Ubiquitylomics in Cancer Research: Comprehensive Analysis of Ubiquitination Landscapes in Malignant vs Normal Tissues

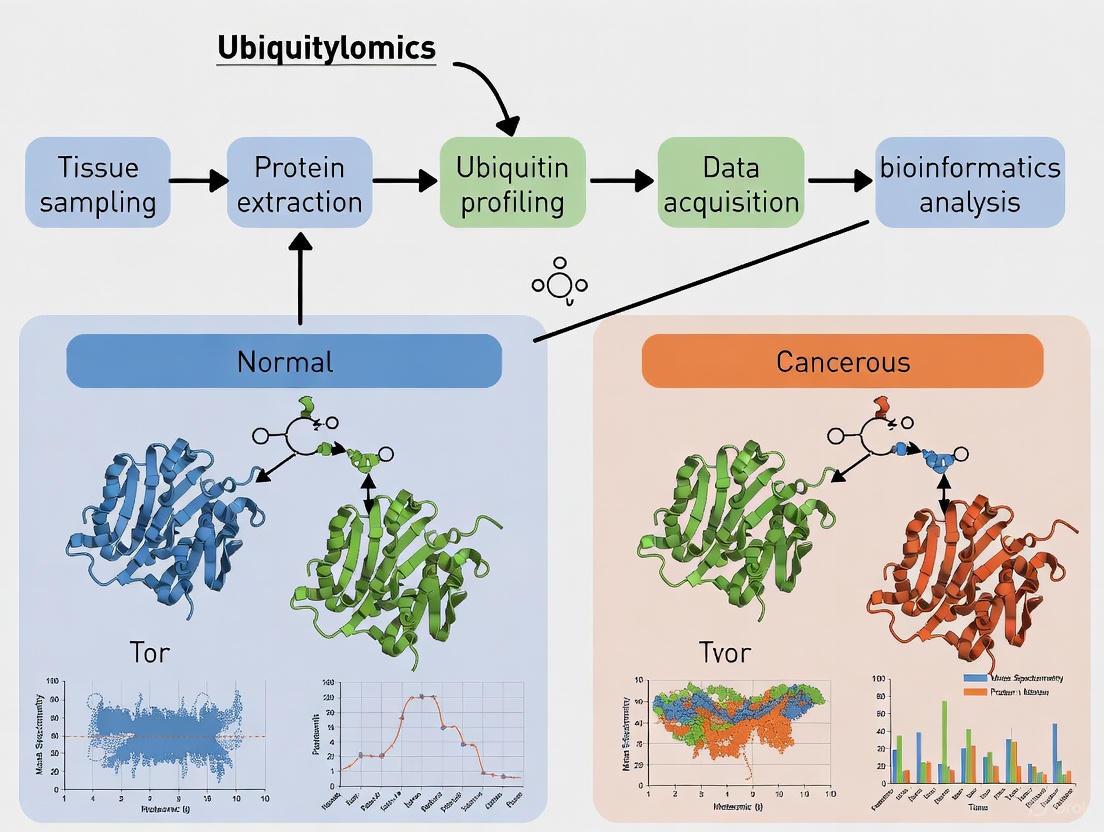

This article provides a comprehensive examination of ubiquitylomics—the large-scale study of protein ubiquitination—in the context of cancer biology and therapeutic development.

Ubiquitylomics in Cancer Research: Comprehensive Analysis of Ubiquitination Landscapes in Malignant vs Normal Tissues

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of ubiquitylomics—the large-scale study of protein ubiquitination—in the context of cancer biology and therapeutic development. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the fundamental principles of ubiquitin signaling dysregulation in tumorigenesis, advanced mass spectrometry methodologies for ubiquitination profiling, optimization strategies for overcoming technical challenges in tissue analysis, and validation approaches for translating findings into clinical applications. Through comparative analysis of cancerous versus normal tissues, this review highlights how ubiquitylomics identifies novel therapeutic targets, reveals disease mechanisms, and informs the development of targeted cancer therapies including proteasome inhibitors and E3 ligase modulators.

Decoding the Ubiquitin Code: Fundamental Principles and Cancer Relevance

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) is a crucial mechanism for maintaining cellular protein homeostasis, responsible for the controlled degradation of short-lived, misfolded, and damaged proteins [1] [2]. This system regulates the turnover of over 80% of cellular proteins and is integral to fundamental biological processes, including cell cycle progression, gene expression, DNA damage repair, and responses to oxidative and inflammatory stress [1] [3]. The UPS operates through a coordinated enzymatic cascade that tags target proteins with ubiquitin chains, marking them for degradation by the 26S proteasome [1] [2]. Dysregulation of the UPS has been implicated in the pathogenesis of numerous diseases, most notably cancer, making it a focal point for therapeutic development [1] [4]. In cancerous tissues, alterations in UPS components lead to aberrant stability of oncoproteins and tumor suppressors, driving tumorigenesis and progression [4]. This application note details the core components of the UPS and provides methodological frameworks for ubiquitylomics analysis in cancer research.

The Enzymatic Cascade of Ubiquitination

Ubiquitination involves a sequential, ATP-dependent cascade mediated by three key enzyme families: E1 (ubiquitin-activating enzyme), E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme), and E3 (ubiquitin ligase) [2] [5]. The process culminates in the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to target proteins, which can signal for proteasomal degradation or alter the protein's function, localization, or interactions [1].

Table 1: Core Enzymes of the Ubiquitination Cascade

| Enzyme | Number in Humans | Primary Function | Key Functional Domains |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Activating Enzyme) | Few | Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner and transfers it to E2 enzymes. | Active cysteine site for thioester bond formation with ubiquitin. |

| E2 (Conjugating Enzyme) | ~40 | Accepts activated ubiquitin from E1 and collaborates with E3 to transfer ubiquitin to the substrate. | Active cysteine site for thioester bond with ubiquitin. |

| E3 (Ligase Enzyme) | >600 | Confers substrate specificity by recognizing and binding target proteins, facilitating ubiquitin transfer from E2 to substrate. | RING, HECT, or RBR domains that determine the mechanism of ubiquitin transfer. |

The Ubiquitin Transfer Mechanism

The ubiquitination cascade begins with the E1 enzyme, which activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction, forming a high-energy thioester bond between its own active cysteine residue and the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin [5]. The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to the active cysteine site of an E2 enzyme. Finally, an E3 ubiquitin ligase recruits the E2~ubiquitin complex and a specific substrate protein. The E3 catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine residue on the substrate protein, forming an isopeptide bond [1] [2]. The mechanism of this final transfer depends on the E3 type: RING-type E3s facilitate direct transfer from the E2 to the substrate, while HECT and RBR-type E3s form a transient thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate [1] [5].

Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Functional Consequences

Ubiquitin itself contains eight primary attachment sites: seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and the N-terminal methionine (M1) [6] [1] [2]. These sites allow for the formation of diverse polyubiquitin chains, each encoding distinct cellular signals.

Table 2: Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Primary Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Cellular Functions | Proteasomal Degradation |

|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | The primary signal for proteasomal degradation of substrate proteins. [1] [5] | Yes |

| K63-linked | Regulates non-proteolytic processes: DNA damage repair, kinase activation, inflammatory signaling, and endocytosis. [6] [1] | No |

| M1-linked (Linear) | Activates NF-κB signaling by modulating the IKK complex; regulates inflammation. [6] [1] | No |

| K11-linked | Involved in cell cycle regulation and ER-associated degradation (ERAD). [1] | Yes (Hybrid chains) |

| K27/K29-linked | DNA damage response, mitochondrial quality control, and innate immune signaling. [1] | Context-dependent |

| K6/K33-linked | DNA damage repair and regulation of intracellular trafficking. [1] | No |

E3 Ubiquitin Ligases and Deubiquitinases (DUBs)

Classification and Function of E3 Ubiquitin Ligases

E3 ubiquitin ligases are the most diverse components of the UPS, providing substrate specificity. With over 600 members in the human genome, they are classified based on their structural domains and mechanisms of ubiquitin transfer [1] [5].

- RING (Really Interesting New Gene) E3 Ligases: This is the largest family of E3 ligases. They function as scaffolds that simultaneously bind the E2~Ub complex and the substrate, facilitating the direct transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to the substrate without forming an E3-Ub intermediate [1]. Examples include TRAF6 and Cullin-RING Ligases (CRLs), which are multi-subunit complexes [6] [1].

- HECT (Homologous to the E6AP C-Terminus) E3 Ligases: HECT E3s feature an active cysteine residue within their HECT domain. They catalyze a two-step reaction: first, they accept ubiquitin from the E2 enzyme, forming a thioester bond; then, they transfer the ubiquitin to the substrate protein. The Nedd4 family and HERC family are prominent subclasses [1].

- RBR (RING-Between-RING) E3 Ligases: RBR E3s hybridize the mechanisms of RING and HECT types. They contain a RING1 domain that binds the E2~Ub and an intermediate "RING2" domain with an active cysteine residue that accepts ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate, similar to HECT E3s [1] [5].

The Role of Deubiquitinases (DUBs)

Deubiquitination is the reverse process, catalyzed by Deubiquitinases (DUBs). DUBs are proteases that cleave ubiquitin from substrate proteins, thereby reversing ubiquitin signals and maintaining the pool of free ubiquitin [2]. They play critical editing roles by:

- Rescuing proteins from proteasomal degradation by removing K48-linked chains.

- Terminating ubiquitin-mediated signals, such as those in kinase activation or DNA repair.

- Processing ubiquitin precursors and cleaving polyubiquitin chains to recycle ubiquitin [2].

DUBs are classified into several families, including Ubiquitin-Specific Proteases (USPs), Otubain (OTU) proteases, Ubiquitin C-terminal Hydrolases (UCHs), and JAMM/MPN metalloenzymes [6] [2].

Quantitative Ubiquitylomics in Cancer Research

Quantitative ubiquitylomics is a powerful proteomic approach for globally profiling ubiquitination sites, enabling the systematic comparison of ubiquitinated proteins between cancerous and normal tissues [4]. This methodology is critical for identifying dysregulated pathways and novel therapeutic targets.

Key Experimental Protocol: 4D Label-Free Quantitative Ubiquitylomics

The following protocol is adapted from a study investigating ubiquitination in Oral Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma (OACC) [4].

Objective: To identify and quantify differentially ubiquitinated proteins between OACC tumor tissues and adjacent normal tissues.

Workflow Overview:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize frozen tissue samples (OACC vs. normal) in a lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors, phosphatase inhibitors, and deubiquitinase inhibitors (e.g., N-Ethylmaleimide).

- Protein Digestion: Denature and reduce lysates. Alkylate cysteine residues. Digest proteins to peptides using trypsin.

- Ubiquitinated Peptide Enrichment: Use anti-di-glycine (K-ε-GG) antibody-conjugated beads to immunoaffinity purify peptides containing the diglycine remnant left after tryptic digestion of ubiquitinated proteins. This is a critical step for enriching low-abundance ubiquitinated peptides.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Chromatography: Separate enriched peptides using nano-scale liquid chromatography (nanoLC).

- Mass Spectrometry: Analyze peptides using a timsTOF mass spectrometer configured for 4D proteomics (adding ion mobility as a fourth dimension). Data is acquired in a data-independent acquisition (DIA) mode for deep, reproducible quantification.

- Data Processing and Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Identification: Search MS/MS spectra against a human protein database to identify ubiquitination sites.

- Quantification: Use label-free quantification algorithms to compare ubiquitination site abundance between tumor and normal groups.

- Bioinformatics: Perform Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis, and motif analysis on the differentially ubiquitinated proteins.

Key Findings from Ubiquitylomics Profiling

The application of quantitative ubiquitylomics in OACC research successfully identified 4,152 ubiquitination sites on 1,993 proteins [4]. Bioinformatic analysis of these sites revealed distinct protein clusters and ubiquitination motifs that are dysregulated in carcinoma compared to normal tissues. This systematic mapping provides a rich resource for identifying potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for this rare salivary gland tumor [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitylomics and UPS Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| K-ε-GG Motif Antibody | Immunoaffinity enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides for mass spectrometry. Critical for ubiquitylomics. [4] | Available as monoclonal antibodies from several vendors (e.g., Cell Signaling Technology, PTM Bio). |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | To block protein degradation and stabilize ubiquitinated proteins for study. | Bortezomib, MG132. Used in cell culture and in vivo studies. [6] [3] |

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors | To preserve ubiquitin chains during sample preparation by preventing their cleavage by endogenous DUBs. | N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM), PR-619. Added to lysis buffers. [4] |

| PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) | Bifunctional molecules that recruit E3 ligases to target proteins of interest, inducing their degradation. A major therapeutic modality. [6] [1] | Consist of a target protein ligand linked to an E3 ligase ligand (e.g., von Hippel-Lindau or Cereblon). |

| TUBE (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entity) | Affinity matrices to purify polyubiquitinated proteins from complex lysates. | Used for pull-down assays to study endogenous protein ubiquitination. |

| Recombinant E1, E2, E3 Enzymes | For in vitro ubiquitination assays to study specific enzyme activities, kinetics, and substrate identification. | Available from specialized protein suppliers. |

Ubiquitination is a critical post-translational modification that regulates nearly every cellular process in eukaryotes, employing a simple 9.6 kDa protein—ubiquitin—to generate complex signals that control protein fates [7]. The remarkable functional diversity of ubiquitination stems from the various architectures of ubiquitin chains that can be formed, known collectively as the "ubiquitin code" [7]. These architectures include monoubiquitination, multi-monoubiquitination, and polyubiquitin chains that can be homotypic (uniformly linked through the same ubiquitin residue), heterotypic mixed (containing multiple linkage types but with each ubiquitin modified at only one site), or heterotypic branched (containing ubiquitin monomers simultaneously modified at two or more different sites) [8]. The specificity of ubiquitin signaling is determined by the combination of linkage types, chain length, and overall architecture, which are recognized by specific ubiquitin-binding proteins (UBPs) containing ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) to execute appropriate cellular responses [7] [8].

The two most abundant and well-studied linkage types are lysine 48-linked (K48) and lysine 63-linked (K63) ubiquitin chains. K48-linked chains represent the classical degradation signal, predominantly targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains primarily regulate non-degradative functions including signal transduction, protein trafficking, autophagy, and DNA repair pathways [7] [8] [9]. Recent research has revealed that these linkage types do not always function independently; they can combine to form branched ubiquitin chains that create unique signaling properties not present in homotypic chains [7] [8] [10]. Understanding the intricacies of ubiquitin linkage diversity is particularly crucial in cancer research, where dysregulation of ubiquitin signaling contributes to tumor development, progression, and therapeutic resistance [11] [12] [13].

Ubiquitin Chain Types and Their Cellular Functions

Specification of Major Ubiquitin Linkages

The ubiquitin code encompasses a diverse array of chain types that regulate distinct cellular outcomes. Table 1 summarizes the key ubiquitin linkage types, their structural characteristics, and primary cellular functions.

Table 1: Major Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Functions

| Linkage Type | Chain Architecture | Primary Cellular Functions | Key Recognition Proteins/Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Homotypic or branched | Proteasomal degradation, cell cycle control | Proteasome, RAD23B, DDI2 [7] [8] |

| K63-linked | Homotypic or branched | NF-κB signaling, autophagy, DNA repair, protein trafficking | TAB2/3, EPN2, CCDC50 [7] [8] [9] |

| K48/K63-branched | Heterotypic branched | NF-κB signaling amplification, proteasomal degradation (context-dependent) | TAB2, HIP1, PARP10, UBR4 [7] [10] |

| K11-linked | Homotypic or branched | ER-associated degradation, cell cycle regulation | Proteasome, CDC50 [8] |

| M1-linked (linear) | Homotypic | NF-κB activation, inflammation | NEMO, HOIP [8] |

| K6-, K27-, K29-, K33-linked | Homotypic or branched | DNA damage response, immune signaling, kinase regulation (less characterized) | Various specialized UBPs [8] [14] |

K48-Linked Chains: The Classical Degradation Signal

K48-linked ubiquitin chains represent the most abundant linkage type in cells and serve as the primary signal for proteasomal degradation [7] [8]. The conventional understanding holds that proteins tagged with K48-linked chains containing at least four ubiquitin molecules (K48-Ub4) are recognized by the 26S proteasome, leading to their ATP-dependent degradation [7]. This pathway is essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis by controlling the turnover of regulatory proteins, eliminating misfolded proteins, and supporting cell cycle progression [7] [12]. Recent research has identified specific interactors that recognize K48-linked chains, including RAD23B and the ubiquitin-directed endoprotease DDI2, which exhibit preference for longer K48-linked chains (Ub3 over Ub2) [7]. The K48 linkage also participates in branched chain architectures, particularly in combination with K63 linkages, creating complex signals that can influence protein stability and function in ways distinct from homotypic K48 chains [7] [8] [10].

K63-Linked Chains: Multifunctional Non-degradative Signals

In contrast to K48-linked chains, K63-linked ubiquitin chains primarily mediate non-degradative functions across multiple cellular pathways [7] [8] [9]. These chains serve as scaffolds for the assembly of signaling complexes in the NF-κB and MAPK pathways, where they facilitate protein-protein interactions and kinase activation [7] [9]. In autophagy, K63 chains mark cargo proteins for lysosomal degradation through recognition by autophagy receptors [7]. They also play critical roles in DNA damage repair mechanisms, endocytic trafficking, and inflammatory responses [7] [8] [9]. The functional diversity of K63-linked chains is enabled by specialized receptors that recognize this linkage type, including TAB2 in the NF-κB pathway and EPN2 in protein trafficking [7]. Like K48 linkages, K63 chains can form branched architectures, expanding their signaling capabilities beyond homotypic chains [7] [8] [10].

Branched Ubiquitin Chains: Complex Signals with Unique Properties

Branched ubiquitin chains containing K48 and K63 linkages (K48/K63-branched Ub) represent a emerging area of research that reveals how combinations of linkage types can generate unique signaling outcomes [7] [8] [10]. These branched chains constitute approximately 20% of all K63 linkages in cells and exhibit functions distinct from their homotypic counterparts [7] [10]. For instance, during IL-1β signaling, the E3 ligase HUWE1 generates K48 branches on K63 chains assembled by TRAF6, creating K48/K63-branched chains that simultaneously promote NF-κB activation while protecting the K63 linkages from deubiquitination by CYLD [10]. This combination of K48 and K63 linkages creates a stabilized signaling platform that amplifies NF-κB responses [10]. In other contexts, such as during the apoptotic response, K48/K63-branched chains formed by collaboration between ITCH and UBR5 target the pro-apoptotic regulator TXNIP for proteasomal degradation [8]. These findings illustrate how branched chains can either enhance signaling or promote degradation depending on cellular context and the specific E3 ligases involved.

Ubiquitin Linkages in Cancer: Implications for Diagnosis and Therapy

Ubiquitylome Alterations in Cancer Progression

Comprehensive proteomic analyses have revealed significant alterations in ubiquitination patterns across multiple cancer types, highlighting the diagnostic and therapeutic potential of targeting ubiquitin signaling pathways [11] [15]. In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cell lines with increasing metastatic potential, systematic ubiquitylome profiling identified 83 ubiquitinated proteins with steadily changing abundance according to metastatic potential [11]. These proteins participate in biological processes tightly associated with tumor metastasis, with ribosome and proteasome pathways significantly over-activated in highly metastatic cells [11]. Notably, Ku80 ubiquitination was significantly down-regulated in high-metastatic cells compared to low-metastatic cells, establishing a clear correlation between specific ubiquitination events and metastatic behavior [11].

Pan-cancer proteomic studies encompassing 16 major cancer types have identified both universally expressed proteins and cancer-type-specific proteins within the ubiquitin system, providing a resource for understanding how ubiquitination contributes to cancer-specific pathways [15]. These proteomic signatures not only advance our understanding of cancer biology but also facilitate the development of diagnostic and therapeutic targets [15]. The ability to analyze formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples using advanced mass spectrometry has further enabled retrospective biomarker discovery, identifying ubiquitination-related proteins associated with therapeutic resistance in colorectal cancer [16].

USP39: A Ubiquitin System Component in Cancer Progression

The deubiquitinating enzyme USP39 exemplifies how components of the ubiquitin system contribute to cancer progression [13]. Although initially classified as an inactive ubiquitin-specific protease due to atypical catalytic residues, USP39 has demonstrated deubiquitination capabilities, stabilizing oncogenic proteins such as CHK2 and β-catenin by removing degradative ubiquitin chains [13]. USP39 is overexpressed in various cancers including hepatocellular, lung, gastric, breast, and ovarian carcinomas, where it promotes cell proliferation, invasion, metastasis, and drug resistance [13]. Beyond its deubiquitinating activity, USP39 functions as a splicing factor that affects the maturation of specific mRNAs, including those encoding oncogenic proteins such as EGFR and Aurora B [13]. This dual functionality enables USP39 to promote tumor development through both regulation of protein stability and control of gene expression, making it a promising therapeutic target [13].

Targeting Ubiquitin Pathways for Cancer Therapy

The therapeutic potential of targeting ubiquitin system components is increasingly recognized in cancer drug development [12] [9]. Several strategies have emerged, including small-molecule inhibitors targeting specific E3 ligases or DUBs, and novel approaches such as proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) that hijack E3 ubiquitin ligases to selectively degrade target proteins [12] [9]. PROTACs are heterobifunctional molecules that simultaneously bind to a target protein and an E3 ligase, facilitating target ubiquitination and degradation via the proteasome [9]. This approach has been successfully applied to target previously "undruggable" proteins in cancer, including androgen receptor, estrogen receptor, BTK, and BCL2 [9]. The development of chain-specific TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) with nanomolar affinities for specific polyubiquitin chains enables high-throughput screening of compounds that modulate linkage-specific ubiquitination, accelerating drug discovery in this area [9].

Experimental Protocols for Ubiquitin Linkage Analysis

Ubiquitin Interactor Pull-Down with Mass Spectrometry

Purpose: To identify linkage-specific ubiquitin-binding proteins (UBPs) and characterize their chain length preferences [7].

Workflow:

- Ubiquitin Chain Synthesis: Enzymatically synthesize native homotypic (K48 or K63) Ub2, Ub3, and heterotypic branched K48/K63 Ub3 chains using linkage-specific E2 enzymes (e.g., CDC34 for K48, Ubc13/Uev1a for K63, Ubc1 for K48-branching) [7].

- Immobilization: Add a serine/glycine linker with a single cysteine residue after the C-terminus of the proximal Ub. Conjugate biotin molecules using cysteine-maleimide chemistry and immobilize on streptavidin resin [7].

- Lysate Preparation: Prepare cell lysates (HeLa or yeast) in lysis buffer supplemented with deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitors (chloroacetamide, CAA, or N-ethylmaleimide, NEM) to preserve chain integrity [7].

- Pulldown Experiment: Incubate immobilized ubiquitin chains with lysate. Wash extensively to remove non-specific binders [7].

- Protein Identification: Elute bound proteins and identify by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [7].

- Data Analysis: Statistically compare enrichment patterns across different chain types to identify linkage-specific, chain length-dependent, and branch-specific interactors [7].

Critical Considerations: The choice of DUB inhibitor significantly impacts results. NEM provides more complete chain stabilization but may have off-target effects on cysteine-containing proteins, while CAA is more cysteine-specific but allows partial chain disassembly [7]. Validation of identified interactors using complementary techniques such as surface plasmon resonance (SPR) is recommended [7].

TUBE-Based Analysis of Linkage-Specific Ubiquitination

Purpose: To investigate context-dependent linkage-specific ubiquitination of endogenous proteins in high-throughput format [9].

Workflow:

- Cell Stimulation/Treatment: Treat cells (e.g., THP-1 human monocytic cells) with stimuli that induce specific ubiquitination (e.g., L18-MDP for K63 ubiquitination of RIPK2) or PROTACs that induce K48 ubiquitination for degradation [9].

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells in DUB-inhibiting buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.15 M NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with DUB inhibitors to preserve ubiquitination states [9].

- TUBE Enrichment: Incubate cell lysates with chain-specific TUBEs (K48-TUBE, K63-TUBE, or pan-TUBE) conjugated to magnetic beads [9].

- Target Detection: Wash beads extensively, elute bound proteins, and detect specific ubiquitinated targets by immunoblotting with target-specific antibodies [9].

- Quantification: Quantify signals to compare linkage-specific ubiquitination under different conditions [9].

Applications: This protocol enables rapid assessment of PROTAC efficiency and specificity, evaluation of inflammatory signaling activation, and screening for compounds that modulate specific ubiquitination events [9].

Di-Gly Antibody-Based Ubiquitylome Profiling

Purpose: To comprehensively profile ubiquitination sites and identify alterations in cancer tissues or cell lines [11] [14].

Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Extract proteins from tissues or cells. For FFPE tissues, use extended lysis with high concentrations of urea and SDS, followed by multiple heating and sonication steps [16].

- Protein Digestion: Digest proteins with trypsin/Lys-C mix to generate peptides [11] [16].

- Di-Gly Peptide Enrichment: Incubate peptides with anti-di-glycine remnant antibody-conjugated beads to specifically enrich ubiquitinated peptides [11].

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Analyze enriched peptides using liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry [11].

- Data Analysis: Identify ubiquitination sites by detecting the di-glycine remnant signature (114.04 Da mass shift on modified lysine residues) and quantify differences between sample groups [11] [14].

Applications: This approach has been successfully used to identify ubiquitination patterns associated with cancer metastasis and therapeutic response, enabling biomarker discovery from clinical specimens [11] [16].

Visualization of K48/K63-Branched Ubiquitin in NF-κB Signaling

The following diagram illustrates how K48/K63-branched ubiquitin chains regulate NF-κB signaling through collaboration between K63-linked chain assembly and K48-specific branching events, protecting the signal from deubiquitination.

Figure 1: K48/K63-Branched Ubiquitin Chain Regulation of NF-κB Signaling

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Ubiquitin Linkage Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific TUBEs | K48-TUBE, K63-TUBE, Pan-TUBE [9] | High-affinity capture of linkage-specific ubiquitinated proteins from native cell lysates | Enables high-throughput screening; preserves native ubiquitination states |

| DUB Inhibitors | Chloroacetamide (CAA), N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) [7] | Prevent deubiquitination during lysis and purification | NEM more potent but has off-target effects; CAA more cysteine-specific |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K48-linkage specific, K63-linkage specific [14] | Immunoblotting and immunofluorescence detection of specific chain types | Variable specificity between commercial sources requires validation |

| Tagged Ubiquitin Variants | His-tagged Ub, Strep-tagged Ub, HA-tagged Ub [14] | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates | May not perfectly mimic endogenous ubiquitin; potential for artifacts |

| Activity-Based Probes | Ub-VS, Ub-AMC, Linkage-specific DUB probes [14] | Profiling DUB activity and specificity | Can distinguish functional DUB activities in complex mixtures |

| Branched Ubiquitin Chains | K48/K63-branched Ub3, K11/K48-branched chains [7] [8] | Study of branched chain recognition and function | Require complex enzymatic synthesis; structural validation essential |

The complexity of the ubiquitin code extends far beyond the simple dichotomy of K48-mediated degradation versus K63-mediated signaling. The emerging understanding of branched ubiquitin chains and their unique functions reveals how combinations of linkage types can create signaling outputs not achievable by homotypic chains alone [7] [8] [10]. In cancer biology, comprehensive ubiquitylome analyses have demonstrated that specific ubiquitination patterns correlate with disease progression, metastatic potential, and therapeutic response [11] [15] [16]. The continued development of sophisticated tools for ubiquitin research—including chain-specific TUBEs, improved DUB inhibitors, and advanced mass spectrometry methods—is enabling increasingly precise dissection of ubiquitin linkage functions in both physiological and pathological contexts [9] [14]. As our understanding of ubiquitin linkage diversity grows, so too does the potential for developing targeted therapies that exploit specific ubiquitin signals, such as PROTACs for targeted protein degradation and DUB inhibitors for modulating ubiquitin-dependent signaling pathways in cancer and other diseases [12] [13] [9].

Protein ubiquitination is an evolutionarily conserved post-translational modification that regulates diverse cellular functions, primarily through targeting substrate proteins for proteasomal degradation [17]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system consists of numerous enzymes, including ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinases (DUBs), which regulate intracellular processes such as cell cycle progression, selective autophagy, and response to growth factors [18]. Dysregulation of this system contributes to loss of cell cycle control and carcinogenesis, making ubiquitylomics—the system-wide study of ubiquitinated proteins—essential for understanding cancer mechanisms and identifying therapeutic targets [18] [17].

Mass spectrometry-based ubiquitinomics provides a system-level understanding of ubiquitin signaling, enabling researchers to profile thousands of ubiquitination events simultaneously [18]. This approach is particularly valuable for comparing cancerous and normal tissues, as it can reveal disease-specific ubiquitination signatures and identify novel drug targets. In oncology research, ubiquitylomics facilitates rapid mode-of-action profiling of candidate drugs targeting DUBs or ubiquitin ligases with high precision and throughput [18].

Key Methodological Advances in Ubiquitylomics

Optimized Sample Preparation for Deep Ubiquitinome Coverage

Sample preparation is critical for comprehensive ubiquitinome profiling. Traditional urea-based lysis buffers have been superseded by sodium deoxycholate-based protocols that significantly improve ubiquitin site coverage. This optimized lysis method, when supplemented with chloroacetamide for immediate cysteine protease inactivation, yields approximately 38% more K-ε-GG remnant peptides compared to conventional urea buffer [18]. This enhancement occurs without compromising enrichment specificity, simultaneously improving both quantification precision and reproducibility across experimental replicates.

The protein input amount dramatically affects identification numbers in ubiquitylomics studies. Experimental data demonstrates that 2 mg of protein input typically yields approximately 30,000 identifiable K-ε-GG peptides, while inputs of 500 µg or less result in identification numbers dropping below 20,000 peptides [18]. This relationship underscores the importance of sufficient starting material for achieving deep ubiquitinome coverage, particularly when studying subtle ubiquitination changes between cancerous and normal tissues.

Table 1: Comparison of Lysis Buffer Performance in Ubiquitylomics

| Parameter | SDC-Based Lysis | Urea-Based Lysis |

|---|---|---|

| Average K-ε-GG Peptide Identification | 26,756 | 19,403 |

| Enrichment Specificity | High | High |

| Reproducibility (CV < 20%) | Significantly Improved | Standard |

| Recommended Protein Input | 2 mg | 2 mg |

| Cysteine Protease Inactivation | Immediate with CAA | Less effective |

Data-Independent Acquisition Mass Spectrometry

Data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry represents a transformative advancement over traditional data-dependent acquisition methods for ubiquitylomics. While DDA typically identifies approximately 21,434 K-ε-GG peptides per sample, DIA more than triples this coverage to over 68,429 peptides in single MS runs [18]. This dramatic improvement stems from DIA's comprehensive fragmentation of all eluting peptides within sequential isolation windows, eliminating the semi-stochastic sampling inherent to DDA.

The quantitative precision of DIA-based ubiquitylomics significantly exceeds DDA performance, with median coefficients of variation below 10% for quantified K-ε-GG peptides [18]. This enhanced reproducibility is particularly valuable for cancer versus normal tissue studies, where robust quantification is essential for identifying genuine ubiquitination differences amid biological variability. When coupled with deep neural network-based processing tools like DIA-NN, which includes specialized scoring modules for modified peptides, identification confidence for K-ε-GG peptides matches or exceeds that achieved with DDA workflows [18].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of MS Acquisition Methods in Ubiquitylomics

| Performance Metric | DIA-MS | DDA-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Average K-ε-GG Peptides Identified | 68,429 | 21,434 |

| Median Quantitative CV | <10% | >20% |

| Missing Values in Replicates | Minimal | Substantial (~50%) |

| Required Spectral Library | Optional (library-free mode available) | Mandatory |

| Compatibility with Neural Network Processing | Excellent (DIA-NN) | Limited |

Experimental Protocol for Ubiquitylomics Profiling in Cancer Research

Sample Preparation and Protein Extraction

Tissue Collection and Preservation: Snap-freeze freshly excised cancerous and matched normal tissues in liquid nitrogen. Store at -80°C until processing. For cancers without available adjacent normal tissues, consult resources like the GTEx project for reference normal samples [19].

Protein Extraction with SDC Buffer: Homogenize tissue samples in SDC lysis buffer (1% sodium deoxycholate, 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 10 mM TCEP, 40 mM chloroacetamide) using a mechanical homogenizer. Immediate addition of chloroacetamide is crucial for rapid inactivation of cysteine ubiquitin proteases [18].

Protein Digestion: Digest proteins with Lys-C (1:100 enzyme-to-protein ratio) for 3 hours at 30°C, followed by trypsin digestion (1:100 ratio) overnight at 37°C. Acidify with trifluoroacetic acid to precipitate SDC, then centrifuge to remove the precipitate.

K-ε-GG Peptide Enrichment: Use anti-K-ε-GG antibody-conjugated beads for immunoaffinity purification. Incubate digested peptides with antibody beads for 2 hours at 4°C with gentle rotation. Wash beads thoroughly before peptide elution with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid.

Liquid Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Chromatographic Separation: Desalt enriched K-ε-GG peptides using C18 stage tips and separate with nanoflow liquid chromatography employing a 75-minute linear gradient from 2% to 30% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid [18].

DIA-MS Acquisition: Utilize a Q-Exactive HF-X or similar mass spectrometer with optimized DIA methods. Fragment ions using higher-energy collisional dissociation with normalized collision energy of 27-30%. Set MS1 resolution to 120,000 with an m/z range of 350-1650, and MS2 resolution to 30,000 [18].

Data Processing: Process raw files using DIA-NN software in "library-free" mode against the human UniProt database. Enable the neural network-based scoring for K-ε-GG peptides and set the false discovery rate to 1% at both peptide and protein levels [18].

Data Analysis and Normal Tissue Selection Strategy

For cancers lacking matched normal tissues, implement a computational strategy to select appropriate reference samples from databases like GTEx. Employ autoencoder neural networks to create reduced features for similarity measurement between cancer samples and potential normal references [19]. This approach correctly predicts tissue of origin for 12 of 14 cancers and ensures that disease signatures derived from GTEx normal samples show strong consistency with those derived from adjacent samples in TCGA [19].

Differential expression analysis between tumor and selected normal tissues should be performed using tools like edgeR, with significance thresholds set at absolute log fold change >1 and adjusted p-value <0.001 [19]. For signature validation, assess consistency based on overlapping gene significance and correlation of fold changes between TCGA-derived and GTEx-derived disease signatures.

Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitylomics

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitylomics Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-K-ε-GG Antibody Beads | Immunoaffinity purification of ubiquitinated peptides | Critical for enriching low-abundance ubiquitinated peptides from complex digests |

| Sodium Deoxycholate (SDC) | Lysis buffer detergent | Superior to urea for ubiquitinome coverage; prevents di-carbamidomethylation artifacts |

| Chloroacetamide (CAA) | Cysteine alkylating agent | Rapidly inactivates DUBs during lysis; preferred over iodoacetamide |

| Recombinant Lys-C/Trypsin | Proteolytic enzymes | Generate K-ε-GG remnant peptides with C-terminal diglycine motif |

| DIA-NN Software | Data processing | Deep neural network-based analysis specifically optimized for ubiquitinomics data |

| USP7 Inhibitors | DUB targeting compounds | Enable studies of ubiquitination dynamics and substrate identification |

Application in Cancer Biology: USP7 Target Profiling

The power of advanced ubiquitylomics is exemplified in comprehensive mapping of substrates for deubiquitinase USP7, an actively investigated anticancer drug target [18]. Following USP7 inhibition, simultaneous monitoring of ubiquitination changes and corresponding protein abundance alterations at high temporal resolution reveals that while ubiquitination of hundreds of proteins increases within minutes, only a small fraction of those targets undergo degradation [18]. This critical distinction helps dissect the scope of USP7 action, separating regulatory ubiquitination events from those leading to proteasomal degradation.

In specific cancer types like oral adenoid cystic carcinoma, ubiquitylomics profiling has identified 4,152 ubiquitination sites across 1,993 proteins, revealing potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets [17]. Systematic bioinformatics analysis of differentially modified proteins between tumor and adjacent normal tissues provides important references for developing targeted therapies for this rare salivary gland tumor with poor prognosis [17].

Advanced ubiquitylomics workflows combining optimized sample preparation, DIA-MS, and sophisticated computational analysis now enable unprecedented insights into ubiquitin signaling dynamics in cancer. The ability to distinguish degradative from non-degradative ubiquitination events provides a more nuanced understanding of cancer mechanisms and reveals novel therapeutic opportunities. As these methodologies continue to evolve, ubiquitylomics will play an increasingly central role in cancer drug development, particularly for targeted protein degradation therapies and DUB inhibitor programs.

The commercialization of antibodies specifically recognizing the lysine-ε-glycine-glycine (K-ε-GG) remnant has fundamentally transformed the proteomic landscape of ubiquitination research [20]. This methodology capitalizes on a fundamental biochemical event: when trypsin digests ubiquitinated proteins, it cleaves after the arginine residue at position 74 of ubiquitin, leaving a characteristic diGly remnant attached via an isopeptide bond to the modified lysine residue on the substrate peptide [21]. This diGly signature serves as a universal handle for enriching low-abundance ubiquitination sites from complex proteomic digests.

Prior to the development of these highly specific antibodies, proteomics studies were limited to identifying only several hundred ubiquitination sites, severely constraining the scope of biological investigations [20]. The advent of K-ε-GG immunoenrichment has enabled researchers to identify >50,000 ubiquitylation sites in human cells, providing unprecedented insights into the breadth and regulatory complexity of the ubiquitin system [21]. This approach has become an indispensable tool for systematically interrogating protein ubiquitylation with site-level resolution, revealing dynamic changes in ubiquitination in response to cellular stimuli, stressors, and in disease pathologies such as cancer [21] [22].

It is critical to note that while this method primarily captures ubiquitination events, the C-terminal sequences of ubiquitin-like proteins (NEDD8 and ISG15) also generate identical diGly remnants upon trypsinolysis [21]. However, methodological studies have demonstrated that approximately 95% of all diGly-peptides identified using this enrichment approach arise from genuine ubiquitination events rather than neddylation or ISGylation [21].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of the DiGly Remnant Enrichment Technology

| Aspect | Technical Specification | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Target Epitope | K-ε-GG remnant after trypsin digestion [21] | Enables specific enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides from complex mixtures |

| Coverage | >50,000 ubiquitination sites identifiable in human cells [21] | Provides systems-level view of ubiquitination landscape |

| Specificity | ~95% of enriched peptides derive from ubiquitin (vs. NEDD8/ISG15) [21] | Ensures biological relevance of identified modifications |

| Quantitative Capability | Compatible with SILAC, TMT, and label-free quantification [20] [22] [23] | Enables dynamic tracking of ubiquitination changes |

| Sample Compatibility | Cell lines, primary tissues, and in vivo models [21] [22] | Facilitates translation from basic research to clinical applications |

Optimized Experimental Workflow and Protocols

Sample Preparation and Lysis Considerations

Proper sample preparation is paramount for preserving the endogenous ubiquitination landscape, given the transient nature of many ubiquitination events and the rapid activity of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs). Effective lysis requires denaturing conditions to inactivate DUBs and proteases immediately upon cell disruption [24].

A recommended lysis buffer consists of:

- 8 M Urea or other strong denaturant [20] [21]

- 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5-8.0 [20] [21]

- 150 mM NaCl [20] [21]

- Protease and DUB inhibitors (e.g., 5 mM N-Ethylmaleimide/NEM, 50 μM PR-619) [20] [21] [24]

- Phosphatase inhibitors (e.g., 1 mM NaF, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate) when studying crosstalk with phosphorylation [21]

For cancer tissue samples, as used in OACC research, samples should be snap-frozen and powdered under liquid nitrogen before adding lysis buffer [22]. Including proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) can stabilize ubiquitination events targeting proteins for degradation, but requires caution due to potential compensatory effects and toxicity in vivo [23] [24].

Protein Digestion and Pre-Fractionation

Following reduction and alkylation, proteins are digested using trypsin, which generates the diagnostic diGly remnant. A two-step enzymatic digestion is often beneficial:

To achieve deep ubiquitinome coverage, offline high-pH reverse-phase fractionation is recommended prior to diGly enrichment. This reduces sample complexity and minimizes interference from highly abundant non-modified peptides [20] [25]. A typical workflow involves separating peptides using a basic reversed-phase (bRP) column with ammonium formate (pH 10) and acetonitrile gradients, followed by non-contiguous pooling of fractions to maximize efficiency [20]. For instance, pooling fractions 1, 9, 17, etc., into eight final pooled fractions significantly enhances identifications without increasing MS instrument time [20].

DiGly Peptide Immunoenrichment

The core enrichment process utilizes cross-linked antibody beads to capture diGly-modified peptides:

Diagram: DiGly Peptide Immunoenrichment Workflow

Critical parameters for optimal enrichment:

- Antibody cross-linking using dimethyl pimelimidate (DMP) prevents antibody leaching and improves specificity [20]

- Input optimization: ~1 mg peptide material with 31.25 μg antibody provides excellent yield [23]

- Incubation conditions: 1-2 hours at 4°C with rotation in IAP buffer (50 mM MOPS, pH 7.2, 10 mM sodium phosphate, 50 mM NaCl) [20]

- Stringent washing with ice-cold PBS to remove non-specifically bound peptides [20] [25]

- Gentle elution with 0.15% TFA to preserve peptide integrity [20]

Mass Spectrometry Analysis and Acquisition Strategies

Recent advances in mass spectrometry have significantly enhanced diGly peptide detection. Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) methods have demonstrated particular advantages for ubiquitinome analysis, identifying approximately 35,000 distinct diGly peptides in single measurements—nearly double the identification rate of traditional Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) methods [23].

Key MS parameter considerations:

- Optimized DIA window schemes tailored to diGly precursor characteristics [23]

- High MS2 resolution (30,000) for improved specificity [23]

- LC gradient optimization: 60-120 minute gradients depending on depth requirements [22] [23]

- Spectral libraries: Comprehensive libraries (>90,000 diGly peptides) enable robust DIA analysis [23]

Quantitative Profiling in Cancer Research

The application of diGly proteomics to cancer research has revealed profound alterations in ubiquitination networks between tumor and normal tissues. In adenoid cystic carcinoma (OACC), quantitative ubiquitylomics identified 4,152 ubiquitination sites on 1,993 proteins, with 1648 sites on 859 proteins quantifiable between tumor and adjacent normal tissues [22]. This analysis revealed 555 significantly up-regulated ubiquitination sites in 385 proteins and 112 down-regulated sites in 95 proteins in OACC tumors [22].

Table 2: Quantitative DiGly Proteomics Applications in Cancer Models

| Study Model | Quantitative Approach | Key Findings | Technical Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma (OACC) [22] | 4D-label-free quantification | 4152 ubiquitination sites identified; 555 up-regulated and 112 down-regulated sites in tumors | Applied to clinical tissue samples; requires appropriate normalization strategies |

| TNF Signaling Pathway [23] | DIA with SILAC labeling | Comprehensive capture of known and novel ubiquitination sites in signaling networks | DIA provides superior data completeness and quantitative accuracy for signaling studies |

| E3 Ligase Substrate Identification [26] | SILAC with inducible RNAi | Identification of DDIT4 as novel substrate for HUWE1 E3 ligase | Combines genetic perturbation with diGly proteomics for substrate discovery |

| Circadian Biology [23] | DIA with label-free quantification | Hundreds of cycling ubiquitination sites discovered on membrane receptors and transporters | Reveals dynamic regulation of ubiquitination across time courses |

The integration of diGly proteomics with functional bioinformatics enables systems-level interpretation of cancer-related ubiquitination changes. This includes:

- Pathway enrichment analysis of differentially ubiquitinated proteins [22]

- Protein interaction network mapping to identify coordinated regulatory modules [22]

- Motif analysis to identify sequence preferences around cancer-associated ubiquitination sites [22]

- Crosstalk analysis with other PTMs (e.g., phosphorylation, acetylation) that may compete for the same lysine residues [23]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DiGly Proteomics

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-K-ε-GG Antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) [20] [21] | Immunoaffinity enrichment of diGly-modified peptides | Core reagent; cross-linking recommended to prevent antibody leaching |

| DUB Inhibitors (PR-619, NEM) [20] [21] [24] | Preserve endogenous ubiquitination by inhibiting deubiquitinases | Essential in lysis buffers; concentration must be sufficient for complete inhibition |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (MG-132, Bortezomib) [20] [23] | Stabilize ubiquitinated proteins targeted for degradation | Use with caution due to potential compensatory pathways and toxicity |

| Stable Isotope Labels (SILAC amino acids) [20] [21] | Enable accurate quantification of ubiquitination dynamics | Heavy Lys8 and Arg10 recommended for minimal label incorporation errors |

| Basic Reverse-Phase Chromatography | Pre-fractionation to reduce sample complexity | Significant improvement in depth of coverage; non-contiguous pooling recommended |

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) [14] [24] | Alternative enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins | Useful for protein-level enrichment; does not provide site-specific information |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies [14] | Detection of specific polyubiquitin chain types | Limited to known linkage types; commercial availability varies |

The development of K-ε-GG antibodies and optimized diGly remnant enrichment protocols represents a transformative advancement in ubiquitin research, enabling unprecedented characterization of the ubiquitinome in cancer and other disease contexts. The continued refinement of these methodologies—including enhanced fractionation strategies, antibody cross-linking techniques, and advanced mass spectrometry acquisition methods—has progressively increased the depth and quantitative accuracy of ubiquitination site mapping. When applied to cancer research, these approaches reveal extensive rewiring of ubiquitination networks in tumors, offering new insights into cancer mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. As these technologies continue to evolve and integrate with complementary proteomic approaches, they promise to further illuminate the complex landscape of ubiquitin signaling in health and disease.

Ubiquitination, a fundamental post-translational modification, governs nearly all cellular processes in eukaryotic cells, including protein degradation, cell cycle progression, DNA repair, and immune responses [27] [28]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) mediates approximately 80-90% of intracellular protein degradation, making it a critical regulator of cellular homeostasis [27]. This enzymatic cascade involves three key components: ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3), which work in concert to attach ubiquitin molecules to substrate proteins, targeting them for proteasomal degradation or functional modification [29] [27]. The reverse process, deubiquitination, is mediated by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that remove ubiquitin chains from substrates [29] [27].

Mounting evidence from multi-cancer studies demonstrates that dysregulation of ubiquitination pathways is a hallmark of cancer pathogenesis [27] [28]. Genetic alterations, expression perturbations, and functional abnormalities in ubiquitination regulators (UBRs) have been identified across diverse cancer types, contributing to tumor initiation, progression, metabolic reprogramming, immune evasion, and therapeutic resistance [27] [28] [30]. This application note synthesizes evidence from recent pan-cancer analyses to elucidate the critical roles of ubiquitination dysregulation in cancer and provides detailed protocols for investigating ubiquitination-related mechanisms in cancer research.

Results

Expression Perturbations of Ubiquitination Regulators in Pan-Cancer

Comprehensive analysis of UBRs across multiple cancer types has revealed widespread expression perturbations affecting E1, E2, E3 enzymes, and DUBs. Systematic characterization of 877 human UBRs demonstrated heterogeneous expression patterns across tissues, with the testis showing the most distinct pattern [28]. In malignant tissues, these expression perturbations have profound functional consequences.

Table 1: Pan-Cancer Expression Patterns of Key Ubiquitination Regulators

| Ubiquitination Regulator | Cancer Types with Overexpression | Functional Consequences | Prognostic Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| UBA1 (E1 enzyme) | BRCA, COAD, KIRC, LUAD [31] | Promotes tumor proliferation, associated with poor prognosis [31] | Shorter overall survival in multiple cancers [31] |

| UBA6 (E1 enzyme) | BRCA, COAD, KIRC, LUAD [31] | Regulates immune response, linked to cancer stage [31] | Correlated with unfavorable prognosis [31] |

| UBD/FAT10 (Ubiquitin-like protein) | 29 cancer types including GBM, COAD, LIHC, BRCA [32] | Induces chromosomal instability, activates NF-κB, Wnt signaling [32] | Reduced overall survival in amplified cases [32] |

| UBE2T (E2 enzyme) | Hepatocellular carcinoma [27] | Regulates γH2AX monoubiquitination, enhances radioresistance [27] | Contributes to treatment resistance [27] |

| FBXO45 (E3 ligase) | Ovarian cancer [33] | Promotes growth via Wnt/β-catenin pathway [33] | Independent prognostic factor [33] |

A notable example is UBD (Ubiquitin D), which shows overexpression in 29 cancer types and is linked to poor prognosis and higher histological grades [32]. Genetic alterations, particularly gene amplifications, are common in UBD, and patients with these alterations exhibit significantly reduced overall survival rates [32]. Epigenetically, reduced UBD promoter methylation has been observed in 16 cancer types, suggesting a potential mechanism for its overexpression [32].

Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Models Across Cancers

The development of ubiquitination-related prognostic signatures has demonstrated remarkable utility in stratifying cancer patients across multiple tumor types.

In ovarian cancer, a 17-gene ubiquitination-related prognostic model effectively stratified patients into high-risk and low-risk groups with significantly different overall survival (1-year AUC = 0.703, 3-year AUC = 0.705, 5-year AUC = 0.705) [33]. The high-risk group showed markedly lower overall survival (P < 0.05), and immune analysis revealed higher levels of CD8+ T cells (P < 0.05), M1 macrophages (P < 0.01), and follicular helper T cells (P < 0.05) in the low-risk group [33]. High-risk patients had more mutations in MUC17 and LRRK2, while low-risk patients had more RYR2 mutations [33].

Similarly, in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), a risk model based on nine ubiquitination-related genes (B4GALT4, DNAJB4, GORAB, HEATR1, LPGAT1, FAT1, GAB2, MTMR4, and TCP11L2) effectively classified patients into low-risk and high-risk groups [34]. Low-risk patients had significantly better overall survival than those in the high-risk group, and substantial differences in immune cell infiltration were observed between the two groups [34].

A pan-cancer ubiquitination-related prognostic signature (URPS) developed from 4,709 patients across 26 cohorts and five solid tumor types (lung cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, urothelial cancer, and melanoma) effectively stratified patients into high-risk and low-risk groups with distinct survival outcomes across all analyzed cancers [30]. This signature also served as a novel biomarker for predicting immunotherapy response, with potential to identify patients more likely to benefit from immunotherapy in clinical settings [30].

Ubiquitination in Cancer Immune Regulation

Ubiquitination plays a crucial role in regulating tumor immune microenvironment components and immune checkpoint expression. UBD expression shows significant correlations with tumor microenvironment features, including immune infiltration, checkpoints, microsatellite instability (MSI), tumor mutational burden (TMB), and neoantigens (NEO) [32].

Table 2: Ubiquitination-Mediated Regulation of Immune Checkpoints in Cancer

| Immune Checkpoint | Ubiquitination Regulator | Mechanism of Action | Cancer Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| PD-L1 | MTSS1/AIP4 complex [27] | Promotes monoubiquitination at K263, leading to internalization and lysosomal degradation [27] | Lung adenocarcinoma |

| PD-1 | USP2 [27] | Stabilizes PD-1 through deubiquitination, promoting tumor immune escape [27] | Multiple cancers |

| PD-L1 | UBD/FAT10 [32] | Upregulates PD-L1 expression, fostering immunosuppressive microenvironment [32] | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

The correlation between UBR expression and immune cell infiltration has been extensively documented. For instance, UBA1 and UBA6 expression shows close ties with immune scores, immune subtypes, and tumor-infiltrating immune cells across various cancer types [31]. In ovarian cancer, the ubiquitination-related prognostic model revealed distinct immune infiltration patterns between risk groups, with low-risk patients exhibiting significantly higher levels of CD8+ T cells, M1 macrophages, and follicular helper T cells [33].

Ubiquitination in Metabolic Reprogramming

Cancer cells undergo metabolic reprogramming to support rapid growth and proliferation, and ubiquitination plays a crucial regulatory role in this process. Key enzymes in lipid metabolism are particularly regulated by ubiquitination.

Table 3: Ubiquitination Regulation of Lipid Metabolism Enzymes in Cancer

| Metabolic Enzyme | Ubiquitination Regulator | Mechanism | Cancer Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACLY | NEDD4 [29] | E3 ligase NEDD4 binds to ACLY, promoting its ubiquitination and degradation [29] | Lung cancer |

| ACLY | UBR4 [29] | Reduced binding with acetylated ACLY decreases ubiquitination, enhancing stability [29] | Lung cancer |

| ACLY | CUL3-KLHL25 complex [29] | Ubiquitinates and degrades ACLY, inhibiting lipid synthesis [29] | Lung cancer |

| FASN | COP1/Shp2 complex [29] | Forms FASN-Shp2-COP1 complex, mediating ubiquitination and degradation [29] | Liver cancer |

| FASN | TRIM21 [29] | HDAC3 deacetylates FASN, enhancing TRIM21 binding and ubiquitination [29] | Multiple cancers |

| FASN | SPOP [29] | E3 ligase reduces FASN expression and fatty acid synthesis [29] | Prostate cancer |

The regulation of metabolic enzymes by ubiquitination represents a critical interface between metabolic reprogramming and oncogenic signaling. For instance, the E3 ligase Parkin facilitates the ubiquitination of pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), while the deubiquitinase OTUB2 interacts with PKM2 to inhibit its ubiquitination by Parkin, thereby enhancing glycolysis and accelerating colorectal cancer progression [27].

Discussion

Therapeutic Implications and Emerging Strategies

The comprehensive understanding of ubiquitination dysregulation in cancer has paved the way for novel therapeutic strategies. Several approaches have shown promising results:

PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) represent a breakthrough technology that leverages the ubiquitin-proteasome system to target specific proteins for degradation. ARV-110 (bavdegalutamide) and ARV-471 (vepdegestrant) are pioneering PROTAC drugs that have progressed to phase II clinical trials [27]. ARV-110 is designed to selectively target and bind to the androgen receptor (AR), facilitating its degradation by recruiting an E3 ubiquitin ligase, showing promising results in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer [27].

Molecular Glues offer another innovative approach. CC-90009 facilitates the ubiquitination-mediated degradation of G1-to-S phase transition 1 (GSPT1) by recruiting the E3 ligase complex CUL4-DDB1-CRBN-RBX1 (CRL4CRBN) and is in phase II clinical trials for leukemia therapy [27]. Compared to PROTACs, molecular glues have smaller molecular dimensions, simplifying the optimization of their chemical characteristics [27].

Targeting Specific UBRs has shown therapeutic potential. For instance, LCL161, an IAP inhibitor, induces TNF-dependent apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells and enhances the anti-tumor immune response [29]. The small molecule inhibitor SIM0501, which targets USP1, has FDA clinical approval and is planned for trials in advanced solid tumors [29].

Future Perspectives

The integration of multi-omics data continues to reveal the complexity of ubiquitination networks in cancer pathogenesis. Future research directions should focus on:

Comprehensive Ubiquitinome Mapping: Systematic characterization of ubiquitination patterns across cancer types and stages will provide deeper insights into the dynamic regulation of oncogenic pathways.

Single-Cell Ubiquitination Analysis: Advancements in single-cell technologies will enable the exploration of ubiquitination heterogeneity within tumor ecosystems, potentially revealing novel cell-type-specific therapeutic targets.

Ubiquitination-Based Biomarker Development: The development of standardized ubiquitination-related prognostic signatures across cancer types could revolutionize patient stratification and treatment selection.

Combination Therapies: Strategic combinations of ubiquitination-targeting agents with conventional therapies, targeted therapies, and immunotherapies may overcome resistance mechanisms and improve clinical outcomes.

Methods

Pan-Cancer Analysis of Ubiquitination Regulators

Data Collection and Processing

Data Sources: Collect transcriptomic data from public repositories including The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project, and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [31] [28] [34]. For comprehensive analysis, include data from at least 33 cancer types covering major anatomical sites [28].

UBR Gene Set Curation: Compile a comprehensive list of ubiquitination regulators from specialized databases such as UUCD (http://uucd.biocuckoo.org/) [33] [28]. The standard UBR set should include E1 activating enzymes (8 genes), E2 conjugating enzymes (39 genes), E3 ligases (882 genes), and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) [33].

Data Normalization: Process raw RNA-seq data using standardized pipelines. Convert counts to reads per million mapped (FPKM) format and apply log2 transformation to normalize expression distributions [34]. For microarray data, perform background correction, quantile normalization, and probe summarization using the "limma" R package [34].

Differential Expression Analysis

Expression Comparison: Use the Wilcoxon rank sum test to identify differentially expressed UBRs between tumor and normal tissues [28] [34]. Apply multiple testing correction using the Benjamini-Hochberg method to control false discovery rate.

Inclusion Criteria: Define significant differential expression using thresholds of |logFC| ≥ 1 (fold change ≥ 2) and adjusted p-value < 0.01 [28]. For studies with limited normal samples, include cancer types with at least ten normal samples to ensure statistical reliability [28].

Validation: Verify protein-level expression differences using the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) database for immunohistochemical staining patterns in normal and cancer tissues [31].

Survival Analysis

Prognostic Assessment: Evaluate the association between UBR expression and patient survival using overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) as endpoints [32].

Statistical Methods: Perform univariate Cox regression analysis to identify UBRs with significant prognostic value [33] [28]. For multivariate analysis, include clinical parameters such as age, stage, and grade as covariates.

Stratification: Divide patients into high-expression and low-expression groups based on median expression or optimal cut-off values determined by maximally selected rank statistics [32]. Generate Kaplan-Meier survival curves and compare using log-rank tests.

Construction of Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Models

Feature Selection

Preliminary Screening: Perform univariate Cox regression analysis on ubiquitination-related genes to identify candidates with significant prognostic association (p < 0.05) [33] [34].

Regularization: Apply LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) Cox regression to prevent overfitting and select the most informative genes for the prognostic model [33] [34]. Use 10-fold cross-validation to determine the optimal penalty parameter λ.

Final Gene Selection: Further refine the gene set using the DEVIANCE test with selection criteria of |logFC| ≥ 1 and adjusted p-values < 0.05 [33].

Risk Score Calculation

Formula Application: Calculate risk scores for each patient using the formula: Risk score = Σ(Coefi × Expri), where Coefi represents the regression coefficient from multivariate Cox analysis, and Expri represents the expression level of each selected gene [33].

Patient Stratification: Classify patients into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median risk score or optimal cut-off value determined by survival analysis [33] [34].

Model Validation: Assess model performance using time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves at 1, 3, and 5 years [33]. Validate the model in independent datasets using the same risk score formula and stratification criteria [34].

Clinical Utility Assessment

Nomogram Construction: Develop a comprehensive nomogram that integrates the risk score with clinical parameters (age, stage, grade) to predict individual patient prognosis [33] [34].

Decision Curve Analysis: Evaluate the clinical net benefit of the model compared to traditional staging systems across different threshold probabilities [34].

Drug Sensitivity Prediction: Correlate risk scores with IC50 values of common chemotherapeutic and targeted agents using databases such as GDSC or CTRP to guide treatment selection [34].

Immune Infiltration Analysis

Immune Cell Quantification

Algorithm Selection: Employ multiple deconvolution algorithms (e.g., CIBERSORT, EPIC, TIMER, QUANTISEQ) to estimate immune cell abundances from bulk tumor transcriptomes [31] [32]. Use the consensus of multiple methods to increase reliability.

Immune Scoring: Calculate immune scores, stromal scores, and estimate scores using the ESTIMATE algorithm to characterize the tumor microenvironment [31] [33].

Statistical Comparison: Compare immune cell infiltration between risk groups using Wilcoxon rank sum test with significance threshold of p < 0.05 [33].

Immune Checkpoint and Microenvironment Analysis

Checkpoint Expression: Examine the correlation between UBR expression and immune checkpoint genes (PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4, LAG-3, etc.) using Spearman correlation analysis [31] [32].

Tumor Immunogenicity Assessment: Evaluate the relationship between UBR expression and tumor mutational burden (TMB), microsatellite instability (MSI), and neoantigen load using Spearman correlation tests [32].

Immunotherapy Response Prediction: Analyze differential response rates to immune checkpoint inhibitors between risk groups in available immunotherapy cohorts (e.g., IMvigor210, GSE135222) [30].

Functional Validation Experiments

In Vitro Cellular Assays

Gene Modulation: Perform knockdown or overexpression of target UBRs in cancer cell lines using siRNA, shRNA, or cDNA expression vectors. Use Lipofectamine 2000 or similar transfection reagents with optimization for specific cell types [33].

Proliferation Assessment: Evaluate cell viability using CCK-8 assay according to manufacturer's protocol. Measure absorbance at 450nm at 0, 24, 48, and 72 hours post-treatment [34].

Migration and Invasion Evaluation: Conduct wound healing assays by creating a scratch wound and monitoring closure at 0, 24, and 48 hours. Perform transwell invasion assays using Matrigel-coated chambers with 10% FBS as chemoattractant [34].

Western Blot Analysis: Extract proteins using high-performance RIPA lysis buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE, transfer to PVDF membranes, and probe with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C [33].

Pathway Analysis

Gene Set Enrichment: Perform Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) using hallmark gene sets from MSigDB to identify pathways enriched in high-risk groups or UBR-overexpressing samples [28] [30].

GSVA Scoring: Calculate pathway activity scores using Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) with the "GSVA" R package [28]. Use Spearman correlation to assess associations between UBR expression and pathway activity.

Protein-Protein Interaction Networks: Construct PPI networks using the STRING database and identify functional modules using Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE) plugin in Cytoscape [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Ubiquitination Studies in Cancer

| Category | Resource/Reagent | Specification/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Databases | TCGA (https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga) [28] [32] | Pan-cancer molecular and clinical data | Multi-omics data for 33+ cancer types |

| GTEx (https://www.gtexportal.org/) [28] [32] | Normal tissue transcriptome reference | Normal tissue expression baseline | |

| UUCD (http://uucd.biocuckoo.org/) [33] [28] | Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like conjugation database | Curated repository of UBRs | |

| cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org/) [32] | Cancer genomics data exploration | User-friendly visualization tools | |

| Computational Tools | GEPIA2 (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/) [32] | Gene expression analysis | TCGA and GTEx data integration |

| UALCAN (https://ualcan.path.uab.edu/) [31] [32] | Protein expression and promoter methylation | CPTAC proteomics data integration | |

| TISIDB (http://cis.hku.hk/TISIDB/) [31] | Tumor-immune system interactions | Immunogenomics analysis | |

| TIMER (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/) [32] | Immune infiltration estimation | Multiple deconvolution algorithms | |

| Experimental Reagents | CCK-8 assay kit [34] | Cell proliferation and viability assessment | Non-radioactive, high sensitivity |

| Transwell chambers [34] | Cell migration and invasion measurement | Matrigel coating for invasion assays | |

| RIPA lysis buffer [33] | Protein extraction from cells and tissues | Compatible with phosphatase/protease inhibitors | |

| Protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail [33] | Preservation of protein phosphorylation | Maintains ubiquitination status |

Visualizations

Ubiquitination Cascade and Cancer Dysregulation

Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Model Workflow

Advanced Ubiquitylomics Workflows: From Tissue Processing to Data Acquisition

The pursuit of reliable ubiquitylomics data from clinical tissue samples, particularly in the context of cancer research, demands rigorous and reproducible sample preparation. The quality of this initial stage fundamentally determines the success of all downstream analyses, including mass spectrometry, which is used to characterize the ubiquitin code in cancerous versus normal tissues [22] [35]. This protocol details the essential steps for the preparation of tissue lysates suitable for ubiquitination profiling, with a specific focus on preserving the post-translational modifications of interest and maintaining the integrity of the proteome. The methods described herein are framed within a broader research objective of identifying differentially ubiquitinated proteins that may serve as biomarkers or therapeutic targets in human cancers, drawing from established practices in ubiquitinomics studies [22] [35] [36].

Experimental Workflow and Key Reagents

The journey from tissue specimen to analytical-ready sample involves a coordinated sequence of steps, each critical for preserving the native ubiquitinome.

The diagram below outlines the core experimental workflow for tissue sample preparation in ubiquitylomics studies.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the essential reagents required for the successful implementation of this protocol.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Tissue Lysis and Protein Preparation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Buffers | RIPA, NP-40, Urea-based Buffer (8 M Urea, 50 mM TEAB) [37] [16] [36] | Disrupts tissue architecture and cell membranes to solubilize proteins. Choice depends on protein localization and downstream application [38] [37]. |

| Protease Inhibitors | PMSF (1 mM), Aprotinin (2 µg/mL), Leupeptin (1-10 µg/mL), Pepstatin A (1 µg/mL), EDTA (1-5 mM) [37] | Prevents co-extracted proteases from degrading target proteins, preserving the native protein and ubiquitination state [38] [39]. |

| Phosphatase Inhibitors | Sodium Fluoride (5-10 mM), Sodium Orthovanadate (1 mM), β-Glycerophosphate (1-2 mM) [37] | Preserves labile phosphorylation states, which is often crucial for signaling studies in cancer [38]. |

| Chaotropic Agents | Urea (8 M), Guanidine HCl [16] [40] | Denatures proteins and increases solubility, particularly effective for membrane and insoluble proteins [40]. |

| Detergents | SDS, Triton X-100, Sodium Deoxycholate [37] [16] | Aids in membrane solubilization. SDS is a strong denaturant ideal for total protein extraction [38] [37]. |

| Reducing Agents | Dithiothreitol (DTT, 10-100 mM), β-Mercaptoethanol (5%) [39] [37] [16] | Breaks disulfide bonds, linearizing proteins for consistent migration in electrophoresis. |

| Alkylating Agent | Iodoacetamide (IAA, 30-50 mM) [22] [35] [16] | alkylates cysteine thiol groups to prevent reformation of disulfide bonds. |

Detailed Methodologies

Tissue Lysis and Homogenization

Efficient lysis is the cornerstone of effective protein extraction, requiring mechanical force combined with optimized buffer chemistry.

- Tissue Collection and Stabilization: Following surgical resection, dissect the tissue of interest (e.g., tumor and adjacent normal) rapidly on ice. Snap-freeze the tissue fragments by immersing them in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C until processing [22] [39] [35].

- Homogenization: For a ~5 mg piece of tissue, add 300 µL of ice-cold lysis buffer (e.g., RIPA or 8 M Urea-based buffer) supplemented with fresh protease and phosphatase inhibitors [39] [37] [16].

- Homogenize using an electric homogenizer.

- Rinse the homogenizer blade with two additional 300 µL volumes of lysis buffer to maximize recovery [39].

- Solubilization: Maintain constant agitation for 2 hours at 4°C (e.g., on an orbital shaker) to ensure complete solubilization [39].

- Clarification: Centrifuge the lysate at 12,000–15,000 × g for 10–20 minutes at 4°C to pellet insoluble debris, lipids, and nuclei. Gently transfer the supernatant (soluble protein fraction) to a fresh pre-cooled tube [39] [37] [36].

Protease and Phosphatase Inhibition

The moment of lysis releases endogenous enzymes that can rapidly degrade proteins and remove modifications. The composition of the inhibitor cocktail must be tailored to the specific sample.

Table 2: Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Preparation

| Inhibitor | Target Enzymes | Stock Concentration | Final Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| PMSF | Serine proteases | 100 mM (in isopropanol) | 1 mM |

| Aprotinin | Trypsin, Chymotrypsin, Plasmin | 1 mg/mL | 2 µg/mL |

| Leupeptin | Lysosomal proteases (Cysteine, Serine) | 1 mg/mL | 1-10 µg/mL |

| Pepstatin A | Aspartic proteases (e.g., Cathepsin D) | 1 mg/mL | 1 µg/mL |

| EDTA | Metalloproteases (Mg²⁺, Mn²⁺ dependent) | 500 mM, pH 8.0 | 1-5 mM |

| Sodium Orthovanadate | Tyrosine phosphatases | 200 mM (activated) | 1 mM |

| Sodium Fluoride | Serine/Threonine phosphatases | 1 M | 5-10 mM |

Protein Denaturation and Reduction

For most western blot and mass spectrometry applications, proteins must be denatured and reduced to ensure uniform behavior.

- Protein Quantification: Determine the protein concentration of the clarified lysate using a compatible assay (e.g., BCA or Bradford), with BSA as a standard [39] [37] [16].

- Buffer Addition: Mix the protein lysate with an equal volume of 2X Laemmli sample buffer [39] [37].

- Denaturation and Reduction: Heat the samples at 95–100°C for 5 minutes. This step, in the presence of SDS and a reducing agent, fully denatures the proteins and reduces disulfide bonds, linearizing them for analysis [39] [37].

Table 3: Standard 2X Laemmli Buffer Composition and Purpose

| Component | Final Concentration | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | 4% | Strong anionic detergent that binds to and denatures proteins, imparting a uniform negative charge. |

| Glycerol | 10-20% | Increases sample density for easy loading into gel wells. |

| Bromophenol Blue | 0.004% | Tracking dye to monitor electrophoresis progress. |

| Tris HCl | 62.5-125 mM, pH ~6.8 | Buffering agent to maintain stable pH. |

| 2-Mercaptoethanol or DTT | 5% or 100-500 mM | Reducing agent that breaks disulfide bonds. |

Critical Factors for Ubiquitylomics

The following considerations are paramount when preparing samples specifically for ubiquitination analysis.

- Inhibition of Deubiquitinases (DUBs): Beyond standard protease inhibitors, include specific DUB inhibitors like PR-619 in the lysis buffer to prevent the loss of ubiquitin chains by endogenous deubiquitinating enzymes, thereby preserving the in vivo ubiquitination state [22].