Beyond Lysine: A Comprehensive Guide to Non-Canonical Ubiquitination Detection Methods

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of non-canonical ubiquitination detection.

Beyond Lysine: A Comprehensive Guide to Non-Canonical Ubiquitination Detection Methods

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of non-canonical ubiquitination detection. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it bridges the gap between foundational knowledge of non-lysine ubiquitination and advanced methodological applications. The content explores the chemical diversity of N-terminal, cysteine, serine, and threonine ubiquitination, details cutting-edge enrichment and proteomic strategies, and offers practical troubleshooting guidance for common experimental challenges. A comparative analysis of validation techniques equips scientists to confidently characterize these elusive modifications, ultimately accelerating research into their roles in disease and therapeutic targeting.

Expanding the Ubiquitin Code: An Introduction to Non-Canonical Ubiquitination

Ubiquitination represents one of the most versatile post-translational modifications in eukaryotic cells, traditionally characterized by the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to the ε-amino group of lysine residues in substrate proteins through an isopeptide bond [1] [2]. This canonical process, mediated by the sequential action of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligase) enzymes, regulates diverse cellular functions including protein degradation, signal transduction, and DNA repair [3]. However, emerging research has substantially expanded our understanding of ubiquitination beyond this conventional paradigm, revealing multiple non-canonical forms that significantly increase the complexity of the ubiquitin code.

Non-canonical ubiquitination encompasses covalent attachments to sites other than lysine residues, including protein N-termini, cysteine, serine, and threonine residues, through chemically distinct linkages [4] [1] [2]. The discovery of these alternative modification sites represents a fundamental shift in our comprehension of ubiquitin signaling, suggesting previously unappreciated layers of regulatory complexity. Furthermore, recent evidence indicates that the reach of ubiquitination extends beyond the proteome to include intracellular lipids, sugars, and even drug-like small molecules [4] [5]. This expansion of substrate scope, combined with the discovery of non-canonical enzymatic mechanisms—including pathogen-derived ubiquitination systems—has established non-canonical ubiquitination as a critical frontier in ubiquitin research with profound implications for understanding cellular physiology and developing therapeutic interventions.

Chemical and Biological Foundations of Non-Canonical Ubiquitination

Fundamental Chemical Linkages

The biochemical basis of non-canonical ubiquitination revolves around alternative nucleophilic attacks on the electron-deficient carbonyl carbon of the thioester linkage between ubiquitin and E2 or E3 enzymes [4]. While canonical ubiquitination involves attack by the ε-amino group of lysine residues, non-canonical ubiquitination occurs when other nucleophiles initiate this attack, resulting in chemically distinct linkages with potentially unique functional consequences.

Table: Chemical Linkages in Non-Canonical Ubiquitination

| Modification Site | Bond Type | Chemical Properties | Known Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein N-terminus | Peptide bond | Stable, analogous to native protein backbone | MyoD, p21, p14ARF, Ngn2 [1] [2] |

| Cysteine residue | Thioester bond | Labile, acid-sensitive | MHC I (viral E3 ligases MIR1/MIR2) [1] |

| Serine/Threonine residue | Oxyester bond | Hydroxyl-dependent, base-sensitive | MHC I (viral E3 mK3) [1] |

| Phosphoribosyl-serine | Phosphodiester bond | Unconventional, pathogen-mediated | Legionella SidE effectors [2] |

The stability and dynamics of these non-canonical linkages differ significantly from traditional isopeptide bonds. Thioester and oxyester bonds demonstrate increased lability under acidic and basic conditions respectively, suggesting they may represent more transient signaling modifications compared to their lysine-targeted counterparts [4]. This inherent chemical lability may explain why these modifications remained undetected for decades and why they continue to present technical challenges for identification and characterization.

Biological Significance and Functional Consequences

Non-canonical ubiquitination events mediate diverse biological outcomes comparable in significance to canonical ubiquitination. N-terminal ubiquitination has been demonstrated to target proteins for proteasomal degradation, modulate catalytic activity of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) such as UCHL1 and UCHL5, and delay aggregation of amyloid proteins associated with neurodegenerative disorders [2]. Similarly, non-lysine ubiquitination of cysteine, serine, and threonine residues regulates critical processes including immune evasion by pathogens through modification of MHC I molecules [1].

The functional consequences of these modifications extend beyond protein degradation to include alterations in subcellular localization, protein-protein interactions, and enzymatic activity. For example, N-terminal ubiquitination of the transcriptional regulator Ngn2 controls its degradation independently of lysine targeting [2], while oxyester-linked ubiquitination events participate in bacterial infection mechanisms through pathogen-encoded E3 ligases [1]. These diverse functional outcomes underscore the biological significance of non-canonical ubiquitination as a complementary regulatory layer to the established canonical ubiquitin code.

Experimental Methodologies for Detection and Characterization

Proteomic Approaches for Ubiquitination Site Mapping

Comprehensive characterization of non-canonical ubiquitination requires specialized proteomic methodologies capable of capturing chemically diverse ubiquitin conjugates. Traditional mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics often overlooks non-canonical ubiquitination sites due to their lower abundance and distinct biochemical properties compared to lysine modifications [1] [2]. Several enrichment strategies have been developed to address this limitation:

Ubiquitin Tagging-Based Approaches utilize epitope-tagged ubiquitin (e.g., His, Strep, or HA tags) expressed in living cells to affinity-purify ubiquitinated substrates [6]. The stable tagged ubiquitin exchange (StUbEx) system, which replaces endogenous ubiquitin with His-tagged ubiquitin, has enabled identification of hundreds of ubiquitination sites [6]. While this approach provides a relatively low-cost method for screening ubiquitinated substrates, potential artifacts may arise because tagged ubiquitin cannot completely mimic endogenous ubiquitin structure and function.

Endogenous Enrichment Strategies employ anti-ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., P4D1, FK1/FK2) or linkage-specific antibodies to purify ubiquitinated proteins without genetic manipulation [6]. This approach is particularly valuable for clinical samples and animal tissues where genetic tagging is infeasible. Additionally, tandem ubiquitin-binding entities (TUBEs) have been developed with higher affinity for ubiquitinated proteins compared to single ubiquitin-binding domains, enabling more efficient enrichment of endogenous ubiquitin conjugates [6].

Table: Comparison of Ubiquitinated Protein Enrichment Methods

| Methodology | Principles | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| His-tag purification | Ni-NTA affinity chromatography | Easy implementation, relatively low cost | Co-purification of histidine-rich proteins, may not mimic endogenous Ub [6] |

| Strep-tag purification | Strep-Tactin affinity resin | Strong binding, different specificity | Co-purification of endogenously biotinylated proteins [6] |

| Anti-ubiquitin antibodies | Immunoaffinity enrichment | Works with endogenous ubiquitin, applicable to tissues | High cost, potential non-specific binding [6] |

| TUBEs | Tandem ubiquitin-binding domains | High affinity, recognizes endogenous ubiquitin | May have linkage preferences [6] |

Specialized Protocols for Non-Canonical Ubiquitination Analysis

Protocol 1: Detection of HUWE1-Mediated Small Molecule Ubiquitination

Background: Recent research has demonstrated that the HECT E3 ligase HUWE1 can ubiquitinate drug-like small molecules containing primary amino groups, expanding the substrate scope of ubiquitination beyond biological macromolecules [5]. This protocol outlines methods to detect and characterize these unusual ubiquitination events.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Purified HUWE1HECT or full-length HUWE1

- E1 enzyme (UBA1)

- E2 enzyme (UBE2L3 or UBE2D3)

- Ubiquitin

- ATP

- Small molecule inhibitors (BI8622, BI8626) or test compounds

- SDS-PAGE equipment

- Mass spectrometry system (LC-MS/MS)

- Size-exclusion chromatography columns

Procedure:

- Reconstitute Ubiquitination Reactions:

- Prepare 50 μL reactions containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM ATP, 50 nM E1 (UBA1), 100-500 nM E2 (UBE2L3), 1-2 μM HUWE1HECT or full-length HUWE1, 10-20 μM ubiquitin, and 10-100 μM test compound

- Incubate at 30°C for 60 minutes

- Terminate reactions with SDS-PAGE loading buffer (non-reducing)

Analyze Reaction Products:

- Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE and visualize using Coomassie staining or immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin antibodies

- Excise bands corresponding to ubiquitin (~9 kDa) for MS analysis

- Digest with LysC protease and analyze by LC-MS/MS to identify modified ubiquitin peptides

Confirm Compound Modification:

- Monitor for mass shifts of +408.21 Da (BI8622) or +422.23 Da (BI8626) on ubiquitin C-terminal peptides

- Verify modification site through MS/MS fragmentation patterns

Alternative Detection by SEC:

- Fractionate reaction mixtures by size-exclusion chromatography

- Monitor compound elution by UV absorbance at compound-specific wavelengths

- Confirm ubiquitinated compounds by MS analysis of relevant fractions

Applications: This protocol enables detection of unconventional ubiquitination events on small molecules, facilitating drug mechanism studies and expanding understanding of E3 ligase substrate specificity [5].

Protocol 2: Linkage-Specific Analysis of Linear (M1-Linked) Ubiquitination

Background: The linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC) specifically generates Met1-linked linear ubiquitin chains through unique mechanisms involving conjugation to the N-terminal methionine of ubiquitin [4]. This protocol details methods for analyzing this specialized non-canonical ubiquitination.

Reagents and Equipment:

- LUBAC components (HOIP, HOIL-1, Sharpin)

- E2 enzyme (appropriate for LUBAC)

- Met1-linkage specific ubiquitin binding domains (e.g., NZF domain of HOIL-1)

- M1-linkage specific antibodies

- Deubiquitinases with linear linkage specificity (OTULIN)

- Immunoprecipitation reagents

- Confocal microscopy equipment

Procedure:

- In Vitro Linear Ubiquitination Assay:

- Reconstitute reactions with purified LUBAC components, E1, E2, ubiquitin, and ATP

- Include 10-50 μM candidate substrates

- Incubate at 30°C for 0-120 minutes

- Terminate reactions at various timepoints for analysis

Linkage-Specific Detection:

- Perform immunoblotting with M1-linkage specific antibodies

- Confirm specificity using OTULIN treatment as negative control

- Utilize tandem ubiquitin-binding entities (TUBEs) with preference for linear linkages

Cellular Visualization:

- Express tagged ubiquitin constructs (e.g., GFP-ubiquitin) in appropriate cell lines

- Stimulate pathways known to activate LUBAC (e.g., TNF-α signaling)

- Fix cells and stain with M1-linkage specific antibodies

- Analyze by confocal microscopy or super-resolution techniques (dSTORM, PALM)

Functional Validation:

- Employ CRISPR/Cas9 to generate HOIP-deficient cells

- Monitor NF-κB activation and cell death pathways as functional readouts

- Express LDD domain mutants defective in linear chain formation

Applications: This protocol enables comprehensive analysis of linear ubiquitination in immune signaling and cell death regulation, providing insights into this non-canonical ubiquitination form [4] [3].

Visualization and Imaging Techniques

Advanced microscopy techniques have significantly enhanced our ability to visualize non-canonical ubiquitination in cellular contexts. Confocal fluorescence microscopy combined with linkage-specific ubiquitin binders or antibodies enables spatial resolution of different ubiquitin chain types [3]. Recent developments in super-resolution microscopy (STED, PALM, STORM) permit visualization of ubiquitination at nanometer resolution, revealing previously unappreciated subcellular distributions of ubiquitin signals [3].

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) and ubiquitination-induced fluorescence complementation (UiFC) approaches provide tools to monitor ubiquitination dynamics in living cells, offering temporal resolution complementary to the spatial information obtained from fixed-cell imaging [3]. These techniques are particularly valuable for studying the dynamic nature of non-canonical ubiquitination events, which may be more transient than their canonical counterparts due to differences in bond stability.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table: Essential Reagents for Non-Canonical Ubiquitination Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epitope-tagged ubiquitin | His-Ub, Strep-Ub, HA-Ub | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins | May not fully mimic endogenous ubiquitin [6] |

| Linkage-specific antibodies | M1-, K48-, K63-specific antibodies | Enrichment and detection of specific chain types | Variable specificity between lots [6] |

| Ubiquitin-binding domains | TUBEs, NZF, UBA, UIM domains | Enrichment of endogenous ubiquitinated proteins | May have linkage preferences [6] |

| Activity-based probes | Ubiquitin-dehydroalanine (Ub-Dha) | Detection of deubiquitinating enzyme activity | Can profile DUB specificity toward different linkages [3] |

| E3 ligase expression constructs | HUWE1, LUBAC, viral E3s | Functional studies of specific E3s | May require co-expression of specific E2s [4] [5] |

| DUB inhibitors | OTULIN inhibitors, PR-ubiquitin erasers | Pathway modulation and functional studies | Specificity must be carefully validated [2] [7] |

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks

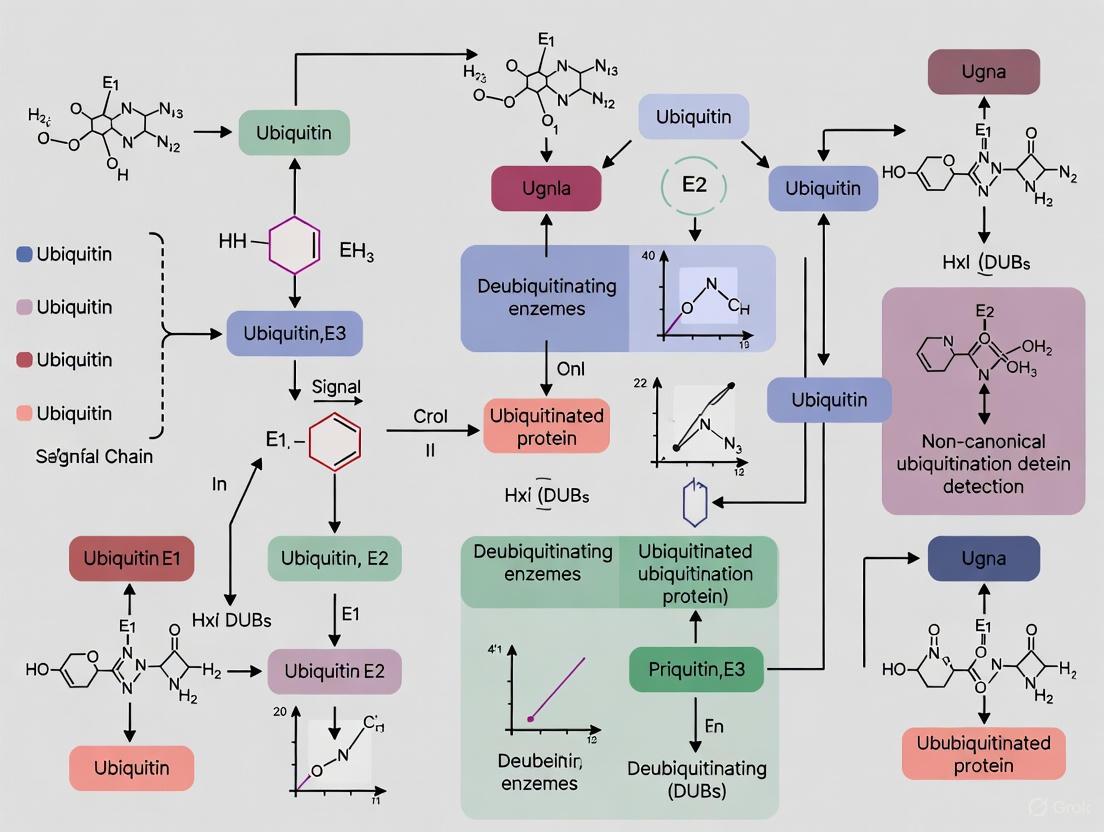

The following diagrams illustrate key signaling pathways and experimental workflows relevant to non-canonical ubiquitination research.

LUBAC-Mediated Linear Ubiquitination Pathway

Diagram Title: Linear Ubiquitination in NF-κB Signaling

Experimental Workflow for Non-Canonical Ubiquitination Detection

Diagram Title: Ubiquitination Site Mapping Workflow

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The study of non-canonical ubiquitination remains a rapidly evolving field with significant challenges and opportunities. Current methodologies still face limitations in comprehensively capturing the full diversity of non-canonical ubiquitination events, particularly those involving labile thioester and oxyester linkages that may be lost during standard sample preparation [4] [1]. Future methodological developments should focus on stabilizing these delicate modifications and enhancing the sensitivity of detection techniques.

The expansion of ubiquitination to include non-proteinaceous substrates such as lipids, nucleic acids, and small molecules suggests an even broader cellular role for ubiquitination than previously appreciated [4] [5]. This paradigm shift necessitates re-evaluation of established ubiquitination functions and development of new experimental approaches capable of detecting these unconventional modifications in physiological contexts.

From a therapeutic perspective, understanding non-canonical ubiquitination opens new avenues for drug development. The recent discovery that the deubiquitinase OTULIN regulates tau expression at the RNA level [7], alongside demonstrations that small molecules can serve as ubiquitination substrates [5], highlights the potential for targeting non-canonical ubiquitination pathways in neurodegenerative diseases and cancer. As our methodological toolkit expands, so too will our understanding of the physiological significance and therapeutic potential of these non-canonical ubiquitination events.

In the intricate world of post-translational modifications, non-canonical ubiquitination has emerged as a critical regulatory mechanism extending beyond traditional lysine targeting. While canonical ubiquitination involves isopeptide bond formation on lysine residues, non-canonical pathways utilize diverse chemical linkages including thioester and oxyester bonds that significantly expand the ubiquitin code's functional repertoire. These alternative chemistries regulate protein stability, activity, and localization through distinct mechanisms that remain challenging to detect and characterize. This article explores the chemical foundations of peptide, thioester, and oxyester linkages within the context of ubiquitination biology, providing researchers with advanced methodological frameworks for their investigation. As our understanding of these modifications grows, so does our appreciation of their roles in cellular homeostasis and disease pathogenesis, highlighting the urgent need for refined detection strategies in both basic research and drug development.

Table 1: Fundamental Chemical Linkages in Protein Modification

| Linkage Type | Bond Description | Chemical Stability | Primary Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide/Isopeptide | Amide bond between carboxyl and amino groups | High; requires specialized hydrolases | Substrate degradation, signaling transduction |

| Thioester | Sulfur ester between carboxyl and thiol groups | Moderate; susceptible to hydrolysis and thiol exchange | E1/E2 enzyme intermediates, metabolic activation |

| Oxyester | Ester between carboxyl and hydroxyl groups | Lower; susceptible to hydrolysis and enzymatic cleavage | Non-canonical ubiquitination, pathogen-host interactions |

Chemical Foundations and Biological Significance

Peptide and Isopeptide Linkages

The isopeptide bond represents the cornerstone of traditional ubiquitination, formed between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin (G76) and the ε-amino group of a lysine residue on substrate proteins. This enzymatic cascade begins with E1 activation through a thioester intermediate, proceeds through E2 conjugation, and culminates in E3 ligase-mediated isopeptide formation. The resulting ubiquitin modifications can manifest as monoubiquitination, multi-monoubiquitination, or elaborate polyubiquitin chains with diverse biological consequences dictated by chain topology. These isopeptide linkages exhibit remarkable stability, requiring specialized deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) for reversal, making them ideal for durable signaling functions such as targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation via K48-linked chains [2] [6].

Thioester Bond Chemistry and Function

Thioesters serve as indispensable chemical intermediates in both synthetic chemistry and biological systems, characterized by their general structure R-C(=O)-S-R'. These linkages possess distinct reactivity profiles compared to their oxygen ester counterparts, displaying enhanced electrophilicity at the carbonyl carbon due to poorer p-orbital overlap between carbon and sulfur versus carbon and oxygen. This electronic configuration renders thioesters more susceptible to nucleophilic attack, making them ideal for group transfer reactions in biochemical pathways. In ubiquitination chemistry, thioester intermediates are essential during the E1-E2-E3 cascade, where ubiquitin is transferred between catalytic cysteine residues of activating and conjugating enzymes prior to final substrate attachment [2] [8].

The biological importance of thioesters extends far beyond ubiquitination, encompassing central roles in metabolic pathways including fatty acid biosynthesis (acyl-CoA derivatives) and energy production (acetyl-CoA). Their chemical properties have even prompted hypotheses about a "Thioester World" in prebiotic chemistry, suggesting they may have served as primordial energy currency before ATP [8]. Recent prebiotic chemistry research demonstrates that mercaptoacids can condense with amino acids under plausible early Earth conditions to form thiodepsipeptides containing both peptide and thioester bonds, highlighting the fundamental nature of these linkages in chemical evolution [9].

Oxyester Bond Formation and Detection Challenges

Oxyester linkages represent a non-canonical ubiquitination pathway where the C-terminus of ubiquitin forms an ester bond with hydroxyl groups of serine, threonine, or potentially tyrosine residues on substrate proteins. First documented in 2005, these modifications introduce unique biochemical properties compared to isopeptide bonds, including increased sensitivity to hydrolysis under both acidic and basic conditions due to the less stable ester linkage. This inherent lability creates significant challenges for detection and characterization, as standard biochemical procedures may inadvertently cleave these modifications before analysis [2].

Perhaps the most striking examples of oxyester ubiquitination come from pathogen-host interactions, particularly Legionella pneumophila effectors. The SidE family enzymes bypass the conventional E1-E2 cascade entirely, instead catalyzing a unique phosphoribosyl-linked serine ubiquitination using NAD+ as a cofactor. This remarkable mechanism involves ADP-ribosyltransferase and phosphodiesterase domains that ultimately conjugate ubiquitin's Arg42 (rather than the conventional Gly76) to substrate serine residues via a phosphoribosyl linker [2]. This pathogen-mediated ubiquitination subversion highlights the functional importance of non-canonical linkages in host-pathogen warfare while presenting additional complexity for researchers developing comprehensive ubiquitination detection strategies.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Selenol-Catalyzed Peptide Thioester Synthesis

The production of peptide thioesters represents a critical step in chemical protein synthesis via native chemical ligation, yet their synthesis remains challenging under standard Fmoc-SPPS conditions. Recent methodological advances have employed selenol-based catalysts to facilitate efficient thioester formation from bis(2-sulfanylethyl)amido (SEA) peptides at mildly acidic pH [10].

Protocol: Selenol-Catalyzed SEA/Thiol Exchange

Reagents:

- SEA peptide substrate (1 mM)

- Diselenide precatalyst (e.g., 17 or 18, 6.25-200 mM)

- Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP·HCl, 100 mM)

- 3-Mercaptopropionic acid (MPA, 5% v/v)

- 6 M Guanidine hydrochloride (Gn·HCl)

- Buffer: pH 4.0

Procedure:

- Prepare reaction mixture containing SEA peptide (1 mM) in 6 M Gn·HCl buffer (pH 4.0)

- Add TCEP·HCl (100 mM) to reduce diselenide precatalyst and cyclic SEAoff disulfide

- Introduce diselenide precatalyst at desired concentration (6.25-200 mM)

- Add MPA (5% v/v) as thiol exchange partner

- Incubate at 37°C under inert atmosphere with continuous mixing

- Monitor reaction progress by HPLC at regular intervals

- Terminate reaction by freezing or direct injection onto preparative HPLC

Kinetic Analysis:

- Fit kinetic data to extract apparent second-order rate constants

- Compare half-reaction times (t½) across catalyst concentrations

- Optimal catalyst concentration: ≥50 mM for maximal rate constant

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Selenol Catalysts in SEA/Thiol Exchange

| Catalyst | Concentration (mM) | Half-Reaction Time (h) | Relative Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8a | 6.25 | 3.35 | Benchmark |

| 13 | 6.25 | 5.87 | ~57% of 8a |

| 8a | 50 | 1.95 | Optimal range |

| 13 | 50 | 2.22 | ~88% of 8a |

| 14 | 50 | 3.60 | ~54% of 8a |

| Uncatalyzed | - | 7.28 | Baseline |

Mechanistic Insights: The catalytic cycle begins with spontaneous N,S-acyl shift in the SEA peptide to generate a transient SEA thioester. The selenol catalyst (in its nucleophilic selenoate form at acidic pH) attacks this thioester to form a selenoester intermediate. This intermediate subsequently undergoes exchange with the excess thiol additive (MPA) to yield the desired peptide thioester product while regenerating the selenol catalyst. The enhanced catalytic efficiency of selenols over thiols stems from their lower pKa values, ensuring greater concentration of the active selenoate nucleophile at the working pH [10].

Detection Strategies for Non-Canonical Ubiquitination

Characterizing non-canonical ubiquitination presents unique challenges due to the lability of thioester and oxyester linkages, low stoichiometry of modification, and competition with abundant canonical ubiquitination. Integrated methodological approaches are required for comprehensive analysis [2] [6].

Protocol: Ubiquitin Branching Analysis Using Linkage-Specific Tools

Reagents:

- Linkage-specific ubiquitin antibodies (M1, K6, K11, K27, K48, K63)

- Tandem ubiquitin-binding entities (TUBEs)

- Lysis buffer (containing N-ethylmaleimide and protease inhibitors)

- Protein A/G affinity resin

- Ubiquitin tagging plasmids (His-, FLAG-, or Strep-tagged Ub)

Procedure:

- Stabilization: Harvest cells in lysis buffer containing 20 mM N-ethylmaleimide to preserve thioester linkages

- Enrichment: Employ one of three enrichment strategies:

- Antibody-based: Incubate lysate with linkage-specific ubiquitin antibodies (2-4 hours, 4°C)

- TUBE-based: Use TUBEs with pan-ubiquitin or linkage specificity (2 hours, 4°C)

- Tag-based: Express epitope-tagged ubiquitin in cells; enrich with appropriate affinity resin

- Immunoprecipitation: Capture ubiquitinated proteins with Protein A/G resin (1 hour, 4°C)

- Washing: Wash resin extensively with lysis buffer followed by PBS

- Elution: Elute with SDS-PAGE sample buffer (for immunoblotting) or competitive elution (for MS analysis)

- Analysis:

- Immunoblotting: Probe with linkage-specific antibodies

- Mass Spectrometry: Digest with trypsin; identify signature peptides and diGly remnants

Critical Considerations:

- Avoid alkaline conditions during processing to preserve oxyester linkages

- Include DUB inhibitors in lysis buffers to prevent deubiquitination

- Use hydroxylamine treatment to distinguish thioester/oxyester linkages (cleaves esters but not amides)

- Employ control mutations (serine/threonine to alanine) to verify non-canonical sites

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Non-Canonical Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Inhibitors | N-Ethylmaleimide, Iodoacetamide | Thiol alkylating agents that stabilize thioester intermediates by blocking transthioesterification |

| Catalysts | Selenol compounds (8a, 13, 14) | Facilitate peptide thioester synthesis from SEA peptides at acidic pH via selenoester intermediates |

| Enrichment Tools | TUBEs (tandem ubiquitin-binding entities) | High-affinity capture of ubiquitinated substrates from native systems without genetic manipulation |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K48-, K63-, M1-linkage specific antibodies | Detect and characterize specific ubiquitin chain architectures in immunoblotting and enrichment |

| Epitope Tags | His-, FLAG-, Strep-tagged ubiquitin | Enable affinity purification of ubiquitinated substrates from cellular lysates for proteomic analysis |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | DiGly-Lys peptide standards, TMT labels | Quantify ubiquitination sites and relative abundance across experimental conditions |

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Non-canonical Ubiquitination Detection Workflow

Ubiquitination Mechanism Pathways

The expanding landscape of peptide, thioester, and oxyester linkages in protein ubiquitination represents a frontier in understanding cellular regulation and developing targeted therapeutic interventions. As this field advances, researchers must employ integrated methodological approaches that account for the unique chemical properties and labilities of these distinct linkage types. The protocols and reagents detailed herein provide a foundation for investigating these non-canonical modifications, with particular relevance to drug discovery targeting ubiquitination pathways in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and infectious diseases. Future methodological developments will likely focus on improving sensitivity for low-abundance modifications, distinguishing between simultaneous modification types, and enabling single-cell analysis of ubiquitination dynamics. Through continued refinement of these chemical and analytical tools, researchers will undoubtedly uncover new biological insights and therapeutic opportunities within the complex landscape of non-canonical ubiquitination.

Ubiquitination is a fundamental post-translational modification that regulates virtually all cellular processes, traditionally known for its role in targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation via canonical lysine linkages [1] [11]. However, the expanding field of non-canonical ubiquitination has revealed a complex regulatory landscape where ubiquitin conjugates to non-lysine residues, substantially increasing the diversity and functional scope of ubiquitin signaling [1] [2]. These non-canonical modifications encompass several distinct chemical linkages: peptide bonds with the α-amino group of protein N-termini, thioester-based linkages with cysteine residues, and oxyester bonds with serine or threonine residues [1] [2] [12]. The first observations of lysine-independent ubiquitination emerged in 2005, and since then, evidence has steadily accumulated demonstrating that non-canonical ubiquitination represents a crucial regulatory mechanism with distinct functional consequences [1] [2].

The biological significance of these modifications extends across critical cellular pathways, from inflammatory signaling to protein aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases [11] [2]. Despite their importance, non-canonical ubiquitination events remain understudied compared to their canonical counterparts, largely due to methodological challenges in detection and characterization [1] [13]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of the key biological roles, detection methodologies, and research tools for investigating non-canonical ubiquitination, with particular emphasis on recent advances that are transforming our understanding of this complex regulatory system.

Key Biological Roles and Functional Significance

Regulatory Mechanisms and Cellular Functions

Non-canonical ubiquitination serves diverse regulatory functions that often differ substantially from canonical ubiquitination. The functional consequences depend on both the modified residue type and the specific substrate involved, creating a sophisticated regulatory network that fine-tunes cellular processes [1] [2].

Table 1: Types and Functions of Non-Canonical Ubiquitination

| Modification Type | Bond Formation | Key Functions | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-terminal Ubiquitination | Peptide bond with α-amino group | Protein degradation, altered catalytic activity, delayed protein aggregation | Ngn2, p14ARF, p21, UCHL1, UCHL5 [2] |

| Cysteine Ubiquitination | Thioester bond | Immune regulation, receptor modulation | MHC I modification by viral E3 ligases MIR1/MIR2 [1] [2] |

| Serine/Threonine Ubiquitination | Oxyester bond | Immune regulation, aggregate formation | MHC I modification by mK3 [1] [2] |

| Branched Ubiquitination | Multiple linkage types | Priority signal for proteasomal degradation, NF-κB signaling, p97 processing | K11-K48, K29-K48, K48-K63 branched chains [14] |

| Non-protein Ubiquitination | Varies by substrate | Expanding ubiquitin system to non-protein targets | HUWE1-mediated small molecule modification [5] |

N-terminal ubiquitination has been demonstrated to target proteins for proteasomal degradation, as evidenced by studies on Ngn2, p14ARF, and p21 [2]. Interestingly, this modification also distinctly alters the catalytic activity of deubiquitinating enzymes UCHL1 and UCHL5, and delays aggregation of amyloid proteins associated with neurodegenerative disorders [2]. The E2 enzyme UBE2W has been identified as particularly adept at facilitating N-terminal ubiquitination due to its flexible C-terminus that selectively targets α-amino groups of N-termini [2].

Cysteine and serine/threonine ubiquitination were initially discovered through viral E3 ligases that modify MHC I molecules, representing a pathogen-mediated subversion of host immunity [1] [2]. Subsequent research has revealed that these modifications also occur in endogenous cellular regulation, particularly in inflammatory responses and protein aggregate formation [11].

Branched ubiquitin chains represent another dimension of non-canonical signaling, where at least one ubiquitin moiety within a chain is modified at two or more positions simultaneously, creating bifurcation points that give rise to chain branches [14]. These complex architectures significantly expand the signaling capacity of the ubiquitin system, with K11-K48 branched chains regulating protein degradation and cell cycle progression, K29-K48 chains mediating proteasomal degradation, and K48-K63 chains serving multiple functions including proteasomal degradation, NF-κB signaling, and as signals for p97/valosin-containing protein (VCP) processing [14].

Recent research has expanded the substrate realm of ubiquitination beyond proteins, revealing that the human ligase HUWE1 can target drug-like small molecules, connecting them to ubiquitin via their primary amino groups [5]. This discovery opens avenues for harnessing the ubiquitin system to transform exogenous small molecules into novel chemical modalities within cells.

Quantitative Proteomic Profiles

Comprehensive profiling of ubiquitination events reveals the extensive scope of these modifications in cellular regulation. When OTULIN was completely removed from neuroblastoma cells, RNA sequencing showed dramatic changes in gene expression – 13,341 genes were downregulated and 774 were upregulated, with even more dramatic effects on RNA transcripts (43,003 downregulated, 1,113 upregulated) [7]. Comparing Alzheimer's patient neurons to healthy controls revealed over 4,500 genes and 5,600 transcripts were differentially expressed [7].

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Ubiquitination System Perturbations

| Experimental Condition | Genes Downregulated | Genes Upregulated | Biological Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| OTULIN knockout in neuroblastoma cells | 13,341 genes | 774 genes | Tau mRNA disappearance, massive changes in RNA processing and gene expression control [7] |

| Alzheimer's patient neurons vs. healthy controls | 4,500+ differentially expressed genes | 5,600+ differentially expressed transcripts | Elevated OTULIN and phosphorylated tau, contributing to disease progression [7] |

| Pharmacological OTULIN inhibition | Reduced phosphorylated tau | No apparent neuronal toxicity | Therapeutic reduction of pathological tau forms without eliminating total tau [7] |

The functional significance of non-canonical ubiquitination extends to numerous pathological conditions. In Alzheimer's disease research, scientists discovered that the brain enzyme OTULIN controls the expression of tau, the protein that forms toxic tangles in the disease [7]. Surprisingly, when the OTULIN gene was completely knocked out in neurons, tau disappeared entirely – not because it was being degraded faster, but because it wasn't being produced at all, representing a paradigm shift in understanding tau regulation [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Enrichment and Identification of Ubiquitinated Proteins

Principle: This protocol describes methods for enriching and identifying ubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates, utilizing affinity tags, antibodies, or ubiquitin-binding domains to isolate ubiquitinated substrates for subsequent mass spectrometry analysis [13] [6].

Materials:

- Lysis Buffer (8 M urea, 100 mM Na₂HPO₄, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0)

- Affinity Purification Resins (Ni-NTA for His-tag, Strep-Tactin for Strep-tag)

- Ubiquitin Branch-Specific Antibodies (e.g., K48-, K63-, M1-linkage specific)

- Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs)

- Trypsin/Lys-C Mix for Protein Digestion

- Mass Spectrometry-Compatible Desalting Columns

Procedure:

Cell Lysis and Preparation:

- Harvest cells of interest and lyse in lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors and deubiquitinase inhibitors (e.g., N-ethylmaleimide).

- Clear lysates by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- Determine protein concentration using bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay.

Affinity Enrichment of Ubiquitinated Proteins (choose one approach):

- Tag-Based Purification: For cells expressing His- or Strep-tagged ubiquitin, incubate lysates with appropriate resin for 2 hours at 4°C with gentle rotation. Wash with 10 column volumes of lysis buffer followed by 5 column volumes of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate [6].

- Antibody-Based Purification: Incubate lysates with ubiquitin branch-specific antibodies conjugated to protein A/G beads overnight at 4°C. Wash extensively with lysis buffer followed by 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate [6].

- TUBE-Based Purification: Incubate lysates with TUBE reagents for 2 hours at 4°C. Capture complexes using appropriate affinity system and wash as above [6].

On-Bead Digestion and Peptide Preparation:

- Reduce bound proteins with 5 mM dithiothreitol for 30 minutes at 37°C.

- Alkylate with 15 mM iodoacetamide for 30 minutes at room temperature in darkness.

- Digest proteins with trypsin/Lys-C mix (1:50 w/w) overnight at 37°C.

- Acidify peptides with trifluoroacetic acid to pH < 3 and desalt using C18 columns.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis and Data Processing:

Technical Notes: Tag-based approaches may co-purify histidine-rich or endogenously biotinylated proteins, while antibody-based methods can be limited by antibody specificity and cost. TUBEs offer the advantage of protecting ubiquitinated proteins from deubiquitinase activity during purification [6].

Protocol 2: Biochemical Analysis of Non-Canonical Ubiquitination

Principle: This protocol outlines methods for in vitro reconstitution of non-canonical ubiquitination using purified enzyme components, allowing controlled investigation of specific E2-E3 combinations and their substrate specificity [1] [5].

Materials:

- Purified E1 Activating Enzyme (UBA1)

- Purified E2 Conjugating Enzymes (e.g., UBE2W for N-terminal ubiquitination)

- Purified E3 Ligases (e.g., HUWE1, viral E3s MIR1/MIR2/mK3)

- Wild-type and Mutant Ubiquitin

- ATP Regeneration System

- Reaction Buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl₂, 0.5 mM DTT)

Procedure:

Reaction Setup:

- Prepare 50 μL reactions containing reaction buffer, 100 nM E1, 1-5 μM E2, 1-5 μM E3, 50 μM ubiquitin, and 2 mM ATP.

- Include substrate proteins or small molecules (e.g., BI8622/BI8626 for HUWE1 studies) at appropriate concentrations [5].

- Incubate reactions at 30°C for 60 minutes.

Reaction Analysis:

- Stop reactions by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer with or without reducing agents (thioester bonds are reducing-sensitive).

- Analyze products by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with ubiquitin-specific antibodies.

- For small molecule substrates, analyze reaction mixtures by size-exclusion chromatography or mass spectrometry to detect ubiquitinated compounds [5].

Product Validation:

- For putative non-canonical ubiquitination sites, mutagenize candidate residues (N-terminal amine, cysteine, serine, threonine) to confirm modification sites.

- Utilize mass spectrometry to directly identify modification sites through detection of signature mass shifts.

Technical Notes: Non-canonical thioester and oxyester linkages are more labile than canonical isopeptide bonds, requiring careful handling and specific analytical conditions. For cysteine ubiquitination, include control reactions without reducing agents to preserve thioester bonds [1] [2].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Relationships

The molecular relationships in non-canonical ubiquitination signaling can be visualized through the following pathway diagram:

Diagram 1: Non-canonical Ubiquitination Signaling Pathway. This diagram illustrates the enzymatic cascade and alternative ubiquitination sites that expand the functional repertoire of ubiquitin signaling beyond canonical lysine modification.

The experimental workflow for profiling non-canonical ubiquitination events involves multiple complementary approaches:

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Ubiquitination Profiling. This workflow outlines the major methodological approaches for enrichment and identification of ubiquitination events, culminating in mass spectrometric analysis and data interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Non-Canonical Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity Tags | His-tag, Strep-tag, HA-tag | Purification of ubiquitinated proteins; requires genetic manipulation [6] | Potential co-purification of endogenous His-rich proteins; may alter Ub structure/function |

| Ubiquitin Antibodies | P4D1, FK1/FK2 (pan-specific); linkage-specific (K48, K63, M1) | Enrichment of endogenous ubiquitinated proteins; linkage-specific studies [6] | High cost; variable specificity; suitable for tissue samples without genetic manipulation |

| Ubiquitin-Binding Domains | Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Protection of ubiquitinated proteins from DUBs; enrichment of polyubiquitinated proteins [6] | Enhanced affinity compared to single UBDs; protects ubiquitin chains during purification |

| Activity-Based Probes | Ubiquitin-based probes with warheads | DUB activity profiling; enzyme specificity studies [14] | Can target specific DUB families; useful for functional characterization |

| Chemical Inhibitors | UC495 (OTULIN inhibitor); BI8622/BI8626 (HUWE1 inhibitors) | Functional studies of specific enzymes; therapeutic potential [7] [5] | Potential off-target effects; dose optimization required; may act as substrates [5] |

| Recombinant Enzymes | E1 (UBA1), E2s (UBE2W, UBE2L3), E3s (HUWE1) | In vitro reconstitution of ubiquitination cascades; mechanistic studies [1] [5] | Requires optimization of enzyme combinations; specific for different linkage types |

The study of non-canonical ubiquitination has evolved from incidental observations to a recognized fundamental aspect of ubiquitin signaling with broad implications for cellular regulation and disease pathogenesis. Current methodologies, particularly advanced mass spectrometry techniques combined with sophisticated enrichment strategies, have dramatically improved our ability to detect and characterize these elusive modifications. The ongoing development of linkage-specific reagents, including antibodies and ubiquitin-binding domains, continues to enhance the resolution at which we can monitor the ubiquitin landscape.

Future advances in this field will likely focus on overcoming current methodological limitations, particularly the detection of non-lysine ubiquitination sites that are not captured by standard diGly remnant approaches [13]. Chemical biology approaches, including development of specialized enrichment strategies and advanced mass spectrometry fragmentation techniques, will be essential for comprehensive mapping of the non-canonical ubiquitinome. Additionally, the emerging capability to target ubiquitination pathways for therapeutic intervention, exemplified by PROTAC technology and small molecule inhibitors of specific ubiquitin pathway components, highlights the translational potential of fundamental research in this area [11] [15].

As these methodologies continue to mature, our understanding of the biological roles of non-canonical ubiquitination will expand, potentially revealing new regulatory mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities for diverse human diseases including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and inflammatory conditions.

Phosphoribosyl (PR)-linked serine ubiquitination represents a paradigm-shifting mechanism in pathogen-host interactions, distinct from the canonical three-enzyme ubiquitination cascade. Secreted by the bacterial pathogen Legionella pneumophila, SidE family effectors (SdeA, SdeB, SdeC, SidE) catalyze this unique post-translational modification using NAD+ as an energy source, completely bypassing host E1 and E2 enzymes [16] [2]. This Application Note details the mechanistic insights and experimental methodologies for investigating this non-canonical ubiquitination pathway, which remodels host cell processes including ER fragmentation, membrane recruitment to Legionella-containing vacuoles (LCVs), and xenophagy evasion to establish intracellular replication niches [16] [17]. We provide structured quantitative data, optimized protocols, and visualization tools to accelerate research in this emerging field of bacterial manipulation of host ubiquitin signaling.

Quantitative Analysis of PR-Ubiquitination System Components

Table 1: Core Effectors in Legionella's PR-Ubiquitination Pathway and Their Functions

| Effector Protein | Gene Locus | * enzymatic Function* | Key Catalytic Residues/Domains | Primary Substrate Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SidE/SdeA | - | PR-Ubiquitin Ligase | mART domain, PDE domain (E340, H277, H407) | Serine residues on host proteins |

| DupA (LaiE) | Lpg2154 | PR-Deubiquitinase | PDE domain (E340, H277, H407) | PR-Ubiquitinated serine residues |

| DupB (LaiF) | Lpg2509 | PR-Deubiquitinase | PDE domain (E340, H277, H407) | PR-Ubiquitinated serine residues |

| MavL | Lpg2526 | (ADP-ribosyl)hydrolase | D315, D323, D333 (catalytic loop) | ADPR-Ubiquitin |

| LnaB | - | Adenylyltransferase | SHxxxE motif | PR-Ubiquitin to ADPR-Ubiquitin |

Table 2: Experimentally Identified PR-Ubiquitinated Host Substrates and Functional Consequences

| Host Substrate Category | Specific Protein Targets | Identified Modification Sites | Documented Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| ER Structural Proteins | Reticulon 4 (Rtn4) | Serine residues | ER fragmentation, membrane recruitment to LCV [16] |

| Rab GTPases (ER-associated) | Rab33b, others | Serine residues | Impairs GTP-loading and hydrolysis; regulates mTORC1 activity via Rag GTPases [16] |

| Ubiquitin System Enzymes | USP14 | Multiple serine residues | Disrupts interaction with p62; excludes p62 from bacterial phagosome [17] |

| Autophagy Adaptors | p62 (indirectly via USP14) | - | Evasion of host xenophagy response [17] |

Molecular Mechanism of Phosphoribosyl-Linked Serine Ubiquitination

The SidE family effectors catalyze PR ubiquitination through a two-step, bi-domain mechanism that represents a significant departure from canonical ubiquitination:

Biochemical Pathway

- ADP-ribosylation: The mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase (mART) domain utilizes NAD+ to transfer ADP-ribose (ADPR) to Arg42 of ubiquitin, forming ADPR-Ub [16] [2].

- Phosphodiester Bond Formation: The phosphodiesterase (PDE) domain cleaves ADPR-Ub to generate phosphoribosylated ubiquitin (PR-Ub), which is then conjugated to serine residues of substrate proteins via a phosphodiester bond [16] [2].

This unique phosphoribosyl linkage connects ubiquitin's Arg42 to substrate hydroxyl groups through a phosphoribosyl linker, rather than the canonical isopeptide bond between ubiquitin's C-terminal glycine and substrate lysine ε-amino groups [2].

Regulatory Circuitry

Legionella employs sophisticated regulation of PR ubiquitination through additional effectors:

- Reversal Mechanism: DupA and DupB specifically cleave PR-ubiquitin from substrate serines, but cannot process canonical lysine-linked ubiquitination [16].

- Homeostasis Control: The sequential actions of LnaB (converting PR-Ub to ADPR-Ub) and MavL (hydrolyzing ADPR-Ub to ADP-ribose and functional ubiquitin) maintain ubiquitin homeostasis in infected cells [18].

Diagram 1: PR-Ubiquitination Pathway. SidE effectors catalyze a two-step reaction, reversed by DupA/B and regulated by LnaB/MavL for ubiquitin homeostasis.

Experimental Protocols for PR-Ubiquitination Detection and Analysis

Protocol: Trapping PR-Ubiquitinated Substrates Using Catalytically Inactive DupA

Principle: Catalytically inactive DupA mutants retain high binding affinity for PR-ubiquitinated substrates while lacking hydrolytic activity, enabling enrichment and identification of endogenous PR-ubiquitinated proteins during Legionella infection [16].

Methodology:

- Generation of Trapping Mutant:

- Engineer point mutations in DupA PDE catalytic residues (E340, H277, H407) to alanine while maintaining PR-ubiquitin binding capability [16].

- Express and purify the mutant DupA protein with appropriate affinity tags (e.g., His-tag, GST-tag).

Infection and Lysate Preparation:

- Infect mammalian host cells (e.g., HEK293, macrophages) with wild-type Legionella pneumophila at MOI 10-50 for 6-12 hours.

- Harvest cells and lyse in denaturing buffer (6M Guanidine-HCl, 100mM NaH₂PO₄, 10mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0) supplemented with 10mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) and protease inhibitors to preserve PR-ubiquitination and prevent deubiquitination [16] [19].

Affinity Purification:

- Incubate cleared lysates with immobilized mutant DupA (coupled to affinity resin) for 2-4 hours at 4°C.

- Wash sequentially with:

- Buffer A: 6M Urea, 20mM Tris-Cl, 100mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, pH 8.0

- Buffer B: 20mM Tris-Cl, 500mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 8.0

- Buffer C: 20mM Tris-Cl, 200mM NaCl, pH 8.0

- Elute bound PR-ubiquitinated complexes with competitive elution (3M MgCl₂) or by boiling in SDS-PAGE sample buffer [16] [19].

Downstream Analysis:

- Immunoblotting: Use anti-ubiquitin and phosphoprotein-specific staining to confirm PR-ubiquitinated proteins [16].

- Mass Spectrometry: Identify trapped substrates and modification sites via LC-MS/MS after tryptic digestion.

Applications: This approach identified >180 PR-ubiquitinated host proteins, revealing ER structural proteins and membrane trafficking regulators as major SidE targets [16].

Protocol: In Vitro PR-Ubiquitination and Deubiquitination Assays

Principle: Recombinant SidE and Dup proteins reconstitute PR ubiquitination and its reversal in cell-free systems, enabling biochemical characterization of the modification [16] [20].

Methodology:

- Protein Purification:

- Express and purify recombinant SdeA (or other SidE members), DupA, DupB, and substrate proteins (e.g., Rab33b, USP14) from E. coli with appropriate tags.

- Purify ubiquitin from E. coli or purchase commercially.

PR-Ubiquitination Reaction:

Deubiquitination Reaction:

- Generate PR-ubiquitinated substrates as above.

- Add DupA or DupB (1-2μM) to the reaction mixture.

- Continue incubation at 30°C for 30-60 minutes [16].

- Monitor cleavage by immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin antibodies and phosphoprotein staining.

Analysis:

- Resolve proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to PVDF membranes.

- Probe with anti-ubiquitin and substrate-specific antibodies.

- Use phosphoprotein staining (e.g., Pro-Q Diamond) to confirm phosphoribosyl linkage [16].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for in vitro PR-ubiquitination and deubiquitination assays.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating PR-Ubiquitination

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features/Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity Enrichment Tools | Catalytically inactive DupA mutant | Trapping endogenous PR-ubiquitinated substrates | High affinity for PR-ubiquitin; no hydrolysis [16] |

| OtUBD affinity resin | Enriching ubiquitinated proteins from lysates | High-affinity ubiquitin-binding domain; works with various ubiquitin conjugates [19] | |

| Biochemical Reagents | Recombinant SidE family effectors | In vitro ubiquitination assays | Requires both mART and PDE domains for full activity [16] [20] |

| Recombinant DupA/DupB | Deubiquitination controls and specificity tests | Specific for PR-ubiquitin; cannot cleave canonical ubiquitination [16] | |

| Detection Reagents | Anti-ubiquitin antibodies (P4D1, E4J12) | Immunoblotting of ubiquitinated species | Recognize ubiquitin but cannot distinguish linkage types [19] |

| Phosphoprotein staining solutions | Confirming phosphoribosyl linkage | Stains PR-Ub but not canonical ubiquitin [16] | |

| Cell Culture Models | Macrophage infection systems | Physiological relevance studies | Primary macrophages or cell lines (e.g., THP-1) support Legionella replication [16] [17] |

| Legionella Strains | Wild-type and ΔSidE mutants | Functional studies of PR-ubiquitination | Compare phenotypes with and without SidE effectors [16] [17] |

Technical Considerations and Applications in Drug Discovery

Methodological Challenges

- Specificity Issues: Conventional ubiquitin enrichment methods (e.g., TUBEs, diGly antibody-based proteomics) often fail to detect PR-ubiquitination due to distinct chemistry and linkage [2] [19].

- Stability Concerns: PR-ubiquitin linkages may be labile under certain pH and temperature conditions, requiring optimized lysis buffers.

- Dynamic Range: PR-ubiquitinated substrates may be low-abundance compared to canonical ubiquitination, necessitating highly sensitive enrichment strategies.

Translational Applications

The unique mechanistic aspects of PR-ubiquitination present attractive opportunities for therapeutic intervention:

- Target Specificity: Bacterial enzymes with distinct mechanisms from host machinery offer potential for selective inhibition with reduced off-target effects.

- Anti-virulence Strategies: Inhibiting SidE effectors or their regulators (DupA/B, LnaB, MavL) could disarm the pathogen without imposing direct lethal pressure, potentially reducing resistance development.

- Chemical Probe Development: The well-defined structural features of SidE catalytic pockets (mART and PDE domains) enable rational design of small-molecule inhibitors.

The protocols and tools outlined herein provide a foundation for systematic investigation of PR-ubiquitination in bacterial pathogenesis and the development of novel anti-infective strategies targeting this unique non-canonical signaling mechanism.

The ubiquitin system, a crucial regulator of eukaryotic cellular physiology, has expanded beyond its traditional role of modifying protein lysine residues. Non-canonical ubiquitination involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to non-proteinaceous substrates and non-lysine amino acids, creating a complex layer of regulatory capacity within cells [21] [11]. This expansion encompasses modifications of lipids, carbohydrates, nucleic acids, and even small molecule drugs, significantly diversifying the functional scope of ubiquitin signaling [21] [5]. Understanding the enzymatic players driving these unconventional modifications—specifically E2 conjugating enzymes and E3 ligases—provides critical insights for developing novel detection methodologies and therapeutic strategies. This application note details the key E2 and E3 enzymes involved in non-canonical conjugation, presents quantitative data on their activities, and provides standardized protocols for their study in vitro and in cellular contexts, framed within the broader research on detection methods for non-canonical ubiquitination.

Key Enzymatic Players in Non-Canonical Ubiquitination

The enzymatic cascade of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes facilitates non-canonical ubiquitination. While E1 enzymes activate ubiquitin universally, specific E2 and E3 combinations determine substrate specificity and the nature of the ubiquitin linkage formed.

Table 1: E2 Conjugating Enzymes in Non-Canonical Ubiquitination

| E2 Enzyme | Reactive Residues/Substrates | Key Features | Characterized Bond Type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBE2Q1 | Serine, Threonine, Glycerol, Glucose, Maltoheptaose | Lacks canonical HPN triad; extended N-terminus; E3-independent activity | Oxyester bond | [22] |

| UBE2Q2 | Serine, Threonine, Glycerol, Glucose | Similar to UBE2Q1; shows comparable reactivity toward Ser/Thr | Oxyester bond | [22] |

| UBE2J2 | Serine, Glycerol, Glucose, Maltoheptaose | Reacts with serine and lysine, but not threonine | Oxyester bond | [22] |

| UBE2L3 | N-GlcNAc (with SCFFBS2-ARIH1) | RBR-specific E2; required for ubiquitinating N-GlcNAc on Nrf1 | Oxyester bond | [21] [23] |

Table 2: E3 Ligases in Non-Canonical Ubiquitination

| E3 Ligase | Type | Non-Canonical Substrates | Partner E2(s) | Linkage/Bond | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOIL-1 | RBR | Glycogen, unbranched glucosaccharides (e.g., Maltoheptaose) | Not specified | Oxyester bond (C6-OH of glucose) | [21] |

| SCFFBS2-ARIH1 | RBR (ARIH1) | N-GlcNAc on Nrf1, Serine/Threonine | UBE2L3 | Oxyester bond | [21] [23] |

| RNF213 | RING | Lipid A moiety of bacterial LPS | Not specified | Ester bond (alkaline-sensitive) | [21] |

| HUWE1 | HECT | Drug-like small molecules (e.g., BI8622, BI8626) | UBE2L3, UBE2D3 | Isopeptide bond (to primary amine) | [5] |

| Tul1 | RING | Phosphatidylethanolamines (PE) | Ubc4 | Amide bond | [21] |

The diagram below illustrates the complex coordination between E2 and E3 enzymes in catalyzing non-canonical ubiquitination of diverse substrates.

Quantitative Profiling of Enzyme Activities

Systematic profiling of non-canonical E2 and E3 activities reveals distinct substrate preferences and catalytic efficiencies. Quantitative assays are indispensable for characterizing these enzymes and developing sensitive detection methods.

Table 3: Relative Discharge Activity of Non-Canonical E2 Enzymes

| E2 Enzyme | Lysine | Serine | Threonine | Glycerol | Glucose | Maltoheptaose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBE2Q1 | + + | + + + | + + + + | + + + | + + + | + + + + |

| UBE2Q2 | + | + + + | + + + | + + + | + + + | N/D |

| UBE2J2 | + + + | + + + | - | + + + | + + + | + + |

| UBE2D3 | + + + + | - | - | - | - | N/D |

| UBE2L3 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Activity levels are relative, based on data from MALDI-TOF discharge assays. + + + + indicates the highest activity; - indicates no detectable activity; N/D indicates no data available. Note: UBE2L3 shows no intrinsic discharge activity but is crucial for E3-dependent non-canonical ubiquitination [22].

Table 4: Characterization of Non-Canonical E3 Ligase Activities

| E3 Ligase | Complex | Key Non-Canonical Substrate | Cellular Function / Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| HOIL-1 | LUBAC | Unbranched glucosaccharides | Prevents polyglucosan deposits in mice [21] |

| SCFFBS2-ARIH1 | with UBE2L3 | N-GlcNAc on Nrf1 | Inhibits DDI2-mediated Nrf1 activation [23] |

| RNF213 | Monomeric / Complex | Lipid A (LPS) | Forms bacterial ubiquitin coat on S. Typhimurium [21] |

| HUWE1 | with UBE2L3/UBE2D3 | BI8622/BI8626 (small molecules) | Ubiquitinates primary amine on drug-like compounds [5] |

| Tul1 | with Ubc4 | Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) | Conserved in mammals; role in membrane curvature [21] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standardized protocols are essential for the reproducible study of non-canonical ubiquitination. Below are detailed methodologies for key assays, designed to be integrated into a pipeline for detecting and validating these unconventional modifications.

Protocol 1: MALDI-TOF MS-Based E2 Discharge Assay

This protocol identifies E2 enzymes capable of discharging ubiquitin onto hydroxyl-containing nucleophiles and is ideal for initial screening [22].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Recombinant E2 Enzymes: 23 human E2s, purified (e.g., UBE2Q1, UBE2J2).

- Nucleophile Panel: Acetyl-lysine (Ac-K), Acetyl-serine (Ac-S), Acetyl-threonine (Ac-T), Glycerol, Glucose (50 mM final in reaction).

- Ubiquitin and Internal Standard: Unlabeled ubiquitin and 15N-labeled ubiquitin for quantification.

- Reaction Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM ATP.

Procedure:

- E2~Ub Thioester Formation: In a 20 µL reaction volume, incubate 250 nM E1, 2.5 µM E2, 50 µM Ub, and 2 mM ATP in reaction buffer for 10 minutes at 30°C to form the E2~Ub intermediate.

- Nucleophile Discharge: Add one of the nucleophiles (Ac-S, Ac-T, Glucose, etc.) to a final concentration of 50 mM. Incubate the reaction for 1 hour at 30°C.

- Reaction Quenching: Stop the reaction by adding 1 µL of 20% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA).

- MS Analysis and Quantification:

- Desalt the samples using C4 ZipTips.

- Spot onto a MALDI target plate with α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) matrix.

- Acquire spectra on a MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer in positive ion mode.

- Identify ubiquitin-adduct peaks (Ub + nucleophile mass). Use the 15N-ubiquitin internal standard for absolute and relative quantification of discharge products.

Technical Notes: The ester bonds formed on hydroxyl-groups are labile. Avoid basic conditions (pH > 8.5) during sample preparation to prevent hydrolysis. Include UBE2D3 as a canonical (lysine-specific) control and UBE2L3 as a negative control.

Protocol 2: Reconstitution of Glycoprotein Ubiquitination

This protocol outlines the steps for in vitro ubiquitination of a glycoprotein substrate, specifically Nrf1, by the SCFFBS2-ARIH1-UBE2L3 complex [21] [23].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Enzyme Complex: Recombinant SCFFBS2 complex, ARIH1, and UBE2L3.

- Glycoprotein Substrate: N-terminal fragment of Nrf1 (Nrf1-NT) or synthetic glycopeptides.

- ENGASE Enzyme: Endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase to generate N-GlcNAc acceptor sites.

- Ubiquitination Mix: E1 enzyme (UBA1), Ubiquitin, ATP regeneration system (ATP, Creatine Phosphate, Creatine Kinase).

Procedure:

- Substrate Pre-treatment (Deglycosylation): To generate N-GlcNAc sites, incubate the glycoprotein substrate (e.g., 1 µM Nrf1) with ENGASE (e.g., 100 nM) in a compatible buffer (e.g., PBS) for 1 hour at 37°C.

- Ubiquitination Reaction Assembly:

- Combine the following in a 30 µL reaction volume:

- Pre-treated substrate (e.g., 1 µM final)

- SCFFBS2 (e.g., 100 nM), ARIH1 (e.g., 100 nM), UBE2L3 (e.g., 1 µM)

- E1 (50 nM), Ub (10 µM), and ATP regeneration system (2 mM ATP, 10 mM CP, 20 ng/µL CK)

- Reaction Buffer: 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl₂, 0.5 mM DTT

- Incubate the reaction at 30°C for 2 hours.

- Combine the following in a 30 µL reaction volume:

- Reaction Termination and Analysis:

- Stop the reaction by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer containing DTT (to reduce thioesters) or β-mercaptoethanol.

- Analyze by SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting using anti-ubiquitin and anti-substrate antibodies.

- For linkage type confirmation, treat samples with 1 M hydroxylamine (pH 8.5) for 2 hours at 45°C to cleave oxyester-linked ubiquitin, or with the specific DUB JOSD1 [22].

Technical Notes: The use of UBE2L3 is critical as it is the RBR-specific E2 for ARIH1. Hydroxylamine sensitivity is a key indicator of oxyester bond formation. Always include a control without E3 to assess E2-independent activity.

Protocol 3: Cellular Detection of Small Molecule Ubiquitination

This protocol describes methods to detect the ubiquitination of drug-like small molecules (e.g., BI8626) in a cellular context [5].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Compound: BI8626 or derivative with a primary amino group.

- Cell Line: HEK293T or other relevant cell line (e.g., HCT116).

- Plasmids: For expression of HUWE1 (full-length or HECT domain).

- Lysis & Detection Buffer: RIPA buffer supplemented with DUB inhibitors (e.g., 10 µM PR-619) and protease inhibitors. Anti-Ub antibody for immunoprecipitation.

Procedure:

- Cell Transfection and Treatment:

- Transfect cells with a plasmid expressing HUWE1FL or an empty vector control.

- 24-48 hours post-transfection, treat cells with the compound (e.g., 10-50 µM BI8626) for 2-4 hours.

- Cell Lysis and Compound Enrichment:

- Lyse cells in RIPA buffer with inhibitors.

- Clarify lysates by centrifugation.

- Option A (SEC): Fractionate the lysate by Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) using a Superdex Increase 200 column. Monitor compound absorbance at 320-400 nm where proteins do not absorb.

- Option B (IP/LC-MS): Immunoprecipitate ubiquitinated species using an anti-Ub antibody. Elute and analyze by LC-MS.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Analyze SEC fractions or IP eluates by LC-MS/MS.

- For Ub-modified compound detection, monitor for a mass shift corresponding to Ub (≈8.6 kDa) + compound mass (e.g., +422.23 Da for BI8626) or look for signature Ub-derived peptides modified with the compound after proteolytic digestion (e.g., with LysC).

Technical Notes: Compound ubiquitination may be low in abundance. SEC is advantageous as it separates small molecule conjugates from the bulk of cellular proteins. The primary amine on the compound is essential for this reaction; confirm its requirement using amine-lacking derivatives as negative controls.

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow for characterizing non-canonical ubiquitination, integrating the protocols described above.

The Scientist's Toolkit

A curated set of research reagents and tools is fundamental for experimental success in this field.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Non-Canonical Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Utility | Example Use Case | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| UBE2Q1/2 Proteins | Identify E2s with intrinsic Ser/Thr/sugar ubiquitination activity. | Initial screening for non-canonical E2 activity [22]. | E3-independent discharge activity. |

| HUWE1HECT Protein | Study ubiquitination of small molecule drugs. | Probe HUWE1 substrate scope and inhibition [5]. | Modifies primary amines on compounds. |

| JOSD1 DUB | Selective cleavage of oxyester-linked ubiquitin. | Confirm non-lysine ubiquitination on Ser/Thr [22]. | Linkage-specific deubiquitinase. |

| Hydroxylamine | Chemical cleavage of ester/oxyester bonds. | Distinguish oxyester from isopeptide linkages [22]. | pH-dependent hydrolysis. |

| 15N-Ubiquitin | Internal standard for MS quantification. | Quantify ubiquitin discharge in MALDI-TOF assays [22]. | Allows absolute quantification. |

| ENGASE Enzyme | Generates N-GlcNAc residues from N-glycans. | Create acceptor sites for SCFFBS2-ARIH1 [23]. | Prerequisite for N-GlcNAc ubiquitination. |

| BI8626/BI8622 Compounds | Substrates and substrate-competitive inhibitors of HUWE1. | Study E3-substrate interactions and kinetics [5]. | Contain a critical primary amine. |

Concluding Remarks

The expanding landscape of non-canonical ubiquitination, mediated by specialized E2 and E3 enzymes, represents a significant frontier in cell signaling and drug discovery. The enzymatic players detailed here—including the UBE2Q family, HOIL-1, SCFFBS2-ARIH1, and HUWE1—highlight the mechanistic diversity of this system, targeting substrates from complex sugars to small molecule drugs. The standardized application notes and protocols provided herein for in vitro and cellular detection form a critical foundation for ongoing research. Further development of highly specific substrates, inhibitors, and detection reagents, particularly against these non-canonical enzymatic targets, will unlock deeper functional insights and potential therapeutic applications.

Advanced Methodologies for Mapping the Non-Canonical Ubiquitinome

The study of non-canonical ubiquitination, a rapidly expanding frontier in proteomics, presents unique challenges for the isolation and detection of target proteins. Unlike canonical ubiquitination that occurs on lysine residues, non-canonical forms involve ubiquitin conjugation to protein N-termini or cysteine, serine, and threonine residues through distinct chemical bonds. These modifications regulate diverse cellular processes including protein degradation, localization, and activity, but their low abundance and labile nature complicate purification. This application note details optimized protocols using His-tag and Strep-tag affinity purification strategies specifically tailored for the capture and study of non-canonically ubiquitinated proteins, providing researchers with robust methodologies to advance understanding of this complex post-translational modification system.

Ubiquitination is a dynamic post-translational modification that regulates virtually all cellular processes by modulating protein function, localization, interactions, and turnover [2] [1]. While canonical ubiquitination involves conjugation of ubiquitin to lysine residues via an isopeptide bond, non-canonical ubiquitination expands this regulatory landscape through modification of alternative amino acid sites [2]. These non-canonical forms include: (1) N-terminal ubiquitination through peptide bonds to the α-amino group of protein N-termini; (2) thioester-based linkages to cysteine residues; and (3) oxyester bonds to serine or threonine residues [2] [1].

The biological significance of non-canonical ubiquitination is increasingly recognized. N-terminal ubiquitination targets proteins such as Ngn2, p14ARF, and p21 for degradation, alters deubiquitinating enzyme activity, and delays aggregation of amyloid proteins associated with neurodegenerative disorders [1]. Furthermore, pathogens like Legionella pneumophila have evolved unique forms of non-canonical ubiquitination, such as phosphoribosyl-linked serine ubiquitination, to hijack host cell processes [2]. Despite these important functions, non-canonical ubiquitination remains challenging to detect due to the lower abundance of modified proteins and the chemical lability of some linkages, particularly thioester and oxyester bonds [2] [1]. Effective purification strategies are therefore essential for advancing research in this field.

Affinity Tag Selection for Ubiquitination Studies

Comparative Properties of His and Strep Tags

The selection of an appropriate affinity tag is critical for successful purification of ubiquitinated proteins. The table below compares key characteristics of His and Strep tags:

Table 1: Comparison of His-tag and Strep-tag Properties for Protein Purification

| Property | His-tag | Strep-tag |

|---|---|---|

| Tag Composition | Typically 6-10 consecutive histidine residues | Short peptide (WSHPQFEK) |

| Tag Size | Small (~0.8 kDa for 6xHis) | Small (~1 kDa) |

| Binding Ligand | Immobilized metal ions (Ni²⁺, Co²⁺) | Strep-Tactin (engineered streptavidin) |

| Binding Mechanism | Coordinate covalent bonds | High-affinity molecular recognition |

| Elution Conditions | Imidazole or low pH | Desthiobiotin |

| Purification Cost | Low | Moderate |

| Purity from Complex Extracts | Moderate to low [24] | High [24] |

| Impact on Protein Function | Possible [25] | Possible [25] |

Tag Selection Considerations for Non-Canonical Ubiquitination Research

For research on non-canonical ubiquitination, several factors favor the use of Strep-tag systems. The high specificity of Strep-tag/Strep-Tactin interaction minimizes co-purification of endogenous proteins, which is particularly valuable when studying low-abundance ubiquitinated species [26]. This system maintains function under physiological buffer conditions, preserving labile non-canonical ubiquitin linkages that may be sensitive to harsh conditions [26]. While His-tags offer cost advantages and high binding capacity, they demonstrate only moderate purity from E. coli extracts and relatively poor purification from more complex eukaryotic extracts [24] [27], limiting their utility for studying endogenous non-canonical ubiquitination in mammalian systems.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Affinity Tags Across Expression Systems

| Affinity Tag | E. coli Extracts | Yeast Extracts | Drosophila Extracts | HeLa Extracts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| His-tag | Moderate purity | Relatively poor purification | Relatively poor purification | Relatively poor purification |

| Strep-tag II | Excellent purification | Good purification | Good purification | Good purification |

| FLAG-tag | High purity | High purity | High purity | High purity |

| GST-tag | Good yield | Moderate purity | Moderate purity | Moderate purity |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for His-tag and Strep-tag Purification

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Strep-TactinXT 4Flow Resin | High-capacity affinity matrix for Strep-tag purification | Compatible with a wide range of buffer conditions; suitable for labile non-canonical ubiquitin conjugates |

| Ni-NTA Agarose | Immobilized metal affinity chromatography resin for His-tag purification | Cost-effective for high-yield purification; prone to nonspecific binding in complex lysates |

| Printed Monolith Adsorption (PMA) Columns | 3D-printed monolithic structures with IMAC functionality | Enables rapid purification (≈3 mg/mL dynamic binding capacity) from crude lysate [28] |

| Desthiobiotin | Competitive ligand for elution from Strep-Tactin | Gentle elution under physiological conditions preserves protein function and labile modifications |

| Imidazole | Competitive ligand for elution from IMAC resins | Can require optimization of concentration for specific elution; may denature labile ubiquitin conjugates |

| Protease Cleavage Reagents | Removal of affinity tags after purification | TEV, PreScission, or SUMO proteases; critical when tags interfere with protein function |

Experimental Protocols

Strep-tag Based Purification of Ubiquitinated Proteins

This protocol is optimized for the purification of non-canonically ubiquitinated proteins, preserving labile thioester and oxyester linkages.

Materials and Buffers

- Strep-TactinXT 4Flow high capacity resin (IBA Lifesciences)

- Lysis Buffer: 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 1x Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (add 1 mM PMSF and 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide immediately before use to preserve ubiquitin conjugates)

- Wash Buffer: 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA

- Elution Buffer: Wash Buffer supplemented with 50 mM desthiobiotin

Detailed Procedure

Cell Lysis: Resuspend cell pellet (from 1L culture) in 25 mL ice-cold Lysis Buffer. Lyse cells by sonication (3 pulses of 30 seconds each at 40% amplitude) or using a mechanical homogenizer. Maintain samples at 4°C throughout the procedure.

Clarification: Centrifuge lysate at 20,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Transfer supernatant to a fresh tube, avoiding the lipid layer and pellet.

Column Preparation: Pack 2 mL of Strep-TactinXT 4Flow resin into a suitable chromatography column. Equilibrate with 10 column volumes (CV) of Wash Buffer.

Sample Loading: Apply clarified lysate to the column at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Collect flow-through for analysis.

Washing: Wash column with 10-15 CV of Wash Buffer until A280 stabilizes at baseline. Monitor by UV absorbance at 280 nm.

Elution: Apply 5 CV of Elution Buffer. Collect 1 mL fractions and monitor A280 to identify protein peaks.

Characterization: Analyze fractions by SDS-PAGE and western blotting using ubiquitin-specific antibodies. For non-canonical ubiquitination analysis, include controls with hydroxylamine treatment (100 mM, pH 9.0, 1 hour) to detect thioester linkages, which are labile under these conditions.

Diagram 1: Strep-tag purification workflow for ubiquitinated proteins.

His-tag Based Purification Using Printed Monolith Adsorption

This protocol leverages recent advances in 3D-printed monolith adsorption (PMA) technology for rapid purification of His-tagged ubiquitination complexes [28].

Materials and Buffers

- IMAC-functionalized PMA columns (3D-printed with iminodiacetic acid ligand)

- Lysis Buffer: 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4), 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10 mM imidazole, 1x Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail

- Wash Buffer: 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4), 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole

- Elution Buffer: 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4), 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole

Detailed Procedure

Column Preparation: Equilibrate IMAC-functionalized PMA column with 5 CV of Lysis Buffer.

Sample Preparation: Lysate cells in Lysis Buffer (5 mL per gram cell pellet) by sonication. Centrifuge at 15,000 × g for 20 minutes to clarify.

Direct Purification: Load clarified lysate directly onto the pre-equilibrated PMA column at a flow rate of 1 mL/min.