From Biochemical Curiosity to Clinical Breakthrough: The Discovery and Evolution of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

This article chronicles the seminal discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), a fundamental pathway for regulated intracellular protein degradation.

From Biochemical Curiosity to Clinical Breakthrough: The Discovery and Evolution of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

Abstract

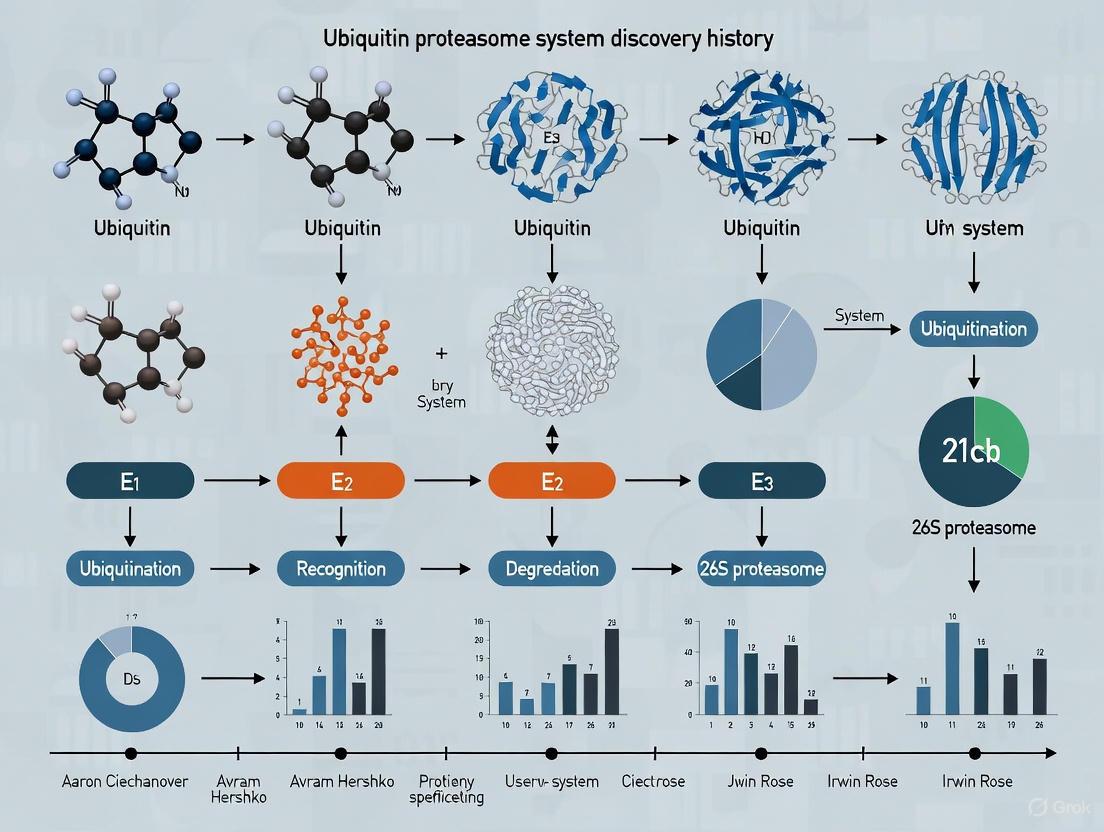

This article chronicles the seminal discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), a fundamental pathway for regulated intracellular protein degradation. It details the foundational biochemical work in the 1980s by Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose that identified the E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade, followed by the pivotal biological validation of its roles in cell cycle, DNA repair, and stress responses. The review further explores the translation of this basic science into clinical applications, including the development of proteasome inhibitors for multiple myeloma and the revolutionary emergence of targeted protein degradation technologies like PROTACs and molecular glues. Finally, it addresses current challenges and future directions in troubleshooting UPS-targeting therapies and validating their efficacy against a broadening range of diseases, providing a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Pioneering Experiments: Unraveling the Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway

For much of the scientific history preceding the discovery of the ubiquitin system, intracellular protein degradation was considered a non-specific, largely constitutive process that occurred without energy expenditure. This perception was rooted in the understanding of digestive proteases like trypsin and the function of lysosomes, which degrade extracellular proteins without requiring adenosine triphosphate (ATP) [1]. However, this model failed to explain a critical paradox observed as early as the 1950s: the breakdown of the cell's own proteins clearly required metabolic energy [1]. This energy requirement was chemically perplexing; while dietary proteins provide energy upon degradation, the cell apparently needed to invest energy to break down its own proteins to amino acids. Resolving this paradox became the fundamental challenge that would lead to the discovery of a sophisticated regulatory system rivaling transcription and translation in biological importance [2] [3].

The Experimental System: Reticulocyte Lysate as a Model

Rationale for System Selection

Avram Hershko's decision to employ a reticulocyte lysate system proved instrumental to the discovery. The reticulocyte, an immature red blood cell, presented unique experimental advantages. As it matures into a fully differentiated erythrocyte, the reticulocyte extensively degrades its intracellular machineries and organelles, including lysosomes [4] [5]. This elimination of lysosomal activity created a clean background to identify and characterize non-lysosomal, energy-dependent proteolytic pathways. Researchers hypothesized that the same mechanism responsible for the maturation-related degradation also handled the removal of abnormal proteins in pathological conditions like thalassemia and sickle cell anemia [4].

Key Technical Challenges

The primary technical obstacle was the overwhelming presence of hemoglobin, which constituted approximately 85% of the total cellular protein in reticulocytes [5]. This abundance interfered with biochemical fractionation and analysis. Initial attempts to separate the proteolytic activity from hemoglobin using standard chromatography methods were unsuccessful, as the activity co-eluted with the hemoglobin fraction [5]. This impediment necessitated the development of innovative separation techniques.

The Critical Experiments: Fractionation and Identification

The Seminal Fractionation Experiment

The breakthrough came when Aaron Ciechanover and Michael Fry, while Hershko was on sabbatical, attempted a radical approach: heat treatment of the reticulocyte extract [5]. They boiled the hemoglobin-rich fraction, which resulted in the precipitation of hemoglobin "like mud," leaving a heat-stable, yellowish supernatant that retained full activity [5]. This simple yet decisive experiment demonstrated that the active component was a heat-stable polypeptide, which they designated APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1) [1] [5].

The subsequent reconstitution experiments revealed that the reticulocyte lysate could be separated into two complementary fractions (Table 1):

- Fraction I: Contained the heat-stable APF-1.

- Fraction II: Contained the remaining essential components.

Individually, these fractions were proteolytically inactive. However, when recombined in the presence of ATP, they restored ATP-dependent protein degradation [1]. This critical finding indicated that the system involved multiple cooperating factors.

Table 1: Key Experimental Findings from Reticulocyte Lysate Fractionation

| Experimental Observation | Interpretation | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| ATP required for proteolysis in lysates [1] | Energy-dependent process | Contradicted prevailing models of passive degradation |

| System separable into two fractions (I and II) [1] | Multiple components involved | Suggested a complex, multi-step mechanism |

| APF-1 is heat-stable [5] | APF-1 is a robust, small protein | Enabled its purification and characterization |

| Activity restored upon fraction recombination [1] | Components are complementary | Confirmed a defined biochemical pathway |

The Discovery of Covalent Conjugation

Collaboration with Irwin Rose at the Fox Chase Cancer Center was pivotal for the next conceptual leap. In 1980, Ciechanover, Hershko, and Rose demonstrated that APF-1 was not merely a cofactor but was covalently conjugated to target protein substrates via a stable peptide bond [1] [4]. Furthermore, they observed that multiple molecules of APF-1 could be attached to a single target protein, a phenomenon they termed polyubiquitination [1]. This conjugation was identified as the energy-requiring step, solving the long-standing paradox: ATP was consumed not for proteolysis itself, but for the precise labeling of specific proteins for destruction [1] [5].

The Identity of APF-1 Revealed

The connection was made through a parallel line of research. In 1975, ubiquitin had been isolated and named for its ubiquitous presence in tissues and organisms [1]. Independently, a chromatin-associated protein, Ub-H2A (a ubiquitin-histone H2A conjugate), had been discovered in 1977 [2]. In 1980, Wilkinson, Urban, and Haas in Rose's laboratory established the critical link by proving that APF-1 was identical to ubiquitin [2] [5]. This unification of the protein degradation and chromatin biology fields revealed that ubiquitin's role extended far beyond histone modification, positioning it as a central player in a general regulatory mechanism.

Diagram 1: The experimental pathway from the initial paradox to the discovery of the ubiquitin system.

Elucidating the Enzymatic Machinery: E1, E2, and E3

Between 1981 and 1983, the collaborative efforts of Ciechanover, Hershko, and Rose led to the formulation of the "multistep ubiquitin-tagging hypothesis" and the identification of a cascade of three enzymes (Table 2) [1]:

- E1 (Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme): This enzyme activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction, forming a high-energy thioester bond.

- E2 (Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme): Activated ubiquitin is transferred to a cysteine residue on an E2 enzyme.

- E3 (Ubiquitin Ligase): This enzyme confers specificity by recognizing target proteins and facilitating the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to a lysine residue on the substrate, forming an isopeptide bond [2] [1].

The successive action of these enzymes results in the attachment of a polyubiquitin chain to the target protein, which serves as the recognition signal for degradation by the proteasome [1].

Table 2: The Enzymatic Cascade of the Ubiquitin System

| Enzyme | Key Function | Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| E1 (Ubiquitin-Activating) | Activates ubiquitin using ATP | A single type or few types per cell [1] |

| E2 (Ubiquitin-Conjugating) | Carries activated ubiquitin | Several tens of types per cell [1] |

| E3 (Ubiquitin Ligase) | Recognizes specific protein substrates | Several hundred types, determines specificity [1] [3] |

Diagram 2: The ubiquitin conjugation cascade involving the sequential action of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Studying the Ubiquitin System

| Reagent / Method | Function in Research | Role in Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | Cell-free system for biochemical analysis | Provided the source for initial fractionation and identification of APF-1/Ubiquitin [4] [5] |

| ATP (Adenosine Triphosphate) | Energy source for enzymatic reactions | Used to demonstrate energy dependence of conjugation and proteolysis [1] |

| Heat Inactivation | Method to isolate heat-stable proteins | Critical for separating APF-1 (heat-stable) from hemoglobin (heat-labile) [5] |

| Chromatography | Protein separation and purification technique | Used to fractionate the lysate into complementary active fractions (I and II) [1] |

| Immunochemical Methods | Isolate and detect ubiquitin-protein conjugates | Developed later to confirm the system's activity in living cells [1] |

| Fluorogenic Ub/UBL Probes | Assess activity of deubiquitinases (DUBs) | Modern tool (e.g., Ub-ACA) for studying enzyme activities in the pathway [6] |

From Biochemical Mechanism to Biological Principle

The initial characterization of the ubiquitin system in a cell-free extract was a biochemical triumph, but its true physiological significance was cemented by subsequent genetic and cellular studies. The identification of a temperature-sensitive mouse cell mutant (ts85) with a defective cell cycle was a key link [2] [1]. Researchers, including Alexander Varshavsky's group, demonstrated that the heat-sensitive protein in these cells was the E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme [1] [5]. This proved that the ubiquitin system was not only essential for cell viability but was also a master regulator of critical processes like the cell cycle, DNA repair, and transcriptional regulation [2] [3]. The discovery of degradation signals, such as the N-end rule, further revealed how the system achieves its exquisite specificity [3].

The journey from an obscure heat-stable polypeptide (APF-1) in a reticulocyte extract to the identification of the ubiquitous protein regulator, ubiquitin, represents a cornerstone of modern molecular biology. The elegant biochemical work of Ciechanover, Hershko, and Rose, which elucidated the E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade, solved the fundamental energy paradox of intracellular proteolysis and established a new biological paradigm: that regulated protein degradation is a selective, dynamic, and essential regulatory process [2] [3]. This discovery laid the foundation for understanding the mechanistic basis of numerous cellular pathways and has provided critical insights into the pathogenesis of many diseases, including cancer and neurodegenerative disorders, opening avenues for targeted therapeutic interventions [7] [8].

The discovery of the E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade marked a pivotal advancement in our understanding of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS). This hierarchical enzymatic pathway, culminating in the precise ligation of ubiquitin to target proteins, governs essential cellular processes ranging from protein degradation to cell signaling. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the core biochemical principles of this cascade. It details the historical discovery of the ubiquitin thioester relay, summarizes key quantitative data on enzyme specificity, outlines modern experimental protocols for probing cascade activity, and visualizes critical workflows. Framed within the context of UPS research history, this review equips researchers and drug development professionals with the foundational knowledge and contemporary methodologies to study and therapeutically target this complex system.

The elucidation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system represents a cornerstone of modern cell biology. The initial discovery of ubiquitin as a tag for protein degradation was followed by a formidable challenge: unraveling the enzymatic mechanism of its conjugation. For years, it was postulated that ubiquitination required a three-enzyme cascade, but the precise biochemical steps remained enigmatic. The prevailing model suggested that E3 ubiquitin ligases functioned merely as passive "docking proteins," binding a substrate and an E2 enzyme to facilitate the direct transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to the substrate [9].

A critical breakthrough in this field was published in Nature in 1995, which provided the first biochemical evidence for a more complex "ubiquitin thioester cascade." The Scheffner et al. study demonstrated that for the E3 ligase E6-AP, ubiquitin is transferred from the E2 enzyme to an active-site cysteine on the E3 itself, forming a distinct E3-ubiquitin thioester intermediate before the final ligation to the substrate [9]. This finding fundamentally redefined the enzymatic role of HECT-family E3 ligases, establishing that they are not simple docking adaptors but active catalysts that form a critical transient intermediate in the ubiquitin transfer pathway. This mechanistic insight opened the door for the biochemical dissection of the entire cascade, a process essential for understanding cellular regulation and developing novel therapeutics for diseases like cancer and neurodegeneration where the UPS is often dysregulated [10] [11].

The Core E1-E2-E3 Enzymatic Mechanism

The ubiquitination cascade is an ATP-dependent process involving three distinct classes of enzymes that work in sequence to activate and conjugate ubiquitin to substrate proteins. The following diagram illustrates this conserved mechanism, highlighting the key thioester intermediates at each step.

Figure 1: The Ubiquitin Transfer Cascade. The pathway involves sequential thioester transfers from E1 to E2 and, for HECT E3s, to E3, before final isopeptide linkage to a substrate lysine. RING E3s facilitate direct transfer from E2 to substrate.

The Three-Step Enzymatic Cascade

- E1: Ubiquitin Activation. The cascade initiates with a single E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme. E1 consumes ATP to catalyze the adenylation of the C-terminus of ubiquitin, forming a high-energy ubiquitin-AMP intermediate. This activated ubiquitin is then transferred to the catalytic cysteine residue of the E1 itself, forming an E1~ubiquitin thioester bond. This step is the "alarm clock" of the UPS, committing ubiquitin to the degradation pathway [12].

- E2: Ubiquitin Conjugation. The second step involves a family of E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (also called UBCs). The E1~ubiquitin thioester complex interacts with an E2 enzyme, and through a transthiolation reaction, the ubiquitin is transferred from the E1's catalytic cysteine to the catalytic cysteine of the E2, forming an E2~ubiquitin thioester intermediate. The E2 thus acts as the "baton passer" in the relay [12].

- E3: Ubiquitin Ligation. The final step is mediated by a large family of E3 ubiquitin ligases, which provide substrate specificity. E3s are broadly categorized based on their mechanism:

- HECT E3 Ligases: As definitively shown for E6-AP, HECT E3s form a mandatory thioester intermediate with ubiquitin. The ubiquitin is transferred from the E2~ubiquitin complex to a catalytic cysteine on the HECT domain of the E3, before the E3 directly ligates it to a lysine residue on the substrate protein [9].

- RING E3 Ligases: RING E3s function as scaffolds and do not form a covalent bond with ubiquitin. Instead, they simultaneously bind both the E2~ubiquitin complex and the substrate, facilitating the direct transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to the substrate [10].

This cascade can be repeated to form polyubiquitin chains of different linkages (e.g., K48 for proteasomal degradation, K63 for signaling), with the specific topology determining the fate of the modified protein [10] [11].

Quantitative Biochemical Profiling of the Cascade

A thorough biochemical dissection requires quantitative data on enzyme kinetics, specificities, and interactions. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from foundational and modern studies.

Table 1: Key Enzyme Classes and Specificity Determinants in Human Ubiquitin/NEDD8 Cascades

| Enzyme Class | Representative Members | Key Specificity Determinant | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Ubiquitin) | UBA1 | Specific for Ubiquitin-Arg72 | Recognizes and activates ubiquitin, not NEDD8 [13] |

| E1 (NEDD8) | APPBP1-UBA3 heterodimer | Specific for NEDD8-Ala72; UBA3-Arg190 as negative gate | Prevents spurious activation of ubiquitin-Arg72 [13] |

| E2 (Ubiquitin) | ~50 different E2s (e.g., UBE2D2) | Interaction surfaces for specific E1 and E3 partners | Determines possible E3 partnerships and chain topology [12] [14] |

| E3 (HECT) | E6-AP, NEDD4L | Catalytic Cysteine residue | Forms E3~Ub thioester intermediate essential for transfer [9] |

| E3 (RING) | Mdm2, MuRF1 | No catalytic cysteine; mediates E2-substrate interaction | Facilitates direct Ub transfer from E2 to substrate [10] |

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Kinetic and Functional Parameters

| Parameter Studied | Experimental System | Key Quantitative Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1-E2 Ubiquitin Transfer | Orthogonal UB Transfer (OUT) | Engineered xUB-xE1-xE2 pairs showed zero cross-reactivity with native enzymes | [14] |

| E3 Substrate Scope | Quantitative Ubiquitin Profiling (Yeast) | 27% of identified UPS substrates required Rpn10 for turnover; UIM domain responsible for only 1/5 of these | [15] |

| E1 Heterodimer Function | FRET-based NEDD8 Activation | UBA3 alone activated NEDD8; APPBP1 acted as a scaffold to accelerate reaction rate | [16] |

| Proteasome Inhibition | GFPu Reporter Assay | Inhibition by Bortezomib or MG-132 causes accumulation of GFPu, measurable by increased fluorescence | [10] |

Key Experimental Protocols for Dissecting the Cascade

Protocol 1: Identification of E3-Ubiquitin Thioester Intermediates

This protocol is based on the seminal study that first demonstrated the E3-ubiquitin thioester intermediate for E6-AP [9].

- Objective: To provide biochemical evidence that an E3 ligase forms a covalent thioester bond with ubiquitin.

- Principle: Thioester bonds are labile and susceptible to cleavage by reducing agents like β-mercaptoethanol or DTT, whereas isopeptide bonds (the final substrate-ubiquitin linkage) are stable. This property allows for differential analysis.

- Methodology:

- Reconstituted System: Set up a complete in vitro ubiquitination reaction containing E1 enzyme, E2 enzyme, E3 ligase (e.g., E6-AP), ubiquitin, ATP, and an energy-regenerating system. Omit the protein substrate.

- Control Reactions: Include control reactions missing individual components (e.g., -E1, -E2, -ATP).

- Electrophoresis: Split the reaction products and subject them to non-reducing SDS-PAGE (without β-mercaptoethanol/DTT) and reducing SDS-PAGE (with β-mercaptoethanol/DTT).

- Detection: Perform western blotting using an anti-ubiquitin antibody.

- Expected Results: In the non-reducing gel, a higher molecular weight band corresponding to the E3-ubiquitin thioester complex will be observed. This band will disappear in the reducing gel, confirming its thioester nature. Control reactions will show no such band.

- Significance: This experiment is definitive proof of a catalytic E3-ubiquitin intermediate and distinguishes HECT E3 mechanisms from RING E3 mechanisms.

Protocol 2: Measuring UPS Activity with GFPu Reporter

This protocol details a widely used cellular assay to monitor global UPS functionality [10].

- Objective: To measure proteasome activity in living cells in a quantitative manner.

- Principle: A reporter protein (e.g., GFP) is fused to a potent degron sequence (e.g., CL1). This constitutively targets the reporter (GFPu) for ubiquitination and rapid degradation by the proteasome, resulting in low basal fluorescence. Upon proteasome inhibition, GFPu accumulates, leading to a measurable increase in fluorescence.

- Methodology:

- Cell Line Generation: Stably transfect cells with a plasmid encoding the GFPu construct.

- Treatment: Treat cells with a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., Bortezomib, MG-132) or vehicle control (DMSO) for a defined period.

- Quantification: Measure cellular fluorescence using flow cytometry, fluorescence microscopy, or a plate reader.

- Data Analysis: Fluorescence intensity in treated samples is normalized to control samples. A fold-increase in fluorescence is directly correlated with the degree of proteasome inhibition.

- Applications: This reporter is ideal for high-throughput screening of novel proteasome inhibitors, studying UPS dysfunction in disease models (e.g., neurodegeneration), and investigating the role of the UPS in cellular processes like differentiation [10].

The workflow for this and other proximity-labeling assays is complex, as visualized below.

Figure 2: ProteasomeID Workflow for Mapping E3/Proteasome Interactions. This proximity-labeling approach uses a biotin ligase (BirA) fused to a proteasome subunit to tag and identify interacting proteins and endogenous substrates in vivo [17].*

Protocol 3: Mapping Proteasome Interactomes and Substrates with ProteasomeID

For a systems-level view, ProteasomeID uses proximity labeling to capture the dynamic environment of the proteasome, including E3 ligases [17].

- Objective: To comprehensively identify proteins that interact with the proteasome in vivo, including transient E3 contacts and endogenous substrates.

- Principle: A promiscuous biotin ligase (BirA*) is genetically fused to a subunit of the core (20S) or regulatory (19S) proteasome particle. Upon expression in cells or a transgenic mouse model and addition of biotin, the ligase biotinylates all proteins within a ~10 nm radius.

- Methodology:

- Tagging: Generate stable cell lines or mice expressing BirA* fused to a proteasome subunit (e.g., PSMA4-BirA*).

- In Vivo Biotinylation: Administer biotin to the system to allow labeling of proximal proteins.

- Affinity Purification: Lyse cells/tissues and capture biotinylated proteins using streptavidin beads under stringent conditions.

- Mass Spectrometry: After on-bead digestion, identify and quantify the captured peptides using Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), ideally in Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) mode for depth and reproducibility.

- Applications: This method allows for the unbiased discovery of novel proteasome-interacting proteins (E3s, shuttling factors), characterization of proteasome composition across different tissues, and identification of endogenous proteasome substrates by comparing samples with and without proteasome inhibition [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table catalogues essential reagents for studying the ubiquitin-proteasome system, as featured in the cited research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for UPS Investigation

| Reagent / Technology | Core Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal UB Transfer (OUT) Cascades | Engineered xUB, xE1, xE2 enzymes that function orthogonally to native machinery. | Mapping substrates of a specific E3 ligase without background from native cascades [14]. |

| Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Engineered high-affinity reagents with multiple UBA domains to bind polyUb chains. | Isolation of polyubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates; protection from DUBs [12]. |

| GFPu Reporter | A degron (CL1)-tagged Green Fluorescent Protein. | Real-time, live-cell measurement of global proteasome activity [10]. |

| Ub^G76V^-GFP Reporter | GFP fused to a non-cleavable ubiquitin mutant. | Monitoring proteasome-dependent degradation independent of DUB activity [10]. |

| ProteasomeID (e.g., PSMA4-BirA*) | Proximity-dependent biotinylation system targeted to the proteasome. | Unbiased mapping of proteasome interactomes and substrates in vivo [17]. |

| Natural Product Inhibitors | Small molecules from natural sources that target specific UPS components. | Probing UPS function and serving as leads for drug development (e.g., Bortezomib) [18]. |

The biochemical dissection of the E1-E2-E3 cascade has evolved from initial mechanistic discoveries to the current era of systems-level quantitative analysis. The journey began with critical experiments demonstrating covalent E3-ubiquitin intermediates [9] and has advanced to sophisticated technologies like ProteasomeID that provide holistic views of proteasome networks in living animals [17]. This deep mechanistic understanding has firmly established the UPS as a premier therapeutic target.

The future of targeting this cascade lies in increasing specificity. The clinical success of proteasome inhibitors like Bortezomib for multiple myeloma validated the UPS as a drug target but also highlighted the need for more precise strategies [10] [11]. Current research is focused on moving downstream from the proteasome to target specific E3 ligases or even developing molecules like PROTACs (PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras) that hijack the E3 machinery to degrade disease-causing proteins [12]. The continued development of quantitative tools, such as engineered orthogonal cascades [14] and sensitive in vivo reporters [10] [17], will be essential for deciphering the complex biology of the UPS and for translating this knowledge into the next generation of targeted therapeutics for cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and immune diseases.

The discovery that ubiquitin, initially identified as a chromatin-associated protein, serves as a central regulator of intracellular protein degradation represents a fundamental paradigm shift in cell biology. This whitepaper traces the critical historical pathway through which researchers connected ubiquitin's role in chromatin modification to its function in the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS). We examine the key experimental evidence that bridged these seemingly disparate fields, the methodological approaches that enabled this connection, and the profound implications this synthesis has had for understanding cellular regulation and therapeutic development. The convergence of chromatin biology and protein degradation research exemplifies how interdisciplinary investigation can revolutionize our understanding of fundamental biological processes.

The ubiquitin field emerged from two distinct research pathways that converged to establish a new understanding of cellular regulation. For decades, intracellular proteins were largely believed to be long-lived, with regulated protein degradation not considered a major control mechanism for cellular processes [2]. The discovery of the ubiquitin system fundamentally overturned this conception, revealing that controlled proteolysis rivals transcriptional and translational regulation in significance [2].

Ubiquitin was independently discovered through separate investigative streams:

- Immunological research: Gideon Goldstein and colleagues identified a universally present polypeptide they termed "ubiquitin" (originally UBIP for "ubiquitous immunopoietic polypeptide") during studies of thymic hormones influencing lymphocyte differentiation [19].

- Chromatin research: A separate track identified a protein conjugate between histone H2A and a non-histone moiety, initially termed protein A24, which was subsequently shown to contain ubiquitin [2] [19].

The connection between these disparate research domains—chromatin biology and protein degradation—represented one of the most significant conceptual breakthroughs in modern cell biology, fundamentally altering our understanding of how cells regulate protein stability and function.

Historical Timeline of Key Discoveries

Table 1: Chronological Development of the Ubiquitin Field

| Year | Discovery | Key Researchers | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1975 | Identification of ubiquitin as a universal protein | Goldstein et al. [19] | Initial characterization of ubiquitin as a distinct molecular entity |

| 1977 | Identification of A24 (ubiquitin-H2A conjugate) in chromatin | Goldknopf & Busch [2] | First evidence of ubiquitin modification of histones |

| 1978-1980 | APF-1 (later identified as ubiquitin) conjugated to proteins before degradation | Hershko, Ciechanover, Rose [2] [19] | Establishment of ubiquitin's role in protein degradation |

| 1980 | APF-1 identified as ubiquitin | Wilkinson et al. [2] | Critical connection between chromatin and degradation research |

| 1980-1982 | Ubiquitin-containing nucleosomes localized to transcribed genes | Levinger & Varshavsky [2] | Functional connection between ubiquitin and gene regulation |

| 1982-1983 | E1, E2, E3 enzymatic cascade characterized | Hershko, Ciechanover, Rose [2] | Mechanistic understanding of ubiquitin conjugation |

| 1984-1990 | Biological functions of ubiquitin system identified in cell cycle, DNA repair | Varshavsky group [2] | Expansion of ubiquitin functions beyond degradation |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Evidence

Critical Experimental Workflows

The paradigm shift connecting chromatin ubiquitin to protein degradation relied on several key experimental approaches that enabled researchers to bridge these domains.

Biochemical Fractionation and Enzymology

The Hershko laboratory employed systematic biochemical fractionation of reticulocyte extracts to identify the components of the protein degradation machinery:

Figure 1: Biochemical Workflow for UPS Discovery

This approach identified APF-1 (ATP-dependent proteolytic factor 1) as a key component that became covalently conjugated to proteins before their degradation in cell extracts [2]. The critical breakthrough came when APF-1 was recognized as identical to ubiquitin, creating the conceptual link between the chromatin and degradation fields [2] [19].

Genetic and Cell Biological Approaches

Parallel genetic approaches in yeast and mammalian cells established the biological relevance of the ubiquitin system:

Figure 2: Genetic Approaches to Ubiquitin Biology

The identification of a temperature-sensitive mouse cell line (ts85) that lost ubiquitin-histone conjugates at restrictive temperatures provided crucial genetic evidence connecting the ubiquitin system to cellular viability [2].

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: Core Mechanisms

The core ubiquitin-proteasome system comprises a coordinated enzymatic cascade:

Figure 3: Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Cascade

The system features a single E1 activating enzyme, multiple E2 conjugating enzymes, and numerous E3 ligases that provide substrate specificity [20] [21]. Polyubiquitinated substrates are recognized and degraded by the 26S proteasome, a massive 2.5 MDa protease complex [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methods

Table 2: Essential Research Tools in Ubiquitin Research

| Category | Specific Reagents/Methods | Function/Application | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Systems | Rabbit reticulocyte lysate | In vitro reconstitution of ubiquitination and degradation | Hershko et al. [2] |

| ts85 mouse cell line | Temperature-sensitive mutant for functional studies | Varshavsky [2] | |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast) | Genetic dissection of ubiquitin pathway | Varshavsky, Hochstrasser [2] | |

| Biochemical Tools | ATPγS (non-hydrolyzable ATP analog) | Study of ATP dependence in ubiquitin activation | Hershko et al. [2] |

| Proteasome inhibitors (MG132, lactacystin) | Investigation of proteasome function | Goldberg [22] | |

| Ubiquitin conjugation enzymes (E1, E2, E3) | In vitro reconstitution of ubiquitination | Ciechanover et al. [2] | |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | Ubiquitin mutants (K48R, K63R, etc.) | Study of chain linkage specificity | Pickart et al. [21] |

| N-end rule substrates | Identification of degradation signals | Varshavsky [2] | |

| siRNA/shRNA libraries | Functional screening of ubiquitin system components | Multiple groups |

Quantitative Analysis of Ubiquitin System Components

Table 3: Quantitative Aspects of the Ubiquitin System

| Parameter | Value/Magnitude | Biological Significance | Experimental Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Diversity | ~1 E1, 14 E2s, >1000 E3s | Extraordinary substrate specificity potential | Genomic analysis [20] |

| Polyubiquitin Chain Linkages | 8 types (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63, M1) | Differential functional consequences | Mass spectrometry [21] |

| Proteasome Size | 2.5 MDa | Massive degradation machinery | Structural studies [2] |

| Ubiquitin-H2A Conjugate Stability | Cell cycle-dependent | Regulation of chromatin structure | Cell biological studies [19] |

| Histone Modification Sites | H2A: 13 sites, H2B: 12 sites, H3: 21 sites, H4: 14 sites | Complex regulatory potential | Mass spectrometry [20] |

Implications and Future Directions

Therapeutic Applications

The understanding of ubiquitin biology has spawned entirely new therapeutic approaches, most notably in the field of targeted protein degradation [21]. Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) represent a groundbreaking application that harnesses the ubiquitin system to selectively degrade disease-causing proteins [21]. These bifunctional molecules simultaneously bind to a target protein and an E3 ubiquitin ligase, inducing target ubiquitination and degradation [21]. The first PROTAC molecule was developed in 2001, and by 2022, several candidates had entered clinical trials [21].

Expanding Paradigms: Beyond Proteasomal Degradation

Subsequent research has revealed that ubiquitin's roles extend far beyond proteasomal targeting, including:

- Histone regulation: Ubiquitination of histones H2A and H2B regulates chromatin structure and gene expression through both proteasome-independent and dependent mechanisms [20] [23].

- DNA repair: Specific ubiquitin modifications on histones recruit DNA repair proteins like 53BP1 to sites of damage [24].

- Lysosomal targeting: Certain ubiquitin chain types (particularly K63-linked) target proteins to lysosomal degradation pathways [25] [26].

- Selective autophagy: Ubiquitin serves as a signal for selective autophagy of protein aggregates, organelles, and pathogens [26].

The connection between ubiquitin in chromatin and protein degradation represents one of the most fruitful syntheses in modern cell biology. What began as separate investigations into lymphocyte biology and chromatin structure converged to reveal a universal regulatory system of profound importance. This paradigm shift transformed our understanding of cellular regulation, demonstrating that controlled protein degradation rivals transcriptional control in significance. The continued exploration of ubiquitin biology promises further insights into cellular regulation and new therapeutic opportunities for human disease.

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) represents one of the most sophisticated and selective mechanisms for intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotic cells. Since its groundbreaking discovery, which earned Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, the UPS has been recognized as a central regulator of cell viability and function [22]. This complex system operates through a sequential enzymatic cascade— involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes—that tags target proteins with ubiquitin chains, marking them for destruction by the proteasome [7] [22]. This targeted degradation is not merely a disposal mechanism but a crucial regulatory process controlling fundamental cellular processes including cell cycle progression, apoptosis, DNA repair, and stress response [22]. The indispensability of the UPS is underscored by its involvement in eliminating damaged or misfolded proteins and precisely regulating the concentrations of key regulatory proteins, thereby maintaining cellular homeostasis. This whitepaper examines the experimental evidence validating the UPS as essential for cell viability and explores the technical approaches used to demonstrate its critical functions.

Historical Context and Fundamental Principles

The Discovery of a Revolutionary Cellular System

The elucidation of the UPS began with pioneering work in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose discovered the ATP-dependent proteolytic system that would revolutionize our understanding of cellular regulation. Their initial experiments, conducted with limited resources but extraordinary intellectual rigor, unveiled an unprecedented concept: a 2.5 million Dalton protease complex, three tagging enzymes, and a small protein tag (ubiquitin) working in concert to selectively target proteins for degradation [22]. This discovery was particularly remarkable because it revealed that protein degradation was not a passive process but a highly specific, regulated mechanism central to cellular control. The historical significance of this discovery was celebrated two decades later in a 2025 symposium titled "The Ubiquitin Revolution: Celebrating 20 Years of Avram Hershko's Nobel Legacy," highlighting how this fundamental biological insight continues to fuel major biomedical advances [27].

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Cascade

The UPS operates through a carefully orchestrated enzymatic cascade:

- Activation: The E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction

- Conjugation: Activated ubiquitin is transferred to an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme

- Ligation: E3 ubiquitin ligases facilitate the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to specific substrate proteins

- Polyubiquitination: Repeated cycles lead to polyubiquitin chain formation on substrate proteins

- Degradation: The 26S proteasome recognizes and degrades polyubiquitinated proteins, recycling ubiquitin

This system provides the structural basis for targeted protein degradation that is essential for cellular health, and its dysfunction is implicated in numerous pathological conditions including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and infectious diseases [7] [22].

Table 1: Key Components of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

| Component | Function | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| E1 Enzyme | Activates ubiquitin using ATP | Initiates the entire ubiquitination cascade |

| E2 Enzyme | Carries activated ubiquitin | Determines ubiquitin chain topology |

| E3 Ligase | Binds specific substrates and facilitates ubiquitin transfer | Provides substrate specificity (>600 identified) |

| Proteasome | Degrades ubiquitinated proteins | Recycles amino acids and regulates protein turnover |

| Deubiquitinases (DUBs) | Remove ubiquitin from proteins | Provide counter-regulation and ubiquitin recycling |

Methodological Framework: Assessing Cell Viability in UPS Research

Cell Viability Assays: Principles and Applications

Validating the essential nature of the UPS for cell viability requires robust methodological approaches that can accurately distinguish between live and dead cells. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) classification, cell viability methods can be categorized into four groups: non-invasive cell structure damage, invasive cell structure damage, cell growth, and cellular metabolism [28]. The careful selection of appropriate viability assays is crucial for researchers, as each method operates on different principles with distinct advantages and disadvantages [28].

Cell viability is fundamentally defined as the proportion of living, healthy cells within a population, with viable cells capable of performing essential metabolic functions [28] [29]. A cell is considered dead when it irreversibly loses plasma membrane barrier function, forms apoptotic bodies, or is engulfed by phagocytes [28]. This distinction is critical when studying UPS function because UPS inhibition can trigger various cell death pathways, including apoptosis and necrosis.

OECD-Classified Viability Assessment Methods

Table 2: Cell Viability Assays Classified by OECD Guidelines with Relevance to UPS Research

| Assay Category | Examples | Principle | Applications in UPS Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-invasive Structural Damage | LDH release, AK release | Measures cytoplasmic enzymes released upon membrane damage | Detects necrosis secondary to UPS inhibition |

| Invasive Structural Damage | Trypan blue, Propidium iodide, Hoechst stains | Dyes penetrate compromised membranes of dead cells | Distinguishes viable/non-viable cells after UPS disruption |

| Cell Growth Assays | Cell counting, BrdU incorporation | Measures proliferation capacity | Assesses long-term consequences of UPS impairment |

| Cellular Metabolism Assays | MTT, XTT, ATP assays | Measures metabolic activity via mitochondrial function | Evaluates metabolic consequences of UPS inhibition |

Specialized Viability Assessment in UPS Studies

For research specifically focused on validating UPS function, several specialized approaches provide critical insights:

Apoptosis Detection Assays: Since UPS inhibition frequently induces programmed cell death, apoptosis-specific assays are particularly valuable. These include:

- Caspase activity assays measuring activation of executioner caspases

- Annexin V staining detecting phosphatidylserine externalization

- DNA fragmentation analysis identifying endonuclease activation [28] [29]

Cell Proliferation Monitoring: As proliferating cells are always viable, proliferation assays serve as excellent indicators of cell health in UPS studies. These include:

- DNA content analysis using propidium iodide to identify cells in different cell cycle phases

- BrdU incorporation measuring DNA synthesis during S phase

- Proliferation protein detection (PCNA, Ki67, Phospho-histone H3) [29]

Metabolic Activity Assays: The MTT and XTT assays quantify the reduction of tetrazolium dyes by mitochondrial enzymes in viable cells, providing a colorimetric readout of cell health [29]. Similarly, ATP measurement assays quantify ATP content using luminescent, fluorometric, or colorimetric readouts, with signal generation proportional to the number of healthy, metabolically active cells [29].

Experimental Validation: Key Protocols and Techniques

Pharmacological Inhibition of the UPS

The most direct approach to validate the essential nature of the UPS involves targeted inhibition followed by comprehensive viability assessment:

Protocol: Proteasome Inhibitor Treatment and Viability Analysis

- Cell Preparation: Plate cells at appropriate density (e.g., 5,000-10,000 cells/well in 96-well plates) and allow attachment for 24 hours

- Inhibitor Treatment: Apply proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG132, Bortezomib/PS-341, Lactacystin) across a concentration gradient (typically 1 nM-10 μM) and multiple time points (6-72 hours)

- Viability Assessment:

- Metabolic Activity: Add MTT (0.5 mg/mL) for 2-4 hours, solubilize formazan crystals with DMSO or isopropanol, measure absorbance at 570 nm [29]

- Membrane Integrity: Collect culture supernatant, measure LDH activity colorimetrically (absorbance at 490-500 nm) [28]

- Direct Counting: Trypan blue exclusion with automated cell counters (e.g., Bio-Rad TC20, ThermoFisher Countess II) [30]

Expected Results: Proteasome inhibition typically produces a dose-dependent reduction in viability evidenced by decreased metabolic activity, increased LDH release, and rising trypan blue-positive cells. Research demonstrates that proliferating malignant cells show particular sensitivity to proteasome blockade, providing the therapeutic rationale for drugs like Bortezomib in multiple myeloma [22].

Genetic Manipulation of UPS Components

Genetic approaches provide targeted validation of specific UPS components:

RNA Interference Protocol for E3 Ligase Validation

- Design and Transfection: Design siRNA sequences targeting specific E3 ligases or other UPS components; transfert using appropriate reagents (e.g., lipofectamine)

- Efficiency Validation: Confirm knockdown efficiency via Western blotting or qRT-PCR 48-72 hours post-transfection

- Phenotypic Assessment:

CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout Approaches

- Generate knockout cell lines for essential E3 ligases or proteasome subunits

- Assess compensatory mechanisms and potential adaptations

- Evaluate cell viability under various stress conditions

Monitoring UPS-Specific Cell Death Pathways

UPS disruption typically activates specific cell death programs that require specialized detection methods:

Apoptosis Pathway Analysis Protocol

- Caspase Activation: Use fluorogenic caspase substrates (e.g., DEVD-afc for caspase-3) or antibody-based detection of cleaved caspases

- Mitochondrial Assessment: Measure mitochondrial membrane potential using JC-1 or TMRM dyes

- Morphological Analysis: Assess nuclear condensation and fragmentation with Hoechst 33342 or DAPI staining [28] [29]

Research has demonstrated that UPS inhibitors potentiate cisplatin-induced apoptosis and can reverse drug resistance by inhibiting nucleotide excision repair pathways, highlighting the interconnectedness of UPS function with other cellular processes [22].

Technical Visualization: Experimental Workflows and Pathway Diagrams

UPS Mechanism and Experimental Validation Pathway

Cell Viability Assessment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for UPS and Cell Viability Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib (PS-341), Lactacystin, Carfilzomib | Specifically inhibit proteasomal activity | Varying specificity, different chemical classes (peptide aldehydes, boronic acids, β-lactones) |

| E1/E2/E3 Inhibitors | PYR-41 (E1 inhibitor), CC0651 (E2 inhibitor), Nutlin (MDM2 inhibitor) | Target specific components of ubiquitination cascade | Varying selectivity, potential off-target effects |

| Viability/Cytotoxicity Assay Kits | MTT/XTT kits, LDH release kits, ATP measurement kits, Live/Dead staining kits | Quantify viable cells through different mechanisms | Differ in sensitivity, dynamic range, and compatibility with high-throughput screening |

| Apoptosis Detection Reagents | Annexin V kits, Caspase activity assays, TUNEL assay kits | Detect and quantify apoptotic cells | Multiple parameters needed for definitive apoptosis confirmation |

| Cell Permeable Dyes | Propidium iodide, 7-AAD, Hoechst 33342, Acridine Orange | Distinguish viable/non-viable cells based on membrane integrity | Varying spectral properties, potential cytotoxicity with prolonged exposure |

| Automated Cell Counters | Bio-Rad TC10/TC20, ThermoFisher Countess II, Nexcelom Cellometer | Automated viability assessment using trypan blue or fluorescent dyes | Improve reproducibility and throughput for large-scale studies |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The experimental validation of the UPS as essential for cell viability has transformed our understanding of cellular regulation and created new therapeutic paradigms. The fundamental discovery of the ubiquitin system has evolved into a sophisticated research field with profound clinical implications, particularly in oncology where proteasome inhibitors have become standard care for multiple myeloma [22]. The continuing revolution in ubiquitin research, highlighted by recent symposiums honoring the legacy of the original discovery, points toward an expanding frontier of therapeutic opportunities [27].

Future research directions include:

- Advanced Targeted Protein Degradation: Developing novel therapeutic strategies like molecular glues and PROTACs that harness the UPS to target previously "undruggable" proteins [27]

- Tissue-Specific UPS Function: Understanding how UPS components perform specialized functions in different tissues and cellular contexts

- System-Wide UPS Monitoring: Developing comprehensive approaches to monitor ubiquitination events and proteasome activity in real-time within living cells

- Combination Therapies: Optimizing UPS-targeted therapies in combination with other treatment modalities to overcome resistance mechanisms

The critical role of the UPS in maintaining cell viability through regulated protein degradation represents one of the most significant conceptual advances in modern cell biology. As noted by Dr. Lan Huang, "Prof. Hershko's Nobel-recognized discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system has been one of the most profound scientific advances in modern biology" [27]. The continued validation of this system's essential functions ensures that UPS research will remain at the forefront of biomedical science, driving both fundamental discoveries and transformative therapies for decades to come.

From Mechanism to Medicine: Therapeutic Targeting of the UPS

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a primary conduit for selective intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, regulating a vast array of cellular processes including cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and stress response [2] [22]. This highly conserved system involves a cascade of enzymes (E1, E2, E3) that tag target proteins with ubiquitin chains, marking them for recognition and degradation by the 26S proteasome—a large, multi-subunit complex comprising a 20S catalytic core and 19S regulatory particles [31] [2]. The critical discovery that proliferating malignant cells exhibit heightened sensitivity to proteasome inhibition fundamentally transformed oncology therapeutics, establishing the UPS as a validated target for anticancer drug development [32] [22]. This review traces the scientific trajectory from fundamental discoveries of the UPS to the clinical implementation of proteasome inhibitors, focusing on the research tool MG132 and the first-in-class therapeutic bortezomib.

Historical Foundations of Ubiquitin-Proteasome Research

The conceptual foundation for proteasome inhibition was established through pioneering work on the UPS in the late 1970s and 1980s. Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose discovered the ATP-dependent proteolytic system in reticulocyte extracts, identifying ubiquitin (initially termed APF-1) as the central tag in this degradation pathway [2] [22]. Their elucidation of the enzymatic cascade (E1, E2, E3) responsible for ubiquitin conjugation, coupled with the identification of the 26S proteasome as the degradation machinery, earned them the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry [22]. Concurrently, Alexander Varshavsky's laboratory uncovered the biological functions of the UPS, demonstrating its essential roles in cell cycle regulation, DNA repair, and transcriptional control [2]. These complementary discoveries revealed that regulated protein degradation rivals transcriptional regulation in significance for cellular circuit control, fundamentally reshaping understanding of intracellular physiology and pathology [2].

Table 1: Key Historical Discoveries in the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

| Year Range | Key Discovery | Principal Investigators | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1978-1980 | ATP-dependent protein degradation & APF-1 (ubiquitin) conjugation | Hershko, Ciechanover, Rose | Established enzymatic pathway for targeted protein degradation |

| 1980-1983 | Identification of E1, E2, E3 enzymes | Hershko and colleagues | Elucidated the ubiquitin conjugation machinery |

| 1984-1990 | Biological functions in cell cycle, DNA repair, and degradation signals | Varshavsky and colleagues | Revealed physiological roles of UPS in living cells |

| 1990s | Proteasome as target for apoptosis induction | Goldberg and others | Validated proteasome inhibition as anticancer strategy |

| 2003 | FDA approval of bortezomib | Millennium Pharmaceuticals | First proteasome inhibitor approved for human therapy |

The Research Tool: MG132 and Laboratory Applications

MG132 (carbobenzoxyl-L-leucyl-L-leucyl-leucinal) represents a potent, reversible peptide aldehyde inhibitor that primarily targets the chymotrypsin-like activity of the 20S proteasome's β-subunits [33] [22]. As a laboratory reagent, MG132 has been instrumental in elucidating proteasome functions and mechanisms of apoptosis, serving as a fundamental tool for basic research long before clinical applications were realized.

Experimental Protocols for MG132 Applications

Standardized experimental methodologies have been established for investigating MG132 effects in cellular models:

Cytotoxicity Assessment (CCK-8 Assay): Cells are inoculated into 96-well plates and treated with MG132 concentration gradients (typically 0.5-10 μM) for 8-48 hours. After treatment, CCK-8 solution is added and optical density (OD450) measured to determine cell viability and calculate IC50 values [33].

Apoptosis Quantification: Following 24-hour MG132 treatment (0.5-2 μM), cells are collected, stained with Annexin V-FITC/PI, and analyzed by flow cytometry to distinguish early apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI-), late apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI+), and necrotic (Annexin V-/PI+) populations [33].

Wound Healing/Migration Assay: Cells are cultured to confluence in 6-well plates, a scratch created with a pipette tip, and MG132 (0.125-0.5 μM) added in serum-free medium. Migration is quantified at 0, 12, and 24-hour intervals using microscopy and ImageJ software analysis [33].

Western Blot Analysis: After 24-hour MG132 treatment (0.5-2 μM), cellular proteins are extracted, separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed with primary antibodies against targets of interest (e.g., p53, p21, caspase-3, Bcl-2, CDK2), followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and ECL detection [33].

Mechanism of Action: MG132 as a Multi-Target Agent

Research in A375 melanoma cells has elucidated MG132's dual regulatory capacity, demonstrating potent anti-tumor activity with an IC50 of 1.258 ± 0.06 μM [33]. Mechanistic studies reveal that MG132 simultaneously activates the p53/p21/caspase-3 axis while suppressing CDK2/Bcl-2 signaling, triggering cell cycle arrest and DNA damage cascades [33]. Additionally, MAPK pathway activation emerges as a critical apoptosis driver, with western blot analyses confirming dose-responsive modulation of these molecular targets [33]. The compound induces concentration-dependent apoptosis, with 2 μM treatment producing early apoptosis in 46.5% and total apoptotic response in 85.5% of cells within 24 hours, while significantly suppressing cellular migration at therapeutic concentrations [33].

Diagram 1: MG132 mechanism of action in cancer cells

From Bench to Bedside: Bortezomib as First-Line Therapy

The transition from research tool to clinical therapeutic culminated with the development of bortezomib (PS-341, Velcade), a first-in-class, reversible dipeptidyl boronic acid proteasome inhibitor. Bortezomib's journey from concept to clinic radically overturned initial skepticism about UPS inhibition as a feasible therapeutic approach, ultimately establishing proteasome inhibition as a validated strategy for cancer treatment [32].

Pharmacology and Mechanism of Action

Bortezomib exhibits high specificity for the 26S proteasome, forming reversible covalent bonds with the threonine residues in the active sites of the 20S subunit's β-rings, preferentially inhibiting the chymotrypsin-like activity [34]. Its pleiotropic mechanisms of action include:

NF-κB Pathway Inhibition: By stabilizing Iκ-B, bortezomib prevents nuclear translocation of NF-κB, thereby inhibiting transcription of anti-apoptotic factors (Bcl-2, XIAP), growth factors (IL-6, VEGF), and adhesion molecules (VCAM-1, ICAM-1) [34].

Apoptosis Induction: Bortezomib activates both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways through JNK activation, mitochondrial membrane potential disruption, ROS generation, and caspase activation [34].

Cell Cycle Disruption: The drug induces cell cycle arrest by accumulating cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors and disrupting cyclin regulation [35].

Bortezomib is typically administered intravenously or subcutaneously at 1.3 mg/m² on a twice-weekly schedule for two weeks followed by a treatment-free week in a 21-day cycle [34]. It demonstrates approximately 80% plasma protein binding, rapid tissue redistribution with preferential accumulation in gastrointestinal tissues, and hepatic metabolism via CYP-450 isoenzymes with oxidative deboronation forming inactive metabolites [34].

Table 2: Pharmacological Properties of Clinical Proteasome Inhibitors

| Parameter | Bortezomib | Carfilzomib | Ixazomib |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor Class | Reversible boronic acid | Irreversible epoxyketone | Reversible boronic acid |

| Administration | IV, subcutaneous | IV | Oral |

| Half-life | 9-15 hours (first dose) | ≤1 hour | 3.4-9.5 days |

| Major Toxicities | Peripheral neuropathy, cytopenias | Cardiotoxicity, cytopenias | Gastrointestinal, rash |

| FDA Approval | 2003 (multiple myeloma) | 2012 (multiple myeloma) | 2015 (multiple myeloma) |

Clinical Efficacy and Real-World Evidence

The phase 3 VISTA trial established bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone (VMP) as a standard regimen for elderly patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma ineligible for transplantation [35]. Real-world studies have corroborated this efficacy; a retrospective analysis of 164 elderly patients (median age 75 years) demonstrated an overall response rate of 81.7% with complete response rate of 10.36% [35]. After median follow-up of 38.51 months, median overall survival was 34.33 months and event-free survival after VMP was 18.51 months [35]. Importantly, VMP efficacy extended to high-risk cytogenetic profiles, with no significant differences in response rates or survival parameters between patients with t(4;14), t(14;16), or del17p and those with normal cytogenetics [35].

Diagram 2: Bortezomib's multifaceted mechanism in multiple myeloma

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Contemporary proteasome inhibitor research employs a sophisticated array of reagents and methodologies to elucidate mechanisms and therapeutic potential:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Proteasome Inhibition Studies

| Reagent/Cell Line | Application | Key Features | Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| MG132 | Reversible proteasome inhibition | Peptide aldehyde, primarily inhibits chymotrypsin-like activity | Mechanism studies, apoptosis induction (0.5-10 μM) |

| Bortezomib | Clinical compound testing | Dipeptidyl boronic acid, reversible inhibition | Preclinical models, combination therapy studies |

| A375 Melanoma Cells | Melanoma research | Human malignant melanoma cell line | Migration, apoptosis, mechanism studies (in vitro) |

| H1299 Non-Small Cell Lung | Reporter cell assays | p53-null lung carcinoma | Proteasome Inhibition Reporter (PIR) development |

| PIR-YFP Reporter | High-throughput screening | YFP-tagged p53 mutant with defective NLS | Cytoplasm-to-nucleus translocation upon proteasome inhibition |

| Fluorogenic Proteasome Substrates | Enzymatic activity assays | Suc-LLVY-AMC (chymotrypsin-like) | Direct proteasome activity measurement in cell lysates |

| Ubi(G76V)-GFP Reporter | UPS functionality | Ubiquitin fusion degradation substrate | Continuous monitoring of UPS activity in live cells |

High-Throughput Screening Methodologies

Innovative screening approaches have accelerated proteasome inhibitor discovery. The image-based screening assay utilizing H1299 cells stably expressing a fluorescent Proteasome Inhibition Reporter (PIR) protein enables high-throughput compound evaluation [31]. This system exploits the cytoplasm-to-nucleus translocation of PIR upon proteasome inhibition, with automated microscopy (e.g., WiScan Cell Imaging System) and image processing facilitating rapid screening of chemical libraries [31]. Using this approach, researchers screened the NCI Diversity Set (1,992 compounds) and identified four proteasome inhibitors, three with novel structures [31].

Clinical Landscape and Future Directions

The proteasome inhibitors market continues to expand, valued at approximately $2.7 billion in 2024 with projected growth to $6.1 billion by 2034, driven by increasing hematologic cancer incidence and therapeutic advancements [36]. Bortezomib's patent expiry in 2022 has accelerated development of next-generation inhibitors and generic formulations, while clinical applications continue to broaden beyond multiple myeloma to include mantle cell lymphoma and investigation in solid tumors [37] [36].

Current research focuses on overcoming limitations of first-generation inhibitors, particularly peripheral neuropathy associated with bortezomib and cardiotoxicity with carfilzomib [34] [35]. Subcutaneous administration and once-weekly dosing regimens have demonstrated reduced neurotoxicity while maintaining efficacy [34]. Additionally, combination strategies with other targeted therapies, immunomodulatory agents, and CAR-T cell therapies represent promising approaches to enhance efficacy and overcome resistance [37] [36]. The recent FDA approval of Abecma (idecabtagene vicleucel), a CAR-T cell therapy for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma, highlights the ongoing integration of proteasome inhibitors with emerging immunotherapeutic modalities [37].

The trajectory from MG132 as a fundamental research tool to bortezomib as first-line therapy exemplifies the successful translation of basic biological discoveries into transformative cancer therapeutics. The initial characterization of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, once considered a fundamental but therapeutically inaccessible pathway, has yielded an entirely new class of anticancer agents that have fundamentally improved outcomes for patients with multiple myeloma and other hematologic malignancies. Ongoing research continues to refine proteasome inhibitor chemistry, administration strategies, and combination approaches, while basic investigations using tools like MG132 continue to reveal novel biological insights and potential therapeutic applications beyond oncology. The continued evolution of proteasome-targeted therapeutics underscores the enduring impact of fundamental biochemical research on clinical medicine.

Targeted protein degradation (TPD) represents a transformative approach in drug discovery, moving beyond the occupancy-driven model of traditional small-molecule inhibitors toward a paradigm of event-driven pharmacology [38] [39]. While conventional drugs transiently block protein activity by binding to active sites, TPD strategies harness the cell's intrinsic protein quality control machinery to achieve irreversible removal of disease-causing proteins [21] [39]. This approach has unlocked therapeutic possibilities for previously "undruggable" targets, including transcription factors, scaffolding proteins, and mutant oncoproteins that lack conventional binding pockets [38]. Among TPD strategies, PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs) and molecular glue degraders have emerged as the most prominent technologies, both exploiting the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) but differing fundamentally in their design principles and mechanisms of action [21] [39].

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: Cellular Foundation for Targeted Degradation

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is the primary intracellular pathway for maintaining protein homeostasis in eukaryotic cells, responsible for degrading damaged, misfolded, and regulatory proteins [21] [40]. This highly regulated process involves a sequential enzymatic cascade:

- Ubiquitin Activation: A ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner [21] [40].

- Ubiquitin Conjugation: The activated ubiquitin is transferred to a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) [21] [40].

- Ubiquitin Ligation: A ubiquitin ligase (E3) recognizes specific substrate proteins and catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to the target protein [21] [40].

Repeated cycles of ubiquitination result in polyubiquitin chains attached to substrate proteins. While several ubiquitin linkage types exist, K48-linked chains serve as the primary signal for proteasomal recognition and degradation [21]. The 26S proteasome then recognizes these polyubiquitinated proteins, degrades them into small peptides, and recycles ubiquitin molecules [21]. With approximately 600 E3 ligases in the human genome that confer substrate specificity, the UPS provides an ideal framework for developing targeted degradation strategies [21].

Figure 1: The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Pathway. This diagram illustrates the sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1, E2, and E3 enzymes that leads to protein ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation.

PROTACs: Heterobifunctional Inducers of Targeted Degradation

Design Principles and Mechanism of Action

PROTACs are heterobifunctional molecules consisting of three covalently linked components: a ligand that binds the protein of interest (POI), a ligand that recruits an E3 ubiquitin ligase, and a chemical linker that connects these two moieties [21] [38]. The molecular weight of PROTACs typically exceeds 700 Da, often placing them outside the conventional "rule of five" for drug-like compounds [41]. The mechanism of action involves:

- Simultaneous Binding: The PROTAC molecule simultaneously engages both the target protein and an E3 ubiquitin ligase [21] [38].

- Ternary Complex Formation: This binding induces the formation of a POI-PROTAC-E3 ternary complex [38].

- Ubiquitin Transfer: The E3 ligase catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin chains from its associated E2 enzyme to lysine residues on the target protein [21] [38].

- Proteasomal Degradation: Polyubiquitinated proteins are recognized and degraded by the 26S proteasome [21] [38].

- Catalytic Recycling: The PROTAC molecule is released unchanged and can participate in additional degradation cycles [38].

A key advantage of PROTACs is their sub-stoichiometric, catalytic mode of action, enabling potent degradation at low concentrations [38]. The degradation efficiency depends critically on the formation of a productive ternary complex with appropriate spatial geometry, which is influenced by linker length, flexibility, and composition [38].

Historical Development and Clinical Progress

The conceptual foundation for PROTACs was established in 2001 with the development of PROTAC-1, a peptide-based molecule that recruited methionine aminopeptidase-2 (MetAP-2) to the Skp1-Cullin-F-box (SCF) ubiquitin ligase complex [21]. A significant advancement occurred in 2008 with the first small-molecule PROTAC, which utilized nonsteroidal androgen receptor and MDM2 ligands to degrade the androgen receptor (AR) [21]. The field accelerated with the identification of small-molecule ligands for E3 ligases, particularly cereblon (CRBN) in 2010 and Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) in 2012, which now represent the most commonly utilized E3 ligases in PROTAC design [21] [41].

The clinical translation of PROTAC technology has progressed rapidly, with multiple candidates reaching advanced clinical stages:

Table 1: Clinical-Stage PROTAC Candidates

| Molecule | Target Protein | E3 Ligase | Clinical Phase | Indication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARV-471 | Estrogen Receptor (ER) | CRBN | NDA/BLA | ER+/HER2− Breast Cancer |

| ARV-110 | Androgen Receptor (AR) | CRBN | Phase II | Prostate Cancer |

| ARV-766 | Androgen Receptor (AR) | CRBN | Phase II | Prostate Cancer |

| DT-2216 | Bcl-XL | VHL | Phase I/II | Hematologic Malignancies |

| NX-2127 | Bruton's Tyrosine Kinase (BTK) | CRBN | Phase I | B-cell Malignancies |

| KT-474 | IRAK4 | CRBN | Phase II | Auto-inflammatory Disorders |

Advantages and Challenges

PROTACs offer several advantages over traditional inhibitors:

- Expanded Target Range: Capable of degrading proteins without deep binding pockets [21] [38]

- Complete Function Ablation: Eliminate all protein functions rather than just inhibiting specific activities [21]

- Catalytic Efficiency: Function sub-stoichiometrically, enabling efficacy at low doses [21] [38]

- Potential Resistance Mitigation: May overcome resistance mutations that impair inhibitor binding [21]

However, PROTAC development faces significant challenges:

- Molecular Size: Large molecular weights can compromise cellular permeability and oral bioavailability [38] [41]

- Hook Effect: High concentrations can paradoxically reduce degradation efficiency by forming inactive binary complexes [38]

- Linker Optimization: Requires extensive empirical optimization of linker length and composition [38]

- Limited E3 Ligase Toolkit: Current approaches predominantly utilize CRBN and VHL, limiting tissue-specific targeting [38]

Molecular Glue Degraders: Monovalent Inducers of Protein-Protein Interactions

Design Principles and Mechanism of Action

Molecular glue degraders are small, monovalent molecules that induce novel protein-protein interactions (PPIs) between an E3 ubiquitin ligase and a target protein [39] [42]. Unlike PROTACs, molecular glues typically function by binding to a single protein (usually the E3 ligase) and subtly remodeling its surface to create a novel interface that can recognize and engage target proteins that would not normally interact with the ligase [42]. The mechanism involves:

- Surface Remodeling: The molecular glue binds to an E3 ubiquitin ligase and induces conformational changes or creates new molecular interaction surfaces [42] [40].

- Neo-Substrate Recruitment: The modified E3 ligase surface recognizes and engages target proteins (neo-substrates) that it does not normally interact with [42] [40].

- Ubiquitination and Degradation: The induced proximity leads to ubiquitination of the neo-substrate and its subsequent degradation by the proteasome [42] [40].

Molecular glues typically have lower molecular weights than PROTACs and exhibit better compliance with Lipinski's rule of five, resulting in improved cellular permeability and more favorable drug-like properties [42] [43].

Historical Development and Clinical Examples

The concept of "molecular glues" first emerged in the early 1990s with the characterization of immunosuppressants cyclosporine A (CsA) and FK506, which were found to function by forming ternary complexes between immunophilins and calcineurin [21] [43]. However, the discovery of their protein degradation capabilities came later. Key historical milestones include:

- Thalidomide and Analogs: Originally marketed for morning sickness in the 1950s, thalidomide was later discovered to act as a molecular glue that binds to cereblon (CRBN) and induces degradation of transcription factors IKZF1 and IKZF3 [21] [42]. This mechanism explains both its therapeutic effects in multiple myeloma and its teratogenicity [42].

- Auxin: The plant hormone auxin functions as a natural molecular glue that promotes the interaction between TIR1 and SCF E3 ubiquitin ligase, leading to degradation of Aux/IAA transcriptional repressors [40].

- Indisulam: This anticancer compound was discovered to induce interaction between RBM39 and DCAF15 E3 ligase, resulting in RBM39 degradation [40].

Table 2: Clinically Approved Molecular Glue Degraders

| Molecule | E3 Ligase | Target Protein(s) | Clinical Indication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thalidomide | CRBN | IKZF1, IKZF3, others | Multiple Myeloma, Erythema Nodosum |

| Lenalidomide | CRBN | IKZF1, IKZF3, CK1α | Multiple Myeloma, Myelodysplastic Syndromes |

| Pomalidomide | CRBN | IKZF1, IKZF3 | Multiple Myeloma |

Advantages and Challenges

Molecular glue degraders offer distinct advantages:

- Favorable Drug Properties: Lower molecular weight improves cellular permeability and oral bioavailability [42] [43]

- Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration: Potential for treating CNS disorders [42]

- Targeting Undruggable Proteins: Can degrade proteins without conventional binding pockets [42] [43]

- Synthetic Tractability: Simpler structure-activity relationships compared to PROTACs [42]

However, significant challenges remain:

- Serendipitous Discovery: Most molecular glues have been discovered accidentally rather than through rational design [42] [43]

- Limited Predictive Frameworks: Difficulty in anticipating which compounds will induce productive PPIs [42]

- Specificity Concerns: Potential for off-target effects due to promiscuous degradation [42]

Comparative Analysis: PROTACs vs. Molecular Glues

Figure 2: Comparative Analysis of PROTACs and Molecular Glues. This diagram highlights the fundamental differences in structure, mechanism, and discovery approaches between these two targeted protein degradation technologies.

Table 3: Direct Comparison of Key Characteristics

| Characteristic | PROTACs | Molecular Glues |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Structure | Heterobifunctional (three components) | Monovalent (single molecule) |

| Molecular Weight | Typically >700 Da | Typically <500 Da |

| Rule of Five Compliance | Often non-compliant | Generally compliant |

| Mechanism of Action | Simultaneous binding to POI and E3 | Primarily binds E3, induces surface remodeling |

| Design Strategy | Rational, modular design | Primarily serendipitous discovery |

| Linker Requirement | Essential component requiring optimization | No linker required |

| Cell Permeability | Challenging due to size and polarity | Favorable due to smaller size |

| Oral Bioavailability | Limited | Generally favorable |

| Discovery Approach | Structure-based design, library screening | Phenotypic screening, repurposing |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

The development and characterization of targeted protein degraders require specialized reagents and experimental approaches. Key research tools include:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for TPD Investigations

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant E3 Ligases | CRBN, VHL, BIRC3, BIRC7, HERC4, MGRN1, RanBP2, RNF34, TRIM37, WWP2, CBL | Screening for ternary complex formation, binding assays, structural studies |

| Target Proteins | Kinases, nuclear hormone receptors, transcription factors, epigenetic regulators | PROTAC warhead validation, degradation efficiency assessment |

| Ubiquitination System Components | E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes, ubiquitin | In vitro ubiquitination assays, mechanism studies |

| Functional Assay Reagents | Multi-omics profiling tools, proteasome activity assays, cellular viability assays | High-throughput screening, mechanistic validation, off-target assessment |

| Cellular Model Systems | Cancer cell lines, primary cells, engineered lines with specific mutations | Functional assessment of degradation, resistance mechanism studies |

Key Experimental Protocols

Ternary Complex Formation Assay

Purpose: To evaluate the ability of PROTACs or molecular glues to induce productive interactions between the target protein and E3 ligase.

Methodology:

- Incubate purified POI, E3 ligase, and degrader molecule under physiological conditions

- Employ techniques such as surface plasmon resonance (SPR), analytical ultracentrifugation, or HTRF (Homogeneous Time-Resolved Fluorescence) to detect complex formation

- Quantify binding affinity (Kd) and cooperativity factors to assess complex stability [42]

Cellular Degradation Efficiency Assessment

Purpose: To evaluate target protein degradation potency and kinetics in relevant cellular models.

Methodology:

- Treat cells with varying concentrations of degrader molecule for different time periods

- Lyse cells and quantify target protein levels using Western blotting or targeted proteomics

- Determine DC50 (half-maximal degradation concentration) and Dmax (maximal degradation) values

- Assess protein recovery kinetics after degrader removal [38] [41]

Ubiquitination Detection Assay

Purpose: To confirm that observed degradation occurs through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway.

Methodology:

- Treat cells with degrader molecule in presence of proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG132)

- Immunoprecipitate target protein under denaturing conditions

- Detect ubiquitin conjugation via anti-ubiquitin Western blotting or mass spectrometry [38]

Future Directions and Concluding Perspectives

The TPD field continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising directions emerging:

- Expanding the E3 Ligase Toolkit: Moving beyond CRBN and VHL to leverage tissue-specific and conditionally active E3 ligases for improved therapeutic windows [38]

- Lysosomal-Targeting Degraders: Developing technologies such as LYTACs, AbTACs, and AUTACs that harness lysosomal degradation pathways for extracellular proteins and organelles [21] [40]

- Rational Molecular Glue Design: Applying structural biology, computational modeling, and machine learning to transition from serendipitous discovery to predictive design [39] [43]

- Tissue-Specific Targeting: Engineering degraders with improved pharmacokinetic properties for specific tissue applications, including central nervous system disorders [38] [42]