Decoding Cancer's Ubiquitination Blueprint: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications

This comprehensive review synthesizes current knowledge on the systematic alterations in ubiquitination patterns between cancerous and normal tissues.

Decoding Cancer's Ubiquitination Blueprint: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review synthesizes current knowledge on the systematic alterations in ubiquitination patterns between cancerous and normal tissues. Ubiquitination, a crucial post-translational modification, is extensively dysregulated across cancer types, affecting tumor metabolism, immune evasion, cancer stem cell maintenance, and therapeutic responses. We explore foundational concepts of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, methodological approaches for profiling ubiquitination signatures, troubleshooting strategies for technical challenges, and validation frameworks for translating these findings into clinical applications. For researchers and drug development professionals, this article provides critical insights into ubiquitination-based biomarkers and emerging therapeutic strategies, including proteasome inhibitors, molecular glues, and PROTACs that are revolutionizing cancer treatment.

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: Core Mechanisms and Cancer-Specific Alterations

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a crucial regulatory mechanism for maintaining cellular homeostasis, orchestrating the controlled degradation and modulation of vast numbers of intracellular proteins [1]. This system employs a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 (ubiquitin-activating), E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating), and E3 (ubiquitin-ligating) enzymes to tag substrate proteins with ubiquitin, a small 76-amino-acid protein [2] [3]. The human genome encodes a limited number of E1 enzymes (2), approximately 40 E2 enzymes, and an estimated 600-1000 E3 enzymes, which confer substrate specificity [1] [3]. The reverse reaction, deubiquitination, is performed by deubiquitinases (DUBs), with nearly 100 human DUB genes identified that counterbalance ubiquitination to maintain precise protein stability [2] [4]. This dynamic equilibrium ensures proper regulation of vital cellular processes including cell cycle progression, signal transduction, DNA repair, and apoptosis [2] [1]. The integrity of this system is fundamental to cellular health, and its dysregulation is a hallmark of numerous pathological states, most notably cancer.

Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitination Patterns in Cancerous vs. Normal Tissues

Comprehensive multi-omics studies have revealed distinct and pervasive dysregulation of ubiquitination machinery across various cancer types, impacting mRNA expression, protein stability, and enzymatic activity.

Pan-Cancer Genetic and Expression Alterations

Integrated genomic analyses demonstrate widespread perturbations of ubiquitination regulators (UBRs) in pan-cancer cohorts. A systematic investigation of UBRs revealed widespread genetic alterations and expression perturbations across multiple cancer types [5]. The expression patterns of UBRs show significant heterogeneity across different tissues, with the testis exhibiting the most distinct profile; however, in carcinogenesis, these expression programs become profoundly disrupted [5]. Furthermore, the relationship between UBR expression and cancer hallmark pathways is remarkably extensive, with 79 UBRs showing close correlation with the activity of 32 cancer hallmark-related pathways, indicating a global reprogramming of ubiquitin-mediated regulatory networks in malignancy [5].

Table 1: Ubiquitination Regulator Alterations in Pan-Cancer Analyses

| Analysis Type | Key Finding | Cancer Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Alterations | Somatic mutations and copy number variations in UBRs | Disrupted substrate specificity and protein turnover |

| mRNA Expression | Widespread expression perturbations of UBRs | Altered abundance of ubiquitination machinery components |

| Pathway Correlation | 79 UBRs correlated with 32 cancer hallmark pathways | Reprogrammed cellular signaling and metabolic networks |

| Clinical Relevance | >90% of UBRs affect cancer patient survival | Potential prognostic and therapeutic significance |

Tissue-Specific Ubiquitinome Reprogramming

Ubiquitinomics technologies, which utilize anti-K-ε-GG antibody-based enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides coupled with mass spectrometry, have enabled precise mapping of ubiquitination alterations in specific cancer types.

In sigmoid colorectal cancer, the first ubiquitinome analysis identified 1,249 ubiquitinated sites within 608 differentially ubiquitinated proteins (DUPs) compared to para-carcinoma control tissues [6]. Bioinformatics analysis revealed these DUPs participate in 35 significantly altered signaling pathways, including Salmonella infection, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and ferroptosis pathways [6]. The relationship between ubiquitination and corresponding gene expression revealed four distinct regulatory models (DUP-up/DEG-up; DUP-up/DEG-down; DUP-down/DEG-up; DUP-down/DEG-down), indicating complex layers of ubiquitination control in cancer pathogenesis [6].

In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), integrated multi-omics analysis demonstrated that ubiquitination-related genes are significantly upregulated in tumor tissues, with high expression levels correlating with poor patient prognosis [7]. These ubiquitination alterations were enriched in critical pathways including cell cycle regulation, DNA repair, metabolic reprogramming, and p53 signaling, collectively contributing to a tumor-permissive microenvironment through enhanced proliferation, matrix remodeling, and angiogenesis [7].

Table 2: Tissue-Specific Ubiquitinome Alterations in Cancer

| Cancer Type | Ubiquitination Alterations | Affected Pathways/Biological Processes | Clinical Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sigmoid Colorectal Cancer | 1,249 altered ubiquitination sites on 608 proteins | Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, ferroptosis, Salmonella infection | 46 overall survival-related DUPs identified |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Significant upregulation of ubiquitination-related genes | Cell cycle, DNA repair, metabolic reprogramming, p53 signaling | Poor prognosis associated with high UBR expression |

| Various Cancers | Dysregulation of Met1-linked ubiquitin chains | NF-κB activation, inflammatory signaling, infection response | Immune disorders and cancer progression |

E3 Ligase and DUB Dysregulation in Oncogenesis

Specific components of the ubiquitination machinery are frequently altered in cancer. The anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) and Skp1-Cul1-F-box (SCF) E3 ligase complexes, crucial regulators of cell cycle progression, are frequently dysregulated, leading to uncontrolled proliferation and tumorigenesis [2]. The E3 ligase MDM2, which targets tumor suppressor p53 for degradation, is overactive in many cancers, effectively shutting down p53's protective functions [1] [3]. Conversely, tumor suppressor DUBs like BAP1 are frequently inactivated in cancer, disrupting their roles in regulating cell proliferation, differentiation, and metabolism [2].

The USP28 deubiquitinase is overexpressed in colon and lung cancers, where it stabilizes potent oncogenes including c-Myc, Notch1, and c-jun, driving tumor progression and therapeutic resistance [4]. These specific alterations represent potential therapeutic vulnerabilities in the ubiquitination system that can be exploited for cancer treatment.

Experimental Protocols for Ubiquitination Analysis

Ubiquitinomics Workflow for Profiling Ubiquitination Sites

The comprehensive identification and quantification of ubiquitination patterns in tissues requires specialized ubiquitinomics approaches.

Protocol: Label-Free Quantitative Ubiquitinomics

- Tissue Sample Preparation: Flash-freeze tissue samples in liquid nitrogen and homogenize in lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors [6].

- Protein Digestion: Digest proteins with trypsin following standard proteomics protocols [6].

- Ubiquitinated Peptide Enrichment: Incubate digested peptides with anti-K-ε-GG antibody beads (PTMScan Ubiquitin Remnant Motif Kit) to specifically enrich for ubiquitinated peptides [6].

- Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): Separate enriched peptides using nano-liquid chromatography and analyze by high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry [6].

- Data Analysis: Process raw MS data using specialized software (MaxQuant, Skyline) to identify and quantify ubiquitination sites. Use bioinformatics tools for pathway enrichment analysis and network construction [6].

This protocol enables large-scale qualitative and quantitative analysis of ubiquitinated proteins without expensive isotope labels, making it accessible for multiple sample comparisons [6].

Functional Validation of Ubiquitination Regulators

Protocol: In Vitro Functional Assays for UBR Validation

- Gene Knockdown: Transfect HCC cells (Huh7, Hep3B) with shRNA plasmids specifically targeting UBRs of interest (e.g., UBE2C) using Lipofectamine 3000. Culture cells in DMEM with 10% FBS and select with puromycin for stable knockdown [7].

- qPCR Validation: Extract total RNA 48 hours post-transfection using RNA extraction kits. Synthesize cDNA and perform quantitative PCR with gene-specific primers to confirm knockdown efficiency [7].

- Phenotypic Assays:

- Transwell Assay: Seed 5×10^4 cells in serum-free medium into Transwell chambers (Matrigel-coated for invasion, uncoated for migration). Count migrated/invaded cells after 24 hours [7].

- Wound Healing Assay: Create uniform scratch in confluent cell monolayer and measure migration distance at 0 and 24 hours [7].

- CCK-8 Assay: Seed 2500 cells/well in 96-well plates, add CCK-8 reagent, and measure OD450 after 4 hours to assess viability [7].

- Clonogenic Assay: Seed 600 cells/well in 6-well plates and count colonies after 14 days [7].

These functional assays provide mechanistic insights into how specific UBRs influence cancer phenotypes including proliferation, invasion, and metastasis.

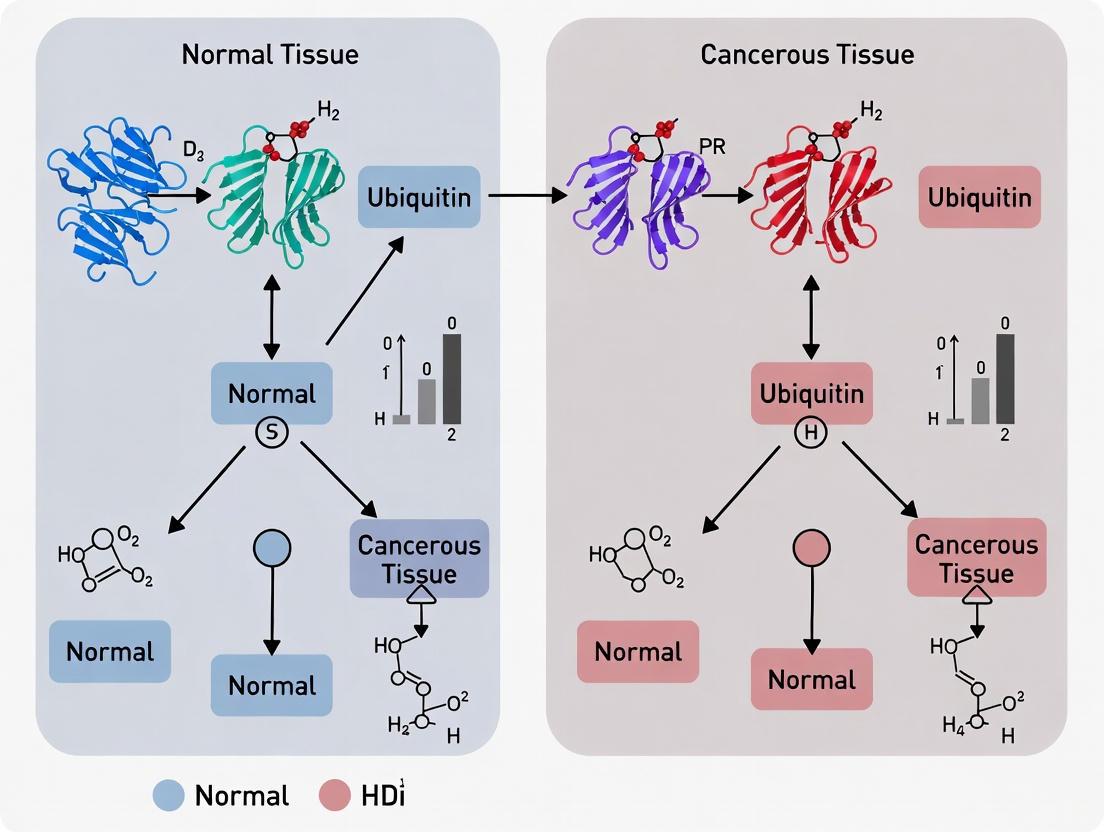

Diagram 1: Ubiquitin-Proteasome System in Normal Homeostasis and Cancer Dysregulation. The enzymatic cascade (E1-E2-E3) mediates ubiquitin transfer to substrates, targeting them for proteasomal degradation, while DUBs reverse this process. In cancer, specific components are dysregulated, disrupting protein homeostasis.

Therapeutic Targeting of Ubiquitination Machinery in Cancer

The profound dysregulation of ubiquitination pathways in cancer has motivated drug development targeting various components of the UPS, with several agents achieving clinical success.

Clinically Approved UPS-Targeting Therapies

Proteasome inhibitors represent the most successful class of UPS-targeting drugs, with bortezomib being the first therapeutic proteasome inhibitor approved by FDA for multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma [1]. Bortezomib's boron atom forms high-affinity bonds with the catalytic site of the 26S proteasome, disrupting protein degradation and causing accumulation of pro-apoptotic proteins in malignant cells [1]. Carfilzomib, a second-generation proteasome inhibitor derived from the natural product epoxomicin, is approved for relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma [1]. Additional proteasome inhibitors in clinical development include marizomib, ixazomib, and CEP-18770, expanding therapeutic options for hematologic malignancies [1].

Emerging Investigational Agents

E1 enzyme inhibitors represent another strategic approach, with TAK-243 (MLN7243) being a potent, mechanism-based small-molecule inhibitor of the primary mammalian E1 enzyme, UAE [8]. TAK-243 treatment depletes cellular ubiquitin conjugates, disrupts signaling events, induces proteotoxic stress, and impairs cell cycle progression and DNA damage repair pathways, resulting in cancer cell death [8]. The NEDD8-activating enzyme (NAE) inhibitor MLN4924 (pevonedistat) exploits the neddylation pathway crucial for Cullin-RING ligase activity, inducing DNA damage and apoptosis in proliferating tumor cells [9]. MLN4924 forms a covalent adduct that mimics NEDD8-AMP, blocking NAE function and disrupting CRL-mediated protein turnover [9].

E2 enzyme inhibitors include CC0651, an allosteric inhibitor of CDC34 that causes conformational rearrangement interfering with ubiquitin discharge [9], and NSC697923 and BAY 11-7082, which inhibit UBE2N-UBE2V1 heterodimer formation and K63-specific polyubiquitin chain synthesis [9].

E3-targeting strategies have focused on disrupting specific E3-substrate interactions. Nutlin-3a and RG7112 target MDM2-p53 interaction, stabilizing p53 in cancers with wild-type TP53 [1]. Immunomodulatory drugs thalidomide, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide recruit novel substrates to the CRL4CRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase, leading to targeted degradation of disease-causing proteins [1].

Table 3: Targeted Therapies Against Ubiquitination System Components

| Target Class | Therapeutic Agent | Molecular Target | Development Status | Primary Cancer Indications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteasome | Bortezomib | 20S proteasome | FDA approved | Multiple myeloma, mantle cell lymphoma |

| Proteasome | Carfilzomib | 20S proteasome | FDA approved | Relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma |

| E1 Enzyme | TAK-243 (MLN7243) | UAE/UBA1 | Phase I/II trials | Advanced solid tumors, hematologic malignancies |

| E1-like Enzyme | MLN4924 (Pevonedistat) | NEDD8-activating enzyme | Phase II/III trials | Acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes |

| E2 Enzyme | CC0651 | CDC34 | Preclinical | Preclinical models |

| E2 Enzyme | NSC697923 | UBE2N-UBE2V1 heterodimer | Preclinical | Lymphoma, multiple myeloma models |

| E3 Interaction | Nutlin-3a | MDM2-p53 interaction | Phase I trials | Cancers with wild-type p53 |

| E3 Recruitment | Lenalidomide | CRL4CRBN E3 ligase | FDA approved | Multiple myeloma, myelodysplastic syndromes |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Diagram 2: Ubiquitinomics Experimental Workflow for Cancer Research. The integrated approach combines ubiquitinated peptide enrichment, mass spectrometry quantification, bioinformatics analysis, and functional validation to decipher ubiquitination alterations in cancer.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitination Enrichment Kits | PTMScan Ubiquitin Remnant Motif Kit (anti-K-ε-GG antibody) | Isolation of ubiquitinated peptides for mass spectrometry | High-affinity motif antibody; enables system-wide ubiquitinome profiling |

| Cell Culture Systems | Huh7, Hep3B hepatocellular carcinoma cells | Functional validation of UBRs in relevant cancer models | Well-characterized HCC models; transfertable with shRNA/siRNA |

| Gene Knockdown Tools | shRNA plasmids targeting UBE2C | Loss-of-function studies to determine UBR roles | Enables stable knockdown; puromycin selection |

| Phenotypic Assay Kits | Transwell chambers, CCK-8 assay, wound healing tools | Functional analysis of proliferation, invasion, migration | Quantifiable metrics for cancer hallmarks |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | Control compounds for UPS disruption studies | FDA-approved; establish expected phenotypic outcomes |

| Bioinformatics Databases | TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas), STRING, UbiBrowser | Integrated analysis of ubiquitination networks | Clinical correlation data; protein-protein interaction networks |

| Pathway Analysis Tools | KEGG, Gene Ontology, GSVA | Interpretation of ubiquitination alterations in biological context | Identifies enriched pathways in cancer ubiquitinomes |

The comprehensive comparison of ubiquitination machinery in cancerous versus normal tissues reveals profound and systematic reprogramming of this critical regulatory system in malignancy. From widespread genetic and expression alterations of UBRs in pan-cancer analyses to tissue-specific ubiquitinome modifications in colorectal and hepatocellular carcinomas, the evidence consistently demonstrates that ubiquitination dysregulation is a fundamental hallmark of cancer. The integrated experimental approaches combining ubiquitinomics, functional validation, and therapeutic targeting provide powerful frameworks for deciphering this complexity. As drug development technologies advance, targeting specific components of the ubiquitination system—from E1 enzymes and E2 conjugating enzymes to the highly specific E3 ligases and DUBs—holds exceptional promise for precision cancer therapeutics. The continued refinement of research tools and methodologies will further accelerate our understanding of ubiquitination patterns in cancer, ultimately enabling more effective patient stratification and targeted interventions in the era of predictive, preventive, and personalized medicine.

Ubiquitination, a critical post-translational modification, regulates protein stability, localization, and function through a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes, and E3 ligases [10]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) mediates approximately 80-90% of cellular protein degradation, playing fundamental roles in maintaining cellular homeostasis [11] [12]. Dysregulation of this system contributes significantly to tumorigenesis by affecting crucial cancer-associated processes including cell cycle progression, DNA repair, immune evasion, and metabolic reprogramming [7] [10].

Pan-cancer analyses have emerged as powerful approaches for identifying consistent molecular patterns across diverse cancer types. Systematic investigation of ubiquitination enzymes across malignancies provides valuable insights into shared oncogenic mechanisms and potential therapeutic vulnerabilities. This review synthesizes current evidence regarding dysregulated expression patterns of key ubiquitination enzymes across multiple cancer types, their prognostic significance, and implications for therapeutic development.

Expression Landscape of Ubiquitination Enzymes in Pan-Cancer

Systematic Pan-Cancer Overexpression Patterns

Comprehensive bioinformatics analyses integrating data from TCGA, GTEx, and other large-scale databases reveal consistent overexpression of specific ubiquitination enzymes across diverse cancer types. These patterns suggest fundamental roles in oncogenic processes that transcend tissue-specific differences.

Table 1: Pan-Cancer Expression Patterns of Key Ubiquitination Enzymes

| Enzyme | Enzyme Class | Overexpressed Cancers | Associated Clinical Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| UBE2T | E2 conjugating enzyme | Multiple myeloma, breast cancer, renal cell carcinoma, ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, retinoblastoma [11] | Reduced OS and PFS [11] |

| UBA1 | E1 activating enzyme | Most cancer types [13] | Poor prognosis [13] |

| UBA6 | E1 activating enzyme | Most cancer types [13] | Poor prognosis [13] |

| TRIM56 | E3 ligase | CHOL, COAD, ESCA, GBM, HNSC, KIRC, KIRP, LIHC, PCPG, READ, SARC, STAD, THYM [14] | Varies by cancer type [14] |

UBE2T constitutes a critical component of the ubiquitin-proteasome system and demonstrates elevated expression across multiple tumor types, where its upregulation associates with poor clinical outcomes and prognosis [11]. Gene variation analysis identifies "amplification" as the predominant alteration in the UBE2T gene, followed by mutations, with data from the GSCALite database demonstrating high frequencies of UBE2T copy number variations across pan-cancer cohorts [11].

The UBA family enzymes UBA1 and UBA6, both classic ubiquitin-activating E1 enzymes, show heightened expression in most cancer types, which may associate with poor patient prognosis [13]. UBA1 participates in the ubiquitination of most proteins in the body, and its abnormal expression relates to malignant phenotypes in lung cancer, liver cancer, and colorectal cancer [13].

E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM56 demonstrates differential expression across various tumors, with high expression in tumor tissues of cholangiocarcinoma, colon adenocarcinoma, esophageal cancer, glioblastoma multiforme, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, clear cell renal carcinoma, and multiple other cancer types [14].

Tissue-Specific Expression Variations

While pan-cancer patterns reveal consistent dysregulation, significant tissue-specific variations exist in ubiquitination enzyme expression, reflecting the complex interplay between ubiquitination pathways and tissue context.

The UBE2T gene shows elevated mRNA expression in multiple myeloma, breast cancer, renal cell carcinoma, ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, and retinoblastoma compared with adjacent normal tissues [11]. Experimental validation in pancreatic cancer cell lines (PANC1, ASPC, BXPC3, MIA2, SW1990, and CAPAN1) confirms elevated UBE2T expression at both mRNA and protein levels compared to normal pancreatic epithelial cells (HPDE) [11].

TRIM56 exhibits particularly complex expression patterns across cancers, with high expression in normal tissues of BLCA (bladder urothelial carcinoma), BRCA (breast invasive carcinoma), CESC (cervical squamous carcinoma and adenocarcinoma), LUAD (lung adenocarcinoma), LUSC (lung squamous cell carcinoma), PRAD (prostate carcinoma), THCA (thyroid carcinoma), and UCEC (endometrial carcinoma), while showing high expression in tumor tissues of numerous other cancer types [14]. This complex expression profile suggests TRIM56 may play context-dependent roles in cancer development.

Prognostic Implications and Clinical Correlations

Survival Analysis Across Cancer Types

Ubiquitination enzyme expression patterns show significant correlations with patient survival outcomes, although these relationships vary by specific enzyme and cancer type, highlighting the context-dependent functions of the UPS in cancer biology.

Table 2: Prognostic Significance of Ubiquitination Enzymes in Various Cancers

| Enzyme | Cancer Type | Survival Correlation | Additional Clinical Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| UBE2T | Pan-cancer | Poor OS and PFS [11] | Associated with advanced stage [11] |

| TRIM56 | BLCA, KIRC, MESO, SKCM | Longer OS [14] | Correlated with B cells, macrophages, CD4+, CD8+ T cell infiltration [14] |

| TRIM56 | COAD, GBM, LGG | Shorter OS [14] | Associated with age in LGG, BLCA, COAD [14] |

| UBA1/UBA6 | Pan-cancer | Poor prognosis [13] | Correlation with clinical stages [13] |

UBE2T upregulation associates with reduced overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), indicating its potential role in tumor progression [11]. Functional analyses link elevated UBE2T expression to changes in key cellular processes including proliferation, invasion, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition [11].

TRIM56 demonstrates cancer-type-specific prognostic associations, with high expression correlating with shorter overall survival in COAD, GBM, and LGG, but longer OS in BLCA, KIRC, MESO, and SKCM [14]. In BLCA and KIRC, high TRIM56 expression closely associates with B cells, macrophages, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cell infiltration, potentially contributing to a favorable prognosis in these specific contexts [14].

UBA1 and UBA6 expression shows correlation with clinical stages in specific tumors, with their differential expression significantly correlated with patient survival rates, tumor grade, and cancer stage [13].

Immune Infiltration and Microenvironment Associations

The tumor immune microenvironment represents a critical interface between cancer cells and host defense mechanisms, with ubiquitination enzymes playing multifaceted roles in modulating immune responses across cancer types.

UBE2T expression demonstrates significant associations with tumor immune markers, checkpoint genes, and immune cell infiltration [11]. Similarly, UBA1 and UBA6 show close relationships with immune score, immune subtypes, and tumor infiltrating immune cells across various cancer types [13].

TRIM56 expression associates with various immune cell populations, and enrichment analysis suggests it may contribute to tumor development through immune-related pathways [14]. These findings position TRIM56 as a potential influencer of tumor immunity and prognostic outcomes, holding potential as both an immunotherapy target and prognostic marker [14].

Methodological Approaches in Ubiquitination Research

Experimental Techniques for Ubiquitination Analysis

Advanced mass spectrometry-based approaches have revolutionized the characterization of ubiquitination patterns in cancer tissues, providing comprehensive insights into the ubiquitinome.

Ubiquitinome Analysis Workflow

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with anti-K-ε-GG-based ubiquitination peptide enrichment enables comprehensive ubiquitinome characterization [15]. This approach has identified 1,690 quantifiable sites and 870 quantifiable proteins in colorectal cancer samples, revealing that highly-ubiquitinated proteins specifically involve in biological processes such as G-protein coupling, glycoprotein coupling, and antigen presentation [16].

In lung adenocarcinoma research, ion mobility separation coupled with liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry provides accurate and reliable ubiquitylome and proteomic analysis of clinical samples [15]. This methodology enables identification of characteristic protein ubiquitination motifs distinct from other cancer types like lung squamous cell carcinoma [15].

Bioinformatics and Multi-Omics Integration

Computational approaches complement experimental methods in ubiquitination research, enabling large-scale pan-cancer analyses and integration with clinical outcomes.

The 'Gene DE' module of TIMER 2.0 database compares UBE2T expression levels between tumor tissues and adjacent normal tissues across various cancer types [11]. Similarly, UALCAN database provides protein expression data for ubiquitination enzymes in pan-cancer contexts, supporting TCGA-based cancer data analysis [11] [13].

Multi-omics analyses integrate genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data to comprehensively characterize the roles of ubiquitination enzymes. Gene Set Cancer Analysis (GSCA) database provides an integrated platform for analyzing genomic mutational landscape, including CNV/SNV modules that visualize the proportion of heterozygous/homozygous and amplification/deletion patterns [13].

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Targeting Ubiquitination Enzymes in Cancer Therapy

The consistent dysregulation of ubiquitination enzymes across cancers positions them as attractive therapeutic targets, with several emerging strategies showing promise.

UBE2T expression demonstrates positive correlation with trametinib and selumetinib sensitivity, and negative correlation with CD-437 and mitomycin, suggesting potential therapeutic applications [11]. These associations indicate that UBE2T expression status may inform treatment selection and predict response to specific therapeutic agents.

Emerging anticancer strategies leveraging the UPS include proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) and molecular glues [12]. PROTAC technology represents a valuable platform for driving targeted protein degradation, with ARV-110 and ARV-471 progressing to phase II clinical trials [12]. Molecular glues such as CC-90009 facilitate ubiquitination-mediated degradation of specific targets by recruiting E3 ligase complexes and are in phase II trials for leukemia therapy [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Application | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-K-ε-GG antibody [15] | Ubiquitinated peptide enrichment | Specific recognition and isolation of ubiquitinated peptides for mass spectrometry |

| K-ε-GG binding resin (PTM-1104) [15] | Ubiquitinated peptide enrichment | Immunoaffinity purification of ubiquitinated peptides |

| Radio Immunoprecipitation Assay buffer [11] | Protein extraction | Cell lysis and protein extraction for western blotting |

| Trichloroacetic acid [15] | Protein precipitation | Concentration and purification of protein samples |

| Tetraethyl ammonium bromide [11] | Protein digestion | Buffer for tryptic digestion of proteins |

| TIMER 2.0 [11] | Bioinformatics analysis | Comparing gene expression levels between tumor and normal tissues |

| UALCAN [11] [13] | Cancer data analysis | TCGA-based cancer data analysis and protein expression retrieval |

| GSCA [13] | Genomic analysis | Analyzing genomic mutational landscape including CNV/SNV patterns |

Therapeutic Targeting Strategies

Comprehensive pan-cancer analyses reveal consistent dysregulation of ubiquitination enzymes across diverse cancer types, with significant implications for tumor progression, prognosis, and therapeutic responses. The ubiquitin-proteasome system represents a complex regulatory network with both universal and context-specific functions in cancer biology. Systematic characterization of ubiquitination patterns provides valuable insights into cancer mechanisms and identifies potential biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection. Emerging therapeutic strategies that target ubiquitination enzymes or exploit the UPS for targeted protein degradation hold significant promise for advancing cancer treatment. Future research should focus on elucidating the specific substrates targeted by dysregulated ubiquitination enzymes in different cancer contexts and developing more selective approaches to modulate their activity for therapeutic benefit.

Ubiquitination, one of the most abundant post-translational modifications in eukaryotic cells, serves as a critical regulatory mechanism controlling virtually all cellular processes. This complex process involves the coordinated action of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes that attach ubiquitin molecules to target proteins, determining their stability, activity, localization, and interactions. In cancer research, understanding the dysregulation of ubiquitination patterns between cancerous and normal tissues has emerged as a pivotal area of investigation, revealing profound implications for tumor initiation, progression, and therapeutic resistance. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of ubiquitination alterations in cancerous versus normal tissues, focusing on three fundamental biological processes: cell cycle control, DNA repair, and apoptosis, while equipping researchers with essential methodologies and tools for continued investigation in this field.

Ubiquitination Alterations in Cancer vs. Normal Tissues

Table 1: Comparative Ubiquitination Patterns in Cancer vs. Normal Tissues

| Biological Process | Key Ubiquitination Components | Normal Tissue Function | Cancer Tissue Alterations | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Cycle Control | APC/C, SCF complex, SKP2, FBW7, CDC20 | Regulates timely degradation of cyclins and CDK inhibitors for proper cell cycle progression [17] [18] | Upregulated SKP2 degrades p27, enabling uncontrolled proliferation; FBW7 mutations stabilize oncoproteins like MYC [17] | SKP2-deficient mice show p27 accumulation and polyploidy; FBW7 mutations common in human cancers [17] |

| DNA Repair | BRCA1-BARD1, RNF4, USP7, Pellino1 | Maintains genomic integrity via controlled repair protein turnover [19] | Dysregulated E3 ligases impair repair mechanisms, increasing mutation rates [19] [20] | RNF4 and USP7 coordinate SLX4 stability in DNA damage response [20] |

| Apoptosis | USP1, USP22, Bcl-2 ubiquitination | Regulates programmed cell death through controlled degradation of pro- and anti-apoptotic factors [21] | Dysregulated USPs (USP1, USP22) lead to uncontrolled cell cycle progression and evasion of cell death [21] | USP22 dysregulation promotes abnormal DNA repair and tumorigenesis [21] |

| Metabolic Reprogramming | NEDD4, APC/CCDH1, SKP2 | Maintains balanced metabolic pathways appropriate for normal cellular demands [19] | E3 ligases reprogram metabolism toward glycolysis; SKP2 regulates Akt ubiquitination and glycolysis [19] | SKP2-SCF E3 ligase regulates Akt ubiquitination, glycolysis, and Herceptin sensitivity [19] |

| Immune Evasion | PD-1/PD-L1 ubiquitination | Controls immune checkpoint protein turnover for proper immune homeostasis [21] | Altered ubiquitination of PD-1/PD-L1 enables immune evasion; UBE2C inhibits anti-tumor immunity [7] [21] | Ubiquitination regulates PD-1/PD-L1 degradation and antigen presentation [21] |

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) demonstrates widespread dysregulation across cancer types, with ubiquitination-related genes (UBRs) showing distinct expression patterns in cancerous versus normal tissues. Comprehensive pan-cancer analyses reveal that more than 90% of UBRs can affect cancer patient survival, with specific UBRs serving as valuable markers for prognostic classification [5]. Notably, UBA1 and UBA6, the two primary E1 activating enzymes, show significantly elevated expression in most cancer types compared to normal tissues, which correlates strongly with poor patient prognosis and advanced disease stages [22]. These alterations create a permissive environment for tumor development by disrupting the precise control of critical cellular processes.

Key Biological Processes Affected by Ubiquitination Dysregulation

Cell Cycle Control

The orderly progression through the cell cycle is predominantly regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome system, which controls the periodic degradation of key regulatory proteins. In normal tissues, the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) and SCF (Skp1-Cul1-F-box protein) complex function as the primary E3 ubiquitin ligases responsible for the timed destruction of cyclins, CDK inhibitors, and other cell cycle regulators [17] [18]. These complexes ensure unidirectional cell cycle progression through specific ubiquitination signals: K11-linked ubiquitin chains primarily target APC/C substrates for degradation during mitosis, while K48-linked polyubiquitination by SCF complexes facilitates proteasomal degradation of various cell cycle regulators [18].

In cancer tissues, this precise regulatory system becomes fundamentally disrupted. SKP2, an F-box protein component of the SCF complex, is frequently overexpressed in human cancers, where it drives excessive degradation of the CDK inhibitor p27, enabling uncontrolled cell cycle progression [17]. Similarly, FBW7, another F-box protein that normally targets positive cell cycle regulators like MYC, JUN, and cyclin E for degradation, is often mutated in human cancers, leading to stabilization of oncoproteins [17]. The critical role of these regulators is evidenced by studies showing that Skp2-deficient mice exhibit accumulation of p27 and cyclin E, resulting in polyploidy and centrosome overduplication [17].

Diagram: Ubiquitination-Mediated Cell Cycle Control in Normal vs. Cancerous Tissues

DNA Repair

Ubiquitination plays an essential role in maintaining genomic integrity through regulated DNA damage response (DDR) pathways. In normal cellular conditions, ubiquitination controls the stability, activity, and recruitment of key DNA repair proteins, creating a coordinated response to DNA lesions. The BRCA1-BARD1 complex, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, monoubiquitinates histone proteins in response to DNA damage, facilitating repair processes [23]. Additionally, E3 ligases such as NEDD4, APC/CCDH1, FBXW7, and Pellino1 function as critical bridges connecting cellular metabolism with DNA damage response, ensuring appropriate repair resource allocation [19].

Cancer tissues exhibit substantial rewiring of these ubiquitination-mediated DNA repair mechanisms. The RNF4 and USP7 deubiquitinating enzymes coordinate spatial regulation of SLX4 stability within PML nuclear bodies, with dysregulation contributing to defective DNA repair in cancer [20]. Recent research has also revealed how ubiquitination controls post-replicative gap formation and repair in response to DNA replication stress, with specific E3 ligases and deubiquitinating enzymes regulating the choice between error-free and error-prone repair pathways [20]. These alterations create a permissive environment for genomic instability while simultaneously presenting therapeutic opportunities, as evidenced by the finding that ubiquitination of ABC transporters and DNA repair enzymes can facilitate chemotherapy resistance [21].

Apoptosis

The controlled process of programmed cell death is extensively regulated by ubiquitination, which determines the stability and activity of key pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic factors. In normal tissues, ubiquitination maintains appropriate apoptotic thresholds through K48 and K63 ubiquitin linkages that regulate proteins including Bcl-2, ACSL4, and p62, thereby controlling cellular survival decisions [21]. Specific deubiquitinating enzymes, particularly ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs) such as USP1 and USP22, provide additional regulatory layers that ensure proper control of cell death pathways in response to cellular damage and stress signals.

Cancer tissues develop numerous mechanisms to evade apoptosis through ubiquitination pathway alterations. Dysregulation of USPs leads to uncontrolled cell cycle progression and abnormal DNA repair capacity, effectively disabling critical apoptotic triggers [21]. Additionally, cancer cells exploit ubiquitination mechanisms to inhibit ferroptosis and autophagy-related cell death pathways, further enhancing their survival potential. Therapeutic targeting of these pathways shows significant promise, as demonstrated by the ability of proteasome inhibitors, E3 ligase inhibitors, and PROTACs to restore apoptotic sensitivity in cancer cells [21].

Experimental Approaches for Ubiquitination Research

Key Methodologies for Ubiquitination Studies

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Ubiquitination Analysis

| Method | Key Procedures | Applications in Cancer Research | Key Reagents |

|---|---|---|---|

| shRNA Knockdown | Plasmid construction targeting specific UBRs; viral transduction; puromycin selection; qRT-PCR validation [7] | Functional validation of ubiquitination enzymes; study of proliferation, invasion, metastasis | shRNA plasmids, polybrene, puromycin, qRT-PCR reagents |

| Transwell Assay | Seed 5×10⁴ cells in Matrigel-coated (invasion) or uncoated (migration) chambers; 24h culture; fix with 4% PFA; crystal violet staining; microscopic quantification [7] | Assess cancer cell migration and invasion capabilities post-UBR manipulation | Transwell chambers, Matrigel, paraformaldehyde, crystal violet |

| CCK-8 Assay | Seed 2500 cells/well in 96-well plates; add 10μL CCK8 reagent; incubate 4h; measure OD450 [7] | Quantify cell viability and proliferation following UBR modulation | Cell Counting Kit-8, 96-well plates, microplate reader |

| Wound Healing Assay | Create linear scratch with pipette tip at 80% confluence; wash with PBS; serum-free medium; document migration at 0h and 24h [7] | Evaluate two-dimensional cell migration capacity | 6-well plates, sterile pipette tips, serum-free medium |

| Single-cell RNA Sequencing | Quality control excluding cells with <200 or >7000 genes; normalize data; PCA/tSNE/UMAP dimensionality reduction; cluster with KNN [24] | Identify ubiquitination heterogeneity across tumor cell subtypes | 10X Genomics platform, Seurat package, clustering algorithms |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Data normalization with LogNormalize; PCA dimensionality reduction; RCTD deconvolution for cell type annotation [24] | Map ubiquitination patterns within tumor architecture | Spacexr package, spatial transcriptomics platforms |

Multi-Omics Integration Approaches

Advanced multi-omics strategies have significantly enhanced our understanding of ubiquitination patterns in cancer. Integrated bioinformatics analysis combining multiple HCC datasets enables comprehensive assessment of ubiquitination status across various cell types in the tumor microenvironment, including plasma cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) cells [7]. These approaches utilize ubiquitination scores to categorize cell types and integrate survival data with spatial transcriptomics to evaluate how different ubiquitination levels influence cancer progression.

Single-cell and spatial transcriptomic methodologies provide unprecedented resolution for mapping ubiquitination patterns within complex tumor architectures. As demonstrated in pancreatic cancer research, these techniques can identify distinct cell populations with high ubiquitination activity, such as endothelial cells exhibiting elevated ubiquitination scores (High_ubiquitin-Endo) that enriched interactions with fibroblasts and macrophages through WNT, NOTCH, and integrin pathways [24]. Spatial validation further confirms the localization patterns of these ubiquitination-active cell populations within tumor tissues.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 Enzyme Inhibitors | UBA1 inhibitors, UBA6 inhibitors [22] | Target validation, therapeutic efficacy studies | Block ubiquitin activation, global ubiquitination inhibition |

| E2 Enzyme Tools | UBE2C shRNA, UBE2C overexpression constructs [7] | Functional studies of specific E2 enzymes | Modulate specific ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme activity |

| E3 Ligase Modulators | TRIM9 constructs, SCF complex components [24] | Pathway analysis, substrate identification | Alter substrate-specific ubiquitination events |

| Deubiquitinase Reagents | USP inhibitors, DUB activity assays [21] | Study ubiquitination reversal, protein stabilization | Investigate deubiquitination processes and consequences |

| Ubiquitin Linkage Tools | Linkage-specific antibodies, ubiquitin mutants [23] | Ubiquitin chain topology studies | Detect specific ubiquitin linkage types (K48, K63, K11, etc.) |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, MG132 [21] | Study protein degradation, therapeutic applications | Block proteasomal degradation, stabilize ubiquitinated proteins |

| Activity Assays | CCK-8, clonogenic formation, wound healing [7] | Functional consequence assessment | Measure proliferation, viability, migration phenotypes |

Signaling Pathways and Therapeutic Implications

The ubiquitin-proteasome system intersects with numerous oncogenic signaling pathways, creating complex regulatory networks that differ substantially between normal and cancerous tissues. Integrated analyses of ubiquitination regulators across pan-cancer datasets reveal that the expression of 79 UBRs closely correlates with the activity of 32 cancer hallmark-related pathways [5]. These correlations highlight the central positioning of ubiquitination networks in controlling fundamental cancer behaviors, with specific hub genes demonstrating excellent prognostic classification power for particular cancer types.

Diagram: Therapeutic Targeting of Ubiquitination Pathways in Cancer

Emerging therapeutic strategies increasingly focus on exploiting the differential ubiquitination patterns between normal and cancerous tissues. Proteasome inhibitors represent the first clinically successful category of UPS-targeting drugs, with additional approaches including E3 ligase inhibitors, PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras), and DUB inhibitors showing significant promise in preclinical and clinical development [21]. These approaches capitalize on the specific dependencies that cancer cells develop on altered ubiquitination pathways, creating therapeutic windows that can be exploited while sparing normal tissues.

The connection between ubiquitination and cancer immune evasion presents particularly compelling therapeutic opportunities. Ubiquitination regulates critical immune checkpoint proteins including PD-1 and PD-L1, with specific E3 ligases controlling their degradation and consequently shaping the anti-tumor immune response [21]. Additionally, ubiquitination mechanisms influence antigen presentation through major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules, further modulating immune recognition of cancer cells [23]. These insights have stimulated development of combination strategies that simultaneously target ubiquitination pathways and immune checkpoints, potentially enabling enhanced and durable anti-tumor immunity.

The comprehensive comparison of ubiquitination patterns between cancerous and normal tissues reveals profound alterations affecting core biological processes including cell cycle control, DNA repair, and apoptosis. These differences are not merely incidental but represent fundamental mechanisms driving tumor development and progression. The continuing development of sophisticated research tools—from single-cell omics technologies to targeted ubiquitination modulators—provides an expanding toolkit for deciphering this complex regulatory landscape. As our understanding of the ubiquitin code in cancer deepens, so too does the potential for innovative therapeutic strategies that specifically target the ubiquitination dependencies of cancer cells while sparing normal tissues, ultimately promising more effective and selective cancer treatments.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) serves as a critical regulatory mechanism for protein homeostasis, dynamically controlling the stability, localization, and activity of numerous cellular proteins. This intricate process involves a sequential enzymatic cascade where E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes, and E3 ligases work in concert to attach ubiquitin chains to target proteins [25]. The specificity of this system is largely governed by E3 ubiquitin ligases, with the human genome encoding approximately 800 such enzymes [26]. Conversely, deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) counteract this process by removing ubiquitin chains, providing an additional layer of regulation [25]. In cancer biology, the precise balance of ubiquitination is frequently disrupted, leading to two fundamental pathogenic mechanisms: the excessive degradation of tumor suppressor proteins and the aberrant stabilization of oncoproteins. This imbalance creates a cellular environment conducive to uncontrolled proliferation, evasion of apoptosis, and ultimately, tumorigenesis. Understanding these opposing mechanisms provides critical insights into cancer pathogenesis and reveals potential therapeutic vulnerabilities for targeted intervention.

Molecular Mechanisms of Tumor Suppressor Degradation

The ubiquitin-mediated degradation of tumor suppressors represents a common pathway hijacked in numerous cancers. This process often involves the overexpression or hyperactivation of specific E3 ubiquitin ligases that target tumor suppressor proteins for proteasomal destruction.

Key Pathways and E3 Ligases

MDM2 and p53 Degradation: The MDM2 E3 ligase serves as a primary negative regulator of the p53 tumor suppressor. By ubiquitinating p53, MDM2 targets it for proteasomal degradation, thus controlling its cellular levels. In many cancers, MDM2 is amplified or overexpressed, leading to excessive p53 degradation and diminished tumor suppressor activity [27]. This pathway is particularly significant given p53's crucial role in cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and DNA repair.

HPV E6-AP and p53 Inactivation: In cancers associated with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV), the viral E6 protein recruits the cellular E6-AP E3 ligase to ubiquitinate p53, resulting in its degradation [27]. This mechanism effectively neutralizes p53's protective function and contributes to viral oncogenesis.

SCF Complexes in Cell Cycle Regulation: SCF (Skp1-Cul1-F-box protein) complexes constitute a major family of E3 ubiquitin ligases that regulate cell cycle progression. The F-box protein Skp2, in particular, targets the cell cycle inhibitors p27 and p21 for degradation, promoting uncontrolled proliferation in cancers such as lung, breast, and colon carcinomas [27].

Table 1: E3 Ubiquitin Ligases Implicated in Tumor Suppressor Degradation

| E3 Ligase | Tumor Suppressor Substrate | Cancer Associations | Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDM2 | p53 | Sarcomas, Breast Cancer | Uncontrolled proliferation, genomic instability |

| E6-AP (with HPV E6) | p53 | Cervical, Head & Neck Cancers | Evasion of apoptosis, impaired DNA repair |

| SCFSkp2 | p27, p21 | Lung, Glioma, Gastric, Prostate | Enhanced cell cycle progression, proliferation |

| VHL | HIF-1α | Renal Cell Carcinoma | Tumor angiogenesis, metabolic adaptation |

Ubiquitin-Independent Degradation Pathways

Not all proteasomal degradation requires ubiquitination. An alternative pathway involves direct degradation of specific tumor suppressors by 20S proteasomes. The tumor suppressors p53 and p73 can be degraded through this ubiquitin-independent mechanism, which is regulated by NQO1 (NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1) in an NADH-dependent manner [28]. NQO1 physically interacts with both p53 and p73, protecting them from 20S proteasomal degradation, and interestingly, most cellular NQO1 is found associated with 20S proteasomes, suggesting it functions as a gatekeeper for this degradation pathway [28].

Mechanisms of Oncoprotein Stabilization in Cancer

While excessive degradation removes protective tumor suppressors, the inappropriate stabilization of oncoproteins provides equally powerful driving forces for tumor development. Multiple distinct molecular mechanisms can lead to oncoprotein stabilization in cancer cells.

Genetic Alterations in Degrons and E3 Ligases

Oncoproteins frequently acquire stabilizing mutations through tumor evolution:

Degron Mutations: Degrons are short amino acid sequences required for E3 ubiquitin ligase recognition. Mutations within these motifs allow oncoproteins to evade recognition and subsequent degradation. In colon cancer and melanoma, mutations substituting Ser33 and Ser37 with Ala within the β-catenin degron prevent its phosphorylation-dependent recognition by the E3 ligase β-TRCP, resulting in a stable and transcriptionally active protein [26]. Similarly, in Burkitt's lymphoma, the Thr58Ala mutation in c-Myc's degron abolishes binding to the Fbw7 E3 ligase, leading to c-Myc stabilization [26] [29].

E3 Ligase Inactivation: Genetic or epigenetic inactivation of E3 ligases that normally target oncoproteins for degradation represents another common mechanism. The Fbw7 ligase, which targets multiple oncoproteins including c-Myc, c-Jun, Notch, and cyclin E, is frequently mutated in cholangiocarcinomas, T-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia, and various solid tumors [26] [27]. Similarly, inactivation of the Cbl ubiquitin ligase stabilizes growth factor receptors like EGFR, leading to sustained oncogenic signaling [26].

Table 2: Mechanisms of Oncoprotein Stabilization in Human Cancers

| Mechanism | Representative Example | Affected Oncoprotein | Cancer Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degron Mutation | Ser33/37Ala in β-catenin degron | β-catenin | Colon Cancer, Melanoma |

| Degron Mutation | Thr58Ala in c-Myc degron | c-Myc | Burkitt's Lymphoma |

| E3 Ligase Inactivation | Fbw7 mutations | c-Myc, Cyclin E, Notch | T-ALL, Various Solid Tumors |

| E3 Ligase Inactivation | Cbl mutations | EGFR | Various Cancers |

| Ubiquitin-Independent Stabilization | NQO1 regulation | p53, p73 | Multiple Cancers |

Active Ubiquitin-Dependent Stabilization Pathways

Beyond passive evasion of degradation, cancer cells also activate specific pathways that actively stabilize oncoproteins. A central enzyme in one such pathway is the RNF4 ubiquitin ligase, which mediates a ubiquitin-dependent protein stabilization pathway that translates transient mitogenic signals into long-lasting protein stabilization, enhancing the activity of key oncoproteins [26]. This active stabilization pathway operates independently of the canonical degradation machinery and represents a promising therapeutic target.

Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitination Patterns: Cancerous vs. Normal Tissues

Advanced proteomic and ubiquitinomic technologies have enabled comprehensive characterization of ubiquitination patterns across cancer types, revealing fundamental differences between cancerous and normal tissues.

Global Ubiquitinome Alterations in Colorectal Cancer

A comprehensive ubiquitinomic analysis of colorectal cancer (CRC) tissues versus normal adjacent mucosa revealed significant alterations in the ubiquitination landscape [30]. This study identified 1,690 quantifiable ubiquitination sites and 870 quantifiable proteins, with 1,172 proteins showing up-regulated ubiquitination and 1,700 proteins demonstrating down-regulated ubiquitination in CRC cells [30]. Highly ubiquitinated proteins (those with ≥10 modification sites) were specifically involved in critical biological processes including G-protein coupling, glycoprotein coupling, and antigen presentation [30]. This widespread reprogramming of the ubiquitinome highlights the profound impact of ubiquitination dysregulation in cancer pathogenesis.

Hepatocellular Carcinoma and UBE2C Overexpression

In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), ubiquitination-related genes are significantly upregulated, with high expression levels correlating with poor patient prognosis [31]. Pathway analysis demonstrates that these genes are enriched in key processes including cell cycle regulation, DNA repair, metabolic reprogramming, and p53 signaling [31]. Notably, UBE2C, a critical E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, emerges as a key player in HCC progression. Experimental data confirms that UBE2C overexpression promotes HCC cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis, while also contributing to immune evasion by potentially inhibiting anti-tumor immune responses [31].

Table 3: Ubiquitinome Alterations in Human Cancers: Quantitative Comparisons

| Cancer Type | Analytical Method | Key Findings | Prognostic Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer | Ubiquitin-proteomic LC-MS/MS (n=6 patients) | 1,172 proteins with up-regulated ubiquitination; 1,700 with down-regulated ubiquitination | FOCAD ubiquitination at Lys583/Lys587 associated with survival |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Bioinformatics analysis of multiple HCC datasets | Ubiquitination-related genes significantly upregulated | High ubiquitination score correlates with poor prognosis |

| Multiple Cancers | Machine learning (deepDegron) | Mutations affecting degrons drive tumorigenesis | Predicts impact of mutations on protein stability |

Experimental Methodologies for Ubiquitination Research

Ubiquitin-Proteomic Workflow

The comprehensive characterization of ubiquitination events relies on sophisticated proteomic approaches. A standard workflow begins with tissue collection and protein extraction, followed by tryptic digestion. For ubiquitinomic analyses, this typically involves enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides using specific antibodies [30]. Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) enables the identification and quantification of ubiquitination sites. Data processing through search engines like MaxQuant against human protein databases allows for the identification of ubiquitination sites, with false discovery rate (FDR) correction to ensure data reliability [30]. Subsequent bioinformatic analyses, including Gene Ontology (GO) annotation and KEGG pathway enrichment, help interpret the functional significance of observed ubiquitination patterns.

Functional Validation Approaches

Gene Knockdown Studies: Plasmid-based shRNA or siRNA-mediated knockdown of target genes, such as UBE2C, followed by phenotypic assays, provides functional validation. Transfection efficiency is typically monitored using qRT-PCR to confirm knockdown efficacy [31].

Cell Proliferation and Viability Assays: The Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay provides a reliable method for assessing cell viability following experimental manipulations. This colorimetric assay measures the metabolic activity of cells and can detect changes in proliferation rates resulting from ubiquitination pathway perturbations [31].

Migration and Invasion Assays: Transwell chambers, either uncoated for migration studies or Matrigel-coated for invasion assays, enable quantitative assessment of cell migratory and invasive capabilities. These assays typically involve staining with crystal violet and microscopic quantification of cells that have traversed the membrane [31].

Wound Healing Assay: This simple yet effective method evaluates collective cell migration by creating a "wound" in a confluent cell monolayer and monitoring closure over time, typically 24 hours, using microscopy to measure migration distance [31].

Visualization of Key Pathways and Concepts

Diagram 1: The Ubiquitination Balance in Normal vs. Cancerous Tissues. This schematic illustrates the shift from balanced protein homeostasis in normal tissues to dysregulated ubiquitination in cancer, characterized by tumor suppressor degradation and oncoprotein stabilization.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Ubiquitinome Analysis. This flowchart outlines the key steps in comprehensive ubiquitination profiling, from sample preparation through LC-MS/MS analysis to functional validation of findings.

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Primary Function | Example Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Identification and quantification of ubiquitination sites | Ubiquitinome characterization, site-specific quantification | High resolution and sensitivity required for modified peptide detection |

| Ubiquitin Motif Antibodies | Immunoenrichment of ubiquitinated peptides | Pull-down assays, Western blot validation | Specificity for ubiquitin remnants (e.g., diGly signature) after trypsin digestion |

| shRNA/siRNA Libraries | Targeted gene knockdown | Functional validation of E3 ligases, DUBs, and ubiquitination targets | Requires confirmation of knockdown efficiency (qRT-PCR) |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132, Bortezomib) | Block protein degradation via proteasome | Stabilization of ubiquitinated proteins, half-life determination | Cytotoxicity at prolonged exposures requires careful dose optimization |

| CCK-8 Assay Kits | Cell viability and proliferation assessment | Measuring phenotypic effects of ubiquitination manipulations | More sensitive and stable alternative to MTT assays |

| Transwell Chambers | Cell migration and invasion quantification | Evaluating metastatic potential in cancer models | Matrigel coating required for invasion (vs. migration) assays |

| Public Databases (CPTAC, GEPIA, HPA) | Bioinformatics analysis of expression and ubiquitination | Correlation with clinical outcomes, tissue expression patterns | Essential for translational relevance and validation |

The intricate balance between tumor suppressor degradation and oncoprotein stabilization represents a fundamental aspect of cancer biology with profound therapeutic implications. The comprehensive characterization of ubiquitination patterns across different cancer types, coupled with mechanistic insights into the molecular pathways involved, provides a robust foundation for developing targeted interventions. Future research directions should focus on expanding the catalog of cancer-relevant ubiquitination events, particularly through pan-cancer ubiquitinome analyses, and developing more specific small-molecule inhibitors targeting oncogenic E3 ligases or stabilizing tumor suppressor proteins. The continuing evolution of proteomic technologies, combined with sophisticated bioinformatic tools and well-validated functional assays, promises to unravel the full complexity of the ubiquitination network in cancer and reveal novel opportunities for therapeutic exploitation.

Ubiquitination is a critical post-translational modification regulating protein degradation, signaling, and localization. This comparison guide analyzes tissue-specific ubiquitination signatures across major cancer types, contrasting them with normal tissue patterns to highlight heterogeneity and its implications for targeted therapy.

Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitinome Alterations

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent ubiquitinome profiling studies across different cancer types, demonstrating the tissue-specific nature of these alterations.

Table 1: Tissue-Specific Ubiquitination Signature Comparison in Cancer vs. Normal Tissues

| Cancer Type | Tissue of Origin | Key Upregulated Ubiquitination Events | Key Downregulated Ubiquitination Events | Primary E3 Ligase/Deubiquitinase (DUB) Alterations | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer (CRC) | Colon Epithelium | K48-linked polyUb on APC, p53 | K63-linked polyUb on Wnt/β-catenin pathway components | RNF43 loss (E3); USP7 overexpression (DUB) | Enhanced Wnt signaling, genomic instability |

| Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD) | Lung Alveolar Cells | K48-linked polyUb on PTEN | K63-linked polyUb on EGFR | SMURF1 overexpression (E3); USP9X downregulation (DUB) | Hyperactive PI3K/AKT and EGFR signaling |

| Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) | Mammary Ductal Cells | K11-linked polyUb on BRCA1 | K48-linked polyUb on Cyclin E | TRIM25 overexpression (E3); BAP1 mutation (DUB) | Defective DNA repair, cell cycle progression |

| Glioblastoma (GBM) | Brain Glial Cells | K48-linked polyUb on PDCD4 | K63-linked polyUb on NF-κB pathway | MDM2 amplification (E3); OTUB1 overexpression (DUB) | Suppressed apoptosis, enhanced invasiveness |

Experimental Protocols for Ubiquitinome Profiling

The data in Table 1 is derived from studies utilizing the following core methodology.

Protocol: TUBE-based Ubiquitinated Peptide Enrichment and LC-MS/MS

- Tissue Lysis: Snap-frozen cancerous and adjacent normal tissues are homogenized in a denaturing lysis buffer (e.g., 8M Urea, 100mM NH₂HCO₃, pH 8.0) containing 10mM N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) to inhibit deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) and 1x protease/phosphatase inhibitors.

- Protein Digestion: Proteins are reduced with Dithiothreitol (DTT), alkylated with Iodoacetamide (IAA), and digested with sequencing-grade Trypsin/Lys-C mix.

- Ubiquitin Remnant Enrichment: Digested peptides are incubated with Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) conjugated to agarose beads. TUBEs specifically bind to ubiquitin chains, enriching for ubiquitinated peptides.

- Washing and Elution: Beads are washed extensively with IP buffer to remove non-specifically bound peptides. Ubiquitinated peptides are eluted with a low-pH buffer.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Enriched peptides are separated by nano-liquid chromatography (nano-LC) and analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) on a high-resolution instrument (e.g., Q-Exactive HF-X).

- Data Analysis: MS/MS spectra are searched against a protein database using software (e.g., MaxQuant) with diGly (K-ε-GG) as a variable modification to identify ubiquitination sites. Quantitative differences are calculated using label-free or TMT-based methods.

Visualization of Core Signaling Pathways

The diagrams below illustrate key pathways where tissue-specific ubiquitination alterations drive oncogenesis.

Diagram 1: Wnt/β-catenin Ubiquitination in CRC

Diagram 2: EGFR-PTEN Axis Ubiquitination in LUAD

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitination Signature Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | High-affinity affinity matrices for enrichment of polyubiquitinated proteins and peptides from complex lysates. | Immunoprecipitation of ubiquitinated conjugates prior to MS/MS analysis. |

| diGly (K-ε-GG) Antibody | Antibody specific for the glycine-glycine remnant left on lysine after tryptic digestion of ubiquitinated proteins. | Enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides for mass spectrometry-based ubiquitinome profiling. |

| Proteasome Inhibitors (e.g., MG132, Bortezomib) | Block the 26S proteasome, preventing degradation of ubiquitinated proteins and leading to their accumulation. | Used in cell culture to stabilize ubiquitinated proteins for easier detection. |

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors (e.g., PR-619, P22077) | Broad-spectrum inhibitors of DUBs, preventing the cleavage of ubiquitin chains. | Preserve the endogenous ubiquitinome state during cell lysis and protein extraction. |

| Activity-Based Probes (UB-AMC, Ub-Rho110) | Fluorescently tagged ubiquitin substrates that report on DUB enzymatic activity in cell lysates. | Quantify functional DUB activity changes between cancer and normal tissues. |

| E3 Ligase-Specific Inhibitors (e.g., Nutlin-3 for MDM2) | Small molecules that block the interaction between a specific E3 ligase and its substrate. | Functional validation of E3 ligase roles in specific ubiquitination events. |

Advanced Techniques for Profiling Ubiquitination Landscapes in Malignancies

The comprehensive characterization of complex diseases like cancer requires interrogation across multiple molecular layers. While single-level omics analyses provide valuable insights, they often lack the resolving power to establish causal relationships between molecular alterations and phenotypic manifestations [32]. Multi-omics data integration strategies across different cellular function levels—including genomes, epigenomes, transcriptomes, proteomes, metabolomes, and ubiquitinomes—offer unparalleled opportunities to understand the underlying biology of cancer [32]. This integrated approach is particularly crucial for investigating ubiquitination patterns, a dynamic and reversible post-translational modification that regulates protein stability, cell differentiation, and immunity [33]. Dysregulation of ubiquitination processes can lead to destabilization of biological processes and contribute significantly to oncogenesis [33].

The integration of transcriptomic, proteomic, and ubiquitinomic data enables researchers to capture distinct dimensions of biological regulation: the transcriptome reflects dynamic gene activity, the proteome encodes functional effectors, and the ubiquitinome represents crucial post-translational modifications that determine protein fate and function [34]. When combined, these layers offer synergistic insights into disease mechanisms and treatment response that cannot be inferred from any single modality alone [34]. This approach has transformed our understanding of tumor heterogeneity, therapeutic resistance, and the intricate regulatory networks within the tumor microenvironment [35].

Methodological Frameworks for Multi-Omics Data Integration

Computational Integration Strategies

The integration of multi-omics data presents significant computational challenges due to the high-dimensional nature of each dataset and their inherent technical variations. Several sophisticated computational frameworks have been developed to address these challenges, each with distinct strengths and applications in cancer research.

Table 1: Computational Methods for Multi-Omics Data Integration

| Method Category | Specific Tools | Underlying Algorithm | Key Applications in Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matrix Factorization | Joint NMF | Non-negative Matrix Factorization | Identified novel signaling pathway perturbations and patient subgroups in ovarian cancer [32] |

| Statistical Integration | iCluster+/iClusterBayes | Gaussian Latent Variable Model | Revealed novel breast cancer subgroups with distinct clinical outcomes beyond classic expression subtypes [32] |

| Network-Based Approaches | PARADIGM | Probabilistic Graphical Models | Identified defects in homologous recombination in ovarian cancer, predicting PARP inhibitor response [32] |

| Bayesian Methods | BCC | Dirichlet Mixture Model | Integrated gene expression, miRNA, methylation, and proteomics without requiring pre-specified cluster numbers [32] |

| Dimensionality Reduction | JIVE | Principal Component Analysis Extension | Improved characterization of glioblastoma types by integrating miRNA and gene expression [32] |

The choice of integration strategy depends heavily on the research question and data characteristics. Unsupervised methods like iCluster and Joint NMF are valuable for discovering novel disease subtypes without prior knowledge of sample classifications [32]. In contrast, supervised and semi-supervised approaches incorporate known sample labels or partial labels to guide the integration process, which can be particularly useful for predictive modeling of treatment response [32]. Network-based methods such as PARADIGM leverage prior knowledge from pathway databases like KEGG to interpret multi-omics data within established biological contexts, enabling researchers to identify pathway-level perturbations that might be missed when analyzing individual molecular layers [32].

Experimental Workflows for Multi-Omics Data Generation

The generation of high-quality multi-omics data requires carefully optimized experimental workflows that preserve molecular integrity while enabling comprehensive profiling. Recent advances have enabled truly integrated data generation from the same tissue specimens, enhancing data comparability and biological relevance.

Figure 1: Integrated Spatial Multi-Omics Workflow. This framework enables transcriptomic, proteomic, and histologic data generation from the same tissue section, ensuring spatial consistency [36].

A key innovation in multi-omics experimental design is the ability to perform spatial transcriptomics and spatial proteomics on the same tissue section, as demonstrated in recent lung cancer studies [36]. This approach ensures consistency in tissue morphology and spatial context, overcoming limitations of analyzing adjacent sections. The workflow typically involves sequential processing of tissue sections through platforms such as 10x Genomics Xenium for transcriptomics, COMET hyperplex immunohistochemistry for proteomics, and standard H&E staining for histopathological annotation [36]. Computational registration using software like Weave then enables accurate alignment and annotation transfer across modalities, facilitating single-cell level comparisons of RNA and protein expression [36].

For ubiquitinomic analyses, researchers typically employ ubiquitination-related gene sets obtained from databases such as GeneCard (using a relevance score >10, resulting in ~405 genes) or curated lists of ubiquitination regulators (UBRs) categorized as writers (E1-E3 enzymes), readers (proteins with ubiquitin-binding domains), and erasers (deubiquitinases) [33] [24]. These gene sets enable the calculation of ubiquitination activity scores and facilitate the identification of hub genes through protein-protein interaction network analysis using topological algorithms like EPC, Degree, MNC, and Closeness [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Multi-Omics Studies

| Category | Specific Product/Platform | Key Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Transcriptomics | 10x Genomics Xenium | Targeted gene expression with spatial context | Human lung cancer panel with 289 genes [36] |

| Spatial Proteomics | COMET (Lunaphore) | Hyperplex immunohistochemistry for 40+ protein markers | Sequential staining of immune and tumor markers [36] |

| Cell Segmentation | CellSAM | Deep learning-based cell segmentation using nuclear/membrane markers | Integrates DAPI and pan-cytokeratin staining [36] |

| Data Integration Software | Weave (Aspect Analytics) | Registration and visualization of multi-omics data | Co-registration of ST, SP, and H&E data [36] |

| Ubiquitination Assays | Ubiquitin-activated E1 enzyme inhibitors (e.g., MLN4924) | Inhibition of ubiquitination initiation | Investigation of ubiquitination-dependent processes [33] |

| Single-Cell Analysis | Seurat R package | Processing and analysis of single-cell RNA-seq data | Identification of 12 cell types in pancreatic cancer [24] |

| Spatial Data Deconvolution | spacexr (RCTD method) | Cell type annotation in spatial transcriptomics | Mapping single-cell clusters to spatial contexts [24] |

The selection of appropriate research tools is critical for generating high-quality multi-omics data. For spatial transcriptomics, the 10x Genomics Xenium platform offers targeted gene expression profiling with subcellular resolution, typically using custom panels focused on cancer-relevant genes [36]. For spatial proteomics, the COMET system enables hyperplex immunohistochemistry through cyclical staining, imaging, and elution of off-the-shelf primary antibodies against 40 or more protein markers, providing comprehensive protein expression mapping [36]. The integration of these datasets requires sophisticated computational tools like Weave software, which employs non-rigid registration algorithms to align different spatial omics readouts, enabling accurate cross-modality analysis at single-cell resolution [36].

For ubiquitination-focused studies, researchers can leverage public databases such as Gene Set Cancer Analysis (GSCA) for genomic, pharmacogenomic, and immunogenomic analysis [37], and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) for multi-omics data across 33 cancer types [37]. Additionally, specialized platforms like CancerSEA enable single-cell functional state analysis by correlating gene expression with 14 predefined cancer-related functional states [37].

Comparative Analysis of Ubiquitination Patterns in Cancer vs. Normal Tissues

Genetic and Transcriptional Alterations in Ubiquitination Machinery

Multi-omics analyses have revealed extensive dysregulation of ubiquitination-related genes across cancer types, providing insights into their potential roles as oncogenic drivers or tumor suppressors.

Table 3: Ubiquitination Regulator Alterations in Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD)

| Ubiquitination Regulator | Mutation Frequency | CNV Pattern | Expression in Tumor vs Normal | Prognostic Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBE2T | Low | High amplification | Overexpressed | Negative [33] |

| AURKA | No mutations detected | Not reported | Overexpressed | Negative [33] |

| CDC20 | Not specified | Not specified | Overexpressed | Negative [38] |

| BRCA1 | 3% (highest frequency) | Amplification leads to higher expression | Overexpressed | Negative [33] |

| BARD1 | 2% | Not specified | Overexpressed | Negative [33] |

| UBA1 | Not specified | Not specified | Overexpressed in most cancers | Negative in BRCA, COAD, KIRC, LUAD [13] |

| UBA6 | Not specified | Not specified | Variable expression | Context-dependent [13] |

In lung adenocarcinoma, comprehensive analysis of 17 hub ubiquitination regulators revealed widespread genetic alterations and expression perturbations [33]. Somatic mutations in these hub UBRs occurred in 68 of 616 LUAD patients (11.04% frequency), with BRCA1 showing the highest mutation frequency (3%), followed by BARD1 (2%) [33]. Copy number variation analysis demonstrated that specific UBRs like DTL and UBE2T exhibit higher frequencies of CNV amplification, while others like CDC34 and UBA7 show higher frequencies of CNV loss [33]. At the transcriptional level, most hub UBRs were dysregulated in cancer compared to normal tissues, with predominant overexpression patterns [33].

Similar patterns have been observed in pancreatic cancer, where single-cell RNA sequencing identified 12 distinct cell types, with endothelial cells exhibiting particularly high ubiquitination scores [24]. These High_ubiquitin-Endo cells showed enriched interactions with fibroblasts and macrophages through WNT, NOTCH, and integrin pathways, suggesting a role for ubiquitination in modulating the tumor microenvironment [24]. Through Summary-data-based Mendelian Randomization analysis, TRIM9 was prioritized as a pancreatic cancer-protective gene, showing downregulation in tumors and correlation with better survival [24].

Functional Consequences of Ubiquitination Dysregulation

The dysregulation of ubiquitination machinery in cancer has profound functional consequences, affecting key oncogenic pathways and therapeutic responses. In colorectal cancer, integrated multi-omics analysis revealed that approximately 80% of PTM pathways are dysregulated, with ubiquitination sustaining Wnt/β-catenin signaling and GALNT6-mediated glycosylation driving immune evasion through PD-L1 stabilization and CD8+ T cell exclusion [39]. Single-cell analysis further revealed GALNT6-specific enrichment in immune-excluded goblet cells, highlighting the cell-type-specific functions of ubiquitination-related processes [39].

In lung adenocarcinoma, E3 ubiquitin ligases such as CDC20 show significant overexpression and association with poor prognosis [38]. Gene set enrichment analysis demonstrated that high CDC20 expression enriches several key oncogenic pathways, including G2MCHECKPOINT, MTORC1SIGNALING, OXIDATIVE_PHOSPHORYLATION, and GLYCOLYSIS [38]. Further correlation analysis indicated that CDC20 is positively correlated with the expression of key genes in the mTORC1 signaling pathway (mTOR, S6K1, and 4E-BP1) and the autophagy-related gene ULK1 [38], suggesting a multifaceted role in regulating cancer cell metabolism and proliferation.

Figure 2: Functional Consequences of Ubiquitination Dysregulation in Cancer. Ubiquitination alterations impact multiple hallmarks of cancer through various molecular mechanisms [33] [39] [38].

Implications for Cancer Diagnostics, Prognostics, and Therapeutics

Clinical Translation and Biomarker Development