Bridging the Gap: A Researcher's Guide to Artifacts in Ubiquitin Detection and Validation

Accurate detection and quantification of ubiquitination are paramount for advancing our understanding of this crucial post-translational modification in health and disease.

Bridging the Gap: A Researcher's Guide to Artifacts in Ubiquitin Detection and Validation

Abstract

Accurate detection and quantification of ubiquitination are paramount for advancing our understanding of this crucial post-translational modification in health and disease. However, the multivalent nature of ubiquitin chains makes ubiquitination assays particularly susceptible to method-specific artifacts, such as avidity-based 'bridging,' which can lead to significant overestimation of binding affinity and incorrect conclusions about specificity. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, addressing the foundational concepts of ubiquitination complexity, current methodological approaches for detection and enrichment, practical strategies for identifying and troubleshooting common artifacts, and robust frameworks for experimental validation. By synthesizing the latest research and protocols, we aim to empower scientists to design more reliable ubiquitination studies and generate data that accurately reflects biological reality, thereby strengthening the foundation for future therapeutic interventions targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

Deconstructing the Ubiquitin Code: Complexity and Sources of Artifacts

Conceptual FAQs: Understanding the Ubiquitination Cascade

What is the ubiquitin conjugation cascade? The ubiquitin conjugation cascade is a three-step enzymatic pathway that attaches the small protein ubiquitin to substrate proteins, thereby modifying their function, location, or stability. The process is sequentially catalyzed by ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), and ubiquitin ligases (E3) [1]. This modification, known as ubiquitylation, is a crucial post-translational mechanism that regulates nearly all biological processes in eukaryotic cells, including protein degradation, DNA repair, and cell signaling [1] [2].

Why is E2-E3 selectivity so important? E2-E3 selectivity is a critical determinant of the functional outcome of ubiquitylation. Although the structural interfaces between E2s and RING/U-box E3s are often conserved, only specific E2-E3 pairings produce productive ubiquitination [3]. The identity of the E2 enzyme influences the type of ubiquitin chain linkage formed on the substrate, which in turn dictates whether the substrate is targeted for degradation or involved in non-proteolytic signaling events [3]. This specificity ensures the precise regulation of diverse cellular pathways.

What are the different types of ubiquitin chains and what do they do? Ubiquitin chains are classified based on which of the seven lysine residues or the N-terminal methionine in one ubiquitin molecule is linked to the C-terminus of the next. The type of linkage creates a unique "code" that determines the fate of the modified protein [1] [4].

Table: Ubiquitin Chain Linkages and Their Primary Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Known Functions |

|---|---|

| K48-linked | The most abundant type; primarily targets substrates for degradation by the 26S proteasome [1]. |

| K63-linked | Mainly involved in non-degradative signaling, such as DNA damage repair, cytokine signaling, and endocytosis [1]. |

| M1-linked (Linear) | Catalyzed by the LUBAC complex; crucial for activating the NF-κB signaling pathway in inflammatory and immune responses [1]. |

| K11-linked | Implicated in cell cycle regulation and proteasomal degradation [1]. |

| K6, K27, K29, K33-linked | "Atypical" chains involved in diverse processes including DNA damage repair, innate immune response, and intracellular trafficking [1]. |

Are there exceptions to the standard three-enzyme cascade? Yes, a notable exception is the E2/E3 hybrid enzyme. Enzymes like UBE2O and BIRC6 possess both E2 and E3 functionalities within a single polypeptide, allowing them to catalyze the transfer of ubiquitin to substrates without requiring a separate E3 ligase [2]. These hybrid enzymes employ a distinct mechanism, often requiring dimerization and specific inter-domain interactions for their activity [2].

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Loss of Ubiquitin Signal During Immunoblotting

Potential Cause: Inadequate inhibition of Deubiquitylases (DUBs) during cell lysis and protein preparation. DUBs are enzymes that rapidly reverse ubiquitination, and their activity can erase the ubiquitination state that existed in the living cell [4].

Solutions:

- Use potent DUB inhibitors: Include high concentrations (up to 50-100 mM) of alkylating agents like N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) or Iodoacetamide (IAA) in your lysis buffer [4]. For preserving K63- and M1-linked chains, NEM is often superior to IAA [4].

- Include metal chelators: Add EDTA or EGTA to chelate heavy metal ions required by metalloprotease-family DUBs [4].

- Rapid denaturation: Lyse cells directly in boiling SDS buffer to instantly denature and inactivate all DUBs [4].

- Consider mass spectrometry: If planning to identify ubiquitylation sites via mass spectrometry, prefer NEM over IAA, as the IAA adduct can interfere with the detection of the diagnostic Gly-Gly remnant on lysines [4].

Problem: Poor Resolution of Polyubiquitin Chains on SDS-PAGE

Potential Cause: Using a suboptimal gel and buffer system for separating the molecular weight range of interest. Ubiquitin monomers are ~8.5 kDa, and chains can extend well over 200 kDa, often appearing as smears rather than discrete bands [4].

Solutions:

- Match the buffer to the chain length: Use MES buffer for better resolution of short ubiquitin oligomers (2-5 ubiquitins). Use MOPS buffer for improved resolution of longer chains (8+ ubiquitins) [4].

- Use high-percentage gels for monomers: To detect mono-ubiquitylation or very short chains, use gels with around 12% acrylamide [4].

- Use low-percentage or gradient gels for long chains: For resolving long polyubiquitin chains, use a single-concentration gel around 8% acrylamide or a gradient gel with Tris-Acetate (TA) buffer, which is superior for the 40-400 kDa range [4].

Problem: Inability to Detect Ubiquitylated Substrates

Potential Cause: The ubiquitylated form of your protein is unstable and rapidly degraded by the proteasome. This is especially true for substrates modified with K48-linked and other proteasome-targeting chains [4].

Solutions:

- Inhibit the proteasome: Treat cells with proteasome inhibitors like MG132 prior to lysis. This blocks degradation and allows ubiquitylated proteins to accumulate, facilitating their detection [4].

- Use capture tools: Employ Tandem-repeated Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) during immunoprecipitation. TUBEs bind all ubiquitin linkage types with high affinity and shield the chains from DUBs during the pull-down process [4].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Preserving the Ubiquitylation State for Immunoblotting

This protocol is optimized to maintain the in vivo ubiquitylation status of proteins from the moment of cell lysis [4].

Prepare Lysis Buffer:

- 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5

- 150 mM NaCl

- 1% NP-40 (or other detergent)

- 50-100 mM NEM (freshly added)

- 10 mM EDTA (freshly added)

- 1x Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (without EDTA)

Cell Lysis:

- Aspirate culture media and immediately add cold lysis buffer to the cells.

- Scrape and transfer the lysate to a microcentrifuge tube.

- Vortex briefly and incubate on ice for 10-30 minutes.

Clarification:

- Centrifuge the lysate at >15,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- Transfer the supernatant to a new tube. The sample is now ready for standard immunoblotting or immunoprecipitation.

Protocol: In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

This is a foundational protocol for reconstituting ubiquitination activity with purified components [3].

Assay Setup:

- Combine the following components in a reaction tube on ice:

- 40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5

- 5 mM MgCl₂

- 100 mM NaCl

- 1 mM DTT

- 5 mM ATP

- Combine the following components in a reaction tube on ice:

Enzyme and Substrate Addition:

- Add the following proteins in sequence:

- 10 µM Ubiquitin

- 75 nM E1 activating enzyme

- 0.6 µM E2 conjugating enzyme

- 0.5 µM E3 ligase (e.g., CHIP)

- Substrate protein (concentration variable)

- Adjust the final volume with distilled water.

- Add the following proteins in sequence:

Incubation:

- Incubate the reaction at 30°C for 1 hour.

Reaction Termination and Analysis:

- Stop the reaction by adding 4x SDS-PAGE loading buffer (with DTT or BME to reduce thioester bonds).

- Boil the samples for 5-10 minutes.

- Analyze the products by immunoblotting using an anti-ubiquitin antibody or an antibody against your substrate.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitination Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | Alkylating agent; irreversible inhibitor of cysteine-based DUBs. | More effective than IAA for preserving K63/M1 chains; compatible with MS [4]. |

| MG132 / Proteasome Inhibitors | Blocks 26S proteasome; stabilizes K48- and other proteasome-targeted ubiquitylated proteins. | Prevents degradation of substrates; can induce stress responses in long incubations [4]. |

| TUBEs (Tandem-repeated Ubiquitin-Binding Entities) | High-affinity ubiquitin "traps"; used for enriching and protecting ubiquitylated proteins from DUBs during IP. | Captures all linkage types; crucial for detecting low-abundance substrates [4]. |

| Linkage-Specific DUBs | Enzymes that selectively cleave one type of ubiquitin linkage (e.g., OTUB1 for K48). | Used as tools to deconvolute ubiquitin chain topology in samples [4]. |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies | Antibodies that recognize a specific ubiquitin linkage (e.g., K48-only, K63-only). | Allows for direct identification of chain type via immunoblotting. Quality and specificity vary by vendor. |

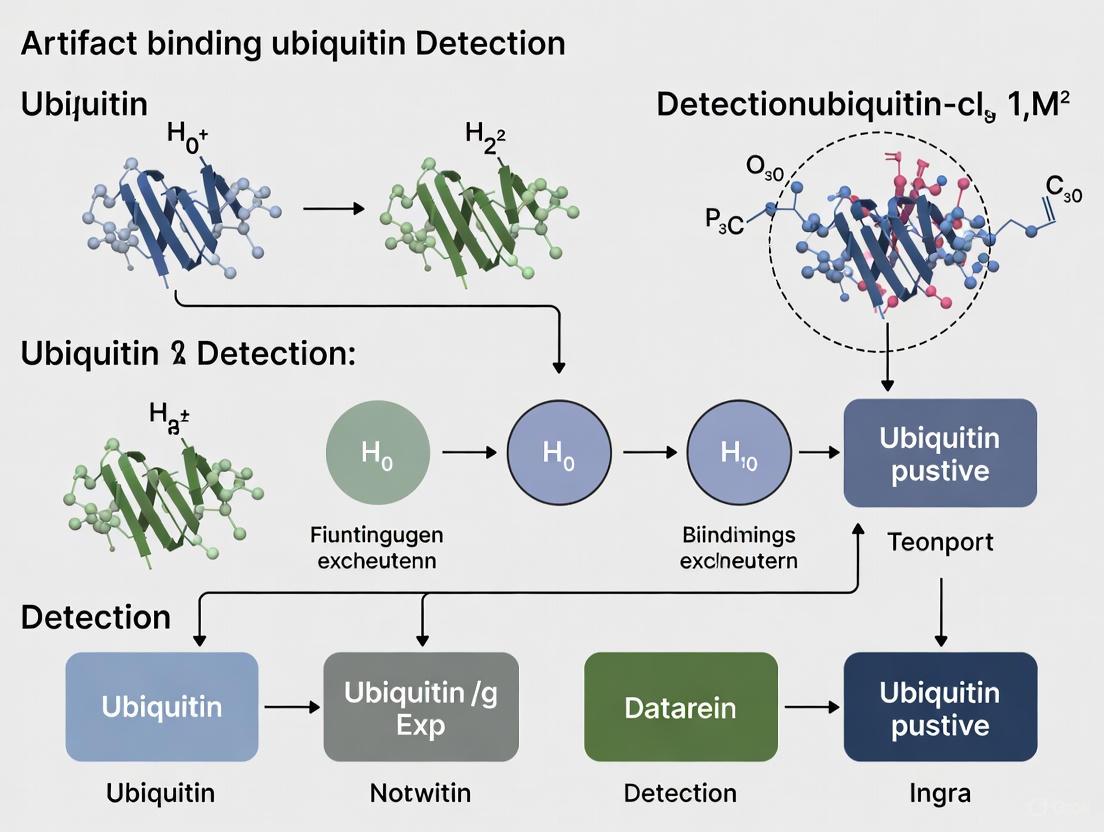

Visualizing the Pathways and Workflows

Ubiquitin Cascade Core Pathway

Experimental Workflow for Ubiquitin Detection

Ubiquitination is a fundamental post-translational modification that extends far beyond the well-characterized K48-linked chains that target proteins for proteasomal degradation. The ubiquitin code encompasses a diverse array of chain architectures, including homotypic chains, mixed chains, and complex branched structures, each capable of directing distinct cellular outcomes. This technical support center addresses the critical experimental challenges in accurately detecting and interpreting this complexity, with a particular focus on mitigating the artifact binding that can compromise research findings. The following guides and FAQs provide researchers with proven methodologies to enhance the reliability of their ubiquitin studies.

FAQ & Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Ubiquitin Detection Artifacts

Artifacts in ubiquitin research frequently arise from two primary sources: (1) Deubiquitinase (DUB) activity during sample preparation, which can remove ubiquitin modifications before analysis, and (2) Method-dependent avidity artifacts (bridging) in surface-based binding assays like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and Biolayer Interferometry (BLI), where the multivalent nature of polyubiquitin chains leads to artificially high affinity measurements due to simultaneous interactions with multiple immobilized binding elements [5] [4].

Troubleshooting: Preventing Deubiquitination During Sample Preparation

Problem: Loss of ubiquitin signal or inconsistent detection due to DUB activity after cell lysis. Solution: Implement a robust DUB inhibition strategy during cell lysis and subsequent processing [4].

- Key Reagents: Include both cysteine protease inhibitors (e.g., N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) or Iodoacetamide (IAA)) and chelating agents (e.g., EDTA or EGTA) in your lysis buffer to target all major DUB families.

- Optimal Concentrations: While 5-10 mM is common, some targets require higher concentrations (up to 50-100 mM) for complete preservation. NEM is often more effective than IAA at preserving K63- and M1-linked chains and is preferred for mass spectrometry applications as it does not interfere with Gly-Gly remnant identification [4].

- Protocol: Add inhibitors directly to chilled lysis buffer immediately before use. For critical experiments, validate efficacy by comparing ubiquitin pattern stability with and without inhibitors.

Table: DUB Inhibitors for Ubiquitin Preservation

| Inhibitor | Recommended Concentration | Target | Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | 10-100 mM | Cysteine-based DUBs | More stable; preferred for K63/M1 chains & MS | Irreversible alkylating agent |

| Iodoacetamide (IAA) | 10-100 mM | Cysteine-based DUBs | Light-sensitive (activity decays quickly) | Adds 114 Da adduct, problematic for MS |

| EDTA/EGTA | 1-10 mM | Metalloprotease DUBs | Removes essential metal cofactors | Standard component of most lysis buffers |

Troubleshooting: Identifying and Mitigating Bridging Artifacts in Binding Assays

Problem: Overestimation of binding affinity and incorrect linkage specificity conclusions in surface-based assays like BLI. Solution: Diagnose and minimize bridging through controlled experimental design [5].

- Diagnosis: Conduct experiments at varying levels of surface saturation (ligand density). A strong dependence of apparent affinity on surface density is indicative of bridging artifacts. A simple fitting model can be applied to quantify the severity of bridging [5].

- Mitigation:

- Reduce Ligand Density: Immobilize the ubiquitin-binding protein (ligand) at the lowest density that still provides a robust signal.

- Reverse Assay Orientation: Where possible, immobilize the monovalent component (e.g., a single ubiquitin-binding domain) and present the multivalent analyte (polyubiquitin chain) in solution.

- Validate with Solution Measurements: Correlate surface-based findings with solution-based techniques like Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC), which are not subject to bridging artifacts [5].

FAQ: How can I specifically capture and study K48- and K63-linked ubiquitination on endogenous proteins?

Chain-specific Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) offer a powerful solution. These are engineered affinity matrices with nanomolar affinity for polyubiquitin chains, which can be made selective for specific linkages (e.g., K48 or K63) or pan-selective [6].

- Application: In a 2025 study, K48-TUBEs specifically captured PROTAC-induced RIPK2 ubiquitination, while K63-TUBEs captured L18-MDP-induced RIPK2 ubiquitination, enabling clear differentiation of context-dependent signaling in high-throughput formats [6].

- Advantage: TUBEs protect ubiquitin chains from DUBs during the pull-down process and allow for the analysis of endogenous proteins without the need for overexpression or tagging [6] [4].

Advanced Methodologies: Synthesis and Detection of Branched Ubiquitin Chains

Branched ubiquitin chains, where a single ubiquitin moiety is modified at two or more lysine residues, represent a complex layer of regulation. For example, branched K11/K48 chains have been shown to possess a unique interdomain interface and exhibit enhanced affinity for the proteasomal subunit Rpn1, suggesting a role in promoting efficient degradation [7].

Experimental Protocol: Enzymatic Assembly of Branched Ubiquitin Trimers

This protocol outlines a standard method for generating defined branched ubiquitin trimers in vitro [8].

- Prepare Proximal Ubiquitin: Use a C-terminally truncated ubiquitin (Ub1–72) or a C-terminally blocked mutant (e.g., UbD77) as the foundation.

- First Ligation: Ligate a distal ubiquitin mutant (e.g., UbK48R,K63R) to a specific lysine (e.g., K63) on the proximal ubiquitin using linkage-specific enzymes (e.g., UBE2N/UBE2V1 for K63).

- Second Ligation: Ligate another distal ubiquitin mutant to a different lysine (e.g., K48) on the same proximal ubiquitin using a different set of enzymes (e.g., UBE2R1 or UBE2K for K48).

- Purification: Purify the resulting branched trimer using standard chromatography techniques.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chain-Specific TUBEs | Affinity enrichment of linkage-specific polyUb chains | Differentiating K48 vs. K63 ubiquitination of endogenous RIPK2 [6] | High affinity, DUB-resistant, linkage-selective |

| Linkage-Specific DUBs | Cleave specific ubiquitin linkages to confirm chain topology | Validating chain identity in immunoblot or pull-down experiments [4] | Serves as an enzymatic scissor for validation |

| Branched Ubiquitin Synthesis (Enzymatic/Chemical) | Production of defined branched chain architectures | Studying enhanced proteasomal targeting by K11/K48-branched chains [8] [7] | Enables functional study of complex ubiquitin signals |

| Activity-Based Probes | Label and detect active enzymes in the ubiquitin pathway | Profiling active DUBs in cell lysates [8] | Chemical tools for functional proteomics |

| P4D1 (Anti-pan ubiquitin Antibody) | Detect ubiquitinated proteins by Western Blot | Standard immunoblotting for total ubiquitin signal [9] | Well-characterized, widely used reagent |

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Immunoblotting for Ubiquitin Chain Resolution

Accurate detection by immunoblotting requires careful optimization of electrophoresis conditions [4].

- Gel and Buffer Selection:

- Short Chains (2-5 Ub): Use gradient gels with MES running buffer for superior resolution.

- Long Chains (8+ Ub): Use gradient gels with MOPS running buffer.

- Broad Range (40-400 kDa): Tris-Acetate (TA) buffers are ideal.

- Sample Preparation: Always lyse cells in the presence of DUB inhibitors (NEM/EDTA) as described above. For degradation-prone substrates, pre-treat cells with a proteasome inhibitor like MG132 (e.g., 10-20 µM for 4-6 hours) to stabilize ubiquitinated species [4].

- Transfer: For high molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins, use PVDF membranes and ensure complete transfer by validating the absence of signal remaining in the gel post-transfer [4].

What is method-based avidity "bridging" and how does it confound my ubiquitin-binding assays?

Method-based avidity "bridging" is an artifactual phenomenon that occurs when the multivalent nature of polyubiquitin chains interacts with ubiquitin-binding proteins that have been artificially affixed to a surface, such as in surface plasmon resonance (SPR) or other immobilized assay formats. This creates a method-dependent, non-physiological avidity effect that is distinct from biologically relevant avid interactions [10].

In this artifact, a single polyubiquitin chain can simultaneously bind to multiple immobilized ubiquitin-binding proteins, forming a "bridge." This leads to dramatic overestimations of binding affinity for specific polyubiquitin chain types and can result in incorrect conclusions about binding specificity [10]. The artifact is particularly problematic because it can make certain chain linkages appear to have much higher affinity than they actually possess in physiological conditions, potentially misleading research on ubiquitin-signaling pathways.

What practical steps can I take to identify bridging artifacts in my data?

To diagnose bridging artifacts, monitor your binding data for these characteristic signs [10]:

- Abnormally high apparent affinity: Binding affinities that are significantly stronger than expected based on biological context

- Specific linkage overestimation: Particular polyubiquitin chain types (e.g., K63-linked) show unexpectedly strong binding compared to others

- Non-physiological binding curves: Data that doesn't fit standard 1:1 binding models

- Immobilization-dependent effects: Binding characteristics that change dramatically based on which binding partner is immobilized

Additionally, researchers can apply a simple fitting model to quantitatively assess the severity of bridging artifacts in their data. This model helps determine whether artifacts can be minimized through experimental adjustments or whether alternative approaches are necessary [10].

What experimental strategies can mitigate bridging artifacts?

Several practical approaches can help minimize or eliminate bridging artifacts:

- Reverse immobilization orientation: If you immobilized the ubiquitin-binding protein, try immobilizing the polyubiquitin chains instead, or vice versa [10]

- Solution-based assays: Employ alternative techniques such as isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) or analytical ultracentrifugation that don't require surface immobilization [10]

- Use monovalent controls: Include monoubiquitin or other monovalent controls to establish baseline binding characteristics

- Optimize density: If immobilization is necessary, systematically vary the density of immobilized molecules to identify conditions that minimize multivalent interactions [10]

- Employ multiple methods: Validate key findings using at least two independent biochemical approaches with different potential artifact profiles

What alternative methodologies avoid surface immobilization entirely?

To completely circumvent bridging artifacts, consider these alternative approaches that don't require surface immobilization:

Ubiquitin-binding domain (UBD)-based enrichment: Tools like the OtUBD (a high-affinity ubiquitin-binding domain from Orientia tsutsugamushi) can enrich ubiquitinated proteins from solution under either native or denaturing conditions. The denaturing workflow (using buffers with SDS and ß-mercaptoethanol) specifically isolates covalently ubiquitinated proteins without associated interacting proteins [11].

Mass spectrometry-based ubiquitinome profiling: This approach enriches tryptic peptides containing the K-ε-GG (diglycine) remnant characteristic of ubiquitination sites. Advanced protocols can routinely identify over 23,000 diGly peptides from a single sample, providing deep coverage of the ubiquitinome without surface immobilization artifacts [12].

Solution-phase binding assays: Techniques like ITC, fluorescence polarization, and analytical ultracentrifugation characterize ubiquitin-binding interactions entirely in solution, eliminating surface-related artifacts [10].

Comparison of Ubiquitin Detection Methods and Artifact Risks

| Method | Principle | Primary Applications | Risk of Bridging Artifacts | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Immobilization (SPR, BLI) | Binding partner immobilized on surface | Affinity measurements, kinetics | High (method-dependent) | Bridging artifacts, overestimated affinity |

| UBD-based Enrichment (OtUBD) | Solution-phase binding with high-affinity UBD | Ubiquitinome profiling, interaction studies | Low (solution-based) | May co-enrich interacting proteins |

| diGly Proteomics (K-ε-GG) | Antibody enrichment of diGly remnant peptides | Ubiquitination site mapping | None (peptide-level) | Requires proteasome inhibition for depth |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Immunoaffinity with linkage-selective antibodies | Specific chain type detection | Moderate (if surfaces used) | Limited to characterized linkages |

How do I implement a bridging-resistant workflow for ubiquitin-binding studies?

The following optimized workflow systematically addresses bridging artifact risks:

Experimental Workflow to Mitigate Bridging Artifacts

Research Reagent Solutions for Artifact-Resistant Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Primary Function | Utility in Artifact Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| OtUBD Affinity Resin | Ubiquitin-binding domain | Enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins | Solution-based enrichment avoids immobilization artifacts [11] |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Antibodies (K48, K63, etc.) | Detection of specific ubiquitin linkages | Validate linkage specificity claims; use in solution [13] |

| K-ε-GG (diGly) Antibodies | Anti-modified peptide antibody | Enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides for MS | Peptide-level analysis eliminates avidity concerns [12] |

| Recombinant Ubiquitin Variants | Engineered proteins (K48, K63-only, etc.) | Specific linkage binding studies | Defined chain types for controlled experiments [10] |

| Ubiquitin-Trap Agarose | Nanobody-based resin | Pulldown of ubiquitin and ubiquitinated proteins | Ready-to-use solution for native or denaturing conditions [14] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (MG-132, Bortezomib) | Small molecule inhibitors | Increase ubiquitinated protein levels | Enhance signal for detection without affecting artifacts [14] [12] |

How can I distinguish true biological avidity from methodological bridging artifacts?

True biological avidity arises from multivalent interactions that occur in physiological contexts, such as when a protein with multiple ubiquitin-binding domains simultaneously engages a polyubiquitin chain. In contrast, methodological bridging is an experimental artifact caused by the assay configuration itself [10].

Key distinguishing characteristics:

- Biological avidity: Persists across multiple assay formats including solution-based methods; demonstrates physiological relevance; consistent with biological function

- Methodological bridging: Highly dependent on specific assay configuration (especially surface immobilization); disappears in solution-based assays; may show non-physiological linkage preferences

To validate that observed avidity is biological rather than methodological, always confirm key findings using a solution-based method such as ITC or analytical ultracentrifugation [10].

How Multivalency and Surface-Based Assays Skew Affinity Measurements

In ubiquitin detection research, obtaining accurate binding affinity measurements is paramount. A significant challenge in this field arises from the use of surface-based assays (like SPR and BLI) to study multivalent interactions, such as those involving polyubiquitin chains. These experimental conditions can introduce artifactual avidity, or "bridging," which leads to dramatic overestimations of binding affinity and incorrect conclusions about specificity [10]. This guide helps you diagnose, troubleshoot, and mitigate these artifacts to ensure the reliability of your data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between true avidity and method-based avidity artifacts?

- True Avidity: A biological phenomenon where a multivalent protein (e.g., a dimer) utilizes multiple binding sites to interact with a multivalent ligand (e.g., a polyubiquitin chain), resulting in a genuinely stronger, often functionally relevant, interaction [15].

- Method-Based Artifact (Bridging): An experimental artifact that occurs in surface-based assays when multiple immobilized proteins on a sensor surface simultaneously bind to a single multivalent ligand in solution. This creates an artificially strong, non-physiological interaction that does not reflect the true binding affinity [10].

2. Why do surface-based assays like SPR and BLI overestimate affinity for multivalent systems? These assays are vulnerable to two key issues:

- Re-binding: During the dissociation phase, a slowly-dissociating ligand can re-bind to a nearby free receptor on the densely packed surface instead of diffusing into the bulk solution. This results in an artificially slow observed off-rate (k~off~), which directly leads to an overestimation of affinity (K~D~ = k~off~/k~on~) [16].

- Cross-linking: At high surface densities, a single multivalent analyte (like a polyubiquitin chain) can act as a bridge, cross-linking multiple immobilized receptors. This creates an extremely stable complex that is difficult to dissociate, further skewing kinetic parameters [16].

3. My positive control shows expected affinity, but my experimental multivalent interaction seems unnaturally strong. Is this an artifact? Not necessarily, but it is a major red flag. True avid interactions can exhibit very high affinity. The key is to perform diagnostic controls, such as varying the density of the immobilized ligand. If the apparent affinity (K~D~) or the off-rate (k~off~) changes significantly with lower immobilization density, it strongly indicates that your measurement is confounded by a surface-based artifact [10] [17].

4. What are the best alternative methods to avoid these artifacts? To circumvent surface-based issues, consider in-solution techniques:

- Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC): Measures binding heat directly in solution, without immobilization. It is often considered a gold standard for affinity measurement and can provide information on stoichiometry [16] [18].

- Fluorescence Proximity Sensing (FPS): A surface-based method that immobilizes the target at a very low density on a DNA nanoswitch, maintaining it in a solution-like environment and minimizing re-binding and avidity effects [16].

- Microfluidic Diffusional Sizing (MDS): An in-solution method that detects binding by measuring changes in the hydrodynamic radius of a complex, requiring no immobilization or purification [18].

5. How can I be sure my binding measurement has reached equilibrium? You must systematically vary the incubation time until the fraction of bound complex shows no further change. The time required to reach equilibrium is highly dependent on concentration and the off-rate. For low-affinity interactions (high K~D~), equilibration can be milliseconds fast, while for high-affinity interactions (low K~D~), it can take hours. Always establish equilibration time at the low end of your concentration range, as it is slowest there [19].

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Mitigating Artifacts

Common Artifacts and Solutions

| Artifact/Symptom | Underlying Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overestimated Affinity (Slower k~off~) [16] | Re-binding of multivalent analyte to dense surface sites. | Vary ligand immobilization density; use low-density surfaces [17]. | Switch to in-solution methods (ITC, MDS) [18]; use low-density FPS [16]. |

| Bridging Artifact [10] | Single polyubiquitin chain cross-links multiple immobilized receptors. | Use a simple fitting model to diagnose severity [10]. | Reduce surface ligand density drastically; use monovalent controls. |

| Failure to Reach Equilibrium [19] | Incubation time too short for complex formation, especially at low concentrations. | Measure fraction bound over time; ensure no change at endpoint [19]. | Extend incubation time; determine equilibration time empirically. |

| Titration Regime Error [19] | Concentration of limiting component is too high relative to K~D~. | Vary the concentration of the limiting component to test for K~D~ shift [19]. | Ensure [Limiting Component] is ≤ 0.1 × K~D~ (or lower for precise work). |

| Low Signal-to-Noise for Small Binders [16] | Technical limitation of BLI with small peptides/molecules. | Compare signal amplitude to reference baseline. | Use more sensitive in-solution techniques like FPS or MST [16] [18]. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating Equilibrium Binding Measurements

This protocol, adapted from best practices for binding measurements [19], is essential for any affinity study.

1. Determine Equilibration Time

- Choose a concentration of the limiting binding component near its expected K~D~.

- Prepare multiple identical binding reaction mixtures.

- Measure the amount of complex formed at multiple time points (e.g., 1, 5, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes).

- Criteria for Success: The fraction bound reaches a plateau and does not change significantly over at least three consecutive time points. The time to reach this plateau is your required incubation time.

2. Control for the Titration Regime

- Perform your binding assay at multiple concentrations of the limiting component, spanning a range below and above the expected K~D~.

- Plot the observed K~D~ as a function of the limiting component's concentration.

- Criteria for Success: The fitted K~D~ value remains constant across different concentrations of the limiting component. If the K~D~ increases as the concentration of the limiting component decreases, your measurement is likely in the titration regime and is unreliable.

3. Test for Surface Artifacts (For SPR/BLI)

- Immobilize your ligand (e.g., the ubiquitin-binding protein) at multiple densities, spanning at least an order of magnitude (e.g., high, medium, low).

- Measure the binding kinetics (k~on~, k~off~) and affinity (K~D~) of your analyte (e.g., polyubiquitin) at each density.

- Criteria for Success: The kinetic and affinity parameters are consistent across different immobilization densities. A significant change in k~off~ or K~D~ with lower density indicates a method-based avidity artifact [10] [17].

Comparison of Biophysical Methods for Multivalent Interactions

Choosing the right tool is critical. The table below summarizes the performance of key technologies for studying multivalent interactions like those in ubiquitination.

| Method | Key Principle | Pros | Cons for Multivalent Systems | Sample Consumption (Relative) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPR / BLI [16] [18] | Immobilization-based real-time kinetics. | Label-free; high information content (kinetics). | Prone to re-binding & bridging artifacts [10] [16]. | High (SPR); Medium (BLI) |

| ITC [16] [18] | In-solution measurement of binding heat. | Gold standard for affinity; provides stoichiometry. | Low throughput; high protein consumption. | Very High |

| FPS [16] | Low-density surface immobilization via DNA. | Minimizes artifacts; resolves slow off-rates. | Requires specialized instrumentation. | Low |

| MDS [18] | In-solution measurement of size change. | No immobilization; works in complex matrices. | Does not directly provide kinetics. | Low |

| TRIC [16] | In-solution fluorescence-based affinity. | High-throughput; low sample consumption. | Limited dynamic range for very high affinity. | Very Low |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

This table lists essential materials and their functions for studying ubiquitination and mitigating artifacts.

| Item | Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Polyubiquitin Chains (Specific Linkages) | Define signaling outcomes (e.g., K48 for degradation, K63 for signaling) [20]. | Use well-characterized chains from reputable suppliers; linkage purity is critical. |

| Deubiquitinating Enzyme (DUB) Inhibitors | Stabilize transient ubiquitination by preventing deubiquitination [20]. | Add to lysis and reaction buffers to preserve ubiquitinated species. |

| Anti-Ubiquitin Antibodies | Detect ubiquitinated proteins via Western Blot or IP [20] [21]. | Select for specific linkages (e.g., K27-linkage specific) or pan-specificity. |

| NEDD8-Activating Enzyme (NAE) Inhibitor (e.g., MLN4924) | Inhibits neddylation, a ubiquitin-like pathway, to probe specific ubiquitination [20]. | A useful control to distinguish ubiquitination from other Ubl modifications. |

| Fluorescence Proximity Sensing (FPS) Biochip | Provides low-density, solution-like immobilization for kinetic studies [16]. | Minimizes avidity artifacts common in SPR/BLI for multivalent binders. |

Visualizing Artifact Mechanisms and Mitigation Strategies

Multivalent Binding Artifacts Diagram

Reliable Affinity Measurement Workflow

FAQ: Understanding and Identifying Bridging Artifacts

What is a "bridging artifact" in polyubiquitin-binding assays? A bridging artifact is a method-dependent avidity effect that can occur in surface-based biophysical techniques like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Biolayer Interferometry (BLI). It happens when a single polyubiquitin chain in solution simultaneously binds to two or more immobilized ubiquitin-binding proteins on the experimental surface, creating a non-physiological "bridge" that does not occur in solution-based biology [5] [10].

How does bridging differ from biologically relevant avidity? Bridging is an experimental artifact resulting from how proteins are immobilized on a surface, whereas biologically relevant avidity occurs when a single protein with multiple ubiquitin-binding elements recognizes a polyubiquitin chain through natural, physiologically relevant interactions. Bridging depends on surface saturation and the random proximity of immobilized ligands, while biological avidity is an intrinsic property of certain ubiquitin-binding proteins and can be observed in solution-based measurements [5].

What are the practical consequences of bridging artifacts? Bridging artifacts lead to dramatic overestimations of binding affinities—sometimes by orders of magnitude—which can result in incorrect conclusions about linkage specificity. This fundamentally skews understanding of ubiquitin-signaling pathways and may misdirect downstream research and drug development efforts [5].

What techniques are most susceptible to bridging artifacts? Surface-based techniques that require immobilization of one binding partner are particularly susceptible, including:

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

- Biolayer Interferometry (BLI) Any method where ubiquitin-binding proteins are affixed to a surface while polyubiquitin chains are in solution [5].

How can I visually identify potential bridging in my binding data? Potential bridging often presents with these characteristics:

- Extraordinarily high apparent affinity (low nM or pM Kd values)

- Steep, almost square-wave association curves

- Very slow dissociation rates that don't follow expected single-site kinetics

- Binding responses that increase disproportionately with surface loading density [5]

FAQ: Troubleshooting and Mitigation Strategies

What is the most effective way to minimize bridging artifacts? The most effective strategy is reducing surface loading density. By immobilizing your ubiquitin-binding protein at lower densities on the SPR or BLI sensor surface, you decrease the probability that a single polyubiquitin chain can simultaneously access multiple binding sites, thereby reducing bridging artifacts [5].

How can I experimentally confirm whether bridging is affecting my measurements? Perform a loading density series: Measure binding responses at multiple surface densities of your immobilized ubiquitin-binding protein. If bridging is significant, you will observe a strong dependence of apparent affinity on surface density, with lower densities giving more accurate (weaker) affinity measurements [5].

What analytical approach can help diagnose bridging severity? Use a simple fitting model that accounts for both monovalent and bivalent binding. Fit your data to determine the fraction of binding that results from bridging versus monovalent interactions. This enables quantitative assessment of whether your data can be salvaged or if experimental redesign is necessary [5].

Are there alternative methods less susceptible to these artifacts? Yes, consider these alternative approaches:

- Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC): A solution-based technique that avoids surface immobilization issues [5]

- TUBE-based assays: Use Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities to capture ubiquitinated proteins without surface artifacts [22] [6]

- UbiCRest: employs linkage-specific deubiquitinases (DUBs) to analyze ubiquitin chain topology [23]

What specific experimental parameters should I optimize?

- Surface density: Aim for the lowest density that still gives measurable signal

- Loading time: Minimize to prevent over-saturation

- Analyte concentration range: Ensure you're not working exclusively at saturation conditions

- Buffer conditions: Include appropriate detergents and carriers to minimize non-specific binding [5]

Experimental Protocols for Bridging Detection

Protocol 1: Loading Density Series for Bridging Diagnosis

Purpose: To diagnose and quantify bridging artifacts by measuring binding responses at varying surface densities of immobilized ubiquitin-binding proteins [5].

Materials:

- BLI or SPR instrument with streptavidin sensors

- Biotinylated ubiquitin-binding protein

- Purified polyubiquitin chains of interest

- Appropriate assay buffer

Procedure:

- Prepare a dilution series of your biotinylated ubiquitin-binding protein

- Load each concentration onto separate streptavidin sensors for varying times (30-600 seconds) to achieve different surface densities

- Measure binding responses against a concentration series of polyubiquitin chains

- Analyze the data by plotting maximum response versus analyte concentration for each loading density

- Fit the data using both monovalent and bivalent binding models

- Compare apparent Kd values across different loading densities

Interpretation: Significant dependence of apparent Kd on surface density indicates bridging artifacts. Data from the lowest loading densities typically provide the most accurate affinity measurements [5].

Protocol 2: UbiCRest for Ubiquitin Linkage Verification

Purpose: To independently verify ubiquitin linkage types using linkage-specific deubiquitinases, complementing surface-based binding studies [23].

Materials:

- UbiCREST Deubiquitinase Enzyme Kit

- TUBE agarose

- Cell lysates or purified ubiquitinated proteins

- Lysis buffer with N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) and iodoacetamide

- SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting equipment

Procedure:

- Isolate ubiquitinated proteins using TUBE agarose

- Divide samples into aliquots for different DUB treatments

- Set up parallel reactions with linkage-specific DUBs

- Incubate at 37°C for 1-3 hours

- Analyze by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with relevant antibodies

Interpretation: Disappearance of specific bands after treatment with particular DUBs indicates the presence of those linkage types. This provides independent validation of linkage specificity separate from binding assays [23].

Table 1: Diagnostic Patterns Indicating Bridging Artifacts

| Observation | Non-Bridging Data | Bridging-Affected Data |

|---|---|---|

| Apparent Kd values | Consistent across loading densities | Strong density dependence |

| Association kinetics | Typical exponential curves | Very steep, square-wave shapes |

| Dissociation rates | Follow single exponential decay | Extremely slow, incomplete dissociation |

| Specificity patterns | Consistent with solution studies | Exaggerated specificity for certain chains |

| Response scaling | Linear with density | Disproportionate increase with density |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) | Affinity reagent | High-affinity capture of polyubiquitinated proteins | Nanomolar affinity; linkage-specific variants available; protects from DUBs [22] [6] |

| Linkage-specific DUBs | Enzymatic tool | Cleave specific ubiquitin linkages for linkage verification | Available for K48, K63, K11, K27, M1 linkages; used in UbiCRest [23] |

| Ubiquitin-Trap | Nanobody-based reagent | Immunoprecipitation of ubiquitin and ubiquitinated proteins | Based on anti-ubiquitin VHH; works across species [24] |

| Linkage-specific antibodies | Immunological reagent | Detect specific ubiquitin chain types | Available for M1, K11, K27, K48, K63 linkages [25] |

| Engineered DUBs (enDUBs) | Cellular tool | Linkage-selective ubiquitin cleavage in live cells | Fuse DUB catalytic domains to target-specific nanobodies [26] |

Visual Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Bridging Diagnosis Workflow

Mitigation Strategy Overview

Toolkit for Detection: From Classic Techniques to Advanced Enrichment Strategies

Western blotting remains a powerful and commonly used technique for detecting specific proteins in complex mixtures, providing critical information about protein presence, molecular weight, and relative abundance [27]. In the specialized field of ubiquitin research, this technique faces particular challenges in accurately detecting and interpreting ubiquitination patterns while distinguishing true signals from artifacts. This technical support center addresses these specific challenges through targeted troubleshooting guides and methodological frameworks to support researchers in drug development and basic research.

Technical Principles and Ubiquitin Detection Framework

Western blotting, also known as immunoblotting, is an antibody-based technique that combines protein separation by molecular weight via gel electrophoresis with specific immunodetection [27]. The process involves multiple steps: sample preparation, gel electrophoresis, protein transfer to a membrane, blocking, and antibody probing [28] [27]. For ubiquitination studies, each step requires careful optimization to preserve the labile ubiquitin-protein interaction and ensure accurate detection.

Figure 1: Western blot workflow highlighting critical steps and ubiquitin-specific considerations for artifact-free detection.

Troubleshooting Guides

Signal Detection Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal | Incomplete transfer [29] | Verify transfer efficiency with protein stains; Increase transfer time/voltage for high MW proteins [29] [30] |

| Low antigen concentration [29] | Load more protein (20-30 μg for whole cell extracts, up to 100 μg for modified targets) [30] | |

| Low antibody affinity [29] | Use validated antibodies; Check species reactivity; Include positive controls [30] [31] | |

| Protein degradation [29] | Use fresh protease inhibitors; Prepare samples on ice [30] [32] | |

| High Background | Antibody concentration too high [29] | Titrate primary and secondary antibodies [29] [32] |

| Insufficient blocking [29] | Increase blocking time (1hr RT or overnight at 4°C); Use compatible blocking buffers [29] [30] | |

| Insufficient washing [29] | Increase wash number/volume; Include 0.05% Tween-20 in wash buffer [29] | |

| Membrane handling issues [29] | Always wear gloves; Keep membrane wet; Avoid damage [29] |

Band Pattern Abnormalities

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Bands | Protein isoforms or splice variants [30] | Review literature for known variants; Check antibody specificity [30] [32] |

| Post-translational modifications [30] | Check for ubiquitination, phosphorylation, glycosylation [30] [32] | |

| Non-specific antibody binding [30] | Optimize antibody concentration; Use different primary antibody [30] [32] | |

| Protein degradation [30] | Use fresh protease inhibitors; Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [30] | |

| Smearing | Protein aggregation [32] | For membrane proteins, avoid heating above 60°C [32] |

| DNA contamination [29] | Shear genomic DNA; Sonicate samples [29] [30] | |

| Transfer issues [32] | Remove bubbles during sandwich assembly; Ensure proper buffer temperature [32] | |

| Incorrect Molecular Weight | Post-translational modifications [32] | Use enzymatic treatments (e.g., PNGase F for glycosylation) [32] |

| Alternative splicing [32] | Review literature for known splicing variants [32] | |

| Incomplete denaturation [32] | Add fresh DTT or β-mercaptoethanol; Ensure proper denaturation [32] |

Frequently Asked Questions

General Western Blotting

What are the key advantages of western blotting over other protein detection methods? Western blotting provides information about both protein presence and molecular weight, offering an advantage over methods like ELISA or immunofluorescence. It remains widely used due to lower costs and complexity compared to mass spectrometry [27] [31].

How can I ensure my western blot results are reproducible? Always include appropriate controls (positive, negative, loading controls), use validated antibodies, maintain consistent sample preparation protocols, and properly document all experimental conditions including antibody sources and dilutions [31].

What is the recommended protein load for western blotting? For whole cell extracts, load 20-30 μg per lane for total/unmodified targets. For detecting modified targets (e.g., phosphorylated proteins) in whole tissue extracts, increase to 100 μg per lane [30].

Ubiquitin-Specific Detection

How can I specifically detect different ubiquitin linkages? Use linkage-specific TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) with nanomolar affinities for specific polyubiquitin chains. K48-linked chains typically target proteins for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains regulate signal transduction [6] [33].

What special sample preparation is needed for ubiquitination studies? Use lysis buffers optimized to preserve polyubiquitination, include protease inhibitors, and consider using specialized ubiquitin enrichment tools like TUBEs to capture specific ubiquitin linkages [6].

How can I distinguish true ubiquitination signals from artifacts? Include proper controls, use validated ubiquitin-specific antibodies, and consider using multiple detection methods. Artifact binding can be minimized through optimized blocking conditions and antibody validation [6] [31].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Prevents protein degradation | Essential for ubiquitination studies to preserve modifications [30] [31] |

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) | Enrich polyubiquitinated proteins | Enables specific capture of ubiquitinated targets; available in linkage-specific formats [6] [33] |

| Phosphatase Inhibitors | Maintain phosphorylation state | Important when studying signaling pathways linked to ubiquitination [30] [31] |

| Validated Primary Antibodies | Target protein detection | Critical for specificity; use databases like Antibodypedia for selection [31] |

| HRP or Fluorescent Secondaries | Signal generation | Choose based on detection system; fluorescent labels enable multiplexing [34] [31] |

Advanced Methodologies for Ubiquitin Detection

Specialized Workflow for Ubiquitination Studies

Figure 2: Decision pathway for verifying true ubiquitination signals and distinguishing artifacts in western blot analysis.

Quantitative Analysis and Normalization

For accurate quantification in ubiquitination studies, implement proper normalization strategies. Traditional housekeeping proteins (e.g., β-actin, GAPDH) may vary under experimental conditions. Total protein normalization using stains like Ponceau S or Fast Green provides more reliable loading controls [31]. Fluorescent detection systems offer wider linear dynamic ranges compared to chemiluminescence, enabling more accurate quantification across protein concentration ranges [34].

Western blotting remains an essential technique for ubiquitin research despite its challenges. By implementing optimized protocols, appropriate controls, and specialized tools like TUBEs, researchers can overcome inherent limitations and generate reliable data on protein ubiquitination. This technical support framework provides the essential guidance needed to troubleshoot common issues and implement best practices in ubiquitin detection workflows.

Protein ubiquitylation is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates a vast array of cellular processes, including protein degradation, DNA repair, and cell signaling. However, studying ubiquitylated proteins presents significant challenges due to their typically low abundance in biological samples and the transient nature of many ubiquitin-mediated interactions. To address these challenges, researchers have developed high-affinity probes for the enrichment of ubiquitylated proteins. Two prominent technologies in this field are Tandem-repeated Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) and the more recently developed Ubiquitin-Binding Domain from Orientia tsutsugamushi (OtUBD). These tools help mitigate issues of artifact binding and protein degradation during analysis, enabling more accurate profiling of the ubiquitinome. This technical support center provides detailed protocols, troubleshooting guides, and FAQs to assist researchers in effectively implementing these methods in their ubiquitin detection research.

Technology Comparison: OtUBD vs. TUBEs

The selection of an appropriate ubiquitin enrichment tool is critical for experimental success. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of OtUBD and TUBEs to guide your decision-making.

Table 1: Comparison of OtUBD and TUBE Technologies for Ubiquitin Enrichment

| Feature | OtUBD | TUBEs (Tandem-repeated UBDs) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Bacterial deubiquitylase from Orientia tsutsugamushi [35] [36] | Multiple linked ubiquitin-binding domains from eukaryotic proteins [36] |

| Affinity Mechanism | Single domain with intrinsically high affinity (low nanomolar Kd) [35] [36] | Avidity effect from multiple low-affinity UBDs [36] |

| Monoubiquitin Enrichment | Strong enrichment capability [35] [36] | Poor enrichment due to low avidity [36] |

| Polyubiquitin Enrichment | Efficient enrichment of all chain types [35] | Highly efficient for polyubiquitin chains [36] |

| DUB Protection | Not explicitly documented | Protects polyubiquitin chains from deubiquitylases [36] |

| Primary Application | Versatile enrichment of mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins for proteomics and immunoblotting [35] | Specialized enrichment of polyubiquitinated proteins, often for degradation studies [36] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

OtUBD-Based Enrichment Protocol

The following protocol describes a step-by-step process for enriching ubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates using OtUBD affinity resin [35].

Reagents and Materials

- Plasmids for OtUBD Purification: pRT498-OtUBD (Addgene #190089) or pET21a-cys-His6-OtUBD (Addgene #190091) [35]

- Cell Lysis Buffer (Native): 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), 10 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), and protease inhibitors [35]

- Denaturing Lysis Buffer: 1% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM TCEP, and protease inhibitors [35]

- OtUBD Affinity Resin: Prepared by coupling recombinant OtUBD to SulfoLink coupling resin [35]

- Wash Buffer 1: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM NEM [35]

- Wash Buffer 2: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM NEM [35]

- Elution Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 2% SDS, 5 mM TCEP [35]

Procedure

Lysate Preparation:

Enrichment:

Washing:

- Pellet resin and remove supernatant.

- Wash sequentially with Wash Buffer 1 (2 times) and Wash Buffer 2 (2 times) [35].

Elution:

- Elute bound proteins with Elution Buffer by heating at 95°C for 5 minutes [35].

- Analyze eluates by immunoblotting or mass spectrometry.

TUBE-Based Enrichment Protocol

This protocol outlines the use of TUBEs for enrichment of polyubiquitylated proteins, particularly when protection from deubiquitylases is required [36].

Reagents and Materials

- TUBE Reagents: Commercially available TUBEs with specific linkage preferences (e.g., K48- or K63-specific) or pan-specific TUBEs

- Lysis Buffer: Similar to native lysis buffer for OtUBD but without NEM, as TUBEs themselves protect against DUBs [36]

- TUBE-Agarose Conjugates: Or alternative immobilization formats

Procedure

Lysate Preparation:

- Prepare cell lysates as described in the OtUBD protocol, but omit NEM from the lysis buffer when using TUBEs for their DUB-protective function [36].

Enrichment:

- Incubate clarified lysate with TUBE-conjugated beads for 2 hours at 4°C [36].

- The multiple UBDs in TUBEs will simultaneously engage polyubiquitin chains.

Washing:

- Wash beads with appropriate buffers to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

Elution:

- Elute with SDS-containing buffer or competing free ubiquitin.

- Analyze by downstream applications.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Issues and Solutions for Ubiquitin Enrichment

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Ubiquitin Enrichment Experiments

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low/No Signal | Protein degradation by DUBs | For OtUBD: Add NEM to lysis buffer [35]. For TUBEs: Use their intrinsic DUB protection [36]. |

| Low abundance of target | Increase amount of input lysate; Use higher affinity OtUBD resin [35] [36]. | |

| Insufficient binding | Extend incubation time with affinity resin; Verify resin binding capacity. | |

| High Background | Non-specific binding | Increase salt concentration in wash buffers; Include mild detergents [37]. |

| Incomplete washing | Increase number and volume of washes; Include a bead-only control [37]. | |

| Incomplete Ubiquitome Coverage | Tool selection bias | Use OtUBD for monoubiquitin; TUBEs for polyubiquitin chains [35] [36]. |

| Linkage-type bias | Use linkage-specific tools or pan-specific reagents like OtUBD [35]. | |

| Irreproducible Results | Protein-protein interaction disruption | Use milder lysis conditions (e.g., avoid RIPA buffer for co-IP studies) [37]. |

| Inconsistent sample preparation | Standardize lysis protocol across all samples; Use fresh protease inhibitors. |

Addressing Artifact Binding in Ubiquitin Research

Artifact binding presents a significant challenge in ubiquitin detection research. The following strategies can help mitigate this issue:

Include Appropriate Controls:

Experimental Validation:

- Confirm putative ubiquitination sites through mutagenesis studies.

- Use multiple enrichment methods to validate findings (e.g., compare OtUBD and TUBE results).

Denaturing vs. Native Conditions:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of OtUBD over traditional ubiquitin enrichment methods? A1: OtUBD offers several advantages: (1) It efficiently enriches both mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins, unlike TUBEs which work poorly for monoubiquitination; (2) It functions as a single high-affinity domain without requiring avidity effects; (3) It can be used in both native and denaturing conditions to distinguish directly ubiquitinated proteins from interacting partners [35] [36].

Q2: How do I decide between using OtUBD or TUBEs for my experiment? A2: The choice depends on your research goals:

- Use OtUBD when you need comprehensive coverage of both mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins, when working with limited sample material, or when studying non-canonical ubiquitination sites [35] [36].

- Use TUBEs when you specifically want to study polyubiquitinated proteins, need protection from deubiquitylases during processing, or are focused on proteasomal degradation pathways [36].

Q3: What specific steps can I take to reduce artifact binding in my ubiquitin pulldown experiments? A3: To minimize artifacts: (1) Always include bead-only and isotype controls; (2) Use stringent wash conditions with higher salt concentrations and detergents; (3) Consider preclearing your lysate with bare beads; (4) Validate your findings with multiple experimental approaches; (5) Use denaturing conditions to distinguish covalent modification from non-covalent interactions [35] [37].

Q4: Can I use OtUBD to study specific ubiquitin chain linkages? A4: The standard OtUBD protocol is designed as a general-purpose tool for enriching all types of ubiquitin modifications. However, you could potentially develop linkage-specific versions by engineering the OtUBD domain or by combining it with linkage-specific antibodies in downstream analysis [35].

Q5: How can I confirm that my enrichment successfully captured ubiquitinated proteins? A5: Several verification methods are available: (1) Perform immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin antibodies; (2) Look for the characteristic GlyGly (GG) remnant on lysine residues via mass spectrometry; (3) Compare patterns between your experimental samples and appropriate negative controls; (4) Test known ubiquitinated proteins in your system as positive controls [35] [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Enrichment

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Purpose | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| OtUBD Affinity Resin | High-affinity enrichment of mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins | Coupled to SulfoLink resin; Works in native and denaturing conditions [35] |

| TUBE Reagents | Enrichment of polyubiquitinated proteins with DUB protection | Available as pan-specific or linkage-specific variants [36] |

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | Deubiquitylase inhibitor | Prevents loss of ubiquitin signal during processing; Use at 1-5 mM [35] |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevent protein degradation | Essential for maintaining integrity of ubiquitinated species during lysis |

| Anti-Ubiquitin Antibodies | Detection of ubiquitinated proteins | P4D1, E412J; For immunoblotting after enrichment [35] |

| diGly Remnant Antibodies | Proteomic identification of ubiquitylation sites | Recognizes GlyGly remnant on lysine after tryptic digest [36] |

In ubiquitin research, distinguishing true biological signals from artifactual binding is a fundamental challenge that can compromise data integrity. Artifacts often arise from incomplete deubiquitinase (DUB) inhibition, non-specific antibody interactions, or off-target effects of cysteine alkylators used in standard protocols. These artifacts can lead to false positives in interactor screens and misinterpretation of ubiquitination dynamics, ultimately affecting biological conclusions and drug discovery efforts. This technical support center provides targeted solutions to these specific experimental challenges, enabling researchers to produce more reliable and reproducible data.

Essential Methodologies for Robust Ubiquitin Research

Ubiquitin Interactor Affinity Enrichment-Mass Spectrometry (UbIA-MS)

The UbIA-MS protocol enables comprehensive identification of ubiquitin-binding proteins from crude cell lysates, preserving endogenous protein levels, post-translational modifications, and native protein complexes [38].

Core Protocol Stages:

- Bait Generation: Chemical synthesis of biotinylated, non-hydrolyzable diubiquitin baits that mimic native diubiquitin and resist cleavage by endogenous DUBs. This is critical for preventing artifact generation from bait disassembly during the experiment [38].

- Affinity Purification: Incubation of baits with cell lysates to enrich for ubiquitin interactors.

- On-Bead Digestion: Proteolytic digestion of enriched proteins while bound to beads.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis of resulting peptides.

- Data Analysis: Computational identification of differentially enriched proteins using specialized open-source R software packages [38].

Typical Workflow Duration: Approximately 5 weeks (3 weeks for non-hydrolyzable diubiquitin synthesis, 2 weeks for interactor enrichment and identification) [38].

Global Ubiquitinome Profiling using DiGly Antibody Enrichment

This method identifies endogenous ubiquitination sites proteome-wide without genetic manipulation, making it suitable for clinical samples [13] [39].

Core Protocol Stages:

- Protein Extraction: Prepare protein lysates from tissues or cells under denaturing conditions.

- Proteolytic Digestion: Digest proteins with trypsin. This generates peptides with a characteristic di-glycine (diGly) remnant on ubiquitinated lysines, with a mass shift of 114.04 Da [13] [39].

- Immunoaffinity Enrichment: Enrich ubiquitinated peptides using anti-diGly-lysine antibodies.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Analyze enriched peptides by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Database searching to identify ubiquitination sites and motifs. Motif-X analysis often reveals conserved sequences like E-Kub, Kub-D, and E-X-X-X-Kub in plants [39].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Experimental Failures

FAQ 1: How do I prevent bait disassembly and identify false positives in Ub interactor screens?

Problem: Partial disassembly of ubiquitin baits by residual DUB activity in lysates generates shorter chains, leading to misinterpretation of binding specificities and false positives [40].

Solutions:

- Use Non-hydrolyzable Ubiquitin Baits: Synthesize ubiquitin baits with non-hydrolyzable linkages (e.g., via click chemistry) that are completely DUB-resistant. This is the most robust solution [38].

- Optimize DUB Inhibition: If using native chains, test and compare different DUB inhibitors. N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) generally provides more complete chain stabilization than Chloroacetamide (CAA) [40].

- Validate with Controls: Always include known linkage-specific ubiquitin-binding proteins (e.g., RAD23B for K48-linkages, EPN2 for K63-linkages) as positive controls to confirm your inhibition is effective and binding is specific [40].

FAQ 2: Why does my ubiquitinome profiling have low coverage and high background?

Problem: Low identification rates of ubiquitinated peptides and high non-specific background signals in diGly enrichment workflows [41] [39].

Solutions:

- Verify Antibody Specificity: Use antibodies specifically validated for diGly-lysine remnant enrichment. Pre-clear lysates to remove non-specifically binding proteins.

- Optimize Lysis and Digestion: Use fully denaturing lysis conditions (e.g., high urea/SDS concentrations) to inactivate endogenous DUBs and proteases. Ensure complete tryptic digestion by checking for missed cleavages, as this directly impacts peptide yield and identification confidence [41].

- Include Proper Controls: Process control samples without enrichment antibody to identify and subtract non-specifically bound peptides.

FAQ 3: How do I address reagent-induced artifacts in my ubiquitin pulldown experiments?

Problem: Cysteine alkylators like NEM and CAA, used to inhibit DUBs, can have off-target effects by alkylating exposed cysteines on non-DUB proteins, potentially altering ubiquitin-binding surfaces and creating artifactual interactions [40].

Solutions:

- Compare Multiple Inhibitors: Perform parallel experiments using NEM and CAA separately, then compare datasets to identify overlapping (high-confidence) and inhibitor-specific (potentially artifactual) interactors [40].

- Use Minimal Effective Concentrations: Titrate inhibitor concentrations to find the lowest level that effectively stabilizes ubiquitin chains, minimizing off-target effects.

- Employ Non-hydrolyzable Baits: As in FAQ 1, switching to non-hydrolyzable baits eliminates the need for these inhibitors altogether, providing the cleanest results [38].

FAQ 4: My DIA ubiquitinomics data shows poor quantification. How can I improve it?

Problem: Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry offers deep coverage but can suffer from poor quantification accuracy due to upstream variability [42] [41].

Solutions:

- Implement Rigorous Sample QC: Before DIA runs, enforce a three-tier check:

- Protein Concentration: Measure via BCA or NanoDrop.

- Peptide Yield Assessment: Quantify digest yield.

- LC-MS Scout Run: Preview a subset digest to check peptide complexity and ion abundance [41].

- Optimize Acquisition Parameters: Avoid "copy-pasting" DDA settings. Use narrow SWATH windows (<25 m/z on average) to reduce precursor interference, and ensure cycle time is fast enough (≤3 seconds) to adequately sample LC peak peaks [41].

- Use Project-Specific Spectral Libraries: Generate libraries from DDA data acquired from the same sample type and LC gradient as your DIA study, rather than relying on generic public libraries, to ensure relevant matching [41].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitin Interactome and Ubiquitinome Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Baits | Non-hydrolyzable diubiquitin (K48, K63, etc.) [38] | DUB-resistant; prevents bait disassembly and artifact generation in interactor screens. |

| DUB Inhibitors | N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM), Chloroacetamide (CAA) [40] | Stabilizes ubiquitin chains in lysates; choice and concentration are critical to avoid off-target effects. |

| Affinity Tags | Tandem Strep-tag, His-tag [13] | For purifying ubiquitinated substrates in tagged-Ub exchange systems (e.g., StUbEx). |

| Enrichment Antibodies | Anti-diGly-lysine (pan-ubiquitin), Linkage-specific Ub antibodies (e.g., K48-, K63-specific) [13] | Immunoaffinity enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides or proteins for MS analysis. |

| Ubiquitin-Binding Domains (UBDs) | Tandem UBDs (e.g., from E3 ligases, DUBs) [13] | High-affinity tools for enriching endogenously ubiquitinated proteins. |

| Cell Lines | StUbEx cell lines (e.g., HEK293T, U2OS) [13] | Cellular systems where endogenous ubiquitin is replaced with tagged ubiquitin for streamlined purification. |

| LC-MS Standards | Indexed Retention Time (iRT) peptides [41] | For consistent retention time calibration and alignment across all MS runs, crucial for DIA. |

Visualizing Key Experimental Workflows and Concepts

Ubiquitin Interactor Screen (UbIA-MS) Workflow

Impact of DUB Inhibitors on Experimental Outcomes

Successfully mapping the ubiquitinome and ubiquitin interactome requires meticulous attention to experimental design, particularly in controlling for artifact binding. By implementing the protocols and troubleshooting guides outlined above—especially the use of non-hydrolyzable baits, careful inhibitor selection, and rigorous sample and data QC—researchers can significantly enhance the reliability and biological relevance of their mass spectrometry-based ubiquitin studies.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) are two powerful label-free technologies for real-time biomolecular interaction analysis. Both techniques provide quantitative data on binding kinetics and affinity, which is crucial for applications ranging from basic research to drug discovery and development [43] [44]. SPR measures changes in the refractive index near a sensor surface [45], while BLI detects interference pattern shifts from the sensor tip layer [43] [46]. For researchers studying artifact binding in ubiquitin detection, understanding the principles, applications, and limitations of these techniques is essential for designing robust experiments and properly interpreting kinetic data.

The fundamental parameters obtained from these analyses include the association rate (kₐ), dissociation rate (kḍ), and equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) [47] [45]. These parameters offer insights into interaction mechanisms that steady-state affinity measurements cannot provide, such as residence times for antibody-receptor complexes and competitor drug mechanisms [48]. This technical support center provides comprehensive troubleshooting guides and FAQs to address specific experimental challenges in kinetic analysis, with particular emphasis on applications relevant to ubiquitin detection research.

Key Principles and Experimental Design

Fundamental Operating Principles

SPR and BLI operate on distinct optical principles but share the common advantage of providing real-time, label-free monitoring of molecular interactions. SPR is an optical phenomenon that occurs when light incident at a critical angle on a metal surface (typically gold) generates electron charge density waves called surface plasmons [45]. When the substance or amount of substance on the metal surface changes, the refractive index changes accordingly, causing a shift in the resonance angle that can be measured in resonance units (RU) [45]. This makes SPR exceptionally sensitive to mass changes at the sensor surface.

BLI employs a different approach, based on white light interferometry from the surface of biosensor tips. A beam of visible light is directed at the biosensor tip, creating two reflection spectra at the tip's interfaces that form an interference spectrum [45]. Any change in optical layer thickness caused by molecular binding or dissociation shifts the interference pattern, which is measured in nanometers [45]. This "dip-and-read" approach typically doesn't require continuous flow, offering operational flexibility for certain applications [43].

Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow for SPR and BLI, highlighting both shared steps and technique-specific processes:

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful kinetic analysis requires careful selection of reagents and surfaces. The table below details essential materials and their functions:

| Reagent/Surface Type | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| CM5 Chip (SPR) | Carboxymethylated dextran for covalent immobilization via NHS/EDC amine chemistry | General protein-protein interactions [47] |

| Ni-NTA Chip (SPR/BLI) | Immobilizes His-tagged ligands through metal affinity | His-tagged protein studies [47] [46] |

| Streptavidin Chip (SPR/BLI) | Captures biotinylated ligands with high affinity | Biotinylated DNA, proteins, or small molecules [47] [45] |

| Protein A/G Chip (SPR/BLI) | Binds antibody Fc regions for oriented immobilization | Antibody-antigen interaction studies [45] [49] |

| Running Buffers (HEPES, PBS, Tris) | Maintain physiological pH and ionic strength during analysis | Various biomolecular interactions [47] |

| Regeneration Buffers (low pH, high salt, mild detergents) | Removes bound analyte without damaging immobilized ligand | System-specific optimization required [47] [45] |

Kinetic Analysis Methodologies

Approaches to Kinetic Measurement

SPR experiments can be performed using two primary kinetic methods: Multi-Cycle Kinetics (MCK) and Single-Cycle Kinetics (SCK). MCK involves alternating cycles of analyte injections and surface regeneration, generating a separate SPR curve for each analyte concentration [48]. This traditional approach allows for buffer blank subtraction from individual binding curves and omission of poor injections during data analysis.

SCK, also known as kinetic titration, uses sequential injections of increasing analyte concentrations without dissociation or regeneration between samples [48]. Only the highest concentration is followed by an extended dissociation phase. This method significantly reduces analysis time and minimizes potential ligand damage from repeated regeneration cycles, making it particularly valuable for ligands that are difficult to regenerate or when using capture methods that would require ligand recapture between cycles [48].

Comparison of Kinetic Methods

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of MCK and SCK approaches:

| Parameter | Multi-Cycle Kinetics (MCK) | Single-Cycle Kinetics (SCK) |

|---|---|---|

| Regeneration Frequency | After each analyte concentration | Minimal (only if reusing sensor) |

| Analysis Time | Longer due to regeneration steps | Shorter by eliminating regeneration between concentrations |

| Ligand Integrity | Risk of damage from repeated regeneration | Reduced risk due to limited regeneration |

| Data Quality Assessment | Individual curves for each concentration | Single continuous binding curve |

| Information Content | Multiple dissociation phases for diagnosis | Single dissociation phase for all concentrations |

| Best For | Interactions with complex kinetics, method development | Ligands difficult to regenerate, high-throughput screening |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Q: The non-specific binding of impurities in the sample to the sensor surface affects the signal. A: This commonly occurs due to impure samples or suboptimal buffer composition. Solutions include: (1) Using appropriate surface chemical modifications to block non-specific binding sites; (2) Employing buffers containing surfactants or high salt concentrations to reduce non-specific interactions; (3) Purifying the sample to remove interfering substances before analysis [45].

Q: Cannot get a strong enough signal for reliable data analysis. A: This typically results from insufficient ligand immobilization or low analyte concentration. To address this: (1) Increase the amount of ligand immobilized on the sensor surface; (2) Optimize analyte concentration and injection time; (3) Use more sensitive biosensors specifically designed for low molecular weight analytes (e.g., CM7 chips for SPR) [45].

Q: The fixation efficiency of the ligand on the sensor surface is low, resulting in unstable signals. A: This suggests improper surface treatment or suboptimal ligand concentration. Remedies include: (1) Optimizing ligand immobilization methods by selecting appropriate cross-linking strategies; (2) Using higher ligand concentrations for immobilization and extending immobilization time; (3) For BLI, ensuring proper biosensor hydration before ligand loading [45] [46].