From APF-1 to Ubiquitin: The Convergent Discovery of a Central Regulatory Pathway in Cell Biology

This article explores the historical convergence of two independent research paths that identified the same fundamental protein—one as ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1) in energy-dependent protein degradation studies, and the...

From APF-1 to Ubiquitin: The Convergent Discovery of a Central Regulatory Pathway in Cell Biology

Abstract

This article explores the historical convergence of two independent research paths that identified the same fundamental protein—one as ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1) in energy-dependent protein degradation studies, and the other as ubiquitin in immunological and chromatin research. Through detailed analysis of foundational discoveries, methodological approaches, technical challenges, and validation experiments, we trace how these parallel investigations ultimately revealed the ubiquitin-proteasome system, a critical pathway for regulated intracellular proteolysis. The synthesis of these findings transformed our understanding of protein turnover, cell cycle regulation, and disease mechanisms, providing valuable insights for researchers and drug development professionals targeting this pathway for therapeutic intervention.

Parallel Pathways: The Independent Discoveries of APF-1 and Ubiquitin

For much of the 20th century, scientific understanding of intracellular protein degradation remained limited and largely attributed to the action of lysosomal proteases [1]. The discovery that protein degradation required adenosine triphosphate (ATP) presented a fundamental biochemical paradox, as the hydrolysis of peptide bonds is an exergonic process that should not require energy input [2] [3]. This energy requirement, first observed by Melvin Simpson in 1953 on liver slices, suggested the existence of a more complex regulatory mechanism than previously assumed [2] [4]. By the late 1970s, researchers had begun to suspect that this ATP dependence reflected energy-dependent regulation of specific proteolytic systems, particularly for the rapid clearance of damaged or abnormal proteins and rate-limiting enzymes in metabolic pathways [2].

The collaboration between Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose proved uniquely positioned to resolve this paradox. Their work, which would eventually earn them the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, unveiled an entirely unexpected mechanism of cellular regulation that extended far beyond simple protein degradation [2] [3]. Using reticulocyte (immature red blood cell) lysates—which lack lysosomes—as a model system, they embarked on a series of experiments that would challenge fundamental assumptions about how cells control their protein composition [2] [5] [3].

Parallel Research Tracks: The APF-1 and Ubiquitin Conundrum

The Discovery of APF-1 in the ATP-Dependent Proteolytic System

Hershko and Ciechanover's approach involved fractionating reticulocyte lysates to isolate the components responsible for ATP-dependent proteolysis. They successfully separated the system into two required fractions: Fraction I and Fraction II [2]. Through innovative biochemical techniques, including the unusual step of boiling Fraction I, they isolated a small, heat-stable protein that was essential for the proteolytic activity. They designated this factor APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1) [3].

Surprisingly, when they radioactively labeled APF-1 and incubated it with Fraction II in the presence of ATP, they observed that APF-1 was covalently attached to multiple proteins in the extract, forming high-molecular-weight conjugates [2] [3]. This conjugation was reversible upon ATP removal and required energy. Critically, they discovered that authentic protein substrates of the degradation system were heavily modified by multiple molecules of APF-1, suggesting a model where poly-conjugation marked proteins for destruction [2]. This series of simple yet elegant experiments, conducted during sabbaticals at Irwin Rose's laboratory at the Fox Chase Cancer Center, demonstrated that APF-1 formed covalent linkages with target proteins through a novel enzymatic process [2].

The Independent Discovery of Ubiquitin

In a seemingly unrelated field, Gideon Goldstein and colleagues discovered a small protein in 1975 while investigating thymic hormones involved in lymphocyte differentiation [6] [7]. They named this protein UBIP (ubiquitous immunopoietic polypeptide), later shortened to ubiquitin to reflect its presence in all tested tissues and eukaryotic organisms [6] [7]. Independently, ubiquitin was identified as a component of chromatin, where it was found to be covalently linked to histone H2A (forming a protein conjugate initially called A24) through an isopeptide bond, a modification whose functional significance remained unclear [6] [7].

Table 1: Initial Characterization of APF-1 and Ubiquitin

| Characteristic | APF-1 | Ubiquitin |

|---|---|---|

| Year Discovered | 1978 [3] | 1975 [6] [7] |

| Field of Discovery | Protein degradation [2] | Immunology/Chromatin biology [6] |

| Known Function | ATP-dependent proteolysis [3] | Lymphocyte differentiation; chromatin modification [6] |

| Size | ~8.6 kDa [3] | ~8.6 kDa [7] |

| Covalent Attachment | Yes, to proteolytic substrates [2] | Yes, to histone H2A [6] |

The Serendipitous Connection

The convergence of these two research tracks occurred through a remarkable instance of scientific serendipity. Michael Urban, a postdoctoral researcher working near Rose's laboratory, recognized the similarity between the covalent attachment of APF-1 to target proteins and the known conjugation of ubiquitin to histones [2] [6]. This critical insight led Keith Wilkinson, Art Haas, and Urban to demonstrate that APF-1 was identical to the previously characterized protein ubiquitin [2]. This connection revealed that the same protein could play roles in seemingly disparate cellular processes—lymphocyte differentiation, chromatin structure, and targeted protein degradation [6].

Table 2: Key Experimental Findings Linking APF-1 to Ubiquitin

| Experimental Approach | Key Finding | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Boiling Fraction I [3] | APF-1 remained active after heat treatment | Demonstrated unusual heat stability, facilitating purification |

| Radiolabeled APF-1 Conjugation [2] [3] | APF-1 formed covalent conjugates with multiple proteins in an ATP-dependent manner | Revealed novel protein modification mechanism |

| Similarity Recognition [2] [6] | Covalent linkage mechanism matched known ubiquitin-histone conjugation | Connected two separate research fields |

| Direct Comparison [2] | APF-1 and ubiquitin shared identical biochemical properties | Established identity between APF-1 and ubiquitin |

Experimental Breakthroughs: Methodologies and Findings

Key Experimental Protocols

The seminal discoveries of Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose relied on several elegantly designed experimental approaches using reticulocyte lysates:

1. Reticulocyte Lysate Fractionation:

- Reticulocytes (immature red blood cells) were selected as they lack lysosomes, allowing isolation of the non-lysosomal proteolytic system [3].

- Lysates were separated by chromatography into two essential fractions: I and II [2].

- Neither fraction alone could support ATP-dependent proteolysis; both were required for activity [2].

2. ATP-Dependent Proteolysis Assay:

- Radioactively labeled protein substrates (e.g., abnormal globin) were incubated with fractions [5].

- Proteolysis was measured by the release of acid-soluble radioactivity [5].

- The system showed absolute dependence on ATP hydrolysis [2].

3. APF-1 Purification and Characterization:

- Fraction I was boiled, causing most proteins to denature and precipitate, while APF-1 remained soluble and active [3].

- This heat-stability provided a critical purification step and distinguished APF-1 from most cellular proteins [3].

- Purified APF-1 was radioiodinated (¹²⁵I-labeled) for tracking experiments [2].

4. Covalent Conjugation Analysis:

- ¹²⁵I-APF-1 was incubated with Fraction II and ATP, then analyzed by SDS-PAGE [2].

- Multiple high-molecular-weight radioactive bands appeared, indicating covalent attachment of APF-1 to various proteins [2] [3].

- The conjugates were stable to high pH and denaturing conditions, confirming covalent bonds [3].

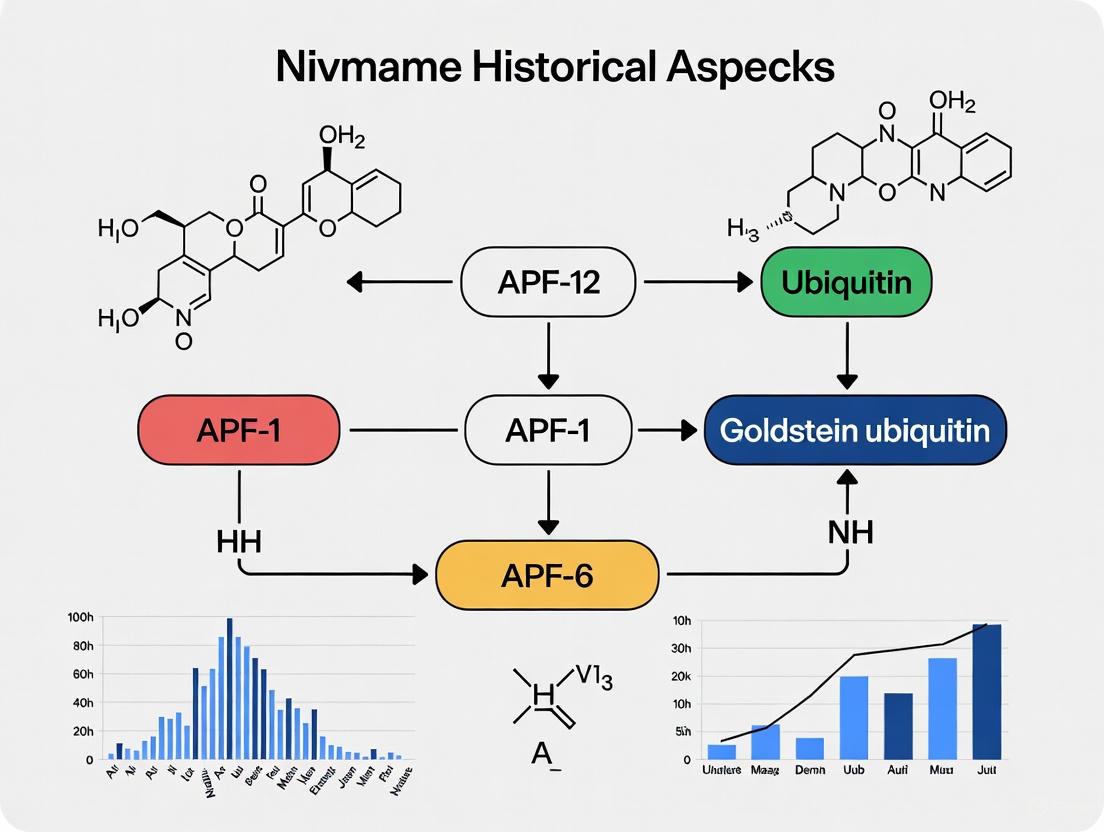

Experimental Workflow: APF-1/Ubiquitin Discovery

Critical Findings and Interpretations

The experimental results led to several groundbreaking conclusions that formed the basis of our modern understanding of the ubiquitin-proteasome system:

1. Energy-Dependent Covalent Modification: The requirement for ATP was not for proteolysis itself, but for the covalent attachment of APF-1/ubiquitin to target proteins. This explained the longstanding biochemical paradox of energy-dependent proteolysis [2] [3].

2. Multi-Ubiquitin Chain Model: Proteins destined for degradation were modified by multiple ubiquitin molecules rather than single copies. Hershko and colleagues proposed that these polyubiquitin chains served as recognition signals for proteolytic machinery [2].

3. Enzymatic Cascade: The researchers identified a three-enzyme cascade (E1, E2, E3) responsible for activating and transferring ubiquitin to substrates. This hierarchical system provided both specificity and regulation [3] [7].

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: From Basic Mechanism to Physiological Significance

The Biochemical Pathway

The ubiquitin system consists of a sequential enzymatic cascade that marks proteins for degradation:

1. Activation (E1): Ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) forms a high-energy thioester bond with ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction [3] [7].

2. Conjugation (E2): Ubiquitin is transferred from E1 to a cysteine residue on a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) [3] [7].

3. Ligation (E3): Ubiquitin ligases (E3) recognize specific protein substrates and facilitate the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to target proteins, forming an isopeptide bond between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin and lysine ε-amino groups on substrates [5] [3] [7].

4. Polyubiquitination: Additional ubiquitin molecules are added to form chains, typically linked through lysine 48 (K48) of ubiquitin, which serves as the recognition signal for the 26S proteasome [2] [8].

5. Degradation: The 26S proteasome recognizes polyubiquitinated proteins, degrades them into small peptides, and recycles ubiquitin for reuse [8] [5].

Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Pathway

Biological and Clinical Implications

The discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system revolutionized our understanding of cellular regulation and has profound clinical implications:

1. Beyond Protein Degradation: While initially characterized as a degradation signal, ubiquitination now is recognized as a versatile post-translational modification comparable to phosphorylation. Different types of ubiquitin chains (e.g., K63-linked) function in diverse processes including DNA repair, endocytosis, and inflammation [8] [7].

2. Disease Connections: Dysregulation of the ubiquitin system is implicated in numerous diseases, including cancer (through regulators like p53, BRCA1, VHL), neurodegenerative disorders (Parkinson's, Alzheimer's), and developmental syndromes (Angelman syndrome) [8].

3. Therapeutic Targeting: The understanding of ubiquitin signaling has enabled new therapeutic approaches, including proteasome inhibitors for cancer treatment and emerging technologies like PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) that harness the ubiquitin system to target specific proteins for degradation [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Tools in Ubiquitin System Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Historical Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | Cell-free system for studying ATP-dependent proteolysis; lacks lysosomes [2] [3] | Key system that enabled fractionation of the ubiquitin pathway components |

| Heat-Stable Fraction | APF-1/ubiquitin remained soluble after boiling while most proteins denatured [3] | Critical purification step that allowed isolation and characterization of ubiquitin |

| ATP-Regeneration Systems | Maintained ATP levels during prolonged incubations [2] | Essential for demonstrating ATP dependence of the conjugation reaction |

| Radioiodinated APF-1 (¹²⁵I) | Tracing covalent modification of target proteins [2] | Enabled visualization of ubiquitin-protein conjugates by autoradiography |

| Fraction II (APF-2) | Contained E1, E2, E3 enzymes and the 26S proteasome [2] | Later understood to contain the enzymatic machinery for ubiquitination |

| Ion-Exchange Chromatography | Separated reticulocyte lysate components [2] | Fundamental technique for fractionating the proteolytic system |

The identification of APF-1 as ubiquitin and the elucidation of its role in targeted protein degradation represents a paradigm shift in cell biology. What began as an investigation into an apparent biochemical paradox—ATP-dependent proteolysis—revealed an elegant system of post-translational regulation that rivals phosphorylation in its complexity and importance. The convergence of two seemingly unrelated research paths—Goldstein's immunological studies and Hershko and Ciechanover's metabolic investigations—exemplifies how fundamental discoveries often emerge from connecting disparate observations.

This discovery has fundamentally altered our understanding of cellular regulation, revealing that protein degradation is a highly specific, tightly controlled process rather than a nonspecific cleanup mechanism. The ubiquitin-proteasome system now is recognized as a master regulator of countless cellular processes, from cell cycle progression to signal transduction, and its clinical relevance continues to expand with new therapeutic strategies that target this pathway. The journey from APF-1 to ubiquitin exemplifies how curiosity-driven basic research into seemingly obscure biochemical phenomena can unravel fundamental biological principles with far-reaching implications for medicine and human health.

The discovery of ubiquitin as a central regulator of cellular function is a classic example of convergent scientific discovery, where two distinct research pathways with different origins and methodologies ultimately revealed different facets of the same fundamental biological system. On one path lay the work of Gideon Goldstein and colleagues, who in 1975 identified a "ubiquitously" present polypeptide during their search for thymic hormones [2] [7]. On the other path was the biochemical investigation of ATP-dependent proteolysis by Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose, who discovered a heat-stable factor they termed APF-1 (ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1) [10] [2]. For a period, these two discoveries proceeded in parallel, until critical experiments revealed that APF-1 and ubiquitin were in fact the same molecule [2]. This convergence fundamentally reshaped our understanding of cellular regulation, revealing that controlled protein degradation rivals transcription and translation in its importance for cellular homeostasis [10]. This article compares these foundational discoveries, their methodological approaches, and their collective impact on modern biomedicine and drug discovery.

Historical Context and Discovery Objectives

The two research streams that culminated in the elucidation of the ubiquitin system originated from profoundly different biological questions, which shaped their respective experimental approaches and initial interpretations.

Table 1: Origins and Context of Ubiquitin and APF-1 Research

| Aspect | Goldstein's Ubiquitin Research | APF-1 (Hershko, Ciechanover, Rose) Research |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Research Goal | Identify biological activities of thymic hormones (thymopoietin) [2] [7] | Understand the biochemical basis of ATP-dependent intracellular protein degradation [10] [2] |

| Initial Designation | Ubiquitin (Ubiquitous Immunopoietic Polypeptide) [7] | ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1 (APF-1) [10] [2] |

| Key Researchers | Gideon Goldstein [2] [7] | Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, Irwin Rose [10] [2] |

| Initial Reported Function | Lymphocyte-differentiating properties; unknown universal function [2] [7] | Heat-stable component essential for ATP-dependent proteolysis in reticulocyte lysates [10] [2] |

| Year of Key Publication | 1975 [7] | 1978 [10] [2] |

The conceptual breakthrough came in 1980, when Wilkinson, Urban, and Haas demonstrated the identity of APF-1 and ubiquitin [10] [2]. This discovery merged the two research paths, instantly suggesting that Goldstein's universally present protein had a fundamental mechanistic role in cellular protein turnover.

Experimental Approaches and Key Methodologies

The distinct research objectives of the two groups necessitated different experimental systems and protocols, which are summarized below.

Goldstein's Identification Protocol

Goldstein's approach centered on protein biochemistry and immunology:

- Source Material: Calf thymus tissue [7].

- Extraction and Purification: Standard protein isolation techniques were used to purify a polypeptide fraction [7].

- Functional Assay: The purified fraction was tested for its ability to induce lymphocyte differentiation [2] [7].

- Observation: The isolated polypeptide was found to be present in all eukaryotic cells tested, leading to the name "ubiquitin" [7].

The APF-1 and Ubiquitin Convergence Experiment

The critical experiment that identified APF-1 as ubiquitin involved a direct biochemical comparison [2]:

- Iodination: ^125^I-labeled APF-1 was prepared.

- Conjugation Assay: The labeled APF-1 was incubated with Fraction II (the second chromatographic fraction from reticulocyte lysate) and ATP.

- Covalent Linkage: The assay demonstrated that APF-1 formed covalent, high-molecular-weight conjugates with multiple proteins in the lysate [2].

- Identity Confirmation: Authentic ubiquitin samples, shared by Gideon Goldstein, were shown to behave identically to APF-1 in the conjugation assay, confirming they were the same molecule [2].

Hershko and Rose's ATP-Dependent Proteolysis Workflow

The team used a well-defined cell-free system to dissect the mechanism of protein degradation [10] [2]:

- System Preparation: Create an ATP-depleted lysate from rabbit reticulocytes.

- Biochemical Fractionation: Separate the lysate into two fractions (I and II) via chromatography.

- Reconstitution Assay: Demonstrate that both fractions I and II are required to restore ATP-dependent degradation of added protein substrates.

- Factor Isolation: Identify APF-1 as a heat-stable, essential component in Fraction I [10] [2].

- Enzymatic Dissection: Characterize the E1, E2, and E3 enzyme cascade responsible for the covalent conjugation of APF-1/Ubiquitin to target proteins [10].

The Unified Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: Structure and Mechanism

The convergence of these research lines revealed a sophisticated enzymatic cascade, now known as the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, which is fundamental to cellular regulation.

Table 2: The Unified Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Components

| Component | Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin | A small (8.6 kDa), highly conserved regulatory protein [7] [11] | Serves as a covalent tag on substrate proteins; contains 7 lysines and an N-terminus for chain formation [7] [11] |

| E1 (Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme) | Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner [10] [7] | Forms a high-energy thioester bond with ubiquitin; the first step in the cascade [7] |

| E2 (Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme) | Accepts activated ubiquitin from E1 [10] [7] | Carries ubiquitin via a thioester bond; ~35 E2s in humans provide some specificity [7] [12] |

| E3 (Ubiquitin Ligase) | Binds to both E2~Ub and specific substrate proteins [10] [7] | Catalyzes the final transfer of ubiquitin to the substrate; >600 E3s provide primary substrate specificity [7] [12] |

| 26S Proteasome | Degrades ubiquitin-tagged proteins [10] | A large, multi-subunit ATP-dependent protease complex; recognizes polyubiquitin chains [10] |

The ubiquitin code is remarkably complex. Ubiquitin itself can form polymers (polyubiquitin chains) through any of its seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or its N-terminal methionine (M1) [7] [11]. Specific chain linkages encode different cellular signals. K48- and K29-linked chains primarily target substrates for degradation by the proteasome, while K63-linked chains and monoubiquitination act as signals in non-proteolytic processes like DNA repair, endocytosis, and inflammatory signaling [7] [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Modern research into the ubiquitin system relies on a sophisticated toolkit of reagents and methodologies, many of which have their roots in the foundational experiments of the 1970s and 1980s.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Ubiquitin System Investigation

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | A cell-free system rich in translation and ubiquitin-proteasome system components [2] | Used historically to discover ATP-dependent proteolysis and APF-1/Ubiquitin conjugation; still used for in vitro degradation assays [10] [2] |

| ATP Depletion/Addition | Controls energy-dependent processes in biochemical assays [10] [2] | Key experimental manipulation to establish ATP requirement for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [10] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Specifically block the catalytic activity of the 20S proteasome (e.g., MG132, Bortezomib) [12] | Used to stabilize ubiquitinated proteins, demonstrate proteasome dependence of degradation, and as therapeutic agents [12] |

| Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme (E1) Inhibitor | Blocks the initial step of ubiquitin activation (e.g., PYR-41, TAK-243) [12] | Used to inhibit the entire ubiquitination cascade; valuable for determining global dependence on ubiquitin signaling |

| Chain-Linkage Specific Antibodies | Antibodies that specifically recognize polyubiquitin chains of a defined linkage (e.g., K48, K63) [11] | Essential for determining the type and function of ubiquitin signals on substrates in Western blot or immunoprecipitation |

| Deubiquitinases (DUBs) | Enzymes that reverse ubiquitination by cleaving ubiquitin from substrates or trimming chains [12] | Used as research tools to edit ubiquitin signals and study their function; therapeutic targets |

| Activity-Based Probes | Chemical probes that covalently label active site residues of specific ubiquitin-system enzymes [11] | Enable profiling of enzyme activity (not just abundance) in complex lysates; used for E1, E2, E3, and DUBs |

The independent discoveries of Goldstein's ubiquitin and the Hershko-Ciechanover-Rose APF-1, and their subsequent unification, exemplify how diverse research approaches can converge to reveal a fundamental biological truth. Goldstein's work provided the initial characterization of a universal cellular component, while the biochemical studies of Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose uncovered its central role in the then-enigmatic process of ATP-dependent proteolysis. This synergy, recognized by the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, laid the foundation for understanding a regulatory system of immense complexity and medical importance.

Today, the frontier of ubiquitin research continues to expand. Structural biology using techniques like cryo-electron microscopy is revealing the intricate mechanics of E3 ligases and the proteasome in stunning detail [11]. The discovery of "non-canonical" ubiquitination on residues like cysteine, serine, and threonine is broadening the definition of the ubiquitin code [7] [11]. Furthermore, the development of computational predictors like 2DCNN-UPP for identifying ubiquitin-proteasome pathway proteins from sequence data highlights the field's maturation into the big-data era [13]. For drug development professionals, this history is particularly instructive: it underscores that fundamental, curiosity-driven research into seemingly disparate biological questions—from thymic hormones to protein degradation—can converge to create entirely new therapeutic paradigms, as evidenced by the success of proteasome inhibitors in treating multiple myeloma and other cancers. The next decade promises to unravel even more complexity in ubiquitin signaling, offering new targets for therapeutic intervention in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and immune disorders.

The discovery of ubiquitin is a classic example of how the same molecular entity can be independently discovered by different research groups focusing on distinct biological problems, leading to the establishment of separate scientific contexts that would later converge. In the mid-1970s, Gideon Goldstein and colleagues identified a small, ubiquitous protein they termed "ubiquitin" while investigating thymic peptide hormones and immune cell differentiation [14]. Simultaneously, Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose were investigating the paradoxical ATP-dependence of intracellular protein degradation, which led them to isolate a heat-stable protein they named ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1) [2] [3]. The convergence of these research paths occurred in 1980 when Wilkinson, Urban, and Haas demonstrated that APF-1 and ubiquitin were the same molecule [2] [14]. This historical foundation established two primary research contexts that would continue to evolve: one focused on ubiquitin's role in protein turnover and degradation, and another exploring its functions in chromatin biology and epigenetic regulation.

Historical Foundation: APF-1 and Goldstein's Ubiquitin

The APF-1/Protein Turnover Research Pathway

The protein turnover pathway emerged from the fundamental question of why energy-dependent proteolysis existed when protein degradation is inherently exergonic [3]. Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose utilized a biochemical fractionation approach with reticulocyte lysates that lacked lysosomes, allowing them to isolate the essential components of the ATP-dependent degradation system [2]. Their key experiments involved:

- Fractionation and Reconstitution: Separating reticulocyte lysates into two fractions (I and II), neither of which could alone support ATP-dependent proteolysis, but when recombined, degradation proceeded [3].

- Heat Stability Experiments: Boiling Fraction I destroyed most proteins but left APF-1 active, enabling its purification and characterization [3].

- Radiolabeling and Covalent Attachment: Using ¹²⁵I-labeled APF-1, they discovered it formed covalent conjugates with multiple cellular proteins in an ATP-dependent manner [2].

- Multi-Subunit Modification: Demonstrating that multiple APF-1 molecules could attach to a single substrate protein, suggesting a signaling mechanism for degradation [2].

This research stream established the fundamental enzymatic cascade of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes that mediate ubiquitin attachment to substrate proteins [3].

The Goldstein/Chromatin Biology Research Pathway

Goldstein's research followed a different trajectory, initially seeking to understand immune system regulation:

- Biological Context: Investigation of thymic polypeptide hormones that could induce T-cell and B-cell differentiation [15] [14].

- Protein Isolation: Identification and purification of a "ubiquitous immunopoietic polypeptide" (UBIP) from bovine thymus, later termed ubiquitin [14].

- Chromatin Connection: Discovery that ubiquitin was identical to a protein already known to be conjugated to histone H2A (forming protein A24) in a "histone-like" chromosomal protein [15].

- Structural Characterization: Determining that protein A24 had two N-termini (from H2A and ubiquitin) and one C-terminus (from H2A), with ubiquitin's C-terminus forming an isopeptide bond with a lysine side chain on H2A [15].

This research stream revealed ubiquitin's presence in chromatin but left its functional significance largely unexplored until the connection with the protein degradation pathway emerged.

Comparative Experimental Approaches

Methodologies in Protein Turnover Research

The protein turnover field has employed distinct methodological approaches centered on biochemical reconstitution and proteomic analysis:

Table 1: Key Experimental Methods in Protein Turnover Research

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Key Applications | Representative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical Reconstitution | Fractionation of reticulocyte lysates; ATP-depletion studies; Enzyme purification | Identification of E1, E2, E3 enzymes; Characterization of ubiquitination cascade | Discovery of APF-1/ubiquitin activation by E1, transfer to E2, and substrate-specific ligation by E3 [2] [3] |

| Proteomic Analysis | 6His-tagged ubiquitin purification; Mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS); diGly antibody enrichment | System-wide identification of ubiquitination substrates; Quantification of ubiquitination changes | Identification of 54,181 ubiquitination sites from 12,038 unique proteins in PLMD database [16]; Salt-induced ubiquitination changes in plants [17] |

| Genetic Approaches | Temperature-sensitive mutant cells; Gene knockout/knockdown; Transgenic overexpression | Functional validation of ubiquitination machinery; Physiological consequences of disrupted ubiquitination | E1 mutation in mouse cells blocked ubiquitination and protein degradation [3]; Contrasting phenotypes in Arabidopsis Ub overexpression lines [18] |

Methodologies in Chromatin Biology Research

Chromatin-focused ubiquitin research has employed different techniques suited to nuclear and epigenetic analysis:

Table 2: Key Experimental Methods in Chromatin Biology Research

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Key Applications | Representative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histone Analysis | Antibody-based detection; Chromatin immunoprecipitation; Site-specific mutagenesis | Identification of ubiquitinated histones; Functional characterization of modifications | H2Aub constitutes ~11% and H2Bub ~1.5% of respective histones [15]; E3-independent histone ubiquitination by UBE2 family enzymes [15] |

| Enzyme Mapping | In vitro ubiquitination assays; CRISPR screening; Domain deletion/ mutation | Identification of histone-modifying enzymes; Reader domain characterization | RING-type E3 ligases dominant in histone modification; BARD1 recognition of H4K20me0 for histone ubiquitination [15] |

| PTM Crosstalk Studies | Sequential chromatin immunoprecipitation; Chemical inhibition of modifying enzymes; Multi-omics integration | Analysis of interactions between ubiquitination and other modifications | "Acetyl-ubiquitin switch" where H2BK120ac blocks H2BK120ub [15]; Phosphorylation-ubiquitination crosstalk on H3.3T11 [15] |

Comparative Data and Research Findings

Quantitative Data from Distinct Research Contexts

The two research contexts have generated distinct types of quantitative data reflective of their different biological questions:

Table 3: Comparative Quantitative Findings Across Research Contexts

| Parameter | Protein Turnover Context | Chromatin Biology Context |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Conjugation Targets | 54,181 ubiquitination sites from 12,038 unique proteins in PLMD database [16] | ~11% of H2A and ~1.5% of H2B is ubiquitinated under normal conditions [15] |

| Enzyme Machinery | 1 E1 → Dozens of E2s → Hundreds of E3s hierarchical organization [14] | UBA1 (not UBA6) as primary nuclear E1; Promiscuous UBE2 family E2s capable of E3-independent histone ubiquitination [15] |

| Functional Outcomes | K48-linked chains target to proteasome degradation; 26S proteasome processes ubiquitinated substrates [2] [14] | Monoubiquitination regulates chromatin structure, transcription, DNA repair; Crosstalk with DNA methylation [15] |

| Chain Topologies | K48 (degradation), K63 (signaling), K6 (DNA repair), K11 (ERAD), K33 (kinase modification) [14] | Linear polyubiquitin chains; Hybrid ISG15/Ub chains; Monoubiquitination dominant [15] [14] |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The protein turnover and chromatin biology contexts have revealed distinct signaling pathways centered on ubiquitin:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Contemporary ubiquitin research across both contexts relies on specialized reagents and tools:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitin Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Function and Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Variants | Hexa-6His-UBQ (6HU); Hexa-6His-TEV-UBQ (6HTU) [18] | Affinity purification of ubiquitylated proteins; Proteomic studies | His-tag enables nickel-NTA purification; TEV site allows cleavage; Differential expression effects on plant growth [18] |

| Enrichment Tools | K-ε-GG antibodies; Tandem ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) [17] | Mass spectrometry sample preparation; Ubiquitinome studies | Antibody recognition of diglycine remnant on lysine after tryptic digest; Enrichment of ubiquitylated peptides from complex mixtures [16] [17] |

| Computational Tools | MMUbiPred; Caps-Ubi; DeepUbi [16] [19] [20] | Prediction of ubiquitination sites; Multi-species analysis | Deep learning models integrating sequence features, physicochemical properties; Plant-specific predictors available [16] [20] |

| Specialized Cell Lines | Temperature-sensitive E1 mutant cells [3] | Functional studies of ubiquitination | E1 inactivation at restrictive temperature blocks global ubiquitination, enabling functional assessment [3] |

The distinct research contexts of protein turnover and chromatin biology, originating from the separate discoveries of APF-1 and Goldstein's ubiquitin, have developed complementary methodological approaches while investigating different aspects of the same fundamental modification. The protein turnover field has emphasized biochemical reconstitution, proteomic quantification, and degradation-focused outcomes, while chromatin biology has prioritized histone modification mapping, nuclear enzyme characterization, and epigenetic regulation. Contemporary research increasingly integrates these approaches, recognizing that ubiquitin functions as a unified signaling system with context-dependent outcomes. The ongoing development of specialized research reagents and computational tools continues to enhance precision in both fields while facilitating their convergence into a comprehensive understanding of ubiquitin biology.

The identification of the small protein ubiquitin, and the subsequent revelation of its functions, represents a foundational pillar of modern cell biology. However, this discovery was not a singular event but rather the convergence of two distinct and initially separate paths of scientific inquiry. For nearly a decade, researchers in different fields were studying the same molecule, unaware of its dual identity and divergent cellular roles. This guide objectively compares these two early functional hypotheses: the APF-1-as-degradation-signal model, championed by Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose, and the ubiquitin-as-chromatin-modifier model, originating from the work of Gideon Goldstein and others. Framed within a broader historical thesis, this analysis delineates the experimental protocols, key findings, and ultimate convergence of these paradigms, which together revealed the multifaceted regulatory power of protein ubiquitination [6] [21].

Historical Context and Foundational Research

The following table summarizes the origins and foundational characteristics of the two research trajectories that defined the early understanding of ubiquitin.

Table 1: Foundational Research on APF-1/Ubiquitin

| Aspect | APF-1 as a Degradation Signal (The Hershko-Ciechanover-Rose Pathway) | Ubiquitin as a Chromatin Modifier (The Goldstein Pathway) |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Designation | ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1 (APF-1) [2] | Ubiquitous Immunopoietic Polypeptide (UBIP) / Ubiquitin [6] [21] |

| Field of Discovery | Biochemistry of intracellular protein degradation [2] | Immunology and chromatin biology [10] [6] |

| Key Researchers | Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, Irwin Rose [2] | Gideon Goldstein, H. Busch, I.L. Goldknopf [10] [6] |

| Initial Proposed Function (Late 1970s) | A heat-stable factor required for ATP-dependent proteolysis in cell extracts [2] [3] | A thymic hormone for lymphocyte differentiation and a component of chromatin [6] [21] |

| Key Initial Finding | Covalent, ATP-dependent conjugation of APF-1 to protein substrates precedes their degradation [2] [22] | Covalent conjugation to histone H2A via an isopeptide bond, forming the protein A24 [10] [6] |

The duality began with nomenclature. The molecule now known as ubiquitin was first isolated in 1975 by Gideon Goldstein and colleagues, who identified it as an 8.6 kDa polypeptide capable of inducing lymphocyte differentiation in vitro [7] [21]. Given its presence in numerous tissues and organisms, it was named "ubiquitin" [6] [21]. Concurrently, and entirely independently, a molecule central to energy-dependent protein degradation was discovered in reticulocyte lysates and termed APF-1 [2]. The critical connection was made in 1980 when Keith Wilkinson, Michael Urban, and Arthur Haas, working in proximity to Irwin Rose's laboratory, recognized the similarity in the covalent conjugation of APF-1 and the known conjugation of ubiquitin to histone H2A, leading to the identification that APF-1 and ubiquitin were the same molecule [2] [10] [6].

Comparative Analysis of Early Hypotheses and Experimental Evidence

The convergence of the two fields did not immediately unify the hypothesized functions of ubiquitin. Instead, it set the stage for a period of parallel exploration to determine whether the molecule's primary role was in targeted proteolysis, chromatin regulation, or both.

Table 2: Comparison of Early Functional Hypotheses and Supporting Evidence

| Aspect | Degradation Signal Hypothesis | Chromatin Modification Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|

| Core Proposition | Covalent attachment of ubiquitin (APF-1) tags substrate proteins for recognition and degradation by a downstream protease [2] [22]. | Covalent attachment of ubiquitin to histones (e.g., H2A, H2B) modulates chromatin structure and function, influencing transcription and other DNA-templated processes [10] [21]. |

| Key Experimental System | ATP-dependent proteolysis in fractionated rabbit reticulocyte lysates [2] [3]. | Biochemical analysis of chromatin from calf thymus and later, physical-chemical studies of nucleosome structure [10] [6]. |

| Critical Experimental Evidence | 1. ATP-dependent Conjugation: (^{125})I-APF-1 formed high molecular weight conjugates in Fraction II only with ATP [2].2. Covalent Linkage: The bond was stable to high pH (NaOH) and SDS treatment, indicating a covalent, isopeptide bond [2] [3].3. Polyubiquitination: Multiple APF-1 molecules were conjugated to a single substrate protein, which was correlated with proteolysis [2] [22]. | 1. Identification of A24: A non-histone chromatin protein was identified as a conjugate of ubiquitin and histone H2A [10] [6].2. Isopeptide Linkage: The bond between ubiquitin and an internal lysine of H2A was characterized as a stable isopeptide linkage [6].3. Correlation with Activity: Ubiquitinated H2A (uH2A) was enriched in transcriptionally active chromatin and disappeared during mitosis [10] [6]. |

| Enzymatic Machinery | A three-enzyme cascade (E1, E2, E3) was identified and reconstituted for ubiquitin conjugation to proteolytic substrates [10] [22]. | The specific E3 ligases for histones (e.g., Bre1 for H2B, Ring1B/BMI1 for H2A) were identified much later [21]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

1. Protocol: Demonstrating ATP-Dependent Ubiquitin Conjugation (Degradation Signal)

- System: Cell-free extract from rabbit reticulocytes, fractionated into Fraction I (containing free APF-1/ubiquitin) and Fraction II (containing the enzymatic machinery and endogenous proteins) [2] [3].

- Labeling: APF-1/ubiquitin is radioiodinated ((^{125})I) for detection.

- Methodology:

- Incubate (^{125})I-APF-1 with Fraction II in the presence of ATP and Mg²⁺.

- As a control, run a parallel reaction without ATP.

- Stop the reaction and analyze proteins by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography.

- Expected Outcome: In the presence of ATP, a ladder of high molecular weight bands (ubiquitin-protein conjugates) appears on the gel. No such ladder forms in the absence of ATP, demonstrating the energy dependence of the conjugation [2].

2. Protocol: Isolating Ubiquitin-Histone Conjugates (Chromatin Modification)

- System: Chromatin isolated from tissues such as calf thymus.

- Methodology:

- Extract chromatin-associated proteins using acid or salt solutions.

- Separate proteins using techniques like acid-urea-Triton (AUT) gel electrophoresis, which can resolve histone variants and their modifications.

- Identify the protein band of interest (e.g., A24/uH2A) via Coomassie staining or western blotting with anti-ubiquitin antibodies.

- For mapping, use proteolytic cleavage (e.g., with trypsin) and peptide sequencing to identify the specific lysine residue on the histone that is ubiquitinated [6] [21].

The Convergence and Synthesis of a Dual-Function System

The two hypotheses were ultimately reconciled not as contradictory, but as complementary. The key insight was that the functional outcome of ubiquitination is dictated by the nature of the ubiquitin chain and the identity of the substrate protein [7].

- For Proteolysis: The work of Hershko, Ciechanover, Rose, and later Varshavsky, demonstrated that a chain of ubiquitin molecules linked through lysine 48 (K48) of one ubiquitin and the C-terminus of the next forms the definitive "kiss of death," marking the substrate for degradation by the 26S proteasome [2] [7] [22].

- For Chromatin Regulation: In contrast, the ubiquitination of histones is typically monoubiquitination (the addition of a single ubiquitin moiety). This modification does not signal degradation but acts as a regulatory mark, much like phosphorylation or acetylation, that alters protein-protein interactions and chromatin dynamics [10] [21]. For example, monoubiquitination of histone H2B is involved in transcriptional activation and can influence other histone modifications such as methylation [21].

The diagrams below illustrate the core pathways and the logical relationship between the two historical hypotheses.

Pathway 1: The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System for Protein Degradation

Pathway 2: The Role of Ubiquitin in Chromatin Modification

Logical Workflow: From Historical Duality to Unified Understanding

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The elucidation of the ubiquitin system relied on several critical experimental tools and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents in Early Ubiquitin Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | A cell-free extract rich in the ubiquitin-proteasome system, lacking lysosomes, ideal for biochemical fractionation [2] [3]. | Served as the source for fractionating APF-1 (ubiquitin) and the E1, E2, and E3 enzymes [2] [22]. |

| Radioiodinated APF-1/Ubiquitin (¹²⁵I) | Enabled sensitive tracking and visualization of ubiquitin conjugation to protein substrates via autoradiography [2] [3]. | Used to demonstrate the ATP-dependent formation of high molecular weight conjugates in reticulocyte fractions [2]. |

| ATP (and ATP-regenerating system) | The essential energy source for the ubiquitin activation step catalyzed by the E1 enzyme [2] [7]. | Required to reconstitute both ubiquitin conjugation and subsequent protein degradation in cell-free assays [3] [22]. |

| Heat-Stable Protein Fraction | The initial crude preparation of APF-1/ubiquitin, leveraging its unusual stability to heat denaturation [3]. | Boiling reticulocyte Fraction I precipitated most proteins (like hemoglobin), leaving active APF-1/ubiquitin in solution [3]. |

| Anti-Ubiquitin Antibodies | Immunochemical tools to isolate and quantify ubiquitin-protein conjugates from intact cells [22]. | Provided the first direct evidence that the ubiquitin system degrades abnormal proteins in vivo [22]. |

| Temperature-Sensitive (ts) Cell Lines | Genetic models with a heat-labile E1 enzyme, allowing conditional disruption of the entire ubiquitin system [10] [22]. | The ts85 mouse cell line proved the ubiquitin system is essential for cell cycle progression and viability [10] [22]. |

The early history of ubiquitin research is a powerful case study in scientific discovery, demonstrating how parallel investigations into seemingly unrelated phenomena—waste disposal in the cytoplasm and fine-tuning of the nuclear genome—can converge to reveal a unified biological principle of immense sophistication. The hypothesis that ubiquitin served as a degradation signal and the hypothesis that it functioned as a chromatin modifier were both correct, representing different facets of a universal language of post-translational regulation. The resolution of this duality laid the groundwork for the modern "ubiquitin code" paradigm, which continues to drive drug discovery, particularly in oncology and neurodegenerative diseases, by targeting the precise enzymes that write, read, and erase this critical regulatory mark [23] [21].

Key Laboratories and Collaborative Networks in the Late 1970s

In the late 1970s, the field of intracellular protein degradation was poised for a paradigm shift. For decades, protein degradation was largely considered an unregulated process, with the lysosome assumed to be the primary site of cellular protein breakdown [24]. However, several observations contradicted this view, particularly the puzzling energy requirement for intracellular proteolysis established by Simpson in 1953, which suggested a more complex regulatory mechanism than simple enzymatic cleavage [2] [22]. This intellectual environment set the stage for the convergence of two seemingly independent research trajectories: the investigation of ATP-dependent proteolysis factors and the characterization of a universally present protein of unknown function.

This comparison guide examines the key laboratories and collaborative networks that elucidated the identity and function of ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1) and ubiquitin (originally known as "ubiquitous immunopoietic polypeptide") [7]. We objectively analyze the experimental approaches, institutional contributions, and collaborative dynamics that ultimately revealed these entities to be the same molecule, revolutionizing our understanding of cellular regulation and earning the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004 for Aaron Ciechanover, Avram Hershko, and Irwin Rose [22].

Laboratory Profiles and Institutional Contexts

Table 1: Key Research Laboratories and Their Primary Contributions

| Laboratory/Institution | Key Researchers | Primary Focus Areas | Major Contributions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technion-Israel Institute of Technology | Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover | ATP-dependent proteolysis in reticulocyte extracts | Discovery of APF-1; development of fractionated system; characterization of covalent conjugation [2] [24] |

| Fox Chase Cancer Center (Philadelphia) | Irwin Rose, Keith Wilkinson, Arthur Haas | Mechanistic enzymology, ubiquitin characterization | Provided research environment for collaboration; identification of APF-1 as ubiquitin [2] [10] |

| MIT (Massachusetts) | Alexander Varshavsky | Chromatin structure, genetic approaches | Established physiological roles of ubiquitin system in living cells [10] [3] |

| Harvard Medical School | Alfred Goldberg | Energy-dependent proteolysis | Developed reticulocyte extract model for ATP-dependent degradation of abnormal proteins [2] |

Table 2: Experimental Systems and Model Organisms

| Experimental System | Advantages for Research | Limitations | Key Findings Enabled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rabbit reticulocyte lysates | ATP-dependent, non-lysosomal proteolysis; amenable to biochemical fractionation | Complex mixture of components; required separation | Identification of two essential fractions (I and II) and APF-1 [2] [4] |

| Temperature-sensitive mouse cell line (ts85) | Defect in ubiquitin system at restrictive temperature | Limited to cultured cell phenotypes | Connection between ubiquitination defect and cell cycle arrest [10] [3] |

| Biochemical fractionation | Separation of complex system into functional components | Potential loss of co-factors during purification | Identification of E1, E2, E3 enzymatic cascade [2] [4] |

Comparative Analysis of Research Trajectories

The APF-1 Research Pathway (Hershko and Ciechanover)

The Hershko laboratory at Technion focused on resolving the biochemical basis for ATP-dependent protein degradation. Their experimental approach utilized a cell-free extract from rabbit reticulocytes (immature red blood cells), which lack lysosomes, thus enabling specific study of the non-lysosomal proteolytic pathway [2] [4]. The critical experimental breakthrough came through biochemical fractionation of the reticulocyte extract, which revealed that ATP-dependent proteolysis required two complementary fractions [24].

Key Experimental Protocol: Fractionation of Reticulocyte Extract

- Preparation of reticulocyte lysate from immature rabbit red blood cells

- Chromatographic separation of lysate components into two fractions (I and II)

- Demonstration that neither fraction alone supported ATP-dependent proteolysis

- Identification of a heat-stable polypeptide component (APF-1) in Fraction I that stimulated proteolysis when recombined with Fraction II [24]

The unexpected heat stability of APF-1 proved to be a critical clue, as it withstood boiling temperatures that denatured most cellular proteins [3]. Further investigation using radiolabeled APF-1 ([¹²⁵I]APF-1) revealed the surprising finding that it formed covalent conjugates with multiple proteins in the extract in an ATP-dependent manner [2]. This conjugation was stable to high pH treatment, confirming the covalent nature of the linkage [2].

The Ubiquitin Research Pathway (Goldstein and Others)

Simultaneously, ubiquitin had been discovered in 1975 by Gideon Goldstein as a universally present protein with suspected immune functions [7] [11]. Independently, Goldknopf and Busch identified a unusual bifurcated protein in chromatin where a small protein was attached to histone H2A [10]. This conjugate, known as protein A24, was subsequently shown to consist of ubiquitin linked to histone H2A [10]. However, the functional significance of this modification remained unknown throughout the mid-1970s.

The structural characterization of ubiquitin and its conjugates provided essential clues that would later connect these research pathways. The covalent linkage in the ubiquitin-H2A conjugate was identified as an isopeptide bond between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin and the ε-amino group of lysine 119 in histone H2A [24].

The Collaborative Network and Critical Convergence

The integration of these research trajectories occurred through a carefully nurtured collaboration between the Israeli biochemists and American researchers. The initial connection formed when Hershko and Rose met at a Fogarty Foundation meeting in 1977 and discovered their mutual interest in ATP-dependent proteolysis [2]. This led to Rose inviting Hershko to spend a sabbatical at his laboratory at the Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, beginning a decade-long collaboration that saw the Israeli researchers visiting every summer [2].

Table 3: Key Collaborative Interactions and Outcomes

| Collaborative Interaction | Nature of Collaboration | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Hershko-Ciechanover-Rose (Fox Chase) | Sabbatical visits; intellectual exchange; shared experimental resources | Elucidation of covalent APF-1 conjugation; multi-step enzymatic mechanism [2] |

| Wilkinson-Urban-Haas (Rose Lab) | Postdoctoral research; knowledge integration across fields | Identification of APF-1 as ubiquitin through protein characterization [2] |

| Ciechanover-Varshavsky (MIT) | Postdoctoral collaboration across institutions | Demonstration of ubiquitin system function in living cells [3] |

Diagram 1: Collaborative Network Linking Key Discoveries. This diagram illustrates the institutional affiliations and collaborative interactions that enabled the identification of APF-1 as ubiquitin and the elucidation of its function.

The critical convergence occurred when postdoctoral researchers in Rose's laboratory noticed similarities between the covalent conjugation of APF-1 and the known modification of histone H2A by ubiquitin [2]. Keith Wilkinson, Michael Urban, and Arthur Haas demonstrated that APF-1 and ubiquitin were identical proteins, unifying the two research pathways [2] [10]. This identification was confirmed through comparative analysis of the proteins, including peptide mapping and characterization of the C-terminal sequence, which was shown to be critical for activity [25].

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

Key Experimental Protocol: Identification of Covalent APF-1 Conjugation

The experimental workflow that established the covalent linkage of APF-1 to substrate proteins exemplifies the sophisticated biochemical approaches employed by these research groups:

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Covalent Conjugation Discovery. This diagram outlines the critical experimental steps that demonstrated the covalent attachment of APF-1/ubiquitin to substrate proteins.

Detailed Methodology:

- Radiolabeling: APF-1 was labeled with ¹²⁵I for detection [2]

- Incubation Conditions: ¹²⁵I-APF-1 was incubated with Fraction II in the presence of ATP and Mg²⁺ [2]

- Size Separation: Proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) [2]

- Stability Tests: The linkage was tested under various conditions including high pH (NaOH) treatment [2]

- Specificity Controls: Experiments included conditions without ATP to demonstrate energy dependence [2]

This experimental protocol revealed that multiple molecules of APF-1/ubiquitin could be attached to a single substrate protein, a phenomenon termed polyubiquitination, which was later shown to be the targeting signal for proteasomal degradation [2] [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Their Experimental Functions

| Research Reagent/Resource | Function in Experiments | Experimental Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Rabbit reticulocyte lysate | Source of ATP-dependent proteolytic system | Provided abundant, lysosome-free experimental system [2] [4] |

| ATP and Mg²⁺ | Energy source and cofactor | Demonstrated energy requirement for conjugation [2] |

| Fraction I (APF-1/ubiquitin) | Heat-stable polypeptide component | Identified as the tagging molecule after surviving boiling [3] [24] |

| Fraction II | High molecular weight fraction | Contained E1, E2, E3 enzymes and proteasome [2] |

| ¹²⁵I-radiolabeled APF-1 | Tracer for conjugation experiments | Enabled detection of covalent protein conjugates [2] |

| Temperature-sensitive ts85 cells | Mutant cell line with thermolabile E1 | Established physiological relevance in living cells [10] [3] |

Impact and Synthesis

The convergence of the APF-1 and ubiquitin research pathways fundamentally transformed our understanding of cellular regulation. The discovery that ubiquitin serves as a specific signal for protein degradation explained the long-standing paradox of energy requirement in intracellular proteolysis [22]. Furthermore, it established a new paradigm in post-translational regulation—where protein modification could target substrates for complete destruction rather than simply modulating their activity [2].

The collaborative network between Technion, Fox Chase, and MIT was instrumental in bridging biochemical mechanism with physiological function. The initial biochemical characterization in cell-free systems [2] was complemented by demonstrations in living cells [10] [3], creating a comprehensive understanding of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. This collaboration exemplified how integrating diverse expertise—from mechanistic biochemistry to genetics and cell biology—can accelerate scientific discovery.

The legacy of this work extends far beyond protein degradation, with ubiquitination now recognized as a central regulatory mechanism in cell cycle control, DNA repair, transcription, immune response, and numerous other cellular processes [10] [22]. The collaborative model established in the late 1970s continues to influence how interdisciplinary teams approach complex biological problems, demonstrating that fundamental breakthroughs often emerge at the intersection of different research traditions and methodologies.

Biochemical and Technical Approaches: From Reticulocyte Extracts to Ubiquitin Conjugation

The isolation of ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1) from reticulocyte lysates in the late 1970s marked a pivotal breakthrough in understanding regulated intracellular protein degradation. This discovery emerged from parallel research pathways that initially seemed unrelated. Gideon Goldstein and colleagues first identified a "ubiquitous immunopoietic polypeptide" in 1975 while studying thymic hormones involved in lymphocyte differentiation [6]. Initially named UBIP and later ubiquitin, this small protein was noted for its remarkable conservation across species [6]. Simultaneously, Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose were investigating ATP-dependent protein degradation in reticulocyte lysates, leading them to identify a heat-stable polypeptide they termed APF-1 that was covalently conjugated to target proteins prior to their degradation [10] [4].

The critical connection between these two lines of research came in 1980 through a serendipitous interaction. Michael Urban, a postdoctoral researcher working near Irwin Rose's laboratory, recognized similarities between the covalent conjugation of APF-1 to target proteins and the known conjugation of ubiquitin to histone H2A [6]. This observation prompted a series of experiments that definitively established that APF-1 was identical to ubiquitin [10] [6]. This convergence of immunological and proteolysis research revealed a fundamental cellular regulatory system and ultimately led to the awarding of the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose.

Comparative Analysis of APF-1/Ubiquitin Purification Methodologies

Core Fractionation Techniques for APF-1 Isolation

The initial purification of APF-1/ubiquitin from rabbit reticulocyte lysates employed a multi-step fractionation approach that combined several biochemical separation techniques. The foundational methodology involved:

- Lysate Preparation: Rabbit reticulocyte lysates served as the starting material, providing a rich source of the ATP-dependent proteolytic system [26] [4].

- Chromatographic Separation: The lysate was subjected to sequential chromatography columns, including DEAE-cellulose and hydroxyapatite chromatography, to separate APF-1 from other cellular components [4].

- Heat Treatment: A critical step involved heat treatment (90°C for 10 minutes) of fractions containing APF-1/ubiquitin, which exploited the remarkable thermostability of this protein while denaturing and removing many other proteins [4].

- Gel Filtration: Final purification steps utilized size-exclusion chromatography to isolate the approximately 8.5 kDa ubiquitin protein from remaining contaminants [4].

This fractionation strategy successfully isolated APF-1/ubiquitin based on its small size, heat stability, and charge characteristics, enabling subsequent biochemical characterization of its role in protein degradation.

Advanced Proteasome Separation from Reticulocyte Lysates

Following the discovery of APF-1/ubiquitin, further fractionation work revealed the protease component of the system. Researchers purified two high molecular weight proteases from rabbit reticulocyte lysate through a approximately 400-fold enrichment process [26]. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these two complexes:

Table 1: Comparative Properties of High Molecular Weight Proteases from Reticulocyte Lysate

| Property | 26S Proteasome | 20S Proteasome (Multicatalytic Proteinase Complex) |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | 1,000,000 ± 100,000 Da | 700,000 ± 20,000 Da |

| ATP Dependence | Required for degradation of proteins and peptide substrates | Not required for degradation activity |

| Subunit Composition | Complex multisubunit structure | 8-10 separate subunits (Mr 21,000-32,000) |

| Sedimentation Characteristics | ~26S | ~20S |

| Inhibitor Sensitivity | Hemin, thiol reagents, chymostatin, leupeptin | Hemin, thiol reagents, chymostatin, leupeptin |

| Substrate Preference | Degrades ubiquitin-conjugated proteins; stimulated by ATP for 125I-lysozyme-ubiquitin conjugates | Hydrolyzes 125I-α-casein and peptide substrates without ubiquitination |

The 26S proteasome was identified as the ATP-dependent complex that degrades ubiquitin-conjugated proteins, while the smaller 20S complex (similar to the "multicatalytic proteinase complex" described by Wilk and Orlowski) functions independently of ATP and ubiquitin [26].

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Reticulocyte Lysate Fractionation for Protein Synthesis

While not specific to APF-1 isolation, an efficient reticulocyte lysate fractionation protocol was developed by Morley et al. (1990) that maintained high protein synthesis activity. Key steps included [27]:

- Ribosome Pellet Formation: Centrifugation of reticulocyte lysate at high speed for 20 minutes to pellet ribosomes.

- Post-Ribosomal Supernatant (S-100) Collection: Careful removal of the supernatant containing soluble proteins, including translation factors.

- High-Salt Ribosome Wash: Treatment of ribosome pellets with high-salt buffer to remove associated proteins.

- Activity Reconstitution: Combining S-100 supernatant, washed ribosomes, and the high-salt wash fraction to restore >70% of the original protein synthesis activity.

This fractionation approach demonstrated the importance of multiple lysate components for maintaining biochemical activity and provided a methodology for studying individual fractions in functional assays.

Ubiquitin-Conjugation Assay System

The critical experimental system that revealed APF-1/ubiquitin function involved several key components [10] [4]:

- ATP-Regeneration System: Consisting of ATP, creatine phosphate, and creatine phosphokinase to maintain constant ATP levels.

- Reticulocyte Fraction II: The fraction containing E1, E2, and E3 enzymes after removal of hemoglobin and endogenous substrates.

- 125I-Labeled Protein Substrates: Radioiodinated proteins such as lysozyme to track degradation.

- Ubiquitin/APF-1: The purified thermostable cofactor.

- Proteasome Fraction: Isolated 26S proteasome complex.

The assay measured the ATP-dependent conversion of substrate proteins to acid-soluble fragments, requiring both ubiquitin conjugation and proteasome activity [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for APF-1/Ubiquitin and Proteasome Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Rabbit Reticulocyte Lysate | Source of ATP-dependent proteolytic system and translation machinery | Freshly prepared or commercially available lysates |

| ATP-Regeneration System | Maintains ATP levels during incubation periods | ATP, creatine phosphate, creatine phosphokinase |

| Protease Inhibitors | Characterize protease sensitivity and specificity | Hemin, leupeptin, chymostatin, thiol reagents |

| Chromatography Media | Fractionate lysate components | DEAE-cellulose, hydroxyapatite, gel filtration resins |

| Radioisotope-Labeled Substrates | Track protein degradation and ubiquitination | 125I-α-casein, 125I-lysozyme-ubiquitin conjugates |

| Synthetic Peptide Substrates | Measure protease activity | Succinyl-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-4-methylcoumaryl-7-amide |

| Centrifugation Equipment | Separate lysate fractions and organelles | Ultracentrifuges for ribosome pelleting and S-100 preparation |

Signaling Pathways and Historical Research Convergence

The diagram below illustrates the convergence of initially separate research pathways that led to the identification of APF-1 as ubiquitin and the elucidation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system:

The fractionation techniques developed for separating APF-1 from reticulocyte lysates established foundational methodologies that continue to influence modern drug development. The identification of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) as a critical regulatory pathway has made it an important target for therapeutic interventions. Proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib have become standard treatments for multiple myeloma and other hematological malignancies, directly stemming from the basic biochemical research on reticulocyte fractionation [4].

Current drug discovery efforts continue to target other components of the ubiquitin system, including E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes, and E3 ligases, across various disease areas including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and inflammatory conditions. The historical comparison between APF-1 and ubiquitin research serves as a powerful reminder that fundamental biochemical discoveries, often arising from seemingly unrelated research fields, can converge to reveal central biological mechanisms with profound therapeutic implications.

The fractionation techniques pioneered in the 1970s and 1980s for reticulocyte lysates have evolved into sophisticated proteomic methods now applied to complex biological systems, enabling continued discovery in the ubiquitin field and beyond.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of the covalent conjugation assays that were pivotal in tracking 125I-labeled ATP-dependent proteolytic factor 1 (APF-1) protein adducts, a discovery that fundamentally shaped the ubiquitin-proteasome system. We objectively evaluate the historical and modern protein labeling techniques, supported by experimental data on their performance in specificity, stability, and applicability. The content is framed within the broader thesis of contrasting the early APF-1 research, which focused on a degradative signal, with Goldstein's contemporaneous work on ubiquitin, which initially highlighted its role in lymphocyte differentiation and chromatin structure. This comparison illuminates how methodological choices in protein tracking can steer scientific understanding toward distinct physiological pathways.

The discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system emerged from the convergence of two independent research pathways, each employing distinct biochemical methodologies to study the same small, ubiquitous protein.

- The APF-1 Pathway (Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose): Research in the late 1970s into ATP-dependent protein degradation in rabbit reticulocyte lysates identified a small, heat-stable protein factor essential for proteolysis, termed ATP-dependent proteolytic factor 1 (APF-1) [10] [6]. This factor was observed to form covalent conjugates with target proteins in an ATP-dependent manner, suggesting it was a signal for degradation [8] [10]. The key assay involved tracking these covalent conjugates, a methodology that would later be revolutionized by the use of 125I-labeled APF-1.

- The Ubiquitin Pathway (Goldstein): Concurrently, the protein ubiquitin (originally UBIP, for "ubiquitous immunopoietic polypeptide") had been isolated from bovine thymus and was studied for its potential role in lymphocyte differentiation [8] [6]. In a separate line of inquiry, a protein known as A24 was found to be a conjugate between histone H2A and a non-histone protein, which was subsequently identified as ubiquitin [10] [7]. This work focused on the non-degradative roles of ubiquitin in chromatin structure and function.

The critical link was established in 1980 when researchers demonstrated that APF-1 and ubiquitin were the same molecule [10] [6] [7]. This convergence revealed that a single protein could signal for vastly different cellular outcomes—protein degradation and chromatin modulation—depending on the context and mode of conjugation. The development of covalent conjugation assays using 125I-labeled APF-1/ubiquitin was instrumental in deciphering the former pathway, providing the sensitivity and specificity needed to track the dynamics of this central regulatory system.

Quantitative Comparison of Iodination Techniques for APF-1/Ubiquitin

The choice of labeling technique was critical for tracking the formation of APF-1-protein adducts without disrupting its native structure and function. The table below compares the primary iodination methods considered for such an application.

Table 1: Performance comparison of key protein iodination techniques relevant for APF-1/Ubiquitin labeling.

| Iodination Technique | Reaction Mechanism | Amino Acid Target | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Suitability for Tracking APF-1 Adducts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bolton-Hunter Reagent [28] | Non-oxidative, active ester acylation | Terminal amino groups, Lysine residues | Mild, non-oxidative; preserves protein structure; high specific activity (di-iodinated: 4400 Ci/mmol) [28] | Potential blocking of critical lysines involved in ubiquitin's own conjugation | High - The mild conditions help preserve the enzymatic activity required for the conjugation cascade. |

| Chloramine-T [28] | Oxidative | Tyrosine, Histidine | High specific activity, carrier-free; rapid reaction | Harsh oxidative conditions can denature proteins and disrupt function | Low - Risk of damaging the delicate structure of APF-1/Ubiquitin and its enzymatic partners. |

| Lactoperoxidase [28] | Enzyme-catalyzed oxidation | Tyrosine | Milder oxidative technique; suitable for methionine-containing proteins | Requires optimization of enzyme and H2O2 concentrations | Medium - A gentler alternative to Chloramine-T if tyrosine labeling is necessary. |

| IODOGEN Reagent [28] | Solid-phase oxidative | Tyrosine, Histidine | Milder than Chloramine-T; reaction confined to tube surface | Still an oxidative method with associated risks | Medium - Improved over Chloramine-T, but oxidative damage remains a concern. |

Experimental Protocols: Deciphering the Ubiquitin Cascade

The following protocols detail the key historical and modern methods that enabled the dissection of the ubiquitin conjugation pathway.

Protocol 1: Bolton-Hunter Iodination of APF-1/Ubiquitin

This method was favored for its mild, non-oxidative conditions, which were crucial for maintaining the biological activity of ubiquitin [28].

- Reconstitution: Dissolve the Bolton-Hunter reagent (N-hydroxysuccinimide ester of iodinated p-hydroxyphenylpropionic acid) in a suitable organic solvent like DMSO.

- Protein Preparation: Transfer 5-20 µg of purified APF-1/Ubiquitin protein into a clean tube. Ensure the protein is in a borate or phosphate buffer (pH 8.0-9.0) and is free of primary amines (e.g., Tris, glycine, azide) which compete in the reaction [29] [28].

- Conjugation: Add the dissolved Bolton-Hunter reagent to the protein solution. Incubate on ice for 15-120 minutes with occasional gentle mixing.

- Quenching & Purification: Terminate the reaction by adding a large molar excess of a primary amine (e.g., glycine or Tris buffer). Separate the 125I-labeled APF-1/Ubiquitin from unreacted iodine and reagents using gel filtration chromatography (e.g., a desalting column) [28].

- Quality Control: Determine the specific activity and radiochemical purity of the labeled product using gamma counting and TLC or SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography.

Protocol 2: Covalent Conjugation Assay for E1-E2-E3 Enzymology

This functional assay uses the 125I-APF-1/Ubiquitin to track the formation of covalent intermediates and substrate adducts, recapitulating the landmark experiments of the early 1980s [8] [10] [7].

- Reaction Setup: In a series of tubes, assemble the following components:

- ATP-regenerating system (ATP, Mg2+)

- Purified E1 activating enzyme

- Purified E2 conjugating enzyme

- Purified E3 ligating enzyme (for substrate-specific assays)

- Target protein substrate

- 125I-APF-1/Ubiquitin (from Protocol 1)

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction mix at 30°C for a time course (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 minutes).

- Termination: Stop the reaction by adding SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing a reducing agent (e.g., DTT or β-mercaptoethanol).

- Analysis: Resolve the proteins by SDS-PAGE. Visualize the 125I-labeled complexes by exposing the dried gel to X-ray film or using a phosphorimager. The resulting autoradiograph will show a ladder of high-molecular-weight adducts corresponding to multi-monoubiquitinated and polyubiquitinated substrates, as well as potential E1~Ub and E2~Ub thioester intermediates if a reducing agent was omitted in a parallel experiment [8] [7].

Diagram 1: The core enzymatic cascade in the formation of 125I-APF-1/Ubiquitin protein adducts, as tracked in the covalent conjugation assay.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

The following tools are essential for conducting historical and modern ubiquitin conjugation assays.

Table 2: Essential research reagents for ubiquitin conjugation and tracking studies.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Assay | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Bolton-Hunter Reagent (125I) [28] | Labels ubiquitin on primary amines for high-sensitivity tracking without oxidation. | Mono-iodinated form is standard; di-iodinated offers higher specific activity (4400 Ci/mmol) [28]. |

| E1 Activating Enzyme [8] [7] | Initiates the ubiquitination cascade by activating ubiquitin's C-terminus in an ATP-dependent manner. | Human genome encodes two E1 enzymes: UBA1 and UBA6 [7]. |

| E2 Conjugating Enzyme [8] [7] | Accepts activated ubiquitin from E1 and cooperates with E3 to transfer it to the substrate. | Humans possess ~35 E2 enzymes, characterized by a conserved UBC fold [7]. |

| E3 Ubiquitin Ligase [8] [7] | Confers substrate specificity by recognizing target proteins and facilitating ubiquitin transfer. | Can contain HECT or RING domains; humans have ~600 E3s [8]. |

| ATP-Regenerating System [10] | Provides the energy required for the E1-mediated activation step. | Essential for in vitro reconstitution of the ubiquitination cascade. |

| Proteasome Inhibitor (e.g., MG132) | Blocks degradation of ubiquitinated substrates, allowing adduct accumulation for detection. | Critical for visualizing polyubiquitinated chains in cell-based assays. |

Data Interpretation and Historical Contextualization

The data generated from these conjugation assays using 125I-APF-1 was transformative. Autoradiographs revealing ladders of high-molecular-weight adducts provided the first visual evidence of a processive, enzyme-catalyzed protein tagging system [8] [10]. This directly supported the model that multiple molecules of APF-1/Ubiquitin were conjugated to a single substrate molecule, a finding that was initially described in the characterization of APF-1 [10] [7].

The ability to track these adducts with high sensitivity was crucial for the biochemical fractionation and identification of the E1, E2, and E3 enzymes [10]. It cemented the concept of a sequential catalytic cascade, which stands in stark contrast to the single, stoichiometric modification of histone H2A to form the A24 protein that was studied in the Goldstein ubiquitin lineage [6]. This methodological divergence underscores a broader thesis: the tools of covalent conjugation tracking revealed the dynamic, signal-like nature of the ubiquitin system in proteolysis, while the tools of chromatin biochemistry revealed its stable, structural role. The convergence of these paths, sparked by the identification of APF-1 as ubiquitin, demonstrates how a protein's function is defined by the context of its conjugation, a context first illuminated by the choice of assay.