The ATP-Dependent Proteolysis System in Rabbit Reticulocyte Lysate: From Foundational Mechanisms to Modern Research Applications

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the ATP-dependent proteolysis system in rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RRL), a foundational in vitro tool for studying intracellular protein degradation.

The ATP-Dependent Proteolysis System in Rabbit Reticulocyte Lysate: From Foundational Mechanisms to Modern Research Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the ATP-dependent proteolysis system in rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RRL), a foundational in vitro tool for studying intracellular protein degradation. We explore the historical discovery of this soluble, non-lysosomal system and its core mechanism involving ubiquitin conjugation and ATP hydrolysis. The content details methodological applications in protein degradation assays and drug discovery, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and presents validation data through comparative analyses with other proteolytic systems. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes decades of research to guide effective experimental utilization and contextualize the continued relevance of RRL in biomedical research.

Discovering the RRL Proteolysis System: Historical Foundations and Core Mechanisms

In 1977, a landmark study by Etlinger and Goldberg established the existence of a soluble, non-lysosomal, ATP-dependent proteolytic system in rabbit reticulocytes, fundamentally reshaping our understanding of intracellular protein degradation. This pioneering work, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, demonstrated for the first time that the energy-dependent degradation of abnormal proteins could be reconstituted in a cell-free extract, providing a crucial experimental system for dissecting the biochemical machinery governing regulated proteolysis in eukaryotic cells. This discovery laid the essential groundwork for the subsequent identification of the ubiquitin-proteasome system and other ATP-dependent proteases, forming the foundation of a research field of immense importance to cellular physiology and drug development.

Prior to the 1970s, the prevailing paradigm attributed intracellular protein degradation primarily to the lysosome, an organelle discovered by Christian de Duve and known to contain a battery of acid hydrolases [1]. However, several lines of evidence were inconsistent with this view. Notably, the degradation of many abnormal and short-lived regulatory proteins was observed to be energy-dependent, occurring under conditions where lysosomal function was impaired [1]. A key experimental model for studying this phenomenon was the rabbit reticulocyte, which actively degrades abnormal proteins, such as globin synthesized in the presence of the valine analog 2-amino-3-chlorobutyric acid (ClAbu) [2] [3]. This analog-containing globin was degraded with a half-life of approximately 15 minutes, while normal hemoglobin was stable, highlighting the selectivity and regulatory potential of the process [3]. The central enigma was the biochemical mechanism responsible for this ATP-dependent, non-lysosomal proteolysis.

The Pioneering Experiment: Key Methodology and Findings

The seminal 1977 paper by Etlinger and Goldberg provided the first direct biochemical characterization of this system in a cell-free environment [2] [3].

Experimental Workflow and Setup

The researchers established a robust assay to probe the proteolytic machinery directly. The core experimental workflow is summarized below.

Key Experimental Steps [2] [3]:

- Reticulocyte Isolation: Reticulocytes were isolated from phenylhydrazine-induced anemic rabbits.

- Synthesis of Abnormal Protein Substrate: Cells were incubated with the amino acid analog 2-amino-3-chlorobutyric acid (ClAbu) to produce a population of abnormal, rapidly degraded globin.

- Preparation of Cell-Free Extract: A soluble cytosolic fraction (S100) was prepared by lysing the cells and centrifuging the lysate at 100,000 × g for 90 minutes. This step deliberately removed membranes and organelles, including lysosomes.

- Proteolysis Assay: The cell-free extract was incubated with the radioactively labeled abnormal globin under various conditions. Proteolysis was quantified by measuring the release of acid-soluble radioactivity, indicating the hydrolysis of the protein substrate into small peptides and amino acids.

Critical Results and Quantitative Data

The experimental results provided unambiguous evidence for a novel proteolytic system. The key quantitative findings are consolidated in the table below.

Table 1: Key Experimental Findings from the Etlinger & Goldberg (1977) Study [2] [3]

| Experimental Condition | Effect on Proteolysis of Abnormal Globin | Key Implication |

|---|---|---|

| ATP Addition | Stimulated degradation several-fold | Process is energy-dependent |

| ADP Addition | Slight stimulation | Specific requirement for nucleotide triphosphates |

| AMP / cAMP Addition | No significant effect | Specific requirement for nucleotide triphosphates |

| Lysosomal Inhibitors | No inhibition reported | System is non-lysosomal in origin |

| Serine Protease Inhibitors (TPCK, TLCK) | Inhibited proteolysis | Involves serine protease catalytic activity |

| Sulfhydryl Reagents (NEM, Iodoacetamide) | Inhibited proteolysis | Essential cysteine residues are required |

| Metal Chelator (o-Phenanthroline) | Inhibited proteolysis | Dependence on metal ions (e.g., Zn²⁺) |

The correlation between inhibitor sensitivities in the cell-free system and in intact reticulocytes confirmed the physiological relevance of the reconstituted system [3]. Furthermore, the system exhibited a pH optimum of 7.8, distinct from the acidic pH optimum of lysosomal proteases, providing additional evidence for its unique identity [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The investigation of the ATP-dependent proteolytic system relied on a specific set of biochemical reagents and materials.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Studying ATP-Dependent Proteolysis in Reticulocytes

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| Rabbit Reticulocytes | Biological source of the ATP-dependent proteolytic machinery; ideal model due to high proteolytic activity and lack of lysosomes. |

| Amino Acid Analog (ClAbu) | Incorporated into proteins during synthesis to generate defined "abnormal" protein substrates (e.g., globin) that are rapidly recognized and degraded. |

| Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) | The key nucleotide used to stimulate the proteolytic system; its non-hydrolyzable analogs helped define the energy requirement. |

| Protease Inhibitors (TPCK, TLCK) | Serine protease inhibitors used to characterize the catalytic class of the protease(s) involved and confirm the proteolytic nature of the activity. |

| Sulfhydryl Reagents (NEM, Iodoacetamide) | Used to alkylate free cysteine thiol groups, demonstrating the essential role of cysteine residues in the proteolytic pathway. |

| Metal Chelator (o-Phenanthroline) | Chelator of divalent cations (e.g., Zn²⁺, Fe²⁺); its inhibitory effect suggested the involvement of a metalloprotease or a metal-dependent step. |

Mechanistic Insights and the Path Forward

The 1977 discovery was a breakthrough that opened the door to mechanistic dissection. The core finding was that ATP serves two distinct roles in the degradation pathway, a concept later clarified by subsequent studies.

The Dual Role of ATP

Following the initial discovery, further research, including a key 1983 study, demonstrated that ATP hydrolysis is required for two distinct steps in the pathway [4]:

- Conjugation to Ubiquitin: The covalent attachment of the small protein ubiquitin to substrate proteins, marking them for degradation.

- Proteolysis per se: A step independent of ubiquitin conjugation, later understood to involve the unfolding of protein substrates and their translocation into the proteolytic core of the proteasome.

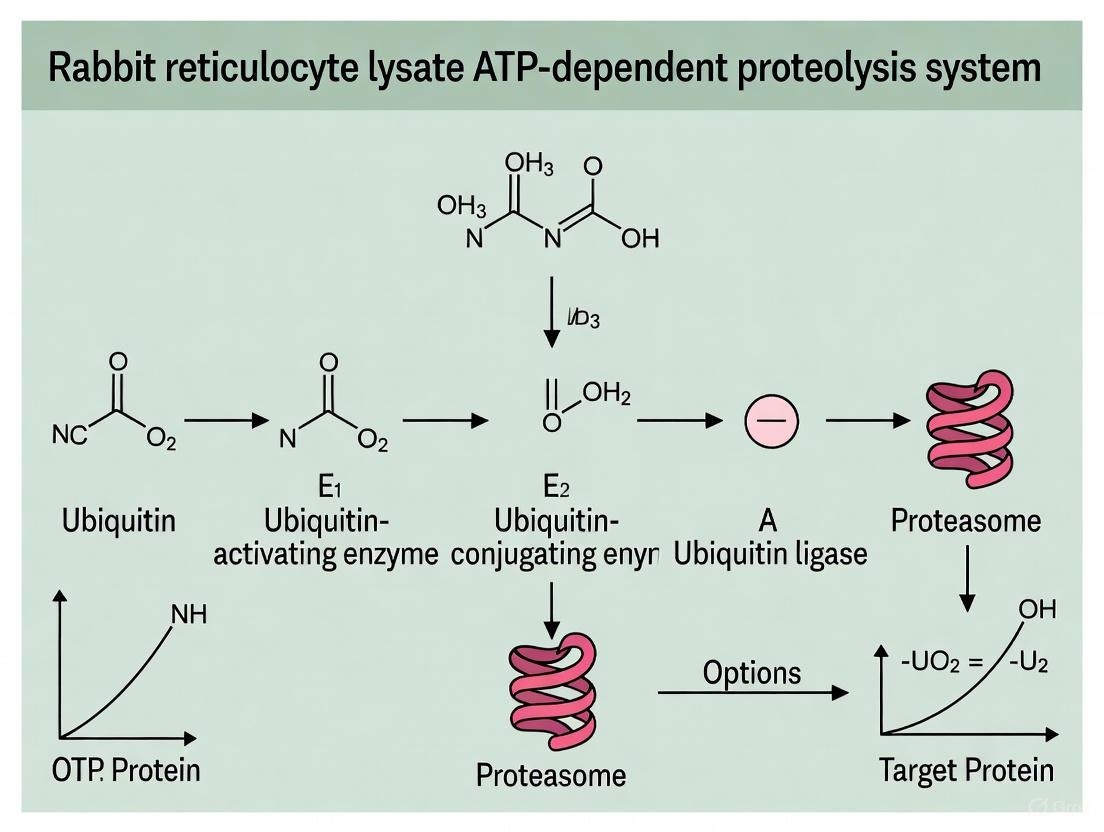

This dual requirement is illustrated in the following mechanism diagram.

The Etlinger and Goldberg system was thus the starting point for separating these two energy-dependent functions. Experiments with amino-blocked proteins that could not be ubiquitinated showed they were still degraded in an ATP-stimulated manner, proving the existence of the second, conjugation-independent role for ATP [4].

Legacy and Evolution of the Model

The cell-free system developed from rabbit reticulocytes was the direct experimental foundation for the next decade of Nobel Prize-winning work. It enabled the fractionation of the proteolytic machinery, leading directly to:

- The identification of ubiquitin as the ATP-dependent proteolysis factor (APF-1) [1].

- The purification and characterization of the 26S proteasome, the large proteolytic complex that degrades ubiquitin-tagged proteins [5] [6].

- The elucidation of the complex enzymatic cascade (E1, E2, E3) responsible for ubiquitin conjugation [6] [1].

The discovery also had conceptual breadth, as it paralleled findings in bacteria where ATP-dependent proteases like Lon (protease La) were being identified as key regulators of protein quality control and the degradation of specific regulatory proteins [7] [4].

The initial identification of a soluble ATP-dependent proteolytic system in rabbit reticulocytes was a transformative event in cell biology. By providing a well-defined and reproducible cell-free system, Etlinger and Goldberg enabled the reductionist biochemical dissection of a process fundamental to cellular regulation. This pioneering work moved the field beyond the lysosomal paradigm and laid the indispensable groundwork for discovering the ubiquitin-proteasome system, a discovery that has profoundly impacted our understanding of human disease mechanisms and created entirely new avenues for therapeutic intervention, particularly in cancer and neurodegenerative disorders. The reticulocyte lysate system remains a vital tool in biochemical research, a testament to the power of its initial discovery.

Within the broader context of research on the rabbit reticulocyte lysate ATP-dependent proteolysis system, the subcellular localization and origin of the proteolytic machinery are fundamental characteristics. The discovery that an ATP-dependent proteolytic system was present in the soluble fraction of reticulocytes and was non-lysosomal marked a significant departure from the then-prevailing understanding of cellular protein degradation [3]. This characteristic is essential for understanding the system's mechanism, its role in cellular physiology, and its distinction from other degradative pathways. This guide details the experimental evidence and methodologies that established these core system characteristics, providing a technical resource for researchers aiming to apply or build upon this knowledge.

Core Experimental Findings

The definitive characterization of the ATP-dependent proteolytic system in rabbit reticulocytes was established through a series of key experiments. The foundational study by Etlinger and Goldberg (1977) provided direct evidence for its soluble and non-lysosomal nature [3].

Table 1: Key Experimental Findings on System Localization and Origin

| Experimental Characteristic | Finding | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Subcellular Fractionation | Proteolytic activity was recovered in the 100,000 x g supernatant fraction [3]. | The active components are soluble cytosolic proteins, not associated with heavy organelles or membranes. |

| Sedimentation Analysis | The activity did not sediment under high-speed centrifugation [3]. | Confirms the system is not part of large, sedimentable structures like lysosomes, mitochondria, or the cytoskeleton. |

| pH Optimum | The system exhibited a pH optimum of 7.8 [3]. | This alkaline pH preference is distinct from the acidic pH optimum (∼4.5-5.0) characteristic of lysosomal proteases. |

| Comparative Cell Biology | A sedimentable, ATP-dependent proteolytic activity was found in less mature erythroleukemia cells [8]. | Suggests the system's form may change with cellular maturation, becoming soluble in terminally differentiated reticulocytes. |

These findings collectively demonstrated the existence of a novel, energy-dependent proteolytic pathway operating in the cytosol, separate from the lysosomal system.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Subcellular Fractionation of Reticulocytes

This protocol is used to isolate the soluble cytosolic fraction containing the ATP-dependent proteolytic activity.

Principle: Differential centrifugation separates cellular components based on size and density, allowing for the isolation of the 100,000 x g supernatant (S-100) as the soluble cytosolic fraction.

Procedure:

- Lysate Preparation: Isolate rabbit reticulocytes from phenylhydrazine-treated animals. Wash the cells and lyse them in a hypotonic buffer (e.g., 1-2 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM dithiothreitol).

- Low-Speed Centrifugation: Remove cell membranes and any unlysed cells by centrifuging the lysate at 10,000 x g for 20 minutes. Retain the supernatant.

- High-Speed Centrifugation: Transfer the 10,000 x g supernatant to ultracentrifuge tubes. Centrifuge at 100,000 x g for 1-2 hours at 4°C. This step pellets ribosomes, large organelles, and any remaining particulate matter.

- Fraction Collection: The resulting supernatant (S-100 fraction) contains the soluble cytosolic proteins, including the ATP-dependent proteolytic activity. The pellet can be resuspended in buffer for comparison.

- Activity Assay: Assay both the S-100 supernatant and the resuspended pellet for ATP-dependent proteolytic activity using a labeled substrate like analog-containing globin [3].

Assaying ATP-Dependent Proteolytic Activity

This protocol measures the degradation of abnormal proteins in the isolated fractions.

Principle: The degradation of a radiolabeled or otherwise tagged abnormal protein substrate is measured by the release of acid-soluble fragments in an ATP-dependent manner.

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a reaction mixture containing:

- Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8.

- Cofactors: 5 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM dithiothreitol.

- Energy Source: 1-2 mM ATP (an ATP-regenerating system, e.g., creatine phosphate and creatine kinase, is often included).

- Substrate: ³H-labeled abnormal protein (e.g., globin containing the valine analog 2-amino-3chlorobutyric acid) [3].

- Enzyme Source: The S-100 fraction or other subcellular fraction.

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction at 37°C for 30-60 minutes.

- Reaction Termination: Stop the reaction by adding an equal volume of cold 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA).

- Quantification: Keep the samples on ice for 30 minutes to precipitate intact protein, then centrifuge. Measure the radioactivity in the TCA-soluble supernatant, which represents the peptides and amino acids released by proteolysis [3].

- Controls: Include control reactions without ATP and without the enzyme source to determine background and ATP-stimulated activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Studying the ATP-Dependent Proteolytic System

| Reagent | Function in the Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| Rabbit Reticulocyte Lysate | The biological source material for preparing the S-100 fraction and studying the native proteolytic system [3]. |

| Abnormal Protein Substrate (e.g., ClAbu-globin) | A selectively degraded model substrate that demonstrates the system's specificity for misfolded or abnormal proteins [3]. |

| Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) | The essential energy source required to stimulate proteolysis; its hydrolysis is a key characteristic of the system [3]. |

| ATP-regenerating System | Prevents the depletion of ATP during the assay, ensuring sustained proteolytic activity. |

| Protease Inhibitors (TPCK, TLCK) | Serine protease inhibitors used to characterize the protease components and distinguish the system from other proteases [3]. |

| Sulfhydryl Reagents (N-ethylmaleimide, Iodoacetamide) | Inhibitors that target cysteine residues, demonstrating the essential role of cysteine proteases in the system [3]. |

| Metal Chelator (o-phenanthroline) | Inhibits metalloproteases; its inhibitory effect helps characterize the type of proteases involved [3]. |

Experimental and Conceptual Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the key experimental and conceptual frameworks for establishing the system's characteristics.

Reticulocyte Fractionation Workflow

Non-Lysosomal Evidence Synthesis

Discussion and Research Context

The localization of the ATP-dependent proteolytic system in the 100,000 x g supernatant firmly established its identity as a soluble, cytosolic pathway. This characteristic differentiates it from the lysosomal/vacuolar system and from other particulate-associated ATP-dependent activities found in less mature erythroid cells, such as erythroleukemia cells [8]. The non-lysosomal origin was further supported by the system's alkaline pH optimum and its specific inhibitor profile, which did not align with known lysosomal protease inhibitors. Subsequent research built upon this foundational characteristic, revealing that ATP plays two distinct roles in the pathway: one in the ubiquitin conjugation pathway and another, independent of ubiquitination, in the proteolytic process itself [4]. Understanding these system characteristics is crucial for drug development professionals targeting specific intracellular proteolytic pathways, as it allows for the rational design of inhibitors that avoid off-target effects on the lysosomal system.

The ATP-dependent proteolysis system in rabbit reticulocytes represents a fundamental biological pathway responsible for the selective degradation of abnormal proteins. Initial investigations into this system revealed a surprising requirement for metabolic energy in a process that is thermodynamically favorable, suggesting the involvement of sophisticated regulatory mechanisms [3] [1]. This energy-dependent pathway was subsequently shown to be non-lysosomal and present in the cytosol, representing a major breakthrough in understanding cellular protein quality control [3] [5]. The discovery of this system laid the foundation for identifying the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, which has since been recognized as a critical regulator of diverse cellular processes, with aberrations leading to various human diseases [1]. This technical guide examines the precise roles of ATP binding and hydrolysis in proteolytic activation, focusing specifically on insights gained from the rabbit reticulocyte lysate model system.

Historical Context and Fundamental Discoveries

The investigation of ATP-dependent proteolysis began with the observation that abnormal proteins in reticulocytes are rapidly degraded through an energy-requiring process. Seminal work in 1977 demonstrated that cell-free extracts from rabbit reticulocytes could hydrolyze abnormal proteins in the 100,000 × g supernatant fraction, exhibiting a pH optimum of 7.8 and showing no evidence of lysosomal involvement [3]. This soluble proteolytic system was stimulated several-fold by ATP, with ADP providing slight stimulation, while AMP and cyclic AMP had no significant effect [3]. The energy requirement was particularly puzzling because peptide bond hydrolysis is thermodynamically favorable, suggesting that ATP hydrolysis must be fulfilling other functions beyond driving the proteolytic reaction itself.

Further fractionation studies revealed that the ATP-dependent proteolytic system could be separated into distinct functional components. Researchers demonstrated that rabbit reticulocytes contain two distinct high molecular weight proteases: one approximately 1500 kDa enzyme that degrades proteins only when ATP and conjugating fractions are added, and a smaller 670 kDa protease that does not require ATP or ubiquitin [5]. The larger protease, described as the ubiquitin-conjugate degrading enzyme (UCDEN), was found to be labile in the absence of nucleotides and was strongly inhibited by various compounds including heparin, hemin, and N-ethylmaleimide [5]. This fractionation approach enabled researchers to dissect the individual steps in the ATP-dependent proteolytic pathway.

The 26S Proteasome: Architecture and ATP-Dependent Assembly

The 26S proteasome represents the central proteolytic machine in eukaryotic cells, comprising a 20S core particle (CP) and one or two 19S regulatory particles (RP). The 20S proteasome is a barrel-shaped structure composed of four stacked heptameric rings, with the catalytic sites located in an interior chamber [9]. Access to these catalytic sites is restricted by narrow pores (approximately 13 Å) at either end of the cylinder, which are further occluded by N-terminal peptide extensions of the outer ring subunits [9]. The 19S regulatory particle contains six homologous AAA ATPase subunits arranged in a ring that interfaces with the 20S proteasome, positioning them to mediate various ATP-dependent functions [9].

Table 1: Components of the 26S Proteasome Complex

| Component | Structure | Molecular Weight | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20S Core Particle (CP) | 4 stacked heptameric rings | 700,000 Da | Catalytic core; contains proteolytic active sites |

| 19S Regulatory Particle (RP) | 18 different subunits including 6 AAA ATPases | 700,000 Da | Substrate recognition, unfolding, translocation |

| 26S Proteasome (singly-capped) | 1 RP + 1 CP | 1,400,000 Da | Primary functional form in reticulocytes |

| 26S Proteasome (doubly-capped) | 2 RP + 1 CP | 2,400,000 Da | Enhanced degradation capacity |

Research using purified 26S proteasome from rabbit reticulocytes has demonstrated that ATP binding is necessary and sufficient for assembly of the 26S proteasome from 20S core and 19S regulatory subcomplexes [9]. This assembly is accompanied by a 20- to 50-fold increase in hydrolysis of peptide substrates, resulting from the opening of the gated pores at the ends of the 20S proteasome [9]. The stability of the assembled 26S proteasome is also maintained by ATP binding, as nucleotide depletion promotes dissociation into subcomplexes [9].

Distinct Roles of ATP Binding Versus ATP Hydrolysis

A critical advancement in understanding ATP-dependent proteolysis came from studies delineating the separate functions of ATP binding and ATP hydrolysis. Investigations with non-hydrolyzable ATP analogs revealed that ATP binding alone is sufficient for proteasome assembly and activation, though hydrolysis is required for complete proteolytic function [9].

Table 2: Nucleotide Requirements for 26S Proteasome Functions

| Proteasome Function | ATP Requirement | Nucleotide Specificity | Magnitude of Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assembly | Binding only | ATPγS, AMP-PNP effective | Half-maximal at ~40 μM ATP |

| Peptidase Activation | Binding only | ATPγS, AMP-PNP effective | 20-50 fold activation |

| Unstructured Protein Degradation | None | Not nucleotide dependent | Similar rates regardless of ATP |

| Folded Protein Degradation | Hydrolysis required | ATP specific | No degradation with analogs |

| Polyubiquitinated Protein Degradation | Hydrolysis required | ATP specific | Coupled to deubiquitination |

Experimental evidence demonstrated that half-maximal proteasome activation occurs at approximately 40 μM ATP, while non-hydrolyzable analogs ATPγS and AMP-PNP promoted assembly and activation at similar or lower concentrations (1 μM for ATPγS and 20 μM for AMP-PNP) [9]. Neither the 26S proteasome nor isolated PA700/19S complex hydrolyzed ATPγS at detectable rates, confirming that hydrolysis is not required for assembly [9].

The energy requirement for degradation depends significantly on substrate characteristics. The 26S proteasome can degrade non-ubiquitinated, unstructured proteins without ATP hydrolysis, indicating that substrate translocation through the opened pore does not inherently require energy [9]. However, both folded proteins and polyubiquitinated proteins require ATP hydrolysis for degradation, suggesting that the energy requirement is imposed by the mechanistic coupling of multiple processes rather than any single proteolytic step [9].

Diagram 1: ATP utilization in proteasome functions. ATP binding (green) is sufficient for assembly and pore opening, while ATP hydrolysis (red) is required for substrate unfolding and coupled processes.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Proteasome Purification and Assembly Assays

Purification of intact 26S proteasome from rabbit reticulocytes requires ATP in all buffers to maintain complex stability [9]. In contrast, the 20S proteasome and PA700/19S subcomplexes can be purified separately in ATP-free buffers [9]. This differential stability provides a key methodological advantage for studying assembly mechanisms.

Native Gel Electrophoresis for Assembly Monitoring: The assembly of 26S proteasome from 20S core and PA700/19S subcomplexes can be monitored by native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis [9]. Assembly is accompanied by a dramatic increase (20-50 fold) in hydrolysis of fluorogenic peptide substrates like Suc-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-AMC, which can be quantified using solution assays or substrate overlay assays in native gels [9].

Nucleotide Dependency Experiments: To test the specific roles of ATP binding versus hydrolysis, researchers employ non-hydrolyzable ATP analogs including ATPγS and AMP-PNP [9]. These experiments require careful depletion of ATP from proteasome preparations using apyrase pretreatment, followed by repletion with the nucleotide of choice [9]. Such approaches demonstrated that ATPγS supports proteasome assembly despite being completely resistant to hydrolysis by the proteasomal ATPases [9].

Substrate-Specific Degradation Assays

Different classes of substrates reveal distinct ATP requirements:

Unstructured Protein Degradation: Non-ubiquitinated, unstructured proteins can be degraded without ATP hydrolysis, requiring only initial ATP-dependent proteasome activation [9].

Folded Protein Degradation: Folded proteins and certain polyubiquitinated folded proteins require ATP hydrolysis for degradation [9]. Those that are refractory to proteolysis may be deubiquitinated through an ATP-independent mechanism [9].

Deubiquitination Activity: The 26S proteasome contains deubiquitinating activity that can function without ATP, though for some substrates, ATP hydrolysis is required for both degradation and deubiquitination [9].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying ATP-Dependent Proteolysis

| Reagent/Condition | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ATPγS | Non-hydrolyzable ATP analog | Distinguishes binding vs hydrolysis requirements; 1 μM for half-maximal effect |

| AMP-PNP | Non-hydrolyzable ATP analog | Confirms binding sufficiency; 20 μM for half-maximal effect |

| Apyrase | ATP depletion enzyme | Used to remove endogenous ATP before nucleotide repletion studies |

| Suc-LLVY-AMC | Fluorogenic peptide substrate | Standard activity assay; 20-50 fold activation upon assembly |

| Mg²⁺ | Essential cofactor | Required for all nucleotide effects on assembly and activation |

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | Ionic activator | Stimulates peptidase activity with AMP-PNP; eliminates time lag |

| Ubiquitin-Conjugating System | Substrate targeting | Required for ubiquitin-dependent degradation pathways |

Regulatory Mechanisms and Physiological Significance

The ATP-dependent proteolytic system displays sophisticated regulation that maintains cellular protein homeostasis. The intracellular ATP concentration serves as a key regulator of proteolytic activity, particularly during nutrient stress. Research in Salmonella Typhimurium has demonstrated that reduced ATP concentrations during stationary phase decrease proteolysis by AAA+ proteases, thereby stabilizing functional proteins and facilitating rapid recovery when nutrients become available [10]. This mechanism appears to be conserved across species, including yeast [10].

The ATP dependence also provides a crucial control mechanism that prevents inappropriate degradation of normal cellular proteins. The 19S regulatory particle contains six AAA ATPase subunits that undergo conformational changes during ATP binding and hydrolysis, driving mechanical unfolding of substrate proteins [9] [11]. This unfolding activity is essential for translocation of folded substrates through the narrow proteasome pore, explaining why ATP hydrolysis is required for degradation of structured proteins but not unstructured polypeptides [9].

Comparative Analysis with Related ATP-Dependent Proteases

The principles discovered in the rabbit reticulocyte system extend to other AAA+ proteases across evolution. The bacterial protease HslVU exhibits similar uncoupling of ATP binding and hydrolysis functions. Notably, AMP-PNP together with K⁺ can induce a form of HslVU that degrades proteins without energy consumption [12]. Similarly, ClpXP complexes in bacteria use cycles of ATP hydrolysis to unfold and translocate substrates through the central pore of the complex [11]. These conserved mechanisms highlight the fundamental nature of ATP utilization in cellular proteolysis.

Diagram 2: Substrate processing workflow. ATP binding initiates recognition and unfolding, while hydrolysis powers mechanical unfolding and translocation before degradation.

The rabbit reticulocyte lysate system has provided profound insights into the critical role of ATP hydrolysis in proteolytic activation. The separation of ATP binding and hydrolysis functions represents a sophisticated regulatory mechanism that enables controlled protein degradation without compromising cellular protein homeostasis. The 26S proteasome utilizes ATP binding for complex assembly and gated pore opening, while reserving ATP hydrolysis for the mechanistically demanding processes of substrate unfolding and translocation. These fundamental principles, first discovered in the reticulocyte system, have broad relevance to AAA+ proteases throughout biology and continue to inform drug discovery efforts targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in human diseases.

The controlled degradation of proteins is a fundamental cellular process, essential for maintaining homeostasis, regulating critical signaling pathways, and disposing of damaged or misfolded proteins. The rabbit reticulocyte lysate system has been a cornerstone model for elucidating the biochemical mechanisms of ATP-dependent proteolysis [13]. Within this framework, two distinct yet complementary pathways have been characterized: the well-established ubiquitin-dependent pathway and the increasingly recognized ubiquitin-independent pathway. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is responsible for the degradation of most intracellular proteins, where a polyubiquitin chain acts as the primary signal for proteasomal recognition and degradation [14] [15] [16]. Conversely, ubiquitin-independent proteasomal degradation (UbInPD) allows for the direct recognition and processing of specific substrates by the proteasome without the need for a ubiquitin tag [17] [18] [19]. This article delves into the mechanisms, key players, and experimental dissection of these dual degradation pathways, framed within the context of seminal research on rabbit reticulocyte lysate.

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS)

The ubiquitin-dependent pathway is a multi-step enzymatic cascade that results in the tagging of a protein substrate with a polyubiquitin chain, marking it for degradation by the 26S proteasome.

The Ubiquitination Cascade

The process of ubiquitination involves a sequential action of three key enzymes [15] [16]:

- E1 (Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme): This enzyme initiates the pathway by activating ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction, forming a high-energy thioester bond.

- E2 (Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme): The activated ubiquitin is then transferred from E1 to the catalytic cysteine residue of an E2 enzyme.

- E3 (Ubiquitin Ligase): Finally, an E3 ligase facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to a lysine residue on the target protein, forming an isopeptide bond. The E3 ligase is primarily responsible for substrate recognition, providing specificity to the system.

Repeated cycles of this cascade lead to the formation of a polyubiquitin chain on the substrate. The type of ubiquitin chain linkage determines the fate of the modified protein. While all eight polyubiquitin chain types (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, and K63) exist, K48-linked chains are the principal signal for proteasomal degradation [14] [20].

The 26S Proteasome and Substrate Processing

The 26S proteasome is the executive component of the UPS and is a multi-subunit complex composed of two primary entities [14] [19]:

- The 20S Core Particle (20S): This barrel-shaped structure contains the proteolytically active sites (β1, β2, β5 subunits) within its inner chamber, sequestered from the cellular environment.

- The 19S Regulatory Particle (19S): This cap structure recognizes polyubiquitinated substrates, unfolds them, and translocates the unfolded polypeptide into the 20S core for degradation.

The 19S regulatory particle contains several key components that facilitate degradation [14]:

- Ubiquitin Receptors (e.g., Rpn1, Rpn10, Rpn13): These subunits recognize and bind the polyubiquitin chain on the substrate.

- Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs, e.g., Rpn11): These enzymes remove the ubiquitin chain from the substrate prior to its entry into the 20S core, allowing for ubiquitin recycling.

- AAA-ATPase Motor: This hexameric ring utilizes ATP hydrolysis to unfold the target protein and thread it into the degradation chamber of the 20S core.

For some substrates, particularly those embedded in complexes or membranes, an additional ATPase complex, p97/VCP (Cdc48 in yeast), is required to extract and unfold the ubiquitinated protein before delivery to the proteasome [14].

dot-1-Biochemical Pathway of Ubiquitin Dependent Degradation

Ubiquitin-Independent Proteasomal Degradation (UbInPD)

Contrary to long-held beliefs, ubiquitin is not an obligatory tag for proteasomal degradation. A subset of cellular proteins can be degraded in a ubiquitin-independent manner.

Mechanisms and Key Players

Ubiquitin-independent degradation is mediated primarily by the 20S core proteasome alone, often facilitated by alternative regulatory complexes instead of the 19S cap [18] [19]. The 20S proteasome can directly recognize and degrade specific substrate proteins that possess inherent structural features making them susceptible to degradation.

Key aspects of UbInPD include [17] [18] [19]:

- C-degron Pathways: Specific amino acid sequences at the C-terminus of a protein (C-degrons) can act as potent signals for ubiquitin-independent degradation.

- Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs): Proteins or protein regions that lack a stable three-dimensional structure can directly access the proteolytic chamber of the 20S proteasome without requiring ATP-dependent unfolding.

- Oxidized/Damaged Proteins: The 20S proteasome serves as a major defender against oxidative stress by selectively degrading proteins that have been damaged and partially unfolded by reactive oxygen species.

- Alternative Proteasome Activators: Complexes such as PA28αβ (11S regulator) and PA200 can bind to the 20S core and activate its peptidase activity in an ATP- and ubiquitin-independent manner, facilitating the degradation of specific substrates like acetylated histones or damaged proteins.

Recent systematic studies using GPS-peptidome technology have revealed that UbInPD is far more prevalent than previously appreciated, identifying thousands of potential degron sequences and dozens of full-length human proteins subject to this pathway, including regulatory proteins like REC8 and CDCA4 [17]. Furthermore, certain Ubiquilin family proteins have been identified as adaptors that can mediate the proteasomal targeting of a subset of UbInPD substrates, bridging the gap between the two pathways [17].

dot-2-Ubiquitin Independent Degradation Pathways

Comparative Analysis of Degradation Pathways

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of ubiquitin-dependent and ubiquitin-independent degradation pathways.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitin-Dependent and Ubiquitin-Independent Degradation Pathways

| Feature | Ubiquitin-Dependent Pathway | Ubiquitin-Independent Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Key Signal | Polyubiquitin chain (primarily K48-linked) [14] [20] | C-degrons, Intrinsically Disordered Regions, oxidative damage [17] [18] [19] |

| Primary Proteasome Complex | 26S (20S core + 19S cap) [14] [15] | 20S core alone or with alternative activators (PA28, PA200) [18] [13] [19] |

| ATP Requirement | Yes (for ubiquitination & 19S cap function) [14] [16] | No (for 20S core degradation) [13] |

| Energy of Activation (Ea) | ~27 kcal/mol (in rabbit reticulocyte lysate) [21] | Not explicitly defined, but lower due to lack of ubiquitination and unfolding requirements |

| Primary Function | Regulated turnover of normal proteins; quality control [15] [16] | Quality control (oxidized/misfolded proteins); rapid regulation of specific proteins [17] [19] |

| Example Substrates | Cyclins, transcription factors, misfolded proteins [14] [16] | Ornithine decarboxylase, thymidylate synthase, p21, oxidized proteins [17] [18] |

Experimental Analysis in Reticulocyte Lysate Systems

The rabbit reticulocyte lysate has been an indispensable model system for reconstituting and studying both ubiquitin-dependent and independent degradation.

Key Experimental Workflow

The foundational experiments involved fractionating the lysate to isolate and characterize the proteolytic machinery. The following workflow outlines the key steps for analyzing ATP-dependent and independent degradation:

dot-3-Experimental Workflow for Analyzing Degradation Pathways

Key Research Reagents and Tools

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Protein Degradation Pathways

| Reagent/Tool | Primary Function | Key Insights Enabled |

|---|---|---|

| Rabbit Reticulocyte Lysate | A cell-free system rich in proteasomes, ubiquitin, and associated enzymes [13] | Enabled initial fractionation and identification of 20S and 26S proteasomes; demonstration of ATP-dependent and independent proteolysis [21] [13] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132) | Reversibly inhibits the proteolytic activity of the 20S core particle [15] | Confirms proteasome involvement in a degradation process; leads to accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins in UPS studies [15] |

| ATPγS (Non-hydrolyzable ATP analog) | Inhibits ATP-dependent processes by replacing ATP without supporting hydrolysis [14] | Differentiates between ATP-dependent (26S/UPS) and ATP-independent (20S/UbInPD) degradation pathways [14] [13] |

| Ubiquitin Enrichment Kits | Isolate polyubiquitinated proteins from cell or tissue lysates using high-affinity resins [15] | Allows for specific detection and analysis of proteins targeted for ubiquitin-dependent degradation via Western blot or mass spectrometry |

| E1 Inhibitor (e.g., PYR-41) | Specifically inhibits the E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme, blocking the entire ubiquitination cascade [15] | Used to distinguish ubiquitin-dependent from ubiquitin-independent degradation of a specific substrate |

| GPS-Peptidome Screening | A systematic method for high-throughput discovery of degron sequences [17] | Identified thousands of sequences, including C-degrons, that promote ubiquitin-independent degradation, revealing its prevalence |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Assessing Pathway Dependence

To determine whether a protein of interest is degraded via a ubiquitin-dependent or independent pathway in a reticulocyte lysate system, the following experimental approach can be employed, based on classical and modern methodologies [17] [15] [13]:

- Reaction Setup: Set up a series of degradation reactions containing rabbit reticulocyte lysate and the substrate protein (radiolabeled for sensitive detection).

- Inhibitor/Addback Conditions:

- Condition A (Control): Lysate + ATP-regenerating system.

- Condition B (ATP-depletion): Lysate + ATPase (e.g., Apyrase) or non-hydrolyzable ATP analog (ATPγS).

- Condition C (Proteasome Inhibition): Lysate + ATP-regenerating system + MG132 (or other proteasome inhibitor).

- Condition D (E1 Inhibition): Lysate + ATP-regenerating system + E1 inhibitor (e.g., PYR-41).

- Condition E (UbInPD Promotion): Lysate where 26S is dissociated (e.g., by mild oxidative stress) and 20S activity is assessed.

- Incubation and Analysis:

- Incubate reactions at a defined temperature (e.g., 37°C). The degradation of proteins in this system exhibits a high Energy of Activation (Ea) of ~27 kcal/mol, a characteristic feature of the rate-limiting step in this pathway [21].

- At timed intervals, stop the reactions.

- Analyze the remaining substrate by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography (for radiolabeled substrates) or immunoblotting.

- Interpretation of Results:

- Degradation that is inhibited in Conditions B, C, and D indicates a Ubiquitin-Dependent process.

- Degradation that occurs in Conditions B and D but is blocked in Condition C indicates a Ubiquitin-Independent, 20S-mediated process.

- Degradation that is enhanced in Condition E further supports a UbInPD mechanism.

Discussion and Pathological Significance

The coexistence of ubiquitin-dependent and independent pathways provides the cell with a versatile and layered system for protein degradation. The UPS is optimized for the highly specific, regulated turnover of normal cellular proteins, such as cyclins and transcription factors [14] [16]. In contrast, the UbInPD pathway, particularly via the 20S proteasome, acts as a first line of defense against proteotoxic stress by rapidly degrading damaged, misfolded, or intrinsically disordered proteins that might otherwise aggregate [18] [19].

The importance of these pathways is starkly evident in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's disease. These conditions are characterized by the accumulation of toxic protein aggregates like tau, α-synuclein, and huntingtin. Evidence suggests that many of these aggregation-prone proteins are substrates for both degradation pathways, and a decline in proteasomal activity with age contributes to pathology [22] [19]. Notably, some of these pathogenic proteins, especially in their native or modified states, can be degraded directly by the 20S proteasome in a ubiquitin-independent manner, highlighting this pathway's role in neuroprotective protein quality control [19].

From a therapeutic perspective, the ubiquitin-dependent pathway is being successfully targeted by PROTACs (PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras) and molecular glues, which are bifunctional molecules that recruit E3 ubiquitin ligases to neosubstrates, inducing their degradation [20]. A deeper understanding of the UbInPD pathway, including its C-degron signals and associated adaptors like Ubiquilins, may open new avenues for drug development, potentially allowing for the targeted degradation of proteins currently considered "undruggable" [17].

Research originating from the rabbit reticulocyte lysate system was instrumental in uncovering the complexity of intracellular proteolysis, revealing not one but two major pathways for proteasomal degradation. The ubiquitin-dependent pathway represents a sophisticated, energy-dependent mechanism for precise regulatory control, while the ubiquitin-independent pathway provides an efficient, streamlined system for protein quality control and the rapid degradation of specific substrates. Rather than operating in isolation, these pathways likely form an integrated network, with cross-talk facilitated by shared components like the proteasome core and adaptor proteins. Future research will continue to elucidate the full scope of UbInPD substrates, the detailed mechanisms of degron recognition, and the therapeutic potential of harnessing both pathways to combat disease.

The ATP-dependent proteolytic system in rabbit reticulocyte lysate serves as a foundational model for understanding intracellular protein degradation. This in-depth technical guide characterizes three critical chemical inhibitors—hemin, vanadate, and N-ethylmaleimide—that have been instrumental in mapping the components and mechanistic principles of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Through their distinct and specific inhibitory profiles, these compounds have enabled researchers to dissect the multi-step proteolytic pathway, from ubiquitin conjugation to final substrate hydrolysis by the 26S proteasome. This whitepaper synthesizes historical and current research findings into structured quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and visual workflows, providing life science researchers and drug development professionals with essential tools for investigating proteasome function and developing targeted therapeutic interventions.

Rabbit reticulocyte lysate has served as a premier cell-free system for elucidating the biochemical mechanisms of ATP-dependent intracellular protein degradation. This system is uniquely capable of selectively degrading abnormal or damaged proteins while sparing normal cellular proteins, mirroring a critical quality control process in living cells. Early seminal work established that reticulocytes contain a soluble, nonlysosomal proteolytic pathway that requires adenosine triphosphate (ATP) for function [3]. This system operates through a consecutive biochemical cascade: first, the ATP-dependent covalent attachment of ubiquitin to protein substrates, and second, the ATP-dependent degradation of these ubiquitin-protein conjugates by a high-molecular-weight protease complex [5].

The discovery and characterization of specific inhibitors have been paramount to disentangling this complex proteolytic machinery. Hemin, vanadate, and N-ethylmaleimide each inhibit distinct steps in the pathway through different mechanisms, enabling researchers to isolate and study individual components. Their use has been fundamental in identifying the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) as the primary executor of energy-dependent proteolysis in eukaryotic cells—a discovery with profound implications for understanding cellular regulation and human disease pathogenesis [1]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical resource on these essential inhibitors, framing their mechanisms within the broader context of UPS research.

Inhibitor Profiles and Mechanisms of Action

Hemin: Regulator of Ubiquitin Conjugate Degradation

Hemin acts as a specific allosteric inhibitor of the final degradation step in the UPS pathway. Research demonstrates that hemin exclusively targets the ATP-dependent ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic system without affecting basal proteolysis that occurs independently of ATP or ubiquitin [23] [24].

Quantitative Inhibition Data

Table 1: Quantitative Characterization of Hemin Inhibition

| Parameter | Value | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| IC₅₀ | ~25 µM | 50% inhibition of ¹²⁵I-BSA degradation [23] [24] |

| Conjugate Formation Impact | ~50% of control | ATP-dependent ubiquitin conjugation at fully inhibitory hemin concentrations [23] [24] |

| Conjugate Degradation Impact | Complete blockade | Full inhibition at concentrations that completely block overall proteolysis [23] [24] |

| Specificity | Ubiquitin-dependent pathway exclusive | No effect on basal ATP-independent or ubiquitin-independent proteolysis [23] [24] |

Mechanistic Insights

Hemin functions as a negative allosteric effector specifically targeting the initial step in the degradation of ubiquitin-protein conjugates. At concentrations that completely inhibit proteolysis (approximately 25-50 µM), hemin still permits continued ATP-dependent formation of ubiquitin conjugates at approximately half the control rate, but completely blocks their subsequent breakdown [23] [24]. This results in the accumulation of higher molecular weight ubiquitin conjugates that rapidly disappear when hemin is removed, indicating the reversibility of its inhibitory effect. The specific molecular target is the ubiquitin conjugate-degrading enzyme (UCDEN), an approximately 1500 kDa protease essential for ATP-dependent proteolysis [5]. This specificity has made hemin an invaluable tool for distinguishing the conjugation and degradation phases of the UPS.

Vanadate: Inhibitor of ATP-Stimulated Proteolysis

Vanadate represents a distinct class of inhibitor that blocks ATP-stimulated proteolysis without affecting the ubiquitin conjugation system, providing crucial evidence for the multi-component nature of the UPS.

Quantitative Inhibition Data

Table 2: Quantitative Characterization of Vanadate Inhibition

| Parameter | Value | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Kᵢ | 50 µM | Inhibition of ATP-dependent [³H]methylcasein and denatured ¹²⁵I-BSA degradation [25] |

| Specificity | ATP-stimulated step | Does not affect ubiquitin conjugation to protein substrates [25] |

| Reversibility | Yes | Inhibition is reversed by dialysis [25] |

| Specificity Marker | Not mimicked by molybdate | Distinguishes from lysosomal protease inhibition [25] |

Mechanistic Insights

Vanadate inhibits an ATP-stimulated proteolytic step that is functionally distinct from the ATP requirement for ubiquitin conjugation. This was demonstrated through experiments using proteins with covalently modified amino groups that prevent ubiquitin conjugation—these derivatized proteins still undergo ATP-stimulated degradation that remains sensitive to vanadate inhibition [25]. Additionally, vanadate does not reduce the ATP-dependent conjugation of ¹²⁵I-ubiquitin to endogenous reticulocyte proteins, despite markedly inhibiting their degradation. This clear dissociation between conjugation and degradation established that these are functionally separable processes with distinct ATP requirements. In intact reticulocytes, vanadate also inhibits endogenous protein degradation, though secondary effects on protein synthesis and ATP levels complicate interpretation in cellular contexts [25].

N-Ethylmaleimide: Differential Effects on Proteolytic Components

N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) exhibits complex, differential effects on the various components of the UPS, highlighting the biochemical diversity within this proteolytic system.

Quantitative Inhibition Data

Table 3: Effects of N-Ethylmaleimide on Proteolytic Components

| Protease Component | NEM Effect | Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|

| UCDEN (Ubiquitin-Conjugate Degrading Enzyme) | Inhibition | Essential for ATP-dependent proteolysis; contains sulfhydryl groups critical for activity [5] |

| 670 kDa Protease (Non-essential) | Stimulation | Does not require ATP or ubiquitin; not required for ATP-dependent proteolysis [5] |

| Overall ATP-Dependent Proteolysis | Inhibition | Consistent with blockade of the essential UCDEN component [3] |

Mechanistic Insights

The differential effects of NEM on distinct protease components revealed the existence of multiple high molecular weight proteases in reticulocyte cytosol. The essential ubiquitin conjugate-degrading enzyme (UCDEN) is inhibited by NEM, consistent with its classification as a cysteine protease or a protease requiring reduced sulfhydryl groups for activity [5]. In contrast, the smaller 670 kDa protease, which is not required for ATP-dependent proteolysis and hydrolyzes proteins that cannot be conjugated to ubiquitin, is actually stimulated by NEM treatment. This contrasting sensitivity highlights fundamental biochemical differences between these co-existing proteolytic complexes and underscores the value of NEM as a tool for distinguishing their individual contributions to overall proteolysis.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Reticulocyte Lysate Preparation and Fractionation

The standard methodology for investigating ATP-dependent proteolysis begins with preparation of rabbit reticulocyte lysate and its subsequent fractionation into functionally distinct biochemical components.

Protocol Steps:

- Lysate Preparation: Collect rabbit reticulocytes and lyse cells in low-ionic-strength buffer (e.g., 1-5 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.5-8.0) followed by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 60 minutes to obtain the soluble cytosolic fraction [5] [3].

DEAE Chromatography: Apply the cytosolic fraction to a DEAE-cellulose column equilibrated with low-salt buffer. Elute with a linear NaCl gradient (0-0.5 M) to separate the ubiquitin conjugation system (eluting at approximately 0.15-0.25 M NaCl) from the proteolytic components [5].

Ammonium Sulfate Fractionation: Precipitate proteolytic activities by sequential ammonium sulfate fractionation. The UCDEN activity precipitates at 0-38% saturation, while the non-essential 670 kDa protease precipitates at 40-80% saturation [5].

Gel Filtration Chromatography: Further purify precipitated fractions by size exclusion chromatography (e.g., Sephacryl S-300 or S-400) to isolate high molecular weight protease complexes (>450 kDa) [5].

Standard ATP-Dependent Proteolysis Assay

The foundational assay for monitoring ATP-dependent proteolysis utilizes radiolabeled protein substrates to quantify degradation rates.

Protocol Steps:

- Substrate Preparation: Prepare ¹²⁵I-labeled bovine serum albumin (BSA) or incorporate amino acid analogs (e.g., 2-amino-3-chlorobutyric acid) into proteins to generate abnormal substrates recognized by the UPS [23] [3].

Reaction Conditions: In a standard 100-250 µL reaction volume, combine reticulocyte fraction(s), 1-2 mg/mL substrate protein, 2 mM ATP, 10 mM MgCl₂, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 1 mM DTT, and an ATP-regenerating system (e.g., 10 mM creatine phosphate, 0.1 mg/mL creatine phosphokinase) [5] [3].

Inhibitor Addition: Add inhibitors at specified concentrations: hemin (25-50 µM), vanadate (50-100 µM), or N-ethylmaleimide (0.1-1 mM). Include appropriate solvent controls.

Incubation and Measurement: Incubate at 37°C for 30-120 minutes. Terminate reactions by adding trichloroacetic acid (TCA) to 10% final concentration. Measure TCA-soluble radioactivity by gamma counting as an index of protein degradation [23] [3].

Data Analysis: Calculate ATP-dependent proteolysis by subtracting values from parallel reactions without ATP. Express inhibitor effects as percentage inhibition relative to uninhibited controls.

Ubiquitin Conjugation Assay

This specialized assay specifically monitors the first step in the UPS pathway independently of downstream degradation.

Protocol Steps:

- Reaction Conditions: Combine the conjugation fraction (DEAE-purified), ¹²⁵I-ubiquitin, substrate protein, 2 mM ATP, 10 mM MgCl₂, and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8) in a total volume of 50-100 µL [23].

Inhibitor Testing: Include hemin (25-50 µM) or other inhibitors to assess their specific effects on conjugation separate from degradation.

Analysis: Terminate reactions with SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE and visualize high molecular weight ubiquitin conjugates by autoradiography or Western blotting [23].

Interpretation: Hemin typically reduces conjugation by approximately 50% while completely blocking degradation, confirming its primary site of action at the degradation step [23] [24].

Pathway Diagrams and Experimental Workflows

Ubiquitin-Proteasome System with Inhibitor Targets

The following diagram illustrates the sequential steps of the ATP-dependent ubiquitin-proteasome system in reticulocyte lysate, with specific inhibitor targets indicated:

Experimental Workflow for Inhibitor Characterization

This workflow outlines the standard experimental approach for characterizing inhibitors in the reticulocyte lysate system:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for UPS Inhibition Studies

| Reagent | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Rabbit Reticulocyte Lysate | Source of ATP-dependent proteolytic system | Contains complete ubiquitin conjugation and degradation machinery; can be fractionated [5] |

| ATP-Regenerating System | Maintains constant ATP levels during assays | Typically includes creatine phosphate and creatine phosphokinase [3] |

| ¹²⁵I-Labeled Substrate Proteins | Proteolysis quantification | BSA or abnormal proteins containing amino acid analogs; TCA-soluble radioactivity measures degradation [23] [3] |

| ¹²⁵I-Ubiquitin | Conjugation assay substrate | Tracks ubiquitin conjugation to proteins independently of degradation [23] |

| DEAE-Cellulose | Chromatographic separation | Separates conjugation factors from proteolytic components [5] |

| Ammonium Sulfate | Protease fractionation | Precipitates UCDEN at 0-38% saturation; 670 kDa protease at 40-80% saturation [5] |

Research Implications and Future Directions

The characterization of hemin, vanadate, and N-ethylmaleimide has provided fundamental insights into the UPS that continue to resonate through modern biomedical research. The differential inhibition patterns established that ubiquitin conjugation and substrate degradation are biochemically separable processes with distinct enzymatic requirements and regulatory mechanisms [5] [23] [25]. This conceptual framework directly enabled the subsequent identification and purification of the 26S proteasome as the molecular machine responsible for ubiquitin-conjugate degradation [1] [26].

Contemporary research continues to build upon these foundational inhibitor studies. The recognition that UPS dysregulation contributes to cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and cardiovascular disorders has stimulated intensive efforts to develop targeted UPS modulators [1]. Current investigations are exploring natural metabolites, including circulating polyphenol-derived compounds such as valerolactones and urolithins, as potential proteasome modulators with therapeutic applications [27]. These modern approaches benefit greatly from the established experimental paradigms and mechanistic insights generated through earlier inhibitor studies using the reticulocyte lysate system.

Future research directions include developing increasingly specific inhibitors that target distinct proteasome subpopulations or regulatory particles, building upon the recognition that multiple forms of both 20S multicatalytic complexes and 26S ubiquitin/ATP-dependent proteases exist in rabbit reticulocyte lysate [26]. The continued integration of classic biochemical approaches with modern structural biology and chemical biology techniques promises to yield new generations of UPS-targeted therapeutics with enhanced specificity and reduced off-target effects.

Practical Implementation: RRL Proteolysis Assays in Contemporary Research

Rabbit Reticulocyte Lysate (RRL) is a premier cell-free protein expression system derived from the lysates of immature red blood cells from rabbits, which are naturally engaged in high rates of hemoglobin synthesis [28]. These systems are a cornerstone of molecular biology, providing a versatile platform for in vitro translation of a wide array of viral, prokaryotic, and eukaryotic mRNAs [28]. A critical distinction in these systems lies in their pre-treatment: untreated RRL contains endogenous mRNAs, while nuclease-treated RRL has been processed with micrococcal nuclease to degrade these endogenous mRNAs, thereby reducing background translation and favoring the synthesis of proteins from exogenously added templates [29] [28]. The choice between these systems is fundamental, as it significantly influences the physiological relevance of the experimental environment, particularly for research focused on ATP-dependent proteolysis and the intricate regulation of protein degradation pathways.

Comparative Analysis: Untreated vs. Nuclease-Treated RRL

The decision to use an untreated or nuclease-treated RRL system hinges on the specific scientific question. The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and optimal applications of each system.

Table 1: Direct Comparison of Untreated and Nuclease-Treated RRL Systems

| Feature | Untreated RRL | Nuclease-Treated RRL |

|---|---|---|

| Endogenous mRNA | Present (e.g., globin, lipoxygenase) [29] | Degraded via micrococcal nuclease [28] |

| Background Translation | Higher, due to endogenous mRNAs [29] | Very low, enabling high signal-to-noise for exogenous templates [28] |

| Key Advantage | Recapitulates a 'near to physiological' environment; supports cap/poly(A) tail synergy [29] | Ideal for controlled expression of a single exogenous protein [28] |

| Primary Application | Studying regulated translation, mRNA circularization, and competitive translation [29] | Standard protein expression, identification of mRNA products, and functional proteomics [28] |

| Proteolysis Research Context | Superior for studying endogenous ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis in a more native context [30] | Useful for controlled studies on the degradation of specific, in vitro synthesized substrate proteins [30] |

Essential Supplementations for RRL Systems

To function effectively in vitro, both untreated and nuclease-treated RRL require supplementation with key components that mimic the intracellular environment. These additions provide energy, building blocks, and regulatory factors necessary for efficient translation and proteolysis.

Table 2: Essential Supplementations for RRL Systems

| Supplementation | Function | Typical Concentration | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy System | |||

| Creatine Phosphate | ATP regeneration substrate [29] [28] | 5 mg/mL [29] | |

| Creatine Phosphokinase | Enzyme for ATP regeneration from creatine phosphate [29] [28] | 25 µg/mL [29] | |

| Cofactors & Regulators | |||

| Hemin | Prevents activation of heme-regulated eIF-2α kinase (HRI), avoiding translation inhibition [29] [28] | 25 µM [29] | Critical for maintaining high translation efficiency |

| Building Blocks | |||

| Amino Acid Mix | Provides substrates for protein synthesis [29] | 20 µM (minus methionine) [29] | Often used with labeled methionine for detection |

| Bovine Liver tRNAs | Balances tRNA populations, optimizing codon usage for a wider range of mRNAs [29] [28] | 50 µg/mL [29] | |

| Salts | |||

| KCl & MgCl₂ | Optimizes ionic conditions for translation initiation and elongation [29] | 75 mM and 0.5 mM, respectively [29] | Concentrations may require optimization |

RRL in ATP-Dependent Proteolysis Research

The RRL system is not only a powerful tool for protein synthesis but also an established model for studying ATP-dependent proteolysis, the primary pathway for targeted protein degradation in eukaryotic cells. This system contains the necessary machinery, including the ubiquitin-proteasome system, which recognizes and degrades proteins tagged with polyubiquitin chains [6]. The proteasome and other ATP-dependent proteases are complex molecular machines that unfold and translocate substrate proteins into an internal chamber for hydrolysis, a process fueled by ATP [6].

Research has demonstrated key differences in proteolytic function between RRL and other systems. For instance, a comparative study found that a retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cell line supernatant showed a more pronounced ubiquitin-dependent enhancement in degrading rod outer segment proteins compared to RRL [30]. This highlights the value of selecting the appropriate in vitro system for specific proteolysis questions. The untreated RRL, with its more physiological milieu, may provide a more accurate picture of how ubiquitin-dependent degradation occurs in a competitive cellular environment.

Diagram 1: Ubiquitin-proteasome pathway.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Preparation of a Functional Untreated RRL System

The following protocol is adapted from studies utilizing untreated RRL to recapitulate physiological translation and proteolysis [29].

- Supplement Preparation: Prepare a master mix containing the following components to be added to 1 mL of commercial untreated RRL (e.g., from Promega):

- Lysate Supplementation: Thaw the untreated RRL on ice. Gently add the master mix to the lysate and mix by pipetting slowly. Avoid introducing air bubbles.

- Aliquoting and Storage: Dispense the supplemented lysate into small, single-use aliquots. Flash-freeze the aliquots in liquid nitrogen and store them at -70°C or below to preserve activity.

Protocol for ATP-Dependent Proteolysis Assay

This protocol outlines a method for studying ATP- and ubiquitin-dependent degradation of substrates in the RRL system, based on established comparative methodologies [30].

- Reaction Setup: For a standard 50 µL degradation reaction, combine the following on ice:

- 35 µL of supplemented untreated or nuclease-treated RRL.

- 1-2 µL of your substrate (e.g., in vitro translated, radiolabeled protein or purified protein).

- An ATP-regenerating system (if not already present in the supplementation). This typically includes 2 mM ATP, 10 mM creatine phosphate, and 0.1 mg/mL creatine phosphokinase.

- Optionally, include 12-120 µM ubiquitin to stimulate ubiquitin-dependent pathways [30].

- Controls: Prepare control reactions containing:

- An ATP-depleting system (e.g., apyrase or hexokinase/glucose) to confirm ATP dependence.

- Specific inhibitors of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, such as hemin or vanadate, to confirm the mechanism [30].

- Incubation: Transfer the reaction tubes to a 30°C or 37°C water bath and incubate for 30-120 minutes.

- Termination and Analysis: Stop the reactions by adding 2x SDS-PAGE loading buffer and heating to 95°C for 5 minutes. Analyze the degradation of the substrate by:

- SDS-PAGE and Autoradiography: If the substrate is radiolabeled, run the samples on a gel, dry it, and expose it to a phosphorimager screen or X-ray film. Quantify the band intensity to determine the rate of substrate degradation.

- Western Blotting: For non-radiolabeled substrates, use specific antibodies to detect the full-length substrate and its degradation products.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for RRL and Proteolysis Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Untreated RRL | Creates a competitive, physiological environment for studying translation and endogenous proteolysis [29]. | Used to demonstrate cap/poly(A) tail synergy in translation initiation [29]. |

| Nuclease-Treated RRL | Enables high-efficiency, specific expression of a single exogenous protein with low background [28]. | Used to express and then degrade a specific rod outer segment protein in proteolysis assays [30]. |

| Ubiquitin | Key regulator of proteasome targeting; its addition stimulates ATP-dependent degradation of specific substrates [30] [6]. | Addition of 12 µM ubiquitin to RPE supernatant stimulated degradation of multiple substrates by ≥3-fold [30]. |

| ATPγS (ATP analog) | A non-hydrolyzable ATP analog used to probe the energy dependence of a process. | Expected to inhibit both the ubiquitination cascade and proteasome activity, serving as a critical control. |

| Hemin | An inhibitor of the heme-regulated eIF-2α kinase and of ATP-/ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis [30] [28]. | Completely inhibited ATP-dependent degradation of ROS proteins in reticulocyte lysate [30]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132) | Specific inhibitors of the proteasome's proteolytic activity, used to confirm proteasome involvement. | Useful for distinguishing proteasome-dependent degradation from other protease activities in the lysate. |

Proteolysis, the enzymatic cleavage of peptide bonds, is a critical biochemical process for cellular function, regulating everything from cell proliferation and death to immune response and digestion [31] [32]. The rabbit reticulocyte lysate system has been a foundational model for studying one specialized class of these events: ATP-dependent proteolysis [3]. This system is responsible for the selective degradation of abnormal proteins, a crucial quality-control mechanism in cells [3]. Early work demonstrated that reticulocyte lysates contain a soluble, non-lysosomal proteolytic system that requires ATP and can be inhibited by agents like N-ethylmaleimide and iodoacetamide [3]. Subsequent research revealed that this system comprises multiple high molecular weight proteases, including a ~1500 kDa enzyme essential for degrading ubiquitin-protein conjugates [5]. Mastery of standard proteolysis protocols is therefore indispensable for researchers investigating protein turnover, protease function, and drug mechanisms. This guide provides an in-depth technical framework for setting up proteolysis experiments, optimizing incubation parameters, and selecting detection methods, with specific emphasis on the context of ATP-dependent proteolysis research.

Core Principles of Proteolytic Systems

The Rabbit Reticulocyte Lysate System

The ATP-dependent proteolytic system in rabbit reticulocytes has served as a key model for understanding intracellular protein degradation. This system is characterized by several defining features:

- Location and ATP Dependence: It is a soluble, non-lysosomal system located in the 100,000 × g supernatant fraction of the lysate. Its activity is stimulated several-fold by ATP, while ADP provides a slight stimulation, and AMP and cAMP have no significant effect [3].

- Inhibitor Profile: The proteolysis in this system is inhibited by agents such as N-ethylmaleimide, iodoacetamide, and L-1-tosylamido-2-phenylethylchloromethyl ketone (TPCK), indicating a reliance on specific catalytic residues and a distinct mechanism from lysosomal degradation [3].

- Enzymatic Complexity: The system can be fractionated into multiple components. A "Conjugation Fraction" (30-300 kDa) handles the ATP-dependent conjugation of ubiquitin to substrates, while a high mass fraction (>450 kDa) is necessary for the hydrolysis of the conjugated proteins [5]. This high mass fraction contains at least two distinct proteases: a ~1500 kDa protease that degrades ubiquitin conjugates (UCDEN) and requires ATP, and a ~670 kDa protease that does not require ATP or ubiquitin [5].

Signaling Pathway of ATP-Dependent Proteolysis

The following diagram illustrates the core biochemical pathway of the ATP-dependent ubiquitin-proteasome system as characterized in rabbit reticulocytes.

Figure 1: ATP-dependent ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in rabbit reticulocytes. The pathway involves ubiquitin conjugation followed by degradation via a high-molecular-weight protease complex.

Experimental Setup and Protocol

Reagent Preparation

A successful proteolysis experiment begins with the careful preparation of reagents. The following buffers are commonly used in proteolysis studies, including those involving reticulocyte lysates.

Table 1: Essential Buffers for Proteolysis Studies

| Buffer Name | pH | Key Components | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spin Buffer [33] | 6.8 | 50 mM MOPS, 25 mM NaCl | Provides a stable ionic environment for spin-labeling and EPR studies. |

| HEPES Buffer [33] | 7.4 | 50 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl | Maintains physiological pH for a wide range of proteolytic reactions. |

| Lysis Buffer [34] | 7.4 | 50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100 (EDTA-free protease inhibitors optional) | Efficiently extracts proteins while preserving native conformations and ligand-binding capabilities. |

Sample Preparation

The initial quality of the biological sample is paramount. For cell-based systems like reticulocyte lysates, the protocol involves:

- Harvesting and Lysis: Cells should be harvested and rinsed with cold PBS. Lysis is then performed using an ice-cold, appropriate buffer (e.g., Table 1). For tissues, mechanical homogenization under cold conditions is required [34].

- Clarification: The lysate is centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble debris. The clear supernatant is carefully collected [34].

- Quantification: The total protein concentration of the lysate should be determined using an assay like the BCA assay. Lysates are typically normalized to a consistent concentration (e.g., 1–3 mg/mL) for reproducible experimental conditions [34].

Protease Immobilization (Optional)

A powerful technique to simplify downstream analysis is protease immobilization. Metal-Organic Materials (MOMs) like Ca-BPDC can be used for this purpose via co-crystallization [33].

- Preparation of BPDC-Na₂: Biphenyl-4,4′-dicarboxylic acid (BPDC-COOH) is dissolved in a 1:2 molar ratio with NaOH in water. After vigorous stirring for 2 hours, the soluble BPDC-Na₂ is precipitated with cold 2-isopropanol, collected by filtration, and dried [33].

- Immobilization: Stock solutions of CaCl₂ and BPDC-Na₂ are mixed in the presence of the target protease, allowing the enzyme to be trapped within the growing MOM crystals. This enables the physical separation of the protease from the reaction mixture by centrifugation, preventing self-degradation and simplifying the mass spectrometric analysis of substrate cleavage products [33].

Incubation Parameters and Optimization

The conditions under which proteolysis occurs are critical for the efficiency and specificity of the reaction. The key parameters to control and optimize are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Key Incubation Parameters for Proteolysis Experiments

| Parameter | Typical Range | Impact on Proteolysis | Considerations for Reticulocyte System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 37°C (for most assays); 4°C for unstable ligands [34] | Higher temperatures increase reaction rates but may denature proteins. | The native ATP-dependent system operates at physiological temperature [3]. |

| Time | 10–30 min (kinetic); Overnight (for complete digestion) [35] [34] | Duration must be optimized to balance completeness of digestion with protease stability. | Time courses can reveal early vs. late cleavage events during processes like apoptosis [32]. |

| ATP | 1–5 mM [3] | Essential for the activity of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. | ATP concentration is a critical variable; the system shows maximal stimulation with ATP over ADP or AMP [3]. |

| Protease:Substrate Ratio | 1:20 to 1:100 (w/w) for trypsin [35] | Higher ratios accelerate digestion but may increase non-specific cleavage. | The endogenous protease concentration is fixed in lysates; activity is modulated by ATP and inhibitors. |

| pH | 7.4–7.8 (physiological); specific proteases have unique optima [3] [36] | Drastically affects protease activity and protein conformation. | The ATP-dependent system in reticulocytes has a pH optimum of 7.8 [3]. |

Compound Incubation for Binding Studies

When studying the effect of small molecules (e.g., potential drugs or inhibitors) on proteolysis:

- The lysate is split into compound-treated and vehicle-treated control groups.

- The small molecule is added to the desired final concentration (commonly 1–10 μM), ensuring the solvent concentration (e.g., DMSO) is matched and does not exceed 1% (v/v) in all samples [34].

- Incubation is typically performed at room temperature for 15 minutes to 2 hours to allow for ligand-target engagement [34].

Detection and Analysis Methods

A variety of methods exist to monitor proteolytic activity and identify cleavage products. The choice of method depends on the specific research question, whether it is measuring general activity, identifying specific cleavage sites, or probing structural changes.

Table 3: Comparison of Proteolysis Detection and Analysis Methods

| Method | Principle | Key Applications | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorometric Assays (e.g., Red Protease Kit) [36] | Protease cleaves quenched substrate, releasing a fluorescent signal. | Screening protease activity/inhibitors; quantifying contamination. | High |

| Limited Proteolysis-Coupled MS (LiP-MS) [37] | Non-specific protease under native conditions cleaves accessible regions; peptides analyzed by MS. | Identifying protein structural changes; drug target discovery. | Medium-High |

| Gel-Based Methods (e.g., PROTOMAP) [32] | Proteins separated by SDS-PAGE; cleavage observed by band shifts or disappearance. | Identifying protein substrates and approximating cleavage sites. | Low-Medium |

| N-Terminal Enrichment (e.g., COFRADIC, Subtiligase) [32] | Isolation and MS-identification of native or neo-N-terminal peptides. | Unbiased discovery of cleavage sites and substrates. | Medium |

| EPR/SDSL with MS [33] | Site-directed spin labeling tracks local molecular motion via EPR; MS confirms sequences. | Residue-level, time-resolved analysis of proteolytic kinetics and cleavage sites. | Low-Medium |

Detailed Protocol: Limited Proteolysis-Coupled Mass Spectrometry (LiP-MS)

LiP-MS is a powerful method for detecting protein structural changes on a proteome-wide scale [37]. The workflow is illustrated below and involves the following steps:

Figure 2: Limited Proteolysis-Coupled Mass Spectrometry (LiP-MS) workflow for detecting protein structural changes.

- Perturbation and Lysis: Subject cells or tissues to the condition of interest (e.g., drug treatment, pH change). Prepare the proteome extract via lysis [37].