E3 Ubiquitin Ligases in Tumorigenesis: Molecular Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targeting, and Future Directions

This review comprehensively examines the critical roles of E3 ubiquitin ligases in cancer development and progression.

E3 Ubiquitin Ligases in Tumorigenesis: Molecular Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targeting, and Future Directions

Abstract

This review comprehensively examines the critical roles of E3 ubiquitin ligases in cancer development and progression. It explores the foundational biology of ubiquitination and the specific mechanisms by which E3 ligases regulate oncoproteins, tumor suppressors, and key signaling pathways in various cancers, including multiple myeloma, colorectal, and gastric cancers. The article delves into cutting-edge therapeutic strategies such as PROTACs and molecular glues that harness E3 ligases for targeted protein degradation, while also addressing key challenges in the field, including drug resistance and limited E3 ligase diversity. By synthesizing insights from foundational research and clinical applications, this work aims to guide future drug discovery efforts and the development of novel cancer therapeutics.

The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System and E3 Ligase Biology in Cancer

Protein ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification (PTM) that regulates virtually all aspects of eukaryotic cellular function [1] [2]. This highly conserved process involves the covalent attachment of a small, 76-amino acid protein called ubiquitin to target substrate proteins, thereby influencing their stability, activity, localization, and interactions [1] [3]. The ubiquitination process is orchestrated by a sequential enzymatic cascade involving three distinct enzymes: ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), and ubiquitin-ligase (E3) enzymes [1] [4]. Understanding the precise mechanisms of this pathway is particularly relevant in tumorigenesis research, as dysregulation of ubiquitination contributes significantly to cancer development, progression, and therapeutic resistance [5] [2] [6].

The Biochemical Pathway of Ubiquitination

The ubiquitination pathway proceeds through three well-defined, ATP-dependent enzymatic steps that ultimately conjugate ubiquitin to specific substrate proteins.

Step 1: Ubiquitin Activation by E1 Enzymes

The process initiates with the E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme, which activates ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent reaction [1] [7] [4]. This step involves the formation of a high-energy thioester bond between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin and a cysteine residue within the E1 enzyme's active site [7] [6]. The human genome encodes only a few E1 enzymes (such as UBE1), highlighting that this initial activation step represents a common gateway for the entire ubiquitination system [6].

Step 2: Ubiquitin Conjugation by E2 Enzymes

Following activation, ubiquitin is transferred to an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme through a transesterification reaction, maintaining the thioester bond between ubiquitin and the E2 enzyme [1] [7]. The human genome contains approximately 40 E2 enzymes, which begin to introduce specificity into the system by selecting different E3 partners and contributing to determining the type of ubiquitin chain formed on the substrate [1] [6].

Step 3: Substrate Recognition and Ubiquitin Ligation by E3 Enzymes

The final and most diverse step involves E3 ubiquitin ligases, which function as critical specificity determinants by simultaneously binding to E2-ubiquitin complexes and substrate proteins, facilitating the transfer of ubiquitin to the target lysine residue on the substrate [1] [7] [6]. Humans possess nearly 600 E3 ligases that recognize specific subsets of substrates, enabling precise regulation of protein fate within the cell [1] [6]. The transfer mechanism varies between E3 types; RING E3s typically act as scaffolds that facilitate direct ubiquitin transfer from E2 to substrate, while HECT E3s form an intermediate thioester complex with ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate [1] [7].

Table 1: Enzymatic Components of the Ubiquitination Cascade

| Enzyme Type | Number in Humans | Core Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 (Activating) | ~2-8 | Ubiquitin activation via ATP hydrolysis | Forms E1~Ub thioester; ATP-dependent; common gateway |

| E2 (Conjugating) | ~40 | Ubiquitin carrier | Forms E2~Ub thioester; influences chain topology |

| E3 (Ligase) | ~600 | Substrate recognition | Determines specificity; diverse families (RING, HECT, RBR) |

Diagram 1: The Three-Step Ubiquitination Enzymatic Cascade

Complexity of the Ubiquitin Code

Ubiquitination generates diverse signals through different ubiquitin chain configurations, creating a sophisticated "ubiquitin code" that determines the functional outcome for modified substrates [3] [2].

Types of Ubiquitin Modifications

- Monoubiquitination: Attachment of a single ubiquitin molecule to a substrate lysine, typically involved in non-proteolytic functions such as histone regulation, DNA repair, endocytosis, and viral budding [1] [6].

- Multi-monoubiquitination: Multiple single ubiquitin molecules attached to different lysines on the same substrate [1].

- Polyubiquitination: Chains of ubiquitin molecules linked through specific lysine residues, with different linkage types dictating distinct functional consequences [1] [3].

Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Functional Consequences

Ubiquitin contains seven internal lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1) that can form polyubiquitin chains [1] [3] [2]. The specific linkage type creates structurally distinct surfaces that are recognized by proteins containing ubiquitin-binding domains, leading to different cellular outcomes [3].

Table 2: Ubiquitin Linkage Types and Their Primary Functions

| Linkage Type | Primary Cellular Function | Biological Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| K48-linked | Proteasomal degradation [1] | Targets substrates to 26S proteasome; regulates protein half-life |

| K63-linked | Non-degradative signaling [1] | DNA repair, endocytosis, kinase activation, inflammation |

| M1-linked (Linear) | NF-κB signaling [3] [2] | Inflammatory signaling, immune responses, cell death |

| K11-linked | Proteasomal degradation [3] | Cell cycle regulation, ER-associated degradation |

| K27-linked | Mitophagy, immune signaling [3] | Mitochondrial quality control, interferon responses |

| K29-linked | Proteasomal degradation [3] | Non-canonical degradation signals |

| K33-linked | Non-degradative signaling [3] | Kinase regulation, intracellular trafficking |

| K6-linked | DNA damage response [3] | DNA repair pathways, mitochondrial function |

Diagram 2: Ubiquitin Chain Linkages and Functional Specificity

E3 Ubiquitin Ligases: Masters of Specificity in Tumorigenesis

E3 ubiquitin ligases represent the most diverse and specialized components of the ubiquitination cascade, with approximately 600 members in humans that determine substrate specificity [1] [6]. In cancer research, understanding E3 ligases is paramount as they regulate the stability of crucial oncoproteins and tumor suppressors.

Major Classes of E3 Ubiquitin Ligases

E3 ligases are classified into three primary structural families based on their mechanism of action and domain architecture [1] [7] [6]:

RING (Really Interesting New Gene) E3 Ligases: The largest family, characterized by a RING finger domain that simultaneously binds E2-ubiquitin complexes and substrates, acting as scaffolds to facilitate direct ubiquitin transfer without forming a covalent intermediate [1] [6]. Examples include MDM2, which regulates p53 tumor suppressor stability [8].

HECT (Homologous to E6-AP C-Terminus) E3 Ligases: Contain a HECT domain that forms a thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate, providing an additional layer of regulation [1] [7].

RBR (RING-Between-RING-RING) E3 Ligases: Hybrid enzymes that combine RING and HECT-like mechanisms, featuring a RING1 domain that binds E2s and a catalytic domain that forms a transient thioester with ubiquitin [6].

E3 Ligase Dysregulation in Cancer Mechanisms

Dysregulation of E3 ligase function contributes to tumorigenesis through multiple mechanisms [5] [2] [6]:

- Loss-of-function mutations in tumor suppressor E3s (e.g., VHL) lead to accumulation of oncoproteins

- Overexpression of oncogenic E3s (e.g., MDM2) enhances degradation of tumor suppressors

- Altered substrate recognition enables evasion of growth inhibitory signals

A key example is the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) protein, an E3 ligase component mutated in renal cell carcinoma [1]. Under normal conditions, VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-α) for degradation, preventing inappropriate angiogenesis [1]. In VHL disease, mutation results in inability to bind HIF-α, leading to uncontrolled VEGF production and tumor-associated angiogenesis [1].

Another critical mechanism involves competitive ubiquitination, as demonstrated by ATF3, which acts as an "ubiquitin trap" for MDM2, preventing p53 degradation and activating this tumor suppressor in response to DNA damage [8]. Cancer-derived ATF3 mutants that cannot be ubiquitinated fail to stabilize p53, highlighting the importance of this regulatory mechanism in tumor suppression [8].

Experimental Methods for Studying Ubiquitination

Advanced methodologies have been developed to investigate ubiquitination pathways, with particular importance for identifying novel cancer-relevant substrates and regulatory mechanisms.

Ubiquitination Proteomics

4D label-free quantitative ubiquitination proteomics represents a cutting-edge approach for global ubiquitinome profiling [9]. This methodology was applied to adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC), identifying 4,152 ubiquitination sites on 1,993 proteins, with 555 up-regulated and 112 down-regulated ubiquitination sites in tumor compared to normal tissues [9]. The experimental workflow includes:

- Sample Preparation: Tissue samples are ground to powder in liquid nitrogen, followed by ultrasonic pyrolysis in lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors and deubiquitinase inhibitors [9].

- Protein Digestion: Proteins are precipitated, reduced, alkylated, and digested with trypsin overnight [9].

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Peptides are separated by nanoUPLC and analyzed by Tims-TOF mass spectrometry with PASEF acquisition [9].

- Data Processing: MS data are processed using MaxQuant with specific search parameters including GlyGly(K) as variable modification for ubiquitination site identification [9].

Imaging and Visualization Techniques

Microscopy-based imaging of ubiquitination enables spatial and temporal analysis of ubiquitin dynamics in fixed and living cells [3]:

- Confocal fluorescence microscopy with ubiquitin-specific antibodies (FK1, FK2) detects ubiquitin signals in fixed cells

- Super-resolution microscopy (STED, PALM, STORM) provides nanoscale resolution of ubiquitin chain organization

- Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) and ubiquitination-induced fluorescence complementation (UiFC) visualize ubiquitination events in live cells

- FRET-based reporters monitor real-time ubiquitination dynamics

Functional Validation Approaches

- In vitro ubiquitination assays: Reconstitute ubiquitination using purified E1, E2, E3 enzymes, ubiquitin, and ATP to test specific substrate ubiquitination [8]

- CRISPR-Cas9 screening: Identify novel E3-substrate relationships through genome-wide functional screens [1]

- Global Protein Stability (GPS) profiling: Systematically identify E3 ligase substrates using reporter-based screening [1]

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Ubiquitination Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| E1 Inhibitors | PYR-41, TAK-243 | Block ubiquitin activation; study global ubiquitination dependence |

| E2 Enzymes | UbcH5a, UBE2J2 | In vitro ubiquitination assays; chain type specificity studies |

| E3 Ligase Inhibitors | Nutlins (MDM2), SMER3 (SCFMet30) | Specific pathway inhibition; cancer therapeutic development |

| DUB Inhibitors | PR-619, P22077 | Block deubiquitination; study ubiquitin dynamics |

| Ubiquitin Mutants | K48R, K63R, K0 (all lysines mutated) | Study specific chain type functions; dominant-negative approaches |

| Affinity Reagents | TUBEs (Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities) | Enrich ubiquitinated proteins; protect chains from DUBs |

| Ubiquitin Antibodies | FK1, FK2, linkage-specific antibodies | Detect ubiquitin signals in WB, IF; distinguish chain types |

| Activity-Based Probes | Ub-Dha (dehydroalanine) | Identify active DUBs and E3 ligases in complex proteomes |

Therapeutic Targeting of the Ubiquitin System in Cancer

The ubiquitin-proteasome system represents a promising therapeutic target in oncology, with several approaches already in clinical use or development.

Proteasome Inhibitors

Drugs such as bortezomib inhibit the proteasome, preventing degradation of ubiquitinated proteins and causing ER stress and apoptosis in rapidly dividing cells [1]. However, their non-specific nature limits therapeutic applications due to off-target effects [1].

E3 Ligase-Targeted Therapies

The development of specific E3 ligase inhibitors represents a more precise therapeutic strategy:

- MDM2 inhibitors (Nutlins, MI-63) block MDM2-p53 interaction, stabilizing p53 in cancers with wild-type TP53 [7] [8]

- IAP antagonists (SM-406, GDC-0152) counter apoptosis resistance in cancer cells [7]

- CRL3KLHL21 inhibitors target specific cullin-RING ligases implicated in tumorigenesis [3]

Targeted Protein Degradation Strategies

PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) represent a revolutionary approach that hijacks E3 ligases to selectively degrade disease-causing proteins [5] [4] [6]. These bifunctional molecules consist of:

- A target protein-binding ligand

- An E3 ligase-recruiting ligand

- A linker connecting both moieties

PROTACs form a ternary complex with the target protein and E3 ligase, leading to polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of the target [6]. This approach significantly expands the druggable proteome beyond traditional enzyme and receptor targets to include scaffolding and regulatory proteins [5] [6].

The E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade constitutes a sophisticated regulatory system that controls protein fate and function through ubiquitination. The remarkable specificity of E3 ubiquitin ligases, which recognize particular substrates and determine ubiquitin chain topology, positions these enzymes as critical players in cellular homeostasis and tumorigenesis. Dysregulation of specific E3 ligases contributes fundamentally to cancer pathogenesis through altered stability of oncoproteins and tumor suppressors. Advanced research methodologies, including ubiquitin proteomics and novel imaging approaches, continue to unravel the complexity of the ubiquitin code in cancer biology. Therapeutic exploitation of the ubiquitin system, particularly through E3-targeted agents and PROTAC technology, represents a promising frontier in precision oncology with potential to address previously undruggable cancer targets.

E3 ubiquitin ligases are pivotal enzymes in the ubiquitin-proteasome system, conferring substrate specificity and facilitating the transfer of ubiquitin to target proteins. Based on their distinct structural domains and catalytic mechanisms, E3 ligases are classified into three main families: RING (Really Interesting New Gene), HECT (Homologous to E6AP C-terminus), and RBR (RING-in-Between-RING). Growing evidence demonstrates that the structural diversity of these ligases underpins their functional specialization in critical cellular processes, and their dysregulation is intimately linked to tumorigenesis. This review provides an in-depth analysis of the structural characteristics, catalytic mechanisms, and regulatory modes of the RING, HECT, and RBR E3 ligase families. Furthermore, we frame this structural diversity within the context of their roles in cancer development, highlighting how specific structural features determine substrate recognition, ubiquitin chain topology, and ultimately, oncogenic or tumor-suppressive functions. The synthesis of this knowledge is essential for the targeted development of novel cancer therapeutics.

The covalent attachment of ubiquitin to substrate proteins is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates a diverse array of intracellular processes, including protein degradation, cell signaling, DNA repair, and immune response [10] [11]. The ubiquitination process is executed via a sequential enzymatic cascade involving an E1 activating enzyme, an E2 conjugating enzyme, and an E3 ubiquitin ligase [10] [12]. The human genome encodes only two E1s, approximately 40 E2s, and over 600 E3 ligases [11] [13]. The E3 ligase serves as the pivotal determinant of substrate specificity within this cascade, directly mediating the interaction between the ubiquitin-loaded E2 and the target protein [14] [11]. The structural and mechanistic diversity of E3 ligases is the foundation for their precise regulation of countless substrate proteins. In tumorigenesis, mutations or aberrant expression of E3 ligases can lead to the destabilization of tumor suppressors or the accumulation of oncoproteins, thereby driving cancer development and progression [15] [11] [16].

Structural and Mechanistic Classification of E3 Ligases

E3 ubiquitin ligases are primarily categorized into three families based on their domain architecture and mechanism of ubiquitin transfer: RING, HECT, and RBR. Table 1 provides a comprehensive quantitative overview of these families.

Table 1: Quantitative Overview of E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Families in Humans

| E3 Family | Estimated Members | Catalytic Mechanism | Key Structural Domains | Ubiquitin Transfer Path |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RING | ~600 [13] | Direct (Scaffold) | C3HC4-RING domain, often with additional substrate-binding domains [10] [11] | E2 → Substrate |

| HECT | 28 [14] [16] | Indirect (Thioester Intermediate) | N-terminal C2/WW/RLD domains, C-terminal HECT domain [14] [16] | E2 → HECT (Cys) → Substrate |

| RBR | ~14 [15] [12] [17] | Hybrid (RING-HECT) | RING1-IBR-RING2 (Rcat) domains [15] [12] | E2 → RING2 (Cys) → Substrate |

RING Family E3 Ligases

The RING family is the largest and most abundant class of E3 ligases, characterized by a canonical C3HC4-type RING domain that coordinates two zinc ions [10] [13]. Structurally, RING E3s function primarily as scaffolds, facilitating the direct transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 enzyme to the substrate without forming a covalent intermediate [11] [18]. The RING domain binds to the E2~Ub conjugate and allosterically activates it, positioning the thioester bond for nucleophilic attack by a lysine residue on the substrate [13]. A critical feature of many RING domains is a conserved cationic "linchpin" residue (often an arginine) that stabilizes the closed, active conformation of the E2~Ub complex, thereby enhancing ubiquitin transfer efficiency [13]. RING E3s can function as monomers, homodimers, or as part of large multi-subunit complexes, such as Cullin-RING ligases (CRLs), which greatly expand the substrate repertoire [18].

HECT Family E3 Ligases

HECT E3s constitute a distinct family of 28 members characterized by a C-terminal HECT domain of approximately 40 kDa that contains an active-site cysteine residue [14] [16]. Unlike RING E3s, HECT ligases employ a two-step catalytic mechanism involving a covalent thioester intermediate. First, the HECT domain accepts ubiquitin from the E2~Ub complex, forming a transient HECT~Ub intermediate. Second, the ubiquitin is transferred from the catalytic cysteine to a lysine residue on the substrate protein [14] [16]. The N-terminal regions of HECT E3s are highly diverse and are responsible for substrate recognition. They often feature domains such as the C2 domain (for membrane binding), WW domains (for interacting with proline-rich motifs), or RLD domains, which define the NEDD4, HERC, and "Other" subfamilies, respectively [14].

RBR Family E3 Ligases

RBR E3 ligases represent a unique hybrid family that incorporates mechanistic features from both RING and HECT types. Although they contain RING domains, their catalytic mechanism requires a transthioesterification step [15] [12] [17]. The RBR architecture consists of three core domains: RING1, which binds the E2~Ub complex; an IBR (In-Between-RING) domain; and RING2, which contains a catalytic cysteine residue essential for activity [15] [12]. Recent structural insights have led to the renaming of the RING2 domain to the "Rcat" (Required-for-catalysis) domain to more accurately reflect its function [17]. The ubiquitination process involves RING1 recruiting the E2~Ub, followed by the transfer of ubiquitin to the cysteine in the Rcat domain, which then catalyzes the final transfer to the substrate [12]. This "RING-HECT hybrid" mechanism distinguishes RBRs from classical RING E3s [15].

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanistic pathways for ubiquitin transfer employed by the three E3 ligase families.

Experimental Analysis of E3 Ligase Mechanisms

Understanding the catalytic mechanisms and regulation of E3 ligases relies on a suite of biochemical, biophysical, and structural techniques. The following section details a key experimental workflow used to dissect the mechanism of RING E3 ligases, serving as a paradigm for probing E3 function.

Detailed Protocol: Investigating the RING Linchpin Mechanism

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating the role of the conserved "linchpin" residue in RING E3-mediated ubiquitination [13].

- Objective: To determine how the identity of a specific linchpin residue in a RING domain influences E2~Ub binding, conformation, and ubiquitin transfer activity.

Key Research Reagents:

- Recombinant Proteins: Purified RING domain (e.g., RNF38 RING), E1 enzyme, E2 enzyme (e.g., UBE2D2), and ubiquitin.

- Mutagenesis Kit: For generating point mutations in the RING domain linchpin position.

- ATP and Mg²⁺: Essential cofactors for the ubiquitination reaction.

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) & Crystallography Reagents: For structural complex formation and analysis.

- NMR Instrumentation: For analyzing protein conformation and dynamics in solution.

Methodology:

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Generate a comprehensive library of RING domain mutants where the native linchpin arginine is substituted with all other 19 amino acids.

- In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay:

- Set up reaction mixtures containing E1, E2, ubiquitin, ATP, and the wild-type or mutant RING protein.

- Incubate at 37°C and stop the reaction at various time points.

- Analyze the products via SDS-PAGE and western blotting to detect the formation of polyubiquitin chains or ubiquitinated substrates. Quantify the activity of each mutant relative to the wild-type.

- Binding Affinity Measurement:

- Use techniques such as Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) or Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) to measure the binding affinity (KD) between the RING mutants and the E2~Ub conjugate.

- Structural Analysis:

- NMR Spectroscopy: Perform NMR chemical shift perturbation analysis to assess the degree to which different linchpin mutants stabilize the closed, catalytically competent conformation of the E2~Ub complex.

- X-ray Crystallography: Co-crystallize key RING mutants (e.g., a low-activity mutant like LPTyr) with E2~Ub and solve the crystal structure to visualize atomic-level interactions and conformational changes.

- Cellular Validation:

- Express selected RING mutants (e.g., a gain-of-function mutant like XIAPY485R) in cell lines (e.g., HEK293).

- Assess downstream effects on substrate ubiquitination levels and pathway activity using immunoprecipitation and western blotting.

Expected Outcomes: This integrated approach reveals that the linchpin residue identity modulates ubiquitination not merely by altering E2~Ub binding affinity, but by fine-tuning the stabilization of the active E2~Ub conformation. Arginine is typically the most effective, but other residues can be engineered to enhance or abolish activity [13].

E3 Ligase Dysregulation in Tumorigenesis

The deregulation of E3 ubiquitin ligases is a hallmark of many cancers. They can function as oncogenes, tumor suppressors, or exhibit dual roles depending on cellular context. Table 2 summarizes examples from each family and their roles in cancer.

Table 2: Roles of E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Families in Tumorigenesis

| E3 Family | Example Member | Role in Cancer | Key Substrates & Pathways | Cancer Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RING | RNF114 | Oncogenic [10] | Degrades EGR1, JUP; promotes cell cycle progression [10] | Gastric Cancer, Colorectal Cancer [10] |

| RING | RNF125 | Oncogenic / Context-dependent [10] | Regulates immunity and inflammation [10] | Various Cancers [10] |

| HECT | NEDD4 (NEDD4-1) | Oncogenic [14] [16] | Promotes PTEN degradation; activates PI3K/AKT pathway [16] | Gastric Cancer, others [14] |

| HECT | HUWE1 | Oncogenic [14] | Ubiquitinates TGFBR2; promotes proliferation [14] | Gastric Cancer [14] |

| HECT | ITCH | Dual Role [14] | Ubiquitinates SMAD7; regulates TGF-β and Wnt/β-catenin pathways [14] | Gastric Cancer [14] |

| RBR | ARIH1, RNF31 | Primarily Oncogenic [15] [12] | Regulates NF-κB signaling; promotes cell survival [12] | Breast Cancer, others [12] |

| RBR | PARK2 (Parkin) | Tumor Suppressor [15] [12] | Promotes degradation of oncoproteins; regulates mitophagy [12] | Various Cancers [15] |

| RBR | ARIH2 | Tumor Suppressor [15] [12] | Negatively regulates NF-κB and JAK-STAT pathways [12] | Leukaemia [12] |

Regulatory Mechanisms in Cancer

The activity of E3 ligases in cancer is controlled through multiple layers of regulation:

- Oligomerization: Homotypic and heterotypic assembly is a key regulatory mechanism. For instance, HECT ligases like SMURF1 and NEDD4 are auto-inhibited by oligomerization, while RING ligases like MDM2 and TRAF6 are activated by it [18].

- Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs): Phosphorylation, sumoylation, and auto-ubiquitination can directly modulate E3 ligase activity, substrate specificity, and localization. For example, phosphorylation of HECT E6AP by c-Abl kinase disrupts its active trimeric form, inhibiting its function [18].

- Altered Expression: The expression of E3 ligases is frequently dysregulated in cancers via genetic mutations, gene amplification, promoter hypermethylation, or microRNA-mediated silencing [14] [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The study of E3 ubiquitin ligases requires a specific set of reagents and tools. The following table details essential materials for functional and mechanistic studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Active E1, E2, and Ubiquitin | Core components for reconstituting ubiquitination reactions in vitro [13]. | Recombinantly purified, high activity; Biotin- or fluorophore-labeled ubiquitin variants are available for detection. |

| Recombinant E3 Proteins | For structural studies, in vitro activity assays, and interaction mapping. | Full-length or truncated proteins containing functional domains (e.g., RING, HECT, RBR); both wild-type and catalytic mutants (e.g., Cys-to-Ala in HECT/RBR) are essential controls. |

| E3 Ligase Inhibitors | To probe E3 function and as potential therapeutic leads. | Includes small molecules targeting the HECT domain (e.g., Heclin) [16], and RING E2-interaction inhibitors. PROTACs leverage E3s to induce targeted protein degradation. |

| Cell Lines with E3 KO/KN | To study the physiological role of an E3 in a relevant cellular context. | CRISPR-Cas9 knockout (KO) or knock-in (KN) cell lines; inducible shRNA knockdown (KD) lines. |

| Specific Antibodies | For detecting protein expression, localization, and ubiquitination status in vivo. | Antibodies against the E3 of interest, its known substrates, and specific ubiquitin linkages (e.g., K48-, K63-linkage specific antibodies). |

| X-ray Crystallography & NMR | For determining high-resolution structures of E3s alone or in complex with E2~Ub/substrates [13]. | Enables visualization of catalytic mechanisms, like the RING linchpin interaction and the HECT/RBR thioester intermediate. |

The structural diversity of E3 ubiquitin ligases—encompassing the scaffold-like RING, the intermediate-forming HECT, and the hybrid RBR families—directly dictates their unique catalytic mechanisms and regulatory complexities. This diversity is a cornerstone of their ability to precisely control cellular proteostasis. In cancer, the delicate balance of E3 activity is frequently disrupted, leading to the pathological degradation of tumor suppressors or stabilization of oncoproteins. A deep mechanistic understanding of how specific structural domains (e.g., the RING linchpin, the HECT catalytic cysteine, or the RBR Rcat domain) govern function is paramount. Future research, leveraging the experimental tools and reagents outlined, will continue to unravel the intricate roles of E3 ligases in tumorigenesis. This knowledge is actively being translated into novel therapeutic strategies, including the development of specific small-molecule inhibitors and bifunctional degraders (PROTACs), offering promising avenues for targeted cancer therapy.

Ubiquitination is a crucial post-translational modification that regulates virtually all cellular processes in eukaryotes. This modification involves the covalent attachment of a small, 76-amino acid protein, ubiquitin, to target substrates. The process is mediated by a sequential enzymatic cascade comprising ubiquitin-activating (E1), conjugating (E2), and ligase (E3) enzymes [11]. The human genome encodes two E1 enzymes, approximately 35 E2 enzymes, and over 600 E3 ligases, which confer substrate specificity [11]. Ubiquitin itself contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1), each capable of forming polyubiquitin chains with distinct structures and functions [19].

The specific cellular outcomes of ubiquitination are determined by the topology of the ubiquitin chain—a concept known as the "ubiquitin code." Among the different chain types, K48- and K63-linked ubiquitinations are the most abundant and well-studied, accounting for approximately 52% and 38% of all ubiquitination events in HEK293 cells, respectively [20]. Historically, these linkages were associated with distinct functions: K48-linked chains primarily target substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains regulate non-proteolytic processes including signal transduction, DNA repair, endocytosis, and inflammation [20] [11]. However, emerging research reveals significant functional complexity and crosstalk between these pathways, particularly in the context of tumorigenesis where ubiquitination regulates crucial processes including cell proliferation, survival, and metabolic adaptation [11] [21].

Structural and Functional Dichotomy of K48 and K63 Linkages

K48-Linked Ubiquitin Chains

K48-linked polyubiquitination represents the canonical signal for proteasomal degradation. This linkage type serves as the principal degradation signal for multiple short-lived proteins, targeting them to the 26S proteasome for processing [20] [19]. The K48 linkage establishes a specific chain conformation that is efficiently recognized by proteasomal receptors.

Recent technological advances have refined our understanding of K48 chain requirements. The UbiREAD (Ubiquitinated Reporter Evaluation After intracellular Delivery) system has demonstrated that K48-linked chains require at least three ubiquitin molecules to effectively target substrates for degradation, with shorter chains being susceptible to disassembly [22] [23]. Intracellular degradation of K48-ubiquitinated substrates occurs remarkably fast, with a half-life of approximately one minute in cellular environments—significantly faster than degradation rates observed in cell-free systems [22].

K63-Linked Ubiquitin Chains

K63-linked ubiquitination has emerged as a key regulator of diverse non-proteolytic functions. These chains facilitate the endocytosis and lysosomal sorting of membrane proteins such as the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [20]. In the DNA damage response, K63 linkages coordinate repair complex assembly [11], while in inflammatory pathways, they regulate NF-κB signaling [24]. Additionally, K63 chains function in ribosomal quality control, where they recruit the RQT complex to resolve colliding ribosomes [25].

Unlike the compact structure of K48 chains, K63-linked chains adopt more open, extended conformations that are not recognized by the proteasome but instead serve as scaffolds for protein-protein interactions [20]. UbiREAD analyses have confirmed that K63-linked chains are rapidly deubiquitinated in cells and do not typically target substrates for proteasomal degradation [22] [23].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of K48 and K63 Ubiquitin Linkages

| Feature | K48-Linked Chains | K63-Linked Chains |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Functions | Proteasomal degradation [20] [19] | Signaling, endocytosis, DNA repair, inflammation [20] [11] |

| Structural Conformation | Compact [20] | Extended, open [20] |

| Cellular Abundance | ~52% of polyubiquitin chains [20] | ~38% of polyubiquitin chains [20] |

| Minimum Chain Length for Function | 3 ubiquitin molecules [22] [23] | Not established |

| Intracellular Half-Life | ~1 minute [22] | Rapidly deubiquitinated [22] |

| Key Deubiquitinases | Not specified in results | CYLD, USP30 [19] [24] |

| Proteasomal Targeting | Direct [19] | Indirect (via branching) [24] [26] |

Experimental Evidence Challenging the Simple Dichotomy

Despite the classical functional separation, rigorous experimental evidence challenges the exclusivity of this dichotomy. A seminal study employing an inducible RNAi strategy to replace endogenous ubiquitin with linkage-specific mutants demonstrated that the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) can be targeted for lysosomal degradation by either K48 or K63 linkages [20]. This finding indicates that both linkages can signal lysosomal degradation, contradicting the simple model where K63 linkages exclusively mediate this process.

The E3 ligase inducible degrader of the LDL receptor (IDOL) catalyzes ubiquitin transfer to itself and LDLR using chains "that do not contain exclusively K48 or K63 linkages" [20]. Furthermore, although both UBE2D and UBE2N/V1 E2 enzymes can catalyze LDLR ubiquitination in cell-free systems, UBE2Ds appear to be the major E2 enzymes employed by IDOL in cells, consistent with their ability to catalyze both K48 and K63 linkages [20].

The Ubiquitin Code in Tumorigenesis: Beyond Simple Dichotomies

Regulation of Cancer-Relevant Signaling Pathways

Ubiquitination, particularly through K48 and K63 linkages, plays a pivotal role in regulating oncogenic and tumor-suppressive pathways. Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), including EGFR, are tightly controlled by ubiquitination following activation [21]. While c-CBL-mediated ubiquitination typically targets activated RTKs for lysosomal degradation, mutations in CBL or RTKs that impede ubiquitylation contribute to oncogenic hyperactivation [21]. Such mutations occur in approximately 5% of myeloid neoplasms [21].

The RAS-MAPK and PI3K-AKT pathways—critical drivers of proliferation—are similarly regulated by ubiquitination. The LZTR1 E3 ligase, part of the CRL3 complex, mediates ubiquitination of small GTPases including RIT1, with pathogenic mutations leading to RIT1 accumulation and dysregulated growth signaling [21]. Additionally, the multifaceted E3 ligase HUWE1 regulates numerous cancer-relevant substrates including MYC, p53, and Mcl-1, demonstrating both tumor-promoting and suppressive activities depending on cellular context [27].

Table 2: Key E3 Ligases in Cancer-Relevant Ubiquitination

| E3 Ligase | Substrates | Linkage Specificity | Role in Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| HUWE1 | MYC, p53, Mcl-1 [27] | K6, K48, K63, mono-ubiquitination [27] | Context-dependent; frequently overexpressed in solid tumors, downregulated in brain tumors [27] |

| CBL | EGFR, PDGFR, c-Kit [21] | Not specified | Tumor suppressor; mutations in ~5% of myeloid neoplasms [21] |

| LZTR1 | RIT1, RAS GTPases [21] | Not specified | Tumor suppressor; mutations in Noonan syndrome and cancer [21] |

| ITCH | TXNIP [26] | K63 (initial) [26] | Tumor modulator; collaborates with UBR5 to form branched chains [26] |

| TRAF6 | NF-κB pathway components [24] | K63 (initial) [24] | Promotes inflammation and tumorigenesis [24] |

Branched Ubiquitin Chains in Oncogenic Signaling

Recent research has unveiled the importance of branched ubiquitin chains in signal regulation, particularly in cancer-relevant pathways. Branched chains containing both K48 and K63 linkages have been identified as critical regulators of NF-κB signaling [24]. In response to interleukin-1β (IL-1β), the E3 ligase TRAF6 first assembles K63-linked chains, which are subsequently modified by HUWE1 to add K48 branches, forming K48-K63 branched ubiquitin chains [24].

These branched ubiquitin chains serve dual functions: they permit recognition by TAB2 (a component of the NF-κB signaling pathway) while simultaneously protecting K63 linkages from CYLD-mediated deubiquitination [24]. This mechanism amplifies NF-κB signaling and demonstrates how the integration of different linkage types creates unique regulatory properties not present in homotypic chains.

Similar collaborative E3 mechanisms occur in apoptosis regulation, where the HECT E3s ITCH and UBR5 sequentially modify the pro-apoptotic regulator TXNIP—first with K63-linked chains (by ITCH), then with K48 linkages (by UBR5)—producing branched K48/K63 chains that target TXNIP for proteasomal degradation [26]. This conversion from non-degradative to degradative signaling represents an efficient mechanism for controlling protein stability in dynamic cellular processes.

Diagram 1: Branched ubiquitin chain regulation of NF-κB signaling. Created with DOT language.

Methodologies for Deciphering the Ubiquitin Code

Ubiquitin Replacement Strategy

Studying specific ubiquitin linkages has been challenging due to the essential nature of ubiquitin and the presence of four ubiquitin-encoding genes in the human genome. To address this, researchers developed an inducible RNAi replacement strategy where endogenous ubiquitin is depleted while simultaneously expressing mutant ubiquitins [20]. This approach was used to demonstrate that neither K48 nor K63 linkages are exclusively required for IDOL-mediated degradation of LDLR, revealing unexpected flexibility in linkage usage for lysosomal targeting [20].

Protocol Overview:

- Engineer cells with tetracycline-inducible RNAi constructs targeting endogenous ubiquitin genes

- Co-express RNAi-resistant wild-type or mutant ubiquitin (e.g., K48R or K63R)

- Induce RNAi expression with tetracycline to replace endogenous ubiquitin pool

- Assess substrate ubiquitination and degradation under defined linkage conditions

UbiREAD Technology for Ubiquitin Chain Function Analysis

The UbiREAD (Ubiquitinated Reporter Evaluation After intracellular Delivery) system represents a technological breakthrough for systematically analyzing how specific ubiquitin chains control protein stability in living cells [22] [23]. This method enables researchers to deliver precisely defined ubiquitin chains into cells and monitor their fate.

Detailed Protocol:

- Reporter Preparation:

- Generate fluorescent reporter protein (e.g., GFP) conjugated to defined ubiquitin chains

- Utilize enzymatic assembly or chemical synthesis to create specific ubiquitin linkages (K48, K63, or branched chains)

- Purify ubiquitinated reporters using affinity chromatography

Intracellular Delivery:

- Deliver ubiquitinated reporters into mammalian cells via electroporation or microinjection

- Optimize delivery conditions to maintain cell viability while ensuring efficient uptake

Degradation Monitoring:

- Track fluorescence intensity over time using live-cell imaging or flow cytometry

- Calculate protein half-life from fluorescence decay kinetics

- Compare degradation rates between different ubiquitin chain types

Data Analysis:

- Determine minimum chain length requirements for degradation

- Assess competition between degradation and deubiquitination

- Evaluate hierarchical relationships in branched chains

Diagram 2: UbiREAD workflow for ubiquitin code analysis. Created with DOT language.

Mass Spectrometry-Based Quantification of Branched Chains

Advanced proteomic approaches have been developed to identify and quantify branched ubiquitin chains. A mass-spectrometry-based quantification strategy revealed that K48-K63 branched ubiquitin linkages are surprisingly abundant in mammalian cells [24]. This method utilizes absolute quantification (AQUA) with stable isotope-labeled ubiquitin peptides to precisely measure different chain types.

Protocol Overview:

- Enrich ubiquitinated proteins from cells under specific conditions

- Digest proteins with specific proteases (e.g., trypsin)

- Spike in stable isotope-labeled internal standards for different ubiquitin linkages

- Analyze by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

- Quantify linkage types based on signature peptides and retention times

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Studying K48 and K63 Ubiquitin Linkages

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Linkage-Specific Ubiquitin Mutants | Studying specific linkage requirements [20] | K48R, K63R point mutations; expressed via RNAi-resistant vectors |

| UbiREAD System | Analyzing intracellular fate of defined ubiquitin chains [22] [23] | Enables delivery of predefined ubiquitin chains into living cells |

| Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) | Affinity purification of polyubiquitinated proteins [24] | Linkage-specific TUBEs available for different chain types |

| AQUA Peptides | Absolute quantification of ubiquitin linkages by MS [24] | Stable isotope-labeled internal standards for precise quantification |

| HECT Domain Inhibitors | Targeting HECT E3 ligases like HUWE1 [27] | Small molecules or ubiquitin variants (UbVs) that block catalytic activity |

| Deubiquitinase Inhibitors | Studying chain stability and turnover [19] | Specific inhibitors for DUBs such as USP30, CYLD |

| Linkage-Specific Antibodies | Immunodetection of specific ubiquitin linkages [20] | Antibodies specifically recognizing K48 vs K63 linkages |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Perspectives

The complexity of the ubiquitin code presents both challenges and opportunities for cancer therapeutics. Several strategies are emerging to target ubiquitination pathways for cancer treatment:

Proteasome Inhibitors: Drugs such as bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib have achieved tangible success in treating hematological malignancies by globally disrupting protein degradation [11]. However, their efficacy is limited by compensatory mechanisms and toxicity.

E1 and E2 Inhibitors: Compounds including MLN7243 and MLN4924 (targeting E1), and Leucettamol A and CC0651 (targeting E2 enzymes) have shown potential in preclinical models [11]. MLN4924 (pevonedistat) specifically inhibits NEDD8 activation, thereby disrupting Cullin-RING ligase activity, and has advanced to clinical trials [21].

E3-Targeted Therapies: Strategies to modulate E3 ligase activity include nutlin and MI-219, which block MDM2-p53 interaction to stabilize p53 [11]. Additionally, proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) harness E3 ligases to selectively degrade target proteins, showing exceptional promise in drug development.

Branched Chain Modulation: Emerging understanding of branched ubiquitin chains suggests new therapeutic avenues. For instance, disrupting the formation of K48-K63 branched chains in NF-κB signaling could potentially dampen inflammatory responses in the tumor microenvironment [24]. Similarly, modulating the collaboration between ITCH and UBR5 in apoptosis regulation might sensitize cancer cells to programmed cell death [26].

The functional complexity between K48 and K63 linkages, including their roles in branched chains, highlights the need for more sophisticated approaches to therapeutic intervention. Future research should focus on developing linkage-specific probes and inhibitors that can precisely modulate specific aspects of the ubiquitin code without globally disrupting protein homeostasis. As our understanding of the ubiquitin code deepens, we move closer to realizing the potential of targeted ubiquitin-based therapies for cancer treatment.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) represents a crucial regulatory mechanism for protein homeostasis, with E3 ubiquitin ligases serving as its central arbiters of specificity. These enzymes catalyze the final step in the ubiquitination cascade, determining the fate of target proteins through proteasomal degradation or functional modulation. In tumorigenesis, E3 ligases exhibit remarkable functional duality, acting as either oncogenes or tumor suppressors in a context-dependent manner. This review comprehensively examines the molecular mechanisms underlying this duality, exploring how cellular context, substrate specificity, genetic alterations, and tissue microenvironment influence E3 ligase function in cancer. We further summarize experimental approaches for investigating E3 ligase functions and discuss the therapeutic implications of targeting these enzymes in cancer treatment, with particular focus on emerging proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC) technology.

Ubiquitination is a sophisticated post-translational modification process that involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin molecules to target proteins, thereby influencing their stability, localization, and activity [11]. This process is mediated through a sequential enzymatic cascade involving ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), and ubiquitin-ligating (E3) enzymes [28] [6]. The human genome encodes only two E1 enzymes, approximately 35 E2 enzymes, and over 600 E3 ligases, highlighting the critical role of E3s in determining substrate specificity [11].

E3 ubiquitin ligases are classified into three major families based on their structural domains and mechanisms of ubiquitin transfer [28] [21]:

Really Interesting New Gene (RING) Finger Family: The largest E3 family, characterized by a RING domain that directly catalyzes ubiquitin transfer from E2 to substrate without forming an E3-ubiquitin thioester intermediate. RING E3s can function as monomers, dimers, or multi-subunit complexes [28] [21].

Homologous to E6AP C-Terminus (HECT) Family: Distinguished by a HECT domain that forms a thioester intermediate with ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate [28].

RING-In-Between-RING (RBR) Family: Hybrid enzymes that employ a RING-HECT mechanism, combining features of both major families [28].

The fate of ubiquitinated proteins is determined by the type of ubiquitin modification. Monoubiquitination typically regulates subcellular localization and protein activity, while polyubiquitin chains linked through different lysine residues signal distinct outcomes: K48-linked chains primarily target proteins for proteasomal degradation, K63-linked chains mediate non-proteolytic functions including signal transduction and DNA repair, and other linkages (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33) participate in various cellular processes [28] [11] [29].

The Dual Nature of E3 Ligases in Cancer

E3 ubiquitin ligases occupy critical positions in cellular regulation, and their dysregulation contributes significantly to tumorigenesis. The functional outcome of E3 activity—tumor-promoting or tumor-suppressing—is context-dependent, influenced by factors such as substrate profile, cellular environment, genetic alterations, and tissue type [21].

Table 1: E3 Ligases as Oncogenes or Tumor Suppressors in Different Cancers

| E3 Ligase | Cancer Type | Oncogenic/Tumor Suppressive Role | Key Substrate(s) | Molecular Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDM2 | Various (with wild-type p53) | Oncogenic | p53 | Promotes degradation of tumor suppressor p53 [30] |

| CRL4CRBN | Multiple Myeloma | Context-dependent | IKZF1/3 | IMiDs alter substrate specificity to degrade transcription factors [29] |

| HUWE1 | Multiple Myeloma | Oncogenic | c-Myc | Enhances K63-linked ubiquitination stabilizing c-Myc [29] |

| LZTR1 | Various | Tumor Suppressive | RIT1 | Targets proto-oncoprotein RIT1 for degradation [21] |

| c-CBL | Myeloid Neoplasms | Tumor Suppressive | RTKs (EGFR, PDGFR) | Downregulates activated receptor tyrosine kinases [21] |

| RNF114 | Colorectal, Gastric | Oncogenic | JUP, EGR1 | Promotes proliferation, migration, invasion [10] |

| DTX3L | Prostate, Breast | Oncogenic | p53, AR | Degrades tumor suppressors in specific cancer contexts [31] |

| FBXW7 | Various | Tumor Suppressive | c-Myc, Cyclin E | Degrades several oncoproteins [30] |

E3 Ligases as Oncogenic Drivers

Many E3 ligases function as oncogenes by promoting the degradation of tumor suppressor proteins or stabilizing oncoproteins. A prominent example is MDM2, which targets the p53 tumor suppressor for proteasomal degradation [30]. In cancers retaining wild-type p53, MDM2 amplification or overexpression effectively neutralizes p53's tumor-suppressive function, facilitating uncontrolled proliferation and survival [30]. The therapeutic targeting of the MDM2-p53 interaction represents a promising strategy for reactivating p53 in these malignancies [30].

The RING-UIM subfamily of E3 ligases (RNF114, RNF125, RNF138, RNF166) demonstrates oncogenic potential across various cancers [10] [32]. RNF114 is upregulated in colorectal and gastric cancers, where it promotes proliferation, migration, and invasion by ubiquitinating substrates such as junction plakoglobin (JUP) and early growth response protein 1 (EGR1) [10]. Similarly, DTX3L exhibits oncogenic properties in prostate and breast cancers by targeting tumor suppressors like p53 and androgen receptor for degradation [31].

In multiple myeloma, HUWE1 plays a critical oncogenic role by stabilizing the c-Myc oncoprotein through K63-linked ubiquitination, thereby promoting myeloma cell proliferation and survival [29].

E3 Ligases as Tumor Suppressors

Conversely, many E3 ligases function as tumor suppressors by targeting oncoproteins for degradation. The c-CBL family proteins suppress tumorigenesis by ubiquitinating activated receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) such as EGFR, PDGFR, and c-Kit, targeting them for lysosomal degradation [21]. Loss-of-function mutations in CBL genes are associated with myeloid malignancies, leading to sustained RTK signaling and oncogenic transformation [21].

LZTR1, a substrate receptor for CUL3 RING ligase complexes, acts as a tumor suppressor by targeting the small GTPase RIT1 for degradation [21]. Mutations in LZTR1 disrupt this regulation, resulting in RIT1 accumulation and dysregulated growth factor signaling [21].

FBXW7, a component of the SCF E3 complex, represents another crucial tumor suppressor that targets multiple oncoproteins for degradation, including c-Myc, Cyclin E, and Notch [30]. FBXW7 mutations are prevalent across various human cancers, leading to stabilization of its oncogenic substrates [30].

Context-Dependent Functional Switching

Some E3 ligases exhibit remarkable functional plasticity, acting as either oncogenes or tumor suppressors depending on cellular context. The CRL4CRBN complex exemplifies this duality in multiple myeloma. In its native state, CRL4CRBN likely functions as a tumor suppressor; however, when bound to immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) such as lenalidomide or pomalidomide, its substrate specificity is altered to target the transcription factors IKZF1 and IKZF3 for degradation, resulting in therapeutic anti-myeloma effects [29].

This context-dependent functionality is influenced by multiple factors:

- Substrate availability: Tissue-specific expression of substrates determines functional outcomes

- Genetic alterations: Mutations in E3s or their substrates can alter functional consequences

- Cellular microenvironment: Factors such as hypoxia, nutrient availability, and stromal interactions influence E3 activity

- Post-translational modifications: Phosphorylation, acetylation, and other modifications regulate E3 ligase activity and specificity

Molecular Mechanisms of E3 Regulation in Cancer Hallmarks

E3 ligases regulate all recognized hallmarks of cancer through their precise control of key regulatory proteins. The molecular mechanisms underlying E3-mediated cancer progression involve complex interactions with diverse signaling pathways.

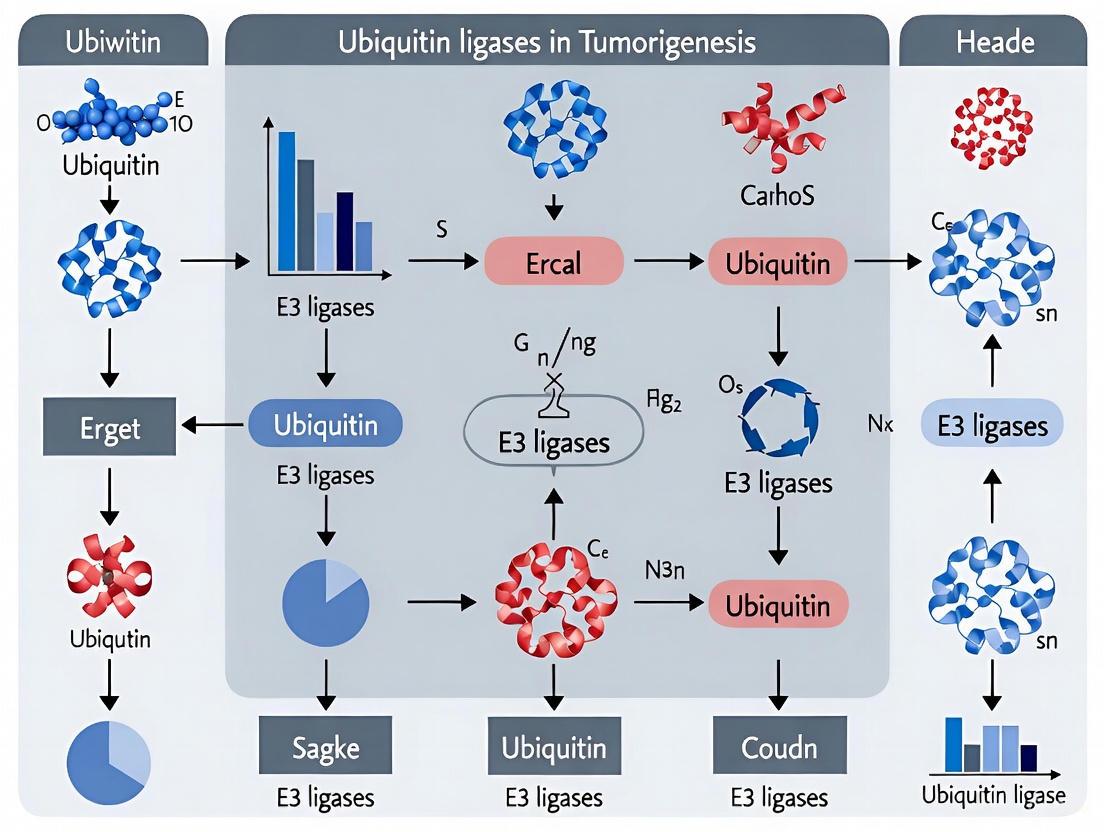

Diagram 1: E3 Ligase Regulation of Cancer Pathways. E3 ubiquitin ligases regulate multiple cancer-relevant pathways by targeting key proteins for ubiquitination. The diagram illustrates specific E3-substrate relationships in critical cellular processes.

Sustained Proliferative Signaling

E3 ligases regulate proliferative signaling at multiple levels, from receptor initiation to downstream effector pathways [21]. They control the abundance and activity of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) through ubiquitin-mediated endocytosis and degradation [21]. For example, c-CBL targets activated EGFR for degradation, limiting downstream signaling [21]. At the intracellular level, E3s regulate key signal transducers such as RAS family GTPases and components of the PI3K-AKT pathway [21]. The CRL1SKP2 complex promotes G1-S cell cycle progression by degrading CDK inhibitors p27 and p21, facilitating uncontrolled proliferation in many cancers [28] [21].

Evasion of Growth Suppressors and Cell Death

E3 ligases play crucial roles in bypassing tumor-suppressive mechanisms. The MDM2-p53 axis represents the most prominent example, where MDM2-mediated degradation of p53 allows cancer cells to evade apoptosis and cell cycle arrest [30]. Additionally, E3s such as the inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) family proteins directly block apoptotic pathways by ubiquitinating and inhibiting caspases [28]. In multiple myeloma, MDM2 promotes cell survival by mediating K48-linked ubiquitination and degradation of p53 [29].

Activation of Invasion and Metastasis

The process of cancer metastasis involves multiple steps—epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), invasion, migration, and colonization—all regulated by E3 ubiquitin ligases [33]. E3s modulate the stability of key transcription factors controlling EMT, such as Snail, Slug, and Twist, thereby influencing metastatic potential [33]. In breast cancer, various E3 ligases have been implicated in regulating metastasis through targeting cell adhesion molecules, matrix metalloproteinases, and chemokine receptors [33].

Table 2: E3 Ligase Involvement in Cancer Hallmarks

| Cancer Hallmark | Regulatory E3 Ligases | Molecular Targets | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustained Proliferation | CRL1SKP2, HUWE1, RNF114 | p27, p21, c-Myc, JUP | Enhanced cell cycle progression [10] [21] [29] |

| Evasion of Growth Suppression | MDM2, COP1, PIRH2 | p53, p27 | Bypass of tumor suppressor pathways [30] |

| Resistance to Cell Death | IAP Family, MDM2 | Caspases, p53 | Inhibition of apoptosis [28] [29] |

| Activation of Invasion & Metastasis | Various RING ligases | EMT transcription factors, adhesion molecules | Enhanced metastatic potential [33] |

| Dysregulated Metabolism | Multiple E3s | mTOR, AMPK, PTEN | Metabolic reprogramming [11] |

| Genome Instability | RNF138, BRCA1/BARD1 | DNA repair proteins | Accumulation of mutations [10] [21] |

Experimental Approaches for Studying E3 Ligase Functions

Investigating the roles of E3 ligases in tumorigenesis requires a multidisciplinary approach combining biochemical, cellular, and animal model systems. Below we outline key methodological frameworks for characterizing E3 ligase functions.

Identifying E3-Substrate Interactions

Diagram 2: E3-Substrate Interaction Studies. Experimental workflow for identifying and validating E3 ubiquitin ligase substrates and their functional relationships.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and Pull-down Assays: These fundamental techniques establish physical interactions between E3 ligases and potential substrates. For endogenous interactions, co-IP using specific antibodies against the E3 ligase or substrate protein is performed from cell lysates, followed by immunoblotting to detect associated proteins [21]. For direct interaction mapping, recombinant E3 and substrate proteins are used in vitro pull-down assays [21].

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening: This system identifies novel E3 binding partners by expressing the E3 ligase as "bait" and screening cDNA libraries as "prey." Protein interactions reconstitute transcription factors that activate reporter genes, enabling identification of novel substrates [21].

Ubiquitination Assays: Direct demonstration of E3 activity requires in vitro and in vivo ubiquitination assays. In vitro systems combine purified E1, E2, E3, ubiquitin, ATP, and substrate to reconstitute the ubiquitination cascade, followed by immunoblotting to detect ubiquitinated substrates [21]. For cellular assays, cells are co-transfected with E3, substrate, and epitope-tagged ubiquitin constructs, followed by immunoprecipitation of the substrate and detection of ubiquitin conjugation [21].

Functional Characterization in Cellular Models

Gene Knockdown and Knockout Approaches: RNA interference (shRNA/siRNA) and CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing techniques are employed to deplete E3 ligases in cancer cells, followed by assessment of phenotypic changes including proliferation, apoptosis, cell cycle progression, migration, and invasion [10] [29]. Rescue experiments with wild-type or mutant E3 constructs establish specificity.

Substrate Stability Assays: To determine if an E3 regulates substrate degradation, cycloheximide chase experiments are performed wherein protein synthesis is inhibited, and substrate stability is monitored over time in control versus E3-depleted cells [29]. Alternatively, proteasome inhibitors (MG132, bortezomib) can be used to assess substrate accumulation when E3 activity is compromised [29].

Pathophysiological Validation

Clinical Correlation Studies: Analyzing E3 ligase expression in human cancer specimens using immunohistochemistry, RNA sequencing, or protein arrays, followed by correlation with clinicopathological parameters (stage, grade, survival) establishes clinical relevance [10] [31].

Animal Models: Genetically engineered mouse models with tissue-specific E3 deletion or overexpression demonstrate causal roles in tumor initiation and progression [21] [30]. Xenograft models using cancer cells with modulated E3 expression assess effects on tumor growth and metastasis in vivo [29].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for E3 Ligase Studies

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Inhibitors | Nutlin-3 (MDM2-p53), MLN4924 (NEDD8 activation) | Pathway inhibition, mechanistic studies | Specificity, off-target effects, cytotoxicity [11] [30] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | Bortezomib, Carfilzomib, MG132 | Substrate stabilization, UPS function | Broad effects beyond specific E3s [11] [29] |

| Activity-Based Probes | Ubiquitin vinyl sulfones, HA-Ub-VS | E3 activity profiling, mechanistic studies | Limited availability for specific E3s [6] |

| Expression Constructs | Wild-type vs. catalytic mutants, tagged variants (HA, FLAG, Myc) | Functional studies, localization, interaction mapping | Tag placement may affect function [21] |

| CRISPR Libraries | Whole-genome, E3-focused custom libraries | High-throughput functional screening | Validation required for hit confirmation [29] |

| Clinical Compounds | Immunomodulatory drugs (Lenalidomide, Pomalidomide) | CRL4CRBN manipulation, targeted degradation | Context-dependent substrate degradation [29] |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Perspectives

The pivotal role of E3 ubiquitin ligases in cancer pathogenesis, coupled with their substrate specificity, makes them attractive therapeutic targets. Several strategies have emerged for targeting the UPS in cancer therapy:

Proteasome Inhibitors: Drugs such as bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib inhibit the proteasome broadly, resulting accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins and cell death [11] [29]. These agents have demonstrated significant efficacy in multiple myeloma and other hematological malignancies [29].

E3-Targeted Small Molecules: Specific inhibitors of E3 ligases, particularly MDM2 antagonists (nutlins, RG7112), disrupt MDM2-p53 interaction and stabilize p53 in cancers with wild-type TP53 [30]. Several MDM2 inhibitors have entered clinical trials with promising results in specific cancer types [30].

PROTAC Technology: Proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) are bifunctional molecules that simultaneously bind an E3 ligase and a target protein of interest, facilitating target ubiquitination and degradation [6]. This innovative approach harnesses endogenous E3 machinery for targeted protein degradation, expanding the druggable proteome [6].

Context-Dependent Therapeutic Considerations: The dual nature of E3 ligases necessitates careful patient stratification for E3-targeted therapies. Factors such as E3 expression levels, substrate mutation status (e.g., TP53 status for MDM2 inhibitors), and tissue specificity must be considered for optimal therapeutic efficacy [30].

Future research directions should focus on:

- Comprehensive mapping of E3-substrate networks in different cancer types

- Elucidation of mechanisms underlying context-dependent E3 functions

- Development of more specific E3 modulators with reduced off-target effects

- Exploration of combination therapies targeting multiple E3 ligases or parallel pathways

- Advanced delivery systems for tissue-specific targeting of E3 therapies

E3 ubiquitin ligases represent critical regulatory nodes in cellular homeostasis whose dysregulation contributes significantly to tumorigenesis. Their ability to function as either oncogenes or tumor suppressors—depending on cellular context, substrate profile, and genetic background—highlights the complexity of their roles in cancer biology. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying this functional duality provides valuable insights for developing targeted cancer therapies. The continued elucidation of E3 ligase functions in specific cancer contexts, coupled with advances in therapeutic modalities such as PROTACs, promises to yield more effective and precise strategies for cancer treatment in the coming years.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) stands as a critical regulatory mechanism for maintaining cellular homeostasis, with E3 ubiquitin ligases serving as the pivotal determinants of substrate specificity within this pathway. These enzymes orchestrate the final step in the ubiquitination cascade, recognizing specific target proteins and facilitating their modification with ubiquitin molecules, which ultimately dictates protein fate—including degradation by the 26S proteasome, altered cellular localization, or modified activity [21]. The human genome encodes more than 600 E3 ubiquitin ligases, which are classified into several families based on their structural domains and mechanisms of ubiquitin transfer, with RING (Really Interesting New Gene), HECT (Homologous to the E6-AP C-Terminus), and RBR (RING-Between-RING) representing the major classes [21] [34]. Through their capacity to regulate the stability of oncoproteins and tumor suppressors, E3 ligases occupy a central position in the molecular circuitry governing tumorigenesis, functioning as both drivers and suppressors of cancer depending on their specific substrate profiles and cellular contexts [21] [35].

The role of ubiquitin ligases in cancer pathogenesis represents a rapidly advancing frontier in molecular oncology, with accumulating evidence demonstrating that dysregulated E3 activity contributes fundamentally to the acquisition of hallmark cancer capabilities. By controlling the degradation of critical regulatory proteins, E3 ligases modulate diverse cancer-relevant processes including cell cycle progression, proliferative signaling, apoptosis, DNA repair, and metabolic adaptation [21] [36]. Perturbations of E3 ligase function through genetic alterations, epigenetic changes, or post-translational modifications can therefore disrupt precise protein homeostasis, leading to the stabilization of oncoproteins or accelerated destruction of tumor suppressors [21]. This whitepaper comprehensively examines the mechanistic basis by which E3 ubiquitin ligases influence tumorigenesis through their roles in degrading oncoproteins, modulating signaling pathways, and regulating apoptotic processes, while also exploring the translational implications of these mechanisms for cancer therapeutics.

Ubiquitin Ligase Families and Their Functional Mechanisms

Classification and Structural Features

E3 ubiquitin ligases employ distinct catalytic mechanisms based on their structural organization. RING-type E3 ligases, the largest family with over 500 members, function as scaffolds that simultaneously bind both the E2-ubiquitin conjugate and the substrate protein, facilitating the direct transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to the substrate without forming a covalent intermediate [34] [37]. In contrast, HECT-type E3s form a transient thioester bond with ubiquitin before transferring it to the substrate, while RBR-type E3s utilize a hybrid mechanism that incorporates aspects of both RING and HECT mechanisms [34]. The modular cullin-RING ligases (CRLs) represent a particularly important subclass of multi-subunit RING E3s, with eight cullin proteins (CUL1-9) serving as scaffolds that bring together substrate receptor modules and RING-bound E2 enzymes [21]. CRL complexes demonstrate remarkable versatility, with variable substrate receptor subunits (such as F-box proteins in SCF complexes or VHL/BC-box proteins in CRL2 complexes) providing specificity toward distinct sets of cellular targets [21].

Table 1: Major Classes of E3 Ubiquitin Ligases and Their Characteristics

| E3 Class | Catalytic Mechanism | Representative Members | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| RING | Direct transfer from E2 to substrate | Mdm2, c-CBL, SCF complexes | RING finger domain, acts as scaffold |

| HECT | Forms thioester intermediate | NEDD4, ITCH, SMURFs | HECT domain with conserved cysteine |

| RBR | Hybrid RING-HECT mechanism | PARKIN, HOIP | Two RING domains separated by IBR |

| Multi-subunit CRLs | RING-based with modular receptors | CRL1 (SCF), CRL2, CRL3 | Cullin scaffold, substrate receptor, RING protein |

Ubiquitin Chain Topologies and Functional Outcomes

The functional consequences of ubiquitination depend critically on the topology of the ubiquitin modification. K48-linked polyubiquitin chains typically target substrates for proteasomal degradation, while K63-linked chains generally serve non-proteolytic functions in signaling transduction, DNA repair, and trafficking events [38] [36]. Other linkage types, including K11, K27, K29, and linear (M1) chains, mediate diverse cellular processes such as cell cycle regulation, immune signaling, and mitophagy [36]. The specificity of these linkages is determined by the coordinated actions of E2 enzymes and E3 ligases, with particular E3s exhibiting preferences for generating specific chain topologies. For instance, CUL3 has been shown to promote both K48- and K63-linked polyubiquitination of caspase-8 in response to TRAIL stimulation, with the different linkages mediating distinct aspects of caspase regulation [38].

Diagram 1: Ubiquitination Cascade and E3 Ligase Mechanisms. This diagram illustrates the sequential enzymatic cascade of ubiquitination and the distinct catalytic mechanisms employed by major E3 ligase families.

Degradation of Oncoproteins by E3 Ligases

Regulation of Classical Oncoproteins

Tumor suppressor E3 ligases play a crucial role in constraining oncogenic potential by targeting proto-oncoproteins for destruction, thereby maintaining controlled proliferative signaling. Among the best-characterized examples is Fbw7 (F-box and WD repeat domain-containing 7), the substrate recognition component of an SCF (SKP1-CUL1-F-box protein) ubiquitin ligase complex. Fbw7 recognizes multiple critically important oncoproteins including Cyclin E, c-Myc, c-Jun, c-Myb, and Notch, typically following their phosphorylation at specific degron motifs [35]. The fundamental importance of Fbw7-mediated degradation is evidenced by the frequent deletion or mutation of the FBXW7 gene across diverse human cancers, which leads to stabilization of its oncogenic substrates and consequent malignant transformation [35]. Similarly, the E3 ligase TRIM22 has recently been identified as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer that targets the oncogenic copper chaperone CCS (copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase) for K27-linked ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, thereby inhibiting proliferation and invasion through modulation of STAT3 signaling [39].

The degradation of oncogenic GTPases represents another critical tumor-suppressive mechanism mediated by E3 ligases. The CRL3 complex containing the substrate receptor LZTR1 mediates the ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of RIT1, a small GTPase and proto-oncoprotein [21]. Pathogenic mutations in LZTR1 that impair its interaction with RIT1 lead to RIT1 accumulation and subsequent dysregulation of growth factor signaling, contributing to the development of Noonan syndrome and potentially to tumorigenesis [21]. This mechanism highlights how E3 ligases can function as molecular safeguards against the uncontrolled activity of potent signaling molecules.

Table 2: Tumor Suppressor E3 Ligases and Their Oncoprotein Substrates

| E3 Ligase | Oncoprotein Substrate | Biological Consequence of Degradation | Cancer Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fbw7 | Cyclin E, c-Myc, c-Jun, Notch | Cell cycle control, proliferation restriction | Frequently mutated in cancers |

| TRIM22 | CCS | Inhibition of STAT3 signaling | Breast cancer tumor suppressor |

| LZTR1 | RIT1 | Regulation of growth factor signaling | Noonan syndrome, tumorigenesis |

| c-CBL | RTKs (EGFR, PDGFR, c-Kit) | Attenuation of proliferative signaling | Mutated in myeloid neoplasms |

| β-TrCP | β-catenin, EMI1 | Regulation of Wnt signaling, cell cycle | Deregulated in various cancers |

Methodologies for Studying Oncoprotein Degradation

The experimental characterization of E3 ligase-mediated oncoprotein degradation typically employs a multifaceted approach combining molecular, cellular, and biochemical techniques. Standard methodologies include co-immunoprecipitation assays to demonstrate physical interaction between the E3 and its putative substrate, followed by in vitro ubiquitination assays using purified components to establish direct E3 activity [39]. To monitor protein turnover in living cells, researchers commonly employ cycloheximide chase experiments, where new protein synthesis is blocked and the decay rate of the protein of interest is measured by immunoblotting over time [39]. For instance, in the recent study identifying TRIM22 as an E3 for CCS, the investigators demonstrated that TRIM22 overexpression accelerated CCS degradation, while TRIM22 knockdown stabilized CCS protein, with proteasome inhibition (using MG132) but not lysosomal inhibition preventing this effect, confirming proteasomal dependency [39]. Additional validation often involves mutational analysis of both the E3 ligase (e.g., in catalytic domains or substrate-binding interfaces) and the substrate (at putative ubiquitination sites) to establish the molecular determinants of the degradation mechanism.

Modulation of Signaling Pathways in Cancer

Receptor Tyrosine Kinase and Downstream Signaling

E3 ubiquitin ligases serve as critical modulators of oncogenic signaling pathways at multiple levels, from cell surface receptors to intracellular signal transducers. The Casitas B-lineage lymphoma (CBL) family of E3s provides a paradigm for ligand-induced downregulation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) such as EGFR, PDGFR, c-Kit, and Met [21]. Following receptor activation and phosphorylation, c-CBL recognizes and ubiquitinates these RTKs, promoting their internalization through endocytosis and subsequent lysosomal degradation—a fundamental desensitization mechanism that prevents sustained proliferative signaling [21]. Cancer-associated mutations in CBL or RTKs that disrupt this regulatory interaction result in RTK hyperactivation and contribute to oncogenesis, with CBL mutations occurring in approximately 5% of myeloid neoplasms [21]. Beyond receptor regulation, E3 ligases also control downstream signaling components, as exemplified by the CRL3^LZTR1-mediated degradation of RAS family GTPases, which constrains MAPK pathway activation [21].

Stem Cell and Developmental Signaling Pathways

Emerging evidence indicates that E3 ligases play pivotal roles in regulating signaling pathways that control cancer stem cell (CSC) maintenance and function, including Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, Hedgehog, TGF-β, and JAK-STAT pathways [34]. The self-renewal capacity and therapeutic resistance of CSCs are supported by core transcription factors such as Oct-3/4, Sox2, and Nanog, whose stability is modulated by ubiquitination [34]. The ubiquitin-proteasome system thereby contributes to the dynamic control of stemness properties in malignant cells, offering potential therapeutic opportunities for targeting this therapeutically challenging subpopulation. Additionally, E3 ligases regulate developmental pathways frequently co-opted in cancer; for example, SCF^Fbw7-mediated degradation of Notch intracellular domain (NICD) provides an essential constraint on Notch signaling, with FBXW7 mutations leading to excessive pathway activation in various malignancies [35].

Diagram 2: E3 Ligase Regulation of Oncogenic Signaling Pathways. This diagram illustrates how different E3 ligases target multiple components of signaling pathways that drive oncogenesis.

Regulation of Apoptosis and Cell Death

Control of Extrinsic Apoptotic Pathways

E3 ubiquitin ligases exert sophisticated control over apoptotic processes, thereby influencing cellular sensitivity to programmed cell death. In the extrinsic apoptotic pathway initiated by TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), multiple E3s regulate key components including death receptors (DR4/DR5) and caspase-8 [38]. The E3 ligase c-CBL directly binds to DR4/DR5, inducing their mono-ubiquitination and lysosomal degradation, which can confer early-phase TRAIL resistance [38]. Conversely, knockdown of c-CBL enhances sensitivity to TRAIL-induced apoptosis through increased death receptor expression [38]. Similarly, MARCH-8 promotes polyubiquitination of DR4 (but not DR5) on lysine 273, leading to lysosomal degradation and reduced TRAIL sensitivity [38]. At the level of caspase activation, CUL3 facilitates both K48- and K63-linked polyubiquitination of caspase-8 following TRAIL stimulation, with K63-linked chains promoting caspase-8 activation through formation of ubiquitin-rich foci, while TRAF2 mediates K48-linked ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of activated caspase-8, thereby terminating apoptotic signaling [38].

Regulation of Intrinsic Apoptosis and IAP Family

The inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) family of E3 ligases, including cIAP1, cIAP2, and XIAP, plays a central role in suppressing both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways. These proteins are characterized by the presence of baculovirus IAP repeat (BIR) domains that mediate protein-protein interactions, along with RING domains that confer E3 ligase activity [40] [36]. cIAP1 and cIAP2 are recruited to TNFR1 complexes through TRADD/TRAF2, where they ubiquitinate RIPK1 and other components, modulating the decision between pro-survival NF-κB signaling and cell death initiation [40]. In rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes (RA-FLS), which exhibit tumor-like proliferation and apoptosis resistance, BIRC3 (encoding cIAP2) is highly expressed and promotes aberrant survival and inflammatory responses [40]. Beyond apoptosis regulation, E3 ligases also control other forms of programmed cell death such as ferroptosis, with ubiquitination of proteins including Bcl-2, ACSL4, and p62 influencing cancer cell survival decisions [36].

Table 3: E3 Ligases Regulating Apoptotic Pathways in Cancer

| E3 Ligase | Apoptotic Component Regulated | Mechanism of Action | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| c-CBL | Death Receptors (DR4/DR5) | Mono-ubiquitination, lysosomal degradation | TRAIL resistance |

| MARCH-8 | DR4 | Polyubiquitination on K273, lysosomal degradation | Reduced TRAIL sensitivity |

| CUL3 | Caspase-8 | K48/K63-linked ubiquitination | Activation and foci formation |

| TRAF2 | Caspase-8 | K48-linked ubiquitination | Proteasomal degradation, apoptosis termination |

| cIAP1/2 | RIPK1, Caspases | Ubiquitination in TNFR complex | Survival/Death decision |

| HECTD3 | Caspase-8 | K63-linked ubiquitination | Apoptosis enhancement |

Experimental Approaches and Research Toolkit

Core Methodologies for E3 Ligase Research