The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: From Molecular Mechanism to Therapeutic Application in Disease and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), a crucial pathway for intracellular protein degradation and regulation.

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: From Molecular Mechanism to Therapeutic Application in Disease and Drug Development

Abstract

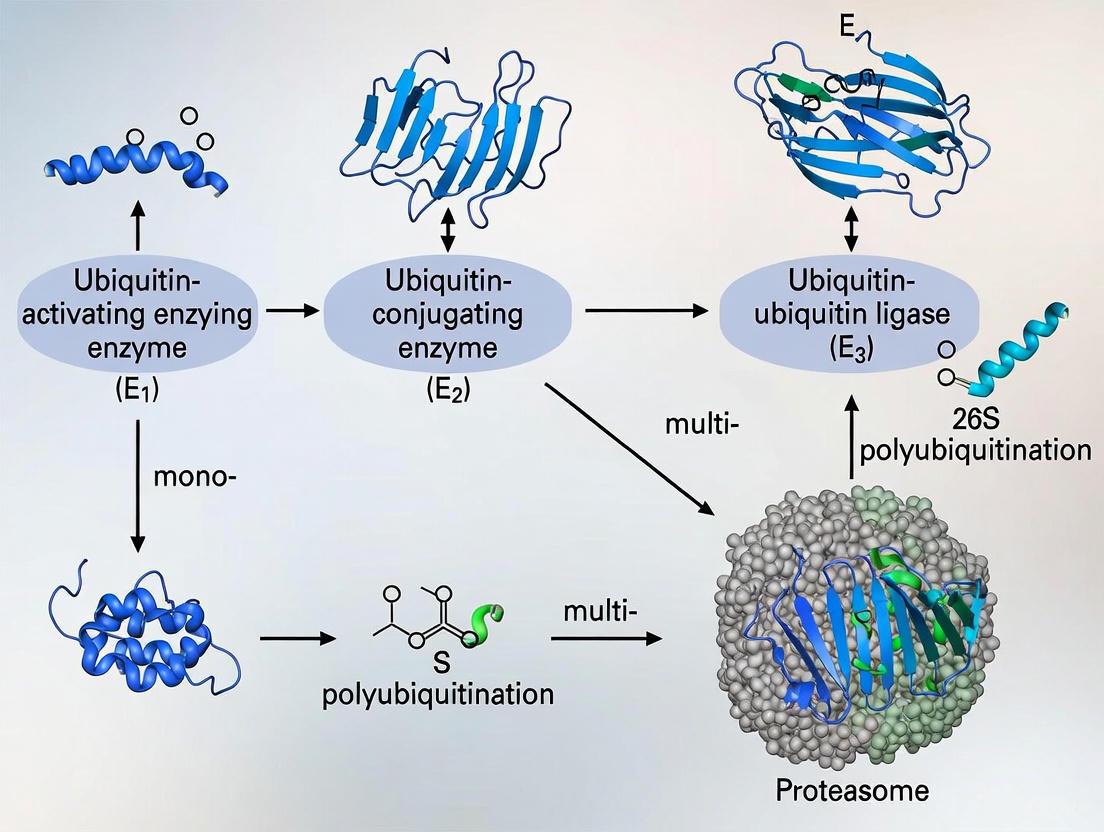

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), a crucial pathway for intracellular protein degradation and regulation. We examine the foundational biochemistry of the UPS, including the E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade and proteasome structure. The review highlights cutting-edge methodological applications, particularly targeted protein degradation technologies like PROTACs and molecular glues, with updates on their clinical progression. We address system crosstalk with autophagy and common research challenges. Finally, we evaluate the UPS as a therapeutic target across cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and other pathologies, offering a vital resource for researchers and drug development professionals navigating this dynamic field.

Decoding the UPS: Architecture, Mechanism, and Cellular Functions

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a highly conserved and selective mechanism for protein degradation and signaling, playing an indispensable role in virtually all aspects of eukaryotic cell biology [1]. This sophisticated system regulates protein turnover through a cascade of enzymatic reactions that culminate in the covalent attachment of ubiquitin, a 76-amino acid protein, to target substrates [2]. The process of ubiquitination serves as a critical post-translational modification (PTM) that influences diverse cellular processes including cell cycle progression, DNA repair, immune signaling, and apoptosis [2] [1]. Dysregulation of the ubiquitination cascade contributes to numerous pathological conditions, making its components attractive therapeutic targets for cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and immune diseases [3] [1]. This technical guide examines the core enzymatic machinery—E1, E2, and E3 enzymes—that executes and regulates the ubiquitination cascade, with particular emphasis on recent mechanistic insights and experimental approaches relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

The Ubiquitination Enzymatic Cascade

The ubiquitination process proceeds through a three-step enzymatic cascade involving E1 (ubiquitin-activating), E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating), and E3 (ubiquitin-ligase) enzymes [2]. This coordinated mechanism ensures precise targeting and modification of substrate proteins.

E1 Ubiquitin-Activating Enzymes

The initial step in ubiquitination involves E1 enzymes, which activate ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner [2]. The human genome encodes only two E1 enzymes, making this the most limited component of the cascade [4]. The activation mechanism proceeds as follows:

- ATP-dependent activation: E1 catalyzes the formation of a thioester bond between its active-site cysteine residue and the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin, with concomitant generation of AMP [2].

- E2 transfer: The activated ubiquitin is subsequently transferred to the catalytic cysteine of an E2 conjugating enzyme via a trans-thiolation reaction [2] [5].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of E1 Ubiquitin-Activating Enzymes

| Feature | Description | Research Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Number in Humans | 2 genes | Limited diversity facilitates broad inhibition strategies |

| Reaction Mechanism | ATP-dependent thioester formation with ubiquitin | Requires Mg²⁺ and ATP for in vitro reconstitution |

| Primary Function | Initiate ubiquitination cascade by activating ubiquitin | Essential for all downstream ubiquitination events |

| Key Structural Features | Ubiquitin-fold domain, active site cysteine, adenylation domain | Target for structural biology and inhibitor design |

E2 Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzymes

E2 enzymes serve as central intermediaries in the ubiquitination cascade, receiving activated ubiquitin from E1 and cooperating with E3 ligases to modify specific substrates [2]. The human genome encodes approximately 40 E2 enzymes, each exhibiting distinct specificities for particular E3s and substrate types [6] [4]. Key functional aspects include:

- Ubiquitin charging: E2 enzymes form a thioester bond with ubiquitin transferred from E1 [2].

- Chain-type specificity: Different E2s determine the topology of polyubiquitin chains formed on substrates [6]. For instance, UBE2G2 primarily generates Lys48-linked chains targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation, while UBE2J2 can modify serine and threonine residues in addition to lysines [6].

- Regulatory sensing: Recent research reveals that certain E2s, such as the membrane-anchored UBE2J2, can sense lipid packing density in endoplasmic reticulum membranes, directly linking ubiquitination to organelle homeostasis [6].

Table 2: Selected E2 Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzymes and Their Functions

| E2 Enzyme | Ubiquitin Linkage Preference | Cellular Functions | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| UBE2J2 | K48, K63, serine/threonine | ER-associated degradation (ERAD), lipid sensing | Membrane reconstitution required for functional studies |

| UBE2G2 | Primarily K48 | Proteasomal degradation, ERAD | Requires AUP1 for membrane association |

| UBE2J1 | K48, K63 | ERAD, protein quality control | Functional in ER-like membranes without additional activation |

| Ubc13 (Yeast) | K63 | DNA damage response, NF-κB signaling | Often paired with E2 variants for K63 chain formation |

E3 Ubiquitin Ligases

E3 ubiquitin ligases represent the most diverse and specialized components of the ubiquitination cascade, with over 600 members in the human genome [5] [4]. These enzymes confer substrate specificity by simultaneously recognizing target proteins and E2-ubiquitin conjugates, thereby catalyzing ubiquitin transfer to specific substrates [5] [3]. E3 ligases are categorized into several structural families based on their mechanism of action:

- RING (Really Interesting New Gene) E3 ligases: The largest E3 family, characterized by a RING domain that directly recruits E2-ubiquitin conjugates and facilitates direct ubiquitin transfer without forming an E3-ubiquitin intermediate [5] [4]. RING E3s can function as single polypeptides (e.g., MDM2, CBL) or as multi-subunit complexes (e.g., Cullin-RING ligases/CRLs) [5] [4].

- HECT (Homologous to E6AP C-Terminus) E3 ligases: Utilize a conserved HECT domain that forms a thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to substrates [5] [4]. This family includes the NEDD4 subfamily, HERC subfamily, and other HECT ligases such as E6AP and HUWE1 [4].

- RBR (RING-Between-RING) E3 ligases: Hybrid enzymes that employ a RING domain for E2 binding and a catalytic domain that forms a thioester intermediate with ubiquitin, similar to HECT ligases [7] [4]. Key examples include Parkin and HOIP (component of the LUBAC complex) [7] [4].

Table 3: Major E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Families and Their Characteristics

| E3 Family | Catalytic Mechanism | Representative Members | Key Structural Domains |

|---|---|---|---|

| RING | Direct transfer from E2 to substrate | MDM2, CBL, BRCA1, APC/C | RING domain, substrate recognition domains |

| HECT | E3-ubiquitin thioester intermediate | NEDD4, HERC, HUWE1, E6AP | HECT domain, C2 domain, WW domains |

| RBR | Hybrid RING-HECT mechanism | Parkin, HOIP, HOIL-1 | RING1, IBR, RING2 domains |

| U-box | Structurally similar to RING | CHIP, UFD2 | U-box domain, tetratricopeptide repeats |

Ubiquitin Signaling Diversity and Functional Outcomes

The ubiquitination code extends beyond simple monoubiquitination to include diverse polyubiquitin chains that dictate distinct functional outcomes for modified substrates.

Ubiquitin Chain Linkages and Functions

Ubiquitin contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1) that serve as linkage points for polyubiquitin chain formation [1] [4]. The specific topology of these chains determines the fate and function of the modified protein:

- K48-linked chains: The most abundant linkage type, primarily targeting substrates for proteasomal degradation [2] [4].

- K63-linked chains: Mainly involved in non-proteolytic signaling processes including DNA damage repair, kinase activation, and intracellular trafficking [2] [4].

- M1-linked (linear) chains: Assembled by the LUBAC complex (HOIP, HOIL-1), these regulate inflammatory signaling pathways, particularly NF-κB activation [7] [1].

- Atypical linkages (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33): Participate in diverse processes including DNA damage response, cell cycle regulation, and innate immunity [4].

Recent research has revealed additional complexity through heterotypic and branched ubiquitin chains, which may integrate multiple signals to fine-tune cellular responses [3] [1].

Diagram 1: The three-step ubiquitination cascade. This diagram illustrates the sequential action of E1 (activation), E2 (conjugation), and E3 (ligation) enzymes in mediating ubiquitin transfer to substrate proteins.

Experimental Approaches for Studying the Ubiquitination Cascade

In Vitro Reconstitution of Ubiquitination

Recent advances in biochemical reconstitution have enabled detailed mechanistic studies of ubiquitination components. The following protocol, adapted from research on UBE2J2 regulation, demonstrates methodology for analyzing lipid-dependent E2 activity [6]:

Objective: Assess ubiquitin loading of membrane-anchored E2 enzymes in liposomes of defined lipid composition.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Purified E1, E2 (e.g., UBE2J2, UBE2J1), ubiquitin

- Phospholipids: phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE)

- ATP regeneration system

- Detergents for solubilization (e.g., n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside)

- Fluorescent labeling reagents (optional)

- Equipment: Fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC), SDS-PAGE, immunoblotting apparatus

Procedure:

- Liposome Preparation: Form liposomes with defined lipid compositions (e.g., ER-like membranes: 80:20 PC:PE molar ratio with 33% saturated fatty acyl chains) using extrusion or dialysis methods [6].

- E2 Reconstitution: Incorporate purified E2 enzymes into pre-formed liposomes via detergent dilution and removal.

- Ubiquitin Loading Assay: Incubate E2-containing proteoliposomes with E1 (100 nM), ubiquitin (5 μM), and ATP (2 mM) in reaction buffer at 30°C.

- Time-course Sampling: Remove aliquots at specified time points (0, 30s, 1, 2, 5, 10, 30 min) and immediately mix with non-reducing SDS sample buffer to preserve thioester linkages.

- Analysis: Resolve proteins by non-reducing SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin or anti-E2 antibodies.

Key Controls:

- Include detergent-solubilized E2 as an activation-positive control

- Verify E2 orientation in liposomes via protease protection assays

- Test lipid packing effects using liposomes with varying saturation levels (10% vs. 50% SFAs)

Identification of E3 Substrates

Determining physiological substrates for E3 ligases remains a central challenge in ubiquitin research. The Global Protein Stability (GPS) profiling system represents a powerful approach for substrate identification [2]:

Methodology:

- Library Construction: Generate a comprehensive library of reporter proteins fused to potential substrate candidates.

- E3 Perturbation: Employ CRISPR-Cas9-mediated knockout or RNA interference to deplete specific E3 ligases.

- Stability Monitoring: Quantify reporter accumulation resulting from reduced ubiquitination and degradation.

- Validation: Confirm direct ubiquitination through in vitro assays with purified components.

Technical Considerations:

- Genome-wide screening enables discovery of novel E3-substrate relationships

- Requires rigorous validation to distinguish direct from indirect effects

- Complementary approaches include ubiquitin remnant profiling and BioID proximity labeling

Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitination Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Cascade Investigations

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 Inhibitors | PYR-41, TAK-243 | Pan-inhibition of ubiquitination cascade | High toxicity in live cells; use for acute inhibition |

| E2 Tools | UBE2J2, UBE2G2, UBE2J1 purified proteins | In vitro ubiquitination, chain linkage specificity | Require co-expression with E1 for functional assays |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, MG132, Carfilzomib | Block substrate degradation, stabilize ubiquitinated proteins | Non-specific effects on overall protein turnover |

| DUB Inhibitors | PR-619 (broad-specificity), VLX1570 (USP14) | Stabilize ubiquitin signals, study deubiquitination | Varying specificity profiles require careful controls |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Anti-K48, Anti-K63, Anti-M1 ubiquitin | Detection of specific ubiquitin chain types | Cross-reactivity validation essential |

| Reconstitution Systems | Purified E1-E2-E3 components, liposome kits | Mechanistic studies of ubiquitination | Lipid composition critically affects membrane-associated E2s |

| Activity Reporters | Ubiquitin vinyl sulfones, diGly remnant antibodies | Proteomic identification of ubiquitination sites | Require specialized mass spectrometry expertise |

Therapeutic Targeting of the Ubiquitination Cascade

Components of the ubiquitination cascade represent promising targets for therapeutic intervention, particularly through strategies that exploit E3 ligases for targeted protein degradation [3]. Key approaches include:

- Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs): Bifunctional molecules that simultaneously bind E3 ligases and target proteins, inducing proximity and ubiquitination of disease-relevant proteins [3].

- Molecular Glues: Small molecules that enhance or induce interactions between E3 ligases and specific substrates [3].

- Ubiquitin Variants (UbVs): Engineered ubiquitin mutants that selectively inhibit or modulate specific E2-E3 interactions.

Recent structural studies have revealed new mechanistic classes of E3 ligases, including RING-Cys-Relay and RZ finger ligases, expanding the potential toolbox for therapeutic development [3]. Additionally, research into branched and mixed-linkage ubiquitin chains has uncovered complex regulatory signals that integrate cellular stress pathways, offering new opportunities for intervention in cancer and neurodegenerative diseases [3].

The ubiquitination cascade, comprising the coordinated action of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes, represents a sophisticated regulatory system that controls protein fate and function in eukaryotic cells. Continued elucidation of the mechanisms underlying ubiquitin signal specification, including the expanding roles of atypical ubiquitin linkages and the regulatory potential of E2 enzymes as environmental sensors, promises to unlock new therapeutic strategies for human diseases. For researchers and drug development professionals, leveraging advanced tools such as in vitro reconstitution systems, substrate identification platforms, and targeted degradation technologies will be essential for translating fundamental insights into clinical applications.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents the primary pathway for selective intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, responsible for degrading over 80% of cellular proteins [8]. This system maintains protein homeostasis, regulates critical cellular processes including cell cycle progression, DNA repair, signal transduction, and eliminates damaged or misfolded proteins [8] [9]. At the heart of the UPS lies the 26S proteasome, a massive 2.6 MDa multi-subunit complex that degrades ubiquitin-tagged proteins into small peptides [10]. The 26S proteasome comprises two main subcomplexes: the 20S core particle (CP) that executes proteolysis, and the 19S regulatory particle (RP) that recognizes ubiquitinated substrates, prepares them for degradation, and regulates access to the core [10]. Understanding the intricate structure and functional mechanics of these components is fundamental to biomedical research, particularly in drug development for cancer and neurodegenerative diseases where proteasomal function is frequently impaired [8] [11].

Architectural Organization of the 26S Proteasome

The 20S Core Particle: Proteolytic Chamber

The 20S core particle forms the catalytic heart of the proteasome, organized as a hollow cylinder composed of four stacked heptameric rings [8]. The two outer rings consist of seven distinct α-subunits (α1-α7) that form a gated channel, while the two inner rings contain seven different β-subunits (β1-β7), three of which (β1, β2, and β5) harbor the proteolytic active sites [8] [10]. The organization creates an enclosed degradation chamber where substrates are sequestered to prevent uncontrolled protein destruction.

Table 1: 20S Core Particle Subunits and Their Functions

| Subunit Type | Yeast Gene | Human Gene | Proteolytic Activity/Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-subunits | PRE9 | PSMA4 | N-terminal tail constitutes major component of 20S gate |

| PRE6 | PSMA7 | Structural component of outer ring | |

| PRE5 | PSMA1 | Structural component of outer ring | |

| β-subunits | PRE3 | PSMB6 | Caspase-like (C-L) activity |

| PUP1 | PSMB7 | Trypsin-like (T-L) activity | |

| PRE2 | PSMB5 | Chymotrypsin-like (CT-L) activity; primary target of proteasome inhibitors |

The 20S core particle maintains a gated channel that restricts access to the proteolytic chamber, requiring regulatory particles to open for substrate entry [10]. Recent research has demonstrated that the 20S proteasome can also function independently of the 19S regulator, providing a specialized pathway for degrading intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and oxidatively damaged proteins without ubiquitination [12].

The 19S Regulatory Particle: Substrate Recognition and Processing

The 19S regulatory particle recognizes ubiquitinated substrates, removes ubiquitin chains, unfolds target proteins, and translocates them into the 20S core particle [10]. This complex can be structurally and functionally divided into two subcomplexes: the base and the lid.

Table 2: Major 19S Regulatory Particle Subunits and Functions

| Subcomplex | Subunit | Human Gene | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base | Rpt1-Rpt6 | PSMC2-PSMC6 | AAA-ATPase unfoldase; substrate translocation |

| Rpn1 | PSMD2 | Scaffold; ubiquitin receptor docking | |

| Rpn2 | PSMD1 | Scaffold; Rpn13 docking site | |

| Rpn10 | PSMD4 | Ubiquitin receptor (UIM domain) | |

| Rpn13 | ADRM1 | Ubiquitin receptor (PRU domain) | |

| Lid | Rpn11 | PSMD14 | Deubiquitinase (MPN+ domain) |

| Rpn3,5,6,7,8,9,12 | PSMD3,12,11,6,7,13,8 | PCI domain proteins; structural scaffold |

The base contains six AAA-ATPase subunits (Rpt1-Rpt6) that form a heterohexameric ring, which uses ATP hydrolysis to unfold substrates and translocate them into the 20S core [10]. The base also contains three ubiquitin receptors (Rpn1, Rpn10, and Rpn13) that recognize polyubiquitin chains on substrates [13]. The lid consists of nine non-ATPase subunits (Rpn3, Rpn5-Rpn9, Rpn11, Rpn12, and Sem1) and contains the deubiquitinating enzyme Rpn11, which removes ubiquitin chains from substrates prior to degradation [9] [10].

Functional Mechanics of Proteasomal Degradation

Substrate Recognition Mechanisms

The proteasome employs multiple ubiquitin receptors to recognize substrates with diverse ubiquitin chain configurations. Rpn10 serves as the primary receptor for proteins with single chains of K48-linked ubiquitin, while Rpn1 can act as a co-receptor with Rpn10 for K63 chains and other chain types [13]. Surprisingly, Rpn13 appears to retard degradation of various single-chain substrates in steady-state assays, suggesting complex regulatory roles for different receptors [13]. Substrates with multiple short ubiquitin chains can be presented for degradation through any of the known receptors, indicating remarkable versatility in recognition mechanisms [13].

Diagram 1: Proteasomal Degradation Pathway

Ubiquitin-Independent Degradation Mechanisms

While ubiquitin-dependent degradation represents the canonical pathway, recent research has revealed significant ubiquitin-independent proteasomal degradation mechanisms. The 20S core particle can directly degrade intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and oxidatively damaged proteins without 19S regulation [12]. A 2025 study demonstrated that a hyperactive 20S proteasome (α3ΔN) engineered in C. elegans markedly enhanced IDP and misfolded protein degradation, reduced oxidative damage, and improved endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) [12].

Furthermore, research published in 2025 revealed that depletion of 19S PSMD lid proteins causes aberrant ubiquitin-independent degradation of the kinesin motor protein KIF11 by the 20S core, leading to defects in bipolar spindle assembly during mitosis [14]. This demonstrates that the 19S particle not only facilitates ubiquitin-dependent degradation but also restrains inappropriate ubiquitin-independent degradation, highlighting a dual regulatory function.

Experimental Approaches for Proteasome Research

Structural Analysis Methods

Structural elucidation of proteasome complexes has advanced significantly through cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). Recent technical breakthroughs have enabled near-atomic resolution views of the 26S proteasome, revealing conformational states during substrate processing [10]. For example, a 2025 cryo-EM study of human thioredoxin-like protein 1 (TXNL1) bound to the 19S regulatory particle revealed key interaction interfaces with PSMD1 (Rpn2), PSMD4 (Rpn10), and PSMD14 (Rpn11), establishing structural requirements for stress-induced ubiquitin-independent degradation [15].

Table 3: Key Experimental Methods in Proteasome Research

| Method | Application | Key Insights Generated |

|---|---|---|

| Cryo-EM | Structural analysis of proteasome complexes | Conformational states during substrate processing; ubiquitin receptor organization |

| Reconstituted proteasomes with mutated subunits | Functional analysis of specific ubiquitin receptors | Role of Rpn10, Rpn13, and Rpn1 in different substrate degradation pathways |

| Genetic engineering (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9) | Generation of hyperactive proteasome mutants | Mechanism of ubiquitin-independent degradation; proteostasis regulation |

| Affinity purification + Mass spectrometry | Identification of proteasome-interacting proteins | TXNL1-proteasome interactions; stress-induced degradation pathways |

| Tandem Mass Tag Mass Spectrometry (TMT-MS) | Proteomic analysis of proteasome function | Global proteome changes in response to proteasome hyperactivation |

Functional Assays and Genetic Approaches

Genetic manipulation combined with biochemical assays has been instrumental in deciphering proteasome function. Site-directed mutagenesis of ubiquitin receptors in yeast proteasomes has revealed specialized functions: Rpn10 primarily mediates degradation of K48-linked ubiquitin chains, while Rpn1 acts as a co-receptor for K63 chains and other chain types [13]. The development of hyperactive 20S proteasome models using CRISPR-Cas9 to induce N-terminal truncation of the α3 subunit (α3ΔN) has enabled research into ubiquitin-independent degradation pathways and their role in proteostasis [12].

RNA interference (RNAi) approaches have demonstrated the essential nature of 20S proteasome subunits across species. In Locusta migratoria, RNAi-mediated knockdown of 20S proteasome subunits resulted in complete mortality, midgut and gastric cecum atrophy, and significant reductions in body length and weight [16]. Similarly, silencing of proteasome subunits impaired ovarian growth, underscoring the crucial role of proteasomal function in development and tissue homeostasis [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Proteasome Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Inhibit proteolytic activity of 20S core particle; study substrate accumulation |

| E1 Inhibitors | PYR-41, PYZD-4409 | Block ubiquitin activation; investigate upstream ubiquitination |

| NEDD8-Activating Enzyme (NAE) Inhibitor | MLN4924 | Disrupts cullin neddylation and SCF E3 ligase function; in clinical trials |

| E2 Inhibitors | CC0651, NSC697923, BAY 11-7082 | Allosteric inhibition of specific E2 enzymes; study chain assembly |

| Genetic Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 (α3ΔN mutant), RNAi constructs | Generate hyperactive proteasomes; study subunit-specific functions |

| Affinity Tags | 3xFLAG tags on Rpn11, Pre1 | Purify proteasome subcomplexes; study assembly and interactions |

| Ubiquitin Chain Linkage-Specific Reagents | K48-only, K63-only ubiquitin mutants | Study substrate targeting specificity; receptor preferences |

Implications for Therapeutic Development

The intricate mechanics of the 20S core and 19S regulatory particles present multiple therapeutic intervention points. Cancer cells exhibit heightened dependence on proteasomal function, making proteasome inhibitors valuable therapeutics [8] [17]. Bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib target the 20S core particle and have been approved for treating multiple myeloma and other hematological malignancies [8].

Emerging strategies focus on more specific targeting of ubiquitin system components to enhance therapeutic efficacy while reducing side effects. The NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor MLN4924 is currently in phase II clinical trials, demonstrating promising results in disrupting cullin-RING ligase function [11]. Research into 20S proteasome hyperactivation presents a novel approach for treating neurodegenerative diseases characterized by protein aggregation, with studies showing that enhanced 20S activity reduces toxic protein accumulation in models of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease [12].

The structural and mechanistic insights into proteasome function continue to reveal new therapeutic opportunities. Understanding the specialized roles of ubiquitin receptors, the regulation of ubiquitin-independent degradation, and the assembly pathways of proteasome subcomplexes provides a foundation for developing next-generation therapeutics targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome system in cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and other human diseases.

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification wherein a small, 76-amino acid protein, ubiquitin, is covalently attached to substrate proteins. The versatility of this signal arises from ubiquitin's ability to form polymers, or chains, through its seven lysine (K) residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or its N-terminal methionine (M1) [18] [19]. The type of linkage, the length of the chain, and its architecture (homotypic, mixed-linkage, or branched) constitute a sophisticated "ubiquitin code" that determines the fate and function of the modified substrate [20]. This code is decoded by ubiquitin-binding proteins (UBPs) containing ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs), which direct downstream cellular processes [20]. Among the different linkage types, K48 and K63 represent the most abundant and well-studied chain types, with K48-linked chains being the classical signal for proteasomal degradation and K63-linked chains playing key roles in non-proteolytic signaling pathways [21] [20]. This review delves into the diversity of the ubiquitin code, with a specific focus on the biological roles, recognition, and experimental dissection of K48, K63, and other key linkages.

The Functional Spectrum of Ubiquitin Linkages

Different ubiquitin chain linkages create a functional spectrum of cellular signals. The table below summarizes the key characteristics and functions of the major linkage types.

Table 1: Diversity of Ubiquitin Chain Linkages and Their Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Functions | Key E2 Enzymes / E3 Complexes | Representative Decoders / Effectors |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Proteasomal degradation [21] [20] | CDC34 [20] | Proteasome (RPN10, RPN13) [22], RAD23B [20] |

| K63-linked | DNA repair, endocytosis, NF-κB signaling, inflammation, kinase activation [18] [21] [20] | Ubc13/Uev1a (Mms2) heterodimer [18] [20] | EPN2 [20], USP53/USP54 (DUBs) [23] |

| K11-linked | Proteasomal degradation (cell cycle regulators, ERAD) [24] | UbcH10 (with APC/C) [24] | Proteasome (RPN1, RPN10) [22] |

| K11/K48-branched | Priority signal for proteasomal degradation [22] | Not specified in search results | Proteasome (RPN1, RPN2, RPN10) [22], UCHL5 (DUB) [22] |

| Linear (M1-linked) | Innate immune response, NF-κB signaling [18] | LUBAC (HOIP/HOIL-1/SHARPIN) [18] | NF-κB pathway components [18] |

K48-Linked Ubiquitin Chains: The Canonical Degradation Signal

Discovery and Core Function

The discovery of K48-linked polyubiquitin chains by Chau et al. was a landmark event that established the paradigm of ubiquitin as a signal for protein degradation [18]. This linkage is the most abundant in the cell and serves as the primary signal for targeting substrates to the 26S proteasome for degradation [20]. The modification of a substrate with a chain of four or more K48-linked ubiquitins is conventionally considered the signal for efficient proteasomal recognition and degradation [20].

Mechanism of Proteasomal Recognition

The 26S proteasome recognizes K48-linked chains through its intrinsic ubiquitin receptors, including RPN10 and RPN13 [22]. Structural studies have revealed that these receptors bind to the hydrophobic patch centered around Ile44 on ubiquitin, facilitating substrate engagement and translocation into the proteolytic core particle.

K63-Linked Ubiquitin Chains: Masters of Non-Proteolytic Signaling

A Paradigm-Shifting Discovery

The discovery of K63-linked ubiquitin chains fundamentally changed the perception of ubiquitin's role in cell signaling. In 1999, Hofmann and Pickart found that a K63R ubiquitin mutation in yeast caused defects in DNA repair, a process independent of the proteasome [18]. They subsequently identified the Ubc13/Mms2 heterodimer as the specific E2 complex responsible for synthesizing K63-linked chains [18]. This revealed that ubiquitin functions as a signaling molecule beyond protein degradation.

Structural Basis of K63-Linked Chain Assembly

The structural basis for K63-chain specificity was elucidated through a collaboration that determined the crystal structure of Ubc13/Mms2. The structure revealed that Mms2, a catalytically inactive ubiquitin E2 variant (UEV), acts as a scaffold. It positions the acceptor ubiquitin molecule so that its K63 residue is oriented towards the active site cysteine of Ubc11 [18]. A key hydrophobic residue in Mms2 engages the Ile44 patch of the acceptor ubiquitin, ensuring linkage specificity [18].

Diverse Cellular Roles

K63-linked ubiquitin chains are involved in a wide array of non-degradative processes.

- Intracellular Trafficking and MVB Sorting: K63-linked chains act as a specific signal for sorting membrane proteins, like the Gap1 permease and carboxypeptidase S (CPS), into the multivesicular body (MVB) pathway for vacuolar/lysosomal degradation [21]. In contrast, monoubiquitination is often sufficient for the initial internalization of these proteins from the plasma membrane [21].

- DNA Damage Response: K63 chains play a critical role in recruiting DNA repair proteins to sites of damage [18] [20].

- Innate Immunity and Inflammation: The K63 linkage is essential for activating NF-κB signaling pathways in response to inflammatory stimuli [20].

- Kinase Activation: K63 ubiquitination can directly activate protein kinases, such as the nerve growth factor receptor TrkA [21].

Beyond K48 and K63: K11-Linked and Branched Ubiquitin Chains

K11-Linked Chains in Cell Cycle and Degradation

The Anaphase-Promoting Complex/Cyclosome (APC/C), a key regulator of the cell cycle, preferentially assembles K11-linked ubiquitin chains to trigger the degradation of mitotic regulators like cyclin B1 and securin [24]. The E2 enzyme UbcH10 provides specificity for K11-chain assembly. A unique surface on ubiquitin, the TEK-box, is critical for the elongation of K11-linked chains by facilitating the interaction between the E2 and the acceptor ubiquitin [24]. Strikingly, similar TEK-box motifs are found in APC/C substrates, enabling the ligase to switch from modifying substrate lysines to elongating chains on ubiquitin itself [24]. K11-linked chains are also recognized as efficient proteasomal targeting signals [24].

The Complexity of Branched Ubiquitin Chains

Branched ubiquitin chains, where a single ubiquitin molecule has more than one ubiquitin attached to it, represent a higher level of complexity in the ubiquitin code. Among these, K48/K63-branched chains are the best characterized, accounting for a significant portion of cellular K63 linkages [20]. Recent cryo-EM structures have revealed how the human 26S proteasome recognizes K11/K48-branched chains. The proteasome uses a multivalent recognition mechanism involving a novel K11-linked Ub binding site in a groove formed by RPN2 and RPN10, in addition to the canonical K48-linkage binding site [22]. This branched architecture acts as a "priority signal" for the proteasomal degradation of substrates during cell cycle progression and proteotoxic stress [22].

Experimental Toolkit for Decoding the Ubiquitin Code

Studying specific ubiquitin linkages requires specialized reagents and methodologies. The following table outlines key tools used in this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies for Ubiquitin Research

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function and Specificity | Key Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) | High-affinity reagents (nanomolar Kd for tetra-ubiquitin) with specificity for K48 or K63 linkages. Protect polyubiquitinated proteins from deubiquitination and degradation [19]. | Immunoprecipitation of endogenous K48- or K63-polyubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates without cross-reactivity [19]. |

| Linkage-Specific DUBs | Deubiquitinases that cleave specific ubiquitin linkages. Used for linkage validation (UbiCRest assay) [20]. | OTUB1 (K48-specific) and AMSH (K63-specific) can be used to confirm chain linkage in pulldown experiments [20]. |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | Ubiquitin where all lysines are mutated to arginine except one (e.g., ubi-K48 only, ubi-K63 only), or single lysine-to-arginine mutants (e.g., ubi-K63R) [24]. | Determining if a specific linkage is required or sufficient for a biological process in in vitro assays or in cells [24]. |

| DUB Inhibitors (CAA, NEM) | Cysteine alkylators used in lysate-based pulldowns to inhibit endogenous DUBs and prevent disassembly of ubiquitin chains on bait proteins [20]. | Stabilizing immobilized Ub chains during ubiquitin interactor pulldown screens from cell lysates. Choice of inhibitor (CAA vs. NEM) can affect results and must be considered [20]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Ubiquitin Interactor Pulldown Screen

This protocol, adapted from [20], is used to identify proteins that bind to specific ubiquitin chain types.

- Synthesis and Immobilization of Ubiquitin Chains: Enzymatically synthesize the desired homotypic or branched ubiquitin chains (e.g., K48-Ub3, K63-Ub3, Br-Ub3) using linkage-specific E2 enzymes (e.g., CDC34 for K48, Ubc13/Uev1a for K63). Purify the chains and immobilize them on streptavidin resin via a C-terminal biotin tag.

- Cell Lysate Preparation and DUB Inhibition: Prepare lysates from the cell line of interest (e.g., HeLa cells). Divide the lysate and treat with either Chloroacetamide (CAA) or N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) to inhibit deubiquitinases. Note that the choice of inhibitor can impact the stability of the bait chains and the set of interactors identified.

- Pulldown Incubation: Incubate the immobilized ubiquitin chains with the inhibited cell lysates to allow ubiquitin-binding proteins (UBPs) to bind.

- Wash and Elution: Wash the resin thoroughly to remove non-specifically bound proteins. Elute the bound proteins.

- Identification by Mass Spectrometry: Analyze the eluted proteins using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS).

- Data Analysis: Statistically compare the enrichment of proteins across the different chain types to identify linkage-specific, chain length-specific, or branch-specific interactors.

The workflow for this screen is visualized below.

Advanced Concepts and Recent Discoveries

Linkage-Specific Deubiquitinases (DUBs)

DUBs are essential for editing the ubiquitin code. A landmark 2025 study revised the annotation of USP53 and USP54, previously thought to be inactive, as highly specific K63-linkage-directed DUBs [23]. Disease-associated mutations in USP53 abrogate this activity, linking loss of K63-deubiquitination to pediatric cholestasis [23]. The study also revealed distinct mechanisms: USP54 cleaves within K63-linked chains, while USP53 performs "en bloc" deubiquitination of substrate proteins in a K63-specific manner, a previously unobserved activity [23]. Structural analysis identified cryptic S2 ubiquitin-binding sites within their catalytic domains that underpin this specificity [23].

The Role of Chain Length

Beyond linkage type, the length of a ubiquitin chain contributes to the specificity of its decoding. Some UBPs and DUBs display a clear preference for longer chains. For instance, the proteasome may require a chain of at least four ubiquitins (K48 ≥Ub4) for efficient substrate degradation, although this is debated [20]. Recent interactome screens have identified proteins like CCDC50, FAF1, and DDI2 that prefer Ub3 over Ub2 chains, highlighting the importance of chain length as a parameter in the ubiquitin code [20].

Concluding Perspectives

The exploration of the ubiquitin code has evolved from a simple dichotomy of K48 (degradation) versus K63 (signaling) to an appreciation of a complex language comprising multiple linkage types, chain lengths, and branched architectures. Advanced structural biology techniques, such as cryo-EM, are revealing how cellular machinery like the proteasome multivalently recognizes complex signals like K11/K48-branched chains [22]. Simultaneously, the development of more sophisticated tools, such as linkage-specific TUBEs and quantitative interactome screens, is enabling researchers to decode this language with ever-greater precision [20] [19]. Understanding the nuances of the ubiquitin code is not only fundamental to cell biology but also holds immense therapeutic potential, as dysregulation of ubiquitin signaling is implicated in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and other disorders [25] [26]. Future research will continue to unravel how the combinatorial complexity of ubiquitin modifications is integrated to control cellular homeostasis.

Cellular Roles in Protein Homeostasis and Quality Control

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a cornerstone of cellular protein homeostasis, orchestrating the precise, selective degradation of myriad regulatory, damaged, and misfolded proteins. This targeted degradation is fundamental to critical physiological processes, including cell cycle progression, signal transduction, immune responses, and synaptic plasticity. Dysregulation of the UPS is mechanistically linked to a spectrum of human diseases, most notably cancer, neurodegenerative proteinopathies, and renal disorders, positioning it as a prime target for therapeutic intervention. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the UPS pathway, detailing its molecular mechanisms, exploring its multifaceted roles in disease pathogenesis, and highlighting cutting-edge research methodologies and reagent toolkits that are propelling both fundamental discovery and drug development in this field. The content is framed within the context of advancing UPS pathway research to unravel novel biological insights and therapeutic opportunities.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system is a highly conserved and regulated cascade responsible for the majority of selective intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotic cells. It governs the turnover of approximately 80% of cellular proteins, particularly short-lived, regulatory, damaged, or misfolded proteins, thereby maintaining protein homeostasis [27]. The process involves two major coordinated steps: first, the covalent attachment of a ubiquitin chain to a target protein, and second, the recognition and degradation of that tagged protein by the proteasome [28]. The exquisite specificity of the UPS is largely conferred by a vast array of E3 ubiquitin ligases, which recognize specific substrates, while the proteasome provides the proteolytic core. Beyond its fundamental housekeeping role, the UPS is a rapid and potent regulator of key signaling pathways, dynamically controlling the levels of proteins critical for processes as diverse as photomorphogenesis in plants [29] and neuronal plasticity in the mammalian brain [30]. The system's centrality to cellular function means that even minor perturbations can contribute to disease pathogenesis, making its components attractive diagnostic and therapeutic targets.

Core Mechanism of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway

The UPS functions through a precise, ATP-dependent enzymatic cascade that results in the targeted degradation of substrate proteins.

The Ubiquitination Cascade

Ubiquitination is a multi-step process mediated by a sequential enzyme cascade:

- E1 (Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme): This initiation step involves a single or few E1 enzymes that activate ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction, forming a high-energy thiol-ester bond between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin and a cysteine residue in the E1 active site [28] [30].

- E2 (Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme): The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to the active site cysteine of an E2 enzyme. Humans possess approximately 25-30 different E2s, which begin to impart specificity to the process [30].

- E3 (Ubiquitin Ligase): This final and most diverse group of enzymes (numbering over 600 in humans) functions as a scaffold, simultaneously binding the E2~ubiquitin complex and the specific protein substrate. The E3 catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to a lysine residue on the substrate protein [28] [30]. Successive rounds of this process build a polyubiquitin chain on the substrate.

Table 1: Key Enzymatic Components of the Ubiquitination Cascade

| Component | Estimated Number in Humans | Primary Function | Families/Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 Enzyme | ~2 | Ubiquitin activation via ATP hydrolysis | UBA1, UBA6 |

| E2 Enzyme | 25-30 | Accepts activated ubiquitin from E1 | UbcH5, UbcH7 |

| E3 Ligase | >600 | Substrate recognition & ubiquitin transfer | RING, HECT, RBR [30] |

E3 ligases are primarily categorized into two major families:

- RING Finger E3s: These facilitate the direct transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 enzyme to the substrate. They can function as single subunits (e.g., Mdm2) or as multi-subunit complexes (e.g., CRL4COP1-SPA in plants) [29] [30].

- HECT Domain E3s: These form a thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate. A well-characterized example is E6-AP (Ube3a) [30].

The nature of the polyubiquitin chain linkage determines the fate of the modified protein. A chain linked through lysine 48 (K48) of ubiquitin is the canonical signal for proteasomal degradation, whereas other linkages, such as K63, often play roles in non-proteolytic signaling pathways [30] [27].

The Proteasome and Degradation

The 26S proteasome is the macromolecular machine that recognizes and degrades polyubiquitinated proteins. It is composed of two primary complexes:

- 20S Core Particle (CP): A barrel-shaped structure comprising four stacked heptameric rings (α7β7β7α7) that contains the proteolytically active sites (housed in the β-subunits) facing the inner chamber. The activities include caspase-like, trypsin-like, and chymotrypsin-like hydrolysis [28] [27].

- 19S Regulatory Particle (RP): One or two RP "caps" attach to the 20S CP to form the 26S or 30S proteasome, respectively. The RP is responsible for recognizing ubiquitinated substrates, deubiquitinating them, unfolding the polypeptide, and translocating it into the 20S core for degradation in an ATP-dependent manner [28] [27].

Specialized proteasome variants, such as the immunoproteasome, incorporate alternative catalytic subunits and play specific roles in processes like antigen presentation [31].

Quantitative Data on UPS Composition and Function

The functionality of the UPS can be quantified by measuring the activity of its enzymatic components and the proteasome itself. The following table summarizes key quantitative assays and typical findings in disease contexts.

Table 2: Quantitative Profiling of UPS Components and Activity

| Assay Target | Experimental Method | Exemplary Finding / Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| E1 Activating Activity | Thioester assay, ATP/AMP quantification | A single E1 enzyme activates ubiquitin in most mammalian cells [27]. |

| E2 Conjugating Diversity | MS-based proteomics, yeast two-hybrid | ~25-30 E2 enzymes in humans interact selectively with specific E3s [30]. |

| E3 Ligase Specificity | IP-MS, protein microarrays, CRISPR screens | >600 E3 ligases provide substrate specificity; e.g., CRL1EBF1/2 degrades PIFs in light-grown plants [29]. |

| Proteasome Hydrolytic Activity | Fluorogenic peptide substrates (e.g., Suc-LLVY-AMC) | Cancer cells (e.g., multiple myeloma) show elevated chymotrypsin-like activity, targeted by drugs like Bortezomib [28]. |

| Global Ubiquitination Levels | Anti-Ub Western Blot, Ubiquitinome MS | Viral infection in maize significantly increases total protein ubiquitination levels [32]. |

| Proteasome Interactome | Proximity Labeling (ProteasomeID), APEX-MS | ProteasomeID identified novel interacting proteins and substrates across mouse organs [31]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: ProteasomeID for Mapping Interactomes

The following methodology details the ProteasomeID approach, a state-of-the-art technique for quantitatively mapping proteasome interactomes and substrates in vivo [31].

Background and Principle

Traditional methods like co-immunoprecipitation often fail to capture the dynamic and transient interactions of the proteasome. ProteasomeID utilizes proximity-dependent biotinylation (e.g., using the promiscuous biotin ligase BirA*) fused to specific proteasome subunits. This allows for the labeling of proteins within a ~10 nm radius, enabling subsequent streptavidin-based capture and mass spectrometric identification of interactors and induced substrates in their native cellular context.

Required Materials and Reagents

- Cell Line: HEK293 FlpIn TREx (HEK293T) cells or similar.

- Expression Constructs: Plasmids encoding BirA* fusions to proteasome subunits (e.g., PSMA4-BirA, PSMC2-BirA, BirA*-PSMD3), under a tetracycline-inducible promoter with an N- or C-terminal FLAG tag.

- Control: A construct expressing BirA* alone.

- Chemicals: Biotin, Tetracycline, Proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG132), Streptavidin-coated magnetic beads.

- Buffers: Lysis buffer (e.g., RIPA with protease inhibitors), Wash buffers.

- Instrumentation: Mass spectrometer capable of Data Independent Acquisition (DIA).

Step-by-Step Procedure

Cell Line Generation & Induction:

- Generate stable HEK293T cell lines expressing the BirA* fusion proteins and the BirA*-only control.

- Induce expression with Tetracycline and supplement the culture medium with biotin for a defined period (typically 18-24 hours) to allow for biotinylation.

Cell Lysis and Protein Extraction:

- Harvest cells and lyse using an optimized lysis buffer.

- Clarify the lysate by centrifugation to remove insoluble debris.

Streptavidin Affinity Purification:

- Incubate the clarified lysate with chemically modified streptavidin magnetic beads to capture biotinylated proteins.

- Wash the beads stringently with a series of buffers to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

On-Bead Digestion and Peptide Preparation:

- Subject the beads to on-bead digestion with a protease (e.g., trypsin) to release peptides from the captured proteins.

- Use an optimized protocol to minimize co-elution of streptavidin-derived peptides, which can interfere with MS analysis.

Mass Spectrometric Analysis and Data Processing:

- Analyze the resulting peptides by Liquid Chromatography tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) using a DIA method for deep, quantitative profiling.

- Process the raw data using a dedicated bioinformatics pipeline to identify and quantify biotinylated peptides and their corresponding proteins.

Key Applications and Validation

- Identification of Novel Interactors: ProteasomeID has been used to chart tissue-specific proteasome interactomes across different mouse organs, revealing previously unknown regulatory associations [31].

- Substrate Identification: When combined with proteasome inhibition (e.g., with MG132), the method enables the identification of endogenous proteasome substrates, including low-abundance transcription factors, by capturing proteins that accumulate near the proteasome upon inhibition.

- Validation: Findings should be validated using orthogonal methods such as immunofluorescence co-localization, co-immunoprecipitation, or functional assays measuring protein half-life.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Advanced research into the UPS relies on a suite of specialized reagents and molecular tools. The following table catalogs essential materials for probing UPS function.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for UPS Investigation

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function in Research | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Small Molecule Inhibitors | Inhibit proteolytic activity of the 20S core particle; used for mechanistic studies and cancer therapy. | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib, MG132 [28] [32] |

| E1/E2/E3 Inhibitors/Modulators | Small Molecule Inhibitors | Target specific steps in the ubiquitin cascade to dissect pathway mechanics and for therapeutic targeting. | PYR-41 (E1 inhibitor), Lenalidomide (Cereblon E3 modulator) [28] |

| Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme (E1) | Recombinant Protein | For in vitro ubiquitination assays to study the enzymatic cascade and screen for inhibitors. | Recombinant UBA1 [27] |

| Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme (E2) | Recombinant Protein | For in vitro ubiquitination assays to study specific E2-E3-substrate relationships. | Recombinant UbcH5, UbcH7 [30] |

| E3 Ligase Expression Constructs | Plasmid DNA/CRISPR Tools | To overexpress or knockout specific E3s for functional studies of substrate recognition and degradation. | Plasmids for CRL4COP1-SPA, Mdm2 [29] [30] |

| Anti-Ubiquitin Antibodies | Immunological Reagent | Detect mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins via Western Blot or Immunoprecipitation. | Anti-K48-linkage, Anti-K63-linkage specific antibodies [32] [27] |

| Anti-Proteasome Subunit Antibodies | Immunological Reagent | Detect proteasome composition, assembly, and localization. | Anti-PSMA4, Anti-PSMC2 [31] |

| Fluorogenic Proteasome Substrates | Activity Probe | Quantitatively measure the chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like, and caspase-like activities of the proteasome. | Suc-LLVY-AMC [28] |

| BirA* Proximity Labeling System | Molecular Biology Tool | To map proteasome interactomes and proximal substrates in live cells and in vivo models. | PSMA4-BirA* knock-in mouse model [31] |

| PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) | Bifunctional Molecules | Induce targeted degradation of specific proteins of interest by recruiting them to an E3 ligase. | ARV-471 (targets ER for degradation) [28] |

UPS Dysregulation in Disease and Therapeutic Targeting

The critical role of the UPS in maintaining cellular homeostasis means its dysregulation is a contributory factor in numerous pathologies.

Cancer: Many oncoproteins (e.g., cyclins) are short-lived and controlled by the UPS, while tumor suppressors (e.g., p53) are often inactivated via ubiquitin-mediated degradation. Proteasome inhibitors, such as Bortezomib, are first-line therapies for blood cancers like multiple myeloma, inducing apoptosis by disrupting protein homeostasis in malignant cells [28]. Furthermore, targeted protein degradation strategies, including PROTACs, are a revolutionary class of therapeutics that hijack the UPS to degrade previously "undruggable" oncogenic targets [28].

Neurodegenerative Diseases: Conditions like Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's disease are characterized by the accumulation of toxic protein aggregates (e.g., Aβ, α-synuclein, huntingtin). This is frequently associated with an age-related decline in UPS activity and a failure in protein quality control [30] [33]. Neurons are particularly vulnerable to UPS impairment due to their post-mitotic nature and high metabolic demands [33].

Renal Diseases: The UPS is implicated in acute kidney injury (AKI), diabetic kidney disease, and renal fibrosis. For example, the E3 ligase RBBP6 promotes K48-linked ubiquitination and degradation of ERRα, exacerbating mitochondrial damage in tubular cells in diabetic kidney disease [27]. The balance between ubiquitination and deubiquitination is crucial for renal health.

Infection and Immunity: Viruses can manipulate the host UPS to promote their own replication. For instance, maize chlorotic mottle virus (MCMV) and sugarcane mosaic virus (SCMV) infection significantly alter the host ubiquitinome, and inhibition of the proteasome with MG132 enhances viral accumulation, indicating a role for the UPS in antiviral defense [32]. Specialized immunoproteasomes are also critical for generating peptides for antigen presentation [31].

Once considered exclusively a marker for proteasomal degradation, ubiquitination is now recognized as a versatile post-translational modification regulating diverse non-proteolytic cellular processes. This technical review examines the mechanisms by which non-degradative ubiquitination controls intracellular signaling cascades and membrane trafficking pathways. We detail how specific ubiquitin chain linkages and attachment sites directly modulate protein function, complex assembly, and subcellular localization through structural and conformational changes. The review synthesizes current experimental approaches for investigating these processes and discusses the implications for therapeutic intervention in human diseases characterized by disrupted ubiquitin signaling.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a crucial pathway for maintaining cellular proteostasis through targeted protein degradation. However, contemporary research has revealed that ubiquitination serves functions far beyond mere protein destruction [34]. The ubiquitin code—comprising monoubiquitination, multiple monoubiquitination, and various polyubiquitin chain linkages—generates tremendous functional diversity that regulates nearly all cellular processes [34] [35].

Non-degradative ubiquitination operates through distinct mechanisms that differ fundamentally from proteasome-targeting signals. Whereas K48-linked polyubiquitin chains typically target substrates for proteasomal degradation, K63-linked chains, monoubiquitination, and other atypical linkages (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, M1) mediate regulatory functions including signal transduction, protein trafficking, DNA repair, and inflammatory responses [34] [36]. This functional divergence stems from both structural differences in chain conformation and the specific recognition of ubiquitin signals by proteins containing ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) [37].

The importance of non-degradative ubiquitination is particularly evident in immune signaling, where components like TRAF6 and TAK1 undergo K63-linked ubiquitination to activate NF-κB signaling independently of degradation [36]. Similarly, monoubiquitination regulates membrane trafficking by controlling the endocytosis of surface receptors [35]. This review systematically examines the mechanisms, experimental approaches, and pathophysiological significance of non-degradative ubiquitination in cellular signaling and trafficking regulation.

Mechanisms of Non-degradative Ubiquitin Signaling

Ubiquitin Chain Linkages and Their Functional Consequences

The structural basis for non-degradative ubiquitin signaling lies in the diverse topologies of ubiquitin chains, which determine specific interactions with ubiquitin-binding proteins.

Table 1: Non-degradative Ubiquitin Linkages and Their Cellular Functions

| Linkage Type | Structural Features | Primary Functions | Key Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| K63-linked | Extended, open conformation [37] | DNA repair, endocytosis, NF-κB signaling, inflammation [37] [34] | TAK1 activation, histone ubiquitylation in DDR [34] |

| K6-linked | Not well characterized | Mitophagy, protein stabilization [34] | Parkin-mediated mitophagy [34] |

| K11-linked | Mixed features | DNA damage response [34] | Not specified |

| K27-linked | Not well characterized | Innate immunity, DDR recruitment [34] | RNF168-mediated histone marking [34] |

| K29-linked | Not well characterized | Wnt signaling, neurodegenerative disorders [34] | SPOP-mediated 53BP1 regulation [34] |

| K33-linked | Extended structure [37] | Protein trafficking, TCR signaling [34] | TCR-zeta regulation [37] |

| M1-linear | Linear structure | Immune signaling, cell death [34] | LUBAC in NF-κB activation [38] |

| Monoubiquitination | Single ubiquitin moiety | Endocytosis, chromatin regulation, protein activation [37] [35] | Histone H2B, Ras activation [37] |

Molecular Mechanisms of Action

Non-degradative ubiquitination regulates cellular processes through several distinct mechanisms:

Steric Regulation and Conformational Changes

Ubiquitin moieties can directly alter protein conformation and function. Molecular dynamics simulations of ZAP-70 kinase revealed that monoubiquitination at specific sites induces distinct conformational shifts—ubiquitination at K377 disrupted the active conformation, while modification at K476 stabilized an active-like state [37] [39]. This demonstrates how ubiquitin can allosterically regulate enzyme activity independent of degradation.

Platform for Complex Assembly

K63-linked and linear polyubiquitin chains serve as scaffolds for protein complex assembly. In NF-κB signaling, K63-linked polyubiquitin chains generated by TRAF6 create binding platforms that recruit and activate the TAK1 kinase complex through proteins with ubiquitin-binding domains like TAB2 [36]. Similarly, during Salmonella infection, linear ubiquitination promotes complex formation necessary for NF-κB activation [38].

Regulation of Protein-Protein Interactions

Monoubiquitination can either promote or inhibit specific protein interactions. For example, monoubiquitination of PCNA at K164 creates a binding site for specialized polymerases that facilitate translational DNA synthesis [37]. Conversely, monoubiquitination can sterically hinder interactions, as demonstrated in histone H2B, where ubiquitination prevents chromatin compaction [37].

Methodologies for Studying Non-degradative Ubiquitination

Proteomic Identification of Ubiquitination Sites

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics has revolutionized the identification of ubiquitination sites. The following workflow represents a standard approach for ubiquitin remnant profiling:

Key Experimental Details:

- Cell Lysis: Use denaturing conditions (e.g., 8M urea, 1% SDS) to preserve modifications and inhibit deubiquitinases [37].

- Digestion: Trypsin digestion generates di-glycine remnants (K-ε-GG) on modified lysines, serving as mass tags (+114.0429 Da) [37].

- Enrichment: Immunoaffinity purification with K-ε-GG-specific antibodies significantly enhances detection sensitivity [37] [38].

- Quantification: Stable Isotope Labeling with Amino acids in Cell culture (SILAC) or tandem mass tag (TMT) approaches enable comparative analysis between conditions [37].

- Proteasome Inhibition: Treatment with MG132 or bortezomib helps distinguish degradative from non-degradative ubiquitination by revealing sites unaffected by proteasomal blockade [37].

Functional Validation Approaches

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Computational approaches provide mechanistic insights into how ubiquitin modifications affect protein dynamics. For ZAP-70 kinase studies:

- System Setup: Generate ubiquitinated protein structures using native chemical ligation or in silico modeling [37].

- Simulation Parameters: Run all-atom simulations in explicit solvent for hundreds of nanoseconds to capture conformational sampling [39].

- Analysis: Measure metrics like root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), radius of gyration, and inter-residue distances to quantify structural changes [39].

Functional Assays

- Kinase Activity Assays: Measure activity of ubiquitinated versus non-ubiquitinated kinases using radioactive or fluorescence-based phosphorylation assays [39].

- Co-immunoprecipitation: Assess protein-protein interactions affected by ubiquitination status [37].

- Pulldown Assays: Use ubiquitin-binding domains to detect specific chain linkages [34].

Signaling Pathways Regulated by Non-degradative Ubiquitination

Immune and Inflammatory Signaling

The NF-κB pathway represents a paradigm for non-degradative ubiquitin signaling, employing multiple chain types for precise regulation:

Key Mechanisms:

- K63-linked Ubiquitination: TRAF6 auto-ubiquitination creates K63 chains that recruit TAK1 through TAB2/3 ubiquitin-binding domains, facilitating IKK phosphorylation and activation [36].

- Linear Ubiquitination: The LUBAC complex (HOIP, HOIL-1L, SHARPIN) generates M1-linked chains on NEMO/IKKγ, reinforcing NF-κB signaling [38] [34].

- Negative Regulation: Deubiquitinating enzymes like A20/TNFAIP3 terminate signaling by removing K63 chains from key signaling intermediates [36].

During bacterial infection, Salmonella Typhimurium induces extensive rewiring of the host ubiquitinome, promoting CDC42 activity and linear ubiquitination to activate NF-κB [38]. Pathogens have evolved effector proteins that manipulate host ubiquitination to promote survival, highlighting the critical role of ubiquitin signaling in host-pathogen interactions.

DNA Damage Response

The DNA damage response employs a sophisticated ubiquitin signaling system for repair protein recruitment:

Table 2: Ubiquitin Ligases and Linkages in DNA Damage Response

| E3 Ligase | Ubiquitin Linkage | Substrate | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNF168 | K27-linked [34] | Histones H2A/H2A.X [34] | Recruitment of 53BP1 and BRCA1 to damage sites |

| RNF8 | K63-linked [34] | H1 histones [34] | Initial ubiquitin platform for RNF168 recruitment |

| RNF8 | K63-linked [34] | Akt [34] | Facilitates Akt membrane translocation and activation |

| SPOP | K27-linked [34] | Geminin [34] | Prevents DNA re-replication during S phase |

| SPOP | K29-linked [34] | 53BP1 [34] | Excludes 53BP1 from chromatin during S phase |

The sequential action of RNF8 and RNF168 establishes a ubiquitin-dependent recruitment platform that amplifies the DNA damage signal and facilitates the assembly of repair complexes at damage sites [34]. This exemplifies how different ubiquitin linkages create a sophisticated signaling code that coordinates the temporal and spatial organization of DNA repair.

Kinase Regulation and Cell Signaling

Protein kinases represent prominent targets for regulatory ubiquitination. Global ubiquitinome analyses reveal that kinases are frequently ubiquitinated within structured domains critical for catalytic activity and regulation [37] [39]. Unlike phosphorylation, which predominantly occurs in disordered regions, ubiquitination sites cluster in regions governing conformational stability and substrate access.

The TGF-β signaling pathway demonstrates how non-degradative ubiquitination both positively and negatively regulates signaling. Smad proteins undergo mono- and polyubiquitination that modulates their activity and complex formation without targeting them for degradation [37] [39]. Similarly, TAK1 activation requires K63-linked polyubiquitination, which facilitates its association with upstream regulators [37].

Membrane Trafficking and Protein Localization

Monoubiquitination serves as a versatile signal for controlling membrane trafficking processes:

Endocytic Trafficking

Monoubiquitination of cell surface receptors targets them for internalization and endosomal sorting [35]. The ubiquitin signal is recognized by endocytic proteins containing UBDs, such as epsins and Hrs, which facilitate cargo selection and vesicle formation.

Inflammatory Signaling and Trafficking

During Salmonella infection, host cells remodel their ubiquitinome to regulate actin cytoskeleton components and small GTPases like CDC42, linking membrane trafficking to inflammatory responses [38]. This coordination ensures precise spatiotemporal control of immune signaling.

Research Tools and Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Non-degradative Ubiquitination

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Antibodies | K-ε-GG monoclonal antibodies [37] | Ubiquitin remnant immunoaffinity enrichment | Enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides for MS |

| Linkage-specific Antibodies | K63-linkage specific, K48-linkage specific, M1-linear specific antibodies [34] | Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence | Detection of specific chain types |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, MG132, Carfilzomib [40] [41] | Distinguishing degradative vs non-degradative ubiquitination | Selective inhibition of proteasomal activity |

| Activity-Based Probes | Ubiquitin vinyl sulfones, HA-Ub-VS [40] | DUB activity profiling | Identification of active deubiquitinating enzymes |

| Cell Lines | HEK293, Jurkat T-cells [37] [39] | Ubiquitin proteomics, signaling studies | Well-characterized models for ubiquitin research |

| Expression Plasmids | Wild-type ubiquitin, ubiquitin mutants (K63R, K48R, K63-only, K48-only) [37] | Mechanistic studies in cell culture | Linkage-specific ubiquitin signaling |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Perspectives

The regulatory functions of non-degradative ubiquitination have profound implications for human disease and therapeutic development. In Alzheimer's disease, UPS proteins are elevated in cerebrospinal fluid decades before symptom onset, with increases correlating with tau pathology [42]. This suggests UPS dysregulation contributes to neurodegeneration through both degradative and non-degradative mechanisms.

In cancer, multiple components of non-degradative ubiquitination pathways are dysregulated. The success of proteasome inhibitors like bortezomib in multiple myeloma validates the UPS as a therapeutic target, though these agents broadly affect both degradative and non-degradative functions [40] [41]. More selective targeting of specific E3 ligases or deubiquitinases represents an emerging therapeutic strategy.

Viral myocarditis progression to dilated cardiomyopathy involves UPS-mediated regulation of inflammatory signaling, particularly through modulation of NF-κB and interferon responses [43]. Targeting specific ubiquitin pathways in inflammatory heart disease may offer therapeutic opportunities while minimizing global proteostatic disruption.

Future research directions include:

- Developing linkage-specific ubiquitin probes to precisely manipulate non-degradative signaling

- Elucidating the structural basis for ubiquitin-induced conformational changes

- Exploring crosstalk between ubiquitination and other post-translational modifications

- Investigating tissue-specific functions of non-degradative ubiquitination in disease contexts

Non-degradative ubiquitination has emerged as a crucial regulatory mechanism that parallels phosphorylation in its complexity and functional significance. Through specific chain linkages and attachment sites, ubiquitin modifications directly control protein function, complex assembly, and subcellular localization across diverse cellular processes. The continued development of experimental tools and analytical approaches will further illuminate the intricacies of the ubiquitin code and its therapeutic potential in human disease.

UPS in Neurodevelopment and Synaptic Plasticity

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a crucial regulatory pathway for protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, functioning as a master coordinator of neurodevelopment and synaptic plasticity. This highly conserved system targets proteins for degradation through a coordinated enzymatic cascade involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes that tag substrates with ubiquitin chains, leading to their recognition and processing by the 26S proteasome [44]. In neurons, the UPS maintains proteostatic balance—a particularly challenging task given their extreme polarization, complex subcellular compartmentalization, and the need for rapid, localized responses to synaptic activity [45]. Emerging research has firmly established that beyond its housekeeping functions, the UPS actively participates in shaping neuronal connectivity and information processing through precise control of protein abundance at critical locations and times [45] [44].

The importance of the UPS in nervous system function is underscored by the growing number of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) linked to genetic lesions in UPS components. Strikingly, genomic alterations in genes encoding various UPS elements—including ubiquitin-activating (E1), -conjugating (E2) enzymes, ubiquitin ligases (E3), ubiquitin hydrolases, and proteasome subunits—have been identified as causative factors in monogenic forms of NDDs [44]. This connection highlights the non-redundant roles that specific UPS components play during brain development and function, positioning the UPS as a central pathway in both neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative conditions.

Fundamental Mechanisms of the UPS

The UPS Enzymatic Cascade

The ubiquitination process begins with E1 ubiquitin-activating enzymes, which activate ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction. The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, which cooperates with an E3 ubiquitin ligase to catalyze the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to specific substrate proteins [44]. E3 ligases provide substrate specificity and can be divided into three major classes based on their mechanism of action: RING (Really Interesting New Gene), HECT (Homologous to E6AP C-Terminus), and RBR (RING-Between-RING) types [44].

The fate of ubiquitinated proteins depends on the topology of the ubiquitin modification. Monoubiquitination (single ubiquitin moiety) or multiple monoubiquitination (single ubiquitin on multiple sites) typically regulates subcellular localization, endocytosis, and protein trafficking [44]. Alternatively, ubiquitin itself can be modified on any of its eight acceptor sites (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63, and M1), generating polyubiquitin chains with distinct biological functions. Whereas K48-linked chains predominantly target substrates for proteasomal degradation, other linkage types (e.g., K63-linked) often serve non-proteolytic functions in signaling and trafficking [44].

The 26S Proteasome Complex

The 26S proteasome is a massive multi-subunit complex comprising a 20S core particle capped by one or two 19S regulatory particles. The 20S core particle contains the proteolytic active sites within its hollow cylindrical structure, while the 19S regulatory particle recognizes ubiquitinated substrates, removes ubiquitin chains, unfolds target proteins, and translocates them into the proteolytic chamber [44]. The regulatory particle contains ubiquitin receptors such as PSMD4 and ADRM1 that recognize K48-linked polyubiquitin chains, facilitating substrate engagement and processing [44].

Table 1: Major Components of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

| Component Type | Key Subtypes/Families | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|

| E1 Enzymes | UBA1-UBA6 | Ubiquitin activation via ATP hydrolysis |

| E2 Enzymes | ~40 members in humans | Ubiquitin conjugation; determines chain topology |

| E3 Ligases | RING, HECT, RBR | Substrate recognition; specific ubiquitin transfer |

| E3 Complexes | Cullin-RING ligases (CRLs) | Multi-subunit complexes; cullins scaffold substrate receptors to RING proteins |

| Deubiquitinases | ~100 members in humans | Ubiquitin removal; proteasome processing; chain editing |

| Proteasome | 20S core, 19S regulatory cap | Protein degradation; substrate recognition & unfolding |

Recent research has revealed additional complexity in proteasomal regulation, including the existence of ubiquitin-independent proteasomal protein degradation (UIPP) pathways that can degrade intrinsically unstructured proteins without prior ubiquitination [46]. Furthermore, proteasome activators such as PA28γ (REGγ) can modulate proteasomal function in ways that are still being elucidated, particularly in the context of chromatin remodeling and DNA repair [46].

UPS in Neurodevelopmental Processes

Regulation of Neural Progenitor Fate and Cortical Development

During embryonic brain development, the UPS plays instrumental roles in determining neuronal cell fate through precise control of key developmental regulators. Recent research using ribosome profiling and RNA sequencing in mouse embryos has revealed that mRNA translation is dynamically regulated during cortical development, with the UPS contributing to the degradation of specific factors that must be eliminated at precise developmental transitions [45]. This regulated protein degradation is particularly important for the maintenance of neural progenitor pools and the timing of their differentiation into specific neuronal subtypes.

Studies have demonstrated that the protein translation rate itself serves as a critical determinant of neocortical neuron fate, with the UPS potentially contributing to the degradation of factors that maintain progenitor identity [45]. The development of advanced technologies allowing examination of protein synthesis and degradation at cellular resolution has revealed that proteostatic mechanisms are actively regulated during neurogenesis, rather than simply maintaining static protein levels [45]. This dynamic regulation ensures the proper progression of developmental programs and the emergence of appropriate neuronal diversity in the developing cortex.

Axonal and Dendritic Development

The UPS plays a particularly important role in shaping neuronal morphology by regulating the stability of proteins involved in axon guidance, dendritic arborization, and synapse formation. During axon development, the UPS facilitates the remodeling of the axonal proteome in response to guidance cues, eliminating proteins that are no longer required while allowing the accumulation of those needed for the next developmental phase [45]. This localized proteostatic control is essential for the proper pathfinding of growing axons and the establishment of functional neural circuits.

In dendritic development, the UPS regulates the stability of cytoskeletal components, adhesion molecules, and signaling proteins that collectively determine dendritic complexity and targeting specificity. The importance of this regulation is highlighted by the identification of several UPS components, including ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinating enzymes, that when mutated cause neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by altered dendritic morphology and connectivity [44]. These findings position the UPS as a central regulator of the structural development of both pre- and postsynaptic compartments.

UPS in Synaptic Plasticity

Presynaptic Mechanisms

At the presynaptic terminal, the UPS regulates neurotransmitter release, synaptic vesicle cycling, and active zone organization through the controlled degradation of key presynaptic proteins. Recent research has revealed an impressive amount of ongoing translation in presynaptic terminals, with the UPS providing a complementary mechanism for rapidly adjusting the presynaptic proteome in response to activity [45]. This localized protein synthesis and degradation allows presynaptic terminals to autonomously control their protein composition without relying on somatic supply.

Studies examining presynaptic protein synthesis have shown that it supports structural and functional plasticity of glutamatergic axon terminals [45]. The UPS interacts with these local translation mechanisms to maintain presynaptic function, with disruption of either system leading to impaired neurotransmission. For instance, inhibition of presynaptic protein synthesis alters transmitter release, while proteasome inhibition similarly disrupts presynaptic function, indicating that both systems must be coordinately regulated to maintain synaptic efficacy [45].

Postsynaptic Mechanisms and Density Regulation