Ubiquitination Signatures in Cancer: Prognostic Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets

This article explores the rapidly evolving field of ubiquitination-based prognostic signatures in cancer.

Ubiquitination Signatures in Cancer: Prognostic Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets

Abstract

This article explores the rapidly evolving field of ubiquitination-based prognostic signatures in cancer. It details how bioinformatics analyses of ubiquitination-related genes (URGs) are enabling the construction of powerful risk models that predict patient survival, therapy response, and tumor microenvironment features across diverse cancers, including lung adenocarcinoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, ovarian cancer, and sarcoma. The content covers foundational concepts of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, methodologies for signature development, strategies to address analytical challenges, and extensive multi-cancer validation. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes current evidence to highlight the clinical potential of these signatures in personalizing cancer treatment and guiding the development of novel therapeutics like PROTACs.

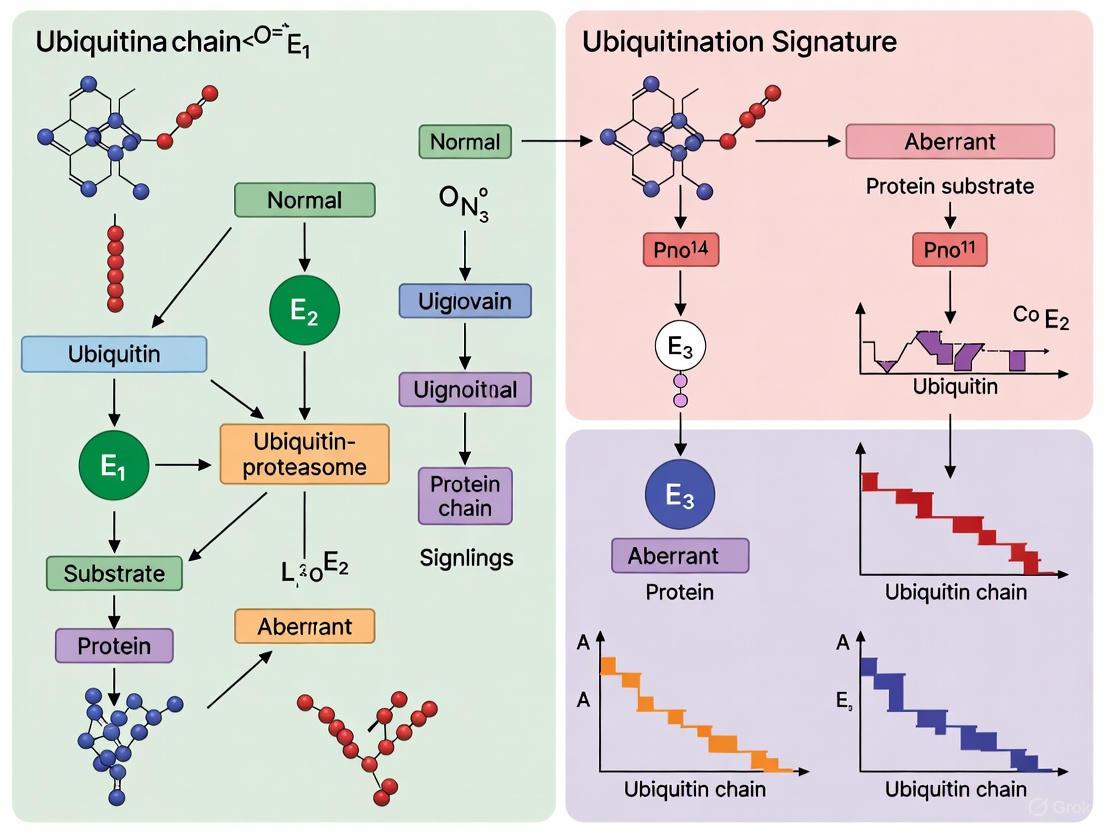

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: From Basic Biology to Cancer Prognosis

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a crucial regulatory mechanism in eukaryotic cells, controlling the stability, function, and localization of a vast array of proteins [1]. At its core, the system involves the covalent attachment of a small protein, ubiquitin, to lysine residues on substrate proteins [1]. This post-translational modification is a highly orchestrated process carried out by a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 activating, E2 conjugating, and E3 ligating enzymes [1]. The type of ubiquitin chain formed—determined by which of the seven lysine residues in ubiquitin itself is used for linkage—dictates the biological fate of the modified protein. K48 and K11-linked chains typically target substrates for proteasomal degradation, whereas K63 and linear chains play prominent roles in non-proteolytic signaling processes such as inflammation [1]. Countering this process is a family of proteases known as deubiquitinases (DUBs), which cleave ubiquitin from substrates, providing reversibility and dynamic regulation to ubiquitin signaling [2] [3].

The following diagram illustrates the core enzymatic cascade of the ubiquitination process and its reversal by DUBs:

Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitination System Components

E1 Activating Enzymes: Gatekeepers of the Ubiquitin Cascade

E1 enzymes sit at the apex of the ubiquitination cascade, initiating the process through an ATP-dependent mechanism that forms a thioester bond between the C-terminal carboxyl group of ubiquitin and the catalytic cysteine of the E1 itself [1]. Humans possess two primary ubiquitin E1 enzymes—UBA1 and UBA6—that control ubiquitination of all downstream targets [1]. The significance of E1 enzymes as therapeutic targets is exemplified by inhibitors such as PYR-41 and PYZD-4409, which preferentially induce cell death in malignant cells [1]. MLN4924, an inhibitor of the NEDD8 activating enzyme (NAE), has shown particular promise in clinical settings by disrupting cullin RING ligase (CRL) activity and is currently being evaluated in multiple phase II studies [1].

E2 Conjugating Enzymes: Specificity and Chain Formation

E2 enzymes serve as crucial intermediaries, receiving activated ubiquitin from E1 enzymes and collaborating with E3 ligases to transfer ubiquitin to substrate proteins [1]. With approximately 38 E2 enzymes in mammals, this enzyme class offers greater potential for specificity than E1 enzymes [1]. E2 enzymes not only function as "ubiquitin carriers" but also dictate ubiquitin chain linkage specificity and length [1]. Notable E2 inhibitors include CC0651, an allosteric inhibitor of CDC34 that interferes with ubiquitin discharge [1], and NSC697923, which inhibits UBE2N~Ub thioester formation, thereby blocking K63-specific polyubiquitin chain synthesis [1].

E3 Ubiquitin Ligases: The Substrate Recognition Specialists

E3 ubiquitin ligases constitute the largest and most diverse family within the ubiquitin system, with approximately 700 members predicted to possess ligase activity in humans [1]. These enzymes are categorized into three main subfamilies: RING E3s (which act as scaffolds bringing E2~Ub complexes in contact with substrates), HECT E3s (which form a thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to substrates), and RING-Between-RING (RBR) E3s that function as hybrids [1]. The F-box protein SKP2, which forms the SCFSKP2 complex with CUL1, SKP1, and RBX1, exemplifies the importance of E3 ligases in cancer, as it ubiquitinates critical cell cycle regulators like p27KIP1 and is overexpressed in various human malignancies [1].

Deubiquitinases (DUBs): Regulators of Ubiquitin Signaling

DUBs constitute a superfamily of proteases that reverse ubiquitination by cleaving the isopeptide bond between ubiquitin and substrate proteins [2] [3]. In mammals, DUBs are classified into seven major families based on their catalytic domains: ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolases (UCH), ubiquitin-specific proteases (USP), Machado-Josephin domain-containing proteases (MJD), ovarian tumor proteases (OTU), JAMM/MPN+ metalloproteases (JAMM), MINDY, and ZUP1 [3]. Most DUBs are cysteine proteases featuring a catalytic triad with cysteine and histidine residues, while JAMM/MPN+ DUBs are zinc-dependent metalloproteases [3]. DUBs are regulated through complex mechanisms including intramolecular interactions, oligomerization, binding partners, and post-translational modifications [3]. For example, USP7 utilizes its C-terminal UBL domains to stabilize and coordinate its catalytic site, switching between active and inactive conformations [3].

Table 1: Key Enzyme Classes in the Human Ubiquitin System

| Enzyme Class | Representative Members | Core Function | Catalytic Mechanism | Therapeutic Targeting Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 Activating Enzymes | UBA1, UBA6 | Ubiquitin activation & transfer to E2s | ATP-dependent thioester formation | PYR-41, PYZD-4409, MLN4924 (NAE inhibitor) |

| E2 Conjugating Enzymes | CDC34, UBE2N, UBE2V1 | Ubiquitin chain formation & elongation | Thioester intermediate with ubiquitin | CC0651 (CDC34 inhibitor), NSC697923 (UBE2N inhibitor) |

| E3 Ligating Enzymes | SKP2, PARKIN, BAP1 | Substrate recognition & ubiquitin transfer | RING: scaffold; HECT: intermediate | Multiple in development targeting specific E3s |

| Deubiquitinases (DUBs) | USP7, BAP1, UCHL5 | Ubiquitin removal & signal reversal | Cysteine protease (most); Metalloprotease (JAMM) | Research compounds targeting USP28, BAP1 |

Ubiquitination Signatures in Cancer Prognosis: Experimental Evidence

Prognostic Ubiquitination Signatures in Lymphoma and Breast Cancer

Recent bioinformatics approaches have revealed that ubiquitination-related gene expression signatures hold significant prognostic value in cancer patients. In Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), a three-gene ubiquitination signature comprising CDC34, FZR1, and OTULIN effectively stratified patients into high-risk and low-risk groups [4]. Elevated expression of CDC34 and FZR1 coupled with low OTULIN expression correlated with poor prognosis, with significant differences in immune scores and drug sensitivity observed between risk groups [4]. Similarly, in breast cancer, a six-gene ubiquitination signature (ATG5, FBXL20, DTX4, BIRC3, TRIM45, and WDR78) demonstrated robust prognostic power across multiple validation datasets, outperforming traditional clinical indicators [5].

The experimental workflow for developing and validating these prognostic signatures typically follows a standardized bioinformatics pipeline, as detailed below:

Methodologies for Ubiquitination Kinetics and Proteomic Profiling

The experimental study of ubiquitination kinetics employs sophisticated biochemical approaches to quantify degron functionality and ubiquitin transfer rates. In one representative methodology [6], researchers synthesized a library of degron-based substrates incorporating known degradation sequences from various E3 ligase substrates. These substrates were designed with four components: a fluorophore (5,6-carboxyfluorescein) for detection, a flexible polyethyleneglycol spacer, the portable degron sequence, and a C-terminal lysine residue as the ubiquitination site [6]. Ubiquitination kinetics were then measured by incubating these substrates in rabbit reticulocyte lysate containing the complete ubiquitination machinery, followed by capillary electrophoresis analysis to separate and quantify ubiquitinated species [6]. Computational modeling incorporating first-order reaction kinetics helped distinguish between multi-monoubiquitination and polyubiquitination mechanisms [6].

For proteome-wide ubiquitination profiling, affinity reagents such as the GST-qUBA protein—consisting of four tandem repeats of the ubiquitin-associated domain from UBQLN1 fused to GST—enable large-scale identification of endogenous ubiquitination sites without proteasome inhibition or ubiquitin overexpression [7]. This approach has identified hundreds of endogenous ubiquitination sites from human cells, revealing unexpected prevalence of mitochondrial protein ubiquitination [7].

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Ubiquitination Analysis

| Methodology | Key Reagents & Tools | Experimental Steps | Output & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitination Kinetics Assay [6] | Degron-based peptide substrates, Reticulocyte lysate, Capillary electrophoresis | 1. Substrate synthesis with fluorophore & degron2. Incubation with ubiquitination machinery3. Separation & quantification of ubiquitinated species4. Computational modeling of kinetics | Quantification of ubiquitination rates, Identification of efficient degrons for proteasome targeting |

| Prognostic Signature Development [4] [5] | GEO/TCGA datasets, R packages (limma, survminer, glmnet) | 1. Differential gene expression analysis2. Survival-associated gene filtering3. LASSO Cox regression for feature selection4. Multi-dataset validation5. Immune/drug sensitivity correlation | Risk stratification models, Identification of ubiquitination-related biomarkers for cancer prognosis |

| Proteomic Ubiquitination Site Mapping [7] | GST-qUBA affinity reagent, Mass spectrometry | 1. Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins2. Trypsin digestion3. LC-MS/MS analysis4. Database search & false discovery rate control | System-wide identification of endogenous ubiquitination sites, Discovery of novel ubiquitination targets |

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Category | Function & Application | Example Sources / Identifiers |

|---|---|---|---|

| MLN4924 (Pevonedistat) | Small Molecule Inhibitor | NEDD8 activating enzyme (NAE) inhibitor; disrupts cullin RING ligase activity | Clinical phase II studies [1] |

| CC0651 | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Allosteric E2 (CDC34) inhibitor; interferes with ubiquitin discharge | Research compound [1] |

| NSC697923 | Small Molecule Inhibitor | UBE2N inhibitor; blocks K63-specific polyubiquitin chain formation | Research compound [1] |

| GST-qUBA Affinity Reagent | Proteomic Tool | Tandem UBA domains for enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins; mass spectrometry identification of ubiquitination sites | Recombinant protein [7] |

| Degron-Based Substrates | Kinetic Assay Tool | Custom peptides with portable degrons for measuring ubiquitination kinetics & proteasome targeting | Synthetic peptides [6] |

| Public Genomics Datasets | Bioinformatics Resource | Gene expression and clinical data for prognostic signature development | GEO (GSE10846, GSE181063, GSE56315), TCGA [4] [5] |

The intricate interplay between E1, E2, E3 enzymes, and DUBs creates a sophisticated regulatory network that maintains cellular homeostasis. Dysregulation of this system contributes significantly to cancer pathogenesis, making its components attractive therapeutic targets. While proteasome inhibitors like bortezomib have demonstrated clinical success, the development of targeted agents against specific E3 ligases and DUBs represents the next frontier in targeting the ubiquitin system for cancer therapy [1]. The emergence of ubiquitination-based prognostic signatures in cancers like DLBCL and breast cancer further highlights the clinical translatability of understanding this vital biological system, offering opportunities for personalized treatment approaches based on the ubiquitination status of individual tumors [4] [5].

Ubiquitination Dysregulation as a Hallmark of Cancer Progression and Metastasis

Ubiquitination, a fundamental and reversible post-translational modification, has emerged as a critical regulator in cellular homeostasis, governing protein stability, localization, and function [8]. This enzymatic process involves the coordinated action of E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes, and E3 ligases, which conjugate ubiquitin to target proteins, while deubiquitinases (DUBs) remove these modifications [8]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) controls approximately 80-90% of intracellular proteolysis, positioning it as a master regulator of vital cellular processes including cell cycle progression, DNA damage repair, and signal transduction [9] [10]. In oncology, dysregulation of the ubiquitin system has been increasingly recognized as a hallmark of cancer progression and metastasis, driving tumorigenesis through multiple mechanisms including stabilization of oncoproteins, degradation of tumor suppressors, and modulation of the tumor immune microenvironment [8] [9] [11]. This review comprehensively analyzes the prognostic value of ubiquitination signatures across cancer types and explores emerging therapeutic strategies targeting the ubiquitin system.

Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Signatures Across Cancers

Robust prognostic models based on ubiquitination-related genes (URGs) have been developed across various malignancies, demonstrating consistent value in stratifying patient survival and informing treatment approaches.

Table 1: Ubiquitination-Based Prognostic Signatures in Solid Tumors

| Cancer Type | Key Ubiquitination-Related Genes | Statistical Performance | Clinical Implications | Reference Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD) | DTL, UBE2S, CISH, STC1 | HR = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.39-0.73, p < 0.001; Validated in 6 external cohorts | High risk score associated with worse prognosis, higher PD1/L1 expression, TMB, and TNB | TCGA-LUAD, GEO validation sets [12] |

| Ovarian Cancer | 17-gene signature including FBXO45 | 1-year AUC = 0.703, 3-year AUC = 0.704, 5-year AUC = 0.705 | High-risk group had significantly lower overall survival (P < 0.05) | TCGA-OV, GTEx [13] |

| Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) | CDC34, FZR1, OTULIN | Elevated CDC34/FZR1 with low OTULIN predicted poor prognosis | Correlation with immune microenvironment and drug sensitivity | GSE181063, GSE56315, GSE10846 [4] |

| Pan-Cancer Analysis | OTUB1-TRIM28 axis | Stratified patients across 5 cancer types with distinct survival | Predictive of immunotherapy response; associated with macrophage infiltration | 26 cohorts across 5 cancer types [9] |

Table 2: Immune and Therapeutic Correlations of Ubiquitination Signatures

| Cancer Type | Immune Microenvironment Features | Drug Sensitivity Correlations | Mutation Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ovarian Cancer | Higher CD8+ T cells (P < 0.05), M1 macrophages (P < 0.01), and follicular helper T cells (P < 0.05) in low-risk group | N/A | High-risk: More MUC17 and LRRK2 mutations; Low-risk: More RYR2 mutations [13] |

| Lung Adenocarcinoma | Higher TME scores (p < 0.001) in high-risk group | Lower IC50 values for various chemotherapy drugs in high-risk group | Higher TMB (p < 0.001) and TNB (p < 0.001) in high-risk group [12] |

| DLBCL | Significant differences in immune scores between risk groups | Increased sensitivity to Boehringer Ingelheim compound 2536 and Osimertinib in risk groups | Correlated with endocytosis-related mechanisms [4] |

| Pan-Cancer | Association with macrophage infiltration | Predictive of immunotherapy response across multiple cancers | Linked to squamous/neuroendocrine transdifferentiation in adenocarcinoma [9] |

Methodologies for Ubiquitination Signature Development

Bioinformatics Workflow for Prognostic Model Construction

The development of ubiquitination-related prognostic signatures follows a standardized bioinformatics pipeline that integrates multi-omics data and rigorous statistical validation.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Differential Gene Expression and Ubiquitination Gene Screening

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between tumor and normal tissues are identified using the limma R package with standard thresholds (Fold Change > 2, FDR < 0.05) [4]. The ubiquitination-related gene universe is typically compiled from established databases such as the Ubiquitin and Ubiquitin-like Conjugation Database (UUCD), encompassing E1 (approximately 8 genes), E2 (approximately 39 genes), and E3 (approximately 882 genes) enzymes [13]. Intersection of DEGs with ubiquitination-related genes yields ubiquitination-associated DEGs for further analysis. Survival-associated URGs are identified through univariate Cox regression analysis with significance threshold of P < 0.05 [13].

Feature Selection and Model Construction

LASSO Cox regression analysis is performed using the glmnet R package with ten-fold cross-validation to determine the optimal penalty parameter (lambda) and identify the most prognostic genes while preventing overfitting [4] [12]. The ubiquitination-related risk score is calculated using the formula: Risk score = Σ(βi * Expi), where β represents the coefficient from multivariate Cox regression and Exp denotes the gene expression level [13]. Patients are stratified into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median risk score. Model performance is assessed using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with log-rank tests and time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves at 1, 3, and 5 years [13] [12].

Immune Microenvironment and Drug Sensitivity Analysis

The composition of immune cell infiltration is evaluated using CIBERSORT or ESTIMATE algorithms to calculate stromal and immune scores [4] [13]. Drug sensitivity analysis is performed using the oncoPredict R package to calculate the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of various therapeutic compounds [4]. Significant differences in drug sensitivity between risk groups are identified using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests.

Key Signaling Pathways Regulated by Ubiquitination

Ubiquitination exerts its profound influence on cancer progression through regulation of critical oncogenic signaling pathways and cellular processes.

Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) Regulation

Ubiquitination precisely controls EMT through dynamic regulation of key EMT transcription factors (EMT-TFs) including Snail, Slug, ZEB1, ZEB2, Twist1, and Twist2 [8]. The stability of Snail, a critical EMT-TF, is dynamically controlled by opposing ubiquitination and deubiquitination activities. In colorectal cancer, mitogen and stress-activated protein kinase 1 (MSK1) recruits USP5 to deubiquitinate and stabilize Snail, facilitating EMT and metastasis [8]. Conversely, in triple-negative breast cancer, the E3 ligase MARCH2 ubiquitinates Snail, driving its degradation and suppressing tumor growth and metastasis [8]. Multiple signaling pathways that regulate EMT, including TGF-β, Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, and Hedgehog, are themselves subject to ubiquitination regulation, creating complex feedback loops that control cancer cell plasticity and metastatic potential [8].

Cancer Stem Cell (CSC) Maintenance

The ubiquitin system governs CSC functionality by modulating transcription factors essential for self-renewal and differentiation, including SOX2, OCT4, KLF4, and c-Myc [11]. E3 ubiquitin ligases and DUBs interact with key signaling pathways that regulate stem-like properties in cancer cells, including Notch, Wnt/β-catenin, Hedgehog, and Hippo-YAP pathways [11]. Dysregulation of these ubiquitination-dependent mechanisms enhances CSC maintenance, contributing to tumor initiation, recurrence, and therapy resistance. The involvement of the UPS in maintaining CSC characteristics highlights an opportunity for drug development focused on modulating ubiquitin ligases and DUBs to selectively degrade or stabilize proteins essential for CSC survival [11].

Apoptosis Evasion via Bcl-2 Regulation

The UPS plays a pivotal role in determining the fate of pro- and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members through targeted degradation [10]. Several E3 ubiquitin ligases specifically target different Bcl-2 family proteins for degradation, thereby fine-tuning apoptotic responses. Anti-apoptotic members including Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Mcl-1 are frequently overexpressed in cancer cells through disrupted ubiquitination, tipping the balance toward cell survival [10]. In breast cancer cells, estrogen receptor alpha activation directly induces Bcl-2 transcription by binding to the Bcl-2 promoter, while in gastric cancer, miR-383 negatively regulates Bcl-2 by targeting its 3'-untranslated region [10]. Dysregulation of the UPS leads to accumulation of anti-apoptotic proteins and degradation of pro-apoptotic proteins, amplifying cell survival and tumor growth.

RAS and MYC Pathway Modulation

RAS proteins, the most frequently mutated oncoproteins in human cancers, are regulated by ubiquitination which dynamically controls their stability, membrane localization, and signaling transduction [14]. A series of ubiquitination sites, E3 ligases, deubiquitinases, and regulatory proteins are involved in RAS ubiquitination, exhibiting heterogeneity across different RAS isoforms (KRAS4A, KRAS4B, NRAS, and HRAS) [14]. The OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination regulatory axis influences cancer cell fate by modulating MYC and its downstream pathways, altering oxidative stress, ultimately leading to immunotherapy resistance and poor prognosis [9]. Targeting these ubiquitination pathways offers novel strategies to overcome RAS-driven and MYC-driven malignant phenotypes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Tools | limma R package, ConsensusClusterPlus, CIBERSORT, ESTIMATE | Differential expression analysis, clustering, immune microenvironment characterization | Identifies ubiquitination-related DEGs, stratifies molecular subtypes, quantifies immune infiltration [4] [13] [12] |

| Survival Analysis Packages | survminer, survival, glmnet | Prognostic model development, LASSO Cox regression | Performs survival analysis, feature selection, and risk score calculation [4] [13] |

| Ubiquitination Databases | UUCD, iUUCD 2.0 | Comprehensive ubiquitination gene compendium | Provides reference sets of E1, E2, E3 enzymes and DUBs [13] [12] |

| Drug Sensitivity Tools | oncoPredict R package | In silico drug response prediction | Calculates IC50 values for various therapeutic compounds [4] |

| Single-Cell Analysis Tools | Seurat, SingleR | Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis | Cell type annotation and gene expression distribution at single-cell resolution [4] [13] |

Emerging Therapeutic Strategies and Clinical Implications

Targeted Protein Degradation Approaches

Molecular glues represent a new generation of small molecules that reshape an E3 ubiquitin ligase surface to promote novel protein-protein interactions, triggering ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of target proteins [15]. These monovalent compounds offer advantages over bivalent proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) through their smaller size, enhanced drug-like properties, and oral bioavailability [15]. Clinically validated molecular glues including lenalidomide and next-generation cereblon E3 ligase modulators (CELMoDs) redirect the CRL4CRBN complex to degrade transcription factors IKZF1 and IKZF3, producing durable responses in multiple myeloma [15]. Emerging programs are targeting historically "undruggable" oncoproteins including STAT3 and MYC, with early compounds showing promise in collapsing oncogene-dependent transcriptional programs [15].

Proteasome Inhibitors and Combination Strategies

Proteasome inhibitors including bortezomib and carfilzomib disrupt the proteasome-Bcl-2 axis, leading to accumulation of pro-apoptotic factors that push cancer cells toward apoptosis [11] [10]. These agents have demonstrated clinical efficacy in hematological malignancies, though their application in solid tumors remains challenging. Emerging combination strategies seek to enhance therapeutic efficacy while overcoming resistance mechanisms. The potential of combining ubiquitin-targeted therapies with traditional chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted drugs represents a novel frontier in oncological treatment strategies [11]. Research efforts are increasingly focused on developing inhibitors against specific E3 ligases and DUBs that regulate EMT, metastasis, and chemoresistance, offering promising approaches to reverse aggressive cancer phenotypes [8].

Immunotherapy Response Prediction

Ubiquitination-related prognostic signatures demonstrate growing utility in predicting immunotherapy response across multiple cancer types [9] [12]. The URPS signature effectively stratified patients receiving immunotherapy in pan-cancer analysis, with potential to identify patients most likely to benefit from immune checkpoint inhibition [9]. In lung adenocarcinoma, patients with higher ubiquitination-related risk scores had significantly higher PD1/L1 expression levels (p < 0.05), tumor mutation burden (p < 0.001), and tumor neoantigen burden (p < 0.001), suggesting enhanced responsiveness to immunotherapy [12]. These findings position ubiquitination signatures as valuable biomarkers for guiding immunotherapy selection and optimizing treatment outcomes.

Ubiquitination dysregulation represents a fundamental hallmark of cancer progression and metastasis, with ubiquitination-related gene signatures providing robust prognostic value across diverse malignancies. The intricate regulation of oncogenic pathways including EMT, apoptosis, stemness maintenance, and immune responses by the ubiquitin system underscores its central role in cancer biology. Standardized bioinformatics pipelines have enabled development of clinically relevant prognostic models that stratify patient survival and inform therapeutic approaches. Emerging targeted protein degradation strategies, particularly molecular glues and PROTACs, offer promising avenues for targeting previously "undruggable" oncoproteins. As research continues to unravel the complexity of the ubiquitin code in cancer, ubiquitination-focused biomarkers and therapies are poised to significantly advance precision oncology and improve patient outcomes.

Defining Ubiquitination-Related Genes (URGs) and Their Expression Landscapes in Tumors

Ubiquitination, a fundamental post-translational modification, has emerged as a critical regulator of oncogenesis and tumor progression. This process involves the coordinated activity of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes that attach ubiquitin molecules to target proteins, determining their stability, localization, and activity [16] [13]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) degrades approximately 80% of intracellular proteins, thereby maintaining genomic stability and modulating signaling pathways that regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis [16]. Dysregulation of ubiquitination-related genes (URGs) has been implicated across diverse cancer types, offering new avenues for prognostic assessment and therapeutic intervention. This review synthesizes current research defining URGs and their expression landscapes across tumors, providing a comparative analysis of their prognostic value and potential clinical applications.

URG Expression Landscapes Across Major Cancers

Comprehensive genomic profiling studies have revealed distinct URG expression patterns across cancer types, with therapeutic actionability observed in approximately 92.0% of solid tumor samples [17]. The expression landscapes of key URGs demonstrate both tissue-specific patterns and common themes across malignancies, reflecting the complex role of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in cancer biology.

Table 1: Ubiquitination-Related Gene Signatures and Their Prognostic Value Across Cancers

| Cancer Type | Key Ubiquitination-Related Genes Identified | Prognostic Value | Associated Biological Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical Cancer | MMP1, RNF2, TFRC, SPP1, CXCL8 [16] | AUC >0.6 for 1/3/5-year survival [16] | Immune cell infiltration, immune checkpoint regulation [16] |

| Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma | CDC34, FZR1, OTULIN [4] | Poor prognosis with elevated CDC34/FZR1 and low OTULIN [4] | Endocytosis, T-cell correlation, drug sensitivity [4] |

| Colon Cancer | ARHGAP4, MID2, SIAH2, TRIM45, UBE2D2, WDR72 [18] | Stratified patient risk groups [18] | Epithelial-mesenchymal transition, immune escape, immunosuppressive cell infiltration [18] |

| Ovarian Cancer | 17-gene signature including FBXO45 [13] | 1-year AUC = 0.703, 3-year AUC = 0.704, 5-year AUC = 0.705 [13] | Wnt/β-catenin pathway, immune microenvironment modulation [13] |

| Lung Adenocarcinoma | DTL, UBE2S, CISH, STC1 [12] | HR = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.39-0.73, p < 0.001 [12] | Immune infiltration, tumor mutation burden, PD1/L1 expression [12] |

The contrasting expression patterns and prognostic associations of these URGs across cancer types highlight the tissue-specific nature of ubiquitination signaling. For instance, in lung adenocarcinoma, elevated expression of STC1, UBE2S, and DTL correlates with poorer outcomes, while higher CISH expression appears protective [12]. Similarly, in DLBCL, CDC34 and FZR1 overexpression coupled with OTULIN underexpression defines a high-risk profile [4]. These patterns underscore the potential of URG signatures to refine prognostic stratification beyond conventional clinicopathological parameters.

Methodological Framework for URG Identification and Validation

Bioinformatics Approaches for URG Discovery

The identification of prognostic URG signatures typically follows a structured bioinformatics pipeline that integrates multiple datasets and analytical methods. A representative workflow begins with data acquisition from public repositories such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [16] [18] [13]. Differential expression analysis between tumor and normal tissues identifies significantly dysregulated genes, which are then intersected with curated URG lists from databases like the Integrated Annotations for Ubiquitin and Ubiquitin-like Conjugation Database (iUUCD) or Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) [18] [19].

Following URG identification, unsupervised clustering methods such as non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) often reveal molecular subtypes with distinct clinical outcomes [18]. Prognostic feature selection employs multiple algorithms including univariate Cox regression, Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) Cox regression, and Random Survival Forests to identify the most predictive gene subsets [16] [12]. Risk models are subsequently constructed using multivariate Cox regression coefficients, with patients stratified into high- and low-risk groups based on median risk scores [4] [13]. Validation in independent datasets confirms model robustness, with performance assessed through Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, and concordance indices [16] [13].

Experimental Validation Strategies

Bioinformatic discoveries require experimental validation to confirm both expression patterns and functional roles. Common validation approaches include:

Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR): Used to verify differential gene expression in patient tissues, cell lines, or animal models [16] [20] [12]. For example, in cervical cancer, RT-qPCR confirmed upregulation of MMP1, TFRC, and CXCL8 in tumor tissues compared to normal controls [16].

Western Blot Analysis: Provides protein-level confirmation of URG expression and assesses functional consequences. In IPF research, Western blot validated increased ITCH and CDC20 expression in TGF-β1-treated MRC-5 cells [19].

Functional Assays: Include colony formation, EdU staining, xenograft tumorigenesis, and cell migration/invasion assays to elucidate biological roles. In ovarian cancer, FBXO45 was experimentally demonstrated to promote cancer growth, spread, and migration via the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [13].

Immunohistochemistry (IHC): Enables spatial localization of URG expression in tissue sections and correlation with pathological features. In colon cancer, IHC confirmed the diagnostic potential of ARHGAP4 and SIAH2 [18].

The Ubiquitination Machinery in Cancer

The ubiquitination process involves a sequential enzymatic cascade that regulates numerous cellular processes. Understanding this machinery provides context for interpreting URG expression patterns in cancer.

The ubiquitination cascade begins with E1 activating enzymes that initiate the process through ATP-dependent ubiquitin activation. E2 conjugating enzymes then carry the activated ubiquitin, while E3 ligating enzymes facilitate substrate recognition and catalyze ubiquitin transfer to specific target proteins [16] [13]. The human genome encodes approximately 8 E1s, 39 E2s, and over 800 E3s, enabling exquisite substrate specificity [13]. This system regulates critical cancer-relevant processes including cell cycle control, DNA damage repair, signal transduction, and protein degradation [16]. Dysregulation of specific components—particularly E3 ligases and deubiquitinating enzymes—has been identified across multiple cancers, underscoring their importance in tumor pathogenesis [16] [18].

URG Associations with Tumor Microenvironment and Therapy Response

URG expression patterns significantly influence tumor immune microenvironments and therapeutic responses. In cervical cancer, immune microenvironment analysis revealed that 12 immune cell types, including memory B cells and M0 macrophages, showed significant differences between high-risk and low-risk groups defined by URG signatures [16]. Similarly, in ovarian cancer, the low-risk URG group exhibited higher infiltration of CD8+ T cells, M1 macrophages, and follicular helper cells, suggesting a more immunologically active microenvironment [13].

Table 2: URG Associations with Therapeutic Response and Immune Features

| Cancer Type | URG Influence on Immune Microenvironment | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Cervical Cancer | Differential infiltration of 12 immune cell types between risk groups; 4 immune checkpoints significantly different [16] | Risk model may guide immunotherapy approaches |

| Ovarian Cancer | Low-risk group: higher CD8+ T cells, M1 macrophages, follicular helper cells [13] | Enhanced immune surveillance in low-risk patients |

| Colon Cancer | High-risk group: enhanced EMT, immune escape, MDSC, Treg infiltration [18] | Low-risk group better response to CTLA4 inhibitors [18] |

| Lung Adenocarcinoma | High URRS group: higher PD1/L1, TMB, TNB, TME scores [12] | Lower IC50 values for various chemotherapy drugs [12] |

| DLBCL | Correlation with endocytosis mechanisms, T-cell function, and drug sensitivity [4] | Differential sensitivity to Boehringer Ingelheim compound 2536 and Osimertinib [4] |

The connection between URGs and therapy response extends beyond immune modulation. In lung adenocarcinoma, patients with higher ubiquitination-related risk scores (URRS) showed lower IC50 values for various chemotherapy drugs, suggesting enhanced susceptibility to conventional chemotherapies [12]. Similarly, in DLBCL, significant differences in drug sensitivity for Boehringer Ingelheim compound 2536 and Osimertinib were observed between URG-defined risk groups [4]. These findings highlight the potential of URG signatures to inform treatment selection across therapeutic modalities.

Research Reagent Solutions for URG Investigation

The experimental investigation of URGs requires specialized reagents and tools. The following table summarizes key resources for studying ubiquitination processes in cancer models.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for URG Investigation

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| RT-qPCR Systems | Gene expression validation | Confirming URG differential expression in tumor vs. normal tissues [16] [20] |

| Western Blot Reagents | Protein expression and modification analysis | Detecting ubiquitination changes and URG protein levels [19] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Gene knockout and editing | Functional validation of specific URGs in cancer models |

| Immunohistochemistry Kits | Spatial protein localization in tissues | Determining URG expression patterns in tumor sections [18] |

| Cell Culture Models | In vitro cancer systems | Functional assays (proliferation, migration, drug sensitivity) [13] [19] |

| Xenograft Mouse Models | In vivo tumor studies | Assessing URG effects on tumor growth and metastasis [18] [13] |

| Ubiquitination Databases | URG reference resources | iUUCD, MSigDB, UUCD for gene set identification [18] [13] [12] |

The systematic definition of ubiquitination-related genes and their expression landscapes across tumors represents a significant advance in cancer biology with direct translational implications. URG signatures provide robust prognostic information across diverse malignancies, often surpassing conventional clinicopathological parameters in predictive accuracy. These signatures consistently correlate with distinct tumor microenvironment features and therapy responses, highlighting their potential as biomarkers for treatment selection. The integration of bioinformatic discovery with experimental validation has established credible frameworks for continued exploration of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in cancer. As therapeutic strategies targeting ubiquitination pathways continue to emerge, particularly with the development of proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs), comprehensive understanding of URG expression patterns will become increasingly essential for advancing precision oncology approaches [13]. Future research directions should focus on validating these signatures in prospective clinical trials and developing standardized assays for implementation in routine oncologic practice.

Protein ubiquitination, a crucial post-translational modification, regulates fundamental cellular processes including proteasomal degradation, cell cycle progression, and DNA damage repair. Recent advances in transcriptomic analysis have revealed that specific ubiquitination-related gene (URG) signatures provide powerful prognostic value across diverse cancer types. These signatures reflect underlying tumor biology and microenvironment interactions, offering insights beyond conventional histopathological classifications. This guide compares key URG exemplars—OTULIN in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and FBXO45 in ovarian cancer—highlighting their prognostic significance, experimental validation, and clinical implications for researchers and drug development professionals.

URG Prognostic Signatures at a Glance

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Ubiquitination-Related Genes in Cancer Prognosis

| Feature | OTULIN in DLBCL | FBXO45 in Ovarian Cancer |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Function | Linear linkage-specific deubiquitinase [4] | F-box protein, substrate recognition component of E3 ubiquitin ligase [13] |

| Expression in Tumor | Low expression correlated with poor prognosis [4] | Overexpressed in tumor tissues [13] |

| Prognostic Value | Favorable prognostic marker [4] | Poor prognostic marker [13] |

| Risk Association | Low expression → High risk [4] | High expression → High risk [13] |

| Key Pathways | Endocytosis-related mechanisms, T-cell function [4] | Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [13] |

| Therapeutic Implications | Correlated with sensitivity to Boehringer Ingelheim compound 2536 and Osimertinib [4] | Potential target for proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) [13] |

Table 2: Multi-Gene Ubiquitination Signatures in Cancer Prognosis

| Cancer Type | Signature Genes | Prognostic Performance | Biological Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ovarian Cancer | HSP90AB1, FBXO9, SIGMAR1, STAT1, SH3KBP1, EPB41L2, DNAJB6, VPS18, PPM1G, AKAP12, FRK, PYGB [21] | 1-year AUC: 0.737, 3-year AUC: 0.762, 5-year AUC: 0.793 [21] | B-cell receptor signaling, ECM receptor interaction, focal adhesion [21] |

| DLBCL | CDC34, FZR1, OTULIN [4] | Validated in GSE10846 and GSE181063 datasets [4] | Endocytosis-related mechanisms, T-cell function, drug sensitivity [4] |

| Ovarian Cancer | FBXO9, UBD [22] | Accurate OS prediction in TCGA-OV and GSE32062 datasets [22] | DNA damage repair activity, immunocyte infiltration [22] |

OTULIN in DLBCL: Mechanisms and Methodologies

Biological Functions and Prognostic Significance

OTULIN (OTU Deubiquitinase with Linear Linkage Specificity) functions as a deubiquitinating enzyme with specificity for linear ubiquitin chains. In DLBCL, decreased OTULIN expression associates with significantly poorer patient outcomes, positioning it as a favorable prognostic biomarker [4]. The gene participates in endocytosis-related mechanisms and T-cell function, with its expression pattern correlating with differential responses to targeted therapeutics including Boehringer Ingelheim compound 2536 and Osimertinib [4].

Experimental Protocols and Analytical Workflows

Data Acquisition and Processing: Researchers analyzed three DLBCL datasets (GSE181063, GSE56315, and GSE10846) encompassing 1,800 DLBCL samples. The GSE10846 dataset served as the training set, while GSE181063 provided independent validation [4].

Differential Gene Screening: Using the limma package, investigators identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between tumor and normal tissue groups with thresholds of Fold Change > 2 and FDR < 0.05. Survival-associated ubiquitination-related genes were selected through univariate Cox regression analysis [4].

Prognostic Model Construction: LASSO Cox survival analysis implemented via the "glmnet" package identified the most valuable prognostic genes. Ten-fold cross-validation determined the optimal penalty parameter. Risk scores were calculated using the formula: β1 * Exp1 + β2 * Exp2 + βi * Expi, where β represents coefficients from multivariate Cox regression and Exp denotes gene expression levels [4].

Immune Microenvironment Assessment: The CIBERSORT package analyzed immune cell infiltration in DLBCL samples, with Wilcoxon rank-sum tests identifying differences between risk groups. Drug sensitivity analysis employed the oncoPredict package to calculate IC50 values for 198 therapeutic compounds [4].

FBXO45 in Ovarian Cancer: Mechanisms and Methodologies

Biological Functions and Prognostic Significance

FBXO45 functions as a critical substrate-recognition component of E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes. In ovarian cancer, FBXO45 overexpression promotes tumor growth, spread, and migration through activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [13]. Experimental evidence confirms FBXO45 enhances cell viability and glycolysis in cancer models through DUSP2 ubiquitination-mediated ERK1/2 activation [23]. The high-risk group defined by URG signatures demonstrates significantly lower overall survival (P < 0.05) and distinct immune microenvironment characteristics, including altered CD8+ T cell and macrophage infiltration patterns [13].

Experimental Protocols and Analytical Workflows

Transcriptomic Data Processing: Researchers obtained transcriptomes and clinical profiles for 376 tumor and 88 normal ovarian tissue samples from TCGA-OV and GTEx databases. Differential gene expression analysis used the 'edgeR' package with thresholds of |logFC| ≥ 1 and corrected p-value < 0.01 [13].

Ubiquitination Gene Selection: The ubiquitin-related gene set (929 genes) came from the UUCD database, categorized into E1 (8 genes), E2 (39 genes), and E3 (882 genes) enzyme classes. Intersection with DEGs identified 162 co-expressed ubiquitination-related genes for model construction [13].

Prognostic Model Development: LASSO regression analysis and DEVIANCE test applied to candidate genes identified 17 genes for the final prognostic model. The risk score calculation formula: Risk score = Σ(Coefi × Ai), where Coefi represents regression coefficient and Ai represents gene expression level [13].

Immune and Mutation Analysis: ESTIMATE algorithm calculated stromal and immune scores, while "maftools" package analyzed somatic mutation data. Single-cell RNA sequencing data from E-MTAB-8381 dataset enabled cellular resolution analysis of the tumor microenvironment [13].

Experimental Validation: Cell culture studies using A2780 and HEY ovarian cancer cell lines included STR analysis and mycoplasma testing. Functional assays measured cell viability (CCK-8), metabolic characteristics (Seahorse assays), lactate production, and protein expression (Western blotting). Mouse xenograft models validated in vivo effects [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for URG Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | A2780, HEY (ovarian cancer); DLBCL-derived lines | In vitro functional validation of URG mechanisms [13] |

| Culture Media | DMEM, RPMI 1640 (Gibco) | Cell maintenance and propagation [13] |

| Antibodies | Anti-Ubiquitin linkage-specific K48 (Abcam); FBXO9 Rabbit Polyclonal Antibody (ORIGENE) | Immunohistochemistry, Western blot analysis [22] |

| Transfection Reagent | Lipo8000 | Genetic manipulation (knockdown/overexpression) [13] |

| Analysis Packages | limma, edgeR, glmnet, survminer, ClusterProfiler (R/Bioconductor) | Bioinformatics analysis of differential expression, survival, enrichment [13] [4] |

| Database Resources | TCGA, GTEx, GEO, UUCD, iUUCD 2.0, STRING | Data source for model building and validation [13] [4] [22] |

| Animal Models | Mouse xenograft models | In vivo validation of URG functions [13] |

The systematic comparison of OTULIN in DLBCL and FBXO45 in ovarian cancer reveals both shared and distinct patterns of ubiquitination-related gene function in cancer prognosis. While both genes enable risk stratification and inform therapeutic approaches, they operate at different regulatory levels—OTULIN as a deubiquitinating enzyme and FBXO45 as an E3 ligase component. These exemplars demonstrate how ubiquitination signatures reflect fundamental cancer biology while offering clinically actionable insights. The experimental methodologies outlined provide a framework for extending similar analyses to other cancer types and ubiquitination-related genes, potentially accelerating the development of ubiquitination-targeted therapies across oncology.

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification process that regulates specific protein degradation in eukaryotes through a highly-specific, adenosine triphosphate-dependent pathway. This reversible process is mediated by three enzyme types: E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme, E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, and E3 ubiquitin ligase, which collectively recognize substrate proteins and catalyze ubiquitin transfer [24]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system plays important roles in numerous cell signaling pathways and biological processes, including protein activation, DNA replication and repair, cell cycle control, chromatin dynamics, transcription signaling transduction, autophagy, and immune response [24]. Given these fundamental functions, ubiquitination-related genes (URGs) have emerged as important biomarkers and therapeutic targets in cancer research.

In recent years, numerous studies have demonstrated that aberrant expression of URGs correlates with clinical outcomes across various cancer types. The development of prognostic signatures based on URG expression patterns represents a promising approach for improving risk stratification and clinical decision-making for cancer patients. This guide comprehensively compares published URG-based prognostic signatures, their experimental validation, and clinical applications to provide researchers and drug development professionals with an objective assessment of this rapidly evolving field.

Comparative Analysis of URG Prognostic Signatures Across Cancers

Signature Composition and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparison of URG Prognostic Signatures Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Signature Genes | Patient Cohort | Performance (AUC) | Clinical Utility | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | CDC20, PCGF2, UBE2S, SOCS2 | GSE42568 (104 BC + 17 normal), TCGA (1089 tumors + 112 normal) | Favorable in test set (GSE20685) | Independent risk factor; Classifies high/low-risk groups | [24] |

| Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma | CDC34, FZR1, OTULIN | GSE181063, GSE56315, GSE10846 (1,800 DLBCL samples) | Validated in independent sets | Correlates with immune microenvironment; Drug sensitivity predictor | [4] |

| Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma | 3-gene signature (unspecified) | TCGA-PAAD (178 tumors + 4 normal), GTEx, ICGC-PACA-AU (88 samples) | Robust validation across multiple sets | Predicts immune status; Guides therapy selection | [25] |

| Ovarian Cancer | 17-gene signature including FBXO45 | TCGA-OV (376 tumors), GTEx (88 normal) | 1-year: 0.703, 3-year: 0.704, 5-year: 0.705 | Reflects immune microenvironment; FBXO45 promotes growth via Wnt/β-catenin | [13] |

| Laryngeal Cancer | PPARG, LCK, LHX1 | TCGA-LC, GSE65858 | Strong discrimination of OS | Predicts immunotherapy response; Guides personalized treatment | [26] |

| Gastric Cancer | 9-consensus-gene signature | GEO cohorts (921 patients total) | HR: 3.81 (95% CI: 2.44-5.96) | Predicts chemo-/immunotherapy response; Superior to TNM alone | [27] |

Methodological Approaches for Signature Development

Table 2: Experimental Protocols and Analytical Methods for URG Signature Development

| Methodological Step | Standard Protocols | Key Software/Packages | Output Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | TCGA, GEO, ICGC database mining | GEO2R, UCSC Xena | Cross-platform normalization |

| Differential Expression Analysis | limma package (∣log₂FC∣ > 1, adjust p < 0.05) | Volcano plots, heatmaps | |

| Prognostic Gene Screening | Univariate Cox regression | survival package | Hazard ratios with significance (p < 0.05) |

| Signature Construction | LASSO Cox regression | glmnet package (10-fold cross-validation) | Minimum lambda selection |

| Model Validation | Kaplan-Meier analysis | survminer package | Log-rank test p-values |

| Performance Assessment | Time-dependent ROC curves | timeROC package | AUC calculations (1, 3, 5-year) |

| Immune Microenvironment Analysis | CIBERSORT, ESTIMATE, ssGSEA | Immunedeconv, e1071 packages | Immune cell infiltration scores |

| Drug Sensitivity Prediction | oncoPredict | pRRophetic algorithm | IC50 values |

Key URG Biomarkers and Their Functional Roles

Multi-Gene Signatures Versus Single URG Biomarkers

Research has followed two complementary approaches for linking URG expression to clinical outcomes: multi-gene prognostic signatures and single URG biomarkers. Multi-gene signatures typically demonstrate superior predictive power by capturing the complexity of ubiquitination pathways, while single URG biomarkers offer more straightforward mechanistic insights and potential as therapeutic targets.

The 4-URG signature for breast cancer (CDC20, PCGF2, UBE2S, SOCS2) exemplifies the multi-gene approach. According to the development study, this signature demonstrated significant capacity to classify breast cancer patients into high-risk and low-risk groups with markedly different overall survival outcomes (p < 0.001) [24]. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) revealed that this 4-URG signature may be functionally related to DNA replication, DNA repair, and cell cycle pathways, providing biological plausibility for its prognostic value [24].

In contrast, studies focusing on URG4 (Upregulator of Cell Proliferation 4) demonstrate the single-biomarker approach. URG4 has been investigated across multiple cancer types including gastric carcinoma, cervical cancer, and osteosarcoma, with consistent findings associating its overexpression with poor clinical outcomes [28] [29] [30].

URG4 as a Pan-Cancer Prognostic Indicator

Table 3: URG4 as a Prognostic Biomarker Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Study Details | Key Findings | Clinical Implications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric Cancer | 61 patients; IHC scoring | High URG4 (61%) correlated with T stage (p < 0.005) and lymphovascular invasion (p < 0.005); Significant association with 2-year survival (p < 0.05) | Independent prognostic factor; Similar predictive value to HER2 | [28] |

| Cervical Cancer | 167 patients (FIGO Ib1-IIa); IHC | High URG4 (35.13%) correlated with stage (p < 0.0001), tumor size (p = 0.012), T classification (p = 0.023), lymph node metastasis (p = 0.001); Independent prognostic factor in multivariate analysis | Shorter OS and DFS, especially in patients receiving CCRT (p < 0.0001) | [29] |

| Osteosarcoma | 46 patients; IHC | High URG4 (86.96%) in osteosarcoma specimens; Increased in recurrence (p < 0.05) and metastasis (p < 0.05); Correlation with PCNA | Mean OS: 54.08 months (high URG4) vs 70.01 months (low URG4) | [30] |

Experimental Validation Workflows

The development and validation of URG prognostic signatures follows a systematic workflow that integrates bioinformatics analysis with experimental validation. The standard methodology encompasses multiple stages from data collection through clinical correlation analysis, with rigorous statistical validation at each step.

Key Methodological Components

Data Collection and Preprocessing: Studies typically begin with acquiring large-scale transcriptomic data from public databases such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), and International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC). For example, the ovarian cancer URG signature development utilized 376 tumor samples from TCGA-OV and 88 normal ovarian tissue samples from GTEx [13]. Normalization and batch effect correction are critical steps at this stage, often performed using R packages like "sva" [27].

Differential Expression and Prognostic Screening: Differentially expressed URGs are identified using thresholds such as |log₂FC| > 1 and adjusted p-value < 0.05 via the "limma" package [24] [25]. Prognostic significance is then assessed through univariate Cox regression analysis to identify genes significantly associated with overall survival.

Signature Construction Using LASSO Regression: The most informative genes are selected using Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) Cox regression analysis with 10-fold cross-validation to prevent overfitting [24] [4] [27]. This method reduces the dimensionality of the genetic data while retaining the most prognostically relevant genes.

Experimental Validation Approaches: Promising signatures and individual URGs typically undergo experimental validation. For example, the pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma study used RT-qPCR to verify gene expression differences between normal and cancerous tissues [25]. Functional validation often includes in vitro assays such as colony formation, Transwell migration and invasion assays, and gene knockdown or overexpression experiments to establish causal relationships [25] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for URG Prognostic Signature Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Tools | limma, glmnet, survminer, ESTIMATE | Signature development | Differential expression analysis, LASSO regression, survival analysis, immune microenvironment estimation |

| Databases | TCGA, GEO, ICGC, UUCD | Data sourcing | Provide transcriptomic, clinical, and ubiquitination-related gene data |

| Immunohistochemistry Antibodies | Anti-URG4 (Abcam Cat NO: 103,323), Anti-upregulator of cell proliferation 4 antibody (Sigma, HPA020134) | Protein validation | Detect and quantify URG protein expression in tissue specimens |

| Cell Lines | PANC-1 (pancreatic), A2780 (ovarian), HepG2 (hepatocellular), GES-1 (gastric) | Functional studies | Investigate URG functions through in vitro manipulation |

| Gene Manipulation Reagents | siRNA, Lipo8000 transfection reagent | Mechanistic studies | Knockdown specific URGs to study functional consequences |

| PCR and Western Blot Reagents | SYBR Green Real-Time PCR Master Mix Plus, RIPA buffer, PVDF membranes | Expression validation | Confirm gene and protein expression patterns |

Clinical Applications and Therapeutic Implications

Prognostic Stratification and Treatment Guidance

URG-based signatures show significant promise for enhancing prognostic stratification beyond conventional clinicopathological parameters. In gastric cancer, the 9-consensus-gene signature demonstrated significant prognostic value across multiple validation cohorts with hazard ratios of 3.81 (95% CI: 2.44-5.956) in GSE62254 and 2.65 (95% CI: 1.892-3.709) in GSE15459 [27]. Multivariate analysis confirmed these signatures as independent prognostic factors, suggesting they provide complementary information to traditional staging systems.

Therapeutic implications represent perhaps the most promising application of URG signatures. Studies consistently reveal correlations between risk groups and sensitivity to various treatment modalities. For example, in gastric cancer, researchers proposed that low-risk patients might be more suitable for 5-fluorouracil therapy, while high-risk patients could potentially benefit more from anti-CTLA4 immunotherapy [27]. Similarly, in laryngeal cancer, analyses suggested that chemotherapy would be more effective in high-risk patients, while immune checkpoint inhibitors would show better efficacy in low-risk patients [26].

Immune Microenvironment Modulation

URG signatures provide significant insights into tumor immune microenvironment composition, which has implications for immunotherapy response prediction. The ovarian cancer study found that low-risk patients had significantly higher levels of CD8+ T cells (p < 0.05), M1 macrophages (p < 0.01), and follicular helper cells (p < 0.05) [13]. Similarly, in pancreatic cancer, the low-risk group demonstrated elevated ESTIMATE scores, ImmuneScores, and StromalScores, indicating distinct immune microenvironments between risk groups [25].

The connection between ubiquitination processes and immune regulation provides biological plausibility for these observations. For instance, in laryngeal cancer, researchers identified correlations between signature genes (PPARG, LCK, LHX1) and immune-promoting microenvironments, with LCK showing positive correlation while PPARG and LHX1 demonstrated negative correlations with favorable immune characteristics [26].

The growing body of evidence supports the clinical potential of URG-based prognostic signatures across diverse cancer types. These signatures demonstrate consistent value in risk stratification, treatment selection guidance, and understanding tumor biology, particularly regarding immune microenvironment interactions. The convergence of ubiquitination pathway biology with cancer prognosis offers exciting opportunities for both prognostic tool development and therapeutic target identification.

Future research directions should include larger prospective validations of the most promising signatures, standardization of analytical approaches across institutions, and integration of URG signatures with other molecular markers to create comprehensive prognostic systems. Furthermore, the therapeutic targeting of high-risk URGs represents a promising avenue for drug development, particularly as proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC) technologies advance. As these biomarkers continue to undergo refinement and validation, they hold significant promise for advancing personalized cancer care.

Building and Applying Ubiquitination-Based Prognostic Models in Oncology

The discovery of ubiquitination-related genes (URGs) with prognostic value in cancer hinges on robust data sourcing from major public repositories. This guide provides a structured comparison of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), and the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) projects, outlining experimental protocols for data retrieval and analysis. We objectively compare the data accessibility, types, and volumes across these platforms, providing a foundational framework for researchers to design efficient URG discovery pipelines. By integrating practical methodologies with visualization of workflows, this guide serves as an essential toolkit for cancer researchers and drug development professionals.

The landscape of cancer genomics research is powered by large-scale public databases that provide comprehensive molecular profiling data. For investigators studying the role of ubiquitination in cancer prognosis, three databases are particularly fundamental: The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), and the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Each offers unique strengths—TCGA provides multi-omics data from thousands of cancer patients alongside clinical outcomes, enabling direct prognostic association studies. GEO serves as a vast repository of curated gene expression datasets from diverse experimental conditions, allowing for validation and meta-analysis. GTEx provides essential reference data from normal human tissues, crucial for distinguishing cancer-specific ubiquitination patterns from normal biological variation. Understanding the architecture, data types, and access methods for these resources is the critical first step in building a rigorous URG discovery pipeline.

Database Comparative Analysis

A systematic evaluation of database characteristics reveals complementary strengths for URG discovery. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of core attributes.

Table 1: Core Database Characteristics for URG Discovery

| Feature | TCGA | GEO | GTEx |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Cancer genomics & clinical correlation | Curated gene expression datasets | Normal tissue gene expression |

| Key Data Types | Genomic, transcriptomic, epigenetic, clinical | Gene expression, methylation, SNP arrays | RNA-seq, WGS, histopathology |

| Data Access Method | GDC API, Data Portal [31] [32] | GEO Accession Viewer, FTP [33] | GTEx Portal, dbGaP |

| API Availability | Comprehensive REST API [34] [32] | Limited, bulk FTP preferred [33] | Limited public API |

| Use Case in URG Research | Primary discovery & prognostic modeling | Independent validation & meta-analysis | Normal tissue baseline reference |

A deeper analysis of technical accessibility and data structure further differentiates these resources.

Table 2: Technical Accessibility and Data Structure

| Characteristic | TCGA (via GDC) | GEO | GTEx |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Structure | Harmonized, standardized processing [31] | Submitter-provided, heterogeneous | Standardized processing pipeline |

| Metadata Richness | Highly standardized clinical & molecular data [31] | Varies by submitter; can be extensive | Detailed donor and tissue metadata |

| Best For | Building unified, large-scale cohorts | Finding specific experimental conditions | Establishing normal expression baselines |

Experimental Protocols for Data Sourcing

Programmatic Data Retrieval from TCGA via GDC API

The Genomic Data Commons (GDC) provides a powerful API for programmatic data access, which is essential for reproducible URG research [32]. The following R code demonstrates a robust protocol for mapping file UUIDs to TCGA patient barcodes and downloading data, addressing common issues with legacy archive queries [34].

For efficient file downloads using the obtained metadata, a POST request with a file of UUIDs is recommended for large datasets [32].

Targeted Dataset Retrieval from GEO

GEO dataset sourcing relies on accession numbers and understanding its SOFT format. The protocol emphasizes dataset curation and meta-information extraction.

Establishing Normal Baselines with GTEx

GTEx data provides normal tissue expression baselines. While access often involves dbGaP authorization, the analysis pipeline focuses on VST-normalized RNA-seq TPM values from the GTEx Portal for comparison with TCGA tumor data.

Visualizing Data Sourcing Workflows

The integrated workflow for URG discovery leverages all three databases in a complementary fashion, as shown in the following diagram.

Figure 1: Integrated URG Discovery Workflow. This diagram outlines the synergistic use of TCGA for primary discovery, GTEx for normal tissue reference, and GEO for independent validation.

The specific process for programmatic data retrieval from the TCGA via the GDC API is detailed below.

Figure 2: TCGA Data Retrieval via GDC API. This protocol ensures efficient, reproducible acquisition of genomic data linked to clinical outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit for URG Discovery

Successful data sourcing and analysis require a suite of computational tools and reagents. The following table details essential components of the URG discovery pipeline.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for URG Discovery

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Primary Function in URG Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| GDC Data Transfer Tool | Data Access | High-performance reliable download of TCGA data [31] |

| cURL | Data Access | Command-line tool for API interactions and data transfer [34] [32] |

| R/Bioconductor | Analysis | Statistical analysis, visualization, and package ecosystem (TCGAbiolinks) |

| TCGAbiolinks | Analysis | Specialized R package for TCGA data harmonization and analysis |

| Python Requests | Analysis | HTTP library for programmatic API access in Python environments [34] |

| Ubiquitin Antibodies | Wet-lab Reagent | Validation of URG protein expression via Western Blot/IHC |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Wet-lab Reagent | Stabilize ubiquitinated proteins for functional studies |

| Mutation-Specific Antibodies | Wet-lab Reagent | Detect specific ubiquitination marks (e.g., K48-/K63-linked chains) |

This guide provides a comprehensive framework for leveraging TCGA, GEO, and GTEx databases to advance ubiquitination signature research. The comparative analysis reveals that while TCGA offers the most structured platform for primary discovery with integrated clinical data, GEO and GTEx provide essential complementary functions for validation and baseline establishment. The experimental protocols and visualizations offer actionable pathways for researchers to implement these data sourcing strategies. By applying these standardized methodologies, the research community can accelerate the identification and validation of ubiquitination-related genes with significant prognostic value in cancer, ultimately contributing to improved therapeutic strategies.

Ubiquitination-related genes (URGs) have emerged as pivotal regulators of tumor progression and therapy resistance. This review objectively compares bioinformatics pipelines for identifying survival-associated URGs across multiple cancer types, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), laryngeal cancer, glioma, and lung adenocarcinoma. By evaluating experimental protocols, predictive performance metrics, and clinical applicability of URG-based prognostic signatures, we demonstrate that integrated approaches combining differential expression analysis with Cox regression consistently yield robust risk stratification models. These signatures show significant prognostic value across cancer types, with hazard ratios (HR) for high-risk groups ranging from 1.04 to 3.27 across studies. Furthermore, URG signatures provide insights into tumor immune microenvironment composition and therapeutic response, positioning them as valuable tools for personalized cancer treatment.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system represents a crucial regulatory mechanism in cellular homeostasis, controlling protein degradation, cell cycle progression, DNA repair, and immune response. Dysregulation of ubiquitination processes has been implicated in various aspects of tumorigenesis, including uncontrolled proliferation, metastasis, and treatment resistance. Recent advances in bioinformatics have enabled the systematic identification of ubiquitination-related gene signatures with prognostic significance across cancer types.

Bioinformatics pipelines integrating differential expression analysis with survival regression models have proven particularly effective in extracting meaningful prognostic information from transcriptomic data. These approaches have revealed that ubiquitination signatures not only predict patient outcomes but also reflect the immunological status of tumors and potential response to therapies, including immune checkpoint inhibitors and targeted agents.

Comparative Analysis of URG Signature Performance Across Cancers

Table 1: Performance Metrics of URG-Based Prognostic Signatures Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Signature Genes | Cohort Size | Prediction AUC | Hazard Ratio (HR) | Clinical Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) | CDC34, FZR1, OTULIN | 1,800 samples | 1-year: ~0.752-year: ~0.723-year: ~0.70 | High vs. Low Risk: 2.18-3.27 | Independent dataset (GSE181063) [4] |

| Laryngeal Cancer | PPARG, LCK, LHX1 | 116 TCGA + 46 GEO | 1-year: 0.722-year: 0.693-year: 0.71 | High vs. Low Risk: 2.45 | External validation (GSE65858) [35] |

| Glioma | USP4 + 7-gene signature | TCGA cohort | 1-year: ~0.783-year: ~0.75 | High vs. Low Risk: 2.85 | In vitro functional validation [36] |

| Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD) | 8-gene signature | 461 TCGA samples | 12-month: 0.7618-month: 0.753-year: 0.74 | Not reported | Comparison with established signatures [37] |

Table 2: Immune and Therapeutic Correlations of URG Signatures

| Cancer Type | Immune Microenvironment Associations | Therapeutic Implications | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| DLBCL | Correlation with T-cell infiltration and endocytosis mechanisms; Significant differences in immune scores between risk groups | Differential sensitivity to Boehringer Ingelheim compound 2536 and Osimertinib | Single-cell sequencing; Drug sensitivity analysis [4] |

| Laryngeal Cancer | Low-risk: Activated immune function, higher anti-cancer immune cells, immune-promoting cytokinesHigh-risk: Immunosuppressive microenvironment | Chemotherapy more effective in high-risk; ICIs more effective in low-risk | Western blot, qRT-PCR, ELISA for PPARG, LCK, LHX1 [35] |

| Glioma | Risk grouping guided immunotherapy strategies; Association with immune microenvironment | Potential for targeting USP4 to reduce invasion/migration | USP4 knockdown/overexpression in U87-MG, LN229, A172 cell lines [36] |

Core Bioinformatics Methodology: Differential Expression and Cox Regression

Experimental Protocol for URG Signature Development

The standard workflow for identifying survival-associated URGs follows a multi-stage analytical process, consistently applied across cancer types with minor variations:

1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- RNA-seq data and clinical information are obtained from public repositories (TCGA, GEO)

- Data normalization using TPM, FPKM, or similar methods

- Quality control including removal of samples with excessive missing data or outliers

- Integration of ubiquitin-related genes from specialized databases (iUUCD 2.0, UbiBrowser 2.0) [35]

2. Identification of Differentially Expressed URGs:

- Differential expression analysis using limma package with criteria typically set at fold change > 2 and FDR < 0.05

- Stratification of samples into high and low expression groups using survival-based cutpoints

- Intersection of differentially expressed genes with ubiquitination-related genes [4]

3. Survival-Associated URG Selection:

- Univariate Cox regression to identify URGs significantly associated with overall survival

- Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) Cox regression with 10-fold cross-validation to prevent overfitting

- Multivariate Cox regression to identify independently prognostic genes [4] [35]

4. Prognostic Signature Construction:

- Risk score calculation using the formula: Risk score = Σ(βi × Expi)

- Stratification of patients into high-risk and low-risk groups based on median risk score

- Validation in independent datasets to assess generalizability [4] [35]

5. Functional and Clinical Correlations:

- Immune microenvironment analysis using CIBERSORT or similar tools

- Drug sensitivity prediction using oncoPredict or comparable platforms

- Gene ontology and pathway enrichment analysis [4] [35]

Figure 1: Bioinformatics workflow for identifying survival-associated ubiquitination-related genes

Statistical Foundation: Cox Proportional Hazards Regression

Cox regression serves as the statistical cornerstone for identifying survival-associated URGs. The method models the hazard function as:

H(t) = H₀(t) × exp(b₁X₁ + b₂X₂ + b₃X₃ + ⋯ + bₖXₖ)

where H(t) represents the hazard at time t, H₀(t) is the baseline hazard, X₁...Xₖ are predictor variables (gene expression values), and b₁...bₖ are coefficients estimated by the regression [38].

The exponentiated coefficients, exp(bᵢ), represent hazard ratios (HR) – the instantaneous relative risk of the event (e.g., death) associated with a one-unit increase in the predictor variable, assuming other variables remain constant. For continuous variables like gene expression, exp(bᵢ) > 1 indicates increased risk with higher expression, while exp(bᵢ) < 1 indicates decreased risk [38].

Model performance is typically evaluated using Harrell's C-index (concordance index), with values near 1 indicating excellent predictive discrimination and values near 0.5 indicating no better than random prediction [38].

Key Ubiquitination Pathways and Biological Mechanisms

Figure 2: Biological mechanisms and pathways of prognostic ubiquitination-related genes

The ubiquitination-related genes identified through these bioinformatics pipelines participate in diverse but interconnected biological processes:

Cell Cycle Regulation: CDC34 and FZR1, identified in the DLBCL signature, function as regulators of cell cycle progression. Elevated expression of these genes promotes uncontrolled proliferation, correlating with poor prognosis [4].

Immune Microenvironment Modulation: Multiple URG signatures demonstrate strong associations with immune cell infiltration and function. In laryngeal cancer, PPARG expression correlates with immunosuppressive cytokines (IL6, TGFB1, TGFB2, VEGFC), while LCK shows positive association with immuno-promoting microenvironment [35]. Similarly, in DLBCL, the URG signature correlates with T-cell infiltration and endocytosis-related mechanisms [4].

Treatment Response Mechanisms: USP4 in glioma enhances cell invasion, migration, and colony formation capacity, as demonstrated through knockdown and overexpression experiments [36]. URG signatures also show predictive value for drug sensitivity, with differential responses to targeted therapies observed between risk groups in DLBCL and laryngeal cancer [4] [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for URG Prognostic Signature Development

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Application in URG Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas)GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus)GTEx (Genotype-Tissue Expression) | Source of RNA-seq data and clinical information for analysis [4] [35] |

| Ubiquitin Databases | iUUCD 2.0UbiBrowser 2.0 | Comprehensive collections of experimentally verified ubiquitination-related genes and interactions [35] |

| Bioinformatics Packages | limma (R)survival (R)glmnet (LASSO)CIBERSORToncoPredict | Differential expression analysis, survival modeling, feature selection, immune deconvolution, drug sensitivity prediction [4] [38] |

| Validation Platforms | GEPIA2UALCANPROGgene V2 | Independent validation of expression patterns and survival correlations [39] |

| Experimental Validation | Western blotqRT-PCRELISACell line models (e.g., U87-MG, LN229, A172) | Confirmation of gene expression and functional characterization of URGs [36] [35] |

Bioinformatics pipelines integrating differential expression analysis with Cox regression have consistently demonstrated utility in identifying ubiquitination-related gene signatures with prognostic significance across cancer types. These signatures not only stratify patients into distinct risk categories but also provide insights into tumor biology, immune microenvironment composition, and potential therapeutic responses.

The reproducibility of findings across independent datasets and cancer types underscores the robustness of this methodological approach. Furthermore, the experimental validation of key signature genes in model systems strengthens the biological plausibility of these computational predictions.