Ubiquitin vs. SUMO: Decoding the Complex Crosstalk in Cellular Regulation and Therapeutic Targeting

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the ubiquitin and SUMO post-translational modification pathways, essential regulatory systems in eukaryotic cells.

Ubiquitin vs. SUMO: Decoding the Complex Crosstalk in Cellular Regulation and Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the ubiquitin and SUMO post-translational modification pathways, essential regulatory systems in eukaryotic cells. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental biochemical mechanisms, distinctive functions in health and disease, and the dynamic interplay between these pathways. We delve into cutting-edge methodological approaches for studying these modifications, examine challenges in pathway-specific research, and validate their roles through comparative analysis in oncology and neurology. The content synthesizes current knowledge on therapeutic strategies that exploit these pathways, including proteasome inhibitors, SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases (StUbLs), and emerging technologies like PROTACs, offering insights for future drug discovery efforts.

Core Machinery and Distinct Cellular Functions of Ubiquitin and SUMO

The precise and dynamic nature of cellular signaling is largely governed by post-translational modifications (PTMs), with ubiquitin and small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) representing two pivotal regulators in this intricate landscape [1]. These proteins are conjugated to target substrates through dedicated enzymatic cascades involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes [1] [2]. While these cascades share a fundamental three-step architecture, they diverge significantly in their complexity, enzyme specificity, and biological outcomes. Understanding the distinct mechanisms governing ubiquitin versus SUMO conjugation is crucial for dissecting their roles in cellular homeostasis and disease pathogenesis. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these two systems, focusing on architectural principles, experimental methodologies for their study, and the implications for therapeutic development.

Core Architectural Principles: A Side-by-Side Comparison

The ubiquitin and SUMO conjugation pathways, while mechanistically analogous, are defined by distinct components that dictate their specificity and functional scope.

Enzyme Complexity and Specificity

A primary distinction lies in the number of enzymes involved at each step, which directly correlates with the system's functional versatility.

- Ubiquitin System: Exhibits remarkable complexity, particularly at the E2 and E3 levels. The human genome encodes 2 E1 enzymes (Uba1 and Uba6), approximately 38 E2s, and over 600 E3 ligases [1] [2]. This expansion allows for immense substrate specificity and the generation of diverse ubiquitin chain topologies, directing targets toward proteasomal degradation or altering their function and localization [2].

- SUMO System: Operates with a significantly narrower enzyme repertoire. In humans, a single heterodimeric E1 (SAE1/SAE2) and one E2 (UBC9) are responsible for activating and transferring SUMO to all substrates [1] [3]. Specificity is conferred by a smaller, though diverse, set of E3 ligases and direct recognition of substrates by UBC9 itself [3].

Table 1: Core Enzyme Components in Human Ubiquitin and SUMO Pathways

| Component | Ubiquitin System | SUMO System |

|---|---|---|

| E1 Activating Enzyme | 2 (Uba1, Uba6) [1] | 1 Heterodimer (SAE1/SAE2) [1] [3] |

| E2 Conjugating Enzyme | ~38 [1] | 1 (UBC9) [1] [3] |

| E3 Ligase Enzymes | >600 [1] | Limited number (e.g., PIAS family, RanBP2) [3] |

| Primary E3 Types | RING, HECT, RBR [1] [2] | Not as extensively classified |

Structural Mechanisms of E1-E2 Thioester Transfer

Structural studies have revealed conserved yet distinct conformational changes that enable the transfer of the activated protein from E1 to E2.

- Ubiquitin E1-E2 Architecture: A crystal structure of the S. pombe Ub E1-E2 (Ubc4) complex revealed that E2 recognition is combinatorial, involving both the ubiquitin-fold domain (UFD) and the Cys domain of the E1 [4]. This interaction requires a ~25-degree rotation of the UFD and displacement of residues masking the E1 catalytic cysteine to bring the E1 and E2 active sites into proximity for thioester transfer [4].

- SUMO E1-E2 Architecture: The SUMO E1 undergoes a dramatic 130-degree rotation of its Cys domain after SUMO adenylation. This "active site remodeling" transits the catalytic cysteine over 35 Å to facilitate thioester bond formation with SUMO [5]. Subsequent unlocking of the UFD domain presents the E2 (UBC9) in an orientation where the active sites face each other, though they may remain separated by over 20 Å before final transfer [4].

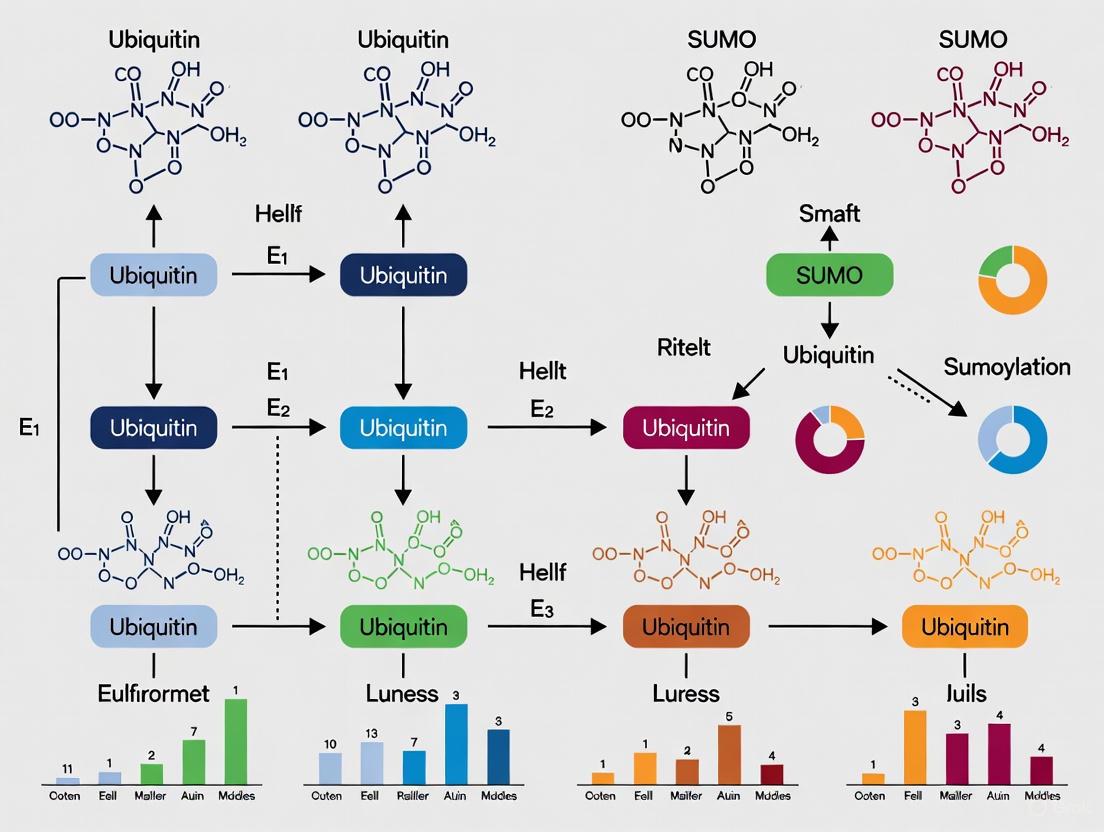

Diagram 1: Core E1-E2-E3 Cascades for Ubiquitin and SUMO

Experimental Dissection: Methodologies and Reagents

A detailed understanding of these pathways relies on robust biochemical and biophysical assays. The following section outlines key experimental approaches and the necessary reagents.

Key Assays for Mechanistic Insight

- FRET-Based Kinetics Assays: High-sensitivity FRET (Förster Resonance Energy Transfer) assays are powerful for monitoring real-time dynamics and intermediate formation. This method has been used to determine kinetic parameters (Km) for SUMO1 and ATP binding to the E1 enzyme and to observe specific substrate recognition and thioester intermediates in both ubiquitin and SUMO cascades [5]. The assay typically involves labeling the E1, E2, or Ubl with donor and acceptor fluorophores. Conformational changes or binding events alter the FRET efficiency, allowing for quantitative measurement of reaction progress and affinity [5].

- Thioester Transfer Assays: These are fundamental biochemical assays to monitor the transfer of ubiquitin/SUMO from E1 to E2, and subsequently to a substrate. Reactions are performed in vitro with purified E1, E2, ATP, and ubiquitin/SUMO. The formation of the thioester-linked E2~Ub/SUMO conjugate is visualized by non-reducing SDS-PAGE, as the thioester bond is sensitive to reducing agents like β-mercaptoethanol [4] [6]. Coupling this assay with mutagenesis of E1-E2 interface residues has been critical for identifying contact points essential for activity [4].

- X-ray Crystallography: As demonstrated by the structure of the Ub E1-E2(Ubc4)/Ub/ATP·Mg complex (PDB: 4II2), crystallography provides atomic-resolution snapshots of enzymatic complexes [4]. These structures reveal conformational states, key interacting residues, and the spatial organization of active sites, offering an unparalleled view of the mechanistic underpinnings of the cascade. Stabilizing transient complexes, for example by introducing disulfide bonds, is often necessary for successful structural determination [4].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Experimental Kits

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function / Application | Key Features & Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant E1 Enzymes | Catalyzes ATP-dependent activation of Ub/SUMO | Human Uba1 (Ubiquitin E1), S. pombe Uba1, Heterodimeric SAE1/SAE2 (SUMO E1) [4] [5] |

| Recombinant E2 Enzymes | Accepts activated Ub/SUMO from E1; determines chain topology | Ubc4 (Ubiquitin), Ube2L3 (Ubiquitin, for HECT/RBR E3s), UBC9 (SUMO-specific) [4] [6] [3] |

| Fluorophore-Labeled Ubiquitin/SUMO | Enables FRET-based kinetic and binding studies | Site-specifically labeled (e.g., on cysteine residues); allows real-time monitoring of conjugation dynamics [5] |

| Active E3 Ligases | Provides substrate specificity for final conjugation step | RING-type (e.g., BRCA1/BARD1), HECT-type, RBR-type (e.g., Parkin), or SUMO E3s (e.g., PIAS) [1] [2] |

| SUMOylation & Ubiquitination Assay Kits | In vitro reconstitution of entire conjugation pathway | Includes E1, E2, E3, Ub/SUMO, ATP, and reaction buffers for streamlined experimental workflow |

Functional Consequences and Therapeutic Implications

The architectural differences between the ubiquitin and SUMO systems directly translate to their distinct cellular roles and their potential as therapeutic targets.

Biological Output and Cross-Talk

- Ubiquitin: The primary functional outcomes are tied to proteasomal degradation (via K48-linked chains), DNA repair, endocytosis, and immune signaling (via K63-linked and linear chains) [2]. The vast number of E3s allows for precise, signal-responsive control of a huge array of substrate proteins.

- SUMO: Sumoylation generally modulates protein-protein interactions, transcriptional activity, subcellular localization, and stability, often by competing with ubiquitination on the same lysine residue [1] [3]. It plays critical roles in processes like nuclear transport, stress response, and, as recent research highlights, uterine receptivity and embryo implantation [3].

- Convergence in StUbL Pathways: A fascinating point of convergence is the SUMO-Targeted Ubiquitin Ligase (StUbL) pathway. Here, proteins modified by SUMO are recognized by specialized RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligases that promote their ubiquitylation and degradation [7]. This "SUMO-primed ubiquitylation" is exploited by existing anti-cancer therapeutics like arsenic trioxide, which promotes the degradation of the PML-RARα oncoprotein by enhancing its sumoylation and subsequent StUbL-dependent ubiquitylation [7].

Diagram 2: StUbL Pathway Convergence

Application in Drug Discovery

The enzymatic cascades, particularly the E3 ligases, represent attractive drug targets. Strategies include:

- Protac Technology: Leverages the ubiquitin system to degrade specific disease-causing proteins by engineering bifunctional molecules that recruit a target protein to a E3 ubiquitin ligase [2].

- SUMO-Targeting Chimeras: A nascent approach mirroring Protacs, where a chimera recruits an E3 SUMO ligase to a target protein to induce its sumoylation, which can inactivate it or mark it for degradation via the StUbL pathway [7]. This holds promise for targeting oncogenic transcription factors.

- Direct E1 Inhibition: Small-molecule inhibitors of the SUMO E1 have been identified and characterized, showing potential as a new approach to cancer treatment by disrupting the entire SUMO conjugation pathway [5].

The comparative analysis of ubiquitin and SUMO E1-E2-E3 architectures reveals a elegant balance between conserved mechanistic principles and distinct biological strategies. The ubiquitin pathway employs a strategy of massive diversification at the E2 and E3 levels to achieve precise and irreversible outcomes like degradation. In contrast, the SUMO pathway achieves broad regulatory control through a minimal, streamlined enzymatic core, favoring reversible modulation of protein function. The emerging understanding of their interplay, particularly through the StUbL pathway, opens up novel therapeutic avenues. Future research, powered by the advanced experimental tools outlined in this guide, will continue to unravel the complexities of these systems and solidify their role in the next generation of therapeutics for cancer, neurological disorders, and beyond.

The precise regulation of cellular processes relies heavily on post-translational modifications (PTMs), with ubiquitin and small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) representing two pivotal pathways. Although these modifiers share structural similarities and enzymatic cascades, they generate distinct functional outcomes through diverse modification patterns. Ubiquitination primarily targets proteins for proteasomal degradation but also regulates endocytosis, DNA repair, and kinase activation [8]. Conversely, SUMOylation predominantly modulates protein localization, activity, and stability, playing key roles in transcription, cell cycle, and DNA repair [9]. The diversity of modifications—mono, multi, and poly-chains—creates a complex language that controls virtually all aspects of eukaryotic cell biology. Understanding the nuances of these modifications is fundamental for research in targeted protein degradation and the development of novel therapeutics for cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and other pathologies [7] [9].

Comparative Analysis of Modification Types

The following tables summarize the core characteristics and functional outcomes of the diverse modification types for ubiquitin and SUMO.

Table 1: Overview of Ubiquitin and SUMO Modification Types

| Feature | Ubiquitin | SUMO |

|---|---|---|

| Modifier Size | 76 amino acids [10] [8] | ~100 amino acids (including N-terminal extension) [11] |

| Primary Chain Types | MonoUb; Homotypic PolyUb (Lys6, Lys11, Lys27, Lys29, Lys33, Lys48, Lys63, Met1); Heterotypic/Branched Chains [10] | MonoSUMO; Multi-SUMO; PolySUMO (mainly SUMO2/3) [9] |

| Key Enzymes | E1 (2 in humans: UBA1, UBA6), E2 (~38 in humans), E3 (>600 in humans, RING, HECT, RBR families) [1] | E1 (SAE1/SAE2 heterodimer), E2 (UBC9), E3 (PIAS, RanBP2, Pc2 families) [1] [9] |

| Consensus Motif | None universal; recognized by E3 ligases [8] | ψ-K-X-D/E (where ψ is a hydrophobic residue) [9] |

Table 2: Functional Consequences of Different Modification Types

| Modification Type | Ubiquitin | SUMO |

|---|---|---|

| Monoconjugation | Endocytosis, histone regulation, DNA repair, viral budding, nuclear export [8]. | Alters protein-protein interactions, subcellular localization, and protein activity [12] [11]. |

| Multi-Conjugation | (Often grouped under polyubiquitination with mixed chain types or multiple monoUb sites) | Multiple acceptor lysines on a single substrate are modified [9]. Functional outcomes can be synergistic or distinct. |

| Homotypic Poly-Chains | Lys48-linked: Proteasomal degradation [10] [8]. Lys63-linked: DNA repair, signal transduction, endocytosis [10] [8]. Other linkages (Lys6, Lys11, Lys27, Lys29, Lys33, Met1) have distinct "atypical" roles [10]. | Poly-SUMO chains (primarily SUMO2/3): Serve as a platform for recruiting proteins containing SUMO-interacting motifs (SIMs) and for SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases (StUbLs) that direct substrates for degradation [7] [9]. |

Experimental Methodologies for Analysis

Investigating the diversity of ubiquitin and SUMO modifications requires specialized experimental protocols to capture their dynamic and complex nature.

Protocol: Investigating SUMO-Ubiquitin Cross-Talk at PML Nuclear Bodies

This methodology, adapted from a key study, examines the convergence of SUMO and ubiquitin pathways upon proteasome inhibition [13].

- 1. Cell Culture and Treatment: Utilize a cell line constitutively expressing an epitope-tagged version of SUMO1 (e.g., Hep2-SUMO cells). Culture cells under standard conditions (e.g., Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal calf serum). Treat cells with a proteasome inhibitor such as MG132 (10-20 µM) for 4-6 hours to block protein degradation [13].

- 2. Immunofluorescence and Microscopy: Plate cells on glass coverslips. Post-treatment, wash cells with PBS and fix with ice-cold methanol. Permeabilize cells and incubate with primary antibodies against the SUMO1 epitope-tag (e.g., anti-c-myc) and ubiquitin. Following washes, apply fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies. Use high-resolution fluorescence or confocal microscopy to visualize the co-localization of SUMO1 and ubiquitin at PML nuclear bodies [13].

- 3. Western Blot Analysis: Harvest cells and prepare whole-cell lysates. Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a membrane. Probe the membrane with antibodies against ubiquitin to confirm an overall increase in ubiquitin-conjugated species due to proteasome inhibition. Re-probe with antibodies against free SUMO1 to observe the depletion of the free pool, indicating its shift into conjugated species [13].

- 4. Data Interpretation: Co-localization of SUMO and ubiquitin signals at discrete nuclear foci (PML bodies) upon MG132 treatment indicates pathway convergence. The increase in high-molecular-weight ubiquitin smears on Western blots, coupled with a reduction in free SUMO1, supports the hypothesis of SUMO-primed ubiquitination and a shared recycling mechanism [13].

Protocol: Identification of SUMO Substrates Using Denaturing Pull-Down

This mass spectrometry-based approach is used to identify novel SUMO substrates and characterize chain types [14].

- 1. Preparation of Cell Extract: Generate a cellular lysate with high sumoylation activity, such as from Xenopus egg extracts or cultured mammalian cells (e.g., HEK293T) [14].

- 2. His-Tagged SUMO Pull-Down: Incubate the extract with His-tagged SUMO1 or SUMO2 proteins. Under denaturing conditions (e.g., using 6 M guanidine hydrochloride), isolate the SUMO-conjugated substrates by immobilization on nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose beads. This harsh denaturation prevents non-specific binding and co-purification of non-covalent interactors [14].

- 3. Mass Spectrometry (MS) Analysis: After extensive washing under denaturing conditions, elute the bound proteins. Digest the eluted proteins with trypsin and analyze the resulting peptides by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The identified proteins not present in control pull-downs (from extracts without His-SUMO) are considered putative SUMO substrates [14].

- 4. Data Validation and Functional Analysis: Validate the sumoylation of candidate substrates by co-transfecting them with SUMO in HEK293T cells and performing immunoprecipitation and Western blotting. Perform gene ontology (GO) analysis on the identified protein list to determine their enrichment in specific biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions [14].

Pathway Diagrams and Molecular Logic

The diagrams below illustrate the core conjugation pathways and a key collaborative mechanism between SUMO and ubiquitin.

Ubiquitin and SUMO Conjugation Cascades

Diagram Title: Ubiquitin and SUMO Conjugation Cascades

SUMO-Targeted Ubiquitin Ligase (StUbL) Pathway

Diagram Title: SUMO-Targeted Ubiquitin Ligase Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This section details essential reagents and tools for studying ubiquitin and SUMO modifications.

Table 3: Key Reagents for Ubiquitin and SUMO Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132, PSI) | Blocks the 26S proteasome, leading to accumulation of ubiquitinated and SUMOylated proteins, allowing study of pathway dynamics and cross-talk [13]. | Reversible inhibitor; used to investigate protein turnover and the fate of modified proteins. |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Detect and characterize specific polyubiquitin (Lys48, Lys63, etc.) or polySUMO chains in techniques like Western blotting and immunofluorescence [10]. | Essential for deciphering the "ubiquitin code" and understanding the functional consequence of specific chain types. |

| Epitope-Tagged Ubiquitin/SUMO (e.g., His-, HA-, Myc-) | Enable affinity purification of modified substrates from cell lysates under native or denaturing conditions for mass spectrometry analysis [13] [14]. | His-tag allows purification under denaturing conditions to minimize non-specific interactions. |

| SUMO-Targeting Chimeras (SUMO-TACs) | Novel proximity-inducing modality that recruits E3 SUMO ligases to oncogenic transcription factors, promoting their inactivation and degradation [7]. | Emerging therapeutic strategy that leverages the StUbL system for targeted protein degradation. |

| Deubiquitinases (DUBs) & SENPs | Enzymes that reverse ubiquitination and SUMOylation, respectively. Used to validate the nature of modifications and study dynamics [9] [8]. | SENPs have dual roles in SUMO maturation (pre-cleavage) and deconjugation from substrates [9]. |

In eukaryotic cells, post-translational modifications (PTMs) serve as crucial regulatory mechanisms that expand the functional repertoire of the proteome. Among these, ubiquitin and SUMO (Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier) represent two evolutionarily conserved ubiquitin-like proteins with fundamentally distinct biological roles. While both modifiers share structural similarities and utilize parallel enzymatic cascades for conjugation, they direct target proteins to vastly different cellular fates. Ubiquitin predominantly serves as a degradation signal, marking proteins for destruction via the proteasome system to maintain protein homeostasis and regulate vital processes. In contrast, SUMO modification primarily functions as a regulatory signal within the nuclear compartment, fine-tuning protein interactions, localization, and activity without typically triggering degradation. This comparison guide examines the specialized cellular roles, molecular mechanisms, and experimental approaches for investigating these two essential modification pathways, providing researchers with a structured framework for understanding their unique and occasionally intersecting functions.

Molecular Machinery and Enzymatic Cascades

The conjugation pathways for ubiquitin and SUMO involve analogous E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascades, yet employ entirely distinct sets of enzymes that ensure pathway specificity.

Table 1: Comparative Enzymatic Machinery of Ubiquitin and SUMO Pathways

| Component | Ubiquitin System | SUMO System |

|---|---|---|

| E1 Activating Enzyme | UBA1 (single enzyme) | SAE1-SA2 heterodimer [15] [16] |

| E2 Conjugating Enzyme | ~35 enzymes (e.g., UBE2L3) [17] | Single enzyme: UBC9 [15] [16] |

| E3 Ligases | >600 enzymes (RING, HECT, RBR types) [18] | Limited number (PIAS, RanBP2, etc.) [16] |

| Proteases | ~100 Deubiquitinases (DUBs) | SENP, DeSI families [16] |

The SUMO E1 enzyme, a heterodimer of SAE1 and UBA2 (SAE2), activates SUMO in an ATP-dependent two-step process involving adenylation and thioester bond formation before transferring it to the sole SUMO E2 enzyme, UBC9 [15] [16]. Structural studies using cryo-EM have revealed that this transfer involves dramatic conformational changes, including a ~175° rotation of the ubiquitin-fold domain (UFD) to align the E1 and E2 active sites [15]. For ubiquitin, the E1 enzyme UBA1 charges one of approximately 35 E2 enzymes, which then partner with hundreds of different E3 ligases (RING, HECT, or RBR types) to provide substrate specificity [18]. The RBR-type E3 ubiquitin ligases, such as RNF19A and RNF19B, share characteristics of both RING and HECT types and have been shown to work with E2 enzymes like UBE2L3 [17] [18].

Figure 1: Comparative Enzymatic Cascades of Ubiquitin and SUMO Conjugation Pathways. While both systems utilize E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascades, they employ distinct enzyme sets that ensure pathway specificity and different functional outcomes for modified substrates.

Functional Specialization and Biological Roles

Ubiquitin and SUMO pathways have evolved specialized cellular functions, with ubiquitin primarily governing protein degradation and turnover, while SUMO modification predominantly regulates nuclear processes without triggering target destruction.

Ubiquitin: Master Regulator of Protein Fate

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents the primary pathway for controlled protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, functioning as a crucial regulator of protein homeostasis (proteostasis) [16]. Through formation of polyubiquitin chains linked via lysine 48 (K48), ubiquitin tags proteins for recognition and degradation by the 26S proteasome, thereby recycling amino acids for new protein synthesis [16] [18]. This degradative function regulates fundamental cellular processes including cell cycle progression, signal transduction, and quality control of misfolded proteins. Beyond its canonical role in proteasomal targeting, ubiquitin also serves non-proteolytic functions through different chain linkages. K63-linked polyubiquitin chains act as scaffolding elements in inflammatory signaling pathways, such as NF-κB activation, by facilitating protein complex assembly rather than degradation [18]. Similarly, M1-linked linear ubiquitin chains regulate inflammasome assembly and necroptosis signaling [18].

SUMO: Nuclear Regulatory Architect

SUMOylation predominantly functions as a regulatory modification within the nuclear compartment, influencing diverse processes including transcriptional regulation, DNA repair, chromatin organization, and mitosis [15] [16]. Unlike ubiquitin, SUMO modification typically alters protein function through mechanisms such as modulating protein-protein interactions, changing subcellular localization, or masking interaction surfaces rather than targeting proteins for degradation [16]. In myeloid cells, SUMO operates as a potent repressor of innate immunity, maintaining a metastable heterochromatin state at specific genomic loci to prevent spontaneous type I interferon responses [19]. SUMO achieves this repression through modification of chromatin-associated factors like MORC3, which maintains repressive chromatin marks on interferon-responsive enhancers [19]. The mammalian SUMO family comprises three main members (SUMO1, SUMO2, and SUMO3) with partially specialized functions. While SUMO2 and SUMO3 can form polySUMO chains and are dynamically regulated by various cellular stresses, SUMO1 typically functions as a monomer or chain terminator [16] [19].

Table 2: Functional Specialization of Ubiquitin and SUMO Pathways

| Characteristic | Ubiquitin | SUMO |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Protein degradation [16] [18] | Protein regulation [15] [16] |

| Chain Types | K48, K63, M1, K11, K27, K29, K33 [18] | PolySUMO (SUMO2/3) [16] |

| Cellular Localization | Cytoplasmic, nuclear [13] | Predominantly nuclear [16] |

| Stress Response | Misfolded protein clearance [16] | Heat shock, osmotic stress [20] |

| Immune Function | NF-κB activation [18] | Repression of innate immunity [19] |

Experimental Approaches and Research Methodologies

Investigating ubiquitin and SUMO pathways requires specialized methodologies to capture their dynamic nature and complex substrate profiles. Recent structural biology advances have provided unprecedented insights into the molecular mechanisms of these pathways.

Structural Biology Techniques

Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has emerged as a powerful tool for elucidating the structural basis of ubiquitin and SUMO conjugation. Recent cryo-EM studies of the human SUMO E1 (SAE1-UBA2 heterodimer) in complex with UBC9 (E2) and SUMO1 adenylate have revealed dramatic conformational changes accompanying thioester transfer [15]. These structures demonstrate a ~175° rotation of the UFD domain, aligning the active sites of E1 and E2 enzymes separated by ~67 Å in E2-free structures [15]. The resolution of these complexes at 2.7 Å enables detailed analysis of interaction networks governing E1-E2 specificity and the conformational flexibility required for catalysis.

Functional and Phenotypic Screening Approaches

Genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 screens provide powerful functional insights into ubiquitin and SUMO pathway components. In studies investigating the cytotoxic mechanism of the small molecule BRD1732, CRISPR screens identified RNF19A, RNF19B (RBR-type E3 ubiquitin ligases), and their shared E2 conjugating enzyme UBE2L3 as essential for compound sensitivity [17]. Parallel profiling using the PRISM platform across ~580 cancer cell lines further validated RNF19A expression as strongly associated with BRD1732 sensitivity, demonstrating the integration of genetic and pharmacogenetic approaches [17].

Quantitative proteomics methods, particularly those employing stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC), enable system-wide analysis of ubiquitin and SUMO modifications. Proteomic studies of SUMO-2 conjugates purified from cells treated with proteasome inhibitors have identified 73 SUMO-2-conjugated proteins whose accumulation depends on proteasome activity, revealing extensive cross-talk between SUMOylation and the ubiquitin-proteasome system [21]. These approaches demonstrate that a significant subset of SUMO-2-conjugated proteins are subsequently ubiquitinated and degraded by the proteasome, establishing cooperative integration between these pathways [21].

Figure 2: Experimental Approaches for Studying Ubiquitin and SUMO Pathways. Complementary methodologies ranging from genetic screens to structural biology provide comprehensive insights into the mechanisms and functions of these post-translational modification systems.

Pathway Crosstalk and Integrated Regulation

Despite their distinct primary functions, ubiquitin and SUMO pathways exhibit extensive cross-talk that enables integrated regulation of cellular processes. This interconnectivity is particularly evident in DNA repair, transcriptional regulation, and the cellular stress response.

Competitive modification occurs when ubiquitin and SUMO target the same lysine residue on substrate proteins. Approximately a quarter of SUMO-acceptor lysines also serve as ubiquitin conjugation sites, creating potential for direct competition [16]. This phenomenon was first observed in IκB-α, where SUMOylation protects against signal-induced ubiquitination and degradation [16] [13]. Similarly, the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) can be modified at lysine 164 by either SUMO or ubiquitin, with SUMOylation occurring during S-phase and ubiquitination triggered by DNA damage, resulting in different functional outcomes [16].

Sequential modification represents another mode of cross-talk, where SUMOylation precedes ubiquitination. This mechanism is exemplified by SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases (STUbLs) such as yeast Slx5/Slx8 and mammalian RNF4, which specifically recognize SUMO-modified proteins and catalyze their ubiquitination [20]. STUbLs use SUMO-interacting motifs (SIMs) to bind SUMO chains or SUMOylated substrates, then mediate ubiquitin transfer to target them for proteasomal degradation [20]. This sequential modification system provides a quality control mechanism for disposing of excessively SUMOylated proteins and regulates SUMO-dependent signaling events.

The proteasome inhibition model demonstrates functional integration between these pathways. Inhibition of the proteasome leads to accumulation of ubiquitinated conjugates at PML nuclear bodies, which also recruit SUMOylated proteins [13]. Under these conditions, the free SUMO pool becomes depleted but can be regenerated from the conjugated pool upon recovery, suggesting that SUMO deconjugation may be required prior to proteasomal processing of SUMOylated proteins [13].

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Crosslinking Strategy | Stabilizes E1-E2 complexes for structural studies | Disulfide bond between UBA2 C173 and UBC9 C93 for cryo-EM [15] |

| SUMO Inhibitors (SUMOi) | Chemical inhibition of sumoylation | TAK-981, ML-792 for probing SUMO function in innate immunity [19] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Block protein degradation | MG132, PSI for studying ubiquitin-SUMO cross-talk [13] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 KO Lines | Gene function analysis | RNF19A/B KO cells for validating E3 ligase dependencies [17] |

| SILAC Proteomics | Quantitative modification profiling | Identification of SUMO-2 targets affected by proteasome inhibition [21] |

| STUbL Mutants | Study SUMO-ubiquitin cross-talk | slx5Δ yeast strains accumulating SUMO chains [20] |

Ubiquitin and SUMO represent two highly specialized ubiquitin-like modification systems with distinct yet complementary cellular functions. Ubiquitin primarily serves as a degradation signal through the proteasome system, but also functions in non-proteolytic signaling through specific chain linkages. SUMO modification predominantly acts as a regulatory mechanism within the nuclear compartment, controlling transcription, DNA repair, and chromatin organization. Despite their specialization, these pathways exhibit extensive cross-talk through competitive modification at shared lysine residues and sequential modification via STUbLs, enabling integrated cellular responses to stress and DNA damage. The continued development of research tools including selective inhibitors, CRISPR-based screening approaches, and high-resolution structural methods will further advance our understanding of these essential regulatory pathways and their therapeutic potential in human disease.

PML nuclear bodies (PML-NBs) are dynamic, membrane-less organelles that function as central regulatory hubs within the nucleus, serving as a critical interface between the SUMOylation and ubiquitin modification pathways. These spherical structures, ranging from 0.1 to 2 µm in diameter, are nucleated by the PML protein, which polymerizes into a scaffold that concentrates hundreds of unrelated partner proteins [22] [23]. The integrative function of PML-NBs is particularly evident in their role in facilitating SUMO-primed ubiquitylation, a sequential post-translational modification process where SUMO modification serves as a signal for subsequent ubiquitin conjugation [7]. This unique capability positions PML-NBs as a key convergence point in cellular regulation, enabling the nucleus to efficiently coordinate diverse processes including protein quality control, transcriptional regulation, and stress response through spatial proximity [22] [23].

The architectural organization of PML-NBs directly supports their integrative function. Their core structural component, the PML protein, contains three critical lysine residues (K65, K160, and K490) that undergo SUMOylation and a SUMO-interacting motif (SIM) that facilitates non-covalent interactions with other SUMOylated proteins [22]. This combination of covalent SUMO modification and non-covalent SIM interactions creates a SUMO-rich environment within PML-NBs that serves as a platform for recruiting SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases (StUbLs) such as RNF4, which bridge the SUMO and ubiquitin pathways [7] [24]. The ability of PML-NBs to spatially concentrate these modification systems allows them to function as efficient sensors and integrators of cellular stress signals, ultimately directing client proteins toward specific fates including activation, sequestration, or degradation [22] [23].

Mechanistic Foundations: SUMO-Ubiquitin Networking in PML-NBs

The SUMO-Ubiquitin Sequential Modification Cascade

The integrative function of PML-NBs is exemplified by a well-defined biochemical cascade in which SUMO modification primes proteins for subsequent ubiquitylation. This SUMO-primed ubiquitylation pathway begins with stress-induced SUMOylation of client proteins, which can occur either directly within PML-NBs or in the nucleoplasm prior to recruitment [7] [24]. SUMOylated proteins are then recognized and concentrated within PML-NBs through SUMO-SIM interactions with the PML scaffold [22]. The high local concentration of SUMOylated proteins within PML-NBs facilitates their recognition by StUbLs, particularly RNF4, which contains multiple SIMs that bind polySUMO chains [24]. Once bound to SUMOylated substrates, RNF4 catalyzes their ubiquitylation, marking them for proteasomal degradation or altering their functional properties through non-proteolytic ubiquitin signaling [7] [25].

This sequential modification system is not limited to degradation pathways. Recent research has revealed that SUMO-primed ubiquitylation within PML-NBs can also trigger protective functions through the action of the p97/VCP disaggregase, which extracts ubiquitylated proteins from condensates and aggregates [25]. This dual capacity for directing proteins toward degradation or disaggregation highlights the versatile regulatory output generated by the SUMO-ubiquitin networking within PML-NBs and establishes them as decision-making hubs that determine protein fate in response to proteotoxic stress.

Structural Basis for PML-NB Function

The unique architecture of PML-NBs enables their role as integrative centers for post-translational modifications. PML proteins self-assemble into spherical shells through oligomerization of their N-terminal RBCC domains (RING, B-boxes, and coiled-coils), forming a stable insoluble scaffold [22] [23]. The interior of this shell is filled with a dynamic mixture of client proteins that undergo constant exchange with the nucleoplasm, creating a liquid-like condensate that concentrates modification enzymes and their substrates [23]. This structural organization is maintained through a combination of SUMO-SIM interactions and liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) driven by the multivalent nature of the PML protein and its associated partners [22].

Table 1: Core Structural Components of PML Nuclear Bodies

| Component | Type | Key Features | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| PML (isoforms I-VI) | Scaffold protein | RBCC domain, SUMOylation sites (K65, K160, K490), SIM motif | Forms structural shell, nucleates body assembly, recruits client proteins |

| SUMO (1, 2/3) | Modifier | Forms polymeric chains, stress-inducible (SUMO2/3) | Primes proteins for ubiquitylation, mediates protein-protein interactions |

| RNF4 | SUMO-targeted E3 ubiquitin ligase | Multiple SIM motifs, RING domain | Recognizes SUMOylated proteins, catalyzes ubiquitylation |

| SP100 | Permanent component | SUMOylation-dependent recruitment | Structural stabilization, contributes to antiviral function |

Post-translational modifications play a crucial role in regulating PML-NB dynamics. Arsenic treatment, for example, sharply increases PML-NB formation and promotes the recruitment of both the SUMO-conjugating enzyme UBC9 and substrate proteins like SP100, creating an environment that facilitates SUMOylation [23]. This stress-induced enhancement of PML-NB biogenesis demonstrates how these structures dynamically respond to cellular conditions to modulate the flux of proteins through the SUMO-ubiquitin modification system.

Functional Comparison: PML-NBs in Oncology vs. Neurology

PML-NBs in Leukemia Therapy

The therapeutic potential of manipulating PML-NBs is best established in oncology, particularly in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). In APL, the oncogenic PML-RARα fusion protein disrupts normal PML-NB organization, blocking myeloid differentiation and promoting leukemogenesis [26]. Two effective therapeutic agents, arsenic trioxide (ATO) and all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), both function through PML-NB-dependent mechanisms to eliminate the PML-RARα oncoprotein [7] [26]. ATO induces SUMOylation of PML-RARα, leading to its recognition by RNF4, ubiquitylation, and subsequent proteasomal degradation [24]. ATRA, meanwhile, activates RAR signaling and promotes PML-NB reorganization, releasing normal PML protein to reassemble into functional nuclear bodies [26].

Recent research has revealed additional therapeutic opportunities for targeting PML-NBs in non-APL leukemias. The combination of CDK4/6 inhibitors with ATRA synergistically enhances the formation of enlarged PML-NBs through conflicting cell cycle signals, leading to potent cytotoxicity across multiple acute myeloid leukemia cell lines [26]. This combination treatment triggers irreversible cell growth arrest, myeloid differentiation, or apoptosis depending on the cellular context, demonstrating how modulation of PML-NB dynamics can produce diverse anti-leukemic effects.

Table 2: PML-NB Targeting Therapeutics in Oncology

| Therapeutic Agent | Molecular Target | Effect on PML-NBs | Therapeutic Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic Trioxide (ATO) | PML/PML-RARα | Induces SUMOylation, recruits RNF4 | Degradation of PML-RARα, differentiation/apoptosis |

| All-trans Retinoic Acid (ATRA) | RARα/PML-RARα | Reorganizes PML-NB structure | Releases normal PML, promotes differentiation |

| CDK4/6 inhibitor + ATRA | Cell cycle signaling | Forms enlarged PML-NBs | Conflicting signal-induced cytotoxicity, differentiation |

PML-NBs in Neurodegenerative Disease

In neurological contexts, PML-NBs have emerged as potential therapeutic targets for countering protein aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases. Recent groundbreaking research has demonstrated that recruiting TDP-43—a protein that forms pathological inclusions in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and Alzheimer's disease—to PML-NBs triggers a protective SUMOylation-ubiquitylation cascade that limits its aggregation [25]. This protective pathway involves compartmentalization of TDP-43 within PML-NBs, followed by SUMO-primed ubiquitylation that requires the p97/VCP disaggregase to maintain TDP-43 in a soluble state under proteotoxic stress conditions [25] [27].

The mechanistic difference between the oncological and neurological applications of PML-NB targeting lies in the ultimate fate of the modified client proteins. In oncology, SUMO-primed ubiquitylation typically directs oncoproteins toward proteasomal degradation, while in neurological contexts, this modification pathway appears to facilitate extraction from aggregates and maintenance of solubility without necessarily leading to degradation [7] [25]. This functional divergence highlights the remarkable versatility of PML-NBs as cellular tools for managing different types of proteostasis challenges.

Experimental Approaches and Data Comparison

Methodologies for Studying PML-NB Functions

Research into PML-NB functions employs diverse methodological approaches designed to characterize their dynamic composition, organizational changes under stress conditions, and functional outcomes. Key experimental protocols include:

PML-NB Formation and Drug Response Assay [26]:

- Cell lines (e.g., NB4 APL cells, HL60 non-APL cells) treated with ATRA (1µM), CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib (1µM), or combination

- PML-NB quantification via immunofluorescence using anti-PML antibodies at 24, 48, and 72 hours

- Assessment of myeloid differentiation markers (CD11b, CD38) by flow cytometry

- Cell cycle analysis by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry

- Irreversible growth arrest measured by cell counting after drug washout

SUMO-Ubiquitin Cascade Analysis [25]:

- HEK293T cells transfected with Flag-tagged TDP-43 constructs (WT, SUMO2-TDP-43, tetra-SUMO2-TDP-43)

- Stress induction via sodium arsenite (0.5mM, 1h) or heat shock (43°C, 1h)

- Cellular fractionation into detergent-soluble and insoluble components

- Immunoblot analysis of fractions with anti-Flag antibodies

- Ubiquitylation assessment under proteasome (MG132) or p97 (CB-5083) inhibition

Protein Recruitment and Interaction Studies [24] [25]:

- Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) to measure protein dynamics in PML-NBs

- Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) to detect molecular interactions

- Proximity-inducing recruitment systems (e.g., rapamycin-induced dimerization) to force client localization to PML-NBs

- Immunoprecipitation of SUMOylated and ubiquitylated proteins under stress conditions

Comparative Experimental Data

Table 3: Quantitative Analysis of PML-NB Interventions Across Disease Models

| Experimental Condition | System | Key Metrics | Results | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATRA + CDK4/6 inhibitor (palbociclib) | HL60 leukemia cells | PML-NB signal intensity | ~3.5-fold increase vs. control | [26] |

| Irreversible growth arrest | 80-90% after 72h pre-exposure | [26] | ||

| AML mouse model | Therapeutic efficacy | Significant improvement with minimal effect on normal hematopoiesis | [26] | |

| Arsenic trioxide treatment | APL cells | PML-RARα degradation | Complete clearance at therapeutic concentrations | [24] |

| Tetra-SUMO2-TDP-43 recruitment to PML | HEK293T cells + arsenite stress | Insoluble TDP-43 fraction | Reduced to <10% vs. 40% in WT TDP-43 | [25] |

| Tetra-SUMO2-TDP-43 + heat stress | HEK293T cells | Insoluble TDP-43 fraction | Reduced to ~20% vs. 80% in WT TDP-43 | [25] |

The experimental data demonstrate consistent patterns across different cellular models and stressors. First, interventions that enhance PML-NB formation or function consistently produce protective outcomes in their respective disease contexts. Second, the combination of multiple stressors or signals (e.g., cell cycle arrest plus mitogenic signaling) generates synergistic effects on PML-NB dynamics and function. Third, the recruitment of aggregation-prone proteins to PML-NBs consistently reduces their accumulation in insoluble fractions, supporting a general protective function of this compartment against proteotoxicity.

Visualization of Core Signaling Pathways

SUMO-Primed Ubiquitylation in PML-NBs

Diagram 1: SUMO-primed ubiquitylation pathway in PML nuclear bodies. Cellular stress induces PML-NB formation and SUMOylation of client proteins. SUMOylated proteins are recognized by the StUbL RNF4, which catalyzes ubiquitylation, determining final protein fate (degradation or disaggregation).

Therapeutic Targeting of PML-NBs in Disease

Diagram 2: Comparative therapeutic strategies targeting PML-NBs. In oncology (top), ATO induces SUMOylation and RNF4-mediated degradation of PML-RARα, while ATRA promotes PML-NB reorganization and differentiation. In neurology (bottom), TDP-43 recruitment to PML-NBs triggers a protective SUMO-ubiquitin cascade requiring p97 disaggregase.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for PML-NB Studies

| Reagent/Cell Line | Specific Function | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| NB4 APL cell line | Expresses PML-RARα fusion protein | Modeling APL, studying ATO/ATRA mechanisms |

| HL60 non-APL cell line | PML-RARA-negative myeloid leukemia | Studying non-APL differentiation therapies |

| Anti-PML antibodies (5E10) | Detect endogenous PML protein | Immunofluorescence, Western blotting |

| Palbociclib | CDK4/6 inhibitor | Inducing G1 cell cycle arrest, studying conflict signals |

| Arsenic trioxide (ATO) | Induces PML SUMOylation | Triggering SUMO-primed ubiquitylation cascade |

| All-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) | Activates RAR signaling | Promoting differentiation, PML-NB reorganization |

| RNF4 shRNA/siRNA | Depletes cellular RNF4 | Assessing requirement for SUMO-targeted ubiquitylation |

| MG132 proteasome inhibitor | Blocks proteasomal degradation | Distinguishing degradative vs. non-degradative ubiquitylation |

| CB-5083 p97 inhibitor | Inhibits p97/VCP disaggregase | Testing p97 role in aggregate resolution |

| Rapamycin-induced dimerization system | Forces protein proximity to PML-NBs | Studying recruitment effects on client proteins |

This comprehensive toolkit enables researchers to manipulate and monitor PML-NB dynamics across multiple experimental contexts. The combination of specific cell lines, pharmacological inhibitors, and molecular tools allows for detailed dissection of the SUMO-ubiquitin networks centered on these nuclear bodies, facilitating both basic mechanistic studies and therapeutic development.

PML nuclear bodies serve as a critical integration point for SUMO and ubiquitin signaling pathways, coordinating cellular responses to diverse stress signals through spatial organization of sequential post-translational modifications. The experimental data consistently demonstrate that therapeutic strategies targeting PML-NB function produce potent effects in both oncological and neurological contexts, albeit through distinct mechanistic endpoints—directing proteins toward degradation in cancer therapy while promoting solubility maintenance in neurodegenerative models. This functional versatility stems from the core capacity of PML-NBs to concentrate SUMOylation machinery and SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases, creating a modular system that can be adapted to different proteostasis challenges.

The emerging paradigm of induced proximity to PML-NBs as a therapeutic strategy represents a promising avenue for future drug development across multiple disease contexts. Whether through small molecule-induced recruitment, such as the combination of CDK4/6 inhibitors with ATRA in leukemia, or through more targeted proximity-inducing modalities like SUMO-targeting chimeras, the controlled spatial reorganization of disease-relevant proteins within PML-NBs offers a powerful approach to reprogram cellular fate decisions. As our understanding of PML-NB composition, dynamics, and regulatory networks continues to advance, so too will opportunities to develop innovative therapies that leverage this key convergence point in nuclear organization and signaling.

The post-translational modification of proteins by ubiquitin (Ub) and small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) constitutes sophisticated regulatory languages that cells use to control nearly all aspects of eukaryotic biology. These modifications operate through analogous "writer-reader-eraser" paradigms, where dedicated enzymatic cascades covalently attach modifiers to substrates (writers), specialized domains interpret these modifications (readers), and protease activities remove the signals (erasers) [10] [28]. While sharing structural similarities, the ubiquitin and SUMO pathways have evolved distinct specificities and functions. The ubiquitin code exhibits tremendous complexity through the formation of polyubiquitin chains of eight different linkage types—Lys6, Lys11, Lys27, Lys29, Lys33, Lys48, Lys63, and Met1—each capable of encoding distinct cellular outcomes [10] [29]. In contrast, the SUMO pathway primarily modulates protein-protein interactions, subcellular localization, and stability through more limited chain formation [28] [30]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the molecular machinery governing pathway specificity in these systems, with experimental approaches for their study.

Comparative Architecture of Ubiquitin and SUMO Systems

Table 1: Core Machinery of Ubiquitin and SUMO Pathways

| Component | Ubiquitin System | SUMO System |

|---|---|---|

| E1 Activating Enzymes | Dozens of E1 variants [31] | Single heterodimeric E1 (SAE1-SAE2) [28] |

| E2 Conjugating Enzymes | ~53 E2 enzymes in humans [31] | Single E2 (UBC9) [28] |

| E3 Ligating Enzymes | >500 E3 ligases (RING, HECT, RBR) [31] [30] | Limited E3s (PIAS family, RanBP2) [28] |

| Modification Types | MonoUb, multi-monoUb, 8 homotypic chains, heterotypic chains, branched chains [10] [30] | MonoSUMO, polySUMO chains (primarily SUMO2/3) [28] [30] |

| Reader Domains | Ubiquitin-Binding Domains (UBDs) [32] [10] | SUMO-Interacting Motifs (SIMs) [28] [30] |

| Eraser Enzymes | ~100 Deubiquitinases (DUBs) [33] | 7 Sentrin-specific proteases (SENPs) in humans [28] |

Figure 1: Comparative architecture of Ubiquitin and SUMO pathway machinery showing dramatic differences in enzyme complexity.

Writers: Specificity in Modification

Ubiquitin Writers: Extreme Diversification

The ubiquitination cascade begins with E1 activation, proceeds through E2 conjugation, and culminates in E3-mediated substrate modification. Humans possess dozens of E1 enzymes, approximately 53 E2s, and over 500 E3 ligases [31]. This extensive diversification enables exquisite substrate specificity and functional variety. E3 ligases fall into three major structural classes: RING types that facilitate direct Ub transfer from E2 to substrate, HECT types that form a catalytic E3-Ub thioester intermediate, and RBR types that employ a hybrid mechanism [30]. Linkage specificity is determined by cooperative interactions between E2 and E3 enzymes. For example, the RING E3 ligase RNF8 collaborates with the E2 enzyme Ubc13 to promote Lys63-linked ubiquitination on histone H1 in DNA damage response [32], while other E2-E3 pairs generate different chain types.

SUMO Writers: Constrained Specificity

In stark contrast, the SUMO pathway employs a single heterodimeric E1 (SAE1-SAE2) and a single E2 (UBC9) [28]. UBC9 uniquely recognizes SUMO consensus motifs (ψKxE, where ψ is a hydrophobic residue) on substrates, enabling direct E2-substrate recognition rarely observed in the ubiquitin system. This limited enzymatic repertoire is supplemented by a small number of E3 ligases, primarily from the PIAS family and RanBP2, which enhance conjugation efficiency and specificity but are not always essential [28]. SUMO chain formation occurs predominantly through SUMO2/3, which contain internal consensus sites, while SUMO1 primarily acts as a chain terminator [30].

Table 2: Writer Enzyme Specificity and Functions

| Feature | Ubiquitin Writers | SUMO Writers |

|---|---|---|

| E1 Diversity | Multiple E1 enzymes [31] | Single heterodimeric E1 (SAE1-SAE2) [28] |

| E2 Diversity | ~53 E2s with distinct functions [31] | Single E2 (UBC9) with broad specificity [28] |

| E3 Diversity | Hundreds of RING, HECT, RBR E3s [31] [30] | Limited E3 families (PIAS, RanBP2) [28] |

| Substrate Recognition | Primarily through E3-substrate interactions [31] | E2 (UBC9) directly recognizes consensus motifs [28] |

| Chain Formation | Extensive homotypic, heterotypic, and branched chains [10] [30] | Primarily SUMO2/3 chains; SUMO1 as chain terminator [30] |

| Stress Response | Diverse DNA damage responses via RNF8, RNF168 [32] | Heat shock, oxidative stress induce SUMO2/3 chains [28] [30] |

Readers: Decoding the Signals

Ubiquitin Readers: Linkage-Specific Recognition

Ubiquitin signals are interpreted by ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) that exhibit remarkable specificity for different ubiquitin chain architectures. Over 11 distinct UBD families have been identified, including UIM, UBA, UBZ, and NZF domains [31]. These domains often function cooperatively in multi-domain proteins to achieve linkage selectivity. For instance, in DNA double-strand break repair, RNF168 possesses tandem UDM motifs that specifically recognize ubiquitinated H1 and H2A histones, enabling propagation of DNA damage signals [32]. Different UBD arrangements allow discrimination between ubiquitin chain types—Lys48-linked chains typically target substrates for proteasomal degradation, while Lys63-linked and linear Met1-linked chains regulate signaling pathways in inflammation and beyond [29].

SUMO Readers: SIM-Dependent Interactions

SUMO modifications are recognized by proteins containing SUMO-interacting motifs (SIMs)—short hydrophobic sequences typically flanked by acidic residues [28] [30]. SIM-containing proteins often function in transcriptional regulation, DNA repair, and protein localization. Unlike the diverse UBD repertoire, SIMs represent a more uniform recognition system. The functional outcomes of SUMO recognition include altered subcellular localization, modified enzymatic activity, and changes in protein-protein interactions. SIM-mediated interactions frequently promote the assembly of multi-protein complexes at specific genomic locations or sites of DNA damage.

Figure 2: Reader domains decode Ubiquitin and SUMO modifications into distinct functional outcomes.

Erasers: Precision Signal Removal

Ubiquitin Erasers: Extensive DUB Diversity

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) provide temporal control of ubiquitin signals, with approximately 100 DUBs in humans belonging to several protease families [33]. DUBs exhibit remarkable specificity for different ubiquitin chain types and cellular contexts. Some DUBs preferentially cleave specific linkage types, while others edit ubiquitin chains or recycle ubiquitin from proteasomal substrates. This extensive DUB repertoire allows precise spatial and temporal control of ubiquitin signaling, with mutations in specific DUBs linked to various human diseases.

SUMO Erasers: SENP Specificity

SUMO deconjugation is mediated by sentrin-specific proteases (SENPs)—seven human enzymes with distinct subcellular localizations and substrate preferences [28]. SENPs exhibit specificity for different SUMO paralogs: SENP1 and SENP2 process all SUMO isoforms, while SENP3, SENP5, SENP6, and SENP7 preferentially deconjugate SUMO2/3 and SUMO chains [28]. This compartmentalization and paralog specificity ensures precise regulation of SUMYLATION dynamics in response to cellular signals.

Table 3: Eraser Enzyme Specificity and Regulation

| Feature | Ubiquitin Erasers (DUBs) | SUMO Erasers (SENPs) |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Diversity | ~100 deubiquitinases [33] | 7 sentrin-specific proteases [28] |

| Specificity Basis | Linkage type, cellular context [10] | SUMO paralog preference, subcellular localization [28] |

| Functional Roles | Signal termination, ubiquitin recycling, chain editing [33] | SUMO precursor processing, deconjugation [28] |

| Regulatory Mechanisms | Oxidation, phosphorylation, subcellular localization [34] | Transcriptional regulation, protein stability, oxidation [28] |

| Pathway Crosstalk | Regulation of SUMO pathways via ubiquitination [30] | Regulation of ubiquitin pathways via deSUMOylation [30] |

Experimental Approaches for Pathway Analysis

Ubiquitinomics and SUMO Proteomics

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics has revolutionized the study of ubiquitin and SUMO modifications. The key challenge is the low stoichiometry of these modifications, requiring efficient enrichment strategies before LC-MS/MS analysis.

Ubiquitin Modification Analysis: The most successful approach uses tandem ubiquitin-binding entities (TUBEs) or anti-K-ε-GG antibodies to enrich ubiquitinated peptides [31] [33]. After trypsin digestion, ubiquitinated sites are marked by a characteristic di-glycine (GG) remnant with a mass increment of 114.043 Da on modified lysines [31]. For comprehensive analysis, His-tagged ubiquitin expressed in cells enables purification under denaturing conditions, significantly reducing contaminating proteins [31]. Label-free quantification provides more reliable results than isotope-labeling methods for ubiquitinomics, as the latter can interfere with antibody-antigen interactions during enrichment [33].

SUMO Modification Analysis: SUMO proteomics faces additional challenges due to the larger tryptic fragments. Innovative approaches use mutated SUMO variants (Q87T or T90K) that generate shorter tags upon trypsin digestion, enabling better MS identification [30]. Antibodies specific for SUMO isoforms facilitate the enrichment of SUMOylated proteins, though the field lags behind ubiquitinomics in site-level mapping.

Functional Validation Experiments

Genetic Manipulation: RNAi or CRISPR-Cas9-mediated knockout of specific writers, readers, or erasers reveals their functional roles. For example, RNF168 deficiency causes defective DNA damage repair due to impaired H2A ubiquitination [32].

In Vitro Reconstitution: Purified E1, E2, and E3 components allow biochemical characterization of modification specificity. These systems can determine linkage specificity and kinetic parameters [30].

Cross-linking Mass Spectrometry: Identifies direct interactions between readers and specific ubiquitin/SUMO modifications, revealing structural basis for recognition [34].

Figure 3: Experimental workflows for ubiquitinomics and SUMO proteomics analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitin/SUMO Studies

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Applications and Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity Tools | Anti-K-ε-GG antibody [33], TUBE domains [35], GST-qUBA [35] | Enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins/peptides for proteomics |

| Activity Probes | HA-Ub-VS, SUMO-VS [34] | Active-site directed profiling of DUBs and SENPs |

| Linkage-Specific Reagents | Linkage-specific UBDs [10], linkage-specific antibodies [10] | Detection and purification of specific ubiquitin chain types |

| Expression Constructs | His-tagged ubiquitin [31], SUMO mutants (Q87T/T90K) [30] | Affinity purification and improved MS identification |

| Inhibitors | Ginkgolic acid [28], ML792 [34] | Selective inhibition of SUMO E1 and other pathway components |

| Mass Spec Standards | AQUA ubiquitin peptides [10] | Absolute quantification of ubiquitin modifications |

Pathway Crosstalk and Hybrid Chains

An emerging paradigm in ubiquitin and SUMO biology is the extensive crosstalk between these modification systems, particularly through the formation of hybrid ubiquitin-SUMO chains [30]. Proteomic studies have identified ubiquitination on multiple lysine residues in all SUMO isoforms (SUMO1-3), suggesting diverse hybrid chain architectures [30]. These hybrid chains appear to be particularly important during cellular stress responses, where they may confer enhanced specificity and affinity for cognate receptors [30]. The SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases (STUbLs) represent a direct molecular bridge between these pathways, recognizing SUMOylated proteins and promoting their ubiquitination, often targeting them for degradation [36] [30]. This sophisticated interplay expands the coding potential of both systems and enables integrated response to genomic and proteostatic challenges.

Concluding Perspectives

The ubiquitin and SUMO pathways represent two sophisticated post-translational regulatory systems with distinct evolutionary strategies for achieving specificity. The ubiquitin system employs massive diversification of its enzymatic components to generate an incredibly complex code with diverse functional outcomes. In contrast, the SUMO pathway achieves specificity through a minimalist enzymatic core complemented by context-dependent factors that guide its functions. For drug development professionals, these differences present unique opportunities: the ubiquitin system offers numerous specific targets (e.g., individual E3s or DUBs) for therapeutic intervention, while the SUMO pathway presents challenges and opportunities for more global modulation. The emerging understanding of hybrid chains and pathway crosstalk reveals even greater complexity than previously appreciated and highlights the need for continued investigation into how these two systems collaboratively regulate cellular physiology and pathophysiology.

Advanced Technologies for Pathway Interrogation and Therapeutic Exploitation

Proteomic Workflows for Mapping the Ubiquitinome and SUMOylome

Protein post-translational modifications (PTMs) are crucial regulatory mechanisms that expand protein functionality by modifying amino acid chains after translation [37]. Among the diverse PTMs, ubiquitination and SUMOylation represent two essential pathways that regulate virtually all cellular processes. Ubiquitination primarily targets proteins for proteasomal degradation but also regulates protein-protein interactions, while SUMOylation modifies protein stability, subcellular localization, and molecular interactions [38] [39]. The systematic study of these modifications—termed the "ubiquitinome" and "SUMOylome"—has been revolutionized by advanced proteomic technologies, enabling researchers to map modification sites on a proteome-wide scale. These approaches provide critical insights for drug development, particularly in oncology and infectious diseases, where these pathways are frequently dysregulated [40] [41]. This guide compares contemporary proteomic workflows for ubiquitinome and SUMOylome analysis, highlighting methodological innovations, performance benchmarks, and practical applications for research and drug discovery.

Comparative Workflow Performance: Ubiquitinome vs. SUMOylome

Table 1: Performance comparison of ubiquitinome profiling workflows using different mass spectrometry acquisition methods.

| Workflow Parameter | Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) | Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) | Fractionated DDA (UbiSite) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical K-GG Peptide Identifications | 21,434 | 68,429 | ~30% more than single-shot DDA |

| Quantitative Precision (Median CV) | >20% | ~10% | Not specified |

| Protein Input Requirement | 500 µg - 2 mg | 2 mg | 40 mg |

| MS Acquisition Time | 125 min | 75 min | ~20x longer than DIA |

| Missing Values in Replicates | ~50% | Minimal | Not specified |

| Key Advantages | Well-established | Superior coverage, precision, reproducibility | High identification numbers |

| Main Limitations | Semi-stochastic sampling, missing values | Complex data processing | High input, extensive fractionation |

Table 2: Characteristic features of ubiquitinome versus SUMOylome profiling.

| Feature | Ubiquitinome | SUMOylome |

|---|---|---|

| Modification Type | Ubiquitin (76 amino acids) | SUMO (∼100 amino acids) |

| Primary Enrichment Strategy | K-ε-GG antibody immunoaffinity | SUMO antibody immunoprecipitation |

| Typical Scale of Identifications | >70,000 ubiquitinated peptides | 803 SUMO2/3 targets (synaptic preparation) |

| Cellular Abundance | Highly abundant | Relatively low abundance |

| Key Biological Functions | Proteasomal degradation, signaling, DNA repair | Protein stability, nuclear transport, stress response |

| Technical Challenges | High dynamic range, chain topology | Low stoichiometry, rapid reversal |

| Recommended Lysis Buffer | Sodium deoxycholate (SDC) with chloroacetamide | Denaturing buffers with N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) |

| Protease Inhibition | Proteasome inhibitors (MG-132) | SENP inhibitors (NEM) |

Ubiquitinome Profiling: Methodologies and Applications

Advanced Ubiquitinome Workflow Optimizations

Recent innovations in ubiquitinome profiling have dramatically enhanced coverage, reproducibility, and quantitative accuracy. A groundbreaking development comes from the implementation of sodium deoxycholate (SDC)-based lysis protocols supplemented with chloroacetamide (CAA), which when compared to conventional urea-based buffers, yields approximately 38% more K-GG peptides (26,756 vs. 19,403) without compromising enrichment specificity [41]. This protocol immediately inactivates cysteine ubiquitin proteases through alkylation, preserving the ubiquitination landscape. When coupled with data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry (DIA-MS) and processed through deep neural network-based software (DIA-NN), this workflow quantifies over 70,000 ubiquitinated peptides in single MS runs—more than tripling the identification numbers achievable with data-dependent acquisition (DDA) while significantly improving quantitative precision (median CV of ~10%) [41].

The power of advanced ubiquitinomics is exemplified in studies mapping substrates of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs). When profiling USP7 inhibition, researchers simultaneously monitored ubiquitination changes and abundance shifts for more than 8,000 proteins at high temporal resolution [41]. This approach revealed that while ubiquitination of hundreds of proteins increased within minutes of USP7 inhibition, only a small fraction underwent degradation, effectively distinguishing regulatory ubiquitination from degradative ubiquitination events—a critical distinction for drug development efforts targeting DUBs.

Application in Host-Pathogen Interactions

Ubiquitinome profiling has yielded significant insights into host-pathogen interactions, particularly in the context of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection. A comprehensive ubiquitinome analysis of human macrophages infected with Mtb identified 1,618 proteins with altered ubiquitination levels, with 1,182 lysine-ubiquitination sites in 828 proteins showing increased ubiquitination and 1,077 sites in 790 proteins displaying decreased ubiquitination [40]. Bioinformatic analysis revealed that proteins involved in immune response pathways, including autophagy, lysosomal function, NF-κB signaling, necroptosis, and ferroptosis, were predominantly upregulated. Additionally, the ubiquitination levels of numerous proteins governing conserved physiological processes—ribosome biogenesis, spliceosome function, nucleocytoplasmic transport, and mRNA surveillance—were significantly altered, suggesting these pathways are regulated by ubiquitination during pathogen challenge [40].

Diagram 1: Ubiquitination in host-pathogen interactions. This pathway illustrates how Mtb infection triggers ubiquitination changes that regulate immune pathways and cellular processes, ultimately determining infection outcome.

SUMOylome Profiling: Techniques and Research Applications

SUMOylome Workflow Specifications

SUMOylome mapping presents unique technical challenges compared to ubiquitinome analysis, primarily due to the lower stoichiometry of SUMOylation and its dynamic, reversible nature. Successful SUMOylome profiling typically requires denaturing immunoprecipitation with specific SUMO antibodies under conditions that preserve the relatively labile isopeptide bond while preventing deSUMOylation by SENP enzymes [42] [43]. Standard protocols incorporate N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) during sample preparation to inhibit SENP activity, maintaining the endogenous SUMOylation state [42]. Unlike ubiquitinome studies that benefit from tryptic digestion generating characteristic K-GG remnant peptides, SUMOylome analyses may utilize either trypsin or Lys-C digestion, with the latter producing longer remnant peptides (K-GGRLRLVLHLTSE) that can enhance identification specificity [41].

A notable application of SUMOylome profiling comes from neuroscience research, where investigators combined subcellular fractionation of postnatal day 14 rat brains with denaturing immunoprecipitation using SUMO2/3 antibodies followed by tandem mass spectrometry [42]. This approach identified 803 candidate SUMO2/3 targets, representing approximately 18% of the synaptic proteome, including neurotransmitter receptors, transporters, adhesion molecules, scaffolding proteins, and vesicular trafficking machinery. The findings established SUMO2/3 as a central regulator of synaptic organization and function, with particular relevance during synaptogenesis [42].

Plant SUMOylome Research Advances

While SUMOylation is essential for plant survival, studies of plant SUMOylome have been relatively scarce compared to mammalian systems due to challenges in identifying SUMOylated proteins and their specific modification sites [38] [43]. Recent advances in proteomic workflows are now enabling more comprehensive mapping of SUMO signaling pathways in plants, revealing SUMOylation's critical roles in stress tolerance, cell proliferation, protein stability, and gene expression regulation [38]. These developments are particularly significant for understanding plant stress response mechanisms and developing strategies to enhance crop resilience.

Diagram 2: SUMOylome profiling workflow. This experimental workflow illustrates the key steps in SUMOylome analysis, from sample preparation to target identification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential research reagents for ubiquitinome and SUMOylome studies.

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lysis Reagents | Sodium deoxycholate (SDC), Urea, RIPA buffer | Protein extraction while preserving PTMs |

| Protease Inhibitors | MG-132 (proteasome), NEM (SENP), PR-619 (DUB) | Inhibit modification reversal and degradation |

| Enrichment Antibodies | K-ε-GG, SUMO1, SUMO2/3 antibodies | Immunoaffinity purification of modified peptides |

| Digestion Enzymes | Trypsin, Lys-C | Protein digestion to generate characteristic remnant peptides |

| MS Acquisition Modes | DDA, DIA | Peptide identification and quantification |

| Data Processing Tools | MaxQuant, DIA-NN | Spectral analysis and false discovery rate control |

| Validation Methods | Parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) | Targeted verification of identified sites |

Contemporary proteomic workflows for ubiquitinome and SUMOylome mapping have achieved unprecedented depth and precision, enabling researchers to decipher the complex regulatory networks governed by these essential post-translational modifications. The implementation of SDC-based lysis protocols coupled with DIA-MS acquisition and neural network-based data processing has particularly transformed ubiquitinome profiling, tripling identification numbers while significantly improving reproducibility [41]. For SUMOylome studies, refined immunoprecipitation strategies and specialized digestion protocols are illuminating the roles of SUMOylation in diverse biological contexts, from synaptic function to plant stress responses [38] [42].

These advanced methodologies are proving indispensable for drug discovery, particularly for targeting deubiquitinating enzymes and ubiquitin ligases in oncology and host-pathogen interactions [40] [41]. The ability to distinguish degradative from regulatory ubiquitination events provides crucial insights for developing more specific therapeutic agents. As these technologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly uncover new biological insights and therapeutic opportunities in the complex landscapes of ubiquitin and SUMO signaling pathways.

High-Throughput Screening for UPS and SUMO Pathway Modulators

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) pathways represent two crucial post-translational modification systems with profound implications for cellular homeostasis and disease pathology. While both systems utilize parallel enzymatic cascades involving E1 activating, E2 conjugating, and E3 ligase enzymes, they regulate distinct cellular processes with the UPS primarily targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation and SUMOylation modulating protein-protein interactions, localization, and stability [44] [45]. The dysregulation of these pathways is increasingly recognized in various diseases, particularly in oncology and neurology, making them attractive targets for therapeutic intervention [7] [45]. High-throughput screening (HTS) technologies have emerged as powerful approaches for identifying small molecule modulators of these pathways, offering new opportunities for drug development against challenging targets. This review comprehensively compares current HTS methodologies for identifying UPS and SUMO pathway modulators, providing experimental protocols, performance data, and practical implementation guidance for researchers in the field.

Comparative HTS Platform Technologies

HTS Assay Formats and Their Applications

Table 1: Comparison of HTS Platforms for UPS and SUMO Pathway Screening

| HTS Platform | Biological Target | Throughput | Z'-factor | Key Advantages | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| URT-Dual-Luciferase [46] | E3 Ubiquitin Ligases (SMURF1) | 96/384-well | 0.69 | Internal reference normalization, minimizes well-to-well variation | E3 ligase substrate degradation quantification |

| TR-FRET [47] | SUMO-SIM interactions | 1536-well | 0.88 | Homogeneous format, minimal interference, high sensitivity | Protein-protein interaction disruption |

| Fluorescence Polarization [47] | SUMO-SIM interactions | 384-well | Good (not specified) | Orthogonal validation, solution-based measurement | Secondary confirmation screening |

| Small Molecule Microarray [48] | E2 Enzymes (Ubc9) | Array-based | N/A | Targets "undruggable" E2 enzymes, direct binding detection | Challenging protein target screening |

| miRNA-focused qHTS [49] | Global SUMOylation via miRNA | 96/384-well | 0.5-0.66 | Functional cellular readout, pathway-level modulation | Phenotypic screening for SUMOylation enhancement |

| HTRF [50] | Skp2-Cks1 PPI | 384-well | Excellent (not specified) | High sensitivity, low protein consumption | E3-substrate interaction inhibition |

Quantitative Performance Metrics of HTS Systems

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Representative HTS Assays

| Assay System | Signal-to-Background Ratio | Hit Rate | IC50 Range | Key Reagents | Validation Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TR-FRET SUMO-SIM [47] | 4.0 | 0.33% (≥40% inhibition) | <10 μM for confirmed hits | GST-SUMO1, FITC-S1 peptide, Tb-anti-GST | FP assay, NMR binding studies |

| URT-SMURF1 [46] | Significantly improved with normalization | Not specified | Compound-dependent | 3×FLAG-RL-UbR48-3×FLAG-FL-RHOB, SMURF1 | Immunoblotting, proteasome inhibition |

| HTRF Skp2-Cks1 [50] | High (specific values not provided) | Not specified | Not specified | GST-Skp2/Skp1, His6-Cks1, anti-GST-Eu, anti-His6-d2 | Pull-down assays, SDS-PAGE |

| miRNA qHTS [49] | High luciferase activation | Not specified | Functional in OGD protection | Dual-luciferase reporters, miRNA inhibitors | Immunoblotting, OGD protection assays |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

URT-Dual-Luciferase Assay for E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Modulators

The Ubiquitin-Reference Technique (URT) integrated with Dual-Luciferase reporting represents a sophisticated cell-based HTS platform for identifying E3 ubiquitin ligase modulators. The methodology involves the construction of a specialized fusion protein (3×FLAG-RL-UbR48-3×FLAG-FL-RHOB) where Renilla luciferase (RL) is connected to firefly luciferase (FL)-tagged substrate via a ubiquitin mutant (UbK48R) [46]. This design enables precise monitoring of substrate degradation through luciferase activity ratios.

Protocol Steps:

- Plasmid Construction: Generate pRUF(RL-UbR48-FL)-RHOB vector encoding the fusion protein with ubiquitin reference moiety

- Cell Transfection: Co-transfect HEK293T cells with pRUF-RHOB and E3 ligase (e.g., SMURF1) expression vectors

- Compound Screening: Seed transfected cells in 96/384-well plates and treat with small molecule libraries (typically 1-20 μM concentrations)

- Luciferase Measurement: After 16-24 hours, measure firefly and Renilla luciferase activities using Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System

- Data Analysis: Calculate FL/RL ratio for each well; increased ratio indicates inhibition of substrate degradation

Critical Implementation Notes: The URT system dramatically improves assay quality (Z-factor: -0.12 to 0.69) by normalizing for cell density variations and transfection efficiency [46]. The UbK48R mutation prevents potential degradation of the reference signal, while MG-132 proteasome inhibition serves as essential validation control.