Navigating Sample Heterogeneity in Ubiquitination Studies: Strategies for Robust Profiling and Data Interpretation

This article addresses the critical challenge of sample heterogeneity in ubiquitination research, a major obstacle to obtaining reproducible and biologically relevant data.

Navigating Sample Heterogeneity in Ubiquitination Studies: Strategies for Robust Profiling and Data Interpretation

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of sample heterogeneity in ubiquitination research, a major obstacle to obtaining reproducible and biologically relevant data. It provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational sources of heterogeneity in the ubiquitin system, current methodological approaches for its management, troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls, and frameworks for data validation. By synthesizing insights from recent technological advancements and large-scale ubiquitome studies, this resource aims to equip scientists with practical knowledge to design more robust experiments, accurately interpret complex ubiquitin codes, and advance therapeutic targeting of the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

Understanding the Ubiquitin Code: The Molecular Roots of Sample Heterogeneity

Structural and Conformational Plasticity of Ubiquitin

Ubiquitin is a small, highly conserved regulatory protein that is ubiquitous in eukaryotes. The post-translational modification of proteins with ubiquitin, known as ubiquitylation, regulates a vast array of cellular processes, including protein degradation, DNA repair, signal transduction, and endocytosis. The functional diversity of ubiquitin signaling is encoded through the formation of polyubiquitin chains of different lengths and linkage topologies. While static structural studies have provided invaluable insights, the conformational dynamics and structural plasticity of ubiquitin are fundamental to its ability to engage with numerous binding partners and function in distinct pathways. This technical support article, framed within a broader thesis on addressing sample heterogeneity in ubiquitination studies, explores the critical roles of ubiquitin dynamics. It provides troubleshooting guidance for researchers studying these complex phenomena, with a particular focus on NMR-based approaches and biochemical reconstitution experiments.

Core Concepts: Ubiquitin Plasticity and Recognition

This section addresses fundamental questions about the dynamic nature of ubiquitin and its implications for research.

FAQ 1: What is meant by the "structural plasticity" of ubiquitin?

Structural plasticity refers to the ability of ubiquitin to adopt subtly different conformations when interacting with various binding partners. Although ubiquitin maintains a stable overall fold, specific regions, particularly its binding surfaces, exhibit flexibility. This plasticity allows it to engage with a diverse repertoire of ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs), such as Ubiquitin-Interacting Motifs (UIMs). Research shows that while UIMs generally bind a common hydrophobic patch on ubiquitin formed by residues L8, I44, and V70, the atomic details of the interaction can vary, leading to a "plethora of UIM binding modes" [1] [2]. This adaptability is a key feature of ubiquitin's functionality.

FAQ 2: How do conformational dynamics influence ubiquitin's function?

Conformational dynamics are motions within the protein structure that occur across various timescales, from picoseconds to milliseconds. These dynamics are critical for molecular recognition. NMR relaxation studies on a ubiquitin-UIM fusion protein revealed that UIM binding not only increases rigidity at the direct interaction interface but also induces dynamic changes in distal parts of ubiquitin [1] [2] [3]. This demonstrates that a localized binding event can have global effects on protein motion, potentially facilitating allosteric regulation and influencing how ubiquitin is recognized by downstream components in a pathway [1].

FAQ 3: Why is the polyubiquitin chain linkage type critical for signaling?

The fate of a ubiquitylated protein is largely determined by the linkage type of its polyubiquitin chain. Different linkages form distinct architectures that are recognized by specific receptors.

- K48-linked chains: Typically target proteins for degradation by the 26S proteasome [4].

- K63-linked chains: Often involved in non-proteolytic pathways, such as DNA repair, signal transduction, and endocytosis [1] [2].

- Other linkages (e.g., K11, K29, linear): Mediate unique signaling outcomes, including autophagy and immune signaling.

Furthermore, the chain length itself can be a regulatory factor. For example, K48-linked tetra-ubiquitin is the minimal signal for efficient proteasomal recognition, and chains longer than four units can exhibit slowed elongation kinetics due to compaction, suggesting a self-restraining mechanism [4].

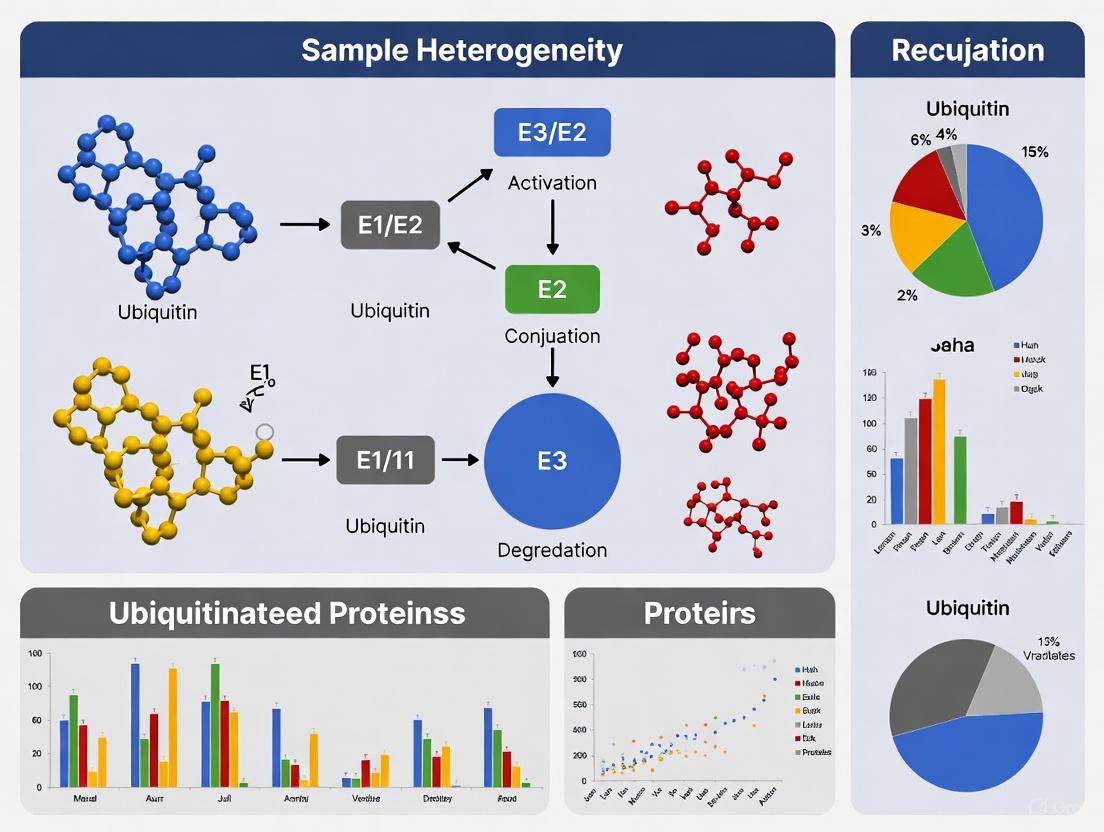

The following diagram illustrates how the conformational dynamics of ubiquitin contribute to its functional cycle, from chain elongation to recognition and eventual signal outcome.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Sample Heterogeneity in Ubiquitin-Conjugate Preparations

- Challenge: Inconsistent results in binding assays or structural studies due to heterogeneous mixtures of ubiquitin chains with varying lengths and linkages.

- Solution:

- Use Defined Chain Assembly Systems: Employ in vitro reconstitution with specific E2 enzymes and E3 ligases that produce a predominant linkage type. For example, Cdc34 with SCF E3 ligases primarily generates K48-linked chains [4].

- Utilize Elongation Intermediates: As done in mechanistic studies, use substrates linked to ubiquitin chains of a defined, pre-synthesized length to isolate the effects of chain architecture [4].

- Optimized Purification Protocols: Employ multi-step purification, including size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) and ion-exchange chromatography, to separate chains by length. The use of fusion proteins can also improve complex stability and homogeneity for structural studies [1] [2].

Problem: Detecting and Characterizing Low-Population Conformational States

- Challenge: High-energy or sparsely populated conformational states that are critical for function are invisible to many static structural techniques.

- Solution:

- Implement NMR Relaxation Dispersion: Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) relaxation dispersion experiments are sensitive to microsecond-to-millisecond timescale dynamics and can detect and characterize low-population excited states [1] [2] [3].

- Measure Residual Dipolar Couplings (RDCs): RDCs provide long-range structural restraints that can reveal the presence and nature of conformational ensembles [1].

- Integrate Multiple Biophysical Techniques: Combine NMR with single-molecule FRET (smFRET) and cross-linking mass spectrometry (XL-MS) to obtain a multi-scale view of protein dynamics and validate findings across different techniques [5].

Problem: Low Affinity or Transient Ubiquitin-Binding Domain (UBD) Interactions

- Challenge: Many UBDs, like UIMs, bind ubiquitin with modest (micromolar) affinity, making structural and biophysical characterization difficult [1] [2].

- Solution:

- Engineer Fusion Proteins: Creating a covalent fusion between ubiquitin and the UBD, as demonstrated in the study of the Vps27 UIM, ensures 100% complex occupancy. This simplifies NMR spectra and allows for detailed investigation of the interface dynamics in the bound state [1] [2].

- Employ Paramagnetic Relaxation Enhancement (PRE): PRE can provide long-distance structural restraints that are particularly useful for characterizing transient, low-affinity complexes.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Characterizing Ubiquitin Dynamics via NMR Relaxation

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating the dynamics of ubiquitin in complex with a UIM domain [1] [2] [3].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Isotopic Labeling: Prepare uniformely

¹⁵N-labeled and¹⁵N/¹³C-labeled ubiquitin protein. For complex studies, the binding partner (e.g., UIM domain) can be unlabeled. - Foprotein Strategy: For low-affinity interactions, consider engineering a fusion protein where ubiquitin is connected to the UIM via a flexible linker (e.g., SMGG peptide linker). This guarantees a stable, homogeneous complex [1] [2].

- Buffer Conditions: Use a standard NMR buffer (e.g., 20-50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.5-7.0, 50-100 mM NaCl). Include a reducing agent like DTT (1-2 mM) and 5-10% D₂O for the NMR lock signal.

2. Data Acquisition:

- Backbone Assignment: Perform standard triple-resonance experiments (HNCA, HNCOCA, HNCACB, etc.) on the

¹⁵N/¹³C-labeled sample for complete backbone resonance assignment. ¹⁵N R₁and¹⁵N R₂Relaxation: Measure longitudinal (R₁) and transverse (R₂) relaxation rates for the¹⁵Nnuclei to probe picosecond-to-nanosecond dynamics.¹⁵N Heteronuclear NOE: Measure¹⁵N-{¹H}NOE values to identify flexible regions in the protein backbone.¹⁵N CPMG Relaxation Dispersion: Conduct a series of CPMG experiments with varying CPMG frequencies (ν_CPMG) to detect and quantify conformational exchange processes on the microsecond-to-millisecond timescale.

3. Data Analysis:

- Model-Free Analysis: Fit the R₁, R₂, and NOE data using the model-free formalism of Lipari and Szabo to extract the generalized order parameter (S²), which reports on the amplitude of bond vector motion on fast timescales, and the effective correlation time (τ_e`).

- Relaxation Dispersion Analysis: Fit the CPMG data to appropriate models of conformational exchange (e.g., two-state exchange) to extract kinetic rate constants (kex = k₁ + k₋₁), populations of the minor state (p_B), and the chemical shift difference (Δω) between the exchanging states.

Protocol: In Vitro Reconstitution of Polyubiquitin Chain Elongation

This protocol is based on studies of SCFβTrCP-directed ubiquitination of IκBα and β-catenin [4].

1. Reagent Preparation:

- Enzymes: Purify or purchase the necessary enzymes: E1 activating enzyme, E2 conjugating enzyme (e.g., UbcH5, Cdc34), and the E3 ligase complex (e.g., SCFβTrCP). Nedd8-modified CUL1 (within SCF) is often used for full activity.

- Substrate: Prepare a

³²P-radiolabeled substrate, such as a peptide derived from IκBα (residues 1-54) or β-catenin, that contains a phosphorylated degron motif recognized by βTrCP [4]. - Other Components: Ubiquitin, ATP, and an ATP-regenerating system.

2. Elongation Reaction:

- Assemble reactions on ice. A typical reaction mixture (e.g., 10-20 µL) contains:

- 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4

- 5 mM MgCl₂

- 2 mM ATP

- 0.5-1 mM DTT

- 0.1 mg/mL BSA

- E1 enzyme (50-100 nM)

- E2 enzyme (1-5 µM)

- E3 ligase (SCFβTrCP, concentration depends on preparation)

³²P-labeled substrate (1-5 µM)- Ubiquitin (50-100 µM)

- Initiate the reaction by transferring the tube to a 30-37°C heat block.

- Quench the reaction at various time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 min) by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer.

3. Analysis:

- SDS-PAGE and Autoradiography: Resolve the reaction products by SDS-PAGE. Visualize the polyubiquitin chain ladder formation using a phosphorimager or by autoradiography.

- Kinetic Analysis: Quantify the intensity of the unmodified substrate and the various ubiquitin-conjugated species to determine the rate of chain initiation and elongation.

The experimental workflow for a comprehensive study of ubiquitin plasticity, integrating biochemistry and biophysics, is outlined below.

Key Data and Reagent Reference

This table summarizes quantitative parameters derived from NMR relaxation experiments that characterize the conformational dynamics of ubiquitin upon UIM binding [1] [2] [3].

| Parameter | Description | Value/Observation in Free Ubiquitin | Value/Observation in Ubiquitin-UIM Complex | Functional Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Order Parameter (S²) | Measures amplitude of ps-ns backbone motions (0 = flexible, 1 = rigid). | Lower values at the I44 hydrophobic patch and flexible loops. | Increased S² at the UIM-binding interface (L8, I44, V70). | UIM binding rigidifies the interaction surface. |

| Conformational Exchange (k_ex) | Rate of µs-ms dynamics between conformational states. | Detectable in specific loops. | Two types of motion: 1) At binding interface; 2) Induced in distal loops (e.g., around K6, K48). | Binding introduces/allosterically communicates dynamics to functionally key sites. |

| Population of Minor State (p_B) | Fraction of the protein populating a low-abundance conformational state. | Varies by residue. | Altered for residues undergoing conformational exchange. | Reflects the shifting energy landscape due to partner binding. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitin Plasticity Studies

A list of key materials and their applications for investigating ubiquitin structure and dynamics.

| Reagent / Material | Specifications / Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| E2 Conjugating Enzymes | Cdc34 (K48-chain elongation), UbcH5 (chain initiation) | Define the linkage type and kinetics of polyubiquitin chain synthesis in reconstituted systems [4]. |

| E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Complexes | SCFβTrCP (Nedd8-modified for full activity) | Confer substrate specificity and enhance the efficiency of ubiquitin transfer from E2 to target protein [4]. |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | Lysine-to-Arg (K-to-R) point mutants (e.g., K48R) | To study the specificity of ubiquitin chain linkages and their functional consequences. |

| Isotopically Labeled Ubiquitin | ¹⁵N-Ubiquitin, ¹³C/¹⁵N-Ubiquitin |

Enables NMR spectroscopy for structural and dynamic studies, including resonance assignment and relaxation measurements. |

| Ubiquitin-Binding Domains (UBDs) | UIM from Vps27, S5a | Used as probes to study ubiquitin recognition, to purify ubiquitinated proteins, and to validate functional interactions [1] [2]. |

| NMR Fusion Protein Constructs | Ubiquitin connected to UIM via a flexible linker (e.g., SMGG) | Stabilizes low-affinity complexes for high-resolution NMR studies of the bound state, ensuring 100% occupancy [1] [2]. |

The Complex Landscape of Ubiquitin and Ubiquitin-Like Proteins (UBLs)

Foundational Concepts: The Ubiquitin and UBL System

What are the core components of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS)?

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a hierarchical enzymatic cascade responsible for regulated proteolysis and numerous other cellular functions. Its core components include [6] [7]:

- E1 Enzymes (Activating Enzymes): Two E1s (UBA1 and UBA6) in humans activate ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner, forming a high-energy thioester bond [8] [6].

- E2 Enzymes (Conjugating Enzymes): Approximately 40 E2s accept the activated ubiquitin from E1 via a transthiolation reaction [9] [8].

- E3 Enzymes (Ligases): Over 600 E3s provide substrate specificity and facilitate the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to the target protein. They fall into three main classes: RING, HECT, and RBR [9] [10].

- Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs): Nearly 100 DUBs counter the action of E3s by cleaving ubiquitin from substrates, processing ubiquitin precursors, and recycling ubiquitin [9] [6].

- The Proteasome: The 26S proteasome recognizes and degrades proteins tagged primarily with K48-linked polyubiquitin chains, recycling ubiquitin in the process [11] [6].

How do Ubiquitin-Like Proteins (UBLs) relate to ubiquitin?

Ubiquitin-like proteins (UBLs) are a family of small proteins that share the characteristic β-grasp fold three-dimensional structure with ubiquitin but are distinct in sequence and function [11] [12]. They can be divided into two types [12]:

- Type I UBLs are capable of covalent conjugation to target proteins (or lipids) via a C-terminal glycine, using enzymatic cascades (E1-E2-E3) analogous to, but distinct from, the ubiquitin pathway [11].

- Type II UBLs are typically protein domains genetically fused to other domains and function in protein-protein interactions rather than covalent conjugation [12].

Table 1: Major Human Ubiquitin-Like Proteins (Type I) and Their Functions

| UBL Name | Identity with Ubiquitin | Key Functions | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEDD8 (Rub1) | ~55% [11] | Activates cullin-based E3 ligases [8] | Regulates SCF ubiquitin ligase activity [6] |

| SUMO (Smt3) | ~18% [11] | Transcription, DNA repair, stress response [12] | Multiple isoforms in vertebrates (SUMO1-5) [13] |

| ISG15 | 32-37% [11] | Antiviral immune response [11] [13] | Induced by interferons; two Ub-like domains [11] |

| Atg8 (LC3) | ND | Autophagosome biogenesis [13] | Conjugated to phospholipid phosphatidylethanolamine [12] |

| Atg12 | ND | Autophagy [13] | Conjugated to Atg5; acts as E3 for Atg8 [11] |

| UFM1 | ND | ER homeostasis, vesicle trafficking [13] | Conserved in metazoans and plants [13] |

| FAT10 | 32-40% [11] | Immune regulation, proteasomal degradation [13] | Induced by interferon gamma/TNF-α; two Ub-like domains [13] |

| Urm1 | ND | Antioxidant pathways, tRNA modification [6] | Functions as both a UBL and a sulfur carrier [12] |

The following diagram illustrates the core enzymatic cascade shared by ubiquitin and UBLs, highlighting the parallel pathways for different modifiers:

Ub/UBL Conjugation Cascade

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: Why is my ubiquitination/UBL conjugation efficiency low, and how can I improve it?

Low conjugation efficiency is a common problem often stemming from issues with enzyme activity, substrate recognition, or cellular conditions.

Potential Cause 1: Instability of the E2~Ub/UBL Thioester Intermediate.

- Explanation: The thioester bond between the E2 and ubiquitin/UBL is highly labile and susceptible to hydrolysis or reducing agents present in lysates [14] [8].

- Solution:

- Include 10-20 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) in your lysis buffer. NEM alkylates free cysteine thiols, inhibiting deconjugating enzymes and preventing thioester breakdown [14].

- Use non-reducing conditions during the initial stages of protein extraction.

- Consider using E2 enzymes with mutations that stabilize the thioester linkage for in vitro assays.

Potential Cause 2: Inadequate Proteasome Inhibition.

- Explanation: If your goal is to visualize polyubiquitinated proteins destined for degradation, the proteasome may rapidly degrade your substrate before you can detect it.

- Solution: Treat cells with proteasome inhibitors such as MG132 (10-20 µM) or Bortezomib (Velcade, 100 nM) for 4-6 hours prior to lysis [14]. This leads to the accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins.

Potential Cause 3: Overwhelming Deconjugating Enzyme (DUB/ULP) Activity.

- Explanation: Cellular lysates are rich with DUBs and UBL-specific proteases (ULPs) that can rapidly strip ubiquitin/UBL modifications from your substrate during sample preparation [13] [6].

- Solution: Lyse cells under fully denaturing conditions (e.g., 1% SDS, 8 M Urea) to instantly inactivate all enzymatic activity. The lysate can then be diluted for subsequent pull-down steps [13].

FAQ 2: How can I reduce high background and non-specific binding in Ub/UBL pull-down assays?

High background is frequently due to non-covalent interactors and incomplete removal of unconjugated Ub/UBL.

Problem: Co-purification of Non-covalent Interactors.

- Explanation: Many proteins contain ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) that bind non-covalently to ubiquitin or UBLs, leading to their co-purification even in the absence of direct conjugation [10].

- Solution: Perform pull-downs under stringent washing conditions. After the initial binding, wash beads with buffers containing high salt (e.g., 500 mM NaCl), 0.1-0.5% SDS, or 1% Triton X-100 to disrupt non-covalent interactions [13].

Problem: Persistence of Unconjugated Ub/UBL.

- Explanation: Free, unconjugated Ub/UBL in the lysate can compete for binding to affinity matrices, reducing the effective capture of conjugated material and increasing background.

- Solution: Implement a Tandem Purification Strategy. Using a dual tag system (e.g., 6xHis-BioUbL) allows for sequential purification under native and then denaturing conditions, drastically improving specificity [13].

Advanced Methodologies for Targeted Analysis

Experimental Protocol: Ubiquitin-Specific Proximity-Dependent Labeling (Ub-POD) for E3 Ligase Substrate Identification

Objective: To identify direct substrates of a specific E3 ubiquitin ligase by exploiting the proximity between the E3, its E2~Ub complex, and the substrate during the ubiquitination event [14].

Background: Conventional co-immunoprecipitation often fails to capture the transient E3-substrate interaction. Ub-POD uses proximity-dependent biotinylation to permanently mark the substrate at the moment of ubiquitination.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Ub-POD Protocol

| Reagent | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| BirA-E3 Fusion Plasmid | E3 ligase fused to wild-type E. coli biotin ligase (BirA). | Wild-type BirA (not the promiscuous mutant) ensures high specificity [14]. |

| (-2) AP-Ub Plasmid | Ubiquitin fused to a modified biotin acceptor peptide (AviTag variant). | The specific AviTag variant (-2)AP is efficiently biotinylated only by wild-type BirA [14]. |

| Biotin | Substrate for BirA. The activated biotin-AMP is transferred to the (-2)AP tag. | Use at standard culture concentrations (e.g., 50 µM) [14]. |

| Streptavidin Agarose | To pull down biotinylated proteins. | Use under fully denaturing conditions to inactivate enzymes and remove interactors [14]. |

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Transfection: Co-transfect cells (e.g., HEK-293) with the BirA-E3 and (-2)AP-Ub constructs [14].

- Biotinylation: Incubate cells with biotin to allow biotinylation of the (-2)AP-Ub by the BirA-E3 ligase when they are in close proximity within the E2-E3-substrate complex.

- Ubiquitination & Lysis: The biotinylated Ub is transferred onto the lysine residue of the substrate. Lyse cells under fully denaturing conditions (e.g., in SDS buffer with NEM and protease inhibitors) to "freeze" the ubiquitination state and prevent deubiquitination [14].

- Streptavidin Pull-Down: Incubate the denatured lysate with streptavidin agarose beads. Wash stringently with high-salt and detergent buffers to remove non-specifically bound proteins [14].

- Analysis: Elute bound proteins and identify putative substrates by mass spectrometry or validate by immunoblotting [14].

The logical workflow and key components of the Ub-POD method are summarized below:

Ub-POD Workflow

Experimental Protocol: The BioUbL Platform for Comprehensive UBL Conjugate Analysis

Objective: To isolate and identify conjugates for a wide range of ubiquitin-like proteins using in vivo biotinylation and purification under denaturing conditions [13].

Principle: This system uses a multicistronic vector to co-express a biotinylated UBL (bioUBL) and the BirA biotin ligase. Conjugates are purified with high specificity and low background using streptavidin affinity capture.

Key Advantage: The high affinity of the streptavidin-biotin interaction allows for purification under fully denaturing conditions, which effectively inactivates deconjugating enzymes and removes non-covalent interactors, leading to a cleaner sample of true conjugates [13].

Procedure Summary:

- Vector Design: Clone your UBL of interest (e.g., SUMO, UFM1, NEDD8) into the multicistronic bioUbL vector, which separately expresses the Bio-tagged UBL and the BirA enzyme [13].

- Expression: Express the vector in your model system (e.g., mammalian cells, Drosophila cells, or transgenic flies).

- Purification: Lyse cells in denaturing buffer. Capture bioUbL conjugates on streptavidin beads and perform stringent washes [13].

- Identification: Analyze the purified conjugates by mass spectrometry or immunoblotting to identify novel UBL targets [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Ub/UBL Studies

| Tool / Reagent | Primary Function | Example & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Block degradation of polyubiquitinated proteins, causing their accumulation. | Bortezomib (Velcade): FDA-approved drug for myeloma research [6]. MG132: Common lab-grade inhibitor for acute treatment [14]. |

| E1 Inhibitors | Block the apex of the ubiquitin cascade, inhibiting global ubiquitination. | PYR-41: Inhibits UBA1; can have off-target effects [8]. MLN4924: Inhibits NAE (NEDD8 E1); blocks cullin neddylation and SCF activity [8] [6]. |

| E2 Inhibitors | Provide more selective inhibition than E1 inhibitors. | CC0651: Allosteric inhibitor of CDC34 (E2) [8]. NSC697923: Inhibits UBE2N (Ubc13), blocking K63-linked ubiquitination [8]. |

| Denaturing Lysis Buffers | Instantaneously inactivate all enzymes including DUBs and ULPs to preserve the in vivo conjugation state. | SDS/Urea-based buffers: Critical for accurate assessment of conjugation levels. Must be used for all quantitative studies [13]. |

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | Irreversible alkylating agent that inhibits cysteine-dependent DUBs and protects E2~Ub thioester bonds. | Essential additive to lysis buffers (10-20 mM) to prevent deconjugation during sample prep [14]. |

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) | Recombinant proteins with high affinity for polyubiquitin chains. Used to enrich and protect ubiquitinated proteins from DUBs. | Aid in the purification of labile ubiquitinated species and can be used for in vitro ubiquitination assays [10]. |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Immunoblot detection of specific polyubiquitin chain types (e.g., K48 vs K63). | Crucial for deciphering the ubiquitin code. Specificity must be validated, as cross-reactivity can occur [10]. |

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification where a small, 76-amino-acid protein called ubiquitin is covalently attached to substrate proteins. This process regulates nearly all cellular pathways in eukaryotes, from protein degradation and DNA repair to cell signaling and immune responses [15] [10]. The process is catalyzed by a sequential enzymatic cascade involving ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), and ubiquitin-ligase (E3) enzymes [15]. A key challenge in studying this system is the inherent sample heterogeneity, stemming from the diversity of ubiquitination forms and the dynamic nature of the process, which is counteracted by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that reverse the modification [9] [16].

Understanding this heterogeneity is paramount, as the specific pattern of ubiquitination—whether a protein is monoubiquitinated, multi-monoubiquitinated, or polyubiquitinated—directs its ultimate cellular fate, influencing stability, activity, and interaction partners [17] [18].

The Ubiquitin Code: Types and Functional Consequences

The "ubiquitin code" refers to the concept that different ubiquitination patterns are recognized as distinct signals by the cellular machinery. The table below summarizes the primary types of ubiquitin modifications and their general functional outcomes.

Table 1: Types of Ubiquitin Modifications and Their Biological Functions

| Modification Type | Description | Primary Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Monoubiquitination | A single ubiquitin moiety attached to one lysine residue on a substrate protein [16]. | Endocytosis, histone modification, DNA damage responses, and DNA repair [16] [18]. |

| Multi-Monoubiquitination | Single ubiquitin molecules attached to multiple different lysine residues on the same substrate protein [10]. | A specialized form of monoubiquitination that can amplify signals or create multiple interaction platforms [10]. |

| Polyubiquitination | A chain of ubiquitin molecules linked together, where one ubiquitin is conjugated to another [18]. | Function depends on the linkage type between ubiquitin molecules [17] [18]. |

| ↳ K48-linked | Polyubiquitin chain linked through lysine 48 of ubiquitin. | The classic "kiss of death"; targets substrate for degradation by the 26S proteasome [17] [18]. A chain of at least three ubiquitins is required for efficient degradation [19]. |

| ↳ K63-linked | Polyubiquitin chain linked through lysine 63 of ubiquitin. | Non-proteolytic signaling in immune responses, inflammation, lymphocyte activation, and DNA repair [16] [18]. |

| ↳ M1-linked (Linear) | Polyubiquitin chain linked through the N-terminal methionine of ubiquitin. | Regulation of cell death and immune signaling [16]. |

| ↳ Other Linkages (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33) | Chains linked through other lysine residues in ubiquitin. | Involved in diverse processes including antiviral responses, autophagy, cell cycle progression, and Wnt signaling [16]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the different ubiquitination patterns and their primary cellular fates.

Common Experimental Challenges & Troubleshooting Guide

Researchers often face significant hurdles when studying specific ubiquitination patterns. The transient nature of the modification, the low abundance of ubiquitinated species, and antibody cross-reactivity are common sources of experimental variability and artifacts [16].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Problems in Ubiquitination Studies

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or no ubiquitination signal | The ubiquitination event is transient and reversed by deubiquitinases (DUBs) [16]. The target protein is ubiquitinated at a very low level. | Treat cells with proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG-132 at 5-25 µM for 1-2 hours before harvesting) to prevent degradation and stabilize ubiquitin conjugates [16]. Use catalytically inactive DUB mutants or DUB inhibitors in lysis buffers [15]. |

| High background or smeared bands in Western Blot | Non-specific antibody binding; detection of non-canonical ubiquitination or heterogeneous chain types [16]. | Use high-affinity, well-validated ubiquitin antibodies [16]. Employ enrichment strategies (e.g., ubiquitin traps, TUBE) to purify ubiquitinated proteins before Western blotting [16]. |

| Inability to distinguish between polyubiquitination and multi-monoubiquitination | Standard Western blot cannot differentiate a protein with a single polyubiquitin chain from one with multiple monoubiquitins. | Perform linkage-specific immunoprecipitation using antibodies against specific chain types (e.g., K48- or K63-specific) [16]. Use ubiquitin binding domains (UBDs) with known linkage preferences for pull-down. |

| Difficulty identifying the specific ubiquitinated lysine residue | Mass spectrometry analysis is complicated by the large tryptic peptide generated from ubiquitin. | Utilize di-glycine remnant proteomics. Trypsin cleavage of a ubiquitin-conjugated substrate leaves a characteristic di-glycine "remnant" on the modified lysine, which can be detected by mass spectrometry to identify the exact site of ubiquitination [18]. |

Essential Methodologies and Protocols

Protocol: Enriching Ubiquitinated Proteins with Ubiquitin-Trap

The Ubiquitin-Trap is a powerful tool that uses a high-affinity anti-ubiquitin nanobody (VHH) coupled to beads to immunoprecipitate monomeric ubiquitin, ubiquitin chains, and ubiquitinated proteins from complex cell extracts [16].

Detailed Protocol:

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells in a recommended lysis buffer (e.g., RIPA buffer) supplemented with protease inhibitors and DUB inhibitors (e.g., N-ethylmaleimide) to preserve ubiquitin conjugates.

- Sample Preparation: Clarify the lysate by centrifugation at >10,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Transfer the supernatant to a new tube.

- Incubation with Beads: Incubate the cleared lysate with the appropriate amount of Ubiquitin-Trap Agarose or Magnetic Agarose for 1-2 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation.

- Washing: Pellet the beads by brief centrifugation or use a magnetic rack. Carefully remove the supernatant (flow-through). Wash the beads 3-4 times with 1 mL of ice-cold wash buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elution: Elute the bound ubiquitinated proteins by adding SDS-PAGE sample loading buffer and boiling the beads for 5-10 minutes. The eluate can now be analyzed by Western blotting or mass spectrometry.

Protocol: In Vitro Ubiquitination Reaction

This protocol allows you to reconstitute the ubiquitination cascade for a specific substrate using purified components, providing a controlled system to study the activity of particular E2 or E3 enzymes [20].

Detailed Protocol:

- Reaction Setup: Assemble a 50 µL reaction mixture containing:

- 50-100 nM E1 enzyme

- 1-5 µM E2 enzyme

- 1-5 µM E3 ligase (e.g., Nedd4 for GluA1 subunit ubiquitination [15])

- 10-20 µg of substrate protein

- 5-10 µg of ubiquitin

- 2 mM ATP

- 5 mM MgCl₂

- Appropriate reaction buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5)

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction at 30°C for 1-2 hours.

- Termination and Analysis: Stop the reaction by adding SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiling. Analyze the products by Western blotting, using an antibody against your substrate to observe a mobility shift, or an anti-ubiquitin antibody.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Selecting the right reagents is critical for successful and interpretable ubiquitination experiments.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Ubiquitination

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin-Trap (Agarose/Magnetic) | High-affinity anti-ubiquitin nanobody coupled to beads for immunoprecipitation of ubiquitinated proteins [16]. | Pull down endogenous ubiquitinated proteins from mammalian, yeast, or plant cell extracts for downstream Western blot or mass spectrometry analysis [16]. |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies | Antibodies that recognize a specific polyubiquitin linkage type (e.g., K48-only or K63-only). | Determine the topology of a polyubiquitin chain on a substrate of interest to predict its functional outcome (e.g., degradation vs. signaling) [16]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (MG-132, Bortezomib) | Inhibit the 26S proteasome, preventing the degradation of polyubiquitinated proteins and stabilizing them for detection [16]. | Increase the cellular pool of K48-polyubiquitinated proteins before lysis to enhance detection sensitivity. |

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors | Small molecules or cysteine-alkylating agents that inhibit the activity of DUBs. | Added to cell lysis buffers to prevent the artificial removal of ubiquitin during sample preparation, preserving the native ubiquitination state. |

| Recombinant E1, E2, and E3 Enzymes | Purified, active components of the ubiquitination cascade. | Used in in vitro ubiquitination assays to study the activity of a specific E3 ligase or to ubiquitinate a purified substrate protein [20]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do I see a smear, rather than discrete bands, when I probe for ubiquitin in a Western blot? This is a classic characteristic of ubiquitinated proteins. The smear represents a heterogeneous mixture of your target protein conjugated to ubiquitin chains of varying lengths (mono-Ub, di-Ub, tri-Ub, etc.), as well as proteins modified at different lysine residues. This heterogeneity in molecular weight results in the smeared appearance on the gel [16].

Q2: Can the Ubiquitin-Trap differentiate between K48 and K63-linked chains? No, the standard Ubiquitin-Trap is not linkage-specific. It can bind monomeric ubiquitin and all polyubiquitin chain linkage types with high affinity. To differentiate between linkages, you must perform the pull-down with the Ubiquitin-Trap and then probe the Western blot with linkage-specific antibodies [16].

Q3: How can I increase the amount of ubiquitinated protein in my cell samples? The most common and effective method is to treat your cells with a proteasome inhibitor like MG-132 before harvesting. This prevents the constitutive degradation of K48-polyubiquitinated proteins, causing them to accumulate. A typical starting point is a 1-2 hour treatment with 5-25 µM MG-132, though conditions should be optimized for your specific cell type. Be aware that overexposure can lead to cytotoxic effects [16].

Q4: What is the minimum polyubiquitin chain length required for proteasomal degradation? Recent research using advanced tools like UbiREAD has shown that for K48-linked ubiquitin chains, a chain of at least three ubiquitin molecules is required to efficiently target a substrate for degradation. Shorter chains (e.g., di-ubiquitin) are rapidly disassembled by DUBs and do not signal for degradation [19].

Homotypic vs. Heterotypic Ubiquitin Chain Architectures

FAQs on Ubiquitin Chain Architecture

1. What is the fundamental difference between homotypic and heterotypic ubiquitin chains?

Homotypic chains are polymers in which every ubiquitin subunit is linked through the same specific lysine residue (e.g., all Lys48 or all Lys63 linkages). These chains are often associated with specific, well-defined cellular functions; for instance, Lys48-linked chains primarily target proteins for degradation by the proteasome, while Lys63-linked chains are involved in non-proteolytic signaling processes like DNA damage repair and inflammation [21] [22].

Heterotypic chains are more complex polymers that contain more than one type of ubiquitin linkage. They can be further classified as:

- Mixed chains: Contain different linkage types, but each ubiquitin monomer is modified on only one site.

- Branched chains: Contain at least one ubiquitin monomer that is simultaneously modified on two or more different acceptor sites (e.g., a single ubiquitin with both Lys11 and Lys48 linkages) [21] [23] [22]. These chains greatly expand the ubiquitin code and are implicated in enhancing signaling specificity and efficiency, such as ensuring the rapid degradation of aggregation-prone proteins or key mitotic regulators [23] [22] [24].

2. Why does my ubiquitinated protein appear as a smear on a Western blot, and how can I interpret it?

The appearance of a high-molecular-weight "smear" is a common characteristic of ubiquitinated proteins and is a direct manifestation of sample heterogeneity. This heterogeneity arises from several factors [21]:

- Multiple Ubiquitination Sites: The target protein may be modified at multiple different lysine residues.

- Variable Chain Length: The attached ubiquitin chains can be of different lengths.

- Diverse Chain Linkages: The smear can indicate a mixture of different chain types (homotypic and heterotypic) attached to your substrate.

- Distinct Gel Motilities: Even ubiquitin chains of identical mass but different linkage types can run at different positions on SDS-PAGE gels because ubiquitin does not fully unfold, leading to differences in molecular shape and migration [21].

Rather than being a problem, this smear can be an opportunity. Using techniques like UbiCRest (see troubleshooting guide below) can help you deconvolute this smear to identify the specific linkage types present in your sample [21].

3. What methods can I use to distinguish between homotypic and heterotypic ubiquitin chains?

No single method can fully characterize complex ubiquitin chains. A combination of techniques is required to overcome their respective limitations. The table below compares key approaches for ubiquitination characterization, focusing on topology analysis [25].

Table: Comparison of Strategies for Ubiquitin Chain Architecture Characterization

| Level / Method | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages / Limitations | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| UbiCRest [21] [26] | Qualitative; provides insights into linkage type and architecture within hours; can use endogenous protein. | Cannot reliably distinguish branched from mixed chains; low specificity for some linkage types. | Validation of ubiquitin chain linkage in all samples. |

| Middle-Down Proteomics (e.g., Ub-clipping) [25] | Can identify and quantify branched chains; reveals the ratio of branched to unbranched linkages. | Cannot determine the specific chain linkage types at the branch point itself. | Screening and validation of ubiquitination sites and topologies. |

| Top-Down Proteomics [25] | Can fully characterize branched chains, including linkage types at the branch point. | Low signal-to-noise ratio for high molecular weight species; challenging sample preparation and analysis. | Identifying ubiquitination sites and topologies in all samples. |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies [23] | Can be used for endogenous proteins in Western blot or immunoprecipitation; some bispecific antibodies exist for heterotypic chains. | High cost; can have high background; most antibodies are for homotypic chains. | Validation of specific linkage types. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Sample Heterogeneity

Problem: Determining the Architecture of Heterotypic Ubiquitin Chains

A common challenge is confirming whether a chain is branched or simply a mixture of different homotypic chains, and then identifying the specific linkages involved.

Solution: Employ the UbiCRest (Ubiquitin Chain Restriction) Protocol.

UbiCRest is a qualitative method that uses a panel of linkage-specific deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) to digest ubiquitinated samples, followed by gel-based analysis to infer chain architecture [21] [26].

Table: Key DUBs for UbiCRest Analysis Toolkit [21]

| Linkage Specificity | Recommended DUB | Useful Final Concentration | Important Notes on Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pan-specific (All linkages) | USP21 or USP2 | 1-5 µM (USP21) | Use as a positive control for complete digestion. |

| Lys48 | OTUB1 | 1-20 µM | Highly specific for Lys48 linkages; not very active so can be used at higher concentrations. |

| Lys63 | OTUD1 | 0.1-2 µM | Very active enzyme; can become non-specific at high concentrations. |

| Lys11 | Cezanne | 0.1-2 µM | Very active; non-specific at very high concentrations. |

| Lys6 | OTUD3 | 1-20 µM | Also cleaves Lys11 chains equally well. |

| Lys27 | OTUD2 | 1-20 µM | Also cleaves Lys11, Lys29, and Lys33. |

| Lys29 / Lys33 | TRABID | 0.5-10 µM | Cleaves Lys29 and Lys33 equally well, and Lys63 with lower activity. |

Step-by-Step UbiCRest Workflow:

- Prepare Your Sample: Use immunopurified ubiquitinated protein or purified ubiquitin chains as your substrate [21].

- Set Up Parallel DUB Reactions: Incubate your substrate in separate parallel reactions with a panel of pre-profiled, linkage-specific DUBs (see table above) and appropriate buffer controls [21].

- Terminate Reactions and Analyze: Stop the reactions, typically by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer, and analyze the digestion products by Western blotting, probing for ubiquitin or your protein of interest [21].

- Interpret the Results:

- Identify Linkages Present: The disappearance of high-molecular-weight smears after treatment with a specific DUB indicates the presence of that linkage type in the sample.

- Deduce Chain Architecture:

- If a DUB that cleaves a single linkage type (e.g., OTUB1 for Lys48) completely disassembles the entire chain, it suggests a homotypic Lys48 chain.

- If multiple DUBs are required to fully disassemble the chain, it indicates a heterotypic chain.

- The order of digestion can provide clues about architecture. For example, if a Lys48-specific DUB must act before a Lys11-specific DUB can fully disassemble the chain, it suggests a branched architecture where the Lys11 chain is built upon a Lys48-linked base chain [21] [22].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and interpretation of a UbiCRest experiment.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Studying Ubiquitin Chain Architecture

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Utility | Key Characteristics & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific DUBs [21] | Enzymatic tools for dissecting chain topology in UbiCRest assays. | Purified recombinant enzymes with defined linkage preferences (e.g., OTUB1 for Lys48, Cezanne for Lys11). Must be pre-profiled for specificity. |

| Bispecific Antibodies [23] | Detect heterotypic chains containing two specific linkages via Western blot or immunoprecipitation. | Functions as a "coincidence detector"; e.g., K11/K48-bispecific antibody has high affinity only when both linkages are present in the same polymer. |

| Ubiquitin Mutants (K-to-R) [21] | Used in vitro and in cells to study the requirement of specific lysines for chain formation. | Lysine-to-Arginine mutations prevent chain formation through that residue. Can alter chain structure/dynamics, so results require validation. |

| Mass Photometry [27] | Rapidly assesses sample heterogeneity and molecular mass under native conditions. | Measures mass distribution in minutes with minimal sample; helps evaluate sample purity and complex integrity before complex structural studies. |

Cellular Compartmentalization and Tissue-Specific Ubiquitination

Cellular compartmentalization serves as a fundamental physical regulatory mechanism that organizes biochemical processes in space and time. This organization is particularly crucial for ubiquitination, a pervasive post-translational modification that regulates nearly all aspects of cellular function, from protein degradation to signal transduction [28] [29]. The spatial regulation of ubiquitination components creates specialized microenvironments that determine signaling specificity, with disruptions in this organization contributing to sample heterogeneity that complicates research interpretation.

The nuclear membrane represents one of the most significant compartmentalization barriers, physically separating transcription factors from their targets and actively regulating signal transduction dynamics [29]. When combined with the complex ubiquitin code—featuring multiple chain linkages and modifications—this spatial regulation generates enormous signaling diversity that varies by tissue type and cellular context. Understanding these layered regulatory mechanisms is essential for designing robust experiments and accurately interpreting ubiquitination data across different biological systems.

Key Technical Challenges and Troubleshooting Guides

Challenge: Inconsistent Ubiquitination Detection Across Tissue Samples

Issue: Researchers frequently observe variable ubiquitination signals when analyzing the same pathway across different tissue types or sample preparations, raising questions about biological reality versus technical artifact.

Troubleshooting Guide:

Problem: Differential ubiquitin chain stability during sample preparation

- Solution: Implement linkage-specific ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., K48, K63) and include deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitors (e.g., PR-619) in all lysis buffers [30] [31]

- Rationale: Different ubiquitin chain linkages exhibit varying susceptibility to DUBs, which remain active during sample extraction unless properly inhibited

Problem: Subcellular compartment-specific ubiquitination loss

- Solution: Optimize fractionation protocols with cross-validation using compartment-specific markers

- Rationale: Nuclear, cytoplasmic, and membrane-associated ubiquitination may require specialized extraction conditions [29]

Problem: Tissue-specific epitope masking

- Solution: Employ multiple detection methods (e.g., immunofluorescence, immunoblotting, mass spectrometry) for cross-validation

- Rationale: Fixation methods or protein-protein interactions may differentially obscure ubiquitin epitopes across tissues [31]

Challenge: Resolving Cell-to-Cell Variability in Ubiquitination Patterns

Issue: Single-cell analyses reveal striking heterogeneity in ubiquitination patterns within seemingly homogeneous cell populations, creating uncertainty in bulk measurement interpretation.

Troubleshooting Guide:

Problem: Stochastic fluctuations in E3 ligase condensation

- Solution: Monitor E3 ligase localization and condensation status via live-cell imaging

- Rationale: TRIM family E3 ligases and others form biomolecular condensates that regulate their activity in a context-dependent manner [32]

Problem: Compartment-specific DUB activity variation

- Solution: Implement compartment-specific DUB activity probes and inhibitors

- Rationale: DUBs such as USP48 exhibit distinct subcellular localization and function in a compartment-dependent manner [33]

Problem: Cell cycle-dependent ubiquitination patterns

- Solution: Synchronize cell populations and analyze cell cycle markers in parallel with ubiquitination assays

- Rationale: Ubiquitination regulates cell cycle progression, creating inherent heterogeneity in asynchronized cultures [31]

Essential Methodologies for Compartment-Specific Ubiquitination Analysis

Subcellular Fractionation with Ubiquitination Preservation

Protocol Objective: To isolate intact subcellular compartments while preserving native ubiquitination states for downstream analysis.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Cell Disruption: Use gentle mechanical homogenization in isotonic buffer (250 mM sucrose, 20 mM HEPES, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM EDTA) with added DUB inhibitors (1 mM PR-619) and proteasome inhibitors (10 µM MG-132) [30] [31]

Nuclear-Cytoplasmic Separation:

- Centrifuge homogenate at 720 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C

- Collect supernatant (cytoplasmic fraction)

- Wash nuclear pellet 3x with homogenization buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100

- Validate separation with compartment markers (e.g., Lamin A/C for nucleus, GAPDH for cytoplasm) [29]

Membrane Protein Extraction:

- Incubate fractions with 1% digitonin for 30 minutes on ice

- Centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 20 minutes

- Collect membrane-associated proteins in pellet fraction [29]

Ubiquitination Analysis:

- Process each fraction for immunoblotting with linkage-specific ubiquitin antibodies

- Alternatively, proceed to ubiquitinated peptide enrichment for mass spectrometry [30]

Quality Control Measures:

- Monitor cross-contamination between fractions with compartment-specific markers

- Assess protein integrity by SDS-PAGE before ubiquitination detection

- Include positive and negative controls for ubiquitination in each compartment

Cross-Linking Mass Spectrometry for Ubiquitination Compartment Mapping

Protocol Objective: To capture transient, compartment-specific ubiquitination events through spatial stabilization.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

In Situ Cross-Linking:

- Treat intact cells with membrane-permeable cross-linker (e.g., DSS, 1 mM final concentration) for 30 minutes at room temperature

- Quench with 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) for 15 minutes [9]

Compartment Fractionation:

- Perform subcellular fractionation as described in Section 3.1

- Maintain cross-linking throughout fractionation process

Ubiquitinated Peptide Enrichment:

- Digest proteins with trypsin (1:50 ratio) overnight at 37°C

- Enrich ubiquitinated peptides using K-ε-GG antibody-conjugated resin (e.g., PTMScan) [30]

- Wash resin 4x with IP buffer (100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5% NP-40, pH 8.0)

- Elute with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid

LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Separate peptides using nanoElute UHPLC system

- Analyze with timsTOF Pro mass spectrometer

- Search data using MaxQuant against appropriate database with GlyGly(K) as variable modification [30]

Data Interpretation Guidelines:

- Compare ubiquitination sites across subcellular fractions

- Validate compartment-specific ubiquitination with orthogonal methods

- Correlate ubiquitination patterns with protein abundance in each compartment

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Compartmentalized Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application Notes | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| DUB Inhibitors | PR-619 (broad-spectrum) | Use at 50 μM in lysis buffers; prevents ubiquitin chain degradation during processing | [30] |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K48-, K63-, K11-linked ubiquitin | Validation with linkage-specific standards crucial; differential performance across applications | [31] |

| Compartment Markers | Lamin A/C (nuclear), GAPDH (cytoplasmic), COX IV (mitochondrial) | Essential for fractionation quality control; confirm purity before ubiquitination analysis | [29] |

| E3 Ligase Modulators | MLN4924 (NAE1 inhibitor) | Controls CRL E3 ligase activity; useful for probing compartment-specific E3 functions | [31] |

| Cross-linkers | DSS (membrane-permeable), DTSSP (membrane-impermeable) | Spatial stabilization of transient interactions; concentration optimization required | [9] |

| Ubiquitin Enrichment Resins | K-ε-GG antibody-conjugated beads | Specific enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides for mass spectrometry; commercial options available | [30] |

Signaling Pathway Visualization: TGF-β and Ubiquitination Crosstalk

The TGF-β pathway exemplifies how compartmentalization and ubiquitination integrate to regulate signal transduction. The following diagram illustrates the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and ubiquitination regulation within this pathway:

Diagram 1: TGF-β signaling pathway showing compartmentalization and ubiquitination regulation. The diagram illustrates how nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and spatial regulation of ubiquitination events control TGF-β signal transduction.

Advanced Methodologies: Biomolecular Condensation in Ubiquitination Regulation

TRIM E3 Ligase Condensation Analysis

Background: TRIM family E3 ligases form biomolecular condensates via their coiled-coil domains, creating specialized compartments that modulate ubiquitination activity in a context-dependent manner [32].

Experimental Approach:

Live-Cell Imaging of TRIM Condensates:

- Transfect cells with GFP-tagged TRIM constructs

- Monitor condensation dynamics under varying stress conditions

- Correlate condensate formation with ubiquitination activity using ubiquitin sensors

Functional Validation:

- Introduce disease-associated SNPs in coiled-coil domains

- Assess impact on condensate formation and ubiquitination efficiency

- Link biophysical properties to functional outcomes in specific cellular compartments

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does cellular compartmentalization specifically affect ubiquitination signaling outcomes?

Compartmentalization creates distinct microenvironments with varying compositions of E3 ligases, DUBs, and substrate proteins, leading to compartment-specific ubiquitination patterns. For example, nuclear ubiquitination often regulates transcription factor activity and DNA repair, while cytoplasmic ubiquitination frequently targets proteins for proteasomal degradation. The physical separation also allows the same E3 ligase to perform different functions in different compartments, as demonstrated by TRIM proteins whose activity is modulated by condensation in a location-dependent manner [32] [29].

Q2: What are the best practices for minimizing technical artifacts in tissue-specific ubiquitination studies?

Implement a standardized protocol across all tissue samples that includes: (1) rapid processing and flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen, (2) uniform lysis conditions with fresh DUB and protease inhibitors, (3) cross-validation with multiple detection methods (immunoblotting, mass spectrometry, immunofluorescence), and (4) normalization to both total protein and compartment-specific markers. Additionally, include internal controls such as spiked-in ubiquitination standards to account for technical variation between samples [30] [31].

Q3: How can we distinguish true biological heterogeneity from technical variability in ubiquitination patterns?

Employ single-cell analysis techniques where possible, and always perform technical replicates using independent sample preparations. Biological heterogeneity typically shows consistent patterns across replicates (e.g., specific subpopulations always exhibiting high or low ubiquitination), while technical variability appears random. Additionally, correlate ubiquitination patterns with functional outcomes; true biological heterogeneity should correlate with measurable functional differences in protein activity, localization, or stability [32] [29].

Q4: What computational approaches help address sample heterogeneity in ubiquitination datasets?

Utilize batch correction algorithms specifically designed for proteomics data, and employ dimensionality reduction techniques (PCA, t-SNE) to identify patterns of heterogeneity. Implement mixed-effects models that can account for both technical and biological variability, and use pathway enrichment analysis to determine if observed ubiquitination patterns correlate with specific biological processes. For mass spectrometry data, apply intensity normalization and missing value imputation methods robust to heterogeneous sample types [30].

Experimental Workflow for Compartment-Specific Ubiquitination Analysis

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive workflow for analyzing compartment-specific ubiquitination while addressing sample heterogeneity:

Diagram 2: Comprehensive workflow for analyzing compartment-specific ubiquitination while monitoring and controlling for sample heterogeneity.

Understanding the intricate relationship between cellular compartmentalization and tissue-specific ubiquitination patterns is essential for advancing our knowledge of cellular regulation and disease mechanisms. By implementing the troubleshooting guides, standardized methodologies, and quality control measures outlined in this technical support resource, researchers can significantly improve the reliability and interpretability of their ubiquitination studies. The integration of spatial information with ubiquitination signaling not only addresses technical challenges but also reveals new layers of biological complexity in cellular regulation.

Dynamic Regulation by E1/E2/E3 Enzymes and DUBs

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

This section addresses frequent issues encountered in ubiquitination research, with a specific focus on mitigating the confounding effects of sample heterogeneity.

FAQ 1: How can I improve the detection of weak or transient ubiquitination signals from heterogeneous cell populations?

- Challenge: In a mixed population of cells, such as a tumor sample containing various subclones, a ubiquitination event critical for a specific pathway might be present in only a fraction of the cells. This dilutes the signal, making it difficult to detect above the background noise.

- Solutions:

- Utilize TUBE Technology: Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) are recombinant reagents comprising multiple ubiquitin-associated domains that act as affinity probes with ultra-high avidity for polyubiquitin chains. Using pan-selective TUBEs (e.g., TUBE1 or TUBE2) during your pull-down can significantly enrich for polyubiquitinated proteins from complex lysates, thereby enhancing the detection of low-abundance ubiquitination events [34].

- Employ Sample Decomplexing: For certain targets, using a urea-based decomplexing buffer after cell lysis can disrupt native protein complexes that might shield ubiquitin epitopes or cause high background. This step can improve the signal-to-noise ratio in subsequent detection assays like ELISA [34].

- Optimize Lysis and Inhibition: Ensure your lysis buffer contains a sufficient concentration of denaturants (e.g., 1% SDS) and a complete cocktail of protease and DUB inhibitors to instantly halt enzymatic activity and preserve the native ubiquitination state, preventing the loss of labile modifications.

FAQ 2: My ubiquitination assay results are inconsistent. Could sample heterogeneity be a factor?

- Challenge: Variations in the cellular composition of your samples (e.g., differing ratios of tumor to stromal cells, or varying stages of the cell cycle) can lead to high variability in ubiquitination readouts between experimental replicates.

- Solutions:

- Characterize Your Heterogeneity: Use complementary techniques to profile your sample. For cell lines, flow cytometry for cell cycle markers can indicate proliferation heterogeneity. For complex tissues, spatial transcriptomics can help correlate ubiquitination signatures with specific cell types in the tumor microenvironment [35].

- Implement Robust Normalization: Move beyond total protein loading controls. Normalize your ubiquitination signal to the expression level of the target protein itself (e.g., by re-probing an immunoblot for the target) and to a housekeeping protein. For E3 ligase or DUB activity assays, use positive and negative controls in every experiment.

- Adopt Tiered Mutation Calling in Genomic Analyses: If your work involves sequencing to correlate mutations in ubiquitination machinery with phenotypes, use bioinformatics tools like MuSE that employ sample-specific error models. This improves the sensitivity and specificity of detecting subclonal mutations in heterogeneous tumors, providing a more accurate genetic picture [36].

FAQ 3: How do I determine the specific type of ubiquitin chain linkage in my experiment?

- Challenge: Different ubiquitin chain linkages (e.g., K48 vs. K63) have distinct biological functions, from proteasomal degradation to signal activation. Standard antibodies may not differentiate between them.

- Solutions:

- Use Linkage-Selective TUBEs: LifeSensors and other vendors offer TUBEs with high fidelity for specific linkages like K48, K63, and M1 (linear). These can be used in pull-downs or far-Western blots to selectively enrich and detect particular chain types from your samples [34].

- Leverage Linkage-Specific Antibodies: Several validated antibodies are available that can distinguish common chain types via immunoblotting or immunofluorescence. Always confirm their specificity using appropriate controls (e.g., ubiquitin mutants).

- Mass Spectrometry (Ubiquitin Profiling): For a comprehensive and unbiased analysis, mass spectrometry remains the gold standard. It can identify the specific lysine residues within ubiquitin that are used to form chains, revealing homotypic, heterotypic, and atypical ubiquitination [9] [37].

FAQ 4: I suspect a specific DUB regulates my protein of interest. How can I experimentally validate this?

- Challenge: Confidently assigning a DUB to a specific substrate requires a multi-pronged approach to rule out indirect effects.

- Solutions:

- Follow a Validation Workflow: A combination of experimental evidence is required to establish a high-confidence DUB-substrate relationship, as outlined in the table below [37].

Table: Criteria for Validating a DUB-Substrate Relationship

| Criterion | Experimental Approach | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Interaction | Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP), Proximity Ligation Assay | Physical association between the DUB and the substrate protein [38]. |

| Functional Effect | DUB Knockdown/Knockout (siRNA, shRNA, CRISPR) | Increase in substrate ubiquitination levels and/or decrease in substrate protein stability [35]. |

| Functional Effect | DUB Overexpression | Decrease in substrate ubiquitination levels and/or increase in substrate protein stability [38]. |

| Direct Deubiquitination | In Vitro Deubiquitination Assay with purified components | The DUB can directly remove ubiquitin from the substrate in a reconstituted system, without other cellular proteins [37]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: TUBE-Based Enrichment of Polyubiquitinated Proteins

This protocol is used to efficiently pull down polyubiquitinated proteins from cell or tissue lysates to enhance detection or for downstream proteomic analysis [34].

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells or tissue in a recommended buffer (e.g., RIPA buffer) supplemented with 1% SDS, 10mM N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM), and protease inhibitors. Heat the lysate at 95°C for 5 minutes to denature proteins and inactivate DUBs.

- Dilution and Clearing: Dilute the lysate 10-fold with a non-SDS lysis buffer to reduce SDS concentration. Clear the lysate by centrifugation at >15,000 x g for 15 minutes.

- Incubation with TUBE Beads: Incubate the supernatant with agarose or magnetic beads conjugated to pan-TUBE (e.g., 20-100 µL bead slurry per mg of total protein) for 2-4 hours at 4°C with gentle rotation.

- Washing: Pellet the beads and wash 3-4 times with a mild wash buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100).

- Elution: Elute the bound polyubiquitinated proteins using a proprietary elution buffer (e.g., LifeSensors #UM411B) or by directly boiling the beads in 1X SDS-PAGE loading buffer.

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps:

Protocol 2:In VitroUbiquitination Assay for PROTAC Validation

This ELISA-based kit protocol (e.g., LifeSensors PA770) is used to validate PROTAC efficiency by monitoring targeted ubiquitination of a protein of interest (POI) in a cell-free system [34].

- Reaction Setup: In a tube, combine the following purified components:

- E1 enzyme

- E2 enzyme (e.g., UBE2C, relevant to cancer studies [35])

- E3 ligase (e.g., Cereblon, VHL)

- PROTAC molecule

- Target protein of interest (POI)

- Ubiquitin

- ATP

- Reaction buffer Incubate at 30°C for 60-90 minutes to allow the ubiquitination reaction to proceed.

- Capture: Transfer the reaction mixture to a microtiter plate pre-coated with TUBE reagent. Incubate to allow polyubiquitinated proteins to be captured.

- Detection: Wash the plate to remove unbound material. Add a primary antibody specific to your POI, followed by an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody.

- Quantification: Add a chemiluminescent substrate and measure the signal with a plate reader. The generated signal is a quantitative measure of PROTAC-induced ubiquitination of the POI.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This table lists essential tools and reagents for studying the dynamic regulation of ubiquitination.

Table: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitination Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| TUBEs (Pan-Selective) [34] | Enrichment and detection of polyubiquitinated proteins from lysates. High-avidity ubiquitin-binding entities used in pull-downs, Western blots, and immunofluorescence. | Binds all lysine linkage types (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63). Available conjugated to FLAG, biotin, agarose, or magnetic beads. |

| TUBEs (Linkage-Specific) [34] | Selective enrichment and analysis of specific ubiquitin chain topologies. | Available for K48, K63, and M1 (linear) linkages with high fidelity (nM Kd range). Crucial for determining chain-specific functions. |

| Active E1, E2, and E3 Enzymes | Reconstitution of ubiquitination cascades in vitro for mechanistic studies. | Recombinantly expressed and purified. Essential for in vitro ubiquitination assays and profiling E2/E3 specificities. |

| DUB Inhibitors | Pharmacological probing of DUB function in cells. | Small-molecule inhibitors targeting specific DUBs like USP14, UCHL1, etc. Used to study consequences of DUB inhibition on pathways. |

| PROTAC Assay Plates (e.g., PA950) [34] | Cell-based detection of endogenous target protein ubiquitination. | A sandwich ELISA format using TUBE capture and target-specific antibody detection. Measures polyubiquitination of proteins directly in cell lysates. |

| In Vitro Ubiquitination Kits (e.g., PA770) [34] | Validation of PROTAC or molecular glue efficiency in a cell-free system. | A plate-based assay providing all necessary components (E1, E2, E3, Ub, ATP) to monitor PROTAC-induced ubiquitination of a target protein. |

Visualization of Ubiquitin Chain Types and Functions

Understanding the "ubiquitin code" is fundamental. Different chain linkages direct substrates to distinct cellular fates, a process that can be dysregulated in heterogeneous samples [39] [40].

Analytical Strategies for Heterogeneous Samples: From Enrichment to Quantification

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates nearly all facets of cellular function, from protein degradation to DNA repair and cell division [9]. This process involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin, a 76-amino acid protein, to substrate proteins via a complex enzymatic cascade [9]. However, studying ubiquitination presents significant challenges due to the transient nature of enzyme-substrate interactions, the rapid degradation of many ubiquitinated proteins, and the remarkable heterogeneity of ubiquitin modifications—including monoubiquitination, multiple monoubiquitination, and various polyubiquitin chain types [41] [9]. Affinity purification methods are indispensable tools for overcoming these challenges, with tagged ubiquitin and antibody-based approaches representing two fundamental strategies. This technical resource center provides detailed protocols, troubleshooting guides, and FAQs to support researchers in selecting and optimizing these methods for their specific experimental needs.

Technical Comparison of Core Methodologies

Tagged Ubiquitin Approaches

Tagged ubiquitin approaches involve genetic fusion of an affinity tag to ubiquitin itself, enabling purification of ubiquitin-protein conjugates. The polyhistidine (His) tag is a particularly well-established tag for this purpose [42].

Key Protocol: Purification of Ubiquitin-Protein Conjugates Using Polyhistidine-Tagged Ubiquitin [42]

- Principle: A polyhistidine-tagged ubiquitin molecule (HisUb) serves as an affinity ligand for metal chelate chromatography, enabling purification of ubiquitin-protein conjugates.

- Procedure:

- Expression: Express HisUb in E. coli or other suitable expression systems.

- Lysate Preparation: Prepare crude cell extracts containing HisUb and its conjugates.

- Affinity Chromatography: Pass the extract through a nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose column containing immobilized Ni²⁺ ions (Ni-NTA column). HisUb and its conjugates are retained on the column.

- Washing: Wash the column thoroughly to remove unbound and nonspecifically bound proteins.

- Elution: Elute the highly purified HisUb-protein conjugates using an imidazole gradient or a pH 4.5 buffer.

- Applications: Purification of ubiquitin-protein conjugates for biochemical characterization; can also be used as an affinity ligand for purifying ubiquitin-specific hydrolases (deubiquitinating enzymes) when bound to a solid support [42].

Antibody-Based Approaches

Antibody-based affinity purification relies on antibodies immobilized on a solid support to capture specific target proteins or ubiquitin conjugates. This can target the protein of interest itself or ubiquitin modifications.

Key Protocol: Immunoprecipitation for Ubiquitinated Substrates [41]

- Principle: Specific antibodies are used to immunoprecipitate a target protein of interest along with its associated ubiquitin conjugates.

- Procedure:

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells under native conditions to preserve protein complexes.

- Pre-clearing: Incubate the lysate with control agarose beads (e.g., Protein A/G) to reduce nonspecific binding.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate the pre-cleared lysate with antibody-bound beads. The antibody can be covalently coupled or passively adsorbed to Protein A/G beads.

- Washing: Wash the beads extensively with appropriate buffers to remove non-specifically bound contaminants.

- Elution: Elute the captured protein complexes using a low-pH buffer (e.g., 0.1-0.2 M glycine-HCl, pH 2.5-3.0), followed by immediate neutralization with Tris buffer, pH 8.5. Alternatively, Laemmli sample buffer can be used for direct western blot analysis [43] [44].

- Applications: Isolating specific ubiquitinated proteins for western blot analysis or mass spectrometry identification; studying endogenous protein complexes without genetic modification.

Table 1: Comparison of Tagged Ubiquitin vs. Antibody-Based Affinity Purification

| Feature | Tagged Ubiquitin | Antibody-Based |

|---|---|---|

| Basis of Purification | Affinity of a genetic tag (e.g., His-tag) to a resin [45] [42] | Specificity of an antibody for its antigen (protein or ubiquitin) [43] |

| Typical Elution Conditions | Imidazole (for His-tag), specific competitors (e.g., glutathione for GST-tag), or low pH [43] [45] | Low pH (e.g., glycine-HCl), high salt, chaotropic agents, or denaturing buffers [43] |

| Key Advantage | High specificity for the tag; can purify entire pools of ubiquitinated proteins; genetic control [45] [42] | Can target endogenous proteins without cloning; high affinity of specific antibodies [43] |

| Main Limitation | Requires genetic manipulation and expression of tagged construct [45] | Antibody cost and quality; potential for nonspecific binding; harsher elution conditions may denature proteins [43] [46] |

| Ideal for... | Global profiling of ubiquitin conjugates, purification of ubiquitin-specific hydrolases [42] | Studying specific, endogenous proteins or ubiquitin linkages where specific antibodies exist |

Advanced and Hybrid Methods

Ligase Trapping (Tandem Affinity Purification) [41] This sophisticated method isolates ubiquitinated substrates of specific E3 ligases. An E3 ubiquitin ligase is fused to a polyubiquitin-binding domain, creating a "ligase trap." This fusion protein binds its own ubiquitinated substrates, stabilizing the otherwise transient interaction. Subsequent affinity purification under denaturing conditions captures proteins conjugated with hexahistidine-tagged ubiquitin for identification by mass spectrometry.

Strep/FLAG Tandem Affinity Purification (SF-TAP) [47] A modified TAP method using a tag with two StrepII tags and one FLAG tag. It simplifies the traditional TAP by eliminating proteolytic cleavage steps, allowing mild purification conditions and yielding high-purity complexes with reduced non-specific binding, ideal for studying virus-host protein interactions.

Workflow Visualization

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: When should I choose a tagged ubiquitin approach over an antibody-based method? Choose tagged ubiquitin when you need to profile the global ubiquitin conjugate landscape, when studying a protein that lacks a good quality antibody, or when you require very high purity for structural studies. Choose antibody-based methods when working with endogenous proteins without genetic modification or when specific antibodies for your target or ubiquitin linkage type are available and well-validated [45] [42].

Q2: How can I preserve labile ubiquitin conjugates during purification? The transient nature of enzyme-substrate interactions and rapid degradation are major challenges [41]. To address this:

- Use rapid lysis and work quickly at 4°C.

- Include proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG132) and deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitors (e.g., PR-619) in all lysis and wash buffers.

- Consider using "ligase trap" strategies that stabilize the interaction between the E3 ligase and its ubiquitinated substrate [41].

- For some experiments, use fully denaturing lysis conditions (e.g., with SDS) to instantly inactivate all enzymes, though this disrupts native complexes.

Q3: What are the major sources of sample heterogeneity in ubiquitination studies, and how can affinity purification help? Heterogeneity arises from: the type of ubiquitin chain (e.g., K48, K63, linear), chain length, the number of ubiquitin modifications on a substrate (mono vs. poly), and mixed chain types [9]. Affinity purification helps by:

- Enrichment: Isolating the low-abundance ubiquitinated species from the complex cellular milieu.

- Specificity: Using linkage-specific ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., for K48- or K63-linked chains) to isolate specific chain types.

- Targeting: Using tagged ubiquitin mutants (e.g., lysine-less Ub or specific lysine-to-arginine mutants) to restrict the formation to specific chain types.

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Issues in Affinity Purification

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Yield of Target Protein | Inefficient binding to resin, harsh elution conditions, protein degradation. | Optimize binding buffer (pH, ionic strength); use gentler, specific elution (e.g., competitive elution); add fresh protease/DUB inhibitors to buffers [43] [41]. |

| High Non-Specific Binding | Inefficient washing, overloading the column, non-specific interactions with resin. | Increase wash buffer stringency (moderate salt, low detergent); reduce amount of lysate loaded; use a different resin with lower non-specific binding; pre-clear lysate [43] [45]. |

| Loss of Protein Activity Post-Purification | Denaturation from low pH elution. | Immediately neutralize low pH eluates (e.g., with 1M Tris, pH 8.5) [43]. Test alternative elution methods like competitive elution if available. |

| Inability to Detect Ubiquitinated Substrates | Low steady-state levels of conjugates, conjugate deubiquitination during purification, poor antibody specificity. | Enrich for conjugates using His-tagged ubiquitin and denaturing Ni-NTA purification [41] [42]. Use DUB inhibitors. Validate antibodies with known positive and negative controls. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Affinity Purification in Ubiquitination Studies