Ubiquitin and Ubiquitin-like Signaling: Evolutionary Origins, Mechanisms, and Pathogen Interactions in Prokaryotes vs. Eukaryotes

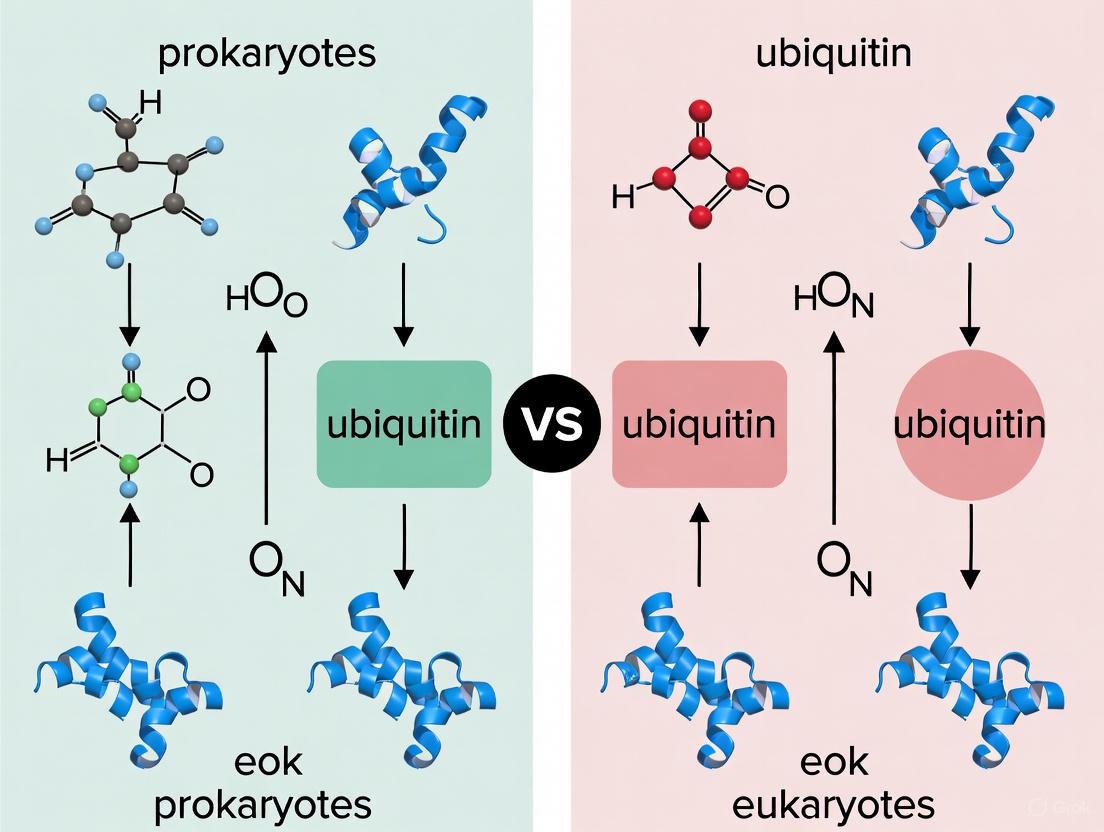

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like (Ubl) protein conjugation systems across eukaryotes and prokaryotes.

Ubiquitin and Ubiquitin-like Signaling: Evolutionary Origins, Mechanisms, and Pathogen Interactions in Prokaryotes vs. Eukaryotes

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like (Ubl) protein conjugation systems across eukaryotes and prokaryotes. For researchers and drug development professionals, we synthesize foundational knowledge on the eukaryotic ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) with groundbreaking discoveries of Ubl pathways in bacteria, such as Pup and newly identified bacterial E1-E2-E3 cascades. The scope spans evolutionary origins, structural and mechanistic parallels, methodological approaches for studying these systems, and how pathogens manipulate host ubiquitination. We highlight the implications of these fundamental differences and similarities for developing novel therapeutic strategies, including targeting bacterial virulence mechanisms and the bacterial ubiquitination machinery itself.

Ubiquitin and Ubls: From Eukaryotic Hallmark to Prokaryotic Ancestors

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents the primary pathway for targeted protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, operating as a sophisticated master regulator of cellular processes ranging from cell cycle progression to stress response [1] [2]. This system typically recognizes specific protein substrates and tags them with polyubiquitin chains, marking them for destruction by the proteasome—a massive proteolytic complex [3]. The UPS is remarkable not only for its precision in selecting targets among thousands of cellular proteins but also for its ability to regulate virtually all aspects of eukaryotic biology through both proteolytic and non-proteolytic mechanisms [2]. The discovery that bacteria possess ubiquitination-like pathways with striking mechanistic parallels to eukaryotic systems has revolutionized our understanding of the evolutionary origins of this complex machinery, suggesting these pathways arose first in bacteria before being adopted and refined by eukaryotes for expanded regulatory purposes [4] [5]. This comparison guide examines the canonical eukaryotic UPS, its core components, operational dogma, and experimental methodologies for studying its function, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for understanding this essential biological system.

Core Components of the Eukaryotic Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

The Enzymatic Ubiquitination Cascade

The ubiquitination process employs a three-tiered enzymatic cascade comprising E1 (ubiquitin-activating), E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating), and E3 (ubiquitin-ligating) enzymes that work sequentially to tag substrate proteins [6] [2] [7].

E1 Activating Enzymes: The human genome encodes two ubiquitin E1 enzymes (UBA1 and UBA6) that initiate the ubiquitination cascade [6]. These enzymes use ATP to activate ubiquitin through the formation of a high-energy thioester bond between a catalytic cysteine residue in E1 and the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin [6] [3]. This energy-dependent step makes the ubiquitin molecule competent for subsequent transfer reactions.

E2 Conjugating Enzymes: Approximately 38 E2 enzymes in humans receive the activated ubiquitin from E1 through transesterification, forming a similar thioester linkage [6]. E2 enzymes function not merely as passive carriers but play an active role in determining the topology of polyubiquitin chains, thereby influencing the fate of modified substrates [6].

E3 Ligating Enzymes: The human genome contains approximately 700 E3 ubiquitin ligases, which provide substrate specificity by recognizing target proteins and facilitating ubiquitin transfer from E2 to substrate lysine residues [6]. E3 ligases fall into three main subfamilies: RING E3s that act as scaffolding molecules to bring ubiquitin-charged E2 enzymes in close proximity to substrates; HECT E3s that form a transient thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transfer; and RING-Between-RING (RBR) E3s that function as hybrids between RING and HECT mechanisms [6].

Table 1: Major E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Families and Their Characteristics

| E3 Family | Catalytic Mechanism | Representative Members | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| RING E3s | Scaffold for direct ubiquitin transfer from E2 to substrate | SCF complexes, MDM2 | Largest E3 family; often multi-subunit complexes |

| HECT E3s | Forms E3~Ub thioester intermediate before substrate transfer | NEDD4, HACE1 | Catalytic cysteine residue; regulates diverse trafficking pathways |

| RBR E3s | Hybrid mechanism with RING and HECT-like features | PARKIN, ARIH1 | RING1 domain binds E2; RING2 domain has catalytic cysteine |

The Proteasome: Architecture and Degradation Machinery

The 26S proteasome is a 2.6 MDa molecular machine responsible for degrading ubiquitinated proteins [1]. It consists of two primary subcomplexes:

20S Core Particle (CP): This barrel-shaped structure contains the proteolytic active sites within its interior chamber, sequestered from the cellular environment to prevent uncontrolled protein degradation [1]. The CP is composed of four stacked heptameric rings: two identical outer α-rings that regulate gate opening, and two identical inner β-rings that contain the protease active sites [1].

19S Regulatory Particle (RP): This cap complex recognizes ubiquitinated substrates, removes ubiquitin chains, unfolds target proteins, and translocates them into the CP for degradation [1]. The RP contains at least 19 subunits organized into two subcomplexes: the "base" with six AAA+ ATPases (Rpt1-6) that unfold substrates, and the "lid" with ubiquitin receptors and deubiquitinating enzymes [1].

Table 2: Proteasome Subunits and Their Functions

| Subcomplex | Subunit Category | Representative Subunits | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20S Core Particle | α-subunits | PSMA1-PSMA7 (human) | Form gated channel for substrate entry |

| 20S Core Particle | β-subunits | PSMB1-PSMB7 (human) | Contain proteolytic active sites |

| 19S Regulatory Particle Base | AAA+ ATPases | Rpt1-Rpt6 (yeast) | Substrate unfolding and translocation |

| 19S Regulatory Particle Base | Non-ATPases | Rpn1, Rpn2, Rpn10, Rpn13 | Ubiquitin receptor docking |

| 19S Regulatory Particle Lid | PCI domain proteins | Rpn3, Rpn5-Rpn7, Rpn9, Rpn12 | Structural scaffolding |

| 19S Regulatory Particle Lid | MPN domain proteins | Rpn8, Rpn11 | Deubiquitination (Rpn11) |

The following diagram illustrates the complete ubiquitination and degradation pathway:

The Central Dogma: ubiquitin Code and Signal Interpretation

The Ubiquitin Code: A Complex Signaling Language

Ubiquitination creates a sophisticated post-translational modification code that extends far beyond a simple degradation signal [2] [7]. The "ubiquitin code" consists of:

Monoubiquitination: Single ubiquitin modifications that typically alter protein activity, localization, or interactions without triggering degradation [7].

Polyubiquitin Chains: Ubiquitin polymers formed through isopeptide bonds between the C-terminus of one ubiquitin and a lysine residue of another [2] [7]. With seven lysine residues in ubiquitin (Lys6, Lys11, Lys27, Lys29, Lys33, Lys48, Lys63) plus the N-terminal methionine (Met1), eight structurally and functionally distinct chain types can be formed [2] [7].

Chain Topology Diversity: Beyond homogeneous chains, cells generate heterogeneous (mixed linkage) and branched (multiple ubiquitination sites on a single ubiquitin) chains that expand the coding potential [7].

Table 3: Ubiquitin Chain Linkages and Their Primary Functions

| Linkage Type | Abundance in Cells | Primary Functions | Key Readers/Effectors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lys48 | >50% of all linkages | Proteasomal degradation | Proteasome receptors |

| Lys63 | Second most abundant | NF-κB signaling, DNA repair, endocytosis | TAB2/TAB3, ESCRT components |

| Lys11 | Moderate | ER-associated degradation, cell cycle | Proteasome, Cdc48/p97 |

| Met1 (Linear) | Low | NF-κB activation, inflammation | NEMO/IKK complex |

| Lys29 | Low | Proteasomal degradation (with Lys48) | Proteasome receptors |

| Lys33 | Low | AKT signaling, trafficking | - |

| Lys6 | Low | DNA damage repair, mitophagy | - |

| Lys27 | Low | Immune signaling, autophagy | - |

Interpretation and Reversal of Ubiquitin Signals

The ubiquitin code is interpreted by ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) present in hundreds of cellular proteins [7]. These domains recognize specific ubiquitin modifications and translate them into appropriate cellular responses, such as proteasomal targeting, altered protein interactions, or changes in subcellular localization [7].

Ubiquitination is counterbalanced by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that remove ubiquitin modifications, providing dynamic regulation [6] [2]. The human genome encodes approximately 100 DUBs categorized into five major families: ubiquitin-specific proteases (USP), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCH), ovarian tumor proteases (OTU), Machado-Joseph disease proteases (MJD), and JAMM/MPN metalloproteases [6]. DUBs not only reverse ubiquitination events but also process ubiquitin precursors and edit ubiquitin chains to refine signaling outcomes [6].

The following diagram illustrates the complexity of ubiquitin chain architecture and recognition:

Experimental Methods for UPS Analysis

Key Methodologies for Studying UPS Components

Research into the ubiquitin-proteasome system employs diverse experimental approaches to decipher its complexity:

Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics: Advanced quantitative mass spectrometry techniques, including SILAC (stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture) and TMT (tandem mass tag) labeling, enable comprehensive identification and quantification of ubiquitination sites [7]. The AQUA (absolute quantification) method using labeled ubiquitin peptide standards provides precise measurement of specific ubiquitin chain linkages [7].

Linkage-Specific Reagents: Antibodies specific for Met1-, Lys11-, Lys48-, and Lys63-linked chains have been developed and validated, allowing immunohistochemical and immunoblotting applications [7]. Similarly, tandem ubiquitin-binding entities (TUBEs) serve as affinity reagents that protect polyubiquitinated proteins from deubiquitination during purification [8].

Structural Biology Approaches: Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has been instrumental in determining the architecture of the 26S proteasome at near-atomic resolution [1]. X-ray crystallography continues to provide high-resolution structures of individual UPS components, such as the recent structural analysis of bacterial E1:E2:Ubl complexes that reveal evolutionary conservation [5].

Protein Engineering Techniques: Unnatural amino acid incorporation, expressed protein ligation (EPL), and phage/yeast display systems have generated specialized tools for probing UPS mechanisms, including ubiquitin variants (Ubvs) that selectively inhibit specific DUBs or E3 ligases [8].

Research Reagent Solutions for UPS Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for UPS Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 Inhibitors | PYR-41, PYZD-4409 | Block global ubiquitination | Irreversible covalent modification of E1 active site |

| E2 Inhibitors | CC0651, NSC697923 | Selective pathway inhibition | CC0651: allosteric inhibitor of CDC34; NSC697923: blocks UBE2N~Ub formation |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | FDA-approved cancer therapeutics | Reversible vs. irreversible binding to proteolytic sites |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Anti-K48, Anti-K63, Anti-M1 Ub | Chain linkage detection in cells | Enable monitoring of specific chain types in signaling |

| DUB Probes | Ubiquitin-based activity probes | DUB activity profiling | Covalent trapping of active DUBs for identification |

| Ubiquitin Variants (Ubvs) | Engineered Ub mutants | Specific pathway interruption | Phage display-derived inhibitors of E3s or DUBs |

| Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Multi-UBD fusion proteins | PolyUb protein enrichment | Protect Ub chains from DUBs during purification |

UPS-Targeted Therapeutic Applications

The ubiquitin-proteasome system presents numerous attractive targets for therapeutic intervention, particularly in oncology and neurodegenerative diseases [6] [2]. Several targeting strategies have shown clinical promise:

Proteasome Inhibitors: Drugs like bortezomib and carfilzomib inhibit the proteolytic activity of the 20S proteasome, leading to accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins and apoptosis in rapidly dividing cells, particularly multiple myeloma cells [6].

E1 Enzyme Targeting: The NEDD8-activating enzyme (NAE) inhibitor MLN4924 (pevonedistat) has shown promise in clinical trials by blocking neddylation of cullins, thereby impairing the function of cullin-RING ligases (CRLs) and inducing DNA damage in cancer cells [6].

E3 Ligase Modulation: Molecular glues such as thalidomide and related immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) redirect the CRL4CRBN E3 ligase to target novel substrates for degradation, demonstrating the therapeutic potential of targeted protein degradation [8].

DUB Inhibition: Specific inhibitors of USP7, USP14, and other DUBs are under investigation for cancer therapy, aiming to stabilize tumor suppressors or disrupt oncogenic signaling pathways [6].

The following diagram illustrates major therapeutic targeting strategies within the UPS:

Evolutionary Perspective: Bacterial Antecedents of Eukaryotic UPS

Recent research has revealed that bacteria possess complete ubiquitination-like pathways with remarkable architectural and mechanistic parallels to eukaryotic systems [4] [5]. The discovery of Type II BilABCD operons in bacteria encoding E1, E2, Ubl, and DUB proteins demonstrates that these pathways likely originated in bacteria before being adopted by eukaryotes [5]. Key findings include:

Structural Conservation: Bacterial E1 proteins display the same domain architecture (IAD, AAD, and CYS domains) as eukaryotic E1s, despite limited sequence similarity [5].

Functional Parallels: Bacterial ubiquitination systems participate in antiviral defense, modifying virion structural proteins to provide immunity against phage infection—a functional analogy to eukaryotic immune signaling through ubiquitin [5].

Evolutionary Insight: These bacterial pathways challenge previous models that placed the origin of ubiquitination systems in archaea and suggest that eukaryotic ubiquitination machinery evolved from bacterial antecedents [5].

This evolutionary perspective provides researchers with a more comprehensive framework for understanding the fundamental principles of ubiquitin signaling across domains of life and may facilitate the development of novel experimental approaches based on these more ancient, simplified systems.

The canonical eukaryotic ubiquitin-proteasome system represents a sophisticated protein regulatory network that governs virtually all aspects of cell biology through both proteolytic and non-proteolytic mechanisms. Its core components—the E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade and the 26S proteasome—operate with remarkable specificity to control protein stability, activity, and interactions. The complexity of the ubiquitin code, with its diverse chain topologies and modifications, enables precise signal encoding that is interpreted by specialized receptors and reversed by deubiquitinating enzymes. From an evolutionary perspective, the discovery of analogous systems in bacteria highlights the ancient origins of this regulatory paradigm. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the detailed composition, operational dogma, and experimental methodologies of the UPS provides critical insights for developing novel therapeutic strategies that target this system in cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and other human diseases.

Ubiquitin-like proteins (UBLs) are a family of small proteins involved in the post-translational modification of other proteins, thereby regulating an enormous range of physiological processes in eukaryotic cells [9] [10]. These modifiers share a common three-dimensional core structure known as the β-grasp fold and are conjugated to target proteins via a conserved enzymatic cascade [9] [11]. The first discovered and best-understood UBL is ubiquitin itself, best known for targeting proteins for degradation by the proteasome [9] [10]. Following the discovery of ubiquitin, many evolutionarily related UBLs were described, including SUMO (Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier), NEDD8 (Neural precursor cell-expressed, Developmentally down-regulated 8), and ISG15 (Interferon-Stimulated Gene 15) [9] [12].

These UBLs, while mechanistically parallel, are functionally distinct, controlling diverse processes such as transcription, the cell cycle, DNA repair, autophagy, immune responses, and inflammation [9] [12] [13]. Mounting evidence suggests that UBL-protein modification evolved from prokaryotic sulfurtransferase systems or related enzymes [10] [11]. Proteins similar to UBL-conjugating enzymes appear to have been present in the last universal common ancestor, indicating that UBL-protein conjugation is not a eukaryotic invention [10]. This review provides a comparative analysis of the major eukaryotic UBLs—SUMO, NEDD8, and ISG15—focusing on their distinct roles, regulatory mechanisms, and experimental approaches for their study, framed within the broader evolutionary context of ubiquitin-like systems.

The following table provides a systematic comparison of the core characteristics of SUMO, NEDD8, and ISG15, highlighting their structural and functional specialization.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Major Eukaryotic Ubls

| Feature | SUMO | NEDD8 | ISG15 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Identity to Ubiquitin | ~18% (SUMO1) [10] | ~55% [10] | ~32-37% (per domain) [10] [12] |

| Protein Structure | Single UBL domain [14] | Single UBL domain [14] | Tandem UBL domains [12] [14] |

| Primary Known Functions | Transcription, DNA repair, nuclear transport, stress response [9] [13] | Activation of cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin ligases (CRLs) [9] [11] | Antiviral immunity, DNA damage response, autophagy, translation regulation [9] [12] |

| E1 Activating Enzyme | Heterodimer Aos1/Uba2 [11] | Heterodimer Uba3/NAE1 [11] | UBA7 (UBE1L) [12] |

| E2 Conjugating Enzyme | Ubc9 [11] [14] | Ubc12 [11] [14] | UBCH8 (UBE2L6) [12] [14] |

| Representative E3 Ligases | PIAS, RanBP2, ZNF451 [14] | RBX1/2, DCN1 [14] | HERC5, EFP (TRIM25), HHARI [12] [14] |

| Specific Proteases | SENPs, DeSI, USPL1 [14] | NEDP1, DEN1, SENP8 [14] | USP18 (UBP43) [12] [14] |

| Chain Formation | Yes (poly-SUMO) [9] [15] | Yes [9] | Yes (mixed Ub-ISG15 chains) [12] |

Ubl-Specific Conjugation Pathways and Cellular Functions

The SUMOylation Pathway

SUMOylation is crucial for nuclear processes, particularly transcription, DNA repair, and the maintenance of genome stability [13]. A unique feature of SUMOylation is the common use of a single E2 conjugating enzyme, Ubc9, which interacts directly with a consensus motif (ΨKxE/D, where Ψ is a hydrophobic residue) on the substrate [14]. SUMO can be conjugated as a monomer or form poly-SUMO chains, which act as scaffolds for the recruitment of proteins containing SUMO-interacting motifs (SIMs) [14] [15].

Figure 1: The SUMO Conjugation Pathway. SUMO is activated by the E1 heterodimer, transferred to the E2 enzyme Ubc9, and ligated to target substrates with the help of E3s, ultimately regulating key nuclear processes.

The NEDD8ylation Pathway

NEDD8, which shares the highest sequence identity with ubiquitin, primarily regulates the ubiquitin-proteasome system itself [15]. Its best-characterized function is the activation of cullin proteins, which are the core scaffolding components of Cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin ligases (CRLs) [9] [11]. NEDD8 is activated by its specific E1 (Uba3/NAE1) and E2 (Ubc12) enzymes. Conjugation of NEDD8 to a cullin, known as "neddylation," induces a conformational change that promotes the ubiquitin ligase activity of the CRL, thereby stimulating the polyubiquitination and degradation of proteins that control cell cycle progression and signaling [11].

Figure 2: The NEDD8 Conjugation Pathway. NEDD8 modification of cullins activates CRLs, which in turn drive the ubiquitination and degradation of a wide array of downstream proteins.

The ISGylation Pathway

ISG15 is a unique UBL composed of two ubiquitin-like domains [12] [14]. It is a central component of the innate immune response, strongly induced by interferons and viral infection [12]. Its conjugation cascade involves the E1 enzyme UBA7, the E2 enzyme UBCH8, and E3s such as HERC5. ISG15 can antagonize viral replication by conjugating to viral proteins or host factors, but it also has emerging roles in DNA damage response, autophagy, and cancer stem cell regulation [12] [16]. ISG15 can function both as a conjugated modifier and as a free cytokine, stimulating IFNγ secretion [12].

Figure 3: The ISG15 Conjugation Pathway. ISG15 is induced by interferon and conjugated to target proteins, playing key roles in antiviral defense and other cellular processes.

Experimental Data and Methodologies for Ubl Research

Key Experimental Protocols

Studying UBL modifications presents challenges, including the low abundance of endogenous conjugates and the activity of deconjugating enzymes. The following protocols are central to the field.

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols in Ubl Research

| Method | Core Principle | Key Steps | Application & Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denaturing Immuno-affinity Purification [15] | Use of epitope-tagged UBLs and purification under denaturing conditions. | 1. Express tagged UBL (e.g., HIS, FLAG, biotin) in cells.2. Lyse cells under denaturing conditions (e.g., SDS, Guanidine HCl).3. Purify conjugates with affinity resin (e.g., Ni-NTA, Streptavidin).4. Identify substrates by mass spectrometry. | Inactivates isopeptidases, reduces non-covalent interactors, and allows identification of low-abundance substrates. |

| In vivo Biotinylation (bioUbL) [15] | In vivo biotinylation of a short tag (AviTag) on the UBL by co-expressed BirA ligase. | 1. Co-express bio-tagged UBL and BirA from a multicistronic vector.2. Lyse under denaturing conditions.3. Capture biotinylated conjugates with streptavidin beads.4. Analyze by western blot or MS. | High-affinity streptavidin-biotin interaction enables stringent washes and minimal background. Ideal for proteomic studies in cells and model organisms. |

| Activity-Based Profiling with Chemical Synthesis [14] | Chemical synthesis of UBLs with tailored probes (e.g., fluorogenic, cross-linkers). | 1. Synthesize UBLs with C-terminal electrophilic traps or fluorogenic groups (e.g., AMC).2. Incubate with enzymes or cell lysates.3. Monitor activity via fluorescence or covalent capture. | Provides homogeneously modified substrates and probes to study enzyme kinetics, specificity, and inhibition. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Ubl Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Epitope-Tagged Ubl Plasmids | Enables overexpression and purification of UBL conjugates. | HIS-SUMO, FLAG-NEDD8, Bio-ISG15 (for bioUbL system) [15]. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Protects UBL conjugates from deconjugating enzymes during lysis. | Inclusion of N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) or iodoacetamide to alkylate cysteine proteases [15]. |

| Activity-Based Probes | Monitors enzymatic activity and identifies interacting proteins. | UBL-AMC conjugates (e.g., Ub-AMC, ISG15-AMC) for kinetic assays; suicide inhibitors [17] [14]. |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Detects endogenous UBL conjugates and specific chain linkages. | Antibodies against SUMO1, SUMO2/3, ISG15, or di-Gly remnant after tryptic digest (for MS) [15]. |

| Recombinant E1/E2/E3 Enzymes | Reconstitutes conjugation and deconjugation pathways in vitro. | Uba2/Aos1 (SUMO E1), Uba3/Nae1 (NEDD8 E1), Ubc9 (SUMO E2), USP18 (DeISGylase) [11] [14]. |

| Specific Small Molecule Inhibitors | Selectively inhibits UBL pathways for functional studies. | MLN4924 (NEDD8 E1 inhibitor) [11], GRL0617 (SARS-CoV-2 PLpro inhibitor affecting Ubl domain) [17]. |

Evolutionary Context: Prokaryotic Antecedents to Eukaryotic Ubls

The eukaryotic UBL conjugation system is believed to have evolved from ancient prokaryotic sulfur-transfer pathways [9] [10]. Key evidence for this includes:

- Structural and Mechanistic Homology: The bacterial sulfur carrier proteins ThiS and MoaD, involved in thiamine and molybdopterin biosynthesis, share the β-grasp fold and a similar activation mechanism involving adenylation and thiocarboxylate formation with eukaryotic UBLs [9] [10] [11].

- A Molecular Fossil: The eukaryotic UBL URM1 functions both as a protein modifier and a sulfur carrier, establishing a direct evolutionary link between these two systems [9] [10].

- Prokaryotic Ubl-like Systems: Some archaea and bacteria possess simplified UBL systems. For example, SAMPs in archaea and Pup in actinobacteria perform ubiquitin-like tagging for proteasomal degradation, though Pup is intrinsically disordered and lacks the β-grasp fold [9].

Figure 4: Evolutionary Trajectory of Ubl Systems. Eukaryotic UBL pathways evolved from prokaryotic sulfur-transfer systems involved in cofactor biosynthesis, through gene duplication and functional diversification.

SUMO, NEDD8, and ISG15 exemplify the functional diversification of ubiquitin-like proteins in eukaryotes. While they share a common structural fold and a conserved enzymatic cascade for conjugation, they regulate distinct cellular processes: SUMO in nuclear organization and stress, NEDD8 in ubiquitin ligase activation, and ISG15 in immunity and beyond. This specialization is enforced by dedicated sets of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes, as well as specific proteases. Research in this field relies on sophisticated methods like denaturing affinity purification and chemical biology tools to overcome the challenges of studying these dynamic modifications. The evolutionary perspective, which roots these complex eukaryotic systems in primordial prokaryotic sulfur metabolism, provides a unifying framework for understanding the biology of these critical regulatory proteins. Continued comparative research will deepen our understanding of their roles in health and disease and open new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

For decades, the ubiquitin-proteasome system was considered a hallmark of eukaryotic complexity, a sophisticated regulatory mechanism absent from prokaryotic organisms. This historical paradigm positioned ubiquitin as a eukaryote-specific modifier, fundamentally distinguishing eukaryotic cell biology from its supposedly simpler prokaryotic counterparts. The discovery of the ubiquitin-like protein (Pup) in prokaryotes has fundamentally challenged this long-standing assumption [18]. This revelation emerged from studies on Mycobacterium tuberculosis, where Pup was found to target proteins for proteolysis by the bacterial proteasome, representing a functional analogue to the eukaryotic ubiquitin system [18]. This discovery not only overturned the notion of ubiquitin as exclusively eukaryotic but also opened new avenues for understanding the evolution of post-translational modification systems and their implications for bacterial pathogenesis and drug development.

The subsequent identification of additional ubiquitin-like modifiers in archaea (SAMPs) and Thermus (TtuB), which share a common β-grasp fold with ubiquitin despite sequence differences, further eroded the eukaryotic monopoly on ubiquitin-like signaling [19] [20]. These findings suggest that the evolutionary origins of ubiquitin-like protein modifiers predate the divergence of life's domains, with prokaryotes possessing their own sophisticated protein-tagging systems that affect cellular processes, including targeted proteolysis [18]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison between the eukaryotic ubiquitin system and its prokaryotic counterparts, examining their mechanisms, functions, and the experimental approaches used to characterize them.

Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitin and Prokaryotic Ubiquitin-Like Proteins

Core Structural and Functional Divergence

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Eukaryotic Ubiquitin and Prokaryotic Ubiquitin-like Proteins

| Feature | Eukaryotic Ubiquitin | Prokaryotic Pup (Mycobacteria) | Prokaryotic SAMPs/TtuB (Archaea/Thermus) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Size & Structure | 76 amino acids; compact, globular β-grasp fold [21] | ~64 amino acids; intrinsically disordered [19] | β-grasp fold similar to Ub, but different sequence [19] |

| C-terminal Motif | Gly-Gly [21] | Gly-Gly-Gln (deamidated to Gly-Gly-Glu) [19] | Gly-Gly (in TtuB and some SAMPs) [19] |

| Conjugation Bond | Isopeptide bond (via C-terminal Gly α-carboxylate) [21] | Isopeptide bond (via C-terminal Glu γ-carboxylate) [19] | Isopeptide bond (presumably via C-terminal Gly) [19] |

| Enzymatic Cascade | E1-E2-E3 enzyme cascade (ATP-dependent) [22] | Deamidase (Dop) + Ligase (PafA) [19] | Appears streamlined; requires E1 but not E2/E3 [19] |

| Primary Function | Diverse: Proteasomal degradation, signaling, endocytosis [22] [23] | Targets proteins for bacterial proteasome degradation [18] | Protein modification & sulfur transfer for biosynthesis [19] |

| Proteasome Association | 26S proteasome (20S core + 19S regulatory cap) [18] | 20S core + ATPase (Mpa) regulator [18] | Not fully characterized |

Enzymatic Machinery and Conjugation Pathways

The fundamental distinction between these systems lies in their enzymatic machineries. The eukaryotic ubiquitination cascade is a three-step process involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes, which results in an isopeptide bond between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin and a lysine residue on the target protein [22] [21]. This system is highly complex, with humans encoding two E1s, ~35 E2s, and approximately 600-700 E3s, allowing for immense specificity and regulation [6] [24].

In contrast, the best-characterized prokaryotic system, pupylation, requires only two enzymes: the deamidase Dop (deamidase of Pup) and the ligase PafA (proteasome accessory factor A) [19]. Dop deamidates the C-terminal glutamine of Pup to glutamate in an ATP-dependent manner, and PafA then catalyzes the ATP-dependent formation of an isopeptide bond between the γ-carboxylate of this glutamate and the ε-amino group of a lysine residue on the target protein [19]. This mechanism is distinct from ubiquitylation in both enzymology and chemistry, despite the analogous functional outcome of targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation [19].

Table 2: Comparative Enzymology of Ubiquitin-like Modification Pathways

| Enzyme Type | Eukaryotic Ubiquitin System | Prokaryotic Pup System | Key Distinctions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activating Enzyme | E1 (e.g., UBA1, UBA6); adenylates Ub, forms thioester [6] [21] | Dop; deamidates C-terminal Gln of Pup to Glu using ATP [19] | Dop does not form a thioester intermediate. |

| Conjugating Enzyme | E2 (e.g., CDC34, UBE2N); ~35 in humans, carries activated Ub [6] | Not present in pupylation pathway. | The E2 step is entirely absent in the pupylation cascade. |

| Ligating Enzyme | E3 (e.g., HECT, RING, RBR); ~600 in humans, provides substrate specificity [6] | PafA; directly ligates deamidated Pup to substrate lysine [19] | PafA is related to carboxylate-amine/ammonia ligases, not E3s. |

| Deconjugating Enzyme | Deubiquitinases (DUBs); ~100 in humans, remove Ub [23] [24] | Dop; also exhibits depupylase activity to reverse modification [19] | Dop is a bifunctional enzyme, unlike most DUBs. |

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

Key Methodologies for Studying Prokaryotic Ubiquitin-like Systems

1. Bacterial Two-Hybrid Screening for Protein Interaction Partners: The initial discovery of Pup relied on a bacterial two-hybrid screen using the proteasomal ATPase Mpa as bait to identify interacting partners [19]. This method involves co-expressing two putative interacting proteins fused to separate domains of a transcription factor in bacteria. If the proteins interact, they reconstitute the transcription factor and activate reporter genes, allowing for the selection and identification of novel binding partners like Pup.

2. Detection of Covalent Conjugates via Co-expression and Immunoblotting: To confirm the formation of covalent Pup-protein conjugates, researchers co-express Pup (or its mutants) with a candidate substrate protein (e.g., FabD, PanB) in mycobacteria or E. coli [19]. Cell lysates are then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using an antibody specific for the substrate or Pup. A shift in the molecular weight of the substrate indicates the formation of a covalent complex, which can be further verified by mass spectrometry.

3. In Vitro Reconstitution of the Pupylation/Depupylation Cycle: This biochemical assay uses purified components to delineate the enzymatic pathway.

- Procedure:

- Purification: Recombinant Pup (GGQ form), Dop, PafA, and a candidate substrate protein (e.g., FabD) are purified.

- Deamidation Reaction: Pup is incubated with Dop and ATP (or a non-hydrolyzable analog). Deamidation to Pup-GGE can be monitored by gel shift or mass spectrometry.

- Ligation Reaction: Deamidated Pup is incubated with PafA, ATP, and the substrate. The formation of pupylated substrate is analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining or immunoblotting [19].

- Depupylation Assay: The pupylated conjugate is incubated with Dop, and the cleavage of the isopeptide bond is monitored over time, demonstrating the reversibility of the modification [19].

4. Tandem Mass Spectrometry (MS/MS) for Mapping Conjugation Sites: To definitively identify the specific lysine residue on a target protein that is modified by Pup, pupylated proteins are isolated and digested with a protease like trypsin. The resulting peptides are analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry. A diagnostic "di-glycine" remnant (or a modified mass for Glu) attached to a lysine residue identifies the precise site of modification, confirming an isopeptide linkage [19].

5. Genetic Deletion/Proteasome Inhibition to Identify Native Substrates: Steady-state levels of potential proteasomal substrates are analyzed in wild-type bacteria versus mutant strains lacking key components (e.g., ΔpafA, Δmpa, or Δproteasome) or treated with proteasome inhibitors [19]. Proteins that accumulate in the mutants or under inhibition are strong candidates for being native pupylation targets. These candidates can then be validated using the co-expression and in vitro reconstitution methods described above.

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Characterizing Prokaryotic Ubiquitin-like Systems. This flowchart outlines the key methodological steps, from initial discovery to validation.

Signaling Pathways and Functional Outcomes

The functional consequences of ubiquitin and Pup modification reveal both convergent evolution and fundamental divergence. In eukaryotes, ubiquitination regulates a vast array of cellular processes. K48-linked polyubiquitin chains predominantly target proteins for degradation by the 26S proteasome, controlling the half-lives of key regulators like cyclins and transcription factors [22]. In contrast, K63-linked chains and monoubiquitination play critical non-proteolytic roles in signaling pathways, endocytosis, and DNA repair [22] [23]. A prime example is the NF-κB pathway, where K63-linked chains act as scaffolds to activate kinases, while K48-linked chains lead to the degradation of the inhibitor IκB, releasing NF-κB to initiate an inflammatory response [18] [22].

In prokaryotes such as mycobacteria, the current evidence indicates that pupylation primarily serves to target proteins for destruction by the proteasome, a function critical for virulence and resistance to nitric oxide stress from host immune cells [18] [19]. Substrates like FabD (malonyl Co-A acyl carrier protein transacylase) and PanB (ketopantoate hydroxymethyl-transferase) accumulate when the pupylation or proteasomal systems are disrupted, linking the pathway directly to metabolic regulation and stress adaptation [19]. Unlike the multifaceted ubiquitin code, evidence for a diverse "Pup code" with non-proteolytic functions is still emerging.

Diagram 2: Comparative Signaling Pathways: Ubiquitin vs. Pup. This diagram contrasts the multi-enzyme cascade in eukaryotes with the simpler, two-enzyme system in prokaryotes, highlighting different functional outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Prokaryotic Ubiquitin-like Systems

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-Pup Antibodies | Detect endogenous Pup and pupylated conjugates via immunoblotting. | Identify native pupylation substrates in mycobacterial lysates [19]. |

| ΔpafA / Δmpa / Δdop Mutant Strains | Genetically inactivate the pupylation system to study its physiological role. | Identify proteins that accumulate when pupylation is blocked, indicating potential substrates [19]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132, Lactacystin) | Chemically inhibit the 20S proteasome to block degradation of pupylated targets. | Validate that a protein's turnover is dependent on both pupylation and the proteasome [19]. |

| Recombinant Dop, PafA, Pup (GGQ/GGE) | Purified components for in vitro biochemical reconstitution of the pathway. | Define the specific enzymatic steps of deamidation, ligation, and depupylation [19]. |

| Mycobacterial Protein Expression Systems | Express candidate substrate proteins and Pup variants in vivo. | Test for covalent conjugate formation via co-expression and pulldown assays [19]. |

| Pup-derived Peptides | Synthetic peptides spanning the C-terminus of Pup. | Use as interaction probes or competitors in binding assays with Mpa [18]. |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Development

The comparison between eukaryotic and prokaryotic ubiquitin-like systems has profound implications for drug development, particularly in targeting bacterial pathogens. The essential role of the pupylation-proteasome system in the virulence of M. tuberculosis makes its components attractive, pathogen-specific drug targets [18] [19]. Unlike the essential eukaryotic ubiquitin system, inhibiting the bacterial system could offer a therapeutic window with reduced host toxicity.

Drug discovery efforts targeting the ubiquitin system are advancing on multiple fronts. For eukaryotic targets, strategies include proteasome inhibitors (e.g., Bortezomib for multiple myeloma), NEDD8-activating enzyme (NAE) inhibitors (e.g., MLN4924 in clinical trials), and the development of E3 ligase and DUB inhibitors [6] [24]. Emerging technologies like Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) hijack the endogenous ubiquitin system to degrade specific disease-causing proteins, opening new therapeutic modalities [24]. Fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD), which uses small molecular fragments for efficient screening, is also being applied to target E1, E2, E3, and DUB enzymes with high specificity [25].

The simpler, two-enzyme pupylation pathway (Dop and PafA) in bacteria presents a unique opportunity for antibiotic development. The distinct mechanism of these enzymes from their eukaryotic counterparts suggests that specific inhibitors could be designed to disrupt bacterial proteostasis and virulence without affecting the human ubiquitin system, representing a promising avenue for novel anti-infectives.

The ubiquitin (Ub) signaling system, once considered a hallmark exclusive to eukaryotic cells, is a sophisticated protein modification machinery that regulates critical processes such as protein degradation, DNA repair, and stress response [26]. This system involves a cascade of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes that attach ubiquitin to target proteins, marking them for various fates [26]. Surprisingly, the evolutionary origins of this complex system trace back to ancient prokaryotic sulfur carriers—ThiS and MoaD. These small proteins, involved in fundamental biosynthetic pathways, share striking structural and mechanistic similarities with eukaryotic ubiquitin and its activating enzymes [27] [28]. This article provides a comparative analysis of ThiS and MoaD, examining their roles as evolutionary precursors to the ubiquitin system. We explore their structural biology, functional mechanisms, and the experimental evidence linking them to eukaryotic ubiquitination, providing researchers with a foundational understanding of this conserved evolutionary module.

Structural and Functional Comparison of ThiS and MoaD

ThiS and MoaD are central components in the biosynthesis of essential cofactors in prokaryotes. Despite their lack of significant sequence similarity to ubiquitin, both proteins exhibit profound structural homology and operate through mechanistically similar activation pathways [27] [26]. The table below summarizes their core characteristics and functional roles.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Prokaryotic Sulfur Carriers ThiS and MoaD

| Feature | ThiS | MoaD |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Function | Sulfur carrier in thiamine (vitamin B1) biosynthesis [26] | Sulfur carrier in molybdenum cofactor (Moco) biosynthesis [27] [26] |

| Activating Enzyme | ThiF [26] | MoeB [27] [26] |

| Final Sulfurated Form | ThiS-thiocarboxylate [26] | MoaD-thiocarboxylate [27] [26] |

| Structural Fold | β-grasp fold, identical to ubiquitin [26] | β-grasp fold, identical to ubiquitin [27] [26] |

| C-terminal Motif | Conserved Gly-Gly [26] | Conserved Gly-Gly [27] [26] |

| Activation Mechanism | Adenylation by ThiF → covalent acyl-adenylate → thiocarboxylate formation [26] | Adenylation by MoeB → covalent acyl-adenylate → thiocarboxylate formation [27] [26] |

| Covalent Intermediate with E1-like enzyme | Acyl-persulfide linkage with ThiF [26] | No direct covalent linkage with MoeB reported [26] |

The mechanistic similarities between these prokaryotic systems and eukaryotic ubiquitin activation are profound. Both ThiS and MoaD are activated by their respective E1-like enzymes (ThiF and MoeB) through adenylation of their C-terminus, consuming ATP to form a covalent acyl-adenylate intermediate [27] [26]. This activated form then receives sulfur from a sulfurtransferase to form a thiocarboxylate, which serves as the sulfur donor in the synthesis of thiamine and molybdenum cofactor [26]. The eukaryotic ubiquitin system follows an analogous initial step, where the E1 enzyme adenylates ubiquitin's C-terminal glycine before forming a thioester bond with a conserved cysteine residue [27] [26]. This conservation highlights the deep evolutionary connection between these distinct biochemical pathways.

Experimental Evidence and Key Methodologies

Structural Biology Techniques

The revelation that ThiS and MoaD are structural homologs of ubiquitin emerged primarily from X-ray crystallography studies. Seminal work on the MoeB-MoaD complex from Escherichia coli provided the first atomic-level view of this relationship [27] [29]. Researchers determined the crystal structures of the complex in three distinct states: apo (ligand-free), ATP-bound, and MoaD-adenylate form [27]. These structures revealed that despite minimal sequence similarity, MoaD possesses the characteristic β-grasp fold identical to ubiquitin, complete with the conserved C-terminal Gly-Gly motif essential for activation [27] [29]. The activation mechanism observed in the MoeB-MoaD complex provided a direct molecular framework for understanding the eukaryotic E1-ubiquitin interaction [27].

Table 2: Key Experimental Evidence Supporting the Ubiquitin-ThiS/MoaD Evolutionary Relationship

| Experimental Approach | Key Findings | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography (MoeB-MoaD complex) [27] [29] | MoaD shares the β-grasp fold with ubiquitin; MoeB shares structural homology with E1 Uba domain; Revealed adenylate intermediate | Provided structural proof of evolutionary relationship; elucidated activation mechanism |

| Biochemical Analysis (ThiS-ThiF system) [26] | ThiF adenylates ThiS; ThiS forms acyl-persulfide with ThiF; ThiS-thiocarboxylate is sulfur donor | Demonstrated mechanistic parallels to ubiquitin activation cascade |

| Comparative Genomics [26] | Identified Ub-like β-grasp proteins in prokaryotes; discovered conserved gene neighborhoods linking Ub-like proteins, E1-like enzymes, JAB peptidases | Revealed functional associations in prokaryotes predating eukaryotic Ub-system |

| Functional Studies (Urm1 system) [28] | Urm1 acts as both sulfur carrier in tRNA thiolation and protein modifier | Identified molecular fossil linking prokaryotic sulfur carriers to eukaryotic Ub-like proteins |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Crystallographic Analysis of MoeB-MoaD Complex [27] [29]

- Protein Expression and Purification: Clone moeB and moaD genes into expression vectors. Express proteins in E. coli BL21. Purify using affinity and size-exclusion chromatography.

- Complex Formation: Mix purified MoeB and MoaD proteins in equimolar ratio.

- Crystallization: Use vapor-diffusion method to crystallize the complex. Obtain crystals in multiple states: apo, ATP-bound, and adenylate forms.

- Data Collection and Structure Determination: Collect X-ray diffraction data at synchrotron facilities. Solve structure using molecular replacement with known ubiquitin and E1 enzyme structures as search models.

- Structure Analysis: Compare molecular architectures with eukaryotic E1-ubiquitin complexes to identify conserved features.

Protocol 2: Analysis of ThiS Activation and Thiocarboxylate Formation [26]

- Adenylation Assay: Incubate ThiS with ThiF in reaction buffer containing ATP and Mg²⁺. Include [α-³²P]ATP to monitor adenylate formation.

- Sulfur Transfer Assay: After adenylation, add sulfur donor (cysteine desulfurase system) to reaction.

- Product Analysis: Resolve reaction products using non-reducing SDS-PAGE and autoradiography to detect thiocarboxylate formation.

- Functional Validation: Test thiocarboxylated ThiS in enzymatic assays for thiamine biosynthesis to confirm biological activity.

Visualization of Evolutionary and Mechanistic Relationships

Diagram 1: Evolutionary and mechanistic relationship between prokaryotic sulfur carriers and the eukaryotic ubiquitin system

This diagram illustrates the conserved module between prokaryotic sulfur carrier systems and eukaryotic ubiquitination. Both systems share the core mechanism of ATP-dependent adenylation by E1-like enzymes, followed by transfer to downstream components—sulfur carriers in prokaryotes and protein targets in eukaryotes via E2-E3 cascades. The structural conservation of the β-grasp fold in ThiS, MoaD, and ubiquitin, along with their similar activation mechanisms, provides compelling evidence for an evolutionary continuum [27] [26] [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Prokaryotic Ubiquitin-like Systems

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant MoeB Protein [29] | E1-like enzyme for biochemical assays; protein crystallization | Structural studies of MoeB-MoaD complex; ATPase activity assays |

| Recombinant ThiS Protein [26] | Ubiquitin-like sulfur carrier for mechanistic studies | Analysis of adenylation and thiocarboxylation kinetics |

| MoeB-MoaD Crystallization Kits [27] [29] | Obtaining protein crystals for structural analysis | Determining atomic structures of complex in different catalytic states |

| Anti-ThiS / Anti-MoaD Antibodies | Detection and quantification of proteins in cellular extracts | Monitoring protein expression levels in genetic studies |

| ATP Analogues (e.g., ATPγS) | Probing enzyme mechanism and trapping intermediates | Characterizing adenylate formation in E1-like enzymes |

| E. coli Deletion Strains (ΔmoaD, ΔthiS) | Genetic analysis of pathway function | Phenotypic characterization of sulfur carrier mutants |

| pET Expression Vectors with MoaD/ThiS [30] | Heterologous protein expression in E. coli | Production of recombinant proteins for biochemical studies |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography Matrix | Protein complex purification | Isolating native MoeB-MoaD complexes for biochemical analysis |

The structural and functional parallels between prokaryotic sulfur carriers ThiS/MoaD and the eukaryotic ubiquitin system represent a remarkable case of evolutionary conservation and adaptation. These proteins not only share the β-grasp structural fold but also operate through mechanistically similar activation pathways involving E1-like enzymes and ATP-dependent adenylation [27] [26]. The evolutionary journey from sulfur metabolism to protein modification highlights nature's capacity to repurpose successful molecular strategies for new biological functions.

Understanding these evolutionary relationships has practical significance beyond fundamental science. The conserved features of these systems offer opportunities for developing novel antimicrobial agents that target essential biosynthetic pathways in pathogenic bacteria [30]. Furthermore, the Urm1 system, which represents a "molecular fossil" bridging prokaryotic sulfur carriers and eukaryotic ubiquitin-like modifiers, provides insights into the evolutionary assembly of complex signaling networks [28]. Continued comparative studies of these systems will undoubtedly yield further surprises and deepen our understanding of how cells evolved sophisticated regulatory mechanisms from basic metabolic building blocks.

The discovery of a ubiquitin-like protein modification system in prokaryotes fundamentally expanded our understanding of protein homeostasis and degradation across life domains. In eukaryotes, the ubiquitin (Ub) system—comprising a conserved cascade of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes—tags proteins for proteasomal degradation and regulates numerous cellular processes [14] [31]. For decades, this system was considered a eukaryotic hallmark. However, the identification of prokaryotic ubiquitin-like protein (Pup) in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) revealed that bacteria too employ small protein modifiers to target substrates for degradation [32] [19]. This Pup-proteasome system (PPS) is functionally analogous to eukaryotic ubiquitination yet distinct in its enzymology and evolutionary origin [19] [33]. The discovery of Pup has profound implications for understanding bacterial physiology and virulence, particularly in Mtb, where it is essential for surviving host immune responses [33]. This guide compares the core components, mechanisms, and experimental approaches defining the Pup system against eukaryotic ubiquitin signaling.

System Components and Comparative Mechanisms

The Pup-proteasome system and the eukaryotic ubiquitin system represent convergent evolutionary solutions for targeted protein degradation. The table below provides a structured comparison of their core components.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis: Prokaryotic Pup System vs. Eukaryotic Ubiquitin System

| Feature | Prokaryotic Pup System (PPS) | Eukaryotic Ubiquitin System |

|---|---|---|

| Key Modifier | Prokaryotic ubiquitin-like protein (Pup) [32] | Ubiquitin (Ub) [14] |

| Modifier Structure | Intrinsically disordered in free state; folds upon binding [32] | Stable β-grasp fold in solution [32] |

| Terminal Residue | C-terminal glutamate (or glutamine requiring deamidation) [34] [19] | C-terminal glycine with diglycine motif [14] |

| Conjugation Chemistry | Isopeptide bond via γ-carboxylate of Pup glutamate [19] | Isopeptide bond via α-carboxylate of Ub glycine [19] |

| Ligase Enzyme | PafA (Proteasome accessory factor A) [34] [33] | Cascade of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes [14] |

| Deconjugase Enzyme | Dop (Depupylase) [34] [19] | Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) [14] |

| ATPase Unfoldase | Mpa (Mycobacterial proteasomal ATPase) [35] [33] | 19S Regulatory Particle (e.g., Rpt1-6 ATPases) [35] |

| Proteolytic Core | Bacterial 20S Core Particle (α7β7β7α7) [33] | Eukaryotic 20S Core Particle [33] |

| Primary Function | Target proteins for proteasomal degradation [19] | Target proteins for proteasomal degradation; diverse signaling [31] |

The PPS is phylogenetically restricted, found primarily in Actinobacteria (including mycobacteria) and Nitrospirae [19]. In Mtb, this system is a critical virulence factor, enabling the pathogen to resist nitric oxide stress from host macrophages [33]. The evolutionary origins of the enzymes are distinct; PafA and Dop are homologs derived from glutamine synthetase-like enzymes, not the E1/E2/E3 cascade used for ubiquitination [34] [19].

Key Experimental Methodologies and Findings

Structural Elucidation of the Pup-Dop Complex

Experimental Objective: To determine the high-resolution crystal structure of the depupylase Dop in complex with its substrate, Pup, to understand the mechanism of catalytic phosphate formation and substrate recognition [34].

Table 2: Key Reagents for Structural Studies of the Pup-Dop Complex

| Research Reagent | Function/Description in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| AcelDop Protein | Depupylase from Acidothermus cellulolyticus; the model enzyme for structural studies [34] |

| AcelPupQΔN43 | N-terminally truncated Pup fragment with C-terminal glutamine; used for co-crystallization [34] |

| AMP-PCP | A non-hydrolyzable ATP analog; used to trap the enzyme-substrate complex in a pre-hydrolysis state [34] |

| Crystallography | Method used to determine atomic structures at resolutions as high as 1.65 Å [34] |

Protocol Summary:

- Protein Purification and Complex Formation: Recombinantly express and purify AcelDop. Generate an N-terminally truncated Pup (PupQΔN43) to aid crystallization. Incubate Dop with Pup and AMP-PCP to form a stable complex [34].

- Crystallization and Data Collection: Crystallize the Dop-Pup-AMP-PCP complex using standard screening methods. Flash-cool crystals and collect X-ray diffraction data at a synchrotron source [34].

- Structure Determination and Refinement: Solve the crystal structure by molecular replacement using a known Dop structure as a model. Iteratively refine the atomic model to fit the electron density map [34].

Key Findings:

- Pup undergoes a disorder-to-order transition upon binding to Dop, forming two well-resolved helices that fit into a conserved binding groove on Dop [34].

- The C-terminal residue of Pup (glutamine in the structure) forms an extensive network of interactions within the Dop active site, more extensive than those observed in the homologous ligase, PafA [34].

- The structure revealed the role of the "Dop-loop," a conserved region that acts as an allosteric sensor for Pup binding and ATP cleavage [34].

Structural Analysis of the Mpa-Proteasome Complex

Experimental Objective: To visualize the structure of the mycobacterial proteasome ATPase (Mpa) engaged with the 20S core particle (CP) and a pupylated substrate during translocation, using single-particle cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) [35].

Table 3: Key Reagents for Mpa-Proteasome Cryo-EM Studies

| Research Reagent | Function/Description in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Mpa Hexamer | Mycobacterial proteasomal AAA+ ATPase unfoldase; forms a ring-shaped complex [35] |

| Δ7PrcA 20S CP | 20S core particle with N-terminal 7 residues deleted from α-subunits; promotes stable Mpa binding [35] |

| PupDHFR | Linear fusion protein model substrate; Pup domain recruits the complex, DHFR is the degradation target [35] |

| ATPγS | A slowly-hydrolyzable ATP analog; used to stall the translocation cycle for structural analysis [35] |

Protocol Summary:

- Complex Assembly and Substrate Engagement: Assemble the Mpa-20S CP complex in the presence of ATP. Add the PupDHFR substrate under ice-cold conditions to slow down the reaction and allow for initial engagement [35].

- Reaction Quenching and Vitrification: Add ATPγS to the reaction mixture to halt further ATP hydrolysis and stall the complex at a specific translocation step. Apply the sample to an EM grid and rapidly vitrify it by plunging into liquid ethane [35].

- Cryo-EM Data Collection and Processing: Collect micrographs of the frozen-hydrated particles. Use 2D and 3D classification to isolate homogeneous particle subsets. Reconstruct high-resolution density maps for the Mpa motor in different conformational states [35].

Key Findings:

- The cryo-EM structure revealed Mpa in a spiral-staircase arrangement around the substrate, a hallmark of AAA+ ATPase mechanism [35].

- Two distinct conformational states were resolved, corresponding to sequential steps in the ATP-hydrolysis cycle that drives substrate unfolding and translocation [35].

- The N-terminal coiled-coil domains of Mpa engage Pup in an antiparallel coiled-coil interaction, inducing Pup to form a single long helix [35].

Pathway and Mechanism Visualization

The following diagrams illustrate the core pathway of pupylation and the structural transitions of Pup during the process, synthesized from the experimental data.

Diagram 1: The Pup-Proteasome System Pathway. This diagram illustrates the complete cycle of pupylation, starting with the deamidation of Pup by Dop, ligation to a target protein by PafA, and culminating in recognition, unfolding, and degradation by the Mpa-20S proteasome complex. Dop also provides regulatory control through its depupylase activity [34] [19] [33].

Diagram 2: Induced Folding of Pup Upon Target Binding. Pup is intrinsically disordered in its free state but undergoes specific disorder-to-order transitions upon binding to different partners. When engaging the pupylation enzymes PafA and Dop, it folds into two orthogonal helices. In contrast, when bound to the unfoldase Mpa, it forms a single, long helix that engages in a coiled-coil interaction [35] [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below catalogues critical reagents and materials used to study the Pup-proteasome system, as identified from the cited experimental approaches.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating the Pup-Proteasome System

| Reagent / Material | Critical Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Pup (Wild-type & Mutants) | The central ubiquitin-like modifier; C-terminal (Gln/Glu) variants are essential for studying enzyme specificity and the pupylation cycle [34] [19]. |

| PafA (Ligase) | The enzyme responsible for covalently attaching deamidated Pup to target protein lysines [34] [33]. |

| Dop (Deamidase/Depupylase) | The dual-function enzyme that deamidates Pup-Gln and also reverses pupylation by cleaving the isopeptide bond [34] [19]. |

| Mpa (AAA+ ATPase) | The hexameric unfoldase that recognizes pupylated substrates, unfolds them, and translocates them into the proteasome [35] [33]. |

| 20S Core Particle (CP) | The proteolytic chamber where pupylated substrates are ultimately degraded [35] [33]. |

| Non-hydrolyzable ATP Analogs (e.g., AMP-PCP, ATPγS) | Used to trap and stabilize transient intermediate complexes for structural studies (e.g., X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM) [34] [35]. |

| Linear Pup-Substrate Fusions (e.g., PupDHFR) | Well-defined model substrates that facilitate in vitro degradation assays and structural studies of the complete machinery [35]. |

| pLink-UBL Software | A dedicated mass spectrometry search engine for the precise identification of UBL modification sites on protein substrates [36]. |

The β-grasp fold (β-GF) represents one of the most remarkable examples of evolutionary optimization in structural biology. Prototyped by the eukaryotic protein ubiquitin, this compact fold comprises a β-sheet with five anti-parallel strands that appears to "grasp" a single α-helical segment, creating a stable yet versatile structural platform [37] [38]. Initially discovered in ubiquitin and immunoglobulin-binding proteins of Gram-positive bacteria, subsequent research has revealed the β-grasp fold to be a widespread structural scaffold recruited for a strikingly diverse range of biochemical functions across all domains of life [37] [39]. The fold's extraordinary functional versatility encompasses sulfur transfer in metabolite biosynthesis, RNA and soluble ligand binding, enzymatic activities such as phosphohydrolase function, iron-sulfur cluster binding, adaptor functions in cellular signaling, and post-translational protein modification [37] [38]. This structural analysis will explore the genomic evidence demonstrating how this simple fold has been extensively deployed throughout evolution, with specific adaptations in prokaryotic versus eukaryotic systems, particularly focusing on its implications for ubiquitin-like signaling pathways.

Evolutionary reconstruction analyses indicate that the β-grasp fold had already differentiated into at least seven distinct lineages by the time of the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) of all extant organisms, encompassing much of the structural diversity observed in modern versions of the fold [37] [38]. The earliest β-grasp fold members were likely involved in RNA metabolism, subsequently radiating into various functional niches through extensive diversification in prokaryotes, while eukaryotic evolution was characterized by a specific expansion of ubiquitin-like β-grasp members [37]. This review will systematically compare the genomic distribution, structural variations, and functional adaptations of β-grasp fold domains across the tree of life, with particular emphasis on the evolutionary relationships between prokaryotic ubiquitin-like systems and the eukaryotic ubiquitin-signaling apparatus.

Comparative Genomic Analysis of β-Grasp Fold Domains

Phylogenetic Distribution and Diversity

Comprehensive sequence and structural analyses of β-grasp fold domains reveal their extensive presence across bacteria, archaea, and eukarya, demonstrating their ancient origin and adaptive radiation throughout evolutionary history. The fold has been recruited for an astonishing variety of molecular functions in different organisms, with specific lineages showing remarkable phylogenetic conservation patterns [37] [20].

Table 1: Major Lineages of β-Grasp Fold Domains and Their Distribution

| Lineage/Superfamily | Representative Members | Primary Functions | Distribution Across Domains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin-like | Ubiquitin, SUMO, NEDD8, ThiS, MoaD | Protein modification, Sulfur transfer | Eukaryotes (Ub/Ubls), Bacteria (ThiS/MoaD), Archaea |

| SLBB Superfamily | Transcobalamin, ComEA, Nqo1 | Soluble ligand binding, Vitamin B12 uptake, DNA uptake | Bacteria, Eukaryotes (animal-specific transcobalamin) |

| Enzymatic β-GF | NUDIX phosphohydrolases, Staphylokinases | Phosphohydrolase activity, Fibrinolysis | Widespread across all domains |

| Fe-S Cluster Binding | 2Fe-2S Ferredoxins | Electron transport | Bacteria, Archaea, Eukaryotes |

| Adaptor Domains | TGS, RA, PB1, FERM | RNA binding, Protein-protein interactions | Primarily eukaryotes, some bacterial versions |

Systematic genomic surveys indicate that most structural diversification of the β-grasp fold occurred in prokaryotes, with at least seven distinct lineages already established before the divergence of bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes [37]. The eukaryotic phase of β-grasp evolution was predominantly marked by a specific expansion of ubiquitin-like family members, which diversified into at least 67 distinct families, with approximately 19-20 families already present in the eukaryotic common ancestor [37] [38]. Another key aspect of eukaryotic evolution was the dramatic increase in domain architectural complexity related to the expansion of Ub-like domains in numerous adaptor roles [37].

Ubiquitin-Like β-Grasp Domains: Prokaryotic Antecedents of Eukaryotic Systems

The evolutionary relationship between prokaryotic and eukaryotic ubiquitin-like systems provides compelling evidence for the deep conservation of the β-grasp fold. Originally considered a eukaryotic innovation, ubiquitin-mediated signaling is now understood to have profound connections to prokaryotic systems, particularly through the sulfur carrier proteins ThiS and MoaD, which are involved in thiamine and molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis, respectively [20]. These prokaryotic proteins share significant structural similarity with eukaryotic ubiquitin and even undergo analogous biochemical processes, including C-terminal adenylation and thiocarboxylate formation catalyzed by enzymes (ThiF and MoeB) that are structurally related to eukaryotic E1 ubiquitin-activating enzymes [37] [20].

Recent research has uncovered novel ubiquitin-like proteins in phylogenetically diverse bacteria that form functional associations with E1-like enzymes, JAB hydrolases, and E2-like enzymes, suggesting the existence of primitive ubiquitin-signaling systems in prokaryotes [20]. One significant discovery is the prokaryotic ubiquitin-like protein (Pup) in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which targets proteins for degradation by the bacterial proteasome, demonstrating that post-translational protein tagging systems are not exclusive to eukaryotes [18]. This finding fundamentally challenges the paradigm that ubiquitin-like signaling is a uniquely eukaryotic feature and suggests that the eukaryotic ubiquitin-signaling apparatus was pieced together from prokaryotic antecedents [20].

Table 2: Comparison of Ubiquitin-Like Systems in Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes

| Feature | Prokaryotic Systems | Eukaryotic Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Representative β-GF | ThiS, MoaD, Pup, YukD | Ubiquitin, SUMO, NEDD8, URM1 |

| Modification Enzymes | ThiF, MoeB, PafA | E1, E2, E3 enzymes |

| Deconjugation Enzymes | JAB domain peptidases | Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) |

| Primary Functions | Sulfur transfer, Cofactor biosynthesis, Proteasomal degradation | Protein degradation, Signaling, Trafficking |

| Structural Features | Core β-grasp fold with minimal inserts | Core β-grasp fold with family-specific modifications |

Methodologies for Identifying and Characterizing β-Grasp Fold Domains

Sequence and Structure Analysis Protocols

The identification and characterization of β-grasp fold domains across diverse organisms relies on sophisticated bioinformatic approaches that leverage both sequence and structural information. Due to the small size and extensive divergence of β-grasp domains, exhaustive identification requires multi-pronged computational strategies [37].

Protocol 1: Iterative Sequence Profile Searches

- Objective: Identify remote homologs with significant sequence similarity

- Methodology:

- Use known β-grasp structures from PDB as seeds for PSI-BLAST searches against NCBI NR database

- Iterate searches until convergence (e-value < 0.01 with statistical correction)

- Conduct transitive searches with newly detected members

- Evaluate sub-threshold hits for potential homologs

- Applications: Effective for identifying novel Ub-like domains and SLBB superfamily members [37] [39]

Protocol 2: Structural Similarity Searches

- Objective: Detect homologs with conserved structure but divergent sequence

- Methodology:

- Perform DALI structural comparisons with characterized β-grasp domains

- Analyze Z-scores for significant structural alignment

- Superimpose structures to identify core elements and variable inserts

- Map functional sites through conserved structural features

- Applications: Identification of SLBB domains through structural alignment with transcobalamin and Nqo1 [39]

Protocol 3: Genomic Context Analysis

- Objective: Infer functional associations through conserved gene neighborhoods

- Methodology:

- Identify conserved operons and gene clusters

- Analyze domain architectures in multidomain proteins

- Examine phylogenetic patterns of association

- Correlate with biochemical pathway information

- Applications: Revealed connections between Ub-like proteins, E1-like enzymes, and JAB peptidases in bacteria [20]

Experimental Validation Techniques

While bioinformatic analyses provide essential insights into the distribution and evolution of β-grasp domains, experimental validation is crucial for confirming functional predictions. Several key methodologies have been employed to characterize the biochemical and cellular functions of β-grasp proteins.

X-ray Crystallography and Structural Analysis: Determination of three-dimensional structures has been instrumental in characterizing the core β-grasp fold and its variations. For example, structural analysis of transcobalamin revealed how inserts in the SLBB superfamily create specialized ligand-binding sites for vitamin B12 [39]. Similarly, comparison of ubiquitin with ThiS and MoaD structures demonstrated conserved structural features despite divergent functions [20].

Enzymatic Assays: Biochemical characterization of enzymatic activities associated with β-grasp domains, such as the phosphohydrolase activity of NUDIX enzymes and the adenylation activity of E1-like enzymes, provides functional validation of predictions derived from sequence and structural analyses [37].

Interaction Studies: Investigation of protein-protein and protein-ligand interactions through methods such as co-immunoprecipitation, yeast two-hybrid screening, and surface plasmon resonance has been essential for understanding the diverse functional roles of β-grasp domains, particularly in ubiquitin-like signaling pathways and adaptor functions [37] [18].

Structural and Functional Adaptations Across Evolutionary Lineages

Key Structural Innovations in Major β-Grasp Lineages

The functional diversity of β-grasp domains arises from strategic structural elaborations on the conserved core fold. These innovations include distinctive insertions between core elements, modifications of surface properties, and development of specialized interaction interfaces [37].

The ubiquitin-like superfamily maintains the most conserved version of the fold, characterized by minimal inserts and a prominent β-sheet surface that facilitates diverse protein-protein interactions [37] [38]. In contrast, the SLBB (Soluble-Ligand-Binding β-grasp) superfamily exhibits two major structural variations: the transcobalamin-like clade features a β-hairpin insert after the helix that participates in ligand binding, while the Nqo1-like clade contains an insert between strands 4 and 5 of the core fold [39]. These inserts create specialized binding pockets for soluble ligands such as vitamin B12, with genomic context analyses supporting roles in B12 uptake, polysaccharide export, and DNA uptake in bacteria [39].

Enzymatic β-grasp domains like the NUDIX phosphohydrolases have evolved active sites on the common scaffold, demonstrating that the fold can support catalytic functions beyond binding and mediation of interactions [37]. Similarly, iron-sulfur cluster binding versions have developed unique cysteine-containing flaps that chelate iron atoms, representing one of the most striking functional adaptations of the fold [20].

Evolutionary Trajectory of Ubiquitin-Like Signaling Systems

The evolution of ubiquitin-like signaling systems from primitive sulfur transfer machinery illustrates how the β-grasp fold has been adapted for increasingly complex cellular functions throughout evolutionary history. Evolutionary reconstruction suggests that sulfur carrier proteins like ThiS and MoaD represent the ancestral state from which eukaryotic ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like modifiers descended [20].

The fundamental evolutionary transition involved a shift from sulfur transfer for cofactor biosynthesis to protein modification for regulatory purposes [20]. This transition was facilitated by the recruitment of additional enzymatic components, including E2-conjugating enzymes and E3 ligases, which increased the specificity and regulatory potential of the system. The discovery of Pup in mycobacteria demonstrates an independent evolutionary trajectory in which a β-grasp protein was recruited for proteasomal targeting, representing a convergent solution to the problem of substrate recognition for regulated proteolysis [18].

The eukaryotic ubiquitin system represents the most elaborate development of β-grasp-based signaling, with extensive diversification of E3 ligases that provide substrate specificity and the integration of deubiquitinating enzymes that add reversible control to the system [37] [20]. The expansion of ubiquitin-like modifiers with distinct functions (SUMO, NEDD8, etc.) further illustrates how gene duplication and functional specialization have built an intricate regulatory network on the versatile β-grasp scaffold.

Visualization of Evolutionary Relationships and Functional Diversity

Diagram Title: Evolutionary Radiation of β-Grasp Fold from LUCA

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Research Toolkit for β-Grasp Fold Domain Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSI-BLAST | Algorithm | Remote homology detection | Position-specific scoring matrices, Iterative search |

| DALI | Algorithm | Structural similarity search | Pairwise structure alignment, Z-score significance |

| HMMER | Algorithm | Profile hidden Markov models | Sensitive domain detection, Multiple sequence alignment |

| PDB | Database | 3D structural data | Experimentally determined structures, Standardized formats |

| SCOP | Database | Structural classification | Evolutionary relationships, Structural hierarchy |

| ThiS/MoaD Proteins | Biochemical Reagents | Sulfur transfer studies | Prokaryotic Ub antecedents, C-terminal thiocarboxylate formation |

| E1-like Enzymes | Biochemical Reagents | Ub activation mechanism | Adenylation domain, Rossmann fold, Conserved cysteine |

| JAB Proteases | Biochemical Reagents | Deubiquitinating activity | Metalloprotease activity, Isopeptidase function |

The comprehensive genomic evidence presented in this analysis demonstrates that the β-grasp fold represents an extraordinary example of structural conservation coupled with functional diversification throughout the history of life. From its origins in the last universal common ancestor, this compact fold has been adapted for an astonishing array of molecular functions, with distinct evolutionary trajectories in prokaryotic and eukaryotic lineages [37] [38]. The fold's remarkable versatility stems from its stable core structure that can tolerate extensive surface modifications and strategic insertions, creating specialized binding sites and interaction surfaces while maintaining structural integrity [37].

The evolutionary relationship between prokaryotic sulfur carrier systems and the eukaryotic ubiquitin-signaling apparatus provides a compelling case study in molecular evolution, illustrating how complex regulatory systems can emerge through the elaboration and integration of simpler ancestral components [20]. The recent discovery of ubiquitin-like modification systems in diverse bacteria, including the Pup-proteasome system in Actinomycetes, further blurs the distinction between prokaryotic and eukaryotic post-translational regulatory mechanisms and suggests that the evolutionary history of ubiquitin-like signaling is more complex than previously appreciated [18] [4].

Future research directions should include more comprehensive surveys of β-grasp diversity in understudied bacterial and archaeal lineages, structural characterization of the novel β-grasp groups identified through bioinformatic analyses, and experimental investigation of the potential functional connections between prokaryotic ubiquitin-like proteins, JAB peptidases, and E2-like enzymes [20]. Such studies will not only provide deeper insights into the evolutionary history of this remarkable structural fold but may also reveal novel biological mechanisms with implications for understanding cellular regulation and developing therapeutic interventions.

Decoding Ubl Mechanisms: From Enzymatic Cascades to Pathogen Hijacking

The targeted degradation of proteins is a fundamental biological process conserved across all domains of life. While eukaryotes rely on a sophisticated ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) characterized by a multi-enzyme cascade, certain bacteria have evolved an analogous but mechanistically distinct system centered on prokaryotic ubiquitin-like protein (Pup) tagging, or pupylation [40]. This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of these two systems, focusing on their core enzymatic mechanisms. The eukaryotic pathway utilizes a trio of enzymes (E1, E2, E3) that function sequentially to attach ubiquitin to substrate proteins, often forming polyubiquitin chains that serve as a degradation signal [22] [21]. In contrast, the bacterial pupylation system, found primarily in Actinobacteria, employs a single ligase, PafA, to directly attach Pup to target proteins, enabling their recognition by the bacterial proteasome [41] [42] [40]. This comparison will explore the structural, mechanistic, and regulatory differences between these pathways, providing researchers with a foundation for understanding their biological implications and potential as therapeutic targets.