Ubiquitin's Double-Edged Sword: Orchestrating DNA Repair and Driving Cancer

This article explores the critical and dualistic role of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) in the DNA damage response (DDR) and cancer pathogenesis.

Ubiquitin's Double-Edged Sword: Orchestrating DNA Repair and Driving Cancer

Abstract

This article explores the critical and dualistic role of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) in the DNA damage response (DDR) and cancer pathogenesis. We first establish the foundational mechanisms by which ubiquitination—through specific E3 ligases like RNF8, RNF168, and MDM2—controls key DDR pathways, including homologous recombination and non-homologous end joining. The discussion then progresses to methodological advances, detailing how this knowledge is being translated into innovative therapeutic strategies, such as proteasome inhibitors, PROTACs, and molecular glues. We further address the challenges in targeting the UPS, including drug resistance and specificity, and present optimization strategies. Finally, we validate these concepts by examining emerging links between DDR-associated ubiquitination and other cancer hallmarks, such as metabolic reprogramming, providing a comparative analysis of therapeutic targets for precision oncology.

The Ubiquitin Code: Decoding Its Fundamental Role in DNA Damage Signaling and Repair

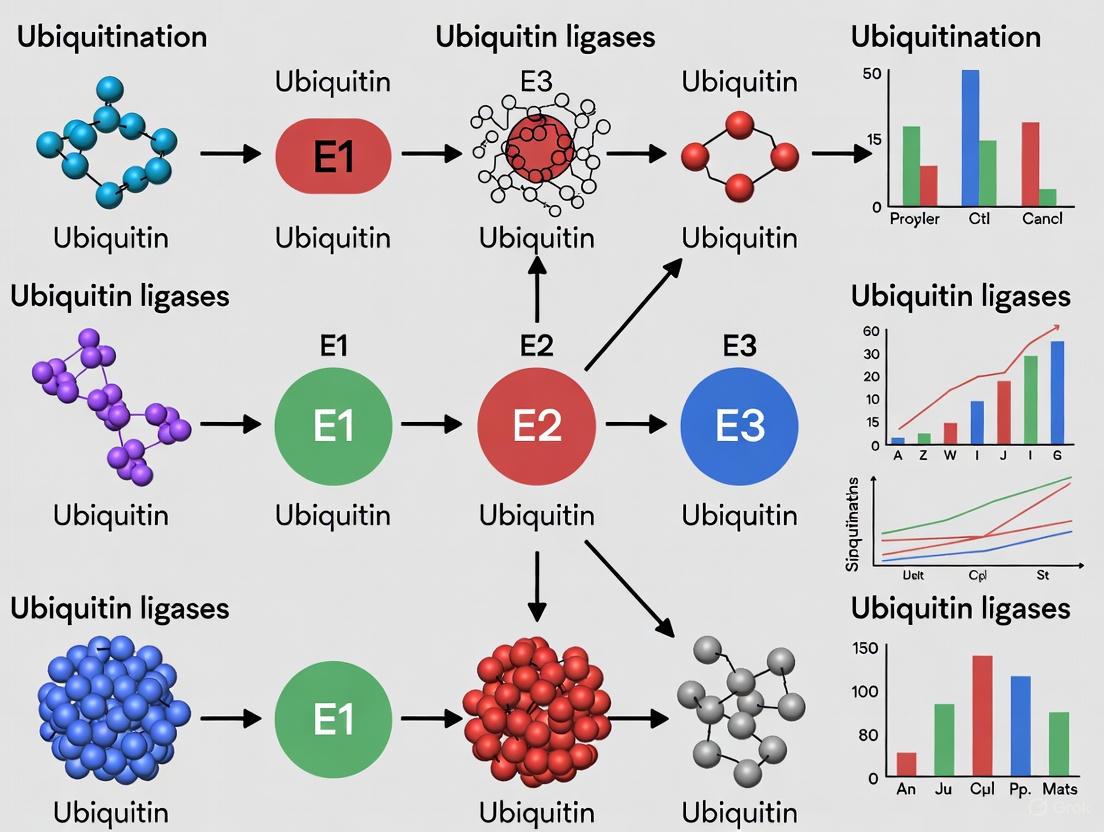

The DNA Damage Response (DDR) is a complex signaling network essential for maintaining genomic integrity. Its failure is a hallmark of cancer. Post-translational modifications, particularly ubiquitination, are central to the precise spatiotemporal regulation of the DDR. Ubiquitination, the covalent attachment of the small protein ubiquitin to substrate proteins, is orchestrated by a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes. This process can target proteins for proteasomal degradation, alter their activity, or mediate critical protein-protein interactions at DNA repair foci. Understanding this cascade is paramount for developing novel cancer therapeutics that target the DDR.

The Enzymatic Cascade: E1, E2, and E3 Mechanics

The ubiquitination cascade is a three-step process that results in the attachment of ubiquitin to a lysine residue on a substrate protein.

- Step 1: Activation by E1. The E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme uses ATP to form a high-energy thioester bond between its active-site cysteine and the C-terminus of ubiquitin.

- Step 2: Conjugation by E2. The activated ubiquitin is transferred to the active-site cysteine of an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme.

- Step 3: Ligation by E3. An E3 ubiquitin ligase facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a specific substrate protein, forming an isopeptide bond. E3s provide the critical substrate specificity to the system.

Ubiquitin itself contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63), allowing for the formation of polyubiquitin chains. Chain topology determines the fate of the modified protein. K48-linked chains typically target proteins for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked and linear/Met1-linked chains are key non-proteolytic signals in DDR signaling, serving as scaffolds to recruit repair proteins.

Diagram 1: Core Ubiquitination Cascade

Title: Core ubiquitination enzyme mechanism.

E1, E2, and E3 Enzymes in DDR Pathways

The DDR employs a specific repertoire of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes to coordinate the detection, signaling, and repair of DNA lesions. The following table summarizes key players.

Table 1: Key Ubiquitination Enzymes in the DNA Damage Response

| Enzyme | Example | Role in DDR | Ubiquitin Linkage | Primary Function in DDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | UBA1 | Master activator for most ubiquitination events in DDR. | N/A | Primes the entire ubiquitination response. |

| E2 | UBC13/UEV1A | Works with RNF168 and others. | K63 | Generates K63-linked chains for repair protein recruitment. |

| E2 | BRCA1/BARD1 | Heterodimer with E3 activity. | K6 | Involved in DNA repair; role in homologous recombination. |

| E3 (RING) | RNF8 | Early responder to DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). | K63, K48 | Initiates the histone ubiquitination cascade to amplify the signal. |

| E3 (RING) | RNF168 | Amplifies the ubiquitin signal at DSBs. | K63, K13 | Ubiquitinates H2A/H2AX; essential for recruiting 53BP1, BRCA1. |

| E3 (RING) | BRCA1 | Tumor suppressor; functions in complex with BARD1. | Multiple | Promotes homologous recombination (HR) repair. |

| E3 (HECT) | HERC2 | Regulates RNF8 and RNF168. | Multiple | Facilitates RNF168 accumulation at damage sites; regulates XPA in NER. |

| E3 (RBR) | Parkin | Implicated in mitochondrial quality control and DDR. | Multiple | Accumulates at DSBs; promotes mitophagy in response to damage. |

The canonical pathway for DSB repair involves the sequential action of E3s. The E3 RNF8 is recruited to sites of DNA damage and ubiquitinates histones, creating a platform for the recruitment of RNF168. RNF168 then amplifies this signal by further ubiquitinating histone H2A, which recruits downstream effectors like 53BP1 (promoting non-homologous end joining, NHEJ) and BRCA1 (promoting homologous recombination, HR).

Diagram 2: RNF8/RNF168 Cascade at DSBs

Title: RNF8/RNF168 signaling at DNA breaks.

Quantitative Data in DDR Ubiquitination

Quantitative studies are crucial for understanding the kinetics and dynamics of the ubiquitin cascade in DDR.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics of Ubiquitination in DDR

| Parameter | Experimental Finding | Method Used | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNF168 Turnover | Half-life at DSBs: ~90 seconds (live-cell imaging). | FRAP (Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching) | Indicates a highly dynamic and regulated process at repair foci. |

| Ubiquitin Chain Type at DSBs | ~60-70% K63-linked; ~15-20% K48-linked (by mass spectrometry). | Ubiquitin Chain Restriction (UbiCRest) Assay | Dominance of K63 chains underscores their scaffolding role in DDR. |

| Inhibitor Potency (TAK-243) | IC₅₀ for global ubiquitination: ~5-10 nM; IC₅₀ for cancer cell growth: ~1-50 nM. | Cell Viability Assay (CTG), Immunoblotting | Demonstrates high potency of E1 inhibition as an anticancer strategy. |

| BRCA1/BARD1 Activity | Catalytic rate (k~cat~) for ubiquitin discharge: ~0.02 min⁻¹. | In vitro ubiquitination assay | Provides kinetic insight into the efficiency of this tumor suppressor complex. |

Experimental Protocols for Studying DDR Ubiquitination

Protocol 1: In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay This assay reconstitutes the ubiquitination cascade using purified components to study a specific E2-E3 pair.

- Reaction Setup: In a 30 µL volume, combine:

- 50-100 nM E1 enzyme

- 1-2 µM E2 enzyme

- 0.5-1 µM E3 enzyme (or E3 complex like BRCA1/BARD1)

- 2-5 µM Substrate protein

- 10-20 µg Ubiquitin

- 2 mM ATP

- Reaction Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM DTT.

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction at 30°C for 60-90 minutes.

- Termination: Stop the reaction by adding 4x Laemmli SDS-PAGE sample buffer with 100 mM DTT.

- Analysis: Resolve proteins by SDS-PAGE and analyze by immunoblotting using antibodies against the substrate, ubiquitin, or specific ubiquitin linkages (e.g., anti-K63-Ub).

Protocol 2: Monitoring Ubiquitination in Cells after DNA Damage

- Cell Treatment: Treat cells (e.g., U2OS, HeLa) with a DNA-damaging agent (e.g., 2 Gy Ionizing Radiation (IR), 1 µM Camptothecin, or 10 µM Etoposide).

- Lysis: At desired time points post-treatment (e.g., 1, 4, 8 hours), lyse cells in RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0) supplemented with 10 mM N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) to inhibit deubiquitinases (DUBs), and protease/phosphatase inhibitors.

- Immunoprecipitation (IP): Pre-clear the lysate. Incubate with an antibody against the protein of interest (e.g., anti-H2AX, anti-53BP1) and Protein A/G beads for 2-4 hours at 4°C.

- Wash and Elute: Wash beads extensively with lysis buffer. Elute bound proteins with SDS sample buffer.

- Analysis: Perform SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Probe for ubiquitin (anti-Ub) to detect ubiquitination of the immunoprecipitated protein.

Diagram 3: IP-Based Ubiquitination Workflow

Title: Immunoprecipitation assay for ubiquitination.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for DDR Ubiquitination Research

| Reagent | Function/Application | Example |

|---|---|---|

| TAK-243 (MLN7243) | A potent, specific inhibitor of the E1 enzyme UBA1. Used to block global ubiquitination and study its functional consequences in DDR. | MedChemExpress, HY-107469 |

| Neratinib | An EGFR/HER2 inhibitor that also covalently inhibits the E2 enzyme UBC13, specifically blocking K63-linked ubiquitination in DDR. | Selleckchem, S2150 |

| Ubiquitin Mutants (K0, K48-only, K63-only) | Mutant ubiquitin plasmids or proteins where all lysines are mutated to arginine (K0) or only a single lysine remains. Essential for defining chain topology in assays. | Boston Biochem, UbiSelect Kits |

| Linkage-Specific Ub Antibodies | Antibodies that specifically recognize polyubiquitin chains linked through K48, K63, etc. Critical for immunoblotting and immunofluorescence. | Cell Signaling Tech (#8081 for K48, #5621 for K63) |

| TUBE (Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entity) | Recombinant proteins with high affinity for polyubiquitin chains. Used to enrich and purify ubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates, protecting them from DUBs. | LifeSensors, UM401, UM402 |

| DNA Damage Inducers | Pharmacological agents to induce specific DNA lesions (e.g., Etoposide for DSBs, Hydroxyurea for replication stress). | Sigma-Aldrich |

The ubiquitination cascade in the DDR represents a fertile ground for cancer drug discovery. The dependency of many cancers on robust DDR pathways for survival, especially those with underlying DNA repair deficiencies (e.g., BRCA-mutant cancers), creates a therapeutic window. Key strategies include:

- E1 Inhibition: TAK-243 is in clinical trials, inducing global ubiquitination shutdown and catastrophic proteotoxic stress.

- Targeting Specific E3s: PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) hijack E3s like VHL or CRBN to degrade oncoproteins. Developing inhibitors for DDR-specific E3s is an active area.

- USP Inhibitors: Inhibiting Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs) that reverse DDR signaling, such as USP1 or USP7, can hyper-stabilize ubiquitin signals and disrupt repair.

In conclusion, the E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade is a master regulator of the DDR, controlling the fidelity and choice of DNA repair pathways. Its precise mechanistic dissection, aided by the quantitative and experimental approaches outlined here, continues to reveal novel vulnerabilities that can be exploited for targeted cancer therapy.

Ubiquitination, a pivotal post-translational modification, was initially recognized for its role in targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation. However, it is now established as a versatile regulatory mechanism influencing nearly every aspect of cellular function, with particular significance in the DNA damage response (DDR) and cancer pathogenesis [1] [2]. The modification involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin, a 76-amino acid polypeptide, to substrate proteins. This process is catalyzed by a sequential enzymatic cascade involving ubiquitin-activating (E1), conjugating (E2), and ligase (E3) enzymes [1] [3]. The functional outcome of ubiquitination is profoundly determined by the topology of the ubiquitin modification. Monoubiquitination, the attachment of a single ubiquitin moiety, and polyubiquitination, the formation of ubiquitin chains, can produce diverse signals interpreted by the cell through specific ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) [1]. The complexity of this "ubiquitin code" is immense, as ubiquitin itself contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1), all of which can form structurally and functionally distinct polyubiquitin chains [2]. This review delineates the functional diversity of mono-ubiquitination and various polyubiquitin chains, framing their roles within the context of DDR and the subsequent implications for cancer research and therapeutic development.

The Ubiquitination Machinery and Signaling Output

The Enzymatic Cascade

The ubiquitination process is a ATP-dependent, three-step enzymatic cascade:

- Activation (E1): A ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) utilizes ATP to adenylate the C-terminus of ubiquitin, forming a high-energy thioester bond between a cysteine residue in its active site and ubiquitin (E1~Ub) [1] [3].

- Conjugation (E2): The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to a cysteine residue of a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2), forming a similar E2~Ub thioester intermediate [1] [3].

- Ligation (E3): Finally, a ubiquitin ligase (E3) facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine ε-amino group on the substrate protein. E3s, of which there are ~600 in humans, provide substrate specificity. They primarily fall into two classes: RING E3s that act as scaffolds to bring the E2 and substrate together, and HECT E3s that form a catalytic thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate [1] [3].

This process is reversible through the action of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), which cleave ubiquitin from substrates, providing dynamic control over ubiquitin signaling [1] [2].

Ubiquitin Chain Diversity and Functional Consequences

The modification is not a single event but can take several forms, each with distinct functional consequences:

- Monoubiquitination: Attachment of one ubiquitin molecule to a single lysine on a substrate. It often serves as a signaling event, regulating processes like endocytosis, histone function, and DNA repair [1] [2].

- Multi-Monoubiquitination: Attachment of single ubiquitin molecules to multiple different lysine residues on the same substrate protein [1].

- Polyubiquitination: Formation of a chain of ubiquitin molecules linked through one of the eight linkage sites on ubiquitin itself. The chain topology dictates the functional outcome [1] [2]:

- K48-linked chains: The canonical signal for proteasomal degradation of the modified substrate [1] [4].

- K63-linked chains: Primarily involved in non-proteolytic signaling, regulating processes like DNA repair, kinase activation, and inflammation [1] [4].

- Other linkages (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, M1/linear): Implicated in various processes, including DNA repair, autophagy, and immune signaling [1] [2].

The following diagram illustrates the ubiquitination cascade and the diverse functional outcomes driven by different ubiquitin modifications.

The different ubiquitin linkages are utilized by the cell to generate a complex code, with distinct chain topologies directing specific biological outcomes. The table below summarizes the key characteristics and primary functions of the major ubiquitin linkage types.

Table 1: Functional Diversity of Ubiquitin Linkages in Cellular Signaling and Disease

| Linkage Type | Chain Topology | Primary Functional Role | Role in DNA Damage Response (DDR) | Implication in Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoubiquitination | Single ubiquitin moiety | Signal for DNA repair, endocytosis, histone regulation, transcriptional activation [1] [2] | Recruitment of repair factors like BRCA1 and RAD51; H2A/H2B monoubiquitination in chromatin remodeling [1] [5] | Altered DNA repair fidelity; dysregulated growth factor signaling [2] |

| K48-linked | Closed conformation | Canonical signal for proteasomal degradation [1] [4] | Termination of DDR by degrading checkpoint and repair proteins [1] | Stabilization of oncoproteins (e.g., c-Myc) or destabilization of tumor suppressors (e.g., p53) [3] [2] |

| K63-linked | Extended conformation | Non-proteolytic signaling: kinase activation, DNA repair, protein trafficking, inflammation [1] [4] | Facilitates recruitment and activation of DDR kinases (e.g., ATM, ATR) and repair complexes at damage sites [1] [4] | Activates pro-tumorigenic pathways (PI3K/Akt, NF-κB); promotes invasion and metastasis [4] |

| K6-linked | Not well characterized | Implicated in DNA repair, mitochondrial homeostasis [1] | Involved in the Fanconi Anemia pathway for interstrand crosslink repair [1] | Potential role in genomic instability [1] |

| K11-linked | Unique mixed conformation | Cell cycle regulation, ER-associated degradation (ERAD) [1] | Regulation of mitotic checkpoints in response to damage [1] | Dysregulated in various cancers; target of APC/C E3 ligase [1] |

| K27-linked | Not well characterized | Innate immune signaling, mitophagy [2] | Emerging role in DDR pathway choice [2] | Linked to tumor immune evasion [2] |

| K29-linked | Not well characterized | Targeting to proteasomal/lysosomal degradation [1] | Potential role in degrading DDR proteins [1] | Altered degradation of oncogenic substrates [1] |

| M1-linear | Linear chain | NF-κB activation, inflammation, cell death [2] | Regulates NF-κB-mediated survival signaling in response to genotoxic stress [2] | Promotes pro-survival signaling in lymphoma and other cancers [2] |

Mono-ubiquitination and K63-Linked Ubiquitination in DNA Damage Response

The DDR is a paradigm for the non-degradative functions of ubiquitination. The coordinated actions of monoubiquitination and K63-linked polyubiquitination are critical for the efficient detection, signaling, and repair of DNA lesions, particularly double-strand breaks (DSBs).

Monoubiquitination in DDR

Monoubiquitination acts as a dynamic beacon in the DDR:

- Histone Monoubiquitination: The E3 ligases RNF2 and BMI1 catalyze the monoubiquitination of histone H2A at lysine 119. This modification contributes to chromatin condensation and transcriptional repression around DSB sites, facilitating the assembly of repair complexes [2]. Conversely, monoubiquitination of histone H2B is involved in transcription-coupled repair mechanisms.

- Recruitment of Repair Factors: Key DDR proteins are regulated by monoubiquitination. For instance, the monoubiquitination of FANCD2 and FANCI within the Fanconi Anemia (FA) pathway is an essential step for their recruitment to DNA interstrand crosslinks and their function in repair [1].

- Regulation of Immune Checkpoints: Beyond direct repair, monoubiquitination of the immune checkpoint protein PD-L1 at K263 by the E3 ligase AIP4 promotes its internalization and lysosomal degradation, thereby potentially inhibiting immune escape of cancer cells [2].

K63-Linked Ubiquitination in DDR

K63-linked ubiquitin chains serve as a central scaffolding platform for the DDR:

- RNF8/RNF168 Cascade: Following DNA damage, the E3 ligases RNF8 and RNF168 are sequentially recruited to DSB sites. They catalyze the extensive deposition of K63-linked ubiquitin chains on histones H2A and H2AX. This creates a binding platform that is recognized by UBD-containing proteins such as BRCA1, 53BP1, and RAP80, which are essential for mediating downstream repair processes like homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) [1].

- Kinase Activation: K63-linked ubiquitination directly activates key kinases in the DDR. For example, the ubiquitination of the kinase Akt by the E3 ligase TRAF6 promotes its membrane translocation and activation, contributing to cell survival signals upon damage [4].

The diagram below integrates these mechanisms into a cohesive signaling pathway activated at DNA double-strand break sites.

Experimental Methods for Studying Ubiquitination

Deciphering the ubiquitin code requires sophisticated methodologies to identify substrates, specific linkage types, and functional consequences.

Ubiquitinomics and Proteomic Profiling

Label-free Quantitative Ubiquitinomics is a powerful mass spectrometry-based approach for system-wide profiling of ubiquitination sites [6].

- Workflow: Complex protein extracts from tissues or cells (e.g., cancer vs. normal) are digested with a protease like trypsin.

- Ubiquitin Remnant Enrichment: The resulting peptides are incubated with anti-K-ε-GG antibody beads (PTMScan Ubiquitin Remnant Motif Kit), which specifically enrich for peptides containing the diglycine (K-ε-GG) remnant left on lysine residues after tryptic digestion of ubiquitinated proteins.

- Identification and Quantification: The enriched peptides are analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The identification of the K-ε-GG signature allows for the precise mapping of ubiquitination sites, while label-free quantification compares the abundance of these sites across different samples [6].

- Application: This technique was used to identify 1,249 ubiquitinated sites within 608 differentially ubiquitinated proteins (DUPs) in human sigmoid colon cancer tissues, revealing pathway alterations in glycolysis, ferroptosis, and Salmonella infection [6].

Functional Validation Experiments

Following proteomic discovery, functional validation is crucial:

- In Vitro Ubiquitination Assays: These reconstitute the ubiquitination cascade using purified components: E1 enzyme, E2 enzyme, E3 ligase (e.g., RNF168), ATP, ubiquitin, and the substrate protein (e.g., histone H2A). The reaction products are analyzed by western blot to detect slower-migrating ubiquitinated forms of the substrate, confirming a direct relationship [1].

- Mutagenesis: To confirm the functional importance of a specific ubiquitination site, the target lysine residue in the substrate is mutated to arginine (K→R), which prevents ubiquitination. The functional properties of the wild-type and mutant protein (e.g., ability to activate signaling, localize to DNA damage sites, or be degraded) are then compared in cellular models [2] [4].

- DUB Specificity Assays: To determine which DUB reverses a specific modification, purified DUBs (e.g., OTUD7B for K63 chains, OTULIN for M1-linear chains) are incubated with ubiquitinated substrates or defined ubiquitin chains. Chain cleavage is monitored by western blot or mass spectrometry to establish DUB linkage specificity [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table details essential reagents and tools used in ubiquitination research, as featured in the cited studies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function and Application in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-K-ε-GG Antibody (PTMScan) | Immuno-enrichment of tryptic peptides containing the di-glycine lysine remnant for LC-MS/MS-based ubiquitinome analysis [6]. | Identification of differentially ubiquitinated proteins (DUPs) and sites in cancer tissues versus normal controls [6]. |

| Specific E3 Ligase Inhibitors (e.g., Nutlin-3a) | Small molecule that disrupts the MDM2-p53 interaction, stabilizing p53 and activating its tumor suppressor function [3]. | Studying p53-dependent apoptosis and cell cycle arrest; model therapeutic for cancers with wild-type p53 [3]. |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies | Antibodies that specifically recognize polyubiquitin chains formed through a particular lysine linkage (e.g., K48-only or K63-only). | Determining the topology of ubiquitin chains on a substrate protein via western blot or immunofluorescence [4]. |

| Activity-Based DUB Probes | Ubiquitin derivatives with electrophilic traps that covalently bind to the active sites of catalytically active DUBs. | Profiling active DUB families in cell lysates and identifying specific DUBs involved in a pathway [2]. |

| Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Engineered protein reagents with high affinity for polyubiquitin chains, which can protect substrates from deubiquitination and be used for purification. | Isolation and characterization of ubiquitinated proteins and protein complexes from cellular extracts [1]. |

| PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) | Bifunctional molecules that recruit an E3 ligase to a target protein of interest, inducing its ubiquitination and degradation [2]. | Targeted protein degradation for functional studies and as a novel therapeutic strategy (e.g., ARV-110 targeting the androgen receptor) [2]. |

The functional diversity of ubiquitination presents a rich landscape for therapeutic intervention in cancer. Strategies have evolved beyond proteasome inhibition (e.g., Bortezomib) to include highly specific agents [3].

- E3 Ligase-Targeted Therapies: Small molecules like Nutlin-3a (targeting MDM2) aim to reactivate p53 in tumors. Immunomodulatory drugs (Thalidomide, Lenalidomide) recruit novel substrates to the CRL4CRBN E3 complex, leading to their degradation [3].

- DUB Inhibitors: Inhibiting specific DUBs can modulate the stability of oncoproteins or key signaling molecules. For instance, targeting USP2, which stabilizes PD-1, could enhance anti-tumor immunity [2].

- Next-Generation Degraders: PROTACs and molecular glues (e.g., ARV-110, ARV-471, CC-90009) represent a paradigm shift, hijacking the ubiquitin system to deliberately degrade previously "undruggable" oncogenic targets [2].

In conclusion, the functional roles of monoubiquitination and the various polyubiquitin chains extend far beyond protein degradation. They form a sophisticated code that orchestrates the DNA damage response, and its dysregulation is a hallmark of cancer. The continued elucidation of this code, powered by advanced ubiquitinomics and functional studies, is uncovering a new generation of therapeutic targets and modalities, offering promising avenues for precise cancer interventions.

The RNF8/RNF168 signaling axis constitutes a critical ubiquitination cascade in the DNA damage response (DDR), orchestrating the repair of double-strand breaks (DSBs) through coordinated recruitment of repair factors. This ubiquitin-driven pathway amplifies DNA damage signals, facilitates the assembly of BRCA1 and 53BP1 repair complexes at chromatin lesions, and ultimately influences the critical choice between homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair pathways. Dysregulation of this axis contributes to genomic instability, cancer predisposition, and human diseases such as RIDDLE syndrome. This technical review examines the molecular architecture, regulatory mechanisms, and experimental approaches for investigating the RNF8/RNF168 pathway, providing researchers with foundational knowledge and methodologies to advance targeted therapeutic strategies in cancer treatment.

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) represent one of the most deleterious forms of DNA damage, with unrepaired lesions leading to genomic instability, chromosomal translocations, and cell death. To counteract this threat, cells have evolved sophisticated DNA damage response (DDR) mechanisms that sense, signal, and repair DSBs [7]. The cellular response to DSBs occurs in the context of chromatin and involves a highly coordinated series of post-translational modifications (PTMs) including phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and SUMOylation, which collectively regulate the recruitment and activity of DNA repair proteins [8] [9].

Ubiquitination has emerged as a central regulatory mechanism in the DDR, with E3 ubiquitin ligases serving as critical determinants of substrate specificity. The ubiquitination process involves a sequential enzymatic cascade: a ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) activates ubiquitin, a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) receives the activated ubiquitin, and a ubiquitin ligase (E3) facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin to specific substrate proteins [10] [11]. RING-type E3 ligases, the largest class of E3 enzymes, function as scaffolds that bring E2 enzymes into proximity with their substrate proteins, thereby promoting ubiquitin transfer [10]. The RNF8/RNF168 axis represents a pivotal ubiquitin signaling pathway that controls DSB repair by regulating the assembly of repair complexes at damaged chromatin, making it a focus of intense research in cancer biology and therapeutic development [9] [12].

The RNF8/RNF168 Signaling Cascade: Molecular Mechanisms

Pathway Initiation and RNF8 Recruitment

The RNF8/RNF168 signaling cascade initiates with the activation of the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase at DSB sites. ATM phosphorylates the histone variant H2AX on serine 139 (generating γ-H2AX), creating a binding platform for the mediator protein MDC1 [9]. RNF8 is then recruited to DSBs through the interaction of its N-terminal FHA domain with ATM-phosphorylated TQXF motifs on MDC1 [13] [9]. Once localized to chromatin lesions, RNF8, in concert with the E2 enzyme UBC13, catalyzes the formation of K63-linked ubiquitin chains on currently unidentified non-nucleosomal target proteins in the vicinity of damaged chromatin, referred to as "Target X" [9].

Table 1: Key Domains and Functions of RNF8

| Domain | Location | Function | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| FHA Domain | N-terminal | Recruits RNF8 to DSBs via interaction with phosphorylated MDC1 | Phosphopeptide recognition domain |

| RING Domain | C-terminal | Catalyzes ubiquitin transfer from E2 to substrates | C3HC4-type RING finger; E2 interaction |

RNF168 Recruitment and Amplification

RNF168 is recruited to DSBs through its ubiquitin-dependent recruitment modules (UDM1 and UDM2), which recognize the K63-linked ubiquitin chains deposited by RNF8 [7]. The UDM1 module, consisting of LRM1, UMI, and MIU1 motifs, preferentially binds K63-linked ubiquitin chains and functions downstream of RNF8 [7]. Once recruited, RNF168 catalyzes the monoubiquitination of histone H2A and H2AX at K13/K15, creating an amplification loop that facilitates robust accumulation of RNF168 at damage sites through its UDM2 module [7] [9]. This self-amplifying mechanism establishes a strong local ubiquitin signal that serves as a docking platform for downstream repair factors.

Table 2: Structural and Functional Domains of RNF168

| Domain | Location | Function | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| RING Domain | N-terminal (a.a. 15-58) | Catalytic E3 ligase activity; recognizes E2~Ub conjugate | Mutations associated with RIDDLE syndrome |

| UDM1 | Middle region | Initial recruitment via K63-ubiquitin chain binding | Contains LRM1, UMI, and MIU1 motifs |

| UDM2 | C-terminal region | Self-amplification via H2A/X K15ub binding | Contains UAD, MIU2, and LRM2 motifs |

Recruitment of Downstream Effectors: BRCA1 and 53BP1

The ubiquitin landscape established by RNF8 and RNF168 directly regulates the recruitment of two critical downstream effectors with opposing functions in DSB repair pathway choice: the BRCA1-BARD1 complex and 53BP1 [9] [12]. BRCA1 is recruited to DSBs through its interaction partner RAP80, which binds to K63-linked ubiquitin chains deposited by RNF8/RNF168 [9] [12]. In contrast, 53BP1 recruitment requires RNF168-mediated H2A/X ubiquitination and recognizes dimethylated histone H4K20, with the RNF8/RNF168 pathway facilitating the removal of competing factors like KDM4A/JMJD2A that antagonize 53BP1 binding [14]. The balanced recruitment of these factors determines whether cells prioritize homologous recombination (HR) or non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair pathways.

Table 3: Experimental Evidence for RNF8/RNF168 in DSB Repair

| Experimental Approach | Key Findings | Biological Significance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNF168 knockout mice | 60% developed hyperplastic lesions at 13 months; 18% developed mammary adenocarcinomas | RNF8 deficiency promotes genomic instability and tumorigenesis | [13] |

| Clinical data analysis (5,143 cases) | Low full-length RNF8 expression correlates with poor prognosis in luminal B and basal-like breast cancer | RNF8 serves as a potential prognostic biomarker | [13] |

| RNF8/RNF168-dependent degradation | Degradation of KDM4A/JMJD2A triggers 53BP1 recruitment to DNA damage sites | Regulation of repair pathway choice through histone mark accessibility | [14] |

| ZNF451-RNF168 SUMOylation | ZNF451 catalyzes SUMO2 modification of RNF168, stabilizing it at damage sites | SUMO-ubiquitin crosstalk regulates RNF168 activity | [15] |

Table 4: RNF8/RNF168-Dependent Ubiquitination Events in DSB Repair

| Ubiquitination Target | Ubiquitin Linkage Type | Functional Consequence | Regulating E3 Ligase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histone H2A/H2AX (K13/K15) | Monoubiquitination | Recruitment of 53BP1 and BRCA1 complexes | RNF168 |

| KDM4A/JMJD2A | K48-linked (proteasomal degradation) | Removal of 53BP1 antagonist, promotes NHEJ | RNF8/RNF168 |

| Unknown "Target X" | K63-linked polyubiquitination | Recruitment of RNF168 to damage sites | RNF8 |

Experimental Protocols for Studying the RNF8/RNF168 Axis

Assessing RNF8/RNF168 Recruitment to DSBs by Immunofluorescence

Purpose: To visualize and quantify the recruitment of RNF8 and RNF168 to sites of DNA damage. Methodology:

- Cell Culture and DNA Damage Induction: Seed appropriate cells (e.g., U2OS, HeLa, or MEFs) on glass coverslips. Induce DSBs using ionizing radiation (2-10 Gy) or laser microirradiation, or treat with DSB-inducing agents such as neocarzinostatin (NCS).

- Immunostaining: At specific time points post-damage, fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilize with 0.5% Triton X-100, and block with 5% BSA. Incubate with primary antibodies against RNF8 or RNF168, followed by species-appropriate fluorescent secondary antibodies.

- Counterstaining and Microscopy: Counterstain with DAPI to visualize nuclei and γ-H2AX to mark DSB sites. Analyze samples by confocal microscopy, quantifying foci number and intensity using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ). Key Controls: Include cells treated with siRNA targeting RNF8 or RNF168 to verify antibody specificity [13] [7].

Analyzing RNF168-Dependent Ubiquitination by Immunoblotting

Purpose: To detect RNF168-mediated ubiquitination of histone H2A/H2AX. Methodology:

- Cell Lysis and Fractionation: Harvest cells after DNA damage induction and lyse using RIPA buffer. For chromatin-enriched fractions, pre-extract cells with CSK buffer before solubilizing chromatin.

- Immunoblotting: Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to PVDF membranes. Probe with antibodies specific for ubiquitinated H2A (K13/K15) or H2AX (K13/K15). Validate equal loading with histone H3 or total H2A/H2AX antibodies.

- Quantification: Use densitometry to quantify ubiquitination levels normalized to loading controls. Key Reagents: Commercial antibodies specifically recognizing H2A ubiquitinated at K13/K15 are essential for accurate detection [7] [9].

Functional Assays for DSB Repair Pathway Choice

Purpose: To determine how RNF8/RNF168 activity influences HR versus NHEJ efficiency. HR and NHEJ Reporter Assays:

- Stable Cell Line Generation: Transfect cells with DR-GFP (for HR) or EJ5-GFP (for NHEJ) reporter constructs and select stable integrants.

- DSB Induction and Repair Measurement: Introduce DSBs in the reporter locus using I-SceI endonuclease. Quantify repair efficiency by flow cytometric analysis of GFP-positive cells 48-72 hours post-transfection.

- Pathway Manipulation: Knock down RNF8 or RNF168 using siRNA and compare repair efficiency to control cells. Alternative Approach: Monitor the formation of RAD51 foci (HR marker) versus 53BP1 foci (NHEJ promoter) in cells with modulated RNF8/RNF168 expression [9] [12].

Signaling Pathway Visualization

Diagram 1: RNF8/RNF168 Signaling Cascade in DSB Repair. This diagram illustrates the sequential recruitment and activation of RNF8 and RNF168 at DNA double-strand breaks, culminating in the recruitment of BRCA1 and 53BP1 to influence repair pathway choice between homologous recombination and non-homologous end joining.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Key Research Reagents for Studying RNF8/RNF168 Function

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Example | Experimental Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNF8/RNF168 Antibodies | Anti-RNF168 (e.g., Abcam ab154833) | Immunofluorescence, Immunoblotting | Detect protein localization and expression |

| Ubiquitin Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Anti-K63-ubiquitin chain antibodies | Immunoblotting | Identify specific ubiquitin linkages |

| H2A Ubiquitination-Specific Antibodies | Anti-H2A-K13ub/K15ub | Chromatin immunoprecipitation, Immunoblotting | Detect RNF168-dependent histone modification |

| siRNA/shRNA Libraries | ON-TARGETplus siRNA pools | Functional knockdown studies | Deplete RNF8/RNF168 to assess functional consequences |

| DDR Inhibitors | ATM inhibitors (KU-55933) | Pathway modulation | Dissect regulatory relationships in the cascade |

| Reporter Cell Lines | DR-GFP (HR), EJ5-GFP (NHEJ) | Repair pathway choice assays | Quantify HR and NHEJ efficiency |

| DNA Damaging Agents | Neocarzinostatin (NCS), Etoposide | Controlled induction of DSBs | Activate the DDR under experimental conditions |

Regulatory Mechanisms and Cross-Talk

The RNF8/RNF168 axis is subject to multiple layers of regulation to ensure appropriate signaling amplitude and duration. Negative feedback mechanisms involve RNF169, which competes with RNF168 for binding to ubiquitinated histones, thereby attenuating the signal [12]. Additionally, the E3 ligase RNF126 directly ubiquitinates RNF168, inhibiting its ability to ubiquitinate γH2AX [12]. Recent research has revealed important SUMO-ubiquitin cross-talk, with ZNF451 catalyzing SUMOylation of RNF168 to stabilize it and enhance its accumulation at damage sites [15]. The mTOR-S6K pathway has also been shown to regulate RNF168, linking growth signaling to DNA damage response [15].

The RNF8/RNF168 pathway interfaces with other post-translational modification systems, including crosstalk with the SUMOylation pathway through proteins like HERC2, which promotes RNF8 oligomerization and facilitates RNF168 recruitment [12]. The proteasome-associated deubiquitinase USP14 regulates DNA damage repair by targeting RNF168-dependent ubiquitination, adding another layer of control [15]. These intricate regulatory networks ensure that the RNF8/RNF168 signaling axis responds appropriately to DNA damage while preventing excessive signaling that could disrupt chromatin structure and function.

The RNF8/RNF168 signaling axis represents a master regulatory module that controls the cellular response to DNA double-strand breaks through coordinated ubiquitin signaling. By establishing a specific ubiquitin landscape at damaged chromatin, this pathway regulates the critical balance between homologous recombination and non-homologous end joining repair pathways. The detailed mechanistic understanding of RNF8/RNF168 function has significant implications for cancer therapy, particularly in exploiting synthetic lethal relationships for targeted treatment approaches.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the structural basis of RNF8/RNF168 interactions, identifying novel substrates of these E3 ligases, and developing small molecule modulators that can selectively target components of this pathway. The integration of advanced techniques such as cryo-electron microscopy, proximity-dependent biotinylation, and chemical biology approaches will further illuminate the dynamic regulation of this crucial DNA repair pathway. As our understanding of the RNF8/RNF168 axis deepens, so too will opportunities for therapeutic intervention in cancer and other diseases characterized by genomic instability.

The post-translational modification of proteins by ubiquitin is a master regulatory mechanism that controls virtually all aspects of the cellular response to DNA damage, including replication stress. Ubiquitylation involves a sequential enzymatic cascade whereby the E1 activating enzyme, E2 conjugating enzyme, and E3 ligase work in concert to attach the 76-amino acid ubiquitin protein to specific substrate lysine residues [1] [16]. The versatility of this modification arises from the ability of ubiquitin to form different topological structures—including monoubiquitination and various polyubiquitin chains—that create distinct signaling platforms recognized by proteins containing ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) [1]. Within the context of DNA damage and cancer research, understanding how ubiquitination regulates specific repair and tolerance pathways has become paramount, as dysregulation of these processes contributes directly to genome instability, cancer predisposition, and response to genotoxic therapies [17].

When replication forks stall at DNA lesions, cells activate sophisticated mechanisms to bypass the damage and complete DNA synthesis. Two crucial ubiquitin-regulated pathways that respond to replication-blocking lesions are Translesion Synthesis (TLS) and the Fanconi Anemia (FA) pathway. While both pathways utilize specialized E3 ubiquitin ligases and ubiquitin-binding effectors to maintain genome stability, they operate through distinct yet interconnected mechanisms. This review provides an in-depth examination of how ubiquitination controls TLS and FA pathway activation in response to replication stress, with particular emphasis on experimental approaches, key regulatory nodes, and therapeutic implications for cancer treatment.

The Ubiquitin Code in DNA Damage Tolerance

Principles of Ubiquitin Signaling

Ubiquitin modification creates a complex "code" that cells decipher to coordinate DNA repair and damage tolerance. Monoubiquitination typically serves as a recruitment signal for DNA repair proteins containing ubiquitin-binding domains, while Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chains often create signaling platforms that facilitate protein complex assembly at damage sites [1]. In contrast, Lys48-linked polyubiquitin chains primarily target substrates for proteasomal degradation [16]. This ubiquitin code is dynamically written by E3 ubiquitin ligases and erased by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), providing exquisite temporal and spatial control over DNA damage response pathways [16].

Ubiquitin-Dependent Recruitment in DNA Repair

The recruitment of repair proteins to sites of DNA damage frequently depends on their ability to recognize specific ubiquitin signals through specialized ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) such as ubiquitin-interacting motifs (UIMs) and ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) [1]. For example, in the FA pathway, multiple downstream effectors including FAN1 and SLX4 contain ubiquitin-binding motifs that are essential for their recruitment to monoubiquitinated FANCD2-FANCI complexes at stalled replication forks [18]. Similarly, TLS polymerases possess ubiquitin-binding domains that facilitate their interaction with monoubiquitinated PCNA [19]. This paradigm of ubiquitin-dependent recruitment ensures that specialized DNA repair and damage tolerance machinery are specifically localized to sites of replication stress while minimizing inappropriate activity at undamaged DNA.

Ubiquitination in the Fanconi Anemia Pathway

The FA Pathway: From Core Complex to ICL Repair

The Fanconi Anemia pathway represents a specialized DNA repair system dedicated primarily to the resolution of DNA interstrand crosslinks (ICLs), which covalently link both strands of the DNA double helix and present formidable blocks to replication and transcription [18] [20]. The FA pathway comprises at least 23 FANC proteins that function in a coordinated, multi-step process to recognize, incise, and repair ICLs [20]. Pathogenic mutations in any of these genes cause Fanconi anemia, a recessive disorder characterized by bone marrow failure, developmental abnormalities, and extreme cancer predisposition [18].

The central regulatory event in the FA pathway is the monoubiquitination of the FANCD2-FANCI (ID) complex, which serves as a molecular switch that activates the entire repair cascade [18] [20]. This critical modification is catalyzed by the FA core complex—a multi-subunit E3 ubiquitin ligase consisting of FANCA, FANCB, FANCC, FANCE, FANCF, FANCG, FANCL, and associated proteins FAAP20 and FAAP100 [20]. Within this complex, FANCL provides the catalytic RING domain that confers E3 ligase activity, while FANCT/UBE2T serves as the dedicated E2 conjugating enzyme [20]. The monoubiquitination occurs specifically at lysine 561 of FANCD2 and lysine 523 of FANCI, creating a binding platform for downstream repair factors including nucleases and homologous recombination proteins [18].

Table 1: Core Components of the Fanconi Anemia Ubiquitin Ligase Complex

| Component | Gene | Function | Domain Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| FANCL | FANCL | Catalytic E3 ubiquitin ligase | RING, ELF, DRWD domains |

| FANCT | UBE2T | E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme | Ubiquitin-conjugating (E2) domain |

| FANCA | FANCA | Core complex scaffold | - |

| FANCB | FANCB | Core complex scaffold | - |

| FANCC | FANCC | Core complex scaffold | - |

| FANCE | FANCE | Substrate recognition | Facilitates FANCD2 binding |

| FANCF | FANCF | Core complex stabilization | - |

| FANCG | FANCG | Core complex stabilization | - |

Downstream Effectors of the Monoubiquitinated ID Complex

Once monoubiquitinated, the ID complex undergoes a conformational change that enables it to stably associate with chromatin and recruit structure-specific nucleases including FANCQ/XPF and the FANCP/SLX4 scaffold complex [20]. These nucleases perform the critical "unhooking" step whereby incisions are made on either side of the ICL, releasing the crosslink and allowing translation synthesis polymerases to synthesize DNA across the resulting lesion [20]. The repair process is completed through homologous recombination (HR), which involves multiple FA/HR proteins including FANCD1/BRCA2, FANCN/PALB2, FANCO/RAD51C, FANCR/RAD51, and FANCS/BRCA1 [20]. Finally, the pathway is inactivated through deubiquitination of the ID complex by the USP1 deubiquitinating enzyme, restoring the pathway to its basal state [20].

Figure 1: The Fanconi Anemia DNA Repair Pathway. The FA core complex, with FANCL as the catalytic E3 subunit and UBE2T as the E2, monoubiquitinates the FANCI-FANCD2 (ID) complex in response to interstrand crosslinks. The monoubiquitinated ID complex recruits nucleases and other downstream effectors to complete ICL repair.

Pathophysiological Implications of FA Pathway Deficiency

The clinical manifestations of Fanconi anemia underscore the critical importance of the FA pathway in maintaining genomic stability. Studies using mouse models have revealed that endogenous metabolites, particularly reactive aldehydes such as acetaldehyde and formaldehyde, constitute a major source of endogenous DNA damage that requires the FA pathway for repair [20]. This has led to a "two-tier" model of genome protection in which the first tier consists of detoxifying enzymes like ALDH2 and ADH5 that convert reactive aldehydes to harmless metabolites, while the second tier is the FA pathway that repairs any DNA lesions that escape detoxification [20]. Deficiency in both tiers leads to accelerated bone marrow failure and leukemogenesis, highlighting the synergistic relationship between metabolic protection and DNA repair in preventing tissue degeneration and cancer [20].

Ubiquitination in Translesion Synthesis

TLS Polymerases and Their Regulation

Translesion Synthesis is a DNA damage tolerance mechanism that enables replication to proceed past blocking DNA lesions through the deployment of specialized DNA polymerases. Unlike high-fidelity replicative polymerases, TLS polymerases possess more open active sites that can accommodate damaged DNA templates, though this comes at the cost of reduced fidelity when copying undamaged DNA [19]. The mammalian TLS machinery includes several specialized polymerases such as Polη, Polκ, Polι, Rev1, and Polζ (a complex containing Rev3L, Rev7, and other subunits), each with distinct lesion bypass specificities [21] [19].

The central regulatory mechanism governing TLS polymerase recruitment involves monoubiquitination of PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear antigen), the sliding clamp that tethers DNA polymerases to the replication machinery [19]. In response to replication-blocking lesions, PCNA becomes monoubiquitinated at lysine 164 through the coordinated action of the Rad6 E2 enzyme and Rad18 E3 ligase [22] [19]. Monoubiquitinated PCNA then serves as a binding platform for TLS polymerases, many of which contain ubiquitin-binding domains that facilitate their recruitment to stalled replication forks [19].

Temporal and Mechanistic Aspects of TLS

The precise timing and location of TLS activity has been a subject of ongoing investigation. Early models proposed that TLS polymerases are recruited directly to stalled replication forks to restart replication in an "on-the-fly" manner. However, recent evidence indicates that TLS frequently occurs after replication fork restart, primarily filling single-stranded DNA gaps left behind by re-priming events downstream of lesions [21]. This gap-filling model is supported by studies showing that TLS polymerase recruitment depends on PrimPol, a primase-polymerase that re-initiates DNA synthesis downstream of replication-blocking lesions [21].

Table 2: Translesion Synthesis Polymerases and Their Characteristics

| Polymerase | Lesion Specificity | Ubiquitin Binding Domain | Cellular Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polη | Cisplatin adducts, UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers | UBZ | Error-free bypass of UV lesions |

| Polκ | Benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide (BPDE) adducts | - | Error-free bypass of bulky adducts |

| Polι | Minor groove adducts | - | Insertion polymerase |

| Rev1 | Template for deoxycytidine monophosphate insertion | UBM | Scaffold function, dCMP transferase |

| Polζ (Rev3-Rev7) | Extension across from various lesions | - | Major extender polymerase |

The requirement for PCNA ubiquitination in TLS appears to vary across organisms and experimental systems. In avian DT40 cells, PCNA ubiquitination is not required for maintaining normal fork progression on damaged DNA but is essential for filling post-replicative gaps [23]. Similarly, in mammalian cells, PCNA ubiquitination significantly enhances TLS efficiency but is not absolutely essential, as TLS polymerases can be recruited through alternative mechanisms in its absence [19]. This partial redundancy ensures maintenance of essential DNA damage tolerance capacity even when the primary regulatory mechanism is compromised.

Lesion-Specific Polymerase Recruitment

Different types of DNA damage trigger the recruitment of specific TLS polymerases through mechanisms that are still being elucidated. Recent studies using proximity ligation assays (PLA) to monitor endogenous polymerase recruitment have demonstrated that Polκ is specifically recruited to benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide (BPDE) lesions, while Polη is preferentially recruited to cisplatin adducts [21]. This lesion-specific polymerase recruitment depends on PrimPol-mediated replication restart and occurs predominantly during gap filling rather than directly at stalled forks [21]. When the appropriate TLS polymerase is deficient, unrepaired ssDNA gaps accumulate and are subsequently converted to cytotoxic double-strand breaks, explaining the lesion-specific sensitivity patterns observed in polymerase-deficient cells [21].

Experimental Approaches for Studying Ubiquitination in Replication Stress

Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA) for TLS Polymerase Recruitment

Purpose: To detect and quantify the recruitment of specific TLS polymerases to DNA lesions during replication stress.

Methodology:

- Cell Treatment and EdU Labeling: Treat cells with DNA damaging agents (e.g., 10 μM BPDE or cisplatin) for 1-2 hours, with EdU added during the final 30 minutes to label nascent DNA [21].

- Cell Fixation and Permeabilization: Fix cells with paraformaldehyde and permeabilize with Triton X-100.

- Click Chemistry Reaction: Use copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition to conjugate biotin to EdU-labeled DNA.

- Antibody Incubation: Incubate with primary antibodies against the TLS polymerase of interest (e.g., Polκ or Polη) and streptavidin to detect biotinylated EdU.

- Proximity Ligation: Apply PLUS and MINUS PLA probes against the primary antibody and streptavidin, followed by ligation and amplification using fluorescently labeled oligonucleotides.

- Microscopy and Quantification: Image PLA foci by fluorescence microscopy and quantify foci per nucleus [21].

Key Controls:

- Include untreated controls to establish baseline signals.

- Use polymerase-depleted cells (siRNA) to confirm signal specificity.

- Compare different DNA damaging agents to establish lesion specificity [21].

SIRF Assay for Protein Recruitment to Nascent DNA

Purpose: To quantitatively analyze protein interactions at DNA replication forks using the in situ analysis of protein interactions at DNA replication forks (SIRF) assay.

Methodology:

- EdU Labeling: Pulse-label cells with EdU (10 μM, 10-30 minutes) to incorporate thymidine analog into nascent DNA.

- Cell Fixation and Permeabilization: Fix cells with formaldehyde and permeabilize with 0.5% Triton X-100.

- Click Chemistry: Conjugate biotin-azide to EdU using copper-catalyzed cycloaddition.

- Immunostaining: Incubate with primary antibody against protein of interest and anti-biotin antibody.

- Proximity Ligation: Apply species-specific PLA probes, followed by ligation and rolling circle amplification.

- Fluorescence Detection and Analysis: Detect amplification products with fluorescent oligonucleotides and quantify SIRF foci per cell [21].

Applications:

- Measure recruitment of TLS polymerases (Polκ, Polη) to nascent DNA.

- Assess PCNA ubiquitination at replication forks.

- Analyze PrimPol recruitment to stalled replication forks [21].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Proximity Ligation Assays. The diagram illustrates the key steps in PLA-based detection of protein recruitment to DNA damage sites, incorporating EdU labeling for nascent DNA detection and proximity ligation for signal amplification.

Analysis of PCNA Ubiquitination

Purpose: To detect and quantify PCNA monoubiquitination in response to replication stress.

Methodology:

- Cell Lysis: Prepare whole cell extracts or chromatin-enriched fractions in denaturing lysis buffer.

- Immunoprecipitation: Use anti-PCNA antibody conjugated to protein A/G beads for immunoprecipitation.

- Western Blotting: Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to PVDF membrane.

- Detection: Probe with anti-ubiquitin and anti-PCNA antibodies to distinguish monoubiquitinated PCNA (shifted band) from unmodified PCNA [19].

Alternative Approach:

- Use cells expressing epitope-tagged ubiquitin (e.g., His-Ub or HA-Ub) for nickel pull-down under denaturing conditions followed by PCNA immunoblotting [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Ubiquitination in Replication Stress

| Reagent/Cell Line | Specific Application | Function/Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| PcnaK164R/K164R MEFs | Study PCNA ubiquitination-deficient TLS | Expresses PCNA mutant that cannot be ubiquitinated at K164 [19] |

| Rad18-/- cells | Analyze Rad18-dependent ubiquitination | Lacks the E3 ligase responsible for PCNA monoubiquitination [19] |

| Usp1-/- cells | Study enhanced PCNA ubiquitination | Lacks the deubiquitinating enzyme that removes Ub from PCNA [19] |

| siRNA libraries | Gene knockdown studies | Deplete specific TLS polymerases or FA proteins [21] |

| Anti-BPDE DNA adduct antibody | Detect specific DNA lesions | Recognizes and binds to BPDE-DNA adducts for PLA [21] |

| EdU (5-ethynyl-2'-deoxyuridine) | Nascent DNA labeling | Incorporates into replicating DNA for click chemistry detection [21] |

| PLA (Proximity Ligation Assay) kits | Protein-protein/DNA interactions | Amplifies signals from proximal binding events [21] |

Interplay Between TLS and FA Pathways

Emerging evidence indicates significant functional crosstalk between the TLS and FA pathways in responding to replication stress. The E3 ubiquitin ligase Rad18, which monoubiquitinates PCNA to activate TLS, also contributes to FANCD2 monoubiquitination and FA pathway activation [22]. This functional connection was demonstrated through experiments showing that Rad18 overexpression induces DNA damage-independent FANCD2 monoubiquitination, while Rad18 deficiency attenuates DNA damage-induced FANCD2 modification [22]. However, Rad18-mediated FANCD2 ubiquitination requires an intact FA core complex, indicating that Rad18 functions upstream of the core complex rather than directly ubiquitinating FANCD2 [22].

This interplay between TLS and FA pathways creates a coordinated response network wherein both pathways are activated by common upstream regulators but specialize in different aspects of replication stress management. The FA pathway primarily handles the complex task of ICL repair through nucleolytic incision and homologous recombination, while TLS provides a more rapid mechanism for bypassing simpler replication-blocking lesions. The shared regulation through ubiquitination ensures that both pathways can be coordinately activated in response to different types and levels of replication stress.

Therapeutic Implications and Cancer Relevance

Targeting Ubiquitination in Cancer Therapy

The critical role of ubiquitination in DNA damage response pathways presents attractive opportunities for cancer therapeutic intervention. Many E3 ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinating enzymes are deregulated in human cancers, making them potential targets for small molecule inhibitors [17]. For example, inhibitors of USP1, the deubiquitinating enzyme that inactivates the FA pathway, have shown promise in sensitizing cancer cells to DNA crosslinking agents [20]. Similarly, targeting the Rad18-mediated PCNA ubiquitination could modulate TLS activity and alter the response to genotoxic therapies.

The synthetic lethal relationships between DNA repair pathways provide particularly promising therapeutic avenues. Cancers with deficiencies in specific DNA repair pathways (e.g., homologous recombination deficiencies in BRCA-mutant cancers) often develop heightened dependence on backup pathways such as TLS [21]. Inhibition of these backup pathways can therefore selectively target repair-deficient cancer cells while sparing normal cells. For instance, the finding that BRCA-deficient cells are hypersensitive to TLS inhibition suggests that TLS polymerases could be therapeutic targets in BRCA-mutant cancers [21].

Biomarker Development and Treatment Stratification

Understanding the regulation of TLS and FA pathways has important implications for cancer biomarker development and treatment stratification. The lesion-specific recruitment patterns of TLS polymerases [21] suggest that polymerase expression levels could predict responses to specific chemotherapeutic agents. Similarly, the expression levels of FA pathway components may serve as biomarkers for sensitivity to crosslinking agents such as cisplatin and mitomycin C [18] [20].

The role of endogenous metabolites in driving DNA damage accumulation in FA-deficient cells [20] also suggests potential preventive strategies aimed at reducing exposure to genotoxic metabolites, particularly in individuals with inherited FA pathway deficiencies. This might include dietary modifications or pharmacological approaches to enhance detoxification of reactive aldehydes in FA patients.

Ubiquitination serves as a central regulatory mechanism that coordinates the cellular response to replication stress through both the Fanconi Anemia and Translesion Synthesis pathways. The FA pathway utilizes a sophisticated multi-component E3 ubiquitin ligase complex to monoubiquitinate the FANCD2-FANCI heterodimer, triggering a complex repair process for DNA interstrand crosslinks. In parallel, the TLS pathway employs Rad18-dependent monoubiquitination of PCNA to recruit specialized polymerases that bypass replication-blocking lesions. While these pathways operate through distinct mechanisms, they exhibit significant functional crosstalk and are often co-regulated in response to replication stress.

Future research directions include elucidating the structural basis for ubiquitin-dependent protein recruitment in these pathways, developing more specific inhibitors targeting key ubiquitin-regulating enzymes, and exploring the therapeutic potential of manipulating these pathways for cancer treatment. The continued dissection of ubiquitin signaling in DNA damage response will undoubtedly yield new insights into genome maintenance mechanisms and provide novel approaches for targeting the vulnerabilities of cancer cells.

The integrity of the genome is continuously challenged by endogenous and exogenous DNA-damaging agents. Among the most deleterious lesions are DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), which can lead to genomic instability, cellular senescence, and tumorigenesis if not properly repaired [24] [25] [26]. Eukaryotic cells have evolved sophisticated DNA damage response (DDR) systems that detect lesions, signal their presence, and facilitate repair. These processes occur in the context of chromatin, the complex of DNA and proteins that packages the genome within the nucleus. Central to the DDR are post-translational modifications (PTMs) of histones, which alter chromatin structure and create binding platforms for repair factors [27] [24]. Ubiquitination of histones—the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to lysine residues—has emerged as a pivotal regulatory mechanism that guides DNA repair pathway choice and efficiency [28] [24] [25]. Within cancer research, understanding these mechanisms is crucial, as dysregulation of chromatin ubiquitination contributes to tumorigenesis and influences responses to DNA-damaging chemotherapeutics [29] [27].

This review examines the mechanisms and functions of histone ubiquitination in the recruitment of DNA repair factors. We detail the specific ubiquitin marks deposited in response to damage, the enzymatic cascades that create them, the reader proteins that interpret them, and the functional consequences for repair pathway choice, with a particular focus on implications for cancer biology.

Core Mechanisms of Histone Ubiquitination

Histone Ubiquitination Writers and Erasers

Protein ubiquitylation is an enzymatic process involving a cascade of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes. Histone ubiquitination primarily results in monoubiquitylation, which serves a signaling rather than degradative function [28] [30]. The reversal of these marks is catalyzed by deubiquitylating enzymes (DUBs), ensuring dynamic control over the DDR [28].

Table 1: Major Histone Ubiquitin Marks in the DNA Damage Response

| Histone Mark | E3 Ligase(s) | Deubiquitinase(s) | Primary Function | Associated Repair Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2AK13ub/H2AK15ub | RNF168 | n.d. | DSB signaling; 53BP1 recruitment | NHEJ [31] [25] |

| H2AK119ub | Ring2 (PRC1), 2A-HUB | BAP1 | Transcription repression; DDR role emerging | Multiple [28] [30] |

| H2Bub1 (H2BK120ub) | RNF20/RNF40 | USP22, USP3 | Transcription activation; H3K4/H3K79 methylation | HR, NER [29] [28] |

| H2AK127/129ub | BRCA1-BARD1 | n.d. | SMARCAD1 recruitment; HR promotion | HR [25] |

n.d.: not definitively established in the search results.

The RNF8-RNF168 ubiquitin ligase cascade plays a central role in DSB signaling. RNF8 is recruited to DSBs by phosphorylated MDC1 and initiates histone ubiquitination. RNF168 then amplifies this signal by depositing non-canonical K27-linked ubiquitin chains and catalyzing monoubiquitylation of H2A at K13 and K15, creating a binding site for the key repair factor 53BP1 [31] [25]. Another critical E3 ligase, BRCA1-BARD1, promotes homologous recombination by ubiquitinating H2A at K127/129, which is recognized by the ubiquitin reader SMARCAD1 to initiate chromatin remodeling [25].

Readers of Ubiquitinated Histones

The ubiquitin marks deposited on histones are interpreted by specialized "reader" proteins that contain ubiquitin-binding domains. These readers transduce the ubiquitin signal into specific downstream biological outcomes, such as the recruitment of repair machinery.

Table 2: Key Readers of Ubiquitinated Histones in DNA Repair

| Reader Protein | Histone Ubiquitin Mark Recognized | Functional Outcome | Impact on Repair Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| 53BP1 | H2AK15ub | Promotes NHEJ; Blocks HR | NHEJ promotion [24] [25] |

| SMARCAD1 | H2AK127/129ub | Initiates chromatin remodeling for resection | HR promotion [25] |

| BRPF1 | H2AK119ub | n.d. | n.d. [30] |

| ZMYM2 | H2AK119ub | n.d. | n.d. [30] |

The 53BP1 reader exemplifies the precision of this recognition system. It binds to H2AK15ub in a bivalent manner, simultaneously recognizing both H2AK15ub and H4K20me2 marks. This dual recognition ensures specific recruitment to DSB sites, where 53BP1 promotes non-homologous end joining by protecting DNA ends from resection [24] [25].

Figure 1: The RNF8-RNF168 Ubiquitin Signaling Cascade in DSB Repair. This pathway initiates with double-strand break detection and culminates in 53BP1 recruitment to promote non-homologous end joining (NHEJ).

Pathway-Specific Regulation by Ubiquitination

The Balance Between NHEJ and HR

The choice between the two major DSB repair pathways—non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR)—is critically regulated by histone ubiquitination and its crosstalk with other modifications. The RNF8-RNF168 axis establishes a chromatin platform marked by H2AK15ub that promotes the recruitment of 53BP1, a key NHEJ factor [24] [25]. Conversely, when HR is the preferred pathway, the TIP60/NuA4 acetyltransferase complex acetylates H2AK15, directly blocking its ubiquitination and thereby impairing 53BP1 binding [25]. TIP60 also acetylates H4K16, which physically inhibits 53BP1 binding to H4K20me2, further promoting HR [25]. Additionally, the removal or absence of methylation at H4K20 (H4K20me0) creates a binding site for the BRCA1-BARD1 complex, which ubiquitinates H2A at K127/129 to recruit SMARCAD1 and initiate the chromatin remodeling necessary for end resection [25].

Figure 2: Histone Modification Crosstalk Regulates Repair Pathway Choice. The competition between ubiquitination and acetylation at H2AK15 determines whether 53BP1 or BRCA1-BARD1 is recruited, guiding the choice between NHEJ and HR.

Ubiquitination in Replication Stress and Other Repair Pathways

Beyond DSB repair, chromatin ubiquitination plays crucial roles in managing replication stress. The MRN complex, traditionally associated with DSB sensing, is recruited to stalled replication forks in an ubiquitin-dependent manner. Recent research has shown that RNF168 and its histone targets H2AK13ub and H2AK15ub are required for proper replication fork progression and prevention of reversed fork accumulation, particularly at repetitive genomic sequences [31]. This suggests that DSB signaling factors are co-opted for replication fork stability, with ubiquitin marks serving as central regulators.

In nucleotide excision repair (NER), H2B ubiquitination (H2Bub1) has been implicated in the repair of platinum-based chemotherapeutic lesions. Following platinum-induced DNA damage, global H2Bub1 levels decrease, but H2Bub1 becomes specifically enriched downstream of transcription start sites of genes involved in NER, ERK/MAPK signaling, and immune response [29]. This gene-specific enrichment correlates with increased expression of these cancer-related genes, suggesting H2Bub1 helps regulate the transcriptional response to therapeutic DNA damage.

Chromatin Ubiquitination in Cancer and Therapy

Dysregulation of histone ubiquitination contributes significantly to tumorigenesis and cancer progression. Abnormal levels of histone ubiquitination modifiers disrupt gene expression patterns and DNA repair fidelity, leading to genomic instability [27] [32]. For instance, the H2AK119ub-specific E3 ligase Ring1B is a Polycomb group protein frequently mutated in human cancers, while the corresponding DUB BAP1 is a recognized tumor suppressor [30]. The proper balance of these opposing activities is essential for maintaining epigenetic programs that suppress malignant transformation.

The response to cancer therapeutics is also heavily influenced by chromatin ubiquitination. Platinum-based chemotherapeutics like cisplatin induce DNA damage that triggers ubiquitin-mediated chromatin remodeling [29]. This remodeling is associated with the expression of key cancer genes and pathways, including p53 target genes, DNA repair genes like XPC and POLH, and genes linked to platinum resistance. Understanding these mechanisms provides opportunities for therapeutic intervention, such as targeting the ubiquitin ligases or readers that control repair pathway choice in cancer cells.

Experimental Approaches and Research Tools

Key Methodologies for Studying Chromatin Ubiquitination

Investigating the role of ubiquitination in the DDR requires a combination of biochemical, cellular, and genomic approaches. Key methodologies include:

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Sequencing: Used to map the localization of ubiquitinated histones and repair factors genome-wide. For example, this approach revealed H2Bub1 enrichment downstream of transcription start sites of specific cancer-related genes after platinum treatment [29].

Co-immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting: Essential for identifying protein-protein interactions and monitoring protein modifications. These techniques demonstrated the interaction between βTrCP and MRN complex proteins and the GSK3 kinase dependence of this association [26].

In vitro Ubiquitination Assays: Employ purified E1, E2, and E3 enzymes with histone substrates to reconstitute ubiquitination events biochemically. This approach confirmed SCF(βTrCP) as a novel ubiquitin ligase for MRN complex proteins [26].

Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Used to identify critical residues for ubiquitination and protein interactions. Mutagenesis of the putative degron motif in MRE11 (MRE11Δβ) abrogated its interaction with βTrCP, localizing the binding site to amino acids 596-603 [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Chromatin Ubiquitination

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Ligase Inhibitors | Small molecule inhibitors of RNF168, Ring2 | Probe function of specific E3 ligases; Potential therapeutic agents | Study of DSB signaling pathway choice [27] |

| Deubiquitinase Inhibitors | BAP1 inhibitors, USP22 inhibitors | Stabilize ubiquitin marks; Enhance DNA damage sensitivity | Cancer therapy combination approaches [27] [30] |

| Kinase Inhibitors | PF4708671 (p70S6K inhibitor), Lithium Chloride (GSK3 inhibitor) | Disrupt kinase-dependent ubiquitin ligase interactions | MRN complex regulation studies [26] |

| Site-Directed Mutants | MRE11Δβ (degron mutant), H2A K13/15R mutants | Disrupt specific protein interactions or ubiquitination sites | Mechanism of reader recruitment and repair pathway choice [31] [26] |

| Antibodies for Detection | Anti-H2AK15ub, Anti-H2Bub1, Anti-53BP1 | Detect specific ubiquitin marks and recruited factors in IF, ChIP, WB | Monitoring DDR activation and repair progression [29] [25] |

Concluding Perspectives

Chromatin ubiquitination represents a sophisticated signaling system that orchestrates the cellular response to DNA damage by creating platforms for the recruitment of specific repair factors. The precise placement and interpretation of ubiquitin marks on histones guides critical decisions in DNA repair, including pathway choice between NHEJ and HR. In cancer biology, the dysregulation of these processes contributes to tumorigenesis and influences therapeutic responses. Future research will likely focus on developing more specific modulators of ubiquitin writers, erasers, and readers as potential cancer therapeutics, particularly in combination with existing DNA-damaging agents. The integration of chromatin ubiquitination signaling with other epigenetic networks and with the broader context of nuclear organization represents an exciting frontier for understanding genome maintenance in health and disease.

From Mechanism to Medicine: Therapeutic Targeting of the Ubiquitin System in Cancer

The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (UPP) represents the major pathway for intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotic cells, regulating critical processes including cell cycle progression, apoptosis, transcription, and DNA repair [33]. More than 80% of cellular proteins are degraded through this highly specific system, wherein proteins are tagged with polyubiquitin chains for recognition and breakdown by the 26S proteasome [33]. The 26S proteasome consists of a core 20S catalytic particle capped by two 19S regulatory particles that recognize ubiquitinated substrates [33]. Malignant cells exhibit heightened dependence on proteasome function to maintain protein homeostasis and eliminate misfolded proteins, creating a therapeutic vulnerability that can be exploited pharmacologically [33]. Proteasome inhibitors have emerged as powerful therapeutic agents that disrupt this critical cellular pathway, inducing apoptosis preferentially in cancer cells.

Bortezomib, a first-in-class dipeptidyl boronic acid proteasome inhibitor, has revolutionized the treatment landscape for hematologic malignancies, particularly multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma [34]. This whitepaper examines the clinical success of bortezomib and next-generation proteasome inhibitors within the broader context of ubiquitination in DNA damage response and cancer research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical resource on the mechanisms, applications, and experimental methodologies underlying this critical drug class.

Mechanistic Foundations of Proteasome Inhibition

Molecular Pharmacology of Proteasome Inhibitors

Bortezomib exerts its antineoplastic activity through reversible, high-affinity inhibition of the chymotrypsin-like (CT-L) activity of the 26S proteasome's β5 subunit [34]. This inhibition disrupts the regulated degradation of intracellular proteins, leading to accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins and induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress [34] [35]. The primary mechanisms through which bortezomib exerts cytotoxic effects include:

- Inhibition of NF-κB signaling: By preventing degradation of IκB, bortezomib inhibits nuclear translocation of the transcription factor NF-κB, downregulating expression of anti-apoptotic and proliferative genes [33]

- Cell cycle arrest: Stabilization of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (e.g., p21, p27) and tumor suppressors (e.g., p53) induces G1/S and G2/M phase arrest [34] [33]

- Activation of apoptotic pathways: Accumulation of pro-apoptotic proteins (NOXA, BIM), caspase activation, and JNK pathway stimulation promote mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis [34] [35]

- Disruption of protein homeostasis: Accumulation of misfolded proteins triggers the unfolded protein response and endoplasmic reticulum stress [35]

Ubiquitination in DNA Damage Response and Cancer

The ubiquitin-proteasome system plays an integral role in the DNA damage response (DDR), particularly in double-strand break (DSB) repair pathway choice between non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR) [24]. Key E3 ubiquitin ligases, including RNF8 and RNF168, establish a ubiquitin-dependent signaling cascade at DNA damage sites that recruits repair proteins such as 53BP1 (promoting NHEJ) and BRCA1 (promoting HR) [24]. Proteasome inhibition disrupts this delicate regulatory network, potentially sensitizing cancer cells to DNA-damaging agents and contributing to genomic instability.

The intersection between ubiquitination, DDR, and cancer metabolism represents an emerging research frontier. E3 ubiquitin ligases such as NEDD4, APC/CCDH1, FBXW7, and Pellino1 regulate enzymes in key metabolic pathways including glycolysis, the TCA cycle, and fatty acid metabolism, while simultaneously modulating DDR components [36]. This dual regulatory capacity positions the ubiquitin-proteasome system as a critical link between metabolic reprogramming and genomic integrity maintenance in cancer cells.

Clinical Applications and Efficacy Data

Regulatory Approvals and Indications

Bortezomib has received extensive regulatory approvals for hematologic malignancies, demonstrating its transformative clinical impact [34]. The table below summarizes key regulatory milestones:

Table 1: Bortezomib Regulatory Approval Timeline

| Year | Regulatory Agency | Indication |

|---|---|---|

| 2003 | FDA | Accelerated approval for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM) after ≥2 prior therapies |

| 2005 | FDA | Regular approval for MM progressing after ≥1 prior therapy |

| 2006 | FDA | Relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) |

| 2008 | FDA | Previously untreated MM |

| 2014 | FDA | Retreatment of MM patients with previous response to bortezomib who relapsed ≥6 months after completion |

| 2014 | FDA & EMA | Previously untreated MCL |

Beyond its approved indications, bortezomib demonstrates clinical efficacy in several off-label hematologic malignancies, including light chain (AL) amyloidosis, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenström macroglobulinemia, and peripheral T-cell lymphomas [34]. The drug's clinical utility has been further expanded by the availability of generic formulations since 2015, potentially improving accessibility in lower-income countries [34].

Efficacy Across Hematologic Malignancies