A Comprehensive Guide to Preventing Deubiquitination During Cell Lysis: Strategies for DUB Inhibitor Implementation in Proteostasis Research

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for preserving cellular ubiquitination states during protein extraction.

A Comprehensive Guide to Preventing Deubiquitination During Cell Lysis: Strategies for DUB Inhibitor Implementation in Proteostasis Research

Abstract

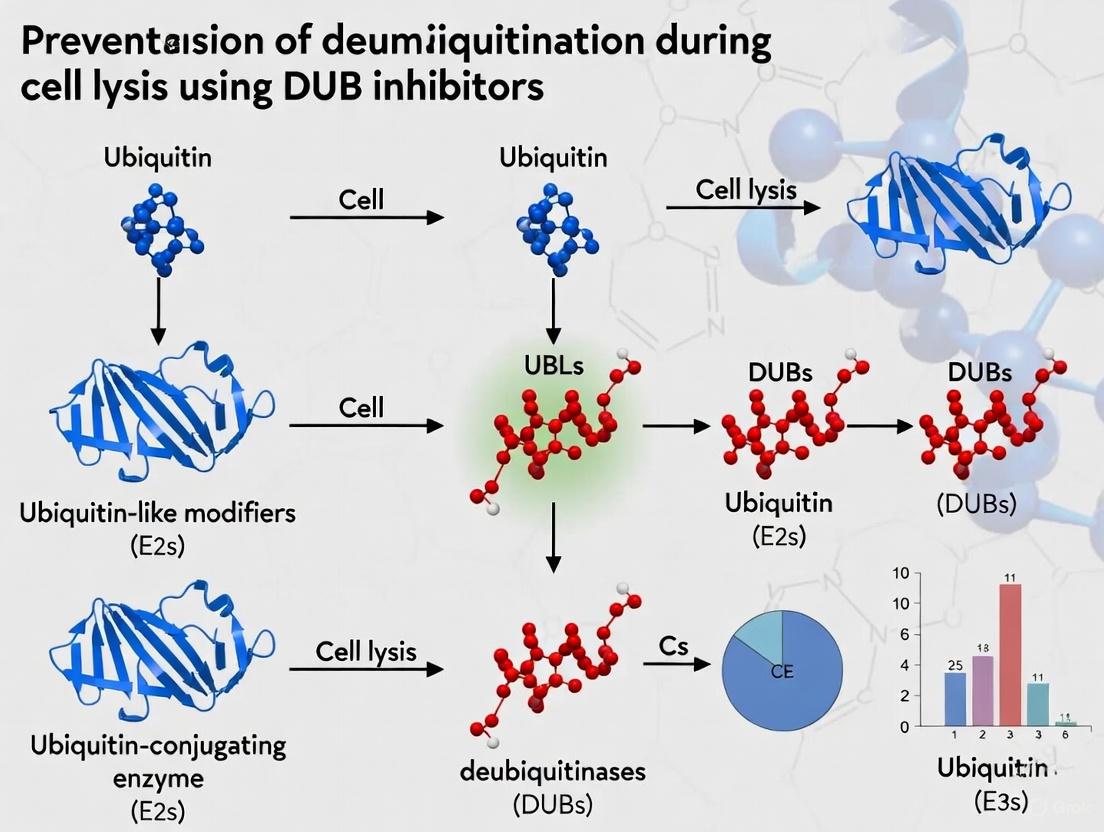

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for preserving cellular ubiquitination states during protein extraction. We explore the fundamental biology of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) and their disruptive potential during cell lysis, present methodological approaches for implementing DUB inhibitors in experimental workflows, troubleshoot common challenges in inhibitor selection and optimization, and establish validation protocols for assessing ubiquitin preservation efficacy. By integrating foundational principles with practical applications, this guide aims to enhance experimental reproducibility and data quality in ubiquitin-proteasome system research, supporting advancements in targeted protein degradation therapeutics and proteostasis investigation.

Understanding DUB Biology and the Critical Need for Inhibition During Cell Disruption

Technical Troubleshooting Guide: Preserving the Ubiquitinome during Cell Lysis

A primary challenge in ubiquitin research is maintaining the integrity of the ubiquitinome during cell lysis, as the natural activity of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) can rapidly erase these post-translational modifications. The table below outlines common experimental issues and their solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Issues in Ubiquitinome Analysis

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid loss of ubiquitin signal | DUB activity during lysis | Add DUB inhibitors (e.g., 10-50 µM PR-619 [1] [2]) and alkylating agents (e.g., 5-20 mM NEM [3] [4]) to lysis buffer. | Irreversibly blocks the catalytic cysteine of most DUBs [5] [6]. |

| High background in ubiquitin pulldowns | Non-specific protein binding or inefficient capture | Use Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) instead of single domains for purification [3]. | TUBEs have ~100-1000x higher affinity for poly-ubiquitin chains, enabling efficient capture under native conditions [3]. |

| Inconsistent DUB inhibition | Reversible DUB inhibitors being diluted or inactivated | Use covalent, irreversible DUB inhibitors like RA-9 [1] to ensure sustained inhibition. | Compound exposes a carbonyl group to a nucleophilic attack from the SH- group of the catalytic cysteine, forming a permanent bond [1]. |

| Altered mass signatures in MS | Iodoacetamide (IAA) forming protein adducts [3] | Use N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) as an alternative cysteine alkylating agent [3]. | NEM modifies cysteine residues without creating adducts that mimic a double glycine signature, preventing misinterpretation of mass spectrometry data [3]. |

| Loss of specific ubiquitin chain types | Preferential cleavage of certain linkages by co-purifying DUBs | Include linkage-specific DUB inhibitors if available, and perform lysis in the presence of TUBEs [3]. | TUBEs protect poly-ubiquitin chains from both proteasomal degradation and deubiquitinating activity present in cell extracts [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is it so critical to inhibit DUBs during cell lysis for ubiquitination studies?

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) are highly active cysteine proteases that constantly reverse ubiquitination. During cell lysis, the compartmentalization that may regulate their activity is lost. Without immediate and potent inhibition, DUBs will rapidly remove ubiquitin chains from your protein substrates, leading to a significant underestimation of ubiquitination levels and potentially erroneous conclusions [5] [3]. The fundamental goal is to "freeze" the ubiquitination state of the proteome as it existed in the living cell at the moment of lysis.

Q2: What are the key advantages of using TUBEs over traditional ubiquitin pulldown methods?

TUBEs (tandem-repeated ubiquitin-binding entities) offer several key advantages [3]:

- Superior Affinity: By linking four ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domains in tandem, TUBEs bind tetra-ubiquitin with an affinity 100 to 1,000 times greater than single UBA domains.

- Native Condition Purification: Their high affinity allows for the purification of ubiquitylated proteins from cell extracts under native conditions, without the need for harsh denaturants.

- Built-in Protection: TUBEs physically shield ubiquitin chains from the activity of DUBs and the proteasome, preserving the ubiquitinome during the purification process. They are more effective than using cysteine protease inhibitors like iodoacetamide or NEM alone [3].

Q3: Are there any risks associated with using pan-DUB inhibitors like PR-619 in my experiments?

Yes, while pan-DUB inhibitors are powerful tools, their non-specific nature can induce complex and sometimes unintended cellular phenotypes that complicate data interpretation. For instance, PR-619 has been shown to inhibit cell adhesion and proliferation in lung cancer and mesothelioma cell lines. However, its effect on cell motility was cell line-specific, increasing motility in one line while decreasing it in another [1]. Furthermore, broad DUB inhibition induces ER stress, apoptosis, and autophagy due to the accumulation of ubiquitylated proteins [2]. Therefore, for functional studies, more specific DUB inhibitors are recommended once a target of interest is identified.

Q4: How does oxidative stress impact DUB activity, and how should this be controlled?

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) like H~2~O~2~ can reversibly inactivate many DUBs of the USP and UCH subfamilies by oxidizing the catalytic cysteine residue [5]. This is a regulatory mechanism in cells. To control for this in experiments, maintain consistent reducing conditions. The inclusion of reducing agents like DTT (dithiothreitol) in lysis buffers can reverse this oxidation and restore DUB activity [5]. If studying redox regulation of DUBs, omit DTT and carefully control the oxidative environment.

Essential Protocols

Protocol for Cell Lysis with Optimized DUB Inhibition

This protocol is designed to maximally preserve ubiquitin conjugates for downstream analysis like western blotting or mass spectrometry.

Materials:

- Lysis Buffer (e.g., RIPA or NP-40 based)

- Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (without DUB inhibitors)

- Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (if needed)

- N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM), 1M stock in ethanol

- PR-619, 50 mM stock in DMSO

- TUBEs (commercially available with GST or other tags [3])

Procedure:

- Prepare Inhibitor-Enriched Lysis Buffer: Add NEM to a final concentration of 5-20 mM and PR-619 to a final concentration of 10-50 µM to the chilled lysis buffer immediately before use [3] [1] [2].

- Lyse Cells: Aspirate media from culture dishes and immediately add cold lysis buffer. Scrape cells and transfer the lysate to a microcentrifuge tube.

- Incubate: Maintain lysates on ice for 15-30 minutes with occasional vortexing.

- Clarify: Centrifuge at >12,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble debris.

- Proceed to Analysis: The clarified lysate is now ready for protein quantification, immunoprecipitation, or direct analysis by western blot. For ubiquitin pulldowns, add TUBEs directly to the lysate.

Protocol for qHTS of DUB Inhibitors Using a Cell Lysate-Based AlphaLISA Assay

This protocol enables high-throughput screening for DUB inhibitors in a more physiologically relevant cell lysate environment [4].

Materials:

- HEK293 cells expressing HA-tagged DUB of interest

- Biotinylated Ubiquitin Vinyl Methyl Ester (biotin-UbVMe) probe [4]

- AlphaLISA Anti-HA Acceptor Beads

- AlphaLISA Streptavidin Donor Beads

- White 1536-well microplates

- Test compound library

Workflow: The assay relies on the covalent binding of the biotin-UbVMe probe to the active site of the HA-tagged DUB. This proximity brings the donor and acceptor beads together, generating a signal inhibited by active compounds.

Diagram 1: AlphaLISA DUB Assay Workflow

Procedure [4]:

- Prepare Lysate: Lyse cells expressing the HA-tagged DUB in a suitable buffer (potentially without DUB inhibitors to preserve activity).

- Dispense: Transfer lysate and test compounds to a 1536-well plate.

- Probe Incubation: Add the biotin-UbVMe probe and incubate to allow covalent labeling of the DUB.

- Bead Addition: First, add Anti-HA Acceptor Beads, followed by Streptavidin Donor Beads.

- Read Plate: Illuminate the plate at 680nm and measure light emission at 615nm. A reduction in signal compared to a DMSO control indicates inhibition of the DUB's activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitinome Preservation and Analysis

| Reagent | Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| PR-619 | Pan-DUB inhibitor, cell-permeable [1] [2]. | Broad-spectrum, inhibits many USPs, UCHs, and OTUs. Useful for initial proof-of-concept studies. |

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | Cysteine alkylating agent [5] [3]. | Irreversibly inactivates cysteine-dependent DUBs. Preferred over IAA for mass spectrometry. |

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities) | High-affinity capture of poly-ubiquitinated proteins [3]. | Protects ubiquitin chains from DUBs and the proteasome during purification; enables native purifications. |

| Ubiquitin-Vinyl Methyl Ester (UbVMe) | Activity-based DUB probe [4]. | Covalently labels active site of DUBs; used for activity profiling and inhibitor screening (e.g., in AlphaLISA). |

| PYR-41 | Ubiquitin E1 Activating Enzyme inhibitor [2]. | Blocks the entire UPS upstream; useful as a control to confirm UPS-related phenotypes. |

| Biotin-UbVMe | Functionalized DUB probe for affinity applications [4]. | Contains a biotin tag for pulldown or bead-based assays (e.g., AlphaLISA) to detect active DUBs. |

Signaling Pathways in DUB Inhibition

Broad-spectrum DUB inhibition triggers a defined cellular stress response. The following diagram summarizes the key pathway activated upon treatment with inhibitors like PR-619, leading to cell death.

Diagram 2: Cellular Response to DUB Inhibition

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) constitute a critical regulatory protein superfamily that opposes the action of ubiquitin ligases by cleaving ubiquitin from protein substrates [7] [8]. This reversible process governs protein stability, localization, activity, and interactions, making DUBs essential regulators of cellular homeostasis [7] [9]. The human genome encodes approximately 100 DUBs, which are classified into two main classes based on their catalytic mechanisms: cysteine proteases and metalloproteases [7] [10]. These enzymes perform several essential functions, including processing ubiquitin precursors, removing degradative and non-degradative ubiquitin signals from target proteins, editing ubiquitin chain types, and maintaining the cellular pool of free ubiquitin [7] [8] [9]. Understanding these enzyme families is particularly crucial for experiments aimed at preserving ubiquitin signaling states during cell lysis, where uncontrolled deubiquitination can compromise experimental results.

DUB Classification and Biochemical Mechanisms

Cysteine Protease DUBs

Cysteine protease DUBs represent the majority of deubiquitinating enzymes and utilize a catalytic triad or dyad involving a cysteine residue for nucleophilic attack on the isopeptide bond [7] [9]. This class encompasses several families with distinct structural and functional characteristics, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Major Cysteine Protease DUB Families

| Family | Representative Members | Catalytic Mechanism | Key Characteristics | Substrate/Linkage Preferences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USP | USP1, USP7, USP10, USP28 | Catalytic triad (Cys, His, Asp/Asn) [7] | Largest and most diverse family; often regulated by protein-protein interactions and domains [7] [11] | Varied; often specific to particular substrates or chain types [10] |

| UCH | UCH-L1, UCH-L3, UCH-L5 | Catalytic triad (Cys, His, Asp/Asn) [7] | Small molecules with narrow active site clefts; prefer small protein adducts [8] | Primarily cleaves ubiquitin from small nucleophiles and peptide substrates [7] |

| OTU | OTUB1, OTUD5, A20, OTULIN | Catalytic triad (Cys, His, Asp/Asn) [7] | Often exhibit high linkage specificity; regulated by oxidative stress and protein interactions [9] [11] | Specific for particular ubiquitin chain types (e.g., K48, K11, linear) [11] |

| MJD | Ataxin-3, Ataxin-3L | Catalytic triad (Cys, His, Asp/Asn) [7] | Josephin domain proteins; some associated with neurological disorders [7] [8] | Prefer K63-linked chains (Ataxin-3) [8] |

| MINDY | N/A | Catalytic triad (Cys, His, Asp/Asn) [12] | Recently identified family [12] | Prefer K48-linked ubiquitin chains [13] |

| ZUFSP | N/A | Catalytic triad (Cys, His, Asp/Asn) [13] | Recently identified family [13] | Specific for K63-linked polyubiquitin [13] |

Metalloprotease DUBs

The metalloprotease DUBs represent a distinct mechanistic class with a single family:

- JAMM/MPN+ Proteases: These zinc-dependent metalloproteases constitute the only metalloprotease class among DUBs [7] [9]. Unlike cysteine proteases, they employ a catalytic mechanism that coordinates zinc ions with histidine, aspartate, and serine residues to activate water molecules for nucleophilic attack on the isopeptide bond [7]. Representative members include POH1 (yeast homologue Rpn11), AMSH, and AMSH-LP [8] [10]. These enzymes often require integration into macromolecular complexes for full activity, such as the proteasome (POH1/Rpn11) or endosomal sorting complexes (AMSH) [10] [11]. Their metal-dependent mechanism renders them insensitive to cysteine-directed inhibitors, a crucial consideration for experimental design.

DUB Domain Architecture and Regulation

DUBs frequently contain accessory domains beyond their catalytic domains that regulate their activity, specificity, and subcellular localization [7]. Key regulatory domains include:

- Ubiquitin-Like (UBL) Domains: Present in many USPs, these domains can autoinhibit catalytic activity or facilitate proteasomal localization [7] [11].

- DUSP Domains: Found in several USPs, these tripod-like domains may contribute to substrate recognition and protein-protein interactions [7].

- Zinc Finger Domains: Various zinc finger motifs (e.g., ZnF-UBP, ZnF-MYND) mediate specific ubiquitin binding and substrate recognition [7].

DUB activity is tightly regulated through multiple mechanisms, including post-translational modifications, subcellular localization, protein-protein interactions, and oxidative inactivation [9] [11]. For instance, the catalytic activity of USP7 is enhanced through interactions with its C-terminal UBL domains and binding partners like GMP synthase [11]. Similarly, OTULIN specificity for linear ubiquitin chains is governed by unique interactions with the N-terminal methionine of ubiquitin [11]. Understanding these regulatory mechanisms is essential for designing effective strategies to control DUB activity during experimental procedures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting appropriate reagents is fundamental for successful DUB research, particularly for inhibiting DUB activity during cell lysis. Table 2 summarizes key reagents and their applications.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for DUB Inhibition and Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Mechanism of Action | Primary Applications | Important Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broad-Spectrum Cysteine DUB Inhibitors | PR-619 [14] [15] | Inhibits cysteine proteases but not metalloproteases [14] | Cell lysis preparation; global DUB inhibition studies | Batch-to-batch variability in activity reported [14]; not suitable for JAMM metalloproteases |

| Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme (E1) Inhibitors | TAK243 [14] | Blocks ubiquitin activation, preventing all ubiquitination | Control for ubiquitination dynamics; depletes ubiquitin conjugates | Affects entire ubiquitin system; not specific to DUBs |

| Activity-Based Probes | Biotin-UbVMe [12], Biotin-Ub-PA [15] | Covalently labels active DUBs with specified warheads | DUB profiling, identification, and validation in cell lysates | Confirms DUB activity status; useful for competitive assays |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K48- and K63-linkage antibodies [14] | Immunodetection of specific ubiquitin chain types | Monitoring specific ubiquitin signals by immunoblotting | Verify specificity; some cross-reactivity may occur |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib [14] | Inhibit proteasomal degradation of ubiquitinated proteins | Stabilizing ubiquitinated substrates; studying degradation-independent ubiquitination | Does not prevent deubiquitination by DUBs |

Experimental Protocols for DUB Inhibition During Cell Lysis

Comprehensive DUB Inhibition Protocol for Cell Lysis

Principle: This protocol ensures maximal preservation of ubiquitin conjugates during cell lysis by combining broad-spectrum cysteine DUB inhibitors with appropriate buffer conditions.

Reagents:

- Lysis Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA

- Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (without DUB inhibitors)

- Phosphatase Inhibitors (if studying phospho-ubiquitin)

- 10× DUB Inhibitor Cocktail: 10 mM PR-619 in DMSO (or equivalent concentration)

- N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM): 500 mM stock in ethanol (optional, for additional cysteine protection)

- Dithiothreitol (DTT): 1 M stock (AVOID in lysis buffer as it inactivates cysteine-directed inhibitors)

Procedure:

- Prepare complete lysis buffer freshly by adding protease inhibitors and 1× final concentration of DUB inhibitor cocktail (e.g., 1:1000 dilution of 10 mM PR-619 stock for 10 µM final concentration).

- Pre-chill complete lysis buffer on ice.

- Harvest cells by rapid centrifugation (500 × g, 3 min, 4°C) and wash once with cold PBS.

- Lyse cell pellet in appropriate volume of complete lysis buffer (typically 3-5× pellet volume).

- Incubate on ice for 15-30 minutes with occasional vortexing.

- Clarify lysate by centrifugation (14,000 × g, 15 min, 4°C).

- Transfer supernatant to fresh pre-chilled tube and proceed immediately to downstream applications.

- For long-term storage, flash-freeze aliquots in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C.

Critical Considerations:

- DUB inhibitors must be present BEFORE cell disruption to prevent immediate deubiquitination.

- Avoid reducing agents (DTT, β-mercaptoethanol) in lysis buffers as they will inactivate cysteine-directed inhibitors.

- Include appropriate controls: DMSO-only treated lysates to demonstrate endogenous DUB activity.

- For metalloprotease JAMM family DUBs, additional specific inhibitors (e.g., orthophenanthroline) may be required as they are insensitive to cysteine protease inhibitors.

Validation Protocol: Assessing DUB Inhibition Efficiency

Principle: Verify the effectiveness of DUB inhibition by monitoring ubiquitin conjugate accumulation through immunoblotting.

Procedure:

- Prepare parallel cell lysates with and without DUB inhibitor cocktail.

- Separate equal protein amounts (20-30 µg) by SDS-PAGE (4-12% gradient gels recommended).

- Transfer to PVDF membrane and immunoblot with specified antibodies.

- Probe with anti-ubiquitin antibody to visualize global ubiquitin conjugate accumulation.

- Reprobe with anti-β-actin or other loading control antibodies for normalization.

- Compare ubiquitin signal intensity between inhibited and non-inhibited samples.

Expected Results: Successful DUB inhibition should yield significantly enhanced high-molecular-weight ubiquitin smears in inhibitor-treated samples compared to controls [14].

Troubleshooting:

- Weak ubiquitin signal: Increase inhibitor concentration; verify inhibitor solubility and activity.

- Excessive background: Optimize antibody concentrations; include no-primary-antibody controls.

- Incomplete inhibition: Combine multiple inhibitor classes; ensure rapid lysis and inhibitor penetration.

DUB Inhibitor Mechanisms and Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the strategic approach to preserving ubiquitin conjugates during cell lysis through DUB inhibition, integrating key reagents and validation steps.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is DUB inhibition critical during cell lysis, and what happens if inhibitors are omitted? A: DUBs are highly active and can rapidly remove ubiquitin modifications from substrates upon cell disruption. Without inhibition, this results in significant loss of ubiquitin signals, compromising downstream analyses like ubiquitin immunoblotting, proteomic studies, or activity assays. Research shows that DUBs can process the bulk of ubiquitin conjugates within 3 hours after inhibition of new ubiquitination [14].

Q2: What are the key differences between cysteine protease and metalloprotease DUB inhibitors? A: Cysteine protease inhibitors (e.g., PR-619) target the catalytic cysteine residue in USP, UCH, OTU, MJD, MINDY, and ZUFSP families through covalent or non-covalent mechanisms. Metalloprotease inhibitors (e.g., 1,10-phenanthroline) chelate zinc ions essential for JAMM family enzyme activity. A comprehensive inhibition strategy requires both approaches since neither inhibitor class affects the other DUB family [7] [14].

Q3: How do I select the appropriate DUB inhibitor concentration for my experiment? A: Optimal concentration depends on cell type, abundance of target DUBs, and experimental goals. For broad-spectrum inhibition during lysis, start with 10-50 µM for PR-619 [14] [15]. Perform dose-response experiments using ubiquitin immunoblotting to visualize ubiquitin conjugate accumulation. Include DMSO-only controls to assess inhibition efficiency.

Q4: Can I use DTT or β-mercaptoethanol in lysis buffers with cysteine DUB inhibitors? A: No. Reducing agents react with and inactivate cysteine-directed inhibitors. Use alternative protease inhibitor cocktails without reducing agents. If protein reduction is essential, consider adding inhibitors after reduction or using non-covalent inhibitors unaffected by reducing conditions.

Q5: How can I validate that my DUB inhibition strategy is working effectively? A: Employ multiple validation approaches:

- Monitor high-molecular-weight ubiquitin conjugates by immunoblotting [14]

- Use activity-based probes (e.g., biotin-UbVMe) to assess residual DUB activity in lysates [12] [15]

- Analyze specific ubiquitin chain types (K48, K63) with linkage-specific antibodies [14]

- Compare with E1 inhibitor (TAK243) treated samples to distinguish DUB-mediated effects [14]

Q6: Are there specific considerations for studying JAMM metalloprotease DUBs? A: Yes. JAMM family DUBs (e.g., POH1, AMSH) are insensitive to cysteine protease inhibitors. For comprehensive inhibition, include metalloprotease inhibitors like 1,10-phenanthroline. Be aware that these zinc chelators may affect other metalloenzymes, so include appropriate controls.

Q7: What are the limitations of current DUB inhibitors? A: Key limitations include:

- Most commercial inhibitors target cysteine proteases, with fewer options for metalloproteases

- Selectivity varies significantly, with many inhibitors affecting multiple DUBs

- Batch-to-batch variability for some inhibitors like PR-619 [14]

- Cellular permeability challenges for in vivo applications

- Potential off-target effects on other cysteine-dependent enzymes

Q8: How can I assess DUB selectivity when using inhibitors? A: Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) using ubiquitin-based probes provides a powerful method to assess inhibitor selectivity across multiple endogenous DUBs simultaneously in cell lysates [15]. This approach allows screening against 50+ DUBs in a single experiment and can identify off-target effects.

When cells are lysed for experimental analysis, the careful compartmentalization maintained in living cells is abruptly destroyed. This breakdown releases deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) from their regulated environments and provides them with artificial access to ubiquitinated substrates from which they would normally be separated. DUBs are cysteine proteases that cleave ubiquitin from protein substrates, thereby reversing ubiquitin signaling and preventing proteasomal degradation [5] [6]. During cell lysis, the sudden mixing of cellular components can trigger artifactual deubiquitination events that compromise experimental results by altering the true ubiquitination status of proteins within living cells. Understanding and controlling this phenomenon is crucial for researchers investigating ubiquitin-dependent processes in signaling, DNA repair, and protein degradation pathways [5].

Key Concepts: DUB Biology and Experimental Artifacts

DUB Families and Mechanisms

Deubiquitinating enzymes comprise approximately 100 proteases in humans, categorized into several subfamilies based on their catalytic domains and mechanisms [16] [6]. The major families include:

- Ubiquitin-Specific Proteases (USPs): The largest subfamily with diverse structural variations

- Ubiquitin C-terminal Hydrolases (UCHs): Involved in ubiquitin precursor processing

- Ovarian Tumor Proteases (OTUs): Known for linkage specificity toward ubiquitin chains

- JAMM/MPN metalloproteases: Zinc-dependent metalloproteases (the only non-cysteine protease DUBs)

- MJD, MINDY, and ZUP1 families

With the exception of JAMM metalloproteases, most DUBs are cysteine proteases that utilize a catalytic triad (Cys, His, Asp/Asn) to cleave isopeptide bonds between ubiquitin and substrate proteins [16]. This catalytic cysteine has a low pKa, making it particularly sensitive to oxidation and other modifications that can affect activity [5].

Compartmentalization Breakdown During Lysis

In intact cells, DUBs and their substrates are strategically localized within different cellular compartments—nucleus, cytoplasm, organelles, and membrane-bound structures. This spatial separation ensures that deubiquitination occurs only at specific times and locations in response to cellular signals. During cell lysis, these physical barriers are disrupted, resulting in:

- Artificial substrate access: DUBs encounter substrates they would not normally access in living cells

- Loss of regulatory complexes: DUBs are separated from binding partners that modulate their activity

- Mixing of cofactors: Cellular reductants and oxidants are redistributed, altering DUB redox states

Vulnerability of the Catalytic Cysteine

The catalytic cysteine residue in DUB active sites is particularly sensitive to oxidative modification. Reactive oxygen species can reversibly inactivate many DUBs by oxidizing this cysteine, abrogating isopeptide-cleaving activity without affecting ubiquitin binding affinity [5]. This redox sensitivity is associated with DUB activation wherein the active site cysteine is converted to a deprotonated state that is prone to oxidation. During cell lysis, changes in the redox environment can significantly impact DUB activity and create experimental artifacts.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution | Verification Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unexpected loss of ubiquitin signals | Artifactual DUB activation during lysis | Add DUB inhibitors to lysis buffer; optimize lysis conditions | Compare with/without inhibitors; use multiple ubiquitin antibodies |

| Inconsistent DUB activity measurements | Redox fluctuations affecting catalytic cysteine | Include redox regulators (DTT, GSH) in lysis buffer; work under anaerobic conditions | Measure DUB activity with/without reducing agents |

| Incomplete DUB inhibition | Insufficient inhibitor concentration or specificity | Use combination inhibitors; validate inhibitor efficacy | Test inhibitor concentration series; use activity-based probes |

| Variability between experimental replicates | Inconsistent lysis conditions or timing | Standardize lysis protocol; minimize time between lysis and analysis | Include internal controls; standardize protein quantification |

| Difficulty detecting specific DUB-substrate relationships | Compartmentalization loss allowing non-specific deubiquitination | Use crosslinking before lysis; implement rapid lysis and inhibition | Compare crosslinked vs. non-crosslinked samples |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does cell lysis specifically activate DUBs rather than inhibit them? Cell lysis disrupts cellular compartmentalization that normally separates DUBs from their potential substrates. Additionally, lysis alters the redox environment, which can activate certain DUBs by reducing their catalytic cysteine residues. The sudden mixing of cellular contents provides artificial access to substrates that DUBs would not encounter in intact cells [5] [17].

Q2: What are the most critical factors to control during lysis to prevent artifactual deubiquitination? The most critical factors are:

- Temperature: Perform all lysis steps at 4°C to slow enzymatic activity

- Inhibitors: Include DUB inhibitors in your lysis buffer

- Speed: Process samples quickly and consistently

- Redox environment: Control reducing/oxidizing conditions based on your experimental needs

- Standardization: Use consistent lysis conditions across all samples [17] [18]

Q3: How can I verify that my lysis conditions are effectively preserving native ubiquitination states? Several verification approaches include:

- Using activity-based probes to monitor residual DUB activity after lysis

- Comparing time-course experiments to check for progressive loss of ubiquitin signals

- Implementing crosslinking strategies before lysis to capture native interactions

- Testing different inhibitor combinations to identify optimal conditions [18] [15]

Q4: Are certain cell types more susceptible to DUB activation during lysis? Yes, cell types with higher inherent DUB activity or different subcellular organizations may show greater susceptibility. For example, animal cells lyse more readily but may release DUBs more quickly, while plant and bacterial cells with rigid cell walls require more vigorous disruption methods that could potentially activate stress-responsive DUBs [17].

Q5: Can I use the same DUB inhibitors for all DUB families? No, different DUB families have distinct structural features and catalytic mechanisms that require specific inhibitors. Broad-spectrum DUB inhibitors like PR-619 can be useful for initial experiments but may not fully inhibit all DUB classes. For specific research questions, selective inhibitors against particular DUBs (e.g., USP1, UCHL5, or VCPIP1 inhibitors) may be necessary [16] [6] [15].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Standardized Lysis Protocol for Preserving Ubiquitination States

This protocol minimizes artifactual deubiquitination during cell processing:

Reagents Required:

- Lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 250 mM sucrose, 5 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM ATP)

- DUB inhibitor cocktail (see Section 6 for specific recommendations)

- Protease inhibitors (without DUB inhibitory activity)

- 500 mM DTT stock solution

- N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) for cysteine alkylation

Procedure:

- Pre-chill all equipment and buffers to 4°C

- Prepare fresh lysis buffer supplemented with DUB inhibitors immediately before use

- For adherent cells: Remove media, rinse with cold PBS, and add lysis buffer directly to cells

- For suspension cells: Pellet cells, rinse with cold PBS, and resuspend in lysis buffer

- Incubate on ice for 15-30 minutes with gentle agitation

- For mechanical disruption, use glass beads (1:1 mass:volume ratio) and vortex at maximum agitation for 30 minutes at 4°C [18]

- Clear lysates by centrifugation at 5,030 × g for 5 minutes to remove nuclei and unbroken cells

- Transfer supernatant to fresh tubes and process immediately or flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen

Critical Steps:

- Maintain temperature at 4°C throughout the process

- Include appropriate controls without DUB inhibitors to assess artifact magnitude

- Process all samples consistently with the same lysis duration and conditions

- Use NEM (10-20 mM) after lysis to alkylate free cysteines and "trap" DUBs in their current state [5]

Assessing DUB Activity During Lysis Using Activity-Based Probes

Activity-based probes (ABPs) covalently modify active DUBs and allow direct visualization of their activity status:

Protocol:

- Prepare cell lysates as described above, with and without DUB inhibitors

- Perform bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay to determine protein concentration

- Incubate 20 μg of total protein with HA-Ub-VS probe (50 nM final concentration) for 1 hour at 37°C [18]

- Stop reaction with Laemmli sample buffer and heat at 95°C for 5 minutes

- Resolve proteins by SDS-PAGE using 4-20% Tris-glycine gels

- Transfer to PVDF membrane and block with 5% milk in PBS

- Incubate with anti-HA primary antibody (1:10,000 dilution) followed by appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody

- Develop blot and compare signal intensity between samples with and without DUB inhibitors

Interpretation: Reduced ABP labeling in inhibitor-treated samples indicates effective DUB inhibition. Persistent labeling suggests incomplete inhibition and potential for artifacts.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PR-619 | Broad-spectrum DUB inhibitor | Useful for initial experiments but lacks specificity; typical working concentration: 10-50 μM |

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | Cysteine alkylating agent | Irreversibly inactivates cysteine-dependent DUBs; use at 10-20 mM; add after lysis |

| HA-Ub-Vinyl Sulfone (HA-Ub-VS) | Activity-based DUB probe | Covalently labels active DUBs; confirms inhibitor efficacy; use at 50 nM [18] |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Reducing agent | Maintains catalytic cysteine in reduced state; can activate certain DUBs; use at 1-5 mM [5] [18] |

| MG-132 | Proteasome inhibitor | Prevents degradation of deubiquitinated proteins; use at 10-20 μM |

| B-PER Bacterial Protein Extraction Reagent | Specialized lysis reagent | Mild extraction for gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria; includes lysozyme and nuclease [17] |

| Inclusion Body Solubilization Reagent | Denaturing lysis conditions | Useful for studying insoluble ubiquitinated proteins; may require refolding steps [17] |

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: DUB Activation During Cell Lysis: Problem and Prevention Pathways. This workflow illustrates the cascade from cell lysis to experimental artifacts, alongside key prevention strategies.

Diagram 2: Catalytic Cysteine Regulation and Detection. This diagram shows the redox sensitivity of the DUB catalytic cysteine and methods for controlling and detecting its activity state.

| DUB Family | Sensitivity to Redox Changes | Effective Inhibitors | Recommended Lysis Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| USP | High (reversible oxidation) [5] | PR-619, specific USP inhibitors [16] | Reducing environment (1-5 mM DTT) + inhibitor cocktail |

| UCH | Moderate to high | Ub-VS derivatives, LDN-57444 [16] | Oxidizing conditions can preserve inactivity; NEM alkylation |

| OTU | Variable | PR-619, specific OTU inhibitors [15] | Test reducing vs. non-reducing conditions empirically |

| JAMM | Low (metalloproteases) | Metal chelators (EDTA, 1,10-phenanthroline) [16] | Metal chelators in lysis buffer |

| MJD | High | Broad-spectrum cysteine inhibitors | Strong reducing agents required |

Advanced Applications: DUB Inhibitors in Research

The development of selective DUB inhibitors has accelerated significantly in recent years, with new compounds emerging against various DUB family members [16] [15]. These inhibitors serve not only as potential therapeutics but also as essential research tools for controlling DUB activity during experimental procedures:

Recent Advances:

- USP1 inhibitors: Target USP1-UAF1 complex for DNA damage response studies

- UCHL5 inhibitors: Investigated for NLRP3 inflammasome regulation and HCV infection [19]

- VCPIP1 inhibitors: New selective probes with nanomolar potency [15]

- Compound screening platforms: Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) enables high-throughput screening against multiple endogenous DUBs [15]

These advanced chemical tools provide researchers with more specific options for preventing artifactual deubiquitination during cell lysis, moving beyond broad-spectrum approaches to targeted inhibition of specific DUB families implicated in particular experimental systems.

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) comprise a family of approximately 100 proteases that catalyze the removal of ubiquitin from protein substrates, thereby reversing ubiquitination signals [20] [9]. This dynamic process regulates diverse cellular functions including protein degradation, localization, protein-protein interactions, and signal transduction pathways [21] [9]. In research settings, uncontrolled DUB activity during sample preparation can generate significant experimental artifacts that compromise data interpretation, particularly in protein detection assays and signaling pathway analysis. When cell lysis occurs without adequate DUB inhibition, naturally occurring DUBs remain active and can rapidly deubiquitinate substrates, leading to: (1) loss of biologically relevant ubiquitination signals, (2) misinterpretation of protein regulation mechanisms, and (3) incorrect conclusions about signaling pathway activation states. This technical support article provides comprehensive troubleshooting guidance and validated protocols to prevent these artifacts, ensuring accurate experimental outcomes in ubiquitination-related research.

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Deubiquitination Artifacts

Weak or Absent Ubiquitin Signal in Western Blotting

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Active DUBs during cell lysis | Add pan-DUB inhibitors (e.g., PR-619) to lysis buffer immediately before use [2] | PR-619 is a broad-spectrum DUB inhibitor that induces ubiquitinated protein accumulation by blocking deubiquitination [2] |

| Insufficient inhibition of DUB activity | Use combination inhibitor approach (e.g., 20µM PR-619 + 10µM PYR-41) [2] | PYR-41 inhibits ubiquitin E1 enzyme, reducing ubiquitin charging and working synergistically with DUB inhibitors [2] |

| Protein degradation during processing | Keep samples on ice, use pre-chilled buffers, and process quickly | DUBs remain active at low temperatures; inhibition is required regardless of temperature control |

| Incompatible lysis buffer composition | Ensure DUB inhibitors are compatible with detergent system; avoid reducing agents that may inhibit certain inhibitors | Some DUB inhibitors rely on cysteine modification and may be compromised by strong reducing agents |

Unusual Banding Patterns in Ubiquitin Detection

| Observed Artifact | Potential Interpretation | Resolution Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Smearing throughout lanes | Accumulation of heterogeneous ubiquitinated species | Optimize inhibitor concentration; confirm efficacy using positive controls |

| Loss of high-molecular-weight ubiquitin conjugates | Excessive DUB activity preferentially removing polyubiquitin chains | Use fresh DUB inhibitors; avoid freeze-thaw cycles of inhibitor stocks |

| Extra bands at unexpected molecular weights | Non-specific antibody binding or protein degradation | Include control without DUB inhibitor to distinguish specific ubiquitination patterns |

| Complete absence of signal | Over-blocking or antigen masking | Compare different blocking agents (BSA vs. non-fat milk); optimize antibody concentrations [22] |

Experimental Protocols: Preserving Ubiquitination States During Sample Preparation

Optimized Cell Lysis Protocol with DUB Inhibition

Purpose: To effectively extract proteins while preserving ubiquitination states by inhibiting endogenous DUB activity.

Materials Needed:

- Pan-DUB inhibitor (e.g., PR-619 at 50-100mM stock in DMSO)

- Ubiquitin E1 inhibitor (e.g., PYR-41 at 10mM stock in DMSO) [2]

- Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (without DUB inhibitors)

- Lysis buffer (e.g., RIPA or NP-40 based)

- Pre-chilled PBS

- Cell scrapers (for adherent cells)

Procedure:

- Prepare fresh working inhibitor solution by diluting PR-619 to 20µM and PYR-41 to 10µM in lysis buffer.

- Aspirate culture media from cells and wash once with ice-cold PBS.

- Add appropriate volume of inhibitor-containing lysis buffer to cells (e.g., 100-200µL for a 6-well plate).

- Incubate on ice for 5-10 minutes with occasional rocking.

- Scrape adherent cells thoroughly and transfer lysate to pre-chilled microcentrifuge tube.

- Clarify by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

- Transfer supernatant to new tube and proceed immediately to protein quantification or store at -80°C.

Validation: Confirm efficacy of DUB inhibition by comparing with samples lysed without DUB inhibitors, monitoring accumulation of high-molecular-weight ubiquitinated proteins [2].

Activity-Based Profiling of DUB Inhibition Efficacy

Purpose: To validate the effectiveness of DUB inhibition protocols using activity-based probes.

Materials Needed:

- Ubiquitin-based active site-directed probes (Ub-VME or Ub-PA) [23]

- Cell lysates prepared with and without DUB inhibitors

- Streptavidin beads (for pull-down)

- SDS-PAGE equipment

- Anti-ubiquitin antibodies

Procedure:

- Incubate cell lysates (10-20µg) with Ub-VME or Ub-PA probes (1µM) for 30 minutes at 37°C [23].

- Stop reaction with SDS sample buffer.

- Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to membrane.

- Detect labeled DUBs using streptavidin-HRP or anti-ubiquitin antibodies.

- Compare labeling intensity between samples prepared with and without DUB inhibitors.

Interpretation: Effective DUB inhibition should show reduced probe labeling in inhibitor-treated samples, confirming DUB inactivation during lysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Controlling Deubiquitination

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Mechanism of Action | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broad-Spectrum DUB Inhibitors | PR-619 | Pan-DUB inhibitor inducing ubiquitin-protein aggregation [2] | Use at 20-50µM in lysis buffer; compatible with various detection methods |

| E1 Ubiquitin Activating Enzyme Inhibitors | PYR-41 | Inhibits ubiquitin activation, reducing substrate ubiquitination [2] | Use at 10µM in combination with DUB inhibitors for enhanced effect |

| Activity-Based Probes | Ub-VME, Ub-PA | Covalently label active site cysteine of DUBs [23] | Essential for validating DUB inhibition efficacy; use at 1µM concentration |

| Selective DUB Inhibitors | VLX1570 (targets USP14/UCHL5) [24] | Specific inhibition of proteasome-associated DUBs | Useful for studying specific DUB functions; limited for general lysis protection |

| Ubiquitin Chain Reference Standards | K48-linked, K63-linked di-Ub/tetra-Ub chains [23] | Linkage-specific ubiquitin standards | Critical controls for assessing DUB activity and linkage specificity |

FAQs: Addressing Common Technical Challenges

Q1: Why do I still detect background DUB activity even when using recommended DUB inhibitors?

A: Persistent DUB activity typically results from: (1) insufficient inhibitor concentration - perform dose optimization for your specific system; (2) incomplete inhibition of all DUB classes - consider combining inhibitors with different specificities; (3) inhibitor degradation - prepare fresh stocks and avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles; or (4) lysis buffer incompatibility - ensure detergent system doesn't interfere with inhibitor function. Validation with activity-based probes is recommended [23].

Q2: How does uncontrolled deubiquitination specifically affect interpretation of Wnt signaling pathways?

A: In Wnt signaling, ubiquitination directly regulates key components including β-catenin, Axin, GSK3, and Dvl [21]. Unchecked deubiquitination during sample preparation can: (1) artificially stabilize β-catenin, leading to false conclusions about pathway activation; (2) alter the degradation kinetics of pathway regulators; and (3) obscure phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination events that are crucial for pathway regulation. These artifacts fundamentally compromise mechanistic studies of Wnt signaling modulation.

Q3: What are the best practices for storing and handling DUB inhibitors to maintain efficacy?

A: Follow these guidelines: (1) aliquot inhibitors in single-use volumes to avoid freeze-thaw cycles; (2) store at -80°C in anhydrous DMSO; (3) protect from light and moisture; (4) add inhibitors to lysis buffer immediately before use; and (5) avoid extended storage of inhibitor-containing buffers even at -20°C. Periodically validate inhibitor efficacy using activity-based probes [23].

Q4: Can I use the same DUB inhibition strategy for all cell types and tissues?

A: While the fundamental principles apply universally, optimization may be required for: (1) tissues with high intrinsic DUB activity (e.g., brain tissue); (2) cells expressing unusual DUB profiles (e.g., cancer cells with DUB amplification); and (3) subcellular fractionation studies where compartment-specific DUBs may be enriched. Always validate your inhibition strategy for each novel experimental system.

Advanced Applications: DUB Inhibitors in Cancer Research and Therapeutic Development

The controlled inhibition of DUBs has significant implications beyond preventing experimental artifacts, particularly in cancer research and drug development. Many DUBs are genetically altered or dysregulated in various cancers, functioning as either oncogenes or tumor suppressors [20] [24]. For instance, USP6 overexpression due to chromosomal rearrangements drives aneurysmal bone cysts, while CYLD mutations are associated with familial cylindromatosis [20]. The pan-DUB inhibitor PR-619 has demonstrated profound anti-cancer effects in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma, inducing G2/M cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and autophagy through ubiquitin-protein aggregation-activated ER stress [2]. Several DUB-targeting therapeutics have entered clinical development, including VLX1570 (targeting USP14/UCHL5) for multiple myeloma and KSQ-4279 for solid tumors [24]. These developments highlight the dual importance of DUB inhibition: as a crucial methodological approach for accurate research and as a promising therapeutic strategy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for DUB Research

| Reagent Name | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Biotin-UbVMe [12] | Activity-based DUB probe; covalently binds active site cysteine of DUBs. | Contains N-terminal Avi-Tag for biotinylation, C-terminal vinyl methyl ester (VME) electrophile; used for enrichment and detection. |

| Ub-AMC / Ub-Rho110 [12] | Fluorogenic DUB substrates for enzymatic activity assays. | DUB cleavage releases fluorescent AMC or Rhodamine 110; Ub-Rho110 offers red-shifted spectra, reducing compound interference. |

| DUB-Glo Assay [12] | Bioluminescent assay for DUB activity. | Offers low background signal, suitable for high-throughput screening (HTS) campaigns. |

| MLN4924 [25] | Inhibitor of NEDD8-activating E1 enzyme. | Indirectly affects a subset of Cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin ligases; used as a control or tool compound. |

| Auranofin [25] | Inhibitor of proteasome-associated DUBs UCHL5 and USP14. | Used to study the role of 19S proteasome-associated DUBs in cancer cell survival. |

| PR-619 / HBX41108 [26] | Broad-spectrum, covalent DUB inhibitors. | Useful as positive controls in activity assays and for validating DUB-dependent cellular phenomena. |

| XL177A [26] | Selective USP7 inhibitor. | Example of a selective chemical probe; used to interrogate specific DUB biology. |

| SB1-F-22 (N-cyanopyrrolidine) [26] | Covalent inhibitor targeting UCHL1 active site cysteine. | Represents a chemotype inspired by patent literature; used for UCH-family DUB targeting. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is preventing deubiquitination during cell lysis critical for my experiments, and how can I achieve it?

Answer: Preventing deubiquitination during cell lysis is essential to preserve the in vivo ubiquitination status of your proteins of interest. DUBs remain active in cell lysates and can rapidly remove ubiquitin chains from substrates after lysis, leading to inaccurate representation of protein stability, degradation, and signaling events [12]. This is a fundamental consideration for any research framed within the context of investigating DUB functions.

Solution:

- Use Comprehensive DUB Inhibitors: Add a cocktail of broad-spectrum DUB inhibitors to your lysis buffer immediately upon cell disruption. Common choices include:

- PR-619: A cell-permeable, pan-DUB inhibitor effective in the low micromolar range.

- N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM): An alkylating agent that inhibits cysteine proteases, including most DUB families.

- Optimize Buffer Conditions: Keep lysates on ice and perform procedures rapidly to minimize enzymatic activity. The use of these inhibitors in lysis buffers is a standard practice for assays like the cell lysate-based AlphaLISA, which relies on capturing the true state of DUB activity and ubiquitination [12].

FAQ 2: My high-throughput screen against a DUB yielded numerous hits, but I suspect many are non-selective or false positives. How can I triage them effectively?

Answer: This is a common challenge in DUB drug discovery. Early-generation DUB inhibitors are often multitargeted, and false positives can arise from compound interference (e.g., fluorescence, aggregation) [26].

Solution: Implement an Orthogonal Assay Cascade:

- Primary Screening: Use a robust, physiologically relevant primary screen. The cell lysate-based ABPP (Activity-Based Protein Profiling) platform is highly recommended. It screens compounds against endogenous, full-length DUBs in their native cellular environment, providing selectivity data across many DUBs simultaneously [26].

- Orthogonal Validation: Confirm hits from your primary screen using a different assay technology.

- Fluorometric Assays: Use Ub-AMC or Ub-Rho110 cleavage assays with the purified recombinant DUB to confirm direct enzymatic inhibition [12].

- Gel-Based Assays: Employ western blotting to monitor stabilization of known ubiquitinated substrates of the DUB in cells treated with your hit compounds.

- Counter-Screening: Test your hits against a panel of other DUBs and related enzymes (e.g., other cysteine proteases) to define selectivity. The ABPP platform is ideal for this, as it can profile compound selectivity against dozens of endogenous DUBs in a single experiment [26].

FAQ 3: I am struggling to obtain sufficient quantities of active, recombinant DUB protein for biochemical assays. What are my options?

Answer: Many human DUBs are large, multi-domain proteins that are challenging to express and purify in active form in sufficient quantities for high-throughput screening (HTS) [12].

Solution:

- Consider Alternative Expression Systems: If E. coli expression fails, try baculovirus-mediated expression in insect cells, which often better handles the folding and post-translational modifications of complex human proteins.

- Utilize Cell Lysate-Based Assays: Shift your strategy to a platform that does not require purified protein. The AlphaLISA DUB assay and the ABPP platform are designed to work with DUBs expressed in and extracted from human cells. This not only circumvents the purification problem but also recapitulates a more physiologically relevant environment, as many DUBs require binding partners for full activity and specificity [12] [26].

- Focus on Catalytic Domains: For initial mechanistic or structural studies, consider expressing and purifying only the well-characterized catalytic domain of the DUB, which is often more tractable.

FAQ 4: How can I determine if a DUB is a realistic therapeutic target for a specific cancer or neurodegenerative disease?

Answer: Target validation requires demonstrating that the DUB is functionally involved in a disease-relevant pathway and that its inhibition has a therapeutic effect.

Solution: A Multi-Faceted Validation Approach:

- Genetic Evidence: Use siRNA, shRNA, or CRISPR-Cas9 to knock down or knock out the DUB in disease-relevant cell models (e.g., cancer cell lines, neuronal models). Look for phenotypic changes such as reduced cell proliferation, induction of apoptosis, or decreased levels of pathogenic proteins (e.g., α-synuclein, Tau) [27] [28].

- Clinical Correlation: Analyze human tissue databases (e.g., The Cancer Genome Atlas) for evidence of DUB dysregulation (overexpression, amplification, mutation) in patient tumors and correlate this with clinical outcomes [27] [25].

- Chemical Probe Validation: Use a selective, well-characterized small-molecule inhibitor (chemical probe) of the DUB. The phenotypic effects of genetic knockdown should be recapitulated by pharmacological inhibition. The development of probes for DUBs like USP7, USP28, and VCPIP1 provides a blueprint for this approach [26].

- Mechanistic Insight: Identify the key substrates stabilized by the DUB (e.g., MYC, HIF1α stabilized by USP29 [27] or pathogenic proteins in NDs [28]). Rescuing the phenotype by reconstituting the substrate can confirm the mechanism.

Experimental Protocol: Cell Lysate-Based DUB Inhibitor Screening via ABPP

This protocol outlines a method for screening compounds for DUB inhibition using endogenous DUBs in cell lysates, leveraging the power of Activity-Based Protein Profiling (ABPP) and quantitative mass spectrometry [26].

1. Reagent Preparation:

- Biotinylated Ubiquitin Probes: Prepare a 1:1 mixture of biotin-Ub-VME (vinyl methyl ester) and biotin-Ub-PA (propargylamide). These probes covalently label the active site cysteine of most DUBs [12] [26].

- Compound Library: Dissolve compounds in DMSO. A final concentration of 50 µM is typical for a primary screen.

- Cell Lysate: Harvest HEK293 or other relevant cells. Lyse cells in a appropriate buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40) supplemented with broad-spectrum DUB inhibitors. Clear the lysate by centrifugation. Determine protein concentration.

2. Primary Screening Incubation:

- In a 96-well plate, mix 50 µg of cell lysate per well with 1 µL of compound (or DMSO for controls).

- Incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature to allow compound binding.

- Add the biotin-Ub probe mixture (final concentration ~100 nM) and incubate for an additional 60 minutes. The probe will label all DUBs not blocked by a bound inhibitor.

3. Sample Processing for Mass Spectrometry:

- Denature the samples and digest with trypsin.

- Label the peptides from different samples with isobaric TMT (Tandem Mass Tag) reagents. This allows for multiplexing (e.g., 16-plex) and relative quantification across samples.

- Enrich biotinylated peptides (which contain the DUB-derived peptides covalently linked to the probe) using streptavidin beads.

4. Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Analyze the enriched peptides by nanoflow liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

- Use database searching to identify the DUB peptides. The TMT reporter ion intensities for each DUB peptide are proportional to the amount of probe labeling, and thus inversely proportional to compound inhibition.

- A "hit compound" is typically defined as one that reduces ABP labeling of a specific DUB by ≥50% compared to the DMSO control [26].

DUB Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram: DUB Regulation of Key Oncogenic Pathways

Diagram: Workflow for DUB Inhibitor Discovery & Validation

Practical Implementation of DUB Inhibitors in Cell Lysis Protocols

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) represent a family of approximately 100 proteases that catalyze the removal of ubiquitin from protein substrates, thereby reversing the activity of E3 ubiquitin ligases and playing central roles in regulating cellular processes such as protein degradation, DNA repair, and cell signaling [29] [20]. The pharmacologic interrogation of this important protein family has been hampered by a historical lack of selective chemical probes, impeding both basic research and therapeutic development [29]. DUB inhibitors have emerged as critical tools for disrupting deubiquitination processes, with applications ranging from fundamental mechanism discovery to potential cancer therapeutics [20].

Two primary classes of DUB inhibitors have been developed: broad-spectrum inhibitors that simultaneously target multiple DUBs, and selective inhibitors that specifically target individual DUB family members. Each class possesses distinct characteristics, applications, and limitations that researchers must consider when designing experiments. Broad-spectrum inhibitors like PR-619 provide valuable tools for initial discovery research and for preserving ubiquitinated proteins during cell lysis, while selective inhibitors such as ML323 (targeting USP1-UAF1) and XL177A (targeting USP7) enable precise pharmacological interrogation of specific DUB functions [30] [31] [32].

The following sections provide a comprehensive technical resource for researchers working with DUB inhibitors, including comparative characterization data, experimental protocols, troubleshooting guidance, and reagent information specifically framed within the context of preventing deubiquitination during cell lysis and advancing DUB-targeted therapeutic discovery.

DUB Inhibitor Classes: Characteristics and Applications

Comparative Analysis of Inhibitor Classes

Table 1: Characteristics of Broad-Spectrum vs. Selective DUB Inhibitors

| Characteristic | Broad-Spectrum Inhibitors | Selective Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|

| Target Range | Multiple DUBs across subfamilies (e.g., PR-619 inhibits many cysteine-reactive DUBs) [30] | Individual DUBs or specific complexes (e.g., ML323 specifically inhibits USP1-UAF1; XL177A targets USP7) [31] [32] |

| Primary Applications | - Preservation of ubiquitinated proteins during cell lysis [30]- Initial screening and phenotyping- Studying global ubiquitination dynamics | - Precise target validation- Therapeutic development- Mapping specific DUB-substrate relationships [32] |

| Common Examples | PR-619 (reversible, 5-20 μM IC₅₀ range) [30] | ML323 (USP1-UAF1, nM potency), XL177A (USP7, 0.34 nM IC₅₀) [31] [32] |

| Key Advantages | - Immediate effects on global ubiquitination- Useful for pathway discovery- Cost-effective for initial studies | - Minimal off-target effects- Clear interpretation of results- Better therapeutic potential |

| Major Limitations | - Difficult to attribute effects to specific DUBs- Potential compensatory mechanisms- Higher risk of cellular toxicity | - Require prior knowledge of target- More resource-intensive development- Limited for complex polygenic diseases |

| Recommended Use Cases | - Lysis buffer additive (50-100 μM) to preserve ubiquitination [30]- Initial studies of DUB involvement in processes- Identifying DUB-sensitive cellular processes | - Validating individual DUB functions- Probe development for specific DUBs- Targeted therapeutic applications |

Molecular Mechanisms and Structural Basis

The structural basis for DUB inhibitor selectivity stems from the diverse active site architectures across DUB subfamilies. Broad-spectrum inhibitors typically target conserved catalytic cysteine residues found in multiple DUB families, while selective inhibitors exploit unique structural features surrounding individual DUB active sites. For instance, the broad-spectrum inhibitor PR-619 contains thiocyanate groups that react with catalytic cysteine residues across numerous cysteine protease DUB families [30].

In contrast, selective inhibitors achieve their specificity through optimized interactions with unique structural elements. The development of selective inhibitors has been accelerated by structure-guided approaches that analyze DUB-ligand and DUB-ubiquitin co-structures to identify regions around the catalytic site that favor compound interaction and potential selectivity determinants [29]. For example, the selective USP1-UAF1 inhibitor ML323 achieves its exceptional selectivity profile by specifically engaging with unique structural features of the USP1-UAF1 complex rather than simply targeting the conserved catalytic domain [31].

Recent advances in rational library design have embraced this structural complexity through chemical diversification strategies that incorporate noncovalent building blocks, linkers, and electrophilic warheads designed to interact with both conserved and unique regions around DUB catalytic sites [29]. This approach has successfully yielded selective inhibitors for previously untargeted DUBs, demonstrating the feasibility of developing selective compounds across this important gene family.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol for Cell Lysis with DUB Inhibition

Purpose: To effectively preserve ubiquitin conjugates during cell extraction by inhibiting endogenous deubiquitinating enzymes.

Equipment:

- Sonicator or vortexer

- Micropipette

- Conical tube (sized accordingly for cell sample)

- Microcentrifuge tube (sized accordingly for cell sample)

- Microcentrifuge

- Cell scraper or spatula [33]

Reagents:

- Mammalian cells grown in adherent culture or suspension

- Ice-cold RIPA Lysis Buffer or other appropriate lysis buffer

- Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (100X)

- DUB inhibitor (e.g., PR-619 or selective inhibitors)

- Ice-cold PBS [33]

Procedure:

Preparation of Lysis Buffer: Add 0.1 mL of protease and phosphatase inhibitors to 10 mL RIPA buffer. Add DUB inhibitor to appropriate concentration (e.g., 50-100 μM for PR-619) [30] [33].

Cell Preparation:

- For adherent cells: Culture to ~80% confluence. Aspirate media and keep plate on ice. Wash cell monolayer gently with 10 ml ice-cold PBS. Aspirate excess PBS [33].

- For suspension cells: Culture to 1-2 x 10⁶ cells/ml. Pellet cells at 300 × g for 5 minutes at room temperature. Aspirate media and keep cells on ice. Wash pellet with 5-10 ml ice-cold PBS. Centrifuge again at 300 × g for 5 minutes and aspirate supernatant [33].

Lysis:

Incubation: Incubate lysate on ice for 15 minutes [33].

Homogenization: Sonicate or vortex the lysate three times for 2 seconds each. Rest the lysate at least one minute between pulses. Repeat if lysate remains viscous [33].

Secondary Incubation: Incubate lysate on ice for additional 15 minutes [33].

Clarification: Centrifuge lysate at 13,000 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C [33].

Collection: Transfer supernatant to new microcentrifuge tubes, avoiding disruption of pellet [33].

Storage: Aliquot and store lysate at -20°C for short-term use or -80°C for long-term storage [33].

Validation: Determine protein concentration using Bradford, BCA, or other appropriate protein assay before proceeding to downstream applications [33].

Workflow for DUB Substrate Identification Using Selective Inhibitors

Diagram 1: Proteomics workflow for DUB substrate identification using selective inhibitors. This approach enables comprehensive mapping of DUB substrates by monitoring protein stabilization/destabilization following targeted DUB inhibition [32].

High-Throughput Screening Protocol for DUB Inhibitor Discovery

Purpose: To identify selective DUB inhibitors through high-throughput screening of compound libraries against recombinant DUB enzymes.

Equipment:

- FPLC system with size exclusion chromatography

- Sonicator

- Centrifuge

- Microplate reader for fluorescence-based assays

- Liquid handling robotics for HTS (optional)

Reagents:

- DUB expression vectors (pET28 with 6xHis tag or pGEX6P1 with GST tag)

- BL21(DE3) Competent E. coli

- LB medium with appropriate antibiotics

- IPTG for protein induction

- Lysis buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 8, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 M NaCl)

- Ni-NTA Agarose (for 6xHis-tagged proteins) or Glutathione Agarose (for GST-tagged proteins)

- Elution buffers with imidazole (6xHis-tagged) or GST 3C protease (GST-tagged)

- Size exclusion column buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT)

- Ubiquitin-Rhodamine110 (Ub-Rho) substrate

- Test compounds in DMSO [34]

Procedure:

Protein Expression:

- Transform BL21(DE3) E. coli with DUB plasmid

- Inoculate single colony into 5 mL LB medium with antibiotic, grow at 37°C for 16-18h

- Dilute culture into 1L LB medium, grow until OD₆₀₀ reaches 0.8-1.0

- Induce protein expression with 100 mg/L IPTG, incubate at 16°C for 18-24h

- Pellet cells by centrifugation at 4,540 × g for 20min at 4°C [34]

Protein Purification:

- Resuspend cell pellet in 50-100mL lysis buffer, stir at 4°C for 30min

- Add PMSF to 10 μg/mL, lyse by sonication on ice

- Centrifuge lysate at 30,000 × g for 40min at 4°C

- Equilibrate appropriate affinity resin in lysis buffer

- Incubate cell lysate with resin at 4°C for 2-4h with gentle agitation

- Wash resin with wash buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 8, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 M NaCl, 25 mM imidazole for 6xHis-tagged proteins)

- Elute protein with elution buffer (containing 300 mM imidazole for 6xHis-tagged proteins or GST 3C protease for GST-tagged proteins)

- Concentrate protein using centrifugal filter units

- Further purify via FPLC size exclusion chromatography [34]

Enzyme Activity Assay:

- Prepare reaction buffer optimized for each DUB

- Incubate purified DUB with Ub-Rho substrate in presence of test compounds

- Monitor fluorescence increase (excitation 485 nm, emission 535 nm) over time

- Calculate inhibition relative to DMSO controls [34]

Hit Validation:

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why should I include DUB inhibitors in my cell lysis buffer, and which type should I choose?

A: Deubiquitinating enzymes remain active during cell lysis and can rapidly remove ubiquitin from proteins of interest, potentially obscuring detection of physiologically relevant ubiquitination events. Including DUB inhibitors in lysis buffers preserves ubiquitin conjugates that would otherwise be lost. For general ubiquitin preservation, broad-spectrum inhibitors like PR-619 (50-100 μM) are recommended. For studies focused on specific DUB substrates, consider including selective inhibitors targeting highly active DUBs in your system, if available [30].

Q2: What is the difference between reversible and irreversible DUB inhibitors?

A: Reversible inhibitors (e.g., PR-619) bind non-covalently to DUBs and their effects can be diluted or reversed. Irreversible inhibitors (e.g., XL177A) typically form covalent bonds with catalytic cysteine residues, resulting in permanent enzyme inhibition. Reversible inhibitors are often preferred for acute treatments, while irreversible inhibitors can provide prolonged inhibition but may require careful concentration optimization to minimize off-target effects [30] [32].

Q3: How do I validate the selectivity of a DUB inhibitor for my study?

A: Several approaches can assess inhibitor selectivity: (1) In vitro profiling against panels of recombinant DUBs; (2) Cellular chemoproteomic methods like activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) that assess engagement of endogenous DUBs; (3) Monitoring changes in known substrate ubiquitination status; (4) Genetic validation using DUB knockout or knockdown cells. For comprehensive selectivity assessment, ABPP platforms can evaluate compound activity against 65+ endogenous DUBs simultaneously [29] [32].

Q4: Can DUB inhibitor treatment itself affect cellular ubiquitin levels?

A: Yes, particularly with broad-spectrum inhibitors. Treatment with non-selective DUB inhibitors like PR-619 causes accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins by blocking the recycling of ubiquitin. This can potentially deplete free ubiquitin pools over extended treatments and cause secondary effects. Selective inhibitors typically have minimal impact on global ubiquitination, making them preferable for prolonged treatments [30].

Q5: What cellular phenotypes should I expect after DUB inhibition?

A: This depends on the specific DUB targeted. Inhibition of DUBs regulating stability of oncoproteins or tumor suppressors may affect cell proliferation and survival. Inhibition of DUBs involved in DNA damage response (e.g., USP1) can sensitize cells to genotoxic agents. Broad-spectrum inhibition typically causes accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins and may activate stress pathways. Phenotypes should be interpreted cautiously with non-selective inhibitors, as effects may result from combined inhibition of multiple DUBs [31] [20].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Table 2: Troubleshooting DUB Inhibitor Experiments

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor preservation of ubiquitinated proteins during lysis | - Inadequate DUB inhibitor concentration- Insufficient inhibition speed- Improper lysis buffer composition | - Increase DUB inhibitor concentration (e.g., 100 μM PR-619) [30]- Ensure rapid inhibition by adding inhibitors directly to lysis buffer- Include complementary protease inhibitors |

| High background in ubiquitin detection | - Non-specific antibody binding- Incomplete lysate clarification- Protein overloading | - Optimize antibody concentrations- Increase centrifugation speed/time for better clarification- Reduce protein loading; validate with positive/negative controls |

| Cellular toxicity with inhibitor treatment | - Off-target effects- Excessive inhibitor concentration- Prolonged exposure | - Titrate inhibitor to find minimum effective concentration- Use selective inhibitors instead of broad-spectrum- Shorten treatment duration |

| Lack of expected phenotype with selective inhibitor | - Inadequate target engagement- Compensation by related DUBs- Incorrect biological hypothesis | - Verify target engagement using cellular assays- Test combination of inhibitors targeting related DUBs- Validate with genetic approaches (e.g., CRISPR) |

| Inconsistent results between experiments | - Inhibitor stability issues- Variable cell culture conditions- Differences in lysis efficiency | - Prepare fresh inhibitor stocks; avoid freeze-thaw cycles- Standardize cell culture and treatment conditions- Monitor lysis efficiency visually and by protein quantification |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for DUB Inhibition Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Key Applications & Functions | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broad-Spectrum DUB Inhibitors | PR-619 [30] | - Preserve ubiquitinated proteins during cell lysis (50-100 μM) [30]- Initial studies of DUB involvement in cellular processes | - Reversible inhibitor- Use for acute treatments- Can affect global ubiquitination |

| Selective DUB Inhibitors | ML323 (USP1-UAF1) [31]XL177A (USP7) [32] | - Precise target validation- Therapeutic mechanism studies- Mapping specific DUB substrates [31] [32] | - Validate selectivity for your system- Titrate for optimal concentration- Consider covalent vs. reversible mechanism |

| Activity-Based Probes | Biotin-Ub-VME/Biotin-Ub-PA [29] | - Assess endogenous DUB activity- Profiling inhibitor selectivity- DUB discovery [29] | - Can be combined for broader DUB coverage- Use with quantitative mass spectrometry |

| Lysis & Stabilization Reagents | RIPA Buffer [33]Protease Inhibitor Cocktails [33] | - Maintain protein integrity during extraction- Prevent non-specific proteolysis- Preserve post-translational modifications | - Include DUB inhibitors specifically for ubiquitin preservation- Keep samples cold throughout processing |

| Detection Reagents | Anti-ubiquitin antibodiesTMT multiplexed reagents [32] | - Detect ubiquitinated proteins- Quantitative proteomics for substrate identification [32] | - Validate antibody specificity- Use appropriate multiplexing design for statistical power |

DUB Signaling Pathways in Cancer

Diagram 2: USP1-UAF1 signaling in DNA damage response and chemosensitization. ML323 inhibition of USP1-UAF1 prevents deubiquitination of key DNA repair proteins, enhancing cisplatin sensitivity in cancer cells [31].

The strategic application of both broad-spectrum and selective DUB inhibitors provides powerful approaches for advancing our understanding of deubiquitination biology and developing novel therapeutic strategies. Broad-spectrum inhibitors remain invaluable tools for initial discovery research and for preserving ubiquitination signatures during cell lysis, while selective inhibitors enable precise dissection of individual DUB functions and target validation. The continuing development of increasingly selective chemical probes, coupled with advanced screening platforms such as activity-based protein profiling, is rapidly accelerating pharmacological interrogation of this important gene family. As the field progresses, the appropriate selection and application of these inhibitor classes—with careful consideration of their distinct characteristics and limitations—will be essential for designing robust experiments and generating meaningful biological insights with potential therapeutic applications in cancer and other diseases.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core mechanism of action of the pan-DUB inhibitor PR-619? PR-619 is a broad-spectrum, cell-permeable inhibitor that targets the active site cysteine of cysteine protease DUBs, including USP, UCH, MJD, OTU, and MINDY families [16] [35]. Its primary action is to induce the accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins by blocking deubiquitinating activity. This accumulation can trigger downstream cellular events, most notably Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) stress, which then activates apoptosis and autophagy pathways [2].

FAQ 2: How can I confirm that PR-619 is working in my cell lysate experiment? The most direct method is to detect the increase in global ubiquitin conjugates via western blotting. Use an anti-ubiquitin antibody to compare lysates treated with PR-619 against a DMSO vehicle control. You should observe a characteristic smear of high-molecular-weight proteins in the treated sample, indicating successful inhibition of DUBs and the accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated substrates [14] [36].

FAQ 3: What is a typical working concentration for PR-619 in cell-based assays? Effective concentrations can vary based on cell type and treatment duration. The table below summarizes concentrations used in published studies.

| Cell Type/Model | Typical Concentration Range | Key Observed Effect | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma | 20 - 40 µM | Induced apoptosis & autophagy [2] | |

| Renal fibrosis (mouse model, in vivo) | 100 µg per dose (daily IP injection) | Suppressed renal fibrosis [37] | |

| Retinal ganglion cells (in vivo) | 8.23 µM (intravitreal injection) | Enhanced mitophagy, neuroprotection [38] | |

| U2OS cells (ubiquitinome study) | 10 - 50 µM | Global accumulation of ubiquitin substrates [14] |

FAQ 4: Why does PR-619 treatment lead to autophagy in some cellular models? The induction of autophagy is often a secondary consequence of cellular stress. PR-619-induced ubiquitinated protein aggregates activate ER stress, leading to an increase in cytosolic Ca²⁺ levels. This calcium release activates the CaMKKβ-AMPK signaling pathway, which is a key positive regulator of autophagy [2].

FAQ 5: Are the effects of PR-619 reversible? The inhibition is not considered easily reversible because PR-619 acts as a covalent modifier of the active site cysteine in target DUBs [35]. However, the cellular ubiquitin landscape can recover over time as the inhibitor is cleared and new DUB proteins are synthesized. One study showed that the bulk of ubiquitin conjugates accumulated by DUB inhibition were turned over within 3 hours after co-treatment with a ubiquitin E1 inhibitor (TAK243), which blocks new ubiquitination [14].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem 1: Excessive Cell Death or Unintended Apoptosis

- Potential Cause: The concentration of PR-619 is too high for your specific cell type, leading to an overwhelming ER stress response and rapid induction of apoptosis [2].

- Solutions:

- Perform a dose-response curve to determine the optimal concentration that achieves DUB inhibition without excessive toxicity. Start testing in the range of 10-50 µM.

- Shorten the treatment duration. Instead of continuous exposure, consider a pulse-treatment followed by a recovery period in fresh medium.

- Use an orthogonal assay (e.g., caspase activity assay) to quantify apoptosis and better define the therapeutic window for your experiment.

Problem 2: No Apparent Increase in Ubiquitin Smear on Western Blot