Optimizing Proteasome Inhibition Assays in Cancer Cells: A 2025 Guide from Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing proteasome inhibition assays in cancer models.

Optimizing Proteasome Inhibition Assays in Cancer Cells: A 2025 Guide from Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing proteasome inhibition assays in cancer models. It covers the foundational biology of the ubiquitin-proteasome system and its critical role in cancer cell survival, detailing current methodological approaches for assessing proteasome activity and inhibition. The content explores common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies for improving assay reliability and translational value, and concludes with advanced validation techniques and comparative analyses of established and novel inhibitors. By integrating the latest 2025 research findings, this resource aims to support the development of more effective proteasome-targeted cancer therapies.

The Proteasome in Cancer Biology: Establishing a Foundation for Effective Assay Design

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Assay Issues and Solutions

Problem: Inconsistent Proteasome Activity Readings Between Experiments

| Observation | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Highly variable activity measurements (Chymotrypsin-like, Trypsin-like, Caspase-like) when using different microplates. | The binding surface of the microplate (non-binding, medium-binding, high-binding) significantly influences the fluorescence measurement and can even affect the apparent effect of modulators like betulinic acid [1]. | Standardize microplate type across all experiments. For a new assay, empirically determine the optimal plate by testing different binding surfaces (non-binding, medium-binding) with your specific sample type (e.g., crude lysate vs. purified 20S) [1]. |

| Low signal-to-noise ratio in fluorescent readouts. | Adsorption of the fluorescent tag (e.g., AMC) or the peptide substrate to the microplate walls, reducing the detectable signal [1]. | Use plates with low-binding surfaces for minimal protein/peptide interaction. Always include a standard curve for free AMC in the same type of microplate to accurately convert fluorescence units to concentration [1]. |

| Apparent activation or inhibition of proteasomal activity that is not reproducible. | The properties of the microplate can alter the interaction between small molecule effectors and the proteasome, leading to artifactual results [1]. | Verify all modulator effects using multiple plate types or an alternative assay method. The non-binding surface microplate may provide the most reliable data for inhibitor/activator studies [1]. |

Problem: Handling Solid Tumors and Resistant Cell Lines

| Observation | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of efficacy of Proteasome Inhibitors (PIs) in solid tumor models or certain resistant hematological malignancy models. | Intrinsic or acquired resistance mechanisms; the tumor microenvironment may confer protection; specific functional phenotypes of resistant cells (e.g., altered Bcl-2 family protein phosphorylation) [2]. | Consider combination therapies. Target addiction scoring in resistant models has revealed a high dependence on the proteasome, suggesting PIs remain effective. Combinations with Bcl-2 inhibitors (e.g., venetoclax) have shown additive effects [2]. |

| Development of resistance after initial successful treatment with a PI. | Cellular adaptation, such as upregulation of alternative survival pathways (e.g., Mcl-1, Bim) or changes in the immunoproteasome subunit composition [3] [2]. | Profile (phospho)protein changes in resistant lines. Monitor changes in Bcl-2 family proteins and stress response pathways. Switching between different classes of PIs (e.g., from boronate to epoxyketone) may be effective [3] [2]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the core catalytic activities of the 20S proteasome, and what substrates are used to measure them?

The 20S core particle contains three distinct proteolytic activities, each housed in different β-subunits and characterized by their cleavage preference [1] [4]:

- Chymotrypsin-like (β5) activity: Prefers cleavage after hydrophobic residues. It is measured using the substrate Suc-LLVY-AMC.

- Trypsin-like (β2) activity: Prefers cleavage after basic residues. It is measured using the substrate Boc-LSTR-AMC.

- Caspase-like (β1) activity: Prefers cleavage after acidic residues. It is measured using the substrate Z-LLE-AMC. Upon proteolytic cleavage, all substrates release the fluorescent tag 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC), whose fluorescence is measured to quantify activity [1].

Q2: How does the assembly of the 26S proteasome occur, and why is it important?

The 26S proteasome is formed by the association of the 20S core particle with one or two 19S regulatory particles [5] [4]. The biogenesis of the 20S core is a multi-step, chaperone-assisted process that ensures the correct arrangement of its 28 subunits (α1-7 and β1-7 rings) and the activation of the proteolytic β-subunits in a late assembly stage [5]. This precise assembly is critical for forming the central proteolytic chamber and the gated entry channel, which prevents unregulated protein degradation [4]. The 19S cap recognizes polyubiquitinated proteins, unfolds them, and translocates them into the 20S core for degradation in an ATP-dependent manner [6].

Q3: What are the major differences between the constitutive proteasome and the immunoproteasome?

The immunoproteasome is an alternative form of the proteasome expressed in response to inflammatory signals like interferon-gamma. It contains catalytically active alternative subunits [4]:

- β1i (PSMB9) replaces β1, altering the Caspase-like activity.

- β2i (PSMB10) replaces β2, altering the Trypsin-like activity.

- β5i (PSMB8) replaces β5, altering the Chymotrypsin-like activity. This substitution results in altered cleavage preferences, optimizing the generation of antigenic peptides for MHC class I presentation, and is a validated target for autoimmune conditions and specific cancers [3].

Q4: What are the key safety signals associated with common proteasome inhibitors in clinical use?

Real-world safety data from the FAERS database reveals distinct safety profiles for common PIs [7]:

- Bortezomib & Carfilzomib: Strongest safety signal is for "blood and lymphatic system disorders" (e.g., thrombocytopenia, neutropenia). Bortezomib has a well-known signal for peripheral neuropathy [7].

- Ixazomib: Strongest safety signal is for "gastrointestinal disorders" (e.g., diarrhea, nausea, vomiting) [7]. The median time-to-onset of AEs also differs, being shortest for bortezomib (38 days) and longest for ixazomib (81 days) [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Proteasome Research |

|---|---|

| Fluorogenic Peptide Substrates (Suc-LLVY-AMC, Boc-LSTR-AMC, Z-LLE-AMC) | Synthetic peptides used to selectively measure the three proteolytic activities of the proteasome. Cleavage releases the fluorescent AMC group, allowing quantitative activity measurement [1]. |

| Purified 20S Proteasome | Isolated 20S core complex, essential for biochemical characterization of catalytic activities and for screening potential inhibitors without the complexity of the full 26S proteasome [1]. |

| Specific Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., Bortezomib, Carfilzomib, MG132, Epoxomicin) | Tool compounds used to confirm that observed activity in a complex lysate is specifically due to the proteasome. They also serve as benchmarks for new inhibitor development [1] [2]. |

| Black 96-Well Microplates with Low-Binding Surface | The standard platform for fluorescent activity assays. A low-binding surface is critical to minimize adsorption of proteins, peptides, and the fluorescent AMC tag, which can significantly skew results [1]. |

| ATP-Regeneration System | A mixture of ATP and regenerating enzymes (e.g., Creatine Phosphate & Creatine Kinase). Crucial for assays targeting the 26S proteasome, as its assembly and function are ATP-dependent [1]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring 26S Proteasome Activity in Cell Lysates

This protocol is designed to quantify the ATP-dependent activity of the intact 26S proteasome from cultured cell lines or tissue samples [1].

- Lysate Preparation: Homogenize cells or tissue in a non-denaturing lysis buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, pH 7.5). Clarify the lysate by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Collect the supernatant (cytosolic fraction) and determine protein concentration.

- Assay Setup: In a black, low-binding 96-well plate, add 20 μg of lysate protein. Bring the total volume to 100 μL with 26S assay buffer (lysis buffer supplemented with 100 μM ATP).

- Reaction Initiation: Initiate the reaction by adding a specific fluorogenic substrate (e.g., 100 μM Suc-LLVY-AMC for chymotrypsin-like activity). Include control wells with a specific proteasome inhibitor (e.g., 20 μM bortezomib) to confirm signal specificity.

- Measurement: Immediately place the plate in a fluorometer preheated to 37°C. Measure the fluorescence (Ex/Em = 390/460 nm) at regular intervals (e.g., every 15 minutes) for 2 hours. Ensure the reaction kinetics are within the linear range.

- Data Calculation: Calculate the velocity of AMC release (slope of the fluorescence increase over time). Convert fluorescence units to pmoles of AMC using a standard curve generated in the same plate. Express activity as nmol AMC released/min/mg of total protein.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Proteasome Inhibitor Efficacy in Cell Viability Assays

This protocol uses a cell viability readout to assess the functional consequence of proteasome inhibition in malignant cells [2].

- Cell Seeding: Seed target cells (e.g., KARPAS1718 B-cell malignancy models, primary CLL cells) into 384-well cell culture microplates at an optimized density (e.g., 5,000 cells/well for cell lines).

- Compound Treatment: Treat cells with a serial dilution of the proteasome inhibitor (e.g., ixazomib, bortezomib) across a physiologically relevant concentration range (e.g., 1 nM to 10,000 nM). Incubate the plates for 72 hours at 37°C in a humidified CO2 incubator.

- Viability Quantification: Add an equal volume of CellTiter-Glo reagent to each well. Shake the plate to induce cell lysis and mix the contents. Measure the resulting luminescent signal, which is proportional to the amount of ATP present and thus the number of viable cells.

- Data Analysis: Normalize the luminescence data to negative control (DMSO-treated) and positive control (100 μM benzethonium chloride, 100% killing) wells. Use software (e.g., KNIME, GraphPad Prism) to generate dose-response curves and calculate IC50 values.

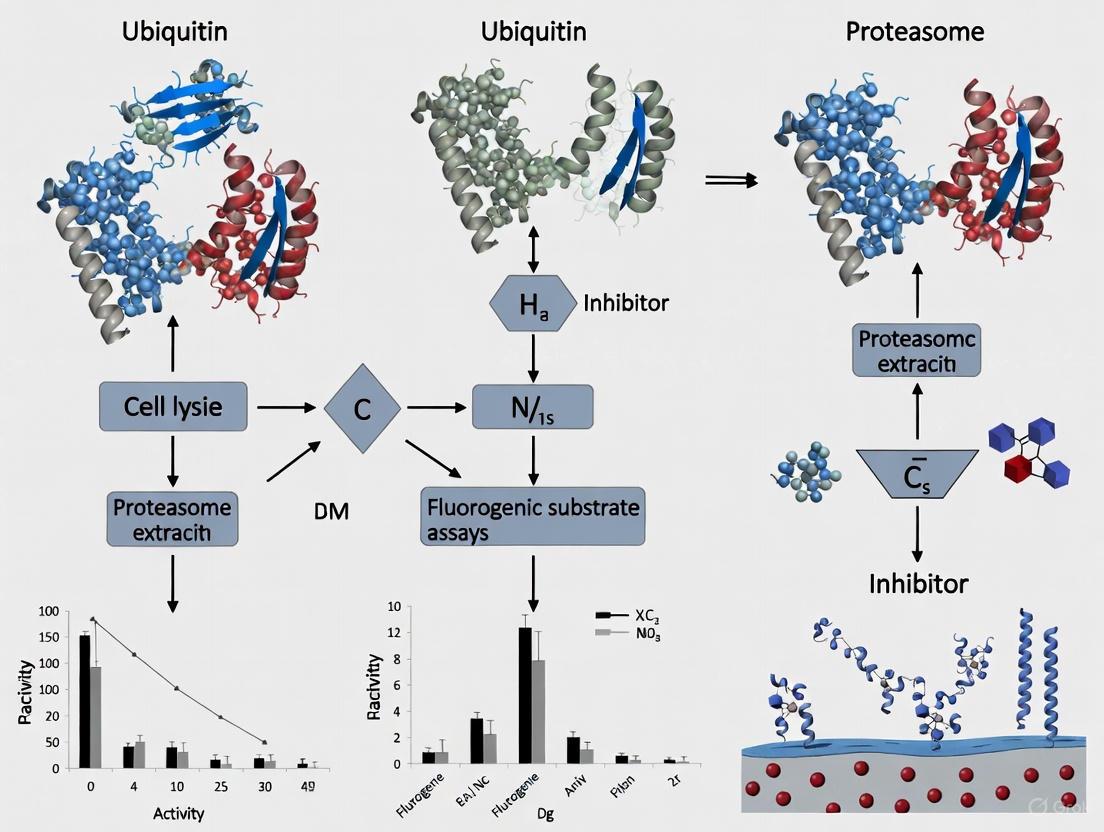

System Architecture and Experimental Workflow

UPS Architecture and Protein Degradation Pathway

(Diagram: The Ubiquitin-Proteasome Protein Degradation Pathway)

26S Proteasome Structure

(Diagram: 26S Proteasome Composition)

20S Core Particle Detailed Architecture

(Diagram: 20S Core Particle Subunit Organization)

Proteasome Activity Assay Workflow

(Diagram: Proteasome Activity Assay Steps)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Proteasome Inhibition Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Bortezomib | First-generation proteasome inhibitor; used to induce proteotoxic stress and study UPS disruption in cancer models [3]. |

| Carfilzomib | Second-generation, irreversible proteasome inhibitor; used to overcome resistance and study mechanisms of apoptosis induction [3]. |

| HSF1 Knockout Cell Lines | Genetic model to disable the Heat Shock Response and study its role as a resistance mechanism to proteasome inhibition [8]. |

| Lys05 (Autophagy Inhibitor) | Small molecule inhibitor of autophagy; used in combination with PIs to disrupt compensatory protein clearance pathways [8]. |

| Antibodies (p-HSF1, ATF4, CHOP) | Key reagents for detecting activation of the Integrated Stress Response (ISR) via Western Blot or immunofluorescence [8]. |

| GFP-LC3-RFP Autophagy Reporter | Fluorescent cellular reporter system to quantify autophagy flux in response to proteasome inhibition [8]. |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is proteasome inhibition an effective strategy against some cancers, and what are the primary resistance mechanisms? Cancer cells have a high protein synthesis rate and produce substantial misfolded proteins, creating a dependency on the proteostasis network, particularly the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS), for survival [9]. Proteasome inhibitors (PIs) disrupt this balance, leading to proteotoxic stress and cell death [3]. A primary resistance mechanism is the activation of adaptive stress responses, specifically the Heat Shock Response (HSR) and autophagy, which help clear accumulating toxic proteins and maintain proteostasis [8].

FAQ 2: How can we overcome resistance to proteasome inhibitors in the lab? Combination therapies that target multiple nodes of the proteostasis network are the most promising strategy. Research shows that simultaneously inhibiting the proteasome and HSR (e.g., via HSF1 deletion) or autophagy (e.g., using Lys05) leads to a synergistic increase in unfolded proteins, terminal Integrated Stress Response (ISR) activation, and massive apoptosis in cancer cells like AML, which are otherwise resistant to single-agent PIs [8].

FAQ 3: What are the key molecular markers to monitor when performing a proteasome inhibition assay? Beyond simple cell viability, you should monitor markers indicating effective proteostasis disruption and cell death commitment. Key markers include:

- Proteotoxic Stress: Accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins.

- HSR Activation: Phosphorylation and nuclear localization of HSF1 [8].

- Autophagy Activation: Lipidation of LC3-I to LC3-II and use of GFP-LC3-RFP reporters [8].

- Terminal ISR Activation: Upregulation of phospho-eIF2α, ATF4, and CHOP [8].

- Apoptosis: Cleavage of caspases and PARP.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Weak or No Effect of Proteasome Inhibitor on Cancer Cell Viability This is a common problem, especially in solid tumors or hematological cancers like AML.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Proteasome Inhibitor Efficacy

| Observation | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low cell death in AML cells. | Activation of compensatory autophagy and HSR [8]. | Co-treat with an autophagy inhibitor (e.g., Lys05) or use HSF1-deficient models to disable the HSR [8]. |

| Resistance in B-cell malignancy models. | Altered dependence on anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins [10]. | Test sensitivity to Bcl-2 inhibitors (e.g., venetoclax) or use PI/Bcl-2i combination therapy [10]. |

| Failure to activate apoptosis. | Insufficient proteotoxic stress or failure to engage the ISR. | Validate that your treatment increases unfolded proteins and confirm upregulation of CHOP and ATF4 to ensure the ISR is engaged [8]. |

| High toxicity in normal cells. | Lack of a therapeutic window. | Validate selectivity by comparing effects on primary healthy cells (e.g., CD34+ cells) in parallel; research indicates a tractable window exists for PI + autophagy inhibition [8]. |

Issue: Interpreting Signaling Pathways in Proteostasis Disruption

Diagram 1: Proteasome inhibition triggers adaptive responses and cell death.

Experimental Data & Protocols

Key Experimental Findings

Table 3: Quantitative Data from Proteostasis-Targeting Studies

| Experimental Model / Condition | Key Measured Outcome | Result | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSF1-/- AML cells + PI | Unfolded Protein | Significant accumulation | [8] |

| HSF1-/- AML cells + PI | Apoptosis Induction | Massive induction | [8] |

| HSF1-/- AML xenograft + PI | In vivo median survival | Extended from 40 to 140 days | [8] |

| VL51 (PI3Ki-RES) | Sensitivity to Bcl-2i | Reduced vs. parental | [10] |

| Primary CLL cells + PI | Efficacy | Effective independent of PI3Ki/Bcl-2i sensitivity | [10] |

| Multi-refractory CLL Patient (Bcl-2i + PI) | Clinical response | Relapsed within 4 months | [10] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Combined Proteasome and Autophagy Inhibition in AML Cells

Aim: To synergistically disrupt proteostasis and induce cell death in Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) cells by concurrently inhibiting the proteasome and the adaptive autophagy pathway.

Materials:

- Human AML cell lines (e.g., MV4-11, MOLM-13) or primary patient-derived AML cells.

- Proteasome Inhibitor: Bortezomib (reconstituted in DMSO).

- Autophagy Inhibitor: Lys05 (reconstituted in DMSO).

- Cell culture medium and reagents.

- Antibodies for: LC3, p62, p-HSF1, ATF4, CHOP, Cleaved Caspase-3, and β-Actin (loading control).

- GFP-LC3-RFP reporter construct.

Methodology:

- Cell Seeding and Treatment:

- Seed AML cells in appropriate culture plates and allow to adhere overnight.

- Set up treatment groups: Vehicle (DMSO) control, Bortezomib alone, Lys05 alone, and Bortezomib + Lys05 combination.

- Perform a dose-response matrix to determine synergistic concentrations (e.g., start with Bortezomib 5-20 nM and Lys05 1-10 µM). Treat cells for 12-48 hours.

Functional Phenotype Analysis:

- Cell Viability/Proliferation: Use MTT or CellTiter-Glo assays at 24h and 48h.

- Apoptosis Assay: Perform Annexin V/PI staining and flow cytometry after 24h of treatment.

Mechanistic Evaluation (Downstream Signaling):

- Western Blotting: Harvest cells after 6-18h of treatment. Probe for ubiquitinated proteins (to confirm proteasome inhibition), LC3-II and p62 (for autophagy flux), p-HSF1 (HSR activation), and ATF4/CHOP (ISR engagement).

- Autophagy Flux Measurement: Transfect cells with the GFP-LC3-RFP reporter. Treat and analyze via fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry. A increased red/green ratio indicates blocked autophagic flux.

- Global Protein Synthesis Assay: Use a surface sensing of translation (SUnSET) assay with puromycin to measure translation rates, which should decrease upon terminal ISR activation.

Expected Results: The combination treatment should show a significant reduction in viability and increase in apoptosis compared to either agent alone. Mechanistically, you should observe a marked accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins and p62, alongside strong upregulation of ATF4 and CHOP, indicating a collapse of proteostasis and commitment to cell death [8].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for combination proteostasis disruption.

FAQ: Core Mechanisms and Experimental Implications

Q1: What is the fundamental chemical difference between reversible and irreversible proteasome inhibitors?

The fundamental difference lies in the nature and stability of the covalent bond formed with the catalytic threonine residue (Thr1) in the β5 subunit of the proteasome.

- Reversible Inhibitors (e.g., Bortezomib, Ixazomib): These compounds typically contain a boronic acid electrophile. They form a slow, reversible, tetrahedral adduct with the Thr1Oγ atom [11] [12]. This bond can eventually break, freeing the proteasome to resume its function. The recovery of proteasome activity is a combination of this bond dissociation and the cellular production of new proteasomes [13].

- Irreversible Inhibitors (e.g., Carfilzomib, Marizomib): These often feature an epoxyketone or related electrophile. They form a dual covalent, morpholino-like adduct with both the Thr1Oγ and the primary amine of the adjacent N-terminal threonine [11] [12]. This two-point attachment creates a much stronger, irreversible bond. Consequently, the return of proteasome function depends solely on the synthesis of new proteasome complexes by the cell [13].

Q2: How does the binding mechanism influence my choice of inhibitor for in vitro assays?

Your choice should be guided by the desired duration of inhibition and the experimental timeline.

- Reversible Inhibitors: Ideal for experiments requiring a transient or pulsatile inhibition of the proteasome. The activity will gradually recover, which can be useful for studying cellular recovery mechanisms [13]. However, this may lead to variable inhibition levels over time if not carefully controlled.

- Irreversible Inhibitors: Best suited for experiments demanding sustained and complete inhibition throughout the assay period. The irreversible binding ensures the proteasome remains inhibited, which is critical for studying downstream apoptotic events that require prolonged stress signaling [11]. Be mindful that this can lead to more pronounced and rapid accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins and ER stress.

Q3: What are the key off-target effects to consider when interpreting my results?

While designed to target the proteasome's chymotrypsin-like (β5) activity, inhibitors can have different off-target profiles.

- Bortezomib: At higher concentrations, it can also inhibit the caspase-like (β1) and trypsin-like (β2) activities of the proteasome [14] [15]. It has also been reported to inhibit several non-proteasomal serine proteases [11].

- Carfilzomib: Demonstrates greater selectivity for the β5 subunit and has shown minimal off-target activity against non-proteasomal proteases in preclinical studies, which may contribute to an improved toxicity profile [11]. This higher specificity makes it easier to attribute observed phenotypes directly to β5 inhibition.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem 1: High Background Cell Death in Control Groups

- Potential Cause: The solvent used for inhibitor reconstitution (e.g., DMSO) is cytotoxic due to improper handling or storage.

- Solution: Ensure high-quality, sterile DMSO. Aliquot solvents to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles and water absorption. When adding solvent to cell culture, keep the final concentration low (typically <0.1%) and include a vehicle-only control in every experiment.

Problem 2: Inconsistent Inhibition Readouts Between Replicates

- Potential Cause: Instability of the inhibitor in aqueous cell culture media over the duration of your assay.

- Solution: This is particularly relevant for reversible inhibitors. Prepare fresh drug solutions immediately before each treatment. For long-term assays (>24 hours), consider media replacement with a fresh inhibitor dose to maintain consistent inhibition pressure, especially when using reversible inhibitors [13].

Problem 3: Acquired Resistance in Long-Term Studies

- Potential Cause: Cancer cell lines can adapt by upregulating proteasome subunit expression or acquiring mutations in the PSMB5 (β5) gene, reducing drug binding affinity [14] [12].

- Solution:

- Validate Resistance: Confirm resistance via viability assays and measure proteasome activity in treated vs. naive cells.

- Combine Agents: Use a combination approach. For instance, co-treatment with an aggresome inhibitor (e.g., Panobinostat) can overcome resistance by blocking an alternative protein disposal pathway [13].

- Switch Inhibitor Class: If resistance is due to a PSMB5 mutation, switching from a boronate (bortezomib) to an epoxyketone (carfilzomib) might be effective, as the binding mechanism differs [12].

Quantitative Data Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Profile of Key Proteasome Inhibitors

| Feature | Bortezomib (Reversible) | Ixazomib (Reversible) | Carfilzomib (Irreversible) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrophilic Warhead | Boronate [11] [12] | Boronate [15] | Epoxyketone [11] [12] |

| Primary Target | β5 subunit (Chymotrypsin-like) [15] [11] | β5 subunit (Chymotrypsin-like) [15] | β5 subunit (Chymotrypsin-like) [11] |

| Binding Kinetics | Slowly reversible [13] [11] | Reversible [13] | Irreversible [13] [11] |

| Common Administration | Intravenous/Subcutaneous [15] [13] | Oral [15] [13] | Intravenous [15] [13] |

| Key Experimental Toxicity | Peripheral Neuropathy [15] [13] | Lower incidence of Neuropathy [13] | Cardiovascular/ Renal [15] [13] |

| β5 IC₅₀ / Kinact/Ki | 7.9 nM (IC₅₀) [12] | Information Not Specified | 2,600 M⁻¹s⁻¹ (Kinact/Ki) [12] |

Table 2: Summary of Resistance Mechanisms and Proposed Solutions

| Resistance Mechanism | Underlying Molecular Event | Proposed Experimental Workaround |

|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Subunit Mutation [12] | Mutations in the PSMB5 gene encoding the β5 subunit, reducing drug-binding affinity. | Switch inhibitor class (e.g., from boronate to epoxyketone); Use combination therapy. |

| Proteasome Overexpression [14] [12] | Upregulation of proteasome subunits, increasing total cellular proteasome capacity. | Co-inhibition of the NRF1-mediated "bounce-back" response; Increase inhibitor concentration. |

| Activation of Alternate Pathways [14] [13] | Increased reliance on aggresome-autophagy pathway for protein clearance. | Combine PI with HDAC inhibitors (e.g., Panobinostat) to block the alternate pathway. |

Key Signaling Pathways and Cellular Responses

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanisms of reversible and irreversible inhibition and the primary downstream consequences that lead to cell death.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Proteasome Inhibition Research

| Item | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Bortezomib | First-generation, reversible PI. Benchmark for in vitro studies. | Reconstitute in DMSO. Monitor for off-target effects on β1 and β2 subunits at high doses [11]. |

| Carfilzomib | Second-generation, irreversible PI. High β5 selectivity. | Typically supplied as a lyophilized powder. Requires reconstitution and use immediately or according to stability data [11]. |

| Ixazomib | First oral, reversible PI for cell-based assays. | Useful for studies modeling prolonged, lower-dose inhibition [15] [13]. |

| CellTiter-Glo Assay | Luminescent assay to measure cell viability based on ATP content. | Standard for endpoint viability readings after 48-72h PI treatment [2]. |

| Proteasome Activity Assay Kits | Fluorogenic substrates (e.g., Suc-LLVY-AMC for β5 activity) to directly measure proteasome inhibition. | Crucial for confirming target engagement and quantifying inhibition kinetics in cell lysates or intact cells [12]. |

| Antibodies: Anti-Polyubiquitin | Western blot detection of accumulated polyubiquitinated proteins. | Key pharmacodynamic marker to confirm effective proteasome inhibition in your model system [14] [16]. |

| Antibodies: Cleaved Caspase-3 | Immunoblotting or flow cytometry to confirm induction of apoptosis. | Essential for linking proteasome inhibition to the intended mechanistic outcome of cell death [15] [11]. |

Core Mechanism: From Proteasome Inhibition to Apoptosis Execution

Q: What is the primary molecular mechanism connecting proteasome inhibition to the activation of apoptosis?

A: The primary link is the critical role of the pro-apoptotic BH3-only protein, NOXA (encoded by the gene PMAIP1). Research has solidly demonstrated that NOXA is the essential, non-redundant protein responsible for initiating apoptosis in response to the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Upon proteasome inhibition, NOXA accumulates and uniquely binds to and neutralizes two key anti-apoptotic proteins, MCL-1 and BCL-XL, simultaneously. This dual inactivation relieves the suppression on the executioner proteins BAX and BAK, allowing them to oligomerize and induce Mitochondrial Outer Membrane Permeabilization (MOMP). This leads to cytochrome c release, activation of caspase-9 and then caspase-3/7, culminating in apoptotic cell death [17].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues & Solutions

Q: My proteasome inhibition treatment is not inducing adequate apoptosis in my cancer cell lines. What could be wrong?

A: The following table outlines common issues and evidence-based solutions to sensitize cells to proteasome inhibitor-induced apoptosis.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Apoptosis | Overexpression of anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins (e.g., BCL-2, BCL-XL, MCL-1) counteracting NOXA. | Combine proteasome inhibitor with a BH3 mimetic (e.g., Venetoclax for BCL-2, A-1331852 for BCL-XL). | [18] [19] [20] |

| Low NOXA Protein | Constitutive degradation of NOXA by the CRL5WSB2 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. | Co-target WSB2 (via genetic knockdown) to stabilize NOXA protein levels and enhance apoptosis. | [20] |

| Insufficient Pathway Engagement | Reliance on alternative, less efficient death pathways. | Verify the essential role of NOXA using genetic knockout controls; ensure intrinsic apoptosis pathway components (caspase-9, BAX/BAK) are functional. | [17] |

| Lack of Expected Phenotype | Compensatory ER stress or JNK pathways not contributing to cell death as assumed. | Focus analysis on the NOXA/BCL-XL/MCL-1 axis, as bortezomib-induced apoptosis can occur independently of CHOP and JNK. | [17] |

Q: The cell death morphology I observe is a "bubbling" or lytic phenotype, not classic membrane blebbing. Is this still apoptosis?

A: Yes. Bortezomib treatment can lead to a lytic cell death phenotype often classified as secondary necrosis or pyroptosis. This occurs because the initial apoptotic activation of caspase-3 can cleave the pore-forming protein GSDME. Cleaved GSDME creates pores in the plasma membrane, leading to the characteristic "bubble-blow" phenotype and lytic death. This process is a consequence of the initial apoptotic signaling, not an indication of a non-apoptotic pathway [17].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Validating Protein Ubiquitination and Stabilization

Aim: To confirm that your protein of interest (POI) is polyubiquitinated and accumulates upon proteasome inhibition.

Method: Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and Western Blot [21] [22].

- Cell Treatment & Lysis: Treat cells with a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., 50 nM Bortezomib or 10 µM MG132) for a suitable duration (e.g., 4-16 hours). Include a DMSO vehicle control. Lyse cells using a RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitors.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate the clarified cell lysate with an antibody specific to your POI and Protein A/G beads overnight at 4°C.

- Washing and Elution: Wash beads thoroughly with lysis buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins. Elute the bound proteins by boiling in SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

- Western Blot Analysis:

- Resolve the eluted proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a PVDF membrane.

- Probe the membrane with an anti-ubiquitin antibody to detect polyubiquitinated forms of your POI, which will appear as a high-molecular-weight smear above the main POI band.

- Re-probe the membrane with the antibody against your POI to confirm successful immunoprecipitation and show its accumulation in the bortezomib-treated sample.

Protocol: Confirming Apoptosis via Caspase-3/7 Activation

Aim: To quantitatively measure the induction of apoptosis following proteasome inhibition.

Method: Caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay or Western Blot for cleaved caspase-3.

- Cell Treatment: Seed cells in a white-walled 96-well plate. Treat with your proteasome inhibitor and appropriate controls.

- Caspase-Glo Assay: At the desired timepoint, add an equal volume of Caspase-Glo 3/7 reagent to each well. Incubate for 30-60 minutes at room temperature and measure luminescence. Increased luminescence indicates caspase-3/7 activation [17].

- Western Blot Validation: In parallel, prepare whole-cell lysates from treated cells. Perform Western blotting as described below and probe with an antibody against cleaved caspase-3 to confirm its activation [22].

Standard Western Blot Workflow [22]:

Key Signaling Pathway

The following diagram integrates the core mechanism, based on research findings, linking proteasome inhibition to apoptosis via the Bcl-2 protein family [17] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This table lists critical reagents and their functions for studying this pathway.

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Bortezomib (Velcade) | Reversible proteasome inhibitor; induces ER stress and NOXA accumulation. | Primary inducer to study the connection between proteasome inhibition and intrinsic apoptosis [17]. |

| MG132 | Peptide-aldehyde proteasome inhibitor; used frequently in vitro. | To broadly inhibit the proteasome and cause accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins in cell culture [21]. |

| Venetoclax (ABT-199) | Selective, potent BCL-2 inhibitor (BH3 mimetic). | To test synthetic lethality or combinatorial effects with proteasome inhibitors, especially in BCL-2-dependent cancers [19] [20]. |

| ABT-737 / Navitoclax | BH3 mimetics inhibiting BCL-2, BCL-XL, and BCL-w. | To sensitize cells to apoptosis by neutralizing anti-apoptotic proteins beyond MCL-1 [20]. |

| Anti-NOXA Antibody | Detects NOXA protein levels by Western blot or immunofluorescence. | To confirm NOXA stabilization post-proteasome inhibition [17]. |

| Anti-K48-linkage Specific Ubiquitin Antibody | Detects ubiquitin chains linked via K48, the primary signal for proteasomal degradation. | To confirm that a protein is tagged for proteasomal degradation [21]. |

| Caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay | Luminescent assay to measure caspase-3 and -7 activity. | To quantitatively assess apoptosis induction in a high-throughput format [17]. |

| WSB2 shRNA/sgRNA | Genetic tool to knock down or knock out the E3 ligase receptor WSB2. | To stabilize endogenous NOXA levels and test its effect on sensitizing cells to bortezomib [20]. |

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a critical pathway for intracellular protein degradation, maintaining cellular homeostasis by regulating the turnover of proteins involved in cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and signal transduction [6]. In cancer cells, this system is often dysregulated, leading to the uncontrolled accumulation of oncoproteins and evasion of cell death. Proteasome inhibitors (PIs) are a class of anticancer agents that target the 20S proteasome core, disrupting protein degradation and triggering apoptosis in malignant cells [23]. This guide provides a technical overview of current clinical PIs, their mechanisms, and practical applications in cancer research, with a focus on optimizing assays and troubleshooting common experimental challenges.

Proteasome inhibitors have revolutionized the treatment of hematological malignancies, particularly multiple myeloma, and are being investigated for solid tumors [23] [6]. They work primarily by inhibiting chymotrypsin-like (β5) activity of the proteasome, leading to the accumulation of pro-apoptotic proteins and cell cycle arrest.

Table 1: Clinically Used and Investigational Proteasome Inhibitors

| Inhibitor Name | Generation | Primary Target | Administration | Key Clinical Applications | Common Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bortezomib | First | Reversible inhibition of β5 subunit | Intravenous, Subcutaneous | Multiple Myeloma (MM), Mantle Cell Lymphoma | Peripheral neuropathy, thrombocytopenia, gastrointestinal distress [23] |

| Carfilzomib | Second | Irreversible inhibition of β5 subunit | Intravenous | Relapsed/Refractory MM | Cardiotoxicity, renal toxicity, thrombocytopenia [23] |

| Ixazomib | Second | Reversible inhibition of β5 subunit | Oral | Relapsed/Refused MM | Thrombocytopenia, rash, gastrointestinal distress [23] [2] |

| Marizomib | Investigational | Irreversible inhibition of multiple subunits (β5, β1, β2) | Intravenous | Clinical trials for MM and solid tumors, including CNS malignancies | CNS-related adverse effects (e.g., mood changes, hallucinations) [23] |

| Oprozomib | Investigational | Irreversible inhibition of β5 subunit | Oral | Clinical trials for hematologic malignancies | Gastrointestinal toxicity [23] |

| BC12-3 | Novel (Preclinical) | Selective inhibition of β5 subunit | N/A (Preclinical) | Preclinical studies in MM | Excellent safety profile in vivo models [24] |

Mechanism of Action: Signaling Pathways

Proteasome inhibitors exert their anticancer effects through multiple interconnected pathways. The core mechanism involves disrupting the balance of regulatory proteins, pushing cancer cells toward apoptosis.

Diagram 1: Core signaling pathways of proteasome inhibitors in cancer cells.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful experimentation with PIs requires a suite of reliable reagents and tools. The following table details essential materials for investigating proteasome inhibition.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Proteasome Inhibition Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Viability Assay Kits(e.g., CellTiter-Glo) | Measures ATP levels to quantify metabolically active cells; used for dose-response and IC50 determination. | Standardized viability readout after 72-hour PI treatment [2]. |

| Apoptosis Detection Kits(e.g., Annexin V/Propidium Iodide) | Distinguishes between live, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic cells via flow cytometry. | Mechanistic validation of cell death induced by PI. |

| Proteasome Activity Assay Kits(Fluorogenic substrates) | Directly measures chymotrypsin-like (β5), trypsin-like (β2), and caspase-like (β1) proteasome activities. | Confirming on-target engagement of the inhibitor in cell lysates or purified proteasome. |

| Western Blot Antibodies(e.g., anti-BIM, anti-Mcl-1, anti-p21) | Detects accumulation of key regulatory proteins downstream of proteasome inhibition. | Verifying upstream mechanism; e.g., upregulated BIM and Mcl-1 after PI treatment [2] [25]. |

| Idelalisib-Resistant Cell Lines(e.g., KARPAS1718, VL51 models) | Models for studying resistance mechanisms and evaluating efficacy of PIs in resistant disease. | Testing PI efficacy in overcoming resistance to targeted therapies like PI3K inhibitors [2]. |

| Primary CLL Co-culture System(with APRIL/BAFF/CD40L fibroblasts) | Mimics the tumor microenvironment to maintain primary cancer cell viability and study drug response ex vivo. | Evaluating PI sensitivity in primary patient cells in a more physiologically relevant context [2]. |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Protocol: In Vitro Drug Sensitivity and Viability Screening

This protocol is adapted from dose-response experiments used to establish the efficacy of PIs like ixazomib in resistant B-cell malignancy models [2].

Cell Preparation:

- Harvest exponentially growing cells (e.g., KARPAS1718, VL51, or primary CLL cells co-cultured with fibroblasts).

- For primary CLL cells, isolate PBMCs and co-culture with irradiated APRIL/BAFF/CD40L-expressing fibroblasts for 24 hours prior to assay to enhance survival [2].

- Create a single-cell suspension and seed into 384-well assay plates at an optimized density (e.g., 5,000 cells/well for cell lines, 10,000 cells/well for primary CLL cells).

Compound Treatment:

- Prepare a dilution series of the proteasome inhibitor (e.g., from 1 nM to 10,000 nM). Include a negative control (0.1% DMSO vehicle) and a positive control (100 µM benzethonium chloride for 100% death).

- Add compounds to the assay plates, ensuring technical replicates for each condition.

Incubation and Readout:

- Incubate plates at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 72 hours.

- Equilibrate plates to room temperature. Add CellTiter-Glo reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol.

- Measure luminescence using a plate reader. The luminescent signal is proportional to the amount of ATP present, which indicates viable cell mass.

Data Analysis:

- Normalize the raw data:

% Viability = (Sample - Positive Control) / (Negative Control - Positive Control) * 100. - Process the dose-response data using analysis software (e.g., KNIME, GraphPad Prism) to generate dose-response curves and calculate IC₅₀ values.

- Normalize the raw data:

Protocol: Mechanistic Validation via (Phospho)Protein Profiling

This methodology is critical for confirming the proposed mechanism of action, such as the upregulation of BIM and Mcl-1 following PI treatment [2].

Cell Treatment and Lysis:

- Treat cells with the PI at a relevant concentration (e.g., near the IC₇₂) and a DMSO vehicle control for a predetermined time (e.g., 24 hours).

- Collect cells, wash with PBS, and lyse using a suitable RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

Protein Quantification and Separation:

- Determine protein concentration using a Bradford or BCA assay.

- Separate equal amounts of protein (e.g., 20-30 µg) by SDS-PAGE.

Western Blotting:

- Transfer proteins from the gel to a PVDF or nitrocellulose membrane.

- Block the membrane with 5% non-fat milk or BSA in TBST for 1 hour.

- Probe the membrane overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against proteins of interest (e.g., anti-BIM, anti-Mcl-1, anti-Bcl-2, anti-p21, and a loading control like GAPDH or β-actin).

- Incubate with an appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Develop the blot using a chemiluminescent substrate and visualize with a digital imager.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Our proteasome inhibitor shows high efficacy in cell lines but fails in primary patient cells co-cultured with stromal cells. What could be the cause, and how can we overcome this?

- Answer: The tumor microenvironment (TME) confers significant survival signals and drug resistance. Stromal cells secrete cytokines (e.g., IL-10) and provide contact-dependent signals that upregulate anti-apoptotic proteins like Bcl-2 and Mcl-1 in cancer cells, counteracting the PI's pro-apoptotic pressure [2].

- Solution: Implement a rational combination strategy.

- Combination with Bcl-2 inhibitors: Co-treatment with venetoclax (Bcl-2i) can synergize with PIs. PIs upregulate BIM, which primes the cell for apoptosis, while Bcl-2i frees BIM to activate Bax/Bak. This combination has shown additive effects in resistant models [2] [25].

- Experimental Validation: Perform a combination index (CI) assay using the method described in Protocol 4.1 with fixed molar ratios of PI and Bcl-2i. Confirm synergistic cell death and mechanistic synergy via Western blot (Protocol 4.2) showing enhanced BIM stabilization and PARP cleavage.

FAQ 2: We observe an initial response to proteasome inhibitor treatment in our models, but resistance develops rapidly. What are the key mechanisms, and what are the next-step strategies?

- Answer: Resistance is multifactorial. Key mechanisms include:

- Upregulation of Alternative Survival Pathways: Increased expression of other anti-apoptotic proteins, particularly Mcl-1, can compensate for continuous proteasome blockade [2] [25].

- Mutations in the Proteasome β5 Subunit (PSMB5): Can reduce the binding affinity of specific PIs.

- Activation of Efflux Pumps: Increased expression of drug transporters can reduce intracellular concentrations of the inhibitor.

- Solution:

- Next-Generation PIs: Evaluate irreversible PIs (e.g., carfilzomib) or PIs with different subunit specificity (e.g., marizomib) that can overcome β5 subunit mutations [23].

- Novel Compound Screening: Investigate new PIs like BC12-3, which has shown potent, broad-spectrum antitumor activity and a strong safety profile in preclinical MM models, potentially offering a new option to circumvent resistance [24].

- Sequential or Combination Therapy: As resistance to one targeted therapy (e.g., PI3K inhibitor idelalisib) does not confer cross-resistance to PIs, they can be an effective salvage strategy. Profiling patient samples for "target addiction" to the proteasome can identify candidates for this approach [2].

FAQ 3: The in vivo efficacy of our proteasome inhibitor is limited by poor pharmacokinetics or toxicity. How can we improve its therapeutic window?

- Answer: This is a common challenge with small-molecule PIs, often due to off-target effects or suboptimal biodistribution.

- Solution:

- Nano-sized Drug Delivery Systems (NDDS): Encapsulating PIs in nanocarriers (e.g., liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles) can significantly improve their pharmacokinetics. NDDS enhance bioavailability, prolong circulation time, and promote accumulation in tumor tissue via the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect, thereby reducing systemic exposure and toxicity [26].

- Oral Formulations: The development of oral PIs like ixazomib and oprozomib improves patient convenience and can potentially lead to more sustained, lower-level target inhibition, which may mitigate certain toxicities associated with intravenous bolus dosing [23].

Advanced Methodologies for Proteasome Activity Assessment in Cellular Models

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the recommended fluorogenic substrates for selectively measuring the activity of individual proteasome catalytic subunits? Selective fluorogenic substrates are designed based on the oligopeptide recognition elements of known proteasome inhibitors [27]. The table below summarizes recommended substrates and their performance for assessing the activity of constitutive proteasome (cCP) and immunoproteasome (iCP) subunits in cell lysates and with purified 20S proteasome [27].

Table 1: Substrate Specificity and Performance for Proteasome Subunits

| Target Subunit | Proteasome Type | Preferred Substrate Sequence/Name | Reported Activity & Selectivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| β1c | Constitutive | LU-FS01c | Effective and selective [27] |

| β1i | Immuno | LU-FS01i | Effective and selective [27] |

| β2c | Constitutive | LU-FS02c | Effective and selective (minor background activity noted) [27] |

| β2i | Immuno | LU-FS02i | Poor substrate [27] |

| β5c | Constitutive | LU-FS05c | Poor substrate [27] |

| β5i | Immuno | LU-FS05i | Effective and selective [27] |

| Chymotrypsin-like | Mixed | Suc-LLVY-aminoluciferin | Commercial substrate (e.g., Proteasome-Glo Assay) [28] |

| Trypsin-like | Mixed | Z-LRR-aminoluciferin | Commercial substrate (e.g., Proteasome-Glo Assay) [28] |

| Caspase-like | Mixed | Z-nLPnLD-aminoluciferin | Commercial substrate (e.g., Proteasome-Glo Assay) [28] |

Q2: I am observing low signal from my β5c or β2i selective substrates. Is this expected? Yes, this is a known experimental finding. Research has demonstrated that fluorogenic substrates reverse-designed from inhibitors for the β5c and β2i subunits often show low enzymatic activity, making them poor reporters despite the parent inhibitors being selective [27]. If your assay requires monitoring these specific activities, you may need to:

- Use alternative methods, such as activity-based probes, which are covalent inhibitors equipped with a fluorophore or biotin tag that bind directly to the active site [27].

- Consider commercial luminescent assays for broader activity profiling (e.g., chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like, caspase-like) [28].

Q3: How can I confirm that the fluorescence signal in my assay is specifically from proteasome activity and not from other cellular proteases? To validate the specificity of your signal, run parallel assays in the presence of proteasome-specific inhibitors [27]. A significant reduction in fluorescence signal upon inhibitor treatment confirms proteasome-specific activity.

- Use a pan-proteasome inhibitor like epoxomicin to block all proteasome activity [27].

- Use subunit-selective inhibitors (e.g., LU-001c for β1c) complementary to your fluorogenic substrate to confirm selective subunit targeting [27].

- Pre-incubate your cell lysate or purified proteasome with the inhibitor for 30-60 minutes before adding the fluorogenic substrate.

Q4: What are the critical steps for preparing cell lysates for proteasome activity assays? Proper cell lysis is crucial for preserving enzymatic activity. The following protocol is adapted from studies using Raji (human B-cell lymphoma) cell lysates [27].

- Harvest and Wash Cells: Collect cells by centrifugation and wash once with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Lysis: Resuspend the cell pellet in a lysis buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 250 mM sucrose, 5 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM DTT, 0.5% NP-40). Use a volume that yields a total protein concentration of 5-10 mg/mL.

- Incubation: Incubate on ice for 10-15 minutes with occasional vortexing.

- Clarification: Centrifuge the lysate at high speed (e.g., 16,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C) to remove insoluble debris.

- Aliquoting and Storage: Transfer the clear supernatant to a new tube. Use the lysate immediately for assays or snap-freeze in aliquots for storage at -80°C. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

Q5: How do I activate purified 20S proteasome for in vitro assays, and what are the differences between activation methods? Purified 20S proteasome has a gated channel and may require activation for optimal activity in vitro. The two common methods are:

- SDS Treatment: Brief exposure to a low concentration of SDS (e.g., 0.035%) induces a conformational change that opens the gate, allowing substrate entry [27]. This is a common method for initial characterization.

- PA28 (11S Regulator) Activation: The PA28 regulator binds to the α-ring of the 20S core particle in a physiological manner to facilitate gate opening and stimulate substrate unfolding and translocation [27] [29]. This method may better reflect a native activation state and can sometimes yield different activity profiles compared to SDS [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Low or No Fluorescence Signal

Table 2: Troubleshooting Low Fluorescence Signal

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Substrate is not being cleaved | Verify proteasome activity by testing with a commercial, non-selective proteasome substrate (e.g., Suc-LLVY-AMC). Check substrate specificity; remember that β5c and β2i are inherently poor substrates [27]. |

| Loss of proteasome activity | Use fresh cell lysates; avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. Include a positive control (e.g., a known active proteasome preparation) in your experiment. Confirm that inhibitors are not contaminating your assay. |

| Incorrect assay conditions | Ensure the assay buffer is correct (pH, ionic strength). Check that the fluorometer is set to the correct excitation/emission wavelengths for your fluorophore (e.g., ~380 nm excitation, ~460 nm emission for AMC). |

| Proteasome concentration too low | Increase the amount of lysate or purified proteasome in the reaction. Perform a protein concentration assay to standardize inputs. |

High Background Fluorescence or Non-Specific Signal

Table 3: Troubleshooting High Background Signal

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Cleavage by non-proteasome proteases | Always include controls with proteasome-specific inhibitors (e.g., epoxomicin) to confirm the signal origin [27]. |

| Substrate auto-fluorescence or degradation | Protect substrate stocks from light and store as recommended. Run a "no-enzyme" control to check for inherent substrate fluorescence. |

| Contaminated buffers or reagents | Prepare fresh buffers using high-purity water. Filter-sterilize buffers if necessary. |

Poor Subunit Selectivity

Table 4: Troubleshooting Poor Subunit Selectivity

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Cross-reactivity with other proteasome subunits | Validate selectivity using purified constitutive proteasome (cCP) and immunoproteasome (iCP). Confirm selectivity by pre-treating with highly selective inhibitors for the target and off-target subunits [27]. |

| Substrate concentration is too high | Perform a kinetic experiment to determine the optimal substrate concentration (Km). High substrate concentrations can lead to off-target cleavage. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Reagents for Fluorogenic Proteasome Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Fluorogenic Substrates (e.g., peptide-ACC/AMC) | Core assay component. The peptide backbone confers specificity, and cleavage releases the fluorescent dye (e.g., AMC or ACC) [27]. |

| Selective Proteasome Inhibitors | Essential controls for verifying signal specificity and substrate selectivity (e.g., epoxomicin for pan-inhibition, LU-001c for β1c) [27]. |

| Purified 20S Proteasome (cCP & iCP) | Positive control and essential tool for validating substrate selectivity without interference from other cellular proteases [27]. |

| Cell Lysis Buffer with Detergent | For extracting active proteasomes from cultured cancer cells. A mild non-ionic detergent (e.g., NP-40) is often used [27]. |

| Proteasome-Glo Assay Kits | Commercial luminescent assays for convenient, homogeneous measurement of chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like, and caspase-like activities in cultured cells [28]. |

| Activity-Based Probes | Chemical tools for direct labeling and visualization of active proteasome subunits in gels or by protein profiling, useful when substrates perform poorly [27]. |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Context

The following diagrams illustrate the core experimental workflow for a fluorogenic substrate assay and the role of the proteasome in the context of cancer cell signaling relevant to therapeutic inhibition.

Figure 1: Fluorogenic Substrate Assay Workflow.

Figure 2: Proteasome Inhibition Overcomes Therapy Resistance.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why do my IC50 values for covalent inhibitors show significant variability between experiments, and how can I improve replicability?

Answer: Variability in IC50 values, especially with covalent inhibitors like proteasome inhibitors, is often due to the time-dependent nature of the inhibition and suboptimal assay conditions. The IC50 value for an irreversible inhibitor is not a fixed constant but changes with the pre-incubation time, making it a poor stand-alone measure of potency [30]. Furthermore, technical confounders like evaporation of diluted drug stocks and DMSO solvent effects can significantly impact cell viability readings and dose-response curves [31].

- Solution:

- Adopt Advanced Fitting Methods: For covalent inhibitors, move beyond single time-point IC50 values. Use global fitting methods like EPIC-Fit to determine the fundamental potency parameters: the inactivation rate constant (

k_inact) and the inhibitor constant (K_I) [30]. - Optimize Drug Storage: Avoid storing diluted drugs in 96-well plates, even at 4°C or -20°C, as evaporation leads to concentration increases. Prepare fresh dilutions for each experiment [31].

- Control for DMSO: Use matched DMSO vehicle controls for each drug concentration instead of a single control for the entire assay to prevent artifacts from solvent cytotoxicity [31].

- Adopt Advanced Fitting Methods: For covalent inhibitors, move beyond single time-point IC50 values. Use global fitting methods like EPIC-Fit to determine the fundamental potency parameters: the inactivation rate constant (

FAQ 2: For a slow-binding inhibitor, my initial velocity data gives a mixed-type inhibition pattern, but I suspect it is actually competitive. How can I resolve this?

Answer: Your suspicion is likely correct. For inhibitors with a long drug-target residence time (slow off-rate, k_off), conventional steady-state analysis of initial velocities after pre-incubation can be misleading. The slow dissociation of the enzyme-inhibitor (E-I) complex can cause a truly competitive inhibitor to appear as mixed-type or noncompetitive in double-reciprocal plots [32].

- Solution:

- Pre-steady-state Analysis of Progress Curves: Instead of relying solely on initial velocities, perform a global fitting of the entire reaction progress curve. This method extracts information from the pre-steady-state phase and allows for the direct determination of the microscopic rate constants (

k_onandk_off) and the trueK_i[32]. This approach revealed that the potency of the Alzheimer's drug galantamine was previously underestimated by a factor of ~100 due to its time-dependent inhibition [32].

- Pre-steady-state Analysis of Progress Curves: Instead of relying solely on initial velocities, perform a global fitting of the entire reaction progress curve. This method extracts information from the pre-steady-state phase and allows for the direct determination of the microscopic rate constants (

FAQ 3: What are the critical parameters I must define and control when moving from a single endpoint IC50 to a pre-steady-state kinetic analysis for my proteasome inhibition assay?

Answer: A robust pre-steady-state analysis requires meticulous control and knowledge of all experimental parameters. The following table summarizes the key components needed for a method like EPIC-Fit [30].

Table 1: Essential Experimental Parameters for Pre-steady-state Kinetic Fitting

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameters | Purpose in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme & Substrate | Enzyme concentration ([E]), Substrate concentration ([S]), K_M (Michaelis constant), k_cat (catalytic rate constant) |

Defines the baseline catalytic activity and substrate turnover in the absence of inhibitor. |

| Inhibitor | Estimated k_inact and K_I (for fitting) |

Initial estimates for the non-linear regression algorithm to optimize. |

| Assay Conditions | Pre-incubation time, Incubation time, Dilution factors upon substrate addition | Critical for accurately simulating the biphasic nature of the pre-incubation experiment. |

Answer: High variation often stems from suboptimal cell culture and assay protocols. A systematic variance component analysis has shown that variations are primarily associated with the choice of drug and cell line, but technical artifacts can dominate [31].

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Edge effects and evaporation.

- Cause: Evaporation from outer wells of a microplate during incubation alters drug concentration and osmolality [31].

- Solution: Use microplates designed to minimize evaporation. Ensure the incubator has a humidified atmosphere and consider omitting perimeter wells or using them for buffer controls [31].

- Problem: Dose-response curves start above 100% viability.

- Problem: Unstable dose-response curves with large error bars.

- Cause: Cell seeding density is too high or too low, or growth medium is not optimized.

- Solution: Empirically determine the optimal seeding density for your cell line to ensure sub-confluent, logarithmic growth throughout the assay duration. Using growth medium with 10% FBS can improve data quality versus serum-free conditions [31].

- Problem: Edge effects and evaporation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Optimized IC50 Determination

| Item | Function/Explanation | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Covalent Proteasome Inhibitors | Irreversibly bind to the catalytic threonine residue in the proteasome's β-subunits, blocking protein degradation and inducing cell death in cancer cells [33] [29]. | Bortezomib (reversible), Carfilzomib (irreversible), Ixazomib [33] [2]. |

| Cell Viability Assay Kits | Measure the metabolic activity or ATP content as a proxy for the number of viable cells after drug treatment. | CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Assay (measures ATP) [2], Resazurin Reduction Assay (measures metabolic activity) [31]. |

| EPIC-Fit Spreadsheet | A tool implemented in Microsoft Excel that uses numerical modeling and the Solver add-in to globally fit endpoint pre-incubation IC50 data and determine k_inact and K_I [30]. |

Used for the characterization of the tissue transglutaminase inhibitor AA9 [30]. |

| Stopped-Flow Instrument | A rapid-mixing device used for pre-steady-state kinetic analysis to study reactions on millisecond timescales, ideal for measuring fast association/dissociation rates [34]. | Used to elucidate the key steps in the mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 main protease interaction with inhibitors [34]. |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Workflow for Pre-steady-state IC50 Determination

The following diagram illustrates the optimized experimental and computational workflow for accurately determining the potency of time-dependent enzyme inhibitors, integrating steps to minimize common pitfalls.

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway and Inhibition Mechanism

This diagram outlines the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), a key target in cancer therapy, and the site of action for proteasome inhibitors like bortezomib and carfilzomib.

For researchers in cancer research and drug development, selecting the appropriate assay system is a critical step in the experimental pipeline. This is particularly true for specialized applications such as optimizing proteasome inhibition assays, where the choice between cell-based and cell-free systems can significantly impact the relevance, throughput, and success of the project. Cell-based assays use live cells as biologically active sensors to measure complex responses like viability, apoptosis, and pathway modulation [35] [36]. In contrast, cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) systems utilize the essential molecular machinery for transcription and translation—such as ribosomes, tRNAs, and energy sources—removed from the confines of a living cell, enabling direct and rapid protein production [37] [38].

This guide provides a technical support center to help you navigate this decision, offering troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and structured data to directly address experimental challenges within the context of cancer drug discovery.

Systematic Comparison: Advantages and Limitations

The decision to use a cell-based or cell-free system hinges on the specific goals of your experiment. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each system to guide your selection.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Cell-Based and Cell-Free Assay Systems

| Feature | Cell-Based Assays | Cell-Free Assays |

|---|---|---|

| Physiological Relevance | High; maintains cellular context, signaling pathways, and membrane integrity [35] [36]. | Low; lacks cellular organization, compartmentalization, and complex interactions [38]. |

| Speed & Workflow | Slow (days to weeks); requires cell culture, cloning, and transfection [37]. | Rapid (hours to 1-2 days); direct template addition bypasses cloning and culture steps [37] [38]. |

| Control & Manipulation | Limited; once cells are dosed, the internal environment is difficult to manipulate [37]. | High; open system allows direct adjustment of buffer, cofactors, and energy sources in real-time [37] [38]. |

| Toxic Protein Expression | Problematic; toxic proteins can harm host cells, leading to poor yields [37]. | Ideal; absence of living cells allows for expression of proteins lethal to cells [37] [39]. |

| Post-Translational Modifications | Supported; can provide native-like modifications depending on the host cell [36]. | Limited; for example, wheat germ systems lack the ER and do not support glycosylation [39]. |

| Cost-Effectiveness for Scaling | Economical for large-scale protein production [38]. | Not economical for large-scale prep; cost-effective for small-scale, high-throughput screening [37] [38]. |

| Throughput for Genetic Screening | High; well-established for flow cytometry and NGS, screening thousands of variants [38]. | Lower (traditional); the number of variants screened in a single experiment is typically lower than in vivo [38]. |

For research on proteasome inhibitors, like the novel compound BC12-3 studied in multiple myeloma, this choice is paramount. Cell-based assays are indispensable for confirming the antitumor effect—such as inducing G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis—in a physiologically relevant environment [24]. Meanwhile, cell-free systems could be leveraged to rapidly produce and test various inhibitor constructs or to study the direct binding of a compound like BC12-3 to the purified β5 subunit of the proteasome without cellular interference [24].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Cell-Based Assay Troubleshooting

Cell-based assays are dynamic and can be susceptible to variability. Below are common issues and their solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Cell-Based Assays

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background Signal | Contamination (bacterial, fungal, or cellular carryover) [40]. | Sterilize equipment with ethanol, use new pipette tips, and ensure aseptic technique [40]. |

| Edge Effect (cells in outer wells behave differently) | Evaporation and temperature gradients across the plate [40]. | Incubate newly seeded plates at room temperature before placing in incubator; use plates with lids [40]. |

| Poor Cell Viability | Incorrect CO₂ concentration or exposure to room temperature [40]. | Validate and monitor incubator CO₂ levels; keep cells on ice during plate plating [40]. |

| High Data Variability | Inconsistent cell density or pipetting errors [40]. | Generate a cell density standard curve for optimization; perform regular pipette calibrations [40]. |

| Weak or No Signal | Incorrect instrument settings (e.g., filter sets, gain) [40]. | Confirm fluorophore Ex/Em maxima and instrument filter sets; adjust instrument gain [40]. |

Cell-Free Assay Troubleshooting

Cell-free systems, while simpler, have their own set of optimization parameters.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Cell-Free Protein Synthesis

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Protein Yield | Degraded DNA template or suboptimal reaction conditions [39]. | Use high-quality, supercoiled DNA vector (e.g., pEU series); optimize Mg²⁺ and K⁺ concentrations [39]. |

| Protein Synthesis Failure | Inhibitors in the reaction (e.g., detergents, chelators) [39]. | Avoid EDTA/EGTA; if using detergents, titrate to a concentration that does not inhibit translation [39]. |

| Incorrect Protein Modification | Lack of specific machinery in the extract [39]. | For glycosylation, choose a different CFPS system (e.g., mammalian); for disulfide bonds, use specialized oxidative extracts [39]. |

| Difficulty with Protein Labeling | System not compatible with the labeling strategy. | For fluorescence, use kits like FluoroTect GreenLys; for biotin, co-express with BirA ligase [39]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My goal is to study the mechanism of action of a new proteasome inhibitor. Which system should I start with? You will likely need both, but in a specific sequence. Begin with a cell-based cytotoxicity assay (e.g., CCK-8 assay) to confirm the compound has a cytotoxic effect on your target cancer cells (e.g., multiple myeloma cells) and to determine the IC₅₀ value [24]. Follow-up with cell-based assays for apoptosis (e.g., Annexin V staining) and cell cycle analysis (e.g., flow cytometry) to understand the phenotypic consequences [35] [41]. A cell-free system can be used later to conduct binding studies and confirm direct inhibition of the proteasome's β5 subunit in a isolated environment [24].

Q2: Can I produce active membrane proteins, like GPCRs, using a cell-free system? Yes. The key advantage of cell-free systems for membrane proteins is the ability to add membrane-mimetic environments directly to the reaction. For example, you can add liposomes or nanodiscs during the synthesis reaction. As the membrane protein is produced, it can directly integrate into the provided lipid bilayers, forming proteoliposomes that can preserve its structure and function [37] [39].

Q3: How do I improve the physiological relevance of my cell-based assays for cancer research? Consider moving from traditional 2D monolayers to 3D cell culture models, such as spheroids or organoids. These models better mimic the tumor microenvironment, including nutrient gradients, cell-cell interactions, and drug penetration barriers [42] [36]. Furthermore, using co-culture systems with stromal or immune cells can provide even more insightful data on tumor biology and drug response [42].

Q4: What is the Z'-factor statistic and why is it important? The Z'-factor is a quantitative measure of the quality and robustness of an assay, particularly for high-throughput screening. It takes into account the signal-to-noise ratio and the data variability of both positive and negative controls [40]. A Z'-value > 0.5 is generally considered acceptable for a reliable HTS assay. A perfect assay would have a value of 1 [40].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Cell-Based Viability Assay for Proteasome Inhibitor Screening

This protocol outlines the steps to assess the cytotoxicity of a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., BC12-3 or bortezomib) on cancer cells, using a CCK-8 assay as an example [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit:

- Cell Line: Relevant cancer cell line (e.g., Multiple Myeloma cell line).

- Compounds: Proteasome inhibitor (e.g., BC12-3, Bortezomib), control vehicle (e.g., DMSO).

- Assay Kit: CCK-8 kit, which contains a water-soluble tetrazolium salt.

- Equipment: CO₂ incubator, multi-well plate reader, laminar flow hood, multi-channel pipettes.

- Consumables: 96-well cell culture plates (black-sided for fluorescence assays) [40].

Procedure:

- Seed Cells: Harvest exponentially growing cells and seed them at an optimized density (e.g., 5,000-10,000 cells/well) in a 96-well plate. Include a "no-cell" control well with media only. Incubate for 24 hours to allow cell adhesion [40].

- Dose Compound: Prepare serial dilutions of your proteasome inhibitor in culture media. Remove the old media from the plate and add the compound-containing media to the test wells. Add vehicle-only media to the negative control wells. Each condition should be performed in at least triplicate.

- Incubate: Incubate the plate for the desired treatment period (e.g., 48-72 hours) in a humidified 37°C, 5% CO₂ incubator.

- Add CCK-8 Reagent: Following incubation, add a predetermined volume of CCK-8 solution directly to each well. Gently shake the plate to mix.

- Measure Absorbance: Incubate the plate for 1-4 hours and then measure the absorbance at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

- Analyze Data: Calculate the percentage of cell viability relative to the vehicle control. Plot the dose-response curve and determine the IC₅₀ value using appropriate statistical software.

Protocol: Cell-Free Production of a Protein Target

This protocol describes a general workflow for producing a protein of interest using a commercial wheat germ cell-free system, which could be used to generate a proteasome subunit for biochemical studies [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit:

- Template DNA: A vector (e.g., pEU series) containing your target gene (e.g., proteasome subunit) under an SP6 promoter [39].

- CFPS Kit: A commercial wheat germ cell-free kit (e.g., CFS Premium ONE Expression Kit).

- Equipment: Thermocycler or water bath, microcentrifuge.

- Consumables: PCR tubes or small reaction vessels.

Procedure:

- Template Preparation: Prepare a high-quality, purified plasmid DNA template. Alternatively, a PCR-amplified linear template can be used, though yields may be lower [39].

- Reconstitution: Thaw all kit components on ice and prepare the master mix according to the manufacturer's instructions. This typically includes the wheat germ extract, reaction buffer, amino acids, and energy sources.

- Start Reaction: Combine the master mix with your DNA template in a reaction vessel. Mix gently and briefly centrifuge to collect the contents at the bottom.

- Incubate: Incubate the reaction at a defined temperature (e.g., 15-26°C) for several hours (e.g., 4-24 hours) to allow for protein synthesis.

- Harvest and Analyze: Stop the reaction as needed. The synthesized protein can be analyzed directly by SDS-PAGE, Western Blot, or used in functional assays like activity measurements.

Visual Workflows and Pathways

To better understand the logical flow of selecting an assay system and the core components of a cell-free reaction, refer to the following diagrams.

Assay System Selection Workflow

Core Components of a Cell-Free System

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Immunoprecipitation (IP) for Ubiquitination Detection

Immunoprecipitation followed by western blot is a foundational method for detecting protein ubiquitination. [43]

Detailed Protocol:

- Cell Lysis: Collect and lyse cell or tissue samples using an appropriate cell lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) to preserve ubiquitination signals by preventing deubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. For tissues, mechanical disruption or sonication may be required. [44] [43]

- Antibody-Bead Complex Preparation: Incubate your chosen antibody with Protein A/G agarose or magnetic beads to form the antibody-bead complex. Common choices include anti-ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., P4D1, FK1/FK2) for pan-ubiquitin detection or a specific antibody against the protein substrate of interest. [43] [45]

- Immunoprecipitation: Add the antibody-bead complex to the cell lysate and incubate with rotation or shaking (typically 2 hours to overnight at 4°C) to allow specific binding. [43]

- Washing: Pellet the beads and wash multiple times with a suitable wash buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins and reduce background. [43]

- Elution and Analysis: Elute the bound proteins using a low-pH buffer or SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Separate the eluted proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a membrane for western blot analysis. Detect the target protein using a specific antibody to determine the presence and level of ubiquitination, which often appears as a characteristic smear or ladder of higher molecular weight species. [44] [43]

Enrichment of Ubiquitinated Proteins Using Ubiquitin-Trap

For more specific enrichment, affinity-based pulldown methods like the ChromoTek Ubiquitin-Trap are recommended. [44]

Detailed Protocol:

- Sample Preparation and Pre-treatment: Lyse cells as described in the IP protocol. Treating cells with a proteasome inhibitor such as MG-132 (e.g., 5-25 µM for 1-2 hours) prior to harvesting is strongly recommended to increase the levels of ubiquitinated proteins. [44]

- Ubiquitin-Trap Pulldown: Use the ready-to-use Ubiquitin-Trap Agarose or Magnetic Agarose. Incubate the clarified cell lysate with the beads for at least 1 hour at 4°C with gentle agitation. [44]

- Washing and Elution: Wash the beads thoroughly under stringent conditions to minimize non-specific binding. Elute the captured ubiquitin and ubiquitinated proteins for downstream analysis. This method is compatible with western blot or mass spectrometry (IP-MS) workflows. [44]

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my western blot for ubiquitin show a smear instead of discrete bands? A: A smear is a typical and expected result for polyubiquitinated proteins. Since the Ubiquitin-Trap and anti-ubiquitin antibodies bind to proteins with varying numbers of ubiquitin modifiers attached, this creates a mixture of species with different molecular weights, which appears as a smear or ladder on the gel. [44]

Q2: How can I increase the ubiquitination signal in my samples? A: Pre-treat cells with a proteasome inhibitor like MG-132 before harvesting. This prevents the degradation of ubiquitinated proteins, leading to their accumulation and stronger detection signals. Optimization of inhibitor concentration and treatment time (e.g., 5-25 µM for 1-2 hours) is recommended for different cell types. [44]

Q3: My ubiquitination signal is weak. What could be the reason? A: Weak signals can stem from several factors:

- Low Abundance: The stoichiometry of protein ubiquitination is inherently low under physiological conditions. Enrichment via IP or Ubiquitin-Trap is essential. [45]

- Instability of Modification: Ubiquitination is a highly transient and reversible process. Use deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitors in your lysis buffer and perform experiments quickly on ice to stabilize the modification. [44]

- Inefficient Enrichment: Ensure your antibody or trap has high affinity and specificity. The ChromoTek Ubiquitin-Trap, for instance, uses a high-affinity nanobody for clean pulldowns. [44]

Q4: Can I differentiate between different types of ubiquitin chain linkages? A: Standard IP or Ubiquitin-Trap methods are not linkage-specific. To study specific linkages, you must use linkage-specific ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., for K48, K63, M1) in your western blot analysis following the pulldown. [44] [45]

Troubleshooting Common Problems

| Problem | Potential Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background | Non-specific antibody binding or insufficient washing. | Increase number and stringency of washes; use a control IgG; optimize antibody concentration. [43] |

| No Signal | Ubiquitinated proteins are degraded or modification is unstable. | Use proteasome (e.g., MG-132) and DUB inhibitors in lysis buffer; work quickly on ice. [44] |