Advanced Strategies to Resolve Ubiquitin Smears in Western Blotting: A Guide for Protein Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to resolve the challenging ubiquitin smears in Western blots.

Advanced Strategies to Resolve Ubiquitin Smears in Western Blotting: A Guide for Protein Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to resolve the challenging ubiquitin smears in Western blots. It covers the foundational understanding of the ubiquitin code, detailing how specific chain linkages like K48 and K63 contribute to smear patterns. The guide presents optimized methodological protocols for sample preparation, gel electrophoresis, and transfer, alongside advanced application tools such as chain-specific TUBEs and engineered deubiquitinases (enDUBs) for precise detection. A dedicated troubleshooting section addresses common issues like weak signal and high background, while validation techniques including mass spectrometry and functional degradation assays are explored to confirm results. By integrating these strategies, scientists can significantly enhance the resolution and interpretability of ubiquitin Western blots, accelerating research in targeted protein degradation and the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

Decoding the Ubiquitin Smear: Understanding Linkages, Chains, and Complexity

Why does my ubiquitin western blot show a smear instead of sharp bands?

In ubiquitin western blotting, a smear is not a sign of failure but a characteristic and expected result that provides important biological information. The smear represents the heterogeneous population of ubiquitinated proteins in your sample [1].

- Polymerization: Ubiquitination involves attaching ubiquitin molecules to protein substrates. A poly-ubiquitin chain is produced when a ubiquitin molecule on a substrate is modified by additional ubiquitin monomers conjugating onto any of the seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or the N-terminal methionine (M1) of ubiquitin [1].

- Heterogeneous Populations: Your sample contains the same target protein with varying numbers of ubiquitin molecules attached. Each addition of an 8.6 kDa ubiquitin molecule increases the molecular weight, creating a ladder of different molecular species [2] [1].

- Continuous Distribution: Since the number of attached ubiquitin molecules varies continuously across the protein population, this creates a smear pattern rather than discrete bands on your western blot [1].

Table: Ubiquitin Linkages and Their Functional Consequences

| Linkage Site | Chain Type | Primary Biological Function |

|---|---|---|

| K48 | Polymeric | Targeted protein degradation by the proteasome [1] |

| K63 | Polymeric | Immune responses, inflammation, lymphocyte activation [1] |

| K6 | Polymeric | Antiviral responses, autophagy, DNA repair [1] |

| K11 | Polymeric | Cell cycle progression, proteasome-mediated degradation [1] |

| K27 | Polymeric | DNA replication, cell proliferation [1] |

| K29 | Polymeric | Neurodegenerative disorders, autophagy [1] |

| M1 | Polymeric | Cell death and immune signaling [1] |

| Substrate lysines | Monomer | Endocytosis, histone modification, DNA damage responses [1] |

How can I distinguish meaningful ubiquitin smears from technical artifacts?

While smears are expected in ubiquitin western blots, it's crucial to distinguish biologically relevant smearing from artifacts caused by technical issues. The table below compares characteristic features of true ubiquitination patterns versus common artifacts.

Table: Differentiating Ubiquitination Smears from Technical Artifacts

| Feature | True Ubiquitination Signal | Technical Artifact |

|---|---|---|

| Pattern Appearance | Continuous smear extending upward from expected molecular weight [1] | Irregular, blotchy, or localized speckling [3] |

| Reproducibility | Consistent across experimental replicates | Variable between replicates |

| Response to Proteasome Inhibition | Enhanced with MG-132 treatment (5-25 µM for 1-2 hours) [1] | Unchanged |

| Band Pattern | No distinct bands within smear (unless studying specific chain types) | Multiple discrete non-specific bands [3] |

| Background | Clean background with specific smear pattern | High uniform background or speckling [3] |

What are the most effective methods to preserve ubiquitination signals before detection?

Ubiquitination is a transient and reversible modification, making preservation of these signals challenging. Proper sample handling is critical for accurate detection [1].

Sample Preparation Protocol for Ubiquitination Studies

Cell Treatment:

Lysis:

Protein Quantification:

Storage:

- Process samples immediately or store at -70°C to prevent degradation [5].

- Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

How can I reduce high background in my ubiquitin western blots?

High background is a common issue that can obscure ubiquitination smears. These troubleshooting strategies can improve signal-to-noise ratio [3] [6].

Optimization Strategies for Clean Background

Blocking Optimization:

Antibody Incubation:

Washing Enhancement:

Detection Optimization:

What controls should I include to validate my ubiquitination results?

Proper controls are essential for interpreting ubiquitination smears correctly and ensuring experimental validity [3] [7].

Essential Control Experiments

Secondary Antibody-Only Control: Incubate membrane with secondary antibody alone to identify non-specific binding [3].

Proteasome Inhibition Control: Treat cells with MG-132 to stabilize ubiquitinated proteins and enhance smear intensity [1].

Positive Control: Use a known ubiquitinated protein or lysate from cells treated with proteasome inhibitor [3].

Loading Control: Include housekeeping proteins (GAPDH, actin, tubulin) to normalize protein loading [7].

Genetic Controls: Express wild-type and ubiquitination-deficient mutants (e.g., lysine-to-arginine mutations) of your target protein [4].

Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitination Studies

Table: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitin Research

| Reagent | Function | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Stabilizes ubiquitinated proteins by blocking degradation | MG-132 (5-25 µM for 1-2 hours) [1] |

| Ubiquitin-Trap | Immunoprecipitates ubiquitin and ubiquitinated proteins | ChromoTek Ubiquitin-Trap Agarose/Magnetic Beads [1] |

| Ubiquitin Antibodies | Detects ubiquitin and ubiquitinated proteins | Ubiquitin Recombinant Antibody (Proteintech 80992-1-RR) [1] |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Identifies specific ubiquitin chain linkages | K48-, K63-, M1-specific ubiquitin antibodies [1] |

| Plasmid DNA | Expresses ubiquitin and target proteins in cells | pCDNA3.1+ vectors with His-Ub or Flag-tagged constructs [4] |

| Enrichment Resins | Purifies ubiquitinated proteins for detection | Ni-NTA Agarose for His-Ub pulldowns [4] |

Can I use the sheet protector method to conserve antibodies in ubiquitin western blots?

Yes, the sheet protector (SP) strategy is an effective method to reduce antibody consumption while maintaining detection sensitivity for ubiquitin smears [5].

Sheet Protector Protocol for Ubiquitin Blots

Membrane Preparation:

- After transfer, block membrane conventionally with 5% skim milk for 1 hour.

- Briefly immerse in TBST to wash away excess milk.

- Blot membrane thoroughly with paper towel to absorb residual moisture.

Antibody Application:

- Place semi-dried membrane on a cropped sheet protector leaflet.

- Apply minimal antibody volume (20-150 µL for mini-gels) directly to membrane.

- Gently place upper leaflet over membrane, allowing solution to disperse as a thin layer.

Incubation:

- Incubate SP unit at room temperature for 15 minutes to several hours.

- For extended incubations, place SP unit on wet paper towel in sealed bag to prevent evaporation.

Detection:

- Proceed with standard washing and secondary antibody incubation.

- This method can reduce antibody consumption by up to 95% while maintaining comparable sensitivity to conventional methods [5].

What advanced techniques can I use to study specific ubiquitin chain linkages?

To move beyond simple smear detection and characterize specific ubiquitin linkages, consider these advanced methodologies [1].

Linkage-Specific Ubiquitination Analysis

Ubiquitin Traps with Linkage-Specific Antibodies: Use non-linkage specific Ubiquitin-Trap for pulldown followed by western blot with linkage-specific antibodies for differentiation [1].

In Vitro Ubiquitination Assays: Reconstitute ubiquitination using purified E1, E2, and E3 enzymes with recombinant target proteins to study specific enzymatic pathways [8].

Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Combine Ubiquitin-Trap immunoprecipitation with mass spectrometry (IP-MS) to identify specific ubiquitination sites and chain linkages [1].

Mutagenesis Studies: Create lysine-to-arginine mutations in target proteins (e.g., K190A, K450A) to identify specific ubiquitination sites [4].

FAQs: Core Concepts and Biological Significance

Q1: What are the primary cellular functions of K48-linked and K63-linked ubiquitin chains?

K48 and K63 linkages are the two most abundant ubiquitin chain types in cells and serve fundamentally different roles [9] [10].

- K48-linked chains are the principal signal for proteasomal degradation. Chains of four or more ubiquitins (Ub4) are particularly efficient, triggering degradation with half-lives as short as one minute [11].

- K63-linked chains are primarily non-proteolytic signals regulating diverse processes including DNA damage repair, inflammatory signaling (e.g., NF-κB and MAPK pathways), endocytosis, protein trafficking, and lysosomal degradation of membrane proteins [9] [12] [10].

Q2: Can K63 linkages ever signal for degradation?

Yes, the functional roles are not absolute. While K48 is the canonical proteasomal signal, K63 linkages can also target proteins for lysosomal degradation. For example, the LDL receptor (LDLR) can be targeted to the lysosome by either K48 or K63 linkages [12] [10]. Furthermore, when K63 chains are incorporated into certain branched structures, they can be converted into proteasomal degradation signals [13].

Q3: What are branched ubiquitin chains, and what is their functional significance?

Branched ubiquitin chains form when a single ubiquitin moiety is modified with two or more other ubiquitins via different linkages [9] [13]. A prominent example is the K48/K63-branched chain.

- Function: These chains add a layer of complexity to the ubiquitin code. They can act as superior degradation signals or regulate signaling pathways. For instance, K48/K63-branched chains can protect K63 linkages from deubiquitinating enzymes, thereby amplifying NF-κB signaling [14]. In other contexts, they trigger rapid proteasomal degradation [11] [13].

- Mechanism: Branched chains can increase ubiquitin density to enhance proteasome recruitment, and specific linkages within the branch can protect the chain from substrate-specific deubiquitinases (DUBs), ensuring the signal is not erased [14] [13].

Table 1: Primary Functions and Characteristics of K48 and K63 Ubiquitin Linkages

| Feature | K48-Linked Chains | K63-Linked Chains |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Proteasomal degradation [11] [15] | Non-proteolytic signaling (DNA repair, inflammation, endocytosis) [9] [10] [15] |

| Secondary Degradation Role | - | Lysosomal degradation [12] [10] |

| Minimal Efficient Degradation Signal | K48-Ub3/Ub4 [11] | Not typically a direct proteasomal signal |

| Abundance in Cells | ~52% of all linkages [10] | ~38% of all linkages [10] |

| Key Regulatory Role in Branched Chains | Can serve as the proteasome-targeting branch in K48/K63 chains [14] [13] | Can be protected from DUBs (e.g., CYLD) by K48 branching, amplifying signaling [14] |

Experimental Guide: Methodologies and Workflows

Q4: What are the best practices for studying linkage-specific ubiquitination in pull-down assays?

Using ubiquitin interactor pulldown coupled with mass spectrometry is a powerful method, but the choice of deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitor is critical [9].

- Inhibitor Choice: The commonly used DUB inhibitors N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) and chloroacetamide (CAA) have different efficacies and potential off-target effects.

- Recommendation: The choice of inhibitor can influence the identified interactors. It is advisable to perform experiments with both inhibitors separately and compare the datasets to distinguish overlapping interactors from inhibitor-specific ones [9].

Q5: How can I systematically compare the degradation capacity of different ubiquitin chains inside cells?

The UbiREAD (ubiquitinated reporter evaluation after intracellular delivery) technology is designed for this purpose [11].

- Workflow:

- Synthesis: Prepare GFP conjugated to ubiquitin chains of defined linkage, length, and composition in vitro.

- Delivery: Electroporate the ubiquitinated GFP protein directly into mammalian cells (e.g., RPE-1, HeLa).

- Quantification: Monitor degradation kinetics at high temporal resolution using flow cytometry or in-gel fluorescence to track the loss of the ubiquitinated GFP signal [11].

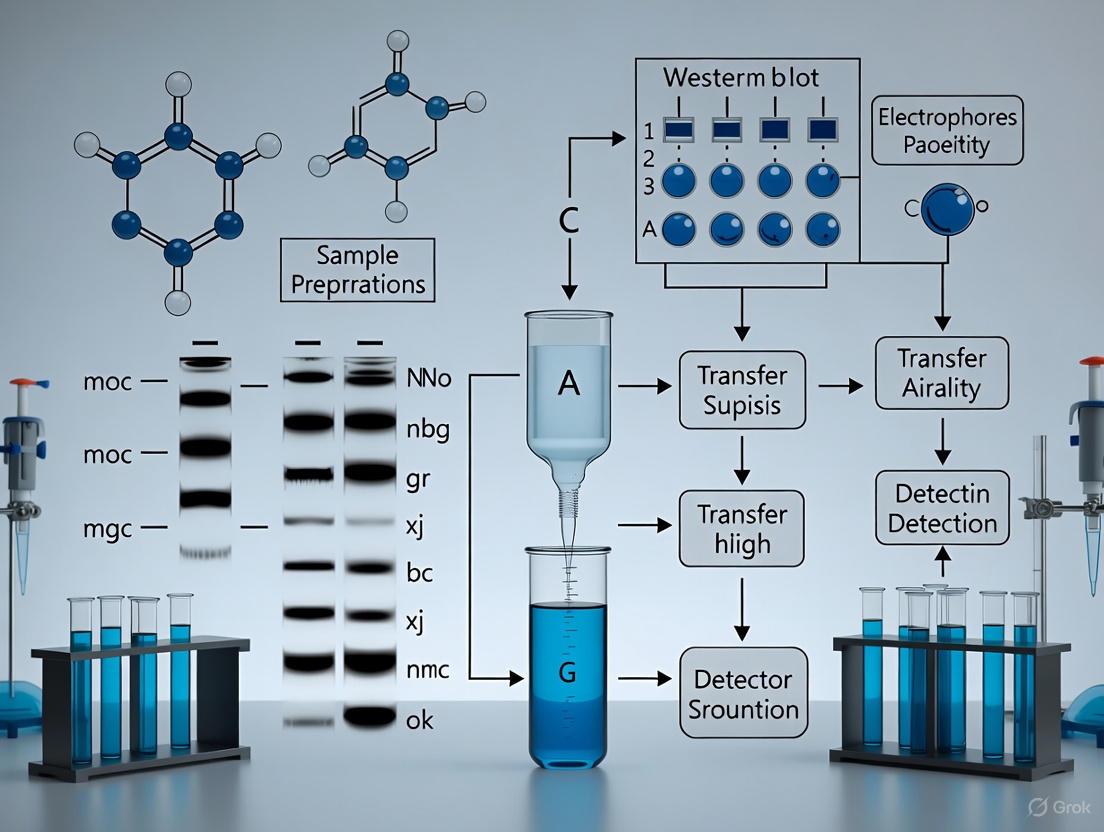

The following diagram illustrates the UbiREAD workflow for analyzing ubiquitin-dependent degradation.

Q6: What techniques are available for mapping the connectivity of ubiquitin chains?

Targeted mass spectrometry using Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM) is a highly sensitive and quantitative method.

- Principle: This approach uses chemically synthesized, heavy isotope-labeled reference peptides that correspond to tryptic fragments of different ubiquitin linkages (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) [16].

- Advantage: It allows for the unambiguous detection and quantification of linkage frequency in complex biological samples, overcoming the limitations of linkage-specific antibodies, which may not recognize denatured epitopes or exist for all linkage types [16].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Q7: My western blots show smearing, and I cannot distinguish specific linkages. What are my options?

Ubiquitin smearing is common due to heterogeneous chain lengths and mixed linkages.

- Use Linkage-Specific Tools:

- TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities): These are engineered reagents with high affinity for polyubiquitin chains. Using lysine-specific TUBEs (e.g., K48- or K63-specific) in a pull-down assay, often in a 96-well plate format, allows for the high-throughput separation and study of specific linkages before western blotting [15].

- Linkage-Specific DUBs: Employ enzymes like OTUB1 (K48-specific) and AMSH (K63-specific) in UbiCRest assays to selectively disassemble chains and confirm linkage composition [9].

- Validate with Mass Spectrometry: For definitive linkage identification, combine biochemical methods with targeted MS (SRM) or Ub-AQUA/PRM techniques [13] [16].

Q8: My ubiquitinated protein is not being degraded, despite having ubiquitin chains. Why?

This can occur if the chains are not an efficient proteasomal signal or if they are actively counteracted.

- Check Chain Length and Linkage: Ensure the chains are of sufficient length (≥Ub3 for K48) and of the correct linkage. K63 chains will not typically signal for proteasomal degradation unless they are part of a branched chain [11].

- Consider Branched Chains and DUB Protection: Your substrate might be modified with a K63 chain that is being protected by a DUB. In such cases, degradation requires the formation of a branched chain. For example, a K29 linkage (resistant to the DUB OTUD5) can act as a foundation for a K48 branch, overcoming DUB protection and targeting the substrate for degradation [13].

The diagram below illustrates how branched ubiquitin chains can integrate signals for proteasomal targeting.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Studying K48 and K63 Ubiquitination

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Specificity | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) [15] | High-affinity, linkage-specific binders (K48, K63, pan) | Enrichment and detection of specific ubiquitinated proteins from lysates; reduces DUB activity. |

| Linkage-Specific DUBs (OTUB1, AMSH) [9] | Cleave K48 or K63 linkages, respectively. | Validation of chain linkage composition in UbiCRest assays. |

| DUB Inhibitors (NEM, CAA) [9] | Cysteine alkylators that inhibit the largest family of DUBs. | Preserving ubiquitin chain integrity during pulldown and purification experiments. |

| SRM Mass Spectrometry Assays [16] | Quantifies all possible ubiquitin linkages using heavy isotope-labeled peptides. | Comprehensive and quantitative profiling of ubiquitin chain connectivity in complex samples. |

| UbiREAD System [11] | Delivers bespoke ubiquitinated reporters into cells. | Directly measuring intracellular degradation kinetics of defined ubiquitin chains. |

Advanced Topics: Signaling Pathways and Complex Regulation

Q9: How do K48/K63-branched ubiquitin chains regulate the NF-κB pathway?

In the NF-κB pathway, branched chains play a critical role in signal amplification.

- Mechanism: In response to IL-1β, the E3 ligase HUWE1 generates K48 branches onto K63-linked chains assembled by TRAF6.

- Functional Outcome: The resulting K48/K63-branched chain performs two functions:

- It is still recognized by the K63-binding domain of TAB2, maintaining signaling.

- The K48 branch protects the underlying K63 chain from the deubiquitinating enzyme CYLD. This prevents signal termination and leads to amplified NF-κB activation [14].

Fundamental Concepts: Why Atypical Linkages Cause Smears

Why do I get heterogeneous smears instead of clean bands when probing for ubiquitinated proteins? Heterogeneous smears on western blots are a common characteristic of polyubiquitinated proteins, not necessarily an indication of a failed experiment. Atypical ubiquitin linkages (K11, K29, K33) contribute significantly to this smear pattern for several key reasons [17] [18]:

- Mixed Chain Topologies: Your protein sample may be modified with ubiquitin chains of different linkages (homotypic), or even mixed/branched chains, simultaneously. Each topology has a slightly different molecular weight and migration pattern through the gel.

- Open Conformations: Biophysical studies show that K29- and K33-linked chains adopt open, dynamic conformations in solution, similar to K63-linked chains [17]. This flexible structure can lead to less uniform migration in SDS-PAGE compared to the compact structure of K48 chains.

- Variable Chain Length: Proteins can be modified with ubiquitin chains of varying lengths (e.g., from 2 to 10+ ubiquitins). This inherent heterogeneity in the number of ubiquitin moieties per substrate results in a continuum of molecular weights, visualized as a smear.

How do the properties of atypical linkages compare to canonical ones? The table below summarizes key characteristics of different ubiquitin chain linkages that influence their appearance on western blots and their cellular functions.

Table 1: Characteristics of Ubiquitin Chain Linkages

| Linkage Type | Common Structural Conformation | Primary Associated Functions | Key E3 Ligase Examples | Impact on Western Blot Appearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K48 | Compact, closed | Proteasomal degradation [17] | UBE3C (also makes K29) [17] | Can produce discrete bands or tight smears |

| K63 | Open, extended | Non-degradative signaling (DNA repair, inflammation) [17] | NEDD4 family [17] | Often produces a diffuse smear |

| K11 | Mixed | Cell cycle regulation, ER-associated degradation [17] | AREL1 [17] | Contributes to heterogeneous smearing |

| K29 | Open, dynamic [17] | Proteotoxic stress, autophagy [17] | UBE3C, TRIP12 [17] [18] | Contributes to heterogeneous smearing |

| K33 | Open, dynamic [17] | Kinase signaling, endosomal trafficking [17] | AREL1 [17] | Contributes to heterogeneous smearing |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Smear Resolution

The smear on my ubiquitin western blot is too diffuse to draw any conclusions. What are the first steps I should take? A diffuse smear can be challenging to interpret. Follow this systematic troubleshooting approach:

- Verify Antibody Specificity: Ensure your primary antibody is validated for the specific linkage you are studying. Many "pan-ubiquitin" antibodies have varying affinities for different linkages.

- Optimize Gel Electrophoresis: Use an appropriate gel percentage. For large ubiquitin conjugates, a lower percentage acrylamide gel (e.g., 4-12% gradient Bis-Tris gel with MOPS buffer) improves separation of high molecular weight species [19]. Ensure you do not overload the gel with too much protein; 10–40 µg of lysate is typically recommended [19].

- Optimize Transfer Conditions: Use PVDF membranes for better retention of high molecular weight proteins. Confirm your transfer buffer and method (semi-dry vs. wet) are appropriate for your gel system [20].

I need to confirm the presence of a specific atypical linkage (e.g., K29) in my smear. What is the best methodological approach? Confirming a specific linkage requires a combination of enzymatic and genetic tools.

- Linkage-Specific Deubiquitinases (DUBs): Treat your purified protein or immunoprecipitated sample with linkage-specific DUBs in vitro before western blotting. For example, the DUB TRABID is highly specific for cleaving K29 and K33 linkages [17]. A collapse of the smear after treatment strongly indicates the presence of these chains.

- Ubiquitin Mutants: Co-express your protein of interest with ubiquitin mutants where all lysines except one are mutated to arginine (e.g., K29-only Ub). If the smear is preserved only with the K29-only mutant, it confirms the formation of K29-linked chains on your substrate [17].

- Mass Spectrometry (AQUA): Absolute quantification (AQUA) mass spectrometry using isotope-labeled internal standards can precisely quantify all linkage types present in a sample [17]. This is the gold standard for confirmation.

My negative control shows a background smear. What could be the cause? Background smear in controls is often due to non-specific antibody binding or incomplete blocking.

- Troubleshoot Blocking and Washing:

- Blocking Buffer: Use a high-quality blocking buffer (e.g., 5% non-fat milk or commercial blocking buffers) for 30-60 minutes at room temperature [20].

- Wash Stringency: Increase the number and duration of washes after primary and secondary antibody incubation. A standard protocol is 3 washes for 10 minutes each after primary antibody, and 6 washes for 5 minutes each after secondary antibody, using TBST or PBST [20].

- Antibody Concentration: Titrate your primary and secondary antibodies. High concentrations can increase background. Refer to the table below for general guidance on antibody dilution.

Table 2: Western Blot Antibody Dilution Guidelines with Chemiluminescent Detection

| Chemiluminescent Substrate Sensitivity | Recommended Primary Antibody Dilution | Recommended Secondary Antibody Dilution |

|---|---|---|

| Standard / Moderate (e.g., Pierce ECL) | 1:1,000 (0.2–10 µg/mL) [20] | 1:1,000 to 1:15,000 (0.07–1.0 µg/mL) [20] |

| High (e.g., SuperSignal West Pico Plus) | 1:1,000 (0.2–1.0 µg/mL) [20] | 1:20,000 to 1:100,000 (10–50 ng/mL) [20] |

| Very High / Ultra (e.g., SuperSignal West Femto) | 1:5,000 (0.01–0.2 µg/mL) [20] | 1:100,000 to 1:500,000 (2–10 ng/mL) [20] |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro Ubiquitin Chain Assembly Analysis for K29/K33 Linkages This protocol uses recombinant E3 ligases to generate atypical chains for in vitro assays or as standards [17] [18].

- Key Reagents:

Protocol 2: Linkage-Specific Deconvolution of Cellular Smears This workflow outlines how to confirm the presence of specific atypical linkages in a heterogeneous smear from cell lysates.

- Workflow Overview:

- Treat Cells under desired experimental conditions.

- Lysate Preparation: Lyse cells using RIPA or non-denaturing lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (e.g., 1 mL per 1x10^7 cells). Centrifuge at 14,000–17,000 g for 5 min at 4°C to clear lysate [19].

- Immunoprecipitation (IP): Immunoprecipitate your protein of interest or ubiquitinated proteins under denaturing conditions to preserve complexes.

- Elute and Split: Split the eluted protein into aliquots.

- DUB Treatment: Treat aliquots with buffer-only (control), non-specific DUB (e.g., USP2), or linkage-specific DUBs (e.g., TRABID for K29/K33).

- Analyze by Western Blot: A specific collapse of the smear in the TRABID-treated sample indicates the presence of K29/K33 linkages.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Studying Atypical Ubiquitin Linkages

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific E3 Ligases (e.g., UBE3C, AREL1, TRIP12) | Enzymes that catalyze the formation of specific Ub chain linkages [17] [18]. | In vitro reconstitution of K29 or K33 chains to use as standards or for functional assays. |

| Linkage-Specific DUBs (e.g., TRABID) | Enzymes that selectively cleave a specific Ub linkage [17]. | Validation of a specific linkage type in a heterogeneous smear from cell lysates or in vitro reactions. |

| Ubiquitin Mutants (K-only, R-mutants) | Ub variants where only one lysine is available for chain formation (K-only) or all lysines are mutated to arginine (K0) [17]. | Identifying which lysines are used for chain formation on your substrate in cellular overexpression studies. |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Antibodies raised against specific diUb linkages. | Detecting the presence and relative levels of a specific chain type directly on western blots. Requires careful validation for specificity. |

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Engineered proteins with high affinity for polyUb chains, used to enrich ubiquitinated proteins from lysates [17]. | Pulling down ubiquitinated proteins while protecting them from DUBs during extraction, enriching signal on blots. |

| Mass Spectrometry (AQUA) | Gold-standard method for absolute quantification of all Ub linkage types in a sample [17]. | Unambiguous identification and quantification of the complex linkage composition within a smear. |

The ubiquitin code is a sophisticated post-translational language that regulates nearly all cellular processes. Its complexity stems from the ability of ubiquitin to form diverse polymeric chains through its seven internal lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or N-terminal methionine (M1) [21] [22]. These chains exist in three principal architectures that create a spectrum of biological signals:

- Homotypic Chains: Uniform chains where all ubiquitin molecules are connected through the same linkage type (e.g., all K48 or all K63 linkages) [23] [24].

- Heterotypic Mixed Chains: Linear chains containing more than one linkage type, but each ubiquitin is modified by only one other ubiquitin molecule [24].

- Branched Chains: Complex structures where at least one ubiquitin molecule is connected to two or more other ubiquitins, forming branch points [24].

The following diagram illustrates the structural relationships and functional implications of these different chain architectures:

Critical Sample Preparation for Preserving Ubiquitin Chains

FAQ: Why do my ubiquitinated proteins disappear during sample preparation?

Answer: The loss typically occurs due to active deubiquitinases (DUBs) and proteasomes in your lysate. Ubiquitination is a reversible modification, and DUBs can rapidly remove ubiquitin chains during cell lysis and subsequent processing [21].

Troubleshooting Guide: Sample Degradation Issues

| Problem | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Disappearing ubiquitin signal | DUB activity during lysis | Increase N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to 50-100 mM or IAA to 20-50 mM [21] |

| Incomplete K63 chain preservation | Insufficient cysteine alkylation | Use higher concentrations of NEM (up to 100 mM) rather than IAA [25] [21] |

| Loss of ubiquitinated substrates | Proteasomal degradation | Include MG132 (10-20 µM) during cell treatment and lysis [25] [21] |

| Erroneous ubiquitination after MG132 | Cellular stress response | Limit MG132 treatment to <12 hours to avoid stress-induced artifacts [21] |

Experimental Protocol: Optimized Lysis for Ubiquitin Preservation

Prepare fresh lysis buffer containing:

- 50-100 mM NEM (freshly prepared)

- 5-10 mM EDTA or EGTA

- 10-20 µM MG132 or other proteasome inhibitor

- Standard protease inhibitors [21]

Lys cells directly in pre-heated SDS buffer (1% SDS) for complete DUB inactivation when subsequent immunoprecipitation isn't required [21].

Clarify lysates by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

Transfer supernatant to fresh tubes and store at -80°C if not used immediately.

Gel Electrophoresis and Transfer Optimization for Ubiquitin Smears

FAQ: Why do I get poor resolution of ubiquitin smears on my western blots?

Answer: Poor resolution often results from using suboptimal gel and buffer systems for your target chain length. Different ubiquitin chain lengths require specific electrophoretic conditions for optimal separation [25] [21].

Quantitative Data: Buffer and Gel Selection Guide

| Target Analysis | Gel Type | Running Buffer | Benefits | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short chains (2-5 ubiquitins) | 12% acrylamide | MES | Excellent separation of small oligomers | Poor resolution of long chains |

| Long chains (>8 ubiquitins) | 8% acrylamide | MOPS | Optimal for large ubiquitin polymers | Reduced small chain separation |

| Broad range analysis | 8-12% gradient | Tris-Glycine | Good separation up to 20 ubiquitins | Less optimal for extremes |

| High molecular weight | 3-8% gradient Tris-Acetate | Tris-Acetate | Superior 40-400 kDa separation | Specialized equipment needed |

Experimental Protocol: Western Blot Transfer for Ubiquitinated Proteins

Membrane selection: Use PVDF membranes (0.2 µm pore size) for higher signal strength compared to nitrocellulose [25].

Activation: Wet PVDF membrane in 100% methanol for 30 seconds, then equilibrate in transfer buffer.

Transfer conditions: Use wet transfer system at 30V for 2.5-3 hours [25].

Validation: After transfer, stain the gel with Coomassie or reversible protein stain to confirm transfer efficiency [26].

Advanced Detection Methods for Specific Chain Types

FAQ: How can I distinguish between different ubiquitin linkage types?

Answer: Use a combination of linkage-specific antibodies, ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs), and deubiquitinase (DUB) digestion assays to characterize specific ubiquitin linkages [27] [24].

Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Analysis

| Reagent | Function | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | High-affinity ubiquitin chain capture | Pull-down assays, protection from DUBs [27] |

| Linkage-specific DUBs (UbiCRest assay) | Selective cleavage of specific linkages | Chain linkage mapping [24] |

| K48/K63-chain specific TUBEs | Preferential binding to specific chains | Differentiation of degradation vs. signaling chains [27] |

| K11/K48 bispecific antibodies | Detection of branched chains | Identification of hybrid ubiquitin chains [24] |

| Denatured-Refolded Ubiquitinated Sample Prep (DRUSP) | Improved ubiquitinome analysis | Mass spectrometry sample preparation [28] |

Experimental Protocol: UbiCRest Linkage Analysis

Prepare ubiquitinated samples using standard immunoprecipitation or TUBE pull-down [27].

Aliquot samples into multiple tubes for parallel DUB digestion.

Incubate with linkage-specific DUBs:

- OTUB1 (K48-specific)

- AMSH/OTUD1 (K63-specific)

- OTULIN (M1-specific)

- Cezanne (K11-specific)

- vOTU/USP21 (pan-specific controls) [24]

Analyze cleavage patterns by western blotting with linkage-specific antibodies.

Interpret results: Resistance to specific DUBs may indicate branched chains or atypical structures [24].

The workflow for this comprehensive linkage analysis is illustrated below:

Functional Consequences of Chain Diversity in Biological Systems

The structural diversity of ubiquitin chains translates to specific functional outcomes in cellular regulation:

Heterotypic K11/K48 Branched Chains in Cell Cycle Regulation

- Structure: Branched ubiquitin chains containing both K11 and K48 linkages [23] [24]

- Function: Efficient targeting of cyclin B1 and other cell cycle regulators to proteasomal degradation [23]

- Mechanism: Heterotypic K11/K48 chains bind proteasomes more effectively than homotypic K11 chains [23]

- Biological context: Mitotic exit regulated by APC/C with Ube2S E2 enzyme [23]

K63-Linked Chains in Inflammatory Signaling

- Structure: Typically homotypic K63 chains, but can form heterotypic structures [27] [22]

- Function: Activation of NF-κB and MAPK pathways through signalosome assembly [27]

- Specific example: RIPK2 ubiquitination upon NOD2 activation by bacterial MDP [27]

- Detection: K63-specific TUBEs can capture this signaling event [27]

Comprehensive Troubleshooting Guide for Ubiquitin Western Blots

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High background | Antibody concentration too high | Decrease primary and/or secondary antibody concentration [26] [29] |

| Insufficient blocking | Increase blocking time to ≥1 hour; use 5% BSA for phosphoproteins [26] | |

| Membrane drying | Ensure membrane remains wet throughout processing [26] | |

| Weak or no signal | Incomplete transfer | Verify transfer efficiency with reversible protein stain [26] |

| Antigen masked by blocking buffer | Try different blocking agents (BSA vs. milk) [26] | |

| Low abundance targets | Use high-sensitivity chemiluminescent substrates [26] | |

| Non-specific bands | Antibody cross-reactivity | Include proper controls; validate antibodies [29] |

| Protein degradation | Use fresh protease inhibitors; avoid sample overheating [30] | |

| Too much protein loaded | Reduce total protein load (10-15 μg/lane recommended) [26] | |

| Diffuse bands/smears | Transfer too fast | Increase transfer time; ensure proper cooling [29] |

| Improper gel/buffer system | Match gel percentage and buffer to target size range [21] |

Experimental Protocol: Enhanced Denaturation for Better Antibody Recognition

After transfer, incubate PVDF membrane in boiling water for 15-30 minutes [25]

Treat membrane with denaturing solution:

- 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5

- 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol

- 6 M guanidine-HCl

- Incubate 30 minutes at 4°C [25]

Autoclave the membrane for additional denaturation (optional) [25]

Proceed with standard blocking and antibody incubation steps

This technical support resource provides comprehensive guidance for researchers investigating the complex landscape of polyubiquitin chain diversity. By implementing these optimized protocols and troubleshooting strategies, scientists can significantly improve their ability to resolve and interpret the spectrum of ubiquitin modifications in their experimental systems.

Optimized Protocols and Cutting-Edge Tools for Sharper Ubiquitin Detection

Proper sample preparation is the most critical step in western blotting, profoundly influencing the detection, resolution, and accurate interpretation of protein data. During cell lysis, the carefully controlled cellular environment is disrupted, releasing endogenous proteases and phosphatases that can rapidly degrade proteins and modify their activation states, leading to irreproducible results, loss of signal, or misleading bands [31] [32]. For researchers studying complex post-translational modifications like ubiquitination—which often appears as characteristic high-molecular-weight smears on western blots—meticulous sample preparation is not merely optional but essential for meaningful data [25]. This guide provides detailed troubleshooting and methodologies to preserve protein integrity from the moment of lysis, with particular emphasis on resolving ubiquitin-related signals.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is adding protease inhibitors to my lysis buffer so critical? Cell lysis disrupts cellular compartmentalization, releasing sequestered proteases that become unregulated and can digest your proteins of interest [31] [32]. Protease inhibitors are chemical or biological compounds that prevent this protein degradation by binding to and inactivating these enzymes, thereby preserving the protein's native state, yield, and post-translational modifications for accurate analysis [32] [33].

Q2: What is a "protease inhibitor cocktail" and why should I use one? No single chemical compound can inhibit all protease types effectively [31] [33]. A protease inhibitor cocktail is a pre-formulated mixture of several inhibitors that broadly targets the major protease classes (serine, cysteine, aspartic, metallo-, and aminopeptidases) [32] [33]. Using a cocktail ensures comprehensive protection, saves time, and provides consistency compared to individually optimizing and mixing separate inhibitors [33].

Q3: My western blot shows a high background smear instead of clean bands. Could this be a sample preparation issue? Yes. Smearing, particularly in high molecular weight regions, can indicate protein degradation during sample preparation due to insufficient protease inhibition [34] [35]. It can also result from overloading too much protein, incomplete sample reduction, or, in the specific case of ubiquitination, the natural appearance of poly-ubiquitin chains of different lengths [34] [25] [35]. Using fresh, optimized protease inhibitor cocktails and appropriate protein loads can resolve this.

Q4: I am specifically studying ubiquitination. Are there special considerations for my lysis buffer? Yes. Ubiquitination is a dynamic and reversible modification. Standard protease inhibitors are insufficient, as you must also inhibit deubiquitinase (DUB) enzymes and the proteasome [25].

- DUB Inhibitors: Add 5-100 mM N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) to your lysis buffer (K63-linked chains require higher concentrations, up to 50-100 mM) [25].

- Proteasome Inhibitors: Use MG132 to prevent the destruction of ubiquitinated proteins. However, avoid prolonged treatments (>12-24 hours) to prevent stress-induced ubiquitination [25].

- Chelators: Include EDTA or EGTA, as many DUBs are metalloproteases [25].

Troubleshooting Guide: Sample Preparation Issues

Table 1: Common Problems and Solutions Related to Sample Preparation

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No or Very Weak Signal | Protein degraded during/after lysis due to inactive or missing protease inhibitors [34] [36]. | Use fresh, functional protease inhibitor cocktails. Aliquot inhibitors to avoid freeze-thaw cycles. Keep samples on ice [34] [32] [35]. |

| Multiple Non-specific Bands or Smearing | Partial proteolysis by endogenous proteases creates protein fragments [34] [35]. | Optimize inhibitor cocktail concentration, especially for problematic tissues. Ensure lysis is performed quickly at cold temperatures [34] [35]. |

| High Molecular Weight Smear (Ubiquitin) | Inadequate preservation of ubiquitin chains during lysis [25]. | Incorporate specific DUB (NEM) and proteasome (MG132) inhibitors into the lysis buffer [25]. |

| Bands at Unexpected Molecular Weights | Post-translational modifications (e.g., glycosylation, phosphorylation) or alternative splicing [34] [35]. | Use phosphatase inhibitors when studying phosphorylation. Consult databases for known PTMs. Run appropriate positive and negative controls [34] [31] [35]. |

| Poor Gel Resolution / Smiling Bands | Sample viscosity from DNA contamination or excess salt [26]. | Shear genomic DNA by sonication or needle passage. Reduce salt concentration via dialysis or dilution [26] [35]. |

Table 2: Commonly Used Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitors

| Inhibitor | Target Enzyme Class | Mechanism | Typical Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| AEBSF | Serine Proteases | Irreversible | 0.2 - 1.0 mM [31] [32] |

| Aprotinin | Serine Proteases | Reversible | 100 - 200 nM [31] [32] |

| E-64 | Cysteine Proteases | Irreversible | 1 - 20 µM [31] [32] |

| EDTA | Metalloproteases | Reversible (Chelator) | 2 - 10 mM [31] [32] |

| Leupeptin | Serine & Cysteine Proteases | Reversible | 10 - 100 µM [31] [32] |

| Pepstatin A | Aspartic Proteases | Reversible | 1 - 20 µM [31] [32] |

| PMSF | Serine Proteases | Reversible | 0.1 - 1.0 mM [31] [32] |

| Sodium Orthovanadate | Tyrosine Phosphatases | Irreversible | 1 - 100 mM [31] |

| Sodium Fluoride | Ser/Thr & Acidic Phosphatases | Irreversible | 1 - 20 mM [31] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Preparation of Complete Lysis Buffer for General Use

This protocol is designed for routine protein extraction while maximizing protein stability.

Materials Needed:

- RIPA Buffer or your preferred lysis buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl based)

- Broad-spectrum protease inhibitor cocktail (e.g., 100X stock)

- Phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (optional, for phospho-protein studies) [31]

- EDTA (0.5 M stock, pH 8.0) [32]

Procedure:

- Calculate Volumes: Determine the total volume of lysis buffer required.

- Add Inhibitors: To the lysis buffer, add:

- Protease inhibitor cocktail to a 1X final concentration (e.g., 10 µL of 100X stock per 1 mL of buffer) [33].

- Phosphatase inhibitor cocktail to a 1X final concentration, if needed [31].

- EDTA to a 2-10 mM final concentration to inhibit metalloproteases (if compatible with downstream applications) [31] [32].

- Mix and Store: Prepare the complete lysis buffer fresh immediately before use. Keep it on ice.

Protocol 2: Specialized Lysis Buffer for Ubiquitin Studies

This protocol is optimized for preserving labile ubiquitin conjugates.

Materials Needed:

- Standard Lysis Buffer (e.g., RIPA)

- N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM): 1 M stock in ethanol or water [25]

- Proteasome Inhibitor (e.g., MG132): 10 mM stock in DMSO

- EDTA: 0.5 M stock, pH 8.0

- Standard Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (100X)

Procedure:

- Prepare a standard complete lysis buffer as in Protocol 1.

- Add NEM to a final concentration of 10-100 mM. For K63-linked ubiquitin chains, use higher concentrations (50-100 mM) [25].

- Add MG132 to a final concentration of 10-50 µM.

- Vortex thoroughly and keep on ice. Use immediately.

Protocol 3: Step-by-Step Cell Lysate Preparation

Procedure:

- Harvest Cells: Culture cells and quickly aspirate media. Wash cells once with ice-cold PBS.

- Lysis: Add an appropriate volume of freshly prepared, ice-cold complete lysis buffer directly to the cell culture dish (e.g., 100-200 µL for a 6-well plate).

- Scrape and Collect: Using a cold cell scraper, gently but swiftly dislodge the lysed cells. Transfer the lysate to a pre-chilled microcentrifuge tube.

- Incubate: Keep the lysate on ice for 10-30 minutes with occasional gentle vortexing to ensure complete lysis.

- Clarify: Centrifuge the lysate at >12,000 x g for 15-20 minutes at 4°C to pellet insoluble debris.

- Collect Supernatant: Carefully transfer the clarified supernatant (which contains your soluble proteins) to a new pre-chilled tube.

- Quantify and Denature: Determine protein concentration using an assay like Bradford. Mix the lysate with an equal volume of 2X SDS-PAGE sample buffer, boil for 5-10 minutes, and then store at -80°C or load onto a gel.

Essential Workflow and Visual Guides

Sample Preparation Workflow for Optimal Western Blots

Protease Inhibitor Mechanism of Action

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sample Preparation

| Reagent | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Broad-Spectrum Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Inhibits serine, cysteine, aspartic proteases, and aminopeptidases [32] [33]. | Buy pre-made for consistency and convenience. Available with or without EDTA [33]. |

| Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail | Preserves protein phosphorylation status by inhibiting serine/threonine and tyrosine phosphatases [31]. | Essential for studying signaling pathways. Often sold as a combined protease/phosphatase cocktail [31] [35]. |

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | Irreversibly inhibits deubiquitinase (DUB) enzymes by covalently modifying active site cysteines [25]. | Critical for ubiquitination studies. Use at high concentrations (10-100 mM) [25]. |

| MG132 (Proteasome Inhibitor) | Prevents degradation of poly-ubiquitinated proteins by the proteasome, enriching them for detection [25]. | Avoid prolonged treatment of live cells to prevent stress artifacts [25]. |

| EDTA / EGTA | Chelates metal ions (Zn²⁺, Ca²⁺), inhibiting metalloproteases and many DUBs [31] [25] [32]. | Incompatible with downstream IMAC protein purification (strips Nickel ions) [32]. |

| PMSF (Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) | Irreversibly inhibits serine proteases. | Highly unstable in aqueous solutions; must be added fresh. Toxic—handle with care [32]. |

Gel Electrophoresis and Transfer Optimization for High-Molecular-Weight Complexes

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Resolving Ubiquitin Smears and High-Molecular-Weight Complexes

Why does my western blot for a ubiquitinated protein show a high molecular weight smear?

A high molecular weight smear is a classic indicator of polyubiquitinated proteins [25]. Each ubiquitin molecule adds approximately 8.5 kDa to your protein's apparent molecular weight [37]. As proteins can be modified with chains of varying lengths (from one ubiquitin to over twenty), this heterogeneity results in a smear rather than a discrete band [25]. This can be a valid biological signal, but the smear's appearance can be optimized for clearer interpretation.

How can I improve the transfer of very large proteins (>150 kDa) to the membrane?

Transferring high-molecular-weight (HMW) proteins is challenging because they migrate slowly out of the gel. Key optimizations include [38] [39] [40]:

- Adding SDS: Include 0.01-0.1% SDS in your transfer buffer to help elute large proteins from the gel [38] [39].

- Reducing Methanol: Lower the methanol concentration in your transfer buffer to 10-15%. Methanol can cause gel shrinkage and precipitate large proteins, trapping them in the gel [38] [40].

- Extending Transfer Time: Use a low voltage (25-30 V) and transfer overnight at 4°C to facilitate complete movement of large proteins [40].

- Pre-equilibration: Pre-equilibrate the gel in transfer buffer containing 0.02-0.04% SDS for 10 minutes before assembling the transfer sandwich [38].

My high molecular weight bands are faint or absent after transfer. What should I check?

This is a common sign of inefficient transfer. First, verify that the protein was present in the gel by post-transfer Coomassie blue staining [41]. If the protein was not transferred, implement the HMW transfer optimizations listed above. Also, ensure your membrane pore size is appropriate (0.45 µm is standard, but 0.2 µm may provide better retention) [38] and carefully roll out all air bubbles during sandwich assembly, as they create barriers to transfer [38] [40].

The bands for my ubiquitinated protein are diffuse and swirled. What caused this?

Swirling or diffuse banding patterns are typically caused by poor contact between the gel and the membrane or issues with sandwich compression [38].

- Poor Contact: Ensure all air bubbles are removed by thoroughly rolling a glass pipette or tube over each layer during assembly [38] [40].

- Over-compression: If the gel appears excessively flattened, the sandwich may be over-compressed. Remove enough pads or sponges so the blotter closes without excess pressure [38].

- Under-compression: The gel/membrane assembly should be held securely. If it's too loose, try adding fresh, resilient pads or sponges to ensure good contact [38].

Troubleshooting Table: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Faint/No HMW Bands | Inefficient transfer out of gel | Add 0.01-0.1% SDS to transfer buffer; Reduce methanol to 10-15%; Extend transfer time (overnight at low voltage) [38] [39] [40]. |

| High Background | Non-specific antibody binding | Optimize antibody concentrations; Use an alternate blocking agent (e.g., serum vs. BSA/milk); Increase number and stringency of washes [39]. |

| Ubiquitin Smear Lost | Deubiquitinase (DUB) activity in lysate | Include DUB inhibitors (e.g., 5-50 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM)) and proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG132) in lysis buffer [25]. |

| Protein Aggregation | Improper sample preparation for hydrophobic proteins | For membrane proteins, avoid heating above 60°C during denaturation. Heat at 50°C for 20 minutes and optimize [39]. |

| Smearing During Electrophoresis | Gel running too hot or overloading | Run gel at a lower voltage; Ensure buffer composition is correct; Reduce the amount of protein loaded [42]. |

| Poor Gel-Membrane Contact | Air bubbles or over/under-compression of transfer sandwich | Roll out bubbles meticulously with a glass pipette; Adjust the number of pads/sponges for secure but not excessive compression [38] [40]. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Optimized Western Blot for HMW Ubiquitinated Proteins

Sample Preparation (Lysate Collection)

- Lysis: Lyse cells or tissue in an appropriate lysis buffer supplemented with:

- Protease Inhibitors: To prevent general protein degradation.

- Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors: 10-50 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) is critical to prevent the cleavage of ubiquitin chains, especially K63-linked chains which are particularly sensitive [25].

- Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132): To prevent the degradation of ubiquitinated proteins by the proteasome. Note that prolonged use can induce cellular stress [25].

- Denaturation: Denature protein samples in Laemmli buffer. For membrane proteins or HMW complexes prone to aggregation, heat at 50-60°C for 20 minutes instead of boiling at 95°C [39].

Gel Electrophoresis for Ubiquitin Chain Separation

- Gel Percentage: For resolving large ubiquitin chains (over 8 ubiquitin units), use 8% Tris-Glycine gels. For better separation of smaller chains (2-5 units), use 12% gels [25].

- Buffer System:

- Running Conditions: Run the gel at a constant voltage. To prevent smearing and overheating, use a lower voltage for a longer duration and/or run the gel in a cold room or with a cooling unit [42].

Transfer of High-Molecular-Weight Complexes

- Method Selection: Wet (tank) transfer is generally recommended for HMW proteins due to its higher efficiency and better heat dissipation [40].

- Gel Equilibration: Pre-equilibrate the gel in transfer buffer for 10 minutes [40].

- Membrane Preparation:

- Transfer Buffer Composition: Modify the standard Tris-Glycine buffer to enhance HMW protein transfer:

- Assembly and Transfer:

Immunodetection

- Blocking: Block the membrane with 5% BSA or non-fat milk in TBST for 1 hour at room temperature. For phospho-specific antibodies, BSA is preferred.

- Antibody Incubation: Incubate with primary antibody diluted in blocking buffer or TBST. Optimize concentration and incubation time (1 hour at RT or overnight at 4°C). Follow with appropriate secondary antibody.

- Validation: To confirm a smear is due to ubiquitination, treat samples with DUB enzymes or use ubiquitin linkage-specific antibodies [25].

Workflow Diagram: HMW Ubiquitin Detection

Transfer Method Comparison Table

| Transfer Method | Best For Protein Size | Typical Conditions | Advantages | Disadvantages for HMW Complexes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Transfer | All sizes, especially >100 kDa | 25-30 V, Overnight, 4°C [40] | High efficiency, good cooling, versatile [40] | Time-consuming, high buffer consumption [40] |

| Semi-Dry Transfer | Low to Mid MW (up to ~120 kDa) | 10-25 V, 15-60 min, RT [40] | Fast, low buffer consumption [40] | Risk of incomplete transfer for HMW proteins, can overheat [40] |

| Dry Transfer | Varies with system | 7-10 min, RT [40] | Very fast, no buffer preparation [40] | Costly, less flexibility for optimization [40] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent / Material | Function in HMW Ubiquitin Research |

|---|---|

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | A deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibitor critical for preserving labile ubiquitin chains (e.g., K63-linked) during cell lysis and sample preparation [25]. |

| MG132 / Proteasome Inhibitors | Prevents the degradation of polyubiquitinated proteins by the proteasome, allowing for their accumulation and detection [25]. |

| PVDF Membrane (0.2 µm) | Provides higher protein binding capacity and signal strength for ubiquitinated proteins compared to nitrocellulose. The smaller pore size helps retain smaller proteins and complexes [38] [25]. |

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) | High-affinity tools used to enrich and stabilize polyubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates, improving detection and reducing DUB activity [27]. |

| Ubiquitin Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Antibodies that specifically recognize distinct polyubiquitin chain linkages (e.g., K48 vs. K63), allowing for the functional interpretation of ubiquitin signals [25]. |

| SDS (Electrophoresis Grade) | Added in small quantities (0.01-0.1%) to the transfer buffer to facilitate the elution of large, hydrophobic protein complexes from the gel matrix [38] [39]. |

| Pre-cast Low-% Gels | Gels with low acrylamide percentage (e.g., 8%) or gradient gels are essential for resolving high-molecular-weight complexes effectively [39] [25]. |

Ubiquitination is a critical post-translational modification that regulates diverse cellular processes, including protein degradation, signal transduction, and immune responses. The specific biological outcome is often determined by the topology of the polyubiquitin chain, dictated by the linkage between ubiquitin molecules. Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) are engineered affinity tools designed to overcome historical challenges in capturing this complex ubiquitin code. They are constructed by linking multiple ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) in a single polypeptide, resulting in remarkably high affinity for polyubiquitin chains [43].

The ability to specifically enrich for proteins modified by particular chain types is paramount for understanding precise regulatory mechanisms. For instance, K48-linked polyubiquitin chains are primarily associated with targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains are largely involved in non-proteolytic signaling pathways, such as NF-κB activation and DNA repair [27] [43]. Traditional methods, such as the use of antibodies against ubiquitin or epitope-tagged ubiquitin, often lack the sensitivity and linkage specificity required for detailed analysis and can be hampered by the activity of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that rapidly remove ubiquitin signals during sample preparation [44] [43]. TUBEs address these limitations by not only providing high-affinity capture but also protecting ubiquitin chains from DUB activity and proteasomal degradation during the enrichment process [43]. This technical guide outlines strategies for employing chain-specific TUBEs to improve the resolution and reliability of ubiquitin western blot research.

Technical Specifications and Quantitative Performance of TUBEs

The utility of TUBEs in biochemical assays is defined by their affinity and specificity. The quantitative data below summarizes the performance of different ubiquitin enrichment tools, highlighting the advantages of TUBEs.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitin Enrichment Tools

| Method | Affinity/Sensitivity | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chain-Specific TUBEs | Nanomolar affinity (Kd) [27] | High linkage specificity; protects from DUBs; works with endogenous proteins. | Commercial availability may be linkage-dependent. | Investigating specific signaling pathways (e.g., K63 in inflammation). |

| Pan-Selective TUBEs | Nanomolar affinity (Kd) [27] | Broad recognition of all chain types; strong DUB protection. | Does not differentiate chain linkages. | Global ubiquitinome analysis and co-interactome studies. |

| Anti-Ubiquitin Antibodies | Variable; can lack sensitivity [44] | Widely available; can be linkage-specific. | Variable linkage recognition; sensitive to protein denaturation [25]. | General detection after enrichment; immunoblotting. |

| UBD-based Resins (e.g., OtUBD) | Low nanomolar range (Kd) [44] | High affinity; enriches both mono- and poly-ubiquitinated proteins. | Requires preparation of affinity resin. | Proteomic studies where monoubiquitination is significant. |

Table 2: Application-Based Selection Guide for TUBEs

| Research Goal | Recommended TUBE Type | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Study PROTAC-induced Degradation | K48-TUBEs | Faithfully captures PROTAC RIPK2-2 induced K48-ubiquitination [27]. |

| Investigate Inflammatory Signaling | K63-TUBEs | Specifically captures L18-MDP-induced K63-ubiquitination of RIPK2 [27]. |

| Global Ubiquitinome Profiling | Pan-Selective TUBEs | Identified 643 ubiquitinated proteins from MCF7 cells after Adriamycin treatment [43]. |

| Enrichment of Monoubiquitination | OtUBD Resin | Strongly enriches both mono- and poly-ubiquitinated proteins from crude lysates [44]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for TUBE-Based Experiments

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for TUBE Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation | Example Products / Components |

|---|---|---|

| Chain-Specific TUBEs | Recombinant proteins used as affinity baits to pulldown specific ubiquitin linkages (e.g., K48 or K63). | K48-TUBE, K63-TUBE (e.g., from LifeSensors) [27]. |

| Lysis Buffer with Inhibitors | Preserves the ubiquitin signal during cell disruption by inhibiting DUBs and the proteasome. | N-ethylmaleimide (NEM, 5-50 mM), EDTA, MG132 [25] [27]. |

| Magnetic or Beaded Agarose | Solid support for immobilizing TUBEs and performing pulldown assays. | Glutathione beads (for GST-TUBEs), magnetic beads [27] [43]. |

| Elution Buffer | Releases captured ubiquitinated proteins from TUBEs for downstream analysis. | Glycine buffers (low pH) or competition with free ubiquitin [43]. |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Validate TUBE enrichment specificity via western blot. | Anti-K48 Ubiquitin, Anti-K63 Ubiquitin antibodies [25]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for TUBE-Mediated Enrichment

This protocol is adapted from methodologies successfully used to investigate endogenous RIPK2 ubiquitination [27] and global ubiquitinome analysis [43].

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of a TUBE-based enrichment experiment:

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Cell Lysis and Sample Preparation

- Culture and treat cells according to your experimental design (e.g., treat THP-1 cells with 200 ng/mL L18-MDP for 30 minutes to induce K63 ubiquitination of RIPK2) [27].

- Lyse cells on ice using a non-denaturing lysis buffer that preserves protein interactions. A recommended buffer consists of 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, and 10% glycerol.

- CRITICAL: Add fresh inhibitors to the lysis buffer immediately before use:

- 5-50 mM N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) to inhibit deubiquitinases (DUBs). Note that K63 linkages are particularly sensitive and may require higher concentrations (~50 mM) [25].

- 10-20 µM MG132 (or other proteasome inhibitors) to prevent degradation of ubiquitinated proteins.

- 1x concentration of a broad-spectrum protease inhibitor cocktail [25] [27] [45].

- Clear the lysate by centrifugation at 15,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Quantify the protein concentration of the supernatant using a BCA or Bradford assay. Typically, 500 µg to 1 mg of total protein is used as input for a TUBE pulldown.

Step 2: Immobilization of TUBEs

- If using GST-tagged TUBEs, incubate 10-20 µg of recombinant TUBE protein with 50 µL of glutathione-sepharose bead slurry for 1-2 hours at 4°C with gentle rotation [43].

- Wash the beads twice with ice-cold lysis buffer to remove unbound TUBE.

Step 3: Affinity Pulldown

- Incubate the cleared cell lysate (from Step 1) with the TUBE-immobilized beads for 2-4 hours at 4°C with constant rotation.

- Tip: Reserve a small aliquot of the input lysate (e.g., 20 µg) for later comparison by western blot.

Step 4: Washing

- Pellet the beads by brief centrifugation and carefully remove the supernatant.

- Wash the beads 3-4 times with 1 mL of ice-cold lysis buffer (without inhibitors) to remove non-specifically bound proteins. Each wash should involve 5-10 minutes of rotation followed by centrifugation.

Step 5: Elution

- Elute the bound ubiquitinated proteins using one of two methods:

- Low-pH Elution: Incubate beads with 50-100 µL of 0.2 M glycine (pH 2.5) for 10 minutes at room temperature. Neutralize the eluate immediately with 1/10 volume of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) [43].

- Competition Elution: Incubate beads with a buffer containing 1-2 mg/mL of free ubiquitin to compete for binding to the TUBEs.

Step 6: Downstream Analysis

- The eluted proteins can now be analyzed by:

- Western Blotting: Resuspend the eluate in Laemmli sample buffer, boil for 5-10 minutes, and load onto an SDS-PAGE gel for immunoblotting with your target protein antibody.

- Mass Spectrometry (Ubiquitinomics): Process the eluted proteins for LC-MS/MS analysis to identify ubiquitination sites and endogenous ubiquitin-modified proteins [43].

Data Interpretation and Pathway Visualization

Signaling Context of Ubiquitin Linkages

Understanding the biological context of different ubiquitin linkages is crucial for interpreting TUBE enrichment data. The diagram below illustrates the distinct fates of proteins modified by K48 vs. K63 chains in a relevant signaling pathway:

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My TUBE pulldown shows a high background of non-specifically bound proteins. How can I improve specificity?

- A: Increase the stringency of your wash buffers. This can be done by:

- Increasing the salt concentration (e.g., to 300-500 mM NaCl).

- Adding a mild detergent (e.g., 0.1% SDS or Tween-20) to the wash buffer.

- Increase the number of washes from 3 to 4-5 times.

- Ensure your TUBEs are cross-linked to the beads to prevent leakage of the TUBE protein itself, which can co-elute and appear as a background band [43].

Q2: I am not able to detect my target protein after TUBE enrichment, even though the input lysate shows a clear signal. What could be wrong?

- A: Consider the following:

- Verify Ubiquitination Status: Confirm that your target is indeed ubiquitinated under your experimental conditions. Check the literature or use a pan-selective TUBE first.

- Insufficient Inhibitors: The ubiquitin signal may have been lost to DUBs or proteasomes. Ensure NEM and MG132 are fresh and used at appropriate concentrations.

- Antibody Compatibility: The epitope recognized by your detection antibody might be masked after ubiquitination or multiprotein complex formation. Try a different antibody targeting another region of the protein.

- Low Abundance: The ubiquitinated fraction of your target might be low. Scale up the amount of input protein (e.g., to 2 mg) [27].

Q3: Can TUBEs be used to enrich for monoubiquitinated proteins?

- A: While traditional TUBEs are highly efficient for polyubiquitin chains, they may work poorly for monoubiquitinated proteins [44]. For studies where monoubiquitination is significant, consider alternative high-affinity UBDs such as OtUBD, which has been shown to strongly enrich both mono- and poly-ubiquitinated proteins from crude lysates [44].

Q4: How do I validate that my K48-TUBE or K63-TUBE is working in a linkage-specific manner?

- A: Include control stimulations that are known to induce specific ubiquitin linkages. For example:

- For K63-TUBEs, treat cells with L18-MDP (an inflammatory agent known to induce K63-linked ubiquitination of RIPK2) and check for enrichment [27].

- For K48-TUBEs, use a validated PROTAC molecule that induces K48-linked ubiquitination and degradation of its target protein [27].

- The positive signal in the expected TUBE pulldown and the absence of signal in the other linkage-specific TUBE confirms specificity.

Troubleshooting Table

Table 4: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal | 1. DUB/proteasome activity.2. Inefficient binding or elution.3. Target is not ubiquitinated. | 1. Verify inhibitor freshness (NEM, MG132).2. Test different elution methods (low pH, free ubiquitin).3. Use a positive control stimulus. |

| High Background | 1. Non-specific binding to beads.2. Incomplete washing. | 1. Include an empty bead control.2. Increase wash stringency (salt, detergent).3. Pre-clear lysate with bare beads. |

| Poor Western Blot Resolution (Smears) | 1. Heterogeneous ubiquitination.2. Gel/transfer issues. | 1. This may be expected; optimize gel percentage (e.g., 8% for long chains) [25].2. Use PVDF membrane and optimize transfer conditions [25]. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Replicates | 1. Variable lysis or incubation times.2. Improper bead handling. | 1. Standardize all protocol steps and timings.2. Always use a consistent and precise bead slurry volume. |

Core Challenges in Linkage-Specific Ubiquitination Research

The study of the ubiquitin code is complicated by inherent technical challenges that often manifest as unresolved data, such as the classic "ubiquitin smear" on a Western blot.

- The Ubiquitin Smear: A common issue when probing for ubiquitin is a smeared appearance on the blot rather than distinct bands. This smear represents a heterogeneous mixture of proteins with varying numbers and linkages of ubiquitin chains [46]. While it confirms the presence of ubiquitination, it obscures critical information about the chain type and the molecular weight of the modified protein.

- Limitations of Standard Tools: Broad-spectrum ubiquitin enrichment tools (e.g., TUBEs, certain Ubiquitin-Traps) are excellent for confirming global ubiquitination but cannot differentiate between linkage types [46] [47]. Similarly, many commercial ubiquitin antibodies are non-specific and struggle to detect the small proportion of a specific protein that is ubiquitinated without prior enrichment [46].

- The Central Problem: Without linkage-specific insight, it is impossible to assign a functional consequence to a ubiquitination event, as different chain topologies signal for distinct cellular outcomes, such as proteasomal degradation (K48-linked) or activation of immune signaling (K63, M1-linked) [46].

Troubleshooting Guide: From Smears to Resolution

This guide addresses common experimental hurdles when working with linkage-selective tools to study ubiquitination.

Problem 1: Persistent Smear and High Background on Western Blot

- Potential Cause: Non-specific antibody binding or overloading of total protein.

- Solution:

- Optimize Blocking: Ensure sufficient blocking time (at least 1 hour) and use the recommended blocking agent. For some antibodies, BSA is superior to non-fat milk [48] [49].

- Titrate Antibodies: Run a reagent gradient to determine the optimal primary and secondary antibody concentrations that maximize signal-to-noise ratio [48] [34].

- Validate Transfer Efficiency: Use a reversible stain like Ponceau S after transfer to confirm proteins have moved evenly from the gel to the membrane and to check for air bubbles that cause blank spots [34] [48].

- Increase Wash Stringency: Ensure wash buffers contain a detergent like 0.05% Tween 20 and that washes are performed with sufficient volume and frequency [34] [49].

Problem 2: Weak or No Signal for the Protein of Interest

- Potential Cause: The target protein is of low abundance, or the epitope is masked by the ubiquitin chain.

- Solution:

- Enrich the Target: Use immunoprecipitation (IP) or Ubiquitin-Traps to concentrate the polyubiquitylated proteins from your lysate prior to Western blotting [45] [46] [47].

- Preserve Ubiquitination: Treat cells with a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG-132 at 5-25 µM for 1-2 hours) prior to harvesting to prevent the degradation of ubiquitylated proteins [46].

- Epitope Unmasking: If your primary antibody fails to detect the target because the epitope is buried, the UbiTest platform uses pan-selective deubiquitylating enzymes (DUBs) to cleave the chains, converting the smear into a single, quantifiable band corresponding to the unmodified protein [47].

Problem 3: Differentiating Specific Linkages in a Complex Sample

- Potential Cause: Standard tools cannot discriminate between the biologically distinct ubiquitin chain types.

- Solution:

- Linkage-Specific DUBs: Following a ubiquitin enrichment step (e.g., with TUBEs), treat your sample with linkage-specific DUBs. The cleavage of the smear into a discrete band indicates the presence of that specific linkage [47].

- Linkage-Specific Antibodies: Use antibodies validated for specific ubiquitin linkages (e.g., K48-only, K63-only) for detection after enrichment [46].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following tools are essential for advancing from detecting general ubiquitination to performing linkage-specific functional analysis.

| Tool / Reagent | Core Function | Key Application in Ubiquitin Research |

|---|---|---|

| TUBE (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entity) | High-affinity enrichment of polyubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates [47]. | Pulls down diverse ubiquitinated proteins; used upstream of linkage-specific DUB digestion or Western blotting to reduce background [47]. |

| Ubiquitin-Trap (Nanobody-based) | Immunoprecipitation of ubiquitin and ubiquitinated proteins using a VHH nanobody [46]. | Clean, low-background pulldowns compatible with harsh wash conditions; ideal for IP-MS workflows [46]. |

| Linkage-Specific DUBs (enDUBs) | Enzymes that selectively cleave one type of ubiquitin linkage (e.g., K48, K63, M1) [47]. | Identifies linkage type on a protein of interest in assays like UbiTest by digesting a ubiquitin smear into a clear band [47]. |

| Ubiquiton System | A synthetic biology tool for inducing specific polyubiquitination on a target protein [50]. | Causally explores the function of a defined ubiquitin chain type (e.g., K48 for degradation, K63 for endocytosis) on a protein of interest [50]. |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Antibodies that recognize a single topology of ubiquitin chain (e.g., anti-K48, anti-K63). | Detects the presence of a specific chain linkage by Western blot after general ubiquitin enrichment [46]. |

Experimental Protocols for Functional Insight

Protocol 1: Using the UbiTest Platform for Linkage Identification

This protocol leverages the UbiTest service to identify the types of polyubiquitin chains on your protein of interest (POI) [47].

- Sample Preparation & Enrichment:

- Generate cell lysates from treated and control conditions.

- Enrich the polyubiquitylated protein fraction using TUBE technology.

- Linkage-Specific Digestion:

- Divide the enriched sample into aliquots.

- Treat each aliquot with a different linkage-specific deubiquitylase (enDUB) (e.g., one for K48, one for K63) or a pan-selective DUB. Include a no-DUB control.

- Analysis by Immunoblotting:

- Analyze all samples by Western blot, probing for your POI.

- Interpretation: The appearance or increased intensity of a lower molecular weight band (the unmodified POI) in a DUB-treated sample indicates that the POI was modified with that specific ubiquitin linkage. The pan-DUB treatment shows the total pool of ubiquitinated POI [47].

The workflow for this protocol is illustrated below.

Protocol 2: Employing the Ubiquiton System for Functional Testing

This protocol outlines how to use the Ubiquiton system to induce specific ubiquitination and study its functional consequences [50].

- System Setup:

- Engineer your target protein to fuse with the CUbo tag.

- Co-express the tagged protein with the rapamycin-inducible, linkage-specific E3 ligase (e.g., K48-Ubo or K63-Ubo) in your cellular system.

- Induction and Validation:

- Induce polyubiquitylation by adding rapamycin.

- Harvest cells and validate successful ubiquitination by running a Western blot probed for your protein of interest. Expect a characteristic upward smear or shift.

- Functional Assay:

- In parallel, after induction, perform an assay relevant to the expected function of the linkage.

The logic of applying the Ubiquiton system to a research question is shown below.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My ubiquitin blot is still a smear even after using a linkage-specific antibody. What is wrong? This often indicates that the protein of interest is modified with multiple different chain linkages simultaneously or that the antibody lacks sufficient specificity. To resolve this, first enrich for your protein via immunoprecipitation, then probe the blot with the linkage-specific antibody. Alternatively, use the UbiTest approach with linkage-specific DUBs for clearer results [46] [47].

Q2: Can the Ubiquiton system be used for endogenous proteins? The current Ubiquiton technology requires genetic engineering to tag your protein of interest with the CUbo acceptor tag. Therefore, it is best suited for the study of transfected or transgenically expressed proteins in model systems [50].

Q3: How can I increase the ubiquitination signal in my samples? Treating cells with a proteasome inhibitor like MG-132 (typically 5-25 µM for 1-2 hours before harvesting) is highly effective. This prevents the rapid turnover of polyubiquitinated proteins, allowing them to accumulate and be more easily detected [46].

Q4: What is the advantage of using TUBEs or Ubiquitin-Traps over traditional immunoprecipitation? These reagents have a much higher affinity for polyubiquitin chains and can protect them from deubiquitylases (DUBs) during the purification process. This results in a more efficient and comprehensive capture of the ubiquitinated proteome, leading to stronger signals and fewer false negatives [46] [47].

Solving Ubiquitin Western Blot Problems: From Weak Signal to High Background

Troubleshooting Guide: Weak or No Ubiquitin Signal

| Problem Area | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Degradation of ubiquitin chains by Deubiquitinases (DUBs) | Add deubiquitinase inhibitors (e.g., 5-100 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM)) to lysis buffer [25]. |

| Degradation of target protein by proteasome | Use proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) in cell culture prior to lysis [25] [51]. | |

| Gel Electrophoresis | Poor resolution of ubiquitin smears | Use 8% gels for resolving large chains (>8 ubiquitin units); use 12% gels for smaller chains [25]. |

| Suboptimal separation | Use MOPS buffer for large chains; use MES buffer for smaller chains (2-5 units) [25]. | |

| Protein Transfer | Inefficient transfer of high molecular weight (MW) ubiquitinated proteins | Optimize transfer conditions; for long chains, use 30V for 2.5 hours instead of faster transfers [25]. |

| Poor retention of low MW proteins on membrane | For low MW antigens, add 20% methanol to transfer buffer; for high MW antigens, add 0.01–0.05% SDS [26]. | |

| Membrane & Blocking | Low signal strength | Use PVDF membranes instead of nitrocellulose for higher signal [25]. |

| High background | Use a different blocking buffer (e.g., BSA in TBS for phosphoproteins); ensure sufficient blocking time (≥1 hour at RT) [26]. | |

| Antibody Incubation | Low antibody affinity or concentration | Titrate primary antibody to find optimal concentration; increase antibody concentration if signal is weak [26]. |

| High background from antibody | Decrease concentration of primary and/or secondary antibody [29] [26]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my ubiquitin blot show a smear instead of distinct bands? A: A smear is a typical and often expected pattern for ubiquitinated proteins. Ubiquitination is a heterogeneous modification where target proteins can be modified by a varying number of ubiquitin molecules (from one to dozens), and at different lysine residues. This heterogeneity results in a distribution of molecular weights that appears as a smear or ladder on a Western blot [25] [52] [51].