Ubiquitin and ATP-Dependent Proteolysis: From Nobel Discovery to Targeted Protein Degradation Therapeutics

This article explores the groundbreaking discovery of ATP-dependent proteolysis by Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose, which earned them the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Ubiquitin and ATP-Dependent Proteolysis: From Nobel Discovery to Targeted Protein Degradation Therapeutics

Abstract

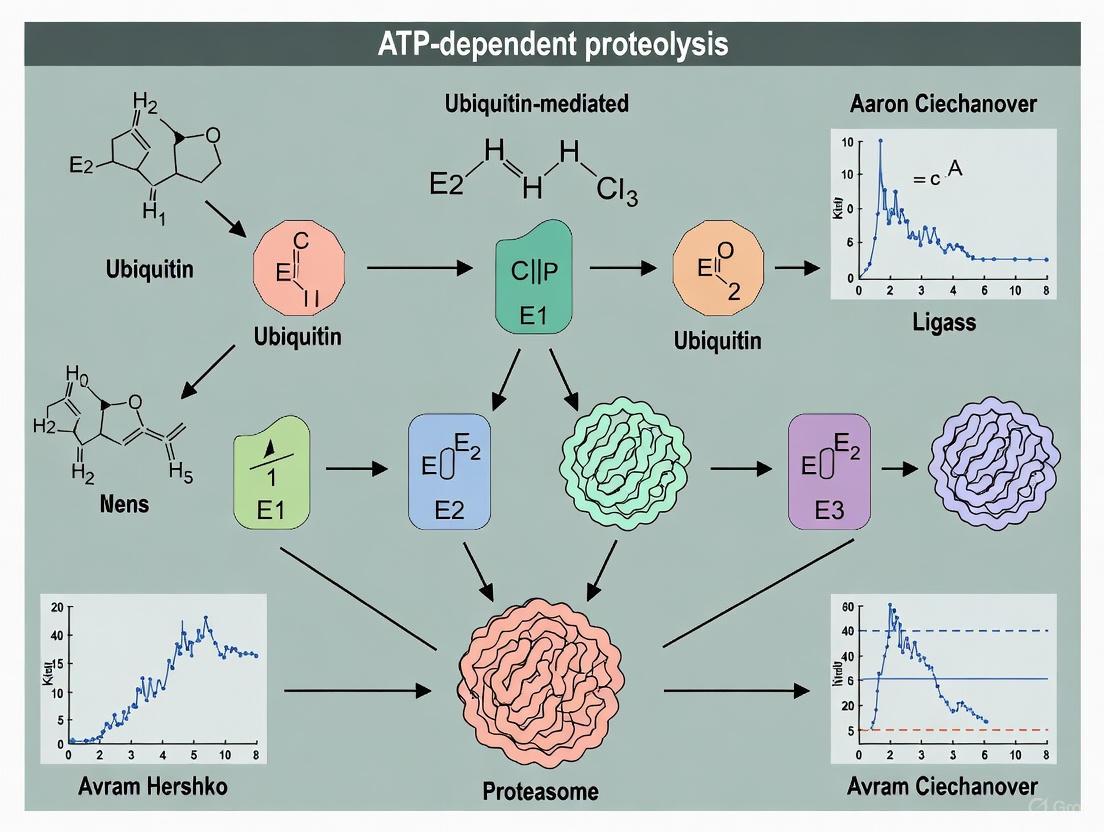

This article explores the groundbreaking discovery of ATP-dependent proteolysis by Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose, which earned them the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. We trace the foundational research that identified the ubiquitin-proteasome system as a crucial regulatory mechanism for intracellular protein degradation, moving beyond the lysosomal paradigm. The content examines the methodological breakthroughs that enabled this discovery and their direct application in modern drug development, particularly in PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) and other targeted protein degradation technologies. For researchers and drug development professionals, we analyze current challenges in optimizing these therapeutic strategies and compare the ubiquitin system with other ATP-dependent proteases. The synthesis provides a comprehensive resource for understanding both the historical significance and future directions of this transformative field in biomedical research.

The Paradigm Shift: Discovering the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

The fundamental understanding of cellular protein degradation was revolutionized in the late 20th century by the groundbreaking work of Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose, who discovered the ubiquitin-mediated ATP-dependent proteolytic system. Their research addressed a central biochemical paradox: why would the hydrolysis of peptide bonds, an exergonic process, require energy input in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP)? This energy requirement suggested the existence of a complex regulatory mechanism far beyond simple enzymatic cleavage [1].

Before this discovery, intracellular proteolysis was poorly understood, with many scientists believing it occurred primarily through lysosomal action or via bacterial Lon protease. The key breakthrough came from the convergence of intellectual curiosity and rigorous biochemical experimentation, which revealed that ATP-dependent proteolysis involved a sophisticated system of covalent protein modification [1]. This review examines the foundational experiments that uncovered the ubiquitin system, the methodological approaches used, and the implications of these discoveries for understanding cellular regulation.

Historical and Theoretical Background

The Energy Paradox in Cellular Protein Turnover

The energy paradox of intracellular proteolysis was first highlighted by Melvin Simpson in 1953 through isotopic labeling studies, which demonstrated that protein degradation in mammalian cells required energy [1]. For the next 25 years, this observation remained largely unexplained, as the hydrolysis of peptide bonds is thermodynamically favorable and thus should not require energy input. The scientific community recognized that this energy requirement must indicate unknown regulatory complexity in cellular proteolytic systems [1].

Concurrently, research by Goldberg's group revealed that damaged or abnormal proteins were rapidly cleared from cells in an energy-dependent manner [1]. They also observed that rate-limiting enzymes in metabolic pathways were often short-lived, with their concentrations responsive to metabolic conditions. These findings suggested that energy-dependent proteolysis served regulatory functions beyond simple protein disposal [1].

Prelude to Discovery: Key Observations

Several critical observations set the stage for the discovery of the ubiquitin system:

- ATP dependence: Reticulocyte lysates, which lack lysosomes, exhibited ATP-dependent proteolysis of denatured proteins

- Fractionation potential: The proteolytic system could be separated into biochemical fractions that required recombination for activity

- Heat-stable factors: Initial fractionation studies revealed the existence of heat-stable components essential for proteolysis [1]

These observations suggested that ATP-dependent proteolysis involved multiple protein components rather than a single protease, pointing to a more complex system than previously imagined.

Experimental Breakthroughs: Methodology and Key Findings

The Reticulocyte Lysate System and Biochemical Fractionation

The Hershko and Ciechanover laboratory developed a reticulocyte lysate system that reproduced ATP-dependent proteolysis, enabling biochemical dissection of the process. Their experimental approach involved several key steps [1]:

Table 1: Key Experimental Steps in the Discovery of Ubiquitin-Mediated Proteolysis

| Experimental Step | Methodological Approach | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| System Development | Use of reticulocyte lysates lacking lysosomes | Established ATP-dependent proteolysis in cell-free system |

| Biochemical Fractionation | Separation of lysate into Fractions I and II | Identified requirement for multiple components |

| Factor Identification | Heat stability and chromatographic purification | Isolated APF-1 (later identified as ubiquitin) |

| Conjugation Analysis | Use of ¹²⁵I-labeled APF-1 and SDS-PAGE | Demonstrated covalent attachment to multiple proteins |

The experimental workflow began with separating reticulocyte lysates into two essential fractions: Fraction I contained a heat-stable protein component, while Fraction II contained higher molecular weight components. Both fractions were required to reconstitute ATP-dependent proteolysis [1].

Identification of APF-1 and the Covalent Modification System

The critical breakthrough came from the identification and characterization of ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1 (APF-1), a small, heat-stable protein that was absolutely required for ATP-dependent proteolysis. The key experiments included [1]:

- Covalent linkage demonstration: Incubation of ¹²⁵I-labeled APF-1 with Fraction II and ATP resulted in the formation of high molecular weight complexes

- Stability analysis: The linkage between APF-1 and target proteins was stable to NaOH treatment, indicating a covalent bond

- Specificity controls: The conjugation required ATP and specific metal ions, with requirements matching those for proteolysis

Art Haas, a postdoctoral fellow in Rose's laboratory, made the crucial observation that the association survived high pH treatment, demonstrating its covalent nature [1]. This finding was particularly surprising because it revealed that proteolytic targeting involved covalent modification of substrates rather than simple receptor-ligand interactions.

Identification of APF-1 as Ubiquitin

The discovery that APF-1 was identical to the previously known protein ubiquitin (first discovered by Gideon Goldstein in his search for thymopoietin) connected the ATP-dependent proteolysis system to known biology [1]. This identification came through:

- Biochemical comparison: Direct comparison of APF-1 with authentic ubiquitin samples

- Functional analysis: Demonstration that ubiquitin could replace APF-1 in supporting ATP-dependent proteolysis

- Historical connection: Recognition that histone H2A was known to be modified by ubiquitin, suggesting broader biological significance

This connection revealed that the covalent attachment of proteins to other proteins served as a regulatory mechanism, analogous to phosphorylation or acetylation [1].

Key Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents in the Discovery of Ubiquitin-Mediated Proteolysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Role in Discovery | Key Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | ATP-dependent proteolysis system | Cell-free model for biochemical analysis |

| Fraction I | Source of APF-1/ubiquitin | Reconstitution of proteolytic activity |

| Fraction II | High molecular weight components | Contains conjugation enzymes and proteolytic machinery |

| ¹²⁵I-labeled APF-1 | Radiolabeled tracer | Tracking covalent conjugation to target proteins |

| ATP and ATP-regenerating System | Energy source | Driving conjugation and proteolytic reactions |

| Ion-exchange Chromatography | Protein separation and purification | Isolation of APF-1 and other essential factors |

The experimental system relied heavily on classical biochemical techniques, including fractionation, ion-exchange chromatography, and radiolabeling. The reticulocyte lysate system was particularly valuable because it contained minimal lysosomal contamination, allowing clear observation of the ATP-dependent cytoplasmic proteolytic system [1].

Mechanistic Insights: From Covalent Modification to Proteolysis

The seminal PNAS papers from 1980 outlined the essential mechanism of ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, which can be summarized in several key steps:

- Activation of ubiquitin: ATP-dependent activation of ubiquitin for conjugation

- Target recognition: Identification of protein substrates for modification

- Covalent conjugation: Formation of isopeptide bonds between ubiquitin and substrate proteins

- Polyubiquitin chain formation: Processive addition of multiple ubiquitin molecules

- Proteolytic targeting: Recognition of polyubiquitinated substrates by the proteasome

- ATP-dependent degradation: Unfolding and proteolysis of targeted substrates

The researchers demonstrated that authentic substrates of the system were heavily modified, with multiple molecules of APF-1/ubiquitin attached to each molecule of substrate [1]. This polyubiquitination was later shown to involve chains linked through K48 of one ubiquitin and the C-terminus of the next, forming the specific signal for proteasomal recognition [1].

Comparative Analysis: Bacterial vs. Eukaryotic ATP-Dependent Proteolysis

The discovery of ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis highlighted fundamental differences between eukaryotic and bacterial protein degradation systems, though both utilize AAA+ proteases (ATPases Associated with diverse cellular Activities) [2].

Table 3: Comparison of ATP-Dependent Proteolytic Systems in Eukaryotes and Bacteria

| Feature | Eukaryotic Ubiquitin-Proteasome System | Bacterial AAA+ Protease Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Targeting Mechanism | Covalent ubiquitin modification | Direct recognition of degron sequences |

| Key Proteases | 26S Proteasome | Lon, ClpXP, ClpAP, FtsH, HslUV |

| ATPase Components | AAA-ATPases in regulatory particle | Integral AAA+ domains in proteases |

| Specificity Control | Multiple E3 ubiquitin ligases | Adaptor proteins (e.g., SspB) |

| Energy Requirements | ATP for ubiquitination and degradation | ATP primarily for unfolding/degradation |

| Quality Control Role | Misfolded protein clearance | Misfolded protein clearance |

While eukaryotic cells use the ubiquitin tagging system, bacteria employ AAA+ proteases that recognize specific degradation signals (degrons) directly or through adaptor proteins. For example, the bacterial ClpXP protease recognizes the ssrA tag added during trans-translation, with enhanced recognition through the SspB adaptor protein [2]. Similarly, Lon protease recognizes misfolded proteins through exposed hydrophobic patches or specific degrons without requiring covalent modification [2].

Impact and Implications of the Discovery

The discovery of ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis had far-reaching implications for understanding cellular regulation:

- New regulatory paradigm: The system established protein degradation as a regulated process rather than simply a disposal mechanism

- Connection to key cellular processes: Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis was quickly connected to cell cycle regulation through cyclin degradation

- Therapeutic targeting: The system has become a major target for drug development, particularly in cancer therapy

- Disease connections: Dysregulation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system has been implicated in numerous diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders

The discovery exemplified how fundamental biochemical curiosity could unravel complex regulatory mechanisms with broad biological significance. The convergence of intellectual curiosity, collaboration, and rigorous biochemistry enabled this paradigm-shifting discovery that ultimately earned Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004 [1].

The discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, a cornerstone of modern cell biology, was propelled by the innovative use of an unassuming biochemical tool: the rabbit reticulocyte lysate. While the scientific community of the 1970s was largely focused on protein synthesis and lysosomal degradation, the pioneering work of Avram Hershko and Aaron Ciechanover leveraged this cell-free system to uncover a fundamental, ATP-dependent proteolytic pathway. This technical guide explores the pivotal role of reticulocyte lysates as a model system that enabled the dissection of ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation. We detail the experimental methodologies, key findings, and contemporary applications of this powerful in vitro platform, framing its development within the broader context of Hershko and Ciechanover's seminal research on regulated proteolysis.

Prior to the groundbreaking work of Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose, intracellular protein degradation was considered a largely unregulated process occurring primarily within the lysosome, a membrane-bound organelle containing digestive enzymes [3]. However, several observations contradicted this view, including the finding that ATP was required for the degradation of many cellular proteins—a thermodynamic paradox given that protein breakdown is an energy-liberating process [3] [4].

Hershko encountered this paradox during his postdoctoral research and, upon establishing his own laboratory at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, sought to unravel its mechanism. He and his graduate student, Aaron Ciechanover, made a strategic decision to use a cell-free system derived from rabbit reticulocytes (immature red blood cells) for several key reasons [4]:

- Absence of Lysosomes: Reticulocytes naturally lose their lysosomes during maturation, allowing study of non-lysosomal proteolytic pathways without contamination.

- High Degradation Activity: As reticulocytes mature into erythrocytes, they extensively degrade their internal organelles and proteins, making them a rich source of the relevant proteolytic machinery.

- Biochemical Tractability: A cell-free extract could be fractionated, manipulated, and studied in a controlled manner, unlike intact cells.

This experimental choice was instrumental in leading to the discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, for which Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose were awarded the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry [5]. The reticulocyte lysate system provided the essential platform for identifying the key components and biochemical steps of this pathway.

The Reticulocyte Lysate System: Fundamental Principles and Advantages

Reticulocyte lysates are translationally active cytoplasmic extracts that retain the core machinery for protein synthesis, modification, and degradation. Their utility extends far beyond their initial application, serving as a foundational tool for biochemical reconstitution.

Table: Key Characteristics of Rabbit Reticulocyte Lysates in Proteolysis Research

| Characteristic | Description | Experimental Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Lysosome-free | Naturally lacking lysosomal compartments [4] | Enables isolated study of non-lysosomal, ATP-dependent proteolysis. |

| ATP-dependent | Contains functional machinery for energy-dependent ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [6] | Allows investigation of the energy requirement for targeted protein degradation. |

| Reconstitution Capability | Can be separated into complementary fractions that regain activity upon mixing [3] | Permits fractionation, identification, and purification of individual system components (E1, E2, E3, proteasome). |

| Heat-Stable Components | Contains heat-stable factors (e.g., Ubiquitin/APF-1) that remain active after boiling [3] [4] | Enabled the critical purification and identification of ubiquitin. |

The system's power lies in its biochemical flexibility. Researchers can supplement lysates with radiolabeled substrates, energy-regenerating systems, specific inhibitors, or purified recombinant proteins to dissect complex processes [6] [7]. Furthermore, the ability to create a "dialyzed" lysate—depleted of endogenous small molecules like ATP and ubiquitin—allows for precise control over reaction conditions and the addition of defined components [6].

Historical Breakthrough: The Discovery of Ubiquitin-Mediated Proteolysis

The elucidation of the ubiquitin pathway serves as a masterclass in biochemical discovery using the reticulocyte lysate model.

Key Experimental Workflow

The initial experiments followed a logical progression of fractionation and reconstitution, as visualized below.

The Discovery of APF-1/Ubiquitin and the Conjugation Mechanism

A critical breakthrough came when the researchers, struggling to separate the active component in Fraction I from hemoglobin, decided to boil the fraction. Unlike most proteins, the active factor remained soluble, allowing them to purify it and name it ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 (APF-1) [3] [4].

Subsequent experiments revealed APF-1's unique behavior: in the presence of ATP, it formed covalent conjugates with a wide range of proteins in the lysate. This observation, supported by crucial input from Irwin Rose, led to the then-heretical hypothesis that proteins are marked for degradation by the covalent attachment of a label, not by direct protease recognition [3]. APF-1 was later identified by others as ubiquitin, a previously known but functionally enigmatic small protein [5].

Further work in the reticulocyte lysate system elucidated the enzymatic cascade responsible for ubiquitin conjugation:

- E1 (Ubiquitin-activating enzyme): Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction.

- E2 (Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme): Accepts ubiquitin from E1.

- E3 (Ubiquitin ligase): Recognizes specific protein substrates and facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to the target, forming an isopeptide bond [3].

The power of multi-ubiquitin chains as the definitive degradation signal was also demonstrated using this system [3].

Contemporary Applications and Methodologies

Reticulocyte lysates remain a vital tool for studying protein degradation and other complex cellular processes.

Studying Endoplasmic Reticulum-Associated Degradation (ERAD)

Reticulocyte lysates, when supplemented with canine pancreas microsomal membranes, provide a powerful system to reconstitute ERAD. This combined system supports:

- ER targeting, translocation, and glycosylation of newly synthesized proteins.

- Generation of ³⁵S-labeled, membrane-integrated substrates with defined topology.

- ATP-dependent degradation of misfolded ER proteins via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway [6].

The degradation process can be quantitatively tracked by monitoring the conversion of radiolabeled, full-length substrate into trichloroacetic acid (TCA)-soluble peptides [6].

Analysis of Translation Mechanisms

Nuclease-treated reticulocyte lysates are a cornerstone for in vitro translation studies. They support various initiation mechanisms (cap-dependent, IRES-mediated) and allow for the analysis of ribosomal complex formation via sucrose density gradients. A key advantage is that reactions in lysates occur at or near the in vivo rate, unlike systems reconstituted from purified factors [7].

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Reticulocyte Lysate Experiments

| Research Reagent | Function/Description | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclease-Treated Lysate | Lysate treated with micrococcal nuclease to degrade endogenous mRNA. | Ensures that translation of added reporter mRNA can be monitored without background [7]. |

| Energy Mix (ATP, GTP) | Provides essential energy for both translation and ubiquitination. | Required for efficient protein synthesis and for the activity of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. |

| ³⁵S-Methionine/Cysteine | Radiolabeled amino acids incorporated into newly synthesized proteins. | Allows sensitive detection and quantification of synthesized or degraded proteins via SDS-PAGE and autoradiography [7]. |

| Canine Microsomal Membranes | Membrane vesicles derived from the endoplasmic reticulum. | Used to study co-translational translocation, glycosylation, and ERAD of membrane proteins [6]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132) | Specific inhibitors of the 26S proteasome's proteolytic activity. | Used to confirm ubiquitin-proteasome-dependent degradation and to accumulate ubiquitinated substrates [6]. |

A standard translation reaction in a 50 µl volume typically contains 35 µl of lysate, a mixture of amino acids (minus methionine), ²⁵S-methionine, RNase inhibitor, and the experimental mRNA [7]. Optimization of mRNA and salt concentrations (particularly Mg²⁺ and K⁺) is critical for maximal efficiency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Core Methodologies

This section provides a concise protocol for key experiments enabled by the reticulocyte lysate system.

Protocol: Reconstituting ATP-Dependent Proteolysis

This foundational protocol is adapted from the original approaches used to discover ubiquitination [3] [4].

- Lysate Preparation: Use fresh or commercially available rabbit reticulocyte lysate. For degradation assays, the lysate may be dialyzed to remove endogenous amino acids and small molecules.

- Reaction Setup:

- Test Sample: Combine lysate (e.g., 25 µl), ²⁵S-labeled substrate (e.g., 1 µl), and an energy-regenerating system (e.g., 2 µl of 10x ATP/GTP mix).

- Negative Control: Set up an identical reaction without ATP or with a non-hydrolyzable ATP analog.

- Incubation: Incubate reactions at 30-37°C for 0-120 minutes.

- Termination and Analysis:

- Stop reactions at desired time points by adding an equal volume of 2x SDS-PAGE sample buffer (for visualizing ubiquitin conjugates) or by transferring to ice.

- For degradation quantification, precipitate proteins with 10% Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA). The amount of TCA-soluble radioactivity (degraded peptides) in the supernatant, measured by scintillation counting, is directly proportional to proteolytic activity.

Protocol: In Vitro Translation for Degradation Substrate Generation

This protocol is used to generate a radiolabeled protein substrate for subsequent degradation assays [7].

- mRNA Template: Prepare the mRNA of interest via in vitro transcription. A 5' cap structure (m7G) is recommended for efficient initiation.

- Translation Reaction:

- Assemble a 50 µl reaction containing:

- 35 µl Nuclease-Treated Reticulocyte Lysate

- 2 µl 1mM Amino Acid Mixture (minus Methionine)

- 2 µl ¹⁵S-Methionine (10 mCi/ml)

- 1 µl RNasin Ribonuclease Inhibitor

- 0.5-1 µg of mRNA template

- Nuclease-free water to 50 µl.

- Incubate at 30°C for 60-90 minutes.

- Assemble a 50 µl reaction containing:

- Product Verification: Analyze 2-5 µl of the reaction by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography to confirm synthesis of the full-length, radiolabeled protein.

The relationship between these core applications is summarized below.

The rabbit reticulocyte lysate system stands as a testament to the power of a well-chosen model system in driving scientific revolution. It was the indispensable biochemical canvas upon which Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose painted their picture of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, fundamentally altering our understanding of how cells control their protein repertoire. From its historic role in discovering fundamental principles to its continued utility in modeling complex processes like ERAD and translational regulation, the reticulocyte lysate remains a versatile and powerful platform for mechanistic cell biology. Its legacy underscores the importance of methodological innovation in enabling the discovery of profound biological truths.

Identifying APF-1: The Heat-Stable Factor Later Recognized as Ubiquitin

This whitepaper delineates the seminal discovery of ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1 (APF-1) and its subsequent identification as the protein ubiquitin, the central component of a novel proteolytic system. The research, pioneered by Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose, fundamentally reconfigured our understanding of intracellular protein degradation, moving from a model of nonspecific lysosomal digestion to one of a highly specific, energy-dependent, and enzymatically controlled process [1] [8]. This document provides a comprehensive technical account of the key experiments, methodologies, and biochemical evidence that established APF-1/ubiquitin's role in targeted protein degradation—a pathway now recognized as critical in regulating cell cycle, DNA repair, and numerous other cellular functions, with profound implications for therapeutic drug development [8] [3].

Prior to the 1980s, intracellular protein degradation was largely considered an unregulated, bulk process occurring within lysosomes. A key biochemical paradox challenged this view: the hydrolysis of peptide bonds is an exergonic process, yet the degradation of intracellular proteins was demonstrated to require metabolic energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) [1] [8]. This ATP requirement suggested the existence of a previously unrecognized, non-lysosomal proteolytic pathway characterized by high specificity and complex regulation.

The collaborative work of Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose was instrumental in resolving this paradox. They utilized a cell-free extract derived from rabbit reticulocytes, which, due to their lack of lysosomes, provided an ideal model system for studying ATP-dependent, non-lysosomal proteolysis [9] [10]. Through biochemical fractionation of this system, they identified an essential, heat-stable polypeptide they designated APF-1, which would later be recognized as the previously described but functionally enigmatic protein, ubiquitin [1] [11].

Experimental Breakthroughs: The APF-1 Discovery Pipeline

The identification and characterization of APF-1 involved a series of critical experiments that systematically uncovered its unique properties and central role.

Initial Fractionation and the Discovery of a Heat-Stable Factor

The initial breakthrough came from the fractionation of the reticulocyte lysate using anion-exchange chromatography (DEAE-cellulose). This process separated the lysate into two complementary fractions:

- Fraction I: Contained proteins not adsorbed to the resin, including the bulk of hemoglobin.

- Fraction II: Contained proteins adsorbed to and eluted from the resin [9] [10].

Critically, neither fraction alone could support ATP-dependent proteolysis; activity was only restored upon their recombination. The key finding was that the essential component in Fraction I was a low-molecular-weight (~8.5 kDa), heat-stable protein that retained its activity even after being boiled, a treatment that denatures most cellular proteins. This factor was named APF-1 [12] [10].

Table 1: Key Properties of the Reticulocyte Lysate Fractions and APF-1

| Component | Key Characteristics | Role in Proteolysis |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | Cell-free system from immature red blood cells; lacks lysosomes. | Source of ATP-dependent proteolytic activity [9]. |

| Fraction I | Not adsorbed to DEAE-cellulose; contained hemoglobin and heat-stable proteins. | Provided an essential factor (APF-1) for reconstituting activity [10]. |

| Fraction II | Adsorbed to and eluted from DEAE-cellulose. | Contained additional essential enzymes and the proteolytic machinery [10]. |

| APF-1 | Heat-stable polypeptide; molecular weight ~8.5 kDa. | Essential stimulating factor; later identified as ubiquitin [12]. |

The Covalent Conjugation Hypothesis

A pivotal experiment involved incubating iodine-125-labeled APF-1 (¹²⁵I-APF-1) with Fraction II and ATP. Instead of observing free APF-1, researchers discovered the label was incorporated into multiple high-molecular-weight complexes [1]. This association was:

- ATP-dependent: Required the presence of ATP.

- Covalent: The complexes were stable to treatment with sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), indicating a strong, covalent linkage [1] [9].

- Reversible: The process could be reversed upon ATP depletion.

This led to the then-revolutionary hypothesis that APF-1 was not an enzyme activator but was itself covalently conjugated to protein substrates,

marking them for degradation [1] [8]. Further work demonstrated that a single target protein could be modified by multiple molecules of APF-1, a process termed polyubiquitination [8].

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for APF-1 Isolation.

The Critical Identification: APF-1 is Ubiquitin

The discovery of covalent protein conjugation prompted a search for precedents. Researchers noted that a known protein, ubiquitin, had been previously found conjugated to histone H2A in a similar isopeptide linkage [1]. This prompted a direct comparison, which confirmed APF-1 and ubiquitin were identical through several lines of evidence [11]:

Table 2: Experimental Evidence Identifying APF-1 as Ubiquitin

| Assay Type | Observation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Gel Electrophoresis & Isoelectric Focusing | APF-1 and authentic ubiquitin co-migrated identically across five different polyacrylamide gel systems and in isoelectric focusing [11]. | The two proteins share identical molecular weight and isoelectric point. |

| Amino Acid Analysis | The amino acid composition of APF-1 showed excellent agreement with that of ubiquitin [11]. | The two proteins share an identical primary structure. |

| Functional Reconstitution | Purified ubiquitin could replace APF-1 in activating the ATP-dependent proteolytic system from reticulocytes [11]. | The two proteins are functionally interchangeable. |

| Covalent Conjugation | ¹²⁵I-ubiquitin formed electrophoretically identical covalent conjugates with reticulocyte proteins as ¹²⁵I-APF-1 [11]. | The conjugation mechanism and targets are identical. |

This conclusive evidence, published in 1980, established that the ATP-dependent proteolysis factor, APF-1, was the protein ubiquitin [11].

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: A Modern Technical Perspective

The initial discoveries around APF-1/ubiquitin laid the foundation for the elaborate ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) as it is understood today. The process involves a tightly regulated enzymatic cascade.

The Enzymatic Cascade

The attachment of ubiquitin to a substrate protein is a multi-step process mediated by three key enzyme classes:

- E1 (Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme): Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction, forming a high-energy thioester bond with the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin.

- E2 (Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme): Accepts the activated ubiquitin from E1 via a trans-thioesterification reaction.

- E3 (Ubiquitin Ligase): Recognizes specific protein substrates and facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to a lysine residue on the substrate, forming an isopeptide bond [8] [3].

A polyubiquitin chain is built by reiterating this process, where additional ubiquitin molecules are attached to a lysine residue (typically Lys48) on the previously conjugated ubiquitin. This K48-linked polyubiquitin chain serves as the definitive recognition signal for the 26S proteasome [1] [8].

Diagram 2: The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The discovery of the UPS was enabled by specific reagents and model systems. The following toolkit details resources critical for both foundational and contemporary research in this field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin System Studies

| Reagent / Model System | Function in Research | Key Application in Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | A cell-free system capable of protein synthesis and degradation. | Served as the source for fractionating and identifying the essential components of the UPS, including APF-1/ubiquitin [9] [10]. |

| DEAE-Cellulose Resin | An anion-exchange chromatography medium for separating protein mixtures. | Used to fractionate the reticulocyte lysate into complementary Fractions I and II, enabling the identification of APF-1 [9] [10]. |

| Heat-Stable Protein Fractions | A preparation enriched for proteins that resist denaturation at high temperatures (e.g., 100°C). | The key step that allowed for the separation of APF-1/ubiquitin from the bulk of hemoglobin and other denatured proteins in Fraction I [3] [10]. |

| ATPγS (ATP analog) | A non-hydrolyzable analog of ATP. | Used in modern studies to probe ATP-dependent steps; its failure to support conjugation would confirm an ATP hydrolysis requirement [1]. |

| ts20 Cell Line | A temperature-sensitive mutant mouse cell line with a thermolabile E1 enzyme. | Provided crucial genetic evidence in intact cells that a functional ubiquitin system is essential for cell cycle progression and degradation of short-lived proteins [8] [3]. |

Research Applications and Drug Development Implications

The elucidation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system has created a vast field of therapeutic opportunity. By understanding the rules of targeted protein degradation, researchers can now design strategies to eliminate specific disease-causing proteins.

- Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD): Modern modalities like PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) are heterobifunctional molecules that recruit a target protein to an E3 ubiquitin ligase, inducing its ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome [13]. This approach can target proteins previously considered "undruggable."

- Cancer Therapeutics: The UPS is crucial for regulating cell cycle proteins (e.g., cyclins) and tumor suppressors (e.g., p53). Bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor, is a validated therapy for multiple myeloma, proving the clinical relevance of this pathway [8].

- Quality Control and Disease: The UPS is the primary system for eliminating misfolded and damaged proteins. Defects in this system are implicated in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, making UPS components attractive targets for therapeutic intervention [8] [9].

The journey from an unknown, heat-stable factor dubbed APF-1 to its identification as the pivotal regulatory protein ubiquitin represents a paradigm shift in cell biology. The rigorous biochemical approaches of Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose—centered on fractionation, functional reconstitution, and covalent linkage analysis—uncovered a previously unimaginable layer of cellular regulation. Their work demonstrated that cells employ a highly specific, energy-dependent system to label and destroy individual proteins, a process as sophisticated and vital as protein synthesis itself. This discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system has not only illuminated fundamental biological processes but has also forged a new and expanding frontier in drug development, enabling innovative strategies to treat cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and other human diseases.

The concept of deliberately tagging proteins for destruction represents a paradigm shift in chemical biology and therapeutic development. This approach, known as targeted protein degradation, has evolved from a fundamental understanding of cellular protein turnover into a powerful strategy for eliminating disease-causing proteins. At its core lies the revolutionary discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system by Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and their colleagues, who elucidated the ATP-dependent proteolytic machinery that cells use to selectively mark and destroy proteins [3]. Their pioneering work in the late 1970s and 1980s identified the crucial role of a small, heat-stable protein they initially termed APF-1 (later identified as ubiquitin), which serves as a molecular "death tag" for proteins [14] [3]. This foundational research uncovered the enzymatic cascade (E1, E2, E3) that conjugates ubiquitin to target proteins, marking them for destruction by the proteasome [3]. The conceptual breakthrough that proteins must be covalently modified to be recognized for degradation paved the way for developing intentional protein degradation strategies that now dominate modern drug discovery efforts.

Historical Context: Hershko and Ciechanover's ATP-Dependent Proteolysis

The intellectual foundation for contemporary protein degradation technologies stems directly from the groundbreaking work on ATP-dependent proteolysis. Hershko's initial curiosity was sparked by an apparent paradox: why would protein degradation, an inherently energy-liberating process, require ATP hydrolysis? [3] This question led to a series of elegant experiments using reticulocyte (immature red blood cell) lysates, which provided a cell-free system for studying non-lysosomal protein degradation.

Key Experimental Breakthroughs and Methodologies

Table: Seminal Experiments in the Discovery of the Ubiquitin System

| Year | Experimental Approach | Key Finding | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1977-1978 | Fractionation of reticulocyte lysates followed by boiling | Identification of heat-stable APF-1 (ubiquitin) | Discovered the central component of the tagging system [3] |

| 1978-1980 | Radiolabeling of APF-1 with ATP addition | Demonstration of covalent APF-1-protein conjugates | Established the tagging mechanism [3] |

| 1980s | Biochemical reconstitution | Identification of E1, E2, E3 enzymatic cascade | Elucidated the complete ubiquitination machinery [3] |

| 1985 | Characterization of multi-ubiquitin chains | Proteins with ubiquitin chains are better degradation substrates | Revealed the polyubiquitin signal requirement [3] |

The critical methodological breakthrough came when Hershko and Ciechanover separated reticulocyte lysates into two fractions (I and II) and discovered that neither could promote ATP-dependent proteolysis alone [14] [3]. The active component in fraction I displayed remarkable heat stability—unusual for a biological effector—remaining active after boiling while hemoglobin and other proteins denatured and precipitated [3]. This observation allowed the purification and characterization of APF-1, later identified as ubiquitin.

The experimental protocol that revealed the tagging mechanism involved radioactively labeling APF-1 and incubating it with cellular fractions. In the absence of ATP, APF-1 migrated as a single small protein, but with ATP added, multiple radioactive protein bands appeared, suggesting covalent attachment of APF-1 to various target proteins [3]. Further experiments confirmed that this conjugation occurred through stable, peptide-like bonds, and that proteins destined for degradation were marked with multiple ubiquitin molecules, creating a recognizable signal for the proteolytic machinery.

The Covalent Conjugation Machinery

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

The ubiquitin-proteasome system represents nature's primary covalent conjugation machinery for targeted protein degradation in eukaryotic cells. This system operates through a precise enzymatic cascade that tags proteins for destruction with high specificity.

The ubiquitination pathway involves three key enzymatic components that work in concert [15] [3]:

- E1 (Ubiquitin-activating enzyme): Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner through the formation of a thioester bond

- E2 (Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme): Receives activated ubiquitin from E1

- E3 (Ubiquitin ligase): Recognizes specific protein substrates and facilitates ubiquitin transfer from E2 to the target protein

The result is a polyubiquitin chain (typically K48-linked) attached to the target protein, which serves as a recognition signal for the proteasome, a large multi-subunit protease complex that degrades the tagged protein into small peptides [15] [3].

Covalent Warheads in Targeted Therapeutics

The understanding of natural ubiquitination inspired the development of synthetic covalent warheads that can deliberately mark proteins for degradation. These warheads form the business end of targeted degradation technologies.

Table: Covalent Warheads in Protein Degradation Technologies

| Warhead Type | Reaction Mechanism | Target Residue | Key Characteristics | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Cyanoacrylamides | Reversible Michael addition | Cysteine | Tunable reactivity, reversible binding [16] | Reversible covalent inhibitors |

| Aldehydes | Reversible hemithioacetal formation | Cysteine | Moderate electrophilicity [16] | TCIs (e.g., FGF401) [16] |

| Acrylamides | Irreversible Michael addition | Cysteine | Irreversible modification [16] | Covalent kinase inhibitors (e.g., ibrutinib) [16] |

| Boronic Acids | Reversible ester formation | Serine | Electrophilic character [16] | Proteasome inhibitors |

| Sulfonyl Fluorides | Irreversible SuFEx chemistry | Serine/Lysine/Tyrosine | High chemoselectivity [16] | Chemoproteomic probes |

These warheads can be classified as either irreversible or reversible covalent modifiers. Irreversible warheads (e.g., acrylamides) form permanent bonds with their target proteins, providing sustained inhibition but potentially increasing off-target risks [16]. Reversible warheads (e.g., α-cyanoacrylamides, aldehydes) form transient covalent bonds, offering a balance between sustained engagement and reduced potential for idiosyncratic toxicity [16].

Modern Covalent Protein Degradation Technologies

Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs)

PROTACs represent the most advanced and widely adopted technology for targeted protein degradation. These heterobifunctional molecules consist of three key elements [15]:

- A warhead that binds to the protein of interest (POI)

- A ligand that recruits an E3 ubiquitin ligase

- A chemical linker that connects these two elements

The mechanism of PROTACs embodies the covalent conjugation principle by hijacking the natural ubiquitination machinery. PROTACs do not themselves covalently modify the target protein, but instead induce proximity-induced ubiquitination, leading to covalent tagging of the POI with ubiquitin chains [16] [15].

The development of PROTAC technology has followed an evolutionary path from peptide-based early constructs to fully small-molecule degraders [15]. The first PROTAC, reported in 2001 by Crews and Deshaies, used a phosphopeptide to recruit the SCF ubiquitin ligase complex and ovalicin to target methionine aminopeptidase-2 (MetAP-2) [15]. This was followed in 2008 by the first fully small-molecule PROTAC, which used non-steroidal androgen receptor ligands and MDM2 E3 ligase ligands to degrade the androgen receptor [15].

Covalent Molecular Glue Degraders

Molecular glue degraders represent a more recent innovation in covalent protein degradation. Unlike the heterobifunctional design of PROTACs, molecular glues are typically monovalent small molecules that induce or stabilize interactions between an E3 ubiquitin ligase and a target protein [15] [17].

A notable advance in this field is the discovery of covalent molecular glue degraders such as EN450, identified through chemoproteomic screening [17]. EN450 covalently targets cysteine 111 (C111) in the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBE2D, acting as a molecular glue that induces proximity between UBE2D and the transcription factor NF-κB (NFKB1), leading to its degradation [17]. This mechanism represents a unique approach where the covalent modification occurs not on the target protein, but on a component of the ubiquitination machinery itself, effectively repurposing it for targeted degradation.

Targeted Covalent Inhibitors (TCIs)

Targeted Covalent Inhibitors represent another application of covalent conjugation in protein targeting. TCIs consist of a reversible binding element and an electrophilic warhead that covalently modifies a nucleophilic residue (typically cysteine) on the target protein [16]. The mechanism follows a two-step process:

- Reversible binding that positions the warhead near the target residue

- Covalent bond formation that irreversibly or reversibly inactivates the protein [16]

The kinetic profile of TCIs is described by the equation:

[E + I \rightleftharpoons{k{off}}^{k{on}} E \cdot I \rightarrow{k_{inact}} E-I]

Where the overall potency is determined by the second-order rate constant of target inactivation (k{inact}/Ki) [16]. This approach has been successfully applied to previously "undruggable" targets like KRAS G12C, with covalent inhibitors such as sotorasib (AMG 510) achieving clinical success [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Degradation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Key Examples | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| E3 Ligase Ligands | Recruit specific E3 ubiquitin ligases | VHL ligands (e.g., VH032), CRBN ligands (e.g., lenalidomide/pomalidomide), MDM2 ligands [15] | Ligand choice influences degradation efficiency and tissue specificity |

| Covalent Warheads | Covalently bind target proteins | α-Cyanoacrylamides, acrylamides, aldehydes, boronic acids [16] | Warhead reactivity must be balanced between efficacy and selectivity |

| Linker Chemistry | Connect warheads to E3 ligands | PEG chains, alkyl chains, heterocyclic linkers [15] [18] | Linker length and composition affect ternary complex formation and degradation efficiency |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Validate proteasome-dependent degradation | Bortezomib, MG132, carfilzomib [15] | Essential control experiments to confirm UPS mechanism |

| NEDDylation Inhibitors | Disrupt cullin-RING ligase activity | MLN4924 [17] | Control for E3 ligase functionality in degradation assays |

| Chemoproteomic Platforms | Identify covalent binding sites and mechanisms | Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) [17] | Enables discovery of novel covalent interactions and mechanisms |

This toolkit enables researchers to design, optimize, and validate covalent protein degradation systems. Recent advances include innovative warhead designs, optimized linker strategies, and expanded E3 ligase ligands that collectively enhance the potency, selectivity, and scope of targeted degradation [18].

Experimental Protocols for Covalent Degradation Studies

Assessing Target Engagement and Degradation

A standard protocol for evaluating covalent protein degraders involves multiple steps to confirm mechanism of action:

Cellular Viability Assays:

- Treat cells with degrader compounds across a concentration range (typically 0.1 nM - 10 μM)

- Assess viability using ATP-based (CellTiter-Glo) or metabolic (MTT) assays after 72-96 hours

- Confirm NEDDylation and proteasome dependence using inhibitors like MLN4924 and bortezomib [17]

Protein Degradation Analysis:

Ternary Complex Assessment:

- Use techniques like cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) or proximity-based methods (BRET, FRET)

- Confirm formation of POI-PROTAC-E3 ternary complex

- Evaluate cooperative binding behavior [15]

Chemoproteomic Profiling for Covalent Degrader Discovery

The discovery of covalent molecular glue degraders like EN450 employed sophisticated chemoproteomic approaches [17]:

Phenotypic Screening:

- Screen covalent ligand libraries against disease-relevant cell models

- Identify hits that impair cell viability in a proteasome-dependent manner

Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP):

- Use probe-based platforms to map cysteine reactivity across the proteome

- Identify specific covalent binding sites (e.g., C111 of UBE2D for EN450)

Quantitative Proteomics:

- Employ multiplexed quantitative mass spectrometry (e.g., TMT, SILAC)

- Monitor global protein abundance changes following degrader treatment

- Identify putative degradation targets (e.g., NF-κB identification for EN450) [17]

This integrated approach enables the rapid discovery of covalent degradation mechanisms directly in native cellular environments.

The field of targeted protein degradation through covalent conjugation has evolved dramatically from the foundational discoveries of Hershko and Ciechanover. What began as fundamental research into ATP-dependent proteolysis has transformed into a sophisticated therapeutic modality with immense potential. Current research focuses on expanding the scope of degradable targets, improving tissue specificity through advanced delivery systems, and developing technologies for spatiotemporal control of degradation activity [18]. The integration of covalent chemistry with targeted degradation represents one of the most promising frontiers in chemical biology, offering potential solutions to previously intractable therapeutic challenges. As the field continues to mature, the covalent conjugation breakthrough promises to revolutionize both biological understanding and therapeutic intervention across a broad spectrum of diseases.

This technical review delineates the seminal discovery of ATP-dependent proteolysis, wherein the initial identification of an ATP-dependent proteolysis factor (APF-1) was subsequently revealed to be the well-known protein ubiquitin. The elucidation of this connection, primarily by Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin A. Rose, established the foundational principles of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS). This review provides an in-depth analysis of the key experimental protocols that uncovered APF-1's identity and function, summarizes the core components of the UPS, and explores the modern therapeutic applications, such as PROTACs, that have emerged from this fundamental research. Framed within the broader context of Hershko and Ciechanover's work, this article serves as a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, connecting a pivotal historical discovery to its extensive implications in contemporary cellular biology and targeted protein degradation.

For decades, the metabolic logic behind ATP-dependent intracellular proteolysis was a biochemical curiosity. As the hydrolysis of peptide bonds is an exergonic process, there was no apparent thermodynamic reason for an energy requirement [1]. The collaboration between Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin A. Rose was uniquely positioned to solve this mystery. Their work, which would later earn them the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004, shifted the paradigm from the view of proteolysis as a simple, unregulated digestive process to the understanding of a highly complex, targeted, and energy-dependent regulatory mechanism [19] [1].

The initial research model used reticulocyte lysates, which are devoid of lysosomes, thus allowing the team to isolate a non-lysosomal ATP-dependent proteolytic system. Fractionation of this lysate revealed that the system could be separated into two essential fractions: Fraction I and Fraction II [1]. Fraction I was found to contain a single, heat-stable component that was crucial for the reaction, which the researchers termed APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1). The journey to connect this unknown factor to a known protein would redefine the landscape of cell biology.

Experimental Breakthrough: The Discovery of APF-1 and its Covalent Attachment

Key Experimental Protocol: Identifying the Covalent Link

The following workflow summarizes the pivotal experiment that demonstrated the covalent nature of APF-1 attachment.

Title: Experimental Workflow for APF-1 Conjugation

Detailed Methodology:

- System Reconstitution: The ATP-dependent proteolytic system was reconstituted by combining Fraction I (containing APF-1) and Fraction II [1].

- Radiolabeling: APF-1 was tagged with iodine-125 (¹²⁵I) to allow for sensitive tracking [1].

- Incubation with ATP: The ¹²⁵I-labeled APF-1 was incubated with Fraction II in the presence of ATP.

- Analysis: The reaction mixture was analyzed using SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis), a technique that separates proteins by molecular weight. The covalent nature of the bond was confirmed by the stability of the complexes to high pH (NaOH) treatment [1].

Interpretation of Results: The appearance of radiolabeled APF-1 in high molecular weight complexes on SDS-PAGE, even under denaturing conditions, provided definitive evidence for the covalent attachment of APF-1 to multiple proteins in Fraction II. This conjugation was reversible upon ATP removal and its requirements for ATP and Fraction II mirrored those of ATP-dependent proteolysis, strongly suggesting a functional link between conjugation and protein degradation [1].

The Critical Connection: APF-1 is Ubiquitin

The discovery of covalent attachment prompted the critical question: What was the identity of APF-1? The observation that a small protein was covalently linked to cellular proteins recalled a previous finding: that histone H2A was modified by a small, ubiquitous protein named ubiquitin [1]. This similarity was pursued, and through direct comparison, it was confirmed that APF-1 was identical to the previously characterized protein, ubiquitin [1] [20]. This connection merged two separate lines of inquiry and revealed the physiological role of ubiquitin.

Table 1: From APF-1 to Ubiquitin - Key Characteristics

| Feature | APF-1 (Initial Discovery) | Ubiquitin (Later Identification) |

|---|---|---|

| Identity | ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1 | Ubiquitous Immunopoietic Polypeptide (UBIP) [21] [20] |

| Known Role | Unknown | Covalent modifier of histone H2A [1] |

| Primary Function | Mediate ATP-dependent proteolysis | Target proteins for degradation via the UPS [19] [20] |

| Size | Small, heat-stable protein | 76 amino acids, 8.6 kDa [21] [20] |

| Conservation | Not initially known | Highly conserved in eukaryotes [21] |

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: From Discovery to Core Mechanism

The connection of APF-1 to ubiquitin unlocked the understanding of a major cellular pathway. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is responsible for the degradation of over 80% of cellular proteins, including damaged, misfolded, and short-lived regulatory proteins [20] [15].

The Enzymatic Cascade and the Ubiquitin Code

The process of ubiquitination involves a sequential enzymatic cascade:

- Activation: A ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner [15].

- Conjugation: The activated ubiquitin is transferred to a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) [15].

- Ligation: A ubiquitin ligase (E3) recognizes the specific substrate protein and facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to a lysine residue on the substrate, forming an isopeptide bond [15].

A critical feature of ubiquitin is that it itself contains seven lysine residues (Lys6, Lys11, Lys27, Lys29, Lys33, Lys48, Lys63). These residues can themselves be ubiquitinated, leading to the formation of polyubiquitin chains. The type of linkage determines the fate of the modified protein, creating a complex "ubiquitin code" [21] [20].

Table 2: The Ubiquitin Code: Linkage and Functional Consequences

| Ubiquitin Linkage | Primary Function | Key Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Proteasomal degradation [20] [15] | The most abundant degradation signal; targets proteins like p53 and HIF1α [20]. |

| K63-linked | Non-proteolytic signaling | Regulates lysosome functions, endocytosis, DNA repair, and inflammatory response [20] [15]. |

| Met1-linked (Linear) | NF-κB activation | Assembled by the LUBAC complex [20]. |

| K11-linked | Proteasomal degradation | Works with K48; key in cell cycle regulation by APC/C [20]. |

| K27-linked | Mitophagy, Immune signaling | Associated with Parkin-mediated mitophagy [20]. |

| K29-linked | Lysosomal degradation? | Implicated in some lysosomal degradation pathways [20]. |

| K33-linked | Non-degradative signaling | Inhibits necroptosis by modulating RIPK3 [20]. |

| K6-linked | DNA repair | Associated with BRCA1 auto-ubiquitination [20]. |

The following diagram illustrates the core ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and the diversity of the ubiquitin code.

Title: The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System and Signaling Outcomes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Applications

The research into the UPS relies on a suite of essential reagents and molecular tools.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions in Ubiquitin and Protein Degradation Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | A cell-free system for biochemical fractionation and reconstitution of ATP-dependent proteolysis. | Used in the original discovery to isolate Fractions I and II, identifying APF-1/Ubiquitin [1]. |

| E1, E2, E3 Enzymes | Recombinant enzymes used to reconstitute specific ubiquitination cascades in vitro. | Studying the activity and specificity of particular E3 ligases for their target substrates. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Small molecules (e.g., Bortezomib, MG132) that selectively inhibit the proteasome's proteolytic activity. | Validating UPS-dependent degradation; used clinically to treat multiple myeloma [20]. |

| Ubiquitin Binding Domains (UBDs) | Protein domains that non-covalently recognize and bind specific ubiquitin chains. | As tools to purify, detect, and characterize the type of ubiquitin linkage on modified proteins [21]. |

| PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) | Heterobifunctional molecules with a warhead for a target protein, a ligand for an E3 ligase, and a linker. | Inducing targeted degradation of disease-causing proteins, a novel therapeutic strategy [15]. |

| Molecular Glue Degraders | Small molecules that induce proximity between an E3 ligase and a target protein, leading to its ubiquitination. | Examples include thalidomide and its analogs, which redirect CRBN E3 ligase activity [15]. |

Modern Applications: Targeted Protein Degradation in Drug Discovery

The profound understanding of the UPS has directly fueled the emergence of a revolutionary therapeutic strategy: Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD). Unlike traditional small-molecule inhibitors that merely block a protein's activity, TPD aims to completely remove the disease-causing protein from the cell [15].

The most prominent TPD technology is PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs). These are heterobifunctional molecules consisting of three elements:

- A warhead that binds to the Protein of Interest (POI).

- A ligand that recruits a specific E3 ubiquitin ligase.

- A linker connecting the two [15].

PROTACs act as a catalytic "matchmaker," bringing the E3 ligase into proximity with the POI, leading to its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the proteasome. This approach has key advantages, including the ability to target proteins previously considered "undruggable" and its event-driven, sub-stoichiometric mechanism of action [15].

The journey from the enigmatic APF-1 to the universally recognized ubiquitin represents one of the most elegant stories of scientific discovery in modern biology. The meticulous biochemical fractionation and reconstitution experiments conducted by Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose not only solved the long-standing puzzle of ATP-dependent proteolysis but also unveiled a universal regulatory mechanism of unparalleled complexity. The connection established that a known protein, ubiquitin, was repurposed by the cell as a precise molecular tag for destruction, a finding that fundamentally altered our understanding of cellular regulation. Today, the legacy of this discovery extends far beyond basic science, directly inspiring a new generation of therapeutic modalities like PROTACs that leverage the cell's own degradation machinery to treat disease. The field continues to evolve, promising further insights into the ubiquitin code and novel applications in research and medicine.

The period from 1978 to 1980 marked a paradigm shift in our understanding of cellular proteolysis. Prior to this groundbreaking work, intracellular protein degradation was largely attributed to lysosomal function or ATP-dependent proteases like bacterial Lon. The collaborative research of Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose revealed a far more sophisticated system—ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis—that would fundamentally alter cell biology and earn them the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry [1] [13]. Their discovery that eukaryotic cells covalently attach a small protein (ubiquitin) to target proteins to mark them for degradation established a new regulatory mechanism now recognized as being as crucial as phosphorylation or acetylation [1].

This research was framed by a fundamental biochemical curiosity: why did intracellular proteolysis require energy? The hydrolysis of peptide bonds is exergonic, presenting no thermodynamic requirement for ATP. Simpson's 1953 observation of this energy dependence had remained unexplained for 25 years, suggesting unknown regulatory mechanisms [1]. The Hershko-Ciechanover-Rose collaboration, forged through international scientific partnership and sabbatical work at Fox Chase Cancer Center, was uniquely positioned to address this mystery using biochemical approaches that would redefine protein turnover regulation [1] [22].

Experimental Foundations and Key Reagents

The Reticulocyte Lysate System and Initial Fractionation

The research program employed rabbit reticulocyte lysates as a model system, building on seminal observations by Etlinger and Goldberg that these lysates (which lack lysosomes) exhibited ATP-dependent proteolysis of denatured proteins [1] [13]. This system proved amenable to biochemical fractionation, allowing the team to separate the lysate into functionally distinct components.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Ubiquitin-Proteasome Research

| Research Reagent | Function in Experimental System | Experimental Role |

|---|---|---|

| Reticulocyte Lysate | ATP-dependent proteolytic extract lacking lysosomes | Source of ubiquitin-system components; foundational experimental system |

| APF-1 (Ubiquitin) | Heat-stable polypeptide; ATP-dependent proteolysis factor 1 | Covalent tag for protein targeting; later identified as ubiquitin |

| Fraction I | Contains APF-1/ubiquitin | Required component for reconstituting ATP-dependent proteolysis |

| Fraction II | High molecular weight fraction containing conjugating enzymes and proteasome | Contains E1, E2, E3 enzymes and 26S proteasome (APF-2) |

| ATP-regenerating System | Maintains constant ATP levels during incubations | Prevents ATP depletion during proteolysis assays |

The initial fractionation experiments demonstrated that the reticulocyte lysate could be separated into two fractions (I and II), both required to reconstitute ATP-dependent proteolysis [1] [13]. Fraction I contained a single essential heat-stable component termed APF-1 (ATP-dependent Proteolysis Factor 1), which would later be identified as ubiquitin [1]. Fraction II contained a high molecular weight component (APF-2) that was stabilized by ATP and later recognized as the 26S proteasome [1].

The Discovery of Covalent Protein Modification

The pivotal experimental breakthrough came from studies examining the association between (^{125})I-labeled APF-1 and components in Fraction II [1]. Surprisingly, the association persisted under denaturing conditions (high pH), suggesting a covalent linkage rather than non-covalent binding [1]. This covalent modification exhibited striking characteristics:

- ATP dependence: The conjugation required low ATP concentrations and was reversed upon ATP removal [1]

- Multi-substrate targeting: APF-1 was bound to many different proteins in Fraction II as judged by SDS-PAGE [1]

- Stability: The bond was stable to NaOH treatment, suggesting an isopeptide linkage rather than ester or thioester bond [1]

The connection to the previously known protein ubiquitin came through collaborative discussions and experimental verification. Art Haas, Keith Wilkinson, and Michael Urban recognized the similarity between APF-1 and ubiquitin, a protein previously identified by Gideon Goldstein and known to conjugate with histone H2A [1]. This critical insight connected the ATP-dependent proteolysis system with a known protein modifier.

Key Publications and Experimental Workflows (1978-1980)

The 1978 Biochemical Characterization

The initial report in 1978 (Ciechanover, Hod, and Hershko) established the heat-stable polypeptide component (APF-1) and its essential role in the ATP-dependent proteolytic system [13]. This work provided the foundational biochemical characterization of the system.

Table 2: Key Experimental Publications in the Discovery of Ubiquitin-Dependent Proteolysis

| Publication Year & Authors | Journal | Key Findings | Experimental Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1978: Ciechanover, Hod, Hershko | Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications | Identification of heat-stable polypeptide component (APF-1) essential for ATP-dependent proteolysis | Biochemical fractionation of reticulocyte lysates; ATP-depletion studies; reconstitution assays |

| 1980: Ciechanover, Heller, Elias, Haas, Hershko | Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences | Demonstration of covalent conjugation of APF-1/ubiquitin to multiple proteins in ATP-dependent manner | (^{125})I-labeled APF-1 tracking; SDS-PAGE analysis; ATP dependence studies |

| 1980: Hershko, Ciechanover, Heller, Haas, Rose | Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences | Evidence that protein substrates are multi-ubiquitinated; relationship between conjugation and proteolysis | Use of natural protein substrates; quantification of ubiquitin conjugates per substrate molecule |

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow Leading to Covalent Modification Discovery

The 1980 PNAS Papers: Mechanistic Insights

Two seminal 1980 PNAS papers established the core mechanism of ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis. The first paper (Ciechanover et al.) systematically characterized the covalent conjugation process [1] [13], while the second (Hershko et al.) demonstrated that authentic protein substrates were heavily modified with multiple ubiquitin molecules [1].

The experimental protocols employed in these studies included:

- ATP-depletion and reconstitution: Preparing Fraction II under ATP-depleted conditions was essential for demonstrating the APF-1 requirement, as endogenous ATP led to pre-formed conjugates [1]

- Radiolabel tracing: (^{125})I-labeled APF-1 allowed visualization and quantification of conjugation events [1]

- Native substrate analysis: Using known proteolytic substrates to demonstrate physiological relevance [1]

- Kinetic correlation: Showing parallel nucleotide and metal ion requirements for conjugation and proteolysis [1]

A critical insight from the second paper was that multiple ubiquitin molecules were attached to each substrate molecule, suggesting a cooperative recognition mechanism [1]. The conjugation system exhibited processivity, preferring to add additional ubiquitin molecules to existing conjugates rather than initiating new conjugation events on free substrates [1].

Diagram 2: Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway Conceptual Relationship

Technical Challenges and Methodological Innovations

The research team encountered and overcame several significant technical challenges:

The ATP Depletion Artifact

A particularly insightful finding emerged from understanding why some laboratories failed to demonstrate APF-1 dependence. When Fraction II was prepared without ATP depletion, most APF-1 existed in pre-formed high molecular weight conjugates that were subsequently disassembled by amidases in the fraction, liberating sufficient free APF-1 to support proteolysis without supplementation [1]. This explained discrepancies between laboratories and highlighted the importance of ATP-depletion protocols.

Identification of the Central Components

The terminology used in the original papers reflected the functional characterization approach:

- APF-1: The heat-stable, essential factor in Fraction I, later identified as ubiquitin [1]

- APF-2: The high molecular weight, ATP-stabilized component in Fraction II, later recognized as the 26S proteasome [1]

The connection to ubiquitin came through collaborative discussions recognizing the similarity between APF-1 and the previously known ubiquitin protein [1]. This connection was experimentally verified by showing that authentic ubiquitin could replace APF-1 in supporting ATP-dependent proteolysis [1].

Impact and Evolution of the Model

The period from 1978-1980 established the fundamental framework for understanding ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis, but subsequent research would reveal additional complexity:

- Enzyme cascade: The conjugation system involves E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligase) enzymes [1]

- Polyubiquitin signaling: Chau et al. later showed that proteolytic targeting requires polyubiquitin chains linked through Lys48 of ubiquitin [1]

- Proteasome structure: The 26S proteasome consists of 20S catalytic core and 19S regulatory particles [1] [23]

The model system established in this work—the fractionated reticulocyte lysate—remained the foundation for purifying and characterizing the individual components of the ubiquitin-proteasome system over the following decades.

The 1978-1980 work established not only a new biochemical pathway but also a novel regulatory paradigm in cell biology: targeted protein destruction through covalent protein tagging. This system would later be recognized as controlling virtually all major cellular processes, from cell cycle progression to signal transduction [1].

The therapeutic implications emerged decades later with the development of proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib (Velcade) for multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma [22] [24]. By 2018, these drugs had treated over half a million patients worldwide [22], demonstrating how fundamental biochemical research into basic cellular mechanisms can yield transformative clinical applications.

The collaboration between Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose—supported by international scientific partnerships and sabbatical opportunities—exemplifies how intellectual curiosity, biochemical rigor, and collaborative spirit can unravel nature's complexities and ultimately benefit human health.

Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Translation: From Ubiquitination to PROTACs

The discovery of a non-lysosomal, ATP-dependent proteolytic pathway by Avram Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover, and Irwin Rose fundamentally reshaped our understanding of intracellular protein degradation and earned them the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry [13]. Their pioneering work in the late 1970s and early 1980s revealed the existence of a biochemical marker that labels doomed proteins for destruction—a molecule they termed ubiquitin [12] [13]. They demonstrated that ubiquitin is activated in an ATP-consuming process and forms a covalent conjugate with target proteins, marking them for degradation by a large protease complex [13]. This process, now known as the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), involves a precise enzymatic cascade wherein E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes work in sequence to transfer ubiquitin onto specific substrate proteins [25] [26]. The UPS has since been recognized as a master regulator of countless cellular processes, governing the controlled destruction of proteins involved in cell cycle progression, signal transduction, and stress response [13] [26]. This technical guide explores the intricate mechanisms of this enzymatic cascade, framed within the revolutionary context of the Hershko and Ciechanover research that laid its foundation.

The Ubiquitination Cascade: A Three-Enzyme Mechanism

The conjugation of ubiquitin to substrate proteins follows a conserved, three-step mechanism that ensures precision and specificity in targeting proteins for degradation.

Step 1: Ubiquitin Activation by E1

The process initiates with the E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme. This step is ATP-dependent, wherein the E1 enzyme catalyzes the formation of a high-energy thioester bond between its active-site cysteine residue and the C-terminal glycine (Gly76) of ubiquitin [27] [26]. Prior to this, ubiquitin is adenylated, forming a UB-AMP intermediate. The human genome encodes two E1 enzymes, Ube1 and Uba6, which launch the ubiquitin transfer cascade [27].

Step 2: Ubiquitin Conjugation by E2

The activated ubiquitin is subsequently transferred from E1 to a cysteine residue of an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (Ubc) via a trans-thioesterification reaction. This results in the formation of a E2~Ub thioester conjugate (where "~" denotes the thioester bond) [27] [26]. The human genome encodes approximately 50 E2 enzymes, which function as central hubs in the cascade [27] [28].

Step 3: Ubiquitin Ligation by E3

The final step is catalyzed by an E3 ubiquitin ligase, which is responsible for the specific recognition of substrate proteins. The E3 facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2~Ub complex to a lysine residue on the substrate protein, forming an isopeptide bond [26]. In some cases, E3 ligases first form a thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate. E3s are the most diverse components of the cascade, with over 600 E3 ligases identified in humans, providing immense substrate specificity [29] [30]. The final product can be a mono-ubiquitinated protein or a polyubiquitin chain, where subsequent ubiquitin molecules are attached to a lysine residue on the preceding ubiquitin [30].

Table 1: Core Enzymes of the Ubiquitin Transfer Cascade

| Enzyme | Role | Human Genes | Key Functional Domain | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Activating) | Activates Ub via ATP hydrolysis | 2 (Ube1, Uba6) | Active-site Cysteine | E1~Ub thioester |

| E2 (Conjugating) | Accepts and carries activated Ub | ~50 | Active-site Cysteine | E2~Ub thioester |

| E3 (Ligating) | Recognizes substrate and catalyzes Ub transfer | >600 | RING, HECT, or RBR | Ubiquitinated substrate |

Figure 1: The E1-E2-E3 Enzymatic Cascade. Ubiquitin is activated by E1 in an ATP-dependent step, transferred to E2, and finally ligated to a protein substrate by an E3 ligase.

Historical and Structural Basis of E1-Ubiquitin Recognition

The C-terminal sequence of ubiquitin is critical for its recognition and activation by E1 enzymes. Early research by Hershko, Ciechanover, and Rose established that a heat-stable polypeptide was essential for the ATP-dependent proteolytic system [13]. Subsequent studies revealed that this polypeptide was ubiquitin and that its C-terminal glycine was indispensable for conjugation [27] [13].

Structural Insights from Phage Display

Phage display profiling of the ubiquitin C-terminal sequence (ending with 71LRLRGG76) has provided deep insights into E1 specificity. Key findings include [27]:

- Arg72 is absolutely required for E1 recognition.

- Residues at positions 71, 73, and 74 can be replaced with bulky aromatic side chains while maintaining E1 reactivity.

- Gly75 can be mutated to Ser, Asp, or Asn, and UB variants can still be efficiently activated by E1 and transferred to E2 enzymes.

- However, these UB mutants are often blocked from further transfer to E3 enzymes, indicating that the C-terminal sequence is also crucial for discharge from E2.

Table 2: Ubiquitin C-Terminal Residue Specificity for E1 Recognition

| Ubiquitin Residue | Wild-Type Amino Acid | Mutant Compatibility | Functional Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 71 | Leucine (L) | Bulky aromatic side chains | Tolerates mutation; not absolute |

| 72 | Arginine (R) | None (Absolute requirement) | Essential for E1 binding; 58-fold ↑ Kd with Leu mutant |

| 73 | Leucine (L) | Bulky aromatic side chains | Tolerates mutation; not absolute |

| 74 | Arginine (R) | Bulky aromatic side chains | Tolerates mutation; not absolute |

| 75 | Glycine (G) | Serine, Aspartate, Asparagine | Required for E1 activation but tolerates some mutation |

| 76 | Glycine (G) | None (Absolute requirement) | Indispensable for thioester formation with E1 |

E3 Ubiquitin Ligases: Architects of Specificity

E3 ubiquitin ligases serve as the primary determinants of substrate specificity within the ubiquitin cascade. They are broadly classified into three major families based on their structural domains and mechanisms of action [30].

RING Domain Family

RING-type E3s (e.g., MDM2, cIAP) contain a Really Interesting New Gene domain. They act as scaffolds that simultaneously bind to both the E2~Ub complex and the substrate protein, facilitating the direct transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to the substrate without forming a covalent E3-Ub intermediate. This is the largest family of E3 ligases [26] [30].

HECT Domain Family

HECT-type E3s (e.g., NEDD4, E6AP) contain a Homologous to E6-AP C-Terminus domain. Unlike RING E3s, they form a covalent thioester intermediate with ubiquitin transferred from the E2~Ub complex before ultimately transferring it to the substrate protein [27] [26].

RBR Type Family