Proteasome Inhibition and Ubiquitin Homeostasis: Mechanisms, Measurement, and Clinical Implications in Disease Therapy

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how proteasome inhibition directly impacts cellular ubiquitin levels and dynamics, a critical consideration in both basic research and drug development.

Proteasome Inhibition and Ubiquitin Homeostasis: Mechanisms, Measurement, and Clinical Implications in Disease Therapy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how proteasome inhibition directly impacts cellular ubiquitin levels and dynamics, a critical consideration in both basic research and drug development. We explore the foundational principles of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), detailing the enzymatic cascade from E1 activation to E3 ligase-mediated substrate targeting. Methodological sections cover established and emerging techniques for quantifying ubiquitination and proteasome activity, including reporter constructs and mass spectrometry-based approaches. The content addresses common experimental challenges, such as distinguishing specific from global protein degradation and interpreting ubiquitin chain linkages. Finally, we validate these concepts with clinical and commercial data on proteasome inhibitors, examining their efficacy, adverse event profiles, and the growing market driven by their application in hematologic cancers. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to deepen their understanding of UPS modulation.

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: Core Machinery and Consequences of Inhibition

The ubiquitin conjugation cascade represents a crucial enzymatic pathway for post-translational modification, directing cellular proteins toward degradation or functional alteration. This E1-E2-E3 enzyme cascade enables precise targeting of substrates through a coordinated mechanism of ubiquitin activation, conjugation, and ligation. Within proteasome inhibition research, understanding this cascade is fundamental, as inhibited proteasomes cause accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins, depleting free ubiquitin pools and disrupting protein homeostasis. This technical guide examines the molecular mechanisms of ubiquitin transfer, experimental methodologies for studying ubiquitination, and the cascade's integration with proteasome function, providing researchers with essential tools for investigating ubiquitin-proteasome system dynamics.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) constitutes the primary pathway for targeted intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, operating through a highly regulated process that involves tagging proteins with ubiquitin for proteasomal destruction [1]. This system controls the degradation of over 80% of cellular proteins, including short-lived, misfolded, and damaged proteins, thereby maintaining cellular homeostasis [2]. The UPS encompasses two major components: the ubiquitin conjugation cascade that marks substrates, and the 26S proteasome that executes degradation.

Ubiquitin itself is a small, 76-amino acid protein (8.6 kDa) that is highly conserved across eukaryotes and ubiquitously expressed in most tissues [3]. Its name derives from this ubiquitous distribution. The ubiquitin protein features seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, and K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1) that serve as potential linkage sites for polyubiquitin chain formation [2]. The modification of proteins with ubiquitin involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to target proteins, most commonly through an isopeptide bond between ubiquitin's C-terminal glycine (Gly76) and the ε-amino group of a lysine residue on the substrate protein [4].

The 26S proteasome is a 2.5 MDa multi-subunit complex that recognizes and degrades polyubiquitinated proteins [5]. It consists of a 20S catalytic core particle capped by one or two 19S regulatory particles. The 20S core contains three primary proteolytic activities: chymotrypsin-like (cleavage after hydrophobic residues), caspase-like (cleavage after acidic residues), and trypsin-like (cleavage after basic residues) [1]. The 19S regulatory cap recognizes ubiquitinated proteins, unfolds them, and translocates them into the catalytic core for degradation [1].

In the context of proteasome inhibition research, understanding the ubiquitin conjugation cascade is paramount. When proteasome function is compromised, polyubiquitinated proteins accumulate, leading to depletion of free ubiquitin pools and disruption of protein homeostasis—a cellular state with significant implications for cancer therapy and neurodegenerative disease [6]. This review comprehensively examines the enzymatic cascade responsible for ubiquitin conjugation, with particular emphasis on its relevance to proteasome inhibition studies.

The Ubiquitin Conjugation Cascade: Mechanism and Key Enzymes

The ubiquitin conjugation cascade comprises three sequential enzymatic steps that activate and transfer ubiquitin to substrate proteins. This pathway involves ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3), working in concert to ensure specific substrate targeting [5]. The hierarchical nature of this cascade—with few E1s, more E2s, and hundreds of E3s—allows for precise regulation of the ubiquitination machinery while enabling diverse substrate recognition [3].

E1: Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme

The initial step in the ubiquitin cascade involves ubiquitin activation by E1 enzymes in an ATP-dependent process [7]. This reaction occurs through a two-step mechanism: first, ubiquitin is adenylated, then transferred to the active-site cysteine of E1 to form a ubiquitin-E1 thioester bond [3]. During this process, the E1 enzyme catalyzes the acyl-adenylation of the C-terminus of ubiquitin, followed by trans-thioesterification that links ubiquitin to the E1 cysteine sulfhydryl group via a high-energy thioester bond [3].

The human genome encodes only two E1 enzymes capable of activating ubiquitin: UBA1 and UBA6 [3]. This limited repertoire contrasts with the expanding number of downstream enzymes, reflecting E1's role as the central entry point for ubiquitin activation. The E1 enzyme must recognize and interact with all downstream E2 conjugating enzymes, necessitating both specificity and versatility in its function.

E2: Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme

Following ubiquitin activation, the ubiquitin moiety is transferred from E1 to the active-site cysteine of an E2 conjugating enzyme, again forming a thioester linkage [8]. This trans-thioesterification reaction requires the E2 to bind both activated ubiquitin and the E1 enzyme [3]. The human genome encodes approximately 35 E2 enzymes, each characterized by a highly conserved ubiquitin-conjugating (UBC) catalytic domain fold [3] [8].

E2 enzymes demonstrate varying specificity for different E3 ligases and substrates, contributing to the diversity of ubiquitination outcomes. Some E2s specialize in building specific ubiquitin chain types, while others collaborate with particular E3 families. The table below summarizes key E2 enzymes and their characteristics:

Table 1: Selected Human Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzymes (E2s)

| Gene Name | Synonyms | Protein Length (aa) | Ubiquitin-Loading Capacity | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBE2A | RAD6A | 152 | Yes | Ubiquitylation |

| UBE2D1 | UBCH5A | 147 | Yes | Ubiquitylation |

| UBE2L3 | UBCH7 | 154 | Yes | Ubiquitylation |

| UBE2N | UBC13 | 152 | Yes | K63-linked chains |

| UBE2S | E2-EPF | 225 | Yes | Ubiquitylation |

| CDC34 | UBE2R1 | 236 | Yes | Cell cycle regulation |

E3: Ubiquitin Ligase

The final step in the cascade involves E3 ubiquitin ligases, which facilitate the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to substrate proteins [2]. E3s serve as matchmakers that recognize specific substrates and bring them into proximity with ubiquitin-charged E2s, enabling ubiquitin transfer [4]. With over 600 members in humans, E3 ligases provide the primary determinant of substrate specificity in the ubiquitin system [2].

E3 ligases are categorized into several families based on their structural features and mechanisms of action:

RING-type E3 ligases constitute the largest family, characterized by a Really Interesting New Gene (RING) domain that binds E2s [2]. Unlike other E3 types, RING E3s catalyze the direct transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to substrate without forming a covalent E3-ubiquitin intermediate [2]. Multi-subunit cullin-RING ligases (CRLs) represent an important subclass that utilize cullin scaffolds to bring together substrate-recognition modules and RING domain proteins [2].

HECT-type E3 ligases contain a Homologous to E6-AP C-Terminus (HECT) domain that forms a thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to substrates [2] [7]. These enzymes first accept ubiquitin from E2 onto their active-site cysteine before catalyzing substrate ubiquitination. The NEDD4 family of HECT E3s contains WW domains that mediate protein-protein interactions and C2 domains involved in membrane targeting [2].

RBR-type E3 ligases (RING-Between-RING) utilize a hybrid mechanism, combining features of both RING and HECT E3s [2]. They contain two RING domains with an intermediate domain, and like HECT E3s, form a thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before substrate transfer.

Table 2: Major E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Families

| E3 Family | Transfer Mechanism | Representative Members | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| RING | Direct transfer from E2 to substrate | MDM2, CBL, APC/C | Largest E3 family; functions as scaffolding proteins |

| HECT | Via E3-ubiquitin thioester intermediate | NEDD4, HERC, E6AP | C-terminal catalytic HECT domain; diverse N-terminal domains for substrate recognition |

| RBR | Via E3-ubiquitin thioester intermediate | HOIP, HOIL-1, PARKIN | Two RING domains with intermediate region; hybrid mechanism |

The sequential action of E1-E2-E3 enzymes results in the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to substrate proteins. Additional ubiquitin molecules can then be added to the first ubiquitin, forming polyubiquitin chains with diverse functions based on their linkage types [2].

Experimental Methods for Studying Ubiquitination

Investigating the ubiquitin conjugation cascade requires specialized methodologies to detect ubiquitinated proteins, analyze degradation kinetics, and identify specific ubiquitination sites. This section details key experimental protocols used in ubiquitination research, particularly relevant to studying the effects of proteasome inhibition on cellular ubiquitin levels.

Detecting Protein Ubiquitination

Ubiquitin Enrichment and Western Blotting: To determine if a specific protein of interest (POI) has been ubiquitinated, researchers commonly employ co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) followed by Western blot analysis [5]. The protocol involves:

- Treating cells with proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG132, bortezomib) to accumulate ubiquitinated proteins by blocking their degradation [5].

- Lysing cells under denaturing conditions to preserve ubiquitin-substrate conjugates and prevent deubiquitination.

- Immunoprecipitating the POI using a specific antibody.

- Separating immunoprecipitated proteins by SDS-PAGE and transferring to membranes.

- Probing with anti-ubiquitin antibodies to detect ubiquitin conjugates of the POI.

This approach allows researchers to confirm whether their protein of interest has been ubiquitinated and to observe changes in ubiquitination status under different experimental conditions, such as proteasome inhibition.

High-Throughput Ubiquitination Assays: For screening applications, LanthaScreen conjugation assay reagents enable monitoring ubiquitin conjugation rates or extent in a high-throughput format [5]. These assays utilize time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET) to quantitatively measure ubiquitination in vitro, facilitating rapid screening of compounds that modulate E1-E2-E3 activity.

Analyzing Polyubiquitinated Proteins

Ubiquitin Enrichment Kits: Commercial ubiquitin enrichment kits employ high-affinity resins to isolate polyubiquitinated proteins from cell or tissue lysates [5]. The basic protocol includes:

- Preparing cell lysates in appropriate buffers.

- Incubating lysates with ubiquitin-binding resins.

- Washing away non-specifically bound proteins.

- Eluting bound polyubiquitinated proteins for downstream analysis.

- Detecting specific proteins of interest by Western blotting with target-specific antibodies.

This method provides a global view of polyubiquitinated proteins and can be used to monitor changes in the ubiquitinome in response to proteasome inhibition.

Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) Proteomics: For comprehensive, quantitative analysis of protein ubiquitination, tandem mass tag labeling combined with mass spectrometry enables large-scale ubiquitinome profiling [5]. This approach allows simultaneous measurement of ubiquitination changes across thousands of proteins in multiple samples, providing systems-level insights into UPS dynamics.

Monitoring Protein Degradation

Pulse-Chase Analysis: To measure protein degradation kinetics, pulse-chase experiments track the fate of radiolabeled or tagged proteins over time [5]. The standard protocol involves:

- "Pulsing" cells with labeled amino acids (e.g., 35S-methionine/cysteine) or methionine analogs for a defined period.

- Replacing the labeling medium with excess unlabeled amino acids ("chase").

- Harvesting cells at various time points during the chase period.

- Immunoprecipitating the protein of interest and quantifying remaining labeled protein.

Click-iT Plus technology provides a non-radioactive alternative using methionine analogs with click chemistry tags for fluorescence detection [5]. This approach enables real-time measurement of protein synthesis and degradation in live cells.

Global Protein Degradation Assessment: To distinguish targeted degradation of specific proteins from general proteolysis, researchers can measure overall protein degradation rates using radioactive pulse-chase methodology [5]. Monitoring the release of acid-soluble radioactivity from pre-labeled cellular proteins over time provides an assessment of global protein turnover.

Experimental Workflow for Ubiquitination Studies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Studying the ubiquitin conjugation cascade requires specialized reagents and tools. The following table compiles essential research materials for investigating ubiquitination mechanisms, particularly in the context of proteasome inhibition research.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib (PS-341), Carfilzomib | Block proteasomal degradation, causing accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins for detection and analysis [5]. |

| E1 Enzyme Inhibitors | PYR-41, TAK-243 | Inhibit ubiquitin activation, blocking the entire ubiquitination cascade for mechanistic studies [1]. |

| Ubiquitin Antibodies | Anti-ubiquitin, Anti-polyubiquitin, Anti-K48/K63-linkage specific | Detect ubiquitinated proteins in Western blot, immunofluorescence, and immunoprecipitation applications [5]. |

| E2 Enzyme Assays | Recombinant E2 enzymes (UBE2D, UBE2L3, UBE2N) | In vitro ubiquitination assays to study E2 specificity and function [8]. |

| E3 Expression Constructs | Plasmids encoding RING, HECT, RBR E3 ligases | Overexpression or knockdown of specific E3s to identify substrates and study mechanisms [2]. |

| Deubiquitinase Inhibitors | PR-619, P5091, G5 | Block deubiquitinating enzymes to stabilize ubiquitin signals and study ubiquitination dynamics [5]. |

| Ubiquitin Enrichment Kits | Agarose-tandem ubiquitin-binding entities (TUBEs) | Isolate and purify polyubiquitinated proteins from complex lysates for proteomic analysis [5]. |

| Activity Assay Kits | LanthaScreen ubiquitination assays | High-throughput screening for modulators of E1-E2-E3 activity using TR-FRET technology [5]. |

| Cell Lines | HEK293, HCT116, specialized ubiquitin-reporters | Model systems for studying ubiquitination in cellular contexts, including reporter lines with engineered degradation signals. |

| Mass Spectrometry Reagents | Tandem Mass Tags (TMT), ubiquitin remnant motifs | Quantitative proteomics to identify ubiquitination sites and quantify changes in ubiquitinome [5]. |

These reagents enable researchers to dissect specific components of the ubiquitin cascade and investigate how proteasome inhibition affects ubiquitin dynamics. For instance, combining proteasome inhibitors with ubiquitin enrichment techniques allows comprehensive mapping of accumulated ubiquitinated proteins under proteasome stress conditions [5] [6].

Ubiquitin Conjugation in the Context of Proteasome Inhibition Research

The relationship between the ubiquitin conjugation cascade and proteasome function is fundamental to cellular homeostasis. When proteasomes are inhibited, the careful balance between ubiquitination and deubiquitination is disrupted, leading to profound cellular consequences. Understanding this relationship is crucial for both basic research and therapeutic development.

Interplay Between Ubiquitination and Proteasome Function

The ubiquitin conjugation cascade and the proteasome operate in a tightly coordinated manner. Under normal conditions, polyubiquitinated proteins are rapidly recognized and degraded by the 26S proteasome, with ubiquitin molecules recycled for reuse [5]. This continuous cycle maintains free ubiquitin pools and prevents accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins.

When proteasome activity is compromised—whether through pharmacological inhibition, genetic manipulation, or pathological conditions—this equilibrium is disturbed. The immediate effect is accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins, as the degradation endpoint is blocked while ubiquitination continues [1] [5]. This accumulation has two significant consequences: sequestration of ubiquitin into stalled conjugates, and activation of compensatory cellular responses.

Research has demonstrated that human cancer cells often possess elevated proteasome activity and show heightened sensitivity to proteasome inhibitors compared to normal cells [1]. This differential sensitivity forms the basis for therapeutic applications of proteasome inhibitors in oncology, particularly for hematological malignancies.

Cellular Response to Ubiquitin Stress

Cells mount specific adaptive responses when ubiquitin homeostasis is disrupted. Unlike proteasome stress, which upregulates proteasome biogenesis, ubiquitin stress triggers alternative compensatory mechanisms [6]. A key finding is that ubiquitin depletion does not increase proteasome abundance but instead alters proteasome composition by enhancing association with the deubiquitinating enzyme Ubp6 (USP14 in mammals) [6].

This compositional change improves ubiquitin recycling efficiency from proteasome-bound substrates, sparing ubiquitin from degradation and replenishing free ubiquitin pools. The adaptation represents a sophisticated feedback mechanism that optimizes ubiquitin usage under stress conditions. Understanding this response is particularly relevant for cancer therapy, as prolonged proteasome inhibitor treatment may induce resistance through such adaptive mechanisms.

Ubiquitin- Proteasome Dynamics Under Inhibition

Therapeutic Implications and Research Applications

The intimate connection between the ubiquitin conjugation cascade and proteasome function has significant therapeutic implications. Proteasome inhibitors like bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib are established cancer therapies that exploit the dependence of certain malignancies on efficient proteasome function [1]. These compounds create an imbalance in protein homeostasis that preferentially kills cancer cells.

More recently, researchers have developed complementary strategies that target earlier steps in the ubiquitin pathway. These include:

- Inhibitors of E1 enzymes to globally block ubiquitin activation

- Specific E3 modulators to target individual substrates for stabilization or degradation

- PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) that hijack E3 ligases to degrade target proteins of interest [2]

For researchers studying proteasome inhibition, monitoring the ubiquitin conjugation cascade provides crucial insights into mechanism of action and resistance patterns. Assaying changes in E1, E2, and E3 activities; quantifying ubiquitin pool dynamics; and profiling the ubiquitinome under treatment conditions all contribute to a comprehensive understanding of how cells respond to proteasome stress.

The ubiquitin conjugation cascade comprising E1, E2, and E3 enzymes represents a sophisticated biological system for targeted protein modification and degradation. Its precise molecular mechanisms—from ubiquitin activation through E1, conjugation via E2, and substrate-specific ligation by E3s—enable exquisite control over protein fate. In the context of proteasome inhibition research, understanding this cascade is paramount, as disrupted equilibrium between ubiquitination and degradation triggers profound cellular stress responses with important implications for disease therapy.

The experimental methodologies and research tools detailed in this guide provide scientists with robust approaches for investigating ubiquitination mechanisms, particularly under conditions of proteasome impairment. As research advances, deepening our knowledge of the ubiquitin conjugation cascade will continue to illuminate cellular homeostasis mechanisms and reveal new therapeutic opportunities for manipulating protein degradation pathways.

The 26S proteasome serves as the central proteolytic machine in eukaryotic cells, responsible for the regulated degradation of the vast majority of intracellular proteins [9] [10]. As the endpoint of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), it controls vital processes ranging from cell cycle progression and signal transduction to stress response and general protein homeostasis [9] [11]. Understanding its intricate structure and mechanistic function is fundamental to biomedical research, particularly in the context of drug development, where the proteasome has emerged as a validated therapeutic target. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the 26S proteasome, with its content framed specifically to support research on how proteasome inhibition impacts cellular ubiquitin levels and proteostasis.

Architectural Organization of the 26S Proteasome

The 26S proteasome is a ∼2.5 MDa complex consisting of two primary subcomplexes: the 20S core particle (CP) and the 19S regulatory particle (RP), with the RP often capping one or both ends of the CP [9] [12] [10].

The 20S Core Particle (CP)

The 20S CP is a barrel-shaped structure composed of 28 subunits arranged in four stacked heptameric rings [12] [10]. The configuration of these rings follows an α-β-β-α pattern. The two outer α-rings, formed by subunits α1-α7, function as a tightly regulated gate, controlling substrate access to the proteolytic chamber [10]. The N-terminal tails of specific α-subunits form a constricted pore that prevents unregulated entry of native proteins [10]. The two inner β-rings, formed by subunits β1-β7, house the proteolytic active sites. Three of these β-subunits—β1 (caspase-like activity), β2 (trypsin-like activity), and β5 (chymotrypsin-like activity)—contain N-terminal threonine residues that confer the proteasome's distinct peptidase activities [12] [10].

Table 1: Catalytic Subunits of the 20S Core Particle

| Subunit | Proteolytic Activity | Catalytic Residue | Primary Cleavage Preference |

|---|---|---|---|

| β1 | Caspase-like | N-terminal Threonine | Acidic residues |

| β2 | Trypsin-like | N-terminal Threonine | Basic residues |

| β5 | Chymotrypsin-like | N-terminal Threonine | Hydrophobic residues |

The 19S Regulatory Particle (RP)

The 19S RP is a multifunctional complex that identifies, prepares, and translocates ubiquitinated substrates into the 20S CP [9] [10]. It is further divided into two subcomplexes: the base and the lid.

The base subcomplex comprises:

- Six AAA-ATPase subunits (Rpt1-Rpt6): Form a heterohexameric ring that uses ATP hydrolysis to unfold substrates and translocate them into the 20S CP [9] [13].

- Three non-ATPase subunits (Rpn1, Rpn2, Rpn13): Rpn1 and Rpn13 function as primary ubiquitin receptors, while Rpn2 serves as a structural scaffold [9] [12].

The lid subcomplex consists of nine non-ATPase subunits (Rpn3, Rpn5-Rpn9, Rpn11, Rpn12, and Sem1) [9] [10]. A crucial component is Rpn11, a Zn²⁺-dependent deubiquitinase (DUB) that catalyzes the en bloc removal of ubiquitin chains from substrates prior to their degradation [9] [13].

Additionally, the proteasome harbors other important subunits not strictly confined to the base or lid. Rpn10 is a ubiquitin receptor that bridges the two subcomplexes [9] [12]. Two associated DUBs, Usp14 (Ubp6 in yeast) and Uch37, bind to Rpn1 and Rpn13, respectively, and function in editing ubiquitin chains and recycling ubiquitin [9] [14].

Functional Mechanism of Substrate Degradation

The degradation of a protein by the 26S proteasome is a multistep, ATP-dependent process that requires precise coordination between the RP and CP.

Substrate Recognition and Ubiquitin Sensing

Most proteasome substrates are marked for degradation by covalent attachment of a polyubiquitin chain, typically linked through lysine 48 (K48) of ubiquitin [15]. The proteasome contains multiple ubiquitin receptors—Rpn1, Rpn10, and Rpn13—that recognize these chains, providing redundancy and versatility in substrate engagement [9] [12]. This multi-receptor system allows the proteasome to handle a vast and diverse array of ubiquitinated proteins.

Conformational Dynamics and Substrate Commitment

The 26S proteasome is a highly dynamic machine that exists in several conformational states. Key states include the resting state (s1 or RS) and multiple processing states (s3/s4 or PS) [9] [13].

- In the resting state, the substrate entrance channel is accessible, but the gate to the 20S CP is closed, and the ATPase motor is inactive.

- Upon ubiquitin binding and substrate engagement, the proteasome undergoes a major conformational change to a processing state. This involves rotation of the lid subcomplex, a shift of Rpn11 to a central position above the ATPase pore, and opening of the 20S CP gate [13]. This state is primed for processive substrate translocation.

These conformational changes represent a critical substrate commitment step, ensuring that only properly engaged proteins are degraded and preventing nonspecific proteolysis [9] [11].

Deubiquitination, Unfolding, and Translocation

Once committed, the substrate is processed through coordinated actions:

- Deubiquitination: The Rpn11 deubiquitinase, positioned directly above the ATPase pore, removes the entire ubiquitin chain from the substrate en bloc just before the polypeptide is translocated into the ATPase motor [9] [13]. This coupling ensures the bulky ubiquitin chain does not enter the degradation chamber and allows for ubiquitin recycling.

- Unfolding and Translocation: The Rpt1-Rpt6 AAA-ATPase hexamer uses the energy from ATP hydrolysis to mechanically unfold the substrate protein. Recent cryo-EM studies have revealed that the ATPase subunits adopt a spiral-staircase arrangement around the substrate polypeptide [13]. Conserved pore loops in the central channel of the ring engage the substrate and, through a concerted "hand-over-hand" mechanism, apply mechanical force to unfold the protein and translocate the unfolded polypeptide into the 20S CP for degradation [13].

Research Toolkit: Methods for Studying Proteasome Function

This section outlines key experimental methodologies for investigating proteasome structure, function, and the effects of its inhibition.

Structural Analysis by Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM)

Protocol Overview: The application of single-particle cryo-EM has been instrumental in elucidating the conformational landscape of the 26S proteasome.

- Sample Preparation: Purify endogenous or recombinant 26S proteasomes. To capture intermediate states, proteasomes can be incubated with substrate (e.g., FAT10-Eos3.2), cofactors (e.g., NUB1, TXNL1), and/or ATPγS (a non-hydrolyzable ATP analog) to stall the cycle [13].

- Vitrification: Apply the sample to an EM grid and rapidly freeze it in liquid ethane to preserve its native state.

- Data Collection & Processing: Acquire thousands of micrographs. Use advanced 3D classification to separate particles into distinct conformational states (e.g., resting state vs. various processing states with different ATPase staircase registers) [13].

- Model Building: Build atomic models into the high-resolution density maps to visualize subunit interactions and substrate engagement.

Application: This approach has revealed how cofactors like TXNL1 bind with high affinity specifically to substrate-engaged proteasomes, coordinating degradation steps [13].

Functional Assays for Degradation and Deubiquitination Activity

Protocol Overview: In Vitro Degradation Assay

- Reconstitution: Incubate purified 26S proteasome with an ATP-regenerating system and a ubiquitinated model substrate (e.g., ubiquitinated Sic1 or a fluorescently tagged substrate) [14].

- Reaction Monitoring: Take aliquots at time intervals and stop the reaction with SDS-PAGE loading buffer.

- Analysis: Analyze samples by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting to monitor the disappearance of the substrate and/or the appearance of degradation products.

Protocol Overview: Deubiquitination Assay

- Reaction Setup: Incubate proteasomes with polyubiquitin chains or a ubiquitinated substrate.

- Inhibition Control: To specifically assess Rpn11 activity, include the specific inhibitor OPA-1 or use proteasomes with a catalytically inactive Rpn11 mutant [13].

- Analysis: Resolve reaction products by SDS-PAGE and visualize by immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin antibodies or Coomassie staining to monitor ubiquitin chain cleavage.

Investigating Proteasome Autoregulation

Protocol Overview: Analyzing In Situ Ubiquitination

- Proteasome Purification: Rapidly purify 26S proteasomes under denaturing conditions (using SDS buffer) or in the presence of deubiquitinase inhibitors to preserve native ubiquitination states of proteasome subunits [14].

- Immunoblotting: Probe for specific proteasomal subunits (e.g., Rpt5, Rpn13/Adrm1, S5a/Rpn10, Uch37) to detect slower-migrating ubiquitinated forms.

- Functional Correlation: Compare the activity of ubiquitinated proteasomes against non-ubiquitinated ones in binding, deubiquitination, and degradation assays to determine the functional consequence of autoregulation [14].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for 26S Proteasome Studies

| Reagent / Method | Category | Primary Function in Research | Key Experimental Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cryo-EM with 3D Classification | Structural Biology | Resolves conformational states and cofactor binding | Revealed spiral-staircase ATPase mechanism and conformation-specific cofactor binding [13]. |

| ATPγS (Adenosine 5′-O-[γ-thio]triphosphate) | Small Molecule | Non-hydrolyzable ATP analog; stalls ATPase cycle | Allows trapping of proteasome in substrate-engaged intermediate states for structural studies [13]. |

| OPA-1 | Inhibitor | Specific, active-site inhibitor of Rpn11 deubiquitinase | Blocks deubiquitination, stalling ubiquitinated substrates for structural and functional analysis [13]. |

| MG132 / Bortezomib | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Reversible/irreversible 20S CP active-site inhibitor | Validates UPS dependency in degradation assays; used therapeutically to induce ER stress and apoptosis [16] [15]. |

| Carfilzomib | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Irreversible 20S CP active-site inhibitor | Rescued expression and function of pathogenic pendrin variants in disease models [16]. |

| Rapid Denaturing Purification | Biochemical Method | Preserves labile post-translational modifications | Enabled discovery of in situ ubiquitination of proteasomal subunits (Rpt5, Rpn13) [14]. |

Implications for Proteasome Inhibition and Ubiquitin Homeostasis

The detailed mechanistic understanding of the 26S proteasome directly informs research on proteasome inhibition and its consequences. A key concept emerging from recent studies is proteasome autoregulation. The 26S proteasome itself can be ubiquitinated in situ on subunits such as Rpt5, Rpn13/Adrm1, and Uch37 [14]. This self-modification impairs the proteasome's ability to bind and degrade ubiquitinated substrates, creating a negative feedback loop. This mechanism is proposed to adjust proteasomal activity in response to fluctuating cellular ubiquitination levels [14].

When proteasome activity is pharmacologically inhibited (e.g., by Bortezomib or Carfilzomib), this feedback is disrupted. The result is a dual impact on cellular ubiquitin economy:

- Substrate Accumulation: Ubiquitinated proteins that are normally degraded begin to accumulate.

- Ubiquitin Depletion: The continuous cycle of ubiquitin conjugation and deubiquitination is halted, as the Rpn11-mediated deubiquitination step is coupled to degradation. This can lead to the sequestering of ubiquitin on undegraded substrates, effectively depleting the free ubiquitin pool.

This model explains why proteasome inhibition can lead to a rapid accumulation of high-molecular-weight ubiquitin conjugates while simultaneously causing stress through a lack of free ubiquitin. Furthermore, novel small molecules like BRD1732, which was recently found to be directly ubiquitinated by E3 ligases RNF19A/B, exacerbate this effect by acting as a ubiquitin "sink," leading to dramatic accumulation of ubiquitin-BRD1732 conjugates and broad inhibition of the UPS [17]. Understanding the proteasome's native structure and regulation is therefore paramount for developing next-generation therapeutics that target the UPS and for interpreting the complex cellular phenotypes that arise from its inhibition.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is the primary pathway for the selective degradation of intracellular proteins, a process essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis. Proteasome inhibitors, a class of therapeutic agents predominantly used in hematological malignancies, function by selectively targeting the proteolytic core of the 26S proteasome. This in-depth technical review examines the molecular mechanisms through which these inhibitors induce the characteristic accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins. We detail the sequential process from initial proteasome engagement to the disruption of protein turnover, highlighting the critical conformational and biochemical changes involved. The document further provides a comprehensive analysis of experimental methodologies for quantifying ubiquitin accumulation and discusses the implications of these findings for drug development and therapeutic applications, particularly within the broader research context of cellular ubiquitin level modulation.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a sophisticated, ATP-dependent proteolytic pathway responsible for the controlled degradation of the majority of intracellular proteins [18] [19]. This system regulates a diverse array of cellular processes, including cell cycle progression, gene expression, and the removal of misfolded or damaged proteins [18] [20]. The UPS operates through two discrete, successive steps: a highly specific ubiquitin conjugation cascade that marks target proteins for destruction, and an indiscriminate destruction process mediated by the proteasome [18].

The ubiquitination process involves a sequential enzymatic cascade. First, the ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction, forming a high-energy thioester intermediate. The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2). Finally, a ubiquitin-protein ligase (E3) facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to a lysine residue on the target protein substrate [18]. This process is repeated to form a polyubiquitin chain, which serves as the primary recognition signal for the 26S proteasome [18] [19].

The 26S proteasome is a multi-subunit complex comprising a 20S core particle (CP) flanked by one or two 19S regulatory particles (RP) [19] [20]. The 20S core particle is a barrel-shaped structure composed of four stacked rings (two identical outer α-rings and two identical inner β-rings) that contain the proteolytic active sites. The three primary catalytic activities within the β-rings are the caspase-like (β1), trypsin-like (β2), and chymotrypsin-like (β5) activities [20]. The 19S regulatory particle is responsible for recognizing polyubiquitinated proteins, cleaving the ubiquitin chains, unfolding the target protein, and translocating the unfolded polypeptide into the 20S core for degradation [19].

Table 1: Core Components of the 26S Proteasome

| Component | Subunit Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| 20S Core Particle (CP) | β1, β2, β5 catalytic subunits | Proteolytic degradation of substrate proteins |

| 19S Regulatory Particle (RP) - Base | Rpt1-Rpt6 ATPases | Substrate unfolding, translocation, and CP gating |

| 19S Regulatory Particle (RP) - Lid | Rpn11 deubiquitinase | Ubiquitin chain removal prior to degradation |

| Ubiquitin Receptors | Rpn1, Rpn10, Rpn13 | Polyubiquitinated substrate recognition |

Molecular Mechanism of Proteasome Inhibitors

Proteasome inhibitors function by directly binding to the catalytic subunits of the 20S core particle, thereby blocking its ability to degrade target proteins [18] [20]. These compounds are typically classified based on their chemical structure and mode of interaction with the proteasome's active sites.

Pharmacological Targeting of the Proteasome

Most clinically relevant proteasome inhibitors, including bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib, primarily target the chymotrypsin-like (β5) activity of the proteasome [20]. At higher concentrations, they also inhibit the caspase-like (β1) and trypsin-like (β2) activities. The inhibitors exhibit different binding kinetics: bortezomib and ixazomib act as reversible inhibitors, while carfilzomib forms an irreversible, covalent bond with the β5 subunit [20].

The binding of an inhibitor to the catalytic sites physically occludes the proteolytic chamber, preventing the insertion and cleavage of polypeptide substrates. This direct steric blockade is the initiating event that triggers the downstream accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins [20].

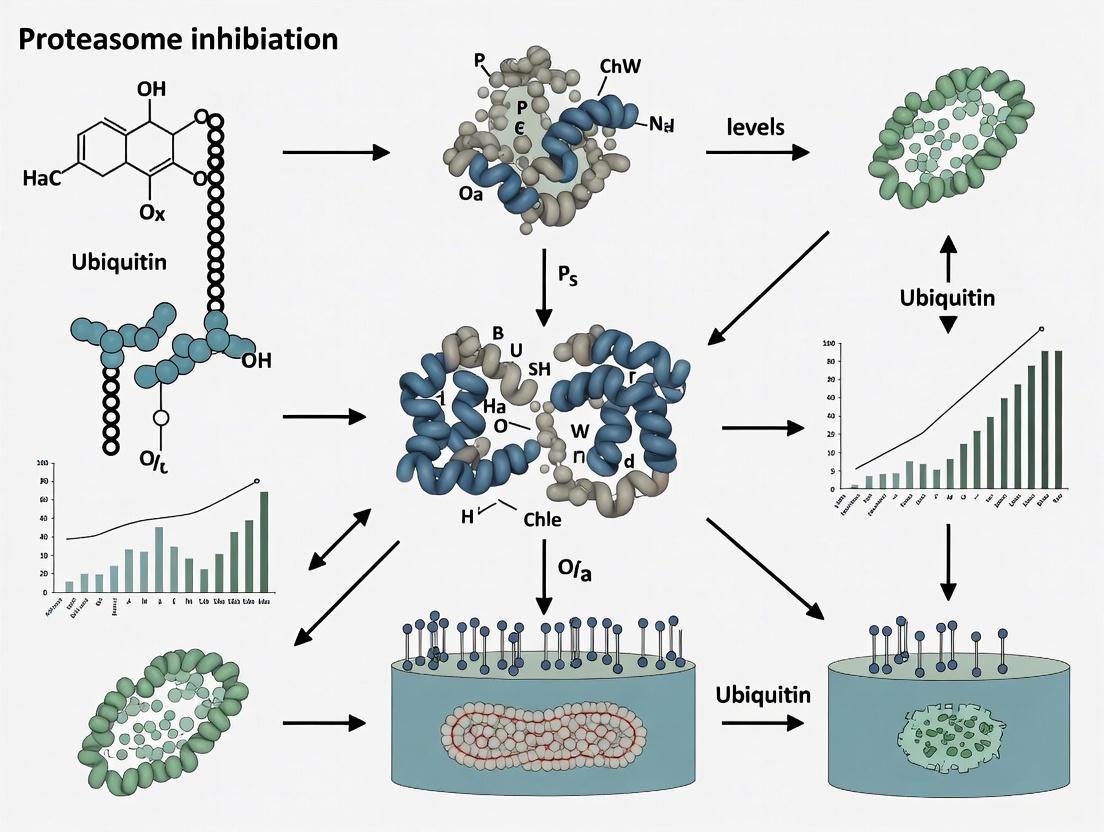

Figure 1: Mechanism of Ubiquitin Accumulation via Proteasome Inhibition. Proteasome inhibitors bind the 20S core, blocking degradation and causing polyubiquitinated protein buildup.

Consequences of Proteasomal Blockade

The inhibition of the proteolytic core triggers a cascade of cellular events. With the degradation machinery incapacitated, polyubiquitinated proteins that are continuously produced by the ubiquitination cascade can no longer be processed and thus begin to accumulate within the cell [18] [21]. This accumulation is not merely a passive consequence but actively contributes to cellular stress and death signaling.

The resulting accumulation of undegraded proteins, particularly in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), leads to ER stress and the activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) [20]. The UPR initially attempts to restore proteostasis by reducing global protein synthesis and upregulating chaperone production. However, sustained proteasome inhibition overwhelms this adaptive response, pushing the cell toward apoptosis via several pathways, including JNK activation and caspase-8 and caspase-3 activation [20]. Furthermore, proteasome inhibition stabilizes various pro-apoptotic proteins (e.g., NOXA, Bim, Bid) that are normally short-lived and rapidly turned over by the UPS, further tilting the cellular balance toward programmed cell death [20].

Table 2: Clinically Approved Proteasome Inhibitors and Their Properties

| Inhibitor | Primary Target | Binding Kinetics | Key Clinical Indications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bortezomib | β5 subunit | Reversible | Multiple Myeloma, Mantle Cell Lymphoma |

| Carfilzomib | β5 subunit | Irreversible | Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma |

| Ixazomib | β5 subunit | Reversible | Multiple Myeloma (oral administration) |

Experimental Analysis of Ubiquitin Accumulation

Standardized Methodologies for Detection

The experimental validation of ubiquitin accumulation following proteasome inhibition relies on well-established biochemical and cellular techniques. The most fundamental approach involves treating cells with a proteasome inhibitor and analyzing cell lysates via western blotting using anti-ubiquitin antibodies.

Protocol 1: Western Blot Analysis of Ubiquitinated Proteins

- Cell Treatment: Incubate cells (e.g., SK-N-SH, MelJuSo) with a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., 1-10 µM MG132, 100 nM bortezomib, or 100 nM epoxomicin) for a defined period (typically 4-24 hours) [21] [22]. DMSO is used as a vehicle control.

- Cell Lysis: Harvest cells and lyse in RIPA buffer or 1x SDS sample buffer containing protease inhibitors.

- Protein Separation and Immunoblotting: Resolve equal amounts of protein by SDS-PAGE (e.g., 4-12% Bis-Tris gels), transfer to PVDF or nitrocellulose membranes, and probe with a monoclonal anti-ubiquitin antibody (e.g., Cell Signaling Technology #3933) [22]. An anti-β-actin or anti-GAPDH antibody should be used as a loading control.

- Expected Outcome: A characteristic smear of high-molecular-weight bands, representing accumulated polyubiquitinated proteins, is observed in inhibitor-treated samples but not in controls [21].

Protocol 2: Functional Assessment Using Reporter Cell Lines To quantitatively assess UPS function, specialized reporter cell lines can be utilized.

- Reporter Constructs: Generate or obtain cell lines (e.g., MelJuSo) stably expressing UPS reporter substrates such as Ub-YFP, Ub-R-GFP, or YFP-CL1 [22]. These fusion proteins are constitutively ubiquitinated and targeted for rapid proteasomal degradation.

- Experimental Procedure: Treat reporter cells with the proteasome inhibitor. Inhibition of the proteasome will block the degradation of the reporter, leading to its intracellular accumulation.

- Quantification: Measure fluorescence accumulation over time using flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy. Alternatively, measure protein levels by western blotting with an anti-GFP antibody [22].

Quantitative Data and Comparative Inhibition

Experimental evidence consistently demonstrates a strong quantitative increase in ubiquitinated proteins upon proteasome inhibition. One study directly compared different classes of inhibitors and found that the proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin raised ubiquitinated protein levels at least 3-fold higher than the lysosomotropic agent chloroquine, which inhibits autophagy [21]. This underscores the primary role of the proteasome in the clearance of ubiquitinated proteins under normal conditions.

Furthermore, genetic inhibition of autophagy (e.g., in Atg5 −/− MEFs) failed to elevate ubiquitinated protein levels unless the proteasome was concurrently impaired [21]. These findings highlight the distinct roles of the proteasome and autophagy in protein quality control, with the proteasome serving as the primary pathway for ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Detecting Ubiquitin Accumulation via Western Blot.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Proteasome Inhibition and Ubiquitin Accumulation

| Reagent / Assay | Function / Purpose | Example Products / Citations |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological Inhibitors | Chemically inhibit proteasome activity to induce ubiquitin accumulation. | MG132 (investigational); Bortezomib, Carfilzomib (clinical) [23] [16] [20] |

| Anti-Ubiquitin Antibodies | Detect global ubiquitinated proteins in western blot, immunofluorescence. | Cell Signaling Technology #3933; P4D1 [22] |

| UPS Reporter Cell Lines | Real-time, quantitative assessment of UPS function in live cells. | Stably expressing Ub-YFP, YFP-CL1, ZsGreen-ODC [22] |

| Proteasome Activity Assays | Directly measure chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like, and caspase-like activity. | Fluorogenic substrates (e.g., Suc-LLVY-AMC) [20] |

| Lysosomal Inhibitors | Control experiments to distinguish UPS from autophagic degradation. | Bafilomycin A1, Chloroquine, Ammonium Chloride [21] |

Research Implications and Therapeutic Context

The accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins is more than a simple biomarker of proteasome inhibition; it represents a critical node in the mechanism of action for this drug class. This effect is strategically exploited in oncology, particularly in multiple myeloma, where malignant plasma cells exhibit high protein synthesis rates and are exceptionally dependent on the UPS to manage their proteotoxic stress [20]. The resulting accumulation of misfolded proteins triggers irreversible ER stress and apoptosis, creating a favorable therapeutic window.

Beyond cancer therapy, understanding this mechanism is crucial for researching neurodegenerative diseases. Conditions like Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and cerebral ischemia are associated with impaired proteasomal activity and the prominent accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in inclusion bodies [24]. Interestingly, a pathogenic feed-forward loop has been identified in which impaired proteasomal activity leads to the accumulation of a cytosolic PINK1 fragment (sPINK1), which in turn phosphorylates ubiquitin. This S65-phosphorylated ubiquitin (pUb) further inhibits proteasome function by interfering with ubiquitin chain elongation and proteasome-substrate interactions, exacerbating protein aggregation and neurodegeneration [24].

Conversely, modulating the UPS presents therapeutic opportunities beyond inhibition. Recent research demonstrates that proteasome activators, such as those in the ZFAND family, can enhance the degradation of misfolded proteins and may have therapeutic potential in conditions like tauopathy and cardiac failure [25]. Furthermore, a novel approach for treating genetic disorders like Pendred syndrome involves using proteasome inhibitors to rescue the expression and function of pathogenic pendrin protein variants by slowing their degradation, highlighting the nuanced and context-dependent applications of UPS modulation [23] [16].

Proteasome inhibition triggers a cascade of intracellular events, beginning with the acute disruption of protein homeostasis and culminating in the initiation of apoptotic cell death. This whitepaper delineates the molecular mechanisms underlying this critical transition, with a specific focus on the resultant fluctuations in cellular ubiquitin levels. By synthesizing findings from recent high-impact studies, we provide a technical guide detailing the experimental frameworks and quantitative assessments essential for researchers investigating the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and its therapeutic targeting in oncology and beyond.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) serves as the primary pathway for regulated intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, responsible for approximately 80–90% of cellular protein turnover [26]. This system orchestrates the timely destruction of damaged, misfolded, and short-lived regulatory proteins, thereby playing a pivotal role in maintaining cellular homeostasis. The canonical degradation pathway involves a three-enzyme cascade (E1-E2-E3) that tags target proteins with polyubiquitin chains, which are then recognized and degraded by the 26S proteasome complex into short peptides [20] [27]. The 26S proteasome itself is a multiprotein complex comprising a 20S catalytic core particle (CP) capped by one or two 19S regulatory particles (RP) [20]. The 20S core possesses three primary catalytic activities: chymotrypsin-like (β5), trypsin-like (β2), and caspase-like (β1), with the chymotrypsin-like site being the principal target of most clinically approved proteasome inhibitors [20]. Given its central role in controlling protein stability and abundance, targeted inhibition of the UPS presents a powerful strategy for probing cellular physiology and a validated therapeutic approach for hematological malignancies.

Molecular Architecture of the UPS

Proteasome Composition and Regulatory Complexes

The 20S core proteasome is a barrel-shaped structure composed of 28 subunits arranged in four stacked heptameric rings (αββα) [26]. The outer α-rings regulate substrate entry, while the inner β-rings contain the proteolytic active sites. Beyond the standard constitutive proteasome, cells can express the immunoproteasome, which incorporates inducible catalytic subunits (β1i, β2i, β5i) upon stimulation by inflammatory cytokines like interferon-γ, enhancing peptide generation for major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I antigen presentation [26].

Proteasome activity is further modulated by associated regulatory particles:

- 19S Regulatory Particle (PA700): Binds in an ATP-dependent manner to form the 26S proteasome, responsible for recognizing ubiquitinated substrates, deubiquitinating them (via Rpn11 and USP14), and unfolding them for translocation into the 20S core [26].

- PA28αβ (11S REG): A heptameric activator induced by interferon-γ that binds the 20S core in an ATP-independent manner, facilitating the degradation of small, unfolded peptides and playing a key role in antigen presentation [26].

- PA200 and PSMF1 (PI31): Nuclear and cytoplasmic regulators, respectively, with PA200 involved in DNA repair and spermatogenesis, and PSMF1 acting as an endogenous proteasome inhibitor whose activity can be counteracted by p97/VCP ATPase [26].

Table 1: Major Proteasome Complexes and Their Regulators

| Complex/Regulator | Structure | Binding | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| 26S Proteasome | 20S CP + 19S RP(s) | ATP-dependent | Degradation of polyubiquitinated proteins |

| Immunoproteasome | 20S with β1i, β2i, β5i | - | Antigen presentation; stress response |

| 19S RP (PA700) | Base (Rpt1-6, Rpn1/2/10/13) + Lid (Rpn3/5-9/11/12/15) | ATP-dependent | Substrate recognition, deubiquitination, unfolding |

| PA28αβ (11S REG) | Heteroheptamer | ATP-independent | Peptide hydrolysis enhancement; antigen presentation |

| PA200 | Monomer | ATP-independent | Nuclear functions; DNA repair; spermatogenesis |

| PSMF1 (PI31) | Monomer | - | Proteasome inhibition; regulation of CP-RP assembly |

Ubiquitin-Dependent and Independent Degradation

While the UPS is synonymous with ubiquitin-dependent degradation, the proteasome can also degrade certain substrates in a ubiquitin-independent manner (UbInPD). This pathway typically targets proteins with intrinsically disordered regions or specific C-terminal sequences. A key example is the oncogenic phosphatase PPM1D, whose rapid degradation is mediated directly by the 20S proteasome via its C-terminal 35 amino acids, without requiring ubiquitination [28]. This UbInPD pathway is estimated to account for up to 20% of intracellular protein degradation and can be activated by regulatory subunits like PSMD14 and PSME3 [28].

Core Mechanisms: From Proteasome Inhibition to Apoptosis

Proteasome inhibitors (e.g., Bortezomib, Carfilzomib, Ixazomib) primarily target the chymotrypsin-like activity of the β5 subunit. This inhibition triggers a multi-faceted cellular stress response, culminating in apoptosis through several interconnected mechanisms.

Disruption of Protein Homeostasis and ER Stress

Cells with high protein synthesis rates, such as multiple myeloma plasma cells producing immunoglobulins, are particularly reliant on efficient UPS function. Proteasome inhibition causes an accumulation of misfolded and polyubiquitinated proteins, leading to proteotoxic stress. A critical consequence is Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Stress. The ER relies on the UPS to dislocate and degrade misfolded proteins via ER-associated degradation (ERAD). When this process is blocked, misfolded proteins accumulate within the ER lumen, triggering the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) [20]. While initially pro-survival, persistent UPR signaling shifts toward pro-apoptotic outcomes, including cell cycle arrest and activation of caspase cascades [20].

Modulation of Apoptotic Signaling Pathways

The accumulation of regulatory proteins due to blocked degradation directly activates both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways.

- Stabilization of Pro-Apoptotic Regulators: Key pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, such as Bim, Bid, and NOXA, are normally short-lived and rapidly turned over by the proteasome. Their stabilization upon proteasome inhibition tips the mitochondrial balance toward apoptosis [20]. NOXA, in particular, binds and neutralizes the anti-apoptotic protein Mcl-1, promoting Bak/Bax activation and mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) [29].

- Activation of Intrinsic Apoptosis: MOMP leads to cytochrome c release, formation of the apoptosome, and sequential activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3, executing the cell death program [29].

- c-Jun NH2-terminal Kinase (JNK) and p53 Pathways: Proteasome inhibition activates JNK, which promotes apoptosis via caspase-8 and caspase-3. It also stabilizes the tumor suppressor p53, either directly or through interaction with MDM2, further amplifying pro-apoptotic signals [20].

- Inhibition of NF-κB Survival Signaling: The NF-κB transcription factor is normally activated by the degradation of its inhibitor, IκBα, via the UPS. Proteasome inhibition prevents IκBα degradation, sequestering NF-κB in the cytoplasm and blocking its pro-survival, anti-apoptotic transcriptional program [20].

Diagram 1: Apoptotic signaling cascade triggered by proteasome inhibition, showing key pathways and regulatory proteins.

Quantitative Profiling of Proteasome Inhibitors

The efficacy and cellular impact of proteasome inhibitors are defined by their pharmacodynamic properties. The table below summarizes quantitative and characteristic data for FDA-approved inhibitors.

Table 2: Clinically Approved Proteasome Inhibitors: Mechanisms and Toxicities

| Name (Brand) | Inhibition Kinetics | Active Moiety | Primary Target | Common Clinical Toxicities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bortezomib (Velcade) | Slowly reversible | Boronate | β5 > β1 > β2 | Peripheral neuropathy, nausea, diarrhea, cytopenias |

| Carfilzomib (Kyprolis) | Irreversible | Epoxyketone | β5 > β2/β1 | Dyspnea, cytopenias, nausea, fatigue, peripheral edema |

| Ixazomib (Ninlaro) | Reversible | Boronate | β5 > β1 | Diarrhea, constipation, cytopenias, peripheral neuropathy |

Experimental Frameworks for Investigating UPS Dysfunction

Protocol 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Screens for UPS Modulator Identification

Objective: To identify genes conferring resistance or sensitivity to proteasome inhibitors or novel UPS-targeting compounds. Methodology: This protocol is based on the genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 resistance screen used to identify mediators of the novel compound BRD1732 [17].

- Cell Line Preparation: Generate a Cas9-expressing cell line (e.g., HAP1, MelJuSo) via lentiviral transduction and antibiotic selection (e.g., blasticidin). Validate Cas9 expression by western blot.

- Library Transduction: Transduce the cell population at a low MOI (e.g., ~0.3) with a genome-wide lentiviral sgRNA library (e.g., Brunello or GeCKO) to ensure single integration. Use a coverage of >500 cells per sgRNA.

- Selection and Treatment: After puromycin selection, split cells into treatment and control arms. Treat the experimental arm with the compound of interest (e.g., BRD1732 at IC50-IC90) for several population doublings. Maintain the control arm in parallel with vehicle (DMSO).

- Genomic DNA Extraction and Sequencing: Harvest genomic DNA from both arms. Amplify the integrated sgRNA sequences by PCR and subject them to next-generation sequencing.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Align sequences to the sgRNA library. Use algorithms (e.g., MAGeCK) to compare sgRNA abundance between treatment and control arms. Significantly enriched sgRNAs indicate genes whose knockout confers resistance.

Protocol 2: Assessing Ubiquitination and Protein Half-Life

Objective: To measure the turnover rate and ubiquitination status of a specific protein (e.g., PPM1D, Mcl-1) under proteasome inhibition. Methodology: This combines cycloheximide chase assays and ubiquitination assessment as applied in recent studies [29] [28].

Cycloheximide Chase Assay:

- Seed cells expressing the protein of interest. Prior to assay, treat with a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., 10 μM MG132) or vehicle for 4-6 hours to establish a baseline.

- Add cycloheximide (e.g., 100 μg/mL) to inhibit new protein synthesis. Harvest cell pellets at defined time points (e.g., 0, 30, 60, 120, 240 minutes).

- Prepare whole-cell lysates and perform SDS-PAGE and western blotting for the target protein and a loading control (e.g., GAPDH, β-actin).

- Quantify band intensity to plot protein decay and calculate half-life.

Ubiquitination Dependency Assay:

- To distinguish ubiquitin-dependent from independent degradation, repeat the chase assay in the presence of TAK-243 (1 μM), a specific E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme inhibitor [28].

- Stabilization of the protein upon TAK-243 treatment indicates ubiquitin-dependent degradation. If the protein remains unstable, it suggests UbInPD.

In Vitro Degradation Assay:

- Purify the recombinant protein of interest (e.g., PPM1D) and incubate it with purified 20S proteasome in a degradation buffer.

- Monitor protein degradation over time via western blot or other detection methods. Direct degradation confirms UbInPD and identifies the protein as a direct proteasome substrate [28].

Diagram 2: Workflow for a genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 screen to identify genes involved in the cellular response to proteasome inhibition or UPS-targeting compounds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating UPS and Apoptosis

| Reagent / Assay | Function / Application | Example Compounds & Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Inhibit catalytic activity of the 20S core; induce ER stress and apoptosis. | Bortezomib (β5), Carfilzomib (β5), MG132 (β5), Epoxomicin (β5) [20] [22] |

| E1 Ubiquitination Inhibitor | Globally blocks ubiquitin activation; tests ubiquitin-dependency of degradation. | TAK-243 (E1 UBA1 inhibitor) [28] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Libraries | Genome-wide forward genetic screens for modifier gene identification. | Brunello/GeCKO libraries; sgRNAs targeting RNF19A, RNF19B, UBE2L3 [17] |

| Ubiquitin Reporters | Live-cell or endpoint reporters for ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis. | Ub-YFP, Ub-R-GFP, YFP-CL1 [22] |

| Apoptosis Assays | Quantify caspase activation and cell death. | Caspase-3/7 activity assays, Annexin V staining [20] [29] |

| Lysosome Inhibitors | Distinguish proteasomal from lysosomal degradation pathways. | Bafilomycin A1, Chloroquine [28] |

| DUB Inhibitors | Investigate the role of deubiquitinating enzymes in UPS function. | USP14 inhibitors, PR-619 (pan-DUB inhibitor) [26] |

Emerging Frontiers and Novel Mechanisms

Recent research has uncovered non-canonical mechanisms of UPS disruption. A landmark study identified a first-in-class small molecule, BRD1732, which is itself directly ubiquitinated within cells [17]. This stereospecific process is dependent on the E3 ligases RNF19A/RNF19B and the E2 enzyme UBE2L3. Ubiquitination occurs on a secondary amine of BRD1732, leading to the accumulation of inert ubiquitin-BRD1732 conjugates and non-canonical K27-linked polyubiquitin chains. This sequestration of ubiquitin pools results in a broad collapse of the UPS, independent of direct proteasome inhibition, and represents a novel MOA for inducing proteotoxic stress [17].

Furthermore, the UPS is increasingly implicated in regulating cancer immunotherapy outcomes. The stability of immune checkpoint proteins like PD-L1 is controlled by E3 ligases such as SPOP and TRIM21, which mediate its ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [30]. Tumor cells can evade this regulation, leading to increased PD-L1 surface expression and immune evasion. Targeting these E3 ligases or associated DUBs presents a promising strategy to enhance the efficacy of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy [30].

Ubiquitination is a pivotal post-translational modification that extends far beyond its canonical role in targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation. While K48-linked ubiquitin chains are well-established as definitive degradation signals, a diverse array of "atypical" ubiquitin linkages—including K63, K11, K29, K33, K6, K27, M1, and various branched forms—orchestrate a complex spectrum of non-degradative cellular processes. These atypical chains function as sophisticated molecular codes that regulate inflammatory signaling, DNA repair, endocytosis, and autophagy. This whitepaper examines the architecture, synthesis, and functional roles of these atypical ubiquitin chains, with particular emphasis on their implications for therapeutic strategies involving proteasome inhibition. Understanding this ubiquitin code is essential for advancing drug development in oncology, neurodegenerative diseases, and inflammatory disorders.

Ubiquitin chains are classified into three structural categories based on their linkage patterns: homotypic (uniformly linked through the same ubiquitin residue), mixed (containing different linkages but each ubiquitin modified at only one site), and branched (featuring ubiquitin monomers simultaneously modified at two or more distinct sites) [31]. Atypical ubiquitin chains encompass all ubiquitin polymers except the classical K48-linked homotypic chains traditionally associated with proteasomal degradation [32].

The diversity of atypical chains arises from ubiquitin's seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and its N-terminal methionine (M1), each capable of forming distinct isopeptide linkages that generate unique three-dimensional structures [32] [31]. This structural diversity enables the transmission of specific biological information, allowing ubiquitin to function as a multifunctional signaling molecule. Beyond protein degradation, atypical ubiquitin chains regulate essential processes including NF-κB signaling, kinase activation, DNA damage repair, protein trafficking, and autophagy [32] [31].

Table 1: Classification of Atypical Ubiquitin Chain Linkages

| Linkage Type | Structural Class | Primary Functions | Key Assembling Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|

| K63-linked | Homotypic | NF-κB signaling, DNA repair, endocytosis, kinase activation | TRAF6, UBC13-UEV1A complex |

| K11-linked | Homotypic/Branched | Cell cycle regulation, ERAD | UBE2S, APC/C, UBE2C |

| M1-linked (linear) | Homotypic | NF-κB activation, inflammatory signaling | LUBAC complex |

| K29/K48-branched | Branched | Proteasomal degradation (enhanced efficiency) | UBE3C, Ufd4/Ufd2 collaboration |

| K48/K63-branched | Branched | Signaling-to-degradation switch, proteasomal processing | TRAF6/HUWE1, ITCH/UBR5 collaboration |

| K6-linked | Homotypic/Branched | DNA damage response, mitophagy | Parkin, BRCA1-BARD1 |

| K27-linked | Homotypic | Immune signaling, kinase activation | Uncharacterized |

| K33-linked | Homotypic | Kinase regulation, TCR signaling | Uncharacterized |

Structural Diversity and Synthesis of Atypical Chains

Homotypic and Mixed Linkage Chains

Homotypic atypical chains are uniformly connected through a single lysine residue other than K48. Among these, K63-linked chains represent one of the most extensively studied atypical linkages. These chains adopt an extended, open conformation that differs dramatically from the compact structure of K48-linked chains, enabling their recognition by proteins containing specific ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) that translate the ubiquitin signal into downstream cellular responses [32]. K63 linkages primarily function in non-degradative signaling pathways, including activation of the NF-κB pathway, DNA damage repair mechanisms, and regulation of receptor endocytosis [32].

The synthesis of homotypic chains is governed by specific E2-E3 enzyme pairs that determine linkage specificity. For instance, the MMS2-UBC13 complex specifically generates K63-linked chains through a mechanism that positions the acceptor ubiquitin such that only K63 is accessible for ubiquitin transfer [32]. Similarly, the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC) exclusively generates M1-linked linear chains that play critical roles in NF-κB signaling and inflammatory responses [31].

Branched Ubiquitin Chains

Branched ubiquitin chains represent a sophisticated level of complexity in the ubiquitin code, where a single ubiquitin moiety serves as a branch point by being simultaneously modified at two or more distinct lysine residues [31]. These branched architectures can be generated through two primary mechanisms:

Collaborative E3 mechanisms: Pairs of E3 ligases with distinct linkage specificities work sequentially to build branched structures. For example, in the ubiquitin fusion degradation (UFD) pathway in yeast, Ufd4 first assembles K29-linked chains on substrates, which are then recognized by Ufd2 through specialized binding loops to add K48-linked ubiquitins, creating K29/K48-branched chains [31]. Similarly, during NF-κB signaling, TRAF6 synthesizes K63-linked chains that are subsequently recognized by HUWE1, which attaches K48 linkages through its UIM and UBA domains to form K48/K63-branched chains [31].

Single E3 mechanisms: Certain E3 ligases possess intrinsic capability to generate branched chains. The anaphase-promising complex/cyclosome (APC/C) collaborates with two different E2s (UBE2C and UBE2S) to form branched K11/K48 chains during mitosis [31]. Additionally, some HECT-family E3s like WWP1 can synthesize branched chains containing both K48 and K63 linkages when paired with a single E2 enzyme (UBE2L3) [31].

Diagram 1: Branch ubiquitin chain formation process.

The functional significance of branched chains often lies in their ability to integrate multiple signals or enhance degradation efficiency. For instance, branched K48/K63 chains on the pro-apoptotic regulator TXNIP facilitate a conversion from non-degradative K63 signaling to degradative K48 signaling, enabling precise temporal control of protein stability during apoptotic responses [31]. Recent research using the UbiREAD technology has demonstrated that in K48/K63-branched chains, the identity of the substrate-anchored chain determines the functional outcome, establishing that "branched chains are not the sum of their parts" [33].

Functional Roles in Cell Signaling

NF-κB and Inflammatory Signaling

Atypical ubiquitin chains play indispensable roles in the activation and regulation of NF-κB signaling pathways. Both K63-linked and M1-linear chains function as critical scaffolds that facilitate the assembly of signaling complexes. K63-linked chains activate IκB kinase (IKK) by promoting the phosphorylation and activation of TAK1 through specific adaptor proteins, while M1-linear chains generated by LUBAC stabilize the signaling complex and prevent its dissociation [32] [31].

The integration of different chain types creates a sophisticated regulatory network. For example, branched K48/K63 chains formed through collaboration between TRAF6 and HUWE1 enable crosstalk between inflammatory signaling and degradation pathways, potentially serving as a mechanism to terminate NF-κB activation after the signaling event [31]. This demonstrates how branched ubiquitin chains can integrate multiple signals to fine-tune cellular responses.

Kinase Activation and DNA Repair

In kinase activation pathways, atypical ubiquitin chains frequently function as allosteric regulators rather than degradation signals. K63-linked ubiquitination of both receptor tyrosine kinases (e.g., EGFR) and cytoplasmic kinases (e.g., MEKK3) can enhance their catalytic activity or promote their translocation to specific cellular compartments where they interact with downstream effectors [32].

The DNA damage response employs multiple atypical ubiquitin linkages to coordinate repair processes. K63-linked chains facilitate the recruitment of DNA repair proteins to damage sites, while K6-linked chains assembled by BRCA1-BARD1 play roles in DNA double-strand break repair [31]. Additionally, K29/K48-branched chains have been implicated in the regulation of DNA repair proteins, potentially modulating their stability or activity in response to genotoxic stress [31].

Selective Autophagy and Membrane Trafficking

Atypical ubiquitin chains serve as specific recognition signals for selective autophagy pathways. During mitophagy, K6-linked chains on mitochondrial proteins can be recognized by autophagy receptors that target damaged mitochondria for degradation [31]. Similarly, K63-linked chains often function as signals for various selective autophagy processes, including aggrephagy (clearance of protein aggregates) and xenophagy (clearance of intracellular pathogens) [32].

In membrane trafficking, monoubiquitination and K63-linked chains function as sorting signals that direct transmembrane proteins to lysosomal degradation via the endosomal system, independent of proteasomal degradation [32]. This is particularly important for the downregulation of activated growth factor receptors and the modulation of immune receptor signaling.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

UbiREAD Technology for Functional Analysis

The Ubiquitinated Reporter Evaluation After Intracellular Delivery (UbiREAD) platform represents a technological breakthrough for systematically deciphering the ubiquitin code, particularly for understanding how chain linkage and topology influence intracellular degradation kinetics [33].

Experimental Workflow:

- Preparation of defined ubiquitin chains: Recombinant ubiquitin chains of defined length and linkage composition are synthesized in vitro using specific E2/E3 enzyme combinations or semisynthetic approaches. Chain length is fixed by incorporating a distal ubiquitin bearing point mutations (e.g., K48R for K48 chains) that prevent further elongation [33].

Substrate conjugation: The pre-assembled ubiquitin chains are enzymatically conjugated to a mono-ubiquitinated GFP-based degradation reporter substrate that has been engineered for efficient proteasomal recognition [33].

Intracellular delivery: The defined ubiquitin-GFP conjugates are introduced into mammalian cells (e.g., RPE-1, THP-1, U2OS) via electroporation, which enables rapid cytoplasmic delivery without significant protein processing or loss of viability [33].

Degradation kinetics monitoring: The fate of the ubiquitinated reporter is tracked using multiple complementary approaches:

- Flow cytometry to measure GFP fluorescence loss over time (as fast as 20-second intervals)

- In-gel fluorescence to distinguish between input, degraded, and deubiquitinated species

- Pharmacological inhibition using specific inhibitors (MG132 for proteasome, TAK243 for E1, CB5083/NMS873 for p97) to validate degradation mechanisms [33]

Key Insights from UbiREAD:

- K48 chains with three or more ubiquitins trigger degradation with half-lives of 1-2 minutes

- K63-ubiquitinated substrates are rapidly deubiquitinated rather than degraded

- In K48/K63-branched chains, the substrate-anchored chain identity determines degradation vs. deubiquitination outcomes [33]

Table 2: Intracellular Degradation Kinetics of Different Ubiquitin Chain Types

| Ubiquitin Chain Type | Intracellular Half-life | Primary Fate | DUB Sensitivity | Proteasome Dependency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K48-Ub4 | 1-2 min | Degradation | Low | High (MG132-sensitive) |

| K48-Ub3 | ~2 min | Degradation | Moderate | High |

| K63-Ub4 | >60 min | Deubiquitination | High | Low |

| K48/K63-branched | Variable (anchor-dependent) | Mixed | Moderate | Partial |

| MonoUb | >120 min | Stable | Low | None |

Structural Biology Approaches

Cryo-EM and Structural Analysis of full-length E3 ligases has provided unprecedented insights into the mechanisms of ubiquitin chain assembly and specificity. For example, structural studies of the HECT-type E3 HACE1 have revealed:

Autoinhibition mechanism: Full-length HACE1 forms a yin-yang-like dimer that constrains the catalytic HECT domain in an autoinhibited state, with dimerization mediated by contacts between the N-helix of one subunit and the small wing of the HECT N-lobe of the other subunit [34].

Activation process: Upon activation, HACE1 transitions to a monomeric state that enables substrate recognition and ubiquitin transfer [34].

Substrate specificity: Activated monomeric HACE1 selectively recognizes GTP-bound RAC1 through specific interaction interfaces, explaining its selectivity for the active form of this GTPase [34].

Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) complements structural approaches by mapping protein dynamics and interaction interfaces, revealing how E3 ligases like HACE1 undergo conformational changes during activation and substrate engagement [34].

Proteomics and Enrichment Strategies

Mass spectrometry-based ubiquitinomics enables system-wide profiling of ubiquitination sites and chain linkages. Key methodological considerations include:

Di-Glycine remnant immunoaffinity enrichment: Antibodies specific for the Lys-ε-GG remnant left after tryptic digestion of ubiquitinated proteins enable enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides for MS identification and quantification [35]. This approach has revealed that aging prominently affects protein ubiquitylation in the mouse brain, with 29% of altered ubiquitylation sites changing independently of protein abundance [35].

Linkage-specific antibodies: Antibodies that recognize specific ubiquitin linkages (e.g., K63, K48, M1) enable the enrichment and detection of particular chain types.

UbiCRest assay: This approach uses linkage-specific deubiquitinases (DUBs) as "restriction enzymes" to fingerprint ubiquitin chain topology by analyzing characteristic cleavage patterns [33].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Studying Atypical Ubiquitin Chains

| Research Tool | Specific Example | Application/Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Defined ubiquitin chains | K48-Ub4-GFP, K63-Ub4-GFP | Substrate degradation kinetics | Pre-assembled chains of specific linkage and length |

| Linkage-specific DUBs | OTUB1 (K48-specific), AMSH (K63-specific) | Chain linkage analysis, UbiCRest | Cleave specific ubiquitin linkages |

| Proteasome inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Block proteasomal degradation | Varying specificity and mechanisms |

| E1 inhibitors | TAK243 | Block global ubiquitination | Prevents ubiquitin activation |

| p97/VCP inhibitors | CB5083, NMS873 | Disrupt p97-mediated extraction | Affects ERAD and substrate processing |

| Linkage-specific antibodies | Anti-K63, Anti-K48, Anti-M1 | Immunodetection and enrichment | Specific recognition of chain linkages |

| Activity-based probes | Ubiquitin-based electrophilic probes | DUB activity profiling | Covalently label active DUBs |

| Recombinant E2/E3 enzymes | UBC13-UEV1A, TRAF6, HACE1 | In vitro ubiquitination assays | Defined linkage specificity |

Implications for Proteasome Inhibition Therapy

The expanding understanding of atypical ubiquitin chains has profound implications for therapeutic strategies involving proteasome inhibitors, particularly in oncology. Multiple myeloma treatment with bortezomib and other PIs exploits the heightened dependency of antibody-producing cells on proteasomal function, but resistance frequently develops through adaptation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system [36].

Compensatory Mechanisms and Resistance

Cancer cells employ multiple adaptive responses to proteasome inhibition:

- NRF1-mediated proteasome bounce-back: Upon proteasome inhibition, the transcription factor NRF1 is stabilized and activates the expression of proteasome subunit genes, enabling cells to compensate for inhibited proteasomes by synthesizing new ones [36].

- Ubiquitin chain editing: Changes in the balance of ubiquitin chain types, particularly increased non-degradative chains, may allow cancer cells to redirect proteins from degradation to alternative fates.

- Enhanced autophagy: When proteasomal function is compromised, cells may increase their reliance on autophagy as an alternative degradation pathway [36].

Therapeutic Opportunities

Understanding atypical ubiquitin chains reveals several promising therapeutic approaches:

- Combination targeting: Simultaneous inhibition of proteasomes and compensatory pathways (e.g., p97/VCP, autophagy, NRF1 activation) may overcome resistance mechanisms [36].

- Chain linkage-specific interventions: Developing agents that specifically modulate the formation or recognition of particular atypical ubiquitin linkages could enable more precise manipulation of specific pathways without global disruption of protein homeostasis.

- Branched chain manipulation: Targeting the E3 ligases that create branched degradation signals (e.g., HUWE1, UBR5) might enhance the efficacy of proteasome inhibitors by promoting the formation of more efficient degradation signals on specific oncoproteins.

Diagram 2: UPS adaptation and therapeutic strategy.