Decoding the Ubiquitinome: Proteomic Profiling of Ubiquitination Patterns in Cancer Pathogenesis and Therapy

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how mass spectrometry-based proteomics is revolutionizing our understanding of protein ubiquitination in cancer.

Decoding the Ubiquitinome: Proteomic Profiling of Ubiquitination Patterns in Cancer Pathogenesis and Therapy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how mass spectrometry-based proteomics is revolutionizing our understanding of protein ubiquitination in cancer. It explores the fundamental role of ubiquitination in regulating oncoproteins, tumor suppressors, and cancer-related pathways. The content details methodological advances for profiling the ubiquitinome, including enrichment strategies, linkage-specific analysis, and data interpretation. It also addresses key challenges in ubiquitination research and discusses the validation of ubiquitination events as biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current knowledge and future directions for exploiting the ubiquitin-proteasome system in oncology.

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: A Master Regulator in Cancer Biology

The Ubiquitination Enzymatic Cascade

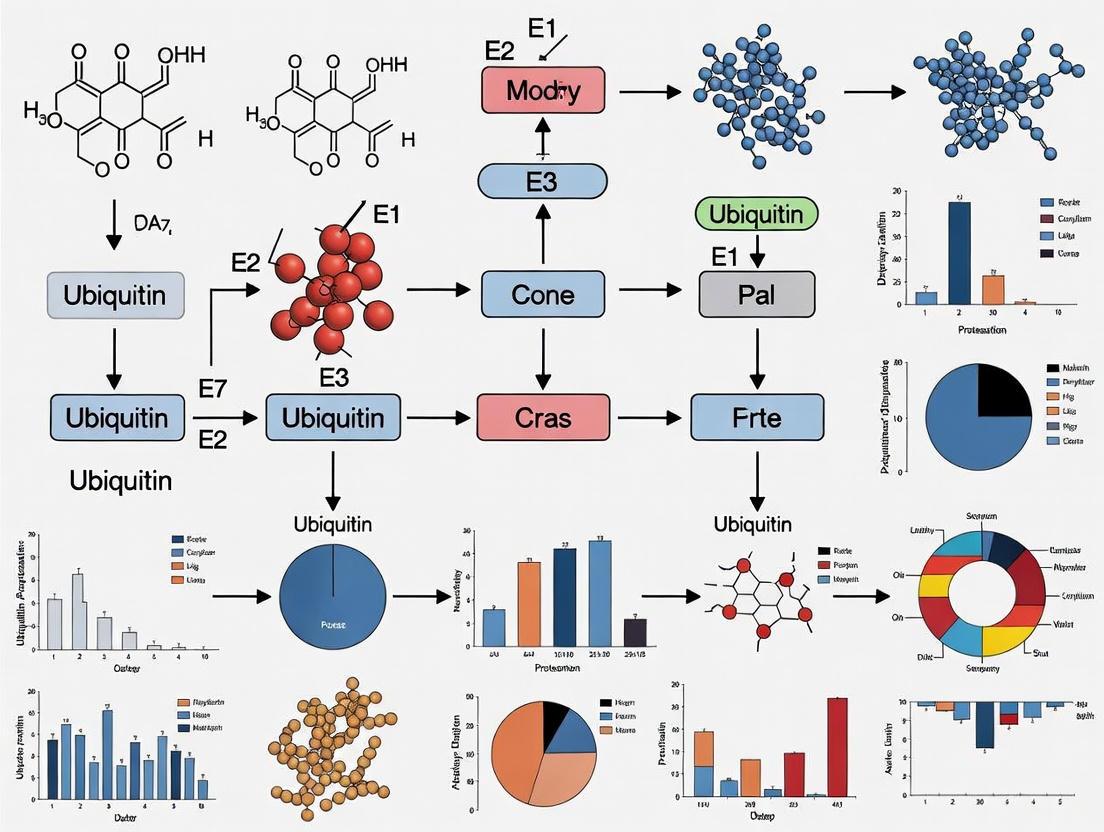

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification process that regulates virtually all aspects of eukaryotic cell biology [1]. This three-step enzymatic cascade results in the covalent attachment of ubiquitin, a 76-amino acid protein, to substrate proteins, thereby influencing their stability, activity, localization, and interactions [2] [3].

The process begins with activation, where the E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme utilizes ATP to form a high-energy thioester bond with the C-terminus of ubiquitin [3]. Subsequently, in the conjugation step, the activated ubiquitin is transferred to an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme [2]. Finally, in the ligation step, an E3 ubiquitin ligase facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to a specific lysine residue on the target substrate, forming an isopeptide bond [2] [3]. E3 ligases provide substrate specificity to the ubiquitination system, with humans possessing hundreds of different E3s compared to only two E1s and approximately thirty-five E2s [2] [3].

Table 1: Core Components of the Ubiquitination Cascade

| Component | Number in Humans | Key Function | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Activating Enzyme) | 2 [3] | Activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner | UBA1, UBA6 [3] |

| E2 (Conjugating Enzyme) | ~35 [3] | Accepts ubiquitin from E1 and cooperates with E3 for substrate transfer | UBC family [2] |

| E3 (Ligase) | >600 [2] | Confers substrate specificity and catalyzes ubiquitin transfer | HECT, RING, RBR types [2] |

The following diagram illustrates the sequential nature of the ubiquitination cascade:

The Complexity of Ubiquitin Signaling

Ubiquitination generates diverse signals through different modification types. Monoubiquitination (attachment of a single ubiquitin) and multi-monoubiquitination (multiple single ubiquitins on different lysines) primarily regulate endocytic trafficking, inflammation, and DNA repair [2] [3]. Polyubiquitination (chains of ubiquitin molecules) creates an extensive "ubiquitin code" where chain topology determines biological function [1].

Ubiquitin contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1) that can serve as linkage points for polyubiquitin chain formation [2] [1]. The K48-linked chains represent the most abundant ubiquitin linkage and primarily target substrates for proteasomal degradation [2]. K63-linked chains typically function in non-proteolytic processes including DNA damage repair, kinase activation, and inflammatory signaling [2]. Other linkage types (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, M1) constitute "atypical" chains with specialized functions in cell cycle regulation, innate immunity, and NF-κB signaling [2].

Table 2: Major Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Functions | Biological Processes Regulated |

|---|---|---|

| K48 | Proteasomal degradation [2] | Protein turnover, homeostasis [2] |

| K63 | Non-proteolytic signaling [2] | DNA repair, kinase activation, endocytosis [2] |

| K11 | Cell cycle regulation [2] | Mitotic progression, ER-associated degradation [2] |

| K27 | Innate immune response [2] | Mitochondrial quality control, antiviral signaling [2] |

| M1 (Linear) | NF-κB activation [2] [1] | Inflammatory signaling, immunity [2] |

The following diagram illustrates how different ubiquitin chain linkages determine specific functional outcomes:

Ubiquitination in Cancer and Targeted Protein Degradation

Dysregulation of the ubiquitin system contributes significantly to tumorigenesis, making it a promising therapeutic target [2] [1]. E3 ubiquitin ligases regulate various biological processes and cellular responses to stress signals associated with cancer development [2]. The ubiquitin-like protein Ubiquitin D (UBD), also known as FAT10, has emerged as a particularly important player in cancer biology [4] [5].

Recent pan-cancer analyses reveal that UBD is frequently overexpressed in 29 cancer types, with elevated expression correlated with poor prognosis and higher histological grades [4] [5]. UBD expression significantly correlates with tumor microenvironment features including immune infiltration, checkpoint expression, microsatellite instability (MSI), tumor mutational burden (TMB), and neoantigens [5]. Mechanistically, UBD engages key oncogenic pathways including NF-κB, Wnt, and SMAD2 signaling, interacting with downstream effectors such as MAD2, p53, and β-catenin to promote tumor survival, proliferation, invasion, and metastasis [5].

Table 3: UBD/FAT10 as a Cancer Biomarker: Pan-Cancer Analysis Findings

| Parameter | Finding | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Expression | Overexpressed in 29 cancer types [4] [5] | Potential diagnostic marker [4] [5] |

| Prognosis | Correlated with poor survival and higher histological grades [4] [5] | Prognostic biomarker [4] [5] |

| Genetic Alterations | Most common variation: gene amplification [5] | Patients with alterations show reduced overall survival [5] |

| Epigenetic Regulation | Reduced promoter methylation in 16 cancer types [5] | Potential epigenetic therapeutic target [5] |

| Immune Microenvironment | Correlated with immune infiltration, checkpoints, MSI, TMB [5] | Predictor of immunotherapy sensitivity [5] |

Experimental Protocol: In Vitro Ubiquitination Conjugation Reaction

The following detailed protocol enables researchers to investigate ubiquitination mechanisms in a controlled in vitro setting [6]. This approach can determine whether a specific protein is ubiquitinated, identify the type of ubiquitination (mono vs. poly), and characterize the required E2 and E3 enzymes [6].

Materials and Reagents

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitination Experiments

| Reagent | Stock Concentration | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| E1 Enzyme | 5 µM | Activates ubiquitin in ATP-dependent manner [6] |

| E2 Enzyme | 25 µM | Accepts ubiquitin from E1; determines chain topology [6] |

| E3 Ligase | 10 µM | Provides substrate specificity; catalyzes ubiquitin transfer [6] |

| 10X E3 Ligase Reaction Buffer | 500 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM TCEP | Maintains optimal pH and ionic strength; prevents disulfide formation [6] |

| Ubiquitin | 1.17 mM (10 mg/mL) | Substrate for modification cascade [6] |

| MgATP Solution | 100 mM | Energy source for E1-mediated ubiquitin activation [6] |

| Substrate Protein | 5-10 µM | Target protein for ubiquitination [6] |

Procedure for 25 µL Reaction

Reaction Setup: In a microcentrifuge tube, combine components in the following order to achieve indicated working concentrations [6]:

- dH₂O (to final volume of 25 µL)

- 10X E3 Ligase Reaction Buffer (2.5 µL for 1X final concentration)

- Ubiquitin (1 µL for ~100 µM final)

- MgATP Solution (2.5 µL for 10 mM final)

- Substrate Protein (volume adjusted for 5-10 µM final)

- E1 Enzyme (0.5 µL for 100 nM final)

- E2 Enzyme (1 µL for 1 µM final)

- E3 Ligase (volume adjusted for 1 µM final)

Note: For negative control, replace MgATP solution with equivalent volume of dH₂O [6].

Incubation: Incubate the reaction mixture in a 37°C water bath for 30-60 minutes [6].

Reaction Termination: Choose appropriate termination method based on downstream applications [6]:

- For SDS-PAGE analysis: Add 25 µL of 2X SDS-PAGE sample buffer

- For downstream enzymatic applications: Add 0.5 µL of 500 mM EDTA (20 mM final) or 1 µL of 1 M DTT (100 mM final)

Analysis: Separate reaction products by SDS-PAGE and analyze by:

- Coomassie blue staining to visualize total protein patterns

- Western blotting with anti-ubiquitin antibodies to confirm ubiquitination

- Western blotting with anti-substrate antibodies to verify substrate modification

- Western blotting with anti-E3 ligase antibodies to detect autoubiquitination

The following workflow diagram outlines the key experimental steps and analysis options:

Data Interpretation Guidelines

- Successful Ubiquitination: Appearance of higher molecular weight smears or discrete ladder patterns above the substrate band [6]

- Negative Control: Lack of higher molecular weight species in reactions without ATP [6]

- E3 Autoubiquitination: Detection of ubiquitinated E3 ligase in Western blots with anti-E3 antibodies [6]

- Substrate Specificity: Ubiquitination patterns dependent on specific E2-E3 combinations [6]

Concluding Perspectives

The ubiquitin system represents a complex regulatory network that extends far beyond its initial characterization as a simple degradation signal. Understanding the enzymatic cascade, diverse ubiquitin chain architectures, and their functional consequences provides critical insights into normal cellular physiology and disease pathogenesis, particularly in cancer [2] [1]. The experimental approaches outlined here, combined with emerging technologies such as PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) that harness the ubiquitin system for therapeutic purposes, continue to expand our ability to decipher and manipulate ubiquitin signaling in biomedical research [2].

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a crucial regulatory machinery for maintaining cellular protein homeostasis, primarily responsible for the specific recognition and degradation of proteins within eukaryotic cells [7]. The UPS process encompasses a sequential enzymatic cascade involving ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), ubiquitin ligases (E3), and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) [8]. Through ubiquitination and deubiquitination modifications, the UPS precisely controls the stability, localization, and activity of substrate proteins, thereby regulating fundamental cellular processes including cell cycle progression, apoptosis, DNA damage repair, and metabolic reprogramming [7] [8].

In carcinogenesis, dysregulation of UPS components leads to aberrant accumulation or degradation of oncoproteins and tumor suppressors, fundamentally contributing to tumor initiation, progression, and therapeutic resistance [7] [9]. This application note delineates the mechanistic insights into UPS dysregulation in cancer, provides experimental protocols for profiling ubiquitination patterns, and discusses emerging therapeutic strategies targeting the UPS, with particular emphasis on their application within proteomics-based cancer research.

Mechanistic Insights: UPS Dysregulation in Cancer

Dysregulation Patterns of Core UPS Components

Table 1: Dysregulation of UPS Components in Human Cancers

| UPS Component | Dysregulation Pattern | Cancer Type | Substrate/Pathway Affected | Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E3 Ligase MDM2 | Overexpression | Multiple Cancers | p53 degradation [9] | Uncontrolled tumor growth [9] |

| E3 Ligase RNF2 | Upregulation | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | H2A K119 monoubiquitination, E-cadherin repression [8] | Enhanced metastasis [8] |

| E3 Ligase Parkin | Dysregulated | Colorectal Cancer | PKM2 ubiquitination [8] | Altered glycolysis |

| E3 Ligase SPOP | Mutations/Inactivation | Prostate Cancer | FASN stabilization [10] | Enhanced lipogenesis |

| DUB USP22 | Overexpression | Pancreatic Cancer | Stabilizes DYRK1A [11] | Promotes proliferation |

| DUB USP28 | Upregulation | Pancreatic Cancer | Stabilizes FOXM1, activates Wnt/β-catenin [11] | Cell cycle progression, apoptosis inhibition |

| DUB USP21 | Overexpression | Pancreatic Cancer | Stabilizes TCF7 [11] | Maintains stemness |

| DUB USP9X | Context-dependent | Pancreatic Cancer | Hippo pathway (LATS kinase, YAP/TAZ) [11] | Dual roles (suppressor/promoter) |

| DUB OTUB2 | Upregulation | Colorectal Cancer | Inhibits PKM2 ubiquitination [8] | Enhanced glycolysis, progression |

| DUB BAP1 (UCH family) | Mutations | Mesothelioma, Melanoma | Multiple substrates [11] | "BAP1 cancer syndrome" |

Key Oncogenic Pathways Modulated by UPS Dysregulation

The dysregulation of E3 ligases and DUBs exerts profound effects on every hallmark of cancer by controlling the stability of key oncoproteins and tumor suppressors.

- Genome Instability and Proliferation: The well-characterized MDM2-p53 axis exemplifies UPS involvement in tumor suppression. MDM2, an E3 ligase, targets p53 for degradation; its overexpression leads to p53 inactivation, allowing uncontrolled proliferation [9]. Similarly, the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBE2T monoubiquitinates the histone variant γH2AX, inducing CHK1 phosphorylation and enhancing radioresistance in hepatocellular carcinoma [8].

- Metabolic Reprogramming: The UPS directly regulates cancer metabolic pathways, including the Warburg effect and lipid metabolism. For instance, the E3 ligase Parkin facilitates the ubiquitination of pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), while the DUB OTUB2 inhibits this process, enhancing glycolysis and accelerating colorectal cancer progression [8]. In lipid metabolism, the E3 ligase NEDD4 targets ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY), a key enzyme in lipogenesis, for degradation. Dysregulation of this process, such as through reduced ACLY acetylation, stabilizes ACLY and promotes lipid synthesis in lung cancer [10].

- Immunity and Tumor Microenvironment: Ubiquitination modifications critically influence immune checkpoint protein stability. For example, the DUB USP2 stabilizes PD-1, thereby promoting tumor immune escape [8]. Conversely, metastasis suppressor protein 1 (MTSS1) promotes the monoubiquitination of PD-L1 at K263, mediated by the E3 ligase AIP4, leading to PD-L1 internalization and lysosomal degradation, thus inhibiting immune escape in lung adenocarcinoma [8].

- Histone Modification and Epigenetics: The UPS functions as a crucial determinant of the epigenetic landscape in cancer. It regulates the state of chromatin by influencing histones and histone modifiers through both proteolytic and non-proteolytic means [12]. For instance, RNF2-mediated monoubiquitination of histone H2A at lysine 119 leads to transcriptional repression of E-cadherin, enhancing the metastatic potential of hepatocellular carcinoma [8].

Experimental Protocols: Profiling Ubiquitination in Cancer

Protocol 1: Ubiquitination Site Mapping via Mass Spectrometry

Objective: To identify and quantify specific lysine ubiquitination sites on proteins from cancer cell lines or tumor tissues.

Workflow:

Cell Lysis and Protein Extraction:

- Lyse cells or homogenize tissue samples in a denaturing lysis buffer (e.g., 8 M Urea, 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0) supplemented with protease inhibitors (e.g., 10 μM MG132) and DUB inhibitors (e.g., 10 mM N-Ethylmaleimide) to preserve ubiquitination states.

- Quantify protein concentration using a BCA assay.

Trypsin Digestion with Lysine Blocking:

- Reduce disulfide bonds with 5 mM DTT (30 min, 37°C) and alkylate with 15 mM Iodoacetamide (30 min, room temperature in the dark).

- Digest proteins with Lys-C (1:100 enzyme-to-protein ratio) for 4 hours at 30°C.

- Dilute the urea concentration to 2 M and continue digestion with trypsin (1:50 ratio) overnight at 37°C.

Ubiquitin Remnant Affinity Purification:

- Use anti-diGly remnant motif antibodies (e.g., K-ε-GG) conjugated to beads for immunoprecipitation.

- Incubate the digested peptides with the antibody beads for 2 hours at 4°C.

- Wash beads stringently to remove non-specifically bound peptides.

Mass Spectrometric Analysis:

- Elute the enriched ubiquitinated peptides from the beads.

- Desalt the peptides using C18 StageTips.

- Analyze by LC-MS/MS on a high-resolution instrument (e.g., Orbitrap Fusion Lumos).

- Use a data-dependent acquisition method with HCD fragmentation.

Data Processing and Bioinformatics:

- Search MS/MS data against a human protein database using software (e.g., MaxQuant) with the following parameters:

- Fixed modification: Carbamidomethyl (C)

- Variable modifications: Oxidation (M), Acetylation (Protein N-term), and GlyGly (K) for the ubiquitin remnant.

- Apply a false discovery rate (FDR) of <1% at both the peptide and protein levels.

- Use tools like Perseus for statistical analysis and visualization of differentially regulated ubiquitination sites.

- Search MS/MS data against a human protein database using software (e.g., MaxQuant) with the following parameters:

Protocol 2: Validation of E3 Ligase-DUB-Substrate Relationships

Objective: To validate the functional interaction between a specific E3 ligase or DUB and its putative substrate in a cancer context.

Workflow:

Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP):

- Transfect cells with plasmids expressing the E3/DUB (e.g., OTUB1 [13] or TRIM28 [13]) and the candidate substrate (e.g., MYC pathway components [13]).

- After 48 hours, lyse cells in a non-denaturing IP lysis buffer.

- Incubate the cell lysate with an antibody against the E3/DUB or the substrate. Use normal IgG as a control.

- Add Protein A/G beads to capture the antibody-protein complex.

- Wash beads and elute the bound proteins by boiling in SDS-PAGE loading buffer.

Western Blot Analysis:

- Separate the eluted proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a PVDF membrane.

- Probe the membrane with antibodies against the E3/DUB, the substrate, and ubiquitin (e.g., anti-polyubiquitin or anti-K48/K63-linkage specific antibodies) to assess co-precipitation and ubiquitination status.

Cycloheximide (CHX) Chase Assay:

- Treat cells (e.g., PANC-1 [11]) transfected with the E3/DUB or a control vector with CHX (50-100 μg/mL) to inhibit new protein synthesis.

- Harvest cells at different time points (e.g., 0, 2, 4, 8 hours).

- Analyze the protein levels of the substrate by Western blot to determine its half-life.

In Vivo Ubiquitination Assay:

- Co-transfect cells with plasmids for the substrate, HA- or Myc-tagged ubiquitin, and the E3 ligase or DUB.

- Treat cells with a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG132, 10 μM) for 4-6 hours before harvesting to accumulate ubiquitinated proteins.

- Lyse cells in a denaturing buffer (e.g., containing 1% SDS) and boil to dissociate protein complexes.

- Dilute the lysate and perform immunoprecipitation of the substrate.

- Detect poly-ubiquitinated forms of the substrate by Western blot using an anti-HA or anti-Myc antibody.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for UPS and Cancer Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Example | Function/Application | Key Feature/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib (BTZ), Carfilzomib [7] | Clinical PIs; induce ER stress & apoptosis in MM [7] | First-line therapy for Multiple Myeloma [7] |

| DUB Inhibitors | SIM0501 (USP1 inhibitor) [10] | Targeted DUB inhibitor for advanced solid tumors | FDA-approved for clinical trials [10] |

| E1 Enzyme Inhibitor | TAK-243 (MLN7243) | Inhibits ubiquitin activation | Broad-spectrum upstream inhibition |

| IAP Antagonists | LCL161 [10] | Induces TNF-dependent apoptosis | Enhances anti-tumor immune response [10] |

| PROTACs | ARV-110 (Bavdegalutamide), ARV-471 (Vepdegestrant) [8] | Targeted protein degradation; recruit E3 ligase to target | Phase II clinical trials [8] |

| Molecular Glues | CC-90009 [8] | Induces degradation of GSPT1 via CRL4CRBN | Phase II trials for leukemia [8] |

| Ubiquitin Mutation Plasmids | Ub(K48R), Ub(K63R) | Study specific ubiquitin chain linkage roles | K48: Proteasomal degradation; K63: Signaling |

| Activity-Based Probes | HA-Ub-VS, Cy5-Ub-PA | Label active DUBs and E1/E2 enzymes in complexes | Chemoproteomics applications |

| Critical Antibodies | Anti-K-ε-GG (diGly) [13] | Enrich ubiquitinated peptides for MS | Essential for ubiquitinomics |

| Anti-Polyubiquitin (linkage-specific) | Detect specific chain types in WB/IP | K48, K63, M1 (linear) | |

| Anti-OTUB1, Anti-TRIM28 [13] | Study specific UPS components | Validated in pancancer networks [13] |

Data Analysis & Visualization in Ubiquitinomics

Integrating proteomics data requires specialized bioinformatics pipelines. Key steps include:

- Differential Analysis: Identify ubiquitination sites significantly altered between experimental conditions (e.g., high-risk vs. low-risk ovarian cancer groups [14]).

- Pathway Enrichment: Utilize tools like GSEA to map ubiquitination targets to oncogenic pathways (e.g., MYC, oxidative phosphorylation [13]).

- Network Integration: Construct protein-protein interaction networks to visualize clusters of ubiquitination targets and identify key regulatory hubs [13] [14].

The precise dysregulation of E1, E2, E3 ligases, and DUBs constitutes a fundamental mechanism in carcinogenesis, impacting genomic stability, metabolism, immunity, and the epigenetic landscape. Modern proteomics and ubiquitinomics approaches provide powerful tools to map these alterations systematically. The continued development of targeted therapies, such as PROTACs and specific DUB inhibitors, underscores the immense translational potential of decoding the ubiquitin code in cancer. Integrating these molecular insights with robust experimental protocols will be pivotal for advancing diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic strategies in oncology.

Within the landscape of molecular oncology, the post-translational modification of proteins by ubiquitination serves as a critical regulatory mechanism controlling the stability and activity of key oncoproteins. Proteomics profiling of ubiquitination patterns in cancer research has unveiled complex regulatory networks that drive tumorigenesis [15] [8]. This application note examines the specific ubiquitination mechanisms governing two pivotal oncoproteins: c-Myc and Ras. Understanding these mechanisms provides fundamental insights into cancer cell proliferation, survival, and metabolic reprogramming, while also revealing potential therapeutic vulnerabilities. The aberrant stabilization of these oncoproteins through disrupted ubiquitination represents a common hallmark across diverse cancer types, making this area of research particularly compelling for drug development.

Ubiquitination and Stabilization of c-Myc in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

Mechanism of c-Myc Stabilization by 66CTG

The c-Myc oncoprotein functions as a master transcriptional regulator driving cell proliferation, metabolic reprogramming, and ribosome biogenesis. Its abnormal high expression is a hallmark of numerous malignancies, directly correlated with tumor invasion, metastasis, recurrence, and drug resistance [16]. Traditionally, c-Myc is regulated by the GSK-3β/FBW7α ubiquitination pathway, where phosphorylation by GSK-3β prompts FBW7α recognition, leading to c-Myc ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation [16].

Recent research has uncovered a novel mechanism in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), where the long non-coding RNA CDKN2B-AS1 encodes a 66-amino acid peptide called 66CTG that stabilizes c-Myc. This peptide competes with c-Myc for binding to the F-box protein FBW7α, thereby reducing c-Myc ubiquitination. Through "sacrificing" itself, 66CTG stabilizes c-Myc protein levels in cancer cells, enhancing Cyclin D1 transcription and enabling cancer cells to bypass the G1 phase restriction point, accelerating cell cycle progression and promoting tumor growth [16].

Table 1: Key Components in c-Myc Stabilization Pathway

| Component | Type | Function in Pathway | Effect on c-Myc |

|---|---|---|---|

| c-Myc | Transcription Factor | Drives cell proliferation & metabolism | Core regulatory target |

| FBW7α | E3 Ubiquitin Ligase | Recognizes & ubiquitinates phosphorylated c-Myc | Promotes degradation |

| GSK-3β | Kinase | Phosphorylates c-Myc for FBW7α recognition | Facilitates degradation |

| 66CTG | Regulatory Peptide | Competes with c-Myc for FBW7α binding | Prevents degradation, stabilizes protein |

| CDKN2B-AS1 | lncRNA | Encodes 66CTG peptide | Upstream regulator |

Experimental Protocol for Studying c-Myc Ubiquitination

Objective: To assess c-Myc ubiquitination and stabilization in response to 66CTG expression in triple-negative breast cancer models.

Materials and Reagents:

- Cell lines: TNBC cell lines (MDA-MB-231, BT-549)

- Plasmid constructs: CDKN2B-AS1 expression vector, 66CTG mutant constructs

- Antibodies: Anti-c-Myc, anti-ubiquitin, anti-FBW7α, anti-66CTG custom antibody

- Proteasome inhibitor: MG132

- Protein synthesis inhibitor: Cycloheximide

Methodology:

Cell Culture and Treatment:

- Maintain TNBC cell lines in appropriate media supplemented with 10% FBS.

- For serum starvation experiments, wash cells with PBS and culture in serum-free media for 12-16 hours.

- Treat cells with MG132 (10 μM) for 6 hours prior to harvesting to inhibit proteasomal degradation.

Gene Modulation:

- Transient transfection: Use lipofection method to introduce CDKN2B-AS1 expression vectors or siRNA targeting 66CTG.

- Generate stable knockdown cells using lentiviral shRNA constructs targeting CDKN2B-AS1.

Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) Assay:

- Lyse cells in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

- Pre-clear lysates with protein A/G beads for 30 minutes at 4°C.

- Incubate 500 μg of total protein with 2 μg of anti-c-Myc antibody overnight at 4°C.

- Add protein A/G beads and incubate for 2 hours at 4°C.

- Wash beads 3 times with lysis buffer and elute proteins with 2× Laemmli buffer.

Ubiquitination Detection:

- Resolve immunoprecipitated proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to PVDF membrane.

- Probe membrane with anti-ubiquitin antibody (1:1000) to detect ubiquitinated c-Myc.

- Reprobe membrane with anti-c-Myc antibody (1:2000) to confirm equal precipitation.

Protein Stability Assay:

- Treat cells with cycloheximide (100 μg/mL) to inhibit new protein synthesis.

- Harvest cells at 0, 30, 60, 120, and 240 minutes post-treatment.

- Analyze c-Myc protein levels by Western blotting and quantify by densitometry.

Functional Assays:

- Perform cell cycle analysis using propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry.

- Conduct cell proliferation assays using MTT or CCK-8 reagents.

Ras Ubiquitination and Its Impact on Signaling Dynamics

Dual Regulatory Mechanisms of Ras Ubiquitination

The Ras oncoprotein represents a critical signaling node transducing signals that control cell proliferation, differentiation, motility, and survival. Research has revealed that Ras ubiquitination occurs through distinct mechanisms with opposing functional consequences, creating a complex regulatory network [17] [18].

Activating Monoubiquitination: Site-specific monoubiquitination of Ras at primary lysine residues activates Ras by impeding GTPase-activating protein (GAP) function [18]. This modification has little effect on Ras GTP binding, intrinsic GTP hydrolysis, or exchange factor activation but severely abrogates the response to GAPs. This mechanism enables Ras to trigger persistent signaling without oncogenic mutations or receptor activation, representing a previously unrecognized pathway for Ras activation in cancer.

Inhibitory Polyubiquitination: In contrast, Rabex-5-mediated ubiquitination promotes Ras endosomal localization and suppresses ERK activation [17]. This process requires RIN1, a Ras effector, suggesting a feedback mechanism coupling Ras activation to subsequent ubiquitination and attenuation of signaling. This pathway defines essential elements in the regulatory circuitry linking Ras compartmentalization to signaling output.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Ras Ubiquitination Types

| Ubiquitination Type | Key Enzymes | Cellular Localization | Functional Outcome | Biological Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoubiquitination | Unknown E3 Ligase | Plasma Membrane | Ras Activation | Persistent signaling, tumor growth |

| Polyubiquitination | Rabex-5 (E3), RIN1 | Endosomal Compartments | Signal Suppression | Attenuated ERK activation |

| K63-Linked Polyubiquitination | Ubc13 (E2) | Various Membranes | Enhanced Signaling | Breast cancer metastasis |

Experimental Protocol for Analyzing Ras Ubiquitination

Objective: To characterize site-specific monoubiquitination of Ras and its functional consequences on GAP sensitivity.

Materials and Reagents:

- Purified Ras protein (wild-type and K-Ras mutants)

- Ubiquitination system: E1 enzyme, UbcH5 (E2), ubiquitin

- GTPase Activating Protein (GAP: p120GAP or NF1)

- Nucleotides: GTP, GDP, GTPγS

- NMR reagents: Deuterated buffers

Methodology:

In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay:

- Prepare reaction mixture containing: 50 nM E1, 100 nM E2 (UbcH5), 5 μM Ras, 10 μM ubiquitin in ubiquitination buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 2.5 mM MgCl₂, 0.5 mM DTT, 2 mM ATP).

- Incubate at 30°C for 2 hours.

- Stop reaction with SDS sample buffer and analyze by Western blotting with anti-Ras and anti-ubiquitin antibodies.

Chemical Ubiquitination of Ras (for Structural Studies):

- Express and purify recombinant Ras protein with a cysteine mutation at the desired site.

- Generate ubiquitin vinyl sulfone as the chemical modifier.

- Incubate Ras protein with ubiquitin vinyl sulfone in molar ratio 1:3 for 4 hours at room temperature.

- Purify ubiquitinated Ras using size exclusion chromatography.

NMR Spectroscopy Analysis:

- Prepare 15N-labeled Ras protein samples in NMR buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl₂, 50 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 10% D₂O).

- Collect 1H-15N HSQC spectra of unmodified and ubiquitinated Ras.

- Analyze chemical shift perturbations to identify structural changes upon ubiquitination.

GTPase Activity Measurements:

- Load Ras with [γ-32P]GTP by incubation in nucleotide exchange buffer.

- Monitor GTP hydrolysis by thin-layer chromatography at time points 0, 5, 15, and 30 minutes.

- For GAP sensitivity assays, add 10-100 nM GAP protein and measure acceleration of GTP hydrolysis.

Computational Modeling:

- Generate structural models of ubiquitinated Ras using molecular dynamics simulations.

- Analyze steric clashes between ubiquitin and GAP using docking simulations.

Cellular Localization Studies:

- Express GFP-tagged Ras constructs in HEK293 or cancer cells.

- Treat cells with EGF (100 ng/mL) to stimulate Ras activation.

- Fix cells and visualize Ras localization by confocal microscopy.

- Use image analysis software to quantify plasma membrane vs. endosomal distribution.

Proteomics Approaches for Ubiquitination Profiling

Advanced proteomics technologies have enabled comprehensive mapping of ubiquitination events in cancer tissues, providing systems-level insights into oncoprotein regulation.

Ubiquitin Remnant Profiling Protocol

Objective: To identify and quantify differentially regulated ubiquitination sites in primary versus metastatic colon adenocarcinoma tissues using K-ε-GG antibody-based enrichment.

Materials and Reagents:

- Tissue samples: Primary colon adenocarcinoma and matched metastatic tissues

- Lysis buffer: 8 M urea, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT, 1% protease inhibitor cocktail

- Trypsin: Sequencing grade modified trypsin

- Antibody: Anti-Lys-ε-Gly-Gly (K-ε-GG) remnant antibody beads (PTMScan Ubiquitin Remnant Motif Kit)

- HPLC system: Shimadzu LC20AD with C18 column

- Mass spectrometer: Q-Exactive HF X

Methodology:

Sample Preparation:

- Homogenize tissue samples in lysis buffer using a high-intensity ultrasonic processor.

- Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C and collect supernatant.

- Determine protein concentration using 2D Quant kit.

Protein Digestion:

- Reduce proteins with 10 mM DTT for 1 hour at 56°C.

- Alkylate with 30 mM iodoacetamide for 45 minutes at room temperature in darkness.

- Dilute samples with 100 mM NH₄HCO₃ to reduce urea concentration below 2 M.

- Digest with trypsin (1:50 ratio) overnight at 37°C, followed by second digestion (1:100 ratio) for 4 hours.

Peptide Fractionation:

- Desalt peptides using Strata-X C18 column.

- Fractionate peptides by high-pH reverse-phase HPLC into four fractions.

- Dry fractions by vacuum centrifugation.

Ubiquitinated Peptide Enrichment:

- Resuspend peptides in NETN buffer (100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5% NP-40, pH 8.0).

- Incubate with anti-K-ε-GG antibody beads overnight at 4°C with gentle shaking.

- Wash beads four times with NETN buffer and twice with H₂O.

- Elute bound peptides with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid.

LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Resuspend peptides in 0.1% formic acid and load onto trap column.

- Separate peptides on homemade nanocapillary C18 column (75 μm × 25 cm, 3 μm particles) using 5-35% acetonitrile gradient over 40 minutes.

- Analyze peptides using Q-Exactive HF X mass spectrometer in data-dependent acquisition mode.

- Set MS1 resolution to 60,000 and MS2 resolution to 30,000.

Data Processing:

- Process raw files using MaxQuant software (v1.5.2.8).

- Search against SwissProt Human database with reverse decoy.

- Set carbamidomethylation as fixed modification, and Gly-Gly modification on lysine and methionine oxidation as variable modifications.

- Set false discovery rate (FDR) to <1% for peptide identification.

Table 3: Proteomics Analysis of Ubiquitination in Colon Adenocarcinoma

| Sample Comparison | Differentially Modified Ubiquitination Sites | Upregulated Sites | Downregulated Sites | Key Pathways Enriched |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metastatic vs Primary Colon Adenocarcinoma | 375 sites on 341 proteins | 132 sites on 127 proteins | 243 sites on 214 proteins | RNA transport, Cell cycle |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Studying Oncoprotein Ubiquitination

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Application/Function |

|---|---|---|

| E3 Ligase Targets | FBW7α, Rabex-5, VHL | Recognize specific substrates and catalyze ubiquitin transfer |

| Deubiquitinases (DUBs) | OTUB2, USP2, CYLD | Remove ubiquitin marks, reverse ubiquitination |

| Ubiquitination Detection | Anti-K-ε-GG antibody, Ubiquitin remnant motif kit | Enrich and identify ubiquitinated peptides in proteomics |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG132, Bortezomib | Block proteasomal degradation to stabilize ubiquitinated proteins |

| Mass Spectrometry | Q-Exactive HF X, LC-MS/MS systems | Identify and quantify ubiquitination sites proteome-wide |

| PROTAC Molecules | ARV-110, ARV-471 | Induce targeted protein degradation via ubiquitin-proteasome system |

The intricate regulation of oncoproteins like c-Myc and Ras through ubiquitination represents a critical layer of control in cancer development and progression. The stabilization of c-Myc via the 66CTG-FBW7α axis in triple-negative breast cancer and the dual regulatory mechanisms of Ras monoubiquitination versus Rabex-5-mediated polyubiquitination exemplify the complexity of these pathways. Advanced proteomics approaches utilizing K-ε-GG antibody-based enrichment have enabled comprehensive mapping of ubiquitination events, revealing novel regulatory mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. These findings not only deepen our understanding of cancer biology but also pave the way for developing innovative therapeutic strategies targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome system, including PROTACs and molecular glues, for more effective cancer treatments.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a critical regulatory mechanism for cellular protein degradation, playing a fundamental role in maintaining cellular homeostasis. Ubiquitination, a pivotal post-translational modification, involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin molecules to target proteins, ultimately influencing their stability, activity, and localization [8]. This process is executed through a sequential enzymatic cascade involving ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), and ubiquitin-ligase (E3) enzymes [19] [8]. The specificity of substrate recognition is primarily determined by E3 ubiquitin ligases. Conversely, deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) can reverse this process, removing ubiquitin chains and stabilizing substrate proteins [8].

Dysregulation of the UPS is a hallmark of cancer, leading to the aberrant degradation of tumor suppressor proteins. Among the most critical tumor suppressors targeted by ubiquitination are p53 and PTEN. p53, often referred to as the "guardian of the genome," is a transcription factor that regulates cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, apoptosis, and senescence [20]. PTEN functions as a phosphatase that antagonizes the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, a key driver of cell metabolism, growth, proliferation, and survival [21]. The loss of these proteins through genetic mutation or accelerated degradation is a common event in numerous human malignancies, underscoring the importance of understanding their regulation by ubiquitination for developing novel cancer therapeutics.

Ubiquitination Mechanisms and Key Regulatory Factors

The Ubiquitination Cascade and p53 Regulation

The regulation of p53 stability is predominantly controlled by the E3 ubiquitin ligase MDM2. Under normal conditions, MDM2 binds to p53 and promotes its polyubiquitination, primarily through K48-linked chains, leading to proteasomal degradation and maintenance of low intracellular p53 levels [22] [20]. This process is tightly regulated; in response to genotoxic stress, post-translational modifications on both p53 and MDM2 disrupt their interaction, stabilizing p53 and activating its tumor-suppressive transcriptional programs [20]. MDM2 itself is an E3 ligase for p53, and its activity is modulated by interaction with its homolog, MDMX [22]. Beyond MDM2, other E3 ligases, including ARF-BP1, and various deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) also contribute to the fine-tuning of p53 stability [22].

A novel mechanism of p53 regulation involves competitive ubiquitination. The transcription factor ATF3 can act as an "ubiquitin trap" by binding directly to the RING domain of MDM2. This binding allows ATF3 to compete with p53 for MDM2-mediated ubiquitination. When ATF3 is ubiquitinated by MDM2, it reduces the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of p53, leading to p53 stabilization and activation in response to DNA damage. Cancer-derived mutants of ATF3 (e.g., R88G) that cannot be ubiquitinated fail to stabilize p53, highlighting the critical nature of this competitive mechanism for tumor suppression [23].

Consequences of PTEN Loss and Ubiquitination

PTEN loss is one of the most frequent events in cancer, observed in a high percentage of high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HG-PIN) lesions and advanced prostate cancers [21]. The conditional knockout of the Pten gene in mouse prostate epithelium rapidly leads to HG-PIN that progresses to invasive adenocarcinoma, closely mimicking the disease progression in humans [21]. While the canonical consequence of PTEN loss is hyperactivation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathway, recent proteomic and phosphoproteomic analyses of PTEN-deficient cells reveal a more complex landscape. PTEN deficiency induces widespread activation of tyrosine kinase signaling, including Src kinase and the receptor tyrosine kinase EphA2, suggesting that PTEN loss drives oncogenesis through both AKT-dependent and AKT-independent mechanisms [24].

Table 1: Key E3 Ligases and Regulatory Proteins for p53 and PTEN

| Target Protein | Regulatory Protein | Type | Function | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p53 | MDM2 | E3 Ubiquitin Ligase | Major negative regulator; promotes p53 polyubiquitination and degradation [22] [20]. | Binds p53; RING domain recruits E2 enzyme for ubiquitin transfer. |

| p53 | MDMX (MDM4) | Binding Partner / Regulator | Homolog of MDM2; forms heterodimers with MDM2 to enhance its E3 ligase activity towards p53 [22]. | Stabilizes a closed E2-Ub conformation to promote ubiquitin transfer. |

| p53 | ATF3 | Transcription Factor / Substrate | Acts as a competitive "ubiquitin trap" for MDM2 [23]. | Binds MDM2 RING domain; its ubiquitination spares p53 from degradation. |

| p53 | Various DUBs | Deubiquitinating Enzyme | Reverses p53 ubiquitination; can stabilize p53 (e.g., USP7/HAUSP) [22]. | Cleaves ubiquitin chains from p53. |

| PTEN | Unknown E3 Ligases | E3 Ubiquitin Ligase | Putative regulators of PTEN stability; specific identities less characterized than for p53. | Promotes PTEN ubiquitination, potentially affecting stability and localization. |

Experimental Protocols for Profiling Ubiquitination

Protocol: Affinity Enrichment and Proteomic Analysis of Ubiquitinated Proteins

This protocol outlines a robust method for the global identification and quantification of ubiquitination sites from tissue samples, adapted from studies on human colon adenocarcinoma tissues [19]. It utilizes an antibody specific for the di-glycine (K-ε-GG) remnant left on ubiquitinated lysine residues after tryptic digestion.

I. Sample Preparation and Protein Extraction

- Homogenization: Snap-frozen tissue samples (30-50 mg) are incubated in a urea-based lysis buffer (e.g., 8 M Urea, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT, 1% Protease Inhibitor Cocktail) on ice.

- Sonication: Sonicate the tissue slurry on ice using a high-intensity ultrasonic processor (e.g., 3 cycles of 10-second pulses with 15-second intervals).

- Clarification: Centrifuge the lysate at 12,000-20,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble debris.

- Protein Quantification: Collect the supernatant and determine protein concentration using a compatible assay kit (e.g., 2D Quant kit).

II. Trypsin Digestion and Peptide Cleanup

- Reduction and Alkylation: Reduce the protein extract with 10 mM DTT for 1 hour at 56°C. Alkylate with 30 mM iodoacetamide for 45 minutes at room temperature in darkness.

- Digestion: Dilute the sample with 100 mM NH₄HCO₃ to reduce the urea concentration below 2 M. Digest proteins first with trypsin (1:50 enzyme-to-protein ratio) overnight at 37°C, followed by a second digestion (1:100 ratio) for 4 hours.

- Desalting: Acidify peptides with 0.1% formic acid (FA) and load onto a C18 solid-phase extraction cartridge. Wash with 0.1% FA + 5% acetonitrile (ACN) and elute with 0.1% FA + 80% ACN. Dry the eluate using a vacuum concentrator.

III. High-pH Reverse-Phase Peptide Fractionation

- HPLC Setup: Reconstitute the dried peptides and fractionate using a Shimadzu LC20AD HPLC system equipped with a C18 column (5 μm particles, 10 mm ID, 250 mm length) with a high-pH mobile phase.

- Pooling: Combine the collected fractions based on UV chromatogram peaks to reduce complexity (e.g., into 4-6 pools). Dry the pooled fractions by vacuum centrifugation.

IV. Affinity Enrichment of K-ε-GG Peptides

- Incubation with Antibody Beads: Dissolve the dried peptide fractions in NETN buffer (100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5% NP-40, pH 8.0). Incubate with pre-washed anti-K-ε-GG antibody beads (e.g., from PTMScan Ubiquitin Remnant Motif Kit, Cell Signaling Technology) with gentle shaking overnight at 4°C.

- Washing: Wash the beads 4 times with NETN buffer and twice with HPLC-grade water to remove non-specifically bound peptides.

- Elution: Elute the bound K-ε-GG-modified peptides from the beads with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid.

- Final Cleanup: Desalt the eluted peptides using C18 ZipTips per the manufacturer's instructions. The peptides are now ready for LC-MS/MS analysis.

V. LC-MS/MS Analysis and Data Processing

- Liquid Chromatography: Separate the peptides using a UHPLC system (e.g., Thermo Scientific UltiMate 3000) with a C18 trap and analytical column. Use a gradient from 5% to 35% buffer B (98% ACN, 0.1% FA) over 45-60 minutes.

- Mass Spectrometry: Analyze the eluting peptides using a high-resolution tandem mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-Exactive HF-X) operating in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode. Key settings: MS1 resolution: 60,000; MS2 resolution: 30,000; top 15 most intense precursors for fragmentation.

- Database Search: Process the raw MS/MS data using search engines (e.g., MaxQuant) against the appropriate SwissProt database. Search parameters: Trypsin/P as enzyme, up to 2 missed cleavages, carbamidomethylation (C) as fixed modification, and oxidation (M) and GlyGly (K) as variable modifications. Set the false discovery rate (FDR) to <1% for protein and modification site identification.

Protocol: In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

This protocol is used to validate specific E3 ligase-substrate relationships, such as MDM2-mediated ubiquitination of p53 or ATF3 [23].

I. Reaction Setup

- Component Assembly: In a low-volume reaction tube (25 μl total volume), combine the following:

- In vitro translated (IVT) substrate protein (e.g., p53, ATF3) - 0.5 μl of IVT reaction.

- Recombinant E1 activating enzyme (e.g., 50 ng).

- Recombinant E2 conjugating enzyme (e.g., UbcH5a, 210 ng).

- Recombinant E3 ligase (e.g., GST-MDM2, 200 ng).

- Ubiquitin (5 μg).

- Energy regenerating components: 2 mM ATP, 5 mM MgCl₂, in a buffer of 40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 2 mM DTT.

- Optional Competition: To test competitive ubiquitination, include varying amounts of a potential competitor protein (e.g., recombinant ATF3).

II. Incubation and Termination

- Incubate the reaction mixture at 37°C for 90 minutes.

- Stop the reaction by adding SDS-loading buffer and boiling for 5 minutes.

III. Analysis

- Western Blotting: Resolve the reaction products by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a PVDF membrane.

- Detection: Probe the membrane with an antibody against the substrate protein (e.g., p53 or ATF3). A successful ubiquitination reaction will result in a characteristic laddering pattern, representing the substrate with multiple ubiquitin molecules attached, visible as higher molecular weight smears.

Table 2: Quantitative Ubiquitination Profiles in Cancer Models

| Study Model | Ubiquitination Change | Key Quantitative Findings | Downstream Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Colon Adenocarcinoma (Metastatic vs Primary) [19] | Global Ubiquitinome | 375 differentially regulated ubiquitination sites (341 proteins). 132 sites upregulated, 243 sites downregulated in metastasis. | Enrichment in RNA transport and cell cycle pathways; altered CDK1 ubiquitination speculated as pro-metastatic. |

| PTEN-KO Mouse Prostate Tumors [21] | Proteomic & Transcriptomic Signature | Overexpression signatures: inflammation/immune alterations, neutrophil/myeloid lineage features, chromatin/histones, nutrient transporters. | Key nodal activities through Akt, NF-κB, and p53 predicted; immune/inflammation changes dominate molecular landscape. |

| PTEN-Deficient Human Cells [24] | Phosphoproteomic & Tyrosine Kinase Signaling | Widespread activation of tyrosine kinases; Src-mediated upregulation of EphA2 receptor tyrosine kinase. | Dual AKT and Src inhibition synergistically suppresses tumor growth, overcoming resistance to AKT inhibition alone. |

Signaling Pathways and Therapeutic Targeting

Pathway Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitination Profiling and Functional Studies

| Reagent / Kit | Provider Examples | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-K-ε-GG Ubiquitin Remnant Motif Kit | Cell Signaling Technology | Immunoaffinity enrichment of tryptic peptides containing the di-glycine remnant for LC-MS/MS-based ubiquitinome profiling [19]. |

| Recombinant E1, E2 (UbcH5), E3 (MDM2) Enzymes | Boston Biochem, Sigma-Aldrich | Reconstitution of the ubiquitination cascade in vitro for mechanistic studies and validation of ligase-substrate relationships [23]. |

| Proteasome Inhibitor (MG132) | Selleck Chemicals, MilliporeSigma | Inhibits the 26S proteasome, blocking degradation of ubiquitinated proteins. Used to accumulate polyubiquitinated species in cells for detection [23]. |

| PTEN-Knockout Cell Models | ATCC, generated via CRISPR/Cas9 | Isogenic cell models to study the comprehensive proteomic and phosphoproteomic consequences of PTEN loss and identify therapeutic vulnerabilities [24]. |

| AKT and Src Inhibitors (Capivasertib, Dasatinib) | AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb | FDA-approved small molecule inhibitors used in combination to test synthetic lethality in PTEN-deficient cancer models [24]. |

Discussion and Application in Cancer Research

The intricate ubiquitination networks governing p53 and PTEN stability represent a central node in cancer biology. Proteomic profiling, as outlined in the provided protocols, has been instrumental in moving beyond canonical pathways. For instance, in PTEN-deficient cancers, these approaches revealed a critical co-dependency on Src kinase signaling, explaining the limited efficacy of AKT inhibitors alone and paving the way for rational combination therapies [24]. Similarly, the discovery of non-canonical regulatory mechanisms, such as ATF3-mediated competitive trapping of MDM2, adds a new layer of complexity to the p53 regulatory network and opens novel avenues for therapeutic intervention [23].

From a drug development perspective, the UPS is a rich source of targets. While restoring the function of lost tumor suppressors like p53 and PTEN has been historically challenging, emerging strategies are showing promise. These include PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) and molecular glues that leverage the UPS to degrade oncogenic proteins, and small molecules that disrupt the p53-MDM2 interaction or inhibit oncogenic DUBs [8] [20]. The quantitative ubiquitination data generated from experiments like those described herein are crucial for identifying new druggable components within these pathways, validating the mechanism of action of new compounds, and discovering biomarkers for patient stratification. Integrating ubiquitinome profiling with other omics datasets will provide a systems-level understanding of how ubiquitination rewires signaling networks in cancer, ultimately accelerating the development of novel targeted therapies.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a crucial post-translational modification mechanism that governs the stability, activity, and localization of proteins involved in fundamental cellular processes. In cancer research, profiling ubiquitination patterns provides critical insights into the molecular mechanisms driving tumorigenesis. Ubiquitination involves a sequential enzymatic cascade comprising E1 activating, E2 conjugating, and E3 ligating enzymes, which culminate in the attachment of ubiquitin chains to substrate proteins [25] [26]. The specificity of this process is largely determined by E3 ubiquitin ligases, which recognize target substrates, while deubiquitinases (DUBs) reverse this modification by removing ubiquitin chains [25]. Dysregulation of this delicate equilibrium results in aberrant degradation or stabilization of oncoproteins and tumor suppressors, directly contributing to the acquisition of cancer hallmarks such as sustained proliferation, genomic instability, and metabolic reprogramming [25] [27] [26]. This Application Note outlines experimental frameworks for investigating ubiquitination in key cancer hallmarks, providing methodologies for proteomic profiling and functional validation.

Ubiquitination in Cell Cycle Regulation

Key Mechanisms and Experimental Analysis

Cell cycle progression is predominantly controlled by the timed degradation of key regulatory proteins via ubiquitination. Two multi-subunit E3 ligase complexes, the Anaphase-Promoting Complex/Cyclosome (APC/C) and the Skp1-Cul1-F-box (SCF) complex, are master regulators of cell cycle transitions [25] [28]. The APC/C, activated by its cofactors CDC20 and CDH1, targets mitotic cyclins and securing for degradation to facilitate mitotic exit and G1 maintenance [28]. Conversely, the SCF complex, which utilizes variable F-box proteins to recognize specific substrates, governs the degradation of G1/S regulators, enabling cell cycle commitment [28].

Table 1: Key Ubiquitination Targets in Cell Cycle Regulation

| Target Protein | Function | Regulating E3 Ligase | Ubiquitin Chain Type | Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclin B1 | Mitotic progression | APC/CCDC20 | K11-linked | Promotes metaphase-to-anaphase transition [28] |

| p27Kip1 | CDK inhibitor | SCFSKP2 | K48-linked | Facilitates G1/S transition [25] [28] |

| Cyclin D1 | G1 progression | SCFFBXW7/APC/CCDH1 | K48-linked | Regulates G1 phase duration [25] |

| Wee1 | G2/M checkpoint kinase | APC/CCDH1/SCFβ-TrCP | K48-linked | Promotes mitotic entry [25] |

Figure 1: Ubiquitination regulates key cell cycle transitions. The SCF and APC/C E3 complexes trigger the degradation of specific proteins to drive unidirectional cell cycle progression.

Protocol: Co-immunoprecipitation for Analyzing E3-Substrate Interactions

Objective: To validate the interaction between a specific E3 ubiquitin ligase and its putative cell cycle substrate.

Materials:

- Plasmids: HA-Ubiquitin, Flag-tagged E3 ligase, Myc-tagged substrate (e.g., cyclin or CKI)

- Antibodies: Anti-Flag M2 Affinity Gel (Sigma, A2220), anti-Myc antibody (Cell Signaling, 2276S), anti-HA antibody (Cell Signaling, 3724S)

- Cell Line: HEK293T or relevant cancer cell line

- Proteasome Inhibitor: MG132 (Cayman Chemical, 10012628)

Procedure:

- Transfection: Seed HEK293T cells in a 6-well plate. At 60-70% confluency, co-transfect with plasmids encoding Flag-E3, Myc-substrate, and HA-Ubiquitin using a standard transfection reagent.

- Inhibition: 24-48 hours post-transfection, treat cells with 10 μM MG132 for 4-6 hours before harvesting to prevent substrate degradation.

- Lysis: Harvest cells using ice-cold IP Lysis Buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate 500 μg of total protein lysate with 20 μL of anti-Flag M2 agarose beads overnight at 4°C with gentle rotation.

- Washing: Wash beads 3-4 times with ice-cold lysis buffer.

- Elution & Analysis: Elute bound proteins by boiling in 2X Laemmli buffer. Analyze the immunoprecipitates and total cell lysates by Western blotting using anti-Myc (substrate) and anti-HA (ubiquitin) antibodies.

Ubiquitination in DNA Damage Response (DDR)

Signaling and Repair Pathway Choice

Ubiquitination plays an instrumental role in the DNA damage response (DDR), particularly in the signaling and repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). A well-characterized ubiquitination cascade initiated by the E3 ligases RNF8 and RNF168 establishes a platform at DNA damage sites that recruits repair factors [27] [29]. This cascade modulates the choice between the two primary DSB repair pathways: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR) [29]. The RNF8-RNF168 axis promotes the accumulation of K48- and K63-linked ubiquitin chains on histones H2A and H2AX, creating a binding site for 53BP1, which favors NHEJ [29]. In contrast, during the S/G2 phases, HR is promoted by BRCA1, which can displace 53BP1, a process regulated by competing ubiquitination and acetylation events on histone H2A [29].

Table 2: Ubiquitination Enzymes and Targets in DNA Damage Response

| Ubiquitin Enzyme | Target Protein/Pathway | Function in DDR | Impact on Repair Choice |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNF8 | Histone H2A/H2AX | Initiates ubiquitin cascade at DSBs [29] | Recruitment platform for 53BP1/BRCA1 |

| RNF168 | Histone H2A/H2AX | Amplifies ubiquitin signaling [27] [29] | Stabilizes 53BP1 focus formation (NHEJ) |

| BRCA1/BARD1 | - | E3 ligase complex [29] | Promotes HR, antagonizes 53BP1 |

| VHL | HIF-1α (Indirect) | Degrades HIF-1α [27] | Affects genomic stability under hypoxia |

Figure 2: The ubiquitination cascade dictates DNA repair pathway choice. Following a DSB, the RNF8/RNF168 axis recruits 53BP1 to favor NHEJ in G1 or BRCA1 to favor HR in S/G2.

Protocol: Immunofluorescence for Monitoring Ubiquitin Foci at DSB Sites

Objective: To visualize and quantify the formation of ubiquitin conjugates at sites of DNA double-strand breaks.

Materials:

- Antibodies: Anti-γH2AX (phospho S139) antibody (Millipore, 05-636), Anti-K63-Ubiquitin (Abcam, ab179434), Secondary antibodies conjugated with different fluorophores

- Cell Line: U2OS or other adherent cell line

- DSB Inducer: Neocarzinostatin (NCS) (Sigma, N9162)

- Microscopy: Confocal microscope

Procedure:

- Induction of DSBs: Seed cells on glass coverslips in a 12-well plate. At 60-70% confluency, treat cells with 100-500 ng/mL NCS for 1 hour to induce DSBs.

- Fixation and Permeabilization: Rinse cells with PBS and fix with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature. Permeabilize cells with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes.

- Immunostaining: Incubate cells with a blocking solution (3% BSA in PBS) for 1 hour. Incubate with primary antibodies (anti-γH2AX and anti-K63-Ubiquitin) diluted in blocking solution overnight at 4°C.

- Detection: The next day, wash coverslips and incubate with appropriate fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark. Counterstain nuclei with DAPI.

- Imaging and Analysis: Mount coverslips and image using a confocal microscope. Co-localization of γH2AX (DSB marker) and K63-ubiquitin foci indicates active ubiquitin signaling at DNA damage sites.

Ubiquitination in Cancer Metabolism

Regulation of Metabolic Reprogramming

Cancer cells undergo metabolic reprogramming to meet the energetic and biosynthetic demands of rapid proliferation, a process heavily influenced by ubiquitination. Key enzymes in glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and other metabolic pathways are regulated by specific E3 ligases, affecting their stability, localization, and activity [27] [26]. For instance, the glycolytic enzyme HK2 is stabilized by K63-linked ubiquitination by HUWE1, enhancing aerobic glycolysis and tumorigenesis [27]. Conversely, the E3 ligase TRIM21 mediates the degradation of PFK1, and its downregulation in some cancers leads to glycolytic upregulation [27]. Furthermore, central metabolic regulators like mTORC1 are controlled by ubiquitination; K63-linked ubiquitination by TRAF6 promotes mTORC1 activation and anabolic metabolism [26].

Table 3: Ubiquitination Targets in Cancer Metabolic Pathways

| Metabolic Enzyme/Regulator | Regulating E3 Ligase/DUB | Type of Modification | Effect on Cancer Metabolism |

|---|---|---|---|

| HK2 (Hexokinase 2) | HUWE1, TRAF6 | K63-linked ubiquitination [27] | Enhances glycolysis, promotes tumor growth |

| PFK1 (Phosphofructokinase) | TRIM21, A20 | K48-linked ubiquitination [27] | Downregulation increases glycolytic flux |

| PKM2 (Pyruvate Kinase M2) | TRIM58, Parkin | K48-linked ubiquitination [27] | Stabilization promotes Warburg effect |

| mTOR | TRAF6, FBXW7 | K63-/K48-linked ubiquitination [26] | Regulates activation and stability of mTORC1 |

Figure 3: Ubiquitination regulates key rate-limiting enzymes in the glycolytic pathway. E3 ligases can either activate (via K63-Ub) or target for degradation (via K48-Ub) glycolytic enzymes to modulate metabolic flux in cancer cells.

Protocol: Glycolytic Rate Measurement Following E3 Ligase Inhibition

Objective: To functionally assess the impact of a specific E3 ligase on cellular glycolytic metabolism.

Materials:

- Extracellular Flux Analyzer: Seahorse XF96 Analyzer (Agilent)

- Inhibitor: Small-molecule inhibitor of the target E3 ligase or siRNA for knockdown

- Seahorse Kits: XF Glycolysis Stress Test Kit (Agilent, 103020-100)

- Cell Line: Cancer cell line of interest

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Seed cells in XF96 cell culture microplates at an optimal density (e.g., 20,000-40,000 cells/well) and culture for 24 hours.

- Ligase Modulation: Treat cells with the E3 ligase inhibitor or corresponding siRNA for 24-48 hours. Include DMSO or scrambled siRNA controls.

- Assay Preparation: On the day of the assay, replace growth medium with XF Base Medium (supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine) and incubate cells in a non-CO2 incubator for 1 hour.

- Glycolysis Stress Test: Using the Seahorse XF Analyzer, sequentially inject:

- Port A: 10 mM Glucose

- Port B: 1 μM Oligomycin

- Port C: 50 mM 2-Deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG)

- Data Analysis: Calculate key parameters from the recorded extracellular acidification rate (ECAR): Glycolysis (after glucose injection), Glycolytic Capacity (after oligomycin), and Glycolytic Reserve.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Ubiquitination and Cancer Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Product (Supplier) |

|---|---|---|

| MG132 Proteasome Inhibitor | Blocks proteasomal degradation, stabilizes ubiquitinated proteins for detection. | MG132 (Cayman Chemical, 10012628) |

| HA-Ubiquitin Plasmid | Epitope-tagged ubiquitin for overexpression and pulldown of ubiquitinated proteins. | pRK5-HA-Ubiquitin (Addgene, 17608) |

| TUBE (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entity) | Affinity resin to enrich for polyubiquitinated proteins from cell lysates. | TUBE1 (LifeSensors, UM401) |

| K-ε-GG Motif Antibody | Immunoenrichment of ubiquitinated peptides for mass spectrometry-based ubiquitinomics. | Anti-K-ε-GG Ubiquitin Remnant Motif Antibody (Cell Signaling, 5562) |

| siRNA/E3 Ligase Inhibitors | To knock down or chemically inhibit specific E3 ligases for functional studies. | Custom siRNA pools (Dharmacon) |

| Deubiquitinase (DUB) Inhibitors | To inhibit DUB activity and study stabilized ubiquitination events. | PR-619 (Broad-spectrum DUB inhibitor, Sigma, 662141) |

Ubiquitination serves as a central regulatory mechanism intersecting the core cancer hallmarks of unchecked cell cycle progression, dysregulated DNA damage response, and metabolic reprogramming. The experimental protocols and analytical frameworks outlined in this Application Note provide a foundation for researchers to profile ubiquitination patterns, validate specific E3 ligase-substrate relationships, and assess functional consequences in cancer models. A deep understanding of the "ubiquitin code" in these processes not only elucidates tumor biology but also opens avenues for novel therapeutic strategies, including the development of targeted protein degraders and specific E3 ligase modulators. Integrating ubiquitinomic profiling with functional assays is paramount for advancing predictive diagnostics and personalized cancer treatment.

Cutting-Edge Proteomic Methodologies for Ubiquitinome Profiling

Protein ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification (PTM) that regulates diverse cellular processes, including proteasomal degradation, DNA damage repair, and immune responses [30]. The dysregulation of ubiquitination signaling networks is deeply implicated in tumorigenesis, influencing tumor metabolism, the immunological tumor microenvironment, and cancer stem cell stemness [30]. Consequently, profiling ubiquitination patterns provides a powerful approach for uncovering novel therapeutic targets and biomarkers in cancer research.

A breakthrough in ubiquitinomics was the development of antibodies specifically recognizing the di-glycine (K-ε-GG) remnant left on lysine residues after tryptic digestion of ubiquitylated proteins [31]. This innovation, coupled with advanced mass spectrometry (MS), enables the systematic identification and quantification of thousands of endogenous ubiquitination sites from complex biological samples [32] [15]. This Application Note details refined protocols and applications of K-ε-GG remnant antibody profiling, providing a structured framework for implementing this technology in cancer proteomics.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential reagents and tools for conducting K-ε-GG remnant profiling experiments.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for K-ε-GG Remnant Profiling

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| K-ε-GG Motif Antibody | Immunoaffinity enrichment of ubiquitinated peptides from complex digests. | PTMScan Ubiquitin Remnant Motif Kit; central to all protocols [33]. |

| Automation Platform | High-throughput, reproducible bead handling and peptide enrichment. | KingFisher Apex/Flex (bead-handler); AssayMAP Bravo (hybrid platform) [33]. |

| Isobaric Label Reagents | Multiplexed quantitative comparison of ubiquitylation sites across samples. | Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) reagents; used in on-antibody labeling protocols [31]. |

| Fractionation Methods | Pre-fractionation to reduce sample complexity and increase depth of analysis. | High-pH reversed-phase chromatography [32]. |

| Advanced MS Add-ons | Improves quantitative accuracy for PTM analysis in complex samples. | High-field Asymmetric Waveform Ion Mobility Spectrometry (FAIMS) [31]. |

Performance Metrics and Quantitative Data

Optimized K-ε-GG antibody workflows enable deep-scale ubiquitinome profiling. The table below summarizes typical performance data from published studies, which can be used for benchmarking.

Table 2: Representative Performance Data from Ubiquitin Profiling Studies

| Experimental Method / Context | Sample Input | Ubiquitination Sites Identified | Key Enabling Factors | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refined SILAC Workflow | Moderate protein input | ~20,000 sites | Optimized antibody input, cross-linking, off-line fractionation [32]. | [32] |

| UbiFast (On-Antibody TMT) | 500 μg peptide per sample (tissue) | ~10,000 sites | On-antibody TMT labeling, FAIMS, no need for pre-fractionation [31]. | [31] |

| Label-Free in Sigmoid Cancer | Human tissue samples | 1,249 sites within 608 proteins | PTMScan-based enrichment, LC-MS/MS, bioinformatics analysis [34]. | [34] |

| On- vs. In-Solution TMT | 1 mg Jurkat peptide | On-Antibody: 6,087 PSMs; In-Solution: 1,255 PSMs | Protection of K-ε-GG remnant during on-bead labeling [31]. | [31] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Core Manual Enrichment Protocol for Ubiquitinated Peptides

This protocol is adapted from methods used in sigmoid colon cancer ubiquitinome analysis and other large-scale studies [34] [15].

Step 1: Protein Extraction and Digestion

- Homogenize tissue or lyse cells in an appropriate denaturing buffer (e.g., SDS-based).

- Reduce disulfide bonds with dithiothreitol (DTT) and alkylate with iodoacetamide.

- Digest proteins to peptides using sequence-grade trypsin at a 1:50 (w/w) enzyme-to-protein ratio for 12-16 hours at 37°C.

Step 2: Peptide Clean-up and Desalting

- Acidify the digested peptide mixture to pH < 3 using trifluoroacetic acid (TFA).

- Desalt peptides using C18 solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges or columns.

- Lyophilize the eluted peptides and reconstitute in immunoaffinity purification (IAP) buffer.

Step 3: Immunoaffinity Enrichment (IAP) with K-ε-GG Antibody

- Incubate the peptide solution with the anti-K-ε-GG antibody conjugated to magnetic beads for 1-2 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation. The antibody-to-peptide ratio should be optimized [32].

- Pellet the beads using a magnetic rack and carefully remove the supernatant.

- Wash the beads multiple times with cold IAP buffer, followed by a final wash with water to remove residual salts and non-specifically bound peptides.

Step 4: Peptide Elution and Preparation for MS

- Elute the enriched K-ε-GG peptides from the antibody-bead complex using a diluted acid solution (e.g., 0.15% TFA).

- Desalt the eluted peptides using C18 StageTips or micro-columns.

- Lyophilize and reconstitute in a suitable MS injection solvent (e.g., 0.1% formic acid).

Automated High-Throughput Protocol Using KingFisher Apex

Automation significantly improves reproducibility and throughput [33].

Key Setup:

- Use the PTMScan HS Ubiquitin/SUMO Remnant Motif (K-ε-GG) Kit.

- Distribute magnetic beads, peptide samples (in IAP buffer), and wash/elution buffers across a 96-well plate according to the KingFisher Apex requirements.

Automated Enrichment:

- Load the plate onto the KingFisher Apex system.

- Run an automated protocol that sequentially mixes beads with samples for incubation, moves beads magnetically through a series of wash wells, and finally elutes the bound peptides into a collection plate.

- The total processing time is significantly reduced compared to manual protocols, with minimal user intervention.

Post-Processing:

- Desalt the eluted peptides and proceed directly to LC-MS analysis. Comparative data shows this automated workflow performs as well as, or better than, manual enrichment in terms of PTM peptide recovery and reproducibility [33].

Advanced Multiplexed Quantification: UbiFast Protocol

The UbiFast method allows for highly sensitive, multiplexed quantification of ubiquitylation sites, ideal for translational research with limited sample [31].

Step 1: Sample Preparation and Individual Enrichment

- Digest protein extracts from up to 10 different conditions (e.g., cell lines, treated vs. untreated tumors) individually.

- For each sample, enrich for K-ε-GG peptides using the core manual or automated protocol described above. Do not elute peptides.

Step 2: On-Antibody TMT Labeling

- While the K-ε-GG peptides are still bound to the antibody beads, resuspend the beads in a solution containing a unique TMT10plex or TMT11plex reagent.

- Incubate for 10 minutes to label the N-termini and lysine side chains of the enriched peptides. The di-glycine remnant is protected from derivatization by the antibody [31].

- Quench the reaction with 5% hydroxylamine.

Step 3: Peptide Pooling and Clean-up

- Combine the TMT-labeled samples from all conditions into a single tube. Since the samples are now multiplexed, they can be eluted from the beads as one pooled sample.

- Desalt the pooled peptide sample.

Step 4: LC-MS Analysis with FAIMS

- Analyze the sample by single-shot LC-MS/MS on an instrument equipped with a FAIMS device. The use of FAIMS improves quantitative accuracy by reducing background chemical noise [31].

- This entire workflow, from enriched peptides to ready-to-run sample, can be completed in approximately 5 hours.

Data Analysis and Biological Interpretation

Following LC-MS/MS, database searching identifies peptides and their corresponding ubiquitination sites. Label-free or isobaric tag-based quantification (LFQ/TMT) is used to determine abundance changes. Subsequent bioinformatics analysis is critical for biological insight:

- Pathway Analysis: Tools like KEGG and Gene Ontology (GO) can reveal ubiquitination-regulated pathways. In sigmoid colon cancer, this included glycolysis/gluconeogenesis and ferroptosis [34].

- Network Analysis: Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks can highlight co-expressed, differentially ubiquitinated proteins [34].

- Integration with Transcriptomics/Proteomics: Correlating ubiquitination levels (DUPs) with gene (DEGs) and protein (DEPs) expression data can reveal complex regulatory models and potential biomarkers [34].

- Survival Analysis: Linking the expression of genes encoding DUPs to patient overall survival (e.g., via TCGA data) can identify prognostically relevant ubiquitination events [34].

Visualizing Workflows and Pathways

Experimental Workflow for UbiFast

(Diagram 1: UbiFast method for multiplexed ubiquitinome profiling)

Ubiquitination's Role in Cancer Signaling

(Diagram 2: Ubiquitination mechanisms in cancer pathogenesis)

In the field of cancer research, understanding the complex dynamics of protein regulation is paramount. Protein ubiquitylation, a key post-translational modification, involves the attachment of ubiquitin to substrate proteins, regulating a plethora of cellular processes including protein degradation, cell cycle progression, and signal transduction [31]. Dysregulation of ubiquitylation pathways has been strongly implicated in oncogenesis, cancer progression, and metastasis [31]. To systematically study these processes, researchers employ various tagging approaches that allow for the purification, detection, and quantification of ubiquitinated proteins. His tags, Strep tags, and epitope tags (such as V5 and HA) represent crucial biological tools that enable precise interrogation of ubiquitination patterns within cancer models. These tags function as universal epitopes, genetically engineered onto recombinant proteins, and are readily detected by commercially available antibodies or other binding molecules without typically compromising the native structure or function of the protein [35]. The integration of these tagging approaches with advanced mass spectrometry techniques has revolutionized our ability to profile ubiquitination patterns in cancer, providing insights that could lead to novel therapeutic strategies.

Tag Characteristics and Selection Criteria

Comparative Analysis of Common Tags

Selecting the appropriate tag for studying ubiquitylation in cancer research requires careful consideration of multiple biochemical and experimental factors. The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of the most commonly used tags in proteomics studies:

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Affinity Tags Used in Ubiquitylation Studies

| Tag Name | Length (Sequence) | Source/Origin | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Important Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| His | H-H-H-H-H-H (6xHis) | Synthetic | Protein purification via IMAC | Most common purification tag; works under denaturing conditions; regenerable affinity matrix [35] | Nonspecific binding to endogenous histidine-rich proteins; requires controlled imidazole conditions [36] |

| Strep-tag II | WSHPQFEK or AWAHPQPGG | Synthetic | Protein purification | Regenerable affinity matrix; compatible with anaerobic conditions [35] | Lower binding capacity compared to His-tag systems |

| V5 | GKPIPNPLLGLDST (14 aa) | Simian virus 5 RNA polymerase α-subunit [37] | Immunoassays, membrane protein studies | Low hydrophilicity ideal for membrane proteins; high-affinity antibodies available (~20 pM) [37] [35] | Potential cross-reactivity in mammalian systems [35] |

| HA | YPYDVPDYA (9 aa) | Human influenza hemagglutinin [35] | Immunoassays, affinity purification | Strong immunoreactive epitope; mild elution conditions for purification [35] | Cleaved by Caspase-3/7 during apoptosis, losing immunoreactivity [35] |

| FLAG | DYKDDDDK (8 aa) | Synthetic [35] | Protein purification, immunoassays | Hydrophilic; contains internal enterokinase cleavage site [35] | May require specific proteases for tag removal |

| c-Myc | EQKLISEEDL (10 aa) | Human c-Myc protein [35] | Immunoassays | Well-characterized for various immunoassays | Not recommended for affinity purification due to harsh elution conditions [35] |

Strategic Selection for Cancer Ubiquitylation Studies

When investigating ubiquitination patterns in cancer research, tag selection must align with specific experimental goals and constraints. For purification applications in cancer proteomics, the His-tag remains the most practical choice due to its robust performance under various buffer conditions, including those containing chaotropes like 8M urea, which is particularly valuable when purifying proteins from inclusion bodies [36]. The Strep-tag II offers an excellent alternative when working under anaerobic conditions or when higher specificity is required [35]. For detection and imaging applications in cancer models, epitope tags such as V5 and HA provide superior performance. The V5 tag is particularly valuable for studying membrane-bound proteins like chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) in cancer immunotherapy research due to its low hydrophilicity, which minimizes interference with membrane integration [37]. When designing experiments for cancer tissue analysis, researchers must consider tag immunogenicity and background signals, especially in mouse models where humanized antibodies such as hu_SV5-Pk1 can significantly reduce cross-reactivity and improve signal-to-noise ratios in immunohistochemistry [37].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

His-Tagged Protein Purification via Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC)