K48 vs. K63 Polyubiquitin Chains: Decoding the Ubiquitin Code for Protein Fate and Signaling

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of K48- and K63-linked polyubiquitin chains, the two most abundant and functionally distinct ubiquitin codes.

K48 vs. K63 Polyubiquitin Chains: Decoding the Ubiquitin Code for Protein Fate and Signaling

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of K48- and K63-linked polyubiquitin chains, the two most abundant and functionally distinct ubiquitin codes. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it delves into the foundational biology governing their unique roles in proteasomal degradation versus non-proteolytic signaling. The content further explores advanced methodologies for chain-specific analysis, addresses common experimental challenges, and validates functional distinctions through comparative case studies in inflammation, cancer, and neurodegeneration. By synthesizing current research and emerging concepts like branched chains, this review serves as a strategic guide for exploiting ubiquitin chain specificity in therapeutic development, including the growing field of targeted protein degradation.

The Ubiquitin Code: Unraveling the Distinct Biological Roles of K48 and K63 Linkages

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a fundamental regulatory mechanism in eukaryotic cells, controlling the precise degradation of proteins to maintain cellular homeostasis. Central to this system is the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to target proteins, a process that generates a complex array of signals known as the "ubiquitin code." Among the diverse ubiquitin chain linkages, the canonical function of lysine 48-linked polyubiquitin (K48-Ub) chains as the principal signal for proteasomal degradation has been extensively documented. This canonical role stands in contrast to the predominantly non-degradative functions of other linkages, particularly lysine 63-linked polyubiquitin (K63-Ub) chains, which are primarily associated with signaling pathways, DNA repair, and protein trafficking [1] [2].

The foundational understanding of K48-Ub chains emerged from seminal work in the 1980s, which revealed K48-linked polyubiquitin as the specific chain topology directing proteins to the proteasome for degradation [1]. This established a paradigm in which different ubiquitin linkages encode distinct cellular functions, with K48 specialization for degradation and K63 specialization for signaling. However, recent research has uncovered greater complexity, demonstrating that branched ubiquitin chains containing both K48 and K63 linkages can serve as potent degradation signals, suggesting sophisticated interplay between these linkage types [3] [4]. This guide systematically compares the degradation-related functions of K48 and K63 ubiquitin chains, providing experimental data and methodologies essential for researchers investigating targeted protein degradation.

Quantitative Comparison of K48 and K63 Degradation Efficiency

Intracellular Degradation Kinetics

The development of UbiREAD (Ubiquitinated Reporter Evaluation After Intracellular Delivery) technology has enabled precise quantification of intracellular degradation kinetics for substrates modified with defined ubiquitin chains. This approach allows direct comparison of degradation rates by conjugating bespoke ubiquitin chains to a GFP reporter substrate and delivering them into human cells via electroporation [5] [6].

Table 1: Intracellular Degradation Kinetics of Ubiquitin Chain Types

| Ubiquitin Chain Type | Chain Length | Degradation Half-Life | Cellular Process | Key Experimental System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K48-linked Ubiquitin | Ub4 | ~1 minute | Proteasomal Degradation | UbiREAD in RPE-1 cells [5] |

| K48-linked Ubiquitin | Ub3 | Efficient degradation | Proteasomal Degradation | UbiREAD [5] |

| K48-linked Ubiquitin | Ub2 | Less efficient degradation | Proteasomal Degradation | UbiREAD [5] |

| K63-linked Ubiquitin | Multiple lengths | Rapid deubiquitination | Signal Transduction | UbiREAD [5] |

| K48/K63-branched Ubiquitin | Branched Ub3/Ub4 | Dependent on substrate-anchored chain | Proteasomal Degradation | UbiREAD, MS analyses [5] [4] |

Functional Specialization of Ubiquitin Linkages

The distinct functional roles of K48 and K63 ubiquitin linkages are reflected in their interaction networks and structural features.

Table 2: Functional Specialization of K48 and K63 Ubiquitin Linkages

| Characteristic | K48-linked Ubiquitin | K63-linked Ubiquitin |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Cellular Function | Proteasomal degradation [1] [2] | Signal transduction, DNA repair, protein trafficking [1] [2] |

| Structural Configuration | Closed conformation with I44 patch interactions [4] | Open, extended conformation [4] |

| Proteasomal Association | Preferentially associates with proteasomes [3] | Limited direct proteasomal association |

| Minimal Degradation Signal | K48-Ub3 [5] | Not typically a standalone degradation signal |

| Branched Chain Contribution | Component of K48/K63-branched degradation signals [3] [4] | Can serve as "seed" for branched degradation chains [3] |

Experimental Approaches for Studying Ubiquitin-Dependent Degradation

UbiREAD Technology for Degradation Kinetics

The UbiREAD methodology enables systematic interrogation of how K48, K63, and K48/K63-branched ubiquitin chains impact intracellular degradation of model substrates [5] [6].

Experimental Protocol:

- Ubiquitinated Substrate Synthesis: Prepare ubiquitin chains of defined length and composition using distal ubiquitin moieties with lysine-to-arginine mutations to prevent further elongation (e.g., K48R for K48 chains)

- Substrate Conjugation: Conjugate purified ubiquitin chains to a mono-ubiquitinated GFP model degradation substrate

- Intracellular Delivery: Introduce ubiquitinated GFP constructs into mammalian cells (RPE-1, THP-1, U2OS, A549, HeLa, or 293T) via electroporation

- Degradation Monitoring: Quantify degradation kinetics using flow cytometry and in-gel fluorescence to distinguish input and deubiquitinated species

- Inhibitor Validation: Confirm proteasome dependence using MG132 (proteasome inhibitor) and TAK243 (E1 inhibitor) [5]

Key Findings:

- K48-Ub4-GFP degradation occurs with a half-life of approximately 1 minute

- K48-Ub3 represents the minimal efficient intracellular degradation signal

- K63-ubiquitinated substrates undergo rapid deubiquitination rather than degradation

- In K48/K63-branched chains, the identity of the substrate-anchored chain determines degradation behavior [5]

Figure 1: UbiREAD Experimental Workflow for Analyzing Ubiquitin-Dependent Degradation

Ubiquitin Interactor Screens for Binding Specificity

Pulldown assays with immobilized ubiquitin chains enable identification of linkage-specific ubiquitin-binding proteins, revealing how the ubiquitin code is interpreted by cellular machinery [7] [4].

Experimental Protocol:

- Ubiquitin Chain Synthesis: Enzymatically synthesize homotypic K48-Ub2, K48-Ub3, K63-Ub2, K63-Ub3, and K48/K63-branched Ub3 using linkage-specific E2 enzymes (CDC34 for K48, Ubc13/Uev1a for K63)

- Immobilization: Add serine/glycine linker with cysteine residue to proximal ubiquitin and attach biotin molecule via cysteine-maleimide reaction

- Affinity Purification: Immobilize biotinylated ubiquitin chains on streptavidin resin and incubate with cell lysates

- DUB Inhibition: Treat lysates with deubiquitinase inhibitors (chloroacetamide or N-ethylmaleimide) to preserve ubiquitin chains during assay

- Interactor Identification: Identify bound proteins using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

- Validation: Confirm binding specificity using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) [7]

Key Findings:

- Identification of K48/K63 branch-specific ubiquitin interactors including PARP10, UBR4, and HIP1

- Discovery of interactors with preference for Ub3 over Ub2 chains (CCDC50, FAF1, DDI2)

- Demonstration that deubiquitinase inhibitor choice significantly affects ubiquitin binding profiles [7]

TUBE-Based Assays for Linkage-Specific Ubiquitination

Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) provide a high-throughput approach for investigating linkage-specific ubiquitination of endogenous proteins [2].

Experimental Protocol:

- Cell Stimulation: Treat THP-1 cells with stimuli to induce specific ubiquitination (e.g., L18-MDP for K63 ubiquitination of RIPK2, PROTACs for K48 ubiquitination)

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells in buffer optimized to preserve polyubiquitination

- Affinity Capture: Incubate lysates with chain-specific TUBEs (K48-TUBE, K63-TUBE, or pan-TUBE) immobilized in 96-well plates

- Target Detection: Detect captured ubiquitinated proteins using target-specific antibodies

- Quantification: Quantify linkage-specific ubiquitination signals [2]

Key Findings:

- K63-TUBEs specifically capture L18-MDP-induced RIPK2 ubiquitination

- K48-TUBEs specifically capture PROTAC-induced RIPK2 ubiquitination

- Pan-selective TUBEs capture both K48 and K63 ubiquitination events [2]

Branched Ubiquitin Chains in Degradation Signaling

K48/K63-Branched Chains as Potent Degradation Signals

Recent research has revealed that branched ubiquitin chains containing both K48 and K63 linkages constitute a sizable fraction of ubiquitin polymers in human cells and function as efficient proteasomal degradation signals [4].

Experimental Evidence:

- Quantitative analysis demonstrates that K48/K63-branched linkages preferentially associate with proteasomes in cells [3]

- ITCH-dependent K63 ubiquitination of TXNIP serves as a "seed" for subsequent assembly of K48/K63-branched chains by recruiting ubiquitin-interacting ligases like UBR5, leading to efficient degradation [3]

- K48/K63-branched chains account for approximately 20% of all K63 linkages in cells [7]

- Multiple valosin-containing protein (VCP/p97)-associated proteins bind to or debranch K48/K63-linked ubiquitin, suggesting specialized handling of branched chains [4]

Figure 2: K63 as Seed for Branched Degradation Signal Pathway

Debranching Enzymes and Branched Chain Regulation

The identification of debranching enzymes specific for K48/K63-branched ubiquitin chains reveals sophisticated regulatory mechanisms for controlling branched ubiquitin signals.

Key Findings:

- ATXN3 and MINDY family deubiquitinases function as debranching enzymes for K48/K63-branched chains [4]

- Engineered K48/K63 branch-specific nanobodies enable detection of branched chains in cellular contexts

- K48-K63-branched ubiquitin accumulation increases following VCP/p97 inhibition and after DNA damage [4]

- Branched ubiquitin chains are not simply the sum of their parts but exhibit functional hierarchy based on substrate-anchored chain identity [5]

Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Ubiquitin-Dependent Degradation

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Function | Application Examples | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chain-Specific TUBEs | High-affinity capture of linkage-specific polyubiquitin chains [2] | Differentiation of K48 vs. K63 ubiquitination in PROTAC treatments or signaling studies | Nanomolar affinity; linkage specificity (K48, K63, pan) |

| UbiCRest Assay | Linkage composition confirmation via selective disassembly with linkage-specific DUBs [7] | Validation of synthesized ubiquitin chain linkage specificity | Uses DUBs like OTUB1 (K48-specific) and AMSH (K63-specific) |

| Defined Ubiquitin Chains | Bespoke ubiquitin chains of specific length and linkage for in vitro assays [7] [5] | UbiREAD degradation assays; pulldown experiments | Native isopeptide bonds; defined architecture |

| Branch-Specific Nanobodies | Selective detection of K48/K63-branched ubiquitin chains [4] | Cellular detection of branched ubiquitin accumulation | Picomolar affinity; crystal structures available |

| DUB Inhibitors | Prevention of chain disassembly during assays [7] | Pulldown assays with cell lysates | Chloroacetamide (CAA) and N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) compared |

| Linkage-Specific E2 Enzymes | Enzymatic synthesis of defined linkage ubiquitin chains [7] | In vitro ubiquitin chain assembly | CDC34 (K48-specific), Ubc13/Uev1a (K63-specific) |

The canonical function of K48-linked polyubiquitin chains as the principal signal for proteasomal degradation remains a foundational principle in ubiquitin biology. However, contemporary research has revealed substantial complexity in the ubiquitin code, demonstrating that K48 linkages function within a sophisticated network that includes chain length requirements, branched architectures, and dynamic regulation by debranching enzymes. The quantitative data presented in this guide establishes K48-Ub3 as the minimal efficient degradation signal, operating with remarkably fast kinetics in cellular environments. The emerging role of K48/K63-branched chains as potent degradation signals further expands our understanding of how ubiquitin linkage combinations create specialized functions. For researchers and drug development professionals, the experimental approaches and reagent solutions detailed here provide essential methodologies for investigating targeted protein degradation mechanisms, with significant implications for developing therapeutic strategies that exploit the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that governs virtually every cellular process in eukaryotes. The covalent attachment of ubiquitin to target proteins can signal for diverse outcomes, largely determined by the topology of the polyubiquitin chain formed. Among the eight possible ubiquitin linkage types, lysine 48 (K48) and lysine 63 (K63) represent the most abundant and functionally distinct polyubiquitin chains. While K48-linked ubiquitination is the canonical signal for proteasomal degradation, K63-linked ubiquitination has emerged as a key regulator of non-proteolytic signaling pathways. This comparison guide examines the distinct functions of K48 and K63 polyubiquitin chains, with a focused analysis of K63's roles in inflammation, DNA repair, and endocytosis, providing researchers with experimental data and methodologies for studying these pathways.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of K48 and K63 Polyubiquitin Chains

| Feature | K48-Linked Chains | K63-Linked Chains |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Proteasomal degradation | Non-proteolytic signaling |

| Structural Architecture | Compact conformation [8] | Relaxed, extended conformation [8] |

| Chain Length Requirement | ≥ 3 ubiquitins for efficient degradation [5] | ≥ 4 ubiquitins for DNA binding [8] |

| Proteasome Association | Highly enriched [9] | Minimal association [9] |

| Cellular Abundance | ~60% of total linkages [7] | ~20% of total linkages [7] |

| Response to Proteasome Inhibition | Accumulates significantly [9] | Largely unchanged [9] [10] |

Structural and Functional Distinctions Between K48 and K63 Chains

The functional divergence between K48 and K63 ubiquitin chains originates from their distinct structural properties. K48-linked chains adopt a compact helical structure that facilitates recognition by the proteasome. In contrast, K63-linked chains exhibit a relaxed and labile conformation [8] that mirrors DNA double strands, enabling non-proteolytic functions. This structural difference fundamentally dictates their cellular recognition and downstream consequences.

Recent research using the UbiREAD technology has quantitatively demonstrated these functional differences. K48-Ub4-GFP substrates undergo rapid intracellular degradation with a half-life of approximately 1 minute, whereas K63-ubiquitinated substrates are rapidly deubiquitinated rather than degraded [5]. This kinetic competition between degradation and deubiquitination is encoded in the ubiquitin chain linkage type, with K48 chains of three or more ubiquitins triggering efficient proteasomal recognition.

The functional distinction extends to branched ubiquitin chains containing both linkages. K48/K63 branched linkages preferentially associate with proteasomes in cells, while unbranched K63 linkages are largely excluded [9]. This indicates that the cellular interpretation of the ubiquitin code can be altered by combinations of ubiquitin linkages, adding complexity to the simple K48-degradation/K63-signaling paradigm.

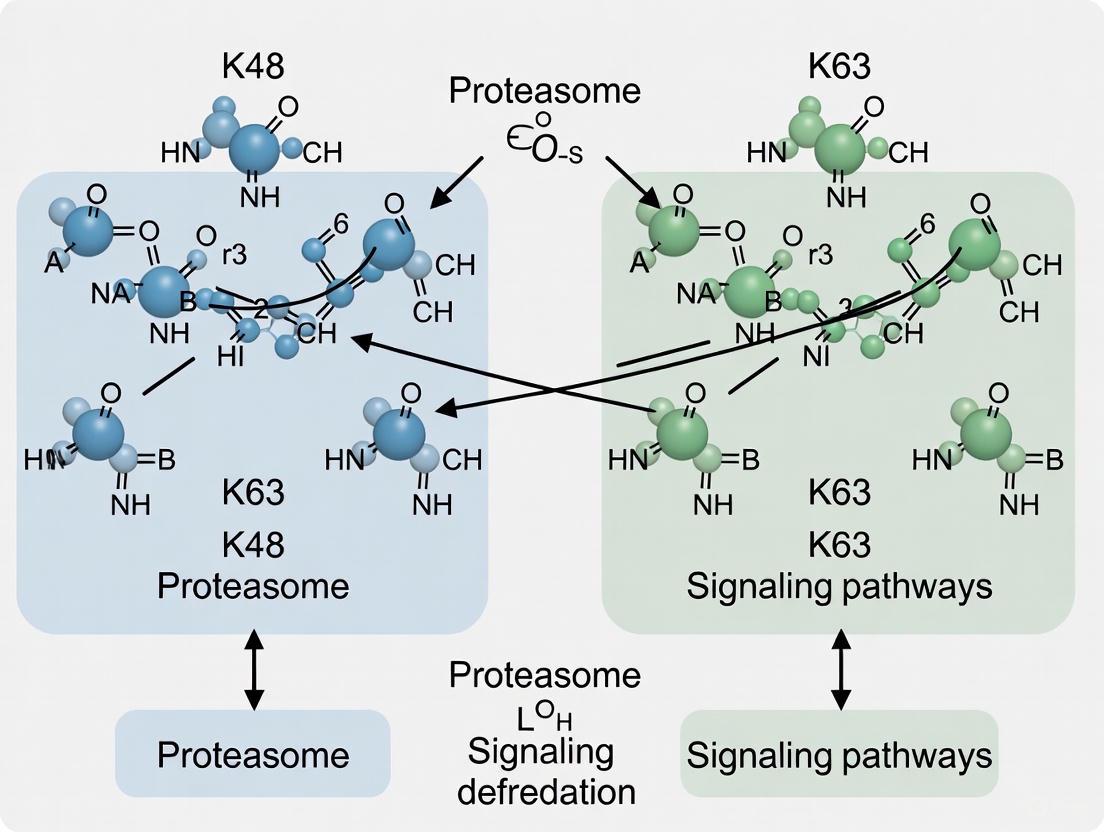

Diagram 1: Structural and functional divergence between K48 and K63 ubiquitin chains.

K63-Linked Ubiquitination in Inflammatory Signaling

K63-linked ubiquitination serves as a critical control point in immune and inflammatory signaling pathways, particularly in NF-κB and MAPK activation. This linkage type facilitates the formation of molecular scaffolds that bring together signaling components to amplify inflammatory responses.

NF-κB Pathway Activation

In the NF-κB pathway, K63 ubiquitination creates platforms for the recruitment and activation of the IKK complex. Quantitative studies using chain-specific TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) have demonstrated that inflammatory stimuli like muramyldipeptide (L18-MDP) induce K63-linked ubiquitination of RIPK2, a key regulator of inflammatory signaling [11]. This K63 ubiquitination serves as a signaling scaffold to recruit TAK1/TAB1/TAB2/IKK kinase complexes, leading to NF-κB activation and proinflammatory cytokine production.

The E3 ligase XIAP binds RIPK2 via its BIR2 domain and builds K63-linked ubiquitin chains on multiple lysine residues of RIPK2 [11]. This modification can be specifically inhibited by RIPK2 inhibitors such as Ponatinib, which completely abrogates L18-MDP-induced RIPK2 ubiquitination, providing a potential therapeutic strategy for inflammatory diseases.

SARS-CoV-2 Immune Evasion

Recent research has revealed that K63 ubiquitination plays a role in antiviral immunity, including SARS-CoV-2 infection. Many pathogens, including SARS-CoV-2, target K63 ubiquitination to inhibit immune responses [12]. Ubc13 catalyzes K63-linked ubiquitin chains on STING (stimulator of interferon genes), while UbcH5c catalyzes monoubiquitination, both having important roles in antiviral immunity.

Table 2: K63 Ubiquitination in Inflammatory Signaling Pathways

| Signaling Component | K63 Function | Regulating Enzymes | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| RIPK2 | Scaffold for TAK1/IKK complex recruitment | XIAP, cIAP1/2, TRAF2 | K63-TUBE enrichment after L18-MDP stimulation [11] |

| NEMO | IKK complex assembly | Multiple E3 ligases | Essential for NF-κB activation [11] |

| STING | Antiviral signaling | Ubc13 | Role in SARS-CoV-2 immune response [12] |

| T Cell Receptor | T cell activation | SHARPIN, CBL-B | Balance between Treg and effector T cells [12] |

K63-Linked Ubiquitination in DNA Repair

K63-linked ubiquitination plays a critical role in maintaining genomic stability through its involvement in DNA damage repair, particularly in the response to double-strand breaks.

Direct DNA Binding Mechanism

Groundbreaking research has revealed a non-canonical function for K63-linked polyubiquitin chains in directly binding to DNA. Unlike other linkage types, K63-linked chains interact with DNA through a DNA-interacting patch (DIP) composed of adjacent residues Thr9, Lys11, and Glu34 [8]. This interaction is chain length-dependent, requiring four or more ubiquitin molecules for stable binding, and shows preference for single-stranded DNA and linear DNA with free ends.

This direct DNA binding enhances the recruitment of repair factors to damage sites through their interaction with the Ile44 patch in ubiquitin, facilitating efficient DNA repair. Experimental or cancer patient-derived mutations within the DIP impair DNA binding capacity and attenuate K63-linked polyubiquitin chain accumulation at DNA damage sites, resulting in defective DNA repair and increased cellular sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents [8].

Double-Strand Break Repair

In response to DNA double-strand breaks, the E3 ubiquitin ligases RNF8 and RNF168 promote K63-linked polyubiquitination of histones, leading to recruitment of various repair factors such as Rap80 to sites of DNA damage to direct homologous recombination [8]. The accumulation of K63-linked chains at DSB sites is critical for efficient DNA damage repair, with loss of this modification leading to repair deficiencies.

Diagram 2: K63-linked ubiquitination in DNA double-strand break repair.

Methodologies for Studying K63-Linked Ubiquitination

Chain-Specific TUBE Technology

Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) are powerful tools for studying linkage-specific ubiquitination. These specialized affinity matrices with nanomolar affinities for polyubiquitin chains enable precise capture of chain-specific polyubiquitination events on native proteins with high sensitivity [11]. The methodology involves:

- Coating 96-well plates with chain-selective TUBEs (K48-specific, K63-specific, or pan-selective)

- Incubating with cell lysates under conditions that preserve ubiquitination

- Washing to remove non-specifically bound proteins

- Detecting captured ubiquitinated proteins using target-specific antibodies

This approach has been successfully used to differentiate context-dependent ubiquitination, such as L18-MDP-induced K63 ubiquitination of RIPK2 versus PROTAC-induced K48 ubiquitination [11].

UbiREAD for Degradation Kinetics

Ubiquitinated Reporter Evaluation After Intracellular Delivery (UbiREAD) is a technology that monitors cellular degradation and deubiquitination at high temporal resolution after defined ubiquitinated proteins are delivered into human cells [5]. The protocol includes:

- Synthesis of ubiquitinated GFP reporters with defined chain types

- Electroporation for efficient cytoplasmic delivery

- Flow cytometry and in-gel fluorescence to monitor degradation kinetics

- Pharmacological inhibition to validate mechanisms

Using UbiREAD, researchers have demonstrated that K48-Ub4-GFP is degraded with a half-life of ~1 minute, while K63-ubiquitinated substrates are rapidly deubiquitinated rather than degraded [5].

DNA Binding Assays

To study the novel DNA binding function of K63-linked ubiquitin chains, researchers have employed:

- In vitro pull-down assays with synthetic ubiquitin chains and DNA oligonucleotides

- Length dependency studies using defined chain lengths

- Mutation analysis of the DNA-interacting patch (T9, K11, E34)

- Salt sensitivity experiments to characterize binding under physiological conditions

These assays have demonstrated that K63-linked chains specifically bind DNA, while K48-linked, K11-linked, linear, and poly-SUMO chains show minimal binding [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying K63 Ubiquitination

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Chain-Specific TUBEs | Enrichment of linkage-specific ubiquitinated proteins | Differentiating K48 vs K63 ubiquitination of RIPK2 [11] |

| UbiREAD System | Monitoring intracellular degradation kinetics | Comparing half-lives of K48 vs K63 ubiquitinated substrates [5] |

| Linkage-Specific DUBs | Chain linkage verification (OTUB1 for K48, AMSH for K63) | UbiCRest assay for chain confirmation [7] |

| TRAF6 Overexpression | Inducing K63-linked chain formation in cells | Enhancing DNA-ubiquitin chain interactions [8] |

| DNA-Damaging Agents | Inducing DNA repair responses | Studying K63 accumulation at damage sites (etoposide, doxorubicin) [8] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Differentiating degradative vs non-degradative functions | MG132 stabilizes K48 chains but not K63 chains [9] |

K63-linked ubiquitination represents a versatile signaling mechanism distinct from the proteolysis-oriented K48-linked ubiquitination. Through its roles in inflammatory signaling, DNA repair, and other non-proteolytic processes, K63 ubiquitination expands the functional complexity of the ubiquitin code. The development of sophisticated tools like chain-specific TUBEs and UbiREAD has enabled researchers to precisely dissect these functions, opening new avenues for therapeutic intervention in cancer, inflammatory diseases, and neurodegenerative disorders. As our understanding of branched and mixed ubiquitin chains grows, so too will our appreciation of the nuanced regulation afforded by the combinatorial ubiquitin code.

Ubiquitination is a critical post-translational modification that regulates virtually every cellular process, from protein degradation to signal transduction and DNA repair. The versatility of ubiquitin signaling stems from the ability of this 76-amino acid protein to form diverse polyubiquitin chains through eight distinct linkage types, connecting ubiquitin molecules via lysine residues K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63, or the N-terminal methionine (M1). Among these, K48- and K63-linked chains represent the most abundant and well-characterized ubiquitin linkages, each encoding distinct cellular functions through specific structural architectures. The structural basis for how reader proteins specifically recognize and decode these different chain topologies represents a fundamental question in ubiquitin biology with significant implications for understanding disease mechanisms and developing targeted therapies. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of K48 versus K63 polyubiquitin chain recognition, integrating recent structural insights with experimental approaches for studying linkage-specific interactions.

Functional Dichotomy of K48 and K63 Polyubiquitin Chains

The biological functions of K48- and K63-linked polyubiquitin chains diverge significantly, with each linkage type directing specific cellular outcomes through engagement with distinct reader proteins and effector complexes.

Table 1: Functional Comparison of K48- vs. K63-Linked Polyubiquitin Chains

| Feature | K48-Linked Chains | K63-Linked Chains |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Canonical signal for proteasomal degradation [13] [14] | Non-proteolytic signaling in inflammation, endocytosis, DNA repair, and translation [15] [16] |

| Cellular Pathways | Oxidative stress response, cell cycle regulation, protein quality control [13] [17] | NF-κB signaling, NLRP3 inflammasome activation, PI3K/Akt signaling, endosomal trafficking [2] [15] |

| Temporal Dynamics | Sustained accumulation during stress response [13] | Rapid, transient pulse in response to specific stimuli (e.g., peroxides) [16] |

| Disease Associations | Impaired protein clearance in neurodegenerative diseases [13] | Cancer development, metastasis, and inflammatory disorders [15] |

| Chain Length Significance | ≥Ub4 conventionally required for proteasomal recognition [7] | Variable length requirements depending on specific signaling context [7] |

The K48-linked ubiquitin chain serves as the primary degradation signal, targeting modified proteins to the 26S proteasome for destruction. This pathway is essential for maintaining cellular proteostasis, with K48 linkage accumulation observed during oxidative stress to facilitate the removal of damaged proteins [13]. In contrast, K63-linked chains function predominantly in non-proteolytic signaling, serving as scaffolds to assemble protein complexes in inflammatory signaling (e.g., RIPK2 ubiquitination in NOD2 pathway) [2], kinase activation (e.g., Akt ubiquitination in PI3K signaling) [15], and DNA damage response. Recent research has revealed that K63 ubiquitination accumulates as a rapid, transient pulse specifically in response to peroxides, unlike the more sustained K48 response, indicating specialized regulatory mechanisms for this linkage type [16].

Structural Mechanisms of Linkage-Specific Recognition

The specificity of ubiquitin chain recognition arises from precise structural interfaces between reader proteins and distinctive conformational states adopted by different chain topologies.

Conformational Landscape of Ubiquitin Chains

K48- and K63-linked diubiquitin (diUb) exhibit fundamentally different conformational properties that enable selective recognition by specific reader proteins:

K48-diUb conformational dynamics: Single-molecule FRET studies reveal that K48-linked chains fluctuate among multiple conformational states - compact (∼48%), semi-open (∼39%), and open (∼13%) - with the compact state selectively recognized by proteasomal receptor Rpn13 [18]. The compact state buries key hydrophobic residues (L8, I44, V70) at the dimer interface, creating a unique recognition surface.

K63-diUb structural features: K63-linked chains adopt more open, extended conformations that expose both I44 and I36 hydrophobic patches, enabling interactions with proteins containing ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) like NZF domains in TAB2/3 [19]. The greater flexibility and accessibility of interaction surfaces in K63 chains facilitate their signaling functions.

Theoretical binding landscapes: Computational studies suggest that covalent linkage topology breaks binding symmetry and selects functional landscapes from the underlying binding landscape of free ubiquitin monomers, with hydrophobic interactions dominating in K48 chains and electrostatic interactions playing a more significant role in K63 recognition [20].

Molecular Interfaces in Linkage-Selective Recognition

Structural biology approaches have revealed precise molecular mechanisms governing linkage-specific ubiquitin chain recognition:

Rpn13-K48 chain recognition: The N-terminal domain of proteasomal receptor Rpn13 (Rpn13NTD) employs a bivalent binding mechanism, simultaneously interacting with both proximal and distal ubiquitin subunits in K48-linked chains. The proximal Ub binds similarly to monomeric Ub, while the distal Ub engages a largely electrostatic surface on Rpn13NTD [18]. This dual interaction provides linkage selectivity and enhances binding affinity for K48 chains.

TAB2-NZF dual specificity: The NZF domain of TAB2, a component of the TAK1 complex in inflammatory signaling, exhibits dual specificity for both K63- and K6-linked ubiquitin chains. Structural analyses reveal similar binding mechanisms for both linkage types, with flexibility in the C-terminal region of the distal ubiquitin contributing to this dual recognition capability [19].

Met4 UIML domain specificity: The Ubiquitin Interacting Motif-Like (UIML) domain of transcription factor Met4 demonstrates strict K48-specific binding, with no detectable interaction with monoubiquitin or other polyubiquitin chain configurations. This domain exhibits nanomolar affinity (Kd = 100 nM) for K48 tetraubiquitin, enabling selective recognition of degradation signals [14].

Table 2: Structural Bases for Linkage-Selective Ubiquitin Chain Recognition

| Reader Protein/Domain | Preferred Linkage | Structural Mechanism | Biological Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rpn13NTD | K48 | Bivalent binding to both proximal and distal Ub subunits [18] | Proteasomal substrate recognition [18] |

| TAB2-NZF | K63 (and K6) | Simultaneous interaction with distal and proximal Ub moieties [19] | TAK1 complex activation in NF-κB signaling [19] |

| Met4 UIML | K48 | Strict K48-specific binding with nanomolar affinity [14] | Transcriptional regulation in response to degradation signals [14] |

| RAP80 UIM | K63 | UIM domain binding to K63 chains on histone H2A [17] | DNA damage response and recruitment of BRCA1 [17] |

Experimental Approaches for Studying Linkage-Specific Interactions

Chain-Specific Affinity Tools and Pull-Down Assays

Advanced biochemical tools have been developed to investigate linkage-specific ubiquitin interactions, with chain-selective Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) representing a particularly powerful approach:

TUBE-based capture technology: Chain-specific TUBEs with nanomolar affinities for particular polyubiquitin chains enable selective enrichment of endogenous proteins modified with specific ubiquitin linkages. K63-TUBEs selectively capture RIPK2 ubiquitination induced by inflammatory stimulus L18-MDP, while K48-TUBEs specifically enrich PROTAC-induced RIPK2 ubiquitination, demonstrating precise linkage discrimination in cellular contexts [2].

Ubiquitin interactor screens: Systematic screens using immobilized native ubiquitin chains of defined linkage and length have identified interactors with preferences for specific chain architectures. Recent studies revealed the first K48/K63-branched chain-specific interactors, including PARP10, UBR4, and HIP1, and demonstrated chain length preferences (Ub3 over Ub2) for proteins like CCDC50, FAF1, and DDI2 [7].

Considerations for DUB inhibition: Pull-down experiments require deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibition to preserve chain integrity, with common inhibitors (N-ethylmaleimide/NEM and chloroacetamide/CAA) exhibiting different off-target effects that can influence experimental outcomes. Studies show inhibitor-dependent variations in identified interactors, highlighting the importance of inhibitor selection in experimental design [7].

Structural and Biophysical Methodologies

Multiple biophysical approaches provide complementary insights into the structural basis of ubiquitin chain recognition:

Single-molecule FRET (smFRET): This technique enables real-time observation of conformational dynamics in ubiquitin chains under near-physiological conditions. smFRET revealed the multi-state conformational equilibrium of K48-diUb and identified the compact state as the species selectively recognized by Rpn13 [18].

Solution NMR spectroscopy: NMR provides atomic-resolution information on protein dynamics and weak interactions in solution. Combined with smFRET, NMR determined the complex structure between Rpn13NTD and K48-diUb, confirming simultaneous engagement of both ubiquitin subunits [18].

X-ray crystallography: Crystallographic analyses have defined atomic structures of ubiquitin-binding domains in complex with specific linkage types, such as the TAB2-NZF domain with K63-diUb, revealing precise interaction interfaces [19].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for linkage-specific ubiquitin interactor capture, highlighting specialized bait variants for probing different aspects of ubiquitin chain recognition.

Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Ubiquitin Chain-Protein Interactions

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Chain-specific TUBEs | Selective enrichment of proteins modified with specific ubiquitin linkages (K48, K63, or pan-specific) [2] | Investigation of endogenous RIPK2 ubiquitination in inflammatory signaling [2] |

| Linkage-specific DUBs | Selective cleavage of specific ubiquitin linkages to verify chain composition (e.g., OTUB1 for K48, AMSH for K63) [7] | UbiCRest assay for confirmation of chain linkage composition [7] |

| DUB Inhibitors (CAA, NEM) | Prevention of chain disassembly during experiments by inhibiting deubiquitinating enzymes [7] | Stabilization of ubiquitin chains in pull-down assays [7] |

| DiUb/TriUb Probes | Defined linkage and length ubiquitin chains for structural and binding studies [7] [18] | smFRET studies of K48-diUb conformational states [18] |

| Linkage-specific Antibodies | Immunodetection of specific ubiquitin linkage types in cellular contexts [13] | Monitoring K48 and K63 accumulation during oxidative stress [13] [16] |

| PROTACs/Molecular Glues | Inducers of targeted protein ubiquitination and degradation via specific E3 ligases [2] | Study of K48-linked ubiquitination in targeted protein degradation [2] |

The structural basis for ubiquitin chain recognition represents a sophisticated decoding system where chain topology dictates specific reader protein interactions through precise structural interfaces and conformational dynamics. The comparative analysis of K48 and K63 linkages reveals how identical ubiquitin building blocks generate functionally distinct signals through variation in chain architecture. K48 chains predominantly adopt compact conformations recognized by proteasomal receptors like Rpn13, while K63 chains utilize more open conformations for signaling complex assembly. Advanced tools including chain-specific TUBEs, defined ubiquitin probes, and sophisticated biophysical methods continue to expand our understanding of the ubiquitin code. Future research directions include elucidating the functions of less-characterized ubiquitin linkages, understanding the recognition of mixed and branched chains, and developing therapeutic strategies targeting linkage-specific reader interactions in cancer, inflammatory disorders, and neurodegenerative diseases. The continuing dissection of ubiquitin chain recognition mechanisms promises not only fundamental biological insights but also novel therapeutic approaches for manipulating ubiquitin signaling in human disease.

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that controls virtually every cellular process in eukaryotes, with functional outcomes dictated by the architecture of polyubiquitin chains. Among the various chain linkage types, lysine 48-linked (K48) and lysine 63-linked (K63) polyubiquitin represent the two most abundant and extensively studied ubiquitin signals in the cell [21] [7] [22]. These linkages constitute fundamental components of the "ubiquitin code," with K48 primarily targeting substrates for proteasomal degradation and K63 regulating non-proteolytic functions including signal transduction, DNA repair, and endocytosis [23] [22]. Understanding the precise prevalence and functional hierarchy of these linkages provides critical insights for drug development targeting ubiquitin pathway components in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and inflammatory disorders. This guide objectively compares the cellular abundance, functional specializations, and experimental methodologies for quantifying K48 and K63 ubiquitin chains, synthesizing current quantitative data to inform research and therapeutic targeting strategies.

Table 1: Core Functional Specializations of K48 and K63 Ubiquitin Linkages

| Attribute | K48-Linked Ubiquitin | K63-Linked Ubiquitin |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Proteasomal degradation signal [21] [22] | Non-degradative signaling [23] [22] |

| Key Pathways | Protein turnover, cell cycle regulation, quality control [24] [25] | NF-κB signaling, endocytosis, DNA repair, autophagy [21] [23] [22] |

| Proteasome Recruitment | Directs substrates to 26S proteasome [24] | Typically does not target for degradation [26] |

| Chain Length Requirement | ≥4 ubiquitins for efficient degradation [21] [26] | Variable; often shorter chains sufficient [21] |

| Branched Chain Context | Forms functional hybrids with K63 and K11 [21] [24] | Branched with K48 enhances signaling complexity [21] [26] |

Quantitative Prevalence in the Cellular Ubiquitome

Comprehensive quantification of ubiquitin chain prevalence reveals K48 as the dominant linkage type, with K63 representing the second most abundant form. Systematic analyses indicate K48-linked chains constitute the most abundant linkage type in human cells, followed by K63 linkages [21] [7]. Specifically, K48 linkages represent the predominant proteasomal degradation signal, while K63 chains account for a substantial portion of non-degradative ubiquitin signals. Notably, branched ubiquitin chains containing both K48 and K63 linkages constitute approximately 20% of all K63 linkages in cellular contexts, representing a significant hybrid population with specialized functions [21] [7]. This branched architecture creates recognition surfaces for specialized receptors that simultaneously engage both linkage types, potentially enabling crosstalk between degradative and non-degradative ubiquitin signaling pathways.

The relative abundance of these linkages is not static but responds dynamically to cellular conditions. Environmental stressors, DNA damage, metabolic changes, and pathogen infections can trigger rapid remodeling of the ubiquitin landscape through the coordinated actions of E3 ligases and deubiquitinases (DUBs) [25] [23]. For instance, inflammatory signaling through NF-κB pathways rapidly increases K63 ubiquitination events, while proteotoxic stress and cell cycle transitions elevate K48 chain production [24] [23]. Technological advances in mass spectrometry-based ubiquitinomics now enable researchers to track these dynamic changes with unprecedented precision, revealing context-specific fluctuations in the K48:K63 ratio across different physiological and disease states [27].

Table 2: Quantitative Abundance and Characteristics of Major Ubiquitin Linkages

| Linkage Type | Relative Cellular Abundance | Branched Chain Prevalence | Key Functional Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48 | Highest abundance [21] [7] | 20% of K63 linkages form K48/K63 branched chains [21] | Proteasomal degradation [21] [22] |

| K63 | Second most abundant [21] [7] | Component of K48/K63 branched chains [21] | NF-κB signaling, endocytosis, DNA repair [23] [22] |

| K11 | Lower than K48/K63 [24] [22] | Forms K11/K48 branched degradation signals [24] | Cell cycle regulation, proteasomal degradation [24] [22] |

| M1 (Linear) | Context-dependent [23] | Can form heterotypic chains [23] | NF-κB signaling, inflammation [23] |

Methodologies for Ubiquitin Chain Quantification

Mass Spectrometry-Based Ubiquitinomics

Advanced mass spectrometry (MS) approaches form the cornerstone of modern ubiquitin chain quantification. The dominant methodology employs anti-diGly antibody enrichment following tryptic digestion, which specifically captures the characteristic glycine-glycine remnant left on ubiquitinated lysine residues after trypsinization [27]. This approach has been scaled through tandem mass tagging (TMT) methods like UbiFast, which enables multiplexed comparison of up to 11 conditions simultaneously with reduced sample requirements [27]. Recent innovations including Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) MS have dramatically expanded coverage, with studies now identifying >90,000 ubiquitination sites in single experiments [27]. For specialized applications requiring distinct ubiquitin chain architectures, the UbiCRest assay utilizes linkage-specific deubiquitinases (DUBs) to characterize chain composition by monitoring cleavage patterns through immunoblotting [21] [7]. This method is particularly valuable for verifying the composition of synthetically generated ubiquitin chains used as standards in quantitative experiments.

Diagram 1: Ubiquitinomics MS Workflow

Functional Interaction and Degradation Assays

Beyond direct quantification of ubiquitin chains, functional proteomics approaches provide complementary insights into linkage-specific biology. Ubiquitin interactor pulldowns utilize immobilized ubiquitin chains of defined linkage and length as bait to enrich for linkage-specific binding proteins from cell lysates [21] [7]. This approach has identified specialized interactors including HIP1 and PARP10 that show preferential binding to K48/K63-branched ubiquitin chains over homotypic chains [21] [7]. For degradation monitoring, the UbiREAD (Ubiquitinated Reporter Evaluation After Intracellular Delivery) platform introduces bespoke ubiquitinated substrates into cells and tracks their fate with high temporal resolution [26]. This technology has revealed fundamental differences in degradation kinetics, with K48-tetraubiquitin triggering substrate degradation within minutes, while K63-ubiquitinated substrates undergo rapid deubiquitination rather than degradation [26]. For branched chains, UbiREAD demonstrates that the substrate-anchored chain identity dictates degradation behavior, establishing that branched chains are not simply the sum of their parts [26].

Structural Recognition Mechanisms

The functional specialization of K48 and K63 linkages originates from distinct structural recognition by ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) within effector proteins. The 26S proteasome contains multiple ubiquitin receptors that preferentially engage K48-linked chains, with recent cryo-EM structures revealing sophisticated recognition mechanisms for branched chains. For K11/K48-branched ubiquitin chains, the proteasome employs a multivalent recognition mechanism involving a novel K11-linked ubiquitin binding site at the groove formed by RPN2 and RPN10, in addition to the canonical K48-linkage binding site formed by RPN10 and RPT4/5 [24]. This cooperative engagement creates a "priority signal" that enhances degradation efficiency for substrates marked with K11/K48-branched chains [24].

In contrast, K63-linked chains are preferentially recognized by proteins involved in signaling complexes. For example, in the NF-κB pathway, K63 chains and linear M1 chains create protein interaction platforms that recruit and activate the IKK complex through its NEMO subunit [23]. The MyD88-IRAK-TRAF6 signaling axis in innate immunity depends on K63 ubiquitination to initiate downstream kinase activation without triggering degradation of the signaling components [23]. Structural analyses reveal that UBDs have evolved linkage-specific binding preferences, with some domains like the UBA domain of RAD23 exhibiting strong preference for K48 chains, while others like the UIM domains of EPN2 selectively bind K63 linkages [21] [7].

Diagram 2: Ubiquitin Linkage Recognition Systems

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table summarizes essential reagents and methodologies for investigating K48 and K63 ubiquitin linkages, compiled from current experimental approaches.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for K48/K63 Research

| Reagent/Method | Specific Application | Key Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific Ub Antibodies | Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence | Detection of endogenous K48 vs K63 chains [21] [24] |

| K-GG Antibody (CST) | Ubiquitin remnant enrichment for MS | Proteome-wide ubiquitination site mapping [27] |

| Di-Ub/Tri-Ub Probes | In vitro binding assays, crystallography | Structural studies of linkage-specific UBD interactions [21] [7] |

| UbiCRest Assay | Linkage composition analysis | DUB-based fingerprinting of chain linkage types [21] [7] |

| TMT Multiplexing | Quantitative ubiquitinomics | Comparison of multiple conditions (e.g., time courses) [27] |

| UbiREAD Platform | Degradation kinetics | Monitoring fate of specific ubiquitinated substrates [26] |

| Branch-Specific Binders (HIP1, PARP10) | Detection of branched chains | Specific recognition of K48/K63-branched ubiquitin [21] |

Discussion and Research Implications

The quantitative dominance of K48 and K63 linkages positions them as central players in the ubiquitin system, with significant implications for both basic research and therapeutic development. The consistent finding that K48 constitutes the most abundant linkage underscores the central importance of controlled protein degradation in cellular homeostasis, while the substantial representation of K63 linkages highlights the critical role of ubiquitin in non-proteolytic signaling [21] [7] [22]. The significant prevalence of K48/K63-branched hybrids (approximately 20% of K63 linkages) reveals an additional layer of complexity, suggesting cells extensively utilize mixed topology chains for specialized regulatory functions that may simultaneously engage degradative and non-degradative pathways [21].

From a therapeutic perspective, the linkage-specific enzymes governing K48 and K63 chain assembly and disassembly represent promising drug targets. Specific E2 enzymes and E3 ligases show strong linkage preferences – for example, the CDC34 and Ubc13/Uev1a E2 complexes specifically generate K48 and K63 linkages respectively [21] [7]. Similarly, deubiquitinases like OTUB1 and AMSH exhibit pronounced linkage selectivity for K48 and K63 chains [21] [7]. Small molecules targeting these enzymes could potentially rebalance the ubiquitin landscape in disease states, such as reducing K48-mediated degradation of tumor suppressors or modulating K63-dependent inflammatory signaling. The developing recognition of branched chain biology further suggests therapeutic opportunities for compounds that specifically target the readers, writers, and erasers of these hybrid ubiquitin signals.

Future research directions should focus on expanding quantitative mapping of ubiquitin chain dynamics across different cell types, disease states, and subcellular compartments. The development of additional branch-specific reagents will be particularly valuable for deciphering the functional significance of hybrid chains. Finally, integrating ubiquitin linkage data with other omics datasets will provide a more comprehensive understanding of how the ubiquitin code controls cellular physiology in health and disease.

Abstract While the roles of K48-linked ubiquitin chains in proteasomal degradation and K63-linked chains in non-proteolytic signaling are well-established pillars of ubiquitin biology, the functions of atypical polyubiquitin chains are rapidly emerging as critical components of cellular regulation. This guide provides a systematic comparison of the structures, synthesis, and functions of K6-, K11-, K27-, K29-, and K33-linked ubiquitin chains, contextualizing them within the broader framework of ubiquitin signaling. We summarize key experimental data in comparative tables, detail essential methodologies for linkage determination, and visualize complex signaling pathways and experimental workflows to equip researchers with the tools needed to decode the expanding landscape of atypical ubiquitin chains.

1. Introduction: Beyond K48 and K63

The ubiquitin code represents a complex post-translational language wherein different polyubiquitin chain topologies encode distinct functional outcomes [21] [28]. For decades, research has focused predominantly on the canonical K48 linkage, which targets substrates for proteasomal degradation, and the K63 linkage, which regulates processes like DNA repair, NF-κB signaling, and protein trafficking [29]. However, advances in biochemical tools and mass spectrometry have unveiled the significance of the "atypical" ubiquitin chains—K6, K11, K27, K29, and K33—which collectively constitute a sophisticated regulatory layer controlling vital cellular pathways from cell division to innate immunity [30] [31] [28]. Far from being minor variants, these chains are now recognized as specialized signals with unique structural properties and recognition codes. This guide objectively compares the functions, regulatory enzymes, and experimental approaches for studying these atypical chains, framing them within the foundational K48/K63 paradigm to provide a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug discovery professionals.

2. Comparative Functions and Regulatory Machinery

Atypical ubiquitin chains are specialized in their functions, influencing processes from innate immunity to cell cycle progression. The table below provides a systematic comparison of their roles, along with the specific E3 ligases and deubiquitinases (DUBs) that govern their dynamics.

Table 1: Functional Roles and Regulatory Enzymes of Atypical Ubiquitin Chains

| Ubiquitin Linkage | Known Functions & Biological Roles | Regulatory E3 Ligases (Examples) | Regulatory DUBs (Examples) |

|---|---|---|---|

| K11 | - Regulates degradation of innate immune factors (e.g., STING) [30].- Associated with cell cycle regulation and proteasome-mediated degradation [30]. | RNF26, USP19 (as E3 for Beclin-1) [30] | USP19 [30] |

| K27 | - Potentiates NF-κB and IRF3 activation in antiviral innate immunity [30].- Can also signal for autophagy-mediated degradation of immune signaling proteins (e.g., MAVS) [30]. | TRIM23, TRIM26, TRIM40, RNF185, AMFR [30] | USP13, USP21, USP19 [30] |

| K29 | - Induces production of IFNβ and IL-6 [30].- Can form branched chains with K48 linkages [28]. | SKP1-Cullin-Fbx21 complex, UBE3C [30] [32] | Information Missing |

| K33 | - Prevents TBK1 degradation and induces IRF3 activation [30].- Suppresses ISG transcription [30]. | RNF2, AREL1 [30] [32] | USP38 [30] |

| K6 | - Less defined roles in innate immunity; reported in DNA damage repair and mitophagy [28]. | Information Missing | Information Missing |

3. Atypical Ubiquitin Chains in Antiviral Innate Immune Signaling

The antiviral innate immune response provides a compelling context for understanding the specialized functions of atypical chains. Recent findings underscore that these chains are potent regulators of intracellular signaling pathways triggered by viral infection [30]. The pathway diagram below illustrates how atypical ubiquitin chains precisely control the activation of key transcription factors NF-κB and IRF3/7, which induce the production of proinflammatory cytokines and type I interferons, respectively.

Diagram 1: Atypical ubiquitin chains in antiviral signaling. Green arrows (K27, K11, K33) denote activating roles; red arrows (K27/K29) denote inhibitory roles via targeted degradation.

4. Experimental Protocol for Determining Ubiquitin Chain Linkage

A definitive method for establishing the linkage type of a ubiquitin chain involves in vitro ubiquitination assays using a panel of ubiquitin mutants. The protocol below, adapted from a key resource, details this critical experimental workflow [33].

Table 2: Key Reagents for Linkage Determination Assays

| Reagent | Function / Purpose in the Assay |

|---|---|

| E1 Activating Enzyme | Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner, forming the foundational step for the cascade. |

| E2 Conjugating Enzyme | Accepts ubiquitin from E1 and collaborates with the E3 ligase to determine linkage specificity. |

| E3 Ubiquitin Ligase | Catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to the substrate, ultimately defining substrate specificity and often influencing chain topology. |

| Wild-type Ubiquitin | The positive control for the conjugation reaction, should form polyubiquitin chains. |

| Ubiquitin K-to-R Mutants | Each mutant (K6R, K11R, etc.) lacks a single lysine residue. If chain formation is blocked with a specific mutant, it indicates that lysine is required for linkage. |

| Ubiquitin 'K-Only' Mutants | Each mutant contains only one lysine (e.g., K6-only). Chain formation only occurs with the mutant that matches the E2/E3's linkage specificity, providing verification. |

| MgATP Solution | Provides the essential energy source for the E1-mediated activation step. |

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Reaction Setup: Set up two parallel sets of nine 25 µL reactions each. The first set uses wild-type ubiquitin and the seven "K-to-R" mutants. The second set uses wild-type ubiquitin and the seven "K-Only" mutants. Each reaction contains E1, E2, E3, substrate, and ATP in an appropriate buffer [33].

- Incubation: Incubate all reactions at 37°C for 30-60 minutes to allow the ubiquitination cascade to proceed.

- Reaction Termination: Terminate the reactions by adding SDS-PAGE sample buffer (for direct analysis by Western blot) or EDTA/DTT (if the products are needed for downstream enzymatic applications) [33].

- Analysis by Western Blot: Analyze the reaction products by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting using an anti-ubiquitin antibody.

The logic for data interpretation is visualized in the following workflow:

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for linkage determination. The use of ubiquitin mutants allows for the identification and verification of a specific ubiquitin chain linkage.

5. The Emergence of Branched Ubiquitin Chains

A paradigm-shifting discovery in the ubiquitin field is the existence and functional significance of branched ubiquitin chains, where a single ubiquitin monomer is modified on two different lysine residues, creating a forked structure [28]. These chains dramatically increase the complexity of the ubiquitin code and can transmit unique biological information.

Table 3: Examples of Branched Ubiquitin Chains and Their Synthesis

| Branched Chain Type | Reported Functions | Proposed Synthetic Machinery (E3 Enzymes) |

|---|---|---|

| K48/K63 | Can enhance NF-κB signaling or trigger proteasomal degradation, potentially depending on cellular context [21] [28]. | TRAF6 & HUWE1 collaboration; ITCH & UBR5 collaboration [28]. |

| K11/K48 | Assembled by the APC/C during mitosis, potentially enhancing substrate degradation efficiency [28]. | APC/C with E2 enzymes UBE2C and UBE2S [28]. |

| K29/K48 | Targets substrates for degradation in the yeast Ubiquitin Fusion Degradation (UFD) pathway [28]. | Ufd4 & Ufd2 collaboration in yeast [28]. |

Branched chains can be synthesized through the collaboration of two different E3 ligases, each specializing in a distinct linkage type. The sequential model of branched K48/K63 chain formation is illustrated below.

Diagram 3: Model for branched chain synthesis. Two E3 ligases collaborate to first build a homotypic chain and then initiate a branch with a different linkage.

6. The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Progress in deciphering atypical and branched ubiquitin chains relies on specialized research tools. The following table details key reagents that form the foundation for experimental work in this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Atypical Ubiquitin Chains

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function |

|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Immunodetection of specific ubiquitin chain topologies in Western blot, immunofluorescence, and immunoprecipitation experiments. |

| Ubiquitin Mutants (K-to-R, K-Only) | Essential for in vitro linkage determination assays (as detailed in Section 4) and for probing chain function in cellular studies [33]. |

| Recombinant E1, E2, and E3 Enzymes | Reconstitute specific ubiquitination pathways in vitro to dissect the biochemical activity and linkage specificity of enzymes of interest. |

| Activity-Based DUB Probes | Profile the activity and specificity of deubiquitinases that may target atypical ubiquitin chains. |

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Affinity reagents used to enrich polyubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates while protecting them from DUB-mediated cleavage. |

| DiUbiquitin & Polyubiquitin Chains | Defined linkage chains are used as standards in mass spectrometry, for in vitro binding assays, and to study DUB specificity. |

7. Conclusion

The landscape of ubiquitin signaling is far more complex and interconnected than the classical K48/K63 dichotomy suggests. The atypical K6, K11, K27, K29, and K33 chains, along with the emerging class of branched polymers, constitute a sophisticated regulatory network that controls pivotal cellular processes with high specificity. Their prominent roles in pathways such as innate immunity position them as attractive targets for therapeutic intervention. Future research, powered by the advanced tools and methodologies summarized in this guide, will continue to decode these complex signals, deepening our understanding of cell biology and opening new avenues for drug development.

From Bench to Drug Discovery: Tools and Techniques for Analyzing Chain-Specific Ubiquitination

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a crucial regulatory mechanism in eukaryotic cells, controlling protein stability, function, and localization through the post-translational modification of target proteins with polyubiquitin chains. The biological outcome of ubiquitination is primarily determined by the topology of the polyubiquitin chain attached to the substrate protein. Among the eight distinct ubiquitin linkage types, lysine 48 (K48)-linked chains are predominantly associated with targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation, whereas lysine 63 (K63)-linked chains primarily regulate non-proteolytic processes including signal transduction, protein trafficking, and inflammatory signaling pathways [2] [11]. The ability to specifically capture and analyze these distinct chain types is therefore fundamental to advancing our understanding of cellular regulation and for developing targeted therapeutic strategies.

Traditional methods for studying ubiquitination, including ubiquitin antibodies and mass spectrometry approaches, face significant limitations in specificity, throughput, and the ability to preserve native ubiquitin chain architecture [34]. The emergence of Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) has revolutionized this field by providing high-affinity tools specifically designed to capture polyubiquitinated proteins while protecting them from deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) and proteasomal degradation [34] [35]. This technology enables researchers to dissect the complex ubiquitin code with unprecedented specificity and sensitivity, particularly in the context of distinguishing between K48 and K63 polyubiquitin functions.

TUBE Technology: Mechanism and Advantages

Fundamental Principles of TUBEs

Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities are engineered protein domains composed of multiple ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domains arranged in tandem, which confer nanomolar affinity for polyubiquitin chains (Kd 1-10 nM) [34]. This structural configuration significantly enhances binding avidity compared to single UBA domains, enabling efficient capture of polyubiquitinated proteins even at low endogenous expression levels. TUBEs exist in two primary forms: pan-selective TUBEs that bind all polyubiquitin linkage types with high affinity, and chain-selective TUBEs that exhibit specificity for particular linkages such as K48, K63, or M1 (linear) chains [34] [35].

A critical advantage of TUBE technology is their ability to protect ubiquitin chains from deubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, even in the absence of the DUB and proteasome inhibitors normally required in ubiquitination studies [34]. This protective function preserves the native ubiquitin chain architecture during experimental procedures, providing a more accurate representation of cellular ubiquitination states than alternative methods.

Comparative Advantages Over Traditional Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Ubiquitin Capture Methodologies

| Method | Specificity | Sensitivity | Throughput Potential | Ability to Preserve Native Architecture | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TUBEs | High (especially chain-selective TUBEs) | Nanomolar affinity | High (adaptable to HTS formats) | Excellent (protects from DUBs/proteasomes) | Commercial cost |

| Ubiquitin Antibodies | Variable, often non-selective | Moderate | Low to moderate | Poor (requires inhibitors) | Artifacts, non-specific binding |

| Mass Spectrometry | High (with enrichment) | Variable | Low | Moderate (requires sample processing) | Labor-intensive, sophisticated instrumentation |

| Mutant Ubiquitin Expression | Linkage-specific | High | Low to moderate | Questionable (non-physiological) | May not reflect wild-type ubiquitin biology |

When compared to antibody-based approaches, TUBEs offer superior specificity and avoid the notorious non-selectivity associated with many commercial ubiquitin antibodies [34]. Unlike mass spectrometry-based methods, TUBE-based approaches are more readily adaptable to high-throughput screening (HTS) formats, making them particularly valuable for drug discovery applications [2] [36]. Furthermore, TUBEs circumvent the potential artifacts associated with exogenously expressed mutant ubiquitins, which may not accurately represent modifications involving wild-type ubiquitin [2].

Experimental Applications and Protocols

Chain-Specific Capture of Endogenous Protein Ubiquitination

The utility of chain-specific TUBEs for deciphering ubiquitin-dependent signaling pathways has been demonstrated in the context of inflammatory signaling mediated by Receptor-Interacting Serine/Threonine-Protein Kinase 2 (RIPK2). In response to inflammatory stimuli such as L18-MDP (a muramyldipeptide), RIPK2 undergoes K63-linked ubiquitination, which serves as a signaling scaffold for NF-κB activation [2] [11]. Conversely, RIPK2-directed PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) induce K48-linked ubiquitination of the same protein, targeting it for proteasomal degradation [2].

Table 2: Chain-Specific TUBE Capture of RIPK2 Ubiquitination

| Experimental Condition | K48-TUBE Capture | K63-TUBE Capture | Pan-TUBE Capture | Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L18-MDP stimulation | Minimal signal | Strong signal | Strong signal | NF-κB signaling activation |

| RIPK2 PROTAC treatment | Strong signal | Minimal signal | Strong signal | Proteasomal degradation |

| Ponatinib pre-treatment + L18-MDP | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected | Abrogated signaling |

This experimental paradigm illustrates how chain-selective TUBEs can differentiate context-dependent linkage-specific ubiquitination of an endogenous protein, providing critical insights into the molecular mechanisms governing inflammatory signaling and targeted protein degradation [2].

Detailed Protocol for Chain-Specific TUBE Assay

The following protocol outlines the key steps for performing chain-specific TUBE capture assays, adapted from methodologies successfully applied to RIPK2 ubiquitination studies [2] [11]:

Cell Treatment and Lysis:

- Culture THP-1 monocytic cells under standard conditions.

- Treat cells with either inflammatory stimuli (e.g., 200-500 ng/ml L18-MDP for 30-60 minutes) or degradation-inducing compounds (e.g., RIPK2 PROTAC).

- Lyse cells using a specialized lysis buffer optimized to preserve polyubiquitination (typically containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, supplemented with fresh 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide to inhibit DUBs).

TUBE-Mediated Capture:

- Coat 96-well plates or magnetic beads with chain-specific TUBEs (K48-TUBEs, K63-TUBEs, or pan-TUBEs as controls).

- Incubate clarified cell lysates (50-100 μg total protein) with TUBE-coated surfaces for 2-4 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation.

- Wash extensively with lysis buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

Detection and Analysis:

- Elute bound proteins with SDS-PAGE sample buffer or directly detect captured proteins while bound to TUBE-coated plates.

- Analyze ubiquitinated proteins by immunoblotting with target protein-specific antibodies (e.g., anti-RIPK2).

- For quantitative assessments, combine with luminescence-based detection systems for enhanced throughput and sensitivity [36].

This protocol can be adapted for high-throughput screening formats, making it particularly valuable for profiling compound libraries in drug discovery applications focused on ubiquitin pathway modulation [2] [36].

Signaling Pathways in K48 vs K63 Ubiquitination

The differential roles of K48 and K63 ubiquitin linkages are exemplified in their distinct signaling pathways, as illustrated below for inflammatory signaling and targeted protein degradation.

The K63 ubiquitination pathway initiates inflammatory signaling cascades through receptor activation and downstream kinase complex formation, ultimately leading to NF-κB activation and pro-inflammatory cytokine production [2] [11]. In contrast, the K48 ubiquitination pathway mediates targeted protein degradation through the proteasome, a mechanism exploited by PROTAC technology for therapeutic purposes [2].

Advanced Concepts: Branched Ubiquitin Chains

Beyond homotypic chains, recent research has revealed the existence and functional significance of branched ubiquitin chains, which incorporate multiple linkage types within a single ubiquitin polymer. Notably, K48/K63-branched chains have been identified as important regulatory elements in NF-κB signaling [21] [28] [37]. These branched chains are synthesized through the collaborative actions of distinct E3 ligases; for example, TRAF6 first builds K63-linked chains, which are subsequently modified by HUWE1 to add K48 branches [37].

The functional significance of K48/K63-branched chains includes both signal amplification and protection from deubiquitination. Specifically, the K48 branch can shield adjacent K63 linkages from cleavage by the deubiquitinating enzyme CYLD, thereby prolonging the inflammatory signal [37]. This discovery illustrates the sophisticated complexity of the ubiquitin code and suggests that branched chains represent a distinct regulatory layer beyond simple homotypic chains.

Current evidence suggests that branched ubiquitin chains may be preferentially recognized by specific effector proteins. Recent ubiquitin interactor screens have identified potential K48/K63 branch-specific binders, including histone ADP-ribosyltransferase PARP10/ARTD10, E3 ligase UBR4, and huntingtin-interacting protein HIP1 [21]. The emerging complexity of branched ubiquitin chains underscores the need for sophisticated capture tools like TUBEs that can preserve these delicate architectural features during experimental analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for TUBE-Based Ubiquitin Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Function | Key Features | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pan-Selective TUBEs | Broad capture of all polyubiquitin linkages | High affinity (Kd ~1-10 nM), protects from DUBs/proteasomes | Initial ubiquitination detection, total ubiquitin load assessment |

| K48-Selective TUBEs | Specific capture of K48-linked chains | Preferentially binds degradative ubiquitin signals | PROTAC validation, degradation pathway analysis |

| K63-Selective TUBEs | Specific capture of K63-linked chains | Preferentially binds signaling ubiquitin signals | Inflammatory signaling studies, DNA repair pathway analysis |

| M1-Selective TUBEs | Specific capture of linear ubiquitin chains | Binds M1-linked chains important in NF-κB signaling | Linear ubiquitin assembly complex (LUBAC) studies |

| TAMRA-Labeled TUBEs | Fluorescent detection of ubiquitin chains | Single fluorophore on fusion tag不影响ubiquitin binding | Imaging applications, ubiquitin localization studies |

| TUBE-Conjugated Magnetic Beads | Pulldown of ubiquitinated proteins | Magnetic separation for high-throughput processing | Proteomics sample preparation, target protein enrichment |

| DUB Inhibitors (NEM, CAA) | Preservation of ubiquitin chains | Prevent chain disassembly during processing; choice affects results | Required in traditional methods, less critical with TUBEs |

This toolkit enables researchers to design comprehensive experiments to decipher the ubiquitin code, from initial detection to functional characterization of specific chain types. The commercial availability of these reagents from specialized companies like LifeSensors has significantly increased their accessibility to the research community [34].

Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities represent a transformative technology in the field of ubiquitin research, providing unprecedented capabilities for the capture and analysis of linkage-specific polyubiquitin chains. The rigorous comparison presented in this guide demonstrates that TUBE technology outperforms traditional methods in specificity, sensitivity, and preservation of native ubiquitin architecture. The continued refinement of chain-specific TUBEs, coupled with their adaptation to high-throughput screening formats, positions this technology as an indispensable tool for advancing both basic research into the ubiquitin-proteasome system and drug discovery efforts focused on targeted protein degradation and modulation of ubiquitin-dependent signaling pathways.

Ubiquitination represents one of the most versatile post-translational modifications, with linkage-specific polyubiquitin chains encoding distinct cellular functions. Among these, K48- and K63-linked chains constitute the most abundant ubiquitin signals, directing proteasomal degradation and non-degradative signaling respectively. Advances in mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics have revolutionized our ability to decipher this ubiquitin code, enabling systematic characterization of endogenous ubiquitin linkages without genetic manipulation. This review comprehensively compares contemporary methodologies for identifying and quantifying K48 versus K63 polyubiquitin chains, highlighting enrichment strategies, quantitative approaches, and functional readouts. We provide detailed experimental protocols and synthesize performance data across platforms, offering researchers a framework for selecting appropriate techniques based on their specific research questions in ubiquitin signaling and drug development.

The ubiquitin system regulates nearly every cellular process in eukaryotes, from protein degradation to DNA repair and signal transduction [38]. This functional diversity stems from the structural complexity of ubiquitin modifications, which can form various chain architectures through different linkage types. K48-linked polyubiquitin chains predominantly target substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains primarily regulate non-proteolytic processes including kinase activation, protein trafficking, and DNA repair pathways [21] [37]. More recently, branched ubiquitin chains containing both K48 and K63 linkages have emerged as specialized signals with unique functional properties [28].

Deciphering this "ubiquitin code" requires precise tools for identifying linkage types, quantifying their abundance, and mapping their substrate proteins. Mass spectrometry has become the cornerstone technology for these analyses, with continuous methodological refinements enhancing sensitivity, specificity, and throughput. This review systematically compares the current mass spectrometry approaches for studying endogenous ubiquitin linkages, with particular emphasis on differentiating K48 and K63 chain functions in physiological and pathological contexts.

Methodological Approaches for Ubiquitin Linkage Analysis

Enrichment Strategies for Endogenous Ubiquitinated Proteins

Studying endogenous ubiquitination presents significant challenges due to low stoichiometry, chain heterogeneity, and the lability of isopeptide linkages. Successful analysis typically requires enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins prior to MS analysis, with several established methods available.

Ubiquitin-Binding Domain (UBD)-Based Enrichment: Tandem ubiquitin-binding entities (TUBEs) exhibit high affinity for polyubiquitin chains and protect them from deubiquitinase (DUB) activity during extraction. This approach preserves the endogenous ubiquitome without requiring genetic manipulation, making it suitable for clinical samples and animal tissues [39]. Commercial kits (e.g., LifeSensors UM420) leverage this technology for ubiquitome profiling [40].

Antibody-Based Enrichment: Linkage-specific antibodies enable direct isolation of particular chain types. Pan-ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., P4D1, FK1/FK2) enrich ubiquitinated proteins regardless of linkage type, while linkage-specific antibodies target particular architectures (e.g., K48- or K63-specific antibodies) [39]. This approach is particularly valuable for hypothesis-driven studies focusing on specific linkage types.

Considerations for Endogenous Studies: Unlike tagged ubiquitin expression systems, which may introduce artifacts, these methods maintain physiological relevance but often require optimization of lysis conditions and DUB inhibitors to preserve chain integrity [21] [7]. The choice between broad ubiquitome analysis and linkage-specific investigation dictates the optimal enrichment strategy.

Mass Spectrometry Platforms and Quantitative Methods

Modern ubiquitin research employs both discovery-based and targeted MS approaches, each with distinct strengths for linkage analysis.

Shotgun Proteomics: This discovery approach involves enzymatic digestion of enriched ubiquitinated proteins, liquid chromatography separation of peptides, and automated tandem mass spectrometry analysis. It enables untargeted identification of ubiquitination sites and linkage types through detection of signature diglycine (Gly-Gly) remnants on modified lysines [38] [39].

Targeted Quantification Methods: For precise quantification, targeted MS methods such as parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) and multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) offer superior sensitivity and reproducibility. These approaches typically use stable isotope-labeled internal standards for absolute quantification of specific ubiquitin linkages [37].

Stable Isotope Labeling: Metabolic labeling (e.g., SILAC) or chemical tagging (e.g., TMT, iTRAQ) enables multiplexed comparative analyses across multiple conditions. These approaches are particularly powerful for time-course experiments or drug treatment studies where relative quantification of linkage dynamics is required [38].

Table 1: Comparison of Mass Spectrometry Approaches for Ubiquitin Linkage Analysis

| Method | Principle | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shotgun Proteomics | LC-MS/MS analysis of digested ubiquitinated proteins | Ubiquitome mapping, discovery of novel ubiquitination sites | Untargeted, comprehensive coverage | Lower sensitivity for low-abundance modifications |

| Targeted MS (PRM/MRM) | Monitoring specific precursor-fragment transitions | Precise quantification of known ubiquitin linkages | High sensitivity and reproducibility | Requires prior knowledge of targets |

| Stable Isotope Labeling | Incorporation of heavy isotopes for quantification | Comparative studies across conditions | Multiplexing capability, reduced technical variance | Cost and complexity of sample processing |

| AQUA/PRM | Absolute quantification using synthetic heavy peptides | Absolute quantification of specific linkages | Highest quantification accuracy | Requires synthetic standards for each linkage |