Ubiquitination in Cancer Stem Cell Maintenance: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targeting

This article comprehensively examines the critical role of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) in regulating cancer stem cell (CSC) maintenance, a key driver of tumor progression, metastasis, and therapy resistance.

Ubiquitination in Cancer Stem Cell Maintenance: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article comprehensively examines the critical role of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) in regulating cancer stem cell (CSC) maintenance, a key driver of tumor progression, metastasis, and therapy resistance. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational mechanisms—including the regulation of core stemness transcription factors (SOX2, OCT4, Nanog, c-Myc) and key signaling pathways (Notch, Wnt/β-catenin, Hedgehog)—with emerging methodological applications such as PROTACs and molecular glues. It further addresses challenges in therapeutic targeting, including functional redundancy and biomarker identification, and validates these approaches through preclinical and clinical evidence. The review aims to provide a framework for developing novel UPS-targeted strategies to eliminate the CSC population and overcome treatment resistance in oncology.

The Ubiquitin Code: Mastering Core Mechanisms in Cancer Stem Cell Biology

The Core Enzymatic Cascade of the UPS

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) is the primary pathway for targeted protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, governing essential cellular processes through a sophisticated enzymatic cascade. This system regulates the stability, function, and localization of a vast array of proteins, making it a critical determinant of cellular homeostasis [1] [2].

Ubiquitination initiates with a three-step enzymatic cascade involving E1 (ubiquitin-activating enzyme), E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme), and E3 (ubiquitin ligase) enzymes [1] [3] [2]. The process begins when E1 activates ubiquitin, a 76-amino acid protein, in an ATP-dependent reaction, forming a high-energy thiol ester intermediate [4] [5]. The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to an E2 enzyme. Finally, an E3 ligase facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine residue on the target substrate protein, culminating in substrate ubiquitination [4].

This modification is dynamically reversible through the action of deubiquitinases (DUBs), which cleave ubiquitin from substrate proteins, providing a crucial regulatory counterbalance to ubiquitination [1] [3]. Collectively, these components form a precise regulatory system that controls protein fate and function.

Table 1: Core Components of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

| Component | Key Function | Representative Examples | Mechanistic Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Activating Enzyme) | Activates ubiquitin via ATP hydrolysis | UBA1, UBA6, UBA7 | Forms ubiquitin-adenylate intermediate, initiates catalytic cascade [5] |

| E2 (Conjugating Enzyme) | Carries activated ubiquitin | UBE2T, UBE2B, UBE2C | Transfers ubiquitin from E1 to E3 or directly to substrate [3] |

| E3 (Ligase) | Confers substrate specificity | MDM2, PARKIN, TRIM family, CRLs | Recognizes specific substrates and catalyzes ubiquitin transfer [1] [4] |

| DUBs (Deubiquitinases) | Removes ubiquitin modifications | USP2, OTUB2, OTULIN, BAP1 | Cleaves ubiquitin from substrates, recycles ubiquitin [1] [3] |

E3 Ubiquitin Ligases: Architects of Specificity

E3 ubiquitin ligases represent the most diverse and specialized component of the UPS, with over 600 identified in the human genome [4]. These enzymes are categorized into three major families based on their structural domains and mechanisms of ubiquitin transfer: RING (Really Interesting New Gene), HECT (Homologous to the E6AP C terminus), and RBR (RING-Between-RING) [4].

RING-type E3 ligases, the largest class, function as scaffolds that directly catalyze ubiquitin transfer from E2-ubiquitin complexes to substrate proteins [4]. In contrast, HECT-type E3 ligases employ a two-step mechanism where the HECT domain first receives ubiquitin on a cysteine residue from the E2 enzyme before transferring it to the substrate [4] [6]. RBR-type E3 ligases incorporate features of both, possessing RING domains but utilizing a HECT-like catalytic mechanism [4].

This classification system reflects the diverse evolutionary strategies for achieving substrate specificity in ubiquitination, with different E3 families employing distinct molecular mechanisms to ensure precise target selection.

Table 2: Major Families of E3 Ubiquitin Ligases

| E3 Family | Representative Members | Catalytic Mechanism | Biological Functions in Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| RING-type | MDM2, CBL, TRIM8, TRIM31 | Direct transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to substrate [4] | Regulates p53 stability (MDM2), modulates inflammatory signaling (TRIM8) [1] [4] |

| HECT-type | NEDD4, SMURF, E6AP | Two-step mechanism with ubiquitin-thioester intermediate on E3 cysteine residue [4] [6] | Controls cell growth, signal transduction; implicated in various cancers [1] |

| RBR-type | PARKIN, HOIP, HOIL-1L | Hybrid mechanism with RING domains and HECT-like catalysis [4] | Regulates mitophagy (PARKIN), linear ubiquitin chain assembly (HOIP) [3] |

Deubiquitinases (DUBs): Regulators of Reversibility

Deubiquitinases (DUBs) constitute a family of approximately 100 enzymes that counterbalance ubiquitination by removing ubiquitin modifications from substrate proteins [3] [6]. DUBs perform two essential functions: they disassemble polyubiquitin chains from substrate proteins, thereby rescuing them from degradation, and they recycle ubiquitin molecules by processing ubiquitin precursors or editing ubiquitin chains [3].

DUBs are classified into several families based on their catalytic domains and mechanisms, including ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), ovarian tumor proteases (OTUs), Josephin domain-containing proteases, and JAB1/MPN/Mov34 metalloenzymes (JAMMs) [7] [3]. Each family exhibits distinct preferences for specific ubiquitin chain linkages and cellular localizations, enabling precise regulation of ubiquitin signaling [3].

The balanced interplay between E3 ligases and DUBs creates a dynamic regulatory system that allows cells to rapidly respond to changing environmental conditions and maintain protein homeostasis.

The Ubiquitin Code: Molecular Language of Fate Determination

Ubiquitination represents a sophisticated molecular code that extends far beyond a simple degradation signal. This complexity arises from the ability of ubiquitin to form diverse polymeric chains through its seven internal lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or its N-terminal methionine (M1) [3] [2]. These structurally distinct ubiquitin modifications are recognized as functionally discrete signals that determine specific protein fates [2].

K48-linked polyubiquitin chains typically target substrates for proteasomal degradation, serving as the canonical degradation signal [4] [8]. In contrast, K63-linked chains generally mediate non-proteolytic functions including protein-protein interactions, activation of kinase pathways, and DNA repair processes [4] [4]. Monoubiquitination (attachment of a single ubiquitin molecule) and multimonoubiquitination (multiple single ubiquitins on different lysines) regulate processes such as DNA repair, signal transduction, and protein trafficking [3].

The emerging understanding of heterotypic polyubiquitin chains (mixed linkage), branched chains, and ubiquitin-like modifications (e.g., NEDD8, SUMO) further expands the complexity of this regulatory system, creating a sophisticated signaling network that controls virtually all aspects of cell biology [3].

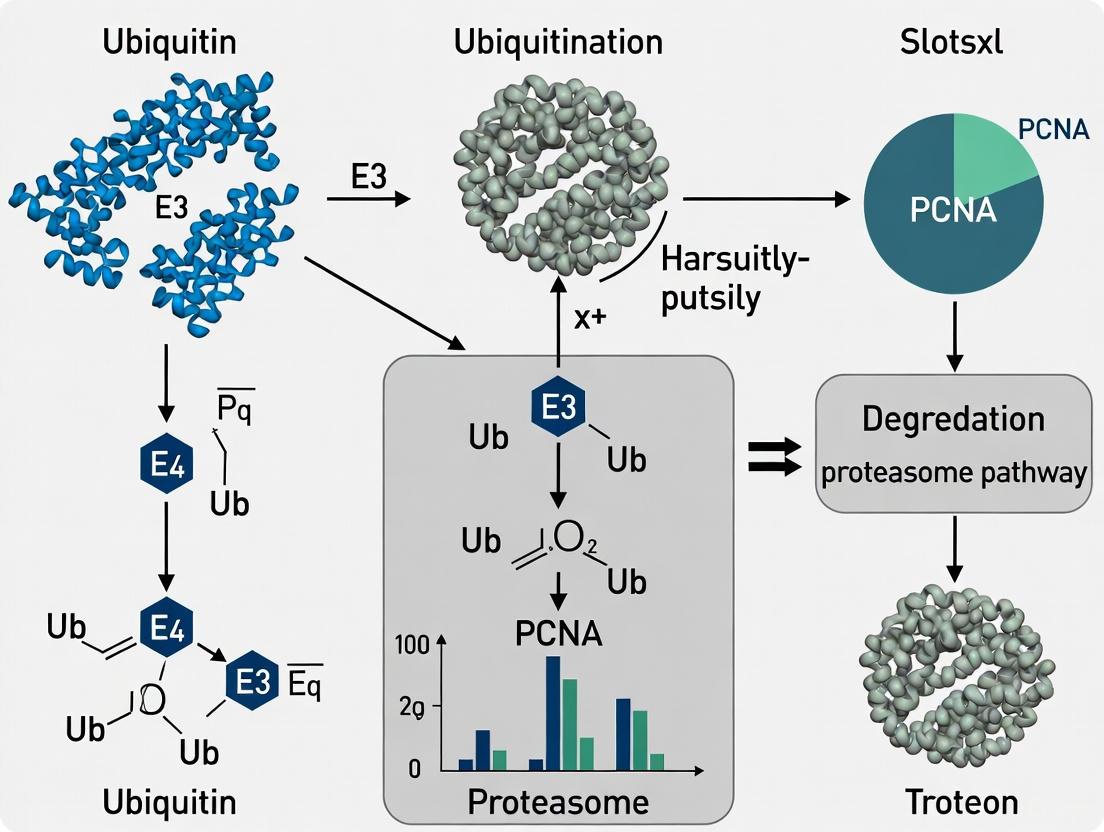

Diagram Title: UPS Enzymatic Cascade and Regulatory Dynamics

UPS in Cancer Stem Cell Maintenance: Mechanistic Insights

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System plays a pivotal role in maintaining cancer stem cell (CSC) populations, which drive tumor initiation, metastasis, recurrence, and therapeutic resistance [9] [5]. CSCs typically constitute approximately 1% of total cells in various malignancies, though this proportion can escalate to 30% in metastatic contexts, correlating with enhanced treatment resistance [5].

E3 ubiquitin ligases and DUBs precisely regulate core transcription factors governing CSC self-renewal and pluripotency, including SOX2, OCT4, KLF4, and c-MYC [9] [5]. Quantitative proteomics analyses have revealed that these core transcription factors are themselves ubiquitination targets, suggesting that ubiquitination plays a fundamental role in maintaining stemness and pluripotency [5]. For instance, the CSN6-TRIM21 axis regulates colorectal cancer stemness by stabilizing OCT1 through modulation of TRIM21 E3 ligase activity [5].

The UPS also interfaces with key developmental signaling pathways essential for CSC maintenance, including Notch, Wnt/β-catenin, Hedgehog, and Hippo-YAP pathways [9] [10]. In non-small cell lung cancer, PKMYT1 stabilizes β-catenin protein and activates Wnt signaling, thereby bolstering CSC self-renewal capacity [5]. Similarly, dysregulation of ubiquitination in these pathways can promote the acquisition and maintenance of stem-like properties in cancer cells.

Diagram Title: UPS Regulation of Cancer Stem Cell Properties

Experimental Methodologies for UPS Research

Ubiquitin Variant (UbV) Technology

UbV technology employs a structure-based protein engineering strategy to develop ubiquitin variants that selectively modulate UPS components in human cells [1]. This approach involves generating UbV phage display libraries followed by screening against target E3 ligases or DUBs to identify high-affinity binders [1]. For instance, Hewitt et al. utilized computational approaches to create UbV-based activity-based probes (ABPs) for UCHL1, a DUB overexpressed in various cancers and neurodegenerative disorders [1]. Subsequently, the same research group generated a selective triple-mutant UbV-ABP for UCHL3, validating its function across multiple human cell lines [1].

Protocol: UbV Generation and Validation

- Library Construction: Generate UbV phage display libraries with randomized ubiquitin surface residues

- Biopanning: Screen libraries against purified target E3 ligases or DUBs over multiple rounds

- Hit Characterization: Sequence positive clones and characterize binding affinity using surface plasmon resonance (SPR)

- Functional Validation: Test UbV effects on enzyme activity in vitro using ubiquitination/deubiquitination assays

- Cellular Studies: Express selected UbVs in human cell lines and assess target modulation and phenotypic outcomes

Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs)

PROTACs represent an innovative therapeutic strategy that artificially recruits E3 ligases to non-native substrates, inducing targeted protein degradation [1] [8]. These bifunctional molecules consist of a target-binding moiety linked to an E3 ligase-recruiting ligand, enabling selective degradation of disease-causing proteins [1]. Aminu et al. utilized structure-based protein engineering to create Ubiquitin Variant Induced Proximity (UbVIP), generating non-inhibitory UbV binders for selected E3 ligases and screening UbVIP libraries to identify novel E3 ligases capable of degrading target proteins like 53BP1 [1].

Protocol: PROTAC Development and Testing

- Design: Synthesize bifunctional molecules linking target protein ligand to E3 ligase recruiter

- Binding Validation: Confirm simultaneous binding to target protein and E3 ligase using pull-down assays

- Degradation Assessment: Treat cells with PROTACs and measure target protein levels by immunoblotting

- Specificity Profiling: Use quantitative proteomics to assess degradation selectivity across the proteome

- Functional Consequences: Evaluate phenotypic effects of target degradation in disease-relevant models

Mass Spectrometry-Based Ubiquitomics

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics has been instrumental in mapping ubiquitination sites and understanding the ubiquitin code [1] [3]. Lacoursiere et al. employed biochemical, biophysical, and proteomics assays to reveal the comprehensive Ub and UPS post-translational modification landscape, providing insights into how these modifications impact ubiquitin signaling in human diseases [1]. These approaches typically involve enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides using ubiquitin remnant motifs (e.g., diGly residues) followed by high-resolution mass spectrometry analysis.

Table 3: Key Experimental Approaches in UPS Research

| Methodology | Key Application | Technical Output | Research Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Variants (UbVs) | Selective inhibition/modulation of E3s or DUBs [1] | High-affinity protein binders | Functional dissection of specific UPS components; therapeutic development [1] |

| Activity-Based Probes (ABPs) | Profiling enzyme activity in complex proteomes [1] | Active-site directed chemical probes | Target engagement studies; inhibitor screening; mechanistic studies [1] |

| PROTACs | Targeted protein degradation [1] [8] | Bifunctional degradation molecules | Therapeutic development; target validation; chemical genetics [1] |

| Mass Spectrometry Ubiquitomics | System-wide identification of ubiquitination sites [1] [3] | Quantitative ubiquitin site maps | Discovery of novel regulatory mechanisms; biomarker identification [1] |

Research Reagent Solutions for UPS Investigation

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for UPS Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| E3 Ligase Inhibitors | Hinokiflavone (MDM2 inhibitor) [1] | Functional studies of specific E3 ligases | Validated natural product inhibitor identified through virtual screening of compound libraries [1] |

| DUB Probes | UbV-based ABPs for UCHL1/UCHL3 [1] | DUB activity profiling and inhibition | Selective triple-mutant UbV-ABPs enable cell-specific DUB targeting and functional characterization [1] |

| PROTAC Molecules | ARV-110, ARV-471 [3] | Targeted protein degradation research | Clinical-stage PROTACs that recruit E3 ligases to degrade target oncoproteins [3] |

| Ubiquitin Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K48-linkage, K63-linkage antibodies [3] | Ubiquitin chain type determination | Immunoblotting and immunofluorescence detection of specific polyubiquitin chain architectures [3] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib [9] | UPS functional blockade | Clinical inhibitors used to validate UPS-dependent processes and as cancer therapeutics [9] |

Therapeutic Targeting and Clinical Implications

Targeting the UPS represents a promising strategic approach for eliminating therapy-resistant cancer stem cells in multiple cancer types [9] [5]. Existing proteasome inhibitors, including bortezomib and carfilzomib, have demonstrated efficacy in certain hematological malignancies, though their application in solid tumors remains challenging [9]. More precise targeting of specific E3 ligases and DUBs offers potential for enhanced therapeutic specificity with reduced off-target effects [9].

The integration of UPS-targeted therapies with conventional chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and molecularly-targeted drugs represents an emerging frontier in oncological treatment strategies [9] [5]. For instance, targeting DUBs that stabilize immune checkpoints like PD-1/PD-L1 could synergize with existing immunotherapies to overcome resistance mechanisms [3]. USP2, a DUB that stabilizes PD-1 and promotes tumor immune escape through deubiquitination, represents one such promising target [3].

Advanced therapeutic modalities including PROTACs and molecular glue degraders offer innovative approaches to target traditionally "undruggable" oncoproteins by hijacking the endogenous UPS [1] [8]. ARV-110 and ARV-471 represent pioneering PROTAC drugs that have progressed to phase II clinical trials, demonstrating the clinical viability of this approach [3]. Molecular glue degraders such as CC-90009, which promotes GSPT1 degradation by recruiting the CRL4CRBN E3 ligase complex, further expand the toolkit for targeted protein degradation [3].

As research continues to decipher the complex roles of the UPS in cancer stem cell biology, therapeutic interventions targeting this system hold significant promise for addressing the persistent challenges of tumor recurrence, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance that characterize advanced malignancies.

Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs), also referred to as tumor-initiating cells (TICs), represent a distinct subpopulation within tumors that exhibit stem cell-like properties, including self-renewal capability, multi-lineage differentiation, and enhanced tumor-driving capacity [11] [12]. Although they constitute only a minority of tumor cells, CSCs have been identified as the central drivers of tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, therapeutic resistance, and relapse [12] [13]. The CSC concept challenges the traditional view of tumor homogeneity, proposing instead that tumors are organized hierarchically, with CSCs at the apex capable of regenerating the entire tumor heterogeneity [12]. The existence of CSCs was first definitively demonstrated in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in the 1990s by John Edgar Dick and colleagues, who showed that only a specific subpopulation with a CD34⁺CD38⁻ phenotype could reconstitute leukemia in immunodeficient mice [13]. This foundational discovery has since been extended to various solid tumors, including breast cancer, glioblastoma, lung cancer, and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, establishing CSCs as a fundamental component of tumor biology across cancer types [13] [14].

Biological Properties and Identification of CSCs

Defining Functional Properties of CSCs

CSCs possess three defining functional characteristics that distinguish them from the bulk of tumor cells. These properties collectively enable CSCs to initiate and maintain tumors, adapt to therapeutic pressures, and drive disease progression:

- Self-Renewal Capacity: The ability to undergo symmetrical or asymmetrical division to generate identical daughter cells that maintain the stem cell pool indefinitely [12]. This property ensures the long-term persistence of CSCs within tumors.

- Multi-Lineage Differentiation Potential: The capacity to differentiate into the heterogeneous cell populations that constitute the entire tumor mass, thereby establishing and maintaining tumor heterogeneity [12].

- Tumor-Initiating Ability: The potential to initiate and sustain tumor growth when transplanted into suitable host environments, which represents the functional gold standard for identifying CSCs [12] [13]. This capacity has been demonstrated through limiting dilution assays in immunodeficient mice, where CSCs can form tumors with far fewer cells compared to non-CSC populations [12].

CSC Markers and Identification

The identification and isolation of CSCs rely on specific surface markers and functional assays, though these markers vary significantly across different cancer types, reflecting tissue-specific origins and microenvironmental influences [13]. The table below summarizes key CSC markers across various cancer types:

Table 1: Cancer Stem Cell Markers Across Different Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Key CSC Markers | Additional Functional Markers | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) | CD34⁺CD38⁻ | - | [13] |

| Breast Cancer | CD44⁺CD24⁻/low | ALDH1⁺ | [11] [12] |

| Glioblastoma (GBM) | CD133⁺ | Nestin⁺, SOX2⁺ | [13] |

| Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC) | CD44⁺ | - | [14] |

| Gastrointestinal Cancers | LGR5⁺, CD166⁺ | - | [13] |

| Multiple Solid Tumors | CD133⁺ | - | [13] |

It is important to note that no universal CSC marker exists, and CSC identity appears to be shaped by both intrinsic genetic programs and extrinsic microenvironmental cues [13]. Furthermore, non-CSCs can acquire stem-like characteristics de novo in response to environmental stimuli such as hypoxia, inflammation, or therapeutic pressure, indicating that the CSC state represents a dynamic functional status rather than a fixed cellular hierarchy [13].

Molecular Mechanisms Governing CSC Maintenance

Core Signaling Pathways in CSC Regulation

CSCs utilize several evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways that normally regulate stem cell maintenance in development and adult tissues. These pathways form complex interconnected networks that sustain CSC self-renewal, survival, and plasticity:

- Wnt/β-catenin Signaling: Promotes self-renewal and maintains stemness by regulating key transcription factors. In the absence of Wnt, β-catenin is targeted for ubiquitination and degradation by the destruction complex [15]. Wnt activation stabilizes β-catenin, allowing its nuclear translocation and activation of stemness-associated genes [15].

- Notch Signaling: Regulates cell fate decisions and maintains CSC populations through cell-cell interactions. Notch activation leads to proteolytic cleavage of the receptor and release of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD), which translocates to the nucleus and activates target genes [9].

- Hedgehog Signaling: Contributes to CSC maintenance, particularly in cancers like glioblastoma and pancreatic cancer. The pathway is initiated when Hedgehog ligands bind to Patched receptors, relieving suppression of Smoothened and activating GLI transcription factors [12].

- Hippo-YAP Signaling: Regates organ size and stem cell function. In CSCs, YAP/TAZ activation promotes stemness and survival. The pathway is regulated by a kinase cascade that ultimately controls the localization and stability of YAP/TAZ transcriptional coactivators [9].

The diagram below illustrates the core regulatory network of these signaling pathways in maintaining CSC properties:

Ubiquitination in CSC Regulation

Ubiquitination, a fundamental post-translational modification, has emerged as a critical regulatory mechanism governing CSC functionality [9]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) consists of a cascade of enzymes including ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3) that work in concert to attach ubiquitin molecules to target proteins, determining their stability, activity, and localization [3]. The reverse process, deubiquitination, is mediated by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that remove ubiquitin chains, providing an additional layer of regulation [7].

In CSCs, the ubiquitin system exerts precise control over key stemness transcription factors and signaling pathways:

- Stemness Transcription Factors: E3 ubiquitin ligases and DUBs modulate the stability of core pluripotency factors including SOX2, OCT4, KLF4, and c-MYC, which play crucial roles in CSC self-renewal and differentiation [9]. For instance, the E3 ligase FBXW7 targets c-MYC for degradation, while various DUBs can stabilize these factors to maintain stemness.

- Signaling Pathway Components: Ubiquitination regulates core CSC signaling pathways including Notch, Wnt/β-catenin, Hedgehog, and Hippo-YAP by controlling the turnover of key pathway components [9]. The E3 ligase Itch, for example, ubiquitinates Notch receptors, influencing Notch signaling activity in CSCs.

- Metabolic Regulators: The UPS controls metabolic enzymes crucial for CSC maintenance, such as pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2). The E3 ligase Parkin facilitates PKM2 ubiquitination, while the DUB OTUB2 inhibits this process, enhancing glycolysis and promoting colorectal cancer progression [3].

The table below summarizes key ubiquitin system components involved in CSC regulation:

Table 2: Ubiquitination System Components Regulating Cancer Stem Cells

| Component Type | Specific Elements | Targets/Function in CSCs | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| E3 Ubiquitin Ligases | FBXW7 | Targets c-MYC for degradation | [9] |

| Parkin | Ubiquitinates PKM2 to regulate CSC metabolism | [3] | |

| Itch | Regulates Notch signaling in CSCs | [9] | |

| Deubiquitinases (DUBs) | OTUB2 | Inhibits PKM2 ubiquitination, enhancing glycolysis | [3] |

| USP2 | Stabilizes PD-1, promoting immune escape | [3] | |

| Ubiquitin Chains | K48-linked chains | Target proteins for proteasomal degradation | [7] |

| K63-linked chains | Regulate signal transduction and endocytosis | [7] | |

| Linear ubiquitin chains | Regulate NF-κB signaling through LUBAC complex | [3] |

The intricate regulation of CSCs by the ubiquitin system offers promising therapeutic opportunities. Existing proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib and carfilzomib have shown promise in certain cancers, and more targeted approaches focusing on specific E3 ligases and DUBs are under development to selectively disrupt CSC maintenance while sparing normal stem cells [9].

CSCs in Tumor Initiation, Metastasis, and Drug Resistance

Role in Tumor Initiation and Progression

CSCs are defined by their remarkable tumor-initiating capacity, which represents the functional hallmark of this cellular subpopulation [12]. When transplanted into immunodeficient mice, CSCs can regenerate tumors that recapitulate the heterogeneity of the original tumor, while non-CSC populations lack this capacity [12] [13]. The tumor-initiating potential of CSCs is strongly correlated with the expression of specific genes and transcription factors. For instance:

- In glioblastoma, adenosine deaminase RNA-specific binding protein (ADAR1) promotes tumor initiation by enhancing ganglioside GM2 activator (GM2A) expression and inducing specific mutations in GLI1 that improve its nuclear localization [12].

- The transcription factor SOX9 plays a crucial role in regulating mammary stem and progenitor cells, with SOX9high cells exhibiting significantly higher tumor-inducing capacity compared to SOX9low counterparts [12].

- In melanoma, colon, and pancreatic cancers, CDK1 expression regulates the phosphorylation, localization, and transcriptional activity of the pluripotency-associated transcription factor SOX2, thereby influencing tumor initiation capacity [12].

Role in Metastasis

CSCs play a central role in the metastatic cascade, from initial departure from the primary tumor to successful colonization of distant organs [15]. The metastatic process involves multiple steps including local invasion, intravasation into blood or lymphatic vessels, survival in circulation, extravasation at distant sites, and eventual colonization [16]. CSCs contribute to each of these stages through several mechanisms:

- Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT): CSCs can undergo EMT, a process where cells lose epithelial characteristics and gain mesenchymal properties, enhancing migratory capacity and invasiveness [16]. EMT is regulated by transcription factors such as Snail, Slug, and Twist, which are activated by pathways like TGF-β and Wnt/β-catenin [16].

- Proteolytic Enzyme Systems: CSCs utilize proteolytic systems including the urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) system and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) to degrade extracellular matrix components and facilitate invasion and intravasation [16]. The uPA system is particularly significant, as it activates plasminogen to plasmin and subsequently activates MMPs like MMP-2 and MMP-9 that degrade basement membranes [16].

- Stem Cell-Like Migratory Properties: CSCs share molecular mechanisms with normal stem cell migration, utilizing overlapping sets of molecules and pathways that facilitate movement and colonization [15].

- Pre-Metastatic Niche Formation: Primary tumors can prepare distant sites for metastasis by secreting factors that create a supportive "pre-metastatic niche." CSCs subsequently colonize these prepared microenvironments [15].

The diagram below illustrates the role of CSCs in the metastatic cascade:

Mechanisms of Therapy Resistance

CSCs employ multiple sophisticated mechanisms to evade conventional cancer therapies, making them central players in treatment failure and disease recurrence:

- Enhanced DNA Repair Capacity: CSCs possess more efficient DNA repair mechanisms than non-CSCs, enabling them to survive DNA-damaging therapies like radiation and chemotherapy [14].

- Drug Efflux Transporters: CSCs highly express ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters that actively pump chemotherapeutic drugs out of the cell, reducing intracellular drug accumulation [12].

- Quiescence: A subset of CSCs can enter a quiescent or dormant state, making them resistant to therapies that target rapidly dividing cells [14].

- Epigenetic Plasticity: CSCs exhibit dynamic epigenetic modifications that allow for adaptive responses to therapeutic stress, including transitions between drug-sensitive and resistant states [12].

- Metabolic Flexibility: CSCs can switch between different metabolic pathways (glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, and alternative fuel sources) to survive under diverse environmental conditions, including therapy-induced stress [13].

- Interaction with the Tumor Microenvironment (TME): The TME provides protective niches that shield CSCs from therapies. Components such as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), and other stromal cells secrete factors that promote CSC survival and drug resistance [12].

Experimental Models and Methodologies for CSC Research

In Vitro Models and Functional Assays

The study of CSCs relies on specialized experimental models and functional assays that enable the identification, isolation, and characterization of this critical cellular subpopulation:

- Sphere Formation Assays: Under non-adherent, serum-free conditions, CSCs form three-dimensional spheroids that enrich for stem-like cells and demonstrate self-renewal capacity in vitro [17]. This assay serves as a fundamental method for assessing CSC frequency and functional properties.

- Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting: Surface markers such as CD44, CD24, CD133, and ALDH1 activity are used to identify and isolate CSC populations using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [11] [12].

- Organoid Cultures: Three-dimensional organoid models derived from patient tumors or cancer cell lines maintain CSC populations and recapitulate tumor heterogeneity more effectively than traditional 2D cultures [13]. These models enable long-term expansion of CSCs while preserving their stemness properties.

- Migration and Invasion Assays: Transwell assays with or without Matrigel coating are used to evaluate the migratory and invasive capabilities of CSCs, which are critical for metastatic potential [16].

- Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Degradation Assays: These assays assess the ability of CSCs to degrade ECM components using fluorescently-labeled matrix proteins, evaluating the activity of proteolytic systems like uPA and MMPs [16].

In Vivo Models for CSC Study

In vivo models provide essential physiological context for studying CSC biology and therapeutic responses:

- Xenograft Models: Immunodeficient mice (such as SCID or NSG strains) are transplanted with human tumor cells to assess tumor-initiating capacity through limiting dilution assays [12] [13]. This represents the gold standard for functional validation of CSCs.

- Genetically Engineered Mouse Models (GEMMs): These models enable the study of CSCs in their native microenvironment, with spontaneous tumor development that recapitulates the natural history of human cancers [16].

- Lineage Tracing: Advanced genetic approaches allow tracking of CSC fate and dynamics in living animals, providing insights into CSC hierarchy, plasticity, and contribution to tumor maintenance [12].

- Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDX): Tumors obtained directly from patients are engrafted into immunodeficient mice, preserving the original tumor heterogeneity and CSC characteristics better than cell line-derived models [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CSC Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Research Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Marker Antibodies | Anti-CD44, Anti-CD24, Anti-CD133 | Identification and isolation of CSCs by FACS | [12] [13] |

| ALDH Activity Assay | ALDEFLUOR Kit | Functional identification of CSCs based on ALDH enzyme activity | [12] |

| CSC Culture Media | Serum-free media with growth factors (EGF, FGF) | Sphere formation assays and CSC expansion | [17] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Investigating ubiquitin system in CSC regulation | [9] |

| Pathway Inhibitors | Wnt, Notch, Hedgehog inhibitors | Targeting core stemness signaling pathways | [9] [14] |

| 3D Culture Matrices | Matrigel, Collagen I | Organoid and spheroid cultures for CSC maintenance | [13] [16] |

| CSC Reporter Systems | GFP/Luciferase under stemness promoters | Lineage tracing and in vivo CSC tracking | [12] [16] |

Therapeutic Targeting of CSCs and Clinical Implications

Emerging Therapeutic Strategies

The development of effective therapies targeting CSCs represents a promising frontier in oncology, with multiple approaches under investigation:

- Ubiquitin System-Targeted Therapies: Small molecules targeting specific E3 ubiquitin ligases or deubiquitinases (DUBs) offer precision approaches to disrupt CSC maintenance [9]. Proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) represent an innovative technology that harnesses the ubiquitin system to degrade specific oncoproteins in CSCs [3].

- Immunotherapy Approaches: Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapies targeting CSC-specific surface markers such as EpCAM have shown promise in preclinical models [13]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors combined with CSC-targeted vaccines are also being explored to overcome CSC-mediated immune evasion [12].

- Differentiation Therapy: Agents that induce CSC differentiation into more mature, therapy-sensitive states represent a promising strategy to reduce the CSC pool [14].

- Metabolic Interventions: Targeting CSC metabolic vulnerabilities, such as dual inhibition of glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation, can exploit the metabolic dependencies of CSCs [13].

- Nanoparticle-Based Delivery Systems: Nanotechnology enables targeted delivery of CSC-active agents to tumor sites, improving efficacy while reducing systemic toxicity [17].

- Epigenetic Modulators: Inhibitors of DNA methyltransferases and histone deacetylases can reverse epigenetic modifications that maintain CSC stemness [14].

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances, several challenges remain in translating CSC-targeted therapies to clinical practice:

- Biomarker Development: The lack of universal, reliable CSC biomarkers hampers patient stratification and treatment monitoring [13]. Developing robust biomarkers to track CSC dynamics in real-time represents a critical need.

- Therapeutic Toxicity: Achieving selective toxicity against CSCs while sparing normal stem cells remains challenging due to shared signaling pathways and regulatory mechanisms [13].

- Tumor Heterogeneity and Plasticity: The dynamic nature of CSCs and their ability to transition between states complicates therapeutic targeting [12].

- Microenvironmental Protection: The TME provides sanctuary for CSCs, necessitating combination approaches that simultaneously target CSCs and their supportive niches [12].

Future research directions include the integration of multi-omics technologies (single-cell sequencing, spatial transcriptomics) with artificial intelligence to decipher CSC heterogeneity and identify novel vulnerabilities [13]. Additionally, advanced preclinical models that better recapitulate human tumor biology and the development of rational combination therapies will be essential for overcoming CSC-mediated therapy resistance [14].

Cancer Stem Cells represent a critical subpopulation within tumors that drive tumor initiation, metastasis, therapy resistance, and recurrence. Their unique biological properties, including self-renewal capacity, differentiation potential, and remarkable plasticity, are maintained by complex molecular networks involving core signaling pathways and precise regulation through mechanisms such as ubiquitination. While significant challenges remain in targeting CSCs therapeutically, advances in our understanding of CSC biology, coupled with innovative therapeutic approaches targeting their specific vulnerabilities, offer promising avenues for overcoming treatment resistance and improving patient outcomes. The continued integration of basic mechanistic studies with translational and clinical research will be essential for developing effective CSC-targeted therapies that can ultimately change the landscape of cancer treatment.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) constitute a minor subpopulation within tumors characterized by unlimited self-renewal, differentiation potential, and enhanced resistance to conventional therapies. These cells drive tumor initiation, metastasis, and recurrence, presenting a significant challenge in oncology [5] [18]. The molecular foundation of CSC maintenance relies on a network of core stemness transcription factors, primarily SOX2, OCT4, and Nanog, alongside the pleiotropic regulator c-Myc [19]. These factors coordinate a transcriptional program that sustains the undifferentiated, self-renewing state of CSCs, mirroring their roles in embryonic stem cells [20].

Post-translational modifications, particularly ubiquitination, provide a critical regulatory layer controlling the stability and activity of these core stemness factors. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) precisely governs the "quantity" and "quality" of specific proteins to ensure cellular homeostasis, making it a fundamental process in determining CSC fate [5]. Ubiquitination involves a sequential enzymatic cascade comprising ubiquitin-activating (E1), conjugating (E2), and ligase (E3) enzymes, with E3 ligases conferring substrate specificity [21]. The reverse process, deubiquitination, is catalyzed by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that remove ubiquitin moieties, protecting proteins from degradation [21]. Dysregulation of this balance directly influences CSC properties by modulating the key transcription factors that define their identity, offering promising therapeutic avenues for selectively targeting this resilient cell population [5] [9].

Ubiquitination Landscapes of Core Stemness Transcription Factors

The stability and activity of core stemness transcription factors are precisely regulated by specific E3 ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinating enzymes. The following table summarizes the key regulatory mechanisms for each factor.

Table 1: Ubiquitination Regulation of Core Stemness Transcription Factors

| Transcription Factor | Regulating E3 Ubiquitin Ligases | Regulating DUBs (if mentioned) | Ubiquitination Type & Function | Biological Outcome in CSCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCT4 | WWP2, ITCH, CHIP [20] | Information not covered in search results | K48-linked degradation [20] | Reduces OCT4 stability, inhibits breast CSC production [20] |

| SOX2 | Information not covered in search results | Information not covered in search results | Information not covered in search results | Information not covered in search results |

| Nanog | Information not covered in search results | Information not covered in search results | Target of ubiquitination [5] | Role in maintaining stemness and pluripotency [5] |

| c-Myc | FBW7 (SCF complex) [22] | Information not covered in search results | K48-linked degradation [22] | FBW7 deletion causes c-Myc overexpression; can induce apoptosis in leukemic initiating cells [22] |

OCT4 Ubiquitination

OCT4 is a pivotal transcription factor for maintaining pluripotency, and its protein stability is controlled by several E3 ubiquitin ligases. The E3 ligase WWP2 promotes the ubiquitination and degradation of OCT4 in human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) [20]. Similarly, ITCH regulates OCT4 transcription and degradation in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) [20]. Notably, the E3 ligase CHIP (Carboxy terminus of HSP70-interacting protein) ubiquitinates OCT4 at lysine 284, which reduces OCT4 stability and subsequently inhibits human breast CSC production [20]. Furthermore, OCT4 is subject to other post-translational modifications that influence its activity, including phosphorylation and SUMOylation, which can interact with ubiquitination to fine-tune its function [20].

Nanog and SOX2 as Ubiquitination Targets

Quantitative proteomic analyses have revealed that core transcription factors, including Nanog and SOX2, are targets for ubiquitination, hinting at a crucial role for this modification in sustaining stemness and pluripotency [5]. While the specific E3 ligases and DUBs for SOX2 are not detailed in the provided search results, its regulatory partnership with OCT4 is emphasized. Acetylation of both OCT4 and SOX2 can attenuate their transcriptional activity by impairing heterodimer formation, indicating a complex interplay between different post-translational modifications [20].

c-Myc Ubiquitination by the SCFFBW7 Complex

The stability of the c-Myc oncoprotein is rigorously controlled by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. The SCF (SKP1-CUL1-F-box protein) complex, a major class of RING-type E3 ligases, targets c-Myc for degradation. Specifically, FBW7 (F-box and WD repeat domain-containing 7), the substrate-recognition component of the SCF complex, directs the ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of c-Myc [22]. This regulation is critical in CSC populations; for instance, the ablation of Fbw7 in leukemic initiating cells (LICs) results in c-Myc overexpression, which, contrary to expectations, can lead to p53-dependent apoptosis and exhaustion of LICs, demonstrating the context-dependent effects of ubiquitination regulation [22].

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Ubiquitination

Investigating the ubiquitination of stemness factors requires a combination of molecular biology, biochemistry, and cellular functional assays. Below are detailed protocols for key experiments cited in the literature.

Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and Ubiquitination Assays

This protocol is used to identify interactions between an E3 ligase and its substrate (e.g., CHIP and OCT4) and to detect protein ubiquitination.

- Objective: To confirm physical interaction and specific ubiquitination of a target protein.

- Detailed Procedure:

- Cell Lysis and Preparation: Harvest cells expressing the protein of interest (e.g., OCT4). Lyse cells using a non-denaturing RIPA buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with protease inhibitors (e.g., PMSF, aprotinin) and 10 mM N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) to inhibit endogenous DUBs.

- Immunoprecipitation: Pre-clear the cell lysate with Protein A/G agarose beads. Incubate the pre-cleared lysate with an antibody specific to the target protein (e.g., anti-OCT4 antibody) or a control IgG overnight at 4°C with gentle rotation. Then, add Protein A/G beads and incubate for 2-4 hours.

- Bead Washing: Pellet the beads and wash extensively with lysis buffer (3-5 times) to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Immunoblotting: Elute the bound proteins by boiling in SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Separate the proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a PVDF membrane. Probe the membrane with an anti-ubiquitin antibody (e.g., P4D1) to detect ubiquitination. To confirm the interaction, reprobe the membrane with an antibody against the suspected E3 ligase (e.g., anti-CHIP antibody) [20].

- Key Controls:

- IgG control for immunoprecipitation specificity.

- Total cell lysate input control.

- Use of proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG132) to enhance detection of ubiquitinated species.

Cycloheximide (CHX) Chase Assay

This assay measures the half-life of a protein to determine if an E3 ligase or DUB affects its stability.

- Objective: To assess the degradation rate of a protein (e.g., OCT4) upon inhibition of protein synthesis.

- Detailed Procedure:

- Cell Treatment: Culture cells and transfect with plasmids expressing the E3 ligase (e.g., CHIP) or a control vector. Optionally, treat cells with a proteasome inhibitor (MG132, 10-20 µM) or a DUB inhibitor to confirm UPS dependency.

- Inhibition of Protein Synthesis: Add cycloheximide (CHX, typically 100 µg/mL) to the culture medium to block new protein synthesis.

- Time-Course Harvesting: Harvest cell pellets at predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 30, 60, 120, 240 minutes) after CHX addition.

- Protein Level Analysis: Lyse the cells and quantify protein concentration. Analyze the levels of the target protein (OCT4) and a loading control (e.g., GAPDH or Tubulin) by western blotting.

- Quantification: Use densitometry software to quantify band intensities. Plot the relative protein level against time to calculate the half-life [20].

- Key Controls:

- Control vector transfection.

- Untreated (0-hour) time point as a baseline.

In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

This is a direct, cell-free assay to confirm that an E3 ligase can ubiquitinate a substrate protein.

- Objective: To reconstitute the ubiquitination reaction in vitro using purified components.

- Detailed Procedure:

- Protein Purification: Purify the recombinant E3 ligase (e.g., CHIP), the substrate (e.g., OCT4), E1 enzyme, E2 enzyme (e.g., UbcH5a), and ubiquitin.

- Reaction Setup: In a reaction tube, combine the following components in a suitable buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 2 mM ATP, 5 mM MgCl2):

- E1 enzyme (50 nM)

- E2 enzyme (200 nM - 1 µM)

- E3 ligase (1-2 µM)

- Substrate protein (1-2 µM)

- Ubiquitin (10-20 µM)

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction at 30°C for 1-2 hours.

- Reaction Termination: Stop the reaction by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer and boiling.

- Analysis: Analyze the products by western blotting. A smear or ladder of higher molecular weight species when probed with an anti-substrate (OCT4) or anti-ubiquitin antibody indicates successful polyubiquitination [20].

- Key Controls:

- Omission of E1, E2, E3, or ATP from the reaction as negative controls.

Diagram 1: A flowchart summarizing the key experimental methodologies used to study the ubiquitination of stemness transcription factors, from initial interaction confirmation to functional validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table lists essential reagents and tools for investigating the ubiquitination of core stemness factors, as derived from the cited research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Ubiquitination in CSCs

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Example | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Constructs | CHIP, WWP2, ITCH, FBW7 expression plasmids [22] [20] | To overexpress or knock down specific E3s and assess their impact on substrate stability and CSC function. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib [9] | To block proteasomal degradation, allowing accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins for detection and functional studies. |

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors | Information not covered in search results | To prevent deubiquitination, stabilizing ubiquitin chains on substrates and helping identify DUB-substrate relationships. |

| Specific Antibodies | Anti-OCT4, Anti-SOX2, Anti-Nanog, Anti-c-Myc, Anti-Ubiquitin [5] [20] | For detection, immunoprecipitation, and localization of target proteins and their ubiquitinated forms via western blot, immunofluorescence, and Co-IP. |

| Protein Synthesis Inhibitor | Cycloheximide (CHX) [20] | To halt new protein synthesis in chase assays, enabling measurement of protein half-life and degradation kinetics. |

| CSC Functional Assays | Sphere Formation Assay, ALDH Activity Assay [5] [23] | To assess the functional consequences of manipulating ubiquitination on self-renewal and stemness in vitro. |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Perspectives

Targeting the ubiquitination machinery regulating stemness factors presents a promising but complex strategy for eradicating CSCs. The development of PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) is a leading therapeutic approach. PROTACs are bifunctional molecules that recruit a target protein (e.g., a stemness transcription factor) to a specific E3 ligase, inducing its degradation [21]. This offers the potential to directly dismantle the core regulatory network of CSCs. Furthermore, existing proteasome inhibitors like bortezomib and carfilzomib have shown efficacy in some cancers, but their broad activity limits specificity [9]. Future efforts are focused on developing small-molecule inhibitors or activators that target specific E3 ligases or DUBs, offering a more precise method to modulate the stability of individual oncoproteins like c-Myc or OCT4 [21] [24].

A significant challenge in this field is the context-dependent duality of many E3 ligases. For example, while FBW7 acts as a tumor suppressor by degrading c-Myc and Notch, its loss in some leukemic models can lead to cell death due to excessive c-Myc accumulation [22]. This highlights the need for a deep understanding of tissue and cancer-type specific effects. The intricate crosstalk between ubiquitination and other PTMs adds another layer of complexity. For instance, phosphorylation of OCT4 can regulate its ubiquitination, and acetylation can affect its partnership with SOX2 [20] [24]. Therefore, successful therapeutic strategies will likely require an integrated approach that considers the entire PTM landscape governing CSC maintenance.

Diagram 2: A regulatory network showing the balance between ubiquitination and deubiquitination in controlling stemness factor stability, its modulation by other PTMs, and potential therapeutic intervention points.

The ubiquitination of core stemness transcription factors represents a critical regulatory node in maintaining the CSC state. As detailed in this review, E3 ligases such as CHIP, WWP2, and FBW7 precisely control the protein levels of OCT4, c-Myc, and other key players, directly influencing self-renewal, tumor initiation, and drug resistance. The experimental frameworks and toolkits outlined provide a roadmap for ongoing research into these complex mechanisms. While challenges remain, particularly regarding the contextual duality of ubiquitin components and their crosstalk with other signaling pathways, the continued development of targeted therapies like PROTACs holds significant promise. By strategically manipulating the ubiquitin system, the scientific community moves closer to the goal of effectively targeting the resilient CSC population, a crucial step toward overcoming cancer recurrence and therapeutic resistance.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) represent a subpopulation within tumors characterized by high capacities for self-renewal, differentiation, and reconstitution of tumor heterogeneity [25]. These cells are major contributors to tumor initiation, metastasis, and therapy resistance in cancer [25]. The regulation of CSC maintenance and function is controlled by key developmental signaling pathways, including Notch, Wnt/β-catenin, and Hedgehog (HH) [9] [25]. Emerging evidence indicates that ubiquitination-mediated post-translational modification plays a fundamental role in the maintenance of CSC characteristics [25].

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) comprises a sequential enzymatic network where E3 ubiquitin ligases (E3s) and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) serve as the main actors [26]. The dynamic balance between E3s and DUBs dictates the abundance and fate of cellular proteins, affecting both physiological and pathological processes [26]. This technical review examines the intricate mechanisms through which E3 ligases and DUBs regulate the core CSC signaling pathways, highlighting their implications for targeted therapeutic interventions.

Ubiquitination is a post-translational modification process wherein a highly conserved 76-amino acid ubiquitin protein is covalently conjugated to lysine residues on substrate proteins through a sequential enzymatic cascade [27]. The process involves E1 (ubiquitin-activating), E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating), and E3 (ubiquitin-ligase) enzymes [25] [27]. E3 ligases are particularly crucial as they confer substrate specificity, with approximately 600 identified in humans [25]. These enzymes are classified based on their structural domains and mechanisms of ubiquitin transfer:

- HECT domain E3s: Transfer ubiquitin directly from E2 to the substrate [25]

- RING domain E3s: Facilitate ubiquitin transfer by binding both E2 and substrate [25]

- RBR E3s: Utilize a hybrid RING-HECT mechanism [25]

Ubiquitination is reversible through the action of DUBs, which cleave ubiquitin from substrate proteins [25] [27]. Approximately 100 DUBs have been identified in the human genome, categorized into several families including ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), ovarian-tumor proteases (OTUs), and JAMM/MPN domain-associated metallopeptidases [27].

Table 1: Major Enzyme Classes in the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

| Enzyme Class | Representative Members | Function in Ubiquitination | Role in Reversal |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 Activating Enzymes | UBA1, UBA6 | Activates ubiquitin in ATP-dependent manner | - |

| E2 Conjugating Enzymes | ~30 members in humans | Carries activated ubiquitin | - |

| E3 Ligases | ~600 members in humans | Confers substrate specificity | - |

| HECT-type E3s | SMURF1/2, ITCH, WWP1/2, NEDD4 | Direct ubiquitin transfer to substrate | - |

| RING-type E3s | RNF43, ZNRF3, β-TrCP | Facilitates ubiquitin transfer | - |

| DUBs | USP22, OTUB2, CYLD | - | Removes ubiquitin from substrates |

Regulation of Notch Signaling by E3 Ligases and DUBs

The Notch signaling pathway is highly conserved throughout evolution and plays crucial roles in cell fate determination, embryonic development, organ formation, and tissue repair [28]. In mammals, four Notch receptors (Notch1-4) and five ligands (JAG1, JAG2, DLL1, DLL3, DLL4) have been identified [28]. The canonical Notch signaling activation involves a series of proteolytic cleavages upon ligand-receptor interaction, resulting in the release of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) which translocates to the nucleus and activates transcription of target genes [28].

Figure 1: Regulation of Notch Signaling by E3 Ligases and DUBs. The diagram illustrates the canonical Notch signaling pathway and its regulation by ubiquitination machinery. E3 ligases (green) promote NICD degradation, while DUBs (red) stabilize NICD.

Key Regulatory E3 Ligases and DUBs in Notch Signaling

The stability and activity of Notch signaling components are tightly regulated by E3 ligases and DUBs. FBXW7 (a subunit of the SCF E3 ubiquitin ligase complex) targets NICD for proteasomal degradation, acting as a critical negative regulator of Notch signaling [28]. Additionally, several E3 ligases including CBL, ITCH, and DELTEX have been implicated in regulating Notch receptor turnover and activity [28].

On the reversal side, specific DUBs counteract E3 ligase activity to maintain Notch signaling homeostasis. While the search results do not specify all DUBs regulating Notch, the intricate balance between ubiquitination and deubiquitination is crucial for proper pathway function [27] [28].

Table 2: E3 Ligases and DUBs Regulating Notch Signaling in CSCs

| Regulator | Type | Target | Functional Outcome | Role in CSCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBXW7 | E3 Ligase | NICD | Promotes degradation of activated NICD | Suppresses stemness; loss promotes CSC maintenance |

| CBL | E3 Ligase | Notch Receptor | Regulates receptor turnover | Modulates CSC self-renewal |

| ITCH | E3 Ligase | Notch Components | Controls pathway activity | Affects CSC proliferation |

| Unspecified DUBs | DUB | NICD/Notch Receptor | Stabilizes signaling components | Promotes stemness properties |

Regulation of Wnt/β-catenin Signaling by E3 Ligases and DUBs

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway plays critical roles in embryonic development, adult tissue homeostasis, cell proliferation, and stem cell regulation [29] [30]. In the absence of Wnt ligands, cytoplasmic β-catenin is phosphorylated by a destruction complex comprising AXIN, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), and casein kinase 1 (CK1), leading to its ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [29] [30]. When Wnt ligands bind to Frizzled (Fz) receptors and LRP5/6 coreceptors, the destruction complex is disrupted, allowing β-catenin to accumulate and translocate to the nucleus where it activates target gene expression through TCF/LEF transcription factors [29] [30].

Key Regulatory E3 Ligases and DUBs in Wnt/β-catenin Signaling

Multiple E3 ligases and DUBs precisely regulate Wnt/β-catenin signaling components:

E3 Ligases:

- β-TrCP: Recognizes phosphorylated β-catenin, targeting it for ubiquitination and degradation [29]

- RNF43/ZNRF3: Membrane-associated E3 ligases that ubiquitinate Frizzled receptors, promoting their endocytosis and degradation [29]

- APC: Component of the destruction complex that facilitates β-catenin recognition by E3 ligases [30]

DUBs:

- USP22: Promotes stemness and tumor progression; identified as a promising therapeutic target in CSCs [31]

- CYLD: Removes ubiquitin chains from multiple Wnt pathway components [3]

- OTULIN: Regulates genotoxic Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation through linear deubiquitination [3]

Figure 2: Regulation of Wnt/β-catenin Signaling by E3 Ligases and DUBs. The diagram illustrates key regulatory points in the Wnt pathway where E3 ligases (green) promote degradation of pathway components, while DUBs (red) stabilize them.

Table 3: E3 Ligases and DUBs Regulating Wnt/β-catenin Signaling in CSCs

| Regulator | Type | Target | Functional Outcome | Role in CSCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-TrCP | E3 Ligase | β-catenin | Targets phosphorylated β-catenin for degradation | Limits CSC self-renewal |

| RNF43/ZNRF3 | E3 Ligase | Frizzled Receptors | Promotes receptor degradation | Negative regulators of Wnt signaling in CSCs |

| APC | E3 Ligase Complex Component | β-catenin | Facilitates β-catenin recognition | Tumor suppressor in CSC maintenance |

| USP22 | DUB | Unspecified Wnt Components | Stabilizes pathway components | Promotes stemness; therapeutic target |

| CYLD | DUB | Multiple Wnt Components | Removes ubiquitin chains | Suppresses CSC properties |

| OTULIN | DUB | Linear Ubiquitin Chains | Activates Wnt/β-catenin pathway | Enhances CSC signaling |

Regulation of Hedgehog Signaling by E3 Ligases and DUBs

The Hedgehog (HH) pathway governs cell proliferation and patterning during embryonic development and is involved in regeneration, homeostasis, and stem cell maintenance in adult tissues [26]. In mammals, three HH ligands (SHH, IHH, DHH) bind to the Patched (PTCH) receptor, relieving its inhibition of Smoothened (SMO) [26]. Activated SMO triggers the nuclear localization of GLI transcription factors (GLI1, GLI2, GLI3), which activate target gene expression [26]. The primary cilium plays a crucial role in coordinating HH signal transduction in vertebrates [26].

Key Regulatory E3 Ligases and DUBs in Hedgehog Signaling

HH signaling is finely modulated at multiple levels by E3 ligases and DUBs:

E3 Ligases:

- SCFβ-TrCP: Promotes proteolytic processing of GLI proteins into repressor forms and degradation of GLI1 [26]

- HIB/Roadkill/SPOP: Cullin3-based E3 ligase complex that targets GLI proteins for degradation [26]

- ITCH: HECT-type E3 ligase that mediates degradation of GLI1 and PTCH1 [26]

- SMURF: Regulates SMO ubiquitylation and trafficking in Drosophila [26]

DUBs:

- USP48: Stabilizes GLI proteins, enhancing HH signaling output [26]

- USP7: Modulates GLI1 stability and activity [26]

- UCHL5: Regulates SMO ciliary accumulation and HH pathway activation [26]

Table 4: E3 Ligases and DUBs Regulating Hedgehog Signaling in CSCs

| Regulator | Type | Target | Functional Outcome | Role in CSCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCFβ-TrCP | E3 Ligase | GLI Proteins | Promotes processing into repressors & degradation | Limits CSC maintenance |

| SPOP Complex | E3 Ligase | GLI Proteins | Targets GLI for degradation | Suppresses stemness |

| ITCH | E3 Ligase | GLI1, PTCH1 | Mediates degradation of key pathway components | Negative regulator of HH in CSCs |

| SMURF | E3 Ligase | SMO | Regulates SMO trafficking and stability | Modulates HH signaling in CSCs |

| USP48 | DUB | GLI Proteins | Stabilizes GLI transcription factors | Enhances HH signaling in CSCs |

| USP7 | DUB | GLI1 | Modulates GLI1 stability and activity | Promotes CSC maintenance |

| UCHL5 | DUB | SMO | Regulates SMO ciliary accumulation | Activates HH pathway in CSCs |

Experimental Approaches for Studying Ubiquitination in CSC Pathways

Methodologies for Assessing Protein Ubiquitination

Ubiquitination Assays:

- Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) with Ubiquitin Detection: Cells are transfected with tagged ubiquitin (HA-Ub, FLAG-Ub, Myc-Ub) and target plasmids. After treatment with proteasome inhibitor (MG132), cell lysates are immunoprecipitated with target protein antibody and probed with ubiquitin antibody to detect ubiquitination [29] [26].

- Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs): Utilize recombinant UBA domains with high affinity for polyubiquitin chains to isolate ubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates, protecting them from DUBs during extraction [26].

- In vivo Denaturation Techniques: Use of strong denaturants (SDS, Guanidine HCl) in lysis buffers to preserve labile ubiquitin linkages while disrupting non-covalent interactions [26].

Pulse-Chase Experiments: Measure protein half-life by metabolic labeling with 35S-methionine/cysteine followed by immunoprecipitation of target protein at time intervals. Treatment with cycloheximide to block new protein synthesis enhances assessment of degradation kinetics [26].

Identification of E3 Ligases and DUBs

RNA Interference Screens:

- siRNA/shRNA Libraries: Targeted or genome-wide screens to identify E3s/DUBs regulating specific CSC pathways. Readouts include luciferase reporters (TOPFlash for Wnt, GLI-luc for HH), target gene expression (qRT-PCR), and protein stability (Western blot) [26] [27].

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening: Identification of novel E3-DUB interactions using known pathway components as bait against human E3/DUB libraries [26].

CRISPR-Cas9 Screening:

- GeCKO Libraries: Genome-wide knockout screens to identify essential E3s/DUBs for CSC maintenance using viability, sphere formation, and drug resistance as endpoints [26] [27].

Functional Validation in Cancer Stem Cells

In vitro CSC Models:

- Tumor Sphere Formation: Primary tumorspheres are dissociated and plated as single cells in ultra-low attachment plates with growth factors (EGF, bFGF). Sphere number and size are quantified after E3/DUB modulation [25].

- Flow Cytometry for CSC Markers: Analysis of ALDH activity (ALDEFLUOR assay) and surface markers (CD44, CD133, CD24) following E3/DUB targeting [25].

- Clonogenic Assays: Assessment of self-renewal capacity through limiting dilution assays in semisolid media [25].

In vivo Tumorigenesis Models:

- Limiting Dilution Transplantation: Serial dilutions of control vs. E3/DUB-modified cells injected into immunocompromised mice (NSG) to assess CSC frequency using extreme limiting dilution analysis (ELDA) software [25].

- Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDXs): Treatment of established PDX tumors with E3/DUB inhibitors to assess effects on tumor growth and CSC frequency [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Ubiquitination in CSC Pathways

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Experimental Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Expression Constructs | HA-Ub, FLAG-Ub, Myc-Ub, K-only mutants (K48R, K63R) | Ubiquitination assays | K-only mutants determine chain topology specificity |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Stabilize ubiquitinated proteins | Cytotoxic at prolonged exposures; optimize treatment duration |

| E3 Ligase Modulators | MLN4924 (NEDD8 activator inhibitor), PROTACs | Functional studies of E3 activity | MLN4924 inhibits cullin-RING ligases broadly |

| DUB Inhibitors | PR-619 (pan-DUB inhibitor), USP-specific inhibitors | Functional validation of DUB targets | Pan-inhibitors lack specificity; use with validation controls |

| CSC Culture Supplements | B27, N2, EGF, bFGF, Noggin | Tumorsphere assays | Serum-free conditions essential for stem cell maintenance |

| Pathway Reporters | TOPFlash (Wnt), GLI-luc (HH), CBF1-luc (Notch) | Pathway activity screening | Normalize to constitutive controls (Renilla luciferase) |

| Antibody Resources | Anti-ubiquitin (P4D1, FK2), anti-K48/K63 linkage-specific | Detection of ubiquitinated proteins | FK2 recognizes polyUb chains; linkage-specific for topology |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Perspectives

The strategic targeting of E3 ligases and DUBs regulating CSC pathways represents a promising approach for cancer therapy. Several strategies have emerged:

Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs): These bifunctional molecules recruit target proteins to E3 ligases for ubiquitination and degradation. ARV-110 and ARV-471 represent advanced PROTACs in clinical trials for cancer therapy [3].

DUB Inhibitors: Selective inhibition of oncogenic DUBs such as USP22 presents a viable strategy for eliminating CSCs [31]. Computational drug repurposing approaches have identified Ergotamine as a potential USP22 inhibitor with anticancer properties [31].

Combination Therapies: Targeting ubiquitination regulators in combination with conventional chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or pathway-specific inhibitors may overcome therapy resistance mediated by CSCs [9] [3].

The continued elucidation of E3 ligase and DUB functions in CSC regulation will provide novel insights into tumor biology and enable the development of more effective therapeutic strategies against treatment-resistant cancers.

The ubiquitin system, a crucial post-translational modification platform, governs cancer stem cell (CSC) maintenance through specialized chain topologies. K48-linked ubiquitination primarily targets key regulatory proteins for proteasomal degradation, K63-linked chains coordinate non-proteolytic signaling processes driving stemness, and monoubiquitination regulates protein trafficking and chromatin dynamics. This whitepaper examines how these distinct ubiquitin codes integrate to control CSC fate, therapy resistance, and metastatic potential. We present quantitative analyses of linkage-specific functions, detailed experimental methodologies for topology interrogation, and visualization of ubiquitin signaling networks in CSCs, providing a technical framework for targeting ubiquitin signaling in cancer stem cell populations.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) represent a subpopulation of tumor cells with capabilities for self-renewal, differentiation, and driving tumor initiation, progression, and therapy resistance [27] [32]. The functional properties of CSCs are regulated by post-translational modifications, with ubiquitination emerging as a master regulator of stemness pathways. Ubiquitin topology—the spatial arrangement of ubiquitin monomers and polymers on substrate proteins—encodes specific biological outcomes that determine CSC fate decisions [33] [27].

The ubiquitin system comprises E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes, and E3 ligases that work in concert to attach ubiquitin to substrate proteins, with approximately 600 E3 ligases providing substrate specificity in humans [34] [35]. Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) reverse this process, creating a dynamic regulatory system. The seven lysine residues in ubiquitin (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and the N-terminal methionine (M1) serve as linkage sites for polyubiquitin chain formation, each generating distinct structural signatures recognized by specific effector proteins [34] [27].

Table 1: Major Ubiquitin Chain Types and Their General Functions in Cellular Regulation

| Chain Type | Primary Functions | Key Effectors/Receptors |

|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Proteasomal degradation | Proteasome, RAD23B [36] |

| K63-linked | Kinase activation, DNA repair, endocytosis, signaling complexes | EPN2, TAB2/3, CYLD [36] [34] |

| Monoubiquitination | Endocytosis, protein trafficking, histone regulation, chromatin modulation | Tsg101, ESCRT complex [37] [33] |

| K11/K48-branched | Enhanced proteasomal degradation, protein quality control | Bispecific antibodies, proteasome [38] [39] |

| K11-linked | ER-associated degradation, cell cycle regulation | Proteasome, CCDC50 [36] [27] |

| K27/K29-linked | DNA damage response, stress signaling | RNF168 [33] [27] |

Within CSC populations, the balance between different ubiquitin chain types regulates key stemness pathways including Wnt, Notch, Hedgehog, and TGF-β signaling [27]. Understanding the functional consequences of specific ubiquitin topologies provides critical insights into CSC maintenance and reveals potential therapeutic vulnerabilities for eradicating this therapy-resistant cell population.

Functional Specialization of Ubiquitin Chain Types

K48-Linked Ubiquitination: Proteostatic Control of Stemness Factors

K48-linked polyubiquitin chains represent the canonical degradation signal, targeting proteins for proteasomal destruction. In CSCs, K48-linked ubiquitination regulates the stability of transcription factors, cell cycle regulators, and metabolic enzymes that control stem cell identity and proliferation [33] [27].

The context-dependent function of K48 chains in CSC regulation is exemplified by FBXW7, an E3 ligase that displays dual roles in radiation response. In p53-wild type colorectal tumors, FBXW7 promotes radioresistance by degrading p53 and inhibiting apoptosis. Conversely, in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with SOX9 overexpression, FBXW7 enhances radiosensitivity by destabilizing SOX9 and alleviating p21 repression [33]. This functional switch underscores how tissue-specific genetic backgrounds influence ubiquitin signaling outcomes in CSC populations.

K48-linked ubiquitination also intersects with CSC metabolism through SMURF2-mediated HIF1α degradation, which compromises hypoxic survival, and SOCS2/Elongin B/C-driven SLC7A11 destruction, which increases ferroptosis sensitivity in liver cancer [33]. Additionally, TRIM21 utilizes K48 ubiquitination to degrade VDAC2 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma, suppressing cGAS/STING-mediated immune surveillance and potentially enabling CSC immune evasion [33].

Table 2: K48-Linked Ubiquitination in CSC-Regulatory Proteins

| E3 Ligase | CSC Substrate | Functional Consequence | Cancer Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| FBXW7 | p53 | Promotes radioresistance | Colorectal cancer [33] |

| FBXW7 | SOX9 | Enhances radiosensitivity | Non-small cell lung cancer [33] |

| SMURF2 | HIF1α | Compromises hypoxic survival | Multiple cancer types [33] |

| SOCS2/Elongin B/C | SLC7A11 | Increases ferroptosis sensitivity | Liver cancer [33] |

| TRIM21 | VDAC2 | Suppresses cGAS/STING immunity | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma [33] |

K63-Linked Ubiquitination: Signaling Amplification in Stemness Pathways

K63-linked ubiquitin chains serve as non-proteolytic signaling scaffolds that activate kinase pathways and assemble macromolecular complexes essential for CSC maintenance. Unlike K48 linkages, K63 chains function in NF-κB activation, protein trafficking, DNA repair, and kinase activation—processes frequently hijacked in CSCs to promote survival and self-renewal [34] [35].

In CSCs, K63 ubiquitination directly regulates prosurvival signaling cascades. TRAF4 utilizes K63 modifications to activate the JNK/c-Jun pathway, driving overexpression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL in colorectal cancer and MCL-1 in oral cancers [33]. K63 chains can also repurpose tumor suppressors; TRAF6 modifies p53 with K63 linkages, converting it into a pro-survival mitochondrial factor that may enhance CSC resistance to apoptosis [33]. Furthermore, K63 ubiquitination integrates metabolic and immune regulation in CSCs: TRIM26 stabilizes GPX4 via K63 ubiquitination to prevent ferroptosis in gliomas, while USP14 inhibition leads to accumulation of K63-modified IRF3, triggering STING-dependent antitumor immunity [33].

The E3 ligase TRAF6 exemplifies the specialized role of K63-specific enzymes in CSC signaling. As one of only two known E3s that selectively target substrates for K63-linked ubiquitination (along with RNF168), TRAF6 activates AKT through K63-linked ubiquitination, promoting CSC survival and expansion across multiple cancer types [34]. This signaling function depends on the unique structural properties of K63 chains, which create extended interfaces for protein-protein interactions without triggering proteasomal degradation.

Figure 1: K63-Linked Ubiquitin Chains Coordinate Multiple Pro-Survival Pathways in CSCs. K63 linkages serve as molecular scaffolds for complex assembly in kinase activation, DNA damage response, and metabolic regulation—processes essential for CSC maintenance.

Monoubiquitination: Trafficking and Epigenetic Control in CSCs

Monoubiquitination—the attachment of a single ubiquitin molecule to substrate proteins—regulates protein trafficking, endocytosis, and epigenetic programming in CSCs. Unlike polyubiquitin chains, monoubiquitination typically alters protein interaction landscapes and subcellular localization without triggering degradation [38] [27].

A paradigm for monoubiquitination in CSC regulation is CD133 (PROM1), a well-established CSC marker in multiple malignancies. CD133 undergoes monoubiquitination at lysine 848 within its intracellular carboxyl terminus, which facilitates its interaction with tumor susceptibility gene 101 (Tsg101) and subsequent incorporation into extracellular vesicles [37]. This monoubiquitination-dependent vesicle secretion promotes cell migration and potentially establishes metastatic niches for CSCs. Knockdown of the E3 ubiquitin protein ligase Nedd4 significantly impairs CD133 ubiquitination and vesicle secretion, confirming the importance of this modification for CSC trafficking and communication [37].

Monoubiquitination also regulates chromatin dynamics and DNA damage responses in CSCs through histone modifications. UBE2T/RNF8-mediated H2AX monoubiquitylation accelerates DNA damage detection in hepatocellular carcinoma, while RNF40-generated H2Bub1 recruits the FACT complex (SUPT16H) to relax nucleosomes [33]. For non-histone targets, FANCD2 monoubiquitylation resolves carbon ion-induced DNA crosslinks, and γ-tubulin monoubiquitylation maintains centrosome integrity—processes that may be co-opted by CSCs to maintain genomic stability despite heightened replication stress [33].

Branched Ubiquitin Chains: Complex Topologies in CSC Regulation

Branched ubiquitin chains, containing ubiquitin molecules modified on two or more residues simultaneously, represent an emerging layer of complexity in ubiquitin coding. These heterotypic polymers integrate signals from different linkage types and can encode qualitative and quantitative information beyond homotypic chains [38] [40] [39].

K11/K48-branched chains exemplify the specialized functions of branched topologies in CSC-relevant processes. These heterotypic polymers are synthesized by coordinated actions of E2 enzymes and E3 ligases, such as the anaphase-promoting complex (APC/C) working with UBE2C and UBE2S during mitosis [38] [39]. K11/K48-branched chains promote rapid proteasomal degradation of aggregation-prone proteins and mitotic regulators, serving as potent degradation signals that may be critical for maintaining proteostasis in rapidly dividing CSCs [38]. Endogenous substrates of K11/K48-branched chains include misfolded nascent polypeptides and pathological Huntingtin variants, suggesting a role in protein quality control pathways relevant to CSC stress adaptation [38].

K48/K63-branched chains represent another functionally significant heterotypic topology that integrates degradative and non-degradative signaling. These branched chains are produced by collaboration between E3s with distinct specificities, such as TRAF6 and HUWE1 during NF-κB signaling, or ITCH and UBR5 during apoptotic responses [39]. In the case of the pro-apoptotic regulator TXNIP, ITCH first modifies the substrate with non-proteolytic K63-linked chains before UBR5 attaches K48 linkages to produce branched K48/K63 chains, resulting in proteasomal degradation [39]. This conversion from non-degradative to degradative signaling may provide a regulatory switch for controlling protein stability in response to CSC microenvironmental cues.

Experimental Approaches for Ubiquitin Topology Analysis

Bispecific Antibody Technology for Heterotypic Chain Detection

The development of linkage-specific antibodies has revolutionized ubiquitin chain analysis. For branched chain detection, bispecific antibodies that recognize two different linkage types simultaneously provide unprecedented specificity. The K11/K48-bispecific antibody was engineered using knobs-into-holes heterodimerization technology, pairing one arm that recognizes K11-linkages with another that binds K48-linkages [38].