Ubiquitin Signaling in the Tumor Microenvironment: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targeting, and Clinical Frontiers

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the ubiquitin signaling network's critical role in shaping the tumor microenvironment (TME).

Ubiquitin Signaling in the Tumor Microenvironment: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targeting, and Clinical Frontiers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the ubiquitin signaling network's critical role in shaping the tumor microenvironment (TME). It explores foundational mechanisms by which E3 ligases and deubiquitinases regulate cellular and non-cellular TME components, including immune cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts, and the extracellular matrix. The content covers methodological advances in targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome system, troubleshooting for therapeutic resistance, and comparative validation of emerging strategies like PROTACs and molecular glues. Synthesizing recent research and clinical insights, this review serves as a strategic resource for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to exploit ubiquitination for novel cancer therapeutics.

Decoding the Ubiquitin Code: Core Mechanisms and Key Regulators in the TME

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) represents a highly complex, temporally controlled, and conserved pathway that maintains cellular protein homeostasis through the targeted degradation of short-lived, misfolded, or damaged proteins [1] [2]. This selective proteolysis mechanism regulates a myriad of critical cellular processes, including immune response, apoptosis, cell cycle progression, and differentiation [1]. The UPS operates through a hierarchical enzymatic cascade that conjugates the small, 76-amino acid protein ubiquitin to substrate proteins, marking them for destruction by the 26S proteasome [3] [4].

Within the context of tumor biology, the UPS has emerged as a critical regulator of the tumor microenvironment (TME), influencing immune cell function, cancer cell survival, and response to therapy [5]. Dysregulation of UPS components contributes significantly to oncogenesis and tumor immune evasion by altering the stability of key regulatory proteins [6] [7]. The intricate role of ubiquitination signaling in the TME underscores the therapeutic potential of targeting specific UPS elements to overcome resistance to cancer treatments, particularly immunotherapy [8] [5].

The Core Enzymatic Machinery of the UPS

The Ubiquitination Cascade: E1, E2, and E3 Enzymes

Protein ubiquitination involves a sequential three-step enzymatic cascade that requires ATP and culminates in the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to substrate proteins [2] [4]. This process is mediated by the coordinated actions of ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), and ubiquitin-ligase (E3) enzymes [1] [3].

E1: Ubiquitin-Activating Enzymes - The initiating step involves E1 enzymes, which activate ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner. The E1 forms a high-energy thioester bond between its active-site cysteine residue and the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin [2] [4]. This "charged" ubiquitin is then transferred to the next enzyme in the cascade. E1 function is crucial for cellular homeostasis, as chemical inhibition of E1 activity results in the almost immediate shutdown of the entire UPS [3].

E2: Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzymes - The intermediate step involves E2 enzymes, which receive the activated ubiquitin from E1 via a trans-thioesterification reaction, forming an E2-ubiquitin conjugate intermediate [2] [3]. E2s function as the central ubiquitin carriers of the system, working in conjunction with E3 ligases to ultimately transfer ubiquitin to the target protein [3].

E3: Ubiquitin Ligases - The final and most diverse step involves E3 ubiquitin ligases, which provide substrate specificity by recognizing and binding target proteins while simultaneously interacting with the E2-ubiquitin complex [1] [4]. E3s facilitate the direct transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine residue on the substrate protein [2]. Humans possess hundreds of E3 ligases, enabling the recognition of a vast array of specific substrates [7].

Table 1: Core Enzymes of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

| Enzyme Class | Number in Humans | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Activating) | Limited number (e.g., UBE1) | Ubiquitin activation via ATP hydrolysis | Forms E1-Ub thioester; essential for all downstream UPS function [2] [3] |

| E2 (Conjugating) | ~40 members (e.g., UBE2D2) | Ubiquitin carrier protein | Forms E2-Ub thioester; determines ubiquitin chain topology with E3 [2] [3] |

| E3 (Ligase) | ~600 members (e.g., MurRF1) | Substrate recognition and ubiquitin transfer | Determines substrate specificity; largest class with diverse domains [1] [7] |

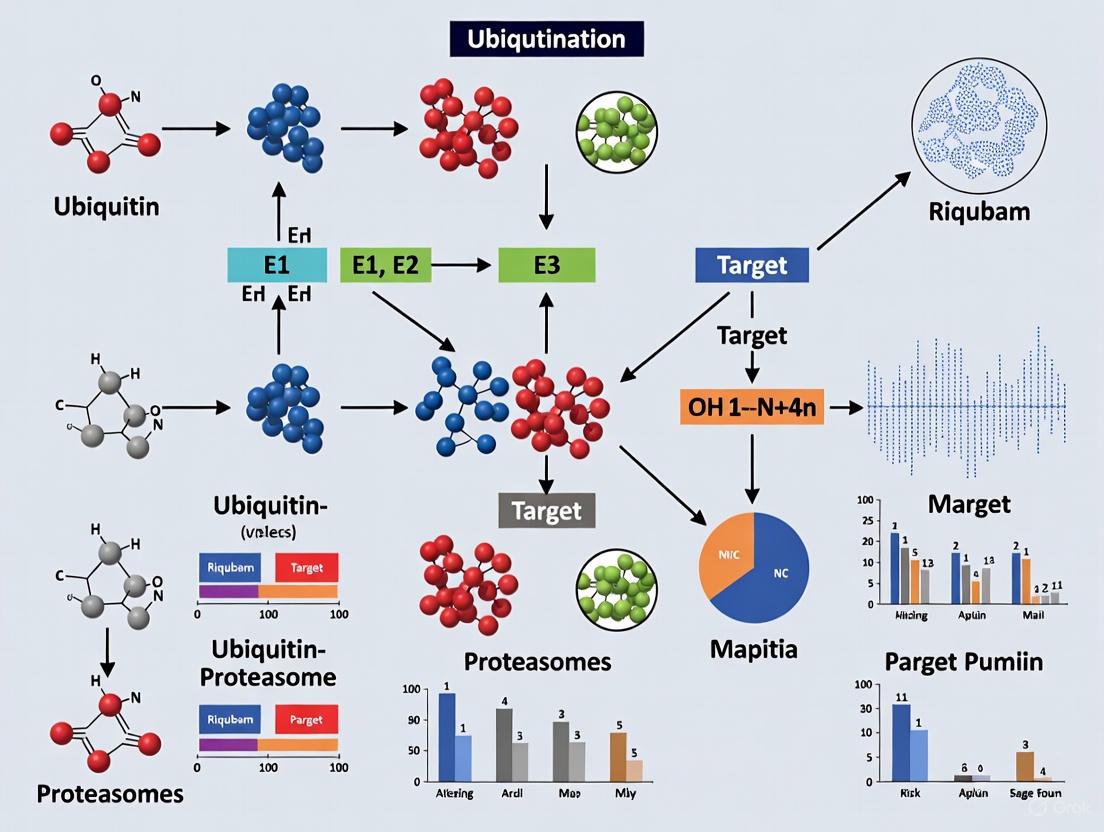

The following diagram illustrates the sequential flow of the ubiquitin conjugation cascade:

E3 Ubiquitin Ligases: Masters of Specificity

E3 ubiquitin ligases constitute the most diverse and specialized component of the UPS, functioning as critical decision-makers in determining which proteins are targeted for degradation [1]. They can be broadly categorized into three major families based on their structural characteristics and mechanisms of action:

RING (Really Interesting New Gene) E3s: Function primarily as scaffolds that simultaneously bind the E2-ubiquitin complex and the substrate, facilitating the direct transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to the substrate without forming a covalent intermediate [4]. A prominent subclass is the Cullin-RING Ligases (CRLs), multi-subunit complexes that represent the largest family of E3s [7].

HECT (Homologous to the E6AP C-terminus) E3s: Form a catalytic intermediate by accepting ubiquitin from the E2 onto a conserved cysteine residue in their HECT domain before transferring it to the substrate [6].

RBR (RING-Between-RING-RING) E3s: Utilize a hybrid mechanism that combines features of both RING and HECT E3s [6].

A particularly well-characterized subset of CRLs is the SCF (SKP1-CUL1-F-box protein) complex, which exemplifies the modularity and specificity of the UPS. The SCF complex consists of a constant core (CUL1, RBX1, SKP1) and a variable substrate recognition module, the F-box protein [7]. The approximately 70 human F-box proteins are categorized into three subfamilies based on their protein-protein interaction domains: FBXW (WD repeat domain), FBXL (Leucine-rich repeat), and FBXO (other or uncharacterized domains) [7]. These F-box proteins typically recognize their substrates by binding to specific degrons—short, defined motifs within the substrate proteins—often requiring specific post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation for efficient recognition [7].

Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs): The Editors of Ubiquitination

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) perform the reverse reaction of E3 ligases, countering ubiquitination by removing ubiquitin molecules from substrate proteins [1] [4]. This editing function serves several critical purposes: (1) maintaining cellular pools of free ubiquitin; (2) rescuing substrate proteins from degradation by reversing ubiquitin tagging; and (3) processing ubiquitin precursors to generate mature ubiquitin [5]. DUBs are categorized into five major subfamilies based on their catalytic mechanisms: USP (ubiquitin-specific proteases), UCH (ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases), OTU (ovarian tumor proteases), MJD (Machado-Joseph disease proteases), and JAMM (JAB1/MPN/Mov34 metalloenzymes) [4]. Within the proteasome itself, three DUBs—PSMD14 (POH1/RPN11), UCH37 (UCH-L5), and USP14—work to recycle ubiquitin molecules before substrate degradation [4].

The Proteasome: Terminal Destination for Ubiquitinated Proteins

The 26S proteasome is the final executioner of the UPS pathway, responsible for the actual degradation of ubiquitinated proteins into short peptides [5]. This macromolecular protease complex consists of two primary components:

The 20S Core Particle (CP): A barrel-shaped structure containing proteolytically active sites (caspase-like, trypsin-like, and chymotrypsin-like activities) within its interior chamber, where protein digestion occurs [5].

The 19S Regulatory Particle (RP): Caps one or both ends of the 20S core and performs three key functions: (i) recognizing ubiquitinated substrates; (ii) cleaving off ubiquitin chains via its resident DUBs; and (iii) unfolding the target protein and translocating it into the 20S core for degradation [5] [4].

The proteasome's recognition of ubiquitinated substrates is a key regulatory step in the degradation process. The 19S RP contains ubiquitin receptors that specifically bind polyubiquitin chains, initiating the degradation sequence [3].

The Ubiquitin Code: A Language of Signals

The functional consequences of ubiquitination are determined by the type of ubiquitin chain assembled on the substrate protein—a concept often referred to as the "ubiquitin code" [2]. Ubiquitin contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1), each serving as potential linkage sites for polyubiquitin chain formation [1] [7]. Different chain topologies encode distinct functional outcomes for the modified substrate:

- K48-linked chains: Primarily target substrates for proteasomal degradation and represent the most abundant degradation signal [1] [2].

- K11-linked chains: Also serve as potent signals for proteasomal degradation, particularly for substrates involved in endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) and during cell cycle regulation [1].

- K63-linked chains: Typically mediate non-proteolytic functions, including regulation of signal transduction, DNA repair, endocytic trafficking, and inflammation [5] [4].

- M1-linked (linear) chains: Important for regulating NF-κB signaling and immune and inflammatory responses [4].

- K6, K27, K29, K33-linked chains: Less characterized but implicated in various processes including DNA damage response, autophagy, and kinase signaling [7].

Table 2: Major Ubiquitin Chain Linkages and Their Cellular Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Function | Key Roles and Processes |

|---|---|---|

| K48 | Proteasomal Degradation | Primary signal for degradation; regulates most short-lived proteins, cell cycle regulators [1] [2] |

| K11 | Proteasomal Degradation | Targets misfolded ER proteins (ERAD); regulates cell cycle proteins [1] |

| K63 | Non-degradative Signaling | DNA repair, endocytosis, NF-κB and kinase activation, inflammatory signaling [5] [4] |

| M1 (Linear) | Non-degradative Signaling | NF-κB activation, immune regulation, inflammation [4] |

| K29/K33 | Diverse Functions | Atypical degradation signals; implicated in autophagy [1] |

The following diagram summarizes the ubiquitin code and the fates of ubiquitinated proteins:

Experimental Analysis of the UPS

Key Methodologies for UPS Research

Investigating the components and functions of the UPS requires a combination of molecular, biochemical, and cellular techniques. Below are detailed protocols for key experiments commonly used in the field.

Protocol 1: Immunoprecipitation (IP) and Ubiquitination Assay

- Purpose: To detect and characterize ubiquitination of a specific protein of interest.

- Procedure:

- Cell Lysis: Harvest and lyse cells in RIPA buffer supplemented with N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to inhibit deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) and preserve ubiquitin conjugates.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate cell lysates with an antibody specific to your protein of interest. Use Protein A/G beads to pull down the antibody-protein complex.

- Washing: Wash beads extensively with lysis buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Denaturation: Elute proteins from beads by boiling in SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

- Immunoblotting: Resolve proteins by SDS-PAGE, transfer to a membrane, and probe with an anti-ubiquitin antibody to detect ubiquitinated forms of the protein, which appear as higher molecular weight smears.

- Key Controls: Include a negative control using normal IgG or beads alone. For chain linkage specificity, use ubiquitin mutants (K48-only, K63-only) or linkage-specific antibodies.

Protocol 2: In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

- Purpose: To reconstitute the ubiquitination cascade using purified components and define the minimal requirements for substrate ubiquitination.

- Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a tube, combine purified E1 enzyme, E2 enzyme, E3 ligase, ubiquitin, and the substrate protein in a reaction buffer containing ATP and an energy-regenerating system.

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction at 30°C for 1-2 hours.

- Termination and Analysis: Stop the reaction by adding SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiling. Analyze the products by immunoblotting for the substrate to detect upward mobility shifts indicative of ubiquitination.

- Key Controls: Omit individual components (E1, E2, E3, or ATP) one at a time to confirm the requirement for each factor.

Protocol 3: Cycloheximide Chase Assay to Measure Protein Half-Life

- Purpose: To determine the in vivo half-life of a protein and assess the impact of UPS perturbation on its stability.

- Procedure:

- Inhibition of Translation: Treat cells with cycloheximide to block new protein synthesis.

- Time-Course Sampling: Harvest cells at various time points after cycloheximide addition (e.g., 0, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes).

- Analysis: Prepare lysates from each time point and analyze the levels of the protein of interest by immunoblotting. Quantify band intensities and plot the natural logarithm of protein level versus time.

- Proteasome Inhibition: To confirm UPS involvement, parallel experiments can be performed using proteasome inhibitors like MG132 or bortezomib. Stabilization of the protein upon inhibitor treatment suggests UPS-mediated degradation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for UPS Research

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for UPS Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Block proteolytic activity of the 20S proteasome; used to validate UPS-dependent degradation and accumulate ubiquitinated proteins [5]. |

| E1 Inhibitor | PYR-41, TAK-243 | Inhibit ubiquitin activation; used to shut down the entire UPS pathway for functional studies [3]. |

| DUB Inhibitors | PR-619 (broad-spectrum), P5091 (USP7 inhibitor) | Block deubiquitinating enzyme activity; used to study DUB function and increase global ubiquitination levels [5]. |

| Linkage-Specific Ub Antibodies | K48-linkage specific, K63-linkage specific | Identify specific ubiquitin chain topologies on substrates via immunoblotting or immunofluorescence [2]. |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | K48R, K63R, K48-only, K63-only | Define the role of specific lysine residues in ubiquitin chain formation in cellular and in vitro assays [5]. |

| PROTACs | ARV-471, ARV-110 | Bifunctional molecules that recruit E3 ligases to target non-enzyme proteins for degradation; used as chemical tools and therapeutic agents [1]. |

The UPS in the Tumor Microenvironment: Therapeutic Implications

The UPS plays a multifaceted role in shaping the tumor microenvironment (TME), influencing the behavior of both cancer cells and immune cells. A key mechanism of tumor immune evasion involves the UPS-mediated regulation of immune checkpoint proteins, particularly PD-1/PD-L1 [5]. The E3 ubiquitin ligase SPOP has been identified as a critical regulator that promotes the ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of PD-L1 in various cancers, including colorectal cancer [5]. However, tumor cells can counteract this by upregulating proteins like ALDH2 or the transcription factor BCLAF1, which competitively bind to SPOP or PD-L1, thereby stabilizing PD-L1 and enhancing immune evasion [5]. This dynamic interplay presents a promising therapeutic avenue, as demonstrated by studies showing that the SGLT2 inhibitor canagliflozin can disrupt the SGLT2-PD-L1 interaction, restoring SPOP-mediated degradation of PD-L1 and enhancing T cell-mediated anti-tumor activity [5].

Beyond immune checkpoints, F-box proteins within the SCF E3 ligase complex are increasingly recognized as master regulators of cancer hallmarks within the TME. They control critical processes such as cancer cell proliferation, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), metabolic reprogramming, and the integrated stress response [7]. The adaptability and wide coverage of F-box proteins, governed by a sophisticated regulatory hierarchy, make them attractive potential targets for cancer therapy. Emerging therapeutic strategies are moving beyond broad proteasome inhibition (e.g., bortezomib) toward more precise targeting of specific E3 ligases or DUBs. The development of PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) and molecular glues represents a paradigm shift, enabling the re-purposing of E3 ligases to selectively degrade disease-driving proteins that have been historically difficult to target with conventional inhibitors [1]. These approaches hold significant potential for modulating the TME and overcoming resistance to current immunotherapies.

Ubiquitination is a critical post-translational modification that regulates virtually every cellular process in eukaryotes, with particular significance in cancer biology. This modification involves the covalent attachment of a small 76-amino acid protein, ubiquitin, to substrate proteins, thereby altering their fate, function, or localization [9] [10]. The remarkable functional diversity of ubiquitin signaling stems from the ability of ubiquitin molecules to form polymers (polyubiquitin chains) of different topologies—defined by the linkage type between ubiquitin monomers, chain length, and branching patterns—creating a sophisticated "ubiquitin code" that can be interpreted by cellular machinery [9] [11]. Within the context of the tumor microenvironment (TME), understanding this code is paramount, as ubiquitination regulates key processes including immune cell function, hypoxia response, angiogenesis, and cancer stemness [12] [13].

The seven lysine residues in ubiquitin (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) plus its N-terminal methionine (M1) serve as potential linkage sites for chain formation [10]. Among these, K48-linked chains represent the most abundant linkage type and typically target substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains generally serve non-proteolytic functions in signaling pathways related to DNA repair, inflammation, and protein trafficking [9] [14]. Beyond these well-characterized homotypic chains, heterotypic chains including mixed linkage and branched chains dramatically expand the complexity of ubiquitin signaling, enabling sophisticated regulation of cellular processes [9] [11]. This review comprehensively examines ubiquitin chain topology from classical K48/K63 linkages to monoubiquitination, with special emphasis on their functional consequences in the context of tumor microenvironment regulation.

Ubiquitin Chain Topologies: Structures and Functions

Monoubiquitination and Multi-Monoubiquitination

Monoubiquitination, the attachment of a single ubiquitin molecule to a substrate lysine residue, represents the simplest form of ubiquitin modification. Despite its simplicity, monoubiquitination regulates crucial cellular processes including DNA damage repair, histone function, chromatin remodeling, and receptor endocytosis [10] [15]. In the DNA damage response, the E3 ligase Rad18 mediates monoubiquitination of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), facilitating the recruitment of specialized DNA polymerases [10]. Similarly, TRAF6-driven monoubiquitination of H2AX serves as a prerequisite for recruiting ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) to DNA damage sites [10]. Membrane protein monoubiquitination can modulate interactions with autophagy adapter proteins such as p62, thereby promoting organelle-specific autophagy including mitophagy and pexophagy [10].

Multi-monoubiquitination, wherein multiple single ubiquitin molecules attach to different lysine residues on the same substrate, further expands the regulatory potential of monoubiquitination. This modification type can create specialized interaction surfaces for proteins containing multiple ubiquitin-binding domains, allowing for fine-tuned regulation of processes such as endocytosis and protein sorting [11].

Homotypic Polyubiquitin Chains

Table 1: Major Homotypic Polyubiquitin Chain Linkages and Their Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Functions | Cellular Processes | Key Effectors/Readers |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Proteasomal degradation | Protein turnover, cell cycle progression | Proteasome, RAD23B [9] |

| K63-linked | Non-proteolytic signaling | DNA repair, NF-κB signaling, endocytosis, autophagy | EPN2, TAB2/3 [9] [14] |

| K11-linked | Proteasomal degradation (ERAD), cell cycle regulation | Mitosis, endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation | Proteasome, CDC48/p97 [10] |

| K6-linked | DNA damage response, mitophagy | DNA repair, mitochondrial quality control | Parkin, BRCA1-BARD1 [10] |

| K27-linked | Mitochondrial autophagy, immune signaling | Mitophagy, NF-κB pathway | - |

| K29-linked | Proteasomal degradation (less common) | Protein quality control | - |

| K33-linked | Kinase modification, trafficking | Endosomal sorting, kinase regulation | - |

| M1-linked | Inflammatory signaling, cell death | NF-κB activation, necroptosis | LUBAC complex, NEMO [13] |

K48-linked polyubiquitination serves as the principal signal for proteasomal degradation, representing one of the best-characterized ubiquitin signals [9] [10]. This chain type facilitates the recognition and degradation of myriad regulatory proteins, including cell cycle regulators, transcription factors, and damaged proteins. The proteasome recognizes K48-linked chains typically containing at least four ubiquitin monomers, though the importance of chain length specificity continues to be elucidated [9].

In contrast, K63-linked polyubiquitination typically serves non-proteolytic functions across diverse signaling pathways [14]. In DNA damage response, K63 chains facilitate the recruitment of repair proteins to damage sites. In inflammatory signaling, K63 ubiquitination of key signaling molecules such as RIP kinases and IKK complex components activates NF-κB signaling pathways [14]. Additionally, K63 chains play crucial roles in endocytic trafficking and selective autophagy, wherein they serve as recognition signals for autophagy receptors [14] [10].

Other linkage types including K11, K27, K29, and K33 constitute specialized ubiquitin signals with more restricted functions. K11-linked chains, for instance, collaborate with K48 chains to target cell cycle regulators for degradation during mitosis and participate in endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) [10]. M1-linked linear chains, assembled by the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC), play specialized roles in inflammatory signaling and cell death pathways [13].

Heterotypic and Branched Ubiquitin Chains

Table 2: Characterized Branched Ubiquitin Chains and Their Proposed Functions

| Branched Chain Type | Biosynthesis Mechanism | Proposed Functions | Biological Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48/K63-branched | TRAF6 + HUWE1; ITCH + UBR5 [11] | Enhanced degradation signal; regulation of NF-κB signaling [9] | Apoptosis regulation, immune signaling |

| K11/K48-branched | APC/C with UBE2C + UBE2S [11] | Enhanced substrate degradation during mitosis [11] [15] | Cell cycle progression |

| K29/K48-branched | Ufd4 + Ufd2 collaboration [11] | Protein quality control, ubiquitin fusion degradation pathway | Ubiquitin fusion degradation |

| K6/K48-branched | Parkin, NleL [11] | Mitochondrial quality control, unknown functions | Mitophagy, bacterial infection |

Branched ubiquitin chains represent the most topologically complex ubiquitin signals, wherein a single ubiquitin monomer serves as the branching point for two or more distinct chain types [11]. These structures exponentially increase the coding potential of ubiquitin signaling and have recently emerged as important regulatory signals, particularly in the context of protein degradation and signal transduction [9] [11].

The biosynthesis of branched chains frequently involves collaboration between E3 ligases with distinct linkage specificities. For instance, during NF-κB signaling, TRAF6 (a K63-specific E3) collaborates with HUWE1 (a K48-specific E3) to synthesize K48/K63-branched chains on signaling components [11]. Similarly, in the ubiquitin fusion degradation pathway, Ufd4 (K29-specific) and Ufd2 (K48-specific) cooperate to assemble K29/K48-branched chains [11]. Alternatively, single E3 ligases can synthesize branched chains, such as the APC/C which collaborates with distinct E2 enzymes (UBE2C and UBE2S) to assemble K11/K48-branched chains during mitosis [11].

Branched chains appear to function as specialized degradation signals that enhance substrate targeting to the proteasome. K11/K48-branched chains assembled by the APC/C more efficiently target mitotic regulators for destruction compared to homotypic K48 chains [11]. Similarly, K48/K63-branched chains can convert non-proteolytic K63-linked ubiquitination into a degradation signal, as demonstrated in the regulation of the apoptotic regulator TXNIP, where ITCH-mediated K63 ubiquitination is subsequently branched with K48 linkages by UBR5 to trigger proteasomal degradation [11].

Diagram 1: Ubiquitin chain topologies and their primary functional associations. Different chain architectures encode distinct biological information, with branched chains representing particularly complex signaling entities.

The Ubiquitin Code in Tumor Microenvironment Regulation

Ubiquitination in Tumor-Immune Cell Interactions

The tumor microenvironment represents a complex ecosystem wherein cancer cells interact with various stromal components, including immune cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and extracellular matrix components [12] [13]. Ubiquitination plays pivotal roles in regulating these interactions, particularly in controlling immune cell function and immune checkpoint expression.

Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) stability represents a key node of ubiquitin-dependent regulation in the TME. Multiple E3 ligases including CHIP (STUB1), β-TrCP, HRD1, and SPOP mediate the ubiquitination and degradation of PD-L1, thereby influencing tumor immune evasion [12]. Conversely, the deubiquitinase CSN5 removes ubiquitin from PD-L1, stabilizing it and enabling tumors to escape T-cell-mediated immune surveillance [12]. Additionally, CMTM6 stabilizes PD-L1 through a non-enzymatic mechanism, protecting it from ubiquitin-mediated degradation [12].

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) represent another crucial component of the TME regulated by ubiquitination. Macrophage polarization toward the pro-tumorigenic M2 phenotype is controlled by ubiquitin-dependent signaling pathways, particularly those involving NF-κB and inflammatory cytokine receptors [12] [13]. E3 ligases such as TRAF6 mediate K63-linked ubiquitination events that promote M2 polarization, thereby fostering an immunosuppressive TME conducive to tumor progression [13].

Ubiquitin-Dependent Signaling Pathways in Cancer Progression

Multiple oncogenic signaling pathways operating within the TME are subject to ubiquitin-dependent regulation. The PI3K/AKT pathway, frequently hyperactivated in cancer, is regulated by K63-linked ubiquitination of AKT itself. The E3 ligases Skp2 and TRAF6 mediate K63 ubiquitination of AKT, promoting its membrane translocation and activation, thereby driving tumorigenesis [14]. Similarly, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is regulated by K63 ubiquitination events that control β-catenin stability and nuclear localization, as exemplified by Rad6B-mediated K63 ubiquitination of β-catenin at K394 in breast cancer [14].

The Hippo-YAP/TAZ pathway, which controls tissue growth and organ size, is similarly regulated by ubiquitination. The E3 ligase complex SKP2 mediates non-proteolytic K63-linked ubiquitination of YAP, controlling its nuclear localization and oncogenic activity, while the deubiquitinase OTUD1 reverses this modification [14]. Additionally, TAK1 inhibits YAP/TAZ proteasomal degradation by promoting TRAF6-mediated K63 ubiquitination in contrast to K48 ubiquitination [14].

Diagram 2: Key nodes of ubiquitin-dependent regulation in the tumor microenvironment. Multiple E3 ligases and deubiquitinases control critical processes in tumor progression and immune evasion.

Methodological Approaches for Ubiquitin Chain Analysis

Ubiquitin Interactor Pull-Down and Mass Spectrometry

Comprehensive analysis of ubiquitin chain functions requires specialized methodological approaches. Ubiquitin interactor pull-down coupled with mass spectrometry represents a powerful technique for identifying linkage-specific ubiquitin-binding proteins [9]. This approach typically involves immobilizing specific ubiquitin chain types (e.g., K48-Ub2, K63-Ub3, branched K48/K63-Ub3) on solid supports followed by incubation with cell lysates to enrich for specific ubiquitin-binding proteins, which are subsequently identified by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [9].

Critical methodological considerations include the use of deubiquitinase inhibitors to prevent chain disassembly during experiments. Commonly used inhibitors include chloroacetamide (CAA) and N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), though each presents distinct advantages and limitations [9]. NEM more completely inhibits chain disassembly but has potential off-target effects, while CAA is more cysteine-specific but permits partial chain disassembly [9]. Comparative studies using both inhibitors can identify inhibitor-dependent interactors, highlighting the importance of methodological considerations in experimental design.

Advanced Mass Spectrometry for Topology Determination

Top-down tandem mass spectrometry approaches enable detailed structural analysis of polyubiquitin chains without requiring proteolytic digestion [16]. This methodology preserves post-translational modifications and linkage information that would be lost with traditional bottom-up approaches. The protocol typically involves liquid chromatography separation followed by tandem MS analysis using fragmentation techniques such as electron transfer dissociation (ETD) combined with collision-induced dissociation (CID) or higher-energy CID (HCD) [16].

This approach facilitates discrimination between ubiquitin chain linkage types and can identify branched chains based on their unique fragmentation patterns [16]. The methodology is universally applicable to all chain linkage types and can be extended to ubiquitin-like proteins, providing a powerful tool for comprehensive ubiquitinome characterization.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies for Ubiquitin Chain Analysis

| Reagent/Methodology | Specific Application | Key Features and Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage-specific Ubiquitin Chains | Ubiquitin interactor pull-downs | Native isopeptide bonds; susceptible to DUBs; requires DUB inhibitors [9] |

| Chloroacetamide (CAA) | DUB inhibition in pull-downs | Cysteine-specific; partial chain disassembly may occur [9] |

| N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) | DUB inhibition in pull-downs | More potent cysteine alkylator; potential off-target effects [9] |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry | Ubiquitin interactor identification | High sensitivity; requires specialized statistical analysis [9] |

| Top-down Tandem MS | Ubiquitin chain topology analysis | Preserves linkage information; identifies branched chains [16] |

| UbiCRest Assay | Linkage composition confirmation | Uses linkage-specific DUBs (OTUB1 for K48, AMSH for K63) [9] |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance | Binding affinity validation | Quantitative analysis of ubiquitin-binding protein interactions [9] |

Therapeutic Targeting of Ubiquitin Signaling

The ubiquitin-proteasome system represents a promising therapeutic target in cancer treatment, with several FDA-approved drugs already in clinical use. Proteasome inhibitors including bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib have demonstrated efficacy in hematological malignancies, particularly multiple myeloma [10]. These agents disrupt protein homeostasis, leading to accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins and ultimately apoptosis in cancer cells.

Beyond proteasome inhibition, targeted approaches against specific components of the ubiquitin system are under active development. Inhibitors targeting E1 enzymes (e.g., MLN7243 and MLN4924), E2 enzymes (e.g., Leucettamol A and CC0651), and specific E3 ligases (e.g., nutlin and MI-219 targeting MDM2) have shown promise in preclinical models [10]. Additionally, deubiquitinase inhibitors represent emerging therapeutic opportunities, with compounds such as G5 and F6 demonstrating potential in preclinical cancer models [10].

Novel therapeutic strategies including proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) hijack the endogenous ubiquitin machinery to selectively target oncoproteins for degradation [15]. These bifunctional molecules simultaneously bind to a target protein and an E3 ubiquitin ligase, facilitating target ubiquitination and degradation. This approach expands the druggable proteome to include proteins traditionally considered undruggable, representing a promising frontier in cancer therapeutics.

Ubiquitin chain topology constitutes a sophisticated regulatory system that governs protein fate and function through diverse structural configurations. From the classical degradation signal of K48-linked chains to the non-proteolytic signaling functions of K63 linkages and the emerging complexity of branched chains, the ubiquitin code represents a fundamental regulatory layer in cellular homeostasis. Within the tumor microenvironment, ubiquitin-dependent regulation impacts virtually all aspects of tumor biology, from cancer cell-intrinsic signaling to immune cell function and stromal interactions.

Ongoing methodological advances, particularly in mass spectrometry and interactome analysis, continue to reveal new dimensions of ubiquitin signaling complexity. The expanding toolkit for ubiquitin research, combined with developing therapeutic approaches targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome system, promises to yield new insights and treatment strategies for cancer and other diseases characterized by ubiquitin pathway dysregulation. As our understanding of the ubiquitin code deepens, so too will our ability to therapeutically manipulate this system for cancer treatment, particularly in the complex context of the tumor microenvironment.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a complex ectopic ecosystem composed of multiple cell types, including immune cells, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells, along with non-cellular components such as the extracellular matrix and secreted mediators [17]. Bidirectional communication between tumor cells and the TME is directly responsible for tumor genesis, progression, and metastasis, and is closely related to therapeutic efficacy and patient prognosis [17]. Ubiquitination, an essential and reversible post-translational modification, plays a vital role in modulating the stability, activity, and localization of proteins through a three-enzyme cascade involving E1 activating, E2 conjugating, and E3 ligase enzymes [17]. E3 ubiquitin ligases are particularly crucial as they confer substrate specificity, determining which proteins are targeted for ubiquitination and subsequent degradation or functional modification [18] [10]. Recognition of specific substrates is achieved through degrons—short peptide motifs that serve as minimal but sufficient elements for recognition by the degradation machinery within substrate proteins [17]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a major regulatory axis in cellular homeostasis, and its dysregulation contributes significantly to carcinogenesis [19] [10]. Emerging evidence indicates that E3 ligases extensively regulate the TME by controlling key cellular processes in both tumor and stromal cells, making them attractive therapeutic targets for cancer treatment [17] [19].

Classification and Mechanisms of E3 Ubiquitin Ligases

E3 ubiquitin ligases are categorized into several families based on their structural domains and mechanisms of action. The four principal families are RING, HECT, RBR, and CRLs (Cullin-RING Ligases), each employing distinct mechanisms to transfer ubiquitin to substrate proteins [17] [19].

Table 1: Major E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Families and Their Characteristics

| E3 Family | Mechanism of Action | Representative Members | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| RING | Direct transfer of Ub from E2~Ub to substrate [20] | MDM2, MARCH1 [19] | Characterized by a RING fold domain with zinc-binding sites; functions via monomers, homodimers, heterodimers, or multiple subunits [19] |

| HECT | Forms catalytic intermediate (HECT~Ub) before substrate transfer [20] | NEDD4, WWP2, Mule [19] | Bilobal HECT domain: N-lobe binds E2, C-lobe contains catalytic cysteine [19] |

| RBR | Hybrid mechanism; RING1 recruits E2~Ub, ubiquitin transferred to catalytic cysteine in Rcat domain, then to substrate [17] [20] | Parkin, HOIP, HHARI [17] [20] | Triad of RING1, BRcat (benign-catalytic), and Rcat (required-for-catalysis) domains [20] |

| CRLs | Multisubunit RING E3s; scaffold cullin protein binds substrate adapter and RING protein [21] | CUL1-5 complexes with FBXO17, FBXW [19] | Modular assembly: cullin scaffold, substrate-binding module (e.g., F-box protein), and RING protein (RBX1/2) [21] |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanistic differences in ubiquitin transfer among the major E3 ligase families:

RING E3 Ubiquitin Ligases

RING (Really Interesting New Gene) E3 ligases represent the largest family of E3 ubiquitin ligases and function primarily as scaffolds that simultaneously bind to E2~Ub complexes and substrate proteins, facilitating the direct transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 enzyme to the substrate without forming a covalent intermediate [20]. These ligases are characterized by a RING fold domain that coordinates two zinc ions in a cross-brace formation, which is essential for their structural integrity and function [20]. RING E3s can function as monomers, homodimers, heterodimers, or multi-subunit complexes, with Cullin-RING ligases (CRLs) representing a particularly important and diverse subclass of multi-subunit RING E3s [19]. The modular nature of CRLs allows for tremendous diversity in substrate recognition, as different substrate-binding modules can associate with the core cullin-RING scaffold [21].

HECT E3 Ubiquitin Ligases

HECT (Homologous to E6-AP C-terminus) E3 ligases employ a two-step catalytic mechanism that involves the formation of a covalent thioester intermediate between a conserved cysteine residue in the HECT domain and ubiquitin before ultimate transfer to the substrate [20] [19]. Structurally, the HECT domain consists of an N-terminal lobe that binds the E2 enzyme and a C-terminal lobe containing the catalytic cysteine residue, connected by a flexible linker [19]. This distinct mechanism allows HECT E3s to determine the topology of the ubiquitin chain being assembled, as the chain-building process occurs while ubiquitin is attached to the HECT domain itself. The human genome encodes approximately 28 HECT E3 ligases, which regulate diverse cellular processes and have been implicated in various pathological conditions, including cancer [19].

RBR E3 Ubiquitin Ligases

RBR (RING-BetweenRING-RING) E3 ligases represent a unique family that employs a hybrid mechanism combining features of both RING and HECT-type E3s [17] [20]. Recent structural and biochemical studies have prompted a revision in the nomenclature of RBR domains to more accurately reflect their structures and functions: the former RING2 domain is now designated Rcat (Required-for-catalysis) domain, while the intermediate IBR domain is renamed BRcat (benign-catalytic) domain [20]. Mechanistically, the RING1 domain first recruits the E2~Ub complex in a manner similar to canonical RING E3s, following which ubiquitin is transferred to a conserved cysteine residue in the Rcat domain through a trans-thioesterification reaction, forming a covalent intermediate analogous to HECT E3s [20]. Finally, the Rcat domain catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin to the substrate protein. This sophisticated mechanism allows RBR E3s to precisely control the ubiquitination of specific substrates involved in critical cellular processes.

Cullin-RING Ligases (CRLs)

Cullin-RING ligases constitute the largest family of multi-subunit E3 ubiquitin ligases, characterized by a modular architecture assembled around a cullin scaffold protein (CUL1-5, CUL7, or CUL9) that serves as a molecular platform [21]. The cullin protein binds a substrate-recognition module at its N-terminus and a RING-domain protein (RBX1 or RBX2) at its C-terminus, which in turn recruits the E2 enzyme [21]. CRL activity is primarily regulated by neddylation—the covalent attachment of the ubiquitin-like protein NEDD8 to a specific lysine residue on the cullin subunit [21]. Neddylation induces a conformational change that enhances the recruitment and activation of the E2 enzyme, thereby increasing ubiquitination efficiency by up to 1000-fold [21]. The modular nature of CRLs allows for tremendous diversity, with hundreds of distinct CRL complexes possible through combinatorial assembly of different substrate-recognition modules, enabling precise control over the degradation of a vast array of cellular proteins.

Experimental Approaches for Studying E3 Ligases in TME Regulation

Conformation-Specific Profiling of CRL Networks

Recent advances in profiling E3 ligase activities have enabled more precise assessment of their functional states in biological systems. For CRLs, a key regulatory mechanism involves neddylation, which activates these complexes by inducing a specific conformational state. The following experimental workflow has been developed to profile active CRL repertoires using conformation-specific probes:

This approach utilizes synthetic antibodies (Fabs) generated through phage display that specifically recognize the active conformation of NEDD8-linked cullins [21]. The selection process involves a negative>negative>positive strategy that enriches Fabs binding specifically to neddylated cullin–RING complexes while depleting binders to unneddylated cullins or NEDD8 alone [21]. These conformation-specific probes enable:

- Activity-based profiling: Direct assessment of neddylated CRL complexes without requiring genetic manipulation [21]

- Network analysis: Identification of CRL complexes responding to cellular stimuli or targeted protein degradation [21]

- Cell-type specific repertoires: Comparison of baseline neddylated CRL landscapes across different cell types [21]

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for E3 Ligase Studies in TME

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conformation-Specific Probes | N8C_Fab series [21] | Recognize active NEDD8-linked cullins with nanomolar affinity | Activity-based profiling of CRL networks; immunoprecipitation of neddylated CRLs |

| E3 Ligase Inhibitors | MLN4924 (Neddylation inhibitor) [21] | Inhibits NEDD8-activating enzyme, blocking CRL activation | Validation of CRL-dependent processes; studying neddylation dynamics |

| Targeted Degraders | PROTACs, Molecular Glues [18] [22] | Harness E3 ligases to degrade specific target proteins | Therapeutic exploration; studying substrate degradation mechanisms |

| Activity-Based Probes | Catalytic cysteine-reactive probes [21] | Label active HECT, RBR, and other cysteine-dependent E3s | Profiling enzymatic activities of cysteine-dependent E3 ligases |

Methodologies for Assessing E3 Ligase Function in TME

Comprehensive analysis of E3 ligase functions in the tumor microenvironment requires integrated experimental approaches:

- Genetic manipulation: Knockdown or knockout of specific E3 ligases in tumor or stromal cells to assess effects on TME composition and function [19]

- Substrate identification: Ubiquitinome profiling through mass spectrometry to identify novel E3 substrates in TME contexts [17]

- Functional assays: Assessment of tumor cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and immune cell functions following E3 modulation [19]

- Therapeutic validation: Testing E3-targeting agents in combination with immunotherapies to overcome treatment resistance [19]

E3 Ligase Regulation of Tumor Microenvironment Components

E3 ubiquitin ligases extensively regulate the tumor microenvironment by controlling the stability and function of key proteins in various TME components. The following sections detail specific mechanisms through which different E3 families influence TME dynamics.

Immune Cell Regulation in TME

E3 ligases play pivotal roles in modulating immune cell composition and function within the TME. In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), RNF125 expression levels show positive correlation with infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as well as macrophages [19]. Similarly, WD repeat 4 (WDR4), when serving as a substrate receptor for CRL complexes, promotes degradation of the tumor suppressor PML protein, leading to expansion of Treg cells and M2 macrophages while reducing CD8+ T cells, thereby establishing an immunosuppressive TME [19]. Parkin, an RBR family E3 ligase, exhibits tumor-suppressive functions in HCC through direct degradation of TRAF2 and TRAF6, which drives HCC cell apoptosis by inhibiting the NF-κB pathway [19]. These examples illustrate how specific E3 ligases can shape the immunological landscape of tumors, potentially influencing response to immunotherapy.

Cancer Cell Signaling Pathways in TME

E3 ligases extensively regulate oncogenic signaling pathways that influence TME communication. In HCC, the HECT-type E3 ligase NEDD4 targets LATS1, a core component of the Hippo pathway, for ubiquitin-mediated degradation, thereby increasing YAP transcriptional activity and promoting tumor progression [19]. The RING-type E3 ligase MDM2 diminishes YAP's interaction with other proteins and promotes its cytoplasmic translocation and degradation, thereby inhibiting tumorigenesis [19]. Monomeric MARCH1 upregulates the PI3K-AKT-β-catenin pathway, promoting HCC growth and progression [19]. These pathway regulations not only affect cancer cell-intrinsic properties but also alter secretory profiles that influence stromal and immune cells within the TME.

Table 3: E3 Ligase Functions in Hepatocellular Carcinoma and TME Regulation

| E3 Ligase | E3 Family | Substrate(s) | Function in HCC/TME | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBXO17 | RING (CRL) | Unknown Wnt pathway component [19] | Promoter | Inhibits Wnt/β-catenin signaling [19] |

| MARCH1 | RING | PI3K-AKT pathway components [19] | Promoter | Upregulates PI3K-AKT-β-catenin pathway [19] |

| Hakai | RING (Dimer) | E-cadherin [19] | Promoter | Promotes E-cadherin degradation, driving EMT [19] |

| MDM2 | RING | YAP [19] | Suppressor | Promotes YAP cytoplasmic translocation and degradation [19] |

| WWP2 | HECT | Caspase-7, caspase-8, Bax [19] | Promoter | Regulates apoptosis; knockdown increases apoptosis markers [19] |

| Mule | HECT | β-catenin [19] | Suppressor | Targets β-catenin for degradation, suppressing cancer stem cell activity [19] |

| NEDD4 | HECT | LATS1 [19] | Promoter | Targets LATS1 for degradation, increasing YAP activity [19] |

| Parkin | RBR | TRAF2, TRAF6 [19] | Suppressor | Drives apoptosis via NF-κB pathway inhibition [19] |

Extracellular Matrix and Stromal Component Regulation

E3 ligases directly and indirectly regulate extracellular matrix (ECM) composition and stromal cell functions within the TME. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), key enzymes involved in ECM remodeling and cancer invasion, are regulated by E3 ligases [19]. Additionally, E3 ligases influence epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a critical process in cancer progression that alters tumor-stroma interactions. For instance, the Hakai E3 ligase promotes degradation of E-cadherin, resulting in nuclear translocation of β-catenin proteins and ultimately driving EMT in HCC [19]. Similar mechanisms operate in other cancer types, highlighting conserved roles for E3 ligases in regulating ECM dynamics and stromal-tumor interactions across different TME contexts.

Therapeutic Targeting of E3 Ligases in TME

Targeted Protein Degradation Strategies

The understanding of E3 ligase mechanisms has enabled the development of innovative therapeutic strategies that harness the ubiquitin-proteasome system for targeted protein degradation. Several approaches have shown significant promise:

PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras): Heterobifunctional molecules that simultaneously bind to an E3 ligase and a target protein of interest, thereby recruiting the target for ubiquitination and degradation [18] [22]. PROTACs have shown efficacy against various cancer-associated proteins previously considered "undruggable."

Molecular Glues: Small molecules that induce or stabilize interactions between E3 ligases and target proteins, leading to selective degradation [18] [22]. Unlike PROTACs, molecular glues are monovalent and typically function by altering the surface of either the E3 or target protein to create novel protein-protein interfaces.

Antibody-Based Degraders: Emerging technologies that utilize antibody-mediated targeting to deliver degradation signals to specific proteins or cell types [18].

These targeted degradation approaches offer several advantages over traditional inhibition strategies, including event-driven pharmacology, potential targeting of non-enzymatic functions, and ability to achieve profound and sustained target suppression.

E3 Ligase Inhibitors and Modulators

Beyond degradation strategies, direct targeting of E3 ligases themselves represents a viable therapeutic approach:

Neddylation Inhibitors: MLN4924 (Pevonedistat) inhibits the NEDD8-activating enzyme, blocking activation of CRL complexes and inducing apoptosis in various cancer models [21] [10].

E3-Specific Inhibitors: Compounds such as nutlin and MI-219 target the MDM2 E3 ligase, disrupting its interaction with p53 and stabilizing this critical tumor suppressor [10].

DUB Inhibitors: Compounds targeting deubiquitinating enzymes that counteract E3 ligase function, such as G5 and F6, have shown potential in preclinical cancer models [10].

Therapeutic targeting of E3 ligases in the TME context offers the potential for dual benefit—direct antitumor effects combined with TME modulation that may enhance response to conventional therapies and overcome resistance mechanisms.

E3 ubiquitin ligases represent master regulators of the tumor microenvironment, extensively controlling protein stability and function across cancer cells, immune cells, and stromal components. The four major E3 families—RING, HECT, RBR, and CRLs—employ distinct mechanistic strategies to achieve substrate specificity, enabling precise regulation of key cellular processes in the TME. Advanced experimental approaches, including conformation-specific probes and activity-based profiling, have revealed the dynamic nature of E3 networks and their complex regulation in biological systems. Growing understanding of E3 functions in TME regulation has catalyzed the development of innovative therapeutic strategies, particularly targeted protein degradation technologies that hijack endogenous E3 machinery to eliminate disease-driving proteins. As research continues to elucidate the intricate relationships between specific E3 ligases and TME components, promising opportunities emerge for developing novel cancer therapeutics that simultaneously target tumor cells and modulate the supportive microenvironment, potentially overcoming limitations of current treatment modalities.

This whitepaper provides a comprehensive analysis of phosphodegrons—phosphorylation-dependent recognition motifs that serve as pivotal regulatory elements in the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS). Within the context of the tumor microenvironment (TME), phosphodegrons integrate signaling inputs to control the stability of oncoproteins, tumor suppressors, and immune regulators, thereby influencing tumor progression and therapeutic responses. We detail the molecular mechanisms of phosphodegron recognition, present quantitative proteomic methodologies for their system-wide identification, and discuss emerging therapeutic strategies, including proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs), that exploit these motifs for targeted protein degradation. The content is structured to serve researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working at the intersection of ubiquitination signaling and cancer biology.

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) constitute a critical regulatory layer that controls protein stability, function, and localization. Among these, phosphorylation and ubiquitination engage in extensive crosstalk to direct the timed degradation of cellular proteins [23] [24]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), responsible for the degradation of most intracellular proteins, relies on E3 ubiquitin ligases to recognize specific degradation signals, or degrons, on their substrates [24] [25]. A phosphodegron is a specific type of degron that becomes activated upon phosphorylation of its serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues, creating a high-affinity binding site for a cognate E3 ligase [26] [25]. This phosphorylation event acts as a molecular switch, converting a stable protein into a target for polyubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal destruction [24].

The functional importance of phosphodegrons lies in their ability to confer precise, rapid, and reversible control over the abundance of key regulatory proteins. They are essential for fundamental processes including cell cycle progression, DNA damage response, apoptosis, and signal transduction [26]. Within the complex signaling networks of the tumor microenvironment (TME), dysregulation of phosphodegron-mediated degradation is frequently implicated in oncogenesis, immune evasion, and therapy resistance [27] [28] [29]. For instance, the stability of transcription factor FOXP3 in regulatory T cells (Tregs), a critical mediator of immunosuppression, is controlled by a complex balance of ubiquitin ligases and opposing PTMs on its phosphodegron [27]. Therefore, understanding the dynamics of phosphodegrons is not only fundamental to cell biology but also paramount for developing novel cancer therapeutics.

Molecular Mechanisms and Biological Significance

Structural Basis of Phosphodegron Recognition

Phosphodegrons are not merely phosphorylated residues; they consist of specific primary sequences surrounding the phosphorylatable residue that are complementary to the binding pocket of a specific E3 ubiquitin ligase [26]. The SCF (SKP1-CUL1-F-box protein) complex represents one of the best-characterized classes of E3 ligases that recognize phosphodegrons. Within the SCF complex, the variable F-box protein subunit (e.g., FBXW7, β-TrCP) acts as the substrate receptor that directly binds the phosphorylated motif [30] [26].

- Conserved Phosphodegron Motifs: Different F-box proteins recognize distinct, phosphorylated consensus sequences.

- FBXW7 recognizes the motif TPPx(S/T) (where S/T is phosphorylated) [30] [26]. This motif is found in oncoproteins such as MYC, NOTCH, and cyclin E, facilitating their regulated degradation.

- β-TrCP typically binds to the DpSGXXpS motif (where both serine residues are phosphorylated) [30] [25]. Substrates include β-catenin, IκBα, and CDC25A.

- FBXO22 was recently shown to recognize the motif XXPpSPXPXX (where pS is phospho-serine) to target proteins like the co-chaperone BAG3 for degradation [30].

The following diagram illustrates the generalized mechanism of phosphodegron recognition and subsequent protein degradation.

Phosphodegrons in the Tumor Microenvironment

The TME is a complex ecosystem where tumor cells interact with immune cells, fibroblasts, and other components. Phosphodegron-mediated regulation of protein stability is a key mechanism exploited by both tumor and stromal cells to adapt and survive.

Regulation of Immune Cell Function: In Tregs, the stability of the transcription factor FOXP3 is controlled by a battle between competing E3 ligases and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) acting on its phosphodegron. The E3 ligase STUB1 promotes FOXP3 degradation, weakening Treg immunosuppressive function. Conversely, the E3 ligase Itch catalyzes non-degradative K63-linked ubiquitination, promoting FOXP3's nuclear localization and activity [27]. Targeting this axis with a KLHDC2-recruiting PROTAC to degrade FOXP3 is a potential strategy to enhance anti-tumor immunity [27].

Therapeutic Resistance: The ubiquitin system, including phosphodegron recognition, is a master regulator of radiotherapy resistance [28]. For example, the E3 ligase FBXW7 exhibits contextual duality: in p53-wild type tumors, it can promote radioresistance by degrading p53, whereas in SOX9-overexpressing non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), it enhances radiosensitivity by degrading SOX9 [28]. This highlights that the functional outcome of phosphodegron recognition is highly dependent on the genetic and signaling context of the TME.

Metabolic Reprogramming: Protein stability controlled by phosphodegrons directly impacts cancer metabolism. For instance, ERK-dependent phosphorylation of BAG3 at S377 creates a phosphodegron for SCFFBXO22, targeting this pro-survival co-chaperone for degradation. Disruption of this ERK-FBXO22-BAG3 axis promotes tumor growth by impairing apoptosis and cell cycle progression [30].

Table 1: Key E3 Ligases and Their Phosphodegron Substrates in Cancer

| E3 Ligase | Phosphodegron Motif | Key Substrate(s) | Role in Tumor Microenvironment | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBXW7 | TPPx(pS/pT) | c-MYC, Cyclin E, NOTCH | Controls proliferation and growth; function is context-dependent (can be tumor suppressive or promote resistance). | [26] [28] |

| β-TrCP | DpSGXXpS | β-catenin, CDC25A, IκBα | Regulates WNT signaling, cell cycle checkpoints, and NF-κB-mediated inflammation. | [26] [25] |

| SCFFBXO22 | XXPpSPXPXX | BAG3 | Targets pro-survival co-chaperone BAG3; axis is involved in tumorigenesis. | [30] |

| STUB1 | Not fully defined | FOXP3 | Destabilizes FOXP3 in Tregs, potentially reducing immunosuppression. | [27] |

Experimental Protocols for System-Wide Identification

Mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics has become the mainstay technology for the system-wide, unbiased identification of phosphodegrons and phosphorylation-dependent substrates of E3 ligases [23] [30]. The following section outlines a detailed protocol for a quantitative phosphoproteomic screen to identify phospho-dependent SCF substrates.

Protocol: Quantitative Phosphoproteomic Screen for SCF Substrates

This protocol, adapted from a 2021 study, uses a neddylation inhibitor to inactivate Cullin-RING Ligases (CRLs), including SCF complexes, combined with Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino acids in Cell culture (SILAC) for quantitative MS [30].

Objective: To globally identify phosphorylation-dependent substrates of SCF E3 ligases by quantifying changes in the proteome and phosphoproteome upon CRL inhibition.

Key Reagent Solutions: Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Phosphoproteomic Screening

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| MLN4924 (Neddylation Inhibitor) | Inhibits the neddylation of cullins, thereby inactivating CRL E3 ligases. This prevents the degradation of phosphorylated substrates, causing their accumulation. |

| SILAC (Stable Isotope Labeling) | Metabolic labeling for quantitative proteomics. "Light" and "Heavy" isotope-labeled amino acids allow for precise comparison of protein/phosphosite abundance between control and treated samples. |

| Immunoaffinity Phosphopeptide Enrichment | Enrichment of phosphorylated peptides from complex protein digests using titanium dioxide (TiO2) or anti-phosphomotif antibodies, enabling comprehensive phosphosite mapping. |

| LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography-Tandem MS) | High-resolution separation and identification of peptides, and localization of phosphorylation sites with high confidence. |

| Motif Analysis (e.g., Motif-X) | Bioinformatics tool to identify statistically overrepresented phosphorylation motifs (e.g., potential novel phosphodegrons) from the list of upregulated phosphosites. |

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Cell Culture and SILAC Labeling: Grow two populations of HEK 293T cells (or other relevant cell lines) in SILAC "light" (L-lysine/L-arginine) and "heavy" (L-lysine-13C6/L-arginine-13C6) media until full isotopic incorporation is achieved [30].

CRL Inhibition and Cell Lysis:

- Treat the "heavy"-labeled cells with 1 µM MLN4924 for 4 hours.

- Treat the "light"-labeled control cells with vehicle (e.g., DMSO).

- Harvest cells and mix the light (control) and heavy (MLN4924-treated) populations at a 1:1 protein ratio.

- Lyse the combined cells and perform protein digestion with trypsin.

Phosphopeptide Enrichment: Subject the resulting peptide mixture to phosphopeptide enrichment using TiO2 beads or immunoaffinity purification with phosphomotif antibodies to isolate phosphorylated peptides for analysis [23] [30].

LC-MS/MS Analysis and Data Processing:

- Analyze the enriched phosphopeptides by high-resolution LC-MS/MS.

- Use database search engines (e.g., MaxQuant) to identify peptides and localize phosphorylation sites, calculating the Heavy/Light (H/L) ratio for each phosphosite and protein.

- Apply statistical analysis (e.g., t-test) to identify significant changes.

Bioinformatic Triage of Candidate Substrates:

- Apply screening criteria to identify potential phospho-dependent substrates. A successful screen identified candidates showing a >1.2-fold increase in both protein abundance and specific phosphorylation site intensity upon MLN4924 treatment [30].

- Integrate the resulting list with external datasets (e.g., BioGRID for SCF interactors, GPS for global protein stability data) to prioritize high-confidence candidates.

- Perform Kinase Enrichment Analysis (KEA) on upregulated phosphosites to identify kinases responsible for creating the phosphodegrons [30].

- Use motif analysis tools to discover enriched phosphorylation motifs that may represent novel phosphodegrons.

The experimental workflow for this protocol is summarized below.

Biochemical Validation of Candidate Phosphodegrons

Following the proteomic screen, putative phosphodegrons require rigorous biochemical validation.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Mutate the identified phosphorylated serine/threonine residue to alanine (S/T → A) to create a phosphorylation-deficient mutant. Compare the stability of the wild-type and mutant protein upon inhibition of the UPS (e.g., with MG132) or upon CRL inactivation (e.g., with MLN4924 or DN-CUL1). A true phosphodegron mutant will show increased basal stability and fail to accumulate further with MLN4924 treatment [30].

In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay: Purify the SCF E3 ligase complex and its substrate. Perform an in vitro reaction with E1, E2, ubiquitin, and ATP. Assess whether ubiquitination of the wild-type substrate is enhanced by its prior phosphorylation (e.g., using an active kinase) and whether this effect is abolished in the phospho-mutant [30].

Quantitative Data and Therapeutic Targeting

Quantitative Insights from Global Studies

High-throughput phosphoproteomic studies provide a systems-level view of phosphodegron dynamics. One systematic screen for phospho-dependent SCF substrates quantified over 12,276 phosphorylation sites across 4,322 proteins. Upon CRL inhibition, 369 phosphosites met the criteria for potential phosphodegron-associated sites (increased in both phosphorylation and total protein abundance) [30]. This data richness underscores the vast regulatory network controlled by phosphorylation-dependent degradation. Furthermore, kinase analysis revealed that CDKs, GSK3B, and MAPKs were significantly enriched upstream of the accumulated phosphosites, highlighting these kinases as primary drivers of phosphodegron creation [30].

Therapeutic Exploitation: PROTACs and Beyond

The understanding of phosphodegron biology has directly enabled the development of novel therapeutic modalities, most notably Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) [27] [28] [25].

PROTAC Mechanism: PROTACs are heterobifunctional molecules with one ligand that binds an E3 ubiquitin ligase (e.g., VHL or CRBN) and another that binds a protein of interest (POI), connected by a linker. The PROTAC induces proximity between the E3 ligase and the POI, leading to the POI's ubiquitination and degradation, bypassing the need for a native phosphodegron [27] [25].

Application in the TME: In cancer immunotherapy, a proposed strategy involves designing PROTACs that recruit the E3 ligase KLHDC2 to degrade FOXP3 in Tregs, thereby potentially reversing immunosuppression in the TME [27]. Additionally, radiation-responsive PROTACs (RT-PROTACs) are being developed to achieve spatially controlled degradation of oncoproteins like BRD4 specifically within irradiated tumors, enhancing radiotherapy efficacy [28].

Table 3: Targeting the Ubiquitin System in Cancer Therapy

| Therapeutic Class | Example(s) | Molecular Target / Mechanism | Clinical/Preclinical Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitor | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Inhibit the proteasome's proteolytic activity, causing accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins. | Approved for multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma. [27] [31] |

| E3 Ligase Inhibitor | P5091 (USP7 inhibitor) | Inhibits a deubiquitinase (DUB), leading to degradation of its substrates (e.g., MDM2, activating p53). | Preclinical promise in multiple myeloma. [27] |

| PROTAC | ARV-471, FOXP3-targeting PROTACs | Recruit E3 ligase to target oncoproteins or immune regulators for degradation. | Clinical trials and preclinical investigation for solid tumors and immuno-oncology. [27] [28] |

Phosphodegrons represent a fundamental mechanism of cellular information processing, where phosphorylation signals are translated into proteolytic outcomes. Within the dynamic and complex tumor microenvironment, the precise regulation of protein stability via phosphodegrons governs cell fate decisions, immune responses, and therapeutic susceptibility. The integration of quantitative mass spectrometry-based proteomics with sophisticated biochemical validation provides a powerful framework for decoding the global landscape of phosphodegron networks. As our mechanistic understanding deepens, so does the potential for innovative therapies. The transformative success of PROTAC technology exemplifies how hijacking the cell's intrinsic degradation machinery can lead to novel treatment strategies for cancer and other diseases, heralding a new era in targeted protein degradation.

F-box proteins, the critical substrate-recognition subunits of the SKP1-CUL1-F-box (SCF) ubiquitin ligase complex, have emerged as pivotal regulators at the intersection of cancer cell plasticity and immune evasion. These proteins mediate the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of specific target proteins, playing essential roles in cell cycle regulation, signal transduction, and immune homeostasis. Within the tumor microenvironment, F-box proteins demonstrate remarkable functional heterogeneity, dynamically modulating key oncogenic processes including epithelial-mesenchymal transition, metabolic reprogramming, and immune checkpoint functionality. This whitepaper systematically examines the molecular mechanisms through which F-box proteins coordinate cancer cell adaptation and immunosuppression, reviews current experimental methodologies for their investigation, and discusses emerging therapeutic strategies targeting F-box proteins for combination immunotherapy. The comprehensive analysis presented herein aims to provide researchers and drug development professionals with both foundational knowledge and advanced insights into this crucial protein family's role in tumor progression.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a crucial post-translational modification pathway that regulates diverse cellular processes through the targeted degradation of specific proteins. Ubiquitination involves a sequential enzymatic cascade catalyzed by ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), and ubiquitin ligase (E3) enzymes [7]. E3 ubiquitin ligases, the most critical components of this cascade, directly bind substrates and determine specificity. Among the hundreds of E3 ligases encoded in the human genome, the Cullin-RING ligase (CRL) complex family constitutes the largest group, with CRL1 (also known as the SCF complex) being the best-characterized member [7].

F-box proteins serve as the variable substrate-recognition components of the SCF complex, which consists of four essential subunits: the scaffold protein CUL1, the RING-finger protein RBX1, the adaptor protein SKP1, and an F-box protein that provides specificity [7]. The F-box domain, a characteristic motif of approximately 50 amino acids, facilitates binding to SKP1, while diverse C-terminal domains enable recognition of specific substrates [32] [33]. The human genome encodes approximately 69 F-box proteins, classified into three subfamilies based on their C-terminal domain structures: FBXW (WD40 repeats, 10 members), FBXL (leucine-rich repeats, 21 members), and FBXO (other domains, 38 members) [7].

Table 1: Classification of F-box Protein Subfamilies

| Subfamily | Distinguishing Feature | Number of Members | Representative Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| FBXW | WD40 repeats at C-terminus | 10 | Cell cycle regulation, targeting of oncoproteins like c-MYC |

| FBXL | Leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) at C-terminus | 22 | Regulation of multiple signaling pathways, metabolic control |

| FBXO | Diverse C-terminal domains not fitting FBXW or FBXL categories | 38 | Broad regulatory roles in various cellular processes |

The evolutionary pattern of the F-box gene family primarily follows the birth-death model, characterized by gene duplication and loss events [32] [33]. Population genetic analyses reveal that domain regions within F-box genes experience significantly stronger purifying selection compared to non-domain regions, highlighting the critical functional importance of these conserved structural elements [32] [33].

Molecular Mechanisms of F-box Proteins in Cancer Cell Plasticity

Regulation of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT)

F-box proteins extensively regulate cancer cell phenotypic plasticity, particularly through epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), during which epithelial cells lose their junctions and apical-basal polarity and remodel their cytoskeleton to acquire mesenchymal characteristics [7]. This process enhances cell motility and invasiveness, critical steps in metastasis. Multiple F-box proteins target key regulators of EMT for ubiquitin-mediated degradation:

β-TrCP (FBXW1/FBXW11): This F-box protein demonstrates dual functionality in EMT regulation. It activates NF-κB signaling by degrading IκB (NF-κB inhibitors), promoting pro-inflammatory factors that enhance tumor cell survival and metastasis [32] [33]. Simultaneously, β-TrCP mediates the ubiquitination and degradation of β-catenin to inhibit the classical Wnt pathway. Dysfunction in this regulatory axis leads to β-catenin accumulation, promoting EMT and the formation of an immunosuppressive microenvironment [32] [33].

FBXO25: Recent research has identified FBXO25 as a promoter of ovarian cancer progression through its interaction with α-actinin 1 (ACTN1) [34]. The FBXO25/ACTN1 axis activates ERK1/2 signaling and promotes EMT, driving tumor cell invasion and metastasis. This pathway exemplifies how F-box proteins can directly influence the mesenchymal transition of cancer cells through specific substrate interactions [34].

The complexity of F-box protein function is highlighted by their context-dependent roles, where individual F-box proteins can target different substrates to exert either pro-tumorigenic or anti-tumorigenic effects depending on cellular conditions [7].

Metabolic Reprogramming and Phenotypic Adaptation

Cancer cells exhibit remarkable metabolic plasticity, and F-box proteins serve as critical regulators of this adaptive capability. Through targeted protein degradation, they modulate key metabolic enzymes and signaling pathways that enable cancer cells to survive in challenging microenvironmental conditions:

β-TrCP in Pancreatic Cancer: In the low-glucose and hypoxic microenvironment of pancreatic cancer, β-TrCP indirectly regulates HIF1α and c-MYC signaling, both central drivers of metabolic adaptation [33]. The gene BZW1, functionally related to β-TrCP, enhances glycolytic metabolism by stabilizing HIF1α and c-MYC, exacerbating the formation of an immunosuppressive microenvironment [33].

β-TrCP-Mediated Lipid Metabolism: Research led by Wei Wenyi demonstrated that β-TrCP degrades Lipin1, a key enzyme in lipid metabolism, through ubiquitination, thereby regulating liver lipid metabolism homeostasis [32] [33]. Lipid overload in the tumor microenvironment can induce M2-type macrophage polarization and inhibit T cell function, creating an immunosuppressive niche [32] [33].

Table 2: F-box Proteins Regulating Cancer Cell Plasticity

| F-box Protein | Molecular Target | Biological Outcome | Cancer Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-TrCP (FBXW1) | IκB, β-catenin, Lipin1 | NF-κB activation, Wnt regulation, metabolic reprogramming | Pan-cancer (LUAD, KIRC, Pancreatic) |

| FBXO25 | α-actinin 1 (ACTN1) | ERK1/2 activation, EMT promotion | Ovarian cancer |

| FBXW7 | c-MYC, Cyclin E | Cell cycle control, stemness regulation | Multiple cancers |

| FBXO32 | Cyclin D1 | Cell cycle progression | Under investigation |

Diagram 1: F-box Protein Regulation of Cancer Cell Plasticity. F-box proteins integrate microenvironmental signals to drive plastic phenotypes through multiple signaling pathways.

F-box Proteins in Immune Evasion and Tumor Microenvironment Remodeling

Direct Regulation of Immune Checkpoint Molecules

F-box proteins directly regulate tumor immune microenvironments by targeting immune-related molecules for degradation, thereby modulating T-cell activation, macrophage polarization, and immune checkpoint functionality [32] [33] [35]. Specifically, they impact the PD-1/PD-L1 axis and CTLA-4 signaling, although the complete mechanistic details remain an active area of investigation [32] [33]. The regulatory dimensions of F-box proteins in the tumor immune microenvironment are increasingly recognized as critically important, particularly their mechanisms in mediating immune escape through reshaping immune cell metabolism or regulating immune checkpoint molecules [32] [33].

Control of Immune Cell Infiltration and Function

Pan-cancer analyses have revealed significant correlations between specific F-box protein expression patterns and immune cell infiltration:

β-TrCP and Immune Exclusion: Expression of FBXW1 (β-TrCP) shows significant negative correlation with immune score and matrix score, and positive correlation with tumor purity [32] [33]. In lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC), high FBXW1 expression associates with reduced infiltration of immunocompetent cells including NK cells and CD8+ T cells, suggesting it promotes immunosuppression by inhibiting anti-tumor immune responses [32] [33].

Macrophage Polarization: The FBXO25/ACTN1/ERK1/2 axis in ovarian cancer not only promotes tumor progression but also facilitates M2 macrophage polarization [34]. When ovarian cancer cells were co-cultured with macrophages, ACTN1 overexpression promoted M2 polarization, as evidenced by increased CD163 expression, an effect reversible with ERK1/2 inhibition [34]. This demonstrates how F-box protein-mediated signaling in cancer cells can directly shape the immune landscape.

The functional heterogeneity of F-box proteins in tumor development has led to their classification into three categories: tumor-suppressive F-box proteins, proto-oncogenic F-box proteins, and context-dependent F-box proteins [32] [33]. This classification reflects their adaptable roles in different cancer types and stages.

Experimental Approaches for Investigating F-box Protein Functions

Model Systems for Studying F-box Proteins in Tumor-Immune Interactions

Research into F-box protein functions employs diverse model systems that recapitulate different aspects of the tumor microenvironment:

Organoid Cultures: Tumor organoids maintain the 3D structure of tumors and can incorporate multiple cell types from the tumor immune microenvironment [36]. Differences have been observed in therapeutic intervention efficacy between 2D models and 3D organoids, emphasizing the importance of modeling complex 3D cellular interactions when studying F-box protein function [36].

Genetically Engineered Mouse Models: Both syngeneic tumor models and genetically engineered mice enable investigation of F-box proteins in the context of an intact immune system [36]. Conditional knockout or overexpression systems allow tissue-specific manipulation of F-box protein expression to dissect their physiological functions.

Lineage Tracing Models: Given the importance of phenotypic plasticity in F-box protein function, lineage tracing models that follow markers like N-cadherin expression or employ genetic barcoding provide powerful tools for monitoring EMT and other plasticity events during tumor progression [36].

Methodologies for Identifying F-box Protein Substrates