Decoding the Ubiquitin Code: From Molecular Complexity to Therapeutic Innovation

This article comprehensively explores the sophisticated architecture and functional diversity of the ubiquitin code, a critical post-translational regulatory system.

Decoding the Ubiquitin Code: From Molecular Complexity to Therapeutic Innovation

Abstract

This article comprehensively explores the sophisticated architecture and functional diversity of the ubiquitin code, a critical post-translational regulatory system. We examine the foundational mechanisms of ubiquitin signaling, including novel chain topologies, unconventional modifications, and their roles in diseases like cancer. The review details cutting-edge methodological approaches for investigating and targeting this system, from fragment-based drug discovery to PROTAC technology. We analyze current challenges in therapeutic development, including specificity and toxicity issues, and present validation strategies through comparative biology and clinical insights. This synthesis provides researchers and drug development professionals with a roadmap for translating ubiquitin code complexity into innovative precision medicines.

The Expanding Universe of Ubiquitin Signaling: Mechanisms and Biological Significance

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a crucial post-translational regulatory mechanism that governs virtually all aspects of eukaryotic cell biology through targeted protein modification and degradation [1] [2]. This sophisticated system employs a three-enzyme cascade (E1-E2-E3) to covalently attach ubiquitin, a highly conserved 76-amino acid protein, to substrate proteins, thereby generating a complex "ubiquitin code" that dictates diverse functional outcomes [2]. The complexity of this code arises from the ability of ubiquitin to form structurally distinct polyubiquitin chains through its seven internal lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and N-terminal methionine (M1), with each linkage type potentially encoding different cellular signals [2] [3]. Beyond its well-established role in targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation, the ubiquitin system regulates a vast array of cellular processes including DNA repair, cell signaling, membrane trafficking, immune response, and apoptosis [1] [2]. The functional diversity encoded within the ubiquitin system, coupled with its implications in human diseases from cancer to neurodegenerative disorders, establishes it as a critical focus for fundamental research and therapeutic development [2] [4] [5].

The Core Enzymatic Cascade: E1, E2, and E3 Mechanisms

The ubiquitination process proceeds through a tightly coordinated, ATP-dependent cascade involving three key enzyme classes that sequentially activate, conjugate, and ligate ubiquitin to specific substrate proteins [1] [6] [7].

E1: Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme

The ubiquitination cascade initiates with the ATP-dependent activation of ubiquitin by the E1 enzyme [1] [6]. This process involves E1 first catalyzing the adenylation of ubiquitin's C-terminal glycine residue, followed by the formation of a high-energy thioester bond between the C-terminal carboxyl group of ubiquitin and a specific cysteine residue within the E1 active site [6] [7]. This initial activation step is highly conserved across eukaryotes and represents a crucial commitment point in the ubiquitination pathway, with E1 inhibition resulting in the rapid shutdown of the entire UPS [7]. The human genome encodes only two E1 enzymes, making this the most limited component of the system [3].

E2: Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme

Activated ubiquitin is subsequently transferred from E1 to the active site cysteine of a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) through a transesterification reaction, maintaining the thioester linkage [1] [6]. The E2 enzyme family exhibits greater diversity than E1, with approximately 40 distinct E2s encoded in the human genome [3] [4]. While traditionally viewed primarily as ubiquitin carriers, E2 enzymes contribute significantly to substrate specificity and ubiquitin chain topology through their selective interactions with particular E3 ligases and inherent preferences for specific ubiquitin linkage types [4] [7]. Some E2s can directly conjugate ubiquitin to substrates without E3 involvement, though this is less common [4].

E3: Ubiquitin Ligase - The Specificity Determinant

The final and most specific step involves an E3 ubiquitin ligase facilitating the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a lysine residue on the target protein [1] [6]. E3s achieve this either by directly catalyzing ubiquitin ligation or by acting as scaffolds that bring the E2~ubiquitin complex into close proximity with the substrate [7]. The human genome encodes approximately 600 E3 ligases, which are primarily categorized into two major families based on their structural features and catalytic mechanisms [1] [6] [4]:

- RING (Really Interesting New Gene) E3 Ligases: Typically function as scaffolds that simultaneously bind E2~ubiquitin and substrate proteins, facilitating direct ubiquitin transfer without forming a covalent intermediate [1] [4]. RING E3s can be single-subunit proteins (e.g., Mdm2) or multi-subunit complexes (e.g., Cullin-RING ligases) [1].

- HECT (Homologous to E6-AP Carboxyl Terminus) E3 Ligases: Form a catalytic thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate, employing a conserved cysteine residue in their HECT domain [1] [4].

A third category, RING-between-RING (RBR) ligases, employs a hybrid mechanism combining aspects of both RING and HECT types [7]. The substantial diversity of E3 ligases enables the recognition of thousands of specific substrates, providing the UPS with its remarkable specificity [4].

Table 1: Core Enzymes of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

| Enzyme Class | Human Genome Count | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Activating) | 2 | ATP-dependent ubiquitin activation | Forms ubiquitin-AMP intermediate and E1-thioester; Rate-limiting step |

| E2 (Conjugating) | ~40 | Ubiquitin carrier | Determines ubiquitin chain topology; Selective E3 pairing |

| E3 (Ligase) | ~600 | Substrate recognition | Two major families (RING & HECT); Primary specificity determinant |

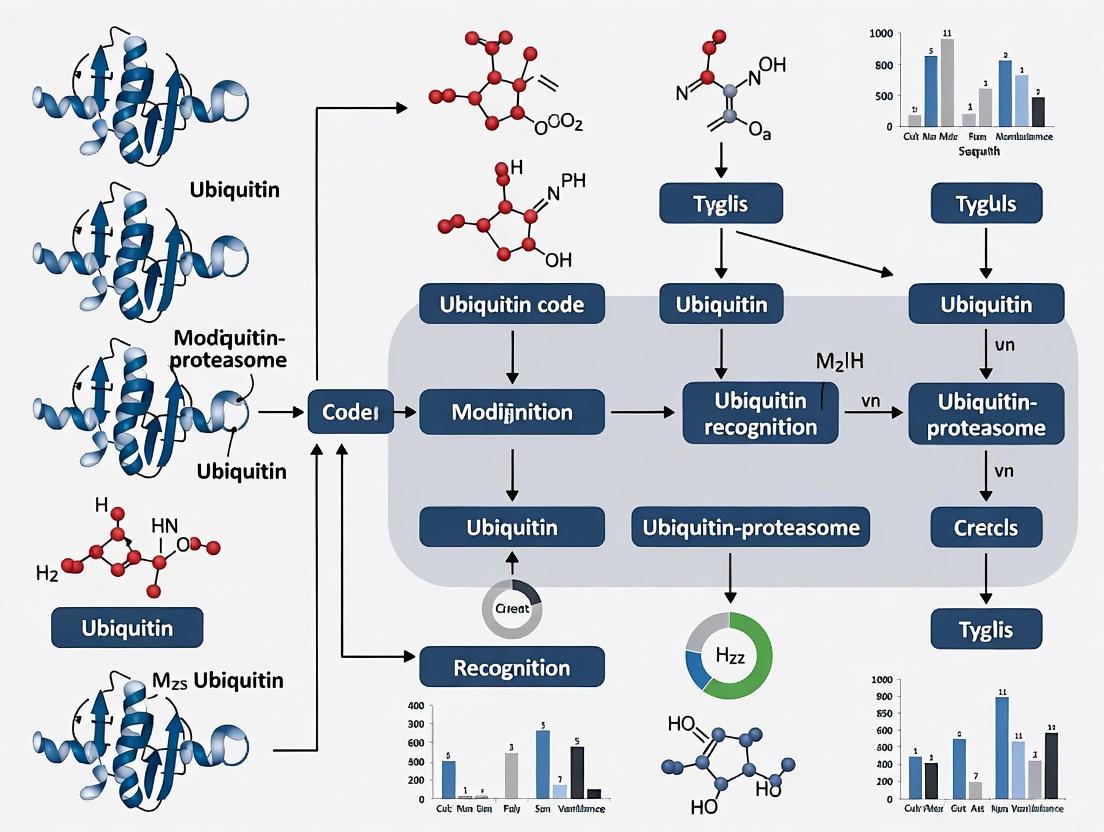

Diagram 1: Ubiquitin Enzymatic Cascade

The Ubiquitin Code: Complexity and Functional Diversity

The concept of a "ubiquitin code" encompasses the remarkable structural and functional diversity generated through different ubiquitin modifications, which are decoded by specific effector proteins to produce distinct cellular outcomes [2] [3]. This coding capacity extends far beyond simple degradation signals to include sophisticated regulatory information.

Types of Ubiquitin Modifications

Ubiquitin modifications exist in several topologically distinct forms, each with characteristic functional implications:

- Monoubiquitination: Attachment of a single ubiquitin molecule, typically involved in membrane trafficking, histone regulation, and DNA repair [1] [5]. For example, monoubiquitylation of both histone and non-histone proteins critically regulates radiation adaptation and genome stability [5].

- Multi-monoubiquitination: Multiple single ubiquitin molecules attached to different lysines on the same substrate, often regulating endocytosis and protein localization [3].

- Homotypic Polyubiquitination: Chains composed of a single linkage type, with K48 and K63 being the best characterized [2] [3]. K48-linked chains primarily target proteins for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains typically function in DNA repair, signal transduction, and endocytosis without promoting degradation [1] [5].

- Heterotypic and Branched Chains: Mixed linkage chains that may incorporate multiple linkage types within a single chain, substantially expanding the coding potential [2].

Linkage-Specific Functional Consequences

Different ubiquitin linkage types create structurally distinct surfaces that are recognized by specific ubiquitin-binding domains in effector proteins, enabling the translation of ubiquitin modifications into appropriate cellular responses [3] [5]. The functional specialization of major linkage types includes:

- K48-linked chains: The principal signal for proteasomal degradation; often but not exclusively associated with protein destruction [1] [5].

- K63-linked chains: Key regulators of inflammatory signaling, DNA damage response, and protein-protein interactions; promote complex assembly rather than degradation [1] [5].

- K11-linked chains: Implicated in cell cycle regulation and ER-associated degradation [2].

- K29/K33-linked chains: Involved in lysosomal degradation and protein kinase regulation [3].

- Linear/M1-linked chains: Important in NF-κB signaling and inflammatory responses [2].

Table 2: Major Polyubiquitin Linkage Types and Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Functions | Structural Features | Cellular Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48 | Proteasomal targeting | Compact structure | Protein degradation, cell cycle regulation |

| K63 | Signal transduction | Extended conformation | DNA repair, NF-κB signaling, endocytosis |

| K11 | Proteasomal targeting | Compact structure | ER-associated degradation, cell cycle |

| K29/K33 | Non-proteolytic signaling | Variable structures | Kinase regulation, lysosomal degradation |

| M1/Linear | Inflammatory signaling | Extended structure | NF-κB activation, immune responses |

Diagram 2: Ubiquitin Code Diversity

Experimental Methodologies for UPS Research

Advancing our understanding of the ubiquitin code requires sophisticated methodological approaches capable of deciphering the complexity of ubiquitin signaling networks. Several key technologies have emerged as particularly valuable for UPS research.

Global Profiling and Screening Approaches

High-throughput functional genomics screens have proven instrumental in identifying novel components of ubiquitin pathways and their physiological roles. For example, shRNA- or CRISPR-Cas9-mediated screening enables systematic identification of E3 ligase substrates and components essential for specific ubiquitin-dependent processes [1]. The recently developed Global Protein Stability (GPS) profiling represents a particularly powerful genome-wide screening strategy for identifying previously unknown substrates of specific E3 ligases [1]. This system utilizes reporter proteins fused with hundreds of potential substrates independently; by inhibiting ligase activity and monitoring accumulated reporters, researchers can comprehensively map E3-substrate regulatory networks [1].

Mass spectrometry-based ubiquitin proteomics has revolutionized our ability to characterize ubiquitin modifications on a global scale. Modern workflows incorporate di-glycine remnant immunoaffinity enrichment following tryptic digestion, which specifically captures peptides containing the characteristic lysine-glycine-glycine signature left after ubiquitin modification [3]. This approach enables quantitative mapping of ubiquitination sites and linkage types under different physiological conditions, as demonstrated in studies of KCNQ1 ion channel regulation where K48 linkages dominated (72%) followed by K63 (24%) [3].

Linkage-Selective Mechanistic Tools

The development of linkage-selective engineered deubiquitinases (enDUBs) represents a breakthrough in functional ubiquitin research [3]. These tools are created by fusing catalytic domains of deubiquitinases with specific polyubiquitin chain preferences to target-specific nanobodies (e.g., anti-GFP nanobody). The enDUB toolkit includes:

- OTUD1-based enDUB: Selective for K63-linked chains

- OTUD4-based enDUB: Selective for K48-linked chains

- Cezanne-based enDUB: Selective for K11-linked chains

- TRABID-based enDUB: Selective for K29/K33-linked chains

- USP21-based enDUB: Non-specific deubiquitinase control

Application of these enDUBs to KCNQ1-YFP revealed distinct functional roles for different polyubiquitin chains in regulating channel trafficking, with K11 and K63 linkages enhancing endocytosis while K48 was necessary for forward trafficking [3]. This technology enables precise dissection of linkage-specific functions on specific target proteins in live cells.

Structural Biology Approaches

Cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has provided unprecedented insights into the structural mechanisms of ubiquitin cascade components. Recent structural work on the cereblon (CRBN) E3 ligase complex with the molecular glue degrader MRT-31619 revealed a unique mechanism whereby two molecular glues assemble into a helix-like structure that drives CRBN homodimerization by mimicking a neosubstrate G-loop degron [8]. Such structural insights are invaluable for understanding the molecular basis of ubiquitin transfer and for rational drug design targeting the UPS.

Table 3: Key Experimental Approaches in UPS Research

| Methodology | Key Applications | Technical Resolution | Key Insights Generated |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPS Profiling | E3-substrate network mapping | Genome-wide | Comprehensive identification of E3 ligase substrates |

| enDUB Technology | Linkage-specific function analysis | Single protein level | Chain-type specific regulation of target proteins |

| Cryo-EM | Structural mechanisms | Near-atomic | Molecular basis of ubiquitin transfer and regulation |

| DiGly Proteomics | Ubiquitin site mapping | Proteome-wide | Global quantification of ubiquitination changes |

Diagram 3: Experimental Workflow for UPS Research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for UPS Investigations

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Research Application | Key Functions & Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, MG132 | Pathway inhibition studies | Reversible/irreversible proteasome inhibition; Stabilizes ubiquitinated proteins |

| E1 Inhibitors | MLN4924 (NEDD8 E1) | Cascade initiation blockade | NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor; Blocks cullin-RING ligase activity |

| Molecular Glue Degraders | Lenalidomide, MRT-31619 | Targeted protein degradation | Induces neo-substrate recognition by E3 ligases; Chemical knockout tools |

| Linkage-Specific enDUBs | OTUD1, OTUD4, Cezanne fusions | Chain-specific function analysis | Selective hydrolysis of specific polyubiquitin linkages on target proteins |

| Ubiquitin Binding Reagents | Linkage-specific UBDs, TUBEs | Ubiquitin chain detection and purification | Affinity reagents for specific chain types; protect chains from DUBs |

| CRISPR Screening Libraries | E3/UPS-focused libraries | Functional genomics | Genome-wide identification of UPS components and substrates |

| N-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybenzamide | N-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybenzamide, CAS:710311-79-8, MF:C9H11NO4, MW:197.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| L-Seryl-L-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine | L-Seryl-L-leucyl-L-alanyl-L-alanine Peptide | Bench Chemicals |

The ubiquitin-proteasome system represents one of the most sophisticated post-translational regulatory mechanisms in eukaryotic cells, with its complexity arising from the intricate interplay between the core E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade and the diverse ubiquitin code it writes, edits, and interprets. Future research directions will likely focus on deciphering the contextual regulation of ubiquitin signaling in different cellular compartments, under various physiological conditions, and in disease states. The development of increasingly precise chemical and genetic tools, such as the linkage-selective enDUBs and molecular glue degraders described herein, will continue to accelerate our understanding of this complex system [8] [3]. Furthermore, the integration of ubiquitin proteomics with other functional genomic approaches will enable comprehensive mapping of the ubiquitin network and its perturbations in human diseases. As our knowledge expands, so too will opportunities for therapeutic intervention targeting specific nodes within the UPS, offering promising avenues for treating cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and other human diseases linked to ubiquitin system dysregulation [2] [4] [5]. The continued elucidation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system promises not only to advance our fundamental understanding of cell biology but also to unlock novel therapeutic strategies for a wide range of human disorders.

Ubiquitination represents a crucial post-translational modification that regulates diverse cellular functions, ranging from protein degradation to DNA repair and immune signaling. The complexity of ubiquitin signaling, often referred to as the "ubiquitin code," stems from the ability of this 76-amino acid protein to form polymers of remarkable structural diversity [9]. Since Goldstein's initial discovery of ubiquitin 50 years ago, our understanding of its biological roles has evolved tremendously from its narrow characterization as a degradation signal to its current status as a versatile regulator of cellular processes [10] [9]. The ubiquitin code's complexity arises from variations in chain length, linkage types between ubiquitin monomers, and overall architecture—including homotypic, mixed, and branched chains [9]. This technical guide comprehensively summarizes the current understanding of ubiquitin chain topologies, their biological functions, recognition mechanisms, and the experimental methodologies driving discoveries in this rapidly advancing field, framed within the broader context of ubiquitin code complexity and functional diversity research.

Historical Perspective and Key Discoveries

The understanding of ubiquitin signaling has undergone significant evolution since its initial discovery. Goldstein's 1975 isolation of what would later be named ubiquitin revealed a protein ubiquitous across eukaryotic cells [10] [9]. The critical breakthrough came when Goldknopf and Busch discovered that the chromatin-associated protein A24 contained ubiquitinated histone H2A, marking the first evidence of ubiquitin as a post-translational modification [10]. Concurrently, Hershko and Ciechanover's work on ATP-dependent protein degradation identified APF-1 (later recognized as ubiquitin by Wilkinson et al.) as the protein conjugated to substrates marked for proteasomal degradation [10]. These parallel discoveries connected two seemingly divergent functions of ubiquitin: chromatin compaction and protein degradation.

The next major milestone came with the elucidation of the stepwise enzymatic mechanism involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes by Hershko and Ciechanover in 1982 [10]. However, the first glimpse into the complexity of the ubiquitin code emerged when Chau et al. identified K48-linked polyubiquitin chains as the specific topology signaling proteasomal degradation [10]. For many years, the field maintained this narrow view of ubiquitin's role until Hofmann and Pickart's 1999 discovery that K63-linked chains functioned in DNA repair independent of proteasomal degradation, forever expanding the functional repertoire of ubiquitin signaling [10]. This was followed by the structural elucidation of the Ubc13/Mms2 complex that specifically synthesizes K63-linked chains, revealing the first mechanistic insights into linkage specificity [10].

The subsequent expansion of the ubiquitin code has been remarkable, with discoveries of non-canonical linkages including linear (M1-linked) chains synthesized by the LUBAC complex, and more recently, the identification of ubiquitination on non-lysine residues (serine, threonine) and even non-protein substrates [10]. The emerging understanding of branched ubiquitin chains with multiple linkage types within a single polymer represents the current frontier in mapping the complexity of the ubiquitin code [11] [12].

Ubiquitin Chain Topologies: Structures and Functions

Canonical Homotypic Chains

Table 1: Major Ubiquitin Chain Linkages and Their Primary Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Functions | Key Effectors/Receptors | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Proteasomal degradation [10] [13] | RPN1, RPN10, RPN13 proteasome subunits [11] | Compact conformation targeting to proteasome [9] |

| K63-linked | DNA repair, NF-κB signaling, endocytosis [10] [13] | RAP80, TAB2/3 [9] | Extended conformation facilitating signaling complex assembly [9] |

| M1-linear (N-terminal) | Innate immune signaling, NF-κB activation [10] | NEMO/IKKγ, ABIN-1 [9] | Rigid linear structure recognized by specific UBDs [9] |

| K11-linked | ER-associated degradation, cell cycle regulation [11] | Proteasome receptors (with K48 branches) [11] | Mixed open/compact conformation [9] |

| K29-linked | Proteasomal degradation (in branched chains) [12] | Proteasome receptors, UBDs [12] | Part of heterotypic branched chains [12] |

Atypical and Branched Ubiquitin Chains

Beyond homotypic chains, heterotypic ubiquitin chains significantly expand the coding potential of ubiquitin signaling. Branched ubiquitin chains, where a single ubiquitin moiety is modified with two or more ubiquitin molecules through different linkages, function as priority signals for proteasomal degradation [12]. Among these, K11/K48-branched chains are particularly efficient in targeting substrates for degradation during cell cycle progression and proteotoxic stress [11]. Structural studies have revealed that the human 26S proteasome recognizes K11/K48-branched ubiquitin chains through a multivalent mechanism involving a previously unidentified K11-linked ubiquitin binding site at the groove formed by RPN2 and RPN10, in addition to the canonical K48-linkage binding site [11].

Similarly, K29/K48-branched chains have been identified as critical degradation signals, especially for deubiquitylation-protected substrates [12]. In these architectures, the K29 linkage provides resistance to deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) like OTUD5, while the K48 linkage provides the proteasome-targeting signal, creating a synergistic effect that ensures efficient substrate degradation despite the presence of protective DUBs [12].

Non-Canonical Ubiquitination chemistries

Recent discoveries have further expanded the ubiquitin code beyond traditional isopeptide bonds. These include:

- Oxyester linkages: Formation between the ubiquitin C-terminus and serine/threonine hydroxyl groups, catalyzed by E3 ligases like MYCBP2 through a novel RING-Cys-relay mechanism [10].

- Phosphoribosyl linkages: Demonstrated by Legionella pneumophila effectors that conjugate Arg42 of ubiquitin to substrate serine residues [10].

- Non-protein substrates: Ubiquitination of bacterial lipopolysaccharides, demonstrating the expansion of ubiquitination beyond protein targets [10].

Molecular Mechanisms of Chain Formation and Recognition

Structural Basis of Linkage-Specific Ubiquitination

The formation of specific ubiquitin chain linkages is determined by the coordinated action of E2 enzymes and E3 ligases. Structural studies have revealed how these enzymes achieve linkage specificity. For example, the Ubc13/Mms2 heterodimer specifically generates K63-linked chains through a mechanism where Mms2 serves as a scaffold to position K63 of the acceptor ubiquitin toward Ubc13's active site [10]. A hydrophobic residue in Mms2 engages with the I44 hydrophobic patch of the bound acceptor ubiquitin to specifically orient K63 toward the catalytic cysteine [10].

For K48-linked chain formation, recent structural insights into the HECT E3 UBR5 reveal an intricate mechanism involving a ≈620 kDa UBR5 dimer as the functional unit [14]. The structures demonstrate how a UBA domain captures an acceptor Ub, with its K48 positioned into the active site through numerous interactions between the acceptor Ub, UBR5 elements, and the donor Ub [14]. The HECT domain undergoes specific conformational changes during Ub transfer, cycling between distinct states to receive ubiquitin from E2 and transfer it to the acceptor [14].

Proteasomal Recognition of Ubiquitin Chains

The 26S proteasome recognizes ubiquitinated substrates through multiple ubiquitin receptors, including RPN1, RPN10, and RPN13 within the 19S regulatory particle [11]. Structural studies using cryo-EM have revealed that K11/K48-branched ubiquitin chains are recognized through a multivalent mechanism involving:

- The canonical K48-linkage binding site formed by RPN10 and RPT4/5 coiled-coil

- A previously unknown K11-linked Ub binding site at the groove formed by RPN2 and RPN10

- RPN2 recognition of an alternating K11-K48-linkage through a conserved motif similar to the K48-specific T1 binding site of RPN1 [11]

This multivalent recognition explains the preferential degradation of substrates modified with K11/K48-branched chains and illustrates how the proteasome decodes complex ubiquitin signals.

Methodologies for Ubiquitin Chain Characterization

Experimental Approaches for Ubiquitination Analysis

Table 2: Key Methodologies for Ubiquitin Chain Characterization

| Methodology | Principle | Applications | Key Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin tagging (His/Strep) | Expression of tagged Ub in cells; affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins [15] | Identification of ubiquitination sites and substrates [15] | Advantage: Easy, low-cost; Limitation: Potential artifacts from tagged Ub [15] |

| Antibody-based enrichment | Use of linkage-specific antibodies to enrich particular chain types [15] | Enrichment and detection of specific ubiquitin linkages [15] | Advantage: Applicable to tissues/clinical samples; Limitation: High cost, potential non-specific binding [15] |

| Tandem Ub-binding entities (TUBEs) | Tandem-repeated Ub-binding domains with high affinity for ubiquitin chains [15] | Protection of ubiquitinated proteins from deubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [15] | Advantage: High affinity, pan-specific recognition; Limitation: May not distinguish specific linkages [15] |

| Ub-AQUA/PRM mass spectrometry | Absolute quantification using heavy isotope-labeled ubiquitin peptides [11] [12] | Precise quantification of specific ubiquitin linkage types [11] [12] | Advantage: Highly specific and quantitative; Limitation: Requires specialized expertise and instrumentation [11] |

| Linkage-specific DUB profiling | Use of DUBs with known linkage specificity to cleave specific ubiquitin chains [15] | Characterization of linkage types in complex ubiquitin samples [15] | Advantage: Can resolve complex chain architectures; Limitation: Requires validation of DUB specificity [15] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage-specific antibodies | K48-specific, K63-specific, M1-linear specific antibodies [15] | Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence, and immunoprecipitation of specific ubiquitin linkages |

| Ubiquitin variants | K63R, K48R single mutants; K11-only, K48-only ubiquitin mutants [11] [12] | Determination of linkage specificity in in vitro ubiquitylation assays |

| E3 ligase inhibitors | Small molecule inhibitors targeting HECT, RING, or RBR E3 ligases [13] | Functional studies of specific E3 ligases and potential therapeutic applications |

| DUB inhibitors | USP14 inhibitors, UCHL1 inhibitors, OTUB1 inhibitors [13] | Investigation of DUB functions and stabilization of ubiquitin signals |

| Activity-based probes | Ub-VME, Ub-AMC, linkage-specific DUB probes [15] | Profiling DUB activities and specificities in complex proteomes |

| Proteasome inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib [12] | Stabilization of ubiquitinated proteins by blocking proteasomal degradation |

| TUBE reagents | TUBE1, TUBE2 (tandem ubiquitin-binding entities) [15] [12] | Affinity purification of ubiquitinated proteins and protection from deubiquitination |

| sec-Butylnaphthalenesulfonic acid | sec-Butylnaphthalenesulfonic Acid | High-purity sec-Butylnaphthalenesulfonic acid for research. Used in lubricants, coatings, and dispersants. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 5-Bromo-5'-methyl-2,2'-bithiophene | 5-Bromo-5'-methyl-2,2'-bithiophene | 5-Bromo-5'-methyl-2,2'-bithiophene is a key reagent for synthesizing conjugated polymers and organic electronic materials. For Research Use Only. Not for human or therapeutic use. |

Signaling Pathways and Functional Networks

DNA Damage Response and Repair

Ubiquitin signaling plays critical roles in the DNA damage response through multiple mechanisms. Histone H2A ubiquitination at K15 serves as a marker for recruitment of DNA damage repair proteins such as 53BP1 [10]. Additionally, RNF126-mediated K63-linked ubiquitination activates the ATR-CHK1 pathway, and its inhibition creates synthetic lethality with ATM inhibition [13]. The deubiquitinating enzyme USP14 disrupts non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and promotes homologous recombination (HR), making it a potential target for disrupting DNA damage response in cancer therapy [13].

NF-κB Signaling Pathway

Figure 1: Ubiquitin Signaling in NF-κB Pathway Regulation. This diagram illustrates the antagonistic relationship between TRIP12 and OTUD5 in regulating NF-κB signaling through formation and disassembly of K29/K48-branched ubiquitin chains.

Cancer Radiotherapy Resistance

The ubiquitin system orchestrates radiotherapy resistance through spatiotemporal control of DNA repair fidelity, metabolic reprogramming, and immune evasion [13]. K48-linked ubiquitination demonstrates contextual duality in radiation response—FBXW7 promotes radioresistance in p53-wildtype tumors by degrading p53, but enhances radiosensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer with SOX9 overexpression by destabilizing SOX9 and alleviating p21 repression [13]. K63-linked chains directly orchestrate cell survival pathways, with TRAF4 utilizing K63 modifications to activate the JNK/c-Jun pathway, driving overexpression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL in colorectal cancer [13].

Emerging Research Frontiers and Therapeutic Applications

Targeted Protein Degradation

The understanding of ubiquitin chain topology has enabled the development of novel therapeutic strategies, particularly PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) that harness the ubiquitin-proteasome system to degrade specific disease-causing proteins [10] [13]. EGFR-directed PROTACs selectively degrade β-TrCP substrates in EGFR-dependent tumors, suppressing DNA repair while minimizing impact on normal tissues [13]. Innovative radiation-responsive PROTAC platforms include radiotherapy-triggered PROTAC (RT-PROTAC) prodrugs activated by tumor-localized X-rays to degrade BRD4/2, synergizing with radiotherapy in breast cancer models [13].

Branching as a Regulatory Mechanism

Recent research has illuminated how branched ubiquitin chains enable the degradation of deubiquitylation-protected substrates [12]. The combinatorial ubiquitin code employing K29/K48-branched chains represents a strategy to overcome the protective effects of DUBs like OTUD5, which readily cleaves K48 linkages but has weak activity against K29 linkages [12]. Consequently, K29 linkages provide a DUB-resistant foundation that facilitates UBR5-dependent K48-linked chain branching, ensuring proteasomal targeting despite the presence of protective DUBs [12].

Ubiquitin Chain Topology in Immune Regulation

The ubiquitin system plays crucial roles in innate immune regulation, with linear ubiquitin chains assembled by the LUBAC complex serving as key platforms for downstream effectors in NF-κB activation [10]. Additionally, TRIM21 utilizes K48 ubiquitination to degrade VDAC2 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma, suppressing cGAS/STING-mediated immune surveillance [13]. Targeting these ubiquitin-dependent immune regulatory pathways represents a promising therapeutic approach for cancer and inflammatory diseases.

The complexity of ubiquitin chain topologies extends far beyond the initial dichotomy of K48-linked degradation signals versus K63-linked signaling scaffolds. The expanding repertoire of ubiquitin linkages, chain architectures, and non-canonical ubiquitination chemistries illustrates the remarkable sophistication of the ubiquitin code. Understanding these diverse topologies—from homotypic chains to complex branched structures—provides critical insights into cellular regulation and offers new therapeutic opportunities for manipulating ubiquitin signaling in disease contexts. As research methodologies continue to advance, enabling more precise characterization of ubiquitin chain architecture and function, our understanding of this complex post-translational modification system will undoubtedly continue to expand, revealing new layers of regulation and novel therapeutic targets.

The ubiquitin code, a critical post-translational regulatory system in eukaryotes, has traditionally been understood through the canonical formation of an isopeptide bond between the C-terminus of ubiquitin and the ε-amino group of a lysine residue on substrate proteins. However, emerging research has revealed an expansive landscape of unconventional ubiquitination mechanisms that dramatically increase the complexity and functional diversity of this system. These non-canonical modifications include ester linkages to serine and threonine residues, non-lysine modifications targeting cysteine and N-terminal amines, and remarkable phosphoribosyl bridges where ubiquitin attaches to substrates via a phosphodiester bond [16] [17]. The discovery of these diverse ubiquitination mechanisms represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of ubiquitin signaling, revealing previously unappreciated layers of regulation that operate alongside the conventional ubiquitination machinery. These unconventional pathways expand the reach of ubiquitination beyond the proteome to include intracellular lipids and sugars, and introduce novel enzymatic mechanisms that function independently of canonical E1 and E2 enzymes [16] [17]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical guide to these unconventional ubiquitination mechanisms, with detailed experimental methodologies, quantitative analyses, and visualization of the complex signaling networks they govern, framed within the broader context of ubiquitin code complexity and its implications for therapeutic development.

Molecular Mechanisms of Non-Canonical Ubiquitination

Ester Linkages: Serine and Threonine Ubiquitination

The discovery of ubiquitin ester linkages represents a fundamental expansion of the ubiquitin code's chemical vocabulary. Unlike conventional isopeptide bonds, ester linkages form between the C-terminal carboxyl group of ubiquitin and the hydroxyl side chains of serine or threonine residues on substrate proteins [17]. This oxyester bond formation introduces distinct chemical properties to the ubiquitination, including increased sensitivity to hydrolysis under alkaline conditions and reducing environments, which has implications for both experimental detection and biological regulation [17].

The molecular machinery responsible for ester bond formation employs unique catalytic mechanisms. The human E3 ligase MYCBP2 utilizes a RING-Cys-relay (RCR) mechanism involving two catalytic cysteine residues that relay ubiquitin to the substrate via thioester intermediates [16] [17]. This RCR mechanism preferentially targets threonine residues, establishing a specific writer for this unconventional modification. Structural analyses reveal that enzymes capable of forming ester linkages contain specialized active sites that position the hydroxyl nucleophile for attack on the ubiquitin thioester, contrasting with the orientation required for lysine side chain modification [16]. The biological significance of serine/threonine ubiquitination is particularly evident in processes such as endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD), peroxisomal protein translocation, and transcriptional regulation, where these modifications provide regulatory versatility beyond canonical ubiquitination [16].

Non-Lysine Ubiquitination: Cysteine and N-Terminal Modifications

Beyond ester linkages, the ubiquitin system targets additional non-lysine sites, including cysteine thiol groups and N-terminal amines, further expanding the chemical diversity of ubiquitin signaling. Cysteine ubiquitination occurs through thioester bonds that are chemically distinct from both isopeptide and oxyester linkages [18]. These modifications were initially identified in viral E3 ligases and have since been observed in endogenous cellular processes, though their relative lability has complicated comprehensive characterization [17] [18].

N-terminal ubiquitination involves the formation of a standard peptide bond between the C-terminus of ubiquitin and the α-amino group of a substrate protein's N-terminus [17]. The most extensively characterized example is Met1-linked (linear) polyubiquitin, which is specifically generated by the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC) and plays critical roles in immune signaling and cell death regulation [17]. LUBAC contains a unique linear ubiquitin chain-determining domain (LDD) that positions the N-terminal amine of the acceptor ubiquitin for conjugation, representing a specialized writer for this linkage type [17].

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Non-Lysine Ubiquitination Types

| Modification Type | Chemical Bond | Known Writers | Cellular Functions | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ser/Thr Ubiquitination | Oxyester | MYCBP2 (RCR mechanism) | ERAD, transcriptional regulation, peroxisomal import | Hydrolysis-sensitive, targets hydroxyl groups |

| Cysteine Ubiquitination | Thioester | Viral E3s, RNF213 (RZ domain) | Unknown endogenous functions | Highly labile, redox-sensitive |

| N-terminal Ubiquitination | Peptide bond | LUBAC (HOIP subunit) | NF-κB signaling, cell death, immunity | Linear chains, unique readers |

| Phosphoribosyl Ubiquitination | Phosphodiester | SidE effectors (SdeA) | Bacterial pathogenesis | E1/E2-independent, Arg42 modification |

Phosphoribosyl Ubiquitination: A Pathogen-Driven Mechanism

Perhaps the most remarkable deviation from conventional ubiquitination is the phosphoribosyl ubiquitination pathway employed by the intracellular pathogen Legionella pneumophila. This mechanism completely bypasses the canonical E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade, instead utilizing the SidE family of effector proteins (including SdeA) to catalyze ubiquitination through a two-step process [16] [19]. First, the mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase (mART) domain of SdeA catalyzes the transfer of ADP-ribose from NAD+ to Arg42 of ubiquitin, generating ADP-ribosylated ubiquitin (ADPR-Ub) [19]. Subsequently, the phosphodiesterase (PDE) domain of SdeA processes ADPR-Ub to conjugate phosphoribosylated ubiquitin (PR-Ub) to serine residues of host substrates via a phosphodiester bond [19].

Structural studies have revealed that SdeA contains two distinct functional units: a PDE domain and an mART domain, with their catalytic sites separated by over 55Ã…, indicating independent functionality [19]. This spatial separation allows the two activities to function independently while being housed within a single protein. The phosphoribosyl ubiquitination mechanism represents a striking example of how pathogens can rewrite the host ubiquitin code to promote infection, revealing unprecedented chemical versatility in ubiquitin signaling [16] [19].

Experimental Methods and Detection Techniques

Identifying and Characterizing Ester Linkages

The experimental characterization of ester-linked ubiquitination presents unique challenges due to the relative lability of these modifications compared to conventional isopeptide bonds. A multidisciplinary approach combining chemical biology tools with advanced mass spectrometry techniques has proven essential for definitive identification [16]. Critical methodologies include:

NMR Spectroscopy: Solution-state NMR, particularly 1H, 15N-HSQC-TROSY experiments, enables direct detection of ester linkages by monitoring chemical shift perturbations upon ubiquitin modification. This approach revealed the interaction between ubiquitin and the PDE domain of SdeD, a homolog in the SidE family [19].

Hydrazine and Hydroxylamine Sensitivity Assays: These nucleophiles specifically cleave thioester and oxyester linkages while leaving isopeptide bonds intact. Treatment with 0.2M hydrazine or 1M hydroxylamine at pH 8.5 for 2-4 hours followed by immunoblotting provides chemical evidence for ester linkage formation [17].

Site-directed Mutagenesis of Candidate Residues: Systematic mutation of serine, threonine, and cysteine residues in putative substrates, combined with ubiquitination assays, helps identify modification sites. For example, mutation of specific serine residues in Rab33b abrogates its phosphoribosyl ubiquitination by SdeA [19].

Stable Isotope Labeling with Amino Acids in Cell Culture (SILAC): Quantitative proteomics with SILAC labeling enables comparative analysis of ubiquitination sites under different conditions, facilitating identification of non-lysine modifications when combined with hydroxylamine treatment [16].

Structural Biology Approaches for Mechanism Elucidation

Structural biology has been instrumental in deciphering the molecular mechanisms of unconventional ubiquitination. X-ray crystallography of SdeA fragments revealed the distinct PDE and mART domains and their spatial organization [19]. Key structural insights include:

Crystal Structure Determination: Structures of SdeA catalytic cores (residues 211-910) at 2.5-3.0Ã… resolution revealed the deep, positively charged groove in the PDE domain that houses the active site [19].

Small Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS): Solution-phase SAXS analysis confirmed that the extended conformation observed in SdeA crystal structures, with the mART domain separated from the PDE domain, represents the physiological state in solution [19].

Complex Structures with Ubiquitin: Co-crystallization of SdeD (a SidE family homolog) with ubiquitin revealed two ubiquitin molecules contacting a single PDE domain, with one molecule (Ub1) binding at the opening of the catalytic groove through interactions involving the T9 loop region, the C-terminus, and Arg42 [19].

Table 2: Experimental Approaches for Studying Unconventional Ubiquitination

| Methodology | Application | Key Insights Generated | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| NMR Spectroscopy | Mapping interactions, detecting ester bonds | Revealed Ub binding mode to SdeD PDE domain | Requires stable isotope labeling, specialized expertise |

| X-ray Crystallography | Determining atomic structures | Elucidated SdeA domain architecture and active sites | Challenging for flexible multidomain proteins |

| Hydrazine Hydrolysis | Differentiating ester vs isopeptide bonds | Confirmed non-lysine linkages in ERAD substrates | Non-specific protein cleavage can occur |

| Mutagenesis of Catalytic Residues | Establishing essential residues | Identified H277, N723, Q727, R729 as critical for SdeA | May cause structural perturbations beyond active site |

| Mass Spectrometry Proteomics | Identifying modification sites | Detected di-glycine signatures on non-lysine residues | Specialized sample preparation needed for labile bonds |

| SAXS | Solution-state structural analysis | Confirmed extended SdeA conformation in solution | Lower resolution than crystallography |

Functional Assays for Biological Relevance

Establishing the physiological significance of unconventional ubiquitination requires functional assays that connect these modifications to specific cellular processes:

In Vitro Reconstitution Assays: Purified components (E1, E2, E3, ubiquitin) allow biochemical characterization of ubiquitination mechanisms. For phosphoribosyl ubiquitination, SdeA fragments with isolated mART or PDE domains can process ADPR-Ub and ubiquitinate substrates like Rab33b independently [19].

Linkage-Selective Engineered Deubiquitinases (enDUBs): Fusion proteins combining GFP-targeted nanobodies with catalytic domains of linkage-selective DUBs (e.g., OTUD1 for K63, OTUD4 for K48, Cezanne for K11, TRABID for K29/K33) enable selective hydrolysis of specific polyubiquitin chains in live cells [3]. This approach revealed distinct functions for different linkage types in regulating KCNQ1 ion channel trafficking.

Cellular Ubiquitination Monitoring: Transfection-based assays with epitope-tagged ubiquitin, combined with immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting, assess substrate ubiquitination under different conditions. Co-expression of SdeA with candidate substrates in HEK293 cells demonstrates phosphoribosyl ubiquitination capability [19].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Unconventional Ubiquitination

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Key Features | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linkage-selective enDUBs | Selective hydrolysis of specific ubiquitin linkages in live cells | GFP-nanobody fusions with DUB catalytic domains | Determining functional roles of specific chains on KCNQ1 [3] |

| Hydrazine/Hydroxylamine | Chemical cleavage of ester linkages | Specific hydrolysis of thioester/oxyester bonds | Differentiating ester vs isopeptide ubiquitination [17] |

| SdeA fragments (mART, PDE) | Mechanistic studies of phosphoribosyl ubiquitination | Isolated functional domains | In vitro reconstitution of ubiquitination cascade [19] |

| ADPR-Ub | Intermediate in phosphoribosyl ubiquitination | Chemically defined substrate | PDE domain activity assays [19] |

| Ubiquitin Mutants (R42A) | Studying phosphoribosyl ubiquitination | Defective in ADP-ribosylation | Determining mART domain specificity [19] |

| MYCBP2 (RCR mutant) | Ester linkage formation studies | Altered relay mechanism | Identifying serine/threonine ubiquitination substrates [16] |

| LUBAC Complex | N-terminal ubiquitination studies | Only E3 generating Met1 chains | Linear ubiquitination signaling assays [17] |

| Mass Spectrometry with Di-Glycine Remnant Enrichment | Proteomic identification of ubiquitination sites | Antibodies recognizing K-ε-GG motif | System-wide mapping of unconventional sites [3] |

| N-(4-Methyl-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)urea | N-(4-Methyl-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)urea|Research Chemical | Bench Chemicals | |

| C15H16FN3OS2 | C15H16FN3OS2|RUO | High-purity C15H16FN3OS2 for research applications. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Signaling Pathways and Biological Networks

The unconventional ubiquitination mechanisms described herein are integrated into complex cellular signaling networks that regulate fundamental biological processes. The following diagram illustrates the key pathways and their functional relationships:

Ubiquitin Code Signaling Network

This network diagram illustrates how unconventional ubiquitination mechanisms integrate with canonical pathways to regulate diverse cellular processes. The writer-reader-eraser framework provides a conceptual structure for understanding how these modifications establish specific functional outcomes [16]. Writers (E1, E2, and E3 enzymes) establish the ubiquitin code through specific modifications; readers (proteins with ubiquitin-binding domains) interpret these modifications to initiate downstream signaling; and erasers (deubiquitinating enzymes, DUBs) dynamically edit the code to ensure signal termination and homeostasis [18].

The biological outputs of these networks span fundamental cellular processes. DNA damage repair utilizes K63-linked ubiquitination for non-proteolytic signaling, while immune signaling depends heavily on Met1-linear ubiquitination for NF-κB pathway activation [17]. Protein trafficking events, such as the regulation of KCNQ1 surface expression, are controlled by specific ubiquitin linkages that direct proteins between subcellular compartments [3]. Targeted degradation remains primarily mediated by K48-linked chains but increasingly involves atypical chains including K11 and branched architectures [20] [18]. Finally, microbial pathogenesis exploits unconventional mechanisms like phosphoribosyl ubiquitination to hijack host cell processes [16] [19].

Technical Challenges and Methodological Considerations

Studying unconventional ubiquitination presents unique technical challenges that require specialized methodological approaches. The inherent chemical lability of ester linkages necessitates careful sample preparation under controlled pH conditions and avoidance of strong nucleophiles that might cleave these modifications [17]. The low abundance of many non-lysine modifications demands highly sensitive detection methods, including enrichment strategies prior to mass spectrometry analysis [16].

A significant challenge in the field is the definitive assignment of modification sites, particularly for ester linkages that may be disrupted during standard proteomic workflows. The development of hydrolysis-resistant ubiquitin analogs and improved crosslinking strategies represents an active area of methodological innovation [16]. Additionally, the functional redundancy between conventional and unconventional ubiquitination pathways complicates genetic approaches, as single mutations may not produce clear phenotypic consequences [17].

For phosphoribosyl ubiquitination studies, the requirement for specialized reagents including purified SidE effectors, ADPR-Ub intermediates, and specific antibodies against PR-Ub modifications presents barriers to entry for many laboratories [19]. The field would benefit from commercial availability of these reagents to accelerate discovery. Furthermore, the dynamic regulation of these modifications by cellular factors necessitates live-cell imaging approaches and real-time monitoring capabilities that are still under development [3].

The discovery and characterization of unconventional ubiquitination mechanisms has fundamentally expanded our understanding of the ubiquitin code, revealing unprecedented chemical diversity and functional complexity. Ester linkages, non-lysine modifications, and phosphoribosyl bridges represent not just biochemical curiosities but established regulatory mechanisms with significant roles in cellular physiology and disease pathogenesis. These findings underscore the remarkable plasticity of the ubiquitin system and its capacity for evolutionary innovation, particularly evident in the pathogen-driven rewiring of host ubiquitination through effectors like the SidE family [16] [19].

Future research directions will likely focus on several key areas. First, the systematic identification of endogenous substrates for these unconventional modifications across different cell types and conditions will establish their full physiological scope. Second, the structural basis for recognition of these modifications by specialized reader domains remains largely unexplored territory. Third, the crosstalk between unconventional ubiquitination and other post-translational modifications creates complex regulatory networks that await comprehensive mapping. Finally, the therapeutic targeting of these pathways, particularly in cancer and infectious diseases, represents a promising frontier for drug development [20] [16].

The continued development of innovative tools, including linkage-selective enDUBs [3], chemical biology probes, and advanced structural methods, will be essential for deciphering the full complexity of the ubiquitin code. As these unconventional ubiquitination mechanisms become increasingly integrated into our understanding of cellular signaling, they promise to reveal new biological insights and therapeutic opportunities for manipulating ubiquitin-dependent processes in human health and disease.

The reader-writer-eraser paradigm represents a fundamental conceptual framework for understanding dynamic post-translational modification systems that control cellular signaling networks. Within this paradigm, ubiquitin signaling stands as one of the most complex and versatile codes, governing virtually all cellular processes through a sophisticated language of covalent modifications. The ubiquitin system employs E1, E2, and E3 enzymes as "writers" that covalently attach the 76-amino acid protein ubiquitin to substrate proteins, deubiquitinases (DUBs) as "erasers" that remove these modifications, and ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) as "readers" that interpret these signals to generate specific biological outcomes [21] [5]. This intricate regulatory system enables cells to respond with high specificity to a nearly limitless set of cues while varying the sensitivity, duration, and dynamics of the response [22]. The remarkable complexity of ubiquitin signaling arises from its ability to form diverse chain structures and linkages, creating a "ubiquitin code" that remains largely enigmatic despite decades of research [3]. Understanding how UBDs decode this complex language represents a critical frontier in cell signaling research with profound implications for therapeutic intervention in cancer, inflammatory diseases, and neurodegenerative disorders.

The Core Components of the Ubiquitin Signaling Machinery

Writers: The Architects of Ubiquitin Signals

Ubiquitin writers constitute a sophisticated enzymatic cascade that builds specific ubiquitin signals with remarkable precision. The human genome encodes 2 E1 activating enzymes, approximately 40 E2 conjugating enzymes, and over 600 E3 ligases that work in concert to conjugate ubiquitin to specific substrate proteins [3] [21]. These enzymes can generate an astonishing diversity of ubiquitin modifications, including monoubiquitination, multiple monoubiquitination, and various polyubiquitin chains connected through different lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) or the N-terminal methionine (M1) [21]. The linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC), composed of HOIP, HOIL-1L, and SHARPIN subunits, represents a particularly specialized writer that exclusively generates M1-linked linear ubiquitin chains [21]. LUBAC's RING-IBR-RING (RBR) domain utilizes a unique RING-HECT-hybrid mechanism whereby the donor ubiquitin is transiently transferred to the active cysteine residue (Cys885 in HOIP) before being conjugated to an acceptor ubiquitin captured in the C-terminal linear ubiquitin chain determining domain (LDD) [21]. This exquisite specificity enables LUBAC to regulate critical inflammatory and cell survival pathways, particularly the canonical NF-κB signaling pathway [21].

Erasers: The Editors of Ubiquitin Signals

Deubiquitinases (DUBs) provide the editing capacity to the ubiquitin signaling system, offering dynamic reversibility and temporal control. The human genome encodes approximately 100 DUBs that hydrolyze ubiquitin chains in distinctive ways, creating an intricate regulatory layer that shapes signaling outcomes [3] [5]. These enzymes demonstrate remarkable specificity for particular ubiquitin chain linkages, enabling precise editing of ubiquitin signals. For instance, OTULIN and CYLD specifically hydrolyze linear M1-linked ubiquitin chains and physically associate with HOIP's PUB domain to directly regulate LUBAC function [21]. The development of engineered deubiquitinases (enDUBs) represents a recent technological breakthrough, wherein catalytic domains of linkage-selective DUBs are fused to target-specific nanobodies, enabling substrate-selective ubiquitin chain editing in live cells [3]. This approach has revealed how distinct polyubiquitin chains regulate the trafficking of membrane proteins like KCNQ1 among different subcellular compartments, demonstrating the critical importance of erasers in shaping spatial organization of cellular components [3].

Readers: The Decoders of Ubiquitin Signals

Ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) serve as the fundamental readers that interpret ubiquitin signals by binding non-covalently to ubiquitin modifications. These modular elements, typically ranging from 30-150 amino acids, recognize specific surface patches on ubiquitin with varying affinities and specificities [23]. More than 20 distinct UBD families have been identified, including NZF, UBA, UIM, UBAN, and CUE domains, each with characteristic structural features that determine their binding preferences [23] [21]. The specificity of UBD-ubiquitin interactions is central to diverse cellular functions, including protein degradation, DNA damage responses, inflammatory signaling, and membrane trafficking [23]. Recent structural studies have revealed that despite their small size, many UBDs achieve remarkable specificity through multivalent interactions that simultaneously engage ubiquitin and substrate components [24]. For instance, the NZF1 domain of HOIP preferentially binds site-specifically ubiquitinated forms of NEMO and optineurin, demonstrating how readers can recognize composite surfaces consisting of both ubiquitin and substrate elements [24].

Table 1: Major Ubiquitin-Binding Domains and Their Functions

| UBD Family | Representative Domains | Structural Features | Cellular Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| NZF | TAB2, HOIP NZF1, HOIL-1L NZF | Compact ~30 amino acid zinc finger | Linear ubiquitin binding, NF-κB signaling, mitophagy |

| UBA | HR23A, EPS15 | Three-helix bundle | Proteasomal degradation, endocytosis |

| UIM | Vps27, HRS | Single α-helix | Endosomal sorting, receptor downregulation |

| UBAN | NEMO | Coiled-coil domain | Linear ubiquitin-specific, NF-κB activation |

| CUE | Cue1, Vps9 | Two-helix bundle | Ubiquitin signaling, endocytic trafficking |

Quantitative Aspects of Ubiquitin Signaling

Stoichiometry and Dynamics of Ubiquitin Modifications

The functional outcomes of ubiquitin signaling depend critically on the stoichiometry and kinetics of modification, necessitating quantitative approaches to understand pathway flux and threshold behaviors. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics has revealed that ubiquitin-driven signaling systems are integrated with phosphorylation networks, with flux dictated by the fractional stoichiometry of distinct regulatory modifications and protein assemblies [25]. For example, in SCF-type E3 ligases, the primary ubiquitin transfer step is rate-limiting, with phosphorylation of substrates generating "phosphodegron" recognition motifs that control ubiquitylation kinetics [25]. Advanced quantitative proteomic methods, including SILAC (Stable Isotope Labeling with Amino acids in Cell Culture) and TMT (Tandem Mass Tagging), now enable researchers to determine modification stoichiometries with temporal precision, revealing how signaling dynamics control biological outcomes [25]. These approaches have been particularly valuable for understanding how the ubiquitin code is rewired in pathological conditions, such as in radioresistant cancer cells where K63-linked chains stabilize DNA repair factors while K48-mediated degradation of survival proteins is inhibited [5].

Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Chain Distributions

Different biological contexts produce characteristic distributions of ubiquitin chain linkages that determine functional outcomes. Mass spectrometry analysis of polyubiquitin chains on KCNQ1-YFP expressed in HEK293 cells revealed a striking linkage distribution where K48 linkages dominated (72%), followed by K63 linkages (24%), with atypical chains (K11, K27, K29, K33, and K6) accounting for only 4% of the total [3]. This distribution controls the ion channel's subcellular localization and stability, with different linkages directing the protein to distinct cellular compartments. The development of linkage-specific antibodies has further enabled researchers to quantify these chain architectures in different signaling contexts, revealing how specific pathways utilize characteristic ubiquitin topologies [25]. For instance, DNA damage signaling employs predominantly K63-linked and linear ubiquitin chains to recruit repair factors, while proteasomal degradation relies heavily on K48-linked chains [26] [5].

Table 2: Ubiquitin Chain Linkages and Their Functional Roles

| Linkage Type | Primary Writers | Readers | Major Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| K48 | UBE2R1-3, many RING E3s | UBA domains, proteasomal receptors | Proteasomal degradation, cell cycle control |

| K63 | UBE2N/Ube2V1, many RING E3s | TAB2, UIM domains | DNA repair, NF-κB signaling, endocytosis |

| M1 (Linear) | LUBAC (HOIP/HOIL-1L/SHARPIN) | NEMO, ABINs, optineurin | Inflammation, immune signaling, anti-apoptosis |

| K11 | UBE2S, APC/C | Cezanne, certain UBDs | Cell cycle regulation, ER-associated degradation |

| K29/K33 | UBE2H, UBE3C | TRABID | Proteasomal degradation, kinase regulation |

Methodologies for Deciphering the Ubiquitin Code

Experimental Workflow for Ubiquitin Signaling Analysis

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Ubiquitin Signaling Analysis. This diagram outlines key steps in quantitative ubiquitin proteomics, from sample preparation with metabolic labeling to ubiquitin enrichment using diGly antibodies or TUBE reagents, followed by mass spectrometric analysis and data interpretation with linkage-specific tools.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitin Signaling Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Composition | Experimental Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Multiple UBDs fused in tandem | Protect polyubiquitin chains from DUBs, enrich ubiquitinated proteins | Identification of ubiquitinated substrates, purification of ubiquitin conjugates |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Antibodies recognizing specific ubiquitin linkages | Detect and quantify particular chain types | Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence for pathway-specific ubiquitination |

| Engineered DUBs (enDUBs) | DUB catalytic domains fused to target-specific nanobodies | Substrate-selective ubiquitin chain editing in live cells | Functional analysis of ubiquitin chain roles on specific proteins |

| DiGly Antibody (K-ε-GG) | Antibody recognizing diglycine remnant on lysines | Enrich and identify ubiquitination sites by mass spectrometry | Ubiquitin proteomics, site-specific ubiquitination mapping |

| LUBAC Inhibitors (HOIPINs) | α,β-unsaturated carbonyl-containing chemicals | Specifically inhibit linear ubiquitination | Functional analysis of linear ubiquitination in inflammatory signaling |

| Activity-Based DUB Probes | Ubiquitin derivatives with warhead groups | Label active DUBs for identification and characterization | DUB activity profiling, inhibitor screening |

| C23H21ClN4O7 | C23H21ClN4O7, MF:C23H21ClN4O7, MW:500.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| C24H23ClFN3O4 | C24H23ClFN3O4, MF:C24H23ClFN3O4, MW:471.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Detailed Protocol: Linkage-Specific Analysis of Protein Ubiquitination

For investigators requiring precise analysis of ubiquitin chain linkages on specific proteins, the following protocol adapted from mass spectrometry-based approaches provides a robust methodology [3]:

Sample Preparation and Metabolic Labeling

- Culture HEK293 cells (or relevant cell line) in SILAC media containing heavy lysine (13C6, 15N2) and arginine (13C6, 15N4) for at least 6 cell doublings to achieve complete incorporation

- Transfect cells with plasmid encoding target protein (e.g., KCNQ1-YFP) using PEI or preferred transfection reagent

- Treat cells with proteasomal inhibitor (10 μM MG132) and/or DUB inhibitors (5 μM PR-619) for 4-6 hours before harvesting to stabilize ubiquitin conjugates

Immunoprecipitation of Target Protein

- Lyse cells in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide, protease inhibitors, and 20 μM PR-619

- Pre-clear lysate with protein A/G beads for 30 minutes at 4°C

- Incubate with target-specific antibody (e.g., anti-KCNQ1) or GFP-nanobody for YFP-tagged proteins overnight at 4°C

- Capture immune complexes with protein A/G beads, wash 3× with lysis buffer and 2× with PBS

Ubiquitin Chain Analysis by Mass Spectrometry

- Separate immunoprecipitated proteins by SDS-PAGE, excise bands corresponding to target protein and associated complexes

- Reduce with 10 mM DTT, alkylate with 55 mM iodoacetamide, and digest with trypsin (1:50 enzyme:substrate) overnight at 37°C

- Enrich for ubiquitinated peptides using diGly antibody-conjugated beads (K-ε-GG immunoaffinity enrichment)

- Analyze by LC-MS/MS on Orbitrap Fusion Lumos with MultiNotch MS3 method for TMT quantification

- Identify ubiquitin linkage types by quantifying the relative abundance of diGly-modified ubiquitin peptides, particularly focusing on signature peptides containing K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, and K63 residues with GG modification

Ubiquitin Signaling in DNA Damage Response: A Case Study

The DNA damage response provides a compelling case study of the reader-writer-eraser paradigm in action, demonstrating how ubiquitin signaling coordinates complex cellular processes. Upon DNA double-strand break formation, the ATM kinase phosphorylates the histone variant H2AX, creating a binding site for the MDC1 scaffold protein via its tandem BRCT domain [26]. This recruitment initiates a sophisticated ubiquitin signaling cascade where RNF8 serves as the primary writer, recognizing phosphorylated MDC1 through its FHA domain and catalyzing K63-linked ubiquitination of histone H1 [26]. This ubiquitin mark is then read by RNF168 through its UDM1 motif, triggering a second wave of ubiquitin writing wherein RNF168 catalyzes ubiquitylation of H2A-type histones at K13/K15 [26]. The resulting ubiquitin landscape is subsequently read by repair factors including 53BP1 and BRCA1 through their UBDs, directing appropriate repair pathway choice between non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR) [26] [5]. This exquisite coordination between writers, readers, and erasers ensures faithful DNA repair while maintaining appropriate signal duration and spatial restriction.

Figure 2: Ubiquitin Signaling in DNA Damage Response. This diagram illustrates the hierarchical reader-writer-eraser cascade in DNA double-strand break repair, highlighting how sequential ubiquitin writing and reading events orchestrate repair factor assembly and pathway choice.

Implications for Therapeutic Intervention

The reader-writer-eraser paradigm in ubiquitin signaling presents numerous attractive targets for therapeutic intervention across diverse disease contexts. In cancer, malignant cells frequently exploit ubiquitin signaling to drive proliferation, evade cell death, and develop therapy resistance [5]. For example, in radiotherapy-resistant tumors, rewiring of the ubiquitin code creates dependencies that can be therapeutically targeted, as demonstrated by the development of PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) that redirect E3 ligases to degrade oncoproteins [5]. The reversible nature of ubiquitin modifications offers particular advantages for drug development, as inhibition of writers or erasers can produce rapid, dynamic effects on signaling pathways [5]. Additionally, the chain topology diversity enables highly specific targeting of particular ubiquitin signals without globally disrupting protein homeostasis. Emerging strategies include developing LUBAC inhibitors (HOIPINs) for inflammatory diseases, linkage-specific DUB inhibitors for cancer, and targeted protein degraders that exploit endogenous ubiquitin machinery [21] [5]. As our understanding of the ubiquitin code deepens, particularly through single-cell transcriptomics and CRISPR-based functional screens, we are identifying novel therapeutic vulnerabilities that can be exploited for precision medicine approaches targeting specific ubiquitin signaling nodes in disease contexts.

The reader-writer-eraser paradigm provides a powerful conceptual framework for understanding how ubiquitin-binding domains decode complex cellular signals to orchestrate precise biological outcomes. Through sophisticated integration of writers that create diverse ubiquitin codes, erasers that provide dynamic editing capability, and readers that interpret these signals to drive specific cellular responses, this system enables exquisite contextual control of virtually all cellular processes. Recent technological advances, including quantitative proteomics, linkage-specific tools, and engineered DUBs, are rapidly accelerating our deciphering of the ubiquitin code, revealing both fundamental biological principles and novel therapeutic opportunities. As we continue to unravel the complexities of ubiquitin signaling networks, particularly through spatial proteomics and single-cell approaches, we move closer to comprehensively understanding how cells utilize this sophisticated language to maintain homeostasis and how its dysregulation drives disease pathogenesis.

The ubiquitin code represents one of the most sophisticated post-translational signaling systems in eukaryotic biology, functioning as a central regulator of protein stability, localization, and function through the covalent attachment of the small protein modifier ubiquitin [27] [28]. This complex code encompasses not only single ubiquitin modifications (monoubiquitination) but also diverse polyubiquitin chains formed through different linkage types between ubiquitin molecules, each capable of directing distinct cellular outcomes [27] [3]. The human genome encodes approximately 600 E3 ubiquitin ligases and roughly 100 deubiquitinases (DUBs) that collectively write, edit, and erase ubiquitin signals to maintain cellular homeostasis [3] [29]. The critical importance of ubiquitin signaling in fundamental processes—including inflammatory signaling through NF-κB, DNA damage response, autophagy, and antigen presentation—has made it an attractive target for manipulation by microbial pathogens [27] [30].

Bacterial and viral pathogens have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to subvert the host ubiquitin system, despite generally lacking conventional ubiquitin machinery of their own [27] [30]. Through secreted effector proteins and toxins, pathogens actively rewrite the ubiquitin code to suppress host immune responses, redirect cellular resources, and create favorable niches for replication and persistence [27] [31]. These microbial interventions in ubiquitin signaling follow two broad strategic patterns: "rule-following" mechanisms that employ structural mimics of eukaryotic ubiquitin regulators, and "rule-breaking" mechanisms that introduce entirely novel enzymatic activities and modifications foreign to eukaryotic biology [27] [31]. This ongoing molecular arms race between host and pathogen has not only revealed fundamental aspects of microbial pathogenesis but has also illuminated previously unrecognized complexities and possibilities within the ubiquitin system itself [27]. The following sections provide a comprehensive technical analysis of the molecular mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and therapeutic implications of pathogen-mediated manipulation of the host ubiquitin code.

Bacterial Manipulation of Host Ubiquitination

Rule-Following Strategies: Molecular Mimicry of Eukaryotic Enzymes

Many bacterial pathogens employ effector proteins that structurally and functionally mimic host E3 ubiquitin ligases, utilizing similar catalytic domains and mechanisms to redirect ubiquitination toward host proteins crucial for immunity.

Table 1: Bacterial E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Effectors and Their Functions

| Bacterial Pathogen | Effector Protein | E3 Ligase Type | Host Target/Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas syringae | AvrPtoB | U-box | Inhibits plant pattern-triggered immunity | [27] [30] |

| Escherichia coli (EPEC/EHEC) | NleG | RING | Not fully characterized (ND) | [27] [30] |

| Salmonella Typhimurium | SopA | HECT | Regulates host inflammation | [30] |

| Escherichia coli (EPEC/EHEC) | NleL | HECT | Regulates actin pedestal formation | [30] |

| Shigella flexneri | IpaH family | NEL | Multiple targets in NF-κB pathway | [30] |

The Pseudomonas syringae effector AvrPtoB represents a paradigm of molecular mimicry, containing a C-terminal U-box domain that structurally resembles eukaryotic RING-type E3 ligases despite minimal sequence similarity [27]. This domain maintains the characteristic cross-brace zinc coordination and preserves a critical "linchpin" lysine/arginine residue essential for allosteric activation of E2~Ub conjugates [27]. AvrPtoB directly ubiquitinates host pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) to suppress plant immunity, with disruption of its E2-binding interface abolishing both ligase activity and virulence function [27]. Similarly, the NleG effectors from enteropathogenic E. coli encode RING-type domains that facilitate ubiquitination of unidentified host targets, though their precise roles in pathogenesis remain under investigation [27] [30].

Rule-Breaking Strategies: Novel Mechanisms of Ubiquitin Manipulation

In contrast to molecular mimics, some bacterial effectors employ completely novel mechanistic and structural solutions for ubiquitin manipulation that diverge from established eukaryotic paradigms.

Table 2: Unconventional Bacterial Effectors in Ubiquitin Signaling

| Effector/Pathogen | Novel Mechanism | Catalytic Activities | Functional Consequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SidE family (Legionella pneumophila) | Non-canonical, E1/E2-independent ubiquitination | mART, PDE | Serine ubiquitination of RAB GTPases | [30] [31] |

| SdeA (Legionella pneumophila) | Phosphoribosyl-linked ubiquitination | mART, PDE | Impairs TNF signaling and mitophagy | [31] |

| OspI (Shigella flexneri) | Deamidation of E2 enzyme | Gln deamidase | Inactivates UBE2N/UBC13 (NF-κB pathway) | [30] |

| NleB (E. coli) | N-acetylglucosamine modification | Glycosyltransferase | Inhibits TRAF2 ubiquitination | [30] |

The SidE family effectors from Legionella pneumophila exemplify this rule-breaking approach, catalyzing ubiquitination through a completely E1- and E2-independent mechanism [30] [31]. These large multidomain proteins employ mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase (mART) and phosphodiesterase (PDE) activities in sequence to first ADP-ribosylate ubiquitin using NAD+ as a cofactor, then phosphoribosylate serine residues of host substrates including RAB GTPases and RTN4 [31]. This unique two-step reaction proceeds through a transient phosphoribosyl-ubiquitin intermediate covalently linked to a catalytic histidine residue (H277) within the PDE domain, forming a phosphoramidate bond before final transfer to substrate serine residues [31]. This non-canonical ubiquitination pathway allows Legionella to fundamentally reshape host membrane trafficking without engaging the conventional ubiquitination machinery.

Host Countermeasures: Ubiquitin-Mediated Pathogen Sensing and Restriction

In response to bacterial manipulation, host cells have evolved sophisticated ubiquitin-dependent surveillance mechanisms to detect and eliminate intracellular pathogens. Recent research has identified a novel innate immune sensing strategy involving the recognition of bacterial surface proteins containing degron-like motifs that are ubiquitinated by host E3 ligases [32].

The SCF(^{FBW7}) E3 ligase complex, regulated by glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), plays a crucial role in this defense mechanism by recognizing tripartite degron motifs in bacterial surface proteins [32]. These motifs consist of a primary degron sequence followed by a proximal lysine residue and a disordered intervening region, mirroring the recognition elements typically found in cellular proteins destined for K48-linked ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [32]. In Streptococcus pneumoniae, the surface proteins BgaA (β-galactosidase/adhesin) and PspA (choline-binding protein) contain such degron-like motifs and undergo K48-linked ubiquitination, leading to enhanced bacterial clearance [32]. Deletion of these ubiquitination targets significantly reduces K48-ubiquitin decoration and improves intracellular bacterial persistence, confirming their role in antimicrobial defense [32]. This degron-mediated recognition strategy appears to be a conserved mechanism operating across phylogenetically diverse bacterial pathogens, representing a fundamental aspect of cell-autonomous immunity [32].

Figure 1: Host ubiquitin-mediated pathogen sensing mechanism. Host E3 ligase SCF(^{FBW7}), regulated by GSK3β, recognizes degron-like motifs on bacterial surface proteins, leading to K48-linked polyubiquitination and pathogen clearance.

Viral Manipulation of Host Ubiquitination

Viruses employ equally sophisticated strategies to manipulate the host ubiquitin system, though their compact genomes often necessitate multifunctional proteins that interface with multiple components of the ubiquitination machinery. The specificity in viral manipulation of ubiquitination is controlled through several mechanisms: substrate selection, lysine prioritization within substrates, and specific lysine linkages in polyubiquitin chains [28]. Viral proteins frequently exploit the diversity of ubiquitin chain topologies to achieve specific outcomes, with K48-linked chains typically targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains more often modulate signaling pathways and protein trafficking [28].