Ubiquitination Patterns in Cancer: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications in Biomarker and Therapy Development

This comprehensive review synthesizes current research on dysregulated ubiquitination patterns in cancer versus normal tissues, exploring their profound implications for tumor biology and clinical practice.

Ubiquitination Patterns in Cancer: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications in Biomarker and Therapy Development

Abstract

This comprehensive review synthesizes current research on dysregulated ubiquitination patterns in cancer versus normal tissues, exploring their profound implications for tumor biology and clinical practice. It examines foundational mechanisms by which ubiquitination drives oncogenesis, details advanced methodologies for profiling the cancer ubiquitinome, analyzes challenges in therapeutic targeting, and evaluates clinical validation strategies for ubiquitination-based biomarkers. By integrating findings from recent pancancer analyses and tissue-specific studies, this article provides researchers and drug development professionals with a critical resource for understanding ubiquitination as a dynamic regulatory layer in cancer, highlighting its emerging role in prognostic stratification, immunotherapy response prediction, and the development of novel targeted therapies like PROTACs.

The Ubiquitin Code in Malignancy: Decoding Cancer-Specific Patterns and Biological Consequences

The ubiquitin system represents a crucial post-translational modification pathway that maintains cellular homeostasis by regulating the stability, activity, and localization of a vast array of intracellular proteins [1]. This system encompasses a coordinated enzymatic cascade that conjugates the small protein ubiquitin to substrate proteins, thereby generating a complex "ubiquitin code" that dictates diverse cellular outcomes [2]. The process is highly reversible, with deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) counterbalancing ubiquitination to ensure dynamic regulation [3]. While initially recognized for its role in targeting proteins for degradation via the proteasome, the ubiquitin system is now known to govern virtually all aspects of cellular function, including cell cycle progression, DNA repair, immune response, and signal transduction [4]. Notably, dysregulation of this finely tuned system is increasingly implicated in human pathologies, particularly in cancer, where mutations in ubiquitination pathway genes contribute to tumorigenesis, immune evasion, and therapeutic resistance [5] [6]. This technical guide examines the core components of the ubiquitination machinery—E1, E2, E3 enzymes, and DUBs—with emphasis on their mechanisms, interactions, and relevance to oncogenic processes.

The Ubiquitination Cascade: E1, E2, and E3 Enzymes

Fundamental Mechanism

Protein ubiquitination occurs through a sequential, ATP-dependent enzymatic cascade comprising three distinct steps catalyzed by ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), and ubiquitin-ligase (E3) enzymes [4]. This process initiates with ubiquitin activation, followed by conjugation, and culminates in ligation to specific substrate proteins.

Table 1: Core Enzymes in the Ubiquitination Cascade

| Enzyme Type | Key Function | Representative Family Members | Catalytic Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Activating) | Activates ubiquitin in ATP-dependent manner | UBA1, UBA6 | Forms thioester bond with ubiquitin |

| E2 (Conjugating) | Accepts and carries activated ubiquitin | UBE2T, UBE2N, UBE2B | Transient E2~Ub thioester intermediate |

| E3 (Ligase) | Recognizes substrates and catalyzes ubiquitin transfer | RING, HECT, RBR types | Direct transfer (RING) or intermediate (HECT) |

The process initiates when the E1 enzyme activates ubiquitin through an ATP-dependent reaction that adenylates the ubiquitin C-terminal glycine, subsequently forming a high-energy thioester bond between E1's catalytic cysteine and ubiquitin [1] [3]. Activated ubiquitin is then transferred to a cysteine residue on an E2 conjugating enzyme via transesterification [4]. The final step involves an E3 ubiquitin ligase that recognizes specific substrate proteins and facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine residue on the substrate, forming an isopeptide bond [1]. Humans possess approximately 40 E2 enzymes and over 600 E3 ligases, which confer substrate specificity and determine the nature of ubiquitin modifications [3] [5].

E3 Ligase Classification and Mechanisms

E3 ubiquitin ligases are categorized into three major families based on their structural domains and mechanisms of ubiquitin transfer:

RING-type E3 ligases (Really Interesting New Gene) represent the largest class and function primarily as scaffolds that simultaneously bind both the E2~Ub complex and the substrate protein, facilitating direct ubiquitin transfer without forming a covalent intermediate [3] [7]. Prominent examples include the tripartite motif (TRIM) family proteins such as TRIM8 and TRIM31, which have been implicated in cancer-relevant signaling pathways [3].

HECT-type E3 ligases (Homologous to E6-AP Carboxyl Terminus) employ a two-step mechanism wherein ubiquitin is first transferred from the E2 to a conserved cysteine residue within the HECT domain, forming a thioester intermediate, before final transfer to the substrate [3] [7].

RBR-type E3 ligases (RING-Between-RING) represent a hybrid class that utilizes both RING-like domains for E2 binding and a catalytic domain that transiently accepts ubiquitin similar to HECT-type E3s [3].

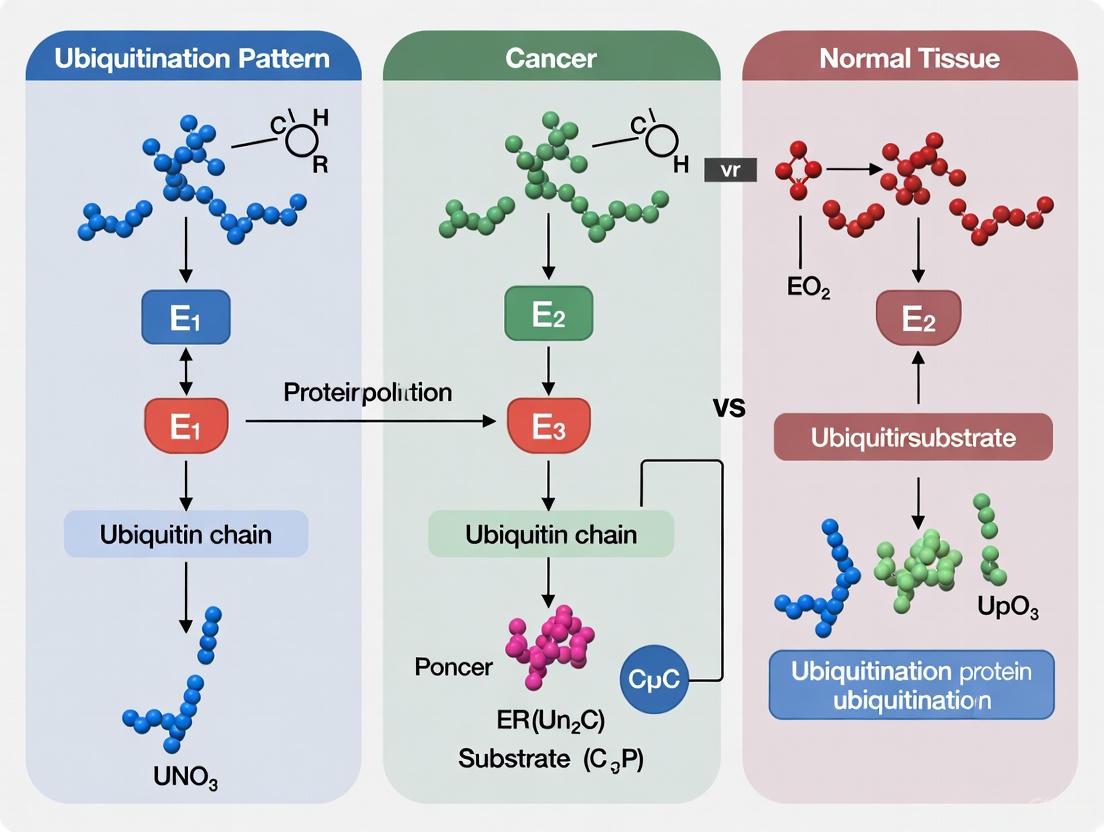

Figure 1: Ubiquitination Enzymatic Cascade. E1 activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent process, E2 carries the activated ubiquitin, and E3 facilitates transfer to the substrate protein.

Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs): Reversibility and Regulation

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) constitute a diverse family of proteases that counterbalance ubiquitination by removing ubiquitin modifications from substrate proteins, thereby providing critical regulatory control over ubiquitin signaling [3]. DUBs are categorized into two major classes based on their catalytic mechanisms: cysteine proteases and metalloproteases [7]. The cysteine protease class includes multiple subfamilies, with ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs) representing the largest group with over 60 members in humans [7]. These enzymes perform several essential functions, including processing ubiquitin precursors, reversing ubiquitin signals to regulate pathways, rescuing proteins from degradation, and maintaining ubiquitin homeostasis by recycling ubiquitin from substrates targeted to the proteasome or lysosome [3].

A well-characterized example is USP22, a catalytic component of the human Spt-Ada-Gcn5 Acetyltransferase (hSAGA) complex, which plays a vital role in transcriptional regulation through histone modification [7]. USP22 removes monoubiquitin from histone H2B, facilitating transcriptional elongation and affecting additional histone modifications. This DUB has been implicated in various cancers, where its elevated expression correlates with poor patient outcomes, positioning it as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target [7]. Beyond histone modification, DUBs regulate key signaling pathways relevant to cancer, including p53 signaling, NF-κB pathway, and MAPK cascade, highlighting their broad impact on cellular homeostasis and disease processes [3] [6].

The Ubiquitin Code: Complexity and Signaling Diversity

The ubiquitin system generates remarkable complexity through diverse ubiquitin modifications that constitute a sophisticated "ubiquitin code" [2]. Ubiquitin itself contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1) that can serve as attachment points for subsequent ubiquitin molecules, forming polyubiquitin chains with distinct structures and functions [2]. The specific linkage types within these chains determine the fate and function of the modified protein:

Table 2: Major Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Cellular Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Cellular Function | Key Recognizers/Effectors |

|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Proteasomal degradation | Proteasome receptors |

| K63-linked | Signal transduction, DNA repair, endocytosis | Proteins with UBDs in signaling complexes |

| M1-linked (linear) | NF-κB activation, inflammation | LUBAC, NEMO |

| K11-linked | Proteasomal degradation, cell cycle regulation | Proteasome receptors |

| K27-linked | DNA damage response, mitophagy | Autophagy receptors |

| K29-linked | Proteasomal degradation, Wnt signaling | Proteasome receptors |

| K33-linked | Kinase modification, trafficking | Undefined |

Beyond homogeneous chains, ubiquitin modifications can form heterotypic chains (mixed linkages) or branched chains (multiple ubiquitins attached to a single ubiquitin molecule), creating exceptional diversity in signaling outcomes [2]. Additionally, ubiquitin itself can be modified by phosphorylation, acetylation, or other ubiquitin-like proteins (SUMO, NEDD8), adding further layers of regulation [2]. This complex ubiquitin code enables precise control over numerous cellular processes, with different chain architectures recruiting specific ubiquitin-binding proteins that dictate downstream consequences such as proteasomal degradation, altered subcellular localization, or modified activity [1] [2].

Experimental Approaches for Studying Ubiquitination

Key Methodologies and Workflows

Investigating the ubiquitination process requires specialized methodologies to identify substrates, characterize enzymatic activities, and decipher the ubiquitin code. Several well-established experimental approaches include:

In Vitro Ubiquitination Assays: These reconstitution experiments utilize purified E1, E2, E3 enzymes, ubiquitin, and ATP to examine specific ubiquitination events. Reactions are typically analyzed by immunoblotting to detect ubiquitinated species, often under denaturing conditions to preserve the thioester linkages between E2 and ubiquitin [4]. This approach allows researchers to dissect the minimal components required for ubiquitination and test the effects of mutations or inhibitors on the enzymatic cascade.

Global Protein Stability (GPS) Profiling: This genome-wide screening strategy employs reporter proteins fused with hundreds of potential substrates to systematically identify E3 ligase substrates [4]. By inhibiting E3 ligase activity and monitoring reporter accumulation, researchers can map E3-substrate regulatory networks on a global scale, revealing previously unknown relationships in the ubiquitin system.

Mass Spectrometry-Based Ubiquitinomics: Advanced proteomic techniques represent powerful tools for comprehensively characterizing the ubiquitin code. These approaches typically involve enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides using ubiquitin remnant motifs or linkage-specific antibodies, followed by high-resolution mass spectrometry analysis [2]. Quantitative methods such as SILAC (Stable Isotope Labeling with Amino Acids in Cell Culture) or TMT (Tandem Mass Tag) enable comparative analysis of ubiquitination sites and chain topology under different physiological conditions or in response to perturbations.

Figure 2: Ubiquitinomics Workflow. Mass spectrometry-based approach for system-wide analysis of ubiquitination sites and chain architectures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application and Function |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Anti-K48-Ub, Anti-K63-Ub, Anti-M1-Ub | Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence to detect specific chain types |

| Activity-Based Probes | Ubiquitin-vinylsulfone, HA-Ub-VS | DUB activity profiling and identification |

| Recombinant Enzymes | Purified E1, E2, E3 complexes | Reconstitution of ubiquitination cascades in vitro |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, MG132 | Stabilize ubiquitinated proteins by blocking degradation |

| DUB Inhibitors | PR-619, P22077 | Pan-DUB inhibitors to study ubiquitination dynamics |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | K48R, K63R, K0 (all lysines mutated) | Define chain specificity and requirements |

| CRISPR Libraries | E3/DUB knockout pools | Functional genomic screens for ubiquitin pathway components |

Ubiquitination Machinery in Cancer: Pathophysiological and Therapeutic Implications

Dysregulation in Oncogenesis

Dysregulation of ubiquitination enzymes is a hallmark of many cancers, with mutations in E2s, E3s, and DUBs contributing to tumor initiation, progression, and therapeutic resistance [5]. For instance, UBE2T, an E2 conjugating enzyme, demonstrates elevated expression across multiple tumor types where its upregulation correlates with poor clinical outcomes [8]. UBE2T functions in the Fanconi anemia DNA repair pathway and promotes oncogenesis through stabilization of proto-oncogenes and cell cycle regulators [8]. Another E2 enzyme, UBE2N, which primarily synthesizes K63-linked ubiquitin chains to stabilize proteins or alter their function, has been identified as a critical dependency in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [9]. Inhibition of UBE2N catalytic function suppresses leukemic cells through selective degradation of critical proteins, revealing its potential as a therapeutic target [9].

E3 ligases also play pivotal roles in cancer pathogenesis. The TRIM family of RING-type E3 ligases exhibits diverse functions in oncogenesis. TRIM8 expression is increased in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) and promotes hepatic lipid accumulation, inflammation, and fibrosis by activating TAK1 through ubiquitination [3]. Conversely, TRIM31 exerts protective effects against MASH progression by promoting the degradation of RHBDF2 via K48-linked polyubiquitination, thereby attenuating inflammatory signaling [3]. In von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease, loss-of-function mutations in the VHL E3 ligase result in accumulation of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), driving renal cell carcinoma and other tumors [4].

Emerging Therapeutic Strategies

The therapeutic potential of targeting ubiquitination pathways is being realized through several innovative approaches:

Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) are bifunctional molecules that recruit E3 ubiquitin ligases to target proteins of interest, inducing their ubiquitination and subsequent degradation [6]. PROTACs such as ARV-110 (targeting androgen receptor) and ARV-471 (targeting estrogen receptor) have advanced to clinical trials, demonstrating promising results in cancer treatment [6]. These molecules offer advantages over traditional inhibitors by catalytically inducing protein degradation rather than merely inhibiting function.

Molecular Glues represent another class of degraders that induce neo-interactions between E3 ligases and target proteins, leading to ubiquitination and degradation [6]. CC-90009, which promotes degradation of GSPT1 by recruiting the CRL4CRBN E3 ligase complex, is currently in phase II trials for leukemia therapy [6].

Small-Molecule Inhibitors targeting specific components of the ubiquitin system continue to be developed. For instance, inhibitors of the E1 enzyme have shown antitumor activity, while specific inhibitors targeting oncogenic E3 ligases or DUBs are under investigation [5]. The clinical success of proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma validates the ubiquitin-proteasome system as a viable therapeutic target in oncology [4].

A comprehensive pan-cancer analysis has revealed that ubiquitination-related gene signatures can effectively stratify patients into prognostic subgroups and predict response to immunotherapy [10]. Specifically, the OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination axis was found to modulate MYC pathway activity and influence tumor histology, suggesting novel strategies for targeting traditionally "undruggable" oncoproteins like MYC through their ubiquitination regulatory networks [10]. These advances highlight the growing importance of understanding ubiquitination machinery for developing targeted cancer therapies.

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that governs virtually all cellular processes in eukaryotes, serving as a master regulatory mechanism for protein stability, function, and localization. This sophisticated signaling system employs a 76-amino acid protein, ubiquitin, which can be conjugated to substrate proteins as a single moiety (monoubiquitination) or as polymeric chains (polyubiquitination) through an enzymatic cascade involving E1 activating, E2 conjugating, and E3 ligating enzymes [11] [12]. The diversity of ubiquitin signaling stems from the various topological arrangements possible when ubiquitin molecules form chains, with all seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and the N-terminal methionine (M1) serving as potential linkage sites [13] [14]. In human cells, this complex system is orchestrated by a limited set of enzymes: only two E1 enzymes, approximately 40 E2 enzymes, and over 600 E3 enzymes, which work in concert to achieve remarkable substrate specificity [14] [12]. The resulting "ubiquitin code" is interpreted by specialized receptors containing ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs), with more than 20 distinct UBD families identified to date [13]. When decoded incorrectly or dysregulated, this intricate system contributes significantly to human diseases, particularly cancer, making it a compelling area for therapeutic intervention [14] [8] [12].

Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Functional Consequences

The ubiquitination system generates remarkable functional diversity through variations in chain linkage and architecture. The specific lysine residues used to connect ubiquitin molecules create structurally and functionally distinct signals that are interpreted differently by cellular machinery [13] [15].

Table 1: Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Primary Cellular Functions

| Linkage Type | Structural Features | Primary Cellular Functions | Representative E2/E3 Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monoubiquitination | Single ubiquitin attached | DNA damage repair, chromatin remodeling, endocytosis [11] [12] | Rad18 (E3) for PCNA [12] |

| K48-linked | Compact "closed" conformation | Proteasomal degradation [11] [15] | Cdc34/SCF complexes [11] |

| K63-linked | Extended "open" conformation | Kinase activation, DNA repair, endocytosis, inflammation [11] [15] | UBC13/MMS2 heterodimer (E2) [13] |

| K11-linked | Mixed open/closed states | Cell cycle regulation, ER-associated degradation [14] [12] | UBE2S with APC/C (E3) [13] |

| K6-linked | Not well characterized | DNA damage repair, mitochondrial homeostasis [12] | BRCA1/BARD1 (E3) [13] |

| K27-linked | Heterogeneous structures | Mitophagy, innate immunity [12] | - |

| K29-linked | Not well characterized | Proteasomal degradation, lysosomal degradation [14] | - |

| K33-linked | Not well characterized | Endosomal sorting, kinase regulation [12] | - |

| M1-linked | Linear chains | NF-κB signaling, inflammation [12] | LUBAC complex (E3) [12] |

| Branched | Multiple linkage types in single chain | Enhanced signaling complexity [14] | Multiple E2 combinations [13] |

The functional specificity of different ubiquitin linkages arises from their distinct three-dimensional structures, which create unique interaction surfaces for ubiquitin-binding domains. For instance, K48-linked chains predominantly adopt a "closed" conformation where the hydrophobic patches are sequestered at ubiquitin-ubiquitin interfaces, while K63-linked chains maintain an extended "open" structure that exposes these hydrophobic surfaces for recognition by specific receptors [13]. This structural diversity enables the ubiquitin system to coordinate a vast array of cellular processes, with distinct chain types directing proteins to different fates—K48 linkages typically target substrates for proteasomal degradation, whereas K63 linkages generally serve non-proteolytic roles in signaling complex assembly [11] [15].

The Ubiquitination Enzyme Cascade

The process of ubiquitination involves a sequential enzymatic cascade that begins with ubiquitin activation and culminates in its transfer to specific substrate proteins [11] [12].

Diagram 1: Ubiquitin Enzymatic Cascade (55 characters)

The cascade initiates when the E1 activation enzyme utilizes ATP to adenylate ubiquitin's C-terminus, forming a ubiquitin-adenylate intermediate. The E1 then captures activated ubiquitin via a thioester bond between its catalytic cysteine and ubiquitin's C-terminal glycine [12]. This activated ubiquitin is subsequently transferred to the E2 conjugating enzyme, which forms a similar thioester bond with ubiquitin through its conserved catalytic cysteine residue [11]. Finally, E3 ligases orchestrate the final transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to specific substrate proteins, facilitating the formation of an isopeptide bond between ubiquitin's C-terminus and a lysine ε-amino group on the substrate [11] [12].

Table 2: Classification of Human Ubiquitination Enzymes

| Enzyme Class | Subtypes | Representative Members | Catalytic Mechanism | Human Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 Activating Enzymes | - | UBA1, UBA6 | Ubiquitin activation via ATP-dependent adenylation, forms E1~Ub thioester [12] | 2 |

| E2 Conjugating Enzymes | Class I (UBC only) | Cdc34, UBE2T, Ube2c | Accepts Ub from E1, forms E2~Ub thioester, often determines chain topology [11] [14] | ~40 |

| Class II (C-terminal extension) | - | - | - | |

| Class III (N-terminal extension) | - | - | - | |

| Class IV (both extensions) | - | - | - | |

| E3 Ligase Enzymes | RING-type | SCF complexes, MDM2 | Brings E2~Ub and substrate together, direct Ub transfer [11] [14] | >500 |

| HECT-type | Nedd4 family | Forms HECT-Ub thioester intermediate before substrate transfer [14] | ~30 | |

| RBR-type | HOIP, HOIL-1 | Hybrid mechanism with RING1 and RING2 domains [14] | 14 |

The exceptional specificity of ubiquitin signaling is largely achieved through the combinatorial action of E2 and E3 enzymes. While E2 enzymes often determine chain topology, E3 enzymes provide substrate recognition through specialized protein-protein interaction domains [11] [14]. For example, in the well-characterized SCFCdc4/Cdc34 system, the RING E3 SCFCdc4 binds the substrate Sic1 while the E2 Cdc34 catalyzes ubiquitin transfer, with specific residues in Cdc34's catalytic core determining whether Sic1 undergoes monoubiquitination or K48-linked polyubiquitination [11]. This sophisticated division of labor enables the ubiquitin system to achieve remarkable regulatory precision with a limited set of components.

Experimental Methods for Studying Ubiquitination

Investigating ubiquitination mechanisms requires specialized methodologies that can capture transient enzyme-substrate interactions and determine linkage specificity. The following protocols represent core experimental approaches in the field.

In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay Protocol

Purpose: To reconstitute ubiquitination using purified components and identify specific E2-E3-substrate combinations responsible for particular ubiquitin chain types [11].

Reagents and Equipment:

- Purified E1, E2, E3 enzymes

- Ubiquitin (wild-type and mutant forms)

- ATP regeneration system

- Substrate protein

- Reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM DTT)

- SDS-PAGE equipment

- Immunoblotting apparatus

- Ubiquitin linkage-specific antibodies

Procedure:

- Prepare master mix containing 100 nM E1, 1-5 μM E2, 5-20 μM ubiquitin, and ATP regeneration system in reaction buffer

- Aliquot master mix into separate tubes containing different E3 enzymes (100-500 nM) and substrate (1-2 μM)

- Incubate reactions at 30°C for 60-90 minutes

- Terminate reactions by adding SDS-PAGE sample buffer with DTT

- Analyze by immunoblotting with ubiquitin antibodies or substrate-specific antibodies

- For linkage determination, include ubiquitin mutants (e.g., K48R, K63R) or use linkage-specific antibodies

Key Controls:

- Omit individual components (E1, E2, E3, or substrate) to confirm requirement of all factors

- Include catalytically inactive E2 (Cys-to-Ser mutant) to verify enzymatic activity requirement

- Test ubiquitin lysine mutants to determine linkage specificity [11]

Acceptor Lysine Identification Protocol

Purpose: To identify specific lysine residues targeted for ubiquitination and characterize sequence determinants influencing lysine selection [11].

Reagents and Equipment:

- Substrate protein with wild-type and mutant lysine residues

- In vitro ubiquitination components (as above)

- Mass spectrometry equipment

- Site-directed mutagenesis kit

Procedure:

- Perform in vitro ubiquitination reaction with wild-type substrate

- Resolve ubiquitinated products by SDS-PAGE and excise bands

- Digest with trypsin and analyze by mass spectrometry to identify modified lysines

- Create point mutants converting target lysines to arginine

- Test ubiquitination efficiency of lysine mutants compared to wild-type

- Create chimeric proteins swapping sequences around poorly and efficiently ubiquitinated lysines

- Quantify ubiquitination efficiency via immunoblotting and densitometry

Applications: This approach revealed that residues surrounding Sic1 lysines are critical for ubiquitination efficiency, and that amino acid determinants in Cdc34's catalytic region specify whether Sic1 undergoes monoubiquitination or polyubiquitination [11].

Ubiquitin Signaling in Cancer Biology

Dysregulation of ubiquitin signaling is implicated in numerous cancers, with specific E3 ligases and deubiquitinases acting as oncogenes or tumor suppressors. The functional consequences of ubiquitination in cancer depend critically on both the substrate and the linkage type.

Diagram 2: Ubiquitination in Cancer (34 characters)

The tumor suppressor p53 provides a classic example of ubiquitin-mediated regulation in cancer. The E3 ligase MDM2 binds to p53 through its N-terminus to ubiquitinate p53 protein, with monoubiquitination promoting nuclear export and polyubiquitination mediating degradation in the nucleus [14]. MDM2 overexpression, detected in various human cancers including osteosarcoma and neuroblastoma, results in excessive p53 degradation and diminished tumor suppressor activity [14]. Beyond p53, numerous other critical cancer regulators are controlled by ubiquitination, including the core stem cell factors Nanog, Oct4, and Sox2, whose ubiquitination status helps maintain cancer stem cell stemness [12].

Table 3: Selected Ubiquitination Enzymes Dysregulated in Cancer

| Enzyme | Gene | Cancer Type | Molecular Function | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDM2 | MDM2 | Osteosarcoma, Neuroblastoma, Lung Cancer | E3 ligase for p53 degradation [14] | Nutlin, MI-219 (MDM2 inhibitors) [12] |

| UBE2T | UBE2T | Multiple Myeloma, Breast Cancer, Ovarian Cancer | E2 enzyme in Fanconi anemia pathway, interacts with FANCL [8] | Potential biomarker for prognosis and immunotherapy response [8] |

| Ube2c | UBE2C | Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Esophageal Cancer, Breast Cancer | E2 cooperating with APC/C for cell cycle regulation [14] | Overexpression enhances proliferation; inhibition induces apoptosis [14] |

| Gp78 | AMFR | Sarcomas, Metastatic Cancers | Endoplasmic reticulum-associated E3 ligase for KA11/CD82 [14] | Inhibition reduces metastasis by stabilizing KA11 [14] |

| OTUB1 | OTUB1 | Pan-cancer (Ubiquitination Regulatory Network) | Deubiquitinase regulating MYC pathway with TRIM28 [10] | High expression associated with immunotherapy resistance [10] |

Recent pan-cancer analyses have revealed that ubiquitination patterns effectively stratify patients into molecular subtypes with distinct clinical outcomes. A comprehensive study integrating data from 4,709 patients across 26 cohorts identified a conserved ubiquitination-related prognostic signature (URPS) that effectively stratified patients into high-risk and low-risk groups with distinct survival outcomes across all analyzed cancers [10]. This signature demonstrated significant associations with tumor immune markers, checkpoint genes, and immune cell infiltration, highlighting the immune-modulatory functions of ubiquitination in cancer [8] [10]. Furthermore, ubiquitination scores showed a positive correlation with squamous or neuroendocrine transdifferentiation in adenocarcinoma, suggesting ubiquitination pathways help drive histological fate decisions in cancer cells [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Mutants | K48-only, K63-only, K48R, K63R | Linkage specificity determination [11] | Single lysine ubiquitins prevent alternative chain formation; arginine mutants block specific linkages |

| E2 Enzyme Inhibitors | CC0651, Leucettamol A [12] | E2 functional studies | Target E2-ubiquitin thioester formation; demonstrate therapeutic potential in preclinical models |

| E1 Enzyme Inhibitors | MLN7243, MLN4924 [12] | Global ubiquitination blockade | MLN4924 inhibits NEDD8-activating enzyme; causes apoptosis in hematological malignancies |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib, Ixazomib [12] | Clinical translation; K48-linked pathway studies | FDA-approved for multiple myeloma; validate ubiquitin system as drug target |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K48-linkage specific, K63-linkage specific | Immunoblotting, immunohistochemistry | Recognize unique epitopes formed by specific ubiquitin linkages |

| DUB Inhibitors | Compounds G5, F6 [12] | Deubiquitination pathway studies | Target ubiquitin-specific proteases; show potential in preclinical cancer models |

| Activity-Based Probes | Ubiquitin-based probes with reactive groups | DUB substrate profiling | Covalently trap active DUBs for identification and characterization |

The diverse signaling capabilities of monoubiquitination and polyubiquitin chains represent a sophisticated regulatory language that coordinates cellular homeostasis. The structural plasticity of ubiquitin chains—from monoubiquitination to complex polyubiquitin architectures—enables this system to direct an extraordinary range of biological outcomes, with specific chain topologies recruiting distinct receptor proteins to initiate appropriate downstream responses [13] [15]. In cancer biology, dysregulation of ubiquitination contributes fundamentally to tumorigenesis through multiple mechanisms, including excessive degradation of tumor suppressors, stabilization of oncoproteins, and rewiring of signaling networks [14] [12]. The expanding repertoire of ubiquitin-targeting therapeutics, particularly those exploiting linkage-specific vulnerabilities, represents a promising frontier in precision oncology [12] [16]. As our understanding of ubiquitin signaling complexity deepens through multiomics approaches and single-cell technologies, we anticipate increasingly sophisticated strategies for manipulating this system to overcome therapeutic resistance and improve patient outcomes across diverse cancer types [10] [17] [16].

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a critical post-translational regulatory mechanism responsible for controlling approximately 80-90% of intracellular proteolysis in eukaryotic cells [8] [10]. This system employs a precise enzymatic cascade comprising E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes to tag substrate proteins with ubiquitin chains, ultimately determining their stability, localization, and function [16]. Dysregulation of this finely tuned system has emerged as a hallmark of cancer pathogenesis, driving uncontrolled proliferation, metabolic reprogramming, immune evasion, and therapeutic resistance across diverse malignancies [16] [18].

Global ubiquitinome remodeling represents a fundamental molecular process wherein cancer cells systematically rewire ubiquitination networks to acquire malignant capabilities. Unlike genetic mutations, which are static alterations, the ubiquitinome constitutes a dynamic, adaptable layer of regulation that enables tumors to fine-tune oncogenic and tumor-suppressive pathways in response to selective pressures [16]. Recent pan-cancer analyses have begun to illuminate conserved patterns of ubiquitin pathway alterations that transcend tissue-of-origin classifications, revealing both universal vulnerabilities and context-specific dependencies [8] [10] [19].

This technical review synthesizes current evidence quantifying ubiquitinome alterations across solid tumors, delineates the experimental methodologies enabling these discoveries, and explores the therapeutic implications of targeting the ubiquitin system in oncology. By framing these findings within the context of a broader thesis on ubiquitination patterns in cancer versus normal tissues, we aim to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive reference for understanding and exploiting ubiquitin-based mechanisms in cancer biology.

Quantitative Landscape of Ubiquitin Pathway Alterations in Solid Tumors

Systematic pan-cancer analyses have revealed consistent patterns of ubiquitin pathway dysregulation across diverse solid tumors. The integration of genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic datasets has enabled researchers to quantify these alterations at multiple molecular levels, from gene expression changes to protein abundance and post-translational modifications.

Table 1: Ubiquitin Enzyme Expression Alterations Across Solid Tumors

| Ubiquitin Enzyme | Cancer Types with Significant Overexpression | Associated Clinical Outcomes | Primary Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| UBE2T [8] | Multiple myeloma, breast cancer, renal cell carcinoma, ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, retinoblastoma, pancreatic cancer | Reduced overall and progression-free survival | Enhanced proliferation, invasion, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, DNA repair dysregulation |

| UBD [19] | 29 cancer types including glioma, colorectal carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer | Poor prognosis, higher histological grades | Promotion of chromosomal instability, interaction with NF-κB, Wnt, and SMAD2 pathways |

| OTUB1 [10] | Lung cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, urothelial cancer, melanoma | Immunotherapy resistance, poor prognosis | Modulation of MYC pathway, oxidative stress alteration, squamous/neuroendocrine transdifferentiation |

| E3 Ligases [20] | HERC5 (esophageal cancer), RNF5 (liver cancer) | Cancer type-specific progression | Tumor type-specific substrate targeting, potential therapeutic vulnerabilities |

The ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBE2T demonstrates particularly widespread oncogenic roles across solid tumors. Comprehensive analyses using TIMER 2.0, GEPIA2, and TCGA datasets have revealed elevated UBE2T expression in numerous malignancies compared to adjacent normal tissues [8]. This overexpression correlates strongly with adverse clinical outcomes, including reduced overall survival and progression-free survival across multiple cancer types. Functional studies indicate that UBE2T upregulation drives key oncogenic processes including enhanced cellular proliferation, invasion, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and dysregulation of DNA repair mechanisms [8].

Table 2: Genetic and Epigenetic Alterations in Ubiquitin Pathway Genes

| Alteration Type | Representative Genes | Frequency Across Cancers | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene amplification [8] [19] | UBE2T, UBD | High frequency in pan-cancer cohorts | Increased enzyme dosage, enhanced oncogenic signaling |

| Somatic mutations [8] | UBE2T | Relatively infrequent | Potential functional alterations, neoantigen generation |

| Promoter hypomethylation [19] | UBD | 16 cancer types | Transcriptional derepression, increased expression |

| Copy number variations [8] | UBE2T | Predominant alteration type | Gene dosage effects, pathway amplification |

Beyond individual enzyme dysregulation, ubiquitination-related prognostic signatures (URPS) have demonstrated remarkable utility in stratifying patients across multiple cancer types. A comprehensive study integrating data from 4,709 patients across 26 cohorts and five solid tumor types (lung cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, urothelial cancer, and melanoma) established that URPS effectively identifies high-risk and low-risk patient groups with distinct survival outcomes [10]. This signature further correlates with immunotherapy response, enabling identification of patients most likely to benefit from immune checkpoint blockade [10].

Experimental Methodologies for Ubiquitinome Profiling

Multi-Omics Data Integration Frameworks

Advanced bioinformatics pipelines integrating data from multiple omics layers have proven essential for comprehensive ubiquitinome characterization. The following experimental protocol outlines a standardized approach for pan-cancer ubiquitinome analysis:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Source transcriptomic data and clinical metadata from TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) and GTEx (Genotype-Tissue Expression) projects using platforms such as GEPIA2.0, UALCAN, and Sangerbox [8] [19].

- Implement rigorous quality control measures including log2(x + 0.001) transformation of expression values, exclusion of samples with zero expression levels, and removal of cancer types with fewer than three representative samples [19].

- For ubiquitination-focused analyses, obtain reference ubiquitin enzyme catalogs from specialized databases such as the Unified Ubiquitin-Code Database (UUCD), typically comprising approximately 929 genes categorized into E1 (8 genes), E2 (39 genes), and E3 (882 genes) enzyme classes [21].

Differential Expression Analysis

- Identify differentially expressed ubiquitination-related genes (Ubi-DEGs) using the 'edgeR' package in R, applying thresholds of |logFC| ≥ 1 and adjusted p-value < 0.01 [21].

- Validate findings across multiple independent cohorts (e.g., GSE165808, GSE26712 for ovarian cancer) to ensure reproducibility [21].

- Correlate expression patterns with clinicopathological parameters including histological grade, clinical stage, and T-stage using logistic regression models [19].

Genetic and Epigenetic Alteration Mapping

- Interrogate mutation frequency, amplification events, and other genetic alterations using cBioPortal with data sourced from TCGA Pan-Cancer Atlas Studies [19].

- Analyze promoter DNA methylation levels in both normal tissues and pan-cancer samples using UALCAN to identify epigenetic deregulation mechanisms [19].

- Employ single nucleotide variation (SNV) analysis using "maftools" to characterize somatic mutation patterns in ubiquitin pathway genes [21].

Proteomic Profiling of Ubiquitination Networks

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics has emerged as a cornerstone technology for directly quantifying ubiquitinome alterations in cancer:

The Pan-Cancer Proteome Atlas (TPCPA) Framework

- Utilize data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry (DIA-MS) to enable high-throughput proteome characterization without sample multiplexing limitations [20].

- Process 9,670 proteins from 999 primary tumors representing 22 cancer types to ensure comprehensive coverage [20].

- Implement co-expression analysis to identify protein modules, including those centered on ubiquitin pathway components, using weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) [20].

- Validate cancer type-enriched E3 ubiquitin ligases (e.g., HERC5 in esophageal cancer, RNF5 in liver cancer) through orthogonal methods including immunohistochemistry and functional assays [20].

Ubiquitin Chain Typing and Functional Characterization

- Employ chain-specific antibodies and ubiquitin binding domains to differentiate between ubiquitin linkage types (K48, K63, monoubiquitination) in tumor samples [16].

- Integrate phosphoproteomic data to map crosstalk between phosphorylation and ubiquitination events, particularly relevant for DNA damage response pathways [16].

- Analyze ubiquitin chain hierarchies in therapy-resistant tumors, with particular focus on K48-linked proteolysis, K63-linked signaling scaffolds, and monoubiquitylation [16].

Functional Validation Approaches

In Vitro and In Vivo Models

- Conduct reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) and western blotting in cancer cell lines (e.g., pancreatic cancer lines PANC1, ASPC, BXPC3) compared to normal epithelial cells (e.g., HPDE) to validate expression findings [8].

- Perform gene silencing (siRNA/shRNA) and overexpression studies to establish causal relationships between ubiquitin enzyme expression and oncogenic phenotypes [8] [21].

- Utilize patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models and genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) to assess therapeutic targeting of ubiquitin pathway components in physiologically relevant contexts [10].

Immune Microenvironment Characterization

- Analyze correlations between ubiquitin enzyme expression and immune cell infiltration using algorithms such as TIMER and QUANTISEQ [19].

- Assess relationships with immune checkpoint genes, microsatellite instability (MSI), tumor mutational burden (TMB), and neoantigen load [19].

- Employ single-cell RNA sequencing to resolve ubiquitination patterns across distinct cell types within the tumor microenvironment [10].

Visualization of Core Ubiquitin Signaling Networks in Cancer

The following diagrams illustrate key ubiquitin-mediated signaling pathways commonly altered in solid tumors, generated using Graphviz DOT language.

Ubiquitin Enzymatic Cascade and Outcomes

Ubiquitin Pathway Alterations in Cancer

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitinome Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA & GTEx Databases [8] [19] | Source of multi-omics cancer data | Differential expression analysis, survival correlations | Requires sophisticated bioinformatics pipelines for integration |

| DIA Mass Spectrometry [20] | High-throughput protein quantification | Pan-cancer proteome atlas construction, E3 ligase discovery | Enables analysis of >9,000 proteins across 22 cancer types |

| CCLE Cell Lines [8] | Ubiquitin enzyme expression profiling | Validation of cancer-specific targets | Provides mRNA profiles across diverse cancer cell lines |

| UUCD Database [21] | Curated ubiquitin enzyme catalog | Reference for ubiquitination-related gene sets | Contains 929 genes categorized into E1, E2, E3 classes |

| cBioPortal [19] | Genetic alteration analysis | Mutation frequency, amplification events | Integrates data from TCGA Pan-Cancer Atlas |

| TIMER/QUANTISEQ Algorithms [19] | Immune infiltration estimation | Correlation with immune cell abundance | Links ubiquitin enzymes to tumor microenvironment |

| Chain-Specific Ub Antibodies [16] | Differentiation of ubiquitin linkage types | Functional characterization of ubiquitin signatures | Critical for understanding non-proteolytic ubiquitination |

| PROTAC Molecules [16] [21] | Targeted protein degradation | Therapeutic exploitation of ubiquitin system | Recruit E3 ligases to neo-substrates |

Therapeutic Implications and Clinical Translation

The systematic characterization of ubiquitinome remodeling in solid tumors has unveiled numerous therapeutic opportunities. Several targeting strategies have emerged with significant clinical potential:

Direct Targeting of Ubiquitin Pathway Components

Small molecule inhibitors targeting specific E3 ligases and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) have demonstrated preclinical efficacy across multiple cancer types. However, functional redundancy and contextual duality present significant challenges. For instance, FBXW7 exhibits tumor-suppressive or oncogenic functions depending on cellular context—promoting radioresistance in p53-wild type colorectal tumors by degrading p53, while enhancing radiosensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer with SOX9 overexpression [16]. This highlights the critical importance of patient stratification biomarkers when targeting ubiquitin pathway components.

Immunomodulation Through Ubiquitin Pathway Manipulation

Ubiquitination plays a pivotal role in regulating tumor-immune interactions, making it an attractive target for enhancing immunotherapy efficacy. Key mechanisms include:

- Regulation of PD-L1 stability through ubiquitin-mediated degradation, potentially reversing immune evasion [18]

- Modulation of interferon signaling pathways that control tumor cell susceptibility to immune-mediated cytotoxicity [18]

- Influence on macrophage infiltration and functional polarization within the tumor microenvironment [10]

The ubiquitination-related prognostic signature (URPS) has demonstrated particular utility in predicting immunotherapy response, potentially identifying patients most likely to benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors [10].

PROTACs and Targeted Protein Degradation

Proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) represent a revolutionary therapeutic modality that exploits the ubiquitin system for targeted protein degradation. These bifunctional molecules simultaneously bind to E3 ubiquitin ligases and target proteins of interest, inducing selective ubiquitination and degradation [16] [21]. Recent advances include:

- Radiation-responsive PROTAC (RT-PROTAC) prodrugs activated by tumor-localized X-rays to degrade specific oncoproteins [16]

- EGFR-directed PROTACs that selectively degrade β-TrCP substrates in EGFR-dependent tumors [16]

- Nanomicelle-based delivery systems for spatially controlled PROTAC release within irradiated tumors [16]

To date, 50 ubiquitination-related genes have been targeted by PROTACs, with several emerging as promising clinical drug targets for cancer treatment [21].

Global ubiquitinome remodeling represents a fundamental layer of cancer pathophysiology that transcends individual cancer types. Pan-cancer analyses have revealed consistent patterns of ubiquitin pathway alteration, including overexpression of specific E2 enzymes (e.g., UBE2T), E3 ligases, and deubiquitinating enzymes across diverse solid tumors. These alterations drive oncogenic transformation through multiple mechanisms, including dysregulation of DNA repair, cell cycle control, immune evasion, and metabolic reprogramming.

The ongoing development of sophisticated proteomic technologies, particularly DIA mass spectrometry, coupled with advanced bioinformatics pipelines, continues to expand our understanding of ubiquitin-based signaling networks in cancer. These insights are now being translated into novel therapeutic modalities, including PROTACs and ubiquitin pathway inhibitors, that offer promising approaches for targeting previously "undruggable" oncoproteins.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating context-specific functions of ubiquitin pathway components, developing predictive biomarkers for patient stratification, and optimizing combination strategies that integrate ubiquitin-targeting agents with conventional therapies, immunotherapy, and radiation. As our understanding of the cancer ubiquitinome continues to mature, it promises to yield increasingly precise and effective therapeutic strategies for diverse malignancies.

Ubiquitination, a critical post-translational modification, serves as a master regulator of oncogenic signaling pathways by controlling the stability, localization, and activity of key cancer-associated proteins. This technical review examines the intricate mechanisms through which the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) orchestrates the delicate balance of MYC, RAS, and p53 signaling networks in cancer pathogenesis. We provide a comprehensive analysis of the E3 ligases and deubiquitinases (DUBs) that fine-tune these pathways, alongside quantitative data on their dysregulation across cancer types. The resource integrates detailed experimental methodologies for investigating ubiquitination dynamics and presents visual schematics of critical regulatory networks. Furthermore, we catalog emerging therapeutic strategies that target ubiquitination machinery to manipulate oncogenic signaling, offering researchers a foundational framework for developing novel cancer therapeutics aimed at overcoming the traditional "undruggability" of major oncogenic drivers.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system represents a sophisticated hierarchical mechanism for post-translational regulation, comprising ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), and ubiquitin-ligating (E3) enzymes that collectively coordinate the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to substrate proteins [12]. This enzymatic cascade culminates in the specific recognition of substrates by E3 ligases, of which over 600 exist in human cells, providing exceptional specificity to the process [14]. The functional consequences of ubiquitination are remarkably diverse, ranging from proteasomal degradation to modulation of protein activity, localization, and complex formation, dependent on the topology of ubiquitin chain linkage [14] [12].

In the context of oncogenesis, ubiquitination serves as a pivotal regulatory mechanism that governs the precise control of tumor suppressors and oncoproteins. The balanced regulation of the tumor suppressor p53 ("yin") and the oncoprotein c-Myc ("yang") exemplifies this critical control system, whose disruption represents a fundamental event in cellular transformation [22]. As a library, NLM provides access to scientific literature. Inclusion in an NLM database does not imply endorsement of, or agreement with, the contents by NLM or the National Institutes of Health. Recent pan-cancer analyses have revealed that ubiquitination-related prognostic signatures can effectively stratify patients across multiple cancer types, including lung cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, urothelial cancer, and melanoma, highlighting the broad clinical relevance of ubiquitination networks in oncology [10]. This review systematically examines the specific ubiquitination mechanisms regulating MYC, RAS, and p53 pathways, integrating quantitative data, experimental approaches, and therapeutic implications for research and drug development.

Molecular Mechanisms of Ubiquitination in Core Oncogenic Pathways

p53 Ubiquitination and Regulatory Networks

The p53 tumor suppressor, often termed the "guardian of the genome," is extensively regulated by ubiquitination, with its stability and activity controlled by multiple E3 ubiquitin ligases [22] [23]. As the most frequently mutated gene in human cancers, p53's tight regulation is essential for maintaining genomic integrity, with the MDM2 E3 ligase serving as its primary negative regulator [22] [23]. MDM2 mediates both multiple monoubiquitination to promote nuclear export and polyubiquitination for nuclear degradation of p53 [14]. The critical balance in this regulatory circuit is evidenced by the rescue of embryonic lethality in mdm2 knockout mice through concomitant p53 deletion [22].

Beyond MDM2, several other E3 ligases contribute to p53 regulation, including PirH2, COP1, CHIP, ARF-BP1/HectH9, and complexes containing Cullin 7 [22]. This multilayered regulatory network ensures precise control of p53 activity in response to diverse cellular stresses. The functional diversity of ubiquitination is exemplified by MDM2's ability to not only promote p53 degradation but also directly inhibit its transcriptional activity by binding to its N-terminal transactivation domain and promoting histone monoubiquitination on target gene promoters [22]. Furthermore, MDM2 collaborates with its homolog MDMX to enhance p53 ubiquitylation and degradation, though MDMX lacks intrinsic E3 ligase activity [22].

Table 1: E3 Ubiquitin Ligases Regulating p53 Stability and Activity

| E3 Ligase | Type | Effect on p53 | Role in Cell Growth | Cancer Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDM2 | RING | Degradation, nuclear export, inhibition of transactivation | Promotes cell growth | Oncogene |

| PirH2 | RING | Degradation | Uncertain | Uncertain |

| COP1 | RING | Degradation | Uncertain | Uncertain |

| ARF-BP1/HectH9 | HECT | Degradation | Promotes cell growth | Uncertain |

| Cullin 7 | Cullin-based | Degradation | Uncertain | Uncertain |

MYC Ubiquitination and Stability Control

The MYC oncoprotein is regulated by several E3 ubiquitin ligases that control its stability and oncogenic activity. Skp2, Fbw7, and ARF-BP1/HectH9 have been identified as key regulators of c-Myc turnover [22]. The balance between these enzymes determines c-Myc protein levels and consequently its transcriptional activity. Skp2 promotes cell growth and exhibits oncogenic properties, while Fbw7 acts as a tumor suppressor by targeting c-Myc for degradation [22]. ARF-BP1/HectH9 similarly promotes cell growth and may function as an oncogene [22].

Recent research has identified the OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination axis as a crucial regulator of MYC pathway activity [10]. This regulatory module influences cancer cell fate by modulating MYC and its downstream targets while altering oxidative stress responses, ultimately contributing to immunotherapy resistance and poor patient prognosis [10]. The ubiquitination score derived from this regulatory network positively correlates with squamous or neuroendocrine transdifferentiation in adenocarcinoma, highlighting the clinical relevance of MYC ubiquitination in tumor progression and subtype specification [10].

RAS Ubiquitination and Signaling Modulation

RAS proteins, representing the most frequently mutated oncoproteins in human cancers, are subject to complex ubiquitination regulation that controls their stability, membrane localization, and signaling transduction [24]. The ubiquitination of RAS proteins exhibits significant heterogeneity across different isoforms (KRAS4A, KRAS4B, NRAS, and HRAS), contributing to their functional disparities in cancer pathogenesis [24]. This regulatory mechanism profoundly impacts RAS-driven oncogenic functions, including tumor proliferation, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance.

The functional consequences of RAS ubiquitination extend beyond protein degradation, encompassing modulation of GTPase activity, subcellular localization, and interaction with effector proteins. This regulatory complexity presents both challenges and opportunities for therapeutic intervention in RAS-driven cancers. Current research efforts are focused on exploiting the ubiquitination pathway to develop novel strategies to overcome RAS-driven malignant phenotypes, particularly through combination approaches with direct RAS inhibitors or immunotherapy [24].

Table 2: Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Functional Consequences in Oncogenic Regulation

| Ubiquitin Linkage | Primary Functions | Oncogenic Pathway Examples |

|---|---|---|

| K48 | Proteasomal degradation | p53 degradation by MDM2 |

| K63 | Activity and localization regulation | DNA damage response, kinase activation |

| K11 | Cell cycle regulation, trafficking | β-catenin stabilization in colorectal cancer |

| K29 | Uncertain, potential degradation role | Uncertain in oncogenic pathways |

| K6 | DNA damage repair | Uncertain in oncogenic pathways |

| K27 | Mitochondrial autophagy | Regulation of mitophagy |

| M1 | NF-κB signaling activation | Inflammatory response regulation |

Quantitative Analysis of Ubiquitination Patterns in Cancer

Comprehensive pan-cancer analyses have revealed consistent dysregulation of ubiquitination pathways across multiple cancer types. A study integrating data from 4,709 patients across 26 cohorts and five solid tumor types (lung cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, urothelial cancer, and melanoma) identified key nodes and prognostic pathways within the ubiquitination-modification network [10]. This research established a conserved ubiquitination-related prognostic signature (URPS) that effectively stratified patients into high-risk and low-risk groups with distinct survival outcomes across all analyzed cancers [10].

The clinical utility of ubiquitination signatures extends beyond prognostic stratification. URPS demonstrates significant potential as a novel biomarker for predicting immunotherapy response, with the capacity to identify patients most likely to benefit from immunotherapy in clinical settings [10]. Analysis of URPS-associated proteins has revealed novel cancer-related interaction partners as potential drug targets, expanding the therapeutic landscape for ubiquitination-focused interventions [10].

In ovarian cancer, a prognostic model based on 17 ubiquitination-related genes demonstrated high predictive performance (1-year AUC = 0.703, 3-year AUC = 0.704, 5-year AUC = 0.705) [21]. Patients in the high-risk group had significantly lower overall survival, and immune analysis revealed distinct tumor microenvironment profiles between risk groups, with the low-risk group showing higher levels of CD8+ T cells, M1 macrophages, and follicular helper cells [21]. This model further identified distinct mutation patterns between risk groups, with high-risk patients having more mutations in MUC17 and LRRK2, while low-risk patients had more RYR2 mutations [21].

Table 3: Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Models Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Number of Genes in Signature | Predictive Performance (AUC) | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Cancers (Pan-cancer) | URPS (unspecified number) | Not specified | Stratifies patients into high/low risk groups, predicts immunotherapy response |

| Ovarian Cancer | 17 | 1-year: 0.703, 3-year: 0.704, 5-year: 0.705 | Prognostic stratification, immune microenvironment characterization |

| Colorectal Cancer | USP48-focused | Not specified | Associated with autophagy inhibition, promotes proliferation, migration, and invasion |

Experimental Protocols for Ubiquitination Research

Ubiquitination Regulatory Network Construction

The construction of pancancer ubiquitination regulatory networks involves systematic integration of multi-omics data from large patient cohorts. A standardized methodology includes the following steps [10]:

Data Collection and Integration: Collect RNA-seq data and clinicopathological features from relevant cancer databases (e.g., TCGA, GEO). For immunotherapy-focused studies, include datasets from patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Network Mapping: Map molecular profiles to interaction networks using correlation coefficient matrices standardized through significance screening (p-value < 0.05).

Prognostic Analysis: Employ Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for prognostic assessment of ubiquitination scores. Apply LASSO algorithm to identify key prognostic genes.

Functional Validation: Validate findings using independent patient cohorts, cell line models, and in vivo experiments to confirm biological significance.

Ubiquitination Assay Protocols

Several experimental approaches are essential for characterizing ubiquitination events in cancer pathways:

Co-immunoprecipitation and Ubiquitination Assays [25]:

- Transfect cells with plasmids encoding the E3 ligase (e.g., FBXO22) and potential substrate (e.g., KLF10)

- Treat cells with proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG132) for 4-6 hours before harvesting to stabilize ubiquitinated proteins

- Lyse cells in RIPA buffer containing protease and deubiquitinase inhibitors

- Perform immunoprecipitation with antibody against the substrate protein

- Analyze ubiquitination by western blotting with anti-ubiquitin antibody

In Vivo Ubiquitination Assay:

- Express His-tagged ubiquitin in cells along with the E3 ligase and substrate

- Harvest cells under denaturing conditions (6M guanidine-HCl)

- Purify His-ubiquitinated proteins using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) beads

- Detect specific substrate ubiquitination by western blotting

Functional Validation Assays:

- Conduct proliferation assays (CCK-8, colony formation)

- Perform invasion assays (Transwell with Matrigel)

- Analyze apoptosis (Annexin V staining)

- Validate in vivo using xenograft models in immunodeficient mice

Visualization of Ubiquitination Pathways

p53 Ubiquitination Regulation Network

Diagram 1: p53 Ubiquitination Regulation Network. Multiple E3 ubiquitin ligases, particularly MDM2, target p53 for ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation under normal conditions. Cellular stress stabilizes p53 by disrupting this regulatory balance [22] [23].

MYC-OTUB1-TRIM28 Regulatory Axis

Diagram 2: MYC-OTUB1-TRIM28 Regulatory Axis. The OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination complex modulates MYC pathway activity and oxidative stress responses, driving histological transdifferentiation and therapy resistance [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| E3 Ligase Inhibitors | Nutlin, MI-219 (MDM2 inhibitors) | p53 pathway studies | Block MDM2-p53 interaction, stabilize p53 |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib, MG132 | Ubiquitination assays | Stabilize ubiquitinated proteins by blocking degradation |

| Ubiquitin System Modulators | MLN7243 (E1 inhibitor), MLN4924 (NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor) | Pathway validation | Block ubiquitin activation or neddylation pathway |

| Deubiquitinase Inhibitors | Compounds G5 and F6 | DUB functional studies | Inhibit deubiquitinating enzyme activity |

| Expression Plasmids | His-tagged ubiquitin, E3 ligase constructs, substrate genes | In vivo ubiquitination assays | Enable detection and manipulation of ubiquitination |

| Cell Line Models | BJ fibroblasts with inducible H-RASV12 and MycER | Oncogene cooperation studies | Study senescence and apoptosis in controlled systems |

| Antibodies | Anti-ubiquitin, anti-substrate specific, anti-E3 ligases | Immunoprecipitation, western blot | Detect ubiquitination and protein interactions |

Therapeutic Implications and Drug Development

Targeting ubiquitination pathways represents a promising strategic approach for anticancer drug development, particularly for addressing traditionally "undruggable" targets like MYC [10]. Several therapeutic classes have emerged:

Proteasome Inhibitors: Bortezomib, carfilzomib, oprozomib, and ixazomib have demonstrated tangible clinical success, particularly in hematological malignancies, by disrupting protein homeostasis and inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress [14] [12].

E1-Targeting Compounds: MLN7243 and MLN4924 inhibit E1 enzymes, with MLN4924 specifically blocking the NEDD8-activating enzyme to modulate cullin-RING ligase activity [12].

E2-Targeting Agents: Leucettamol A and CC0651 represent early-stage inhibitors targeting specific E2 enzymes [12].

E3-Targeting Strategies: Nutlin and MI-219 specifically disrupt MDM2-p53 interaction, stabilizing p53 in cancers with wild-type TP53 [12]. Emerging PROTAC (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimera) technology leverages E3 ligases to selectively degrade target proteins, with 50 ubiquitination-related genes currently targeted by PROTACs in development [21].

DUB Inhibitors: Compounds G5 and F6 represent early-stage inhibitors of deubiquitinating enzyme activity [12].

The therapeutic potential of targeting ubiquitination pathways extends beyond direct anticancer effects to modulating immunotherapy response. Recent research indicates that ubiquitination scores may predict immunotherapy efficacy, offering opportunities for patient stratification and combination therapy development [10]. Furthermore, the identification of specific ubiquitination regulators like USP48 in colorectal cancer provides novel targets for intervention, with preliminary success demonstrated using tetrahedral DNA nanomaterials loaded with USP48 siRNA [26].

Ubiquitination represents a master regulatory mechanism that orchestrates the activity of fundamental oncogenic pathways, including MYC, RAS, and p53. The intricate balance of E3 ligases and deubiquitinases that control these pathways offers unprecedented opportunities for therapeutic intervention in cancer. Quantitative ubiquitination signatures demonstrate robust prognostic and predictive value across diverse cancer types, while emerging technologies like PROTACs leverage the ubiquitin-proteasome system for targeted protein degradation. Future research directions should focus on elucidating the context-specific functions of ubiquitination regulators, developing isoform-selective ubiquitination modulators, and exploring rational combination therapies that exploit ubiquitination dependencies in cancer cells. The systematic characterization of ubiquitination networks presented in this review provides a foundation for advancing these efforts and overcoming the therapeutic challenges posed by traditionally intractable oncogenic drivers.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a sophisticated regulatory mechanism that governs protein stability and function through post-translational modification. In cancer, this system undergoes profound dysregulation, leading to the aberrant degradation of tumor suppressor proteins that normally maintain cellular homeostasis. This review examines the molecular mechanisms underlying tumor suppressor destabilization, focusing on the E3 ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinating enzymes that orchestrate these processes. We explore how cancer cells exploit the ubiquitin network to eliminate key protective proteins, thereby gaining proliferative advantages, evading growth suppression, and resisting therapeutic interventions. The clinical implications of these mechanisms are substantial, offering novel avenues for targeted therapeutic strategies aimed at restoring tumor suppressor function through modulation of ubiquitination pathways.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system serves as the primary pathway for controlled protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, regulating approximately 80-90% of cellular proteolysis [6]. This sophisticated system employs a sequential enzymatic cascade to mark specific proteins for destruction: ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1) initiate the process through ATP-dependent ubiquitin activation, ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2) serve as intermediaries, and ubiquitin ligases (E3) provide substrate specificity by recognizing target proteins and facilitating ubiquitin transfer [27] [6]. The resulting polyubiquitin chains, particularly those linked through lysine 48 (K48) of ubiquitin, signal the 26S proteasome to degrade the tagged protein into small peptides [28].

Beyond its role in protein quality control, the UPS precisely regulates the abundance of critical regulatory proteins, including tumor suppressors that constrain uncontrolled cell growth. The specificity of ubiquitination primarily resides with E3 ubiquitin ligases, which recognize distinct degradation signals (degrons) on target proteins [29]. The human genome encodes over 600 E3 ligases, each capable of binding specific subsets of substrates, thereby creating an intricate network of protein stability control [30]. This system is counterbalanced by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), which remove ubiquitin chains and can rescue proteins from degradation, adding another layer of regulation [28] [6].

In cancer pathogenesis, tumor cells frequently hijack this精密调控system to selectively eliminate tumor suppressor proteins. Through overexpression of specific E3 ligases, downregulation of protective DUBs, or mutation of ubiquitination sites on tumor suppressors, cancer cells achieve uncontrolled proliferation and survival [29]. Understanding these mechanisms provides crucial insights for developing novel cancer therapies that target the ubiquitin network to restore tumor suppressor function.

Molecular Mechanisms of Aberrant Ubiquitination in Cancer

Ubiquitin Chain Topology and Functional Diversity

Ubiquitination represents a versatile regulatory mechanism whose functional outcome depends critically on the topology of the ubiquitin chain formed on substrate proteins. The eight linkage types (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63, and M1) create a sophisticated "ubiquitin code" that determines the fate of modified proteins [6]. K48-linked polyubiquitin chains predominantly target proteins for proteasomal degradation and serve as the principal mechanism for tumor suppressor destruction [28]. In contrast, K63-linked chains typically mediate non-proteolytic functions, including signal transduction, DNA repair, and endocytic trafficking, while monoubiquitination can regulate protein activity, localization, and interactions [28] [6].

Cancer cells exploit this ubiquitin code to eliminate tumor suppressors through multiple mechanisms. The contextual duality of certain E3 ligases allows them to function as either oncogenes or tumor suppressors depending on cellular context. FBXW7 exemplifies this complexity: in p53-wild type colorectal tumors, it promotes radioresistance by degrading p53, whereas in non-small cell lung cancer with SOX9 overexpression, it enhances radiosensitivity by destabilizing SOX9 and alleviating p21 repression [28]. This functional switching hinges on tumor-specific genetic backgrounds and signaling microenvironments, highlighting the nuanced regulation of ubiquitination in cancer.

The spatial and temporal control of ubiquitination further contributes to its functional diversity. Linear ubiquitination (M1-linked), assembled exclusively by the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC), activates NF-κB signaling and promotes lymphoma progression [6]. Additionally, heterotypic ubiquitin chains (mixed or branched) increase the complexity of ubiquitin signaling, although their roles in tumor suppressor regulation remain incompletely characterized [6].

E3 Ubiquitin Ligases in Tumor Suppressor Degradation

E3 ubiquitin ligases serve as the critical determinants of specificity in the ubiquitination cascade, recognizing particular tumor suppressor proteins and facilitating their ubiquitination. These enzymes fall into three major classes: RING, HECT, and RBR ligases, each employing distinct catalytic mechanisms [31]. The RING-type E3 ligase MDM2 (HDM2 in humans) represents the most extensively characterized regulator of p53 stability. MDM2 binds directly to p53, inhibiting its transcriptional activity and promoting its polyubiquitination and nuclear export [29]. The biological significance of this interaction is underscored by studies demonstrating that Mdm2-null mice die early in development, but this embryonic lethality is rescued by co-disruption of the Tp53 gene [29].

Other E3 ligases contribute to the regulation of diverse tumor suppressor proteins. UBE3A (E6AP), in partnership with the HPV E6 oncoprotein, targets p53 for degradation in HPV-associated cancers [29]. The LUBAC complex, comprising HOIP, HOIL-1L, and SHARPIN, mediates linear ubiquitination of signaling components and promotes NF-κB activation in lymphoma [6]. RNF2 monoubiquitinates histone H2A at lysine 119, leading to transcriptional repression of E-cadherin and enhanced metastatic potential in hepatocellular carcinoma [6].

The regulation of E3 ligase activity itself represents a critical control point in tumor suppressor stability. MDM2 activity depends on its association with MDMX/MDM4, while phosphorylation of MDM2 by ATM kinase inhibits its function in response to DNA damage, promoting p53 stabilization [29]. Furthermore, many E3 ligases participate in autoregulatory feedback loops; for instance, MDM2 is itself a transcriptional target of p53, creating an oscillatory circuit that maintains p53 at appropriate levels in normal cells [29].

Deubiquitinating Enzymes as Tumor Suppressor Stabilizers

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) counterbalance E3 ligase activity by removing ubiquitin chains from substrate proteins, thereby preventing proteasomal degradation. Approximately 100 DUBs encoded in the human genome regulate diverse cellular processes, and their dysregulation contributes significantly to tumor suppressor destabilization in cancer [28]. The USP family of DUBs demonstrates particularly important roles in tumor suppressor regulation. USP14 stabilizes ALKBH5 to maintain glioblastoma stemness but degrades IκBα to activate NF-κB in head and neck cancers, illustrating the context-dependent functions of these enzymes [28].

Other DUB families also participate in tumor suppressor stabilization. OTUB1 stabilizes CHK1 to enhance DNA repair fidelity in lung cancer and stabilizes GPX4 to suppress ferroptosis in gastric cancer [28]. USP7 stabilizes CHK1 to maintain genomic stability in breast cancer and counteracts ubiquitination of DNA-PKcs to maintain repair competence in HPV-positive tumors [28]. UCHL1 stabilizes HIF-1α to activate the pentose phosphate pathway and enhance antioxidant defense in breast cancer [28].

The therapeutic targeting of DUBs presents both challenges and opportunities. While inhibition of specific DUBs could potentially stabilize tumor suppressors, functional redundancy among DUB family members may limit efficacy. Additionally, many DUBs exhibit tissue-specific or context-dependent functions, necessitating precise therapeutic strategies [28].

Table 1: Major E3 Ubiquitin Ligases in Tumor Suppressor Regulation

| E3 Ligase | Tumor Suppressor Target | Cancer Type | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDM2 | p53 | Various cancers with wild-type p53 | Promotes p53 degradation, enabling unchecked proliferation |

| UBE3A (with HPV E6) | p53 | HPV-associated cancers | Viral oncoprotein-directed p53 degradation |

| FBXW7 | p53, SOX9 | Colorectal cancer, NSCLC | Context-dependent roles in radioresistance or sensitization |

| RNF2 | Histone H2A (K119) | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Transcriptional repression of E-cadherin, enhanced metastasis |

| LUBAC complex | NEMO, other NF-κB signaling components | B-cell lymphoma | Linear ubiquitination and NF-κB activation |

| β-TrCP | Radioprotective LZTS3 | Lung cancer | K48-linked degradation enhances radiation sensitivity |

Key Signaling Pathways and Experimental Analysis

The p53-MDM2 Axis as Paradigm

The regulatory circuit between p53 and MDM2 represents the prototypical example of ubiquitin-mediated tumor suppressor control. This axis exemplifies the sophisticated feedback mechanisms that maintain cellular homeostasis in normal cells and the vulnerability of this system to hijacking in cancer. In normal physiology, p53 activates MDM2 transcription, creating a negative feedback loop that prevents excessive p53 accumulation [29]. Cellular stress signals, such as DNA damage, disrupt this interaction through phosphorylation of both proteins, leading to p53 stabilization and activation of cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, or senescence programs [29].

Cancer cells subvert this regulatory circuit through multiple mechanisms. MDM2 amplification occurs in numerous cancers, resulting in excessive p53 degradation even in the presence of wild-type TP53 genes [29]. Additionally, MDM2 polymorphisms that enhance its expression or activity have been associated with accelerated tumorigenesis [29]. The physical interaction between p53 and MDM2 is driven by key residues of p53 (Phe19, Trp23, Leu26) in its N-terminal transactivation domain burying into a hydrophobic cleft in the N-terminal domain of MDM2 [29]. This precise molecular interaction has enabled the development of therapeutic inhibitors that disrupt the p53-MDM2 interface.

The following diagram illustrates the core regulation and cancer hijacking of the p53-MDM2 axis:

DNA Damage Response Pathway Ubiquitination

The DNA damage response (DDR) represents another critical pathway regulated by ubiquitination that is frequently compromised in cancer. Multiple tumor suppressors in the DDR pathway, including BRCA1, CHK1, and ATM, undergo ubiquitin-mediated regulation. RNF126 catalyzes K63-linked ubiquitination to activate ATR-CHK1 signaling in triple-negative breast cancer, promoting radioresistance [28]. Conversely, USP14 disrupts non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and promotes homologous recombination (HR) in non-small cell lung cancer, with USP14 inhibition disrupting DNA damage response [28].

The interplay between different ubiquitin chain types fine-tunes the DNA damage response. K63-linked ubiquitination of histone H2A and H2AX facilitates the recruitment of DNA repair proteins to damage sites, while K48-linked ubiquitination limits the duration of DDR activation by degrading key mediators [28]. Deubiquitinating enzymes such as USP7 and OTUB1 further modulate this process by stabilizing DDR components, with OTUB1 stabilizing CHK1 to enhance repair fidelity in lung cancer [28].

The following workflow maps the ubiquitin networks in DNA damage response and therapeutic targeting:

Therapeutic Targeting Strategies

Stabilization of Tumor Suppressor Proteins

Therapeutic strategies to stabilize tumor suppressor proteins primarily focus on inhibiting the E3 ubiquitin ligases responsible for their degradation. MDM2 inhibitors represent the most advanced approach, with multiple compounds in clinical development. Nutlin-3a, a cis-imidazoline derivative, was the first small-molecule inhibitor developed to target the p53-MDM2 interaction by mimicking the three key residues of p53 that bind MDM2's hydrophobic cleft [29]. Subsequent compounds, including RG7112, idasanutlin, and AMG-232, have improved potency and pharmacokinetic properties, with several advancing to clinical trials [29].