Irwin Rose and the Ubiquitin Revolution: How a Biochemical Discovery Transformed Cellular Biology and Drug Development

This article details the pivotal role of Irwin Rose in the discovery of ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation, a fundamental cellular process for which he, Aaron Ciechanover, and Avram Hershko were awarded...

Irwin Rose and the Ubiquitin Revolution: How a Biochemical Discovery Transformed Cellular Biology and Drug Development

Abstract

This article details the pivotal role of Irwin Rose in the discovery of ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation, a fundamental cellular process for which he, Aaron Ciechanover, and Avram Hershko were awarded the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational research that uncovered the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), from the initial observation of energy-dependent proteolysis to the identification of the E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade. The article further examines the methodological breakthroughs that enabled this discovery, the troubleshooting of experimental challenges, and the validation of the UPS's physiological significance. Finally, it synthesizes the profound clinical implications of this knowledge, highlighting the development of targeted therapies like proteasome inhibitors for multiple myeloma and the ongoing pursuit of novel treatments for cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.

The Foundational Puzzle: Unraveling the Mystery of Energy-Dependent Protein Degradation

Prior to 1980, the field of intracellular proteolysis was defined by a fundamental biochemical curiosity: the unexpected energy dependence of protein breakdown within cells. The hydrolysis of peptide bonds is an exergonic process, and there was no apparent thermodynamic rationale for requiring adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to fuel it. This paradoxical observation suggested the existence of a complex, energy-requiring regulatory mechanism that was entirely unknown to science. The resolution of this puzzle through the discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system not only addressed a longstanding mystery but also revolutionized our understanding of cellular regulation, earning Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry [1] [2].

The pre-1980 paradigm was characterized by limited understanding of the mechanisms governing protein turnover. While Melvin Simpson first demonstrated ATP-dependent proteolysis in 1953 through isotopic labeling studies, the following 25 years yielded few insights into the underlying processes [1]. The scientific community broadly recognized that damaged or abnormal proteins were rapidly cleared from cells, and that enzymes catalyzing rate-limiting steps in metabolic pathways were generally short-lived, but the molecular machinery responsible remained elusive [1]. This article examines the state of knowledge before the ubiquitin discovery, the key experimental approaches that advanced the field, and the essential contributions of Irwin Rose that helped unravel this biochemical mystery.

Historical Context and Key Observations

The Foundation of ATP-Dependent Proteolysis

The energy requirement for intracellular protein degradation presented a conceptual challenge that intrigued biochemists for decades. By the late 1970s, researchers had begun to suspect that energy dependence reflected some form of energy-dependent regulation of proteolytic systems, but the precise nature of this regulation remained obscure [1]. Several key observations set the stage for the groundbreaking work that would follow:

- Recognition of Selective Degradation: Goldberg's group demonstrated that damaged or abnormal proteins were selectively and rapidly cleared from cells, suggesting a sophisticated quality control mechanism [1].

- Short-Lived Regulatory Proteins: Enzymes that catalyzed rate-limiting steps in metabolic pathways were found to be generally short-lived, with amounts responsive to metabolic conditions [1].

- Lysosome-Independent Pathways: The discovery that reticulocyte lysates (which lack lysosomes) exhibited ATP-dependent proteolysis of denatured proteins indicated the existence of non-lysosomal degradation pathways [1].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Understanding ATP-Dependent Proteolysis (Pre-1980)

| Year | Discovery | Key Researchers | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | ATP-dependent proteolysis | Simpson | First demonstration of energy requirement for protein degradation |

| 1970s | Selective degradation of abnormal proteins | Goldberg's group | Established protein quality control concept |

| Mid-1970s | Non-lysosomal ATP-dependent proteolysis | Etlinger and Goldberg | Discovered lysosome-independent pathway in reticulocytes |

| 1977 | ATP-dependent proteolytic factor (APF-1) | Hershko and Ciechanover | Identified heat-stable factor required for proteolysis |

The Competing Proteolytic Systems

Before the discovery of the ubiquitin system, researchers primarily recognized two major proteolytic pathways in cells:

- Lysosomal Proteolysis: The dominant model for intracellular protein degradation involving acidic compartments containing multiple hydrolases [1].

- ATP-Dependent Proteases: Simple bacterial proteases such as Lon that directly used ATP for proteolytic activity [3] [4].

The bacterial Lon protease represented the prevailing model of ATP-dependent proteolysis before the ubiquitin system's discovery. Lon was known to be a homo-oligomeric ATP-dependent protease highly conserved in archaea, eubacteria, and eukaryotic organelles [3]. Unlike the ubiquitin system, Lon consisted of identical subunits carrying both ATPase and protease domains, with a single polypeptide containing:

- An N-terminal domain for protein substrate binding

- An ATPase domain with Walker A and B motifs

- A substrate sensor and discriminatory domain

- A C-terminal proteolytic domain containing the active site [3]

This simpler model of ATP-dependent proteolysis, where a single enzyme complex directly coupled ATP hydrolysis to protein degradation, formed the conceptual backdrop against which the more complex ubiquitin system would be discovered.

Experimental Models and Methodological Approaches

The Reticulocyte Lysate System

The critical breakthrough in unraveling the ATP-dependence paradox came from the selection of an appropriate experimental model. Hershko and Ciechanover employed rabbit reticulocyte lysates, which provided a cell-free system amenable to biochemical fractionation [1] [5]. This system offered several advantages:

- Lack of Lysosomes: Reticulocytes naturally lack lysosomes, allowing researchers to study non-lysosomal proteolytic pathways in isolation [1].

- High Proteolytic Activity: These lysates exhibited vigorous ATP-dependent proteolysis of denatured proteins [1].

- Biochemical Tractability: The system could be fractionated and reconstituted, enabling identification of essential components [1].

The experimental workflow typically involved:

- Preparation of reticulocyte lysates from rabbit blood

- ATP depletion or supplementation to assess energy dependence

- Fractionation of lysates using chromatographic techniques

- Reconstitution of proteolytic activity by combining fractions

- Use of radiolabeled protein substrates to quantify degradation [1]

Fractionation and Reconstitution Strategies

The power of biochemical fractionation was crucial to dissecting the ATP-dependent proteolytic system. Hershko and Ciechanover's approach involved:

- Separation into Complementary Fractions: The reticulocyte lysate system was separated into two fractions (I and II) that had to be recombined to generate ATP-dependent proteolysis [1].

- Identification of Essential Factors: Fraction I contained a single required component, a small, heat-stable protein they termed APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1) [1].

- Characterization of APF-2: Fraction II contained a high molecular weight fraction (APF-2) that was stabilized by ATP and required for reconstitution of proteolytic activity [1].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents in the Discovery of ATP-Dependent Proteolysis

| Research Reagent | Composition/Type | Function in Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | Cell extract from rabbit reticulocytes | Source of ATP-dependent proteolytic activity; lacking lysosomes |

| ATPγS (Adenosine 5'-O-[γ-thio]triphosphate) | Non-hydrolyzable ATP analog | Used to test ATP dependence and identify ATP-stabilized components |

| Fraction I | Biochemical fraction containing APF-1 | Provided ubiquitin (initially as APF-1) for conjugation |

| Fraction II | Biochemical fraction containing APF-2 | Contained proteolytic activity and conjugation machinery |

| 125I-labeled APF-1 | Radioiodinated APF-1 | Tracer for tracking conjugation to proteins in Fraction II |

| ATP Depletion Systems | Apyrase or hexokinase/glucose | Used to deplete ATP and study ATP-dependent processes |

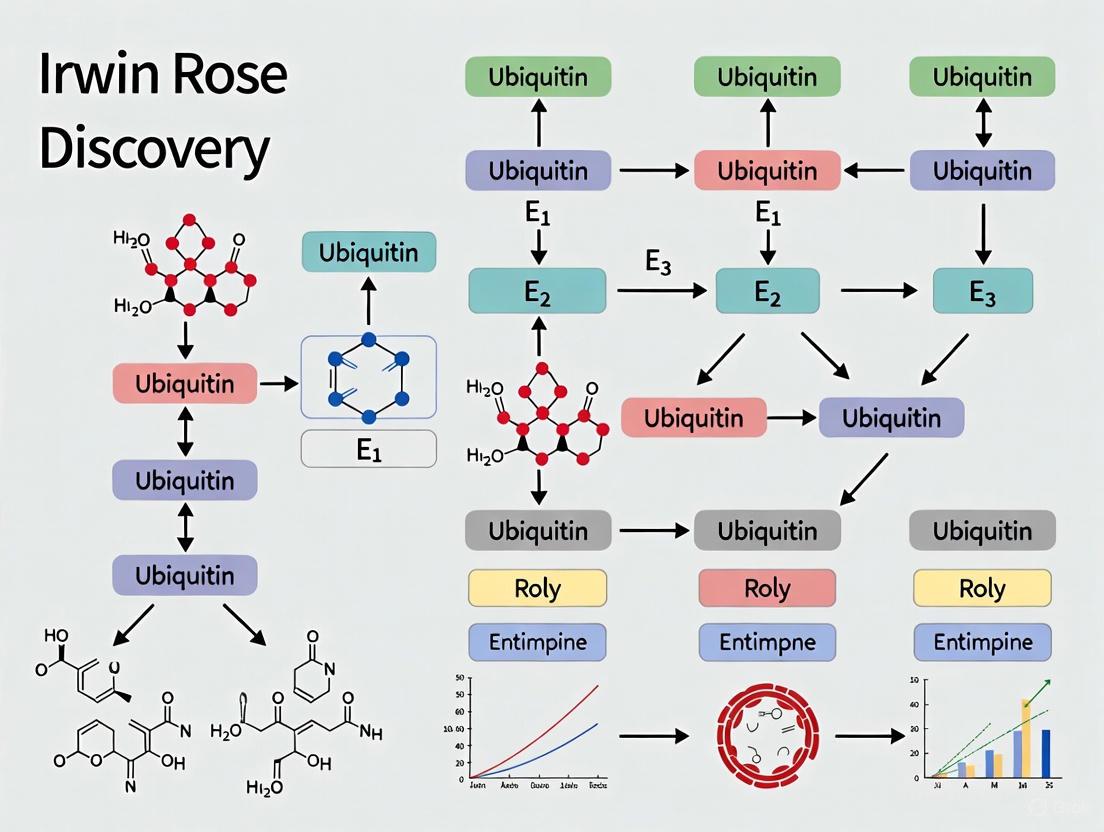

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Dissecting ATP-Dependent Proteolysis. This diagram illustrates the key steps in fractionating reticulocyte lysates to identify essential components of the ATP-dependent proteolytic system.

Irwin Rose's Intellectual and Technical Contributions

The Fox Chase Collaboration

Irwin "Ernie" Rose brought to this problem the perspective of a distinguished mechanistic enzymologist with particular expertise in studying reaction mechanisms using isotopic labeling and stereochemical approaches [1] [6]. His collaboration with Hershko began at a Fogarty Foundation meeting in 1977, where they discovered their mutual interest in ATP-dependent proteolysis [1]. This began a 10-year collaboration that saw Rose hosting the Israeli research group every summer at the Institute for Cancer Research at the Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia [1].

Rose's contributions extended far beyond providing laboratory space. He served as both intellectual contributor and patron, bringing rigorous enzymological thinking to the problem of ATP-dependent proteolysis [1]. His background in studying the stereochemistry of enzyme-catalyzed reactions and the role of magnesium in cellular equilibria provided valuable perspectives for investigating the mysterious energy requirement of proteolysis [6].

Key Experimental Insights

Rose's laboratory made several critical observations that advanced understanding of the ATP-dependence mechanism:

- Covalent Attachment Discovery: A postdoctoral fellow in Rose's laboratory, Art Haas, found that the association of 125I-labeled APF-1 with proteins in fraction II was surprisingly covalent in nature [1].

- ATP Dependence Characterization: The Rose laboratory helped demonstrate that the conjugation required low concentrations of ATP and was reversed upon ATP removal [1].

- Complex Stability Studies: They established that the APF-1-protein complex survived high pH treatment, confirming the covalent nature of the linkage [1].

Perhaps Rose's most significant contribution was fostering the intellectual environment where the identity of APF-1 could be established. Discussions between his postdoctoral fellows led to the recognition that APF-1 was identical to the previously known protein ubiquitin [1] [5]. This connection, made by Wilkinson, Urban, and Haas in Rose's laboratory, linked the ATP-dependent proteolytic system with the previously mysterious ubiquitin protein that had been discovered by Goldstein but whose function was unknown [1] [5].

The Emerging Model: Pre-1980 Understanding

By the eve of the ubiquitin discovery, the emerging model of ATP-dependent proteolysis included several key elements:

- Two-Component System: The requirement for both a small heat-stable factor (APF-1/ubiquitin) and a larger ATP-stabilized component (APF-2, later recognized as the proteasome) [1].

- Covalent Modification: The demonstration that APF-1 formed covalent attachments to multiple proteins in an ATP-dependent manner [1].

- Multiple Modifications: Evidence that substrate proteins were modified with multiple molecules of APF-1, suggesting a signaling mechanism [1].

However, critical questions remained unanswered in the pre-1980 paradigm:

- Was the covalent modification actually required for proteolysis?

- Were the modified proteins enzymes of the system or substrates destined for degradation?

- What was the nature of the ATP requirement - was it for phosphorylation, binding energy, or some other process?

- How did this system achieve specificity for particular protein substrates?

Figure 2: The Pre-1980 Model of ATP-Dependent Proteolysis. This diagram illustrates the understanding of the ATP-dependent proteolytic system just before the full elucidation of the ubiquitin system. The covalent conjugation of multiple APF-1 (ubiquitin) molecules to protein substrates was recognized as ATP-dependent, but the complete mechanism remained unresolved.

The pre-1980 paradigm of ATP-dependent proteolysis represented a field poised for revolutionary change. Researchers had established the biochemical curiosity of energy-dependent protein degradation and had developed the experimental tools to investigate it. The reticulocyte lysate system had been fractionated into essential components, and the covalent modification of proteins by APF-1/ubiquitin had been observed. Irwin Rose's contributions as a mechanistic enzymologist and collaborative partner had been instrumental in reaching this point.

What remained was to connect these observations into a coherent mechanism and to understand the broader biological significance of this pathway. The stage was set for the groundbreaking work that would reveal the ubiquitin-mediated proteolytic system - a discovery that would transform our understanding of cellular regulation and open new avenues for therapeutic intervention. The solution to the biochemical curiosity of ATP-dependent proteolysis would ultimately reveal one of the most sophisticated regulatory systems in eukaryotic cells, rivaling phosphorylation in its importance for controlling protein function and fate.

The discovery of ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation fundamentally altered our understanding of cellular regulation, revealing a sophisticated system that rivals transcription and translation in its importance to cellular homeostasis [5]. This paradigm emerged not from a single laboratory, but from the unique collaboration of three distinct scientific minds: Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose. Their combined expertise conquered a long-standing biochemical curiosity—the puzzling energy requirement for intracellular proteolysis, a process that thermodynamically should not require ATP [1]. For much of the 20th century, protein degradation was considered a nonspecific, scavenging operation, largely attributed to lysosomal activity. The collaborative work of this trio would overturn this perception, unveiling a highly specific, regulated system of protein destruction that governs countless cellular processes.

The significance of their discovery was formally recognized with the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry "for the discovery of ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation" [7]. Within this collaborative effort, Irwin "Ernie" Rose served as the consummate enzymologist, whose mechanistic insights and experimental rigor proved indispensable to deciphering the complex biochemical pathway. This whitepaper examines Rose's particular contributions within the collaborative framework, focusing on the intellectual and methodological rigor he brought to bear on one of cell biology's most fundamental processes.

The Investigators: Complementary Scientific Minds

The collaboration's strength derived from the complementary expertise of its participants, each bringing a distinct skillset to a shared biological problem.

Avram Hershko (Technion, Haifa): As the project's initiator, Hershko's research interest centered on the enigma of ATP-dependent intracellular proteolysis. Having studied under Gordon Tomkins at UCSF, he established his laboratory at the Technion where he focused on biochemical fractionation of the reticulocyte lysate system [1] [8].

Aaron Ciechanover (Technion, Haifa): Hershko's graduate student, Ciechanover immersed himself in the laboratory work, performing the intricate fractionations that would separate the proteolytic system into its functional components [8]. His meticulous experimental work provided the essential raw data for their discoveries.

Irwin Rose (Fox Chase Cancer Center): The pivotal enzymologist, Rose brought a profound understanding of reaction mechanisms and kinetic analysis [1] [6]. His laboratory at Fox Chase became the sabbatical destination for the Israeli scientists, fostering a decade of productive collaboration where Rose acted as "a patron and intellectual contributor far beyond what might be indicated by his authorship on the papers" [1].

Table 1: Key Investigators and Their Primary Contributions

| Investigator | Institutional Affiliation | Primary Expertise | Key Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Irwin Rose | Fox Chase Cancer Center | Mechanistic Enzymology | Experimental design, mechanistic interpretation, isotopic methods |

| Avram Hershko | Technion Institute | Biochemical Fractionation | System development, project direction, biological context |

| Aaron Ciechanover | Technion Institute | Cellular Biochemistry | Experimental execution, fractionation studies, complex analysis |

The Experimental Journey: Key Methodologies and Insights

Establishing a Model System and Initial Fractionation

The collaborative research program began by addressing a fundamental metabolic observation: intracellular proteolysis requires ATP, despite the exergonic nature of peptide bond hydrolysis [1]. The team adopted a reticulocyte (immature red blood cell) lysate system, which lacks lysosomes, thereby focusing on non-lysosomal proteolysis [8]. Initial work by Hershko and Ciechanover demonstrated that the ATP-dependent proteolytic activity could be separated into two essential fractions: Fraction I and Fraction II [1]. Fraction I contained a single, heat-stable component termed APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1), later identified as ubiquitin [1] [9]. Fraction II contained a high molecular weight, ATP-stabilized component that would later be recognized as the proteasome [1].

The Seminal Covalent Conjugation Discovery

The critical breakthrough came when the team, now including Rose and his postdoctoral fellow Art Haas, investigated the interaction between APF-1 and Fraction II components. The experimental protocol was elegantly direct, yet its findings were revolutionary [1]:

- Incubation: 125I-labeled APF-1 was incubated with Fraction II in the presence of ATP.

- Analysis: The reaction mixture was analyzed using SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis).

- Key Observation: APF-1 was promoted to high molecular weight forms, suggesting an association with proteins in Fraction II.

- Stability Tests: The complex was found to be stable to treatment with NaOH, a finding that "to everyone's surprise" indicated a covalent linkage [1].

This covalent attachment was a novel concept in post-translational modification. The requirement for ATP and the reversibility of the conjugation process led the authors to hypothesize that this modification was a targeting signal for proteolysis [1].

Identifying APF-1 as Ubiquitin and the Polyubiquitin Chain

The connection to a known biological molecule came through interdisciplinary conversation. Researchers in Rose's laboratory, including Keith Wilkinson, Michael Urban, and Art Haas, recognized the similarity between APF-1 and a previously characterized protein, ubiquitin, which was known to be conjugated to histone H2A [1] [5]. They subsequently demonstrated that APF-1 and ubiquitin were identical [5]. This identification merged two previously separate fields: chromatin biology and protein degradation.

A second key paper from the team in 1980 demonstrated that substrate proteins were modified by multiple molecules of ubiquitin [1]. This process of polyubiquitination was shown to be processive, with enzymes preferring to add ubiquitins to existing conjugates. Later work would establish that a chain of ubiquitins linked through lysine 48 is the canonical signal for proteasomal degradation [1].

Rose's Enzymological Toolkit

Rose's specific contribution was his deep knowledge of enzyme kinetics and mechanism, which provided the intellectual framework for interpreting the experimental data. His prior work had involved:

- Isotope Trapping: A method used to determine the rate of enzyme-substrate dissociation [9].

- Stereochemical Analysis: Studying the three-dimensional course of enzyme-catalyzed reactions [6].

- Equilibrium Analysis: Precisely determining the state of magnesium and ATP in cells [6].

This enzymological perspective was crucial in recognizing that the covalent ubiquitin conjugation required a cascade of enzymes (E1, E2, E3), a prediction that was soon confirmed [1] [5].

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow Leading to Ubiquitin Discovery. This diagram outlines the key methodological steps taken by Rose, Hershko, and Ciechanover to identify the ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis system.

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: Mechanism and Regulation

The collaborative work elucidated a sophisticated biochemical pathway. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) comprises a sequential enzymatic cascade that labels target proteins for destruction.

- Activation (E1): Ubiquitin is activated in an ATP-dependent manner by the E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme, forming a thioester bond.

- Conjugation (E2): The activated ubiquitin is transferred to an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme.

- Ligation (E3): An E3 ubiquitin ligase recognizes specific substrate proteins and facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to a lysine residue on the substrate, forming an isopeptide bond.

- Chain Elongation: Repeated cycles add multiple ubiquitins, forming a polyubiquitin chain.

- Degradation: The polyubiquitinated substrate is recognized by the 26S proteasome, a large proteolytic complex, which degrades the target protein into small peptides.

- Recycling: Ubiquitin is cleaved from the protein remnant and recycled.

Table 2: The Enzymatic Cascade of Ubiquitin-Mediated Proteolysis

| Enzyme | Designation | Primary Function | Key Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme | ATP-dependent activation of ubiquitin | Identified as part of the covalent conjugation system [5] |

| E2 | Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme | Carries activated ubiquitin | Resolved through biochemical fractionation [5] |

| E3 | Ubiquitin Ligase | Confers substrate specificity | Recognized as a specificity component [5] |

| 26S Proteasome | Proteolytic Complex | Degrades ubiquitin-tagged proteins | Initially observed as high molecular weight APF-2 [1] |

The E3 ubiquitin ligases, of which there are hundreds, provide the specificity that allows the UPS to selectively target individual proteins for degradation at precise times, enabling exquisite regulation of cellular processes [1] [2].

Figure 2: The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Pathway. This diagram illustrates the sequential enzymatic cascade (E1-E2-E3) that results in polyubiquitination of target proteins and their subsequent degradation by the proteasome.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The discovery of the ubiquitin system relied on a specific set of biochemical tools and reagents. The following table details key components used in the foundational experiments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials in Ubiquitin Discovery

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Experimental Role |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | A cell-free system derived from immature red blood cells | Provided a source of ATP-dependent proteolytic activity free from lysosomal contamination [8] |

| ATP (Adenosine Triphosphate) | Energy source for enzymatic reactions | Required for both the conjugation of ubiquitin and the final proteolytic step [1] |

| 125I-labeled APF-1/Ubiqutin | Radioactively tagged protein factor | Enabled tracking and visualization of covalent conjugation to high molecular weight proteins [1] |

| SDS-PAGE | Analytical separation technique | Used to resolve and identify high molecular weight ubiquitin-protein conjugates [1] |

| Heat-Stable Proteins (Fraction I) | Crude protein fraction | Source of APF-1/Ubiquitin; heat stability was a key purification step [9] |

| Ion-Exchange Chromatography | Protein separation method | Critical for fractionating the reticulocyte lysate into functional components (I and II) [1] |

Implications and Therapeutic Applications

The discovery of ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis by Rose, Hershko, and Ciechanover transcended basic biochemistry, fundamentally reshaping our understanding of cellular regulation. The system is now known to be indispensable for controlling the cell cycle, DNA repair, transcription, immune response, and apoptosis by rapidly eliminating key regulatory proteins [5] [2]. The UPS functions as a quality control mechanism, disposing of damaged or misfolded proteins [2].

Dysregulation of the ubiquitin system underlies numerous human diseases. Defects in UPS components are implicated in various cancers, neurodegenerative disorders (such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's), and genetic syndromes [2]. This mechanistic understanding has directly fueled drug development, most successfully with proteasome inhibitors like bortezomib (Velcade), which is now a standard treatment for multiple myeloma [2]. Ongoing research explores targeting specific E3 ubiquitin ligases for therapies in cancer and autoimmune diseases, demonstrating the vast translational potential arising from this foundational biochemical discovery [2].

The reticulocyte cell-free system stands as a cornerstone in the history of biochemical discovery, providing the essential experimental platform that enabled the elucidation of ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation. This immature red blood cell model, characterized by its simplicity and lack of internal organelles, offered researchers an unparalleled tool for dissecting complex cellular processes free from the confounding variables of intact cellular systems. It was within this meticulously prepared reticulocyte lysate that Irwin Rose, alongside Avram Hershko and Aaron Ciechanover, conducted the pioneering experiments that uncovered the ubiquitin-proteasome system, earning them the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004 [1] [10]. Their work demonstrated that the reticulocyte system contained all necessary components for ATP-dependent protein degradation—a phenomenon that had puzzled scientists since the 1950s when energy-dependent intracellular proteolysis was first observed [10].

The critical importance of this cell-free system lies in its ability to be biochemically fractionated and reconstituted, allowing for the precise identification of individual components required for protein degradation. In the late 1970s, the researchers made the crucial observation that the reticulocyte extract could be separated into two complementary fractions (I and II), each inactive alone but capable of restoring ATP-dependent proteolysis when recombined [10]. This fractionation approach led directly to the identification of a heat-stable polypeptide initially termed APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1), which was later identified as ubiquitin [1] [10]. The subsequent discovery that this small protein was covalently attached to target proteins in an ATP-dependent reaction revolutionized understanding of cellular regulation and opened an entirely new field of biochemical investigation.

Reticulocyte Biology and System Fundamentals

Biological Basis of Reticulocytes as an Experimental Model

Reticulocytes represent the penultimate stage in erythrocyte maturation, emerging after the expulsion of the nucleus from orthochromatic normoblasts. These immature red blood cells retain residual ribosomal RNA and mitochondrial elements but lack genomic DNA and most complex organelles, making them ideal for studying translational control and protein degradation without the complicating factor of ongoing transcription [11]. The standard reticulocyte count in healthy human peripheral blood ranges from 0.5% to 2.0% of total erythrocytes, or approximately 25,000 to 85,000 cells per microliter [12]. These cells circulate for approximately 24-48 hours before maturing into fully developed erythrocytes, during which time they progressively lose their remaining protein synthetic machinery [11] [12].

The unique biochemical composition of reticulocytes provides the foundation for their utility in cell-free systems. Unlike mature erythrocytes, reticulocytes maintain active protein synthesis and degradation machinery, including the complete ubiquitin-proteasome system [10]. Their relatively simple cytoplasmic content, dominated by hemoglobin, reduces biochemical complexity while retaining essential regulatory systems. Furthermore, the absence of a nucleus and lysosomes eliminates confounding degradation pathways, allowing researchers to focus specifically on the energy-dependent ubiquitin-proteasome pathway [1]. This unique combination of simplicity and retained biochemical activity makes the reticulocyte lysate an exceptionally powerful tool for reconstituting and analyzing specific cellular processes in a controlled environment.

Historical Significance in Ubiquitin Discovery

The reticulocyte model proved indispensable for the groundbreaking work of Irwin Rose and his colleagues, who utilized this system to decipher the biochemical mechanism of energy-dependent protein degradation. Their approach exemplifed the power of biochemical fractionation applied to a well-chosen cell-free system. The key breakthrough came when they demonstrated that the reticulocyte lysate could be separated into two fractions, I and II, with the active principle in fraction I (APF-1, later identified as ubiquitin) being a small, heat-stable protein [10]. Subsequent experiments in 1980 revealed the astonishing finding that APF-1 was covalently attached to target proteins in an ATP-dependent manner—the first evidence of what would become known as ubiquitination [1].

Table 1: Key Discoveries Enabled by the Reticulocyte Cell-Free System

| Year | Discovery | Experimental Approach | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1977-1978 | ATP-dependent proteolysis requires multiple factors | Fractionation of reticulocyte lysate | Identification of essential components for protein degradation [10] |

| 1980 | Covalent attachment of APF-1 to target proteins | Incubation of ¹²⁵I-labeled APF-1 with fraction II | First evidence of ubiquitin-protein conjugation [1] |

| 1980 | Multiple APF-1 molecules conjugate to single proteins | Analysis of high molecular weight complexes | Discovery of polyubiquitination as degradation signal [10] |

| 1981-1983 | Three-enzyme ubiquitination cascade | Biochemical reconstitution with purified components | Elucidation of E1-E2-E3 mechanism [10] |

The reticulocyte system continued to yield critical insights as Rose, Hershko, and Ciechanover developed the "multistep ubiquitin-tagging hypothesis" between 1981-1983, identifying the three enzyme classes (E1, E2, E3) responsible for the ubiquitination cascade [10]. This foundational work, made possible by the reticulocyte model, revealed a protein regulatory mechanism of comparable importance to phosphorylation and other reversible post-translational modifications.

Technical Establishment of the Reticulocyte Cell-Free System

Reticulocyte Production and Harvest

The initial step in establishing a functional reticulocyte cell-free system involves inducing reticulocytosis in laboratory animals, typically rabbits, and harvesting the immature red blood cells. The standard protocol involves rendering the animals anemic through a carefully controlled regimen of injections with acetylphenylhydrazine (APH) over several days, which stimulates enhanced erythropoiesis [13]. On day 8 post-induction, the animals are bled, and the blood is collected through cheesecloth filtration to remove debris and clots while maintaining the sample on ice to preserve biochemical activity [13].

The harvested blood undergoes centrifugation at 2000 RPM for 10 minutes at 4°C to separate the cellular components from plasma and other soluble factors [13]. The resulting pellet containing the reticulocyte-enriched erythrocyte population is then subjected to multiple washing steps to remove residual plasma proteins and contaminants that could interfere with subsequent fractionation procedures. This careful harvesting process yields a population of cells in which reticulocytes are significantly enriched compared to normal blood, providing the raw material for generating the cell-free extract.

Table 2: Reticulocyte Harvest Protocol Based on Historical Methods

| Step | Parameters | Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Induction | Acetylphenylhydrazine injections over 3 days | Stimulate bone marrow to produce immature RBCs | Optimal dosing critical for yield [13] |

| Harvest Timing | Day 8 post-induction | Collect blood at peak reticulocyte production | Timing affects system activity [13] |

| Initial Processing | Cheesecloth filtration, maintenance on ice | Remove debris while preserving activity | Temperature control essential [13] |

| Separation | Centrifugation at 2000 RPM for 10 min | Pellet RBCs/retics from plasma | Gentle spin preserves cell integrity [13] |

| Washing | Multiple cycles with isotonic buffer | Remove plasma contaminants | Maintains osmotic balance [13] |

Lysate Preparation and Fractionation Techniques

The preparation of active reticulocyte lysate requires careful disruption of the harvested cells while preserving the integrity and function of the proteolytic machinery. The standard methodology involves resuspending the washed reticulocyte pellet in an appropriate lysis buffer, typically containing 20-40 mM HEPES (pH 7.4-7.6), 100 mM potassium acetate, 2 mM magnesium acetate, and 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) to maintain reducing conditions [13]. The exact composition may vary depending on the specific application, but maintenance of isotonic conditions and physiological pH is critical for preserving enzymatic activity.

Several lysis methods can be employed, with freeze-thaw cycling and osmotic shock being particularly effective for reticulocytes due to their relative fragility compared to nucleated cells [14]. The lysate is then clarified through centrifugation at 10,000-30,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C to remove membrane fragments, cytoskeletal components, and other insoluble material [13]. The resulting supernatant contains the soluble cytoplasmic factors necessary for protein synthesis and degradation, including the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

The critical breakthrough in the ubiquitin discovery came from the fractionation of this crude lysate into complementary fractions. Using chromatographic techniques such as ion-exchange or gel-filtration chromatography, researchers separate the lysate into two primary fractions: Fraction I containing the low molecular weight components (including ubiquitin/APF-1) and Fraction II containing the higher molecular weight components (including the E1, E2, and E3 enzymes and the proteasome) [10]. The separation is validated by demonstrating that ATP-dependent proteolytic activity is lost upon fractionation but restored when the fractions are recombined.

Core Reaction System and Reconstitution

The reconstitution of ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic activity from fractionated reticulocyte lysate requires specific reaction conditions optimized to support the multi-step enzymatic process. The standard reaction mixture includes both Fraction I and Fraction II, an energy regeneration system (typically ATP with creatine phosphate and creatine phosphokinase), magnesium ions, and the substrate protein of interest [10]. The reaction is buffered at physiological pH (7.2-7.6) and incubated at 37°C to mimic intracellular conditions.

The ubiquitination and degradation process can be monitored through various methods. Early experiments utilized ¹²⁵I-labeled APF-1 (ubiquitin) to demonstrate covalent attachment to proteins in Fraction II [1]. Alternatively, radiolabeled substrate proteins can be used to track their time-dependent degradation through the appearance of acid-soluble radioactivity or immunoblotting. The essential role of ATP in the process can be confirmed through control reactions containing non-hydrolyzable ATP analogs or ATP-depleting systems, which should abolish both ubiquitin conjugation and substrate degradation.

The successful reconstitution of the system demonstrates that all essential components for ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis are present in the fractionated reticulocyte lysate and provides a functional assay for further purification and characterization of individual factors. This approach ultimately led to the identification and purification of the E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme, multiple E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, and various E3 ubiquitin ligases that confer substrate specificity [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Establishing a functional reticulocyte cell-free system requires carefully selected reagents that preserve biochemical activity while enabling specific experimental manipulations. The following table details essential components and their functions based on historically successful protocols and contemporary applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Reticulocyte Cell-Free Systems

| Reagent Category | Specific Components | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lysis Buffers | HEPES (20-40 mM, pH 7.4-7.6), KOAc (100 mM), Mg(OAc)₂ (2 mM), DTT (2 mM) | Maintain isotonic conditions during cell disruption; preserve enzymatic activity | DTT concentration critical for reducing environment; Mg²⁺ essential for ubiquitination [13] |

| Protease Inhibitors | PMSF (0.5 mM), protease inhibitor cocktails | Prevent nonspecific proteolysis during extract preparation | Use minimal effective concentrations to avoid interfering with studied proteolytic systems [13] |

| Energy Regeneration System | ATP (1-2 mM), creatine phosphate, creatine phosphokinase | Provide sustained ATP supply for energy-dependent ubiquitination and degradation | ATP concentration affects both ubiquitin conjugation and proteasomal degradation [10] |

| Fractionation Media | Sucrose or glycerol gradients (5-20%) | Separate cellular components by density and size | Sucrose concentration affects organelle integrity; gradients optimized for target components [14] |

| Ubiquitination Cofactors | Purified ubiquitin, E1, E2, E3 enzymes (for reconstitution experiments) | Enable specific ubiquitination of target substrates | Commercial preparations now available; purity affects experimental specificity [10] |

| Detection Reagents | ¹²⁵I-labeled ubiquitin, radiolabeled protein substrates, ubiquitin antibodies | Monitor conjugation and degradation processes | Antibody specificity critical for reducing background; radiolabeling provides high sensitivity [1] |

Biochemical Pathways Elucidated Through the Reticulocyte System

The reticulocyte cell-free system provided the experimental platform for delineating the complete ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, from initial ubiquitin activation to final substrate degradation. The biochemical cascade begins with ubiquitin activation by the E1 enzyme in an ATP-dependent reaction, forming a thioester bond between ubiquitin and E1 [10]. The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to an E2 conjugating enzyme, which collaborates with an E3 ubiquitin ligase to catalyze the formation of an isopeptide bond between the C-terminus of ubiquitin and a lysine residue on the target protein.

A critical insight from the reticulocyte system was the discovery of polyubiquitination, whereby multiple ubiquitin molecules are attached to a single substrate protein, often forming chains through linkage between the C-terminus of one ubiquitin and lysine 48 of another [1] [10]. This polyubiquitin chain serves as the recognition signal for the 26S proteasome, which unfolds the substrate protein in an ATP-dependent process and degrades it to small peptides while releasing reusable ubiquitin molecules.

This pathway, first reconstructed using the reticulocyte cell-free system, represents one of the most sophisticated regulatory mechanisms in eukaryotic cells. The specificity of the system resides primarily in the hundreds of different E3 ubiquitin ligases that recognize distinct subsets of substrate proteins, often in response to specific signals such as phosphorylation or allosteric modifications [10]. The proteasome itself represents a massive protease complex whose activity is compartmentalized within a barrel-shaped structure to prevent uncontrolled protein degradation within the cell [10].

Contemporary Applications and Methodological Advancements

While the reticulocyte cell-free system played a historical role in the discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, its utility continues in contemporary research with both methodological refinements and expanded applications. Modern implementations of the system often utilize commercially prepared reticulocyte lysates that offer greater consistency and convenience while retaining the essential biochemical activities. These systems have been adapted for high-throughput screening of ubiquitin pathway modulators, studies of protein-protein interactions in the ubiquitination cascade, and analysis of degradation signals (degrons) that target specific proteins for destruction [2].

The principles established through the reticulocyte system have found broad application in drug development, particularly in the creation of proteasome inhibitors for cancer therapy. Bortezomib (Velcade), the first proteasome inhibitor approved for human use, was developed based on understanding gained from studying the proteasome in cell-free systems [2]. This drug has demonstrated significant efficacy in multiple myeloma and other hematological malignancies, validating the therapeutic potential of modulating the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway.

Recent technical advancements have enhanced the capabilities of reticulocyte-based systems, including the incorporation of non-natural amino acids for studying ubiquitin chain topology, the development of fluorescence-based degradation assays for real-time monitoring, and the integration of artificial intelligence approaches for predicting degradation kinetics [15]. These innovations build upon the foundational work conducted by Irwin Rose and his colleagues, demonstrating the enduring value of the reticulocyte cell-free system as both an historical milestone and a contemporary research tool.

The legacy of the reticulocyte model extends beyond the ubiquitin field, serving as a prototype for the development of other cell-free systems derived from various organisms including E. coli, wheat germ, yeast, and cultured mammalian cells [13] [16]. Each of these systems offers unique advantages for specific applications, but all share the fundamental approach of using biochemical fractionation and reconstitution to dissect complex cellular processes—a methodology whose power was definitively established through the pioneering work with the reticulocyte model.

The discovery of ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1), later identified as ubiquitin, represents a cornerstone of modern cell biology, fundamentally altering our understanding of how cellular processes are regulated. This discovery emerged from a long-standing biochemical paradox: why would intracellular protein degradation, an inherently energy-liberating process, require ATP hydrolysis? [1] [17] For decades, the lysosome was believed to be the primary site of protein turnover. However, observations that cells could distinguish between long-lived and short-lived proteins, and that ATP dependence persisted even in reticulocyte extracts which lack lysosomes, pointed to the existence of a separate, non-lysosomal proteolytic pathway [1] [17]. It was within this context of intellectual curiosity that the collaboration between Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose began to unravel this mystery. Their work, for which they were awarded the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, revealed a sophisticated enzymatic system centered on a small, heat-stable protein [1] [2]. Irwin Rose's role, particularly during Hershko's sabbatical in his laboratory at the Fox Chase Cancer Center, was that of an essential intellectual contributor and patron, providing critical insights that helped frame the novel interpretations emerging from the data [1] [18].

Key Experiments and Methodologies

Initial Fractionation and the Discovery of a Heat-Stable Factor

The experimental journey to identify APF-1 began with a reconstitution approach using a cell-free system derived from reticulocytes, which Goldberg's group had shown exhibited ATP-dependent proteolysis of abnormal proteins [1]. Hershko and Ciechanover separated the reticulocyte lysate into two complementary fractions (I and II) using DEAE-cellulose chromatography [1] [17].

- Fraction I: Contained hemoglobin and other non-adherent components.

- Fraction II: Contained the bulk of other cellular proteins.

When assayed separately, neither fraction could support ATP-dependent proteolysis. However, when recombined, degradation of the test substrate was restored [1]. The key breakthrough came when they attempted to purify the essential component from Fraction I. After conventional separation methods failed due to interference from abundant hemoglobin, the researchers took an unconventional step: they boiled Fraction I [17]. Most proteins, including hemoglobin, denatured and hardened upon boiling. Astonishingly, the required factor remained soluble and fully active in the supernatant, revealing its remarkable heat stability [17]. This property was crucial for its initial purification and identification. The factor was named APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1) [1].

The Covalent Modification Breakthrough

A series of elegant experiments followed to determine APF-1's mechanism of action. The researchers labeled APF-1 with a radioactive iodine-125 (¹²⁵I) tag and incubated it with Fraction II in the presence of ATP [1]. When the reaction mixture was analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), a surprising pattern emerged.

Table: Key Observations from the Covalent Modification Experiments

| Experimental Condition | Observation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| ¹²⁵I-APF-1 + Fraction II, no ATP | Radioactivity migrated as free APF-1. | No association occurred without energy. |

| ¹²⁵I-APF-1 + Fraction II, with ATP | Multiple radioactive bands of higher molecular weight appeared. | APF-1 formed complexes with other proteins. |

| Treatment with denaturants (e.g., NaOH) | Complexes remained stable. | APF-1 was covalently linked to target proteins. |

This covalent association was a revelation. It suggested that proteins were not simply bound to a protease but were being chemically tagged prior to degradation. The bond was later identified as an isopeptide bond between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin and lysine ε-amino groups on the target proteins [1] [17]. Irwin Rose's background as a mechanistic enzymologist was instrumental in guiding the interpretation of these complex bonding patterns, moving the field beyond the initial assumption that APF-2 (a high molecular weight fraction) might be a kinase [1].

The "Aha" Moment: APF-1 is Ubiquitin

The discovery that APF-1 was the previously known protein ubiquitin came from a confluence of observations across laboratories. Ubiquitin (so named for its ubiquitous presence in eukaryotic cells) had been discovered earlier but its physiological function was unknown [1]. A key conversation occurred between postdoctoral fellows in Rose's lab, including Arthur Haas and Michael Urban, who noted the similarity between the covalent attachment of APF-1 and the known conjugation of ubiquitin to histone H2A [1]. This led to a collaborative experiment which definitively showed that APF-1 and ubiquitin were identical [1]. This finding connected a mysterious biochemical activity with a known protein, instantly providing a new and vital functional context for ubiquitin.

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow Leading to APF-1 Identification. This diagram outlines the key biochemical fractionation and reconstitution steps that revealed the essential role of the heat-stable APF-1 and its covalent conjugation to cellular proteins.

The Ubiquitin Conjugation Pathway

Following the identification of APF-1 as ubiquitin, the Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose team meticulously dissected the enzymatic pathway responsible for its conjugation. They discovered that three distinct classes of enzymes were required to attach ubiquitin to protein substrates [17].

- E1 (Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme): This enzyme activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction, forming a high-energy thioester bond between its active-site cysteine and the C-terminus of ubiquitin.

- E2 (Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme): The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to a cysteine residue on an E2 enzyme.

- E3 (Ubiquitin Ligase): Finally, an E3 enzyme facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to a lysine residue on the target protein, forming the stable isopeptide bond. E3s provide the critical substrate specificity to the system.

Further work, notably by Hershko and Varshavsky, revealed that proteins targeted for degradation are typically modified with a chain of ubiquitin molecules (a polyubiquitin chain) linked through Lysine 48 (K48) of one ubiquitin to the C-terminus of the next [1] [17]. This polyubiquitin chain serves as the recognized signal for the 26S proteasome, a massive proteolytic complex that degrades the tagged protein, releasing ubiquitin for reuse [1].

Figure 2: The Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway. This diagram illustrates the sequential action of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes in conjugating ubiquitin to a target protein, forming a polyubiquitin chain that directs the substrate to the 26S proteasome for degradation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The discovery of the ubiquitin system was enabled by a specific set of biochemical tools and reagents. The following table details some of the most critical components used in the foundational experiments.

Table: Essential Research Reagents in the Discovery of APF-1/Ubiquitin

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | A cell-free system derived from immature red blood cells; provided a source of ATP-dependent, non-lysosomal proteolytic activity for biochemical fractionation [1] [17]. |

| DEAE-Cellulose Chromatography | An ion-exchange chromatography method used to separate the reticulocyte lysate into two essential fractions (I and II), enabling the identification of the required components [1]. |

| ATP (Adenosine Triphosphate) | The essential energy source required to drive both the proteolytic process and the covalent conjugation of APF-1/ubiquitin to protein substrates [1]. |

| ¹²⁵I-labeled APF-1 | Radioactively labeled APF-1 (ubiquitin); allowed researchers to trace the fate of APF-1 and discover its covalent attachment to multiple high-molecular-weight proteins via SDS-PAGE [1]. |

| Heat Treatment (Boiling) | A critical purification step; exploited the exceptional heat stability of ubiquitin to separate it from the bulk of other proteins (like hemoglobin) in Fraction I [17]. |

| ts85 Mammalian Cell Line | A temperature-sensitive mutant cell line; provided genetic evidence in a living system that a functional ubiquitin system (specifically, a temperature-sensitive E1 enzyme) was essential for the degradation of short-lived proteins [17]. |

The identification of APF-1 as ubiquitin and the elucidation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system revolutionized cell biology. It revealed that regulated protein degradation is as critical a regulatory mechanism as transcription and translation for controlling cellular processes [18]. This system governs the precise turnover of key proteins involved in the cell cycle, DNA repair, transcriptional regulation, and immune and stress responses [18] [19].

The profound biological significance of this pathway is underscored by its direct relevance to human disease and drug development. Dysregulation of ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis is implicated in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and immune disorders [2] [19]. For instance, the proteasome inhibitor Bortezomib (Velcade) was developed based on this foundational knowledge and is now a standard treatment for multiple myeloma, validating the ubiquitin system as a viable therapeutic target [2] [19].

In conclusion, the journey to identify APF-1 is a testament to the power of curiosity-driven basic research. The collaborative effort, significantly enhanced by Irwin Rose's enzymological insight, solved a long-standing metabolic paradox and unveiled a universal regulatory mechanism. What began as a simple heat-stable factor in a reticulocyte extract is now recognized as a central controller of cell life and death, with enduring implications for our understanding of biology and the treatment of disease.

The year 1980 marked a revolutionary turning point in our understanding of cellular regulation with the publication of two seminal papers by Aaron Ciechanover, Avram Hershko, and Irwin Rose. Their discovery of energy-dependent intracellular proteolysis fundamentally challenged existing models which could not explain why the hydrolysis of peptide bonds, an exergonic process, would require ATP consumption [1]. This apparent paradox hinted at a far more complex regulatory mechanism than previously imagined. The researchers unveiled a system where proteins are marked for destruction through covalent attachment of a small protein tag, a process they initially characterized using ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1), later identified as ubiquitin [1] [10]. This "kiss of death" mechanism, for which they received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004, established an entirely new paradigm for post-translational control of protein fate, every bit as important as phosphorylation or acetylation [1] [10] [20]. This article examines this groundbreaking discovery, with particular focus on the intellectual and experimental contributions of Irwin Rose, whose mechanistic enzymology expertise and collaborative spirit were instrumental in framing this new understanding of cellular regulation.

Historical and Intellectual Context

The Energy Paradox in Protein Degradation

Prior to the landmark 1980 discovery, the scientific understanding of intracellular proteolysis was limited. The prevailing knowledge recognized simple protein-degrading enzymes like trypsin and lysosomal proteolysis, neither of which required energy [10]. However, observations dating back to Simpson's 1953 studies consistently demonstrated that intracellular proteolysis in mammalian cells was energy-dependent [1]. This was biochemically perplexing because the hydrolysis of peptide bonds is inherently exergonic, offering no thermodynamic rationale for ATP consumption [1]. Goldberg's group later advanced this understanding by showing that damaged or abnormal proteins were rapidly cleared from cells in an energy-dependent manner, suggesting that energy dependence reflected sophisticated regulation of proteolytic systems [1]. This conundrum—the unexplained ATP requirement for proteolysis—formed the central mystery that Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose set out to resolve.

The Confluence of Collaborative Minds

The collaboration between Ciechanover, Hershko, and Rose was uniquely positioned to tackle this problem. Avram Hershko had developed an interest in protein degradation during his postdoctoral work with Gordon Tompkins at UCSF and continued this work at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology [1]. Aaron Ciechanover joined Hershko's laboratory as a graduate student after completing his military service [1]. Irwin Rose brought to this collaboration a distinguished background as a mechanistic enzymologist, known for his studies on proton transfer reactions and isotopic labeling to examine enzymatic mechanisms [1]. His interest in protein degradation was long-standing, stemming from earlier conversations with his Yale colleague Simpson about the ATP dependence of proteolysis [1].

The collaboration began in earnest when Hershko and Rose met at a Fogarty Foundation meeting in 1977 and discovered their mutual interests [1]. Rose subsequently invited Hershko to his laboratory at the Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, initiating a decade of collaborative work that saw the Israeli scientists spending summers there [1]. Rose's role extended far beyond typical sabbatical hosting; he served as both patron and intellectual contributor, providing critical insights from his extensive background in enzymatic mechanisms [2]. His laboratory at the Institute for Cancer Research became the nurturing environment where key discoveries were made, underscoring his indispensable role in the ubiquitin story.

The Seminal 1980 Experiments: Methodology and Findings

Preliminary Fractionation and APF-1 Identification

Prior to the 1980 publications, Hershko and Ciechanover had established a critical experimental foundation. Using a cell-free extract from reticulocytes (immature red blood cells) that exhibited ATP-dependent proteolysis of abnormal proteins, they developed a fractionation approach that separated the system into two complementary fractions [1] [10]. When isolated, each fraction was inactive, but when recombined, ATP-dependent proteolysis was restored [10]. This elegant approach enabled them to identify the active component in Fraction I as a small, heat-stable polypeptide with a molecular weight of approximately 9,000 Da, which they termed APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1) [1] [10]. Unbeknownst to them at the time, this protein was identical to ubiquitin, a polypeptide previously isolated by Gideon Goldstein in 1975 but whose function remained unknown [1] [21].

Table 1: Key Research Reagents in the Ubiquitin Discovery

| Reagent/Technique | Function in Experiments | Key Insight Provided |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Cell-Free Extract [1] | ATP-dependent proteolysis model system; amenable to biochemical fractionation | Provided functional reconstitution system for decomposition analysis |

| Biochemical Fractionation (I & II) [1] [10] | Separation of proteolysis machinery into complementary components | Revealed multi-component nature of the system; allowed identification of APF-1 |

| ATP Depletion/Replenishment [1] | Modulation of energy availability in the experimental system | Confirmed energy dependence; revealed conjugate formation regulation |

| 125I-labeled APF-1 [1] | Radioactive tagging for tracking APF-1 fate | Enabled visualization of covalent attachment to high molecular weight proteins |

| Heat Treatment [1] | Stability test for APF-1 | Confirmed APF-1's remarkable stability, characteristic of ubiquitin |

The Critical 1980 Investigations

The two 1980 PNAS papers represented the decisive breakthrough. The first paper, led by Ciechanover et al., addressed the fundamental mechanism of APF-1 action [1]. Using 125I-labeled APF-1, they demonstrated that in the presence of Fraction II and ATP, APF-1 was promoted to high molecular weight forms. A crucial observation came when postdoctoral fellow Art Haas found that this association survived high pH treatment, suggesting something unprecedented: the attachment of APF-1 to proteins in Fraction II was covalent [1].

Further characterization revealed this covalent bond was stable to NaOH treatment, and APF-1 was bound to many different proteins as judged by SDS/PAGE [1]. The researchers established that conjugation required low ATP concentrations and was reversible upon ATP removal [1]. Critically, they noted that the nucleotide and metal ion requirements for conjugation mirrored those for proteolysis, strongly suggesting the processes were functionally linked [1]. This explained why some investigators failed to observe APF-1 requirements—when Fraction II was prepared without ATP depletion, APF-1 was already present in high molecular weight conjugates that could be disassembled by amidases to liberate free APF-1 [1].

The second 1980 paper by Hershko et al. provided the definitive link between ubiquitination and proteolysis [1]. They demonstrated that authentic protein substrates of the system were heavily modified, with multiple molecules of APF-1 attached to each substrate molecule [1]. This polyubiquitination was processive, with the conjugating machinery preferring to add additional ubiquitin molecules to existing conjugates rather than initiating new ones [1]. This work provided the first evidence for enzyme-catalyzed conjugation, hinting at the existence of what would later be termed ubiquitin ligases [1].

Table 2: Key Experimental Findings from the 1980 PNAS Papers

| Experimental Finding | Methodology | Interpretation/Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Covalent Attachment [1] | 125I-APF-1 formed high MW complexes stable to high pH and NaOH | APF-1 forms covalent conjugates with target proteins; revolutionary concept |

| ATP Dependence [1] | ATP depletion prevented conjugate formation; reversal upon ATP restoration | Energy required for conjugation step, explaining the energy paradox |

| Multiplicity of Target Proteins [1] | SDS/PAGE showed APF-1 bound to numerous proteins in Fraction II | Ubiquitination system has broad substrate specificity |

| Polyubiquitination [1] | Multiple APF-1 molecules conjugated per substrate molecule | Established concept of polyubiquitin chains as degradation signal |

| Processive Nature [1] | Conjugation preferred adding to existing conjugates over new substrates | Suggested cooperative mechanism for chain elongation |

Diagram Title: Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway Enzymatic Cascade

The E1-E2-E3 Enzymatic Cascade and Irwin Rose's Mechanistic Insights

Following the seminal 1980 observations, between 1981-1983, Ciechanover, Hershko, Rose and their teams developed the "multistep ubiquitin-tagging hypothesis," defining the E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade that governs ubiquitin conjugation [10] [22]. This hierarchical system consists of:

- E1 (Ubiquitin-Activating Enzymes): A single E1 or small family activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction, forming a high-energy thioester bond between its active-site cysteine and ubiquitin's C-terminal glycine [21] [22].

- E2 (Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzymes): Activated ubiquitin is transferred to the active-site cysteine of an E2 enzyme via trans-thioesterification [21] [22].

- E3 (Ubiquitin Ligases): Hundreds of different E3 enzymes catalyze the final transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to a lysine residue on the target protein, forming an isopeptide bond [10] [21] [22]. E3s provide substrate specificity, determining which proteins are ubiquitinated.

Irwin Rose's background as a mechanistic enzymologist proved invaluable in deciphering this cascade [1]. His expertise in using isotopic labeling and analyzing enzyme mechanisms helped the team design critical experiments to elucidate the energy-dependent steps and covalent intermediates. Rose's intellectual contribution was particularly evident in the conceptual framing of the system as a coordinated enzymatic cascade rather than a simple binary modification [2]. His laboratory at Fox Chase provided not just physical resources but an environment rich in mechanistic thinking, where the fundamental enzymological principles governing ubiquitin transfer could be rigorously explored.

Evolution and Expanding Applications of the Ubiquitin Concept

From Protein Degradation to Multifunctional Signaling

The initial conception of ubiquitin as solely a degradation signal has dramatically expanded. We now recognize that the type of ubiquitin chain determines the functional outcome [21] [22]. While K48-linked polyubiquitin chains typically target proteins for proteasomal degradation, other chain types (e.g., K63-linked, K11-linked, K6-linked, M1-linked) and monoubiquitination regulate diverse non-proteolytic processes including endocytic trafficking, inflammation, translation, DNA repair, and kinase activation [21]. Furthermore, ubiquitination is now known to occur not only on lysine residues but also on cysteine, serine, threonine residues, and protein N-termini through distinct chemical bonds [21].

Recent research has revealed that ubiquitin can even be conjugated to non-protein substrates, including lipids, sugars, and nucleotides, expanding the ubiquitin concept beyond protein modification [23] [24]. These discoveries suggest ubiquitin may serve as a scaffold for recruiting effector proteins in various signaling contexts, dramatically broadening the potential cellular roles of this modification system [24].

Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Relevance

The ubiquitin-proteasome system has emerged as a valuable therapeutic target. Defects in ubiquitin-mediated degradation are implicated in various diseases, including cervical cancer, cystic fibrosis, and neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson's disease [2] [20]. The proteasome inhibitor Bortezomib (Velcade, PS-341) was developed based on this understanding and has been approved for treating multiple myeloma, validating the clinical significance of this pathway [2]. Current research focuses on developing more specific inhibitors targeting particular E3 ligases or deubiquitinating enzymes to achieve greater therapeutic specificity with reduced side effects [2].

The 1980 discovery of ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation by Ciechanover, Hershko, and Rose fundamentally transformed our understanding of cellular regulation. Their work revealed not merely a degradation mechanism but a sophisticated language of post-translational control that rivals phosphorylation in its importance and complexity. Irwin Rose's contributions as a collaborator and mechanistic enzymologist were instrumental in framing the enzymatic logic of the system and guiding its biochemical characterization. From the initial observation of covalent APF-1 attachment to the current understanding of a multifaceted signaling system, the ubiquitin paradigm continues to evolve, offering profound insights into cell biology and providing novel therapeutic avenues for combating disease.

Mechanistic Breakthroughs: Deciphering the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System's Enzymatic Cascade

The discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, a cornerstone of modern cell biology, was propelled not by sophisticated genomics but by classical and rigorous biochemistry. The 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to Aaron Ciechanover, Avram Hershko, and Irwin Rose crowned a series of elegant experiments that decoded the cell's primary mechanism for targeted protein degradation. Central to this breakthrough was the strategic application of three key experimental approaches: biochemical fractionation to separate and identify essential components, functional reconstitution to validate their roles, and radiolabeling to trace the covalent fate of a small protein tag. This guide details the specific methodologies, rooted in the work of Irwin Rose and his colleagues, that uncovered this sophisticated regulatory system. Their approach provides a timeless template for deconstructing complex cellular machinery.

The Biological Puzzle and Irwin Rose's Intellectual Context

In the late 1970s, a central paradox puzzled biochemists: while the hydrolysis of a peptide bond is an exergonic (energy-releasing) reaction, the degradation of intracellular proteins was known to require adenosine triphosphate (ATP) [1]. This energy dependence suggested the process was far more complex than simple proteolysis. Irwin "Ernie" Rose, then at the Fox Chase Cancer Center, had been intrigued by this problem since the 1950s, when his colleague at Yale, Melvin Simpson, first demonstrated the ATP dependence of proteolysis [1] [25]. Rose's background as a distinguished enzymologist, with deep expertise in the stereochemistry and mechanisms of enzymatic reactions [6], primed him to appreciate the complexity of this energy-dependent process.

The collaborative team was uniquely positioned to tackle this problem. Avram Hershko had been studying energy-dependent protein degradation, and after meeting Rose at a conference in 1977, he began a seminal sabbatical in Rose's laboratory [1]. This began a decade of summer collaborations, with Rose acting as both an intellectual contributor and a patron of the research [1]. Their initial model system was a cell-free extract derived from rabbit reticulocytes (immature red blood cells), chosen because it catalyzed the ATP-dependent breakdown of abnormal proteins and, crucially, lacked lysosomes, thus focusing on the non-lysosomal proteolytic pathway [1] [10].

Core Experimental Strategies

The elucidation of the ubiquitin pathway serves as a masterclass in the use of fractionation, reconstitution, and radiolabeling. The following diagram illustrates the overarching experimental workflow that led to the discovery.

Fractionation and Reconstitution: Deconstructing the System

The initial, critical breakthrough came from the decision to separate the reticulocyte lysate into its constituent parts. Hershko and Ciechanover used chromatography to resolve the lysate into two fractions, designated simply as Fraction I and Fraction II [1] [10]. Individually, each fraction was inactive; ATP-dependent proteolysis only occurred when they were recombined [10]. This reconstitution assay provided a powerful functional readout to track the essential components.

Further analysis revealed the identity of the key factors:

- Fraction I was found to contain a single, heat-stable essential component, a small protein they named APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1) [1] [10].

- Fraction II contained a high molecular weight, ATP-stabilized factor (APF-2), which was later understood to be the proteasome itself, as well as the enzymatic machinery necessary for conjugation [1].

This fractionation-reconstitution strategy was the foundational step that made all subsequent discoveries possible, as it allowed for the isolation and individual characterization of the system's parts.

Radiolabeling: Visualizing the Covalent Signal

With APF-1 identified as crucial, the next question was its mechanism of action. Here, the expertise in Rose's laboratory was instrumental. The team, including postdoctoral fellow Art Haas, began using ¹²⁵I-labeled APF-1 as a radioactive tracer [1].

The key experiment involved incubating the labeled APF-1 with Fraction II and ATP. The researchers observed a dramatic shift: the labeled APF-1 was promoted to high molecular weight forms. To their astonishment, this association was covalent—it survived treatment with sodium hydroxide, which would disrupt non-covalent bonds [1] [5]. This finding was the "smoking gun." It demonstrated that APF-1 was not merely a cofactor but was itself chemically linked to target proteins prior to their degradation. The radiolabel was essential for visualizing this conjugation event, which would have been otherwise invisible.

Subsequent work showed that authentic protein substrates were modified by multiple molecules of APF-1, a process termed polyubiquitination [1] [10]. The radiolabeling approach allowed the team to trace the fate of ubiquitin and establish the multi-step enzymatic cascade involving E1, E2, and E3 enzymes [5] [10].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fractionation of Reticulocyte Lysate for ATP-Dependent Proteolysis

This protocol is adapted from the methods used to identify the essential components of the system [1] [10].

- Principle: Separate a active reticulocyte lysate chromatographically into complementary fractions that are individually inactive but regain proteolytic function upon recombination.

Materials:

- Reticulocyte lysate (from rabbit blood)

- Chromatography resin (e.g., DEAE-cellulose)

- Chromatography buffer (e.g., 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT)

- Salt gradient (e.g., 0-0.5 M KCl in chromatography buffer)

- ATP-regenerating system (ATP, Mg²⁺, creatine phosphate, creatine kinase)

- Radiolabeled substrate protein (e.g., ³H- or ¹²⁵I-labeled denatured lysozyme)

Procedure:

- Prepare Lysate: Centrifuge reticulocyte lysate at high speed (e.g., 100,000 × g) to remove membranes and obtain a clear soluble extract.

- Load Column: Apply the soluble lysate to a DEAE-cellulose column pre-equilibrated with low-salt chromatography buffer.

- Elute Fractions: Elute proteins using a linear salt gradient (0-0.5 M KCl). Collect multiple fractions.

- Desalt Fractions: Desalt individual fractions into a low-ionic-strength buffer compatible with the functional assay.

- Assay for Proteolysis: Incubate each fraction individually and in pairwise combinations with the radiolabeled substrate, an ATP-regenerating system, and buffer. A typical reaction would run for 1-2 hours at 37°C.

- Measure Degradation: Precipitate non-degraded protein with trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and measure the radioactivity in the soluble fraction (degraded peptides) by scintillation counting.

Expected Outcome: Two main pools of fractions will be identified. One pool (Fraction I) will contain the small, heat-stable protein APF-1 (ubiquitin). The other (Fraction II) will contain the larger enzymatic machinery and the proteasome. Neither will show significant activity alone, but their combination will restore robust, ATP-dependent proteolysis.

Protocol 2: Radiolabeling and Detection of Ubiquitin Conjugation

This protocol details the critical experiment that demonstrated the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to target proteins [1].

- Principle: Use iodinated ubiquitin to trace its covalent, ATP-dependent conjugation to proteins in Fraction II via SDS-PAGE autoradiography.

Materials:

- ¹²⁵I- labeled APF-1/Ubiquitin (The key reagent, prepared using Iodogen or Chloramine-T method)

- Fraction II (APF-1 depleted)

- ATP-regenerating system

- Incubation buffer

- SDS-PAGE equipment

- X-ray film or Phosphorimager

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Combine the following in a microtube:

- Fraction II (as a source of enzymes)

- ¹²⁵I-labeled Ubiquitin (0.1-1 µg)

- ATP-regenerating system (2 mM ATP, 5 mM MgCl₂, 10 mM creatine phosphate, 0.1 U creatine kinase)

- Incubation buffer to final volume.

- Incubation: Incubate at 37°C for 10-30 minutes.

- Termination and Denaturation: Stop the reaction by adding SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiling for 5 minutes.

- Analysis: Resolve the proteins by SDS-PAGE.

- Visualization: Dry the gel and expose it to X-ray film or a phosphorimager screen to detect the radiolabeled proteins.

- Reaction Setup: Combine the following in a microtube:

Expected Outcome: In the presence of ATP, a "ladder" or "smear" of high molecular weight radioactive bands will be visible on the autoradiogram. These represent ¹²⁵I-ubiquitin covalently linked to various endogenous proteins in Fraction II. This ladder will be absent in control reactions lacking ATP.

Quantitative Data from Foundational Experiments

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from the original research, providing a template for data presentation in similar biochemical studies.

Table 1: Characteristics of Fractions Isolated from Reticulocyte Lysate

| Fraction Name | Key Component(s) Identified | Essential Characteristics | Activity in Proteolysis Assay |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unfractionated Lysate | All components | N/A | Full ATP-dependent activity [10] |

| Fraction I | APF-1 (Ubiquitin) | Heat-stable, small protein (~8.5 kDa) | Inactive alone [1] [10] |

| Fraction II | E1, E2, E3 enzymes; Proteasome (APF-2) | High molecular weight complexes; ATP-stabilized | Inactive alone [1] [10] |

| Fraction I + II | All components | N/A | Full activity restored upon recombination [1] [10] |

Table 2: Key Parameters for Radiolabeled Ubiquitin Conjugation Assay

| Experimental Parameter | Condition/Measurement | Interpretation/Significance |

|---|---|---|

| ATP Dependence | Conjugation required ~2 mM ATP [1] | Explained the energy requirement of intracellular proteolysis |

| Stability of Bond | Stable to NaOH (high pH) treatment [1] | Confirmed covalent isopeptide bond, not non-covalent association |

| Multiplicity | Multiple ubiquitin molecules conjugated per target protein substrate [1] | Discovery of polyubiquitination as the proteolytic signal |

| Inhibitor Sensitivity | Conjugation was inhibited by alkylating agents (e.g., N-ethylmaleimide) [1] | Suggested the involvement of enzyme active sites with cysteine residues |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The discovery of the ubiquitin system relied on a minimal but powerful set of biochemical tools. The following table catalogs the essential reagents used in these landmark experiments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents in the Discovery of Ubiquitin-Mediated Proteolysis

| Reagent / Solution | Function in the Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | A cell-free system rich in the ubiquitin-proteasome machinery and devoid of lysosomes, serving as the starting material for fractionation [1] [10]. |

| ATP-Regenerating System | Maintains a constant, high level of ATP in prolonged incubations, which is crucial for both the conjugation process and the proteasome's activity [1]. |