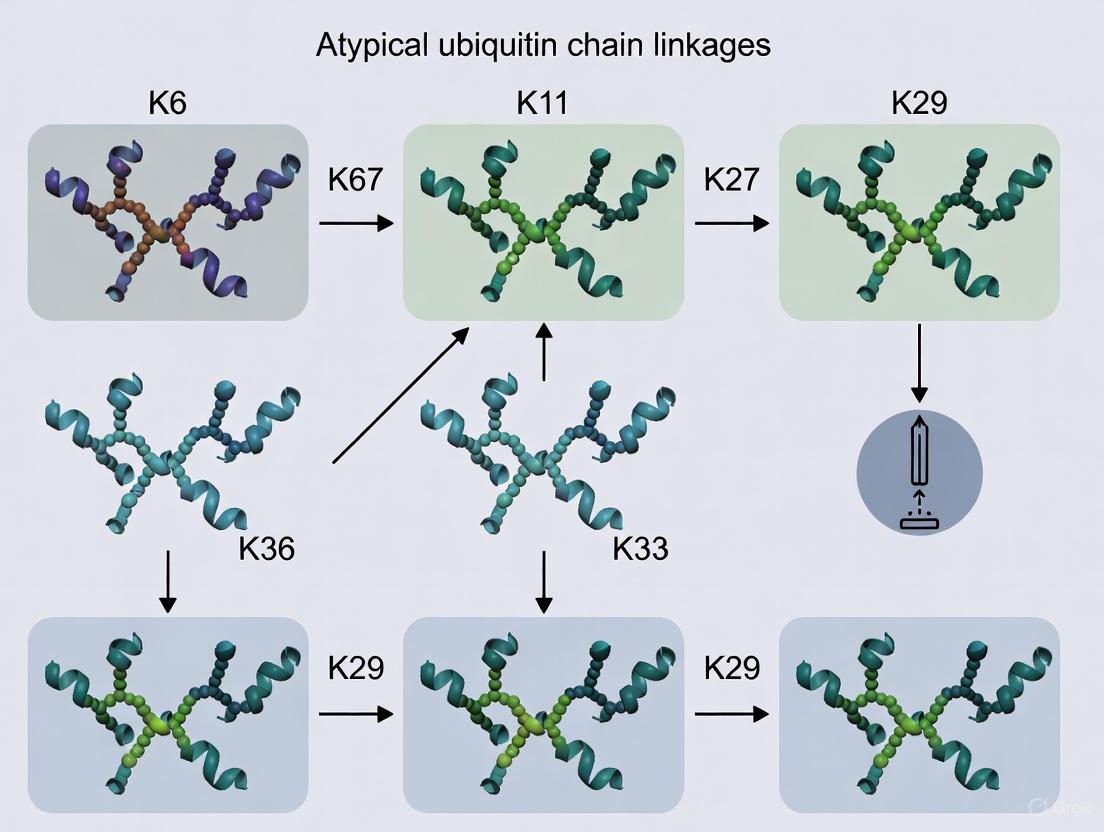

Decoding Atypical Ubiquitin Chains: K6, K11, K27, K29, K33 Functions in Cellular Regulation and Disease

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of atypical ubiquitin chain linkages (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33), targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Decoding Atypical Ubiquitin Chains: K6, K11, K27, K29, K33 Functions in Cellular Regulation and Disease

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of atypical ubiquitin chain linkages (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33), targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational knowledge on their discovery and biological roles, methodological advances for studying and applying these chains in research, troubleshooting common experimental challenges, and validation through comparative analysis with canonical chains. The scope integrates insights from recent studies to highlight implications for understanding disease mechanisms and developing targeted therapies.

Exploring the Biology of Atypical Ubiquitin Chains: K6, K11, K27, K29, and K33

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates virtually every cellular process in eukaryotic cells, ranging from protein degradation and DNA repair to immune signaling and cell cycle progression [1] [2]. This remarkable versatility stems from the ability of ubiquitin—a 76-amino acid protein—to form diverse polymeric chains through eight distinct linkage types [3] [4]. While the functions of K48-linked (proteasomal degradation) and K63-linked (DNA repair, signaling) chains are well-established, the so-called "atypical" ubiquitin chains (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, and linear/Met1) have remained less characterized until recently [5] [6]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of ubiquitin chain linkage diversity, with particular emphasis on the emerging roles and unique properties of atypical chains, experimental methodologies for linkage determination, and the enzymatic machinery governing chain assembly and disassembly.

Ubiquitin contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1) that can be utilized for polyubiquitin chain formation [4]. The specific linkage type directs the modified protein to different cellular fates and signaling outcomes [3]. All eight linkage types have been detected in vivo and differentially affect numerous cellular processes, signaling pathways, and disease states [3].

Table 1: Ubiquitin Chain Linkage Types and Their Known Functions

| Linkage Type | Known Major Functions | Cellular Processes |

|---|---|---|

| K48 | Target proteins for proteasomal degradation [7] | Protein turnover, cell cycle regulation |

| K63 | Non-degradative roles in intracellular trafficking, kinase signaling, DNA damage response [6] [1] | DNA repair, endocytosis, inflammation |

| K6 | DNA damage response, mitophagy, mitochondrial regulation [6] | Mitochondrial quality control, DNA repair |

| K11 | Cell cycle regulation, endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) [4] | Mitotic regulation, protein quality control |

| K27 | Mitochondrial trafficking, innate immunity regulation, resists deubiquitination [4] [5] | Innate immune signaling, mitochondrial dynamics |

| K29 | Wnt/β-catenin signaling, mRNA stability regulation [4] | Growth and development, mRNA decay |

| K33 | Regulation of T-cell receptor signaling, actin stabilization [4] | Immune response, cytoskeletal organization |

| Linear/M1 | Immune signaling, NF-κB activation, inflammation regulation [5] [8] | Innate immunity, cell death decisions |

The structural properties of each chain type create distinct molecular surfaces that are specifically recognized by downstream effector proteins containing ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs), enabling the translation of the ubiquitin code into specific physiological responses [4] [2].

Atypical Ubiquitin Chains: Emerging Roles and Functions

K6-Linked Chains

K6-linked ubiquitination has been linked to DNA repair processes, particularly in the context of the BRCA1-BARD1 ubiquitin ligase complex and its associated substrates [4]. Recent studies have also implicated K6 chains in mitochondrial quality control, where they are assembled by the RBR E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin to promote mitophagy [6]. Additionally, the HECT E3 ligase HUWE1 has been identified as a major source of cellular K6 chains, modifying mitofusin-2 (Mfn2) with K6-linked polyubiquitin to regulate mitochondrial dynamics [6].

K11-Linked Chains

K11-linked chains play important roles in cell cycle regulation and ERAD [4]. During mitosis, K11 linkages interact with the Npl4 adaptor protein in Drosophila development and are essential for proper cell division [4]. The anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C), a key regulator of cell cycle progression, predominantly assembles K11-linked chains to target cyclins and other cell cycle regulators for degradation [1].

K27-Linked Chains

K27-linked ubiquitin chains exhibit unique biochemical properties that distinguish them from all other ubiquitin linkages [4]. Notably, K27-Ub2 is not cleaved by most deubiquitinases (DUBs), including linkage-non-specific enzymes such as USP2, USP5, and Ubp6 [4]. This resistance to deubiquitination allows K27 chains to act as competitive inhibitors of DUB activity toward other linkages [4]. Functionally, K27 linkages are observed on mitochondrial trafficking protein Miro1, where they slow down its degradation by the proteasome and serve as markers of mitochondrial damage [4]. K27 chains also play significant roles in regulating antiviral innate immune responses [5].

K29 and K33-Linked Chains

K29-linked chains participate in growth and development-associated pathways, including Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and are implicated in regulation of mRNA stability via recognition by the adaptor protein UBXD8 [4]. K33-linked polyubiquitination regulates T-cell receptor-ζ function by governing its phosphorylation and protein binding profiles, and contributes to the stabilization of actin for post-Golgi transport [4].

Linear/M1-Linked Chains

Linear ubiquitin chains are exclusively generated by the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC), which consists of HOIP, HOIL-1L, and SHARPIN subunits [9] [8]. Unlike other ubiquitin linkages, linear chains are formed through a peptide bond between the amino-terminal methionine of one ubiquitin and the carboxy-terminal glycine of the next ubiquitin molecule [8]. LUBAC-generated linear chains play essential roles in immune signaling pathways, particularly in TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1) signaling, where they facilitate NF-κB activation and regulate cell death decisions [8]. Recent research has revealed that LUBAC can generate heterotypic ubiquitin chains containing linear linkages with oxyester-linked branches, depending on HOIL-1L catalytic activity [9].

Table 2: Atypical Ubiquitin Chains in Disease Processes

| Chain Type | Associated Diseases | Key Regulatory Proteins |

|---|---|---|

| K6 | Cancer, Parkinson's disease [6] | Parkin, HUWE1, RNF144A/B |

| K11 | Cancer, developmental disorders [4] | APC/C, Cezanne (OTUD7B) |

| K27 | Cancer, autoimmune disorders, viral infection [4] [5] | TRIM23, LMP7, UBE2J1 |

| K29 | Neurodegenerative diseases, cancer [4] | HUWE1, UBE3A, EDD1 |

| K33 | Autoimmune disease, cancer [4] | TRIM21, TRAF6 |

| Linear/M1 | Autoimmunity, immunodeficiency, cancer [9] [8] | LUBAC (HOIP, HOIL-1L, SHARPIN) |

Experimental Approaches for Studying Ubiquitin Chain Linkage

Determining Ubiquitin Chain Linkage Using Mutant Approaches

A powerful method for determining ubiquitin chain linkage involves performing in vitro ubiquitin conjugation reactions utilizing ubiquitin lysine mutants [3]. This approach requires two sets of nine reactions: one utilizing seven Ubiquitin Lysine to Arginine (K to R) Mutants and another utilizing seven Ubiquitin K Only Mutants [3].

The experimental workflow consists of the following steps:

- Set up conjugation reactions: Prepare reactions containing E1 enzyme, E2 enzyme, E3 ligase, 10X E3 Ligase Reaction Buffer, MgATP Solution, substrate, and different ubiquitin variants (wild-type, K-to-R mutants, or K-only mutants) [3].

- Incubation: Incubate reactions at 37°C for 30-60 minutes [3].

- Termination: Terminate reactions using SDS-PAGE sample buffer (for direct analysis) or EDTA/DTT (if using products for downstream applications) [3].

- Analysis: Analyze ubiquitin conjugation reactions by Western blot using an anti-ubiquitin antibody [3].

The Ubiquitin K to R Mutants are used to identify the lysine(s) being utilized for ubiquitin chain linkage. The conjugation reaction containing the Ubiquitin K to R Mutant lacking the lysine required for chain linkage will not be able to form chains, resulting in only mono-ubiquitination observed by Western blot [3]. For example, if ubiquitin chains are linked via K63, then all conjugation reactions except the one containing the Ubiquitin K63R Mutant should yield ubiquitin chains [3].

The Ubiquitin K Only Mutants (containing only one lysine with the remaining six mutated to arginine) are then used to verify ubiquitin chain linkage. Using K63-linked chains as an example, only the conjugation reactions containing wild-type ubiquitin and the Ubiquitin K63 Only Mutant will yield ubiquitin chains [3].

Linkage-Specific Reagents

The development of linkage-specific affinity reagents has significantly advanced the study of atypical ubiquitin chains. Affimers are 12-kDa non-antibody scaffolds based on the cystatin fold that can be engineered for high-affinity, linkage-specific ubiquitin chain recognition [6]. For example, K6-specific affimers recognize K6-diUb with high linkage specificity and have been successfully used in western blotting, confocal fluorescence microscopy, and pull-down applications [6]. Crystal structures of affimers bound to their cognate diUb reveal that they achieve linkage specificity through dimerization that provides two binding sites for ubiquitin I44 patches with a defined distance and relative orientation [6].

Additionally, specialized reagent kits are commercially available for studying atypical ubiquitin chains. For instance, the Panel Customized Ubiquitin Chain Kit (SI200) from LifeSensors provides a convenient collection of all eight possible di-ubiquitin molecules (including K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63, and linear linkages) for determining the linkage-specific activity of individual deubiquitylating enzymes (DUBs) [10].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Chain Analysis

| Reagent Type | Specific Example | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Mutants | Ubiquitin K-to-R Mutants; Ubiquitin K-Only Mutants [3] | Determine ubiquitin chain linkage in conjugation assays | Identify and verify specific lysine linkages |

| Linkage-Specific Affimers | K6-specific affimer; K33/K11-specific affimer [6] | Detect specific chain types in blotting, microscopy, pull-downs | High-affinity, linkage-specific recognition |

| Di-Ubiquitin Kits | Panel Customized Ubiquitin Chain Kit (SI200) [10] | Study linkage-specific DUB activity; substrate specificity | Complete panel of all 8 linkage types |

| E2 Enzymes | Specific E2 conjugating enzymes [1] | Determine linkage specificity in chain assembly | Often dictate chain linkage type in RING E3 systems |

| DUBs | Linkage-specific deubiquitinases (e.g., Cezanne for K11) [4] | Probe chain linkage specificity; validate chain identity | Cleave specific ubiquitin linkage types |

Enzymatic Machinery of Ubiquitin Chain Assembly and Disassembly

The Ubiquitination Cascade

Protein ubiquitination is catalyzed by a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 (ubiquitin-activating), E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating), and E3 (ubiquitin-ligating) enzymes [1] [7]. The human genome encodes approximately 40 E2s and over 600 E3s, enabling tremendous specificity in substrate recognition and modification [1]. E3 ubiquitin ligases fall into three mechanistic classes: RING (really interesting new gene)/U-box, HECT (homologous to E6AP C-terminus), and RBR (RING-between-RING) ligases [1]. RING/U-box ligases catalyze the direct transfer of ubiquitin from a thioester-linked E2-ubiquitin conjugate to a substrate, while HECT and RBR ligases proceed through a two-step mechanism involving an E3-ubiquitin thioester intermediate [1].

The choice of E2 enzyme often determines the type of ubiquitin chain assembled, particularly in RING E3 systems [1]. However, there are notable exceptions to this rule, such as LUBAC, where the E3 complex determines the linkage type (linear) [8]. Some E2-E3 pairs specialize in chain initiation (monoubiquitination or the first ubiquitin in a chain), while others act as chain elongators [1].

Deubiquitinating Enzymes (DUBs)

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) antagonize E3 activity by cleaving isopeptide bonds between ubiquitin moieties or between ubiquitin and target proteins [4] [1]. The approximately 100 human DUBs are categorized into seven families: ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), Machado-Josephins (MJDs), ovarian tumor proteases (OTUs), JAB1/MPN domain-associated metalloisopeptidases (JAMM/MPN+), MINDY, and ZUFSP [1]. Some DUBs exhibit remarkable linkage specificity; for example, Cezanne preferentially cleaves K11-linked chains, OTUB1 selectively cleaves K48-linked chains, and AMSH specifically cleaves K63-linked chains [4]. Strikingly, K27-linked ubiquitin chains resist cleavage by most DUBs, including linkage-non-specific enzymes such as USP2, USP5, and Ubp6 [4].

The diversity of ubiquitin chain linkages represents a sophisticated post-translational regulatory code that expands the functional repertoire of ubiquitin far beyond its initial characterization as a degradation signal. The atypical ubiquitin chains (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, and linear) play particularly important roles in specialized cellular processes, including immune signaling, mitochondrial regulation, and cell cycle control. Continued development of innovative research tools—including linkage-specific affimers, ubiquitin mutants, and specialized detection kits—is progressively unveiling the unique functions and regulatory mechanisms of these atypical ubiquitin modifications. As our understanding of the ubiquitin code deepens, particularly regarding the less-studied atypical linkages, new opportunities will emerge for therapeutic intervention in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, immune disorders, and infectious diseases through targeted manipulation of specific ubiquitin signaling pathways.

Historical Discovery and Characterization of Atypical Linkages

Protein ubiquitination, the covalent attachment of the 76-amino acid protein ubiquitin to substrate proteins, represents one of the most versatile post-translational modifications in eukaryotic cells. For decades, research primarily focused on two ubiquitin chain linkage types: K48-linked chains, widely recognized as the principal signal for proteasomal degradation, and K63-linked chains, known for their roles in DNA repair, signaling, and endocytosis [11] [12]. However, the ubiquitin code is far more complex. Ubiquitin contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63), all of which can form polyubiquitin chains, in addition to the N-terminal methionine (M1) that can form linear chains [4] [12].

The historical perception of ubiquitin signaling was dominated by K48 and K63 linkages, while the other five "atypical" linkages (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33) remained largely unexplored until recent technological advances enabled their specific study. These atypical linkages, though less abundant, have emerged as critical regulators of diverse cellular processes, including cell cycle progression, DNA damage repair, mitophagy, and innate immune signaling [11] [4] [13]. This whitepaper traces the historical discovery and characterization of these atypical ubiquitin linkages, providing researchers with a comprehensive technical guide to their functions, study methodologies, and relevance to therapeutic development.

Historical Context and the Expansion of the Ubiquitin Code

The discovery of the broader ubiquitin code unfolded progressively through key technological and conceptual advances. The initial paradigm, established in the 1980s, identified K48-linked ubiquitin chains as the canonical signal for proteasomal degradation. The subsequent discovery of K63-linked chains in the 1990s revealed that ubiquitination could function beyond protein degradation [12]. This pivotal finding challenged the existing dogma and suggested that ubiquitin could form structurally and functionally distinct polymers.

The systematic exploration of the entire ubiquitin code gained momentum in the early 21st century with several key developments. The advent of advanced mass spectrometry techniques enabled researchers to quantitatively profile all ubiquitin linkage types in cells, revealing that atypical linkages, while less abundant, are consistently present and dynamically regulated [11] [12]. Furthermore, the development of linkage-specific antibodies for certain atypical chains and innovative chemical biology approaches for generating defined ubiquitin chains of every possible linkage provided the essential tools to probe their structures and functions [4] [12].

Table: Historical Timeline of Key Discoveries in Atypical Ubiquitin Linkages

| Time Period | Key Discovery/Advance | Impact on the Field |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-2000 | Establishment of K48 (degradation) and K63 (signaling) as functional ubiquitin linkages | Created a foundational but incomplete paradigm of ubiquitin signaling |

| Early 2000s | Development of mass spectrometry methods to identify endogenous atypical linkages | Provided evidence that all seven lysine-based linkages exist in cells |

| ~2010 | Development of enzymatic and chemical methods to synthesize homogeneous atypical chains | Enabled in vitro biochemical and structural studies of pure linkage types |

| 2010-2015 | Identification of specific E2/E3 enzymes and DUBs for some atypical linkages | Established that the synthesis and recognition of atypical chains are specific and regulated |

| 2015-Present | Functional dissection in cellular models (e.g., DNA repair, immunity, cell cycle) | Revealed critical non-redundant physiological roles for atypical linkages |

Characterization of Individual Atypical Linkages

K6-Linked Ubiquitination

K6-linked ubiquitination was initially characterized in the context of DNA damage response (DDR) and mitophagy. Pioneering studies identified the BRCA1-BARD1 complex, a major DDR ubiquitin ligase, as capable of assembling K6-linked auto-ubiquitination chains [11]. Subsequent work demonstrated the formation of K6-linked chains during replication stress and the repair of double-strand breaks [11].

A major functional role for K6 linkages emerged from research on Parkin-mediated mitophagy. Upon mitochondrial damage, the activated Parkin ligase decorates proteins on the outer mitochondrial membrane with various ubiquitin chains, including K6, K11, K48, and K63 linkages [11]. Among these, K6 and K63 chains are particularly important in designating damaged mitochondria for autophagic clearance. This process is finely tuned by deubiquitinases (DUBs) such as USP30, which antagonizes Parkin by preferentially cleaving K6-linked chains, positioning USP30 as a potential therapeutic target for neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson's disease [11].

More recent findings also implicate K6-linked ubiquitination in innate immune signaling. During viral infection, the transcription factor IRF3 is modified with K6-linked chains, enhancing its DNA-binding affinity and promoting the transcription of type I interferons. This activity is negatively regulated by the DUB OTUD1 [11].

K11-Linked Ubiquitination

K11-linked chains are best known for their role in regulating the cell cycle and facilitating proteasomal degradation. The principal E3 ligase responsible for K11 linkage formation in mitosis is the Anaphase-Promoting Complex/Cyclosome (APC/C) [11]. In cooperation with the E2 enzymes UBE2C/UbcH10 and UBE2S, the APC/C builds K11-linked chains, often as mixed or branched chains with K48 linkages, on substrates such as cyclins, targeting them for degradation to ensure orderly cell cycle progression [11]. Cells depleted of these E2 enzymes display impaired APC/C activity and stabilized mitotic substrates, underscoring the critical nature of K11 ubiquitination in cell division [11].

While K11 and K48 homotypic chains can initiate degradation independently, their combination into branched chains significantly enhances substrate recognition and processing by the proteasome, illustrating the complexity of the ubiquitin code [11]. Beyond the cell cycle, K11 linkages also play roles in ER-associated degradation (ERAD) and the innate immune response, where the E3 ligase RNF26 uses K11 chains to stabilize STING and potentiate type I interferon production [14].

K27-Linked Ubiquitination

K27-linked chains are among the least characterized but have recently been linked to critical cellular processes. A defining biochemical characteristic of K27-linked diubiquitin (K27-Ub2) is its resistance to hydrolysis by a broad range of deubiquitinases (DUBs), including the linkage-nonspecific USP2, USP5, and Ubp6 [4]. This uniqueness suggested a specialized structural and functional role.

Functionally, K27 linkages have been implicated in the DNA damage response and innate immune signaling [4]. Furthermore, a landmark 2022 study demonstrated that K27-linked ubiquitylation is essential for human cell proliferation [13]. Using a sophisticated ubiquitin replacement strategy, researchers showed that selectively abrogating K27-linked ubiquitylation causes severe proliferation defects and deregulates nuclear ubiquitylation dynamics. K27 chains were found to be predominantly nuclear and function epistatically with the p97/VCP ATPase in processing ubiquitylated nuclear proteins, identifying a critical functional niche for this atypical linkage [13].

K29 and K33-Linked Ubiquitination

The functions of K29 and K33 linkages are less established but point toward non-proteolytic regulatory roles.

- K29-linked chains have been associated with proteasomal degradation in some contexts, akin to K48 and K11 linkages [15]. They also participate in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which is crucial for growth and development, and in regulating mRNA stability through the adaptor protein UBXD8 [4].

- K33-linked chains are known to regulate kinase activity and signal transduction. For instance, they control the activity of the T-cell receptor-ζ by modulating its phosphorylation and protein-binding profiles [4]. Furthermore, K33-linked polyubiquitination contributes to the stabilization of actin, thereby facilitating post-Golgi transport [4]. In innate immunity, the DUB USP38 removes K33 chains from TBK1, preventing its degradation and promoting IRF3 activation [14].

Table: Functional Roles and Associated Enzymes of Atypical Ubiquitin Linkages

| Linkage | Key Physiological Functions | Representative E3 Ligases | Representative DUBs |

|---|---|---|---|

| K6 | DNA Damage Response, Mitophagy, Innate Immunity | Parkin, BRCA1-BARD1, HUWE1 | USP30, USP8, OTUD1 |

| K11 | Cell Cycle Regulation, ERAD, Innate Immunity | APC/C (with E2s UBE2C, UBE2S) | Cezanne |

| K27 | Cell Proliferation, p97-substrate processing, Innate Immunity, DNA Repair | Not well characterized; several TRIM proteins implicated (e.g., TRIM23) | Resistant to most DUBs; specific DUBs not fully defined |

| K29 | Wnt Signaling, mRNA Stability, Proteasomal Degradation (context-dependent) | KIAA10, UBR4/UBR5 | — |

| K33 | Kinase Regulation, TCR Signaling, Trafficking | — | USP38 |

Structural and Biophysical Characterization

Structural studies have been instrumental in understanding how the different ubiquitin linkages dictate unique functional outcomes. A seminal finding was that each linkage type confers a unique conformational landscape to the polyubiquitin chain, which is specifically recognized by ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) in downstream effector proteins [16] [4].

Research using NMR spectroscopy and small-angle neutron scattering on diubiquitin of all linkage types revealed that K27-Ub2 is a unique case. It exhibits minimal non-covalent interdomain contacts but shows the largest chemical shift perturbations in the proximal ubiquitin unit among all chains, suggesting a distinct structural dynamic [4]. Computational modeling of the binding landscapes of different diubiquitins proposed that the topological constraint of the covalent linkage breaks the binding symmetry and selects for specific local interactions to achieve functional specificity [16]. The energy landscape further varies between linkages; for instance, hydrophobic interactions dominate in K6-, K11-, K33-, and K48-diUb, while electrostatic interactions are more important for K27, K29, K63, and linear linkages [16].

These structural insights explain functional observations. The compact conformations of K11-linked chains, for example, make them preferential substrates for the DUB Cezanne [17]. Conversely, the unique, constrained conformation of K27-linked chains makes them poor substrates for most DUBs and allows for specific recognition, such as the unanticipated binding by the UBA2 domain of the proteasomal shuttle protein hHR23a, a domain previously thought to be K48-specific [4].

Diagram: The unique structural and dynamic features of K27-linked ubiquitin chains underpin their distinct functional consequences, including DUB resistance and essential roles in cell proliferation. CSPs: Chemical Shift Perturbations; DUBs: Deubiquitinases.

Methodologies for Studying Atypical Linkages

Key Experimental Workflows

The study of atypical ubiquitin linkages has been propelled by specialized methodologies that overcome the challenges of their low abundance and lack of specificity in native enzymatic pathways.

1. Non-Enzymatic Diubiquitin Synthesis: A breakthrough method for biochemical and structural studies involves the chemical synthesis of fully natural diubiquitin chains with native isopeptide linkages. This strategy uses mutually orthogonal, removable amine-protecting groups (Alloc and Boc) to allow for the selective formation of any desired lysine linkage without the need for linkage-specific E2/E3 pairs [4]. This workflow was critical for producing homogeneous K27-, K29-, and K33-linked chains for the first structural and DUB-activity studies.

2. Conditional Ubiquitin Replacement in Cells: To define the cellular function of a specific linkage, a powerful genetic strategy has been developed. This two-step process involves:

- Creating a parent cell line (e.g., U2OS/shUb) with doxycycline (DOX)-inducible shRNAs targeting all four endogenous ubiquitin genes.

- Engineering these cells to inducibly express a ubiquitin mutant where a single lysine is mutated to arginine (e.g., K27R), which prevents chain formation via that residue.

Upon DOX treatment, endogenous Ub is depleted and replaced by the mutant Ub, allowing researchers to observe the phenotypic consequences of ablating a single linkage type without overexpression artifacts. This method was used to demonstrate the essential role of K27 linkages in cell proliferation [13].

Diagram: Conditional ubiquitin replacement workflow for studying the function of specific ubiquitin linkages in human cells.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagents and Tools for Atypical Ubiquitin Linkage Research

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Description | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Defective Ub Mutant (Ub K->R) | A ubiquitin gene with a specific lysine (K) mutated to arginine (R). Prevents chain formation via that lysine. | Used in ubiquitin replacement strategies to abrogate a specific linkage type in cells and study the resulting phenotype [13]. |

| Chemically Synthesized DiUb/TriUb | Homogeneous ubiquitin chains of defined linkage, synthesized via non-enzymatic chemical biology approaches. | Essential for in vitro biochemical studies, structural determination (NMR, X-ray), and profiling DUB specificity [4]. |

| Linkage-Specific DUBs (e.g., Cezanne) | Deubiquitinases with a known preference for cleaving a specific atypical linkage (e.g., Cezanne for K11). | Used as reagents to detect, validate, and manipulate specific chain types in complex mixtures and cell lysates [4]. |

| Linkage-Specific Binders (e.g., UCHL3) | Proteins or engineered domains with high affinity for a specific linkage topology (e.g., UCHL3 for K27). | Can be used to pull down endogenous chains for identification or to competitively inhibit linkage-specific signaling in cells [13]. |

| Tandem Ubiquitin-Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Engineered arrays of ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domains that bind polyUb chains with high affinity, protecting them from DUBs. | Used to enrich and purify endogenous polyubiquitinated proteins from cell extracts for downstream analysis. |

| 3,5-Bis(ethylamino)benzoic acid | 3,5-Bis(ethylamino)benzoic acid, CAS:652968-38-2, MF:C11H16N2O2, MW:208.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Butyl-1,2-dihydroquinoline-2-one | 4-Butyl-1,2-dihydroquinoline-2-one, CAS:647836-38-2, MF:C13H15NO, MW:201.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The historical journey from a binary view of ubiquitin signaling to the appreciation of a complex and multifaceted ubiquitin code represents a major paradigm shift in cell biology. The characterization of atypical ubiquitin linkages (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33) has revealed them to be independent post-translational modifications with non-redundant and essential functions in cell proliferation, stress response, organelle quality control, and immunity [11] [13] [14].

Future research will focus on addressing several remaining challenges. There is a pressing need to identify the full complement of E2 and E3 enzymes responsible for assembling each atypical chain type, as well as the DUBs that reverse these modifications. Furthermore, understanding the prevalence and function of heterotypic and branched chains that incorporate atypical linkages will be crucial to fully decipher the ubiquitin code [18] [12]. The development of high-affinity linkage-specific antibodies for all atypical chains remains a key technical goal, which would greatly facilitate the monitoring of these modifications in physiological and disease contexts.

From a therapeutic perspective, components of the atypical ubiquitin system present novel drug targets. For instance, USP30 inhibitors are being explored for Parkinson's disease to enhance the clearance of damaged mitochondria, while p97 inhibitors are in preclinical development for cancer, a pathway intimately linked with K27-linked ubiquitination [11] [13]. As our knowledge of the physiological roles of atypical linkages deepens, so too will the opportunities for innovative therapeutic interventions targeting this complex and vital regulatory system.

Cellular Functions and Biological Roles of K6, K11, K27, K29, and K33 Chains

Ubiquitination represents one of the most pivotal post-translational modifications in eukaryotic cells, with the topology of polyubiquitin chains directly determining functional outcomes. While K48- and K63-linked chains have been extensively characterized, the so-called "atypical" ubiquitin linkages—K6, K11, K27, K29, and K33—have emerged as critical regulators of diverse cellular processes. This technical review synthesizes current understanding of these atypical chains, detailing their roles in mitochondrial quality control, cell cycle regulation, immune signaling, DNA damage response, and transcriptional regulation. We provide comprehensive experimental methodologies for studying these linkages, visualize key signaling pathways, and catalog essential research tools. The expanding knowledge of atypical ubiquitin chains opens new avenues for therapeutic intervention in cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and immune diseases, presenting novel targets for drug development professionals.

Protein ubiquitination involves the covalent attachment of the 76-amino acid protein ubiquitin to substrate proteins via a three-enzyme cascade comprising ubiquitin-activating (E1), conjugating (E2), and ligase (E3) enzymes [11]. Ubiquitin itself contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1) that can serve as linkage points for polyubiquitin chain formation, creating a complex "ubiquitin code" that determines specific cellular outcomes [11] [19]. The atypical ubiquitin chains (K6, K11, K27, K29, and K33) are less abundant than their K48 and K63 counterparts but have been shown to mediate crucial non-degradative functions alongside proteasomal targeting [11] [6].

The unique structural and dynamical properties of each linkage type enable specific recognition by ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs), which decode the ubiquitin signal into appropriate cellular responses [4]. For instance, K27-linked ubiquitin chains exhibit exceptional resistance to deubiquitinases (DUBs), while K11-linked chains often form mixed chains with K48 linkages to enhance proteasomal degradation [11] [4]. Understanding the distinct functions and recognition patterns of these atypical chains provides critical insights into their roles in cellular homeostasis and disease pathogenesis.

Comprehensive Functional Analysis of Atypical Ubiquitin Linkages

K6-Linked Ubiquitin Chains

K6-linked ubiquitination has been primarily implicated in mitochondrial quality control and the DNA damage response [11] [6]. In mitophagy, the E3 ligase Parkin decorates damaged outer mitochondrial membrane proteins with K6, K11, K48, and K63-linked chains upon mitochondrial depolarization, with K6 and K63 linkages particularly promoting autophagic processing [11]. This process is antagonized by the deubiquitinase USP30, which shows preferential activity toward K6-linked chains and serves as a key regulatory checkpoint [11] [6]. Beyond mitochondrial homeostasis, K6-linked chains play significant roles in genome maintenance, with the BRCA1-BARD1 complex exhibiting K6-linked auto-ubiquitination and HUWE1 generating substantial K6-linked species upon inhibition of VCP/p97 [11] [6]. Recent findings also identify K6-linked ubiquitination of transcription factor IRF3 as a critical enhancer of antiviral innate immunity, promoting IRF3 binding to type I interferon promoters [11].

Table 1: Key Proteins Regulating K6-Linked Ubiquitination

| Protein | Function | Biological Context | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parkin | E3 Ligase | Mitophagy, Mitochondrial Quality Control | [11] |

| HUWE1 | E3 Ligase | DNA Damage Response, Mfn2 Regulation | [11] [6] |

| USP30 | Deubiquitinase | Mitochondrial Outer Membrane, Antagonizes Parkin | [11] |

| USP8 | Deubiquitinase | Removes K6 chains from Parkin | [11] |

| UBE4A | E3/E4 Ligase | Viperin Degradation, Antiviral Response | [11] |

| OTUD1 | Deubiquitinase | Deubiquitinates IRF3, Limits Innate Immunity | [11] |

K11-Linked Ubiquitin Chains

K11-linked ubiquitin chains are principally associated with cell cycle regulation and proteasomal degradation, often functioning in concert with K48-linked chains [11]. The anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C), a multi-subunit E3 RING ligase, coordinates mitosis and meiosis by attaching K11/K48 mixed chains to substrates destined for proteasomal turnover [11]. The E2 enzyme UBE2S specifically generates K11-linked branch-offs in cooperation with APC/C, and cells depleted of both UbcH10 and UBE2S exhibit impaired APC/C activity and stabilization of APC/C substrates [11]. Beyond cell cycle control, K11 linkages regulate innate immune signaling through RNF26-mediated ubiquitination of STING, which inhibits STING degradation and potentiates type I interferon production [20]. Additionally, K11- and K48-linked chains on Beclin-1 promote its proteasomal degradation, thereby limiting autophagy and enhancing type I IFN response, a process reversed by the DUB USP19 [20].

K27-Linked Ubiquitin Chains

K27-linked ubiquitin chains display unique biochemical properties, including resistance to most deubiquitinases, which contributes to their specialized functions in immune regulation and organelle maintenance [4]. The E3 ligase TRIM23 conjugates K27-linked chains to NEMO (NF-κB essential modulator), facilitating activation of NF-κB and IRF3 upon RIG-I-like receptor (RLR) signaling [20]. These K27-linked chains on NEMO serve as platforms for recruiting regulatory proteins such as Rhbdd3, which subsequently recruits A20 to remove K63-linked chains and prevent excessive NF-κB activation [20]. K27 linkages also appear on mitochondrial trafficking protein Miro1, slowing its proteasomal degradation and serving as a marker of mitochondrial damage [4]. Structural analyses reveal that K27-linked di-ubiquitin (K27-Ub2) exhibits no noncovalent interdomain contacts and displays the largest chemical shift perturbations among atypical linkages, potentially explaining its unique recognition properties [4].

Table 2: Functional Roles of K27, K29, and K33-linked Ubiquitin Chains

| Linkage Type | Cellular Functions | Regulatory Proteins | Key Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|

| K27 | Innate Immune Signaling, Mitochondrial Quality Control | TRIM23 (E3), Rhbdd3, A20 | NEMO, Miro1 |

| K29 | Proteasomal Degradation, Growth Factor Signaling | UBR5 (E3), UBXD8 (Adapter) | DELLA Proteins, mRNA Stability Factors |

| K33 | Kinase Regulation, Intracellular Trafficking | Unknown E3s | T-cell Receptor-ζ, Actin |

K29 and K33-Linked Ubiquitin Chains

K29-linked ubiquitin chains participate in growth and development-associated pathways, including Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and contribute to proteasomal degradation in specific contexts [4]. In plants, K29-linked chains target DELLA proteins, growth repressors involved in gibberellic acid response, for proteasomal degradation [19]. K29 linkages also regulate mRNA stability through recognition by the adaptor protein UBXD8 [4]. K33-linked chains primarily function in kinase regulation and intracellular trafficking, modulating T-cell receptor-ζ function by governing its phosphorylation and protein binding profiles [4]. Additionally, K33 polyubiquitination contributes to stabilization of actin for post-Golgi transport, highlighting its role in cytoskeletal organization and vesicular trafficking [4]. While less characterized than other atypical linkages, emerging evidence suggests both K29 and K33 chains play roles in regulating innate immune responses, though the specific mechanisms remain under investigation [20].

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Atypical Ubiquitin Chains

Linkage-Specific Affimer Reagents

The development of linkage-specific affinity reagents has been instrumental in advancing the study of atypical ubiquitin chains. Affimers are 12-kDa non-antibody scaffolds based on the cystatin fold, in which randomization of surface loops enables generation of large libraries (10^10) for selection of high-affinity binders [6]. For K6-linked chain detection, affimers are characterized using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to confirm linkage specificity and binding affinity. Crystal structures of affimer-diUb complexes reveal that specificity is achieved through affimer dimerization, creating two binding sites for Ub I44 patches with defined distance and orientation [6]. Site-specifically biotinylated K6 affimers enable western blotting, confocal fluorescence microscopy, and pull-down applications, with demonstrated utility in identifying HUWE1 as a major E3 ligase for K6 chains and confirming mitofusin-2 (Mfn2) as a K6-linked ubiquitination substrate [6].

Non-enzymatic Di-ubiquitin Synthesis

Chemical, non-enzymatic assembly methods utilizing mutually orthogonal removable amine-protecting groups (Alloc and Boc) allow production of fully natural di-ubiquitins (Ub2s) with native isopeptide linkages for all atypical chain types [4]. This approach involves:

- Selective protection of specific lysine residues using orthogonal protecting groups

- Sequential peptide coupling to build defined ubiquitin chains

- Global deprotection to generate native isopeptide linkages

- Purification using HPLC and confirmation by mass spectrometry

The resulting linkage-defined di-ubiquitins enable biochemical and structural studies, including deubiquitinase specificity profiling and NMR analysis to characterize chain conformation and dynamics [4].

Structural Characterization Techniques

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy provides atom-specific information on Ub2 conformational dynamics. Experiments involve collecting 1H-15N NMR spectra separately for each Ub unit (uniformly 15N-enriched) in K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, and K48-Ub2 [4]. Chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) between distal or proximal Ub and monoUb quantify interdomain interactions and linkage-specific structural features.

Small-Angle Neutron Scattering (SANS) with in silico ensemble modeling determines solution-state structures and population distributions of different conformational states, particularly valuable for flexible chains like K27-Ub2 [4].

X-ray Crystallography of affimer-diUb complexes reveals molecular mechanisms of linkage specificity, showing how engineered protein scaffolds mimic naturally occurring linkage-specific UBDs [6].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Atypical Ubiquitin Chains

| Reagent/Tool | Specificity | Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| K6-Linkage-Specific Affimer | K6-diUb | Western Blotting, Confocal Microscopy, Pull-downs | High affinity (ITC confirmed), Crystal structure available |

| K33/K11-Linkage-Specific Affimer | K33- and K11-diUb | Western Blotting, Immunofluorescence | Cross-reactivity with K11, Dimerization-dependent recognition |

| Non-enzymatic Di-ubiquitin Synthesis | All linkages | Biochemical Assays, Structural Studies | Native isopeptide linkages, No mutations required |

| Linkage-Selective DUBs | Various | Cleavage Specificity Profiling | Cezanne (K11), OTUB1 (K48), AMSH (K63) |

| USP30 Inhibitors | K6-preferential | Mitophagy Modulation | Potential therapeutic for neurodegenerative disorders |

Signaling Pathway Visualizations

The expanding landscape of atypical ubiquitin chain research continues to reveal sophisticated regulatory mechanisms governing cellular homeostasis. The K6, K11, K27, K29, and K33 linkages constitute essential components of the ubiquitin code, mediating functions ranging from organelle quality control to immune response coordination. Technical advances in linkage-specific reagents, chemical biology approaches, and structural methodologies have dramatically accelerated our understanding of these previously enigmatic modifications.

Future research directions include comprehensive identification of linkage-specific E3 ligases and deubiquitinases, structural characterization of atypical chain interactions with ubiquitin-binding domains, and exploration of heterotypic ubiquitin chains containing multiple linkage types. The therapeutic potential of targeting atypical ubiquitin signaling is substantial, with opportunities for developing DUB inhibitors for neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., USP30 inhibitors for Parkinson's disease), immune modulators targeting K27 and K11 linkages, and cancer therapies exploiting the roles of K6 and K11 chains in DNA damage response and cell cycle regulation. As our toolkit for studying these linkages expands, so too will our ability to manipulate these pathways for therapeutic benefit across a spectrum of human diseases.

Key E3 Ligases and Deubiquitinases Involved in Atypical Chain Formation

Ubiquitination, a crucial post-translational modification, extends far beyond the canonical K48- and K63-linked polyubiquitin chains. Atypical ubiquitin chains—linked via K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, and Met1—represent a complex regulatory layer controlling diverse cellular processes. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical guide to the key E3 ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinases (DUBs) governing the formation and removal of these atypical linkages. Within the context of broadening research on atypical ubiquitin chain functions, we detail the mechanistic roles of specific E3s and DUBs, elaborate experimental methodologies for their study, and visualize critical signaling pathways. The emerging understanding of these enzymes offers significant potential for therapeutic intervention in cancer, inflammatory diseases, and metabolic disorders.

The ubiquitin code represents a sophisticated post-translational regulatory system where diverse ubiquitin chain topologies encode distinct functional outcomes. While K48-linked chains primarily target substrates for proteasomal degradation and K63-linked chains regulate signaling transduction, atypical ubiquitin chains (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, and Met1) constitute a less-explored realm with unique biological functions [12]. These chains coexist in cells, with their abundance dynamically changing in response to specific stimuli and in disease states [12]. The structural conformations of each linkage type create unique surfaces that are specifically recognized by ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) and hydrolyzed by deubiquitinases (DUBs) [12]. This specificity enables atypical chains to function as independent post-translational modifications regulating vital processes including cell cycle progression, innate immunity, DNA repair, and protein trafficking [21] [20].

The enzymatic assembly of atypical chains requires coordinated action between E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and E3 ubiquitin ligases, with certain E2-E3 pairs specifically tuned to generate distinct linkage types [12] [22]. Similarly, DUBs negatively regulate these modifications by hydrolyzing ubiquitin chains, with many exhibiting remarkable linkage selectivity [12]. This review systematically examines the key E3 ligases and DUBs involved in atypical chain formation and removal, providing experimental frameworks for their study and highlighting their pathophysiological significance.

E3 Ligases in Atypical Chain Formation

E3 ubiquitin ligases confer substrate specificity to the ubiquitination system and play crucial roles in determining chain linkage type. The human genome encodes approximately 600 E3 ligases, which can be classified into four major families based on their structural features and catalytic mechanisms: RING-finger, HECT, RBR, and U-box types [21] [23]. Different E3 ligase families employ distinct catalytic mechanisms for ubiquitin transfer, with RING and U-box types typically facilitating direct transfer from E2 to substrate, while HECT and RBR types form a catalytic intermediate with ubiquitin before substrate modification [21] [2].

Table 1: Key E3 Ubiquitin Ligases in Atypical Chain Formation

| E3 Ligase | E3 Type | Atypical Linkage | Biological Function | Substrate Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parkin | RBR | K6, K27 | Mitophagy, mitochondrial quality control [24] [12] | Mitochondrial outer membrane proteins [12] |

| RNF185 | RING | K27 | Antiviral innate immune response [21] [20] | cGAS [21] |

| AMFR | RING | K27 | Antiviral innate immune response [21] | STING [21] |

| TRIM23 | RING | K27 | Adipocyte differentiation, antiviral signaling [20] [25] | NEMO, PPARγ [20] [25] |

| RNF26 | RING | K11 | Regulation of innate immune response [20] | STING [20] |

| LUBAC | RBR | M1 (linear) | NF-κB activation, immune signaling [21] [20] | NEMO [21] [20] |

| HOIL-1 | RBR | M1 (linear) | NF-κB activation [21] | NEMO [21] |

| HOIP | RBR | M1 (linear) | NF-κB activation [21] | NEMO [21] |

| APC/C | RING | K11 | Cell cycle regulation [24] [12] | Cell cycle regulators [12] |

K27-Linked Chain Assembly

K27-linked ubiquitination has emerged as a critical regulator of innate immune signaling. The E3 ligase TRIM23 catalyzes K27-linked polyubiquitination of NEMO (NF-κB essential modulator), which is essential for RIG-I/MDA5-mediated antiviral innate immune responses [20]. This modification creates a platform for the recruitment of additional signaling components. Similarly, RNF185 mediates K27-linked ubiquitination of cGAS, while AMFR targets STING with the same linkage, both contributing to antiviral response potentiation [21]. Beyond immune regulation, TRIM23 also stabilizes PPARγ via atypical ubiquitin conjugation during adipocyte differentiation, though the exact linkage for this function requires further characterization [25].

K11-Linked Chain Assembly

K11-linked chains play important roles in cell cycle regulation and immune response. The anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C), a multi-subunit RING-type E3 ligase, coordinates mitosis by catalyzing K11-linked ubiquitination of cell cycle regulators, marking them for proteasomal degradation [12]. In innate immunity, RNF26 mediates K11-linked ubiquitination of STING, which paradoxically stabilizes the protein and potentiates type I interferon production, demonstrating that K11 linkages can serve both degradative and non-degradative functions depending on cellular context [20].

K6, K29, and K33-Linked Chain Assembly

While less characterized, other atypical linkages are gaining recognition for their biological significance. Parkin, an RBR-type E3 ligase associated with Parkinson's disease, mediates K6-linked ubiquitination of mitochondrial outer membrane proteins during mitophagy [12]. K29-linked chains have been implicated in proteasomal degradation, innate immune response, and regulation of AMPK-related protein kinases [21]. K33-linkages are involved in intracellular trafficking and regulation of innate immune response through effects on cGAS-STING and RLR-induced type I interferon signaling [21].

Linear (M1-Linked) Chain Assembly

The linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC), consisting of HOIP, HOIL-1, and Sharpin, uniquely catalyzes Met1-linked linear ubiquitination [21] [20]. LUBAC-mediated linear ubiquitination of NEMO activates the IKK complex, leading to NF-κB signaling activation [21] [20]. Additionally, LUBAC can associate with MAVS and TRAF3, disrupting the MAVS-TRAF3 complex and consequently inhibiting type I interferon signaling while promoting NF-κB activation [21]. This demonstrates how a single E3 complex can differentially regulate interconnected signaling pathways through specific ubiquitin chain types.

Deubiquitinases Regulating Atypical Chains

Deubiquitinases (DUBs) provide the counterbalance to E3 ligase activity by hydrolyzing ubiquitin chains, thereby refining ubiquitin signals and maintaining ubiquitin homeostasis. The human genome encodes approximately 100 DUBs, classified into six families: ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), ovarian tumor proteases (OTUs), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), Josephin family, MINDYs, and JAMMs [24] [26]. Many DUBs display remarkable linkage selectivity, making them crucial for deciphering the functions of atypical ubiquitin chains [24] [12].

Table 2: Key Deubiquitinases Regulating Atypical Chains

| Deubiquitinase | DUB Family | Linkage Specificity | Biological Function | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OTUD1 | OTU | K63 | DNA damage response [24] | Used in enDUB constructs for linkage-specific hydrolysis [24] |

| OTUD4 | OTU | K48 | Proteasomal degradation regulation [24] | Used in enDUB constructs for linkage-specific hydrolysis [24] |

| Cezanne | OTU | K11 | Cell cycle regulation, NF-κB signaling [24] [12] | Used in enDUB constructs for linkage-specific hydrolysis [24] |

| TRABID | OTU | K29/K33 | Intracellular trafficking, Wnt signaling [24] | Used in enDUB constructs for linkage-specific hydrolysis [24] |

| USP21 | USP | Non-specific | Various cellular processes [24] | Used in enDUB constructs as non-specific control [24] |

| A20 | OTU | K63, K48, M1 | Negative regulator of NF-κB signaling [20] [26] | Limits excessive inflammatory response [20] |

| USP19 | USP | K11 | Regulation of autophagy and innate immunity [20] | Removes K11 chains from Beclin-1 [20] |

The OTU (ovarian tumor protease) family of DUBs demonstrates particularly impressive linkage selectivity, with different members specializing in hydrolysis of specific atypical chains [24]. Cezanne preferentially hydrolyzes K11-linked chains and has been implicated in cell cycle regulation and NF-κB signaling [24] [12]. TRABID exhibits specificity for K29- and K33-linked chains and plays roles in intracellular trafficking and Wnt signaling regulation [24]. This inherent specificity of OTU family DUBs has been successfully exploited in the development of engineered deubiquitinases (enDUBs) for deciphering ubiquitin chain functions [24].

Beyond the OTU family, USP19 removes K11-linked chains from Beclin-1, preventing its proteasomal degradation and thereby promoting autophagy while limiting RIG-I-like receptor signaling by disrupting the RIG-I-MAVS interaction [20]. A20, though capable of cleaving multiple linkage types including K63, K48, and linear chains, serves as a critical negative regulator of NF-κB signaling, demonstrating how some DUBs employ broader specificity to coordinate complex signaling outcomes [20] [26].

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Atypical Chains

Linkage-Specific Engineered Deubiquitinases (enDUBs)

Recent methodological advances have enabled more precise dissection of atypical ubiquitin chain functions. The development of linkage-selective engineered deubiquitinases (enDUBs) represents a breakthrough approach for studying specific ubiquitin linkages on individual proteins in live cells [24]. The experimental workflow involves:

- Selection of DUB catalytic domains with known linkage preferences (e.g., OTUD1 for K63, OTUD4 for K48, Cezanne for K11, TRABID for K29/K33) [24]

- Fusion to GFP-targeted nanobodies to create substrate-specific deubiquitinases

- Transfection into target cells expressing the protein of interest (e.g., YFP-KCNQ1 ion channels)

- Assessment of functional outcomes including protein expression, surface density, ionic currents, and subcellular localization

- Mass spectrometry analysis to quantify changes in ubiquitination patterns

This approach revealed that K11, K29/K33, and K63 chains mediate intracellular retention of KCNQ1 channels through distinct mechanisms: K11 promotes ER retention/degradation and enhances endocytosis while reducing recycling; K29/K33 promotes ER retention/degradation; and K63 enhances endocytosis and reduces recycling [24]. Surprisingly, enDUB targeting K48 linkages unexpectedly decreased KCNQ1 surface density, suggesting a previously unappreciated role for K48 chains in forward trafficking [24].

Proteomic Approaches for Ubiquitination Characterization

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics has revolutionized the large-scale identification of ubiquitination sites and linkage types. Key methodological considerations include:

Enrichment strategies: Ubiquitinated proteins are typically enriched prior to MS analysis using:

- Ubiquitin tagging-based approaches: Expression of epitope-tagged ubiquitin (e.g., His, HA, Flag, Strep) enables affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins [27]

- Antibody-based approaches: Anti-ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., P4D1, FK1/FK2) or linkage-specific antibodies enrich endogenously ubiquitinated proteins without genetic manipulation [27]

- UBD-based approaches: Tandem ubiquitin-binding entities (TUBEs) with higher affinity for ubiquitin chains enable purification under native conditions and protect against deubiquitination [27]

Identification of ubiquitination sites: After tryptic digestion, ubiquitinated peptides are identified through the characteristic 114.04 Da mass shift on modified lysine residues [27]

Linkage type determination: Linkage-specific antibodies or Ubiquitin Chain Restriction (UbiCRest) assays using panels of linkage-selective DUBs can determine chain topology [27]

These approaches have revealed that atypical linkages constitute a significant portion of the cellular ubiquitin landscape, with abundance changing dynamically in response to cellular stimuli and in disease states such as Alzheimer's disease and Huntington's disease [12].

Visualization of Atypical Ubiquitin Signaling Pathways

Atypical Ubiquitin Chains in Antiviral Innate Immunity

The following diagram illustrates how atypical ubiquitin chains regulate the antiviral innate immune response through the RIG-I/MAVS and cGAS-STING pathways:

Diagram Title: Atypical Ubiquitin Regulation of Antiviral Innate Immunity

This visualization illustrates how multiple E3 ligases install atypical ubiquitin chains on key signaling components to modulate the antiviral response. K27-linked ubiquitination by TRIM23 on NEMO, and by RNF185 and AMFR on cGAS and STING respectively, promotes pathway activation and antiviral signaling [21] [20]. Simultaneously, K11-linked ubiquitination by RNF26 on STING stabilizes the protein and enhances signaling [20]. The LUBAC complex introduces linear ubiquitin chains onto NEMO to activate NF-κB signaling while simultaneously disrupting the MAVS-TRAF3 complex to inhibit excessive type I interferon production [21] [20].

Experimental Workflow for enDUB Applications

The following diagram outlines the experimental workflow for using engineered deubiquitinases (enDUBs) to study atypical ubiquitin chain functions:

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for enDUB Applications

This workflow demonstrates how linkage-selective DUB catalytic domains are fused to substrate-targeting nanobodies to create specific enDUB tools [24]. After expression in target cells, these enDUBs enable researchers to hydrolyze specific ubiquitin chain types from the protein of interest and subsequently assess the functional consequences through multiple complementary approaches [24]. Mass spectrometry analysis confirms the linkage-specific deubiquitination and helps establish direct correlations between particular chain types and specific functional outcomes [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Atypical Ubiquitin Chains

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Selective DUBs | OTUD1 (K63), OTUD4 (K48), Cezanne (K11), TRABID (K29/K33) [24] | Catalytic domains for enDUB construction; UbiCRest assays | Defined linkage specificity; modular application |

| Engineered DUBs (enDUBs) | GFP-nanobody fused to selective DUB domains [24] | Substrate-specific ubiquitin chain editing in live cells | Target specific proteins without global ubiquitin disruption |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K11-, K27-, K29-, K33-, K48-, K63-, M1-linkage specific antibodies [27] | Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence, immunoprecipitation of specific chain types | Enable detection and enrichment of specific ubiquitin linkages |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | K-to-R ubiquitin mutants (e.g., K6R, K11R, K27R, etc.) [24] | Global disruption of specific chain types in cells | Identify processes dependent on specific linkage types |

| Affinity Tags | His, HA, Flag, Strep-tagged ubiquitin [27] | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins | Enable proteomic identification of ubiquitination sites |

| TUBEs | Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities [27] | High-affinity enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins; protection from DUBs | Native purification; preserve labile ubiquitination |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib [26] | Block proteasomal degradation of ubiquitinated proteins | Stabilize K48-linked ubiquitinated substrates |

| Lysosome Inhibitors | Bafilomycin A1 [26] | Block lysosomal degradation | Differentiate between proteasomal and lysosomal degradation |

| Mass Spectrometry | LC-MS/MS with 114.04 Da mass shift detection [27] | Identification of ubiquitination sites and linkage types | High-throughput ubiquitinome analysis |

| Decyltris[(propan-2-yl)oxy]silane | Decyltris[(propan-2-yl)oxy]silane|C19H42O3Si|RUO | Decyltris[(propan-2-yl)oxy]silane is a silane reagent for materials science research, enhancing composite hydrophobicity. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 1,7-Dioxa-4,10-dithiacyclododecane | 1,7-Dioxa-4,10-dithiacyclododecane|CAS 294-95-1 | 1,7-Dioxa-4,10-dithiacyclododecane (C8H16O2S2) is a 12-membered O2S2 macrocycle for coordination chemistry research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

This toolkit enables researchers to manipulate, detect, and characterize atypical ubiquitin chains using complementary approaches. The development of linkage-selective engineered DUBs represents a particularly significant advance, as it enables precise editing of specific ubiquitin chain types on individual proteins in live cells without globally disrupting ubiquitin signaling [24]. When combined with linkage-specific antibodies for detection and mass spectrometry for comprehensive analysis, these tools provide a powerful platform for deciphering the complex functions of atypical ubiquitin chains.

The expanding landscape of atypical ubiquitin chains and their regulatory enzymes represents a frontier in understanding post-translational control of cellular processes. The specific E3 ligases and DUBs detailed in this review illustrate the sophisticated enzymatic machinery that installs, interprets, and removes these modifications to fine-tune signaling outcomes. From the immune regulatory functions of K27-linked chains installed by TRIM23, RNF185, and AMFR to the cell cycle control mediated by APC/C-catalyzed K11 linkages, these atypical modifications constitute a vital regulatory layer integrating cellular information.

The experimental methodologies outlined, particularly the development of linkage-selective engineered DUBs, provide powerful approaches for moving beyond correlation to establish causal relationships between specific chain types and functional consequences. As these tools become more widely adopted and refined, they will undoubtedly accelerate our deciphering of the complex ubiquitin code. Furthermore, the growing appreciation of the roles atypical ubiquitin chains play in disease pathogenesis, from cancer to metabolic disorders, highlights their potential as therapeutic targets. Continued technical innovations in detecting, manipulating, and understanding these modifications will undoubtedly yield new insights into cellular regulation and opportunities for therapeutic intervention across a broad spectrum of diseases.

Structural Insights and Molecular Mechanisms of Atypical Ubiquitin Signaling

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates virtually every cellular process in eukaryotes, from protein degradation to immune signaling. This versatility stems from the ability of ubiquitin to form diverse polymeric chains through its seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or its N-terminal methionine (M1). While the functions of K48- and K63-linked chains have been extensively characterized, the so-called "atypical" ubiquitin chains (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33) have remained less explored until recently. These atypical chains represent a sophisticated molecular code that expands the functional repertoire of ubiquitin signaling, enabling precise control over specific cellular pathways including immune response, cell cycle regulation, and DNA repair [12] [28].

The term "atypical" historically distinguished these linkages from the "canonical" K48 and K63 chains, though this nomenclature reflects our limited understanding rather than their biological scarcity. All linkage types coexist in cells with varying abundances that can change in response to specific stimuli and become altered in disease states [12]. Recent advances in chemical biology tools, linkage-specific antibodies, and mass spectrometry techniques have accelerated our understanding of these unconventional ubiquitin signals, revealing their essential roles in cellular regulation and their potential as therapeutic targets [5] [27].

Structural Diversity of Atypical Ubiquitin Chains

Unique Conformational Properties

Each atypical ubiquitin chain linkage adopts a unique three-dimensional conformation that dictates its specific interactions with ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) and deubiquitinases (DUBs). The structural diversity arises from the distinct geometric orientations between ubiquitin monomers connected through different lysine residues. Computational and experimental studies have revealed that these structural differences are not random but are encoded within the folding architecture of the ubiquitin monomer itself [29].

Theoretical modeling and molecular dynamics simulations indicate that most compact structures of covalently connected dimeric ubiquitin chains (diUbs) pre-exist on the binding landscape of free ubiquitin monomers. This suggests that the ubiquitin fold has evolutionarily encoded all functional states into its binding landscape, with different chain topologies simply selecting for these pre-existing conformations [29]. The driving forces behind these distinct conformations vary by linkage type: hydrophobic interactions dominate the functional landscapes of K6-, K11-, K33-, and K48-linked diUbs, while electrostatic interactions play a more important role in K27, K29, K63 and linear linkages [29].

Comparative Structural Characteristics

Table 1: Structural and Functional Characteristics of Atypical Ubiquitin Chains

| Linkage Type | Structural Features | Dominant Interactions | Known Cellular Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| K6 | Compact conformations | Hydrophobic | DNA damage response, mitophagy |

| K11 | Mixed open/compact states | Hydrophobic | Cell cycle regulation, ER-associated degradation |

| K27 | Extended conformation | Electrostatic | Immune signaling, inflammatory pathways |

| K29 | Partially compact | Electrostatic | Kinase regulation, Wnt signaling |

| K33 | Compact interface | Hydrophobic | Endosomal trafficking, kinase regulation |

The structural plasticity of atypical chains enables them to adopt multiple conformational states, which can be interconverted through thermal fluctuations or interactions with binding partners. For example, K11-linked chains can populate both open and compact states, allowing them to interact with different receptors in the proteasome [12]. This conformational heterogeneity stands in contrast to the relatively rigid structures of K48-linked chains and contributes to the functional diversity of atypical ubiquitin signals.

Molecular Mechanisms and Biological Functions

Antiviral Innate Immune Signaling

Recent research has highlighted the crucial role of atypical ubiquitin chains in regulating intracellular antiviral innate immune signaling pathways. K27-linked ubiquitination has emerged as a key regulator of the RIG-I/MAVS signaling axis, which detects viral RNA and initiates interferon production. Specifically, K27-linked polyubiquitin chains are attached to mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS), creating a platform for the recruitment and activation of downstream signaling components including TBK1 and IKKε [5].

The NF-κB pathway is another critical immune signaling cascade regulated by atypical ubiquitination. K29-linked ubiquitin chains have been shown to negatively regulate NF-κB activation by targeting key signaling components for proteasomal degradation, while K33-linked chains modulate the amplitude and duration of NF-κB signaling by interfering with the interaction between signaling molecules [5] [28]. This precise control prevents excessive inflammatory responses and maintains immune homeostasis. The following diagram illustrates the role of atypical ubiquitin chains in antiviral signaling pathways:

Cell Cycle Regulation and Protein Homeostasis

K11-linked ubiquitin chains have emerged as critical regulators of cell cycle progression, particularly during mitosis. The anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C), a multi-subunit E3 ubiquitin ligase, preferentially assembles K11-linked chains on cell cycle regulators such as cyclins and securin, targeting them for proteasomal degradation [12]. This degradation is essential for the metaphase-to-anaphase transition and exit from mitosis. The importance of K11 linkages in cell cycle control highlights that different ubiquitin chain types should be considered as functionally independent post-translational modifications rather than redundant signals [12].

Beyond cell cycle regulation, K11-linked chains also participate in endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD), where misfolded proteins are retrotranslocated from the ER lumen to the cytoplasm and degraded by the proteasome. The E3 ligase HRD1 assembles K11-linked chains on ERAD substrates, facilitating their recognition by the proteasome [12]. This function demonstrates how atypical chains can serve as proficient degradation signals similar to K48-linked chains but within specific biological contexts.

Kinase Regulation and Signal Transduction

Atypical ubiquitin chains, particularly K33-linked chains, play important roles in regulating kinase activity and signal transduction pathways. K33-linked polyubiquitination has been shown to control the activity of several protein kinases, including the T cell receptor-regulated kinase Zap70 and the receptor tyrosine kinase EphA2 [28]. Rather than targeting these kinases for degradation, K33-linked chains appear to modulate their enzymatic activity or subcellular localization, adding another layer to the complex regulation of kinase signaling networks.

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which controls cell proliferation and differentiation, is also regulated by atypical ubiquitination. K29-linked ubiquitin chains assembled by the E3 ligase HUWE1 promote the degradation of negative regulators of Wnt signaling, thereby enhancing pathway activity [28]. This mechanism fine-tunes Wnt signaling output and ensures appropriate cellular responses to extracellular cues.

Experimental Approaches for Studying Atypical Ubiquitination

Methodological Framework

Investigating the structure and function of atypical ubiquitin chains presents unique challenges due to their lower abundance compared to canonical chains and the lack of tools to specifically detect and manipulate them. Recent technological advances have begun to overcome these limitations, enabling more precise characterization of atypical ubiquitin signals [5] [27]. The following workflow outlines a comprehensive experimental approach for studying atypical ubiquitin chains:

Chemical and Enzymatic Generation of Defined Ubiquitin Chains

In vitro enzymatic synthesis of atypical ubiquitin chains utilizes specific E2 enzymes and E3 ligases that determine linkage specificity. For example, the E2 enzyme UBE2S preferentially assembles K11-linked chains, while the E3 ligase HOIP generates M1-linked linear chains [30]. Enzymatic synthesis typically involves incubating ubiquitin with the appropriate E1 activating enzyme, E2 conjugating enzyme, E3 ligase (in some cases), and ATP in a suitable reaction buffer. The resulting chains can be purified using size exclusion chromatography or ion exchange chromatography [30].

Chemical protein synthesis offers an alternative approach that provides absolute control over ubiquitin chain architecture. Native chemical ligation (NCL) enables the generation of ubiquitin chains with defined linkages through the chemoselective reaction between a C-terminal thioester of one ubiquitin and an N-terminal cysteine of another [30]. This method allows incorporation of unnatural amino acids, isotopic labels for NMR studies, and fluorescent probes for biochemical assays. The disulfide-directed ubiquitination strategy represents another chemical approach that generates non-hydrolyzable ubiquitin conjugates for structural and biochemical studies [30].

Detection and Enrichment Strategies

Linkage-specific antibodies have been developed for several atypical ubiquitin chains, enabling their detection by immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry. These antibodies work by recognizing the unique structural features around the linkage site between ubiquitin monomers. For example, K11-linkage specific antibodies have been instrumental in revealing the cell cycle-dependent accumulation of K11-linked chains [12] [27]. However, generating high-quality linkage-specific antibodies remains challenging due to the structural similarity between different chain types.

Tandem-repeated ubiquitin-binding entities (TUBEs) provide an alternative approach for enriching ubiquitinated proteins without linkage bias. TUBEs are engineered proteins containing multiple ubiquitin-associated domains (UBAs) connected by flexible linkers, which significantly increase affinity for ubiquitin chains compared to single UBAs [27]. While most TUBEs recognize all chain types with similar affinity, engineering UBA domains with specific mutations can create TUBEs with linkage preference.

Mass spectrometry-based methods have become powerful tools for comprehensive analysis of the ubiquitinome. DiGly antibody enrichment coupled with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) allows system-wide identification of ubiquitination sites by detecting the characteristic diglycine remnant left on tryptic peptides after ubiquitin modification [27]. Middle-down and top-down proteomics approaches can provide additional information about chain linkage and architecture by analyzing larger ubiquitin-containing peptides or intact ubiquitin chains.

Structural Characterization Techniques

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy has been particularly valuable for studying the conformational dynamics of atypical ubiquitin chains in solution. Paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) experiments have revealed that ubiquitin chains sample multiple conformational states, with the relative populations of these states depending on the linkage type [29]. NMR chemical shift perturbations can also identify interaction surfaces between ubiquitin chains and their binding partners.

X-ray crystallography provides high-resolution structural information for atypical ubiquitin chains, though obtaining crystals of flexible chains remains challenging. Several structures of atypical diubiquitin complexes have been solved, including K6-linked, K11-linked, and K33-linked chains [29]. These structures reveal how different linkages impose distinct constraints on the relative orientation of ubiquitin monomers.

Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) offers solution-based structural information that complements crystallographic data. SAXS is particularly useful for studying flexible systems like ubiquitin chains because it provides information about the overall shape and dimensions of molecules in solution without requiring crystallization [29]. Combined with computational modeling, SAXS data can generate structural ensembles that represent the conformational heterogeneity of ubiquitin chains.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Studying Atypical Ubiquitin Chains

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linkage-specific Antibodies | K11-linkage specific (Mab) | Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence | Variable specificity between vendors |

| Chemical Biology Probes | Ub-AMC, Ub-vinyl sulfone | DUB activity assays, mechanism studies | Different reactivity profiles |

| Recombinant E2 Enzymes | UBE2S (K11-specific), UBE2K (K48-specific) | In vitro ubiquitination assays | May require specific E3s for activity |

| TUBE Reagents | K48-TUBE, K63-TUBE, Pan-TUBE | Ubiquitin chain enrichment, proteomics | Tandem UBA domains with enhanced affinity |

| Activity-Based Probes | HA-Ub-VS, HA-Ub-Br2 | DUB profiling, identification | Covalently modifies active site cysteines |

| DUB Inhibitors | PR-619 (pan-DUB inhibitor) | Functional studies of deubiquitination | Varying selectivity profiles |

| Semisynthetic Ubiquitin | K6-, K11-, K27-diUb | Structural studies, in vitro assays | Defined linkage, native isopeptide bond |

The study of atypical ubiquitin chains has progressed from being a biological curiosity to a mainstream research area with profound implications for understanding cellular regulation and disease mechanisms. Structural insights have revealed how identical ubiquitin monomers can form chains with distinct conformations and functions based solely on their linkage topology. Molecular mechanisms are increasingly being elucidated, showing how atypical chains regulate critical processes from immune signaling to cell division.

Future research directions will likely focus on developing more sensitive tools for detecting and manipulating atypical ubiquitin chains in living cells, understanding the complex crosstalk between different chain types, and elucidating the role of branched ubiquitin chains that contain multiple linkage types. The therapeutic potential of targeting atypical ubiquitin signaling is substantial, particularly in cancer and inflammatory diseases where these pathways are often dysregulated. As our toolbox for studying atypical ubiquitination continues to expand, so too will our appreciation of the sophistication and versatility of the ubiquitin code.

Advanced Techniques for Studying and Leveraging Atypical Ubiquitin Linkages

Mass Spectrometry-Based Approaches for Ubiquitin Chain Typing and Quantification