Ubiquitination-Specific Antibodies in Cancer Immunohistochemistry: From Basic Mechanisms to Clinical Prognosis

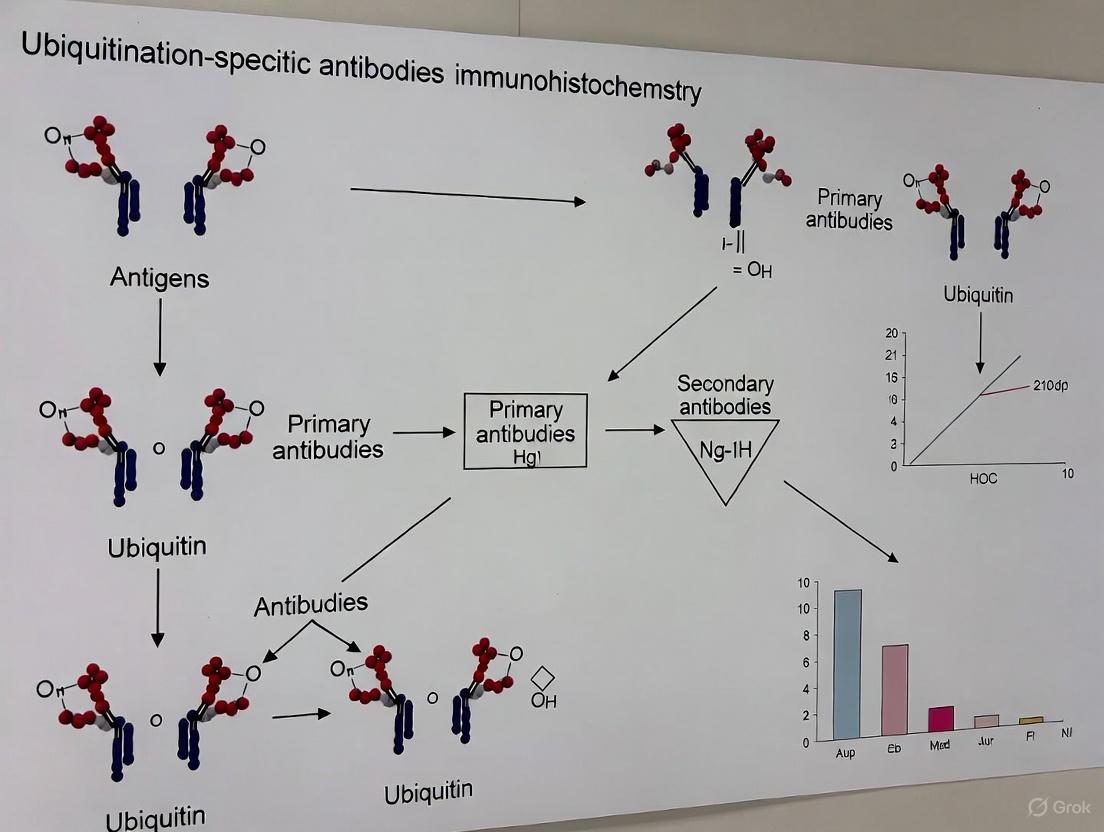

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of ubiquitination-specific antibodies in cancer immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Ubiquitination-Specific Antibodies in Cancer Immunohistochemistry: From Basic Mechanisms to Clinical Prognosis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of ubiquitination-specific antibodies in cancer immunohistochemistry (IHC). It explores the foundational role of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) like USP2 and UBE2C in tumorigenesis, detailing their validated prognostic value in gastric, breast, and prostate cancers. A thorough methodological guide covers antibody selection, protocol optimization, and IHC troubleshooting to ensure assay specificity and reproducibility. Finally, the article emphasizes critical validation strategies, including the use of genetic and pharmacological controls, to confirm antibody specificity for ubiquitination marks, thereby supporting robust biomarker development and precise diagnostic applications in oncology.

The Ubiquitin System in Cancer: Defining Key Targets for Immunohistochemistry

Core Components and Mechanism of the UPS

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) is the primary pathway for targeted intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, playing crucial roles in maintaining protein homeostasis, regulating cell cycle progression, and controlling signal transduction [1]. This highly conserved system ensures the precise elimination of damaged, misfolded, or short-lived regulatory proteins through an ATP-dependent process [1].

The UPS operates through a coordinated enzymatic cascade that tags target proteins for degradation, followed by their recognition and processing by a large proteolytic complex. The process begins with ubiquitin activation by the E1 enzyme, forming a thioester bond between E1's cysteine residue and ubiquitin's C-terminal glycine, powered by ATP hydrolysis. The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2). Finally, a ubiquitin ligase (E3) facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to a lysine residue on the target protein, forming an isopeptide bond [1]. E3 ligases provide substrate specificity, recognizing particular target proteins through specialized domains [1].

The ubiquitinated protein is then recognized and degraded by the proteasome, a large multi-subunit complex. The 26S proteasome consists of a barrel-shaped 20S core particle (CP) that contains the proteolytic active sites, flanked by one or two 19S regulatory particles (RP) that recognize ubiquitinated proteins, remove the ubiquitin tags, unfold the substrate, and translocate it into the catalytic core for degradation [1] [2]. The degradation products are short peptide fragments that are further broken down into amino acids for reuse in protein synthesis [1].

Table 1: Core Components of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

| Component | Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin | A 76-amino acid protein tag | Highly conserved; covalently attached to target proteins [1] |

| E1 Enzyme | Ubiquitin-activating enzyme | Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent process [1] |

| E2 Enzyme | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme | Transfers activated ubiquitin from E1 to E3 [1] |

| E3 Ligase | Ubiquitin ligase | Provides substrate specificity; catalyzes ubiquitin transfer to target protein [1] |

| 26S Proteasome | Proteolytic complex | Degrades ubiquitinated proteins; consists of 20S core and 19S regulatory particles [1] |

| DUBs | Deubiquitinating enzymes | Remove ubiquitin tags; regulate ubiquitin recycling and protein stability [3] |

Diagram 1: The UPS pathway for targeted protein degradation.

Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs): Classification and Functions

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) constitute a diverse family of proteases that counterbalance ubiquitination by removing ubiquitin moieties from substrate proteins. With approximately 100 members identified in the human genome, DUBs regulate virtually all cellular processes influenced by ubiquitination, including protein stability, subcellular localization, and functional activation [3]. DUBs are categorized into six major families based on their sequence and domain conservation:

- USPs (Ubiquitin-Specific Proteases): The largest family, characterized by broad substrate specificity and diverse cellular functions [3].

- OTUs (Ovarian Tumor Proteases): Known for linkage specificity toward particular ubiquitin chain types [3].

- UCHs (Ubiquitin C-Terminal Hydrolases): Primarily involved in processing ubiquitin precursors and recycling ubiquitin [3].

- MJDs (Machado-Josephin Domain-containing Proteases): Characterized by a catalytic Josephin domain [3].

- MINDYs (Motif-Interacting with Ubiquitin-containing Novel DUB Family): Preferentially cleave lysine-48-linked polyubiquitin chains [3].

- JAMMs (JAB1, MPN, MOV34 Family): Metalloproteases that require zinc for catalytic activity [3].

DUBs perform three primary biological functions: (1) maintaining cellular free ubiquitin levels by processing ubiquitin precursors and recycling ubiquitin from degraded proteins; (2) rescuing substrate proteins from degradation by removing ubiquitin chains before proteasomal recognition; and (3) editing ubiquitin chains to alter signaling outcomes [2]. The balance between ubiquitinating enzymes and DUBs determines the fate, activity, and localization of key regulatory proteins in cancer and other diseases [3].

Table 2: Major DUB Families and Their Characteristics

| DUB Family | Catalytic Type | Key Features | Representative Members |

|---|---|---|---|

| USPs | Cysteine protease | Largest family; diverse functions and substrates | USP9X, USP22, USP34 [3] |

| OTUs | Cysteine protease | Often exhibit linkage specificity | OTUD1 [3] |

| UCHs | Cysteine protease | Process ubiquitin precursors; recycle ubiquitin | BAP1 [3] |

| MJDs | Cysteine protease | Characterized by Josephin domain | Ataxin-3 [3] |

| MINDYs | Cysteine protease | Preferentially cleave K48-linked chains | MINDY1, MINDY2 [3] |

| JAMMs | Zinc metalloprotease | Metal-dependent catalysis | POH1, BRCC36 [3] |

UPS and DUBs in Cancer: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications

Dysregulation of the UPS is increasingly recognized as a hallmark of cancer, contributing to tumor initiation, progression, and therapeutic resistance [1]. In multiple myeloma (MM), excessive proteasomal activity is a significant factor in pathogenesis, making proteasome inhibitors like bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib first-line therapeutic agents [1]. The UPS influences cancer through multiple mechanisms, including regulation of cell cycle controllers, transcription factors, and apoptosis regulators [1].

DUBs have emerged as critical players in oncogenesis, functioning as either tumor promoters or suppressors depending on cellular context [3]. For instance, USP9X demonstrates context-dependent roles in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC)—promoting tumor cell survival in human pancreatic tumor cells while acting as a suppressor in mouse models [3]. USP28 promotes cell cycle progression and inhibits apoptosis in PDAC cells by stabilizing FOXM1 to activate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [3]. USP22, identified as a cancer stem cell marker, promotes PDAC cell proliferation by increasing DYRK1A levels [3].

The UPS also plays a crucial role in tumor immune evasion by regulating immune checkpoint proteins such as PD-1/PD-L1 [2]. The E3 ubiquitin ligase SPOP can promote ubiquitination and degradation of PD-L1 in colorectal cancer cells, while competitive binding by ALDH2 or BCLAF1 can inhibit this process, thereby stabilizing PD-L1 and facilitating immune evasion [2]. Small-molecule SGLT2 inhibitors like canagliflozin can disrupt these interactions, promoting SPOP-mediated PD-L1 degradation and enhancing T-cell antitumor activity [2].

DUBs contribute significantly to chemoresistance across various cancers by stabilizing oncogenic proteins, regulating DNA damage repair, and inhibiting apoptosis [4]. In breast cancer, USP22 contributes to chemoresistance, stemness, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition by regulating the Warburg effect through c-Myc deubiquitination [4]. In non-small cell lung cancer, USP35 mediates cisplatin-induced apoptosis by stabilizing BIRC3 [4]. These findings highlight DUBs as promising therapeutic targets to overcome treatment resistance.

Diagram 2: DUB-mediated mechanisms in cancer progression.

Experimental Protocols

In Vitro Ubiquitin Conjugation Assay

The in vitro ubiquitination assay is a fundamental technique for investigating ubiquitination events, enabling researchers to determine if a protein of interest can be ubiquitinated, identify the type of ubiquitination (mono-, poly-, or multi-mono-ubiquitination), characterize chain linkage specificity, and identify the required E2 and E3 enzymes [5].

Table 3: Reaction Components for In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

| Component | Stock Concentration | Volume for 25 µL Reaction | Final Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10X E3 Ligase Reaction Buffer | 10X (500 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM TCEP) | 2.5 µL | 1X (50 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP) |

| Ubiquitin | 1.17 mM (10 mg/mL) | 1 µL | ~100 µM |

| MgATP Solution | 100 mM | 2.5 µL | 10 mM |

| Substrate Protein | Variable (user-specific) | X µL | 5-10 µM |

| E1 Enzyme | 5 µM | 0.5 µL | 100 nM |

| E2 Enzyme | 25 µM | 1 µL | 1 µM |

| E3 Ligase | 10 µM | X µL | 1 µM |

| dH₂O | N/A | Variable (to 25 µL total) | N/A |

Procedure:

- Combine all components in a microcentrifuge tube in the order listed in Table 3.

- For a negative control, replace the MgATP Solution with an equivalent volume of dH₂O.

- Incubate in a 37°C water bath for 30-60 minutes.

- Terminate the reaction by either:

- Adding 25 µL of 2X SDS-PAGE sample buffer (if not for downstream applications)

- Adding 0.5 µL of 500 mM EDTA or 1 µL of 1 M DTT (for downstream enzymatic applications)

- Analyze reaction products by SDS-PAGE and Western blot [5].

Analysis:

- Coomassie Staining: Visualizes all protein species; ubiquitination products typically appear as a smear or ladder of bands above the substrate.

- Western Blot with Anti-Ubiquitin Antibody: Confirms the presence of ubiquitin in modified proteins.

- Western Blot with Anti-Substrate Antibody: Verifies that the substrate of interest is ubiquitinated.

- Western Blot with Anti-E3 Ligase Antibody: Distinguishes substrate ubiquitination from E3 autoubiquitination [5].

Ubi-Tagging for Site-Specific Protein Conjugation

Ubi-tagging is a novel modular technique for site-specific protein conjugation that exploits the natural ubiquitination machinery. This method enables efficient generation of homogeneous multimeric conjugation products within 30 minutes, addressing limitations of traditional conjugation strategies such as heterogeneity and long reaction times [6].

The ubi-tagging system requires three key determinants: (1) ubiquitination enzymes specific for the desired lysine linkage type; (2) a donor ubi-tag having a free C-terminal glycine with the conjugating enzyme-specific lysine mutated to arginine to prevent homodimer formation; and (3) an acceptor ubi-tag carrying the corresponding conjugation lysine residue with an unreactive C terminus [6].

Procedure for Generating Fluorescently Labeled Fab' Fragments:

- Prepare the conjugation reaction containing:

- 10 µM Fab-Ub(K48R)don

- 50 µM Rhodamine-Ubacc-ΔGG

- 0.25 µM E1 enzyme

- 20 µM K48-specific E2-E3 fusion protein (gp78RING-Ube2g2)

- Reaction buffer

- Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes.

- Purify the conjugated product (Rho-Ub2-Fab) using protein G affinity purification.

- Verify conjugation efficiency and product identity by SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry [6].

This technology enables various applications including bispecific T-cell engagers and nanobody-antigen conjugates with superior efficiency compared to traditional methods like sortase-mediated tagging, particularly for hydrophobic, poorly soluble peptides [6].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for UPS and DUB Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Example | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies | Anti-Ubiquitin (linkage-specific K27) [EPR17034] [7] | WB, IHC-P, ICC/IF, Flow Cyt (Intra) | Rabbit recombinant monoclonal; specific for K27-linked ubiquitin chains |

| General Ubiquitin Antibodies | Ubiquitin Polyclonal Antibody (10201-2-AP) [8] | WB, IHC, IF/ICC, FC (Intra), CoIP, ELISA | Rabbit polyclonal; reacts with human, mouse, rat; detects ubiquitin monomers and conjugates |

| Recombinant Enzymes | E1, E2, E3 enzymes [5] | In vitro ubiquitination assays | Essential components for reconstituting ubiquitination cascade |

| Ubiquitin Variants | K48R mutant, ΔGG mutant [6] | Ubi-tagging conjugation | Engineered ubiquitin for controlled conjugation |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib [1] | Functional UPS studies | FDA-approved for multiple myeloma; research tools |

| DUB Inhibitors | Small-molecule DUB inhibitors [4] | Mechanistic and therapeutic studies | Emerging class targeting specific DUB families |

Concluding Remarks

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System and Deubiquitinating Enzymes represent sophisticated regulatory networks essential for cellular homeostasis, with profound implications for cancer biology and therapy. The development of targeted inhibitors against specific UPS components and DUBs holds significant promise for advancing cancer treatment, particularly in combination with existing modalities like chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Continued research into the intricate mechanisms of ubiquitination and deubiquitination will undoubtedly yield novel insights and therapeutic strategies for cancer and other diseases characterized by proteostasis imbalance.

Ubiquitin-Specific Proteases (USPs) as Key Regulators in Cancer Signaling Pathways

Ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs) represent the largest subfamily of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), functioning as critical regulators of protein stability and function through their ability to remove ubiquitin moieties from target proteins. This post-translational modification directly influences protein degradation, localization, and activity, thereby controlling essential cellular processes. In cancer biology, USPs have emerged as pivotal players in tumor initiation, progression, and therapeutic resistance through their regulation of key oncogenic and tumor-suppressive pathways. The context-dependent expression and activity of various USPs across cancer types highlight their significance as potential diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets in oncology.

Recent advances in cancer research have illuminated the complex regulatory networks governed by USP family members, revealing their profound impact on critical cancer hallmarks including sustained proliferation, evasion of growth suppressors, resistance to cell death, and activation of metastasis. The development of targeted therapies against specific USPs represents a promising frontier in precision oncology, with numerous investigational compounds currently under preclinical and clinical evaluation.

USP Family Members and Their Cancer-Related Functions

Key USP Family Members in Oncogenesis

USP7 (HAUSP) has emerged as a critical regulator in multiple cancer types, including breast, ovarian, prostate, cervical, and colorectal cancers [9]. USP7 demonstrates a dual role in oncogenesis through its regulation of the p53-MDM2 axis. By deubiquitinating and stabilizing MDM2, the primary negative regulator of p53, USP7 indirectly suppresses p53-mediated tumor suppression [9]. This mechanism enables cancer cells to bypass critical cell cycle checkpoints and apoptosis mechanisms. USP7 also stabilizes other oncogenic proteins like HIF-1α, further promoting tumor progression and therapy resistance. The enzyme's overexpression has been particularly implicated in cancers with aberrant RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signaling, highlighting its importance in these aggressive tumor subtypes [9].

USP21 demonstrates significant oncogenic potential across multiple cancer types. Research has established that USP21 promotes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) growth by activating mTOR signaling through binding to MAPK3 and inducing micropinocytosis to support amino acid sustainability [3]. Additionally, USP21 maintains cancer stem cell properties in PDAC by stabilizing TCF7, a key transcription factor in the Wnt pathway [3]. In orthotopic pancreatic transplantation models, USP21 expression drives pathological progression from pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) to fully developed PDAC, underscoring its role in tumor initiation [3]. Beyond pancreatic cancer, USP21 overexpression is observed in hepatocellular carcinoma and non-small cell lung cancer, where it stabilizes oncoproteins like NF-κB and β-catenin to drive tumor proliferation and metastasis [10].

USP38 exhibits context-dependent roles in cancer progression, functioning as either an oncogene or tumor suppressor depending on the tissue type [11]. In lung adenocarcinoma, gastric cancer, and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, USP38 is significantly overexpressed, with high expression levels correlating with lymph node metastasis, advanced TNM staging, and poor prognosis [11]. Mechanistically, USP38 regulates the stability of key proteins including HDAC1/3, LSD1, KLF5, METTL14, c-Myc, and HIF-1α, thereby influencing critical signaling pathways such as JAK2/STAT3 [11]. Conversely, in colorectal cancer and clear cell renal carcinoma, USP38 expression is significantly reduced and appears to function as a tumor suppressor [11], highlighting the tissue-specific nature of USP regulation.

USP28 promotes cell cycle progression and inhibits apoptosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by stabilizing FOXM1, a key proliferation-associated transcription factor, thereby activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [3]. Similarly, USP5 accelerates PDAC tumor growth by prolonging the half-life of FOXM1 and regulates DNA damage response, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis to promote tumor formation [3].

USP9X demonstrates particularly complex, context-dependent functions in pancreatic cancer. In human pancreatic tumor cells, USP9X promotes tumor cell survival and malignant phenotypes, while in KPC (KrasLSL-G12D/+; Trp53LSL-R172H/+; Pdx1-Cre) mouse models, it acts as a tumor suppressor [3]. As a suppressor, USP9X regulates the Hippo pathway through cooperation with LATS kinase and YAP/TAZ to impede PDAC growth [3]. Sleeping Beauty transposon-mediated insertional mutagenesis screens revealed that USP9X has the highest mutation frequency in PDAC, observed in at least 50% of tumors [3].

Table 1: USP Family Members and Their Roles in Cancer

| USP Member | Cancer Types Involved | Key Substrates | Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| USP7 | Colorectal, Breast, Ovarian, Prostate, Cervical | MDM2, HIF-1α, p53 | Regulates p53-MDM2 axis, stabilizes oncoproteins, promotes therapy resistance |

| USP21 | Pancreatic, Hepatocellular, Non-small cell lung | β-catenin, TCF7, MAPK3 | Promotes cancer stemness, activates mTOR signaling, enhances micropinocytosis |

| USP38 | Lung adenocarcinoma, Gastric, Esophageal, Colorectal | HDAC1/3, LSD1, KLF5, c-Myc | Context-dependent oncogene/tumor suppressor, regulates JAK2/STAT3 pathway |

| USP28 | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | FOXM1 | Activates Wnt/β-catenin pathway, promotes cell cycle progression |

| USP5 | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | FOXM1 | Regulates DNA damage response, promotes tumor growth |

| USP9X | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | LATS kinase, YAP/TAZ | Context-dependent roles, regulates Hippo pathway |

| USP22 | Pancreatic, Breast | PTEN, DYRK1A | Cancer stem cell marker, regulates PTEN-MDM2-p53 signaling |

| USP33 | Pancreatic, Hepatocellular, Lung | Various metastasis regulators | Influences malignant phenotype and metastatic progression |

| USP34 | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | AKT, PKC pathways | Facilitates cancer cell survival through AKT and PKC signaling |

USP Regulation of Key Signaling Pathways in Cancer

USPs regulate multiple critical signaling pathways that drive cancer progression. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is frequently modulated by USPs including USP28, USP21, and USP5, which stabilize key components such as TCF7 and FOXM1 to promote tumor proliferation and stemness [3]. The p53 pathway is primarily regulated through USP7-mediated stabilization of MDM2, leading to subsequent p53 degradation and impaired tumor suppression [9]. The mTOR signaling pathway is activated by USP21 through MAPK3 stabilization, enhancing nutrient acquisition and metabolic adaptation in pancreatic cancer [3] [10]. Additionally, the JAK2/STAT3 pathway is influenced by USP38 through stabilization of various transcription factors and epigenetic regulators [11].

Table 2: USP-Regulated Signaling Pathways in Cancer

| Signaling Pathway | Regulating USPs | Molecular Mechanisms | Cancer Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wnt/β-catenin | USP28, USP21, USP5 | Stabilization of TCF7, FOXM1 | Enhanced proliferation, stemness, cell cycle progression |

| p53 Tumor Suppressor | USP7 | Stabilization of MDM2, leading to p53 degradation | Evasion of apoptosis, genomic instability, chemoresistance |

| mTOR Signaling | USP21 | Stabilization of MAPK3, induction of micropinocytosis | Metabolic reprogramming, nutrient acquisition, growth |

| JAK2/STAT3 | USP38 | Regulation of HDAC1/3, LSD1, KLF5, c-Myc | Proliferation, survival, inflammation, immune evasion |

| Hippo Pathway | USP9X | Regulation of LATS kinase and YAP/TAZ | Context-dependent tumor promotion or suppression |

| PI3K/Akt | USP34 | Activation of AKT and PKC pathways | Cell survival, growth, metabolism |

| PD-1/PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint | Various USPs | Regulation of PD-L1 stability through ubiquitin machinery | Immune evasion, immunotherapy resistance |

Experimental Protocols for USP Research

Immunohistochemistry Protocols for USP Detection

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) provides a powerful technique for detecting USP expression and localization in tissue samples, offering insights into their potential as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in cancer.

Sample Preparation: For frozen tissue sections, dissect tissue of interest (<10 mm) and place in a pre-labeled tissue mold. Cover the tissue sample in cryo-embedding media (OCT) and freeze the tissue block by slowly submerging in liquid nitrogen or placing on dry ice. Store frozen tissue blocks at -80°C until sectioning. Section the tissue block into 6-15 μm thick sections using a cryostat set at -20°C and transfer sections onto positively charged glass slides. Fix sections in ice-cold acetone for 10 minutes, then wash slides in PBS twice for 5 minutes each [12].

For formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections, following tissue fixation, rinse the tissue in PBS and dehydrate through a series of ethanol solutions (50%, 70%, 80%, 95%, 100%) for 30 minutes each. Clear tissue in three changes of xylene for 20 minutes each, then infiltrate with paraffin through three changes of 60°C paraffin for 1 hour each. Embed in paraffin blocks, section into 5-15 μm slices, and transfer to silanized or gel-coated slides. For immunostaining, deparaffinize slides in xylene and rehydrate through a descending ethanol series [12].

Antigen Retrieval: For heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER), boil slides in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0), 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), or 10 mM Tris/1 mM EDTA (pH 9.0) for 15-20 minutes at approximately 98°C using a pressure cooker, microwave, or steamer. Cool slides completely before proceeding with immunostaining. For protease-induced epitope retrieval (PIER), incubate sections with protease solution (e.g., 0.05% trypsin in 0.1% calcium chloride or 0.5% pepsin in 10mM HCl) at 37°C for 10 minutes in a humidity chamber [12].

Antibody Staining and Detection: For fluorescence-based detection, block non-specific binding by incubating with blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature. Incubate tissue sections with primary antibody diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Wash sections three times with wash buffer (TBS or PBS plus 0.025% Triton X-100), then incubate with fluorescently conjugated secondary antibody (typically 1:500-1:1000 dilution) for 1-2 hours at room temperature. After washing, counterstain with DAPI (0.5 μg/mL) for 5 minutes, then mount with anti-fade mounting medium [12].

For chromogenic detection, after primary antibody incubation and washing, incubate samples with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in TBS for 15 minutes to block endogenous peroxidase activity. Incubate with biotinylated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature, then with ABC reagent for 30 minutes. Develop with DAB substrate for approximately 10 minutes, counterstain with hematoxylin, and mount with appropriate mounting medium [12].

Computational Approaches for USP Inhibitor Discovery

Virtual Screening and QSAR Modeling: Robust quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models can be developed using curated USP inhibitors, molecular fingerprint descriptors, and random forest algorithms. For USP7 inhibitor identification, models have been developed using 837 curated inhibitors, achieving high predictive accuracy (R² = 0.96 ± 0.01, Q² = 0.92 ± 0.02) [9]. Virtual screening identifies high-potential compounds from natural product and chemical databases including NPASS, TCM, and ZINC [9] [10].

Molecular Docking and Dynamics: Molecular docking studies assess binding interactions between potential inhibitors and USPs. For USP7, the catalytic domain (PDB ID: 5UQV) serves as the target structure, with docking validation achieved by redocking the co-crystallized ligand GNE6640 (RMSD = 0.330 Å) [9]. Top hits are evaluated via molecular docking, revealing strong interactions with key residues including Asp163, His217, Arg115, and Gln111 in USP7 [9]. Molecular dynamics simulations (200-500 ns) demonstrate compound stability and binding interactions over time [9] [10]. For USP21 inhibitors, molecular dynamics simulations for 500 ns analyze conformational flexibility and stability of USP21-phytoconstituent complexes [10].

ADMET Profiling: Compounds with promising binding affinities undergo ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) prediction using computational tools to assess drug-likeness. PAINS (pan-assay interference compounds) analysis removes compounds prone to non-specific binding, ensuring selectivity for the target USP [10].

Visualization of USP Signaling Networks

USP Regulation of Cancer Signaling Pathways

Therapeutic Applications and Research Tools

USP-Targeted Therapeutic Strategies

The development of USP inhibitors represents a promising therapeutic strategy in oncology, with several approaches showing significant preclinical potential. For USP7, integrative computational approaches have identified promising inhibitor candidates including NPC472846, TCM11676, TCM36723, ZINC18193314, and ZINC65536649, which demonstrate strong binding interactions and high stability in molecular dynamics simulations [9]. Molecular dynamics simulations (200 ns) revealed that TCM36723 and ZINC65536649 exhibit the highest dynamic stability, while NPC472846 induces well-maintained conformational states [9]. MM-GBSA free energy calculations identified NPC472846 as the top binder (-45.7 kcal/mol), followed by ZINC65536649 (-40.4 kcal/mol) and TCM11676 (-39.9 kcal/mol), all outperforming the reference ligand GNE6640 (-31.6 kcal/mol) [9].

For USP21, bioactive phytoconstituents have emerged as promising inhibitor candidates. Virtual screening of the IMPPAT 2.0 database of Indian medicinal plants identified Ranmogenin A and Tokorogenin as potential USP21 inhibitors [10]. These compounds form stable protein-ligand complexes with USP21 throughout 500 ns molecular dynamics simulations and exhibit favorable pharmacokinetic properties with moderate predicted anticancer activity based on PASS analysis [10].

Combination therapies represent another promising approach, particularly for overcoming resistance to existing treatments. For instance, targeting the ubiquitin machinery in combination with PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors may enhance therapeutic efficacy by modulating PD-L1 expression levels [13]. Similarly, USP inhibition may sensitize cancer cells to conventional chemotherapy and targeted therapies by disrupting protective mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for USP Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | Anti-USP7, Anti-USP21, Anti-USP38 | Immunohistochemistry, Western blotting, Immunoprecipitation | Validation of specificity using knockout controls is essential |

| Cell Lines | Cancer cell lines with USP overexpression/knockdown | Functional assays, Drug screening | Include multiple cell lines representing different cancer types |

| Chemical Inhibitors | USP7 inhibitors (e.g., GNE6640), Natural product derivatives | Mechanism studies, Combination therapy screening | Monitor selectivity and potential off-target effects |

| Expression Vectors | USP overexpression constructs, CRISPR-Cas9 systems | Gain/loss-of-function studies, Structural studies | Use inducible systems for studying essential USPs |

| Computational Tools | Molecular docking software, QSAR models, MD simulation platforms | Virtual screening, Binding mode analysis, Dynamics studies | Validate computational predictions with experimental data |

| Animal Models | Xenograft models, Genetically engineered mouse models | Preclinical efficacy evaluation, Toxicity assessment | Consider species differences in USP expression and function |

Ubiquitin-specific proteases represent master regulators of cancer signaling pathways, with individual USPs demonstrating specialized functions in specific cancer types and contexts. The complex regulatory networks governed by USPs highlight their significance as potential diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets in oncology. Future research directions should focus on elucidating the context-dependent functions of USPs, developing highly selective inhibitors with favorable pharmacological properties, and exploring combination therapies that leverage USP inhibition to enhance existing treatment modalities. As our understanding of USP biology continues to expand, these enzymes will undoubtedly remain at the forefront of cancer research and therapeutic development.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a critical regulator of cellular protein homeostasis, and its dysregulation is a hallmark of cancer. Ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), the largest subfamily of deubiquitinating enzymes, play multifaceted roles in tumorigenesis and cancer progression by stabilizing oncoproteins or tumor suppressors. This application note synthesizes recent evidence on the roles of specific USPs in gastric, breast, and biliary tract cancers, highlighting their clinical relevance, molecular mechanisms, and potential as therapeutic targets. We provide detailed experimental protocols for investigating USP functions and a curated list of essential research reagents to facilitate cancer research and drug development in this emerging field.

Protein ubiquitination is a reversible post-translational modification that regulates virtually all cellular processes, including cell cycle progression, DNA damage repair, and apoptosis [14]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) maintains protein homeostasis through a coordinated enzymatic cascade involving E1 activating, E2 conjugating, and E3 ligase enzymes, which can be reversed by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) [15] [14]. Ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs) constitute the largest DUB subfamily and are increasingly recognized as critical regulators in cancer pathogenesis, functioning as either oncogenes or tumor suppressors depending on cellular context [15].

This application note examines the roles of specific USPs in three cancer types—gastric, breast, and biliary tract cancers—framed within the context of ubiquitination-specific antibodies and immunohistochemistry cancer research. We summarize quantitative clinical data, describe molecular mechanisms with visual pathway diagrams, and provide detailed experimental protocols to support research and therapeutic development in this rapidly advancing field.

USP Roles in Gastric Cancer

Gastric cancer (GC) remains a leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, underscoring the need for novel therapeutic targets [16] [17]. Multiple USPs have been identified as key players in GC progression, metastasis, and treatment response.

Oncogenic USPs in Gastric Cancer

Table 1: Oncogenic USPs in Gastric Cancer and Their Clinical Significance

| USP | Expression in GC | Clinical Correlation | Target/Pathway | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USP15 | Upregulated [16] | Positive correlation with tumor size, depth of invasion, lymph node involvement, TNM stage, perineural and vascular invasion; poor prognosis [16] | Wnt/β-catenin pathway [16] | Promotes cell proliferation, invasion, EMT, and tumor growth [16] |

| USP14 | Upregulated [17] | Associated with unfavorable prognosis; enriched at invasive tumor edge [17] | KPNA2/c-MYC nuclear translocation [17] | Promotes proliferation, migration, and invasion [17] |

| USP35 | Upregulated [18] | Associated with nodal metastasis, higher tumor grade, and poor prognosis; induced by H. pylori infection [18] | Snail1 deubiquitination and stabilization [18] | Promotes EMT, invasion, metastasis, and lung colonization [18] |

Tumor-Suppressive USP in Gastric Cancer

Table 2: Tumor-Suppressive USP in Gastric Cancer

| USP | Expression in GC | Clinical Correlation | Target/Pathway | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USP2 | Significantly reduced [19] | Low expression associated with genetic variations, neoantigen loads, MSI scores, and immune cell infiltration [19] | Focal adhesion and ECM receptor interaction pathways [19] | Suppresses proliferation, migration; enhances apoptosis; correlates with drug sensitivity [19] |

Diagram 1: USP Signaling Network in Gastric Cancer. This diagram illustrates the molecular mechanisms of oncogenic (yellow) and tumor-suppressive (green) USPs in gastric cancer, highlighting their subcellular localization and functional outcomes.

USP Roles in Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is the most prevalent malignancy in women worldwide, with USPs emerging as key regulators of its immune microenvironment and therapeutic response [20] [21].

USP-Mediated Regulation of Breast Cancer Progression

Table 3: Key USPs in Breast Cancer and Their Functions

| USP | Role in Breast Cancer | Molecular Mechanism | Therapeutic Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| USP36 | Oncogenic [21] | Deubiquitinates and stabilizes ERα; enhances estrogen signaling [21] | Promotes tamoxifen resistance; combined USP36 inhibition + tamoxifen potential therapy [21] |

| USP7 | Oncogenic [20] | Stabilizes Foxp3 in Tregs; enhances immunosuppressive function [20] | Contributes to immune evasion; potential target for immunotherapy [20] |

| USP1 | Regulatory [20] | Promotes proteasomal degradation of Foxp3 [20] | Modulates Treg differentiation and function [20] |

| USP12 | Regulatory [20] | Activates CD4+ T-cell responses [20] | Potential role in antitumor immunity [20] |

USP Roles in Biliary Tract Cancer

Biliary tract carcinoma (BTC) encompasses a group of highly heterogeneous malignancies with dismal five-year survival rates of less than 20% [15] [22]. USP dysregulation represents a key molecular event in BTC pathogenesis.

USP-Driven Mechanisms in Biliary Tract Cancer

Table 4: USP Functions in Biliary Tract Cancer

| USP | Expression in BTC | Molecular Target | Functional Role in BTC |

|---|---|---|---|

| USP1 | Upregulated [22] | PARP1 deubiquitination and stabilization [22] | Promotes growth and metastasis; regulated by GCN5-mediated acetylation [22] |

| Multiple USPs (USP1, USP3, USP7, USP8, USP9X, USP21, USP22) | Differential expression profiles [15] | Regulation of key oncoproteins (PTEN, c-Myc) and signaling pathways (Wnt/β-catenin, PI3K/AKT, MAPK) [15] | Promote proliferation, apoptosis evasion, invasion, and metastasis [15] |

Diagram 2: USP Mechanisms in Breast and Biliary Tract Cancers. This diagram illustrates cell-type-specific USP functions, highlighting their roles in therapeutic resistance and cancer progression.

Experimental Protocols for USP Research

Protocol: Immunohistochemical Analysis of USP Expression in Cancer Tissues

Purpose: To evaluate USP protein expression and localization in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) cancer tissues and correlate with clinicopathological characteristics.

Materials:

- FFPE tissue sections (4-5 μm thickness)

- Specific primary antibodies against USPs (e.g., anti-USP15, anti-USP14)

- Antigen retrieval solution (citrate buffer, pH 6.0)

- Hydrogen peroxide block

- Blocking serum

- Biotinylated secondary antibody

- Streptavidin-HRP conjugate

- DAB chromogen substrate

- Hematoxylin counterstain

Procedure:

- Deparaffinize sections in xylene and rehydrate through graded ethanol series.

- Perform antigen retrieval by heating slides in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 minutes.

- Block endogenous peroxidase activity with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes.

- Incubate with blocking serum for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Apply primary antibody diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C.

- Incubate with biotinylated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Apply streptavidin-HRP conjugate for 30 minutes.

- Develop with DAB chromogen for 5-10 minutes.

- Counterstain with hematoxylin, dehydrate, and mount.

Scoring Method: Evaluate staining based on intensity (0-3) and percentage of positive cells (0-100%). Multiply intensity × percentage to generate a final score [16] [19].

Protocol: Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) for USP-Substrate Interaction

Purpose: To validate physical interactions between USPs and their substrate proteins.

Materials:

- Cell lysates (RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors)

- Primary antibodies against target USP and substrate

- Protein A/G agarose beads

- Normal IgG control

- Western blotting equipment and reagents

Procedure:

- Pre-clear 500 μg protein lysate with 20 μL Protein A/G agarose and normal IgG for 2 hours at 4°C.

- Incubate pre-cleared lysate with specific antibody for 4 hours at 4°C.

- Add Protein A/G beads and incubate overnight at 4°C with gentle rotation.

- Wash beads 3-4 times with lysis buffer.

- Elute bound proteins by boiling in 2× SDS sample buffer.

- Analyze by Western blotting with appropriate antibodies [21] [22].

Protocol: Deubiquitination Assay

Purpose: To demonstrate USP-mediated removal of ubiquitin chains from substrate proteins.

Materials:

- Plasmid constructs for USP, substrate, and ubiquitin

- Proteasome inhibitor (MG132)

- Ubiquitin mutants (K48-only, K63-only, K0)

- Co-IP reagents

- Western blotting equipment

Procedure:

- Co-transfect cells with USP, substrate, and ubiquitin expression vectors.

- Treat cells with 10 μM MG132 for 6 hours before harvesting to prevent substrate degradation.

- Lyse cells and perform immunoprecipitation of the substrate.

- Analyze ubiquitination levels by Western blotting with anti-ubiquitin antibody.

- Compare ubiquitination levels in presence of wild-type USP versus catalytically inactive mutant [22] [18].

Protocol: Functional Assays for USP Role in Cancer

Cell Proliferation Assay:

- Seed GC cells (2,000 cells/well) in 96-well plates.

- Assess viability at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours using CCK-8 reagent.

- Measure absorbance at 450 nm [16] [19].

Migration and Invasion Assays:

- For migration: Seed 5 × 10^4 cells in serum-free medium into transwell upper chamber.

- For invasion: Coat membrane with Matrigel before seeding cells.

- Fill lower chamber with medium containing 10% FBS as chemoattractant.

- Incubate for 24-48 hours, then fix, stain, and count migrated/invaded cells [16] [17] [19].

In Vivo Tumorigenesis Assay:

- Subcutaneously inject 5 × 10^6 GC cells into nude mice.

- Measure tumor volume weekly using calipers.

- Harvest tumors after 4-6 weeks for weight measurement and IHC analysis [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Key Research Reagents for USP Investigation in Cancer

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| USP Inhibitors | IU1 (USP14 inhibitor) [17] | Functional validation of USP roles | Specific binding to activated USP14; inhibits catalytic activity |

| Small-molecule USP inhibitors and PROTACs [15] | Therapeutic development | Targeted degradation of specific USPs | |

| Antibodies | Anti-USP15 (#66310; Cell Signaling Technology) [16] | IHC, Western blot, IP | Validated for immunohistochemistry (1:100 dilution) |

| Antibodies for USPs, KPNA2, PARP1, Snail1, ERα [17] [21] [22] | Various applications | Target-specific detection in multiple techniques | |

| Expression Vectors | HA-tagged, Flag-tagged, Myc-tagged USP constructs [21] [22] [18] | Gain-of-function studies | Enable overexpression and tracking of USPs |

| Catalytically inactive mutants (e.g., USP15 C269S, USP36 C131A, USP35 C450A) [16] [21] [18] | Mechanism studies | Control for enzyme activity-dependent effects | |

| Ubiquitin Tools | HA-Ub, HA-K48, HA-K63, HA-K48R mutants [21] [18] | Ubiquitination assays | Determine linkage-specific deubiquitination |

| ΔGG ubiquitin mutant [14] | Negative controls | Cannot be conjugated to substrates | |

| Cell Lines | GC: HGC-27, SGC-7901, MKN-45 [16] [17] | In vitro models | Represent different GC subtypes |

| Breast cancer: MCF-7, T47D [21] | Hormone-responsive models | ER-positive breast cancer models | |

| BTC: HuCC-T1, HCCC-9810, RBE [22] | Cholangiocarcinoma models | For BTC-specific mechanisms |

USPs represent promising therapeutic targets and prognostic biomarkers in gastric, breast, and biliary tract cancers. The experimental protocols and research tools outlined in this application note provide a foundation for investigating USP functions in cancer pathogenesis and developing targeted therapies. Future research should focus on developing more specific USP inhibitors, understanding USP interactions within complex signaling networks, and exploring combination therapies that leverage USP modulation to overcome treatment resistance.

Ubiquitination is a critical post-translational modification that regulates protein degradation and function, playing a fundamental role in cellular homeostasis. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) has emerged as a significant player in cancer pathogenesis, with specific components serving as potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. Among these, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 C (UBE2C) has been extensively validated as a prognostic marker in multiple malignancies, particularly breast and gastric cancers. This application note synthesizes current research on UBE2C, providing structured experimental data, validated protocols, and molecular pathways to facilitate its application in cancer research and drug development.

UBE2C as a Prognostic Marker: Quantitative Evidence

Prognostic Significance in Breast Cancer

Table 1: UBE2C as a Prognostic Marker in Breast Cancer

| Cohort/Study | Sample Size | Detection Method | Key Prognostic Findings | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Node-positive BC [23] | 92 | IHC | Significant impact on MFS and OS | HR=6.79, P=0.002 (MFS); HR=7.14, P=0.009 (OS) |

| Validation Cohort [24] | 121 | IHC, RT-qPCR | High UBE2C = poor prognosis; Predictive model with TN staging & Ki-67 | AUC=0.870 (95% CI: 0.786-0.953) |

| METABRIC [25] | 1,980 | mRNA expression | Correlated with poor prognosis features | Association with LVI: P=0.002 |

| TCGA [25] | 854 | mRNA expression | Correlated with poor prognosis features | Association with LVI: P<0.001 |

| IHC Cohort [25] | 619 | IHC | Independent prognostic predictor | P=0.011, HR=1.45 (95% CI: 1.10-1.93) |

| Multicenter Study [26] | 209 | IHC | Positive expression in 70.8% of tumors; Correlated with aggressive features | Correlated with tumor size, grade, stage (all P<0.05) |

Prognostic Significance in Gastric Cancer

Table 2: UBE2C as a Prognostic Marker in Gastric Cancer

| Study | Sample Size | Cancer Type | Detection Method | Key Findings | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-center [27] | 1,759 | Intestinal-type GC | IHC | Overexpression predicts poor outcome | P<0.05 |

| Multi-center [27] | 6 cell lines | Intestinal-type GC | Copy Number Analysis | CNV gain in 4/5 intestinal-type lines | No CNV in diffuse-type lines |

| Functional Study [27] | In vitro/in vivo | Intestinal-type GC | Functional assays | Knockdown inhibits proliferation, migration, invasion | P<0.05 |

UBE2C in Cancer Biology: Molecular Mechanisms

UBE2C, also known as UBCH10, is a member of the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) family and plays a crucial role in the ubiquitin-proteasome system. It is encoded by the UBE2C gene located at chromosome 20q13.12 and consists of 179 amino acids with a molecular weight of approximately 20 kDa [28]. UBE2C interacts with the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) E3 ubiquitin ligase to regulate the degradation of key mitotic proteins, including securin and cyclin B, facilitating the metaphase-to-anaphase transition and mitotic exit [28].

In cancer, UBE2C overexpression leads to chromosomal instability, missegregation, and aneuploidy, promoting tumorigenesis and progression [28]. The enzyme's expression is tightly regulated throughout the cell cycle, accumulating during S and G2 phases and degrading after mitosis via auto-ubiquitination [28].

Diagram 1: UBE2C in Cell Cycle Regulation and Cancer Pathogenesis. This diagram illustrates the central role of UBE2C in regulating key cell cycle transitions through the targeted degradation of cyclins and securin, ultimately contributing to genomic instability and cancer progression when dysregulated.

Signaling Pathways Regulated by UBE2C

Breast Cancer Pathways

In breast cancer, UBE2C expression correlates with aggressive tumor behavior through multiple signaling pathways. High UBE2C expression is associated with activation of the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, promoting cell proliferation [28]. Additionally, UBE2C downregulates the tumor suppressor Numb, enhancing breast cancer malignancy [29]. The correlation between UBE2C and adhesion molecules (E-cadherin and N-cadherin) suggests its involvement in epithelial-mesenchymal transition, a key process in cancer metastasis [25].

Gastric Cancer Pathways

In intestinal-type gastric cancer, UBE2C overexpression activates the ERK signaling pathway, promoting cancer cell proliferation [27]. Inhibition of UBE2C results in G2/M cell cycle arrest and reduces levels of phosphorylated AURKA through the Wnt/β-catenin and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways, subsequently inhibiting gastric cancer development and progression [28].

Diagram 2: UBE2C-Activated Signaling Pathways in Breast and Gastric Cancers. This diagram summarizes the major signaling pathways regulated by UBE2C across different cancer types, highlighting the diverse mechanisms through which it promotes oncogenesis.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Immunohistochemistry Protocol for UBE2C Detection

Sample Preparation:

- Collect 3-4μm thick sections from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissues

- Mount on Superfrost Plus slides for better adhesion

- Deparaffinize in xylene and rehydrate through graded alcohol series

Antigen Retrieval:

- Use citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for UBE2C antigen retrieval

- Steam samples for 20-30 minutes before incubation

- Block endogenous peroxidase activity with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol

Antibody Incubation and Detection:

- Incubate with primary UBE2C antibody overnight at 4°C

- Recommended antibodies: Boston Biochem (dilution 1:500) [23] or Anti-UBE2C Mouse Monoclonal Antibody (1:100 dilution) [24]

- Use biotin-streptavidin-peroxidase detection system (Kit ChemMate, Dako)

- Visualize with 3,3'-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB)

- Counterstain with haematoxylin

Scoring and Evaluation:

- Evaluate staining intensity (0-3) and percentage of positive cells (0-100%)

- Calculate H-score: (staining intensity × percentage of positive cells)

- For categorical assessment, use cut-off of 11% positive cells [23]

- Have two pathologists independently evaluate samples in a double-blind manner

RNA Expression Analysis Protocol

RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription:

- Extract total RNA using Trizol reagent

- Reverse transcribe to cDNA using First-strand cDNA Synthesis Kit

- Use human GAPDH gene as internal control

qPCR Analysis:

- Prepare reaction mixture with SYBR Green QPCR Master Mix

- Use primers: UBE2C-forward: AGTGGCTACCCTTACAATGCG; UBE2C-reverse: TTACCCTGGGTGTCCACGTT [29]

- Amplification conditions: denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, 40 cycles of 94°C for 30s, 58°C for 30s, and 72°C for 30s

- Analyze relative expression using the 2−ΔΔCt method

Functional Validation Assays

Cell Culture and Transfection:

- Culture cancer cells in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum

- Transfect with siRNAs or eukaryotic expression vectors using Lipofectamine 2000

- Harvest cells 3-5 days post-transfection for analysis

Proliferation and Invasion Assays:

- Perform growth assays using cell counting or MTT assay

- Conduct colony formation assays to assess clonogenic potential

- Use Transwell assays with Matrigel to evaluate invasive capability

- Analyze cell cycle distribution by flow cytometry

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for UBE2C Studies

| Reagent Type | Specific Product | Application | Key Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies | Rabbit anti-human UBE2C monoclonal antibody (Abnova) | IHC | Validated for FFPE tissues; 1:100 dilution | [26] |

| Primary Antibodies | Mouse anti-human UBE2C monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz, SC-100611) | IHC | Suitable for intestinal-type gastric cancer; 1:50 dilution | [27] |

| Primary Antibodies | UBE2C Polyclonal antibody (PTGlab, 12134-2-AP) | WB, IHC, IP, ELISA | Reacts with human, mouse, rat; 1:50-1:500 for IHC | [30] |

| Primary Antibodies | UBE2C (WHO0011065M1, Sigma-Aldrich) | IHC, WB | Validated in SKBR3 cells; single band at ~20 KDa | [25] |

| Detection Systems | Novolink Max Polymer Detection kit | IHC | Enhanced sensitivity for low-abundance targets | [25] |

| Detection Systems | Kit ChemMate (Dako) | IHC | Biotin-streptavidin-peroxidase system | [23] |

| RNA Analysis Kits | First-strand cDNA Synthesis Kit | RT-qPCR | High-efficiency reverse transcription | [24] |

| Transfection Reagents | Lipofectamine 2000 | Functional studies | High efficiency for siRNA delivery | [27] |

UBE2C has been extensively validated as a robust prognostic marker in both breast and gastric cancers, with strong associations with aggressive tumor behavior, metastasis, and poor survival outcomes. The structured protocols and reagents outlined in this application note provide researchers with standardized methodologies for investigating UBE2C in cancer pathology. Furthermore, UBE2C's central role in critical cancer signaling pathways positions it as a promising therapeutic target, warranting further investigation into targeted therapies that modulate its activity in ubiquitination-dependent oncogenesis.

Within the broader context of ubiquitination-specific antibodies and immunohistochemistry in cancer research, the Ubiquitin-Specific Protease (USP) family of deubiquitinating enzymes has emerged as a critical regulator of oncogenic processes. USPs catalyze the removal of ubiquitin moieties from target proteins, thereby modulating their stability, localization, and function [15]. The delicate balance between ubiquitination and deubiquitination is essential for cellular homeostasis, and its disruption can lead to tumorigenesis [31]. This application note provides a detailed framework for analyzing the correlation between USP expression, tumor grade, and patient survival outcomes using data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). By integrating bioinformatic analyses with experimental validation protocols, this resource enables researchers to identify and characterize USP family members as potential prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets across human malignancies.

Results and Data Analysis

USP Expression Patterns Across Human Cancers

Table 1: USP Family Member Expression and Prognostic Significance in Human Cancers

| USP Member | Cancer Type(s) | Expression Pattern | Correlation with Survival | Key Substrates/Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USP35 [32] | Kidney clear cell carcinoma (KIRC) | Significant overexpression in tumor tissues | Poor overall survival | Glycerophospholipid metabolism, immune modulation |

| USP5 [33] | Pan-cancer (multiple types) | Overexpressed in most cancers | Poor prognosis in multiple cancers | Spliceosome, RNA splicing |

| USP13 [34] | High-grade serous ovarian cancer | Highly amplified and overexpressed | Decreased overall and progression-free survival | PI3K/AKT pathway, metastasis |

| USP45 [35] | Pan-cancer (multiple types) | Upregulated in most tumors | Poor overall and recurrence-free survival | Immune checkpoint regulation |

| USP7 [36] | HER2+ breast cancer | Highly expressed | Poor prognosis | HER2 stabilization |

| USP6, USP41 [37] | Osteosarcoma | Overexpressed in tumor cells | Correlated with patient survival | Cell viability, apoptosis regulation |

Analysis of TCGA data reveals that numerous USP family members demonstrate significant overexpression in various cancer types compared to normal tissues. For instance, USP35 shows marked overexpression in kidney clear cell carcinoma (KIRC) tumor tissues, with its high expression correlating with advanced disease stages and poor survival outcomes [32]. Similarly, USP5 exhibits pan-cancer overexpression across multiple cancer types including breast invasive carcinoma, colon adenocarcinoma, and lung adenocarcinoma, with generally poor prognosis associated with its high expression [33]. The genomic amplification of USP13 occurs in approximately 19.5% of ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma cases, with its high mRNA expression significantly associated with decreases in overall survival, progression-free survival, and post-progression survival [34].

Correlation with Tumor Grade and Stage

Table 2: Association Between USP Expression and Clinicopathological Parameters

| USP Member | Cancer Type | Correlation with Tumor Grade/Stage | Other Clinical Correlations |

|---|---|---|---|

| USP35 [32] | KIRC | Correlated with advanced disease stages | Modulated immune cell recruitment |

| USP13 [34] | Ovarian cancer | Increased expression in advanced tumors | Correlation with peritoneal metastasis |

| USP5 [33] | Pan-cancer | Correlated with pathological stage in multiple cancers | Associated with molecular subtypes |

| USP45 [35] | Pan-cancer | Not specified | Correlated with tumor stemness features |

The relationship between USP expression and tumor progression extends to specific correlations with advanced disease stages and aggressive clinicopathological features. In kidney clear cell carcinoma, high USP35 expression correlates with advanced disease stages, suggesting its potential role in disease progression [32]. Similarly, USP13 mRNA expression increases in advanced ovarian tumors and correlates with tumor grade, indicating its involvement in disease aggressiveness [34]. Pan-cancer analysis of USP5 demonstrates correlations with pathological stages across various cancer types, reinforcing the connection between USP expression and tumor progression [33].

Experimental Protocols

TCGA Data Access and Processing Protocol

Protocol 3.1: Accessing and Processing TCGA Data for USP Expression Analysis

- Objective: To systematically access, download, and process TCGA data for analysis of USP family gene expression.

Materials and Equipment:

- GDC Data Portal (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/)

- R software environment (version 4.1.0 or later)

- UCSC Xena browser (https://xena.ucsc.edu/)

- cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org/)

Procedure:

- Data Access:

- Navigate to the GDC Data Portal and select "Cohort Builder" or "Projects" to identify relevant cancer types.

- Apply filters for "Programs" → "TCGA" and select specific projects (e.g., TCGA-BRCA for breast cancer).

- Save the selection as a new cohort for subsequent analysis [38].

- File Selection and Download:

- Navigate to the "Repository" and apply filters to select RNA-Seq data and gene quantification files.

- For USP expression analysis, select "Transcriptome Profiling" → "Gene Expression Quantification" → "RNA-Seq" data.

- Add selected files to the cart and download using the GDC Data Transfer Tool for large datasets [38].

- Data Processing:

- For RNA sequencing data, use transcripts per million (TPM) values for gene expression normalization.

- Process clinical data to extract relevant parameters including tumor stage, grade, and survival outcomes.

- Perform differential expression analysis between tumor and normal tissues using the DESeq2 package in R [32].

- Quality Control:

- Verify data integrity using MD5 checksums provided in the manifest file.

- Assess sample quality and remove outliers based on clinical metadata.

- Data Access:

Troubleshooting Tips:

Survival and Correlation Analysis Protocol

Protocol 3.2: Survival Analysis and Clinical Correlation for USP Genes

- Objective: To evaluate the prognostic significance of USP expression and its correlation with clinicopathological parameters.

Materials and Equipment:

- R software with packages: survival, survminer, ggplot2

- TCGA clinical data files

- Processed USP expression matrix

Procedure:

- Data Integration:

- Survival Analysis:

- Perform Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for overall survival (OS), disease-specific survival (DSS), and progression-free interval (PFI).

- Use log-rank test to assess statistical significance between survival curves.

- Generate hazard ratios and confidence intervals using univariate Cox proportional hazards models [33].

- Clinical Correlation:

- Analyze association between USP expression levels and tumor stage/grade using appropriate statistical tests (Kruskal-Wallis test for multi-group comparisons, Wilcoxon test for two-group comparisons).

- Conduct multivariate analysis to adjust for potential confounding factors such as age, gender, and other clinical variables.

- Visualization:

- Create publication-quality Kaplan-Meier plots using the survminer package in R.

- Generate boxplots or violin plots to visualize USP expression across different tumor stages.

Expected Outcomes:

- Identification of USP family members with significant correlation to patient survival.

- Determination of association between USP expression and tumor progression metrics.

Experimental Validation Protocol

Protocol 3.3: Experimental Validation of USP Role in Cancer Progression

- Objective: To functionally validate the oncogenic role of USPs identified through bioinformatic analysis.

Materials and Equipment:

- Human cancer cell lines (e.g., 786-O and ACHN for renal cancer [32])

- Lentiviral vectors carrying shRNAs targeting USP of interest

- Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent

- Cell culture equipment and reagents

- Quantitative RT-PCR system

- Materials for functional assays: CCK-8 kit, Transwell chambers, crystal violet staining solution

Procedure:

- USP Knockdown:

- Transfect cancer cell lines with lentiviral vectors carrying specific shRNAs targeting the USP of interest (e.g., shUSP35-1, shUSP35-2, shUSP35-3) [32].

- Include a non-targeting control (shNC) for comparison.

- Select stable cell lines using 2 µg/mL puromycin.

- Confirm knockdown efficiency via quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) [32].

- Functional Assays:

- Cell Proliferation: Perform CCK-8 assay by seeding transfected cells in 96-well plates and measuring absorbance at 450nm at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours [32].

- Colony Formation: Seed transfected cells in 6-well plates (500 cells/well), culture for 14 days, fix with 4% paraformaldehyde, stain with crystal violet, and count colonies [32].

- Cell Migration:

- Wound Healing Assay: Create a linear scratch in confluent cell monolayers and monitor wound closure at 0, 24, and 48 hours.

- Transwell Migration Assay: Seed cells in serum-free medium in upper chambers and assess migration toward complete medium in lower chambers after 24-48 hours [32].

- Pathway Analysis:

- Perform gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) using RNA-seq data from USP knockdown vs control cells to identify affected pathways [32].

- Validate key pathway alterations through Western blot analysis of relevant protein markers.

- USP Knockdown:

Data Interpretation:

- Significant reduction in cell proliferation, colony formation, and migration in USP-knockdown cells supports oncogenic function.

- Identification of specific pathways enriched in GSAE provides mechanistic insights.

Visualizations

USP Analysis Workflow and Clinical Correlations

USP-Mediated Oncogenic Signaling Mechanisms

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for USP-Cancer Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Application/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatic Tools | GDC Data Portal, cBioPortal, UCSC Xena | TCGA data access and visualization |

| Statistical Software | R with DESeq2, survival, survminer packages | Differential expression and survival analysis |

| Cell Lines | 786-O (renal cancer), ACHN (renal cancer), HOS (osteosarcoma) | Functional validation of USP roles |

| Knockdown Reagents | Lentiviral shRNAs (shUSP35-1, shUSP35-2, shUSP35-3) | Targeted USP depletion |

| Functional Assays | CCK-8, Colony formation, Transwell migration | Assessment of proliferation and metastatic potential |

| USP Inhibitors | PR619 (broad-spectrum), DUBs-IN-2 (USP8-specific) | Pharmacological targeting of USP activity |

This toolkit encompasses essential resources for conducting comprehensive studies on USP family members in cancer. Bioinformatic tools provide the foundation for initial discovery and hypothesis generation, enabling researchers to access and analyze large-scale genomic data from TCGA [38]. Validation reagents including specific cell lines and knockdown constructs allow for functional assessment of USP roles in cancer progression, as demonstrated in renal carcinoma models with USP35 [32]. The inclusion of USP inhibitors such as PR619, a broad-spectrum DUB inhibitor that has shown efficacy in reducing primary tumor growth and metastasis in osteosarcoma models, provides opportunities for therapeutic exploration [37].

The integrated application of bioinformatic analysis of TCGA data and experimental validation provides a powerful approach for elucidating the roles of USP family members in cancer progression and their potential as prognostic biomarkers. The protocols outlined in this application note establish a standardized framework for identifying USPs with significant correlations to tumor grade and patient survival, enabling researchers to prioritize candidates for further functional characterization. The consistent pattern of USP overexpression across diverse cancer types, coupled with their association with advanced disease stages and poor clinical outcomes, highlights the broader significance of deubiquitination processes in tumorigenesis. These findings reinforce the importance of the ubiquitin-proteasome system as a rich source of therapeutic targets and support continued investigation into USP-directed therapies for cancer treatment.

A Practical Guide to IHC Protocol Development for Ubiquitination Markers

In the field of biomedical research, particularly in the study of complex processes like ubiquitination in cancer, the selection of appropriate antibodies is not merely a preliminary step but a critical determinant of experimental success. Antibodies, the specialized proteins produced by the immune system to recognize and bind to specific molecules, serve as the primary detection tools in techniques such as immunohistochemistry (IHC), which is essential for visualizing protein localization within tissue contexts [39]. For researchers investigating cancer mechanisms, the choice between monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies, coupled with careful consideration of host species compatibility, directly influences the specificity, reproducibility, and biological relevance of their findings. This application note provides a structured framework for selecting antibodies specifically tailored for cancer research, with a focus on ubiquitination studies, and includes detailed protocols to ensure optimal results in IHC experiments.

Core Differences: Monoclonal vs. Polyclonal Antibodies

Fundamental Characteristics and Production

Antibodies are categorized based on their origin and epitope specificity. Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are derived from a single clone of B cells and are characterized by their uniform structure and specificity for a single epitope on the target antigen. Their production involves immunizing a host animal, fusing its B cells with immortal myeloma cells to create hybridomas, and then screening and selecting clones that produce the desired antibody [40] [41]. This process ensures a consistent supply of genetically homogeneous antibodies [40].

In contrast, polyclonal antibodies (pAbs) originate from multiple B cell clones within an immunized animal. They represent a heterogeneous mixture of antibodies that recognize multiple different epitopes on the same target antigen. They are obtained by purifying immunoglobulins directly from the serum of the immunized animal, making their production generally quicker and less expensive [40] [42].

Comparative Analysis: Advantages and Disadvantages

The decision to use monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies involves weighing their distinct advantages and limitations, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Monoclonal and Polyclonal Antibodies

| Feature | Monoclonal Antibodies | Polyclonal Antibodies |

|---|---|---|

| Origin & Specificity | Single B cell clone; binds to a single epitope [40] [41] | Multiple B cell clones; binds to multiple epitopes [40] [42] |

| Production Time | Time-consuming (+/- 6 months) [42] | Relatively quick (+/- 3 months) [42] |

| Cost | Higher due to complex manufacturing [40] | More cost-effective [40] |

| Batch-to-Batch Variability | Low reproducibility and high homogeneity [40] [42] | High variability between different productions [42] |

| Sensitivity | More sensitive for protein level quantification [42] | High sensitivity for detecting low-quantity proteins; superior for capturing native proteins [42] |

| Cross-Reactivity | Low, due to single-epitope recognition [42] | Higher potential, due to recognition of multiple epitopes [42] |

| Typical Applications | Precision-focused applications: diagnostic assays, therapeutic drugs (e.g., cancer therapies) [40] | Applications where broad specificity is needed: IHC, immunofluorescence, western blot [40] |

For general research applications, especially those requiring high sensitivity to detect low-abundance proteins or to capture native protein structures, the advantages of polyclonal antibodies often outweigh those of monoclonals. This is further enhanced when the serum is affinity-purified against the target antigen [42]. However, for applications requiring high specificity and consistency over the long term, such as therapeutic development or diagnostic manufacturing, monoclonal antibodies are the superior choice [42] [41].

The Critical Role of Host Species Compatibility

Strategic Selection of Host Species

The species in which an antibody is raised (the host species) is a critical, yet frequently overlooked, factor in experimental design. The primary consideration is to avoid interference from endogenous immunoglobulins when using secondary antibodies for detection. For example, if studying a mouse protein in mouse tissue, using a primary antibody raised in a mouse would lead to the secondary antibody binding to all endogenous mouse IgG in the tissue, creating overwhelming background signal. Therefore, a primary antibody from a different species (e.g., rabbit) must be selected [39].

Common Host Species and Their Properties

Different host species offer unique advantages based on their immune response characteristics and the volume of serum required.

Table 2: Key Host Species for Antibody Production and Their Properties

| Host Species | Key Characteristics | Common Applications/Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Rabbit | High affinity and robust immune response; broad epitope recognition [40]. | Often preferred for monoclonal antibodies due to strong immune response; suitable for polyclonal production when high sensitivity is needed [40]. |

| Mouse | Well-established hybridoma technology; multiple stable fusion partners [40]. | A classic host for monoclonal antibody production. Not suitable for detecting mouse antigens in murine models without specialized workarounds [40]. |

| Goat | Strong reactivity across species, especially humans; adaptable with adjuvants [40]. | Frequently used for polyclonal antibody production, yielding high-volume serum for applications like blocking or detection [40]. |

| Chicken | Sustainable production (antibodies harvested from egg yolk); unique antibody structure [40]. | Useful as an alternative when mammalian cross-reactivity is a concern; reduced cross-reactivity with mammalian proteins [40]. |

| Llama | Enables production of single-domain VHH antibodies (small, stable) [40]. | Gaining traction for their unique properties, such as ease of use in immunoassays and potential for deep tissue penetration [40]. |

Application in Ubiquitination Cancer Research

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System in Cancer

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) is a critical non-lysosomal pathway responsible for the controlled degradation of intracellular proteins, thereby regulating fundamental cellular processes including cell cycle progression, DNA repair, and immune response [43] [44]. Ubiquitination involves a cascade of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes that attach ubiquitin molecules to target proteins, marking them for degradation by the proteasome [44]. This process is reversible through the action of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), such as Ubiquitin-Specific Proteases (USPs), which remove ubiquitin moieties [43]. Dysregulation of ubiquitination and deubiquitination is a hallmark of various cancers, influencing tumor growth, metastasis, and immune evasion [43] [44]. For instance, USP7 can enhance tumor growth by modifying the immunosuppressive properties of regulatory T cells (Tregs) within the tumor microenvironment [43]. Another example is USP48, which has been shown to promote colorectal cancer progression by stabilizing the autophagy substrate protein SQSTM1/p62 and inhibiting autophagy [45].

Antibody Selection for Investigating USPs in Cancer

Research into USPs and other components of the UPS requires highly specific antibodies capable of distinguishing between different family members and their post-translationally modified states.

- Target Specificity: For differentiating between highly homologous USPs (e.g., USP7 vs. USP48), monoclonal antibodies are preferable due to their high specificity for a single epitope, minimizing cross-reactivity [40] [42]. This is crucial for accurately determining the expression and localization of a specific USP in cancer tissues.

- Detecting Modified Forms: When studying ubiquitination states or protein degradation, polyclonal antibodies can be advantageous because they are more likely to recognize a native protein and may be more sensitive in detecting low-quantity proteins or various conformational states of a target, such as ubiquitinated SQSTM1/p62 [42] [45].

- Multiplexing Experiments: For IHC experiments aiming to co-localize a USP with another protein (e.g., a cell lineage marker like GFAP), antibodies from different host species must be selected. For example, using a rabbit monoclonal anti-USP7 with a mouse monoclonal anti-GFAP allows for simultaneous detection with species-specific secondary antibodies conjugated to different fluorophores [46] [47].

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting antibodies in ubiquitination cancer research.

Detailed IHC Protocol for Ubiquitination Markers

This protocol is optimized for the detection of ubiquitination-related proteins, such as USPs, in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections, incorporating steps to overcome fixation-induced epitope masking [46] [39] [47].

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for IHC

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| FFPE Tissue Sections | Preserves tissue morphology and antigenicity for analysis. | Standard for clinical and research samples; requires deparaffinization. [39] |

| Primary Antibody | Binds specifically to the target protein (e.g., USP7). | Must be validated for IHC; selection of mono- vs. polyclonal is critical. [39] |

| Species-Specific Secondary Antibody | Binds to the primary antibody and is conjugated for detection. | Conjugated to enzyme (HRP) for chromogenic or fluorophore for fluorescent detection. [39] [47] |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffer | Reverses formaldehyde-induced cross-links, unmasking epitopes. | Citrate buffer (pH 6.0) or EDTA/TRIS buffer (pH 9.0); condition must be optimized. [46] [39] |

| Blocking Serum | Reduces non-specific binding of antibodies to the tissue. | Serum from the species in which the secondary antibody was raised. [39] |

| Detection Kit | Generates a visible signal at the site of antibody binding. | DAB chromogen for brown precipitate; or fluorophores for fluorescence. [47] |

| Hematoxylin | Counterstain that labels cell nuclei. | Provides histological context; blue stain. [47] |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Deparaffinization and Rehydration:

- Dewax FFPE sections by immersing them in xylene (or a safe substitute) for 5-10 minutes. Repeat twice.

- Rehydrate the tissue by passing through a series of ethanol solutions: 100% (twice), 95%, 70% (2-5 minutes each).

- Rinse thoroughly with distilled water and place in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). [39] [47]

Antigen Retrieval (Critical Step):

- Heat the retrieval buffer (e.g., 10 mM Sodium Citrate, pH 6.0) in a water bath or pressure cooker to 95-100°C.

- Immerse the slides in the pre-heated buffer and incubate for 20-30 minutes.

- Remove the container from heat and allow the slides to cool slowly in the buffer for at least 20 minutes at room temperature.

- Rinse the slides with distilled water and then with TBS or PBS containing a mild detergent like 0.025% Triton X-100 (TBS-T). [46] [39]

Quenching and Blocking:

- Quench endogenous peroxidase activity by incubating sections with 1.5-3% H₂O₂ in TBS for 10-30 minutes at room temperature (skip for fluorescence detection).

- Rinse slides 3 times in TBS for 5 minutes each.

- Carefully tap off excess liquid and outline the tissue with a hydrophobic pen.

- Apply enough appropriate blocking serum (e.g., 5-10% normal goat serum) to cover the tissue and incubate for 1 hour at room temperature in a humidity chamber. [46] [39]

Primary Antibody Incubation:

- Prepare the primary antibody (e.g., anti-USP48) at the optimal dilution in blocking serum or a commercial antibody diluent.

- Tap off the blocking serum and apply the primary antibody solution to the tissue section.

- Incubate overnight at 4°C in a humidity chamber for optimal results. Alternatively, a 1-2 hour incubation at room temperature can be tested during optimization. [39]

Secondary Antibody Incubation and Detection:

- Rinse the slides 3 times in TBS-T for 5 minutes each to remove unbound primary antibody.

- Apply the enzyme- or fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody (e.g., HRP-Goat anti-Rabbit IgG) diluted in TBS or blocking serum. Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark (for fluorescence).

- Rinse again 3 times with TBS-T for 5 minutes each. [39] [47]

Signal Development and Counterstaining: