Comparative Analysis of Mass Spectrometry Databases for Ubiquitination Site Identification: Strategies, Tools, and Best Practices

The systematic identification of protein ubiquitination sites via mass spectrometry (MS) is fundamental to understanding cellular signaling, protein degradation, and disease mechanisms.

Comparative Analysis of Mass Spectrometry Databases for Ubiquitination Site Identification: Strategies, Tools, and Best Practices

Abstract

The systematic identification of protein ubiquitination sites via mass spectrometry (MS) is fundamental to understanding cellular signaling, protein degradation, and disease mechanisms. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of MS-based databases and computational tools used for ubiquitinome analysis. It covers foundational principles, current methodologies including DDA and DIA acquisition, enrichment strategies like K-ε-GG immunoaffinity purification, and key search algorithms such as MaxQuant and MS-GF+. We also address critical troubleshooting for data analysis and offer a framework for the validation and comparative assessment of database performance. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review serves as a guide for selecting and optimizing computational workflows to achieve robust, high-coverage ubiquitination site identification.

Ubiquitinome Complexity and MS Detection Fundamentals: Building Your Foundational Knowledge

Ubiquitination represents a crucial post-translational modification (PTM) that regulates diverse cellular functions, including protein stability, activity, and localization [1]. This versatility stems from the remarkable complexity of ubiquitin (Ub) conjugates, which can range from a single Ub monomer to polymers with different lengths and linkage types [1]. The Ub code is written through a cascade of enzymatic reactions involving E1 activating, E2 conjugating, and E3 ligase enzymes, and is erased by deubiquitinases (DUBs) [1]. Dysregulation of this intricate system underpins numerous pathologies, including cancer and neurodegenerative diseases [1]. Cracking this code requires sophisticated mass spectrometry (MS) methodologies and specialized data repositories, which we compare herein to guide researchers in selecting optimal tools for ubiquitination site identification.

The Complex Landscape of Ubiquitin Signaling

Architectural Diversity of Ubiquitin Modifications

Ubiquitin's architectural complexity begins with its basic forms. Monoubiquitination involves attaching a single Ub molecule to a substrate, while multiple monoubiquitination modifies several lysine residues simultaneously [1]. The true complexity emerges in polyubiquitin chains, where Ub molecules link through one of eight possible sites: the N-terminal methionine (M1) or any of seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) [1]. These arrangements create homotypic chains (same linkage), heterotypic chains (mixed linkages), and branched chains with multiple linkage types simultaneously [2].

The functional consequences of ubiquitination are predominantly determined by this chain topology. K48-linked chains represent the most abundant linkage type and primarily target substrates for proteasomal degradation [1]. In contrast, K63-linked chains typically regulate non-proteolytic functions, such as protein-protein interactions in the NF-κB pathway and autophagy [1]. Less common "atypical" chains (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, M1) perform specialized functions that remain less characterized [1]. This complexity is further enhanced by cross-talk with other PTMs and the formation of branched ubiquitin chains, which increase signaling versatility and specificity [2].

Functional Consequences in Cellular Processes

The functional repertoire of ubiquitin modifications extends far beyond protein degradation. Non-proteolytic ubiquitin signaling, often mediated by monoubiquitylation or Lys63-linked chains, plays critical roles in DNA damage response, cell cycle control, and immune signaling [3]. For instance, at DNA double-strand breaks, a ubiquitylation cascade involving RNF8 and RNF8 E3 ligases modifies histones and builds K63-linked chains to recruit repair proteins like BRCA1 [3]. Similarly, monoubiquitylation of FANCD2 and FANCI initiates DNA interstrand crosslink repair in the Fanconi anemia pathway [3]. The replication clamp PCNA undergoes both monoubiquitylation and K63-linked polyubiquitylation to control lesion bypass during DNA replication [3]. These examples illustrate how distinct ubiquitin chain architectures orchestrate specific cellular outcomes through specialized effector proteins containing ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) [3].

Comparative Analysis of Mass Spectrometry Data Repositories for Ubiquitination Research

The identification of ubiquitination sites and chain architecture relies heavily on MS-based proteomics, generating vast datasets that require specialized repositories. Below we compare major resources relevant to ubiquitination research.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Proteomics Data Repositories for Ubiquitination Research

| Repository | Primary Focus | Data Types | Organism Coverage | Ubiquitination-Specific Features | User Interface & Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRIDE | Public repository for MS proteomics data | Raw spectral data, peptides, protein identifications, PTM evidence | Multi-organism | Supports PTM data including ubiquitination via standardized formats; requires data conversion to PRIDE XML | Centralized web interface for upload, download, and data viewing [4] |

| PeptideAtlas | Compendium of peptides identified in MS experiments | Identified peptides, spectral libraries, PTM evidence | Multi-organism (Human, Yeast, Mouse, etc.) | Builds specific PTM datasets; regularly updated ubiquitination site mappings | Protein and peptide search interfaces; spectral library browsing [5] |

| YRC PDR | Unified dissemination of proteomics data from multiple technologies | MS data, protein identifications, PTMs, protein-protein interactions, structural data | Multi-organism (emphasis on yeast) | Displays PTM data alongside protein interactions and localizations in biological context | Powerful protein-centric search with Gene Ontology filtering [4] |

| GPM DB | Public data repository for MS proteomics results | Peptide and protein identifications, PTM assignments | Multi-organism | Includes ubiquitination site identifications as part of PTM analysis | Simple web interface for protein and peptide searches [4] |

Repository Specialization and Application to Ubiquitination Studies

Each repository offers distinct advantages for ubiquitination research. PRIDE employs strict adherence to proteomics data standards, making it valuable for standardized data deposition and retrieval of ubiquitination datasets [4]. Its requirement for PRIDE XML format ensures consistency but necessitates data conversion prior to submission. PeptideAtlas excels in providing compendiums of identified peptides, with specialized builds for post-translational modifications including ubiquitination [5]. Recent builds specifically highlight human ubiquitination proteomes, offering researchers curated datasets optimized for ubiquitination site identification.

The YRC Public Data Repository (YRC PDR) stands out for integrating MS data with other proteomics technologies, placing ubiquitination sites in broader biological context [4]. This is particularly valuable when ubiquitination status might affect protein interactions or localization. Its powerful protein search engine allows filtering by Gene Ontology terms and experimental data types, facilitating focused ubiquitination studies [4]. The Global Proteome Machine Database (GPM DB) provides rapid identification of proteins and their modifications from MS data, including ubiquitination sites, through its X! Hunter series of spectral libraries [4].

Experimental Methodologies for Ubiquitination Characterization

Enrichment Strategies for Ubiquitinated Proteins

Identifying ubiquitination sites presents significant challenges due to low stoichiometry, multiplicity of modification sites, and chain architectural complexity [1]. Several enrichment strategies have been developed to address these challenges:

Table 2: Comparison of Ubiquitinated Protein Enrichment Methodologies

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ub Tagging-Based | Expression of affinity-tagged Ub (His, Strep, FLAG) in cells | Relatively low-cost; easy implementation; enables screening in living cells | Potential artifacts from tagged Ub; infeasible for patient tissues; co-purification of non-specific proteins | Proteome-wide ubiquitination screening in cell lines [1] |

| Ub Antibody-Based | Immunoaffinity enrichment using anti-ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., P4D1, FK1/FK2) | Works under physiological conditions; no genetic manipulation required; linkage-specific antibodies available | High cost; non-specific binding; limited availability of high-quality linkage-specific antibodies | Ubiquitination analysis in clinical samples and animal tissues [1] |

| UBD-Based | Enrichment using ubiquitin-binding domains (e.g., TUBEs - tandem-repeated Ub-binding entities) | High affinity (nanomolar range); protects ubiquitinated proteins from degradation and deubiquitination | Requires optimization of binding conditions; potential linkage preference | Stabilization and enrichment of labile ubiquitinated substrates [1] |

| K-ε-GG Antibody | Immunoaffinity enrichment of tryptic peptides containing di-glycine remnant on ubiquitinated lysines | High specificity; direct site identification; reduced sample complexity | Requires efficient tryptic digestion; may miss incompletely digested proteins; destroys chain architecture information | Site-specific ubiquitination mapping for individual proteins and global analyses [6] |

Experimental Workflow for Ubiquitination Site Mapping

The standard MS workflow for ubiquitination site identification involves sample preparation, enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins or peptides, LC-MS/MS analysis, and data interpretation [1]. For protein-level enrichment, cells may be engineered to express tagged ubiquitin, followed by lysis and affinity purification using tag-specific resins [1]. Alternatively, endogenous ubiquitinated proteins can be enriched using antibodies or UBD-based approaches. Following enrichment, proteins are separated by SDS-PAGE, digested with trypsin, and resulting peptides analyzed by LC-MS/MS.

A more sensitive approach utilizes peptide-level immunoaffinity enrichment using antibodies specific for the di-glycine (K-ε-GG) remnant left on ubiquitinated lysines after tryptic digestion [6]. This method consistently yields higher levels of modified peptides (greater than fourfold improvement) compared to protein-level AP-MS approaches [6]. The K-ε-GG peptide immunoaffinity enrichment has proven particularly valuable for mapping ubiquitination sites on challenging substrates like HER2, DVL2, and TCRα, where it identified sites not detected by conventional methods [6].

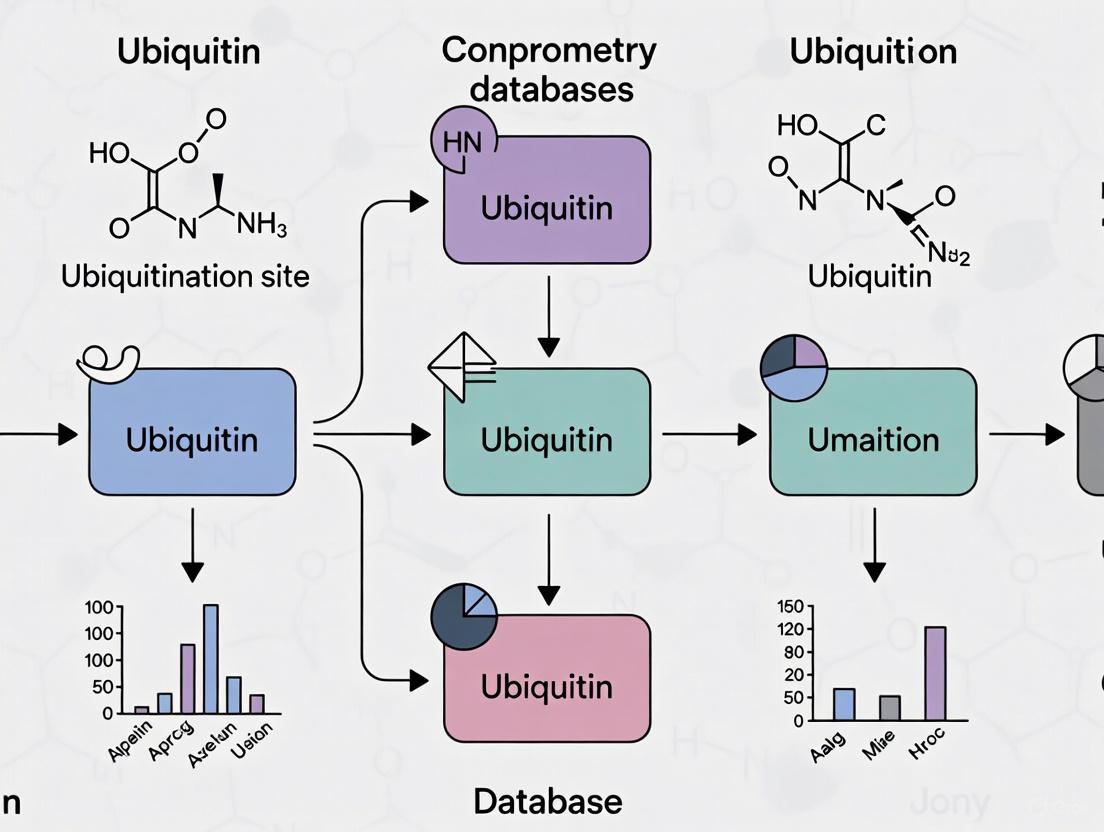

Diagram 1: Ubiquitination Site Mapping Workflow

Mass Spectrometry Analysis and Ubiquitin Chain Topology Determination

Advanced MS techniques are required to decipher ubiquitin chain topology. Tandem mass spectrometry can identify linkage types by detecting signature peptides and fragmentation patterns specific to each ubiquitin-ubiquitin linkage [2]. Methods have been developed to preserve the native ubiquitin chain architecture during sample preparation, allowing researchers to distinguish between homotypic chains, mixed chains, and the increasingly recognized branched ubiquitin chains [2].

The sensitivity of modern MS instruments enables identification of thousands of ubiquitination sites from minimal sample material. For instance, K-ε-GG peptide immunoaffinity enrichment has identified over 5,000 ubiquitination sites from just 1 mg of input material [6]. Quantitative approaches using SILAC labeling allow comparison of ubiquitination dynamics under different conditions, revealing regulated ubiquitination events in response to cellular stimuli [6].

Successful ubiquitination research requires specialized reagents and tools. Below we catalog essential resources for experimental design and execution.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity Tags | 6× His-tag, Strep-tag, FLAG, HA | Purification of ubiquitinated proteins; requires expression of tagged ubiquitin in cells | His-tag may co-purify histidine-rich proteins; Strep-tag may bind endogenous biotinylated proteins [1] |

| Ubiquitin Antibodies | P4D1, FK1/FK2 (pan-specific); linkage-specific antibodies (K48, K63, etc.) | Detection and enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins; Western blotting; immunofluorescence | Linkage-specific antibodies vary in quality and specificity; validation essential [1] |

| UBD Reagents | TUBEs (tandem-repeated Ub-binding entities) | High-affinity enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins; protection from deubiquitination | May exhibit preference for certain chain types; require optimization [1] |

| K-ε-GG Antibodies | Commercial K-ε-GG remnant antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, etc.) | Immunoaffinity enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides for MS; highest sensitivity for site identification | Destroy information about chain architecture; efficiency depends on complete tryptic digestion [6] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Stabilize ubiquitinated proteins by blocking proteasomal degradation | Essential for detecting degradation-targeted ubiquitination; may alter ubiquitination dynamics [6] |

| Data Analysis Tools | MaxQuant, Skyline, X! Tandem, Mascot | Identification of ubiquitination sites from MS data; spectral interpretation | Require appropriate search parameters for GG remnant (+114.0429 Da mass shift) [6] |

The biological complexity of ubiquitin signaling—from monoubiquitination to diverse polyubiquitin chains—demands sophisticated methodological approaches. No single methodology or database suffices for comprehensive ubiquitination analysis. Rather, researchers must select integrated strategies combining complementary enrichment methods, advanced mass spectrometry, and specialized data repositories based on their specific biological questions.

For ubiquitination site mapping, K-ε-GG peptide immunoaffinity enrichment provides superior sensitivity, while linkage-specific reagents offer insights into chain topology. Among data repositories, PeptideAtlas delivers specialized PTM builds, PRIDE ensures standardized data dissemination, and YRC PDR places ubiquitination in broader biological context. As ubiquitination research continues to evolve, particularly in understanding the functional significance of branched and atypical chains, these methodologies and resources will remain indispensable for translating the ubiquitin code into biological mechanism and therapeutic opportunity.

Mass Spectrometry as the Core Technology for Ubiquitinome Profiling

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification (PTM) that regulates diverse cellular functions, including protein stability, activity, and localization [1]. This process involves the covalent attachment of a small protein, ubiquitin (Ub), to substrate proteins via a cascade of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligase) enzymes [1]. The versatility of ubiquitination stems from the complexity of ubiquitin conjugates, which can range from a single ubiquitin monomer to polymers (polyUb chains) of different lengths and linkage types [1]. The full set of ubiquitination events in a biological system—the ubiquitinome—is dynamic and complex.

Mass spectrometry (MS) has emerged as the core technology for system-wide ubiquitinome profiling, enabling researchers to identify ubiquitinated substrates, map the specific lysine residues modified, and determine the architecture of ubiquitin chains [1] [7]. This guide objectively compares the primary MS-based methodologies, their performance, and supporting experimental data to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Mass Spectrometry Methodologies for Ubiquitinome Analysis

The primary strategy for MS-based ubiquitinomics relies on the immunoaffinity purification and MS-based detection of diglycine (K-ɛ-GG) remnant peptides, which are generated by tryptic digestion of ubiquitin-modified proteins [7] [8]. This section details the acquisition and data analysis techniques that form the backbone of modern ubiquitinome profiling.

Data Acquisition Techniques: DDA vs. DIA

Two primary MS data acquisition methods are used in ubiquitinomics: Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) and Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA). Their performance characteristics are systematically compared below.

Table 1: Comparison of DDA and DIA Mass Spectrometry Methods

| Feature | Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) | Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Selects most intense precursor ions from MS1 scan for fragmentation | Fragments all ions within pre-defined, wide m/z windows |

| Identification Numbers | ~21,000 - 30,000 K-GG peptides (single shot) [7] | ~68,000 K-GG peptides (single shot), >3x DDA [7] |

| Quantitative Reproducibility | ~50% peptides without missing values in replicates; semi-stochastic sampling [7] | >68,000 peptides quantified in ≥3 replicates; excellent reproducibility [7] |

| Quantitative Precision (Median CV) | Higher variability | ~10% median coefficient of variation [7] |

| Best Suited For | Standard discovery-mode analyses | Large sample series; applications requiring high quantitative precision and depth |

Data Analysis Software for Ubiquitinomics

The software used to process raw MS data is critical for achieving high coverage and accuracy.

Table 2: Comparison of Data Processing Software for Ubiquitinomics

| Software | Methodology | Key Features / Performance |

|---|---|---|

| MaxQuant [7] | DDA Processing | Standard for DDA data; uses Match-Between-Runs (MBR) to boost identifications. |

| DIA-NN [7] | DIA Processing | Deep neural network-based; significantly increases proteomic depth and quantitative accuracy for DIA; can be used in "library-free" mode or with spectral libraries. |

| Performance Note | DIA-NN identified on average 40% more K-GG peptides than another DIA processing software when applied to the same dataset [7]. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the core steps in a DIA-based ubiquitinome analysis, from sample preparation to data interpretation.

Enrichment Strategies for Ubiquitinated Peptides

Given the low stoichiometry of ubiquitination, enriching ubiquitinated peptides from complex cell lysates is a crucial first step. The three primary enrichment strategies are detailed below, with their performance considerations.

Table 3: Comparison of Ubiquitinated Peptide Enrichment Strategies

| Strategy | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages / Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Tagging [1] | Expression of affinity-tagged Ub (e.g., His, Strep) in cells. Tagged ubiquitinated proteins are purified. | Easy, relatively low-cost, friendly for screening in cell lines. | Cannot mimic endogenous Ub perfectly; potential for artifacts; infeasible for animal/patient tissues. |

| Ubiquitin Antibody-Based [1] [8] | Use of anti-K-ɛ-GG antibodies to enrich diglycine remnant peptides after tryptic digestion. | Applicable to any biological sample (cell lines, tissues, clinical samples); no genetic manipulation needed. | High cost of antibodies; potential for non-specific binding. |

| UBD-Based (TUBEs) [1] | Use of Tandem-repeated Ub-Binding Entities with high affinity for ubiquitinated proteins. | Preserves labile ubiquitination; can protect from DUBs during lysis. | Less commonly used for proteomic profiling compared to antibody-based methods. |

Supporting Experimental Protocols and Data

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in the performance comparisons, enabling researchers to replicate and evaluate these approaches.

Optimized Sample Preparation Protocol for Deep Ubiquitinome Profiling

A robust and scalable workflow is essential for high-quality ubiquitinome data. The following protocol, which uses Sodium Deoxycholate (SDC) for cell lysis, has been demonstrated to boost identification numbers, reproducibility, and quantitative accuracy compared to traditional urea-based methods [7].

Key Protocol Steps:

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells in SDC buffer supplemented with Chloroacetamide (CAA). Immediate boiling post-lysis rapidly inactivates deubiquitinases (DUBs), preserving the native ubiquitinome. CAA is preferred over iodoacetamide to avoid unspecific di-carbamidomethylation of lysines, which can mimic K-GG peptides [7].

- Protein Digestion: Perform tryptic digestion of the extracted proteins to generate peptides, including the K-ɛ-GG remnant peptides.

- Peptide Enrichment: Enrich K-ɛ-GG peptides using cross-linked anti-K-ɛ-GG antibody beads [8].

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze enriched peptides by LC-MS/MS using DIA for maximal coverage and quantitative precision.

Supporting Experimental Data:

- SDC vs. Urea Lysis: In a direct comparison, SDC-based lysis yielded 38% more K-GG peptides on average than urea buffer (26,756 vs. 19,403) from HCT116 cells treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 [7].

- Protein Input: Quantification of ~30,000 K-GG peptides was achieved from 2 mg of Jurkat cell protein input, with identification numbers dropping significantly below 500 µg inputs [7].

- Single-Shot vs. Fractionated UbiSite: This single-shot SDC protocol, while identifying fewer total peptides than a extensively fractionated UbiSite approach, required 20-times less protein input and only 1/10th of the MS acquisition time per sample while achieving better enrichment specificity [7].

Protocol for Large-Scale Ubiquitination Site Identification

This established protocol enables the detection of tens of thousands of distinct ubiquitination sites from cell lines or tissue samples and can be adapted for relative quantification using SILAC labeling [8].

Key Protocol Steps [8]:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare cell or tissue samples for lysis. Stable isotope labeling (e.g., SILAC) can be incorporated at this stage for quantification.

- Protein Digestion and Peptide Fractionation: Digest proteins and perform off-line high-pH reversed-phase chromatography to fractionate peptides. This pre-fractionation reduces complexity and increases depth.

- Immunoaffinity Purification (IP): Immobilize an anti-K-ɛ-GG antibody to beads via chemical cross-linking. Use these beads to enrich ubiquitinated peptides from the fractionated peptide pools.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Analyze the enriched samples by LC-MS/MS (typically using DDA) and process the data with search engines like MaxQuant.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitinome Profiling

| Item | Function / Role in Ubiquitinomics |

|---|---|

| Anti-K-ɛ-GG Antibody [8] | Core reagent for immunoaffinity enrichment of tryptic ubiquitin remnant peptides from complex digests. |

| Linkage-Specific Ub Antibodies [1] | Antibodies specific for M1-, K48-, K63- etc. linkages; used to enrich for proteins or peptides with specific ubiquitin chain types. |

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) [1] | Engineered high-affinity ubiquitin binders used to purify ubiquitinated proteins, often preserving them from deubiquitination. |

| Sodium Deoxycholate (SDC) [7] | Effective detergent for protein extraction during cell lysis; improves ubiquitin site coverage and reproducibility compared to urea. |

| Chloroacetamide (CAA) [7] | Alkylating agent used in lysis buffer to rapidly and specifically cysteine alkylation, inactivating DUBs without causing lysine modifications that mimic K-GG. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) [7] | Used to prevent degradation of ubiquitinated proteins, thereby boosting the ubiquitin signal for detection. |

| DUB Inhibitors (e.g., USP7 Inhibitors) [7] | Used to perturb the ubiquitin system and study the function of specific deubiquitinases on a proteome-wide scale. |

| Stable Isotope Labels (SILAC) [8] | Enable accurate relative quantification of ubiquitination sites across multiple experimental conditions. |

Complementary and Computational Approaches

While MS is the core experimental technology, computational methods provide valuable complementary tools for predicting ubiquitination sites, especially for initial screening or when MS is not feasible.

Machine Learning Prediction: Computational methods use physicochemical properties (PCPs) of protein sequences and machine learning algorithms to predict ubiquitination sites. Methods like Efficient Bayesian Multivariate Classifier (EBMC), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Logistic Regression (LR) have demonstrated effectiveness in this area [9]. These tools can help prioritize lysine residues for experimental validation [9].

The relationship between the major methodologies in ubiquitination research is summarized in the following diagram.

The identification of protein ubiquitination sites by mass spectrometry (MS) has been revolutionized by the ability to specifically target the di-glycine (K-ε-GG) remnant, a tryptic signature left on substrate peptides. This guide provides an objective comparison of the core methodologies that leverage this signature, detailing the experimental protocols, key reagent solutions, and performance data that underpin its success. By focusing on the refined antibody-based enrichment workflow, we delineate how this approach enables the routine quantification of over 10,000 distinct ubiquitination sites in a single experiment, establishing it as a critical tool for ubiquitination site identification research [10].

Protein ubiquitination is an essential post-translational modification that regulates numerous cellular processes, including protein turnover and signaling [11]. The ubiquitination process involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to a substrate protein's lysine residue, forming an isopeptide bond between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin and the epsilon-amino group of the target lysine [12]. For mass spectrometric analysis, trypsin digestion of ubiquitinated proteins cleaves the ubiquitin molecule, leaving a di-glycine (GG) remnant attached to the modified lysine residue on the substrate-derived peptide. This results in the characteristic K-ε-GG signature, with a predictable mass shift of 114.043 Da [11] [12]. This signature is the molecular cornerstone upon which specific enrichment and detection strategies are built, enabling large-scale profiling of the ubiquitinome.

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow from protein ubiquitination to the generation of the K-ε-GG peptide remnant, ready for enrichment and mass spectrometric analysis.

Core Experimental Protocol for K-ε-GG Enrichment

The large-scale identification of ubiquitination sites relies on a multi-step protocol that can be completed in approximately five days post-lysis [11] [13]. The following section details the critical methodologies cited in key studies.

Sample Preparation and Digestion

The process begins with lysing cells or tissues in a fresh, chilled urea lysis buffer (8 M urea, 50 mM Tris HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl) supplemented with protease and deubiquitinase inhibitors (e.g., PMSF, leupeptin, PR-619) to preserve the native ubiquitination state [11]. It is critical to prepare the buffer fresh to prevent protein carbamylation. Proteins are then reduced, alkylated, and digested. A common and effective strategy is a two-step enzymatic digestion: first with LysC, which is active in urea, followed by trypsin digestion after diluting the urea concentration [11]. The resulting peptide mixture is desalted via solid-phase extraction (SPE) before fractionation.

Peptide Fractionation

To reduce sample complexity and increase the depth of analysis, digested peptides are fractionated by basic pH Reversed-Phase (bRP) Chromatography prior to immunoaffinity enrichment [11] [10]. This offline separation uses a volatile salt buffer (e.g., 5 mM ammonium formate pH 10) with an increasing acetonitrile gradient. This step fractionates the complex peptide mixture into multiple samples (e.g., 8-12 fractions), significantly increasing the number of ubiquitination sites identified in the subsequent steps [11].

Immunoaffinity Enrichment of K-ε-GG Peptides

The heart of the protocol is the specific enrichment of K-ε-GG-containing peptides using a monoclonal anti-K-ε-GG antibody. A key refinement in the protocol is the chemical cross-linking of the antibody to protein A or G beads using dimethyl pimelimidate (DMP) [11] [10]. This cross-linking prevents antibody leaching during the enrichment process, drastically reducing contamination from antibody fragments in the final MS sample and improving overall sensitivity [11]. The peptide fractions are incubated with the antibody-bound beads, washed extensively, and the bound K-ε-GG peptides are eluted with a low-pH solution.

Mass Spectrometric Analysis and Database Searching

The enriched peptides are analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). For relative quantification across different cellular states, the protocol can be coupled with Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino Acids in Cell Culture (SILAC) [11] [13]. The resulting MS/MS spectra are searched against a protein database using search engines capable of detecting the K-ε-GG modification. Universal database search tools like MS-GF+ have been developed to improve the sensitive identification of diverse peptide types, including those with PTMs like the K-ε-GG remnant [14]. MS-GF+ uses a robust probabilistic model and computes rigorous E-values, which has been shown to increase the number of confidently identified peptides compared to other commonly used tools [14].

The complete workflow, from sample preparation to data analysis, is summarized below.

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

The refined K-ε-GG antibody-based workflow represents a significant advancement over earlier methods for ubiquitinome analysis. The table below summarizes the performance gains achieved by this method compared to other historical approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Ubiquitination Site Identification Methods

| Method | Key Feature | Typical Scale of Identified Ubiquitination Sites | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Level Enrichment (e.g., His-tagged Ubiquitin) [12] | Enrichment of intact ubiquitinated proteins prior to digestion. | ~1,000 putative ubiquitinated proteins [12] | Broad identification of ubiquitinated substrates. | Low specificity for exact modification sites; high sample complexity. |

| K-ε-GG Peptide-Level Enrichment (Initial Workflow) [11] [13] | Immunoaffinity enrichment of K-ε-GG peptides after digestion. | ~1,000s of sites | Site-specific identification; higher specificity than protein-level enrichment. | Lower throughput and sensitivity compared to refined protocols. |

| Refined K-ε-GG Enrichment (Cross-linked Ab + bRP) [11] [10] | Antibody cross-linking & basic pH fractionation prior to enrichment. | ~10,000 - 20,000 sites in a single experiment [10] | Highest sensitivity and specificity; enables routine large-scale quantification. | Requires specialized antibody and optimized protocol. |

The quantitative impact of methodological refinements is profound. The implementation of antibody cross-linking and offline fractionation has enabled the routine identification and quantification of approximately 20,000 distinct endogenous ubiquitination sites in a single SILAC experiment using moderate protein input [10]. This represents an order-of-magnitude improvement over earlier methods. It is important to note that while the K-ε-GG antibody is highly specific, the same di-glycine remnant is generated by the ubiquitin-like modifiers NEDD8 and ISG15. Control experiments in HCT116 cells have shown that over 94% of K-ε-GG identifications are due to ubiquitination, indicating the method has high specificity for the intended target [11] [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of the K-ε-GG enrichment protocol depends on a suite of specific reagents. The following table details the essential components and their functions within the experimental workflow.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for K-ε-GG Enrichment Experiments

| Reagent / Kit | Function in the Protocol | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-K-ε-GG Antibody | Critical for specific immunoaffinity enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides. Recognizes the diglycine remnant on modified lysine [11] [15]. | PTMScan Ubiquitin Remnant Motif (K-ε-GG) Kit (Cell Signaling Technology) [11]. |

| Cross-linking Reagent | Immobilizes the antibody to beads, preventing contamination of the sample with antibody fragments and improving sensitivity [11] [10]. | Dimethyl Pimelimidate (DMP) [11]. |

| Urea Lysis Buffer | Denaturing buffer for effective cell lysis and protein extraction while inactivating proteases and deubiquitinases. Must be prepared fresh [11]. | 8 M Urea, 50 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM NaCl, supplemented with inhibitors [11]. |

| Protease/Deubiquitinase Inhibitors | Preserves the native ubiquitination state of proteins by blocking endogenous proteolytic and deubiquitinating activities during lysis [11]. | PMSF, Leupeptin, Aprotinin, PR-619 [11]. |

| Fractionation Chromatography Resins | For offline basic pH reversed-phase fractionation, which reduces sample complexity and dramatically increases ubiquitination site identifications [11] [10]. | High-pH stable C18 resin materials. |

| SILAC Amino Acids | Enable metabolic labeling for precise relative quantification of ubiquitination changes between different cell states (e.g., treated vs. untreated) [11] [13]. | L-lysine and L-arginine with stable isotopes (e.g., 13C, 15N). |

Functional Applications in Pathway Analysis

The power of the K-ε-GG methodology extends beyond mere cataloguing, allowing researchers to connect ubiquitination changes to specific biological pathways and diseases. For example, a label-free quantitative study of human pituitary adenoma tissues identified 158 ubiquitination sites on 108 proteins [15]. Bioinformatic analysis of this data mapped these proteins to several key signaling pathways, demonstrating the functional relevance of the technique.

Table 3: Signaling Pathways Regulated by Ubiquitination in Disease Contexts

| Signaling Pathway | Biological Role | Evidence from Ubiquitinome Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| PI3K-AKT Signaling Pathway | Regulates cell survival, proliferation, and metabolism. | Identified as a major hub of ubiquitination in pituitary adenomas [15]. |

| Hippo Signaling Pathway | Controls organ size and tumor suppression by regulating cell proliferation and apoptosis. | Found to be significantly enriched with ubiquitinated proteins in pituitary adenomas [15]. |

| Nucleotide Excision Repair | A DNA repair mechanism crucial for maintaining genomic integrity. | Proteins in this pathway were found to be targeted by ubiquitination [15]. |

The diagram below illustrates how the K-ε-GG enrichment workflow fits into the broader context of biological discovery, from sample to functional insight.

In mass spectrometry-based proteomics, the identification of peptides and proteins from tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) data relies heavily on two primary computational strategies: sequence database searching and spectral library searching [16] [17]. These methods represent fundamentally different approaches for matching experimental spectra to peptide sequences, each with distinct advantages and limitations. Sequence database searching compares observed spectra against theoretical spectra generated in silico from protein sequence databases, while spectral library searching matches observed spectra directly against collections of previously identified experimental spectra [17]. The choice between these approaches significantly impacts sensitivity, specificity, and the overall success of proteomic analyses, particularly in specialized applications such as ubiquitination site identification where post-translational modifications (PTMs) complicate analysis. This guide provides an objective comparison of these database types, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform researchers in selecting appropriate strategies for their mass spectrometry workflows.

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Sequence Databases

Sequence databases contain protein sequences in FASTA format, derived from genomic or transcriptomic data. When used for MS/MS identification, search engines such as MetaMorpheus, MaxQuant, and MSFragger generate theoretical spectra for all possible peptides resulting from enzymatic digestion of these protein sequences [17]. These theoretical spectra typically include only canonical b- and y-ions, lacking real-world fragmentation patterns and peak intensity information [17]. The search space can become extremely large when considering multiple post-translational modifications, missed cleavages, and sequence variants, which complicates the identification process and reduces discrimination between correct and incorrect matches.

Spectral Libraries

Spectral libraries are curated collections of experimental MS/MS spectra that have been previously identified and validated [17]. These libraries capture the true fragmentation patterns of peptides, including characteristic peak intensities and non-canonical fragments such as neutral loss of ammonia or water [16] [18]. Libraries can be generated from experimental data acquired through data-dependent acquisition (DDA) or created in silico using deep learning approaches like DeepDIA [18]. They provide a more realistic representation of peptide fragmentation but are limited to peptides that have been previously observed or predicted.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Database Types

| Feature | Sequence Databases | Spectral Libraries |

|---|---|---|

| Data Type | Protein sequences (FASTA) | Experimental or predicted MS/MS spectra |

| Spectral Content | Theoretical fragments (typically b-/y-ions) | Experimental peaks with intensities |

| Coverage | Comprehensive (all possible peptides) | Limited to previously observed peptides |

| PTM Handling | Can theoretically include any modification | Limited to modifications in library |

| Primary Use | De novo discovery | Targeted identification |

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Sensitivity and Identification Rates

Multiple studies have systematically compared the performance of spectral library searching versus sequence database searching. A comprehensive comparative study demonstrated that spectral library searching provides superior sensitivity for peptide identification across diverse datasets [16]. The success of spectral library searching was primarily attributable to the use of real library spectra for matching, which captured fragmentation characteristics that theoretical spectra could not reproduce [16]. When decoupling the effect of search space, researchers found that without real library spectra, the sensitivity advantage of spectral library searching largely disappeared [16].

Spectral library searching has proven particularly advantageous for identifying low-quality spectra and complex spectra of higher-charged precursors, both important frontiers in peptide sequencing [16]. The use of real peak intensities and non-canonical fragments, both under-utilized information in sequence database searching, significantly contributes to this sensitivity advantage [16].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Recent experimental data from benchmark studies provides direct quantitative comparison between these approaches. In one study comparing Calibr (a spectral library search tool) against conventional database searching, spectral library searching demonstrated substantial improvements in identification rates [19]. When searching against a DDA-based spectral library, Calibr improved spectrum–spectrum match (SSM) numbers by 17.6–26.65% and peptide numbers by 18.45–37.31% over state-of-the-art tools on three different datasets [19].

For data-independent acquisition (DIA) proteomics, DeepDIA demonstrated that the quality of in silico libraries predicted by instrument-specific models was comparable to that of experimental libraries [18]. With peptide detectability prediction, in silico libraries could be built directly from protein sequence databases, breaking through the limitation of DDA on peptide/protein detection [18].

Table 2: Performance Comparison from Experimental Studies

| Performance Metric | Sequence Database Searching | Spectral Library Searching | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral Match Rate | Baseline | 17.6-26.65% increase | Significant [19] |

| Peptide Identification | Baseline | 18.45-37.31% increase | Significant [19] |

| Low-Quality Spectra | Lower sensitivity | Disproportionately more successful | Substantial [16] |

| Higher-Charged Precursors | Moderate success | Enhanced identification | Notable [16] |

| Dot Product Score | Theoretical (variable) | 0.89-0.94 (experimental) | More reliable [18] |

Limitations and Trade-offs

Despite their advantages, spectral libraries have important limitations. The major weakness of spectral library searching is that peptide identification is limited to only peptides that have spectra included in the library [17]. Additionally, few post-translationally modified peptides are represented in spectral libraries because of software limitations [17]. Those programs that do generate quality spectral libraries using deep learning approaches are not yet able to accurately predict spectra for many PTM-modified peptides [17].

Sequence database searching maintains an advantage in comprehensive discovery workflows, as it can theoretically identify any peptide present in the protein sequence database, including novel variants and unexpected modifications not present in spectral libraries.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Spectral Library Generation and Searching

Protocol for Experimental Spectral Library Construction:

Sample Preparation: Complex protein samples (e.g., cell lysates, tissues) are prepared using standard proteomics protocols. For ubiquitination studies, enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides is typically performed using anti-K-ɛ-GG antibodies [8] [20].

Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA): Fractionated samples are analyzed using LC-MS/MS with DDA to generate comprehensive spectral data. High-resolution instruments like Q-Exactive HF are preferred for generating high-quality reference spectra [18].

Database Searching: The acquired DDA data is initially searched against a sequence database using tools like Comet, X!Tandem, and MS-GF+ to identify peptide-spectrum matches (PSMs) [19].

Library Curation: Validated PSMs (at FDR < 1%) are used to construct a consensus spectral library using tools like SpectraST. Quality filters are applied to remove low-quality spectra [19].

Decoy Generation: Decoy spectra are created by reversing sequences or shuffling peaks to enable false discovery rate estimation during searching [17].

Protocol for In Silico Spectral Library Generation with DeepDIA:

Model Training: Deep neural networks combining convolutional neural networks (CNN) and bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM) networks are trained on experimental datasets [18].

Spectrum Prediction: The model takes peptide sequences as input and predicts relative intensities of b/y product ions and retention times [18].

Quality Assessment: Predicted spectra are evaluated using dot products between predicted and experimental peak intensities, with median values >0.90 indicating high quality [18].

Library Construction: Predicted spectra are compiled into searchable spectral libraries compatible with tools like Spectronaut [18].

Hybrid Search Strategies

To overcome the limitations of both approaches, hybrid strategies have been developed:

Preliminary Database Search: Raw spectra are first searched against theoretical target and decoy peptides from a protein sequence database to obtain preliminary identifications [17].

Spectral Angle Calculation: Spectra from preliminary identifications are compared against library spectra to calculate spectral similarity [17].

Binary Decision Tree: Final peptide-spectrum matches are determined using a binary decision tree that considers both database search scores and spectral angles, along with 16 other attributes [17].

This hybrid approach implemented in MetaMorpheus improves identification success rates and sensitivity compared to either method alone [17].

Spectral Library and Sequence Database Hybrid Search Workflow

Application to Ubiquitination Site Identification

Special Considerations for Ubiquitination Research

Ubiquitination site identification presents unique challenges that influence database selection. The stoichiometry of protein ubiquitination is very low under normal physiological conditions, increasing the difficulty of identifying ubiquitinated substrates [1]. Additionally, ubiquitin can modify substrates at one or several lysine residues simultaneously, significantly complicating site localization [1]. Furthermore, ubiquitin itself can serve as a substrate, resulting in complex ubiquitin chains that vary in length, linkage, and overall architecture [1].

For ubiquitination studies, enrichment strategies are essential prior to MS analysis. The most common approach uses antibodies specific to the Lys-ɛ-Gly-Gly (K-ɛ-GG) remnant produced by trypsin digestion of ubiquitinated proteins [8] [1]. This enrichment dramatically improves detection sensitivity for ubiquitinated peptides.

Database Selection for Ubiquitination Studies

Spectral library searching offers advantages for ubiquitination studies when:

- Studying well-characterized ubiquitination sites with available reference spectra

- Analyzing multiple samples where consistency is important

- Working with low-quality spectra from enriched samples

- Prioritizing sensitivity over comprehensive discovery

Sequence database searching is preferable when:

- Discovering novel ubiquitination sites not in existing libraries

- Studying atypical ubiquitin chain linkages

- Analyzing samples with potential novel modifications

- Comprehensive profiling of the ubiquitinome is required

Hybrid approaches are increasingly used in ubiquitination research to balance sensitivity and comprehensiveness. The hybrid strategy implemented in MetaMorpheus has been successfully applied to identify a broad spectrum of PTMs, including ubiquitination [17].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitination Proteomics

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-K-ɛ-GG Antibody | Enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides | Immunoaffinity purification of tryptic peptides with ubiquitin remnants [8] [20] |

| PTMScan Ubiquitin Remnant Motif Kit | Affinity enrichment | Commercial solution for ubiquitinated peptide enrichment [20] |

| SILAC Labeling Reagents | Metabolic labeling for quantification | Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino Acids in Cell Culture for quantitative ubiquitinomics [8] [20] |

| Recombinant Ubiquitin Tags | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins | His-tagged or Strep-tagged ubiquitin for substrate identification [1] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Stabilization of ubiquitinated proteins | MG132 or Epoxomicin to prevent degradation of ubiquitinated substrates [20] |

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) | Affinity purification | High-affinity enrichment of polyubiquitinated proteins [1] |

Ubiquitination Site Identification Workflow

Both spectral libraries and sequence databases play crucial roles in modern proteomics, each with distinct strengths and limitations. Spectral library searching generally provides higher sensitivity and more accurate identification for known peptides, particularly for low-quality spectra and complex precursors [16] [19]. Sequence database searching offers more comprehensive coverage for novel peptide discovery, including unexpected modifications and sequence variants [17].

For ubiquitination site identification research, the choice depends on specific project goals. When studying well-characterized systems with available spectral libraries, spectral library searching provides superior performance. For discovery-oriented research investigating novel ubiquitination sites or atypical chain architectures, sequence database searching remains essential. Hybrid approaches that leverage both strategies offer a promising middle ground, balancing sensitivity and comprehensiveness [17].

As mass spectrometry technologies continue to advance, particularly in data-independent acquisition methods, spectral library approaches are likely to play an increasingly important role. The development of sophisticated in silico spectral prediction tools like DeepDIA further bridges the gap between these approaches, enabling more accurate and comprehensive peptide identification in ubiquitination research and beyond [18].

Protein ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification (PTM) that regulates diverse cellular functions, including protein degradation, DNA repair, and signal transduction. The identification and characterization of ubiquitination sites are fundamental to understanding these processes and their implications in diseases such as cancer and neurodegenerative disorders. However, researchers face significant challenges in this field, primarily due to the low stoichiometry of ubiquitinated proteins, the complex architecture of ubiquitin chains, and the vast dynamic range of protein abundance in biological samples. This article objectively compares the performance of mass spectrometry-based methodologies and computational tools developed to overcome these hurdles, providing a structured analysis of their capabilities and limitations to guide researchers in selecting appropriate strategies for ubiquitination site identification.

The Core Experimental Challenges in Ubiquitination Analysis

The accurate identification of protein ubiquitination sites is technically demanding, and the core challenges are deeply interconnected, often compounding the difficulty of analysis.

Stoichiometry

The stoichiometry of protein ubiquitination is typically very low under normal physiological conditions. This means that at any given moment, only a tiny fraction of a specific protein substrate may be ubiquitinated. This low abundance significantly increases the difficulty of isolating and identifying ubiquitinated substrates amidst a sea of non-modified proteins. Furthermore, ubiquitin can modify substrates at one or several lysine residues simultaneously, complicating the precise localization of the modification sites.

Ubiquitin Chain Architecture

Ubiquitin itself can become a substrate for further ubiquitination, leading to the formation of polyubiquitin chains. This creates a layer of complexity that goes beyond simply identifying the modified substrate protein. Ubiquitin chains vary in:

- Length: The number of ubiquitin monomers in a chain.

- Linkage Type: Ubiquitin contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1), each of which can form a distinct chain type.

- Architecture: Chains can be homotypic (same linkage), heterotypic (mixed linkages), or even branched.

The function of the ubiquitination event is heavily influenced by this topology; for example, K48-linked chains typically target substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains are involved in non-proteolytic signaling. Therefore, simply identifying a ubiquitinated protein is often insufficient—understanding its biological consequence requires knowledge of the chain architecture.

Dynamic Range

The dynamic range of protein abundance in a cell is enormous, spanning several orders of magnitude. Low-abundance regulatory proteins, which are often key ubiquitination targets, can be masked by highly abundant structural proteins. This makes the specific enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides a critical step prior to mass spectrometry analysis, as without it, the signal from modified peptides is lost in the noise.

Table 1: Key Challenges in Ubiquitination Site Identification

| Challenge | Description | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometry | Very low fraction of any specific protein is ubiquitinated at a given time [1]. | Makes isolation and detection difficult; requires highly sensitive enrichment methods. |

| Chain Architecture | Ubiquitin forms complex polymers (chains) with different lengths and linkages (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63, M1) [1]. | A single substrate's ubiquitination can have diverse functions; linkage type determines biological outcome. |

| Dynamic Range | Ubiquitinated proteins exist against a background of a vast excess of non-modified proteins [1]. | Low-abundance ubiquitination signals are obscured without effective enrichment. |

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Approaches

To tackle these challenges, several methodological approaches have been developed, each with distinct strengths and weaknesses. The table below provides a high-level comparison of these strategies.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Ubiquitination Analysis Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Throughput | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tagged Ubiquitin (e.g., His, Strep) | Expression of affinity-tagged Ub in cells; enrichment of conjugates [1]. | Medium | Relatively easy and low-cost; good for cultured cells [1]. | Cannot be used on animal/human tissues; potential for artifacts; non-specific binding [1]. |

| Anti-K-ε-GG Antibody Enrichment | Immunoaffinity purification of tryptic peptides with diglycine remnant on lysine [8] [21]. | High | Applicable to any sample (cells, tissues); identifies endogenous sites; high specificity [1] [8]. | High cost of antibodies; requires optimized protocol to minimize non-specific binding [1]. |

| Ubiquitin-Binding Domain (UBD) Enrichment | Use of proteins with high-affinity Ub-binding domains (e.g., TUBEs) to purify ubiquitinated proteins [1]. | Medium | Can preserve labile ubiquitination and chain architecture; suitable for functional studies [1]. | Less common in proteomic workflows; can be linkage-specific. |

| Computational Prediction (e.g., DeepMVP, Ubigo-X) | Machine/Deep Learning models trained on known ubiquitination sites to predict novel sites [22] [23]. | Very High | Fast, inexpensive; ideal for proteome-wide screening and hypothesis generation [22]. | Predictive only; requires experimental validation; performance depends on training data quality [23]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

For the most widely adopted method, the anti-K-ε-GG antibody-based enrichment, the protocol has been refined for high-depth analysis.

Protocol: Large-Scale Identification of Ubiquitination Sites by Immunoaffinity Enrichment and MS [8] [21]

- Sample Preparation: Cells or tissues are lysed in a denaturing buffer (e.g., containing 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) and boiled to inactivate deubiquitinases. Proteins are reduced, alkylated, and digested into peptides, typically using Lys-C and trypsin.

- Peptide Fractionation (Optional but Recommended): For very deep ubiquitinome analysis, the complex peptide mixture is fractionated using high-pH reverse-phase chromatography. This reduces sample complexity before enrichment, significantly improving the number of identifications [21].

- Immunoaffinity Enrichment: The digested peptides are incubated with antibodies specifically cross-linked to beads. These antibodies recognize the K-ε-GG remnant, the "footprint" left on a lysine after tryptic digestion of a ubiquitinated protein. After incubation, the beads are extensively washed to remove non-specifically bound peptides.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: The enriched K-ε-GG peptides are eluted and analyzed by liquid chromatography coupled to a high-resolution tandem mass spectrometer. The instrument fragments the peptides and collects MS/MS spectra.

- Data Processing: The MS/MS spectra are searched against a protein database using software (e.g., MaxQuant) configured to include the K-ε-GG modification (+114.1 Da on lysine) as a variable modification. This allows for the identification of the peptide sequence and the precise localization of the ubiquitination site [8].

This workflow, when optimized, can routinely identify over 23,000 distinct ubiquitination sites from a single sample of HeLa cells [21].

Diagram 1: K-ε-GG Enrichment Workflow for Ubiquitination Site Identification

The Computational Toolkit: Predicting Ubiquitination Sites

To complement experimental approaches, computational predictors offer a high-throughput means to screen for potential ubiquitination sites.

Evolution of Prediction Tools

Early tools like UbiPred used support vector machines (SVM) and physicochemical properties, while CKSAAP_UbSite utilized the composition of k-spaced amino acid pairs [22]. The field has since evolved to leverage deep learning. For example, DeepUbi employed a convolutional neural network (CNN) with multiple feature encodings, and Ubigo-X, a more recent tool, uses an ensemble model that transforms protein sequence features into image-based representations for CNN training, combined with a weighted voting strategy [22].

Benchmarking the State-of-the-Art

A significant advance is represented by DeepMVP, a deep learning framework trained on PTMAtlas, a large, high-quality dataset of PTM sites generated through systematic reprocessing of public MS data [23]. DeepMVP was designed to predict sites for six PTM types, including ubiquitination.

Table 3: Comparative Performance of Deep Learning Predictors

| Predictor | Approach | Key Features | Reported Performance (AUC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubigo-X [22] | Ensemble Learning, Image-based feature representation | Combines sequence, structure, and function features via weighted voting. | 0.85 (AUC, balanced test) |

| DeepMVP [23] | CNN & Bidirectional GRU, trained on PTMAtlas | Enzyme-agnostic; trained on a large, high-confidence dataset from systematic MS reanalysis. | Outperformed existing tools across all six PTM types, including ubiquitination. |

DeepMVP's performance highlights the critical importance of data quality over mere algorithmic complexity. By curating a high-confidence training set, it achieves superior accuracy in predicting ubiquitination sites and can also be used to assess the impact of genetic variants on PTM landscapes [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful ubiquitination research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| K-ε-GG Motif-specific Antibodies | Immunoaffinity enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides from complex digests. | Large-scale ubiquitinome profiling by LC-MS/MS [8] [21]. |

| Linkage-specific Ubiquitin Antibodies | Detect or enrich for polyubiquitin chains of a specific linkage (e.g., K48, K63). | Immunoblotting to determine the functional fate of a ubiquitinated substrate [1]. |

| Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) | High-affinity enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins, protecting them from deubiquitinases. | Isolating endogenous ubiquitinated proteins for downstream analysis without perturbation [1]. |

| Epitope-tagged Ubiquitin (e.g., His, HA, Strep) | Expression in cells allows for purification of ubiquitin conjugates under denaturing conditions. | Identifying ubiquitination sites for a specific protein or condition in cell culture [1]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., Bortezomib) | Block degradation of ubiquitinated proteins, leading to their accumulation. | Enhancing detection of ubiquitinated proteins, particularly those targeted for degradation [21]. |

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors | Prevent the removal of ubiquitin by DUBs during sample preparation. | Preserving the native ubiquitination state of proteins during lysis and processing. |

Diagram 2: Strategy Mapping for Key Ubiquitination Challenges

The field of ubiquitination research has made remarkable strides in developing methods to confront the fundamental challenges of stoichiometry, chain architecture, and dynamic range. The anti-K-ε-GG antibody enrichment coupled with advanced MS represents the gold standard for experimental, high-throughput site identification, capable of mapping tens of thousands of sites. Meanwhile, computational tools like DeepMVP and Ubigo-X are emerging as powerful allies for proteome-wide prediction and analysis. The choice of method depends on the research question: for discovery-phase studies, computational screening provides unparalleled speed and scale, but for mechanistic insights and validation, experimental MS methods with their ability to precisely map sites and, increasingly, elucidate chain architecture, remain indispensable. An integrated approach, leveraging the strengths of both experimental and computational worlds, is the most robust strategy for advancing our understanding of the complex ubiquitin code.

Methodologies in Practice: Enrichment Strategies, MS Acquisition, and Database Search Engines

Protein ubiquitination is an essential post-translational modification (PTM) that regulates diverse cellular functions, including protein stability, activity, localization, and degradation [24] [12]. This modification involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin, a small 76-residue protein, to substrate proteins via a cascade of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes [24]. The complexity of ubiquitin signaling arises from the ability of ubiquitin to form various chain types and architectures through its seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and N-terminal methionine (M1) [24]. The versatility of ubiquitination presents significant challenges for its characterization, primarily due to the low stoichiometry of modified proteins, the diversity of modification sites, and the complexity of ubiquitin chain architectures [24].

Mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics has become the primary tool for system-level analysis of ubiquitination events, enabling identification and quantification of ubiquitination sites and chain linkages [25] [26]. However, the low abundance of ubiquitinated species within complex biological samples necessitates highly specific enrichment strategies prior to MS analysis [24] [12]. This guide comprehensively compares the three principal enrichment methodologies—antibody-based, tag-based, and ubiquitin-binding domain (UBD)-based approaches—providing researchers with the experimental and performance data necessary to select appropriate methods for their ubiquitination studies.

Methodological Comparison at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the three main ubiquitin enrichment methods.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Ubiquitin Enrichment Methodologies

| Method | Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody-based (K-ε-GG) | Immunoaffinity purification of tryptic peptides containing diGly remnant (K-ε-GG) [11] | High specificity for modified sites; works with endogenous ubiquitin; compatible with clinical samples [24] [11] | Cannot distinguish ubiquitination from other Ubl modifications (NEDD8, ISG15); high antibody cost [11] [27] | System-wide ubiquitinome mapping; quantitative studies across multiple conditions [28] [26] |

| Tag-based | Expression of epitope-tagged ubiquitin (e.g., His, Flag, Strep) in cells, followed by affinity purification [24] | Relatively low cost; high yield; well-established protocols [24] | Requires genetic manipulation; potential artifacts from tag expression; doesn't work with human tissues [24] [25] | Discovery of ubiquitinated substrates in cell culture models [24] [12] |

| UBD-based | Affinity purification using ubiquitin-binding domains (e.g., OtUBD, TUBEs) [24] [27] | Enriches all ubiquitin conjugates including atypical ones; works under native or denaturing conditions [27] | Tandem UBDs preferentially bind polyUb chains; variable affinity for different chain types [27] | Analysis of ubiquitin chain architectures; interactome studies; purification of intact ubiquitinated complexes [27] |

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Antibody-based Enrichment (K-ε-GG Method)

The K-ε-GG method has become the gold standard for large-scale ubiquitinome profiling due to its exceptional specificity for mapping modification sites. This approach leverages a highly specific antibody that recognizes the di-glycine (K-ε-GG) remnant left on modified lysine residues after tryptic digestion of ubiquitinated proteins [11]. The workflow involves multiple critical steps that significantly impact the depth and quality of ubiquitination site identification.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for K-ε-GG Enrichment

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lysis Buffer | SDC (Sodium Deoxycholate) buffer [26] | Efficient protein extraction while maintaining ubiquitin modification integrity |

| Alkylating Agent | Chloroacetamide (CAA) [26] | Cysteine alkylation; preferred over iodoacetamide to prevent di-carbamidomethylation artifacts |

| Proteases | Lys-C, Trypsin [11] [28] | Sequential protein digestion to generate peptides with K-ε-GG remnants |

| Enrichment Antibody | Anti-K-ε-GG antibody [11] | Immunoaffinity purification of diGly-modified peptides |

| Chromatography | Basic pH Reverse-Phase (bRP) [11] | Pre-enrichment fractionation to reduce sample complexity |

| Cross-linking Reagent | Dimethyl pimelimidate (DMP) [11] | Immobilizes antibody to beads to reduce contamination |

A refined protocol for large-scale ubiquitination site analysis involves the following critical steps [11] [28]:

Sample Preparation and Lysis: For optimal results, use SDC-based lysis buffer (1% SDC, 50 mM Tris HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl) supplemented with fresh protease and deubiquitinase inhibitors (e.g., 50 μM PR-619) and alkylating agents (1 mM CAA). Immediate boiling of samples after lysis (95°C for 5 minutes) effectively inactivates enzymes and preserves ubiquitination states [26]. The SDC method has been shown to yield approximately 38% more K-ε-GG peptides compared to traditional urea-based buffers [26].

Protein Digestion and Peptide Cleanup: Following protein quantification (aim for 2-10 mg total protein input for deep coverage), reduce proteins with 5 mM DTT (30 minutes at 50°C) and alkylate with 10 mM CAA (15 minutes in darkness). Perform sequential digestion with Lys-C (4 hours) followed by trypsin (overnight at 30°C). Acidify the digest with TFA to a final concentration of 0.5% to precipitate SDC, then centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes to collect the peptide-containing supernatant [28] [26].

Peptide Fractionation: Fractionate peptides using basic pH reversed-phase chromatography (e.g., 10 mM ammonium formate, pH 10) with increasing acetonitrile gradients (7%, 13.5%, 50%). This pre-fractionation step significantly increases ubiquitination site identifications by reducing sample complexity prior to immunoaffinity enrichment [11] [28].

Immunoaffinity Enrichment: Cross-link anti-K-ε-GG antibody to protein A agarose beads using DMP to minimize antibody leaching and contamination. Incubate peptide fractions with cross-linked antibody beads for 2 hours at 4°C with rotation. Wash beads extensively with ice-cold IAP buffer and purified water, then elute peptides with 0.15% TFA [11] [28].

Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Desalt eluted peptides using C18 StageTips and analyze by LC-MS/MS. For comprehensive coverage, employ data-independent acquisition (DIA) methods, which have been shown to identify >70,000 ubiquitinated peptides in single runs—more than tripling identifications compared to traditional data-dependent acquisition (DDA) while significantly improving quantitative precision [26].

The following diagram illustrates the complete K-ε-GG enrichment workflow:

Tag-based Enrichment

Tag-based approaches involve the genetic engineering of cells to express ubiquitin with an N-terminal epitope tag (e.g., His, FLAG, HA, Strep). This enables purification of ubiquitinated proteins under denaturing conditions, which minimizes non-specific interactions and preserves unstable ubiquitin conjugates [24] [12].

The standard protocol for tag-based enrichment includes:

Cell Engineering: Generate cell lines stably expressing tagged ubiquitin. In yeast systems, endogenous ubiquitin genes can be replaced with tagged variants. For mammalian cells, consider the StUbEx (stable tagged ubiquitin exchange) system, which allows replacement of endogenous ubiquitin with His-tagged ubiquitin [24] [12].

Protein Purification: Lyse cells in denaturing buffer (e.g., 8 M urea, 50 mM Tris HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl) to disrupt non-covalent interactions. Purify ubiquitinated proteins using affinity resins corresponding to the tag—Ni-NTA agarose for His-tags or Strep-Tactin for Strep-tags. Wash extensively with denaturing wash buffers containing 20 mM imidazole (for His-tags) to reduce non-specific binding [12].

Digestion and Analysis: Digest enriched proteins on-bead or following elution. Identify ubiquitination sites by MS detection of the characteristic 114.043 Da mass shift on modified lysine residues, corresponding to the diGly remnant [12].

While this approach enabled the identification of 1,075 ubiquitinated proteins in the first large-scale ubiquitin proteomics study in yeast [12], it presents limitations including co-purification of endogenous His-rich proteins and inability to study endogenous systems without genetic manipulation [24].

UBD-based Enrichment

UBD-based methods utilize natural ubiquitin-binding domains to purify ubiquitinated proteins. Recent developments include engineered high-affinity UBDs such as OtUBD from Orientia tsutsugamushi, which exhibits nanomolar affinity for ubiquitin and can enrich both mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins [27].

The OtUBD enrichment protocol offers both native and denaturing workflows:

Resin Preparation: Express and purify recombinant OtUBD with an N-terminal cysteine and C-terminal His-tag. Immobilize to SulfoLink coupling resin via cysteine residue [27].

Sample Preparation: For the denaturing workflow (specific enrichment of covalently ubiquitinated proteins), lyse cells in denaturing buffer (6 M guanidinium HCl, 100 mM NaH₂PO₄, 10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0). For the native workflow (enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins and their interactors), use non-denaturing lysis buffers (e.g., 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40) supplemented with N-ethylmaleimide to inhibit deubiquitinases [27].

Affinity Purification: Incubate clarified lysates with OtUBD resin for 2-4 hours at 4°C. Wash with appropriate buffers and elute with SDS-PAGE sample buffer or competitive elution with free ubiquitin [27].

The OtUBD method effectively enriches diverse ubiquitin conjugates without linkage preference and can distinguish directly ubiquitinated proteins from interactors through parallel denaturing and native purifications [27].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Recent technological advances have significantly enhanced the performance of ubiquitination enrichment methods. The table below summarizes quantitative performance metrics from recent studies employing these methodologies.

Table 3: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Enrichment Methods

| Method | Sample Input | Identifications | Quantitative Precision | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-ε-GG (DIA-MS) | 2 mg protein (HCT116 cells) [26] | >70,000 ubiquitinated peptides [26] | Median CV <10% [26] | System-wide ubiquitinome profiling; temporal dynamics [26] |

| K-ε-GG (DDA-MS) | 2 mg protein (Jurkat cells) [26] | ~30,000 ubiquitinated peptides [26] | ~50% peptides without missing values [26] | Ubiquitination site discovery; targeted studies [28] |

| Tag-based (His-Ub) | Yeast expressing His-Ub [12] | 1,075 proteins (72 with identified sites) [12] | Semi-quantitative with SILAC [12] | Substrate identification; pathway analysis [24] |

| UBD-based (OtUBD) | Yeast/mammalian cell lysates [27] | Variable by MS method | Compatible with label-free quantification [27] | Chain architecture studies; interactome analysis [27] |

The following diagram illustrates the strategic decision process for selecting the appropriate enrichment method based on research objectives:

The selection of an appropriate enrichment methodology is paramount for successful ubiquitination studies. Antibody-based K-ε-GG enrichment currently offers the deepest coverage for site-specific ubiquitinome profiling, especially when combined with modern DIA-MS acquisition and optimized SDC lysis protocols. Tag-based approaches remain valuable for substrate identification in genetically tractable systems, while UBD-based methods provide unique capabilities for studying ubiquitin chain architectures and protein complexes. Researchers should align their method selection with specific research questions, model system constraints, and desired analytical outcomes, considering that orthogonal validation using multiple methods often strengthens experimental findings. As MS technologies continue to advance with improved sensitivity and quantification capabilities, these enrichment strategies will further empower comprehensive analysis of the complex ubiquitin signaling network.

In the field of proteomics and metabolomics, mass spectrometry (MS) serves as a powerful analytical technique for identifying and quantifying biomolecules. The selection of a data acquisition mode is a critical decision that directly impacts the depth, reproducibility, and quantitative accuracy of results, particularly in specialized applications such as ubiquitination site identification. Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) and Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) represent two fundamental approaches to tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) with distinct operational principles and performance characteristics [29] [30]. Within ubiquitination research, where modified peptides often exhibit low stoichiometry and require confident identification, the choice between these acquisition strategies can significantly influence experimental outcomes [11] [31]. This guide provides a comprehensive objective comparison of DDA and DIA methodologies, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform researchers in their selection process for ubiquitination studies and related applications.

Fundamental Principles and Operational Logic

The core difference between DDA and DIA lies in their approach to selecting precursor ions for fragmentation during MS/MS analysis.

Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA)

DDA operates through a targeted, intensity-driven selection process. The instrument first performs a full MS1 survey scan to detect all intact precursor ions within a specified mass-to-charge (m/z) range. It then automatically selects the most abundant ions (typically the "top N" where N is usually 10-20) based on signal intensity for subsequent fragmentation and MS/MS analysis [29] [30] [32]. This sequential, priority-based approach makes DDA inherently biased toward high-abundance ions, potentially missing lower-abundance species of biological significance, such as certain ubiquitinated peptides [32].

Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA)

DIA employs an unbiased, systematic fragmentation strategy. Instead of selecting individual precursors, the mass spectrometer divides the full m/z range into consecutive, fixed isolation windows (typically 20-25 Da wide). It then systematically steps through these windows, isolating and fragmentating all ions within each window regardless of their abundance [29] [30]. A common DIA implementation is SWATH (Sequential Windowed Acquisition of All Theoretical Fragment ions), which covers the entire mass range (e.g., 400-1200 m/z) through multiple small windows [29]. This comprehensive approach ensures that all detectable precursors, including low-abundance modified peptides, are fragmented and recorded.

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental operational differences between DDA and DIA workflows:

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Quantitative Metrics

Multiple studies have systematically compared the performance characteristics of DDA and DIA across various metrics. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from experimental comparisons:

Table 1: Experimental Performance Comparison of DDA and DIA

| Performance Metric | DDA Performance | DIA Performance | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Identification Capacity | Higher total number of detected compounds (14,958 in Huaihua Powder) [33] | Fewer total compounds detected (9,489 in Huaihua Powder) but greater proportion of high-confidence IDs (10.63% with scores >0.8) [33] | Analysis of traditional Chinese medicine (Huaihua Powder) using UPLC-Q-Orbitrap MS [33] |