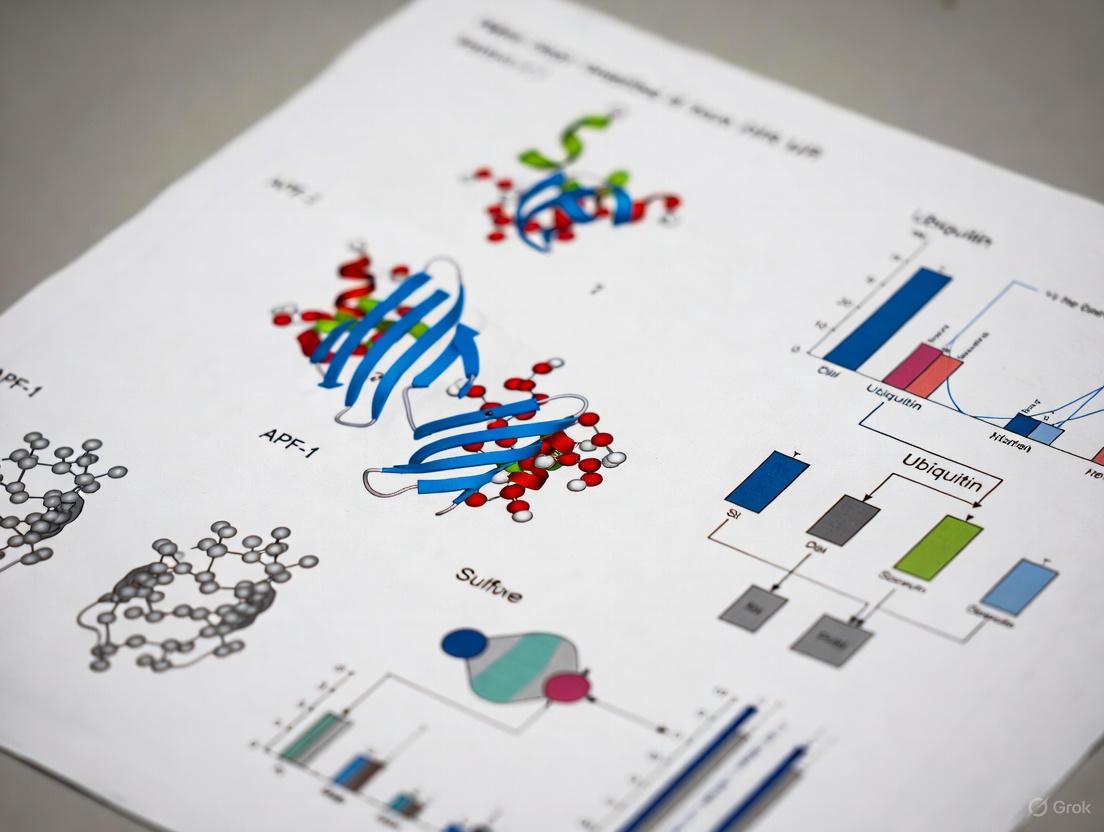

From APF-1 to Ubiquitin: The Discovery of the Molecular Kiss of Death and Its Impact on Modern Therapeutics

This article chronicles the seminal discovery of ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1) and its subsequent identification as the universal protein ubiquitin, a breakthrough that unveiled the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS).

From APF-1 to Ubiquitin: The Discovery of the Molecular Kiss of Death and Its Impact on Modern Therapeutics

Abstract

This article chronicles the seminal discovery of ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1) and its subsequent identification as the universal protein ubiquitin, a breakthrough that unveiled the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS). We detail the foundational biochemical research in the late 1970s and 1980s that revealed a novel, energy-dependent pathway for targeted protein degradation, moving beyond the then-prevailing lysosomal model. The content explores the methodological evolution from fractionated reticulocyte lysates to the characterization of the E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade. For a contemporary research and drug development audience, the article further examines how troubleshooting early experimental challenges and validating the system's biological roles paved the way for targeting the UPS in modern therapeutics, including the development of proteasome inhibitors and novel modalities in the current drug pipeline.

The Energetic Puzzle of Protein Turnover: Uncovering APF-1

For approximately two decades between the mid-1950s and mid-1970s, the lysosomal system was believed to be the primary mechanism for intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotic cells [1]. The lysosome, discovered by Christian de Duve, was recognized as a membrane-bound organelle containing various hydrolytic enzymes that function optimally at acidic pH [1]. This organelle was thought to be responsible for the digestion of cellular proteins through autophagy (for intracellular proteins) and heterophagy (for extracellular proteins) [1]. The prevailing hypothesis suggested that cytosolic proteins were sequestered within autophagosomes through a process of membrane invagination, which then fused with lysosomes, leading to non-selective protein degradation [1] [2]. This model provided an elegant subcellular compartmentalization that separated destructive hydrolytic enzymes from the rest of the cytoplasm, thus preventing uncontrolled proteolysis.

However, several lines of experimental evidence began to challenge this lysosome-centric view. The discovery that intracellular proteolysis requires metabolic energy was particularly puzzling [3] [1]. Melvin Simpson first demonstrated this ATP dependence in 1953 through isotopic labeling studies, showing that protein degradation in mammalian cells consumed energy [3]. This presented a thermodynamic paradox because the hydrolysis of peptide bonds is an exergonic (energy-releasing) process, and there was no apparent biochemical rationale for energy requirement in proteolysis itself [3] [1]. This fundamental contradiction suggested that there were missing components in the understanding of intracellular protein degradation. Additionally, studies using specific lysosomal inhibitors often failed to suppress the degradation of most intracellular proteins, further indicating the existence of nonlysosomal proteolytic pathways [1]. The scientific community increasingly recognized that the lysosomal hypothesis could not adequately explain the high specificity of protein degradation, where different cellular proteins have distinct half-lives that can vary under different physiological conditions [1].

The ATP Dependence Paradox and Emerging Challenges to the Lysosomal Hypothesis

Key Experimental Evidence Challenging the Lysosomal Paradigm

The ATP dependence of intracellular proteolysis represented one of the most significant challenges to the lysosomal hypothesis. If proteins were degraded within lysosomes through autophagy, the process should not require substantial ATP, as the actual peptide bond cleavage is chemically exergonic [3]. The energy requirement suggested additional, unknown biochemical steps were involved in proteolysis. Throughout the 1970s, several critical observations accumulated that fundamentally questioned the lysosomal paradigm:

- Studies demonstrated that damaged or abnormal proteins were rapidly cleared from cells through an ATP-dependent mechanism [3]

- Researchers observed that enzymes catalyzing rate-limiting steps in metabolic pathways were generally short-lived and their degradation was responsive to metabolic conditions [3]

- The use of lysosomal inhibitors failed to suppress the degradation of most intracellular proteins, indicating a nonlysosomal pathway [1]

- Experiments showing different proteins have distinct half-lives could not be reconciled with the presumed non-selective nature of autophagic capture [1]

Table 1: Experimental Evidence Challenging the Lysosomal Proteolysis Hypothesis

| Evidence Type | Experimental Observation | Implied Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Energetics | ATP requirement for proteolysis | Additional energy-requiring steps beyond simple hydrolysis |

| Kinetics | Different proteins exhibit distinct half-lives | Selective recognition mechanism rather than non-selective autophagy |

| Pharmacology | Lysosomal inhibitors do not block most protein degradation | Existence of nonlysosomal proteolytic pathways |

| Specificity | Rate-limiting enzymes rapidly degraded in response to metabolic changes | Regulatory function for proteolysis beyond waste disposal |

The Reticulocyte Breakthrough: A Model System for Nonlysosomal Proteolysis

A critical advancement came with the establishment of the reticulocyte cell-free extract as a model system for studying ATP-dependent proteolysis [1]. Reticulocytes (immature red blood cells) are essentially devoid of lysosomes, yet they efficiently degrade abnormal proteins [3]. The seminal work of Etlinger and Goldberg demonstrated that reticulocyte lysates exhibited ATP-dependent proteolysis of denatured proteins, providing a tractable biochemical system that could be fractionated and reconstituted [3]. This system became the foundation for the groundbreaking discoveries that would follow.

Avram Hershko and Aaron Ciechanover capitalized on this experimental system, demonstrating that the ATP-dependent proteolytic activity could be separated into two essential fractions [3] [1]:

- Fraction I: Contained a small, heat-stable polypeptide component

- Fraction II: Contained higher molecular weight components that were stabilized by ATP

Only when these fractions were recombined would ATP-dependent proteolysis occur. This simple yet powerful experimental approach revealed that intracellular proteolysis was far more complex than previously imagined—it was not mediated by a single protease but required multiple complementing factors [1]. This fundamental insight marked the beginning of the end for the lysosomal paradigm and opened the door to the discovery of a completely novel proteolytic system.

Methodology: Key Experimental Approaches and Technical Breakthroughs

Biochemical Fractionation and Reconstitution Strategies

The initial experimental approach that led to the discovery of the ubiquitin system relied on conventional biochemical fractionation techniques applied to the reticulocyte lysate system [1]. The methodology followed a logical progression of separating cellular components and testing their individual and combined functions:

Preparation of Reticulocyte Lysate: Reticulocytes were obtained from anemic rabbits, lysed, and centrifuged to remove membranes and insoluble material [3] [1]

ATP-Depletion and Chromatographic Separation: The lysate was subjected to ion-exchange chromatography to separate components based on charge properties [3] [1]

Functional Reconstitution Assays: Individual fractions were tested for their ability to support ATP-dependent proteolysis alone and in combination [3] [1]

Identification of Essential Factors: Fractions that were absolutely required for proteolysis were further purified and characterized [3]

This reductionist approach led to the identification of ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1 (APF-1), which was subsequently identified as ubiquitin [3] [1]. The requirement for both Fraction I (containing APF-1) and Fraction II for proteolysis demonstrated the multi-component nature of the system.

Covalent Conjugation Assays and the Discovery of Protein Tagging

A pivotal methodological breakthrough came from experiments designed to track the fate of APF-1 in the proteolytic system. The researchers employed radiolabeling techniques to follow APF-1 during the degradation process [3]:

Iodination of APF-1: 125I-labeled APF-1 was prepared using standard iodination methods

Incubation with Fraction II and ATP: Labeled APF-1 was incubated with Fraction II in the presence of ATP and Mg2+

Analysis of Molecular Complexes: Reaction mixtures were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography to identify high molecular weight complexes

Stability Tests: The nature of the association was tested under various conditions (pH, denaturants)

To everyone's surprise, these experiments revealed that APF-1 formed covalent associations with multiple proteins in Fraction II [3]. This conjugation required ATP and was reversible upon ATP removal. The covalent nature of the association was demonstrated by its stability to high pH (NaOH treatment) and denaturing conditions [3]. This discovery of a protein-tagging mechanism represented a paradigm shift in understanding how proteolysis could be specifically targeted to particular substrates.

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow Leading to Ubiquitin Discovery

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Methods in Early Ubiquitin Research

| Reagent/Method | Function/Role | Key Experimental Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | ATP-dependent proteolysis model system lacking lysosomes | Confirmed existence of nonlysosomal proteolytic pathway [3] [1] |

| ATP Regeneration Systems | Maintained ATP levels during extended incubations | Demonstrated continuous energy requirement for conjugation and degradation [3] |

| 125I-labeled APF-1 | Radiolabeled tracer for tracking APF-1 fate | Revealed covalent attachment to multiple protein substrates [3] |

| Ion-Exchange Chromatography | Separation of crude lysate into functional fractions | Identified multiple essential components (E1, E2, E3 enzymes) [3] [1] |

| Heat Treatment | Fraction I stability to heat denaturation | Distinguished APF-1/ubiquitin from most cellular proteins [1] |

| SDS-PAGE + Autoradiography | Analysis of protein conjugates | Visualized high molecular weight complexes containing APF-1 [3] |

The Conceptual Revolution: From Lysosomal Digestion to Targeted Degradation

The Discovery of ATP-Dependent Protein Tagging

The critical conceptual breakthrough came from the realization that APF-1 (ubiquitin) was covalently attached to protein substrates prior to their degradation [3]. This discovery fundamentally changed the understanding of how intracellular proteolysis could be both energy-dependent and highly specific. The key findings included:

Covalent Linkage: APF-1 formed isopeptide bonds with substrate proteins, primarily through the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin and ε-amino groups of lysine residues on substrates [3]

ATP Requirement: The conjugation process specifically required ATP, explaining the energy dependence of proteolysis [3]

Multiplicity: Multiple molecules of APF-1 could be attached to a single substrate molecule [3]

Polyubiquitin Chains: The modification often involved chains of ubiquitin molecules rather than single ubiquitin tags [3]

This tagging mechanism provided an elegant solution to the specificity problem—the proteolytic machinery itself could be relatively non-specific, while specificity was achieved at the level of target recognition and tagging.

Resolution of the ATP Paradox

The discovery of the ubiquitin tagging system resolved the long-standing paradox of energy requirement in proteolysis. The ATP was not required for the proteolytic step itself, but rather for the enzymatic cascade that marks substrates for degradation [3] [2]:

Ubiquitin Activation: ATP is required for the activation of ubiquitin by E1 enzymes, forming a thioester bond [4] [2]

Conjugation to E2 Enzymes: Activated ubiquitin is transferred to ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2s) [4] [2]

Ligation to Substrates: E3 ubiquitin ligases facilitate the transfer of ubiquitin to specific protein substrates [4] [2]

Each of these steps consumes ATP, explaining the energy dependence that had puzzled researchers for decades. The identification of this enzymatic cascade revealed that targeted protein degradation is an active, regulated process rather than a simple digestive function.

Diagram 2: The Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway Resolving the ATP Paradox

Quantitative Characterization of the Ubiquitin System

Table 3: Quantitative Features of the Early Ubiquitin Proteolytic System

| Parameter | Experimental Measurement | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| ATP Concentration | Low concentrations required (μM range) | High affinity ATP-binding sites in E1 enzymes [3] |

| Ubiquitin Conjugation | Multiple ubiquitins per substrate (polyubiquitination) | More efficient targeting to proteasome [3] |

| Temperature Stability | APF-1/ubiquitin heat-stable | Unusual property distinguishing it from most proteins [1] |

| Molecular Weight of APF-1 | ~8.6 kDa | Identified as small regulatory protein [4] |

| Ubiquitin Genes in Humans | 4 genes (UBB, UBC, UBA52, RPS27A) | Essential function requiring multiple gene copies [4] |

| Enzyme Classes | 1 E1, ~35 E2, hundreds of E3 enzymes | Hierarchical system providing specificity [4] [2] |

Implications and Legacy: From Obscure Mechanism to Central Regulatory Pathway

The discovery of ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis fundamentally transformed our understanding of cellular regulation. What began as an investigation into an apparent biochemical paradox—ATP-dependent proteolysis—evolved into the discovery of one of the most pervasive regulatory mechanisms in eukaryotic biology. The ubiquitin system has since been implicated in virtually all cellular processes, including:

- Cell Cycle Regulation: Controlled degradation of cyclins and other regulators [2]

- Transcriptional Control: Regulation of transcription factor stability and activity [3]

- DNA Repair: Coordination of repair protein availability [4]

- Immune Responses: Processing and presentation of antigens [5]

- Neuronal Function: Maintenance of synaptic plasticity and protein quality control [5]

The trajectory from the pre-ubiquitin paradigm of lysosomal proteolysis to our current understanding exemplifies how investigating anomalous findings—like the unexplained ATP dependence—can lead to fundamental shifts in biological understanding. The ubiquitin system's discovery required challenging established dogma, developing innovative experimental approaches, and recognizing the significance of unexpected results. This journey from a curious observation to a central biological paradigm underscores the dynamic nature of scientific progress and the importance of maintaining intellectual flexibility when confronted with experimental evidence that contradicts prevailing models.

The scientific community has recognized the profound significance of this discovery, awarding the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to Aaron Ciechanover, Avram Hershko, and Irwin Rose for their pioneering work [3] [4]. Their research not only solved the specific problem of ATP-dependent proteolysis but also unveiled a fundamentally new mechanism of cellular regulation that continues to generate insights into both basic biology and disease mechanisms.

The discovery of ATP-dependent protein degradation represents a cornerstone of modern cell biology, fundamentally reshaping our understanding of regulated proteolysis. This breakthrough emerged from pioneering research utilizing rabbit reticulocyte lysates—a unique, lysosome-free experimental system that enabled the identification and characterization of APF-1, later recognized as ubiquitin. This technical guide examines the foundational methodologies that revealed the ubiquitin-proteasome system, detailing the experimental approaches that allowed researchers to dissect this essential pathway without the complicating presence of lysosomal activity. We provide comprehensive protocols, data analysis frameworks, and visualization tools to support contemporary researchers in leveraging these historical approaches for modern drug discovery applications, particularly in targeting protein homeostasis pathways in cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.

In the 1970s, the scientific understanding of cellular protein degradation remained limited, with lysosomes considered the primary site for protein turnover. The discovery of an ATP-dependent proteolytic system independent of lysosomes represented a paradigm shift in cellular biology [6]. This breakthrough was made possible through the strategic use of rabbit reticulocyte lysates as a model system—an environment naturally devoid of lysosomes, thus providing a "clean" background for identifying the core components of what would later be termed the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) [7].

The initial discovery centered on ATP-dependent proteolytic factor 1 (APF-1), a protein that was found to conjugate to other proteins marked for degradation [7]. Through a series of elegant biochemical experiments, researchers demonstrated that APF-1 was identical to the previously characterized protein ubiquitin, thereby connecting two seemingly disparate lines of research: chromatin biology and protein degradation [7]. This convergence revealed ubiquitin as a central player in both gene regulation and proteolysis, establishing the foundation for our current understanding of the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

The reticulocyte model proved uniquely suited for these discoveries due to its distinctive biological characteristics. Reticulocytes are immature red blood cells in a discrete, penultimate phase of maturation, having expelled their nucleus but retaining residual RNA and protein synthesis machinery [8]. Most importantly for these studies, as terminal cells in the differentiation pathway, they are naturally devoid of lysosomes, eliminating the dominant proteolytic system that would otherwise obscure the characterization of ATP-dependent degradation mechanisms [6] [9].

The Reticulocyte Advantage: Biological and Methodological Rationale

Unique Biological Properties of Reticulocytes

Reticulocytes represent a distinctive cohort of cells that have recently entered peripheral blood from the bone marrow. These cells are characterized by several key features that made them ideal for studying ATP-dependent degradation:

- Lysosome-free environment: As terminally differentiated cells transitioning to erythrocytes, reticulocytes naturally lack lysosomes, providing an experimental system free from the dominant lysosomal degradation pathways [6] [9]

- Residual protein synthesis capacity: Despite nuclear expulsion, reticulocytes retain ribosomal RNA and limited protein synthesis machinery, maintaining active metabolic processes [8] [10]

- Simplified proteome: With primarily hemoglobin and minimal organellar complexity, reticulocytes offer a reduced background for biochemical fractionation [10]

- Natural degradation signaling: As cells completing their maturation, reticulocytes possess active systems for removing unnecessary proteins and organelles [10]

Reticulocyte Maturation and Physiological Context

Reticulocytes undergo a complex maturation process over approximately 24 hours in circulation, during which they eliminate remaining organelles and refine their cytoskeleton [10]. This process involves extensive membrane remodeling, with loss of up to 20% of membrane surface area, and represents a natural physiological context for studying targeted protein degradation. The intrinsic maturation machinery within reticulocytes provided the ideal biochemical environment for discovering the ubiquitin-proteasome system, as these cells rely heavily on controlled proteolysis to complete their differentiation into mature erythrocytes.

Table 1: Key Reticulocyte Parameters During Maturation

| Parameter | Early Reticulocyte | Late Reticulocyte | Mature Erythrocyte |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter | ~8% larger than mature RBC | Slightly larger than mature RBC | 6-8 μm |

| RNA Content | High (group I) | Low (group IV) | None |

| Lysosomes | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Nucleus | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Lifespan | Early maturation stage | ~1 day in circulation | 120 days |

| Proteolytic Activity | High ATP-dependent degradation | Declining activity | Minimal |

Core Experimental System: Reticulocyte Lysate Preparation

Reticulocyte Production and Collection

The standard protocol for generating reticulocyte-rich blood from rabbits:

- Animal treatment: New Zealand White rabbits (2-3 kg) receive daily subcutaneous injections of 1% phenylhydrazine (0.2 ml/kg) for 5-8 days to induce hemolytic anemia and subsequent reticulocytosis [8]

- Blood collection: On day 6-9, collect blood via cardiac puncture into heparinized containers

- Reticulocyte quantification: Assess reticulocyte count using new methylene blue stain; experiments require >80% reticulocyte enrichment [8] [11]

- Cell isolation: Purify reticulocytes by density centrifugation through Ficoll-Paque or similar media

Lysate Preparation and Fractionation

- Cell washing: Wash reticulocytes 3x in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove plasma proteins and contaminants

- Lysis preparation: Resuspend packed reticulocytes in 2 volumes of hypotonic buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT)

- Cell disruption: Perform lysis by freeze-thaw cycling (3 cycles) or nitrogen cavitation

- Fractionation: Centrifuge lysate at 100,000 × g for 60 minutes to separate soluble (S100) and particulate fractions

- Storage: Aliquot and flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen; store at -80°C

Table 2: Critical Reagents for Reticulocyte Lysate Studies

| Reagent/Chemical | Function/Application | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Phenylhydrazine | Induces hemolytic anemia and reticulocytosis | Dose optimization required to balance yield and animal welfare |

| Heparin | Anticoagulant for blood collection | Avoid EDTA as calcium is required for certain proteolytic activities |

| New Methylene Blue | Reticulocyte staining and quantification | Identifies residual RNA via supravital staining [8] |

| ATP Regenerating System | Maintains ATP levels during incubations | Typically includes creatine phosphate and creatine phosphokinase |

| Hemoglobin Sepharose | Affinity matrix for binding ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes | Critical for fractionation and identification of APF-1/ubiquitin |

| Ubiquitin Aldehyde | Deubiquitinating enzyme inhibitor | Stabilizes ubiquitin-protein conjugates for detection |

Key Experimental Protocols: From APF-1 to Ubiquitin Identification

ATP-Dependent Proteolysis Assay

The foundational assay that demonstrated energy requirement for protein degradation:

Reaction mixture (50 μL total volume):

- Reticulocyte lysate (S100 fraction): 25 μL

- Tris-HCl (pH 7.5): 25 mM

- MgCl₂: 5 mM

- DTT: 1 mM

- ATP: 2 mM

- ATP-regenerating system: 10 mM creatine phosphate, 10 U creatine kinase

- ¹²⁵I-labeled bovine serum albumin (substrate): 5 μg

- Add H₂O to final volume

Incubation: 37°C for 60 minutes with gentle agitation

- Termination: Add 250 μL of 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA)

- Quantification: Centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 5 minutes, measure radioactivity in supernatant (TCA-soluble peptides)

- Controls: Include reactions without ATP and with non-hydrolyzable ATP analogs

APF-1/Ubiquitin Conjugation Assay

The critical experiment demonstrating covalent modification of target proteins:

Reaction components:

- Reticulocyte lysate: 20 μL

- Tris-HCl (pH 7.5): 25 mM

- MgCl₂: 5 mM

- DTT: 1 mM

- ATP: 2 mM

- ¹²⁵I-APF-1/ubiquitin: 2 μg

- Add H₂O to 40 μL final volume

Incubation: 37°C for 30 minutes

- Termination: Add SDS-PAGE sample buffer with 100 mM DTT

- Analysis: Separate by SDS-PAGE (12% gel), visualize by autoradiography

- Key observation: Multiple high molecular weight bands representing ubiquitin-protein conjugates

Three-Enzyme Cascade Reconstitution

The definitive experiment establishing the sequential action of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes:

Fraction preparation:

- Fraction I: DEAE-cellulose flow-through containing E1

- Fraction II: 0.2M KCl eluate containing E2 enzymes

- Fraction III: 0.5M KCl eluate containing E3 enzymes

Reconstitution assay:

- Ubiquitin: 10 μg

- E1 fraction: 5 μg

- E2 fraction: 5 μg

- E3 fraction: 5 μg

- ATP: 2 mM

- Target protein (e.g., lysozyme): 5 μg

- Incubate at 37°C for 60 minutes

- Analyze conjugates by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting

Diagram 1: Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway Enzyme Cascade

Data Analysis and Interpretation Framework

Quantitative Assessment of Proteolytic Activity

The reticulocyte lysate system generates quantitative data that must be properly analyzed and interpreted:

- TCA-soluble radioactivity: Calculate specific proteolytic activity as pmol of amino acids released per mg lysate protein per hour

- ATP-dependence ratio: Compare degradation rates with and without ATP (typically >10:1 ratio in active lysates)

- Time course analysis: Establish linear range of reaction (typically 0-90 minutes)

- Lysate activity normalization: Standardize activities to lysate protein concentration (Bradford assay)

Table 3: Typical Experimental Results from Reticulocyte Lysate Studies

| Experimental Condition | Proteolytic Activity (pmol/mg/h) | Ubiquitin Conjugation (arbitrary units) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete system | 150-300 | 100 | Optimal ATP-dependent degradation |

| Minus ATP | 10-25 | 5-10 | ATP-dependent process confirmed |

| Plus hemin (inhibitor) | 30-60 | 20-40 | Confirms regulatory mechanisms |

| Fraction I only | <10 | <5 | Requires multiple fractions |

| Fractions I + II | 25-50 | 15-30 | Partial reconstruction |

| Fractions I + II + III | 120-250 | 80-95 | Full pathway reconstruction |

Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Components

The research using reticulocyte lysates systematically identified and characterized the core components of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway:

- APF-1/Ubiquitin: The central tagging protein, initially identified as APF-1 before being recognized as ubiquitin [7]

- E1 (Ubiquitin-activating enzyme): The initial enzyme that activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction [12]

- E2 (Ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes): Intermediate carriers that receive activated ubiquitin from E1 [7]

- E3 (Ubiquitin ligases): Substrate-specific enzymes that facilitate ubiquitin transfer to target proteins [12]

- 26S Proteasome: The multi-subunit proteolytic complex that recognizes and degrades ubiquitinated substrates [13]

Contemporary Research Applications and Drug Discovery Implications

Modern Methodological Adaptations

While the fundamental principles established using reticulocyte lysates remain valid, contemporary research has enhanced these approaches:

- Automated reticulocyte analysis: Modern hematology analyzers use laser excitation and fluorescent dyes (thiazole orange, polymethine) for precise reticulocyte quantification [11]

- Advanced proteomic techniques: Mass spectrometry-based methods now identify ubiquitination sites and quantify dynamics

- Computational prediction tools: Machine learning approaches (e.g., 2DCNN-UPP) predict ubiquitin-proteasome pathway components from sequence data [12]

- High-throughput screening: Adapted reticulocyte lysate systems enable drug screening for proteasome inhibitors and ubiquitination modulators

Therapeutic Targeting of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

The foundational knowledge gained from reticulocyte lysate studies has directly enabled multiple therapeutic advances:

- Proteasome inhibitors: Bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib for multiple myeloma treatment

- Ubiquitination pathway targets: Development of E1, E2, and E3 inhibitors for cancer and inflammatory diseases

- PROTAC technology: Proteolysis-targeting chimeras that harness the ubiquitin-proteasome system for targeted protein degradation

- Neurodegenerative disease approaches: Strategies to enhance clearance of aggregated proteins in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases

Diagram 2: Historical Research Progression from Reticulocyte Models

Technical Challenges and Troubleshooting

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

- Low proteolytic activity: Check ATP regeneration system functionality; verify lysate preparation speed and temperature control

- High non-ATP-dependent background: Ensure complete reticulocyte purification; confirm lysosome absence by marker enzyme assays

- Incomplete fraction complementation: Titrate individual fractions to establish optimal ratios; check for inhibitory components

- Ubiquitin conjugate instability: Include deubiquitinase inhibitors (ubiquitin aldehyde, N-ethylmaleimide) in lysis and reaction buffers

Quality Control Metrics

- Reticulocyte purity: >80% reticulocytes by new methylene blue staining [8]

- Lysate activity: >100 pmol/mg/h TCA-soluble radioactivity with complete system

- ATP dependence: >10:1 ratio of complete to minus ATP activity

- Conjugate formation: Clear high molecular weight bands in ubiquitination assays

The pioneering work utilizing reticulocyte lysates as a lysosome-free system for studying ATP-dependent degradation fundamentally advanced our understanding of cellular proteostasis. This experimental model enabled the discovery of APF-1/ubiquitin and the elaborate enzymatic cascade that targets proteins for degradation, establishing the foundation for the entire field of ubiquitin biology. The methodological approaches developed through this research continue to influence contemporary drug discovery, particularly in the development of targeted protein degradation therapies. As we continue to build upon these foundational discoveries, the reticulocyte lysate system remains a testament to the power of carefully selected experimental models in revealing fundamental biological mechanisms.

The legacy of this research extends far beyond the initial discoveries, having established:

- The biochemical framework for understanding regulated protein degradation

- The molecular basis for numerous disease mechanisms

- Multiple new categories of therapeutic agents

- Technological platforms for targeted protein degradation

Future research will continue to build upon these foundations, potentially enabling new classes of therapeutics that manipulate protein stability for therapeutic benefit across a wide spectrum of human diseases.

The discovery of ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1) represents a landmark achievement in biochemical research that fundamentally transformed our understanding of intracellular protein degradation. Prior to this breakthrough, protein degradation was largely considered an unregulated process occurring within lysosomes. The critical insight emerged from investigating a puzzling biochemical paradox: why would intracellular proteolysis, an inherently energy-releasing process, require adenosine triphosphate (ATP) hydrolysis? This question drove researchers to identify a novel ATP-dependent proteolytic system in reticulocyte extracts, leading to the isolation and characterization of a remarkable heat-stable factor that would later be recognized as ubiquitin—the central component of a sophisticated protein tagging and degradation system [3] [14].

This technical guide examines the pioneering biochemical fractionation strategies that enabled the isolation of APF-1, detailing the experimental methodologies that revealed its function as a heat-stable polypeptide component essential for ATP-dependent proteolysis. The identification of APF-1/ubiquitin not only elucidated a fundamental cellular mechanism but also unveiled an entirely new paradigm for post-translational regulation, earning the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004 for its discoverers [4] [14]. The following sections provide an in-depth analysis of the core experimental approaches, offering researchers a comprehensive resource for understanding this pivotal discovery within the broader context of ubiquitin identity research.

Experimental Foundation: Key Biochemical Principles

The Energy Paradox in Protein Degradation

The investigation that led to APF-1's discovery began with resolving a fundamental biochemical contradiction. While proteolysis is thermodynamically exergonic (energy-releasing), researchers observed that intracellular protein degradation in mammalian cells required ATP hydrolysis [3] [14]. This paradox suggested the existence of a previously unrecognized regulatory mechanism preceding the actual breakdown of peptide bonds. Early work by Goldberg's group had demonstrated that reticulocyte lysates (which lack lysosomes) could degrade abnormal proteins in an ATP-dependent manner, providing a critical experimental system for further investigation [3].

Heat Stability as a Fractionation Strategy

Heat stability represents a key biochemical property that facilitated APF-1's isolation. Many cellular proteins denature and precipitate when heated, but a specific subset of polypeptides remains soluble and functional after heat treatment [15]. This property enables researchers to separate these stable proteins from the majority of the cellular proteome through a simple heating step followed by centrifugation to remove precipitated material. APF-1 belonged to this unusual class of heat-stable proteins, a characteristic that proved instrumental in its purification and identification [14] [1].

Table: Advantages of Heat-Based Fractionation for Protein Isolation

| Advantage | Technical Benefit | Application in APF-1 Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid simplification of complex mixtures | Precipitates majority of proteins while preserving heat-stable fraction | Enabled enrichment of APF-1 from reticulocyte lysates |

| Maintenance of biological activity | Preserves function of stable proteins through mild heating | Confirmed APF-1 remained functional after heat treatment |

| Compatibility with subsequent purification steps | Serves as ideal first step in multi-stage purification | Allowed further fractionation by ammonium sulfate precipitation and chromatography |

Materials and Methods: The Researcher's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents and Instruments

Table: Key Experimental Components for APF-1 Isolation and Analysis

| Reagent/Instrument | Specific Function | Experimental Role in APF-1 Research |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | ATP-dependent proteolysis system | Provided cellular extract containing APF-1/ubiquitin and degradation machinery [3] [14] |

| Radioactively-labeled Proteins (¹²⁵I-APF-1) | Tracing molecular interactions | Enabled detection of APF-1 conjugation to target proteins [3] [14] |

| ATP and Mg²⁺ | Cofactors for enzymatic activity | Required for APF-1 activation and conjugation to substrate proteins [3] [1] |

| Heat Block/Water Bath (90-95°C) | Temperature-controlled incubation | Implemented heat stability step to separate APF-1 from thermolabile proteins [14] [15] |

| Centrifugation Equipment | Separation of soluble and insoluble fractions | Removed denatured proteins after heating, pelleting insoluble material [14] [15] |

| Chromatography Systems (DEAE-Cellulose) | Ion-exchange separation | Further purified APF-1 after initial heat fractionation [15] |

| SDS-PAGE Apparatus | Protein separation by molecular weight | Analyzed APF-1-protein conjugates and assessed purification success [15] |

Preparation of Heat-Stable Protein Fractions

The fundamental protocol for isolating heat-stable proteins like APF-1 involves specific biochemical handling procedures adapted from conventional protein purification methodologies:

- Crude Extract Preparation: Tissue or cell samples are homogenized in appropriate buffer systems (e.g., 10mM Tris-acetate pH=7.5, 10mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA) and clarified by centrifugation at 700×g for 30 minutes to remove insoluble debris [15].

- Heat Treatment: The crude supernatant is incubated at 90-95°C for 7-10 minutes with constant agitation to ensure even heating, then immediately cooled on ice to prevent protein aggregation [15].

- Separation of Fractions: Heat-denatured proteins are pelleted by centrifugation at 13,000×g for 10 minutes, leaving the heat-stable proteins, including APF-1/ubiquitin, in the soluble fraction [14] [15].

- Concentration and Storage: The heat-stable supernatant can be freeze-dried for long-term storage at -20°C, maintaining protein stability and activity for subsequent experiments [16].

Experimental Workflow: Isolating and Characterizing APF-1

Key Experimental Steps and Findings

The seminal experiments that identified APF-1's role followed a logical progression of biochemical fractionation and functional analysis, illustrated in the following workflow:

Critical Experimental Observations and Interpretation

The systematic approach to APF-1 isolation yielded several key findings that fundamentally advanced understanding of regulated protein degradation:

- Fraction Complementation: Researchers discovered that ATP-dependent proteolysis required two complementing fractions (I and II) from reticulocyte lysates, with Fraction I containing a heat-stable component essential for the reaction [1].

- Unusual Conjugation Pattern: When radioiodinated APF-1 was incubated with Fraction II and ATP, the label appeared in numerous higher molecular weight proteins, suggesting covalent attachment rather than non-specific association [3] [14].

- Energy-Dependent Linkage: The formation of APF-1-protein conjugates required ATP, and the bonds proved stable under conditions that disrupt non-covalent interactions, indicating isopeptide linkage [14].

- Multi-point Attachment: Multiple APF-1 molecules conjugated to individual substrate proteins, forming chains that served as enhanced recognition signals for proteolysis [3] [14].

The APF-1 to Ubiquitin Transition: Connecting Biochemical and Molecular Identity

Recognition of Ubiquitin Identity

The critical connection between APF-1 and the previously characterized protein ubiquitin emerged through collaborative scientific investigation:

- Historical Context: Ubiquitin had been discovered in 1975 as a widespread 8.6 kDa protein of unknown function [4].

- Parallel Research: Independent studies had identified a ubiquitin-histone H2A conjugate (uH2A) in chromatin, demonstrating the same isopeptide linkage found in APF-1 conjugates [1].

- Identity Confirmation: Researchers including Keith Wilkinson, Michael Urban, and Arthur Haas recognized the biochemical similarities and demonstrated that APF-1 was identical to ubiquitin [14].

Table: Comparative Properties of APF-1/Ubiquitin

| Property | APF-1 Characterization | Ubiquitin Identity |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | ~8-9 kDa (heat-stable polypeptide) | 8.6 kDa, 76 amino acids [4] |

| Thermal Stability | Remained active after boiling | Heat-stable confirmed [15] |

| Conjugation Mechanism | Covalent isopeptide bond formation | C-terminal Gly76 linkage to lysine ε-amino groups [4] |

| Functional Role | Targeting for ATP-dependent proteolysis | Signal for proteasomal degradation [4] |

| Tissue Distribution | Isolated initially from reticulocytes | Ubiquitous expression across tissues and species [4] |

Elucidation of the Ubiquitin Conjugation Pathway

The recognition that APF-1 was ubiquitin enabled researchers to place this factor within a sophisticated enzymatic cascade:

Technical Applications and Methodological Considerations

Quantitative Analysis of APF-1/Ubiquitin Conjugation

Table: Key Experimental Findings in APF-1/Ubiquitin Research

| Experimental Parameter | Observation | Technical Method Used | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Requirement | Absolute ATP dependence for conjugation and proteolysis | ATP depletion/addition experiments | Explained energy paradox of intracellular proteolysis [3] [1] |

| Thermal Stability | Withstood 95°C treatment with maintained function | Boiling extract followed by centrifugation | Enabled simple purification strategy [14] [15] |

| Conjugation Specificity | Multiple ubiquitin molecules per substrate protein | ¹²⁵I-APF-1 labeling + SDS-PAGE analysis | Revealed polyubiquitin chain signaling mechanism [3] |

| Bond Stability | Resistance to NaOH treatment and denaturing conditions | Chemical and physical challenge experiments | Confirmed covalent isopeptide linkage [14] |

| Evolutionary Conservation | 96% sequence identity between human and yeast | Sequence comparison after identification | Indicated fundamental biological importance [4] |

Optimization Strategies for Heat-Stable Protein Isolation

Based on the original APF-1 research and subsequent methodological refinements, several technical considerations enhance success in isolating heat-stable proteins:

- Temperature Control: Maintain precise temperature during heat treatment (90-95°C) with constant agitation to ensure even heating without localized overheating [15].

- Protective Buffering: Include stabilizing agents like EDTA in homogenization buffers to protect against metalloproteases and prevent protein aggregation [15].

- Rapid Processing: Immediately cool samples on ice after heat treatment to minimize non-specific protein aggregation and maintain protein solubility [15].

- Protease Inhibition: Incorporate protease inhibitors (e.g., PMSF) during initial extraction to prevent degradation before heat treatment, particularly important for labile regulatory components [15].

- Comprehensive Analysis: Combine heat fractionation with subsequent purification techniques (ammonium sulfate precipitation, ion-exchange chromatography) for highest purity preparations [15].

The biochemical fractionation strategies that identified APF-1 as a heat-stable factor exemplify how meticulous methodological approaches can unravel complex biological mechanisms. The recognition that APF-1 was identical to ubiquitin unified previously disparate research pathways and established the foundation for understanding the ubiquitin-proteasome system—now recognized as a central regulatory mechanism governing virtually all cellular processes in eukaryotes.

This technical guide has detailed the experimental workflow and methodological considerations that enabled this groundbreaking discovery, providing researchers with both historical context and practical frameworks for similar biochemical investigations. The isolation of APF-1/ubiquitin stands as a testament to the power of classical biochemical approaches in elucidating fundamental biological mechanisms, demonstrating that heat stability as a fractionation criterion can reveal proteins of exceptional functional importance. The continuing expansion of ubiquitin research—from protein degradation to signaling, trafficking, and DNA repair—underscores the profound impact of these original fractionation methodologies on contemporary biomedical science.

The discovery that ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1) forms covalent conjugates with target proteins represented a fundamental paradigm shift in our understanding of cellular regulation. Prior to this breakthrough, intracellular protein degradation was largely considered a nonspecific process confined to lysosomal compartments. The finding that a small, heat-stable protein could be covalently attached to diverse substrate proteins via an energy-dependent mechanism unveiled an entirely new principle of post-translational modification [3] [1]. This conjugation system, which would later be identified as the ubiquitin system, proved to be every bit as important as phosphorylation or acetylation for eukaryotic cell regulation [3]. The research journey that revealed APF-1's unusual conjugation mechanism exemplifies how intellectual curiosity, preparation, and collaborative science can unravel biological complexities that defy established models.

Historical Context: The Energy Dilemma in Protein Degradation

The scientific path to understanding APF-1's function began with a puzzling observation: intracellular proteolysis required metabolic energy. Melvin Simpson first demonstrated this ATP dependence in 1953 through isotopic labeling studies, creating a thermodynamic paradox since peptide bond hydrolysis is inherently exergonic [3] [17]. For the next 25 years, this apparent contradiction received little mechanistic explanation, though researchers recognized that abnormal proteins were rapidly cleared from cells and that rate-limiting enzymes often had short half-lives [3].

By the late 1970s, the collaboration between Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose was uniquely positioned to address this mystery. Their work utilized reticulocyte lysates (which lack lysosomes) that exhibited ATP-dependent proteolysis, confirming the existence of a non-lysosomal proteolytic system [3] [1]. Fractionation experiments revealed that this system required two complementing fractions: Fraction I contained a single essential heat-stable component designated APF-1, while Fraction II contained a high molecular weight fraction (APF-2) that was stabilized by ATP [3]. In retrospect, APF-1 was ubiquitin and APF-2 contained the 26S proteasome, though at the time researchers speculated about kinase or binding protein activities [3].

Table: Key Historical Milestones in APF-1/Ubiquitin Discovery

| Year | Discovery | Key Researchers | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | ATP-dependent proteolysis | Simpson | Revealed energy requirement for protein degradation |

| 1975 | Ubiquitin identification | Goldstein | Isolated protein of unknown function |

| 1978 | APF-1 characterization | Ciechanover, Hershko | Identified heat-stable factor in ATP-dependent proteolysis |

| 1980 | Covalent conjugation | Ciechanover, Hershko, Rose | Demonstrated APF-1 forms covalent bonds with substrates |

| 1980 | Ubiquitin identity | Wilkinson, Urban, Haas | Recognized APF-1 as previously known ubiquitin protein |

| 2004 | Nobel Prize in Chemistry | Ciechanover, Hershko, Rose | Honored for ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation discovery |

The Experimental Breakthrough: Evidence for Covalent Linkage

Initial Experimental Approach and Unexpected Results

The seminal experiments that demonstrated APF-1's covalent conjugation were reported in two PNAS papers in 1980 [3]. The research team set out to investigate whether APF-1 associated with other components in an ATP-dependent manner. Using ¹²⁵I-labeled APF-1, they incubated it with Fraction II and ATP, then analyzed the mixtures using SDS/PAGE [3]. The results were astounding: APF-1 was promoted to high molecular weight forms upon incubation, suggesting association with Fraction II components.

The critical insight came when postdoctoral fellow Art Haas discovered that these complexes survived high pH treatment, hinting at something more stable than typical protein interactions [3]. Further experimentation revealed that the association was not merely strong but truly covalent in nature—the bond between APF-1 and Fraction II proteins remained stable even after NaOH treatment [3]. This covalent attachment explained why some researchers had difficulty demonstrating APF-1's requirement in ATP-dependent proteolysis; when Fraction II was prepared without prior ATP depletion, most APF-1 was already present in high molecular weight conjugates [3].

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The experimental workflow that revealed APF-1's covalent conjugation can be summarized as follows:

Table: Critical Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Research Reagent | Function in APF-1 Studies | Experimental Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysates | ATP-dependent proteolysis source | Provided native system lacking lysosomes |

| ¹²⁵I-labeled APF-1 | Radioactive tracer | Enabled tracking of APF-1 fate in experiments |

| ATP (and analogs) | Energy source | Demonstrated energy requirement for conjugation |

| Fraction I (APF-1) | Heat-stable factor | Identified as the conjugating protein |

| Fraction II (APF-2) | High molecular weight fraction | Contained conjugating enzymes and proteasome |

| SDS/PAGE | Separation technique | Revealed high molecular weight conjugates |

Characterizing the Conjugation Mechanism

Multiplicity and Specificity of Conjugation

Further investigation revealed that authentic protein substrates of the system were heavily modified, with multiple molecules of APF-1 attached to each substrate molecule [3] [17]. This multi-point attachment suggested a processive mechanism where the conjugation machinery preferred to add additional APF-1 molecules to existing conjugates rather than initiating new modification sites on free substrates [3]. The researchers demonstrated that the conjugation was enzyme-catalyzed, providing the first evidence for what would later be recognized as ubiquitin ligase activity [3].

The nucleotide and metal ion requirements for conjugation mirrored those for proteolysis, as did the amounts of ATP and Fraction II needed for maximal activity [3]. This correlation strongly suggested that conjugation was required for proteolysis, though the initial experiments did not definitively prove this causal relationship. The discovery that substrates were poly-modified rather than singly conjugated was particularly significant, as it foreshadowed the later understanding that polyubiquitin chains serve as the proteasomal targeting signal [3].

Chemical Nature of the Covalent Bond

The unusual stability of the APF-1-protein linkage to both high pH and NaOH treatment provided crucial clues about its chemical nature. Subsequent research would identify this as an isopeptide bond between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin (Gly76) and the ε-amino group of lysine residues on substrate proteins [4]. This linkage explained both the stability of the conjugate and its resistance to typical peptide bond-cleaving conditions.

The discovery of this bifurcated protein structure was not entirely without precedent—Goldknopf and Busch had previously shown that histone H2A was covalently modified by attachment of a small protein called ubiquitin [3]. However, the functional implications differed dramatically: while histone modification involved a single ubiquitin molecule and did not destablize the protein, the APF-1 modification for proteolysis involved multiple ubiquitin molecules and marked proteins for destruction [3] [4].

APF-1's Identity as Ubiquitin and Implications

The pivotal connection between APF-1 and the previously characterized protein ubiquitin came through collaborative discussions and comparative analysis. Following the critical covalent linkage discovery, researchers noted the similarity between APF-1 conjugates and the known ubiquitin-histone H2A conjugate (protein A24) [3]. This insight led to the direct demonstration that APF-1 was identical to ubiquitin, a protein first identified by Gideon Goldstein in 1975 and further characterized throughout the late 1970s [3] [4].

This identification had profound implications. While ubiquitin was known to be widely distributed in eukaryotic cells, its physiological function had remained mysterious until the 1980 PNAS papers suggested its role in ATP-dependent proteolysis [3]. The convergence of these research trajectories explained why four genes in the human genome (UBB, UBC, UBA52, and RPS27A) code for ubiquitin, highlighting its fundamental importance to cellular function [4].

The following diagram illustrates the complete ubiquitin conjugation and degradation pathway as understood today:

The discovery that APF-1 (ubiquitin) forms covalent conjugates with target proteins established entirely new paradigms in cell biology. It explained the long-standing mystery of energy requirement in intracellular proteolysis by revealing the multi-enzyme cascade (E1-E2-E3) needed for protein tagging [4] [17]. The covalent linkage mechanism provided the specificity and regulation necessary for controlled protein degradation, solving the problem of how proteases and their substrates could coexist peacefully in the same cellular compartment [1].

This breakthrough opened research avenues that continue to expand today, revealing ubiquitin's roles in far more than just proteolysis—including DNA repair, endocytic trafficking, inflammation, translation, and chromatin regulation [4]. The unusual covalent connection between ubiquitin and target proteins serves as a remarkable example of how fundamental biochemical curiosity, when pursued with rigorous methodology, can unravel cellular mechanisms of profound importance. The 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to Ciechanover, Hershko, and Rose recognized not just the identification of a protein degradation system, but the discovery of a universal regulatory principle that governs countless cellular processes [3] [4] [17].

Decoding the Enzymatic Cascade: From APF-1 Conjugation to the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

The discovery that ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1) is the previously identified protein ubiquitin represents a pivotal convergence in biochemical research, unifying disparate lines of investigation into a fundamental regulatory mechanism. This identity revelation, established in 1980, connected a factor essential for energy-dependent protein degradation with a universally conserved protein of unknown function. The elucidation of APF-1 as ubiquitin laid the foundation for understanding the ubiquitin-proteasome system, a sophisticated pathway governing intracellular protein degradation with profound implications for cellular regulation and disease pathogenesis. This whitepaper examines the experimental journey and technical evidence that led to this critical identification, framing it within the broader thesis of mechanistic discovery in biochemical research.

For decades, the biochemical community had encountered ubiquitin in various contexts without understanding its fundamental physiological role. Simultaneously, researchers investigating ATP-dependent proteolysis had identified an essential component they termed APF-1, without recognizing it was a previously known molecule.

The Historical Context of Ubiquitin

Ubiquitin was first identified in 1975 by Goldstein et al. as a universally present polypeptide with lymphocyte-differentiating properties [7] [4]. Reflecting its widespread distribution, it was named "ubiquitous immunopoietic polypeptide" (UBIP) [7]. In a seemingly separate line of investigation, Goldknopf and Busch discovered in 1977 that the chromosomal protein A24 contained ubiquitin covalently linked to histone H2A [7] [18]. Despite these observations, the physiological function of ubiquitin remained mysterious throughout the 1970s.

The Energy Paradox of Intracellular Proteolysis

Meanwhile, researchers studying protein turnover had observed a curious biochemical paradox: intracellular proteolysis required ATP hydrolysis [3] [19] [14], despite the fact that peptide bond cleavage is an exergonic process [3]. This apparent contradiction suggested the existence of a previously unrecognized regulatory mechanism. Simpson first demonstrated ATP-dependent proteolysis in 1953 [3] [19], but for the next 25 years, the underlying mechanism remained elusive.

By the late 1970s, researchers understood that protein degradation was not merely a housekeeping function but played regulatory roles in cellular processes [3]. The collaboration between Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose proved instrumental in resolving this paradox through their work with rabbit reticulocyte lysates, which lack lysosomes and thus provided a clean system for studying non-lysosomal proteolysis [3] [18].

The Discovery and Characterization of APF-1

Initial Identification of APF-1

Hershko and Ciechanover's breakthrough began with their investigation of ATP-dependent proteolysis in reticulocyte lysates. They separated the lysate into two fractions:

- Fraction I: Contained a small, heat-stable protein essential for proteolysis

- Fraction II: Contained higher molecular weight components [3]

When they boiled Fraction I, they made a crucial observation: while most proteins denatured and precipitated, the essential component remained soluble and active [14]. This unusual heat stability characterized the factor they named APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1) [14].

The Covalent Conjugation Hypothesis

A series of elegant experiments revealed APF-1's unusual behavior:

Radiolabeling Studies: When researchers incubated ¹²⁵I-labeled APF-1 with Fraction II and ATP, they observed a shift from free APF-1 to high-molecular-weight complexes [3]

ATP Dependence: This shift required ATP and was reversed upon ATP removal [3]

Covalent Linkage: Surprisingly, the association between APF-1 and proteins in Fraction II persisted under denaturing conditions (SDS, urea, extreme pH), indicating a covalent bond rather than non-covalent interaction [3]

Art Haas, a postdoctoral fellow in Rose's laboratory, made the critical observation that the complex survived high pH treatment, further supporting the covalent attachment hypothesis [3].

Table 1: Key Experimental Evidence for APF-1 Covalent Conjugation

| Experimental Approach | Observation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Gel filtration chromatography with ¹²⁵I-APF-1 | Shift to higher molecular weight forms in presence of ATP | APF-1 associates with cellular proteins |

| SDS-PAGE analysis | Multiple radioactive bands of different sizes | APF-1 conjugates to multiple proteins |

| Alkaline conditions (NaOH) | Complex stability maintained | Covalent isopeptide bond formation |

| ATP depletion | Reversal of conjugation | Energy-dependent process |

The Experimental Revelation: APF-1 is Ubiquitin

The Critical Connection

The identity revelation occurred through collaborative science and cross-disciplinary awareness. The key insights came from:

Urban's Observation: Michael Urban, a postdoctoral fellow, noted the similarity between APF-1 conjugation and the previously reported covalent attachment of ubiquitin to histone H2A [3]

Goldknopf and Busch's Precedent: They had shown that the A24 chromosome protein contained ubiquitin linked to histone H2A, establishing the precedent for protein-ubiquitin conjugates [7]

Comparative Analysis: Wilkinson, Urban, and Haas obtained authentic ubiquitin and demonstrated it was identical to APF-1 [3]

This connection was formally established in a 1980 paper by Wilkinson et al. titled "Ubiquitin is the ATP-dependent proteolysis factor I of rabbit reticulocytes" [18].

Experimental Verification

The identity was confirmed through multiple approaches:

- Biochemical Comparison: APF-1 and ubiquitin showed identical migration patterns on gels [14]

- Functional Equivalence: Authentic ubiquitin could replace APF-1 in supporting ATP-dependent proteolysis [18]

- Structural Identity: Both proteins shared the same amino acid sequence and physical properties [4]

Table 2: Properties Establishing APF-1/Ubiquitin Identity

| Property | APF-1 | Ubiquitin |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular weight | ~8.6 kDa | ~8.6 kDa |

| Heat stability | Retained activity after boiling | Retained structure after boiling |

| Amino acid sequence | 76 amino acids | 76 amino acids |

| Covalent attachment | To substrate proteins via C-terminal glycine | To histone H2A via C-terminal glycine |

| Conservation | Universal distribution | Universal distribution |

Methodologies: Key Experimental Protocols

Reticulocyte Lysate Preparation

The foundational methodology enabling these discoveries was the preparation of active reticulocyte lysates:

- Reticulocyte Isolation: Rabbits were made anemic by phenylhydrazine injection, enriching for immature red blood cells [19]

- Lysate Preparation: Cells were lysed in hypotonic buffer and centrifuged to remove membranes [14]

- Fractionation: Lysates were separated into Fractions I and II by ion-exchange chromatography or gel filtration [3]

ATP-Dependent Proteolysis Assay

The standard assay for monitoring APF-1-dependent degradation included:

- Radiolabeled Substrate: ¹²⁵I-labeled lysozyme or other model substrates

- Reaction Mixture: Reticulocyte fractions, ATP regeneration system, Mg²⁺

- Incubation: 37°C for specified time periods

- Detection: Trichloroacetic acid precipitation to measure release of acid-soluble radioactivity [3]

Conjugation Assay

The critical experiments demonstrating covalent attachment:

- Labeling: ¹²⁵I-APF-1 was prepared using chloramine-T method

- Incubation: Labeled APF-1 was incubated with Fraction II and ATP

- Analysis: SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography to detect APF-1-protein conjugates [3]

Diagram 1: APF-1 Experimental Workflow

The Ubiquitin Conjugation Cascade

The identification of APF-1 as ubiquitin opened the path to elucidating the enzymatic cascade responsible for its conjugation:

The E1-E2-E3 Enzymatic Machinery

Subsequent work by Hershko, Ciechanover, Rose, and their colleagues revealed three essential enzyme components:

E1 (Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme): Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction, forming a thioester bond with ubiquitin's C-terminus [18] [20]

E2 (Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme): Accepts activated ubiquitin from E1 via transesterification [20]

E3 (Ubiquitin Ligase): Facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to substrate proteins, conferring specificity [18] [20]

Diagram 2: Ubiquitin Conjugation Cascade

Polyubiquitination Signal

Further research revealed that:

- Multiple ubiquitin molecules attach to substrate proteins [3]

- Polyubiquitin chains linked through specific lysine residues (especially K48) serve as the proteasomal recognition signal [3] [7]

- The proteasome recognizes and degrades polyubiquitinated proteins, releasing ubiquitin for reuse [18]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents in Ubiquitin System Discovery

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Research | Experimental Role |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | ATP-dependent proteolysis system | Provided cell-free experimental platform lacking lysosomes |

| ¹²⁵I-labeled APF-1/Ubiquitin | Radioactive tagging | Enabled tracking of conjugation via autoradiography |

| ATP-regeneration System | Maintained ATP levels | Sustained energy-dependent conjugation reactions |

| Heat Treatment | Protein denaturation | Isolated heat-stable APF-1 from other cellular proteins |

| Ion-exchange Chromatography | Protein fractionation | Separated lysate into functional fractions I and II |

| Authentic Ubiquitin | Comparative standard | Enabled identity confirmation through functional replacement |

Implications and Research Applications

The identification of APF-1 as ubiquitin transformed cell biology by:

Resolving the Energy Paradox: Explaining why ATP is required for proteolysis - to fuel the conjugation cascade [3]

Unifying Disparate Observations: Connecting protein degradation with chromatin structure through the shared involvement of ubiquitin [7]

Establishing a New Regulatory Paradigm: Revealing covalent protein modification by ubiquitin as a fundamental regulatory mechanism analogous to phosphorylation [3]

Providing Therapeutic Targets: Unveiling the ubiquitin system as a target for treating cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and other conditions [19]

This revelation exemplifies how converging lines of investigation can unify seemingly unrelated biological phenomena, advancing our understanding of cellular regulation and creating new therapeutic possibilities. The trajectory from APF-1 to ubiquitin illustrates the importance of fundamental biochemical research in revealing central biological mechanisms that span evolutionary boundaries and govern cellular homeostasis.

The discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of cellular protein regulation. The journey began with the investigation of a simple biochemical curiosity: the ATP-dependent nature of intracellular proteolysis in mammalian cells [3]. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, seminal work by Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose led to the identification of a heat-stable polypeptide they termed APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1) [3]. Their research, conducted using biochemical fractionation of reticulocyte lysates, revealed that APF-1 was covalently conjugated to target proteins in an ATP-dependent manner and that this modification was essential for protein degradation [3] [17]. The critical breakthrough came when APF-1 was identified as the previously known protein ubiquitin [3], a discovery that connected this ATP-dependent proteolytic pathway to a specific modifier. This foundational work, recognized by the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, unveiled the ubiquitin system as a central regulatory mechanism in eukaryotic cell biology, governing virtually all cellular processes through targeted protein modification and degradation [21].

The Enzymatic Cascade: E1, E2, and E3

The ubiquitination pathway operates through a sequential enzymatic cascade comprising E1 (ubiquitin-activating), E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating), and E3 (ubiquitin-ligase) enzymes [22] [23]. This cascade results in the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to substrate proteins, typically forming an isopeptide bond between ubiquitin's C-terminal glycine and a lysine ε-amino group on the substrate [24].

E1: Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme

The E1 enzyme initiates the ubiquitination cascade in an ATP-dependent reaction [23]. It first activates ubiquitin by forming a high-energy thioester bond between its catalytic cysteine residue and the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin [25] [26]. This activation reaction relies on ATP hydrolysis to adenylate ubiquitin's carboxyl group, creating an acyl-AMP intermediate [23]. The E1 enzyme then catalyzes the transfer of activated ubiquitin to the catalytic cysteine of an E2 conjugating enzyme via a trans-thiolation reaction [23]. The human genome encodes only two E1 enzymes, making this the least diverse component of the ubiquitination machinery [22].

E2: Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme

E2 enzymes, also known as ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (UBCs), function as central mediators in the cascade [23]. They accept the activated ubiquitin from E1 via a trans-thiolation reaction, forming a thioester-linked E2~Ub intermediate [26] [23]. E2 enzymes contain a conserved catalytic core domain of approximately 150 amino acids that includes an invariant cysteine residue essential for this thioester bond formation [23]. The human genome encodes approximately 40 E2 enzymes [27], which often determine the type of ubiquitin chain assembled on substrates [22]. E2 enzymes partner with specific E3 ligases to achieve substrate specificity, particularly in monoubiquitination events [23].

E3: Ubiquitin Ligase Enzyme

E3 ubiquitin ligases are the most diverse components of the pathway, with over 600 members in the human genome [24] [27]. They are responsible for substrate recognition and catalyze the final transfer of ubiquitin to the target protein [24]. E3 ligases are classified into three major families based on their structural features and catalytic mechanisms [27]:

- RING (Really Interesting New Gene) E3 Ligases: These function as scaffolds that simultaneously bind the E2~Ub complex and the substrate, facilitating the direct transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to the substrate without forming a covalent E3-ubiquitin intermediate [24] [27].

- HECT (Homologous to E6-AP C-terminus) E3 Ligases: These employ a two-step mechanism where ubiquitin is first transferred from the E2 to a catalytic cysteine within the HECT domain, forming a thioester-linked E3~Ub intermediate, before being transferred to the substrate [25] [27].

- RBR (RING-Between-RING) E3 Ligases: These hybrid ligases combine features of both RING and HECT families, utilizing a RING domain to bind the E2 and a second domain to accept ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate [22] [27].

Table 1: Major E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Families and Their Characteristics

| E3 Family | Catalytic Mechanism | Ubiquitin Intermediate | Representative Members | Human Genomic Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RING | Scaffolds E2~Ub near substrate | No covalent E3~Ub intermediate | SCF complex, APC/C, MDM2 | Most abundant family (>600 members) [24] |

| HECT | Two-step transfer via catalytic cysteine | Covalent thioester E3~Ub intermediate | E6-AP, HUWE1, NEDD4 | ~28 members [28] |

| RBR | Hybrid mechanism | Covalent thioester E3~Ub intermediate | Parkin, HOIP, HHARI | ~14 members [22] |

Diagram 1: The ubiquitin enzymatic cascade. E1 activates ubiquitin using ATP. Ubiquitin is transferred to E2, then E3 facilitates its final attachment to the substrate.

Quantitative Analysis of Ubiquitination Components

The ubiquitin system exhibits a pyramid-like structure with tremendous diversification at the level of E3 ligases, reflecting their crucial role in determining substrate specificity.

Table 2: Quantitative Distribution of Ubiquitin System Components in Humans

| Component Type | Number of Genes in Humans | Functional Role | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 Ubiquitin-Activating Enzymes | 2 [22] | Ubiquitin activation | ATP-dependent; initiates entire cascade |

| E2 Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzymes | ~40 [27] | Ubiquitin conjugation | Determines ubiquitin chain type [22] |

| E3 Ubiquitin Ligases | 500-1000 [24] [27] | Substrate recognition & ubiquitin ligation | Imparts substrate specificity; multiple families |

| Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs) | ~100 [22] | Ubiquitin removal | Reverses modification; provides dynamic control |

Experimental Protocols in Ubiquitin Research

Foundational Protocol: Biochemical Fractionation and Identification of APF-1/Ubiquitin

The original experiments that identified the ubiquitin system provide a classic example of biochemical discovery [3].

Methodology:

- System Preparation: ATP-dependent proteolytic activity was isolated from rabbit reticulocyte lysates (which lack lysosomes) [3].

- Biochemical Fractionation: The lysate was separated into two essential fractions (I and II) by chromatography [3].

- Factor Identification: Fraction I was found to contain a single, heat-stable component essential for proteolysis, designated APF-1 [3].

- Conjugation Analysis: Incubation of ¹²⁵I-labeled APF-1 with Fraction II and ATP resulted in the covalent attachment of APF-1 to multiple proteins in the fraction, forming high molecular weight conjugates [3].

- Identity Revelation: APF-1 was subsequently identified as the previously known protein ubiquitin through immunological and biochemical comparisons [3].

Key Findings:

- The covalent attachment of ubiquitin to target proteins requires ATP [3].

- The conjugation is reversible, and the linkage is stable to high pH treatment [3].

- Authentic proteolytic substrates are heavily modified by multiple molecules of ubiquitin [3].

Modern Protocol: Analysis of E3 Ligase Mechanism and Small-Molecule Ubiquitination

Contemporary research has revealed that ubiquitination can extend beyond proteins to include drug-like small molecules, as demonstrated in recent studies of the HECT E3 ligase HUWE1 [28].

Methodology:

- In Vitro Ubiquitination Reconstitution: Multi-turnover reactions containing E1 (UBA1), E2 (UBE2L3 or UBE2D3), HUWE1HECT (the HECT domain of HUWE1), ubiquitin, and ATP were established [28].

- Inhibition Analysis: Putative HUWE1 inhibitors (BI8622 and BI8626) were tested in dose-dependent manner, showing broad inhibition of HUWE1HECT catalysis [28].

- Single-Turnover Assays: These demonstrated that inhibitors did not obstruct Ub transfer from E2 to HUWE1HECT, indicating interference with the second step of HECT E3 catalysis [28].

- Ubiquitination Detection: Reaction products were separated by SDS-PAGE, and Ub-containing bands were excised for MS/MS analyses to detect compound modification [28].

- Specificity Assessment: Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) was used to separate reaction components and confirm HUWE1HECT-dependent compound ubiquitination [28].

Key Findings:

- The primary amino group of the inhibitors was essential for both inhibition and their ubiquitination [28].

- HUWE1 selectively catalyzes ubiquitination of these small molecules in vitro, transferring ubiquitin to the compound's primary amino group [28].

- This demonstrates the capacity of E3 ligases to modify exogenous, drug-like molecules, expanding the substrate realm of the ubiquitin system [28].

Diagram 2: Foundational APF-1 experimental workflow. Reticulocyte lysate was fractionated, and both fractions were required for ATP-dependent ubiquitin conjugation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | Cell-free system for studying ATP-dependent proteolysis | Original identification of APF-1/ubiquitin and fractionation studies [3] |

| Reconstituted E1-E2-E3 Systems | In vitro analysis of specific ubiquitination cascades | Mechanism studies of HUWE1 and small-molecule ubiquitination [28] |

| Vinylthioether-linked E3~Ub Proxies | Stable mimics of E3-ubiquitin thioester intermediates | Structural and biophysical studies of HECT E3 catalytic mechanisms [28] |

| BioID (Proximity-Dependent Biotin Identification) | Identification of E3 ligase interactors and potential substrates | Mapping E3 ligase-protein interactions in live cells [26] |

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities) | Affinity purification of ubiquitylated proteins | Proteomic identification of ubiquitylated substrates and linkage types [24] |

| Fluorescent Ubiquitin Tracers | Visualization and monitoring of ubiquitination in real-time | SDS-PAGE analysis of ubiquitination reaction products and kinetics [28] |

Diversity of Ubiquitin Signals and Biological Outcomes

The ubiquitin code extends far beyond a simple degradation signal, with different ubiquitin chain linkages producing distinct functional outcomes [27].

Table 4: Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Functional Consequences

| Ubiquitin Linkage | Primary Cellular Functions | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|

| K48-linked Chains | Proteasomal degradation [24] [27] | Canonical degradation signal; requires at least 4 ubiquitins [23] |

| K63-linked Chains | DNA repair, kinase activation, endocytosis, lysosomal targeting [27] | Distinct conformation; roles in signaling and trafficking |

| K11-linked Chains | Proteasomal degradation, cell cycle regulation [27] | Associated with ER-associated degradation (ERAD) |

| M1-linked (Linear) Chains | NF-κB signaling and immune regulation [22] | Generated by LUBAC complex; unique signaling properties |

| Mono-/Multi-Mono Ubiquitination | Endocytosis, protein trafficking, histone regulation [27] | Alters protein interactions and localization |

Diagram 3: Functional outcomes of ubiquitination. Different ubiquitin linkage types direct substrates to distinct cellular fates.

The journey from the discovery of APF-1 as a heat-stable polypeptide required for ATP-dependent proteolysis to our current understanding of the sophisticated ubiquitin system highlights the transformative power of basic biochemical research. The E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade represents a sophisticated regulatory network that extends far beyond its initial characterization in protein degradation, encompassing control of virtually all cellular processes through diverse ubiquitin signals. Contemporary research continues to expand this paradigm, revealing novel substrates including non-protein molecules and developing innovative techniques to map the intricate web of E3-substrate relationships. As we deepen our understanding of ubiquitin pathway mechanisms, we open new avenues for therapeutic intervention in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and numerous other pathological conditions linked to ubiquitin system dysfunction.