Decoding Tissue-Specific Ubiquitination Patterns: A Pan-Cancer Analysis for Biomarker Discovery and Therapeutic Targeting

This comprehensive review synthesizes cutting-edge research on tissue-specific ubiquitination patterns across cancer types, exploring their profound implications for tumor biology and clinical practice.

Decoding Tissue-Specific Ubiquitination Patterns: A Pan-Cancer Analysis for Biomarker Discovery and Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This comprehensive review synthesizes cutting-edge research on tissue-specific ubiquitination patterns across cancer types, exploring their profound implications for tumor biology and clinical practice. We examine the foundational role of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in regulating oncogenic pathways, tumor microenvironment, and therapy response. The article details innovative methodologies for mapping pan-cancer ubiquitination networks, including multi-omics integration and single-cell transcriptomics. It addresses key challenges in targeting ubiquitination pathways and presents validation strategies for clinical translation. For researchers and drug development professionals, this analysis provides critical insights into ubiquitination-based biomarkers, therapeutic vulnerabilities, and emerging technologies like PROTACs that are reshaping cancer treatment paradigms.

The Ubiquitin Landscape: Foundational Mechanisms and Tissue-Specific Patterns in Cancer

Ubiquitination is a pivotal post-translational modification that regulates the stability, activity, and localization of the majority of proteins in eukaryotic cells [1]. This highly conserved process involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin, a 76-amino acid protein, to substrate proteins, thereby influencing fundamental cellular processes ranging from cell cycle progression and DNA repair to immune responses and metabolic regulation [2] [3]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) mediates approximately 80-90% of intracellular protein degradation, establishing ubiquitination as a central regulatory mechanism controlling protein "quantity" and "quality" to maintain cellular homeostasis [1] [3].

The clinical significance of targeting the ubiquitin system in cancer has been validated by the success of proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib and carfilzomib in treating multiple myeloma [4]. These therapeutic achievements have stimulated extensive research efforts to develop novel anticancer strategies targeting specific components of the ubiquitination machinery. With advancements in multi-omics technologies, recent research has revealed tissue-specific ubiquitination patterns across pan-cancer analyses, providing novel insights for biomarker discovery and targeted therapeutic development [5] [6]. This review systematically compares ubiquitination mechanisms across cancer types, summarizes key experimental methodologies, and evaluates emerging therapeutic strategies that leverage our growing understanding of ubiquitination in cancer biology.

Basic Mechanisms of Ubiquitination

The ubiquitination process involves a sequential enzymatic cascade comprising three key steps [2] [1]. Initially, the ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner through the formation of a thioester bond between its catalytic cysteine residue and the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin. The activated ubiquitin is then transferred to a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2). Finally, a ubiquitin ligase (E3) catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 enzyme to a specific lysine residue on the substrate protein [4] [3].

The human genome encodes a limited repertoire of E1 enzymes (only UBA1 and UBA6), approximately 40 E2 enzymes, and over 600 E3 ligases, which confer substrate specificity [4] [3]. This enzymatic hierarchy allows for precise regulation of a vast array of cellular proteins. The complexity of ubiquitination extends beyond mere substrate modification, as ubiquitin itself contains eight potential linkage sites: seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and one N-terminal methionine residue (M1) [1]. These sites enable the formation of diverse polyubiquitin chains with distinct functional consequences, creating a sophisticated "ubiquitin code" that determines the fate of modified proteins [2] [3].

Table 1: Types of Ubiquitin Modifications and Their Primary Functions

| Modification Type | Structural Features | Primary Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Monoubiquitination | Single ubiquitin on substrate | DNA repair, endocytosis, histone regulation |

| Multi-monoubiquitination | Multiple single ubiquitins on different lysines | Endocytic trafficking, signal transduction |

| K48-linked polyubiquitination | Chains linked through K48 residues | Proteasomal degradation, protein turnover |

| K63-linked polyubiquitination | Chains linked through K63 residues | Signal transduction, DNA repair, inflammation |

| Linear ubiquitination | Chains linked through M1 residues | NF-κB activation, immune regulation |

| Heterotypic/Branched chains | Mixed linkage types within chains | Fine-tuning of signaling outcomes |

The ubiquitination process is reversible through the action of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), which remove ubiquitin from substrate proteins [1]. The human genome encodes approximately 100 DUBs, categorized into seven structural families, with ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs) representing the largest and best-studied family [4]. The dynamic balance between ubiquitinating and deubiquitinating activities enables precise spatiotemporal control of protein function, and dysregulation of this equilibrium is frequently observed in cancer pathogenesis [1] [3].

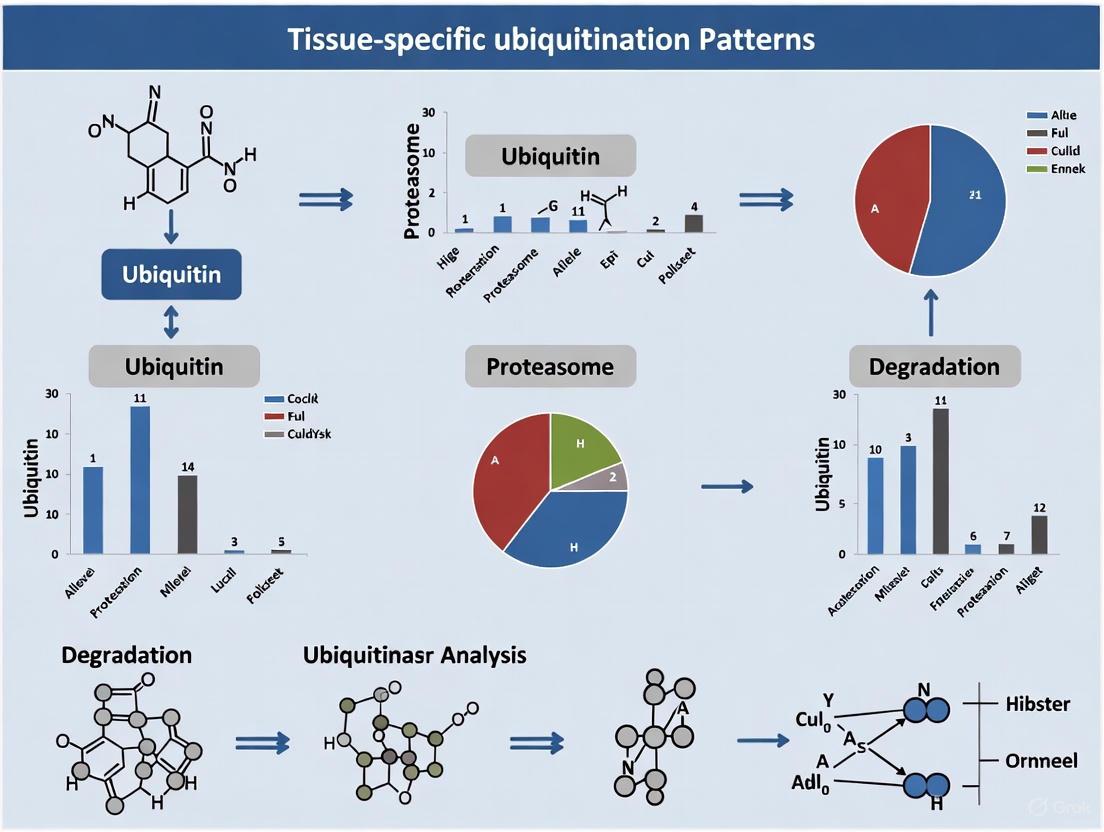

Figure 1: The ubiquitination enzymatic cascade. E1 activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent process, transfers it to E2, and E3 catalyzes final attachment to substrate proteins.

Ubiquitination Enzymes as Pan-Cancer Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets

Comprehensive pan-cancer analyses have revealed that numerous components of the ubiquitination machinery exhibit altered expression across cancer types and correlate with clinical outcomes, positioning them as potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers [5] [6]. The differential expression patterns of ubiquitination enzymes and their clinical associations across multiple cancer types are systematically compared in Table 2.

Table 2: Ubiquitination Enzymes as Biomarkers in Pan-Cancer Analysis

| Enzyme | Cancer Types with Elevated Expression | Prognostic Association | Primary Related Pathways | Immune Infiltration Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBE2T | Multiple myeloma, breast cancer, renal cell carcinoma, ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, retinoblastoma | Reduced overall and progression-free survival | DNA repair, p53 signaling, cell cycle | Associated with checkpoint genes and immune cell infiltration |

| UBA1 | Lung cancer, liver cancer, colorectal cancer | Poor prognosis across multiple cancers | General ubiquitination, cell proliferation | Correlated with immune score and subtypes |

| UBA6 | Selective cancer types | Varies by cancer type | FAT10 pathway, p53 regulation | Linked to T-cell function and inflammation |

UBE2T has emerged as a particularly promising biomarker, with comprehensive pan-cancer analysis demonstrating its elevated expression across multiple tumor types, where its upregulation associates with poor clinical outcomes [5]. Gene variation analysis identified "amplification" as the predominant alteration in the UBE2T gene, and data from the GSCALite database demonstrated high frequencies of UBE2T copy number variations across pan-cancer cohorts [5]. Functional studies have linked elevated UBE2T expression to changes in key cellular processes including proliferation, invasion, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Pathway analyses implicate "cell cycle," "ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis," "p53 signaling," and "mismatch repair" as key mechanisms through which UBE2T exerts its oncogenic effects [5].

The UBA family enzymes UBA1 and UBA6 have also demonstrated significant pan-cancer relevance [6]. Multi-omics analysis reveals that UBA1 and UBA6 are highly expressed in most cancer types, and this elevated expression associates with poor patient prognosis. These enzymes also show correlations with clinical stages in specific tumors and demonstrate significant relationships with immune scores, immune subtypes, and tumor-infiltrating immune cells [6]. The copy number variations and single nucleotide variants of UBA family members influence patient survival across various cancers, further supporting their potential as biomarkers linked to cancer immune infiltration [6].

Figure 2: Ubiquitination enzymes influence cancer progression through multiple mechanisms including direct promotion of cancer phenotypes and modulation of the tumor immune microenvironment.

Ubiquitination in Cancer Hallmarks and Therapeutic Targeting

Ubiquitination regulates all established hallmarks of cancer through its ability to control the stability and function of key regulatory proteins [1] [3]. The UPS plays crucial roles in tumor metabolism, immunological tumor microenvironment regulation, cancer stem cell maintenance, and response to therapeutic interventions [1] [3] [7].

In tumor metabolism, ubiquitination regulates critical metabolic enzymes and signaling pathways. The E3 ligase Parkin facilitates the ubiquitination of pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), while the deubiquitinase OTUB2 inhibits PKM2 ubiquitination, thereby enhancing glycolysis and accelerating colorectal cancer progression [1]. The ubiquitination of key proteins such as RagA, mTOR, PTEN, AKT, c-Myc, and P53 significantly regulates the activity of the mTORC1, AMPK, and PTEN-AKT signaling pathways, thereby influencing nutrient sensing and metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells [3].

Within the tumor microenvironment, ubiquitination modulates immune responses through regulation of immune checkpoint proteins such as PD-1/PD-L1 [1]. USP2 stabilizes PD-1 through deubiquitination, promoting tumor immune escape, while MTSS1 promotes the monoubiquitination of PD-L1 at K263 mediated by the E3 ligase AIP4, leading to PD-L1 internalization and lysosomal degradation, thus inhibiting immune escape in lung adenocarcinoma [1]. Ubiquitination also plays critical roles in the TLR, RLR, and STING-dependent signaling pathways that modulate the tumor microenvironment [3].

Cancer stem cell functionality is extensively regulated by ubiquitination, particularly through modulation of key signaling pathways including Notch, Hedgehog, Wnt/β-catenin, and Hippo-YAP [7]. The ubiquitination of core stem cell regulator triplets (Nanog, Oct4, and Sox2) participates in the maintenance of cancer stem cell stemness, contributing to tumor initiation, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance [3] [7].

Table 3: Emerging Therapeutic Strategies Targeting the Ubiquitin System

| Therapeutic Approach | Mechanism of Action | Development Stage | Example Agents | Primary Targets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROTACs | Bifunctional molecules recruiting E3 ligases to target proteins | Phase II clinical trials | ARV-110, ARV-471 | Androgen receptor, estrogen receptor |

| Molecular Glues | Induce neo-interactions between E3 ligases and target proteins | Phase II clinical trials | CC-90009 | GSPT1 protein |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Block protein degradation by proteasome | FDA-approved | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib | 26S proteasome |

| E1 Inhibitors | Inhibit ubiquitin activation | Preclinical | MLN7243, MLN4924 | UBA1, NAE1 |

| E2 Inhibitors | Block ubiquitin conjugation | Preclinical | Leucettamol A, CC0651 | Ubc13-Uev1A |

| E3 Inhibitors | Modulate substrate-specific ubiquitination | Preclinical/Clinical | Nutlin, MI-219 | MDM2 |

| DUB Inhibitors | Inhibit deubiquitinating activity | Preclinical | Compounds G5, F6 | USP7, USP9x |

Novel anticancer strategies that leverage the UPS have emerged as promising therapeutic approaches [4] [1]. PROTAC (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimera) technology represents a breakthrough strategy that utilizes bifunctional molecules to recruit E3 ubiquitin ligases to target proteins of interest, thereby inducing their degradation [1]. ARV-110 and ARV-471 represent the forefront of PROTAC drug development and have progressed to phase II clinical trials [1]. Molecular glue degraders offer an alternative approach with smaller molecular dimensions that simplify optimization of chemical characteristics [1]. CC-90009 facilitates the ubiquitination-mediated degradation of GSPT1 by recruiting the E3 ligase complex CUL4-DDB1-CRBN-RBX1 and is in phase II clinical trials for leukemia therapy [1].

Figure 3: PROTAC mechanism of action. Bifunctional molecules simultaneously bind target proteins and recruit E3 ligases to induce targeted protein degradation.

Experimental Methodologies for Ubiquitination Characterization

The characterization of protein ubiquitination presents unique challenges due to the low stoichiometry of modification, the diversity of ubiquitination sites on substrate proteins, and the complexity of ubiquitin chain architectures [8]. Several methodological approaches have been developed to address these challenges and enable comprehensive analysis of ubiquitination events.

Ubiquitin Tagging-Based Approaches

Ubiquitin tagging methodologies involve the expression of affinity-tagged ubiquitin (e.g., His, Flag, HA, Strep) in cells to enable purification and identification of ubiquitinated substrates [8]. The stable tagged Ub exchange (StUbEx) cellular system allows replacement of endogenous ubiquitin with His-tagged ubiquitin, facilitating the identification of hundreds of ubiquitination sites from cell lines [8]. Similarly, expression of Strep-tagged ubiquitin has enabled identification of 753 lysine ubiquitylation sites on 471 proteins in U2OS and HEK293T cells [8]. While these approaches provide an accessible method for ubiquitination profiling, limitations include potential co-purification of non-ubiquitinated proteins and the inability to fully replicate endogenous ubiquitin dynamics.

Antibody-Based Enrichment Strategies

Endogenously ubiquitinated proteins can be enriched using anti-ubiquitin antibodies such as P4D1, FK1, and FK2 that recognize all ubiquitin linkages [8]. Linkage-specific antibodies have also been developed for enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins with specific chain architectures (M1-, K11-, K27-, K48-, K63-linkage specific antibodies) [8]. For example, researchers have generated antibodies specifically recognizing K48-linked polyubiquitin chains and demonstrated abnormal accumulation of K48-linked polyubiquitinated tau proteins in Alzheimer's disease [8]. The key advantage of antibody-based approaches is their applicability to animal tissues or clinical samples without genetic manipulation, though high cost and potential non-specific binding remain limitations.

Ubiquitin-Binding Domain (UBD) Based Approaches

Proteins containing ubiquitin-binding domains (such as some E3 ubiquitin ligases, DUBs, and ubiquitin receptors) can be utilized to bind and enrich endogenously ubiquitinated proteins [8]. Tandem-repeated ubiquitin-binding entities (TUBEs) exhibit enhanced affinity for ubiquitinated proteins and protect ubiquitin chains from cleavage by deubiquitinases during purification [8]. These approaches leverage natural ubiquitin recognition mechanisms but may exhibit bias toward specific chain types depending on the UBDs employed.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity Tags | His-tag, Strep-tag, HA-tag, Flag-tag | Purification of ubiquitinated proteins | Compatible with various purification resins |

| Ubiquitin Antibodies | P4D1, FK1, FK2 | Western blot, immunoprecipitation | Pan-ubiquitin recognition |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | K48-specific, K63-specific, M1-linear specific | Enrichment of specific chain types | Selective recognition of chain architectures |

| Ubiquitin-Binding Domains | TUBEs, UIM, UBA domains | Enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins | Enhanced affinity in tandem arrangements |

| Activity-Based Probes | Ubiquitin-dehydroalanine (Ub-Dha) | DUB activity profiling | Covalent modification of active DUBs |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, MG132 | Stabilization of ubiquitinated proteins | Enhances detection of ubiquitinated species |

Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics

Advanced mass spectrometry techniques have revolutionized the identification and quantification of protein ubiquitination [8]. Following enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins, tryptic digestion generates characteristic di-glycine remnants on modified lysine residues, which produce a distinct mass signature (114.0429 Da mass shift) detectable by high-resolution mass spectrometry [8]. Quantitative proteomic approaches using stable isotope labeling (SILAC, TMT) enable comparison of ubiquitination dynamics across different experimental conditions or disease states. These methods provide unprecedented depth in profiling the ubiquitinome but require specialized instrumentation and computational expertise for data analysis.

Ubiquitination serves as a master cellular regulator that influences virtually all aspects of cancer biology through its sophisticated control of protein stability, function, and interaction networks. The integration of pan-cancer analyses has revealed tissue-specific ubiquitination patterns and identified numerous components of the ubiquitination machinery as potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets [5] [6]. Continued advancement in mass spectrometry, chemical biology tools, and computational methodologies will further enhance our understanding of the complex ubiquitin code and its dysregulation in cancer pathogenesis.

Emerging therapeutic strategies that target the ubiquitin system, particularly PROTACs and molecular glue degraders, represent a paradigm shift in drug discovery by leveraging the cell's natural degradation machinery to eliminate pathogenic proteins [1]. As our understanding of ubiquitination mechanisms in cancer continues to expand, so too will opportunities for developing innovative therapeutic approaches that exploit this fundamental regulatory system. Future research directions will likely focus on achieving greater selectivity in targeting specific E3 ligases, developing non-degradative ubiquitination modulators, and elucidating the functional consequences of atypical ubiquitin chain architectures in cancer biology.

Ubiquitination is a critical post-translational modification that governs virtually all cellular processes in eukaryotes. The versatility of ubiquitin signaling arises from its ability to form diverse architectures—including monoubiquitination and various polyubiquitin chain types—that constitute a complex "ubiquitin code" read by cellular machinery to determine protein fates [9] [10]. Among these, monoubiquitination, K48-linked chains, and K63-linked chains represent three fundamentally distinct signaling modes with specialized biological functions. K48-linked ubiquitin chains primarily target proteins for proteasomal degradation and represent the most abundant linkage type, while K63-linked chains serve as non-proteolytic signaling scaffolds in pathways such as autophagy, DNA repair, and immune signaling [9] [11] [12]. Monoubiquitination regulates processes like histone function and DNA damage response through mechanisms distinct from chain-based signaling [12]. Recent pan-cancer analyses reveal that dysregulation of these specific ubiquitination patterns contributes significantly to oncogenesis, therapy resistance, and altered immune responses across cancer types, highlighting their clinical relevance and potential as therapeutic targets [13] [14] [12].

Functional Specialization of Ubiquitin Signals

Molecular Distinctions and Physiological Roles

The table below summarizes the core structural and functional characteristics of each ubiquitination type:

Table 1: Functional Specialization of Major Ubiquitination Types

| Feature | Monoubiquitination | K48-Linked Ubiquitin | K63-Linked Ubiquitin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Definition | Single ubiquitin moiety attached to substrate | Ubiquitin chains linked via K48 residues | Ubiquitin chains linked via K63 residues |

| Primary Functions | Chromatin modulation, DNA damage response, epigenetic regulation, endocytosis | Proteasomal degradation signal, cell cycle control, metabolic regulation | Signaling scaffold in autophagy, DNA repair, inflammation, immune response |

| Key Regulatory Enzymes | RNF8, RNF40, UBE2T, RNF168 | CDC34, UBE2C, UBE2T, APC/C | Ubc13/Uev1a, TRAF family E3s |

| Cellular Processes | Histone modification (H2A, H2B, H2AX), FANCD2 activation, centrosome integrity | Cell cycle progression, oxidative stress response, hypoxia adaptation | Mitophagy, selective autophagy, NF-κB signaling, endosomal trafficking |

| Representative Substrates | H2AX, FANCD2, γ-tubulin, PCNA | p53, SOX9, HIF1α, SLC7A11 | BRCA1, GPX4, IRF3, XRCC4 |

| Pan-Cancer Significance | Genome stability maintenance, radiation adaptation | Contextual oncogene/tumor suppressor, metabolic reprogramming | Therapy resistance, immune evasion, ferroptosis regulation |

K48-Linked Ubiquitination: Beyond Degradation Signaling

While historically characterized as the principal proteasomal degradation signal, recent research reveals unexpected complexity in K48-linked ubiquitination. In pancancer analyses, K48 linkages demonstrate contextual duality—functioning as either oncogenic or tumor-suppressive depending on genetic background [12]. For instance, FBXW7-mediated K48 ubiquitination can promote radioresistance in p53-wildtype colorectal tumors by degrading p53, yet enhances radiosensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer with SOX9 overexpression by destabilizing SOX9 and alleviating p21 repression [12]. This linkage type also governs metabolic adaptation through mechanisms like SMURF2-mediated HIF1α degradation (compromising hypoxic survival) and SOCS2/Elongin B/C-driven SLC7A11 destruction (increasing ferroptosis sensitivity in liver cancer) [12]. Quantitative ubiquitinome profiling indicates K48 chains constitute the most abundant linkage type in human cells, with specialized E2 enzymes like CDC34 and UBE2C driving their assembly [9] [14].

K63-Linked Ubiquitination: Master Regulator of Cellular Signaling

K63-linked ubiquitin chains serve as versatile signaling scaffolds that coordinate complex cellular processes without targeting substrates for degradation. In autophagy, K63 chains play indispensable roles in multiple selective autophagic pathways, including mitophagy, xenophagy, and aggrephagy, by providing recognition signals for autophagy receptors [11]. Recent work demonstrates their critical function in radiation resistance, where K63 ubiquitination orchestrates adaptive survival pathways—FBXW7 employs K63 chains to modify XRCC4, enhancing non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair accuracy, while TRAF4 utilizes K63 modifications to activate the JNK/c-Jun pathway, driving overexpression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL in colorectal cancer [12]. K63 chains also integrate metabolic and immune regulation, with TRIM26 stabilizing GPX4 via K63 ubiquitination to prevent ferroptosis in gliomas, while USP14 inhibition leads to K63-modified IRF3 accumulation, triggering STING-dependent antitumor immunity [12]. This functional diversity establishes K63 networks as central hubs coordinating DNA repair suppression and immune modulation simultaneously.

Monoubiquitylation: Guardian of Chromatin and Genome Stability

Monoubiquitination of both histones and non-histone proteins critically regulates genome maintenance and epigenetic states. In DNA damage response, UBE2T/RNF8-mediated H2AX monoubiquitylation accelerates damage detection in hepatocellular carcinoma, while RNF40-generated H2Bub1 recruits the FACT complex (SUPT16H) to relax nucleosomes, facilitating DNA repair [12]. For non-histone targets, FANCD2 monoubiquitylation specifically resolves carbon ion-induced DNA crosslinks, and γ-tubulin monoubiquitylation maintains centrosome integrity—a process whose disruption by high-LET radiation triggers mitotic catastrophe [12]. These functions position monoubiquitylation as a key coordinator of DNA repair and genomic integrity, with distinct mechanistic outcomes compared to polyubiquitin chain signaling.

Experimental Methodologies for Ubiquitin Code Analysis

Ubiquitin Interactor Pull-Down and Mass Spectrometry

Elucidating linkage-specific ubiquitin interactions requires specialized pull-down approaches coupled with advanced mass spectrometry. Recent methodology employs native enzymatically synthesized Ub chains of varying lengths (Ub2, Ub3) and architectures (homotypic, heterotypic branched) immobilized on streptavidin resin to enrich specific ubiquitin-binding proteins from cell lysates [9]. Critical methodological considerations include:

- Chain Synthesis: Enzymatic synthesis using linkage-specific E2 enzymes (CDC34 for K48, Ubc13/Uev1a for K63, Ubc1 for branched chains) ensures native isopeptide bonds and physiological structure [9].

- Deubiquitinase Inhibition: Cysteine alkylators like chloroacetamide (CAA) or N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) prevent chain disassembly during assays, with NEM providing more complete inhibition but CAA offering greater cysteine specificity [9].

- Immobilization Strategy: Site-specific biotin conjugation via cysteine-maleimide chemistry on a serine/glycine linker at the proximal Ub C-terminus enables controlled orientation and presentation [9].

- Identification and Validation: Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) identifies enriched proteins, with surface plasmon resonance (SPR) validating binding specificity and affinity for candidate interactors [9].

This approach has revealed novel K48/K63-branched Ub specific interactors including PARP10, UBR4, and HIP1, plus chain-length preferences for proteins like DDI2, CCDC50, and FAF1 that discriminate between Ub2 and Ub3 chains [9].

Advanced Ubiquitinomics Profiling

Comprehensive ubiquitinome mapping has been revolutionized by mass spectrometry-based proteomics, particularly through diGlycine (K-GG) remnant enrichment following tryptic digestion. Recent innovations include:

- SDC-Based Lysis Protocol: Sodium deoxycholate (SDC) buffer supplemented with chloroacetamide (CAA) increases ubiquitin site coverage by 38% compared to conventional urea buffer while improving reproducibility and quantitative precision [15].

- Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA-MS): This approach more than triples ubiquitinated peptide identification compared to data-dependent acquisition (DDA), quantifying >70,000 ubiquitination sites in single runs with excellent reproducibility (median CV ~10%) [15].

- High-Throughput Capabilities: DIA-NN software with neural network-based processing enables rapid, precise ubiquitinome profiling from minimal protein input (2mg sufficient for ~30,000 K-GG peptides) [15].

- Temporal Resolution: Time-resolved ubiquitinome profiling following deubiquitinase inhibition (e.g., USP7) can simultaneously track ubiquitination dynamics and consequent protein abundance changes, distinguishing regulatory from degradative ubiquitination [15].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitin Studies

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity-Based Probes | Biotin-Ahx-Ub-MTC (UbiQ-378) | DUB identification and profiling | Covalent labeling of active DUBs; biotin tag for enrichment |

| Defined Ubiquitin Chains | K48 Ub2/Ub3, K63 Ub2/Ub3, K48/K63 BrUb3 | Interaction studies, in vitro assays | Native isopeptide bonds; site-specific biotin conjugation |

| Ubiquitinated Peptides | Custom synthetic ubiquitinated peptides | Enzyme kinetics, structural studies | Site-specific modification; various linkage types |

| DUB Inhibitors | USP7-specific inhibitors | Target validation, functional studies | Selective enzyme inhibition; cell-permeable variants |

| Enzymatic Machinery | E1, E2, E3 enzyme sets | In vitro ubiquitination assays | Linkage-specific chain synthesis |

These methodologies enable researchers to decode the complex ubiquitin landscape with unprecedented depth and precision, facilitating the discovery of novel regulatory mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities.

Signaling Pathways and Functional Networks

The following diagrams illustrate key signaling pathways governed by specialized ubiquitination types, highlighting their distinct mechanistic roles:

K48-Linked Ubiquitination in Protein Homeostasis

K48 Ubiquitin in Proteostasis: K48-linked ubiquitination targets proteins for proteasomal degradation, regulating key cellular processes. Its functional outcomes are highly context-dependent, with both oncogenic and tumor-suppressive roles observed in different cancer types.

K63-Linked Ubiquitination in Cellular Signaling

K63 Ubiquitin in Signaling: K63-linked ubiquitin chains serve as non-proteolytic signaling scaffolds that coordinate diverse cellular processes. In cancer, these pathways contribute significantly to therapy resistance and immune evasion mechanisms.

Experimental Workflow for Ubiquitin Interaction Mapping

Ubiquitin Interaction Mapping: Comprehensive workflow for identifying linkage-specific ubiquitin interactors using immobilized ubiquitin chains, mass spectrometry, and validation approaches.

Pan-Cancer Implications and Therapeutic Targeting

Ubiquitination Dysregulation Across Cancer Types

Comprehensive pancancer analyses reveal that ubiquitination pathway components are frequently dysregulated across malignancies, with significant prognostic implications. A conserved ubiquitination-related prognostic signature (URPS) effectively stratifies patients into distinct risk categories with differential survival outcomes across lung cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, urothelial carcinoma, and melanoma [13]. Key findings include:

- Histological Associations: Ubiquitination scores positively correlate with squamous or neuroendocrine transdifferentiation in adenocarcinoma, with upregulated ubiquitination in squamous cell carcinomas (SQCs) and neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs) associated with activation of oxidative phosphorylation and MYC pathways [13].

- Immune Microenvironment: Ubiquitination signatures associate with macrophage infiltration within the tumor microenvironment and demonstrate predictive value for immunotherapy response, with potential to identify patients most likely to benefit from immune checkpoint blockade [13].

- Enzyme-Specific Roles: Specific ubiquitin-system components show pancancer dysregulation—UBE2T demonstrates elevated expression across multiple tumor types where its upregulation correlates with poor clinical outcomes, while USP7-TRIM28 ubiquitination regulates MYC pathway activity and influences patient prognosis [13] [14].

Therapeutic Exploitation of Ubiquitination Pathways

The diverse ubiquitin code presents unique therapeutic opportunities, with several targeting strategies under development:

- DUB Inhibition: Targeting deubiquitinases like USP7 shows promise for disrupting oncogenic signaling, with USP7 inhibition causing rapid ubiquitination increases for hundreds of proteins and subsequent degradation for a subset, effectively dissecting USP7's scope of action [15].

- Targeted Protein Degradation: Proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) exploit the ubiquitin system to selectively degrade target proteins, with EGFR-directed PROTACs effectively suppressing DNA repair in EGFR-dependent tumors and radiation-responsive PROTAC platforms (RT-PROTAC) enabling tumor-localized activation [12].

- Fragment-Based Drug Discovery: FBDD approaches efficiently target challenging ubiquitin system components, with covalent and non-covalent fragment screening identifying starting points for inhibitor development against E1, E2, E3, and DUB enzymes [16].

- Linkage-Specific Targeting: Emerging strategies aim to selectively disrupt specific ubiquitin linkage types, potentially offering greater precision than broad pathway inhibition while minimizing off-target effects [9] [12].

The diverse ubiquitin code—exemplified by the functional specialization of monoubiquitination, K48 linkages, and K63 linkages—represents a crucial regulatory layer in cellular homeostasis and cancer biology. Advanced methodologies for ubiquitin interactor profiling and ubiquitinome mapping now enable comprehensive decoding of these complex signals with unprecedented resolution. Pancancer analyses confirm the clinical significance of ubiquitination dysregulation, with distinct patterns associating with histological subtypes, therapy responses, and patient outcomes. As targeting technologies continue to advance—from DUB inhibitors to PROTACs and fragment-based approaches—therapeutic exploitation of the ubiquitin system offers promising avenues for precision oncology. Future research will undoubtedly further elucidate the complexity of branched, mixed, and atypical ubiquitin chains, expanding our understanding of this sophisticated regulatory system and its therapeutic potential.

Ubiquitination, a pivotal post-translational modification, plays complex regulatory roles in cancer pathogenesis. Recent pan-cancer analyses reveal that while core ubiquitination machinery and prognostic signatures are conserved across diverse malignancies, their functional impacts and expression patterns exhibit significant tissue-specific variation. This review synthesizes findings from comprehensive multi-omics studies to delineate both universal and context-dependent ubiquitination signatures, providing a framework for understanding their implications in cancer biology, tumor microenvironment regulation, and therapeutic development. The conserved ubiquitination-related prognostic signature (URPS) effectively stratifies patient survival outcomes across multiple cancer types, while molecular components including UBE2T, UBD, and various deubiquitinating enzymes demonstrate cancer-type specific expression and functional roles.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a crucial regulatory mechanism in eukaryotic cells, coordinating the degradation of approximately 80-90% of cellular proteins [13] [14]. This sophisticated system operates through a sequential enzymatic cascade involving E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes that collectively tag target proteins with ubiquitin, marking them for proteasomal degradation [17] [18]. The process is reversible through the action of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), which remove ubiquitin chains from substrates, creating a dynamic regulatory balance [18]. Beyond its canonical role in protein degradation, ubiquitination regulates diverse cellular processes including cell cycle progression, DNA damage repair, signal transduction, and immune responses [17] [19]. Dysregulation of ubiquitination signals is increasingly recognized as a hallmark of cancer pathogenesis, with distinct patterns emerging across different cancer types [13] [19].

Conserved Ubiquitination Patterns Across Cancers

Universal Prognostic Signatures

Pan-cancer analyses have identified conserved ubiquitination-related molecular patterns with significant prognostic value across diverse malignancies. A seminal study integrating data from 4,709 patients across 26 cohorts and five solid tumor types (lung cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, urothelial cancer, and melanoma) established a ubiquitination-related prognostic signature (URPS) that effectively stratifies patients into distinct risk categories [13]. This signature demonstrates remarkable conservation in predicting overall survival, with high-risk patients consistently showing poorer outcomes across the analyzed cancer types [13]. The URPS further serves as a novel biomarker for predicting immunotherapy response, potentially identifying patients most likely to benefit from immune checkpoint blockade therapy [13].

Table 1: Conserved Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Signatures Across Cancers

| Signature Name | Cancer Types Validated | Key Components | Prognostic Value | Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| URPS [13] | Lung, esophageal, cervical, urothelial, melanoma | Multi-gene signature from ubiquitination network | Stratifies high/low risk groups (HR = 0.54-0.58) | Predicts immunotherapy response and overall survival |

| URRS (LUAD) [20] | Lung adenocarcinoma | DTL, UBE2S, CISH, STC1 | HR = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.39-0.73, p < 0.001 | Prognosis, immune infiltration assessment, drug response prediction |

| UBE2T Pan-Cancer [14] | Multiple cancer types | UBE2T expression | Associated with poor clinical outcomes | Correlates with trametinib/selumetinib sensitivity |

| UBD Pan-Cancer [17] | 29 cancer types | UBD overexpression | Poor prognosis, higher histological grades | Predictor of immunotherapy sensitivity |

Common Genetic and Epigenetic Alterations

Comprehensive genomic analyses reveal recurrent genetic alterations in ubiquitination regulators across multiple cancer types. Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBE2T demonstrates frequent gene amplification as its predominant alteration, with copy number variations occurring more frequently than single nucleotide variants [14]. Similarly, ubiquitin D (UBD) shows consistent overexpression in 29 cancer types, with gene amplification representing the most common genetic variation [17]. Epigenetically, reduced UBD promoter methylation has been observed in 16 cancer types, suggesting a conserved mechanism for its upregulation [17]. These recurring alterations highlight the selective pressure to disrupt ubiquitination homeostasis during oncogenesis.

Diagram 1: Overview of Pan-Cancer Ubiquitination Signatures

Tissue-Specific Variations in Ubiquitination

Histological Subtype Associations

Ubiquitination patterns demonstrate remarkable tissue and histological subtype specificity. In non-small cell lung cancer, ubiquitination scores positively correlate with squamous or neuroendocrine transdifferentiation in adenocarcinoma, revealing a previously unappreciated link between ubiquitination signaling and histological fate decisions [13]. The prognostic impact of specific ubiquitination components varies significantly by cancer type; for instance, COMMD7 functions as a risk factor in ESCA, HNSC, LGG, LIHC, PAAD, and UVM, while COMMD9 acts as a protective factor in KIRC but as a risk factor in KICH [21]. Similarly, FHL2 exhibits upregulated expression in cholangiocarcinoma, colon adenocarcinoma, esophageal carcinoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, and lung cancers, while showing downregulation in breast invasive carcinoma, kidney chromophobe, liver hepatocellular carcinoma, prostate adenocarcinoma, and thyroid carcinoma [22].

Context-Dependent Functional Roles

The functional consequences of ubiquitination component expression are highly context-dependent. USP9X exemplifies this duality, promoting tumor cell survival and malignant phenotypes in human pancreatic tumor cells while acting as a tumor suppressor in KPC (Kras; Trp53; Pdx1-Cre) mouse models [18]. Sleeping Beauty transposon-mediated insertional mutagenesis screens identified USP9X with the highest mutation frequency in PDAC tumors, where it functions as a major tumor suppressor with high prognostic value [18]. Similarly, the four-member ubiquitination-related risk score (URRS) for lung adenocarcinoma demonstrates cancer-type specific prognostic performance, with upregulation of STC1, UBE2S, and DTL associated with worse prognosis, while upregulation of CISH correlates with better outcomes specifically in this malignancy [20].

Table 2: Tissue-Specific Variations in Ubiquitination Components

| Ubiquitination Component | Cancer Type(s) with Elevated Expression | Cancer Type(s) with Reduced Expression | Context-Dependent Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| FHL2 [22] | CHOL, COAD, ESCA, HNSC, LUAD, LUSC | BRCA, KICH, LIHC, PRAD, THCA, UCEC | Promotes progression in ovarian, cervical, pancreatic cancers |

| USP9X [18] | Human pancreatic cancer | KPC mouse models | Oncogenic in humans vs. tumor suppressor in mouse models |

| UBD [17] | 29 cancer types including glioma, colorectal, HCC, breast cancer | Limited normal tissue expression | Promotes immune evasion via PD-L1 upregulation in HCC |

| COMMD Family [21] | COMMD1,2,4,5,7,8,9 elevated in most tumors | COMMD6 reduced in most tumors | COMMD7 promotes progression in ccRCC and bladder cancer |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Pan-Cancer Analytical Frameworks

The investigation of ubiquitination signatures employs sophisticated multi-omics approaches and bioinformatics pipelines. A standardized workflow typically includes: (1) collection of ubiquitination regulators from specialized databases (iUUCd 2.0, UbiBrowser); (2) integration of transcriptomic data from TCGA, GTEx, and GEO datasets; (3) genetic alteration analysis using cBioPortal and GSCALite; (4) immune infiltration assessment via TIMER, EPIC, and other algorithms; and (5) survival analysis using Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier methods [13] [14] [19]. For ubiquitination-related risk model construction, studies typically apply unsupervised clustering, univariate Cox regression, Random Survival Forests, and LASSO Cox regression to identify prognostic ubiquitination-related genes, followed by validation in independent cohorts [20].

Functional Validation Approaches

In vitro and in vivo models provide crucial functional validation of ubiquitination components. Standard experimental protocols include:

- Gene manipulation: Knockdown of targets (e.g., COMMD7) using lentiviral transduction in cancer cell lines (786-O, ACHN, T24, UM-UC3) followed by functional assays [21]

- Proliferation assays: Plate cloning experiments with 14-day incubation, fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde, and crystal violet staining [21]

- Migration/invasion assessment: Wound-healing assays (0h and 48h timepoints) and Transwell assays with 24-hour incubation and crystal violet staining [21]

- Xenograft models: Subcutaneous injection of control and knockdown cells (e.g., 786-O) into nude mice, followed by 30-day monitoring and tumor measurement [21]

- Molecular validation: Western blotting using specific primary antibodies (e.g., UBE2T 1:2,000; β-actin 1:2,000) with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5,000) and Super ECL detection [14]

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Ubiquitination Signature Analysis

Ubiquitination in Tumor Microenvironment and Therapy

Immune Microenvironment Regulation

Ubiquitination significantly shapes the tumor immune microenvironment through multiple mechanisms. UBD expression strongly correlates with tumor microenvironment features including immune infiltration, checkpoints, microsatellite instability, tumor mutational burden, and neoantigens [17]. The URPS signature enables precise classification of distinct cell types at single-cell resolution and associates with macrophage infiltration within the tumor microenvironment [13]. CD83+ tumor-associated neutrophils identified through pan-cancer single-cell transcriptomic analysis represent a senescent state with immunosuppressive properties, regulating T-cell activation and cytotoxicity while correlating with poor prognosis and immunotherapy resistance [23]. COMMD family members show distinct immune correlations, with COMMD1, COMMD8, and COMMD9 positively correlating with most immune cells across various tumors, while COMMD2 and COMMD6 show negative correlations with immune infiltration [21].

Therapeutic Implications and Biomarker Potential

Ubiquitination signatures hold significant promise as therapeutic biomarkers and targets. The URPS demonstrates value in predicting immunotherapy response across multiple cancer types [13]. USP37 expression strongly correlates with tumor mutational burden, microsatellite instability, and immune checkpoint genes, highlighting its potential as a predictor for immunotherapy outcomes [24]. Ubiquitination-related risk scores can predict response to chemotherapy, with high URRS groups showing lower IC50 values for various chemotherapeutic drugs [20]. For traditionally "undruggable" targets like MYC, ubiquitination regulatory modifiers offer novel therapeutic opportunities, as demonstrated by the OTUB1-TRIM28 ubiquitination axis that critically modulates MYC pathway activity and influences patient prognosis [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function in Ubiquitination Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Line Models | PANC-1, AsPC-1, BxPC-3, SW1990, 786-O, ACHN, T24, UM-UC3 [24] [21] | In vitro functional studies | Provide cellular context for studying ubiquitination mechanisms in specific cancer types |

| Antibodies for Detection | UBE2T (1:2,000; Abclonal A6853), β-actin (1:2,000; Cell Signaling 4967S) [14] | Western blotting, immunofluorescence | Enable protein expression validation and subcellular localization |

| Lentiviral Vectors | COMMD7 knockdown constructs [21] | Gene manipulation studies | Facilitate stable gene knockdown to assess functional consequences |

| Animal Models | Nude mouse xenografts [21] | In vivo therapeutic validation | Provide physiological context for assessing tumor growth and metastasis |

| Bioinformatics Tools | TIMER2.0, GEPIA2, cBioPortal, UALCAN, TISIDB [14] [17] [22] | Multi-omics data analysis | Enable comprehensive analysis of expression, alterations, and clinical correlations |

| Databases | iUUCD 2.0, UbiBrowser, TCGA, GTEx, GEO [20] [19] | Ubiquitination regulator compilation | Provide curated gene sets and expression data for pan-cancer analysis |

Pan-cancer analyses of ubiquitination signatures reveal a sophisticated regulatory landscape characterized by both deeply conserved patterns and striking tissue-specific variations. The conserved ubiquitination-related prognostic signature (URPS) demonstrates remarkable stability in predicting patient outcomes across diverse malignancies, while individual components like UBE2T, UBD, and various DUBs exhibit context-dependent expression and functions. The integration of multi-omics data with functional validation provides a powerful framework for elucidating the complex roles of ubiquitination in cancer biology. Future research directions should focus on: (1) developing more comprehensive ubiquitination networks incorporating spatial transcriptomics data; (2) elucidating the mechanistic basis for tissue-specific functions of ubiquitination components; and (3) advancing therapeutic strategies that target ubiquitination regulators, particularly for recalcitrant malignancies. The continued investigation of ubiquitination signatures promises to yield novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets that leverage the intricate balance of ubiquitination signaling in cancer pathogenesis and treatment response.

E3 Ligases and DUBs as Tissue-Specific Orchestrators of Tumor Progression

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a crucial regulatory mechanism in cellular homeostasis, with E3 ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) serving as the precise arbiters of protein fate. These enzymes collectively regulate virtually all cellular processes through specific substrate recognition, determining protein stability, localization, and activity [25]. In oncogenesis, the balance between E3 ligases and DUBs becomes frequently disrupted, leading to either aberrant degradation of tumor suppressors or stabilization of oncoproteins across diverse cancer types [26]. Emerging pan-cancer analyses reveal that these disruptions follow tissue-specific patterns, creating distinct ubiquitination landscapes that orchestrate tumor progression through mechanisms tailored to particular organ microenvironments and cell types [13].

The clinical relevance of understanding these tissue-specific patterns is underscored by the success of UPS-targeting therapies, particularly in hematological malignancies like multiple myeloma, where proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs targeting the CRL4CRBN E3 ligase complex have revolutionized treatment [27]. This review systematically compares the tissue-specific functions of E3 ligases and DUBs across major cancer types, providing structured experimental data and analytical frameworks to guide future therapeutic development.

Pan-Cancer Ubiquitination Patterns and Prognostic Significance

Large-scale transcriptomic analyses across multiple cancer types have identified conserved ubiquitination patterns with significant prognostic implications. A comprehensive study integrating data from 4,709 patients across 26 cohorts of five solid tumor types (lung cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, urothelial cancer, and melanoma) established a ubiquitination-related prognostic signature (URPS) that effectively stratifies patients into distinct risk categories [13]. This signature demonstrates that ubiquitination modifiers collectively influence survival outcomes and treatment responses in patterns transcending individual cancer types yet exhibiting tissue-specific variations.

Table 1: Ubiquitination-Based Prognostic Signatures Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Key Ubiquitination Regulators | Prognostic Value | Biological Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Cancer | OTUB1-TRIM28, FBXW7 | Stratifies adenocarcinoma vs. squamous outcomes | MYC signaling, oxidative stress |

| Colorectal Cancer | FBXW7, TRIM6, ITCH, HERC3 | Predicts recurrence and chemo-resistance | Cell cycle progression, EMT |

| Pancreatic Cancer | USP9X, USP34, USP22 | Associates with metabolic reprogramming | Wnt/β-catenin, mTOR signaling |

| Multiple Myeloma | CRL4CRBN, HUWE1, MDM2 | Predicts IMiD response and survival | Protein homeostasis, apoptosis |

| Melanoma & Urothelial Cancer | URPS signature | Immunotherapy response prediction | Immune cell infiltration |

Notably, ubiquitination scores derived from these analyses show positive correlation with squamous or neuroendocrine transdifferentiation in adenocarcinoma subtypes, suggesting that ubiquitination pathways fundamentally influence histological fate decisions in epithelial cancers [13]. At single-cell resolution, ubiquitination signatures enable precise classification of distinct cell types within the tumor microenvironment and show particular association with macrophage infiltration patterns, highlighting the role of ubiquitination in shaping immune microenvironments across tissues [13].

Tissue-Specific Regulatory Mechanisms

Gastrointestinal Cancers

Colorectal Cancer

In colorectal cancer (CRC), E3 ligases demonstrate remarkable functional diversity in regulating distinct aspects of tumor biology. The proliferation of CRC cells is controlled by opposing E3 ligase activities: TRIM6 promotes proliferation through degradation of the anti-proliferative protein TIS21, while ITCH and HERC3 suppress proliferation by targeting CDK4 and RPL23A for degradation, respectively [28]. The migratory and metastatic capabilities of CRC cells are regulated through EMT control, where FBXO11 and TRIM16 inhibit EMT by mediating the degradation of Snail, a transcription factor that represses E-cadherin expression [28]. Meanwhile, cancer stem cell (CSC) maintenance is governed by E3 ligases including FBXW11, which targets tumor suppressor HIC1 for degradation, thereby sustaining stem-cell-like properties [28].

The experimental validation of these mechanisms typically employs standardized methodologies. For instance, the interaction between ITCH and CDK4 was confirmed through co-immunoprecipitation assays in HCT116 and SW480 CRC cell lines, demonstrating direct binding, followed by cycloheximide chase experiments showing prolonged CDK4 half-life upon ITCH knockdown [28]. Functional outcomes were assessed through colony formation assays and flow cytometric cell cycle analysis, revealing G0/G1 phase arrest following ITCH overexpression [28].

Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) presents a distinct ubiquitination landscape characterized by DUB-mediated regulation of critical signaling pathways. USP28 promotes cell cycle progression and inhibits apoptosis by stabilizing the transcription factor FOXM1, thereby activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [18]. Similarly, USP21 interacts with and stabilizes TCF7 to maintain PDAC cell stemness, with orthotopic pancreatic transplantation models demonstrating that USP21-expressing cells undergo pathological progression from PanIN to PDAC [18].

The USP9X enzyme exemplifies context-dependent functionality in PDAC. In human pancreatic tumor cells, USP9X promotes tumor cell survival and malignant phenotypes, whereas in KPC (KrasLSL-G12D/+; Trp53LSL-R172H/+; Pdx1-Cre) mouse models, it acts as a tumor suppressor by regulating the Hippo pathway in cooperation with LATS kinase and YAP/TAZ to impede PDAC growth [18]. This duality highlights the importance of model system selection when investigating ubiquitination enzymes.

Hematological Malignancies

Multiple Myeloma

In multiple myeloma (MM), E3 ubiquitin ligases regulate pathogenesis through seven principal mechanisms: (1) degrading oncoproteins like c-Myc and c-Maf; (2) modulating tumorigenic signaling pathways including PI3K/AKT and NF-κB; (3) controlling cell cycle regulators such as p27; (4) regulating apoptosis-related proteins including p53; (5) regulating DNA repair factors; (6) governing autophagy-related proteins; and (7) influencing proteasome function [27].

The CRL4CRBN ubiquitin ligase complex holds particular therapeutic significance in MM. This complex, composed of Roc1/RBX1, cullin4 scaffold protein, and the substrate receptor cereblon (CRBN), mediates the therapeutic effects of immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) like lenalidomide and pomalidomide [27]. These drugs induce conformational changes in CRBN, altering its substrate specificity to target the transcription factors IKZF1 and IKZF3 for ubiquitination and degradation, resulting in subsequent depletion of their targets IRF4 and c-Myc, ultimately inhibiting MM cell proliferation [27].

Table 2: E3 Ubiquitin Ligases in Multiple Myeloma Pathogenesis and Treatment

| E3 Ligase | Substrates | Biological Function | Therapeutic Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDM2 | p53 | Promotes MM cell survival by degrading p53 | Potential target for MDM2 inhibitors |

| HUWE1 | c-Myc, p53, MCL-1 | Sustains MM proliferation; depletion promotes c-Myc degradation | Caution required due to bone marrow toxicity in models |

| CRL4CRBN | IKZF1, IKZF3 | Mediates IMiD action; degradation of transcription factors | Target of lenalidomide, pomalidomide |

| SCF-FBXW7 | Notch, c-Myc, Cyclin E | Regulates oncoprotein turnover; often mutated in MM | Potential for combination therapies |

Radiation Resistance Across Cancers

Ubiquitin system enzymes orchestrate radiotherapy resistance through spatiotemporal control of DNA repair fidelity, metabolic reprogramming, and immune evasion, with mechanisms varying significantly by tissue context [29]. The K48-linked polyubiquitin chain primarily targets proteins for proteasomal degradation, while K63 linkages facilitate non-proteolytic signaling complex assembly, with both pathways exploited differently across cancers [29].

FBXW7 exemplifies contextual duality in radiation response. In p53-wild type colorectal tumors, it promotes radioresistance by degrading p53 and inhibiting apoptosis, whereas in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with SOX9 overexpression, FBXW7 enhances radiosensitivity by destabilizing SOX9 and alleviating p21 repression [29]. This functional switch depends on tumor-specific genetic backgrounds, particularly p53 status, and signaling microenvironment components.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Pan-Cancer Ubiquitination Network Analysis

The construction of pancancer ubiquitination regulatory networks employs integrated multi-omics approaches. A standardized methodology includes:

Data Collection and Integration: RNA-seq data and clinicopathological features are collected from large-scale databases such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), typically encompassing datasets from lung, esophageal, cervical, urothelial cancers, and melanoma [13].

Ubiquitination Score Calculation: Correlation coefficient matrices are standardized with significance screening (p value < 0.05) to identify key nodes within the ubiquitination-modification network [13].

Prognostic Model Construction: Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) Cox regression identifies ubiquitination-related genes with prognostic significance, generating a ubiquitination-related prognostic signature (URPS) that stratifies patients into high-risk and low-risk groups [13].

Functional Validation: Findings are validated using independent patient cohorts, cell line models, and in vivo experiments, with single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) employed to resolve cell-type-specific ubiquitination patterns within the tumor microenvironment [13].

Functional Validation Experiments

Standardized experimental protocols for validating E3 ligase and DUB functions include:

Protein-Protein Interaction Studies: Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and proximity ligation assays confirm physical interactions between ubiquitination enzymes and their substrates [28].

Protein Stability Assessments: Cycloheximide chase experiments measure substrate half-life following modulation of E3 ligase or DUB expression [28] [30].

Ubiquitination Status Analysis: In vivo and in vitro ubiquitination assays detect specific ubiquitin chain topology formation using ubiquitin mutants (e.g., K48-only, K63-only) [30].

Functional Consequences: Colony formation, cell cycle analysis, apoptosis assays, and migration/invasion assays evaluate the phenotypic outcomes of ubiquitination enzyme manipulation [28].

In Vivo Validation: Xenograft models, including patient-derived xenografts (PDXs), and genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) assess therapeutic potential and tissue-specific effects [18].

Visualization of Key Signaling Pathways

CRL4CRBN Mechanism in Multiple Myeloma

Diagram Title: CRL4CRBN Mechanism in Multiple Myeloma

OTUB1-TRIM28 Regulation of MYC Signaling

Diagram Title: OTUB1-TRIM28 Regulation of MYC Signaling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Mutants | K48-only, K63-only, K48R, K63R | Ubiquitin chain topology determination | Define specific chain linkages in ubiquitination assays |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, MG132, Carfilzomib | Validation of proteasome-dependent degradation | Confirm UPS involvement in protein turnover |

| E3 Ligase Modulators | MLN4924 (NAE inhibitor), Lenalidomide | Specific E3 ligase complex manipulation | CRL4CRBN targeting for functional studies |

| DUB Inhibitors | P5091 (USP7 inhibitor), PR-619 (pan-DUB inhibitor) | DUB functional characterization | Assess deubiquitination effects on substrate stability |

| Expression Vectors | HA-Ub, Myc-Ub, GFP-Ub | Ectopic ubiquitin expression | Tagged ubiquitin for detection and purification |

| Activity Probes | Ub-AMC, TAMRA-Ub-VME | DUB activity profiling | Measure enzymatic activity in cell lysates |

| Antibody Reagents | Anti-K48-linkage, Anti-K63-linkage, Anti-HA | Ubiquitination detection | Specific recognition of ubiquitin chain types |

The tissue-specific orchestration of tumor progression by E3 ligases and DUBs represents a fundamental layer of cancer biology with profound therapeutic implications. The comparative analysis presented herein demonstrates that while conserved ubiquitination pathways operate across cancer types, their specific implementations, substrate preferences, and functional outcomes exhibit remarkable tissue specificity. This understanding enables more precise targeting of ubiquitination pathways for therapeutic benefit.

Future research directions should prioritize several key areas: First, expanding single-cell ubiquitination signatures across additional cancer types will refine our understanding of cell-type-specific regulation within tumor microenvironments. Second, developing more selective E3 ligase and DUB modulators with reduced off-target effects remains crucial for clinical translation. Finally, integrating ubiquitination profiling into clinical trial design may identify biomarkers predicting treatment response, particularly for combinations targeting ubiquitination pathways alongside conventional therapies, immunotherapy, or radiotherapy.

The rapidly advancing toolkit for studying ubiquitination networks—including activity-based probes, targeted degradation technologies, and multi-omics integration—promises to accelerate the translation of these insights into improved patient outcomes across the spectrum of human malignancies.

Ubiquitination in Tumor Microenvironment Remodeling and Immune Evasion

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) has emerged as a critical, multifaceted regulator of antitumor immunity, extending far beyond its classical role in intracellular protein degradation. Comprising a cascade of E1 (activating), E2 (conjugating), and E3 (ligating) enzymes that coordinate the attachment of ubiquitin chains to target proteins, the UPS dynamically controls the stability, function, and localization of numerous immune signaling molecules [31]. Within the complex ecosystem of the tumor microenvironment (TME), ubiquitination has been revealed as a powerful mechanism that cancer cells exploit to evade immune destruction. By selectively degrading tumor suppressors, stabilizing immune checkpoint proteins, and reprogramming the metabolic and functional states of immune cells, ubiquitination pathways establish formidable barriers to effective antitumor immunity [13] [31]. This review synthesizes recent advances in understanding tissue-specific ubiquitination patterns across cancers, comparing their roles in immune evasion and highlighting emerging therapeutic strategies aimed at targeting the UPS to revitalize antitumor immune responses.

Key Ubiquitination-Related Mechanisms of Immune Evasion: A Pan-Cancer Perspective

Direct Regulation of Immune Checkpoint Protein Stability

The UPS exerts precise control over immune checkpoint molecules, directly influencing the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapies. A well-characterized mechanism involves the E3 ubiquitin ligase speckle-type POZ protein (SPOP), which normally promotes the ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of PD-L1, thereby limiting immune suppression. However, this protective mechanism is frequently subverted in cancers [31]. In colorectal cancer, the enzyme ALDH2 competitively binds to PD-L1, shielding it from SPOP-mediated degradation. Similarly, in hepatocellular carcinoma, the transcription factor BCLAF1 binds to and inhibits SPOP, resulting in PD-L1 stabilization and enhanced immune evasion [31]. The sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) also stabilizes PD-L1 through competitive binding, a process that can be reversed by the SGLT2 inhibitor canagliflozin, leading to restored PD-L1 degradation and enhanced T-cell cytotoxicity [31]. Beyond PD-L1, the expression of other critical immune regulators including CD80, CD40, and CD274 is significantly correlated with ubiquitination-related gene signatures, as demonstrated in cervical cancer and Crohn's disease studies [32] [33].

Table 1: Ubiquitin-Mediated Regulation of Key Immune Checkpoints

| Target Protein | Regulating Ubiquitin Enzyme | Effect on Stability | Cancer Context | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD-L1 | E3 Ligase SPOP | Destabilization/Degradation | Colorectal Cancer | Enhanced T-cell attack [31] |

| PD-L1 | ALDH2 (SPOP inhibition) | Stabilization | Colorectal Cancer | Immune Evasion [31] |

| PD-L1 | BCLAF1 (SPOP inhibition) | Stabilization | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Immune Evasion [31] |

| PD-L1 | SGLT2 (SPOP inhibition) | Stabilization | Pan-Cancer | Immune Evasion [31] |

| PD-1 | Various E3 Ligases | Destabilization/Degradation | T cells | Regulation of T-cell exhaustion [34] |

Ubiquitination-Dependent Metabolic Reprogramming and Mitochondrial Transfer

A novel and paradigm-shifting mechanism of immune evasion involves the ubiquitination-mediated transfer of dysfunctional mitochondria from cancer cells to tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). Genomic analyses of clinical specimens have revealed that TILs can harbor mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations identical to those in neighboring cancer cells, indicating a direct intercellular transfer [35]. This transfer is facilitated by tunneling nanotubes (TNTs) and small extracellular vesicles (EVs), which carry not only the mutated mitochondria but also mitophagy-inhibitory molecules that prevent the recipient T cells from eliminating the defective organelles. Consequently, the TILs undergo severe metabolic dysfunction, adopting a senescent phenotype with impaired effector functions and memory formation, which ultimately cripples the antitumor immune response [35]. The presence of such shared mtDNA mutations correlates with poor prognosis in patients with melanoma or non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) receiving ICIs, highlighting the clinical significance of this pathway [35].

Pancancer Ubiquitination Signatures and Histological Fate Determination

Large-scale pancancer transcriptomic analyses have established that ubiquitination-related prognostic signatures (URPS) effectively stratify patients with diverse cancer types into distinct risk groups with significant differences in overall survival and response to immunotherapy [13]. A key finding from these studies is the strong association between ubiquitination scores and tumor histology. Elevated ubiquitination activity is linked to squamous cell carcinoma (SQC) and neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) transdifferentiation in adenocarcinomas (ADC), a process driven by the ubiquitination-mediated activation of the MYC pathway and alterations in oxidative stress responses [13]. The ubiquitination-related enzyme pair OTUB1-TRIM28 has been identified as a critical upstream regulator of MYC, influencing both histological fate and immunotherapy resistance. This suggests that ubiquitination pathways are not merely passive correlates but active drivers of the molecular and phenotypic characteristics that define aggressive tumor subtypes [13].

Table 2: Ubiquitination-Related Prognostic Signatures (URPS) Across Cancers

| Cancer Type | Key Ubiquitination-Related Genes | Association with High Risk | Impact on Immunotherapy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pancancer (SQC/NEC) | OTUB1, TRIM28, MYC pathway genes | Poor overall survival | Immunotherapy resistance [13] |

| Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma | CDC34 (high), FZR1 (high), OTULIN (low) | Poor prognosis | Correlated with T-cell infiltration & drug sensitivity [36] |

| Cervical Cancer | MMP1, RNF2, TFRC, SPP1, CXCL8 | Poor survival (AUC >0.6, 1/3/5 years) | Altered immune checkpoint expression (CD40, CD80, CD274) [33] |

| Pan-Cancer (UBE2T) | UBE2T (Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme) | Poor clinical outcomes | Correlated with immune cell infiltration & checkpoint genes [14] |

| Pan-Cancer (UBD) | UBD (Ubiquitin D) | Poor prognosis, higher tumor grade | Predictor of immunotherapy sensitivity [17] |

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Investigating Ubiquitination in the TME

Key Experimental Protocols

Research into ubiquitination within the TME relies on a combination of sophisticated bioinformatics, molecular biology, and cell culture techniques.

- Mitochondrial Transfer Co-culture Assay: To visually track and quantify mitochondrial transfer, cancer cells (e.g., MEL02, MEL04) are transfected with a MitoDsRed plasmid to label their mitochondria with a red fluorescent protein [35]. These labeled cells are then co-cultured with T cells (e.g., TILs). The transfer of red fluorescent mitochondria into T cells is monitored over time using live-cell time-lapse imaging. To delineate the mechanism, inhibitors are employed: cytochalasin B to disrupt TNTs, GW4869 to block small EV release, and Y-27632 to inhibit larger microvesicles. Transwell inserts (0.4 µm and 3.0 µm) are used to physically separate cells and assess the necessity of direct contact [35].

- Ubiquitination-Regulated PD-L1 Stability Assay: The stability of PD-L1 is frequently assessed by treating cancer cells with a proteasome inhibitor like MG132. If PD-L1 protein levels increase upon proteasome inhibition, it suggests that it is constitutively degraded via the UPS [31]. To identify specific E3 ligases, co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) experiments are performed to test for physical interaction between PD-L1 and candidate ligases (e.g., SPOP). Furthermore, cells are transfected with plasmids overexpressing the E3 ligase or its mutant forms, followed by cycloheximide chase assays to measure the half-life of PD-L1 and western blotting to detect its ubiquitination levels [31].

- Pancancer Bioinformatic Analysis of Ubiquitination Signatures: This typically involves downloading RNA-seq data and clinical information from public repositories like TCGA and GEO [13] [36] [33]. Differential expression analysis is conducted to identify ubiquitination-related genes (URGs) that are dysregulated in tumors versus normal tissues. LASSO Cox regression is then applied to narrow down the gene list and construct a multi-gene prognostic signature. Patients are stratified into high- and low-risk groups based on their risk scores, and survival differences are evaluated using Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests. The model is validated in independent patient cohorts, and its association with the immune microenvironment is assessed using algorithms like CIBERSORT [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Investigating Ubiquitination in the TME

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| MitoDsRed / MitoTracker | Fluorescent labeling of mitochondria | Visualizing and quantifying intercellular mitochondrial transfer [35] |

| Cytochalasin B | Inhibitor of actin polymerization (disrupts TNTs) | Blocking direct cell-to-cell mitochondrial transfer [35] |

| GW4869 | Inhibitor of neutral sphingomyelinase (blocks small EV release) | Inhibiting extracellular vesicle-mediated mitochondrial transfer [35] |

| MG132 / Bortezomib | Proteasome inhibitors | Stabilizing ubiquitinated proteins to demonstrate UPS-mediated degradation [31] |

| Canagliflozin | SGLT2 inhibitor | Disrupting SGLT2-PD-L1 interaction to promote SPOP-mediated PD-L1 degradation [31] |

| LASSO Cox Regression | Statistical algorithm for variable selection | Developing prognostic models from high-dimensional ubiquitination gene data [13] [36] [33] |

| CIBERSORT / TIMER | Computational deconvolution algorithms | Inferring immune cell infiltration abundance from bulk tumor RNA-seq data [36] [17] |

The intricate role of ubiquitination in remodeling the TME and promoting immune evasion underscores the UPS as a promising therapeutic frontier. The mechanisms are multifaceted, ranging from the direct stabilization of PD-L1 to the novel pathway of mitochondrial sabotage of TILs. The consistency of ubiquitination-related prognostic signatures across diverse cancers highlights their potential as robust biomarkers for predicting patient survival and response to immunotherapy. Future research should focus on developing small-molecule inhibitors or proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) that can precisely modulate specific E3 ligases or deubiquitinating enzymes involved in immune suppression. Combining these novel agents with existing ICIs represents a rational strategy to overcome resistance and restore effective antitumor immunity, ultimately improving outcomes for cancer patients.

Analytical Frameworks and Applications: Mapping Ubiquitination Networks for Clinical Translation

Protein ubiquitination, a fundamental post-translational modification, regulates virtually all cellular processes including protein degradation, cell cycle progression, DNA damage repair, and immune responses [19] [37]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) comprises a sophisticated enzymatic cascade involving E1 activating enzymes, E2 conjugating enzymes, and E3 ligases that collectively tag proteins for proteasomal degradation, while deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) reverse this process [38] [14]. Dysregulation of ubiquitination signaling is intimately linked with tumorigenesis, cancer progression, and treatment resistance across diverse cancer types [13] [19]. The multifaceted roles of ubiquitination in oncology include regulating oncoprotein stability, modulating tumor suppressor degradation, influencing immune checkpoint expression, and controlling cancer cell metabolism [39] [37].

The emergence of multi-omics approaches has revolutionized our ability to systematically characterize ubiquitination patterns across cancers. By integrating genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic data, researchers can now decipher the complex regulatory networks governed by ubiquitination in malignant cells [19] [37]. Large-scale consortium databases like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx), and Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) provide comprehensive resources for pan-cancer ubiquitination profiling [40] [19] [14]. These datasets enable the identification of tissue-specific ubiquitination patterns, discovery of prognostic ubiquitination biomarkers, and development of targeted therapeutic strategies aimed at the ubiquitin system [19] [37].

Database Comparison: Capabilities and Applications

The strategic integration of TCGA, GTEx, and CCLE databases provides complementary strengths for comprehensive ubiquitination profiling across normal tissues, tumors, and model systems.

Table 1: Database Comparison for Ubiquitination Profiling

| Database | Primary Content | Sample Types | Key Ubiquitination Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA | Multi-dimensional molecular data from human tumor samples | ~33 cancer types with matched clinical data | Identification of ubiquitination-related genetic alterations, expression perturbations, and clinical correlations [40] [19] | Limited normal tissue controls; variable sample numbers across cancer types |

| GTEx | Molecular data from normal human tissues | ~54 normal tissue sites from ~1000 donors | Establishment of tissue-specific ubiquitination baselines; identification of ubiquitination regulators with tissue-restricted expression [19] | Post-mortem tissue collection; limited clinical annotation |

| CCLE | multi-omics data from cancer cell lines | ~1000+ human cancer cell lines | Drug sensitivity correlation with ubiquitination gene expression; functional validation of ubiquitination dependencies [37] [14] | In vitro models may not fully recapitulate tumor microenvironment |

TCGA provides the most comprehensive cancer genomics resource, with ubiquitination-related analyses revealing widespread genetic alterations and expression perturbations in ubiquitination regulators across cancer types [19]. For example, a systematic pan-cancer analysis of ubiquitination regulators identified that more than 90% can affect cancer patient survival, with specific hub genes showing excellent prognostic classification for particular cancer types [19]. The clinical correlation data within TCGA enables researchers to link ubiquitination signatures with patient outcomes, histological grades, and cancer stages [40].

GTEx serves as an essential normal tissue reference for establishing physiological baselines of ubiquitination activity. Studies leveraging GTEx have revealed remarkable heterogeneity in ubiquitination regulator expression patterns across tissues, with the testis showing the most distinct signature [19]. This tissue-specific patterning is critical for understanding the potential on-target toxicities of ubiquitination-targeted therapies and for identifying ubiquitination regulators with restricted physiological expression profiles.

CCLE bridges the gap between discovery and functional validation by providing preclinical models for testing ubiquitination-focused hypotheses. The integration of CCLE drug sensitivity data with ubiquitination gene expression has revealed compelling correlations, such as the association between UBE2T expression and sensitivity to trametinib and selumetinib [14]. These findings highlight the potential for leveraging ubiquitination signatures to predict treatment responses and identify novel therapeutic opportunities.

Experimental Methodologies for Ubiquitination Analysis

Ubiquitination Regulator Expression Profiling

The analysis of ubiquitination regulator expression across normal and malignant tissues follows a standardized workflow. RNA-seq data from TCGA and GTEx are processed using uniform pipelines to enable cross-dataset comparisons. For example, a pan-cancer study of ubiquitin D (UBD) employed TCGA and GTEx data through analytical platforms including GEPIA2.0, cBioPortal, UALCAN, and Sangerbox to comprehensively characterize UBD expression, promoter methylation, genetic alterations, and immune infiltration patterns [40]. The differential expression analysis typically employs tools like DESeq2 with thresholds of adjusted p-value < 0.05 and |log2FoldChange| > 0.5 to identify significantly dysregulated ubiquitination genes in tumors versus normal controls [33].