A Comprehensive Guide to Detecting Ubiquitin Protein Conjugates by Western Blot: From Basics to Advanced Validation

This article provides a complete resource for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to detect and analyze ubiquitin-protein conjugates via Western blot.

A Comprehensive Guide to Detecting Ubiquitin Protein Conjugates by Western Blot: From Basics to Advanced Validation

Abstract

This article provides a complete resource for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to detect and analyze ubiquitin-protein conjugates via Western blot. It covers foundational principles of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, detailing how ubiquitination alters protein molecular weight and generates characteristic laddering patterns. The guide offers step-by-step methodological protocols, including sample preparation under denaturing conditions and choice of antibodies. It extensively addresses troubleshooting for common issues like smears and non-specific bands and explores advanced validation techniques such as mass spectrometry and the use of tandem ubiquitin-binding entities (TUBEs) for linkage-specific analysis. By integrating foundational knowledge with practical application and advanced validation strategies, this content equips scientists to accurately interpret ubiquitination data in contexts ranging from basic research to targeted protein degradation drug discovery.

Ubiquitination 101: Understanding the Target and Its Western Blot Signature

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS) is a highly complex, temporally controlled, and conserved pathway that plays a major role in a myriad of cellular functions, from cellular differentiation to cell death [1]. At its core, the UPS is responsible for much of the regulated proteolysis in the cell, performing both degradative and non-degradative functions [2]. The process involves the covalent attachment of a small, 76-amino-acid protein called ubiquitin to substrate proteins, which tags them for proteasomal degradation or alters their function, stability, or localization [2] [1]. The fundamental importance of the UPS to normal cell function means that its malfunction is a key factor in various human diseases, including numerous cancer types, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative disorders [2]. Consequently, the UPS represents a promising therapeutic target, as demonstrated by the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, which is approved for treating multiple myeloma [2].

The conjugation of ubiquitin to a target protein is a precise, three-step enzymatic cascade often termed the E1-E2-E3 pathway [1]. This ATP-dependent process involves the sequential action of ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), and ubiquitin-ligase (E3) enzymes [2] [1]. The specificity and outcome of ubiquitination are profoundly influenced by the enzymes involved, particularly the E3 ligases, which impart substrate specificity, and the type of ubiquitin chain formed on the substrate [3]. This application note details the function of these enzymes and provides a validated protocol for detecting ubiquitin conjugates, a critical technique for research and drug development focused on the UPS.

The Enzymatic Cascade of Ubiquitin Conjugation

The process of ubiquitin conjugation is a precise, three-step enzymatic cascade that ensures the specific tagging of target proteins.

The E1-E2-E3 Enzymatic Cascade

The conjugation of ubiquitin to a substrate protein is achieved through a coordinated, three-step enzymatic cascade [2] [1].

E1: Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme

- The initiating step involves an E1 activating enzyme, such as UBE1 (Ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1) [1]. The E1 enzyme consumes ATP and activates ubiquitin, forming a high-energy thioester bond between its catalytic cysteine residue and the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin [2] [3]. This step is described as the "alarm clock of the UPS," initiating the degradation process [1]. There is one major E1 enzyme shared by all ubiquitin ligases, though other E1-like enzymes exist for specific ubiquitin-like proteins [3].

E2: Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme

- The activated ubiquitin is then transferred from the E1 to the catalytic cysteine of an E2 conjugating enzyme (e.g., UBE2D2) through a transthiolation reaction [2] [1]. The E2 enzyme acts as a "baton passer," carrying the ubiquitin to the final step in the pathway [1]. Humans possess several different E2 enzymes, which help determine the type of ubiquitin linkage formed on the substrate [2].

E3: Ubiquitin-Ligase Enzyme

- The final and most diverse step is mediated by an E3 ubiquitin ligase. The E3 recruits the ubiquitin-charged E2 and a specific protein substrate, facilitating the direct or indirect transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine residue on the substrate, forming an isopeptide bond [3]. The E3 is "the anchor of the UPS," ultimately linking the ubiquitin to the protein [1]. With over 600 E3 ligases encoded in the human genome, this family of enzymes is primarily responsible for imparting substrate specificity to the entire ubiquitination process [3].

Table 1: Core Enzymes in the Ubiquitin Conjugation Cascade

| Enzyme | Core Function | Key Example | Mechanistic Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Activating) | Activates ubiquitin | UBE1 (UBA1) | ATP-dependent formation of E1~Ub thioester |

| E2 (Conjugating) | Carries activated ubiquitin | UBE2D2 | Transthiolation from E1, forms E2~Ub thioester |

| E3 (Ligase) | Recognizes substrate & catalyzes transfer | c-Cbl, MDM2, SCF complexes | Brings E2~Ub and substrate together; catalyzes isopeptide bond formation |

This cascade results in the attachment of a ubiquitin molecule to the substrate. A single ubiquitin (monoubiquitination) can alter a protein's function or location, while the repeated addition of ubiquitin molecules to the first one creates a polyubiquitin chain [3]. The functional consequences of ubiquitination are primarily determined by the type of ubiquitin chain assembled on the substrate.

Polyubiquitin Chain Linkages and Functions

Ubiquitin itself contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63), and the N-terminal methionine, all of which can be used to form polyubiquitin chains [3]. The specific lysine used for chain linkage determines the fate of the modified protein.

- K48-linked chains are the principal signal for proteasomal degradation [1] [3]. Substrates marked with K48-linked polyubiquitin chains are recognized and degraded by the 26S proteasome.

- K63-linked chains are generally not degradative but are essential components of signaling pathways, such as the NF-κB-dependent expression of inflammatory and immune genes [2].

- Monoubiquitination has been linked to processes such as membrane protein endocytosis (e.g., EGFR trafficking) and regulation of cytosolic protein localization (e.g., p53 nuclear export) [3].

The growing recognition of the importance of different chain types has increased the reliance on sensitive and quantitative methods, like western blotting, for validation experiments [4].

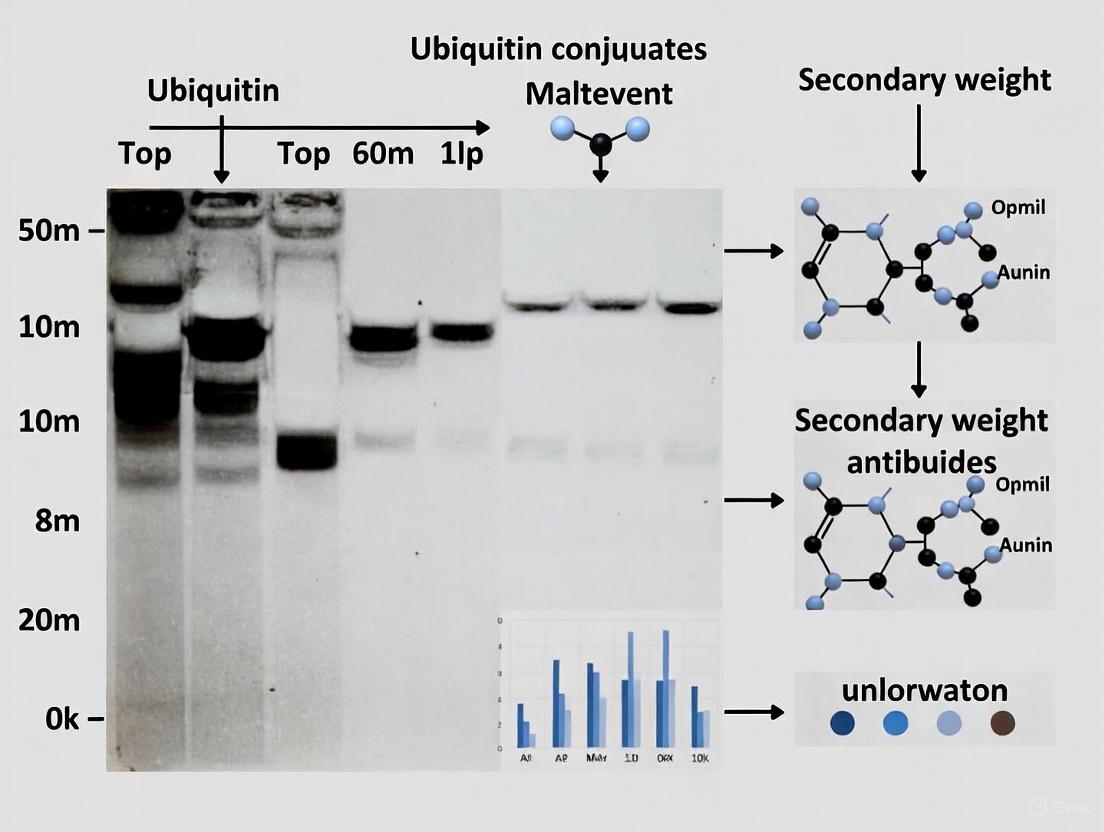

Diagram 1: The E1-E2-E3 ubiquitin conjugation cascade. This ATP-dependent process involves sequential ubiquitin transfer through three enzyme classes.

Protocol: Detecting Protein Ubiquitination by Western Blot

Detecting ubiquitination is crucial for understanding protein regulation. The following protocol is adapted from optimized methods for detecting ubiquitination of both exogenous and endogenous proteins [5].

Sample Preparation and Protein Extraction

- Buffer Selection: Select an appropriate extraction buffer compatible with downstream techniques. A common choice is RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail immediately before use [4].

- Protein Extraction:

- Manually macerate tissue samples using scissors or a scalpel.

- Homogenize the tissue in the prepared extraction buffer at approximately a 1:10 (w/v) ratio using a dounce or electric homogenizer until a smooth consistency is achieved. For precious samples, a 1:5 ratio can be effective [4].

- Centrifuge the homogenate at 20,000 x g for 20 minutes at 4°C.

- Transfer the supernatant (containing solubilized proteins) to a new tube and store at -80°C. Retain the insoluble pellet for potential further extraction.

- Protein Determination: Determine protein concentration using a BCA, Bradford, or similar assay. Ensure all samples for comparison are assayed against the same standard curve, with an R-squared value of ≥ 0.99 for accuracy [4].

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

This section describes the steps for immunoprecipitating the target protein and detecting its ubiquitination status.

- Immunoprecipitation of Target Protein:

- Transfer the encoding plasmid for your protein of interest into the relevant cell line to express the exogenous protein [5].

- Lyse the cells in a suitable lysis buffer.

- Incubate the cell lysate with an antibody specific to the target protein.

- Use Protein A/G beads to pull down the antibody-protein complex.

- Wash the beads thoroughly to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Electrophoretic Separation:

- Prepare a 4-12% Bis-Tris gradient gel for optimal protein separation across a broad molecular weight range [4].

- Choose a running buffer: MES for proteins between 3.5-160 kDa or MOPS for proteins above 200 kDa [4].

- Load the pre-stained molecular weight standard and samples. A typical load for neuronal isolates is 15 μg, but this should be optimized [4].

- Run the gel at 80V for 4 minutes to allow uniform entry into the gel, then increase to 180V for approximately 50 minutes, or until the dye front reaches the bottom.

- Protein Transfer and Immunoblotting:

- Transfer proteins from the gel to a nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane.

- Block the membrane to prevent non-specific antibody binding.

- Incubate the membrane with a primary antibody against ubiquitin (or a specific linkage, e.g., K27-linkage) [5].

- Incubate with a fluorescently-labeled secondary antibody.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Ubiquitination Detection via Western Blot

| Reagent / Equipment | Function / Role | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Buffer | Solubilizes proteins while maintaining ubiquitin modifications | RIPA, NP-40, or Tris-Triton. Must be compatible with protein determination assays [4]. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevents degradation of ubiquitin conjugates during processing | Added fresh to lysis buffer. Critical for preserving post-translational modifications. |

| Ubiquitin Antibody | Detects conjugated ubiquitin | Mono/poly-specific or linkage-specific (e.g., anti-K27, anti-K48) [5]. |

| Protein A/G Beads | Captures antibody-protein complexes for immunoprecipitation | Used to isolate the target protein prior to western blotting [5]. |

| Gradient Gel | Separates proteins by molecular weight | 4-12% Bis-Tris gels provide resolution across a wide mass range [4]. |

| Fluorescent Secondary | Enables quantitative detection of bound primary antibody | Provides a linear detection profile superior to chemiluminescence for quantification [4]. |

Visualization and Quantitative Analysis

- Imaging and Analysis:

- Image the membrane using a digital imaging system capable of detecting fluorescence, such as the LI-COR Odyssey system [4].

- Use the accompanying software (e.g., Image Studio) for lane definition, background subtraction, and band quantification.

- Define the analysis boundary and number of lanes. The software can automatically find bands, but parameters can be manually adjusted to find more or fewer bands as needed [6].

- For molecular weight estimation, select the appropriate marker template from the software's library or create a custom one based on the pre-stained ladder used [6].

- Normalization: To correct for loading variations, normalize the ubiquitin signal to a loading control. This is typically done by using a second channel to detect a housekeeping protein (e.g., actin) or by using a total protein stain on a duplicate gel [4] [6].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for detecting protein ubiquitination, from sample preparation to quantitative analysis.

Research Reagent Solutions for UPS Studies

Advancing research in the UPS requires a toolkit of reliable and specific reagents. The following table details essential materials used in the study of ubiquitin conjugation.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for UPS Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| E1 Enzyme Assays | Recombinant UBA1, UBA6 | Study the initial step of ubiquitin activation; useful for high-throughput inhibitor screening [2]. |

| E2 Enzyme Assays | UBE2D2 (E2~Ub thioester formation) | Investigate transthiolation kinetics and E2-E3 interactions central to ubiquitin transfer [1]. |

| E3 Ligase Tools | c-Cbl, MDM2, SCF complexes, F-box proteins | Determine substrate specificity; E3 ligases are key targets for drug development (e.g., PROTACs) [1] [3]. |

| DUB Inhibitors | Small-molecule DUB inhibitors | Probe the function of deubiquitylating enzymes in reversing ubiquitination and stabilizing proteins [2]. |

| Linkage-Specific Binders | Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) | High-affinity reagents that bind polyubiquitin chains; used to isolate and enrich ubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates [1]. |

| PROTAC Molecules | Heterobifunctional degraders (e.g., dBET1) | Recruit the UPS to degrade specific target proteins of interest, offering a novel therapeutic modality [1]. |

Ubiquitination is a fundamental post-translational modification that regulates diverse cellular processes, primarily through the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to target proteins. In western blot analyses, ubiquitination manifests as characteristic molecular weight shifts, most commonly recognized as an increase of approximately +8 kDa for monoubiquitination. This application note details the biochemical principles underlying these shifts, provides validated protocols for detecting ubiquitinated conjugates, and discusses advanced methodologies for linkage-specific analysis. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this resource serves as a practical guide for interpreting ubiquitination data and troubleshooting common challenges in western blot-based detection, with direct relevance to targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome system for therapeutic development.

Ubiquitination is a highly conserved, enzymatic process that conjugates the 8.6 kDa ubiquitin protein to lysine residues on substrate proteins [7] [8]. This modification significantly alters the apparent molecular weight (MW) of the substrate during SDS-PAGE and western blotting. The observed shift is a direct consequence of the covalent attachment of ubiquitin and is influenced by the type and extent of modification:

- Monoubiquitination: The addition of a single ubiquitin moiety typically results in an ~8 kDa increase in apparent MW [8]. This is the origin of the "+8 kDa rule" commonly used for initial assessment.

- Polyubiquitination: The formation of a chain of ubiquitin molecules on a single lysine residue leads to more substantial shifts. Each additional ubiquitin contributes roughly another 8 kDa, resulting in high-molecular-weight smears or ladders on blots [8] [9].

- Multi-monoubiquitination: The attachment of single ubiquitin molecules to multiple lysine residues on the same substrate also produces large MW increases and a heterogeneous banding pattern [10].

For researchers, recognizing these patterns is crucial for confirming ubiquitination, as the characteristic laddering differentiates it from other modifications. Furthermore, the nature of the shift can offer clues about the type of ubiquitin topology involved, which dictates the functional outcome for the substrate, such as proteasomal degradation (K48-linked) or signal transduction (K63-linked) [9].

Key Concepts and Quantitative Data

Table 1: Ubiquitination-Related Molecular Weight Shifts and Their Interpretations

| Modification Type | Theoretical MW Addition | Common Western Blot Observation | Primary Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monoubiquitination | ~8 kDa | Discrete band shift upwards of ~8 kDa | Signaling, endocytosis, histone regulation |

| Polyubiquitination | >16 kDa (often much larger) | High-MW smears or laddering | Proteasomal degradation (K48-linked); NF-κB signaling (K63-linked) [9] |

| Multi-monoubiquitination | Multiples of ~8 kDa | High-MW smears or laddering | DNA repair, viral budding |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Unexpected Molecular Weights in Western Blotting

| Observation | Potential Cause | Recommended Validation Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Shift is less than +8 kDa | Concurrent cleavage (e.g., signal peptide, caspase) [7] | Check protein sequence for known cleavage sites; use cleavage-specific antibodies. |

| Single band at +8 kDa | Monoubiquitination or single-site modification | Mutate suspected lysine residue(s) to arginine to confirm. |

| High-MW smear or ladder | Polyubiquitination or multi-monoubiquitination [10] [8] | Confirm with linkage-specific antibodies or TUBEs [9]; repeat with proteasome inhibitor (MG132). |

| No shift, but other evidence of ubiquitination | Modification is masked by another PTM (e.g., glycosylation) [7] | Perform deglycosylation (e.g., with PNGase F) prior to ubiquitination analysis [7]. |

| Poor transfer efficiency for HMW species | Inefficient transfer of HMW proteins out of the gel [11] | Use Tris-acetate gels, increase transfer time, add ethanol equilibration step [11]. |

Essential Protocols for Detecting Ubiquitinated Conjugates

Protocol 1: Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot for Endogenous Ubiquitinated Proteins

This protocol is adapted from methods used to study the ubiquitination of PD-L1 and RIPK2 [10] [9] and is designed to capture endogenous ubiquitination events.

Materials and Reagents

- Lysis Buffer: Ice-cold buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (e.g., PMSF, aprotinin), deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitors (e.g., N-ethylmaleimide/NEM), and ubiquitin protease inhibitors [10].

- PTM Enrichment Tools: Ubiquitin affinity beads (e.g., Signal-Seeker UBA01 beads [10]) or chain-specific TUBE-coated magnetic beads [9]. Control beads (e.g., IgG or bare resin) are essential.

- Wash Buffer: Lysis buffer with or without added salt to reduce non-specific binding.

- Elution Buffer: Low-pH buffer (e.g., glycine pH 2.0-3.0) or Laemmli sample buffer containing SDS and DTT/β-mercaptoethanol for direct denaturation.

- Antibodies: Primary antibodies against protein of interest and ubiquitin (e.g., FK2 antibody [12]).

Procedure

- Cell Lysis: Harvest and lyse cells in the provided lysis buffer. Clarify the lysate by centrifugation at high speed [10] [13].

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate the clarified lysate with ubiquitin affinity beads or TUBE-coated beads for 1-2 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation [10] [9].

- Washing: Pellet the beads and wash 3-5 times with wash buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elution: Elute the bound ubiquitinated proteins using elution buffer. If using Laemmli buffer, heat the samples at 95°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Western Blot Analysis: Resolve the eluted proteins by SDS-PAGE. Transfer to a membrane, ensuring optimized conditions for high-MW proteins (see Protocol 3.2). Probe the membrane with an antibody against your protein of interest to visualize the ubiquitinated species, which will appear as higher-MW bands or a ladder above the unmodified protein [10].

Protocol 2: Optimized Western Blot for High-Molecular-Weight Ubiquitinated Proteins

Detecting polyubiquitinated species is challenging due to their large size. This protocol outlines optimizations for successful transfer and detection [11].

Materials and Reagents

- Gel Type: 3-8% Tris-acetate gels are strongly recommended for optimal separation of HMW proteins (>150 kDa) over traditional 4-20% Tris-glycine gels [11].

- Transfer Stack: Nitrocellulose or PVDF membranes with appropriate filter paper and fiber pads.

- Transfer Buffer: Standard wet or semi-dry transfer buffer.

Procedure

- Gel Electrophoresis: Separate your protein samples using a Tris-acetate gel according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Gel Equilibration (if not using Tris-acetate): If using a Bis-Tris or Tris-glycine gel, submerge the gel in 20% ethanol for 5-10 minutes with gentle agitation to shrink the gel and prevent overheating during transfer [11].

- Membrane Preparation: Activate PVDF membrane in methanol or equilibrate nitrocellulose in transfer buffer.

- Assembly: Create a transfer sandwich, ensuring no air bubbles are trapped between the gel and membrane.

- Protein Transfer:

- Detection: Proceed with standard blocking, antibody incubation, and chemiluminescent detection.

Protocol 3: In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

This assay allows for the direct assessment of E1, E2, and E3 enzyme activity in forming ubiquitin chains [12].

Materials and Reagents

- Purified Recombinant Proteins: E1 activating enzyme, E2 conjugating enzyme, E3 ligase (optional), and ubiquitin.

- Reaction Buffer: 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM DTT, and 5 mM ATP [12].

- Stop Solution: 4x LDS sample buffer with β-mercaptoethanol.

Procedure

- Reaction Setup: On ice, combine in a tube: 100 nM E1, 2.5 µM E2, 2.5 µM E2 variant (if applicable), 100 µM ubiquitin, and an E3 ligase in reaction buffer [12].

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction mix at 30°C for 60-90 minutes.

- Termination: Stop the reaction by adding stop solution and heating at 70°C for 10 minutes.

- Analysis: Resolve the products by SDS-PAGE. Perform western blotting using a ubiquitin antibody (e.g., FK2) to detect free di-ubiquitin or polyubiquitin chains. Linkage specificity can be probed with antibodies like anti-K63 [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Ubiquitin Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | High-affinity capture of polyubiquitin chains; protect chains from DUBs [9]. | Enrichment of endogenous ubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates for western blot or proteomics. |

| Linkage-Specific TUBEs (K48, K63) | Selective enrichment of ubiquitin chains with specific linkages (e.g., K48 for degradation, K63 for signaling) [9]. | Differentiating PROTAC-induced K48-ubiquitination from inflammatory K63-ubiquitination of RIPK2 [9]. |

| Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme (E1) Inhibitor (PYR-41) | Inhibits the initial step of ubiquitin activation, blocking all downstream ubiquitination [10]. | Confirming that an observed MW shift is ubiquitin-dependent [10]. |

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors (NEM) | Prevents the cleavage of ubiquitin chains during sample preparation, preserving the ubiquitome [10]. | Added to cell lysis buffer to maintain ubiquitination signals. |

| PNGase F | Enzyme that removes N-linked glycans from glycoproteins [7]. | Unmasking ubiquitination shifts on heavily glycosylated proteins like PD-L1 [7]. |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies | Detect specific polyubiquitin chain topologies (e.g., K48, K63) via western blot [12] [9]. | Determining the type of ubiquitin linkage present on a substrate. |

Workflow and Data Interpretation

Experimental Workflow for Ubiquitin Detection

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for detecting and validating ubiquitinated proteins, integrating the protocols described above.

Interpreting Western Blot Results

When analyzing western blots for ubiquitination, researchers must accurately interpret the banding patterns. The following decision tree aids in correlating observations with biological conclusions.

Understanding the principles behind ubiquitination-induced molecular weight shifts is paramount for accurately identifying and characterizing this critical modification. The "+8 kDa rule" provides a foundational guideline, but a comprehensive analysis requires careful consideration of polyubiquitination ladders, the masking effects of other PTMs, and the use of optimized technical protocols for HMW proteins. The experimental workflows and troubleshooting guides presented here equip researchers to confidently design, execute, and interpret ubiquitination experiments. As drug discovery increasingly targets the ubiquitin-proteasome system with modalities like PROTACs, robust and reliable detection of ubiquitinated conjugates remains a cornerstone of therapeutic development and basic research.

Within the framework of research focused on detecting ubiquitin protein conjugates via Western blot, a fundamental challenge persists: the accurate interpretation of the characteristic "ladder" pattern observed on the blot. This pattern can represent either poly-ubiquitination, where a chain of ubiquitins extends from a single lysine residue, or multi-mono-ubiquitination, where single ubiquitin molecules are attached to multiple lysine residues on the substrate protein [14]. Distinguishing between these two forms is critical, as they dictate divergent functional outcomes for the modified protein, ranging from proteasomal degradation to the regulation of cell signaling [14] [15]. This application note provides detailed methodologies and analytical frameworks to correctly identify and interpret these ubiquitination states.

The Biochemical Distinction

Ubiquitination is a dynamic post-translational modification mediated by a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes [15]. The final modification is characterized by an isopeptide bond between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin and an ε-amino group of a lysine residue in the substrate protein.

- Poly-ubiquitination: Describes the formation of a chain where additional ubiquitin molecules are conjugated end-to-end, utilizing one of the seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or the N-terminal methionine (M1) of the previously attached ubiquitin molecule [14] [16] [15]. These chains can be homotypic, heterotypic, or even branched, with the linkage type encoding a specific functional signal [16] [15]. For instance, K48-linked chains primarily target substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains are involved in non-proteolytic processes like DNA repair and inflammatory signaling [15].

- Multi-mono-ubiquitination: Occurs when single ubiquitin molecules are attached to multiple, distinct lysine residues on the substrate protein. These ubiquitins do not serve as elongation points for chain formation [14].

Despite their different structures, both forms appear as high molecular weight smears or ladders on a Western blot probed with an anti-ubiquitin antibody, making them visually indistinguishable without further experimentation [14].

Critical Reagents and Experimental Design

A definitive diagnosis of ubiquitination type requires a functional assay that exploits the biochemical requirements for chain elongation. The core strategy involves comparing ubiquitination patterns using wild-type ubiquitin versus a mutant ubiquitin that cannot form chains.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential reagents required for the described experiments.

Table 1: Key Reagents for Differentiating Ubiquitination Types

| Reagent | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| E1 Enzyme | Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner, initiating the entire enzymatic cascade [14] [15]. |

| E2 Enzyme | Accepts activated ubiquitin from E1 and works in concert with a specific E3 ligase to transfer ubiquitin to the substrate [14] [15]. |

| E3 Ligase | Confers substrate specificity by recruiting the target protein and facilitating or catalyzing ubiquitin transfer from the E2 enzyme [14] [15]. |

| Wild-Type Ubiquitin | The native form of ubiquitin; can be conjugated to substrates and can also form all types of poly-ubiquitin chains via its lysine residues [14]. |

| Ubiquitin No K (K0) | A mutant form of ubiquitin where all seven lysine residues are mutated to arginines. It can be conjugated to substrates but is incapable of forming poly-ubiquitin chains, thereby blocking chain elongation [14]. |

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors (e.g., NEM) | Added to lysis buffers to prevent the cleavage of ubiquitin chains by endogenous deubiquitinating enzymes during sample preparation, thereby preserving the native ubiquitination state [17]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132) | Prevent the degradation of poly-ubiquitinated proteins by the proteasome, allowing for their accumulation and detection [17]. |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Antibodies that recognize a specific ubiquitin-ubiquitin linkage (e.g., K48 or K63). Their use is limited to folded proteins and not all linkage types have commercially available antibodies [16] [17]. |

Experimental Workflow for Differentiation

The following diagram outlines the logical workflow for designing and interpreting the experiment that distinguishes between poly-ubiquitination and multi-mono-ubiquitination.

Detailed Protocol: In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology to determine the nature of a protein's ubiquitination.

Materials and Reagent Setup

Table 2: Reaction Setup for 25 µL Scale (Adapted from R&D Systems Protocol [14])

| Reagent | Reaction 1 (Wild-Type Ub) | Reaction 2 (Ubiquitin No K) | Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| dH₂O | X µL (to 25 µL total) | X µL (to 25 µL total) | N/A |

| 10X E3 Ligase Reaction Buffer | 2.5 µL | 2.5 µL | 1X (50 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP) |

| Ubiquitin | 1 µL (Wild-Type) | 1 µL (Ubiquitin No K) | ~100 µM |

| MgATP Solution | 2.5 µL | 2.5 µL | 10 mM |

| Substrate Protein | X µL | X µL | 5-10 µM |

| E1 Enzyme | 0.5 µL | 0.5 µL | 100 nM |

| E2 Enzyme | 1 µL | 1 µL | 1 µM |

| E3 Ligase | X µL | X µL | 1 µM |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Reaction Assembly: Prepare two microcentrifuge tubes on ice. Combine the components for Reaction 1 and Reaction 2 in the order listed in Table 2. It is critical to include a negative control where the MgATP solution is replaced with dH₂O.

- Incubation: Incubate both reaction tubes in a 37°C water bath for 30–60 minutes.

- Reaction Termination:

- For direct Western blot analysis: Add 25 µL of 2X SDS-PAGE sample buffer to each 25 µL reaction.

- If reaction products are for downstream applications: Add 0.5 µL of 500 mM EDTA (final 20 mM) or 1 µL of 1 M DTT (final 100 mM) to stop the reaction [14].

- Analysis:

- Separate the reaction products by SDS-PAGE.

- Transfer to a PVDF membrane (recommended for higher signal strength over nitrocellulose) [17].

- Perform a Western blot using an anti-ubiquitin antibody.

- Compare the blotting patterns from Reaction 1 and Reaction 2.

Expected Results and Interpretation

Table 3: Interpretation of Western Blot Results

| Observation in Reaction 1 (WT Ub) | Observation in Reaction 2 (Ub No K) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| High Molecular Weight (HMW) smear/ladder | No HMW smear/ladder | Poly-ubiquitination. Chain formation is dependent on lysines in ubiquitin. |

| HMW smear/ladder | HMW smear/ladder (similar pattern) | Multi-mono-ubiquitination. Ubiquitin attachment is independent of lysines in ubiquitin. |

| HMW smear/ladder in R1, with reduced but not absent HMW in R2 | The substrate is likely both poly- and multi-mono-ubiquitinated. The highest molecular weight species in R2 disappear [14]. |

Optimizing Western Blot Conditions for Ubiquitin Detection

Obtaining clear, interpretable data requires optimization of Western blot conditions to resolve ubiquitinated species effectively.

- Gel and Buffer Selection:

- For resolving large chains (>8 ubiquitin units), use 8% Tris-glycine or MOPS-based buffer systems.

- For better separation of smaller chains (2-5 units), use 12% gels with MES-based buffer systems [17].

- Transfer Conditions: To preserve the structural epitopes needed for linkage-specific antibody recognition, avoid fast transfers. A semi-dry transfer at 30V for 2.5 hours is recommended for long ubiquitin chains [17].

- Membrane and Detection: PVDF membranes with a 0.2 µm pore size generally provide a higher signal strength for ubiquitin blots [17]. For antibodies raised against denatured ubiquitin, a pre-blot membrane treatment involving incubation in a 6 M guanidine-HCl solution can enhance the signal [17].

- Normalization and Replication: Western blotting is prone to analytical variation. To ensure reliable data, run replicate test samples and use normalization methods, such as the sum of target protein values, to effectively reduce variability [18].

Advanced Techniques and Correlation to Degradation

While the Ubiquitin No K assay defines the type of modification, other techniques can provide deeper insights.

- Linkage-Specific Analysis: Mass spectrometry-based approaches, such as Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM), can precisely quantify the frequency of different ubiquitin linkages within a sample, overcoming the limitations of linkage-specific antibodies which are not available for all linkage types and require folded protein epitopes [16].

- Correlating Ubiquitination to Degradation: In drug discovery, particularly for PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras), it is crucial to establish a relationship between target ubiquitination and its degradation. TUBE (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) -based assays can be used to monitor PROTAC-mediated poly-ubiquitination of native target proteins with high sensitivity, allowing for the rank-ordering of candidate molecules based on their ability to induce ubiquitination [19].

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates virtually every cellular process in eukaryotes, from protein degradation and DNA repair to immune signaling and cell cycle progression [9] [20]. This modification involves the covalent attachment of a small 76-amino acid protein, ubiquitin, to substrate proteins. The process is enzymatic, involving a cascade of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes that work in concert to attach ubiquitin to specific target proteins [20] [21]. The versatility of ubiquitin signaling stems from its ability to form diverse chain architectures through its seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or its N-terminal methionine (M1) [22] [20]. These different chain topologies, often referred to as the "ubiquitin code," are specifically recognized by proteins containing ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs), leading to distinct functional outcomes for the modified substrate [23] [24].

Among the various chain types, K48-linked polyubiquitin is the most abundant linkage in cells and represents the canonical signal for proteasomal degradation [9] [24]. In contrast, K63-linked polyubiquitin primarily regulates non-proteolytic functions including inflammatory signaling, protein trafficking, and DNA repair pathways [9] [22]. Recent research has revealed even greater complexity with the discovery of branched ubiquitin chains, particularly those containing both K48 and K63 linkages, which appear to create unique coding signals that are not simply the sum of their parts [23] [25] [26]. Understanding the specific functions and detection methods for these different ubiquitin linkages is essential for researchers investigating protein homeostasis, signal transduction, and targeted protein degradation technologies.

Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Functional Consequences

K48-Linked Ubiquitin Chains

K48-linked ubiquitin chains constitute the most extensively studied ubiquitin linkage and serve as the primary signal for targeting proteins to the proteasome for degradation [9] [24]. The discovery of this specific function by Chau et al. established the foundational principle that different ubiquitin chain topologies encode distinct functional consequences [22]. The proteasomal degradation signal typically requires chains of at least four ubiquitin molecules (Ub4), though recent research using novel technologies like UbiREAD has demonstrated that K48-Ub3 can also serve as an efficient proteasomal targeting signal [26]. This linkage is particularly relevant in the context of PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) and molecular glues, which hijack the ubiquitin-proteasome system to induce targeted degradation of disease-relevant proteins [9].

K63-Linked Ubiquitin Chains

K63-linked ubiquitin chains represent the second most abundant chain type and function primarily in non-proteolytic signaling pathways [24]. These chains play critical roles in activating inflammatory signaling through pathways such as NF-κB, where they serve as scaffolds for the assembly of signaling complexes [9] [25]. The structural basis for K63 chain formation was elucidated through collaborative work revealing how the Ubc13/Mms2 heterodimer specifically orients K63 of the acceptor ubiquitin toward the active site of Ubc13 [22]. In addition to inflammatory signaling, K63 linkages regulate essential processes including protein trafficking, endocytosis, autophagy, and DNA damage repair [9] [24] [20]. Notably, K63-ubiquitinated substrates are often rapidly deubiquitinated rather than degraded, highlighting their distinct fate compared to K48-modified proteins [26].

Branched K48/K63 Ubiquitin Chains

Branched ubiquitin chains containing both K48 and K63 linkages represent a recently appreciated layer of complexity in the ubiquitin code. These heterotypic chains are surprisingly abundant, comprising approximately 20% of all K63 linkages in mammalian cells [25] [24]. Research has revealed that these branched chains are not simply the sum of their parts but exhibit unique functional properties. In NF-κB signaling, K48-K63 branched chains generated by HUWE1 in response to IL-1β stimulation create a specialized signal that permits recognition by TAB2 while simultaneously protecting K63 linkages from CYLD-mediated deubiquitination, thereby amplifying inflammatory signaling [25]. Surprisingly, in branched chains, the substrate-anchored chain identity determines the degradation and deubiquitination behavior, establishing a functional hierarchy within these complex structures [26].

Table 1: Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Cellular Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Functions | Key Regulatory Roles | Cellular Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48-Linked | Proteasomal degradation | Targets proteins for destruction; regulated by PROTACs | Protein turnover, cell cycle progression |

| K63-Linked | Signal transduction | NF-κB activation, kinase regulation | Inflammation, DNA repair, protein trafficking, autophagy |

| K48/K63 Branched | Signal amplification & regulation | Protects from deubiquitination; creates unique degradation signals | NF-κB signaling, proteasomal degradation |

Experimental Approaches for Studying Ubiquitination

In Vitro Ubiquitination Assays

In vitro ubiquitination reactions provide a controlled system for investigating the biochemical properties of ubiquitin conjugation. These assays can determine whether a protein of interest can be ubiquitinated, identify the chain linkage type, and establish which specific E2 enzymes and E3 ligases are required [27]. A standard 25 μL reaction includes E1 enzyme (100 nM), E2 enzyme (1 μM), E3 ligase (1 μM), ubiquitin (100 μM), and substrate protein (5-10 μM) in reaction buffer containing MgATP [27]. The reaction is typically incubated at 37°C for 30-60 minutes before termination with SDS-PAGE sample buffer or EDTA/DTT for downstream applications. Analysis involves SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie staining or western blotting with anti-ubiquitin, anti-substrate, or anti-E3 ligase antibodies to distinguish between substrate ubiquitination and E3 autoubiquitination [27].

Cellular Ubiquitination Detection

Detecting ubiquitination of endogenous proteins in cells presents significant challenges due to the transient nature of this modification and the low abundance of ubiquitinated species. Key methodological considerations include using lysis buffers optimized to preserve polyubiquitination and including deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitors such as N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) or chloroacetamide (CAA) in the lysis buffer to prevent chain disassembly during processing [23] [28]. Proteasome inhibitors like MG-132 (typically 5-25 μM for 1-2 hours) can enhance detection by preventing degradation of ubiquitinated proteins [21]. For enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins, researchers can use Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) with specificity for different chain types, or ubiquitin traps such as ChromoTek's Ubiquitin-Trap, which contains an anti-ubiquitin nanobody coupled to agarose beads [9] [21]. These tools enable pulldown of ubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates followed by western blot analysis with linkage-specific antibodies.

Diagram 1: Cellular ubiquitin detection workflow

Linkage-Specific Detection Methods

Differentiating between ubiquitin linkage types requires specialized tools that can distinguish chain architecture. Chain-specific TUBEs with nanomolar affinities for particular polyubiquitin chains enable selective capture of linkage-specific ubiquitination events [9]. For example, K63-TUBEs effectively capture L18-MDP-induced K63 ubiquitination of RIPK2, while K48-TUBEs specifically capture PROTAC-induced K48 ubiquitination of the same protein [9]. Linkage-specific antibodies provide another approach for detecting particular chain types in western blot applications after protein pulldown [21]. More recently, UbiREAD (ubiquitinated reporter evaluation after intracellular delivery) technology has enabled systematic comparison of degradation capacities for different ubiquitin chains by introducing bespoke ubiquitinated proteins into cells and monitoring their fate at high temporal resolution [26]. This approach has revealed that K48 chains with three or more ubiquitins trigger rapid degradation (within minutes), while K63-ubiquitinated substrates are preferentially deubiquitinated rather than degraded [26].

Table 2: Comparison of Ubiquitin Detection Methods

| Method | Principle | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TUBEs | Tandem ubiquitin-binding entities with chain specificity | Enrichment of linkage-specific ubiquitinated proteins from lysates | High affinity; preserves labile modifications; linkage-specific variants available | Requires validation of linkage specificity |

| Ubiquitin-Trap | Anti-ubiquitin nanobody coupled to beads | Pan-specific ubiquitin pulldown | Works across species; low background; compatible with IP-MS | Not linkage-specific |

| UbiREAD | Delivery of predefined ubiquitinated reporters into cells | Systematic comparison of chain degradation kinetics | Controlled chain architecture; high temporal resolution; direct functional readout | Technically challenging; not for endogenous proteins |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Antibodies recognizing specific chain linkages | Western blot detection after enrichment or IP | High specificity; widely accessible | Sensitivity issues; limited quantitative capability |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitination Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| DUB Inhibitors | Prevent deubiquitination during processing | N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), Chloroacetamide (CAA) |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Stabilize ubiquitinated proteins | MG-132 (5-25 μM for 1-2 hours) |

| Chain-Specific TUBEs | Enrichment of linkage-specific ubiquitinated proteins | K48-TUBEs, K63-TUBEs, Pan-TUBEs |

| Ubiquitin Traps | Pan-specific ubiquitin pulldown | ChromoTek Ubiquitin-Trap (agarose or magnetic) |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Detect specific ubiquitin linkages | Anti-K48 ubiquitin, Anti-K63 ubiquitin |

| Recombinant Ubiquitin System | In vitro ubiquitination assays | E1, E2s, E3s, Ubiquitin (Boston Biochem) |

| 10X E3 Ligase Reaction Buffer | In vitro ubiquitination reactions | 500 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM TCEP |

Signaling Pathways and Functional Networks

K63 Ubiquitination in Inflammatory Signaling

The RIPK2 signaling pathway provides an excellent example of K63 ubiquitination in inflammatory signaling. When muramyldipeptide (MDP) from bacterial cell walls binds to NOD2 receptors, it triggers recruitment of RIPK2 and E3 ligases including XIAP, leading to K63 ubiquitination of RIPK2 [9]. These K63 chains serve as a scaffolding platform that recruits and activates the TAK1/TAB1/TAB2/IKK kinase complexes, ultimately resulting in NF-κB activation and production of proinflammatory cytokines [9]. This K63-dependent signaling can be specifically inhibited by compounds such as Ponatinib, which completely abrogates L18-MDP-induced RIPK2 ubiquitination [9]. The ability to differentially detect K63 versus K48 ubiquitination in this pathway using chain-specific TUBEs highlights the importance of linkage-specific tools for understanding signaling mechanisms.

Branched Ubiquitin Chains in Signal Regulation

Branched K48/K63 ubiquitin chains represent a sophisticated mechanism for regulating signal duration and intensity. In response to IL-1β stimulation, TRAF6 generates K63-linked chains that are subsequently modified with K48 branches by the E3 ligase HUWE1 [25]. The resulting branched chains exhibit unique properties: they maintain recognition by TAB2 (a reader of K63 chains) while gaining protection from CYLD-mediated deubiquitination [25]. This combination allows for signal amplification while limiting premature signal termination. Recent research using UbiREAD has further revealed that in branched chains, the identity of the chain directly attached to the substrate determines the functional outcome, establishing a hierarchical organization within these complex ubiquitin structures [26].

Diagram 2: Branched ubiquitin chain signaling pathway

The intricate world of ubiquitin linkages, particularly K48, K63, and their branched combinations, represents a sophisticated coding system that governs critical cellular decisions from protein degradation to signal amplification. The development of increasingly refined tools including chain-specific TUBEs, ubiquitin traps, and novel technologies like UbiREAD continues to enhance our ability to decipher this complex language. For researchers focused on detecting ubiquitin protein conjugates using western blot methods, understanding the strengths and limitations of different enrichment and detection strategies is paramount. As we continue to unravel the nuances of the ubiquitin code, particularly the context-dependent functions of branched chains, we open new possibilities for therapeutic intervention in cancer, inflammatory diseases, and neurodegenerative disorders where ubiquitin signaling is disrupted.

A Robust Western Blot Protocol for Ubiquitin Conjugate Detection

The reliable detection of ubiquitin-protein conjugates via western blotting is a cornerstone of proteostasis research, informing on critical processes in cellular regulation and drug development. The labile nature of the ubiquitin-proteasome system means that the success of these experiments is critically dependent on the initial sample preparation. This application note details the use of denaturing lysis buffers to irreversibly inactivate endogenous deubiquitinases (DUBs) and proteases at the moment of cell disruption, thereby preserving the native ubiquitination state of proteins for accurate analysis. The protocols herein are designed to provide researchers with robust methodologies to capture the dynamic landscape of protein ubiquitination.

Principles of Denaturing Lysis for Ubiquitin Preservation

Protein ubiquitination is a transient modification that can be rapidly reversed by cellular DUBs. Standard, mild lysis buffers (e.g., RIPA) may not fully inactivate these enzymes, leading to the loss of ubiquitin signals during sample preparation. The fundamental principle of the denaturing approach is the immediate application of harsh conditions—specifically, heat and strong ionic detergents like Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS)—upon cell lysis.

Concentrated solutions of specific ions, such as Lithium Bromide (LiBr), can disrupt the water network structure, leading to protein denaturation through an entropy-driven mechanism rather than direct protein binding [29]. However, for the specific purpose of rapidly and completely inactivating enzymes to "freeze" post-translational modifications, direct chemical denaturation with SDS is the most effective and widely adopted method. This instantaneous denaturation halts all enzymatic activity, preserving the ubiquitin conjugates as they existed in the living cell and providing a true snapshot of the cellular state for downstream western blot analysis.

Comparative Analysis of Lysis Buffers

The choice of lysis buffer is a primary determinant of experimental outcome. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of denaturing buffers compared to a common non-denaturing alternative.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Lysis Buffer Properties for Ubiquitin Studies

| Buffer Type | Key Components | Recommended Ubiquitin Ladder Detection | Compatibility with Downstream Ubiquitin Enrichment | Primary Advantage for Ubiquitin Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1% SDS Hot Lysis Buffer [30] | 1% SDS, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1.0 mM Na-Orthovanadate | Excellent | High (after dilution) | Superior DUB/protease inactivation; best for preserving labile modifications. |

| RIPA Buffer [30] | Detergents (e.g., Triton X-100, Deoxycholate), Salts, Tris | Moderate to Poor | High | Maintains some protein-protein interactions; milder denaturation. |

Experimental Protocols

This protocol is optimized for the preservation of ubiquitin conjugates from adherent and suspension cell cultures.

Cell Harvesting:

- Discard culture medium and wash the cell monolayer once with ice-cold PBS.

- Add 3 mL of pre-chilled PBS per flask and use a cell scraper to dislodge and collect cells.

- Transfer the cell suspension to a 50 mL centrifuge tube and centrifuge at 300 x g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Discard the supernatant and wash the pellet twice with ice-cold PBS.

Denaturing Lysis:

- Pre-heat a volume of 1% SDS Hot Lysis Buffer to 90–95°C.

- Resuspend the cell pellet in the pre-heated buffer by pipetting.

- Immediately transfer the sample to a boiling water bath (90–95°C) for a total of 10–20 minutes. Mix the samples periodically during boiling.

Shearing and Clarification:

- Use an ultrasonic cell disruptor to break all cell clusters until the lysate becomes clear. A typical setting is: ultrasound time 3 s, 10 s interval, repeated 5–15 times, at 40 kW power.

- Centrifuge the lysate for 5–10 minutes at 15,000–17,000 x g to pellet insoluble debris.

- Carefully transfer the clear supernatant (the protein lysate) to a new tube.

This protocol is designed for tough tissue samples and includes a flash-freezing step to improve lysis efficiency.

Tissue Disruption:

- Shatter the frozen tissue using pre-cooled scissors.

- Using a mortar and pestle pre-cooled with liquid nitrogen, grind the tissue into a fine powder.

Denaturing Lysis:

- Pre-heat 1% SDS Hot Lysis Buffer until bubbling.

- Add the hot buffer to the powdered tissue and resuspend by pipetting.

- Incubate in a boiling water bath for 10–20 minutes.

Shearing and Clarification:

- Use an ultrasonic cell disruptor with the same settings as in Protocol 1 to achieve a clear lysate.

- Centrifuge for 5–10 minutes at 15,000–17,000 x g.

- Collect the supernatant for analysis.

This control experiment validates the functionality of the ubiquitination machinery and is typically performed under native conditions.

Reaction Setup: For a 25 µL reaction, combine the following components in order:

- dH₂O (to a final volume of 25 µL)

- 2.5 µL of 10X E3 Ligase Reaction Buffer (500 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM TCEP) [27]

- 1 µL Ubiquitin (≈100 µM final)

- 2.5 µL MgATP Solution (10 mM final)

- Substrate protein (5–10 µM final)

- 0.5 µL E1 Enzyme (100 nM final)

- 1 µL E2 Enzyme (1 µM final)

- E3 Ligase (1 µM final)

Incubation: Incubate the reaction in a 37°C water bath for 30–60 minutes.

Termination:

- For direct analysis by SDS-PAGE, add 25 µL of 2X SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

- For downstream enzymatic applications, terminate the reaction by adding 0.5 µL of 500 mM EDTA (20 mM final) or 1 µL of 1 M DTT (100 mM final) [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Western Blot Research

| Reagent / Solution | Critical Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| 1% SDS Hot Lysis Buffer [30] | Instantly denatures proteins, inactivating DUBs and proteases to preserve ubiquitin chains. | The gold-standard for preserving labile ubiquitin modifications; requires heating during use. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Inhibits a broad spectrum of proteolytic enzymes that degrade target proteins. | Must be added fresh to any lysis buffer immediately before use. |

| Phosphatase Inhibitors [30] | Preserves phosphorylation states, which can cross-talk with ubiquitination pathways. | Essential for studies investigating interplay between phosphorylation and ubiquitination. |

| DTT or β-Mercaptoethanol [30] | Reducing agents that break disulfide bonds for complete protein denaturation. | A key component of the SDS-PAGE sample buffer to ensure linearization of proteins. |

| Ubiquitin (Recombinant) [27] | Essential substrate for setting up in vitro ubiquitination conjugation assays. | Used as a positive control to validate the activity of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes. |

| E1, E2, and E3 Enzymes [27] | The enzymatic cascade required for the transfer of ubiquitin to a substrate protein. | Necessary for in vitro validation of specific ubiquitination events. |

Workflow Visualization and Data Interpretation

Ubiquitin Conjugate Preservation Workflow

In Vitro Ubiquitination Cascade

Best Practices for Quantification and Analysis

Accurate quantification of ubiquitin western blots presents unique challenges, such as the characteristic "smear" of polyubiquitinated species.

- Normalization: To account for loading variations, normalize the ubiquitin signal using a total protein normalization (TPN) method. Staining the membrane with a reversible dye like No-Stain Protein Labeling Reagent provides a linear response over a wide dynamic range and is superior to housekeeping proteins (HKPs) like GAPDH or β-actin, which can easily become saturated and non-linear [31].

- Avoiding Overexposure: The smear of high-molecular-weight ubiquitin conjugates can easily become overexposed during chemiluminescent detection, leading to saturated pixels and loss of quantitative data. Capture multiple exposures of your blot and use the one where the signal intensity is within the linear range of your imaging system [32].

- Interpretation of Results: A successful ubiquitin conjugation reaction analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot will show a characteristic "ladder" or "smear" of higher molecular weight bands above the unmodified substrate when probed with an anti-ubiquitin antibody. The negative control reaction, lacking ATP, should show only the unmodified substrate and free ubiquitin [27].

The critical step of sample preparation using denaturing hot SDS lysis buffer is non-negotiable for the accurate detection and analysis of ubiquitin-protein conjugates. By ensuring the immediate and complete inactivation of DUBs and proteases, this method preserves the delicate ubiquitination landscape, allowing researchers to obtain biologically relevant data. When combined with optimized quantification and careful interpretation, this protocol provides a robust foundation for advancing research in protein regulation and therapeutic development.

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates diverse cellular processes, including proteasomal degradation, cell signaling, DNA repair, and inflammatory responses [15]. This modification involves a coordinated enzymatic cascade where ubiquitin is activated by an E1 enzyme, transferred to an E2 conjugating enzyme, and finally attached to substrate proteins via an E3 ligase [15]. The resulting ubiquitin conjugates can be monoubiquitinated, multi-monoubiquitinated, or polyubiquitinated with chains of varying lengths and linkage types, each dictating distinct functional outcomes for the modified substrate [15]. Detecting these modifications requires specific antibodies and well-optimized protocols. This application note provides detailed guidance on selecting appropriate antibodies and establishing robust protocols for the precise detection of ubiquitin conjugates in Western blot research.

Antibody Selection Guide

Choosing the correct antibody is paramount for accurate ubiquitin detection. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three primary antibody classes used in ubiquitination studies.

Table 1: Overview of Ubiquitin Detection Antibodies

| Antibody Class | Target Epitope | Detection Capability | Typical Western Blot Result | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-Ubiquitin [33] [34] | Native ubiquitin protein (full-length or domains) | Free ubiquitin, monoubiquitin, and polyubiquitin chains | Smeared pattern (polyubiquitin) or discrete bands (free/monoubiquitin) [35] | Global ubiquitination assessment; immunoprecipitation [35] |

| Linkage-Specific Anti-Ubiquitin [36] | Specific ubiquitin chain linkages (e.g., K48, K63) | Polyubiquitin chains with a defined linkage type | Discrete bands or smears corresponding to the specific linkage | Determining chain topology to infer function (e.g., K48 for degradation) [15] |

| Anti-K-ε-GG [8] [35] | Di-glycine (GG) remnant left on ubiquitinated lysine after trypsin digestion | Ubiquitination sites on target proteins | Not applicable for Western blot; used for mass spectrometry | Mass spectrometry-based ubiquitinome studies [8] |

| Tag-Specific [28] | Affinity tags (e.g., His, HA, Flag) fused to ubiquitin | Ectopically expressed tagged ubiquitin conjugates | Smeared pattern or ladders | High-specificity pulldown and detection of newly synthesized conjugates [28] |

Anti-Ubiquitin Antibodies

Broad-spectrum anti-ubiquitin antibodies, such as the rabbit polyclonal antibody targeting amino acids 1-229 of ubiquitin [33] or the recombinant rabbit monoclonal antibody (clone 6H6) [34], are workhorses for general ubiquitination detection. They recognize various forms of ubiquitin, including free ubiquitin, monoubiquitinated proteins, and polyubiquitin chains.

A critical consideration is the antibody's epitope accessibility. Antibodies recognizing "open" epitopes will bind to free ubiquitin, monoubiquitination modifications, and ubiquitin molecules within polyubiquitin chains, typically producing a characteristic smeared pattern on a Western blot. This pattern reflects the heterogeneous population of polyubiquitinated proteins in the sample and is ideal for assessing global ubiquitination levels, especially in cells treated with proteasome inhibitors like MG-132 [35] [34]. In contrast, antibodies targeting "cryptic" epitopes can only bind to free ubiquitin and monoubiquitinated proteins, as the epitope becomes buried within polyubiquitin chains. These antibodies yield discrete bands on a Western blot, making them suitable for analyzing the free ubiquitin pool or performing immunoprecipitation [35].

Linkage-Specific Anti-Ubiquitin Antibodies

Linkage-specific antibodies are essential for determining the functional consequences of ubiquitination, as different chain linkages signal distinct cellular outcomes. For example, K48-linked chains primarily target substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains are involved in non-proteolytic processes like DNA damage repair and inflammatory signaling [15]. Antibodies like the anti-Ubiquitin (linkage-specific K48) [EP8589] (ab140601) are recombinant rabbit monoclonal antibodies rigorously validated for specificity. They show strong reactivity for K48-linked ubiquitin chains with minimal cross-reactivity against other linkage types (e.g., K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K63) or monoubiquitin [36]. These antibodies are suitable for techniques including Western blotting, immunohistochemistry, and immunocytochemistry [36].

Anti-K-ε-GG Antibodies

Anti-K-ε-GG antibodies do not detect intact ubiquitinated proteins directly in Western blots. Instead, they are designed to recognize the di-glycine (GG) remnant that is covalently attached to a lysine residue after tryptic digestion of ubiquitinated proteins [8]. This makes them an indispensable tool for mass spectrometry-based proteomics, enabling the system-wide identification and mapping of ubiquitination sites [8] [35]. These antibodies are often used for immunoaffinity enrichment of GG-modified peptides from complex digests, significantly increasing the depth of ubiquitinome analysis.

Tag-Specific Antibodies

Utilizing epitope-tagged ubiquitin (e.g., His, HA, FLAG) is a powerful strategy to reduce background and enhance detection specificity. In this approach, tagged ubiquitin is expressed in cells, and conjugates are purified under denaturing conditions using tag-specific antibodies or resin (e.g., Ni-NTA for His-tags) before detection by Western blot [28] [8]. This method minimizes the co-purification of endogenous proteins and allows for the specific analysis of newly synthesized ubiquitin conjugates. Tag-specific antibodies provide high sensitivity and are less prone to the background issues that can plague antibodies detecting endogenous ubiquitin.

Experimental Protocols

In Vivo Ubiquitination Assay Protocol

This protocol describes how to detect ubiquitination of a target protein within cells, using IGF2BP1 and the E3 ligase FBXO45 as an example [28].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Plasmids: pCDNA3.1+ constructs for His-Ubiquitin, Flag-FBXO45, and HA-IGF2BP1 [28].

- Cell Lines: HEK293T, HepG2, HCCLM3 [28].

- Critical Reagents: MG-132 proteasome inhibitor, Lipofectamine 2000, Ni-NTA Agarose, protease inhibitor cocktail [28].

Procedure:

- Preparation: Prepare high-quality, endotoxin-free plasmid DNAs. Culture and passage HEK293T cells until they are 80-90% confluent [28].

- Transfection: Co-transfect cells with plasmids encoding His-Ubiquitin and your protein of interest (e.g., HA-IGF2BP1) with or without the E3 ligase (e.g., Flag-FBXO45). Include a proteasome inhibitor like MG-132 (10-20 µM) 6-8 hours before harvesting to stabilize ubiquitinated conjugates [28].

- Cell Lysis: Harvest cells 24-48 hours post-transfection. Lyse cells in a denaturing buffer (e.g., containing 6 M Guanidine-HCl or 8 M Urea) to inactivate deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) and ensure complete disruption of non-covalent interactions. A recommended buffer is 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.1 M NaH₂PO₄, 8 M urea, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol [28] [8].

- Affinity Purification: Purify the His-tagged ubiquitin conjugates using Ni-NTA agarose beads. Incubate the clarified lysate with beads for several hours at room temperature. Wash the beads stringently with denaturing wash buffer (e.g., with 8 M urea, pH 6.3) to reduce non-specific binding [28] [8].

- Elution and Detection: Elute the bound proteins with SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing 200-300 mM imidazole or at low pH. Analyze the eluates by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using an antibody against your protein of interest (e.g., anti-HA) to detect its ubiquitinated forms, which will appear as higher molecular weight smears or discrete bands [28].

In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay Protocol

This reconstituted biochemical assay allows you to test whether a specific E1/E2/E3 enzyme combination can directly ubiquitinate your purified substrate protein [27].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Enzymes: Recombinant E1 (5 µM stock), E2 (25 µM stock), E3 ligase (10 µM stock) [27].

- Substrates: Purified ubiquitin (1.17 mM stock) and purified substrate protein of interest [27].

- Buffers: 10X E3 Ligase Reaction Buffer (500 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM TCEP), 100 mM MgATP solution [27].

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: For a 25 µL reaction, combine the following components in order on ice:

- X µL dH₂O (to a final volume of 25 µL)

- 2.5 µL 10X E3 Ligase Reaction Buffer

- 1 µL Ubiquitin (≈100 µM final)

- 2.5 µL MgATP Solution (10 mM final)

- X µL Substrate protein (5-10 µM final)

- 0.5 µL E1 Enzyme (100 nM final)

- 1 µL E2 Enzyme (1 µM final)

- X µL E3 Ligase (1 µM final) For a negative control, replace the MgATP solution with an equal volume of dH₂O [27].

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction mix in a 37°C water bath for 30-60 minutes [27].

- Reaction Termination:

- For direct analysis by Western blot: Add 25 µL of 2X SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

- If reaction products are needed for downstream enzymatic applications: Add 0.5 µL of 500 mM EDTA (20 mM final) or 1 µL of 1 M DTT (100 mM final) [27].

- Analysis: Analyze the reaction products by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

- Use Coomassie staining to visualize all protein species. A successful reaction will show a ladder or smear of higher molecular weight bands and a reduction in the mono-ubiquitin and substrate bands.

- Use anti-ubiquitin and anti-substrate antibodies to confirm the identity of the modified bands. An anti-E3 ligase antibody can distinguish substrate ubiquitination from E3 autoubiquitination [27].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Issues in Ubiquitination Assays

| Problem | Potential Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal | Low ubiquitination efficiency; DUB activity | Optimize E2/E3 enzyme combinations; increase E3 concentration; include DUB inhibitors in lysis buffer. |

| High Background | Non-specific antibody binding; inefficient washing | Include negative controls (e.g., -ATP, no E3); optimize antibody dilution; increase number and stringency of washes. |

| Smear Not Visible | Substrate not ubiquitinated; missing component | Verify activity of all enzymes (E1, E2, E3) and ATP; try a known positive control substrate. |

| Discrete Bands Instead of Smear | Limited ubiquitination (mono or few ubiquitins) | This may be biologically relevant; prolong reaction time or use chain-elongating E2s (e.g., Ube2K) to promote polyubiquitination. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Key Features | Example Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitination Assay Kit [37] | Facilitates controlled ubiquitin conjugation in a cell lysate system. | Contains HeLa S100 fraction, E1/E2 enzymes, ubiquitin, and ATP-regeneration system; detects endogenous and exogenous substrates. | Ubiquitylation Assay Kit (HeLa lysate-based), ab139471 [37] |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Generates lysine mutants of substrate proteins to map ubiquitination sites. | Essential for confirming specific lysines targeted for modification. | QuikChange Lightning Kit [28] |

| Proteasome Inhibitor | Stabilizes polyubiquitinated proteins in cells by blocking degradation. | Critical for in vivo assays to enhance detection of labile ubiquitin conjugates. | MG-132 [28] |

| Deubiquitinating Enzyme (DUB) Inhibitor | Prevents removal of ubiquitin during cell lysis and protein preparation. | Preserves the ubiquitination state of proteins; used in lysis buffers. | Ubiquitin Aldehyde [37] |

| Ni-NTA Agarose | Affinity purification of His-tagged ubiquitin conjugates from cell lysates. | Used under denaturing conditions for high-specificity pulldowns. | Qiagen Ni-NTA Agarose [28] |

| Linkage-Specific Antibody | Detects polyubiquitin chains with a specific topology (e.g., K48, K63). | Infers functional outcome of ubiquitination (e.g., degradation vs. signaling). | Anti-Ubiquitin (K48-linkage specific) [EP8589] [36] |

The precise detection of ubiquitin conjugates relies on a strategic combination of antibody selection and rigorous experimental protocol. Researchers must align their choice of antibody—whether broad-spectrum anti-ubiquitin, linkage-specific, anti-K-ε-GG, or tag-specific—with their specific research question. Furthermore, the successful application of these reagents is dependent on carefully optimized protocols that account for factors such as enzyme specificity, the use of appropriate controls, and the inhibition of proteasome and deubiquitinase activity. By integrating the antibody selection principles and detailed methodologies outlined in this application note, scientists can effectively advance our understanding of the ubiquitin system in health and disease.

Within the broader research on detecting ubiquitin protein conjugates via Western blot, the critical separation step by SDS-PAGE presents unique challenges. Ubiquitinated proteins can exhibit a substantial increase in apparent molecular weight—approximately 8 kDa for mono-ubiquitination and even larger for polyubiquitination events—and often appear as heterogeneous smears or ladders on blots [8]. These characteristics demand precise electrophoretic separation to resolve the modified species from unmodified proteins and to distinguish between different ubiquitination states. This application note provides detailed, optimized protocols for SDS-PAGE to achieve high resolution for both high and low molecular weight (MW) targets, specifically within the context of ubiquitin conjugate analysis.

Gel Percentage Selection Guide

The concentration of polyacrylamide in the resolving gel is the primary factor determining the resolution of proteins by size. The fundamental principle is that higher percentage gels create smaller pores, ideal for resolving smaller proteins, while lower percentage gels with larger pores are better for separating large proteins [38] [39]. The following table provides optimized gel percentage recommendations for specific molecular weight ranges, incorporating considerations for ubiquitinated proteins which often run at higher-than-expected molecular weights.

Table 1: Optimized Gel Percentage for Target Protein Size

| Target Protein Size Range | Recommended Gel Percentage | Key Considerations for Ubiquitin Conjugates |

|---|---|---|

| >200 kDa | 4% - 8% [38] [39] | Essential for resolving polyubiquitinated high-MW species. May require agarose gels for complexes >700 kDa [40]. |

| 50 - 200 kDa | 8% - 10% [38] [39] | Suitable for many mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins. |

| 15 - 100 kDa | 10% - 12% [38] [39] | A standard range for many unmodified proteins. |

| 10 - 70 kDa | 12.5% [38] | For lower MW ubiquitinated targets. |

| < 25 kDa | 15% or higher [41] [42] | Tricine SDS-PAGE is strongly recommended for superior resolution of small proteins and ubiquitin-cleaved products [41]. |

For experiments where the target molecular weight is unknown or when analyzing complex samples with multiple ubiquitinated species, 4-20% gradient gels are highly recommended as they provide a broad separation range and can resolve both low and high molecular weight proteins simultaneously [38] [43].

Experimental Protocols

Standard SDS-PAGE Protocol for General Protein Separation

This protocol is suitable for proteins and ubiquitin conjugates within the 30-250 kDa range using a Tris-Glycine buffer system [41] [40].

- Gel Preparation: Prepare or purchase a pre-made polyacrylamide gel with an appropriate percentage based on Table 1. A discontinuous system with a stacking gel (e.g., 4-5%) and a resolving gel is standard [40].

- Sample Preparation: Mix protein samples (10-50 µg for cell lysate, 10-100 ng for purified protein) with 2X Laemmli sample buffer. For reduced conditions, include a reducing agent like DTT or β-mercaptoethanol. Denature at 95°C for 5 minutes to ensure complete unfolding [38] [43].

- Gel Loading: Load samples and a prestained protein molecular weight marker into the wells. Use gel loading tips for precision and to avoid cross-contamination [43].

- Electrophoresis:

- Fill the apparatus with 1X running buffer (25 mM Tris base, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.3) [38].

- Run the gel at 100-150 V for 40-60 minutes, or until the dye front reaches the bottom. Monitor temperature; running in a cold room or with a stirrer can prevent "smiling" effects from overheating [38] [43] [40].

- Post-Run Processing: Proceed to Western blot transfer. For low MW targets (<25 kDa), refer to the specialized protocol below for critical transfer adjustments.

Specialized Tricine-SDS-PAGE Protocol for Low MW Targets (<25 kDa)

For low molecular weight proteins, peptides, or to resolve the fine details of ubiquitin ladders, the Tris-Tricine system offers superior resolution [41] [42].

Table 2: Tricine vs. Glycine SDS-PAGE Buffer Systems

| Parameter | Tris-Glycine System (Standard) | Tris-Tricine System (Low MW) |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Range | 30 - 250 kDa [41] | < 30 kDa [41] [42] |

| Running Buffer | Tris, Glycine, SDS [38] | 100 mM Tris, 100 mM Tricine, 0.1% SDS [41] |

| Key Advantage | Robust, standard protocol | Improved stacking and resolution of small proteins [41] [42] |

| Gel Percentage | As in Table 1 | 15-16.5% for proteins <10 kDa; 10-12% for 10-30 kDa [41] |

Protocol Steps:

- Gel Casting: Prepare a Tricine gel with a 10-12% stacking gel and a 15-16.5% resolving gel, using Tris-HCl at pH 6.8 and pH 8.45, respectively [41].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare samples as in the standard protocol. Consider loading 20-40 µg of total protein per lane to enhance detection of low-abundance small proteins [41].

- Electrophoresis: Use the Tricine running buffer. Run the gel at 150 V for approximately 1 hour using pre-chilled buffer to manage heat [41].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Western Blotting

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Tricine Buffer | Superior resolution of low MW proteins/peptides in SDS-PAGE [41] [42]. | Use in resolving gel and running buffer for targets <25 kDa [41]. |

| High-Affinity Ubiquitin Binding Domains (e.g., OtUBD) | Enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins from lysates for downstream Western blot analysis [44]. | Use OtUBD affinity resin under denaturing conditions to covalently enrich ubiquitin conjugates [44]. |

| Fine-Pore PVDF Membrane | Membrane for Western blotting; essential for retaining low MW proteins during transfer [41] [45]. | Use 0.22 µm PVDF membrane. Activate with methanol before transfer [41] [45]. |

| Ubiquitin Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Detection of specific polyubiquitin chain topologies (e.g., K48, K63) by Western blot [46]. | Use validated linkage-specific antibodies (e.g., K48-specific) for functional characterization of ubiquitin signals [46]. |

| Modified Transfer Buffer | Optimized buffer for efficient transfer of low MW proteins while retaining them on the membrane. | Add 20% methanol to standard transfer buffer. Omit SDS to prevent over-transfer [41]. |

Workflow Visualization for Ubiquitin Conjugate Detection

The following diagram summarizes the key decision points and optimized pathways for detecting ubiquitin conjugates, from sample preparation through to analysis.

Figure 1: Optimized Workflow for Ubiquitin Conjugate Detection via Western Blot. Critical decision points for gel selection and transfer optimization are highlighted based on the target protein's molecular weight.

Critical Steps and Troubleshooting

- Verifying Ubiquitination: A successful experiment for ubiquitin conjugates will typically show a characteristic upward shift in molecular weight and/or a smear or ladder pattern on the blot, corresponding to mono- and polyubiquitinated species [8]. The observed shift can be dramatic, with each ubiquitin moiety adding approximately 8 kDa [8].

- Transfer Optimization for Molecular Weight: Electrotransfer conditions must be tailored to protein size. For instance, while a 70 kDa protein may show increased signal intensity with longer transfer times (25-35 min), a 15 kDa protein can be completely lost from the membrane with transfers longer than 25 minutes [45]. Always optimize transfer time and voltage for your specific target.

- Troubleshooting Poor Resolution: Smeared bands can result from insufficient denaturation (ensure boiling for 5 minutes at 95°C with fresh reducing agent) or overloading (load ≤20 µg of complex lysate per lane) [43] [40]. "Smiling" bands indicate overheating; run at lower voltage or with cooling [40]. Faint or missing bands for low MW targets may require increased protein loading and the use of Tricine gels [41].

Transfer Conditions for High-Molecular-Weight Ubiquitinated Species