Standardizing Ubiquitination Quantification: From Foundational Principles to Cross-Tissue Applications in Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to standardize the quantification of ubiquitination across diverse tissue types.

Standardizing Ubiquitination Quantification: From Foundational Principles to Cross-Tissue Applications in Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to standardize the quantification of ubiquitination across diverse tissue types. We explore the foundational role of ubiquitination in cellular processes and disease, with examples from cervical and ovarian cancer. The piece critically evaluates current high-throughput methodologies—including TUBE-based assays, APEX2 proximity labeling, DIA mass spectrometry, and HiBiT/NanoBRET systems—highlighting their application in proteomics, drug discovery for PROTACs, and immune microenvironment analysis. A dedicated troubleshooting section addresses tissue-specific challenges and optimization strategies for detection sensitivity and specificity. Finally, we outline robust validation frameworks involving independent prognostic analysis, cross-platform verification, and single-cell RNA sequencing to ensure data reliability and translational potential for biomarker discovery and therapeutic development.

Ubiquitination Fundamentals: Decoding a Key Regulatory Mechanism in Health and Disease

Core Mechanism of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

What is the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and its primary function?

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) is the primary pathway for selective protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, responsible for maintaining cellular protein homeostasis (proteostasis) [1] [2]. This highly conserved system eliminates short-lived, misfolded, damaged, and regulatory proteins, thereby controlling vital cellular processes including immune response, apoptosis, cell cycle, differentiation, and signaling [3] [4]. The UPS functions as a hierarchical process where proteins are first tagged with ubiquitin chains and then degraded by the proteasome [3].

What are the key steps in the E1-E2-E3 enzyme cascade?

The process of ubiquitination involves a three-step, ATP-dependent enzymatic cascade [5] [6]:

- Step 1: Ubiquitin Activation (E1)

- Step 2: Ubiquitin Conjugation (E2)

- Step 3: Ubiquitin Ligation (E3)

After initial ubiquitination, additional ubiquitin molecules are attached to internal lysines on the previously attached ubiquitin, forming polyubiquitin chains that mark the protein for degradation by the 26S proteasome [5].

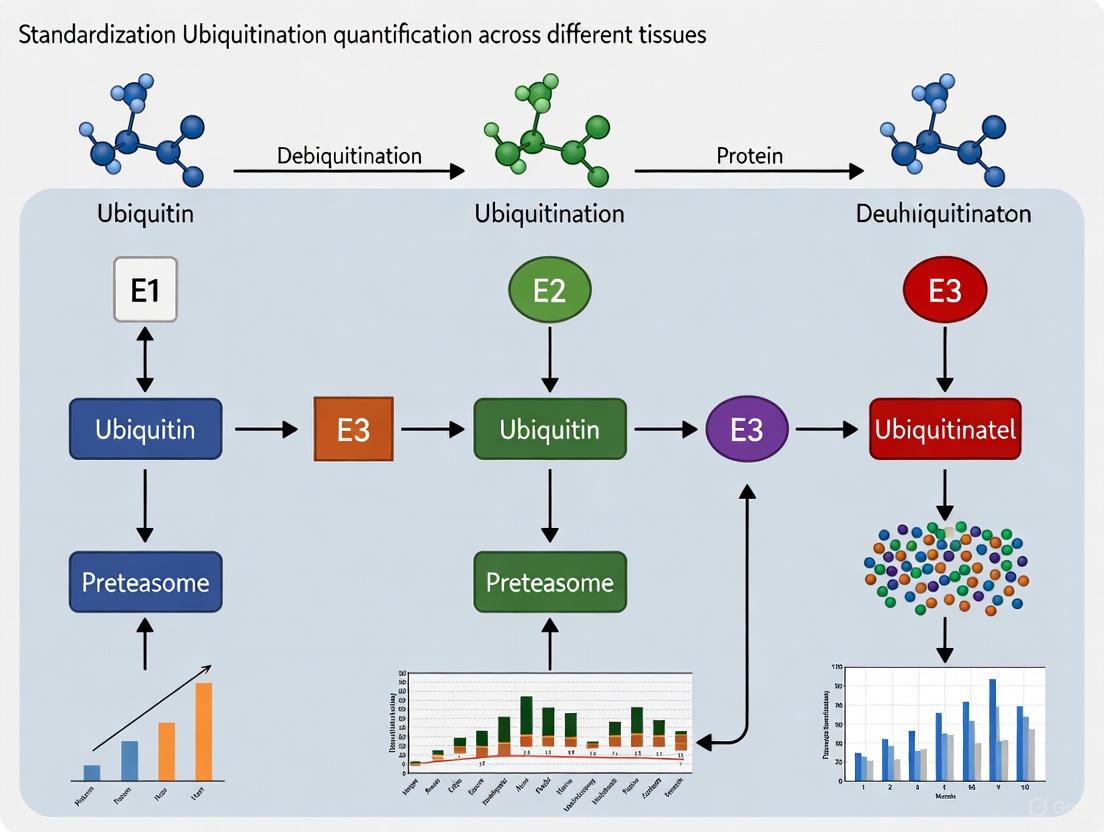

Diagram 1: The E1-E2-E3 enzyme cascade in the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System. Ubiquitin is sequentially activated by E1, conjugated to E2, and finally ligated to the target protein by E3, forming a polyubiquitin chain that targets the protein for proteasomal degradation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What different types of ubiquitin chains exist and what are their functions?

Ubiquitin contains seven internal lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1) that can form polyubiquitin chains with distinct functions [3] [7] [4]. The specific linkage type determines the functional consequence for the modified protein, creating a complex "ubiquitin code" [4].

Table 1: Major Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Primary Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Function | Cellular Process |

|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Proteasomal degradation [3] [7] | Protein turnover, homeostasis [3] |

| K11-linked | Proteasomal degradation, ERAD [3] | Cell cycle regulation, protein quality control [3] |

| K63-linked | Signal transduction, protein trafficking, DNA repair [7] | NF-κB and MAPK signaling, inflammation [3] [7] |

| M1-linked | Inflammatory signaling [4] | NF-κB activation, immune regulation [4] |

| K27/K29-linked | Proteasomal and lysosomal degradation [3] | Protein quality control, autophagy [3] |

How does UPS dysfunction contribute to human diseases?

Dysregulation of UPS components is implicated in numerous human diseases [3] [4]:

- Cancer: Stabilization of oncogenes or degradation of tumor suppressors due to altered E3 ligase or deubiquitinase (DUB) activity [3] [4].

- Neurodegenerative Diseases: Impaired clearance of toxic protein aggregates (e.g., α-synuclein in Parkinson's, Huntingtin in Huntington's, amyloid-β in Alzheimer's) [1] [4].

- Immune Disorders: Aberrant inflammatory signaling due to disrupted ubiquitination of immune regulators like RIPK2, NEMO, and inflammasome components [3] [7].

- Developmental Disorders: Mutations in DUBs and E3 ligases causing congenital developmental defects [4].

- Diabetes: UPS involvement in insulin signaling, β-cell function, and pyroptosis regulation [8].

What are the therapeutic applications of targeting the UPS?

Several therapeutic strategies exploit the UPS:

- PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras): Heterobifunctional molecules that recruit E3 ligases to target specific disease-causing proteins for degradation [3] [6] [7]. This approach can target previously "undruggable" proteins [7].

- Molecular Glues: Small molecules that enhance the interaction between E3 ligases and target proteins [3].

- Proteasome Inhibitors: Drugs like bortezomib that globally inhibit proteasome activity, used in multiple myeloma treatment [3].

- DUB Inhibitors: Compounds targeting deubiquitinating enzymes to modulate ubiquitin-dependent signaling [7].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

How can I detect and quantify protein ubiquitination?

Detecting protein ubiquitination presents challenges due to the dynamic nature of this modification and the potential for rapid deubiquitination. The following protocol and troubleshooting guide addresses common issues.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Ubiquitination Detection

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or no ubiquitin signal | Rapid deubiquitination by DUBs during lysis | Use DUB inhibitors (e.g., N-ethylmaleimide) in lysis buffer [7] |

| Low abundance of ubiquitinated species | Treat cells with proteasome inhibitor (MG132) to accumulate ubiquitinated proteins [5] | |

| Inefficient immunoprecipitation | Use TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) for higher affinity capture [7] | |

| Non-specific bands | Antibody cross-reactivity | Validate antibodies with ubiquitin knockout cells; use linkage-specific TUBEs [7] |

| Incomplete blocking | Optimize blocking conditions; use different blocking buffers (BSA vs. milk) [9] | |

| Cannot distinguish specific ubiquitination | Global ubiquitination changes mask target | Use chain-specific TUBEs (K48 vs. K63) to detect linkage-specific ubiquitination [7] |

| High background | Antibody concentration too high | Titrate primary and secondary antibodies; increase wash stringency [9] |

Protocol: Linkage-Specific Ubiquitination Detection Using TUBEs

Purpose: To specifically capture and detect endogenous K48- or K63-linked ubiquitination on target proteins.

Reagents Needed:

- Chain-specific TUBEs (K48-TUBE, K63-TUBE, Pan-TUBE)

- Proteasome inhibitor (MG132, 10-20µM)

- Appropriate cell lysis buffer with DUB inhibitors

- Antibodies for target protein and ubiquitin

- Magnetic beads for pull-down

Procedure:

- Cell Treatment & Lysis:

- Treat cells with experimental conditions (e.g., L18-MDP for K63 ubiquitination or PROTAC for K48 ubiquitination) [7].

- Pre-treat with proteasome inhibitor for 4-6 hours before harvesting to accumulate ubiquitinated proteins [5].

- Lyse cells in optimized buffer (e.g., 50mM Tris-HCl pH7.5, 150mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1mM EDTA) containing fresh DUB inhibitors (1mM N-ethylmaleimide) and protease inhibitors [7].

Ubiquitin Capture:

- Incubate 200-500µg of cell lysate with chain-specific TUBE-conjugated magnetic beads (1-2µg TUBE/100µg lysate) for 2-4 hours at 4°C with rotation [7].

- Include controls with Pan-TUBE and opposite chain-specific TUBE.

Washing and Elution:

- Wash beads 3-4 times with lysis buffer containing 300-500mM NaCl to reduce non-specific binding.

- Elute bound proteins with 2X SDS sample buffer at 95°C for 10 minutes.

Detection:

- Analyze by Western blotting with target protein-specific antibody.

- Confirm ubiquitination with anti-ubiquitin antibody.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for linkage-specific ubiquitination detection using TUBEs. Cell lysates are prepared with DUB inhibitors and incubated with different chain-specific TUBEs in parallel to capture distinct ubiquitin linkage types.

How do I troubleshoot poor Western blot results for UPS components?

Common Western blot issues and solutions for UPS proteins:

- Smeared Bands: Run gel at lower voltage (10-15V/cm); check for overloading; ensure proper sample preparation [10].

- High Background: Decrease antibody concentration; optimize blocking buffer; increase wash stringency; use Tween-20 in buffers [9].

- Weak Signal: Confirm efficient transfer using reversible protein stain; increase protein loading; use higher sensitivity substrate [9].

- Multiple Non-specific Bands: Validate antibody specificity; check for protein degradation (use fresh protease inhibitors) [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for UPS Studies

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Accumulate ubiquitinated proteins by blocking proteasomal degradation [5] |

| DUB Inhibitors | N-ethylmaleimide, PR-619 | Prevent deubiquitination during sample processing [7] |

| Chain-Specific TUBEs | K48-TUBE, K63-TUBE, M1-TUBE | High-affinity capture of linkage-specific polyubiquitin chains [7] |

| Ubiquitin Activation Inhibitors | PYR-41, TAK-243 | Inhibit E1 enzyme to block global ubiquitination [6] |

| E1/E2/E3 Enzymes | Recombinant UBE1, UBE2D2, E3 ligases | In vitro ubiquitination assays; enzyme activity studies [6] |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Anti-K48-ubiquitin, Anti-K63-ubiquitin | Detect specific ubiquitin chain types by Western blot [7] |

| PROTAC Molecules | RIPK2 PROTAC, ARV-110, ARV-471 | Induce targeted protein degradation for functional studies [3] [7] |

| Activity Assays | LanthaScreen Conjugation Assay | High-throughput screening of ubiquitin conjugation [5] |

The ubiquitin code represents a sophisticated post-translational modification system that regulates nearly all cellular processes through diverse chain topologies. Ubiquitin is a small, highly conserved protein of 76 amino acids that can be covalently attached to substrate proteins via a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 activating, E2 conjugating, and E3 ligase enzymes [11]. This modification can take various forms, including monoubiquitination or polyubiquitination, where additional ubiquitin molecules are attached to one of the eight possible lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or the N-terminal methionine (M1) of the previously conjugated ubiquitin molecule [12] [13]. The specific linkage type determines the downstream fate and function of the modified protein, creating a complex "ubiquitin code" that cells utilize to regulate signaling pathways, protein degradation, and immune responses [11].

The functional specialization of different ubiquitin linkages represents a crucial mechanism for cellular regulation. Among the homotypic ubiquitin chains, K48-linked polymers are predominantly associated with targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation, thereby regulating signal transduction, cell division, stress response, and development [13]. In contrast, K63-linked chains are primarily involved in non-proteolytic functions including inflammatory signaling, lymphocyte activation, and DNA repair processes [7] [11]. The remaining homotypic polyubiquitin chains are collectively classified as atypical and continue to be intensively studied for their specialized cellular roles [13]. Furthermore, recent research has revealed the existence and functional significance of heterotypic branched ubiquitin chains, such as the K48-K63 branched chain that regulates NF-κB signaling by modulating reader protein recognition and deubiquitinase sensitivity [14]. This complex architecture enables highly dynamic and precise regulation of cellular processes, with disruptions in ubiquitin signaling contributing to various diseases including cancer, neurodevelopmental disorders, and inflammatory conditions [15] [16].

Functional Roles of Different Ubiquitin Linkages

Table 1: Functional diversity of ubiquitin chain linkages

| Linkage Type | Chain Length | Primary Functions | Cellular Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48 | Polymeric | Targeted protein degradation [11] | Signal transduction, cell division, stress response [13] |

| K63 | Polymeric | Signal transduction, protein trafficking [7] | Immune responses, inflammation, lymphocyte activation [11] |

| K6 | Polymeric | DNA repair, antiviral responses [11] | Autophagy, mitophagy [11] |

| K11 | Polymeric | Cell cycle progression [11] | Proteasome-mediated degradation [11] |

| K27 | Polymeric | DNA replication [11] | Cell proliferation [11] |

| K29 | Polymeric | Wnt signaling downregulation [11] | Neurodegenerative disorders, autophagy [11] |

| M1 (Linear) | Polymeric | Cell death and immune signaling [11] | NF-κB activation, inflammatory responses [13] |

Specialized Functions and Signaling Roles

Beyond the classical K48 and K63 linkages, research continues to reveal specialized functions for less common ubiquitin chain types. K11-linked chains have been implicated in cell cycle progression and can also target proteins for proteasomal degradation, similar to K48 linkages [11]. K29-linked ubiquitination has been associated with neurodegenerative disorders and participates in the downregulation of Wnt signaling pathways [11]. M1-linked linear ubiquitin chains play crucial roles in regulating cell death and immune signaling, particularly in the activation of NF-κB pathways [11].

The functional diversity of ubiquitin chains is further expanded through the formation of branched ubiquitin chains with complex topologies. Recent studies have identified significant biological roles for heterotypic ubiquitin chains, such as the K48-K63 branched chain that regulates NF-κB signaling [14]. In response to interleukin-1β, the E3 ubiquitin ligase HUWE1 generates K48 branches on K63 chains formed by TRAF6. These branched linkages create a unique ubiquitin code that permits recognition by TAB2 while simultaneously protecting K63 linkages from CYLD-mediated deubiquitylation, thereby amplifying NF-κB signals [14]. This mechanism demonstrates how ubiquitin chain branching can differentially control readout of the ubiquitin code by specific reader and eraser proteins to activate specific signaling pathways.

Experimental Protocols for Ubiquitin Chain Analysis

Determining Ubiquitin Chain Linkage Using Mutant Ubiquitins

Table 2: Key reagents for ubiquitin linkage determination experiments

| Reagent | Function/Description | Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| E1 Enzyme | Ubiquitin-activating enzyme | 100 nM [12] |

| E2 Enzyme | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme | 1 μM [12] |

| E3 Ligase | Ubiquitin ligase (substrate-specific) | 1 μM [12] |

| Wild-type Ubiquitin | Full-length ubiquitin with all lysines | ~100 μM [12] |

| Ubiquitin K-to-R Mutants | Single lysine to arginine mutants | ~100 μM [12] |

| Ubiquitin K-Only Mutants | Single lysine-only mutants | ~100 μM [12] |

| MgATP Solution | Energy source for enzymatic reaction | 10 mM [12] |

| 10X E3 Ligase Reaction Buffer | Reaction conditions maintenance | 1X final concentration [12] |

A critical methodology for determining ubiquitin chain linkage involves utilizing ubiquitin lysine mutants in in vitro ubiquitin conjugation reactions [12]. This protocol requires performing two sets of nine parallel reactions each. The first set utilizes seven ubiquitin Lysine-to-Arginine (K-to-R) mutants, where each mutant lacks a specific lysine residue. The conjugation reaction containing the ubiquitin K-to-R mutant missing the lysine required for chain linkage will be unable to form chains, resulting in only mono-ubiquitination observable by Western blot [12]. For example, if ubiquitin chains are linked via K63, all reactions except the one containing the ubiquitin K63R mutant will yield ubiquitin chains.

The second verification set utilizes seven ubiquitin K-Only mutants, where each ubiquitin mutant contains only one lysine with the remaining six mutated to arginine. In this system, ubiquitin chains formed with a specific ubiquitin K-Only mutant must utilize the single available lysine for linkage [12]. Following the K63 linkage example, only reactions containing wild-type ubiquitin and the ubiquitin K63 Only mutant will yield ubiquitin chains. This systematic approach enables robust identification of the specific lysine residues involved in ubiquitin chain formation.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for determining ubiquitin chain linkage using ubiquitin mutants. This two-step approach utilizes both K-to-R and K-Only mutants for robust linkage identification.

Mass Spectrometry-Based Ubiquitin Chain Analysis

Mass spectrometry-based approaches provide powerful alternatives for ubiquitin chain analysis. The Ub-AQUA/PRM (ubiquitin-absolute quantification/parallel reaction monitoring) method enables direct and highly sensitive measurement of the stoichiometry of all eight ubiquitin-ubiquitin linkage types simultaneously [17]. This targeted proteomics approach takes advantage of the characteristic di-glycine (-GG) modification left after tryptic digestion of ubiquitin incorporated in a chain [18]. By quantifying these topology-characteristic peptides, researchers can determine the relative abundance of each ubiquitin chain topology within a proteome.

The Ub-AQUA/PRM protocol involves several critical steps: stabilization of ubiquitin chains during cell lysis through the use of proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) and deubiquitinase inhibitors; preparation of heavy isotope-labeled peptide standards corresponding to each ubiquitin linkage type; tryptic digestion of protein samples; and parallel reaction monitoring mass spectrometry analysis [18]. This method allows for global assessment of ubiquitin topology landscape changes in response to cellular stimuli or perturbations, providing a comprehensive view of ubiquitin chain dynamics in biological contexts.

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why does my ubiquitin Western blot show a smeared appearance instead of discrete bands?

A: The smeared appearance is actually expected and indicates successful capture of ubiquitinated proteins. Since the Ubiquitin-Trap binds monomeric ubiquitin, ubiquitin polymers, and ubiquitinylated proteins, the bound fraction contains proteins of varying molecular weights, resulting in a continuous smear on the gel [11]. Discrete bands would suggest a very specific, homogeneous ubiquitination event, which is uncommon.

Q: Can ubiquitin traps differentiate between different ubiquitin linkages?

A: Standard ubiquitin traps like the ChromoTek Ubiquitin-Trap are not linkage-specific and will bind multiple different chain types [11]. Differentiation between bound linkages requires subsequent analysis using linkage-specific antibodies during Western blotting or utilizing chain-specific TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) that are designed with nanomolar affinities for specific polyubiquitin chains [7].

Q: How can I increase or protect protein ubiquitination signals in my samples?

A: Ubiquitination signals can be preserved and enhanced by treating cells with proteasome inhibitors such as MG-132 prior to harvesting [11]. A recommended starting point is incubation with 5-25 μM MG-132 for 1-2 hours, though conditions should be optimized for specific cell types. Note that overexposure to MG-132 can lead to cytotoxic effects, so time course and dose-response experiments are advised.

Q: What are the limitations of using mutant ubiquitins for linkage determination?

A: While powerful, the mutant ubiquitin approach may not accurately represent all modifications involving wild-type ubiquitin, particularly for complex branched chains [7]. Additionally, this method typically requires in vitro reconstitution of the ubiquitination cascade, which may not fully recapitulate cellular conditions. Complementary approaches like mass spectrometry or TUBE-based methods may be necessary for comprehensive analysis.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Low ubiquitination signal in cellular assays.

Solutions:

- Pre-treat cells with proteasome inhibitors (e.g., 10-100 μM MG-132 for 4 hours) to stabilize ubiquitinated proteins [18].

- Include deubiquitinase inhibitors (e.g., N-ethylmaleimide) in lysis buffers to prevent deubiquitination during sample preparation [18].

- Optimize lysis conditions using buffers specifically designed to preserve polyubiquitination [7].

- Confirm efficient immunoprecipitation using positive control ubiquitin chains (commercially available K48, K63, and M1-linked chains) [18].

Problem: Inconclusive results from ubiquitin mutant linkage experiments.

Solutions:

- Include both K-to-R and K-Only mutant sets for complementary verification [12].

- Ensure proper negative controls by replacing MgATP with dH₂O to confirm ATP-dependence of reactions [12].

- Verify enzyme concentrations and activity, particularly E3 ligase functionality.

- Consider the possibility of mixed or branched linkages if all single K-to-R mutants still produce chains [12].

Problem: High background in ubiquitin pulldown experiments.

Solutions:

- Increase stringency of wash conditions (higher salt concentrations, detergents).

- Use loBind tubes to prevent non-specific protein adsorption [18].

- Include control beads without ubiquitin-binding entities.

- Optimize binding conditions and input protein amounts to avoid overloading.

Advanced Methodologies: TUBEs and Branched Chain Analysis

The development of Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) has revolutionized the study of linkage-specific ubiquitination in cellular contexts. TUBEs are specialized affinity matrices with nanomolar affinities for polyubiquitin chains that facilitate precise capture of chain-specific polyubiquitination events on endogenous proteins [7]. These reagents can be employed in high-throughput screening assays to investigate ubiquitination dynamics in response to various stimuli.

Recent applications demonstrate how chain-specific TUBEs can differentiate context-dependent ubiquitination. In studies of RIPK2, a key regulator of inflammatory signaling, K63-TUBEs specifically captured L18-MDP-induced K63 ubiquitination, while K48-TUBEs captured RIPK2 PROTAC-induced K48 ubiquitination [7]. This specificity enables researchers to dissect complex ubiquitination events occurring on the same protein in different signaling contexts.

For analyzing complex ubiquitin architectures like branched chains, the Ub-AQUA/PRM method has been adapted to quantify K48/K63 branched ubiquitin chains specifically [17]. Additionally, the Ub-ProT (ubiquitin chain protection from trypsinization) method enables measurement of ubiquitin chain length on specific substrates through combination of a chain protector and limited trypsin digestion [17]. These advanced methodologies provide researchers with powerful tools to decipher the complexity of ubiquitin networks in cellular regulation.

Diagram 2: K48-K63 branched ubiquitin chain signaling pathway in NF-κB activation. This branched topology creates a unique code that enhances signal transduction.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents for ubiquitination studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Applications | Providers/Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Mutants | K-to-R mutants, K-Only mutants | Linkage determination, chain formation analysis [12] | Boston Biochem, R&D Systems [12] |

| Chain-Specific TUBEs | K48-TUBEs, K63-TUBEs, Pan-TUBEs | Linkage-specific enrichment, endogenous protein analysis [7] | LifeSensors [7] |

| Ubiquitin Traps | Ubiquitin-Trap Agarose, Ubiquitin-Trap Magnetic Agarose | General ubiquitin pulldowns, protein isolation [11] | ChromoTek [11] |

| Positive Control Chains | K48-linked chains, K63-linked chains, M1-linear chains | Method validation, standard curves [18] | Boston Biochem [18] |

| Mass Spec Standards | Heavy labeled -GG peptides | Ub-AQUA/PRM quantification [18] | JPT Peptide Technologies [18] |

| Inhibitors | MG-132 (proteasome), NEM (DUB) | Signal stabilization, pathway inhibition [18] | Multiple commercial sources |

This comprehensive toolkit enables researchers to address diverse questions in ubiquitin biology, from basic linkage determination to complex cellular signaling studies. The selection of appropriate reagents depends on the specific research goals, whether studying global ubiquitin chain topology changes, investigating ubiquitination of specific proteins, or dissecting the functional consequences of specific ubiquitin linkages in signaling pathways.

Core Biomarker Findings in Ovarian and Cervical Cancer

This section summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies on ubiquitination-related biomarkers in ovarian and cervical cancer.

Table 1: Prognostic Ubiquitination-Related Gene Signature in Ovarian Cancer

| Aspect | Description | Performance/Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Signature | 17-gene ubiquitination-related prognostic model [19] [20] | - |

| Predictive Performance | Area Under Curve (AUC) for survival prediction [19] [20] | 1-year AUC: 0.7033-year AUC: 0.7045-year AUC: 0.705 |

| Clinical Outcome | Overall Survival (OS) between risk groups [19] [20] | High-risk group: Significantly lower OS (P<0.05) |

| Immune Microenvironment | Immune cell infiltration in low-risk group [19] [20] | Higher levels of CD8+ T cells (P<0.05), M1 macrophages (P<0.01), and follicular helper cells (P<0.05) |

| Key Ubiquitin Ligase | FBXO45 (E3 ligase) functional role [19] [20] | Promotes cancer cell growth, spread, and migration via Wnt/β-catenin pathway |

Table 2: Key Ubiquitination-Related Targets in Cervical Cancer

| Component | Role/Function | Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|

| ECT2 | Guanine nucleotide exchange factor, oncogene [21] | Upregulated in CESC tissues/cells; knockdown inhibits proliferation, migration, invasion, and glycolysis |

| USP13 | Deubiquitinating enzyme (DUB) [21] | Stabilizes ECT2 by removing ubiquitin chains; high expression in cervical cancer |

| USP13-ECT2 Axis | Functional interaction [21] | USP13 inhibition suppresses cervical cancer tumor growth in vivo by promoting ECT2 degradation |

Diagram 1: USP13-ECT2 axis in cervical cancer. USP13 removes ubiquitin from ECT2, preventing its degradation and promoting oncogenic processes.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Constructing a Ubiquitination-Related Gene Prognostic Model

This protocol is adapted from the methodology used to develop a 17-gene prognostic signature for ovarian cancer [19] [20].

1. Data Collection and Processing:

- Obtain transcriptomic data (RNA-Seq) and corresponding clinical data (e.g., survival time, status) for ovarian cancer patients from public databases like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA-OV).

- Acquire data from normal ovarian tissue samples from sources like the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project via the UCSC Xena browser.

- Use the R package

edgeRto identify Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) between tumor and normal tissues. Apply a threshold of |logFC| ≥ 1 and an adjusted p-value < 0.01.

2. Candidate Gene Screening:

- Obtain a comprehensive list of ubiquitination-related genes (UBQ genes). This list can be sourced from databases such as the UUCD (Ubiquitin and Ubiquitin-like Conjugation Database).

- Intersect the UBQ gene list with the identified DEGs to find co-expressed ubiquitination-related genes.

- Perform univariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis on the co-expressed genes to identify those significantly associated (P < 0.05) with overall survival.

3. Predictive Model Construction:

- Apply LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) regression analysis to the candidate genes from the Cox analysis to penalize and select the most robust predictors, reducing overfitting.

- Calculate a risk score for each patient using the formula:

Risk score = Σ(Coef_i × Expr_i), whereCoef_iis the regression coefficient from the LASSO model for each gene, andExpr_iis the gene's expression level. - Split patients into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median risk score.

4. Model Validation:

- Assess the model's performance using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis to visualize the survival difference between the two risk groups (log-rank test p-value < 0.05 indicates significance).

- Evaluate the model's predictive accuracy using time-dependent Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, calculating the Area Under the Curve (AUC) for 1, 3, and 5-year survival.

- Validate the model's stability using an external validation cohort (e.g., from the GEO database, such as GSE165808 or GSE26712).

Protocol: Detecting Protein Ubiquitination using ThUBD-Coated Plates

This protocol describes a high-throughput method for capturing ubiquitinated proteins, offering significant sensitivity improvements over previous technologies [22].

1. Plate Coating:

- Use Corning 3603-type 96-well plates.

- Coat each well with 1.03 μg ± 0.002 of Tandem Hybrid Ubiquitin Binding Domain (ThUBD) fusion protein. This protein exhibits unbiased, high-affinity binding to all types of ubiquitin chains.

- Incubate overnight at 4°C to allow for stable adsorption of ThUBD to the plate surface.

2. Sample Preparation and Incubation:

- Lyse cells or tissues in a lysis buffer that preserves ubiquitination, typically containing protease inhibitors and deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitors (e.g., N-Ethylmaleimide) to prevent the loss of ubiquitin signals.

- Clarify the lysate by centrifugation. Determine the protein concentration.

- Add a standardized amount of protein lysate (e.g., 5-20 μg) to each ThUBD-coated well. For target-specific ubiquitination, include a primary antibody against the protein of interest.

- Incubate the plate for 2-3 hours at room temperature with gentle shaking to allow ubiquitinated proteins to bind to the immobilized ThUBD.

3. Washing and Detection:

- Wash the wells thoroughly with a optimized washing buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.05% Tween-20) to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- For global ubiquitination assessment: Add ThUBD-HRP (Horseradish Peroxidase) conjugate and detect the chemiluminescent signal, which is proportional to the total amount of captured ubiquitinated protein.

- For target-specific ubiquitination: After washing, add an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody specific to the primary antibody and detect via chemiluminescence.

- Quantify the signal, which is proportional to the amount of ubiquitinated protein captured. The ThUBD platform shows a 16-fold wider linear range and superior sensitivity compared to TUBE-based assays [22].

Diagram 2: ThUBD-based ubiquitination detection workflow. This high-throughput method captures ubiquitinated proteins with high affinity and specificity.

Protocol: Investigating Linkage-Specific Ubiquitination using TUBEs

This protocol is useful for differentiating between K48-linked (degradation) and K63-linked (signaling) polyubiquitin chains on a target protein like RIPK2 [7].

1. Cell Stimulation and Lysis:

- Culture relevant cells (e.g., THP-1 monocytic cells for studying RIPK2 in inflammation).

- Treat cells with a stimulus:

- To induce K63-linked ubiquitination: Treat with L18-MDP (200-500 ng/ml for 30-60 min).

- To induce K48-linked ubiquitination: Treat with a specific PROTAC (e.g., RIPK2 degrader-2).

- Lyse cells in a buffer optimized for preserving polyubiquitin chains, including DUB inhibitors.

2. Enrichment with Chain-Specific TUBEs:

- Use 96-well plates or magnetic beads coated with chain-specific Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs):

- K48-TUBEs: Specifically enrich for K48-linked polyubiquitin chains.

- K63-TUBEs: Specifically enrich for K63-linked polyubiquitin chains.

- Pan-TUBEs: Enrich for all chain types.

- Incubate the cell lysate with the TUBE-coated matrix for several hours at 4°C.

3. Analysis:

- Wash the matrix thoroughly to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elute the bound ubiquitinated proteins or proceed directly to immunoblotting.

- Detect the protein of interest (e.g., RIPK2) by Western blot using a specific antibody. The appearance of a higher molecular weight smear indicates successful ubiquitination.

- The specific TUBE type used (K48 vs K63) will determine which ubiquitin linkage is visualized on the blot.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: What are the main advantages of the ThUBD-based detection method over traditional TUBEs?

The ThUBD (Tandem Hybrid Ubiquitin Binding Domain) platform offers two critical advantages [22]:

- Unbiased Binding: ThUBD is engineered to have high affinity for all types of ubiquitin chains (K48, K63, etc.), whereas traditional TUBEs can exhibit linkage bias, potentially skewing results.

- Enhanced Sensitivity: The ThUBD-coated plate technology demonstrates a 16-fold wider linear range and significantly improved detection sensitivity, capturing ubiquitinated proteins from complex proteome samples at levels as low as 0.625 μg.

FAQ 2: How can I distinguish between different types of ubiquitin linkages (e.g., K48 vs. K63) in my cellular experiment?

You can utilize chain-specific TUBEs in a plate-based or bead-based enrichment assay [7].

- For K63-linked ubiquitination (often involved in signaling), use K63-TUBEs. For example, L18-MDP-induced RIPK2 ubiquitination is captured effectively by K63-TUBEs.

- For K48-linked ubiquitination (associated with proteasomal degradation), use K48-TUBEs. For example, PROTAC-induced target ubiquitination is primarily captured by K48-TUBEs.

- By running your sample in parallel with different chain-specific TUBEs, you can determine the predominant linkage type modified on your target protein in a given biological context.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in Ubiquitination Assays

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Ubiquitination Experiment Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or no ubiquitination signal | Rapid deubiquitination after cell lysis; low affinity capture reagent. | Add deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitors (e.g., N-Ethylmaleimide) directly to the lysis buffer. Use high-affinity capture reagents like ThUBD [22]. |

| High background in Western blot | Non-specific antibody binding; inefficient washing. | Include appropriate controls (e.g., no primary antibody). Optimize washing stringency (e.g., increase salt concentration, add detergent). |

| Inability to distinguish ubiquitin linkage type | Using a pan-specific ubiquitin enrichment tool. | Employ chain-specific TUBEs (K48, K63) to selectively capture different ubiquitin linkages [7]. |

| Discrepancy between biochemical and cellular ubiquitination data | Compound cannot cross cell membrane in cellular assays (CETSA). | Verify cell membrane permeability of small molecules in whole-cell assays. Use cell lysate-based assays (e.g., PTSA) as an intermediate step [23]. |

FAQ 3: My compound stabilizes the target protein in a thermal shift assay (CETSA), but I don't see corresponding ubiquitination. Why?

This discrepancy can arise from several factors [23]:

- Cellular Permeability: The compound may not efficiently cross the cell membrane to reach its intracellular target in sufficient concentration. Check the compound's physicochemical properties or use a lysate-based CETSA to bypass permeability issues.

- Assay Sensitivity: The ubiquitination assay may not be sensitive enough to detect the change. Consider switching to a more sensitive method like the ThUBD-platform [22].

- Non-Degradative Mechanism: Stabilization of a protein against thermal denaturation does not automatically mean it is being ubiquitinated. The compound might be stabilizing the protein through a mechanism that does not involve the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitination Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| ThUBD (Tandem Hybrid Ubiquitin Binding Domain) | High-affinity, unbiased capture of all ubiquitin chain types for detection and quantification [22]. | Used coated on 96-well plates for high-throughput screens; 16x more sensitive than TUBEs. |

| Chain-Specific TUBEs | Selective enrichment of proteins modified with specific ubiquitin linkages (e.g., K48 for degradation, K63 for signaling) [7]. | Critical for understanding the functional consequence of ubiquitination on a target protein. |

| HiBiT Tag / NanoBRET Systems | Real-time, live-cell quantification of protein turnover and ubiquitination dynamics [24]. | HiBiT for degradation kinetics; NanoBRET for monitoring ubiquitination events and protein-protein interactions. |

| DUB Inhibitors (e.g., N-Ethylmaleimide) | Preserve ubiquitin signals in cell lysates by inhibiting deubiquitinating enzymes that would otherwise remove ubiquitin chains [7]. | Essential additive to cell lysis buffers for all ubiquitination enrichment experiments. |

| PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) | Heterobifunctional molecules that recruit E3 ligases to target proteins, inducing their ubiquitination and degradation [19] [7]. | Tool molecules for studying targeted protein degradation; RIPK2 degrader is an example. |

Ubiquitination is a critical post-translational modification traditionally known for regulating protein degradation, signal transduction, and cellular homeostasis through the attachment of ubiquitin to lysine residues on target proteins [25]. However, emerging research has revealed that ubiquitination extends beyond canonical protein targets to include non-protein substrates such as saccharides and metabolites. This expansion, termed non-canonical ubiquitination, represents a frontier in understanding the diverse regulatory mechanisms controlling metabolic pathways, immune responses, and cellular signaling networks. The study of these non-canonical modifications presents unique technical challenges, from detection difficulties to experimental artifacts, requiring specialized methodologies and troubleshooting approaches. This technical support center provides a comprehensive framework for standardizing ubiquitination quantification across tissue research, offering detailed protocols, troubleshooting guides, and analytical tools to advance investigations into these novel ubiquitination phenomena.

Technical Challenges in Non-Canonical Ubiquitination Research

Investigating ubiquitination of non-protein substrates presents researchers with several distinct technical hurdles that must be addressed for reliable experimentation and data interpretation.

Detection Sensitivity Issues: The primary challenge in studying non-canonical ubiquitination stems from the inherently low abundance and transient nature of these modifications. As noted in global ubiquitylation studies, ubiquitylation site occupancy spans over four orders of magnitude, with median ubiquitylation site occupancy being three orders of magnitude lower than that of phosphorylation [26]. This low stoichiometry makes detection particularly challenging for non-protein substrates where established enrichment methods may not be optimized.

Methodological Limitations: Traditional ubiquitination research tools were developed specifically for protein substrates. When applied to saccharides and metabolites, these tools often yield suboptimal results. As one resource notes, "ubiquitination signals in a sample can be preserved by treating cells with proteasome inhibitors, such as MG-132, prior to harvesting" [27]. However, the effectiveness of such stabilization methods for non-protein substrates remains inadequately characterized, requiring careful optimization for each experimental context.

Specific Technical Hurdles:

- Antibody Specificity: Many ubiquitin antibodies are non-specific and bind large amounts of artifacts [27], complicating the detection of novel modification types.

- Dynamic Range: The percentage of ubiquitinylated proteins (and presumably other molecules) in a cell lysate is often very small, requiring highly sensitive enrichment methods [27].

- Stability: The ubiquitination process is highly dynamic, rapid, and reversible [28], making capture of transient modifications particularly challenging.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Problems in Non-Canonical Ubiquitination Studies

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal | Low modification stoichiometry; Inefficient enrichment; Incompatible detection method | Pre-treat cells with 5-25 µM MG-132 for 1-2 hours before harvesting [27]; Use chain-specific TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) with nanomolar affinities [7]; Validate with multiple detection platforms |

| High Background Noise | Non-specific antibody binding; Inadequate blocking; Sample degradation | Use high-affinity nanobody traps (e.g., ChromoTek Ubiquitin-Trap) for cleaner pulldowns [27]; Optimize washing stringency; Include appropriate negative controls (e.g., bacterial dapB) [29] |

| Inconsistent Results Between Replicates | Variable enrichment efficiency; Protease activity; Incomplete inhibition of deubiquitinases | Standardize lysis conditions with optimized buffer to preserve polyubiquitination [7]; Include protease and deubiquitinase inhibitors; Use internal reference standards for normalization |

| Failure to Detect Linkage-Specific Modifications | Use of pan-specific detection methods only; Linkage instability | Employ chain-selective TUBEs that differentiate context-dependent linkage specific ubiquitination [7]; Combine with linkage-specific antibodies for verification |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can standard ubiquitin antibodies detect non-canonical ubiquitination on metabolites? Most commercially available ubiquitin antibodies were developed for protein-based applications and may have limited utility for non-protein substrates. Due to weak immunogenicity of small ubiquitin proteins and potential artifacts [27], we recommend using high-affinity capture tools like Ubiquitin-Trap combined with mass spectrometry for verification. Always validate findings with multiple methodological approaches.

Q2: How can we differentiate between K48, K63, and other linkage types on non-protein substrates? Chain-selective TUBEs can differentiate context-dependent linkage specific ubiquitination [7]. For example, K48-linked chains are specifically associated with proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains are primarily involved in regulating signal transduction [7]. These specialized affinity matrices facilitate precise capture of chain-specific polyubiquitination events on native molecules.

Q3: What controls are essential for validating non-canonical ubiquitination? Essential controls include: (1) Positive control probes for housekeeping genes (e.g., PPIB, POLR2A, or UBC) [29]; (2) Negative control probes (e.g., bacterial dapB) [29]; (3) Untreated samples without enrichment; (4) Specificity controls using linkage-specific tools. Proper controls should generate a score ≥2 for PPIB and ≥3 for UBC with relatively uniform signal [29].

Q4: How can we enhance the stability of non-canonical ubiquitination during sample preparation? Ubiquitination signals can be preserved by treating cells with proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) prior to harvesting [27]. While optimal conditions vary by cell type, a standard starting point is 5-25 µM MG-132 for 1-2 hours. Note that overexposure can cause cytotoxic effects, requiring careful optimization.

Experimental Protocols for Non-Canonical Ubiquitination Analysis

Protocol 1: Enrichment of Ubiquitinated Metabolites Using Ubiquitin-Trap

Principle: This protocol uses high-affinity anti-ubiquitin nanobodies coupled to agarose or magnetic beads to immunoprecipitate monomeric ubiquitin, ubiquitin chains, and ubiquitinylated molecules from cell extracts [27].

Materials:

- Ubiquitin-Trap Agarose (uta) or Ubiquitin-Trap Magnetic Agarose (utma) [27]

- Lysis, wash, dilution, and elution buffers (provided in kit) [27]

- Proteasome inhibitor (MG-132, 5-25 µM working solution) [27]

- Cell lines or tissue samples of interest

Procedure:

- Pre-treatment: Incubate cells with 5-25 µM MG-132 for 1-2 hours before harvesting to preserve ubiquitination signals [27].

- Lysis: Harvest cells and lyse using the provided lysis buffer optimized to preserve polyubiquitination.

- Preparation: Clarify lysate by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

- Enrichment: Incubate supernatant with Ubiquitin-Trap beads for 2 hours at 4°C with gentle rotation.

- Washing: Wash beads 3-5 times with provided wash buffer under stringent conditions to reduce background.

- Elution: Elute bound ubiquitinated molecules using provided elution buffer or direct denaturation.

- Analysis: Proceed to downstream applications including mass spectrometry or western blotting.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- For over- or under-fixed tissues, adjustment of pretreatment conditions may be necessary [29].

- The Ubiquitin-Trap is not linkage specific, so differentiation between bound linkages requires subsequent analysis with linkage-specific antibodies [27].

- The bound fraction may contain molecules of varying lengths, potentially resulting in a smeared appearance on gels [27].

Protocol 2: Linkage-Specific Analysis Using TUBE-Based Assay

Principle: This protocol leverages chain-specific Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) with nanomolar affinities for polyubiquitin chains to investigate ubiquitination dynamics in a linkage-specific manner [7].

Materials:

- Chain-specific TUBEs (K48-TUBEs, K63-TUBEs, Pan-selective TUBEs) [7]

- 96-well plates coated with appropriate TUBEs

- Lysis buffer optimized for polyubiquitination preservation

- Target-specific detection antibodies

Procedure:

- Preparation: Coat 96-well plates with chain-specific TUBEs according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Stimulation: Treat cells with appropriate stimuli (e.g., L18-MDP for K63 ubiquitination induction) [7].

- Lysis: Lyse cells in optimized buffer and clarify by centrifugation.

- Incubation: Apply lysates to TUBE-coated plates and incubate for 2 hours at 4°C.

- Washing: Wash plates thoroughly to remove non-specifically bound material.

- Detection: Detect captured ubiquitinated molecules using target-specific antibodies.

- Quantification: Analyze using appropriate plate reader or imaging systems.

Application Example: This approach has been successfully used to demonstrate that inflammatory agent L18-MDP stimulated K63 ubiquitination can be faithfully captured using K63-TUBEs or Pan-selective TUBEs but not K48-TUBEs [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Non-Canonical Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Enrichment Tools | Ubiquitin-Trap Agarose/Magnetic Beads [27]; Chain-specific TUBEs (K48, K63, Pan) [7] | Immunoprecipitation of monomeric ubiquitin, ubiquitin chains, and ubiquitinylated molecules from cell extracts; Linkage-specific capture |

| Stabilization Reagents | MG-132 (proteasome inhibitor) [27]; Protease inhibitor cocktails; Deubiquitinase inhibitors | Preserve ubiquitination signals by preventing degradation and deubiquitination during sample processing |

| Detection Reagents | Ubiquitin Recombinant Antibody [27]; Linkage-specific ubiquitin antibodies; HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies | Western blot detection of ubiquitinated species with reduced cross-reactivity and artifacts |

| Control Systems | Positive control probes (PPIB, POLR2A, UBC) [29]; Negative control probes (dapB) [29] | Quality assessment of sample RNA integrity and optimal permeabilization; Background signal determination |

Standardization and Workflow Optimization

Establishing reproducible methods for quantifying non-canonical ubiquitination across tissue types requires implementation of standardized workflows and quality control measures.

Recommended Workflow:

- Sample Qualification: Run samples alongside control slides using positive and negative control probes to assess sample quality [29].

- Pretreatment Optimization: For tissues not prepared according to recommended guidelines, optimize antigen retrieval and protease digestion conditions [29].

- Ubiquitin Enrichment: Select appropriate enrichment method based on research question (pan-specific vs. linkage-specific).

- Detection and Validation: Use multiple complementary detection methods to verify findings.

- Quantification and Scoring: Implement semi-quantitative scoring guidelines appropriate for your target abundance [29].

Quality Control Metrics:

- Successful positive control staining should generate a score ≥2 for PPIB and ≥3 for UBC with relatively uniform signal throughout the sample [29].

- Negative control samples should display a score of <1, indicating low to no background [29].

- Internal consistency between technical replicates should be maintained with <20% coefficient of variation.

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Non-Canonical Ubiquitination Analysis Workflow

Ubiquitin Linkage Signaling Pathways

The investigation of non-canonical ubiquitination of saccharides and metabolites represents an emerging frontier in post-translational modification research with significant implications for understanding cellular regulation, metabolic pathways, and therapeutic development. The technical frameworks and troubleshooting guides presented here provide a foundation for standardizing research approaches across different tissue types and experimental systems. As the field advances, continued refinement of these methodologies, coupled with the development of increasingly specific research tools, will be essential for elucidating the full scope and biological significance of these non-canonical modifications. By implementing these standardized protocols and quality control measures, researchers can enhance the reproducibility and reliability of their findings, accelerating our understanding of the diverse functional roles played by ubiquitination beyond traditional protein targets.

Protein ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates diverse cellular functions, including protein degradation, cell signaling, and DNA repair [30]. This reversible modification involves a coordinated enzymatic cascade of E1 activating, E2 conjugating, and E3 ligating enzymes, with deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) providing the reverse reaction [31]. The complexity of ubiquitin signaling arises from its ability to form diverse chain topologies—including monoubiquitination, multiple monoubiquitination, and polyubiquitin chains with at least eight different linkage types—each encoding specific biological functions [30].

Studying ubiquitination across different tissue types presents substantial methodological challenges that undermine data comparability and reproducibility. The intrinsic low stoichiometry of ubiquitinated proteins, combined with the transient nature of modification and vast structural diversity of ubiquitin chains, creates significant technical hurdles [30] [32]. Furthermore, tissue-specific differences in enzyme expression, metabolic activity, and protein composition introduce additional variables that complicate cross-tissue comparisons. This technical brief establishes a standardized framework for ubiquitination research to overcome these challenges and enable robust, reproducible cross-tissue analyses.

Technical Challenges in Ubiquitination Research

Researchers face multiple interconnected challenges when investigating ubiquitination across diverse tissue samples:

- Low Abundance and Transient Nature: Ubiquitination is a highly dynamic process with rapid turnover, and ubiquitinated proteins typically represent a very small fraction of the total cellular proteome, necessitating efficient enrichment strategies [30] [32].

- Structural Complexity: Ubiquitin can form polymers with different linkage types (K48, K63, K11, K27, K29, K33, M1) that regulate distinct biological outcomes, requiring linkage-specific analytical approaches [30] [31].

- Sample Compatibility Issues: Tissue samples present unique challenges compared to cell lines, including higher protease activity, varied tissue homogenization efficiency, and differential accessibility to ubiquitination sites [33].

- Antibody Specificity Limitations: Many ubiquitin antibodies demonstrate cross-reactivity or poor affinity, leading to high background noise and non-specific binding that compromise data quality [32].

Impact on Data Reproducibility

These technical challenges manifest as substantial variability in experimental outcomes. Without standardized protocols, ubiquitination studies frequently yield irreproducible results, particularly when comparing different tissue types. Inconsistent sample preparation, enrichment methods, and analytical platforms create systematic biases that undermine data integration and meta-analysis across studies.

Standardized Methodological Framework

Optimized Sample Preparation Protocol

Standardized tissue processing is fundamental for reproducible ubiquitination analysis. The following protocol ensures sample integrity and maximizes ubiquitin recovery:

Tissue Preservation and Lysis

- Flash-freeze tissue samples in liquid nitrogen within 5 minutes of excision

- Use pre-cooled lysis buffer (8M urea, 50mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA) supplemented with fresh protease inhibitors (2μg/ml aprotinin, 10μg/ml leupeptin, 1mM PMSF) and 50μM PR-619 deubiquitinase inhibitor [33]

- Maintain samples at 4°C throughout homogenization using a pre-cooled dounce homogenizer

- Centrifuge lysates at 20,000×g for 10 minutes at 4°C and collect supernatant

Protein Digestion and Peptide Cleanup

- Determine protein concentration using BCA assay

- Reduce proteins with 5mM DTT (45 minutes, room temperature)

- Alkylate with 10mM iodoacetamide (30 minutes, room temperature in dark)

- Dilute lysate 1:4 with 50mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)

- Digest first with Lys-C (1:50 enzyme:substrate, 2 hours, room temperature)

- Follow with trypsin digestion (1:50 enzyme:substrate, overnight, room temperature)

- Acidify with 1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to stop digestion

- Desalt peptides using C18 solid-phase extraction cartridges [33]

Ubiquitinated Peptide Enrichment Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Ubiquitinated Peptide Enrichment Strategies

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Recommended Input |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody-based Enrichment | Anti-K-ε-GG antibodies recognize diGly remnant after trypsin digestion [34] | High specificity; compatible with various sample types | Potential antibody cross-reactivity; relatively high cost | 1-10mg peptide input [34] |

| Ubiquitin-Trap Technology | Ubiquitin-binding nanobody (VHH) coupled to agarose or magnetic beads [32] | Captures full ubiquitin modifications; not limited to tryptic peptides; works across species | Does not differentiate linkage types; may require secondary analysis | 0.5-2mg protein input [32] |

| Tagged Ubiquitin Systems | Ectopic expression of His- or Strep-tagged ubiquitin in cells [30] | High purification efficiency; good for cell culture studies | Not applicable to human tissues; may alter native ubiquitination | N/A (cell-based only) |

For cross-tissue studies, the automated UbiFast method provides exceptional reproducibility. This approach uses magnetic bead-conjugated K-ε-GG antibody (HS mag anti-K-ε-GG) with the following optimized workflow:

Enrichment

- Incubate 1mg peptides with 31.25μg anti-K-ε-GG antibody conjugated to magnetic beads

- Use automated magnetic particle processor for consistent handling

- Perform all steps in 1.5mL low-binding microcentrifuge tubes

- Binding time: 2 hours at 4°C with gentle rotation [33]

Washing and Elution

- Wash twice with ice-cold PBS

- Wash once with HPLC-grade water

- Elute with 0.15% trifluoroacetic acid

- Dry samples in vacuum concentrator [33]

Mass Spectrometry Analysis: DIA vs. DDA

Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry significantly outperforms traditional Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) for ubiquitinome analysis:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of MS Acquisition Methods for Ubiquitinome Analysis

| Parameter | DIA Method | Traditional DDA |

|---|---|---|

| DiGly peptides identified (single run) | 35,000±682 [34] | ~20,000 [34] |

| Quantitative precision (CV) | 45% of peptides <20% CV [34] | 15% of peptides <20% CV [34] |

| Data completeness | >77% of peptides across replicates [34] | ~50% missing values common [34] |

| Recommended settings | 46 precursor isolation windows\nMS2 resolution: 30,000 [34] | TopN method (N=20)\nDynamic exclusion: 30s [34] |

Optimized DIA Parameters for Ubiquitination Analysis:

- Precursor mass range: 400-1000 m/z

- Window placement: 46 variable windows optimized for diGly peptide distribution

- MS1 resolution: 120,000

- MS2 resolution: 30,000

- Normalized HCD collision energy: 28-32% [34]

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Encountered Issues

Low Ubiquitination Signal Detection

Problem: Weak or undetectable ubiquitination signals in tissue samples despite adequate protein input.

Solutions:

- Pre-treat tissues with proteasome inhibitors (5-25μM MG132 for 1-2 hours) before harvesting to stabilize ubiquitinated proteins [32] [34]

- Include deubiquitinase inhibitors (50μM PR-619) in lysis buffer to prevent ubiquitin removal during sample processing [33]

- Optimize antibody-to-peptide ratio (empirically determine for each tissue type)

- Increase peptide input amount (up to 2mg for difficult tissues) while maintaining proper antibody ratio

High Background and Non-Specific Binding

Problem: Excessive non-specific binding during enrichment, leading to high background and reduced specificity.

Solutions:

- Include stringent washing steps with PBS containing 0.1% SDS or deoxycholate [32]

- Use mild detergent conditions during binding (0.1% NP-40 alternative)

- Employ competitive washing with 25mM glycine (pH 2.5) for 2 minutes followed by neutralization

- Implement sequential enrichment with two rounds of antibody capture with intermediate cleaning

Inconsistent Results Across Tissue Types

Problem: Significant variability in ubiquitination detection when analyzing different tissue types.

Solutions:

- Normalize input material based on tissue-specific protein extractability rather than total protein

- Prepare tissue-specific spectral libraries to account for differential peptide detectability

- Include internal standardization with heavy labeled ubiquitin reference peptides

- Process all comparative samples simultaneously using automated platforms to minimize technical variation

Incomplete Digestion and Peptide Bias

Problem: Variable trypsin efficiency across tissue types leading to biased ubiquitin remnant representation.

Solutions:

- Standardize digestion efficiency using Lys-C/trypsin sequential digestion protocol [33]

- Monitor digestion completeness with quality control peptides

- Extend digestion time to 18-24 hours for fibrous tissues

- Incorporate chemical assist agents (Rapigest) for membrane-rich tissues

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Standardized Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Application Notes | Quality Control Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enrichment Antibodies | HS mag anti-K-ε-GG [33]; Ubiquitin-Trap Agarose/Magnetic Agarose [32] | Magnetic beads enable automation; Linkage-specific antibodies available for follow-up | Test lot-to-lot variability with reference sample; Verify specificity with ubiquitin knockout lysate |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | MG-132 (proteasome) [32]; PR-619 (DUB) [33]; Chloroacetamide (alkylating) [33] | Use fresh preparations; Optimize concentration for each tissue type | Confirm activity with fluorogenic substrate assays |

| Mass Spec Standards | TMTpro 18-plex [33]; Heavy labeled diGly reference peptides [34] | Enable multiplexing of up to 18 samples; Use for retention time alignment | Include in every run for quality control |

| Digestion Enzymes | Sequencing-grade trypsin; Lys-C [33] | Sequential digestion improves coverage; Quality varies by vendor | Verify activity with standard protein digest |

| Sample Preparation Kits | Ubiquitin-Trap Kit (includes lysis, wash, dilution, elution buffers) [32] | Standardized buffers improve reproducibility; Compatible with multiple species | Test buffer performance with control experiments |

Quality Control and Validation Framework

Implementation of Quality Control Metrics

Robust quality control measures are essential for cross-tissue ubiquitination studies:

- Process Controls: Include standardized reference tissue samples in each processing batch to monitor technical variability

- Enrichment Efficiency: Calculate K-ε-GG peptide enrichment factor by comparing pre- and post-enrichment samples

- Spectral Library Quality: Assess library completeness using target-decoy false discovery rate (FDR < 1% at peptide level) [34]

- Quantitative Reproducibility: Monitor coefficient of variation (CV) across technical replicates, targeting <20% for high-confidence identifications [34]

Data Normalization and Validation Strategies

- Cross-Tissue Normalization: Apply quantile normalization with tissue-specific adjustments for protein content variability

- Independent Validation: Confirm key findings using orthogonal methods such as Western blotting with linkage-specific antibodies or ubiquitin binding domain assays [30]

- Spike-in Controls: Use heavy labeled ubiquitin standards to correct for tissue-specific ion suppression effects [33]

Standardization of ubiquitination analysis across tissues requires implementation of consistent methodologies from sample collection through data analysis. The integrated framework presented here—encompassing standardized protocols, optimized instrumentation parameters, rigorous quality control measures, and comprehensive troubleshooting guidance—provides a foundation for generating comparable, reproducible ubiquitination data across diverse tissue types. Adoption of these standardized approaches will accelerate our understanding of tissue-specific ubiquitination signaling and facilitate the development of ubiquitin-targeted therapeutics.

High-Throughput Quantification Technologies: Tools for Precision Ubiquitinome Profiling

Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) are engineered, high-affinity reagents designed to overcome the long-standing challenge of detecting and enriching polyubiquitinated proteins from complex biological samples. Ubiquitination, a crucial post-translational modification, regulates diverse cellular functions from protein degradation to signal transduction, with the functional outcome largely dictated by the type of polyubiquitin chain linkage formed on target proteins [35]. Unlike traditional methods such as immunoprecipitation with ubiquitin antibodies, TUBEs incorporate multiple ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) to achieve nanomolar affinity for polyubiquitin chains, significantly improving the capture efficiency and stability of ubiquitinated proteins during experimental procedures [35]. This technology has become indispensable for researchers studying targeted protein degradation, inflammatory signaling, and the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

The versatility of TUBE technology allows for both broad and specific analysis of the ubiquitome. Pan-selective TUBEs bind to all ubiquitin chain linkages, providing a comprehensive view of total protein ubiquitination [36] [35]. In contrast, chain-selective TUBEs offer precise tools for investigating the functional consequences of specific ubiquitin linkages, such as K48-linked chains that target proteins for proteasomal degradation or K63-linked chains involved in signal transduction and DNA repair [7] [35] [37]. This technical support document provides detailed troubleshooting guidance, experimental protocols, and FAQs to standardize the application of TUBE assays for endogenous protein analysis across different tissue types.

TUBE Selection Guide

Table 1: Characteristics and Applications of Different TUBE Types

| TUBE Type | Specificity | Key Applications | Affinity Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pan-Selective TUBE1 | All ubiquitin linkages [35] | Comprehensive ubiquitome analysis; target-agnostic ubiquitination studies [35] | Preferentially binds K63- over K48-polyUb [36] |

| Pan-Selective TUBE2 | All ubiquitin linkages [35] | General ubiquitin pull-down; studies requiring equal affinity for major linkages [35] | Binds K48- and K63-polyUb with equal affinities [36] |

| K48-Selective HF TUBE | K48-linked chains [35] | Studying proteasomal degradation; validating PROTAC efficacy [7] [35] | High-fidelity (HF) version with ~20 nM Kd for tetra-ubiquitin [36] |

| K63-Selective TUBE | K63-linked chains [35] | Investigating NF-κB signaling, DNA repair, autophagy [7] [35] | 1,000 to 10,000-fold preference for K63-linked chains [35] |

| M1-Selective TUBE | M1-linked (linear) chains [36] | Research on NF-κB inflammatory signaling [37] | Comparable high affinity to K63 TUBE [36] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Low Signal in TUBE Assays

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient Enrichment: Ensure you are using the recommended amount of cell extract. As a starting point, use 20 µL of agarose-TUBE beads or 100 µL magnetic-TUBE slurry per milligram of cell extract [36]. The amount may need optimization based on the abundance of your target protein.

- Protein Degradation: Perform all purification steps at 4°C and include a comprehensive cocktail of protease inhibitors during cell lysis to prevent deubiquitination and protein degradation [38].

- Low Abundance Target: For low-abundance endogenous proteins, consider scaling up the starting material. The high affinity of TUBEs makes them suitable for enriching scarce ubiquitinated species [39].

Problem: High Background or Non-Specific Binding

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient Wash Stringency: Incorporate high-stringency washes. This can include increasing the NaCl concentration to 2M or greater, or adding mild detergents like 0.1% NP-40 or Tween-20 to wash buffers [38].

- Non-optimized Lysis Conditions: Vortexing lysates during preparation can cause protein complex dissociation. Avoid vortexing and use gentle pipetting instead. For some protein complexes, performing lysis in the absence of NP-40 may be necessary as they may be unstable in its presence [38].

Problem: Inability to Detect Linkage-Specific Ubiquitination

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Incorrect TUBE Selection: Verify that you are using the appropriate chain-selective TUBE for your biological question. For example, PROTAC-induced degradation should be detected with K48-selective TUBEs, while inflammatory signaling typically involves K63-selective TUBEs [7].

- Suboptimal Cell Stimulation: Ensure proper activation of the pathway of interest. In the RIPK2 model, L18-MDP (200-500 ng/mL) stimulation for 30 minutes effectively induced K63 ubiquitination, while PROTAC treatment induced K48 ubiquitination [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Analyzing Endogenous RIPK2 Ubiquitination

This protocol exemplifies the application of TUBE technology to study context-dependent ubiquitination of an endogenous protein, as demonstrated in recent research [7].

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Cell Culture and Treatment

- Culture THP-1 human monocytic cells in appropriate medium.

- For K63 ubiquitination: Treat cells with L18-MDP (200-500 ng/mL) for 30 minutes [7].

- For K48 ubiquitination: Treat cells with a specific RIPK2 PROTAC (e.g., RIPK2 degrader-2) [7].

- Include control treatments: pre-treat with Ponatinib (100 nM) for 30 minutes to inhibit RIPK2 kinase activity and suppress ubiquitination [7].

Step 2: Cell Lysis and Lysate Preparation

- Lyse cells in a lysis buffer optimized to preserve polyubiquitination. A recommended buffer should contain:

- 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)

- 150 mM NaCl

- 1% NP-40 or Triton X-100

- Protease inhibitors (include DUB inhibitors for optimal ubiquitin preservation)

- 1 mM DTT (optional, check compatibility with your TUBE type)

- Perform lysis using freeze-thaw cycles to minimize protein complex dissociation. Avoid vortexing and trypsinizing cells [38].

- Clear lysates by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. For particularly viscous lysates due to DNA, shear genomic DNA by passing the lysate through an 18-gauge needle several times [38].

Step 3: TUBE-Based Affinity Enrichment

- For each enrichment, use 20 µL of agarose-TUBE beads or 100 µL magnetic-TUBE slurry per 1 mg of total protein [36].

- Incubate the clarified lysate with the appropriate TUBE (Pan-, K48-, or K63-selective) for 2-4 hours at 4°C with gentle rotation.

- After incubation, pellet beads magnetically or by gentle centrifugation.

Step 4: Washing and Elution

- Wash beads 3-4 times with ice-cold lysis buffer. For high background, include one wash with buffer containing 500 mM NaCl.

- Elute bound proteins using LifeSensors proprietary elution buffer (Cat # UM411B) or 2X SDS-PAGE loading buffer with heating at 95°C for 5-10 minutes [36].

Step 5: Detection and Analysis

- Analyze eluates by Western blotting using antibodies against your protein of interest (e.g., anti-RIPK2).

- For quantification, use TUBE-AlphaLISA, TUBE-DELFIA, or other HTS-compatible formats [35].

Table 2: Expected Results for RIPK2 Ubiquitination Pattern

| Experimental Condition | Pan-TUBE | K48-TUBE | K63-TUBE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated Cells | Low/No Signal | Low/No Signal | Low/No Signal |

| L18-MDP Treatment | Strong Signal | Low/No Signal | Strong Signal |

| RIPK2 PROTAC Treatment | Strong Signal | Strong Signal | Low/No Signal |

| Ponatinib + L18-MDP | Low/No Signal | Low/No Signal | Low/No Signal |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do TUBEs compare to traditional ubiquitin antibodies for detection?

TUBEs offer significant advantages over traditional ubiquitin antibodies. They exhibit nanomolar binding affinities for polyubiquitin chains, far exceeding the affinity of most antibodies [35]. Additionally, TUBEs protect polyubiquitin chains from deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) and protasomal degradation during sample processing, preserving the native ubiquitination state in a way antibodies cannot [35].

Q2: Can TUBEs be used for high-throughput screening (HTS)?

Yes, TUBE technology is adaptable to HTS formats. LifeSensors offers specialized assays like the PA950 PROTAC Assay Plate for cell-based ELISA and the PA770 kit for in vitro ubiquitination assays [36]. These enable quantitative, high-throughput analysis of endogenous target protein ubiquitination, which is crucial for drug discovery programs focused on targeted protein degradation [36].

Q3: What is the difference between the PA950 and PA770 kits?

The PA950 kit is designed as a cell-based ELISA to measure ubiquitination in cellular contexts, while the PA770 kit is an in vitro based ELISA that uses pre-coated TUBE plates to capture polyubiquitin chains formed in a PROTAC-dependent reaction, allowing for precise control of reaction components [36].

Q4: How should TUBE reagents be stored and handled?

Recombinant proteins like TUBEs should generally be stored at -80°C [36]. Avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles, as this can compromise activity. For specific storage conditions, always refer to the product datasheet available on the manufacturer's website [36].

Q5: My protein of interest is not RIPK2. Can this protocol be adapted?

Absolutely. The protocol using chain-selective TUBEs to differentiate context-dependent ubiquitination has broad applicability [7]. The key is to first understand the biological context of your protein's ubiquitination to select the appropriate TUBE (e.g., K48-TUBE for degradation studies, K63-TUBE for signaling studies) and then optimize stimulation or inhibition conditions specific to your pathway.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for TUBE-Based Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pan-Selective TUBEs | Comprehensive capture of all polyubiquitinated proteins; ideal for initial discovery phase [35]. | TUBE1 (preferentially binds K63) and TUBE2 (equal K48/K63 affinity); available conjugated to various tags (FLAG, Biotin) and beads [36]. |

| Chain-Selective TUBEs | Precise isolation of proteins modified with specific ubiquitin linkages to determine functional outcome [7] [35]. | K48-TUBE HF (for degradation), K63-TUBE (for signaling), M1-TUBE (for linear ubiquitination in inflammation) [36]. |

| TUBE-Coated Assay Plates | High-throughput screening of ubiquitination in plate-based formats [36]. | PA950 (cell-based) and PA770 (in vitro) assay kits for quantitative analysis of PROTAC/molecular glue activity [36]. |

| Specialized Lysis Buffer | Maintains protein ubiquitination state during extraction by inhibiting DUBs and proteases [38] [7]. | Should contain protease inhibitors (including DUB inhibitors) and be compatible with downstream TUBE binding. |

| Decomplexing Buffer | Disrupts native protein complexes to reduce background and improve signal-to-noise ratio in assays [36]. | Urea-based buffer (available from LifeSensors) used prior to analysis with PA950 kit [36]. |

Ubiquitin Signaling Pathways in Physiological Contexts

Understanding the biological context of different ubiquitin linkages is crucial for designing appropriate experiments. The diagram below illustrates key pathways where specific ubiquitin linkages play definitive roles, highlighting how TUBE technology can be applied to dissect these processes.

Protein ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification regulating virtually all cellular processes, including protein degradation, signal transduction, and circadian biology [34] [40]. The versatility of ubiquitin signaling stems from its ability to form diverse conjugates, ranging from single ubiquitin monomers to complex polyubiquitin chains with different linkage types [41]. Disruption of ubiquitin homeostasis is linked to numerous pathologies, including cancer and neurodegenerative diseases [40] [42], making accurate quantification essential for both basic research and drug development.

A significant challenge in the field has been the lack of standardized methods capable of reliably quantifying ubiquitin pools and ubiquitination sites across diverse biological samples, particularly tissues [43] [44]. Traditional antibody-based methods have struggled to accurately discriminate between free and conjugated ubiquitin species [43]. However, recent advances combining diGly antibody enrichment with data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry (DIA-MS) now enable unprecedented depth and reproducibility in ubiquitinome mapping, offering a path toward standardized quantification across tissue types [34] [45].

Core Methodology: diGly Antibody Enrichment and DIA-MS Workflow

The foundational innovation enabling global ubiquitinome analysis was the development of antibodies specifically recognizing the diglycine (diGly) remnant left on trypsinized peptides from ubiquitinated proteins [34] [46]. When combined with advanced mass spectrometry techniques, this enrichment strategy allows system-wide profiling of ubiquitination events.

diGly Antibody-Based Enrichment

Following tryptic digestion of protein lysates, the K-ε-GG motif serves as an affinity handle for immuno-enrichment, dramatically reducing sample complexity and enabling detection of low-abundance ubiquitination events [44] [46]. This method captures endogenous ubiquitination without genetic manipulation, making it particularly valuable for tissue studies where tagged ubiquitin expression is infeasible [41] [44].

Data-Independent Acquisition Mass Spectrometry