Targeting the Hidden Regulators: Strategies for Isolating and Analyzing Low-Abundance Ubiquitinated Proteins in Cancer

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a critical regulator of oncogenesis, yet the study of low-abundance ubiquitinated proteins presents significant technical challenges.

Targeting the Hidden Regulators: Strategies for Isolating and Analyzing Low-Abundance Ubiquitinated Proteins in Cancer

Abstract

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a critical regulator of oncogenesis, yet the study of low-abundance ubiquitinated proteins presents significant technical challenges. This article provides a comprehensive guide for cancer researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational role of ubiquitination in cancer biology, advanced methodologies for enrichment and detection, strategies for troubleshooting common experimental pitfalls, and frameworks for clinical validation. By synthesizing current research and emerging technologies, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to uncover novel therapeutic targets and biomarkers within the ubiquitin code, ultimately advancing the development of targeted cancer therapies.

The Ubiquitin Code in Cancer: Unveiling the Significance of Low-Abundance Regulators

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What are the primary functions of ubiquitination beyond protein degradation? Ubiquitination is a versatile post-translational modification. While K48-linked polyubiquitin chains primarily target substrates for degradation by the 26S proteasome, other chain types regulate diverse cellular processes [1] [2]. Monoubiquitination and K63-linked polyubiquitination are involved in endocytic trafficking, inflammation, translation, DNA repair, and signal transduction [1] [2]. Furthermore, ubiquitination can alter a protein's cellular location, affect its activity, and promote or prevent protein interactions [1].

FAQ 2: Why is my target ubiquitinated protein difficult to detect in cancer cell lines? Working with low-abundance ubiquitinated proteins, such as specific ubiquitinated oncoproteins like RAS isoforms, is challenging due to their transient nature and rapid turnover [3] [2]. The dynamic balance between E3 ligases and deubiquitinases (DUBs) tightly regulates their levels [3] [4]. Furthermore, a single protein can be modified by various ubiquitin chain types, diluting the specific signal you are detecting [1]. To troubleshoot, use proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG132) to block degradation and enrich for ubiquitinated forms, perform immunoprecipitation under denaturing conditions to preserve unstable modifications, and employ linkage-specific ubiquitin antibodies to distinguish between different chain types.

FAQ 3: What could cause a lack of expected effect when using a UPS modulator in a cancer model? The UPS exhibits significant context-dependent regulation and functional duality [2] [4]. The same E3 ligase can have opposing effects in different cellular contexts or cancer types. Potential reasons for a lack of effect include: compensatory upregulation of alternative degradation pathways (e.g., autophagy), insufficient on-target engagement of the modulator, or the presence of rare, therapy-resistant cell populations that are already wired with resistant metabolic and epigenetic properties [5] [4]. It is crucial to validate target engagement directly and assess the broader cellular response to treatment.

FAQ 4: How does the immunoproteasome differ from the standard proteasome, and why is this relevant in cancer research? The immunoproteasome (IP) is a specialized proteasome isoform induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines like interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) [2]. It replaces the standard catalytic subunits (β1, β2, β5) with inducible immune subunits (β1i/LMP2, β2i/MECL-1, β5i/LMP7). This alteration enhances chymotrypsin-like activity and optimizes the generation of peptides for MHC class I antigen presentation [2]. In cancer, the immunoproteasome can shape antitumor immune responses by influencing the repertoire of tumor antigens presented to cytotoxic T cells, making it a significant factor in immunotherapy research [2].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Table: Troubleshooting Low-Abundance Ubiquitinated Protein Detection

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or no signal for ubiquitinated protein | Low stoichiometry of modification; rapid degradation | Inhibit the proteasome (MG132, Bortezomib) for 4-6 hours prior to lysis; use TUBE (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entity) reagents to enrich ubiquitinated proteins [2]. |

| Non-specific bands in western blot | Antibody cross-reactivity; protein aggregation | Perform immunoprecipitation before western blot; use denaturing lysis buffers (e.g., with 1% SDS); validate antibodies with knockdown/knockout cell controls. |

| Inconsistent results between replicates | Inefficient cell lysis; variable protease/deubiquitinase activity | Use fresh, complete protease inhibitor cocktails (including DUB inhibitors like N-ethylmaleimide); standardize lysis protocol and sonication steps. |

| Failure to detect endogenous ubiquitination | Detection method lacks sensitivity | Switch to more sensitive detection methods (e.g., proximity ligation assay, PLA); utilize tagged-ubiquitin overexpression systems for initial validation. |

Table: Quantitative Data on Ubiquitin Chain Signaling Outcomes [1] [2]

| Ubiquitin Chain Linkage | Primary Functional Outcome | Key Biological Processes |

|---|---|---|

| K48 | Proteasomal Degradation | Cell cycle progression, protein quality control, signal termination |

| K29 | Proteasomal Degradation | Protein quality control |

| K63 | Non-proteolytic Signaling | DNA repair, endocytic trafficking, inflammation, kinase activation |

| K11 | Proteasomal Degradation (ER-associated degradation) | Cell cycle regulation, metabolism |

| M1 (Linear) | Non-proteolytic Signaling | NF-κB pathway activation, inflammatory signaling |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Enrichment and Detection of Ubiquitinated RAS Proteins

Background: RAS proteins are frequently mutated in cancer, and their ubiquitination dynamically regulates stability, membrane localization, and signaling [3]. This protocol is designed to capture these transient modifications.

Methodology:

- Cell Culture and Treatment: Culture cancer cells (e.g., HCT-116 or Panc-1). At ~80% confluency, treat with 10µM MG132 (proteasome inhibitor) for 6 hours to accumulate ubiquitinated proteins.

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells in 1 mL of denaturing lysis buffer (e.g., RIPA buffer with 1% SDS, 5mM N-ethylmaleimide, and complete protease inhibitors) to inactivate DUBs.

- Immunoprecipitation: Dilute the lysate 10-fold with SDS-free buffer. Pre-clear with protein A/G beads for 30 minutes. Incubate the supernatant with an anti-RAS antibody (e.g., pan-RAS) overnight at 4°C. Add protein A/G beads for 2 hours the next day.

- Washing and Elution: Wash beads 3-4 times with wash buffer. Elute proteins by boiling in 2X Laemmli sample buffer.

- Detection: Analyze by SDS-PAGE and western blotting. Probe with anti-ubiquitin antibody (e.g., P4D1) or linkage-specific antibodies (e.g., K48- or K63-linkage specific) to characterize the chain topology.

Protocol 2: Assessing Proteasomal Chymotrypsin-like Activity in Cell Lysates

Background: This functional assay is crucial for confirming the efficacy of proteasome inhibitors or identifying dysregulated UPS activity in cancer models [6] [7].

Methodology:

- Lysate Preparation: Lyse cells in a non-denaturing buffer (e.g., 50mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 250mM sucrose, 5mM MgCl2, 1mM DTT, 2mM ATP). Centrifuge at 12,000g for 15 minutes at 4°C to collect the supernatant.

- Reaction Setup: In a 96-well plate, mix 50µg of total protein lysate with 100µM of the fluorogenic substrate Suc-LLVY-AMC (for chymotrypsin-like activity) in assay buffer. Include a negative control with the specific proteasome inhibitor MG132 (20µM).

- Measurement: Incubate the reaction at 37°C and monitor the release of fluorescent AMC (excitation 380nm, emission 460nm) kinetically over 60-90 minutes using a fluorescence microplate reader.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the rate of fluorescence increase (RFU/min). The MG132-inhibitable activity represents the specific proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table: Essential Reagents for Studying the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

| Reagent / Tool | Function and Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| MG132 | Reversible proteasome inhibitor; used to accumulate ubiquitinated proteins prior to lysis [2]. | Cytotoxic with prolonged exposure; requires optimization of dose and treatment time. |

| Bortezomib | Clinically approved, specific inhibitor of the proteasome's chymotrypsin-like activity [7]. | Can induce compensatory upregulation of immunoproteasome subunits. |

| TUBE (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entity) | High-affinity ubiquitin-binding reagent; used to purify and visualize polyubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates [2]. | Excellent for enrichment but does not distinguish between different ubiquitin chain linkages. |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies | Antibodies specific for K48, K63, etc., linkages; used in western blot to determine chain topology [1] [2]. | Specificity must be rigorously validated; may have varying affinities. |

| HA-Ub or GFP-Ub Plasmids | Plasmids for expressing N-terminally tagged ubiquitin; allow for pulldown of ubiquitinated proteins under denaturing conditions. | Overexpression can saturate the endogenous system and cause artifacts. |

| E1 Inhibitor (e.g., TAK-243) | Inhibits the ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1, blocking the entire ubiquitination cascade [1]. | Highly toxic; used as a broad-spectrum control to confirm ubiquitin-dependent processes. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The study of ubiquitination in cancer requires a specific set of reagents and tools to detect, manipulate, and analyze this dynamic post-translational modification. The table below details essential materials for research in this field.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for Studying Ubiquitination in Cancer

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| E3 Ligase-Targeting Molecules | Nutlin, MI‐219 [8] | Inhibit specific E3 ligase interactions (e.g., MDM2-p53) to stabilize tumor suppressors. |

| Protac-based Degraders | ARV-110, ARV-471, AC0176 [9] [10] | Bifunctional molecules that recruit E3 ligases to target oncoproteins for degradation. |

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors | Compounds G5 and F6 [8] | Inhibit deubiquitinating enzyme activity, promoting the degradation of target proteins. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib, Ixazomib [8] | Block the proteasome, inducing ER stress and apoptosis by preventing protein degradation. |

| Low-Abundance Protein Detection | SuperSignal West Atto Ultimate Sensitivity Substrate [11] | Ultrasensitive chemiluminescent substrate for detecting low-abundance proteins in western blotting. |

| Protein Enrichment Tools | Combinatorial Peptide Ligand Libraries (CPLLs) [12] | Equalize protein dynamic range in complex samples by enriching low-abundance species. |

| Specific Gel Chemistries | Bis-Tris, Tris-Acetate, Tricine Gels [11] | Optimize protein separation and resolution based on molecular weight for better detection. |

Core Signaling Pathways in Cancer Ubiquitination

Ubiquitination is a critical regulator of numerous oncogenic and tumor-suppressive pathways. The diagrams below illustrate key signaling pathways frequently dysregulated in cancer through ubiquitination.

Diagram 1: Ubiquitination in the HIF Signaling Pathway in Renal Cell Carcinoma

In clear cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC), the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor, which is part of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, is frequently inactivated [13]. Under normal oxygen levels (normoxia), prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs) modify HIF-α subunits, allowing VHL to recognize, ubiquitinate, and target them for proteasomal degradation [13]. When VHL is lost or mutated, HIF-α subunits accumulate. Interestingly, HIF-2α often becomes the dominant driver of tumor growth, promoting the expression of genes related to angiogenesis and proliferation [13]. The HAF E3 ligase further shifts this balance by specifically ubiquitinating and degrading the tumor-suppressive HIF-1α while simultaneously binding to and activating the oncogenic HIF-2α [13].

Diagram 2: Ubiquitination in Oncogenic Signaling and Metabolic Reprogramming

Ubiquitination tightly regulates key oncogenic pathways. For instance, activated Receptor Tyrosine Kinases (RTKs) like EGFR are ubiquitinated by E3 ligases such as c-CBL, leading to their internalization and degradation; this is a critical negative feedback mechanism often lost in cancer [14]. In cancer metabolism, the mTORC1 pathway is a master regulator. The E3 ligase TRAF6 can activate mTORC1 via non-degradative K63-linked ubiquitination, promoting its translocation to the lysosome and driving metabolic reprogramming [15]. Furthermore, metabolic enzymes themselves are regulated by ubiquitination. The glycolytic enzyme PKM2 can be ubiquitinated for degradation by the E3 ligase Parkin, while the deubiquitinase OTUB2 counteracts this, stabilizing PKM2 and enhancing glycolysis in colorectal cancer [10] [15].

Technical Support: Troubleshooting Low-Abundance Ubiquitinated Protein Analysis

Troubleshooting Guide: Detecting Low-Abundance Ubiquitinated Proteins

Table 2: Common Issues and Solutions in Low-Abundance Protein Detection

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Faint or no bands on Western Blot | Inefficient protein transfer from gel to membrane. | Use neutral-pH gels (e.g., Bis-Tris, Tris-Acetate) for cleaner protein release and better transfer efficiency. Consider dry electroblotting systems for consistency [11]. |

| High background noise | Non-specific antibody binding or suboptimal substrate. | Use antibodies with verified specificity for Western blotting. Employ high-sensitivity chemiluminescent substrates like SuperSignal West Atto for superior signal-to-noise ratio [11]. |

| Poor resolution of low molecular weight proteins | Unsuitable gel chemistry. | Use Tricine gels instead of Bis-Tris or Tris-Glycine gels for optimal separation and resolution of proteins below 40 kDa [11]. |

| Inability to detect target in complex samples | Target protein masked by high-abundance proteins (e.g., serum albumin). | Implement pre-analytical enrichment strategies such as Combinatorial Peptide Ligand Libraries (CPLLs) to reduce dynamic concentration range and concentrate low-abundance targets [12]. |

| Low protein yield from extraction | Protein degradation or inefficient extraction buffer. | Use broad-spectrum protease inhibitors during extraction. Employ optimized, sample-specific extraction buffers (e.g., for mammalian cells, bacteria, plant tissue) [11]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary technical challenges in studying low-abundance ubiquitinated proteins, and what general strategies can help?

The main challenges are the vast dynamic concentration range of proteomes and the transient nature of some ubiquitination events. High-abundance proteins can obscure the signal of rare, low-abundance species in analytical methods [12]. Key strategies include:

- Enrichment: Use techniques like CPLLs to "normalize" the protein sample, reducing high-abundance proteins and concentrating low-abundance ones [12].

- Optimized Separation: Choose the correct gel chemistry (Bis-Tris, Tris-Acetate, or Tricine) based on your target protein's molecular weight for optimal resolution [11].

- Sensitive Detection: Utilize high-sensitivity chemiluminescent substrates and thoroughly validated antibodies to maximize signal strength and specificity [11].

Q2: Our research focuses on the WNT/β-catenin pathway. How is its activity regulated by ubiquitination, and could this be relevant to therapy resistance?

The stability of the key effector β-catenin is centrally controlled by a destruction complex that promotes its ubiquitination and degradation. The E3 ligase FBXW7, for example, can ubiquitinate partners like CHD4, indirectly suppressing β-catenin signaling [16]. Conversely, deubiquitinases like USP4 and USP10 can stabilize β-catenin or its co-factors, enhancing pathway activity [16]. This is highly relevant to therapy resistance, as β-catenin can promote the transcription of PD-L1, an immune checkpoint protein that helps tumors evade the immune system. Therefore, strategies that promote β-catenin ubiquitination and degradation could potentially reverse immune evasion and overcome resistance to immunotherapy [16].

Q3: Beyond protein degradation, what other functional outcomes does ubiquitination have in cancer cells?

While K48-linked polyubiquitination primarily targets proteins for proteasomal degradation, other ubiquitin chain linkages mediate diverse non-proteolytic functions [8] [10]. For example:

- K63-linked Ubiquitination: Often involved in activating signaling complexes, such as in the mTORC1 [15] and NF-κB pathways.

- Monoubiquitination: Can regulate processes like DNA repair, endocytosis, and histone activity [8] [10].

- Linear Ubiquitination (M1-linked): Assembled by the LUBAC complex, this chain type is crucial for activating NF-κB signaling, which promotes cell survival and inflammation in cancers like lymphoma [10].

Q4: What emerging technologies are being developed to target the ubiquitin system for cancer treatment?

Two of the most promising technologies are:

- PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras): These are bifunctional molecules that simultaneously bind to a target protein and an E3 ubiquitin ligase, bringing them together to ubiquitinate and degrade the target. Examples like ARV-110 (targeting the androgen receptor in prostate cancer) have shown promise in clinical trials [13] [9] [10].

- Molecular Glues: These are smaller molecules that induce or stabilize the interaction between an E3 ligase and a target protein, leading to the target's degradation. CC-90009 is an example that degrades GSPT1 and is in trials for leukemia [10].

Protein ubiquitination is a fundamental post-translational modification that regulates nearly every aspect of cellular function, from protein degradation and DNA repair to cell signaling and immune responses [17] [18]. In cancer research, understanding ubiquitination patterns is particularly crucial as dysregulation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) contributes significantly to tumor initiation, progression, and therapeutic resistance [19] [10]. The UPS maintains cellular proteostasis by selectively degrading key regulatory proteins, and cancer cells often exploit this system to eliminate tumor suppressors or stabilize oncoproteins [19].

Despite its biological significance, the analytical characterization of ubiquitinated proteins presents substantial challenges due to their inherently low abundance, transient nature, and structural complexity [18] [20]. The stoichiometry of protein ubiquitination is typically very low under normal physiological conditions, with ubiquitinated species often representing only a tiny fraction of the total cellular protein pool [20]. This low abundance, combined with the rapid degradation of ubiquitinated proteins by the proteasome and the dynamic nature of ubiquitination signaling, makes these critical regulatory targets particularly elusive for researchers [18].

Understanding the Ubiquitin Code

Ubiquitination is not a single uniform modification but rather a diverse regulatory language comprising different ubiquitin chain architectures that dictate distinct functional outcomes. Understanding this "ubiquitin code" is essential for interpreting experimental results in cancer research.

Types of Ubiquitin Modifications

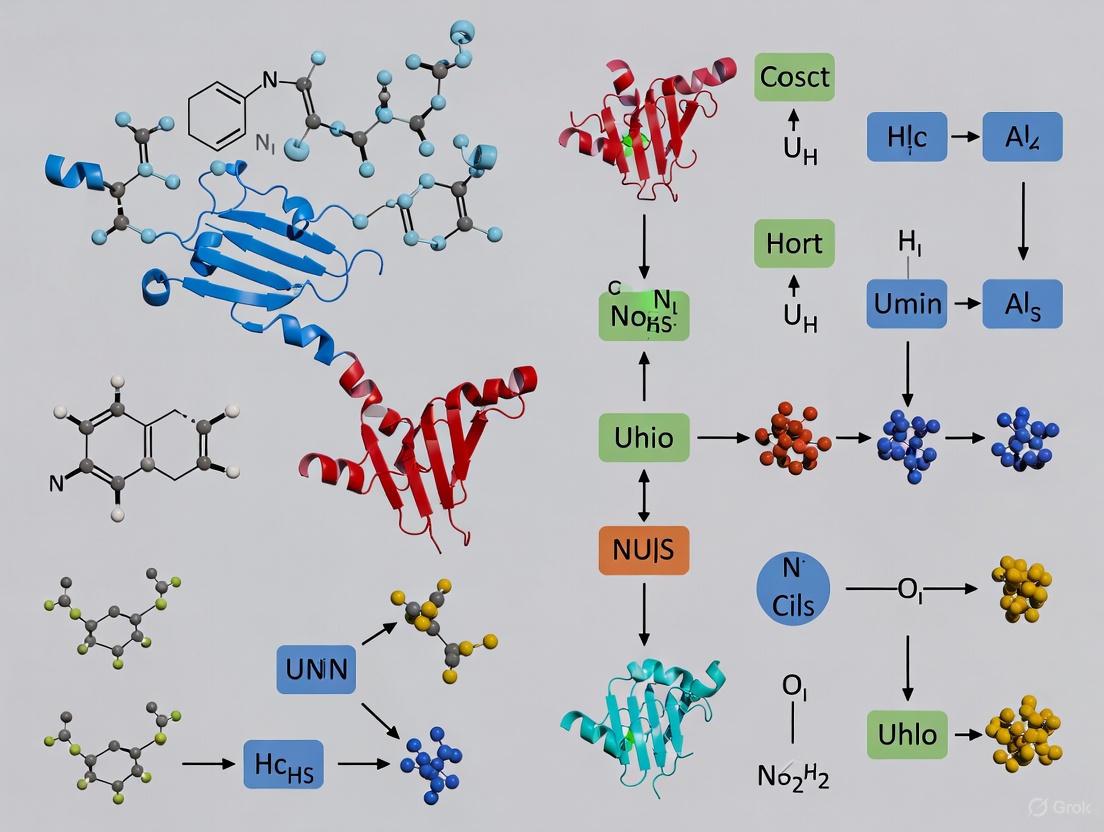

Figure 1: The complexity of the ubiquitin code, showing different ubiquitination types and their primary cellular functions.

Functional Consequences of Different Ubiquitin Linkages

Table 1: Ubiquitin linkage types and their functional significance in cellular signaling and cancer biology

| Linkage Site | Chain Type | Primary Functional Consequences | Relevance in Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48 | Polymeric | Targeted protein degradation via proteasome | Regulates oncoprotein and tumor suppressor stability |

| K63 | Polymeric | DNA repair, kinase activation, endocytosis | Promotes DNA damage response, cell survival |

| M1 | Polymeric | NF-κB activation, inflammation, cell death | Modulates immune signaling in tumor microenvironment |

| K6 | Polymeric | Antiviral responses, mitophagy, DNA repair | Potential role in cancer cell stress adaptation |

| K11 | Polymeric | Cell cycle regulation, proteasomal degradation | Regulates mitotic proteins in proliferating cells |

| K27 | Polymeric | DNA replication, cell proliferation | Emerging role in cancer signaling pathways |

| K29 | Polymeric | Wnt signaling, autophagy | Linked to neurodegenerative disorders and cancer |

| Monoubiquitination | Monomeric | Endocytosis, histone modification, DNA damage responses | Alters subcellular localization and protein interactions |

The information in Table 1 is synthesized from multiple sources examining ubiquitin linkage functions [21] [20] [10]. The diverse outcomes mediated by different ubiquitin linkages underscore why comprehensive ubiquitination analysis must move beyond simple detection to characterization of specific chain architectures, particularly in cancer research where specific linkages may be dysregulated.

Core Challenges in Isolating Low-Abundance Ubiquitinated Proteins

Fundamental Analytical Obstacles

Researchers face multiple interconnected challenges when working with low-abundance ubiquitinated proteins:

- Low Stoichiometry: Under normal physiological conditions, only a very small percentage of any given protein substrate is ubiquitinated at any specific time, making detection difficult against the background of non-modified proteins [18] [20].

- Transient Nature: Ubiquitination is a highly dynamic and reversible process, with deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) rapidly removing ubiquitin modifications, resulting in brief detection windows [22] [20].

- Rapid Turnover: Many ubiquitinated proteins, particularly those marked with K48-linked chains, are quickly targeted for degradation by the 26S proteasome, further reducing their steady-state abundance [19] [18].

- Structural Complexity: The presence of multiple ubiquitination types (mono vs. poly), chain linkage variations, and potential branching creates a heterogeneous population that is difficult to capture comprehensively with single approaches [17] [20].

Technical Limitations in Detection

- Antibody Specificity and Sensitivity: Many commercially available ubiquitin antibodies suffer from non-specific binding and limited affinity due to ubiquitin's small size and conserved nature [21] [20].

- Interference from Abundant Proteins: Without effective enrichment, high-abundance non-ubiquitinated proteins dominate mass spectrometry analysis, masking the detection of low-abundance ubiquitinated species [18].

- Incomplete Proteolytic Digestion: The large size of ubiquitin modification can interfere with tryptic digestion efficiency, reducing peptide yield for mass spectrometry analysis [18].

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Low Yield in Ubiquitinated Protein Enrichment

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Table 2: Troubleshooting low enrichment yield of ubiquitinated proteins

| Problem Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Solution Approaches | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insufficient proteasome inhibition | Low ubiquitin smears on Western blot; rapid target protein turnover | Treat cells with 5-25 μM MG-132 for 1-2 hours before harvesting; optimize concentration for specific cell type [21] | Increased detection of polyubiquitinated proteins |

| Inefficient cell lysis | High percentage of ubiquitinated proteins in insoluble fraction | Use strong denaturing lysis buffers (e.g., 4-6 M urea, 2% SDS) to disrupt protein complexes and access ubiquitinated proteins [21] | Improved recovery of membrane-associated and insoluble ubiquitinated proteins |

| Suboptimal binding conditions | High background in flow-through; low signal in eluate | Include 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100 or similar detergent in lysis and binding buffers to reduce non-specific interactions [23] | Higher specificity enrichment with reduced background |

| Incomplete ubiquitin chain preservation | Predominance of monoubiquitination signals; lack of polyubiquitin smears | Add N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) or iodoacetamide to lysis buffers to inhibit deubiquitinase activity [20] | Better preservation of polyubiquitin chain architecture |

Problem: High Background and Non-Specific Binding

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Endogenous biotinylated proteins or histidine-rich proteins co-purifying with streptavidin or Ni-NTA resins [20].

- Solution: Use competitive elution with biotin or imidazole, followed by additional clean-up steps. Consider switching to alternative tags (Strep-tag vs. His-tag) to minimize background.

Cause: Non-specific antibody binding in immunoaffinity approaches [20] [23].

- Solution: Include competitive washes with increasing salt concentrations (150-500 mM NaCl) and incorporate mild denaturing conditions (0.1-0.5% SDS) in wash buffers.

Cause: Endogenous proteins binding to affinity matrices.

- Solution: Pre-clear lysates with bare resin or beads coupled to control IgG before specific enrichment.

Problem: Inconsistent Mass Spectrometry Identification

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Incomplete tryptic digestion due to steric hindrance from ubiquitin modification [18].

- Solution: Extend digestion time (6-18 hours), increase trypsin-to-protein ratio, or use multiple proteases (trypsin+Lys-C) for more complete digestion.

Cause: Signal suppression from abundant non-modified peptides [18] [20].

- Solution: Implement stronger enrichment steps prior to MS analysis and use peptide-level fractionation to reduce sample complexity.

Cause: Inefficient detection of ubiquitin remnant peptides.

- Solution: Use diGly remnant antibodies (K-ε-GG) for specific enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides after tryptic digestion [18].

Advanced Methodologies for Ubiquitin Characterization

Comprehensive Workflow for Ubiquitinated Protein Analysis

Figure 2: Comprehensive workflow for the isolation and characterization of ubiquitinated proteins, highlighting key steps from sample preparation to final analysis.

Comparison of Ubiquitinated Protein Enrichment Strategies

Table 3: Methodologies for enriching and identifying ubiquitinated proteins

| Methodology | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin-Binding Domains (TUBEs) | Tandem ubiquitin-binding entities with high affinity for polyubiquitin chains [20] | Protects ubiquitin chains from DUBs; recognizes multiple linkage types; compatible with native conditions | May exhibit linkage preference; requires characterization of binding specificity | Preservation of labile ubiquitin signals; functional studies requiring native conditions |

| Immunoaffinity Purification (FK2 Antibody) | Antibody recognizing mono- and polyubiquitinated conjugates [23] | Recognizes endogenous ubiquitination; suitable for native and denaturing conditions; identifies protein complexes | Potential non-specific binding; high antibody cost; may not recognize all linkage types | Isolation of endogenous ubiquitinated complexes; interaction studies |

| Affinity Tagged Ubiquitin (His/Strep) | Expression of epitope-tagged ubiquitin in cells [20] | High-yield purification; controllable expression; cost-effective resin | May not mimic endogenous ubiquitination; requires genetic manipulation; potential artifacts | High-throughput ubiquitylome profiling; controlled experimental systems |

| diGly Antibody Enrichment | Antibodies specific for tryptic remnant (K-ε-GG) after ubiquitination [18] | Site-specific identification; high specificity; works on any sample type | Requires tryptic digestion; misses non-lysine ubiquitination; destroys protein structure | Comprehensive ubiquitin site mapping; clinical samples; quantitative studies |

| Ligase Trapping | E3 ligase fused to polyubiquitin-binding domain captures substrates [22] | Identifies specific E3-substrate relationships; functional context | Limited to specific E3 ligases; may miss substrates of other E3s | Pathway-specific ubiquitination studies; E3 ligase characterization |

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 4: Essential reagents and tools for studying ubiquitination

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG-132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Stabilize ubiquitinated proteins by blocking proteasomal degradation [19] [21] | Optimize concentration and treatment time to minimize cellular stress responses |

| DUB Inhibitors | PR-619, N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | Preserve ubiquitin signals by inhibiting deubiquitinating enzymes [20] | Include in all lysis buffers; use fresh preparations for optimal activity |

| Ubiquitin Enrichment Reagents | ChromoTek Ubiquitin-Trap, UbiQapture-Q, FK2 Antibody Beads | Isolate ubiquitinated proteins from complex mixtures [21] [23] | Validate for specific applications; test binding capacity for polyubiquitin chains |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K48-linkage specific, K63-linkage specific, M1-linkage specific | Characterize ubiquitin chain architecture [20] [10] | Verify specificity with known controls; be aware of potential cross-reactivity |

| Tagged Ubiquitin Constructs | His-Ub, HA-Ub, Strep-Ub, GFP-Ub | Enable affinity purification and visualization of ubiquitination [20] | Consider expression level effects; use inducible systems to minimize artifacts |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | Heavy labeled diGly peptides, SILAC labeled ubiquitin | Enable quantitative ubiquitinome analysis [18] | Incorporate internal standards for accurate quantification |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Method Selection and Optimization

Q: What is the most effective method for isolating low-abundance ubiquitinated proteins from patient tissue samples? A: For patient tissues where genetic manipulation is impossible, immunoaffinity purification using antibodies like FK2 that recognize endogenous ubiquitination is recommended [20] [23]. Combine this with strong DUB inhibition during tissue homogenization and prior proteasome inhibitor treatment if feasible. The FK2 antibody method has successfully isolated endogenous ubiquitinated protein complexes from various cell types and shows promise for tissue applications [23].

Q: How can I enhance ubiquitination signals in my samples without causing excessive cellular stress? A: Optimize proteasome inhibitor treatment using MG-132 at concentrations between 5-25 μM for 1-2 hours before harvesting [21]. Titrate to the lowest effective concentration for your cell type. Combine with DUB inhibitors in lysis buffers, but avoid prolonged inhibitor treatment that can induce stress responses and compromise cell viability.

Q: Why do I see smeared patterns instead of discrete bands when analyzing ubiquitinated proteins by Western blot? A: Smearing is expected and actually indicates successful preservation of polyubiquitinated species [21]. Ubiquitinated proteins exist as heterogeneous populations with varying numbers of ubiquitin modifications, creating a molecular weight continuum. Discrete bands might suggest incomplete ubiquitination or degradation of polyubiquitin chains.

Technical Challenges and Interpretation

Q: Can I differentiate between different ubiquitin linkage types using commercial ubiquitin traps? A: Most general ubiquitin traps (like TUBEs or FK2 antibodies) are not linkage-specific and will capture various ubiquitin chain types [21] [20]. To characterize specific linkages, you need to combine general enrichment with subsequent Western blot analysis using linkage-specific antibodies, or use linkage-specific antibodies for enrichment directly, though these may have lower overall capture efficiency.

Q: How specific are the diGly antibodies used in ubiquitin remnant profiling? A: diGly antibodies specifically recognize the diglycine remnant left on modified lysines after tryptic digestion of ubiquitinated proteins [18]. While highly specific for ubiquitin and some ubiquitin-like modifiers, they may cross-react with other modifications that generate similar structures. Always include appropriate controls and validate key findings with orthogonal methods.

Q: What are the major advantages and disadvantages of tagged ubiquitin systems versus antibody-based approaches? A: Tagged ubiquitin systems (His/Strep-tags) typically provide higher yield and cleaner isolations but require genetic manipulation and may not perfectly mimic endogenous ubiquitination [20]. Antibody-based approaches work on endogenous proteins and clinical samples but may have higher background and significant cost implications [20] [23]. The choice depends on your experimental system and research questions.

Cancer Research Applications

Q: How can I study the role of specific ubiquitin linkages in cancer pathways? A: Combine linkage-specific antibodies [20] with functional assays relevant to your cancer model. For example, use K48-linkage specific antibodies to study protein stability and turnover of oncoproteins/tumor suppressors [10], or K63-linkage specific reagents to investigate DNA damage response and kinase signaling in cancer cells [21] [10].

Q: What considerations are important when studying ubiquitination in the context of cancer therapeutics? A: Consider the dynamic regulation of E3 ligases and DUBs in response to therapy [19] [10]. Many targeted therapies alter ubiquitination patterns, so include appropriate drug treatment controls. When studying proteasome inhibitor resistance, monitor changes in ubiquitin chain homeostasis and alternative degradation pathways that cancer cells may activate.

Q: How can I determine if a ubiquitination event I've identified is functionally relevant in cancer progression? A: Beyond mere identification, perform functional validation through: (1) Mutagenesis of identified ubiquitination sites and assessment of cancer phenotypes (proliferation, invasion, etc.); (2) Modulation of relevant E3 ligases/DUBs and examination of pathway activity; (3) Correlation with clinical parameters in patient datasets when possible [20] [10].

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that controls the stability, localization, and activity of proteins involved in cancer development and progression. For researchers investigating low-abundance ubiquitinated proteins, this process presents unique challenges due to the dynamic nature of ubiquitin signaling and the technical difficulties in capturing these often-rare molecular events. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols to help you navigate these complexities in your cancer research.

► FAQs: Ubiquitination in Oncogenic Signaling

Q1: How does ubiquitination regulate MYC oncoprotein stability and what are the technical challenges in studying this?

MYC is a master transcription factor deregulated in most human cancers. Its protein stability is tightly controlled by ubiquitination [8]. The major technical challenge is that MYC protein has a very short half-life, and its ubiquitination is a transient event. To capture MYC ubiquitination:

- Use proteasome inhibitors (MG132, bortezomib) 4-6 hours before lysis to stabilize ubiquitinated forms

- Employ strong denaturing lysis buffers (containing 1% SDS) to prevent deubiquitinase (DUB) activity

- Combine denaturing lysis with refolding steps (see DRUSP protocol below) for optimal ubiquitin-binding domain recognition

- Implement tandem ubiquitin-binding entities (TUBEs) in your pull-down assays to protect ubiquitin chains from DUBs

Q2: What is the relationship between ubiquitination, histological transformation, and therapy resistance?

Recent pancancer analyses reveal that ubiquitination pathways drive histological fate decisions, particularly adenocarcinoma to squamous cell carcinoma (SQC) or neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) transdifferentiation [24]. The OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination axis activates MYC signaling and promotes squamous transdifferentiation in lung, esophageal, and cervical cancers [24]. Key technical considerations:

- Ubiquitination scores positively correlate with squamous or neuroendocrine features in adenocarcinoma

- Monitor OTUB1-TRIM28 complex formation via co-immunoprecipitation under cross-linking conditions

- Profile ubiquitin chain topology changes during transformation using linkage-specific antibodies (K48 vs K63)

Q3: How does ubiquitination contribute to immune evasion in the tumor microenvironment?

Ubiquitination regulates multiple immune evasion mechanisms by controlling the stability of PD-L1, modulating antigen presentation machinery, and altering cytokine signaling [25] [8]. MYC-driven tumors exploit ubiquitination to upregulate immune checkpoints like PD-L1 and CD47 while suppressing MHC class I/II expression [26]. Technical challenges include:

- Low abundance of ubiquitinated immune regulators requires high-sensitivity enrichment

- Spatial heterogeneity of ubiquitination within tumor microenvironment niches

- Use spatial ubiquitinomics combining multiplex IHC with ubiquitin chain profiling

► Featured Experimental Protocol: DRUSP for Low-Abundance Ubiquitinated Proteins

The Denatured-Refolded Ubiquitinated Sample Preparation (DRUSP) method significantly enhances detection of low-abundance ubiquitinated proteins by addressing key technical limitations of native lysis conditions [27].

Table: DRUSP Protocol Workflow

| Step | Procedure | Critical Parameters | Troubleshooting Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Protein Extraction | Lyse tissues/cells in strong denaturing buffer (4% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM NEM, protease inhibitors) | Maintain temperature <25°C during extraction; use mechanical homogenization | If viscosity is high, add Benzonase (25 U/mL) and incubate 15 min at room temperature |

| 2. Denaturation | Heat samples at 95°C for 10 minutes | Ensure sample pH remains stable during heating | Check pH after heating; adjust with Tris-HCl if needed |

| 3. Refolding | Dilute lysate 10-fold with refolding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100) | Add refolding buffer dropwise while vortexing to prevent aggregation | If precipitate forms, centrifuge at 12,000g for 10 min before proceeding |

| 4. Ubiquitin Enrichment | Incubate with Tandem Hybrid UBD (ThUBD) beads for 2 hours at 4°C | Use rotation instead of shaking for better bead suspension | Pre-clear lysate with control beads for 30 min to reduce non-specific binding |

| 5. Washing | Wash beads 4x with wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40) | Include final wash with 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 only | For phospho-ubiquitin studies, add phosphatase inhibitors to all buffers |

| 6. Elution | Elute with 2x Laemmli buffer + 20 mM DTT at 95°C for 10 min | Do not use acidic elution as it disrupts downstream MS analysis | For mass spectrometry, elute with 8 M urea in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 |

Performance Metrics: DRUSP increases ubiquitin signal detection by approximately 10-fold compared to conventional native lysis methods and improves reproducibility with a coefficient of variation <15% between technical replicates [27].

► Ubiquitination Monitoring: Pathway-Specific Workflows

► Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Enrichment Tools | Tandem Hybrid UBD (ThUBD), TUBEs | High-affinity capture of ubiquitinated proteins; protects ubiquitin chains from DUBs | ThUBD recognizes 8 ubiquitin chain types without bias; superior to single UBD domains [27] |

| DUB Inhibitors | PR-619, N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | Preserve ubiquitination signals during sample processing | NEM (10 mM) more stable for long procedures; PR-619 broader specificity for mechanistic studies |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Stabilize ubiquitinated proteins by blocking degradation | MG132 (10-20 µM, 4-6h) for reversible inhibition; Bortezomib (100 nM) for irreversible inhibition |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K48-, K63-, K11-linkage specific | Determine ubiquitin chain topology in immunoblotting | Validate specificity with linkage-defined di-ubiquitin standards; high lot-to-lot variability |

| Activity-Based Probes | Ub-AMC, HA-Ub-VS | Monitor DUB activity in cell lysates and living cells | Ub-AMC for kinetic studies; HA-Ub-VS for DUB profiling and pull-downs |

| Chain-Specific UBDs | K48- and K63-specific UIMs | Enrich for specific ubiquitin chain linkages | Use combination approach with pan-UBD for comprehensive coverage of ubiquitinome |

► Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent ubiquitination signals between replicates

- Potential Cause: DUB activity during lysis or variable proteasome inhibition

- Solution: Implement DRUSP protocol with immediate denaturation; aliquot NEM fresh for each experiment; include universal DUB inhibitor (1-10 µM PR-619) in all buffers

- Validation: Spike-in control with defined ubiquitinated protein (e.g., ubiquitinated histones)

Problem: Low yield of ubiquitinated proteins after enrichment

- Potential Cause: Insufficient refolding after denaturation or suboptimal UBD binding

- Solution: Optimize refolding buffer composition; test different UBD constructs (ThUBD vs TUBEs); increase input material (3-5 mg total protein recommended)

- Validation: Check efficiency by immunoblotting for known ubiquitinated proteins (e.g., p53, MYC)

Problem: High background in ubiquitin pull-downs

- Potential Cause: Non-specific binding to affinity matrix or protein aggregation

- Solution: Include more stringent washes (500 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS); pre-clear lysates with empty beads; optimize detergent concentration in refolding buffer

- Validation: Run negative control with catalytically inactive UBD mutant

► Advanced Application: Integrating Ubiquitination Data with Multi-Omics

For comprehensive analysis of ubiquitination in cancer pathways, combine ubiquitinomics with:

- Transcriptomics: Correlate OTUB1-TRIM28 expression with MYC target genes [24]

- Metabolomics: Assess acetyl-CoA levels that influence MYC acetylation and stability [26]

- Immunophenotyping: Link ubiquitination patterns with immune cell infiltration in TIME [25]

The ubiquitination regulatory network provides a framework for identifying novel drug targets, particularly for traditionally "undruggable" oncoproteins like MYC [24]. By implementing these optimized protocols and troubleshooting strategies, researchers can significantly enhance the detection and characterization of low-abundance ubiquitinated proteins critical for understanding cancer progression and therapeutic resistance.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a crucial post-translational modification mechanism that regulates protein degradation and function, impacting key cellular processes including cell cycle progression, DNA repair, and immune responses [28] [29]. In cancer research, ubiquitination signatures—patterns of gene expression involving ubiquitin-related enzymes and their targets—have emerged as powerful tools for predicting clinical outcomes and stratifying patients [30] [31] [32]. These signatures capture the complex interplay between E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes, E3 ligases, and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that collectively determine protein fate [28]. For researchers investigating low-abundance ubiquitinated proteins in cancer, analyzing these signatures provides a window into the altered regulatory mechanisms driving tumor progression, metastasis, and treatment resistance. The clinical utility of ubiquitination signatures has been demonstrated across multiple cancer types, including breast cancer [30] [33] [34], glioma [32], osteosarcoma [31], and lung adenocarcinoma [35], establishing them as valuable prognostic biomarkers worthy of incorporation into clinical practice.

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Challenges with Low-Abundance Ubiquitinated Proteins

Table 1: Troubleshooting Low-Abundance Ubiquitinated Protein Detection

| Challenge | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or no ubiquitination signal | Low stoichiometry of modification; Transient nature of ubiquitination | Treat cells with proteasome inhibitors (e.g., 5-25 μM MG-132 for 1-2 hours) prior to harvesting [28] |

| Non-specific bands or high background | Non-specific antibody binding; Inadequate blocking | Use high-affinity ubiquitin traps (e.g., ChromoTek Ubiquitin-Trap) for clean pulldowns; Validate with linkage-specific antibodies [28] [29] |

| Inconsistent results between replicates | Variable enrichment efficiency; Protease contamination | Implement tandem-repeated Ub-binding domains (UBDs) for higher affinity capture; Add protease inhibitors to all buffers [29] |

| Difficulty detecting specific ubiquitin chain linkages | Antibody specificity limitations; Masking by dominant linkages | Combine linkage-specific antibodies with mass spectrometry verification; Use ubiquitin mutants in validation experiments [29] |

| Poor yield from immunoprecipitation | Insufficient binding capacity; Suboptimal lysis conditions | Scale enrichment method to sample size; Optimize lysis buffer composition and incubation times [28] |

Validation Challenges for Ubiquitination Signatures

Table 2: Troubleshooting Ubiquitination Signature Validation

| Challenge | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor correlation between signature predictions and clinical outcomes | Overfitting of signature to training data; Biological heterogeneity | Validate in multiple independent cohorts; Use cross-validation; Incorporate clinical covariates in multivariate analysis [35] [34] |

| Signature not generalizable across cancer types | Cancer-specific ubiquitination pathways; Different driver mutations | Validate cancer-specific signatures; Include pan-cancer analysis during development [30] [32] [35] |

| Discrepancy between mRNA and protein levels | Post-transcriptional regulation; Protein stability issues | Incorporate proteomic data where available; Focus on copy number alterations which may be more stable than mRNA levels [30] |

| Technical variability in risk stratification | Inconsistent assay conditions; Batch effects | Standardize experimental protocols; Apply batch effect correction algorithms (e.g., ComBat) when combining datasets [33] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does ubiquitin often appear as a smear on western blots, and how can I interpret this? A: The smeared appearance occurs because ubiquitinated proteins exist in various states—monoubiquitinated, multiubiquitinated, and polyubiquitinated—with different chain lengths and linkage types. This creates a heterogeneous mixture of molecular weights that appears as a smear rather than discrete bands. The Ubiquitin-Trap can bind all these forms, resulting in this characteristic pattern [28].

Q2: Can I differentiate between different ubiquitin linkage types in my experimental system? A: Standard ubiquitin enrichment methods like Ubiquitin-Trap are not linkage-specific. However, you can use linkage-specific antibodies during western blot analysis after enrichment to distinguish between different chain types. For comprehensive linkage analysis, mass spectrometry-based approaches are recommended [28] [29].

Q3: How can I increase the yield of low-abundance ubiquitinated proteins from patient tissue samples? A: For patient tissues where genetic manipulation isn't feasible, use antibody-based approaches with pan-ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., P4D1, FK1/FK2) or linkage-specific antibodies. These can enrich endogenously ubiquitinated proteins without requiring tagged ubiquitin expression. Supplement with proteasome inhibition during sample collection when possible [29].

Q4: What are the key considerations when building a ubiquitination-related gene signature for clinical prognosis? A: Focus on genes with established roles in cancer progression, use copy number alterations which may be more stable than mRNA levels, include both E3 ligases and deubiquitinating enzymes, and validate extensively across multiple independent cohorts. The SKP2 ubiquitination signature (FZR1 vs. USP10) exemplifies this approach [30].

Q5: How do I determine if my ubiquitination signature has clinical utility beyond established prognostic factors? A: Perform both univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses including standard clinical variables (age, stage, grade) to demonstrate independent prognostic value. Additionally, assess correlation with treatment response and immune microenvironment features [35] [33].

Ubiquitination Signatures as Prognostic Biomarkers: Key Evidence

Established Ubiquitination Signatures Across Cancers

Table 3: Validated Ubiquitination Signatures in Cancer Prognosis

| Cancer Type | Signature Components | Clinical Utility | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer (Luminal) | FZR1 vs. USP10 copy number [30] | Stratifies patients into high/low SKP2 ubiquitination groups; Prognostic for overall survival | Log-rank p = 0.006; Associated with tumor grade (p = 6.7×10⁻³) and stage (p = 1.6×10⁻¹¹) [30] |

| Breast Cancer | 6-gene signature (ATG5, FBXL20, DTX4, BIRC3, TRIM45, WDR78) [34] | Prognostic risk stratification; Predictive for treatment response | Validated across multiple external datasets (TCGA-BRAC, GSE1456, etc.); Superior to traditional clinical indicators [34] |

| Glioma | USP4-based signature [32] | Distinguishes high-risk vs. low-risk patients; Guides immunotherapy decisions | High-risk group had significantly worse prognosis (P<0.05); Associated with immune microenvironment [32] |

| Lung Adenocarcinoma | 4-gene signature (DTL, UBE2S, CISH, STC1) [35] | Prognostic stratification; Predicts immunotherapy response | Hazard Ratio [HR] = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.39-0.73, p < 0.001; Validated in 6 external cohorts [35] |

| Osteosarcoma | TRIM8 and UHRF2 signature [31] | Prognostic risk assessment | High gene significance score associated with worse prognosis; Good prediction accuracy by ROC analysis [31] |

Methodologies for Ubiquitination Signature Development

The development of robust ubiquitination signatures follows a systematic bioinformatics pipeline:

Data Collection and Preprocessing

- Obtain RNA-seq data and clinical information from databases such as TCGA and GEO [32] [33]

- Normalize expression data (e.g., FPKM, TPM, or count normalization) [31] [33]

- Curate ubiquitination-related genes from specialized databases (e.g., iUUCD, MSigDB) [31] [33] [34]

Signature Identification and Validation

- Perform differential expression analysis between clinical subgroups

- Conduct univariate Cox regression to identify prognostic ubiquitination-related genes [32] [35]

- Apply feature selection algorithms (LASSO Cox regression, Random Survival Forests) to prevent overfitting [31] [35] [33]

- Calculate risk scores using gene expression and regression coefficients [31] [33]

- Validate signatures in independent external cohorts [35] [34]

Functional and Clinical Characterization

- Assess association with clinical-pathological features (stage, grade, metastasis) [30] [33]

- Evaluate tumor microenvironment features and immune cell infiltration [32] [35] [33]

- Analyze predictive value for therapy response and drug sensitivity [35] [33]

Experimental Protocols for Ubiquitination Signature Validation

Protocol 1: Ubiquitinated Protein Enrichment and Detection

Purpose: To enrich and detect low-abundance ubiquitinated proteins from cancer tissue samples for signature validation.

Materials:

- Ubiquitin-Trap Agarose or Magnetic Agarose (ChromoTek) [28]

- Proteasome inhibitor (MG-132) [28]

- Lysis, wash, dilution, and elution buffers [28]

- Ubiquitin recombinant antibody [28]

- Appropriate secondary antibodies [28]

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Treat cells with 5-25 μM MG-132 for 1-2 hours before harvesting to preserve ubiquitination signals. Optimize concentration and duration for specific cell types to minimize cytotoxicity [28].

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells or tissue samples in appropriate buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors.

- Enrichment: Incubate lysates with Ubiquitin-Trap beads for immunoprecipitation. Use harsh washing conditions to reduce background.

- Elution: Elute bound ubiquitinated proteins using appropriate elution buffer.

- Detection: Analyze by western blot using ubiquitin-specific antibodies. For linkage-specific analysis, use appropriate linkage-specific antibodies.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Smear appearance on western blot is normal and indicates successful enrichment of various ubiquitinated species [28]

- For low-yield samples, consider increasing starting material or optimizing lysis conditions

- Include positive and negative controls to validate enrichment efficiency

Protocol 2: Functional Validation of Signature Genes

Purpose: To experimentally validate the functional role of key genes identified in ubiquitination signatures.

Materials:

- Relevant cancer cell lines

- siRNA or overexpression constructs for target genes

- Transfection reagents

- Antibodies for functional assays (e.g., USP4, E-cadherin, N-cadherin) [32]

- Cell culture materials and invasion/migration assay kits

Procedure (based on USP4 validation in glioma [32]):

- Gene Modulation: Knock down or overexpress target gene (e.g., USP4) in appropriate cell lines using siRNA or expression vectors.

- Functional Assays:

- Assess cell activity, invasion, and migration capabilities

- Perform colony formation assays

- Evaluate markers of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (E-cadherin, N-cadherin)

- Validation: Confirm protein level changes by western blot and functional effects.

Interpretation: Expected results: Knockdown of oncogenic ubiquitination genes (e.g., USP4 in glioma) should significantly reduce activity, invasion, migration capacity, and colony formation ability. Overexpression should produce opposite effects [32].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitination Signature Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Enrichment Tools | Ubiquitin-Trap Agarose/Magnetic Agarose (ChromoTek) [28] | Immunoprecipitation of monomeric ubiquitin, ubiquitin chains, and ubiquitinated proteins from various cell extracts |

| Ubiquitin Antibodies | Ubiquitin Recombinant Antibody [28]; Linkage-specific antibodies (K48, K63, etc.) [29] | Detection of total ubiquitination or specific ubiquitin chain linkages |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG-132 [28]; Syringolin A [36] | Preserve ubiquitinated proteins by blocking proteasomal degradation |

| Tagged Ubiquitin Systems | His-tagged Ub [29]; Strep-tagged Ub [29] | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins in living cells |

| Cell Line Models | Cancer cell lines relevant to studied cancer type (e.g., U87-MG, LN229 for glioma) [32] | Functional validation of signature genes through knockdown/overexpression experiments |

| Computational Tools | ConsensusClusterPlus [33]; ESTIMATE [32]; CIBERSORT [32] | Bioinformatics analysis of ubiquitination signatures and tumor microenvironment |

Conceptual Framework and Signaling Pathways

Ubiquitination Signature Development Workflow

SKP2 Ubiquitination Regulation in Breast Cancer

Ubiquitination signatures represent a promising frontier in cancer prognostication and personalized medicine. The consistent demonstration of their prognostic value across multiple cancer types highlights the fundamental role of ubiquitination pathways in tumor biology. For researchers working with low-abundance ubiquitinated proteins, the methodologies and troubleshooting approaches outlined here provide practical pathways to overcome technical challenges. Future directions include standardizing signature validation protocols, developing multi-omics approaches that integrate ubiquitination signatures with other molecular data, and creating targeted therapies based on specific ubiquitination pathway alterations. As evidence continues to accumulate, ubiquitination signatures are poised to transition from research tools to clinically implemented biomarkers that guide cancer treatment decisions and improve patient outcomes.

Advanced Methodologies for Enrichment, Detection, and Profiling of Ubiquitinated Proteins

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is the signal for my ubiquitinated protein so low or undetectable in Western blot?

Low detection signal is one of the most common challenges when studying ubiquitination. The causes and solutions are multifaceted [37].

- Low Abundance and Transient Nature: Ubiquitination is a highly dynamic and reversible post-translational modification. The percentage of a specific protein that is ubiquitinated at any given time can be very small [38] [20].

- Solution: Treat cells with proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) before harvesting. A good starting point is 5-25 µM for 1–2 hours. This prevents the degradation of polyubiquitinated proteins, thereby preserving and accumulating the ubiquitination signal. Avoid overexposure as it can lead to cytotoxic effects [38].

- Solution: Use deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitors in your lysis buffer. Pan-selective Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) are particularly effective as they not only enrich ubiquitinated proteins but also shield the ubiquitin chains from DUBs during the isolation process [39].

- Inappropriate Lysis Buffer: Using a strongly denaturing lysis buffer like RIPA (which contains sodium deoxycholate) can disrupt protein-protein interactions and may denature the ubiquitination machinery or epitopes [37].

- Solution: Use a milder, non-denaturing cell lysis buffer (e.g., Cell Lysis Buffer #9803) for immunoprecipitation (IP) and co-IP experiments to preserve native interactions [37].

- Antibody Specificity: Many ubiquitin antibodies are non-specific and bind large amounts of artifacts due to the small and weakly immunogenic nature of ubiquitin [38].

- Solution: Validate your antibody with appropriate controls. For enrichment, consider using high-affinity nano-traps (e.g., ChromoTek Ubiquitin-Trap) or TUBEs, which are engineered for high-affinity capture of ubiquitin and ubiquitinated proteins [38] [39].

Q2: My ubiquitin pulldown experiment shows a high background or non-specific bands. How can I resolve this?

High background is often due to non-specific binding to the solid support or the antibody itself [37].

- Solution: Include rigorous controls. A bead-only control (incubating lysate with bare beads) identifies proteins that bind non-specifically to the beads. An isotype control (using a non-specific antibody from the same host species) identifies background caused by the immunoprecipitating antibody.

- Solution: Pre-clear your lysate. Incubate the lysate with the beads alone for 30-60 minutes at 4°C before performing the actual IP. This pre-clearing step can remove proteins that non-specifically bind to the beads.

- Solution: Optimize wash stringency. Increase the number or stringency of washes (e.g., by increasing salt concentration or adding mild detergents) after the pulldown to reduce non-specific binding without disrupting specific interactions.

Q3: How can I specifically study a particular type of ubiquitin chain linkage (e.g., K48 vs. K63)?

Different ubiquitin linkages trigger distinct downstream signaling events, and their specific characterization is crucial [38].

- Solution: Use linkage-specific reagents. Linkage-specific antibodies are available for several chain types (e.g., K48, K63, M1). These can be used for Western blotting after a general ubiquitin enrichment or, in some cases, for immunoprecipitation [20].

- Solution: Employ linkage-specific TUBEs. LifeSensors offers TUBEs that are specific for K48 and K63 linkages, allowing for targeted enrichment and a deeper exploration of specific ubiquitination pathways [39].

- Solution: Mass Spectrometry (MS). MS-based proteomics is the gold standard for determining ubiquitin chain architecture. Following enrichment with pan-selective or linkage-specific reagents, digested peptides can be analyzed by MS to identify the specific lysine residues on ubiquitin that are involved in chain formation, revealing the linkage type [40] [20].

Troubleshooting Guide for Common Experimental Issues

The table below summarizes specific problems, their causes, and recommended actions.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Low/No Signal | Ubiquitinated proteins degraded by proteasomes or DUBs during lysis [38] [39] | - Use proteasome inhibitors (MG-132) and DUB inhibitors during cell preparation and lysis.- Perform lysis on ice or at 4°C, and process samples quickly.- Use TUBEs to shield ubiquitin chains from DUBs [39]. |

| Low/No Signal | Target protein or its ubiquitinated form is lowly expressed [37] | - Check protein expression levels using databases (BioGPS, Human Protein Atlas).- Always include an input lysate control in Western blots to confirm protein presence and antibody functionality [37]. |

| High Background / Non-specific Bands | Non-specific binding of proteins to beads or antibody [37] | - Include bead-only and isotype control IPs.- Pre-clear lysate with beads.- Optimize wash buffer stringency. |

| High Background / Non-specific Bands | Post-translational modifications (PTMs) causing band shifts [37] | - Consult resources like PhosphoSitePlus to see if your protein has known PTMs.- The input control helps determine if multiple bands are specific. |

| IgG Heavy/Light Chains Obscuring Target | Denatured IgG chains from IP antibody detected by Western secondary antibody [37] | - Use antibodies from different species for IP and Western blot (e.g., rabbit for IP, mouse for WB).- Use biotinylated primary and streptavidin-HRP for Western detection.- Use light-chain specific secondary antibodies. |

| Inability to Differentiate Linkages | Pan-specific enrichment methods capture all linkage types [38] [39] | - Follow pan-enrichment with Western blot using linkage-specific antibodies.- Use linkage-specific TUBEs (e.g., K48 or K63 specific) for pulldown [39].- Utilize MS-based proteomics for definitive linkage identification [40]. |

Essential Workflow Diagrams

Ubiquitinated Protein Analysis Workflow

This diagram outlines the core steps for the isolation and analysis of ubiquitinated proteins, integrating key tools to address major challenges like deubiquitination and low abundance.

The Ubiquitin Code and Functional Consequences

This diagram illustrates the "Ubiquitin Code," showing how different chain linkages correspond to specific cellular functions, a key concept for data interpretation in cancer research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table details essential materials for studying ubiquitination, emphasizing their specific function in the workflow.

| Research Reagent | Function & Application in Ubiquitination Workflows |

|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) | Preserves polyubiquitinated proteins (especially K48-linked) by blocking their degradation by the 26S proteasome, thereby enhancing detection signal [38]. |

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities) | Engineered, high-affinity reagents (multiple UBA domains) for pan-selective or linkage-specific enrichment of polyubiquitin chains. Critically, they shield ubiquitin chains from DUBs and proteasomal degradation during isolation, maintaining native architecture [39]. |

| Ubiquitin-Trap (Nanobody) | A recombinant anti-ubiquitin VHH nanobody coupled to beads for immunoprecipitation of monomeric ubiquitin, ubiquitin chains, and ubiquitinated proteins from various cell extracts. Provides a clean, low-background pulldown [38]. |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Allows for the detection or immunoprecipitation of ubiquitin chains with a specific linkage (e.g., K48, K63, M1), enabling the study of distinct ubiquitin-dependent signaling pathways [20]. |

| Tagged Ubiquitin (e.g., His, HA, Strep) | Used in Ub tagging-based approaches. Cells are engineered to express tagged ubiquitin, which is incorporated into ubiquitinated proteins. The tag allows for affinity-based purification (e.g., with Ni-NTA or Strep-Tactin resin) of the entire ubiquitinated proteome for MS analysis [20]. |

Advanced Methodologies: MS-Based Proteomics

Mass spectrometry is a powerful, untargeted technology for discovering ubiquitinated proteins, identifying modification sites, and deciphering ubiquitin chain architecture [39]. Key methodologies include:

- TUBE-based Pulldown for MS: Pan-selective or linkage-specific TUBEs are used to enrich ubiquitinated proteins from complex cell lysates. The enriched proteins are then digested with trypsin, and the resulting peptides are analyzed by LC-MS/MS. This workflow is highly effective for identifying ubiquitination sites and substrates [39].

- Tandem Enrichment with SCASP-PTM: A recent (2025) protocol allows for the sequential enrichment of ubiquitinated, phosphorylated, and glycosylated peptides from a single protein digest sample without intermediate desalting steps. This efficient multiplexing saves precious sample material and provides a more comprehensive view of the PTM landscape [41].

- DiGly Antibody Enrichment: A common peptide-centric approach. Proteins are digested, and peptides containing the characteristic diglycine (Gly-Gly) remnant left on ubiquitinated lysines after trypsin digestion are enriched with specific antibodies. This method directly identifies the exact site of ubiquitination [39].

Ubiquitination is a pivotal post-translational modification that regulates the stability, activity, and localization of proteins involved in virtually all cellular processes. In cancer research, profiling the "ubiquitinome" is essential for understanding tumor metabolism, the immunological tumor microenvironment, and cancer stem cell stemness [8] [24]. However, the low stoichiometry of ubiquitinated proteins and the complexity of ubiquitin (Ub) chain architectures present significant technical challenges. This technical support center provides a comprehensive guide to the three primary affinity-based enrichment strategies—Ubiquitin Antibodies, Tagging (His/Strep), and Ubiquitin-Binding Domains (UBDs)—to help researchers successfully isolate and analyze low-abundance ubiquitinated proteins from complex biological samples in cancer research.

Core Methodologies and Strategic Comparison

The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics, applications, and key considerations for the three primary enrichment strategies.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Affinity-Based Enrichment Strategies for Ubiquitinated Proteins

| Method | Principle | Best For | Throughput | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Tagging (e.g., His/Strep) | Ectopic expression of tagged Ub; affinity purification of tagged conjugates [20]. | Proteomic profiling of ubiquitination sites; controlled cell culture systems [20]. | High | Relatively easy and low-cost; enables global site mapping [20]. | Requires genetic manipulation; tagged Ub may not fully mimic endogenous Ub [20]. |

| Ubiquitin Antibodies | Immunoaffinity purification using antibodies specific to Ub or particular chain linkages [20]. | Studying endogenous ubiquitination under physiological conditions; clinical samples; specific chain linkage analysis [20]. | Medium | Applicable to any biological sample, including animal and patient tissues [20]. | High cost of quality antibodies; potential for non-specific binding [20]. |

| Ubiquitin-Binding Domains (UBDs) | Affinity purification using recombinant proteins with high-affinity Ub-binding domains (e.g., TUBEs) [42] [20]. | Capturing native ubiquitin-protein complexes; protecting ubiquitylated proteins from deubiquitinases (DUBs) [42]. | Medium | Protects ubiquitinated proteins from DUBs and the proteasome during purification; preserves native complexes [42] [20]. | Requires production of recombinant UBD proteins. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful enrichment relies on a suite of specialized reagents. The following table catalogs key solutions for your experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Enrichment

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | High-affinity ubiquitin traps for purifying ubiquitylated proteins under non-denaturing conditions [42] [20]. | Based on tandem UBA domains; protects from DUBs; can be pan-specific or linkage-selective [42]. |

| Linkage-Specific Ub Antibodies | Enrichment and detection of polyUb chains with specific linkages (e.g., K48, K63, M1) [20]. | Essential for deciphering the ubiquitin code; used in immunoblotting, immunofluorescence, and enrichment [20]. |

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors | Added to cell lysis and purification buffers to prevent loss of ubiquitin signal during processing [42]. | e.g., N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) or iodoacetamide; critical for preserving the native ubiquitome [42]. |

| Ni-NTA Agarose/Resin | Standard affinity resin for purifying 6xHis-tagged ubiquitin-protein conjugates [20]. | Used under native or denaturing conditions; can co-purify histidine-rich proteins [20]. |

| Strep-Tactin Resin | Affinity resin for purifying Strep-tagged ubiquitin-protein conjugates [20]. | High specificity and purity; can be co-purified with endogenously biotinylated proteins [20]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

A. Ubiquitin Tagging (His/Strep) Strategies

Q: My His-tagged ubiquitin constructs are expressed but not binding effectively to the IMAC resin. What could be wrong? A: This is a common issue with several potential causes and solutions:

- Hidden His Tag: The tag may be buried inside the protein's three-dimensional structure. Solutions include: [43]

- Perform purification under denaturing conditions (using urea or guanidinium chloride) and refold the protein after elution.

- Incorporate a flexible linker (e.g., with glycines and serines) between the tag and your protein.

- Move the His tag to the opposite terminus of the construct.

- Non-optimal Binding Buffer: The buffer composition can critically affect binding. [43]

- Imidazole Concentration: Even small amounts of imidazole in the binding buffer can compete with the His tag. Titrate the imidazole concentration (including testing 0 mM) to find the optimal condition.

- Buffer pH: A low pH can protonate histidine side chains, impairing coordination with the nickel resin. Ensure your binding buffer pH is correct and adjust it after adding imidazole.

Q: What are the major caveats of using tagged ubiquitin for proteomic studies? A: While powerful, this method has limitations: [20]

- Non-specific Co-purification: Ni-NTA can bind histidine-rich proteins, and Strep-Tactin can bind endogenously biotinylated proteins, leading to background.

- Potential Artifacts: The tag itself may alter Ub structure/function and not perfectly mimic endogenous Ub.

- Limited Application: It is infeasible for direct use in animal or patient tissues, restricting its use to genetically manipulated cell systems.

B. Ubiquitin Antibody-Based Strategies

Q: How do I choose between different anti-ubiquitin antibodies for enrichment? A: The choice depends on your experimental goal:

- For Global Ubiquitome Profiling: Use antibodies that recognize all ubiquitin linkages, such as FK1, FK2, or P4D1 [20].

- For Specific Ubiquitin Signaling: Use linkage-specific antibodies (e.g., for K48, K63, M1) to investigate the role of particular chain types in processes like proteasomal degradation (K48) or NF-κB signaling (K63) [8] [20].

- For Clinical Samples: Antibody-based approaches are uniquely suited for profiling endogenous ubiquitination in patient-derived tissues without genetic manipulation [20].

C. Ubiquitin-Binding Domain (UBD)-Based Strategies

Q: What is the key advantage of using TUBEs over other methods? A: The primary advantage of Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) is their ability to protect the ubiquitin signal during purification. They exhibit very high affinity for polyubiquitin chains and effectively shield them from the activity of deubiquitinases (DUBs) and the proteasome, preserving the native state of the ubiquitin conjugates [42] [20]. This makes them superior for studying labile ubiquitination events and for capturing intact ubiquitin-protein complexes.

Q: Can UBDs differentiate between ubiquitin chain types? A: Yes, the specificity varies by domain. Some UBDs, like those in CEP55, show preferences for certain chain types (e.g., linear and K63 polyubiquitin chains) [44]. Similarly, engineered TUBEs can be developed to have selectivity for specific chain linkages, much like linkage-specific antibodies [20].

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a generalized strategic workflow for selecting and applying these enrichment methods in a cancer research context, from experimental setup to functional analysis.

Strategic Workflow for Ubiquitin Enrichment in Cancer Research

Advanced Applications in Cancer Research

The versatility of affinity-based enrichment methods enables critical discoveries in oncology. The diagram below illustrates how these tools are applied to dissect ubiquitin-driven mechanisms in cancer, from protein-level analysis to therapeutic development.

Applications of Ubiquitin Enrichment in Cancer Mechanism and Therapy

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: My mass spectrometry experiment failed to detect my ubiquitinated protein of interest. What are the most common causes? A: Failure to detect can stem from several issues. The protein may have been lost during sample processing or degraded despite enrichment. It is crucial to verify protein presence in your input sample by Western Blot and monitor each preparation step. Low-abundance ubiquitinated proteins can be masked by more abundant proteins; scaling up your sample or using immunoprecipitation for further enrichment can help [46].

Q: How can I confirm that a protein identified in my pull-down is a genuine ubiquitin conjugate and not a contaminant? A: The most definitive verification is the identification of the diglycine (K-ε-GG) remnant on a lysine residue via MS/MS spectra. Furthermore, always perform control experiments using isogenic strains or samples without tagged ubiquitin to identify and subtract background proteins that bind non-specifically to your affinity matrix [47].

Q: I am getting low peptide coverage for my protein of interest. How can I improve this? A: Low coverage often results from suboptimal peptide size for detection. Consider adjusting trypsin digestion time or using an alternative protease. A double digestion strategy using two different proteases can also generate a more suitable set of peptides for analysis [46].

Q: What are the key parameters to check in my mass spectrometry data to ensure a reliable identification? A: Focus on three key metrics: Coverage (aim for 40-80% for purified proteins), Peptide Count (the number of unique peptides detected for a protein), and statistical significance, often expressed as a P-value/Q-value/Score, which should be < 0.05 to minimize false positives [46].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Abundance Ubiquitin Conjugates Undetectable | Signal loss during preparation; masked by high-abundance proteins. | Scale up sample; use subcellular fractionation; enrich with immunoprecipitation [46]. |

| High Background in Affinity Purification | Non-specific binding to resin; endogenous His-rich proteins (for His-tag purifications). | Use denaturing conditions (e.g., 6 M Guanidine-HCl) during purification; implement tandem affinity tags (e.g., His-Biotin) [47]. |

| Protein Degradation | Protease activity during lysis and preparation. | Use comprehensive, EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktails; keep samples at 4°C [46]. |

| Inconsistent Ubiquitination Site Identification | Incomplete trypsin digestion; poor peptide ionization. | Optimize trypsin-to-protein ratio and digestion time; use a different protease (e.g., Lys-C) [47] [46]. |

Experimental Protocols for Ubiquitination Analysis

Protocol 1: Enrichment of Ubiquitinated Proteins from Cultured Cells Using His-Tag Purification