Decoding the Ubiquitin Code: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Chain Architecture Using Linkage-Specific DUBs

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide to the theory and application of deubiquitinase (DUB)-based analysis for validating ubiquitin chain architecture.

Decoding the Ubiquitin Code: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Chain Architecture Using Linkage-Specific DUBs

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide to the theory and application of deubiquitinase (DUB)-based analysis for validating ubiquitin chain architecture. We cover the foundational complexity of ubiquitin signaling, from homotypic chains to branched polymers, and detail the step-by-step methodology of the UbiCRest technique. The guide further addresses critical troubleshooting aspects and compares DUB-based validation to other methods like mass spectrometry and linkage-specific antibodies, offering a holistic resource for accurately interpreting the ubiquitin code in physiological and disease contexts.

The Complex Language of Ubiquitin: Understanding Chain Architecture and Signaling Diversity

Ubiquitination is a versatile post-translational modification that regulates nearly all aspects of eukaryotic cell biology, determining the stability, activity, localization, and interaction properties of target proteins [1]. The remarkable functional diversity of ubiquitin signaling stems from its capacity to form various polymeric structures known as ubiquitin chains. These chains are connected through isopeptide bonds between the carboxyl terminus (G76) of one ubiquitin molecule and an acceptor site on another, most commonly one of the seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or the N-terminal methionine (M1) [1] [2].

The topology of these polyubiquitin chains—defined by the types and arrangement of linkages—creates a sophisticated "ubiquitin code" that is decoded by cellular machinery to produce specific biological outcomes [3]. Understanding this code requires precise discrimination between three fundamental topological classes: homotypic, mixed, and branched chains. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these topological categories, supported by experimental methodologies central to current ubiquitin research, with particular emphasis on validation using linkage-specific deubiquitinases (DUBs).

Defining Ubiquitin Chain Topologies

Ubiquitin chains are classified into three distinct topological categories based on their linkage patterns and three-dimensional architectures.

Homotypic chains represent the simplest topology, comprising ubiquitin subunits linked uniformly through the same acceptor site (e.g., all K48-linked or all K63-linked chains) [1] [4]. These chains typically adopt defined three-dimensional structures that determine their specific functions, with K48-linked chains primarily targeting substrates for proteasomal degradation and K63-linked chains regulating non-degradative processes like DNA repair and inflammatory signaling [3] [5].

Mixed chains (also called heterotypic unbranched chains) contain more than one type of linkage, but each ubiquitin subunit within the chain is modified on only a single acceptor site, making them topologically equivalent to linear chains [1] [4]. The sequence of different linkages in mixed chains can create unique interaction surfaces recognized by specific effector proteins.

Branched chains (also called forked chains) represent the most complex topology, containing at least one ubiquitin subunit that is concurrently modified on two or more different acceptor sites, resulting in a branched structure [1] [4]. This architecture creates a dense array of ubiquitin moieties that can function as potent degradation signals or regulate signaling pathways through degradation-independent mechanisms [4].

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Ubiquitin Chain Topologies

| Topology Class | Linkage Pattern | Structural Features | Primary Functions | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homotypic | Single linkage type throughout | Defined 3D conformation; compact or extended | Signal specificity; predictable outcomes | K48 (degradation), K63 (signaling) |

| Mixed | Multiple linkages; each Ub modified at one site | Linear topology; linkage sequence matters | Signal integration; fine-tuning | Various combinations (e.g., K11/K63) |

| Branched | Multiple linkages with ≥1 Ub modified at ≥2 sites | Branched/forked architecture; high Ub density | Potent degradation signals; complex regulation | K48/K63, K11/K48, K29/K48 |

Assembly Mechanisms and Biological Functions

The assembly of ubiquitin chains requires the sequential action of E1 activating, E2 conjugating, and E3 ligase enzymes. The mechanisms of chain formation vary significantly between topological classes, particularly for the more complex branched chains.

Homotypic Chain Assembly

Homotypic chain formation follows relatively straightforward mechanisms. RING E3 ligases typically facilitate direct ubiquitin transfer from E2 enzymes to substrates, with linkage specificity often determined by the E2 [1]. HECT and RBR E3 ligases employ a two-step mechanism, forming a transient thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transfer, with these E3s predominantly determining linkage specificity [1]. For example, the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) with UBE2S specifically synthesizes K11-linked chains, while UBE2N/UBC13 with various RING E3s produces K63-linked chains [1].

Branched Chain Assembly Mechanisms

Branched ubiquitin chains are synthesized through several distinct mechanisms, which can be categorized as follows:

Collaborating E2 Enzymes with a Single E3: The APC/C, a multisubunit RING E3, cooperates sequentially with UBE2C (initiating chain formation) and UBE2S (elongating with K11 linkages) to produce branched K11/K48 chains on mitotic substrates [1] [4].

Collaborating E3 Ligases with Distinct Linkage Specificities: Pairs of E3s with different linkage preferences work together. Examples include Ufd4 and Ufd2 forming branched K29/K48 chains in yeast; TRAF6 and HUWE1 generating branched K48/K63 chains during NF-κB signaling; and ITCH and UBR5 producing branched K48/K63 chains on TXNIP to trigger its proteasomal degradation [1] [4].

Single E3 with Innate Branching Activity: Certain E3s, including HECT E3s (WWP1, UBE3C, NleL) and RBR E3 Parkin, can form branched chains using a single E2, suggesting intrinsic branching capabilities [1] [4].

Table 2: Enzymatic Machinery for Branched Ubiquitin Chain Synthesis

| Branching Mechanism | Key Enzymes | Branched Linkage Formed | Biological Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two E2s + Single E3 | APC/C + UBE2C + UBE2S | K11/K48 | Cell cycle regulation |

| Collaborating E3 Pairs | Ufd4 + Ufd2 | K29/K48 | Ubiquitin fusion degradation pathway |

| Collaborating E3 Pairs | TRAF6 + HUWE1 | K48/K63 | NF-κB signaling |

| Collaborating E3 Pairs | ITCH + UBR5 | K48/K63 | Apoptotic response |

| Single E3 + Single E2 | WWP1 + UBE2L3 | K48/K63 | Unknown |

| Single E3 + Single E2 | UBE3C + UBE2L3 | K29/K48 | VPS34 regulation |

| Single E3 + Single E2 | Parkin + UBE2L3 | K6/K48 | Mitochondrial quality control |

Functional Specialization of Chain Topologies

The different topological classes execute distinct cellular functions through their specific architectures and linkage compositions.

Homotypic chains exhibit specialized functions: K48-linked chains predominantly target proteins to the 26S proteasome for degradation; K63-linked chains activate protein kinases in the NF-κB pathway and regulate autophagy; and M1-linked linear chains activate inflammatory and cell death pathways [3] [5].

Branched chains often function as enhanced degradation signals. Branched K11/K48 chains assembled by the APC/C ensure the robust and irreversible degradation of cell cycle regulators like cyclin B [1] [4]. Similarly, branched K48/K63 chains on TXNIP convert a non-degradative signal into a proteolytic one [1]. Beyond degradation, branched chains also participate in degradation-independent signaling, as demonstrated by branched K48/K63 chains that regulate NF-κB activation by inhibiting CYLD cleavage [1].

Mixed chains likely enable fine-tuning of ubiquitin signals and signal integration, though their functions are less well characterized due to analytical challenges in distinguishing them from branched topologies.

Analytical Approaches for Topology Determination

Mass Spectrometry-Based Methods

Mass spectrometry has become a cornerstone technology for ubiquitin chain characterization, particularly top-down tandem MS approaches that preserve the intact chain architecture.

Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Ubiquitinated proteins or free ubiquitin chains are enriched using Ub-binding domains (TUBEs) or immunoprecipitation with linkage-specific antibodies [2] [5].

- Liquid Chromatography: Separation uses a monolithic C4 column with a water-acetonitrile gradient containing 0.1% formic acid as mobile phases [2].

- Tandem Mass Spectrometry: Analysis employs high-resolution instruments (e.g., Orbitrap Fusion Lumos) using fragmentation techniques such as electron-transfer/higher-energy collision dissociation (EThcD) [2].

- Data Interpretation: Specialized software identifies fragment ions revealing modification sites and linkage patterns, including diagnostic ions for branched chains [2].

This top-down approach allows direct characterization of chain length, linkage types, and branching patterns without proteolytic digestion, distinguishing branched from mixed and homotypic chains [2].

Deubiquitinase (DUB) Restriction Analysis

Linkage-specific DUBs serve as "restriction enzymes" for deciphering ubiquitin chain topology, particularly when integrated with mass spectrometry.

DUB Restriction Analysis Protocol:

- Sample Incubation: Ubiquitin chain samples are treated with highly specific DUBs under optimized conditions. For example, Cezanne (OTUD7B) preferentially cleaves K11 linkages, while OTUB1 is specific for K48 linkages [6].

- Reaction Monitoring: The digestion products are analyzed over time by immunoblotting with linkage-specific antibodies or by mass spectrometry to identify cleavage products [6] [7].

- Topology Assignment: The susceptibility of chains to specific DUBs reveals their linkage composition, while differential cleavage patterns can distinguish branched from mixed chains [6].

This approach, termed "ubiquitin chain restriction analysis," is particularly valuable for identifying branched chains, as the cleavage efficiency of DUBs often changes when their target linkage is incorporated into a branched architecture [6].

DUB and MS Workflow for Topology Determination

Computational and Structural Approaches

Molecular dynamics simulations and theoretical modeling provide insights into how chain topology influences three-dimensional structure and function.

Computational Analysis Protocol:

- System Setup: Building atomic or coarse-grained models of ubiquitin chains with specific linkages using tools like GROMACS with modified force fields to accommodate isopeptide bonds [8].

- Simulation Execution: Running extended molecular dynamics simulations (microsecond timescale) to explore conformational landscapes [8].

- Landscape Analysis: Applying dimensionality reduction and clustering algorithms to identify predominant conformational states and transitions [8].

- Energy Landscape Mapping: Calculating free energy surfaces to understand the thermodynamic preferences of different chain topologies [3].

These approaches reveal that different linkage types create distinct conformational landscapes, with branched chains often sampling unique structural states not accessible to homotypic chains [3] [8].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Chain Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific DUBs | Cezanne (K11-specific), OTUB1 (K48-specific), USP2 (broad specificity) | Chain restriction analysis, topology validation | Cleavage specificity enables linkage mapping |

| Ubiquitin Binding Domains | Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins and chains | High-affinity capture; protects from DUBs |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Anti-K48, Anti-K63, Anti-K11, Anti-M1 | Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence, enrichment | Specific recognition of chain linkages |

| Tagged Ubiquitin Variants | His-Ub, Strep-Ub, HA-Ub, R54A-Ub (branched chain detection) | Pulldown assays, cellular ubiquitination profiling | Affinity purification; specialized mutants |

| Activity-Based Probes | Ubiquitin-based suicide substrates | DUB activity profiling, inhibition studies | Covalent modification of active DUBs |

| Recombinant E2/E3 Enzymes | UBE2C/UBE2S, APC/C, TRAF6/HUWE1 | In vitro ubiquitination assays, branching studies | Defined linkage specificity |

The topological diversity of ubiquitin chains—from simple homotypic to complex branched architectures—greatly expands the coding potential of the ubiquitin system, enabling precise control over countless cellular processes. Each topological class possesses distinct structural features, assembly mechanisms, and functional capabilities, with branched chains emerging as particularly important for generating potent biological signals, especially under conditions requiring robust protein degradation.

The continuing development of sophisticated analytical methodologies, particularly the integration of linkage-specific DUB validation with advanced mass spectrometry and computational approaches, is rapidly advancing our understanding of ubiquitin chain topology. These technical advances, coupled with the growing toolkit of research reagents, promise to unlock further secrets of the ubiquitin code, offering new opportunities for therapeutic intervention in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and other pathologies linked to ubiquitin signaling dysfunction.

Ubiquitination is a versatile post-translational modification that regulates nearly all cellular processes in eukaryotes, governing protein stability, activity, localization, and complex assembly [9] [10]. The remarkable functional diversity of ubiquitin signaling originates from the structural complexity of ubiquitin chains themselves. A ubiquitin molecule contains eight distinct sites—seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and the N-terminal methionine (M1)—that can serve as attachment points for subsequent ubiquitin molecules [9] [11]. This molecular architecture enables the formation of multiple ubiquitin chain types: monoubiquitination (single ubiquitin on a substrate), multi-monoubiquitination (multiple single ubiquitins on different sites of the same substrate), and polyubiquitination (chains of ubiquitins linked through specific residues) [11]. The specific connectivity of these chains, known as the "ubiquitin code," creates distinct structural landscapes that are decoded by cellular machinery to produce specific functional outcomes [12].

The ubiquitin code is written by a hierarchical enzyme cascade involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes, and is erased by deubiquitinases [9] [11]. The human genome encodes approximately 100 DUBs that display varying degrees of linkage specificity, enabling them to selectively recognize and cleave particular ubiquitin chain types [12] [13]. This review will explore how researchers are leveraging linkage-specific DUBs as analytical tools to crack the ubiquitin code, comparing this approach with alternative methodologies and providing experimental frameworks for applying these techniques in drug discovery research.

Ubiquitin Chain Linkages and Their Functional Consequences

Different ubiquitin chain linkages create distinct molecular signatures that are recognized by specific effector proteins, leading to diverse functional consequences. The following table summarizes the key linkages and their primary cellular functions:

Table 1: Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Biological Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Functions | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Proteasomal degradation [9] [11]; Most abundant linkage in cells [9] | Canonical degradation signal; Removal by DUBs prevents degradation [9] |

| K63-linked | Non-degradative signaling [11]: NF-κB activation, DNA repair, endosomal trafficking [9] [12] | Regulates protein-protein interactions and kinase activation [9] |

| K11-linked | Cell cycle regulation [11], ER-associated degradation [12] | Implicated in proteasomal degradation and membrane trafficking [11] |

| K6-linked | DNA damage response [11], Mitophagy [12] | Less studied; Associated with BRCA1-BARD1 ligase complex [14] |

| K27-linked | Immune response [11], Protein secretion [11], Mitochondrial damage [11] | Targets cGAS and STING in innate immunity [11] |

| K29-linked | Proteasomal degradation [11], Innate immune regulation [11] | Regulates AMPK-related kinases [11] |

| K33-linked | Intracellular trafficking [12], Signal transduction [12] | Affects cGAS-STING and RLR signaling pathways [11] |

| M1-linear | NF-κB activation [11], Inflammation regulation [11] | Assembled by LUBAC complex; Inhibits type I interferon signaling [11] |

The complexity of ubiquitin signaling extends beyond homotypic chains (containing a single linkage type) to include heterotypic chains that incorporate multiple linkage types within the same polymer [10] [14]. These mixed and branched chains further expand the coding potential of ubiquitin signaling, creating specialized architectures that can integrate multiple signals or regulate the processing of ubiquitin chains by DUBs and ubiquitin-binding proteins [14]. For example, the bacterial E3 ligase NleL can generate heterotypic chains containing both K6 and K48 linkages, creating unique structural properties that influence their recognition and turnover [14].

Methodological Comparison for Ubiquitin Chain Analysis

Several methodological approaches have been developed to decipher the ubiquitin code, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and applications in research and drug discovery.

Table 2: Methodological Approaches for Ubiquitin Chain Characterization

| Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| UbiCRest (DUB-based restriction) | Uses linkage-specific DUBs to cleave specific chains [10] [15] | Qualitative analysis of chain architecture [10]; Rapid results (hours) [10]; No specialized equipment needed [10] | Qualitative rather than quantitative [10]; Requires well-characterized DUBs [15] |

| Ub-Clipping (Lbpro∗ protease) | Engineered viral protease leaves GlyGly signature on modified residues [16] | Reveals branching architecture [16]; Works on complex samples [16]; Quantifies co-modifications [16] | Requires mass spectrometry [16]; Specialized expertise needed [16] |

| Mass Spectrometry (Bottom-up proteomics) | Detection of GlyGly remnant (114.043 Da) on modified lysines [9] [17] | High-throughput identification of sites [9] [17]; Global ubiquitome profiling [9] | Loss of architectural information [10]; Difficult for heterotypic chains [14] |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Immuno-based detection of specific linkages [9] [10] | Well-established protocols [10]; Suitable for cellular imaging [10] | Limited antibody availability [10]; Potential cross-reactivity [10] |

| Ubiquitin Mutants (K-to-R mutations) | Mutation of specific lysines to restrict chain formation [10] [14] | In vitro and in vivo applications [10]; Identifies linkage requirements [14] | May alter ubiquitin structure/function [10]; Can disrupt chain assembly [10] |

UbiCRest: Experimental Framework and Protocol

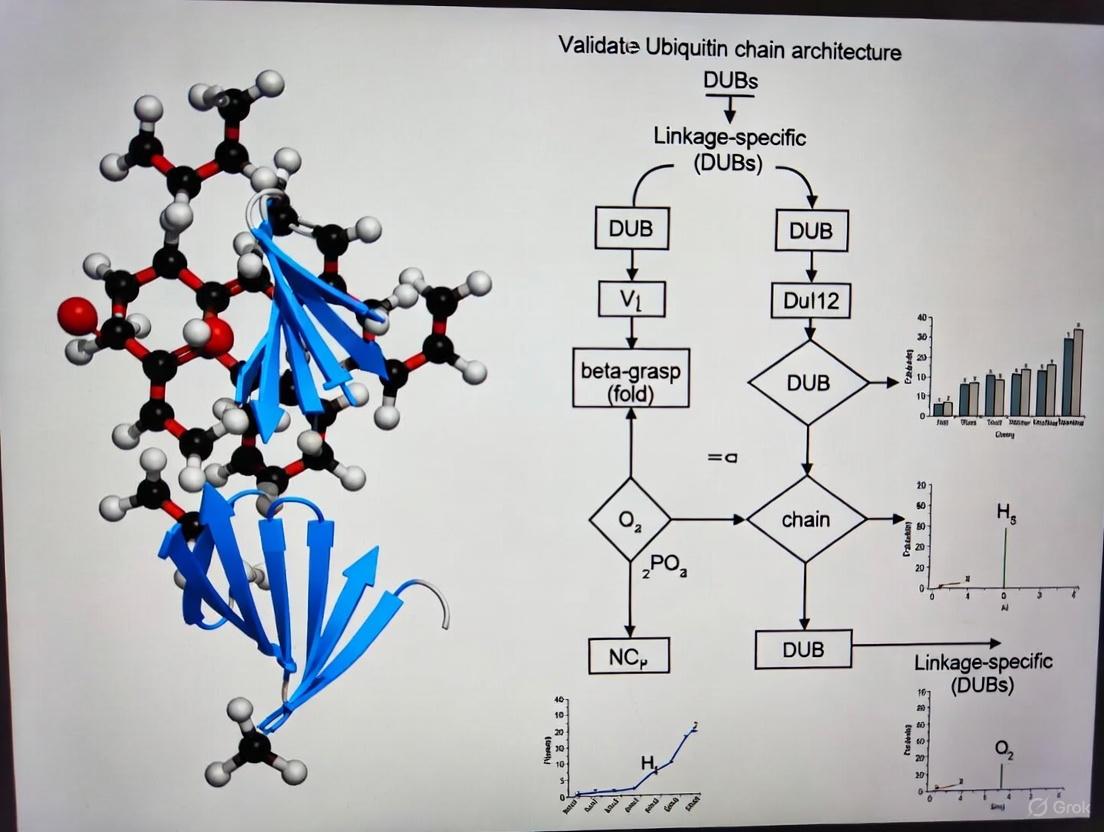

The UbiCRest methodology serves as a cornerstone technique for ubiquitin chain architecture analysis using linkage-specific DUBs. The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow and experimental process:

The UbiCRest protocol involves several critical steps that must be optimized for reliable results. First, the ubiquitinated substrate of interest is purified and transferred into DUB-compatible buffer. The sample is then split into equal aliquots and treated with a panel of linkage-specific DUBs in parallel reactions [10] [15]. It is crucial to include appropriate controls, including a non-specific DUB (such as USP21 or USP2) that cleaves all linkage types as a positive control, and a no-DUB negative control to establish baseline migration patterns [15].

Experimental conditions including DUB concentration, incubation time, and temperature should be optimized. Researchers typically perform assays at both low and high DUB concentrations—activity at low concentrations indicates presence of the preferred linkage type, while higher concentrations reveal whether secondary chain types remain on the substrate [10]. Following DUB treatment, samples are analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using ubiquitin-specific antibodies to visualize the cleavage patterns [15].

Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Analysis

The successful implementation of ubiquitin chain analysis requires specific research reagents with defined linkage specificities. The following table details key reagents used in DUB-based approaches:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DUB-Based Ubiquitin Chain Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Key Specificity/Function | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific DUBs | OTUB1 (K48) [15], OTUD3 (K6/K11) [15], Cezanne (K11) [15], OTUD1 (K63) [15] | Cleave specific ubiquitin linkages [10] [15] | UbiCRest analysis [10]; Chain validation [15] |

| Non-Specific DUBs | USP21 [10] [15], USP2 [10], vOTU [15] | Cleave most or all linkage types [10] [15] | Positive controls [10]; Complete deubiquitination [15] |

| Ubiquitin Binding Reagents | Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) [16], Linkage-specific antibodies [9] [10] | Enrich ubiquitinated proteins [16]; Detect specific chains [9] | Sample preparation [16]; Immunodetection [10] |

| Specialized Proteases | Lbpro∗ (Ub-clipping) [16], Trypsin (bottom-up MS) [9] | Leave GlyGly signature on modified residues [16]; Generate diagnostic peptides [9] | Ub-clipping [16]; Mass spectrometry [9] |

| Ubiquitin Variants | Lysine-to-arginine mutants [10] [14], Tagged ubiquitin (His-, Strep-) [9] | Restrict chain formation to specific linkages [14]; Enable affinity purification [9] | Ubiquitin replacement [10]; Substrate enrichment [9] |

Analytical Framework for Ubiquitin Chain Architecture

Interpreting UbiCRest results requires understanding how different DUBs process various chain architectures. The cleavage patterns observed on SDS-PAGE provide insights into both linkage composition and chain architecture. The following diagram illustrates the decision framework for analyzing results:

When analyzing UbiCRest results, several key patterns indicate specific architectural features. Complete cleavage to monoubiquitin by a linkage-specific DUB indicates the presence of extended homotypic chains of that linkage type. Partial cleavage with intermediate bands suggests heterotypic chains containing the DUB's preferred linkage mixed with other linkage types. For instance, when OTUB1 (K48-specific) treatment of NleL-generated chains produces intermediate bands rather than complete cleavage to monoubiquitin, this indicates the presence of both K48 and non-K48 (K6) linkages within the same polymer [14]. The electrophoretic mobility of the remaining intermediates can provide additional clues about the specific linkage types present, as different ubiquitin linkages exhibit characteristic migration patterns on SDS-PAGE [10] [14].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Development

Understanding ubiquitin chain architecture has profound implications for drug discovery, particularly in the development of targeted protein degradation strategies and DUB inhibitors. The ubiquitin-proteasome system regulates over 80% of cellular proteins, and its dysregulation is implicated in most cancer hallmarks [11]. E3 ligases and DUBs represent promising therapeutic targets due to their specificity and central role in controlling protein stability and signaling outputs.

PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) and molecular glues represent a breakthrough therapeutic modality that redirects E3 ubiquitin ligases to target non-traditional substrates for degradation [11]. The efficacy of these compounds depends on the formation of specific ubiquitin chain types (primarily K48-linked chains) on the target protein. UbiCRest and related methodologies can validate whether these therapeutics induce the intended ubiquitin code on their targets, providing critical mechanistic information during drug development [11]. For example, analyzing the chain architecture induced by a PROTAC molecule can explain unexpected efficacy or toxicity profiles and guide compound optimization.

DUB inhibitors represent another promising therapeutic class, with several compounds in preclinical and clinical development. Different DUB families display distinct linkage preferences—USP family DUBs generally show broad specificity but substrate selectivity, while OTU family DUBs often exhibit marked linkage preference [13] [15]. Understanding the biological functions of specific ubiquitin chain types enables rational design of DUB inhibitors with predicted physiological effects. For instance, inhibitors of K48-specific DUBs would be expected to enhance proteasomal degradation of their substrate proteins, while inhibitors of K63-specific DUBs would modulate signaling pathways such as NF-κB activation [12].

The functional outcomes of ubiquitination are fundamentally determined by the architectural complexity of ubiquitin chains. Methodologies for deciphering this ubiquitin code, particularly DUB-based approaches like UbiCRest, provide critical tools for understanding the mechanistic basis of ubiquitin signaling in health and disease. The integration of these complementary techniques—UbiCRest for architectural analysis, Ub-clipping for branching quantification, and mass spectrometry for site identification—enables researchers to obtain a comprehensive view of the ubiquitin code in specific biological contexts.

As the field advances, several emerging areas will shape future research. First, understanding the dynamics of ubiquitin chain editing—how chains are remodeled by DUBs and E3 ligases during cellular processes—will reveal how signals are integrated and terminated. Second, developing quantitative frameworks for predicting functional outcomes from chain architecture will enhance our ability to manipulate the ubiquitin system therapeutically. Finally, expanding our knowledge of heterotypic and branched chains in physiological contexts will likely uncover new regulatory mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities.

For drug development professionals, mastering these analytical approaches provides a competitive advantage in validating mechanisms of action, understanding compound selectivity, and guiding lead optimization. As targeted protein degradation and DUB modulation continue to gain therapeutic traction, methodologies for ubiquitin code validation will become increasingly essential components of the drug discovery toolkit.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is the major pathway for the degradation of over 80% of intracellular proteins, acting as a critical post-translational regulator of protein stability, activity, and localization [18]. The precise orchestration of protein ubiquitination—the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to target proteins—and its reversal, deubiquitination, governs virtually all aspects of eukaryotic cell biology. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the core enzymatic machinery: the E1, E2, and E3 enzymes that assemble ubiquitin chains, and the deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that disassemble them. Understanding the function, specificity, and experimental analysis of these players is fundamental to research in cell signaling, protein homeostasis, and the development of therapeutics for diseases like cancer and neurodegeneration [5] [18].

The Ubiquitination Cascade: E1, E2, and E3 Enzymes

Protein ubiquitination is executed by a sequential cascade of three enzyme families. This process culminates in the attachment of a single ubiquitin or a polyubiquitin chain to a substrate protein, which can alter its function or mark it for degradation [19] [20].

- E1 (Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme): The process initiates with a single E1 enzyme that activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner, forming a thioester bond between its active-site cysteine and the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin [19] [21].

- E2 (Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme): The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to the cysteine residue of an E2 conjugating enzyme. The human genome encodes approximately 40 E2s, which contribute to the specificity of the modification [5].

- E3 (Ubiquitin Ligase): Finally, an E3 ligase facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine residue on the target protein, forming an isopeptide bond. With over 600 E3s in humans, this enzyme is the primary determinant of substrate specificity. The E3 can also promote the extension of ubiquitin into polymers by catalyzing the attachment of additional ubiquitin molecules to one of the seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or the N-terminal methionine (M1) of the previously attached ubiquitin [19] [5] [1].

The collaboration between these enzymes results in a diverse "ubiquitin code," including monoubiquitination, multi-monoubiquitination, and various polyubiquitin chain architectures (homotypic, mixed, and branched), each with distinct functional consequences for the modified substrate [5] [1] [18].

Table 1: Key Enzyme Classes in the Ubiquitin Cascade

| Enzyme | Number in Humans | Core Function | Key Functional Domains/Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | 2 | Activates ubiquitin via ATP hydrolysis to form E1~Ub thioester [5] [21]. | Adenylation domain, active-site cysteine [21]. |

| E2 | ~40 | Accepts ubiquitin from E1 to form E2~Ub thioester; often determines chain linkage [5]. | Catalytic cysteine residue, determines linkage specificity for some E2s [1]. |

| E3 - RING | >600 | Brings E2~Ub and substrate together for direct ubiquitin transfer [1]. | RING domain, acts as a scaffold [1]. |

| E3 - HECT | 28 | Forms E3~Ub thioester intermediate before transferring ubiquitin to substrate [1]. | HECT domain, determines linkage specificity [1]. |

| E3 - RBR | 14 | Hybrid mechanism; forms E3~Ub thioester like HECT E3s [1]. | RING1, RING2, and In-Between-Ring (IBR) domains [1]. |

| DUBs | ~100 | Cleaves ubiquitin from substrates, proofreads ubiquitination, recycles ubiquitin [18]. | Catalytic triad (Cys-based or Zn-dependent JAMM family) [18]. |

Deubiquitinases (DUBs) in Chain Disassembly

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) perform the reverse reaction of E3 ligases, removing ubiquitin from substrate proteins. This activity is essential for maintaining protein stability, proofreading ubiquitin signals, recycling ubiquitin, and controlling the dynamics of signaling complexes [18]. The human genome encodes approximately 100 DUBs, which are categorized into seven families based on their catalytic mechanisms and structural folds [18].

- Cysteine Protease DUB Families: This group includes Ubiquitin-Specific Proteases (USPs), Ubiquitin C-Terminal Hydrolases (UCHs), Ovarian Tumor Proteases (OTUs), Machado-Joseph Disease Proteases (MJDs), MINDY, and ZUFSP. They all feature a catalytic cysteine residue as part of a catalytic triad [18].

- Zinc-Dependent Metalloprotease DUB Family: The JAMM family is the only group of metalloproteases among DUBs [18].

A key feature of many DUBs is their linkage specificity, which is often imparted by ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) that recognize specific chain architectures. For instance, OTUD1 specifically hydrolyzes K63-linked chains, a function that is impaired if its UIM domain is missing [18]. This specificity allows DUBs to act as precise editors of the ubiquitin code, making them critical targets for therapeutic intervention. Dysregulation of DUBs is implicated in various cancers and neurodegenerative diseases [18].

Table 2: Major Deubiquitinase (DUB) Families and Their Characteristics

| DUB Family | Representative Members | Catalytic Mechanism | Notable Features / Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| USP | USP5, USP7, USP14 | Cysteine protease | Largest DUB family; diverse specificities and regulatory roles [18]. |

| OTU | OTUD1, A20 | Cysteine protease | Often exhibit high linkage specificity (e.g., K63, K48) [18]. |

| JAMM | UCH37, BRCC36 | Zinc metalloprotease | Requires Zn²⁺ for catalysis; often part of large complexes [1] [18]. |

| UCH | UCH-L1 | Cysteine protease | Specialized in cleaving small adducts from ubiquitin's C-terminus [18]. |

| MJD | Ataxin-3 | Cysteine protease | Often involved in protein quality control [18]. |

| MINDY | MINDY-1, MINDY-2 | Cysteine protease | Preferentially cleaves K48-linked polyUb chains [18]. |

| ZUFSP | ZUFSP/ZUP1 | Cysteine protease | Prefers K63-linked and long polyUb chains [18]. |

Experimental Methodologies for Characterization

Studying the ubiquitin system requires specialized methodologies to overcome challenges such as low endogenous stoichiometry, the multiplicity of modification sites, and the complexity of chain architectures [5]. The following protocols outline key approaches for profiling ubiquitinated proteins and characterizing chain linkage.

Profiling Ubiquitinated Proteins: Enrichment Strategies

To identify ubiquitination sites and substrates in a high-throughput manner, ubiquitinated proteins must first be enriched from complex cell lysates. The primary strategies are summarized below.

Ubiquitin Tagging-Based Enrichment: This approach involves engineering cells to express ubiquitin with an affinity tag (e.g., His, Strep, or HA). The tagged ubiquitin is incorporated into the cellular ubiquitin pool, and ubiquitinated proteins can be purified under denaturing conditions using the appropriate resin (e.g., Ni-NTA for His-tag). After purification and tryptic digestion, ubiquitination sites are identified by mass spectrometry (MS) as a 114.04 Da mass shift on modified lysine residues [5].

- Advantages: Easy to implement and relatively low-cost.

- Disadvantages: The tag may alter ubiquitin structure, creating artifacts. It is also infeasible for use in clinical or animal tissues, and co-purification of endogenous biotinylated or histidine-rich proteins can reduce specificity [5].

Ubiquitin Antibody-Based Enrichment: This method uses antibodies (e.g., P4D1, FK1/FK2) that recognize ubiquitin to immunoprecipitate endogenously ubiquitinated proteins from cell or tissue lysates. Linkage-specific antibodies (e.g., for K48, K63, K11) can be used to enrich for proteins modified with a particular chain type [5].

- Advantages: Can be applied to any sample, including clinical tissues, without genetic manipulation.

- Disadvantages: Antibodies are expensive and can have non-specific binding, leading to high background [5].

Ubiquitin-Binding Domain (UBD)-Based Enrichment: Tandem-repeated Ub-binding entities (TUBEs) are engineered proteins with multiple UBDs that exhibit high-affinity, avidity-based binding to polyubiquitin chains. TUBEs can be fused to affinity tags for purification and have the added benefit of protecting ubiquitin chains from disassembly by DUBs during lysis [5].

- Advantages: High affinity and specificity; protects ubiquitin chains.

- Disadvantages: May have inherent linkage preferences based on the UBD used.

Characterizing Ubiquitin Chain Architecture Using Linkage-Specific DUBs

A powerful method to validate ubiquitin chain architecture involves the use of linkage-specific DUBs. This assay provides functional evidence for the presence of a specific ubiquitin linkage on a protein or within a chain.

Protocol: DUB Specificity Assay for Chain Validation

Generate Ubiquitinated Substrate: Produce the ubiquitinated protein of interest. This can be achieved:

- In vivo: By immunoprecipitating the protein from cells under denaturing conditions to preserve ubiquitination and co-purify associated DUBs.

- In vitro: By reconstituting the ubiquitination reaction using purified E1, E2, and E3 enzymes.

Incubate with Recombinant DUBs: Split the purified ubiquitinated substrate into several aliquots. Incubate each aliquot with a different, purified recombinant DUB known to have high specificity for a particular ubiquitin linkage (e.g., OTUB1 for K48-linked chains, AMSH for K63-linked chains). Include a control aliquot with buffer alone.

Analyze the Results: Resolve the reactions by SDS-PAGE and perform immunoblotting with an anti-ubiquitin antibody.

- Interpretation: If a DUB cleaves the ubiquitin chains from the substrate, a loss of high-molecular-weight smearing will be observed on the blot. The disappearance of signal upon treatment with a specific DUB indicates that the substrate is modified with chains containing that particular linkage.

This method is often used in conjunction with MS-based proteomics and linkage-specific antibodies to build a comprehensive picture of the ubiquitin code.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table lists essential chemical and biological tools used to interrogate the ubiquitin system in experimental settings.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Ubiquitination and Deubiquitination

| Reagent Name | Target | Function / Effect | Key Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| TAK-243 (MLN7243) [21] | E1 Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme (UAE) | Selective inhibitor (IC₅₀ = 1 nM); blocks ubiquitin binding and global ubiquitination. | Tool to broadly inhibit the ubiquitin system; induces apoptosis and has antitumor activity. |

| Pevonedistat (MLN4924) [21] | NEDD8-Activating Enzyme (NAE) | Potent and selective inhibitor (IC₅₀ = 4.7 nM); blocks cullin neddylation and activity of Cullin-RING E3 ligases. | Probe for studying the NEDD8 pathway and cullin-dependent ubiquitination; in clinical trials. |

| Nutlin-3 [20] [21] | MDM2-p53 Interaction | MDM2 antagonist (Kᵢ = 90 nM); stabilizes p53 and activates the p53 pathway. | Study p53-dependent apoptosis and cell cycle arrest; a classic E3 ligase inhibitor. |

| Heclin [21] | HECT E3 Ligases (e.g., Smurf2, Nedd4, WWP1) | Inhibitor of HECT E3 ligase activity (IC₅₀ ~6-7 μM). | Selective tool to probe the function of HECT-family E3 ligases. |

| Ginkgolic Acid [21] | Multiple (e.g., USP4, USP5, SENP1) | Natural compound that inhibits several deubiquitinases and SUMO proteases. | Used to study DUB and SUMOylation pathways; exhibits anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory effects. |

| TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) [5] | Polyubiquitin Chains | High-affinity capture reagents for purifying ubiquitinated proteins; protect chains from DUBs. | High-yield enrichment of polyubiquitinated proteins for proteomics or biochemical analysis. |

| Linkage-Specific Ub Antibodies [5] | Specific Ubiquitin Linkages (K48, K63, etc.) | Antibodies that recognize a particular ubiquitin chain topology. | Detect and validate specific chain linkages via immunoblotting or immunofluorescence. |

Signaling Pathways and Logical Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core ubiquitination cascade and the classification of deubiquitinating enzymes, highlighting key logical relationships in this system.

The Ubiquitin Cascade: From Activation to Ligation

Diagram 1: The sequential E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade activates and transfers ubiquitin to a protein substrate, determining its fate.

Deubiquitinase (DUB) Family Classification

Diagram 2: DUBs are classified into seven families based on their catalytic mechanism, with the JAMM family being the only metalloproteases.

Ubiquitination is a versatile and reversible post-translational modification (PTM) that regulates fundamental aspects of protein substrates, including stability, activity, and localization [9]. This versatility stems from remarkable structural complexity—ubiquitin can modify substrates as a single monomer or form polymers of different lengths and linkage types [9]. The ubiquitin code encompasses monoubiquitination, multiple monoubiquitination, and polyubiquitin chains connected through any of eight possible linkage sites (Lys6, Lys11, Lys27, Lys29, Lys33, Lys48, Lys63, or Met1) [9] [22]. This generates homotypic chains (single linkage type), heterotypic chains (mixed linkages), and branched chains with architectural diversity that creates a sophisticated signaling system [15] [22].

Characterizing ubiquitination presents substantial analytical hurdles primarily due to two factors: the low stoichiometry of modification under normal physiological conditions and the extreme structural complexity of ubiquitin chains [9]. These challenges compound each other; the scarce ubiquitination events must be characterized against a backdrop of overwhelming non-modified proteins, while the modifications themselves can take numerous structurally distinct forms that may confer different functional outcomes. This article examines these analytical challenges and compares methodologies for validating ubiquitin chain architecture, with particular focus on deubiquitinase (DUB)-based approaches.

The Core Analytical Challenges

Low Stoichiometry: The Needle in a Haystack Problem

In typical cellular environments, ubiquitination occurs with remarkably low stoichiometry, creating significant detection and identification barriers [9]. Several factors contribute to this challenge:

- Low Abundance: Ubiquitinated proteins represent a minute fraction of the total cellular proteome, requiring highly sensitive enrichment techniques to avoid interference from non-ubiquitinated proteins [9].

- Dynamic Regulation: Ubiquitination is a highly dynamic process balanced by the opposing activities of ubiquitinating enzymes (E1, E2, E3) and deubiquitinases (DUBs) [9] [22]. This constant cycling maintains low steady-state levels of modified substrates.

- Rapid Turnover: Many ubiquitinated proteins are targeted for proteasomal degradation, resulting in transient modification states that are difficult to capture [9].

Structural Complexity: A Multi-Dimensional Challenge

The structural diversity of ubiquitin modifications creates a second layer of analytical complexity:

- Multiple Linkage Types: Eight distinct linkage types create chains with different structures and functions [9] [15]. K48-linked chains typically target substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains regulate protein-protein interactions and signaling pathways [9].

- Chain Architecture Diversity: Beyond homotypic chains, heterotypic mixed and branched ubiquitin chains create a "mind-boggling" number of possible architectures [15]. The functions, abundance, and importance of these complex chains remain largely undefined [15].

- Gel Electrophoresis Limitations: Ubiquitinated proteins often appear as high-molecular weight 'smears' rather than discrete bands due to heterogeneous modification patterns, chain types, and chain lengths that migrate unpredictably in SDS-PAGE [15].

Table 1: Key Challenges in Ubiquitin Characterization

| Challenge | Description | Impact on Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Low Stoichiometry | Minimal abundance of ubiquitinated substrates under normal conditions | Requires extensive enrichment; low identification sensitivity |

| Multiple Modification Sites | Proteins can be ubiquitinated at one or several lysine residues simultaneously | Difficult to localize specific modification sites using traditional methods |

| Chain Linkage Diversity | Eight possible linkage types for polyubiquitin chain formation | Complicates functional interpretation; requires linkage-specific tools |

| Chain Architecture Complexity | Homotypic, heterotypic mixed, and branched chains possible | Standard techniques cannot resolve chain architecture |

| Dynamic Regulation | Continuous ubiquitination and deubiquitination | Capturing transient states difficult; represents a "snapshot" in time |

Methodological Approaches for Ubiquitin Characterization

Enrichment Strategies for Low-Stoichiometry Ubiquitination

To overcome stoichiometry challenges, researchers have developed several enrichment approaches:

Ubiquitin Tagging-Based Approaches: These methods involve expressing ubiquitin with affinity tags (e.g., His, Strep, FLAG) in cells. The tagged ubiquitin incorporates into cellular ubiquitination pathways, allowing purification of ubiquitinated proteins using appropriate resins [9]. While cost-effective and relatively easy to implement, these approaches may generate artifacts as tagged ubiquitin does not completely mimic endogenous ubiquitin, and co-purification of non-ubiquitinated proteins (e.g., histidine-rich proteins with His-tags) can reduce identification sensitivity [9].

Antibody-Based Enrichment: This approach utilizes anti-ubiquitin antibodies (e.g., P4D1, FK1/FK2) or linkage-specific antibodies to enrich endogenously ubiquitinated proteins without genetic manipulation [9]. This allows study of ubiquitination under physiological conditions in animal tissues or clinical samples. However, antibodies represent a high cost and may exhibit non-specific binding [9].

Ubiquitin-Binding Domain (UBD) Approaches: Proteins containing UBDs can recognize and enrich ubiquitinated proteins. While single UBDs typically have low affinity, tandem-repeated UBDs show improved binding capacity [9].

Mass Spectrometry Advances

Mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics has revolutionized ubiquitin research. Bottom-up approaches identify ubiquitination sites by detecting the 114.043 Da mass shift from the Gly-Gly remnant left after tryptic digestion of ubiquitinated peptides [15] [23]. Absolute quantitation techniques can assess relative abundance of various ubiquitin linkages, and enrichment techniques using antibodies against tryptic ubiquitination-site remnants enable global proteomic analysis [15]. However, MS approaches struggle to reveal details on chain architecture, which remains difficult to assess using current technologies [15].

Computational Prediction Tools

To complement experimental methods, computational approaches have been developed for predicting ubiquitination sites:

DeepUbi: A deep learning framework based on convolutional neural networks that extracts features from protein sequences and physicochemical properties. In validation studies, DeepUbi achieved an AUC of 0.9, with accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity exceeding 85% [23].

UBIPredic: This computational method predicts ubiquitinated proteins without relying on ubiquitination site prediction, using features from sequence conservation, functional domain annotation, and subcellular localization. It achieved 90.13% accuracy with Matthew's correlation coefficient of 80.34% in cross-validation [24].

Table 2: Comparison of Ubiquitin Characterization Methods

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tagged Ubiquitin | Expression of affinity-tagged Ub; purification and MS | Relatively low-cost; applicable to various cell types | May not mimic endogenous Ub; genetic manipulation required |

| Antibody Enrichment | Immunoaffinity purification with anti-Ub antibodies | Works with endogenous ubiquitination; applicable to tissues | High cost; potential non-specific binding |

| UbiCRest | Linkage-specific DUBs cleave specific ubiquitin linkages | Qualitative chain architecture data; works with endogenous proteins | Qualitative rather than quantitative |

| Mass Spectrometry | Detection of diGly remnants after tryptic digest | High-throughput site identification; quantitative potential | Limited architectural information; complex data analysis |

| Computational Prediction | Machine learning on sequence/structural features | No experimental work needed; high throughput | Predictive only; requires experimental validation |

DUB-Based Validation: The UbiCRest Approach

Principles of UbiCRest

UbiCRest (Ubiquitin Chain Restriction) represents a powerful approach for addressing both stoichiometry and complexity challenges by exploiting the intrinsic linkage specificity of deubiquitinating enzymes [15]. The method involves treating ubiquitinated substrates or purified ubiquitin chains with a panel of linkage-specific DUBs in parallel reactions, followed by gel-based analysis [15]. This qualitative method quickly assesses ubiquitin chain linkage types and architecture, working with western blotting quantities of endogenously ubiquitinated proteins [15].

The foundation of UbiCRest lies in the carefully characterized linkage preferences of various DUBs. Through biochemical profiling, researchers have identified DUBs with relative specificity for each of the eight ubiquitin linkage types [15]. For example, OTUB1 shows high specificity for Lys48-linked chains, while AMSH is specific for Lys63 linkages [15].

Experimental Protocol for UbiCRest

The UbiCRest protocol can be broken down into key stages:

Step 1: Sample Preparation

- Obtain ubiquitinated proteins of interest through immunoprecipitation or purification

- Alternatively, use purified polyubiquitin chains as substrate

- Prepare reaction buffers compatible with DUB activity

Step 2: DUB Panel Setup

- Set up parallel reactions with individual DUBs at optimized concentrations

- Include positive controls (e.g., USP21 which cleaves all linkages)

- Include negative controls (no enzyme, catalytically dead DUB mutants)

- Incubate at appropriate temperature (typically 37°C) for 1-2 hours

Step 3: Analysis and Interpretation

- Stop reactions with SDS-PAGE loading buffer

- Analyze by immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin antibodies

- Interpret linkage composition based on cleavage patterns

Table 3: Linkage-Specific DUBs for UbiCRest

| Linkage Type | Recommended DUB | Working Concentration | Notes on Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| All linkages | USP21 or USP2 | 1-5 µM (USP21) | Positive control; cleaves all linkages including proximal ubiquitin |

| Lys48 | OTUB1 | 1-20 µM | Highly Lys48-specific; not very active but highly specific |

| Lys63 | OTUD1 | 0.1-2 µM | Very active; may become non-specific at high concentrations |

| Lys11 | Cezanne | 0.1-2 µM | Very active; may cleave Lys63 and Lys48 at high concentrations |

| Lys6 | OTUD3 | 1-20 µM | Also cleaves Lys11 chains equally well |

| Lys27 | OTUD2 | 1-20 µM | Also cleaves Lys11, Lys29, Lys33; prefers longer Lys11 chains |

| Lys29/Lys33 | TRABID | 0.5-10 µM | Cleaves Lys29 and Lys33 equally well; low bacterial expression yields |

| All except Met1 | vOTU | 0.5-3 µM | Positive control that does not cleave Met1 linkages |

Applications and Interpretation

UbiCRest provides insights into three key aspects of ubiquitination:

Identifying Ubiquitination: Treatment with broad-specificity DUBs (e.g., USP21) confirms protein ubiquitination by complete collapse of high-molecular-weight smears to discrete unmodified protein bands [15].

Determining Linkage Composition: Selective cleavage by linkage-specific DUBs identifies which chain types are present. For example, OTUB1 sensitivity indicates presence of Lys48-linked chains, while AMSH sensitivity indicates Lys63 linkages [15].

Assessing Chain Architecture: Sequential digestion with DUBs of different specificities can distinguish homotypic chains from heterotypic or branched architectures. Branched chains may require multiple DUBs for complete disassembly [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful characterization of ubiquitin architecture requires carefully selected reagents. The following table details key solutions for DUB-based ubiquitin analysis:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Characterization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific DUBs | OTUB1 (K48), AMSH (K63), Cezanne (K11), OTUD2 (K27) | Cleave specific ubiquitin linkages to determine chain composition in UbiCRest |

| Broad-Specificity DUBs | USP21, USP2, vOTU (all except Met1) | Positive controls; confirm ubiquitination and cleave most linkage types |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | K48R, K63R, K48-only, K63-only | Define linkage requirements in cellular assays; study chain assembly |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Anti-K48, Anti-K63, Anti-K11, Anti-Met1 | Enrich and detect specific chain types by immunoblotting or immunofluorescence |

| Activity Probes | Ubiquitin-based active site probes | Profile DUB activity and specificity in complex mixtures |

| Ubiquitin Variants (UbVs) | UbVSP.1, UbVSP.3 (STAMBP inhibitors) | Potent and selective inhibitors for JAMM family DUBs [25] |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | Heavy-labeled ubiquitin, Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Quantitative ubiquitin proteomics; affinity enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins |

The analytical challenges in ubiquitin characterization—primarily low stoichiometry and structural complexity—require sophisticated methodological approaches. While traditional techniques like immunoblotting and mass spectrometry provide valuable insights, DUB-based methods like UbiCRest offer unique advantages for deciphering ubiquitin chain architecture. The specificity of deubiquitinating enzymes for particular linkage types enables researchers to decode the complex ubiquitin signals that regulate virtually all cellular processes.

As our understanding of DUB specificity continues to expand and new tools like engineered ubiquitin variants emerge, researchers are better equipped to address the fundamental challenges in ubiquitin characterization. These advances are particularly relevant for drug development professionals seeking to target ubiquitin pathways in diseases such as cancer and neurodegenerative disorders, where ubiquitin signaling is frequently dysregulated. The continued refinement of these methodologies will undoubtedly yield deeper insights into the complex world of ubiquitin signaling and its therapeutic implications.

A Practical Guide to UbiCRest: Implementing DUBs for Linkage and Architecture Analysis

Ubiquitin Chain Restriction (UbiCRest) represents a seminal methodological advancement in the field of ubiquitin biology, providing researchers with a powerful tool to decipher the complex language of polyubiquitin signaling. This technique exploits the intrinsic linkage-specific cleavage preferences of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) to characterize ubiquitin chain architecture on modified proteins. As a qualitative assay that yields insights within hours, UbiCRest has become an essential approach for validating ubiquitin chain architecture, complementing more complex mass spectrometry-based methods. This guide examines the core principles of UbiCRest, its experimental implementation, and its position within the broader toolkit for ubiquitin chain analysis, providing researchers with a comprehensive resource for studying the ubiquitin code.

Protein ubiquitination is a versatile post-translational modification that regulates virtually all cellular processes, with its functional diversity originating from the ability to form polyubiquitin chains through eight distinct linkage types [26]. These include seven lysine positions (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and the N-terminal methionine (M1), giving rise to homotypic chains (single linkage type), mixed chains (multiple linkage types in sequence), and branched chains (multiple linkages on a single ubiquitin molecule) [15]. The combinatorial complexity of these arrangements creates a sophisticated ubiquitin code that controls diverse cellular outcomes, from proteasomal degradation to DNA repair and immune signaling [27].

Traditional methods for analyzing ubiquitin chains, including linkage-specific antibodies and ubiquitin mutants, have provided valuable insights but face limitations in resolving chain architecture [26]. Mass spectrometry approaches, while powerful for identifying linkage types and ubiquitination sites, often struggle to reveal details about chain architecture and require specialized equipment and expertise [15] [26]. UbiCRest emerged to address these limitations by providing a accessible, gel-based method that uses well-characterized DUBs as "restriction enzymes" for ubiquitin chains [28].

The fundamental premise of UbiCRest is that many DUBs exhibit pronounced specificity for particular ubiquitin linkage types [29]. This specificity arises from distinct structural mechanisms, including additional ubiquitin-binding domains and specific recognition surfaces that enable DUBs to discriminate between different chain architectures [29]. By employing a panel of these linkage-specific DUBs, researchers can deduce the architecture of ubiquitin chains present on a substrate through the characteristic cleavage patterns observed on SDS-PAGE gels [15].

Fundamental Principles of the UbiCRest Methodology

Conceptual Framework and Underlying Assumptions

UbiCRest operates on the principle that DUBs with defined linkage specificities can serve as analytical tools to decompose complex ubiquitin signals into interpretable patterns [15] [26]. The method makes several key assumptions that have been validated through extensive biochemical characterization:

- Specificity Conservation: DUBs maintain their linkage preferences when acting on polyubiquitinated substrates in vitro as they do on isolated chains

- Architecture Retention: The cleavage patterns observed reflect the native architecture of ubiquitin chains rather than artifacts of the experimental conditions

- Predictable Cleavage: Complete digestion with a specific DUB indicates the presence of its preferred linkage type in the substrate

The workflow follows a logical progression from sample preparation through pattern interpretation, with controls to validate each step [26]. A critical conceptual aspect is the distinction between different chain architectures: homotypic chains will be completely digested by DUBs specific to their linkage type, while heterotypic chains will require multiple DUBs for complete disassembly, revealing a hierarchical architecture [15].

Core Workflow and Mechanism

The UbiCRest procedure can be divided into four key stages, as illustrated below:

The process begins with a polyubiquitinated substrate or purified ubiquitin chains, which are transferred into DUB-compatible buffer and divided into equal aliquots [26]. Each aliquot is then treated with a different DUB from a carefully curated panel, selected to cover the spectrum of possible linkage types [15]. Positive controls using broad-specificity DUBs like USP21 or USP2 confirm that the high-molecular-weight smears represent genuine ubiquitin modifications, while negative controls without DUB treatment establish the baseline migration pattern [26].

Following incubation, the digestion products are separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized through immunoblotting [28]. The resulting band patterns provide a fingerprint that reveals both the linkage types present and their arrangement within the ubiquitin chain [15]. Interpretation relies on comparing the digestion patterns across the DUB panel – complete collapse to monoubiquitin or specific intermediate bands indicates the presence of that DUB's preferred linkage type, while persistence of high-molecular-weight material suggests chains contain linkages resistant to that particular DUB [26].

The DUB Toolkit: Enzymatic Specificities and Experimental Considerations

Comprehensive DUB Specificity Reference Table

Successful UbiCRest analysis depends on using a well-characterized panel of DUBs with complementary specificities. The table below summarizes key DUBs used in UbiCRest, their linkage preferences, and optimal working concentrations based on established protocols [15]:

| Linkage Type | Recommended DUB | Typical Working Concentration | Specificity Notes | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Linkages | USP21 / USP2 | 1-5 µM (USP21) | Positive control; cleaves all linkages including proximal ubiquitin | [15] |

| All except M1 | vOTU (CCHFV) | 0.5-3 µM | Positive control; does not cleave Met1 linkages | [15] |

| K6 | OTUD3 | 1-20 µM | Also cleaves K11 chains equally well; targets other linkages at high concentrations | [15] |

| K11 | Cezanne | 0.1-2 µM | Very active; non-specific at very high concentrations (K63 > K48 > others) | [15] |

| K27 | OTUD2 | 1-20 µM | Also cleaves K11, K29, K33; prefers longer K11 chains | [15] |

| K29/K33 | TRABID | 0.5-10 µM | Cleaves K29 and K33 equally well, and K63 with lower activity | [15] |

| K48 | OTUB1 | 1-20 µM | Highly K48-specific; not very active but can be used at high concentrations | [15] |

| K63 | OTUD1 / AMSH | 0.1-2 µM (OTUD1) | Very active; non-specific at high concentrations | [15] [26] |

Concentration Optimization and Specificity Validation

A critical aspect of UbiCRest is optimizing DUB concentrations to balance specificity and activity [26]. Most DUBs exhibit their highest linkage specificity at lower concentrations, while becoming progressively promiscuous at higher concentrations [15]. The protocol typically recommends performing assays at both low and high DUB concentrations – cleavage activity at low concentrations strongly indicates the presence of that DUB's preferred linkage type, while cleavage at higher concentrations may reveal secondary specificities or complete digestion of preferred linkages [26].

The incubation conditions (typically 15-30 minutes at 37°C) represent a balance between complete digestion of preferred linkages and minimizing non-specific cleavage [26]. Researchers should empirically determine optimal conditions for their specific experimental system, particularly when working with novel DUBs or substrates. Specificity profiles for DUBs should be established using homotypic ubiquitin chains of known linkage before applying them to complex biological samples [15].

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Ubiquitin Characterization Methods

Methodological Comparison Table

UbiCRest occupies a distinct niche in the ubiquitin researcher's toolkit, complementing rather than replacing existing methodologies. The table below compares UbiCRest with other prominent approaches for ubiquitin chain analysis:

| Method | Key Principle | Linkage Information | Architecture Resolution | Throughput | Equipment Needs | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UbiCRest | Linkage-specific DUB cleavage + SDS-PAGE | Qualitative identification of major linkages | Can distinguish homotypic vs. heterotypic chains | Medium | Standard molecular biology lab | Qualitative; requires antibody detection |

| Mass Spectrometry | LC-MS/MS of tryptic peptides | Quantitative identification of all linkages | Limited for complex architectures | Low | Specialized MS equipment | Difficult for hydrophobic linkages; complex data analysis |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Immunoblot with linkage-selective antibodies | Semi-quantitative for specific linkages | No architecture information | High | Standard molecular biology lab | Limited antibody availability; cross-reactivity concerns |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | In vivo expression of linkage-deficient Ub mutants | Functional implication of specific linkages | No direct architecture information | Low | Cell culture facility | Compensatory mechanisms; pleiotropic effects |

| UbiReal | Fluorescence polarization of labeled ubiquitin | Real-time kinetics of chain formation/disassembly | Limited architectural details | High | Plate reader capable of FP measurements | Requires fluorescent labeling; artificial system [30] |

Strategic Method Selection and Integration

Each method offers distinct advantages that make it suitable for particular research questions. UbiCRest excels in providing rapid, accessible analysis of ubiquitin chain architecture without requiring specialized equipment [28] [26]. Its particular strengths include:

- Architectural Insights: Ability to distinguish between homotypic, mixed, and branched chains through sequential or parallel digestion approaches [15]

- Sensitivity: Capacity to work with western blotting quantities of endogenously ubiquitinated proteins [26]

- Dynamic Range: Capacity to analyze heterogeneous ubiquitin "smears" that challenge MS-based methods [15]

UbiCRest integrates particularly well with mass spectrometry approaches – initial UbiCRest analysis can guide focused MS efforts, while MS can validate and extend UbiCRest findings [15]. Similarly, linkage-specific antibodies can confirm UbiCRest results, creating a orthogonal validation framework [26]. The recent development of highly specific DUB inhibitors further enhances UbiCRest's utility by enabling validation of findings in cellular contexts [27].

Advanced Applications in Decoding Complex Ubiquitin Signals

Architectural Analysis of Heterotypic Ubiquitin Chains

UbiCRest provides unique capabilities for deciphering the architecture of heterotypic ubiquitin chains, which incorporate multiple linkage types within a single polymer [15]. The sequential application of DUBs with different specificities can reveal whether chains are mixed (alternating linkage types) or branched (multiple linkages on single ubiquitin molecules) [26]. For example, treatment with a K48-specific DUB followed by a K63-specific DUB may completely disassemble a chain that resists either DUB alone, indicating a mixed K48/K63 architecture [15].

The interpretation of these complex digestion patterns requires careful controls and sometimes iterative experimental approaches. Including time-course experiments can help distinguish primary from secondary cleavage events, while titration of DUB concentrations helps identify the most abundant linkage types [26]. These approaches have revealed unexpected complexity in ubiquitin signaling, including the existence of branched chains that may function as specialized signals or as protective structures against disassembly [15].

Integration with Functional Genomics and Drug Discovery

UbiCRest has found important applications in functional genomics and drug discovery, particularly as CRISPR/Cas9-based screening approaches have identified novel regulators of ubiquitin pathways [31] [32] [33]. For example, when genetic screens identify E3 ligases or DUBs that regulate specific substrates, UbiCRest can characterize how their manipulation alters the ubiquitin code on those substrates [32].

In drug discovery, UbiCRest provides a valuable medium-throughput method for characterizing the effects of DUB inhibitors on cellular ubiquitin landscapes [33]. The method can determine whether specific inhibitors effectively block cleavage of their intended linkage types in cellular contexts, and identify potential off-target effects on other ubiquitin chain types [27] [33]. This application is particularly relevant as DUB inhibitors advance in clinical development, with compounds targeting USP1 and USP30 currently in clinical trials [33].

Essential Research Reagents and Experimental Solutions

Research Reagent Toolkit Table

Successful implementation of UbiCRest requires access to well-characterized reagents, particularly the linkage-specific DUBs that form the core of the assay. The following table outlines essential research reagents for establishing UbiCRest in a research setting:

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in UbiCRest | Commercial Sources | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broad-Spectrum DUBs | USP21, USP2 | Positive controls; confirm ubiquitinated nature of samples | Boston Biochem, R&D Systems | Verify activity on all linkage types before use |

| Linkage-Specific DUBs | OTUB1 (K48), Cezanne (K11), OTUD1 (K63) | Identify specific linkage types present in samples | Boston Biochem, proprietary expression | Validate specificity under working conditions |

| Ubiquitin Chains | Homotypic chains of all 8 linkages | Specificity validation for DUB panel; positive controls | Boston Biochem, UbiQ Bio | Use as standards to establish DUB specificities |

| Detection Antibodies | Anti-ubiquitin, anti-target protein | Visualize digestion patterns after SDS-PAGE | Cell Signaling, Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Pan-ubiquitin antibodies preferred over linkage-specific for overall pattern |

| Expression Systems | E. coli, insect cell systems | Produce recombinant DUBs not commercially available | ATCC, commercial vectors | Many OTU family DUBs require eukaryotic expression for proper folding |

Implementation Practicalities

For laboratories establishing UbiCRest, several practical considerations determine success. First, DUBs can be obtained commercially or expressed recombinantly, with protocols available for purifying many OTU family DUBs from bacterial expression systems [15]. Second, the choice of detection method depends on the experimental system – while western blotting with pan-ubiquitin antibodies is most common, substrate-specific antibodies can provide more precise information when available [26].

The assay requires careful optimization of buffer conditions, particularly pH and reducing agents, which can affect different DUB families variably [15]. Including controls for non-specific proteolysis is essential, particularly when working with novel DUBs or substrates. Finally, interpretation benefits from comparison with known standards – including homotypic ubiquitin chains of known linkage in parallel experiments provides essential reference points for interpreting digestion patterns [15] [26].

UbiCRest has established itself as an indispensable method in the ubiquitin researcher's toolkit, providing unique insights into ubiquitin chain architecture that complement other analytical approaches. Its strength lies in exploiting the naturally evolved specificities of DUBs to decode complex ubiquitin signals, enabling researchers to move beyond simple linkage identification to understanding the topological arrangement of ubiquitin chains. As research continues to reveal the functional significance of heterotypic ubiquitin chains in cellular regulation, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic responses, UbiCRest will remain a vital method for connecting ubiquitin chain architecture to biological function. The ongoing development of additional linkage-specific DUBs and inhibitors will further expand its capabilities, solidifying its role in the evolving landscape of ubiquitin research methodologies.

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) have emerged as critical regulators of cellular function and promising therapeutic targets. A key to unlocking their potential lies in the specific tools researchers use to study them. This guide provides a comparative analysis of commercially available and purified DUBs, focusing on their application in validating ubiquitin chain architecture, to help you build a robust experimental toolkit.

The Ubiquitin Code and DUB Specificity

Protein ubiquitination is a versatile post-translational modification where ubiquitin molecules can form chains through eight distinct linkage types (seven lysine residues or the N-terminal methionine). This "ubiquitin code" regulates diverse cellular processes, from protein degradation to DNA repair and cell signaling [15] [34]. The reversible process of deubiquitination is carried out by approximately 100 human DUBs, which are categorized into six families: ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases (UCHs), ovarian tumor proteases (OTUs), Machado–Josephin domain-containing proteases (MJDs), motif interacting with ubiquitin-containing novel DUB family (MINDYs), and JAMM/MPN/MOV34 metalloproteases [35] [33].

The combinatorial complexity of homotypic (single linkage type), mixed (multiple types, one per ubiquitin), and branched ubiquitin chains (multiple linkages on a single ubiquitin) poses a significant analytical challenge [15] [34]. Linkage-specific DUBs are indispensable tools for decoding this complexity, as their intrinsic preference for cleaving particular ubiquitin linkages allows researchers to dissect chain composition and architecture.

Commercially Available DUBs: A Linkage-Specific Toolkit

The UbiCRest method exemplifies the use of a DUB panel to qualitatively analyze ubiquitin chains [15]. The table below summarizes key linkage-specific DUBs, their common sources, and their roles in a typical toolkit.

| Ubiquitin Linkage Type | Recommended DUB | Useful Final Concentration Range (1x) | Key Specificity Notes and Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| All eight linkages (positive control) | USP21 / USP2 [15] | 1-5 µM (USP21) [15] | Cleaves all linkage types, including the proximal ubiquitin attached to the substrate [15]. |

| All linkages except Met1 (positive control) | CCHFV viral OTU (vOTU) [15] | 0.5-3 µM [15] | Useful control as it does not cleave linear/Met1 linkages [15]. |

| Lys48 (K48) | OTUB1 [15] | 1-20 µM [15] | Highly specific for K48 linkages. Not very active, so can be used at higher concentrations [15]. |

| Lys63 (K63) | OTUD1 / AMSH [15] | 0.1-2 µM (OTUD1) [15] | Both are very active; OTUD1 can become non-specific at high concentrations [15]. |

| Lys11 (K11) | Cezanne (OTUD7B) [15] | 0.1-2 µM [15] | Very active enzyme; can become non-specific at very high concentrations (Lys63 > Lys48 > others) [15]. |

| Lys6 (K6) | OTUD3 [15] | 1-20 µM [15] | Also cleaves Lys11 chains equally well. Can target other isopeptide linkages at high concentrations [15]. |

| Lys27 (K27) | OTUD2 [15] | 1-20 µM [15] | Also cleaves Lys11, Lys29, and Lys33. Prefers longer Lys11 chains and can be non-specific at high concentrations [15]. |

| Lys29 (K29) & Lys33 (K33) | TRABID (ZRANB1) [15] | 0.5-10 µM [15] | Cleaves Lys29 and Lys33 linkages equally well, with lower activity on Lys63. May have low yields from bacterial expression [15]. |

Key Commercial Considerations:

- Source and Purity: Many DUBs for research are produced via bacterial expression (e.g., E. coli) and require purification via affinity chromatography. Mission Therapeutics, for example, emphasizes purifying full-length DUBs from mammalian cells to ensure proper folding and the presence of co-factors [36].

- Specificity vs. Selectivity: While the OTU family DUBs often display strong linkage preference, USP family DUBs are generally more substrate-specific than linkage-specific [12]. This distinction is crucial for experimental design and data interpretation.

- Concentration is Critical: The linkage specificity of a DUB can be concentration-dependent. Several DUBs, like Cezanne and OTUD1, can lose their specificity and cleave non-cognate linkages at high concentrations. Therefore, using the recommended working concentrations is essential for clean data interpretation [15].

Experimental Protocol: UbiCRest for Ubiquitin Chain Analysis

The UbiCRest assay is a primary application for a linkage-specific DUB toolkit, allowing researchers to determine the types and architecture of ubiquitin chains on a protein of interest [15].

Workflow of UbiCRest Assay

Detailed Step-by-Step Methodology

Sample Preparation: Isolate the ubiquitinated protein of interest. This can be an endogenously ubiquitinated protein purified from cells or an in vitro ubiquitinated substrate. The sample is typically divided into equal aliquots.

DUB Panel Reaction Setup: Set up parallel reactions, each containing:

- A defined amount of your ubiquitinated substrate.

- A suitable reaction buffer.

- One linkage-specific DUB from your toolkit (see table above for concentrations).

- Include control reactions: one with no DUB and one with a pan-specific DUB like USP21.

Incubation and Reaction Termination: Incubate reactions at a defined temperature (e.g., 37°C) for a specific time (e.g., 1-2 hours). The reaction is stopped by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer.

Gel-Based Analysis: Analyze the reactions by denaturing SDS-PAGE followed by western blotting. Use antibodies specific to your protein or to ubiquitin.

Data Interpretation:

- Complete Cleavage: If a substrate's ubiquitination is completely removed by a specific DUB (e.g., OTUB1), it suggests the chains are predominantly of that linkage type (e.g., K48).

- Partial Cleavage / Band Shift: A change in the ubiquitin ladder pattern, but not a complete collapse, indicates the presence of a mixed or branched chain architecture where the DUB is cleaving one type of linkage within a more complex structure.

- No Effect: Indicates the substrate's ubiquitination does not contain the linkage type that the DUB is specific for.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Building a successful DUB research program requires more than just the enzymes. The table below lists other critical reagents and their functions.

| Research Reagent | Function and Importance in DUB Research |

|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific DUBs | Core tools for dissecting ubiquitin chain type and architecture in assays like UbiCRest [15]. |

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Antibodies | Immunological reagents (e.g., for K48, K63, Met1) used in western blotting to confirm chain types identified via DUB panels [15]. |

| Activity-Based DUB Probes | Chemical tools that covalently bind the active site of DUBs, used to profile DUB activity and selectivity in cell lysates or in vivo [33]. |

| Selective DUB Inhibitors | Small molecules (e.g., KSQ's USP1 inhibitor, Mission's MTX325 for USP30) used for functional validation and therapeutic exploration [33] [36]. |