Mapping the Ubiquitinome: Advanced Strategies for Identifying Ubiquitination Substrates in Tumor Samples

The identification of ubiquitination substrates in tumor samples is a critical frontier in cancer research, holding immense potential for understanding tumor biology, developing prognostic biomarkers, and discovering new therapeutic targets.

Mapping the Ubiquitinome: Advanced Strategies for Identifying Ubiquitination Substrates in Tumor Samples

Abstract

The identification of ubiquitination substrates in tumor samples is a critical frontier in cancer research, holding immense potential for understanding tumor biology, developing prognostic biomarkers, and discovering new therapeutic targets. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational role of ubiquitination in cancer, from established pancancer networks like the OTUB1-TRIM28-MYC axis to novel non-proteinaceous substrates. It details cutting-edge methodological toolkits, including BioE3 for specific E3 ligase substrate mapping, TUBEs for stabilizing labile ubiquitination events, and mass spectrometry-based proteomics. The content further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges inherent in working with clinical samples and offers a framework for validating and comparatively analyzing substrate specificity across different tumor contexts. The synthesis of these areas provides a actionable roadmap for advancing cancer diagnostics and drug discovery through the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

The Ubiquitin Landscape in Cancer: From Core Biology to Clinical Relevance

Ubiquitination as a Pivotal Post-Translational Modification in Cellular Homeostasis and Oncogenesis

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates the "quantity" and "quality" of diverse proteins, serving to ensure cellular homeostasis and proper life activities [1]. This process involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin, a highly conserved 76-amino acid protein, to substrate proteins via a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes [1]. The human genome encodes two E1 enzymes, approximately 40 E2 enzymes, and over 600 E3 ligases, which provide remarkable specificity in substrate recognition [2] [1]. This modification is reversible through the action of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), of which approximately 100 exist in humans, creating a dynamic regulatory system [2] [1].

The complexity of ubiquitin signaling arises from the diversity of ubiquitin chain topologies. Ubiquitin can modify substrates as a single moiety (monoubiquitination), as multiple single units (multi-monoubiquitination), or as polymers (polyubiquitination) formed through linkage to any of seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or the N-terminal methionine (M1) of ubiquitin itself [2] [1]. Each linkage type can encode distinct functional consequences for the modified substrate. K48-linked chains primarily target substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains typically regulate non-proteolytic processes such as kinase activation, DNA repair, and endocytosis [2] [1]. The maintenance of ubiquitination homeostasis through the orchestrated interplay of conjugating and deconjugating enzymes is essential for normal cellular function, and its dysregulation represents a hallmark of numerous pathologies, particularly cancer [2] [1].

Ubiquitination in Oncogenesis: Mechanisms and Pathways

Dysregulation of the ubiquitin system contributes profoundly to tumorigenesis through multiple mechanisms, including altered tumor metabolism, modulation of the immunological tumor microenvironment, and maintenance of cancer stem cell (CSC) stemness [1]. In tumor metabolism, ubiquitination regulates key signaling nodes in critical pathways. For instance, ubiquitination of components in the mTORC1, AMPK, and PTEN-AKT signaling pathways significantly influences cancer cell metabolism and growth [1]. Prominent oncoproteins and tumor suppressors such as c-Myc, p53, RagA, mTOR, PTEN, and AKT are all subject to regulatory ubiquitination, highlighting the central role of this modification in cancer-relevant signaling networks [1].

The immunological tumor microenvironment is similarly regulated by ubiquitin-dependent mechanisms. Ubiquitination events in Toll-like receptor (TLR), RIG-I-like receptor (RLR), and STING-dependent signaling pathways modulate immune responses within the tumor microenvironment, influencing cancer progression and therapeutic responses [1]. Additionally, the maintenance of CSC stemness—a property linked to tumor initiation, metastasis, and therapy resistance—is governed by ubiquitination of core stem cell regulators. The pluripotency factors Nanog, Oct4, and Sox2, as well as components of the Wnt and Hippo-YAP signaling pathways, are regulated by ubiquitination, providing a mechanistic link between the ubiquitin system and cancer stemness [1].

Table 1: Key Ubiquitination-Regulated Processes in Oncogenesis

| Process in Oncogenesis | Key Ubiquitination Targets | Biological Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor Metabolism | RagA, mTOR, PTEN, AKT, c-Myc, p53 | Altered activity of mTORC1, AMPK, and PTEN-AKT signaling pathways |

| Immunological Tumor Microenvironment | Components of TLR, RLR, and STING pathways | Modulation of immune responses within the tumor microenvironment |

| Cancer Stem Cell Stemness | Nanog, Oct4, Sox2, Wnt and Hippo-YAP pathway components | Maintenance of stemness properties supporting tumor initiation and metastasis |

Recent multi-omics approaches have further elucidated the prognostic value of ubiquitination signatures in cancer. In lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), ubiquitin-related genes have been used to construct robust risk models that predict patient survival, immune profiles, and drug sensitivity [3]. These models have identified specific ubiquitination-related genes (B4GALT4, DNAJB4, GORAB, HEATR1, LPGAT1, FAT1, GAB2, MTMR4, and TCP11L2) as independent prognostic markers, with high-risk patients showing significantly poorer overall survival [3]. Functional validation has confirmed that knockdown of HEATR1 significantly reduces LUAD cell viability, migration, and invasion, establishing its role as a driver of oncogenic phenotypes [3].

Experimental Approaches for Identifying Ubiquitination Substrates in Tumor Samples

The identification of ubiquitination substrates in tumor tissues presents significant technical challenges due to the low stoichiometry of ubiquitination, the diversity of ubiquitin chain architectures, and the dynamic nature of this modification [2]. Several enrichment strategies have been developed to overcome these challenges, each with distinct advantages and limitations for tumor sample analysis.

Antibody-Based Enrichment Methods

Anti-ubiquitin remnant antibody-based enrichment represents one of the most powerful approaches for mapping ubiquitination sites in clinical samples. This method utilizes antibodies specifically recognizing the di-glycine (K-ε-GG) remnant left on trypsinized peptides derived from ubiquitinated proteins [4] [5]. The workflow involves tissue protein extraction, tryptic digestion, enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides using anti-K-ε-GG antibodies, and subsequent liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis [4]. This approach has been successfully applied to human pituitary adenoma tissues, identifying 158 ubiquitination sites on 108 proteins and revealing altered ubiquitination in signaling pathways including PI3K-AKT and Hippo [4]. A key advantage of this method is its applicability to clinical samples without genetic manipulation, making it ideal for studying human tumor tissues [2] [4].

Ubiquitin-Binding Domain Based Approaches

Ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) from various proteins can be leveraged to enrich ubiquitinated substrates. Recently, a high-affinity UBD from Orientia tsutsugamushi (OtUBD) has been developed that exhibits nanomolar affinity for ubiquitin [6]. The OtUBD resin can enrich both mono- and poly-ubiquitinated proteins from complex lysates and can be used under both native and denaturing conditions [6]. Under denaturing conditions, OtUBD specifically enriches covalently ubiquitinated proteins, while under native conditions it also co-purifies proteins that interact with ubiquitin or ubiquitinated proteins [6]. This method does not require genetic manipulation and works effectively with mammalian cell lysates, making it suitable for tumor tissue analysis.

Ubiquitin Tagging Strategies

The expression of epitope-tagged ubiquitin (e.g., His-, FLAG-, or HA-tagged) enables purification of ubiquitinated proteins using affinity resins directed against the tag [7]. This approach typically involves generating cell lines or animal models stably expressing tagged ubiquitin, followed by affinity purification under denaturing conditions to minimize non-specific interactions [2] [7]. While this method allows stringent purification and has been successfully applied to identify hundreds to thousands of ubiquitination sites in model systems, its application to human tumor tissues is limited by the inability to genetically tag endogenous ubiquitin in clinical samples [2] [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Ubiquitinated Protein Enrichment Methods

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Suitable for Tumor Tissues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody-Based (K-ε-GG) | Antibodies recognize GG-remnant on tryptic peptides | High specificity; works directly with clinical samples; identifies modification sites | Cannot detect non-lysine ubiquitination; expensive antibodies | Yes |

| UBD-Based (OtUBD) | High-affinity ubiquitin-binding domain enriches ubiquitinated proteins | Works with native and denatured conditions; captures all ubiquitin conjugates | May co-purify ubiquitin-interacting proteins under native conditions | Yes |

| Tagged Ubiquitin | Epitope-tagged ubiquitin expressed in cells | High purity and yield; well-established protocols | Requires genetic manipulation; not applicable to human tissues | Limited to engineered models |

Protocol: Ubiquitinome Analysis of Tumor Tissues Using Anti-K-ε-GG Antibody Enrichment

This protocol describes a comprehensive approach for identifying and quantifying ubiquitination sites in human tumor tissues using anti-K-ε-GG antibody-based enrichment and LC-MS/MS analysis, adapted from methodologies successfully applied to lung adenocarcinoma and pituitary adenoma tissues [4] [5].

Sample Preparation and Protein Extraction

Tissue Homogenization: Freshly frozen tumor and matched control tissues (50-100 mg) are cryogenically pulverized using a mortar and pestle cooled with liquid nitrogen. Alternatively, tissue samples can be cut into small pieces on dry ice.

Protein Extraction: Transfer powdered tissue to a pre-chilled tube containing four volumes of lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 1% protease inhibitor cocktail, 50 μM PR-619 deubiquitinase inhibitor, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) [5]. Homogenize using a pre-cooled Dounce homogenizer or by sonication on ice (3 × 10-second pulses at 20% amplitude with 30-second intervals on ice).

Clarification: Centrifuge lysates at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Transfer supernatant to a new tube and determine protein concentration using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay.

Protein Precipitation and Denaturation: Add trichloroacetic acid (TCA) to a final concentration of 20% to precipitate proteins. Incubate for 2 hours at 4°C, then centrifuge at 4,500 × g for 5 minutes. Wash pellet twice with ice-cold acetone and air-dry.

Protein Digestion and Peptide Cleanup

Reduction and Alkylation: Dissolve protein pellet in 200 mM tetraethylammonium bromide (TEAB) buffer. Add dithiothreitol (DTT) to a final concentration of 5 mM and incubate at 56°C for 30 minutes. Then add iodoacetamide to a final concentration of 11 mM and incubate for 15 minutes at room temperature in the dark.

Trypsin Digestion: Add sequencing-grade trypsin at a 1:50 (enzyme:protein) ratio and digest overnight at 37°C with gentle agitation.

Peptide Desalting: Desalt peptides using C18 solid-phase extraction columns according to manufacturer's instructions. Lyophilize desalted peptides and store at -80°C until enrichment.

Enrichment of Ubiquitinated Peptides

Peptide Reconstitution: Dissolve dried peptides in IP buffer (100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5% NP-40, pH 8.0).

Antibody Enrichment: Incubate peptides with anti-K-ε-GG antibody-conjugated beads (commercially available) overnight at 4°C with gentle rotation. Typically, 2-5 mg of antibody-conjugated resin is used per 10-20 mg of starting peptide material.

Washing: Wash resin four times with IP buffer and twice with deionized water to remove non-specifically bound peptides.

Elution: Elute bound peptides with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Collect eluate and lyophilize.

LC-MS/MS Analysis and Data Processing

Liquid Chromatography: Reconstitute peptides in 0.1% formic acid and separate using a nanoflow UHPLC system with a C18 reversed-phase column (75 μm × 25 cm) with a 120-minute gradient from 2% to 30% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze eluting peptides using a timsTOF Pro or similar mass spectrometer operating in data-dependent acquisition mode. MS1 spectra should be acquired at 60,000 resolution, with MS2 spectra triggered for the top 20 most intense precursors.

Database Searching: Process raw files using MaxQuant (version 1.6.6.0 or later) against the appropriate UniProt database. Search parameters should include: trypsin/P as protease with up to 4 missed cleavages; carbamidomethylation of cysteine as fixed modification; oxidation of methionine and N-terminal acetylation as variable modifications; and GlyGly (K) as a fixed modification for ubiquitination sites.

False Discovery Rate (FDR) Control: Set FDR thresholds to 1% at both peptide and protein levels using a target-decoy approach.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies in Tumor Samples

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Examples/Details |

|---|---|---|

| Deubiquitinase Inhibitors | Prevent loss of ubiquitination during sample processing | PR-619 (broad-spectrum DUB inhibitor), N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevent protein degradation during extraction | EDTA-free cocktails for metal-free MS compatibility |

| Anti-K-ε-GG Antibodies | Specific enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides | Commercial kits (PTMScan); recognize diglycine remnant after trypsinization |

| Ubiquitin-Binding Domains | Enrichment of intact ubiquitinated proteins | OtUBD resin; TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) |

| Tag-Specific Resins | Purification of tagged ubiquitin conjugates | Ni-NTA for His-tags; Anti-FLAG/HA affinity gels |

| Trypsin/Lys-C Mix | Protein digestion for MS analysis | Sequencing grade, MS-compatible |

| C18 Desalting Columns | Peptide cleanup prior to enrichment | StageTips; commercial spin columns |

| UHPLC-MS Systems | High-sensitivity peptide separation and detection | nanoElute systems coupled to timsTOF Pro or Orbitrap instruments |

Data Analysis and Bioinformatics Approaches

The analysis of ubiquitinome data requires specialized bioinformatics approaches to extract biological insights from complex mass spectrometry datasets. Following database searching, several analytical steps are essential:

Ubiquitination Site Localization: Use software such as MaxQuant to calculate localization probabilities for ubiquitination sites. Only sites with localization probability >0.75 should be considered for further analysis.

Differential Ubiquitination Analysis: Apply statistical tests (e.g., Student's t-test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction) to identify ubiquitination sites significantly altered between tumor and control tissues. A fold-change threshold of >1.5 or <-1.5 with an adjusted p-value <0.05 is commonly used.

Motif Analysis: Use motif-x or similar algorithms to identify conserved amino acid sequences surrounding ubiquitination sites, which may reveal sequence preferences for specific E3 ligases.

Pathway and Network Analysis: Input significantly altered ubiquitinated proteins into pathway analysis tools such as DAVID or KEGG to identify enriched biological pathways. As demonstrated in pituitary adenoma studies, ubiquitination frequently affects signaling pathways including PI3K-AKT, Hippo, ribosome, and nucleotide excision repair [4].

Integration with Transcriptomic and Proteomic Data: Combine ubiquitinome data with matching transcriptome and proteome datasets to determine whether changes in ubiquitination occur independently of or correlate with changes in protein abundance or mRNA expression.

Therapeutic Targeting of the Ubiquitin System in Oncology

The central role of ubiquitination in oncogenesis has made components of the ubiquitin system attractive therapeutic targets. Several classes of targeted agents have been developed:

Proteasome Inhibitors: Bortezomib, carfilzomib, oprozomib, and ixazomib target the 20S proteasome catalytic core, preventing degradation of ubiquitinated proteins and inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress in cancer cells. These agents have achieved tangible success in multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma [1].

E1 Enzyme Inhibitors: MLN7243 and MLN4924 (pevonedistat) inhibit the NEDD8-activating enzyme, which regulates the activity of cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin ligases. MLN4924 has shown promising anti-tumor activity in preclinical models and clinical trials [1].

E2 Enzyme Inhibitors: Compounds such as Leucettamol A and CC0651 target specific E2 enzymes, disrupting the transfer of ubiquitin to substrates [1].

E3 Ligase-Targeting Agents: Nutlin and MI-219 inhibit the MDM2 E3 ligase, activating p53 tumor suppressor function. Additionally, proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) represent a novel approach that hijacks E3 ligases to selectively degrade target proteins [1].

Deubiquitinase Inhibitors: Compounds G5 and F6 target specific DUBs, preventing removal of ubiquitin from substrates and altering their stability or function [1].

The integration of ubiquitinome analysis with drug sensitivity profiling has revealed promising correlations that could guide therapeutic decisions. In LUAD, drug sensitivity studies have identified that medications including TAE684, Cisplatin, and Midostaurin exhibit significant negative correlations with ubiquitination-based risk scores, suggesting potential efficacy in high-risk patients [3]. These findings highlight the potential of ubiquitination signatures as biomarkers for treatment selection and drug development.

Ubiquitination represents a fundamental regulatory mechanism that maintains cellular homeostasis while serving as a critical driver of oncogenesis when dysregulated. The development of sophisticated proteomic methodologies, particularly anti-K-ε-GG antibody-based enrichment coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry, has enabled comprehensive mapping of the ubiquitinome in human tumor tissues. These approaches have revealed ubiquitination-mediated regulation of key oncogenic processes including tumor metabolism, immune microenvironment modulation, and cancer stem cell maintenance. The continued refinement of ubiquitinome analysis protocols and the development of targeted therapies against specific components of the ubiquitin system hold significant promise for advancing cancer diagnostics and therapeutics. Integration of ubiquitinome data with other omics datasets and clinical outcomes will further enhance our understanding of the prognostic and predictive value of ubiquitination signatures across cancer types.

Application Note & Protocol

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that orchestrates cellular homeostasis and oncogenic pathways, yet it remains underexplored as a pancancer regulatory hub [8]. This application note details comprehensive methodologies and insights from a large-scale study that integrated data from 4,709 patients across 26 cohorts spanning five solid tumor types: lung cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, urothelial cancer, and melanoma [8]. The constructed pancancer ubiquitination regulatory network reveals important pathways and offers insights into predicting patient prognosis and understanding biological mechanisms, with particular focus on identifying ubiquitination substrates in tumor samples.

Key Quantitative Findings

Table 1: Patient Cohort Distribution Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Number of Patients | Data Source | Notable Histological Subtypes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Cancer | 650 (ADC), 840 (SQC) | TCGA | ADC, SQC, NEC |

| Esophageal Cancer | 179 (SQC), 37 (ADC) | GSE53625, GSE183924 | ADC, SQC |

| Cervical Cancer | 64 (ADC), 221 (SQC) | GSE44001, GSE56303 | ADC, SQC |

| Urothelial Carcinoma | 404 | TCGA | NMIBC, MIBC |

| Melanoma | 57 | GSE91061 | - |

| Total | 4,709 | 26 cohorts |

Table 2: Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Signature (URPS) Performance

| Assessment Metric | Finding | Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Risk Stratification | Effectively stratified patients into high-risk and low-risk groups | Distinct survival outcomes across all analyzed cancers |

| Immunotherapy Prediction | Novel biomarker for predicting immunotherapy response | Identifies patients more likely to benefit from immunotherapy |

| Key Molecular Axis | OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination modulates MYC pathway | Influences patient prognosis and histological fate |

| Single-cell Resolution | Enables precise classification of distinct cell types | Associated with macrophage infiltration in TME |

Experimental Protocols

Ubiquitination Regulatory Network Construction

Protocol Title: Construction of Pancancer Ubiquitination Regulatory Network

Principle: This protocol outlines the integration of multi-cohort transcriptomic data to map molecular profiles to ubiquitination interaction networks, enabling identification of key regulatory nodes and pathways across cancer types.

Materials:

- RNA-seq data from TCGA and GEO databases

- Clinical data from 26 patient cohorts

- Computational resources for large-scale bioinformatic analysis

- R statistical environment with appropriate packages

Procedure:

- Data Collection and Integration

- Obtain RNA-seq data and clinicopathological features from TCGA for lung cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, urothelial carcinoma, and melanoma

- Include datasets with at least five patients classified as classic pathological subtypes (SQC or ADC)

- Standardize correlation coefficient matrix through significance screening (p-value < 0.05)

Ubiquitination Score Calculation

- Analyze ubiquitination scores for prognostic significance

- Screen downstream genes using LASSO algorithm to identify key prognosis-associated genes

- Perform functional enrichment and protein-protein interaction analyses

Validation Framework

- Validate findings using independent patient cohorts, cell line models, and in vivo experiments

- Utilize transcriptomic data from non-small cell lung cancer, small cell lung cancer, and non-tumoral lung tissues from GEO dataset GSE30219

- Incorporate transcriptomic profiles of lung cancer patients undergoing immunotherapy from GSE135222 and GSE126044 datasets

Troubleshooting:

- Ensure consistent normalization across datasets from different sources

- Address batch effects through appropriate statistical methods

- Verify histological classification consistency across different grading systems

Ubiquitinomics Profiling in Tumor Tissues

Protocol Title: Label-Free Quantitative Identification of Abnormally Ubiquitinated Proteins in Tumor Tissues

Principle: This mass spectrometry-based protocol enables comprehensive identification of differentially ubiquitinated proteins (DUPs) and ubiquitination sites in clinical tumor samples, providing insights into ubiquitination-involved molecular network alterations.

Materials:

- Fresh frozen tumor tissues and matched controls

- Anti-ubiquitin antibody (specific anti-K-ε-GG group)

- Urea lysis buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 100 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF)

- C18 Cartridges (Empore SPE Cartridges C18) for desalting

- LC-MS/MS system

Procedure:

- Tissue Processing and Protein Extraction

- Mix multiple patient tissue samples (150 mg per patient, n=5) to create pooled LSCC and control samples

- Wash tissues in 0.9% NaCl solution to remove blood contamination

- Homogenize in urea lysis buffer and sonicate (80 W, 10 sec, interval 15 sec, 10×)

- Centrifuge at 15,000×g for 20 minutes at 4°C and collect supernatant

Trypsin Digestion and Peptide Preparation

- Treat samples with DTT (final concentration 10 mM) at 600 rpm, 37°C for 1.5 hours

- Alkylate with iodoacetamide (final concentration 50 mM) in dark for 30 minutes

- Digest with trypsin (trypsin:protein = 1:50 wt:wt) at 37°C for 15-18 hours

- Acidify with TFA (final TFA = 0.1%), adjust to pH ≤ 3

- Desalt tryptic peptides using C18 Cartridges and lyophilize

Ubiquitinated Peptide Enrichment and LC-MS/MS Analysis

- Enrich ubiquitinated peptides using anti-K-ε-GG antibody-based enrichment

- Perform LC-MS/MS analysis to identify DUPs and ubiquitination sites

- Identify ubiquitination motifs through sequence analysis

Data Integration and Validation

- Integrate ubiquitinomics data with transcriptomics data from TCGA

- Perform protein-protein interaction network analysis to identify hub molecules

- Conduct survival analysis to identify prognosis-related mRNAs

- Validate key findings through proteasome inhibition experiments

Troubleshooting:

- Optimize antibody enrichment efficiency through positive controls

- Verify ubiquitination site identification through synthetic peptide validation

- Address sample heterogeneity through adequate sample pooling and replication

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Network Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Enrichment Tools | Anti-K-ε-GG antibody | Immunoaffinity enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides for MS analysis |

| Mass Spectrometry | LC-MS/MS systems | Identification and quantification of ubiquitination sites |

| Computational Tools | UbiBrowser | Prediction of E3/DUB-substrate interactions |

| Database Resources | TCGA, GEO | Access to multi-omics cancer data |

| E3 Ligase Targets | TRIM28, NEDD4L, TRIM2 | Key regulators of ubiquitination in cancer pathways |

| Validation Reagents | siRNA/shRNA for OTUB1, TRIM28 | Functional validation of ubiquitination regulators |

Discussion and Clinical Implications

This comprehensive analysis demonstrates that the OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination regulatory enzyme influences the histological fate of cancer cells by modulating MYC and its downstream pathways and altering oxidative stress, ultimately leading to immunotherapy resistance and poor prognosis in patients [8]. The established ubiquitination-related prognostic signature (URPS) provides a novel strategy for predicting overall survival in pancancer patients receiving surgery or immunotherapy, with significant implications for personalized treatment approaches.

The study further reveals that ubiquitination score positively correlates with squamous or neuroendocrine transdifferentiation in adenocarcinoma, providing mechanistic insights into cancer plasticity and progression [8]. These findings unveil a novel strategy for drug development targeting traditionally "undruggable" targets like MYC, whereby ubiquitination regulatory modifiers for such targets can be screened through the constructed pancancer ubiquitination regulatory network, providing new therapeutic alternatives for improving immunotherapy efficacy and patient prognosis.

The integration of multi-cohort analyses across 4,709 patients has enabled the construction of a comprehensive pancancer ubiquitination regulatory network that offers significant insights into prognostic prediction, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic targeting. The detailed protocols provided herein facilitate the replication and extension of these findings, supporting ongoing efforts to decipher the complex role of ubiquitination networks in cancer biology and treatment response.

Ubiquitination is a critical post-translational modification that orchestrates cellular homeostasis and oncogenic pathways, serving as a pivotal regulatory hub in cancer biology [8] [9]. The reversible and enzymatically regulated process of ubiquitination plays a complex role in cancer development, progression, metabolic reprogramming, and immunotherapy efficacy [8]. Among the intricate network of ubiquitination regulators, the OTUB1-TRIM28-MYC axis has emerged as a crucial pathway influencing tumor progression and patient outcomes across multiple cancer types. This application note details the mechanisms, experimental evidence, and methodological protocols for investigating this pathway within the broader context of identifying ubiquitination substrates in tumor samples.

The OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination regulatory enzyme significantly influences the histological fate of cancer cells by modulating MYC and its downstream pathways, altering oxidative stress, ultimately leading to immunotherapy resistance and poor prognosis in patients [8]. Understanding this axis provides not only prognostic insights but also unveils a novel strategy for drug development targeting traditionally "undruggable" targets like MYC through screening ubiquitination regulatory modifiers [8].

Mechanistic Insights into the OTUB1-TRIM28-MYC Axis

Molecular Regulation

The OTUB1-TRIM28-MYC axis represents a sophisticated regulatory circuit where ubiquitination dynamics control oncogenic signaling:

OTUB1 Functional Mechanisms: OTUB1, an OTU-family deubiquitinase, antagonizes ubiquitination through two distinct mechanisms: (1) direct deubiquitination via its catalytic activity, and (2) non-canonical inhibition of ubiquitin transfer by binding to and blocking ubiquitin-conjugated E2 enzymes [10]. OTUB1 exhibits strong preference for Lys48-linked polyubiquitin chains, which are primarily associated with proteasomal degradation [10].

TRIM28 Multifunctionality: TRIM28 (also known as TIF1β and KAP1) contains an N-terminal TRIM structure and a C-terminal PHD-Bromo dual epigenetic reader domain, functioning as both a canonical RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligase and an E3 SUMO ligase under certain conditions [11]. The B-box2 domain of TRIM28 is necessary for its interaction with PD-L1 [11].

MYC Pathway Modulation: The OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination regulatory enzyme influences the MYC pathway, altering oxidative stress and contributing to immunotherapy resistance [8]. Ubiquitination score positively correlates with squamous or neuroendocrine transdifferentiation in adenocarcinoma, with MYC serving as a central downstream effector [8].

Role in Tumor Immune Regulation

The axis significantly impacts tumor immune evasion through multiple mechanisms:

PD-L1 Stabilization: TRIM28 directly binds to and stabilizes PD-L1 by inhibiting PD-L1 ubiquitination while promoting PD-L1 SUMOylation [11]. TRIM28 depletion significantly shortens the half-life of PD-L1, indicating its crucial role in PD-L1 protein stabilization in cancer cells [11].

Immune Pathway Activation: TRIM28 facilitates K63 polyubiquitination of TBK1, activating TBK1-IRF1 and TBK1-mTOR pathways, resulting in enhanced PD-L1 transcription [11]. This creates a dual mechanism of PD-L1 regulation at both protein stability and transcriptional levels.

Table 1: Functional Roles of Key Components in the OTUB1-TRIM28-MYC Axis

| Component | Molecular Function | Role in Cancer | Regulatory Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| OTUB1 | Deubiquitinase | Oncogenic | Inhibits substrate ubiquitination via catalytic activity and E2 blockade [10] |

| TRIM28 | E3 ubiquitin/SUMO ligase | Oncogenic | Stabilizes PD-L1, activates TBK1 pathways [11] |

| MYC | Transcription factor | Oncogenic | Downstream effector of OTUB1-TRIM28 regulation [8] |

| PD-L1 | Immune checkpoint | Immunosuppression | Stabilized by TRIM28-mediated inhibition of ubiquitination [11] |

Quantitative Analysis of Pathway Significance

Prognostic Implications

Comprehensive studies across multiple cancer types have established the clinical significance of the OTUB1-TRIM28-MYC axis:

Pancancer Ubiquitination Signature: Analysis of 4,709 patients from 26 cohorts across five solid tumor types (lung cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, urothelial cancer, and melanoma) identified a conserved ubiquitination-related prognostic signature (URPS) that effectively stratified patients into high-risk and low-risk groups with distinct survival outcomes [8].

Gastric Cancer Validation: In a cohort of 466 gastric cancer patients, high TRIM28 expression correlated with poor survival, consistent with observations in publicly available databases [11]. Ectopic TRIM28 expression facilitated tumor growth, increased PD-L1 expression, and suppressed T cell activation in mouse models [11].

Therapeutic Response Prediction: The URPS serves as a novel biomarker for predicting immunotherapy response, with potential to identify patients more likely to benefit from immunotherapy in clinical settings [8].

Table 2: Clinical Correlations of OTUB1-TRIM28-MYC Axis Components Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Sample Size | Key Finding | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pancancer Cohort | 4,709 patients | URPS stratification of high/low risk groups | Distinct survival outcomes (p<0.05) [8] |

| Gastric Cancer | 466 patients | High TRIM28 = poor survival | Consistent across databases [11] |

| Multiple Solid Tumors | 26 cohorts | URPS predicts immunotherapy response | Potential for clinical application [8] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Identifying Ubiquitination Substrates in Tumor Samples

Objective: To identify and validate ubiquitination substrates within the OTUB1-TRIM28-MYC axis using patient-derived tumor samples.

Materials:

- Fresh or snap-frozen tumor tissues and matched normal adjacent tissues

- Lysis buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, supplemented with protease inhibitors (complete Mini, Roche) and deubiquitinase inhibitors (N-ethylmaleimide, 10 mM)

- Protein A/G agarose beads (Pierce)

- Anti-TRIM28 antibody (Abcam, ab22553), Anti-OTUB1 antibody (Cell Signaling, 3744S), Anti-c-MYC antibody (Santa Cruz, sc-40)

- Ubiquitin enrichment matrix: TUBE2 (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities, LifeSensors)

- MG132 proteasome inhibitor (10 µM, Selleckchem)

Procedure:

- Tissue Processing: Homogenize 50-100 mg tumor tissue in 1 mL lysis buffer using a Dounce homogenizer. Centrifuge at 15,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C and collect supernatant.

- Protein Concentration Determination: Quantify protein concentration using BCA assay. Use 2 mg total protein for each immunoprecipitation.

- Ubiquitinated Protein Enrichment: Incubate lysate with TUBE2 agarose (25 µL bead volume) for 4 hours at 4°C with gentle rotation.

- Immunoprecipitation: For specific protein interactions, pre-clear lysate with protein A/G beads for 30 minutes. Incubate with primary antibody (1-2 µg) overnight at 4°C, then with protein A/G beads for 2 hours.

- Washing and Elution: Wash beads 3 times with lysis buffer. Elute proteins with 2× Laemmli buffer at 95°C for 10 minutes.

- Western Blot Analysis: Resolve proteins by SDS-PAGE, transfer to PVDF membrane, and probe with antibodies against target proteins and ubiquitin.

Validation:

- Confirm ubiquitination by probing with anti-ubiquitin antibody (P4D1, Santa Cruz)

- Use deubiquitinase treatment as negative control: incubate samples with USP2 catalytic domain (200 nM) for 1 hour at 37°C before analysis

Protocol 2: Functional Validation of OTUB1-TRIM28 Interaction

Objective: To characterize the functional consequences of OTUB1-TRIM28 interaction on MYC pathway activity.

Materials:

- Cancer cell lines (MGC-803, SGC-7901 gastric cancer cells recommended)

- Plasmid constructs: WT OTUB1, catalytic mutant OTUB1 (C91S), WT TRIM28, TRIM28 deletion mutants

- siRNA targeting OTUB1, TRIM28, and non-targeting control

- Dual-luciferase reporter system (Promega)

- MYC activity reporter plasmid

- Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) kit (Millipore)

Procedure:

- Genetic Manipulation:

- Transfect cells with siRNA (50 nM) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX or plasmids (2 µg) using Lipofectamine 3000 according to manufacturer's protocol

- Allow 48-72 hours for protein knockdown or 24 hours for overexpression before analysis

Co-immunoprecipitation Assay:

- Lyse transfected cells in IP lysis buffer

- Incubate 1 mg protein with anti-TRIM28 antibody overnight at 4°C

- Capture immune complexes with protein A/G beads

- Analyze by Western blot with anti-OTUB1 and anti-TRIM28 antibodies

MYC Pathway Activity Assessment:

- Co-transfect MYC reporter plasmid with Renilla control

- Measure luciferase activity 24 hours post-transfection using dual-luciferase system

- Perform ChIP assay using anti-MYC antibody to assess MYC binding to target promoters

Functional Phenotyping:

- Assess cell proliferation using MTT assay at 24, 48, and 72 hours

- Evaluate apoptosis by Annexin V/propidium iodide staining after 48 hours of treatment

- Analyze cell cycle distribution by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry

Pathway Visualization

Diagram 1: OTUB1-TRIM28-MYC Axis in Tumorigenesis. This pathway visualization illustrates the molecular mechanisms through which OTUB1 and TRIM28 coordinately regulate MYC stability and PD-L1 expression to promote tumor progression and immune evasion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating the OTUB1-TRIM28-MYC Axis

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | Anti-TRIM28 (Abcam ab22553), Anti-OTUB1 (CST 3744S), Anti-c-MYC (Santa Cruz sc-40) | Western blot, IP, IHC | Validated for multiple applications including ubiquitination studies |

| Ubiquitination Tools | TUBE2 Agarose (LifeSensors), HA-Ubiquitin plasmid, MG132 proteasome inhibitor | Ubiquitin enrichment, assays | TUBE2 preserves labile ubiquitinated species during extraction |

| Genetic Tools | OTUB1 siRNA (Santa Cruz sc-76310), TRIM28 CRISPR/Cas9 KO plasmid (Origene) | Functional studies | Enable loss-of-function and gain-of-function experiments |

| Cell Lines | MGC-803, SGC-7901 gastric cancer lines; YCCEL1 EBVaGC line | Mechanistic studies | Endogenous expression of pathway components |

| Activity Reporters | MYC luciferase reporter, PD-L1 promoter construct | Pathway activity measurement | Quantify functional output of the axis |

The OTUB1-TRIM28-MYC axis represents a clinically significant ubiquitination pathway with broad implications for tumor progression and patient prognosis. The experimental protocols detailed herein provide a standardized methodology for investigating this pathway in tumor samples, enabling researchers to validate ubiquitination substrates and their functional consequences. The conserved nature of this regulatory module across multiple cancer types highlights its fundamental importance in oncogenesis and positions it as a promising target for therapeutic intervention.

Future research directions should focus on developing small molecule inhibitors targeting OTUB1's non-canonical E2 inhibition function and TRIM28's substrate recognition domains. Additionally, combining OTUB1/TRIM28 targeting with immune checkpoint blockade may yield synergistic therapeutic effects, particularly in tumors with MYC pathway activation. The methodologies and reagents outlined in this application note provide a foundation for these advanced investigations into ubiquitination-mediated oncogenesis.

The ubiquitin system is a central regulator of eukaryotic homeostasis, historically known for modifying protein substrates to govern virtually all aspects of protein-mediated cellular functions [12]. However, the substrate realm of ubiquitination has recently expanded beyond proteins to include non-proteinaceous matter, opening a new chapter in ubiquitin biology [12]. This paradigm shift reveals that ubiquitin can be transferred to diverse biomolecules including lipids, carbohydrates, nucleic acids, and metabolites [12]. Most remarkably, recent research demonstrates that certain ubiquitin ligases can even modify exogenous, drug-like small molecules [12]. This article explores these expanding substrate boundaries within the specific context of identifying ubiquitination substrates in tumor samples, providing application notes and experimental protocols to advance research in cancer metabolism and therapeutic development.

Lipid Substrates in Tumor Metabolism

Lipid metabolic reprogramming is a fundamental hallmark of cancer, driving tumor progression, therapeutic resistance, and immune evasion [13]. In pediatric solid tumors, which account for approximately 60% of new childhood cancer diagnoses, lipid metabolic reprogramming occurs through enhanced fatty acid uptake, increased de novo lipid synthesis, and activated fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO) [13]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) plays a crucial role in regulating this lipid metabolism by modulating the stability and activity of key metabolic enzymes and transporters involved in cholesterol and fatty acid pathways [13].

Table 1: Key Lipid Metabolism Proteins Regulated by Ubiquitination in Cancer

| Target Protein | Role in Lipid Metabolism | Ubiquitination Effect | Cancer Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD36 | Fatty acid translocase facilitating cellular uptake of long-chain fatty acids | Phosphorylation, ubiquitination, glycosylation, and palmitoylation regulate function | Highly expressed in HCC, breast cancer, oral squamous cell carcinoma, AML, and CRC [14] |

| SREBPs (SREBP-1, SREBP-2) | Master transcription factors controlling fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis | HSP90β facilitates ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of mature SREBPs [14] | Key regulators of lipogenesis in multiple cancer types |

| ACLY | Converts citrate to acetyl-CoA for de novo lipogenesis | Protein stability controlled through acetylation and deubiquitination [14] | Regulates de novo lipogenesis and tumor growth |

| FASN | Produces palmitic acid from acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA | Protein stability controlled through dynamic acetylation and deacetylation [14] | Critical for synthesis of basic 16-carbon saturated fatty acids |

| HMGCR | Rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol synthesis | Regulated by SREBP-2 and subject to ubiquitination [14] | Key enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis pathway |

The ubiquitination primarily determines protein fate through proteasomal or lysosomal degradation, with most ubiquitinated proteins being processed by the 26S proteasome [13]. The complexity of ubiquitination is reflected in the diverse enzymatic machinery comprising two E1 enzymes, approximately 40 E2 enzymes, and over 600 E3 ligases in mammals, with E3 ligases conferring substrate specificity [13]. This sophisticated system allows for precise regulation of lipid metabolic pathways in cancer cells.

Diagram 1: Ubiquitination Regulation of Lipid Metabolism in Cancer. Key enzymes and transporters in lipid uptake, de novo synthesis, cholesterol metabolism, and fatty acid oxidation are regulated by ubiquitination (dashed lines).

Drug-like Small Molecules as Ubiquitination Substrates

HUWE1-Mediated Small Molecule Ubiquitination

A groundbreaking discovery has revealed that the human ubiquitin ligase HUWE1 can target drug-like small molecules, expanding the substrate realm of non-protein ubiquitination [12]. This finding originated from investigations into commercially available small-molecule inhibitors of HUWE1, specifically BI8622 and BI8626, which were initially identified as HUWE1 inhibitors but were subsequently found to be substrates of their target ligase [12].

The ubiquitination mechanism for these compounds follows the canonical catalytic cascade, linking ubiquitin to the compound's primary amino group via a covalent bond [12]. In vitro assays demonstrate that compound ubiquitination is selectively catalyzed by HUWE1, allowing the compounds to compete with protein substrates [12]. Cellular detection methods have confirmed that HUWE1 promotes - but does not exclusively drive - compound ubiquitination in cells [12].

Table 2: Characteristics of HUWE1-Targeted Small Molecule Substrates

| Parameter | BI8622 | BI8626 | Derivative 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Amino Group Position | Meta position of benzyl ring | Meta position of benzyl ring | Para position of benzyl ring |

| Inhibition Potency | Low-micromolar IC50 | More potent than BI8622 | Retains HUWE1HECT inhibition |

| Ubiquitination Site | Primary amino group | Primary amino group | Primary amino group |

| Mass Addition to Ubiquitin | +408.21 Da | +422.23 Da | Not specified |

| Cellular Specificity | HUWE1-promoted but not exclusive | HUWE1-promoted but not exclusive | Not determined |

Structure-activity relationship studies demonstrate the critical importance of the primary amino group for the ubiquitination of these small molecules [12]. Shifting this group from the meta to the para position of the benzyl ring (derivative 1) retained HUWE1HECT inhibition, while removal of the amino group or substitution by a secondary or tertiary amine caused a complete loss of inhibition [12]. Mass spectrometry analyses confirmed the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to the inhibitor molecules, with Ub C-terminal peptides showing characteristic mass increases corresponding to the conjugated compounds [12].

Experimental Evidence and Validation

The substrate competitive nature of these inhibitors was demonstrated through comprehensive biochemical assays [12]. In multi-turnover ubiquitination reactions containing E1 (UBA1), E2 (UBE2L3), HUWE1HECT, Ub, and ATP, both BI8622 and BI8626 inhibited ubiquitination dose-dependently in the low-micromolar concentration range [12]. The inhibitors suppressed E3 autoubiquitination, E2 ubiquitination and free Ub chain formation, indicating broad inhibition of HUWE1HECT catalysis independent of the Ub-accepting protein [12].

Single-turnover assays revealed that the inhibitors do not obstruct Ub transfer from the E2 to HUWE1HECT, nor do they perturb the preceding Ub transfer from the E1 to the E2 [12]. This indicates that the compounds inhibit HUWE1HECT after the formation of a thioester-linked intermediate with Ub, specifically interfering with the second step of HECT E3 catalysis [12].

Application Notes: Ub-POD Protocol for Substrate Identification

The Ubiquitin-specific Proximity-Dependent Labeling (Ub-POD) technique represents a significant advancement in identifying E3 ubiquitin ligase substrates in human cells [15] [16]. This method enables the selective biotinylation of substrates of a given ubiquitin ligase, overcoming the challenge of capturing transient substrate-E3 ligase interactions that conventional methods often fail to address [15].

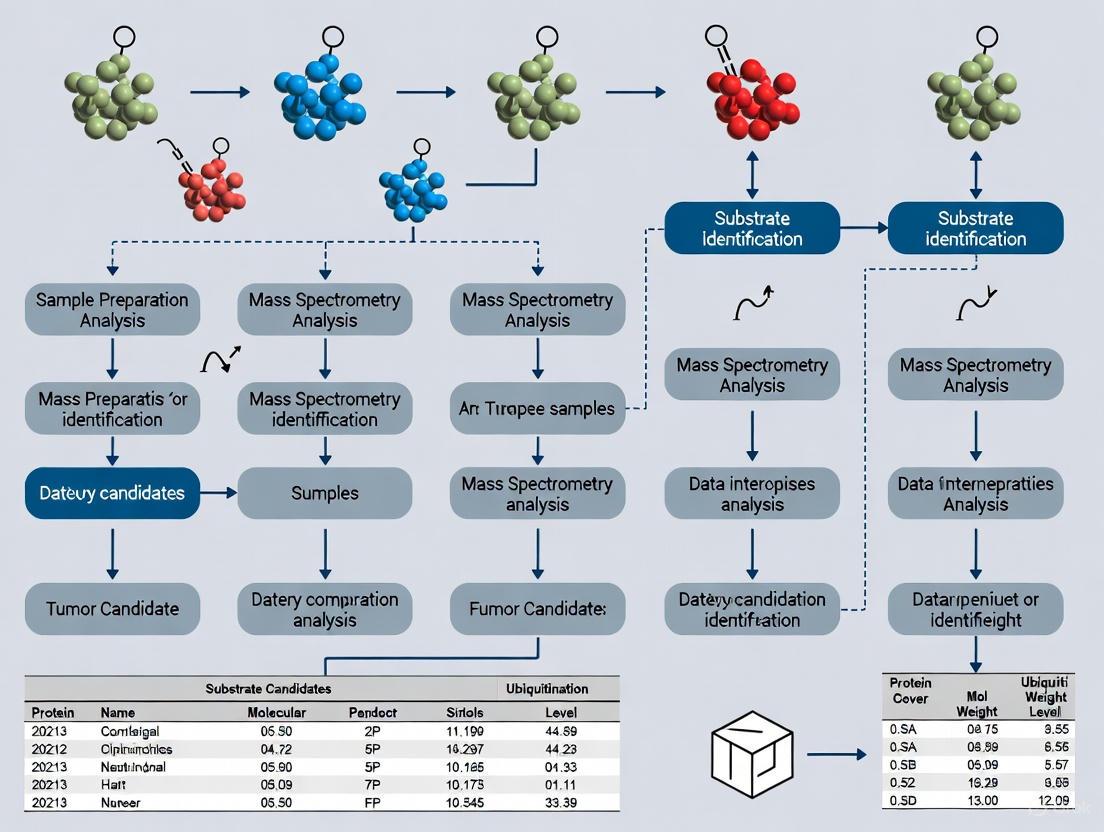

The core principle of Ub-POD involves fusing the candidate E3 ligase to the biotin ligase BirA and ubiquitin to a biotin acceptor peptide, an Avi-tag variant (-2) AP [15]. Cells are co-transfected with these fusion constructs and exposed to biotin, resulting in a BirA-E3 ligase-catalyzed biotinylation of (-2) AP-Ub when in complex with E2 [15]. The biotinylated (-2) AP-Ub is then transferred covalently to the substrate lysine, enabling enrichment via denaturing streptavidin pulldown [15]. Substrate candidates can subsequently be identified via mass spectrometry (MS) or validated through immunoblotting [15].

Diagram 2: Ub-POD Experimental Workflow. The protocol involves co-transfection of BirA-E3 and AP-Ub constructs, biotin exposure, biotinylation and ubiquitination reactions, denaturing lysis, streptavidin pulldown, and mass spectrometry analysis.

Key Advantages and Implementation

Ub-POD offers several distinct advantages over conventional approaches [15]:

- Specificity: Uses wild-type BirA instead of the highly reactive but promiscuous mutant BirA* (R118G mutation) to restrain activity to BirA's acceptor peptide substrate only

- Sensitivity: Incorporates a modified acceptor peptide (-2) AP of BirA attached to the N-terminus of ubiquitin, rendering it selectively biotinylated by BirA WT in a proximity-dependent manner

- Practicality: A simple and cost-effective method using common chemicals that can be implemented in any laboratory setting

The protocol is optimized for identification of novel substrates via mass spectrometry or as a validation tool in combination with immunoblotting or immunofluorescence [15]. Successful implementation benefits from prior knowledge of triggers and constraints of the E3 ligase activity under investigation [15].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Ub-POD Protocol

| Reagent/Material | Function/Role | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| BirA Vectors | Fuses BirA to candidate E3 ligase | Available from Addgene: 232584 (Empty BirA), 232586 (N-terminal tagging), 232587 (C-terminal tagging), 232588 (C-terminal with GSGS linker) [15] |

| Avi-tagged Ub Constructs | Fuses biotin acceptor peptide to ubiquitin | Modified Avi-tagged Ub construct (-2)AP-Ub used in protocol (Addgene: 232577, 232582, 232583) [15] |

| Streptavidin Agarose | Enrichment of biotinylated substrates | Enables pulldown under denaturing conditions [15] |

| MG132 | Proteasome inhibitor | Preserves ubiquitinated substrates by blocking degradation [15] |

| Benzonase Nuclease | Digests nucleic acids | Reduces sample viscosity and non-specific interactions [15] |

| N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) | Deubiquitinase inhibitor | Alkylates cysteine residues to prevent deubiquitination [15] |

Critical Steps and Troubleshooting

Successful application of the Ub-POD protocol requires attention to several critical steps [15]:

- Transfection Efficiency: Optimal transfection reagent should be selected based on the specific cell line of interest

- Proteasome Inhibition: MG132 treatment preserves ubiquitinated substrates by preventing proteasomal degradation

- Denaturing Conditions: Streptavidin pulldown under denaturing conditions reduces non-specific interactions

- Comprehensive Controls: Include appropriate negative controls (e.g., catalytically dead E3 mutants) to distinguish specific substrates

The highly Ub-specific labeling makes Ub-POD more appropriate for identifying ubiquitination substrates compared to other conventional proximity labeling or immunoprecipitation approaches [15].

Implications for Cancer Research and Therapeutics

The expanding substrate realm of ubiquitination has profound implications for cancer research and drug development. In pediatric solid tumors, the complex interplay between ubiquitination and lipid metabolic reprogramming identifies potential UPS-mediated therapeutic targets [13]. Integrating ubiquitination-based strategies with existing treatments may disrupt tumor metabolism and improve treatment efficacy [13].

The discovery that drug-like small molecules can serve as ubiquitination substrates opens avenues for harnessing the ubiquitin system to transform exogenous small molecules into novel chemical modalities within cells [12]. However, converting existing compounds into specific HUWE1 substrates or inhibitors requires enhanced specificity, as BI8626 elicits widespread proteomic effects and broadly reduces ubiquitination at many protein sites [12].

For researchers investigating ubiquitination substrates in tumor samples, these findings highlight the importance of considering non-protein substrates in experimental designs and data interpretation. The Ub-POD protocol provides a robust methodology for identifying novel E3 ligase substrates, while the expanding understanding of lipid metabolism regulation offers new perspectives on cancer metabolic dependencies.

The continued exploration of non-protein ubiquitination substrates will likely yield additional surprises and opportunities for therapeutic intervention in cancer and other diseases. Researchers are encouraged to consider these expanded substrate categories when designing studies on ubiquitination in tumor samples, as they may reveal previously unrecognized regulatory mechanisms and therapeutic targets.

Linking Ubiquitination to Tumor Microenvironment, Immune Infiltration, and Immunotherapy Response

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) has emerged as a critical regulator of cancer immunity, extending far beyond its traditional role in protein degradation. Ubiquitination, a key post-translational modification, orchestrates the stability, function, and trafficking of numerous proteins within the tumor microenvironment (TIME) [17]. This process involves a sequential enzymatic cascade comprising ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3), which collectively tag target proteins with ubiquitin chains [17]. The reverse process, mediated by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), removes these tags, providing a dynamic regulatory mechanism for protein homeostasis [18].

Research now demonstrates that the UPS profoundly influences tumor immune evasion and response to immunotherapy by modulating immune checkpoint expression, immune cell infiltration, and cytokine signaling [17] [19]. Understanding these mechanisms provides novel strategic approaches for enhancing cancer immunotherapy, particularly for patients exhibiting resistance to current immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) [18]. This application note outlines experimental frameworks for investigating ubiquitination pathways within the TIME and their translational potential for biomarker discovery and therapeutic development.

Molecular Mechanisms of Ubiquitination in Immune Regulation

Regulation of PD-1/PD-L1 Stability by Ubiquitination

The PD-1/PD-L1 axis represents a pivotal immune checkpoint pathway subjected to extensive ubiquitination regulation. E3 ubiquitin ligases and DUBs dynamically control the protein levels of PD-L1 on tumor cells and PD-1 on T cells, thereby modulating the strength of immune suppression.

- E3 Ligases in PD-L1 Degradation: The E3 ubiquitin ligase SPOP (Speckle-type POZ protein) directly binds to PD-L1 and promotes its K48-linked ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, particularly in colorectal cancer [17]. This process can be inhibited by competitive binding partners; for instance, ALDH2 and SGLT2 interact with PD-L1, shielding it from SPOP-mediated degradation [17].

- Deubiquitination in PD-L1 Stabilization: Several DUBs counteract E3 ligase activity to stabilize PD-L1. USP5 has been identified as a key DUB that specifically removes K48-linked polyubiquitin chains from PD-L1, preventing its degradation and promoting immune resistance in melanoma [18]. Other DUBs, including CSN5 and USP22, also participate in PD-L1 stabilization across various cancer types [18].

Table 1: Key Ubiquitination Regulators of PD-1/PD-L1 Axis

| Regulator | Type | Target | Effect | Cancer Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPOP | E3 Ligase | PD-L1 | K48-linked ubiquitination and degradation | Colorectal Cancer, Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| β-TrCP | E3 Ligase | PD-L1 | Degradation via GSK3β-phosphorylated PD-L1 | Multiple Cancers |

| FBXO22 | E3 Ligase | PD-L1 | Degradation | Lung Cancer |

| USP5 | DUB | PD-L1 | Deubiquitination and stabilization | Melanoma |

| CSN5 | DUB | PD-L1 | Deubiquitination and stabilization | Multiple Cancers |

| USP22 | DUB | PD-L1 | Deubiquitination and stabilization | Multiple Cancers |

Ubiquitination in Immune Checkpoint Activation

Beyond simply regulating protein abundance, ubiquitination can directly modulate the functional activation of immune checkpoint receptors. Recent research on LAG3 (Lymphocyte Activation Gene 3) reveals a novel non-degradative ubiquitination mechanism essential for its immunosuppressive function [20].

Upon engagement with its ligands (MHC class II or membrane-bound FGL1), LAG3 undergoes robust non-K48-linked polyubiquitination mediated by the E3 ligases c-Cbl and Cbl-b [20]. This ubiquitination induces a conformational change by disrupting the membrane binding of the juxtamembrane basic residue-rich sequence, thereby stabilizing the LAG3 cytoplasmic tail in a membrane-dissociated conformation that enables signal transduction and inhibitory function [20]. Therapeutic LAG3 antibodies function at least partially by repressing this activation-associated ubiquitination event [20].

Signaling Pathway Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the core ubiquitination regulatory network of PD-L1 stability within the tumor microenvironment:

Quantitative Analysis of Ubiquitination in Tumor Immunology

Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Signatures (URPS)

Comprehensive pancancer analyses have revealed that ubiquitination signatures serve as powerful predictors of clinical outcomes and immunotherapy response. A study integrating data from 4,709 patients across 26 cohorts and five solid tumor types (lung cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, urothelial cancer, and melanoma) established a conserved ubiquitination-related prognostic signature (URPS) that effectively stratifies patients into distinct risk categories [21].

The URPS high-risk group demonstrated significantly worse survival outcomes across all analyzed cancers and served as a novel biomarker for predicting immunotherapy response [21]. Single-cell resolution analysis confirmed that URPS enabled precise classification of distinct cell types and correlated strongly with macrophage infiltration within the TIME [21]. Experimental validation identified the OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination axis as a crucial modulator of the MYC pathway and patient prognosis [21].

Table 2: Ubiquitination-Based Biomarkers in Cancer Immunotherapy

| Biomarker Type | Key Components | Predictive Value | Validation Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Signature (URPS) | Multi-gene ubiquitination network | Stratifies high-risk vs low-risk patients; predicts immunotherapy benefit | Pancancer analysis (4,709 patients, 26 cohorts) |

| LAG3/CBL Co-expression | LAG3 + E3 ligases c-Cbl/Cbl-b | Identifies patients likely to respond to LAG3 blockade | Preclinical models and patient cohort analyses |

| PPP2R1A Mutations | PP2A scaffolding subunit | Predicts improved survival after immunotherapy | Ovarian clear cell carcinoma clinical trials |

| F-box Protein Expression Patterns | FBXW1 (β-TrCP) and others | Correlates with immune score and CD8+ T-cell infiltration | Lung cancer (LUAD) and renal cancer (KIRC) analyses |

Tumor Microenvironment and Immune Infiltration Signatures

Advanced profiling of the TIME has identified distinct immune cell infiltration patterns that correlate with ubiquitination regulation and immunotherapy response. Gene expression-based classification of twenty tumor types (7,162 samples) revealed that a signature enriched in B-cell markers consistently associated with improved immunotherapy efficacy across multiple cohorts, including IMvigor210 for urothelial cancer [22].

Notably, these infiltrate population signatures demonstrated more consistent association with treatment outcome than single cell-type models, suggesting they capture complex immunological responses involving multilayered relationships between distinct immune effector cells [22]. The signatures were most highly expressed in tumors with prominent immune cell invasion but consistently identified infiltrate presence even in relatively immune-restricted cases [22].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing PD-L1 Ubiquitination Status and Stability

Purpose: To evaluate the ubiquitination level and protein stability of PD-L1 in tumor cells under various experimental conditions.

Materials:

- Cycloheximide (CHX) - protein synthesis inhibitor

- MG132 - proteasome inhibitor

- Anti-PD-L1 antibody for immunoprecipitation

- Anti-ubiquitin antibody (specific for K48-linked chains if possible)

- Lysis buffer (RIPA buffer with protease and deubiquitinase inhibitors)

- Cell culture models (appropriate tumor cell lines)

Procedure:

- Treat Cells: Culture tumor cells and apply experimental conditions (e.g., small molecule inhibitors, cytokine stimulation).

- Inhibit Protein Synthesis: Add cycloheximide (100 µg/mL) to halt new protein synthesis for time-course stability analysis.

- Harvest Cells: Lyse cells in RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors and N-ethylmaleimide (deubiquitinase inhibitor) at various time points (0, 1, 2, 4, 8 hours).

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate cell lysates with anti-PD-L1 antibody overnight at 4°C, then pull down with protein A/G beads.

- Western Blot Analysis: Resolve immunoprecipitates by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot with anti-ubiquitin and anti-PD-L1 antibodies.

- Quantification: Measure band intensities to determine PD-L1 half-life and ubiquitination levels under different conditions.

Applications: This protocol enables researchers to identify regulators of PD-L1 stability, including E3 ligases and DUBs, and to test potential therapeutic compounds that modulate PD-L1 turnover [17] [18].

Protocol 2: Constructing Ubiquitination Regulatory Networks from Patient Data

Purpose: To develop pancancer ubiquitination regulatory networks for prognostic stratification and therapy response prediction.

Materials:

- RNA-seq data from tumor samples (TCGA, GEO databases)

- Clinical annotation data (survival, treatment response)

- R or Python programming environment with appropriate packages (limma, survival, ggplot2 for R)

- Single-cell RNA sequencing data (if available)

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Obtain transcriptomic data from public databases (TCGA, GEO). Normalize to TPM format and apply batch effect correction using ComBat algorithm.

- Ubiquitination Gene Selection: Curate ubiquitination-related genes from Gene Ontology databases and published literature.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Identify differentially expressed ubiquitination-related genes using limma package (FDR < 0.05, |log2FC| > 1).

- Prognostic Model Construction: Perform univariate Cox regression to identify survival-associated genes. Apply machine learning algorithms (Stepwise Cox, Lasso, Random Survival Forest) with 10-fold cross-validation to build optimal prognostic signature.

- Model Validation: Validate the prognostic model in independent immunotherapy cohorts. Assess predictive performance using ROC curves and C-index.

- Immune Correlations: Evaluate association between ubiquitination signature and immune cell infiltration using deconvolution algorithms (CIBERSORT) or single-cell data.

Applications: This computational approach identifies clinically relevant ubiquitination signatures, enables patient stratification, and reveals novel therapeutic targets [21] [18].

Experimental Workflow Diagram

The following diagram outlines the integrated experimental approach for studying ubiquitination in the tumor microenvironment:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination-Immunology Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Blocks degradation of ubiquitinated proteins; stabilizes substrates for detection |

| DUB Inhibitors | PR-619 (broad-spectrum), P5091 (USP7), EOAI340214 (USP5) | Inhibits deubiquitinating enzymes; increases substrate ubiquitination and turnover |

| E3 Ligase Modulators | MLN4924 (NEDD8 activator), SCF complex inhibitors | Modulates E3 ligase activity; tests specificity of ubiquitination pathways |

| Ubiquitin Binding Reagents | K48- and K63-linkage specific antibodies, TUBE (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entity) reagents | Enrich and detect specific ubiquitin chain linkages; improve ubiquitinated protein recovery |

| Protein Synthesis Inhibitors | Cycloheximide (CHX) | Halts new protein synthesis; enables protein half-life determination in chase assays |

| Immunoprecipitation Antibodies | Anti-PD-L1, anti-PD-1, anti-LAG3, anti-ubiquitin | Target-specific immunoprecipitation for ubiquitination status analysis |

| Cell Line Models | Melanoma, NSCLC, colorectal cancer lines with defined ubiquitination profiles | Provide biological context for mechanistic studies and therapeutic testing |

The integration of ubiquitination regulation into our understanding of cancer immunity represents a paradigm shift in immunotherapy research. The experimental frameworks outlined herein provide systematic approaches for investigating how ubiquitination networks shape the tumor immune microenvironment and influence therapy response. The dynamic interplay between E3 ligases, DUBs, and immune checkpoints offers multiple therapeutic entry points for enhancing current immunotherapies.

Future directions should focus on developing selective small-molecule inhibitors targeting specific ubiquitination regulators in the TIME, validating ubiquitination-based biomarkers in prospective clinical trials, and exploring combination strategies that simultaneously target ubiquitination pathways and immune checkpoints. The convergence of ubiquitination research with artificial intelligence and multi-omics technologies promises to accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutic targets and personalized treatment approaches for cancer patients resistant to current immunotherapies [23] [24]. As our understanding of the ubiquitin code in cancer immunity deepens, targeting these pathways will undoubtedly become an integral component of precision immuno-oncology.

The Methodological Toolkit: From Proteomics to Proximity Labeling for Substrate Identification

Protein ubiquitination, a crucial post-translational modification, regulates diverse cellular functions including protein turnover, cell signaling, and trafficking. The dysregulation of ubiquitination pathways is implicated in various pathologies, most notably cancer. For researchers investigating tumor samples, comprehensively identifying ubiquitination substrates provides invaluable insights into disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. This application note details three core high-throughput proteomic strategies—Ub tagging, antibody-based enrichment, and ubiquitin-binding domain (UBD)-based approaches—for the systematic mapping of ubiquitination events, with a specific focus on their application in tumor tissue research.

Ub Tagging-Based Approaches

Core Principle and Workflow

Ub tagging involves the genetic engineering of ubiquitin (Ub) with an affinity tag (e.g., His, Strep, or HA). When expressed in cells, this tagged Ub is incorporated into the ubiquitination machinery, allowing for the subsequent affinity-based purification of ubiquitinated substrates from complex lysates under denaturing conditions [2]. Following purification, the enriched proteins are digested with trypsin. A key feature of this process is the generation of a diagnostic di-glycine (Gly-Gly) remnant that remains attached to the modified lysine residue of the substrate peptide after tryptic digestion. This 114.04 Da mass shift is a definitive signature used for the mass spectrometry-based identification of ubiquitination sites [2].

Application in Tumor Research

This method is particularly powerful for cell line-based discovery studies. For instance, Danielsen et al. successfully identified 753 lysine ubiquitylation sites on 471 proteins in U2OS and HEK293T cells by constructing a cell line stably expressing Strep-tagged Ub [2]. The primary advantage is the ease of use and relatively low cost for initial, broad screening of ubiquitinated substrates in a controlled cellular environment.

Key Protocols

Protocol 1.1: Generation of Stable Cell Lines for Ub Tagging

- Construct Design: Clone the DNA sequence for the chosen affinity tag (e.g., 6xHis, Strep-tag II) in-frame at the N-terminus of ubiquitin in a mammalian expression vector.

- Cell Transfection: Introduce the construct into your chosen cancer cell line using a standard transfection method (e.g., lipofection, electroporation).

- Selection & Expansion: Select for stable integrants using the appropriate antibiotic (e.g., puromycin, G418) for 2-3 weeks.

- Validation: Confirm tag expression by western blotting of whole-cell lysates using an antibody against the tag or ubiquitin.

Protocol 1.2: Affinity Purification of Tagged Ubiquitinated Proteins

- Lysis: Harvest stable cells and lyse in a denaturing buffer (e.g., 8 M Urea, 100 mM NaH₂PO₄, 10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0) supplemented with 5-10 mM imidazole and protease inhibitors (including deubiquitinase inhibitors like PR-619) [2] [25].

- Clarification: Centrifuge the lysate at 20,000 × g for 15 minutes to remove insoluble debris.

- Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC): Incubate the clarified lysate with Ni-NTA agarose beads for 1-2 hours at room temperature with gentle rotation.

- Washing: Wash the beads sequentially with:

- Wash Buffer I: Lysis buffer.

- Wash Buffer II: Lysis buffer adjusted to pH 6.3.

- Elution: Elute the bound ubiquitinated proteins using an elution buffer containing 250 mM imidazole.

- Preparation for MS: Precipitate or buffer-exchange the eluate, then subject to tryptic digestion for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Advantages and Limitations

Table 1: Pros and Cons of Ub Tagging-Based Approaches

| Aspect | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| General Use | Easy, friendly, relatively low-cost [2] | Tagged Ub may not perfectly mimic endogenous Ub, potentially creating artifacts [2] |

| Sensitivity | Effective for broad substrate screening | Identification efficiency can be relatively low [2] |

| Specificity | Direct covalent labeling of substrates | Co-purification of histidine-rich or endogenously biotinylated proteins causes contamination [2] |

| Tumor Sample Application | Excellent for cell line models | Infeasible for direct use in animal or patient tissue samples [2] |

Antibody-Based Enrichment Strategies

Core Principle and Workflow

Antibody-based enrichment, often referred to as the PTMScan method, utilizes antibodies that are specific to the di-glycine (K-ε-GG) remnant left on ubiquitinated peptides after tryptic digestion. This allows for the direct immunoaffinity purification (IAP) of ubiquitinated peptides from a complex mixture of digested cellular proteins, which are then identified and quantified by LC-MS/MS [26]. This method is "target-agnostic" and does not require genetic manipulation, making it suitable for clinical samples.

High-Throughput Innovations and Applications

Recent advancements have significantly increased the throughput and reproducibility of antibody-based ubiquitinomics. The development of the automated UbiFast method is a key innovation. This approach uses magnetic bead-conjugated K-ε-GG antibodies (HS mag anti-K-ε-GG) and a magnetic particle processor to automate the enrichment and on-bead TMT labeling of Ub-peptides. This automated workflow can process up to 96 samples in a single day, identifies ~20,000 ubiquitylation sites from a TMT10-plex, and greatly improves reproducibility while reducing processing time [27]. This makes it ideal for large-scale patient cohort studies. Furthermore, platform like the one from NEOsphere Biotechnologies combines high-throughput global proteomics to identify protein downregulation with high-throughput interactomics to reveal ternary complex formation, providing a comprehensive view of degrader function in disease-relevant contexts, including primary cells and patient-derived tissues [28].

Key Protocols

Protocol 2.1: Automated UbiFast for Ubiquitinome Profiling (e.g., from Tumor Tissue)

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize patient-derived xenograft (PDX) or frozen tumor tissue. Perform in-solution digestion with trypsin to generate peptides [27].

- Peptide Clean-up: Desalt peptides using a solid-phase extraction cartridge (e.g., Sep-Pak tC18).

- Automated Enrichment: Use a magnetic particle processor with HS mag anti-K-ε-GG beads to enrich for K-ε-GG-containing peptides. The automation handles all washing steps.

- On-Bead TMT Labeling: While peptides are still bound to the magnetic beads, label them with Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) reagents. This step is performed on the automated platform [27].

- Pooling and Elution: Combine the TMT-labeled samples and elute the peptides from the beads.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Analyze the enriched, multiplexed peptide sample by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.

Protocol 2.2: PTMScan Discovery for Ubiquitinated Peptides

- Digestion: Digest the protein sample from tumor lysates into peptides.

- Immunoaffinity Purification (IAP): Incubate the peptide mixture with a PTM-specific anti-K-ε-GG antibody immobilized on beads [26].

- Washing: Wash the beads extensively to remove non-specifically bound peptides.

- Elution: Elute the enriched ubiquitinated peptides using a low-pH buffer.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Identify and quantify the eluted peptides.

Advantages and Limitations

Table 2: Pros and Cons of Antibody-Based Enrichment

| Aspect | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| General Use | Does not require genetic manipulation; can use linkage-specific antibodies [2] | High cost of high-quality antibodies [2] |

| Sensitivity | High sensitivity for modified peptides; automated UbiFast identifies ~20,000 sites [27] | Non-specific binding can occur, requiring careful controls [2] |

| Specificity | Directly targets the definitive K-ε-GG signature | Underlying peptide sequence can influence antibody binding efficiency |

| Tumor Sample Application | Directly applicable to animal tissues and clinical samples [28] [27] [2] | Limited amount of starting material from biopsies can be a constraint |

UBD-Based Strategies

Core Principle and Workflow

This strategy leverages natural Ubiquitin-Binding Domains (UBDs), which are protein modules that recognize and bind to ubiquitin or specific ubiquitin chain linkages. These UBDs (e.g., from certain E3 ligases, DUBs, or Ub receptors) are used as affinity reagents to capture endogenously ubiquitinated proteins from native or denatured cell lysates [2] [25]. The use of tandem-repeated UBDs improves the affinity and specificity of the enrichment.

Advanced Methodology: DRUSP for Enhanced Ubiquitinomics

A major challenge in UBD-based enrichment under native conditions is the interference from deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) and proteasomes, as well as inefficient protein extraction. The Denatured-Refolded Ubiquitinated Sample Preparation (DRUSP) method overcomes this. DRUSP involves lysing samples in a strongly denaturing buffer to inactivate enzymes and fully extract proteins, followed by a refolding step using filters to restore the native spatial structure of ubiquitin and ubiquitin chains. This allows for subsequent highly efficient recognition and enrichment by a tandem hybrid UBD (ThUBD) [25]. This method has been shown to yield a ubiquitin signal nearly three times stronger than control methods and improves overall ubiquitin signal enrichment by approximately 10-fold, significantly enhancing the stability and reproducibility of ubiquitinomics research [25]. It has been successfully applied to deep ubiquitinome profiling of early mouse liver fibrosis.

Key Protocols

Protocol 3.1: DRUSP with ThUBD Enrichment

- Denaturing Lysis: Lyse tumor tissue or cells in a strongly denatured buffer (e.g., containing SDS or Urea) to inactivate DUBs and proteasomes and ensure complete protein extraction [25].

- Refolding: Use a filter-based device to perform buffer exchange, replacing the denaturing buffer with a non-denaturing lysis buffer. This allows the ubiquitinated proteins to refold into their native conformations [25].

- UBD Enrichment: Incubate the refolded lysate with the immobilized ThUBD (or chain-specific UBDs) to capture ubiquitinated proteins.

- Washing: Wash the beads thoroughly with a non-denaturing buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elution and Digestion: Elute the bound ubiquitinated proteins, then proceed with standard tryptic digestion and LC-MS/MS preparation.

Advantages and Limitations

Table 3: Pros and Cons of UBD-Based Strategies

| Aspect | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| General Use | Can be engineered for linkage specificity; DRUSP offers superior versatility [25] | Low affinity of single UBDs can limit purification efficiency [2] |

| Sensitivity | DRUSP significantly enhances signal and positive identifications [25] | Tandem UBDs are more complex to produce |

| Specificity | High specificity for ubiquitin chains; can be tailored for chain-type | Potential for co-purification of UBD-binding partner proteins |

| Tumor Sample Application | DRUSP demonstrates enhanced quantitative accuracy and reproducibility for tissue samples [25] | The refolding step requires optimization for different sample types |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitin Proteomics