state. The addition of proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG132) at this stage is critical to prevent the degradation of proteins marked by productive degradative ubiquitination, thereby allowing their detection [15].

- Enrichment of Ubiquitinated Proteins: To overcome the low stoichiometry of endogenous ubiquitination, specific enrichment is required. This can be achieved using:

- TUBEs (Tandem-repeated Ubiquitin-Binding Entities): These high-affinity tools protect polyubiquitin chains from deubiquitinases (DUBs) during extraction, preserving the endogenous ubiquitin signature [2].

- Anti-Ubiquitin Antibodies: Antibodies specific to the ubiquitin remnant (K-ε-GG) after trypsin digestion are widely used for proteomic studies, while linkage-specific antibodies can pull down chains of a defined topology [2] [16].

- Method Selection for Analysis: The enriched material is then analyzed via a hypothesis-driven or discovery-based path.

- Immunoblotting with linkage-specific antibodies (e.g., for K48 or K63 chains) provides a direct readout of chain type and abundance, useful for confirming a suspected functional outcome [2].

- Mass Spectrometry (Ubiquitylomics) enables the global, unbiased identification of ubiquitination sites and, with advanced techniques, can reveal the architecture of the ubiquitin chain itself [15] [2] [16].

- Functional Validation: Any candidate ubiquitination event requires functional validation. The most common method is site-directed mutagenesis, where the target lysine is replaced with an arginine (K to R). If this mutation stabilizes a protein or abrogates a signaling event, it provides strong evidence that ubiquitination at that specific site was productive [2].

- Data Integration: The final step involves synthesizing data from all sources to assign a functional role to the ubiquitination event, distinguishing productive from non-productive interactions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Success in ubiquitination research relies on a suite of specialized reagents. The table below details key tools and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitination Research

| Research Reagent | Function & Specific Role | Key Consideration for Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific Ub Antibodies [2] | Immunoblot/IP: Detects or enriches for specific polyubiquitin chain linkages (K48, K63, etc.). | Directly links a ubiquitination event to a potential function (e.g., K48 for degradation). |

| K-ε-GG Motif Antibody [15] [16] | MS Sample Prep: Immunoaffinity enrichment of tryptic peptides derived from ubiquitinated proteins for mass spectrometry. | Enables system-wide discovery of ubiquitination sites from endogenous samples. |

| TUBEs (Tandem UBIQUITIN Binding Entities) [2] | Affinity Purification: High-affinity enrichment of polyubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates while protecting from DUBs. | Preserves the labile "productive" ubiquitin signature that might otherwise be lost during preparation. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132) [15] | Cell Treatment: Blocks the 26S proteasome, preventing degradation of proteins marked with degradative ubiquitin chains. | Essential for amplifying the signal of transient, productive degradation signals. |

| Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme (E1) Inhibitor (e.g., TAK-243) | Cell Treatment: Blocks the entire ubiquitination cascade, serving as a critical negative control. | Confirms that a detected signal is truly dependent on ubiquitination. |

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors | Cell Treatment / Lysate Additive: Inhibits DUB activity to prevent loss of ubiquitin signals post-lysis. | Helps maintain the endogenous ubiquitination landscape, reducing false negatives. |

Distinguishing productive from non-productive ubiquitination is a multifaceted challenge that lies at the heart of understanding this critical post-translational modification. There is no single solution; rather, researchers must employ an integrated strategy. This involves stabilizing transient interactions with pharmacological agents, deciphering the ubiquitin code using linkage-specific tools, mapping modifications globally with advanced proteomics, and establishing causal relationships through functional genetics and biochemical reconstitution. As the methodologies detailed herein continue to mature, the scientific community will be better equipped to crack the specificity hurdle, paving the way for a deeper understanding of cellular regulation and the development of more precise therapeutics targeting the ubiquitin system.

The Interplay of E1, E2, and E3 Enzymes in Creating Complexity

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) represents a fundamental regulatory mechanism in eukaryotic cells, governing the controlled degradation of proteins and thereby influencing nearly all aspects of cellular life. The specificity of this system originates from a sophisticated enzymatic cascade comprising E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes, which collectively mediate the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to target proteins. This modification, known as ubiquitination, can signal for proteasomal degradation or alter a protein's function, localization, and interactions. The complexity of this system is staggering; the human genome encodes approximately 2 E1 enzymes, ~40 E2 enzymes, and over 600 E3 ligases, which collectively manage the specificity for thousands of distinct protein substrates [17] [18] [2]. This intricate interplay presents a profound challenge for research, particularly in the accurate detection and characterization of endogenous ubiquitination events. This technical guide will delineate the core mechanisms of the E1-E2-E3 cascade, detail the experimental methodologies essential for its study, and frame these discussions within the pressing challenges of endogenous ubiquitination detection that confront researchers today.

The Core Enzymatic Cascade: Mechanism and Specificity

The ubiquitination pathway is a sequential enzymatic process that results in the attachment of ubiquitin to specific substrate proteins. The process is initiated by the ATP-dependent activation of ubiquitin by an E1 enzyme. The E1 enzyme's catalytic cysteine residue attacks the ATP-activated C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin, forming a high-energy thioester bond [17] [19]. Structural studies have revealed that the C-terminal sequence of ubiquitin (LRLRGG) is critical for E1 recognition, with Arg72 being absolutely indispensable for this interaction [20]. Following activation, ubiquitin is transferred to the catalytic cysteine of an E2 conjugating enzyme via a transthiolation reaction, forming an E2~Ub thioester intermediate [17].

The E3 ubiquitin ligase, the final and most pivotal enzyme in this cascade, is responsible for substrate recognition and the transfer of ubiquitin. E3s achieve this through two primary mechanistic styles:

- RING-type E3s: These function as scaffolds that simultaneously bind the E2~Ub complex and the substrate protein, facilitating the direct transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to the substrate without a covalent E3-ubiquitin intermediate [17] [18].

- HECT-type E3s: These employ a two-step mechanism. First, ubiquitin is transferred from the E2 to a catalytic cysteine within the HECT domain, forming a reactive E3~Ub thioester. Subsequently, the E3 catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin to the target substrate [17] [18].

A third class, known as RBR (RING-Between-RING) E3 ligases, utilizes a hybrid mechanism that combines aspects of both RING and HECT types [18]. The hierarchical nature of this system—with few E1s, a moderate number of E2s, and a vast repertoire of E3s—ensures that substrate specificity is predominantly conferred by the E3 ligases [17]. This specificity is further refined by the ability of E3s to recognize specific degradation signals, or degrons, on their substrates. These degrons can be constitutive or can be activated by post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation (phosphodegrons), or revealed through protein maturation, misfolding, or exposure to specific environmental conditions like oxygen levels [17].

Table 1: Key Enzyme Classes in the Human Ubiquitination Cascade

| Enzyme Class | Number of Human Genes | Primary Role | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Activating) | 2 [2] | Ubiquitin activation | ATP-dependent; forms E1~Ub thioester; one E1 (Ube1) is major [19] |

| E2 (Conjugating) | ~40 [2] | Ubiquitin conjugation | Accepts Ub from E1; forms E2~Ub thioester; ~30 active E2s [21] |

| E3 (Ligating) | >600 [17] | Substrate recognition & Ub transfer | Imparts substrate specificity; determines polyUb chain topology [17] |

The following diagram illustrates the core ubiquitination cascade, highlighting the distinct mechanisms of RING and HECT-type E3 ligases:

The Complexity of the Ubiquitin Code

The biological outcome of ubiquitination is not determined solely by the modification itself but by the intricate "ubiquitin code" written upon the substrate. This code encompasses several layers of complexity, including monoubiquitination, multi-monoubiquitination, and the formation of polyubiquitin chains. Polyubiquitin chains are formed when the C-terminus of one ubiquitin molecule is covalently linked to one of the seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or the N-terminal methionine (M1) of a preceding ubiquitin molecule [17] [21]. The topology of these chains is a primary determinant of the signal they convey.

Table 2: Diversity and Functions of Ubiquitin Chain Linkages

| Linkage Type | Primary Known Functions | Key E3 Ligases / Complexes |

|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Major signal for proteasomal degradation [22] [18] | Many RING E3s (e.g., APC/C, SCF) [17] |

| K63-linked | Non-proteolytic signaling (DNA repair, NF-κB, inflammation) [18] [6] | TRAF6, cIAPs [6] |

| M1-linked (Linear) | NF-κB activation, immunity [18] | LUBAC complex (HOIP, HOIL-1) [18] |

| K11-linked | Cell cycle regulation, ER-associated degradation (ERAD) [18] | APC/C [18] |

| K27-linked | Innate immune response, mitochondrial regulation [18] | Parkin [18] |

| K29-linked | Proteasomal degradation, innate immunity [18] | UBR5, HUWE1 [18] |

| K33-linked | Intracellular trafficking, T-cell receptor signaling [18] | - |

| K6-linked | DNA damage response, mitophagy [18] | Parkin [18] |

Different chain linkages are read by specific effector proteins containing ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs), which interpret the signal and initiate the appropriate cellular response, such as recruitment to the proteasome or activation of a kinase cascade [21]. Furthermore, the ubiquitin code is complicated by the formation of heterotypic and branched chains, which contain multiple linkage types within a single polymer, and by the fact that ubiquitin itself can be subject to post-translational modifications like phosphorylation and acetylation, adding another layer of regulatory potential [21].

Research Challenges in Endogenous Ubiquitination Detection

The complexity of the E1-E2-E3 interplay and the resulting ubiquitin code presents formidable challenges for experimental research, particularly when the goal is to accurately capture endogenous, unperturbed ubiquitination events.

- Low Stoichiometry and Transient Nature: Ubiquitination is a dynamic and often low-abundance modification. The ubiquitinated form of a protein typically represents only a tiny fraction of its total cellular pool at any given moment, making it difficult to detect without enrichment [2]. Furthermore, the thioester bonds between E1/E2 enzymes and ubiquitin are transient and labile, requiring specialized lysis buffers for preservation.

- Complex Chain Architecture: The diversity of ubiquitin chain linkages means that detecting "ubiquitination" as a monolithic event is insufficient. Understanding the biological consequence requires knowledge of the specific chain type involved. For example, a PROTAC designed to degrade a protein by inducing K48-linked chains may be ineffective if it instead primarily triggers non-degradative K63-linked ubiquitination [6]. Standard proteomic approaches often fail to distinguish between these functionally distinct modifications.

- Limitations of Genetic Manipulation: A common strategy to study ubiquitination involves the overexpression of epitope-tagged ubiquitin (e.g., His-, HA-, or Strep-tagged). While powerful for enrichment, this approach can create artifacts. Tagged ubiquitin may not perfectly mimic endogenous ubiquitin, and its overexpression can saturate the native system, altering the physiology of the pathway and leading to non-specific labeling [2]. There is, therefore, a critical need for methods that can probe the endogenous ubiquitin landscape without genetic manipulation, especially for the analysis of clinical tissue samples.

Experimental Methodologies for Deconvoluting Complexity

To overcome these challenges, researchers have developed a suite of sophisticated biochemical and proteomic tools. The selection of an appropriate method depends on the specific research question, whether it is identifying novel substrates, mapping modification sites, or defining chain topology.

Enrichment Strategies for Ubiquitinated Proteins

The first step in most ubiquitination analyses is the specific isolation of ubiquitinated proteins from complex cell lysates.

- Ubiquitin Tagging-Based Approaches: This involves engineering cells to express ubiquitin with an affinity tag (e.g., 6xHis, Strep, or HA). Following lysis, ubiquitinated proteins are purified using the corresponding affinity resin (Ni-NTA for His, Strep-Tactin for Strep) [2]. While this is a relatively easy and low-cost method, its major drawbacks are the potential for artifacts from tag expression and the infeasibility of use in clinical tissues [2].

- Antibody-Based Enrichment: This method uses antibodies, such as P4D1 or FK2, that recognize ubiquitin itself. This allows for the purification of endogenously ubiquitinated proteins without the need for genetic tags, making it suitable for tissue samples [2]. Furthermore, the development of linkage-specific antibodies (e.g., for K48 or K63 chains) enables the selective enrichment of proteins modified with a particular chain type [6] [2].

- Ubiquitin-Binding Domain (UBD)-Based Enrichment: Proteins containing UBDs, such as tandem ubiquitin-binding entities (TUBEs), can be used as affinity reagents. TUBEs exhibit high affinity for polyubiquitin chains and have the added benefit of protecting ubiquitin chains from deubiquitinating enzyme (DUB) activity during purification [6] [2]. Chain-specific TUBEs (e.g., K48-TUBE or K63-TUBE) have been developed to selectively capture proteins modified with specific linkages, providing a powerful tool for dissecting the ubiquitin code [6].

Cutting-Edge Techniques: ProtacID and TUBE-Based Assays

Recent advancements have led to more nuanced techniques that provide deeper insights into ubiquitination in living cells.

ProtacID is a proximity-dependent labeling approach based on the BioID technique. In this method, a biotin ligase (e.g., miniTurbo) is fused to an E3 ligase (such as VHL or CRBN). When a PROteolysis TArgeting Chimera (PROTAC) recruits a target protein to this engineered E3, the biotin ligase labels nearby proteins with biotin. Subsequent streptavidin-based purification and mass spectrometry analysis can then identify both productive and non-productive interactors of the PROTAC, validating targets and identifying potential off-target effects directly in living cells [23]. The workflow for ProtacID is illustrated below:

Chain-Specific TUBE Assays have been adapted for high-throughput screening to quantify linkage-specific ubiquitination of endogenous proteins. For instance, a 96-well plate can be coated with K48-TUBE to specifically capture proteins modified with K48-linked chains. The ubiquitination of a specific target protein, such as RIPK2, can then be quantified by immunoblotting directly from the plate. This allows researchers to distinguish if a stimulus (like an inflammatory agent) or a PROTAC induces K63-linked (signaling) or K48-linked (degradative) ubiquitination of the same protein, providing critical functional insight [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | High-affinity enrichment of polyUb chains; protects from DUBs [6] [2] | Purification of endogenous ubiquitinated proteins; chain-linkage analysis [6] |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Immuno-enrichment/detection of specific Ub chain types (K48, K63, etc.) [6] [2] | Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence, and IP of defined Ub linkages [2] |

| Epitope-Tagged Ubiquitin (His, HA, Strep) | Affinity-based purification of ubiquitinated proteome [2] | Global ubiquitylome analysis via MS; identification of novel substrates/sites [2] |

| PROTACs/Molecular Glues | Induce targeted ubiquitination and degradation of specific proteins [23] | Chemical biology tool to probe E3 ligase function and for therapeutic development [23] |

| Activity-Based DUB Probes | Label and inhibit active deubiquitinating enzymes [21] | Profiling DUB activity; validating DUB inhibitors; studying Ub chain dynamics [21] |

| Neddylation Inhibitor (MLN4924) | Inhibits cullin-RING ligase (CRL) activity by blocking cullin neddylation [23] | Rescues endogenous CRL substrates; confirms E3 ligase involvement in degradation [23] |

The interplay of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes generates a sophisticated system of regulatory control that is fundamental to cellular homeostasis. The complexity arises not only from the hierarchical cascade itself but from the vast combinatorial potential of E2-E3 partnerships and the dense information content of the ubiquitin code they write. For researchers and drug developers, cracking this code requires moving beyond simply detecting ubiquitination to precisely defining its architecture and functional consequences. While challenges in studying endogenous ubiquitination remain significant, the integration of innovative methodologies—such as ProtacID for mapping interactions in living cells and TUBE-based platforms for linkage-specific analysis—is rapidly advancing the field. As these tools continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly accelerate both our fundamental understanding of ubiquitin signaling and the development of novel therapeutics, such as PROTACs, that harness the power of the ubiquitin system to treat human disease.

Advanced Tools and Techniques: A Methodological Toolkit for Ubiquitination Profiling

Protein ubiquitination is a quintessential post-translational modification (PTM), involved in virtually all cellular processes in eukaryotic cells, from protein degradation and DNA repair to cell signaling and immune response [24] [25]. Unlike smaller PTMs, ubiquitination involves the covalent attachment of an 8.6 kDa ubiquitin protein to target substrates, creating extraordinary structural diversity through monoubiquitination, multiubiquitination, or polyubiquitin chains of various linkages [24] [26]. Despite its biological prevalence, the low stoichiometry of ubiquitination at any specific site and its dynamic, transient nature make the confident detection of endogenous ubiquitination a central challenge in the field [26] [2]. Mass spectrometry (MS) has emerged as a powerful, unbiased tool for identifying ubiquitination sites and characterizing ubiquitin chain architecture. However, the direct analysis of ubiquitinated peptides is hampered by their low abundance and signal suppression from unmodified peptides in complex mixtures. Consequently, sophisticated biochemical enrichment strategies are a non-negotiable prerequisite for in-depth ubiquitinome analysis [24] [27]. This guide details these critical enrichment methodologies and subsequent MS workflows, framing them within the overarching challenge of studying endogenous ubiquitination without genetic manipulation.

Biochemical Enrichment Strategies for Ubiquitinated Substrates

A critical first step in ubiquitinomics is enriching ubiquitinated proteins or peptides from complex lysates. The choice of strategy profoundly impacts specificity, compatibility with physiological systems, and the type of biological information obtained.

Table 1: Core Enrichment Strategies for Ubiquitinated Proteins and Peptides

| Strategy | Principle | Key Reagents | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Tagging | Ectopic expression of affinity-tagged ubiquitin (e.g., His, Strep, FLAG) in cells. | His-tag, Strep-tag, Ni-NTA resin, Strep-Tactin resin [2] | Relatively easy, low-cost; enables study of ubiquitination dynamics in live cells [2]. | Cannot be used on clinical/animal tissues; tagged Ub may not fully mimic endogenous Ub; co-purification of endogenous His-rich proteins can cause background [2]. |

| Ubiquitin Antibody-Based | Immunoaffinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins using anti-ubiquitin antibodies. | P4D1, FK1/FK2 antibodies (pan-specific); linkage-specific antibodies (e.g., K48, K63) [2] | Applicable to endogenous proteins in any sample, including tissues and clinical specimens [2]. | High cost of antibodies; potential for non-specific binding; limited availability of high-quality linkage-specific antibodies [24]. |

| UBD-Based (TUBEs) | Enrichment using Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities with high affinity for ubiquitin chains. | Tandem-repeated Ub-binding entities (TUBEs) [2] | Protects ubiquitin chains from deubiquitinases (DUBs) and proteasomal degradation during lysis; preserves endogenous chain architecture [2]. | Does not directly provide information on the specific ubiquitination sites on the substrate protein [28]. |

| diGly Remnant Immunocapture | Post-digestion enrichment of peptides containing the K-ε-GG remnant left after trypsin cleavage. | Anti-K-ε-GG antibody [27] [26] | Directly enables site mapping; highly specific; compatible with quantitative MS; does not require genetic tags [27]. | Cannot distinguish ubiquitination from other Ub-like modifications (e.g., NEDDylation); bias towards certain peptide sequences [28]. |

The following workflow outlines the typical steps from sample preparation to data analysis, integrating the enrichment strategies described above:

Diagram 1: A generalized workflow for ubiquitinomics, showing the two primary enrichment points and the common strategies employed at each stage.

Mass Spectrometry Detection and Ubiquitination Site Identification

Following enrichment, samples are analyzed by liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The core principle of site identification lies in the unique mass signature imparted to peptides during sample preparation.

The diGly Remnant and Bottom-Up Proteomics

In the dominant bottom-up proteomics approach, proteins are digested with a protease like trypsin before MS analysis. Trypsin cleaves after arginine and lysine residues. The C-terminal sequence of ubiquitin is -RLRGG. Cleavage after the final arginine (R) leaves a diGlycine (diGly or K-ε-GG) remnant—a glycine-glycine moiety—attached via an isopeptide bond to the modified lysine on the substrate peptide [26] [29]. This remnant has a monoisotopic mass shift of +114.0429 Da, which is a diagnostic mass tag detectable by MS [29]. During MS/MS fragmentation, the peptide's backbone breaks, and the resulting spectrum reveals the sequence and the precise location of the modified lysine.

Advanced MS Acquisition Methods: DDA vs. DIA

The choice of MS acquisition method significantly impacts the depth and quantitative quality of ubiquitinome coverage.

- Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA): This traditional method selects the most abundant precursor ions from an MS1 scan for subsequent fragmentation. While powerful, it can be stochastic and miss lower-abundance diGly peptides in complex mixtures [27].

- Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA): This newer method fragments all ions within predefined, consecutive m/z windows, capturing all detectable peptides. A 2021 study demonstrated that a DIA-based diGly workflow dramatically outperforms DDA, identifying approximately 35,000 distinct diGly peptides in a single measurement—nearly double the number from DDA—with superior quantitative accuracy and reproducibility [27]. DIA requires spectral libraries for data analysis but provides a more comprehensive and robust solution for profiling ubiquitination.

Determining Ubiquitin Chain Architecture

Identifying the site of substrate ubiquitination is only half the story; understanding the topology of the attached polyubiquitin chain is equally critical, as it determines the functional outcome. Bottom-up MS with diGly enrichment collapses chain information. Several advanced methods have been developed to address this:

- Middle-Down/Top-Down MS: These approaches use limited proteolysis or no digestion, allowing for the analysis of larger proteoforms and the direct reading of ubiquitin chain linkages [24] [30].

- Linkage-Specific Antibodies/UBDs: Antibodies or engineered Ub-binding domains (UBDs) that recognize specific linkages (e.g., K48, K63, M1) can be used to enrich for chains of a particular topology before MS analysis [2].

- Ubiquitin Chain Restriction (UbiCRest): This technique uses a panel of linkage-specific deubiquitinases (DUBs) in vitro to digest polyubiquitin chains, followed by gel analysis to infer chain type based on the DUB's specificity [2] [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Methodologies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Ubiquitinomics

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| His-/Strep-Tagged Ubiquitin | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated conjugates from genetically tractable systems (e.g., cell lines, yeast). | Global profiling of ubiquitinated substrates in a controlled model system [2]. |

| Anti-diGly (K-ε-GG) Antibody | Immunoaffinity enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides from tryptic digests for site-specific mapping. | Ubiquitin remnant profiling for system-wide identification and quantification of ubiquitination sites [27] [26]. |

| Linkage-Specific Ub Antibodies | Selective enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins or chains with a specific linkage (e.g., K48, K63). | Isolating proteins targeted for proteasomal degradation (K48-linkage) or involved in NF-κB signaling (K63-linkage) [2]. |

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) | High-affinity capture of ubiquitinated proteins, protecting them from DUBs and proteasomal degradation. | Stabilizing and studying endogenous ubiquitin conjugates that are otherwise too transient to detect [2]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132) | Blocks degradation of ubiquitinated proteins, leading to their accumulation for enhanced detection. | Increasing the yield of ubiquitinated proteins, particularly those modified with K48-linked chains, for deeper proteome coverage [27]. |

The field of ubiquitinomics has progressed dramatically, moving from identifying a handful of substrates to the system-wide quantification of tens of thousands of ubiquitination sites. This has been driven by robust biochemical enrichment techniques, particularly the anti-diGly antibody approach, coupled with advances in mass spectrometry sensitivity and acquisition methods like DIA. However, significant challenges persist within the broader thesis of endogenous ubiquitination research. These include the need for methods that can seamlessly integrate the identification of the substrate, its modification site, and the architecture of the attached ubiquitin chain from endogenous, patient-derived material. Furthermore, accurately quantifying the often very low stoichiometry of these modifications in a dynamic cellular environment remains a hurdle. Future advancements will likely focus on integrating multiple 'omics layers, improving the sensitivity of label-free quantification, and developing novel chemical biology tools to capture the full complexity of the ubiquitin code in health and disease, thereby accelerating drug development targeting the ubiquitin system.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a crucial regulatory mechanism in eukaryotic cells, controlling virtually all cellular processes through targeted protein degradation and signaling. However, researching this system presents significant methodological challenges. The transient nature of ubiquitination, rapid deubiquitination by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), and immediate proteasomal degradation of substrates have historically obstructed clear analysis of endogenous ubiquitination events [31] [32]. Traditional methods relying on ubiquitin antibodies often yield artifacts due to poor specificity and cannot preserve fragile ubiquitination states during lysis and processing [33]. Within this challenging research context, Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) have emerged as transformative tools that address these fundamental limitations through high-affinity, linkage-specific capture of polyubiquitinated proteins, enabling previously impossible analyses of endogenous ubiquitination.

TUBE Technology: Mechanism and Advantages

Fundamental Principles of TUBEs

TUBEs are engineered recombinant proteins comprising multiple ubiquitin-associated domains (UBDs) arranged in tandem. This architecture enables them to bind polyubiquitin chains with nanomolar affinity (Kds typically 1-10 nM), dramatically outperforming conventional ubiquitin antibodies [33] [34]. The technology circumvents the need for immunoprecipitation of overexpressed epitope-tagged ubiquitin or the use of notoriously non-selective ubiquitin antibodies [33]. By harnessing the strength of multiple UBDs, TUBEs achieve both high affinity and avidity effects, allowing them to compete effectively with endogenous ubiquitin receptors and DUBs.

A critical breakthrough offered by TUBE technology is its capacity to protect the ubiquitinated proteome from the cellular machinery that normally dismantles it. TUBEs shield polyubiquitin chains from both deubiquitylation and proteasome-mediated degradation, even in the absence of inhibitors normally required to block such activities [33]. This protective function enables stabilization of ubiquitination events that would otherwise be too transient to detect, particularly for endogenous proteins at physiological expression levels.

Classification of TUBE Reagents

TUBE reagents are categorized based on their specificity for different ubiquitin chain linkages, providing researchers with tools tailored for distinct biological questions:

Table 1: Classification of TUBE Reagents by Specificity

| TUBE Type | Specificity | Key Applications | Affinity Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pan-Selective (TUBE1, TUBE2) | Binds all polyubiquitin chain types | Comprehensive ubiquitome analysis, total ubiquitination assessment | Kds of 1-10 nM for all linkage types [33] [35] |

| K48-Selective HF TUBE | Enhanced selectivity for K48-linked chains | Studying proteasomal degradation, protein turnover | High specificity for degradation-signaling chains [33] [35] |

| K63-Selective TUBE | 1,000-10,000-fold preference for K63-linked chains | Autophagy-lysosome pathways, DNA repair, signal transduction | Nanomolar affinity for signaling chains [33] [35] |

| M1-Selective TUBE | Specific for linear (M1) polyubiquitin chains | NF-κB inflammatory signaling research | Selective binding to linear ubiquitination [33] |

| Phospho-TUBE (in development) | Specific for Ser65-phosphorylated ubiquitin chains | Mitophagy, Parkinson's disease research, mitochondrial quality control | Designed for phospho-ubiquitin recognition [35] |

Comparative Advantages Over Traditional Methods

When evaluated against conventional ubiquitination detection techniques, TUBEs demonstrate multiple superior characteristics:

Table 2: TUBEs vs. Traditional Ubiquitin Detection Methods

| Method | Sensitivity | Linkage Specificity | Ability to Preserve Ubiquitination | Suitable for Endogenous Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TUBEs | High (nanomolar Kd) | Excellent (with selective TUBEs) | Excellent (protects from DUBs/proteasome) | Yes [33] [34] |

| Ubiquitin Antibodies | Variable, often low | Limited (most are pan-specific) | Poor (requires DUB/proteasome inhibitors) | Challenging due to sensitivity [33] [36] |

| Epitope-Tagged Ubiquitin | High with overexpression | Possible with ubiquitin mutants | Poor (requires inhibitors) | No (requires genetic manipulation) [31] |

| diGly Antibody (MS) | High for proteomics | Limited to MS inference | Requires proteasome inhibition | Yes, but limited to peptide detection [31] [32] |

Experimental Applications and Methodologies

Affinity Enrichment of Ubiquitinated Proteins

The foundational application of TUBE technology involves affinity purification (pull-down) of polyubiquitinated proteins from complex biological samples. The standard protocol employs TUBE-coated beads (such as LifeSensors' UM401M) for efficient capture of the ubiquitinated proteome [33] [3].

Detailed Protocol:

- Cell Lysis: Prepare cell lysates using modified RIPA or HEPES-triton buffer supplemented with 1 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to inhibit deubiquitinating enzymes. Maintain physiological pH and salt concentrations to preserve native interactions [31] [3].

- Incubation with TUBE Beads: Add 50-100 μL of TUBE-conjugated magnetic beads per 500-1000 μg of total protein. Rotate for 2-4 hours at 4°C to maintain complex stability [33].